Exhibition dates: 17th October – 7th December 2014

Artists: Micky Allan, Pat Brassington, Virginia Coventry, Sandy Edwards, Anne Ferran, Sue Ford, Christine Godden, Helen Grace, Janina Green, Fiona Hall, Ponch Hawkes, Carol Jerrems, Merryle Johnson, Ruth Maddison, Julie Rrap, Robyn Stacey.

Curator: Shaune Lakin

Christine Godden (Australian, b. 1947)

Joanie pregnant

1972

From the series Family

Gelatin silver print

15.3 x 22.6cm

Courtesy of the artist

With the National Gallery of Victoria’s photography exhibition program sliding into oblivion – the apparent demise of its only dedicated photography exhibition space on the 3rd floor of NGV International; the lack of exhibitions showcasing ANY Australian artists from any era; and the exhibition of perfunctory overseas exhibitions of mediocre quality (such as the high gloss, centimetre deep Alex Prager exhibition on show at the moment at NGV International) – it is encouraging that Monash Gallery of Art consistently puts on some of the best photography exhibitions in this city. This cracker of an exhibition, the last show curated by Shaune Lakin before his move to the National Gallery of Australia (and his passionate curatorial concept), is no exception. It is one of the best photography exhibitions I have seen all year in Melbourne.

Most of the welcome, usual suspects are here… but seeing them all together is a feast for the eyes and the intellect. While most are social documentary based photographers what I like about this exhibition is that there is little pretension here. The artists use photography as both a means and an end, to tell their story – of mothers, of workers, of dancers, of lovers – and to depict a revolution in social consciousness. What we must remember is the period in which this early work appeared. In the 1970s in Australia there were no formal photography programs at university and photography programs in techs and colleges were only just beginning: Photography Studies College (1973) in South Melbourne, Prahran College of Advanced Education (Paul Cox, John Cato, 1974) and Preston Tech (c. 1973, later Phillip Institute) were all set up in the early 1970s. The National Gallery of Victoria photography department was only set up in 1969 (the third ever in the world) with Jenny Boddington, Assistant Curator of Photography, was appointed in 1972 (later to become the first full time photography curator). There were three commercial photography galleries showing Australian and international work in Melbourne: Brummels (Rennie Ellis), Church Street Photographic Centre (Joyce Evans) and The Photographers Gallery (Paul Cox, John Williams, William Heimerman and Ian Lobb). While some of the artists attended these schools and others were self taught, few had their own darkroom. It was not uncommon for people to develop their negatives and print in bathrooms, toilets, backyard sheds and alike – and the advise was to switch on the shower before printing to clear the dust out of the air, advise in workshops that people did no bat an eyelid at.

What these women did, as Julie Millowick (another photographer who should have been in this exhibition, along with Elizabeth Gertsakis and Ingeborg Tyssen for example) observes of the teaching of John Cato, was “bring to the work knowledge that extended far beyond picking up a camera or going into a darkroom. He [Cato] believed that you must bring to every image you create a wide depth of insight across social, cultural and historical concerns. John was passionate in his belief that an understanding of humanity and society was crucial to our growth as individuals, and ultimately our success as photographers.”1 And so it is with these artists. Never has there been a time in Australian photography when so much social change has been documented by so few for such great advantage. In all its earthiness and connection, the work of these artists is ground breaking. It speaks from the heart for the abused, for the disenfranchised and downtrodden. The work is not only for women by women, as Ponch Hawkes states, but also points the way towards a more enlightened society by opening the eyes of the viewer to multiple points of view, multiple perspectives.

There are few “iconic” images among the exhibition and, as Robert Nelson notes in his review in The Age, little pretension to greatness. One of the surprising elements of the exhibition is how the four photographs by Carol Jerrems (including the famous Vale Street, 1975), seem to loose a lot of their power in this company. They are out muscled in terms of their presence by some of the more essential and earthy series – such as Women at work by Helen Grace and Our mums and us by Ponch Hawkes – and out done in terms of their sensuality by the work of Christine Godden. These were my two favourite bodies of work: Our mums and us and Christine Godden’s sequence of 44 images and the series Family.

Hawkes’ objective series of mother/daughter relationships are deceptively simple in their formal structure (mother and daughter positioned in family homes usually looking directly at the camera), until you start to analyse them. Their unpretentious nature is made up of the interaction that Hawkes elicits from the pairing and the objet trouvé that are worn (the cowgirl boots in Ponch and Ida, 1976) or surround them (the carpet, the table, the plant and the painting in Mimi and Dany, 1976). This relationship adds to the power of the assemblage, juxtaposition of energy and form being a guiding principle in the construction of the image. While the environment might be ‘natural’ it is very much constructed, both physically and psychologically, by the artist.

The work of Christine Godden was a revelation to me. These small, intense images have a powerful magnetism and I kept returning to look at them again and again. There is sensitivity to subject matter, but more importantly a sensuality in the print that is quite overwhelming. Couple this with the feeling of light, space, form and texture and these sometimes fragmentary photographs are a knockout. Just look at the sensitivity of the hands in Untitled, c. 1976. To see that, to capture it, to reveal it to the world – I was almost in tears looking at this photograph. The humanity of that gesture is something that I will treasure.

The only criticism of the exhibition is the lack of a book that addresses one of the most challenging times in Australian photographic history. This important work deserves a fully researched, scholarly publication that includes ALL the players in the story, not just those represented here. It’s about time. As a good friend of mine recently said, “Circles must expand as history moves away from a generation and cohort and, hopefully, the future will ask its own questions” … and I would add, without putting the blinkers on and creating more ideology.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Footnotes

1/ Julie Millowick and Christopher Atkins. “Dr John Cato – Educator,” in Paul Cox and Bryan Gracey (eds.,). John Cato Retrospective. Melbourne: Wilkinson Publishing, 2013.

