Exhibition dates: 16th October 2018 – 27th January 2019

Curators: Drew Heath Johnson, Oakland Museum of California, Alona Pardo and Jilke Golbach, Barbican Art Gallery, Pia Viewing, Jeu de Paume.

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1966)

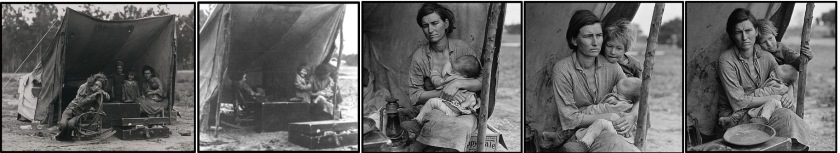

Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California

1936

Gelatin silver print

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

A further posting on this exhibition, now showing at Jeu de Paume in Paris.

Eleven new media images, two videos, a selection of quotes from Dorothea Lange, and text from the exhibition curator Pia Viewing.

The most interesting of the images is the wide shot Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California (1936, above), part of a series of six that Lange took of Florence Owens Thompson and her children, the last image of which was to become the iconic image (see text below). The story of that image is fascinating and is told in detail in text from Wikipedia and other sources below.

It would seem that Lange was mistaken or made up the story to fill in the blanks; and that the image was at first a curse (ashamed that the world could see how poor they were) and now a source of pride, to the Thompson family. As the text pertinently notes, “The photograph’s fame caused distress for Thompson and her children and raised ethical concerns about turning individuals into symbols.”

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to Jeu de Paume for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1966)

Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California [with thumb at bottom right removed]

1936

Gelatin silver print

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1966)

Destitute pea pickers in California. Mother of seven children. Age thirty-two. Nipomo, California [original title, thumb removed; digital file, post-conservation]

1936

Gelatin silver print

Library of Congress

Digital file was made from the original nitrate negative for “Migrant Mother” (LC-USF34-009058-C). The negative was retouched in the 1930s to erase the thumb holding a tent pole in lower right hand corner.

The file print made before the thumb was retouched can be seen at http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/ppmsca.12883

Title from caption card for negative. Title on print: “Destitute pea pickers in California. A 32 year old mother of seven children.”

Destitute pea pickers in California. Mother of seven children. Age thirty-two. Nipomo, California. In the 1930s, the FSA employed several photographers to document the effects of the Great Depression on Americans. Many of the photographs can also be seen as propaganda images to support the U.S. government’s policy distributing support to the worst affected, poorer areas of the country. Dorothea Lange’s image of a migrant pea picker, Florence Owens Thompson, and her family has become an icon of resilience in the face of adversity. Lange actually took six images that day, the last being the famous “Migrant Mother”. This is a montage of the other five pictures. Persons in picture (left to right) are: Viola (Pete) in rocker, age 14, standing inside tent; Ruby, age 5; Katherine, age 4, seated on box; Florence, age 32, and infant Norma, age 1 year, being held by Florence. Pete has moved inside the tent, and away from Lange, in hopes her photo can not be taken. Katherine stands next to her mother. Florence is talking to Ruby, who is hiding behind her mother, as Lange took the picture. Florence is nursing Norma. Katherine has moved back from her mother as Lange approached to take this shot. Ruby is still hiding behind her mother. Left to right are Florence, Ruby and baby Norma. Florence stopped nursing Norma and Ruby has come out from behind her. This photograph was the one used by the newspapers the following day to report the story of the migrants. Portrait shows Florence Owens Thompson with several of her children in a photograph known as “Migrant Mother”.

