Exhibition dates: 23rd September 2022 – 8th January 2023

Curator: Juan Vicente Aliaga

Ilse Bing (American born Germany, 1899-1998)

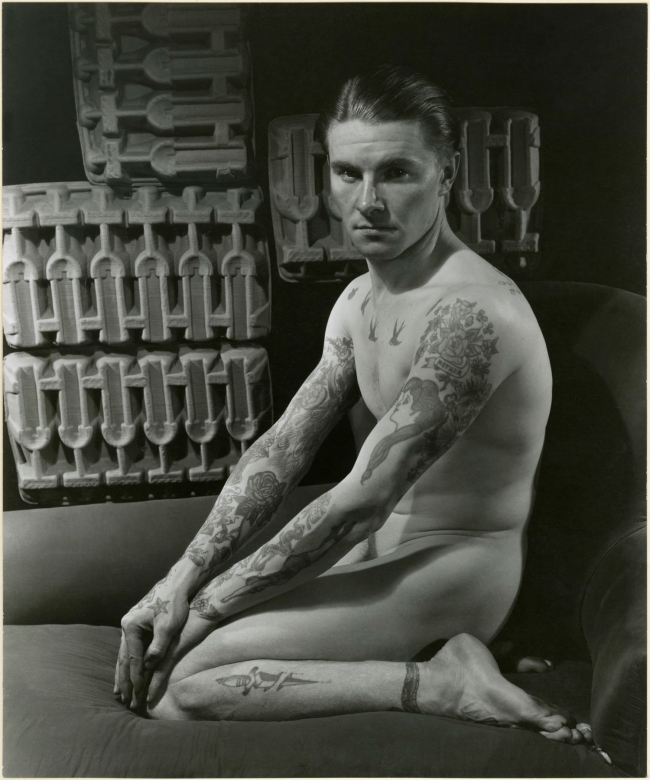

Scandale

1947

Gelatin silver print

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

© Estate of Ilse Bing / Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The first exhibition for Art Blart in 2023!

The Art Blart archive has been going since November 2008. This is the first time I have posted on the avant-garde artist Isle Bing and her documentary humanism. Elements of Modernism, movement, New Vision, Bahuas, Surrealism, abstraction, form, geometry are all spontaneously and intuitively, precisely and poetically expressed in the artist’s work. Manipulation, solarisation, enlargement of fragments and cropping in the darkroom enhance the original negative.

“In addition to numerous portraits, Ilse Bing was primarily interested in urban motifs. They were fascinated by architectural elements and structures as well as urban hustle and bustle. Her way of working repeatedly explores the tracing of symmetry and rhythm in the experience of everyday situations.”1

“In Paris, Ilse Bing forged her style [using a Leica], combining poetry and realism, dreamlike enchantment and the clarity of modernity. She sought contrasts and original juxtapositions that transformed the banal reality of daily life into a new idea.”2

“Ilse Bing was once amongst the very first few women photographers to influentially master the avant-garde handheld Leica 35mm camera in the 1930s. She was also amongst the first to use solarisation, electronic flash and night photography, and established her own distinctive photographic style adoring romanticism, symbolism and dream imagery of surrealism.”3

“It was a time of exploration and discovery. … We wanted to show what the camera could do that no brush could do, and we broke every rule. We photographed into the light – even photographed the light, used distorted perspective, and showed movement as a blur. What we photographed was new, too – torn paper, dead leaves, puddles in the street—people thought it was garbage! But going against the rules opened the doors to new possibilities.” ~ Ilse Bing

Magnificent. Enjoy!

Dr Marcus Bunyan

PS. Many more works can be viewed on the MoMA website.

1/ Anonymous. “Ilse Bing,” on the Wikipedia website [Online] Cited 02/01/2023

2/ Anonymous. “Ilse Bing. Photographs 1928-1935,” on the Galerie Karsten Greve website [Online] Cited 02/01/2023

3/ Anonymous. “Ilse Bing: Paris and Beyond,” on the Exibart street website [Online] Cited 02/01/2023

Many thankx to Fundación MAPFRE for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Ilse Bing (Frankfurt, 1899 – New York, 1998) was born into a well-off Jewish family. Having discovered her true vocation while preparing the illustrations for her academic thesis, in 1929 she abandoned her university studies in order to focus entirely on photography. The medium would be her chosen form of expression for the following thirty years of her fascinating life and career.

In 1930 Bing moved to Paris where she combined photojournalism with her own more personal work, soon becoming one of the principal representatives of the modernising trends in photography which emerged in the cultural melting pot of Paris during those years. With the advance of the Nazi forces, in 1941 she and her husband, the pianist Konrad Wolff, went into exile in New York. Two decades later the sixty-year-old Bing gave up her photographic activities in order to channel her creativity into the visual arts and poetry until her death in 1998.

Bing’s work cannot be ascribed to any of the movements or tendencies that influenced her. She worked in almost all the artistic genres, from architectural photography to portraiture, self-portraits, images of everyday objects and landscapes. The diversity of styles which she employed reflect her significant and notably individual interpretation of the different cultural trends that she assimilated, from the German Bauhaus and New Objectivity to Parisian Surrealism and the ceaseless dynamism of New York.

Text from the Fundación MAPFRE website

“I felt the camera grow as an extension of my eyes and move with me.”

Ilse Bing

Ilse Bing (American born Germany, 1899-1998)

Dead Leaf and Tramway Ticket On Sidewalk, Frankfurt

1929

Gelatin silver print

17.1 x 22.9cm

Galerie Karsten Greve, Saint Moritz / París / Colonia

© Estate of Ilse Bing

Ilse Bing (American born Germany, 1899-1998)

Budgeheim

1930

Gelatin silver print

27.9 x 21.9cm

Galerie Karsten Greve, Saint Moritz / París / Colonia

© Estate of Ilse Bing

Ilse Bing (American born Germany, 1899-1998)

Laban Dance School, Frankfurt

1929

Gelatin silver print

9.7 x 16.6cm

Edwynn Houk Gallery, New York

© Estate of Ilse Bing, courtesy Edwynn Houk Gallery, New York

Photograph: Jeffrey Sturges

Ilse Bing (American born Germany, 1899-1998)

Orchestra Pit, Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, Paris

1933

27.9 × 35.6cm

Gelatin silver print

International Center of Photography, New York

Donation of Ilse Bing, 1991

© Estate of Ilse Bing

Ilse Bing (American born Germany, 1899-1998)

Pommery Champagne Bottles

1933

Gelatin silver print

27.9 × 19.7cm

Galerie Karsten Greve, Saint Moritz / París / Colonia

© Estate of Ilse Bing

Ilse Bing (American born Germany, 1899-1998)

