December 2018

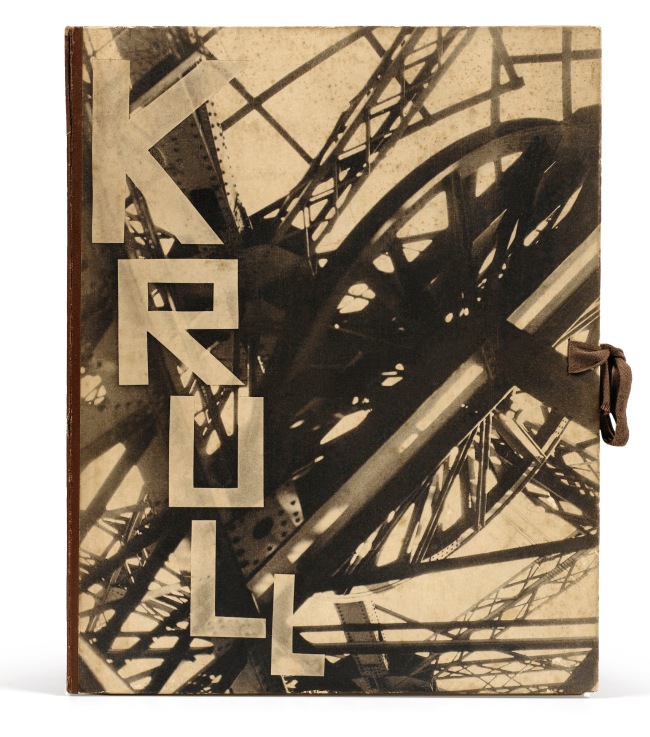

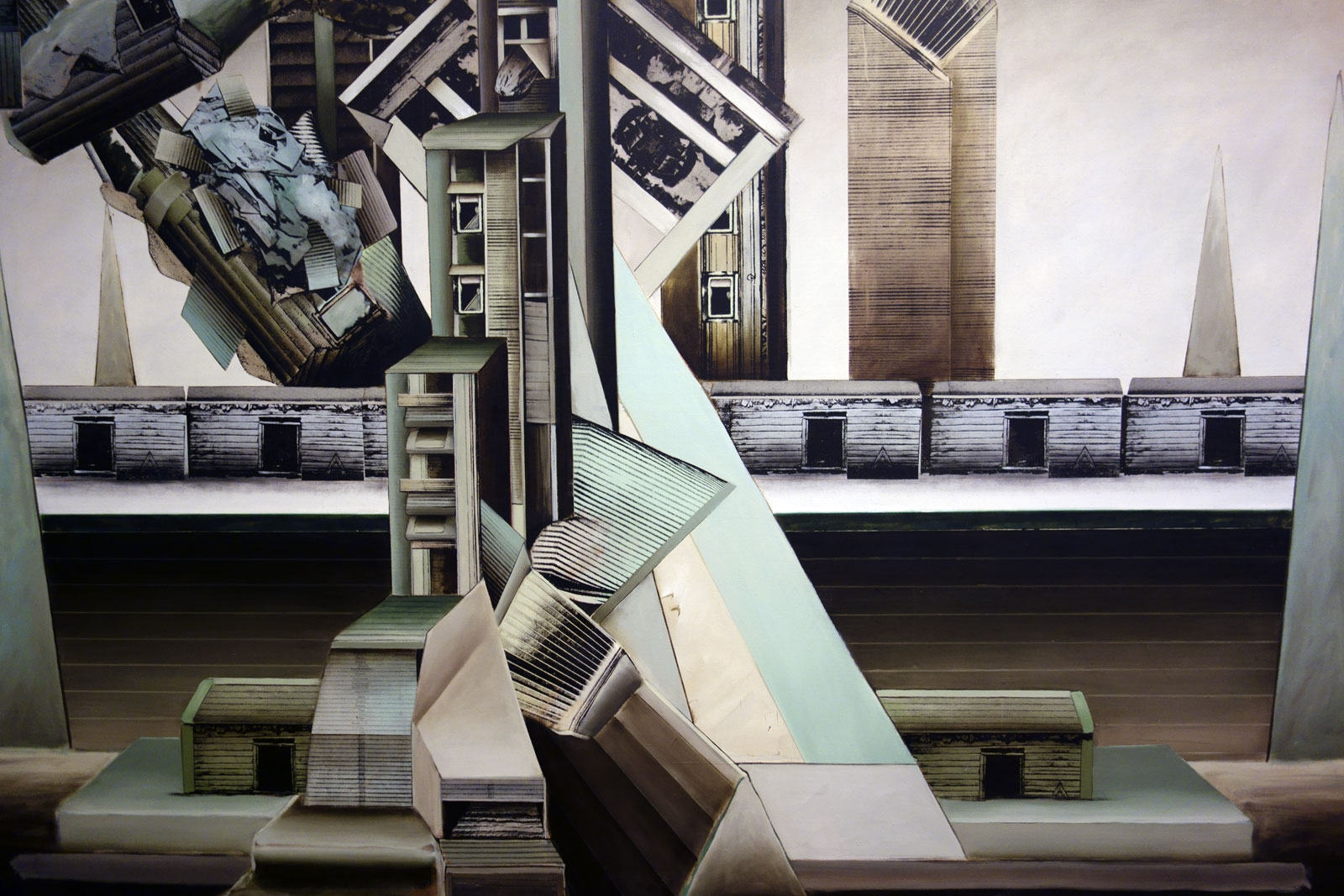

Germaine Krull (European, 1897-1985) (photographer)

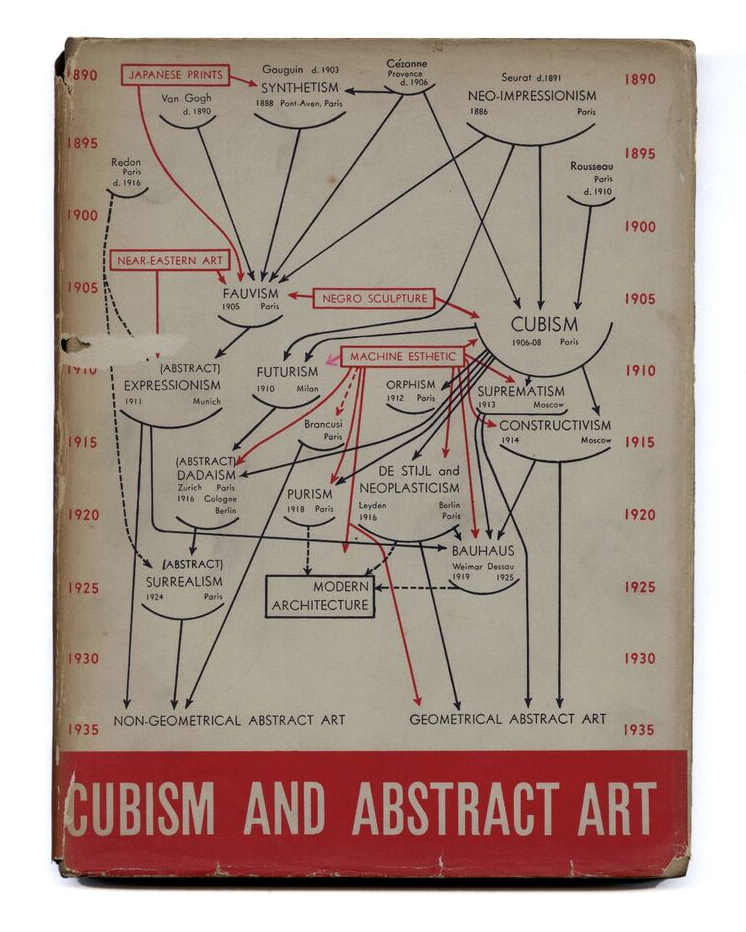

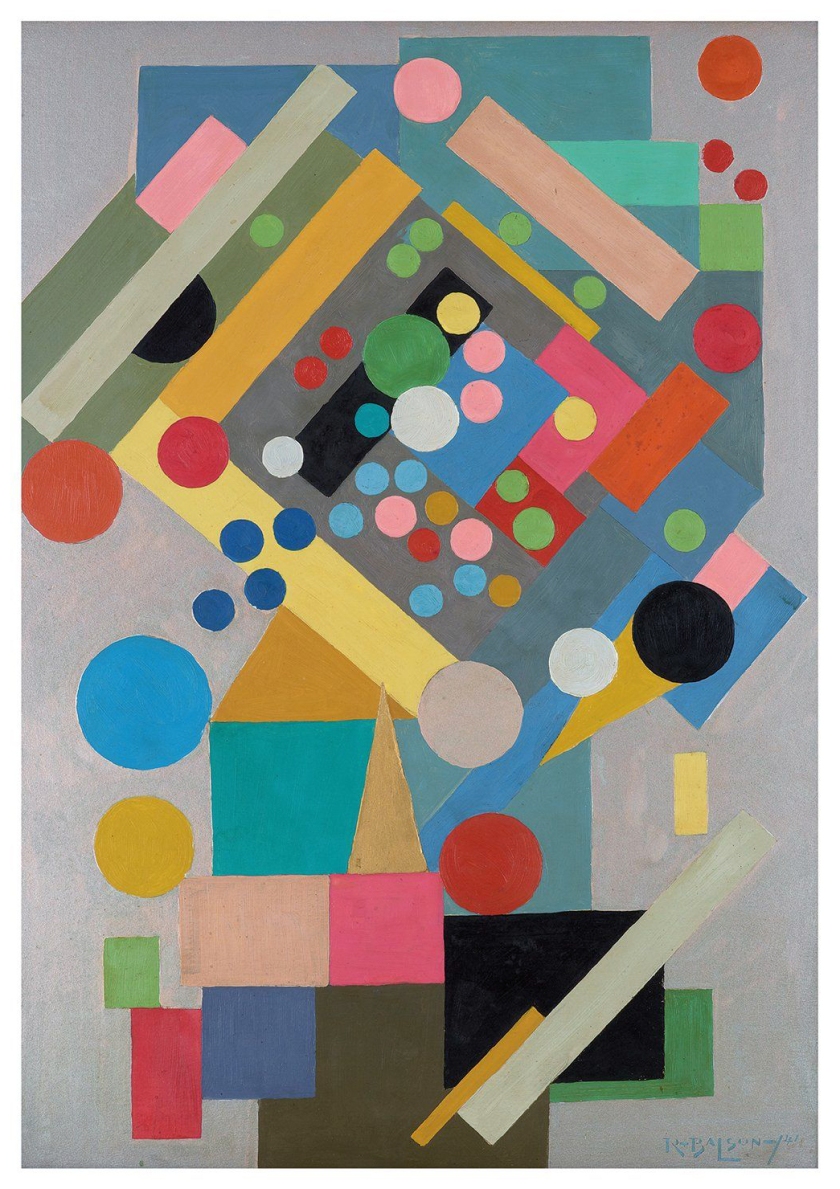

Cover design by M. Tchimoukow (Louis Bonin) (French, 1906-1979)

