Exhibition dates: 27th February – 16th May 2021

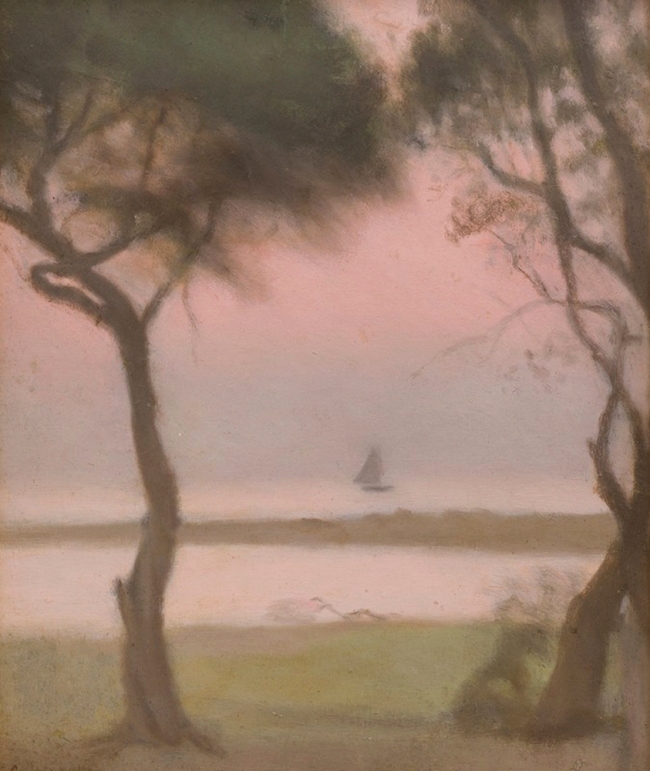

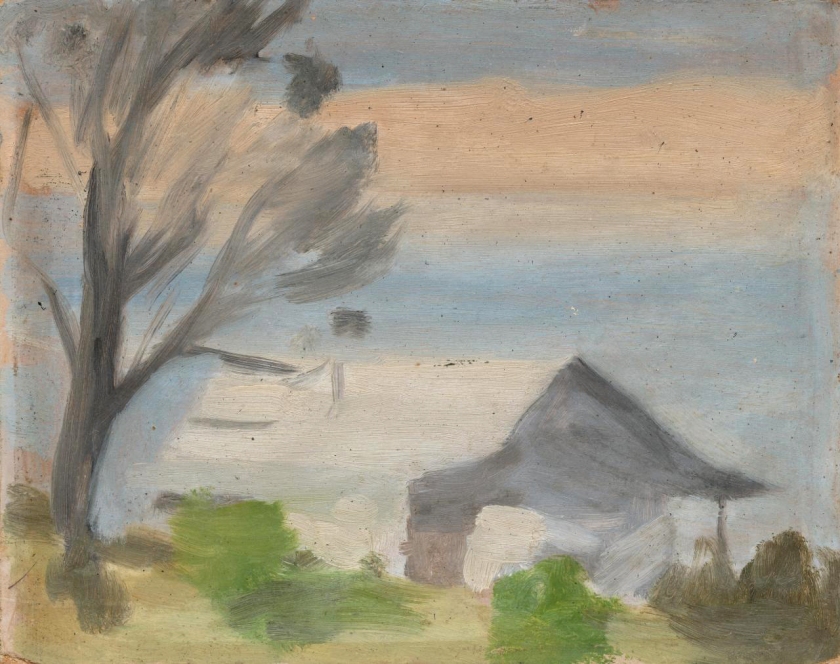

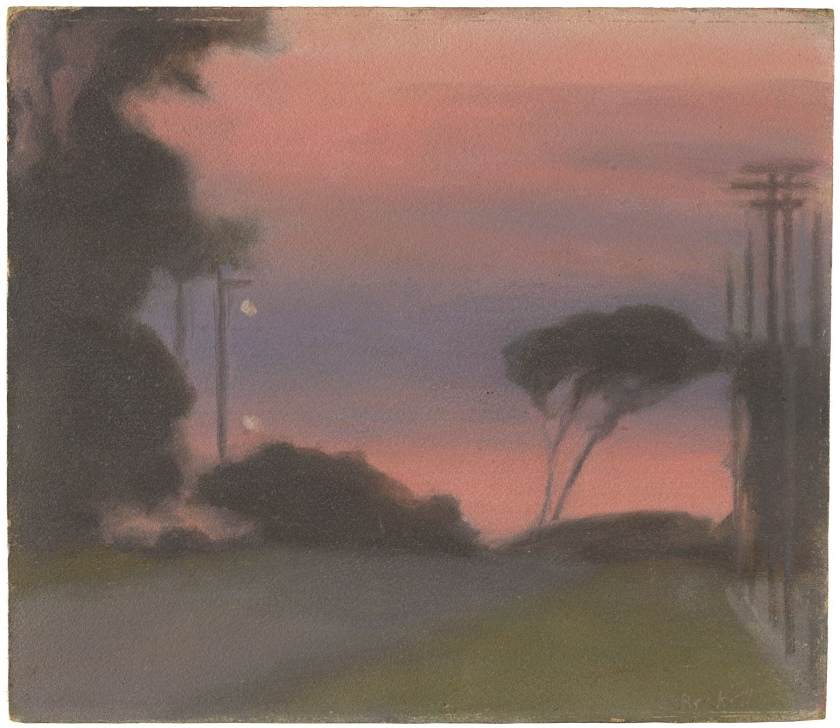

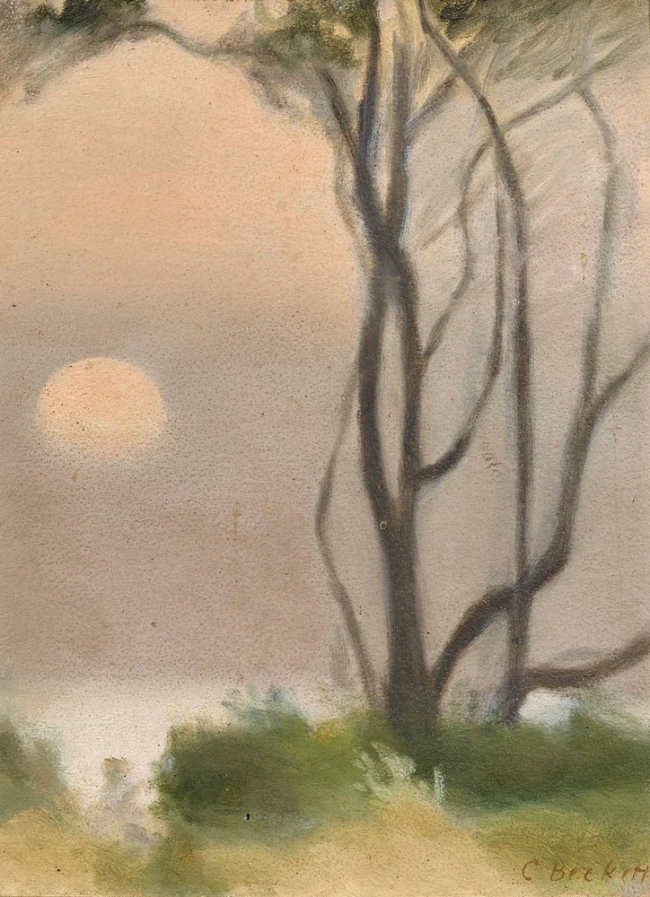

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Solitude

c. 1932

Melbourne

Oil on board

Gift of Alastair Hunter OAM and the late Tom Hunter in memory of Elizabeth through the Art Gallery of South Australia Foundation 2019

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

Realist structuralist illusionist

The only four words that you really need to know are this: I bought the catalogue.

Beckett’s story of tragedy and redemption is briefly told. Trained as a painter under Max Meldrum in the modernist Australian tonalist school (which she far surpassed). Painted the hazy, misty suburbs of Melbourne en plein air in all weather conditions, usually in the early morning or at dusk. Worked incredibly hard at her art but, as with a lot of artists, had little recognition during her brief career despite numerous solo exhibitions. Died at a young age of double pneumonia after an outdoor painting session. Work lost to the mists of time until the art historian Rosalind Hollinrake salvaged a mere 369 paintings – 1,600 were beyond repair – from an open sided barn in country Victoria. Sadness at the loss of a young life cut short, of so many paintings lost to the elements and possums, but a deep gratitude that we still have what remains of her reality, as seen through her paintings. Now become, in my humble opinion, one of the greatest Australian painters of all time.

In her review of the exhibition Catherine Speck observes that Beckett’s works are a “study in transience”; another commentary has her as the “master of the half-light”; curator Tracey Lock has said her work is “luminous, ethereal, and very gentle… producing some of the most radically minimalist landscapes of the period … atmospheric abstractions of the commonplace.” All true.

Beckett had studied theosophy – a belief in divine wisdom via mysticism – and had read Madame Blavatsky’s book The Voice of Silence. Blavatsky urged her followers to seek spiritual knowledge beyond sensory experience – a sense of “limitless” and expanse. As John MacDonald observes, Beckett “explored the spiritual dimension of modernism” but only in so far “as a function of the open-minded, open-hearted way she approached the subject of a painting.” Again, all true.

But I find there is something more grounded in Beckett’s work than just smoke and mirrors.

While Beckett’s work can be seen as both radically minimalist landscapes and “atmospheric abstractions”, if you really look at these paintings – seemingly just daubs of paint over layers of thin background washes – there is an incredible draughtsmanship and structure to all of her paintings. The underpinning of these transient paintings are anything but random tones applied to the canvas. A foundation built on sand cannot last, cannot sustain such a penetrating inquiry.

In many ways I see Beckett as much a structuralist as a modernist or tonalist. Following Meldrum’s ideas about the rational analytic observation of subtle visual patterns of tones and accents, we can say that Beckett worked to uncover the structures that underlie all the things that humans do, think, perceive, and feel in the immediacy of her painting, in her painting outdoors, in her inner vision of a reality that she felt and saw. In the phenomena of her life she envisaged, intimately, her interrelations with the world, and understood that below the surface phenomena there are constant laws of abstract structure.

How she evinces that structure in the solitude of a man in a boat, or passing trams, the warmth of the setting sun, or motor car lights in rain shows her “characteristic ability to catch the spontaneity of a lived moment.” As with a legion of great artists – van Gogh’s bedroom, Cezanne’s still life, Hooper’s diner at night – it is her ability to make the ordinary extraordinary that sets her apart from the rest. “She found a distinctive beauty in the ordinary objects such as telegraph poles, strips of road, trams, cars, buses and the daily activity taking place in the street.”

In paintings such as The Red Bus (Nd), Morning Ride (Nd), Out Walking (c. 1928-1929), The Bus Stop (1930), Evening light, Beaumaris (c. 1925), Beach Road after the rain (Street scene) (c. 1927), Walking home (1931) and Dusk (Nd) it is the spatial distance between objects, not just physically but mentally – that leap of faith that the viewer must make into the space of the painting – that draws you in, that immerses you into that time and space that Beckett observed so truthfully. Poetic and lyrical yes, but also grounded and spatial, opening out this vista in front of you … humans as colourful accretions of paint (in)distinct in their existence, placed in fleeting moments, caught on the wind.

MacDonald notes, “If this show were being staged at Tate Modern or the Museum of Modern Art, Beckett would be hailed as a figure of world renown.” I heartily concur. Much as the Swedish artist Hilma af Klint (1862-1944) – whose lyrical abstract canvases were hidden for 20 years after her death – has recently had blockbuster exhibitions at Moderna Museet Malmö, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York and coming to the Art Gallery of New South Wales Sydney later in 2021, so I believe that Clarice Beckett will be recognised as an important world artist.

You really can’t pick out a bad painting by Beckett. Each has its own personality and seduction. I am ravished by them all.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Art Gallery of South Australia for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“To give a sincere and truthful representation of a portion of the beauty of Nature, and to show the charm of light and shade, which I try to give forth in correct tones so as to give as nearly as possible an exact illusion of reality.”

Clarice Beckett

“It sometimes sounds as though [Max] Meldrum actually invented the idea of tone, but artists had understood this quality since the days of Leonardo da Vinci and Velasquez. In brief, it refers to the lightness or darkness of colours and the way they relate to each other in a composition. Meldrum’s innovation was to make tone the defining feature of painting – the inflexible standard to which every other aspect of a work must conform.”

