26th January – 31st March 2019

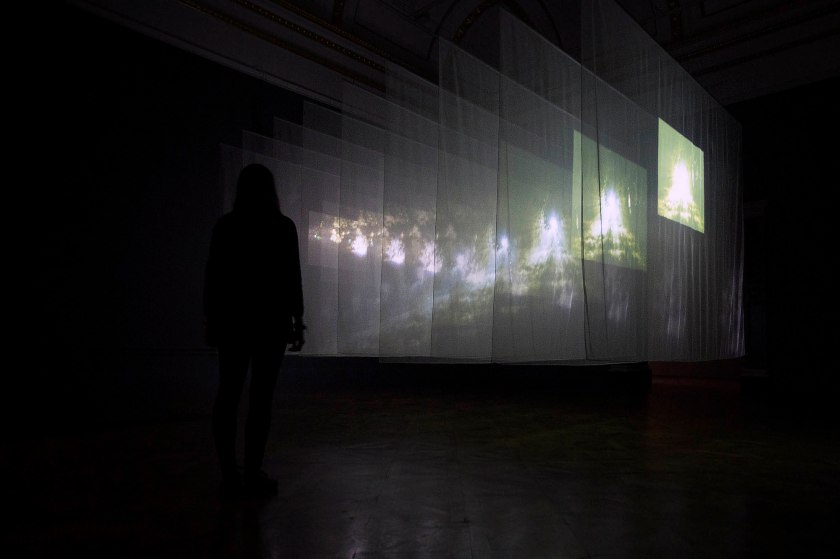

Bill Viola (American, b. 1951)

Nantes Triptych (still)

1992

Video/sound installation

Courtesy Bill Viola Studio

Photo: Kira Perov

Bill Viola (American, b. 1951)

Nantes Triptych (extract)

1992

Video/sound installation

Courtesy Bill Viola Studio

Far from heaven

On the surface (and there’s a key word), this exhibition pairs these two artists together as a form of immaculate concept(ion).

“Though working five centuries apart and in radically different media, these artists share a deep preoccupation with the nature of human experience and existence. Bill Viola / Michelangelo creates an artistic exchange between these two artists… It [the exhibition] proposes a dialogue between the two artists, considering Viola as an heir to a long tradition of spiritual and affective art, which makes use of emotion as a means of connecting viewers with its subject matter.” (Press release)

At the heart of both artists work is an exploration of the body as a vessel for the eternal soul, where the use of the body gives shape (through fundamental human experiences and emotions) to spirituality, and where both artists consider metaphysical questions about the nature of existence and reality.

One of the successes of the exhibition (when seen from afar) is the undoubted connection across time, space and culture between two human beings investigating what it is to be human: as Viola puts it, an understanding and awareness of “a deeper tradition, an undercurrent stretching across time and cultures… the ancient spiritual tradition that is concerned with self-knowledge.” In Viola’s work it is an essence of self reflection, the self reflection in water of the first humans, that recognition of self – that idea of self knowledge that is built into water – and his use of water (and other elements such as fire) as an immersive, nurturing, entombing, womb death environment in many of his video installations, that provides the impetus for his investigation.

But I have a nagging doubt about this pairing.

Viola’s work seems to be of a different order (of being) than that of Michelangelo. Even though Viola’s work connects the viewer to its subject matter through feeling and emotion, these feelings and emotions are viewed from the outside (Man Searching for Immortality / Woman Searching for Eternity). The camera objectifies this theatre of creation for our viewing pleasure. The video installations are performances which seem to be of a different kingdom to me (performance, theatre, spectacle) – whereas Michelangelo’s drawings seem to emanate from within. Not chemical, not organic, but something else which is so deeply embodied that they seem to come close to enlightenment.

How Viola fits into the great catalogue – we can only take in by what he tells us. And in time.