MÉTAL cover

1928

Librairie des Arts décoratifs

A. Calavas, Editeur

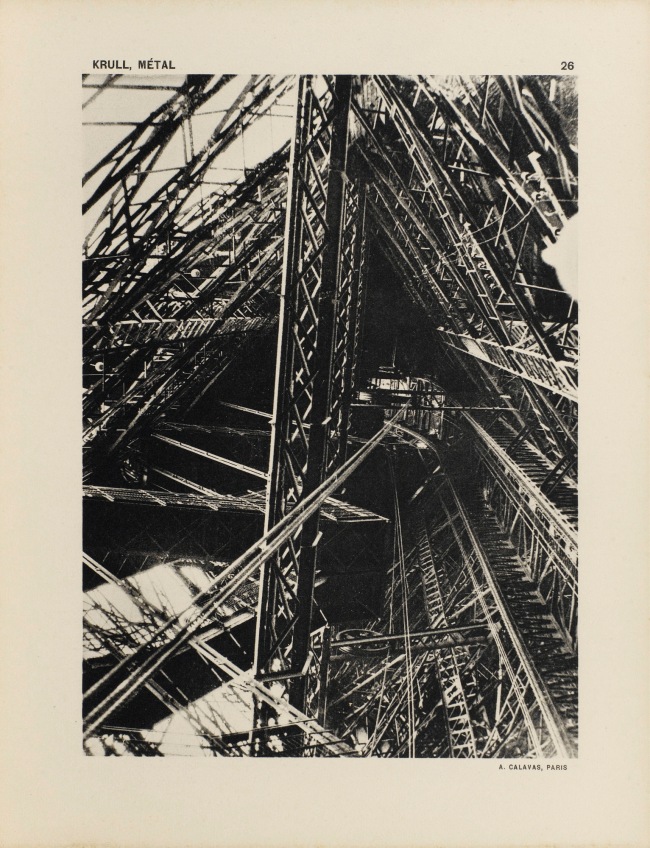

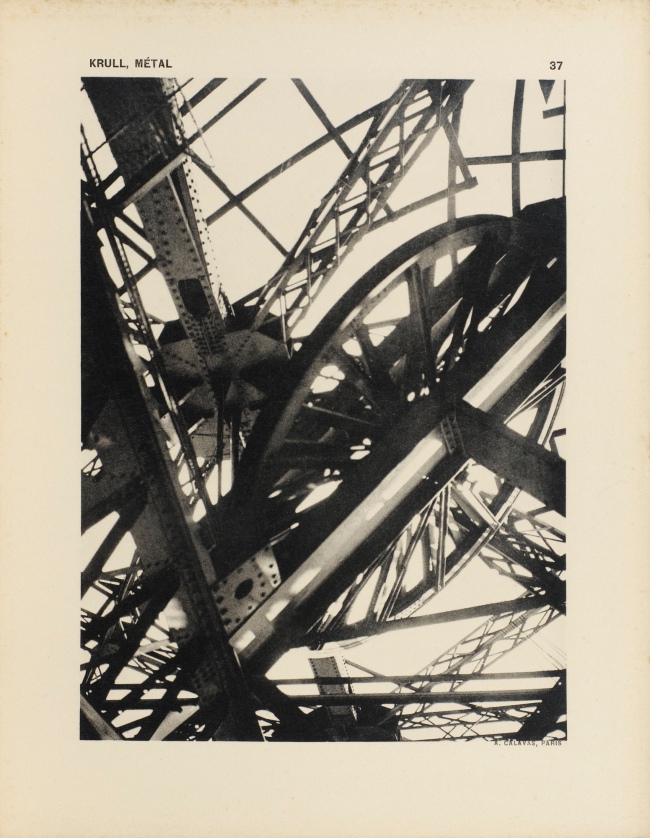

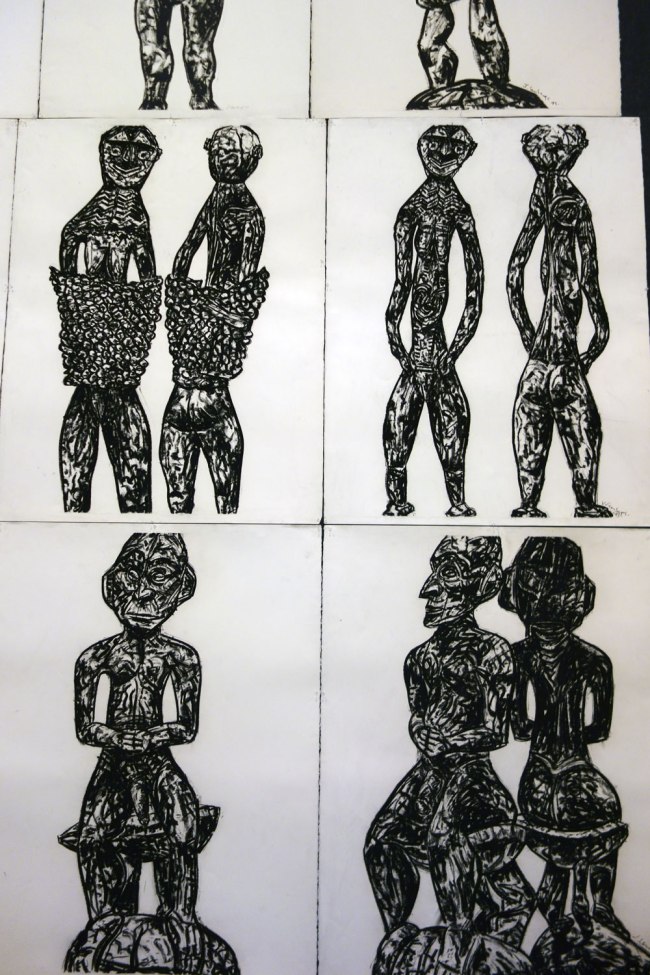

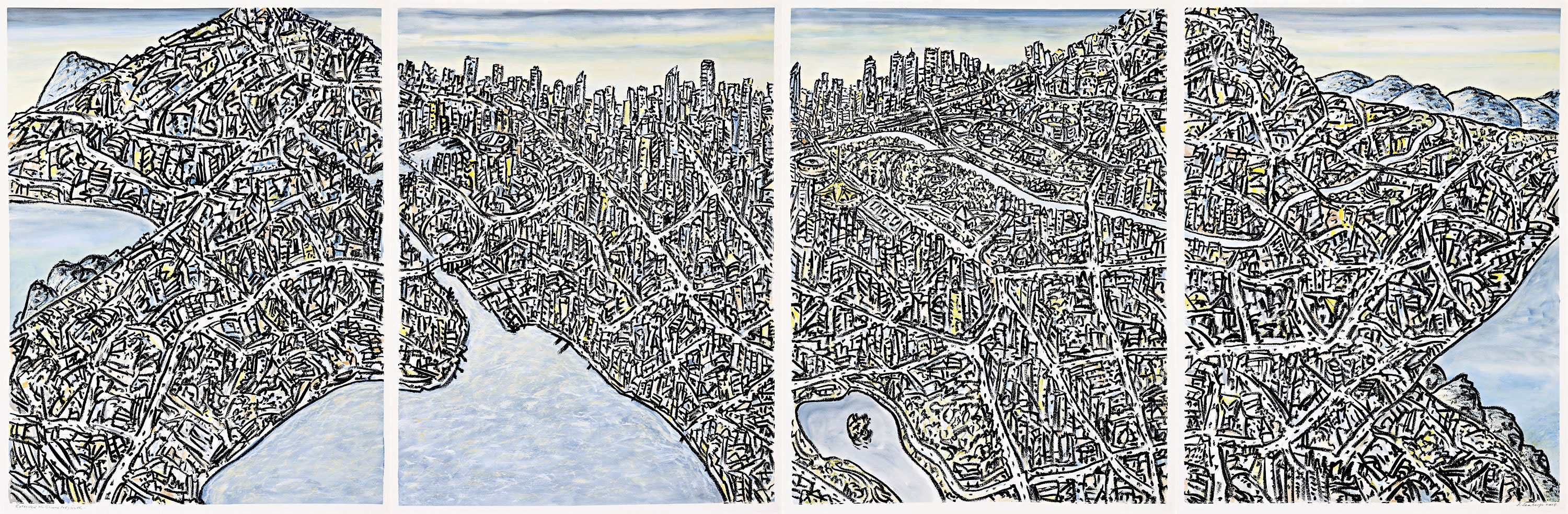

Portfolio comprising a title page, a preface by Florent Fels and sixty four (64) loose photogravures, each mentioning the photographer’s name, titled ‘MÉTAL’, plate number and publisher’s name. Original dust jacket.

Folio: 30 x 23.5cm; 11 3/4 x 9 1/4 in.

Plate: 29.2 x 22.5cm; 11 1/2 x 8 3/4 in.

Image: 23.6 x 17.1cm; 9 1/4 x 6 1/2 in.

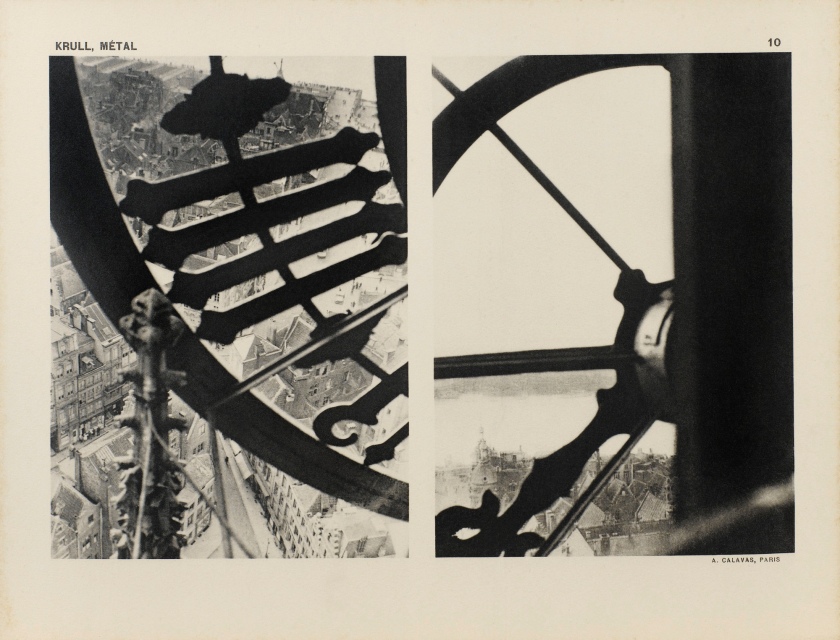

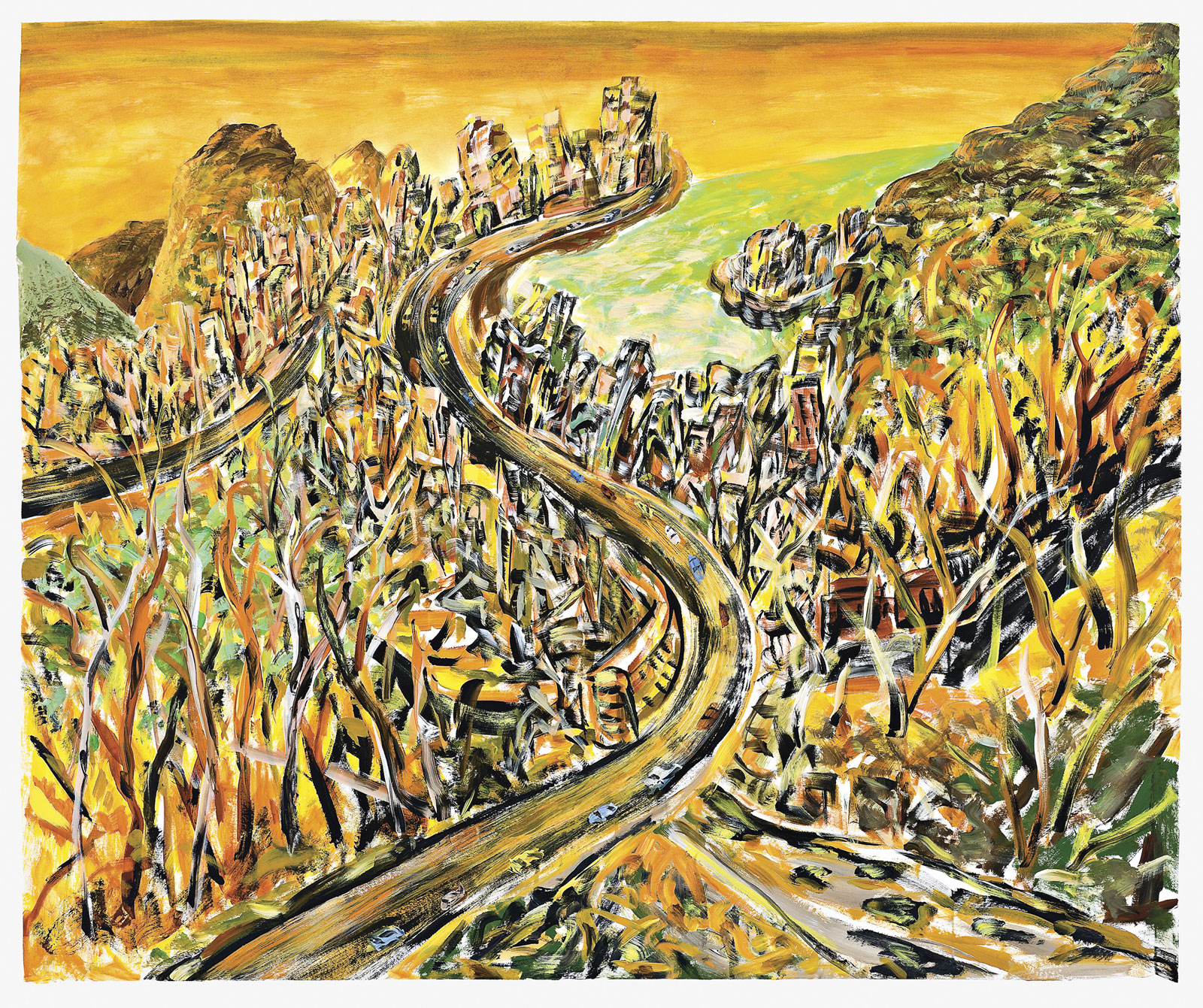

“Dans toute sa force” (In full force)

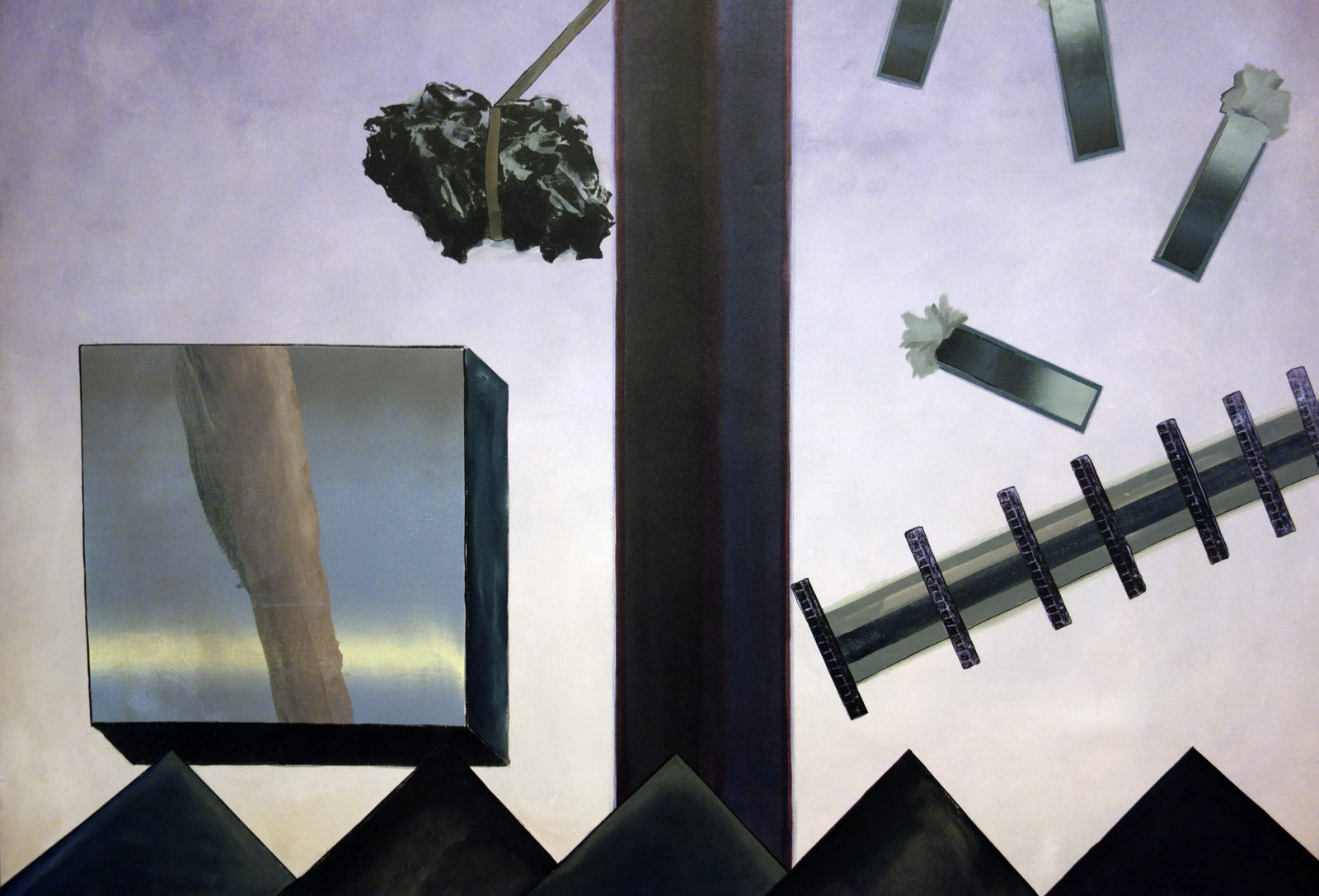

For my new body of work I have been researching the concept of The Oblique Function which was first developed in the 1960’s by Architecture Principe (Claude Parent and Paul Virilio). “The idea was to tilt the ground in order to revolutionise the old paradigm of the vertical wall. In fact, being inclined, the wall becomes experienceable and so are the cities imagined by the two French architects. The oblique is fundamentally interested in how a body physically experiences a space. The slope implies an effort to climb up and a speed to climb down; this way the body cannot abstract itself from the space and feel the degrees of inclination.”1

The key to the concept is: The oblique is fundamentally interested in how a body physically experiences a space.