John MacDonald. “Misty Moderns,” on the Sydney Morning Herald website, November 21, 2009 [Online] Cited 19/03/2021

“The facts of Beckett’s life may be told in short order. She was born in 1887 into a well-heeled, middle-class family. She had a passion for art and literature and would go on to study drawing under Fred McCubbin at the National Gallery School, then spend nine months attending the independent art school run by the outspoken Max Meldrum. It was an experience that would help mould her technique and views on art, although not so much as many have presumed. Although Beckett had admirers, she turned down several offers of marriage and would end her life living at home in the bayside suburb of Beaumaris, having spent years looking after her invalid mother.

In 1935, shortly after her mother’s death, Beckett caught double pneumonia and passed away at the age of 48. What happened next is just as tragic, as her father burnt paintings that he didn’t consider finished or good enough. Her sister, Hilda, would store the remaining 2000 canvases in an open-sided shed in the countryside near Benalla. When Hollinrake tracked them down in 1970, only 369 were salvageable. The weather and the possums had laid waste to the rest.

The loss of so many works ranks as one of the great disasters of Australian art history. We may all be thankful that Hollinrake saved what she could.”

John MacDonald. “This exhibition is so phenomenal I saw it three days in row,” on the Sydney Morning Herald website, March 25, 2021 [Online] Cited 29/03/2021

“Modern science maintains that all colours in the universe are founded in three elements: hue (colour), saturation (chroma) and tone (value). Hue refers to the spectral colours such as red, green, blue, and so on, that are visibly distinct from each other…

Saturation represents the intensity, or quantity, of colour… The best way to understand this is if you take a can of blue paint and gradually stir in some white, rather than getting a new colour, the result is a lighter blue. An exception to this rule is that by adding white to red, we make pink. Red is a highly saturated pink; they are of the same hue but the quantity of red colour is less in pink.

Tone refers to how light or dark a colour is. On a scale of 0 to 10, 0 is colourless (or white), 5 is a medium grey [think Zone V in the black and white zone system] and 10 is black. So, as the tone increases, it intensifies the darkness [of the colour]. Tone begins to impact the saturation … once it reaches a percentage high enough to overpower it. This percentage varies with each colour, just as the saturation range varies with hues. For example, saturation in a yellow … may reach as high as ninety percent, whilst in a blue … it may only reach three percent, with the result that a small percentage increase in tone on a blue … would have a far greater impact on the blue, resulting in the grey becoming more noticeable. [Colours] with a higher saturation, such as yellow, would require correspondingly higher levels of tone for the brown to be observed. When the percentage of tone exceeds the saturation, the brown or grey will actually become the body (primary) colour and the hue the modifier, for example bluish-grey.”

Hamish Sharma. “Colour: How we see diamonds and gemstones,” in the Leonard magazine, Issue 90, February – March 2021 Cited 19/03/2021.

Featuring the artist’s luscious and distinctive soft focus, the Art Gallery of South Australia’s newly opened Clarice Beckett exhibition, curated by Tracey Lock, presents her paintings as a sensorium – with colour, music and video to enhance the experience.

Each room in the gallery’s exhibition space is dedicated to her paintings of specific times of the day, from sunrise, to early morning, then midday and sunset, concluding with the nocturnes. She was fascinated with temporal change. The exhibition is very much an experiential journey. Viewers enter through an elliptical portal to an immersive rounded space filled with magnified projections of her paintings, and music from Simone Slattery’s specially commissioned soundscape.

Beckett was musical too. The transcendence to another realm has begun. The mood changes with each room in the exhibition.

A sad loss but precious works remain

The poignant Clarice Beckett story is known by many. She died from pneumonia in 1935 at 48 years of age, and left behind a large cache of work. It was stored for a number of years in an open-side shed in rural Victoria, only to be discovered in the late 1960s, in a poor state of repair, by art historian Rosalind Hollinrake. She salvaged a mere 369 paintings – 1,600 were beyond repair.

Hollinrake guided the artist’s rediscovery at a time when numerous women artists were reinserted into the canon. The impetus for this exhibition is the generous donation by Alastair Hunter of a large collection of Beckett’s work previously held by Hollinrake.

Mysticism meets science

Theosophy – a belief in divine wisdom via mysticism – was a major influence on her approach to painting. Like others around the world, Beckett came under the popular esoteric movement’s spell in the early years of the 20th century. She owned a well-thumbed copy of Madame Blavatsky’s seminal occult text The Voice of Silence, attended spiritualist meetings and moved in artistic circles where post-dinner seances were often held.

But Beckett also took on board painter Max Meldrum’s quasi-scientific ideas about rational analytic observation of subtle visual patterns of tones and accents. She studied with him for nine months, although it is widely accepted she surpassed him with her brilliant tonal landscapes. This is the hybrid intellectual and artistic milieu she moved in, supplemented by an interest in Eastern philosophy and Freud.

For Beckett, painting was as much about performing her spiritual beliefs as it was about portraying that which was observable. Her friends in the Melbourne Society of Women Painters and Sculptors, to which she belonged, recall she loved talking about theories behind her work.

What emerges in the exhibition is her finely honed and daring visual language.

Artist without a studio

A curatorial coup is achieved with the installation of a domestic kitchen in the exhibition space. Her father had declined her request for a studio to work in. He suggested she use the kitchen table instead.

While most of her paintings were completed outdoors, she did paint still life and portraits, and finish off larger en plein air works at home. This work was indeed done on the kitchen table, which is so tellingly included in the exhibition, surrounded by her still life paintings including Marigolds (1925).

Catherine Speck. “Clarice Beckett exhibition is a sensory appreciation of her magical moments in time,” on The Conversation website March 1, 2021 [Online] Cited 06/03/2021.

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Passing trams

c. 1931

Oil on board

48.60 mm (1.91 in); Width: 44.20 mm (1.74 in)

Art Gallery of South Australia

Public domain, Google Art Project

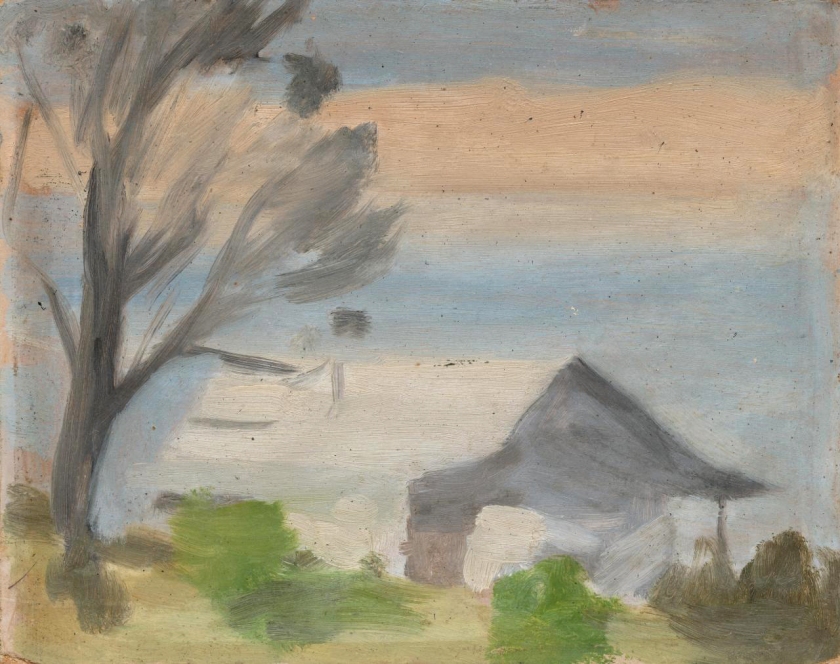

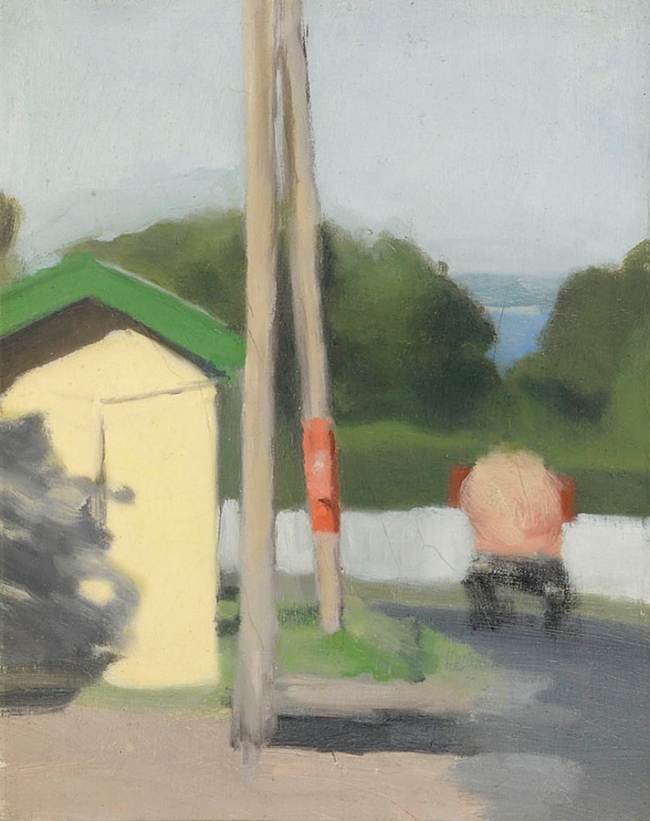

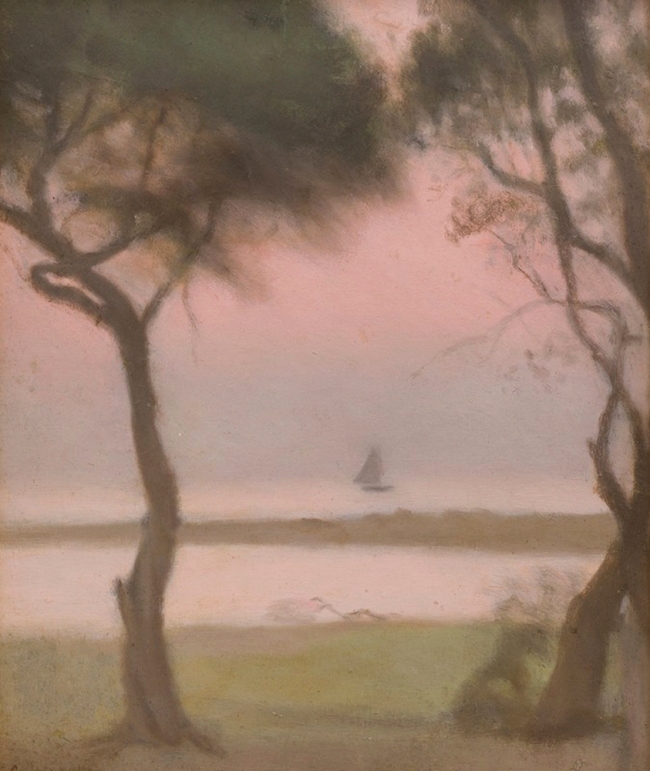

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Summer fields

1926

Naringal, Western District, Victoria

Oil on board

Gift of Alastair Hunter OAM and the late Tom Hunter in memory of Elizabeth through the Art Gallery of South Australia Foundation 2019

