June 2020

Views taken during Cleansing Operations, Quarantine Area, Sydney, 1900, under the supervision of Mr George McCredie, F.I.A., N.S.W. photographed by John Degotardi Jr. also known as The Plague Albums.

6 albums containing 379 photoprints

John Degotardi Jr. (Australian, 1860-1937)

NSW Department of Public Works photographer

264. Professional Ratcatchers

1900

From Vol. IV of Views taken during cleansing operations. Quarantine areas, Sydney, 1900

Gelatin silver print

New South Wales State Archives & Records NRS-12487 Photographs taken during cleansing operations in quarantine areas, Sydney

Public domain

Abstract

This text examines the photographs of John Degotardi Jr., photographer for the New South Wales Department of Public Works, who produced 6 photographic albums containing 379 photoprints of the plague in The Rocks, Sydney, 1900, also known as The Plague Albums.

It proposes alternate interpretations of the photographs, readings that both confirm the original purpose for their existence on the one hand, and subvert that purpose, and their formal legacy, on the other. In so doing we can begin to understand what an incredibly sophisticated photographer John Degotardi Jr. was, and how he deserves much more recognition than has been accorded him at present in the history of Australian photography.

Keywords

John Degotardi Jr., The Plague Albums, Sydney, Australia, bubonic plague, plague in Sydney, photography, art, urban landscape, the Prospect, prospectus, infection, rats, disease, plague, resumption, slum, community, The Rocks, Millers Point, Sydney Harbour Bridge.

Download Prospect/us, protect us (1.6Mb pdf)

Prospect/us, protect us: plague and resumption in fin de siècle Sydney

On John Degotardi Jr.’s The Plague Albums, Sydney, 1900

During this time of pestilence, I came across several online articles about the outbreak of bubonic plague that occurred in Sydney in 1900 (in particular “Purging Pestilence – Plague!”1), the infection more virulent – don’t you love that word – in the harbour side slums around Darling Harbour, Millers Point and The Rocks but covering “the whole of the quarantine area, which stretched from Millers Point east to George Street, along Argyle, Upper Fort, and Essex Streets thence south to Chippendale, covering the area between Darling Harbour and Kent Streets, west to Cowper Street, Glebe, along City Road to the area bounded by Abercrombie, Ivy, Cleveland Streets, and the railway. The area east from George Street enclosed by Riley, Liverpool, Elizabeth and Goulburn Streets; Gipps, Campbell and George Streets were also quarantined, as were certain areas in Woolloomooloo, Paddington, Redfern and Manly.”2

Under the supervision of architect and consulting engineer Mr George McCredie, who was appointed by the Government to take charge of all quarantine activities in the Sydney area, work began on March 23, 1900 to cleanse the infected areas, and through compulsory purchase, or resumption (Australian law: the action, on the part of the Crown or other authority, of reassuming possession of lands, rights, etc., previously granted to another), to demolish slum properties. The buildings selected for demolition because of the health risks they supposedly raised, were recorded by photography,3 through the auspices of John Degotardi Jr., photographer for the New South Wales Department of Public Works, who produced 6 photographic albums containing 379 photoprints of the plague in The Rocks, Sydney, 1900, also known as The Plague Albums.

Degotardi Jr.’s photographs, commissioned as result of the outbreak, “are largely of buildings requiring to be demolished, and include the interior and exterior of houses, stores, warehouses and wharves, and surrounding streets, lanes and yards, thus providing a fairly clear indication of the state of the city during and immediately after the plague.” They document property and living conditions before, during and after the outbreak of plague. “George McCredie noted in a letter to Sir William Lyne that ‘Where it was found necessary to pull down premises or destroy outbuildings photographs were taken of them before their demolition, and in order to prepare in case of future litigation, each inspector was instructed to take careful notes of any property that might be destroyed.'”4

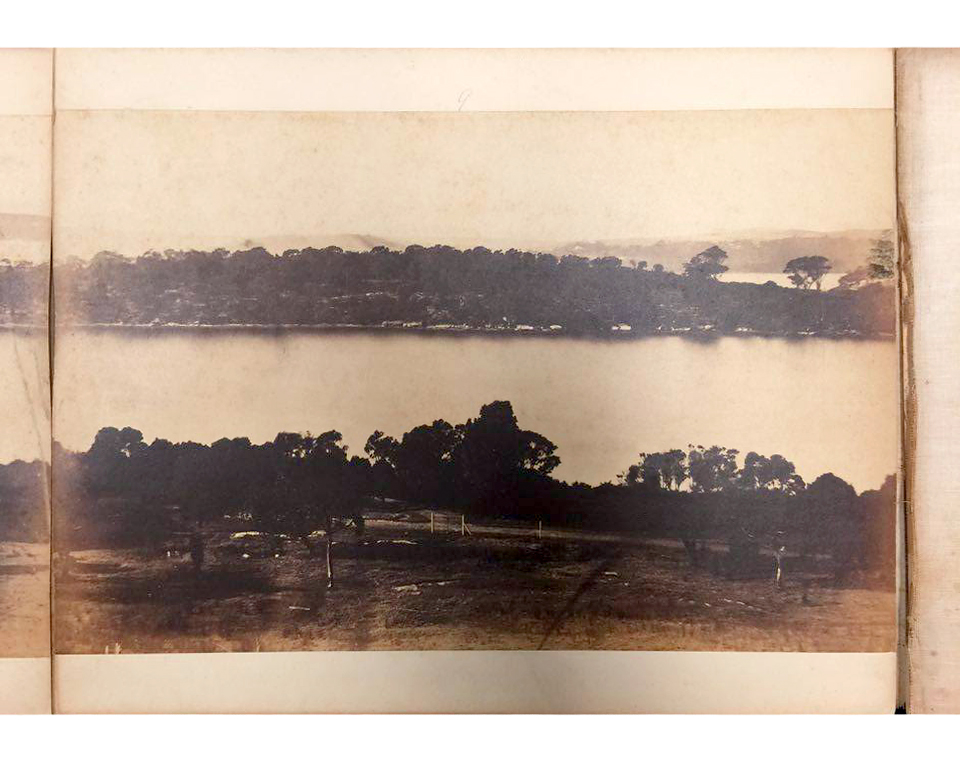

Probably taken on a large format glass plate camera (although no details are given), the resultant album photographs, now scanned, are available at high resolution (600dpi) and 130Mb file size images on the New South Wales State Archives and Records website copyright free, in the public domain. While it is admirable to have these photographs online, the scans have been left in their original condition, as is an archives want, in order to protect the presumed integrity of the original artefact. In other words, over 100 years after the taking of the photograph, this is the current physical state of the object and this is how the images should be seen today. You can see a couple of iterations of the original scans below, replete with their sickly yellow hue, which does not allow the viewer to really appreciate the scene, the photograph as a complete composition, or the skill of the photographer when observing and capturing the urban terrain. This is not how these photographs would have appeared when originally produced and their deterioration is akin to a layer of yellowing varnish that obscures the colours and details of some Old Master painting, which has discoloured with age. Conservators do not leave this layer of yellow in place, they remove it. The same can be said of discoloured photographs.

In this case, I spent many hours restoring these photographs to their pristine condition, removing colour and dust spots, so that I may study the scene intimately, zooming into the image (because of their high quality) to observe everyday nuances of Sydney life in 1900. In so doing we can begin to understand what an incredibly sophisticated photographer John Degotardi Jr. was, and how he deserves much more recognition than has been accorded him at present in the history of Australian photography. Let us set the stage, then, for the taking of these photographs.

We note that for the photographer this was a job, working as he did for the New South Wales Department of Public Works. He was to document the quarantine area to provide a clear indication of the state of the city during and immediately after the plague, those photographs of interiors and exteriors, of buildings and boundaries (streets) – things that “exist to insure order and security and continuity and to give citizens a visible status”5 – also needed in case of future litigation (presumably by aggrieved landowners) after they were compulsorily purchased. Here we begin to understand that the aesthetic of urban landscape photography is always contextual and political. In his photographs Degotardi Jr. maps out the boundaries of his, the governments, and the camera’s authority – one’s position (and that of his all seeing, ambivalent ‘mechanical eye’), “not just a matter of where one stands, but that it is more comprehensively spatial, social and economic.”6

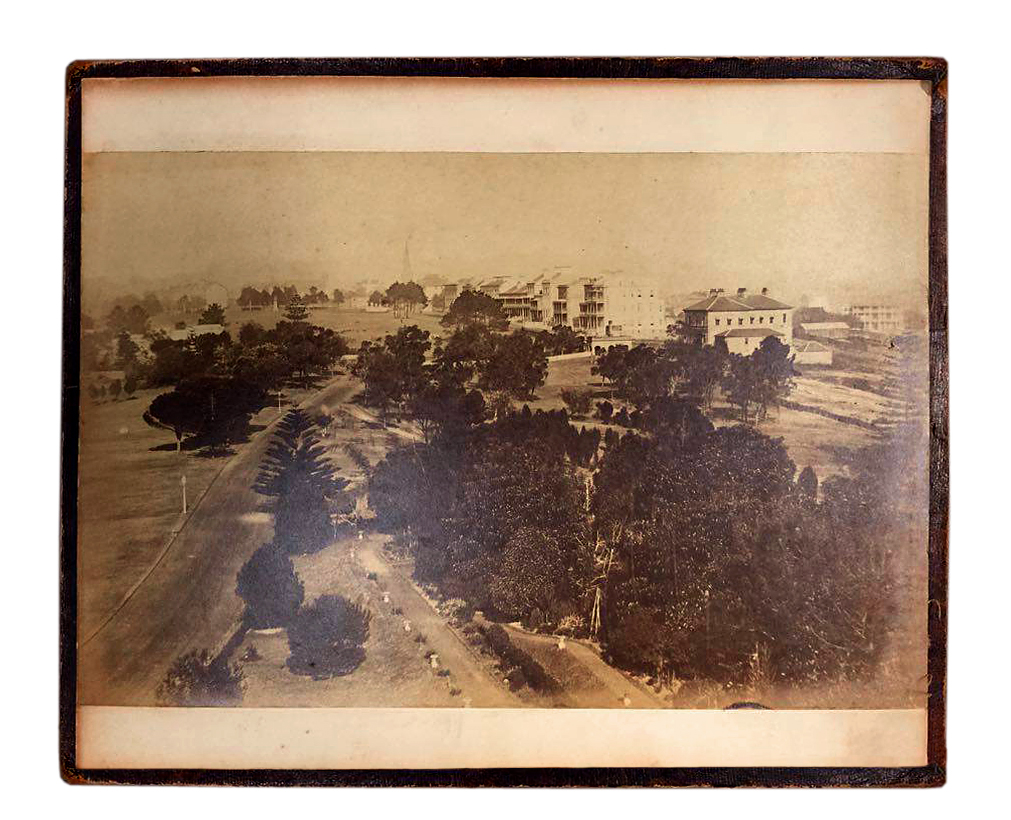

Often in these photographs (not necessarily in this posting, but more generally in the images found online), Degotardi Jr.’s camera occupies and draws on “the seventeenth century device of the ‘prospect’, an oblique landscape viewpoint located between ground and aerial perspectives… The viewpoint of the prospect hovers in mid air between the aerial image and the landscape view, oblique to the terrain it is depicting. It provides an order that would otherwise be illegible to the grounded eye.”7 In other words, Degotardi Jr. positions his camera to best bring order to the urban chaos, picturing through the ritual of taking photographs, a surveyed and regulated order (both economic and legislative) that determines the urban grid – in this case, of the quarantine areas / remediated areas, dis-ease areas / proposed redevelopment, business areas – in some of the oldest suburbs of Sydney. Following Goldswain’s commentary on the photographs of John Joseph Dwyer and his mapping of the gold mining city of Kalgoorlie in Western Australia, we might concur that, “It is not unreasonable to suggest that Dwyer’s [Degotardi Jr.’s] camera is literally prospecting, combining both senses of the word, mapping the city and its suburbs to find an economic potential in its ordered state…”8

In his “views”, Degotardi Jr.’s camera often portrays people (in)congruously in doorways or on streets, used to document scale or to bare witness to their surroundings. People, mainly men, go about their work often demolishing buildings or cleaning rubbish in the streets, stopping as the photograph is taken, or deliberately posed by the photographer. In some images the photographer sets up a scene that has no logic at all. For example, the photograph of Nos. 223, 225 Sussex Street (below) evidence a shoeless lad, a group of young men, a painter, and two firemen who hold a deflated fire hose which leads out of shot in one direction and terminates under the eves of a row of shops in the other direction, seemingly connected to nothing. Their surroundings are declamatory and, for today’s reader, insightful. In a building erected by P.R. Larkin in 1866, the row of shops includes a “Johnny All Sorts” – a business that bought and sold all sorts of things. To the right of the group are pasted billboards, much as today, two of which advertise a plague remedy and disinfectant soap (sound familiar in 2020?):

Avoid the

PLAGUE!

Purchase at Once!!

Prof. VON ELSEBERG’S

‘KALTHA’

Just Arrived

Notice to householders

BLACK DEATH

or Bubonic Plague

SANITOL

Disinfectant soap

3d Double tablets 3d

In other photographs, men stand in doorways, hidden in the shadows (No. 20 Upton Street). Many are images of workers, homeowners, citizens and families who live a hand to mouth existence. The intimacy of these photographs portrays, betrays, the place where societies rejects are housed, the setting (the place or type of surroundings where something is positioned or where an event takes place) of human lives; the “setting”, or settling, of human lives, as in the solidification of space and place, the environment of existence. As a group of photographs the series is an extraordinary social document of poverty and squalor, of the desperation of people just getting by.

To the photographer, and to the people and buildings he was photographing, the familiar serves as a point of departure. Firstly, Degotardi Jr. documents what was there – this diseased land, a landscape not only as a composition of spaces but also a composition of a web of boundaries. Secondly, he photographs to map out what was to be “resumed” through the Resumption Act 1900, the city “fathers” using the outbreak of bubonic plague as a convenient excuse to compulsorily purchase land in the loosely defined quarantine area, offering the residents compensation “estimated without reference to any alteration in the value of such land arising from any purchase or any appropriation or resumption for any purpose mentioned in this Act or the establishing of any public works on any land the subject of any such purchase, appropriation, or resumption.” These albums, then, become a prospectus, a prospect/us, an authentic record of the terms, the conditions and the contexts for the reformist attitude in the minds of these city fathers: not to protect us (the populace) but to prospect us, using land resumption as the tool to get rid of the old and bring in the new. The plan was to demolish the existing structures and rebuild to a grand design.

