Exhibition dates: 15th February – 3rd May 2015

Ivan Albright (American, 1897-1983)

Medical Sketchbook

1918

The Art Institute of Chicago

Gift of Philip V. Festoso

© The Art Institute of Chicago

Again, I am drawn to these impressive avant-garde works of art. I’d have any of them residing in my flat, thank you very much. The Dalí, Delaunay and Léger in painting and drawing for me, and in photography, the muscular Ilse Bing, the divine Umbo and the mesmeric, disturbing can’t take your eyes off it, Witkiewicz self-portrait.

Marcus

Many thankx to the Art Institute of Chicago for allowing me to publish the art works in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“Everything had broken down in any case, and new things had to be made out of the fragments.”

Kurt Schwitters, 1930

Salvador Dalí (Spanish, 1904-1989)

City of Drawers

1936

The Art Institute of Chicago

Gift of Frank B. Hubachek

© Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, 2014

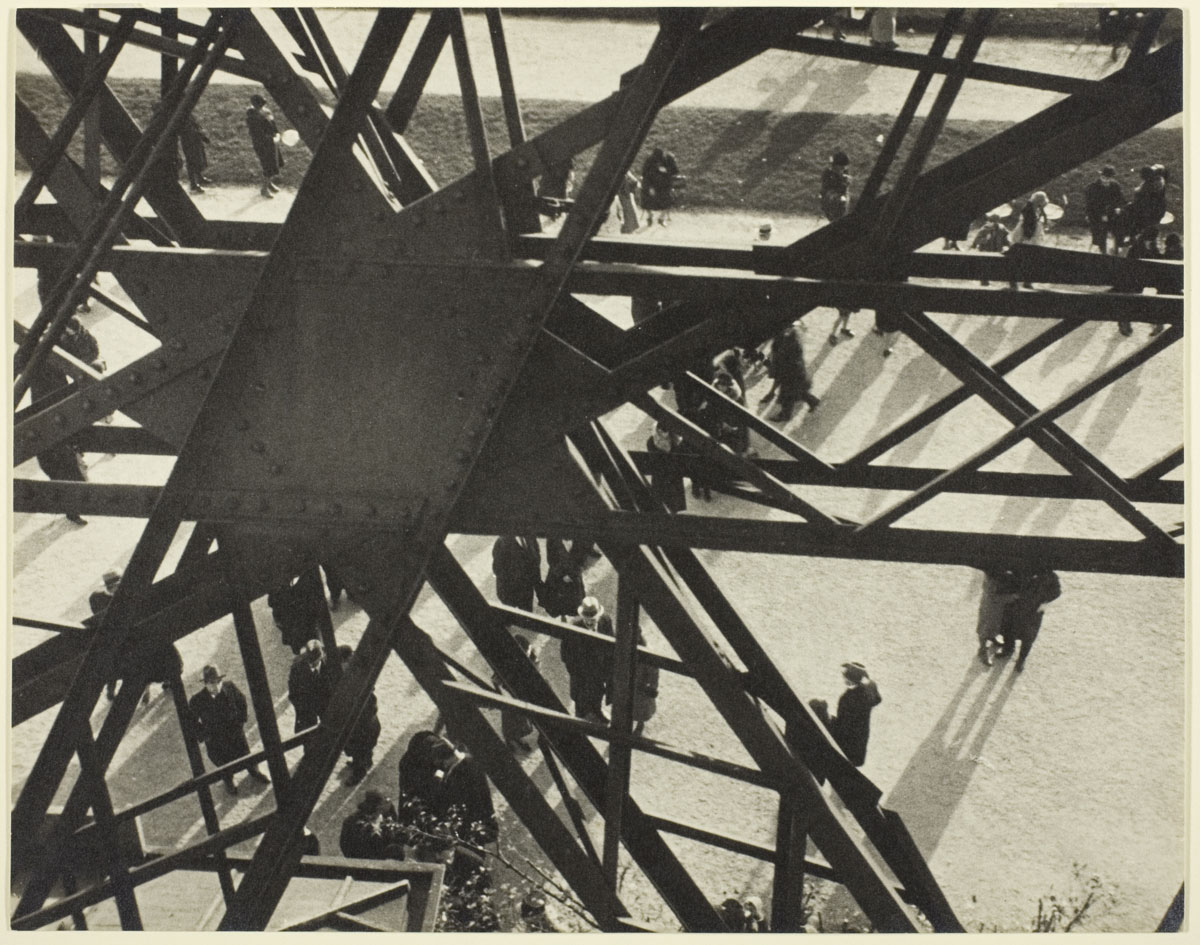

Ilse Bing (German, 1899-1998)

