January 2023

Warning: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers should be aware that this posting contains images and names of people who may have since passed away.

W Lister Lister (27 Dec 1859 – 06 Nov 1943)

The golden splendour of the bush

c. 1906

Oil on canvas

Frame: 294 x 245.0 x 13.5cm

Art Gallery of New South Wales

Used under fair use condition for the purpose for research or study

Abstract

Discovered in an op shop (charity shop in America), this is the most historically important and exciting Australian photo album that I have ever found.

Belonging to John “Jack” Riverston Faviell, a senior New South Wales public accountant and featuring his photographs, the album ranges across the spectrum of Australian life and culture from the East to the West of the continent in the years 1922-1933. A list of locations and topics can be seen below. I have added additional research text, posters and photographs to help illuminate some of the issues under consideration.

Given its importance in documenting through photographs regional NSW, Indigenous Australians and the opening of the Sydney Harbour Bridge, the album is now in the State Library of New South Wales collection.

Keywords

Australian culture, Australian identity, Australian colonialism, Indigenous Australians, photography, photo album, Australian photography, Australian vernacular photography, racism, Australian racism, racism in Australia, White Australia, Sydney Harbour Bridge, Trans-Australian Railway, State Library of New South Wales, New South Wales, Australia, rural New South Wales, country races, Kalgoorlie Boulder, pearling, gold mining, Year of Mourning, Invasion Day, National Day of mourning, First Nations of Australia, reconciliation, pastoralism

Golden splendour: privilege, ceremony and racism in 1920s-1930s Australia

This text investigates the photographs found in an important Australian album discovered in an op shop (charity shop in America) belonging to John “Jack” Riverston Faviell (see part one of the posting), a senior New South Wales public accountant who associated with important pastoralists and bankers of the time, invested in business, travelled across the continent, went to many functions, married Sydney socialite Melanie Audrey Pickburn in February 1925 (divorced October 1930) and built a house on prestigious Darling Point overlooking Sydney Harbour.

The album features Faviell’s photographs and was probably compiled by him, the photographs ranging across the spectrum of Australian life and culture from the East to the West of the continent in the years 1922-1933. A list of locations and topics can be seen below. The album has been assembled in near chronological order although some later dates precede earlier ones (for example, “Frensham Pastoral Play” of 8th December 1923 precedes “La Perouse” 7 November 1923; “Trip to Canberra” 5/6 Nov 1927 precedes “Jenolan Caves Trip” 10/12th July, 1927; and some images from 1927 sit side by side with photographs from October and November 1932). There are no dates for Faviell’s trip to Western Australia (presumably in early 1924) and the dating starts again with a polo competition for “The Dudley Cup” in 1924 after this trip.

Taken in Scotland and sent by a man named Robert Reid from that country there is only one overseas photograph in the album. The photograph, which was presumably taken on Faviell’s honeymoon, is titled “Ellen’s Isle, Loch Katrine, Scotland (Audrey & me in boat) 1925”, and is inserted unceremoniously into photographs dating from 1927. There is no other reference to his marriage or photographs of it or his honeymoon in the album. The handwriting and grid-like layout of the photographs are consistent from front to back, and the photographs are mostly of the same size and shape (meaning he used the same camera throughout the period), other than photographs that Faviell did not take (including the “honeymoon” photograph from Scotland and the photographs of Jenolan Caves taken by Lady Dorothy Hope-Morley).

Thinking of the order that the photographs have been inserted into the album means to my mind that it was consciously assembled by Faviell probably after the date of the last photograph in the album which is November 1933 – although it is possible that he assembled it as he went along, inserting the “honeymoon” photograph from 1925 into the 1927 pages, and some earlier 1927 photographs next to the ones from 1932. But it just doesn’t feel like the latter to me… everything is too ordered to be done as he went along.

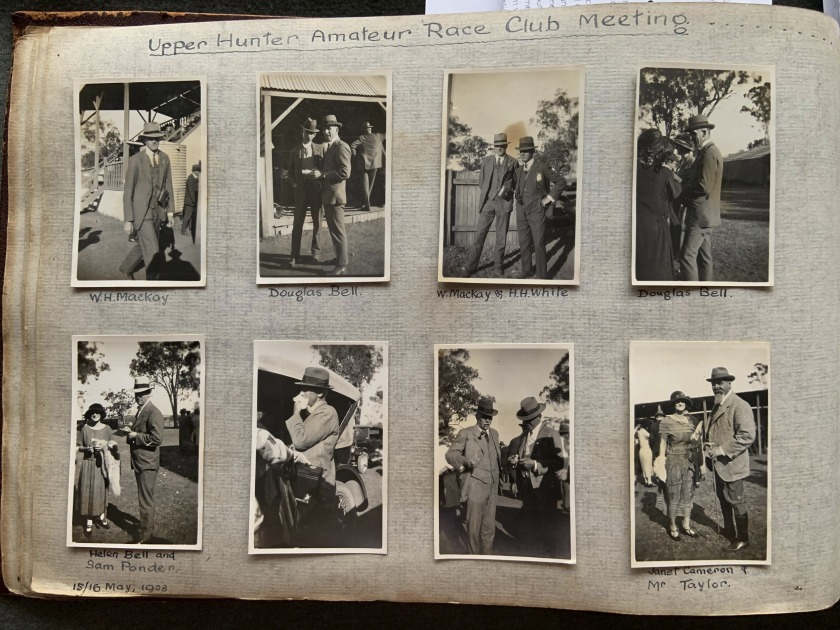

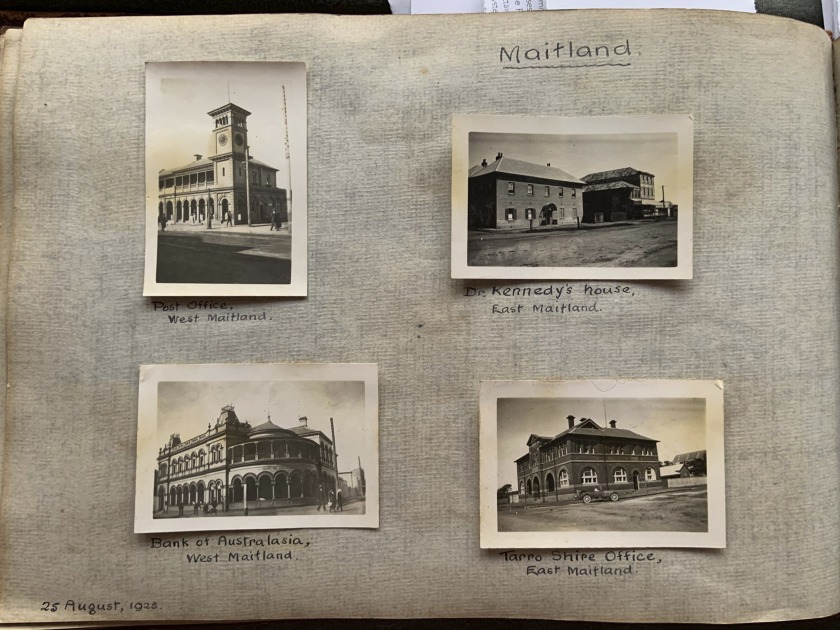

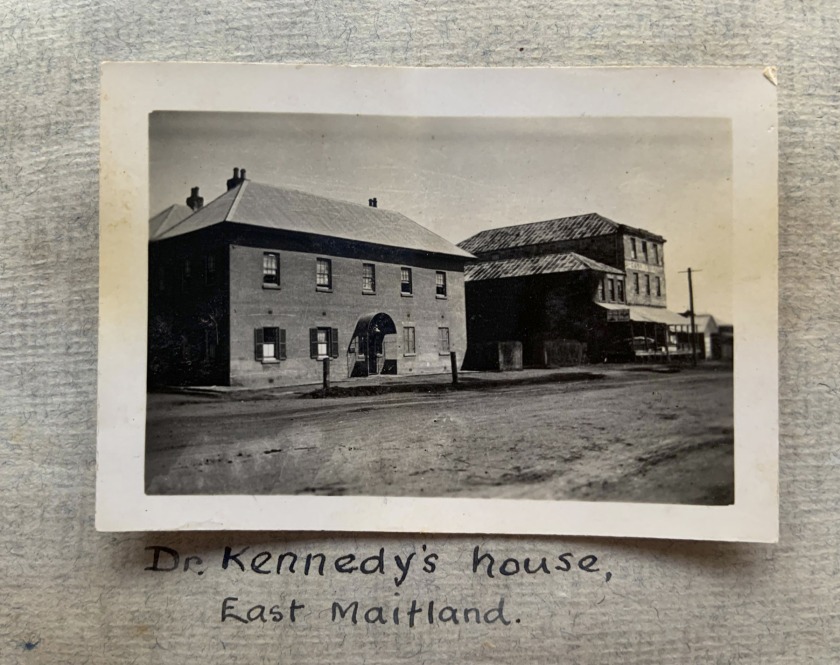

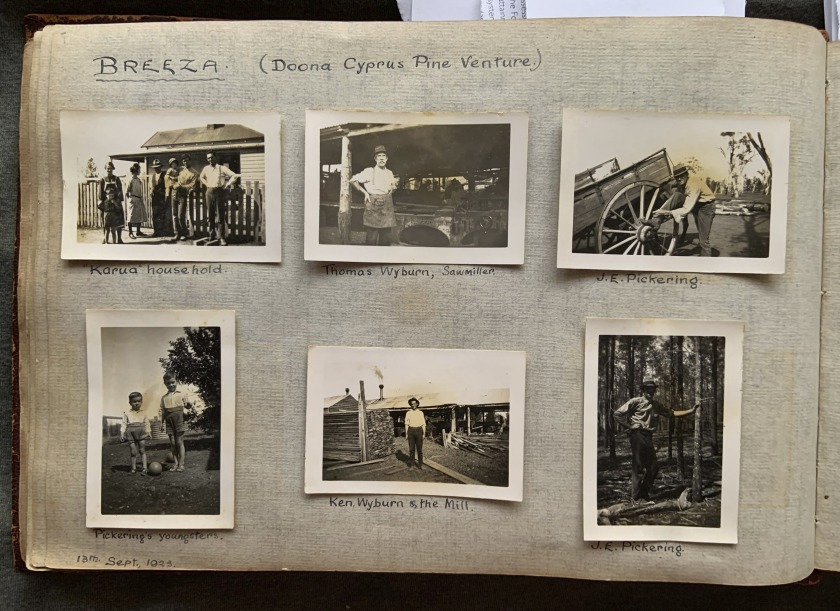

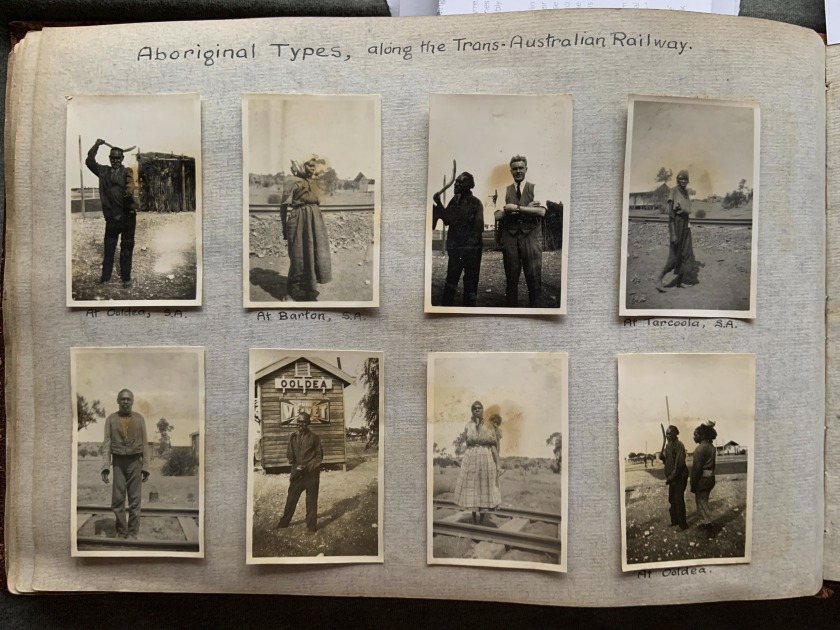

One important element of the album are John Faviell’s photographs which document his life in rural New South Wales as he attends various country race meetings, schools, historic houses, pastoral farms, regatta, and business ventures in the state during the 1920s. A second important element is the documentation of “Aboriginal Types” along the Trans-Australian Railway, gold mining in Kalgoorlie-Boulder, and pearling and Aboriginals in Shark Bay, the latter two in Western Australia. Finally, important unpublished photographs of the opening of the Sydney Harbour Bridge in 1932 give insight into the pageantry and colonialism of white Australia.

Privilege

A feeling of privilege – defined as a special right, advantage, or immunity granted or available only to a particular person or group – pervades the photographs in the album. Faviell belonged to a particular social category which had an inherently privileged and advantageous position.

