November 2018

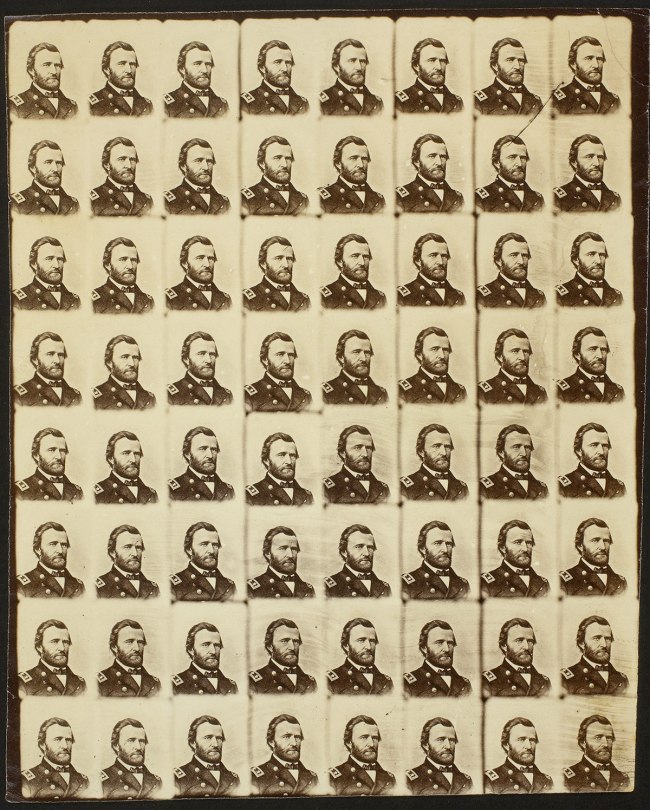

Edward J. Kelty (American, 1888-1967)

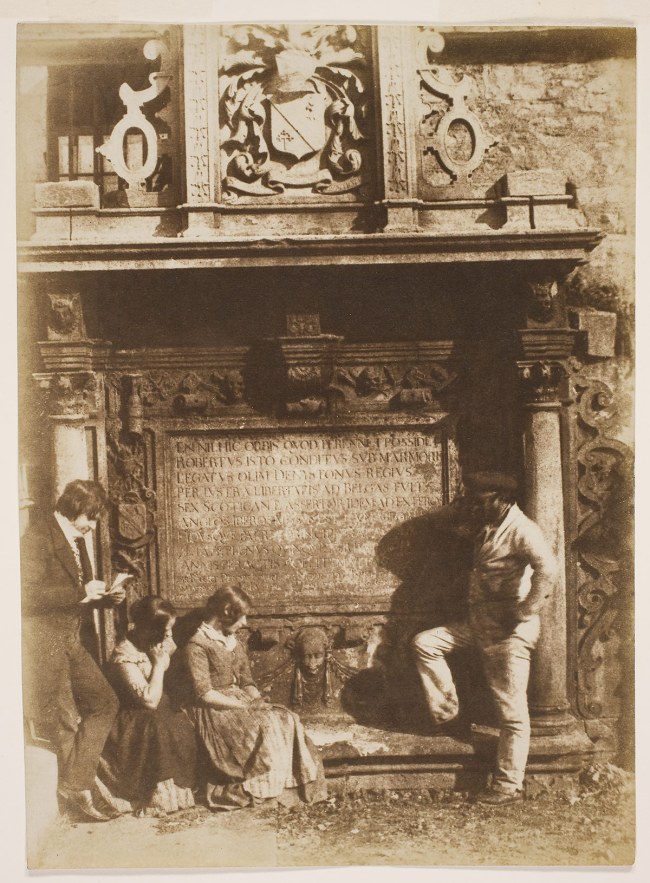

Century Photographers

Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey (Combined) Circus [clowns behind Madison Square Garden]

c. 1925

Cyanotype

7 3/8 × 9 1/4 inches (23.8 × 23.5cm)

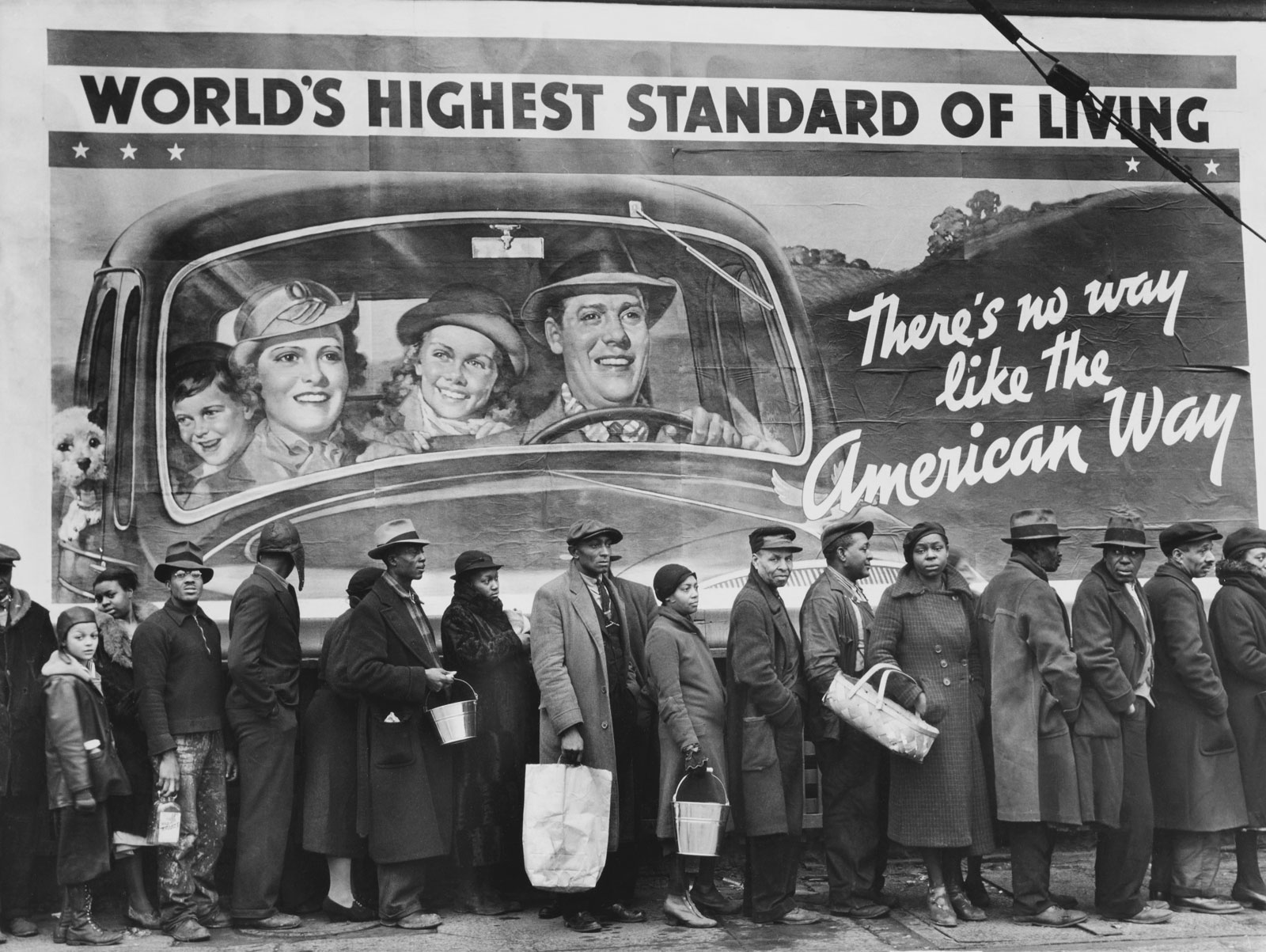

There’s a quality of legend about freaks… I mean, if you’ve ever spoken to someone with two heads, you know they know something you don’t. Most people go through life dreading they’ll have a traumatic experience – freaks were born with their trauma. They’ve already passed their test in life. They’re aristocrats.

Diane Arbus

The aristocrats

During my research for this posting, someone, somewhere, said that Kelty was “not a very adventurous photographer.” What a load of rubbish.

