Exhibition dates: 10th February – 21st May 2018

As is so often the case with an artist, it is the early work that shines brightest in this posting.

The works from On the Alp possess an essential power; the daring capture of actions and performances by the international avant-garde of the day make you wish you had been there; and the installation photograph of ‘The Knie’, Kunsthalle Basel in 1983 (below) makes me want to see more of his 1980s installations, with their shift in scale and repetitive nature. There are no more examples online, but a couple of photographs can be seen in the first installation photograph below.

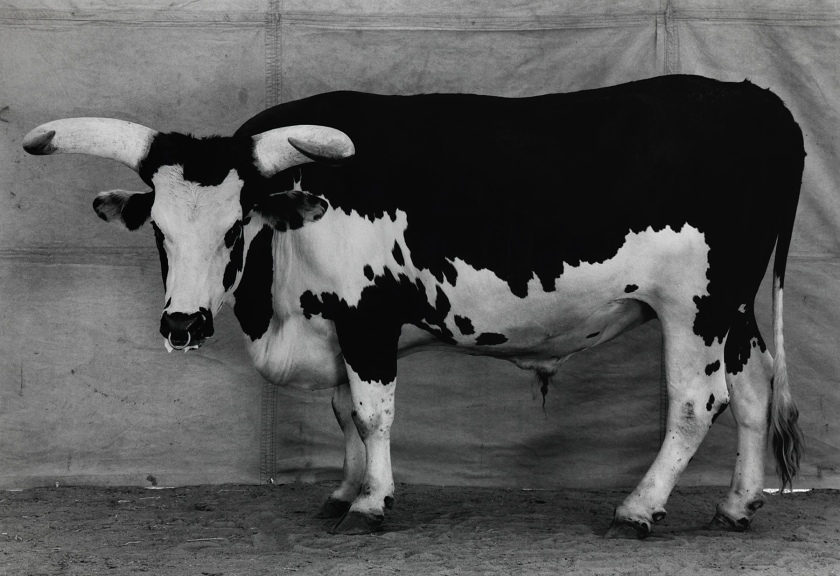

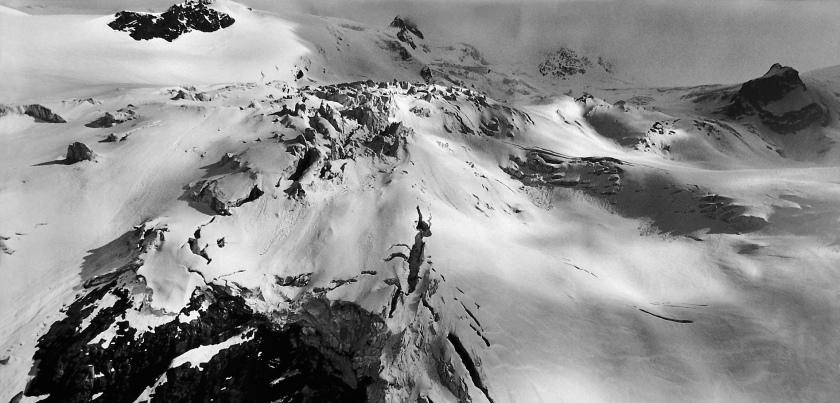

I can leave the underwhelming aerial, cloud and landscape work well alone. There are many people in the history of photography who have taken better photographs of such subject matter. His life-sized photographs of animals again do nothing for me. They possess a reductive minimalism riffing on the canvas backgrounds of Avedon blown up to enormous size (as in most contemporary photography, as if by making something large the photograph gains aura and importance) but they lead nowhere. Perhaps in their actual presence (the physicality of the print) I might be transported to another place, but in reproduction they are a one-dimensional non sequitur.

From the energy of the earlier work emerges “a beauty contest between animals in a photo-shoot”, scrupulous studio photos that demand to be taken seriously, but mean very little. Here, passion has lost out to rigorous and deathly control.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to Fotomuseum Winterthur and Fotostiftung Schweiz for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Together, Fotomuseum Winterthur and Fotostiftung Schweiz will showcase the oeuvre of Swiss artist Balthasar Burkhard (1944-2010) in a major retrospective. Burkhard’s work spans half a century: from his early days as a trainee photographer with Kurt Blum to his seminal role in chronicling the art of his time, eventually becoming a photographic artist in his own right who brought photography into the realms of contemporary art in the form of the monumental tableau. More than 150 works and groups of works chart not only the progress of his own photographic career, but also the emergence of photography as an art form in the second half of the twentieth century. An exhibition in collaboration with Museum Folkwang, Essen, and Museo d’arte della Svizzera italiana, Lugano.