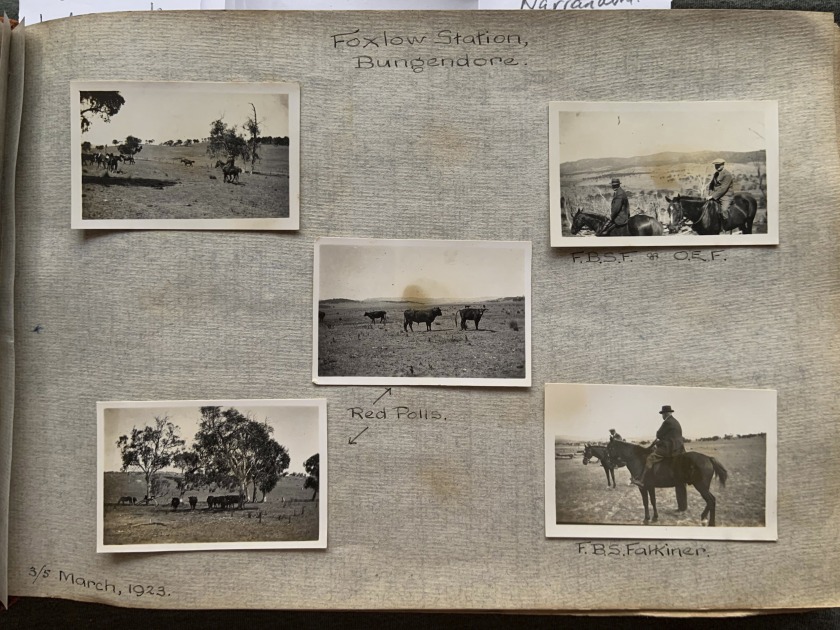

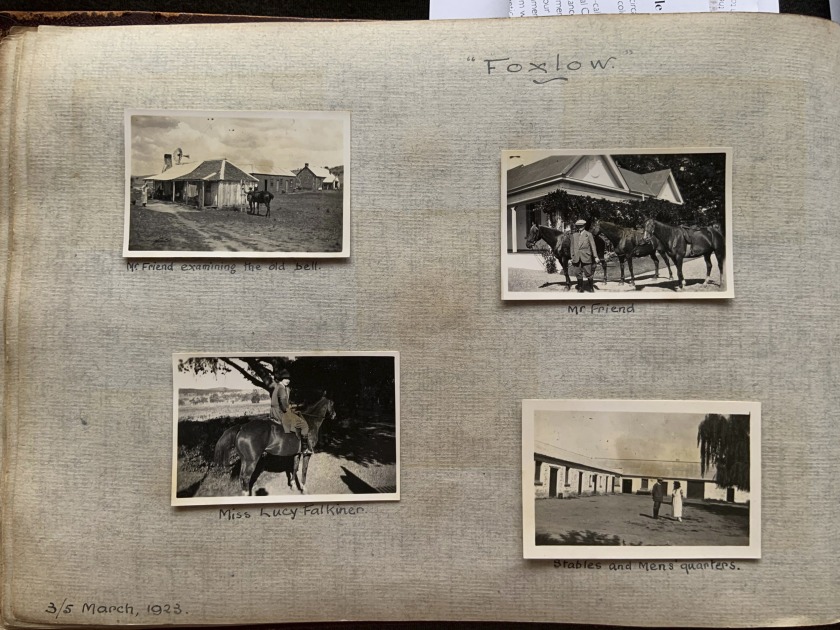

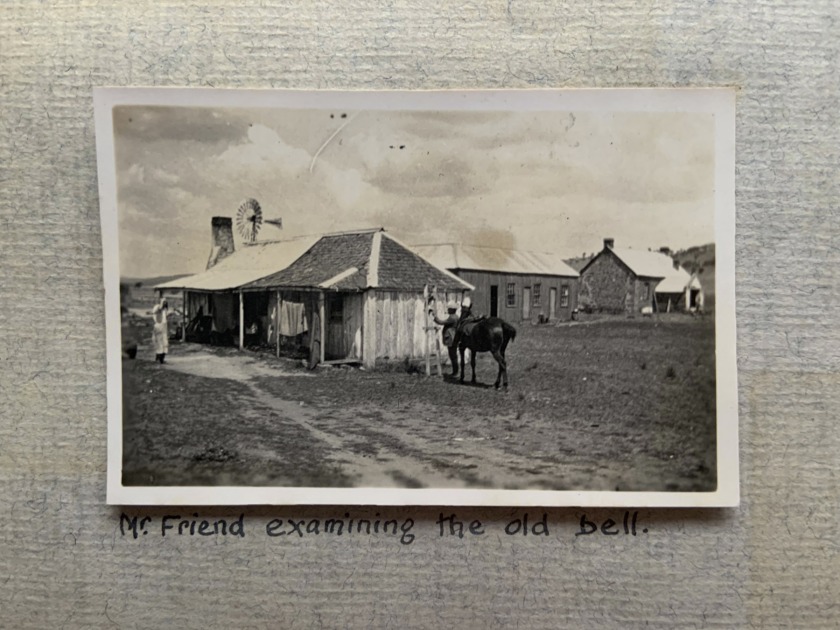

This is evidenced by his friendship with wealthy New South Wales graziers such as O.E. Friend (d. 1942) who was President of the Royal Historical Society and Director of the Commercial Banking Co., and who had a keen interest in pastoral pursuits and business investments; by photographs of large houses and pastoral stations such as “Weroona”, Belmont (demolished 1979), “Doona”, Breeza and “Foxlow”, Bungendore near Canberra which consisted of 7,500 hectares of land; by photographs of country horse races, friends who owned race horses and polo matches; by photographs of new cars; by photographs of his own investment projects such as the Doona Cyprus Pine Venture; by photographs of his travel to Western Australia and five-day cruise on the Cutter “Shark”; by photographs of “Old Boys” from Camden Grammar School, a term redolent of the English public school system; by building a house on one of the most exclusive promontories overlooking Sydney Harbour; by getting married in one of the “biggest social events of the month in Sydney”; and so it goes… the (British) class system alive and well in 1920s Australia, still an extension of the Empire.

What we should remember is that, after the end of the First World War the “1920s saw a higher level of material prosperity for non-Indigenous people than ever before.” Despite the rising affluence of the 1920s the Australian unemployment rate floated between 6% and 11% throughout the decade. Then, in October 1929, the world experienced a stock market crash on Wall Street in New York that plunged the world into the Great Depression (1929-1934). By 1932, one third of all Australians were out of work.

“Australia suffered badly during the period of the Great Depression of the 1930s… As in other nations, Australia suffered years of high unemployment, poverty, low profits, deflation, plunging incomes, and lost opportunities for economic growth and personal advancement. Unemployment reached a record high of around 30% in 1932, and gross domestic product declined by 10% between 1929 and 1931… Many hundreds of thousands of Australians suddenly faced the humiliation of poverty and unemployment. This was still the era of traditional social family structure, where the man was expected to be the sole bread winner. Soup kitchens and charity groups made brave attempts to feed the many starving and destitute. The male suicide rate spiked in 1930 and it became clear that Australia had limits to the resources for dealing with the crisis. The depression’s sudden and widespread unemployment hit the soldiers who had just returned from war the hardest as they were in their mid-thirties and still suffering the trauma of their wartime experiences. At night many slept covered in newspapers at Sydney’s Domain or at Salvation Army refugees.”1

Due to his wealth, his privileged family life and position in society, Faviell obviously felt none of the effects of the Great Depression. Although there are no photographs in the album taken between 1928 and 1931, by November 1932 he was buying a new Chrysler 70 motorcar. You can’t do that without money.

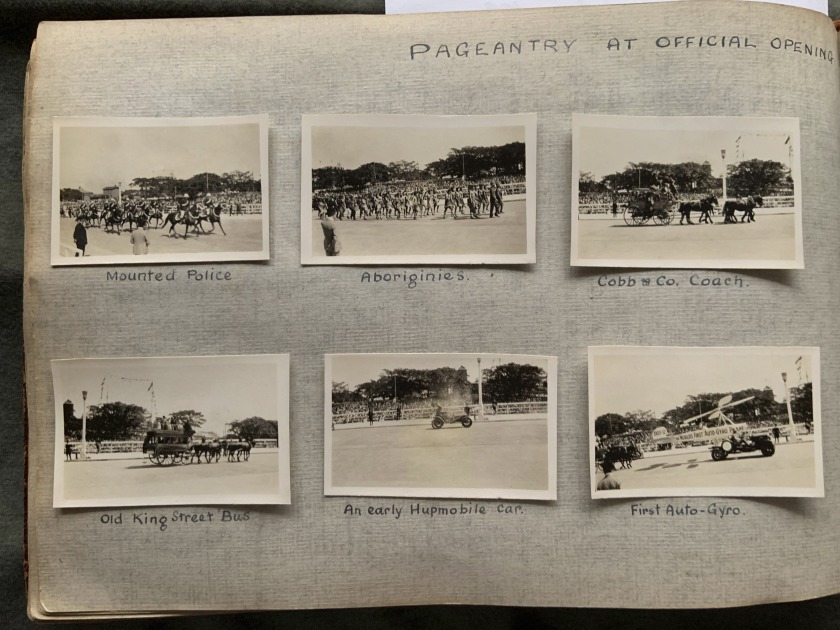

Ceremony

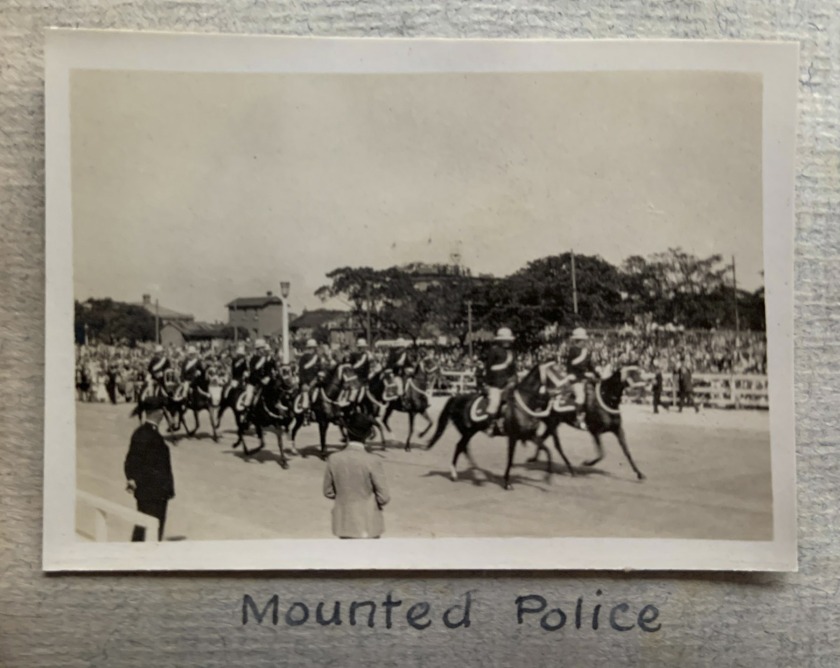

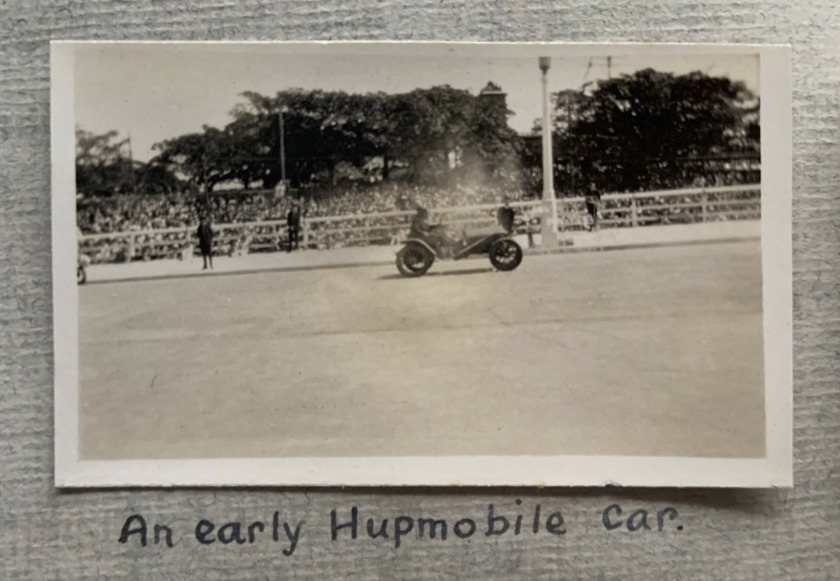

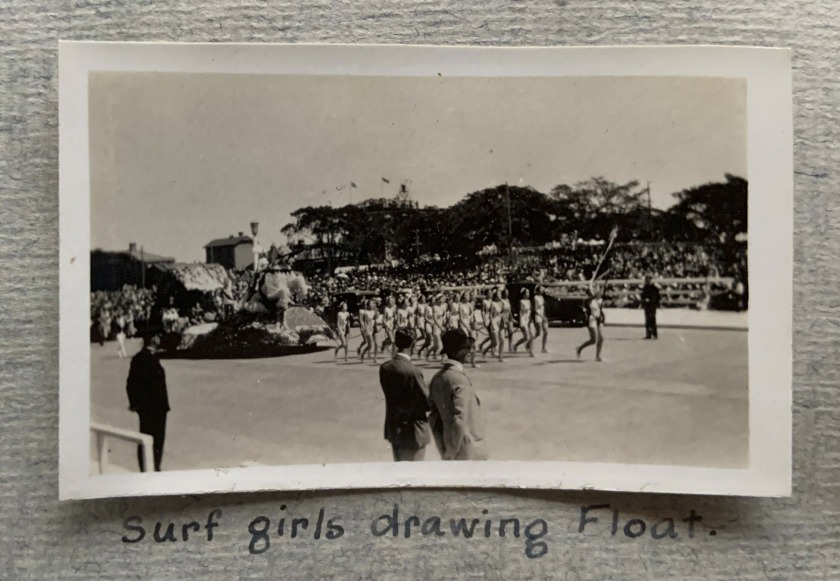

Faviell attended the opening of the Sydney Harbour Bridge on the 20th March 1932 sitting in the official stands, taking what are up until now previously unknown photographs of the Federal and State Governors arriving and the pageantry of the official opening (see photographs below). The ceremony featured a passing parade of groups, floats and attractions including Naval Guard, Mounted Police, Cobb & Co. Coach, Old King Street Bus, an early Hupmobile car, the first Auto-Gyro, Wool Float, surf girls, Pioneers Float and Aborigines. Also present in the parade at the Bridge’s opening ceremony was a contingent from the Aboriginal community of La Perouse on Sydney’s Botany Bay. According to the series Australia in Colour, “The first Australians are a token inclusion in the celebrations. They are not classed as citizens in their own country and have no voting or legal rights…”2 State and federal governments still saw Indigenous Australians as, “the native problem.” “For most city people, the only contact with Indigenous groups was watching tent boxing at the travelling shows which used to flourish in the ’30s.”3 But things were beginning to change. Indigenous Australians were slowly being politicised in order to get their message across, with pleas for better rights, conditions and representation.

