Exhibition dates: 11th April – 25th August 2019

PLEASE NOTE: Postings will be limited over the next 2 months as I travel to see photographic prints and exhibitions in Europe: August Sander, Brassai, Kertesz, Josef Sudek, Fortepan and more.

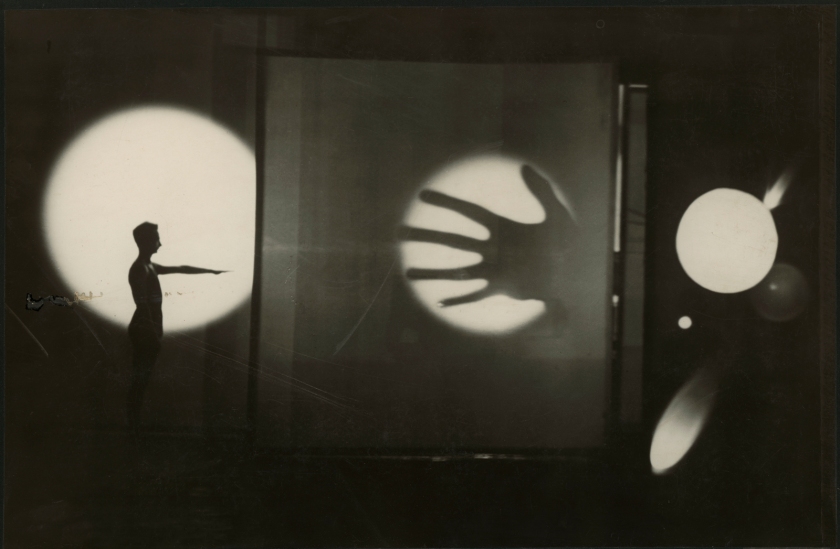

T. Lux Feininger (German-American, 1910-2011)

Bauhausbühne Dessau: ‘Lichtspiel’ von Oskar Schlemmer mit dem Tänzer und Pantomimen Werner Siedhoff / Bauhaus Stage Dessau: ‘Light Play’ by Oskar Schlemmer with the dancer and pantomime Werner Siedhoff

1928

Gelatin silver print

© Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kunstbibliothek

© Estate of T. Lux Feininger

“Im Grunde ist es nichts anderes als die Welt seiner Bilder, die in den Bühnenschöpfungen Schlemmers Gestalt gewinnt. […] Es ist eine künstliche, aber auch eine in hohem Maße künstlerische Welt, die ihren Eindruck auf ein formenempfindliches Auge nicht verfehlen wird.” (Curt Glaser: Schlemmers Bühnenentwürfe, 1932). / “Essentially, it is nothing but the world of his pictures that takes form in Schlemmer’s stage creations. […] It is an artificial, but also to a high degree artistic world which cannot fail to make an impression on an eye that is sensitive to form.” (Curt Glaser: Schlemmer’s Stage Designs, 1932).

A COSMIC posting of all that is good about the Neues Sehen (New Vision) photographic movement (Neues Sehen considered photography to be an autonomous artistic practice with its own laws of composition and lighting, through which the lens of the camera becomes a second eye for looking at the world. This new way of seeing was based on the use of unexpected framings, the search for contrast in form and light, the use of high and low camera angles, etc… Moholy-Nagy, László, (1932) The new vision, from material to architecture. New York: Brewer, Warren & Putnam).

Alien orchids, dizzying perspectives and superlative light shows. Design, film, photo, collage, photogram, reflection, dance, portrait, fragmentation, architecture, beauty.

I’m in love with Florence Henri 🙂

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Museum of Photography, Berlin for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting, and to Nick Henderson for the installation photographs. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

László Moholy-Nagy (Hungarian, 1895-1946)

O.T. (Am Strand) / No title (on the shore) (installation view)

c. 1929

Gelatin silver print

Die Aufnahme war 1929 auf der FiFo in Stuttgart zu sehen. “Ich habe fast nie einen vorbedachten plan bei meinen fotos. Sie sind aber auch nicht zufallsergebnisse. Ich habe – seitdem ich fotografiere – gelernt, eine gegebene situation rasch zu erfassen. Wenn mich dabei die verhältnisse von licht und schatten stark beeindrucken, fixiere ich den am günstigsten erscheinenden ausschnitt. Das strandbild ist auch auf diese weise entstanden.” (László Moholy-Nagy in: Uhu, 1929) / This photo was on view in 1929 at FiFo in Stuttgart. “With my photos, I almost never have a predetermined plan. Nor however are they the result of happenstance. I have learned – ever since I began making photographs – to grasp a given situation quickly. When I am also strongly impressed by relationships of light and shadow, I record the framed view that seems most favorable. The beach picture was also produced in this way.” László Moholy-Nagy in: Uhu, 1929)

Max de Esteban (Spanish, b. 1959)

TOUCH ME NOT: Fleeing the Presence of Death

2013

Inkjet print

Courtesy of Max de Esteban

In Touch Me Not (2013), Max de Esteban focuses on microelectronic de-vices: CDs, plastic boxes, and electronic circuit boards derived from computers. As data carriers that are X-rayed, the metal surfaces and structures do not reveal any information and refuse to be read.