If they meant “adventurous” by being avant-garde to that you can only answer: imagine the passion and dedication, and the skill of the photographer to compose these panoramic images for 15 years, from the mid-1920s to 1940, using a specially made “banquet” camera that produced 12-by-20-inch images.

Just imagine loading up your car with such a monster camera and travelling the roads to the site of these circus encampments, sometimes two or three different circuses a day, to record a veritable feast of difference and diversity. To give equal weight to each and every person. And to then develop the negatives in the back of your car. If this is not adventurous I don’t know what is.

And Kelty had to pay for the privilege. “Kelty was under contract to that circus, meaning he had to pay Ringling Brothers a commission for every circus picture he took. But he was not a circus employee, which had several of its own photographers who specialized in behind-the-scenes candids.”1 The photographs, these grand assemblages of multiculturalism, were not staged for free.

Kelty’s stylised images of sideshow freaks, clowns and other circus exotics are highly idiosyncratic in the world of art photography because, of course, he would not have thought of himself as an artist. Much as Eugène Atget never thought of himself as an artist, hanging a sign on his studio door saying, “Documents pour artistes” (Documents for artists), the sign declaring, “… his modest ambition of providing other artists with images to use as source material in their own work” (MoMA), so Kelty would have only thought he was recording these mise-en-scène for his own benefit, his passion, and to possibly sell a few photographs on the side.

Kelty’s day job was that of professional banquet photographer photographing weddings and the corporate world. The freedom he must have felt going to the circus and engaging with all these wonderful people would have been incredible. And he didn’t discriminate: his egalitarian photographs document the archetypes of the travelling circus, from “group portraits of clowns, sideshow attractions, bands, elephants, menageries, aerialists, equestrians, tractor and train crews, candy butchers (seen with their backs turned to show the “Baby Ruth Candy” logo on their smocks), and even everybody in the Ringling-Barnum cookhouse tent on July 4, 1935.” (Amazon)

Ellen Warren in her article “The mysterious Mr. Kelty”2 observes that Kelty’s photographs are “hopelessly politically incorrect by today’s standards”. In one sense this is true, with the camera documenting and objectifying the “Other”, with the literal naming of difference – “congress of freaks”, “colored review” – but is this objectification little different to the later, more intimate photographs of Diane Arbus documenting a dwarf in his bedroom, a Jewish giant at home with his parents, or an Albino sword swallower at a carnival? Only the archetypal scale is different. In another and perhaps a more generous sense of spirit, Kelty’s images of circus life document a “family” that lived, breathed, ate and travelled together, who looked after each other during fires and vicissitudes, who had a job and food on the table during The Great Depression … people who Kelty imaged as equal and important as each other by placing them in row after row.

In photographs such as Christy Brothers Circus Side Show, H. Emgard – Manager (1927, below), “Living Curiosities” mix it with “Minstrels”, musicians, dancers and comedians and a Scottish family band dressed up in Tartan. All given equal weight in a splendid display, a panopoly of presentation from around the world. And it would seem that the crowds at the circus were equally fascinated by these assemblages, and the process of Kelty taking the photograph, if the glimpses of the audience at left in Congress of the World’s Rough Riders – Celebrating Ringling Golden Jubilee, Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Combined Circus (1933, below) and at right in Col. Tim McCoy and his Congress of Rough Riders of the World Featured on the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus (1935, below) are anything to go by.

Other things to note about the photographs are: the shutter time which can be seen by the moving figures at left in George Denman and His Staff, Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Combined Shows (1931, below); the impeccable use of even light; the use of flash in photographs such as Col. W.T. Johnson’s World Champion Cowgirls – Madison Square Garden – New York City – 1935 (1935, below) and Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Concert Band, Merle Evans – Bandmaster (1927, below); and Kelty’s innate ability to conduct and compose the scene. This is where Kelty excels himself as an artist and photographer, where he rises above the everyday to become extra-ordinary.

Two photographs are instructive in this regard, the earlier Congress of Freaks with Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Combined Circus (1931, below) and the later “Doll Family of Midgets”, Celebrating “Ringling Golden Jubilee”, Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Combined Circus Side Show (1933, below) in which Kelty returns two years later to document more or less the same group of people in the same setting. In the first image, one of the most famous of Kelty’s photographs, two lines of people rise from the outside and then fall (using the height of the subjects) towards the woman seated centrally in the bottom row who grounds the giant, Christ-like figure in the row above, his outstretched arms offering the display to the viewer. In the elegance and placement of figures this is a masterful construction of the image plane. In the later photograph Kelty doubles down, bookending both rows with symmetrical characters (giant women with headdresses, men in black tie) instead of just the one row in the first photograph – the rows again rising and falling towards the central characters, the giants framing the composition with outstretched arms. It might seem simple but it is not.

This is not some hack at work, not some unadventurous photographer with limited imagination, but a man composing a fugue like J.S.Bach, a veritable banquet for the eyes. To suggest otherwise is to not understand the history of photography, the history of representation, and the passion needed to represent life in all its forms.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ Ellen Warren. “The mysterious Mr. Kelty,” on the Chicago Tribune website February 7, 2003 [Online] Cited 23/11/2018

2/ Ibid.,

All of the photographs in this posting are published under “fair use” conditions for the purpose of educational research and academic comment. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Going by the evidence of the photographs, Kelty seems to have had three studio addresses close to each other in Midtown New York during his 15 years photographing the circus: first 144 West 46th (1925-1930), 74 W 47th (1931-1934) and finally 110 W 46th (1935-1940). As can be seen from the map above (with one exception of a photograph in St. Louis MO), Kelty usually travelled close to home to document the circus wherever they set up camp.

Edward J. Kelty (American, 1888-1967)

Century Photographers 144 W 46 N.Y.C.

Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Concert Band, Merle Evans – Bandmaster

1927

Gelatin silver print

Merle Slease Evans (December 26, 1891 – December 31, 1987) was a cornet player and circus band conductor who conducted the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus for fifty years. He was known as the “Toscanini of the Big Top.” Evans was inducted into the American Bandmasters Association in 1947 and the International Circus Hall of Fame in 1975. …

Evans was hired as the band director for the newly merged Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus in 1919. Evans held this job for fifty years, until his retirement in 1969. He only missed performances due to a musicians union strike in 1942 and the death of his first wife. He wrote eight circus marches, including Symphonia and Fredella.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Edward J. Kelty (American, 1888-1967)

Century Photographers 144 W 46 N.Y.C.

Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Combined Circus

Jersey City, N.J. – May 27th 1929

Gelatin silver print

Edward J. Kelty (American, 1888-1967)

Century Photographers 74 W 47 N.Y.C.

George Denman and His Staff, Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Combined Shows

Irvington, N.J. – June 9th, 1931

Gelatin silver print

11 1/4 × 19 5/8 inches (28.6 × 49.9cm)

Edward J. Kelty (American, 1888-1967)

Century Photographers 74 W 47 N.Y.C.

Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus – Greatest Show on Earth –

1931

Gelatin silver print

Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus, also known as the Ringling Bros. Circus, Ringling Bros. or simply Ringling was an American traveling circus company billed as The Greatest Show on Earth. It and its predecessor shows ran from 1871 to 2017. Known as Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Combined Shows, the circus started in 1919 when the Barnum & Bailey’s Greatest Show on Earth, a circus created by P. T. Barnum and James Anthony Bailey, was merged with the Ringling Bros. World’s Greatest Shows. The Ringling brothers had purchased Barnum & Bailey Ltd. following Bailey’s death in 1906, but ran the circuses separately until they were merged in 1919. …

In 1871, Dan Castello and William Cameron Coup persuaded Barnum to come out of retirement as to lend his name, know-how and financial backing to the circus they had already created in Delavan, Wisconsin. The combined show was named “P.T. Barnum’s Great Traveling Museum, Menagerie, Caravan, and Hippodrome”. As described by Barnum, Castello and Coup “had a show that was truly immense, and combined all the elements of museum, menagerie, variety performance, concert hall, and circus”, and considered it to potentially be “the Greatest Show on Earth”, which subsequently became part of the circus’s name.

