Exhibition dates: 15th February – 11th June 2017

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

The State We’re In, A (Room 14)

2015

Ink-jet print

Dimensions variable

© Wolfgang Tillmans

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

The Cock (Kiss)

2002

Ink-jet print

Dimensions variable

© Wolfgang Tillmans

If one thing matters, everything matters

(A love letter to Wolfgang Tillmans)

I believe that Wolfgang Tillmans is the number one photo-media artist working today. I know it’s a big call, but that’s how I see it.

His whole body of work is akin to a working archive – of memories, places, contexts, identities, landscapes (both physical and imagined) and people. He experiments, engages, and imagines all different possibilities in and through art. As Adrian Searle observes in his review of the exhibition, “Tillmans’ work is all a kind of evidence – a sifting through material to find meaning.” And that meaning varies depending on the point of view one comes from, or adopts, in relation to the art. The viewer is allowed to make their own mind up, to dis/assemble or deepen relationships between things as they would like, or require, or not as the case may be. Tillmans is not didactic, but guides the viewer on that journey through intersections and nodal points of existence. The nexus of life.

Much as I admire the writing of art critic John McDonald, I disagree with his assessment of the work of Wolfgang Tillmans at Tate Modern (see quotation below). Personally, I find that there are many memorable photographs in this exhibition … as valuable and as valid a way of seeing the world in a contemporary sense, as Eggleston’s photographs are in a historic visualisation. I can recall Tillmans’ images just an intimately as I can Eggleston’s. But they are of a different nature, and this is where McDonald’s analysis is like comparing apples and pears. Eggleston’s classical modernist photographs depend on the centrality of composition where his images are perfectly self-contained, whether he is photographing a woman in a blue dress sitting on a kerb or an all green bathroom. They are of their time. Times have changed, and how we view the world has changed.

For Tillmans no subject matter is trivial (If One Thing Matters, Everything Matters – the title of a 2003 exhibition at Tate Britain), and how he approaches the subject is totally different from Eggleston. As he says of his work, his images are “calls to attentiveness.” What does he mean by this? Influenced by the work of the philosopher Jiddu Krishnamurti whom I have also studied, a call to attentiveness is a way of being open and responsive to the world around you, to its infinite inflections, and to not walk around as if in a dream, letting the world pass you by. To be open and receptive to the energies and connections of the world spirit by seeing clearly.

Krishnamurti insightfully observed that we do not need to make images out of every word, out of every vision and desire. We must be attentive to the clarity of not making images – of desire, of prejudice, of flattery – and then we might become aware of the world that surrounds us, just for what it is and nothing more.1 Then there would be less need for the absenting of self into the technological ether or the day dreams of foreign lands or the desire for a better life. But being aware is not enough, we must be attentive of that awareness and not make images just because we can or must. This is a very contemporary way of looking at the world. As Krishnamurti says,

“Now with that same attention I’m going to see that when you flatter me, or insult me, there is no image, because I’m tremendously attentive … I listen because the mind wants to find out if it is creating an image out of every word, out of every contact. I’m tremendously awake, therefore I find in myself a person who is inattentive, asleep, dull, who makes images and gets hurt – not an intelligent man. Have you understood it at least verbally? Now apply it. Then you are sensitive to every occasion, it brings its own right action. And if anybody says something to you, you are tremendously attentive, not to any prejudices, but you are attentive to your conditioning. Therefore you have established a relationship with him, which is entirely different from his relationship with you. Because if he is prejudiced, you are not; if he is unaware, you are aware. Therefore you will never create an image about him. You see the difference?”2

Then you are sensitive to every occasion, it brings its own right action. You are attentive and tremendously awake.

This is the essence of Tillmans work. He is tremendously attentive to the images he is making (“a representation of an unprivileged gaze or view” as he puts it) and to the associations that are possible between images, that we make as human beings. He is open and receptive to his conditioning and offers that gift to us through his art, if we recognise it and accept it for what it is. If you really look and understand what the artist is doing, these images are music, poetry and beauty – are time, place, belonging, voyeurism, affection, sex. They are archaic and shapeless and fluid and joy and magic and love…

They are the air between everything.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ Krishnamurti. Beginnings of Learning. London: Penguin, 1975, p. 131

2/ Ibid., pp. 130-131

Many thankx to the Tate Modern for allowing me to publish the art work in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“To look at Eggleston alongside those he has inspire [Wolfgang Tillmans and Juergen Teller for example] is to see a surprisingly old-fashioned artist. No matter how instinctive his approach or how trivial his subjects, Eggleston believes in the centrality of composition. His images are perfectly self-contained. They don’t depend on a splashy, messy installation or a political stance. …

In the current survey of Tillmans’s work at Tate Modern photos of every description are plastered across the walls in the most anarchic manner, with hardly a memorable composition. Yet this shapeless stuff is no longer reviled by the critics – it’s the height of fashion.”

John McDonald for The Sydney Morning Herald column. “William Eggleston: Portraits” on the John McDonald website June 1, 2017 [Online] Cited 17/12/2021

“For a long time in Britain, there was a deep suspicion of my work. People saw me as a commercial artist trying to get into the art world, and the work was dismissed as shallow or somehow lightweight. There are still many misconceptions about what I do – that my images are random and everyday, when they are actually neither. They are, in fact, the opposite. They are calls to attentiveness.”

