Exhibition dates: 15th July – 6th November 2022

Curators: Jeff L. Rosenheim, Joyce Frank Menschel Curator, Department of Photographs, assisted by Virginia McBride, Research Associate, Department of Photographs, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Bernd & Hiller Becher exhibition banner

Ghosts in the machine

In a way that Plato would recognise with his perfect forms (abstract yet perfect, unchanging concepts or ideals that transcend time and space and live on a spiritual plane behind the representation of a physical reality), I feel as though Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) has existed outside of time – a model of directness that was always there – in a timeless way, before the actual concept emerged into consciousness in the 1920s German art tradition.

German photographers Bernd & Hiller Becher (1931-2007; 1934-2015) were devoted to the ideals of Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) and their work evolved from these older traditions of objective photography as practiced by artists such as August Sander (German, 1876-1964) and Karl Blossfeldt (German, 1865-1932) during the 1920s. The typologies that the Bechers collected – their beautiful, multiple, conceptual, objective, documentary fine art ‘record photographs’ – made them among the most important figures in postwar German photography.

Their teaching at the Kunstakademie Dusseldorf in the mid 1970s lead to the formation of the Dusseldorf School of Photography which refers to a group of photographers who studied under the artist duo who also shared (and then modified) their aesthetic – a commitment to controlled objectivity and a documentary orientation. These important next generation artists included people such as Andreas Gursky, Candida Höfer, Axel Hütte, Thomas Ruff and Thomas Struth. The Bechers influence on contemporary documentary fine art photography continues today.

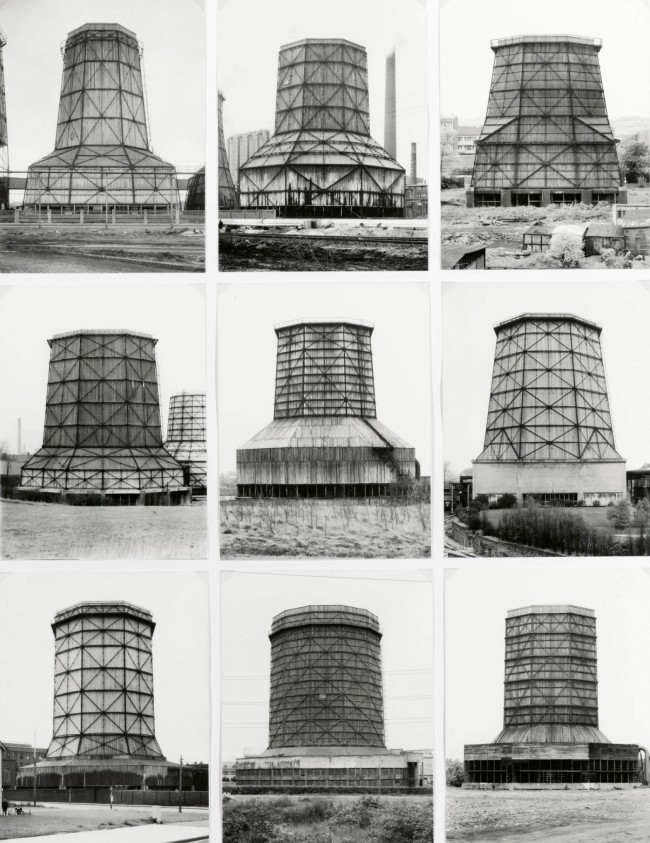

“The Bechers specialized in the photography of anonymous industrial sites and structures, methodically employing the same neutral perspective in each image, as in Water Towers. The nine nineteenth-century metal water towers are displayed in a grid as a single work, the black-and-white images revealing the differences between objects that had an identical function, and so bestowing an aesthetic value on them.”1

Here a definition of typology may be useful. ‘Typology’ is the study and interpretation of types and symbols, a classification according to a general type, especially in archaeology, psychology, or the social sciences. In this sense, the Becher’s photographs of industrial archetypes displayed in grids are excavations of historical types, representations of both pattern (type, grid) and randomness (interpretation, aesthetics). What does this mean? According to Katherine Hayles, pattern (in this case grids of photographs of the same archetype) cannot exist without its opposite, randomness, enacted through mutation of the code.

“Although mutation disrupts pattern, it also presupposes a morphological standard against which it can be measured and understood as mutation. We have seen that in electronic textuality, the possibility for mutation within the text are enhanced and heightened by long coding chains. We can now understand mutation in more fundamental terms. Mutation is critical because it names the bifurcation point at which the interplay between pattern and randomness causes the system to evolve in a new direction…

Mutation is the catastrophe in the pattern/randomness dialectic… It marks a rupture of pattern so extreme that the expectation of continuous replication can no longer be sustained… The randomness to which mutation testifies is implicit in the very idea of pattern, for only against the background of nonpattern can pattern emerge. Randomness is the contrasting term that allows pattern to be understood as such.”2

The pattern of the Bechers photographs are the grids, the randomness evidenced as we move in to observe individual images within the grid, for every water tower is different and its own form… and then we pull back to compare one image with another, one mutation with another. As we move closer the individual image becomes whole in its own right, but contains within the pictorial frame evidence of the subjects mutation through decay, evidence of an industrial revolution and means of production that is now archaic and arcane. It is as though we are looking at a fractal in which similar patterns recur at progressively smaller scales, but which in fact describe partly random or chaotic phenomena, the seeds of their own mutation. And the possibility for mutation within the text is enhanced and heightened by long coding chains, such as large typologies of objects and large grids of images.

As much as the Bechers objective photographs seek a cool sameness, they undermine their own project by their photographs inherent subversiveness. It’s as though the beauty of their object of desire is being played off against a rage against the machine, a critique of what industrialisation is doing to the divine landscape of the earth.

Of course images are always seen in context which, together with their formal characteristics and conditions, limits the meanings available from them at any one moment. As Annette Kuhn observes, “Meanings do not reside in images, then: they are circulated between representation, spectator and social function.”3 We understand the Bechers images then, through a representation of reality which always and necessarily entails, “the use of the codes and conventions of the available cultural forms of presentation. Such forms restrict and shape what can be said by and / or about any aspect of reality in a given place in a given society at a given time, but if that seems like a limitation on saying, it is also what makes saying possible at all.”4 Richard Dyer continues,

“I accept that one apprehends reality only through representations of reality, through texts, discourse, images; there is no such thing as unmediated access to reality. But because one can see reality only through representation, it does not follow that one does not see reality at all. Partial – selective, incomplete, from a point of view – vision of something is not no vision of it whatsoever.”4

Despite the Bechers attempt to catalogue vast typologies, there is no order without disorder. Their vision, and our vision, is only ever selective, incomplete and from a point of view. Much as they desire an enchantment of the subject so that the object of desire falls under their spell in order to validate its presence, so there is no single determinate meaning to any presentation of their work, for people make sense of images in different ways, according to the cultural codes available to them. “What is re-presented in representation is not directly reality itself but other representations. The analysis of images always needs to see how any given instance is embedded in a network of other instances…”4

The ghosts in the machine of the Bechers networks, those random bits of code that lurk behind a not so perfect representation, group together to form unexpected protocols seen from different points of view. “Unanticipated, these free radicals engender questions of free will, creativity, and even the nature of what we might call the soul.” (Asimov)

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Footnotes

1/ Anonymous. “A Movement in a Moment: The Düsseldorf School,” on the Phaidon website [Online] Cited 01/11/2022

2/ Katherine Hayles. How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, and Informatics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999, p. 33.

3/ Annette Kuhn. The Power of the Image: Essays on Representation and Sexuality. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1985, p. 6.

4/ Richard Dyer. The Matter of Images: Essays on Representations. London: Routledge, 1993, pp. 2-3.

Many thankx to the Metropolitan Museum of Art for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“I think it’s best to imagine that they cast a doubting eye on earlier aspirations to scientific and technical order. After all, the Bechers hit their stride as artists in the 1960s and early ’70s, at just the moment when any aspiring intellectual was reading Thomas Kuhn’s “The Structure of Scientific Revolutions,” which pointed to how the sociology of science (who holds power in labs and who doesn’t) shapes what science tells us. The French philosopher Roland Barthes had killed off the all-powerful author and let the rest of us be the true makers of meaning, even if that left it unstable. European societies were in turmoil as they faced the terrors of the Red Brigades and Baader-Meinhof gang, so brilliantly captured in the streaks and smears of Gerhard Richter, that other German giant of postwar art. The Bechers were working in that world of unsettled and unsettling ideas. By parroting the grammar of technical imagery, without actually achieving any technical goals, their photos seem to loosen technology’s moorings. By collecting water towers the way someone else might collect cookie jars, they cut industry down to size… To get the full meaning and impact of the Bechers’ Machine Age black-and-whites, they should really be viewed through the windows of their Information Age orange van.”