French Can-Can Dancer

1931, printed 1941

Gelatin silver print

35.6 x 27.9cm

Galerie Karsten Greve, Saint Moritz / París / Colonia

© Estate of Ilse Bing

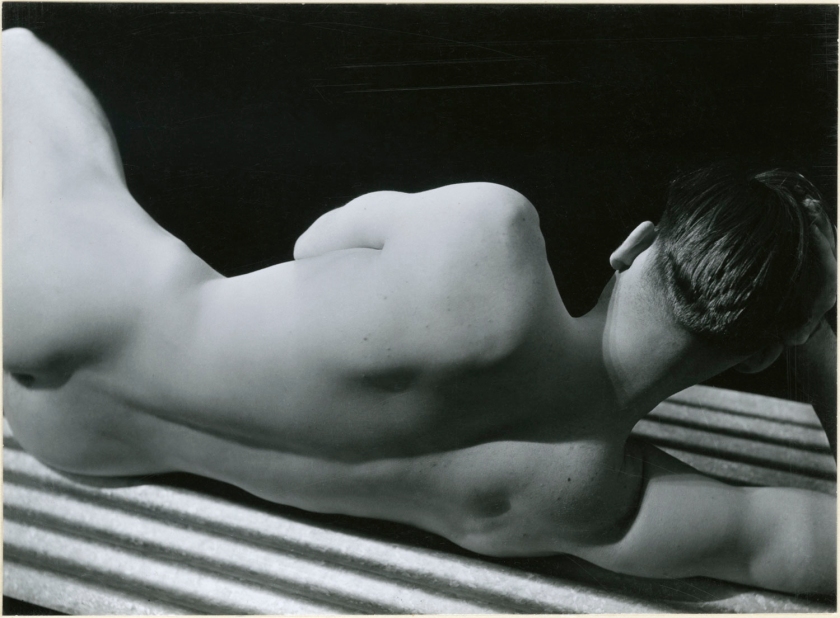

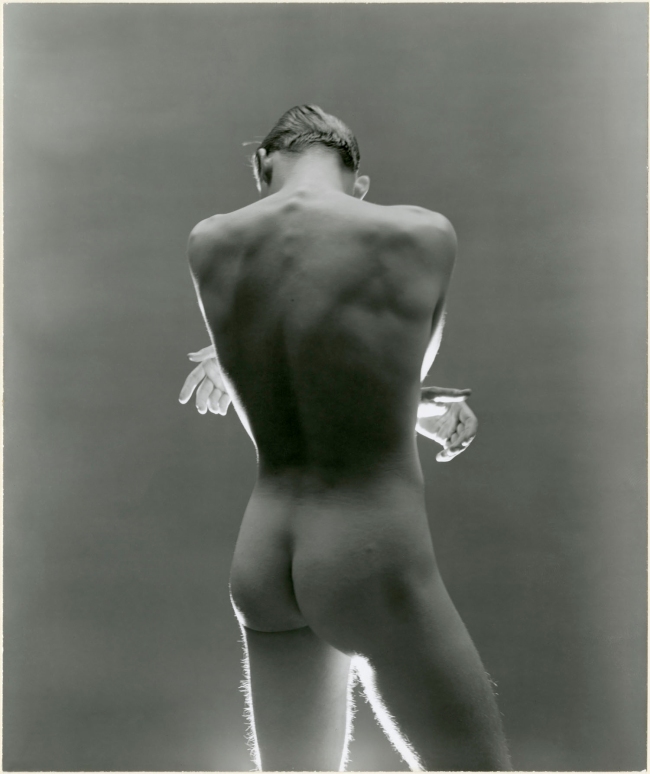

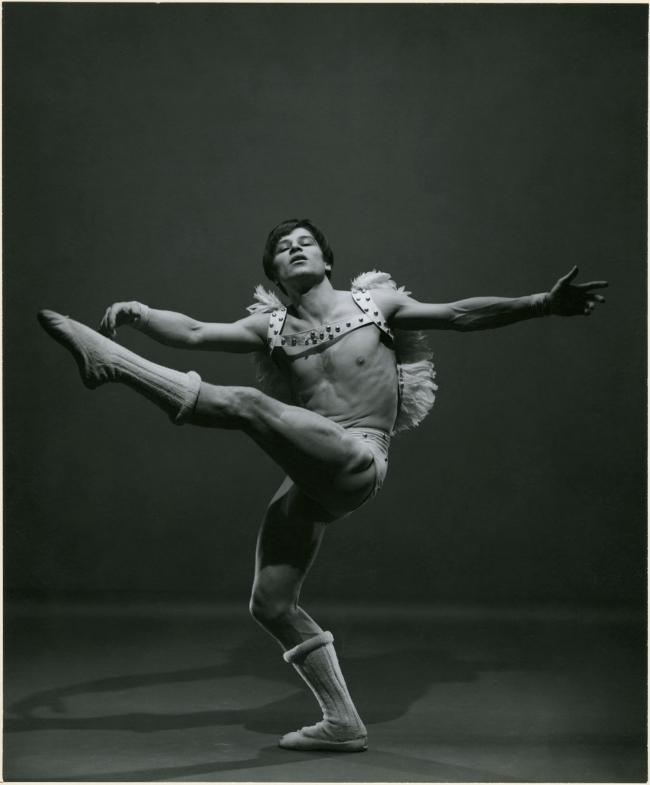

Ilse Bing (American born Germany, 1899-1998)

Dancer Gerard Willem van Loon

1932

Gelatin silver print

49.2 x 34.6cm

Galerie Karsten Greve, Saint Moritz / París / Colonia

© Estate of Ilse Bing

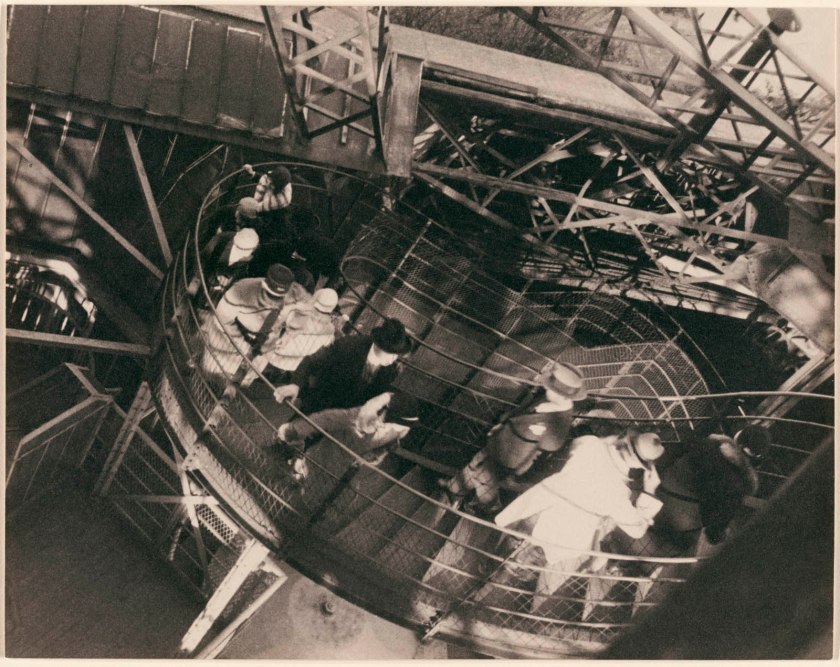

Ilse Bing (American born Germany, 1899-1998)

“It was so Windy on the Eiffel Tower”, Paris

1931

Gelatin silver print

22.2 x 28.2cm

The Art Institute of Chicago, Julien Levy Collection

Donation of Jean and Julien Levy 1977

© Estate of Ilse Bing

© 2022 The Art Institute of Chicago / Art Resource, NY/ Scala, Florence

Ilse Bing’s photographic oeuvre, created between 1929 and the late 1950s, was influenced by the different cities where she lived and worked: Frankfurt prior to the 1930s, Paris in that decade and post-war New York where above all she experienced the situation of an enforced emigré. Her work cannot, however, be easily located within the photographic and cultural trends that she encountered, although it was certainly enriched by all of them. Bing’s output was influenced by Moholy-Nagy’s Das Neue Sehen (The New Vision) and the Weimar Bauhaus, by André Kertész and by the Surrealism of Man Ray, which she encountered when she moved to Paris in 1930. At the time of her arrival the French capital was a melting pot of artistic and intellectual trends and the setting for the emergence of a number of movements that would be crucial for the evolution of the avant-gardes. Surrealist echoes are evident in Bing’s photographs of objects and in her approach to the framing of her shots of chairs, streets and public spaces, images that transmit a sense of strangeness and almost of alienation.

