Exhibition dates: 3rd March – 14th May 2023

Curator: Julie Robinson is Senior Curator, Prints, Drawings and Photographs at AGSA

Bob Adelman (American, 1930-2016)

Andy Warhol on the red couch at the Factory, New York

1964

Pigment print

Courtesy of Bob Adelman Estate

LOOK – SOCIAL

CELEBRITY–POLAROID

SELF – PORTRAIT

STUDIO–STREET

SCREEN – PRINT

QUEER – INFLUENCE(R)

CAMP–POP

PHOTO–GRAPHIC – PRODUCTION

PICTURE–ART

the photograph is a vehicle for performance

“In the scopic field, the gaze is outside, I am looked at, that is to say, I am a picture …. The gaze is the instrument through which light is embodied and through which – if you will allow me to use a word, as I often do, in a fragmented form – I am photo-graphed.”

~ Lacan, The Four Fundamental Concepts, p. 106

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Art Gallery of South Australia for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

SEE MORE INTERESTING AND ESSENTIAL PHOTOGRAPHS BY ANDY WARHOL:

1/ Andy Warhol unplugged 2 May 2015

2/ Andy Warhol unplugged December 2014

3/ ‘Andy Warhol: Polaroids / MATRIX 240’ at Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, University of California, January – May 2012

Andy Warhol and Photography: A Social Media reveals an unseen side of celebrated Pop artist Andy Warhol through his career-long obsession with photography. Whether he was behind or in front of the camera, photography formed an essential part of his artistic practice while also capturing an insider’s view of his celebrity social world.

Exclusive to AGSA, this exhibition features photographs, experimental films and paintings by Warhol, including his famed Pop Art portraits of Marilyn Monroe and Elvis Presley from the 1960s. It also contains works by his photographic collaborators and creative contemporaries such as Christopher Makos, Gerard Malanga, Robert Mapplethorpe, David McCabe, and Duane Michals.

Decades before social media, Warhol’s photography was candid, collaborative and social, attuned to the power of the image to shape his public persona and self-identity. Many of his photographs from the 1970s and 1980s offer behind-the-scenes glimpses into his own life and the lives of friends and celebrities such as Muhammad Ali, Bob Dylan, Debbie Harry, Mick Jagger, John Lennon, Liza Minnelli, Lou Reed and Elizabeth Taylor. This exhibition asks the question, was Warhol the original influencer?

Text from the AGSA website

“A good picture is … of a famous person doing something unfamous. It’s about being in the right place at the wrong time.”

Andy Warhol

“Warhol was a famously detached person, and numerous accounts call attention to the verbal, psychological and technological barriers the artist created between himself and the world around him. Yet, here he describes technology as integrated into the social dynamic of the Factory. Photography became a vital tool in the formation and commemoration of this emerging countercultural community, and the photographs of Name, Berlin and other Factory denizens document everything from the making Warhol’s films and paintings to the Factory crowd at lunch at the local diner. Similar to the family reunion, the tourist vacation or a growing child, the Factory seems to realise itself through this kind of documentation. As the saying goes: pictures, or it didn’t happen.”

Catherine Zuromskis, Associate Professor, School of Photographic Arts and Sciences, College of Art and Design, at Rochester Institute of Technology, USA

“In subtitling the show, A Social Media, Robinson is emphasising the way Warhol surrounded himself with two kinds of people: those who were to be photographed, and those who were photographing him. In the first category there was room for the whole world. In the second, we find a succession of photographers of varying levels of professionalism. Early on there is Billy Name, who took over camera duties when Warhol became bored with the technical stuff. There was David McCabe, whom Warhol paid to follow and photograph him for a whole year in 1964-65. There were long-term friends and colleagues such as Brigid Berlin and Gerard Malanga; and finally, Makos, a constant companion in the latter part of Warhol’s career, who took those startling pictures of the artist made up as a glamorous blonde woman.

John McDonald. “Fame is power: Andy Warhol’s embarrassing pictures of the rich and famous,” on The Sydney Morning Herald website April 28, 2023 [Online] Cited 03/05/2023