Blake Gopnik. “Photography’s Delightful Obsessives,” on The New York Times website July 28, 2022 [Online] Cited 20/10/2022

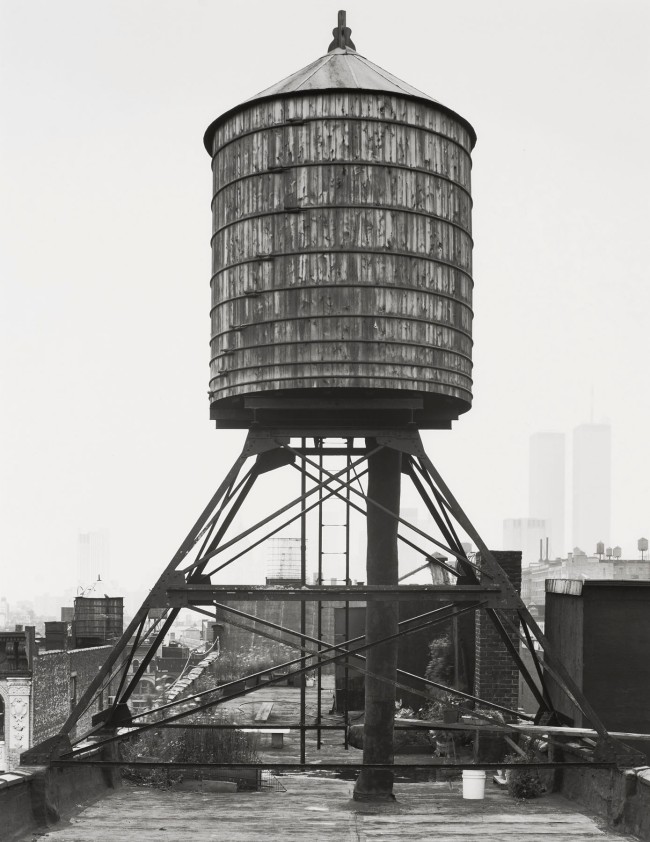

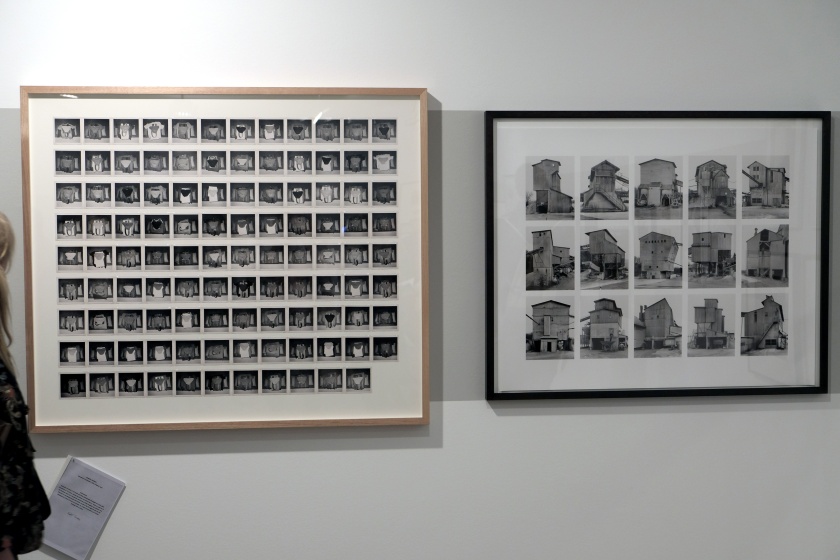

Installation view of the exhibition Bernd & Hilla Becher at The Metropolitan Museum of Art showing at centre, Water Tower, Verviers, Belgium 1983, below

Photo: Anna-Marie Kellen/The Met

00 Basic Forms

01 Framework Houses

02 Early Work

03 Industrial Landscapes

04 Zeche Concordia

05 Art and Evolution

06 Typologies

Bernd and Hilla Becher (German, active 1959-2007)

Bernd Becher (German, 1931-2007)

Hilla Becher (German, 1934-2015)

Water Tower, Verviers, Belgium

1983

Gelatin silver print

Image: 23 7/8 × 19 13/16 in. (60.6 × 50.4cm)

Purchase, The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 1992

Both as artists and teachers, Bernhard and Hilla Becher are among the most important figures in postwar German photography. For the last thirty years, the artists have examined the dilapidated industrial architecture of Europe and North America, from water towers and blast furnaces to the surrounding workers’ houses. Photographing against a blank sky and without any pictorial tricks or effects, the artists treat these forgotten structures as the exotic specimens of a long-dead species.

The renowned German artists Bernd and Hilla Becher (1931-2007; 1934-2015) changed the course of late twentieth-century photography. Working as a rare artist couple, they focused on a single subject: the disappearing industrial architecture of Western Europe and North America that fuelled the modern era. Their seemingly objective style recalled nineteenth- and early twentieth-century precedents but also resonated with the serial approach of contemporary Minimalism and Conceptual art. Equally significant, it challenged the perceived gap between documentary and fine-art photography.

Using a large-format view camera, the Bechers methodically recorded blast furnaces, winding towers, grain silos, cooling towers, and gas tanks with precision, elegance, and passion. Their rigorous, standardised practice allowed for comparative analyses of structures that they exhibited in grids of between four and thirty photographs. They described these formal arrangements as “typologies” and the buildings themselves as “anonymous sculpture.”

This posthumous retrospective celebrates the Bechers’ remarkable achievement and is the first ever organised with full access to the artists’ personal collection of working materials and their comprehensive archive.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

Bernd Becher (German, 1931-2007)

Eisernhardter Tiefbau Mine, Eisern, Germany

1955-1956

Graphite and watercolour on paper

16 5/16 × 16 5/16 in. (41.5 × 41.5cm)

Estate Bernd & Hilla Becher, represented by Max Becher, courtesy Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur – Bernd & Hilla Becher Archive, Cologne

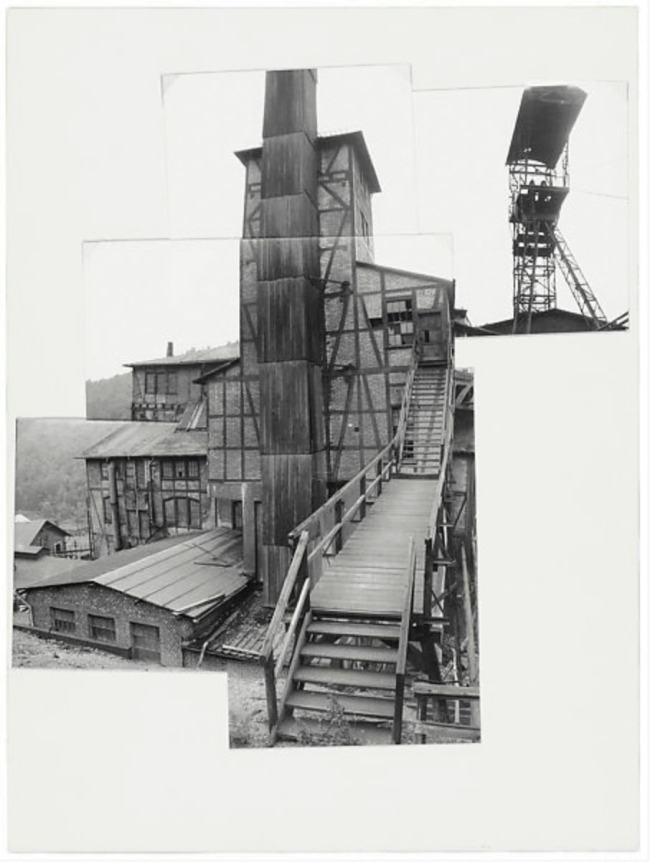

The earliest surviving independent works by Bernd Becher are several rare drawings and photocollages of the Eisernhardter Tiefbau Mine, made before the formation of his artistic partnership with Hilla Wobeser in 1959. These include the works presented on this wall and directly opposite. They reveal the artist’s lifelong interest in the accurate description of mining and manufacturing structures familiar to him from his childhood. Here, Bernd takes special care to focus on the mine’s wooden framework features and its idiosyncratic winding tower, which rises above the buildings like an enormous windblown flag.