Balthasar Burkhard (Swiss, 1944-2010)

from On the Alp

1963

© Estate Balthasar Burkhard

Balthasar Burkhard (Swiss, 1944-2010)

Untitled (Urs Luthi, Balthasar Burkhard, Jean-Frederic Schnyder), Amsterdam

1969

© Estate Balthasar Burkhard

Urs Lüthi (b. 1947) is a Swiss conceptual artist who attended the School of Applied Arts in Zurich. Noted for using his body and alter ego as the subject of his artworks, he has worked in photography, sculpture, performance, silk-screen, video and painting.

Jean-Frédéric Schnyder (Swiss, b. 1945) began producing experimental objects in the late 1960s within the context of pop art and has since gone on to create a broad oeuvre encompassing photographs, sculptures, paintings, objects, and installations.

Balthasar Burkhard (Swiss, 1944-2010)

Untitled (Jean-Christophe Ammann at Andy Warhol’s Factory), New York

1972

© Estate Balthasar Burkhard

Jean-Christophe Ammann (14 January 1939 – 13 September 2015) was a Swiss art historian and curator.

Jean-Christophe Ammann (Swiss, 1939-2015)

Untitled (Balthasar Burkhard), USA

Venice, 1972

© Estate Balthasar Burkhard

Together, Fotomuseum Winterthur and Fotostiftung Schweiz have launched a major retrospective exhibition dedicated to the lifetime achievement of Swiss artist Balthasar Burkhard (1944-2010). His oeuvre is almost unparalleled in the way it reflects not only the self-invention of a photographer but also the emancipation of photography as an artistic medium in its own right during the second half of the twentieth century.

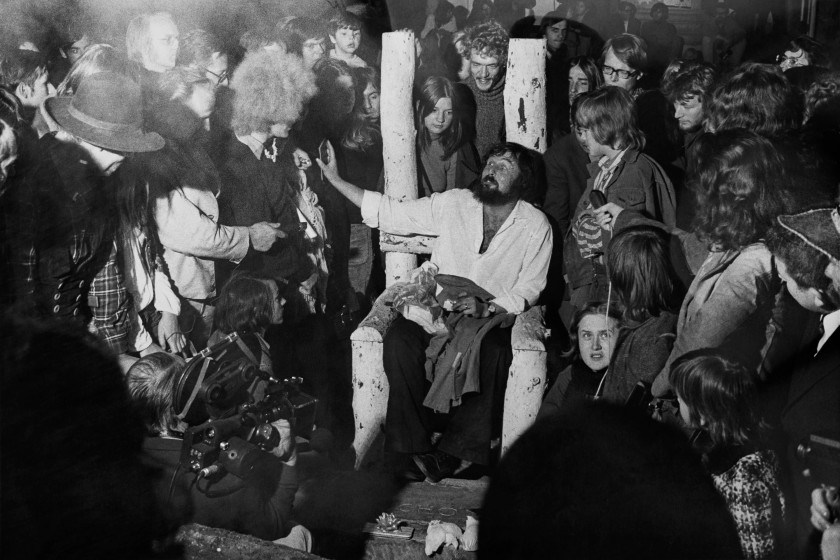

The exhibition charts the many facets of Burkhard’s career, step by step, from his apprenticeship with Kurt Blum – in which he adhered closely to the traditional reportage and illustrative photography of the 1960s, and undertook his first independent photographic projects – to his role alongside legendary curator Harald Szeemann, and his documentation of Bern’s bohemian scene in the 1960s and 1970s. Balthasar Burkhard is the author of many iconic images of such groundbreaking exhibitions as When Attitudes Become Form at Kunsthalle Bern in 1969 and the 1972 documenta 5, capturing radical and frequently ephemeral works, actions and performances by the international avant-garde of the day.