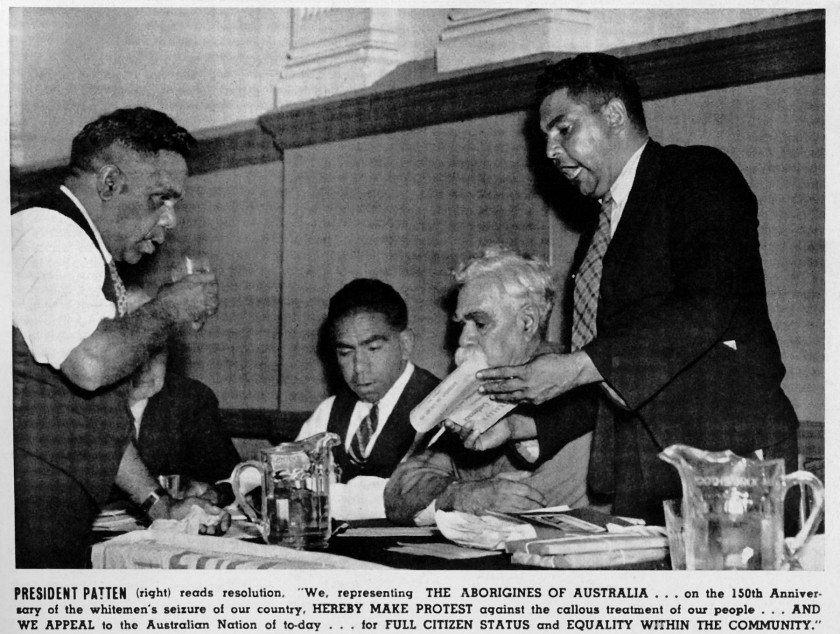

Five years later, on the occasion of the 150th anniversary of European settlement in Australia in 1938 there was a re-enactment of Governor Phillip’s landing in which Aborigines (specially brought in for the occasion) are shown running up the beach as the boats of the First Fleet marines land at Farm Cove (see photograph below). A group of white dignitaries sits in comfortable safety watching the invasion. Elsewhere on that day in 1938 – Wednesday, 26th January – there took place the first Day of Mourning and Protest at the Australian Hall, Sydney. The protest, calling for full citizen status and equality, was led by William Cooper, Pearl Gibbs, Jack Patten and William Ferguson (see photographs and poster below). Cooper and his fellow Aboriginal men Jack Patten and William Ferguson organised a conference to grieve the collective loss of freedom and self-determination of Aboriginal communities as well as those killed during and after European settlement in 1788. “The first Day of Mourning was a culmination of years of work by the Australian Aborigines League (AAL) and the Aborigines Progressive Association (APA). It would became the inspiration for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander activism throughout the remainder of the twentieth century.”4

“In 1938, William Cooper had thrown down a challenge. It was 150 years since the landing of the ragtag British ‘first fleet’ in Sydney Cove on 26 January in 1788. As white Australians were preparing to celebrate, Cooper had branded that landing as the beginning of 150 years of invasion, dispossession and exploitation. Cooper dared white Australia to recognise that their ‘Australia Day’ was no celebration but instead a ‘Day of Mourning’ for invaded Australia. …

A forced reenactment. For the 150th Anniversary, Aboriginal people were forced to participate in a reenactment of the landing of the First Fleet under Captain Arthur Phillip. Aboriginal people living in Sydney had refused to take part so organisers brought in men from Menindee, in western NSW, and kept them locked up at the Redfern Police Barracks stables until the re-enactment took place. On the day itself, they were made to run up the beach away from the British – an inaccurate version of events. It was Cook who was first “threatened and warned off by the Indigenous people on the shore” and he then decided to fire gun shots.”5

Anita Heiss observes of that day in 1938, “The day also saw an appalling contrast. Aboriginal organisations in Sydney refused to participate in the government’s re-enactment of the events of January 1788. In response, the government transported groups of Aboriginal people from western communities in NSW to Sydney to partake in the re-enactments. The visitors were locked up at the Redfern Police Barracks stables and members of the Aborigines Progressive Association were denied access to them. After the re-enactment of the First Fleet landing at Farm Cove (Wuganmagulya), the visiting group of Aboriginal people were featured on a float parading along Macquarie Street.”6

Finally, by 1988, the re-enactments were discontinued. 50 years later to the day, on the occasion of the Australian Bicentenary in 1988 (the same year named a Year of Mourning by and for the Australian Aboriginal people), the protests against British invasion were even more prominent and vigorous, as Aboriginal people and their supporters rallied in Sydney and around the country. “On 26 January that year, up to 40,000 Aboriginal people (including some from as far away as Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory) and their supporters marched from Redfern Park to a public rally at Hyde Park and then on to Sydney Harbour to mark the 200th anniversary of invasion.”7

“On 26 January 1988, more than 40,000 people, including Aborigines from across the country and non-Indigenous supporters, staged what was the largest march in Sydney since the Vietnam moratorium. …

The march was seen as a challenge to the dominant society’s hegemonic construction of Australia day and what it represented. It was a statement of survival, demonstrating that although Australian history had excluded the indigenous voice, Aborigines as the original inhabitants of this place were not going to continue to be beggars in their own country. The march served to draw both national and international attention to Australia’s appalling human rights record. It aimed to educate the public about the poor conditions of Aboriginal health, education and welfare, of the high imprisonment rates and the number of deaths in custody suffered by Indigenous Australians. Activists such as Gary Foley called on Australians to join the Aboriginal protests and to make the point to the rest of Australia that the whole concept of the Bicentennial is based on hypocrisy and lies. …

There had been little emphasis on the need to address indigenous aspirations as a precondition to celebrating the bicentenary. The protest march was both an affirmation of indigenous Australians’ survival and a stark reminder of the falsity on which the celebration was premised. Celebrations focused on the discovery of Australia with a re-enactment of the arrival of the first fleet. However, the Aboriginal protest was a reminder that Australia had been inhabited at least 40,000 years before European arrival.”8

As the editorial in the Sydney Morning Herald newspaper on January 19, 1988 noted, “scarcely a day of the Bicentenary has passed when issues involving Aborigines and their “Year of Mourning” protests have not featured prominently…” which “instigated public debate concerning white and indigenous Australian history, the position of Aborigines in contemporary society and the possibilities of land rights and reconciliation in the future.”9 But despite these protests many Australians, myself included – newly arrived from England and still homesick for the mother country, failing to grasp the enormity of the betrayal – did not understand the protests. “Despite Indigenous people declaring January 26 a National Day of mourning fifty years prior in 1938, many of the non-Indigenous majority still failed to see any disrespect in celebrating an occasion made possible by the murder, massacre, dispossession, slavery and attempted genocide of the Indigenous people of this land.”10

While I could never understand, as an English man, Australia’s treatment of their First Peoples when I first arrived, at the time I had not educated myself or immersed myself in the history of Australia to gain its full import. Now I have. And so have other people.

Importantly, national events happened in the 1990s that led up to the Walk for Reconciliation across Sydney Harbour Bridge on 28 May, 2000 (see photograph below) in which about 250,000 people walked across the Sydney Harbour Bridge to show their support for reconciliation between Australia’s Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples: in 1991 the Australian Parliament passed an Act which created the Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation; in the 1992 Mabo decision the High Court of Australia ruled that Australia was not terra nullius (land belonging to nobody) when it was claimed by Britain in 1770. This led to the Native Title Act 1993, which made it possible for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to claim ownership of their traditional lands; and the Bringing Them Home report, published in 1997, showed that thousands of Aboriginal and Torres Strait children had been taken away from their families by governments around Australia. These children have become known as the Stolen Generations. The report said that all Australian governments should apologise to Indigenous people, especially the Stolen Generations.11 So many people participated in the walk that the event took nearly six hours. It was the largest political demonstration ever held in Australia. Finally, eight years after the walk Prime Minister Kevin Rudd made a national apology to Australia’s Indigenous people. “On 13 February 2008, the Parliament of Australia issued a formal apology to Indigenous Australians for forced removals of Australian Indigenous children (often referred to as the Stolen Generations) from their families by Australian federal and state government agencies.”12

Better late than never…

Racism

By the time John Faviell started taking photographs for his album a twentieth-century, Euro- and U.S.-centric middle class had been dazzled by the “Kodakification” of photography. Small portable cameras with roll film and a faster film speed enabled “amateur” photographers,13 people who “simply wanted pictures as mementos of their daily lives but were hardly interested in learning how to do the rest”14 – that is, developing, printing and toning their own photographs – to document their existence and then send the film away to be developed and printed. George Eastman’s slogan for Kodak, “You Press the Button, We Do the Rest,” revolutionised the photography business in the United States and in the world, allowing the great mass of the general public to take photographs and assemble family albums (for example). In these vernacular photographs – “those countless ordinary and utilitarian pictures made for souvenir postcards, government archives, police case files, pin-up posters, networking Web sites, and the pages of magazines, newspapers, or family albums”15 – the focus is on the social contexts in which the photos were originally made and how they document an aspect of social or photo history. These images, including those by John Faviell, ask us to consider “the ways in which photographs function as significant bearers of complex meaning, rather than mere descriptions or reflections of the world, whether they grace the walls of a museum, the pages of a magazine, the files in a cabinet, or a living room mantel.”16 Commenting on photo postcards but equally applicable to vernacular photographs, Leonard A. Lauder observes that, “The new flexibility and mobility of this medium created citizen photographers who captured life on the ground around them… [and] we learn from them both the grand historical narrative and the smaller events that made up the daily lives of those who participated in that history.”17

Even as the freedom to photograph anywhere, anytime led to the ability of humans with access to a camera and the money to develop and pay for film and prints to document their lives – an intimate portrait of a life in the making, constructed by people for themselves – it also, paradoxically, led to the Kodification, codification, of everyday life… into the haves and the have nots, into people who were portrayed existing at the upper echelons of society, to those that existed as policemen, factory workers, or working on construction sites (for example), or those that existed at the margins of society, the disenfranchised, abused and neglected “other”, subject to the gaze of the photographer and the mechanical observation of the camera.

Even as he welcomes his own ambition and sense of self worth there is a sense of conservatism and privilege in the depiction of his social position in Australian society. In his private photographic album, John Faviell places himself at the centre of the story, at the centre of history, as though he is constructing not only his own place in the history of Australia but the history of Australia itself. His photographs portray his life embedded within the “golden splendour” of the Australian landscape even as the photographs reinforce in private the cultural and photographic norms circulating in public in 1920s-1930s Australia,18 its heteropatriarchy, settler coloniality and the racism prevalent in early 20th century Australia. Through the many titled photographs Faviell projects the inherent racism towards Aboriginal people that was present at that time in white society, the notion of white superiority that was implicit in the White Australia Policy.19 In this regard he would not have seen himself as racist (I have no idea whether he was racist or not) for he was merely reflecting the social attitudes of the day, reflecting a collective racism that pervaded all aspects of white Australian society officially sanctioned through the White Australia Policy, an attitude which continues to haunt Australia’s past, present and future.