Bauhaus and Photography catalogue cover

Installation views of the exhibition Bauhaus and Photography at the Museum für Fotografie, Berlin

International Exhibition of the Deutscher Werkbund Film und Foto (FiFo) at Städtische Ausstellungshallen

Poster for Film und Foto

1929

Offset lithograph

33 x 23 1/8″ (84 x 58.5cm)

Willi Ruge (German, 1892-1961)

Selbstbildnis aus der Regenwurm-Perspektive / Self-portrait from earthworm perspective

c. 1927

Gelatin silver print

© Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kunstbibliothek

© Erbengemeinschaft Ruge

To mark the centenary of the founding of the Bauhaus, this exhibition opens up a dialogue between contemporary art and the photographic avant-garde of the 1930s.

The Bauhaus is not just a key figure in the history of twentieth-century design and art, but also of photography. How are the innovations that were made then still influencing the evolution of the visual language of today’s photography and contemporary aesthetic concepts? What role does the photographic avant-garde of circa 1930 play for contemporary artists? This exhibition juxtaposes works by artists such as László Moholy-Nagy, Lucia Moholy, Man Ray, Jan Tschichold, Hedda Walther, Florence Henri, Hans Robertson and Erich Consemüller with groups of works by Thomas Ruff, Dominique Teufen, Daniel T. Braun, Wolfgang Tillmans, Doug Fogelson, Max de Esteban, Viviane Sassen, Stephanie Seufert, Kris Scholz, Taiyo Onorato & Nico Krebs, Antje Hanebeck and Douglas Gordon.

The historical reference point of the exhibition is the Werkbund exhibition Film and Photo, which was shown in Stuttgart, Berlin and Zurich, among other locations in 1929/1930. The Berlin leg was put together by the Kunstbibliothek. The Hungarian artist László Moholy-Nagy (1895-1946), who had already made a name for himself with his experimental photographic works, curated one room on the history of photography, and one on the future. The Bauhaus artist was interested in conducting a systematic investigation of Neues Sehen (New Vision) in photography. The historical exhibition, which functioned as a kind of manifesto, intervening in the debates of the time around the position of photography in the hierarchy of art, is reconstructed virtually with over 300 exhibits. Additionally, there will be a recreation of part of the Berlin exhibition. The reconstruction of the original exhibition design will be complemented by numerous vintage prints from the holdings of the Kunstbibliothek and a presentation of films from the 1920s. In combination with photographic works by contemporary artists, the exhibition opens up a dialogue between this historical event and the present moment.

Students from the design department at the Darmstadt University of Applied Sciences and the faculty of design at Nuremberg Tech offer a glimpse into the future, presenting their own forward-looking designs, which also incorporate digital media.

Text from the Museum für Fotografie website [Online] Cited 03/08/2019

David Octavius Hill / Robert Adamson (Scottish, 1802-1870 / 1821-1848)

Lady Mary Hamilton (Campbell) Ruthven

1843 / Reprint 1890-1900 by James Craig Annan

Pigment print

David Octavius Hill / Robert Adamson (Scottish, 1802-1870 / 1821-1848)

Newhaven Fisherman. John Henning and Alex H. Ritchie

1843 / Reprint 1890-1900 by James Craig Annan

Oil/bromide transfer print or pigment print

Eugène Atget (French, 1857-1927)

Au Franc Pinot, quai Bourbon, 1

1902

Aus der Folge / From the series L’Art dans le Vieux Paris

Albumen print

Atget, der sich selbst als Dokumentarfotograf verstand, wurde auf der FiFo als Erneuerer der Fotografie vorgestellt. / Atget, who saw himself as a documentary photographer, was presented at FiFo as a renewer of photography.

László Moholy-Nagy (Hungarian, 1895-1946)

Fotogramm (Fotogramm mit Eiffelturm) / Photogram (photogram with Eiffel Tower)

1925 / 1989

Reproduction by the artist from the unique specimen, Silver gelatin print

© Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kunstbibliothek

Das Fotogramm war 1929 auf der FiFo in Stuttgart und Berlin zu sehen. Die Motivvorlage ist 1929 in Moholy-Nagys Buch von material zu architektur abgebildet: “spielzeug / durch die bewegung erzeugtes, virtuelles volumen – optische auflösung des festen materials […] spielzeuge sind in vielen fällen die zeitgemäßen plastiken. Sie enthalten oft geistreiche übersetzungen technischer ideen, die meist mehr von dem wesen technischer vorgänge vermitteln als gelehrte vorträge.” / The photogram was on view in 1929 at FiFo in Stuttgart and Berlin. The template for this motif is reproduced in Moholy-Nagy’s book from material towards architecture (1929): “toy / through the virtual volumes generated by movement – optical dissolution of the solid material […] toys are in many cases contemporary sculptures. They often contain ingenious translations of technical ideas, most convey more concerning the nature of technical procedures than learned lectures.”

Erich Consemüller (German, 1902-1957)

Bauhausbühne Dessau: ‘Vorhangspiel’ von Oskar Schlemmer mit dem Tänzer und Pantomimen Werner Siedhoff / Bauhaus Stage Dessau: ‘Curtain Play’ by Oskar Schlemmer with the dancer and pantomime Werner Siedhoff

1927

Gelatin silver print

© Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kunstbibliothek

© Stephan Consemüller

In 1927, Consemüller was commissioned by Gropius to photographically document Bauhaus’s activities and people. This resulted in the creation of around 300 photographs documenting the school’s work and environment. “Bauhaus Scene,” a frequently reproduced photograph of his, combines three works by Bauhaus artists in one photo. It depicts a woman sitting in Breuer’s Wassily Chair, wearing a theatrical mask made by Oskar Schlemmer and a dress designed by Lis Volger-Beyer. Other notable photographs of his feature Bauhaus architecture, often with figures interposed.