The Bauhaus was an extremely important influence on Bing’s work via both El Lissitzky’s theories and those of Moholy-Nagy’s New Vision, which promoted the fusion of architecture and photography and the autonomy of photography as a medium in relation to painting. New Vision offered infinite possibilities and Bing took full advantage of them, employing some of them in her work, such as abstraction, close-ups, plunging viewpoints, di sotto in sù, photomontages and overprinting, all to be seen in the images on display in the exhibition.

Ilse Bing belonged to a generation of women photographers who achieved unprecedented visibility. It was not the norm that women should be artists in a field habitually occupied by men, who regarded their presence as active agents in the social and cultural realm with disdain and even hostility. Like many of her contemporaries – Germaine Krull, Florence Henri, Laure Albin-Guillot, Madame d’Ora, Berenice Abbott, Nora Dumas and Gisèle Freund – Bing’s camera became an essential tool of self determination and a means to confirm her own identity.

Ilse Bing was born in Frankfurt on 23 March 1899 to a middle-class Jewish family. She took her first photographs at the age of fourteen. Self-taught in this field, she realised that this would become her principal activity when she began photographing in order to illustrate her doctoral thesis. She studied mathematics and physics before opting for art history. In 1929 she gave up her university studies and, armed with her inseparable Leica, devoted herself to photography for the next thirty years. In 1930 she moved to Paris, where she continued active as a photojournalist while also producing her own more creative work, gradually becoming one of the leading representatives of modern French photography. In 1941 and with the advance of National Socialism, Bing moved to New York with her husband, the pianist Konrad Wolff. Two decades later, at the age of 60, she ceased taking photographs and focused her attention on making collages, abstract works, drawings and also poetry writing. Ilse Bing died in New York in 1998.

Text from the Fundación MAPFRE exhibition brochure

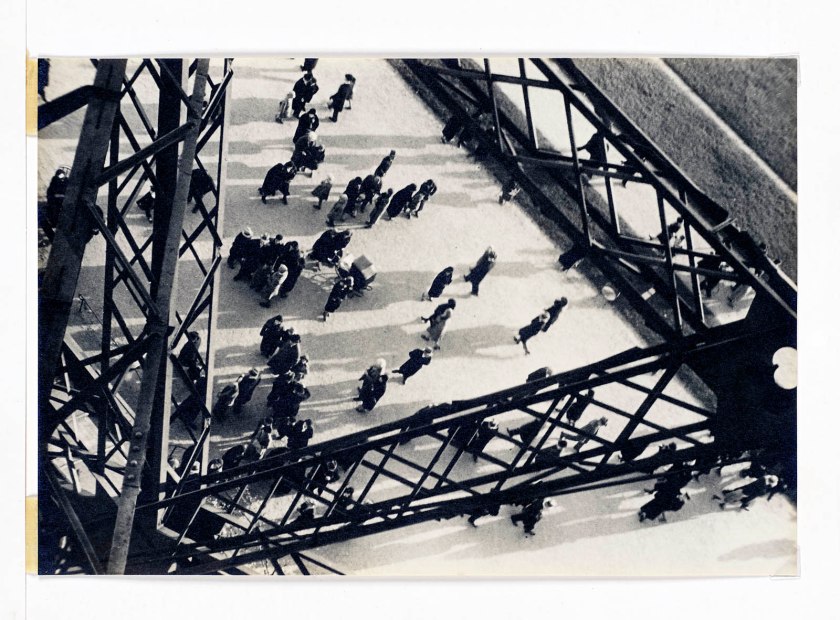

Ilse Bing (American born Germany, 1899-1998)

Champ de Mars from the Eiffel Tower

1931

Gelatin silver print

19.3 x 28.2cm

Collection of Michael Mattis and Judith Hochberg, New York

© Estate of Ilse Bing

Photograph: Jeffrey Sturges

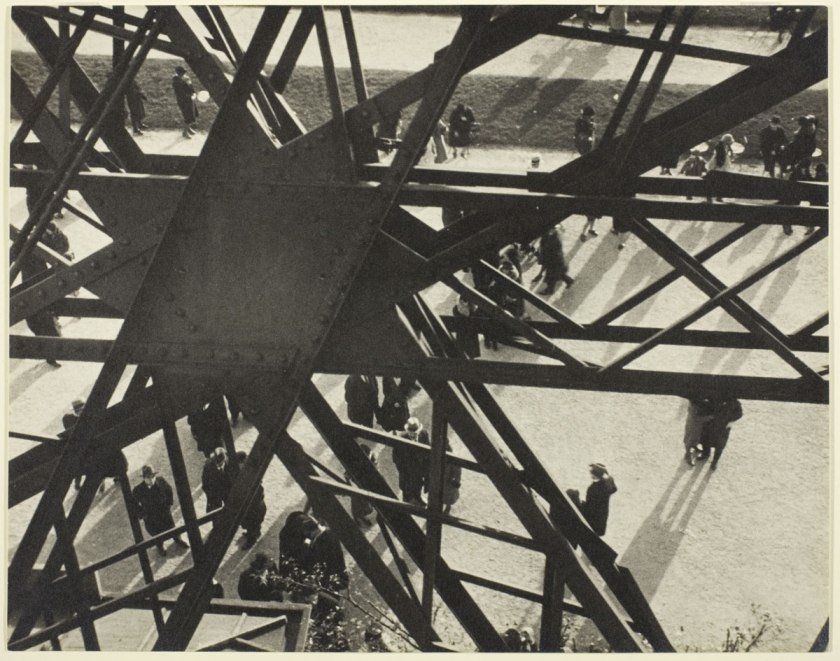

Ilse Bing (American born Germany, 1899-1998)