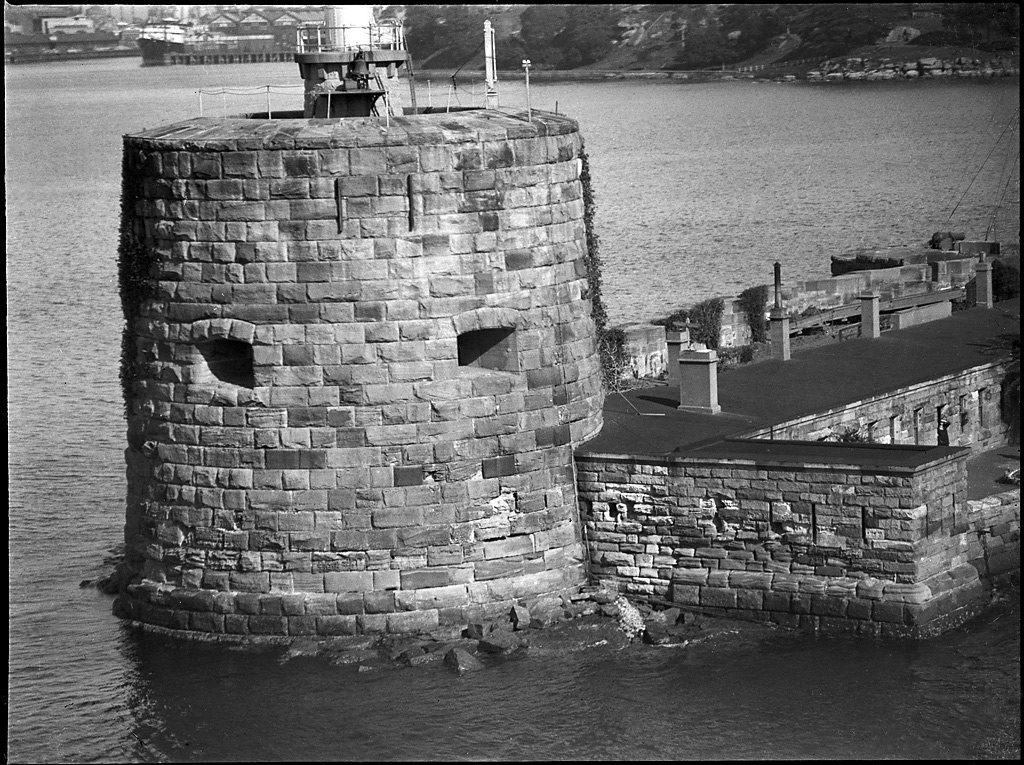

Factored into the design of the Resumption Plans was the need to keep Dawes Point free for the construction of a possible bridge across the harbour. “While public health was a convenient excuse for resumptions, the need for a harbour bridge may also have motivated the authorities.”9

“Plans were underway even at these early stages and a good 23 years before construction of the bridge commenced. Even at the turn of the nineteenth century, it was clear that there would need to be a widened thoroughfare to accommodate traffic entering and exiting the bridge, and many buildings would need to be sacrificed to achieve this. The bubonic plague outbreak offered the ideal opportunity to highlight the inadequacies in a lot of buildings, and the chance to condemn the area as slum, whose only chance of redemption was through mass demolition.”10

But as an article by Gillian McNally in The Daily Telegraph insightfully observes, “The reshaping of the city … provided a convenient “public health” excuse for resumption of private property. The NSW Government took back ownership of virtually the entire headland from Circular Quay to Darling Harbour and demolished hundreds of slum houses and businesses in what are now prime real estate precincts such as George St, Sussex St, Kent St and Martin Place. There was little attempt to define a slum area and there was no recognition of the rights of tenants as resumptions took out a house here, a street there and great swathes of properties in some suburbs to improve crooked roads and thoroughfares.”11

If we define a landscape as an environment modified by the permanent presence of a group of people,12 then what these photographs do, in one sense, is document the death throes of the communities that created this urban landscape. As J.B. Jackson notes, “No group sets out to create a landscape, of course. What it sets out to do is to create a community, and the landscape as its visible manifestation is simply the by-product of people working and living, sometimes coming together, sometimes staying apart, but always recognising their interdependence.”13

But, as Denis Cosgrove observes, the concept of landscape (and thus of community) is always powerful and political.

“Landscape was a ‘way of seeing’ that was bourgeois, individualist and related to the exercise of power over space. The basic theory and technique of the landscape way of seeing was linear perspective … and is closely related by [Alberti] to social class and spatial hierarchy. It employs the same geometry as merchant trading and accounting, navigation, land survey, mapping and artillery. Perspective is first applied in the city and then to a country subjugated to urban control and viewed as landscape. … The visual power given by the landscape way of seeing complements the real power humans exert over land as property.”14

The photographs in these albums, then, evidence the real power of the city fathers over land as property, their property and not that of the citizens or the communities that had grown up in these unregulated buildings and shantytowns. They, the city fathers, ordered these pictures into existence. The landscape thus portrayed, is “a way of seeing, a composition and structuring of the world so that it may be appropriated by a detached, individual spectator to whom an illusion of order and control is offered through the composition of space according to the certainties of geometry.”15 Residents, armed with lime, carbolic acid and sulfuric acid, were then enlisted to cleanse, disinfect and even burn and demolish their own houses in infected areas.16

But in another and far more important sense, what these photographs document are the lives of ordinary people, people who form a community of souls, for whom a sense of community was of vital, life giving importance. The photographs record their existence as traces and energies from the past that impinge on our consciousness in the present. Here are the ratcatchers, modest men with their traps and cages, bowties and pipes, all adorned bar one in the obligatory hat; here are two Chinese gentlemen surrounded by squalor and chopped wood, one sitting on a pile of rocks, both portrayed with a touching dignity; here in a rubble strewn Wexford street men resignedly sit on the ground or stare pensively at the camera, pondering we know not what, while on the other side of the street children stare inquisitively at the camera; and there smoke arises from amongst the demolished Exeter Place as labourers, persons doing unskilled manual work for wages, dance a ballet of destruction amongst the rubble. Children on a veranda, pails in a dirt back yard, chickens, and children, roaming free… and a rock tied on a piece of string guards the entrance to a door.

Pails and tins and rocks and wood and chickens and children and rats and butchers and dirt and sugar… and a rock tied on a piece of string, like the great pendulum of time, marking all their existences. And yet… and yet, what that most excellent photographer John Degotardi Jr. does (in this second sense), is not just to record as instructed, their quarantine, their dispossession – but through his photographs, he empathises with the people, with their community of existence. While his photographs are not sentimental about humankind, traces of humanity are ever-present in his pictures. Unlike the Parisian Eugène Atget, who established a beneficial “distance between man and his environment” here, Degotardi Jr. engages in a conversation with the people and the city. And in so doing, in so immersing himself in (t)his project, he lifts his photographs out of the ordinary, out of (t)his world.

As Jon Kabat-Zinn has so eloquently observed,

“Effortless activity happens at moments in dance and in sports at the highest levels of performance; when it does, it takes everybody’s breath away. But it also happens in every area of human activity, from painting to car repair to parenting. Years of practice and experience combine on some occasions, giving rise to a new capacity to let execution unfold beyond technique, beyond exertion, beyond thinking. Action then becomes a pure expression of art, of being, of letting go of all doing – a merging of mind and body in motion.”17

It would seem to me that this is the great achievement of a Department of Public Works photographer who was hired to do a job: that he transcended his subject matter by letting execution unfold beyond technique, by immersing himself in the derivation of composition, perspective, light and form, place and context, feeling and emotion. So while these photographs in the obvious obey the command of the city fathers, of the planners, of patriarchy and the capital of industry, in the immersive and subversive they undermine the prospectus that first proposed them. Unable to protect the people, to protect us, from the demolition of community (to the benefit of commerce hidden under the “public health” excuse), John Degotardi Jr. leaves, through his photographs, a lasting legacy of lives that matter, not bureaucracy that doesn’t. He imagines streets and buildings and lives, pictured for eternity through the psychogeography of the city. And if we think of the long queues of unemployed in our current pandemic, here are also lives that matter – the lives of the dead and the destitute, each one a valuable, sentient, human being.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Word count: 2,809

Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image. Many thanks to the brains trust on the Lost Sydney Facebook web page for helping in my research in locating exact positions of some of the photographs and the location of the resumption maps online. Apologies if I have got anything incorrect. All photographs are in the public domain. More photographs can be found on the State Library of New South Wales website, New South Wales State Archives and Records website and the John Degotardi Flickr stream.

Footnotes

1/ Anonymous. “Purging Pestilence – Plague!” on the New South Wales State Archives and Records website [Online] Cited 25 May 2020, now located on the Museums of History New South Wales website cited 12/09/2025

2/ NRS-12487 | Photographs taken during cleansing operations in quarantine areas, Sydney. Text from the State Archives of New South Wales website [Online] Cited 11/04/2020.

3/ Alan Davies. “Photography in Australia,” in Celebrating 100 years of the Mitchell Library. Sydney: State Library of NSW, 2000. p. 86.

4/ Footnote 1. NSW Parliamentary Debates, 1900, vol. CIII, p. 111 quoted in Max Kelly. Plague Sydney. Marrickville, NSW: Doak Press, 1981 in NRS-12487 | Photographs taken during cleansing operations in quarantine areas, Sydney. Text from the State Archives of New South Wales website [Online] Cited 11/04/2020.

5/ J.B. Jackson. Discovering the Vernacular Landscape. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1984, p. 12.

6/ Philip Goldswain. “Surveying the Field, Picturing the Grid: John Joseph Dwyer’s Urban and Industrial Landscapes,” in Phillip Goldswain and William Taylor (eds.,). An Everyday Transience: The Urban Imaginary of Goldfields Photographer John Joseph Dwyer. UWA Publishing, 2010, p. 65-66.

7/ Ibid., p. 63.

8/ Ibid., p. 66.

8/ Anonymous. “Purging Pestilence – Plague!” on the State Archives of New South Wales website (archived) [Online] Cited 10 April 2020.

10/ Anonymous. “Bubonic Plague outbreak in Sydney in the 1900s helps Politicians to clear the way for transport progress & landmark,” on The Digger website 13th August 2016 [Online] Cited 10/40/2020.

11/ Gillian McNally. “Bubonic plague Sydney: How a city survived the black death in 1900,” in The Daily Telegraph September 3, 2015 [Online] Cited 16 May 2020.

12/ J.B. Jackson. Discovering the Vernacular Landscape. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1984, p. 12.

13/ Ibid.,

14/ Abstract in Denis Cosgrove. “Prospect, Perspective and the Evolution of the Landscape Idea,” in Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, Vol. 10, No. 1, 1985, pp. 45-62.

15/ Ibid., p. 55.

16/ McNally, op.cit.,

17/ Jon Kabat-Zinn. Wherever You Go There You Are. New York: Hachette Books, 1994, p. 44.

The political landscape

“I am enumerating some of the simplest and most visible elements in what can be called the political landscape: the landscape which evolved partly out of experience, partly from design, to meet some of the needs of men and women in their political [ie. social] guise. The political elements I have in mind are such things as walls and boundaries and highways and monuments and public places; these have a definite role to play in the landscape. They exist to insure order and security and continuity and to give citizens a visible status. They serve to remind us of our rights and obligations and of our history.”

J.B. Jackson. ‘Discovering the Vernacular Landscape’. Yale University Press, New Haven, 1984, p. 12.

Boundaries

“The most basic political element in any landscape is the boundary. Politically speaking what matters first is the formation of a community of responsible citizens, a well-defined territory composed of small holdings and a number of public spaces; so the first step toward organizing space is the defining of that territory, after which we divide it for the individual members. Boundaries, therefore, unmistakable, permanent, inviolate boundaries, are essential.”

J.B. Jackson. ‘Discovering the Vernacular Landscape’. Yale University Press, New Haven, 1984, p. 13.

“If we return to the notion that photography is an extension of pre-existing pictorial conventions, then it could be argued that the common feature of all the preceding images is the photographer’s reliance on the ‘prospect’ as the compositional device. The viewpoint of the prospect hovers in mid air between the aerial image and the landscape view, oblique to the terrain it is depicting. It provides an order that would otherwise be illegible to the grounded eye. John Macarthur suggests that the difference between the grounded landscape views and the prospect was not simply that different kinds of views required different kinds of representations. For theorists of the picturesque, a prospect was kind of view that could not be a picture.16 Macarthur distinguishes between the prospect and the landscape view as the difference between the cadastral [(of a map or survey) showing the extent, value, and ownership of land, especially for taxation] and the pictorial. Geographer Denis Cosgrove argues that the prospect was first used to ‘denote a view outward, a looking forward in time as well as space’ and that by the end of the sixteenth century it carried the ‘sense of an extensive or commanding sight or view, a view of the landscape as affected by one’s position.’17. The inference is that ‘one’s position’ is not just a matter of where one stands, but that it is more comprehensively spatial, social and economic. Cosgrove’s analysis of the prospect suggests an economic imperative behind its use and he cites its importance in Tudor England, where in combination with the ‘Malicious craft’ of surveying, it reflected a command over developed and commercially run farming estates of Tudor enclosures and the new landowners of monastic estates.18 Cosgrove notes the emergence of the verb ‘to prospect’ in the nineteenth century as a result of the speculative activities of gold mining.19.

It is not unreasonable to suggest that Dwyer’s camera is literally prospecting, combining both senses of the word, mapping the city and its suburbs to find an economic potential in its ordered state… Dwyer produces what could be considered Cosgrove’s spatial, chronological and commercial narrative compressed into the frame of the photograph…”

Philip Goldswain. “Surveying the Field, Picturing the Grid: John Joseph Dwyer’s Urban and Industrial Landscapes,” in Phillip Goldswain and William Taylor (eds.,). ‘An Everyday Transience: The Urban Imaginary of Goldfields Photographer John Joseph Dwyer’. UWA Publishing, 2010, p. 65-66.16. J. Macarthur. ‘The Picturesque: Architecture, Disgust and Other Irregularities’. Routledge, London, 2007, p. 190.

17. ‘Oxford English Dictionary’ as cited by D. Cosgrove, “Prospect, Perspective and the Evolution of the landscape Idea”, in ‘Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers’, New Series, Vol. 10, No. 1, 1985, p. 55.

18. Cosgrove, “Prospect,” p. 55.

19. Ibid., p. 61, note 64.

The Bubonic Plague hit Sydney in January 1900. Spreading from the waterfront, the rats carried the plague throughout the city. Within eight months 303 cases were reported and 103 people were dead.

When bubonic plague struck Sydney in 1900, George McCredie (1859-1903) was appointed by the Government to take charge of all quarantine activities in the Sydney area, beginning work on March 23, 1900. At the time of his appointment, McCredie was an architect and consulting engineer with offices in the Mutual Life of New York Building in Martin Place. McCredie’s appointment was much criticised in Parliament, though it was agreed later that his work was successful.

The infected areas, and buildings selected for demolition because of the health risks they supposedly raised, were recorded by photography. Most of the buildings demolished were considered slum buildings. John Degotardi Junior (1860-1937) worked at the NSW Government Printing Office and was photographer with the NSW Department of Public Works from 6 January 1897-1919.

John Degotardi Junior (Australian, 1860-1937)

MR. JOHN DEGOTARDI.

The death occurred yesterday at Lewisham private hospital of Mr John Degotardi formerly Government photographer. He was bom at Peacock’s Point Balmain on February 21 1860 and was a son of Mr John Degotardi one of the first professional photographers in New South Wales. Mr Degotardi, junior, was well known as an interstate oarsman. In recent years he was associated with Judge Backhouse as judge and starter at regattas. He has left a widow three sons (Messrs John, Albert, and Frederick) and three daughters Mrs. Delves, Mrs. Allen, of Nana Glen, and Mrs H R Brown.

Anonymous. “Mr. John Degotardi,” in The Sydney Morning Herald, Mon 15 Feb 1937 on the Trove website [Online] Cited 10/03/2020

A full biography of John Degotardi Jr.’s father can be found on the Design & Art Australia Online website.

Uncredited photographs by John Degotardi Jr. that appear in this posting can be found in “The Bubonic Plague,” By Lana in The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser, Sat 7 Apr 1900, on the Trove website. Download the full text with the newspaper images (6.7Mb pdf)

Grateful thanks to Associate Professor James McArdle for this information.

Darling Harbour Wharves Resumption Act 1900 No 10

Mode of estimating compensation

The amount of compensation in respect of any land resumed, as mentioned in sections two and three of this Act, shall be estimated without reference to any alteration in the value of such land arising from any purchase or any appropriation or resumption for any purpose mentioned in this Act or the establishing of any public works on any land the subject of any such purchase, appropriation, or resumption.

Provided also that the amount of compensation in respect of any land so resumed shall be estimated without reference to any alteration in the value of such land arising from any proclamation declaring any place comprising such land to be a station for the performance of quarantine within the meaning of the Quarantine Act 1897, or arising from any things done in pursuance of any such proclamation.