.

Many thankx to the Monash Gallery of Art for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image. All installation photographs © Marcus Bunyan and Monash Gallery of Art

“As feminism took off among intellectuals of both sexes, art history would sometimes be interrogated to account for the reasons why there were relatively few great female artists.

While art historians would create reasonable apologies and impute the deficit to centuries of disadvantage to women, it was left to women artists to construct a view of art that redefined the stakes.

They sought a vision that didn’t see art as line-honours in transcendent inventions but a conversation that furthered the sympathy and consciousness of the community”

.

Robert Nelson The Age Wednesday November 5, 2014

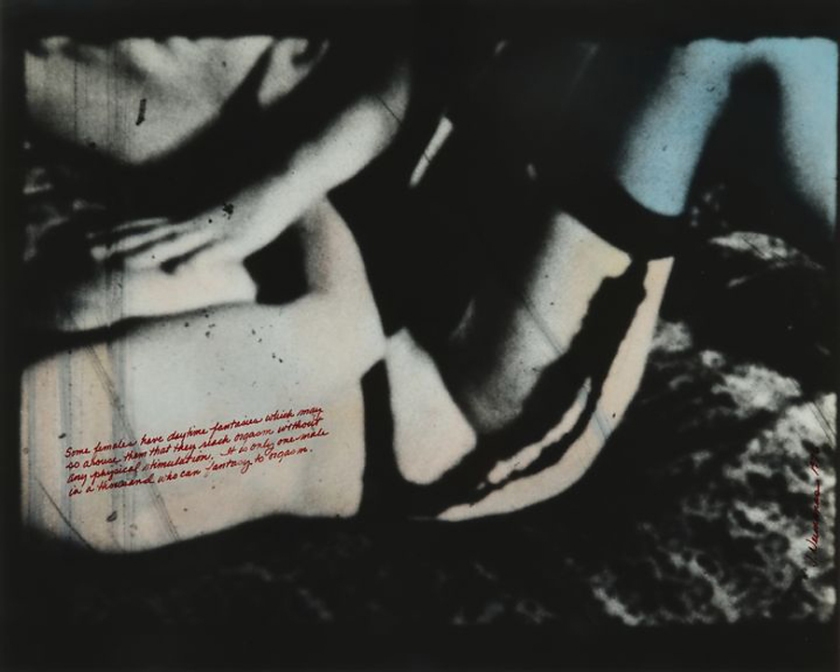

Pat Brassington (Australian, b. 1942)

Untitled

1984 (1)

From the series 1 + 1 = 3

Gelatin silver print

18 x 28cm

Monash Gallery of Art, City of Monash Collection

Courtesy of the artist, ARC ONE Gallery (Melbourne), Stills Gallery (Sydney) and Bett Gallery (Hobart)

Pat Brassington‘s photographs have often made use of the artist’s home and family life as subject matter. The photographs included in this exhibition were taken during the early 1980s and, with their tight cropping and diagonal obliques, suggest that family life is an anxious and ambivalent place. Erotically charged body parts – whether partner’s or offspring – are left to hang, like fetish objects drifting through a dream. Brassington is consciously mining the clichés of psychoanalysis, with her focus on shoes, panties and an ominous father figure, but she reworks this symbolism with a comical lightness that is closer to a teen horror film than the analyst’s couch.

Helen Grace

Women at work, Newcastle

1976

From the series Series 1

Gelatin silver prints

17.5 x 11.6cm (each)

Courtesy of the artist

Helen Grace

Women at work, Newcastle

1976

From the series Series 2

Gelatin silver prints

11.6 x 17.5cm (each)

Courtesy of the artist

Helen Grace

Women at work, Newcastle (detail)

1976

From the series Series 2

Gelatin silver prints

11.6 x 17.5cm (each)

Courtesy of the artist

Helen Grace was a member of the Sydney-based feminist collective Blatant Image (which also included Sandy Edwards), which formed around the Tin Sheds at Sydney University. The collective was interested in examining and reconfiguring the representation of women in popular culture, and also in developing alternative venues for socially conscious art and film. The photographs displayed here point to the two interconnected preoccupations of Grace’s work at this time: the social and cultural construction of motherhood and femininity (and the way that each of these categories are produced by and through consumerism and popular culture), and the documentation of women’s labour. An active member of Sydney’s labour movement, Grace photographed women working in a range of workplaces (including factories and hospitals) for both the historical record and as promotional aids for activist organisations.

Grace’s Women seem to adapt to repetitive-type tasks was widely shown in Sydney and Melbourne, including the exhibition The lovely motherhood show (1981). This work of seven panoramas depicting a string of nappies on a washing line at once points towards the inexorable tediousness of motherhood, and at the same time attempts to demystify the romantic myths of motherhood found in contemporary advertising and popular culture. Grace’s photographs were also widely used in posters produced by trade union and women’s groups. During the 1970s and 1980s screen printing was a cheap and effective way to incorporate photographic imagery into posters. Community groups also embraced screen printing because its aesthetic stood in opposition to commercial advertising, and the process lent itself to a do-it-yourself work ethic.