Text from the Wikipedia website

László Moholy-Nagy (Hungarian, 1895-1946)

Funkturm Berlin / Radio Tower Berlin

1925

Gelatin silver print

Albert Renger-Patzsch (German, 1897-1966)

Catasetum tridentatum. Orchidaceae

1922-1923

Gelatin silver print

“Eines der wundervollsten Fotos, das überhaupt in unserer Zeit entstanden ist, ist die Rengersche Orchideenblüte […]. Hier ist ein fotografischer Bildraum entstanden, der mehr räumlich als plastisch lebendig ist.” (Die Form, 1929) / “One of the most marvellous photographs produced during our time is the orchid blossom by Renger […]. Emerging here is a photographic picture space that is more lively in spatial than in sculptural terms.” (Die Form, 1929)

Albert Renger-Patzsch (German, 1897-1966)

Bügeleisen für Schuhfabrikation. Fagus-Werk Benscheidt in Alfeld / Flat iron for shoe fabrication. Fagus-Werk Benscheidt in Alfeld

1926

Gelatin silver print

Albert Renger-Patzsch (German, 1897-1966)

Gebirgsforst im Winter / Montane woods in winter

1926

Gelatin silver print

Albert Renger-Patzsch (German, 1897-1966)

Töpferhände / Potter’s hands

1925-1927

Gelatin silver print

Aenne Biermann (German, 1898-1933)

Einblick in ein Klavier. Scherzo / View into a piano

1928 or earlier

Gelatin silver print

Die Aufnahme war 1929 auf der FiFo in Stuttgart zu sehen. / This photo was on view in 1929 at FiFo in Stuttgart.

Aenne Biermann (German, 1898-1933)

Finale

before October 1928

Gelatin silver print

Die Aufnahme war 1929 auf der FiFo in Stuttgart zu sehen. / This photo was on view in 1929 at FiFo in Stuttgart.

Jan Tschichold (German, 1902-1974)

Laster der Menschheit / Vice of Humanity

1927

Plakat (Raster- und Tiefdruck) / Poster (halftone and intaglio)

© Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kunstbibliothek

© Familie Tschichold

Das Plakat war 1929 im Raum 1 der FiFo in Berlin zu sehen. “Zu den elementaren Mitteln neuer Typographie gehört in der heutigen, auf Optik eingestellten Welt auch das exakte Bild: die Photographie.” (Jan Tschichold: Elementare Typographie, 1925). / The poster was shown in 1929 in Room 1 at FiFo in Berlin. “In the contemporary world, with its orientation toward optics, among the elementary resources of the new typography is the exact image: photography.” (Jan Tschichold: Elementary Typography, 1925).

Jan Tschichold (2 April 1902 Leipzig, Germany – 11 August 1974 Locarno, Switzerland) (born as Johannes Tzschichhold, also Iwan Tschichold, Ivan Tschichold) was a calligrapher, typographer and book designer. He played a significant role in the development of graphic design in the 20th century – first, by developing and promoting principles of typographic modernism, and subsequently (and ironically) idealising conservative typographic structures. His direction of the visual identity of Penguin Books in the decade following World War II served as a model for the burgeoning design practice of planning corporate identity programs. He also designed the much-admired typeface Sabon.

Text from the Wikipedia website

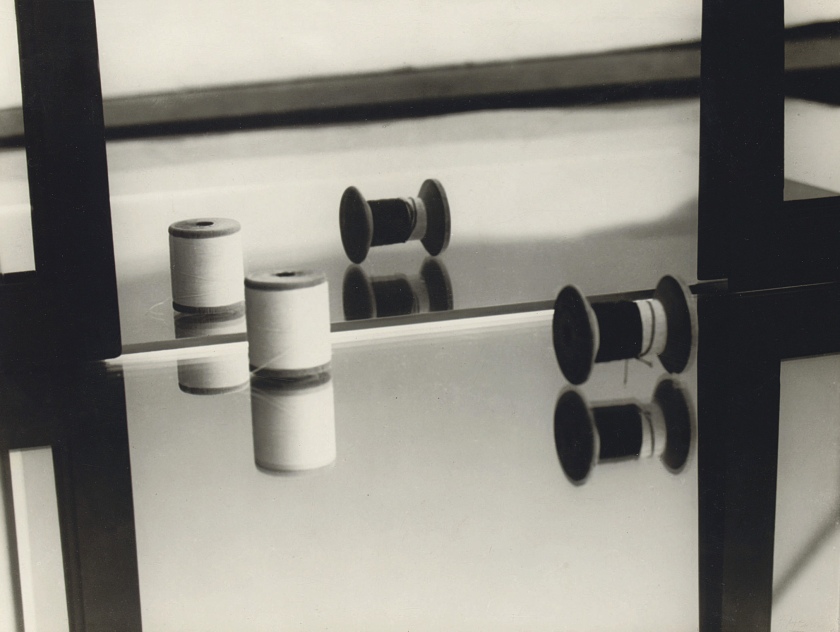

Florence Henri (French, 1893-1982)

Komposition mit Garnrollen / Composition with spools of thread

1928

Gelatin silver print

© Florence Henri

Die Aufnahme war 1929 auf der FiFo in Stuttgart zu sehen. / This photo was on view in 1929 at FiFo in Stuttgart.