1/ Persons in picture (left to right) are: Viola (Pete) in rocker, age 14; standing inside tent, Ruby, age 5; Katherine, age 4; seated on box, Florence, age 32, and infant Norma, age 1 year, being held by Florence

2/ Viola has moved inside the tent. Katherine stands next to her mother. Florence is talking to Ruby, who is behind her mother

3/ Florence is nursing Norma. Katherine has moved back from her mother. Ruby is still behind her mother

4/ Left to right are Florence, Ruby and baby Norma

5/ Florence stopped nursing Norma. Ruby is still next to her mother. This photograph was the one used by the newspapers the following day to report the story of the starving migrants

Text from the Wikipedia website

“We do not know the order in which these photographs were taken, since they are 4″ x 5” individual negatives rather than 35mm film strips, which provide a record of the sequence of continuous exposures. However, Lange indicates in the above statement she moved closer as she continued to photograph. If that is true, then we have a good idea of the general order. We do know that one was selected, likely as a joint decision between Lange and representatives of the Resettlement Administration.

While “Migrant Mother” is well known, what is far less known is that Lange took six or seven pictures, five of which still exist. Lange posed Ms. Florence Thompson in different positions and used some of her seven children to create a series of compelling images. She asked Thompson to shift the position of the child in her arms to get the greatest emotional effect. Linda Gordon’s biography of Lange describes this as follows:

Lange asked the mother and children to move into several different positions. She began with a mid-distance shot. Then she backed up for one shot, then came closer for others. She moved aside a pile of dirty clothes (she would never embarrass her subjects). She then moved closer yet, focusing on three younger children and sidelining the teenage daughter out of the later pictures altogether… she offered the photographs to the press. The San Francisco News published two of them on March 10, 1936. In response, contributions of $200,000 poured in for the destitute farmworkers stuck in Nipomo. (Gordon, 2009, p. 237)

One was eventually selected to represent this scene to the nation.”

Anonymous. “The Great Depression, the Dust Bowl, and the New Deal,” on the Annenberg Learner website [Online] Cited 16/12/2018. No longer available online

Iconic photo

In March 1936, after picking beets in the Imperial Valley, Florence and her family were traveling on U.S. Highway 101 towards Watsonville “where they had hoped to find work in the lettuce fields of the Pajaro Valley.” On the road, the car’s timing chain snapped and they coasted to a stop just inside a pea-pickers‘ camp on Nipomo Mesa. They were shocked to find so many people camping there – as many as 2,500 to 3,500. A notice had been sent out for pickers, but the crops had been destroyed by freezing rain, leaving them without work or pay. Years later Florence told an interviewer that when she cooked food for her children that day little children appeared from the pea pickers’ camp asking, “Can I have a bite?”

While Jim Hill, her husband, and two of Florence’s sons went into town to get the car’s damaged radiator repaired, Florence and some of the children set up a temporary camp. As Florence waited, photographer Dorothea Lange, working for the Resettlement Administration, drove up and started taking photos of Florence and her family. She took six images in the course of ten minutes.

Lange’s field notes of the images read:

Seven hungry children. Father is native Californian. Destitute in pea pickers’ camp … because of failure of the early pea crop. These people had just sold their tires to buy food.

Lange later wrote of the encounter with Thompson:

I did not ask her name or her history. She told me her age, that she was 32. She said that they had been living on frozen vegetables from the surrounding fields and birds that the children killed. She had just sold the tires from her car to buy food.

Thompson claimed that Lange never asked her any questions and got many of the details incorrect. Troy Owens recounted:

There’s no way we sold our tires, because we didn’t have any to sell. The only ones we had were on the Hudson and we drove off in them. I don’t believe Dorothea Lange was lying, I just think she had one story mixed up with another. Or she was borrowing to fill in what she didn’t have.

In many ways, Migrant Mother is not typical of Lange’s careful method of interacting with her subject. Exhausted after a long road-trip, she did not talk much to the migrant woman, Florence Thompson, and didn’t record her information accurately. Although Thompson became a famous symbol of White motherhood, her heritage is Native American. The photograph’s fame caused distress for Thompson and her children and raised ethical concerns about turning individuals into symbols.

