Exhibition dates: 22nd January – 28th May 2017

Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926)

The Customhouse

1882

Oil on canvas

61 x 75cm

Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Bequest of Annie Swan Coburn, 1934

Photo: Imaging Department © President and Fellows of Harvard College

Underlying these “impressions” of light, shadow and reflection is structure. Perceiving the spaces in between things as things… means that you need to define the original things as a first point of call. Order / chaos, pattern / randomness, harmony / discord. One does not exist without the other.

Grounding all of Monet’s work is an intrinsic understanding of the structure of the world.

Marcus

Many thankx to the Fondation Beyeler for allowing me to publish the images in the posting. Please click on the images for a larger version of the art.

“The world’s appearance would be shaken if we succeeded in perceiving the spaces in between things as things.”

Maurice Merleau-Ponty

Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926)

View of Bordighera

1884

Oil on canvas

66 x 81.8cm

The Armand Hammer Collection, Schenkung der Armand Hammer Foundation, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles

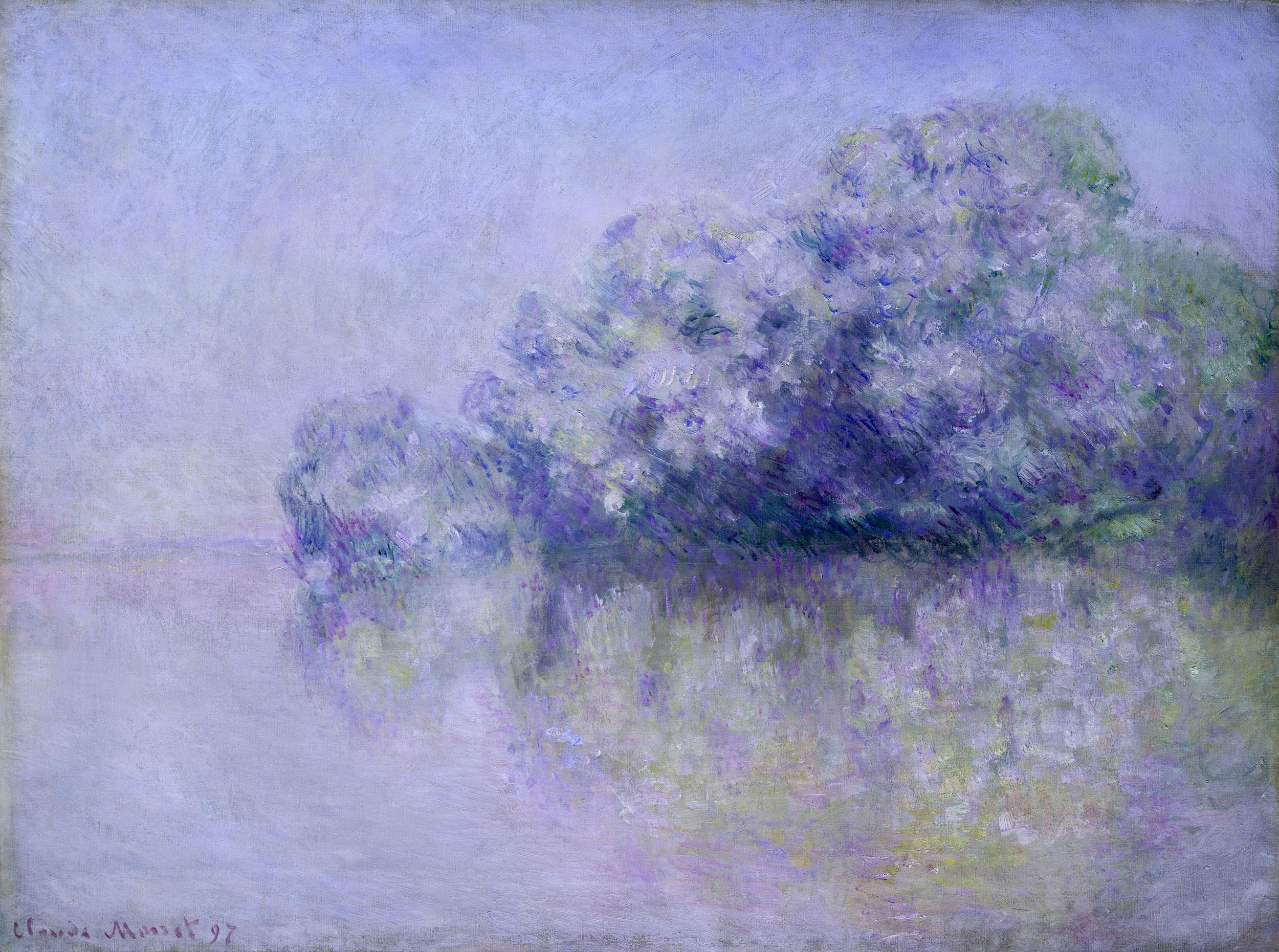

Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926)

Vagues a la Manneporte (Waves at Manneporte)

c. 1885

Oil on canvas

Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926)