Max Burchartz (German, 1887-1961)

Lotte (Eye) (Lotte [Auge])

1928

Gelatin silver print

11 7/8 x 15 3/4″ (30.2 x 40cm)

Max Burchartz (German, 1887-1961)

Grete W. (Augen) / Grete W. (eyes)

c. 1928

Gelatin silver print

Die Aufnahme war 1929 auf der FiFo in Stuttgart zu sehen. / This photo was on view in 1929 at FiFo in Stuttgart.

Charlotte Rudolph (German, 1896-1983)

Sprung / Leap (Gret Palucca)

1928

Gelatin silver print

On permanent loan from Österreichischen Ludwig-Stiftung für Kunst und Wissenschaft

© Albertina, Vienna

Eine ähnliche Aufnahme der Fotografin Charlotte Rudolph von Palucca bildete László Moholy-Nagy 1925 in dem Buch Malerei Photographie Film ab. / This shot of Palucca by the photographer Charlotte Rudolph was reproduced by László Moholy-Nagy in the book Painting Photography Film in 1925.

Florence Henri (French, 1893-1982)

O.T. (Komposition mit Teller und Spiegel) / No title (composition with plate and mirror)

1929 or earlier

Gelatin silver print

© Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kunstbibliothek

© Florence Henri

© Galleria Martini & Ronchetti

Courtesy Archives Florence Henri

Die Aufnahme war 1929 auf der FiFo in Stuttgart zu sehen. / This photo was on view in 1929 at FiFo in Stuttgart.

Florence Henri (French, 1893-1982)

Pariser Fenster / Parisian window

1929 or earlier

Gelatin silver print

© Florence Henri

Die Aufnahme war 1929 auf der FiFo in Stuttgart zu sehen. / This photo was on view in 1929 at FiFo in Stuttgart.

Walter Funkat (German, 1906-2006)

Glaskugeln / Glass spheres

1929

Gelatin silver print

© NRW-Forum

Man Ray (American, 1902-1958)

Rayograph

1921-1928, print 1963

Fotogramm

Gelatin silver print

© Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kunstbibliothek

© Man Ray Trust, Paris / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2019

László Moholy-Nagy and the FiFo

László Moholy-Nagy – Bauhaus artist and pioneer of media art – co-curated the legendary exhibition Film und Foto (FiFo) in 1929, which was set up by the Deutscher Werkbund in the exhibition halls on Interimtheaterplatz in Stuttgart. The FiFo, which subsequently travelled to Zurich, Berlin, Gdansk, Vienna, Agram, Munich, Tokyo and Osaka, presented a total of around 200 artists with 1200 works and showed the creations of the international film and photography scene of those years. Moholy-Nagy curated the hall, which reflected the history and present of photography. His artistic perspective on the history of photography and his efforts to provide a comprehensive overview of the contemporary fields of photo-graphic application were fundamental. At the exit of the large hall, Moholy-Nagy suggestively posed the question of the future of photographic development. On the basis of extensive scientific research, the Moholy-Nagy room was virtually reconstructed with approximately 300 exhibits.

The exhibition Film und Foto took its starting point in 1929 in Stuttgart, but was opened only a short time later in the Kunstgewerbemuseum (today: Gropius Bau) in Berlin. In the inner courtyard of the museum, large partition walls were erected to present the numerous photo exhibits. The hanging concept, handed down through three documentary photos, apparently deviated from the Stuttgart hanging. A corner situation, mainly showing photographs by Lucia Moholy and László Moholy-Nagy, was restored in a 1:1 reconstruction. In this way, the curatorial concept of comparative contemplation, as envisioned by Moholy-Nagy, can be re-experienced.

Play with Images

The rooms organised by László Moholy-Nagy at FiFo illustrated the continuity between the formal and optical qualities of photography, as well as the forward-looking influence of technical image media on contemporary culture. Moholy-Nagy’s works were interpretable as exemplifying visual modernism. They comprised close-up portrait fragments, architectural photographs using unconventional perspectives, and playful photo collages. Appearing entirely new at the time were the technical and material qualities of these photographs, as well as the aesthetic principles upon which they functioned. This was true in particular for the boldly configured light spaces of his photograms. These cameraless photographs embodied Moholy-Nagy’s artistic intentions in a very special way, and the medium offered him maximal autonomy in the use of light as a creative resource.

As examples of the photography of the Neue Sehen (New Vision), his works also entered the Kunstbibliothek, which – as the organiser of the Berlin FiFo – also acquired works by other artists from the show. The selection on view here evokes the comparative play with images and with modes of perception and use that was instigated by Moholy-Nagy, while confronting photographs from the 1920s with those from the 19th century. The form of presentation using passe-partouts and frames, prescribed by museum custom, renders the material and formal properties of each individual original print sensuously graspable.