Wolfgang Tillmans quoted in Sean O’Hagan. “Wolfgang Tillmans: ‘I was hit by a realisation – all I believed in was threatened’,” on The Guardian website Monday 13 February 2017 [Online] Cited 17/12/2021

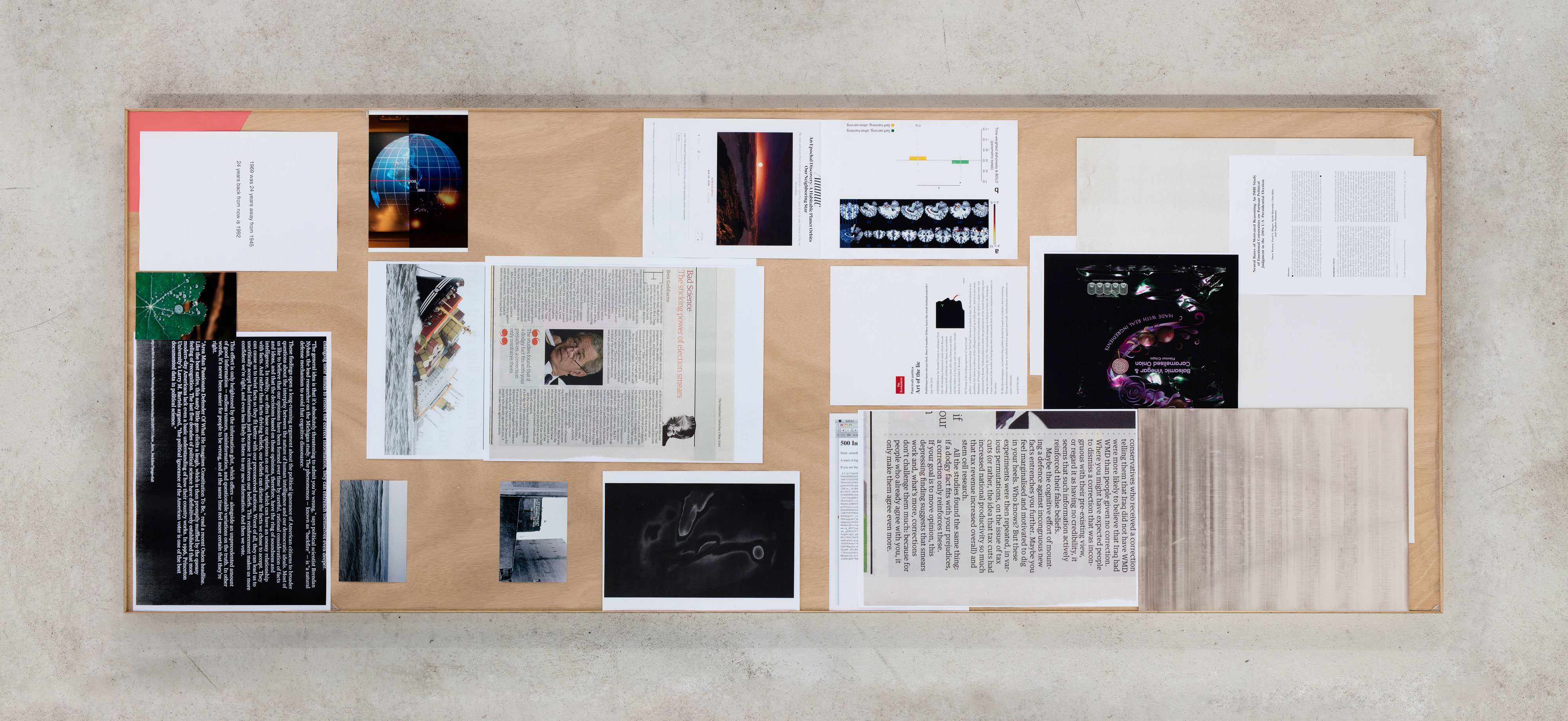

Installation view of room 4 (detail), which includes the latest iteration of the truth study centre project, with

Image © Tate Modern showing Wolfgang Tillmans: 2017 at Tate Modern 15 February – 11 June

The Tate show includes a room full of his “truth study centres”, which comprise often contradictory newspaper cuttings as well as photographs and pamphlets that aim to show how news is manipulated according to the political loyalties of those who produce it. As activists go, though, Tillmans is defiantly centre ground. “This is about strengthening the centre. I can understand left-wing politics from a passionate, idealistic point of view, but I do not think it is the solution to where we are now. The solution is good governance, moderation, agreement. Post-Brexit, post-Trump, the voices of reason need to be heard more than ever.”