Bernd Becher (German, 1931-2007)

Eisernhardter Tiefbau Mine, Eisern, Germany

1957

Collage of five gelatin silver prints

Sheet: 15 3/4 × 11 3/4 in. (40 × 29.9cm)

Estate Bernd & Hilla Becher, represented by Max Becher, courtesy Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur – Bernd & Hilla Becher Archive, Cologne

Bernd Becher (German, 1931-2007)

[Assemblage of Pipes]

1964 or later

Gelatin silver prints with graphite

Sheet: 14 3/8 × 13 1/16 in. (36.5 × 33.2cm)

Estate Bernd & Hilla Becher, represented by Max Becher, courtesy Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur – Bernd & Hilla Becher Archive, Cologne

This exceptional assemblage includes three razor-cut photographs of blast-furnace pipes braided together into a handsome knot. Part Giorgio de Chirico (one of the artist’s favourite painters), part pretzel, the metaphysical work shows Bernd Becher’s playful sense of humour and appreciation for the complexity and visual wonderment of industrial forms.

Hilla Becher (German, 1934-2015)

[Mountain Elm Leaf]

1965

Gelatin silver print

9 5/16 × 6 15/16 in. (23.7 × 17.7cm)

Estate Bernd & Hilla Becher, represented by Max Becher, courtesy Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur – Bernd & Hilla Becher Archive, Cologne

In these studies of tree leaves, Hilla Becher is operating in a long tradition of natural realism that connects her work to that of many earlier German artists, including the photographs of Karl Blossfeldt and the printed botanical and zoological studies of Ernst Haeckel (see display case). What was important to Blossfeldt, Haeckel, and the Bechers was not simple exactitude but a particular type of graphic description and presentation that could reveal the unique, often quirky, and at times humorous structure of any form.

Hilla Becher (German, 1934-2015)

[Spruce Branch]

1965

Gelatin silver print

9 7/16 × 7 1/16 in. (24 × 17.9cm)

Estate Bernd & Hilla Becher, represented by Max Becher, courtesy Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur – Bernd & Hilla Becher Archive, Cologne.

Hilla Becher (German, 1934–2015)

[Shell, for the German Industrial Exhibition, Khartoum, Sudan]

1961

Gelatin silver print

15 3/8 × 11 7/8 in. (39 × 30.1cm)

Estate Bernd & Hilla Becher, represented by Max Becher, courtesy Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur – Bernd & Hilla Becher Archive, Cologne.

Even after the establishment of the Bechers’ professional partnership in 1959, Hilla continued to accept commission work. She produced this study of the inner architecture of a seashell as a graphic for a display of industrial design at a German trade fair in Khartoum. This vintage photograph was copied and used by the pavilion designer as oversize enlargements. Hilla also documented the interior and exterior of the innovative prefabricated shed pavilion with its lively metal banding.

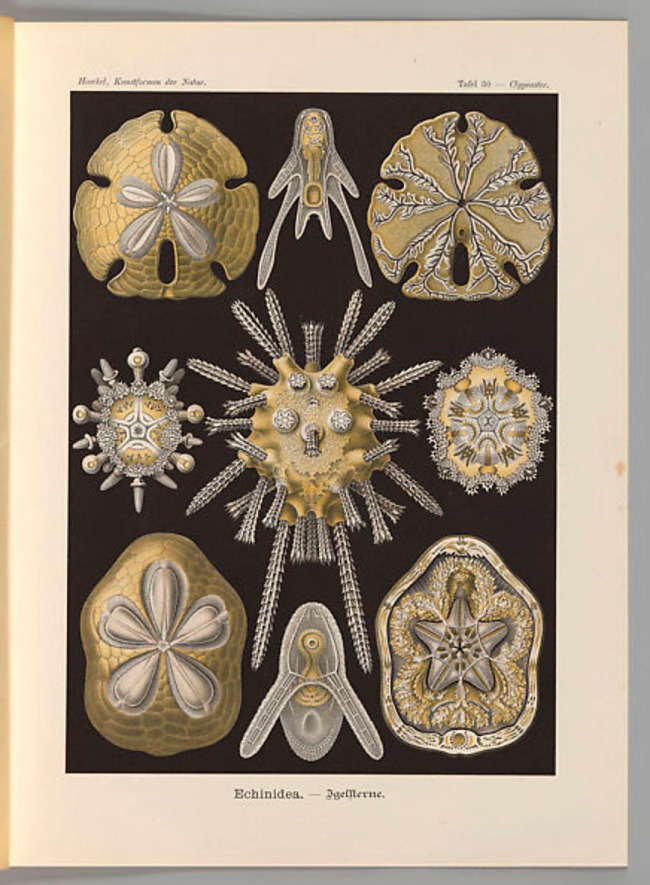

Ernst Haeckel (German, 1834-1919)

“Echinidea. – Igelsterne”

Kunstformen der Natur (Leipzig and Vienna: Verlag des Bibliographischen Instituts, 1904)

1904

Lithograph

Sheet: 13 5/8 × 10 1/4 in. (34.6 × 26cm)

Joyce Frank Menschel Library, Department of Photographs, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

For both research purposes and aesthetic pleasure, Hilla Becher assembled a collection of illustrated books dedicated to scientific classification. None on the theme of biological order was more important to the artists’ development than Ernst Haeckel’s 1904 Kunstformen der Natur. The plate from a disbound volume presented here shows a typological comparison of sea urchins and sand dollars.

From July 15 to November 6, 2022, the renowned American museum is showing a retrospective of the important artist couple in cooperation with Studio Bernd & Hilla Becher, Dusseldorf, and Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur, Cologne.

Bernd and Hilla Becher (1931-2007, 1934-2015) are among the most important artists of the second half of the 20th century. Since the 1960s, their works have provided decisive impetus for photography, art and also generally for dealing with our culture, economy, science and society. For more than 50 years, the artist couple has devoted themselves to the subject of the industrial landscape, the functional buildings and constructions of the mining industry in Western Europe and North America. They created countless black-and-white photographs, which they took with their large-format cameras, of winding towers, blast furnaces, water and cooling towers, coal bunkers, gas tanks, half-timbered houses, entire industrial plants and landscapes. The photographs show precise, at the same time analytical views and individual forms, which Bernd and Hilla Becher subjected to a comparative analysis. So-called typologies, unfolding photographic sets or also large-format typologically conceived individual photographs were the results of their collaboration, which they exhibited internationally and published in monographs. Works that received a special appreciation under the term “Anonymous Sculptures” and attained top-class awards.

The method used by the Bechers can be regarded as style-defining. It transformed the descriptive, objective view of photography of the 19th and early 20th century, which the artist couple highly valued, into a new era, integrating it into clearly sequenced series of images and thus at the same time pointing to perspectives of minimal and conceptual art, which further underscores the innovative power of their work.

Between 1976 and 1996 Bernd Becher taught at the Art Academy in Dusseldorf. Numerous well-known photographers and artists emerged from his photography class. As of the 1960s Bernd and Hilla Becher had their studio in Dusseldorf. Today the studio is being continued as the Bernd & Hilla Becher Studio by their son, estate administrator and artist Max Becher. From 1995 until their death, the artist couple worked together with Die Photographische Sammlung / SK Stiftung Kultur in Cologne, from which the Bernd & Hilla Becher Archive emerged. The majority of the exhibition is furnished from this collection, including numerous previously little-shown and unknown materials by Bernd and Hilla Becher. Overall, the retrospective, which will be on view in a second venue at the SFMoMA between December 17, 2022 and April 2, 2023, introduces all of the artist couple’s areas of work.

The exhibition was curated by Jeff L. Rosenheim, Joyce Frank Menschel Curator, Department of Photographs, assisted by Virginia McBride, Research Associate, Department of Photographs, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