According to Thompson, Lange promised the photos would never be published, but Lange sent them to the San Francisco News as well as to the Resettlement Administration in Washington, D.C. The News ran the pictures almost immediately and reported that 2,500 to 3,500 migrant workers were starving in Nipomo, California. Within days, the pea-picker camp received 20,000 pounds (9,100 kg) of food from the federal government. Thompson and her family had moved on by the time the food arrived and were working near Watsonville, California.

While Thompson’s identity was not known for over 40 years after the photos were taken, the images became famous. The sixth image, especially, which later became known as Migrant Mother, “has achieved near mythical status, symbolising, if not defining, an entire era in United States history.” Roy Stryker called Migrant Mother the “ultimate” photo of the Depression Era: “[Lange] never surpassed it. To me, it was the picture … . The others were marvellous, but that was special … . She is immortal.” As a whole, the photographs taken for the Resettlement Administration “have been widely heralded as the epitome of documentary photography.” Edward Steichen described them as “the most remarkable human documents ever rendered in pictures.”

Thompson’s identity was discovered in the late 1970s. In 1978, acting on a tip, Modesto Bee reporter Emmett Corrigan located Thompson at her mobile home in Space 24 of the Modesto Mobile Village and recognised her from the 40-year-old photograph. A letter Thompson wrote was published in The Modesto Bee and the Associated Press distributed a story headlined “Woman Fighting Mad Over Famous Depression Photo.” Florence was quoted as saying “I wish she [Lange] hadn’t taken my picture. I can’t get a penny out of it. She didn’t ask my name. She said she wouldn’t sell the pictures. She said she’d send me a copy. She never did.”

Lange was funded by the federal government when she took the picture, so the image was in the public domain and Lange never directly received any royalties. However, the picture did help make Lange a celebrity and earned her “respect from her colleagues.”

In a 2008 interview with CNN, Thompson’s daughter Katherine McIntosh recalled how her mother was a “very strong lady”, and “the backbone of our family”. She said: “We never had a lot, but she always made sure we had something. She didn’t eat sometimes, but she made sure us children ate. That’s one thing she did do.”

Later life, death, and aftermath

Though Thompson’s 10 children bought her a house in Modesto, California, in the 1970s, Thompson found she preferred living in a mobile home and moved back into one.

Thompson was hospitalised and her family appealed for financial help in late August 1983. By September, the family had collected $35,000 in donations to pay for her medical care. Florence died of “stroke, cancer and heart problems” at Scotts Valley, California, on September 16, 1983. She was buried in Lakewood Memorial Park, in Hughson, California, and her gravestone reads: “FLORENCE LEONA THOMPSON Migrant Mother – A Legend of the Strength of American Motherhood.”

Daughter Katherine McIntosh told CNN that the photo’s fame had made the family feel both ashamed and determined never to be as poor again. Son Troy Owens said that more than 2,000 letters received along with donations for his mother’s medical fund led to a re-appraisal of the photo: “For Mama and us, the photo had always been a bit of [a] curse. After all those letters came in, I think it gave us a sense of pride.”

Text from the Wikipedia website

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1966)

Cars on the Road

1936

Gelatin silver print

Library of Congress

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1966)

Near Eutah, Alabama

1936

Gelatin silver print

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1966)

Ditched, Stalled, and Stranded, San Joaquin Valley, California

1936

Gelatin silver print

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

Quotes from Dorothea Lange

“One should really use the camera as though tomorrow you’d be stricken blind. To live a visual life is an enormous undertaking, practically unattainable, but when the great photographs are produced, it will be down that road. I have only touched it, just touched it.”

“On the Bowery I knew how to step over drunken men … I knew how to keep an expression of face that would draw no attention, so no one would look at me. I have used that my whole life in photographing.”

Interview with Lange, in Dorothea Lange, Part II : The Closer For Me, film produced by KQED for National Educational Television (NET), USA, 1965

“I never steal a photograph. Never. All photographs are made in collaboration, as part of their thinking as well as mine.”