Wolfgang Tillmans quoted in Sean O’Hagan. “Wolfgang Tillmans: ‘I was hit by a realisation – all I believed in was threatened’,” on The Guardian website Monday 13 February 2017 [Online] Cited 17/12/2021

Installation view of room 13 (detail), which focuses in on Tillmans’ portraiture with Eleanor / Lutz, a (2016) at right

Image © Tate Modern showing Wolfgang Tillmans: 2017 at Tate Modern 15 February – 11 June

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Eleanor / Lutz, a

2016

Ink-jet print

Dimensions variable

© Wolfgang Tillmans

Portrait of Wolfgang Tillmans, Tate Modern Boiler House, Level 3, 14/02/2017 in front of his works, Transient 2, 2015 and Tag/Nacht II, 2010

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Tag/Nacht II

2010

Ink-jet print

Dimensions variable

© Wolfgang Tillmans

The State We’re In, A, is part of Neue Welt [New World], the loose family of pictures I began at the end of the last decade. These had two points of departure: “What does the outside world look like to me 20 years after I began photographing?” and “What does it look like in particular with a new photographic medium?”

Wolfgang Tillmans

“This exhibition is not about politics, it’s about poetry, it’s about installation art. It’s about thinking about the world. I’ve never felt that l can be separated, because the political is only the accumulation of many people’s private lives, which constitute the body politics…”

“My work has always been motivated by talking about society, by talking about how we live together, by how we feel in our bodies. Sexuality, like beauty, is never un-political, because they relate to what’s accepted in society. Two men kissing, is that acceptable? These are all questions to do with beauty.”

Wolfgang Tillmans quoted in Lorena Muñoz-Alonso. “Inside Wolfgang Tillmans’s Superb Tate Modern Survey,” on the artnet website February 15, 2017 [Online] Cited 17/12/2021

“There is music. There is dancing. Bewilderment is part of the pleasure, as we move between images and photographic abstractions. Tillmans’ asks us to make connections of all kinds – formal, thematic, spatial, political. He asks what the limits of photography are. There are questions here about time, place, belonging, voyeurism, affection, sex. After a while it all starts to tumble through me.”

Adrian Searle. “Wolfgang Tillmans review – a rollercoaster ride around the world,” on The Guardian website Wednesday 15 February 2017 [Online] Cited 17/12/2021

What are we to make of the world in which we find ourselves today? Contemporary artist Wolfgang Tillmans offers plenty of food for thought.

This is Wolfgang Tillmans’s first ever exhibition at Tate Modern and brings together works in an exciting variety of media – photographs, of course, but also video, digital slide projections, publications, curatorial projects and recorded music – all staged by the artist in characteristically innovative style. Alongside portraiture, landscape and intimate still lifes, Tillmans pushes the boundaries of the photographic form in abstract artworks that range from the sculptural to the immersive.

The year 2003 is the exhibition’s point of departure, representing for Tillmans the moment the world changed, with the invasion of Iraq and anti-war demonstrations. The social and political form a rich vein throughout the artist’s work. German-born, international in outlook and exhibited around the world, Tillmans spent many years in the UK and is currently based in Berlin. In 2000, he was the first photographer and first non-British artist to receive the Turner Prize.

Room one

Static interference typically appears on a television screen when an analogue signal is switched off. This can occur when a station’s official programme finishes for the night or if a broadcast is censored. In Tillmans’s Sendeschluss / End of Broadcast 2014 it represents the coexistence of two different generations of technology. The chaotic analogue static was displayed on a digital television, which allowed Tillmans’s high-resolution digital camera to record the pattern as it really appeared, something that would not have been possible with a traditional cathode ray tube television. This work shows Tillmans’s interest in questioning what we believe to be true: the seemingly black-and-white image turns out to be extremely colourful when viewed very close up.

Other works in this room reflect on digital printmaking and photography today. For example, the technical ability to photograph a nightscape from a moving vehicle without blurring, as in these images of Sunset Boulevard, is unprecedented. Itself the subject of many famous art photographs, this iconic roadway appears here littered with large format inkjet prints in the form of advertising billboards. In Double Exposure 2012-2013 Tillmans juxtaposes images of two trade fairs – one for digital printers, the other for fruit and vegetables. Encounter 2014 shows a different photo-sensitive process. A pot had been left on top of a planter preventing light from reaching the sprouts underneath and leaving them white, while the surrounding growths that caught the daylight turned green.

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Sendeschluss / End of Broadcast I

2014

Pigmented inkjet print

107 1/2 × 161 1/2″ (273.1 × 410.2cm)

© Wolfgang Tillmans

Television white noise that the artist photographed while in Russia. For Tillmans, the image signifies resistance on his part to making clear images, but without the text its ostensibly radical nature would not be known.

Installation view of room 1 (detail), with Sendeschluss / End of Broadcast I, 2014, at left

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Double Exposure

2012-2013

Pigmented inkjet print

© Wolfgang Tillmans

Room two

Tillmans spends much of his time in the studio, yet he only occasionally uses it as a set for taking portraits. Instead, it is where prints are made and exhibitions are planned in architectural models, and where he collects materials and generates ideas. Over the years this environment has become a subject for his photographs, presenting a radically different view of the artist’s studio to the more traditional depictions seen in paintings over the centuries.

These works made around the studio demonstrate Tillmans’s concern with the physical process of making photographs, from chemical darkroom processes and their potential to create abstract pictures without the camera, to digital technology that is vital to the production of contemporary images, and the paper onto which they are printed. Tillmans’s understanding of the material qualities of paper is fundamental to his work, and photographs can take on a sculptural quality in series such as Lighter, 2005-ongoing and paper drop, 2001-ongoing, seen later in the exhibition.