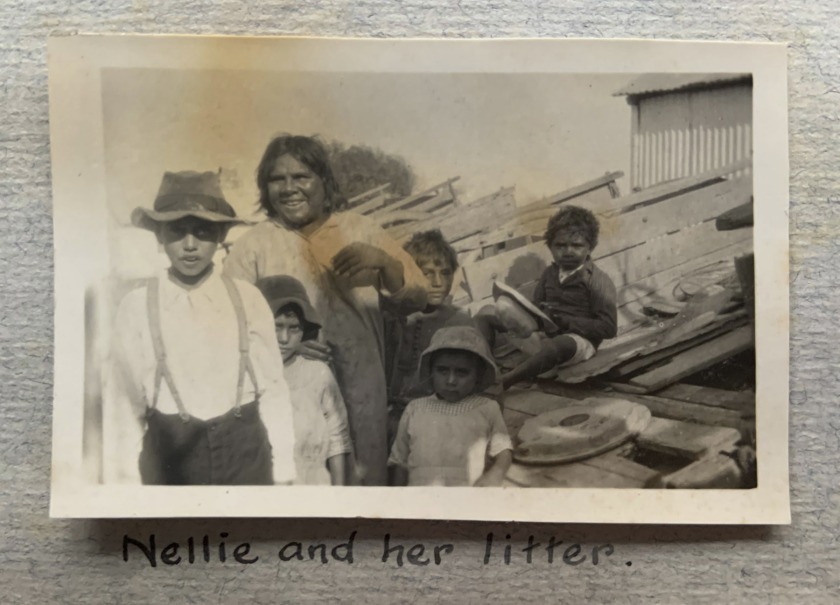

While now totally offensive Faviell would have thought nothing of captioning his photographs with titles such as Grave in Nigger’s Cemetery, Shark’s Bay, 1923; A Nor’ West Gin and Big Nig, Shark’s Bay, 1923; and Nellie and her litter, 1923, where after colonisation “gin” became a racist, derogatory term for an Aboriginal woman quickly used against female Aborigines to express a mix of lust and racial contempt, becoming a “dehumanising weapon essential to the violence of occupation,” which led to the systematic rape, abduction and murder of Aboriginal girls and women. He would have thought nothing of titling his photograph Nellie and her litter, the text loaded with casual racism which compares Indigenous Australians to dogs. But what is important to note here is how individuals make use of images in shaping their identities, and how Faviell’s images informed the construction of his own identity and the embodying of his own power.

Photographs tend to be indispensable in the construction of identity because of the phenomenal aspect of photography – its status as a spatio-temporal capture – where memory traces and their capture become a visible reality, and where contexts (point of view) and power can be replayed over and over again, made present in absence.20 Faviell’s album of photographs and the use of the art of memory (Latin: ars memoriae: a number of loosely associated mnemonic principles and techniques used to organise memory impressions) would have allowed him to organise his memory impressions and improve the recall of them. Faviell could have used a set of associative values given for images in memory texts (Nigger, gin) as a starting point to initiate a chain of recollection. “Techniques commonly employed in the art [of memory] include the association of emotionally striking memory images within visualized locations, the chaining or association of groups of images, the association of images with schematic graphics or notae (“signs, markings, figures” in Latin), and the association of text with images.”21

Here we must acknowledge that human beings, including Faviell, are not just actors in history, they are enablers. Enablers of racism whose slippery tentacles still enslave this country Australia down to its very roots – at the footy, on social media, in government, on the land – even today. As the artist Octora observes, “A photograph is not merely evidence of the past or a slice of a passing moment, it is performative and still performs to distort actual reality today.”22 But changing how photographs perform realities and memories is not easy, for there are other forces at play to which photographs only reinforce social prejudices: “There is a racism that lurks within the Australian consciousness and is fuelled by an uneasy conscience caused by our treatment of Aborigines in the past and out fear from the future.”23

What we must do is confront this fear and propose a narrative that moves beyond those reflected in our existing histories… for memory is not just a personal remembering (the product and property of individual minds) but a collective remembering, “concerned with remembering and forgetting as socially constituted activities… Individual memories cannot be understood as ‘internal mental processes’ which occur independently of the interpretive and communicative practices which characterise a particular society or culture. Individuals ‘read’, account for and negotiate their memories within the pragmatics of social life.”24 As would John Faviell have done.

We must remember that historical memories help form the social and political identities of groups of people and that in Australia there is a collective amnesia surrounding the White Australia policy, a social amnesia where there is a collective forgetting by a group, or nation, of people about the effects of a certain policy – because they are ignorant of it, because they don’t care, because they agree with the policy, or because they benefit from the policy – and they forget about it. Things remain the same, the status quo is maintained, and mythologies of a white nation remain impervious to change. There is also a collective remembering that this is the policy of the government, that it keeps the country homogenous, and wards of the invasion of non-desirables. People of colour and “others”.

So how can looking at historic photographs, such as those in John Faviell’s photographic album, affect change? According to Mika Elo,

“Photographs are nomadic and relational images. They are scalable and can be inscribed in many kinds of material supports, which means that they carry in themselves references to something beyond their own instantiations. Something similar applies to power. Power can be restrictive or productive, personalized or impersonal, but it is always relational. With regard to visual representation, power is neither entirely inherent to specific images nor entirely reducible to the context. Rather, we might consider it a parergonal [a subordinate activity or work: work undertaken in addition to one’s main employment] phenomenon. As we all know, power relations can effectively be built up and worked against with photographic images. This means that in each individual case the borders between information, propaganda and advertising are necessarily indistinct – even if the face offered by the photograph as an image is distinct. The distinctness of an image is always dissimilarity [its groundlessness of meaning in a ‘network’ of significations]. The way in which a photograph cuts itself off from everything else introduces a mute interval that fosters many kinds of speech, whether banal, creative, humiliating or empowering. In any case, the photographic cut necessarily introduces basic conditions for power relations: it introduces a point of view into relational structures. Its effects can be both imaginary and symbolic. Depending on the point of view, the cut can be transformative or conservative, emancipatory or suppressive, subversive or destructive.”25

In this sense images, rather than being a representation of a palpable materiality at a particular point in time and with a particular interpretation, never cease to present their multiple aspects open to reinterpretation. Collectively and individually photographs can seize us, can hold us in their thrall. But we are not passive observers that approach the present which is absent, a particular floating “reality” that is embedded in a photograph, but an active participant in the encounter with performance and gesture… in the eyes of the observer. As Žarko Paić notes of the observer, “His role has changed significantly. It is no longer a Kantian passive subject to the reflection of a beautiful, nor a Nietzschean active producer who disturbs indifferent senses. The observer does not look at what’s happening in a picture like an idle screen. Violence caused by the rise of the chaotic reality of the twentieth century, wars and revolutions, by the technical acceleration of the cinematic energy of one’s life, becomes the “energy” and “intensity” of the image. The image is always an image of something. It is therefore mimetic in its aspiration to turn life into the objectivity of reality. However, the representation of something does not mean that it is only an empty intentional act of observing objects.”26 As Mika Elo states, “… power is necessarily inscribed in technologies, practices and discourses of photography in many ways. Photographic powers have their past, presence and future. They have their visible and invisible forms.”27

And so this is what we can collectively and individually undertake. We can look at John Faviell’s private photographs and confront the racist societal violence28 against Aboriginal people depicted through image and text, and we can disrupt their historicity, in public, in the here and now. We can acknowledge past determinations of these photographs and delimit that determination and identification in a network of significations… so that we celebrate the life of the disenfranchised because they are not to be seen as such. These are human beings living their life and are as equally as valuable as anybody else, and we can acknowledge this because we approach the photograph to embrace the … the “energy” and “intensity” of the image. And the “presence” and spirit of the people not as subject but as the thing itself.29

The observer actively engages with the photograph to bring these human beings to life in their imagination,30 to inhabit a reality that can in the present be changed. Every look performs this operation because only through this recon/figuration, this transformation, this metamorphosis, can we assess the past with fresh eyes and not be complicit in the racism and socially constituted activities of the past which still affect us today. Only by bringing the visible and invisible forms of racism into the open in the present can we open up new possibilities for the future.

As the photographer Frederick Sommer sagely opines,

The world is a reality,

not because of the way it is,

but because

of the possibilities it presents.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

January 2023

Word count: 4,671

Footnotes

1/ “Great Depression in Australia,” on the Wikipedia website [Online] Cited 30/08/2021

2/ Lisa Matthews (director). “Shifting Allegiances,” from Australia in Colour Season One, Episode Two. TV Mini Series. Strange Than Fiction Films, 2019

3/ Ibid.,

4/ Anonymous. “The 1938 Day of Mourning,” on the AIATSIS website Nd [Online] Cited 21/02/2022

5/ Isabella Higgins and Sarah Collard. “Captain James Cook’s landing and the Indigenous first words contested by Aboriginal leaders,” on the ABC News website Wed 29 Apr 2020 quoted in Jens Korff. “Australia Day – Invasion Day,” on the Creative Spirits website 26 July 2021 [Online] Cited 03/05/2022

6/ Anita Heiss. “Significant Aboriginal Events in Sydney,” on the Barani website Nd [Online] Cited 22/07/2021.

7/ Ibid.,

8/ Pose, Melanie. “Indigenous Protest, Australian Bicentenary, 1988,” on the Museums Victoria Collections website 2009 [Online] Cited 03/05/2022 Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International

9/ Ibid.,

10/ Natalie Cromb. “Analysis: The ’88 protests,” on the SBS NTIV website 29 January, 2018 [Online] Cited 03/05/2022. No longer available online

11/ Anonymous. “Walk for reconciliation,” on the National Museum of Australia website 12 May 2021 [Online] Cited 03/05/2022

12/ “Apology to Australia’s Indigenous peoples,” on the Wikipedia website [Online] Cited 03/05/2022

13/ “Vernacular photography is also to be distinguished from amateur photography. While vernacular photography is generally situated outside received art categories (though where the lines are drawn may vary), “amateur photography” contrasts with “professional photography”: “[A]mateur [photography] simply means that you make your living doing something else”.”

Langford, Michael and Bilissi, Efthimia. Langford’s Advanced Photography. Oxford, UK and Burlington, MA: Focal Press. 2011, p. 1 quoted in Anonymous. “Vernacular photography,” on the Wikipedia website Nd [Online] Cited 06/05/2022

14/ Anonymous. “You Press the Button, We Do the Rest,” on the Wikipedia website Nd [Online] Cited 06/05/2022

15/ Anonymous. “In the Vernacular,” on the Art Institute of Chicago website, 2010 [Online] Cited 06/05/2022

16/ Ibid.,

17/ Leonard A. Lauder quoted in the press release for Real Photo Postcards: Pictures from a Changing Nation at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston 17th March – 25th July, 2022 Nd [Online] Cited 06/05/2022

18/ Kris Belden-Adams. “CFP – ‘These Are Our Stories’: Global Expressions of “Other” Histories, Narratives, and Identities in Photographic Albums,” on the Humanities and Social Science Online website January 23, 2020 [Online] Cited 03/05/2022

19/ See Anonymous. “White Australia Policy,” on the Wikipedia website Nd [Online] Cited 25/12/2022; Anonymous. “White Australia Policy,” on the National Museum of Australia website Nd [Online] Cited 25/12/2022; and Anonymous. “The Immigration Restriction Act 1901,” on the National Archives of Australia website Nd [Online] Cited 25/12/2022

20/ Mika Elo. “Introduction: Photography Research Exposed to the Parergonal Phenomenon of “Photographic Powers”,” in Elo, Mika and Karo, Marko (eds.,). Photographic Powers – Helsinki Photomedia 2014. Aalto University publication series, 2015, pp. 7-8.

21/ Anonymous. “Art of Memory,” on the Wikipedia website Nd [Online] Cited 25/12/2022

22/ The artist Octora quoted in James McArdle. “16 July: Writing,” on the On This Date In Photography website 16/07/2021 [Online] Cited 22/07/2021.

23/ The Right Reverend George Hearn quoted in “Birthday hype ‘blurs’ history,” in The Canberra Times Sun 1 May 1988 on the Trove website [Online] Cited 22/07/2021.

24/ David Middleton and Derek Edwards (eds.,). Collective Remembering. Sage Publications, 1990

25/ Mika Elo, Op cit., pp. 7-8

26/ Žarko Paić. “The Dark Core Of Mimesis: Art, Body And Image In The Thought Of Jean-Luc Nancy,” on the TVRDA website August 20, 2022 [Online] Cited 25/12/2022

27/ Mika Elo, Op cit., pp. 7-8

28/ “Racist violence is exemplary. It is the violence that knocks someone in the face, simply because – as the stupid twat might say – it “doesn’t like the look” on his face. The face is denied truth. The truth meanwhile lies in a figure that deduces itself to the blow that it strikes. Here, truth is true because it is violent, and it is true in its violence: it is a destructive truth in the sense in which destruction verifies and makes true.”

Jean-Luc Nancy. The Ground of the Image. Translated by Jeff Fort. Fordham University Press, 2005, p. 17.

29/ Ibid., p. 21.

30/ “The image not only exceeds the form, the aspect, the calm surface of representation, but in order to do so item just draw upon a ground – or a groundlessness – of excessive power. The image must be imagined; that is to say, it must extract from its absence the unity of force that the thing merely at hand does not present. Imagination is not the faculty of representing something in its absence; it is the force that draws the form of presentation out of absence: that is to say, the force of “self-presenting.””

Jean-Luc Nancy. The Ground of the Image. Translated by Jeff Fort. Fordham University Press, 2005, p. 21.