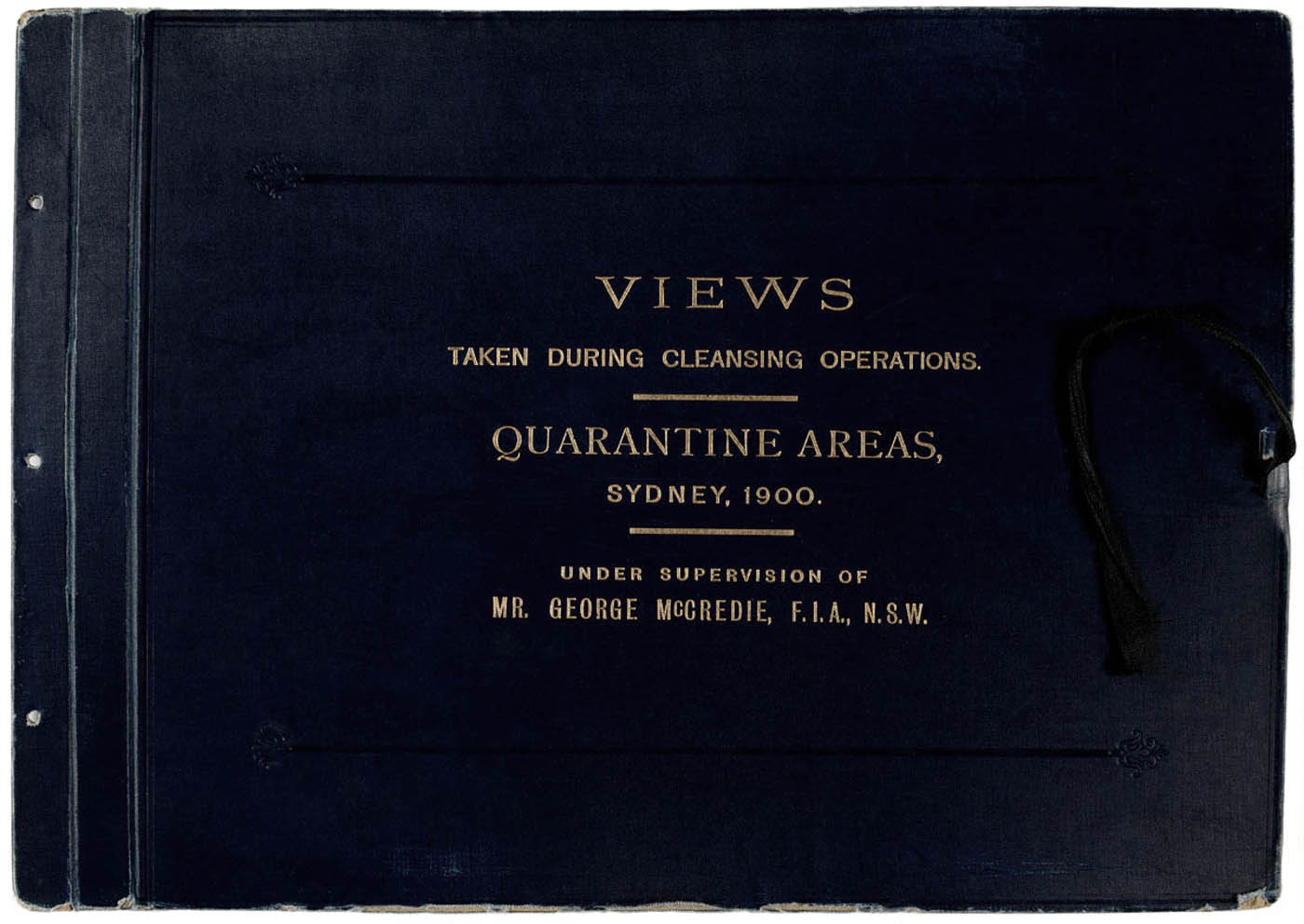

Cover of from Vol. IV of Views taken during Cleansing Operations, Quarantine Area, Sydney, 1900, Vol. IV / under the supervision of Mr George McCredie, F.I.A., N.S.W.

1900

66 silver gelatin photoprints

28 x 49cm

6 albums containing 379 photoprints also known as The Plague Albums

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales 413017

Public domain

Index from Vol. IV of Views taken during Cleansing Operations, Quarantine Area, Sydney, 1900, Vol. IV / under the supervision of Mr George McCredie, F.I.A., N.S.W. including number 264 Professional Ratcatchers (above)

1900

66 silver gelatin photoprints

28 x 49cm

6 albums containing 379 photoprints also known as The Plague Albums

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales 413017

Public domain

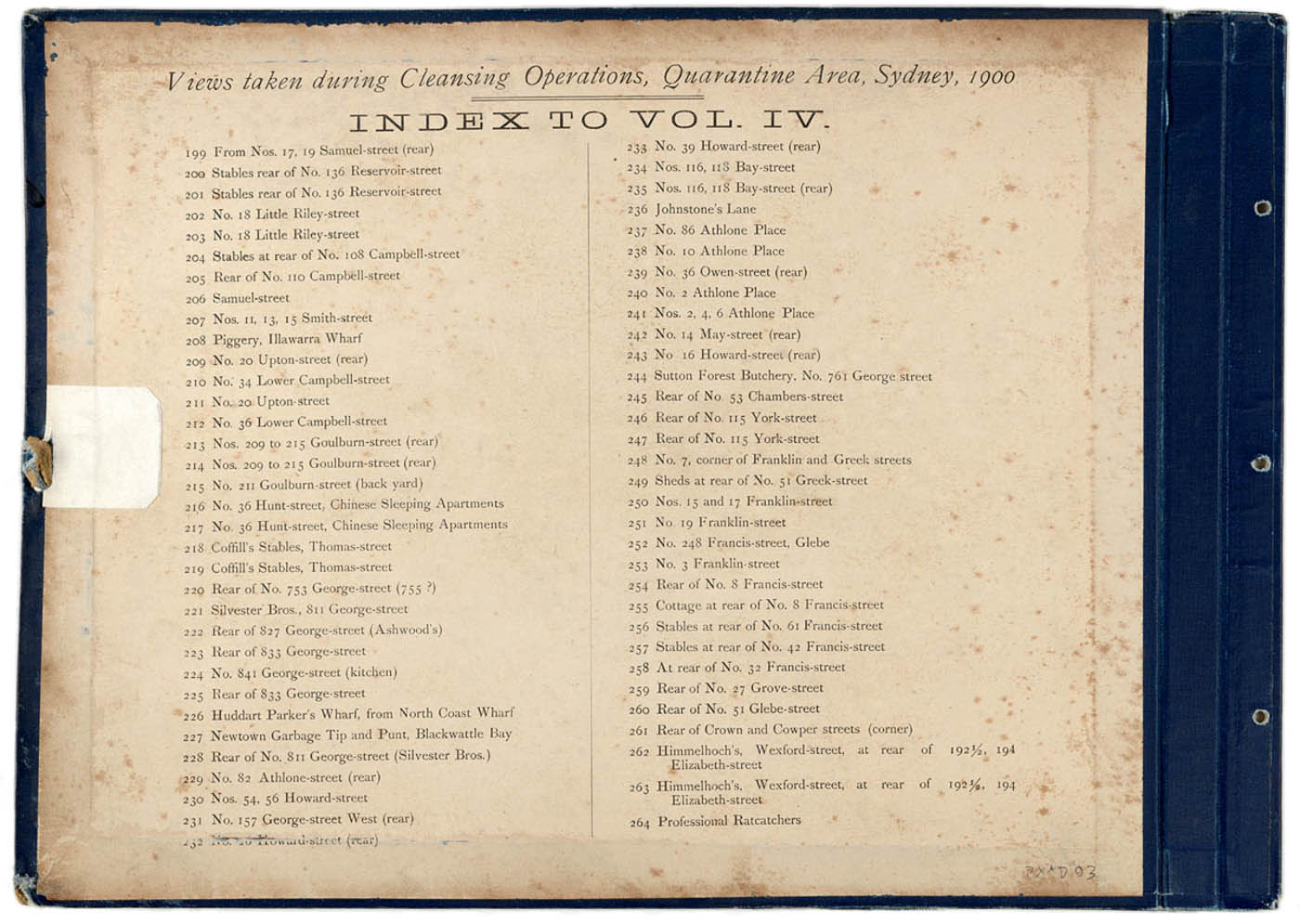

John Degotardi Jr. (Australian, 1860-1937)

NSW Department of Public Works photographer

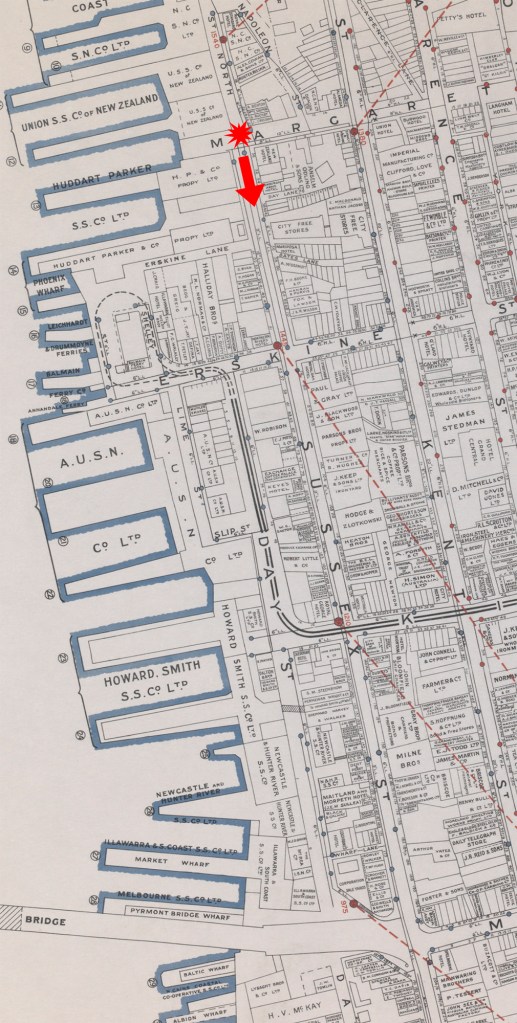

8. Sussex Street, looking South from Margaret Street (cleaned and colour corrected)

1900

From Vol. I of Views taken during cleansing operations. Quarantine areas, Sydney, 1900

Gelatin silver print

New South Wales State Archives & Records NRS-12487 Photographs taken during cleansing operations in quarantine areas, Sydney

Public domain

Intersection of Margaret Street and Sussex Street looking south, with the Edinburgh Arms Hotel at the end of the first block on the left

John Degotardi Jr. (Australian, 1860-1937)

NSW Department of Public Works photographer

8. Sussex Street, looking South from Margaret Street (original scan)

1900

From Vol. I of Views taken during cleansing operations. Quarantine areas, Sydney, 1900

Gelatin silver print

New South Wales State Archives & Records NRS-12487 Photographs taken during cleansing operations in quarantine areas, Sydney

Public domain

Intersection of Margaret Street and Sussex Street looking south, with the Edinburgh Arms Hotel at the end of the first block on the left

John Degotardi Jr. (Australian, 1860-1937)

NSW Department of Public Works photographer

8. Sussex Street, looking South from Margaret Street (details)

1900

From Vol. I of Views taken during cleansing operations. Quarantine areas, Sydney, 1900

Gelatin silver print

New South Wales State Archives & Records NRS-12487 Photographs taken during cleansing operations in quarantine areas, Sydney

Public domain

John Degotardi Jr. (Australian, 1860-1937)

NSW Department of Public Works photographer

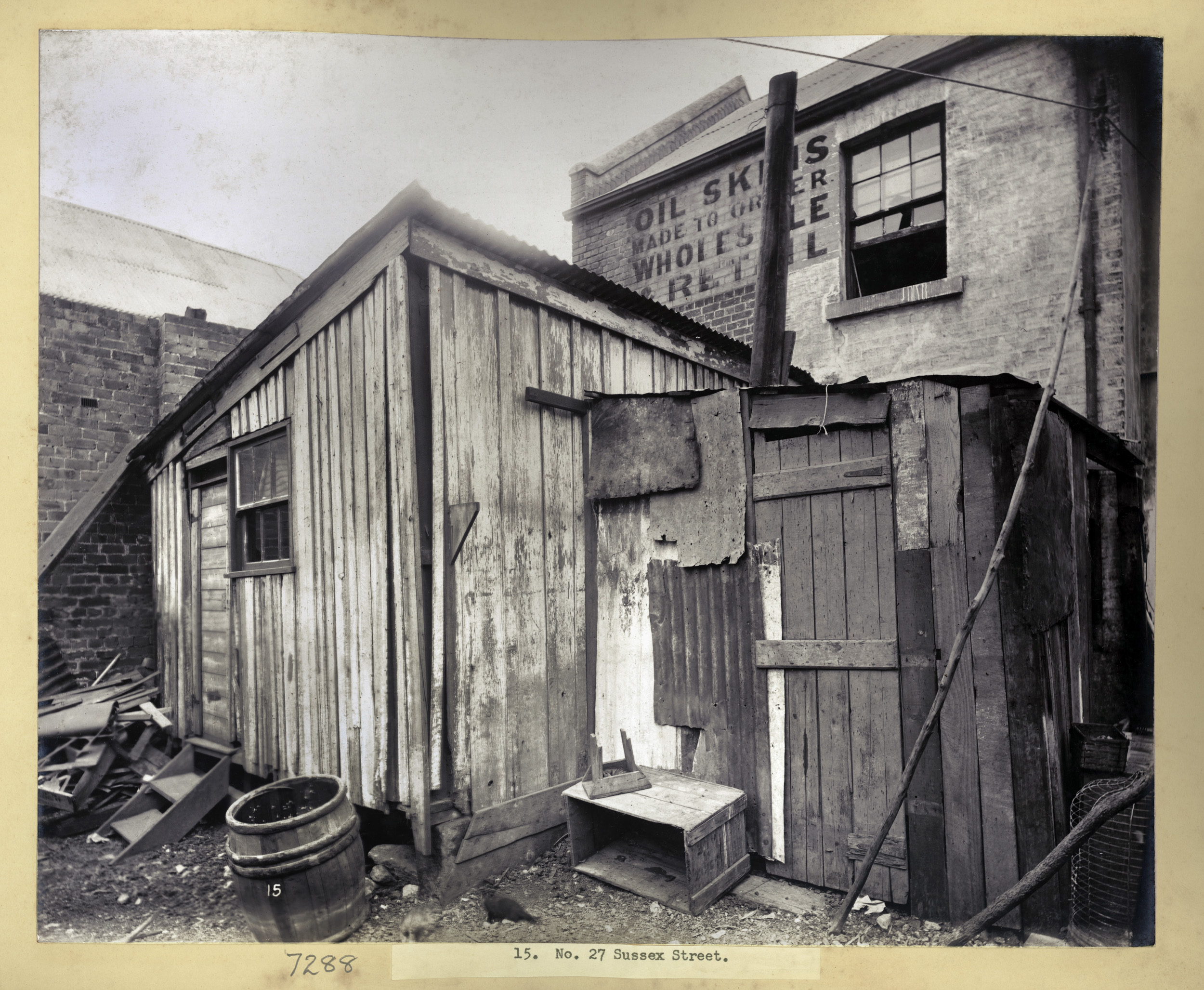

15. No. 27 Sussex Street, Barangaroo (rear of)

1900

From Vol. I of Views taken during cleansing operations. Quarantine areas, Sydney, 1900

Gelatin silver print

New South Wales State Archives & Records NRS-12487 Photographs taken during cleansing operations in quarantine areas, Sydney

Public domain

John Degotardi Jr. (Australian, 1860-1937)

NSW Department of Public Works photographer

16. No. 11 Margaret Street, Barangaroo

1900

From Vol. I of Views taken during cleansing operations. Quarantine areas, Sydney, 1900

Gelatin silver print

New South Wales State Archives & Records NRS-12487 Photographs taken during cleansing operations in quarantine areas, Sydney

Public domain

Views 28 and 29 are diametrically opposite views of the same scene on Kent Street, Sydney

John Degotardi Jr. (Australian, 1860-1937)

NSW Department of Public Works photographer

28. Cleansing the streets (Kent St. looking south across Margaret St. Union Hotel at 206 Kent St., Lazarus Rosenfeld at 208 Kent Street and Imperial Manufacturing Co. at 210-212 Kent St.) (original scan)

1900

From Vol. I of Views taken during cleansing operations. Quarantine areas, Sydney, 1900

Gelatin silver print

New South Wales State Archives & Records NRS-12487 Photographs taken during cleansing operations in quarantine areas, Sydney

Public domain

John Degotardi Jr. (Australian, 1860-1937)

NSW Department of Public Works photographer

28. Cleansing the streets (Kent St. looking north across Margaret St., Sydney to 202 & 204 Kent Street)

1900

From Vol. IV of Views taken during cleansing operations. Quarantine areas, Sydney, 1900

Gelatin silver print

New South Wales State Archives & Records NRS-12487 Photographs taken during cleansing operations in quarantine areas, Sydney

Public domain

This view is of St Phillip’s Anglican church in the distance, standing on Kent St. looking north across Margaret St., Sydney

John Degotardi Jr. (Australian, 1860-1937)

NSW Department of Public Works photographer

28. Cleansing the streets (Kent St. looking north across Margaret St., Sydney to 202 & 204 Kent Street) (detail)

1900

From Vol. I of Views taken during cleansing operations. Quarantine areas, Sydney, 1900

Gelatin silver print

New South Wales State Archives & Records NRS-12487 Photographs taken during cleansing operations in quarantine areas, Sydney

Public domain

John Degotardi Jr. (Australian, 1860-1937)

NSW Department of Public Works photographer

29. Cleansing the streets (Kent St. looking south across Margaret St. Union Hotel at 206 Kent St., Lazarus Rosenfeld at 208 Kent Street and Imperial Manufacturing Co. at 210-212 Kent St.)

