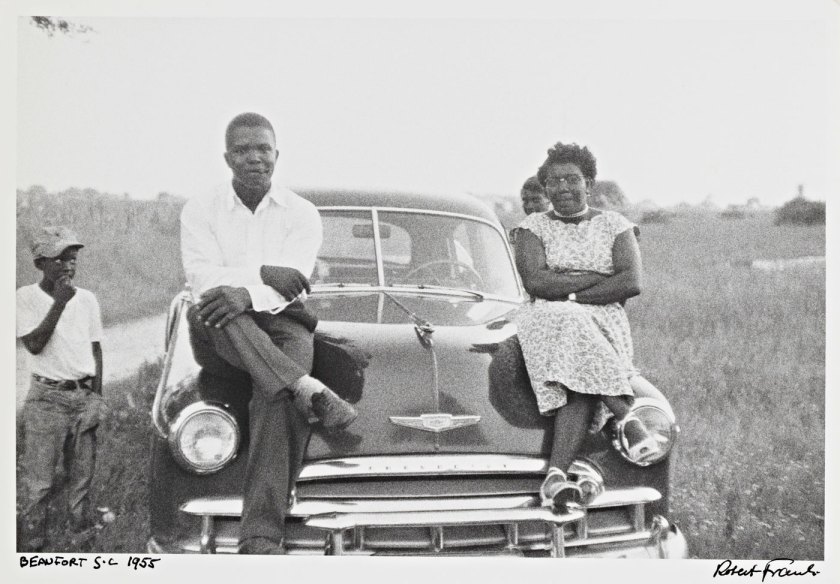

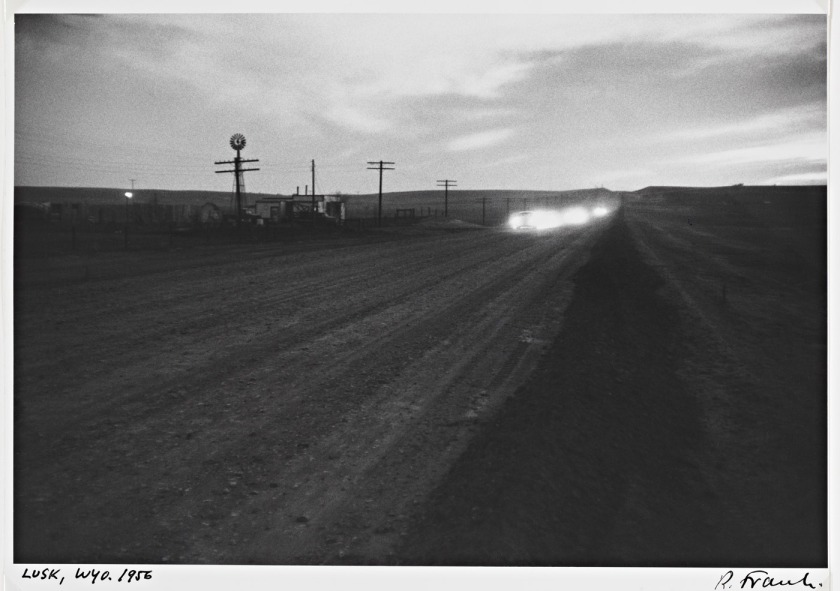

Exhibition dates: 20th February – 17th May 2020? Coronavirus

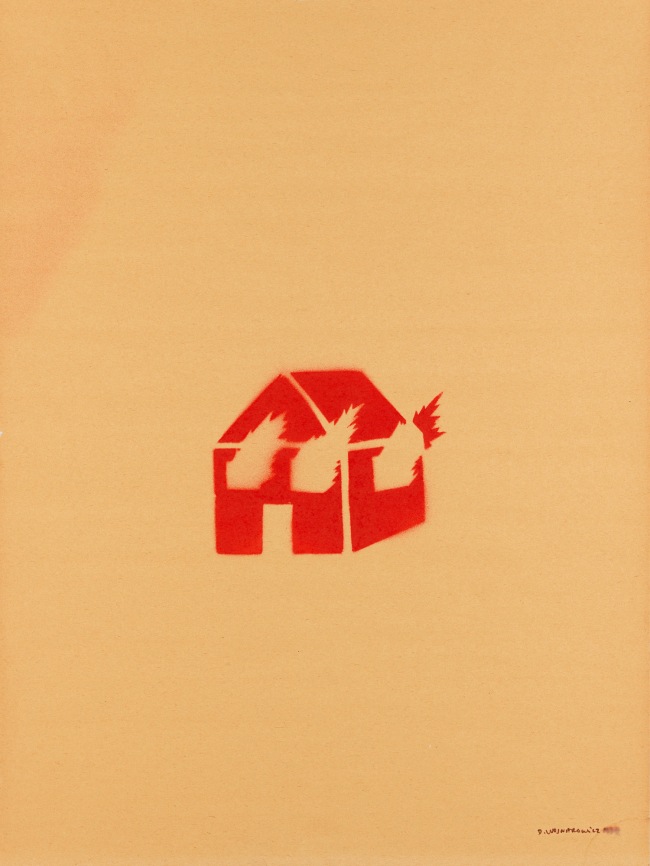

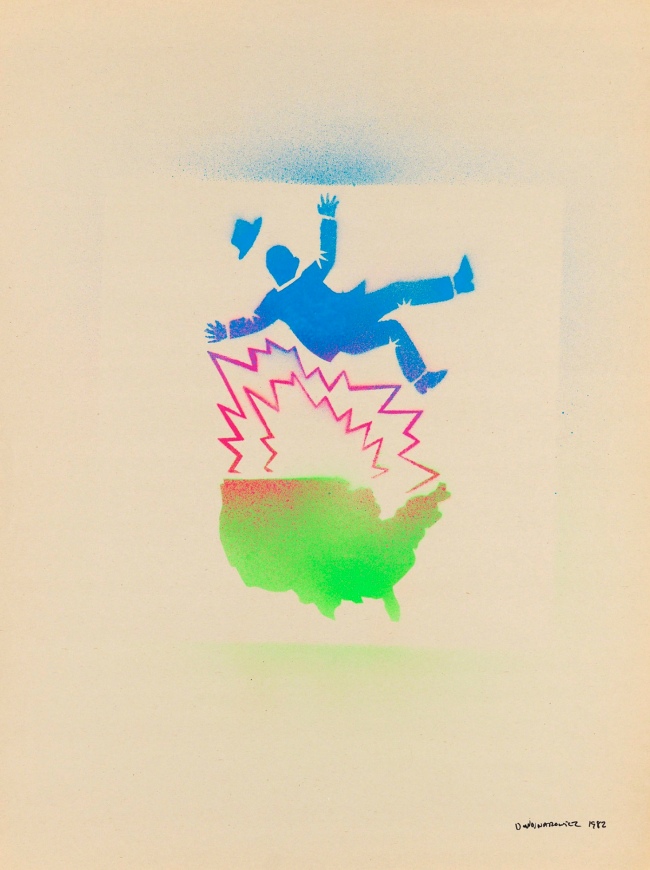

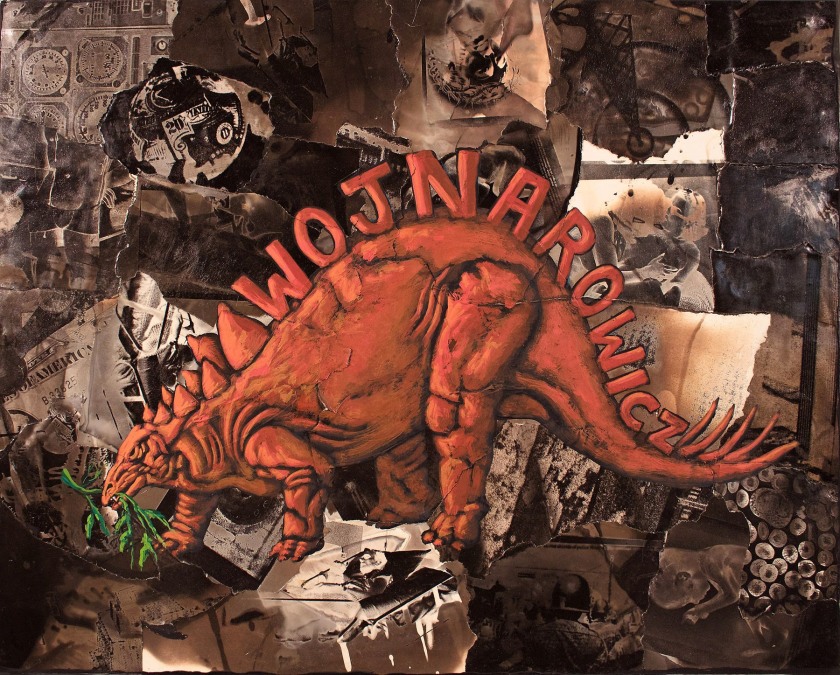

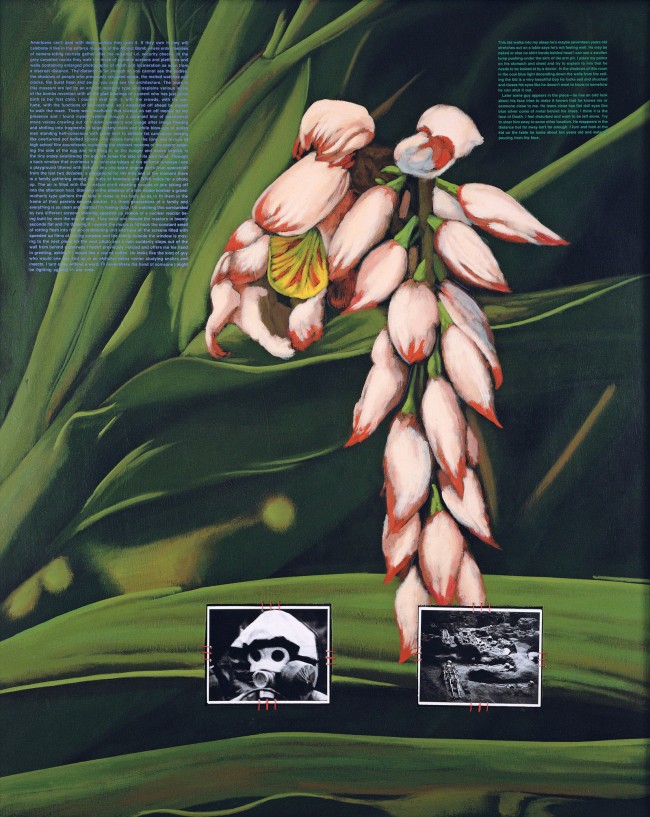

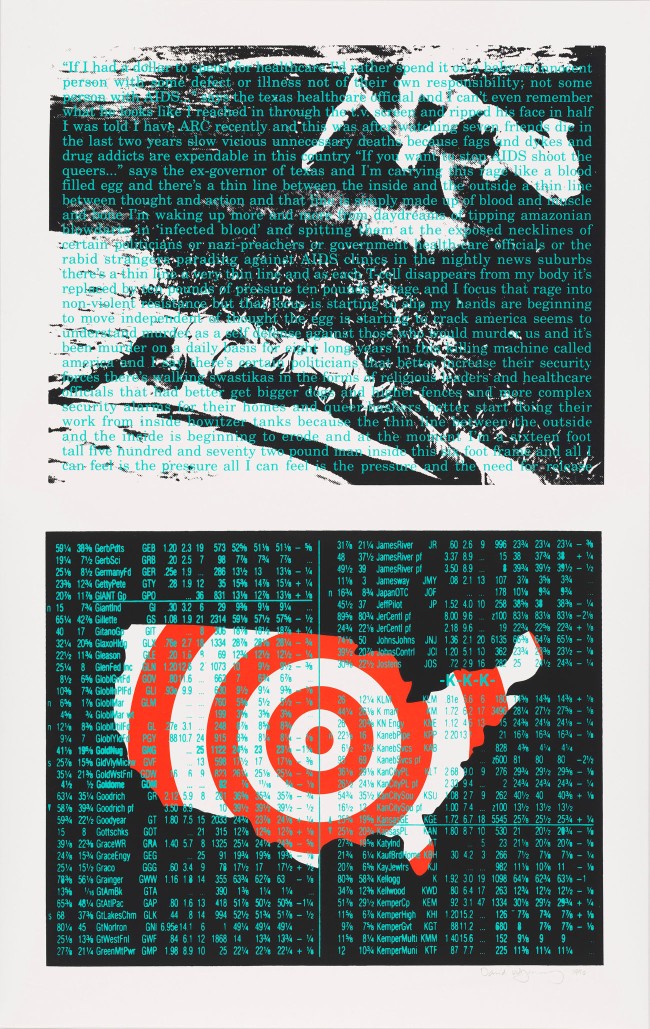

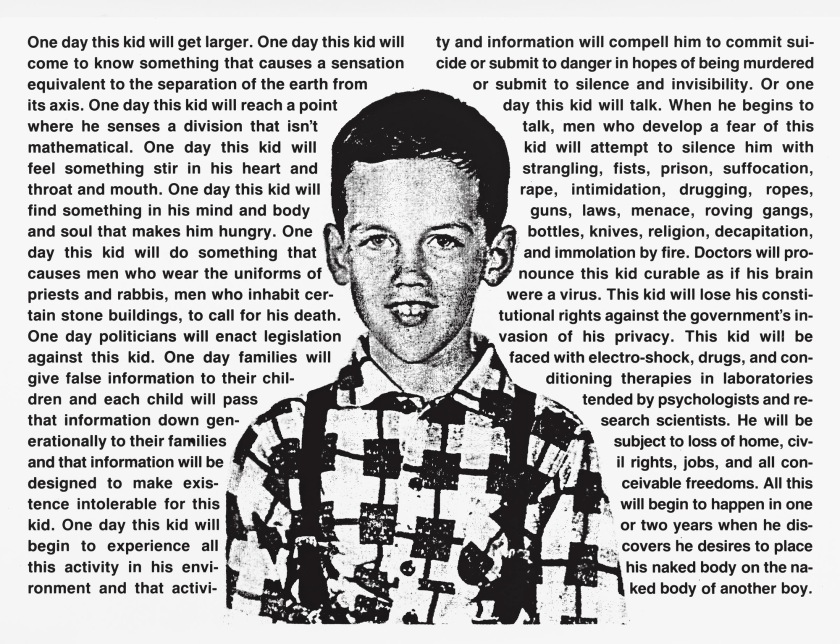

Participating artists: Bas Jan Ader, Laurie Anderson, Kenneth Anger, Knut Åsdam, Richard Avedon, Aneta Bartos, Richard Billingham, Cassils, Sam Contis, John Coplans, Jeremy Deller, Rienke Dijkstra, George Dureau, Thomas Dworzak, Hans Eijkelboom, Fouad Elkoury, Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Hal Fischer, Samuel Fosso, Anna Fox, Masahisa Fukase, Sunil Gupta, Peter Hujar, Liz Johnson Artur, Isaac Julien, Kiluanji Kia Henda, Karen Knorr, Deana Lawson, Hilary Lloyd, Robert Mapplethrope, Peter Marlow, Ana Mendieta, Anenette Messager, Duane Michals, Tracey Moffat, Andrew Moisey, Richard Mosse, Adi Nes, Catherine Opie, Elle Pérez, Herb Ritts, Kalen Na’il Roach, Collier Schorr, Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Clarie Strand, Michael Subotzky, Larry Sultan, Hank Willis Thomas, Wolfgang Tillmans, Piotr Uklański, Andy Warhol, Karlheinz Weinberger, Marianne Wex, David Wojnarowicz, Akram Zaatari.