Rocks at Belle-Île, Port-Domois

1886

Oil on canvas

81.3 x 64.8cm

Cincinnati Art Museum, Fanny Bryce Lehmer Endowment and The Edwin and Virginia Irwin Memorial, 1985

Photo: Bridgeman Images

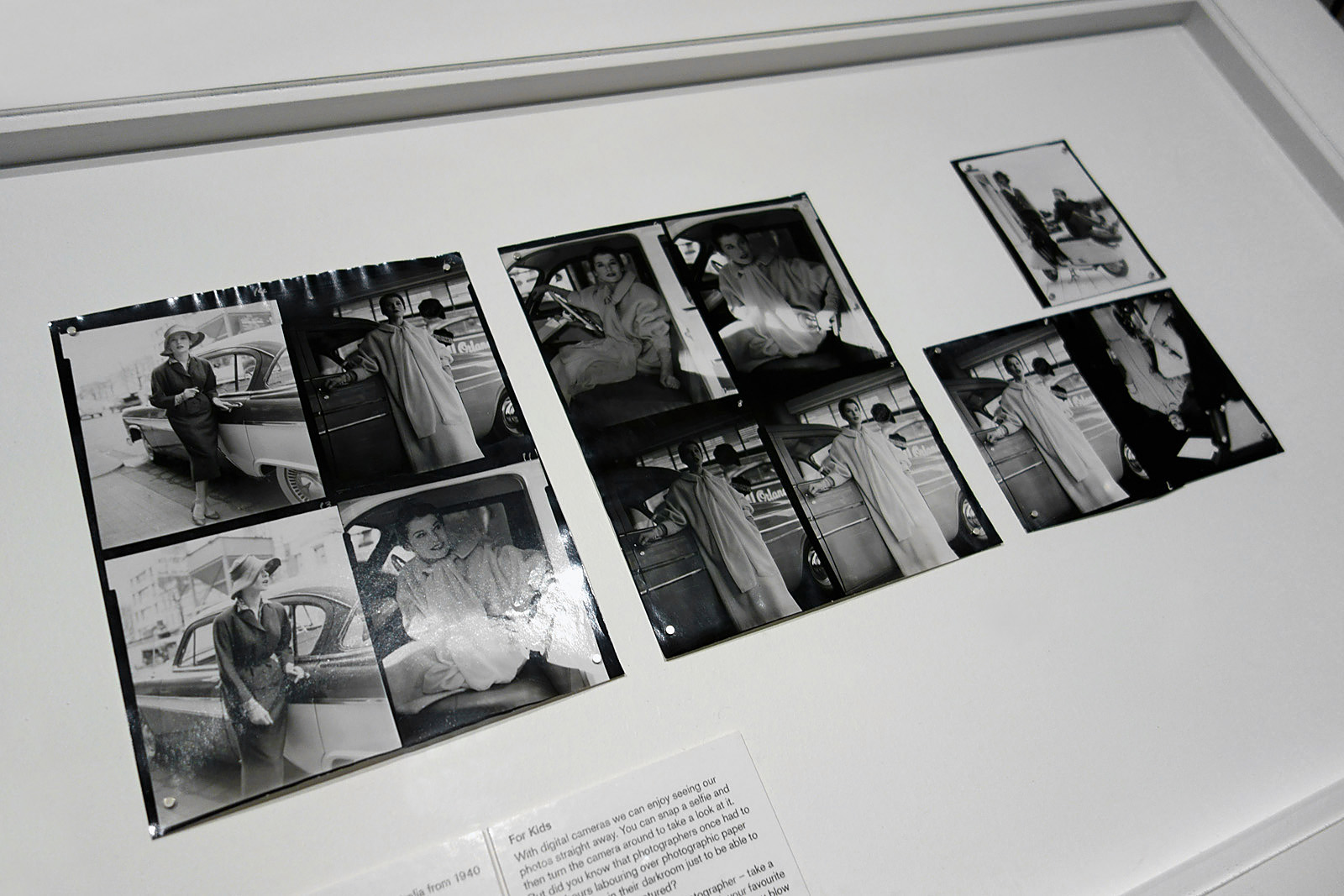

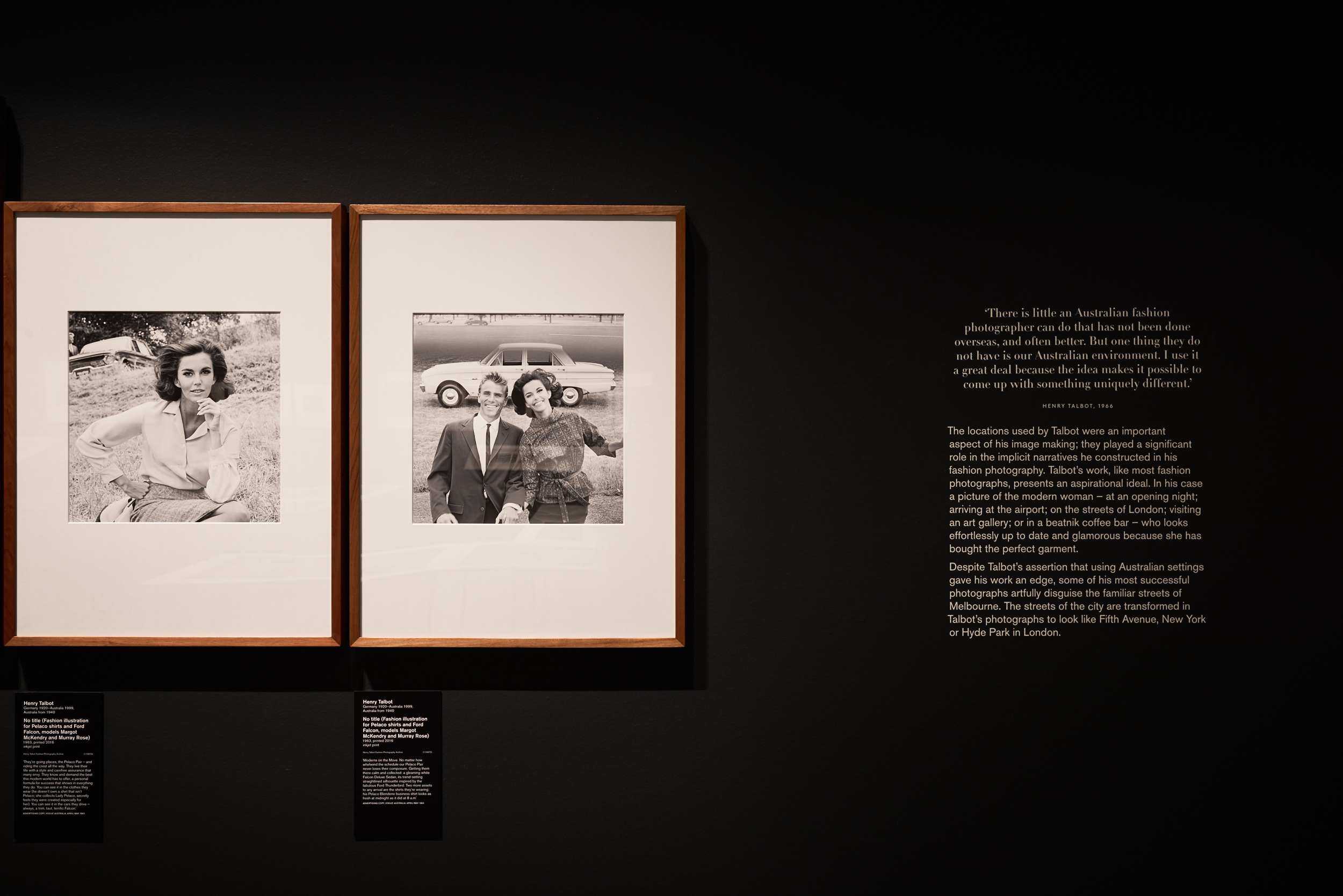

In the year of its 20th birthday, the Fondation Beyeler is devoting an exhibition to Claude Monet, one of the most important artists in its collection. Selected aspects of Monet’s oeuvre will be presented in a distilled overview. By concentrating on his work between 1880 and the beginning of the 20th century, with a forward gaze to his late paintings, the show will reveal a fresh and sometimes unexpected facet of the pictorial magician, who still influences our visual experiencing of nature and landscape today. The leitmotif of the “Monet” exhibition will be light, shadow, and reflection as well as the constantly evolving way in which Monet treated them. It will be a celebration of light and colours. Monet’s famed pictorial worlds – his Mediterranean landscapes, wild Atlantic coastal scenes, various locations places along the course of the River Seine, his flower meadows, haystacks, cathedrals and fog-shrouded bridges – are the exhibition’s focal points.

In his paintings, Monet experimented with the changing play of light and colours in the course of the day and the seasons. He conjured up magical moods through reflections and shade. Claude Monet was a great pioneer, who found the key to the secret garden of modern painting, and opened everyone’s eyes to a new way of seeing the world. The exhibition will show 62 paintings from leading museums in Europe, the USA and Japan, including the Musée d’Orsay, Paris; the Metropolitan Museum, New York; the Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Museum of Fine Art, Boston and the Tate, London. 15 paintings from various private collections that are seen extremely rarely and that have not been shown in the context of a Monet exhibition for many years will be special highlights of the show.

Light, shadow, and reflection

Following the death of his wife in 1879, Monet embarked on a phase of reorientation. His time as a pioneer of Impressionism was over; while by no means generally acknowledged as an artist, he was beginning to become more independent financially thanks to the help of his dealer, as is documented by his frequent journeys. Through them, he was, for example, first able to concern himself with Mediterranean light, which provided new impulses for his paintings. His art became more personal, moving away from a strictly Impressionist style.

