Exhibition dates: 2nd December 2017 – 4th March 2018

John Gollings (Australian, b. 1944)

Berman House (Harry Seidler), Joadja, New South Wales

2007

From ancient to modern; different but same

This is a solid exhibition of the work of architectural photographer John Gollings, which features highly colour saturated photographs of the built environment, from ancient to modern.

The formal, classical images are well seen and photographed, mainly for commercial clients who, at the end of the project, want to document their construction in the most flattering light. And that’s what you get with a Gollings architectural photograph – a known “style” used again and again to document an object devoid of human presence, usually photographed at the bewitching hour for photographers (dawn or dusk) or illuminated, to give the building that special glow. Sounds easy, but it isn’t!

For some people the intention of the photographer is primary… later on comes the successful manifestation of that intention. And of course, there is the public intention stated in the brief directed to a photographer who has accepted that brief. As well, there are the photographer’s private intentions and for these we have to refer to the image(s). I then ask, what happens when the photographer’s private intentions becomes his commercial practice, when his style becomes his trademark?

In these photographs which are about multiplicity / difference (in the sense of a different set of objects) / series and the pursuit of spirit (as compared to the pursuit of ego), Gollings evidences something inherent in man that has shown itself from the start – inhabitation – that has now has become something else. He has put these series together to make sense / no sense / nonsense and through this juxtaposition, he hopes that something transcendent happens when these environments are seen together. The contemporary structures are made by extraordinary people who keep pushing to make an ultimate ideal of their belief, and so they are extraordinary, yet different from each other. Gollings captures this difference.

“What is it that asks a question that cannot be answered” is a question that I believe that Gollings is interested in, and it manifests itself in people and some of their works, e.g. poetry, cinema, photography, music… and this is the scope of that question in architecture. I think that Gollings has just tried to be clear about this question in his work, in the images straightforward yet dramatic way.

In their usually monolithic grounding, the building is always front and centre, even in his views of ancient structures or the landscape. “Gollings will use dramatic lighting and acute points of view to create a moody effect, and draw people into the ambience of the architect’s creation.” (Wall text) That is the key word, effect. While Gollings has stripped everything back to the bare minimum, removed ego, has it got him any closer to that place of magic and noumenality – that place that we can know but never experience (e.g. death). SOME of the images work towards an exploration of this subliminal state of being, the unconscious raised to the surface (images such as Habitat filter (Matt Drysdale, Matt Myers and Tim Dow), Southbank, Victoria, 2017 and The Lotus Building (Studio 505), Changzhou, China, 2013), yet others just sit there, the camera angles too regulated, the monolithic structure too central. How I longed for a more unusual positioning of the camera – something Atget might have done for example – to capture the personality of the building, for I never really “get” the personality of the building in Gollings representational photographs.

Personally, what I love about photography is the magical space of exploration in the image, and that is something that I don’t really get in these photographs, from one image to the next. The same feeling emanates from them time after time. They have little human warmth despite their high colour sheen. But I think that a lot of the absence of the magical that I regret is probably quite intentional. That is not Gollings’ project or his projection, his “effect” if you like, for he is a very intelligent artist, and a very well informed photographer. He has considered all of this, and his photographs come out exactly the way he wants them to come out. They might not be my cup of tea but I can appreciate and understand them on an intellectual and aesthetic, if not a spiritual, level. Gollings’ holistic vision over more than 40 years has stood the test of time, proving that he is, indeed, a damn good photographer.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to Monash Gallery of Art for allowing me to publish the media photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image. All installation photographs © Dr Marcus Bunyan, the artist and the Monash Gallery of Art.