Many thankx to the State Library of New South Wales for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Grateful thankx to Douglas Stewart Fine Books for their research help with this photo album. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“Shark’s Bay,” 1923 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

Locations

Blue Mountains, NSW (1922)

Leura Falls, NSW (1922)

Weeping Rock, Wentworth Falls, NSW (1922)

Tarana Picnic Races, NSW (1922)

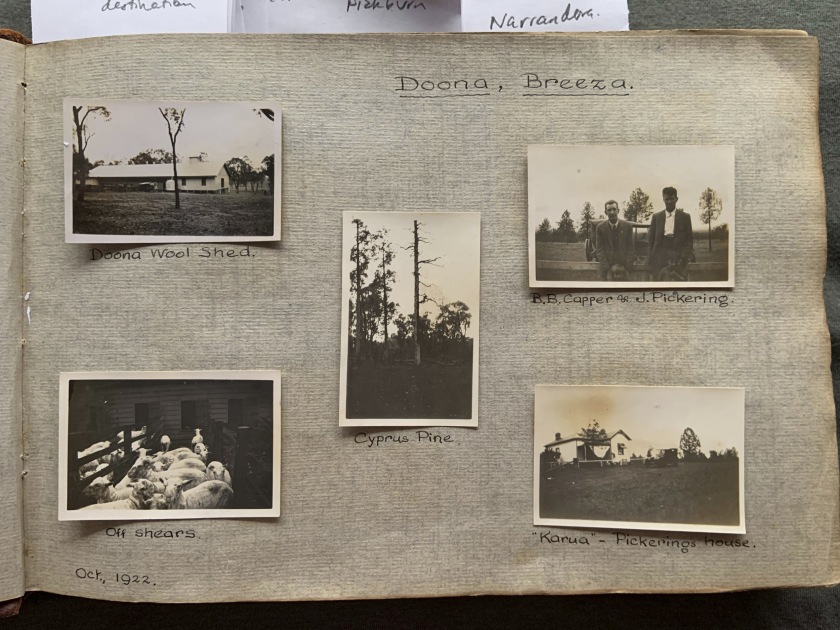

Doona, Breeza, NSW (1922)

Avoca, NSW (1922)

Newcastle Races, NSW (1923)

Belmont / Belmont Regatta, NSW (1923)

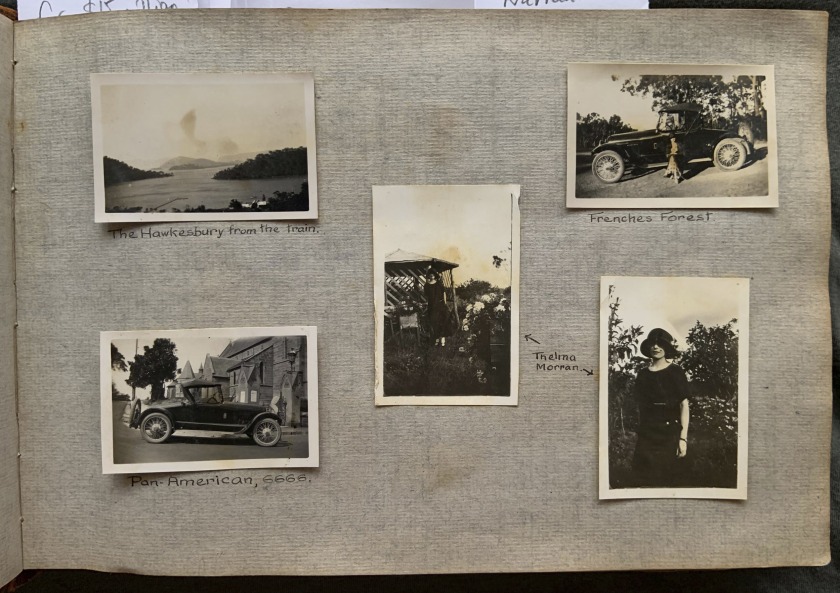

Hawkesbury, NSW (1923)

Frenches Forest, NSW (1923)

“Foxlow” Station, Bungedore, NSW (1923)

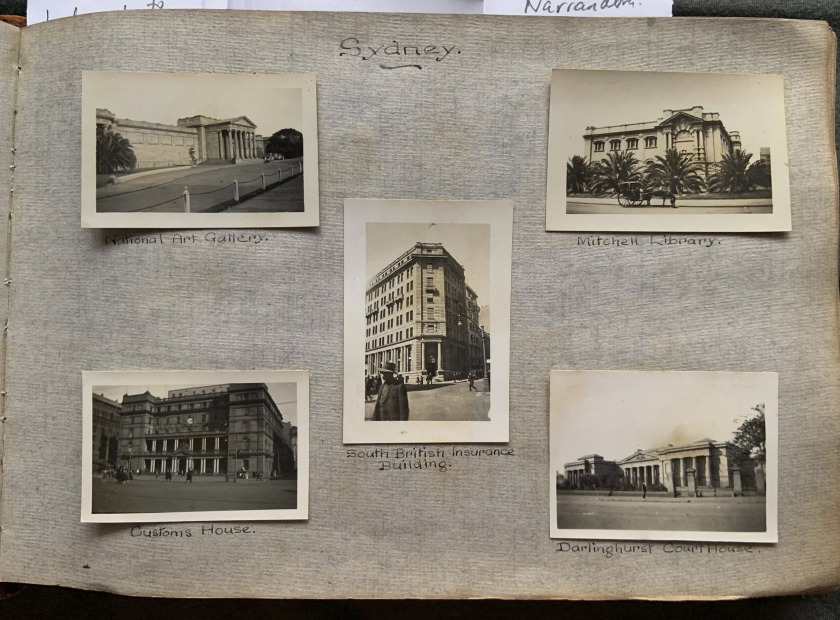

Sydney, NSW (Customs House, National Art Gallery, Mitchell Library, Darlinghurst Courthouse) (1923)

Muswellbrook Picnic Races, NSW (1923)

Maitland / Maitland Cup Meeting, NSW (1923)

Breeza, NSW (1923)

Wiseman’s Ferry, NSW (1923)

Moss Vale / Sutton Forest Church, NSW (1923)

Frensham, NSW (1923)

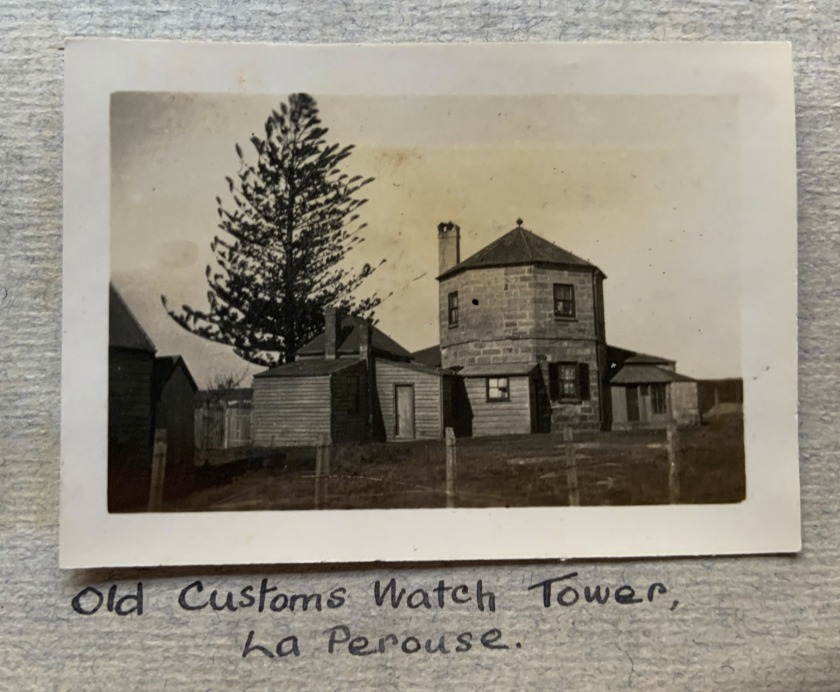

La Perouse, NSW (Historical Society Excursion) (1923)

Old Customs Watch Tower, La Perouse (1923)

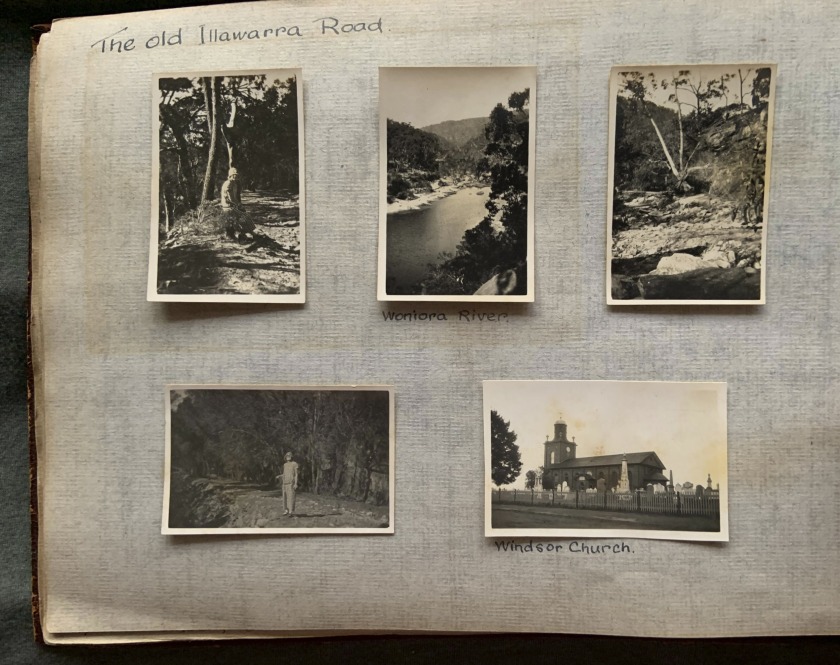

The Old Illawarra Road, NSW (1923)

Yarcowie, SA (1923)

Trans-Australian Railway (Port Augusta to Kalgoorlie) (1923)

Karonie, WA (1923)

Kalgoorlie, WA (1923)

Boulder City, WA (1923)

Fremantle, WA (1923)

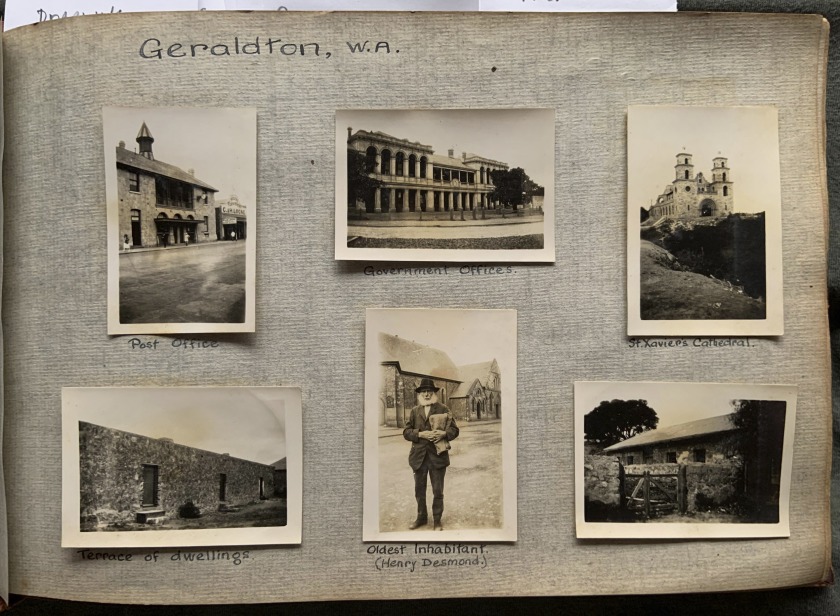

Geraldton, WA (1923)

Shark’s Bay, WA (1923)

Henry Freycinet Estuary, WA (1923)

Tamala Station, WA (1923)

Perth, WA (1923)

Adelaide, SA (Torrens River) (1923)

“Redbank,” Scone, NSW (1924)

Muswellbrook Picnic Races, NSW (1924)

“Craigieburn,” Bowral, NSW (1924)

The Dudley Cup at Kensington, NSW (1924)

Camden Grammar School, NSW (1924)

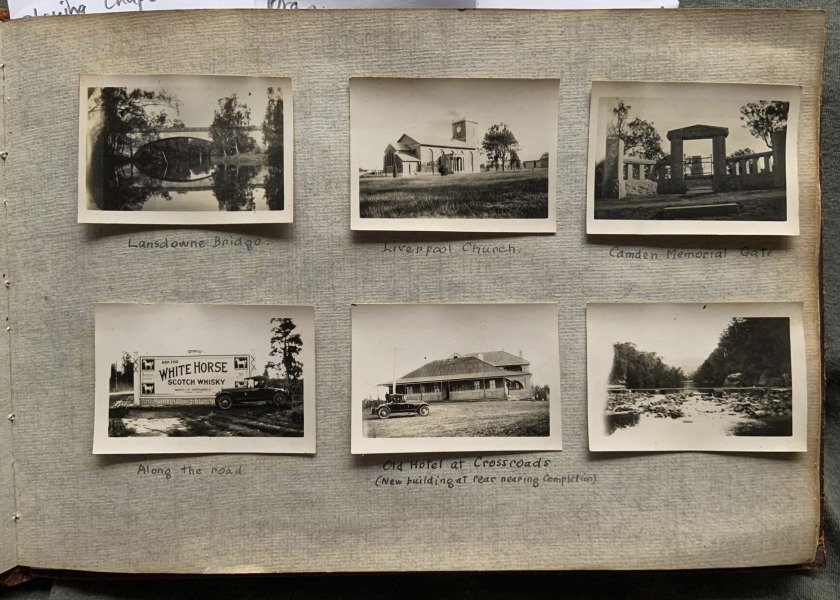

Liverpool Church, NSW (1924)

Landsdowne Bridge, NSW (1924)

Jenolan Caves, NSW (1924)

Avon Dam, NSW (1924)

Herald Office, Pitt Street, NSW (1924)

Camping, Cronulla, NSW (1925)

Roseville, NSW (1926)