Independently of Castello and Coup, James Anthony Bailey had teamed up with James E. Cooper to create the Cooper and Bailey Circus in the 1860s. The Cooper and Bailey Circus became the chief competitor to Barnum’s circus. As Bailey’s circus was outperforming his, Barnum sought to merge the circuses. The two groups agreed to combine their shows on March 28, 1881. Initially named “P.T. Barnum’s Greatest Show On Earth, And The Great London Circus, Sanger’s Royal British Menagerie and The Grand International Allied Shows United”, it was eventually shortened to “Barnum and Bailey’s Circus”. Bailey was instrumental in acquiring Jumbo, advertised as the world’s largest elephant, for the show. Barnum died in 1891 and Bailey then purchased the circus from his widow. Bailey continued touring the eastern United States until he took his circus to Europe. That tour started on December 27, 1897, and lasted until 1902.

Separately, in 1884, five of the seven Ringling brothers had started a small circus in Baraboo, Wisconsin. This was about the same time that Barnum & Bailey were at the peak of their popularity. Similar to dozens of small circuses that toured the Midwest and the Northeast at the time, the brothers moved their circus from town to town in small animal-drawn caravans. Their circus rapidly grew and they were soon able to move their circus by train, which allowed them to have the largest traveling amusement enterprise of that time. Bailey’s European tour gave the Ringling brothers an opportunity to move their show from the Midwest to the eastern seaboard. Faced with the new competition, Bailey took his show west of the Rocky Mountains for the first time in 1905. He died the next year, and the circus was sold to the Ringling Brothers.

Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus

The Ringlings purchased the Barnum & Bailey Greatest Show on Earth in 1907 and ran the circuses separately until 1919. By that time, Charles Edward Ringling and John Nicholas Ringling were the only remaining brothers of the five who founded the circus. They decided that it was too difficult to run the two circuses independently, and on March 29, 1919, “Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Combined Shows” debuted in New York City. The posters declared, “The Ringling Bros. World’s Greatest Shows and the Barnum & Bailey Greatest Show on Earth are now combined into one record-breaking giant of all exhibitions.” Charles E. Ringling died in 1926, but the circus flourished through the Roaring Twenties.

John Ringling had the circus move its headquarters to Sarasota, Florida in 1927. In 1929, the American Circus Corporation signed a contract to perform in New York City. John Ringling purchased American Circus, owner of five circuses, for $1.7 million…

The circus suffered during the 1930s due to the Great Depression, but managed to stay in business. After John Nicholas Ringling’s death, his nephew, John Ringling North, managed the indebted circus twice, the first from 1937 to 1943. Special dispensation was given to the circus by President Roosevelt to use the rails to operate in 1942, in spite of travel restrictions imposed as a result of World War II. Many of the most famous images from the circus that were published in magazine and posters were captured by American photographer Maxwell Frederic Coplan, who traveled the world with the circus, capturing its beauty as well as its harsh realities.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Edward J. Kelty (American, 1888-1967)

Century Photographers 74 W 47 N.Y.C.

Congress of the World’s Rough Riders – Celebrating Ringling Golden Jubilee, Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Combined Circus

Brooklyn, N.Y. May 19th 1933

Gelatin silver print

“In the late nineteenth century, America displayed a new imperialistic mood and a heightened desire to impress her independence upon Europe when she embarked upon a number of military adventures in the Caribbean and Pacific. During the same period, there appeared a new popular hero – the “Rough Rider” – who derived from the Western frontier but expanded the field of heroic action well beyond the shores of America. The creation of this hero and the scene in which he was set demonstrates how popular culture of the period not only embodied but facilitated crucial developments in the nation’s growth.”

Christine Bold. “The Rough Riders at Home and Abroad: Cody, Roosevelt, Remington and the Imperialist hero,” in Canadian Review of American Studies Volume 18 Issue 3, September 1987, pp. 321-350

Edward J. Kelty (American, 1888-1967)

Century Photographers 74 W 47 N.Y.C.

Celebrating “Ringling Golden Jubilee”, Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Combined Circus

Brooklyn, N.Y. May 19th 1933

Gelatin silver print

11 1/4 × 19 5/8 inches (28.6 × 49.9cm)

Edward J. Kelty (American, 1888-1967)

Century Photographers 74 W 47 N.Y.C.

Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Combined Menagerie

Brooklyn, N.Y. May 19th 1933

Gelatin silver print

In mid-20th century America, a typical circus traveled from town to town by train, performing under a huge canvas tent commonly called a “big top”. The Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus was no exception: what made it stand out was that it was the largest circus in the country. Its big top could seat 9,000 spectators around its three rings; the tent’s canvas had been coated with 1,800 pounds (820 kg) of paraffin wax dissolved in 6,000 US gallons (23,000 l) of gasoline, a common waterproofing method of the time.

A menagerie is a collection of captive animals, frequently exotic, kept for display; or the place where such a collection is kept, a precursor to the modern zoological garden. The term was first used in seventeenth century France in reference to the management of household or domestic stock. Later, it came to be used primarily in reference to aristocratic or royal animal collections. The French-language Methodical Encyclopaedia of 1782 defines a menagerie as an “establishment of luxury and curiosity.” Later on, the term referred also to travelling animal collections that exhibited wild animals at fairs across Europe and the Americas.

Texts from the Wikipedia website

Edward J. Kelty (American, 1888-1967)

Century Photographers 74 W 47 N.Y.C.

Ringling Golden Jubilee – Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Combined Circus

Newark, N.Y. June ? 1933

Gelatin silver print

Edward J. Kelty (American, 1888-1967)

Century Photographers 74 W 47 N.Y.C.

Congress of Freaks with Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Combined Circus

1931

Gelatin silver print

Edward J. Kelty (American, 1888-1967)

Century Photographers 74 W 47 N.Y.C.

“Doll Family of Midgets”, Celebrating “Ringling Golden Jubilee”, Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Combined Circus Side Show

1933

Gelatin silver print

11 1/8 × 19 1/2 inches (28.3 × 49.5cm)

Edward J. Kelty (American, 1888-1967)

Century Photographers 110 W 46 NYC

Col. Tim McCoy and his Congress of Rough Riders of the World Featured on the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus

Newark. N.J. June 11th 1935

Gelatin silver print

Timothy John Fitzgerald McCoy (April 10, 1891 – January 29, 1978) was an American actor, military officer, and expert on American Indian life and customs. He was also known Colonel T.J. McCoy.

McCoy worked steadily in movies until 1936, when he left Hollywood, first to tour with the Ringling Brothers Circus and then with his own “wild west” show. The show was not a success and is reported to have lost $300,000, of which $100,000 was McCoy’s own money. It folded in Washington, D.C. and the cowboy performers were each given $5 and McCoy’s thanks. The Indians on the show were returned to their respective reservations by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. …

For his contribution to the film industry, Col. Tim McCoy was honoured with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. In 1973, McCoy was inducted into the Hall of Great Western Performers of the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum. McCoy was inducted into the Cowboy Hall of Fame in 1974.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Edward J. Kelty (American, 1888-1967)

Century Photographers 110 W 46 NYC

Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus

Jersey City, N.J. June 12, 1935

Gelatin silver print

Edward J. Kelty (American, 1888-1967)

Century Photographers 110 W 46 NYC

Congress of Clowns, Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Combined Circus

Patterson, N. J. June 13, 1935

Gelatin silver print

11 1/8 × 19 5/8inches (28.3 × 49.9cm)

Edward J. Kelty (American, 1888-1967)

Century Photographers 110 W 46 NYC

World Renowned Acrobats, Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Combined Circus

Patterson, N. J. June 13, 1935

Gelatin silver print

Edward J. Kelty (American, 1888-1967)

Century Photographers 110 W 46 NYC

“Queens of the Air”, Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Combined Circus

Patterson, N. J. June 13, 1935

Gelatin silver print

11 1/4 × 19 5/8 inches (28.6 × 49.9cm)

Edward J. Kelty (American, 1888-1967)

Century Photographers 110 W 46 NYC

Tommy Atkins Military Riding Maids featured with Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus

Poughkeepsie, N.Y. – June 15th 1935

Gelatin silver print

Dorothy Herbert (1910-1994) joined Ringling Bros and Barnum & Bailey in 1930 when she was only 20 years old. Over the next decade she truly became a headliner – appearing on a variety of posters, including several seen here. Like Lillian Leitzel, May Wirth and Tim McCoy, and later Lou Jacobs and Gunther Gebel-Williams – her star status led to the creation of a number of posters featuring her image.