1900

From Vol. I of Views taken during cleansing operations. Quarantine areas, Sydney, 1900

Gelatin silver print

New South Wales State Archives & Records NRS-12487 Photographs taken during cleansing operations in quarantine areas, Sydney

Public domain

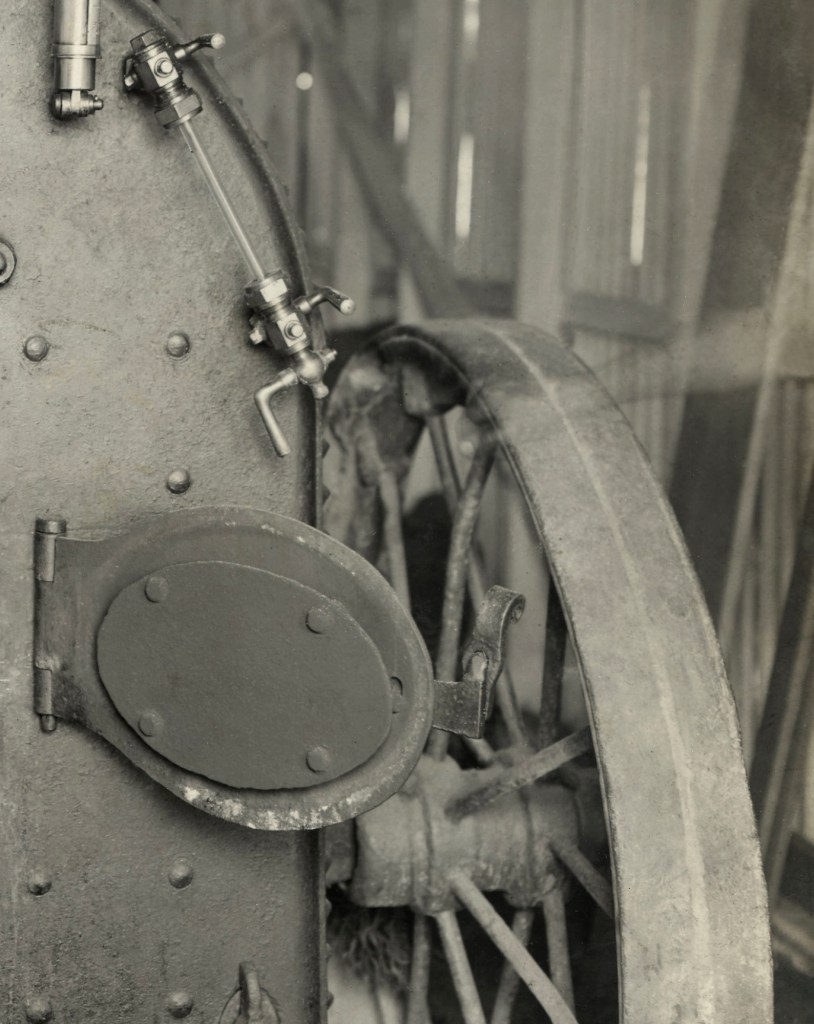

Views 28 and 29 are diametrically opposite views of the same scene on Kent Street, Sydney. Notice the angle of the fire appliance wheels in both photographs. The fire appliance is a 1891 Shand Mason Steamer. The Union Hotel is at 206 Kent St., Lazarus Rosenfeld is at 208 Kent Street and the Imperial Manufacturing Co. is at 210-212 Kent St.

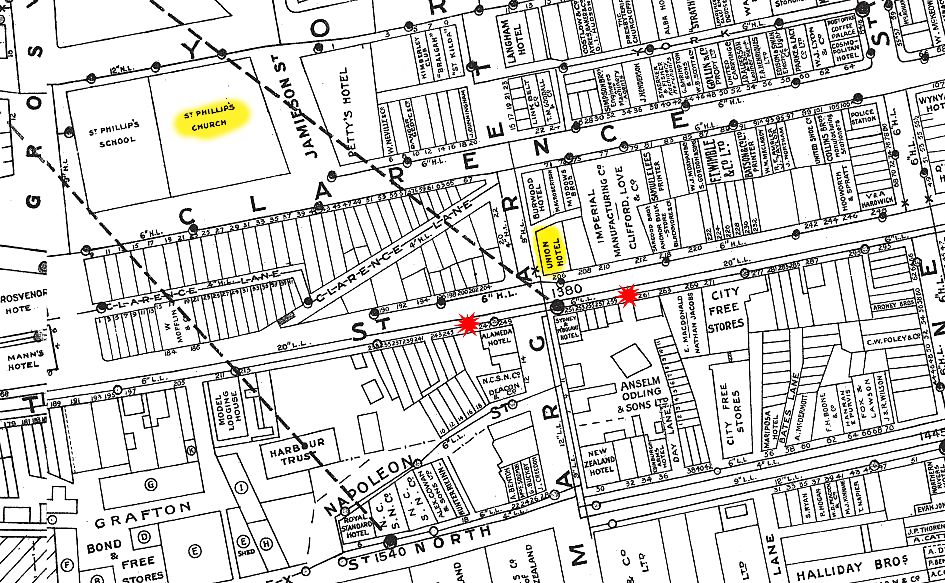

Kent Street, Sydney map showing the position from which both of the above photographs were taken (in red), and the position of the Union Hotel on the corner of Kent Street and Margaret Street, with St Phillip’s Anglican church in the distance.

John Degotardi Jr. (Australian, 1860-1937)

NSW Department of Public Works photographer

69. Nos. 223, 225 Sussex Street

1900

From Vol. II of Views taken during cleansing operations. Quarantine areas, Sydney, 1900

Gelatin silver print

New South Wales State Archives & Records NRS-12487 Photographs taken during cleansing operations in quarantine areas, Sydney

Public domain

John Degotardi Jr. (Australian, 1860-1937)

NSW Department of Public Works photographer

69. Nos. 223, 225 Sussex Street, Sydney (details)

1900

From Vol. II of Views taken during cleansing operations. Quarantine areas, Sydney, 1900

Gelatin silver print

New South Wales State Archives & Records NRS-12487 Photographs taken during cleansing operations in quarantine areas, Sydney

Public domain

The details of Nos. 223, 225 Sussex Street show a shoeless lad, a group of young men, a painter, and two firemen holding a firehouse… that leads nowhere. Behind, in a building erected by P.R. Larkin in 1866, is a row of shops which includes a “Johnny All Sorts” – a business that bought and sold all sorts of things. To the right of the group are pasted billboards, much as today, two of which advertise a plague remedy and disinfectant soap (sound familiar in 2020?):

Avoid the

PLAGUE!

Purchase at Once!!

Prof. VON ELSEBERG’S

‘KALTHA’

Just Arrived

Notice to householders

BLACK DEATH

or Bubonic Plague

SANITOL

Disinfectant soap

3d Double tablets 3d

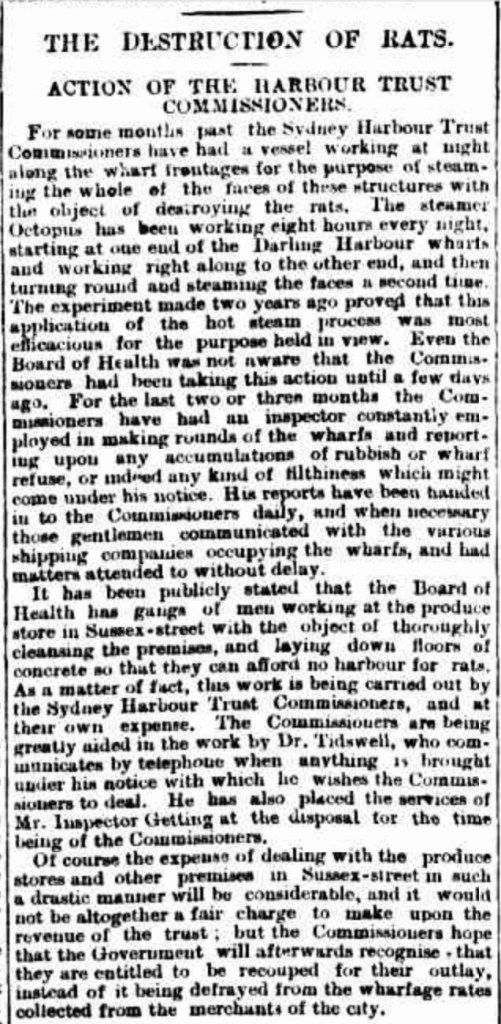

“The Destruction of Rats,” in The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW: 1842-1954) Mon 24 Feb 1902 Page 8 from the Trove website mentioning the steamer Octopus (see below) and Sussex Street (above)

John Degotardi Jr. (Australian, 1860-1937)

NSW Department of Public Works photographer

70. [Octopus] Cleansing the Wharves

1900

From Vol. II of Views taken during cleansing operations. Quarantine areas, Sydney, 1900

Gelatin silver print

New South Wales State Archives & Records NRS-12487 Photographs taken during cleansing operations in quarantine areas, Sydney

Public domain

Housing and other buildings

The photos were taken by Mr. John Degotardi, Jr., photographer from the Department of Public Works and depict the state of the houses, ‘slum’ buildings and streets at the time of the outbreak – interior and exterior of houses, stores, warehouses and wharves, and lanes and yards – and the cleansing and disinfecting operations which followed.

The photos provide a fairly clear indication of the state of the city during and immediately after the plague.

Streetscapes

Quarantine areas were established. These stretched from Millers Point east to George Street, along Argyle, Upper Fort, and Essex Streets then south to Chippendale, covering the area between Darling Harbour and Kent Streets, west to Cowper Street, Glebe, along City Road to the area bounded by Abercrombie, Ivy, Cleveland Streets, and the railway. The area east from George Street enclosed by Riley, Liverpool, Elizabeth and Goulburn Streets, Gipps, Campbell and George Streets were also quarantined, as were certain areas in Woolloomooloo, Paddington, Redfern and Manly.

Cleansing

Cleansing and disinfecting operations in the quarantine areas lasted from 24 March – 17 July and included the demolition of ‘slum’ buildings. Local residents were employed to undertake the cleansing, disinfecting, burning and demolition of the infected areas, including their own homes. Shovels, brooms, mattocks, hoses, buckets, and watering cans, were tools used to clear, clean, lime wash and disinfect. Not only buildings and dwellings were subjected to the cleansing operations but also wharves and docks were cleared of silt and sewerage.

Cleansing agents used during the cleansing operations included: solid disinfectant (chloride of lime); liquid disinfectant (carbolic water: miscible carbolic, 3/4 pint water, 1 gallon); sulphuric acid water (sulphuric acid, 1/2 pint water, 1 gallon); carbolic lime white (miscible carbolic 1/2 pint to the gallon).

Rat catchers were employed and the rats burned in a special rat incinerator. Over 44,000 rats were officially killed in the cleansing operations.

Sydney Harbour Trust

In 1901 the Sydney Harbour Trust resumed hundreds of properties in The Rocks and Millers Point. While public health was a convenient excuse for resumptions,1 the need for a harbour bridge may also have motivated the authorities. Green Bans in the 1970s on the redevelopment of The Rocks helped preserve this historic area which is now a major tourist attraction. The Rocks area has been under the control of the Sydney Cove Redevelopment Authority since 1970 and the Sydney Harbour Foreshore Authority since 1999.

Anonymous. “Purging Pestilence – Plague!” on the State Archives of New South Wales website (archived) [Online] Cited 10 April 2020

1/ The dawn of a new century combined with the Federation of the Australian states to form the Commonwealth of Australia brought a new sense of expectancy, hope and vision for the future to the towns, cites and rural areas of Australia. The outbreak of the Bubonic plague in The Rocks area of Sydney in 1900 was just the catalyst needed to engender a reformist attitude in the minds of the city fathers. Land resumption was the tool used by the city council to get rid of the old and bring in the new. Large sections of The Rocks and Surry Hills were razed and rebuilt. The commercial waterfront areas of Darling Harbour were resumed en masse and redeveloped to better handle the vast amount of goods now passing through the port of Sydney, the existing facilities having become totally inadequate.

Anonymous. “The History of Sydney: Federation Sydney 1902-1917,” on the Visit Sydney Australia website [Online] Cited 10/04/2020

See also Darling Harbour Resumption Maps, 1900-1902 on the NSW State Archives website (archived) [Online] Cited 10/04/2020

John Degotardi Jr. (Australian, 1860-1937)

NSW Department of Public Works photographer

80. No. 50 Wexford Street (rear), Chinese bedroom

1900

From Vol. II of Views taken during cleansing operations. Quarantine areas, Sydney, 1900

Gelatin silver print

New South Wales State Archives & Records NRS-12487 Photographs taken during cleansing operations in quarantine areas, Sydney

Public domain

Wexford Street crops up repeatedly in the Cleansing photos … it was roughly where Wentworth Avenue now is. The whole area was demolished in slum clearance schemes and rebuilt. (Thank you beachcomber australia for the information)

John Degotardi Jr. (Australian, 1860-1937)

NSW Department of Public Works photographer

82. Wexford Street

1900

From Vol. II of Views taken during cleansing operations. Quarantine areas, Sydney, 1900

Gelatin silver print

New South Wales State Archives & Records NRS-12487 Photographs taken during cleansing operations in quarantine areas, Sydney

Public domain

Wexford Street, before it was cleared for the construction of Wentworth Avenue.