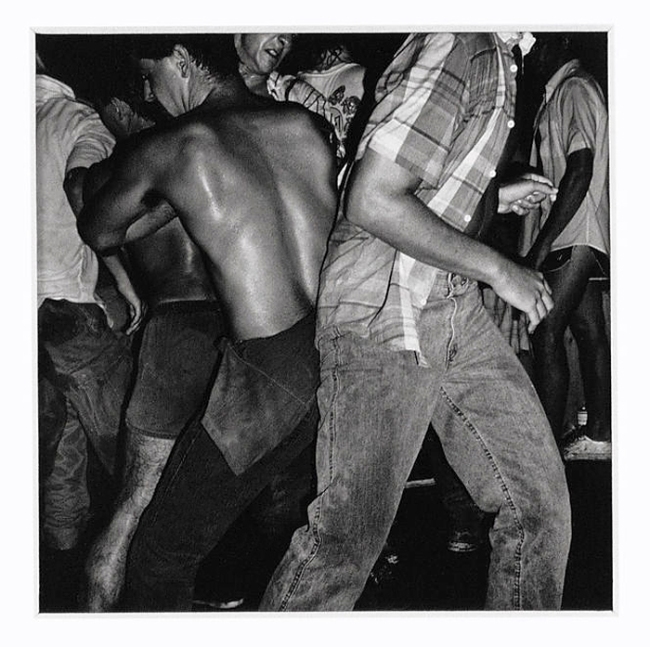

Sunil Gupta (Indian, b. 1953)

Untitled #22

1976

From the series Christopher Street

Courtesy the artist and Hales Gallery

© Sunil Gupta. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2019

“As a writer Berger recognised that experience – whether it be personal, historical or aesthetic – will never conform to theories and systems. To read him today is to accept his failures and detours as a unique willingness to take risks.”

John MacDonald. “John Berger,” in the Sydney Morning Herald, 6 June, 2020

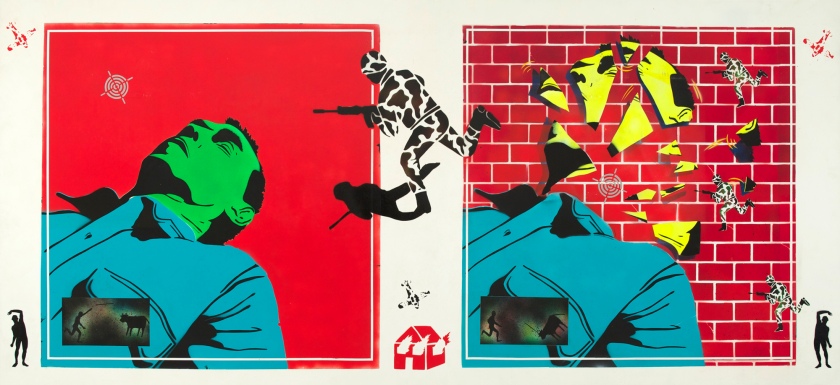

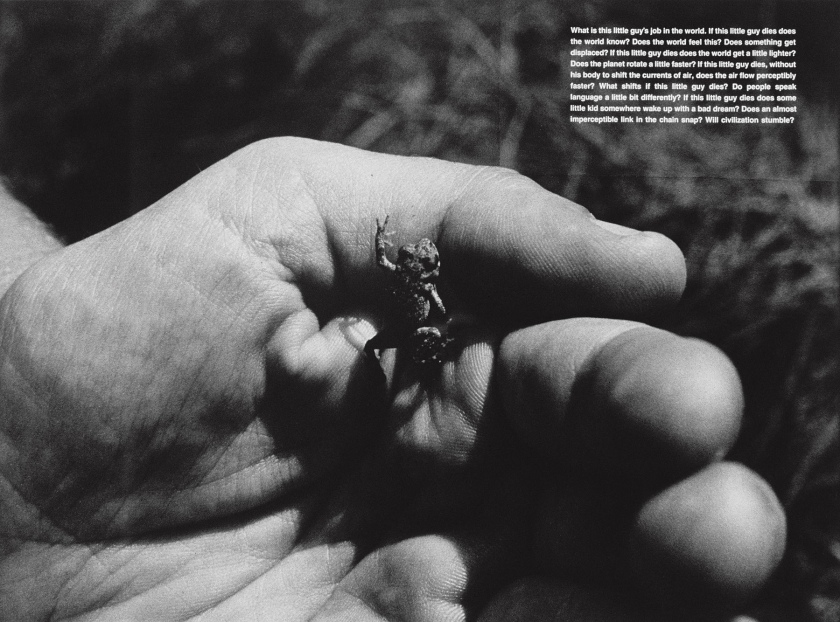

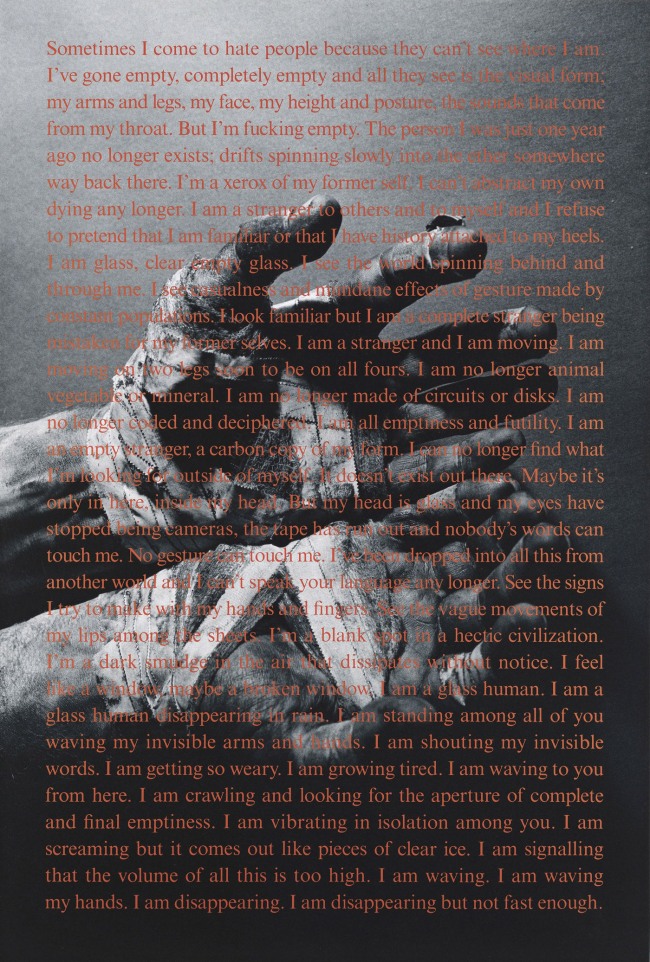

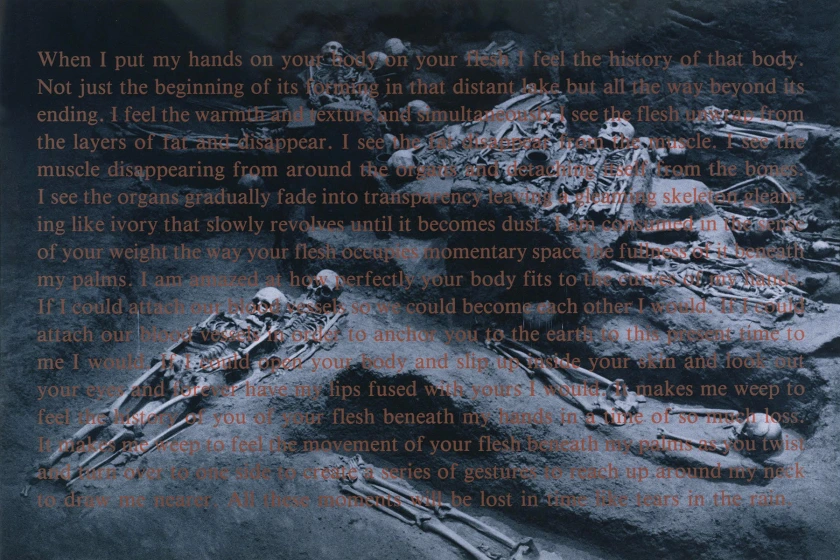

D-Construction: deliberate masculinities in a discontinuous world

Reviewers of this exhibition (see quotations below) have noted the preponderance of images of “traditional masculinity” – defined as “idealised, dominant (and) heterosexual” – and the paucity of images that show men as working, intelligent, sensitive human beings, “that men ever earned a living, cooked a meal or read a book… scarcely anything about the heart or intellect. Men are represented here almost entirely in terms of their bodies, sexuality or supposed type.” I need make no further comment. What I will say is that I believe the title of the exhibition to be a misnomer: a person cannot be “liberated” through photography, for photography is only a tool of a personal liberation. Liberation comes through an internal struggle of acceptance (thence liberation), one that is foremost FELT (for example, the double life one leads before you acknowledge that you are gay; or experiencing discrimination aimed at others and by proxy, yourself) and SEEN (the bashing of a mother as seen by a small child). Photographs picture the outcomes of this struggle for liberation, are a tool of that process not, I would argue, liberation itself.

What I can say is that I believe in masculinities, plural. Fluid, shifting, challenging, loving, working, intimate, spiritual masculinities that challenge normalcy and hegemonic masculinity, which is defined as “a practice that legitimises men’s dominant position in society and justifies the subordination of the common male population and women, and other marginalised ways of being a man.”

What I don’t believe in is masculinities, plural, that seek to fit into this [dis]continuous world (for we are born and then die) through the stability of their outward appearance, conforming to theories and systems – personal, historical or aesthetic – without reference to subversion, small intimacies, the toil of work, love and the passion of sexual bodies. In other words, masculinities that are not afraid to push the boundaries of being and becoming. To take risks, to experience, to feel.

While I was overjoyed at the “YES” vote on gay marriage that took place in December 2017 in Australia because I felt it was a victory for love, and equality… another part of me rejected as anathema the concept of a gay person buying into a historically patriarchal, heterosexual and monogamous institution such as marriage – too honour and obey. This is an untenable concept for a person who wants to be liberated. Coming out as I did in 1975, only 6 short years after the Stonewall Riots, the last thing I EVER wanted to be, was to be the same as a “straight” person. I was different. I fought for my difference and still believe in it.

Of course, in 2020 it’s another world. Today we all mix in together. But there is still something about “masculinities”, which in some varieties, have a sense of privilege and entitlement. Of power and control over others; of violence towards women, trans, other men and anyone who threatens their little ego, who leaves them, or jilts them. Their jealousy, their ego, bruised – they are so insecure, so insular, that they can only see their own world, their own minuscule problems (but massive in their eyes), and enforce their will on others.

My advice to “masculinities’, in fact any human being, is to go out, get yourself informed, experience, accept, and be the person that nobody thinks you can be. Be a human being. Examine your inner self, look at your dark side, your other side, your empathetic side, and try and understand the journey that you are on. Then, and only then, you might begin on that great path of personal enlightenment, that golden path on which there is no turning back.

Below I discuss some of these ideas with my good friend Nicholas Henderson, curator and archivist at the Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Barbican Art Gallery for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Masculinities: Liberation through Photography is a major group exhibition that explores how masculinity is experienced, performed, coded and socially constructed as expressed and documented through photography and film from the 1960s to the present day.

Through the medium of film and photography, this major exhibition considers how masculinity has been coded, performed, and socially constructed from the 1960s to the present day. Examining depictions of masculinity from behind the lens, the Barbican brings together the work of over 50 international artists, photographers and filmmakers including Laurie Anderson, Sunil Gupta, Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Isaac Julien and Catherine Opie.

In the wake of #MeToo the image of masculinity has come into sharper focus, with ideas of toxic and fragile masculinity permeating today’s society. This exhibition charts the often complex and sometimes contradictory representations of masculinities, and how they have developed and evolved over time. Touching on themes including power, patriarchy, queer identity, female perceptions of men, hypermasculine stereotypes, tenderness and the family, the exhibition shows how central photography and film have been to the way masculinities are imagined and understood in contemporary culture.