Eiffel Tower, Paris, 1931

1931

Julien Levy Collection, Gift of Jean and Julien Levy

© Estate of Ilse Bing

Luis Buñuel (Spanish, 1900-1983) and Salvador Dalí (Spanish, 1904-1989)

Un Chien Andalou

1929

Director – Luis Buñuel

Writers – Salvador Dali, Luis Buñuel

Cast – Simone Mareuil, Pierre Batcheff

Un Chien Andalou (An Andalusian Dog) is a 1929 Franco-Spanish silent surrealist short film by Spanish director Luis Buñuel and artist Salvador Dalí. Buñuel’s first film, it was initially released in a limited capacity at Studio des Ursulines in Paris, but became popular and ran for eight months.

Un Chien Andalou has no plot in the conventional sense of the word. With disjointed chronology, jumping from the initial “once upon a time” to “eight years later” without events or characters changing, it uses dream logic in narrative flow that can be described in terms of the then-popular Freudian free association, presenting a series of tenuously related scenes.

Fernand Léger (French, 1881-1955) and Dudley Murphy (American, 1897-1968)

Ballet Mécanique

1924

Ballet Mécanique (1923-1924) is a Dadaist post-Cubist art film conceived, written, and co-directed by the artist Fernand Léger in collaboration with the filmmaker Dudley Murphy (with cinematographic input from Man Ray). It has a musical score by the American composer George Antheil. However, the film premiered in silent version on 24 September 1924 at the Internationale Ausstellung neuer Theatertechnik (International Exposition for New Theater Technique) in Vienna presented by Frederick Kiesler. It is considered one of the masterpieces of early experimental filmmaking.

Ballet mécanique (1924) | MoMA

Ballet mécanique, conceived by painter Fernand Léger and photographed by filmmaker Dudley Murphy (possibly with some involvement from Man Ray), is a rhythmic interplay between human and object. Affected by his experience of fighting in World War I, and in particular by the mustard gas attack that left him hospitalised for a year, Léger became fascinated with mechanical technology, which would feature heavily in his post-1917 art. Ballet mécanique, his only film, is an example of this juxtaposition of man and machine: gears and pendulums vs. eyes and mouths, pistons pumping vs. a woman’s endless climb up the stairs, clocks vs. legs. A kaleidoscopic combination of faces and kitchen utensils, Ballet mécanique was completely unlike contemporary commercial movies, and would pave the way for other revolutionary films like Metropolis and Limite.

If you were to see Ballet mécanique installed in one of our galleries or projected in one of our theaters, it would look a little different than it does here – the frameline would be stabilised and the edges of the picture would either be cropped or camouflaged with masking around the screen. However, we are presenting this version the way a scholar visiting the Film Study Center would see it on a flatbed viewing machine, with a slight bounce to the image and the sprocket holes visible, and without live musical accompaniment. (The score, composed by George Antheil and usually performed as a separate concert piece, was finished several years after Ballet mécanique premiered and is significantly longer than the film.)

MoMA text from the YouTube website

Claude Cahun (French, 1894-1954)

Object

1936

The Art Institute of Chciago

Through prior gift of Mrs. Gilbert W. Chapman

A century ago, society and life were changing as rapidly and radically as they are in today’s digital age. Quicker communication, faster production, and wider circulation of people, goods, and ideas – in addition to the outbreak of World War I – produced a profoundly new understanding of the world, and artists in the early years of the 20th century responded to these issues with both exhilaration and anxiety. Freeing themselves from the restraints of tradition, modern artists developed groundbreaking pictorial strategies that reflect this new shift in perception.