Meanwhile, Burkhard endeavoured to make his mark both as a photographer and as an artist, developing his first large-scale photographic canvases in collaboration with his friend and colleague Markus Raetz, trying out his skills as an actor in the USA, and ultimately being invited to hold his own highly influential exhibitions at Kunsthalle Basel and Musée Rath in Geneva in 1983 and 1984. These enabled him to liberate photography from its purely documentary role by creating monumental tableaux in which he developed the motif of the body into sculptural human landscapes and site-specific architectures.

Throughout the course of his career, Burkhard turned time and again to portraiture. Whereas his early photographs tended to show artists in action within their own setting, his later portraits adopted an increasingly formalised approach. During the 1990s, he transposed this stylistic reduction to a wide-ranging series of animal portraits reminiscent of the encyclopaedic style of nineteenth century photography.

Another milestone of Burkhard’s oeuvre can be found in his vast aerial photographs of major mega cities such as Tokyo and Mexico City. These images, shot from an aircraft, like his images of the earth’s deserts, were destined to become a personal passion. Balthasar Burkhard’s quest for a morphology, for a formula that could encapsulate both nature and culture, is particularly evident in his later work, which ranges from pictures of waves and clouds, Swiss mountains and rivers, to the delicate fragility of plants. His interest was always focused on the materiality of the image. Alongside the highly idosyncratic and somewhat darkly sombre tonality of his prints, Burkhard constantly sought to explore every aspect of photography’s aesthetic and technical potential.

Encompassing half a century of creativity, the joint exhibition by Fotomuseum and Fotostiftung not only shows individual works, but also reflects on Balthasar Burkhard’s own view of how his photographs should be presented, underpinned by a wealth of documents from the archives of the artist. The exhibition is divided in two parts and shown in parallel in the exhibition spaces of Fotomuseum and Fotostiftung.

Press release

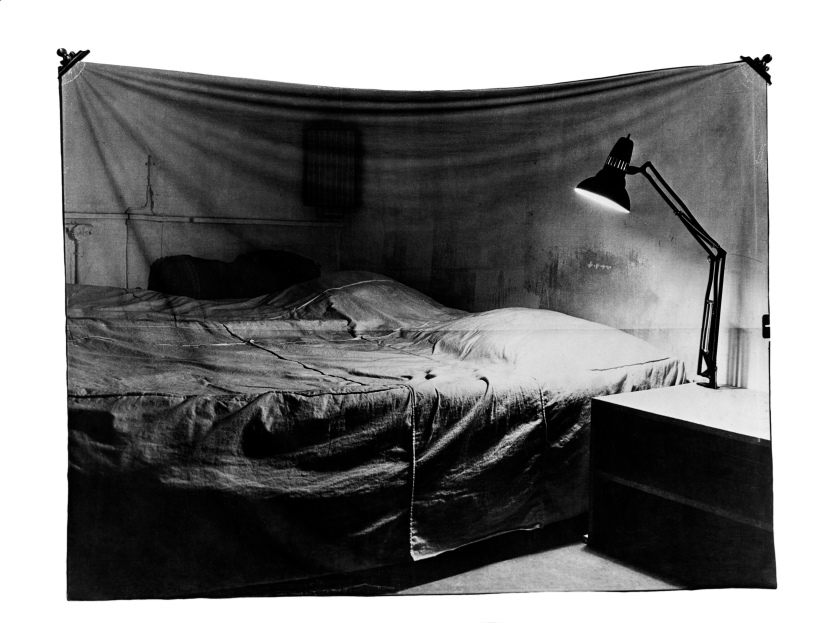

Balthasar Burkhard (Swiss, 1944-2010) / Markus Raetz (Swiss, 1941-2020)

The Bed

1969-1970

© Estate Balthasar Burkhard

Balthasar Burkhard (Swiss, 1944-2010)

Untitled (Michael Heizer, Berne Depression), Berne

1969

© J. Paul Getty Trust. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles

Balthasar Burkhard (Swiss, 1944-2010)

Untitled (Richard Serra, Splash Piece), Berne

1969

© J. Paul Getty Trust. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles

Richard Serra (b. 1938) is an American artist known for his large-scale sculptures made for site-specific landscape, urban, and architectural settings. Serra’s sculptures are notable for their material quality and exploration of the relationship between the viewer, the work, and the site.