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

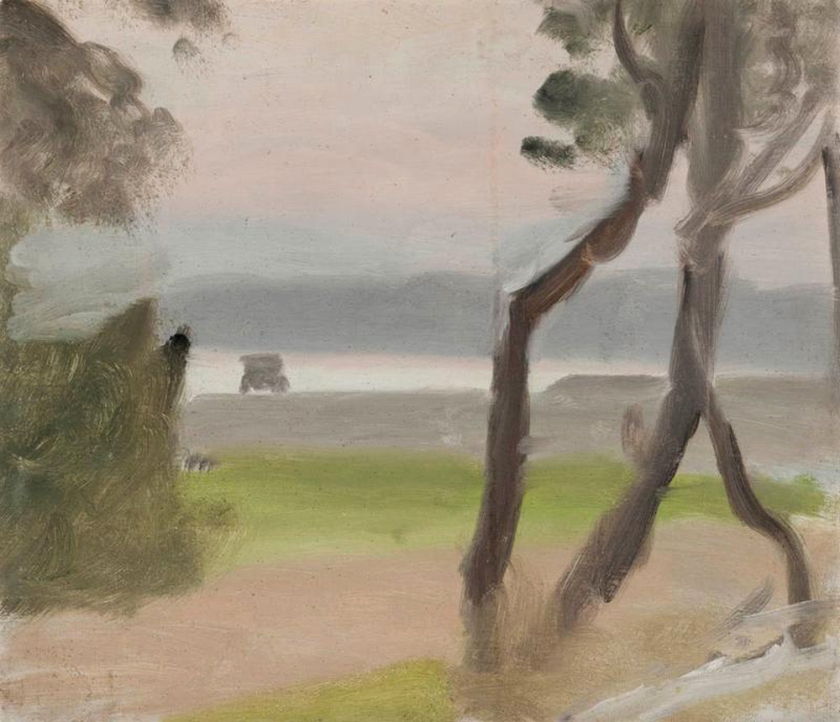

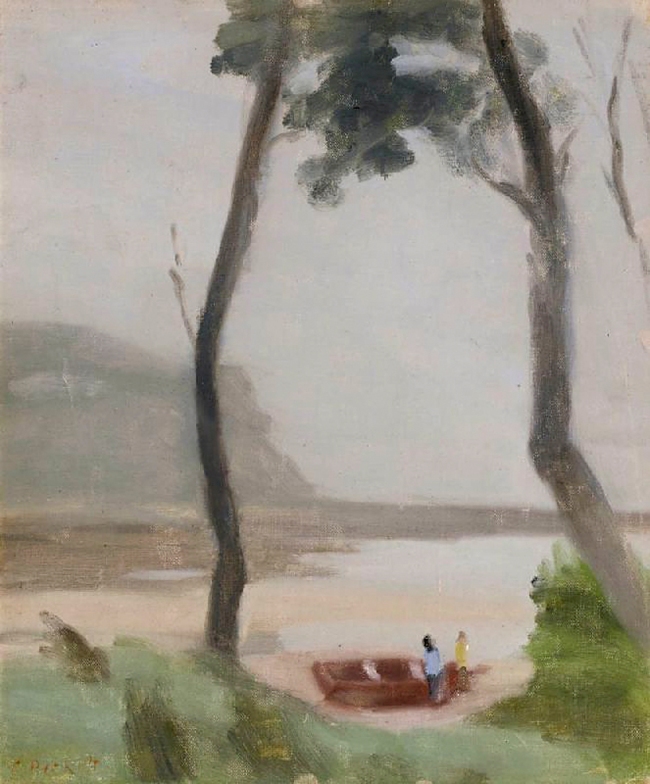

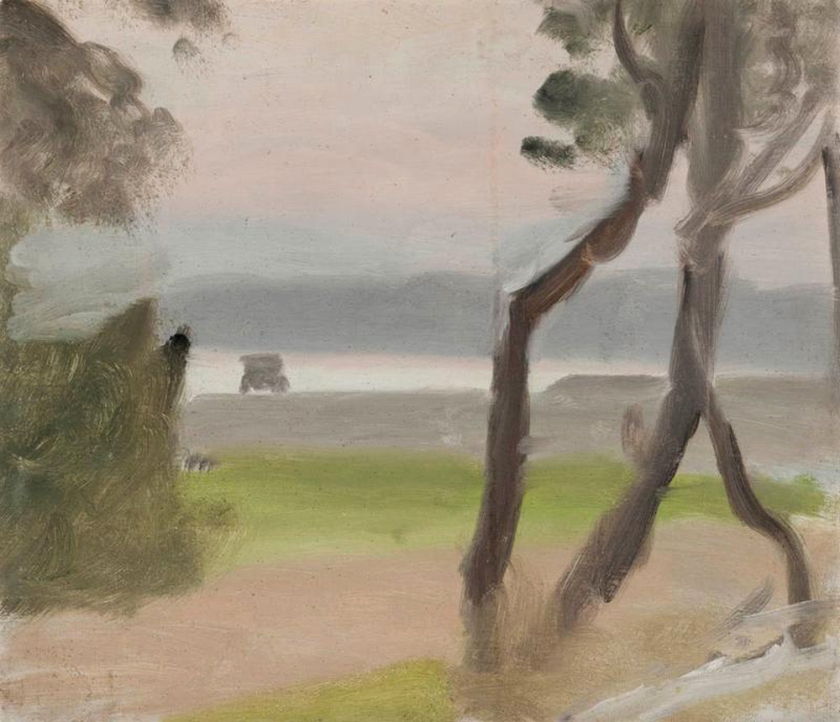

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

The plains

1926

Naringal, Western District, Victoria

Oil on board; Gift of Alastair Hunter OAM and the late Tom Hunter in memory of Elizabeth through the Art Gallery of South Australia Foundation 2019

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Wet sand, Anglesea

1929

Victoria

Oil on board

Gift of Alastair Hunter OAM and the late Tom Hunter in memory of Elizabeth through the Art Gallery of South Australia Foundation 2019

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

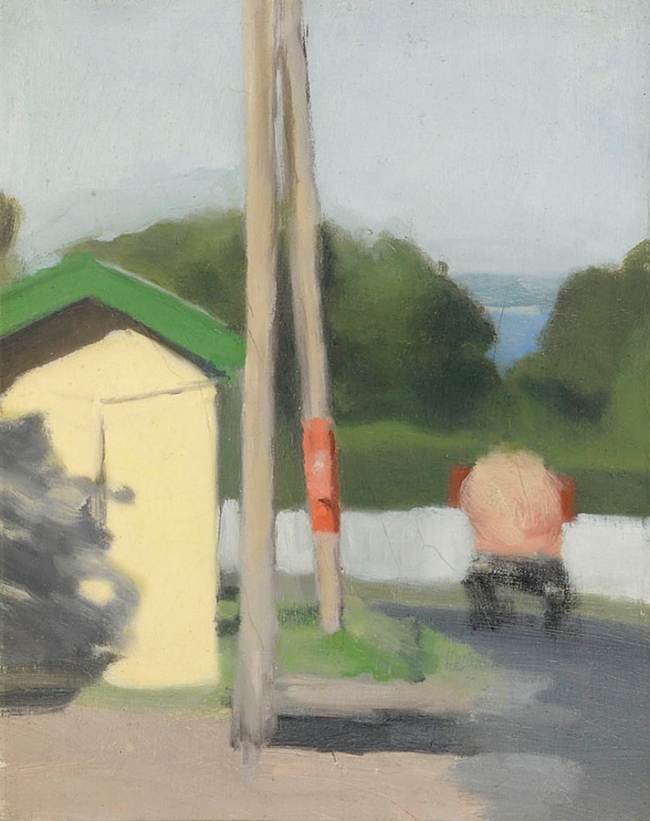

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

The boatshed

1929

Melbourne

Oil on board

Gift of Alastair Hunter OAM and the late Tom Hunter in memory of Elizabeth through the Art Gallery of South Australia Foundation 2019

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

October morning

c. 1927

Melbourne

Oil on board

Gift of Alastair Hunter OAM and the late Tom Hunter in memory of Elizabeth through the Art Gallery of South Australia Foundation 2019

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Walking home

c. 1931

Oil on board

Gift of Alastair Hunter OAM and the late Tom Hunter in memory of Elizabeth through the Art Gallery of South Australia Foundation 2019

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

The Art Gallery of South Australia is presenting the most comprehensive retrospective ever staged of Clarice Beckett, one of Australia’s most enigmatic and admired modernist painters. Clarice Beckett: The present moment, sees nearly 130 works by the artist on display as part of the 2021 Adelaide Festival in February 2021.

Associated with a legendary story of rediscovery, Clarice Beckett is today celebrated for her ethereal, atmospheric landscape paintings that capture the commonplace. In 1935 Clarice Beckett died at the age of forty-eight, and for the next thirty-five years her work vanished from art history before being rescued by Dr Rosalind Hollinrake. Hollinrake salvaged 369 of the artist’s neglected canvases from a remote, open-sided shed in rural Victoria. Hollinrake’s extensive research and promotion led to Beckett’s recognition as a major force in Australian modernism.

The present moment includes many of the salvaged paintings, as well as her master works drawn from national public collections as well as private collections including Russell Crowe and Ben Quilty. Misunderstood in her lifetime, The present moment presents Beckett as a visionary mystic who saw nature as all powerful and as an artist driven by spiritual impulses rather than worldly success.

Her timeless and incidental everyday scenes have been curated to chart the chronology of one single day. The present moment exhibition will take visitors on a sensory journey from the first breath of sunrise, through to the hush of sunset and finally a return into the enveloping mists of nightfall.

AGSA Curator of Australian Art and Exhibition Curator Tracey Lock says, ‘Audiences experience an affinity with the art of Clarice Beckett. On one level Beckett represents the triumph of the spirit over adversity and certainly the ideal of an artist driven by something beyond worldly success. On a deeper level they sense a profound humanity, something that has united the world in such adversity over the past year.

‘There is a certain magnetism to her paintings: an experiential quality of sound, sight or feeling that transcends language. Enveloped in diffused light and exuding peacefulness, her paintings invite a sense of stillness that points to a healing, spiritual quality.’

AGSA Director Rhana Devenport ONZM says, ‘The Art Gallery of South Australia is thrilled to stage this important exhibition which was initiated following the significant acquisition of 21 paintings by Clarice Beckett early in 2020, made possible thanks to the extraordinary generosity of Alastair Hunter OAM.’

Press release from the Art Gallery of South Australia

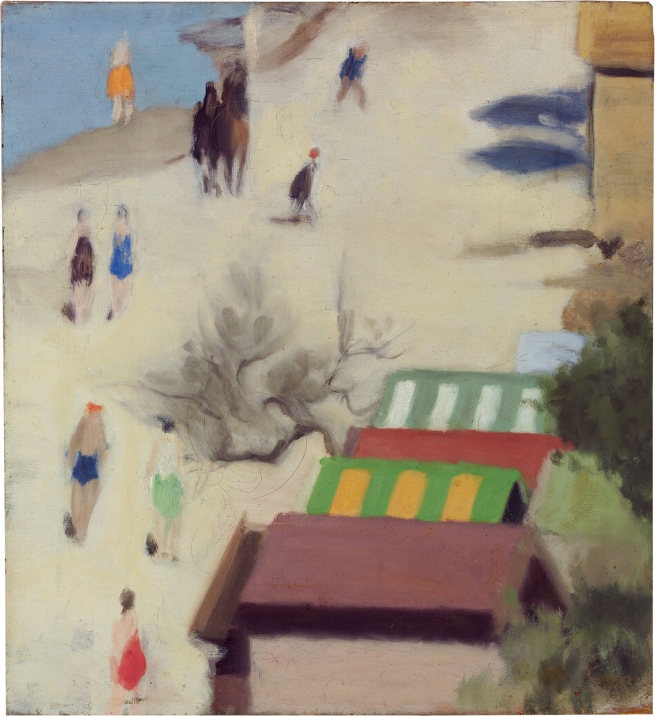

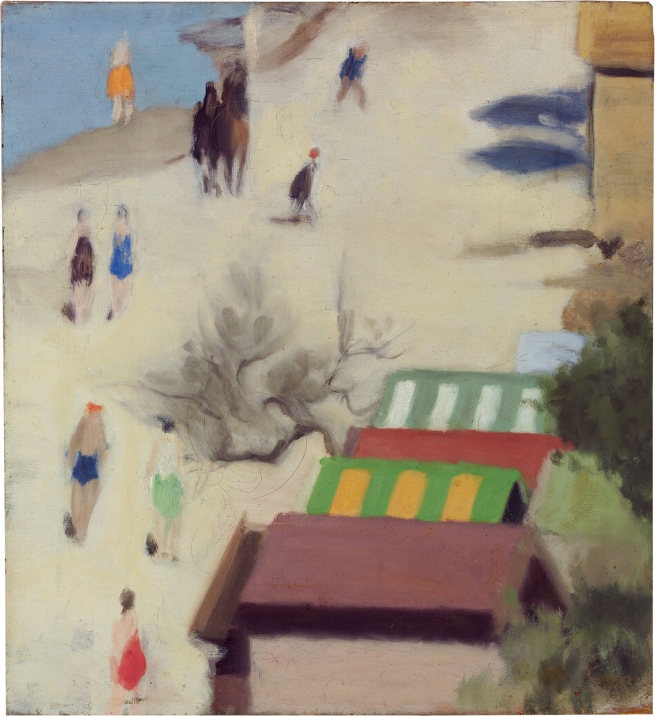

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Sandringham Beach

c. 1933

Oil on canvas

55.8 x 50.9cm

National Gallery of Australia

Centre painting in the second installation image below.