Whale Beach, NSW (1927)

Visit of the Duke and Duchess of York, Macquarie Street, NSW (1927)

20, Yarranabbe Rd., Darling Point, NSW (1926)

Canberra, ACT (1927)

Jenolan Caves, NSW (Lady Dorothy Hope-Morley) (1927)

Ellen’s Isle, Loch Katrine, Scotland (1925)

Sydney Harbour Bridge, NSW (1931-32)

“Springfield,” Byng, Near Orange, NSW (1932)

Lucknow, near Orange, NSW (1933)

Hawkesbury, NSW (1933)

Bathurst, NSW (1933)

“Millambri, ” Canowindra, NSW (1933)

Melbourne, VIC (1933)

Topics

Men

Pastoralism and grazing

Horses / country horse racing

Sheep and shearing

Cows

Mill / logging

Pine plantation

Bush

Bores and dams

Cathedral / churches

Tennis

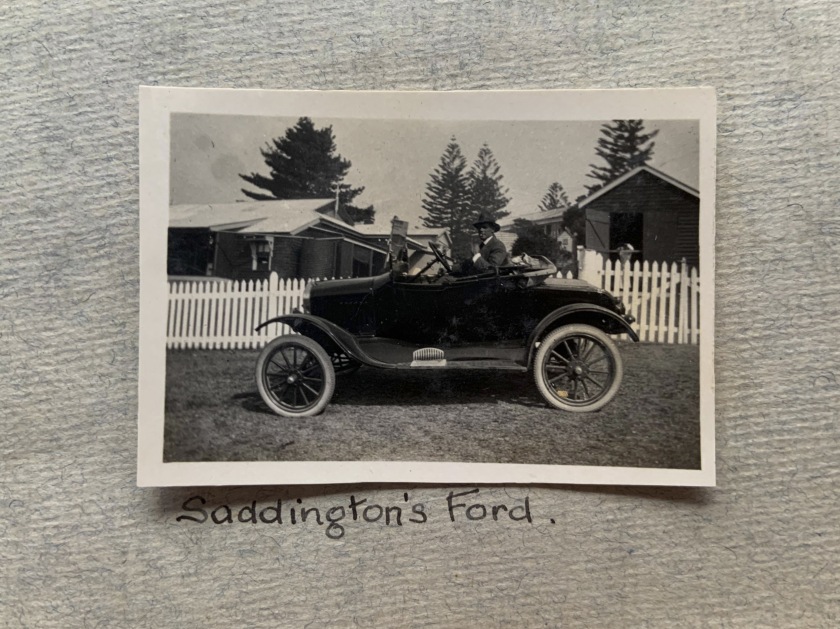

Golf

Cars (Ford, Pan-American, Essex, Oldsmobile, early Hupmobile, Chrysler 70)

Buses

Bank, post office

Pastoral Play

Monuments

Rock carvings

Houses

Cemetery / tombstones

John Dunn, executed 1866

South Australian Railways / locomotives

S.A. constable and Adelaide cop

Indigenous Australians (Aboriginal types, along the Trans-Australian Railway)

Australian Desert Blacks

Gold mine / gold panning

Mining (Boulder and Perseverance Mines)

Convict gaol

Oldest inhabitant (Henry Desmond)

Hotels

Beach and sea, surf girls

Mother of pearl

Dates

Afghan / camels

Yachting, sailing / boats

Guano

Fred Adams, Boss-Pearler

Stations and station hands

Rowing

Dredging

Polo

Rugby

Caves

Guns

Nobility and royalty

Camping, picnics

Tennis

House building / old houses

Parliament House

Prime Ministers residence

Bridges and bridge building

Federal and state governors

The world’s first auto-gyro plane (1909-1912)

The Southern Cross

Pioneers

Mounted police

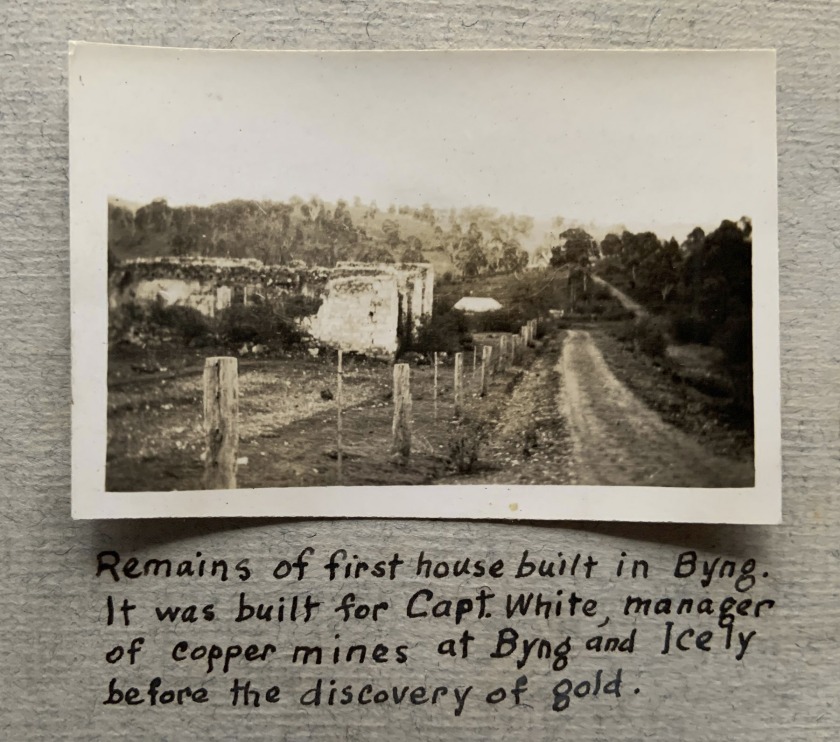

First house in Byng

Rabbiting

Glamour

Social status / socialite

Family

Women and children

Sydney Harbour Bridge opening

Carillon (bells)

Myers and Bourke Street, Melbourne

“An Afghan’s turnout,” 1923 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Shark’s Bay, Lloyd’s Camels (Bred on Dirk Hartog Island),” 1923 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“A five-days cruise on the Cutter “Shark”,” 1923 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Amongst the Islands of Henri Freycinet Estuary,” 1923 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

Henri Freycinet Harbour, also known as Freycinet Estuary, is one of the inner gulfs of Shark Bay, Western Australia, a World Heritage Site that lies to the west of the Peron Peninsula. It has a significantly larger number of islands than Hamelin Pool, and has a number of smaller peninsulas known as “prongs” on its northern area. It has also been identified as a critical dugong habitat area. It is situated within the Shark Bay Marine Park.

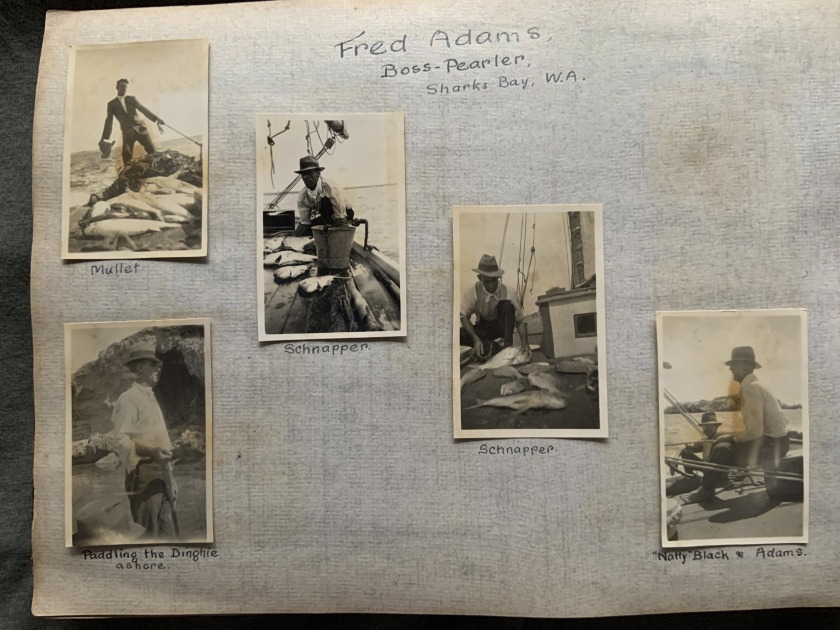

“Fred Adams, Boss-Pearler, Shark’s Bay, W.A.,” 1923 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

Pearling in Western Australia was an important part of the European colonisation of the North West. Although it was never considered a permanent part of the state economy, pearling, with its immediate returns, allowed pastoralists to establish stations and contributed to the foundation of several towns. Some of these towns evolved into centres for agriculture and tourism and some developed their port facilities. Others did not outlive the availability of and market for pearlshell. Uniquely, Shark Bay not only survived the demise of the industry, but developed into the state’s commercial fishing centre. The pearling boats were simply refitted to become fishing boats (OH 2266/8) and the Bay life continued…

Wilyah Miah. An Archaeological Study of the History of the Shark Bay Pearling Industry 1850-1930. University of Western Australia, 1999, p. 7.

“”Natty” Black & Adams,” in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Sharks Bay,” 1923 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“J.F.” 1923 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Boss-pearler Henfrey, and his “missus”, opening shell,” 1923in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

The first labour employed in the industry was that of the local Aboriginal people. Little is known of the pre-European Aboriginal people of the Bay. It is not clear whether it was the territory of the Nanda or the Mulgana people (Bowdler 1992:5) although current consensus among the people of Shark Bay is that they are Mulgana (Bowdler pers. comm. 1999). They were easily accessible and there were no expectations that they should be paid the wages of other labourers. Willingness on the part of the Aboriginal people to participate in the industry was often an issue irrelevant to the interests of the pearlers. Goods such as alcohol may have been an inducement, but, according to Anderson (1978) in her study of the North West industry, coercion was necessary and practices such as blackbirding were employed to acquire labour. The introduction of pastoralism, by its appropriation of land, ensured the destruction of the traditional Aboriginal economy and forced them to provide for the market the only commodity available to them, their labour (Hartwig 1975:32).

Wilyah Miah. An Archaeological Study of the History of the Shark Bay Pearling Industry 1850-1930. University of Western Australia, 1999, p. 18.

“Tamala Station, Shark’s Bay, W.A.,” 1923 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

This pastoral station is in the southern part of Shark Bay World Heritage Area on limestone-dominated landscapes. The main attraction of Tamala Station is the low lying coastline and waters of Henri Freycinet Harbour. Many visitors only cross this property on their way to Steep Point but some spend time here camping, fishing and exploring the prongs and peninsulas. Tamala Station allows access to the general public but you must first contact the station managers for bookings.

Text from the Shark Bay World Heritage website

“Tamala Station Hands,” 1923 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Well Ziffed Stockman,” in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

Ziff, Australian for beard. The Oxford English Dictionary says this slang term originated around 1919, but otherwise the origin is unknown. To be ziffed means to be bearded.

“Untitled,” 1923 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Nellie and her litter,” 1923 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Western Australia,” 1923 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Perth,” 1923 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Returning from the West,” 1923 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Redbank”, Scone, N.S.W.,” 1923 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

W.T. Badgery, horsebreeder, at Scone, Hunter Valley (Information from Douglas Stewart Fine Books)

Scone /ˈskoʊn/ is a town in the Upper Hunter Shire in the Hunter Region of New South Wales, Australia. It is on the New England Highway north of Muswellbrook about 270 kilometres north of Sydney, and is part of the New England (federal) and New England (state) electorates. Scone is in a farming area and is also noted for breeding Thoroughbred racehorses. It is known as the ‘Horse capital of Australia’.

Text from the Wikipedia website

“Muswellbrook Picnic Races,” 1923 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Polo, Scone v Muswellbrook,” 1923 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Craigieburn”, Bowral, N.S.W.,” 1923 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

Craigieburn, Bowral is a house of historical significance as it was built in about 1885. It was originally the mountain retreat for a wealthy Sydney merchant and was owned by him for over twenty years. It was then the home of several other prominent people until about 1918 when it was converted into a hotel. Today it still provides hotel accommodation and is a venue for special events particularly weddings and conferences.

Text from the Wikipedia website

“Bryden Brown and Jack Whitehouse,” 1923 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“The Dudley Cup at Kensington,” 1924 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

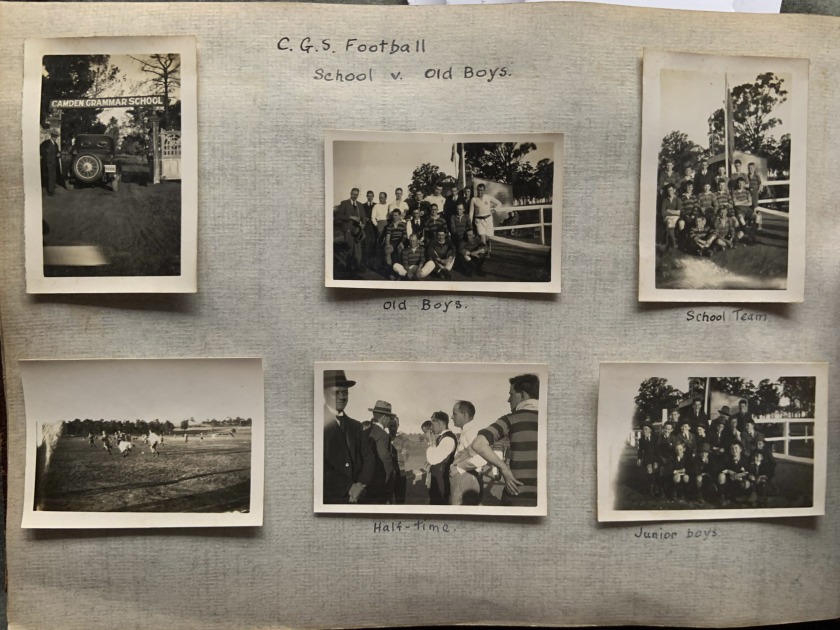

“C.G.S Football, School v Old Boys,” 1924 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

Camden Grammar School

“At the close of the last century the school was moved to the present situation at Studley Park, Narellan, formerly the residence of A. Payne Esq., a magnificent residence standing on the brow of a hill over looking the Nepean Valley and surrounded by 200 acres of rich country.” (Trove) The school was at Studley Park House 1902-1933.