Above all, however, Monet seems to have increasingly turned painting itself into the theme of his paintings. His comment, as passed down by his stepson Jean Hoschedé, that, for him, the motif was of secondary importance to what happened between him and the motif, should be seen in this light. Monet’s reflections on paintings should be interpreted in two ways. The repetition of his motifs through reflections, which reach their zenith and conclusion in his paintings of the reflections in his water-lily ponds, can also be seen as a continuous reflecting on the potential of painting, which is conveyed through the representation and repetition of a motif on a canvas.

Monet’s representations of shade are another way in which he represented the potential of painting. They are both the imitation and the reverse side of the motif, and their abstract form gives the painting a structure that seems to question the mere copying of the motif. This led to the situation in which Wassily Kandinsky, on the occasion of his famous encounter with Monet’s painting of a haystack seen against the light (Kunsthaus Zurich and in the exhibition), did not recognise the subject for what it was: the painting itself had taken on far greater meaning that the representation of a traditional motif.

Monet’s Pictorial Worlds

The exhibition is a journey through Monet’s pictorial worlds. It is arranged according to different themes. The large first room in the exhibition is devoted to Monet’s numerous and diverse representations of the River Seine. One of the most notable exhibits is his rarely shown portrait of his partner and subsequent wife Alice Hoschedé, sitting in the garden in Vetheuil directly on the Seine.

The next room celebrates Monet’s representation of trees: a subtle tribute to Ernst Beyeler, who devoted an entire exhibition to the theme of trees in 1998. Inspired by coloured Japanese woodcuts, Monet repeatedly returned to the motif of trees in different lights, their form, and the shade they cast. Trees often give his paintings a geometric structure, as is particularly obvious in his series.

The luminous colours of the Mediterranean are conveyed by a group of canvases Monet painted in the 1880s. In a letter written at that time, he spoke of the “fairytale light” he had discovered in the South.

In 1886 Monet wrote to Alice Hoschedé that he was “crazy about the sea”. A large section of the exhibition is devoted to the coasts of Normandy and the island Belle-Île as well as to the ever-changing light by the sea. It includes a fascinating sequence of different views of a customs official’s cottage on a cliff that lies in brilliant sunlight at times and in the shade at others. On closer examination, the shade seems to have been created out of myriad colours.

Monet’s paintings of early-morning views of the Seine radiate contemplative peace: the painted motif is repeated as a painted reflection in such a way that the distinction between painted reality and its painted reflection seems to disappear in the rising mist. The entire motif is repeated as a reflection. There is no longer any clear-cut differentiation between the top and bottom parts of the painting, which could equally well be hung upside down. In other words, the convention about how paintings ought to be viewed is abandoned and viewers are left to make their own decision. It is as if Monet sought to convey the constant flux (panta rhei) that is such a fundamental characteristic of nature, capturing not only the way light changes from night to day but also the constant merging of two water courses.

Monet loved London. He sought refuge in the city during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/1871. As a successful and already well known painter, he went back there at the turn of the century, painting famous views of Waterloo and Charing Cross Bridge as well as of the Houses of Parliament in different lights, particularly in the fog, which turns all forms into mysterious silhouettes. A tribute not only Monet’s famous hero / forerunner William Turner, but also to the world power of Great Britain with its Parliament and the bridges it built through trade.

Monet’s late work consists almost exclusively of paintings of his garden and the reflections in his waterlily ponds, of which the Beyeler Collection owns some outstanding examples. The exhibition’s last room contains a selection of paintings of Monet’s garden in Giverny.

Press release from the Fondation Beyeler

Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926)

The Terrace at Vétheuil

1881

Oil on canvas

81 x 65cm

Private Collection

Photo: Robert Bayer

Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926)

In the “Norvégienne”

1887

Oil on canvas

97.5 x 130.5cm

Musée d’Orsay, Paris, legacy of Princesse Edmond de Polignac, 1947

Photo: © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d’Orsay) / Hervé Lewandowski

Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926)

Jean-Pierre Hoschedé and Michel Monet on the Banks of the Epte

c. 1887-1890

Oil on canvas

76 x 96.5cm

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, Gift of the Saidye Bronfman Foundation, 1995

Photo: © National Gallery of Canada

Theodore Robinson (American, 1852-1896)

Portrait of Monet

c. 1888-1890

Cyanotype

24 x 16.8cm

Terra Foundation for American Art, Chicago, gift of Mr. Ira Spanierman, 1985

Photo: © Terra Foundation for American Art, Chicago / Art Ressource, NY

Theodore Robinson (1852-1896) was an American painter best known for his Impressionist landscapes. He was one of the first american artists to take up impressionism in the late 1880s, visiting Giverny and developing a close friendship with Claude Monet. Several of his works are considered masterpieces of American Impressionism.

An early exponent of American Impressionism, Theodore Robinson made a number of visits to France, between the years 1876 and 1892, and became a close friend of Claude Monet, whom he visited at Giverny. Paradoxically, despite his willingness to explore a new type of modern art, his particular style of Impressionism was relatively conservative. Even so, several of his paintings are considered to be masterpieces of American art in the Impressionist style. Best known for his landscape painting, he was also noted for his genre painting of village and farm life, as well as his Connecticut boat scenes. His famous works include: By the River (1887, Private Collection), La Vachere (1888, Smithsonian American Art Museum), La Debacle (1892, Scripps College, Claremont) and Union Square (1895, New Britain Museum of American Art, Conn). Shortly before his premature death from an acute asthma attack, he wrote in-depth articles on the Barbizon painter Camille Corot (1796-1875) and his friend Claude Monet (1840-1926).