Clarice Beckett’s Sandringham Beach is a dynamic and modern composition of sand, bathing boxes and beach walkers. Beckett depicted the scene from an unusual perspective – from a cliff looking down onto the beach. Captured in the glare of a summer day, the smooth body of sand appears to shimmer with ‘white heat’. Backing onto scruffy vegetation, the brightly coloured striped roofs of the bathing boxes are the most solid aspects of the composition.

The ocean occupies a small portion of Beckett’s view, with beachgoers strolling along the water’s edge and a game of beach cricket taking place. The bright modern swimsuits and exposed skin of the walkers have been brushed onto the canvas with soft dabs of colour. The playful atmosphere of Sandringham Beach encapsulates Australian’s love of the beach as a key site of recreation and relaxation.

Beckett first studied in Ballarat, and then from 1914 to 1916 with Frederick McCubbin at the National Gallery School. In 1917 she attended Max Meldrum’s public lecture on tonal painting at Melbourne’s Athenaeum Theatre and, impressed by his theories, enrolled in his classes. While Beckett was considered a ‘Meldrumite’ – a devotee of her teacher’s theories of tonal values as the best means of depicting nature – she adapted his ideas to create her own lyrical vision of the Australian landscape.

Text © National Gallery of Australia, Canberra 2014

From: Collection highlights: National Gallery of Australia, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 2014.

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Beach Scene

1932

Oil on canvas

52.1 x 62.0cm

Cbus art collection

Second left painting in the second installation image below.

Installation view of the exhibition Clarice Beckett: The present moment, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, 2021

Photos: Saul Steed

It may be that a dash of Meldrum had a beneficial effect on artists who took only what they wanted and never became followers. By contrast, those who bought the full package seem to belong to a single family, sharing the same DNA. The true Meldrumites in this show are Colin Colahan, Clarice Beckett, Percy Leason, A.D.Colquhoun, Hayward Veal, Justus Jorgensen, A.E.Newbury, John Farmer and Polly Hurry. Most took part in the first group exhibitions of the Meldrum School held in 1919, 1920 and 1921, in which paintings were exhibited in uniform black frames and identified only by numbers. A photograph in the catalogue shows pictures crammed together like items on a supermarket shelf.

This was not simply a way of submerging the ego of the student into that of the great God, Meldrum, it was intended to demonstrate the futility of any personal, subjective approach. For Meldrum, learning to paint was largely synonymous with learning to look. In his first major public lecture, given in 1917, he argued: “The art of painting is a pure science – the science of optical analysis.”

Needless to say there were numerous techniques to master, all of them expounded at great length in an anthology of 1950, titled The Science of Appearances – which has been freshly issued in a new (but expensive) paperback edition. The Meldrumite palette was restricted to only five tones, with outlines being strictly forbidden. This was one of the master’s articles of faith from his earliest days. …

Meldrum’s famous method required a lot of squinting and stepping back from the canvas to compare one’s impression with the true tones of the motif. Some students wore sunglasses to get the appropriate frisson, some put their palettes on trolleys that could be wheeled back and forth. They cared so little for the subject that detractors thought the School motto should be: “Anything’ll do.”

The paintings that resulted were remarkably similar in their blurred edges and smudgy, atmospheric surfaces. Looking at a large number of these works side by side one begins to see the world as a dim, misty, melancholy place. Even though Meldrum despised the word, this penchant for gloom seems to have been a temperamental preference among his students. They liked to paint on rainy, overcast days, which may explain why Melbourne remained the heartland of the movement.

Despite the self-imposed bondage of Meldrum’s method many of these artists were exceptionally talented. Painting in a doctrinaire style that eschewed individuality, squinting at the most ordinary scenery in the rain, they still managed to produce beautiful and poetic pictures.

Following her rediscovery in recent decades, Clarice Beckett is firmly established as a significant figure in Australian modern art. By almost universal assent she is now considered the greatest of the Meldrumites; her previous obscurity being caused by her early death at the age of forty-eight in 1935 and the misfortune of having many of her works in storage eaten by possums.

John MacDonald. “Misty Moderns,” on the Sydney Morning Herald website, November 21, 2009 [Online] Cited 19/03/2021.

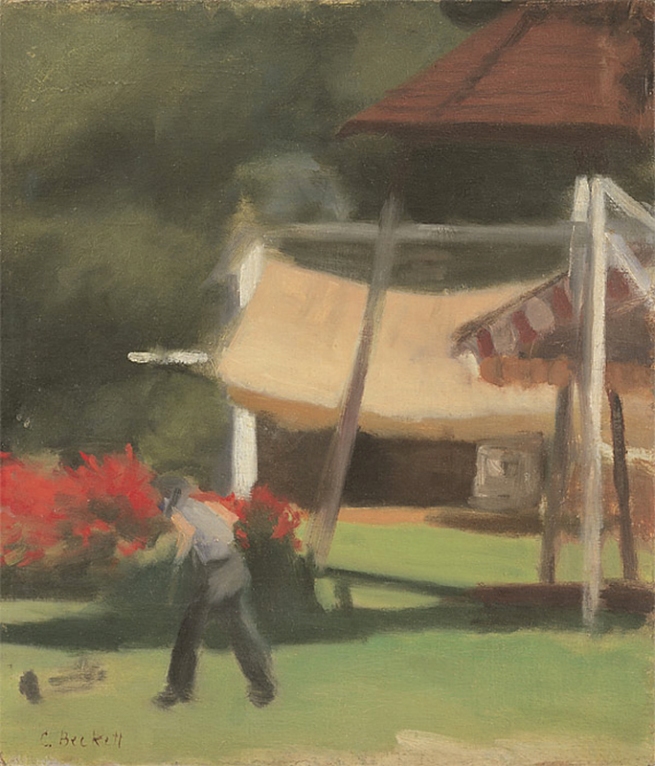

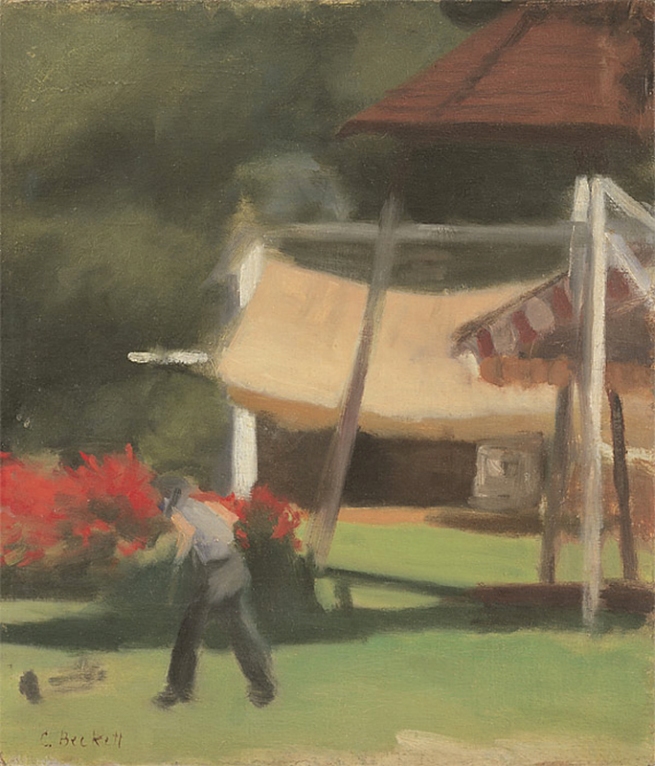

Installation view of the exhibition Clarice Beckett: The present moment featuring Tea Gardens by Clarice Beckett, c. 1933, Gift of Sir Edward Hayward 1980, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, 2021

Photos: Saul Steed

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Hawthorn Tea Gardens

1933

Oil on canvas laid on pulpboard

51.0 x 43.7cm

Gift of Sir Edward Hayward 1980

Art Gallery of South Australia

Installation view of the exhibition Clarice Beckett: The present moment featuring Zinnias (Flower piece) by Clarice Beckett, 1927, Private collection, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, 2021

Photos: Saul Steed

Australian tonalism

Australian tonalism was an art movement that emerged in Melbourne during the 1910s. Known at the time as tonal realism or Meldrumism, the movement was founded by artist and art teacher Max Meldrum, who developed a unique theory of painting, the “Scientific Order of Impressions”. He argued that painting was a pure science of optical analysis, and believed that a painter should aim to create an exact illusion of spatial depth by carefully observing in nature tone and tonal relationships (shades of light and dark) and spontaneously recording them in the order that they had been received by the eye.

Meldrum’s followers – among the most notable being Clarice Beckett, Colin Colahan and William Frater – began staging group exhibitions at the Melbourne Athenaeum in 1919. They favoured painting in adverse weather conditions, and often went out together in the morning or towards evening in search of fog and wintry wet surfaces, which provided increased spatial effects. Their subtle, “misty” depictions of Melbourne’s beaches and parks, as well as its everyday, unadorned suburbia, show an interest in the interplay between softness and structure, nature and modernity.

The movement peaked during the interwar period, and its lingering influence can be seen in experimental works by other Australian artists, such as Lloyd Rees and Roland Wakelin. Although dismissed by many of their art world contemporaries, today the Australian tonalists are well-represented in Australia’s major public art galleries. The minimum of means they used to distil the essence of their subjects has drawn comparisons to the haiku form of poetry, and the movement has been described as prefiguring the late modernist style minimalism. [Tonalism opposed Post-Impressionism and Modernism and is now regarded as a precursor to Minimalism and Conceptualism.]

Text from the Wikipedia website

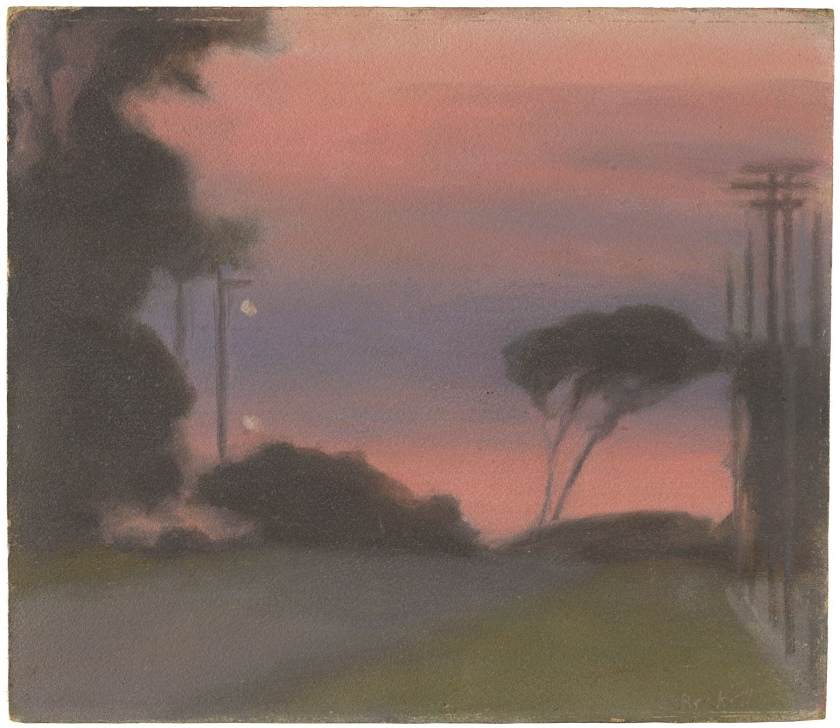

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Evening, after Whistler

c. 1931

Melbourne

Oil on board

Gift of Alastair Hunter OAM and the late Tom Hunter in memory of Elizabeth through the Art Gallery of South Australia Foundation 2019