“Half-time,” 1924 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Untitled,” 1924 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

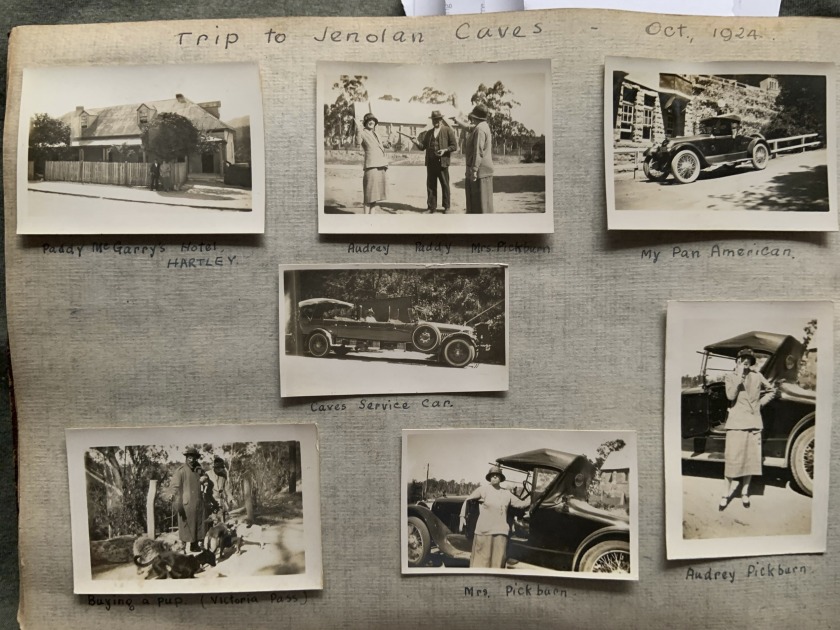

“Trip to Jenolan Caves,” October, 1924 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

Audrey Pickburn

Audrey Pickburn was a Sydney socialite. Her mother who was obviously playing chaperone on this trip to Jenolan Caves (Information from Douglas Stewart Fine Books) (Information from Douglas Stewart Fine Books)

Audrey Pickburn and John Faviell were married on Tuesday 24 February 1925.

AT ST. JAMES’

LAST NIGHT’S WEDDING

FAVIELL – PICKBURN

ST. JAMES Church, Kings Street was crowded last night for the wedding or Miss Audrey Pickburn, only child of the late Judge Pickburn, and Mrs. Pickburn of Springfield, Darllnghurst and Mr John Favlell, of “Collinroobie”. The church was decorated by girl friends of the bride and the ceremony was performed by Rev. T. L—-.

A lovely bridal gown of gleaming white was hand embroidered with pearls and diamente, and made with a long train, which was encrusted with pearls and lined with shell pink georgette. Silver thread embroideries also appeared on the train, which was finished with true-lovers knots. A plain tulle veil, held with a coronet of orange blossom, and a bouquet of orchids completed the ensemble.

Miss Gretel Bullmore was chief bridesmaid wearing a gown of golden lame, flared at the hem. Miss Eileen Wiley and Miss Joyce Russell were also In attendance. Their frocks of lame were made —– effect. All three wore golden crin. hats, trimmed with —- and floating blue scarves, with gold thread embroideries, and they carried bouquets of orchids.

Mr. Claude Pain was in attendance as best man. Mr. Guy Little and Mr Keith Hardie acted as groomsmen. The reception was held at the Queen’s Club where the bride & mother received a big number of guests.

The Labor Daily, Tuesday, 24 February 1925, Page 7 on the Trove website [Online] Cited 05/11/2019

(The Queen’s Club, 137 Elizabeth Street, Sydney established in 1912, is a private Club. The Club was founded for social purposes for country and city women.)

PICKBURN – FAVIELL

The biggest social event of the month was the wedding on Tuesday night of Miss Mclanie Audrey Pickburn, only daughter of the late Judge Pickburn and Mrs. Pickburn, of ‘Springfield,’ Darlinghurst, to Mr. Jack “Riverstone” Faviell, of Sydney, son of the late Mr. A. Faviell, Colinroobie, Narandera, and Mrs. Faviell, Kiribilli, which was celebrated at St. James’s Church, King-street, Sydney, by the Rev. E. C. Lucas, of St. John’s, Darlinghurst. The church was beautifully decorated in white and gold.

Narandera Argus and Riverina Advertiser, Friday, 27 February 1925, Page 6 on the Trove website [Online] Cited 05/11/2019

Jenolan Caves

The Jenolan Caves (Tharawal: Binoomea, Bindo, Binda) are limestone caves located within the Jenolan Karst Conservation Reserve in the Central Tablelands region, west of the Blue Mountains, in Jenolan, Oberon Council, New South Wales, in eastern Australia. The caves and 3,083-hectare (7,620-acre) reserve are situated approximately 175 kilometres (109 mi) west of Sydney, 20 kilometres (12 mi) east of Oberon and 30 kilometres (19 mi) west of Katoomba.

The caves are the most visited of several similar groups in the limestone caves of the country, and the most ancient discovered open caves in the world.

Text from the Wikipedia website

“Caves Service Car,” 1924 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“My Pan American,” 1924 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Audrey Pickburn,” 1924 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Jenolan Caves,” October, 1924 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Audrey,” 1924 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Untitled,” in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

Admiral Sir Dudley Rawson Stratford de Chair, KCB, KCMG, MVO (30 August 1864 – 17 August 1958) was a senior Royal Navy officer and later Governor of New South Wales. …

Governor of New South Wales

De Chair had been interested in serving in a viceregal role as early as 1922, when he put his name forward to the Colonial Office for the position of Governor of South Australia. This position however, went to Sir Tom Bridges instead and the First Lord of the Admiralty, Leo Amery, put de Chair’s name forward for the Governor of New South Wales. This position, which had been vacant since the death of Sir Walter Davidson in September 1923, was the same one his uncle, Sir Harry Rawson, had held twenty years earlier, and to which he was appointed on 8 November 1923.

Arriving in Sydney on 28 February 1924, de Chair became governor in relatively calm political times and was warmly received in the city with great fanfare. On de Chair’s appointment, the President of the Royal Australian Historical Society, Aubrey Halloran, compared Admiral de Chair to the first Governor, Captain Arthur Phillip: “Our new Governor’s reputation as an intrepid sailor and ruler of men evokes from us a hearty welcome and inspires us to place in him the same confidence that [Arthur] Phillip received from his gallant band of fellow-sailors and the English statesmen who sent him.”

The political makeup of the state changed not long after his arrival however, when the conservative Nationalist/Progressive coalition government of Sir George Fuller, whom de Chair had got on well with, was defeated at the May 1925 state election by the Labor Party under Jack Lang. De Chair noted to himself that Lang and his party’s position comprised “radical and far-reaching legislation, which had not been foreshadowed in their election speeches”. He also later wrote that Lang’s “lack of scruple gave me a great and unpleasant surprise”.

With the Labor Government only holding a single seat majority in the Legislative Assembly and only a handful of members in the upper Legislative Council, one of Lang’s main targets was electoral reform. The Legislative Council, comprising members appointed by the Governor for life terms, had long been seen by Lang and the Labor Party as an outdated bastion of conservative privilege holding back their reform agenda. Although previous Labor premiers had managed to work with the status quo, such as requesting appointments from the Governor sufficient to pass certain bills, Lang’s more radical political agenda required more drastic action to ensure its passage. Consequently, Lang and his government sought to abolish the council, along the same lines that their Queensland Labor colleagues had done in 1922 to their Legislative Council, by requesting from de Chair enough appointments to establish a Labor majority in the council that would then vote for abolition.

While Lang’s attempts ultimately failed, de Chair failed to gain the support of an indifferent Dominions Office. With Lang’s departure in 1927, the Nationalist Government of Thomas Bavin invited him in 1929 to stay on as Governor for a further term. De Chair agreed only to a year’s extension and retired on 8 April 1930.

Text from the Wikipedia website

“Old Herald Office – Pitt St.,’ 1924 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Aboard the Orvieto,” September, 1925 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Curtis (Captain Arthur Curtis),” 1925 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

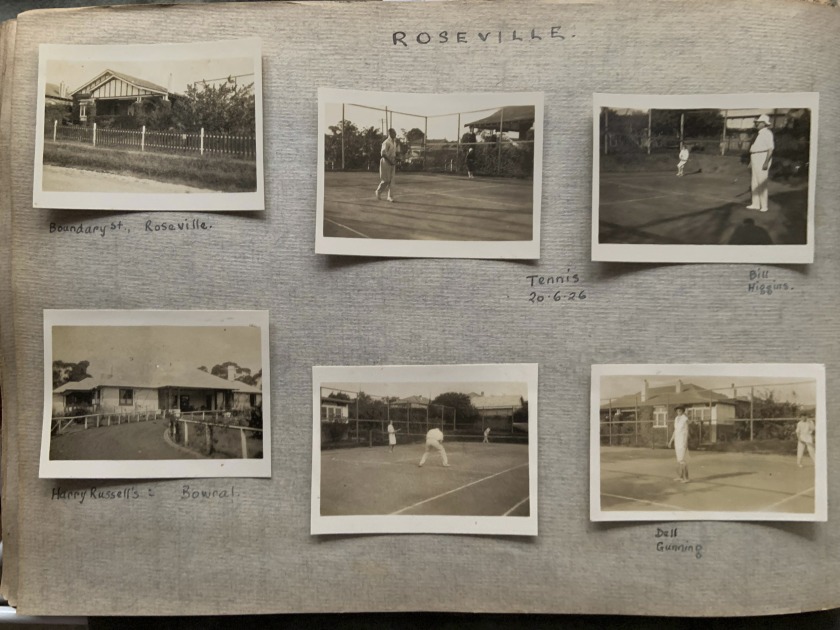

“Roseville,” 1926 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Picnics – Whale Beach / Visit of the Duke & Duchess of York,” 1927 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Visit of the Duke & Duchess of York,” 1927 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“A house is nearly built – 20 Yarranabbe Road, Darling Point,” 1926 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Buying the land,” 1926 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Three harbour views taken from upstairs,” 1926 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Harbour view,” 1926 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

Audrey Pickburn and Jack Faviell divorced in October 1930. Audrey re-married in 1934 and so did Jack (Information from Douglas Stewart Fine Books)

IN DIVORCE

(Before Mr. Justice Pike)

FAVIELL v FAVIELL

Jack Riverstone Faviell sued for divorce from Melanie Audrey Faviell (formerly Pickburn) on the ground of non compliance with a decree for restitution of conjugal rights. The parties were married at Sydney in February, 1925, according to the rites of the Church of England. A decree nisi, returnable in six months, was granted. Mr. Toose (instructed by Messrs. Allen, Allen, and Hemsley) appeared for the petitioner.

The Sydney Morning Herald, Saturday, 11 October 1930. Page 8 on the Trove website [Online] Cited 05/11/2019

The party below is for Jack with his second wife whom he married in 1934; Miss Rosenthal from Melbourne (Information from Douglas Stewart Fine Books)

“Party at Darling Point”

MRS. JOHN FAVIELL, looking very cool in a pink and grey floral sheer frock and shady natural straw hat, was hurrying about town in yesterday’s heat to complete arrangements for the Christmas party and dance at her home, 20 Yarranabbe Road, Darling Point, on Friday.

The party will be held from Ave till ten p.m., and the proceeds will be in aid of the Blind Institution. A Christmas tree will be among the attractions.

The Daily Telegraph, Wednesday, 15 December 1937. Page 12 on the Trove website [Online] Cited 05/11/2019

“Trip to Canberra,” 5/6 November, 1927 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Prime Minister’s Residence,” 1927 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Trip to Canberra,” 5/6 November, 1927 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

The prophetic tombstone of Sarah, George and Betsy Webb. The inscription is prophetic “For here we have no continuing city but seek one to come” St John’s Churchyard, Constitution Avenue, Reid.