Eiffel Tower, Paris

1931

Gelatin silver print

© Estate of Ilse Bing

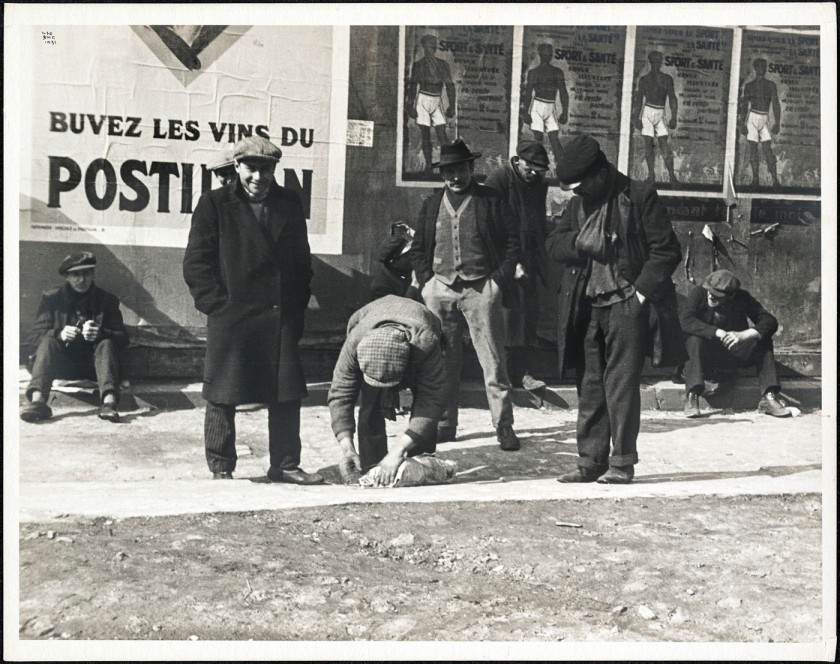

Ilse Bing (American born Germany, 1899-1998)

Poverty in Paris

1931

Gelatin silver print

27.8 x 35.3cm

Galerie Berinson, Berlín

© Estate of Ilse Bing

Ilse Bing (American born Germany, 1899-1998)

Three Men Sitting on the Steps by the Seine

1931

Gelatin silver print

27.9 × 35.6 cm

International Center of Photography, Nueva York

Donation of Ilse Bing, 1991

© Estate of Ilse Bing

Ilse Bing (American born Germany, 1899-1998)

French Can Can Dancers, Moulin Rouge

1931

Gelatin silver print

6 1/4 × 9 in. (15.9 × 22.9cm)

Collection of Michael Mattis and Judith Hochberg

Courtesy Edwynn Houk Gallery, New York

© Estate of Ilse Bing

Ilse Bing (American born Germany, 1899-1998)

Greta Garbo Poster, Paris

1932

Gelatin silver print

22.3 × 30.5 cm

The Art Institute of Chicago

Donation of David C. and Sarajean Ruttenberg 1991

© Estate of Ilse Bing

© 2022 The Art Institute of Chicago / Art Resource, NY/ Scala, Florence

Overview

Ilse Bing (Frankfurt, 1899 – New York, 1998) was born into a well-off Jewish family. Having discovered her true vocation while preparing the illustrations for her academic thesis, in 1929 she abandoned her university studies in order to focus entirely on photography. The medium would be her chosen form of expression for the following thirty years of her fascinating life and career.

In 1930 Bing moved to Paris where she combined photojournalism with her own more personal work, soon becoming one of the principal representatives of the modernising trends in photography which emerged in the cultural melting pot of Paris during those years. With the advance of the Nazi forces, in 1941 she and her husband, the pianist Konrad Wolff, went into exile in New York. Two decades later the sixty-year-old Bing gave up her photographic activities in order to channel her creativity into the visual arts and poetry until her death in 1998.

Bing’s work cannot be ascribed to any of the movements or tendencies that influenced her. She worked in almost all the artistic genres, from architectural photography to portraiture, self-portraits, images of everyday objects and landscapes. The diversity of styles which she employed reflect her significant and notably individual interpretation of the different cultural trends that she assimilated, from the German Bauhaus and New Objectivity to Parisian Surrealism and the ceaseless dynamism of New York.

The exhibition

Featuring around 200 photographs and a range of documentary material, the exhibition presents a chronological and thematic survey of Ilse Bing’s career, divided into ten sections: “Discovering the world through a camera: the beginnings”, “The life of still lifes”, “The dancing body and its circumstances”, “Lights and shadows of modern architecture”, “The hustle and bustle of the street: the French years”, “The seduction of fashion”, “The United States in two phases”, “Self-image revelations”, “Portrait of time”, and “Live nature”.

Four keys

The Bauhaus. From 1910 onwards Frankfurt became the prototype of modern urban design thanks to the architect Ernst May, and the city’s medieval layout was gradually modified in a transformation based on its different societal requirements. This new architecture soon began to echo the ideas of El Lissitzky’s Constructivism, partly via the Dutch architect Mart Stam, a friend of Ilse Bing. Stam and the theories of the Bauhaus had a major influence on her works. László Moholy-Nagy, who taught at the Bauhaus, had promoted the union of architecture and photography as well as the independence of the latter in relation to painting. The possibilities of Das Neue Sehen (The New Vision) seemed endless and Bing applied some of its concepts and devices to her work: abstraction, immediate close-ups, plunging and di sotto in sù viewpoints, photo-montage and overprinting.

Surrealism, the spirit of an era. When Ilse Bing moved to Paris in 1930 the city was a melting pot of artistic and intellectual trends and the setting for the emergence of some of the key movements in the evolution of the avant-gardes. One of them – Surrealism – had a particular influence on her and its echoes are clearly discernible in her photographs of accessories taken for fashion magazines which reflect Surrealist theories on fetishism. It is also evident in the framing she chose for her images of chairs, streets and public spaces, which transmit a sense of strangeness and almost of alienation. Finally, this influence also arose from Bing’s relationship with prominent figures associated with the movement, such as Elsa Schiaparelli.

Movement. Despite her fascination with abstraction and pure compositions, evident in many of her photographs of architecture and her still lifes, Ilse Bing was also captivated by the dynamism and movement of life and changing reality. She expressed this in her photographs of the Moulin Rouge and its surrounding area and in her investigation of dance. Bing captured the dynamism of the dancers twirling their skirts but also the expressivity of their bodies as they moved, jumping into the air or doing the splits.

Woman photographer. Ilse Bing belonged to a generation of women photographers who achieved unprecedented visibility. It was not the norm that women should be artists in a field habitually occupied by men, who regarded their presence as active agents in the social and cultural realm with disdain and even hostility. Like many of her contemporaries – Germaine Krull, Florence Henri, Laure Albin-Guillot, Madame d’Ora, Berenice Abbott, Nora Dumas and Gisèle Freund – Bing’s camera became an essential tool of self-determination and a means to confirm her own identity.