John Degotardi Jr. (Australian, 1860-1937)

NSW Department of Public Works photographer

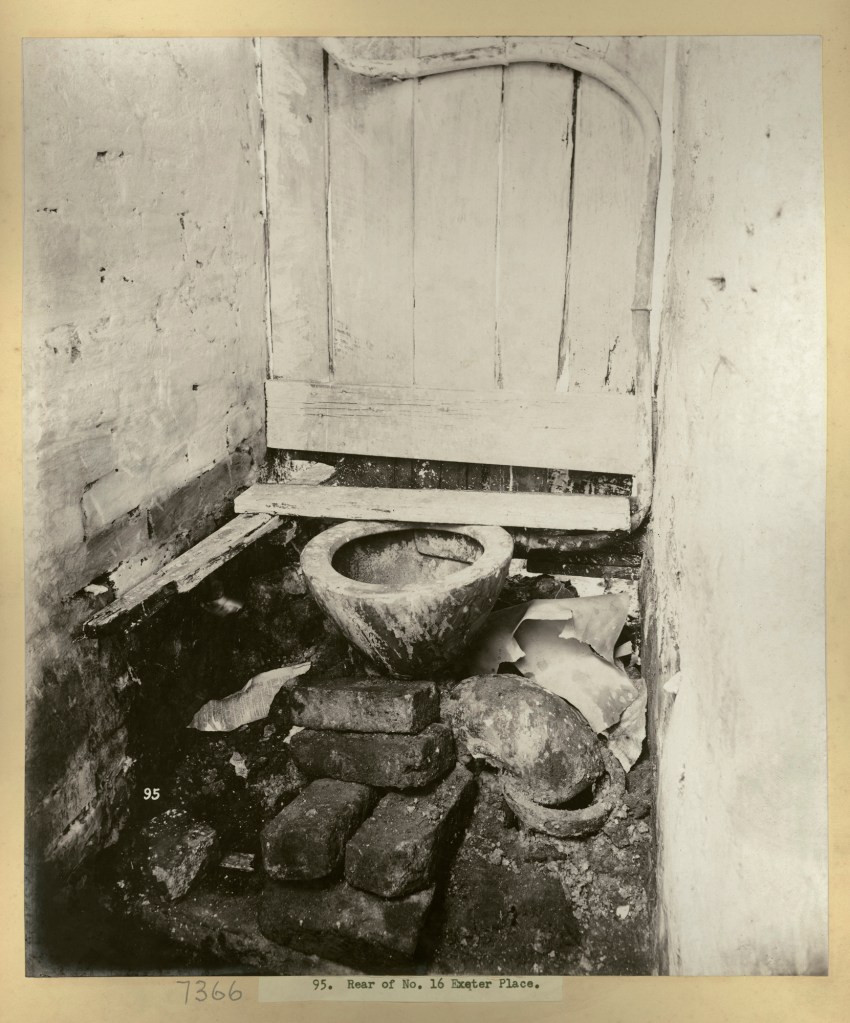

95. Rear of No. 16 Exeter Place

1900

From Vol. II of Views taken during cleansing operations. Quarantine areas, Sydney, 1900

Gelatin silver print

New South Wales State Archives & Records NRS-12487 Photographs taken during cleansing operations in quarantine areas, Sydney

Public domain

John Degotardi Jr. (Australian, 1860-1937)

NSW Department of Public Works photographer

97. Rubbish tip in Campbell Street

1900

From Vol. II of Views taken during cleansing operations. Quarantine areas, Sydney, 1900

Gelatin silver print

New South Wales State Archives & Records NRS-12487 Photographs taken during cleansing operations in quarantine areas, Sydney

Public domain

John Degotardi Jr. (Australian, 1860-1937)

NSW Department of Public Works photographer

97. Rubbish tip in Campbell Street (detail)

1900

From Vol. II of Views taken during cleansing operations. Quarantine areas, Sydney, 1900

Gelatin silver print

New South Wales State Archives & Records NRS-12487 Photographs taken during cleansing operations in quarantine areas, Sydney

Public domain

John Degotardi Jr. (Australian, 1860-1937)

NSW Department of Public Works photographer

105. Exeter Place demolished

1900

From Vol. II of Views taken during cleansing operations. Quarantine areas, Sydney, 1900

Gelatin silver print

New South Wales State Archives & Records NRS-12487 Photographs taken during cleansing operations in quarantine areas, Sydney

Public domain

John Degotardi Jr. (Australian, 1860-1937)

NSW Department of Public Works photographer

105. Exeter Place demolished (details)

1900

From Vol. II of Views taken during cleansing operations. Quarantine areas, Sydney, 1900

Gelatin silver print

New South Wales State Archives & Records NRS-12487 Photographs taken during cleansing operations in quarantine areas, Sydney

Public domain

NRS-12487 | Photographs taken during cleansing operations in quarantine areas, Sydney

These are photographs of quarantine areas in Sydney, following the outbreak of bubonic plague in 1900. The photographs were commissioned as result of the outbreak. Mr. George McCredie was in charge of cleansing and disinfecting operations in the quarantine areas. He commenced work on 23 March 1900. He was one of 28 temporary sanitary inspectors appointed by the Board of Health in conjunction with the Department of Public Works which was made responsible for the cleansing operations.

George McCredie noted in a letter to Sir William Lyne that ‘Where it was found necessary to pull down premises or destroy outbuildings photographs were taken of them before their demolition, and in order to prepare in case of future litigation, each inspector was instructed to take careful notes of any property that might be destroyed.'(1)

The photographs were taken by Mr. John Degotardi, Jr., photographer from the Department of Public Works. The photographs are largely of buildings requiring to be demolished, and include the interior and exterior of houses, stores, warehouses and wharves, and surrounding streets, lanes and yards, thus providing a fairly clear indication of the state of the city during and immediately after the plague.

The views cover the whole of the quarantine area, which stretched from Millers Point east to George Street, along Argyle, Upper Fort, and Essex Streets thence south to Chippendale, covering the area between Darling Harbour and Kent Streets, west to Cowper Street, Glebe, along City Road to the area bounded by Abercrombie, Ivy, Cleveland Streets, and the railway. The area east from George Street enclosed by Riley, Liverpool, Elizabeth and Goulburn Streets; Gipps, Campbell and George Streets were also quarantined, as were certain areas in Woolloomooloo, Paddington, Redfern and Manly.

They provide a visual report of the conditions in the area at the turn of the century. The bubonic plague was epidemic from 19 January to 9 August 1900. 303 people were stricken and 103 people died.

The President of the Board of Health and Chief Medical Advisor, Dr. John Ashburton Thompson, investigated the spread of the disease. In the 1890s it was recognised that there was a connection between rats and the plague. In 1900 the Department of Health believed the first defence against the disease was the extermination of rats. They employed 3000 men at the height of the epidemic to catch and kill rats.

The Government cleansed large areas of the city. Contacts with the disease were isolated, actual cases hospitalised and people living in the infected areas were inoculated. By carefully plotting reported cases on large scale maps the course of the plague was traced and it became evident that rats preceded outbreaks of the disease.

Each volume is labelled: ‘Views taken during cleansing operations, quarantine areas, Sydney, 1900, under supervision of Mr. George McCredie, F.I.A., N.S.W.’ There is a numerical list of photographs [labelled as ‘index’] inside the front cover of each volume. The volumes are incomplete, volume VI lacking almost half the views listed in the ‘index’, the great majority of which are of the Manly area. Sundry pages are also missing from all but volume IV.

Text from the State Archives of New South Wales website [Online] Cited 11/04/2020

Endnote

(1) NSW Parliamentary Debates, 1900, vol. CIII, p.111 quoted in Max Kelly, Plague Sydney, Marrickville, NSW, Doak Press, 1981.

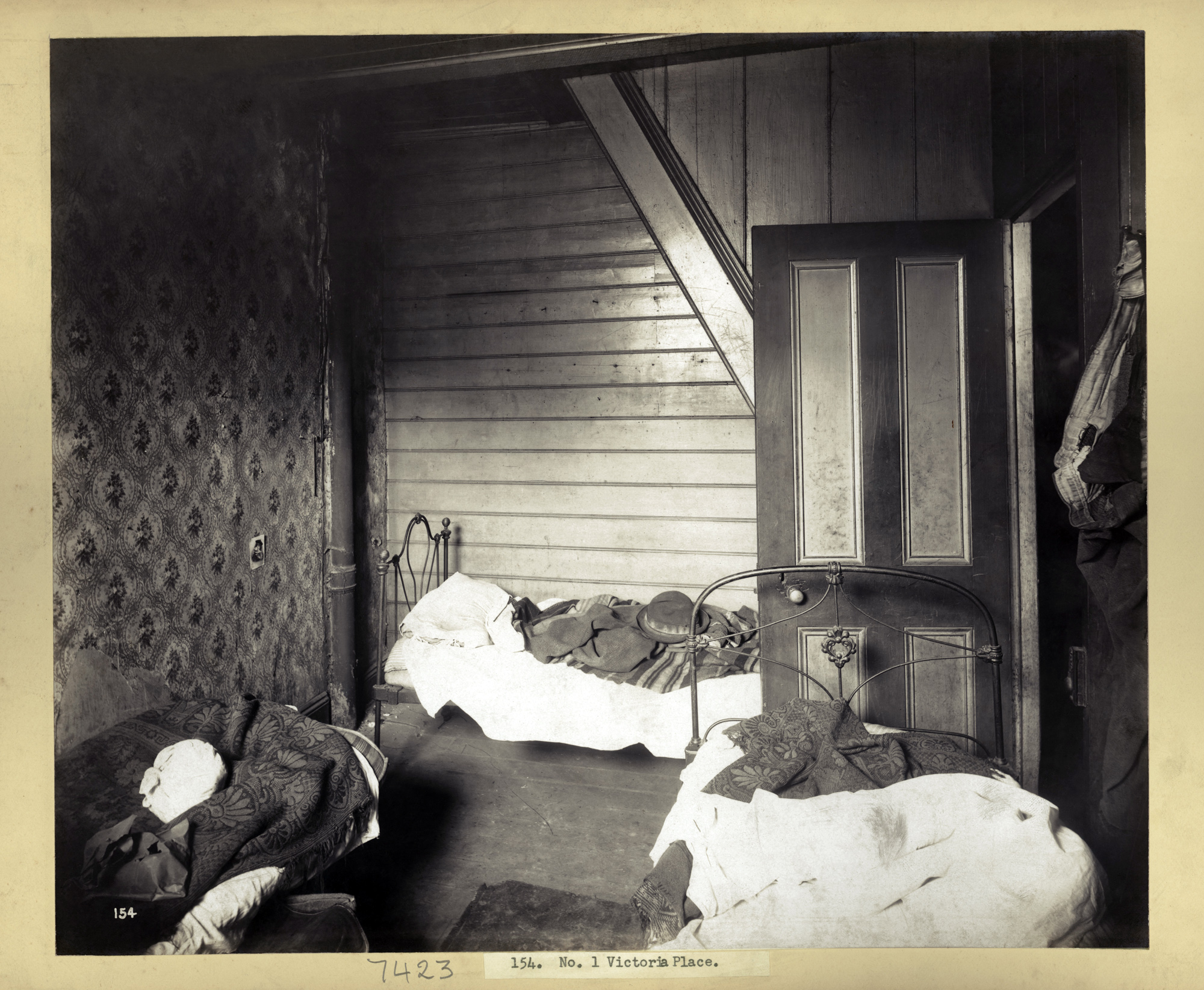

John Degotardi Jr. (Australian, 1860-1937)

NSW Department of Public Works photographer

154. No. 1 Victoria Place

1900

From Vol. III of Views taken during cleansing operations. Quarantine areas, Sydney, 1900

Gelatin silver print

New South Wales State Archives & Records NRS-12487 Photographs taken during cleansing operations in quarantine areas, Sydney

Public domain

John Degotardi Jr. (Australian, 1860-1937)

NSW Department of Public Works photographer

154. No. 1 Victoria Place (detail)

1900

From Vol. III of Views taken during cleansing operations. Quarantine areas, Sydney, 1900

Gelatin silver print

New South Wales State Archives & Records NRS-12487 Photographs taken during cleansing operations in quarantine areas, Sydney

Public domain

John Degotardi Jr. (Australian, 1860-1937)

NSW Department of Public Works photographer

177. Nos. 1, 3, 5 Blackburn Street

1900

From Vol. III of Views taken during cleansing operations. Quarantine areas, Sydney, 1900

Gelatin silver print

New South Wales State Archives & Records NRS-12487 Photographs taken during cleansing operations in quarantine areas, Sydney

Public domain

Amazed to find that this terrace (1, 3, and 5 Blackburn Street) survived the slum clearance and road widening in this area of Surry Hills. The houses are STILL THERE albeit much altered. See Google Maps Street View – goo.gl/maps/nLFbY – (Thank you beachcomber australia for the information)

John Degotardi Jr. (Australian, 1860-1937)

NSW Department of Public Works photographer

179. Clearing the rubbish at Smith’s Wharf

1900

From Vol. III of Views taken during cleansing operations. Quarantine areas, Sydney, 1900

Gelatin silver print

New South Wales State Archives & Records NRS-12487 Photographs taken during cleansing operations in quarantine areas, Sydney

Public domain

“Smith’s Wharf” was on the western edge of Millers Point – we are looking south up Darling Harbour. The wharf was redeveloped shortly after and was then known as “Dalgety’s Wharf”. The amazing thing is that John Degotardi Jnr the photographer managed to make a routine photo of a barge clearing rubbish from a wharf into an interesting study in composition, perspectives, light and shapes. (Thank you beachcomber australia for the information)

I couldn’t have put it better about the photographer – he certainly knew his stuff!

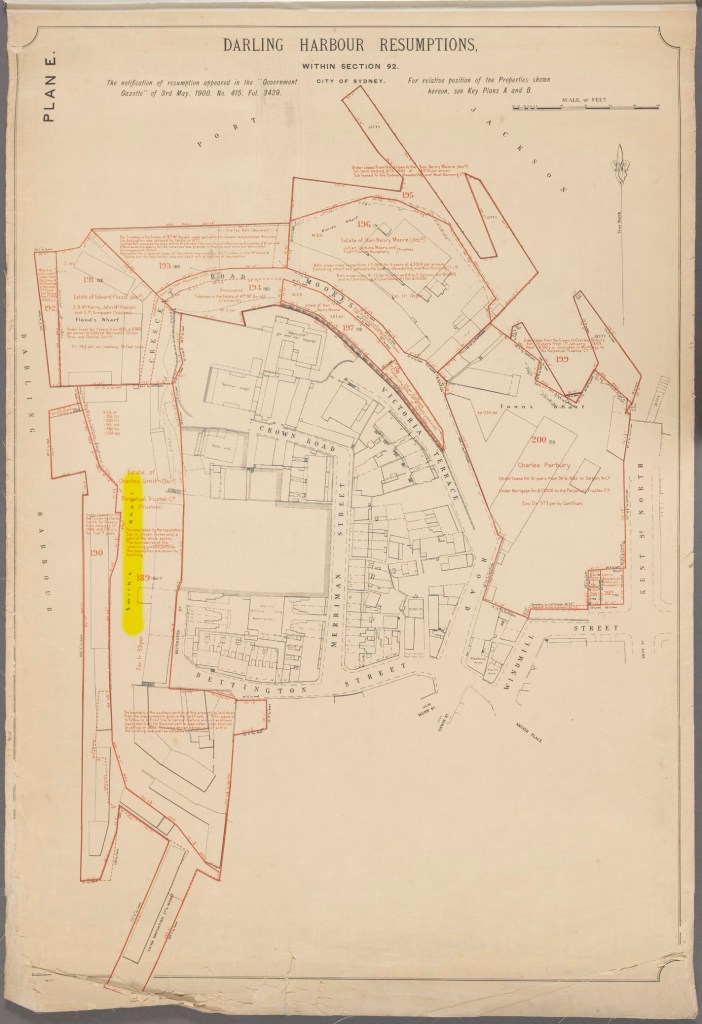

Plan E of the Darling Harbour Resumptions noting the position of Smith’s Wharf

John Degotardi Jr. (Australian, 1860-1937)

NSW Department of Public Works photographer

179. Clearing the rubbish at Smith’s Wharf (details)

1900

From Vol. III of Views taken during cleansing operations. Quarantine areas, Sydney, 1900

Gelatin silver print

New South Wales State Archives & Records NRS-12487 Photographs taken during cleansing operations in quarantine areas, Sydney

Public domain

John Degotardi Jr. (Australian, 1860-1937)

NSW Department of Public Works photographer

211. No. 20 Upton Street

1900

From Vol. IV of Views taken during cleansing operations. Quarantine areas, Sydney, 1900

Gelatin silver print

New South Wales State Archives & Records NRS-12487 Photographs taken during cleansing operations in quarantine areas, Sydney

Public domain

John Degotardi Jr. (Australian, 1860-1937)

NSW Department of Public Works photographer

211. No. 20 Upton Street (details)

1900

From Vol. IV of Views taken during cleansing operations. Quarantine areas, Sydney, 1900

Gelatin silver print

New South Wales State Archives & Records NRS-12487 Photographs taken during cleansing operations in quarantine areas, Sydney

Public domain

La Peste (The Plague)

Albert Camus

What does plague mean for humanity – in his philosophy… we are all, unbeknownst to us, already living through a plague. That is, a widespread, silent invisible disease that may kill any of us at any time and destroy the lives we assumed were solid [death].

