Exhibition dates: 26th July 2020 – 3rd January 2021

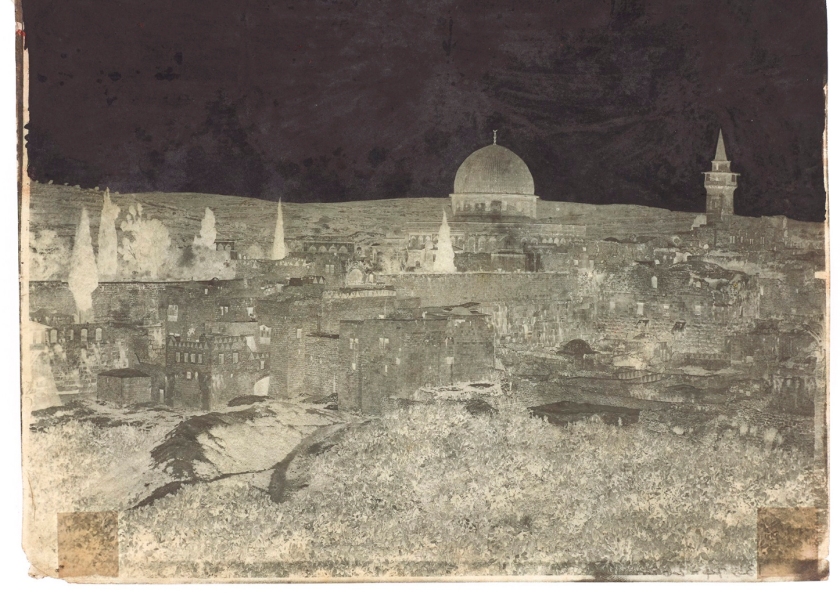

John Shaw Smith (British, 1811-1873)

The Mosque of Omar, Jerusalem

April 1852

Albumen silver print, printed c. 1855

George Eastman Museum, gift of Alden Scott Boyer

Courtesy of the George Eastman Museum

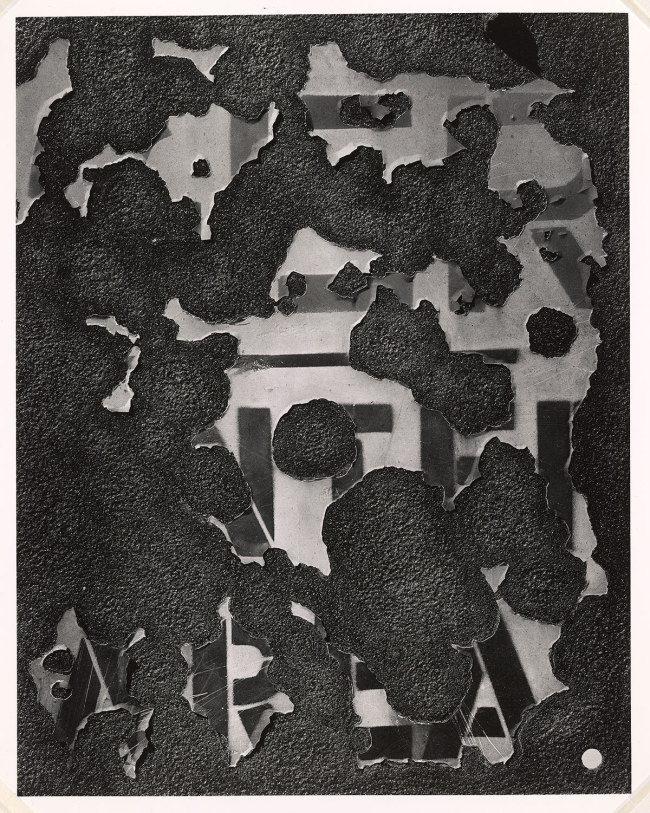

From December 1850 to September 1852, John Shaw Smith travelled throughout the Mediterranean with a camera. He used the paper negative process that William Henry Fox Talbot patented in 1841. Shaw Smith masked out uneven tonality or aberrations in the sky with India ink, a common practice at the time, and he introduced clouds into his prints through combination printing. Rather than a cloud negative made from life, however, his second paper negative consisted of clouds hand-drawn with charcoal.

John Shaw Smith (British, 1811-1873)

The Mosque of Omar, Jerusalem

April 1852

Calotype negative

George Eastman Museum, gift of Alden Scott Boyer

Courtesy of the George Eastman Museum

Completing a triumvirate of postings about aeroplanes, air, and sky … we finish with a posting on a small but perfectly formed exhibition, Gathering Clouds: Photographs from the Nineteenth Century and Today at George Eastman Museum.

The technical competence of the early photographers, and the sheer beauty of their images, is mesmerising. To overcome the technical deficiencies of early photographic processes – where the dynamic tonal range between shadows and highlights was difficult to capture on one negative – the artists used painted clouds, hand-drawn clouds, and combination prints with cloud negatives made from life. You name it, they could do it to fill a sky!

My particular favourites in this elevated selection, these songs of the earth and sky, are three. Firstly, that most divine of daguerreotypes, a woman by Southworth & Hawes c. 1850 (below). “The heavenly realm had long been represented by clouds in Western art.” Secondly, and always a desire of mine, are the seascapes of Gustave Le Gray. There is something so spatial, so serene about his images. One day I know I will own one. And finally, the surprise that is that most beautiful of images, Marsh at Dawn 1906 (below). You could have knocked me over with a feather when I found out it was by that doyen of modernist photography, Imogen Cunningham, a member of the California-based Group f/64, known for its dedication to the sharp-focus rendition of simple subjects. How an artist evolves over the life time of their career.

I have added text to some of the images from the George Eastman Museum virtual tour, and also added further biographical notes on the artists below some of the photographs. I do hope you enjoy the magic of these accumulated – a cumulus related images.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to George Eastman Museum for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Gathering Clouds traces the complex history of photography’s relationship with clouds from the medium’s invention to Alfred Stieglitz’s Equivalents. The exhibition demonstrates that clouds played a seminal role in the development and subsequent reception of photography in the nineteenth century. At the same time, with Equivalents serving as a connection between past and present, the exhibition features contemporary works that forge new aesthetic paths while responding in various ways to the history of cloud photography.

Clouds and the Limitations of Photography

In the nineteenth century, clouds were technically difficult to photograph. As early as the 1830s, the medium’s inventors observe that photographic plates were more sensitive to violet and blue wavelengths of light and less sensitive to warm greens, yellows, oranges and reds. In order to record grass and trees in a landscape, photographers had to expose the plate to light longer, which left the sky overexposed; if they times their exposure to record the sky properly, the grass and trees were underexposed. Furthermore, clouds disappeared from even properly exposed skies because blue and white registered the same tonal value on the plate. Pink and orange skies created enough contrast for photographers to capture clouds, but the yellow hue of the late-day sun made it a challenge to record the browns and greens of the landscape. Cloudless skies are therefore a common feature of nineteenth-century photographs.

Clouds & Combination Printing

Painted Clouds and Combination Prints with Hand-Drawn Clouds

Southworth & Hawes (Albert Sands Southworth, American, 1811-1894; Josiah Johnson Hawes, American, 1808-1901)

Woman

c. 1850

Daguerreotype

George Eastman Museum, gift of Alden Scott Boyer

Courtesy of the George Eastman Museum

Around 1850, Southworth & Hawes began adding hand-painted clouds to select portraits of women. This was undoubtedly an aesthetic decision, but the association of women with clouds also corresponds with mid-nineteenth-century views of white women and their role in American society. At the time, piety was seen as a virtue bestowed on women by God – a strength upon which men were to draw. The heavenly realm had long been represented by clouds in Western art.