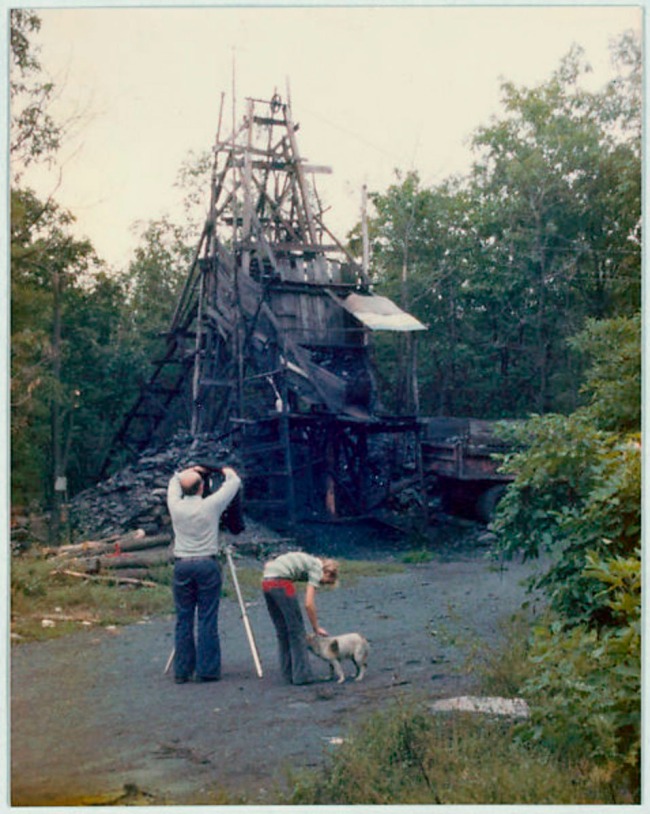

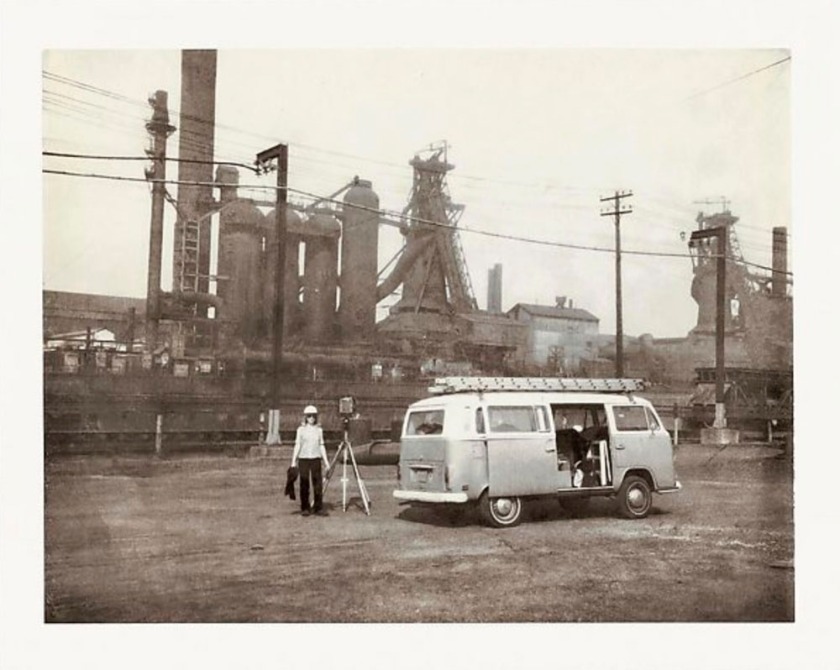

Unknown photographer

Bernd and Max Becher, Kintzel Coal Company, Big Lick Mountains, Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania

1978

Chromogenic print

4 3/8 × 3 7/16 in. (11.1 × 8.8cm)

Estate Bernd & Hilla Becher, represented by Max Becher, courtesy Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur – Bernd & Hilla Becher Archive, Cologne

Unknown photographer

Bernd and Hilla Becher, Ensdorf Mine, Saarland, Germany

1979

Gelatin silver print

4 3/4 × 5 9/16 in. (12 × 14.1cm)

Estate Bernd & Hilla Becher, represented by Max Becher, courtesy Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur – Bernd & Hilla Becher Archive, Cologne

Their camera’s lens, facing Hilla, has been raised higher than the film plane that’s facing Bernd, a trick that lets them capture the tops of tall structures.

Unknown photographer

Hilla Becher, Youngstown, Ohio, United States

1981

Instant diffusion transfer print (Polaroid)

2 7/8 × 3 3/4 in. (7.3 × 9.5cm)

Estate Bernd & Hilla Becher, represented by Max Becher, courtesy Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur – Bernd & Hilla Becher Archive, Cologne

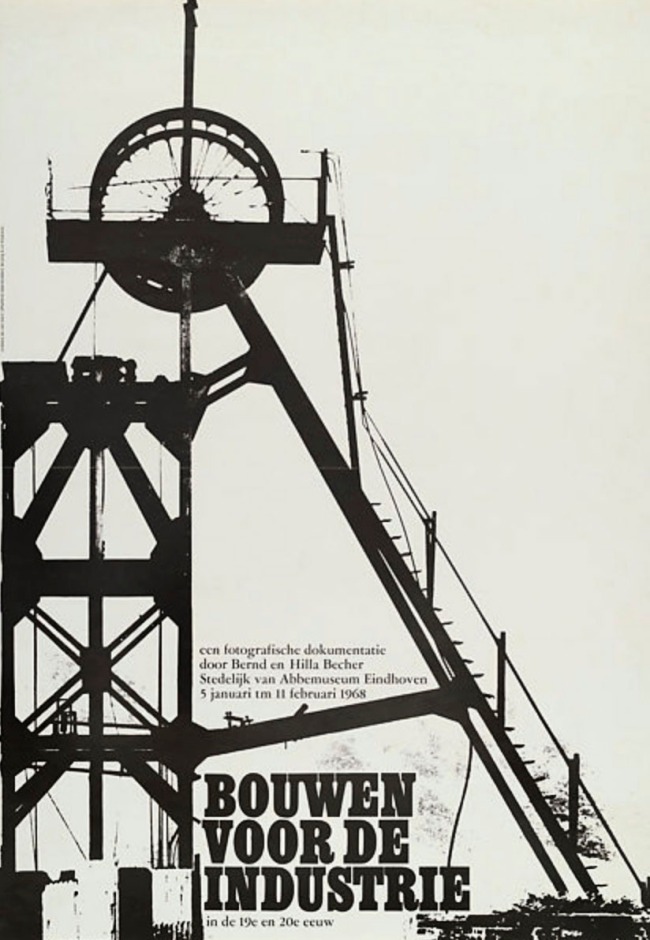

Bouwen voor de Industrie in de 19e en 20e eeuw, een fotografische dokumentatie door Bernd en Hilla Becher, Stedelijk van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, The Netherlands

1968

Photomechanical reproduction

Sheet: 34 5/8 × 24 3/16 in. (88 × 61.5cm)

Frame: 36 15/16 × 26 7/16 in. (93.8 × 67.2cm)

Estate Bernd & Hilla Becher, represented by Max Becher, courtesy Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur – Bernd & Hilla Becher Archive, Cologne