Installation photographs

First gallery

Installation views of the exhibition John Gollings: The history of the built world at the Monash Gallery of Art featuring the opening title and text

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of the exhibition John Gollings: The history of the built world at the Monash Gallery of Art showing the rear of opening wall featuring at right, Kay Street housing (Edmond & Corrigan), Carlton, Victoria 1983

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Installation views of the exhibition John Gollings: The history of the built world at the Monash Gallery of Art showing at left in the bottom image, Melbourne CBD, Melbourne, Victoria 2009; middle, Federation Square, Melbourne, Victoria 2010; and right, Melbourne CBD, Melbourne, Victoria 2010

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of the exhibition John Gollings: The history of the built world at the Monash Gallery of Art showing Gollings’ photograph Melbourne CBD, Melbourne, Victoria 2010

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Installation views of the exhibition John Gollings: The history of the built world at the Monash Gallery of Art showing in the bottom image, Gollings’ photograph Vineyard House (Denton Corker Marshall), Yarra Valley, Victoria 2013

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of the exhibition John Gollings: The history of the built world at the Monash Gallery of Art showing Gollings’ photograph Somers House (Kai Chen), Somers, Victoria 1997

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of the exhibition John Gollings: The history of the built world at the Monash Gallery of Art

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Main gallery

Installation views of the exhibition John Gollings: The history of the built world at the Monash Gallery of Art showing in the bottom image, Gollings’ photograph Sabratha Theatre, Sabratha, Libya 2005

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of the exhibition John Gollings: The history of the built world at the Monash Gallery of Art showing in the bottom image, Gollings’ photograph Underground temple, Kep, Cambodia 2007

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Installation views of the exhibition John Gollings: The history of the built world at the Monash Gallery of Art

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of the exhibition John Gollings: The history of the built world at the Monash Gallery of Art showing Gollings’ photograph Jiaohe Old City, Turfan, China 2005

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of the exhibition John Gollings: The history of the built world at the Monash Gallery of Art showing at right, Sidney Myer Music Bowl refurbishment (Yuncken Freeman/Greg Burgess), Melbourne, Victoria 2001

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of the exhibition John Gollings: The history of the built world at the Monash Gallery of Art showing at second left, The Lotus Building (Studio 505), Changzhou, China 2013; third left, Croft House (James Stockwell), Inverloch, Victoria 2013; second right, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (Wood Marsh), Southbank, Victoria 2002; and right, Habitat filter (Matt Drysdale, Matt Myers and Tim Dow), Southbank, Victoria 2017

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of the exhibition John Gollings: The history of the built world at the Monash Gallery of Art showing Gollings’ photograph Croft House (James Stockwell), Inverloch, Victoria 2013

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Installation views of the exhibition John Gollings: The history of the built world at the Monash Gallery of Art

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of the exhibition John Gollings: The history of the built world at the Monash Gallery of Art showing Gollings’ photograph Nawarla Gabarnmang, Arnhem Land, Northern Territory 2015

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of the exhibition John Gollings: The history of the built world at the Monash Gallery of Art

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Third gallery

Installation view of the exhibition John Gollings: The history of the built world at the Monash Gallery of Art showing at left, El Dorado Motel, Surfers Paradise, Queensland 1973; second left, Golden Sun Motel, Surfers Paradise, Queensland 1973; second right, Biscayne Apartments, Surfers Paradise, Queensland 1973; and right, Cuba Flats, Surfers Paradise, Queensland 1973

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of the exhibition John Gollings: The history of the built world at the Monash Gallery of Art showing at left Mid-century house, Surfers Paradise, Queensland 2017; middle, Mid-century house, Surfers Paradise, Queensland 2017; and right, Mid-century house, Surfers Paradise, Queensland 2017

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Installation views of the exhibition John Gollings: The history of the built world at the Monash Gallery of Art showing at right in the bottom image, Gollings’ Every building on Surfers Paradise Boulevard west 1973

