Exhibition dates: 11th November , 2022 – 16th April, 2023

Curator: Drew Sawyer, Phillip Leonian and Edith Rosenbaum Leonian Curator of Photography, Brooklyn Museum

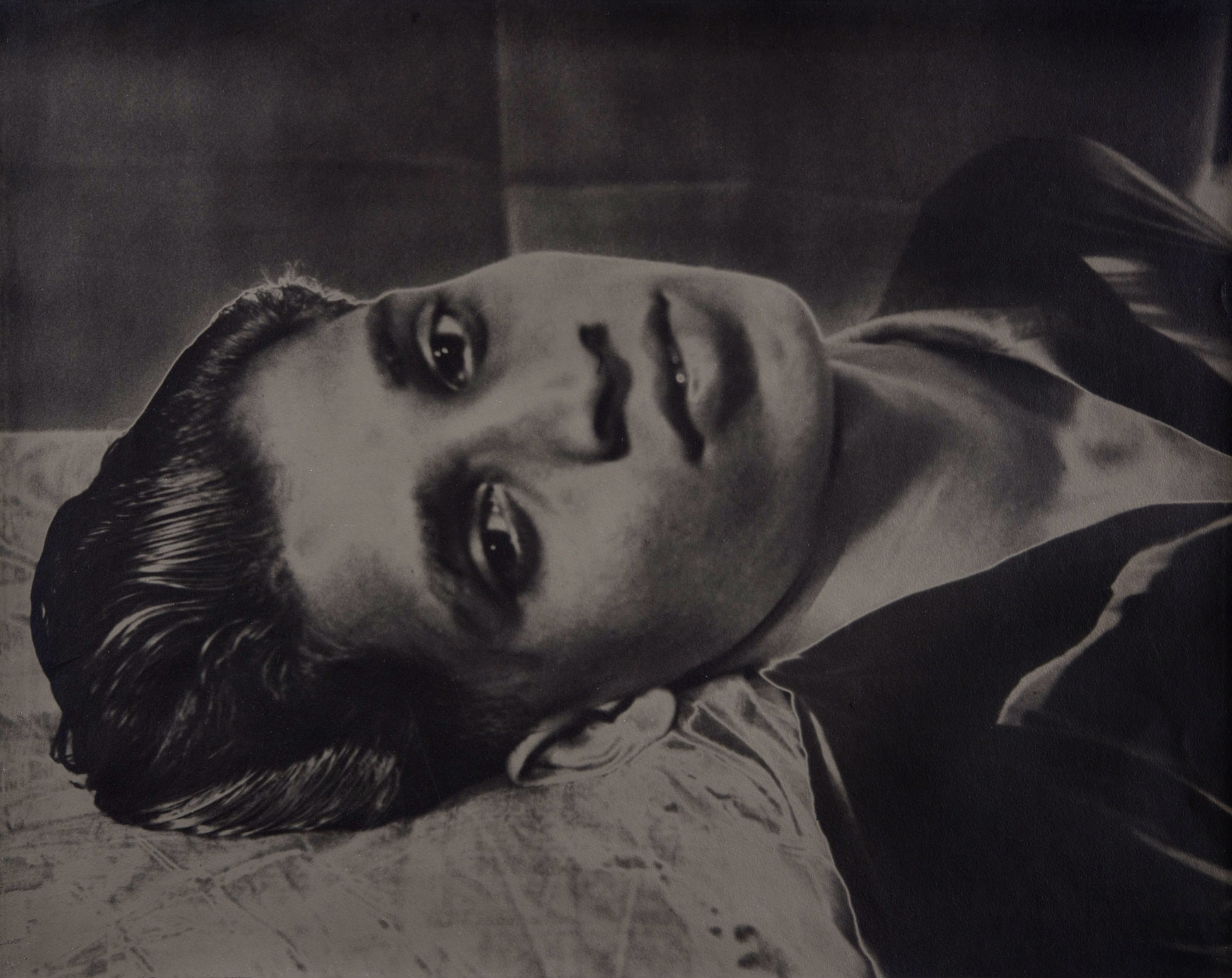

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Marker Cones

1982

Chromogenic print

14 1/4 × 18 1/2 in. (36.2 × 47cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York

© Estate of Jimmy DeSana

Photo: Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York)

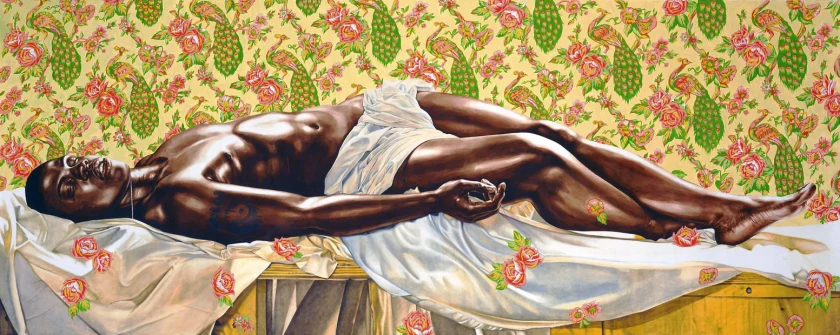

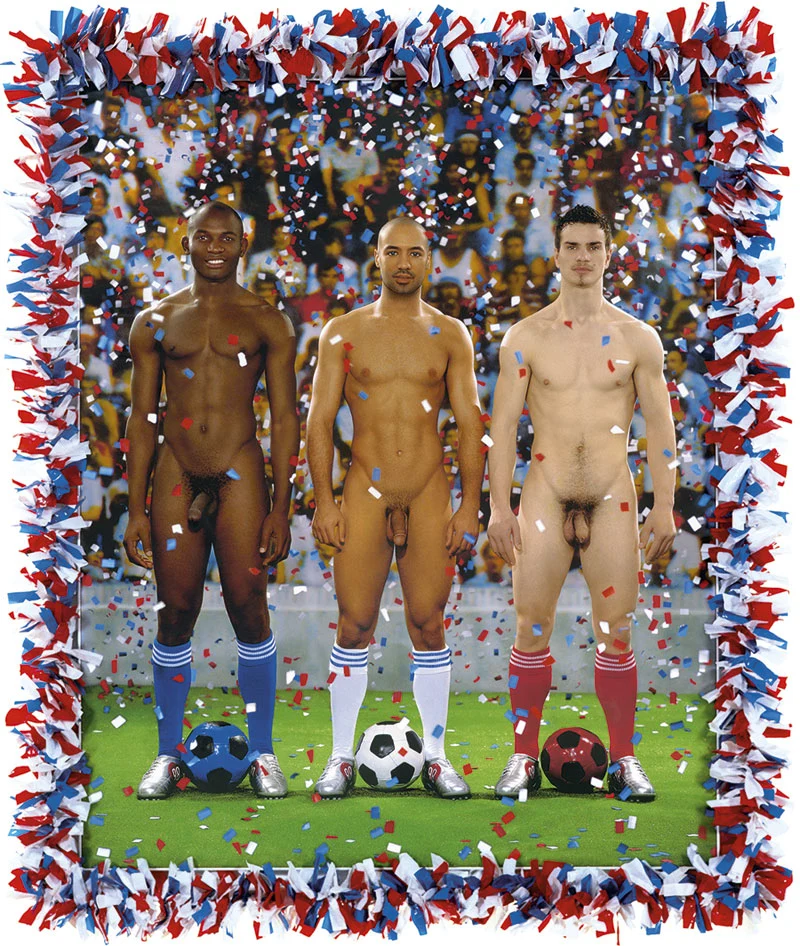

As DeSana developed his Suburban series in the early 1980s, gender and sexuality became increasingly ambiguous in his images. Here, photographed from behind, the body is a headless, unidentifiable creature composed of shapes. The marker cones evoke a similar indeterminacy: they are socially gendered “feminine” as makeshift stilettos and “masculine” as signifiers of roadside construction or sports, perhaps pointing to DeSana’s own experiences or ideas about the disciplining of bodies. A glittering field of bright-green artificial grass adds to this surreal composition, evoking the Astroturf surface of a football field.

Exhibition label

FORGET ME NOT

I have to be honest and say that before I started constructing this posting I had never heard of the artist Jimmy DeSana. You can’t know everything.

But now, having spent many hours reading about his life and his art, now I am at least a little more informed… and stand in awe and wonder at what this artist achieved before he died. It has been a real privilege and honour to imbibe at the fountain of DeSana.

I am still processing the work and what I have learnt about it but it would seem to me that what DeSana left behind is a body of work that is challenging, vital, full of ideas, paradoxes and questions about the human condition. Not who are we, but who can we be if we follow the path of our imagination and our soul.

Written by many other commentators, I have distilled their thoughts about his life, work, subject matter and the concepts he investigated into a few words:

1/ To play and dream

2/ punk rebel, the queer visionary, the wry interpreter of consumerism and media cultures, and the sometime transgressor of “good taste” in photography

3/ masquerades =

4/ the body as object

5/ peeled back the veneer of suburban life

6/ discrepancy between the public and private lives of post-war Americans

7/ queer and radical

8/ surrealistic, S/M-tinged, staged photos

9/ absurdist and unsettling

10/ vagaries of the human heart and the human psyche

11/ his central subject was always himself, and especially his sexual and emotional identity

12/ address the basic enigmas of identity

13/ Punk Provocateur

14/ Fierce

15/ Downtown /East Village scene

16/ post-punk New York

17/ fetishistic work about human bodies, very poetic

18/ mail art

19/ negative prints, double exposures and luridly coloured lighting

20/ psychological portraits, sexually charged tableaux and still lifes

21/ the body as a playground, gender as an ongoing invention, and domestic interiors as surreal constructions

22/ potential to push boundaries

23/ autoerotic asphyxiation

24/ visceral, more lo-fi, and more voyeuristic

25/ Transgressive Vision of Life and Desire

26/ Surrealism, Fluxus, punk and pure Pop

27 queer visibility

28/ strangeness

29/ suburban life

30/ Stonewall

31/ Gay Liberation

32/ interconnectedness of art and life

33/ Pictures Generation

34/ sexual, political, degenerated, ungendered

35/ sexual and emotional identity

36/ AIDS, sexuality and death

But these words tell what the work is about, they don’t tell you how the art makes you feel!

The art makes me feel dis/embodied and at the same time emboldened and strong. It makes me feel queer (in its original sense, when it was primarily used to mean strange, odd, peculiar or eccentric). Personally, it opens up a new vision for exploring my ordered place in the world, pushing boundaries of who I am and who I could be. Never settling for something that you don’t want to be. I love the “queerness” of the art (in the recent use of the word, used to describe a broad spectrum of non-normative sexual or gender identities and politics). I love its panache and bravado, its sensitivity and camp, it raunchiness and colour. The colour of life. Being different.

Sadly, we lost so many people, so many artists during the first wave of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, supremely talented artists such as Peter Hujar, David Wojnarowicz, Stephen Varble, Robert Mapplethorpe and Jimmy DeSana. I would like to have met Jimmy, to have talked to him about his passion, his love, his vision of the world that surrounded him. From a distance in time and space he seems to have a certain magic energy within him.

In the vitality of the work lies his im/mortality. And it is because of this energy that we will never lose the remembrance of Jimmy DeSana. Forget him not.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Brooklyn Museum for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“My dear, it’s all so Christian and medieval and gloomy. Precisely. Jimmy DeSana, your intrepid photographer, has witnessed and preserved for posterity the unspeakable rights of these benighted natives, rites as clearly derived from Christianity as a black mass”

William Burroughs, 1979

“DeSana’s camera was as dear to him as his sexual life; the two were mutually constitutive, and his engagement with the BDSM subculture provided boundless inspiration to him, both as an artist and as a gay man.”

“As a gay man, a photographer, an artist of the AIDS era, a lover, a son, and a friend, DeSana is as beautifully complex as his work. After he died of AIDS in 1990, DeSana left his estate to his best friend and muse, the artist Laurie Simmons. Simmons told me, “I gave myself twenty years to sort out a lifetime’s worth of breathtaking material. I also felt certain that the work would look as fresh twenty years later as it did at the time of its making.” The resurgence of DeSana’s revolutionary career could not come at a more opportune moment; his oeuvre is exemplary of new outlets for reconstituting the Pictures Generation with queer modes of vision and critique.”

