Exhibition dates: 12th February – 18th June 2017

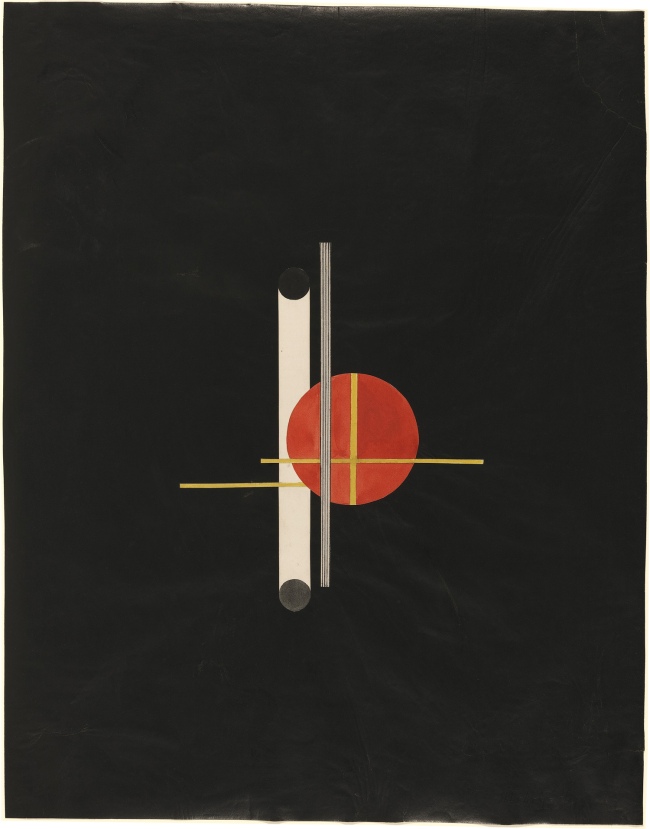

László Moholy-Nagy (Hungarian, 1895-1946)

F in Field

1920

Gouache and collage on paper

8 11/16 × 6 15/16 in.

Private collection, courtesy of Kunsthandel Wolfgang Werner, Bremen/Berlin

© 2017 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

“To meet the manifold requirements of this age with a definite program of human values, there must come a new mentality and a new type of personality. The common denominator is the fundamental acknowledgment of human needs; the task is to recognise the moral obligation in satisfying these needs, and the aim is to produce for human needs, not for profit.”

László Moholy-Nagy in Vision in Motion, published posthumously in 1947

New vision

One of the most creative human beings of the 20th century, and one of its most persuasive artists … “pioneering painter, photographer, sculptor, and filmmaker as well as graphic, exhibition, and stage designer, who was also an influential teacher at the Bauhaus, a prolific writer, and later the founder of Chicago’s Institute of Design.”

New visual creations, new combinations of technology and art: immersive installations featuring photographic reproductions, films, slides, posters, and examples of architecture, theatre, and industrial design that attempted to achieve a Gesamtwerk (total work) that would unify art and technology with life itself. Moholy’s “belief in the power of images and the various means by which to disseminate them” presages our current technological revolution.

It’s time another of his idioms – the moral obligation to satisfy human values by producing for human needs, not for profit – is acted upon.

The aim is to produce for human needs, not for profit.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

The first comprehensive retrospective of the work of László Moholy-Nagy (1895-1946) in the United States in nearly 50 years, this long overdue presentation reveals a utopian artist who believed that art could work hand-in-hand with technology for the betterment of humanity. Moholy-Nagy: Future Present examines the career of this pioneering painter, photographer, sculptor, and filmmaker as well as graphic, exhibition, and stage designer, who was also an influential teacher at the Bauhaus, a prolific writer, and later the founder of Chicago’s Institute of Design. The exhibition includes more than 250 works in all media from public and private collections across Europe and the United States, some of which have never before been shown publicly in the U.S. Also on display is a large-scale installation, the Room of the Present, a contemporary construction of an exhibition space originally conceived by Moholy-Nagy in 1930. Though never realised during his lifetime, the Room of the Present illustrates Moholy’s belief in the power of images and the various means by which to disseminate them – a highly relevant paradigm in today’s constantly shifting and evolving technological world.

Moholy-Nagy: Future Present at LACMA

An exhibition walkthrough of Moholy-Nagy: Future Present at LACMA. Mark Lee, Principal of Johnston Marklee and Carol S. Eliel, Curator of Modern Art at LACMA discuss how Johnston Marklee’s design of the exhibition dialogues with the multiple mediums that constitute Moholy-Nagy’s vast body of work.