Southworth & Hawes (Albert Sands Southworth, American, 1811-1894; Josiah Johnson Hawes, American, 1808-1901)

Woman (detail)

c. 1850

Daguerreotype

George Eastman Museum, gift of Alden Scott Boyer

Courtesy of the George Eastman Museum

Count Camille Bernard Baillieu d’Avrincourt (French, 1824-1862)

Château de Chambord

c. 1855

Salted paper print

George Eastman Museum, gift of Kodak-Pathé

Courtesy of the George Eastman Museum

Count Camille Bernard Baillieu d’Avrincourt received praise from his peers for his technical skill and artistic sentiment. The clouds in Baillieu d’Avrincourt’s photographs of the Château de Chambord demonstrate his commitment to both. Perhaps dissatisfied with the relationship of clouds to the tower, he used combination printing to alter the placement of the cloud formation between the two prints.

Count Camille Bernard Baillieu d’Avrincourt (French, 1824-1862)

Château de Chambord

c. 1855

Salted paper print

George Eastman Museum, gift of Kodak-Pathé

Courtesy of the George Eastman Museum

“We have the sky always before us, therefore we do not recognise how beautiful it is. It is very rare to see anybody go into raptures over the wonders of the sky, yet of all that goes on in the whole world there is nothing to approach it for variety, beauty, grandeur, and serenity.”

H. P. Robinson, ‘The Elements of a Pictorial Photograph’, 1896

At the end of the nineteenth century, Henry Peach Robinson (British, 1830–1901) emphasised the significance of the sky in landscape photography. “The artistic possibilities of clouds,” he further noted, “are infinite.” Robinson’s plea to photographers to attend to the clouds was not new. From photography’s beginnings, clouds had been central to aesthetic and technological debates in photographic circles. Moreover, they featured in discussions about the nature of the medium itself. Gathering Clouds demonstrates that clouds played a key role in the development and reception of photography from the medium’s invention (1839) to World War I (1914-1918). Through the juxtaposition of nineteenth-century and contemporary works, the exhibition further considers the longstanding metaphorical relationship between clouds and photography. Conceptions of both are dependent on oppositions, such as transience versus fixity, reflection versus projection, and nature versus culture.

Gathering Clouds includes cloud photographs made by prominent figures such as Anne Brigman (American, 1869-1950), Alvin Langdon Coburn (British, 1882-1966), Peter Henry Emerson (British, 1856-1936), Gustave Le Gray (French, 1820-1884), Eadweard Muybridge (British, 1830-1904), Henry Peach Robinson, Southworth & Hawes (American, active 1843-1863), and Adam Clark Vroman (American, 1856-1916). Selections from the group of photographs that Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946) titled Equivalents (1923-34) serve as a link between past and present. The featured contemporary artists are Alejandro Cartagena (Mexican, b. Dominican Republic, 1977), John Chiara (American, b. 1971), Sharon Harper (American, b. 1966), Nick Marshall (American, b. 1984), Joshua Rashaad McFadden (American, b. 1990), Sean McFarland (American, b. 1976), Abelardo Morell (American, b. Cuba, 1948), Vik Muniz (Brazilian, b. 1961), Trevor Paglen (American, b. 1974), Bruno V. Roels (Belgian, b. 1976), Berndnaut Smilde (Dutch, b. 1978), James Tylor (Kaurna, Māori & Australian, b. 1986), Carrie Mae Weems (American, b. 1953), Will Wilson (American, Navajo, b. 1969), Byron Wolfe (American, b. 1967), Penelope Umbrico (American, b. 1957), and Daisuke Yokota (Japanese, b. 1983).

Text from the George Eastman House website

Combination Prints with Cloud Negatives Made from Life

Gustave Le Gray (French, 1820-1884)

Mediterranean with Mount Agde

1857

Albumen silver print

George Eastman Museum, gift of Eastman Kodak Company, ex-collection Gabriel Cromer

Courtesy of the George Eastman Museum

The seascapes that Gustave Le Gray made between 1856 and 1858 were both praised and panned by his contemporaries. Some faulted the clouds for being too luminous in relation to the sea. One critic maintained that in Le Gray’s photographs, the clouds and the landscape – made on two separate negatives and combined during printing – were untrue to the laws of nature.

Combination Prints with Cloud Negatives Made from Life

Gioacchino Altobelli (Italian, 1825-1878)

The Colosseum

c. 1865

Albumen silver print

George Eastman Museum, purchase

Courtesy of the George Eastman Museum

Gioacchino Altobelli used combination printing to achieve a “moonlight effect,” made by photographing the sun (not the moon) behind clouds. Altobelli likely made such photographs with foreign travellers in mind. Inspired by Romantic poets like Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Lord Byron, tourists to Rome often visited the Colosseum by moonlight.

At the end of 1865 the two painter-photographers divided and Gioacchino Altobelli moved to a studio at Passeggiata di Ripetta n.16 that had been used by the photographer Michele Petagna. A new company was formed “Photographic Establishment Altobelli & Co.” which leads us to assume that Atobelli was working in conjunction with other photographers probably including Enrico Verzaschi.

In the beginning of 1866 Altobelli asked for a declaration of ownership (a brevet) to the Department of Commerce in Rome for his invention of the application of color to photographic images (a union of photography with chrome-lithography). The manager of the Pontifical Chrome-Lithography strongly opposed his application as they are already using such an invention from his own Company. Few months later Altobelli asked for another brevet that is granted him this time, “to perform in photograph the views of the monuments with effect of sky”. His method, similar if not identical to that of Gustave Le Gray, consisted in taking a first photograph of a monument where the exposure was adjusted to highlight the architectural characteristics sought. Subsequently Altobelli took at another time one or more additional photographs exposed to capture strong sky and cloud contrasts. In the dark room Altobelli captured on photographic paper the double exposure of the two perfectly aligned plates – this resulted in a well illuminated monument contrasted with a strong sky that gave the feeling of “claire de lune”. In November 1866 Altobelli obtained the brevet for 6 years. It is probable that he didn’t know that in Venice the photographers Carlo Ponti and Carlo Naya were already using the “claire de lune” technique – moreover they tinted them with aniline giving their prints a beautiful blue tone as if the water of the lagoon was illuminated at night by the moon. However the brevet allowed the painter-photographer Gioacchino Altobelli to have great notoriety in Rome and this helped him to increase his work as a portraitist.