In CLC 800, dismantled 2011 Tillmans uses photography to record a temporary installation, the result of unfastening every single screw in his defunct colour photocopier. He prefers to photograph his three-dimensional staged scenarios rather than actually displaying them as sculptures. He has often described the core of his work as ‘translating the three dimensional world into two dimensional pictures’.

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

paper drop Prinzessinnenstrasse

2014

Pigmented inkjet print

© Wolfgang Tillmans

Perhaps as a continuation of his more textural photographs – depicting fabrics and still lifes so close up they become difficult to read – experiments in abstraction followed suit, many of them featuring what is perhaps his favourite motif: the fold, which, as the exhibition’s curator Chris Dercon kindly reminded us, was considered by the philosopher Leibniz as one of the most accurate ways to depict the complexities of the human soul.

Lorena Muñoz-Alonso. “Inside Wolfgang Tillmans’s Superb Tate Modern Survey,” on the artnet website February 15, 2017 [Online] Cited 17/12/2021

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

CLC 800, dismantled

2011

Pigmented inkjet print

© Wolfgang Tillmans

Room three

Having spent the preceding decade working largely on conceptual and abstract photographs, in 2009 Tillmans embarked on the four-year project Neue Welt. Looking at the world with fresh eyes, he aimed to depict how it has changed since he first took up the camera in 1988. He travelled to five continents to find places unknown to him and visited familiar places as if experiencing them for the first time. Interested in the surface of things as they appeared in those lucid first days of being in a new environment, he immersed himself in each location for just a brief period. Now using a high resolution digital camera, Tillmans captured images in a depth of detail that is immediately compelling, but also suggests the excess of information that is often described as a condition of contemporary life.

Communal spaces, people, animals, and still-life studies of nature or food are just some of the subjects that feature in Neue Welt. Seen together, these images offer a deliberately fragmented view. Rather than making an overarching statement about the changing character of modern life, Tillmans sought only to record, and to create a more empathetic understanding of the world. Over the course of the project, however, some shrewd observations about contemporary worldviews did emerge. One related to the changing shape of car headlights, which he noted are now very angular in shape, giving them a predatory appearance that might reflect a more competitive climate.

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

astro crusto, a

2012

Pigmented inkjet print

© Wolfgang Tillmans

Installation view of room 3 (detail), with Headlight (f) 2012, at left; and Munuwata sky, 2011 at right

Image © Tate Modern showing Wolfgang Tillmans: 2017 at Tate Modern 15 February – 11 June

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Headlight (f)

2012

Pigmented inkjet print

© Wolfgang Tillmans

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Munuwata sky

2011

Pigmented inkjet print

© Wolfgang Tillmans

Room four

In the mid-2000s, prompted by global events, such as the claim that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction, Tillmans became interested in the assertions made by individuals, groups or organisations around the world that their viewpoint represented the absolute truth about a number of political and ethical questions.

He began his wryly-named truth study center project in 2005. Photographs, clippings from newspapers and magazines, objects, drawings, and copies of his own images are laid out in deliberate – and often provocative – juxtapositions. These arrangements reflect the presentation of information by news outlets in print and online. They also draw attention to gaps in knowledge, or areas where there is room for doubt. For each installation, the material presented in the truth study centers is selected according to its topical and geographic context. In 2017, the subject of truth and fake news is at the heart of political discourse across the world. This iteration of the project focuses in particular on how constructions of truth work on a psychological and physiological level.

The Silver 1998-ongoing prints connect to reality in a different way. Made by passing monochromatically exposed photographic paper through a dirty photo-developing machine, they collect particles and residue from the rollers and liquids. This makes them, in effect, a record of the chemical and mechanical process from which they originate.

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

truth study center

2017

Pigmented inkjet print

© Wolfgang Tillmans

Room five

Tillmans has described how, as a photographer, he feels increasingly less obligated to reflect solely on the outside world through documentary images. In his abstract works, he looks inwards: exploring the rudiments of photographic processes and their potential to be used as a form of self-expression.

Like the Silver works in the previous room, the abstract Greifbar 2014-2015 images are made without a camera. Working in the darkroom, Tillmans traces light directly onto photographic paper. The vast swathes of colour are a record of the physical gestures involved in their construction, but also suggest aspects of the body such as hair, or pigmentation of the skin. This reference to the figurative is reflected in the title, which translates as ‘tangible’.

Tillmans has observed that even though these works are made by the artist’s hand, they look as though they could be ‘scientific’ evidence of natural processes. For him, this interpretation is important, because it disassociates the works from the traditional gestural technique of painting. That the image is read as a photographic record, and not the result of the artist’s brushstroke, is essential to its conceptual meaning.

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Greifbar 29

2014

Ink-jet print

© Wolfgang Tillmans

Room six

Tillmans is interested in social life in its broadest sense, encompassing our participation in society. His photographs of individuals and groups are underpinned by his conviction that we are all vulnerable, and that our well-being depends upon knowing that we are not alone in the world.