Shatter Rupture Break, the first exhibition in The Modern Series, explores the manifold ways that ideas of fragmentation and rupture, which permeated both the United States and Europe, became central conceptual and visual themes in art of the modern age. Responding to the new forms and pace of the metropolis, artists such as Robert Delaunay and Gino Severini disrupted traditional conventions of depth and illusionism, presenting vision as something fractured. Kurt Schwitters and George Grosz explored collage, using trash and bits and pieces of printed material in compositions to reflect social and political upheaval and produce something whole out of fragments. In the wake of new theories of the mind as well as the literal tearing apart of bodies in war, artists such as Hans Bellmer, Salvador Dalí, and Stanisław Witkiewicz produced photographs and objects revealing the fractured self or erotic dismemberment. The theme of fragmentation was ubiquitous as inspiration for both the formal and conceptual revolutions in art making in the modern age.

Shatter Rupture Break unites diverse objects from across the entire holdings of the Art Institute – paintings, sculpture, works on paper, photographs, decorative arts and designed objects, textiles, books, and films – to present a rich cacophony that exemplifies the radical and generative ruptures of modern art.

The Modern Series

A quintessentially modern city, Chicago has been known as a place for modern art for over a century, and the Art Institute of Chicago has been central to this history. The Modern Series exhibitions are designed to bring together the museum’s acclaimed holdings of modern art across all media, display them in fresh and innovative ways within new intellectual contexts, and demonstrate the continued vitality and relevance of modern art for today.

Text from the Art Institute of Chicago website

Robert Delaunay (French, 1885-1941)

Champs de Mars: The Red Tower

1911/1923

The Art Institute of Chicago

Joseph Winterbotham Collection

Fernand Léger (French, 1881-1955)

Composition in Blue

1921-1927

The Art Institute of Chicago

Charles H. and Mary F. S. Worcester Collection

© 2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Stuart Davis (American, 1892-1964)

Ready-to-Wear

1955

The Art Institute of Chicago

Restricted gift of Mr. and Mrs. Sigmund W. Kunstadter; Goodman Endowment

Designed by Ruben Haley

Made by Consolidated Lamp and Glass Company

“Ruba Rombic” Vase

1928/1932

Art Institute of Chicago

Raymond W. Garbe Fund in honor of Carl A. Erikson; Shirley and Anthony Sallas Fund

Kurt Schwitters (German, 1887-1948)

Mz 13 Call

1919

The Art Institute of Chicago

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Maurice E. Culberg

© 2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Diego Rivera (Mexican, 1886-1957)

Portrait of Marevna

c. 1915

The Art Institute of Chicago

Alfred Stieglitz Collection, gift of Georgia O’Keeffe

© 2014 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The Art Institute of Chicago is introducing an innovative new series of exhibitions that presents works from the museum’s acclaimed collection of modern art in reimagined ways that demonstrate the continued vitality and significance these works have today.

The Modern Series debuts with Shatter Rupture Break, opening Sunday, February 15, in Galleries 182 and 184 of the museum’s Modern Wing. The exhibition unites such diverse objects as paintings, sculpture, works on paper, photographs, decorative arts and designed objects, textiles, books, and films.

“We wanted to explore how the idea of rupture permeated modern life in Europe and the Americas,” said Elizabeth Siegel, Associate Curator of Photography, who, with Sarah Kelly Oehler, the Gilda and Henry Buchbinder Associate Curator of American Art, took the lead in organising the first exhibition. “It served as an inspiration for revolutionary formal and conceptual developments in art making that remain relevant today.”

A century ago, society was changing as rapidly and radically as it is in today’s digital age. Quicker communication, faster production, and wider circulation of people, goods, and ideas – in addition to the outbreak of World War I – produced a profoundly new understanding of the world, and artists responded with both anxiety and exhilaration. Freeing themselves from the restraints of tradition, modern artists developed groundbreaking pictorial strategies that reflected this new shift in perception.

Responding to the new forms and pace of cities, artists such as Robert Delaunay (French, 1885-1941) and Gino Severini (Italian, 1883-1966) disrupted traditional conventions of depth and illusionism, presenting vision as something fractured. Delaunay’s Champs de Mars: The Red Tower fragments the iconic form of the Eiffel Tower, exemplifying how modern life – particularly in an accelerated urban environment – encouraged new and often fractured ways of seeing. Picturesque vistas no longer adequately conveyed the fast pace of the modern metropolis.