Merryle Johnson (Australian, b. 1949)

Outside the big top

1979-1980

From the series Circus

Hand coloured gelatin silver prints

Monash Gallery of Art, City of Monash Collection

Donated by Merryle Johnson, 2014

Merryle Johnson‘s photographic feminism sits alongside her contemporaries Micky Allan and Ruth Maddison. In the first instance, it is expressed in the autobiographical nature of her images, which often refer to her family history. And like Allan and Maddison, Johnson also used hand-colouring to reinvigorate documentary photography and to bring a decidedly female perspective to the medium. Johnson’s contribution to feminist photography in Australia is also reflected in her use of photographic sequences – multiple images printed on the same sheet. In these works, the single, perfectly realised photographic image of Modernist photography was replaced with a series of images that draw attention to the fragmentary, contingent and inconclusive nature of photography. The serialisation of photographs also engages a more embodied, spatialised and assertive experience than single pictures alone.

Christine Godden (Australian, b. 1947)

Joanie and baby Jade, Larkspur

1973

From the series Family

Gelatin silver print

8.4 x 13.8cm

Courtesy of the artist

Christine Godden (Australian, b. 1947)

Untitled

c. 1976

Gelatin silver print

15.3 x 22.8cm

Courtesy of the artist

Christine Godden (Australian, b. 1947)

Untitled

c. 1976

Gelatin silver print

15.2 x 22.7cm

Courtesy of the artist

Christine Godden (Australian, b. 1947)

Untitled

c. 1976

Gelatin silver print

15.2 x 22.8cm

Courtesy of the artist

Christine Godden‘s Untitled c. 1976 is part of a sequence of 44 images that represented fragments and textures that combine tenderness and formal rigour in a way that evokes a sense of poetry. The series Family c. 1973 details the domestic environment and experience of young families in the American West.

As well as presenting subjects that engaged a ‘feminine’ subject, Godden’s photographs critically interrogate many of the claims for a distinctly ‘feminine sensibility’ being made by and for women artists at this time. The ‘Untitled’ prints on display here were originally exhibited in 1976 at George Paton Gallery, Melbourne and the Australian Centre for Photography in Sydney. These pictures were originally shown as part of a tightly organised sequence of 44 photographs intended to show ‘how women see [and] how women think’. The tightly cropped glimpses of bodies and textures combine tenderness and formal rigour in a way that evokes a sense of visual poetry.

Christine Godden’s Family series comprises a large number of images detailing the domestic environment and experience of young families living in the American west. Godden was at this time a student at the San Francisco Art Institute and was very active in feminist networks, including the Advocates for Women organisation, for whom she photographed events and actions. Godden’s Family series documents her experience of the counter-cultural families of America’s west coast, who provided and celebrated a new model of family life and women’s work.

Installation view of Photography Meets Feminism at the Monash Gallery of Art with, at right, Anne Ferran’s Scenes on the death of nature, scene I and II (1980-1986)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Anne Ferran (Australian, b. 1949)

Scenes on the death of nature, scene I

1980-1986

Gelatin silver print

122.0 x 162.0cm

Monash Gallery of Art, City of Monash Collection

Courtesy the artist and Sutton Gallery (Melbourne)

Anne Ferran‘s series Scenes on the death of nature presents five tableau-like scenes showing the artist’s daughter and her friends in classical dress. When they were first exhibited, commentators noted the enigmatic quality of the images, and how they resisted clear meaning, narrative and any attribute of personal style. To many, they represented a significant shift away from documentary photography. This might well be the ‘death’ to which the titles refer. For the critic Adrian Martin, the pictures appeared to evoke myth, while also being ambivalent about a photograph’s capacity to point to or allude to anything outside of itself; in this way, they can be seen to exemplify a certain post-modern approach to photography.

All the same, it is possible to see these important pictures as signposts for another kind of death. The photographs allude to some of the ways that the subject of girl/woman has been produced through visual culture, whether the monumental friezes of classical or Victorian architecture, or Pre-Raphaelite tableaux. In this way, they evoke the idea of ‘femininity’ as a source of meaning. Rather than rejoicing in, resisting or critiquing ‘femininity’ as earlier feminist photographers might have done, Ferran’s pictures remain steadfastly, even ‘passively’ ambivalent. As the artist wrote at the time, the works reveal ‘very little of a personal vision or private sensibility’.

Wall text

Installation view of four Carol Jerrems photographs with Vale Street (1975) at left and Lynn (1976) at right

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Carol Jerrems (Australian, 1949-1980)

Vale Street

1975

Gelatin silver photograph

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Purchased 1976

© Ken Jerrems and the Estate of Lance Jerrems

Carol Jerrems (Australian, 1949-1980)

Lynn

1976

Gelatin silver photograph

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

© Ken Jerrems and the Estate of Lance Jerrems

Carol Jerrems was one of a number of Australian women whose work during the 1970s challenged the dominant ideas of what a photographer was and how they worked. She adopted a collaborative approach to making photographs, which often featured friends and associates, and sought a photographic practice that would bring about social change. For Jerrems, as for many of her contemporaries, the photograph was an agent of social change, a means of both bringing people together and creating active and engaged social relationships. As she stated:

“I really like people … I try to reveal something about people, because they are so separate, so isolated; maybe it’s a way of bringing people together … I care about [people], I’d like to help them if I could, through my photographs…”

The iconic Vale Street shows Jerrems’s friend Catriona Brown standing in front of Mark Lean and Jon Bourke, teenage boys from Heidelberg Technical School where Jerrems was teaching at the time. The photograph was taken at a house in Vale Street, St Kilda. Although it is unclear if Jerrems conceived of this image as a feminist gesture, the subject’s assertive, bare-chested pose and Venus symbol led to this photograph being interpreted as a statement of feminist power.