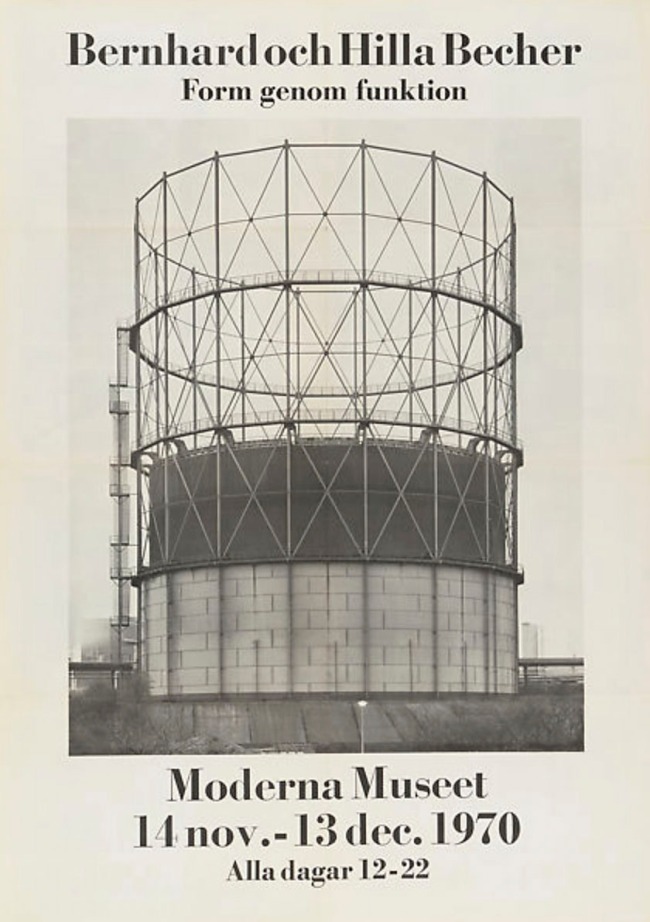

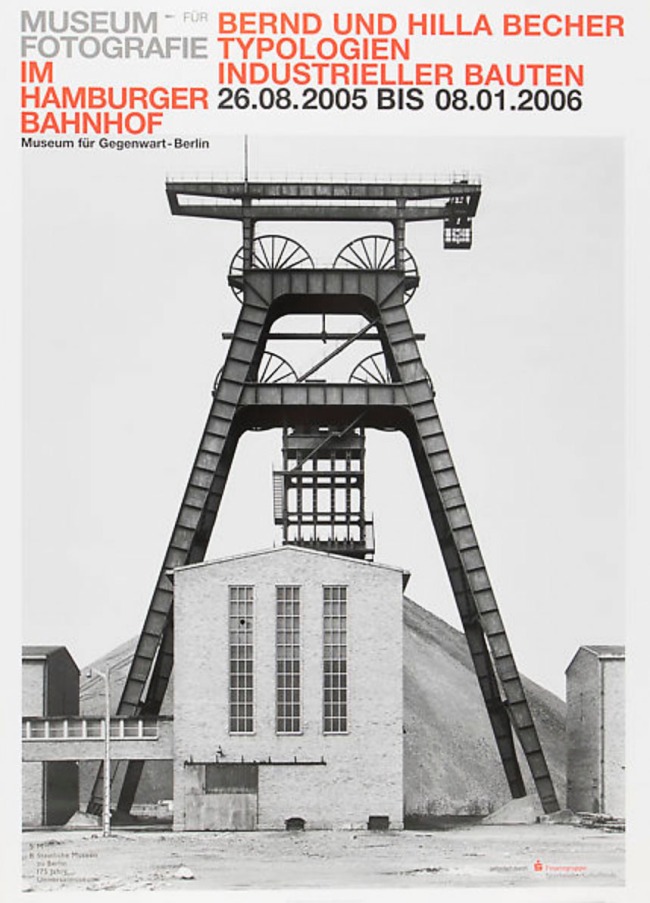

Bernd and Hilla Becher were notoriously exacting about how their photographs were constructed in the camera, printed in the darkroom, and sequenced and reproduced in their many publications. Interestingly, they were rather generous with how and where their photographs were used in other printed materials, such as promotional leaflets, invitations, and exhibition posters. The posters gathered in this exhibition display a variety of typographic treatments and arrangements.

Bernd och Hilla Becher, Form genom Funktion, Moderna Museet, Stockholm, Sweden

1970

Photomechanical reproduction

Sheet: 39 5/16 × 27 1/2 in. (99.8 × 69.8cm)

Frame: 41 9/16 × 29 3/4 in. (105.6 × 75.6cm)

Estate Bernd & Hilla Becher, represented by Max Becher, courtesy Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur – Bernd & Hilla Becher Archive, Cologne

Bernd und Hilla Becher, Typologien industrieller Bauten, Museum für Fotografie im Hamburger Bahnhof, Museum für Gegenwart, Berlin, Germany

2005

Photomechanical reproduction

Sheet: 46 7/8 × 33 1/16 in. (119 × 84cm)

Frame: 49 1/16 × 35 5/16 in. (124.6 × 89.7cm)

Estate Bernd & Hilla Becher, represented by Max Becher, courtesy Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur – Bernd & Hilla Becher Archive, Cologne

Bernd & Hilla Becher, First Posthumous Retrospective of the Highly Influential Photographers to Open at The Met July 15

Bernd and Hilla Becher (1931-2007; 1934-2015) are widely considered the most influential German photographers of the postwar period. Working as a rare artist couple, they developed a rigorous practice focused on a single subject: the disappearing industrial architecture of Western Europe and North America that fuelled the modern era. Opening at The Metropolitan Museum of Art on July 15, 2022, Bernd & Hilla Becher features some 200 works of art and is the artists’ first posthumous retrospective of their 50-year career. It is organised with full access to the Becher’s comprehensive archive and personal collection of working materials and is the first American retrospective since 1974 (when their mature style was still evolving).

The exhibition is made possible by Joyce Frank Menschel, the Barrie A. and Deedee Wigmore Foundation, the Edward John & Patricia Rosenwald Foundation, and Linda Macklowe. It is organised by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, in association with Studio Bernd & Hilla Becher and Die Photographische Sammlung / SK Stiftung Kultur.

“Bernd and Hilla Becher changed the course of late 20th-century photography, and their groundbreaking work continues to influence artists to this day,” said Max Hollein, Marina Kellen French Director of The Met. “It is a privilege to present this first posthumous retrospective and to celebrate their legacy and remarkable artistic achievement.”

Exhibition overview

The Bechers seemingly objective aesthetic looked back to 19th- and early 20th-century precedents but also resonated with the serial, premeditated progressions of contemporary Minimalism and Conceptual art. Equally significant, their aesthetic challenged the perceived gap between documentary and fine-art photography. The artists used a large-format view camera – similar to those used by 19th-century photographers such as the Bisson Frères in France and Carleton Watkins in the American West – and spurned the handheld, 35 mm roll-film cameras of the type preferred by journalists and pre- and postwar artists such as Henri Cartier-Bresson and Robert Frank. They worked exclusively with black-and-white photographic materials, intentionally avoiding the medium’s inevitable move to colour that took place during the 1960s and 1970s, and methodically recorded blast furnaces, winding towers, grain silos, cooling towers, and gas tanks with precision, elegance, and passion. Their standardised approach allowed for comparative analyses of structures that they exhibited in grids of between 4 and 30 photographs. They described these formal arrangements as “typologies” and the buildings themselves as “anonymous sculpture.”

The Bechers had a direct and profound influence on several generations of students at the renowned art academy Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, where Bernd was appointed the first professor of photography in 1976. Among the members of the so-called Becher School or Düsseldorf School of Photography are some of the most recognised German artists of the past 40 years, such as Thomas Struth, Andreas Gursky, Candida Höfer, and Thomas Ruff.

Featured in the exhibition alongside the individual and grids of photographs for which the Bechers are best known are extraordinary works in photography and other media executed by them before and after the formation of their creative partnership in 1959. These rarely seen lithographs, collages, photographs, ink and pencil sketches, Polaroids, and personal snapshots offer a deep understanding of the artists’ working methods and intellectual processes.

Following its debut at The Met, the exhibition will travel to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA), where it will be on view from December 17, 2022 through April 2, 2023. Bernd & Hilla Becher is curated by Jeff L. Rosenheim, Joyce Frank Menschel Curator in Charge of the Department of Photographs, with assistance from Virginia McBride, Research Assistant in the Department of Photographs, both at The Met. The Met developed the exhibition with Max Becher, the artists’ son, and with Gabriele Conrath-Scholl, director of the Photographische Sammlung / SK Stiftung Kultur in Cologne, where the artists’ vast photographic print archive is preserved.

The exhibition is accompanied by a scholarly publication, the first posthumous monograph published on the Bechers. It features essays by Gabriele Conrath-Scholl; Dr. Virginia Heckert, curator of photographs at the J. Paul Getty Museum and an expert on the Bechers; and Lucy Sante, arts critic, essayist, artist, and visiting professor of writing and photography at Bard College. The publication also includes an extensive interview with Max Becher that, together with the essays, introduces and surveys the Bechers’ photographs and the significance of their achievement over a remarkably productive half-century career. The catalogues is made possible by the Mary C. and James W. Fosburgh Publications Fund.

Press release from the Metropolitan Museum of Art

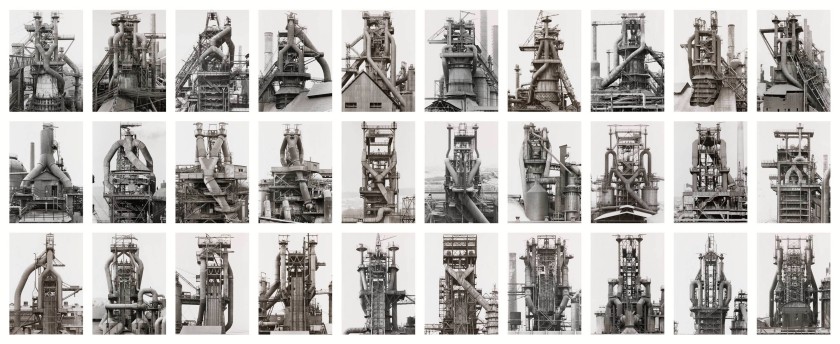

Bernd and Hilla Becher (German, active 1959-2007)

Bernd Becher (German, 1931-2007)

Hilla Becher (German, 1934-2015)

Blast Furnaces (United States, Germany, Luxembourg, France, and Belgium)

1968-1993

Gelatin silver prints

Estate Bernd & Hilla Becher, represented by Max Becher

Such series may have been less about the glories of heavy industry than its approaching demise in the West.