Balthasar Burkhard (Swiss, 1944-2010)

Untitled (Harald Szeemann, the last day of documenta 5), Kassel

1972

© Estate Balthasar Burkhard

With this major retrospective, Fotomuseum Winterthur and Fotostiftung Schweiz pay homage to the Swiss artist Balthasar Burkhard (1944-2010). His oeuvre is almost unparalleled in the way it reflects not only the self-invention of a photographer, but also the emancipation of photography as an artistic medium in its own right during the second half of the twentieth century.

Together, the two institutions chart the many and varied facets of Burkhard’s career, step by step. Fotostiftung presents early works from the days of his apprenticeship with Kurt Blum and his first independent documentary photographs. The exhibition also traces Burkhard’s role as a photographer alongside the curator Harald Szeemann and capturing images of Bern’s bohemian scene in the 1960s and 1970s. During that time, Burkhard carved his niche as a photographer and artist, developing his first large-scale photographic canvases in collaboration with his friend Markus Raetz and eventually breaking away from the European art world in search of both himself and new inspiration in the USA.

The second part of the exhibition at Fotomuseum shows the work created by Burkhard after his return to Europe, and his exploration of the photographic tableau. It was during this phase that he largely succeeded in emancipating photography from its purely documentary function. Using monumental formats, he translated the motif of the human body into sculptural landscapes and site-specific architectures. He went on to apply his stylistic device of formal reduction to portraits and landscapes. This marked the beginning of a series of experiments in the handling of photographic techniques. From long-distance aerial photographs of mega-cities such as Mexico City and Tokyo to close-up studies of flowers and plants, Burkhard seemed to be constantly seeking a formula that would embrace both nature and culture, encapsulating a sensory and sensual grasp of visible reality.

Encompassing half a century of creativity, the exhibition not only shows individual works, but is also underpinned by applied projects, films and many documents from the archives of the artist. This wealth of material allows a reflection both on Balthasar Burkhard’s own view of how his photographs should be presented in the exhibition space as well as his constant weighing-up of other media.

Part I (Fotostiftung Schweiz)

Early photographs

Balthasar Burkhard was just eight years old when his father gave him a camera to take along on a school excursion. Burkhard himself describes this early experience with the camera as the starting point of his career. It was also his father who suggested an apprenticeship with Kurt Blum, one of Switzerland’s foremost photographers, ranking along-side Paul Senn, Jakob Tuggener and Gotthard Schuh. Blum taught the young Balz, as he was nicknamed, all the finer points of darkroom technique as well as the art of large-format photography. The earliest work from Burkhard’s apprentice years is a reportage of the school, in the form of a book, while his documentation of the Distelzwang Society’s historic guildhall in the old quarter of Bern was clearly a lesson in architectural photography. Yet, no sooner had he completed his apprenticeship than Burkhard was already embarking on his very own independent projects inspired by post-war humanist photography, such as Auf der Alp, a study of rural Alpine life, for which he was awarded the Swiss Federal Grant for Applied Arts in 1964.

Chronicler of Bohemian Life in Bern

Even during his apprenticeship, Burkhard moved in the Bernese art circles to which his teacher Kurt Blum also belonged. In 1962, he created a first portrait, in book form, of painter and writer Urs Dickerhof. Shortly after that, he became friends with his near-contemporary Markus Raetz, and started taking photographs for the charismatic curator Harald Szeemann, who was director of Kunsthalle Bern from 1961 to 1969. Burkhard immersed himself in the vibrantly dynamic Swiss art scene, documenting the often controversial exhibitions of conceptual art at the Kunsthalle, and capturing the lives of Bern’s bohemian set with his 35mm camera. These visual mementos would later be collated in a kind of photographic journal. Initial collaborative projects with artists included a 1966 artists’ book about the village of Curogna (Ticino) and a window display for the Loeb department store in Bern featuring photographic portraits of the Bernese artist Esther Altorfer, devised in collaboration with Markus Raetz and his later wife, fashion designer Monika Raetz-Müller.

Landscapes 1969

Inspired by his friend Raetz, Burkhard photographed bleak and rugged snow-covered landscapes in the Bernese Seeland region. Heaps of earth piled up along the wayside reminded him of Robert Smithson’s Earthworks, which had just emerged in contemporary art. As Burkhard would later explain, “I wanted to leave out everything relating to myself, so that I could truly relate to what remained. I distanced myself from my subject-matter. I succeeded in stepping back both from myself and from my work.”