“Often it’s just sticking around and being there, remaining there, not swopping in and swopping out in a cloud of dust; sitting down on the ground with people, letting the children look at your camera with their dirty, grimy little hands, and putting their fingers on the lens, and you let them, because you know that if you will behave in a generous manner, you’re very apt to receive it.”

Anne Whiston, Spirn, Daring to Look, p. 23-24

“My own approach is based upon three considerations. First – hands off! Whatever I photograph I do not molest or tamper with or arrange. Second – a sense of place. Whatever I photograph, I try to picture as part of its surroundings, as having roots. Third – a sense of time. Whatever I photograph, I try to show as having its position in the past or in the present.”

Beaumont and Nancy Newhall, Masters Of Photography, New York Castle Books, 1958, p. 140

“The good photograph is not the object, the consequences of the photograph are the objects.”

“I believe that the camera is a powerful medium for communication and I believe that the camera is a valuable tool for social research which has not been developed to its capacity.”

Dorothea Lange, quoted in Karen Tsujimoto, Dorothea Lange : Archive of an Artist, Oakland, Oakland Museum, 1995, p. 23

“Everything is propaganda for what you believe in, actually, isn’t it? … I don’t see that it could be otherwise. The harder and the more deeply you believe in anything, the more in a sense you’re a propagandist. Conviction, propaganda, faith. I don’t know, I never have been able to come to the conclusion that that’s a bad word […] But at any rate, that’s what the Office of War Information work was.”

“There is a sharp difference, a gulf. The woman’s position is immeasurably more complicated. There are not very many first class woman producers, not many. That is, producers of outside things. They produce in other ways. Where they can do both, it’s a conflict. I would like to try. I would like to have one year. I’d like to take one year, almost ask it of myself, ‘Could I have one year?’ Just one, when I would not have to take into account anything but my own inner demands. Maybe everybody would like that … but I can’t.”

Suzanne Riess, “Dorothea Lange: The Making of a documentary Photographer,” October 1960-August 1961, p. 181; 219-220

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1966)

Drought-abandoned house on the edge of the Great Plains near Hollis, Oklahoma

1938

Gelatin silver print

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1966)

Toward Los Angeles, California

1937

Gelatin silver print

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1966)

Family on the road, Oklahoma

1938

Gelatin silver print

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1966)

Ancienne esclave à la longue mémoire, Alabama

Former slave with a long memory, Alabama

1938

Gelatin silver print

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

The Politics of Seeing features major works by the world famous American photographer Dorothea Lange (1895, Hoboken, New Jersey-1966, San Francisco, California), some of which have never before been exhibited in France. The exhibition focuses on the extraordinary emotional power of Dorothea Lange’s work and on the context of her documentary practice. It features five specific series: the Depression period (1933-1934), a selection of works from the Farm Security Administration (1935-1939), the Japanese American internment (1942), the Richmond shipyards (1942-1944) and a series on a Public defender (1955-1957). Over one hundred splendid vintage prints taken between 1933 and 1957 are enhanced by the presence of documents and screenings broadening the scope of an oeuvre often familiar to the public through images such as White Angel Breadline (1933) and Migrant Mother (1936), which are icons of photographic history. The majority of prints in this exhibition belong to the Oakland Museum of California, where Lange’s considerable archive, donated to the museum after her death by her husband Paul Shuster Taylor, is conserved.

Like John Steinbeck’s famous novel The Grapes of Wrath, Dorothea Lange’s oeuvre has helped shape our conception of the interwar years in America and contributed to our knowledge of this period. However, this exhibition also introduces other aspects of Dorothea Lange’s practice, which she herself considered archival. By placing the photographic work in the context of her anthropological approach, it enables viewers to appreciate how its power also lies in her capacity to interact with her subjects, evident in her captions to the images. She thereby considerably enriched the informative quality of the visual archive and produced a form of oral history for future generations.