Perhaps we can transfer this concept to the portfolio MÉTAL by Germaine Krull, one of the most important photobooks every produced … and ask how does Krull, her camera, and by extension the viewer, inhabit the spaces she creates.

In this portfolio Krull, through “extreme angles, producing dizzying compositions of overlapping and intersecting details”, one upside down image and two multiple exposures, “one showing two overlapped power generators and the other several layered bicycle parts printed at right angles to one another to create an effect of circular motion”2 – produces and directs (Krull was also an avant-garde filmmaker) the creation of a molecular structure – both grand and intimate, macro and micro at one and the same time. Probing further, we can link her filmic structure, this oblique mass of machines and images, to Eisenstein’s dynamic comprehension of a work of art, that is, “The logic of organic form vs. the logic of rational form [which] yields, in collision, the dialectic of the art-form.”3

This dialectic (the tension that exists between two conflicting or interacting forces, elements, or ideas; and, the process, in Hegelian and Marxist thought, in which two apparently opposed ideas, the thesis and antithesis, become combined in a unified whole, the synthesis) rests on Eisenstein’s definition of the organic form as “the passive principle of being”, defining its limit to be nature, and his definition of the rational form as “the active principle of production”, defining its limit to be industry, with art falling where nature and industry intersects.4 How these two forces interact “produces and determines Dynamism”, in which:

The spatial form of this dynamism is expression.

The phases of its tension: rhythm.5

These new concepts and viewpoints are the result of a constantly dynamic evolution from old perceptions to new perceptions which produce contradictions within the spectator’s mind. Eisenstein observes, “That which is not slightly distorted lacks sensible appeal; from which it follows that irregularity – that is to say, the unexpected, surprise and astonishment, are an essential part and characteristic of beauty.”6 “And Baudelaire wrote in his journal: That which is not slightly distorted lacks sensible appeal; from which it follows that irregularity-that is to say, the unexpected, surprise and astonishment, are an essential part and characteristic of beauty. Upon closer examination of the particular beauty of irregularity as employed in painting, whether by Grünewald or by Renoir, it will be seen that it is a disproportion in the relation of a detail in one dimension to another detail in a different dimension. The spatial development of the relative size of one detail in correspondence with another, and the consequent collision between the proportions designed by the artist for that purpose, result in a characterisation – a definition of the represented matter.”7

What could be more appropriate for Krull’s multi-layered, distorted, scaled, twisted representations of the new temples of industry than this definition of represented matter – a symbiosis between nature and industry, acknowledging, through emotion, beauty in the nature of industry, and landscapes of plenty in a people-less world?

An anonymous author on the Cinema Confessions blog comments, “Any art form ought to be understood as a communicative medium in which the thing being communicated is not an idea, but an emotion. Language communicates intellect, whereas art communicates sensation. The two are certainly compatible, as in poetry, but also just as certainly inimitably unique. And as communication requires the process of a message being sent and received, we must acknowledge that distinct communication is impossible without the process of time. Thus, as words in a sentence are given meaning through context of contiguous words in the same sentence, and sentences are given sub-textual meaning through context of other sentences within a conversation, given shots within a scene will conform to an over-tonal meaning intrinsically contextualised by other shots within the same scene, and in a broader sense, other scenes throughout the film.”

They continue: “In the essay The Filmic Fourth Dimension, Eisenstein compares film to music thusly, “There, along with the vibration of a basic dominant tone, comes a whole series of similar vibrations … Their impacts against each other … envelop the basic tone in a whole host of secondary vibrations … We find the same thing in optics, as well. All sorts of aberrations, distortions, and other defects, which can be remedied by systems of lenses, can also be taken into account compositionally, providing a whole series of definite compositional effects.” To simplify, he is describing the methods by which musicians and filmmakers are capable of manipulating audience emotion.”8

Thus, through Krull’s definitive compositional effects, her tonal montages capture more than just linear time, construct more than the spectator’s eye directed along the lines of some immobile object … for her holistic movement of the piece is perceived in a wider sense: where the “montage is based on the characteristic emotional sound of the piece – of its dominant. The general tone of the piece… I do not mean to say that the emotional sound of the piece is to be measured “impressionistically.” The piece’s characteristics in this respect can be measured with as much exactitude as in the most elementary case of “by the ruler” measurement in metrical montage. But the units of measurement differ. And the amounts to be measured are different.”9

This is the key to the effective nature of Krull’s portfolio, the power of the emotional sound of the piece: her understanding of the compositional effects of tonal montage as a piece of theatre measured in a different unit – through rhythm, through the interruption of sequences, through the distortion of spaces – to create a single unit of sensory and emotional experience. As Eisenstein notes, “In the Kabuki … a single monistic sensation of theatrical “provocation” takes place. The Japanese regards each theatrical element, not as an incommensurable unit among the various categories of affect (on the various sense-organs), but as a single unit of theatre. … Directing himself to the various organs of sensation, he builds his summation [of individual “pieces”] to a grand total provocation of the human brain, without taking any notice which of these several paths he is following.”10

Pace Krull. Her holistic compositions are intertextual and multi-faceted at a time when “straight” photography and even avant-garde photography could not string an adequate sentence together, let alone a multi-dimensional visual, sensual and emotional narrative. This is why Krull’s portfolio is so revolutionary for its time. And just to reinforce this shock of the new, of surprise and astonishment, Krull gets the writer Florent Fels – a traditionalist who by this time (1928) did not like contemporary art – to write a romantic eulogy of an introduction to the new gods of the sky, an introduction which gives the reader a sense of the soaring romanticism which is ascribed to these machinic megaliths. Citing Dostoyevsky, Rousseau and Cocteau, Fels’ florid fornications are, just like Krull’s stunning images, a joy for the senses:

“The trains break the horizon with a deafening roar. They leave the ground and glide there on the ether into the inevitable advance of progress, dragging the living with wonder towards the astral stations.

The strong and soft movement of the hammer softens the ingots like lead elephants. And see the Eiffel Tower, now a bell tower of acoustic waves, its improper monstrosity has provided for surprise and confusion. Now lovers are treated there, three hundred metres above the ground, to a rendezvous with the birds. And the poets, from the old Douanier Rousseau to Jean Cocteau, claim that on beautiful spring evenings fairies ride tobogan on its wing.

This giant was missing a heavenly glow: One has been given to it. The luminous progress of industry is evident in every majestic metre of its height.

Aeroplane, elevator and wheel, with which some humans soar up to the kingdom of the birds, are suddenly transformed into elements of our nature.”11

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Word count: 1,438

All of the photographs in this posting are published under “fair use” conditions for the purpose of educational research and academic comment. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

1/ “# Great Speculations /// The Oblique Functon by Claude Parent and Pau Virilio” on The Funambulist website [Online] Cited 09/12/2018. No longer available online

2/ Kim Sichel. “Contortions of Technique: Germaine Krull’s Experimental Photography,” on the MoMA website [Online] Cited 09/12/2018

3/ Sergei Eisenstein. Film Form: Essay in Film Theory. Edited and translated by Jay Leyda. New York and London: A Harvest / HBJ Book, 1949, p. 46

4/ Ibid.,

5/ Ibid., p. 47

6/ Charles Baudelaire, Intimate Journals (13 May 1 856), translated by Christopher Isherwood. New York, Random House, 1930, quoted in Sergei Eisenstein. Film Form: Essay in Film Theory. Edited and translated by Jay Leyda. New York and London: A Harvest/HBJ Book, 1949, p. 51

7/ Anonymous. “Film as Language: The Method and Form of Sergei Eisenstein,” on the Cinema Confessions blog 05/05/2011 [Online] Cited 09/12/2018. No longer available online

8/ Eisenstein op. cit., p. 51

9/ Ibid., p. 75

10/ Ibid., p. 64

11/ Extract of the Preface from Florent Fels to the first edition of MÉTAL. Librairie des Arts décoratifs, A. Calavas, Editeur, 68, Rue la Fayette, Paris, 1928

I did not have a special intention or design when I took the Iron photographs. I wanted to show what I see, exactly as the eye sees it. ‘MÉTAL’ is a collection of photographs from the time. ‘MÉTAL’ initiated a new visual era and open the way or a new concept of photography. ‘MÉTAL’ was the starting point which allowed photography to become an artisanal trade and which made an artist of the photographer, because it was part of this new movement, of this new era which touched all art.

Germaine Krull. Extract from the Preface to the 1976 edition of ‘MÉTAL’

Roland Barthes was skeptical of Krull’s experimental photographs. In his famous 1980 meditation on photography, ‘Camera Lucida’, he wrote: “There are moments when I detest Photographs: what have I to do with Atget’s old tree trunks, with Pierre Boucher’s nudes, with Germaine Krull’s double exposures (to cite only the old names).”3 Barthes discounts what he calls photographic “contortions of technique: superimpressions, anamorphoses, deliberate exploitation of certain defects (blurring, deceptive perspectives, trick framing),” and comments that “great photographers (Germaine Krull, Kertész, William Klein) have played on these surprises, without convincing me, if I understand their subversive bearing.”4 But while such photographs are sometimes subversive, to be sure, they are often celebratory in tone. Krull and her colleagues carried out their “contortions of technique” to produce metaphors for the swirling, confusing, exhilarating urban life in their post-World War I decade.

Roland Barthes. Camera Lucida, p. 33 quoted in Kim Sichel. “Contortions of Technique: Germaine Krull’s Experimental Photography,” on the MoMA website [Online] Cited 25/11/2018