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

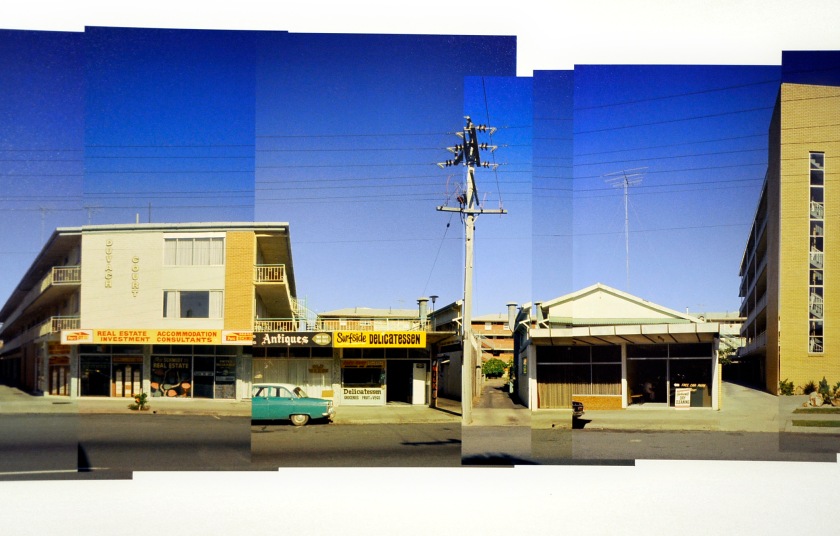

Installation view of the exhibition John Gollings: The history of the built world at the Monash Gallery of Art showing Every building on Surfers Paradise Boulevard west 1973 (detail)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

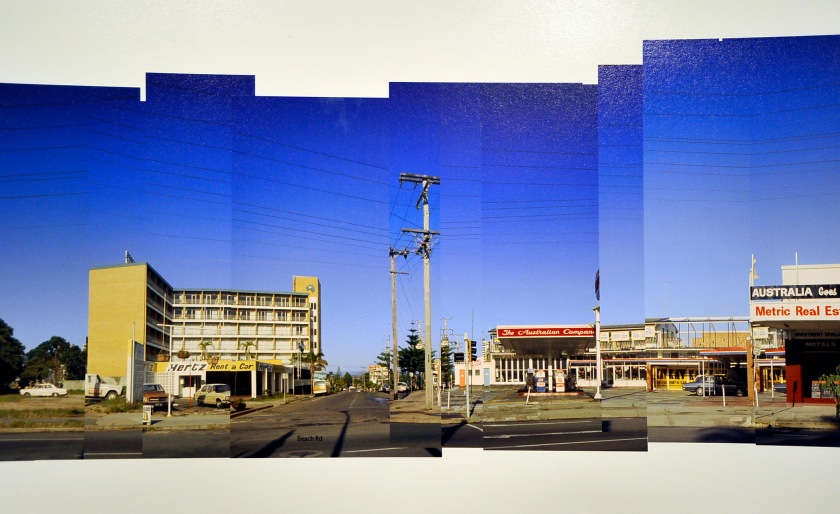

Installation view of the exhibition John Gollings: The history of the built world at the Monash Gallery of Art showing Every building on Surfers Paradise Boulevard west 1973 (detail)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

John Gollings is Australia’s most pre-eminent and prolific photographer of the built environment. For the past 50 years he has been synthesising his parallel interests in photography and architecture to explore the cultural construction of social spaces. From sacred rock art sites and ancient temples to suburban dream homes and the monuments of corporate architecture, Gollings’s catalogue of images provides a remarkable visual history of human habitats. The history of the built world is the first major survey of Gollings photographic practice, and offers a much anticipated opportunity to appreciate the full breadth of his unique photographic vision.

John Gollings (Australian, b. 1944)

Monash Gallery of Art (Harry Seidler), Wheelers Hill, Victoria

1990

Wonderful photograph I love this.

Waverley City Gallery

Gollings photographed Harry Seidler’s Waverley City Gallery before it was extended and renamed as Monash Gallery of Art. Gollings worked under Seidler’s direction to document the building, and the photographs clearly reflect Seidler’s architectural philosophy of organic geometric forms and interlocking planes.