In 1932, during the Great Depression that began in 1929, Lange observed the unemployed homeless people in the streets of San Francisco and decided to drop her studio portrait work because she felt that it was no longer adequate. During a two-year period that marked a turning point in her life, she took photographs of urban situations that portrayed the social impact of the recession. This new work became known in artistic circles and attracted the attention of Paul Schuster Taylor, professor of economics at the University of California, Berkeley. Taylor was a specialist in agricultural conflicts of the 1930s, and in particular Mexican migrant workers. He began using Lange’s photographs to illustrate his articles and in 1935 they started working together for the government agencies of the New Deal. Their collaboration lasted for over thirty years.

During the Second World War, Lange continued to practise photography and to document the major issues of the day, including the internment of Japanese-American families during the war; the economic and social development due to industries engaged in the war effort; and the criminal justice system through the work of a county public defence lawyer.

Dorothea Lange’s iconic images of the Great Depression are well known, but her photographs of Japanese-Americans interned during the Second World War were only published in 2006. Shown here for the first time in France, they illustrate perfectly how Dorothea Lange created intimate and poignant images throughout her career in order to denounce injustices and change public opinion. In addition to the prints, a selection of personal items, including contact sheets, field notes and publications allow the public to situate her work within the context of this troubled period.

The exhibition at the Jeu de Paume offers a new perspective on the work of this renowned American artist, whose legacy continues to be felt today. Highlighting the artistic qualities and the strength of the artist’s political convictions, this exhibition encourages the public to rediscover the importance of Dorothea Lange’s work as a landmark in the history of documentary photography.

Press release from Jeu de Paume

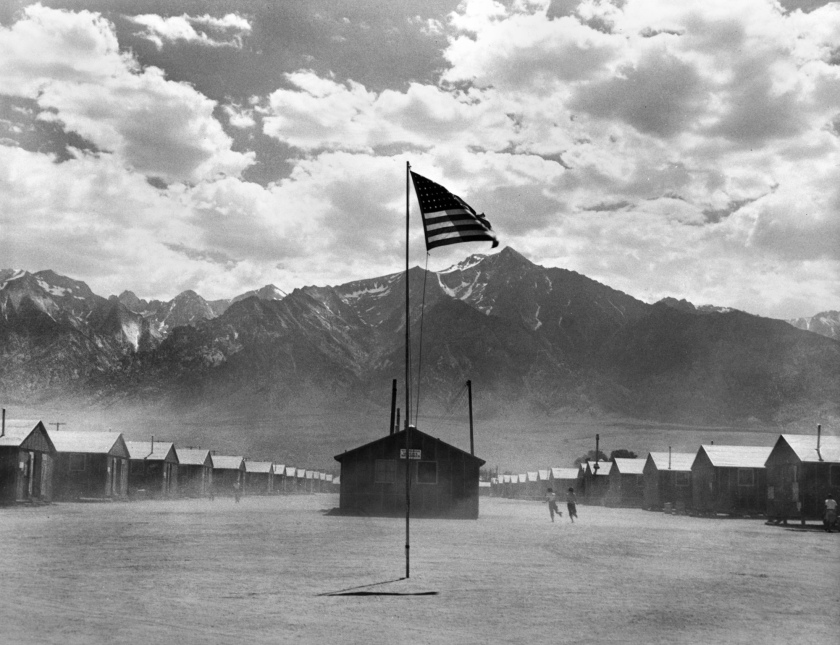

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1966)

Unemployed lumber worker goes with his wife to the bean harvest. Note social security number tattooed on his arm, Oregon

1939

Gelatin silver print

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1966)

Manzanar Relocation Center, Manzanar, California

1942

Gelatin silver print

© Collection of the Oakland Museum of California, gift of Paul S. Taylor

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1966)

Japanese Children with Tags, Hayward, California, May 8 1942

1942

Gelatin silver print

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1966)

Jour de lessive, quarante-huit heures avant l’évacuation des personnes d’ascendance japonaise de ce village agricole du comté de Santa Clara, San Lorenzo, Californie