The actual historical incidents we call plagues are merely concentrations of a universal precondition, they are dramatic instances of a perpetual rule: that we are vulnerable to being randomly exterminated, by a bacillus, an accident or the actions of our fellow humans. Our exposure to plague is at the heart of Camus’s view that our lives are fundamentally on the edge of what he termed ‘the absurd’.

For Camus, when it comes to dying, there is no progress in history, there is no escape from our frailty; being alive always was and will always remain an emergency, as one might put it, truly an inescapable ‘underlying condition’.

Plague or no plague, there is always – as it were – the plague, if what we mean by this is a susceptibility to sudden death, an event that can render our lives instantaneously meaningless.

Life is a hospice, never a hospital.

Camus writes: ‘Pestilence is so common, there have been as many plagues in the world as there have been wars, yet plagues and wars always find people equally unprepared.’

In one of the most central lines of the book, Camus writes: ‘This whole thing is not about heroism. It’s about decency. It may seem a ridiculous idea, but the only way to fight the plague is with decency.’

In the words of one of his characters, Camus knew, as we do not, that ‘everyone has inside it himself this plague, because no one in the world, no one, can ever be immune.’

Anonymous. “Camus and The Plague,” on the School of Life website [Online] Cited 16/05/2020

Albert Camus – The Plague

There is no more important book to understand our times than Albert Camus’s The Plague, a novel about a virus that spreads uncontrollably from animals to humans and ends up destroying half the population of a representative modern town. Camus speaks to us now not because he was a magical seer, but because he correctly sized up human nature. As he wrote: ‘Everyone has inside it himself this plague, because no one in the world, no one, can ever be immune.’

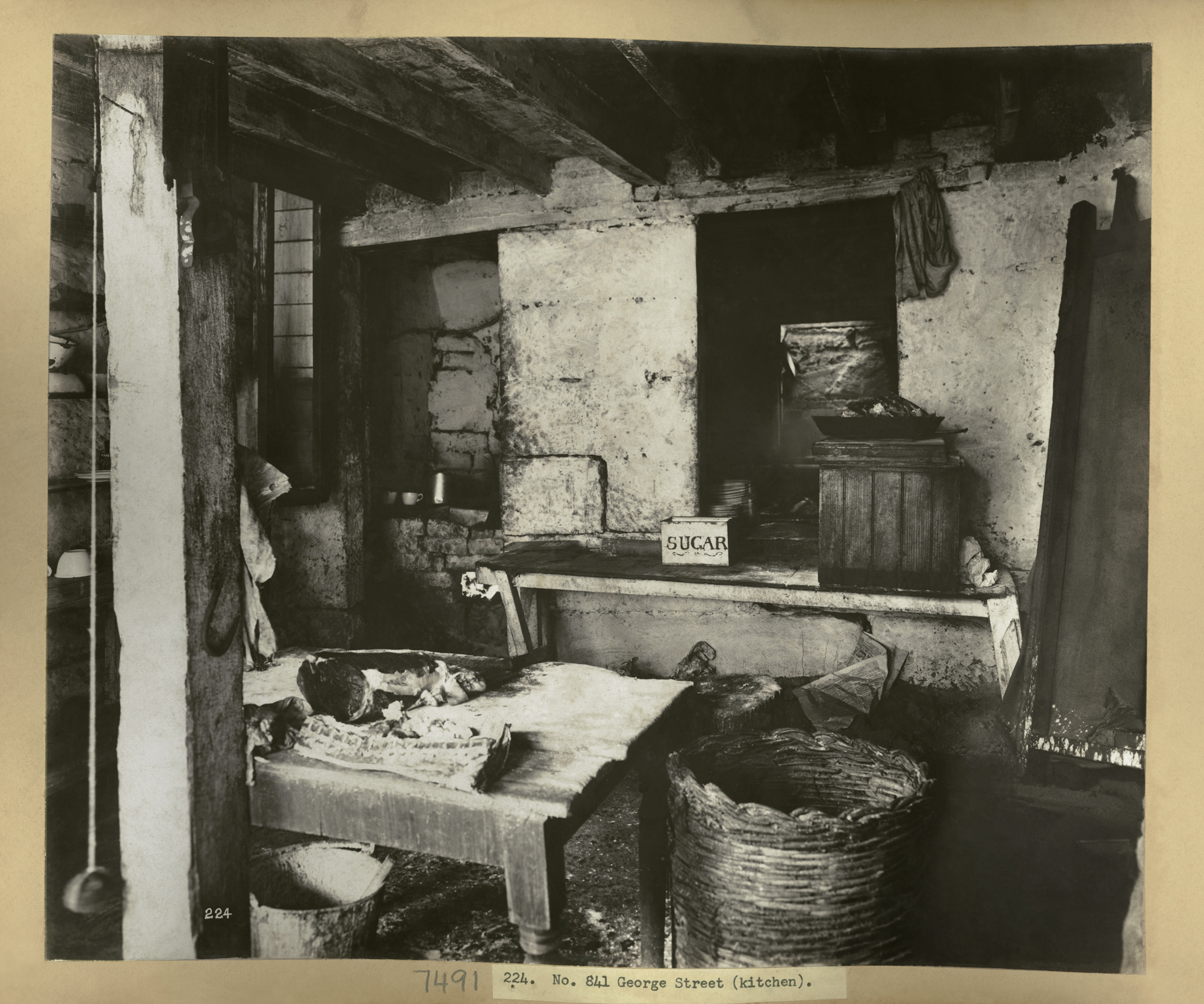

John Degotardi Jr. (Australian, 1860-1937)

NSW Department of Public Works photographer

224. No. 841 George Street (kitchen)

1900

From Vol. IV of Views taken during cleansing operations. Quarantine areas, Sydney, 1900

Gelatin silver print

New South Wales State Archives & Records NRS-12487 Photographs taken during cleansing operations in quarantine areas, Sydney

Public domain

841 George Street was on the site of the TAFE Marcus Clarke Building (1910).

John Degotardi Jr. (Australian, 1860-1937)

NSW Department of Public Works photographer

224. No. 841 George Street (kitchen) (detail)

1900

From Vol. IV of Views taken during cleansing operations. Quarantine areas, Sydney, 1900

Gelatin silver print

New South Wales State Archives & Records NRS-12487 Photographs taken during cleansing operations in quarantine areas, Sydney

Public domain

John Degotardi Jr. (Australian, 1860-1937)

NSW Department of Public Works photographer

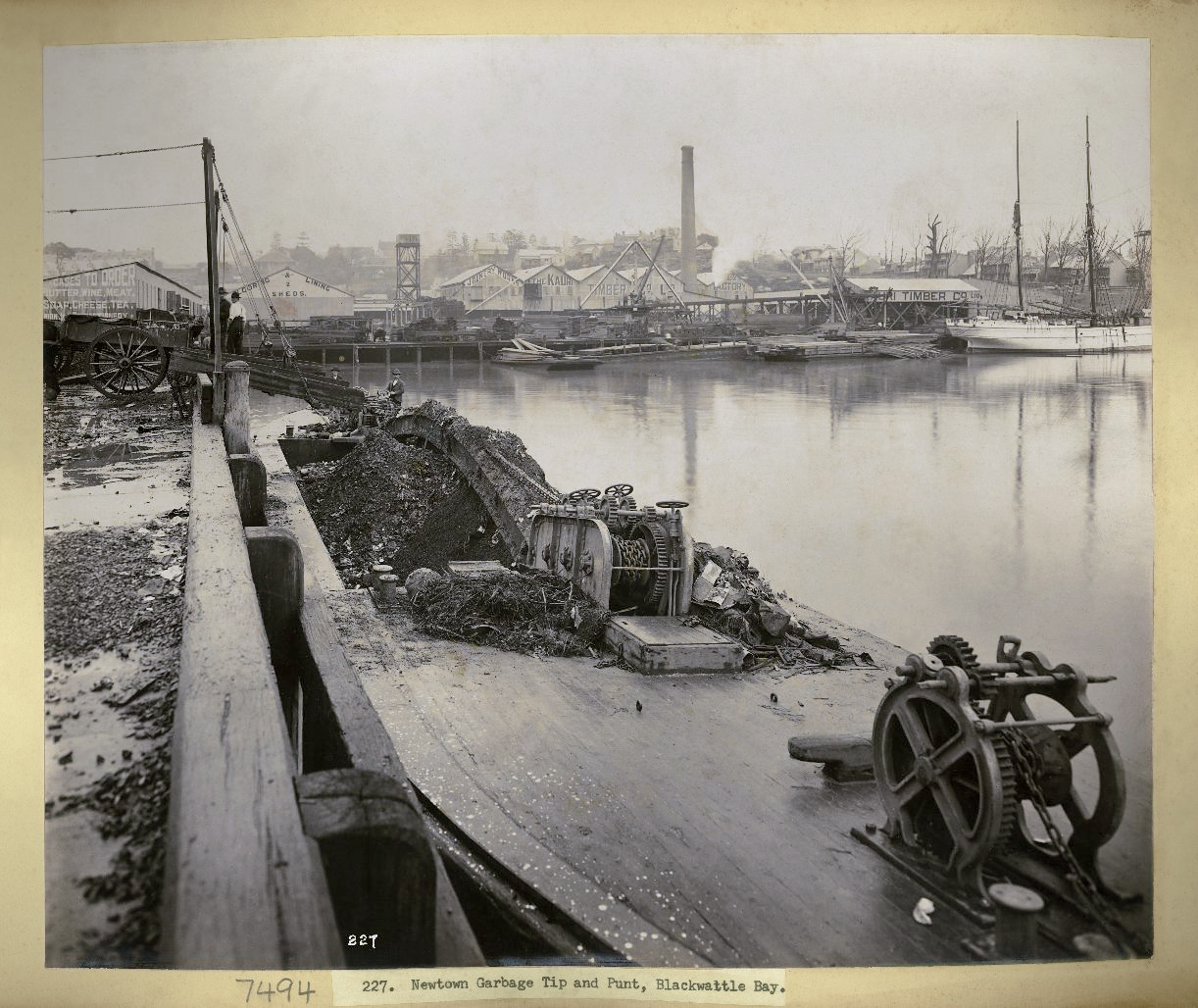

227. Newtown Garbage Tip and Punt, Blackwattle Bay

1900

From Vol. IV of Views taken during cleansing operations. Quarantine areas, Sydney, 1900

Gelatin silver print

New South Wales State Archives & Records NRS-12487 Photographs taken during cleansing operations in quarantine areas, Sydney

Public domain

John Degotardi Jr. (Australian, 1860-1937)

NSW Department of Public Works photographer

236. Johnstone’s Lane

1900

From Vol. IV of Views taken during cleansing operations. Quarantine areas, Sydney, 1900

Gelatin silver print

New South Wales State Archives & Records NRS-12487 Photographs taken during cleansing operations in quarantine areas, Sydney

Public domain

John Degotardi Jr. (Australian, 1860-1937)

NSW Department of Public Works photographer

239. No. 36 Owen Street (rear)

1900

From Vol. IV of Views taken during cleansing operations. Quarantine areas, Sydney, 1900

Gelatin silver print

New South Wales State Archives & Records NRS-12487 Photographs taken during cleansing operations in quarantine areas, Sydney

Public domain

John Degotardi Jr. (Australian, 1860-1937)

NSW Department of Public Works photographer

239. No. 36 Owen Street (rear) (detail)

1900

From Vol. IV of Views taken during cleansing operations. Quarantine areas, Sydney, 1900

Gelatin silver print

New South Wales State Archives & Records NRS-12487 Photographs taken during cleansing operations in quarantine areas, Sydney

Public domain

John Degotardi Jr. (Australian, 1860-1937)

NSW Department of Public Works photographer

244. Sutton Forest Butchery, No. 761 George Street

1900

From Vol. IV of Views taken during cleansing operations. Quarantine areas, Sydney, 1900

Gelatin silver print

New South Wales State Archives & Records NRS-12487 Photographs taken during cleansing operations in quarantine areas, Sydney

Public domain

A Sydney butcher’s, 1900. Taken by Mr. John Degotardi, Jr., photographer from the Department of Public Works, the images depict the state of the houses and ‘slum’ buildings at the time of the outbreak and the cleansing and disinfecting operations which followed. Sutton Forest Butchery, No.761 George Street, Sydney Dated: c. 17/07/1900

Bubonic Plague outbreak in Sydney in the 1900s helps Politicians to clear the way for transport progress & landmark

By the end of August 1900, the outbreak had concluded, and whilst there was only a reported 103 deaths (significantly low when compared to mortality rates from other infectious diseases of the time), the effect that it had on the reputation of The Rocks and Millers Point, as well as its inhabitants, was damaging. The state resumption and its demolition programs left behind a series of questions regarding the motives behind the government’s orchestration of this movement.

The geographical structure of The Rocks, as well as Sydney’s unique historical beginnings as a penal colony credited the often rugged housing conditions. Eleven decades of unregulated building development, as well as uneven and irregular land surfaces meant that often housing was unstructured and haphazardly built. Dwellings sprouted from rocks and other buildings in an “oyster-like” fashion, and the practice of “land sweating” (the construction of multiple structures on one piece of land) was commonplace. The City of Sydney Improvement Act of 1879 highlighted these issues and encouraged demolition of any existing substandard housing.

This set the precedent for the destruction programs that were to follow after the bubonic plague outbreak.

Health Board Acts

On the afternoon of 20th January 1900, van-driver Arthur Payne, a resident of 10 Ferry Lane, The Rocks, became Sydney’s first reported victim of bubonic plague. This was somewhat unremarkably in itself, the arrival of the plague had been duly anticipated by authorities for months prior as it raced through Hong Kong and New Caledonia. What was notably, however, was the wave of public panic that the outbreak prompted, and how it was responsible for community disruption and mass demolition of one of Sydney’s oldest precincts, The Rocks and Millers Point. The outbreak bred panic and brought emphasised authoritative attention to the living conditions of the area, and much time and effort was devoted to surveying conditions and proposing subsequent remedies of improvement. State resumption of the precinct followed swiftly after the outbreak, coming into effect on 3rd May 1900, and forced quarantining of the site swiftly followed, with areas surrounding the wharves being sectioned off, and mass disinfection and demolition processes commencing soon thereafter.

Over the next decade, more than 3,800 properties were inspected, hundreds were pulled down, and hundreds of families and individuals were dispossessed.