William J. Simmons. “Surreal Sexuality,” in Aperture Issue 218, “Queer” on the Aperture website January 18, 2017 [Online] Cited 20/03/2023

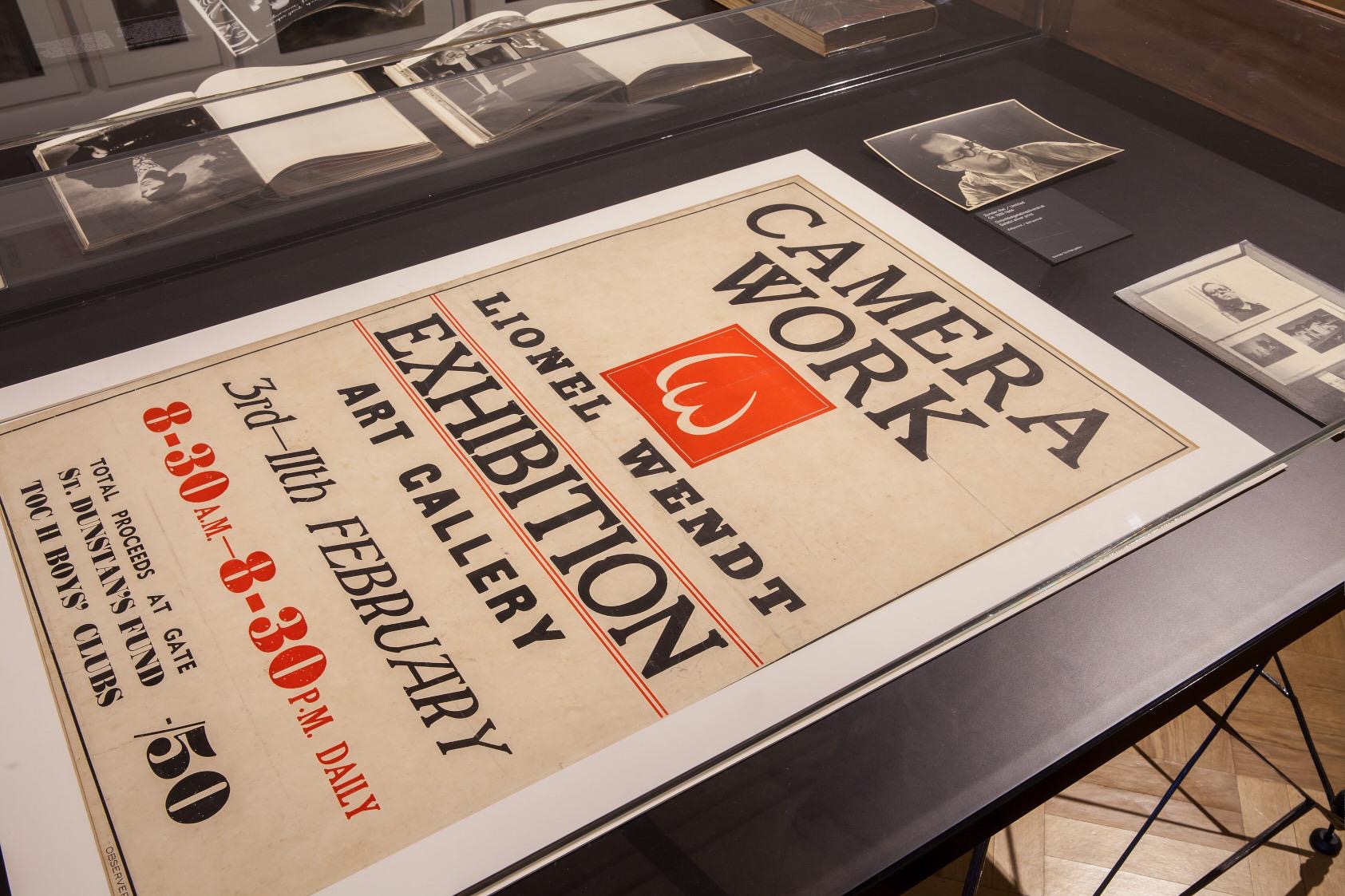

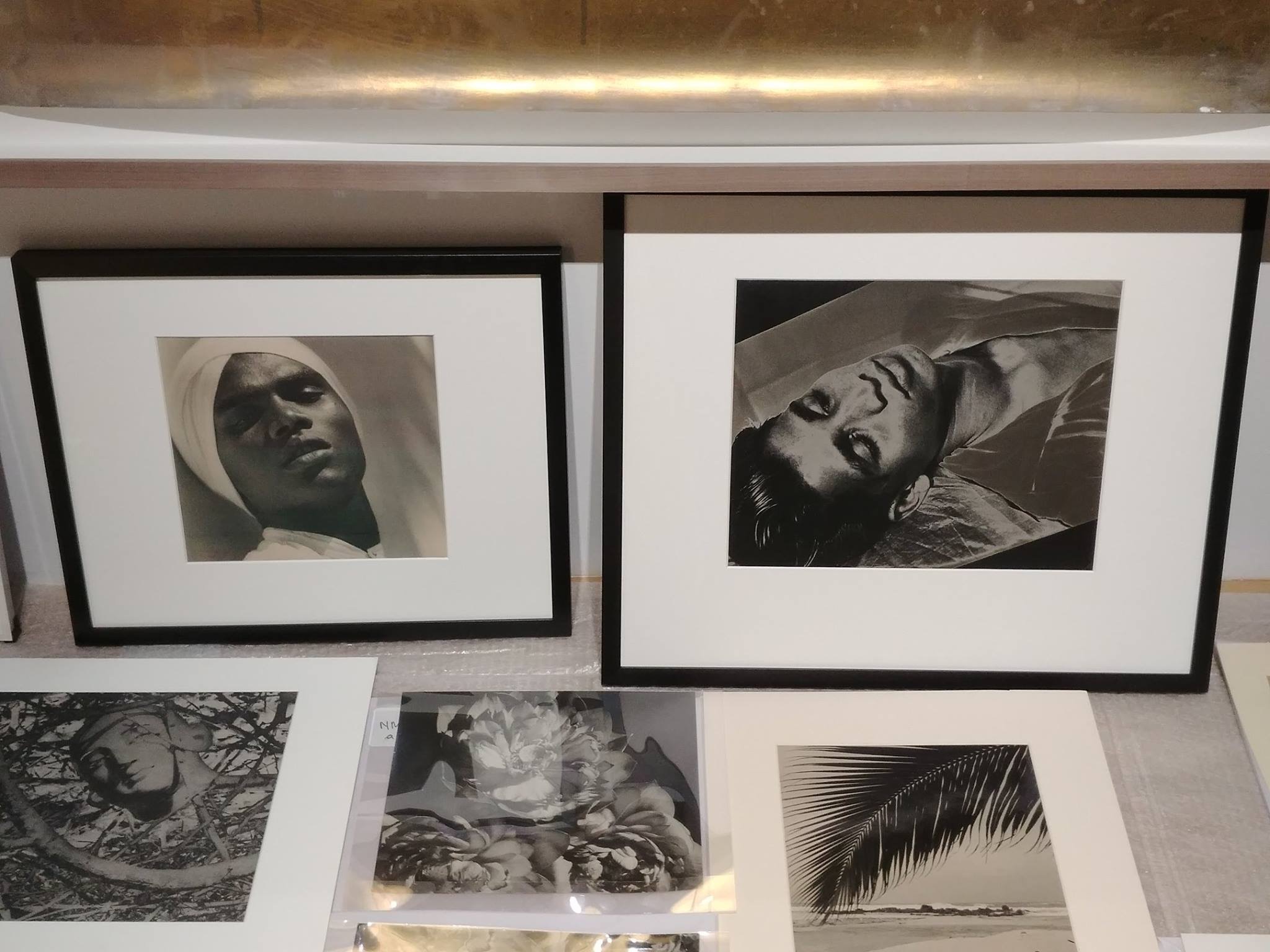

Installation views of the exhibition Jimmy DeSana: Submission at the Brooklyn Museum, New York

The first comprehensive exhibition and book on the surreal, queer and humorous photographic art of Jimmy DeSana, a central figure in New York’s art and music scenes of the 1970s and ’80s

This is the first overview of the work of Jimmy DeSana, a pioneering yet under recognised figure in New York’s downtown art, music and film scenes during the 1970s and 1980s. The book situates DeSana’s work and life within the countercultural and queer contexts in the American South as well as New York, through his involvement in mail art, punk and No Wave music and film, and artist collectives and publications.

DeSana’s first major project was 101 Nudes, made in Atlanta during the city’s gay liberation movement. After moving to New York in 1973, DeSana became immersed in queer networks, collaborating with General Idea and Ray Johnson on zines and mail art, and documenting the genderqueer street performances of Stephen Varble.

By the mid-1970s, DeSana was a fixture in New York’s No Wave music and film scenes, serving as portraitist for much of the period’s central figures and producing album covers for Talking Heads, James Chance and others. His book Submission, made with William S. Burroughs, humorously staged scenes out of a S&M manual that explored the body as object and the performance of desire. DeSana was also an early adopter of colour photography, creating his best-known series, Suburban, in the late 1970s and early 1980s. This body of work explores relationships between gender, sexuality and consumer capitalism in often humorous, surreal ways. After DeSana became sick as a result of contracting HIV, he turned to abstraction, using experimental photographic techniques to continue to push against photographic norms.

Text from the Amazon website Nd [Online] Cited 15/03/2023

Introduction

James, Jim, Jimmy; de Sana, deSana, De Sana, DeSana. Just as Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990) consistently altered his name, he refused to pin down his approach to two main artistic interests: photography and desire. From the 1960s until his death from AIDS-related illness, DeSana created experimental, subversive photographs that upended traditional approaches and viewpoints. He produced and shared these provocative works by participating in a range of avant-garde movements – from queer mail art networks to Fluxus [a loose international group of rebellious artists, poets, and musicians with a shared impulse to integrate art and life] to punk music and cinema, to the “Pictures Generation” and its image-based play with mass culture.

Jimmy DeSana: Submission, the first retrospective on this pioneering yet under recognised figure, unites these bodies of work to demonstrate how DeSana emphasised and expanded photography as a contemporary form. The first section considers his early years in Atlanta and New York (1968-1976), where he began exchanging artworks through the mail and playing with sexuality and identity. The next section follows DeSana’s entree into New York’s dynamic countercultural art, music, film, and club scenes (1976-1984). The final section delves into the artist’s darkroom experiments during his last years (1984-1990), after he was diagnosed with HIV. At a time when his own desires were considered deviant and even criminal, DeSana continually embraced transgression as a path toward both artistic and personal freedom.

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Untitled

1972

From the series 101 Nudes

Offset print

12 3/4 × 8 1/2 in. (32.4 × 21.6cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York

© Estate of Jimmy DeSana

Photo: Allen Phillips

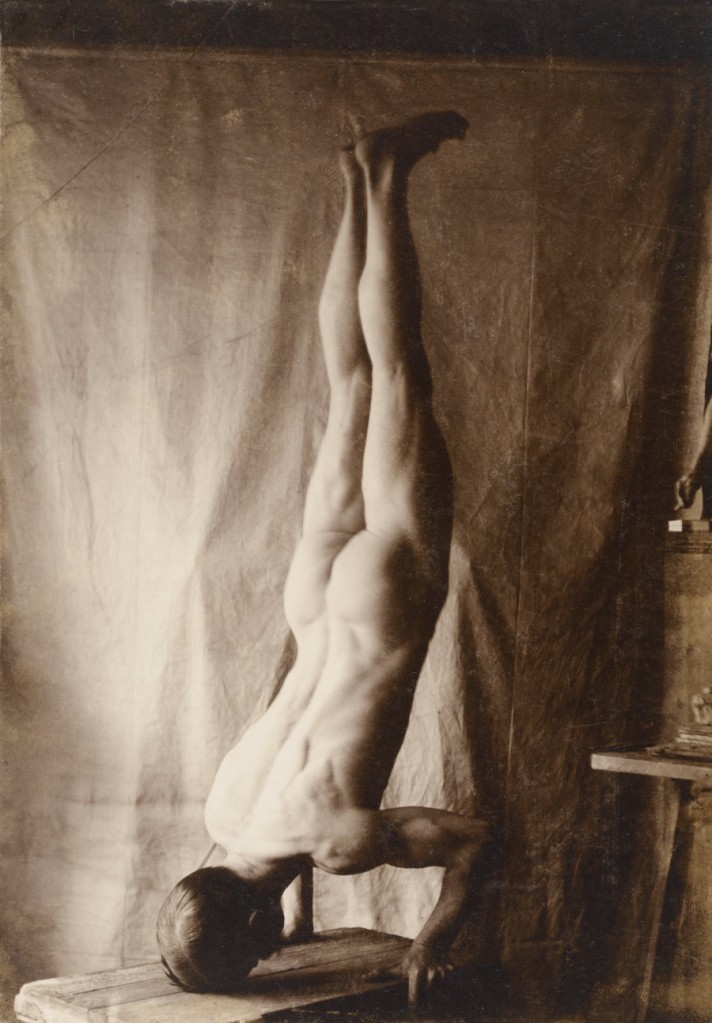

DeSana was born in Detroit in 1949 to middle-class suburbanites, who raised him and his brother in Atlanta. His mother was a strict Methodist; his father abandoned the family as DeSana entered adulthood. While studying art at Georgia State University, DeSana began making precocious, conceptual photography of suburban houses, generally banal, and of his friends, often naked. But his final thesis, 101 Nudes (1972), is a landmark. Likely taken with a Leica IIIf and lit by a flash, as Sawyer notes in his catalog essay, the portraits form a kind of fanzine of queer friends. DeSana shows off their muscles like he’s making Physique Pictorial, or crouches and crops their bodies like a funnier Man Ray. A drag queen looks right into the camera, bold; a man shoves his face into a pillow, ass beckoning. Bodies are unstable, and DeSana captures how funny, and how frightening, that can be, and how those two emotions comprise desire. Sawyer hangs these prints on the wall like Teen Beat posters in a teenage bedroom. It’s hard not to be a fan. …

Jesse Dorris. “Jimmy DeSana’s Transgressive Vision of Life and Desire,” on the Aperture website December 14, 2022 [Online] Cited 02/04/2023

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Cover from the series 101 Nudes

1972

Offset prints in custom portfolio box, fifty-six parts

Each: 11 × 14 inches (27.9 × 35.6cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York

© Estate of Jimmy DeSana

Photographer Jimmy De Sana was part of the countercultural “punk” community of artists and musicians living in New York’s East Village in the 1970s and ’80s. Among his best-known works are portraits of important figures from that scene, including Debbie Harry and Billy Idol, though these constitute only a small part of his practice. With work that is personal, surrealistic, and often shocking in its treatment of sexuality, De Sana helped raise the standing of photography in the art world and increased critical respect for the medium.