Because this spiritual investigation is mostly seen “through a glass darkly”, sometimes it has a, scent of being, not genuine – sometimes because we are all imperfect artists – but sometimes, through someone like Hilma af Klint, or Hokusai or, in this case, Michelangelo (“Michael angel”) it is much much more transparent… and closer to the surface. Am I making sense?

Sometimes they are about something I may somewhat understand in this lifetime (Viola) and sometimes they are about something that I don’t believe has been “released” to humanity fully. Perhaps a form of internal esoteric knowledge that may eventually be revealed to humanity. A mystery (derived from ‘mystic’ or ‘mysticism’ from the Greek μυω, meaning “to conceal”) which may reveal truths that surpass the powers of natural reason, a truth that transcends the created intellect.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

PS. The poem below has the terror of the sublime. A perfect picture of detachment and very nearly a complete picture of enlightenment. Is the human condition different from all other conditions? – that is the $64,000 question – if you say “no”, then this is a true poem. And of course, from the depths of the soul, who is having this conversation?

Many thankx to the Royal Academy of Arts for allowing me to publish the art work in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Is it far to go?

Is it far to go?

A step – no further.

Is it hard to go?

Ask the melting snow,

The eddying feather.

What can I take there?

Not a hank, not a hair.

What shall I leave behind?

Ask the hastening wind,

The fainting star.

Shall I be gone long?

For ever and a day.

To whom there belong?

Ask the stone to say,

Ask my song.

Who will say farewell?

The beating bell.

Will anyone miss me?

That I dare not tell –

Quick, Rose, and kiss me.

Cecil Day-Lewis

Cecil Day-Lewis (1904-1972) was appointed poet laureate by Queen Elizabeth II. He was an Irish poet and essayist, and a writer of mystery novels under the pen name of Nicholas Blake. He is the father of the actor Daniel Day-Lewis. The third stanza of this poem serves as the epitaph on his gravestone. “Rose” refers to Rosamond Lehmann, the British novelist who was his lover when he wrote this verse in the 1940’s.

This exhibition pairs Bill Viola’s powerful installations with rarely-seen drawings by Michelangelo. Journey through the cycle of life in our immersive and unparalleled show.

Michelangelo is best known for the Sistine Chapel and for his large sculptures. Yet his smaller, more intimate drawings take us closer to the spiritual and emotional power of his work. They were created for his private use, or as gifts of love, and would soon become known as “drawings the likes of which was never seen”.

In 2006, the pioneering video artist Bill Viola saw a collection of these works at Windsor Castle. He was moved by their ability to convey fundamental human experiences and emotions, and by Michelangelo’s use of the body to give shape to spirituality.

Viola’s large-scale video installations are likewise works of profound emotional impact. They combine sound and moving image to create absorbing works which slow us down and invite us to experience and reflect. These works are shown alongside Michelangelo drawings, which are on display in the UK for the first time in almost a decade.

This exhibition – created in close collaboration with Bill Viola Studio – is a unique opportunity to experience two artists, born centuries apart, in a new light.