Land Resumption

Another motivating factor for the resumption of the area was to lay the groundwork of the proposed bridge link between Sydney city and the North Shore. Plans were underway even at these early stages and a good 23 years before construction of the bridge commenced. Even at the turn of the nineteenth century, it was clear that there would need to be a widened thoroughfare to accommodate traffic entering and exiting the bridge, and many buildings would need to be sacrificed to achieve this. The bubonic plague outbreak offered the ideal opportunity to highlight the inadequacies in a lot of buildings, and the chance to condemn the area as slum, whose only chance of redemption was through mass demolition.

The middle class mentality and its effect on The Rocks inhabitants

From the 1860s to the early 1900s the middle and upper classes began deserting the area and relocating to the suburbs, divorcing themselves physically from the working and lower classes, who tended to remain in the city and close to the waterfront areas and their place of employment.

Naturally as a point of import and export, and a site that saw a high exchange of people, livestock and products on a global level, the harbour foreshore was more susceptible to the outbreak of disease.

When bubonic plague erupted along the waterfront precinct, the area became heavily associated with disease and unsanitary conditions, and consequently its inhabitants were assumed to be unwashed and living in a state of constant filth. This has helped to create an historical consensus that waterside housing and urban living conditions were universally appalling.

The middle and upper classes were able to dissociate themselves with the presence of the plague, given their geographical distance from the harbour foreshore and the point of outbreak.

The resulting effect was a longstanding assumption that The Rocks was in such dire state that there was no alternative option but for mass slum clearance. Whilst there is no doubt that many properties were definitely substandard, and many families lived in abject poverty and poor conditions, not all the buildings that were demolished were of such a shocking standard, and many were in fact still of a solid and serviceable condition.

…

Following the plague outbreak the NSW Government carried out cleansing and disinfecting operations on the waterfront, and quarantined the residential suburbs of The Rocks and Millers Point. Under the Darling Harbour Resumption Act 1900, the newly created Sydney Harbour Trust oversaw the compulsory resumption of wharves, houses, shops, laneways and pubs in these harbour-side suburbs. The plan was to demolish the existing structures and rebuild to a grand design. The need to keep Dawes Point free for the construction of a possible bridge across the harbour was factored into the design.

Between 1900 and 1910, wharfage was acquired and demolished, along with buildings associated with the Dawes Point Battery. The c. 1870 public bathhouse on the west of Dawes Point was demolished in c. 1910. Works by the Public Works Department and Sydney Harbour Trust, under the presidency of R R P Hickson, included Pier 1 on the bathhouse site (1910-1914), Hickson Road and the widening of Lower Fort Street (1906-1922), and the four Walsh Bay finger wharves (1912-1921).

Works by the Housing Board in The Rocks were also part of the resumption and rebuilding program, and included the realignment of George and Cumberland Streets and the construction of an associated retaining wall between 1913 and 1916. A fountain and garden, and public toilet facilities completed the structure, built in 1916-1920.

These works also anticipated the construction of the approaches for the Sydney Harbour Bridge.

Anonymous. “Bubonic Plague outbreak in Sydney in the 1900s helps Politicians to clear the way for transport progress & landmark,” on The Digger website 13th August 2016 [Online] Cited 10/40/2020

John Degotardi Jr. (Australian, 1860-1937)

NSW Department of Public Works photographer

266. Rat Incinerator

1900

From Vol. V of Views taken during cleansing operations. Quarantine areas, Sydney, 1900

Gelatin silver print

New South Wales State Archives & Records NRS-12487 Photographs taken during cleansing operations in quarantine areas, Sydney

Public domain

John Degotardi Jr. (Australian, 1860-1937)

NSW Department of Public Works photographer

266. Rat Incinerator (detail)

1900

From Vol. V of Views taken during cleansing operations. Quarantine areas, Sydney, 1900

Gelatin silver print

New South Wales State Archives & Records NRS-12487 Photographs taken during cleansing operations in quarantine areas, Sydney

Public domain

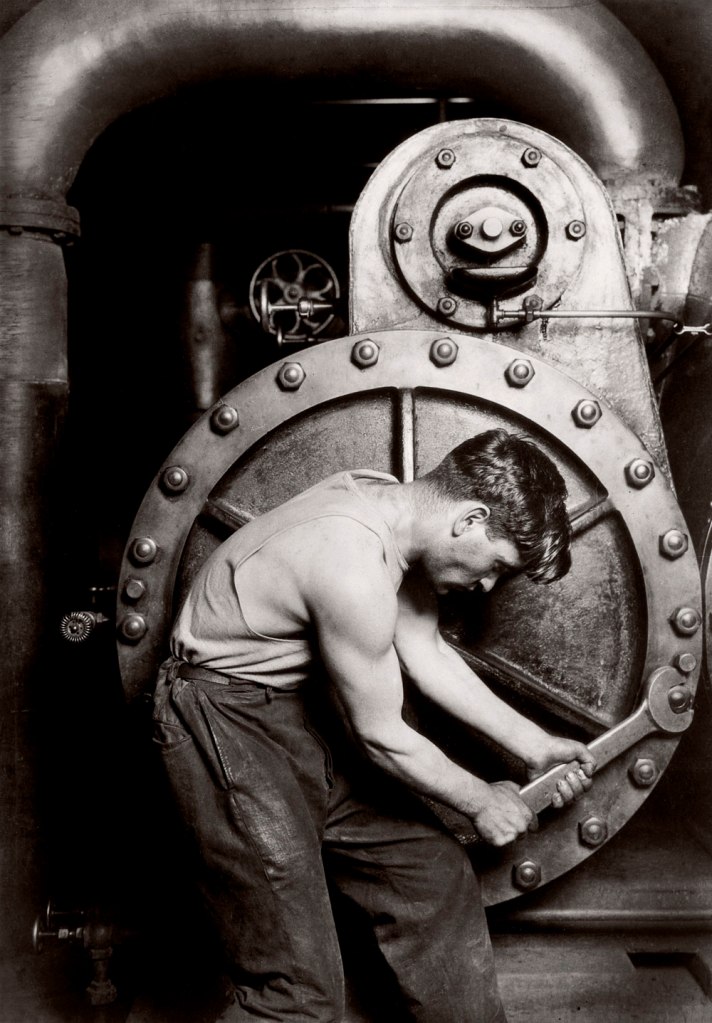

Lewis Hine (American, 1874-1940)

Powerhouse mechanic working on steam pump

1920

Gelatin silver print

John Degotardi Jr. (Australian, 1860-1937)

NSW Department of Public Works photographer

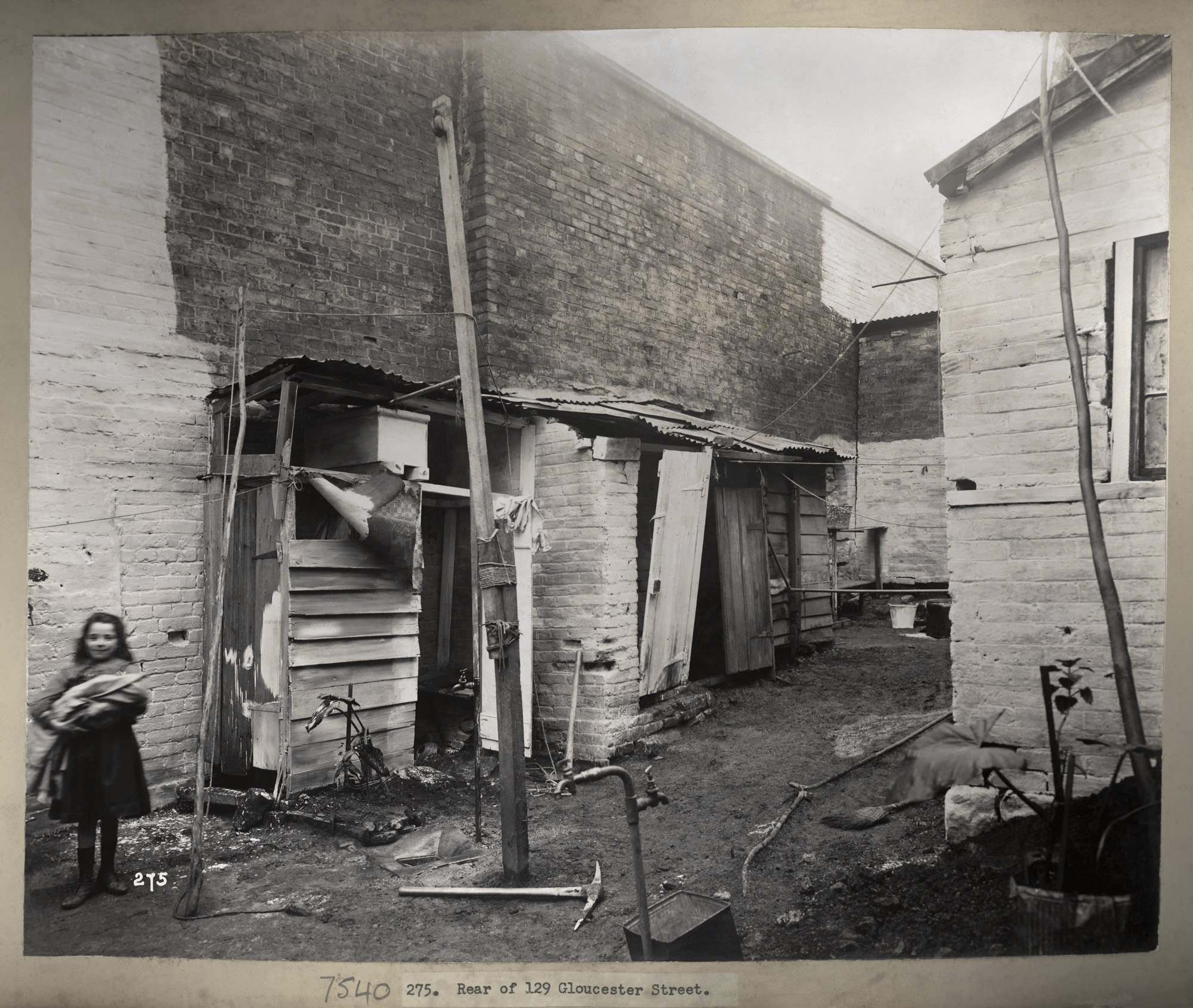

275. Rear of 129 Gloucester Street

1900

From Vol. V of Views taken during cleansing operations. Quarantine areas, Sydney, 1900

Gelatin silver print

New South Wales State Archives & Records NRS-12487 Photographs taken during cleansing operations in quarantine areas, Sydney

Public domain

John Degotardi Jr. (Australian, 1860-1937)

NSW Department of Public Works photographer

275. Rear of 129 Gloucester Street (detail)

1900

From Vol. V of Views taken during cleansing operations. Quarantine areas, Sydney, 1900

Gelatin silver print

New South Wales State Archives & Records NRS-12487 Photographs taken during cleansing operations in quarantine areas, Sydney

Public domain

115 Gloucester Street looking down towards 129 Gloucester Street

John Degotardi Jr. (Australian, 1860-1937)

NSW Department of Public Works photographer

289. From 207 Elizabeth Street

1900

From Vol. V of Views taken during cleansing operations. Quarantine areas, Sydney, 1900

Gelatin silver print

New South Wales State Archives & Records NRS-12487 Photographs taken during cleansing operations in quarantine areas, Sydney

Public domain

St George’s Presbyterian church steeple, Castlereagh Street on the far right.

John Degotardi Jr. (Australian, 1860-1937)

NSW Department of Public Works photographer

289. From 207 Elizabeth Street (detail)

1900

From Vol. V of Views taken during cleansing operations. Quarantine areas, Sydney, 1900

Gelatin silver print

New South Wales State Archives & Records NRS-12487 Photographs taken during cleansing operations in quarantine areas, Sydney

Public domain

John Degotardi Jr. (Australian, 1860-1937)

NSW Department of Public Works photographer

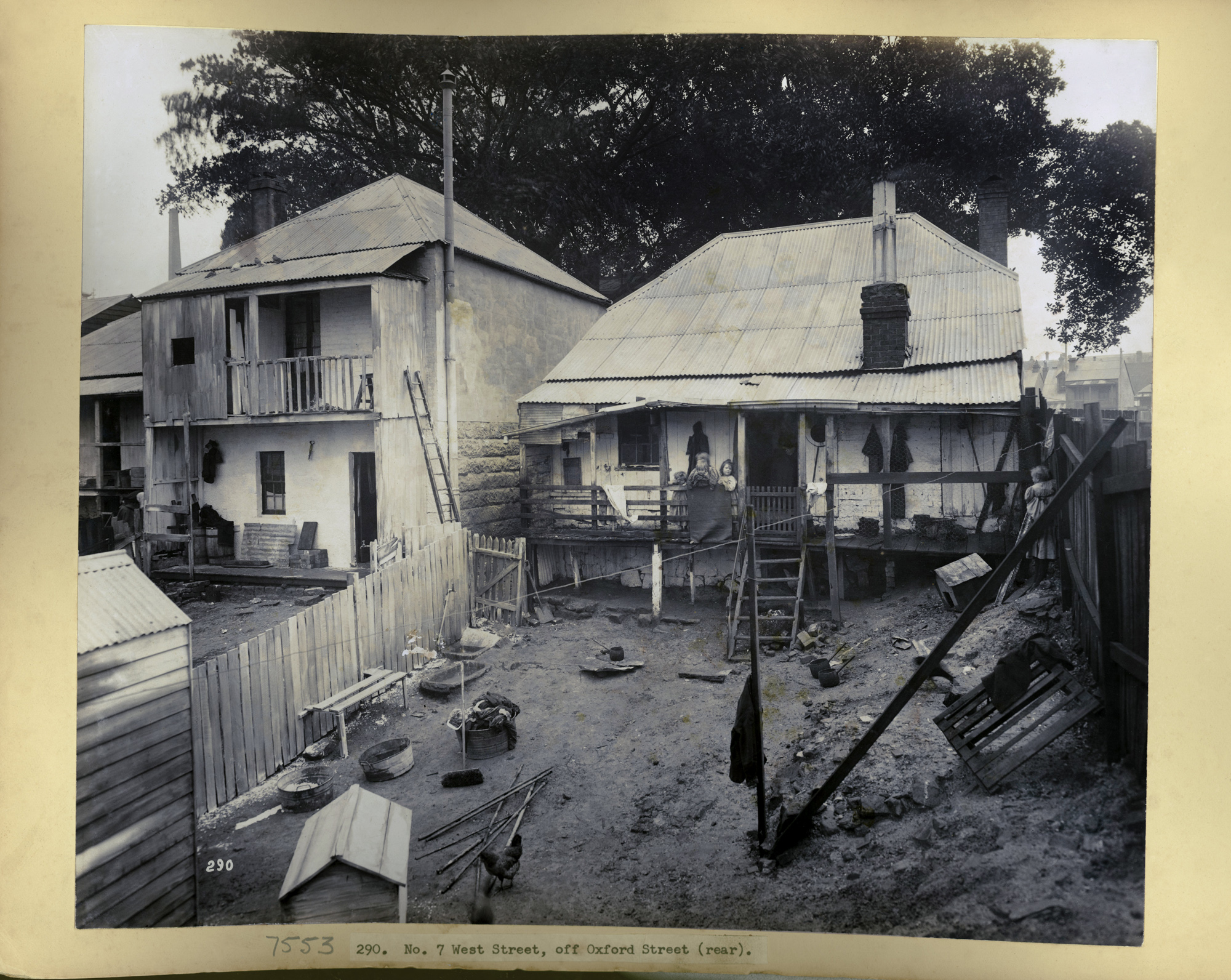

290. No. 7 West Street off Oxford Street (rear)

1900

From Vol. V of Views taken during cleansing operations. Quarantine areas, Sydney, 1900

Gelatin silver print

New South Wales State Archives & Records NRS-12487 Photographs taken during cleansing operations in quarantine areas, Sydney

Public domain

John Degotardi Jr. (Australian, 1860-1937)