Herbert was only 24 years old when a portrait lithograph was added to the Ringling-Barnum billposter hod during the 1934 season. Starting that spring, and for several seasons following, an image of Miss Herbert and her horse Satan appeared in hundreds of store windows as both a one-sheet and a window card, and in a much larger format on the sides of walls and barns. The same portrait was also featured on the cover of the 1934 program book, the first time an individual circus star was featured on the Ringling-Barnum “Program and Daily Review”. …

[Herbert] features in a display that she starred in titled “Miss Tommy Atkins and Her Military Maids” The depiction is of a group of girls on horses, dressed in British red-coat dress uniforms. The act consisted of military equestrian manoeuvres and the reason it carried the name “Miss Tommy Atkins” is that a British soldier of the era was often referred to as a “Tommy Atkins” much in the way that American soldiers have been known as “G.I. Joe”.

Extract from Chris Berry. “Dorothy Herbert (Ringling Bros and Barnum & Bailey),” on the Collectors Weekly website 2012 [Online] Cited 20/10/2018

Edward J. Kelty (American, 1888-1967)

Century Photographers 74 W 47 N.Y.C.

Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus Executive Staff

New Brunswick, N.J. – June 17th 1931

Gelatin silver print

The Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus was a circus that traveled across America in the early part of the 20th century. At its peak, it was the second-largest circus in America next to Ringling Brothers and Barnum and Bailey Circus. It was based in Peru, Indiana.

The circus began as the “Carl Hagenbeck Circus” by Carl Hagenbeck (1844-1913). Hagenbeck was an animal trainer who pioneered the use of rewards-based animal training as opposed to fear-based training.

Meanwhile, Benjamin Wallace, a livery stable owner from Peru, Indiana, and his business partner, James Anderson, bought a circus in 1884 and created “The Great Wallace Show”. The show gained some prominence when their copyright for advertising posters was upheld by the Supreme Court in Bleistein v. Donaldson Lithographing Company. Wallace bought out his partner in 1890 and formed the “B. E. Wallace Circus”.

In 1907, Wallace purchased the Carl Hagenbeck Circus and merged it with his circus. The circus became known as the Hagenbeck-Wallace circus at that time, even though Carl Hagenbeck protested. He sued to prohibit the use of his name but lost in court. …

The circus spent its winters just outside Baldwin Park, California. There, on 35 acres of land, the circus stayed with its huge parade wagons parked alongside a railroad spur. The elephants spent time hauling refuse wagons, shunting railroad cars and piling baled hay. A tent at the eastern edge of the grounds was used by aerialists to practice trapeze and high-wire acts. The circus usually remained there from late November to early spring.

The Great Depression and Ringling’s ill health caused the Ringling empire to falter. In 1935, the circus split from Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey and became the Hagenbeck-Wallace and Forepaugh-Sells Bros. Circus. It finally ceased operations in 1938.

The complex near Peru that formerly housed the winter home of Hagenbeck-Wallace now serves as the home of the Circus Hall of Fame.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Edward J. Kelty (American, 1888-1967)

Century Photographers 74 W 47 N.Y.C.

Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus

1931

Gelatin silver print

11 1/4 × 19 5/8 inches (28.6 × 49.9 cm.)

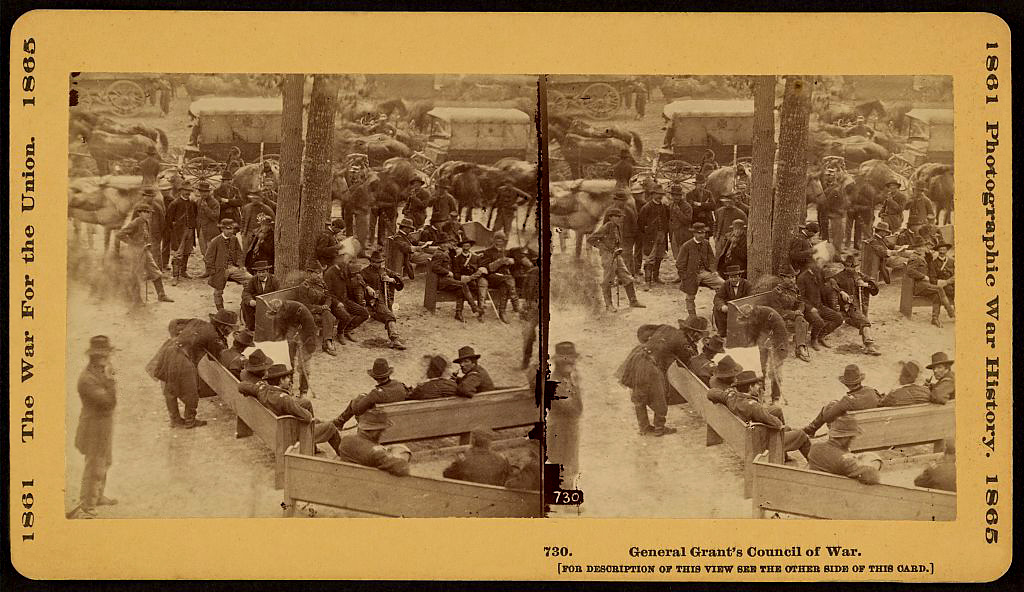

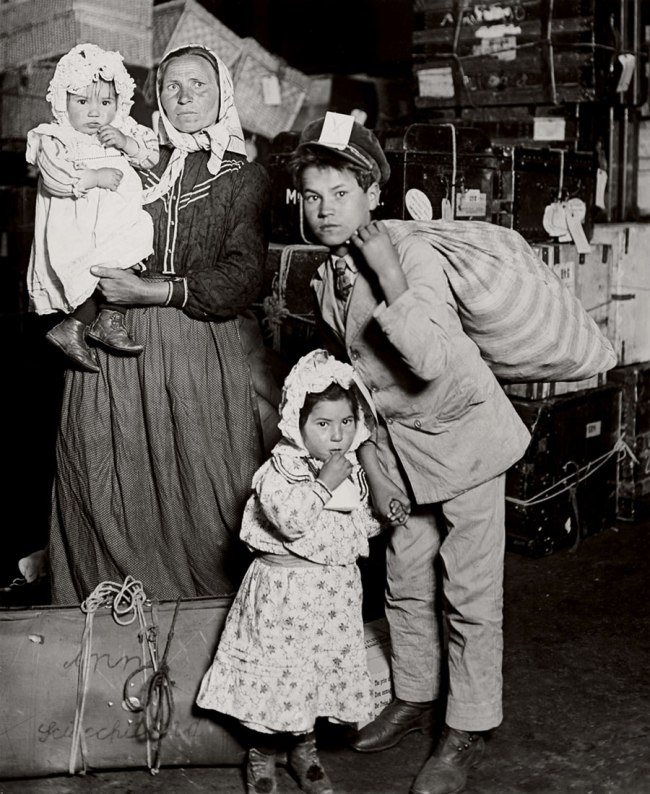

Edward J. Kelty (1888-1967) moved to New York City following his service in the Navy during World War I, and opened up his first studio, Flashlight Photographers. Kelty was drawn to the circus and visited Coney Island often. In the summer of 1922, he transformed his truck into a mini studio, darkroom and living quarters, and traveled across America. His panoramic views captured the performers – human and animal – associated with Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey, Hagenbeck-Wallace, Sells-Floto, Clyde Beatty, Cole Bros. and other train, wagon and truck shows.

A typical day for Kelty would have him waking at dawn to set up cameras and tripods, gathering bearded ladies and sword swallowers, snake charmers and giants and shooting all morning. At times he had as many as 1,000 people in a picture. Afternoons were spent processing film and making proofs, taking orders and printing well into the night. The following day, he distributed prints, most often to circus staff and performers, before returning to his New York studio to work on his wedding and banquet photography business.