Text from the Luminous-Lint website [Online] Cited 21/08/2020

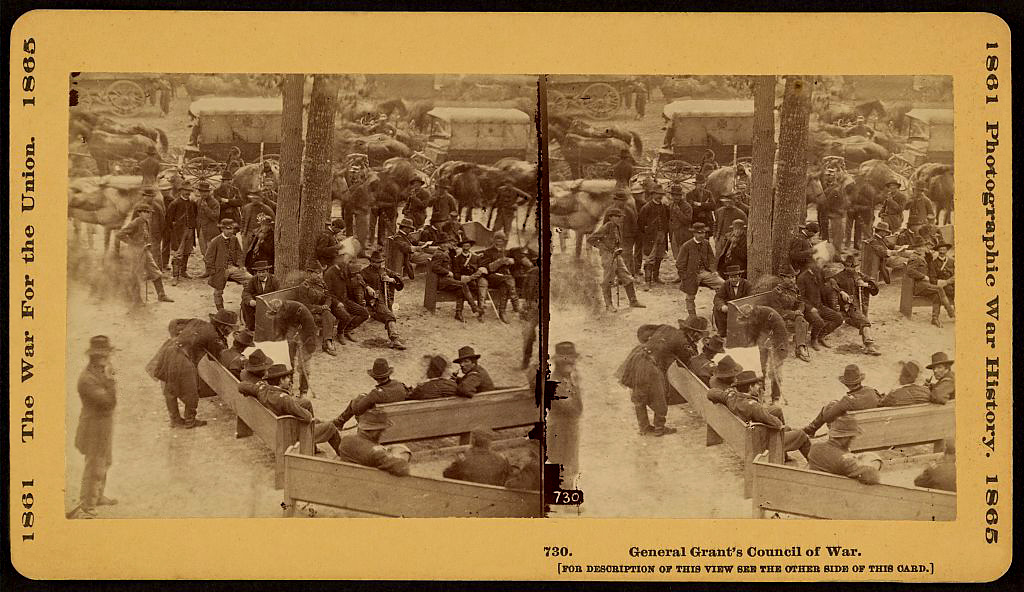

George N. Barnard (American, 1819-1902)

Rebel Works in Front of Atlanta, Ga. No. 1

1866

Albumen silver print

George Eastman Museum, purchase, ex-collection Philip Medicus

Courtesy of the George Eastman Museum

Within one copy of Photographic Views of Sherman’s Campaign (1866), George N. Barnard sometimes used the same cloud negative to print in cloudscapes to two different scenes, such as in the example shown here. Moreover, between two copies of the album, he is also known to have used different cloud negatives to reproduce the same scene. In reviews of the album, the cloudscapes received particular attention. One reviewer claimed that the pictures’ clouds conveyed “a fine idea of the effects of light and shade in the sunny clime in which the scenes are laid.” In part because of Barnard’s practice of re-using cloud negatives, however, it is impossible to know whether Barnard even photographed the clouds while in the South.

George N. Barnard (American, 1819-1902)

Rebel Works in Front of Atlanta, Ga. No. 1 (detail)

1866

Albumen silver print

George Eastman Museum, purchase, ex-collection Philip Medicus

Courtesy of the George Eastman Museum

One of the first persons to open a daguerreotype studio in the United States, George Barnard set up shop in Oswego, New York. In 1854 he moved his operation to Syracuse, New York, and began using the collodion process, a negative / positive process that allowed for multiple prints, unlike the unique daguerreotype.

Along with Timothy O’Sullivan, John Reekie, and Alexander Gardner, Barnard worked for the Mathew Brady studio and is best known for his photo-documentation of the American Civil War. In 1864 he was made the official photographer for the United States Army, Chief Engineer’s Office, Division of the Mississippi. He followed Union General William Tecumseh Sherman’s infamous march to the sea and in 1866 published an album of sixty-one photographs, Photographic Views of Sherman’s Campaign. After the war he continued primarily as a portrait photographer in Ohio, Chicago, Charleston, South Carolina, and Rochester, New York, where he briefly worked with George Eastman, the founder of the Eastman Kodak Company.

Text from the J. Paul Getty website [Online] Cited 21/08/2020

Combination Prints with Cloud Negatives Made from Life

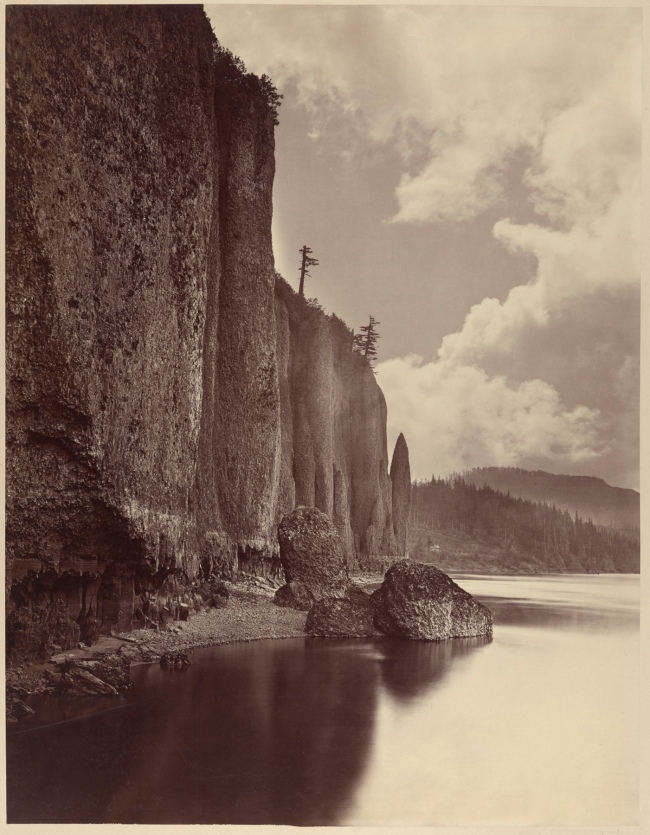

Carleton E. Watkins (American, 1829-1916)

Cape Horn, Columbia River, Oregon

1867

Albumen silver print

George Eastman Museum, museum accession

Courtesy of the George Eastman Museum

In 1867, Carleton E. Watkins travelled to Oregon for two purposes; to photograph the state’s geological features, and to document the sites and scenes along the Oregon Steam Navigation Company’s steamboat and portage railway route. This photograph was circulated with and without clouds, suggesting a third function for his Oregon views. The introduction of clouds into the prints staked a claim for the photograph’s artistic potential, in addition to its original scientific and commercial goals.

Clouds and Landscape on a Single Negative

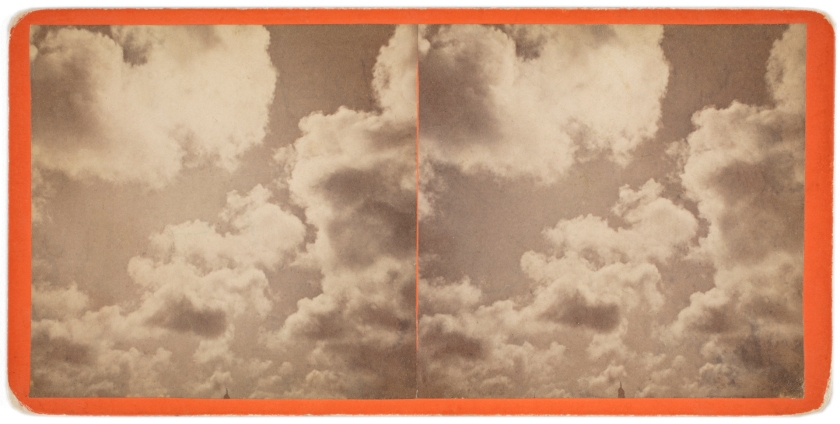

Eadweard J. Muybridge (English, 1830-1904)

Clouds

1868-1872

From the series Great Geyser Springs

Albumen silver print

George Eastman Museum, museum accession

Courtesy of the George Eastman Museum

Painted Clouds and Combination Prints with Hand-Drawn Clouds

Unidentified maker

Mount Fuji

c. 1870

Albumen silver print with applied colour

George Eastman Museum, gift of University of Rochester

Courtesy of the George Eastman Museum

Hand-painted Japanese photographs made for Western tourists often played to their prospective consumers’ assumptions and desires. Near the port city of Yokohama, Mount Fuji was readily accessible to foreign travellers, and photographs of the mountain were common. Guidebooks primed visitors to delight in the clouds surrounding the mountain, an expectation to which this photograph – with its hand-painted clouds – caters.