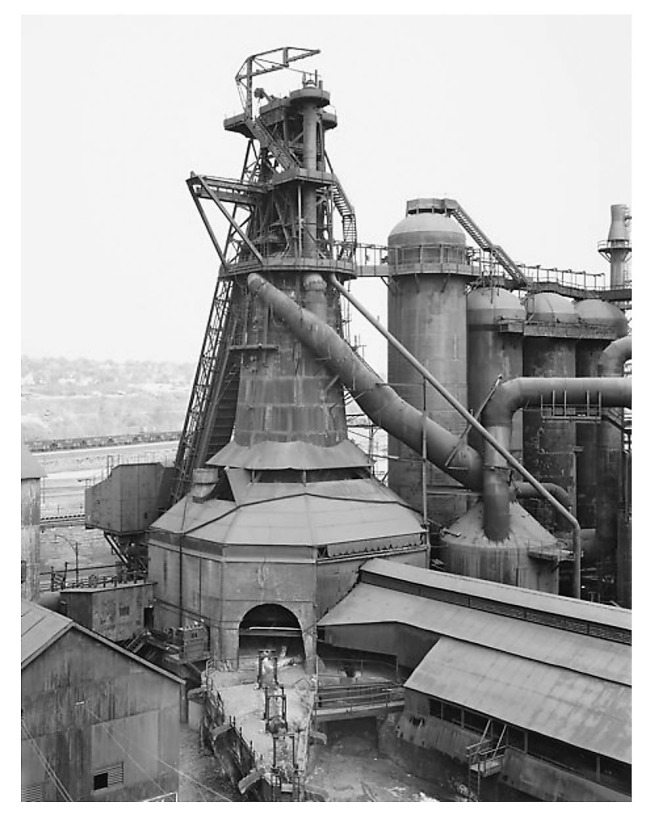

Bernd and Hilla Becher (German, active 1959-2007)

Bernd Becher (German, 1931-2007)

Hilla Becher (German, 1934-2015)

Blast Furnace, Youngstown, Ohio, United States

1983

Gelatin silver print

23 1/8 × 18 1/4 in. (58.8 × 46.4cm)

Estate Bernd & Hilla Becher, represented by Max Becher, courtesy Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur – Bernd & Hilla Becher Archive, Cologne

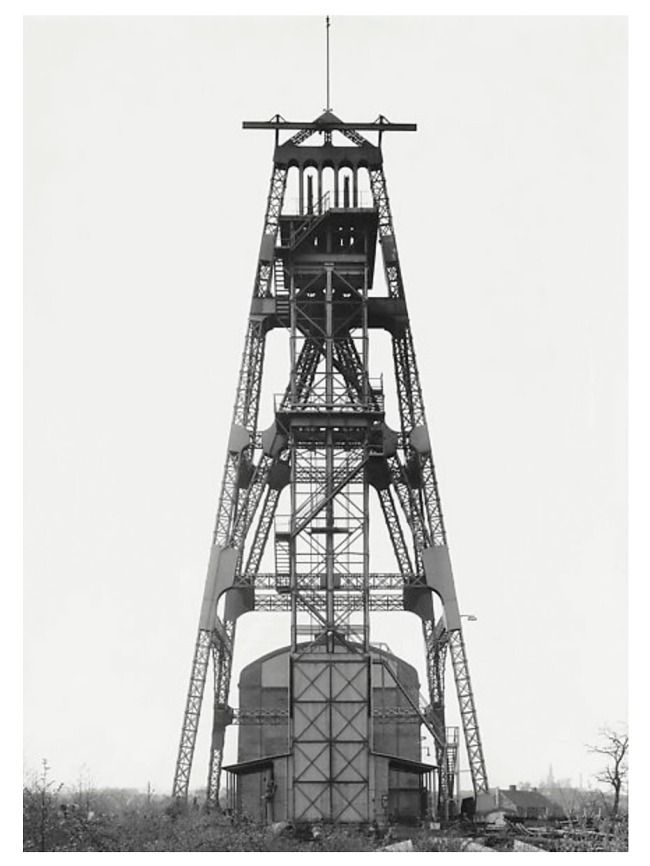

The buildings Bernd and Hilla Becher chose to photograph were meant to be altered or demolished when superseded technologically. Given the planned obsolescence of their subjects, the artists’ timing played an important role in the success of their practice. In one of their last books, Industrial Landscapes (2002), they commented: “Once we were in northern France, where we found a wonderful headgear [the top of a blast furnace] – a veritable Eiffel Tower. When we arrived the weather was hazy and not ideal for our work so we decided to postpone taking the photos for a day. When we arrived the next day, it had already been torn down, the dust was in the air.”

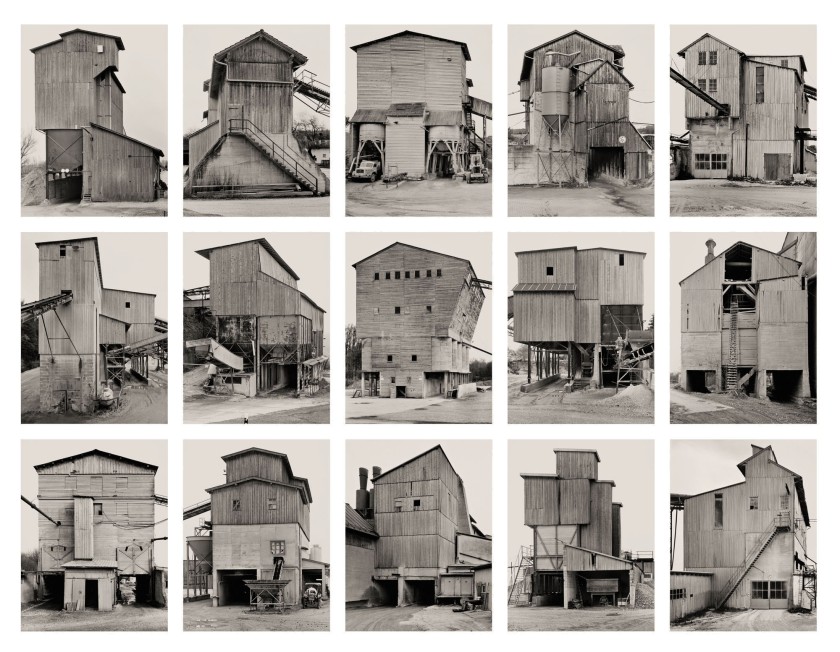

Bernd and Hilla Becher (German, active 1959-2007)

Bernd Becher (German, 1931-2007)

Hilla Becher (German, 1934-2015)

Gravel Plants

1988-2001

Gelatin silver prints

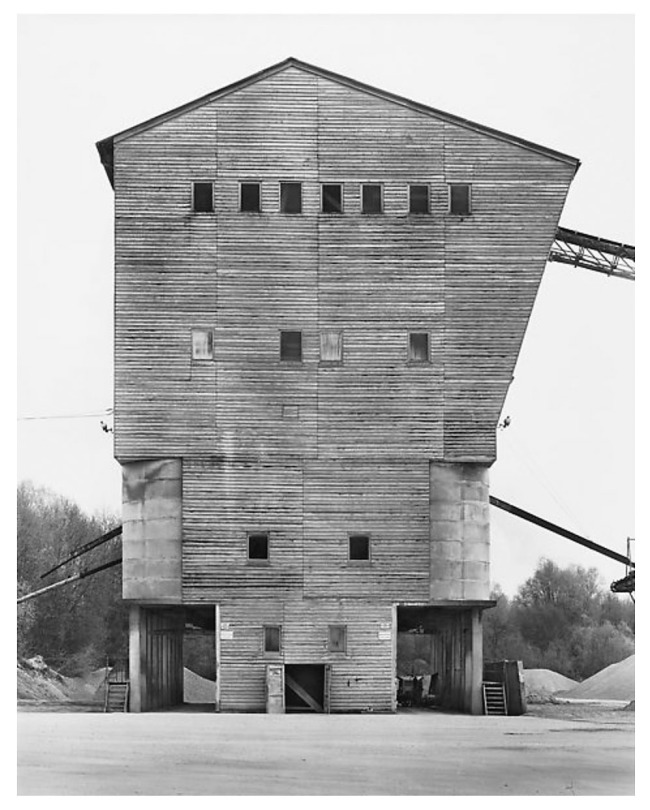

Bernd and Hilla Becher (German, active 1959-2007)

Bernd Becher (German, 1931-2007)

Hilla Becher (German, 1934-2015)

Gravel Plant, Günzburg, Germany

1989

Gelatin silver print

24 3/16 × 19 3/16 in. (61.4 × 48.7cm)

Estate Bernd & Hilla Becher, represented by Max Becher, courtesy Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur – Bernd & Hilla Becher Archive, Cologne