Installation views of Photography Meets Feminism at the Monash Gallery of Art

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of Ponch Hawkes series Our mums and us at the exhibition Photography Meets Feminism. Her photographs were made by women, of women, for women.

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Ponch Hawkes (Australian, b. 1946)

Ponch and Ida

1976

From the series Our mums and us

Gelatin silver print

17.7 x 12.7cm

Monash Gallery of Art, City of Monash Collection

Donated through the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program by Ian Bracegirdle 2012

Courtesy of the artist

Ponch Hawkes (Australian, b. 1946)

Lorna and Mary

1976

From the series Our mums and us

Gelatin silver print

17.7 x 12.7cm

Monash Gallery of Art, City of Monash Collection

Donated through the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program by Ian Bracegirdle 2012

Courtesy of the artist

Ponch Hawkes (Australian, b. 1946)

Mimi and Dany

1976

From the series Our mums and us

Gelatin silver print

17.7 x 12.7cm

Monash Gallery of Art, City of Monash Collection

Donated through the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program by Ian Bracegirdle 2012

Courtesy of the artist

Ponch Hawkes‘s best-known series Our mums and us documents a selection of the photographer’s contemporaries standing with their mothers. The photographs were taken at each subject’s family home and record generational shifts in personal style and domestic decor. Originally shown at Brummels Gallery of Photography in 1976, which was Hawkes’s first solo exhibition, Our mums and us has become one of the most celebrated examples of feminist photography in Australia.

The use of pronouns in the title suggests the series was made by women, of women and for women; it is a defiant and celebratory feminist gesture, which foregrounds women as at once independent and connected to each other. Reflecting on the series, Hawkes explains that ‘feminism helped me to understand that my mother was actually a woman too, and not just a mother, and Our mums and us came out of that realisation.’

Ephemera and books from Ponch Hawkes personal collection, including the cover of the seminal book A Book About Australian Women by Carol Jerrems and Virginia Fraser (Melbourne, 1974)

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

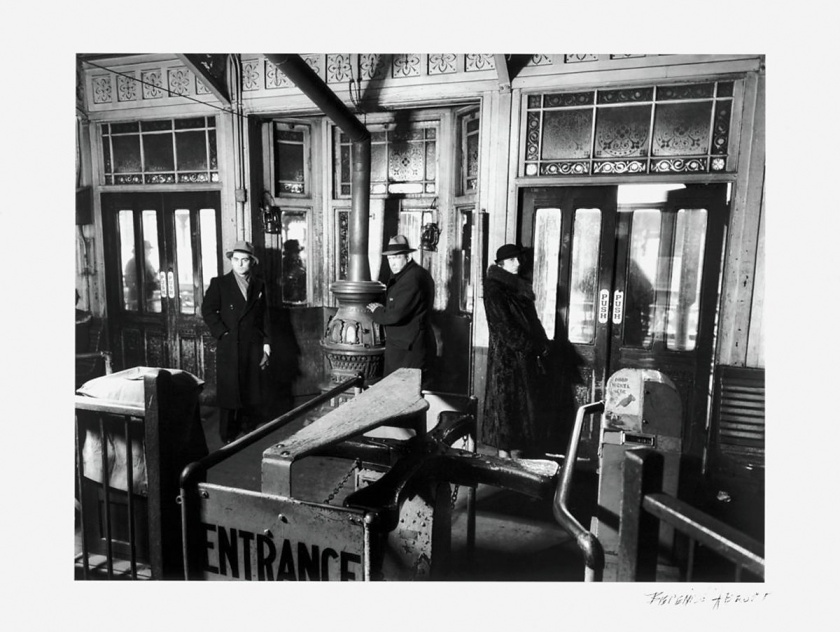

Ruth Maddison (Australian, b. 1945)

Vehicle Builders Union Ball, Collingwood Town Hall, Melbourne

1979

From the series Let’s dance

Gelatin silver print

27.0 x 18.0cm

Collection of the artist

Courtesy of the artist

Ruth Maddison (Australian, b. 1945)

Women’s dance, St Kilda Town Hall, Melbourne

1985

Gelatin silver print

36.5 x 24.5cm

Courtesy of the artist

Ruth Maddison photographed the social spaces that had been important to activist communities but which were in the process of passing away. These were mainly commissioned projects for labour and social movements, otherwise these histories would have been lost.

Dancing and entertainment were features of Ruth Maddison’s work throughout the 1980s. These photographs reflected Maddison’s own social life, which often revolved around Melbourne’s pubs and nightclubs. But there was also a classical documentary function to her photographs of trade union dances and the annual women’s dance at St Kilda Town Hall. These pictures reflected social spaces that had been important to activist communities, but which by the mid-1980s were in the process of passing away; as women’s groups began to fragment, and as the membership of labour organisations changed. The photographs shown here of the Vehicle Builders’ Union Ball at Collingwood Town Hall were part of a commission. Like many photographers in this exhibition (including Helen Grace, Sandy Edwards and Ponch Hawkes), political affiliation and professional practice often came together in commissioned projects for labour and social movements.

Virginia Coventry (Australian, b. 1942)

Miss World televised

1974

Gelatin silver print

15.5 x 13.5cm (each)

Courtesy of the artist

Miss World televised is typical of Virginia Coventry‘s photographic work from this period, which tended to revolve around tightly organised sequences of pictures of the same subject (swimming pools in a Queensland town; the spaces between houses) or an event (a car moving through a carwash; a receding flood).