Laundry day, forty-eight hours before the evacuation of people of Japanese descent from this farming village of Santa Clara County, San Lorenzo, California

1942

Gelatin silver print

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1966)

Oakland, California, March 1942

1942

Gelatin silver print

Library of Congress

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

A large sign reading “I am an American” placed in the window of a store, at 401-403 Eight and Franklin streets, on December 8, the day after Pearl Harbor. The store was closed following orders to persons of Japanese descent to evacuate from certain West Coast areas. The owner, a University of California graduate, will be housed with hundreds of evacuees in War Relocation Authority centers for the duration of the war.

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1966)

Shipyard Worker, Richmond California

c. 1943

Gelatin silver print

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

Dorothea Lange: Politics of Seeing

Dorothea Nutzhorn (1895-1965), who took up photography at the age of eighteen, was born in Hoboken, New Jersey. The daughter of second-generation German immigrants, she adopted her mother’s maiden name, Lange, when she opened a portrait studio in San Francisco in 1918. In 1932, during the Great Depression, Lange shifted her focus from studio portraits to scenes showing the impact of the recession and the social unrest in the streets of San Francisco. This two-year period marked a turning point in her life. Paul Schuster Taylor, professor of economics at the University of California, and a specialist in agricultural conflicts, who later became her second husband, began using her photographs to illustrate his articles in 1934. They worked together for over thirty years. Co-authors of the famous book An American Exodus (1939), they were active in circulating images about social conditions in rural states.

Lange created some of the iconic images of the Great Depression, but this exhibition presents other aspects of her practice, which she herself considered archival. By placing her photographic work in the context of her anthropological approach, it reveals how her images were also rooted in her ability to connect with her subjects, evident in her captions to the images. She thus considerably enriched the informative quality of the visual archive and produced a form of oral history for future generations. Her work for government institutions and the publication of her images in the illustrated press enabled her to denounce injustice and change public opinion.

Her efforts to connect with her subjects can be seen in the five specific series featured in this exhibition: the Depression period (1932-1934), a selection of works from the Farm Security Administration (1935-1941), the Richmond shipyards (1942-1944), the Japanese American internment (1942) and a series on a public defender (1955-1957). By introducing contextual information and important archive material, the Jeu de Paume’s exhibition Dorothea Lange: Politics of Seeing endeavours to situate her majestic works within the social documentary context specific to the 1930s and 1940s, highlighting the artistic qualities of her work and the strength of her political convictions.

1. “The people that my life touched”, 1932-1934

In 1929 America’s urban and rural populations were hard hit by the Great Depression. Leading up to the stock market crash there had been a boom in agricultural production. However, by the late 1920s production was exceeding consumption, causing a drop in prices that had severe consequences for farmers. The textile and coal industries suffered sharp declines in wages and employment. In the 1930s, the oil, transportation and construction sectors declined at an even faster rate than agriculture, causing urban unemployment to rise above that of the rural states. In March 1933, in the midst of this crisis, Franklin D. Roosevelt was elected president.

This context of considerable social unrest prompted a change in direction in Lange’s engagement with photography. From 1932 to 1934, she captured demonstrations and homeless people in the streets of San Francisco. Urban portraits like White Angel Breadline (1933) later became iconic images of the period. Her work from this period was recognised in artistic circles and Paul Shuster Taylor used one of her photographs of the May Day demonstrations to illustrate his article about the longest, largest maritime strike in the history of the USA, which was published in the progressive social welfare journal Survey Graphic in September 1934.

2. The documentary survey – the narration of migration, 1935-1941

In 1935, Lange accompanied Taylor on several field trips to study people migrating to rural California from the Midwest. Taylor used Lange’s images to illustrate the articles as well as his federal reports. Such was the impact of Lange’s powerful images that the authorities built the first migrant camps for agricultural workers as part of Roosevelt’s New Deal policy. The latter consisted of numerous programmes intended to combat the devastating effects of the Depression in all areas of life across the country. One such programme was the Farm Security Administration (FSA), which led to the creation of the largest American photographic archive ever, containing over 130,000 negatives documenting how the New Deal helped to relieve poverty in rural areas.