Gollings’s interior view shows a Josef Albers tapestry hanging in the original foyer; an artwork that Seidler donated to the gallery with the intention of it remaining a permanent feature. Seidler once stated that he learnt more about design from Albers than any architectural school, and two of Albers’s design principles are clearly articulated in the architecture of MGA. The first of these is the notion that a high centre of gravity makes visual forms more dynamic, as evidenced in MGA’s top-heavy roofline. And the second – that irregular forms are more interesting to the eye than symmetrical grids – is apparent in the complex geometry of the building. (Wall text)

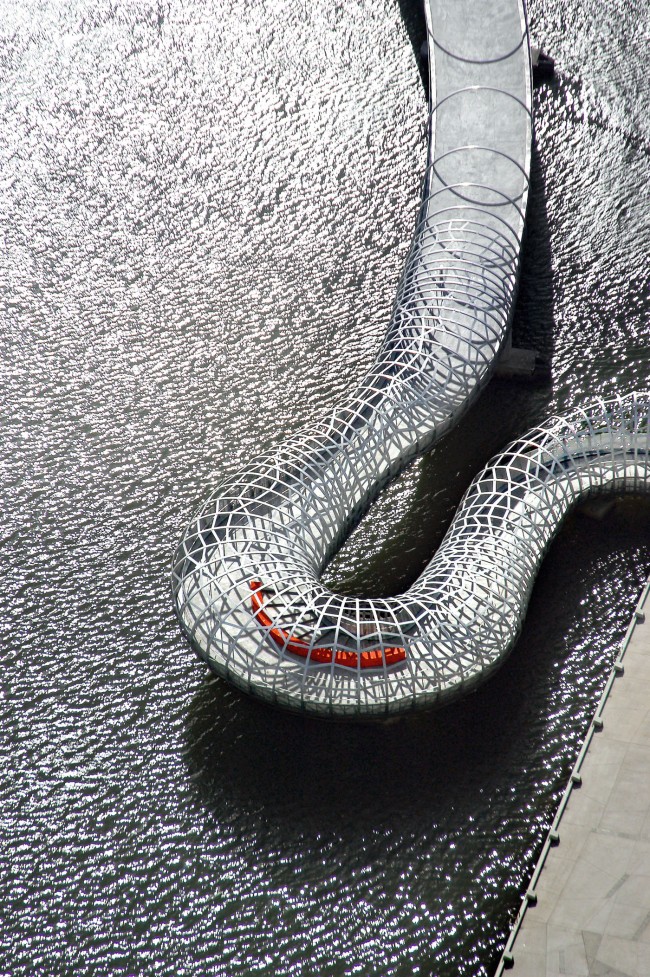

John Gollings (Australian, b. 1944)

Webb Bridge (Robert Owen with Denton Corker Marshall), Docklands, Victoria

2003

Melbourne architecture

Gollings’s photographs of Melbourne offer a compelling portrait of the city he knows best. His aerial photographs draw out different features of Melbourne’s character, from the flatness of its suburban sprawl to the resplendent jewel box quality of its central business district. The sequence of images along this wall emphasises Gollings’s ability to metaphorically crawl inside the skin of his home town. Whether he’s photographing temporary architectural interventions or monumental entertainment stadiums, he finds ways to render them as skeletal structures or translucent surfaces. Gollings’s ability to embed the viewer in a scene is apparent across his work, but this is particularly evident in his images of Melbourne, where it seems he wears the built environment like a second skin. Even in his photograph of the Eureka Tower, Gollings uses the reflected light of a sunset to subdue this monolithic form and embed a reflected image of himself in the glass facade.

Wall text

John Gollings (Australian, b. 1944)

Federation Square, Melbourne, Victoria

2010

John Gollings (Australian, b. 1944)

Hotel Hotel foyer (March Studio), New Acton, Australian Capital Territory

2013

John Gollings (Australian, b. 1944)

Karijini Visitor Centre (Woodhead International BDH), West Pilbara, Western Australia

2001

Modern and contemporary architecture

Gollings’s professional practice has always included fashion and advertising projects, and one could argue that his treatment of architecture is invested with a certain dramatic fl air that owes something to these other genres of photography. Rather than using a sequence of photographs to systematically document different aspects of an architect’s design, Gollings often composes a single shot that captures the personality of a building. These are like portrait photographs, which use props and the surrounding backdrop to accentuate a sitter’s identity. A domestic house might be photographed through foliage in order to give it a bucolic character. Or a photograph might include more sky than building in order to evoke the vista that can be enjoyed by the inhabitants. In a similar vein, Gollings will use dramatic lighting and acute points of view to create a moody effect, and draw people into the ambience of the architect’s creation.