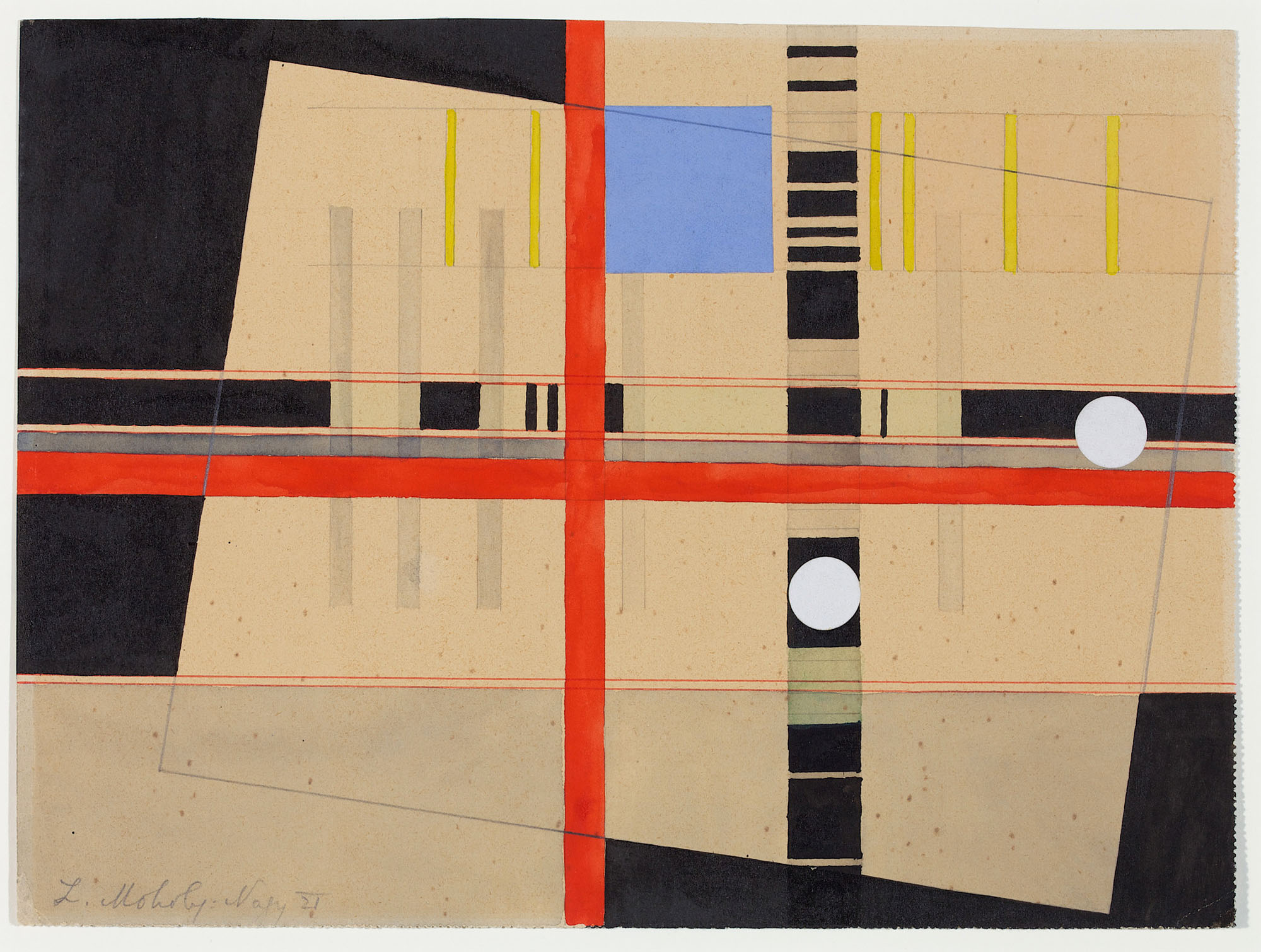

László Moholy-Nagy (Hungarian, 1895-1946)

Title unknown

1920/1921

Gouache, collage, and graphite on paper

9 5/8 × 6 3/8 in.

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Gift of Kate Steinitz

© 2017 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

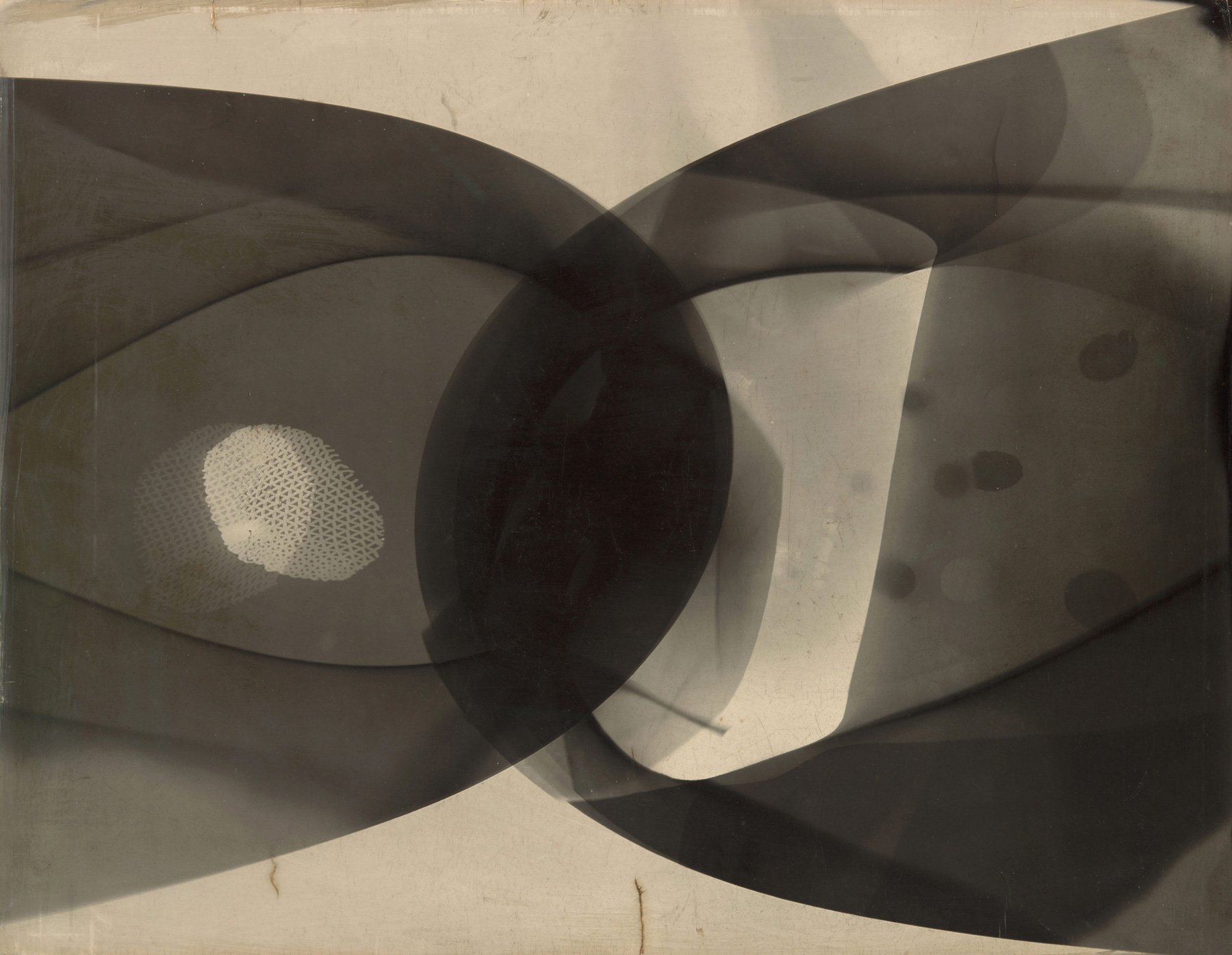

László Moholy-Nagy (Hungarian, 1895-1946)