Text from the Fundación MAPFRE website

Ilse Bing (American born Germany, 1899-1998)

Prostitutes, Amsterdam

1931

Gelatin silver print

25.5 x 34cm

Collection of Michael Mattis and Judith Hochberg, New York

© Estate of Ilse Bing

Photograph: Jeffrey Sturges

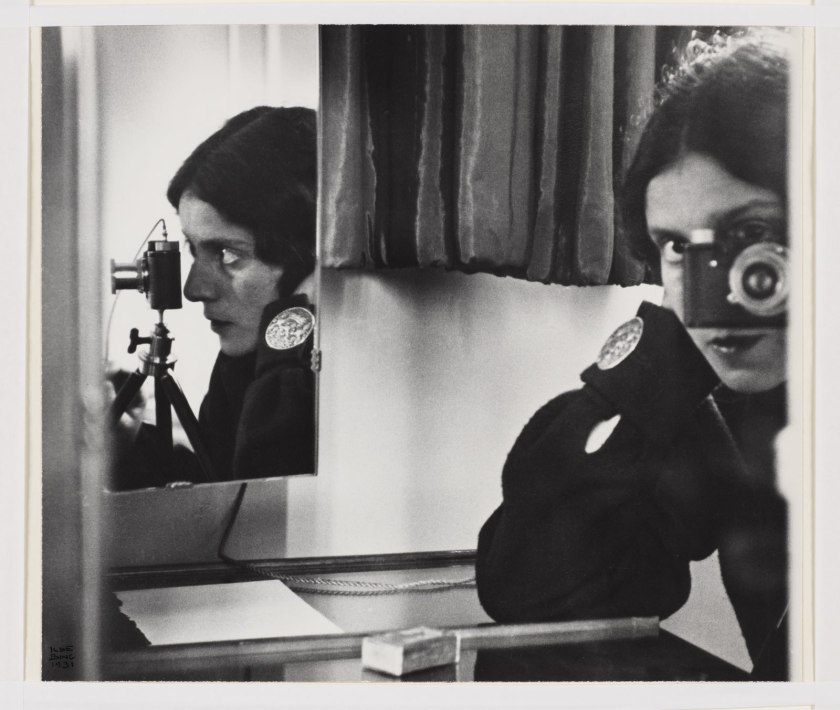

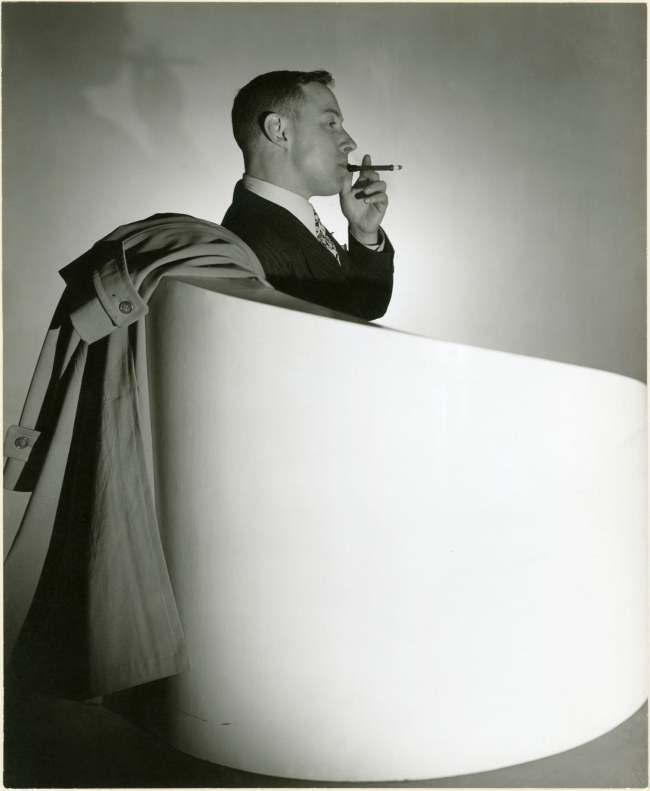

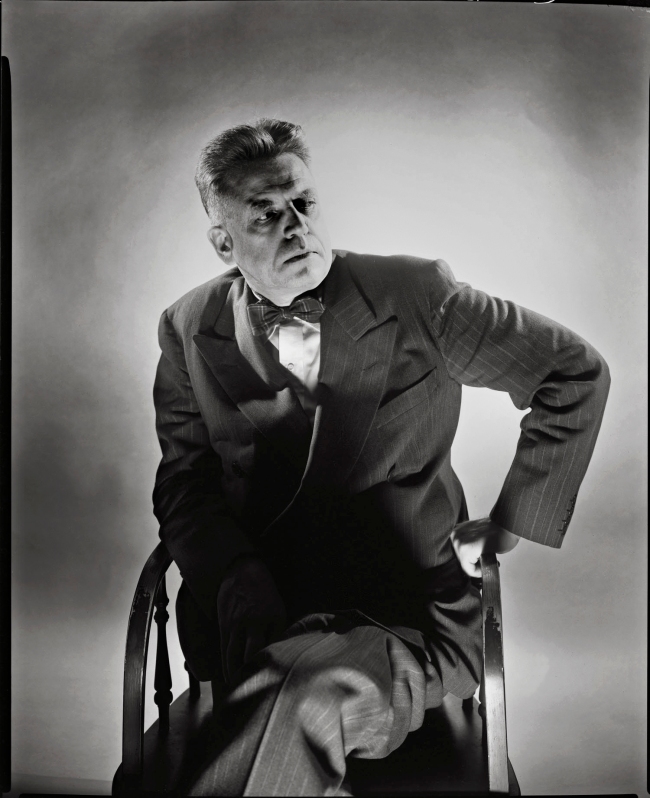

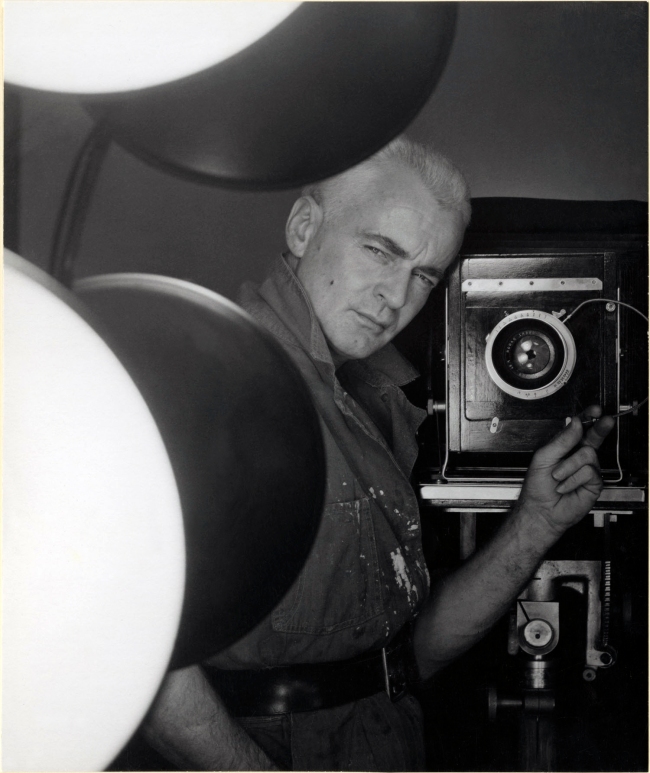

Ilse Bing (American born Germany, 1899-1998)

Self-portrait with Leica

1931

Gelatin silver print

26.5 × 30.7cm

Collection of Michael Mattis and Judith Hochberg, New York

© Estate of Ilse Bing

Photograph: Jeffrey Sturges

Ilse Bing (American born Germany, 1899-1998)

Pantaloons for Sale, Amsterdam

1931

Gelatin silver print

28 x 22cm

The Art Institute of Chicago, Julien Levy Collection

Donation of Jean and Julien Levy 1977

© Estate of Ilse Bing

© 2022 The Art Institute of Chicago / Art Resource, NY/ Scala, Florence

Ilse Bing (American born Germany, 1899-1998)

Street Fair, Paris

1933

Gelatin silver print

28.2 × 22.3cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington D. C.

