Exhibition dates: 17th January – 29th April 2018

Curator: The exhibition is curated by Karolina Ziebinska-Lewandowska, curator at the Centre Pompidou.

Zbigniew Dłubak (Polish, 1921-2005)

Untitled

c. 1946

© Armelle Dłubak/Archeology of Photography Foundation, Warsaw

Photography, the object, conceptual art, reality and the empty sign.

An interesting artist who warrants further investigation. The text and images provide an introduction, but I really need further evidence before I can make informed comment.

Many thankx to the Fondation HCB for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“I’m not interested in stylistic effects, whether they’re derived from modern art or conceptualism. I use shapes, ideas, colours, words, photographs and actions as my materials in a way that best suits my art, to create an empty sign in the context of the reality I live in.”

“The social role of art consists in introducing the factor of negation into the human consciousness, it challenges the rigidity of systems and conventions in the rendering of reality. Art itself is evolution, it’s the introduction of all new means of expression.”

“Photography is in phase with the rhythm of life. It impatiently looks for new images. The more effigies it accumulates, the greater its appetite; it’s increasingly obsessive. Not only does it record but, subject to the imagination, it also creates new phenomena. It constantly takes us on new adventures, it shakes us up, and does not allow us to rest.”

Zbigniew Dłubak

Zbigniew Dłubak (Polish, 1921-2005)

I recall the solitude of the straits

1948

Illustration for Pablo Neruda’s poem “Le coeur magellanique”

© Armelle Dłubak / Archeology of Photography Foundation, Warsaw

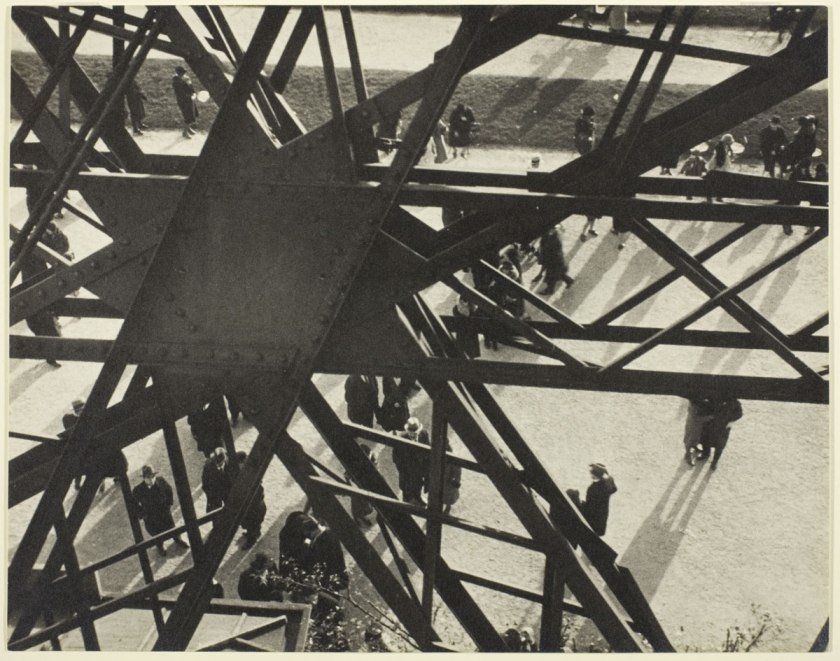

Zbigniew Dłubak (Polish, 1921-2005)

The streets are for the sun and not for people

1948

© Armelle Dłubak / Archeology of Photography Foundation, Warsaw

In the post-war period, Zbigniew Dłubak (1921-2005) was one of the driving forces behind the profound changes in the Polish artistic scene. A great experimenter of photographic forms, he was also a painter, art theoretician, teacher and editor of the Fotografia magazine for twenty years, introducing into this publication a robust photographic critique and interdisciplinary approach to the medium.

Although Dłubak was primarily known as a photographer, he initially aspired to become a painter, tirelessly searching for materials for drawing during the war. Very active in these two traditionally separate disciplines, he greatly influenced the decompartmentalisation of artistic forms. He also defended the right of photography to exist as a completely separate discipline. His first photographic experiments reveal a diversity of inspirations characteristic of pre-war practices, stemming from constructivist and surrealist traditions.

This exhibition proposes to highlight the similarities and complementary focuses on two decisive periods in the artist’s life: the year 1948, which marks the beginning of his career and places it within the avant-garde movement, and the 1970s, which symbolise his ambiguous position regarding conceptual art. The selection presents iconic works and hitherto unseen photographs.