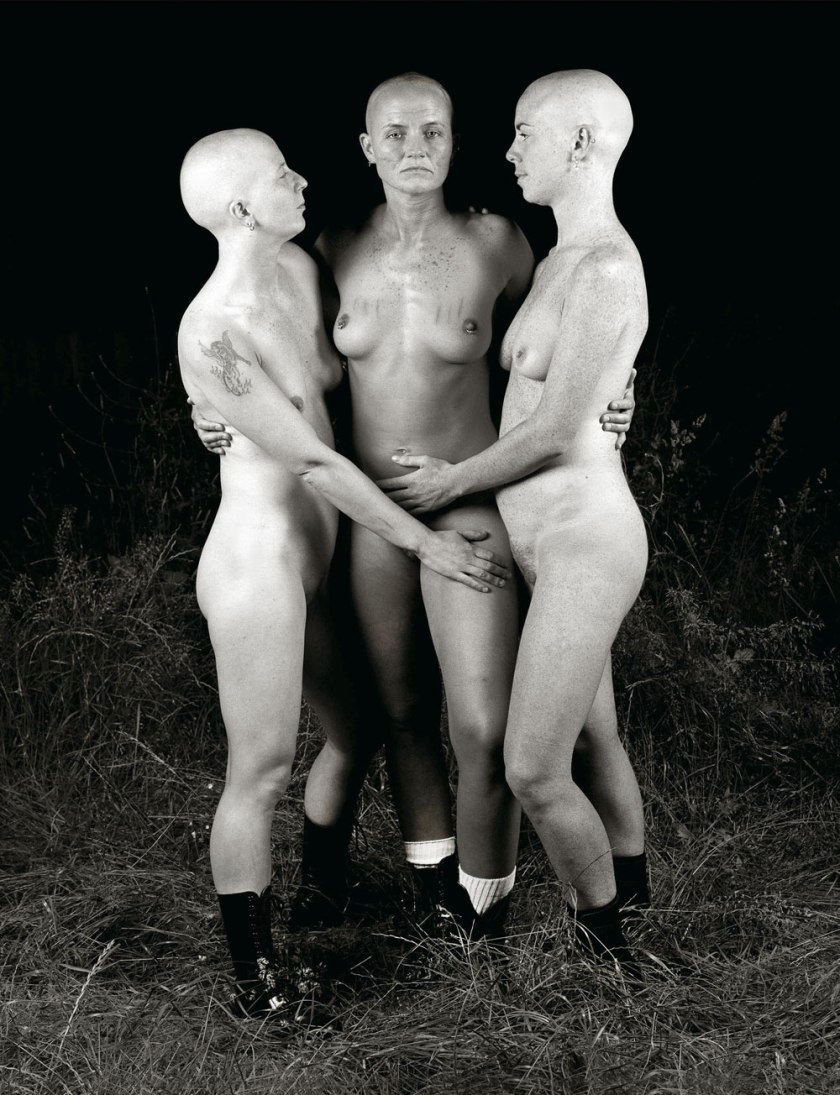

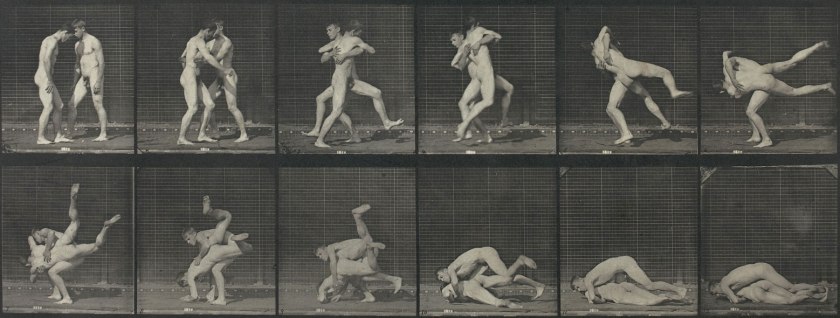

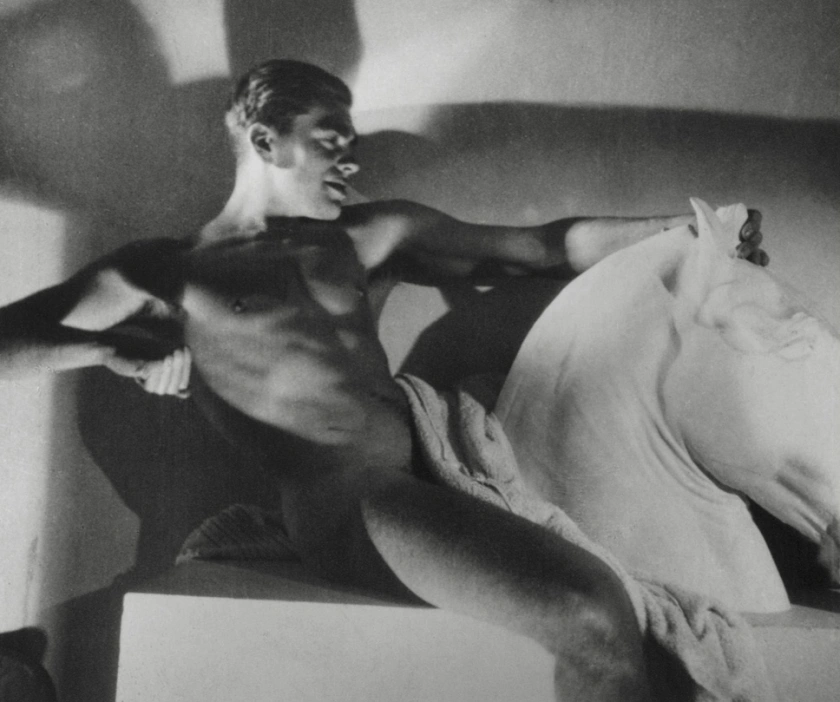

101 Nudes comprises 56 halftone black-and-white photographs of nude and partially nude figures posing inside or just outside homes. The artist was 20 years old and attending college in Atlanta when he first printed the series in 1972. The figures, which include De Sana’s friends as well as himself, are photographed from a variety of viewpoints. Although the series shows the influence of “grainy” pornography from the 1950s, the postures of the figures do not seem to suggest or invite sexual engagement; the artist noted that they are “without eroticism.” Sometimes the photographs feature only a fragment of the body, such as the pelvic area or buttocks. De Sana’s engagement with the history of surrealism has been noted, and these partial views in particular recall the surrealist photography of artists such as Man Ray, who in the 1920s photographed the body parts of friends and lovers in ways that removed them from their context and made them into almost abstract images.

Anonymous. “101 Nudes,” on the ICA website Nd [Online] Cited 20/03/2023

When De Sana (1950-1990) shot and self-published the 56 halftone images that would make up the “101 Nudes” series, he was just 20 years old and still a college student in Atlanta. Using his friends as models, he constructed each photograph as an insight into the possibilities of form, capturing with his flash-camera something both artful and sincere. His subjects (nearly all of them naked) were “without eroticism” as De Sana has said, the series as much about isolation as it is sexuality. The careful, strange postures of his figures, collapsed across a couch or balanced on a dining-room table, often had a touch of the surreal. His later work, in particular the S&M series that came to comprise his 1980 book “Submission” (also on display), explored sexuality and digression front-on in the spirit of William Burroughs, whose writing was a significant influence on the artist from a young age. De Sana created these images – which pre-dated Mapplethorpe’s fetish work – with an even stronger sense for composition, all the while seeking the boundaries of comfort through the bizarrely positioned, leather-bound figures.

Anonymous. “Jimmy De Sana, “101 Nudes and Other Works”,” on the NY Art Beat website 2011 [Online] Cited 20/03/2023

One year later, on June 28, 1969, police raided the Stonewall Inn, the gay bar in New York’s Greenwich Village, sparking an uprising that would launch the modern gay liberation movement. This spark of rebellion and hope made its way to Atlanta’s Ansley Mall Mini Cinema, where Andy Warhol’s homoerotic underground film, “Lonesome Cowboys,” was showing. Fifteen minutes into the film’s only screening, police officers raided the cinema and confiscated the reels. Many of the audience members were harassed, photographed and arrested.

DeSana may or may not have been in the audience that night, but he was certainly aware that his classmates and professors experienced censorship from school officials and the city. In the catalog accompanying the Brooklyn exhibition, curator Sawyer writes that in 1972, DeSana’s teacher, photographer John McWilliams, organized Atlanta’s annual arts festival where he displayed nudes made by his students and invited the highly regarded photographer Frederick Sommer to judge the exhibition.

“Sommer awarded prizes to several of the students, but within days there were letters and reviews in Atlanta’s daily papers complaining of the exhibition’s pornography,” writes Sawyer.

Against this backdrop of censorship and taboos, DeSana turned his perceptions of suburbia into his final thesis project, “101 Nudes,” spoofing the title of Walt Disney’s “101 Dalmations.”

The 56 humorous black-and-white images in “101 Nudes” are all fairly innocent scenes carefully posed in middle-class American homes. It’s kink for beginners: a nude perches on the edge of an overstuffed sofa; another plunges face-first into cushions; a goofy-looking naked boy stands on one leg on a dining room table. There are even close-up shots of buttocks, breasts and genitals, yet, as DeSana himself noted, they are “without eroticism,” adding, “that is the way the suburbs are, in a sense.”

As Jean Cocteau said of a Jean Genet poem, “His obscenity is never obscene.”

Jessica Robinson. “The Prurient Punk Surrealism of Photographer Jimmy DeSana,” on the Brooklyn website December 12, 2022 [Online] Cited 15/03/2023

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Untitled

1972

From the series 101 Nudes

Offset prints in custom portfolio box, fifty-six parts

Each: 11 × 14 inches (27.9 × 35.6cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York

© Estate of Jimmy DeSana

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Untitled

1972

From the series 101 Nudes

Offset prints in custom portfolio box, fifty-six parts

Each: 11 × 14 inches (27.9 × 35.6cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York

© Estate of Jimmy DeSana

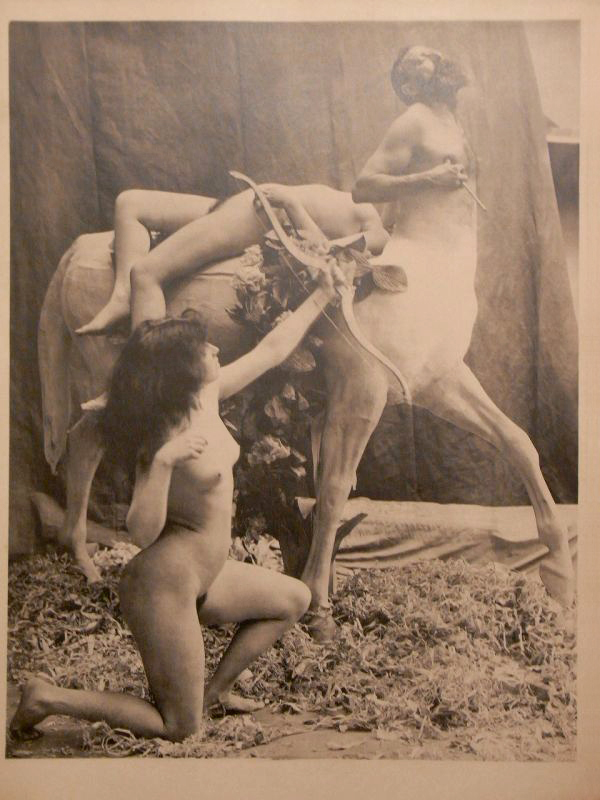

Against a backdrop of gay liberation and censorship in early 1970s Atlanta, DeSana combined his explorations of suburban culture and nude figures into a final thesis project. In 1970-1972, DeSana staged photographs of his mostly queer friends, including the notorious drag performer Diamond Lil, nude in suburban environments. While other Conceptual artists were focused on the architectural homogeneity of suburbia, in 101 Nudes DeSana penetrated the veneer of seriality and conformity.

According to DeSana, both his subjects’ poses and his halftone reproduction techniques mimicked images from mass-market, soft-core pornographic magazines that emerged during his youth. The title sends up that of the wholesome 1961 Disney animated film 101 Dalmatians, which was rereleased in 1972. DeSana would continue to draw from and parody popular cultural forms into the early 1980s.

Exhibition label

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Untitled

1972

From the series 101 Nudes

Offset prints in custom portfolio box, fifty-six parts

Each: 11 × 14 inches (27.9 × 35.6cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York

© Estate of Jimmy DeSana

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Untitled

1972

From the series 101 Nudes

Offset print

12 3/4 × 8 1/2 in. (32.4 × 21.6 cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York

© Estate of Jimmy DeSana. (Photo: Allen Phillips)

Against a backdrop of policing, censorship, and gay liberation in early 1970s Atlanta, DeSana staged photographs of his mostly queer friends, including the notorious drag performer Diamond Lil, nude in suburban environments. While other Conceptual artists using photography like Dan Graham were focused on the architectural homogeneity of suburbia, in “101 Nudes,” a portfolio of 56 photolithographic prints, DeSana penetrated the veneer of seriality and conformity.

Both his subjects’ poses and his halftone reproduction techniques mimicked images from mass-market, soft-core pornographic magazines that emerged during the artist’s youth. The title sends up that of the wholesome 1961 Disney animated film 101 Dalmatians, which was rereleased in 1972.

DeSana eventually sent copies of the portfolio through the mail, which served as an alternative channel for sharing Conceptual art and challenging the privileged spaces of museums and commercial galleries during these years. He embraced “correspondence art” in part to connect with other gay artists and construct identities that defied mainstream standards of “respectability” for gay people.