Henry Peach Robinson (British, 1830-1901)

Evening on Culverden Down

c. 1870

Albumen silver print

Lent by Patrick Montgomery

An influential practitioner of combination printing, H.P. Robinson argued that printing in clouds was essential to the photographer’s endeavour to interpret nature. A “properly selected cloud,” he wrote, allowed the photographer to control the composition, thereby rescuing the “art form from the machine.”

Clouds and Landscape on a Single Negative

Charles Victor Tillot (French, 1825-1895)

Vues instantannées, effets de nuages, Barbizon

Instant views, cloud effects, Barbizon

1874

Albumen silver print

Lent by Patrick Montgomery

Charles Victor Tillot’s instantaneous views were criticised for being to dark. In addition to practicing photography, Tillot was a painter and exhibited with the Impressionists, whose central concerns were the effects of light and the truthfulness to nature. As a photographer, Tillot was attentive to the play of light both on the clouds – the most fleeting aspect of the scene – and in unaltered photographs.

Lala Deen Dayal (Indian, 1844-1905)

Jahaz Mahal

between 1879 and 1881

Albumen silver print

George Eastman Museum, gift of University of Rochester Library

Courtesy of the George Eastman Museum

Lala Deen Dayal (Hindi: लाला दीन दयाल) 1844 – 1905; (also written as ‘Din Dyal’ and ‘Diyal’ in his early years) famously known as Raja Deen Dayal) was an Indian photographer. His career began in the mid-1870s as a commissioned photographer; eventually he set up studios in Indore, Mumbai and Hyderabad. He became the court photographer to the sixth Nizam of Hyderabad, Mahbub Ali Khan, Asif Jah VI, who awarded him the title Raja Bahadur Musavvir Jung Bahadur, and he was appointed as the photographer to the Viceroy of India in 1885.

In the early 1880s he travelled with Sir Lepel Griffin through Bundelkhand, photographing the ancient architecture of the region. Griffin commissioned him to do archaeological photographs: The result was a portfolio of 86 photographs, known as “Famous Monuments of Central India”.

Text from the Wikipedia website [Online] Cited 21/08/2020

Photograph of the Jahaz Mahal at Mandu in Madhya Pradesh, taken by [Indian photographer] Lala Deen Dayal in the 1870s. The Jahaz Mahal or Ship Palace is part of the Royal Enclave in northern Mandu and dates from the late 15th century. It is a long, narrow, two-storey arcaded range crowned with roof-top pavilions and kiosks, built between two artificial lakes, the Munj Talao and Kapur Sagar. It was so named because from a distance in this setting it resembled a ship. Conceived as a pleasure palace, it housed the harem of Ghiyath Shah Khalji, a Sultan of Malwa who ruled between 1469 and 1500. This is a perspective view of the façade taken from one end, showing a flight of steps ascending to the roof terrace at left and rubble in the foreground. The palace is one of several at Mandu, a historic ruined hill fortress which first came to prominence under the Paramara dynasty at the end of the 10th century. It was state capital of the Sultans of Malwa between 1401 and 1531, who renamed the fort ‘Shadiabad’ (City of Joy) and built palaces, mosques and tombs amid the gardens, lakes and woodland within its walls. Most of the remaining buildings date from this period and were originally decorated with glazed tiles and inlaid coloured stone. They constitute an important provincial style of Islamic architecture characterised by an elegant and powerful simplicity that is believed to have influenced later Mughal architecture at Agra and Delhi.

Text from the British Library website [Online] Cited 21/08/2020

Painted Clouds and Combination Prints with Hand-Drawn Clouds

Unidentified maker

The Roman Forum

c. 1885

Albumen silver print

George Eastman Museum, gift of George C. Pratt

Painted Clouds and Combination Prints with Hand-Drawn Clouds

William Henry Jackson (American, 1843-1942)

Mt. Hood from Lost Lake

c. 1890

Albumen silver print

George Eastman Museum, gift of Harvard University

Courtesy of the George Eastman Museum

Writing in 1883, the poet Joaquin Miller declared that the constantly moving cloud effects around Mount Hood added “most of all to the beauty and sublimity of the mount scenery.” Perhaps Miller’s description of the clouds elucidates William Henry Jackson’s decision to print clouds from drawn – as opposed to photographed – negatives. Jackson might have lacked cloud negatives that communicated motion and vigour and felt compelled to draw them himself.

William Henry Jackson (April 4, 1843 – June 30, 1942) was an American painter, Civil War veteran, geological survey photographer and an explorer famous for his images of the American West. He was a great-great nephew of Samuel Wilson, the progenitor of America’s national symbol Uncle Sam. …

The American photographer along with painter Thomas Moran are credited with inspiring the first national park at Yellowstone, thanks to the images they carried back to legislators in Washington, D.C. America’s great, open spaces lured these artists, who delivered proof of the natural jewels that sparkled on the other side of the country.

From 1890 to 1892 Jackson produced photographs for several railroad lines (including the Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) and the New York Central) using 18 x 22-inch glass plate negatives. The B&O used his photographs in their exhibit at the World’s Columbian Exposition.