In fact, while there are a few gender-fluid figures here, they’re vastly outnumbered by manifestations of “traditional masculinity” – defined as “idealised, dominant (and) heterosexual”. Lebanese militiamen (in Fouad Elkoury’s perky full-length portraits from 1980), US marines (in Wolfgang Tillmans’ epic montage Soldiers – The Nineties), Taliban fighters, SS generals, Israel Defence Force grunts, footballers, cowboys and bullfighters fairly spring out of the walls from every direction. And what’s evident from the outset isn’t so much their diversity, as a unifying demeanour: a threatening intentness that comes wherever men are asked to perform their masculinity, but also a childlike vulnerability. …

Masculinity, the viewer is made to feel, criminalises men (Mikhael Subotzky’s images of South African gangsters on morgue slabs); isolates them (Larry Sultan’s poignant image of his elderly father practising his golf swing in his sitting room); renders them stupid (Richard Billingham’s excruciating, but now classic photo essay on his alcoholic father, ‘Ray’s a Laugh’). To be a man, it seems, is to be condemned to endlessly act out archetypal “masculine” behaviour, whether you’re an elderly drunk in a Birmingham high-rise or the elite American students taking part in the shouting competition staged by Irish photographer Richard Mosse.

Mark Hudson. “Does the Barbican’s Masculinities exhibition have important things to say about men?” on the Independent website Friday 21 February 2020 [Online] Cited 03/03/2020

There is not much here about work – unless you count the wall of Hollywood actors playing Nazis. You would never think, from this show, that men ever earned a living, cooked a meal or read a book (though there is a sententious vitrine of ‘Men Only’ magazines). Beyond the exceptions given, there is scarcely anything about the heart or intellect. Men are represented here almost entirely in terms of their bodies, sexuality or supposed type.

Laura Cumming. “Masculinities: Liberation Through Photography review – men as types,” on the Guardian website Sun 23 Feb 2020 [Online] Cited 03/03/2020

“The body can be taken as a reflection of the self because it can and should be treated as something to be worked upon … in order to produce it as a commodity. Overweight, slovenliness and even unfashionability, for example, are now moral disorders,” notes Don Slater

“The state of the body is seen as a reflection of the state of its owner, who is responsible for it and could refashion it. The body can be taken as a reflection of the self because it can and should be treated as something to be worked upon, and generally worked upon using commodities, for example intensively regulated, self-disciplined, scrutinized through diets, fitness regimes, fashion, self-help books and advice, in order to produce it as a commodity. Overweight, slovenliness, and even unfashionability, for example, are now moral disorders; even acute illnesses such as cancer reflect the inadequacy of the self and indeed of its consumption. One gets ill because one has consumed the wrong (unnatural) things and failed to consume the correct (‘natural’) ones: self, body, goods and environment constitute a system of moral choice.”

Slater, Don. Consumer Culture and Modernity. London: Polity Press, 1997, p. 92.

Installation view of Masculinities: Liberation through Photography at Barbican Art Gallery on February 19, 2020 in London, England showing John Coplans’ work Self-portrait, Frieze No 2, Four Panels 1994

Photo: Tristan Fewings/Getty Images for Barbican Art Gallery

John Coplans (British, emigrated America 1960, 1920-2003)

Self-portrait, Frieze No 2, Four Panels

1994

Tate

Presented by the American Fund for the Tate Gallery 2001

Photograph: © John Coplans Trust

Masculinities: Liberation through Photography

Plan of the Masculinities: Liberation through Photography exhibition spaces

Introduction

Masculinities: Liberation through Photography explores the diverse ways masculinity has been experienced, performed, coded and socially constructed in photography and film from the 1960s to the present day.

Simone de Beauvoir’s famous declaration that ‘one is not born a woman, but rather becomes one’ provides a helpful springboard for considering what it means to be a male in today’s world, as well as the place of photography and film in shaping masculinity. What we have thought of as ‘masculine’ has changed considerably throughout history and within different cultures. The traditional social dominance of the male has determined a gender hierarchy which continues to underpin societies around the world.

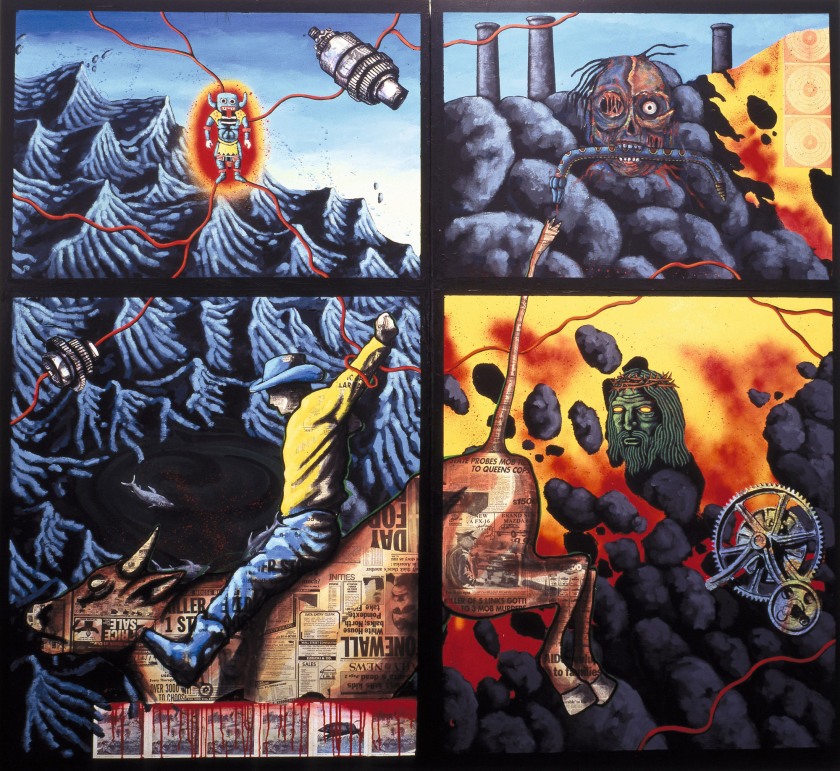

In Europe and North America, the characteristics and power dynamics of the dominant masculine figure – historically defined by physical size and strength, assertiveness and aggression – though still pervasive today, began to be challenged and transformed in the 1960s. Amid a climate of sexual revolution, struggle for civil rights and raised class consciousness, the growth of the gay rights movement, the period’s counterculture and opposition to the Vietnam War, large sections of society argued for a loosening of the straitjacket of narrow gender definitions.

Set against the backdrop of the #MeToo movement, when manhood is under increasing scrutiny and terms such as ‘toxic’ and ‘fragile’ masculinity fill endless column inches, an investigation of this expansive subject is particularly timely, especially given current global politics characterised by male world leaders shaping their image as ‘strong’ men.

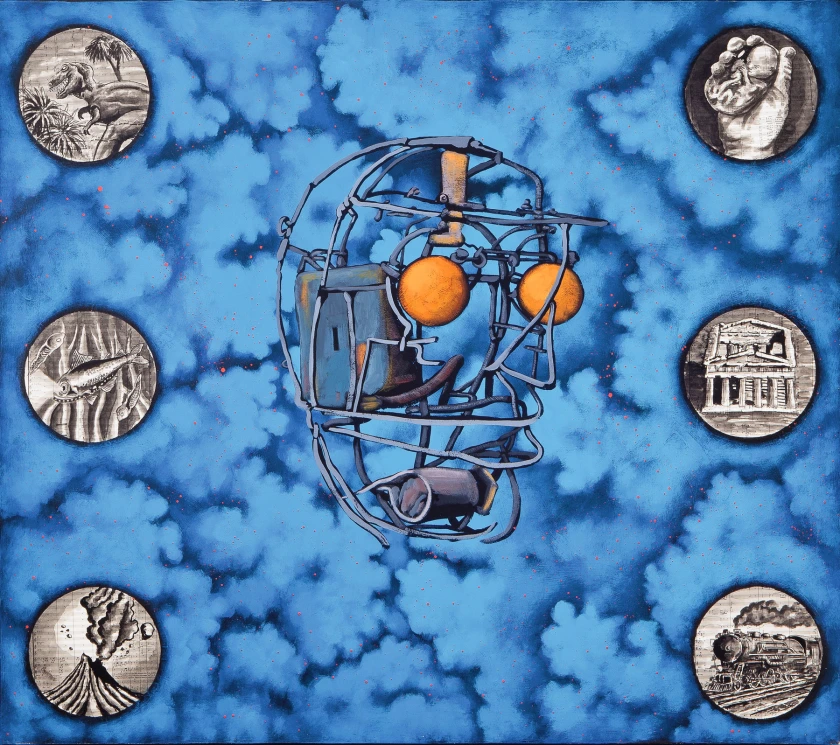

Touching on queer identity, race, power and patriarchy, men as seen by women, stereotypes of dominant masculinity as well as the family, the exhibition presents masculinity in all its myriad forms, rife with contradictions and complexities. Embracing the idea of multiple ‘masculinities’ and rejecting the notion of a singular ‘ideal man’, the exhibition argues for an understanding of masculinity liberated from societal expectations and gender norms.

Room 1-4

Disrupting the Archetype

Over the last six decades, artists have consistently sought to destabilise the narrow definitions of gender that determine our social structures in order to encourage new ways of thinking about identity, gender and sexuality. ‘Disrupting the Archetype’ explores the representation of conventional and at times clichéd masculine subjects such as soldiers, cowboys, athletes, bullfighters, body builders and wrestlers. By reconfiguring the representation of traditional masculinity – loosely defined as an idealised, dominant heterosexual masculinity – the artists presented here challenge our ideas of these hypermasculine stereotypes.

Across different cultures and spaces, the military has been central to the construction of masculine identities – which has been explored through the work of Wolfgang Tillmans (below) and Adi Nes (below) among others, while Collier Schorr (below) and Sam Contis’s powerful works (below) address the dominant and enduring representation of the lone cowboy. Athleticism, often perceived as a proxy for strength which is associated with masculinity, is called into question by Catherine Opie’s and Rineke Dijkstra’s tender portraits (below). The male body, a cornerstone for artists such as John Coplans (above), Robert Mapplethorpe and Cassils (below), is meanwhile exposed as a fleshy canvas, constantly in flux.

Historically, the non-western male body has undergone a complex process of subjectification through the Western gaze – invariably presented as either warlike or sexually charged. Viewed against this context, the work of Fouad Elkoury and Akram Zaatari, as well as the found photographs of Taliban fighters that Thomas Dworzak discovered in Afghanistan (below), can be read as deconstructing the Orientalist gaze.

Installation view of Masculinities: Liberation through Photography at Barbican Art Gallery on February 19, 2020 in London, England showing a detail from Wolfgang Tillmans’ epic montage Soldiers – The Nineties

Photo: Tristan Fewings/Getty Images for Barbican Art Gallery

Installation view of Masculinities: Liberation through Photography at Barbican Art Gallery on February 19, 2020 in London, England showing a detail from trans masculine artist Cassils’ series Time Lapse, 2011

Photo: Tristan Fewings/Getty Images for Barbican Art Gallery

Installation view of Masculinities: Liberation through Photography at Barbican Art Gallery on February 19, 2020 in London, England showing at left a detail from trans masculine artist Cassils’ series Time Lapse, 2011, and at right the work of Rineke Dijkstra

Photo: Tristan Fewings/Getty Images for Barbican Art Gallery

Rineke Dijkstra (Dutch, b. 1959)

Montemor, Portugal, May 1, 1994

1994

Chromogenic print

90 x 72cm

© Rineke Dijkstra

Rineke Dijkstra (Dutch, b. 1959)

Vila Franca de Xira, Portugal, May 8, 1994

1994

Chromogenic print

90 x 72cm

© Rineke Dijkstra

Installation views of Masculinities: Liberation through Photography at Barbican Art Gallery on February 19, 2020 in London, England showing photographs from Adi Nes’ series Soldiers, 1999

Photo: Tristan Fewings/Getty Images for Barbican Art Gallery

Adi Nes (Israeli, b. 1966)

Untitled

2000

From the series Soldiers

Courtesy Adi Nes & Praz-Delavallade Paris, Los Angeles

Adi Nes (Israeli, b. 1966)

Untitled

1999

From the series Soldiers

Courtesy Adi Nes & Praz-Delavallade Paris, Los Angeles

Adi Nes was born in Kiryat Gat. His parents are Jewish immigrants from Iran. He is openly gay. Nes is notable for series “Soldiers”, in which he mixes masculinity and homoerotic sexuality, depicting Israeli soldiers in a fragile way.

Nes creates cinematic images that reference war, sexuality, life, and death with the kind of stylised polish you might expect from a photographer whose images have appeared in the pages of Vogue Hommes. His partially autobiographical work is deliberate and staged in an attempt to raise questions about sexuality, masculinity and identity in Israeli culture. “The beginning point of my art is who I am,” he says. “Since I’m a man and I’m an Israeli, I deal with issues of identity with ‘Israeli-ness’ and masculinity, but my photographs are multi-layered.”

“The challenge of the photographer is to catch the viewer for more than one second in front of the picture,” says Nes, explaining his provocative images. “If you catch the viewer in front of the picture, it can touch the viewer.”