Tillmans has observed that although cultural attitudes towards race, gender and sexuality have become more open over the three decades since he began his artistic practice, there is also greater policing of nightlife, and urban social spaces are closing down. His photographs taken in clubs, for example, testify to the importance of places where people can go today to feel safe, included, and free.

This concern with freedom also extends to the ways in which people organise themselves to make their voices heard. Images of political marches and protests draw attention to the cause for which they are fighting. They also form part of a wider study of what Tillmans describes as the recent ‘re-emergence’ of activism.

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

The Blue Oyster Bar, Saint Petersburg

2014

Ink-jet print

© Wolfgang Tillmans

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

NICE HERE but ever been to KRYGYZSTAN free Gender Expression WORLDWIDE

2006

Ink-jet print

© Wolfgang Tillmans

Room seven

Playback Room is a space designed for listening to recorded music. The project first ran at Between Bridges, the non-profit exhibition space Tillmans opened in London in 2006 and has since transferred to Berlin. In three exhibition (‘Colourbox’, ‘American Producers’ ‘Bring Your Own’) that took place between September 2014 and February 2015, he invited visitors to come and listen to music at almost the same quality at which it was originally mastered.

Whereas live music can be enjoyed in concert halls and stadiums, and visual art can be enjoyed in museums, no comparable space exists for appreciating studio music. Musicians and producers spend months recording tracks at optimal quality, yet we often listen to the results through audio equipment and personal devices that are not fit for perfect sound reproduction. Playback Room is a response to this. An example of Tillmans’s curatorial practice, he has chosen to include it here to encourage others to think about how recorded music can be given prominence within the museum setting.

The three tracks you hear in this room are by Colourbox, an English band who were active between 1982 and 1987. Tillmans, a long-term fan of the band, chose their music for Playback Room because they never performed live, thus emphasising the importance of the studio recordings.

Room eight

Tillmans began experimenting with abstraction while in high school, using the powerful enlargement function of an early digital photocopier to copy and degrade his own photographs as well as those cut from newspapers. He describes the coexistence of chance and control involved in this process as an essential ingredient in most of his work.

Ever since then, he has found ways to resist the idea that the photograph is solely a direct record of reality. In 2011, this area of his practice was compiled for the first time in his book Abstract Pictures. For a special edition of 176 copies Tillmans manipulated the printing press, for example by running it without plates or pouring ink into the wrong compartments, to create random effects and overprinted pages.

Some of his abstract photographs are made with a camera and others without, through the manipulation of chemicals, light, or the paper itself. Importantly, however, Tillmans does not distinguish between the abstract and the representational. He is more interested in what they have in common. The relationship between photography, sculpture and the body, for example, is expressed in abstract photographs made by crumpling a sheet of photographic paper, but also in close-ups of draped and wrinkled clothing such as Faltenwurf (Pines) a, 2016 in Room 9.

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Concorde L433-11

1997

Ink-jet print

Tate

© Wolfgang Tillmans, courtesy Maureen Paley, London

Room nine

Artist books, exhibition catalogues, newspaper supplements and magazine spreads, posters and leaflets are an integral part of Tillmans’s output. These various formats and the ways in which they are distributed or made visible in the public space allow him to present work and engage audiences in a completely different manner to exhibitions. For him the printed page is as valid a venue for artistic creation as the walls of a museum. Many such projects are vital platforms on which he can speak out about a political topic, or express his continued interest in subjects such as musicians, or portraiture in general.

Recently, the print layout has enabled Tillmans to share a more personal aspect of his visual archive. Originally designed as a sixty-six page spread for the Winter 2015/Spring 2016 edition of Arena Homme +, this grid of images looks back at Fragile, the name he gave as a teenager to his creative alter-ego. Spanning 1983 to 1989 – the year before he moved to England to study – the photographs and illustrations provide a sensitive insight into a formative period in Tillmans’s life, predating the time when he chose photography as his main medium of expression.

The layout is also an example of the intricate collaging technique that he has employed in printed matter since 2011, deliberately obscuring some images by overlapping others on top of them

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Faltenwurf (Pines), a

2016

Ink-jet print

© Wolfgang Tillmans

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Tukan

2010

Ink-jet print

© Wolfgang Tillmans

Room ten

An acute awareness of fragility endures across Tillmans’s practice in all of its different forms. Often this is expressed in his attentiveness to textures and surfaces. Collum 2011 is taken from Central Nervous System 2008-2013, a group of portraits featuring only one subject, where the focus on intimate details, such as the nape of the neck or the soft skin of the outer ear, both emphasises and celebrates the frailty of the human body.

Weed 2014, a four-metre tall photograph taken in the garden of the artist’s London home, invites us to consider the beauty and complexity of a plant usually seen as a nuisance. The dead leaf of a nearby fig tree appears as both a sculptural form and a memento mori. Dusty Vehicle 2012, photographed in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, is highly specific in its depiction of texture, yet the reasons leading to this roadside arrangement remain a mystery.

The focus on a very few works in this room serves as an example of Tillmans’s varied approaches to exhibiting his prints. Though best known for installations comprising many pictures, he always places emphasis on the strength of the individual image. By pinning and taping work to the wall, as well as using frames, Tillmans draws attention to the edges of the print, encouraging the viewer to interact with the photograph as an object, rather than a conduit for an image.