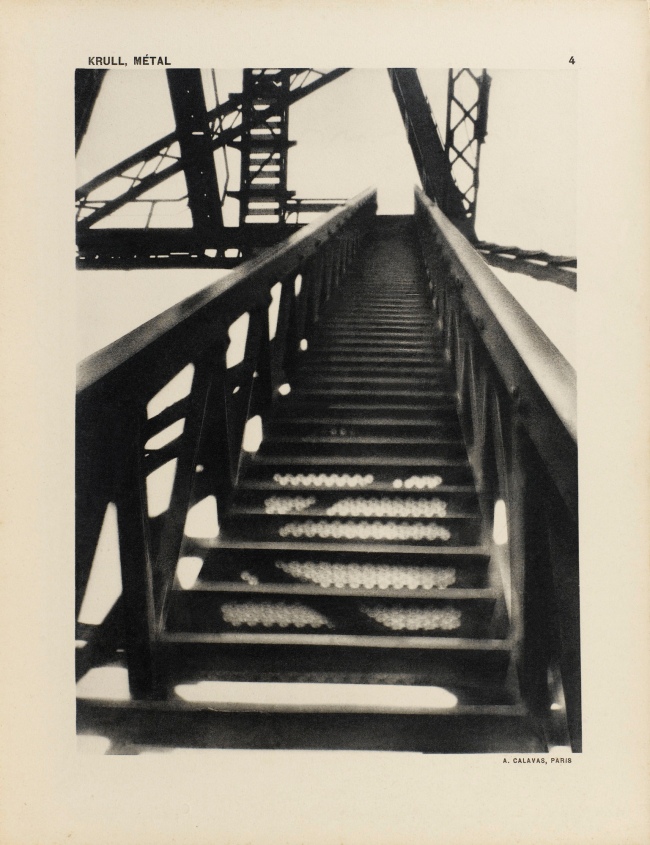

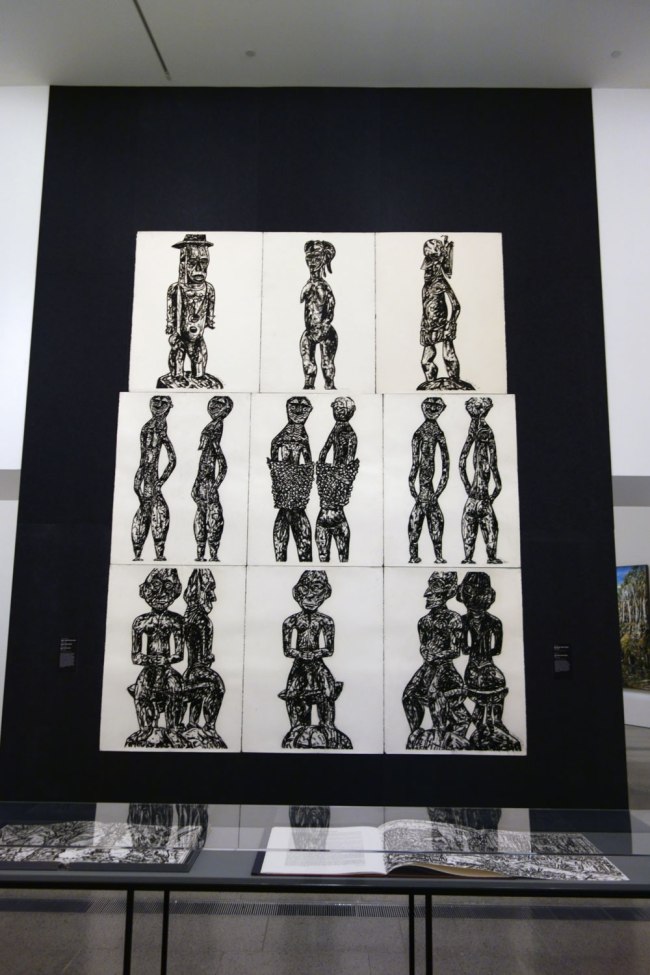

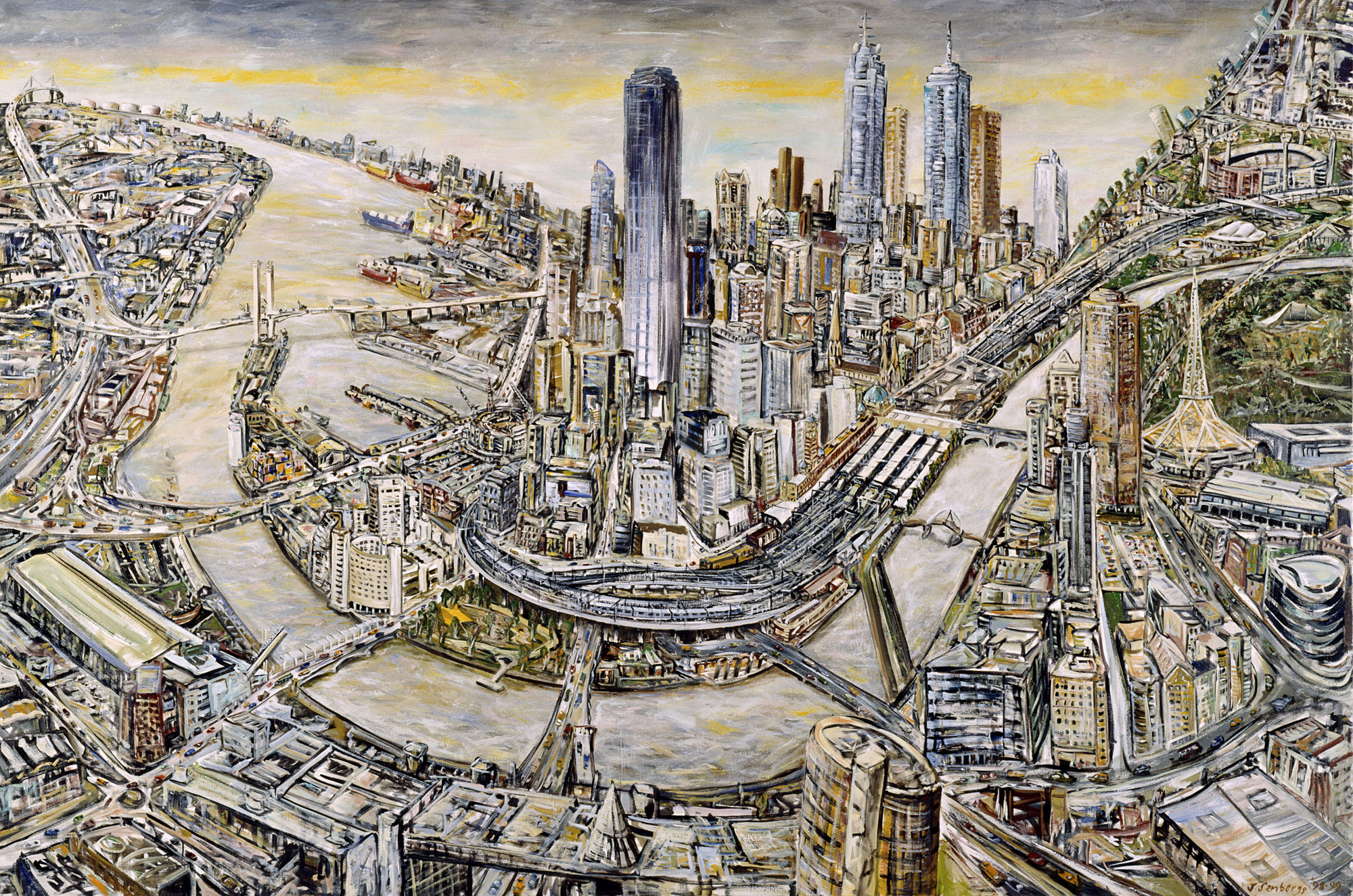

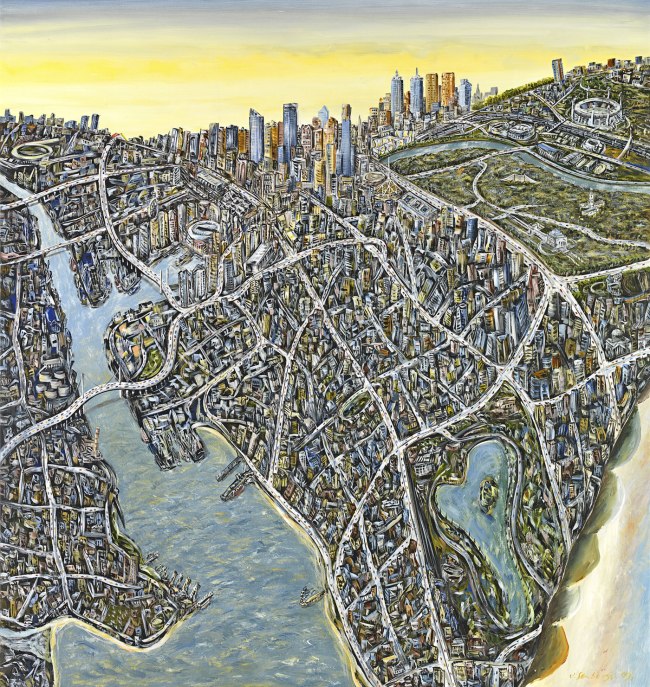

Krull’s most renowned photographs are not street scenes but abstracted views of the Eiffel Tower, and three of these images, accompanied by a short text by Florent Fels and laid out in overlapping fashion, appeared in a ‘Vu’ article titled “Dans toute sa force” (In full force) published in May 1928, just before the tower’s fortieth birthday (fig. 8).19 According to Krull’s memoirs, Vogel told her, “Go and photograph the Eiffel Tower, Germaine. Photograph it as you really see it, and make sure that you don’t bring me a postcard view.”20 As Krull wrote, she did not see much in the “dead old form” until she began climbing the staircases and experiencing the tower from various vantage points. Some of the resultant images – vertiginous views of the wrought iron structure – appeared in the German magazine ‘UHU’ and Philippe Lamour’s journal ‘Grand’route’ as well as in ‘Vu’, and others (eleven in all) grace the pages of ‘Métal’.21

“Protest gegen ein unmögliches Bauwerk,” ‘UHU’ 4 (December 1927): 106-11; Eric Hurel, “La Confusion des arts,” ‘Grand’route’ 1, no. 3 (May 1930): pp. 71-74; and Krull, ‘Métal’, cover and pls. 2, 11, 19, 26, 28, 33, 37, 50, 54, 57. Footnote 21 in Kim Sichel. “Contortions of Technique: Germaine Krull’s Experimental Photography,” on the MoMA website [Online] Cited 25/11/2018

Although a portfolio, rather than a book, MÉTAL is widely considered to be among the most important photographic publications of the 1920s. Not only was Krull able to create work that stood the test of time, but she managed it in a profession dominated by men. It is interesting that with MÉTAL, she embraces a clearly masculine theme.

Krull’s photographs, whether of bridges, cranes, or the Eiffel Tower, tend towards the unconventional. It seems as if her initial approach is quite conservative, but then she questions common rules of composition, avoiding the more obvious ways her subjects would have been photographed at the time. Krull consequently avoids implementing a strict visual language. Instead of striving for a “realistic” documentation of her subject in her photographs she chooses her angles instinctively, cropping the images tightly, or even reversing them. It is exactly this unexpected approach that makes MÉTAL stand out. …

The photographs were taken in Paris, Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Marseille and Saint-Malo.

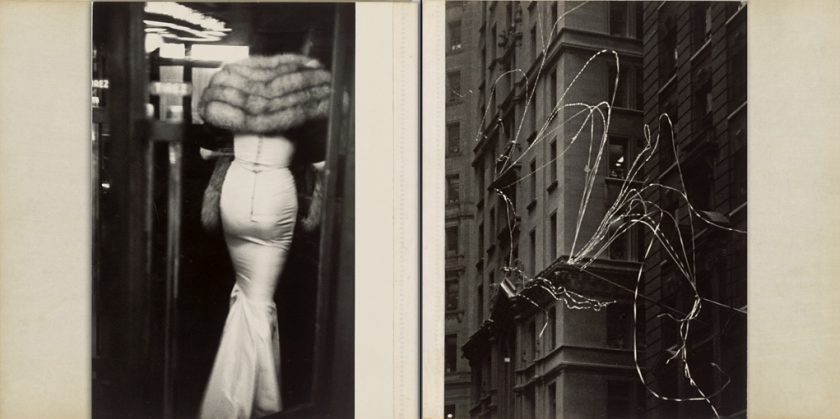

Curiously the cover image of the portfolio (also plate 37) is actually presented upside down. This decision was presumably taken by M. Tchimoukow (real name Louis Bonin), the designer of the portfolio’s cover. There appear to have been at least two versions of the portfolio. One with a black spine and band, and one with a brown spine and band. The brown cloth version (shown below) seems to be the rarer of the two. The portfolio consists of 64 plates with images printed on one side, and two folded sheets unbound resulting in 8 pages which include a two and a half page text by Florent Fels in French and a short explanatory text by Germaine Krull.

Anonymous text. “MÉTAL,” on the achtung.photography website Nd [Online] Cited 07/12/2018