A New Way of Seeing: An Homage to Film und Foto

In the exhibition Film und Foto, the camera emerged as the key to an expanded perception of the world, and as a mediator of new modes of seeing. In conjunction with photographic and cinematic experimentation, the New Objectivity and the New Vision came to epitomise avant-garde production. The central role of film for 20th-century culture was now recognised and manifested for the first time. Today, devices that can produce photographs or filmic scenes depending upon the chosen setting are at our disposal. This medial juxtaposition was conceptualised for the first time at FiFo – not coincidentally in 1929, the year sound film was inaugurated. Questions such as: “What is a photograph?” “What is a cinematic image?” “What is a technically produced image?” were investigated. In the Russian room, El Lissitzky hung photographs in open frames that were reminiscent of filmstrips, and ran excerpts from Soviet films on continuous loops from daylight projectors directly adjacent to them. The presentation of both media in both tandem and on equal terms was realised for the first time here in a modern dispositive. The program The Good Film, assembled by Victor Schamoni, ran at the former Kunstgewerbemuseum, today the GropiusBau, and at other Berlin cinemas, establishing cinema as an art form.

Daniel T. Braun

Daniel T. Braun describes his pictorial work as performative form research. Behind this lies an actionist stubbornness that wrestles unknown facets from the analogue forms of photography. The work group of Rocketograms may serve as an apt example. Following the action forms of action painting, Braun brings light-sensitive colour photographic paper into physical contact with burning pyrotechnics. With the uncommon use of magnesium torches, he refers to undertakings largely forgotten today, which were used for lighting in the early days of photography. In addition, the artefacts created in this way have an emphatically expressive effect. The moment of explosion is inscribed in the unique pieces in a virtually picture-creative way. Referring to Susan Sontag, Braun explicitly directs his goal “not to the creation of harmony, but to the overexpansion of the medium through destructive processes.”

A material-based exploration of light is also reflected in several sculptures, which Daniel T. Braun has transferred into another aspect of being through nuanced lighting and rotations in the studio. In the photographic image, the recorded light traces of the objects develop a strange independence. They seem to elude the observer’s gaze and yet are present in a peculiar way.

Max de Esteban

In the photographic works of Max de Esteban we encounter references critical of civilisation. His digital photo collages are designed as visual textures. They are inscribed with a skepticism based on media theory. He already indicates the vertigo that the works can trigger in their titles: Heads Will Roll is the name of a series of works from 2014. Fragments of perception from the media world are transformed into a visual totality. A spectrum of constructive forms and colour surfaces, as handed down from Modernism, is combined with individual motif elements from the image pool of mass media. In the sense of Zygmunt Bauman, the motifs of Heads Will Roll represent the unredeemed world of a “retrotopia”.

In Touch Me Not (2013), Max de Esteban focuses on microelectronic devices: CDs, plastic boxes, and electronic circuit boards derived from computers. As data carriers that are X-rayed, the metal surfaces and structures do not reveal any information and refuse to be read.

Doug Fogelson

For his series Forms & Records, the American artist Doug Fogelson visited a historically significant site of the New Bauhaus. His analogue black-and-white and colour photographs were taken in the darkroom of the IIT Institute of Design (ID) photography school in Chicago, which was founded by László Moholy-Nagy.

Fogelson’s graphically adept pictorial inventions can be understood as an expression of visual archaeology. He uses architectural models, vinyl singles, film and tape strips from the immediate post-war era as found motifs. In doing so, he refers to concepts of recording, designing, documenting and ephemerality in order to find his way back from a historical distance to the basics of form-finding with light. In addition, Moholy-Nagy’s series also refers to suggestions published in 1922 in his essay “New Plasticism in Music. Possibilities of the Gramophone”. The Bauhaus teacher there implements his ideas on the manipulative use of wax records with the intention of creating new sounds.