Kelty was hit hard by the Depression, and by 1942 had cashed in his glass plate negatives to settle a hefty bar tab. He moved to Chicago and, as legend has it, never took another photograph. His extant negatives eventually made their way into a Tennessee collection of circus memorabilia. Since Kelty used Nitrate-based film, which is unstable when improperly housed, the negatives self-destructed and were disposed of.

After Kelty died in 1967, his estranged family found no photographs, cameras or negatives among his belongings – just one old lens and a union concession employee ID card identifying him as a vendor at Chicago’s Wrigley Field. There was no evidence of the man who, along with his custom mammoth-size banquet camera and portable studio, documented America’s greatest traveling circuses.

Anonymous. “Edward J. Kelty,” on the Swann Galleries website Nd [Online] Cited 21/11/2018. No longer available online

Edward J. Kelty (American, 1888-1967)

Century Photographers 74 W 47 N.Y.C.

Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus, Jess Adkins, Manager – Rex De Rosselli, Producer of Spectacle – Harry McFarlan, Equestrienne Director

Brooklyn, N.J. June 11th 1932

Gelatin silver print

Edward J. Kelty (American, 1888-1967)

Century Photographers 74 W 47 N.Y.C.

Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus, Jess Adkins, Manager – Rex De Rosselli, Producer of Spectacle – Harry McFarlan, Equestrienne Director

St. Louis, MO. – May 11th 1934

Gelatin silver print

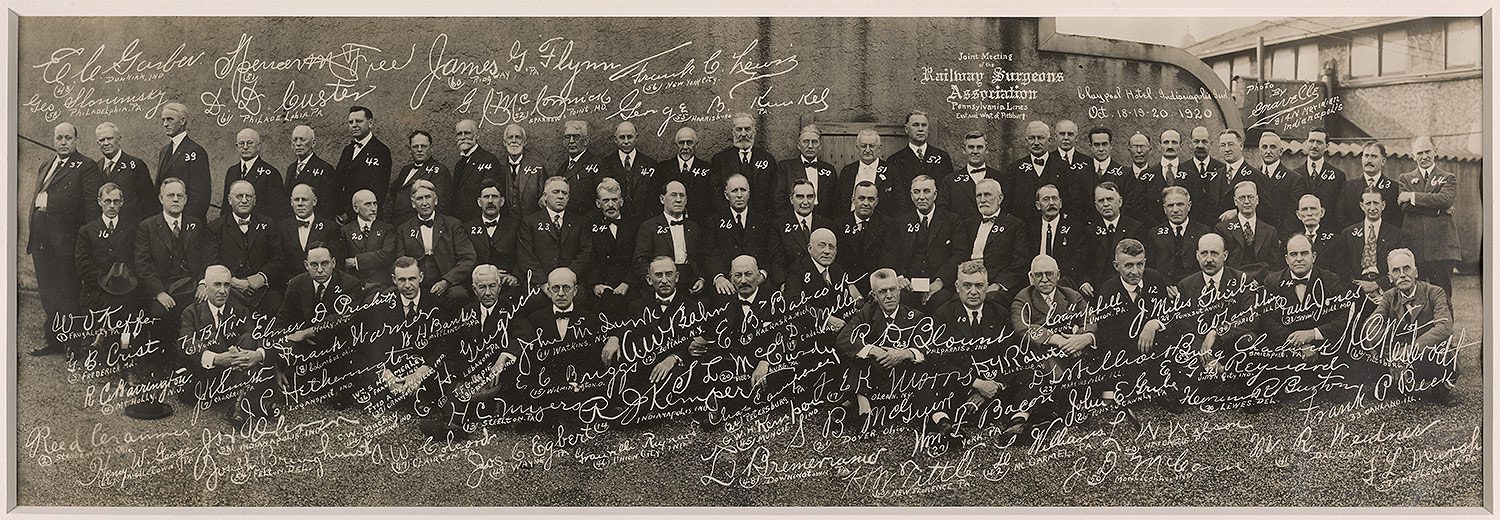

Banquet photography

Banquet photography is the photography of large groups of people, typically in a banquet setting such as a hotel or club banquet room, with the objective of commemorating an event. Clubs, associations, unions, circuses and debutante balls have all been captured by banquet photographers.

A banquet photograph is usually taken in black and white with a large format camera, with a wide angle lens, from a high angle to ensure that each person is in focus while seated at their table. Large cameras such as a 12 × 20 view camera or a panoramic camera were used. The defining characteristic of a banquet photograph is the depth of focus and detail and clarity of the image.

Banquet photography was most popular in the 1890s, and had mostly waned by the 1970s. In part its decline is owed to the difficult technical aspects of producing quality banquet photos, the difficulty of printing such large negatives, and the expense and size of the equipment needed. Today, though hard to find, there are a handful of photographers still shooting banquet photos with flashbulbs and large format film cameras. View cameras use large format sheet film – one sheet per photograph.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Edward J. Kelty (American, 1888-1967)

Century Photographers 144 W 46 N.Y.C.

Christy Brothers Circus Side Show, H. Emgard – Manager

1927

Gelatin silver print

George Washington Christy was born February 22 1889 in Pottstown, Pennsylvania to parents John and Ida Christy.

The circus opened in 1919 under the title of “Christy Hippodrome Shows” (later changed to Christy Bros. Circus). The show opened as a two car show, Christy purchased many of his parade wagons from the Ringling Bros. after they discontinued their downtown parades. The circus wintered first in Galveston, Texas and then in South Houston, where Christy had built a home.

On May 25, the show’s trained wrecked just outside of Cardston Alberta, Canada.. G.W. Christy, being the showman that he was set up in a cornfield near the wreck and gave a performance while the rails were being cleared. In 1925 and 1926, Christy operated a second unit named “Lee Bros.”, but closed it after the the 1926 season.

The “Great Depression” beginning in 1929, was a difficult time for all shows on the road. The Christy Bros. Circus was no exception, not only was the economy in bad shape but weather was also a major factor. Christy and his loyal employees struggled to keep the circus on the road. On July 7, 1930 the Christy Brothers Circus gave it’s last performance in Greeley, Colorado.

After the close of the show, most of the equipment was sold in 1935 to Jess Adkins and Zack Terrell, who were framing their Cole Bros. Circus, some of the parade wagons went to the “Ken Mayner Circus”. Christy kept his elephants and horses, the elephants were used to help build Spencer Highway in South Houston, Texas.

After leaving the circus world George Christy became mayor of the City of South Houston serving from 1949 to 1951 and again from 1960 to 1964. George Washington Christy died August 07, 1975 in Houston Texas.

Anonymous text. “Christy Bros Circus,” on the Circuses and Sideshows website Nd [Online] Cited 13/03/2022

Edward J. Kelty (American, 1888-1967)

Century Photographers 144 W 46 N.Y.C.

Walter L. Main Circus

1927

Gelatin silver print

The Walter L. Main Circus was founded by Walter L. Main in 1886. Walter’s father “William” was a horse farmer, trainer and trader in Trumbull, Ohio. William began supplying horses to circuses, which led to him joining the “Hilliard & Skinner’s Variety and Indian show”. William toured with several shows and in the 1870s began his own, very small circus. …

1904 was the last year that the “Walter L. Main Circus” operated under Walters ownership, the circus was sold that year to William P. Hall. In 1918 Walter leased the Main title to Andrew Downie who made a small fortune operating his circus under the Main name until he sold the show to the Miller Bros. of the 101 Ranch Wild West Show in 1924. In 1925 until 1928 the Main title was used by Floyd King and his brother Howard. The Main title was used by various operators 1930-1937.

Anonymous text. “Walter L. Main Circus,” on the Circuses and Sideshows website Nd [Online] Cited 13/03/2022

Edward J. Kelty (American, 1888-1967)

Century Photographers 74 W 47 N.Y.C.

Harlem Black Birds, Coney Island

1930

12 x 20 in. (30.5 x 50.8cm)

Collection of Ken Harck

© Edward J. Kelty

Edward J. Kelty (American, 1888-1967)

Century Photographers 74 W 47 N.Y.C.