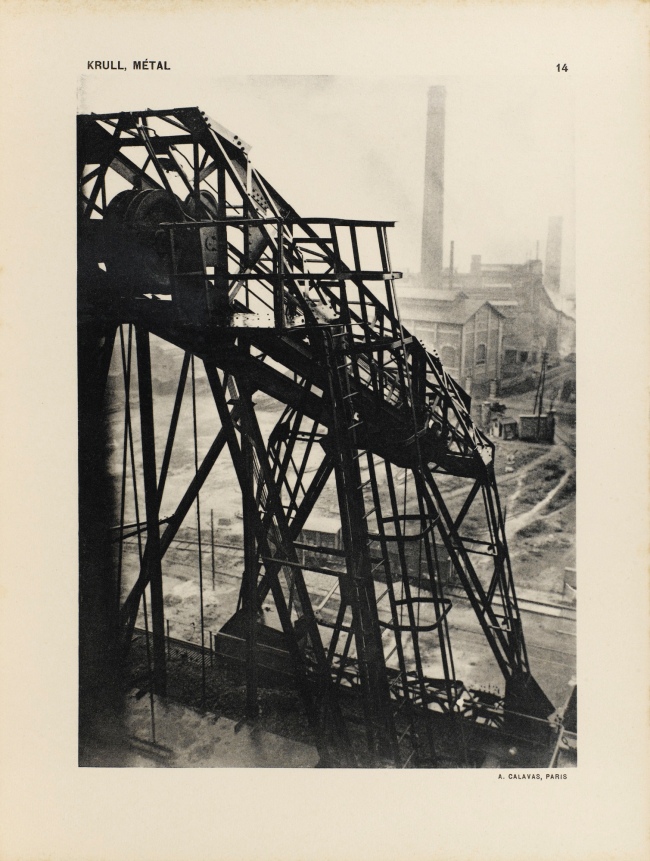

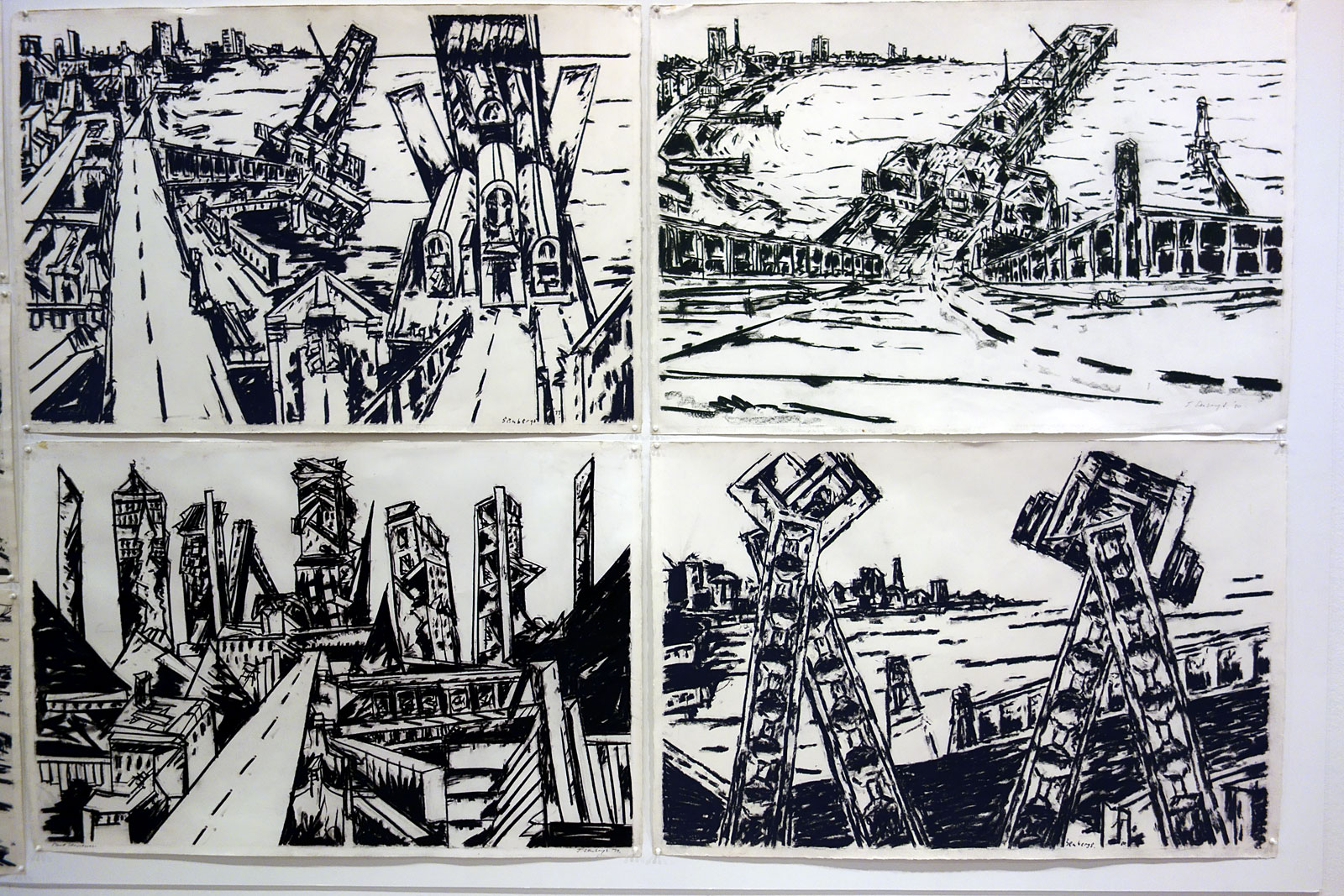

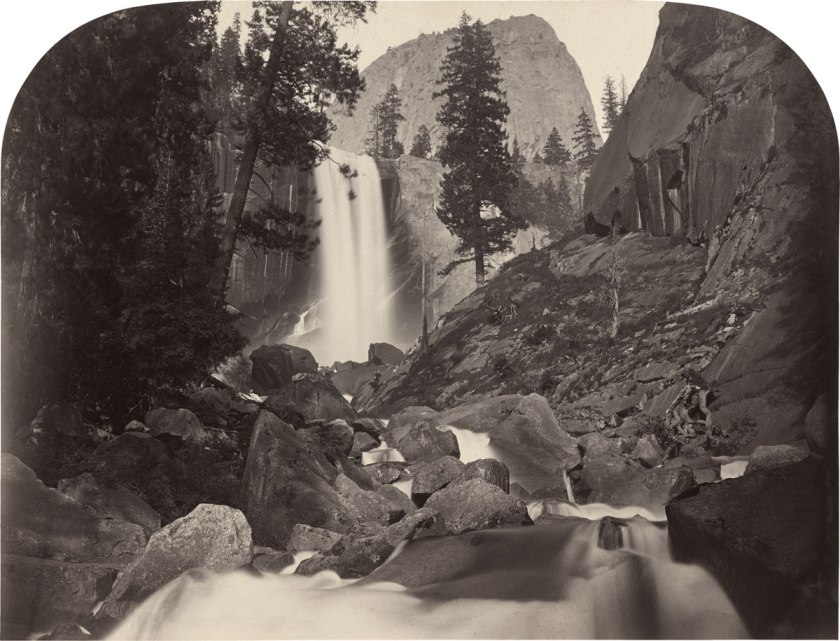

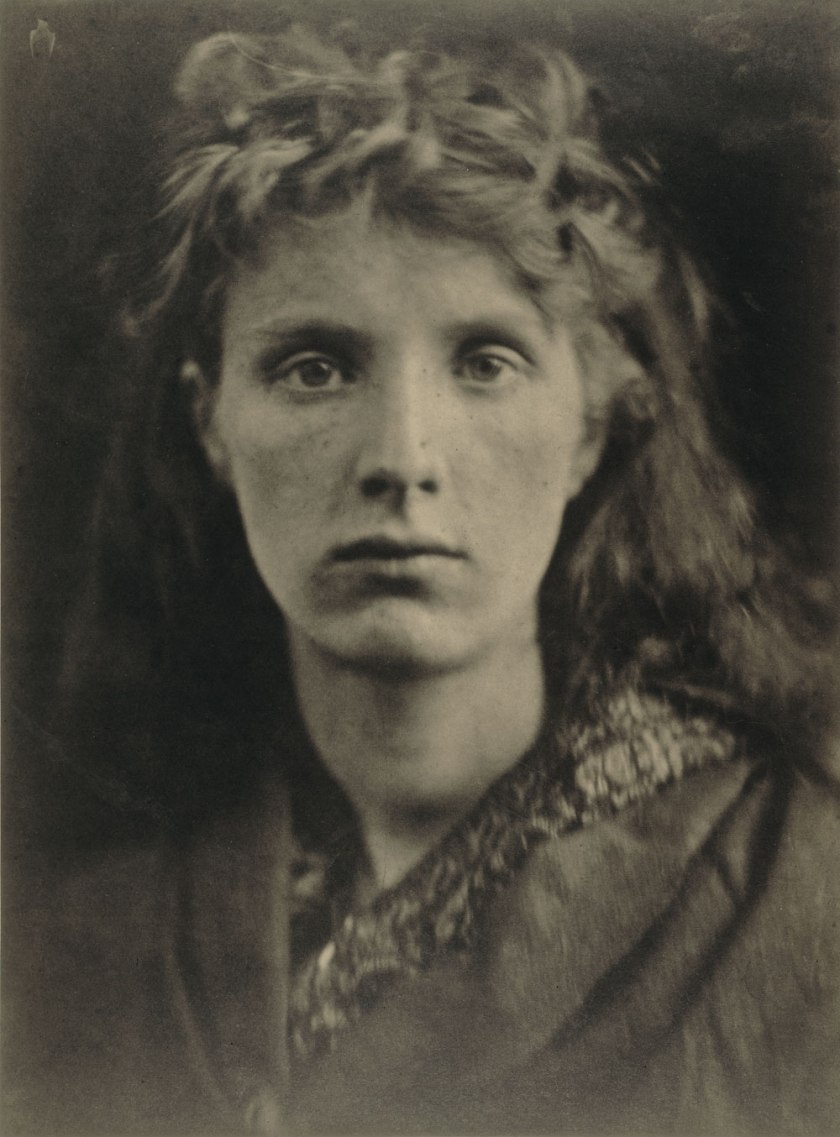

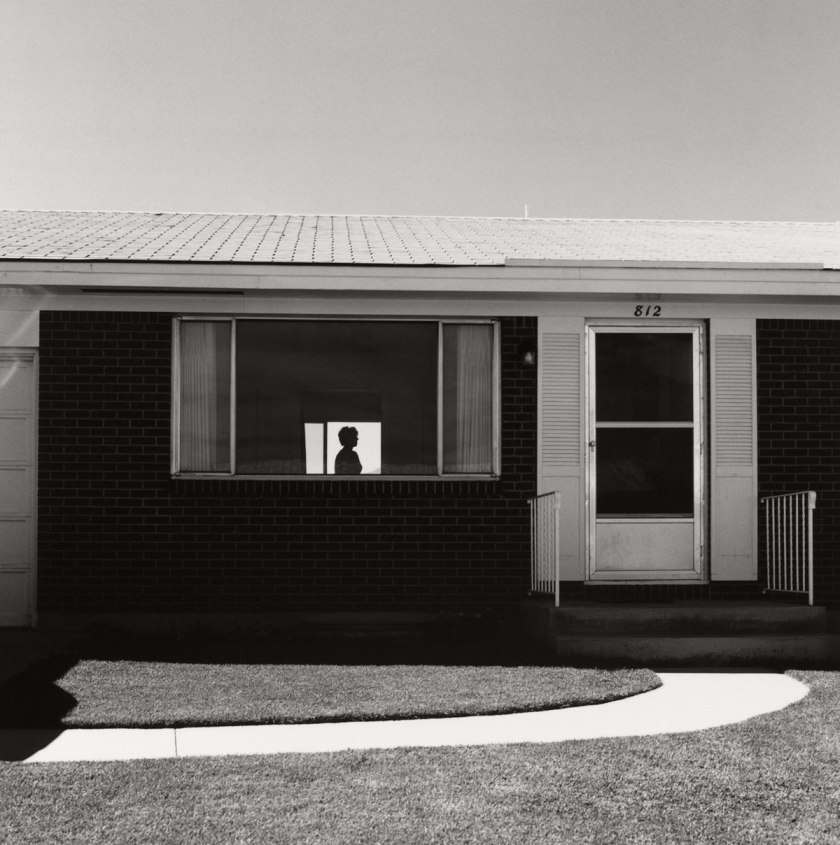

Germaine Krull (European, 1897-1985)

In the port of Amsterdam

1924

Image from the portfolio MÉTAL

1928

Collotype

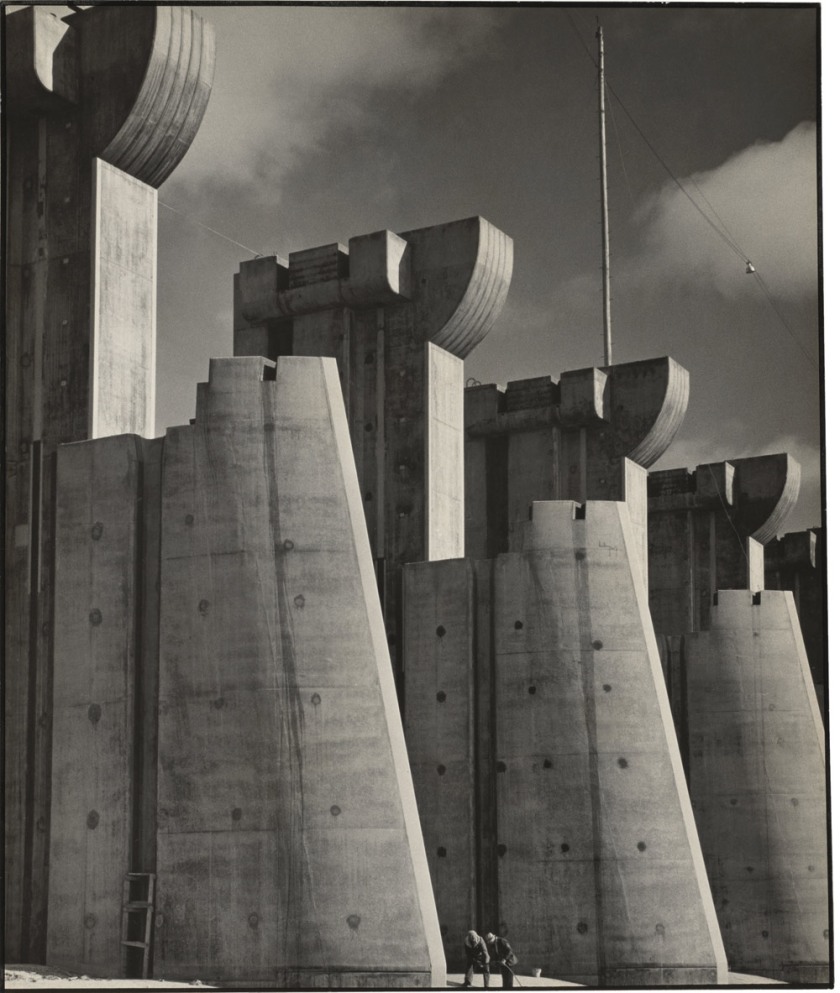

Germaine Krull (European, 1897-1985)

Museum of Technology, Paris

1925

Image from the portfolio MÉTAL

1928

Collotype

Germaine Krull (European, 1897-1985)

Antwerp

1924

Image from the portfolio MÉTAL

1928

Collotype

Preface from Florent Fels to the first edition of MÉTAL

The industrial activity of our times spreads a spectacle before our eyes, to which they have not yet become accustomed. Its newness captures and frightens us like that of a large natural phenomenon. In turn it expresses an attitude of mind, to which painters and poets are among those who devote themselves.

Europe’s cities appear to us as outdated and anachronistic. The provincial towns with their promenades, pleasant fountains and music pavilion suddenly become somewhat old fashioned, whilst the lyricism of our time succeeds in writing itself in concrete and steel cathedrals. Yet we are witness to the paradoxical fact, that the largest enterprises serve as forms of progress with exception of those who can contribute to an improvement in human dwellings. Except for a privileged few the accommodation of our contemporaries shows a similarity with that of our forebears at the time of Richelieu and Cromwell. The people of the cities succumb to the push of commercial practises. We demand houses with windows, which give a free view of the garden. Modern housing for modern people in which the sun and the fresh air find an unhindered inlet. Concrete and steel are their most important constituents: Ten years after the end of the war steel will at last serve a noble purpose, it will perhaps be rehabilitated.

Steel changes our landscape. Forests of masts replacing trees centuries old. Blast furnaces replacing hills.

From this new expression of the world some aspects have no been captured by beautiful photographs representative of a new romanticism.

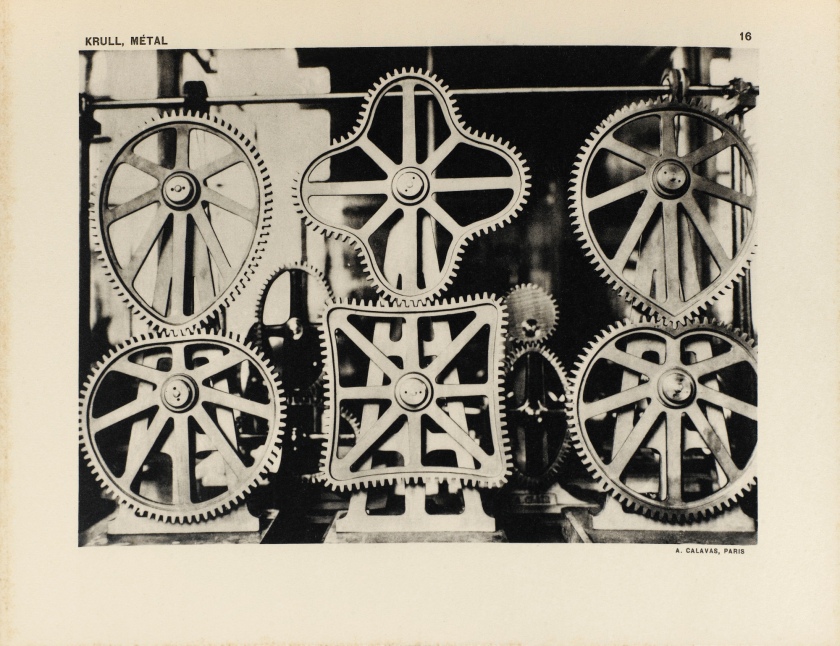

Germaine Krull is the Marceline Desbores-Valmore of this lyricism and her photographs are sonnets of shining, piercing verse. Like an orchid is the driving force of Farcot and like frightening insects are the cogs.