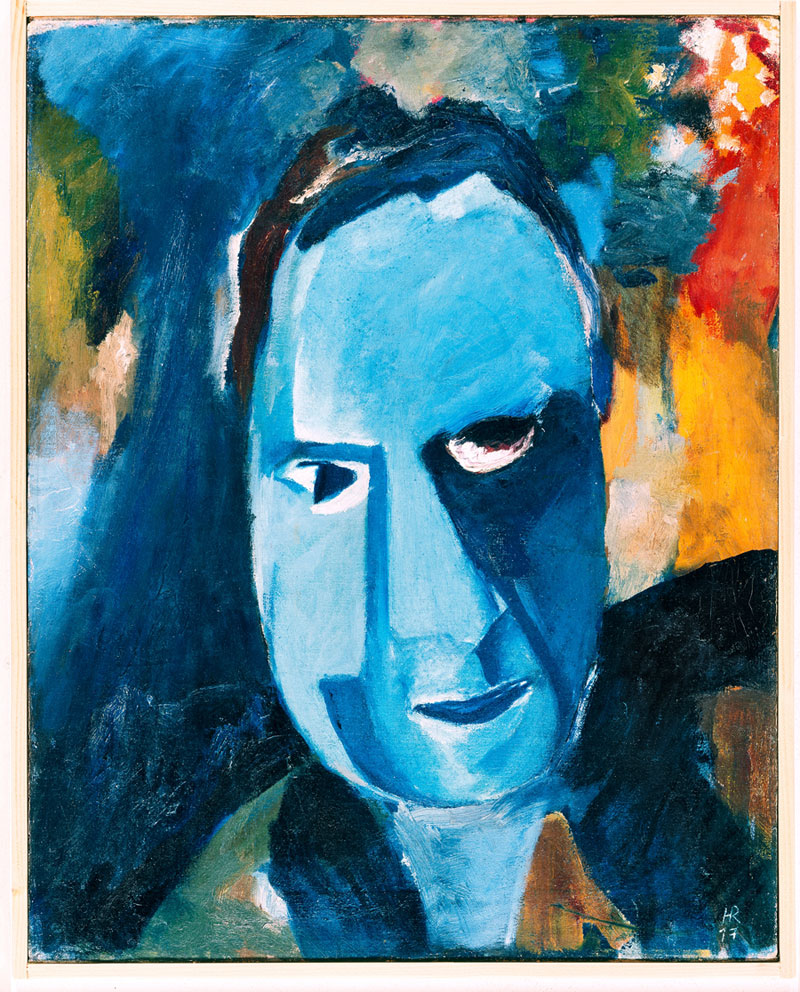

Douglas Gordon

In an obsessive way, the video and photographic works of Douglas Gordon wrestle with the receptive parameters of New Vision. His passionate engagement reveals itself in the leitmotif of the eye. For the artist’s book Punishment Exercise in Gothic (2001), the Scottish Turner Prize winner portrays himself in a black-and-white photograph, which shows his bleached portrait in cut. The fragmented cyclopean gaze is directed straight at the viewer and can be interpreted ambiguously. The motif is based on Max Burchartz’s photograph Lotte (eye), a key image of photo-graphic modernism presented in 1929 at the Stuttgart exhibition Film und Foto. In the book, the artist repeats his self-portrait no less than 118 times.

Antje Hanebeck

Antje Hanebeck dedicates her artistic photography to the architecture of post-war Modernism and the present. A moment of the documentary does not apply to her. Instead, she operates with a coarse-grained, tonal black-and-white aesthetic that seems pre-modern in an confounding way. Graphic and photographic elements are subtly intertwined and contrasted with the captured buildings, which retain their strictly constructive character. “Her pictures are picture puzzles, riddles, question marks, which – also – resist any temporal classification” (Hans-Michael Koetzle). This also applies to the large-format work Borough (2008). Hanebeck’s motif refers to photographs taken by László Moholy-Nagy in 1928 on the viewing platform of the Berlin Radio Tower. However, her spectacular downward gaze leads to a new irritation of perception. The irritation can only be resolved by a change of view – a 90 degree turn of the head to the left. Of course, the artist’s intervention is not limited to the formal. “The Borough motif undergoes transformation into a newly created, utopian, urban land-scape through a rotation.” (Ellen Maurer Zilioli).

Behind the poetic name of the work Desert Rose lies the National Museum of Qatar, designed by Jean Nouvel, which is due to open in March 2019. The French star architect develops his representative buildings from various stylistic concepts, including Bauhaus modernist architecture. It is not uncommon for the buildings to be symbolically formulated. In her horizontal-format photographs, Hanebeck exposes a section of the constructive sub-layers of the “desert rose”. She interprets the functional longwall system of the steel pillars as a deeply vital, vibrating fabric.

Taiyo Onorato & Nico Krebs

“The enemy of photography is the convention, the fixed rules, the ‘how to do it’. The rescue of photography takes place through experimentation.” Programmatically, this quotation by László Moholy-Nagy is prefixed in a catalogue on the works of Taiyo Onorato and Nico Krebs. The Swiss artist duo, who have been working together since 2003, is interested in the shifting of photo-technical boundaries, in a productive confusion of the perception of things and their representation. Onorato & Krebs act inventively, ironically and always with analogue means in their image findings. For their work group Color Spins, created in 2012, they have developed their own rotational apparatuses. The dynamic light sculptures, which are captured by colour photography, create a surprising illusionism. With a wink, the figurations recall the famous ensembles that Oskar Schlemmer developed more than a hundred years ago and later performed on the Bauhaus stage in Dessau.

The ephemeral light sculptures of the black-and-white series Ghost from 2012, on the other hand, step in front of the dreary backdrop of a piece of woodland. A disturbing surreality emanates from the appearances. The medium of photography still retains its magical character in the works of Onorato & Krebs.

Thomas Ruff

The phg series by Thomas Ruff is characterised by digital processes. They can be interpreted as an homage. The work phg.05_II, in its spiral form, recites one of László Moholy-Nagy’s most famous photograms from 1922. The three-letter abbreviation, which recalls the name of a file format, refers to a contemporary approach to image generation. The process is completely virtualised. Both the generation of the objects and the simulation of the shadows on the paper take place in an immaterial space.

“With phg, Ruff transfers an analogue technique into virtual space – and at the same time questions all attributes assigned to the photogram, such as immediacy and objectivity, as they were relevant to Moholy-Nagy’s ‘Photography of New Vision'” (Martin Germann). But the phg series can also be thought of in the opposite way. By radically erasing the analogue essence of the photogram, but retaining the terminology of the photograms, Ruff redeems a central doctrine of photography for the digital present. As early as 1928, László Moholy-Nagy brought the doctrine to a formula: “Photography is the shaping of light.”