Christopher Makos on Andy Warhol

Henry Gillespie on Andy Warhol

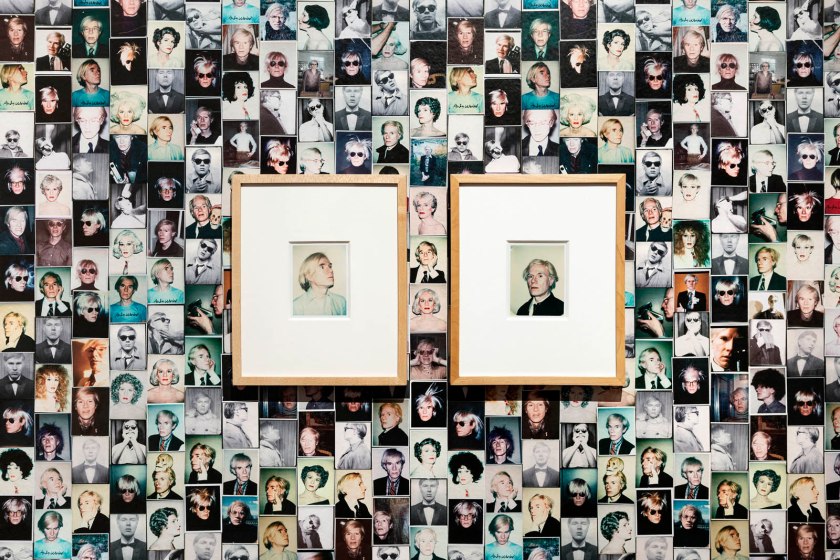

Installation views of the exhibition Andy Warhol and Photography: A Social Media at the Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

Photos: Saul Steed

“My idea of a good photograph is one that’s in focus and of a famous person doing something unfamous. It’s being in the right place at the wrong time.”

~ Andy Warhol

The first exhibition in Australia to explore Andy Warhol’s career-long obsession with photography opens at the Art Gallery of South Australia on 3 March 2023, as part of the 2023 Adelaide Festival. Exclusive to Adelaide, Andy Warhol and Photography: A Social Media will reveal an unseen side of the celebrated Pop artist through more than 250 works, spanning photographs, experimental films, screenprints and paintings, many on display in Australia for the first time.

Warhol’s close friend and collaborator, Christopher Makos, will travel from New York City to join Andy Warhol and Photography curator Julie Robinson in conversation as part of the exhibition’s opening weekend program. Speaking about his decade-long friendship with Warhol and his own career as a photographer, Makos will reminisce about his time as part of Warhol’s inner circle, socialising with celebrities at Studio 54 and Warhol’s studio, always with a camera by his side.

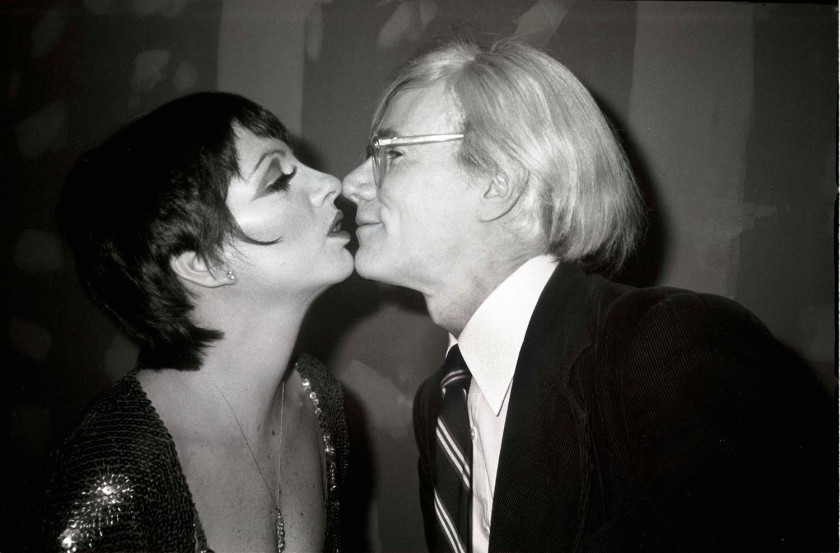

Decades before social media, Warhol’s photography was candid, collaborative and social, attuned to the power of the image to shape his public persona and self-identity. Andy Warhol and Photography offers a fresh perspective on the influential artist, as well as behind-the-scenes glimpses into his own life and the lives of friends and celebrities, including Muhammad Ali, Bob Dylan, Debbie Harry, Mick Jagger, John Lennon, Liza Minnelli, Lou Reed and Elizabeth Taylor.

Headlining the 2023 Adelaide Festival’s visual arts program, Andy Warhol and Photography: A Social Media is curated by AGSA’s Senior Curator of Prints, Drawings & Photographs, bringing together works from national and international collections, as well as AGSA’s own extensive collection of 45 Warhol photographs which will be shown together for the first time.

AGSA Director, Rhana Devenport ONZM says, ‘Some 35 years after his death, this exhibition attests to Andy Warhol’s enduring relevance as an artist and cultural figure in an era defined by social media. With cross-generational appeal, this is an exhibition of our times which begs the question, was Warhol the original influencer?’

Revealing Warhol from both in front of and behind the camera, the exhibition will also feature works by his photographic collaborators and creative contemporaries such as Brigid Berlin, Nat Finkelstein, Christopher Makos, Gerard Malanga, Robert Mapplethorpe, Duane Michals and Billy Name. Andy Warhol and Photography will also include iconic Warhol paintings never-before-seen in Adelaide, including his famed Pop Art portraits of Marilyn Monroe and Elvis Presley from the 1960s, demonstrating how Warhol translated many of his photographs into paintings and screenprints.