Donation of Ilse Bing Wolff

© Estate of Ilse Bing

Ilse Bing (American born Germany, 1899-1998)

Equine butcher shop

1933

Gelatin silver print

19.2 × 28.2cm

Galerie Berinson, Berlín

© Estate of Ilse Bing

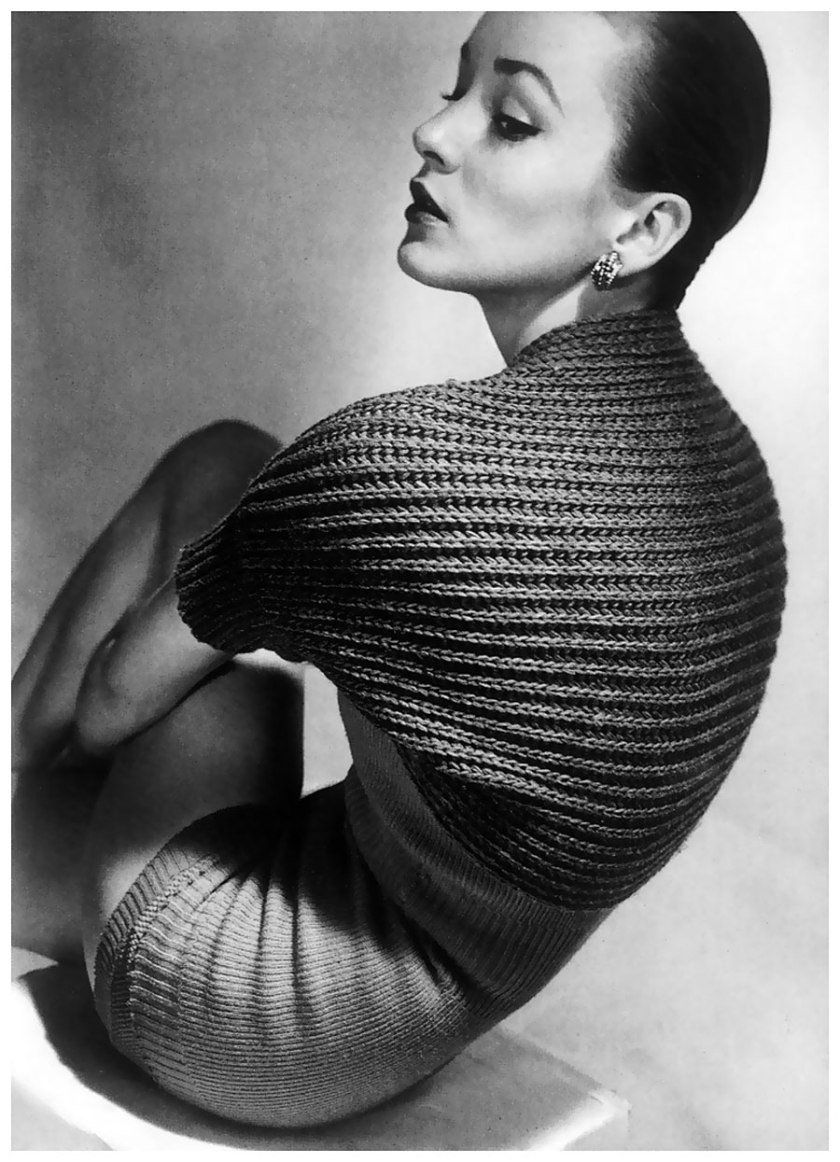

Ilse Bing (American born Germany, 1899-1998)

The Honorable Daisy Fellowes, Gloves by Dent in London for Harper’s Bazaar

1933

Gelatin silver print

27.9 × 35.6cm

International Center of Photography, New York

Donation of Ilse Bing 1991

© Estate of Ilse Bing

Ilse Bing (American born Germany, 1899-1998)

Self-portrait

1934

Gelatin silver print

27.9 × 21.6cm

Galerie Karsten Greve, Saint Moritz / París / Colonia

© Estate of Ilse Bing

Ilse Bing (American born Germany, 1899-1998)

Study for “Salut de Schiaparelli” (Lily Perfume), Paris

1934

Gelatin silver print

Overall: 28.2 x 22.3cm (11 1/8 x 8 3/4 in.)

Frame: 50.8 x 40.64cm (20 x 16 in.)

Frame (outer): 53.34 x 43.18cm (21 x 17 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Gift of Ilse Bing Wolff

© Estate of Ilse Bing

Ilse Bing (American born Germany, 1899-1998)

Gold Lamé Evening Shoes

1935

Gelatin silver print

22.2 × 27.9cm

Galerie Karsten Greve, Saint Moritz / París / Colonia

© Estate of Ilse Bing

Ilse Bing (American born Germany, 1899-1998)

Between France and the USA (Seascapes)

1936

Gelatin silver print

21 × 28.3 cm

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Legacy of Ilse Bing Wolff 2001

© Estate of Ilse Bing

© 2022 Digital image Whitney Museum of American Art / Licensed by Scala

Ilse Bing (American born Germany, 1899-1998)

New York, the Elevated, and Me

1936

Gelatin silver print

Galerie Le Minotaure, Paris

© Estate of Ilse Bing

Ilse Bing (American born Germany, 1899-1998)

New York

1936

Gelatin silver print

19.8 x 22.2cm

Galerie Berinson, Berlín

© Estate of Ilse Bing

The artistic career of Ilse Bing (Frankfurt, 1899-New York, 1998) can be located within a particularly complex temporal and socio-cultural context. This German photographer principally lived and worked in three places: in Frankfurt prior to the 1930s, in Paris in that decade and in post-war New York where she above all experienced the status of enforced emigré. Bing also visited other places, including Switzerland, Italy and Holland, but they never became decisive spaces that significantly influenced her way of working with regard to photography.

Analysed with the distance and perspective offered by the passing of time, Ilse Bing’s artistic corpus cannot easily be located within the various photographic trends she encountered during her lifetime, particularly in her initial German phase and the decade in Paris. While her work is charged with elements associated with both Das Neue Sehen (The New Vision) and the Bauhaus, which emerged during the Weimar Republic, as well as with the Surrealism she assimilated during her years in France, Bing’s position evades any strict norm or visual orthodoxy. In this sense it could be said that hers is a notably unique photographic gaze and approach in which modernity and formal innovation are indissolubly linked to a humanist approach involving a social conscience.

It is also important to emphasise that Ilse Bing’s career within the context of relatively difficult times was marked by a resolute determination to make her way in a world which viewed the presence of women as active agents in the social and thus the cultural realm with disdain or even hostility. Bing belonged to a generation of female photographers that achieved a previously unattainable visibility. The camera became for an essential tool of self-determination for numerous women artists, including figures such as Germaine Krull, Florence Henri, Laure Albin-Guillot, Madame d’Ora, Berenice Abbott, Nora Dumas and Gisèle Freund.