At the time, Coventry shared a house with Micky Allan. One night, while watching Allan’s black-and-white television, she saw footage of the 1974 Miss World pageant on the news. Immediately taken by the way the poor reception distorted the bodies of the contestants, Coventry began to photograph the footage. Once she developed the film, she realised the visual ‘disruption’ caused by the incongruity of the telecast process and the camera’s shutter speed obscured the figures and the beauty of the contestants, without necessarily deriding or critiquing the women themselves. As Coventry has written of the pictures: “I remember discussions with other women at the time about the way that the distortions offered a protection to the integrity of the actual person in the photo-images. Because of the radical slippage between reportage and reception, the individual is no longer the subject. The title operates to focus attention on Miss World telecast as a quite abstract construction – as do the black-and-white, grainy, prints.”

PHOTOGRAPHY MEETS FEMINISM: Australian women photographers 1970s-80s looks at the vital relationship of photography and feminism in Australia during the 1970s and ’80s.

Given the vitality of both feminist politics and art photography during the 1970s, it is not surprising that they entered into a lively exchange that extended into the 1980s. On the one hand, feminists used the highly informative and accessible medium of photography to raise awareness of critical social issues.

On the other hand, photographic artists embraced feminist themes as a way of making their practice less esoteric and more engaged with contemporary life. This productive intersection of feminism and photography fostered a range of technical innovations and critical frameworks that made a significant contribution to the direction of visual culture in Australia.

PHOTOGRAPHY MEETS FEMINISM: Australian women photographers 1970s-80s will feature vintage prints of important photographs, many of which have not been seen for decades.

MGA Interim Director, Stephen Zagala states, “We are proud to present this exhibition, which provides an as-yet untold account of Australian photography and draws heavily on MGA’s nationally significant collection of Australian photography.”

Press release from the Monash Gallery of Art

This exhibition explores the encounter between photography and feminist politics during the 1970s and into the 1980s.

Both photography and feminism thrived during this period. Feminist politics of the 1970s expanded on its earlier fight for equal rights by illuminating discrimination against women in various contexts. This included addressing domestic violence, inequality in the workplace, sexism in the media, and the economics of parenting. Alongside this expanded critique of patriarchy, feminist politics also celebrated ‘sisterhood’ by drawing attention to the undervalued achievements of women and by taking pride in distinctly female perspectives on the world.

Photographic practice also expanded its parameters during the 1970s. Together with other art forms such as painting and sculpture, photography became more experimental and irreverent. Most photographic artists rejected the tradition of highbrow fine art photography and invested the medium with personal sentiment and everyday content. The camera also became a useful tool for a generation of artists more interested in social engagement than aesthetic finesse.

Given the vitality of both feminist politics and art photography during the 1970s, it is not surprising that they entered into a lively exchange that extended into the 1980s. On the one hand, feminists used the highly informative and accessible medium of photography to raise awareness of critical social issues. On the other hand, photographic artists embraced feminist themes as a way of making their practice less esoteric and more engaged with contemporary life. This productive intersection of feminism and photography fostered a range of technical innovations and critical frameworks that made a significant contribution to the direction of visual culture in Australia.

Text from the Monash Gallery of Art website

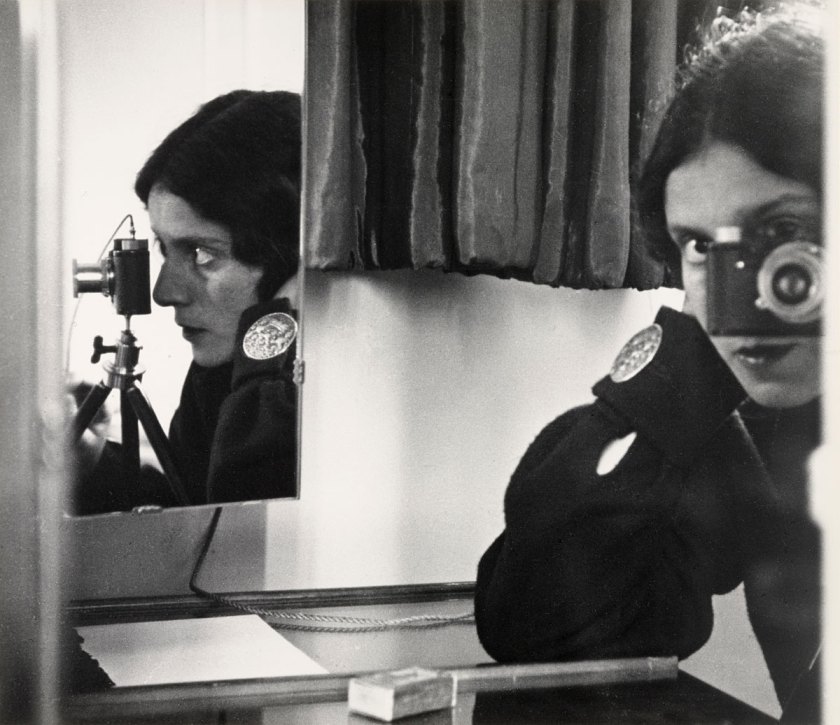

Sue Ford (Australian, 1943-2009)

Untitled

1969-1971

From the series The Tide Recedes

Selenium toned gelatin silver print

Sue Ford (Australian, 1943-2009)

Untitled

1969-1971

From the series The Tide Recedes

Selenium toned gelatin silver print

Sue Ford‘s series The Tide Recedes 1969-1971 was made for her first solo exhibition at the Hawthorn City Art Gallery in 1971. People were becoming more removed from nature but Ford felt that woman share a particular biological and cultural affinity with nature. The contrasty black and white photographs of bodies melding with rocks in montage prints that are as rough as guts work magnificently.