Text from the Brooklyn Museum Tumblr website

John Jack Baylin

Fanzini Goes to the Movies

1974

Periodical; offset print

11 × 8 1/2 in. (27.9 × 21.6cm)

Courtesy of Philip Aarons and Shelley Fox Aarons

Publisher: General Idea, Canadian, 1969-1994

File, vol. 3, no. 1, “Glamour” issue

Autumn 1975

Periodical; off-set print, staple bound, illustrated wrappers

14 × 10 11/16 in. (35.6 × 27.1cm)

Collection of Philip Aarons and Shelley Fox Aarons

Publisher: General Idea, Canadian, 1969-1994

File, vol. 2, no. 4, “Mondo Nudo” issue

December 1973

Periodical; offset print, staple bound, illustrated wrappers

14 × 10 3/4 in. (35.6 × 27.3cm)

Collection of Philip Aarons and Shelley Fox Aarons

Publisher: General Idea, Canadian, 1969-1994

File, vol. 2, no. 3, “Paris” issue

September 1973

Periodical; offset print, staple bound, illustrated wrappers

14 × 11 in. (35.6 × 27.9cm)

Collection of Philip Aarons and Shelley Fox Aarons

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Untitled

1974

Dye diffusion transfer prints

Each 4 1/4 × 3 3/8 in. (10.8 × 8.6cm)

Collection of Philip Aarons and Shelley Fox Aarons

© Estate of Jimmy DeSana

Photo: David Vu

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Untitled

1974

Dye diffusion transfer print

4 1/4 × 3 3/8 in. (10.8 × 8.6cm)

Collection of Philip Aarons and Shelley Fox Aarons

© Estate of Jimmy DeSana

Photo: David Vu

Fluxus and Dada Daddies

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Stephen Varble

1975

Gelatin silver print

11 1/4 × 16 1/2 in. (28.6 × 41.9cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York

© Estate of Jimmy DeSana

Photo: Allen Phillips

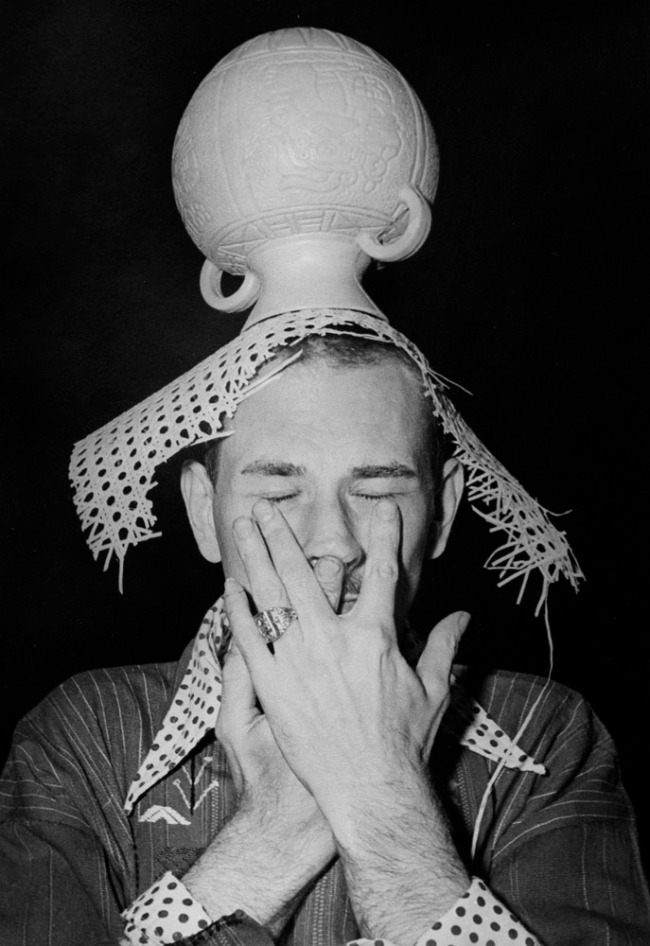

During the golden age of downtown performance art in the 1970s, Jimmy DeSana documented the work of numerous artists, sometimes for income.

In 1975, he photographed public interventions by Stephen Varble, an artist who performed his “Gutter Art” in the streets of Soho and Midtown, while wearing his signature gender-bending ensembles. As the critic Gregory Battcock put it, Varble came to be “considered by some the embarrassment of SoHo, and by others the only touch of real genius south of Houston Street.” DeSana’s photographs of Varble appeared in publications during this time, including General Idea’s FILE Megazine.

DeSana’s photographs are invaluable records of an ephemeral practice, which has only recently been given its proper due thanks in part to the work of art historian David Getsy.

Text from the Brooklyn Museum Tumblr website

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Stephen Varble

1975

Gelatin silver print, printed later

18 1/4 × 23 3/4 in. (46.4 × 60.3cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York

© Estate of Jimmy DeSana

Photo: Allen Phillips

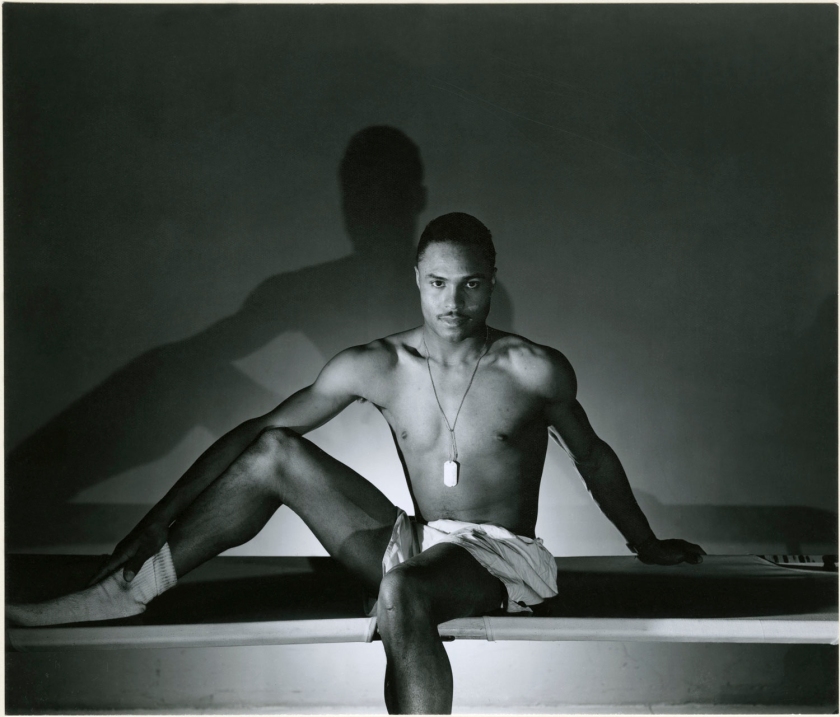

Throughout the 1970s, Jimmy DeSana created campy portraits of his extended circle of friends and collaborators in New York, which included musicians, filmmakers, writers, artists, critics, and curators.

Performance artist and fixture of New York City’s downtown scene Stephen Varble, shown here, was one of DeSana’s repeat subjects. DeSana captured many of the performances staged by Varble whose guerilla practices served as commentary on gender identity, class, and capitalism. These performance-based and ephemeral events would continue to inform DeSana’s work in photography throughout the 1970s and 1980s.

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Stephen Varble

1975

Gelatin silver print

8 × 10 in. (20.3 × 25.4cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W, New York

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Jack Smith

c. 1976

Gelatin silver print

7 × 6 in. (17.8 × 15.2 cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W, New York

Gregory Battcock

Trylon and Perisphere, No. 1

December 1977

Periodical, offset print, saddle stitched, illustrated wrappers

10 × 7 in. (25.4 × 17.8cm)

Courtesy of Philip Aarons and Shelley Fox Aarons

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Eric Mitchell

1977

Gelatin silver print

15 3/4 × 11 1/2 in. (40 × 29.2cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W, New York

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Patti Astor

1977

Gelatin silver print

15 7/8 × 11 1/2 in. (40.3 × 29.2cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York

© Estate of Jimmy DeSana. (Photo: Allen Phillips)

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Sofa

1977-1978

Gelatin silver print

6 1/2 × 9 1/2 in. (16.5 × 24.1cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York

© Estate of Jimmy DeSana

Photo: Allen Phillips

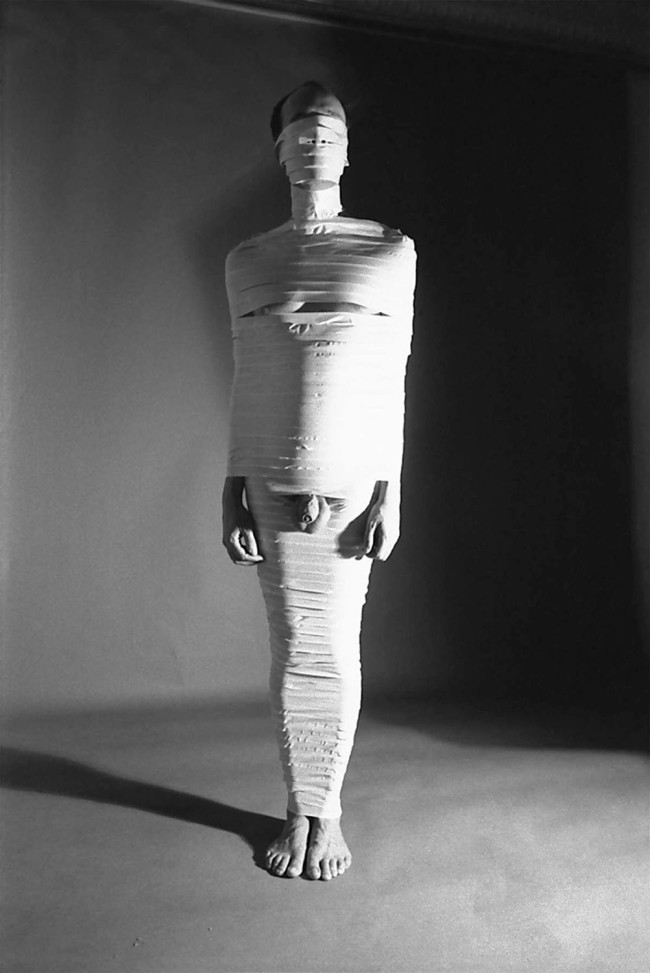

Throughout the 1970s, Jimmy DeSana created theatrical, often comic photographs related to his sexual S-M experiences.

Like other artists in his circle, such as Laurie Simmons and AA Bronson, he parodied advertising and fashion photography, as well as the disciplinary nature of heteronormativity and consumerism in the United States. He eventually published some of these photographs in his first book, Submission (1980), which included an introduction by the punk icon William Burroughs.

The photographs in this series typically feature nude, masked individuals eccentrically interacting with domestic interiors and objects. DeSana staged most images in his studio or the homes of friends and family. He used his signature lighting to create a heightened sense of drama and horror, calling attention to the images’ artifice. DeSana later observed: “I was trying to push sexuality to the limit. As long as I could come up with an idea that related to bizarre sexuality and still make an interesting statement about a product, the photo was successful for me.”

Text from the Brooklyn Museum Tumblr website

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Auto

1978

Gelatin silver print

6 3/4 × 9 9/16 in. (17.1 × 24.3cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W, New York

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Television

1977-1978

Gelatin silver print

12 1/4 × 8 1/4 in. (31.1 × 21cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W, New York

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Refrigerator

1978

Gelatin silver print

9 1/2 × 6 3/4 in. (24.1 × 17.1cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York

© Estate of Jimmy DeSana

Photo: Allen Phillips

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Masking Tape

1977-1978

Gelatin silver print

9 1/2 × 6 1/2 in. (24.1 × 16.5cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W, New York

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Pliers

1977-1978

Gelatin silver print

6 3/4 × 9 1/4 in. (17.1 × 23.5cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W, New York

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Enema

1977-1978

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York

© Estate of Jimmy DeSana

Sadomasochism, Then and Now

DeSana’s photographs and Terence Sellers’s writings engage with a variety of often erotic practices known then as S-M (sadomasochism) and more commonly now as BDSM (bondage, dominance, and submission / sadomasochism). The term “sadomasochism” is derived from the names of two European authors: the Marquis de Sade (1740-1814), who wrote about his exploits and fantasies of deriving pleasure from inflicting pain, and Leopold von Sacher-Masoch (1836-1895), who wrote of the erotic enjoyment he experienced while being dominated and punished.

In the 1970s, DeSana and Sellers were among a growing group of practitioners, writers, artists, and activists attempting to redefine “acceptable” behaviour and desires, as well as sexual and gender identities. In exploring S-M through an aesthetic lens, Sellers and DeSana also joined a long lineage of artists and thinkers who had engaged with these practices to encourage debate on freedom of expression and power.

It was not until 2010 that the American Psychiatric Association announced it would no longer diagnose consenting adults practicing BDSM as mentally ill, which had perpetuated stigmatisation that could lead to legal and social repercussions. More recently, studies have suggested that BDSM can provide therapeutic tools to investigate control and release, and to reclaim one’s sexuality after traumatic experiences.

Exhibition label

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Toilet

1977-1978

Gelatin silver print

9 9/16 × 6 3/4 in. (24.3 × 17.1cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York

© Estate of Jimmy DeSana

Photo: Allen Phillips

“The very word ‘submission’ contains the paradox of wanting and not wanting,” William S. Burroughs wrote in the introduction of Jimmy DeSana’s 1980 book Submission.

For the photogragraphic series featured in the publication, made between 1977 and 1978, DeSana built on 101 Nudes (1972) and his work for File Megazine by creating theatrical and often comic photographs that push the limits of respectability and explore domestic confinement, consumer affluence, and social conformity. He was also mocking the recent trend of S-M scenarios in fashion photography and advertisements.

He titled many of the images after the objects depicted in them – Toilet, Coffee Table, Television, Shoes, Shower – rather than sex acts or the names of the individuals shown, who are always anonymous and often wearing masks. This strategy not only protected the identity of his models, many of whom were friends, but also contrasted with his better-known portrait work during this period, which he did to make money. Many of the photographs comically equate practices of everyday life and consumerism (washing dishes, taking a shower, driving a car) with forms of bondage and discipline.

In exploring S-M through an aesthetic and performative lens, DeSana joined a long history of twentieth-century avant-gardes that engaged with these practices in order to compel debate on freedom of expression and power.