Text from the RA website

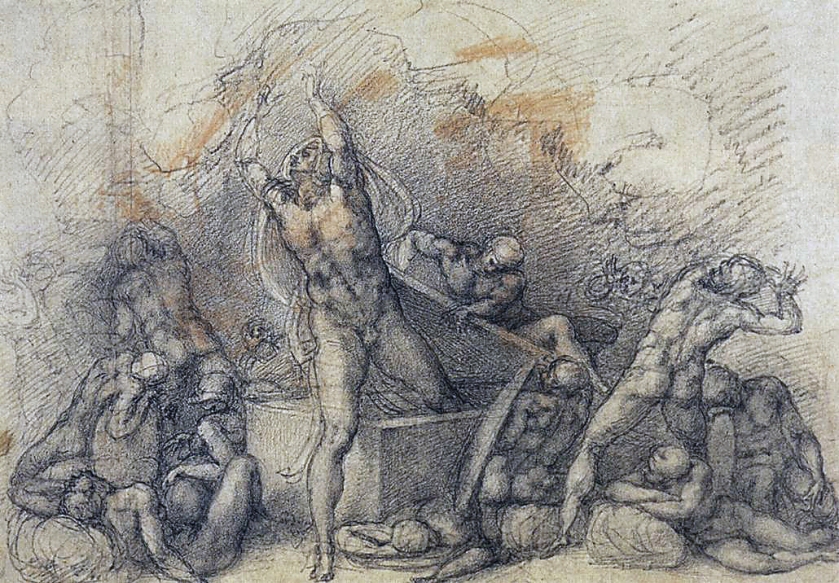

Installation views of the exhibition Bill Viola/Michelangelo: Life, Death, Rebirth at the Royal Academy of Arts, London showing:

Michelangelo Buonarroti (Italian, 1475-1564) LEFT

The Resurrection

c. 1532

Black chalk

Lent by Her Majesty the Queen

Michelangelo Buonarroti (Italian, 1475-1564) CENTRE

The Risen Christ

c. 1532-1533

Black chalk on paper

37.2 x 22.1cm

Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

Michelangelo Buonarroti (Italian, 1475-1564) RIGHT

The Resurrection

c. 1532-1533

Black chalk

Exhibition organised by the Royal Academy of Arts, London in partnership with Royal Collection Trust and with the collaboration of Bill Viola Studio. David Parry / © Royal Academy of Arts

Michelangelo Buonarroti (Italian, 1475-1564) LEFT

The Resurrection

c. 1532

Black chalk

Lent by Her Majesty the Queen

In the early 1530s Michelangelo drew the Resurrection of Christ more than a dozen times, for unknown reasons. Here he presents the transition to the eternal as a triumphant release, Christ as an explosion of energy amid the sepulchral gloom of the terrestrial sphere. The soldiers are prisoners of their earthly existence, lost in a death-like sleep, or recoiling from Christ in confusion at a sight beyond their comprehension.

Wall text from the exhibition

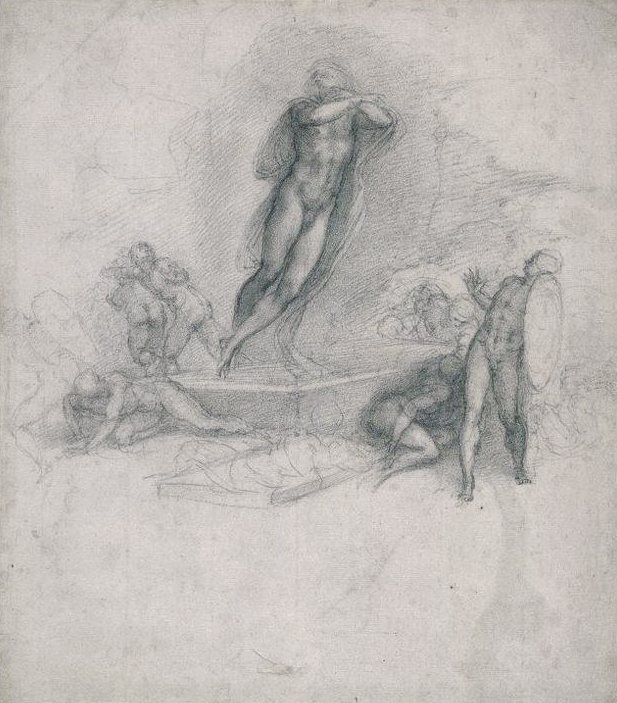

Michelangelo Buonarroti (Italian, 1475-1564) CENTRE

The Risen Christ

c. 1532-1533

Black chalk on paper

37.2 x 22.1cm

Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

In no other work by Michelangelo is the Resurrection expressed with such exuberance. Christ is long and virile, his muscular form modelled with tiny stokes of chalk, as highly finished as any of Michelangelo’s mythological drawings. It is perhaps paradoxical that a drawing of the triumph of the soul should so strongly emphasise Christ’s body, but his almost polished torso reflects the radiant light with a glory that transcends reality.