A close-up of bare agricultural soil, vaguely reminiscent of a lunar landscape, forms the basis for an object with a neon tube created in 1969 for the legendary exhibition When Attitudes Become Form in collaboration with Harald Szeemann, Markus Raetz and Jean-Frédéric Schnyder. In 1969, Burkhard’s brown-toned landscapes were included in the 1969 exhibition photo actuelle suisse in Sion. They were subsequently published as his first independent portfolio by Allan Porter in the May issue of Camera magazine, which was dedicated to avant-garde European photography and its affinity with contemporary art.

The Amsterdam Canvases 1969-1970

When Markus Raetz took a studio in Amsterdam in 1969, he and Burkhard continued to work on joint projects. Photographs of everyday motifs were enlarged, practically life-sized, onto canvas, and caused a sensation in the spring 1970 exhibition Visualisierte Denkprozesse (Visualised thought processes) at Kunstmuseum Luzern, curated by Jean-Christophe Ammann, who wrote: “On huge canvases, they [Raetz and Burkhard] showed, among other things, a spartan studio space, a bedroom, a kitchen, a curtain. They relativised the purely object-like character by hanging the canvases on clips. The resulting folds enriched the images by adding a new dimension.” In other words, the folds in the canvas created a “quasi ironic and disillusioning barrier.” Burkhard’s large-format works foreshadowed the monumental photographic tableaux that would eventually herald the ultimate march of photography into the museum space some ten years later.

Documentarist of the International Art Scene

By the end of the 1960s, Harald Szeemann and his polarising, controversial exhibitions were drawing increasing attention far beyond the boundaries of Switzerland. In particular, his (in)famous 1969 show When Attitudes Become Form unleashed heated debates that ultimately led to Szeemann’s resignation as director of Kunsthalle Bern. Then, in 1970, he shocked the members and visitors of the Kunstverein in Cologne with an exhibition dedicated to Happening & Fluxus. Here, too, Burkhard was on hand with his camera. Jean-Christophe Ammann, with whom Burkhard undertook a research trip to the USA in 1972, photographing many artists’ studios, proved no less controversial a figure. Moreover, Burkhard also photographed artists, actions and installations at the 1972 documenta 5 in Kassel, which was headed by none other than Szeemann himself. Given the expanded concept of art that prevailed at the time, which strengthened the role of performance art and installation works alike, photography, too, gained a newfound core significance. Indeed, it was only through photography that many of these innovative works were preserved for posterity.

Chicago and the Self-Invention of the Artist

Following a relatively unproductive period in the wake of documenta 5, during which he worked, among other things, on an unfinished documentary project about the small Swiss town of Zofingen, Burkhard spent the years between 1975 and 1978 in Chicago, where he taught photography at the University of Illinois. It was while he was there that he once again reprised the series of photo canvases he had been working on in Amsterdam between 1969 and 1970. This led to new large-format works portraying everyday scenes such as the back seat of an automobile or the interior of a home with a TV, as well as three now lost photographs of roller skaters and a very androgynous back-view nude study of a young man. In 1977 the Zolla/Lieberman Gallery in Chicago presented these canvases together with a selection of the Amsterdam works in what was Burkhard’s first solo exhibition. Critics were impressed by his “soft photographs”. The Chicago Tribune, for instance, enthused: “‘European’ grace is wedded to ‘American’ strength in a supreme artistic fiction that suggests the wide-screen format of film.”

Self-Portraits

In Chicago, Burkhard rekindled his friendship with performance and conceptual artist Thomas Kovachevic, whom he had first met at documenta 5 and who now introduced him to the local art scene. At the same time, Burkhard toyed with the notion of trying his chances as a film actor in Hollywood. With Kovachevich’s help, he produced a series of self-portraits, both Polaroids and slides, which he presented in a small snakeskin-covered box as his application portfolio. He approached Alfred Hitchcock and Joshua Shelley of Columbia Pictures, albeit unsuccessfully. His only film role was in Urs Egger’s 1978 Eiskalte Vögel (Icebound; screened in seminar room I). Burkhard later transformed some of his self-portraits into large-scale canvases, through which he asserted his newfound sense of identity as an artist, making himself the subject-matter of his own artistic work. One of these was also shown in the Photo Canvases exhibition at Zolla/Lieberman Gallery.