Juan Vicente Aliaga

Curator

Discovering the World Through A Camera: The Beginnings

With the exception of a few photographs of an amateur type, nothing indicated that Ilse Bing, who was born into a prosperous Jewish family in Frankfurt, would dedicate much of her life to the practice of photography. After an initial focus on scientific subjects and a period studying art history, Bing decided to illustrate her doctoral thesis with images taken in different museums. From that moment onwards and following a study trip to Switzerland when she discovered the work of Vincent van Gogh, she took the decision to focus her attention on photography. While she initially made use of a Voigtländer plate camera, she soon acquired a Leica which she would continue to use for much of her career. This was the camera she employed for the commissions she received from newspapers such as the Frankfurter Zeitung, work that gave her a degree of financial independence during the turbulent years of the Weimar Republic.

At the outset Bing covered a range of subjects, doing so with ease and formal audacity. Everything seemed to attract her attention: men at work, the spatial simplicity of a gallery, the organic lines of a roof, the leg and arm movements of the ballerinas of the Rudolf von Laban company, the modern architecture which she had discovered through her friend the Dutch architect Mart Stam, and more. Bing’s gaze sought out unusual angles, it looked upwards and downwards, at times encountering normally overlooked elements of no monetary value and ones brought together by chance, as in Dead Leaf and Tramway Ticket on Sidewalk, Frankfurt (1929).

The Life of Still Lifes

Objects from daily life are frequently present in modern art: a bottle, a newspaper, a letter, a collage-like fragment of a label, a jug, etc. Surrealism marked a revolution with regard to the representation of the object, which is never literal but rather filled with hidden aspects. The insertion of external objects into the visual space combined with other ones favours the emergence of the imaginary. By the time Ilse Bing arrived in Paris in 1930 she was already captivated by the chance encounter of often humble elements. Her French period served to accentuate her interest in a wide range of cast-off possessions and objects that seemed to allude to a universe in flux. Bing’s gaze always came to rest on real elements. The chairs she photographed existed but the framing she employed, the closeness or distance of the shot, the fact that the chairs are unoccupied and that the floor on which they stand has the silvery darkness of rain are all the result of her choices, adding an air of melancholy to the image.

Over the course of her career Bing used a range of different techniques in parallel while remaining constantly fascinated by inanimate objects. During her Paris years and despite financial difficulties her work is generally characterised by a poetic gaze in which the imagination moves towards undefined, almost dream-like realms. In contrast, in the period of exile in the United States a degree of coolness emerges, with the appearance of formal and symbolic traits such as a closing-in or enclosing of the depicted scene.

The Dancing Body and Its Circumstances

During her initial phase, in 1929 Ilse Bing established contacts with the dance and gymnastics school founded by Rudolf von Laban. She was struck by the way in which he aimed to draw a parallel between geometry and human movements and gestures.

Soon after arriving in Paris, Bing was commissioned to photograph the Moulin Rouge waxworks museum. The old Parisian dance hall where La Goulue and Toulouse-Lautrec had been leading attractions had lost much of its splendour. Bing spent time there and was attracted by numerous aspects of the place: its daily life on and off stage, including the couples who enjoyed a drink there, the boxing matches taking place, a dancer cheering up a weary boxer, the interesting nature of the clients, and the boredom of the doorman at the entrance to the cabaret. Aside from these aspects, what really caught the attention of the Paris photography world were Bing’s images of dancers in movement. Her restless eye was able to represent the vibration of the circular twists and turns, the complex, effortful open leg movements of a dancer captured in action, the troupe of dancers energetically waving their skirts, and more.

Another group of images of the troupe centres around the dancer Gerard Willem van Loon.

The third and last series of images focusing on dance was commissioned in relation to the ballet L’Errante, choreographed by the American George Balanchine and with set designs and libretto by the Russian painter Pavel Tchelitchew. Bing demonstrated her skill at capturing movement without making it seem frozen or trapped in time. Her eye translated the weightlessness of dreamlike fantasies to her images through the dynamic way in which she captured shadows.

Lights and Shadows of Modern Architecture

The architecture of Paris is generally reflected in Bing’s photography through images of middle- or working-class houses or walls and façades of dilapidated buildings. There was one notable exception, namely the Eiffel Tower. This emblematic work, constructed for the Universal Exhibition of 1889, was nothing less than a revelation for Bing. The Tower’s imposing metal structure had been captured by various photographers, including László Moholy-Nagy in 1925, followed by Erwin Blumenfeld, André Kertész, François Kollar and Germaine Krull.

Bing chose to locate herself inside the structure and take shots at different heights, the majority looking downwards. Using this method, the reality of the space occupied by passers-by becomes perfectly visible. In other words, the intention is not to emphasise the abstract core, pure geometry and beauty of the forms, girders, mainstays, braces and other constructional elements but rather to show that this architectural marvel was also located in a specific place, in this case the gardens of the Champ de Mars.

At a later date, New York’s modern architecture astonished Bing for its display of power expressed as imposing constructions. She translated her amazement into a group of images primarily characterised by a distanced and simultaneously critical gaze on the architectural spectacle before her eyes. Her position was not simply an uncritical and admiring one, as evident in various photographs of skyscrapers abutting on poor areas of the city. The thrust of the symbolic power of vertical architecture is called into question by being juxtaposed with humble spaces and buildings, as we see with Chrysler Building (1936).

The Hustle and Bustle of the Street: The French Years

When Ilse Bing arrived in Paris in late November 1930 the city’s cultural context was particularly favourable in terms of the number of illustrated publications that made use of images taken by a large group of male and female photographers. These publications included Vu, Voilà, Marianne, Regards, L’Art Vivant, Arts et Métiers Graphiques and Urbanisme.

One of the commissions that Bing received allowed her to delve into an evident reality: the existence of poverty in certain parts of a major capital such as Paris. She focused her work on portraying the soup kitchens where large numbers of destitute people gathered.

The artist revealed her abilities in Paris, rue de Valois (1932), an image that allows for a questioning of the supposedly objective truth habitually associated with photography. On an inner city street Bing’s gaze focuses on a puddle in which the roofs of an adjacent building are reflected. She shows us the paradox of something that is located above and high up appearing below, on the ground.

While Bing’s Parisian photography has a melancholy, even sombre tone to it, it also looked at areas of human activity characterised by lively bustle and social interaction, such as her images of a gingerbread fair.

These years in France provided the setting for a veritable laboratory of ideas in which the influence of Bing’s Frankfurt years is still evident. It was also a time when the emergence of Surrealism was occupying the Parisian cultural scene, with its exploration of the unconscious and of hidden desires. It can be detected in the ghostly feel of the solarised photographs that Bing took on the Place de la Concorde.

In this context, and thanks to an invitation from the Dutch-born Hendrick Willem van Loon, Bing discovered the Netherlands, visiting places such as Veere and Amsterdam and capturing different moments of daily life. The country’s nature as a terrain regained from the sea also led the artist to reflect this geographical reality in a number of snapshots.