Anonymous text “Adi Nes on masculinity, sexuality and war,” from the Phaidon website 2012 [Online] Cited 07/03/2020

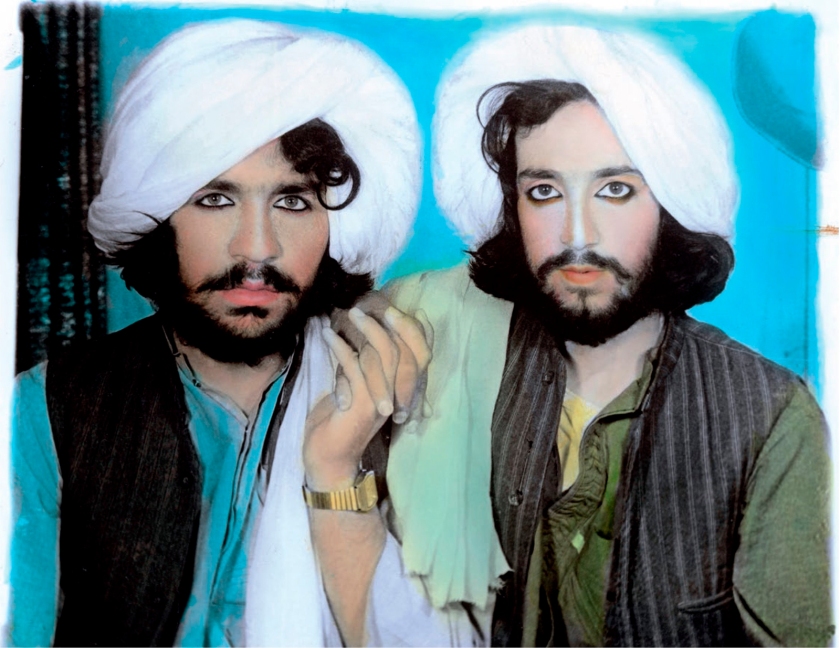

Thomas Dworzak (Germany, b. 1972)

Taliban portraits

2002

Kandahar, Afghanistan

While covering the US invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, Magnum photographer Thomas Dworzak came across a handful of photo studios in Kandahar which despite the Taliban’s ban on photography had been authorised to remain open, for the sole purpose of taking identity photos. Complicating the conventional image of the hypermasculine soldier, the colour portraits Dworzak found in the back rooms of these studios depict Taliban fighters variously posing in front of scenic backdrops, holding hands, using guns or flowers as props or enveloped in a halo of vibrant colours, their eyes heavily made up with black kohl. These stylised photographs directly contradict the public image of the soldier in this overwhelmingly male-dominated patriarchal society.

Sam Contis (American, b. 1982)

Untitled (Neck)

2015

© Sam Contis

Masculinities: Liberation through Photography catalogue cover

Installation view of Masculinities: Liberation through Photography at Barbican Art Gallery on February 19, 2020 in London, England showing photographs from Catherine Opie’s series High School Football, 2007-2009

Photo: Tristan Fewings/Getty Images for Barbican Art Gallery

Catherine Opie (American, b. 1961)

Stephen

2009

From the series High School Football, 2007-2009

Courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles, and Thomas Dane Gallery, London

© Catherine Opie

Catherine Opie (American, b. 1961)

Rusty

2008

From the series High School Football, 2007-2009

Courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Thomas Dane Gallery, London

© Catherine Opie

Catherine Opie (American, b. 1961)

Football Landscape #17 (Waianae vs. Leilehua, Waianae, HI)

2009

From the series High School Football, 2007-2009

Courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles, and Thomas Dane Gallery, London

© Catherine Opie

Kenneth Anger (American, b. 1927)

Kustom Kar Kommandos

1965

3 mins 22 secs

Collier Schorr (American, b. 1963)

Americans #3

2012

© Collier Schorr, courtesy 303 Gallery, New York

Room 5-6

Male Order: Power, Patriarchy and Space

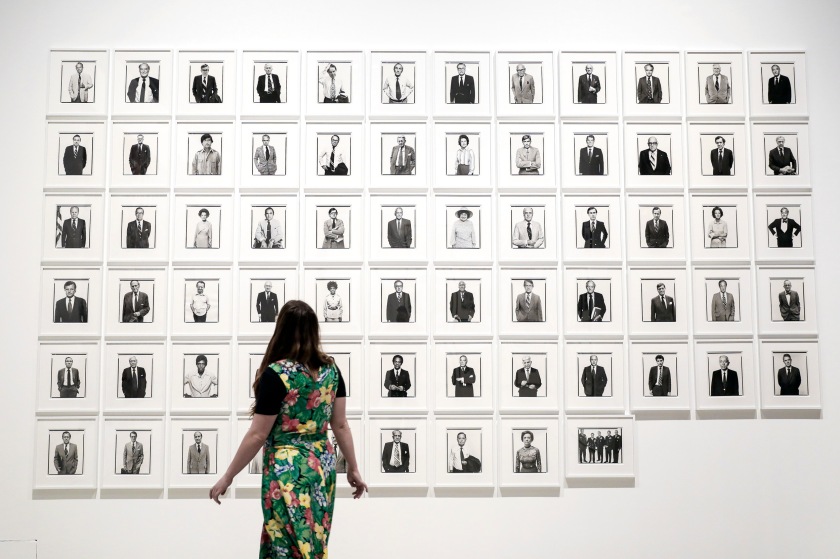

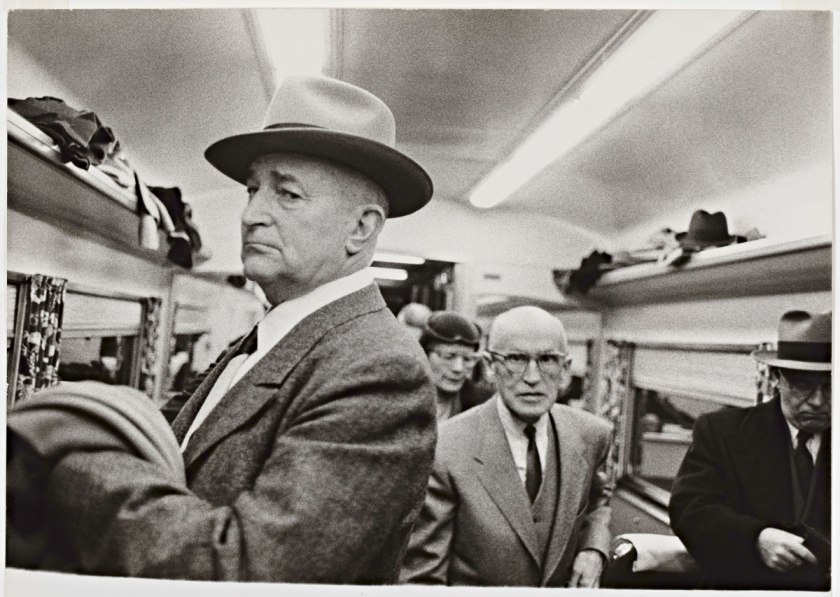

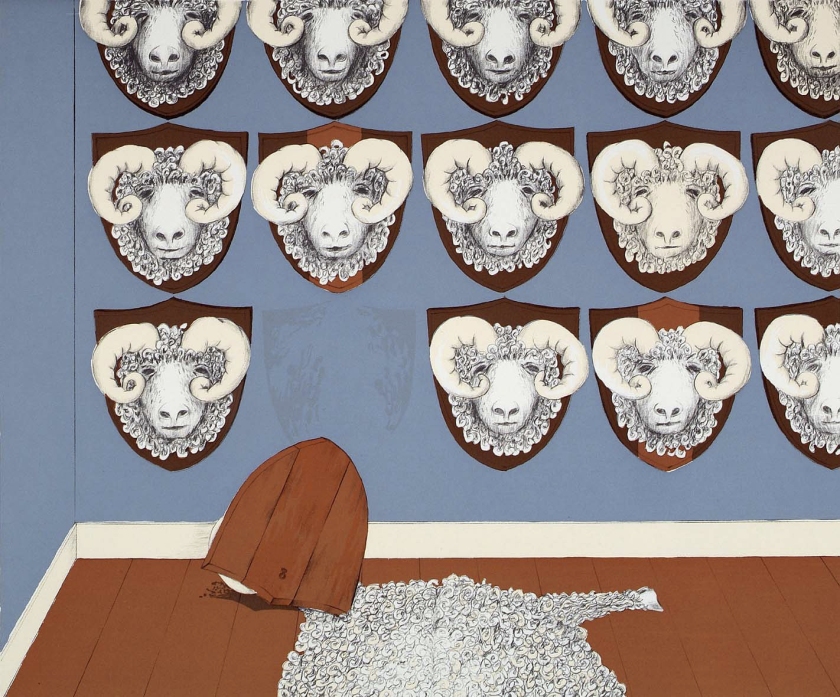

‘Male Order’ invites the viewer to reflect on the construction of male power, gender and class. The artists gathered here have all variously attempted to expose and subvert how certain types of masculine behaviour have created inequalities both between and within gender identities. Two ambitious, multi-part works, Richard Avedon’s The Family, 1976, and Karen Knorr’s Gentlemen, 1981-1983, focus on typically besuited white men who occupy the corridors of power, while foregrounding the historic exclusion not only of women but also of other marginalised masculinities.

Male-only organisations, such as the military, private members’ clubs and college fraternities, have often served as an arena for the performance of ‘toxic’ masculinity, as chronicled in Andrew Moisey’s The American Fraternity: An Illustrated Ritual Manual, 2018. This startling book charts the misdemeanours of fraternity members alongside an indexical image bank of US Presidents, alongside leaders of government and industry who have belonged at one time or another to these fraternities. Richard Mosse’s film, Fraternity, 2007, takes a different tack by painting a portrait of male rage that is both playful and alarming.

Installation view of Masculinities: Liberation through Photography at Barbican Art Gallery on February 19, 2020 in London, England showing photographs from Richard Avedon’s series The Family (1976)

Photo: Tristan Fewings/Getty Images for Barbican Art Gallery

Early in 1976, with both the post-Watergate political atmosphere and the approaching bicentennial celebration in mind, Rolling Stone asked Richard Avedon to cover the presidential primaries and the campaign trail. Avedon counter-proposed a grander idea – he had always wanted to photograph the men and women he believed to have constituted political, media and corporate elite of the United States.

For the next several months, Avedon traversed the country from migrant grape fields of California to NFL headquarters in Park Avenue and returned with an amazing portfolio of soldiers, spooks, potentates, and ambassadors that was too late for the bicentennial but published in Rolling Stone’s Oct. 21, 1976, just in time for the November elections.

Sixty-nine black-and-white portraits … were in Avedon’s signature style – formal, intimate, bold, and minimalistic. Appearing in them are President Ford and his three immediate successors – Carter, Reagan, and Bush. Other familiars of the American polity such as Kennedys and Rockefellers are here, and as are giants who held up the nation’s Fourth Pillar during that challenging decade: A. M. Rosenthal of the New York Times who decided to publish the Pentagon Papers, and Katharine Graham who led Woodward and Bernstein at Washington Post.

Alex Selwyn-Holmes. “The Family, 1976; Richard Avedon” on the Iconphotos website May 18, 2012 [Online] Cited 03/03/2020

Installation views of Masculinities: Liberation through Photography at Barbican Art Gallery on February 19, 2020 in London, England showing photographs from Karen Knorr’s series Gentlemen, 1981-1983

Photo: Tristan Fewings/Getty Images for Barbican Art Gallery

Karen Knorr (American born Germany, b. 1954)

Newspapers are no longer ironed, Coins no longer boiled So far have Standards fallen

1981-1983

From the series Gentlemen

Tate: Gift Eric and Louise Franck London Collection 2013

© Karen Knorr

Installation view of Masculinities: Liberation through Photography at Barbican Art Gallery on February 19, 2020 in London, England showing Piotr Uklanski’s Untitled (The Nazis), 1998, a collage of actors dressed as Nazis, courtesy of Massimo De Carlo

Photo: Tristan Fewings/Getty Images for Barbican Art Gallery

Room 7-8

Too Close to Home: Family and Fatherhood

Since its invention photography has been a powerful vehicle for the construction and documentation of family narratives. In contrast to the conventions of the traditional family portrait, the artists gathered here deliberately set out to record the ‘messiness’ of life, reflecting on misogyny, violence, sexuality, mortality, intimacy and unfolding family dramas, presenting a more complex and not always comfortable vision of fatherhood and masculinity.

Loss and the ageing male figure are central to the work of both Masahisa Fukase and Larry Sultan (both below). Their respective projects marked a new departure in the way men photographed each other, serving as a commentary on how old age engenders a loss of masculinity. An examination of everyday life, Richard Billingham’s tender yet bleak portraits of his father, as chronicled in Ray’s a Laugh, cast a brutally honest eye on his alcoholic father Ray against a backdrop of social decline (below).

Anna Fox’s disturbing autobiographical work undermines expectations of the traditional family album while revealing the mechanics of paternalistic power. Meanwhile, the father-daughter relationship is brought into sharp focus in Aneta Bartos’s sexually charged series Family Portrait which unsettles traditional family boundaries (below).

Masahisa Fukase (Japan, 1934-2012)

Masahisa and Sukezo

1972

From the series Family, 1971-1990

© Masahisa Fukase Archives

Masahisa Fukase (Japan, 1934-2012)

Upper row, from left to right: A, a model; Toshiteru, Sukezo, Masahisa. Middle row, from left to right: Akiko, Mitsue, Hisashi Daikoji. Bottom row, from left to right: Gaku, Kyoko, Kanako, and a memorial portrait of Miyako

1985

From the series Family, 1971-1990

© Masahisa Fukase Archives

Masahisa Fukase (Japan, 1934-2012)

Masahisa and Sukezo

1985

From the series Family, 1971-1990

© Masahisa Fukase Archives

‘A magnificent memorial to paternal love’.

Installation view of Masculinities: Liberation through Photography at Barbican Art Gallery on February 19, 2020 in London, England showing the photographs of Larry Sultan from the series Pictures from Home

Photo: Tristan Fewings/Getty Images for Barbican Art Gallery

Larry Sultan (American, 1946-2009)

Dad on Bed

1984

From the series Pictures from Home

Chromogenic print

Courtesy the Estate of Larry Sultan, Yancey Richardson, Casemore Kirkeby, and Galerie Thomas Zander

© Estate of Larry Sultan

Larry Sultan (American, 1946-2009)

Practicing Golf Swing

1986

From the series Pictures from Home

Chromogenic print

Courtesy the Estate of Larry Sultan, Yancey Richardson, Casemore Kirkeby, and Galerie Thomas Zander

© Estate of Larry Sultan

Installation view of Masculinities: Liberation through Photography at Barbican Art Gallery on February 19, 2020 in London, England showing Richard Billingham’s photographs from the series Ray’s a Laugh

Photo: Tristan Fewings/Getty Images for Barbican Art Gallery

Installation view of Masculinities: Liberation through Photography at Barbican Art Gallery on February 19, 2020 in London, England showing the photographs of Aneta Bartos’s sexually charged series Family Portrait

Photo: Tristan Fewings/Getty Images for Barbican Art Gallery

Aneta Bartos (Born Poland, lives New York)

Mirror

2015

From the series Family Portrait

Archival inkjet print

30 x 30.65 inches

Aneta Bartos (Born Poland, lives New York)

Apple

2015

From the series Family Portrait

Archival inkjet print

30 x 30.65 inches

Since 2013 New York based artist Aneta Bartos has been traveling back to her hometown Tomaszów Mazowiecki, where she was raised by her father as a single parent from the age of eight until fourteen. Then 68 years old, and having spent a lifetime as a competitive body builder, Bartos’ father asked her to take a few shots documenting his physique before it degenerated and inevitably ran its course. The original request of her father inspired Bartos to transform his idea into a long-term project called Dad. A few summers later Dad developed into a new series of portraits, titled Family Portrait, exploring the complex dynamics between father and daughter.