These prints were made as preparation for Sue Ford’s ambitious series The tide recedes, shown as part of Ford’s first solo exhibition at the Hawthorn City Art Gallery in 1971. Throughout this body of work, images of naked women and of men and women embracing merge with a marine landscape. The series expresses Ford’s concern that people were becoming too removed from nature, and allude to the idea that women share a particular biological and cultural affinity with nature. It also draws on a technique that was central to feminist photographic practice – montage, where two disparate fragments are brought together to produce new and often unexpected meanings. While this reflects Ford’s work as a film maker, where montage is often used in storytelling, this strategy also embeds her pictures in the field of activist art. With montage, it is the viewer who ultimately makes sense of a work, as they find and see connections between disparate fragments.

While the prints presented in the 1971 exhibition were ambitious in scale and resolution, Ford preferred prints that were – in her terms – ‘rough as guts’. Prints such as those shown here represented an explicit rejection of the maleness of both the camera as a technological instrument and the arcane knowledge of the darkroom.

Robyn Stacey (Australian, b. 1952)

Queensland out west

1982

Hand-coloured gelatin silver prints

9.2 x 15.2cm (each)

Courtesy of the artist and Stills Gallery (Sydney)

Robyn Stacey (Australian, b. 1952)

Queensland out west (details)

1982

Hand-coloured gelatin silver prints

9.2 x 15.2cm (each)

Courtesy of the artist and Stills Gallery (Sydney)

Robyn Stacey (Australian, b. 1952)

Untitled (Geoff in Bondi)

1981

From the series Modified myths 1938-1988

Hand-coloured gelatin silver print

39.0 x 38.3cm

Courtesy of the artist and Stills Gallery (Sydney)

Robyn Stacey (Australian, b. 1952)

Untitled (Picnic)

1981

From the series Modified myths 1938-1988

Hand-coloured gelatin silver print

39.0 x 38.3cm

Courtesy of the artist and Stills Gallery (Sydney)

Robyn Stacey established a reputation for her hand- coloured prints in the late 1970s and early ’80s. Introduced to the process by Micky Allan, Stacey’s early hand-coloured prints examined the life and culture of Australia, especially her native Queensland. Stacey hand-coloured her photographs so as to invest them with personal attributes: “At the time I was interested in hand colouring [because it was] a technique associated with women’s work and craft. This approach seemed a good way to visually re-enforce the personal and intimate quality of the prints.”

Among Stacey’s most important contributions to the feminist tradition of hand colouring photographs are her pictures of Queensland architecture, taken during a road trip to western Queensland made with her mother. These images refer to an heroic subject in Australian culture – the stoicism of the outback and the people who populate it. But Stacey revises these myths, by presenting the images as intimate and personal.

Robyn Stacey (Australian, b. 1952)

Ice

1989

from the series Redline 7000

Silver dye bleach print

104.0 x 175.3cm

Monash Gallery of Art, City of Monash Collection

Donated through the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program 2012

Courtesy of the artist and Stills Gallery (Sydney)

Robyn Stacey (Australian, b. 1952)

Jet

1989

from the series Redline 7000

Silver dye bleach print

164 x 103cm

Monash Gallery of Art, City of Monash Collection

Donated through the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program 2012

Courtesy of the artist and Stills Gallery (Sydney)

In the late 80s, Stacey began to hand colour her transparencies rather than the print, thereby incorporating an aspect of reproducibility to the images. In this way the work shifted from the unique print, with its references to nostalgia and the careful rendering of places and times, to something resembling the glossy images found in 1980s’ mass media, especially Hollywood cinema.

Julie Rrap (Australian, b. 1950)

Persona and shadow: Madonna

1984

Silver dye bleach print

203.0 x 126.5cm

Monash Gallery of Art, City of Monash Collection acquired 1997

Courtesy of the artist and Arc One Gallery (Melbourne) and Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery (Sydney)

This photograph is from the series of nine works titled Persona and shadow. Julie Rrap produced this series after visiting a major survey of contemporary art in Berlin (Zeitgeist, 1982) which only included one woman among the 45 artists participating in the exhibition. Rrap responded to this curatorial sexism with a series of self-portraits in which she mimics stereotypical images of women painted by the Norwegian artist Edvard Munch (1863-1944). Each pose refers to a female stereotype employed by Munch: the innocent girl, the mother, the whore, the Madonna, the sister, and so on.

Appropriating the work of other artists is one of the strategies that characterises the work of so-called ‘postmodern’ artists active during the 1980s. The practice of borrowing, quoting and mimicking famous artworks was employed as a way of questioning notions of authenticity. Feminist artists tended to use appropriation to specifically question the authenticity of male representations of females. In more straightforward terms, Rrap reclaims Munch’s clichéd images of women and makes them her own. Rrap ultimately becomes an imposter, stealing her way into these masterpieces of art history, but the remarkable thing about these works is the way that the artist foregrounds the process of reappropriation itself. The procedure of restaging, collage, overpainting, and rephotographing becomes part of the final image, testifying to a do-it-herself politic.