Photogram

1941

Gelatin silver photogram

28 x 36cm

The Art Institute of Chicago, Gift of Sally Petrilli, 1985

© 2016 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

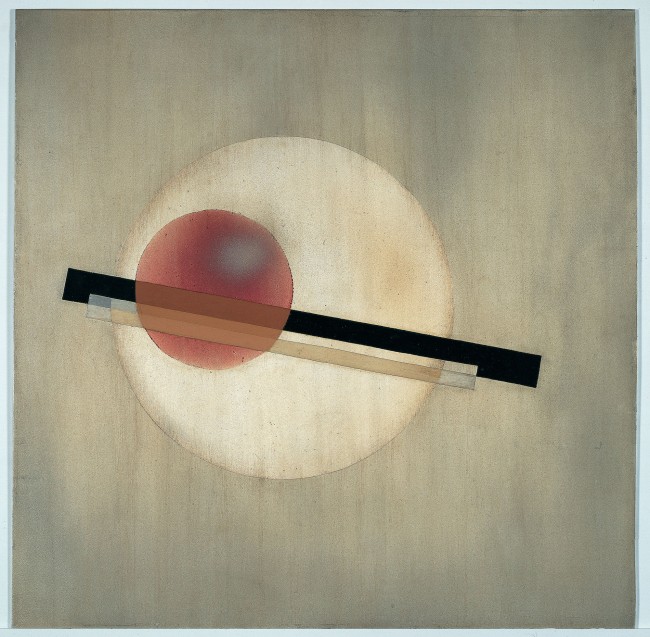

László Moholy-Nagy (Hungarian, 1895-1946)

19

1921

Oil on canvas

44 × 36 1/2 in.

Harvard Art Museums/Busch-Reisinger Museum, Gift of Sibyl Moholy-Nagy

© 2017 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Photo © President and Fellows of Harvard College

László Moholy-Nagy (Hungarian, 1895-1946)

Red Cross and White Balls

1921

Collage, ink, graphite, and watercolour on paper

8 7/16 × 11 7⁄16 in.

Museum Kunstpalast Düsseldorf

© 2017 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, photo © Museum Kunstpalast – Horst Kolberg – ARTOTHEK

László Moholy-Nagy (Hungarian, 1895-1946)

Construction

1922

Oil and graphite on panel

21 3/8 × 17 15/16 in.

Harvard Art Museums/Busch-Reisinger Museum, Gift of Lydia Dorner in memory of Dr. Alexander Dorner

© 2017 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Photo © President and Fellows of Harvard College

László Moholy-Nagy (Hungarian, 1895-1946)

Q

1922/23

Collage, watercolour, ink, and graphite on paper attached to carbon paper

23 3⁄16 × 18 1⁄4 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund

© 2017 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) presents Moholy-Nagy: Future Present, the first comprehensive retrospective of the pioneering artist and educator László Moholy-Nagy (1895-1946) to be seen in the United States in nearly 50 years. Organised by LACMA, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, and the Art Institute of Chicago, this exhibition examines the rich and varied career of the Hungarian-born modernist. One of the most versatile figures of the twentieth century avant-garde, Moholy (as he is often called) believed in the potential of art as a vehicle for social transformation and in the value of new technologies in harnessing that potential. He was a pathbreaking painter, photographer, sculptor, designer, and filmmaker as well as a prolific writer and an influential teacher in both Germany and the United States. Among his innovations were experiments with cameraless photography; the use of industrial materials in painting and sculpture; research with light, transparency, and movement; work at the forefront of abstraction; fluidity in moving between the fine and applied arts; and the conception of creative production as a multimedia endeavour. Radical for the time, these are now all firmly part of contemporary art practice.

The exhibition includes approximately 300 works, including paintings, sculptures, drawings, collages, photographs, photograms, photomontages, films, and examples of graphic, exhibition, and theatre design. A highlight is the full-scale realisation of the Room of the Present, an immersive installation that is a hybrid of exhibition space and work of art, seen here for the first time in the United States. This work – which includes photographic reproductions, films, images of architectural and theatre design, and examples of industrial design – was conceived by Moholy around 1930 but realised only in 2009. The exhibition is installed chronologically with sections following Moholy’s career from his earliest days in Hungary through his time at the Bauhuas (1923-1928), his post-Bauhaus period in Europe, and ending with his final years in Chicago (1937-1946).

Moholy-Nagy: Future Present is co-organised by Carol S. Eliel, Curator of Modern Art, LACMA; Karole P. B. Vail, Curator, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum; and Matthew S. Witkovsky, Richard and Ellen Sandor Chair and Curator, Department of Photography, Art Institute of Chicago. The exhibition’s tour began at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, continued at the Art Institute of Chicago, and concludes at LACMA.

“Moholy-Nagy is considered one of the earliest modern artists actively to engage with new materials and technologies. This spirit of experimentation connects to LACMA’s longstanding interest in and support of the relationship between art and technology, starting with its 1967-1971 Art and Technology Program and continuing with the museum’s current Art + Technology Lab,” according to Michael Govan, LACMA CEO and Wallis Annenberg Director. “This exhibition’s integrated view of Moholy’s work in numerous mediums reveals his relevance to contemporary art in our multi- and new media age.”

Moholy’s goal throughout his life was to integrate art, technology, and education for the betterment of humanity; he believed art should serve a public purpose. These goals defined the artist’s utopian vision, a vision that remained as constant as his fascination with light, throughout the many material changes in his oeuvre,” comments Carol S. Eliel, exhibition curator. “Light was Moholy’s ‘dream medium,’ and his experimentation employed both light itself and a range of industrial materials that take advantage of light.”

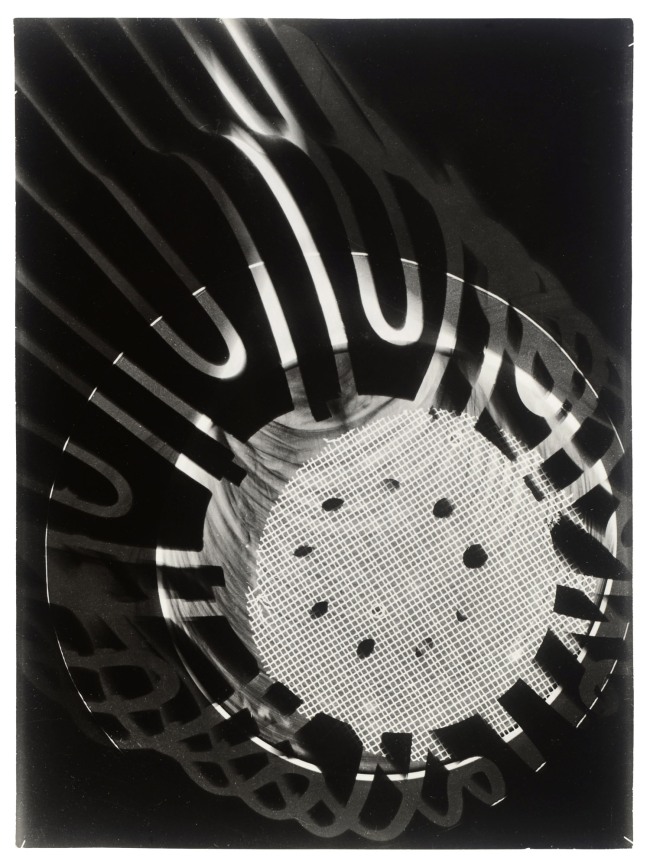

László Moholy-Nagy (Hungarian, 1895-1946)

Photogram

1925/28, printed 1929

Gelatin silver print (enlargement from photogram) from the Giedion Portfolio

15 3/4 × 11 13/16 in.