Text from the Antwerp Art website [Online] Cited 01/03/2020

“The pastoral setting is a romanticised portal to Bartos’s past. Her father’s poses are often heroic; at times the pictures are playful and flirty, almost seductive. Seen together, they display the sadness of a man who knows he is ageing, with the subtext of his waning sexuality. They are bittersweet, images of time passing and memories being preserved.”

Elisabeth Biondi quoted on the Postmasters website 2017 [Online] Cited 01/03/2020

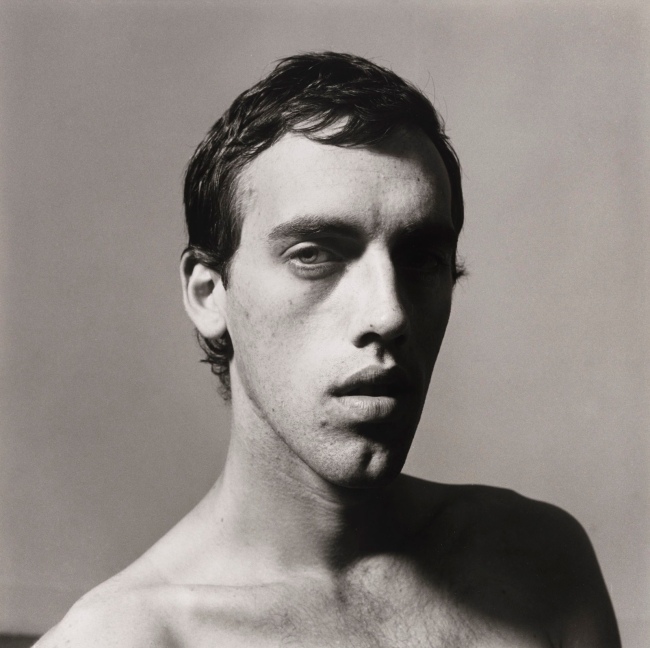

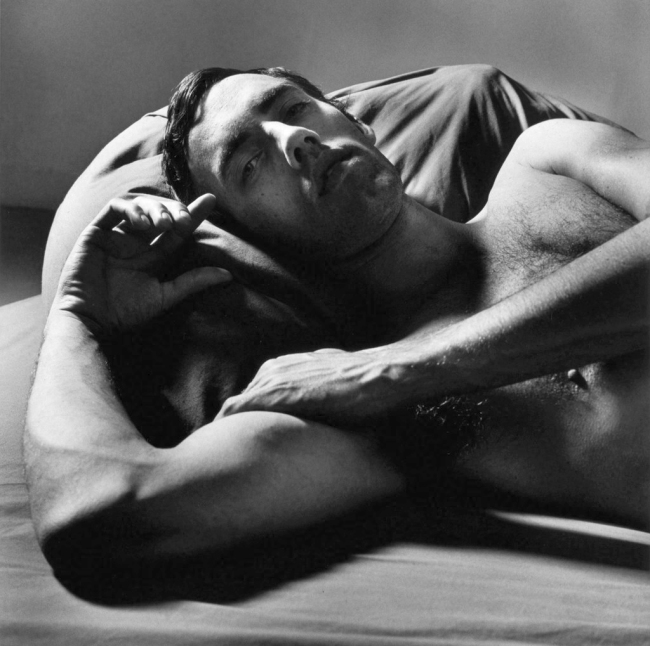

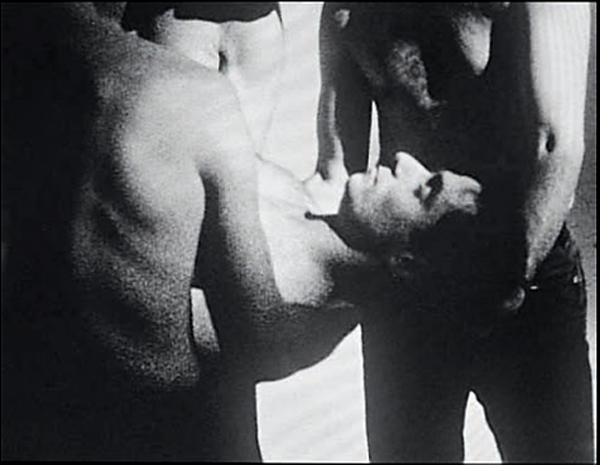

Installation views of Masculinities: Liberation through Photography at Barbican Art Gallery on February 19, 2020 in London, England showing photographs from Peter Hujar’s series Orgasmic Man 1969 (see below)

Photo: Tristan Fewings/Getty Images for Barbican Art Gallery

Room 9-12

Queer Masculinity

In defiance of the prejudice and legal constraints against homosexuality in Europe, the United States and beyond over the last century, the works presented in ‘Queering Masculinity’ highlight how artists from the 1960s onwards have forged a new politically charged queer aesthetic.