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Motor lights

1929

Melbourne

Oil on board

Gift of Alastair Hunter OAM and the late Tom Hunter in memory of Elizabeth through the Art Gallery of South Australia Foundation 2019

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Tranquility

c. 1933

Melbourne

Oil on board

Gift of Alastair Hunter OAM and the late Tom Hunter in memory of Elizabeth through the Art Gallery of South Australia Foundation 2019

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Sea Drift

c. 1930

Melbourne

Oil on canvas on board

Gift of Alastair Hunter OAM and the late Tom Hunter in memory of Elizabeth through the Art Gallery of South Australia Foundation 2019

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

Clarice Beckett

Clarice Marjoribanks Beckett (21 March 1887 – 7 July 1935) was an Australian artist and a key member of the Australian tonalist movement. Her works are featured in the collections of Australia’s major public galleries, including the National Gallery of Australia, National Gallery of Victoria and the Art Gallery of South Australia. …

Work

Beckett is recognised as one of Australia’s most important modernist artists, though some have classified her as a ‘daughter of Monet’. In his review of the first of two exhibitions held at the Rosalind Humphrey Gallery in 1971 and 1972, Patrick McCaughey described Beckett as a remarkable Modernist, because of the ‘flatness of the surface in her painting’. Despite a talent for portraiture and a keen public appreciation for her still lifes, the subject matter favoured by her teacher Meldrum, Beckett preferred the solo, outdoor process of painting landscapes. She persistently and diligently painted sea and beachscapes, rural and suburban scenes, often enveloped in the atmospheric effects of early mornings or evening. Candice Bruce describes “a sense of an ever-present melancholy: a vulnerability mixed with a calm that, even if one were in total ignorance of the details of the artist’s life, would still be felt.” Her subjects were often drawn from the Beaumaris area, where she lived for the latter part of her life. She was one of the first of her group to use a painting trolley, or mobile easel to make it easier to paint outdoors in different locations.

Formal qualities and reception

In her mid-thirties, Beckett elucidated her artistic aims in the catalogue accompanying the sixth annual exhibition of the Twenty Melbourne Painters in 1924:

To give a sincere and truthful representation of a portion of the beauty of Nature, and to show the charm of light and shade, which I try to give forth in correct tones so as to give as nearly as possible an exact illusion of reality.

…

By 1931, however, Percy Leason, writing a long review in Table Talk, draws comparison with Rembrandt, Whistler and Corot to say;

Miss Beckett’s work has so much in common with them: there is a like success in achieving the first essential, a convincing illusion of actual space and air and light; the same refinement and delicacy of true colour; the same regard for true form and character; and the same complete indifference to conventions and the mere clever handling of paint for the sake of it. (Leason in the next issue of Table Talk reiterated his praise, calling the show “one of the best exhibitions of the year.”)

However, like her female contemporaries, Beckett faced considerable prejudice from conservative male artists. Meldrum, commenting as late as 1939 on Nora Heyson’s receiving the Archibald Prize, expressed his opinion on women’s capacity to be great artists; “Men and women are differently constituted. Women are more closely attached to the physical things of life, and to expect them to do some things equally as well as men is sheer lunacy […] A great artist has to tread a lonely road. He becomes great only by exerting himself to the limit of his strength the whole time. I believe that such a life is unnatural and impossible for a women,” an attitude he qualified in relation to his favourite pupil Beckett, announcing in the event of her death that “Beckett had done work of which any nation should be proud.”

During her lifetime no Beckett work was purchased for a public collection, though now almost every major Australian gallery holds examples. By 2001 her paintings had achieved six figures at auction.

Australian Tonalism

Tonalism opposed Post-Impressionism and Modernism, but is now regarded as a precursor to Minimalism. The whole movement had been under fierce controversy and they were unpopular amongst other artists and derided as “Meldrumites”. Influential Melbourne artist and teacher George Bell described Australian Tonalism as a “cult which muffles everything in a pall of opaque density”.

Meldrum blamed social decadence for artists’ exaggerated interest in colour over tone and proportion. Beckett’s painting however represents a departure from Meldrum’s strict principles which dictated that tone should take precedence over colour, as commented upon in a newspaper critique of her 1931 solo exhibition. A reviewer of her 1932 Atheneum show expressed her particular version of this as “an adaptation of art to nature, which belongs neither to the realm of the orthodox normalist or the avowed modern, but is a purely individual expression of certain sensations in light, form and colour…” Rosalind Hollinrake, who was largely responsible for Beckett’s revival, notes a use colour to reinforce form, and more daring design, in the later years of the artist’s short life.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Luna Park

1919

Melbourne

Oil on board

Gift of Alastair Hunter OAM and the late Tom Hunter in memory of Elizabeth through the Art Gallery of South Australia Foundation 2019

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Bathing boxes, Brighton

1933

Melbourne

Oil on board

Gift of Alastair Hunter OAM and the late Tom Hunter in memory of Elizabeth through the Art Gallery of South Australia Foundation 2019

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

The red sunshade

1932

Melbourne

Oil on board

Gift of Alastair Hunter OAM and the late Tom Hunter in memory of Elizabeth through the Art Gallery of South Australia Foundation 2019

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Wet day, Brighton

c. 1928

Melbourne

Oil on board

Gift of Alastair Hunter OAM and the late Tom Hunter in memory of Elizabeth through the Art Gallery of South Australia Foundation 2019

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Bathing boxes in the storm

1934

Melbourne

Oil on board

Gift of Alastair Hunter OAM and the late Tom Hunter in memory of Elizabeth through the Art Gallery of South Australia Foundation 2019

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Bathing boxes after the storm

1934

Melbourne

Oil on board

Gift of Alastair Hunter OAM and the late Tom Hunter in memory of Elizabeth through the Art Gallery of South Australia Foundation 2019

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

During the 1920s and 1930s Clarice Beckett surrendered to the sensory impressions of her everyday world with such intensity that the force of her painted observations created an entirely new visual language. The extreme economy of her painting tested her Australian audiences, and yet distinguished her as working at the avant-garde of international modernism. Drawn from national public and private collections, highlights include the artist’s famed ethereal images of commonplace motifs such as lone figures, waves, trams and cars.

Driven by spiritual impulses beyond worldly success, she was a visionary mystic that saw nature as all powerful. Through veils of natural light she captured the eternal in the temporal. Accordingly, the 130 paintings in The present moment will be thematically displayed around shifts in time that chart the chronology of one single day. The exhibition will take visitors on a sensory journey from the first breath of sunrise, through to the hush of sunset and finally a return into the enveloping mists of nightfall.

The Art Gallery of South Australia is renowned for collecting, displaying and publishing the work of modern Australian women artists. Clarice Beckett: The present moment showcases Alastair Hunter OAM’s recent support of the acquisition of 21 Clarice Beckett paintings and proudly announces the AGSA’s ongoing commitment to the promotion and celebration of the work of great Australian women artists.

Text from the Art Gallery of South Australia website [Online] Cited 19/03/2021

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Pavlova, the dying swan

1929

Melbourne

Oil on board

Gift of Alastair Hunter OAM and the late Tom Hunter in memory of Elizabeth through the Art Gallery of South Australia Foundation 2019

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Pavlova, the dying swan

1929

Melbourne

Oil on board

Gift of Alastair Hunter OAM and the late Tom Hunter in memory of Elizabeth through the Art Gallery of South Australia Foundation 2019

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

The cottage San Remo

c. 1931

Melbourne

Oil on board

Gift of Alastair Hunter OAM and the late Tom Hunter in memory of Elizabeth through the Art Gallery of South Australia Foundation 2019

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Sunset

Nd

Melbourne

Oil on card

Gift of Alastair Hunter OAM and the late Tom Hunter in memory of Elizabeth through the Art Gallery of South Australia Foundation 2019

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Across the Yarra

c. 1931

Oil on cardboard

32.5 × 45.9cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased through The Art Foundation of Victoria with the assistance of the Marjorie Webster Memorial, Governor, 1985

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Marigolds

c. 1925

Oil on board

40.5 x 30.5cm

Unknown photographer

Portrait of Clarice Beckett

Nd

Art Gallery of South Australia

Further works by Clarice Beckett

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

(Phillip Island from San Remo)

c. 1930-1933

Oil on cardboard

18.6 × 23.7cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Gift of Jennifer Rogers in memory of her father, Ron Lilburne, 2008

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Taxi rank

c. 1931

Oil on canvas on board

58.5 x 51.0cm

National Gallery of Australia

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

The Red Bus

Nd

Oil on canvas on composition board

36.5 x 44cm

The Red Bus is an excellent example of one of Clarice Beckett’s outer Melbourne suburban street scenes. It expresses her characteristic ability to catch the spontaneity of a lived moment, in an intensely lyrical and poetic manner. She found a distinctive beauty in the ordinary objects such as telegraph poles, strips of road, trams, cars, buses and the daily activity taking place in the street.

In this painting the everyday scene is made extraordinary by an atmospheric dreamlike slice of landscape which in turn is contrasted with the subtle feeling of action. This comes from the sensation of the motion of the bus travelling uphill in opposition to the gently felt abstract figures moving away downhill. Beckett’s use of the enveloping haze does not detract from the effect of the fresh atmosphere of a bright sunny morning in this painting, but serves to unify the scene and evoke a sense of quiet calm.

Beckett achieves this with her famed use of soft dissolving edges, a difficult technical feat employed to create an atmospheric reality of emotional content, a characteristic of her modernist style. The lumbering red bus moves towards the viewer and alerts our attention with its bright colour and dark windows which eerily suggest no visible driver. This creates an eerie feeling of uncertainty and mystery which is reminiscent of the paintings of Edward Hopper who worked at a similar time to Beckett although half a world away. Beckett’s modernism lies in her minimalist aesthetic and her ability to arouse an emotional response with her images.

She was hailed for making the tarred road artistically acceptable and as the critic Mervyn Skipper wrote in The Bulletin 29 October 1930: “She has become the most original painter. She has merely abandoned conventions which earlier artists brought from Europe, has in fact done quite quietly and as if by accident what Australian poets and writers are only just beginning to do.”

Beckett was an innovative and extremely important figure in Australia’s art history during the 1920’s and early 30’s. Her work is seldom found in auction rooms or galleries, and The Red Bus is a part of the first private collection to have ever come up for sale. Her influence and inspiration has been wide in contemporary Australian art beginning fifty years after her death. Her original label of artist’s artist continues to be vindicated, although a more receptive public now are beginning to appreciate the beauty and allure of her ability to capture transient moments of life and the calming effect of her beautiful meditative images.

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Winter Morning, Beaumaris

c. 1927-1931

Oil on canvas

39.3 x 55cm

Beckett was renowned for her innovative compositions, her remarkable poetic lyricism and the dramatic intensity she was able to create. This work shows the essence of the atmospheric moment as well as creating an illusion of the actual temperature and a sense of atmospheric space all characteristic traits of the artist.

Winter Morning Beaumaris has a typically Melbourne winter mood and is a very strong image due to the compositional choice where the image is dramatically strengthened by a stark tree trunk which contrasts with Zen-like meditative softness of shifting fog shrouding the headland and flora. Subtle in its poetic style, it holds the wonderful sense of the mysterious unknown that sea fog brings to the landscape. Another characteristic of Beckett’s work was her ability to create a sense of place and a sense of the actual temperature of the subject. This was due to her ability to mix the finest degrees of tonal range that the landscape before her held and her ability to run her soft edges into each other to form a unified and genuine sense of airy atmosphere. This is even difficult to achieve in a studio environment.

This large size work is a rare example of a limited number (approx. 10) paintings on canvas and stretcher that survived the destruction of at least 60 works of this size and even larger which were burnt straight after her death. The challenge of painting an impression of nature en plein air on this size canvas is immense. Fleeting sunsets, sunrises and gathering dusk and moving sea fogs last for only minutes and the image and tones in a landscape changes constantly. The painter must work with enormous speed and a great knowledge of tones, being able to know what colours to mix to achieve the perfect reflection of what is being painted. Incredible skill with handling the paint and keeping a freedom of the impression is evident in this image. Beckett was greatly admired for achieving all those requirements of painting to achieve a sense of living breathing elusive reality.