Viviane Sassen

What is photography? Viviane Sassen understands the imaging process as a peculiar “art of darkening”. Umbra (Latin: “shadow”) is the title of her group of works created in 2014. In it, the Dutch fashion and art photographer explores in a number of variations the effect aspects of semi-transparent colour surfaces placed in desert sceneries. For the three-part work Vlei, Viviane Sassen locates square plates of coloured glass in a hollow. In their form and colour, these plates are reminiscent of the abstract paintings by Bauhaus master Josef Albers. The surfaces of the Umbra series are also partly captured in perspective foreshortening. They, too, assert themselves as an autonomous, colour-shaded picture within the picture. Sassen’s arrangements always retain a slight contradictoriness. Moments of realism and abstraction are equally effective in them.

The artist’s book Umbra from 2015 brings together eleven coloured shadow motifs in the form of a loose-leaf collection. The motifs once again operate with variations of gaze and reflections. Sassen’s artistic oeuvre often contains feminist references to modernist photography. The work Marte #03, for example, is based on Germaine Krull’s experimental self-portraits.

Kris Scholz

In the age of the digital, there can be no question of a demand for ahistoricity, as evoked by the New Vision. This is documented by the series Marks and Traces by Kris Scholz. His large-format colour photographs show worn floors, floor boards, and tabletops from German, Spanish, Moroccan and Chinese studios and art academies. One may initially classify the motifs as pictorial documents. “But just as important is the question of who left these markings and traces. As documents, his pictures ‘fail’ because they hardly provide any information” (Gérard A. Goodrow). The perceptual perspective of the pictures is based on a radically lowered gaze that was already applied by Umbo and László Moholy-Nagy in the 1920s. Scholz also uses stretched linen as a medium for his highly abstract large formats, which, despite their sharpness of detail, are, from a greater distance, perceived as painterly artefacts.

Stefanie Seufert

The works of Stefanie Seufert show an architectural reference. Her sculptures from 2016 are titled Towers. Photographic papers serve as the start-ing point for her experimental exploration. In the darkroom, these papers are edited by elaborate folding and exposure processes. From the respective layers and trace-like superimpositions, a materiality of its own is formulated, which the artist consciously expands into space. “Fragile, strangely monumental and oddly alien to themselves, they arise from a folding of the picture, which now occupies a space, encloses a space and suggests the idea of an (interior) space of the pictures themselves” (Ma-en Lübbke-Tidow). As tower-like artefacts, Seufert’s Towers, which are reminiscent of contemporary high-rise buildings, literally stand in the way of the viewer. Like an ensemble of materialised metaphors, they insist on autonomy that includes both alienation and abstraction.

Dominique Teufen

The artistic works of Dominique Teufen are characterised by an expansive drive of photography towards the genres of sculpture and architecture. Her group of Blitzlicht-Skulpturen (flashlight sculptures) was created in 2013. The setting follows a strict arrangement. Like architectural models, glass structures composed of shapes of cubes, slabs, and pyramids are positioned on the stage of a black plinth or white table. Something theatrical happens on it. The camera flashes. Reflective surfaces reflect the light onto the walls, catch these light forms again and connect the perspectival surfaces and lines to an illusion: the concrete moves into the background, the light as a sculpture enters the room; as soon as the eye suspects it, only the photograph remains as a witness to its existence. Teufen’s tableaus explore border areas. What already is architecture? What is sculpture? What, in turn, is photography?

In an ironic way, a catalogue of questions opens up in Teufen’s installation Selfiepoint from 2016. The expansive work formulates the invitation to shoot a selfie with the smartphone and thus to practice a central iconic gesture of our time. The backdrop of a mountain landscape quickly turns out to be a whimsically composed mountain of paper. It originated solely from the copier. What remains is a creative desire for self-reflection. Selfiepoint reminds us that the snapshot aesthetics of amateur photography have already been tried out by the students at the Bauhaus. At that time, the students were already playfully exploring new ways of presenting individual and group portraits with the 35 mm camera.

Wolfgang Tillmans

To what extent was the Bauhaus politically oriented? With a view to photography, the question still arises today as to the degree to which New Vision can be assigned to an artistic avant-garde of Modernism. Because the latter “aims, beyond the aesthetic, at radical social change […] which hardly applies to the protagonists of the New Vision. They were interested in little more than new perspectives from which they put people and things into the picture” (Timm Starl). The accusation of aestheticism arises. It contradicts the thesis that a reflexive visual process already provides political impulses itself. For the self-conception of contemporary art, however, the integration of political fields of thought and action has gained central importance. Both aspects of the political can be found exemplarily in the work of Wolfgang Tillmans. In June 2016, the artist launched an Anti-Brexit campaign for which he designed a 25-part poster series and called for Great Britain to remain in the EU. Tillmans does not want his project to be understood as an art action. He uses images from his Vertical Landscapes, which is a group of motifs of heavens and horizons. His photo-graphs are used as a form of agitation and placed in a tradition of image propaganda. Think, for example, of the collages by John Heartfield.