Wall text from the exhibition

Michelangelo Buonarroti (Italian, 1475-1564) RIGHT

The Risen Christ

c. 1532-1533

Black chalk on paper

37.2 x 22.1cm

Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

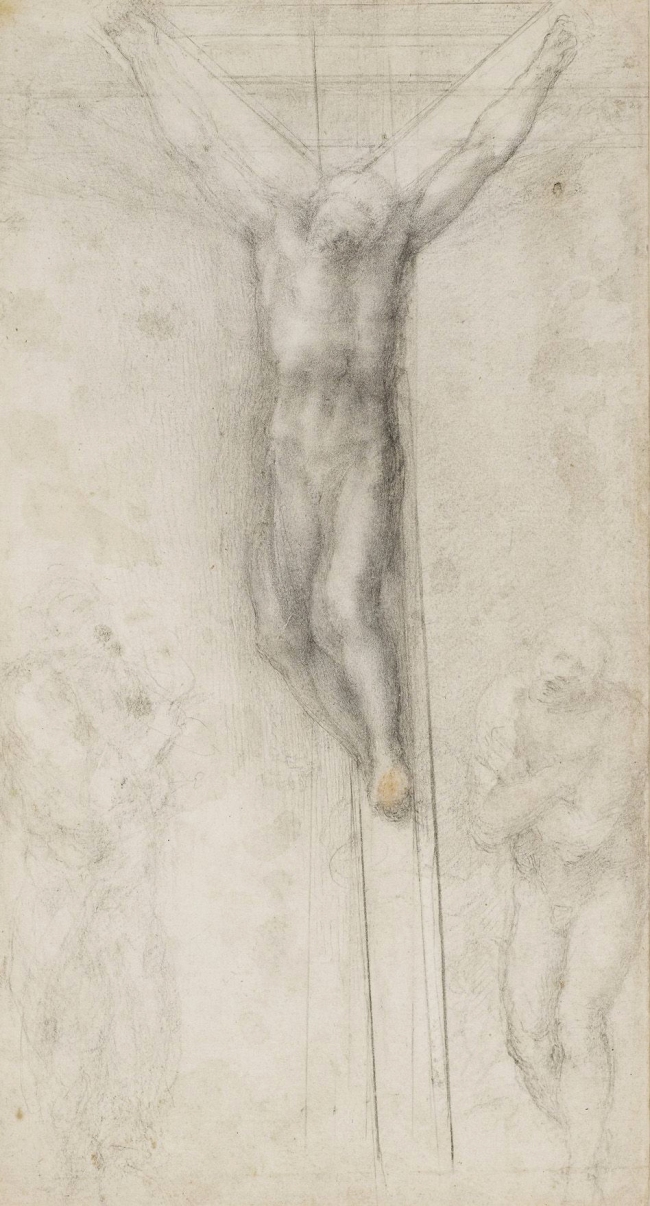

Installation views of the exhibition Bill Viola/Michelangelo: Life, Death, Rebirth at the Royal Academy of Arts, London showing:

Michelangelo Buonarroti (Italian, 1475-1564) LEFT

Christ on the Cross with the Virgin and St John

c. 1560-1564

Black chalk, white heightening and a touch of red chalk

Lent by Her Majesty the Queen

Michelangelo Buonarroti (Italian, 1475-1564) RIGHT

Christ on the Cross with the Virgin and St John

c. 1560-1564

Black chalk with white heightening

Lent by Her Majesty the Queen

Exhibition organised by the Royal Academy of Arts, London in partnership with Royal Collection Trust and with the collaboration of Bill Viola Studio. David Parry / © Royal Academy of Arts

Michelangelo Buonarroti (Italian, 1475-1564) LEFT

Christ on the Cross with the Virgin and St John

c. 1560-1564

Black chalk, white heightening and a touch of red chalk

Lent by Her Majesty the Queen

To the right, the hunched figure of St John is list in desolation, his arms tightly folded as if shivering, his mouth open in a pain both physical and mental. The patch of red chalk at Christ’s feet is probably deliberate, symbolic of the sacrificial blood that was shed on the Cross.

