Visit: Tuesday 10th September 2019, published December 2019

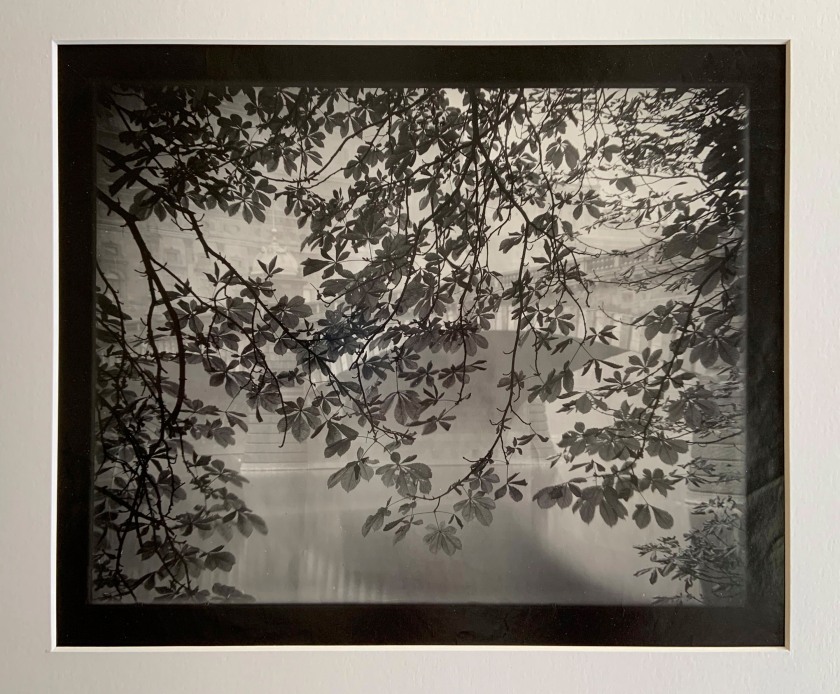

Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976)

Střelecky Ostrov, Prague (Střelecky Island with Legion Bridge and Vltava river, Prague)

1950s-1960s

Gelatin silver print

Spirit has no boundaries

On my European photographic research tour I was invited to visit The Museum of Decorative Arts at their collection headquarters outside Prague for a private viewing of vintage prints of the Czech master photographer Josef Sudek. What a privilege.

My very great thankx to Jan Mlčoch, photography collections curator at u(p)m Prague, for his knowledge, humour and generosity of time and spirit in showing me approx. 40 vintage Josef Sudek prints and 6 rare books. Jan couldn’t believe of an interest in Sudek all the way from Australia!

All vintage photographs were donated by the family to the museum.

1/ Firstly, I was shown 6 rare books of Josef Sudek photographs. The most notable was the book “Praha panoramatická”, an edition of 300 published by SNK LHU in 1959. With a cloth cover and a star design on the front, this book featured 284 gravure panoramic plates. The photos start at the centre of Prague and then work out in a spiral in terms of location, to the countryside looking back at the city. Several double pages featured panorama close up of a house or building on the left hand side and a more distant shot of the same building on the right hand side. Close / far. The images, the tonality and the vision of this man was incredible

2/ Secondly, I was shown vintage contact prints from 1950s-1960s ranging in size from 4 x 5″ negatives (printed on 8 x 10″ paper) up to at least 12 x 16″

3/ All contact prints centred on single weight, some semi matt others slight gloss papers, with the rest of the sheet EXPOSED TO BLACK. This was Sudek’s preferred method of printing – one negative / exposure per piece of paper, not cutting the sheet ever

4/ NO TRUE BLACK AND NO BRIGHT WHITE. Tones ranged from zone 2 to maximum zone 7.5-8. Most unusual – the grey tonality of the prints that almost blended completely across the zone spectrum from 2-8. No hard delineation. On this viewing all reproductions have way too much contrast (including these iPhone images!)

5/ The highlight was 3 originally mounted pigment photographs by Sudek in 1953 (see two below). Photos sandwiched between 2 panes of glass, mounted on different coloured pieces of paper (pink, another almost tissue paper) with pigment prints. Edges of glass sealed with lead in one example. Reminiscent of Stieglitz’s use of coloured mount board for his framing. The prints were so “inky” – “of such extraordinary depth and warmth”

On many occasions I was close to tears the prints were so moving. As a friend of mine Randall Tosh observed of his prints, “his take on prints is so different from the Weston / Adams mid-century canon. I don’t always think they work, but when they do, they are otherworldly.” From what I observed on this viewing, they worked incredibly well.

This was a sublime experience, one of the photographic highlights of my life. Sudek’s magical work has always struck me as a form of psychotherapy and so it proved… photography as a form of healing after his injuries during the First World War.

Spirit has no boundaries.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to Jan Mlčoch for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting and to Alfonso Melendez and the Josef Sudek public Facebook group for their brains trust, for finding out the location and date of some of the images featured here. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“There is no approach, no recipe. Each thing has to be done differently.”