Balthasar Burkhard (Swiss, 1944-2010)

feet 2

1980

© Estate Balthasar Burkhard

Balthasar Burkhard (Swiss, 1944-2010)

‘The Knie’, Kunsthalle Basel (installation view)

1983

© Estate Balthasar Burkhard

Balthasar Burkhard (Swiss, 1944-2010)

Study of The Head

c. 1983

© Estate Balthasar Burkhard

Balthasar Burkhard (Swiss, 1944-2010)

Design for Body II

c. 1983

© Estate Balthasar Burkhard

Part II (Fotomuseum Winterthur)

Body and Sculpture

The 1980s heralded the advent of a particularly productive period for Balthasar Burkhard in which he adopted a more sculptural approach to photography, treating his prints as an integral part of the exhibition architecture. Just as he himself had witnessed how the generation of artists before him had called the classic exhibition space into question, so too did his own latest works now begin to take control of that space. Burkhard became one of the foremost proponents of large-scale photographic tableaux, as evidenced by his groundbreaking exhibitions at Kunsthalle Basel in 1983 and Museé Rath, Geneva, in 1984.

It was in the photo canvases he made in Chicago during the late 1970s that Burkhard first turned towards the motif of the body as a sculptural form with which he would continue to experiment over the coming years. Such an overtly sculptural approach to the body and to the nude as landscape soon began to demand a larger format than Burkhard had previously been using. An arm, almost four metres long, framed by heavy steel, or the multipart installation Das Knie (Knee), reflect the very core of his creative oeuvre in all its many facets: monumentality, fragmentation and the breaking of genre boundaries by transposing two-dimensional images into spatially commanding installations.

Portraits: Types and Individuals

The increasing formal reduction of Balthasar Burkhard’s images continued in the field of portraiture. He invited fellow artists such as Lawrence Weiner and Christian Boltanski to sit for him. With this series, it seemed that he had finally put behind him his days as a chronicler of the art scene, reliant on the techniques of applied photography.

Portraits of a rather different kind are his profiles of animals, in an equally reduced setting, against the backdrop of a tarpaulin. Redolent of Renaissance drawings or nineteenth century animal photography, his images of sheep, wolves and lions come across as representing ideal and typical examples of their species without anthropomorphising them, while at the same time wrenching them out of their natural environment. These images reached a broad audience through the popular 1997 children’s book “Click!”, said the Camera, which was republished in its second edition in 2017.

Architectural Photography

Given his increasing success in the art world, Burkhard could well afford to be selective about his choice of commissioned works. He had already been taking photographs for architects connected with the Bern-based firm Atelier 5 back in the 1960s, and was still accepting commissions in this field in the 1990s. Burkhard’s photographic essay on the Ricola building designed by Swiss architects Herzog & de Meuron indicates just how thoroughly his own distinctive artistic syntax permeates his commissioned and architectural photography, right through to the details of fragments and materials. These photographs were shown in the Swiss Pavilion at the Venice Biennale of Architecture in 1991, having been explicitly designed for this particular exhibition space. As in his artistic oeuvre, Burkhard operates here with spatially commanding installations, skilfully dovetailing the architectural motif with the presentational form.

Aerial Photography

In the 1990s, before the art world had even begun to turn its attention to the subject of megacities, Burkhard was already taking a keen interest in the world’s major conurbations. Following in the footsteps of his father, who had been a Swiss airforce pilot, he took bird’s-eye-view photographs from a plane. His panoramic shots of cities such as London, Mexico City and Los Angeles were preceded by small-format studies of clouds: the so-called Nuages series. Having incorporated a study of rural Switzerland into his formative training in 1963 with the series Auf der Alp (On the Alp), he returned once more to focus on the landscape of his homeland in the early 2000s with an entire series of aerial photographs of the Bernina mountain range.