This work was painted from Beckett’s favourite haunts on the cliff tops along the foreshore looking out to Port Phillip Bay. It shows her classic poetic lyricism and a contemporary daring with her sparing use of paint and her paring back of form.

Rosalind Hollinrake on the Lauraine Diggins Fine Art website [Online] Cited 08/03/2021.

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Out Walking

c. 1928-1929

Oil on canvas on board

29 x 34.5cm

Out Walking, c. 1928-29, depicts a view close to Clarice Beckett’s home in the Melbourne bay-side suburb of Beaumaris. Beckett moved there from Casterton, near Bendigo, in 1919 with her parents whose health was failing; and the suburb is aptly named, being a truncation of the French ‘beau marais’, meaning ‘beautiful marsh’. Following Melbourne’s European settlement, Beaumaris became a popular holiday destination noted for its winding coastal trails, atmospheric tangles of ti-tree and capacious views over Port Phillip Bay. At the base of the weathered sandstone cliffs lie secluded beaches and rock ledges full of fossils. Beckett would return to these familiar sites many times throughout her career – and in all weathers – to such an extent that it is impossible to walk the same territory today and not see it through her eyes.

The family lived at ‘St. Enoch’s’ in Dalgetty Road, and Out Walking shows that street’s intersection with Beach Road, with the shimmering blue of the bay beyond. Beckett would already have been a familiar sight to locals, as she walked the paths with her hand-built painting trolley. Her painting technique was aligned to the group of artists called the ‘tonalists’ who gathered around Max Meldrum; and the trolley, in fact, had a particular use beyond mere transport. ‘Tonalist works were created to be viewed, when complete, from a distance of about six metres (approximately twenty feet). The painting process required much to-ing and fro-ing between the subject and the observation point by both the painter and the painting … Consequently to assist with this process, many of the artists constructed custom-built wheeled easels or painting trolleys. Clarice Beckett was one of the first to adopt a trolley.’1 This description of the dedicated process involved in constructing such images belies the spontaneous sensation given by Out Walking, that of a snapshot briefly glimpsed before being captured in a hurried application of paint. As noted by the curator Ted Gott, ‘Beckett’s compositions have an elusive, phantasmic mystique. [By comparison] everything in our world today is sharp, crystal clear, hard and fast.’2 Not surprisingly, critics often attached the term ‘Whistler-ian’ to her work.

Judging by the long coats, Out Walking was painted on an early Spring morning, with the overcast sky punctured at points by sunshine which illuminates patches of the sandy road and grassed verge. To the left, a carer in a blue coat watches a red-caped girl as she rushes towards the intersection. Two older ladies in grey hats and coats walk the other way, deep in conversation; and, crunching the unsealed road between them, the hand-propelled cart in the middle-centre. The rows of telegraph poles create a frame within the frame, anchored horizontally by the white fence line indicating the cliff path. To the left, a flash of muted red indicates an emergency box, a tiny detail of colour which links visually to the girl’s cape and the man’s cart. Like the companion work with the same title,3 Beckett’s paintings of pedestrians are predominantly solo studies, making this version of Out Walking one of the rarer compositions to include small groups of people.

We are grateful to Rosalind Hollinrake for her assistance with this catalogue entry.

Andrew Gaynor. “Clarice Beckett, Out Walking, c. 1928-29,” on the Invaluable website [Online] Cited 08/03/2021.

1/ Lock-Weir, T. Misty Moderns: Australian tonalists 1915-1950, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, 2008, p. 46

2/ Gott, T. ‘Foreword’, Clarice Beckett: 1887-1935, Niagara Galleries, Melbourne, 29 February – 1 April 2000, p. 5

3/ Rosalind Hollinrake describes this alternate version as being of Beckett’s young niece Patricia walking along the cliff top path

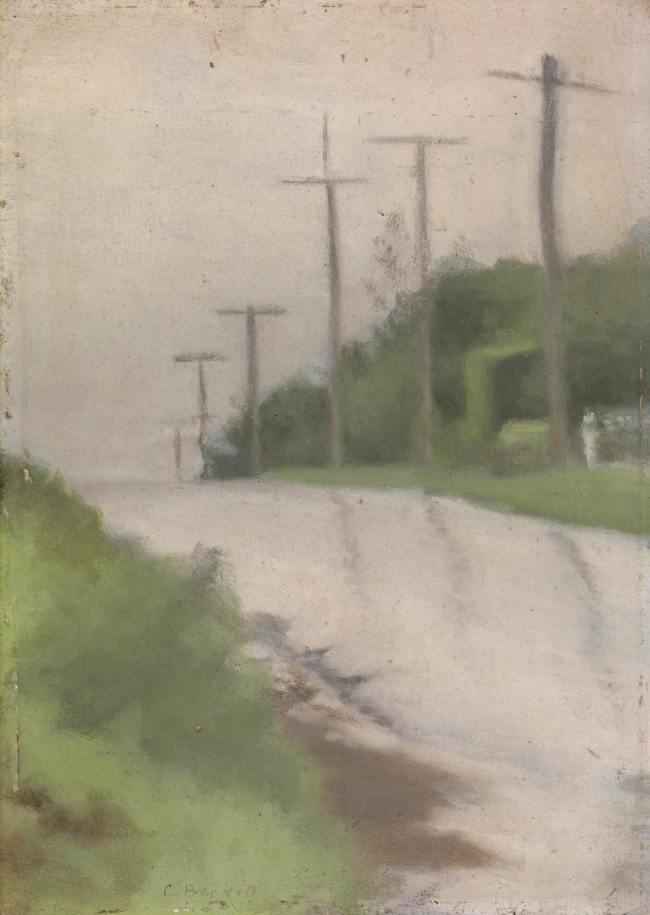

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Silent Approach

c. 1924

Oil on board

48.0 x 58.0cm

National Gallery of Australia

Clarice Beckett, like the visual arts equivalent of a haiku master, was able to distil the essence of her subjects with a minimum of means. Silent approach is a particularly fine example of the strength and delicacy of Beckett’s approach in which no mark is wasted. While the painting exudes a pervasive stillness, the green vegetation in the foreground appears to have a vitality of its own, extending out to the shadowy figure. This fluid organic form is balanced by the vertical power pole (with echoes of the form receding into the distance), a classic Beckett subject indicating modernity. The interplay between structure and softness gives way on the left to the foggy atmosphere in which space itself is the dominant aspect.

A magical aspect of Silent approach is that, for all the restraint of Beckett’s palette, subtle tonalities and subject matter, it is full of presence and imbued with an inner life. In 1919, Beckett moved with her parents to the bayside suburb of Beaumaris, an environment that provided her with evocative inspiration. Despite many challenges, she was driven to paint every day and in all weathers. She also exhibited regularly. While each work is self-sufficient, she felt considerable pleasure in seeing the cumulative effects of her paintings shown together – each illuminating the other.

Beckett’s interest in a tonal approach was informed by Max Meldrum, an influential teacher in Melbourne who espoused a theory of Tonalism. Meldrum considered her his star pupil and, before long, her independent vision shone through – a fact that he acknowledged in a tribute to her at a memorial exhibition at the Athenaeum Gallery in 1936. Tragically, she died far too early, at the age of forty-seven, from pneumonia after catching a chill while painting in inclement weather.

After Beckett’s death, a large number of her paintings were left to deteriorate in a barn and were unsalvageable. Thanks to the great generosity of a number of donors, the Gallery has been able to add Silent approach, one of her most accomplished remaining works, to the national collection.

Deborah Hart, Senior Curator of Australian Painting and Sculpture post 1920 in artonview, issue 80, Summer 2014.

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Princes Bridge Station

c. 1928

Oil on board

25.0 x 35.0cm

Private collection

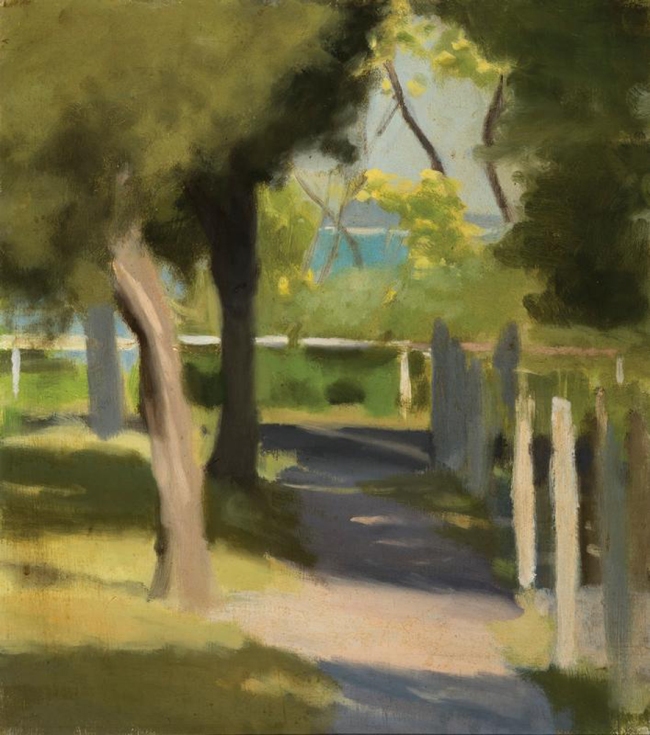

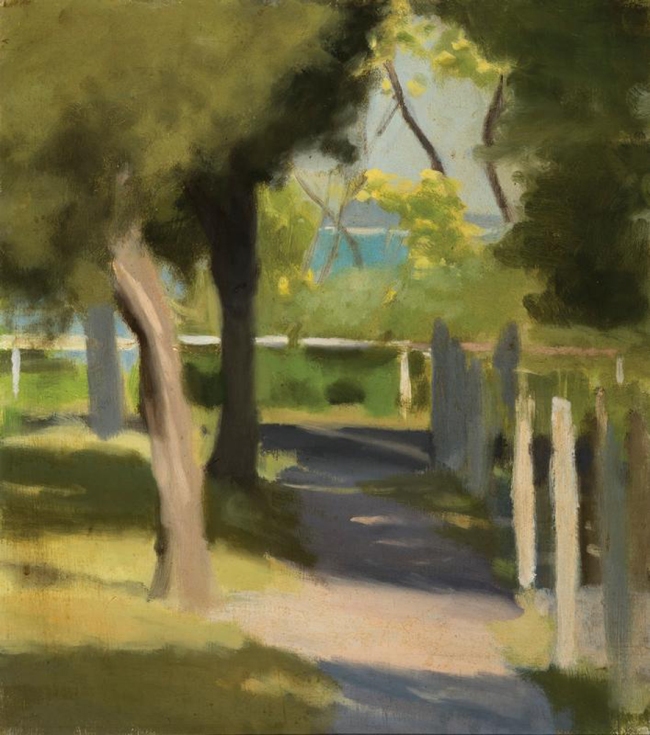

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Chestnut Avenue, Ballarat Gardens

c. 1927

Oil on canvas board

30.5 x 40.5cm

Private collection

Clarice Beckett’s connection with Ballarat was more than that of a happy visit to its beautiful lakeside gardens in 1927. Born in Casterton, she attended school in Ballarat at Queen’s College and also studied charcoal drawing under a Miss Eva Hopkins, before her family moved to Melbourne in 1904. Some years later, in 1914 she returned to art, studying drawing under Frederick McCubbin at the National Gallery School, and then painting with Max Meldrum from 1917. While she became Meldrum’s ‘star’ pupil, the poetic and philosophical inclination of her art was, no doubt, encouraged by McCubbin, whose philosophising had led to him being dubbed ‘The Proff’ by his friends. From 1919, when her parents retired to the Melbourne suburb of Beaumaris, its beach sides and surrounds became a major inspiration for her paintings. Captured early and late in the day, in different seasons, and focused on the everyday of unglamorous roads and telegraph poles, or bathing boxes, through her art the ordinary was metamorphosed into paintings of profound beauty. Evening Light, Beaumaris, c.1925, in the collection of the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, and Sandringham Beach, c. 1933, in the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra are captivating examples of the prosaic transformed into the poetic. In Melbourne city she painted light-filled streets on wet nights and tranquil views across the Yarra River, often embraced by the spans of its most handsome bridges. One such major work, Princes Bridge, 1930, was sold by Deutscher and Hackett in Melbourne on 29 April 2009, lot 100.