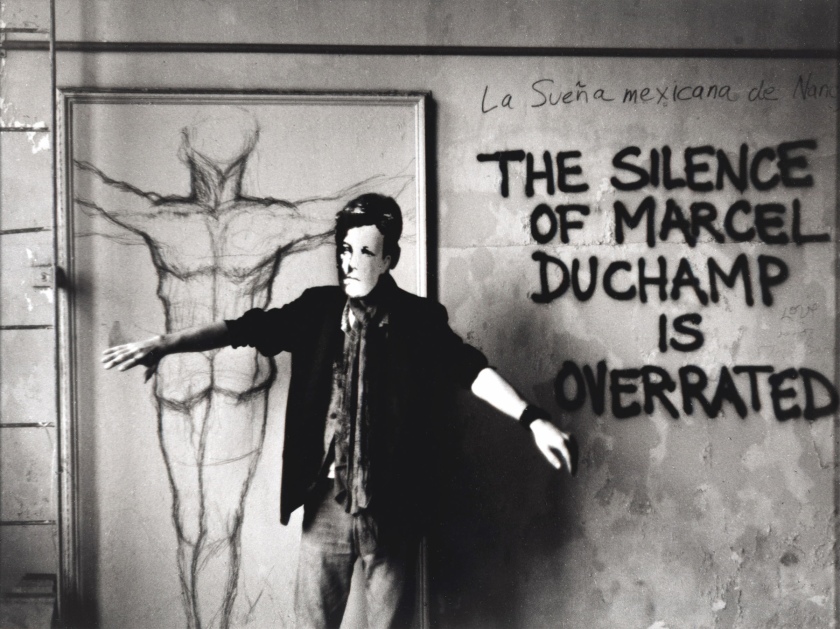

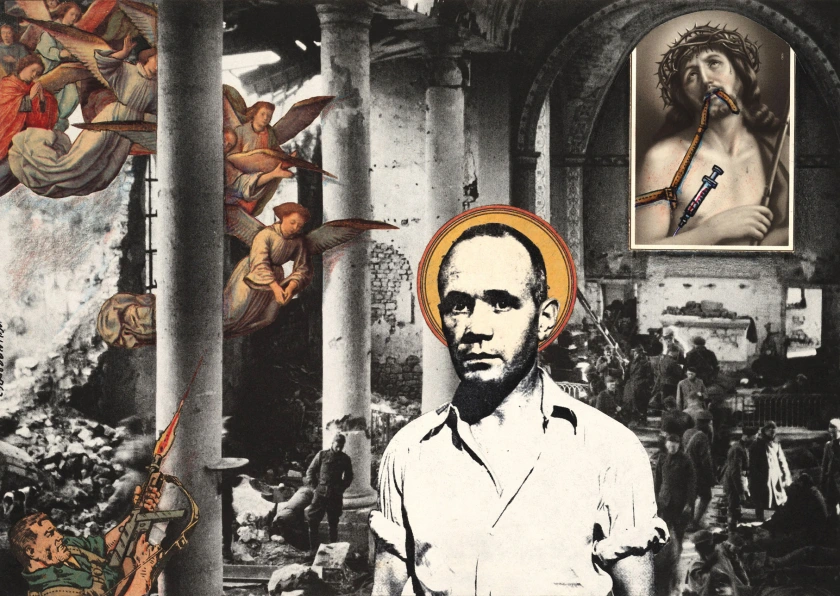

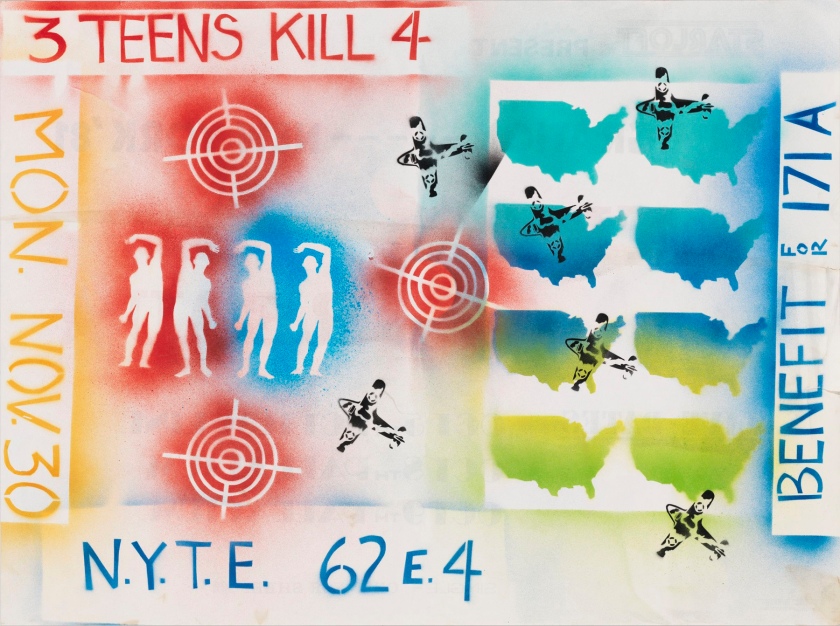

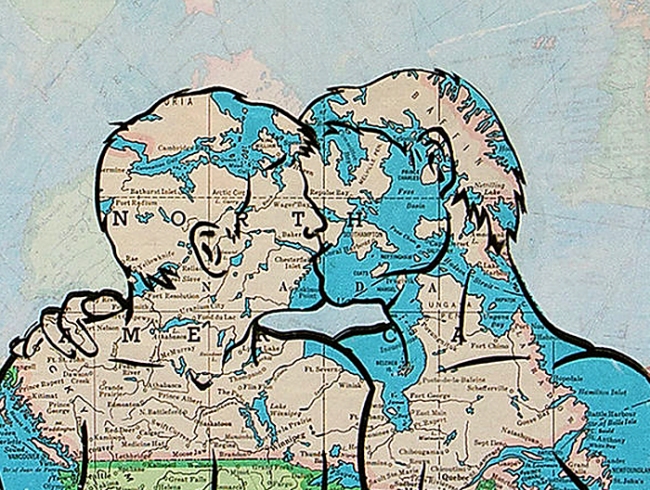

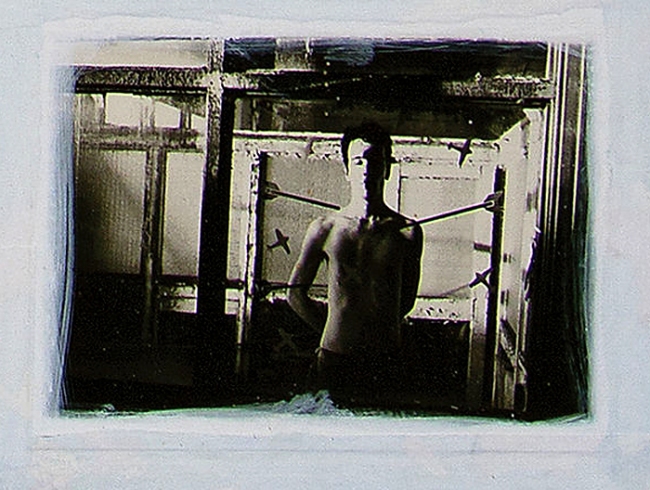

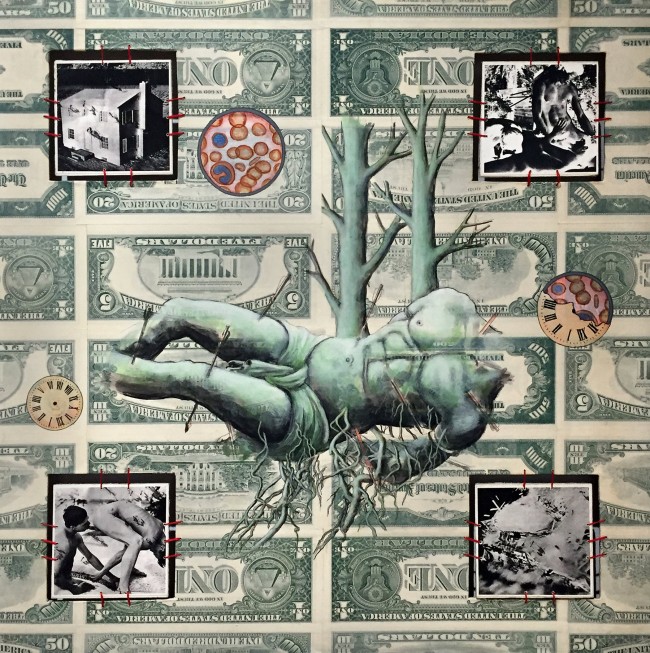

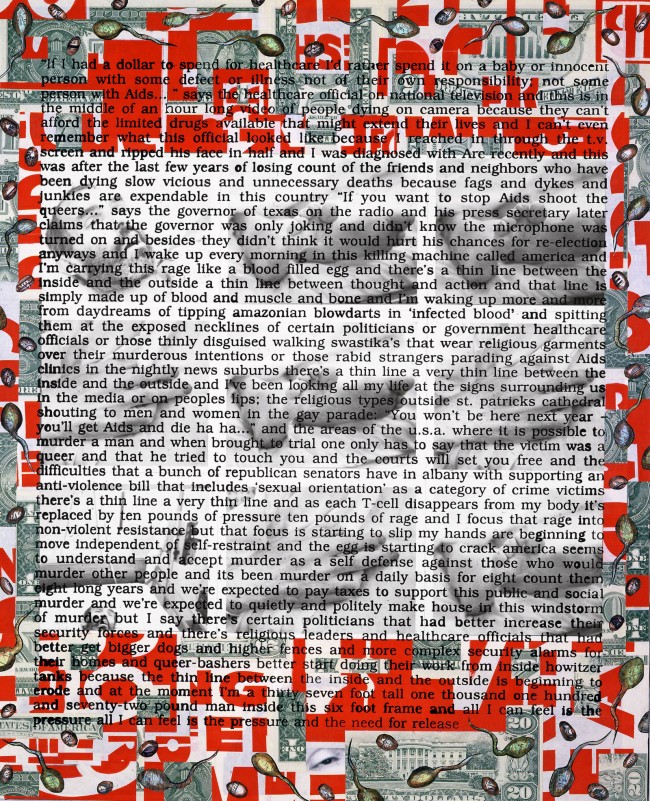

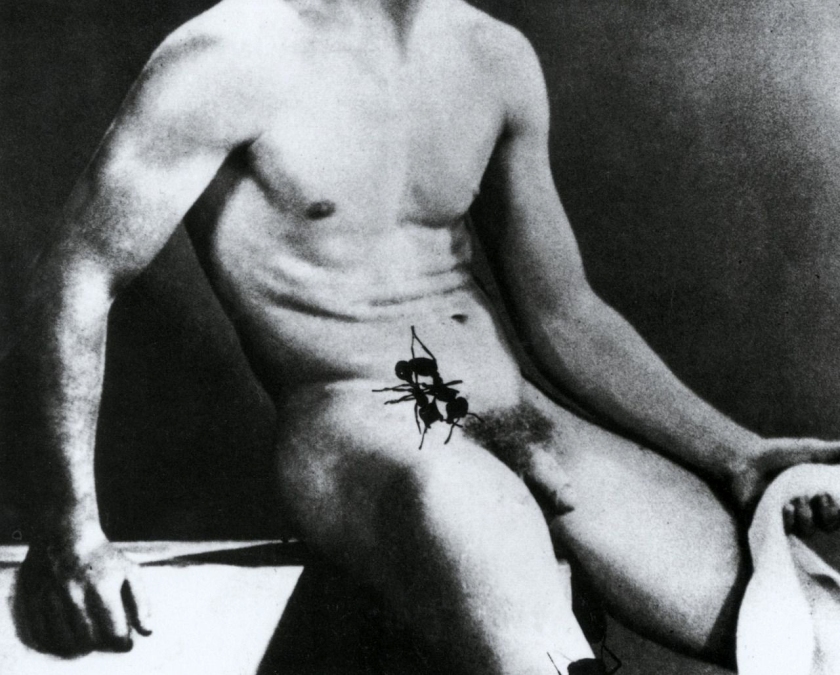

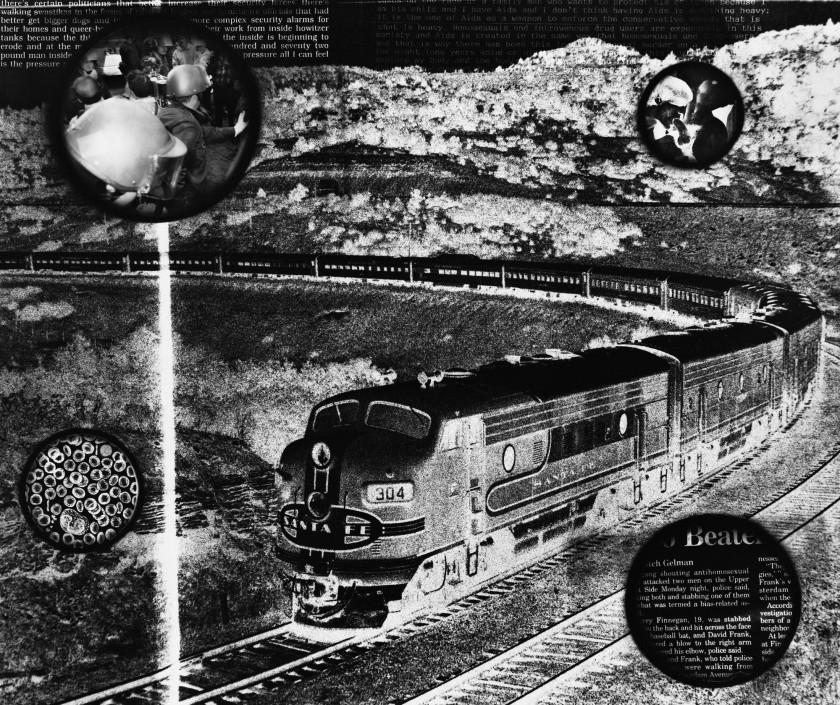

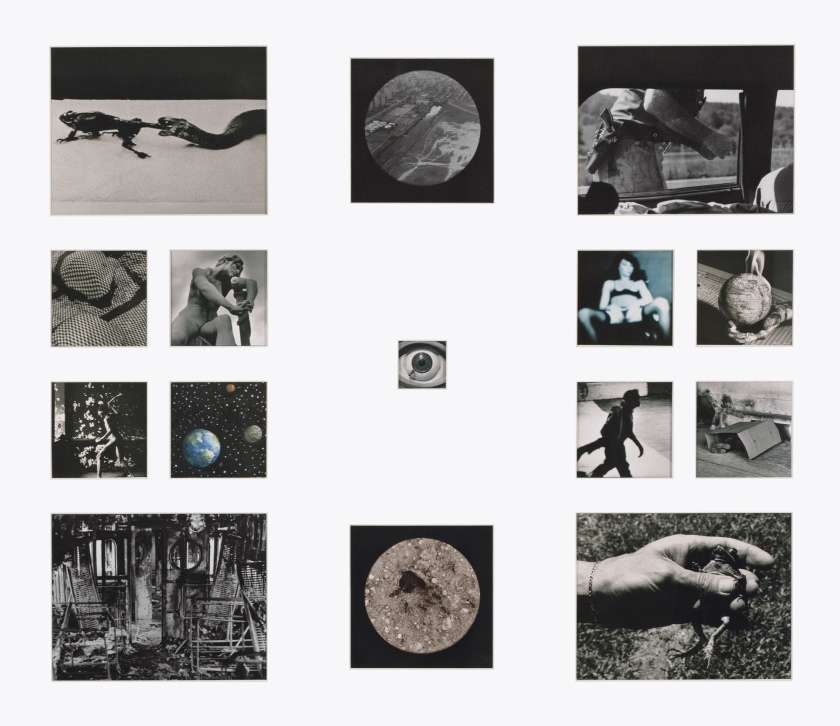

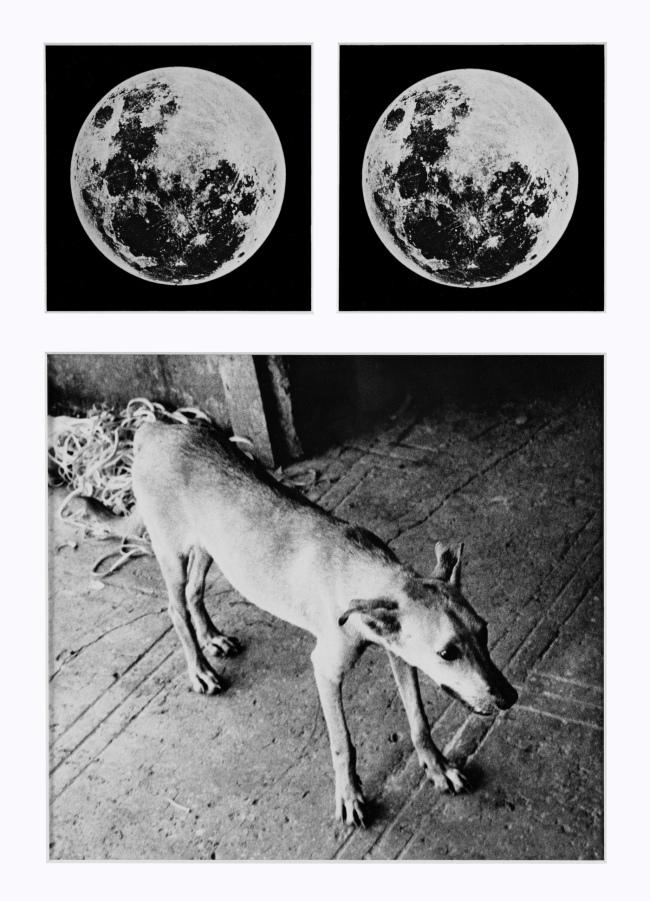

In the 1970s, artists such as Peter Hujar (below), David Wojnarowicz, Sunil Gupta (below) and Hal Fischer (below) photographed gay lifestyles in New York and San Francisco in a bid to claim public visibility and therefore legitimacy at a time when homosexuality was still a criminal offence. Reflecting on their own queer experience and creating sensual bodies of work, artists such as Rotimi Fani-Kayode (below) and Isaac Julien (below) portrayed black gay desire while Catherine Opie’s seminal work Being and Having, 1991 (below), documented members of the dyke, butch and BDSM communities in San Francisco playing with the physical attributes associated with hypermasculinity in order to overturn traditional binary understandings of gender.

Installation views of Masculinities: Liberation through Photography at Barbican Art Gallery on February 19, 2020 in London, England showing photographs by Karlheinz Weinberger

Photo: Tristan Fewings/Getty Images for Barbican Art Gallery

Karlheinz Weinberger (Swiss, 1921-2006)

Horseshoe buckle

1962

Courtesy Galerie Esther Woerdehoff

© Karlheinz Weinberger

Karlheinz Weinberger (Swiss, 1921-2006)

Sitting Boy with Elvis Necklace in KHW studio, Zurich

1961

Courtesy Galerie Esther Woerdehoff

© Karlheinz Weinberger

Peter Hujar (American, 1934-1987)

Orgasmic Man

1969

Gelatin silver print

Peter Hujar (American, 1934-1987)

Orgasmic Man (I)

1969

Gelatin silver print

Peter Hujar (American, 1934-1987)

Orgasmic Man (II)

1969

Gelatin silver print

Peter Hujar (American, 1934-1987)

David Brintzenhofe Applying Makeup (II)

1982

Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York, and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

© 1987 The Peter Hujar Archive LLC

Installation view of Masculinities: Liberation through Photography at Barbican Art Gallery on February 19, 2020 in London, England showing photographs from Sunil Gupta’s series Christopher Street 1976

Photo: Tristan Fewings/Getty Images for Barbican Art Gallery

Sunil Gupta (Indian, b. 1953)

Untitled #21

1976

From the series Christopher Street

Courtesy the artist and Hales Gallery

© Sunil Gupta. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2019

Gupta went on to study under Lisette Model at the New School and take his place among the most accomplished photographers, editors, and curators of his generation, exploring the way identities flower under various sexual, geographical, and historical conditions. But Christopher Street is where it all began. His subjects are engaged in an unprecedented moment in which it seemed possible to build a world of their own. He shows inner lives, barely concealed within the downturned face of a mustachioed man with his hands in his pockets, and outer ones as well, as other men cruise the lens right back, or laugh with each other, unbothered by the stranger with the camera. They were often just engaged in the everyday and extraordinary act of simply existing as gay. In each photograph, Gupta somehow projects a protective and versatile desire: to remember and be remembered at once.

Extract from Jesse Dorris. “Christopher Street Revisited,” on the Aperture website May 30th, 2019 [Online] Cited 29/02/2020

Sunil Gupta (Indian, b. 1953)

Untitled #56

1976

From the series Christopher Street

Courtesy the artist and Hales Gallery

© Sunil Gupta. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2019

The 1976 Christopher Street series marks the first set of photographs Gupta made as a practicing artist, using the camera as a tool for open expression. His decision to use black and white film was partly aesthetic, yet also practical, as he was developing the prints in his bathroom. Although he uses a documentarian style, Gupta was by no means an impartial observer behind the camera, he was a participant, enthralled by his subjects.

The series … captures a specific moment in history – a cross section of a thriving community in one of New York’s most dynamic areas – Manhattan’s Christopher Street. Dressed in the latest fashions, moving confidently and relaxing on street corners, their visible presence is a signifier of a specific period of public consciousness. Un-staged and spontaneous, most of the artist’s subjects are unaware of the camera and are simply going about their day. Now, with hindsight, Gupta is struck by the routineness of the images, stating:

‘There is a poignancy they never had at the time… A few years later, the AIDS crisis took hold. The public nature of gay life was forced back into the shadows. Thousands of men died. New York shut down its bathhouses, gay parties became private, and this whole world became hidden again.’

Fusing the public with the personal, the Christopher Street series reflects the openness of the gay liberation movement, as well as Gupta’s own “coming out” as an artist. More than a nostalgic time capsule, the photographs reveal a community that shaped Gupta as a person and cemented his lifelong dedication to portraying people who have been denied a space to be themselves.