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, museum purchase funded by the Mary Kathryn Lynch Kurtz Charitable Lead Trust, The Manfred Heiting Collection

© 2017 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

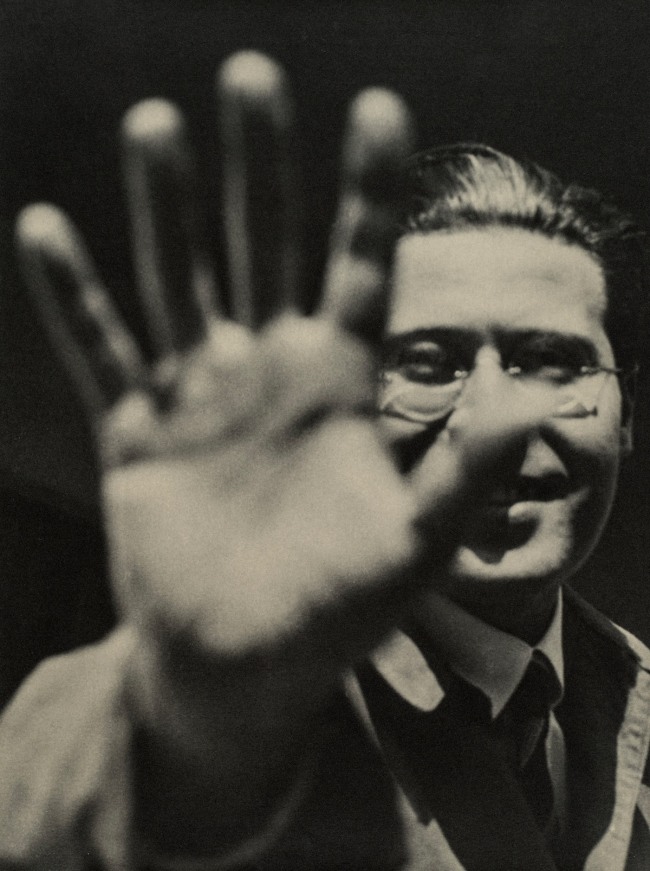

László Moholy-Nagy (Hungarian, 1895-1946)

Photograph (Self-Portrait with Hand)

1925/1929, printed 1940/1949

Gelatin silver print

9 5/16 × 7 in.

Galerie Berinson, Berlin

© 2017 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

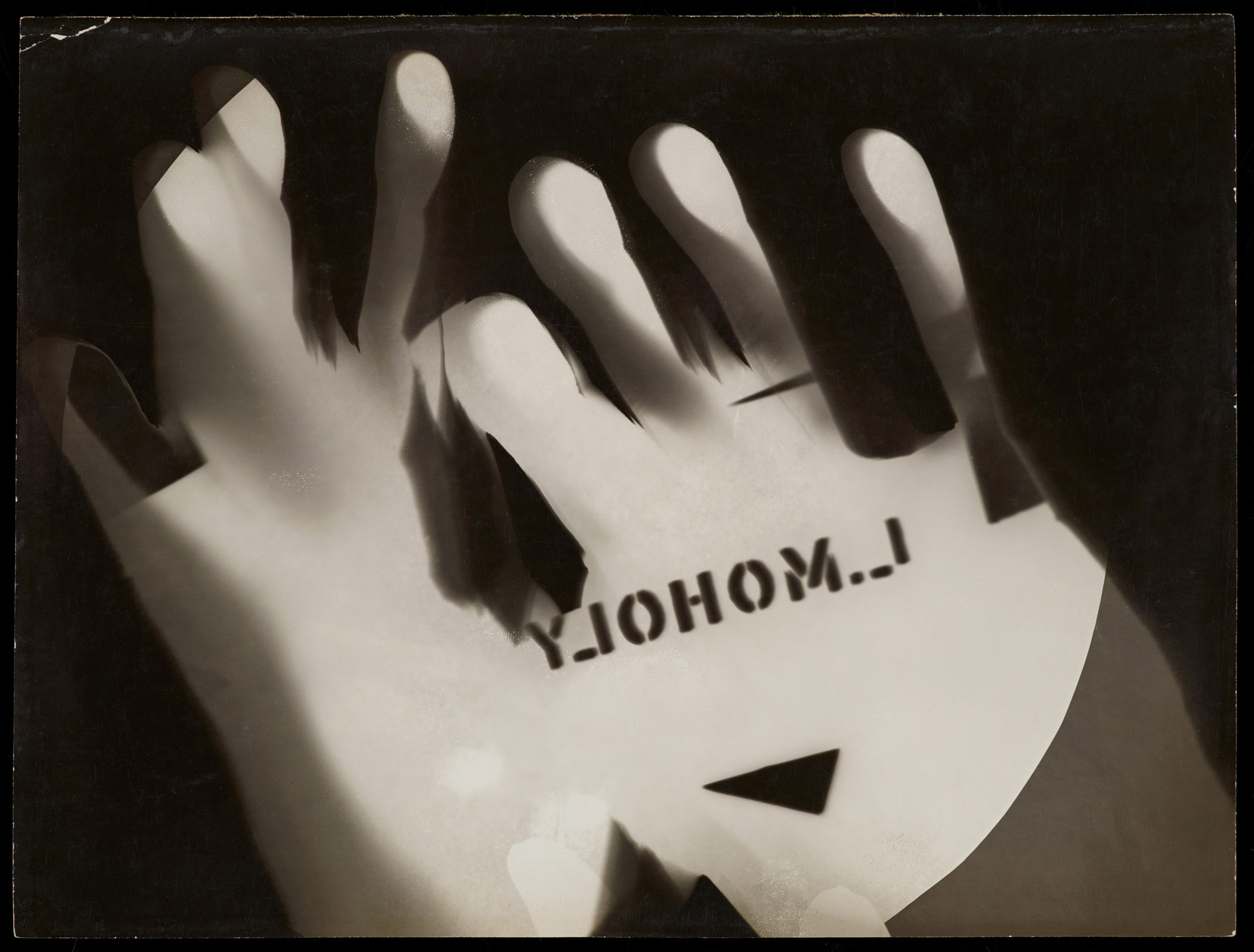

László Moholy-Nagy (Hungarian, 1895-1946)

Photogram

1925/1926

Gelatin silver photogram

7 3/16 × 9 1/2 in.