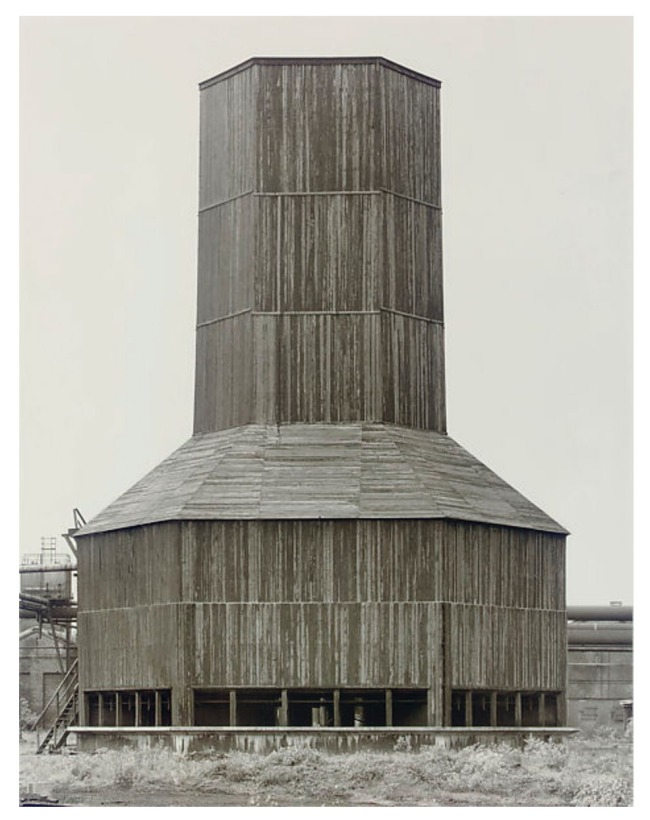

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Bernd and Hilla Becher completed a thorough documentation of the many gravel plants in and near Günzburg, a small city on the Danube River in Bavaria. This oddly shaped yet functional building was used as a stone breaker to produce gravel, the still-lucrative industrial material required for making roads and high-quality concrete. The asymmetrical facade delights the eye, recalling the Bechers’ frequently stated agenda: “We were fascinated above all by the shape of technical architecture, and hardly by its history.”

Bernd and Hilla Becher (German, active 1959-2007)

Bernd Becher (German, 1931-2007)

Hilla Becher (German, 1934-2015)

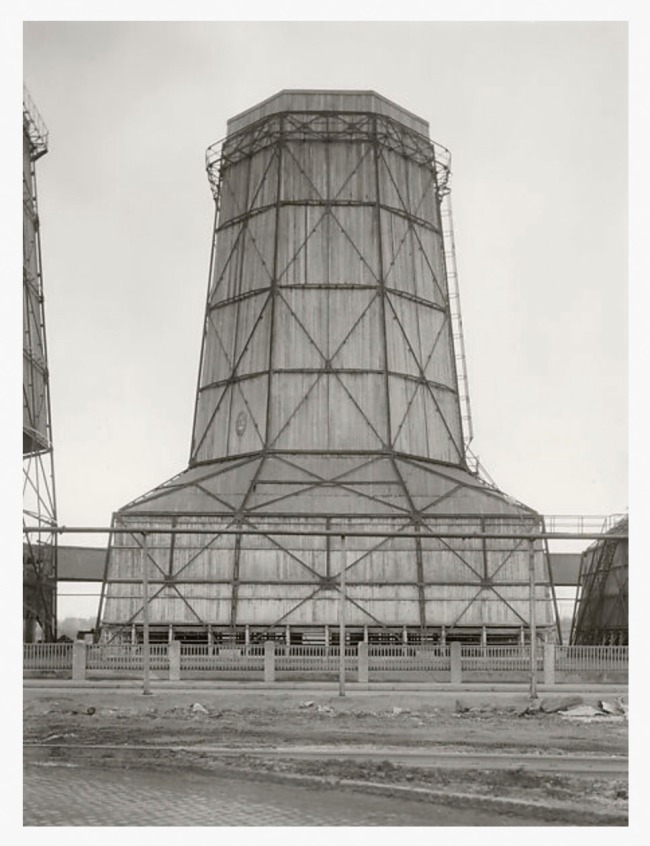

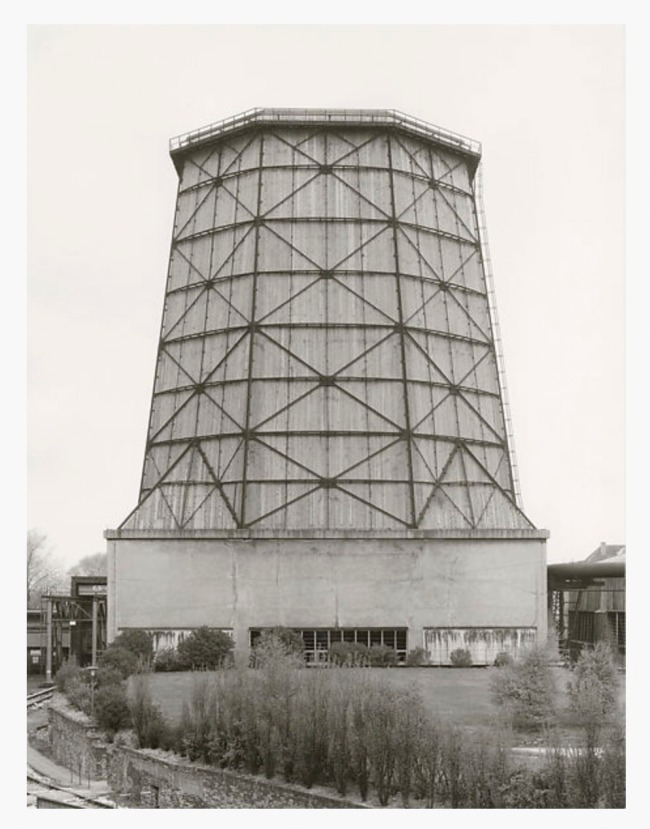

Cooling Tower, Zeche Mont Cenis, Herne, Ruhr Region, Germany

1965

Gelatin silver print

23 5/8 x 18 1/4 in. (60.5 x 46.4cm)

Collection of James Kieth Brown and Eric Diefenbach

Influenced by the formal rigour and conceptual methods of pre-World War II artists, such as August Sander and Walker Evans, Bernd and Hilla Becher were considered equals and fellow travellers by Minimalist sculptors, such as Carl Andre and Sol LeWitt. They treated their subject matter – the disappearing industrial architecture of the West – as “anonymous sculpture.” Here, a fabulous tower used to cool water at the Mont Cenis colliery rises from the ground like a modernist top hat made for a wooden giant. In 1978, just thirteen years after the Bechers visited the busy complex, it closed permanently, ending more than one hundred years of coal extraction on the site.

The Bechers photographed against a blank sky and without any pictorial tricks or effects, using an old-fashioned tripod-mounted view camera of the kind used by Eugène Atget and Walker Evans. They treated their subjects as “anonymous sculpture” (the name of their first monograph) that could only be fully rendered through either multiple views from different perspectives or more often, through the typological accumulation and serial presentation of multiple specimens. Although they were artists not scientists, the Bechers used an almost Linnean system of classification – another important 19th century precedent which they made resolutely modern.

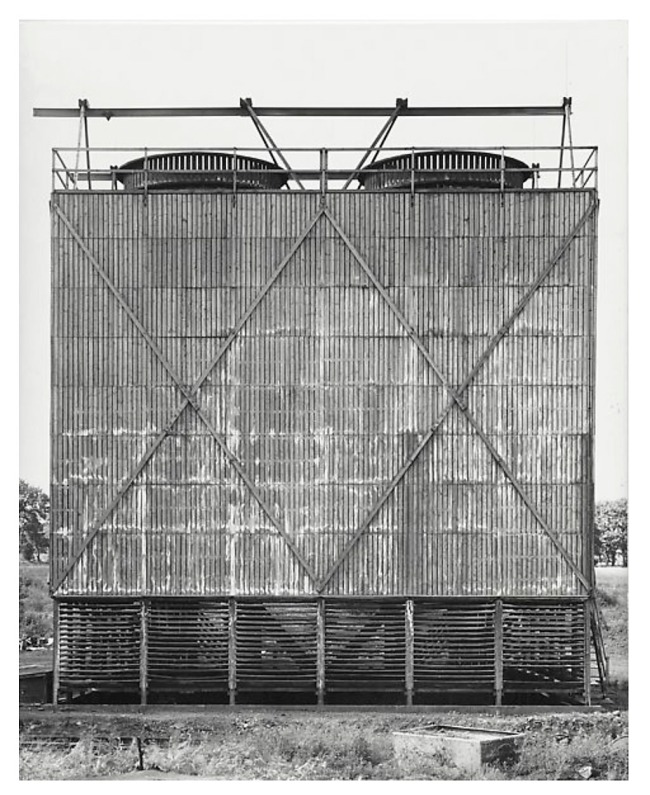

Bernd and Hilla Becher (German, active 1959-2007)

Bernd Becher (German, 1931-2007)

Hilla Becher (German, 1934-2015)

Cooling Tower, Caerphilly, South Wales, Great Britain

1966

Gelatin silver print

Image: 14 5/8 × 11 3/4 in. (37.1 × 29.9cm)

Gift of the LeWitt Family, in memory of Bernd and Hilla Becher, 2018

As both artists and professors at the Kunstakademie in Düsseldorf, the husband-and-wife team of Bernd and Hilla Becher have influenced an entire generation of German photographers with their typological approach to the medium, in which a single archetypal subject is described through an accumulation of diverse examples. For more than three decades, they have systematically examined the dilapidated industrial architecture of Europe and North America, from water towers and blast furnaces to the surrounding workers’ houses, all recorded against a blank sky and without expressive effects. As it developed in the 1960s, the Bechers’ project chimed with Conceptual Art in its emphasis on impersonal series as well as with older traditions of objective photography as practiced by such artists such as August Sander and Karl Blossfeldt.