Wall text

John Gollings (Australian, b. 1944)

Penleigh and Essendon Grammar School (McBride Charles Ryan), Essendon, Victoria

2011

John Gollings (Australian, b. 1944)

Featherston House (Robin Boyd), Ivanhoe, Victoria

2011

“Gollings’s photographic practice is driven by a deep enthusiasm and interest in the built environment,” explains MGA Senior Curator, Stephen Zagala. “He loves architecture and he uses photography to share his passion, bringing constructed spaces to life and drawing viewers into sensual encounters with architectural form.”

John Gollings is Australia’s pre-eminent, and most prolific, photographer of the built environment. For the past 50 years he has been synthesising his parallel interests in photography and architecture to explore the cultural construction of social spaces. While Gollings is well known for his documentation of new buildings and cityscapes, this survey exhibition situates these images within the broader context of his photographic practice. Alongside his commercial work, Gollings has always engaged in projects concerned with architectural history and heritage. This includes photographs of iconic modernist buildings, ancient sites of spiritual significance and the ruins of abandoned cities. Gollings’s interest in architectural heritage is also apparent in his documentation of places such as Melbourne and Surfers Paradise, where he has recorded the evolution of the built environment over extended periods of time.

From sacred rock art sites and ancient temples, to suburban dream homes, iconic monuments and architectural interventions, Gollings’s catalogue of images provides a remarkable visual history of how humans have chosen to inhabit their world. Constantly innovating with photographic technologies, and investigating new architectural subjects with a restless enthusiasm, Gollings has developed a distinctive visual style. This style typically conveys a personal or physical connection with the structure being photographed. Rather than documenting buildings in a way that reproduces the impersonal elevation plans of an architectural diagram, Gollings embeds the viewer in face-to-face encounters with built environments. Using a range of compositional techniques and visual effects to invest architecture with personality, he portrays buildings as lively habitats rather than static monuments.

The history of the built world is the first major survey of Gollings’s photographic practice and offers a much anticipated opportunity to appreciate the full breadth of his unique vision. With academic training in the history of architecture, and a professional grounding in photographic practice, Gollings documents and dramatises architecture with an informed artistic flair. Constantly innovating with photographic technologies, and investigating new architectural subjects with a restless enthusiasm, Gollings’s connoisseurship of the built world is unparalleled.

Press release from the Monash Gallery of Art

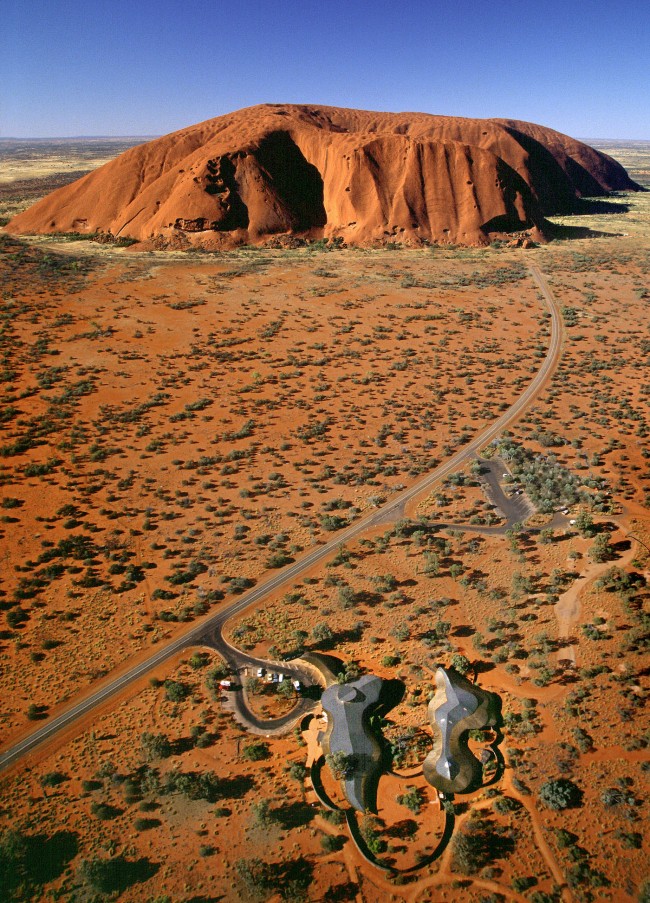

John Gollings (Australian, b. 1944)