“Taken by Lady Dorothy Hope-Morley, Jenolan Caves Trip,’ 10/12th July, 1927 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

Dorothy Edith Isabel Hope-Morley (Hobart-Hampden)

Birthdate: April 11, 1891

Death: December 15, 1972

Daughter of Sidney, 7th Earl of Buckinghamshire, OBE and Georgiana Wilhelmina, Countess of Buckinghamshire

Wife of Hon. Claude Hope-Morley

Mother of Gordon Hope Hope-Morley, 3rd Baron Hollenden and Hon Ann Rosemary Hope Newman

Sister of John Hobart-Hampden-Mercer-Henderson, 8th Earl of Buckinghamshire and Lady Sidney Mary Catherine Anne Hobart-Hampden

“Taken by Lady Dorothy Hope-Morley, Jenolan Caves Trip,’ 10/12th July, 1927 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Taken by Lady Dorothy Hope-Morley, Jenolan Caves Trip,’ 10/12th July, 1927 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Ellen’s Isle, Loch Katrine, Scotland (Audrey & me in boat),” 1925 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

This photograph, the only one from overseas (Scotland), must be from Audrey and Jack’s honeymoon (1925). It is interesting that there are no other photographs from either the wedding or the honeymoon in the album. Of course, the marriage photographs could have been housed in a purpose built wedding album, but the haphazard nature of the construction of this album, with the photographs out of date order, and this the only one from the honeymoon, make me think that this album was assembled in the 1930s. Marcus

“Untitled,” c. 1927-30 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Untitled,” c. 1927-30 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

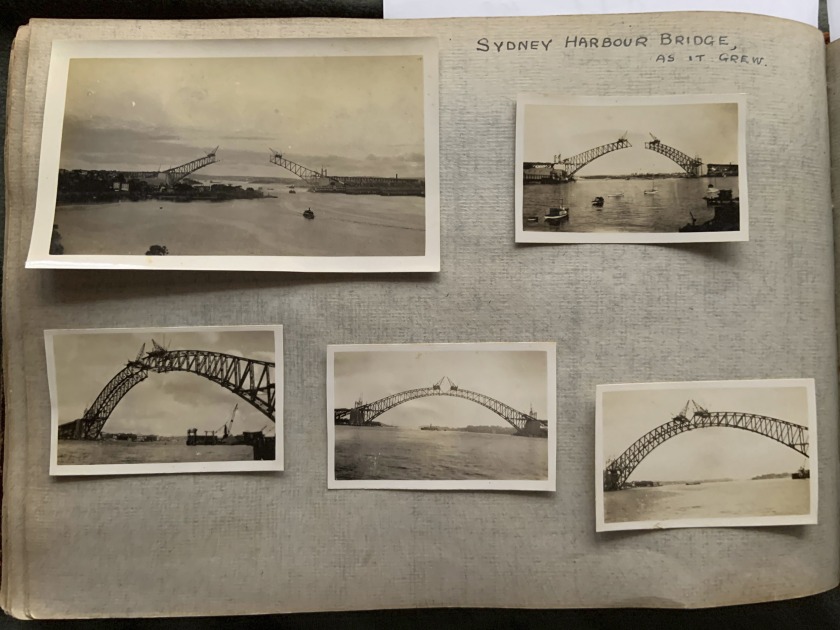

“Sydney Harbour Bridge As It Grew,” 1929-1930 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

Sydney Harbour Bridge construction

Arch construction itself began on 26 October 1928. The southern end of the bridge was worked on ahead of the northern end, to detect any errors and to help with alignment. The cranes would “creep” along the arches as they were constructed, eventually meeting up in the middle. In less than two years, on Tuesday, 19 August 1930, the two halves of the arch touched for the first time. Workers riveted both top and bottom sections of the arch together, and the arch became self-supporting, allowing the support cables to be removed. On 20 August 1930 the joining of the arches was celebrated by flying the flags of Australia and the United Kingdom from the jibs of the creeper cranes.

Text from the Wikipedia website [Online] Cited 31/10/2019

“Sydney Harbour Bridge As It Grew,” 1929-1930 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Sydney Harbour Bridge As It Grew,” 1929-1930 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Sydney Harbour Bridge As It Grew,” 1929-1930 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Sydney Harbour Bridge As It Grew,” 1929-1930 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Bridge Opening, 20th March, 1932,” in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Showing anchor cables,” March, 1932 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Federal and State Govenors arriving,” March, 1932 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Pageantry at Official Opening of Harbour Bridge – 20th March, 1932,” in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Pageantry at Official Opening of Harbour Bridge – 20th March, 1932,” in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Mounted Police,” March, 1932 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Aborigines,” March, 1932 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Old King Street Bus,” March, 1932 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“An early Hupmobile car,” March, 1932 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

Hupmobile was an automobile built from 1909 through 1939 by the Hupp Motor Car Company.

“First Auto-Gyro (The World’s First Auto-Gyro Plane, 1909-12),” March, 1932 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Pageantry at Official Opening of Harbour Bridge – 20th March, 1932,” in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Surf girls drawing Float,” in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“The Southern Cross,” March, 1932 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Pioneers Float,” March, 1932 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

Australian National Travel Association

Smith and Julius Studios (Sydney, N.S.W.) (printer)

Australia’s 150th Anniversary Sydney 1938: Pageantry and carnival January 26th – April 25th

Sydney: The Association, 1938

Poster

101.2 x 62.4cm

© National Library of Australia

Used under fair use condition for the purpose for research or study

‘The 26th of January, 1938, is not a day of rejoicing for Australia’s Aborigines; it is a day of mourning. This festival of 150 years’ so-called “progress” in Australia commemorates also 150 years of misery and degradation imposed upon the original native inhabitants by the white invaders of this country.

‘We, representing the Aborigines, now ask you, the reader of this appeal, to pause in the midst of your sesqui-centenary rejoicings and ask yourself honestly whether your “conscience” is clear in regard to the treatment of the Australian blacks by the Australian whites during the period of 150 years’ history which you celebrate?’

‘You are the New Australians, but we are the Old Australians. We have in our arteries the blood of the Original Australians, who have lived in this land for many thousands of years.’

‘You came here only recently, and you took our land away from us by force. You have almost exterminated our people, but there are enough of us remaining to expose the humbug of your claim, as white Australians, to be a civilised, progressive, kindly and humane nation.’

‘Aborigines Claim Citizen Rights!: A Statement of the Case for the Aborigines Progressive Association’, the Publicist, 1938, p. 3 quoted in Anonymous. “The 1938 Day of Mourning,” on the AIATSIS website Nd [Online] Cited 21/02/2022

Charles Meere (Australian, 1890-1961)

1788-1938, 150 years of progress: Australia celebrates January 26 – April 25, 1938

1938

Poster

101.5 x 63.5cm

© National Library of Australia

Used under fair use condition for the purpose for research or study

Poster advertising the Day of Mourning

1938

AIATSIS Collection

Used under fair use condition for the purpose for research or study

In 1938, a poster invited “Aborigines and persons of Aboriginal blood” to attend the Day of Mourning and Protest at the Australian Hall, Sydney. It was to be held on 26 January, the 150th anniversary of European colonisation. The protest, calling for full citizen status and equality, was led by William Cooper, Pearl Gibbs, Jack Patten and William Ferguson.

Keith Munro, MCA Curator Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Programs, says, “The Day of Mourning event is seen as the first Aboriginal civil rights protest in Australian history. The actions that took place on this day later resulted in the establishment of a national day of celebration and achievement, which turned into a longer event now known as NAIDOC Week.”

Anonymous. “Marking 80 years since the Day of Mourning,” on the Museum of Contemporary Art website 17 May 2018 [Online] Cited 21/02/2022

Unknown photographer (Australian)

The first Day of Mourning. From the left is William Ferguson, Jack Kinchela, Isaac Ingram, Doris Williams, Esther Ingram, Arthur Williams, Phillip Ingram, Louisa Agnes Ingram OAM holding daughter Olive Ingram, and Jack Patten. The name of the person in the background to the right is not known at this stage.

AIATSIS Collection

Used under fair use condition for the purpose for research or study

The first Day of Mourning was a culmination of years of work by the Australian Aborigines League (AAL) and the Aborigines Progressive Association (APA). It would became the inspiration for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander activism throughout the remainder of the twentieth century. In the early 1960s, both organisations would reform and reshape and become the driving force calling for a constitutional referendum that would take place in 1967.

The AAL was able to persuade many religious denominations to declare the Sunday before Australia Day as ‘Aboriginal Sunday’. This was to serve as a reminder of the unjust treatment of Indigenous people. The first of these took place in 1940 and continued until 1955, when it moved to the first Sunday in July.

In 1957, with support and cooperation from federal and state governments, the churches and major Indigenous organisations, a National Aborigines Day Observance Committee (NADOC) was formed, which continues to this day as NAIDOC.

Anonymous. “The 1938 Day of Mourning,” on the AIATSIS website Nd [Online] Cited 21/02/2022

Unknown photographer (Australian)

Jack Patten reads the resolution at the Day of Mourning Conference on 26 January 1938

Mar. 1938 (publication date), Sydney, N.S.W.: Man magazine

12 x 17cm

© Collections of the State Library of New South Wales

Used under fair use condition for the purpose for research or study

Unknown photographer (Australian)

In this 1938 re-enactment of Governor Phillip’s landing, Aborigines (specially brought in for the occasion) are shown running up the beach as the boats of the First Fleet marines land at Farm Cove. A group of white dignitaries sits in comfortable safety watching the invasion

1938

© Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW – Home and Away

Used under fair use condition for the purpose for research or study

Unknown photographer (Australian)

Aboriginal protests on Sydney Harbour, Australia Day, 1988

1988

Used under fair use condition for the purpose for research or study

National Film and Sound Archive of Australia (NFSA)

Pat Fiske (director)

Australia Daze (film still)

1988

National Film and Sound Archive of Australia (NFSA)

Pat Fiske (director)

Australia Daze (film clip)

1988

The production of Australia Daze involved dozens of camera crews across the nation, filming from midnight to midnight on 26 January 1988, in order to capture the many facets of the bicentenary of European settlement in Australia. From First Fleet re-enactments to Indigenous protests, backyard barbeques to royal visits, Australia Daze chronicles a broad array of events on that historic day and diverse voices and perspectives from across Australian society.

Australia Daze is a snapshot of one day in the millennia-long history of the country. The film is an opportunity for Australians to remember where they were, or to catch a glimpse of Australia’s past before they were born or arrived here. It is a chance to reflect on how much things have changed in 33 years – and also how little has changed.

Anonymous media release from the NFSA website Nd [Online] Cited 21/02/2022

Loui Seselja (Australian, b. 1948)

Sydney Harbour Bridge during the Walk for Reconciliation, Corroboree 2000, with the Aboriginal flag flying beside the Australian flag

2000

22.5 x 30.7cm

© National Museum of Australia

Used under fair use condition for the purpose for research or study

“Untitled,” c. 1932-33 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Untitled,” October/November, 1932 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Chrysler 70, bought Nov., 1932,” in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Springfield”, Byng, Near Orange, October 1932″ in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

Byng

… an area of scattered houses in green valleys (when there is no drought) dates back to before 1856.

It was originally named ‘Cornish Village’ after the original Cornish settlers who brought the first fruit trees from Cornwall and gave birth to the Orange district’s fruit industry on the ‘Pendarvis’ property. Apples were produced in Byng for over 100 years but now there are mainly cattle, sheep and a little cropping.

Driving through the winding lanes with hawthorn hedgerows on either side you will see in the distance an old homestead (Springfield) which has an old Celtic custom – on the porch there are three welcome stones. The host stands on one, the guest on another – then they greet each other on the centre stone.

Text from the Orange website [Online] Cited 01/11/2019. No longer available online

“Springfield”, Byng, Near Orange, October 1932″ in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Remains of the first house built in Byng,” October, 1932 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“At Springfield,” 1932 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“J.F. and Woodward,” 1932 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“At Springfield,” 1932 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Untitled (Rabbiting),” 1932 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Hawksbury River,’ 1932-33 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Betty Broad,” 16th October, 1932 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Lucknow, Near Orange,” November, 1933 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

Lucknow

1929-1935: Prospecting rarely ever ceases on a once lucrative gold-field and in 1928-9 companies such as St. Algnan’s (New Guinea) Gold Lodes N.L. and Lucknow Gold Options Co. were quite busy. In particular St. Aignan’s found a rich ‘brown vein’ away from ‘that portion already riddled with holes’, at a depth of only 38 feet. …

The village has a large potential to attract tourists. The iron head-frames at Wentworth Main and at Reform, right beside the highway in the village area with their accompanying equipment, are the most strikingly accessible of gold mining memorials. At Wentworth Main moreover, the largest of the iron sheds still contains a great deal of equipment, including the stamper battery and various engines. In the paddock to the west of the highway there is isolated equipment- a boiler, a winding engine. The winding house for Reform still stands.

Anonymous. “Gold mining at Lucknow,” on the Orange website [Online] Cited 01/11/2019

“Washing for gold on Springfield,” November, 1933 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“St. Aignan Gold Mine,” November, 1933 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Springfield,” November, 1933 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Old Bill on the binder,” November, 1933 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Woodward : McColville ; J.F., filling the ensilage pit,” November, 1933 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

Silage is a type of fodder made from green foliage crops which have been preserved by acidification, achieved through fermentation. It can be fed to cattle, sheep and other such ruminants (cud-chewing animals). The fermentation and storage process is called ensilage, ensiling or silaging, and is usually made from grass crops, including maize, sorghum or other cereals, using the entire green plant (not just the grain).

“At “Millambri”, Canowindra,” 1933 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Bathurst,” November 1933 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Untitled (Victoria),” November, 1933 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Myers, Melbourne,” November 1933 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

“Bourke St., Melbourne,” November 1933 in John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album

John “Jack” Riverstone Faviell 1922-1933 photo album back cover

You must be logged in to post a comment.