Unknown photographer

Portrait of Theodore Robinson

Nd

Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926)

Poplars on the Banks of the Epte

1891

Oil on canvas

92,4 x 73.7 cm

Tate, Presented by the Art Fund 1926

Photo: © Tate, London 2016

The Travels of Monsieur Monet: A Geographical Survey

Hannah Rocchi

Le Havre

Oscar-Claude Monet was born in Paris on November 14, 1840, the son of Claude-Alphonse, a commercial officer, and Louise-Justine Aubrée. From 1845 on he grew up in the port city of Le Havre in Normandy, his father having found employment in the trading house of his brother-in-law, Jacques Lecadre. The Lecadres owned a house three kilometres away in the little fishing village of Sainte-Adresse, which as a burgeoning bathing resort was much loved by the Monets. Claude attended the local high school beginning in 1851 and there received his first drawing lessons. His earliest surviving sketches dating from 1856 show caricatures of his teachers and the landscapes of Le Havre. When Monet’s mother died, in 1857, Claude and his elder brother, Léon, moved in with their aunt, Marie-Jeanne Lecadre, who would become very important to him and support him in his pursuit of an artistic career. As an amateur painter with a studio of her own, she had connections to local artists and made sure that her nephew could continue his drawing lessons in Le Havre. Monet’s caricatures soon attracted notice and were exhibited at the local stationer’s, Gravier, who also sold paints and frames. This brought his work to the attention of Eugène Boudin, a former partner in the business, who became Monet’s new teacher.

Boudin invited the young Monet to join him on plein air painting expeditions around Le Havre, an experience that made a lasting impression on his pupil. Monet twice applied for a municipal scholarship, but was turned down both times. Despite moving to Paris to take painting lessons there in 1859, Monet repeatedly returned to Le Havre, including in 1862, when after a year of military service in Algeria he had to return to France on grounds of poor health. Later that year he was discharged from military service thanks to the replacement fee paid by his aunt. It was in the summer of that year that he met the Dutch painter Johan Barthold Jongkind and claimed to have found in him his “true teacher.” He also spent the months May to November 1864 painting landscapes in and around Le Havre. His lover and future wife, Camille Doncieux, gave birth to their first child, Jean-Armand- Claude Monet, in Paris in 1867; yet, urged by his father, who was against the relationship, to leave Paris, the painter spent the summer without them, painting seascapes, gardens, figural compositions, and regattas in Sainte-Adresse. A year later he won a silver medal at the Le Havre art show. After the death of his aunt, in 1870, followed by that of his father just a year later, his visits to Le Havre became less frequent. At the same time, he was drawn more to the towns further up the Normandy coast, to Étretat, Fécamp, and Pourville, where he found even more impressive subjects for paintings.

Paris

Monet, who was born in Paris, returned to the capital in the spring of 1859 to visit the Salon and take painting lessons. During his stays in “chaotic Paris” he incurred numerous expenses, which he was able to defray thanks only to the support of his father and his aunt. Instead of enrolling at the atelier of the painter Thomas Couture for the preparatory course for admission to the École des Beaux-Arts, he chose the academy of Charles Suisse, where he probably met Camille Pissarro. After his discharge from the army in 1862, Monet returned to Paris and there joined the studio of the Swiss history painter Charles Gleyre, where he made the acquaintance of Alfred Sisley, Frédéric Bazille, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Two years later, when Gleyre ran into financial difficulties and had to close his studio, Monet’s father provided him with the funds he needed to rent a studio together with Bazille on the rue de Furstenberg. Renoir, Sisley, Pissarro, and even Paul Cézanne were all regular visitors there. Monet was experimenting with figural paintings at the time, including his large Déjeuner sur l’herbe (1865-66). When their money troubles came to a head in January 1866, Monet and Bazille had no choice but to relinquish their shared space. Monet then rented a small studio of his own on the place Pigalle, and it was there that he engaged Camille Doncieux, the woman he would marry in 1870, to sit for him. His painting of the nineteen-year-old Camille (Camille, or La Femme à la robe verte, 1866), was accepted for the Salon and not only won fulsome praise from the critic Émile Zola, but also aroused the interest of Édouard Manet.