Uluru Visitor Centre (Gregory Burgess), Uluru, Northern Territory

1999

John Gollings (Australian, b. 1944)

Kabaw Berber Granary, Kabaw, Libya

2005

John Gollings (Australian, b. 1944)

Bayon, Angkor Thom, Cambodia

2012

John Gollings (Australian, b. 1944)

North face, south gate, Angkor Thom, Cambodia

2007

John Gollings (Australian, b. 1944)

Buddha detail, Borobudur, Java, Indonesia

2011

John Gollings (Australian, b. 1944)

Mori Tim Stupa, Silk Road, China

2005

John Gollings (Australian, b. 1944)

Jiaohe Old City, Turfan, China

2005

John Gollings (Australian, b. 1944)

Pushkarani Kund (King’s Bath), Hampi, India

1988

John Gollings (Australian, b. 1944)

Ta Prohm Temple, Angkor Thom, Cambodia

2007

John Gollings (Australian, b. 1944)

Hanuman Temple, Hampi, India

2006

John Gollings (Australian, b. 1944)

Small Ganesh, Hampi, India

2006

John Gollings (Australian, b. 1944)

Vittala Dance Mandapa interior, Hampi, India

2005

Ancient architecture

Gollings has embarked on a number of heritage projects that document the evolution of architectural history under various religious and political regimes across Asia. This includes the Chinese city of Jiaohe, which was carved out of the earth 2 000 years ago and then abandoned after Genghis Khan invaded the area in the 13th century; the Khmer temples of the Angkor Empire that once extended across much of mainland south-east Asia; and the architecture of the Hindu Vijayanagara Empire that ruled over southern India for 200 years before being conquered by Muslim sultanates in the 16th century. Further a fi eld, Gollings has documented the grain stores of the nomadic Berbers in Lybia, and the marble theatres that supplanted them when the Roman Empire occupied northern Africa at the dawn of the Common Era. Gollings brings his characteristic style to bear on all these subjects, drawing the viewer into the built environment with embedded perspectives and dramatic lighting.

Wall text

John Gollings (Australian, b. 1944)

Nawarla Gabarnmang, Arnhem Land, Northern Territory

2015

The Nawarla Gabarnmang rock shelter is the oldest human construction that Gollings has photographed. Located in southwestern Arnhem Land, on the traditional lands of the Jawoyn people, the architecture of this site was created by tunnelling into a naturally eroding cliff face. The roof is supported by 36 pillars, formed by the natural erosion of fissure lines in the bedrock. Archaeologists have shown that some pre-existing pillars were removed, some were reshaped and others were moved to new positions in order to modify the interior space. The ceiling, walls and pillars feature paintings of fi sh, wallabies, crocodiles, people and spiritual figures. Radiocarbon dating of floor deposits indicates that humans have used the shelter for over 45 000 years, and the rock art itself has been firmly dated back 28 000 years, making it some of the oldest surviving artwork in the world. Gollings’s photographs, with their accentuated perspectives and saturated colours, celebrate Nawarla Gabarnmang as a site of imagination and awe.

Wall text

John Gollings (Australian, b. 1944)

Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (Wood Marsh), Southbank, Victoria

2002

John Gollings (Australian, b. 1944)

Habitat filter (Matt Drysdale, Matt Myers and Tim Dow), Southbank, Victoria

2017

Wow! What a scintillating photograph…

John Gollings (Australian, b. 1944)

Jean-Marie Tjibaou Cultural Centre (Renzo Piano), Nouméa, New Caledonia

1997

John Gollings (Australian, b. 1944)

The Lotus Building (Studio 505), Changzhou, China

2013

Illuminated architecture

Photographing an inanimate object in the half light of dusk or dawn tends to invest it with a sense of life. A house with its interior lights on as night falls can seem enlivened with nocturnal possibilities. A building emerging from the shadows at daybreak might appear to be stirring from sleep. Gollings often takes advantage of the half light to give architecture a quiet vitality. He sometimes describes these photographs as ‘efficient images’, when the balance of sunlight and internal lighting allows him to make the interior and exterior of a building simultaneously visible. In effect, these images draw attention to the skin of architecture, rendering buildings as shells or envelopes rather than solid volumes. This approach is a particularly effective way of giving a sense of spiritual lightness to ancient stone temples.