Text from the Wikipedia website

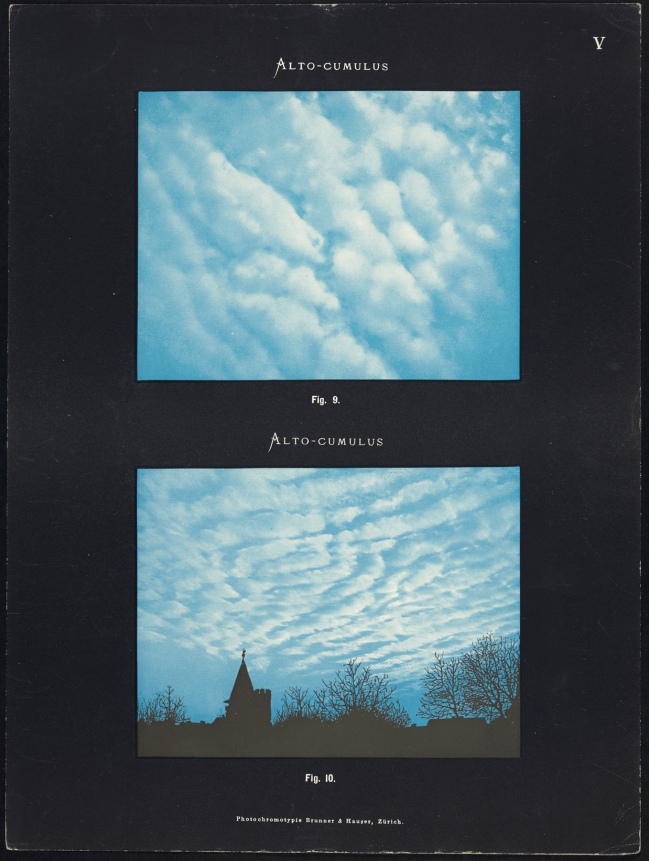

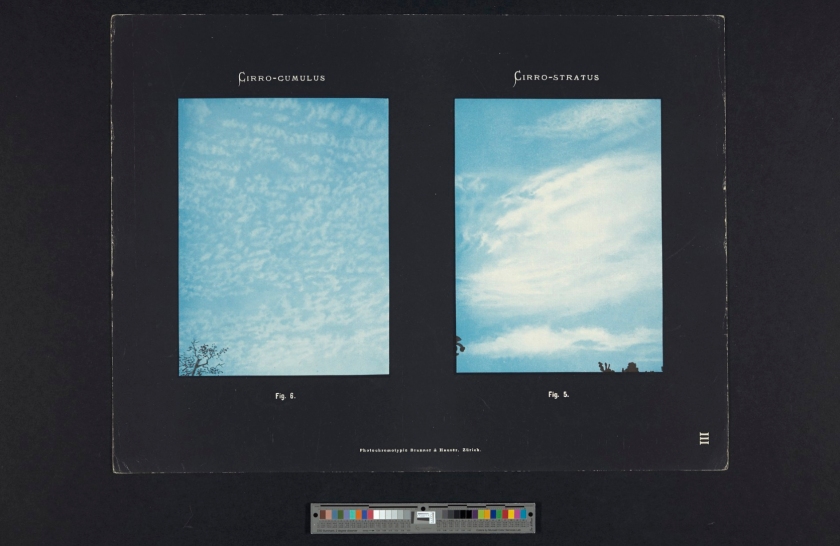

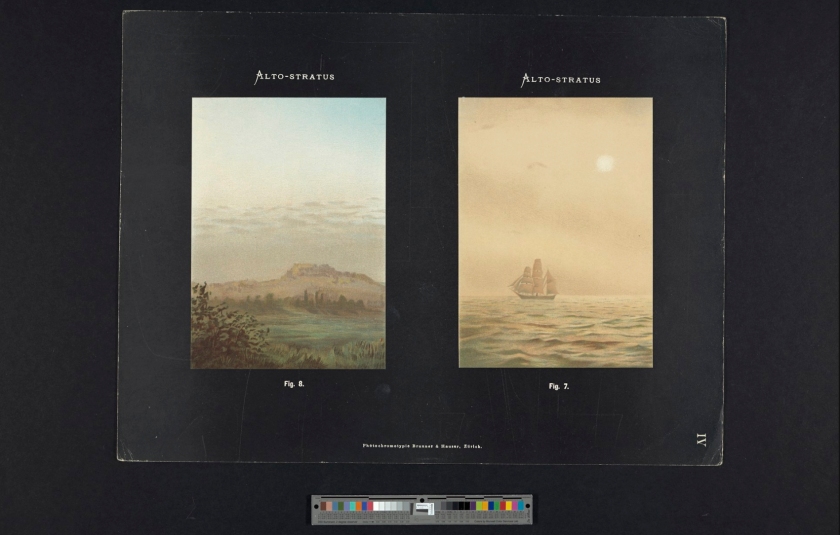

Unidentified maker

Plate V

1896

Chromolithograph

From the International Cloud-Atlas, edited by Hugo Hildebrand Hildebrandsson (Swedish, 1838-1925), Albert Riggenbach (Swiss, 1854-1921), and Léon Philippe Teisserenc de Bort (French, 1855-1913), published by Gauthier-Villars et Fils (Paris)

George Eastman Museum, purchase with funds from the Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation

Courtesy of the George Eastman Museum

Published in 1896, the International Cloud-Atlas standardised the definitions and descriptions of cloud formations and outlined instructions for cloud observations so that scientists could communicate dependable data across borders. The atlas was illustrated with chromolithographs made after photographs. Photography thus played a central role in overcoming the difficulty of applying language to ever-changing cloud formations. To cloud scientists, photograph was valued not for its perceived objectivity but for its ability to capture minute details in a sea of infinite and transient forms. Photographs helped ensure that cloudspotters everywhere could use a standard vocabulary to describe their observations.

Unidentified maker

Plate III

1896

Chromolithograph

From the International Cloud-Atlas, edited by Hugo Hildebrand Hildebrandsson (Swedish, 1838-1925), Albert Riggenbach (Swiss, 1854-1921), and Léon Philippe Teisserenc de Bort (French, 1855-1913), published by Gauthier-Villars et Fils (Paris)

George Eastman Museum, purchase with funds from the Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation

Courtesy of the George Eastman Museum

Unidentified maker

Plate IV

1896

Chromolithograph

From the International Cloud-Atlas, edited by Hugo Hildebrand Hildebrandsson (Swedish, 1838-1925), Albert Riggenbach (Swiss, 1854-1921), and Léon Philippe Teisserenc de Bort (French, 1855-1913), published by Gauthier-Villars et Fils (Paris)

George Eastman Museum, purchase with funds from the Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation

Courtesy of the George Eastman Museum

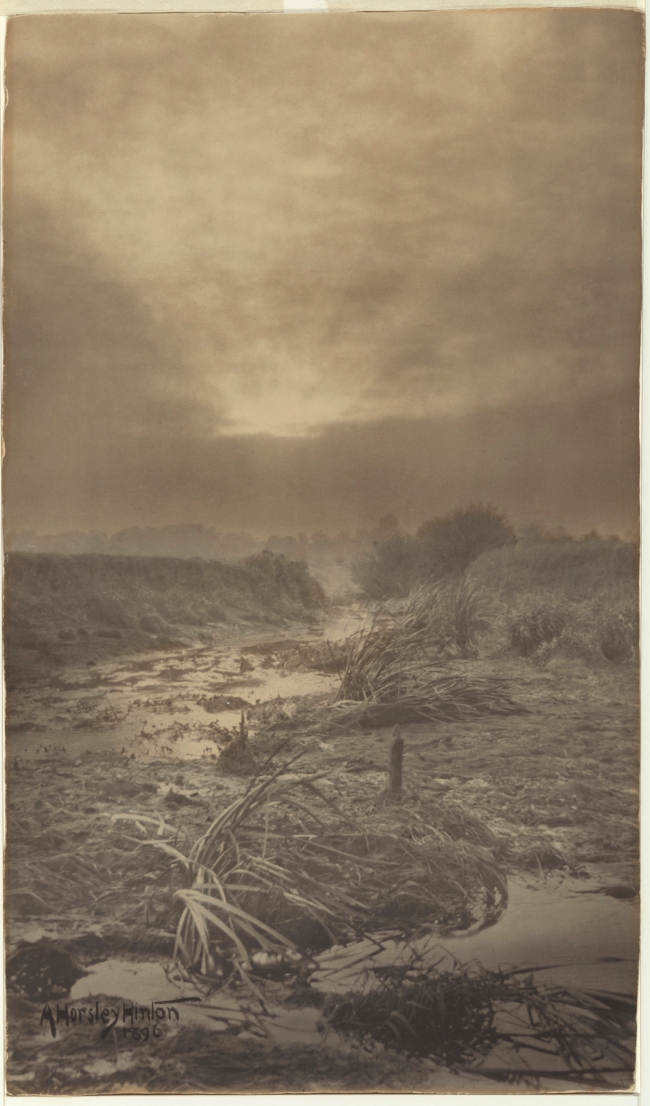

Alfred Horsley Hinton (English, 1863-1908)