NSW Department of Public Works photographer

290. No. 7 West Street off Oxford Street (rear) (details)

1900

From Vol. V of Views taken during cleansing operations. Quarantine areas, Sydney, 1900

Gelatin silver print

New South Wales State Archives & Records NRS-12487 Photographs taken during cleansing operations in quarantine areas, Sydney

Public domain

No. 7 West Street (on the left) looking up towards Oxford Street, Surry Hills

John Degotardi Jr. (Australian, 1860-1937)

NSW Department of Public Works photographer

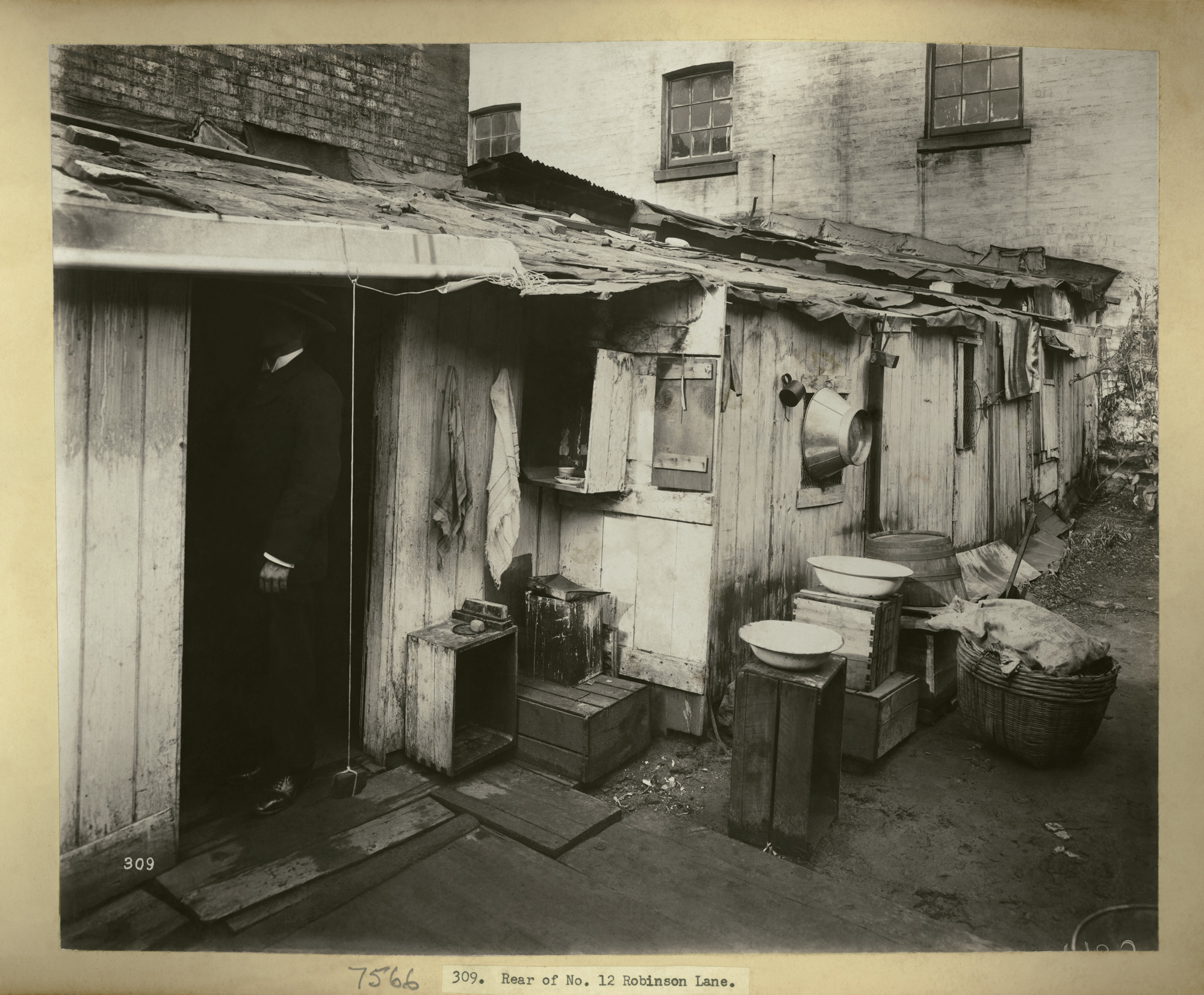

309. Rear of No. 12 Robinson Lane

1900

From Vol. V of Views taken during cleansing operations. Quarantine areas, Sydney, 1900

Gelatin silver print

New South Wales State Archives & Records NRS-12487 Photographs taken during cleansing operations in quarantine areas, Sydney

Public domain

John Degotardi Jr. (Australian, 1860-1937)

NSW Department of Public Works photographer

309. Rear of no. 12 Robinson Lane (details)

1900

From Vol. V of Views taken during cleansing operations. Quarantine areas, Sydney, 1900

Gelatin silver print

New South Wales State Archives & Records NRS-12487 Photographs taken during cleansing operations in quarantine areas, Sydney

Public domain

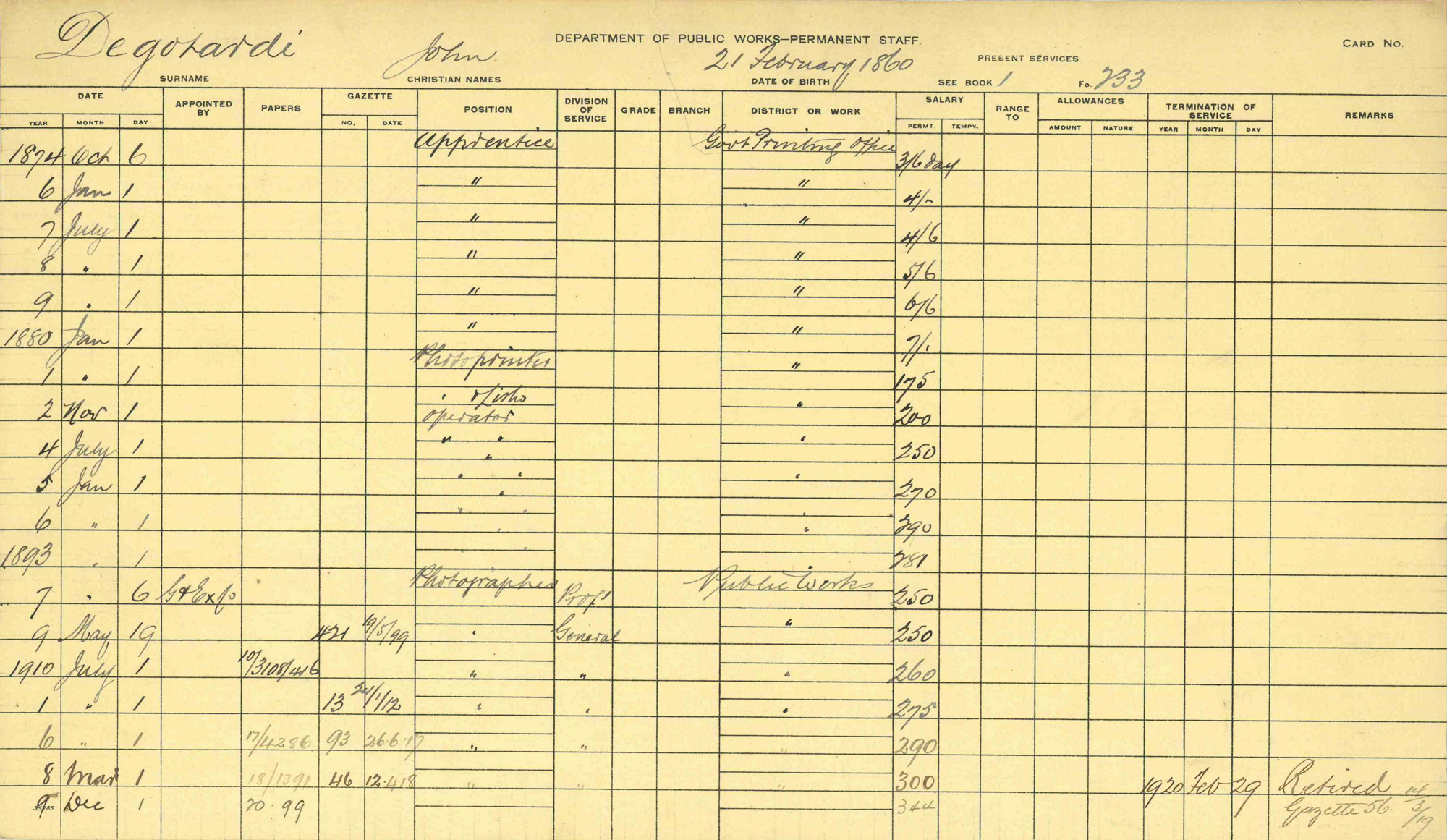

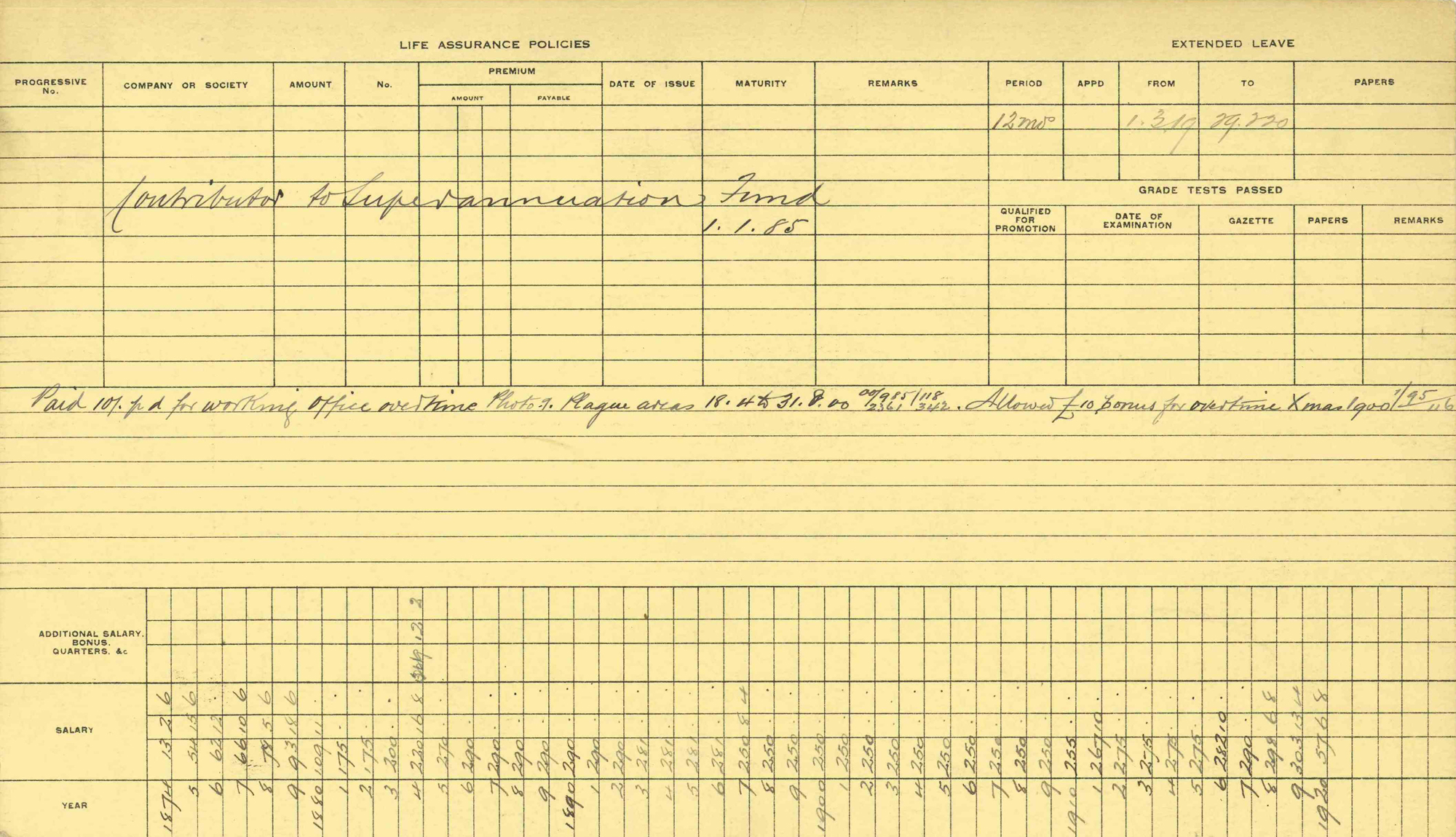

9 – 7-11491 John Degotardi jr PWD card 001

NRS 12535 Staff record cards, c. 1890-1953 [Department of (Secretary of) Public Works]; [7/11491]

What strikes me about this card is the pay drop he took to become a photographer for Public Works and the fact that it took him 10 years to get back to where he was on the salary scale. A dedicated craftsman. (Thank you to ArchivesOutside for the information)

9 – 7-11491 John Degotardi jr PWD card 002

NRS 12535 Staff record cards, c. 1890-1953 [Department of (Secretary of) Public Works]; [7/11491]

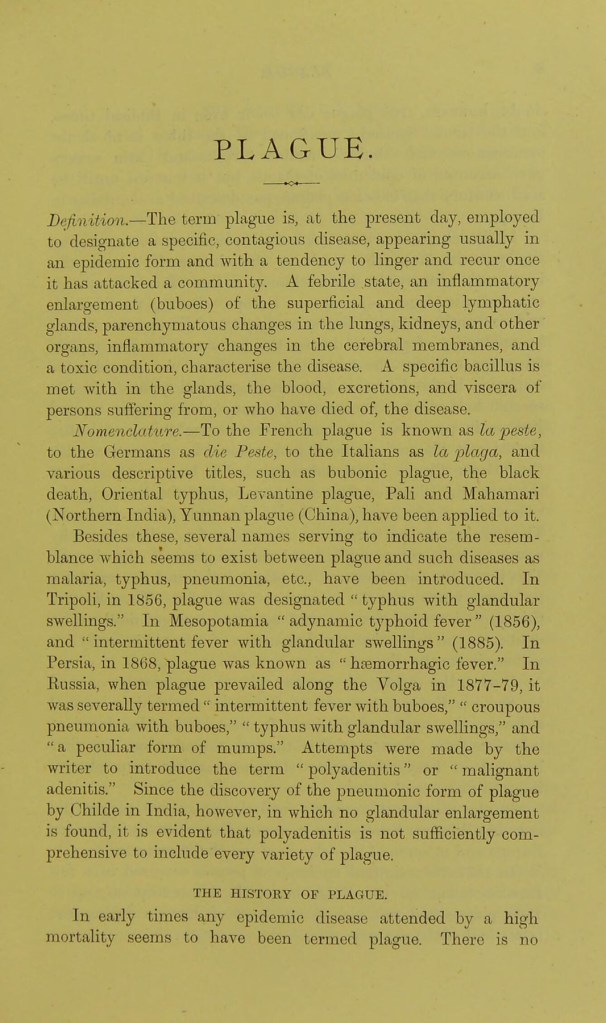

James Cantlie

How To Recognise, Prevent and Treat Plague (Title page, p. 5, p. 8)

1900

Cassell and Company, Limited

![John Degotardi Jr. (Australian, 1860-1937) '70. [Octopus] Cleansing the Wharves' 1900 John Degotardi Jr. (Australian, 1860-1937) '70. [Octopus] Cleansing the Wharves' 1900](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/cleansing-the-wharves.jpg)

![George Roberts (Australian born United Kingdom, c. 1800-1865) '[Mrs Macquarie's chair]' c. 1843-1865 George Roberts (Australian born United Kingdom, c. 1800-1865) '[Mrs Macquarie's chair]' c. 1843-1865](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/mrs-macquaries-chair-web.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.