Together with other Impressionists, Monet founded the Société anonyme coopérative des artistes peintres, sculpteurs, graveurs, etc., whose first group show was held in the studio of the photographer Nadar on the boulevard des Capucines in Paris in 1874. Among the works exhibited was Monet’s work Impression, soleil levant, painted in Le Havre in 1872. The show was savaged by the critics, who in a play on the title of Monet’s painting derided it as an “exhibition of impressionists.” Monet tended to find his subjects in the suburbs of Paris rather than in the capital itself, one exception being Saint-Lazare railway station, which he captured on several canvases in 1877. When Monet moved to Vétheuil, in 1878, he held onto a small studio in Paris, even if he used it mainly as a showroom for art dealers and potential collectors. When Monet’s patron Ernest Hoschedé declared bankruptcy, in 1877, he had no choice but to sell his large collection of works by the Impressionists a year later. It was through the sale of Hoschedé’s paintings that Monet met the collector and gallerist Georges Petit, who in the world of Impressionism would soon come to rival the art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel. In 1882 Durand-Ruel himself commissioned Monet with several still lifes for his home on the rue de Rome. In 1914, in Giverny, Monet began work on his last major project, the famous Grandes Décorations, and after his death, in 1927, twenty-two of these large-format paintings of water lilies were installed in the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris.

The Normandy coast

Although his career necessitated ever more frequent trips to Paris, in 1868 Monet wanted to make a home for himself, his partner Camille Doncieux, and their son, Jean, in Normandy. He wrote to Bazille that he could not imagine spending longer than a month at a time in Paris and that whatever he might paint on the coast of Normandy would be very different from anything produced in the French capital. The cliffs near Fécamp that he painted in early 1881 show how his style of painting was already beginning to change, how his once idyllic landscapes were becoming wilder. Monet spent a few months in Poissy near Paris beginning in December of that year, but found the village uninspiring and returned to the coast, this time to the fishing village of Pourville. This was a landscape of rugged cliffs with several subjects of interest to him, among them the customs officer’s house near Varengeville. Furthermore, the beaches were deserted in the winter months, making them ideal for painting. Monet began several new series, sometimes working on eight canvases at once so that he needed help transporting his equipment and canvases from one place to another.

In the 1880s, when sales of his paintings began to pick up and his financial situation became less dire, Monet was at last able to rent a holiday home in Pourville. His new partner, Alice Hoschedé, and her daughter Blanche, who also painted, often accompanied him on his painting expeditions there, and he received visits from both Durand-Ruel and Renoir. In January 1883 Monet visited the village of Étretat, famed for its precipitous cliffs and arches, and there found several motifs right in front of the hotel. He also sought out remote beaches with views of the Manneporte Arch, which he proceeded to paint in different light conditions, often working on several canvases at once. While painting on a secluded beach on November 27, 1885, Monet miscalculated the incoming tide and was hurled against the face of a cliff by a wave. He told Alice that his brush and painting equipment had fallen into the sea, but that what annoyed him most was that the wave had washed away the canvas he was working on. Monet finished all of his over fifty paintings of Étretat in his studio in Giverny, which by then had become his permanent home.

On the Seine: Argenteuil, Vétheuil, and Poissy

On December 21, 1871, Monet rented a house in Argenteuil, a suburb northwest of Paris that allowed him to live in the country but remain within easy reach of the city. Thanks to the sale of several paintings as well as Camille s dowry and inheritance, the Monets were able to employ three servants and Monet himself bought a boat that he converted into a floating studio. Argenteuil became an important center for the Impressionists; Cézanne, Manet, Pissarro, Sisley, and Renoir all visited Monet there. In 1873 Monet met Gustave Caillebotte. One motif that Monet found especially interesting was the railway bridge of Argenteuil. It was destroyed in the Franco-Prussian War but rebuilt soon afterward, making it a symbol of French resilience – and further evidence of Monet’s general interest in bridges. In 1878 the Monets moved to Vétheuil, a little village on the Seine, some sixty kilometers away from Paris. As Monet’s patron Hoschedé was undergoing financial difficulties at the time, he and his wife, Alice, and their six children shared a house with the Monets. Monet’s wife, Camille, had just given birth to their second son, Michel, but was already ill with cervical cancer.

Their financial situation had deteriorated and they were no longer able to pay their servants. As a devout Christian, Alice Hoschedé took it upon herself to ensure that the Monets, who had married in a civil ceremony only, received the blessing of the Church for their union and that Camille Monet was given the last rites. Camille died on September 5, 1879, in Vétheuil and was buried in the cemetery there. The winter of 1879-1880 was exceptionally cold and the Seine froze over. On January 5, 1880, the Hoschedé-Monet family awoke to the sound of the ice breaking apart, and Monet spent the next few days painting dozens of impressions of this spectacle. As Ernest Hoschedé mainly resided in Paris and visited his family only occasionally, Monet and Alice lived more or less alone with their children in Vétheuil, and before long they were rumoured to be having an affair. In 1881 they decided to move again. Monet had been unable to find a suitable school for his son Jean, and Alice was considering whether to return to Ernest in Paris with the children. In the end, however, both Monet and Alice moved to Poissy in December of that year. When Poissy proved uninspiring, however, the two families resumed their quest for the perfect home, which they would find in Giverny in 1883, some seventy kilometers northeast of Paris.