Curated by Karolina Ziebinska-Lewandowska, a specialist in Dłubak’s work, the exhibition is accompanied by a book published by Éditions Xavier Barral under the direction of Karolina Ziebinska-Lewandowska. The exhibition is being organised in collaboration with the Fundacja Archaeologia Fotografii in Warsaw, with the support of the Adam Mickiewicz Institute and the Polish Institute in Paris.

Text from the Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson

Zbigniew Dłubak (Polish, 1921-2005)

Untitled

c. 1950

© Armelle Dłubak

Zbigniew Dłubak (Polish, 1921-2005)

Sketch for the series Ammonites

1959-1961

© Armelle Dłubak

The Zbigniew Dłubak – Héritier des avant-gardes exhibition is being held at the Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson between January 17 and April 29, 2018. In the post-war period, Zbigniew Dłubak (1921-2005) was one of the driving forces behind the profound changes in the Polish artistic scene. A great experimenter of photographic forms, he was also a painter, art theoretician, teacher and editor of the Fotografia magazine for twenty years, introducing into this publication a robust photographic critique and interdisciplinary approach to the medium. He enjoyed a certain notoriety in Poland during his lifetime. Several monographic exhibitions were dedicated to him and some of his major works are part of Polish public collections.

Although Dłubak was primarily known as a photographer, he initially aspired to become a painter, tirelessly searching for materials for drawing during the war. Very active in these two traditionally separate disciplines, he greatly influenced the decompartmentalisation of artistic forms. He also defended the right of photography to exist as a completely separate discipline.

His first photographic experiments reveal a diversity of inspirations characteristic of pre-war practices, stemming from constructivist and surrealist traditions. Fascinated by linguistics, Dłubak then moves towards the mechanisms of a systematic approach and then onto the disappearance and fading of signs.

The work carried out by the Fundacja Archaeologia Fotografii where his archives have been deposited offers a new insight into his oeuvre and a new way of looking at it. Continuing in this vein of offering a different reading, this exhibition proposes to highlight the similarities and complementary aspects of photography and painting in his work. It focuses on two decisive periods in the artist’s life: the year 1948, which marks the beginning of his career and places it within the avant-garde movement, and the 1970s, which symbolise his ambiguous position regarding conceptual art. The selection presents iconic works and hitherto unseen photographs.

Press release from the Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson

Zbigniew Dłubak (Polish, 1921-2005)

From the series Existences

1959-1966

© Armelle Dłubak / Archeology of Photography Foundation, Warsaw

Zbigniew Dłubak (Polish, 1921-2005)

From the series Existences

1959-1966

© Armelle Dłubak / Archeology of Photography Foundation, Warsaw

Zbigniew Dłubak (Polish, 1921-2005)

Study for Iconosphere I

1967

© Armelle Dłubak / Archeology of Photography Foundation, Warsaw

Extracts from the book

Éditions Xavier Barral

The first photographic images created by Dłubak, who taught himself to paint and draw in the early 1940s, were undoubtedly strictly utilitarian: they documented the activities of the clandestine army he joined and then, when he was deported to the Mauthausen concentration camp after his participation in the Warsaw uprising in 1944, they were dictated by the tasks the Nazis assigned to him in the camp’s photography studio (touchups and perhaps portraits or reproductions). The images he shows in Krakow1 were however preceded by a few more artistic attempts, created in 1947 and early 1948, which show the desire to understand from within two significant trends of what photographic modernism might have constituted in the eyes of a Polish novice. On the one hand, Dłubak creates images of trees using a low-angle shot or fragments of ground using a sharp high-angle shot, stemming from a sort of Pictorialism marked by a superficial link with the Germanic New Vision, in keeping with Jan Bułhak, then considered the father of Polish modern photography. On the other hand, he arranges compositions of insignificant little objects (like matches, springs, buttons, screws and so on) on tables, which he photographs like abstract not-to-scale landscapes, as practised by constructivists and notably Florence Henri (some of whose images he might have known, even though he never seems to have mentioned them). However, nothing in these two series really prepares for what can be seen in the photographs shown in 1948. […]

Dłubak’s key originality comes from the fact that he focuses less on producing the supernatural and more on finding it, by blurring the too-certain habits of ordinary vision but without the factual origin of his image obscuring its poetic efficacy. […]

So, for Dłubak, it’s not just about reconciling previously separate artistic traditions, but dismantling the traditional opposition between abstraction and figuration. The use of the extreme close-up (on the scale of macro photography) and technical manipulations (solarisation or pseudo-solarisation, presentation of the negative as a positive) must not be seen as a distancing from external reality but, on the contrary, as a way of penetrating its core; less like a hidden thing than a spiritual vision, and less like burying than a revelation of what is latent within, giving us a subtler understanding of it. As Dłubak writes in 1948 in an article on method called “Reflections on photography”: “Photographic realism is a different kind of realism and, fittingly, the faithfulness and attachment to the object, which has the nature of a raw material here, prohibits any artifice, because it is immediately unmasked. Such realism requires one to rely essentially on nature avoiding any narration.”2