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Dusty Vehicle

2012

Ink-jet print

© Wolfgang Tillmans

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Collum

2011

Ink-jet print

© Wolfgang Tillmans

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Weed

2014

Photograph, inkjet print on paper

© Wolfgang Tillmans

Room eleven

In this room Tillmans highlights the coexistence of the personal, private, public, and political spheres in our lives. The simultaneity of a life lived as a sexual being as well as a political being, or in Tillmans’s case as a conceptual artist as well as a visually curious individual, plays out through the installation.

The entirely white view taken from the inside of a cloud, a word charged with multiple meanings, is presented alongside the close-up and matter-of-fact view of male buttocks and testicles. Like nackt, 2 2014, the small photograph The Air Between 2016 is the result of a lifelong interest in visually describing what it feels like to live in our bodies. Here the attention lies in photographing the air, the empty space between our skin and our clothes.

In still life, Calle Real II 2013, a severed agave chunk is placed on a German newspaper article describing the online depiction of atrocities by Islamic State. The image is as startling in its depiction of the finest green hues as it is in capturing how, simultaneously, we take in world events alongside details of our personal environment.

This room, which Tillmans considers as one work or installation in its entirety, is an example of his innovative use of different photographic prints and formats to reflect upon how we experience vastly different aspects of the world at the same time.

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

The Air Between

2016

Ink-jet print

© Wolfgang Tillmans

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Still life, Calle Real II

2013

Ink-jet print

© Wolfgang Tillmans

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Nackt, 2 (nude, 2)

2014

Ink-jet print

© Wolfgang Tillmans

Room twelve

Tillmans has always been sensitive to the public side of his role as an artist, acknowledging that putting images out in the public world unavoidably places himself in the picture as well. His participation in activities such as lectures and interviews has been a platform for his voice from the beginning of his career.

Since 2014 he has also allowed performance to become a more prominent strand of his practice. Filmed in a hotel room in Los Angeles and an apartment in Tehran, Instrument 2015 is the first time that Tillmans has put himself in front of the camera for a video piece. Across a split screen, we see two separate occasions on which he has filmed himself dancing. The accompanying soundtrack was created by distorting the sound of his feet hitting the floor. In the absence of any other music, his body becomes an instrument.

On one side of the screen we see his body, on the other only his shadow. Referring to the shadow, New York Times critic Roberta Smith commented that:

“Disconcertingly, this insubstantial body is slightly out of sync with the fleshly one. It is a ghost, a shade, the specter that drives us all. The ease with which we want to believe that the two images are connected, even though they were filmed separately, might also act as a reminder to question what we assume to be true.”

Room thirteen

Portraiture has been central to Tillmans’s practice for three decades. For him, it is a collaborative act that he has described as ‘a good levelling instrument’. No matter who the sitter – a stranger or someone close to him, a public figure, an unknown individual, or even the artist himself – the process is characterised by the same dynamics: of vulnerability, exposure, honesty and always, to some extent, self-consciousness. Tillmans sees every portrait as resulting from the expectations and hopes of both sitter and photographer.

The portrait’s ability to highlight the relationship between appearance and identity is a recurring point of interest. In 2016, at HM Prison Reading, Tillmans took a distorted self-portrait in a damaged mirror once used by inmates. The disfigured result is the artist’s expression of the effects on the soul wrought by physical and psychological confinement and also censorship. Whoever looked into the reflective surface would gain a completely inaccurate impression of what they looked like, and how they are perceived by others.

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Separate System, Reading Prison

2016

Ink-jet print

© Wolfgang Tillmans

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Anders pulling splinter from his foot

2004

Ink-jet print

© Wolfgang Tillmans

“The image’s reference to both Dorian Gray and Francis Bacon is evident. This catapults a new association: perhaps Bacon was painting Gray all along. Insistently, fearlessly, longingly.

As with much of Bacon’s oeuvre, and the very particular picture of Dorian Gray, a distorted, forward-facing male figure intimidates the viewer with his unmade face. However, Tillsman’s piece is not a picture, it is a photograph. Here, the artist (as was the case with Bacon/Wilde) is not the one dissembling what’s inside the frame, subjecting it with his brush. No. In Tillsman’s image, a piece of thick glass distorts the artist. Here, the artist is no longer the lens that is able to affect his surroundings. Here, the surroundings distort the artist.

The message Tillsman delivers is clear: things have changed. The world disfigures the subject while the artist is trapped, forced to stand there and watch.”