Paintings of foggy mornings, dreamy sunsets, Collins Street, the Dandenongs and Olinda were among the sixty works that made up Beckett’s 1927 exhibition, which included Chestnut Walk, Avenue Gardens, c. 1927. There were only two other Ballarat subjects in the show – Ballarat Gardens and Ash Tree, Ballarat Gardens, clearly rare examples in her oeuvre. Ballarat Botanical Gardens would have appealed to Beckett both through recollections from childhood and in their own right as highly significant cool climate gardens. Established in 1858, they are noted for their many mature trees, the avenue of Horse Chestnuts being one of the four main axes running north south through the gardens.1 Beckett captures the quiet, natural grandeur of the avenue in Chestnut Walk, Avenue Gardens, greens contrasted with terracottas, verticals with horizontals, classic in balance. The shadows are as substantial as the trees that cast them, adding a sense of drama within the harmony of forms and colours wrapped in stillness. According to Beckett scholar and curator, Rosalind Hollinrake, one of the most striking features of Beckett’s art is her sense of place, which ‘… became heightened by the growing intimacy she developed for certain locations’.2 While this has been noted in her Beaumaris works, Chestnut Walk, Avenue Gardens captures perfectly the stately feel and calm of the place. Its sense of time past is touched by the universal through a seemingly disarming simplicity that invites contemplation of its profundity. Of art, Beckett said her aim was: ‘To give a sincere and truthful representation of a portion of the beauty of Nature, and to show the charm of light and shade, which I try to set forth in correct tones so as to give as nearly as possible an exact illusion of reality’.3

David Thomas on the Invaluable website [Online] Cited 13/03/2021

1/ Since 1940 this avenue has also accommodated the avenue of Prime Ministers’ bronze busts. The Botanical Gardens are rich in earlier sculptures, especially Italian marble figures donated by Thomas Stoddart in 1884 and the later Flight from Pompeii and others in the Statuary Pavilion of 1887

2/ Hollinrake, R., Clarice Beckett: Politically Incorrect, The Ian Potter Museum of Art, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, 1999, p. 21

3/ Clarice Beckett, Twenty Melbourne Painters, 6th Annual Exhibition Catalogue, Melbourne, 1924

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Beaumaris Foreshore

Nd

Oil on board

37 x 29cm

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Evening landscape

c. 1925

Oil on cardboard

35.5 x 40.7cm

Purchased 1974

National Gallery of Australia

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

From the Boatshed Roof

Nd

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

The Bus Stop

1930

Oil on canvas

41 x 34cm

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

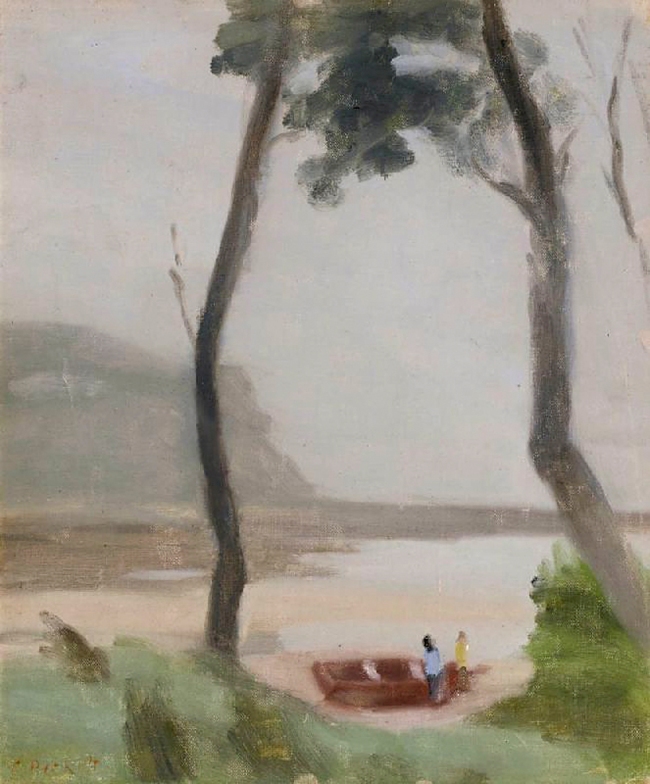

Early Morning (The Fishermen)

c. 1930

Oil on canvas on board

45.5 x 38cm

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Evening light, Beaumaris

c. 1925

Oil on canvas on cardboard

0.3 × 40.2cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Presented by the National Gallery Society of Victoria to mark the retirement of Paton Forster, General Secretary of the Society (1968-1989), 1989

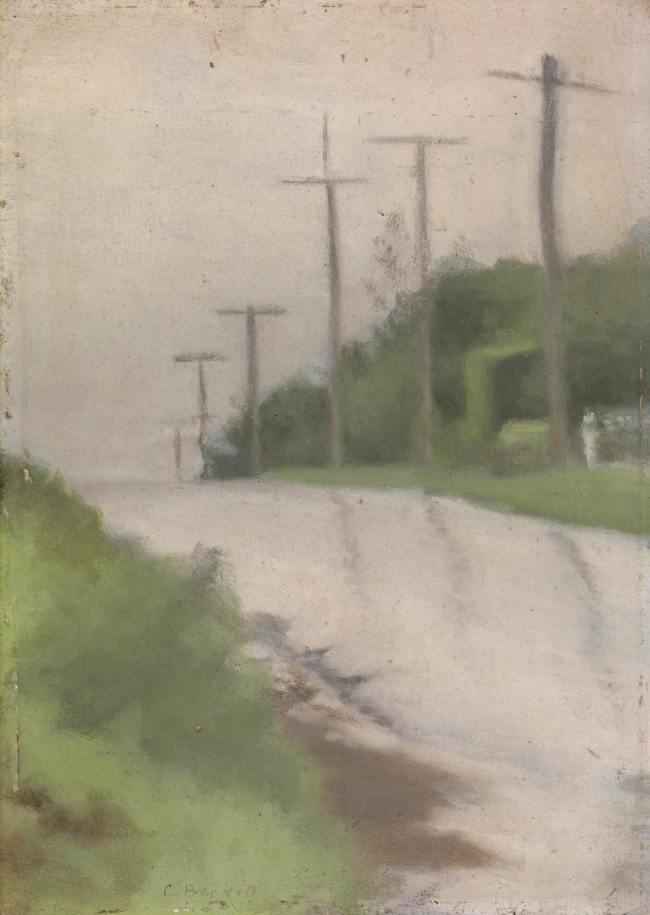

‘For an artist of her time, and especially a woman artist, it must have been a leap of faith on her part to paint four ‘ordinary’ poles as revered and exalted lyrical subject matter. This was not only innovative, it was nothing short of daring.’

Painting ordinary elements of modern suburban life which included wet roads, telegraph poles, motor vehicles, bathing boxes and petrol bowsers was unique for its time. In contrast to the popular idealised views of rural landscapes often painted in panoramic scale, Beckett showed a sensitivity to beauty in the everyday in her modestly scaled paintings. In Evening light Beaumaris (c. 1925), seen above, she has taken a humble telegraph pole and turned it into something worthy of contemplation.

Hollinrake, Rosalind. ‘Clarice Beckett’, The Ordinary Instant, The Gallery at Bayside Arts and Cultural Centre: Melbourne, 2016, p. 11 quoted in Anonymous. “Her Own Path: Clarice Beckett,” in the Bayside City Council website [Online] Cited 08/03/2021.

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Evening on the Yarra from Alexandra Avenue

Nd

Oil on pulpboard

29 x 39.5cm

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Dusk

Nd

Oil on canvas on pulpboard

24.5 x 34.5cm

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Anglesea

1929

Oil on pulpboard

24.5 x 34.5cm

An uncharacteristically sun-drenched work, this scene depicts Beckett’s companions on the foreshore in front of what is now the Anglesea Caravan Park. A land of rich resources for the Wathaurong people, the area had been popular with campers from Geelong since the 1860s. Like all of Beckett’s outdoor images, it was painted in one plein air session, capturing her friends on a perfect summer’s day without a cloud in the sky, and only a single distant yacht sharing the experience. Beckett has utilised broad, simplified bands of colour – caramel and blue highlighted by white – with the only pronounced brush stokes representing the waves rolling to the shore and the casual poses of the figures. Anglesea, is also an environmental record of the time for the foreshore has been much changed by ninety years of storms and erosion. The beach remains but the ochre-coloured limestone cliffs have crumbled leaving the shore strewn with large boulders. Beckett included a group of Anglesea paintings in her solo exhibition at the Athenaeum Gallery in October 1930.

Andrew Gaynor. “Anglesea, 1929,” on the Invaluable website [Online] Cited 08/03/2021

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Beach Road after the rain (Street scene)

c. 1927

Oil on cardboard

35.7 × 25.5cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Bequest of Harriet Minnie Rosebud Salier, 1984

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Sunset across Beaumaris Bay

c. 1930-1931

Oil on composition board

Bayside City Council Art and Heritage Collection

Purchased 2014

In 1919, her father retired due to ill health and the Beckett family moved to the Bayside suburb of Beaumaris, living in a newly built weatherboard house on the corner of Beach Road and Tramway Parade. Built without any consideration for Clarice’s painting practice, the new house had no space for an art studio, however she cleverly constructed a small cart which would hold her easel and painting equipment which she could transport to the sites she was to paint around the area. She had a relentless work ethic, painting most days of her life and became a known character in Beaumaris, wearing her dowdy art clothes as she painted the foreshore and suburban streets, occasionally selling a work to a local passer-by.

Aside from a brief stint teaching art at a girl’s school in Mount Macedon in 1927 and yearly painting trips to San Remo with fellow Meldrumites, Beckett was to remain in Beaumaris for the rest of her life and many of her paintings are synonymous with the area.

Anonymous. “Her Own Path: Clarice Beckett,” in the Bayside City Council website [Online] Cited 08/03/2021.

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Cliff path

c. 1929

Oil on composition board

Bayside City Council Art and Heritage Collection

Purchased 2000

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Ship at sea or Warship on the Bay

c. 1925

Oil on canvas on board

30 x 41.2cm

Courtesy Cruthers Collection of Women’s Art, The University of Western Australia

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Reflected Lights, Beaumaris Bay

c. 1930-1931

Oil on composition board

Bayside City Council Art and Heritage Collection

Purchased 2014

Max Meldrum believed that the tonal values (areas of dark and light) of a subject were of utmost importance and privileged them over detailed draughtsmanship or the use of colour. Despite being criticised for it, Beckett embraced Meldrum’s theories and her work shows his influence in their limited colour and handling of tone.

In Reflected lights, Beaumaris Bay (c. 1930-1931), seen above, through an economy of brushstrokes and paint, Beckett has captured the hazy quality of her nocturnal coastal scene. Here Beckett records the atmosphere and unique evocation of the reflected lights rather than focusing on details.

Anonymous. “Her Own Path: Clarice Beckett,” in the Bayside City Council website [Online] Cited 08/03/2021.

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

(Summer Day, Beaumaris)

c. 1933

Oil on canvas on board

55 x 45cm

Writing in the catalogue of the sixth annual exhibition of the Twenty Melbourne Painters in 1924, Clarice Beckett defined her artistic aim as being ‘To give a sincere and truthful representation of a portion of the beauty of Nature, and to show the charm of light and shade, which I try to give forth in correct tones so as to give as nearly as possible an exact illusion of reality’.1 A student of the Melbourne tonal realist painter Max Meldrum, whose theory and teaching of art as a science based on optical analysis upset conservative art circles and presented a direct challenge to the strict academic approach of the National Gallery School, Beckett absorbed his methods but developed a personal style and distinctive range of subject matter that made her work unique within early twentieth century Australian art. As curator Rosalind Hollinrake has noted, ‘She saw in soft focus and there were no edges in her work. She was concerned with achieving an harmonic atmospheric unity … While many paintings were completed in situ, many others were worked upon indoors, taken from colour notations, sketches and memory with later imaginative touches.’2

Beckett and her family moved to Beaumaris in 1919, the Melbourne bayside suburb where they had previously spent many summer holidays. The streets and surrounding coastal landscape of this and other nearby areas including Black Rock, Sandringham and Brighton soon became favourite subjects for her painting. In a vivid expression of her determination to succeed as a professional artist, Beckett responded to her father’s refusal to build a dedicated studio by constructing a small cart to house her painting materials which she wheeled around as she worked, using the lid of her painting box as a mobile easel.3 Her first solo exhibition was held at the Athenaeum Gallery, Melbourne in 1923 and in another measure of her drive and commitment, Beckett continued to exhibit there annually throughout the next decade before her premature death from pneumonia in 1935. During these years she reportedly painted almost every day, six hours in the morning and another six in the evening when, like so many other female artists, she worked at the kitchen table.