Double exposure lends to the finest mechanisms a fantastic appearance and in considering a milling machine covered in muddy oil and detritus and from water dripping, one thinks of Dostoyevsky. In the halo that surrounds them the powerful, noiseless and quietly working dynamos seem to radiate luminous vibrations, and whose chimneys ring out whose fanfare tones to the heavens, these new godly concepts laid out before us. The bridges penetrate into the space. The trains break the horizon with a deafening roar. They leave the ground and glide there on the ether into the inevitable advance of progress, dragging the living with wonder towards the astral stations.

The strong and soft movement of the hammer softens the ingots like lead elephants. And see the Eiffel Tower, now a bell tower of acoustic waves, its improper monstrosity has provided for surprise and confusion. Now lovers are treated there, three hundred metres above the ground, to a rendezvous with the birds. And the poets, from the old Douanier Rousseau to Jean Cocteau, claim that on beautiful spring evenings fairies ride tobogan on its wing.

This giant was missing a heavenly glow: One has been given to it. The luminous progress of industry is evident in every majestic metre of its height.

Aeroplane, elevator and wheel, with which some humans soar up to the kingdom of the birds, are suddenly transformed into elements of our nature.

The Tower is and remains the highest symbol of the modern age. As he left New York and its vapour crowned palaces it was the Eiffel Tower, this beacon of the air, which Lindbergh envisaged, in order to reach Paris in the sentimental heart of the modern world.

Florent Fels.

The Eiffel Tower, the cranes and bridges of Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Marseille and Saint-Malo provided me with the material for a number of plates which form this album. I am indebted to others for the extreme kindness with which I was welcomed, by the Director of the Conservatoire des Arts-et-Métiers to his museum, by the Director of the CPDE at the Saint-Quen Power Station, and by M. André Citroën in his factories.

The cover of the book is a composition by M. Tchimoukow.

Germaine Krull

Cover design by M. Tchimoukow

Librairie des Arts décoratifs,

A. Calavas, Editeur, 68, Rue la Fayette, Paris, 1928

Portfolio

23.5 x 29.9cm (Portfolio)

22.5 x 29cm (Plates)

64 plates and 2 leaves

Marceline Desbores-Valmore

Marceline Desbordes-Valmore (20 June 1786 – 23 July 1859) was a French poet and novelist…

She published Élégies et Romances, her first poetic work, in 1819. Her melancholy, elegiacal poems are admired for their grace and profound emotion. In 1821 she published the narrative work Veillées des Antilles. It includes the novella Sarah, an important contribution to the genre of slave stories in France…

The publication of her innovative volume of elegies in 1819 marks her as one of the founders of French romantic poetry. Her poetry is also known for taking on dark and depressing themes, which reflects her troubled life. She is the only female writer included in the famous Les Poètes maudits anthology published by Paul Verlaine in 1884. A volume of her poetry was among the books in Friedrich Nietzsche’s library.

Text from Wikipedia website

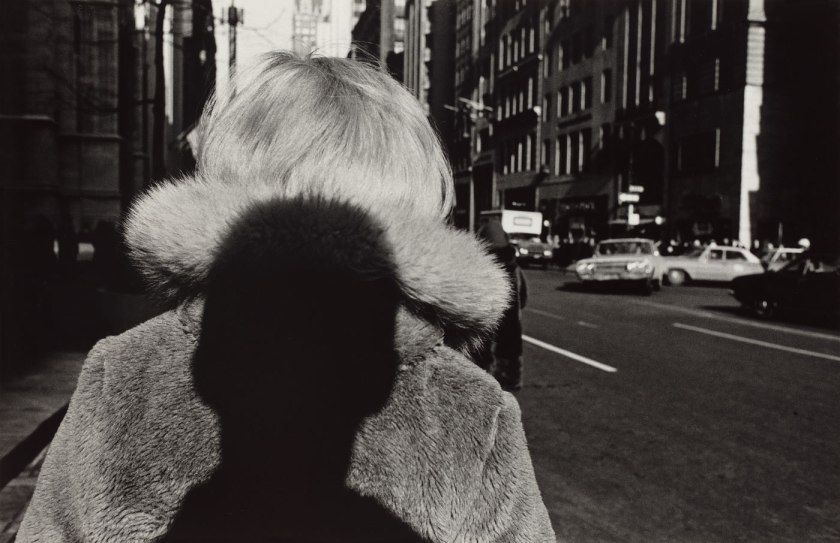

Germaine Krull (European, 1897-1985)

Eiffel Tower

1927

Image from the portfolio MÉTAL

1928

Collotype

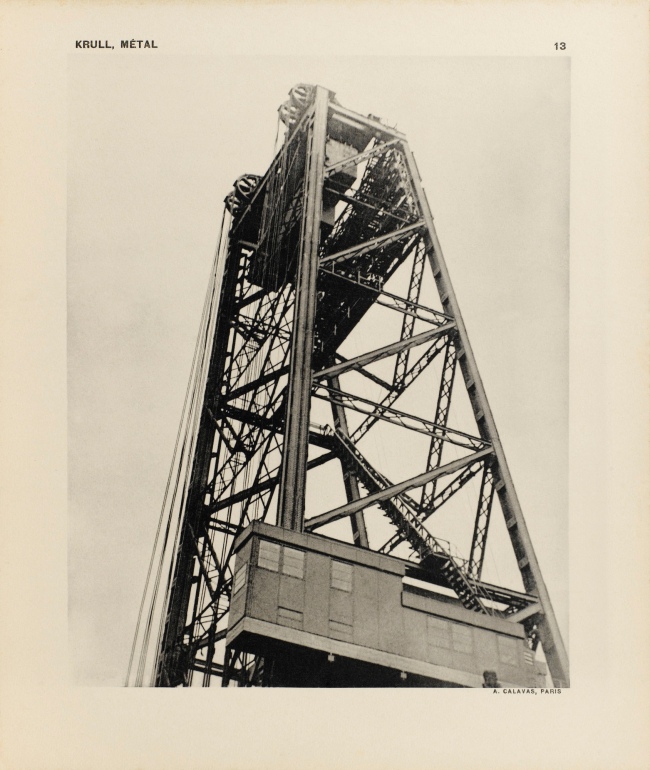

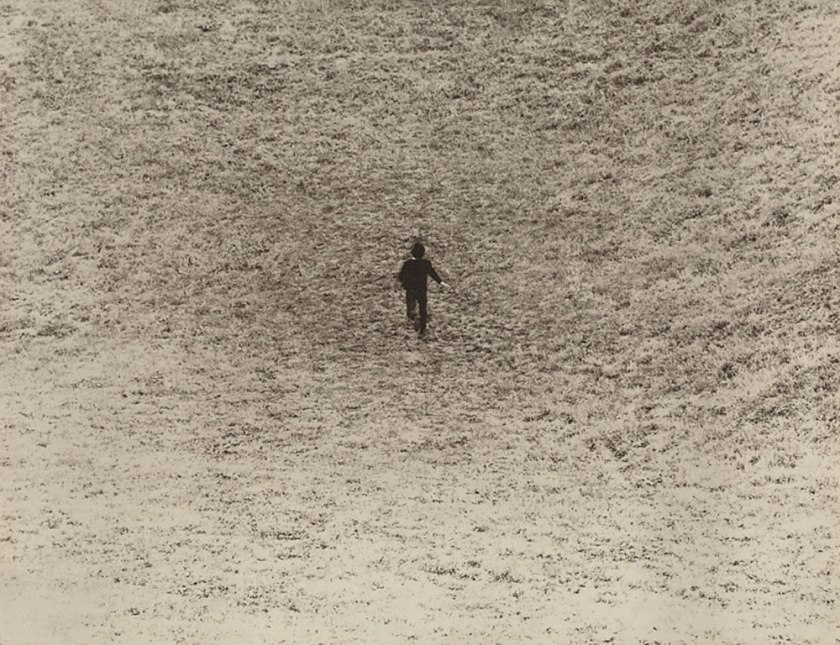

Germaine Krull (European, 1897-1985)

Railway lifting bridge, Rotterdam

1923-1924

Image from the portfolio MÉTAL

1928

Collotype

Germaine Krull (European, 1897-1985)

Factory in Rotterdam

1923

Image from the portfolio MÉTAL

1928

Collotype

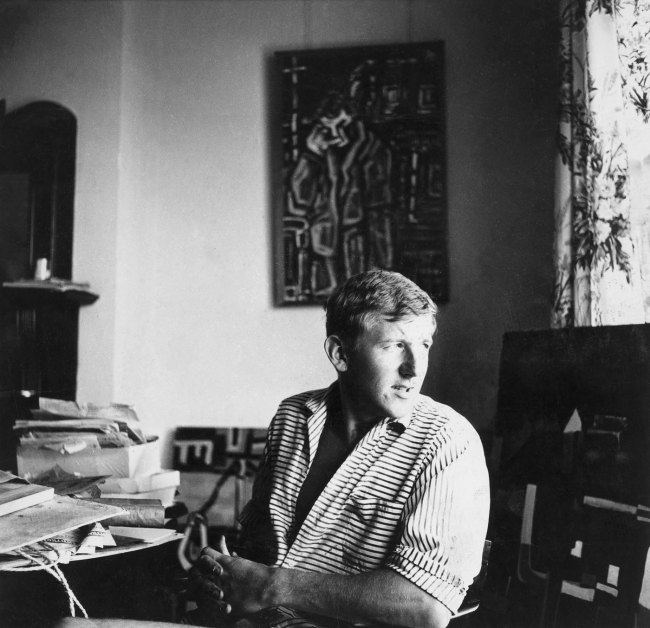

Florent Fels

Ferdinand Florent Fels (1891-1977) was a French journalist, publisher and author prominent in discussing art in France. He often used the pseudonym Felsenberg. Fels launched the art magazine Action: Cahiers individualistes de philosophie et d’art in 1919. Here he expressed his individualist anarchist philosophy. (Text from Wikipedia)

Fels as an art critic before 1925

I now feel the need to make a step back on Fels. Born in 1891, he was recruited as a soldier-interpreter in the First World War thanks to his knowledge of English, and here became an anti-militaristic minded person. His experience at the front was quite parallel to that of Georg Grosz, the only German artist in his anthology, whose sad pages on the role of artists and critics during World War I corresponded largely to the thoughts of the French author. The experience of war convinced the young Fels of the need to overcome the traditional aesthetic models, linked to symbolism, but also of the emptiness of contemporary art, which had propagated or somehow supported the war effort. It is no coincidence that his friend de Vlaminck – in the Propos dedicated to him – used disdainful words on the role of Cubism in the years leading up to the war. According to Fels, the only art that, after the slaughter at the front, could still be trusted was the Dada movement, born in Zurich in 1916 and spread rapidly in Europe (it is also what can be read in the pages of Grosz, an artist about whom Fels published – in addition to the pages in the anthology – several other articles in the French world [14]).

Returning from the war front, in 1919, the twenty-eighty year old Fels launched with Robert Mortier (painter and poet) and Marcel Sauvage (poet) the journal Action. Cahiers individualistes de philosophie et d’art (Action. Individualist Notebooks on Philosophy and Art), which would have a short life (the last issue was 1922). The editors were young ex-soldiers who invested the money they had got from the state at the time they left the army, to launch the new journal. The founders of Action attempted to both awake and open the French culture. In the field of literature, Action hosted a series of poets, writers and literary critics such as Andre Malraux, Max Jacob, Jean Cocteau and Antonin Artaud; in the area of art, the journal liaised with all contemporary avant-garde movements (dada, fauves, cubists), discussed and exalted the production of the greatest artists (Claude Monet, Picasso, Matisse, Henri Rousseau Le Douanier) and gave great emphasis to African art. Looking at the journal’s issues, all available on the Internet [15], it is also easy to find that Action also housed reproductions of paintings and prints by many of the painters who later on were included in Propos d’Artistes: Derain, Kisling, Léger, Lhote, Pascin, Utrillo, Vlaminck. There were also art criticism articles of Duret and poems by Vlaminck.

Within Dadaism, Action preached a ‘subjectivist’, or individualist, version of vanguard aesthetics. It did not propagate revolutions, but proclaimed the need for the absolute freedom of the artists. Fels’ points of reference were in fact the individualistic anarchist movements inspired by Rousseau and Proudhon; in March 1920, he held a conference on “Les Classiques de l’Esprit nouveau” and published the text in the journal L’un [16]: he rejected the traditional Dadaist attitude of total destruction of the past and identified the new classics (Monet, Cézanne, Renoir, Van Gogh) that were due to be the basis of the new art. Fels took distance from the anti-social attitudes typical of Dadaism, and animated a controversy over the direction of new art movements: for him, everyone should make his personal revolution, without destroying any social foundations. At the root of Fels’s aesthetic theory there was “the enhancement of individual psychologies, the free but orderly expression of the heart, the sense of art, inspiration, and individuality”[17].

In 1922, Action‘s experience ended: money was over and the attempt to counter the revolutionary drift within Dadaism had failed. Starting with 1924, André Breton imposed surrealism, inspired by a much more corrosive aesthetic and social criticism. Fels condemned it.