Josef Sudek

Josef Sudek. Praha panoramatická book cover, SNK LHU, 1959

“Praha Panoramaticka (Prague In Panoramic Photographs)” published by Statni Nakladatelstvi, Prague in 1959. Containing 284 striking black-and-white panoramic photogravures of Prague and the surrounding countryside, Sudek masterfully captures the city that he loved and shows why he earned the nickname, “The Poet of Prague”. In The Photobook: A History, Martin Parr and Gerry Badger provide an excellent critique, “Sudek is a photographer whose body of work suggests that photography was as necessary to him as breathing, Josef Sudek claimed the city of Prague and his surroundings as comprehensively as Eugene Atget claimed Paris. His masterpiece is one of the most singular photobooks ever made, Praha panoramaticka (Prague Panorama). To create this wealth of memorable images, Sudek used an antique 1894 Kodak Panorama camera with a spring-drive lens that produced a negative of approximately 4 by 12 inches. Of all his books, this one sums up his love of Prague. The panoramic camera is a strong unifying element in the imagery, but so is Sudek’s democratic eye, which disregards nothing. His feeling for light, weather, and space in combination has never been surpassed. Praha panoramaticka is a veritable encyclopaedia of how to plot, construct and unify a panoramic photograph. And if this were not enough, Sudek even pulls off a near impossible trick at the end of the book: good vertical panoramas”.

Text from the Abebooks website [Online] Cited 09/11/2019

Josef Sudek. Praha panoramatická book pages, SNK LHU, 1959

Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976)

Both Střelecky Ostrov, Prague (Střelecky Island, Prague)

1950s-1960s

Gelatin silver print

Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976)

Střelecky Ostrov, Prague (Střelecky Island, Prague)

1950s-1960s

Gelatin silver print

Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976)

Both Střelecky Ostrov, Prague (Střelecky Island, Prague)

1950s-1960s

Gelatin silver print

Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976)

Střelecky Ostrov, Prague (Střelecky Island, Prague)

1950s-1960s

Gelatin silver print

Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976)

Střelecky Ostrov, Prague (Střelecky Island, Prague) with a statue of St John of Nepomuk?

1950s-1960s

Gelatin silver print

Saint John of Nepomuk (or John Nepomucene) (Czech: Jan Nepomucký; German: Johannes Nepomuk; Latin: Ioannes Nepomucenus) (c. 1345 – 20 March 1393) is the saint of Bohemia (Czech Republic) who was drowned in the Vltava river at the behest of Wenceslaus, King of the Romans and King of Bohemia. Later accounts state that he was the confessor of the queen of Bohemia and refused to divulge the secrets of the confessional. On the basis of this account, John of Nepomuk is considered the first martyr of the Seal of the Confessional, a patron against calumnies and, because of the manner of his death, a protector from floods and drowning.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976)

The Window of My Studio, Prague

1944-1953

Gelatin silver print

© The Museum of Decorative Arts, Prague

Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976)

The Window of My Studio, Prague

1944-1953

Gelatin silver print

© The Museum of Decorative Arts, Prague

Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976)

Jaro v me zahrádce (Spring in my Garden)

1953

Pigment print

© The Museum of Decorative Arts, Prague

Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976)

Jaro v me zahrádce (Spring in my Garden)

1953

Pigment print

© The Museum of Decorative Arts, Prague

Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976)

Jaro v me zahrádce (Spring in my Garden) (detail)

1953

Pigment print

© The Museum of Decorative Arts, Prague

Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976)

Untitled

1953

Pigment print

© The Museum of Decorative Arts, Prague

Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976)

Untitled

1953

Pigment print

© The Museum of Decorative Arts, Prague

Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976)

Untitled (detail)

1953

Pigment print

© The Museum of Decorative Arts, Prague

Plate 38 Untitled 1950-1954 from the book Joseph Sudek Still Lifes, Torst, 2008

From the mid-1920s until his death in 1976, Czech photographer Joseph Sudek shot Gothic and Baroque architecture, street scenes and still lifes – usually leaving the frame free of people and capturing a poetic and highly individualistic glimpse of Prague. The still lifes are the best known aspect of his oeuvre; indeed, his graceful depictions of drinking-glasses and eggs are familiar to those who don’t necessarily even know his name. Acceding to his reclusive nature, Sudek began The Window of My Studio series in the 1940s. It allowed him to capture street scenes without going outside and helped him discover a particular fondness for how glass refracts light. The still lifes emerged from the informal arrangements Sudek would make on his windowsill, and occupied him for a number of years. Depicting a range of quotidian objects with a marked artfulness – some were made in homage to favourite painters like Caravaggio – the series deserves a deeper look. This volume is the first in-depth study of Sudek’s still lifes and also explores his creative use of carbon printing – a pigment process on rag paper not often used photographically – which lent so many of his images such extraordinary depth and warmth.

Text from the Amazon website

Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976)

Labyrinth on My Table

1967

Gelatin silver print

© The Museum of Decorative Arts, Prague

Plate 22 Labyrinth on My Table 1967 from the book by Daniela Hodrová and Antonín Dufek Joseph Sudek Labyrinths, Torst, 2013

Like the previous volumes The Window of My Studio and Still Lifes, this new Josef Sudek monograph collects a series of photographs made within the confines of the Czech photographer’s workspace. Sudek’s studio famously verged on installation art, as the poet Jaroslav Seifert recalled: “Breton’s surrealism would have come into its own there. A drawing by Jan Zrzavy lay rolled up by a bottle of nitric acid, which stood on a plate where there was a crust of bread and a piece of smoked meat with a bite taken out of it. And above this hung the wing of a Baroque angel with Sudek’s beret hanging from it… This disorder was so picturesque, so immensely rich, that it almost came close to being a strange but highly subtle work of art.” Gathered here in all their surreal beauty, the Labyrinths series depicts multilayered assemblages of objects in endlessly permutated combinations.

Text from Google Books website

Folders of vintage Josef Sudek prints at the Central Depository UPM Stodůlky

u(p)m The Museum of Decorative Arts

17. listopadu Street No.2

110 00 Prague 1

Phone: +420 778 543 900

You must be logged in to post a comment.