Sells-Floto Big Double Side Show, Jersey City, N.J. – June 19th 1931, Lew. C. Edelmore – Manager

1931

Gelatin silver print

Edward J. Kelty (American, 1888-1967)

Century Photographers 74 W 47 N.Y.C.

Sam B. Dill’s Circus

Mineola, L.I., N.Y. – June 19th 1933

Gelatin silver print

Early Wednesday morning, July 19, 1933, a long train arrived in York and stopped near the fairgrounds. The Sam B. Dill Circus had arrived.

“Young America, having caught the infectious circus spirit is likely to be in ahead of both morning orb and circus and be on the lot along with enthusiastic adults to greet the show train on its arrival there,” The York Dispatch reported the day before the train’s arrival.

The unloading and setting up of the circus tents and shows worked smoothly. All of the performers knew their jobs. They had been doing it multiple times each week since the circus had opened its season in Dallas on April 9.

Wagons containing the menagerie were rolled down ramps. Trunks were carried off to other areas. Elephants and roustabouts worked to raise the big top as the sun rose. Within a relatively short time, the big top tent was erected, and the performers went to work preparing their equipment inside while the roustabouts set up the bleacher seating.

By the time everything was finished around 9 a.m., the cooks in the circus kitchen had breakfast ready.

The Sam B. Dill Circus was scheduled to play two performances, at 2 p.m. and 8 p.m., for York residents.

“Sam B. Dill’s Circus isn’t the biggest circus in the world, but what it lacks in size it makes up in quality,” the Amarillo Sunday News and Globe wrote about the circus.

Dill had managed the famous John Robinson Circus, but when it was sold to the American Circus Corp., Dill had struck out on his own. Though not a large circus, Dill’s circus was popular and tended to sell out its performances.

After breakfast, everyone had a short rest, and then they began to scurry around getting the menagerie wagons harnessed to horses and in a line. Performers dressed in their bright and flamboyant costumes. At noon, “a long column of red, gold and glitter, with bands playing and banners flying will move sinuously out of the Richland Avenue gate,” The York Dispatch reported.

From Richland Avenue, the parade moved east on Princess Street, then north on George Street to Continental Square. From the square, the circus moved west on Market Street and then back to Richland Avenue. Thousands of spectators lined the route to watch the performers, hear the music and marvel at the wild animals.

The first wagon was the band wagon where Shirley Pitts, the country’s only female calliope player, conducted the band. Then came the wagons pulling tigers, monkeys, seals and more. Other flat wagons featured clowns goofing off and Wild West displays.

When the parade arrived back at the fairgrounds, many of the spectators followed. Although the big top wouldn’t open until 1 p.m., spectators wandered the midway, playing games, getting an up-close look at the menagerie or viewed some of the shows in the smaller tents.

The three-ring show under the big top had dozens of animals such as Oscar the Lion, Buddy the performing sea lion, camels, zebras, horses, elephants, dogs, monkeys and ponies.

Christian Belmont swung on the trapeze, along with aerialist Rene Larue. Mary Miller performed a head-balancing act. The four Bell Brothers showed off their acrobatic skills, and Betha Owen owned the high wire. Among the clowns, young Jimmy Thomas was noted as the “youngest clown in the circus world.” He traveled with his mother, Lorette Jordan, who was also an aerialist with the show.

The circus also liked to feature a western movie star with its Wild West acts. In 1933, that performer was Buck Steel. The following year, Tom Mix joined the circus. He had been a major western movie star who had seen his popularity decline in the 1920s. In 1935, he bought the circus from Dill and renamed it the Tom Mix Circus.

Following the 8 p.m. show, the performers broke down the circus and loaded it back on the train to head out by midnight for the next city.

James Rada Jr. “LOOKING BACK 1933: The circus comes to town,” from the York Dispatch website August 3, 2016 [Online] Cited 13/03/2022

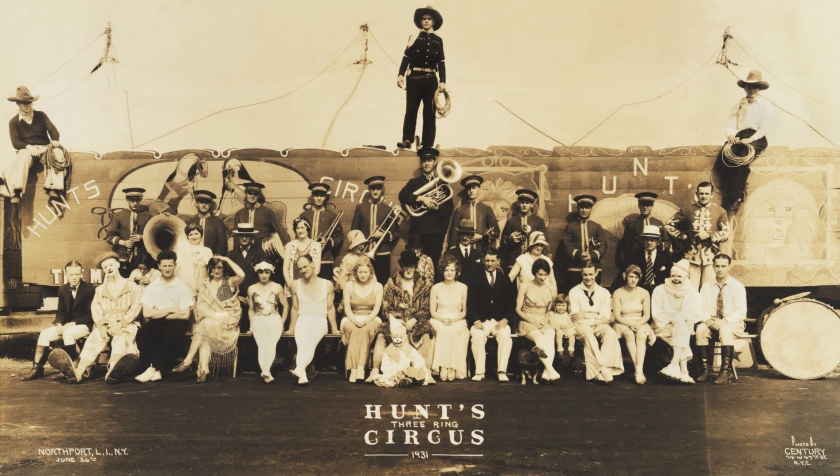

Edward J. Kelty (American, 1888-1967)

Century Photographers 74 W 47 N.Y.C.

Hunt’s Three Ring Circus

Northport, L.I., N.Y. – June 26th 1931

Gelatin silver print

Edward J. Kelty (American, 1888-1967)

Century Photographers 74 W 47 N.Y.C.

James Whalen and His Big Top Department – Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Combined Circus

Reading, P.A. – June 1st 1934

Gelatin silver print

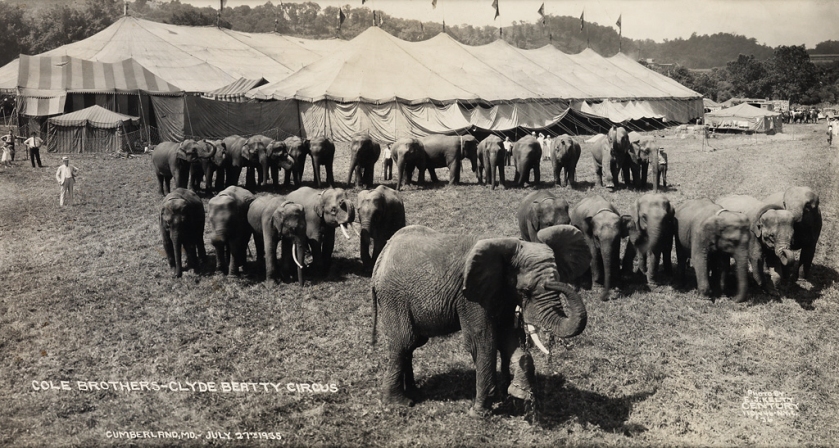

Edward J. Kelty (American, 1888-1967)

Century Photographers 110 W 46 NYC

Cole Brothers – Clyde Beatty Circus

Cumberland, MD July 27th 1935

Gelatin silver print

11 1/4 × 19 5/8 inches (28.6 × 49.9 cm)

Clyde Beatty Circus

Clyde Beatty (June 10, 1903 – July 19, 1965) began his circus career working as a cage boy for Louis Roth, he learned his trade quickly and soon had his own animal act. Beatty’s “fighting act” style and his showmanship propelled him to stardom.

Not only was Clyde a star of the center ring but he also starred in numerous movies, radio shows and his adventures were fictionalised in novels. The name “Clyde Beatty” became a very value asset to circus. The name was used on posters and painted on show equipment alongside the circus’ name on whatever show he was working.

In 1935 Clyde Beatty was on Jess Adkins and Zack Terrell’s “Cole Bros. Circus”, Then in 1943 he worked for Art Concello on the “Clyde Beatty-Russell Bros. Circus”. Beatty continued to be active with the show until his death in 1965.

Anonymous text. “Clyde Beatty Circus,” on the Circuses and Sideshows website Nd [Online] Cited 13/03/2022

Cole Bros. Circus

The Cole Title dates back to 1870 when William Washington Cole (1847-1915), started the W. W. Cole Circus. Cole was very successful in in the circus business and when he died in 1915, left an estate of five million dollars. He is considered to be the first circus millionaire.

in 1906 the title was purchased by Canadian showman Martin Downs and his son James and the title was changed to Cole Bros.. The circus was moved from St. Louis, Mo. to it’s new winter quarters in Birmingham, Al..