Florent Fels between 1923 and 1925

Once the experience of Action was concluded in 1922, Fels joined in 1923 the editorial staff of Les Nouvelles Littéraires. There he dealt not only with contemporary art, but with reviews of exhibitions of all kinds (from Renaissance to Art of Polynesia). Often, his articles updated the public on the developments of decorative arts (in those years, he published his already mentioned essay on French tapestries and carpets).

I already mentioned that Fels stated in the postscript of the anthology: “I wanted to produce a document dated 1925″[18]. The idea was therefore to offer the reader almost an instant book. In fact, as we have already said, the book gave readers a real-time image of the art discussion in 1923-1924. 1925 was however a very important year for Fels. In addition to the anthology, he published a monograph on Claude Monet with Gallimard and became chief editor of the new art journal “L’Art Vivant“, founded by Jacques Guenne (1896-1945) and Maurice Martin du Gard (1896-1970), i.e. the two directors of “Les Nouvelles Littéraires“. The new publication was in fact presented as the artistic attachment (complément artistique) to the literary weekly. Art Vivant. It was published by the house Larousse since January 1925.

As previously mentioned, Fels’s aesthetic taste (think again that only a few years before he had been forced to finance his own publication with the liquidation of the time spent in war as a simple soldier) was becoming closer to those of the great French progressive publishing companies (Gallimard, Larousse). In other words, he was taking on more and more classic aesthetic orientations. The Art Vivant magazine (which will have long life: Fels was his chief editor until 1939, when the magazine closed its doors in the wake of the war) became therefore one of the favourite targets of the communist intellectual and surrealist leader Louis Aragon (1897-1982), who called Fels “Paysan de Paris“, the peasant of Paris. From Aragon’s perspective, the only veritable surrealist anthology of art literature with a Marxist orientation will be published twenty years later by Paul Éluard.

Extract from Review by Francesco Mazzaferro of Florent Fels, Propos d’Artistes (The Propositions of the Artists), 1925. Part One 22 May 2017 [Online] Cited 30/11/2018

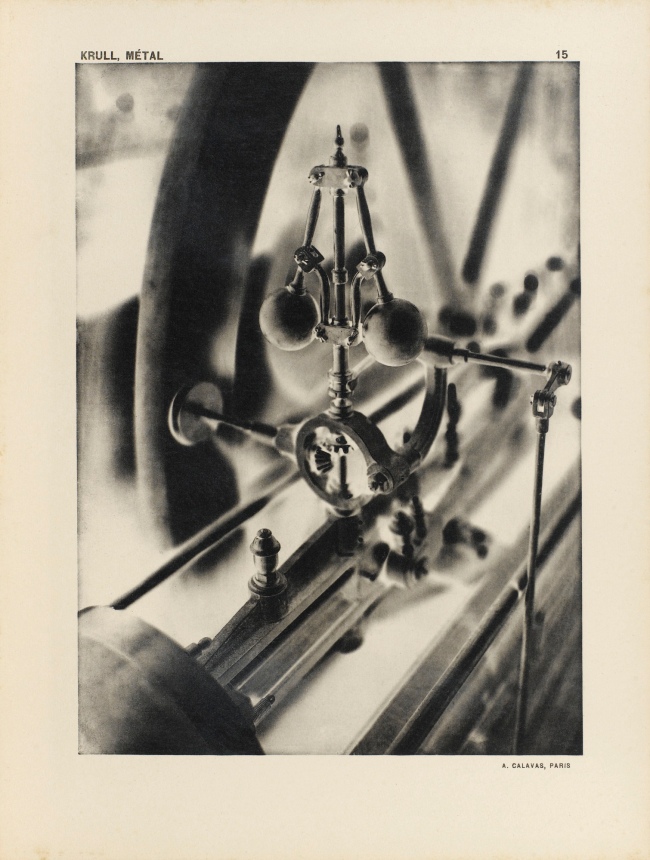

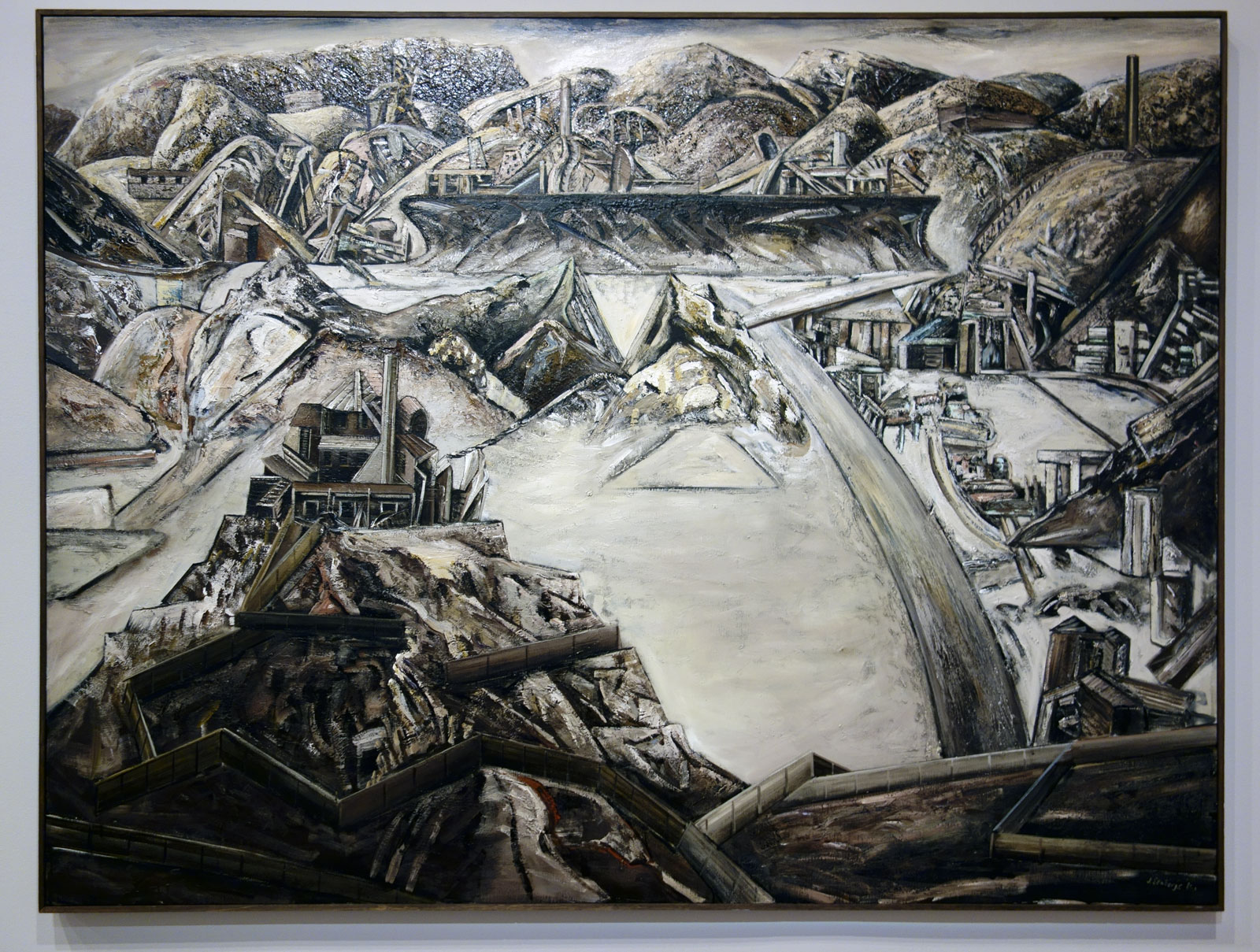

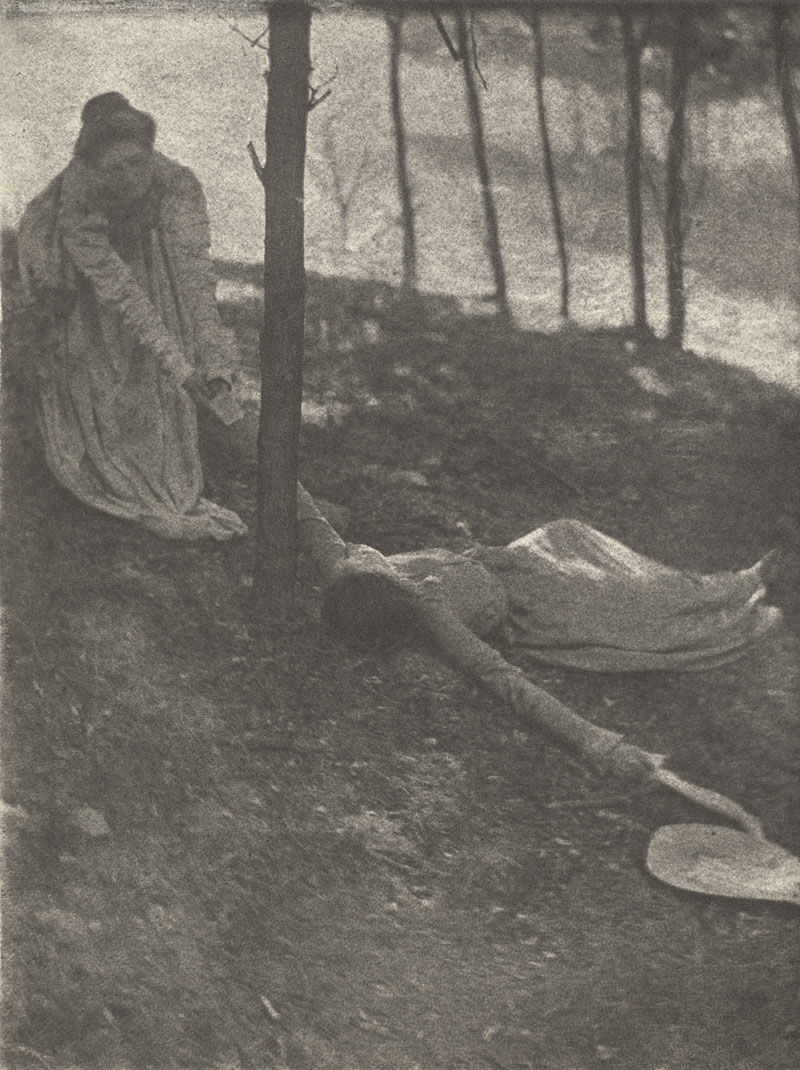

Germaine Krull (European, 1897-1985)

Electricity France, Paris

1925

Image from the portfolio MÉTAL

1928

Negative collotype print

Detail of a centrifugal speed governor?

Germaine Krull (European, 1897-1985)

Technical Museum, Paris

1926

Image from the portfolio MÉTAL

1928

Collotype

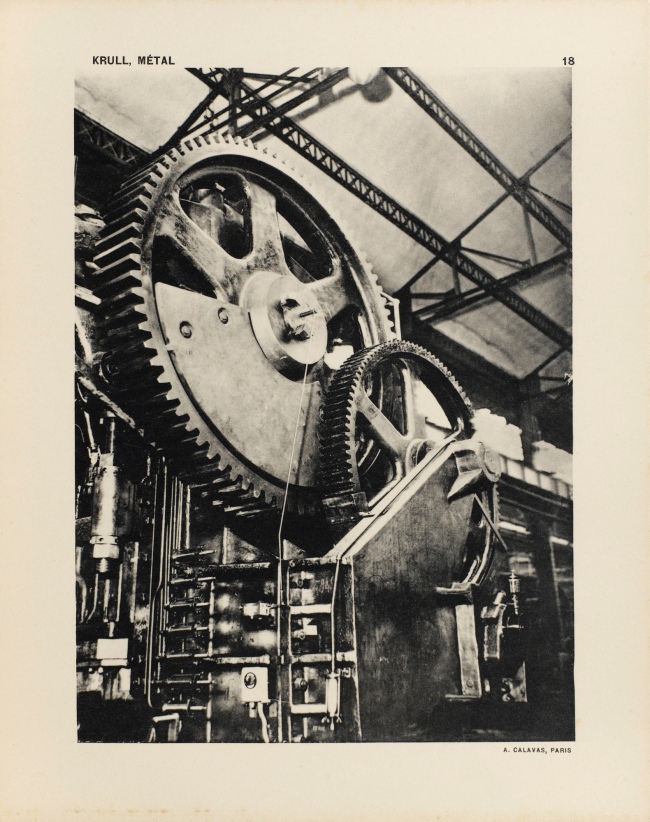

Germaine Krull (European, 1897-1985)

Motor industry Citreon, Paris

1926-1927

Image from the portfolio MÉTAL

1928

Collotype

Germaine Krull (European, 1897-1985)

Technical Museum, Paris

1926

Image from the portfolio MÉTAL

1928

Collotype

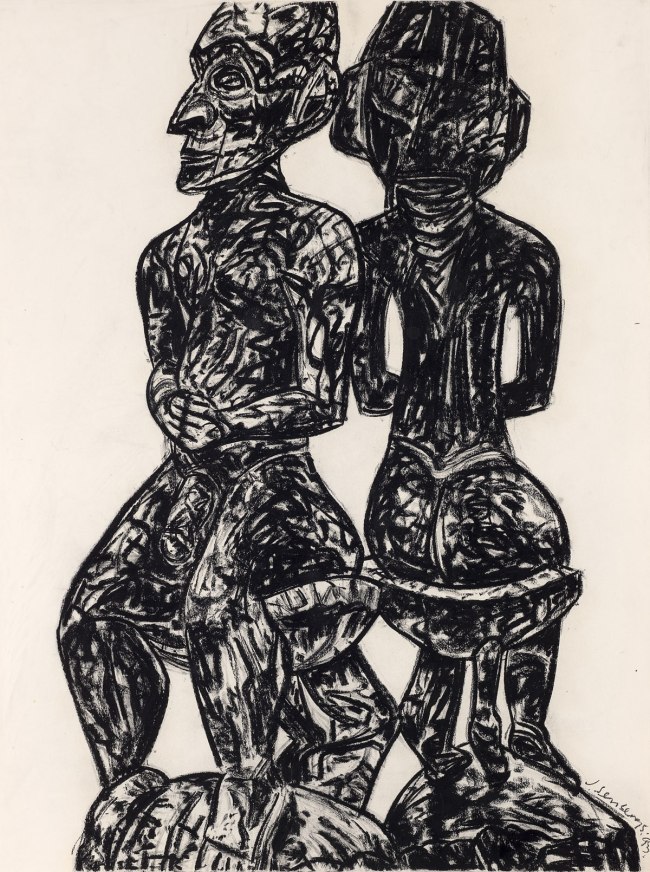

Her book MÉTAL contains only two multiple exposures, one showing two overlapped power generators and the other several layered bicycle parts printed at right angles to one another to create an effect of circular motion.