Michelangelo Buonarroti (Italian, 1475-1564) RIGHT

Christ on the Cross with the Virgin and St John

c. 1560-1564

Black chalk with white heightening

Lent by Her Majesty the Queen

Installation view of the exhibition Bill Viola/Michelangelo: Life, Death, Rebirth at the Royal Academy of Arts, London showing at centre Michelangelo Buonarroti, The Virgin and Child with the Infant St John, c. 1504-1505. Exhibition organised by the Royal Academy of Arts, London in partnership with Royal Collection Trust and with the collaboration of Bill Viola Studio. David Parry / © Royal Academy of Arts

Michelangelo Buonarroti (Italian, 1475-1564)

The Virgin and Child with the Infant St John (Taddei Tondo)

c. 1504-1505

Marble relief

107 x 107 x 22cm

Royal Academy of Arts, London. Bequeathed by Sir George Beaumont, 1830

© Royal Academy of Arts, London

Photo: Prudence Cuming Associates Limited

Installation view of the exhibition Bill Viola/Michelangelo: Life, Death, Rebirth at the Royal Academy of Arts, London with at left Michelangelo’s The Virgin and Child with the Infant St John (Taddei Tondo) c. 1504-1505; and at right, Bill Viola’s Nantes Triptych, 1992. Exhibition organised by the Royal Academy of Arts, London in partnership with Royal Collection Trust and with the collaboration of Bill Viola Studio. David Parry / © Royal Academy of Arts

Installation view of the exhibition Bill Viola/Michelangelo: Life, Death, Rebirth at the Royal Academy of Arts, London showing Bill Viola, Nantes Triptych, 1992. Exhibition organised by the Royal Academy of Arts, London in partnership with Royal Collection Trust and with the collaboration of Bill Viola Studio. David Parry / © Royal Academy of Arts

Michelangelo Buonarroti (Italian, 1475-1564)

The Lamentation over the Dead Christ

c. 1540

Black chalk

28.1 x 26.8cm

The British Museum, London. Exchanged with Colnaghi, 1896, 1896,0710.1

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Installation views of the exhibition Bill Viola/Michelangelo: Life, Death, Rebirth at the Royal Academy of Arts, London. Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019. Exhibition organised by the Royal Academy of Arts, London in partnership with Royal Collection Trust and with the collaboration of Bill Viola Studio. David Parry / © Royal Academy of Arts

In January 2019, the Royal Academy of Arts brings together the work of the pioneering video artist, Honorary Royal Academician Bill Viola (b. 1951), with drawings by Michelangelo (1475-1564). Though working five centuries apart and in radically different media, these artists share a deep preoccupation with the nature of human experience and existence. Bill Viola / Michelangelo creates an artistic exchange between these two artists and is a unique opportunity to see major works from Viola’s long career and some of the greatest drawings by Michelangelo, together for the first time. It is the first exhibition at the Royal Academy largely devoted to video art and has been organised in partnership with Royal Collection Trust.

The exhibition comprises 12 major video installations by Viola, from 1977 to 2013, being shown alongside 15 works by Michelangelo. They include 14 highly finished drawings, considered to be the high point of Renaissance drawing, as well as the Royal Academy’s Taddei Tondo. It proposes a dialogue between the two artists, considering Viola as an heir to a long tradition of spiritual and affective art, which makes use of emotion as a means of connecting viewers with its subject matter. It also aims to recapture the spiritual and emotional core of Michelangelo, beyond the awesome grandeur of his works.