Museum Folkwang, Essen

© 2017 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Photo © Museum Folkwang Essen – ARTOTHEK

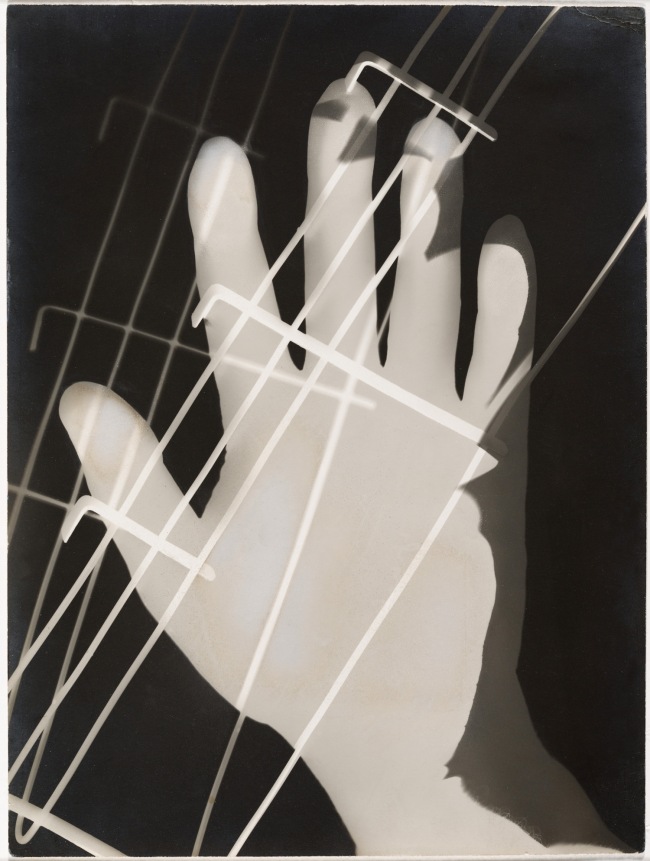

László Moholy-Nagy (Hungarian, 1895-1946)

Photogram

1926

Gelatin silver print

9 3/8 x 7 in.

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Ralph M. Parsons Fund

© 2017 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Photogram (1926): In the 1920s Moholy was among the first artists to make photograms by placing objects – including coins, lightbulbs, flowers, even his own hand – directly onto the surface of light-sensitive paper. He described the resulting images, simultaneously identifiable and elusive, as “a bridge leading to a new visual creation for which canvas, paintbrush, and pigment cannot serve.”

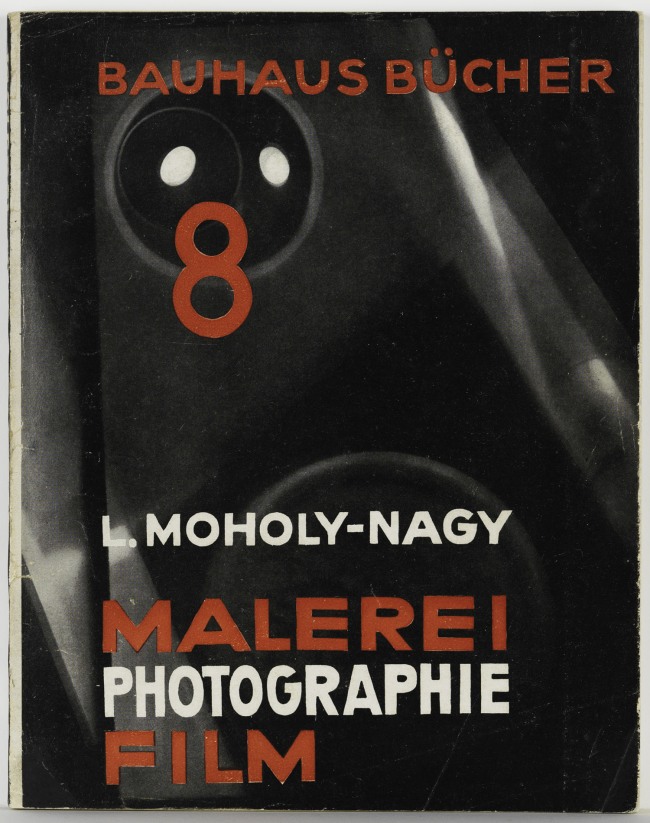

László Moholy-Nagy (Hungarian, 1895-1946)

Cover and design for Malerei Photographie Film (Painting Photography Film)

1st ed., Bauhausbücher (Bauhaus Books) 8 (Albert Langen Verlag, 1925), bound volume

9 1/16 × 7 1/16 in.