Day’s Awakening

1896

Platinum print

George Eastman Museum, gift of the 3M Foundation, ex-collection Louis Walton Sipley. Courtesy of the George Eastman Museum

“In the photographic rendering of clouds, not as atmospheric phenomena, but as vehicles of beautiful thought, we have to-day something of an indication of how much superior the photograph may be wen made and controlled by an artist mind.” ~ A. Horsely Hinton, 1897

Alfred Horsley Hinton (1863 – 25 February 1908) was an English landscape photographer, best known for his work in the Pictorialist movement in the 1890s and early 1900s. As an original member of the Linked Ring and editor of The Amateur Photographer, he was one of the movement’s staunchest advocates. Hinton wrote nearly a dozen books on photographic technique, and his photographs were exhibited at expositions throughout Europe and North America. …

Hinton’s landscape photographs tend to be characterised by prominent foregrounds and dramatic cloud formations, often in a vertical format. He typically used sepia platinotype and gum bichromate printing processes. Unlike many Pictorialists, Hinton preferred sharp focus to soft focus lenses. He occasionally cropped and mixed cloud scenes and foregrounds from different photographs, and was known to rearrange the foregrounds of his subjects to make them more pleasing. His favourite topic was the English countryside, especially the Essex mud flats and Yorkshire moors.

Text from the Wikipedia website [Online] Cited 21/08/2020

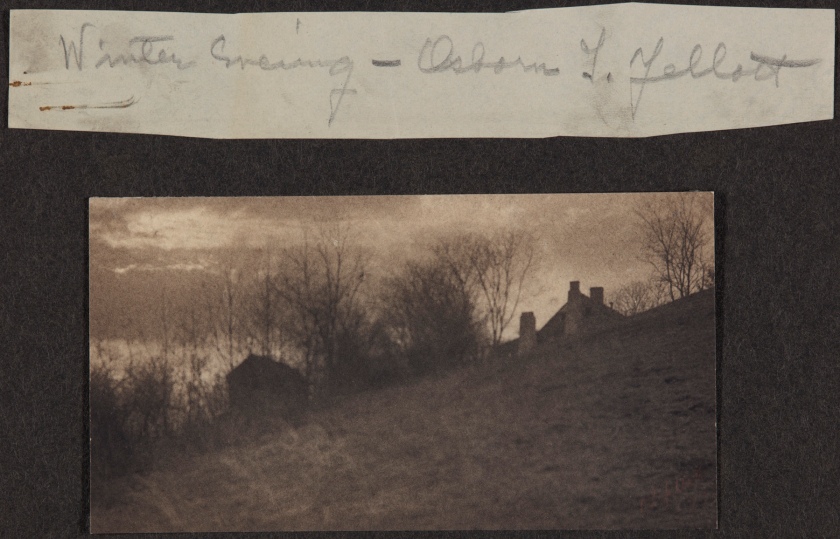

Combination Prints with Cloud Negatives Made from Life

Osborne I. Yellott (American, b. 1871 – d. unknown)

Winter Evening

1898

Albumen silver print

George Eastman Museum

Courtesy of the George Eastman Museum

“Before printing a cloud negative into any view the worked should always ask himself whether those particular clouds are properly appropriate to the scene, or whether they lend expression to the scene.” ~ Osborne I. Yellott, 1901

Yellott distinguished between two branches of cloud photograph: clouds for their own sake and clouds for printing in. The first he identified as a “delightful hobby,” the pursuit of which would lead to a collection of “pleasing or unusual” cloud formations to be viewed as lantern-slide projections or as cyanotypes in an album. The second, practiced by Yellott himself, required more discrimination: the photographer must carefully select their clouds and camera position.

Osborne I. Yellott (American, b. 1871 – d. unknown)

Winter Evening (detail)

1898

Albumen silver print

George Eastman Museum

Courtesy of the George Eastman Museum

Clouds and Landscape on a Single Negative

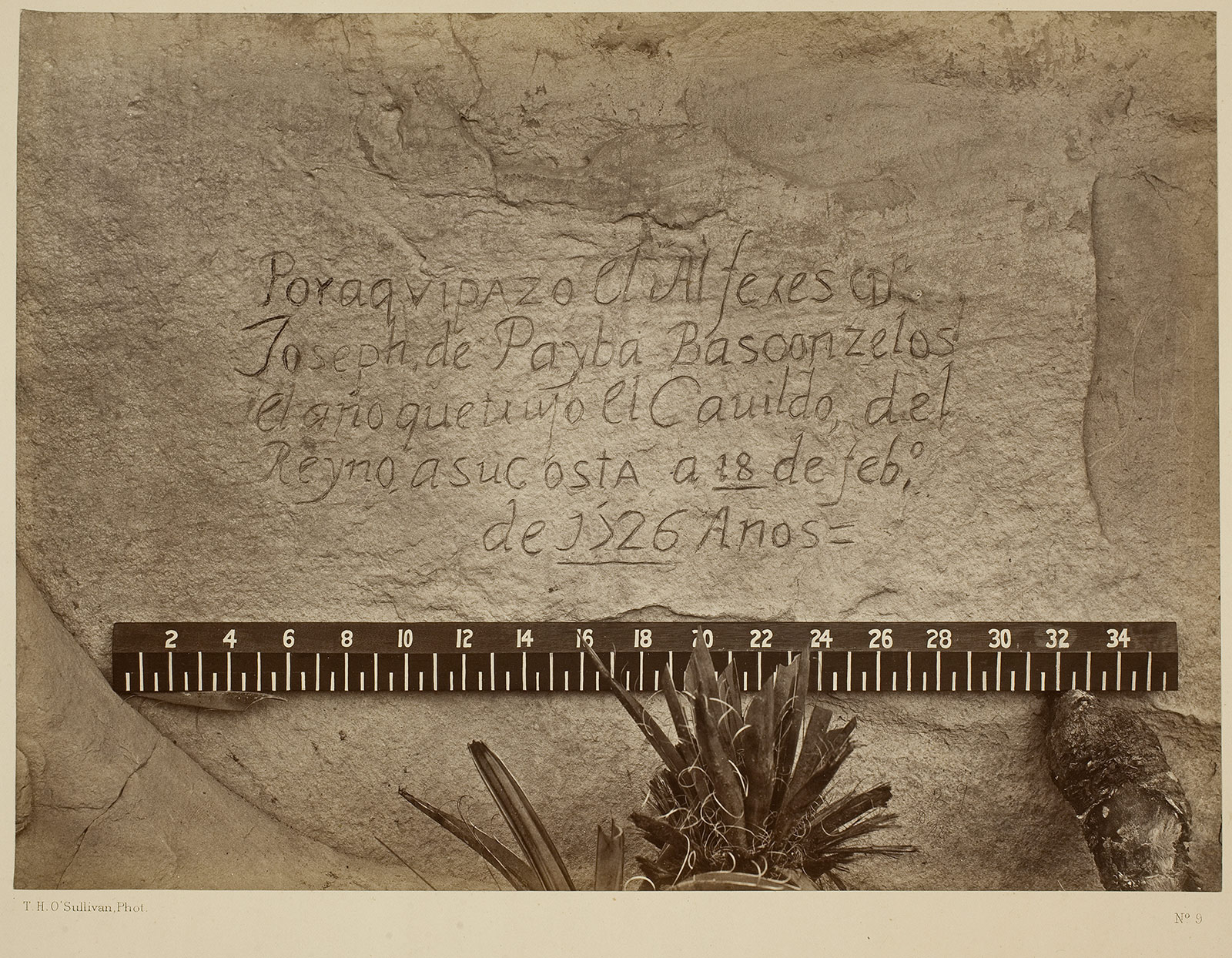

Adam Clark Vroman (American, 1856-1916)

Cibollita Mesa (South from top of Mesa)

1899

Platinum palladium print

George Eastman Museum, purchase with funds from the Charina Foundation

Courtesy of the George Eastman Museum

“… if fortune favours you, you may find a background of such beautiful clouds as only the light clear air of the south-west can produce. All day long these fleecy rolls of cotton-like vapour have tempted you, until you are in danger of using up all your… plates the first day out. You think there never can be such clouds again – but keep a few for tomorrow, they are a regular thing in this land of surprises.”