Germaine Krull (European, 1897-1985)

Germaine Luise Krull (20 November 1897 – 31 July 1985) was a photographer, political activist, and hotel owner. Her nationality has been categorised as German, French, and Dutch, but she spent years in Brazil, Republic of the Congo, Thailand, and India. Described as “an especially outspoken example” of a group of early 20th-century female photographers who “could lead lives free from convention”, she is best known for photographically-illustrated books such as her 1928 portfolio MÉTAL.

Krull was born in Posen-Wilda, a district of Posen (then in Germany; now Poznań, Poland), of an affluent German family. In her early years, the family moved around Europe frequently; she did not receive a formal education, but instead received homeschooling from her father, an accomplished engineer and a free thinker (whom some characterised as a “ne’er-do-well”). Her father let her dress as a boy when she was young, which may have contributed to her ideas about women’s roles later in her life.[6] In addition, her father’s views on social justice “seem to have predisposed her to involvement with radical politics.”

Between 1915 and 1917 or 1918 she attended the Lehr- und Versuchsanstalt für Photographie, a photography school in Munich, Germany, at which Frank Eugene’s teaching of pictorialism in 1907-1913 had been influential. She opened a studio in Munich in approximately 1918, took portraits of Kurt Eisner and others, and befriended prominent people such as Rainer Maria Rilke, Friedrich Pollock, and Max Horkheimer.

Krull was politically active between 1918 and 1921. In 1919 she switched from the Independent Socialist Party of Bavaria to the Communist Party of Germany, and was arrested and imprisoned for assisting a Bolshevik emissary’s attempted escape to Austria. She was expelled from Bavaria in 1920 for her Communist activities, and traveled to Russia with lover Samuel Levit. After Levit abandoned her in 1921, Krull was imprisoned as an “anti-Bolshevik” and expelled from Russia.

She lived in Berlin between 1922 and 1925 where she resumed her photographic career. She and Kurt Hübschmann (later to be known as Kurt Hutton) worked together in a Berlin studio between 1922 and 1924. Among other photographs Krull produced in Berlin were a series of nudes (recently disparaged by an unimpressed 21st-century critic as “almost like satires of lesbian pornography”).

Having met Dutch filmmaker and communist Joris Ivens in 1923, she moved to Amsterdam in 1925. After Krull returned to Paris in 1926, Ivens and Krull entered into a marriage of convenience between 1927 and 1943 so that Krull could hold a Dutch passport and could have a “veneer of married respectability without sacrificing her autonomy.”

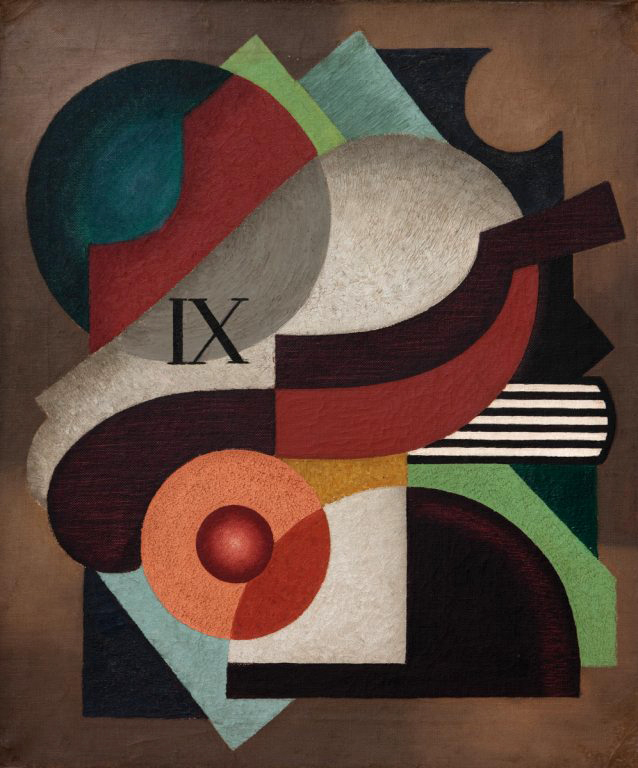

In Paris between 1926 and 1928, Krull became friends with Sonia Delaunay, Robert Delaunay, Eli Lotar, André Malraux, Colette, Jean Cocteau, André Gide and others; her commercial work consisted of fashion photography, nudes, and portraits. During this period she published the portfolio MÉTAL (1928) which concerned “the essentially masculine subject of the industrial landscape.” Krull shot the portfolio’s 64 black-and-white photographs in Paris, Marseille, and Holland during approximately the same period as Ivens was creating his film De Brug (“The Bridge”) in Rotterdam, and the two artists may have influenced each other. The portfolio’s subjects range from bridges, buildings (e.g., the Eiffel Tower), and ships to bicycle wheels; it can be read as either a celebration of machines or a criticism of them. Many of the photographs were taken from dramatic angles, and overall the work has been compared to that of László Moholy-Nagy and Alexander Rodchenko. In 1999-2004 the portfolio was selected as one of the most important photobooks in history.

By 1928 Krull was considered one of the best photographers in Paris, along with André Kertész and Man Ray. Between 1928 and 1933, her photographic work consisted primarily of photojournalism, such as her photographs for Vu, a French magazine. Also in the early 1930s, she also made a pioneering study of employment black spots in Britain for Weekly Illustrated (most of her ground-breaking reportage work from this period remains immured in press archives and she has never received the credit which is her due for this work). Her book Études de Nu (“Studies of Nudes”) published in 1930 is still well-known today. Between 1930 and 1935 she contributed photographs for a number of travel and detective fiction books.

In 1935-1940, Krull lived in Monte Carlo where she had a photographic studio. Among her subjects during this period were buildings (such as casinos and palaces), automobiles, celebrities, and common people. She may have been a member of the Black Star photojournalism agency which had been founded in 1935, but “no trace of her work appears in the press with that label.”

In World War II, she became disenchanted with the Vichy France government, and sought to join the Free French Forces in Africa. Due to her Dutch passport and her need to obtain proper visas, her journey to Africa included over a year (1941-1942) in Brazil where she photographed the city of Ouro Preto. Between 1942 and 1944 she was in Brazzaville in French Equatorial Africa, after which she spent several months in Algiers and then returned to France.

After World War II, she traveled to Southeast Asia as a war correspondent, but by 1946 had become a co-owner of the Oriental Hotel in Bangkok, Thailand, a role that she undertook until 1966. She published three books with photographs during this period, and also collaborated with Malraux on a project concerning the sculpture and architecture of Southeast Asia.

After retiring from the hotel business in 1966, she briefly lived near Paris, then moved to Northern India and converted to the Sakya school of Tibetan Buddhism. Her final major photographic project was the publication of a 1968 book Tibetans in India that included a portrait of the Dalai Lama. After a stroke, she moved to a nursing home in Wetzlar, Germany, where she died in 1985.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Germaine Krull (European, 1897-1985)

Eiffel Tower, Paris

1927

Image from the portfolio MÉTAL

1928

Collotype

Germaine Krull (European, 1897-1985)

Railway lifting bridge, Rotterdam

1923-1924

Image from the portfolio MÉTAL

1928

Collotype

Germaine Krull (European, 1897-1985)

Eiffel Tower, Paris

1927

Image from the portfolio MÉTAL

1928

Collotype

Germaine Krull (European, 1897-1985)

Eiffel Tower, Paris

1927

Image from the portfolio MÉTAL

1928

Collotype

Curiously the cover image of the portfolio (also plate 37) is actually presented upside down. This decision was presumably taken by M. Tchimoukow (real name Louis Bonin), the designer of the portfolio’s cover.

Germaine Krull

Germaine Krull was a pioneer in the fields of avant-garde photomontage, the photographic book, and photojournalism, and she embraced both commercial and artistic loyalties. Born in Wilda-Poznań, East Prussia, in 1897, Krull lived an extraordinary life lasting nine decades on four continents – she was the prototype of the edgy, sexually liberated Neue Frau (New Woman), considered an icon of modernity and a close cousin of the French garçonne and the American flapper. She had a peripatetic childhood before her family settled in Munich in 1912. She studied photography from 1916 to 1918 at Bayerische Staatslehranstalt für Lichtbildwesen (Instructional and Research Institute for Photography), and in 1919 opened her own portrait studio. Her early engagement with left-wing political activism led to her expulsion from Munich. Then, on a visit to Russia in 1921, she was incarcerated for her counterrevolutionary support of the Free French cause against Hitler. In 1926, she settled in Paris, where she became friends with artists Sonia and Robert Delaunay and intellectuals André Malraux, Jean Cocteau, Colette, and André Gide, who were also subjects of her photographic portraits.

Krull’s artistic breakthrough began in 1928, when she was hired by the nascent VU magazine,the first major French illustrated weekly. Along with photographers André Kertész and Éli Lotar, she developed a new form of reportage rooted in a freedom of expression and closeness to her subjects that resulted in intimate close-ups, all facilitated by her small-format Icarette, a portable, folding bed camera. During this period, she published the portfolio, Metal (MÉTAL)(1928), a collection of 64 pictures of modernist iron giants, including cranes, railways, power generators, the Rotterdam transporter bridge, and the Eiffel Tower, shot in muscular close-ups and from vertiginous angles. Krull participated in the influential Film und Foto, or Fifo, exhibition (1929-1930), which was accompanied by two books, Franz Roh’s and Jan Tschichold’s Foto-Auge (Photo-Eye) and Werner Gräff’s Es kommt der neue Fotograf! (Here Comes the New Photographer!). Fifo marked the emergence of a new critical theory of photography that placed Krull at the forefront of Neues Sehen or Neue Optik (New Vision) photography, a new direction rooted in exploring fully the technical possibilities of the photographic medium through a profusion of unconventional lens-based and darkroom techniques. After the end of World War II, she traveled to Southeast Asia, and then moved to India, where, after a lifetime dedicated to recording some of the major upheavals of the twentieth century, she decided to live as a recluse among Tibetan monks.

Introduction by Roxana Marcoci, Senior Curator, Department of Photography, 2016 on the MoMA website [Online] Cited 25/11/2018

Métal and Filmic Montage

For Krull, metal was the most powerful metaphor for the modern world, and her book Métal includes many of the industrial forms she saw in Europe. It features both multiple exposures and straight images, and the entire volume is structured according to the principles of film montage. As noted earlier, Krull was a member of the Dutch avant-garde film collective Filmliga, which was cofounded by Joris Ivens, who in 1927 became her husband. Both of them published work in Arthur Lehning’s related avant-garde journal i10.

They saw screenings of Soviet avant-garde films by Vsevolod Pudovkin and Sergei Eisenstein, and Krull made a portrait of Eisenstein when he visited Paris in 1930. Eisenstein’s theories of montage were particularly important to the couple, and Krull’s Métal serves to demonstrate them. She actively adopted the Soviet filmmaker’s ideas of rupture and “visual counterpoint,” involving graphic, planar, volumetric, and spatial conflicts.26

The book is technically an album, with sixty-four numbered but unbound collotype reproductions that can ostensibly be rearranged at will. There are no captions and no identifying markers, and the images include both vertical and horizontal compositions. In a brief note beneath an introductory text by Florent Fels, Krull tells us that these photographs include a lifting bridge over the Meuse River in Rotterdam (also the subject of Ivens’s renowned avant-garde montage film, The Bridge [De Brug], from that same year); the cranes in the Amsterdam port; the Eiffel Tower; Marseille’s transporter bridge; and other industrial forms she found.27 But it would be difficult to decipher these subjects from the photographs themselves. Although there are eleven Eiffel Tower images in the book, for example, they are often so abstracted that the subject is unidentifiable, and none are on contiguous pages. …

Scholars have often read Métal as a purely formal experiment, but Krull used it as a commentary on contemporary life, producing the kind of montage that her friend Walter Benjamin championed, in which “the superimposed element disrupts the context in which it is inserted. … The discovery is accomplished by means of the interruption of sequences. Only interruption here has not the character of a stimulant but an energizing function.”29 The quality of interruption, according to Benjamin, differentiates truly revolutionary work from the mere aping of the modern world, an approach that he scornfully attributes to the work of Albert Renger-Patzsch.30 For Krull, interruption could occur in a multiple exposure, as in the aforementioned Métal image depicting overlapping views of bicycle parts. Or interruption can be found while turning a book’s pages, moving from a drive-belt detail to ominously large-scale cargo cranes, or from the Rotterdam Bridge over the Meuse to a detail of a centrifugal speed governor. Whether portraying a roller coaster, documenting the Eiffel Tower, or creating her book of industrial fragments, Krull engaged the decade’s cacophony and used provocative experimental techniques to capture its allure.

Kim Sichel. “Contortions of Technique: Germaine Krull’s Experimental Photography,” p. 7 on the MoMA website [Online] Cited 25/11/2018.

Kim Sichel. “Contortions of Technique: Germaine Krull’s Experimental Photography,” in Mitra Abbaspour, Lee Ann Daffner and Maria Morris Hambourg (eds). Object: Photo. Modern Photographs: The Thomas Walther Collection 1909-1949. An Online Project of The Museum of Modern Art. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2014.

27. Sergei Eisenstein, “A Dialectic Approach to Film Form” (1929), in Jay Leyda, ed., Film Form: Essays in Film Theory (New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1949), pp. 52-54

29. Walter Benjamin, “The Author as Producer” (1934), in Reflections: Essays, Aphorisms, Autobiographical Writings (New York: Schocken Books, 1986), pp. 234-235

30. Benjamin, “The Author as Producer,” p. 230

You must be logged in to post a comment.