Text by Ana Maria Caballero on The Drugstore Notebook website [Online] Cited 07/06/2017. No longer available online

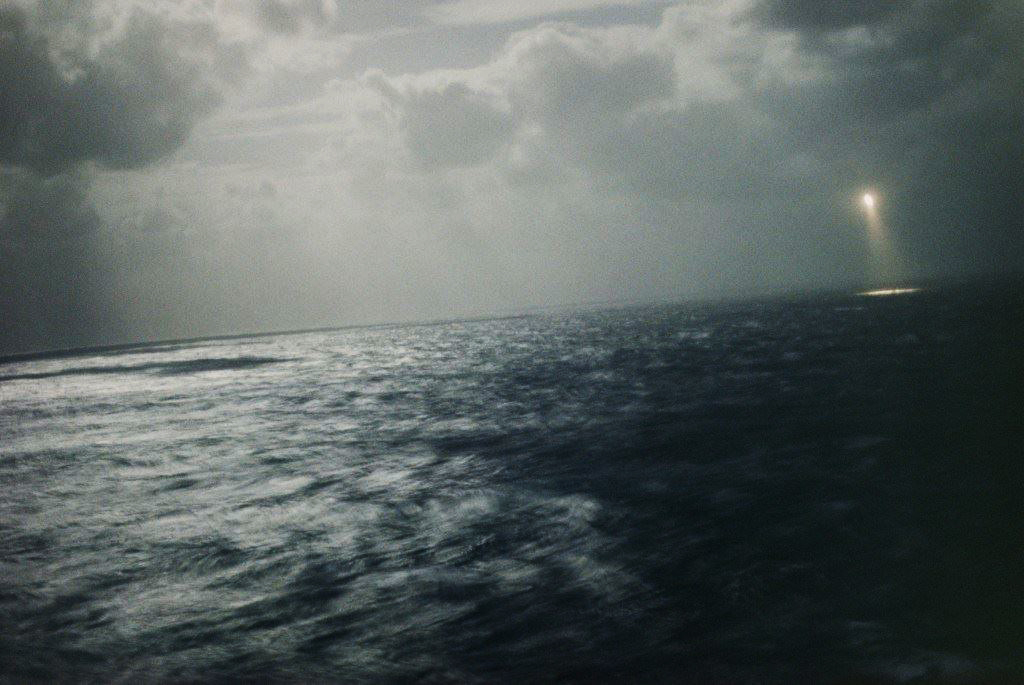

Room fourteen

Symbol and allegory are artistic strategies Tillmans is usually keen to avoid. The State We’re In, A 2015 is a departure from this stance: the work’s title is a direct reference to current global political tensions. Depicting the Atlantic Ocean, a vast area that crosses time zones and national frontiers, it records the sea energised by opposing forces, but not yet breaking into waves. Differing energies collide, about to erupt into conflict.

The photographs in this room deal with borders and how they seem clear-cut but are actually fluid. In these images, borders are made tangible in the vapour between clouds, the horizon itself or the folds in the two Lighter photo-objects. The shipwreck left behind by refugees on the Italian island of Lampedusa, depicted in this photograph from 2008, is a reminder that borders, represented elsewhere in more poetic delineations, can mean a question of life and death.

The text and tables sculpture Time Mirrored 3 2017 represents Tillmans’s interest in connecting the time in which we live to a broader historical context. He always understands the ‘Now’ as the history of the future. Events perceived as having happened over a vast gulf of time between us and the past, become tangible when ‘mathematically mirrored’ and connected to more recent periods of time in our living memory.

In contrast to the epic themes of sea and time, the pictures of an apple tree outside the artist’s London front door, a subject he has photographed since 2002, suggest a day-to-day positive outlook.

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Italian Coastal Guard Flying Rescue Mission off Lampedusa

2008

Ink-jet print

© Wolfgang Tillmans

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Lampedusa

2008

Ink-jet print

© Wolfgang Tillmans

Installation view of room 14 (detail), featuring at left, pictures of an apple tree outside the artist’s London front door and at right, La Palma 2014

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

La Palma

2014

Ink-jet print

© Wolfgang Tillmans

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Apple tree

2007

Ink-jet print

© Wolfgang Tillmans

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Apple tree

Various dates

Ink-jet prints

© Wolfgang Tillmans

Book for Architects

Book for Architects 2014 is the culmination of Tillmans’s longstanding fascination with architecture. First presented at Rem Koolhaas’s 14th International Architecture Exhibition, Venice, 2013, it explores the contrast between the rationality and utopianism that inform design and the reality of how buildings and streets come to be constructed and inhabited.

In 450 images taken in 37 countries, across 5 continents, Tillmans hones in on the resourceful and ingenious ways in which people adapt their surroundings to fit their needs. These are individual and uncoordinated decisions that were not anticipated in architects’ plans, but still impact the contemporary built environment.

Across the double projection, we see examples of how buildings come to sit within a city plan, the ad-hoc ways in which they are modified, and the supposed ‘weaknesses’ of a space such as the corners where there are service doors, fire escapes, or alarm systems.

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Shit buildings going up left, right and centre

2014

Book for Architects Plate 083 2014

© Wolfgang Tillmans

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Untitled

2012

Book for Architects 2014

© Wolfgang Tillmans

“He has said of his photographs that “they are a representation of an unprivileged gaze or view … In photography I like to assume exactly the unprivileged position, the position that everybody can take, that chooses to sit at an airplane window or chooses to climb a tower.”

Wolfgang Tillmans quoted in Peter Halley, Midori Matsui, Jan Verwoert, Wolfgang Tillmans, London 2002, p. 136

Wolfgang Tillmans has earned recognition as one of the most exciting and innovative artists working today. Tate Modern presents an exhibition concentrating on his production across different media since 2003. First rising to prominence in the 1990s for his photographs of everyday life and contemporary culture, Tillmans has gone on to work in an ever greater variety of media and has taken an increasingly innovative approach to staging exhibitions. Tate Modern brings this variety to the fore, offering a new focus on his photographs, video, digital slide projections, publications, curatorial projects and recorded music.