Text from the Brooklyn Museum Tumblr website

Terence Sellers (American, 1952-2016)

The Correct Sadist: The Memoirs of Angel Stern

1983

Book

8 1/2 × 5 9/16 in. (21.6 × 14.1 cm)

Private collection

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Untitled

1978

From the series The Dungeon

Gelatin silver print

6 1/2 × 9 5/8 in. (16.5 × 24.4cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York

© Estate of Jimmy DeSana

Photo: Allen Phillips

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Coffee Table

1977-1978

Gelatin silver print

9 1/2 × 6 1/2 in. (24.1 × 16.5cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York

© Estate of Jimmy DeSana

Photo: Allen Phillips

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Untitled

1978

From the Dungeon series

Gelatin silver print

9 1/2 × 6 5/8 in. (24.1 × 16.8cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W, New York

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Untitled

1978

From the Dungeon series

Gelatin silver print

9 1/2 × 6 5/8 in. (24.1 × 16.8cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W, New York

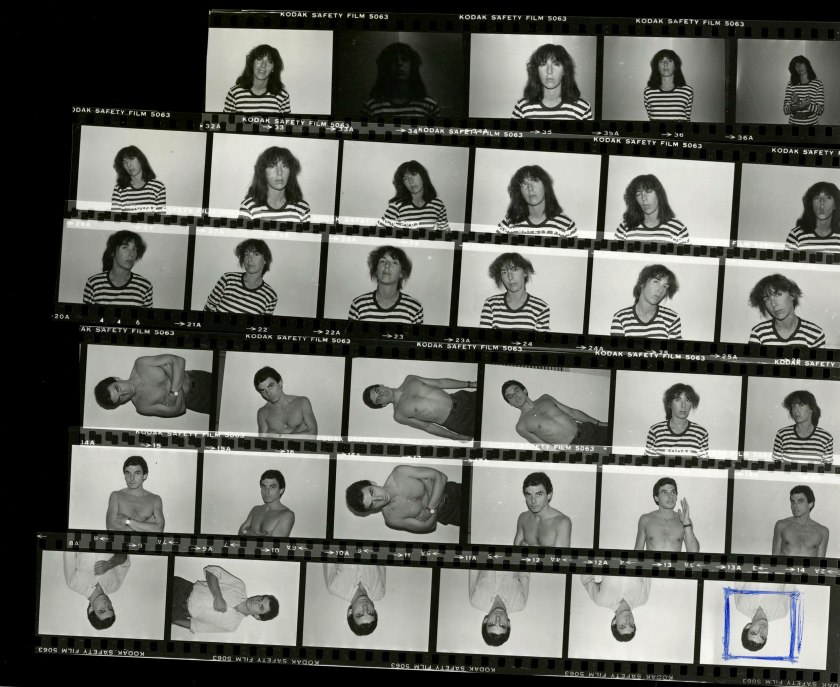

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Contact Sheet of Portraits of Jimmy DeSana and Laurie Simmons

c. 1978

New York University, Fales Library, Jimmy DeSana Papers, MSS.202, Box 66

Photo: Courtesy of Fales Library at NYU

In 1973, shortly after moving to New York, Jimmy DeSana met fellow artist Laurie Simmons while riding the A train to Far Rockaway.

The two soon shared a SoHo loft with twin photographic darkrooms. Simmons has often acknowledged that DeSana, who received a BFA in photography, taught her most of what she knows about the medium, acting as a friend, mentor, and interlocutor until his death in 1990. Simmons also became a model and muse for DeSana’s work.

Now the executor of the Jimmy DeSana Trust for several decades, Simmons writes, “I am immensely grateful for every moment Jimmy and I spent together, for every freezing second I floated naked in a pool or held an awkward pose for way too long, for this was my graduate program in photography – this is really where I learned to make a picture… standing within Jimmy’s quiet but determined force field, emulating his laser-like focus and his ultimate belief that making art was a space to play and dream.”

Text from the Brooklyn Museum Tumblr website

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Terence Sellers

1978

Gelatin silver print

9 5/8 × 6 1/2 in. (24.4 × 16.5cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York

© Estate of Jimmy DeSana. (Photo: Allen Phillips)

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Betsy Sussler

1978

Gelatin silver print

15 7/8 × 11 in. (40.3 × 27.9cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W, New York

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Coat Hanger

1979

Gelatin silver print

9 9/16 × 6 5/8 in. (24.3 × 16.8cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York

© Estate of Jimmy DeSana

Photo: Allen Phillips

The Brooklyn Museum Presents Jimmy DeSana: Submission, the First Museum Survey of Work by the Pioneering Queer, Punk Photographer. The exhibition features more than two hundred works, which trace a career that bridged mail art networks, New York’s 1970s punk and No Wave subcultures, the illuminating image-play of the “Pictures Generation,” and the various artistic and affective responses to the beginning of the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

Jimmy DeSana: Submission is the first museum survey of work by a major yet overlooked figure in the histories of photography, LGBTQ artists, and New York City. Among his many significant contributions, Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990) reintroduced the body and sexuality into the conceptual photographic practices of the late 1960s and early 1970s, helping to elevate the medium within the contemporary art world. The exhibition traces the artist’s brief but prolific career through more than two hundred works on display (some for the first time), created during a time of profound cultural and political transformation in the United States. From his early days photographing suburban landscapes in Atlanta, Georgia, to his time as a key figure in the New York art and music scenes of the 1970s and 1980s, DeSana conveyed the radical spirit of his era and a pointed, ironic critique of the American Dream and its images. Jimmy DeSana: Submission opens November 11, 2022, and is organised by Drew Sawyer, Phillip Leonian and Edith Rosenbaum Leonian Curator of Photography, Brooklyn Museum.

“This retrospective, the first since DeSana’s death from AIDS-related complications in 1990, will enable so many to view for the first time the full breadth of his iconoclastic artistic output, positioning his more well-known series within his interdisciplinary and collaborative practice in mail art, zines, performance, and film,” says Sawyer. “DeSana drew upon punk, Camp, sadomasochism, dreamworlds, performance art, experimental film, club culture, and the legacy of twentieth-century avant-gardes in ways that make his work unique among his peers. Jimmy DeSana: Submission brings together these multiple themes to show why his work is so relevant to artistic practices today.”

Along with his friends and peers, Jimmy DeSana sought to forge arts communities outside of traditional institutions (and the concurrent gentrification that displaced artists from Lower Manhattan). Instead, he chose to display his work via collectives, artist-run spaces, and the informal groupings of the underground nightclub scene, as well as the more democratised dissemination systems of mail art networks. Submission prominently features examples of DeSana’s contributions to early queer zines throughout the 1970s – from General Idea’s File magazine to John Jack Baylin and John Dowd’s Fanzini to Gregory Battcock’s Trylon & Perisphere – as well as his first major series, 101 Nudes (1972), which was circulated through mail art networks. DeSana published this portfolio of photolithographic prints, portraying his friends posing nude in the bland interiors of Atlanta’s postwar houses, at the height of the Gay Liberation Movement and the city’s reactive censorship. These formative images employ a distinctly queer approach to domesticity and invite viewers to look beneath the veneer of suburban propriety, a concept that would capture the artist’s creative attention for the rest of his career.

The exhibition also contains selections from Submission (1980), DeSana’s book of BDSM-related photographs that play with liberation and conformity, and ideological power alongside the myths of postwar capitalism. This section also includes related photographs from a collaboration with writer and sex worker Terence Sellers (American, 1952-2016) that were intended for her first book, The Correct Sadist (1983). Most of these photographs have not been previously displayed or published.

Continuing the survey is DeSana’s series Suburban (1979-1984), perhaps the artist’s best-known photographs and his first in colour. Building off of 101 Nudes, DeSana used a cast of friends and collaborators to explore the queerness of postwar suburban culture by placing nude bodies, often abstracted and contorted, in suburban backyards, wood-panelled living rooms, and tiled bathrooms. Using vivid gel-lighting to produce its characteristic heavily saturated, candy-coloured prints, Suburban mimics the seductive, materialist aesthetics of fashion photography and the set design of television advertisements – strategies that were similarly deployed by his friends and peers during this period, including model and artist Laurie Simmons. The images are often skewed and shot from oblique angles, further destabilising the viewer’s perception of the subjects.

Accompanying the dreamlike colour photographs of the Suburban series are some of DeSana’s subsequent, more abstract efforts from the late 1980s. Made after 1984, when DeSana underwent spleen removal surgery after contracting HIV, the works superimpose warped colour images of everyday objects with collage elements, text, and fragments of figures in motion. DeSana turned away from directly representing the body during this period – in the early years of the ongoing HIV / AIDS epidemic, when gay artists in particular were expected to make work about the epidemic in reaction to government inaction and neglect or misinformation by dominant media.

DeSana was seemingly omnipresent in New York’s punk and No Wave scenes during the late 1970s and 1980s, joining other artists who engaged in symbolic forms of resistance through visual art, literature, music, and film. DeSana photographed a number of prominent figures in those subcultures; the survey will be the first to feature his portraits of art and music luminaries such as Kathy Acker, Laurie Anderson, Kenneth Anger, Patti Astor, David Byrne, John Giorno, Debbie Harry, and Richard Hell. Additionally, the exhibition will highlight DeSana’s photographic contributions to collectives like Collaborative Projects (including their groundbreaking exhibitions and publication, X Motion Picture Magazine), periodicals such as the New York Rocker and Semiotext(e), and No Wave Cinema, in which he was involved as both an actor and a director.

The exhibition will be accompanied by the first scholarly publication on DeSana’s work, featuring essays by Sawyer and artist Laurie Simmons as well as more than two hundred images, co-published with DelMonico Books. Jimmy DeSana: Submission is organised by Drew Sawyer, Phillip Leonian and Edith Rosenbaum Leonian Curator of Photography, Brooklyn Museum.

Press release from the Brooklyn Museum

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Untitled (Self-Portrait w/ Graduation Cap)

1978

Polaroid

Cornell University, Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Diego Cortez No Wave Collection, 1972-1981, Collection Number: 8120, Box 1, Folder 17

Photo: Courtesy of Cornell University

James, Jim, Jimmy; de Sana, deSana, De Sana, DeSana. Just as Jimmy DeSana rarely stuck with one version of his name, he refused to limit two of his main artistic engagements – photography and the theme of desire – to fixed identities.

Born in Detroit on November 12, 1949, James Arthur DeSana Jr. developed an early involvement in photography when he received a Kodak camera for Christmas at age seven. After graduating with a BFA in photography from Georgia State University in 1972, DeSana moved to New York, where he became involved in correspondence art, collectives and alternative publications, post-punk music, underground film, and queer nightlife.

During this time, DeSana amassed a large collection of hats, like the graduation cap he’s wearing in this Polaroid self-portrait. This fervid interest in hats coincided with DeSana’s use of masquerade and invented personae in his mail artworks; he would go on to make use of the hats in his self-portraits throughout the 1970s and 1980s, continuing his subversion of identity.

Text from the Brooklyn Museum Tumblr website

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Stitches

1984

Silver dye bleach print

18 3/4 × 12 5/8 in. (47.6 × 32.1cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W, New York

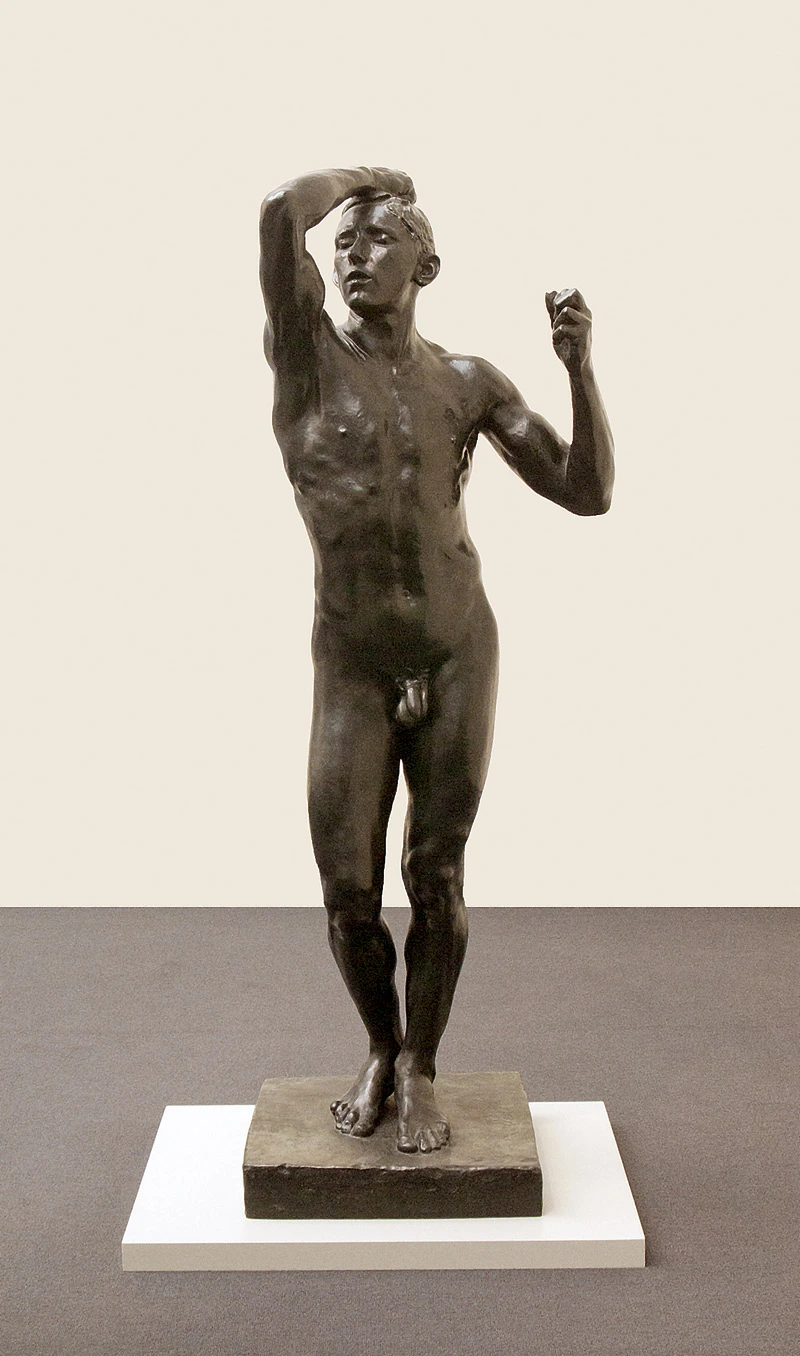

He was extending the legacy of the Surrealist photographers of the period between the World Wars. Man Ray in particular presented his subjects with a disorienting spin: He inverted the head of a female smoker whose cigarette looks like a chimney, cast dark shadows to make the naked torso of a woman with upheld arms resemble the head of a bull, and shot his lover, the photographer Lee Miller, from an extreme lower angle so that her neck and chin take on a phallic form. He mixed genders, even species, with gleeful abandon. DeSana joined in the game.