Wall text

John Gollings (Australian, b. 1944)

Surfers Paradise aerial, Surfers Paradise, Queensland

2012

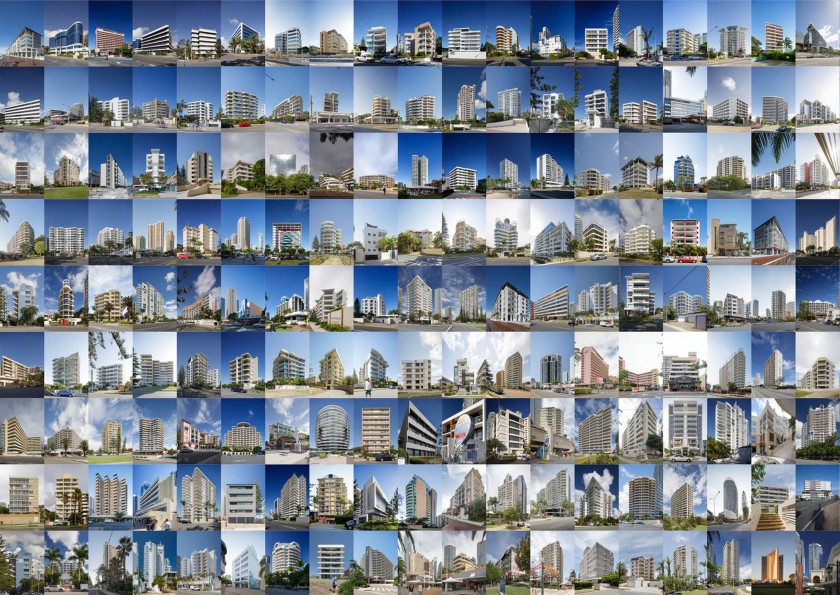

Surfers Paradise

Gollings’s relationship with the Gold Coast stretches back to childhood road trips that he made to Queensland with his parents in the late 1950s and 1960s. While he was still a teenager, Gollings took photographs that testify to an early fascination with the fanciful architecture of roadside motels. And in recent years he has continued to record the quaint postwar architecture of Surfers Paradise, along with the high rise developments that now overshadow them.

During 1973 and 1974 Gollings embarked on a major survey of architecture in Surfers Paradise. This project was specifically inspired by a seminal book on postmodern architecture, Learning from Las Vegas, authored by Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown and Steven Izenour in 1972. This book turned its back on the formal purism of modernist architecture and argued for an approach to urban design that embraced popular culture, personal narratives and humour. Gollings, along with Mal Horner (urban planner), Julie James (graphic designer) and Tony Styant-Browne (architect), set out to produce a complimentary publication, Learning from Surfers Paradise. The publication was abandoned in 1975, but Gollings’s photographs remain an important record of Surfers Paradise and the postmodern condition in Australian culture.

The ideas associated with postmodern architecture have had a lasting influence on Gollings’s approach to photography. Throughout his work, Gollings subverts pure formalism with humorous juxtapositions and personal affectations.

Wall text

John Gollings (Australian, b. 1944)

Every high rise on the Gold Coast, Surfers Paradise, Queensland

2012

John Gollings (Australian, b. 1944)

Every high rise on the Gold Coast, Surfers Paradise, Queensland (detail)

2012

Monash Gallery of Art

860 Ferntree Gully Road, Wheelers Hill

Victoria 3150 Australia

Phone: + 61 3 8544 0500

Opening hours:

Tue – Fri: 10am – 5pm

Sat – Sun: 10pm – 4pm

Mon/public holidays: closed

You must be logged in to post a comment.