Viola first encountered the works of the Italian Renaissance in Florence in the 1970s where he spent some of his formative years. A residency at the J Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, in 1998 renewed his interest in Renaissance art and in the shared affinities with his own practice. In 2006, Viola visited the Print Room at Windsor Castle to see Michelangelo’s exquisite drawings, which he had known in reproduction since his youth. The meeting proved a catalyst for the exhibition, which evolved as a conversation between Viola and Martin Clayton, Head of Prints and Drawings at Royal Collection Trust. Rather than setting up direct comparisons between the artists or suggesting that Michelangelo has been an instrumental influence on Viola’s work, the exhibition examines the affinities between them, bringing together specific works to explore resonances in their treatment of the fundamental questions: the nature of being, the transience of life, and the search for a greater meaning beyond mortality.

Viola stated, “Through my travels and experiences first in Florence, then primarily in non-Western cultures, and in combination with my readings in ancient philosophy and religion, I began to be aware of a deeper tradition, an undercurrent stretching across time and cultures… the ancient spiritual tradition that is concerned with self-knowledge.” Throughout his career, Viola has experimented with large-scale video installations; he is one of the first artists to have conceived video on an immersive architectural scale. He has increasingly utilised his medium’s fundamental elements – light, sound and time – to create visceral works that consider metaphysical questions about the nature of existence and reality. Unusually for video, they give shape to inner states of being rather than mirroring the world around us.

The exhibition presents Michelangelo’s works as more than examples of genius and virtuosity, revealing a personality that was frequently vulnerable. The drawings included were executed in the last 35 years of his life, some as gifts and expressions of love for close friends, others as private meditations on his own mortality. Religious imagery of the Virgin and Child, the Crucifixion and the Resurrection reflect on the presence of death and the eternal. In others, references to Classical mythology act as metaphors for the human condition. At their heart, as with Viola’s work, is an exploration of the body as a vessel for the eternal soul.