But a 1984 DeSana self-portrait pointed to the painful direction his life was about to take. He photographed himself in red Calvin Klein briefs illuminated in a red glow, one hand on his forehead, his eyes upturned and his expression concerned. A bright beam of white light is directed toward two dozen surgical stitches running from his sternum down his left side. His spleen had just been removed, an early warning of H.I.V. infection. The diagnosis of AIDS came a year later.

Arthur Lubow. “Jimmy DeSana, Downtown Pioneer and Provocateur, Goes Mainstream,” on the New York Times website Nov. 8, 2022 [Online] Cited 02/04/2023

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Portrait with Dog

Undated

Chromogenic print

20 × 14 in. (50.8 × 35.6cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W, New York

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Condom

1979

Cibachrome print

12 1/4 × 18 3/4 in. (31.1 × 47.6cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W, New York

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Shoes

1979

Chromogenic print

15 1/4 × 23 1/2 in. (38.7 × 59.7cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W, New York

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Gauze

1979

Chromogenic print

12 3/4 × 19 in. (32.4 × 48.3cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W, New York

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Shoe

1979

Chromogenic print

13 × 19 in. (33 × 48.3cm)

Courtesy of Jimmy DeSana Trust and PPOW

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

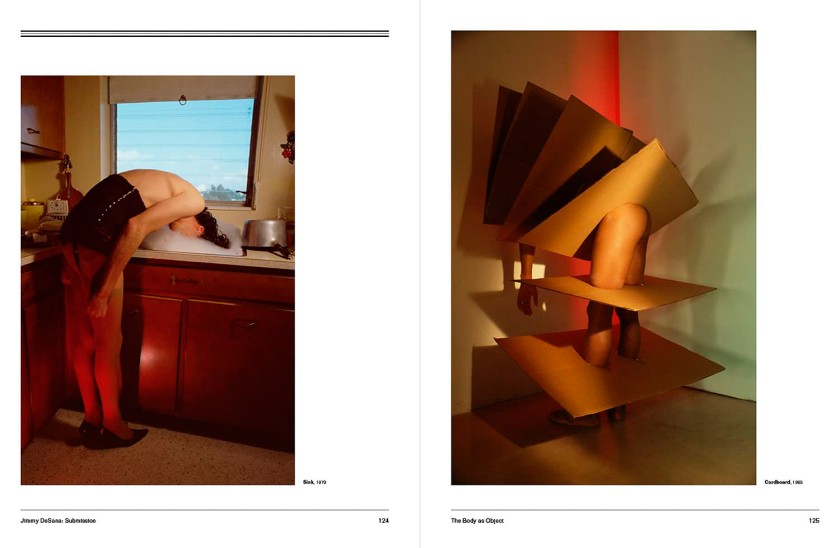

Sink

1979

Silver dye bleach print

19 × 12 5/8 in. (48.3 × 32.1cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York

© Estate of Jimmy DeSana

Photo: Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York

Many of the photographs in Jimmy DeSana’s “Suburban” series explore themes of domestic confinement and social conformity through consumer goods and rituals.

In “Sink” (1979), shown here, an anonymous figure wearing a corset and heels leans over, head dunked in a kitchen sink filled with soap suds. DeSana allows contradictions – between agency and conformity, critique and complicity, punishment and pleasure – to remain open-ended in his work, enabling them to identify and “disidentify” with dominant culture.

Text from the Brooklyn Museum Tumblr website

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Leaves

1979

Chromogenic print

18 3/4 × 12 1/2 in. (47.6 × 31.8cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W, New York

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Storage Boxes

1980

Inkjet print, printed 2022

15 1/2 × 23 1/2 in. (39.4 × 59.7cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York

© Estate of Jimmy DeSana

Photo: Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York

In the late 1970s, the status of colour photography was still disputed within the spaces of museums and art galleries, in part because of its associations with commercial and vernacular uses of the medium, such as fashion photography, advertisements, and home snapshots.

Perhaps even more than the content of his photographs, Jimmy DeSana’s use of gels and tungsten lights to create garish pinks, greens, reds, and oranges flew in the face of accepted taste and allowed him to utilise the medium in decidedly unconventional ways.

In “Storage Boxes” (1980), shown here, a pair of figures sit poolside in lounge chairs, holding hands but with their heads and feet encased in boxes. While many of the figures in his work from this time appear to be confined or dominated by objects, their performances look not like a limitation so much as a relational space that generates a capacity for self-knowledge and pleasure.

Exhibition label

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Auto

1980

Chromogenic print

15 5/16 × 22 7/8 in. (38.9 × 58.1cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York

© Estate of Jimmy DeSana

Photo: Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York

DeSana’s photographs frequently feature visual puns. Here, a nude person, perhaps DeSana himself, lies beneath a car with a breathing tube connecting his gas mask to the exhaust pipe. The image appears to be a visual play on “autoerotic asphyxiation,” or the intentional restriction of oxygen to the brain for the purposes of sexual arousal. The image could also be interpreted as a metaphor for America’s subservience to car culture and the harm that automobiles cause us, the red glow adding an ominous tone.

Exhibition label

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Instant Camera

1980

Chromogenic print

15 1/8 × 23 in. (38.4 × 58.4 cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W, New York

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Soap Suds

1980

Chromogenic print

15 1/8 × 22 3/4 in. (38.4 × 57.8cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W, New York

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Four Legs with Shoes

1980

Chromogenic print

14 3/4 × 18 7/8 in. (37.5 × 47.9cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W, New York

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Party Picks

1981

Inkjet print, printed 2013

32 3/4 × 49 1/2 in. (83.2 × 125.7cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W, New York

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Kenneth Anger

1980

Chromogenic print

20 × 13 1/2 in. (50.8 × 34.3 cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W, New York

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

William S. Burroughs

1981

Chromogenic print

20 × 13 1/2 in. (50.8 × 34.3cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York

© Estate of Jimmy DeSana

Photo: Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York

Throughout his career, DeSana befriended and photographed an older generation of pioneering queer male artists and writers who similarly transgressed societal norms through their work and life. Also like DeSana, many subverted pop culture imagery and operated outside of official institutions.

Exhibition label

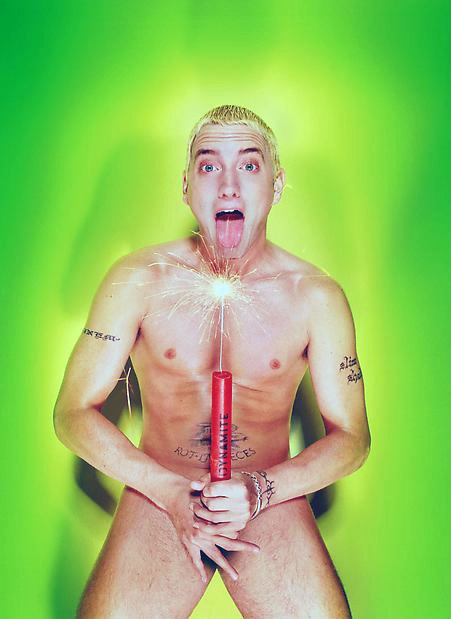

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Bubblegum (Self-Portrait)

1984

Silver dye bleach print

19 5/8 × 15 1/2 in. (49.8 × 39.4cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York

© Estate of Jimmy DeSana

Photo: Allen Phillips

In a group of photographs from 1984 and 1985, DeSana explored America’s obsession with fat and dieting, tying it in with his own interest in consumption and forms of discipline and pleasure. Bubblegum, for example, is a self-portrait with his cheeks puffed out, blowing a bubble, his oversize shirt and pants bursting at the seams from stuffing and his back slightly arched to emphasise his protruding belly. He printed this image in numerous colours, including bright pink and acid green.

Exhibition label

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Cowboy Boots

1984

Silver dye bleach print

20 × 16 in. (50.8 × 40.6cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York

© Estate of Jimmy DeSana

Photo: Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York

With a wink to the commonalities of darkrooms and backrooms, Sawyer built a red-light district for DeSana’s extensive investigations of BDSM, in which piss is expelled and enjoyed, and gimp-masked figures kneel in toilets or near dog bowls. In Party Picks (1981 above), toothpicks stuck into gums between teeth make a crown of thorns around a gasping mouth, or maybe make that mouth St. Sebastian’s wound. Cardboard (1985 below) offers a room with a single, lurid red band of light and corrugated cardboard that slices a bending body. In such a place, you might think of Samuel Steward’s card catalog of his conquests, or if Flavin’s work is really about its shadows, or what to do with that butt. DeSana’s frisky, familiar portraits reject the po-faced posing of Mapplethorpe and the social-climbing sadism of Helmut Newton. He gets that such proclivities are mind games played with bodies and bets you might want to play them too.

Jesse Dorris. “Jimmy DeSana’s Transgressive Vision of Life and Desire,” on the Aperture website December 14, 2022 [Online] Cited 02/04/2023

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Cardboard

1985

Silver dye bleach print

19 × 12 3/4 in. (48.3 × 32.4cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York

© Estate of Jimmy DeSana

Photo: Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York

In his series of photographs titled Suburban, Jimmy DeSana continued to photograph anonymous nude figures while making a more explicit connection between S-M and everyday life.

Many of the photographs comically equate attachments to the objects and ideals of postwar suburban life in the U.S. (washing dishes, taking a shower, driving a car) with forms of bondage and discipline. In Cardboard, from 1985 (shown here), a nude figure is intersected by sheets of cardboard.

Lit with tungsten lights and candy-coloured gels, his collaborators often turned their backs to the camera or buried their heads in purses, sinks, toilets, etc. rather than wearing leather masks. This not only protected the identity of his nude models, many of whom were friends, but also contrasted with his better-known portrait work during this period. Perhaps most important, these images continued his subversion of subjectivity. While all the photographs in the Suburban series feature nude figures, DeSana did not intend for the work to be erotic.

Text from the Brooklyn Museum Tumblr website

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Spoon

1985

Silver dye bleach print

7 1/2 × 9 1/2 in. (19.1 × 24.1 cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W, New York

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Socks

1986

Silver dye bleach print

4 3/4 × 9 1/2 in. (12.1 × 24.1cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W, New York

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Untitled (Self Portrait Sleeping)

1985

Silver dye bleach print

9 1/2 × 7 1/2 in. (24.1 × 19.1cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W, New York

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Untitled (Male Nude)

1985

Silver dye bleach print

9 1/2 × 7 1/2 in. (24.1 × 19.1cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W, New York

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Ties & Roses

1986

Silver dye bleach print

14 3/4 × 19 1/4 in. (37.5 × 48.9cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W, New York

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Balloons

1985

Silver dye bleach print

13 1/4 × 10 1/4 in. (33.7 × 26 cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W, New York

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Cellophane Tape

1985

Silver dye bleach print

13 15/16 × 10 1/2 in. (35.4 × 26.7cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W, New York

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Aluminum Foil #4 (Self-Portrait)

1985

Silver dye bleach print

10 × 8 in. (25.4 × 20.3cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York

© Estate of Jimmy DeSana

Photo: Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York

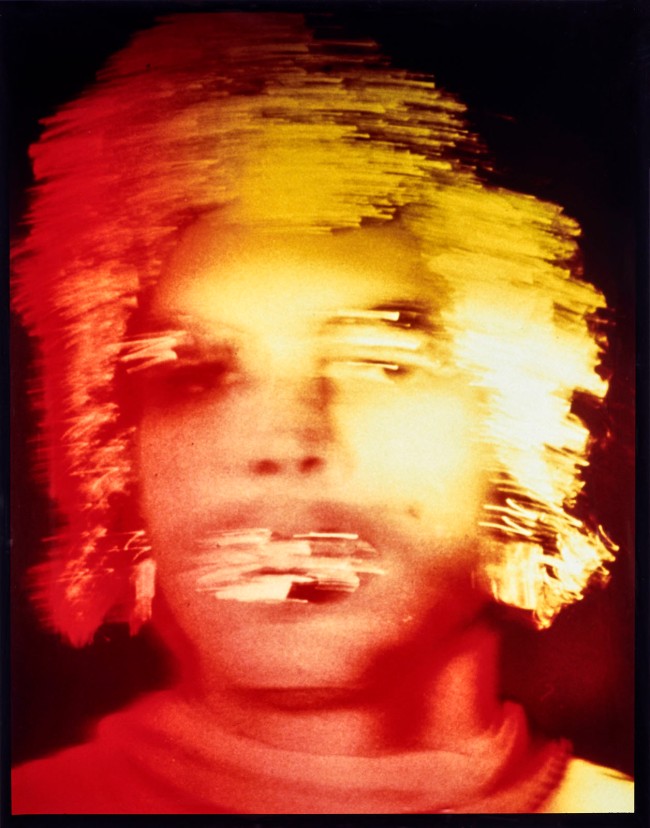

In a series of “auto-portraits” from around 1985, DeSana assumed the guise of figures in famous portraits, such as Andy Warhol’s Marilyn Monroe and Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa. This body of work developed from DeSana’s previous experiments with role-playing, performance, and concealment.

Building on his engagement with colour photography, DeSana transformed these black-and-white negatives by enlarging them with dyed gels and colour dials. After exposing the colour photographic paper, he took the prints to a lab to finish the developing process.