On the Mediterranean

In December 1883 Monet accompanied Renoir on a short trip to the Mediterranean. They traveled from Marseille to Genoa and visited Cézanne in L’Estaque. Monet was especially taken with the little town of Bordighera on the Ligurian Riviera and vowed to return there in January 1884, this time without Renoir, in order to paint in peace. The three-week stay originally planned eventually turned into three months, during which Monet explored the region, visited several mountain villages, and admired the wonderful gardens of Francesco Moreno, where to his great delight he was able to paint palms. The colours and new motifs brought Monet close to despair, and he complained to Alice of how difficult it was to paint the landscape as it really looked. Visibly fascinated by the warm light of the Mediterranean, he declared that he would need a palette of diamonds and jewels to capture its féerique (magical) atmosphere. Although in her replies Alice made no secret of her displeasure at the painter’s constant absences, Monet chose to linger in the south and continued the series he had just begun. He also traveled to Cap Martin and to Monte Carlo, painting as he went. In January 1888 he painted several views of Antibes.

In late September 1908 he visited Venice – one of only a few trips undertaken together with Alice – where he was especially impressed by the Grand Canal, the Doge’s Palace, and the church of San Giorgio Maggiore. When the pair left Venice again, in December 1908, Monet consoled himself with the thought that he would return there the following year, although he already had an inkling that that was “a forlorn hope.” Even so, the 1912 Claude Monet: Venise exhibition, comprising twenty-nine views of Venice and held at the Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, was a great success.

Rouen

Léon Monet, who ran the Rouen branch of a Swiss chemical company, was on good terms with his younger brother, Claude. Jean, the elder of Monet’s two sons, would later work for Léon, providing the painter with another good reason for visiting Rouen. It was probably at his brother’s instigation that Monet took part in the 23ème Exposition municipale des Beaux-Arts, in Rouen in March 1872. Monet discovered his fascination with the Gothic towers of Notre-Dame de l’Assomption, the cathedral in Rouen, which would become such a major preoccupation of his later years. He had planned to return to Rouen for longer painting projects as early as the spring of 1891, but in the end was too busy expanding his garden in Giverny to leave. In February 1892, however, he was offered the use of an empty apartment that looked out onto the cathedral’s west façade. In March of that year he took lodgings above a boutique that offered a similar view but from a slightly different angle. While in Rouen he worked on nine canvases at the same time, painting from early morning to late evening. The intensity was not without consequences, and Monet was afflicted by nightmares in which the cathedral – “it seemed to be blue, pink, or yellow” – came crashing down on top of him. The constantly changing light drove Monet almost to despair, and by 1893 he was working on up to fourteen canvases at once. In early 1894 he began preparing an exhibition of his cathedral paintings, but was plagued by doubts over whether he was up to the task. Twenty paintings in the series were to be exhibited as a solo show at the gallery of his art dealer, Durand-Ruel, in 1895. Believing that this might be an opportunity to raise his market value, he decided to demand 15,000 francs per painting. Durand-Ruel was so appalled that he refused to be involved in the actual sales and left the negotiations to the painter himself. Most of the works were well received in the press and would meet with acclaim in other exhibitions, too. Although Monet never received 15,000 francs for his cathedrals during his lifetime, the French state did at least pay 10,500 francs for the one that it bought for the Musée du Luxembourg in Paris in 1907.

London

On July 19, 1870, Napoléon III declared war on Prussia. Fearful of being conscripted, Monet fled to London at the beginning of October that year, taking Camille and their son Jean with him. There he met Paul Durand-Ruel, who was likewise a refugee and would become Monet’s most important art dealer. Durand-Ruel’s first documented sale of a Monet work was in May 1871. Together with Pissarro, Monet visited London’s many museums and there admired the works of Joseph Mallord William Turner and John Constable. When the war ended in late May 1871, Monet returned to France via the Netherlands. Although he would return to London on several occasions in the following years, his stays would invariably be brief and motivated mainly by visits to fellow painters. His desire to paint various views of the Thames swathed in fog nevertheless comes up in several letters. When his youngest son, Michel, went to London to study, Monet, Alice, and Alice’s daughter Germaine paid him a visit there in September 1899. They stayed at the luxurious Savoy Hotel, which has excellent views of the Thames. Monet was thus able to spend a whole month painting Charing Cross Bridge to excess, dedicating himself intensively to Waterloo Bridge later on.

He would return to London in the next two years, and in 1900 set up his easel in a room in St. Thomas’ Hospital that commanded an especially fine view of Westminster. While there, Monet received a visit from Georges Clemenceau, a personal friend of his and later an important French statesman, through whose good offices he was granted permission to paint in the Tower of London – a dispensation he never made use of. The thick fog that he woke up to toward the end of his stay in 1901 was grounds enough for him to postpone his departure. Many of the canvases begun in London were actually finished back in Monet’s studio in Giverny. There he also began to destroy some of them, admitting to Durand-Ruel that “my mistake is to try to improve them.” An exhibition of selected London paintings held in Paris at Durand-Ruel’s in May 1904 met with great acclaim.