Landscape and Flora

In the last two decades of his life, Burkhard concentrated primarily on landscape and flora, turning to historical precedents both in his techniques and in his choice of motif. The desert formations of Namibia, in which all sense of proportion is lost amid the remote and untouched wilderness, set a counterpoint to the sprawling urban expanses of Mexico City and London. The diptych Welle (Wave), by contrast, pays homage to the work of French artist Gustave Courbet, with Burkhard making a pilgrimage to the tide swept shores where the father of Realism had painted in 1870.

In another series, Burkhard adapts the aesthetics of botanical plant studies, which were as widely used around the turn of the twentieth century as the complex photographic process of heliography, and transposes these to larger-than-life formats. Whereas Burkhard, as a young photographer, had captured the exuberant art scene of the 1960s and 1970s, snapshot-style, he later went on, as an artist-photographer, to explore the potential of the photographic tableau, diligently researching near-forgotten techniques and the sensual details of the visible world.

Artwork and Commissioned Work

The site-specific installations of his photographs and Burkhard’s own dedicated approach to museum spaces warrant an excursion into the archives of the artist, paying particular attention to four exemplary exhibitions.

One spectacular and iconic show was the Fotowerke (Photo works) exhibition at Kunsthalle Basel in 1983. Curated by artist Rémy Zaugg, the installations can be reconstructed thanks to the catalogue and copious documentation. Contact prints and studies, for instance, help to give an insight into the no longer extant thirteen metre work Körper I (Body I) as well as shedding light on the choice of motif for further body fragments.

A 1984 solo exhibition at the Le Consortium in Dijon, on the other hand, shows how Burkhard responded with his group of works Das Knie (Knee) to an entirely different installation context within the given space. Similarly, at the Musée Rath in Geneva that same year, Burkhard, together with his friend Niele Toroni, instigated a radical juxtaposition of photography and painting based on the pillars of the exhibition venue.

At Grand-Hornu in the Belgian town of Mons, by contrast, his life-sized photographs of animals were mounted at eye level. While Burkhard chose a large format for the exhibition venue, the images in his children’s book “Click!”, said the Camera tell of a beauty contest between animals in a photo-shoot. This apparent discrepancy between artwork and commissioned work never seemed to be relevant to Burkhard. The sheer volume of his studio photos, alone, indicates just how scrupulously precise he was about the way he wanted to be perceived as a serious photographer.

Wall text from the exhibition

Installation views of the exhibition Balthasar Burkhard at Fotomuseum Winterthur and Fotostiftung Schweiz, Winterthur, Zurich February – May 2018

Balthasar Burkhard (Swiss, 1944-2010)

Balthasar Burkhard in his studio

1995

© Estate Balthasar Burkhard

Balthasar Burkhard (Swiss, 1944-2010)

Camel

1997

© Estate Balthasar Burkhard

Balthasar Burkhard (Swiss, 1944-2010)

Bull

1996

© Estate Balthasar Burkhard

Balthasar Burkhard (Swiss, 1944-2010)

The Reindeer

1996

© Estate Balthasar Burkhard

Balthasar Burkhard (Swiss, 1944-2010)

Mexico City

1999

© Estate Balthasar Burkhard

Balthasar Burkhard (Swiss, 1944-2010)

Mexico City

1999

© Estate Balthasar Burkhard

Balthasar Burkhard (Swiss, 1944-2010)

Nuages 8

1999

© Estate Balthasar Burkhard

Balthasar Burkhard (Swiss, 1944-2010)

Ecosse (Scotland)

2000

© Estate Balthasar Burkhard

Balthasar Burkhard (Swiss, 1944-2010)

Bernina

2003

© Estate Balthasar Burkhard

Balthasar Burkhard (Swiss, 1944-2010)

Silberen

2004

© Estate Balthasar Burkhard

Balthasar Burkhard (Swiss, 1944-2010)

Rio Negro

2002

© Estate Balthasar Burkhard

Fotostiftung Schweiz

Grüzenstrasse 45

CH-8400 Winterthur (Zürich)

Phone: +41 52 234 10 30

Opening hours:

Tuesday – Saturday 11am – 6pm

Wednesday 11am – 8pm

Closed on Mondays

Fotomuseum Winterthur

Grüzenstrasse 44 + 45

CH-8400

Winterthur (Zürich)

Opening hours:

Tuesday to Sunday 11am – 6pm

Wednesday 11am – 8pm

Closed on Mondays

You must be logged in to post a comment.