Vroman, 1901

Vroman never used combination printing to add cloud effects to his celebrated photographs of the SW landscape. Rather, the Pasadena bookstore owner capture both cloudscapes and landscapes on an orthochromatic plate and made prints from this single negative. By the mid-1880s, orthochromatic plates were available and made the photography of clouds and landscape easier.

Adam Clark Vroman (1856-1916), a native of LaSalle, Illinois, moved to Pasadena, California, in 1892. He was an amateur field photographer who worked primarily with glass plate photography and was the founder of Vroman’s Bookstore located in Pasadena. His impressive body of photographic work from the late 1890s and early 1900s documents his multiple expeditions to the pueblos and mesas of Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah, several of these trips alongside Dr Frederick Webb Hodge with the Bureau of American Ethnology. Vroman’s close friendship with the natives, notably the Zuni, Hopi, and Navajo, allowed him to capture intimate images of their daily lives and customs as well as the lands that they inhabited. These photographs provide a stark contrast from common depictions of the time period that portrayed American Indian peoples as either exotic subjects or as savages.

His work during this period also reflects his extreme fondness of the glowing, superior quality of light found in the Southwest region. During these expeditions he worked primarily with a 6 1/2″ x 8 1/2″ view camera as well as with 4″ x 5″ and 5″ x 7″ cameras. Between 1895 and 1905, Vroman documented the interiors and exteriors of the Spanish missions in California prior to the restoration of the buildings. He photographed areas in California such as Pasadena, Yosemite National Park, as well as the eastern region of the United States, including Illinois, Pennsylvania, and Washington, D.C. Vroman was also an avid art collector with an interest in the crafts of Native Americans and treasures from Japan and the Far East. He spent the last years of his life traveling to the East Coast and Canada, as well as to Japan and to countries in Europe. He died in Altadena, California, in 1916 of intestinal cancer.

Text from the Online Archive of California website [Online] Cited 21/08/2020

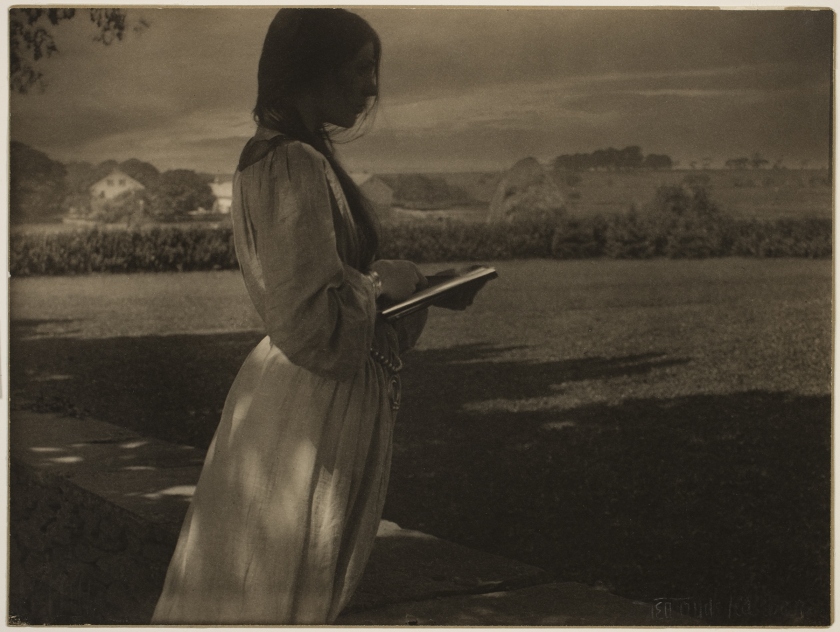

Combination Prints with Cloud Negatives Made from Life

Gertrude Käsebier (American, 1852-1934)

The Sketch (Beatrice Baxter)

1903

Platinum print

George Eastman Museum, gift of Hermine Turner

Gertrude Käsebier’s addition of clouds, which are absent from the original negative, gives this photograph a meditative quality that parallels the subject’s contemplative state. As a leading Pictorialist, Käsebier viewed photographs as an art form and drew inspiration from the work of famous painters. Perhaps, then, she was aware of painter Joghn Constable’s belief that the sky as the “chief organ of sentiment” in a picture.

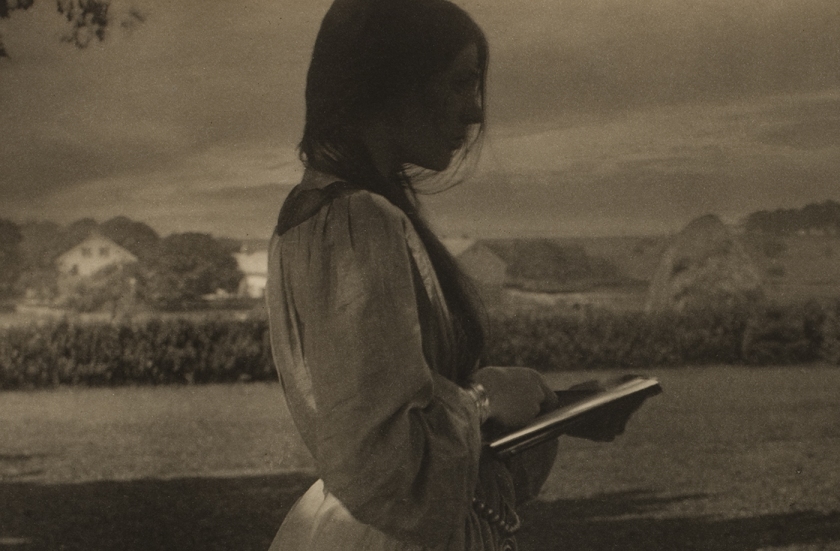

Gertrude Käsebier (American, 1852-1934)

The Sketch (Beatrice Baxter) (detail)

1903

Platinum print

George Eastman Museum, gift of Hermine Turner

Clouds and Landscape on a Single Negative

Imogen Cunningham (American, 1883-1976)

Marsh at Dawn

1906

Platinum print, printed 1910

George Eastman Museum, purchase

© The Imogen Cunningham Trust. All Right Reserved

Alvin Langdon Coburn (British, b. United States, 1882-1966)