Exhibition curator, Julie Robinson says, ‘Photography underpinned Warhol’s whole artistic practice – both as an essential part of his working method and as an end in its own right. He took some 60,000 photographs in his lifetime. His candid images, which capture his own life as well as the lives of his celebrity friends, offer audiences a revealing insight into Warhol the person, taking viewers beneath the veneer of his Pop paintings and persona.’

Adelaide Festival Artistic Director, Ruth Mackenzie CBE, said, ‘It is thrilling to be working with AGSA to explore Andy Warhol’s ground-breaking work which speaks so immediately to everybody. Today more than ever, with the popularity of social media, Warhol’s idea of 15 minutes of fame is incredibly relatable and this exhibition will be a must-see during the festival season next year.’

Press release from the AGSA

Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987)

Elvis

1963

Synthetic polymer paint and screenprint on canvas

208.0 x 91.0cm

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Purchased 1973

© Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. ARS/Copyright Agency

The cultural theorist José Esteban Muñoz gave a name to the process by which those outside a social, racial, or sexual mainstream negotiate majority culture, not by aligning themselves with or against exclusionary representations (staying in their own lane, so to speak), but by transforming mainstream representations for their own purposes. They might do this by identifying with models of aspiration or experience denied to them. Muñoz called this ‘disidentification’; to ‘disidentify’ was ‘to read oneself and one’s own life narrative in a moment, object, or subject’ with which one was ‘not culturally coded to “connect”‘.[7] LGBTQI people have long understood this kind of identification intuitively. (This is not quite the same as drag, though there is similar energy in drag-ball performances of categories like ‘Executive Realness’, for example.[8]) Disidentifying means identifying in spite of, or at an angle to, the model prescribed for you by a dominant culture; it involves the scrambling and reconstructing of coded meanings of cultural objects to expose the encoded message’s universalising – and therefore exclusionary – machinations, recircuiting its workings to include and empower minority identifications.[9]

We see something like this in the early works by Warhol that draw on found photography. Elvis, 1963, [fig1, above] for instance, uses a publicity still from the iconic singer’s role in the Western Flaming Star (1960) as the basis for an image that references the sex idol star’s performative embodiment of a particular mythic trope of US masculinity – the frontiersman caught on the edge of a moral dilemma. The ‘outlaw sensibility’ associated with such a model, Elisa Glick argues, came to signify in gay male culture in a version of what Muñoz would call disidentification.[10] Other examples might include Montgomery Clift in Red River, or James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause (not a Western, but with similar energies).[11] Apparently straight figures, apparently the embodiment of the spirit of liberty, promise and rebellion, a heady (and sometimes internally contradictory) mix in popular US culture, they are also objects of coded identification at an angle (of disidentification) for queer subjects, black subjects (etcetera).

Elvis is emblematic of Warhol’s interest in performance and replication, in other words, but also, viewed as an act of disidentification, deeply transgressive. Most of the celebrities the artist would go on to image in similar serial form would be female, often women who had suffered some kind of trauma. These are disidentificatory subjects too, but they are also perhaps more cautious models for a queer artist (especially one whose sensibilities were formed before the Stonewall Rising), whether models of resilience or of sacrifice, in a hostile, straight-male-dominated world. Or, as Jonathan Katz argues, activating the suggestiveness of Warhol’s most iconic represented commodity, they constitute ‘camp bells’ (perhaps also belles) in Warhol’s oeuvre.[12] They announce something, chiming with popular press adoration of the beautiful, but they do not sound the alarm bells that might have rung had Warhol focused (only) on beautiful men. Perhaps there was something too obviously queer in Elvis more easily hidden in plain sight in representations of women.

Extract from Andrew van der Vlies. “Andy Warhol’s Queer Practice: Disidentification and Utopian Desire,” on the Art Gallery of South Australia website Nd [Online] Cited 03/05/2023

[7] José Esteban Muñoz, Disidentifications, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 1999, p. 12.

[8] One might recall the memorable Harlem Ballroom scenes in Jennie Livingston’s film Paris is Burning (1990).

[9] See Muñoz, Disidentifications, p. 31.

[10] Elisa Glick, Materializing queer desire: Oscar Wilde to Andy Warhol, State University of New York Press, Albany, NY, 2009, 145.

[11] Of course, modern audiences for those films might now know more about both stars’ sexuality, but the point is that they performed a certain kind of sensibility that (closeted) gay men in the 1950s and 1960s did not feel was available to them, or which they performed as cover.

[12] Jonathan D. Katz, ‘From Warhol to Mapplethorpe: postmodernity in two acts’, in Patricia Hickson (ed.), Warhol & Mapplethorpe: guise & dolls, Yale Univ. Press, New Haven, CT, and London, 2015. The allusion is to Campbell’s soup cans, the subject of one of Warhol’s most famous early works. Katz notes the ‘repeated evocation[s] of a historically specific mode of queer political redress spoken in and through the names of iconic female stars’ (p. 22).