Collection of Richard S. Frary

© 2017 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

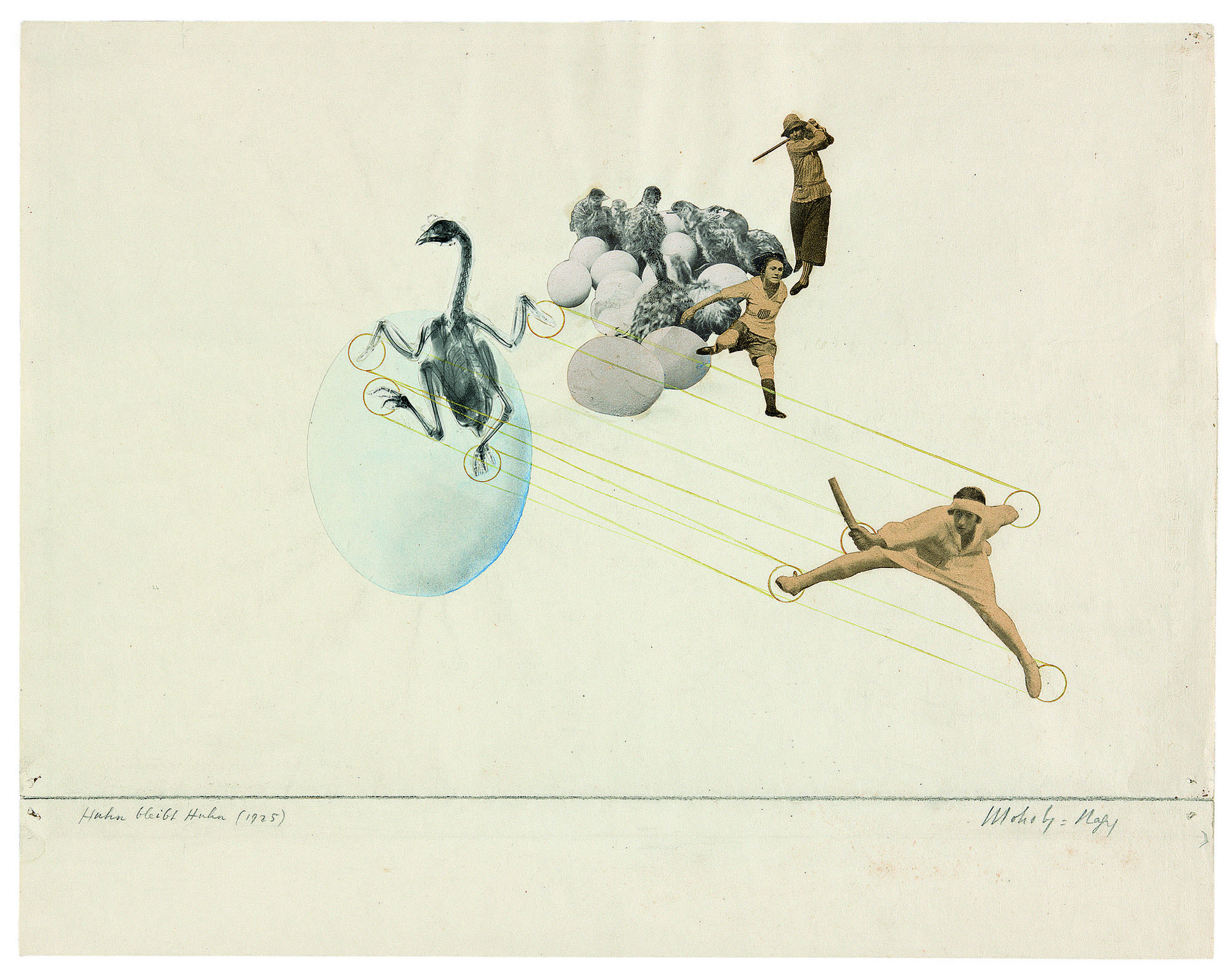

László Moholy-Nagy (Hungarian, 1895-1946)

Once a Chicken, Always a Chicken

1925

Photomontage (halftone reproductions, paper, watercolor, and grapite) on paper

15 × 19 in.

Alice Adam, Chicago

© 2017 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

About the artist

László Moholy-Nagy was born in Hungary in 1895. He enrolled as a law student at the University of Budapest in 1915, leaving two years later to serve as an artillery officer in the Austro-Hungarian army during World War I. He began drawing while on the war front; after his discharge in 1918 Moholy convalesced in Budapest, where he focused on painting. He was soon drawn to the cutting-edge art movements of the period, including Cubism and Futurism. Moholy moved to Vienna in 1919 before settling in Berlin in 1920, where he served as a correspondent for the progressive Hungarian magazine MA (Today).

The letters and glyphs of Dada informed Moholy’s visual art around 1920 while the hard edged geometries and utopian goals of Russian Constructivism influenced his initial forays into abstraction shortly thereafter, particularly works that explored the interaction among coloured planes, diagonals, circles, and other geometric forms. By the early 1920s Moholy had gained a reputation as an innovative artist and perceptive theorist through exhibitions at Berlin’s radical Galerie Der Sturm as well as his writings. His lifelong engagement with industrial materials and processes – including the use of metal plating, sandpaper, and various metals and plastics then newly-developed for commercial use – began at this time.

In 1923 Moholy began teaching at the Bauhaus, an avant-garde school that sought to integrate the fine and applied arts, where his colleagues included Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, and other path breaking modernists. Architect Walter Gropius, founder of the Bauhaus, invited Moholy to expand its progressive curriculum, particularly by incorporating contemporary technology into more traditional methods and materials. He also had a part in Bauhaus graphic design achievements, collaborating with Herbert Bayer on stationery, announcements, and advertising materials.

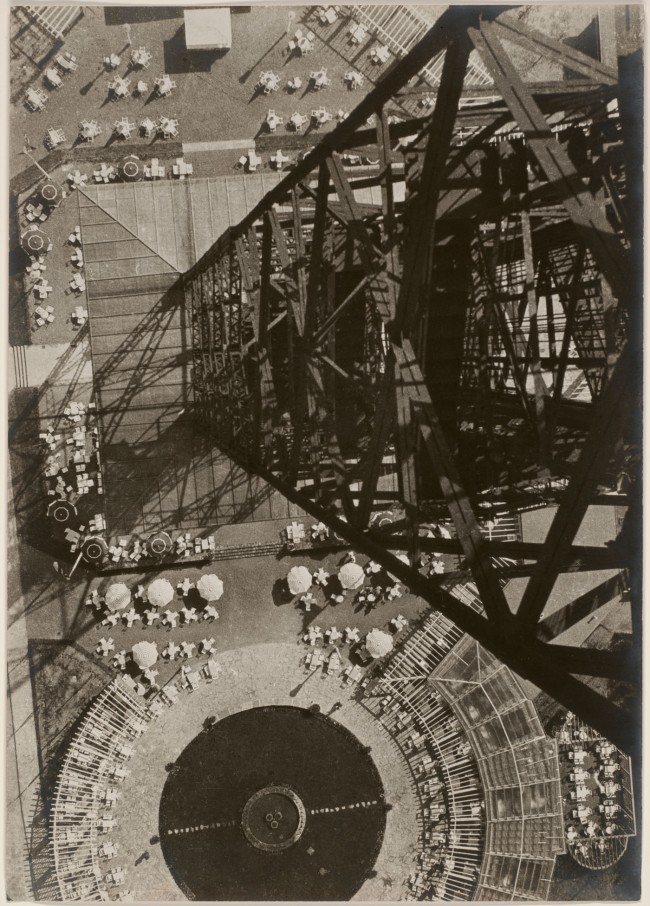

Photography was of special significance for Moholy, who believed that “a knowledge of photography is just as important as that of the alphabet. The illiterates of the future will be ignorant of the use of the camera and pen alike.” In the 1920s he was among the earliest artists to make photograms by placing objects directly onto the surface of light-sensitive paper. He also made photographs using a traditional camera, often employing exaggerated angles and plunging perspectives to capture contemporary technological marvels as well as the post-Victorian freedom of the human body in the modern world. His photographs are documentary as well as observations of texture, captured in fine gradations of light and shadow. Moholy likewise made photomontages, combining assorted elements, typically newspaper and magazine clippings, resulting in what he called a “compressed interpenetration of visual and verbal wit; weird combinations of the most realistic, imitative means which pass into imaginary spheres.” Moholy-Nagy includes the largest grouping of the artist’s photomontages ever assembled.