The human body as well could no longer be seen as intact and whole. A devastating and mechanised world war had returned men from the front with unimaginable wounds, and the fragmented body became emblematic of a new way of understanding a fractured world. Surrealists such as Hans Bellmer (German, 1902-1975), Claude Cahun (French, 1894-1954) and Salvador Dalí (Spanish, 1904-1989) fetishised body parts in images, separating out eyes, hands, and legs in suggestive renderings. A more literal representation of the shattered body comes from Chicago’s own Ivan Albright, who was a medical draftsman in World War I. In his rarely shown Medical Sketchbook, he created fascinatingly gruesome watercolours that documented injured soldiers and the x-rays of their wounds.

Just as with the body, the mind in the modern era also came to be seen as fragmented. Stanislaw Witkiewicz (Polish, 1885-1939) produced a series of self-portraits as an act of psychological exploration. His work culminated in one stunning photograph made by shattering a glass negative, which he then reassembled and printed, thus conveying an evocative sense of a shattered psyche. The artistic expression of dreams and mental imagery perhaps reached a pinnacle not in a painting or a sculpture, but in a film. Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí’s film Un chien andalou (An Andalusian Dog) mystified viewers with its dreamlike narrative, dissolves from human to animal forms, dismembered body parts, and shockingly violent acts in an attempt to translate the unconscious mind onto a celluloid strip.

Kurt Schwitters (German, 1887-1948) and George Grosz (German, 1893-1959) explored collage, which took on new importance for avant-garde artists thanks to the aesthetic appeal and widespread availability of mass-produced media. Schwitters used the ephemera of German society to create what he called Merz, an invented term signifying an artistic practice that included collage, assemblage, painting, poems, and performance. The Art Institute owns a significant group of these collages by Schwitters, and six will appear in the exhibition. The use of thrown-away, ripped up, and scissored-out pieces of paper, divorced from their original meaning and reassembled with nails and glue into new objects, was an act that exposed the social and political disruptions of a German society that seemed broken and on the edge of collapse in the aftermath of World War I.

Shatter Rupture Break is unusual in that it unites objects from across the entire museum – from seven curatorial departments as well as the library. This multiplicity is significant because modern artists did not confine themselves to one medium, but explored different visual effects across a variety of media. As well, the show prominently features the voices of artists, writers, scientists, and other intellectuals of the period. The goal is to create a dynamic space that evokes the electrifying, disruptive, and cacophonous nature of modern art at the time.

“We hope to excite interest in the modern period as a crucial precursor to the changes of our own time, to show how what might seem old now was shockingly fresh then,” said Oehler.

Considered one of the finest and most comprehensive in the world, the Art Institute’s collection of modern art includes nearly 1,000 works by artists from Europe and the Americas. The museum was an early champion of modern artists, from its presentation of the Armory Show in 1913 to its early history of acquiring major masterpieces. This show highlights some recent acquisitions of modern art, but also includes some long-held works that have formed the core of the modern collection for decades. Shatter Rupture Break celebrates this history by bringing together works that visitors may know well, but have never seen in this context or with this diverse array of objects.”

Press release from the Art Institute of Chicago

Hans Bellmer (German born Poland, 1902-1975)

The Doll (La Poupée)

1935

Gelatin silver print overpainted with white gouache

65.6 x 64cm

Anonymous restricted gift; Special Photography Acquisition Fund; through prior gifts of Boardroom, Inc., David C. and Sarajean Ruttenberg, Sherry and Alan Koppel, the Sandor Family Collection, Robert Wayne, Simon Levin, Michael and Allison Delman, Charles Levin, and Peter and Suzann Matthews; restricted gift of Lynn Hauser and Neil Ross

© 2015 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Umbo (Otto Umber) (German, 1902-1980)

Untitled

1928

Julien Levy Collection, Gift of Jean and Julien Levy

© 2014 Phyllis Umbehr/Galerie Kicken Berlin/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz (Polish, 1885-1939)

Self-Portrait, Zakopane [Broken Glass]

1910

Promised Gift of a Private Collection

The Art Institute of Chicago

111 South Michigan Avenue

Chicago, Illinois 60603-6404

Phone: (312) 443-3600

Opening hours:

Thursday – Monday 11am – 5pm

Closed Tuesday and Wednesday

The museum is closed Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year’s days.

![Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz (Polish, 1885-1939) 'Self-Portrait, Zakopane [Broken Glass]' 1910 Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz (Polish, 1885-1939) 'Self-Portrait, Zakopane [Broken Glass]' 1910](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/witkiewicz_self-portrait-zakopane-web.jpg?w=650&h=915)

You must be logged in to post a comment.