Bob Adelman (American, 1930-2016)

Andy Warhol in Gristedes Supermarket, New York City

1965

Pigment print

Courtesy of Bob Adelman Estate

Steve Schapiro (American, 1934-2022)

Edie Sedgwick, Andy Warhol, and others at a party

1965

Gelatin silver photograph

31.5 x 47.1cm (image)

40.0 x 49.9cm (sheet)

Courtesy of Fahey/Klein Gallery

© estate of Steve Schapiro

Nat Finkelstein (American, 1993-2009)

Silver Clouds installation, Leo Castelli Gallery

1966

Pigment print

Private collection

© Nat Finkelstein Estate

Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987)

Cream of mushroom soup

1968

Colour screenprint on paper

81.0 x 47.5cm (image)

88.8 x 58.5cm (sheet)

South Australian Government Grant 1977

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

© Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. ARS/Copyright Agency

Curator’s Insight – Andy Warhol and Photography: A Social Media

Julie Robinson

Exclusive to Adelaide, Andy Warhol & Photography: A Social Media is the first Australian exhibition to survey Warhol’s career-long obsession with photography. As the title suggests, the exhibition explores the social aspects of Warhol’s photography, including the collaborative nature of his photographic practice, the role photography had in his social interactions with others, and the candid social media ‘look’ of his images, which were taken decades before today’s obsession with social media.

These concepts apply to the two strands of Warhol’s photographic practice that are brought together in this exhibition – photography as an essential part of his working method and photography as an end in its own right.

From the beginning of Warhol’s career, photographs became important source material and were used by the artist as the basis of his paintings and screenprints. Included were existing photographs from magazines, advertisements, publicity portraits of movie stars, and photographs taken by his friends. Warhol’s painting of Elvis Presley, for instance, is based on a publicity still from the movie Flaming Star (1960); while photographs by Edward Wallowitch, Warhol’s boyfriend at the time, formed the basis of Warhol’s printed imagery in A Gold Book, 1957.

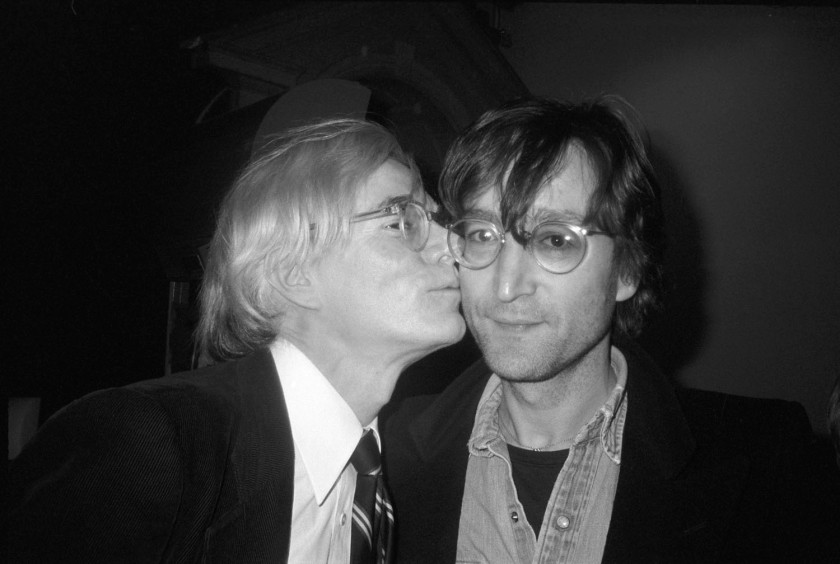

During the 1970s and 1980s, when commissioned portraits became a significant part of his artistic practice, Warhol based these portraits on Polaroid snapshots taken by him during photo shoots in his studio. The instantaneous nature of Polaroid photography allowed Warhol and the sitter to immediately select a favoured image to be transformed into a painting. Warhol’s studio photo shoots were often a social and collaborative affair, with studio assistants and others photographing alongside Warhol, while studio guests watched on. Film and video footage provides rare behind-the-scenes insights into Warhol’s studio practice for several of his portraits, including the excitement in the studio on Friday 17 February 1978, when John Lennon unexpectedly arrived during Liza Minnelli’s photo session, with the two celebrities meeting for the first time.

During the 1960s, in addition to creating his Pop Art paintings, Warhol was a leading underground film maker, making hundreds of experimental films. Some were silent, some were loosely scripted and others were largely improvised; most invariably relied upon friends and acquaintances as ‘actors’, such as in his 1965 film Camp. The exhibition also includes various screentests or ‘stillies’ – three-minute silent portraits of sitters who were instructed to sit motionless and gaze directly at the camera.