After leaving the Bauhaus in 1928, Moholy turned to commercial, theatre, and exhibition design as his primary means of income. This work, which reached a broad audience, was frequently collaborative and interdisciplinary by its very nature and followed from the artist’s dictum “New creative experiments are an enduring necessity.”

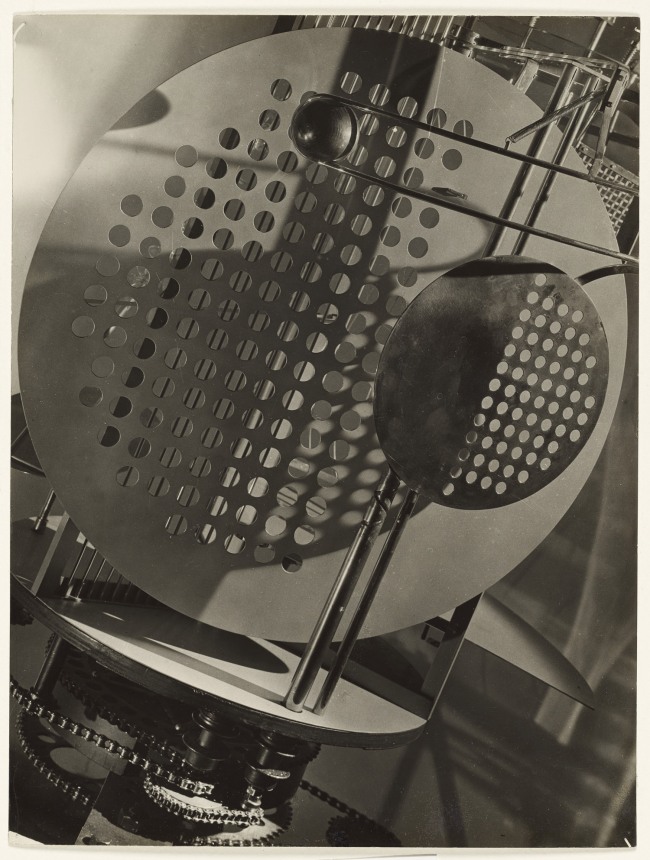

Even as his commercial practice was expanding, Moholy’s artistic innovations and prominence in the avant-garde persisted unabated. He continued to bring new industrial materials into his painting practice, while his research into light, transparency, and movement led to his 35 mm films documenting life in the modern city, his early involvement with colour photography for advertising, and his remarkable kinetic Light Prop for an Electric Stage of 1930. An extension of his exhibition design work, Moholy’s Room of the Present was conceived to showcase art that embodied his “new vision” – endlessly reproducible photographs, films, posters, and examples of industrial design.

Forced by the rise of Nazism to leave Germany, in 1934 Moholy moved with his family to Amsterdam, where he continued to work on commercial design and to collaborate on art and architecture projects. Within a year of arriving the family was forced to move again, this time to London. Moholy’s employment there centred around graphic design, including prominent advertising campaigns for the London Underground, Imperial Airways, and Isokon furniture. He also received commissions for a number of short, documentary influenced films while in England. In 1937, the artist accepted the invitation (arranged through his former Bauhaus colleague Walter Gropius) of the Association of Arts and Industries to found a design school in Chicago, which he called the New Bauhaus – American School of Design. Financial difficulties led to its closure the following year, but Moholy reopened it in 1939 as the School of Design (subsequently the Institute of Design, today part of the Illinois Institute of Technology). Moholy transmitted his populist ethos to the students, asking that they “see themselves as designers and craftsmen who will make a living by furnishing the community with new ideas and useful products.”

Despite working full-time as an educator and administrator, Moholy continued his artistic practice in Chicago. His interest in light and shadow found a new outlet in Plexiglas hybrids of painting and sculpture, which he often called Space Modulators and intended as “vehicles for choreographed luminosity.” His paintings increasingly involved biomorphic forms and, while still abstract, were given explicitly autobiographical or narrative titles – the Nuclear paintings allude to the horror of the atomic bomb, while the Leuk paintings refer to the cancer that would take his life in 1946. Moholy’s goal throughout his life was to integrate art, technology, and education for the betterment of humanity. “To meet the manifold requirements of this age with a definite program of human values, there must come a new mentality,” he wrote in Vision in Motion, published posthumously in 1947. “The common denominator is the fundamental acknowledgment of human needs; the task is to recognise the moral obligation in satisfying these needs, and the aim is to produce for human needs, not for profit.”

László Moholy-Nagy (Hungarian, 1895-1946)

AL 3

1926

Oil, industrial paint, and graphite on aluminium

15 3/4 × 15 3/4 in.

Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena, California, The Blue Four Galka Scheyer Collection

© 2017 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

László Moholy-Nagy (Hungarian, 1895-1946)

Photograph (Berlin Radio Tower)

1928/1929

Gelatin silver print

14 3/16 × 10 in.

The Art Institute of Chicago, Julien Levy Collection, Special Photography Acquisition Fund

© 2017 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Digital image © The Art Institute of Chicago

Photograph (Berlin Radio Tower) (1928/29): Moholy used a traditional camera to take photos that often employ exaggerated angles and plunging perspectives to capture contemporary technological marvels such as the Berlin Radio Tower, which was completed in 1926. This photograph epitomises Moholy’s concept of art working hand-in-hand with technology to create new ways of seeing the world – his “new vision.”

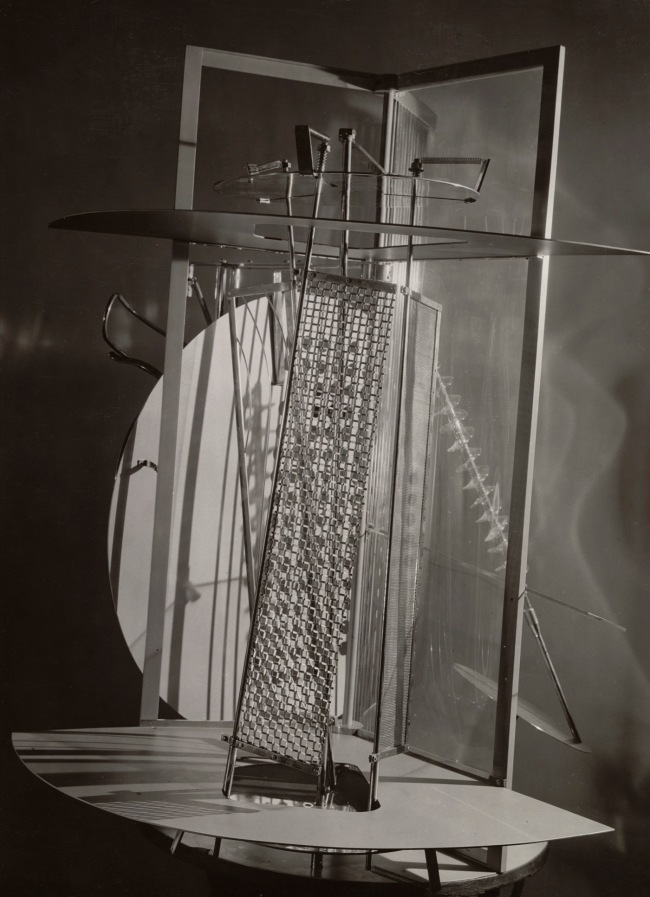

László Moholy-Nagy (Hungarian, 1895-1946)

Photograph (Light Prop for an Electric Stage)

1930

Gelatin silver print

9 7/16 × 7 1/8 in.