Exhibition label

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Aluminum Foil #1 (Self-Portrait)

1985

Silver dye bleach print

13 1/2 × 10 1/2 in. (34.3 × 26.7cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York

© Estate of Jimmy DeSana

Photo: Allen Phillips

The vivid colour profiles of the Suburban series are riotous, yet the scenes are often subdued, serious, even melancholic. These acid-toned prints are more sinister, more surreal, and less eager to please than the images we often associate with the Pictures Generation. It’s easier to draw a line between DeSana and the surrealist photography of Man Ray and Hans Bellmer than to Cindy Sherman’s plucky film tests or the crisp portraits by Robert Mapplethorpe or Peter Hujar. Further distancing his work from that of his contemporaries, DeSana almost never reveals the identity of his sitters. Faces are almost invariably obscured by a prop: a stocking, a helmet, soap suds, or even the camera itself. The viewers’ innate desire to know the subject is stymied by the unrecognisability of these exploded, contorted anonymous bodies. By making chairs, coat hangers, helmets, and even an iguana an extension of the body, the photographs propose a flattening of the hierarchy between prop and actor, blurring the distinction between stage and sitter, foreground and background, organic and artificial. In much the same way that subjugation and compliance are fundamental to BDSM culture, here the camera becomes dominant, imploring the body to perform for the photographer. DeSana uses these bodies are props, stripping them of agency and compelling them serve the needs of the composition.

DeSana made a career of piercing through the realm of the banal and conventional with the queer and radical. His works suggest that the home itself and the objects within it are in themselves a prop to conceal an arena of libidinal play. For DeSana, the camera acts as catalyst and instigator, a tool used to coerce a performance, a device that invites us to subjugate our egos in the service of latent desires.

Bryan Barcena. “Suburban/Submission,” Focus Essay from FOAM exhibition 09.01.2019 on the Salon 94 website [Online] Cited 20/03/2023

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Untitled (Man with Antler)

1985

Silver dye bleach print

13 1/4 × 10 1/4 in. (33.7 × 26cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York

© Estate of Jimmy DeSana

Photo: Allen Phillips

In a 1986 interview with Diego Cortez, Jimmy DeSana remarked on the mutability and transgressive potential of photography: “A photograph is how much you want to lie, how far you want to stretch the truth about the object. And, as photography is always based on real objects, it lends itself, by means of technique or manipulation, to explorations of what may appear to be an absence of reality, balancing on an ambiguous line between concrete and abstract space, between reality and illusion, in a way that no other medium is able to do.”

In a series of “portraits” from the mid 1980s, DeSana played with this tension by obscuring and transforming faces through collage and darkroom techniques. His movement into abstraction – in works that nonetheless address his experience living with HIV / AIDS – was in part a reaction to dilemmas over representations of sexuality and queer bodies during the first decade of the AIDS epidemic, from media bias to conservative censorship to activist demands. Critics recognised DeSana’s masquerades and darkroom experiments in colour as tributes to Surrealist photography of the 1920s and 1930s, which still had the power to confound expectations around photography and realism.

Text from the Brooklyn Museum Tumblr website

Skilled in the art of negation, DeSana staged intimate scenes that tease out the erotic – in Pants, 1984, a model arches his muscular, shirtless back under bold lighting – yet the artist routinely undermined and lampooned this sexual content: The model’s extremely large pants are filled with stuffing, comically emphasizing his ass and thighs. In this sense, DeSana’s work seems to parody Robert Mapplethorpe’s deadpan oeuvre. In 1979, DeSana published Submission, a photobook poking fun at notions of the body as a sexualized, gendered object. As the title implies, a power dichotomy is at play in the series – the camera assumes the dominant role, forcing the models into the passive ‘sub’ position. The photos … are black-and-white, giving them a self-serious quality, yet, as in his other work, DeSana punctured that effect with dark comedy. In Masking Tape, 1978, a latex bodysuit is traded for the household adhesive, with which a male model has been mummified head to toe – scrotum, penis, nipples, and nostrils excluded. Despite occasional comic absurdity, the photographs still retain a beguiling frisson. DeSana also ably mocked the supposed dangers of sexual alterity by allowing it a certain humanity – a melancholy picture of a hog-tied woman in black lingerie and high heels crouched in a refrigerator (empty save for a dozen eggs) exudes pathos and surprising sophistication. In Television, 1978, real danger in the form of electrocution threatens the supine and masked nude performer (DeSana himself) balancing a TV on his feet. Through this action, DeSana drew out the allure of mass media but underscored its potential for propagating constricting ideologies.

The introduction of beautifully jarring, chromatic lighting to DeSana’s post-Submission scenarios amplifies their urgency and defines his work’s signature aesthetic: slick and otherworldly yet proudly homemade. Thrown against domestic spaces and active bodies, strawberry reds and lysergic greens reverberate wildly. One such multi-hued image, Cowboy Boots, 1984, depicts a nude man in the midst of a one-armed handstand, his four splayed limbs straddling a corner of an apartment, feet and hands covered in tooled-leather cowboy boots. This hybridized body à la Hans Bellmer, not quite an object but a morphing being, defies the behavioural dicta of society. Representing a poignant act of shape-shifting, Bubblegum (Self-Portrait), 1985, an image printed with light-pink dye and made five years before the artist’s AIDS-related death, shows DeSana with his cheeks puffed up while blowing a bubble, his oversize shirt and pants bursting at the seams from stuffing. Such a transformation wryly suggests our physical mutability and the unknown extent to which our bodies and selves might evolve – grossly enlarge, wither away.

Beau Rutland. “Jimmy DeSana,” on the Art Forum website 2013 [Online] 20/03/2023

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

String VII

1987

Silver dye bleach print

19 × 15 in. (48.3 × 38.1cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York

© Estate of Jimmy DeSana

Photo: Allen Phillips

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Soft Ball

1985

Silver dye bleach print

9 1/2 × 7 1/2 in. (24.1 × 19.1cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York

© Estate of Jimmy DeSana

Photo: Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York

After his diagnosis with HIV in 1985, DeSana began making a series of still lifes, tackling a genre that for centuries has expressed both the abundance and transitoriness of life and earthly goods.

Like so much of DeSana’s work, this photograph transforms a prosaic object – a softball, with its associations of sports and American culture – into something strange through juxtaposition, scale, and colourisation. The image recalls DeSana’s 1984 self-portrait in which the long, curved scar on his torso evokes a baseball’s stitching.

Exhibition label

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Eyelashes

1986

Silver dye bleach print

9 1/2 × 7 1/2 in. (24.1 × 19.1cm)

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York

© Estate of Jimmy DeSana

Photo: Allen Phillips

“‘Abstract photography’ not only turns its back on [the] incessant desire to know and see everything – it seeks to undermine and invert those very intentions,” Jerry Saltz wrote for the catalog that accompanied Jimmy DeSana’s first major curatorial effort at the Emerson in 1989.

The show, which included the work of 26 artists (including: Vikky Alexander, Ellen Brooks, Charlesworth, Morrisroe, Sherman, and Simmons), spoke to how artists were attempting in this era to move beyond the instrumentalisation of representation during a period of intense political divisiveness, and to expand what photography could be as art.

Text from the Brooklyn Museum Tumblr website

That uncanny language was shared with Laurie Simmons, known for her staged domestic scenes using dolls and miniature objects that, like the works of DeSana, surrealized suburbia. The two shared a studio until DeSana’s death from AIDS-related illness in 1990. Simmons watched her friend transform after his diagnosis, a change that manifested as both physical degeneration and artistic metamorphosis. “We didn’t want to be painters. We didn’t want to be sculptors,” Simmons recalls. “We wanted that sense of distance and remove. We wanted a tool that we could work with, but that didn’t have anything to do with craft.” Illness forced DeSana to put his camera down and collage. Struggling to make sense of the purpose of the body, and especially the sexualized body, amid a vicious disease that mostly took queer, sexually active bodies like his own, DeSana made sense of his world through chopping and repasting it. The distance and remove that he and Simmons craved, that the camera gave him, was impossible as the reality of death loomed so near. …

The thing that drew us to using a camera was [that] we didn’t want to use our hands. We didn’t want to be painters. We didn’t want to be sculptors. We wanted that sense of distance and remove. We wanted a tool that we could work with, but that didn’t have anything to do with craft. Collage took him to a very intimate, hands-on way of working that’s so much more personal. Yet by rephotographing the collages, he could keep that sense of distance and still see himself as a conceptual artist, which I think was part of how he needed to see himself.

“Collage took him to a very intimate, hands-on way of working that’s so much more personal. Yet by rephotographing the collages, he could keep that sense of distance and still see himself as a conceptual artist, which I think was part of how he needed to see himself.”

Laurie Simmons quoted in Megan Hullander. “Jimmy DeSana, an iconoclast even within the ’70s avant-garde, is finally entering mainstream consciousness,” on the Document Journal website July 11, 2022 [Online] Cited 20/03/2023

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Salvation

1987-1988

Maquette for book

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York

© Estate of Jimmy DeSana

Photo: David Vu

“If I could do a show that confused people so much, that was so ambiguous that they didn’t know what to think, but they felt sort of sickened by it and also entertained,” Jimmy DeSana told Laurie Simmons shortly before he passed away from AIDS-related illness in 1990, “then for me that would capture the moment that we;re going through right now.”

For his last major artistic project, DeSana collected his contradictory feelings and images in a book to be titled Salvation. Although he would not complete the volume before his death, he created this maquette. It comprises photomontages of flowers and fragments of male bodies, many recycled from older photographs of DeSana and his partner Darell Bagley. The photographs are black-and-white, but DeSana intended them to be printed with lurid colour through the Cibachrome process.

Ambiguity and opacity became increasingly important to DeSana, especially in reaction to the media’s and other artists’ objectification of queer people living with HIV / AIDS. He also pushed against the expectation that gay artists should somehow counter government inaction and misinformation around the epidemic.

Text from the Brooklyn Museum Tumblr website

Jimmy DeSana (American, 1949-1990)

Salvation (maquette)

1987-1988

Courtesy of the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York

© Estate of Jimmy DeSana

JC: There’s something unrefined about DeSana’s work compared to Mapplethorpe who was more stylistically precise. They must have been aware of each other; their work would feature together in issues of BOMB magazine and such. Of course, back then Mapplethorpe was a lot more famous and upwardly mobile, whereas DeSana seemed more invested in the punk scene. Overall, I appreciate DeSana’s spirit more than his images, many of which strike me as conceptually same-samey. The pictures are cheeky at times though not particularly humorous, so I was as perplexed as you when overhearing someone loudly chuckling at a photograph. To me, there’s too much death-drive going on in the work to laugh. Maybe it’s also because after witnessing Mugler’s flamboyance, finesse, and whimsy, a show like DeSana’s feels like a grim comedown by contrast. I don’t quite know what to make of the “acrobatic” works – contorted nude figures in backbends and pseudo-tantric / yogic poses that sometimes appear as levitation or a magic trick–and then the constant recourse to the stiletto motif – they’re somehow cooler in theory than in practice? The marker cone body as landscape is one of a kind, nobody else thought of that, but beyond this, I feel that had DeSana survived beyond those years of experimentation, he might have been making his best work by now. Of course, that’s total speculation and not entirely fair…

EC: I meant to mention that visitor laughing before, after which we both turned to each other in confusion. She was guffawing at Pink Furniture, which, if I remember correctly, had a blow-up doll hanging in the corner of the room. I do tend to always chuckle at Dog in the Submission series only because it looks like that furious wee puppy is going to bite the shit out of an erection. With his angry little growling face turned towards the camera, it is the perfect shot. Grrr… But I snicker at it more than a full-throated laugh. Full-throated laughing at DeSana feels like you should be put on some sort of watch list.

I agree with what you’re saying about DeSana’s work being still experimental and somewhat unresolved. A lot of work from that Downtown / East Village scene, though I have a special place in my heart for it in all of its flaws, doesn’t quite translate or age well and so much of that is because many of these artists all died so young. That being said, I like DeSana’s work much more than Mapplethorpe’s. Even Mapplethorpe’s self-portrait with a whip in his ass feels so precisely posed. In contrast, DeSana’s work just looks like it smells like ball sweat and assholes (this is a compliment). At least DeSana’s subcultural society pics of figures like Debbie Harry, The Talking Heads, Laurie Anderson, and William S. Burroughs lighten the mood, as do some of the vitrines of zines that don’t include hanging!