Extract from Anonymous. “Sunil Gupta: Christopher Street,” on the Monovisions website 24 May 2019 [Online] Cited 29/02/2020

Hal Fischer (American, b. 1950)

Handkerchiefs

1977

From the series Gay Semiotics

Gelatin silver print

Hal Fischer (American, b. 1950)

Street Fashion Jock

1977

From the series Gay Semiotics

Gelatin silver print

Rotimi Fani-Kayode (Nigerian, 1955-1989)

Untitled

c. 1985

Courtesy of Autograph, London

© Rotimi Fani-Kayode

Installation view of Masculinities: Liberation through Photography at Barbican Art Gallery on February 19, 2020 in London, England showing at left, photographs from Isaac Julien’s series After Mazatlàn, 1999/2000

Photo: Tristan Fewings/Getty Images for Barbican Art Gallery

Isaac Julien (British, b. 1960)

From After Mazatlàn III – VI

1999/2000

Colour photogravures

33 x 43.2cm; 13 x 17 in

Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro, London/Venice

© Isaac Julien

Installation view of Masculinities: Liberation through Photography at Barbican Art Gallery on February 19, 2020 in London, England showing Catherine Opie’s series Being and Having 1991

Photo: Tristan Fewings/Getty Images for Barbican Art Gallery

Catherine Opie (American, b. 1961)

Bo from “Being and Having”

1991

Collection of Gregory R. Miller and Michael Wiener

© Catherine Opie, Courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles; Thomas Dane Gallery, London; and Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

The exhibition brings together over 300 works by over 50 pioneering international artists, photographers and filmmakers such as Richard Avedon, Peter Hujar, Isaac Julien, Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Robert Mapplethorpe, Annette Messager and Catherine Opie to show how photography and film have been central to the way masculinities are imagined and understood in contemporary culture. The show also highlights lesser-known and younger artists – some of whom have never exhibited in the UK – including Cassils, Sam Contis, George Dureau, Elle Pérez, Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Hank Willis Thomas, Karlheinz Weinberger and Marianne Wex amongst many others. Masculinities: Liberation through Photography is part of the Barbican’s 2020 season, Inside Out, which explores the relationship between our inner lives and creativity.

Jane Alison, Head of Visual Arts, Barbican, said: ‘Masculinities: Liberation through Photography continues our commitment to presenting leading twentieth century figures in the field of photography while also supporting younger contemporary artists working in the medium today. In the wake of the #MeToo movement and the resurgence of feminist and men’s rights activism, traditional notions of masculinity has become a subject of fierce debate. This exhibition could not be more relevant and will certainly spark conversations surrounding our understanding of masculinity.’

With ideas around masculinity undergoing a global crisis and terms such as ‘toxic’ and ‘fragile’ masculinity filling endless column inches, the exhibition surveys the representation of masculinity in all its myriad forms, rife with contradiction and complexity. Presented across six sections by over 50 international artists to explore the expansive nature of the subject, the exhibition touches on themes of queer identity, the black body, power and patriarchy, female perceptions of men, heteronormative hypermasculine stereotypes, fatherhood and family. The works in the show present masculinity as an unfixed performative identity shaped by cultural and social forces.

Seeking to disrupt and destabilise the myths surrounding modern masculinity, highlights include the work of artists who have consistently challenged stereotypical representations of hegemonic masculinity, including Collier Schorr, Adi Nes, Akram Zaatari and Sam Contis, whose series Deep Springs, 2018 draws on the mythology of the American West and the rugged cowboy. Contis spent four years immersed in an all-male liberal arts college north of Death Valley meditating on the intimacy and violence that coexists in male-only spaces. Complicating the conventional image of the fighter, Thomas Dworzak‘s acclaimed series Taliban consists of portraits found in photographic studios in Kandahar following the US invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, these vibrant portraits depict Taliban fighters posing hand in hand in front of painted backdrops, using guns and flowers as props with kohl carefully applied to their eyes. Trans masculine artist Cassils‘ series Time Lapse, 2011, documents the radical transformation of their body through the use of steroids and a rigorous training programme reflecting on ideas of masculinity without men. Elsewhere, artists Jeremy Deller, Robert Mapplethorpe and Rineke Dijkstra dismantle preconceptions of subjects such as the wrestler, the bodybuilder and the athlete and offer an alternative view of these hyper-masculinised stereotypes.

The exhibition examines patriarchy and the unequal power relations between gender, class and race. Karen Knorr‘s series Gentlemen, 1981-83, comprised of 26 black and white photographs taken inside men-only private members’ clubs in central London and accompanied by texts drawn from snatched conversations, parliamentary records and contemporary news reports, invites viewers to reflect on notions of class, race and the exclusion of women from spaces of power during Margaret Thatcher’s premiership. Toxic masculinity is further explored in Andrew Moisey‘s 2018 photobook The American Fraternity: An Illustrated Ritual Manual which weaves together archival photographs of former US Presidents and Supreme Court Justices who all belonged to the fraternity system, alongside images depicting the initiation ceremonies and parties that characterise these male-only organisations.

With the rise of the Gay Liberation Movement through the 1960s followed by the AIDS epidemic in the early 1980s, the exhibition showcases artists such as Peter Hujar and David Wojnarowiz, who increasingly began to disrupt traditional representations of gender and sexuality. Hal Fischer‘s critical photo-text series Gay Semiotics, 1977, classified styles and types of gay men in San Francisco and Sunil Gupta’s street photographs captured the performance of gay public life as played out on New York’s Christopher Street, the site of the 1969 Stonewall Uprising. Other artists exploring the performative aspects of queer identity include Catherine Opie‘s seminal series Being and Having, 1991, showing her close friends in the West Coast’s LGBTQ+ community sporting false moustaches, tattoos and other stereotypical masculine accessories. Elle Pérez‘s luminous and tender photographs explore the representation of gender non-conformity and vulnerability, whilst Paul Mpagi Sepuya‘s fragmented portraits explore the studio as a site of homoerotic desire.

During the 1970s women artists from the second wave feminist movement objectified male sexuality in a bid to subvert and expose the invasive and uncomfortable nature of the male gaze. In the exhibition, Laurie Anderson‘s seminal work Fully Automated Nikon (Object/Objection/Objectivity), 1973, documents the men who cat-called her as she walked through New York’s Lower East Side while Annette Messager‘s series The Approaches, 1972, covertly captures men’s trousered crotches with a long-lens camera. German artist Marianne Wex‘s encyclopaedic project Let’s Take Back Our Space: ‘Female’ and ‘Male’ Body Language as a Result of Patriarchal Structures, 1977, presents a detailed analysis of male and female body language and Australian indigenous artist Tracey Moffatt‘s awkwardly humorous film Heaven, 1997, portrays male surfers changing in and out of their wet suits.

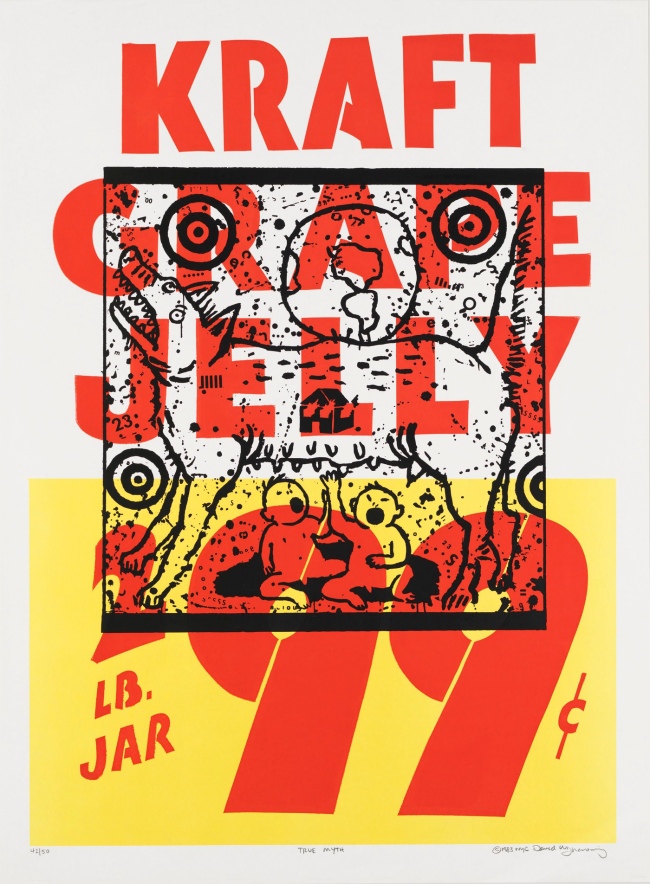

Further highlights include New York based artist Hank Willis Thomas, whose photographic practice examines the complexities of the black male experience; celebrated Japanese photographer Masahisa Fukase‘s The Family, 1971-1989, chronicles the life and death of his family with a particular emphasis on his father; and Kenneth Anger‘s technicolour experimental underground film Kustom Kar Kommandos, 1965, explores the fetishist role of hot rod cars amongst young American men.

Press release from the Barbican Art Gallery

Installation view of Masculinities: Liberation through Photography at Barbican Art Gallery on February 19, 2020 in London, England showing Hank Willis Thomas’ series Unbranded: Reflections in Black by Corporate America 1968-2008 2005-2008 (below)

Photo: Tristan Fewings/Getty Images for Barbican Art Gallery

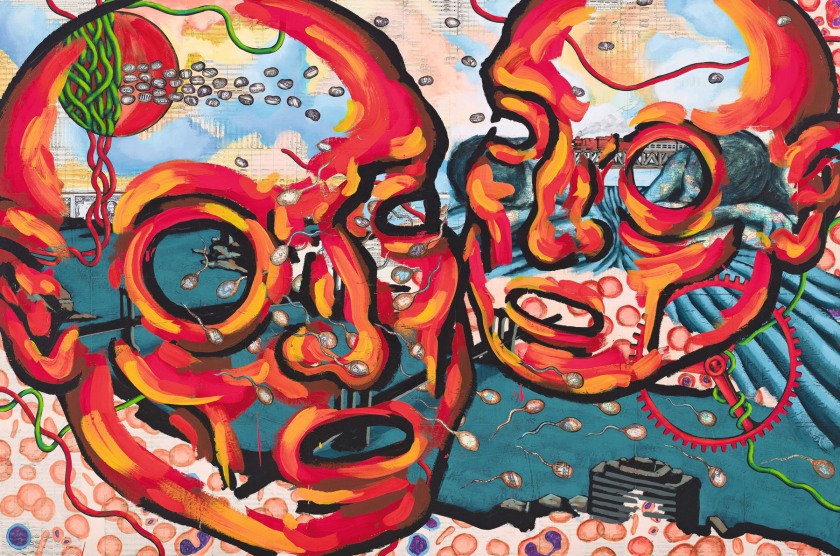

Room 13-14

Reclaiming the Black Body

Giving visual form to the complexity of the black male experience, this section foregrounds artists who over the last five decades have consciously subverted expectations of race, gender and the white gaze by reclaiming the power to fashion their own identities.

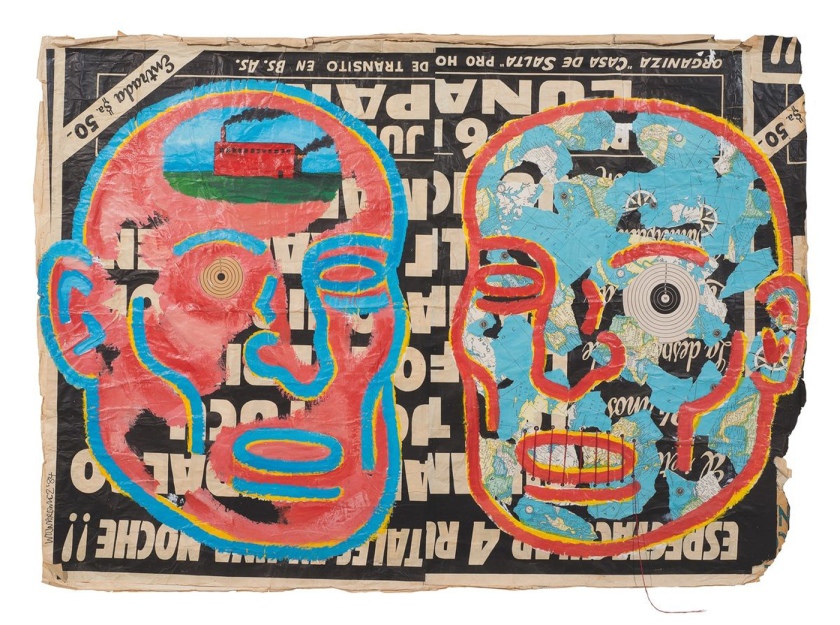

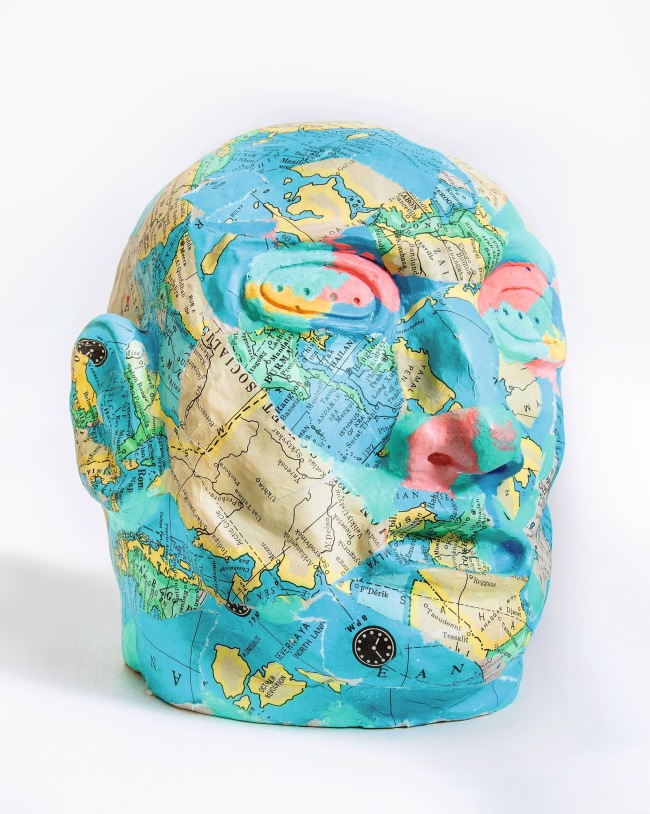

From Samuel Fosso’s playfully staged self-portraits, taken in his studio, in which he performs to the camera sporting flares and platforms boots or flirtatiously revealing his youthful male physique (below) to Kiluanji Kia Henda’s fictional scenarios in which he adopts the troubled personas of African men of power, the works presented here reflect on how black masculinity challenges the status quo (below).