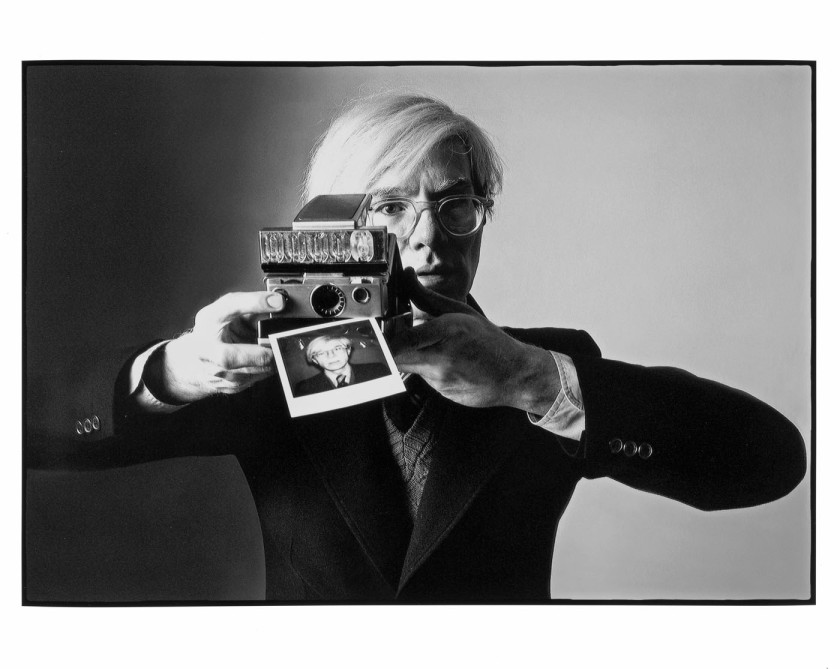

Warhol’s engagement with still photography for most of the 1960s was through the myriad of photographers who were drawn into his circle and studio, which was known as the Silver Factory.[1] Their images captured an insider’s view of Warhol’s world and studio practice, as Billy Name, the Factory’s resident photographer explained, ‘Cameras were as natural to us as mirrors. We were children of technology … It was almost as if the Factory became a big box camera – you’d walk into it, expose yourself and develop yourself’.[2] As well as Name, other photographers from this period represented in the exhibition include Duane Michals, David McCabe, Bob Adelman, Nat Finkelstein and Steve Schapiro. In 1969 Warhol’s closest confidante and a fellow artist, Brigid Berlin, bought a Polaroid camera and over the next five years obsessively photographed her life and surroundings. Inspired by her example and attracted to the immediacy of the medium, Warhol himself bought a Polaroid camera and similarly used it to compulsively document his life and social milieu until 1976, when he purchased a new type of camera, which took on this role in his photographic practice.[3] The new camera, a Minox 35 EL, the smallest type of 35 mm camera at that time, facilitated a new direction for him – black-and-white photography – which lasted until his death in 1987 and resulted in many thousands of 8 x 10 inch gelatin-silver photographs, each of which exists as a work of art in its own right.

Warhol took his camera everywhere; it was a constant presence in private and social situations, where he captured his friends and celebrities in candid moments with a ‘snapshot’ aesthetic. The nature of Warhol’s gelatin-silver photographic practice was publicly revealed when he published his first photographic book, Andy Warhol’s Exposures, in 1979. At that time he described his philosophy on photography: ‘My idea of a good picture is one that’s in focus and of a famous person doing something unfamous. It’s being in the right place at the wrong time’.[4] Warhol also stated that his favourite photographer was paparazzi photographer Ron Galella. The pair occasionally found themselves photographing at the same social events – Galella as a press photographer and Warhol as an invited guest, an insider.

In 1980 Warhol’s Swiss-based gallerist, Bruno Bischofberger, published the only two editioned portfolios of Warhol’s photographs. In this exhibition these two portfolios – one comprising twelve photographs and the other, forty photographs – are for the first time in Australia being shown together. Bischofberger, who had a long association with Warhol, considers Warhol’s gelatin-silver photographs to be part of his diaristic tendency to record his life, writing that Warhol’s tape recordings and dictated diaries could be regarded as his verbal memories, while his photographs became his ‘pictorial or visual memory’.[5] Warhol’s contact sheets reveal his daily journeys, the people he meets, and his wry observations of details from everyday life, including shop windows, signage and roadside rubbish.[6] Warhol’s eye was also drawn to serial imagery and abstract patterns, such as a shadow on a sidewalk, images he was collecting for his intended ‘stitched’ photographs.