A gift from the artist to a friend which is still housed in its original Thallon frame, (Summer Day, Beaumaris), c. 1933 is classic Clarice Beckett. Tall gnarled trees shaped by their coastal environment and a row of bathing boxes – a familiar feature of Melbourne’s bayside beaches that appears frequently in her work – provide the backdrop for a trio of figures walking along the beach. The heat is palpable, glimpses of the pale bleached blue sky appear as part of a scene that has been recorded quickly and viewed through the haze of a hot summer afternoon. Her mature colour sense comes to the fore in this work, the muted tones of the trees enlivened by the subtle play of the pinks, brown and ochres of the bathing boxes and the brilliant flashes of blue and yellow that attract the eye to the movement of the foreground figures. Beckett found a seemingly endless array of inspiration in her immediate surrounds and when asked why she didn’t travel overseas replied, ‘Why would I wish to go somewhere else … I’ve only just got the hang of painting Beaumaris.’4

Kirsty Grant on the Invaluable website [Online] Cited 13/03/2021

1/ Beckett, C., Twenty Melbourne Painters 6th Annual Exhibition Catalogue, 1924 quoted in Hollinrake, R., Clarice Beckett: Politically Incorrect, exhibition catalogue, The Ian Potter Museum of Art, Melbourne, 1999, p. 19

2/ Hollinrake, R., ibid., p. 17

3/ Op. cit., pp. 14-15

4/ Mundy, A., quoted in interview with Hollinrake, R., op. cit., p. 24.

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

(At Rickett’s Point, Beaumaris)

Nd

Oil on canvas on composition board

35.5 x 45.5cm

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Rose and Grey

c. 1928-1929

Oil on pulpboard

27.5 x 37.5cm

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

After Sunset

c. 1929

Oil on canvas on board

26 x 29cm

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Evening on the Yarra

Nd

Oil on board

35 x 39.5cm

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Evening Calm

c. 1928

Oil on board

40.5 x 30.5cm

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Saturday

Nd

Oil on pulpboard

30.5 x 23.7cm

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Collins Street

Nd

Oil on board

39.5 x 29.5cm

Time has been Clarice Beckett’s friend both in terms of her art and her reputation. Largely overlooked during her lifetime, her posthumous recognition as one of Australia’s leading modernists has now far surpassed her initial cool reception at the hands of critics. Beckett’s interest in the everyday features of modern life were long captured through the poetic and ephemeral half-light of dusk and dawn or the soft darkness of the evening light.

To great effect, Beckett employs a rose-gold ambient light in City Street, Melbourne c. 1925 to reveal the dual realities of her hometown where cars share the road with a horse-led delivery cart and a pedestrian in transit – not an uncommon sight, but perhaps also the artist’s subtle signifier of transition as Melbourne transforms itself into the metropolis we know it as today.

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

The Yarra, Sunset

c. 1930

Oil on board

30.5 x 35.5cm

‘When we look back at the 20th century from a vantage point in the next, certain Australian artists stand out, not just for the aesthetic quality of their work, but also for their significant contribution to our understanding of what constitutes the Australian identity. Clarice Beckett is one such artist. Her works capture the essence of Australian city life, in particular that of Melbourne and more specifically that of the bayside suburbs, at a time between the World Wars when the advent of the modern age was signified by the motor car and the ubiquitous telegraph pole’.1

Although enjoying universal admiration and acclaim today, Clarice Beckett’s highly evocative works that celebrated modernity and the quiet beauty of suburbia were nevertheless challenging for her time. Not only was the momentous task of expressing Australian values in landscape painting a distinctly male prerogative, with flower pieces and indoor scenes the only subject matter deemed suitable for women artists. Moreover, the ridicule and critical denigration she frequently encountered in reviews of her paintings was the direct result of her association with her teacher, tonal realist painter Max Meldrum a ferociously argumentative man whose theory and teaching of art as a science based upon exact optical analysis upset conservative art circles and undermined the strict academic approach endorsed by the National Gallery School. Indeed, that Beckett never compromised her unique vision, continuing to paint ‘against all odds’ and that today her legacy endures despite near obscurity at the time of her death in 1935 and the vast destruction of her works subsequently poignantly highlights the compelling and inspirational nature of her achievements.

Recalling Whistler’s lyrical nocturnes, The Yarra, Sunset, c. 1930 offers one of the most exquisite elaborations of the artist’s signature motif the city enveloped in a rosy toned, transparent veil of luminosity evoking the last moments of twilight. Painted on the Richmond side of the Yarra River, from a position near the Chapel Street bridge, the composition features the railway bridge still present today (although altered in appearance) that carries busy suburban trains to and from the city, with the tall gothic spires of the city churches, Scots and the Independent, just perceptible in the palest silhouette of the background. Although conveying a very definite sense of time and place Melbourne of the 1930s paradoxically the work also bears an unmistakable sense of the universal, of silence within its stillness. Rich in lyricism and beauty, it encapsulates the artist’s preference for early evening subjects which, importantly, was not simply to enhance poetic effect. Rather, Beckett delighted in the technical challenge of capturing the essence of her subject within the fleeting moment of observing the transient, atmospheric effects of light to develop delicate tonal nuances that blurred the boundaries between reality and illusion. As the artist herself aptly elucidated in the catalogue accompanying the sixth annual exhibition of the Twenty Melbourne painters in 1924, her artistic aim was always ‘To give a sincere and truthful representation of a portion of the beauty of Nature, and to show the charm of light and shade, which I try to give forth in correct tones so as to give as nearly as possible an exact illusion’.

No author. Text from the Invaluable website [Online] Cited 13/03/2021

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Yacht at Sunset

c. 1928

Oil on board

38 x 32cm

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

The Old Model T Ford

Nd

Oil on board

43 x 52cm

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Sunset Glow

1928

Oil on pulpboard

24.5 x 34.5cm

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Path to the Beach

Nd

Oil on board

49 x 43.5cm

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Morning Ride

Nd

Oil on canvas on composition board

31 x 36cm

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Dusk

Nd

Oil on board

28 x 41cm

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Evening, St Kilda Road

c. 1930

Oil on board

35.5 x 40.5cm

Times of transience and soft-focus realism unite in the art of Clarice Beckett, suited ideally to sunrises and sunsets, foggy days and heat haze. Evening, St Kilda Road, c. 1930 provides the perfect moment as Beckett cloaks the city scene in a diaphanous veil, highlighted by lights and anchored in the darker forms of cars and trams. Its aesthetic appeal is enormous. But there is twofold pleasure in the reminiscence of a scene well known to Melburnians from a time less crowded than today. The absence of narrative allows for the better presentation of beauty, like music, free from the demands of verisimilitude. As Beckett once said, ‘My pictures like music should speak for themselves.’1 The likeness was appreciated in her own time, as witness The Bulletin art critic, who said, when reviewing her solo exhibition at the Athenaeum Hall in 1930, ‘Her counterpoint is so simple in its elements that the intrusion of the slightest false accent would destroy the harmony.’2 Therein lies a happy paradox. The stillness which envelops her paintings, allies itself to silence, leitmotifs wherein comes so much of the magic of her art. In painting, as in music, there is harmony, rhythm, and colour. Painting gives you its pleasures in a moment, its realms of silence are unique. The seeming simplicity with which Beckett creates profoundly moving visual statements is disarming. While her subjects are the everyday, her creativity transforms the pedestrian into poetic vision.

While Beckett painted many scenes of Melbourne’s bayside beaches – Silver Morning (Near Beaumaris), c. 1931 or Sandringham Beach, c. 1933 (National Gallery of Australia, Canberra) – she found the city of Melbourne rich in subject matter, especially the River Yarra and its bridges. City street scenes include Collins Street, Evening, 1931 (National Gallery of Australia) and Taxi Rank, c. 1931. The latter, with its lights reflecting on wet roads, is so free and painterly that it might pass for a work of lyric abstraction. As in Evening, St Kilda Road, the illusion of depth is halted either by reflection or string of lights, with paint thin, and sky and ground similar in tone to maintain a flatness of the picture plane. Beckett seeks no illusion of reality, preferring the beauty of creativity and its inner harmonies. St Kilda Road and the suburb of St Kilda itself featured often as a sources of inspiration, as in St Kilda Road, Wet Night, and from her 1923 exhibition Sand Pump, Foreshore, St Kilda and Grey Morning, St Kilda. The mellifluous luminosity and handling of tone in Evening, St Kilda Road recalls the lyricism of Whistler in a nocturne, mellow of poesy, and dreamily romantic.

David Thomas on the Invaluable website [Online] Cited 13/03/2021

1/ Beckett, quoted in R. Hollinrake, Clarice Beckett: Politically Incorrect, Ian Potter Museum of Art, University of Melbourne, 1999, p. 19

2/ The Bulletin, Sydney, 29 October 1930, p. 33

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Warm Shallows

c. 1930

Oil on card

21 x 25cm

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Summer Morning, Beaumaris

Nd

Oil on pulpboard

22 x 31cm

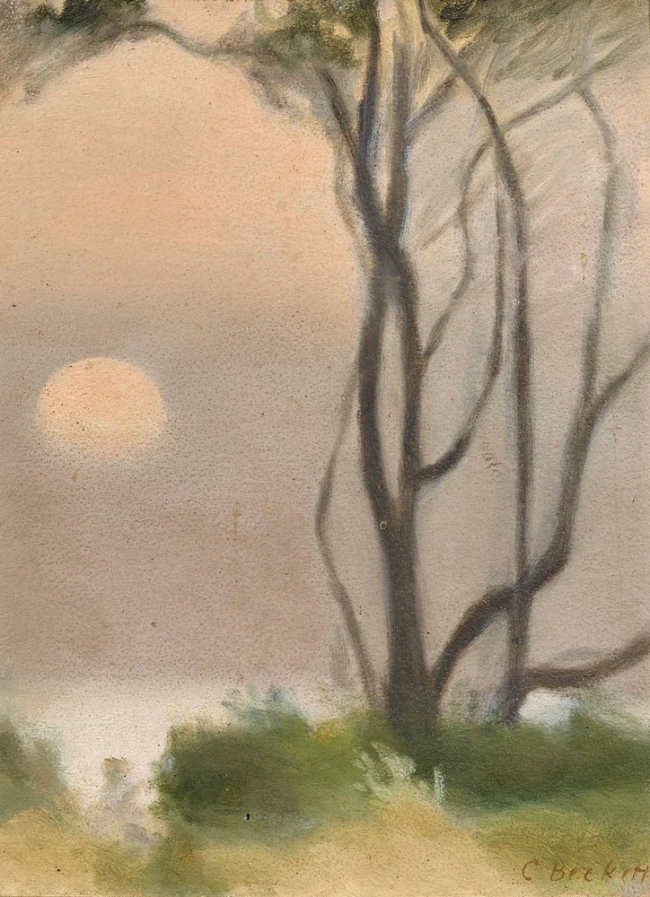

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Moonrise Beaumaris, Sunset and Trees

Nd

Oil on pulpboard

17.5 x 19.5cm

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Wet Evening

c. 1927

25.7 x 30.4cm

Oil on cardboard

Castlemaine Art Museum, Maud Rowe Bequest, acq. 1937

Clarice Beckett (Australia, 1887-1935)

Boatshed, Beaumaris

c. 1928

Oil on cardboard

30.5 x 36.0cm

Castlemaine Art Museum, Maud Rowe Bequest, acq. 1937

Art Gallery of South Australia

North Terrace Adelaide

Public information: 08 8207 7000

Opening hours:

Daily 10am – 5pm (last admissions 4.30pm)

Art Gallery of New South Wales website

LIKE ART BLART ON FACEBOOK

Back to top

You must be logged in to post a comment.