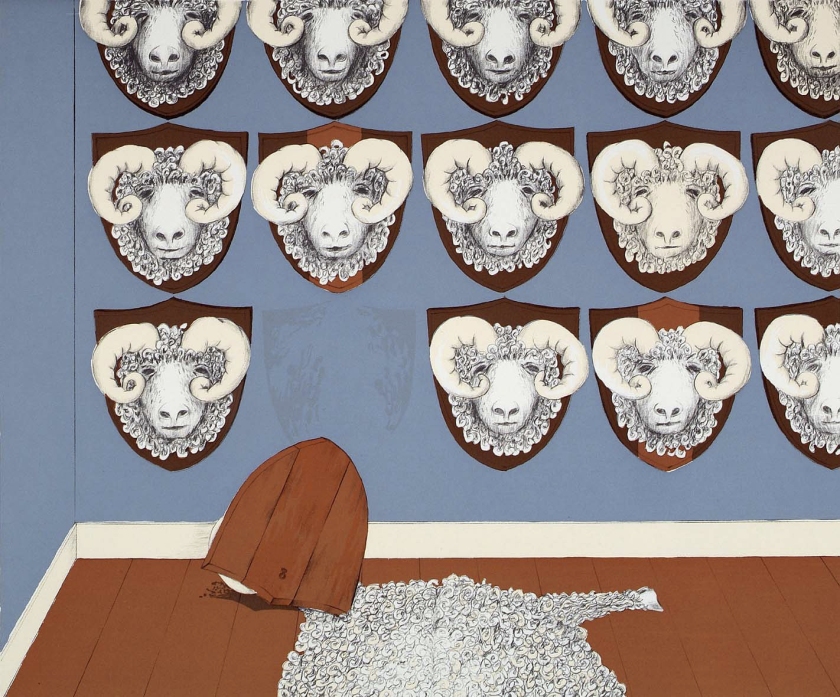

The exhibition is conceived as an immersive journey through the cycles of life, exploring the transience and tumult of existence and the possibility of rebirth. It begins and ends with a pairing of works that reflect on a central paradox: the presence of death in life. Michelangelo’s The Virgin and Child with the Infant St John the Baptist, c. 1504-1505, known as the Taddei Tondo, depicts the Baptist holding a fluttering bird from which the infant Christ recoils, the scene heralding his eventual sacrifice on the Cross. It is being displayed alongside Viola’s The Messenger, 1996 (Bill Viola Studio), which uses the metaphor of water to depict the eternal cycle of birth, life and death. The theme is being further explored in drawings relating to the Virgin and Child, as well as the Lamentation, c. 1540 (British Museum, London), which is being shown facing Viola’s Nantes Triptych, 1992 (Bill Viola Studio), three screens that individually portray a woman giving birth, a figure floating in a mysterious half-light, and Viola’s own mother on her deathbed. Viola stated, “It is the awareness of our own mortality that defines the nature of human beings”.

The exhibition continues with a series of installations by Viola that reflect on the nature of human experience, as one set by moral and ethical choices, besieged by fears and ultimately experienced in solitude. At the centre of the exhibition is Michelangelo’s extraordinary Presentation Drawings of the 1530s (loaned by Her Majesty The Queen, Royal Collection, London), which he produced as gifts for Tommaso de’ Cavalieri, a young Roman nobleman for whom he developed a deep love. Demonstration pieces relating to the craft of drawing with chalk, they also explore complex myths and Neoplatonic concepts, and were created as expressions of devotion towards their recipient. They include the Tityus, 1532, which acts as an allegory for the opposed forms of love in Neoplatonic philosophy: the punishment of base lust devoid of spiritual love. Further drawings by Michelangelo explore similar allegorical struggles in life, from the labours of Hercules to the fall of Phaeton. These are being shown in opposition to the quiet stillness of Viola’s Man Searching for Immortality/Woman Searching for Eternity, 2013 (Bill Viola Studio). Life-size images of an ageing man and woman are projected onto two black granite slabs, showing them slowly examining every inch of their naked bodies by torchlight, unable to hide from their earthly state.

The final galleries include a series of works that more directly consider mortality and the possibility of rebirth. Among them are Michelangelo’s most poignant drawings, two Crucifixions from the final years of his life. The exhibition concludes two of Viola’s most majestic works; the monumental projections, Fire Woman, 2005, (Bill Viola Studio), and Tristan’s Ascension (The Sound of a Waterfall Under a Mountain), 2005 (Bill Viola Studio). They depict bodies falling and rising out of view, in different ways conjuring the body’s final journey and the passage of the spirit, in obscurity or in glory.

Press release from the RA Cited 23/02/2019

Bill Viola (American, b. 1951)

Tristan’s Ascension (The Sound of a Mountain Under a Waterfall) (extract)

2005

Video/sound installation

Performer: John Hay

Courtesy Bill Viola Studio

Photo: Kira Perov

Bill Viola (American, b. 1951)

Tristan’s Ascension (The Sound of a Mountain Under a Waterfall) (still)

2005

Video/sound installation

Performer: John Hay

Courtesy Bill Viola Studio

Photo: Kira Perov

Installation view of the exhibition Bill Viola/Michelangelo: Life, Death, Rebirth at the Royal Academy of Arts, London showing Bill Viola’s Tristan’s Ascension (The Sound of a Mountain Under a Waterfall) 2005 (still). Exhibition organised by the Royal Academy of Arts, London in partnership with Royal Collection Trust and with the collaboration of Bill Viola Studio. David Parry / © Royal Academy of Arts

Bill Viola, Fire Woman and Tristan’s Ascension (The Sound of a Mountain Under a Waterfall), St Carthage’s Church, Parkville, Melbourne

Bill Viola (American, b. 1951)

Fire Woman (still)