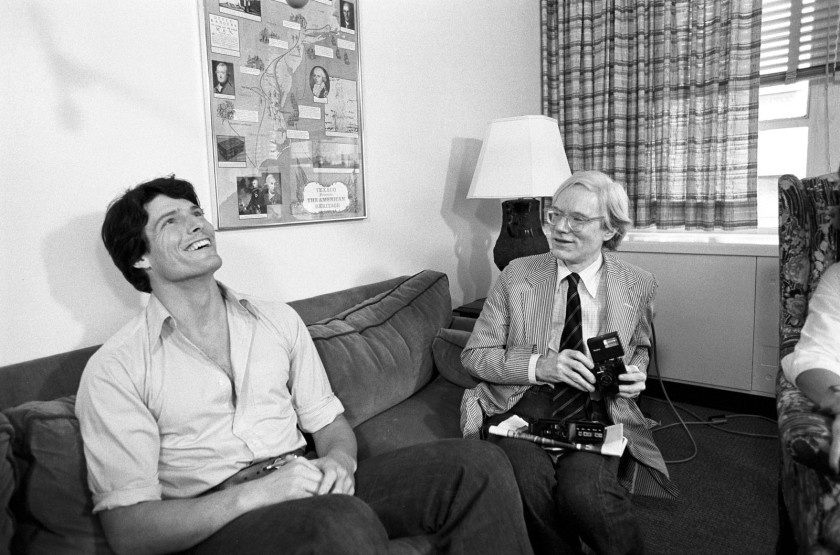

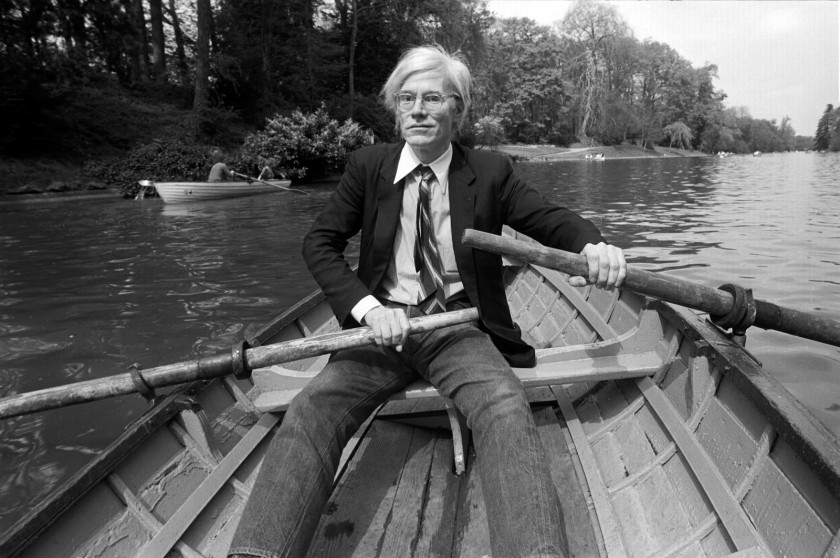

Most of Warhol’s gelatin-silver photographs were printed by Christopher Makos; each week they would review the contact sheets together and select the images for printing. Makos, one of the young photographers working for Warhol’s Interview magazine, was also art director of the book Andy Warhol’s Exposures, and became a key photographic companion of and collaborator with Warhol. As Makos said, ‘I undoubtably learnt a great deal from him, but he also learnt from me, especially about photography. We were in constant confrontation, continually exchanging impressions and ideas’.[7] They often photographed the same subjects side by side – whether travelling or in the studio – and Makos also took many photographs of his friend. The exhibition includes Makos portraits of Warhol doing everyday or ‘unfamous things’, including rowing a boat on a lake in Paris, having a massage, or posing wearing a clown nose. Perhaps their most enduring collaboration was the suite of Altered Image photographs: Warhol dressed in male attire but with female wigs and make-up. Makos remembers that Warhol ‘didn’t want to look like a beautiful woman, he wanted to show the way it felt to be beautiful’.[8]

Warhol exhibited very few of his photographs during his lifetime, although in January 1987, just weeks before he died, he revealed a new approach to his photography in an exhibition of ‘stitched photographs’ at Robert Miller Gallery, New York. Made by sewing several identical photographs together in a grid formation, these works frequently used photographs with strong abstract qualities in order to enhance the visual impact of the work.

AGSA’s exhibition Andy Warhol & Photography: A Social Media presents a new perspective on Warhol for Australian audiences.[9] Tracing Warhol’s photographic practice both behind and in front of the camera, and focusing primarily on portraiture, the exhibition explores the social nature of Warhol’s photographic practice and in doing so offers new insights into his art and life.

Julie Robinson is Senior Curator, Prints, Drawings and Photographs at AGSA

[1] So called because from 1964 to 1968 Warhol’s studio was on the site of a former hat factory on East 47th Street. Warhol asked Billy Linich, known as Billy Name, to decorate the interior with silver foil and paint, as Billy had done for his own apartment.

[2] Billy Name, All tomorrow’s parties, Frieze, London and D.A.P. New York, 1997, p. 18.

[3] In the studio, however, Warhol continued to use his Polaroid camera for portrait shoots for the rest of his career.

[4] Andy Warhol, with Bob Colacello, ‘Introduction: social disease’ in Andy Warhol’s Exposures, Hutchison, London, 1979, p. 19.

[5] Bruno Bischofberger, ‘Andy Warhol’s visual memory’, 2001, p. 4, https://www.brunobischofberger.com/_files/ugd/d90357_015362edc78746d3b4ec6654231933ef.pdf accessed 23 December 2022.

[6] Warhol’s contact sheets archive is held at the Cantor Arts Center, Stanford University.