An edition realised by Wolfgang Tillmans in 2016 at the invitation of Tate Modern in London acts with a different field of photography. The occasion is the reopening of the Switch House, a brick building apse by Swiss architects Herzog & de Meuron. The sequence of images shows the still empty room areas of the museum on colour photocopies. Even this materiality undermines the auratic charge of the building. In their limited colour spectrum, Tillmans’ pictures produce “patterns and reductions that are literally subtracted from the naturalistic image” (Heinz Schütz). Paradoxically enough, the reproductions are transformed back into unique pieces through alienating colour shifts.

Daniel T. Braun (German, b. 1975)

Overseer

2003

Raketogramm / colour photogram

c.170 x 106cm

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2018

Daniel T. Braun (German, b. 1975)

Rafael Shafir

2006

Raketogramm / colour photogram

c. 260 x 130cm

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2018

Antje Hanebeck (German, b. 1968)

Borough

2008

Textildruck im Spannrahmen

230 x 230cm

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2018

Taiyo Onorato & Nico Krebs (Swiss, both b. 1979)

Spin 07 (green brown)

2012

Colour print

Courtesy the artists & Sies + Höke, Düsseldorf

© Taiyo Onorato & Nico Krebs

Daniel T. Braun (German, b. 1975)

SBSVI Nr. 6

2013

C-Print analog

110 x 90cm

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2018

Kris Scholz (German, b. 1952)

Marks and Traces, Caochangdi 1

2013

Fine art print on canvas

200 x 150cm

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2018

Kris Scholz (German, b. 1952)

Marks and Traces, Chongqing 5

2018

Fine art print on canvas

200 x 150cm

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2018

Dominique Teufen (Swiss, b. 1975)

Flashlight Sculpture #3

2013

Colour print

60 x 90cm

Courtesy Christophe Guye Galerie, Zürich

© Dominique Teufen

Dominique Teufen (Swiss, b. 1975)

Flash Sculpture # 5

2013

Colour print

60 x 90cm

Courtesy Christophe Guye Galerie, Zürich

© Dominique Teufen

Doug Fogelson (American, b. 1970)

Forms and Records No. 11

2014

Fotogramm

Silver gelatin paper

Courtesy Doug Fogelson

© Doug Fogelson

Doug Fogelson (American, b. 1970)

Forms And Records No 6

2014

Photogram, light box

© Doug Fogelson

Doug Fogelson (American, b. 1970)

Forms And Records No 08

2014

Photogram, light box

© Doug Fogelson

Doug Fogelson (American, b. 1970)

Forms And Records No 13

2014

Photogram, light box

© Doug Fogelson

Max de Esteban (Spanish, b. 1959)

HEADS WILL ROLL: Geographies of Permanent Emergency

2014

Inkjet print

Courtesy Max de Esteban

© Max de Esteban

Vivianne Sassen (Dutch, b. 1972)

Red Vlei

2014

Colour print

Courtesy Vivianne Sassen

© Vivianne Sassen

Viviane Sassen (Dutch, b. 1972)

Yellow Vlei

2014

Colour print

Courtesy Vivianne Sassen

© Vivianne Sassen

Daniel T. Braun (German, b. 1975)

Atmozons & Horizspheres no. 11

c. 2015

Photogram / luminogram on colour film

114 × 80cm

C-Print analog, 2+1 AP

© Daniel T. Braun und VG Bild-Kunst

Daniel T. Braun (German, b. 1975)

AZ Nr. 6

2016

Photogram on coloUr film / C- Print analog

c. 84 x 120cm

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2018

Stefanie Seufert

owers Option #2, Just Yellow, Atlas Grey, Dark Aubergine

2016

Fotogramm / Colour paper

Courtesy Stefanie Seufert

© Stefanie Seufert

Antje Hanebeck (German, b. 1968)

CaSO4•2 H2O 46

2018

Pigment print

Courtesy Antje Hanebeck

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2019

Museum für Fotografie

Jebensstraße 2, 10623 Berlin, Germany

Phone: +49 30 266424242

Opening hours:

Tues – Sunday 11am – 7pm

![Albert Renger-Patzsch (1897-1966) 'Bügeleisen für Schuhfabrikation, Faguswerk Alfeld [Shoemakers' irons, Fagus factory, Alfeld]' 1928 Albert Renger-Patzsch (1897-1966) 'Bügeleisen für Schuhfabrikation, Faguswerk Alfeld [Shoemakers' irons, Fagus factory, Alfeld]' 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/renger-patzsch-bugeleisen-fur-schuhfabrikation.jpg?w=650&h=874)

![Albert Renger-Patzsch (1897-1966) 'Gebirgsforst im Winter (Fichtenwald im Winter)' [Mountain forest in winter (spruce forest in winter)] 1926 Albert Renger-Patzsch (1897-1966) 'Gebirgsforst im Winter (Fichtenwald im Winter)' [Mountain forest in winter (spruce forest in winter)] 1926](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/renger-patzsch-gebirgsforst-im-winter.jpg?w=650&h=874)

![Max Burchartz. 'Lotte (Eye)' (Lotte [Auge]) 1928 Max Burchartz. 'Lotte (Eye)' (Lotte [Auge]) 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/max-burchartz-lotte-eye-1928-web.jpg?w=840)

![Florence Henri. 'Fenêtre [Window]' 1929 Florence Henri. 'Fenêtre [Window]' 1929](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/florencehenri_06_fenetre-web.jpg?w=650&h=883)

You must be logged in to post a comment.