Giverny

Monet signed a lease for a house with a plot of land in Giverny and moved in on April 29, 1883, bought it in 1890, and lived there until his death, for over forty years all told. Alice and her children moved in the very next day after the lease was signed. The village near the Seine is not far from Vernon, which is where the older children went to school. The two-story house was big enough to accommodate the large family, and the barn was readily converted into a painting studio. In the first summer there, Monet built a boathouse so that he could explore his environs in search of suitable motifs by boat. He also began planting a garden, which soon became an enduring passion. He painted views of the church of Vernon as well as his first fields with grain stacks. It was on the tiny Île aux Orties, which Monet bought as a place to moor his boats, that he painted Alice’s daughter Suzanne with a parasol (Essai de figure en plein-air: Femme à l’obrelle, 1886). Apart from his French painter friends, he was visited by both the American painter John Singer Sargent (in 1885 and 1887) and Georges Clemenceau, the former of whom painted both Monet and Blanche Hoschedé at work. The first grain stacks began to appear in late 1888. Monet traveled much less after 1890 and tended to confine himself to just a few motifs that he painted in series. He clearly felt at home in Giverny and lavished a great amount of time (and money) on the cultivation of his garden there, which became a favourite preoccupation. Many of his motifs were now to be found on his doorstep, among them the aforementioned grain stacks, which in 1890-1891 he painted no fewer than twenty-five times in varying light. Ernest Hoschedé died in Paris in 1891 with his wife, Alice, at his side. He was buried in Giverny. In the spring of 1891 Monet began painting a series of a row of poplars on the Epte River two kilometres away from his home, which he visited in his studio boat. When the poplars came up for auction in August of that year, he paid the timber merchant to leave them standing until he had finished painting them.

A little less than a year later Monet and Alice married in Giverny. Work on their property continued, and in early 1893 Monet purchased the adjoining plot with the aim of creating a water lily pond. In the summer of 1896 Monet began work on his Matinée sur la Seine series, for which he set off for work in his boat at half past three in the morning. In 1899 he had a second studio built specifically for the purpose of finishing paintings begun en plein air, while the first studio, being larger, would henceforth serve mainly as a showroom. Water lilies were becoming an increasingly important subject by now, and in 1901 he purchased land again, to enlarge his pond. He also had a third studio built to allow him to commence work on the monumental water lily wall panels (the Grandes Décorations). From 1909 on, Monet’s sight deteriorated to such an extent that he had to undergo various operations, notwithstanding his fears that these might change his perception of colour. Alice fell ill with a rare form of leukaemia and died in 1911, with a distraught Monet by her side. Following the death of his son Jean, in 1914, Blanche, who was both Monet’s stepdaughter and daughter-in-law, moved into the house at Giverny and cared for the deeply grieved artist. Yet he continued painting, right to the end of his days, finding most of his motifs in his own garden. It was also in Giverny that Monet, who died of lung cancer on December 5, 1926, would find his final resting place. He was buried in the same grave as his son Jean (1914), his wife Alice (1911), her first husband, Ernest Hoschedé (1891), and their daughters Suzanne (1899) and Marthe (1925).

.

The present chronology is based on the accounts provided in Charles F. Stuckey, “Chronology,” in Claude Monet 1840-1926, exh. cat. The Art Institute of Chicago (London and Chicago, 1995), pp. 185-266; and quotations cited from the artist’s letters published in Daniel Wildenstein, Claude Monet: Biographie et catalogue raisonné (Paris and Lausanne, 1974-1991), vols. 1-5.

Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926)

Sunset on the Seine in Winter

1880

Oil on canvas

60.6 x 81.1cm

Pola Museum of Art, Pola Art Foundation

Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926)

Morning on the Seine

1897

Oil on canvas

89.9 x 92.7cm

The Art Institute of Chicago, Mr and Mrs Martin A. Ryerson Collection, 1933

Photo: © The Art Institute of Chicago / Art Resource, NY / Scala, Florence

Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926)

Charing Cross Bridge: Fog on the Thames

1903

Oil on canvas

73.7 x 92.4cm

Harvard Art Museums / Fogg Museum, Donation of Mrs Henry Lyman, 1979

Photo: Imaging Department © President and Fellows of Harvard College

Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926)

Houses of Parliament, Stormy Sky

1904

Oil on canvas

81 x 92cm

Palais des Beaux-Arts de Lille, legs de Maurice Masson, 1949

Photo: © RMN-Grand Palais / René-Gabriel Ojéda

Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926)

Île aux Orties near Vernon

1897

Oil on canvas

73.3 x 92.7cm

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Charles S. McVeigh, 1960

Photo: © bpk / The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926)

Meadow at Giverny, Autumn Effect

1886

Oil on canvas

92.1 x 81.6cm

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Juliana Cheney Edwards Collection

Photo: © 2017 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926)

Water-Lilies

1916-1919

Oil on canvas

200 x 180cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen / Basel, Beyeler Collection

Photo: Robert Bayer

The restoration of this art work is supported by the BNP Paribas Swiss Fondation

Fondation Beyeler

Beyeler Museum AG

Baselstrasse 77, CH-4125

Riehen, Switzerland

Opening hours:

10am – 6pm daily, Wednesdays until 8pm

You must be logged in to post a comment.