[7] Christopher Makos, Andy Warhol, Charta, in collaboration with Edition Bruno Bischofberger, Zurich, 2002, p. 8.

[8] Christopher Makos, ‘Lady Warhol the book, Altered Image’, https://www.makostudio.com/gallery/2717, accessed 23 December 2022.

[9] I am grateful to the many supporters who have made this exhibition possible, including sponsors and donors, lenders in Australia and overseas, artists and artists’ estates, sitters and their families, colleagues at other institutions, and the staff at AGSA.

Gerard Malanga (American, b. 1943)

Andy Warhol

1971

Gelatin silver photograph

33.7 x 22.6cm (image), 35.6 x 27.8cm (sheet)

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Purchased 1973

Oliviero Toscani (Italian, b. 1942)

Andy Warhol

1975

Pigment print

32 x 46cm (image)

40 x 50cm (sheet)

Public Engagement Fund 2021

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

© Oliviero Toscani

Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987)

Bianca Jagger at Halston’s house, New York, no. 1 from the portfolio Photographs

1976, published 1980

Gelatin silver photograph

40.8 x 28.8cm (image)

50.5 x 41.0cm (sheet)

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

James and Diana Ramsay Fund 2020

© Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. ARS/Copyright Agency

Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987)

Halston at home, New York, no. 7 from the portfolio Photographs

c. 1976-1979, published 1980

Gelatin silver photograph

42.2 x 29.4cm (image)

50.5 x 40.8cm (sheet)

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

James and Diana Ramsay Fund 2020

© Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. ARS/Copyright Agency

Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987)

Truman Capote at home, New York, no. 4 from the portfolio Photographs

c. 1976-1979, published 1980

Gelatin silver photograph

30.5 x 42.9cm (image), 41.0 x 50.5cm (sheet)

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

James and Diana Ramsay Fund 2020,

© Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. ARS/Copyright Agency

Christopher Makos (American, b. 1948)

Andy taping Christopher Reeves for ‘Interview’ magazine

1977

Gelatin silver photograph

21.2 x 32.2cm (image), 27.5 x 35.3cm (sheet)

Private collection

© Christopher Makos

Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987)

Muhammad Ali, his infant daughter, Hanna, and wife, Veronica at Ali’s training camp in Deer Lake, PA

August 18, 1977

Gelatin silver photograph

Robin Platzer (American)

Andy Warhol showing his artistry

1978

Pigment print

Getty Images Collection

© Robin Platzer/ Images Press

Photo: Images Press

Christopher Makos (American, b. 1948)

Andy Warhol and Liza Minnelli

1978

Gelatin silver photograph

26.9 x 34.1cm (image)

40.6 x 50.3cm (sheet)

Private collection

© Christopher Makos

Christopher Makos (American, b. 1948)

Andy Warhol Kissing John Lennon

1978

Gelatin silver photograph

27.7 x 41.7cm (image)

40.7 x 50.4cm (sheet)

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

V.B.F. Young Bequest Fund 2022

© Christopher Makos

Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987)

Liza Minnelli

1978

Polaroid™ Polacolor Type 108

9.5 x 7.3cm (image)

10.8 x 8.5cm (sheet)

V.B.F. Young Bequest Fund 2012

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

© Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. ARS/Copyright Agency

Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987)

Debbie Harry

1980

Polaroid™ Polacolor Type 108

10.8 x 8.6cm (sheet)

9.7 x 7.3cm (image)

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

V.B. F. Young Bequest Fund and d’Auvergne Boxall Bequest Fund 2018

© Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. ARS/Copyright Agency

Christopher Makos (American, b. 1948)

Andy Warhol in a row boat in Paris’s Bois de Boulogne

1981

Gelatin silver photograph

27.7 x 35.6cm (sheet)

18.3 x 27.9cm (image)

Private collection

© Christopher Makos

Christopher Makos (American, b. 1948)

Altered Image from the portfolio Altered Image: Five Photographs of Andy Warhol

1981; published 1982

Gelatin silver photograph

44.8 x 32.2cm (image)

50.6 x 40.8cm (sheet)

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Purchased 1982

© Christopher Makos

Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987)

Woman on the street

1982

Gelatin silver photograph

25.3 x 20.3cm (sheet)

22.3 x 15.6cm (image)

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

V.B. F. Young Bequest Fund and d’Auvergne Boxall Bequest Fund 2018

© Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. ARS/Copyright Agency

Christopher Makos (American, b. 1948)

Andy Warhol in American flag, Madrid

1983

Gelatin silver photograph

32.3 x 21.6cm (image)

35.6 x 27.6cm (sheet)

Private collection

© Christopher Makos

Warhol’s queer practice – what we might, with a nod to the mechanics of repetition at the heart of the project, call his queer ‘technics’ – involved less an embrace of commodification than a recognition of radical difference and equality. These were always mutually dependent in Warhol’s work and the basis for what we might regard as a philosophical commitment, one that informed his entire career.