The Seduction of Fashion

During her Paris years Bing experienced financial difficulties, a recurrent problem for her over the years, for which reason in November 1933 she began to contribute to the fashion magazine Harper’s Bazaar, an American publication noted for its modern style. She secured this work with a recommendation from the editor of the French edition, Daisy Fellowes, a fashion-world figure brought up in aristocratic circles. Some of Bing’s photographs are in fact of accessories that belonged to Fellowes, including the grey felt hat and an elegant pair of gloves. In these and other images Bing applied a highly innovative approach in which she brought out the texture of the objects and the sheen of the surfaces by cropping the frame in such a way that the various garments acquired a sensual touch as well as suggesting the attractiveness of a coveted object.

During these years Bing also met Elsa Schiaparelli, the celebrated Italian fashion designer with links to Surrealism. Bing took photographs as advertisements for perfumes such as Salut and Soucis, both of 1934. The aim of these images was to encourage the viewer to desire the product with all its sensual resonances without renouncing a modern aesthetic.

The United States in Two Stages

Bing’s experiences in New York can be divided into two quite distinct phases. The first was a visit in 1936 while the second came in 1941 with her forced departure from France following the Nazi occupation. She continued to live there until her death in 1998, although she brought her photographic activity to an end forty years earlier.

The first American trip lasted from April to June 1936. Bing was impressed by the colossal dimensions of the city’s architecture while her restless gaze also focused on other aspects of the metropolis: the harsh life of down-and-outs (Variation on Dead End), the dirtiness of the streets, a circus show with acrobats and animals, and more.

In these difficult circumstances and experiencing isolation, Bing transferred her sense of solitude to the reality that surrounded her, observing it attentively. The result is a number of desolate images in which her own feelings are transmuted into melancholy landscapes and objects: scrawny, leafless tree branches, picket fences enclosing plots, and a fire hydrant in a snowy landscape next to a fallen tree.

From 1941 onwards, still suffering from the effects of exile and in need of earning a living in a hostile environment, Bing turned her activities to various different jobs, taking passport photographs for immigrants, portrait photographs on commission and even working as a dog groomer, among other things. The illustrated magazine world clearly turned its back on her at this period.

Self-Image Revelations

In 1913 the teenage Bing took what she considered to be her first self-portrait. She poses in her bedroom in the family home in Frankfurt, sitting sideways at a desk and resting her feet on a chair. What we see in reality is her reflection in a cupboard mirror, which shows the young Ilse with her long hair. In front of a background of paintings, she looks out attentively and places her hand on the camera – a Kodak box model. She was unaware at the time that this device (albeit not this make) would become her principal working tool.

Throughout her life as an artist Bing repeated the exercise of portraying herself (usually indoors) with the aim of leaving a record of a specific moment of her existence. Through these self-portraits she forged her own identity as an emancipated and independent woman in times of enormous patriarchal pressure.

During her first visit to New York Bing conceived an image that is a clear indication of the sense of estrangement and alienation she felt at seeing herself so small before the immensity of the mecca of skyscrapers, as in New York, the Elevated, and Me (1936).

Bing would later make the representation of shadow a stark extension of her life and personality, frequently using it throughout her American years.

During the course of her lifetime Ilse Bing explored the transitory states of her own identity, sometimes presenting herself as firm and decided, at times as vulnerable and anxious and on other occasions as a fleeting shadow cast on a wall.

Portrait of Time

In addition to seeking out the intricacies of her subjectivity in her own image, from almost the outset Bing engaged in an intensive photographic activity in which she combined commissions for portraits, especially of children, with the desire to explore the human psyche.

With regard to childhood, Bing saw children as complete beings on the same level as adults, with their own internal struggles and issues. During her own childhood the prevailing view was that they were not fully formed but Bing was uncomfortable with this perception and over time she learned to see adulthood and childhood as two phases of life that had much more in common than was generally thought.

Similarly, she did not share the view that women should be conceived on the male model as if they were a mere accompaniment to their tune. She considered that “the human being can be represented and symbolised by women”, albeit without aiming to idealise them. These concepts, which clearly reflect an underlying feminist attitude, seem to allude to a holistic vision of existence devoid of hierarchies or fixed categories.

Bing went beyond merely capturing the moment, the temporal space in which her models pose. Rather, with both her child sitters and adults she aimed to show them engaged in an activity, extracting aspects of their character and personality from them.

Live Nature

Any assessment of Ilse Bing’s work must necessarily emphasise the impact on her career of her urban experiences in Frankfurt, Paris and New York. While this assertion seems indisputable, an analysis of her corpus would be diminished without a consideration of the close relationship she maintained with nature, both the untamed natural world and nature designed and organised by human hand, as in the case of the gardens of Versailles.

The natural world was also the locus in which Bing’s emotions and feelings took hold. The photographs taken on the banks of the Loire, for example, generally exude an air of calm and balance comparable to that which she felt in her own life at the time, contrasting strongly with the landscapes of wild and rugged places such as those she captured in the mountains of Colorado at a period of greater personal tension.

In 1959 Ilse Bing gave up photography for good. After three decades as a photographer and long before her work started to be recognised in museums in the United States, France and Germany, with exhibitions and publications of her work in Paris, New Orleans, Aachen and New York, the artist, who had proved herself able to represent the vibration of life, considered that she no longer had anything new to say or contribute in this medium.

Fundación MAPFRE exhibition texts

Ilse Bing (American born Germany, 1899-1998)

Street Cleaner, Paris

1947

Gelatin silver print

© Estate of Ilse Bing

Ilse Bing (American born Germany, 1899-1998)

Antigone with Teacher

1950

Gelatin silver print

33.7 × 26.7cm

International Center of Photography

Donation of Ilse Bing, 1991

© Estate of Ilse Bing

Ilse Bing (American born Germany, 1899-1998)

Nancy Harris

1951

Gelatin silver print

50.3 × 40.3cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington D. C.

The Marvin Breckinridge Patterson Fund for Photography 2000

© Estate of Ilse Bing

Ilse Bing (American born Germany, 1899-1998)

All of Paris in a Box

1952

Gelatin silver print

40.1 x 48.4cm

James Hyman Gallery, London

© Estate of Ilse Bing

Ilse Bing (American born Germany, 1899-1998)

Picket Fence

1953

Gelatin silver print

50.5 × 40.6cm

International Center of Photography, New York

Donation of Steven Schwartz 2013

© Estate of Ilse Bing

Ilse Bing (American born Germany, 1899-1998)

Without Illusion, Flea Market, Paris

1957

Gelatin silver print

49.5 x 40cm

Collection of Michael Mattis and Judith Hochberg, New York

© Estate of Ilse Bing

Photograph: Jeffrey Sturges

Fundación MAPFRE – Instituto de Cultura

Paseo de Recoletos, 23

28004 Madrid, Spain

Phone: +34 915 81 61 00

Opening hours:

Mondays (except holidays): 2 pm – 8 pm

Tuesday to Saturday: 11 am – 8 pm

Sunday and holidays: 11 am – 7 pm

![Joseph Cornell (American, 1903-1972) 'Untitled [Sagittarius, Scorpio, and Lupus Constellations]' c.1934 Joseph Cornell (American, 1903-1972) 'Untitled [Sagittarius, Scorpio, and Lupus Constellations]' c.1934](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/joseph-cornell-untitled-c-1934-web.jpg?w=840)

You must be logged in to post a comment.