Wall text

Micky Allan (Australian, b. 1944)

Old age

1978

From the series Old age

Gelatin silver photograph, hand coloured with watercolour and pencil

18.2 x 12.0cm

© Micky Allan

Micky Allan (Australian, b. 1944)

Old age

1978

From the series Old age

Gelatin silver photograph, hand coloured with watercolour and pencil

18.2 x 12.0cm

© Micky Allan

Micky Allan (Australian, b. 1944)

Old age

1978

From the series Old age

Gelatin silver photograph, hand coloured with watercolour and pencil

18.2 x 12.0cm

© Micky Allan

Micky Allan’s two series Babies and Old age were shown in Melbourne and Sydney around 1976-77; their reception revealed much about the anxieties that informed photographic criticism and practice at the time, with critics dismissing the works as ‘slight’ and ‘feminine photographs par excellence’. Across a series of exhibitions between 1976 and 1980, Allan challenged many of the established conventions of fine art photography, in both technique and subject. Allan overpainted the black-and-white print with watercolour, gouache and pencil to the extent of both acknowledging the under recognised history of women’s photographic work – historically, women were employed by studios to hand-paint or tone photographic prints – and transgressing the smooth surface of photographic prints that was prized by traditional art photographers.

For Allan, overpainting rejected the technical sameness of modern photography and introduced an emotional warmth. Allan’s hand-colouring also interrupted the myth of photographic transparency – the notion of the photograph as a ‘disinterested’ window onto the world. Overpainted, the photograph became subjective, contingent and fallible. The lightness of many of Allan’s interventions enhances this sense of fallibility.

Wall text

With a body of work ranging across painting, photography and performance, investigations of subjectivity have been central to Micky Allan’s practice. Allan has consistently drawn on feminist strategies which emphasise the personal and autobiographical. In the early 1970s she became involved with the experimental performance and collective activities based at The Pram Factory in Melbourne, working there as both a set designer and a photographer, documenting early feminist work. Of this time Allan has said that she saw “photography as a form of social encounter … that in comparison with painting it [was] much more integrated to what was going on.”1

Allan has acknowledged social documentary as the basis of her photographic work. For a short period she recorded political figures and the surrounding social changes in which she was both a participant and an observer. Old age, the second of three series whose focus is lifecycles (the other two being Babies 1976 and The prime of life 1979-1980), comprises 40 hand-coloured individual portraits. Allan introduced the technique of hand-colouring in her work in 1976, a technique taken up by many women photographers at that time to counter the then dominant modes of masculine production. While there is stylistic variation across the series, each portrait, close-up in viewpoint, is meticulously rendered in pastel colours. The images do not capture a simple moment but rather work together to poignantly symbolise a rich regard for age. Of this Allan has said: “Altogether they are an attempt to familiarise and personalise “age”, in a society which tends to ignore or stereotype the old.”2

- ‘On paper – survey 12’, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 21 Jun ‘ 20 Jul 1980, as quoted in 1987, Micky Allan: perspective 1975-1987, Monash University Gallery, Clayton p. 4

- Ibid p. 19

© Art Gallery of New South Wales Photography Collection Handbook, 2007

Exhibiting artist’s biographies

Micky Allan (b. Australia 1944) studied Fine Art at the University of Melbourne, and painting at the National Gallery School in the 1960s. Allan began taking photographs in 1974 after joining the loosely formed feminist collective at Melbourne’s experimental arts and theatre space the Pram Factory. During this time Allan was part of a vibrant community of feminist artists that included Virginia Coventry, who taught her how to take and print photographs. Allan returned to painting as her primary medium in the early 1980s.

Pat Brassington (b. Australia 1942) is a Hobart-based artist who studied printmaking and photography at the Tasmanian School of Art, graduating with a Master of Fine Arts in 1985. Brassington draws on a personal archive of visual material to compose her images. This archive includes both photographic and non-photographic material, which has either been found or produced by Brassington. Her work takes inspiration from surrealist photography, with its recurring interest in fetish objects and uncanny domestic scenes. Brassington typically employs digital collage to manufacture disjointed compositions, and she exhibits her work in elliptical series that suggest dream-like narratives.

Virginia Coventry (b. Australia 1942) studied painting at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology during the early 1960s, before undertaking postgraduate studies at the Slade School of Fine Art, University College, London. While painting and drawing have been constant features of Coventry’s practice, she started taking photographs during the mid-1960s and developed a significant reputation for her photo-based work during the 1970s. Her photographic work typically engages with socio-political issues and often incorporates textual elements that give it a discursive form.

Sandy Edwards (b. New Zealand 1948 arr. Australia 1961) has been an important figure in Australian photography as both a maker and advocate since the 1970s. Edwards’s practice has paid particular attention to women and their relationship with the media of photography and film. Most of her work is documentary in nature but her photographic prints are often presented in sequences that elaborate conceptual points. Edwards has also been a prolific curator of exhibitions promoting the work of contemporary photographers, especially in Sydney.

Anne Ferran (b. Australia 1949) is a Sydney-based photographer and academic. She studied humanities and teaching before training in photography at Sydney College of the Arts. She began exhibiting her work in the mid-1980s and has become one of Australia’s most critically acclaimed photographers. Ferran’s practice is largely concerned with using photography to reclaim forgotten pasts, with a specific interest in the histories of women and children in colonial Australia. In pursuing this interest, Ferran often develops her projects through archival research and fieldwork.

Sue Ford (Australia 1943-2009) studied photography at RMIT and was the first Australian photographer to be given a solo exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria in 1974. Over the course of her artistic career Ford worked with still photography and moving images, beginning with traditional analogue film and then embracing the possibilities offered by photomedia and digital technologies. In this respect, Ford is a key figure in the history of avant-garde photographic experimentation. Ford’s artworks are also remarkable for their critical engagement with contemporary social issues, while also expressing deeply personal perspectives on the world.