Jessica Caroline and Emily Colucci. “To Be Gorgeous: A Conversation on Thierry Mugler and Jimmy DeSana at the Brooklyn Museum,” on the Filthy Dreams website February 11, 2023 [Online] Cited 01/04/2023

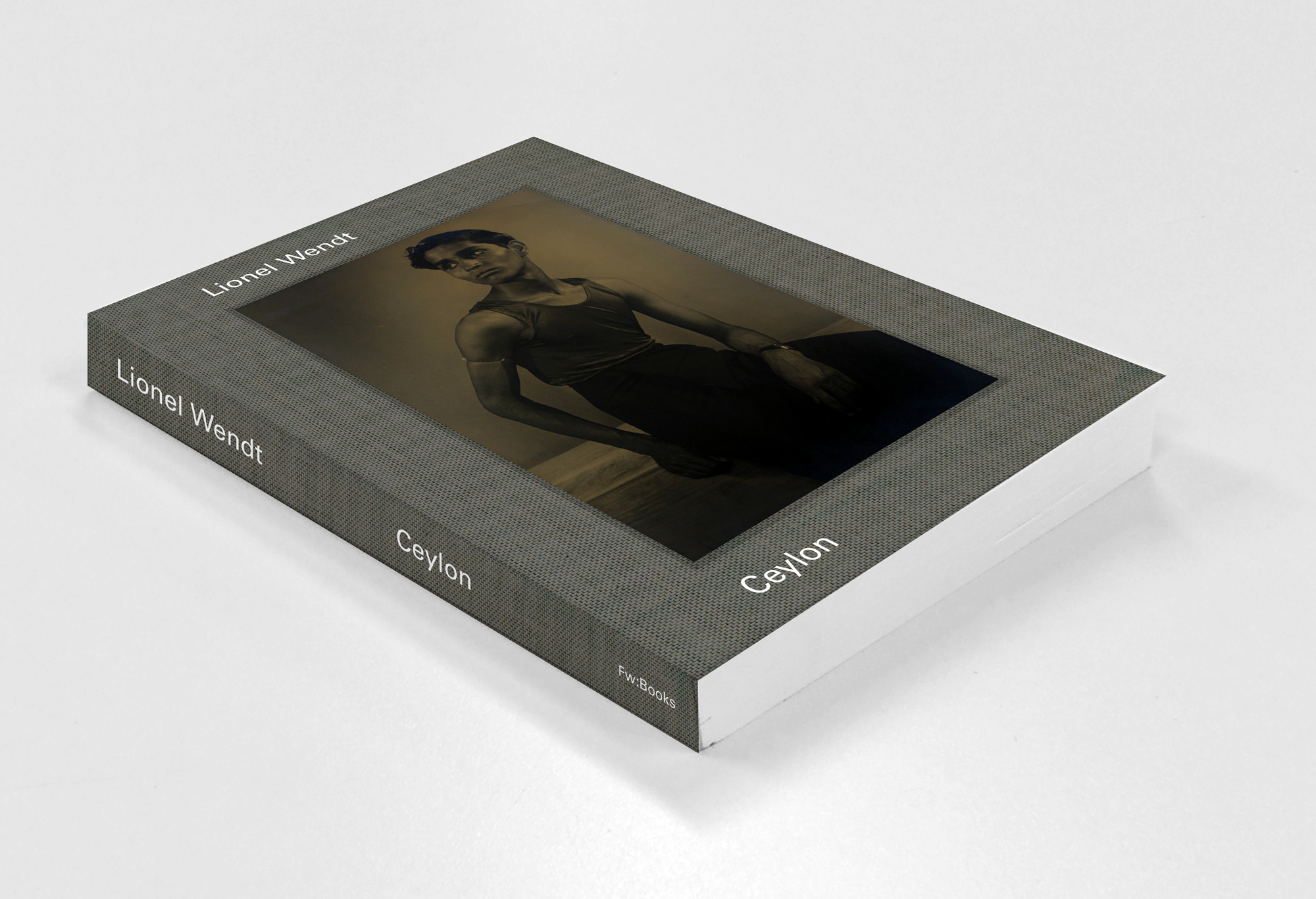

Jimmy DeSana Submission book cover

Book

This book is the first monograph to present the work of Jimmy DeSana, a pioneering yet under recognised figure in New York’s downtown art, music, and film scenes during the 1970s and ’80s. The book situates DeSana’s work and life within the countercultural and queer contexts in the American South as well as New York, through his involvement in mail art, punk, and No Wave music and film, and artist collectives and publications. Featuring an original text by Drew Sawyer, Phillip Leonian and Edith Rosenbaum Leonian Curator of Photography at the Brooklyn Museum, it includes his major series that helped create a No Wave aesthetic as well as his portraits of art and music luminaries of the time.

Jimmy DeSana: Submission is the first monograph of this pioneering queer punk photographer whose brief but prolific career helped elevate the medium of photography within the contemporary art world. This publication traces his brief yet prolific career through nearly two hundred works and over twenty years that bridged mail-art networks, New York’s 1970s and ’80s subcultures, the illuminating image-play of the “Pictures Generation,” and various responses to HIV / AIDS.

The book showcases DeSana’s extensive involvement in zines, artist collectives, performance art, experimental film, and club culture. Included are his most famous series – 101 Nudes (1972), his first major work made during Atlanta’s gay liberation movement; Submission (1977-1979), created with the writer William Burroughs; and Suburban (1979-1984), which showcases his work as an early adopter of colour photography. During the late 1970s and early ’80s, DeSana was heavily involved in New York’s punk and No Wave scenes. Included in this book are his portraits of such art and music luminaries as Kathy Acker, Laurie Anderson, Kenneth Anger, Patti Astor, David Byrne, John Giorno, Debbie Harry, and Richard Hell. Accompanying these works are DeSana’s more abstract efforts from the late 1980s, after he was diagnosed with AIDS, that show an artist who resisted dominant narratives about the body and sexuality in the early years of the ongoing HIV / AIDS epidemic.

Text from the Brooklyn Museum website

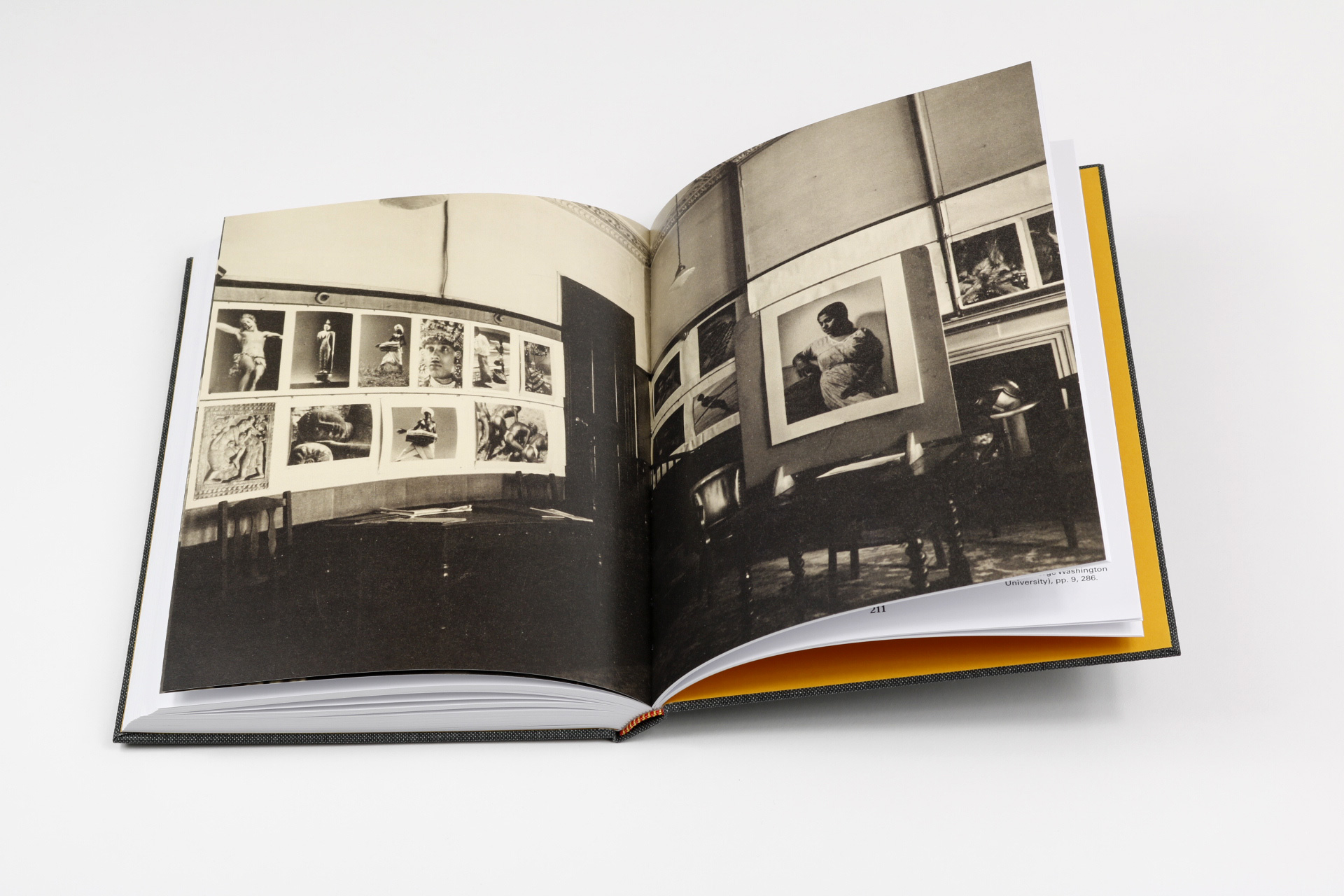

Jimmy DeSana Submission content page

Jimmy DeSana Submission Performative Identities and Radical Networks pp. 10-11

Jimmy DeSana Submission pp. 30-31

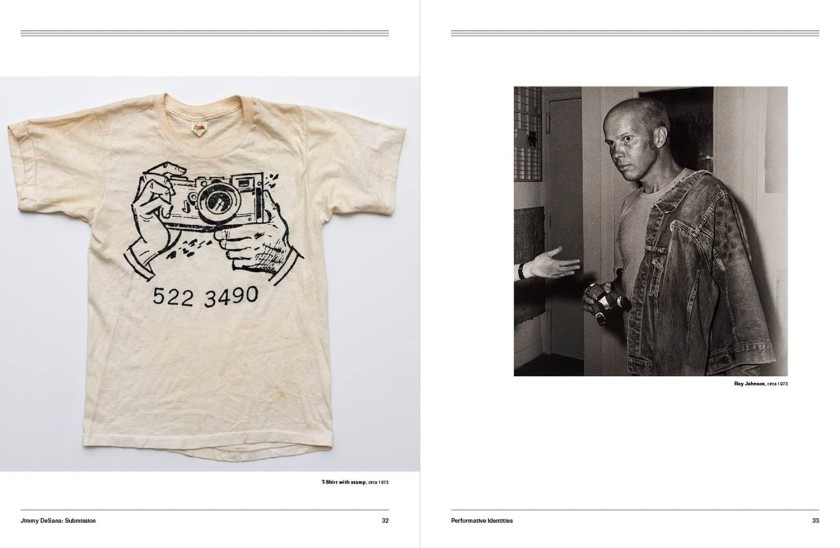

Jimmy DeSana Submission pp. 32-33

Jimmy DeSana Submission pp. 60-61

Jimmy DeSana Submission pp. 66-67

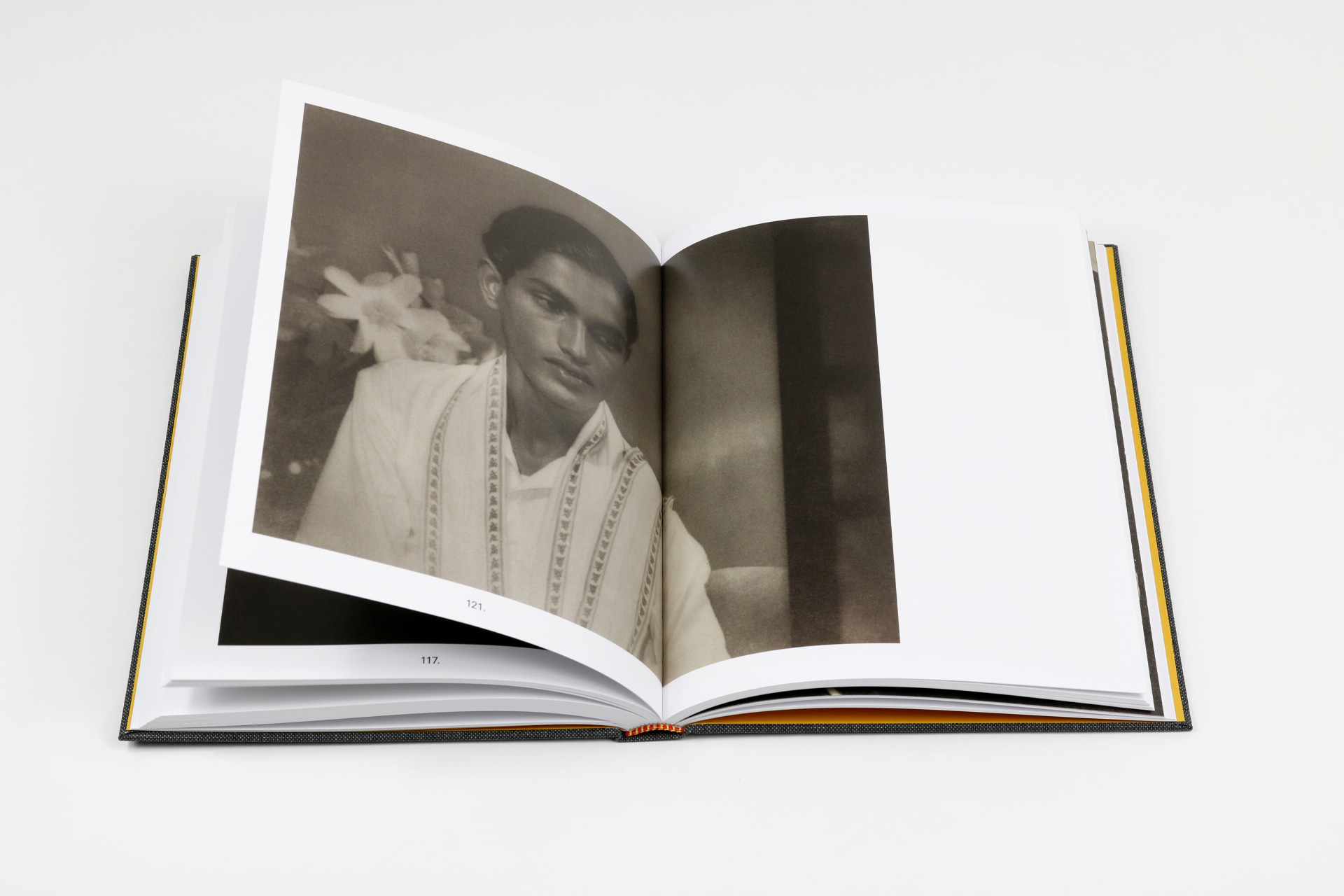

Jimmy DeSana Submission pp. 116-117

Jimmy DeSana Submission pp. 124-125

Jimmy DeSana Submission pp. 126-127

Brooklyn Museum

200 Eastern Parkway

Brooklyn, NY 11238-6052

Phone: (718) 638-5000

Opening hours:

Wednesday – Sunday 11am – 6pm

Closed Mondays and Tuesdays

Closed Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year’s Day

You must be logged in to post a comment.