In the late 1920s the Cole Bros. titled was used by Floyd King and his brother Howard. This version of the Cole Bros. Circus operated mostly in the west, playing mining camps and boomtowns, truly a frontier circus. The new Cole Bros. Circus, 35 railroad car show first took to the road in 1935 with Jess Adkins and Zack Terrell as the circus organisers and owners.

Terrell who had managed the Sells-Floto Circus for the American Circus Corp. from 1921-1932 and in 1934 he managed a circus at the Chicago World’s Fair operated by the Standard Oil Company.

Adkins had managed the Gentry Bros. Circus for Floyd King, the 25 car John Robinson Circus and in 1931 the Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus. Jess Adkins and Zack Terrell were very capable managers however neither had ever owned a circus, however in 1934 each were quietly making plans to take out their own circuses.

Adkins and Terrell went to Lancaster, Mo. and purchased equipment left from the now defunct Robbins Bros. Circus. The purchased included 15 wagons, 6 elephants, 5 camels, school horses, and zebras. The equipment was moved to Rochester, IN where they had bought property to serve as a winter quarters.

Adkins and Terrell hired Floyd King as general agent and Arnold Maley as office manager who both assisted in the organisation of the show.

This was the beginning of the Cole Bros. Circus

Anonymous text. “Cole Bros. Circus,” on the Circuses and Sideshows website Nd [Online] Cited 13/03/2022

Edward J. Kelty (American, 1888-1967)

Century Photographers 110 W 46 NYC

Col. W.T. Johnson’s World Champion Cowgirls – Madison Square Garden – New York City – 1935

1935

Gelatin silver print

11 1/4 × 19 5/8 inches (28.6 × 49.9cm)

The Great Depression of the 1930s was one of the most traumatic periods in American history. The human suffering caused by the Stock Market crash, and the business failures that followed took a toll which has never been fully calculated. Yet through all of the hardships, some business did thrive… One sport which prospered during the Depression was rodeo, Its big-time circuit grew enormously during the 1930s, and incomes of contestants and producers increased as well.

Much of the credit for this must go to Col. William Taylor Johnson of San Antonio, Texas. Johnson became a rodeo producer in 1928, and by the mid-thirties had taken over the prestigious Madison Square Garden Rodeo and created a viable eastern circuit which ushered in a new era of rodeo history. The eastern contests paid excellent prizes and extended the season, so that many cowboys and cowgirls did exceptionally well for those troubled times. During the Depression, average incomes for rodeo professionals on the big-time circuit averaged from one to three thousand dollars annually, while top champions earned from ten to twelve thousand dollars a year… By 1934, every rodeo which Johnson produced had set attendance records, and the eastern circuit was an integral part of rodeo. (“The Story of The Billboard, and Col. W. T. Johnson’s Rodeos,” The Billboard, 29 October 1934, p. 75). In spite of his many contributions, Johnson is honoured by no rodeo Hall of Fame, and has never been nominated. How could such a major figure be ignored?

Extract from the abstract from Mary Lou LeCompte. “Colonel William Thomas Johnson, Premier Rodeo Producer of the 1930s.” The University of Texas at Austin

Edward J. Kelty (American, 1888-1967)

Century Photographers 110 W 46

U.S.W.P.A. Federal Theatre Circus Unit

New York City, Sept. 26th 1936

Gelatin silver print

United States Works Progress Administration (U.S.W.P.A.)

The Works Progress Administration (WPA; renamed in 1939 as the Work Projects Administration) was the largest and most ambitious American New Deal agency, employing millions of people (mostly unskilled men) to carry out public works projects, including the construction of public buildings and roads. In a much smaller project, Federal Project Number One, the WPA employed musicians, artists, writers, actors and directors in large arts, drama, media, and literacy projects.

The Federal Theatre Project (FTP; 1935-1939) was a New Deal program to fund theatre and other live artistic performances and entertainment programs in the United States during the Great Depression. It was one of five Federal Project Number One projects sponsored by the Works Progress Administration. It was created not as a cultural activity but as a relief measure to employ artists, writers, directors and theatre workers. It was shaped by national director Hallie Flanagan into a federation of regional theatres that created relevant art, encouraged experimentation in new forms and techniques, and made it possible for millions of Americans to see live theatre for the first time. The Federal Theatre Project ended when its funding was canceled after strong Congressional objections to the left-wing political tone of a small percentage of its productions.

Texts from the Wikipedia website

Edward J. Kelty (American, 1888-1967)

Century Photographers 74 W 47 N.Y.C.

Marcellus Golden Models

1933

Gelatin silver print

11 1/4 × 8 7/8 inches (28.6 × 22.5cm)

“Fortunately, we aren’t entirely bereft of a visual record of these arcane marvels. A Manhattan banquet photographer name Edward Kelty, whose usual venue was hotel ballrooms and Christmas parties, went out intermittently in the summer from the early 1920s to the mid-1940s, taking panoramic tripod pictures of circus personnel, in what could only have constituted a labor of love. He was expert, anyway, from his bread-and-butter job, at joshing smiles and camaraderie out of disparate collection of people, coaxing them to drape their arms around each other and trust the box’s eye. He had begun close to home, at Coney Island freak shows, when the subway was extended out there, and Times Square flea-circus “museums” and variety halls, and the Harlem Amusement Palace. Later, building upon contact and friendships from those places, he outfitted a truck for darkroom purposes (presumably to sleep in too) and sallied farther to photograph the tented circuses that played on vacant lots in New Jersey, Connecticut, or on Long Island, and gradually beyond. He would pose an ensemble of horse wranglers, canvasmen, ticket takers, candy butchers, teeterboard tumblers, “web-sitters” (the guys who hold the ropes for the ballet girls who climb up them and twirl), and limelight daredevils, or the bosses and moneymen. He took everybody, roustabouts as conscientiously as impresarios, and although he was not artistically very ambitious – and did hawk his prints both to the public and to the troupers, at “six for $5” – in his consuming hobby he surely aspired to document this vivid, disreputable demimonde [a group of people on the fringes of respectable society] obsessively, thoroughly: which is his gift to us.

More of these guys may have been camera-shy than publicity hounds, but Kelty’s rubber-chicken award ceremonies and industrial photo shoots must have taught him how to relax jumpy people for the few minutes required. With his Broadway pinstripes and a news-man’s bent fedora, as proprietor of Century Flashlight Photographers in the West Forties, he must have become a trusted presence in the “Backyard” and “Clown Alley.” He knew show-business and street touts, bookies and scalpers – but also how to flirt with a marquee star. Because his personal life seems to have been a bit of a train wreck, I think of him more as a hatcheck girl’s swain, yet he knew hot to let the sangfroid sing from some of these faces… These zany tribes of showboaters must have amused him, after the wintertime’s chore of recording for posterity some forty-year drudge receiving a gold watch… The ushers, the prop men and riggers, the cookhouse crew, the elephant men and cat men, the show-girls arrayed in white bathing suits in a tightly chaperoned, winsome line, the hoboes who had put the tent up and, in the wee hours, would tear it down, and the bosses whose body language, with arms akimbo and swaggering legs, tells us something of who hey were: these collective images telegraph the complexity of the circus hierarchy, with the starts at the top, winos at the bottom. …