Lange, who worked in twenty-two different states, was given two contracts, one running from 1935 to 1937 and the other from 1938 to the closure of the programme in January 1941. Her photographs highlighted the plight of people who were caught up in the complex economic web of industrial farming, victims of the failure of the American dream. The images and the transcriptions of oral testimonies that Lange made were personal and intimate recollections of a history that became a cause of significant public concern in the late 1930s.

3. “A two-ocean war” – Kaiser Shipyards, Richmond, 1942-1944

During the early 1940s, Lange was interested in a new form of internal migration caused by the rapid expansion of industries, naval training programmes and military defence organisations in the Bay Area, California. Here part of the once scorned and rejected “Okie” population (migrant farm workers) moved to urban districts, where they proudly contributed to the war effort. In 1944, Lange was commissioned by Fortune magazine to photograph the Kaiser Shipyard in Richmond. This young corporation, established to help with the war effort, employed nearly 100,000 unskilled workers thanks to new techniques of manufacture and assembly. Lange captured the changing of shifts and the intensity of the shipyard’s activity, the diversity of the workforce, intimate details of their living conditions, and the isolation and loneliness of the newcomers, and in particular African Americans, who were excluded from the local community. She was also interested in the unions’ unsuccessful efforts to cope with this large, diverse workforce and in women’s new status in the industrial sector.

4. The internment of American citizens of Japanese descent, 1942

Lange’s various series reflect many aspects of America’s cultural geography. Her desire to portray the dignity of people enduring hardship and the complexity of their situations, coupled with the need to produce a historical document, enabled Lange to produce work of universal scope.

In March 1942, in the wake of the Japanese attack on the American naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on 7 December 1941, the US government ordered the internment of over 110,000 Americans of Japanese descent from the Pacific Coast military zones, crowning a century of racism against Asian immigrants. Executive Order 9066 targeted three generations of Japanese Americans, who were “relocated” to ten remote and intemperate camps in California, Arizona, Utah, Idaho, Colorado, Arkansas and Wyoming.

Lange was commissioned by the War Relocation Authority to cover the procedure from March to July 1942. Her sensitivity to the identity of cultural minorities was already evident in her photographs for the FSA commission. A decade later she captured the evacuation and incarceration of Japanese Americans, which lasted for over 18 months. These images belonged to a “military record” and were only released for publication in 2006.

5. The public defender, 1955-1957

A system of public defence for persons in need of legal support in court cases began in California in 1914 and by the 1950s had been introduced in many states throughout the country. Lange supported the idea of justice for all and was given an assignment by Life magazine to cover the subject at the Alameda County Court house, Oakland, to be published in May 1956 to mark Law Day. Lange was given permission to photograph in prison cells, as well as in and around the law court, taking over 450 images. She worked in conjunction with Martin Pulich, an American lawyer of Yugoslav descent, who recognised in Lange’s approach a social and political stance that mirrored his own commitment as a public defender. In this photographic essay she was able to pinpoint issues concerning racial prejudice that were omnipresent in the Bay Area at the time. The assignment did not appear in Life, but it was published in many newspapers, even internationally, and was also used by the national Legal Aid Society of New York to develop public services in the legal system.

Pia Viewing

Curator of the exhibition

Paul Schuster Taylor (American, 1895-1984)

Dorothea Lange on the Plains of Texas

c. 1935

Gelatin silver print

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

Jeu de Paume

1, Place de la Concorde

75008 Paris

métro Concorde

Phone: 01 47 03 12 50

Opening hours:

Tuesday: 11.00 – 21.00

Wednesday – Sunday: 11.00 – 19.00

Closed Monday

You must be logged in to post a comment.