I believe we see this especially in Warhol’s films and photography, those aspects of artistic practice most overlooked by the critical establishment who rushed to canonise Warhol as the High Prince of affectless serial pop in the 1990s. Warhol’s photographs and films not only attest to the radical collectivism and performance-art culture of his Factory (the name is significant), they are also the most resistant to market logic. The photographs have been reproduced as saleable commodities less often – or to lesser degree – than his work in other media (screenprints, paintings). They also attest to some of the key paradoxes at the heart of Warhol’s whole body of work.

Photographs, after all, are often treated as aide-mémoire ephemera and are (almost) endlessly reproducible: the negative renders theoretically infinite numbers of positives. Warhol’s photographs, however, tended to the singular as well as the serial: polaroids (one of a kind) and silver-gelatin prints (from a negative, able to be multiplied), the ephemeral (throwaway records of a moment) and the auratic (emanating the aura of singularity and originality). They could be both simultaneously, too. Warhol’s photographic subjects are also more varied than the celebrity images that many associate with his screenprint practice: they range from unidentified objects of vicarious desire to glitterati – although Warhol’s celebrity subjects were often represented in ways that subverted or manipulated their mass-produced public image for effect, in line with the radical equality that is the essence of machine reproduction.

Extract from Andrew van der Vlies. “Andy Warhol’s Queer Practice: Disidentification and Utopian Desire,” on the Art Gallery of South Australia website Nd [Online] Cited 03/05/2023

Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987)

Henry Gillespie

1985

Synthetic polymer paint and screenprint on canvas

101.6 x 101.6cm

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

South Australian Government Grant 1996

© Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. ARS/Copyright Agency

Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987)

Self-portrait no.9

1986

Synthetic polymer paint and screenprint on canvas

203.5 x 203.7cm

Purchased through The Art Foundation of Victoria with the assistance of the National Gallery Women’s Association, Governor, 1987

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

© Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. ARS/Copyright Agency

Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987)

Curiosity Killed the Cat

1986

Gelatin silver photograph

20.1 x 25.3cm (image & sheet)

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

V.B. F. Young Bequest Fund and d’Auvergne Boxall Bequest Fund 2018,

© Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. ARS/Copyright Agency

Nonetheless, the openness to technology and looseness of approach to the medium that Hujar identifies in Warhol’s practice suggest ways in which we might understand much of Warholian photographic work. This is particularly the case if we consider how his practice predicts our own moment of photographic hyperproduction, casualisation, and omnipresence: Warhol’s use of the Polaroid almost has the immediacy of the camera phone – although without the same capacity for taking an image discreetly, even voyeuristically, or the potential for instant global transmission. But like the inundation of images awash on social media today (and the status of digital photograph as virtual ‘object’), the polaroid has the potential for public circulation, as well as total privacy – the image of the beloved, the erotic image that requires no third party to develop and print it. Warhol’s polaroids of male nudes, but also those of him in drag, activate energies of the private-public continuum, teasing the public viewer with imagery that suggests a zone of private erotic fetish as much as an exploration of the limits and mutability of the self.[11] Warhol’s Polaroid nudes also anticipate the social media phenomenon of people trading explicit images of the self (and sometimes of others as deceptive proxies for a fantasy self) as tease, invitation, or souvenir of intimate encounters.

Despite the clear differences in their practice and philosophy of photography, Warhol and Hujar produced bodies of photographic work that are significantly connected and entangled. This is not only attributable to their having in common queer subjects like Factory stars Candy Darling and Jackie Curtis, early reality television icon Lance Loud, theorist and writer Susan Sontag, and poet John Ashbery, each of whom had their image made by both artists to very different effect.

If Hujar left us with hauntingly beautiful – and often painterly – images of such figures, photographs that seem to capture the sitter’s animating spirt, Warhol offers a more direct impression of what his subjects were like as people in the world on a particular day.

The connections and possible dynamics of influence are also evident in Hujar’s and Warhol’s parallel movement between impulses of street photography [fig 1], studio work, celebrity and self-portraiture, documentation and celebration of the male nude (whether eroticised, stylised, or aestheticised), fascination with animal and architectural subjects, as well as their exploration of the performance culture of drag. While Warhol’s images across these genres may not occupy the same category of ‘beauty’ as Hujar’s, there is unmistakable beauty of a different variety; this might be characterised as a beauty of immediacy, of the candid moment and ephemeral gesture, a beauty that takes informality as its impulse, and which does not try to hide its flaws. It is, in a real sense, a very democratic beauty.

Extract from Patrick Flanery. “Queer Influencers: Hujar and Warhol,” on the Art Gallery of South Australia website Nd [Online] Cited 03/05/2023

Robert Mapplethorpe (American, 1946-1989)

Andy Warhol

1986

Gelatin silver photograph

61.0 x 51.0cm

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Purchased 1989

Art Gallery of South Australia

North Terrace Adelaide

Public information: 08 8207 7000

Opening hours:

Daily 10am – 5pm (last admissions 4.30pm)

You must be logged in to post a comment.