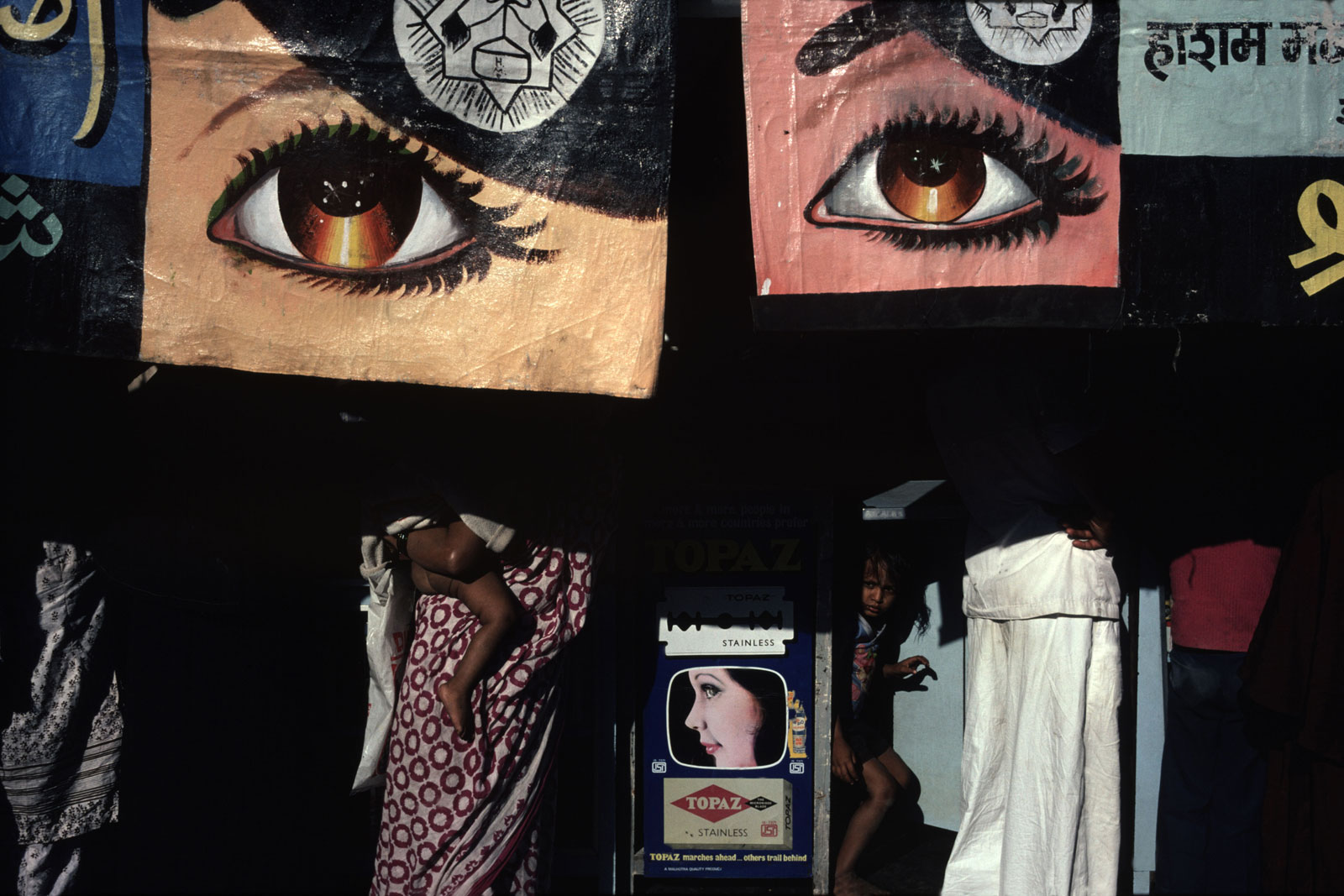

While arranging corporate personnel in the phoney bonhomie of an office get-together, Kelty must have longed for summer, when he would be snapping “Congresses” of mugging clowns, fugue-ing freaks, rodeo sharpshooters, plus the train crews known as “razor-backs” (Raise your backs!), who loaded and unloaded the wagons from railroad flatcars at midnight and dawn… Circuses flouted convention as part of their pitch – flaunted and cashed in on the romance of outlawry, like Old World gypsies. If there hadn’t been a crime wave when the show was in town, everybody sure expected one. And the exotic physiognomies, strangely cut clothes, and oddly focused, disciplined bodies were almost as disturbing – “Near Eastern,” whatever Near Eastern meant (it somehow sounded weirder than “Middle Eastern” or “Far Eastern”), bedouin Arabs, Turks and Persians, or Pygmies, Zulus, people cicatrized, “platter-lipped,” or nose-split. That was the point. They came from all over the known world to parade on gaudy ten-hitch wagons or caparisoned [decked out in rich decorative coverings] elephants down Main Street, and then, like the animals in the cages, you wanted them to leave town.

Edward Hoagland. Sex and the River Styx. Chelsea Green Publishing, 2011, pp. 81-84

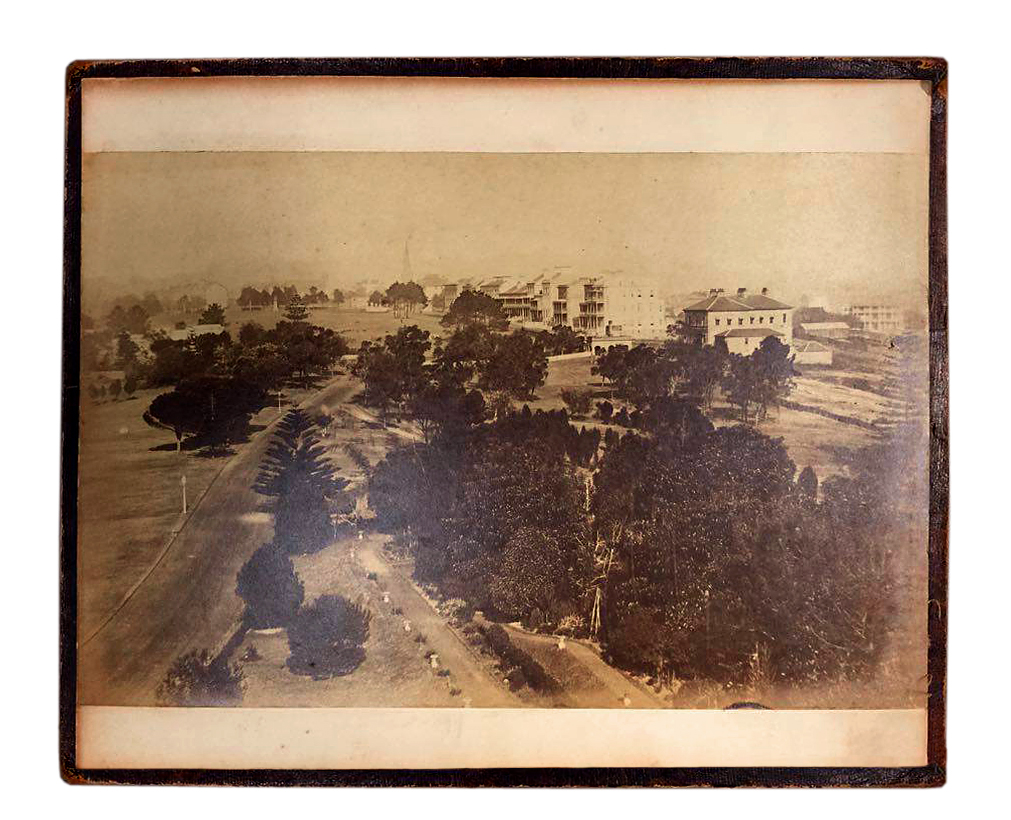

![George Roberts (Australian born United Kingdom, c. 1800-1865) '[Mrs Macquarie's chair]' c. 1843-1865 George Roberts (Australian born United Kingdom, c. 1800-1865) '[Mrs Macquarie's chair]' c. 1843-1865](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/mrs-macquaries-chair-web.jpg)

![Josef Koudelka (Czech-French, b. 1938) 'An Hour of Love by Josef Topol, Divadlo za branou [Theater behind the Door], Prague' 1968 Josef Koudelka (Czech-French, b. 1938) 'An Hour of Love by Josef Topol, Divadlo za branou [Theater behind the Door], Prague' 1968](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/11/par148634-web.jpg?w=840)

![Josef Koudelka (Czech-French, b. 1938) 'Israel-Palestine (Al 'Eizariya [Bethany])' From the series 'Wall', 2010 Josef Koudelka (Czech-French, b. 1938) 'Israel-Palestine (Al 'Eizariya [Bethany])' From the series 'Wall', 2010](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/11/par383535-web.jpg?w=840)

You must be logged in to post a comment.