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© 2017 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

A short documentation from the replica of Moholy-Nagy’s Light Space Modulator in Van Abbe Museum in Eindhoven, Holland

Làslò Moholy Nagy film

1930

László Moholy-Nagy (Hungarian, 1895-1946)

Photograph (Light Prop for an Electric Stage)

c. 1930

Gelatin silver print

14 3/4 × 10 3/4 in.

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Gift of the artist

© 2017 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Digital image © The Museum of Modern Art / licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY

Installation view of Room 2, designed by László Moholy-Nagy, of the German section of the annual salon of the Society of Decorative Artists, Paris, May 14-July 13, 1930

Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

© 2017 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Photo: Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

László Moholy-Nagy (Hungarian, 1895-1946)

Room of the Present

Constructed 2009 from plans and other documentation, dated 1930

Mixed media

Inner dimensions: 137 3/4 x 218 7/8 x 318 3/4 in.

Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, 2953

© 2017 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Photography by Peter Cox, Eindhoven, The Netherlands

The Room of the Present is an immersive installation featuring photographic reproductions, films, slides, posters, and examples of architecture, theatre, and industrial design, including an exhibition copy of Moholy’s kinetic Light Prop for an Electric Stage (1930). The Room exemplifies Moholy’s desire to achieve a Gesamtwerk (total work) that would unify art and technology with life itself. A hybrid between exhibition space and work of art, it was originally conceived around 1930 but realised only in 2009, based on the few existing plans, drawings, and related correspondence Moholy left behind.

László Moholy-Nagy (Hungarian, 1895-1946)

Construction AL6 (Konstruktion AL6)

1933-1934

Oil and incised lines on aluminum

60 × 50cm

IVAM, Institut Valencià d’Art Modern, Generalitat

© 2016 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

László Moholy-Nagy (Hungarian, 1895-1946)

CH BEATA I

1939

Oil and graphite on canvas

46 7/8 × 47 1/8 in.

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Founding Collection

© 2017 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Photo © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York, photography by Kristopher McKay

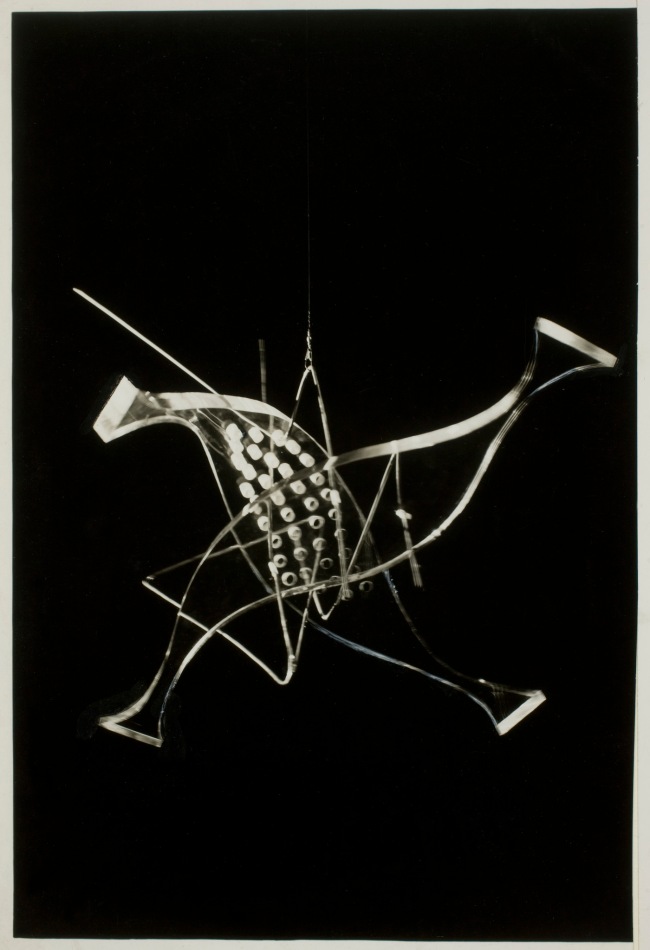

László Moholy-Nagy (Hungarian, 1895-1946)

Photograph (Light Modulator in Motion)

1943

Gelatin silver print

6 9/16 x 4 7/16 in.

George Eastman Museum, Rochester, New York, purchase with funds provided by Eastman Kodak Company

© 2017 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

László Moholy-Nagy (Hungarian, 1895-1946)

Photograph (Light Modulator in Repose)

1943

Gelatin silver print

6 7/16 x 4 1/2 in.

George Eastman Museum, Purchased with funds provided by Eastman Kodak Company

© 2017 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

László Moholy-Nagy (Hungarian, 1895-1946)

Vertical Black, Red, Blue

1945

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, purchased with funds provided by Alice and Nahum Lainer, the Ducommun and Gross Acquisition Fund, the Fannie and Alan Leslie Bequest, and the Modern and Contemporary Art Council, as installed in Moholy-Nagy: Future Present at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art

© 2017 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, photo

© 2017 Museum Associates/LACMA

László Moholy-Nagy (Hungarian, 1895-1946)

Space Modulator CH for R1

1942

Oil and incised lines on Formica

62 3/16 × 25 9/16 in.

Hattula Moholy-Nagy, Ann Arbor, Michigan

© 2017 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Photography by Peter Schälchli

Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA)

5905 Wilshire Boulevard (at Fairfax Avenue)

Los Angeles, CA, 90036

Phone: 323 857 6000

Opening hours:

Monday, Tuesday, Thursday: 11am – 5 pm

Friday: 11am – 8pm

Saturday, Sunday: 10am – 7pm

Closed Wednesday

You must be logged in to post a comment.