Christine Godden (b. Australia 1947) has played a significant role in Australian photography as a maker, curator and advocate. After studying in Melbourne, Godden completed a Bachelor of Fine Arts at the San Francisco Art Institute in 1975 and a Master of Fine Arts at the Visual Studies Workshop in Rochester, New York in 1980. On her return to Australia, she became director of the Australian Centre for Photography, Sydney, and was consequently a prominent spokesperson for Australian photography during the 1980s. Her own photography is couched in a highly personal and poetic form of documentary practice.

Helen Grace (b. Australia 1949) is a self-taught artist who began making work as an active member of feminist and labour organisations in Sydney during the mid-1970s. Often straight-forwardly documentary in style, Grace’s approach to photography is closely aligned with political consciousness raising. Her work for the labour and women’s movements was widely circulated around the time of its production, both in the pages of publications and in posters produced by trade unions and women’s groups. Grace’s writing on photography and film, history and politics have also made a significant contribution to the critical discussion that surrounds feminist practice in Australia.

Janina Green (b. Germany 1944 arr. Australia 1949) studied Fine Arts at Melbourne University and Victoria College before training as a printmaker at RMIT. In the 1980s she taught herself photography and subsequently specialised in this medium. Green held her first solo exhibition of photography in 1986 and has exhibited regularly since then, participating in over 30 group exhibitions and producing over 20 solo shows. Green’s photographs are distinguished by their sophisticated and often sensuous surfaces, which testify to her early training in printmaking. In her role as a teacher in the photography department at the Victorian College of the Arts, Green has also played a significant role as a mentor for younger photographers.

Fiona Hall (b. Australia 1953) initially trained as a painter, and has ultimately become a celebrated sculptor, but photography was her primary medium in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Hall developed an interest in photography at art school and worked as an assistant to the well-known landscape photographer Fay Godwin while she lived in London between 1977-78. Hall subsequently studied photography at the Visual Studies Workshop in New York during 1982. Hall’s photographic practice demonstrates a fascination with decoration and style, which is informed by a critical interest in the premise of a ‘feminine’ sensibility.

Ponch Hawkes (b. Australia 1946) took up photography in 1972 while working as a journalist for the counter-cultural magazines Digger and Rolling Stone. Her early photography was informed by her role as a commentator on alternative social issues, and she has often used her images to engage with contemporary critical debates. During the 1970s Hawkes was part of a loosely formed feminist collective based at Melbourne’s experimental arts and theatre space the Pram Factory. Since that time she has continued to work closely with community groups around Australia and remains a key figure in contemporary photographic practice.

Carol Jerrems (Australia 1949-80) was born in Melbourne and studied photography at Prahran Technical College under Paul Cox and Athol Shmith between 1967 and 1970. Although she practised as an artist for only a decade, Jerrems has acquired a celebrated place in the annals of Australian photography. Her reputation is based on her compassionate, formally striking pictures, her intimate connection with the people involved in social movements of the day, and her role in the promotion of ‘art photography’ in this country.

Merryle Johnson (b. Australia 1949) graduated from Bendigo College of Advanced Education in 1969 with a major in painting. She took up photography in 1970 and it subsequently became central to her professional life, both as an arts educator and an exhibiting artist. Johnson’s approach to photography is informed by her broader training as an artist. This is particularly evident in her use of hand-colouring and sequencing. While the subject matter of her images is largely drawn from everyday life, she employs artistic devices to bring a sense of drama and fantasy to documentary photography.

Ruth Maddison (b. Australia 1945) is a self-taught photographer and artist. Maddison began working as a professional photographer in 1976, and she has been regularly exhibiting her work since 1979. Photography has been her primary medium, but in later years her artistic practice has expanded to include moving-image, textiles and sculpture. An interest in personal biography and the celebration of everyday existence informs her artistic practice. She is most well-known for her hand-coloured photographs of domestic life. In 1996 Maddison relocated from Melbourne to Eden, on the south coast of NSW.

Julie Rrap (b. Australia 1950) studied humanities at the University of Queensland (1969-71) before establishing her career as an exhibiting artist in Sydney during the 1980s. Rrap’s involvement with performance art and avant-garde politics during the 1970s laid the foundations for her later work in photography, painting, sculpture and video, which is largely concerned with the representation and experience of women’s bodies. The photographic objectification of female bodies is a persistent theme in Rrap’s work, but her highly expressive self-portraits invest the medium with a subjective intensity that affronts the clinical quality of voyeurism.

Robyn Stacey (b. Australia 1952) is a Sydney-based photographer who has been exhibiting since the mid-1980s. During the 1980s Stacey produced staged or ‘directorial’ photographs that drew on the visual language of cinema and television. Through the 1990s Stacey engaged in further training and study, and experimented extensively with new media including digital photography and lenticular prints. In 2000 Stacey began working with natural history collections in Australia and overseas, using photography to bring the contents of these archives to life. Throughout her career, Stacey has been interested in photography as an expressive medium that can be used to reiterate, remix and reanimate visual information.

Monash Gallery of Art

860 Ferntree Gully Road, Wheelers Hill

Victoria 3150 Australia

Phone: + 61 3 8544 0500

Opening hours:

Tue – Fri: 10am – 5pm

Sat – Sun: 10pm – 4pm

Mon/public holidays: closed

Monash Gallery of Art website

LIKE ART BLART ON FACEBOOK

Back to top

![Ana Mendieta. 'Itiba Cahubaba (Esculturas Rupestres)' [Old Mother Blood (Rupestrian Sculptures)] 1982](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/ana-mendieta_itiba-cuhababa-web.jpg?w=840)

You must be logged in to post a comment.