2005

Video/sound installation

Performer: Robin Bonaccorsi

Courtesy Bill Viola Studio

Photo: Kira Perov

Installation view of the exhibition Bill Viola/Michelangelo: Life, Death, Rebirth at the Royal Academy of Arts, London showing Bill Viola’s Fire Woman 2005 (still). Exhibition organised by the Royal Academy of Arts, London in partnership with Royal Collection Trust and with the collaboration of Bill Viola Studio. David Parry / © Royal Academy of Arts

Installation view of the exhibition Bill Viola/Michelangelo: Life, Death, Rebirth at the Royal Academy of Arts, London showing Bill Viola’s The Veiling, 1995. Exhibition organised by the Royal Academy of Arts, London in partnership with Royal Collection Trust and with the collaboration of Bill Viola Studio. David Parry / © Royal Academy of Arts

Installation view of the exhibition Bill Viola/Michelangelo: Life, Death, Rebirth at the Royal Academy of Arts, London showing Bill Viola’s Five Angels for the Millenium, 2001. Exhibition organised by the Royal Academy of Arts, London in partnership with Royal Collection Trust and with the collaboration of Bill Viola Studio. David Parry / © Royal Academy of Arts

Bill Viola, “Departing Angel”, from Five Angels for the Millennium 2001 (excerpt)

Installation views of the exhibition Bill Viola/Michelangelo: Life, Death, Rebirth at the Royal Academy of Arts, London showing Bill Viola’s The Dreamers, 2013. Exhibition organised by the Royal Academy of Arts, London in partnership with Royal Collection Trust and with the collaboration of Bill Viola Studio. David Parry / © Royal Academy of Arts

The Dreamers (2013) consists of seven individual screens, which depict underwater portraits of people who appear to be sleeping. Accompanied by the gentle sounds of water, the viewer is led to feel as if they themselves are submerged with these figures. In this spiritual, immersive subterranean environment, ultimate interpretation is left for the viewer to define, through the lens of their own experiences. (excerpt)

Bill Viola, The Dreamers (excerpt)

Installation view of the exhibition Bill Viola/Michelangelo: Life, Death, Rebirth at the Royal Academy of Arts, London showing Bill Viola’s Man Searching for Immortality/Woman Searching for Eternity, 2013. Exhibition organised by the Royal Academy of Arts, London in partnership with Royal Collection Trust and with the collaboration of Bill Viola Studio. David Parry / © Royal Academy of Arts

Bill Viola, Man Searching for Immortality/Woman Searching for Eternity, 2013 (excerpt)

Installation view of the exhibition Bill Viola/Michelangelo: Life, Death, Rebirth at the Royal Academy of Arts, London showing Bill Viola’s The Sleep of Reason, 1988. Exhibition organised by the Royal Academy of Arts, London in partnership with Royal Collection Trust and with the collaboration of Bill Viola Studio. David Parry / © Royal Academy of Arts

Installation view of the exhibition Bill Viola/Michelangelo: Life, Death, Rebirth at the Royal Academy of Arts, London showing Bill Viola’s Slowly Turning Narrative, 1992. Exhibition organised by the Royal Academy of Arts, London in partnership with Royal Collection Trust and with the collaboration of Bill Viola Studio. David Parry / © Royal Academy of Arts

Bill Viola, The Messenger 1996 (excerpt)

Installation views of the exhibition Bill Viola/Michelangelo: Life, Death, Rebirth at the Royal Academy of Arts, London showing Bill Viola’s The Messenger, 1996. Exhibition organised by the Royal Academy of Arts, London in partnership with Royal Collection Trust and with the collaboration of Bill Viola Studio. David Parry / © Royal Academy of Arts

Royal Academy of Arts

Burlington House, Piccadilly,

London, W1J 0BD

Opening hours:

Daily 10am – 6pm

Friday 10am – 10pm

You must be logged in to post a comment.