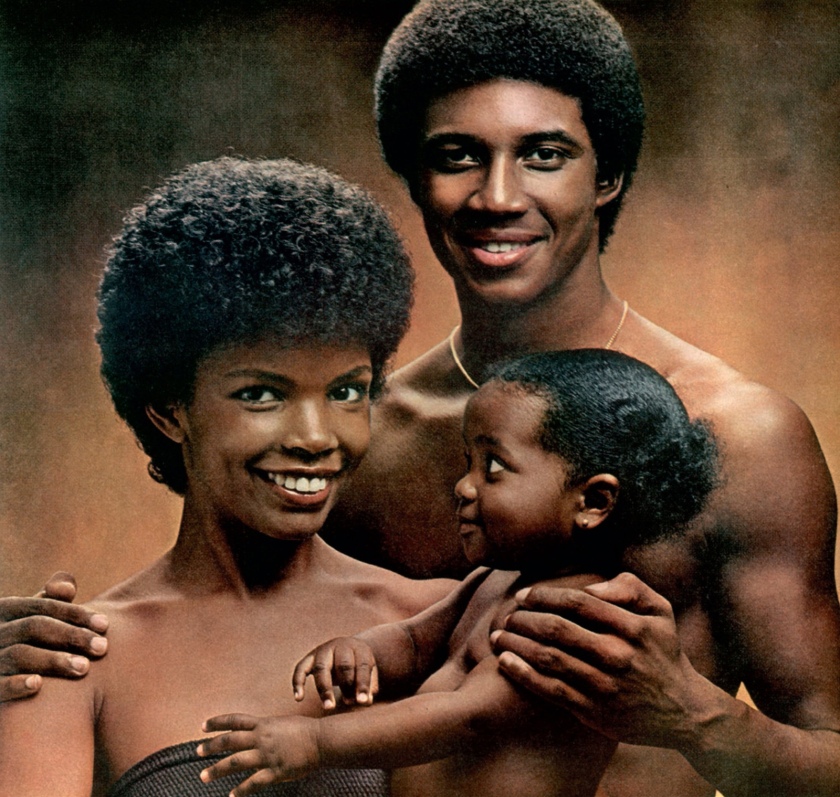

The representation of black masculinity in the US is born out of a violent history of slavery and prejudice. Unbranded: Reflections in Black by Corporate America 1968-2008 by Hank Willis Thomas (below) draws attention to the ways in which corporate America has commodified the African American male experience while simultaneously perpetuating and reinforcing cultural stereotypes. Similarly, Deana Lawson’s powerful work Sons of Cush, 2016, highlights how the black male figure is often ‘idealised (in their physical beauty) and pathologised by the culture (as symbols of violence or fear)’.

Hank Willis Thomas (American, b. 1976)

The Johnson Family

1981/2006

From the series Unbranded: Reflections in Black by Corporate America 1968-2008

2005-08

Concerned with the literal and figural objectifications of the African American male body, in his complex series Unbranded Hank Willis Thomas redeploys magazine adverts featuring African Americans made between 1968 – a pivotal moment in the struggle for civil rights – and 2008, which witnessed the accession of Barack Obama to the US presidency. By digitally stripping the ads of all text, branding and logos, Thomas draws attention to the ways in which corporate America has commodified the African American experience while simultaneously perpetuating and reinforcing cultural stereotypes.

Hank Willis Thomas (American, b. 1976)

It’s the Real Thing!

1978/2008

From the series Unbranded: Reflections in Black by Corporate America 1968-2008

2005-2008

Samuel Fosso (Cameroonian, b. 1962)

Self-portrait

1975-1977

From the series 70s lifestyle

Courtesy Jean Marc Patras, Paris

© Samuel Fosso

Installation view of Masculinities: Liberation through Photography at Barbican Art Gallery on February 19, 2020 in London, England showing a photograph from Kiluanji Kia Henda’s series The Last Journey of the Dictator Mussunda Nzombo Before the Great Extinction Act I

Photo: Tristan Fewings/Getty Images for Barbican Art Gallery

Hilary Lloyd (British, b. 1964)

Colin #2

1999

Courtesy Galerie Neu, Berlin; Sadie Coles HQ, London; Greene Naftali, New York

© Hilary Lloyd

Installation view of Masculinities: Liberation through Photography at Barbican Art Gallery on February 19, 2020 in London, England showing part of Marianne Wex’s encyclopaedic project Let’s Take Back Our Space: ‘Female’ and ‘Male’ Body Language as a Result of Patriarchal Structures, 1977

Photo: Tristan Fewings/Getty Images for Barbican Art Gallery

Room 15-16

Women on Men: Reversing the Male Gaze

As the second-wave feminist movement gained momentum through the 1960s and ’70s, female activists sought to expose and critique entrenched ideas about masculinity and to articulate alternative perspectives on gender and representation. Against this background, or motivated by its legacy, the artists gathered here have made men their subject with the radical intention of subverting their power, calling into question the notion that men are active and women passive.

In the early 1970s pioneers of feminist art such as Laurie Anderson (below) and Annette Messager consciously objectified the male body in a bid to expose the uncomfortable nature of the dominant male gaze. In contrast, filmmakers such as Tracey Moffatt (below) and Hilary Lloyd (above) turn the tables on male representations of desire to foreground the power of the female gaze.

In his humorous series The Ideal Man, 1978 (below), Hans Eijkelboom invited ten women to fashion him into their image of the ‘ideal’ man. Through this act Eijkelboom reverses the male to female power dynamic and inverts the traditional gender hierarchy.

Laurie Anderson (American, b. 1947)

Man with a Cigarette

1973

From the series Fully Automated Nikon (Object/Objection/Objectivity)

Laurie Anderson (American, b. 1947)

Two men in a car

1973

From the series Fully Automated Nikon (Object/Objection/Objectivity)

Anderson photographed men who called to her or whistled her on the street. In her artist statement she writes about one experience,

“As I walked along Houston Street with my fully automated Nikon. I felt armed, ready. I passed a man who muttered ‘Wanna fuck?’ This was standard technique: the female passes and the male strikes at the last possible moment forcing the woman to backtrack if she should dare to object. I wheeled around, furious. ‘Did you say that?’ He looked around surprised, then defiant ‘Yeah, so what the fuck if I did?’ I raised my Nikon, took aim began to focus. His eyes darted back and forth, an undercover cop? CLICK.

As it turned out, most of the men I shot that day had the opposite reaction. When i confronted them, the acted innocent, then offended, like some nasty invisible ventriloquist had ticked them into saying dirty words against their will. By the time I took their pictures they were posing, like taking their picture was the least I could do.”

“I decided to shoot pictures of men who made comments to me on the street. I had always hated this invasion of my privacy and now I had the means of my revenge. As I walked along Houston Street with my fully automated Nikon, I felt armed, ready. I passed a man who muttered ‘Wanna fuck?’ This was standard technique: the female passes and the male strikes at the last possible moment forcing the woman to backtrack if she should dare to object. I wheeled around, furious. ‘Did you say that?’ He looked around surprised, then defiant. ‘Yeah, so what the fuck if I did?’ I raised my Nikon, took aim, began to focus. His eyes darted back and forth, an undercover cop? CLICK.”

Anderson takes the power from her male pursuers, allowing them nothing more than the momentary fear that their depravity has just been captured in a picture.

Tracey Moffatt (Australian, b. 1960)

Heaven (still)

1997

Video tape (28 minutes)

© Tracey Moffatt / DACS Courtesy of the artist and Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney, Australia

“A playful video that glories in the female gaze and objectification of men. It zeros in on the Australian national sport, surfing, and in particular on several dozen good-looking muscular men changing into or out of their swimming trunks. This ritual is usually conducted in parking lots or on sidewalks, always near cars and sometimes inside them; it usually but not always involves a beach towel wound carefully around the torso. Ms Moffatt begins by shooting her subject unseen from inside a house and gradually moves closer and closer, engaging some in conversations that are never heard. The soundtrack alternates between the ocean surf and the sounds of drumming and chanting, male rituals of another, more authentic Australian culture. By the tape’s end, the artist’s voyeurism has shifted to participation; the camera shows her free hand, the one not holding the camera, darting into view, trying to undo the towel of the last surfer.”

New York Times

Installation view of Masculinities: Liberation through Photography at Barbican Art Gallery on February 19, 2020 in London, England showing part of Hans Eijkelboom’s series The Ideal Man, 1978

Glossary of Terms by CN Lester

Homosociality: Typically non-romantic and/or non-sexual same-sex relationships and social groupings – may sometimes include elements of homoeroticism, as they are frequently interdependent phenomena.

Normativity: The process by which some groups of people, forms of expression and types of behaviour are classified according to a perceived standard of what is ‘normal’, ‘natural’, desirable and permissible in society. Inevitably, this process designates people, expressions and behaviours that do not fit these norms as abnormal, unnatural, undesirable and impermissible.

Hegemonic Masculinity: ‘Hegemonic’ means ‘ruling’ or ‘commanding’ – hegemonic masculinity, therefore, indicates male dominance and the forms of masculinity occupying and perpetuating this dominant position. The term was coined in the 1980s by the scholar R. W. Connell, drawing on the Marxist philosopher Antonio Gramsci’s notion of cultural hegemony.

Hierarchy: Across many cultures throughout history, and continuing into the present moment throughout large parts of the world, gender functions as a hierarchy: some gender categories and gender expressions are granted higher value and more power than others. Men are often higher up the gender hierarchy than women, but the gender hierarchy is affected by racism, disablism, ageism, transphobia and other factors; in the West, men in their thirties are likely to be considered higher up the gender hierarchy than men in their eighties, for example.

Gender roles: Specific cultural roles defined by the weight of gendered ideas, restrictions and traditions. Men and women are often expected, sometimes forced, to occupy oppositional gender roles: aggressor versus victim, protector versus nurturer and so on. Many gender roles are specific to intersections of race, class, sexuality, religion and disabled status – examples of these types of gender roles can be seen in the stereotypes of the Jezebel or the Dragon Lady.

Patriarchy: Literally ‘the rule of the father’, a patriarchy is a society or structure centred around male dominance and in which women (and those of other genders) are not treated as or considered equal.

Queer: A slur, a term of reclamation and a specific and radical site of community and activism in solidarity with many kinds of difference, and specifically opposed to heteronormativity and cisnormativity. Queer studies and queer theory are important emerging fields of study.

Gender identity: Identity refers to what, who, and how someone or something is, both in the way this is understood as selfhood by an individual, and also the self as it is shaped and positioned by the world. Gender identity can be a surprisingly difficult term to pin down and is perhaps best understood as the stated truth of a person’s gender (or lack of gender), which is in itself the sum of many different factors.

Fetishisation: To turn the subject into a fetish, sexually or otherwise. Fetishisation in terms of gender and desire frequently occurs in conjunction with objectification and power. Men and women of colour are frequently fetishised by white people, in society and in artistic practice, through different stereotypes and limitations. Trans and disabled people are also subject to fetishisation, particularly in bodily terms. Kobena Mercer’s critical essay on Robert Mapplethorpe, ‘Reading Radical Fetishism’,1 and David Henry Hwang’s play and afterword to M. Butterfly (1988) both explore the notion of fetishisation.

1. Kobena Mercer, ‘Reading Racial Fetishism: The Photographs of Robert Mapplethorpe’, in Emily Apter and William Pietz, eds, Fetishism as Cultural Discourse (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1993), pp. 307-29.

Critical race theory: A branch of scholarship emerging from the application of critical theory to the study of law in the 1980s, critical race theory (CRT) is now taken as an approach and theoretical foundation across both academic and popular discourse. CRT names, examines and challenges the social constructions and functions of race and racism. Rejecting the idea of race as a ‘natural’ category, CRT looks instead to the cultural, structural and legal creation and maintenance of difference and oppression. Scholars working in this field include Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw, Eduardo Bonilla-Silva and Patricia Williams.

Me Too movement: ‘#MeToo is a movement that was founded in 2006 to support survivors of sexual violence, in particular black and brown girls, who were in the program that we were running. It has grown since then to include supporting grown people, women, and men, and other survivors, as well as helping people to understand what community action looks like in the fight to end sexual violence’ – Tarana Burke, founder of the Me Too movement.

Male gaze: A term coined by film critic Laura Mulvey, the notion of the male gaze develops Jean-Paul Sartre’s concept of le regard (the gaze) to take into account the power differentials and gender stereotyping inherent in ways of looking within patriarchal, sexist culture. The male gaze refers to how the world – and women in particular – are looked at and presented from a cisgender, straight, frequently white male perspective. In visual art the male gaze can be understood in multiple ways, from the male creator of the work, to men within the work viewing women or the world around them, to the (assumed) male viewer of the work itself. Many women artists have countered the male gaze through deconstruction and through the creation and promotion of works that centre the ‘female gaze’.

Installation views of Masculinities: Liberation through Photography at Barbican Art Gallery on February 19, 2020 in London, England

Photo: Tristan Fewings/Getty Images for Barbican Art Gallery

Barbican Art Gallery

Silk Street, London

EC2Y 8DS

Opening hours:

Mon – Tue 12 noon – 6pm

Wed – Fri 12 noon – 9pm

Sat 10am – 9pm

Sun 10am – 6pm

![Peter Hujar (American, 1934-1992) 'Canal Street Piers: Krazy Kat Comic on Wall [by David Wojnarowicz]' 1983 Peter Hujar (American, 1934-1992) 'Canal Street Piers: Krazy Kat Comic on Wall [by David Wojnarowicz]' 1983](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/07/peter-hujar-canal-street-piers-krazy-kat-comic-on-wall-by-david-wojnarowicz-web.jpg?w=650&h=656)

You must be logged in to post a comment.