Éric de Chassey

Extracts from “1948-1949: un réalisme de l’extrême proximité”

1/ At the “1st Exhibition of Modern Art” (I Wystawa Sztuki Nowoczesnej) opened on 19 December 1948. This exhibition included artists from across the country, often young (the vast majority were under thirty): painters, sculptors but also, and this was a huge novelty in Poland, photographers. Zbigniew Dłubak was even one of the key organisers of the event

2/ Zbigniew Dłubak, “Rozmyślania o fotografii II,” Świat fotografii, no 11, January-February 1949, reproduced in Lech Lechowicz and Jadwiga Janik (dir.), cat. exp. Dłubak, fotografie photographs, 1947-1950, Lodz, Muzeum Sztuki, 1995, p. 47

Two events occurred in 1970 which are traditionally considered by Polish historiography as key manifestations of conceptual art: the Wrocław Symposium ’70 and the Świdwin-Osieki ’70 (Osieki open air events). It would of course be illusory to bring the appearance of conceptual art in Poland down to this one year, since it was a much more complex process, as demonstrated by Piotr Piotrowski and Luiza Nader in particular. However, referring to these events helps explain the work and engagement of Zbigniew Dłubak during these years. Organised thanks to a close collaboration between local authorities and artistic circles, they brought together artists and art critics, representing various experimental trends in Polish art. The aim of the Wrocław Symposium was to attract an audience not accustomed to experimental art. The primary idea, justifying the participation of local organisations, was to bring contemporary art into the public space, particularly social housing areas, squares and undefined suburban sites. […]

Finally, for Dłubak, 1970 marks the beginning of a series to which he is to dedicate the next eight years: Systems – Gesticulations. This series which, at first glance perfectly conforms to the codes of conceptual art, in reality indicates Dłubak’s break from conceptualism. Although he saw theoretical activity as an integral part of his artistic practice, he was convinced of the need to preserve a role of mediation in the artistic object. So why did Zbigniew Dłubak, one of the ardent protagonists of the development of conceptualism in Poland, finally break away from the movement?

His writings suggest some answers to this question. In 1977, when the movement was still very much alive, he wrote: “In aspiring to total purification, conceptual art has created a list of ‘don’ts’ regarding methods of recording and transmission. […] But conceptualism immediately developed a morphology of its own means [of expression] and became frozen.”1 In an (undated) manuscript, he added: “The causes of the failure of conceptualism: an erroneous interpretation of art (false models of ancient art); an under-estimation of the fight against aestheticism in the first half of the 20th century; too much attention paid to ways of recording ideas; unjustified faith in the existence of the idea outside its recording; the belief in the advent of a new era of art through the choice of another material for realising ideas.”2 He too relied on this new morphology but tried nevertheless to preserve his autonomy. He didn’t believe in the annihilation of the artistic object, considering the work of art as the result of an encounter. The object started the social dialogue.

Karolina Ziebinska-Lewandowska

Extracts from “1970: l’art du concept (non) assimilé”

1/ Uwagi o sztuce i fotografii (Comments about art and photography), 1977, Fotografia, no 8, 1969

2/ Untitled text, reproduced in Teoria sztuki Zbigniewa Dłubaka (Theory of art of Zbigniew Dłubak), Magdalena Ziółkowska (dir.), Warsaw, Fundacja Archeologia Fotografii, 2013, p. 145

Zbigniew Dłubak (Polish, 1921-2005)

Untitled

c. 1970

© Armelle Dłubak / Archeology of Photography Foundation, Warsaw

Zbigniew Dłubak (Polish, 1921-2005)

Tautologies

1971

© Armelle Dłubak / Archeology of Photography Foundation, Warsaw

Zbigniew Dłubak (Polish, 1921-2005)

Gesticulations

1970-1978

© Armelle Dłubak / Archeology of Photography Foundation, Warsaw

Zbigniew Dłubak (Polish, 1921-2005)

Desymbolisations

1978

© Armelle Dłubak / Archeology of Photography Foundation, Warsaw

Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson

79 rue des Archives

75003 Paris

Opening hours:

Tuesday – Sunday 11am – 7pm

Closed on Mondays

![Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz. 'Self-Portrait, Zakopane [Broken Glass]' 1910](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/witkiewicz_self-portrait-zakopane-web.jpg?w=840)

You must be logged in to post a comment.