Clouds in the Canyon

1911

Gum bichromate over platinum print

George Eastman Museum, bequest of the photographer

Unidentified maker (French)

Cumulus

c. 1918

Gelatin silver print

George Eastman Museum, purchase

Courtesy of the George Eastman Museum

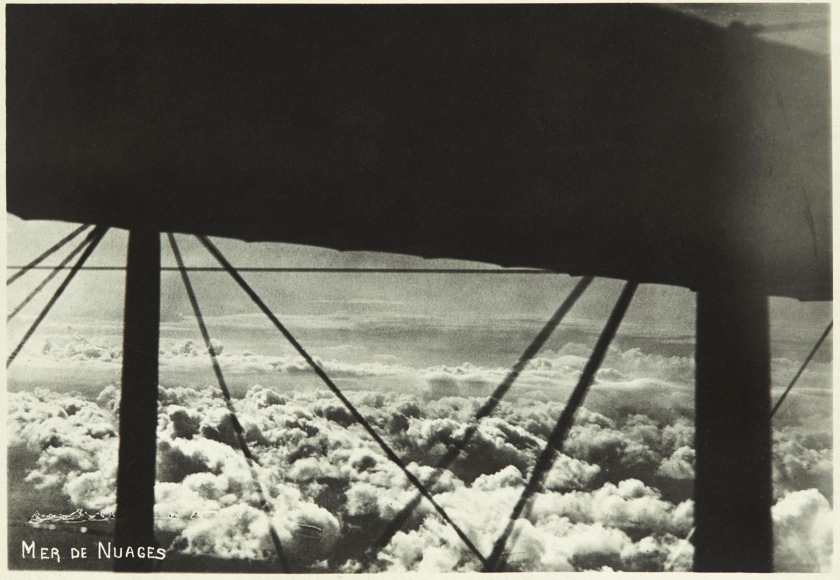

Unidentified maker (French)

Mer de nuages (Sea of clouds)

c. 1918

Gelatin silver print

George Eastman Museum, purchase

Courtesy of the George Eastman Museum

Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946)

Equivalent

1925

Gelatin silver print

George Eastman Museum, purchase and gift of Georgia O’Keeffe

Courtesy of the George Eastman Museum

Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946)

Equivalent

probably 1926

Gelatin silver print

George Eastman Museum, purchase and gift of Georgia O’Keeffe

Courtesy of the George Eastman Museum

Vik Muniz (Brazilian, b. 1961)

Reclining Girl and Dog Cloud

1993

Gelatin silver print

George Eastman Museum, purchase with funds from the Charina Foundation

Courtesy of the George Eastman Museum

© 2020 Vik Muniz / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Sometimes we see a cloud that’s dragonish;

A vapour sometime like a bear or lion,

A tower’d citadel, a pendent rock,

A forked mountain, or blue promontory

With trees upon’t, that nod unto the world,

And mock our eyes with air.

Shakespeare, “Antony and Cleopatra”, (IV, xii, 2-7)

Trevor Paglen (American, b. 1974)

Untitled (Reaper Drone)

2013

Chromogenic development print

Courtesy of the Artist and Altman Siegel, San Francisco

© Trevor Paglen

Trevor Paglen’s artwork draws on his long-time interest in investigative journalism and the social sciences, as well as his training as a geographer. His work seeks to show the hidden aesthetics of American surveillance and military systems, touching on espionage, the digital circulation of images, government development of weaponry, and secretly funded military projects. …

Since the 1990s, Paglen has photographed isolated military air bases located in Nevada and Utah using a telescopic camera lens. Untitled (Reaper Drone) reveals a miniature drone mid-flight against a luminous morning skyscape. The drone is nearly imperceptible, suggested only as a small black speck [in] the image. The artist’s photographs are taken at such a distance that they abstract the scene and distort our capacity to make sense of the image. His work both exposes hidden secrets and challenges assumptions about what can be seen and fully understood.

Text from the Institute of Contemporary Art / Boston website [Online] Cited 21/08/2020

Abelardo Morell (American, b. Cuba 1948)

Rapidly Moving Clouds over Field, Flatford, England, #1

2017

From After Constable

Inkjet print

Courtesy of Edwynn Houk Gallery

© Abelardo Morell

After Constable, [is] a series of unique visions of the landscape of Hamstead Heath by Abelardo Morell.

In June of 2017, the photographer Abelardo Morell took a pilgrimage to England, visiting the landscape of nineteenth-century Romantic painter John Constable. In the hopes of capturing the spirit of Constable’s work, Morell pitched a tent in the middle of London’s Hampstead Heath. This tent, a constructed camera obscura, projected the surrounding landscape onto the earthen ground through a small aperture at the tent’s top. Describing his camera obscura, Morell stated, “I invented a device – part tent, part periscope – to show how the immediacy of the ground we walk on enhances our understanding of the panorama, the larger world it helps to form.”

Photographing the ground below him, Morell captured both the texture of the earth as well as its vast surrounding landscape: both macro- and micro-visions of Constable’s surroundings, caught in harmony on one plane. With this layering, the photographs blend both image and texture. Always drawn to the dimension of a painting’s surface, Morell sought to emulate texture in his own photographs. In Constable’s romantic visions of Hampstead Heath from the early nineteenth century, the painter captured the english landscape in gestures of tactile, thick paint. With the roughness of the ground underneath the projected sky, each photograph’s plane echoes a painting’s surface.

Text from the Rosegallery website [Online] Cited 21/08/2020

James Tylor (Kaurna, Māori and Australian, b. 1986)

Turalayinthi Yarta (Wirramumiyu)

2017

Inkjet print with ochre

George Eastman Museum, purchase with funds from the Charina Foundation

Courtesy of the George Eastman Museum

© James Tylor

This series explores my connection with Kaurna yarta (Kaurna land) through learning, researching, documenting and traveling on country. Turalayinthi Yarta* is a Kaurna phrase “to see yourself in the landscape” or “landscape photography”. In a two year period I travelled over 300 km of the southern part of the Hans Heysen trail that runs parallel along the Kaurna nation boundary line in the Mount Lofty ranges. Combining photographs and traditional Nunga** designs to represent my connection with this Kaurna region of South Australia.

*Yarta means Land, Country and Nation in Kaurna language

**Nunga means South Australian Aboriginal people or person (Nunga language)

Text from the James Tylor website [Online] Cited 21/08/2020

John Chiara (American, b. 1971)

Old River Road: Stovall Road: Oakhurst Road

2018

Silver dye bleach print

Courtesy of ROSEGALLERY

© John Chiara

John Chiara is an experimental photographer who makes unique works by directly manipulating photosensitive paper. Chiara always believed that too much was lost in the final photograph because of the enlargement processes in the darkroom. In 1995, he was working primarily with making contact prints with large-format negatives, but in subsequent years he developed equipment and processes that allowed him to make large-scale, colour, positive photographic images without the use of film. The largest of his devices is a field camera that is large enough for Chiara to enter; he attaches the paper to this camera’s back wall and uses his hands and body to burn and dodge the image instinctively. Chiara’s developing process often leaves anomalies in the resulting images, which he embraces.

Text from the Artsy website [Online] Cited 21/08/2020

George Eastman Museum

900 East Ave, Rochester, NY 14607, USA

Opening hours:

Wednesday – Saturday 10am – 5pm

Sunday 11am – 5pm

Closed Mondays and Tuesdays

You must be logged in to post a comment.