Social and political themes form a rich vein throughout Tillmans’s work. The destabilisation of the world has arisen as a recurring concern for the artist since 2003, an important year when he felt the world changed with the invasion of Iraq and anti-war demonstrations. In 2017, at a moment when the subject of truth and fake news is at the heart of political discourse, Tillmans presents a new configuration of his tabletop installation truth study center 2005-ongoing. This ongoing project uses an assembly of printed matter from pamphlets to newspaper cuttings to his own works on paper to highlight Tillmans’s continued interest in word events and how they are communicated in the media.

Wolfgang Tillmans: 2017 will particularly highlight the artist’s deeper engagement with abstraction, beginning with the important work Sendeschluss / End of Broadcast I 2014. Based on images the artist took of an analogue TV losing signal, this work combines two opposing technologies – the digital and the analogue. Other works such as the series Blushes 2000-ongoing, made without a camera by manipulating the effects of light directly on photographic paper, show how the artist’s work with abstraction continues to push the boundaries and definitions of the photographic form.

The exhibition includes portraiture, landscape and still lives. A nightclub scene might record the joy of a safe social space for people to be themselves, while large-scale images of the sea such as La Palma 2014 or The State We’re In, A 2015 document places where borders intersect and margins are ever shifting. At the same time, intimate portraits like Collum 2011 focus on the delicacy, fragility and beauty of the human body. In 2009, Tillmans began using digital photography and was struck by the expanded opportunities the technology offered him. He began to travel more extensively to capture images of the commonplace and the extraordinary, photographing people and places across the world for the series Neue Welt 2009-2012.

The importance of Tillmans’s interdisciplinary practice is showcased throughout the exhibition. His Playback Room project, first shown at his Berlin exhibition space Between Bridges, provides a space within the museum for visitors to experience popular music by Colourbox at the best possible quality. The video installation Instrument 2015 shows Tillmans dancing to a soundtrack made by manipulating the sound of his own footsteps, while in the Tanks Studio his slide projection Book for Architects 2014 is being shown for the first time in the UK. Featuring thirty-seven countries and five continents, it reveals the tension between architectural form and function. In March, Tillmans will also take over Tate Modern’s south Tank for ten days with a specially-commissioned installation featuring live music events.

Wolfgang Tillmans: 2017 is co-curated by Chris Dercon and Helen Sainsbury, Head of Programme Realisation, Tate Modern with Emma Lewis, Assistant Curator, Tate Modern. The exhibition is accompanied by a catalogue from Tate Publishing designed by Wolfgang Tillmans and a programme of talks and events in the gallery.

Press release from Tate Modern

Images from the exhibition

Installation view of the exhibition Wolfgang Tillmans: 2017 with at left, Sunset night drive (2014) and at centre right, Young Man, Jeddah (2012)

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Sunset night drive

2014

Ink-jet print

© Wolfgang Tillmans

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Young Man, Jeddah

2012

Ink-jet print

© Wolfgang Tillmans

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Young Man, Jeddah (B)

2012

Ink-jet print

© Wolfgang Tillmans

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

17 Years Supply

2014

Ink-jet print

© Wolfgang Tillmans

“Now the camera is staring into a big cardboard box, half-filled with pharmacist’s tubs and packages, 17 years’ supply of antiretroviral and other medications to treat HIV/AIDS. I imagine the sound that box would make if you shook it, what that sound might say about a human life, its vulnerability and value.”

Adrian Searle. “Wolfgang Tillmans review – a rollercoaster ride around the world,” on The Guardian website Wednesday 15 February 2017 [Online] Cited 17/12/2021

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Market I

2012

Ink-jet print

© Wolfgang Tillmans

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Studio still life, c

2014

Ink-jet print

© Wolfgang Tillmans

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Juan Pablo & Karl Chingaza

2012

Ink-jet print

© Wolfgang Tillmans

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Iguazu

2010

Ink-jet print

© Wolfgang Tillmans

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Oscar Niemeyer

2010

Ink-jet print

© Wolfgang Tillmans

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Tube escalator joint

2009

Ink-jet print

© Wolfgang Tillmans

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

JAL

1997

Ink-jet print

© Wolfgang Tillmans

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Port-au-Prince

2010

Ink-jet print

© Wolfgang Tillmans

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

London Olympics

2012

Ink-jet print

© Wolfgang Tillmans

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Fespa Car

2012

Ink-jet print

© Wolfgang Tillmans

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

The Spectrum Dagger

2016

Ink-jet print

© Wolfgang Tillmans

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Gaza Wall

2009

Ink-jet print

© Wolfgang Tillmans

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Simon, Sebastian Street

2013

Ink-jet print

© Wolfgang Tillmans

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Arms and Legs

2014

Ink-jet print

© Wolfgang Tillmans

Tate Modern

Bankside

London SE1 9TG

United Kingdom

Opening hours:

Daily 10.00 – 18.00

You must be logged in to post a comment.