Bernd and Hilla Becher (German, active 1959-2007)

Bernd Becher (German, 1931-2007)

Hilla Becher (German, 1934-2015)

Cooling Towers (Wood)

1976

Gelatin silver prints

16 × 12 in. (40.6 × 30.5cm), each

Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

Bernd and Hilla Becher (German, active 1959-2007)

Bernd Becher (German, 1931-2007)

Hilla Becher (German, 1934-2015)

Cooling Towers (Wood) (detail)

1976

Gelatin silver prints

16 × 12 in. (40.6 × 30.5cm), each

Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

Bernd and Hilla Becher (German, active 1959-2007)

Bernd Becher (German, 1931-2007)

Hilla Becher (German, 1934-2015)

Cooling Towers (Wood) (detail)

1976

Gelatin silver prints

16 × 12 in. (40.6 × 30.5cm), each

Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

The Bechers’ purpose has always been to make the clearest possible photographs of industrial structures. They are not interested in making euphemistic, socio-romantic pictures glorifying industry, nor doom-laden spectacles showing its costs and dangers. Equally, they have nothing in common with photographers who seek to make pleasing modernist abstractions, treating the structures as decorative shapes divorced from their function.

The Bechers’ goal is to create photographs that are concentrated on the structures themselves and not qualified by subjective interpretations. To them, these structures are the ‘architecture of engineers’ and their pictures should be seen as the photography of engineers – that is, record pictures. …

[Record photographers are the unsung heroes of the history of photography. They are the anonymous commercial photographers who were commissioned to record both great and everyday industrial and civic projects, from the construction of canals to the blooming of floral clocks.]

The Bechers are fascinated by the idiosyncratic appearance of each structure. The mass-produced, design-conscious assemblies devised by architects with an eye on appearance do not appeal as much as those with a mindfulness of function. What interests the Bechers are constructions made by engineers whose plans are pragmatic, where function dictates the form, rather than, as is increasingly the case, the other way round. In the words of Bernd: ‘There is a form of architecture that consists in essence of apparatus, that has nothing to do with design, and nothing to do with architecture either. They are engineering constructions with their own aesthetic.’

Their fascination is rooted in an understanding of the structures. The Bechers are the first to acknowledge the primarily functional role of the constructions, that their existence is justified solely by their industrial performance, and that once this has been superseded the structures will be modified or demolished. They liken the way a blast furnace develops over time, as furnaces and pipework are added, to the organic but apparently chaotic growth of a medieval city. This purpose-led rationale is what attracts them. They refer to some of the structures as ‘nomadic architecture’. Once they photographed a blast furnace that was being dismantled by Chinese workers in Luxembourg, who then had to reassemble it in China.

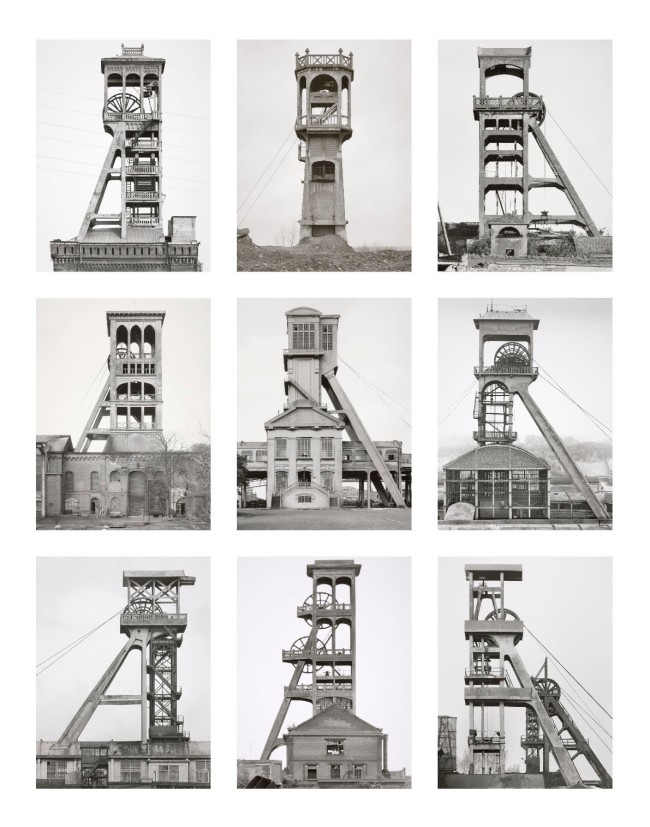

By placing photographs of similar subjects alongside each other, the individual differences emerge, making the fine details in each picture more noticeable, more distinct. Drawing on this, they began exhibiting the pictures as typologies; by the early 1960s they showed their work only in typological groups. Typically, a piece of work would comprise four small prints of, for example, water towers, adjacent to a larger print of one of the four. They would not supply prints of individual pictures; the typology was the work. Later, their typologies contained prints of equal size, measuring 30 cm by 40 cm. It could be three rows of five prints, a grid of nine or, in one case, 28 blast furnaces in three rows; a symphony of industrial structures.

The Bechers’ pictures do not have to be viewed in typologies in order to make sense, as they have validity as individual images. The typology has been developed for two reasons. First, by amassing such a detailed survey of industrial structures they are revealing sets and subsets, much like 19th-century zoologists did. With water towers, for example, there are round steel ones with conical tops, like hats, and semi-circular ones. Others are circular with sloping roofs, or without roofs, or on steel derricks, or brick towers, and so on. The more fine the differences, the better they are illustrated by the typology.

Second, the typology used by the Bechers emphasises the rewards of close scrutiny, and it is this that makes each and every one of their pictures fascinating. By presenting 15 water towers in a grid, the first effect is an imposing mass of industrial structures. You must stand back in order to take them all in as a group, but to look closer at an individual picture it is necessary to draw nearer.

Up close, only one tower is visible at a time. Isolated in pristine, black-and-white definition, this everyday object is revealed as an ‘anonymous sculpture’, an unostentatious but fabulous creation by mankind. To compare it with the others is to stand back again, and from here the impulse is to step up and examine another. Just as the beauty of the individual structure (for that is what they are) is there to see, so together as a typology they are a thrilling spectacle. …

There is a wisdom and honour in the Bechers’ work which frees them from imposing a conditional reading upon the viewer. The wisdom is the methodology they recognise in the ‘neutral’ depiction of record photography. The honour stems from a principle about not imposing their ideas on other people.

Hilla and Bernd both grew up under Adolf Hitler. They saw how he corrupted German art to promote his propaganda. This was particularly pertinent to photography, and it remained tainted after the war; witness the grim examples of Leni Riefensthal’s glorifying images of Nazis and the pseudo-scientific eugenic portrait studies that were published to defend anti-semitism and supremacism. This is why the legacy of August Sander (1876-1964), whose neutral approach to portraiture was damned by the Nazis, is so precious in Germany. It is also why the Bechers’ continuing example is extremely important. …

Because photography has, for so long, been used for commercial reasons, notably in advertising, people are accustomed to absorbing manipulative images, and have come to expect – or even rely on – a conditional presentation. Take away this interpretative control and the viewer is left free, which is unnerving if one is not used to it. This is why some regard the Bechers’ photographs as ‘cold’. There is no editorial, no soundtrack, no suggestions nor judgments. You are left to your own devices.

Of course, their motivations are not invisible, nor their presence unfelt. What does it mean when something ‘rings true’? How is it that one can sense the sincerity in another’s words? Perhaps this lies in the realm of intuition, not explanation. To analyse art is not necessarily to experience it. Sometimes, by focusing on a deliberation of it, one limits the engagement to a cerebral encounter. In the West particularly, we use explanations to try to control the unknown, to make uncertainties certain. Maybe there is a wisdom we have that is not learnt but is within us. Far better to look rather than puzzle, and to open one’s senses to what is there.

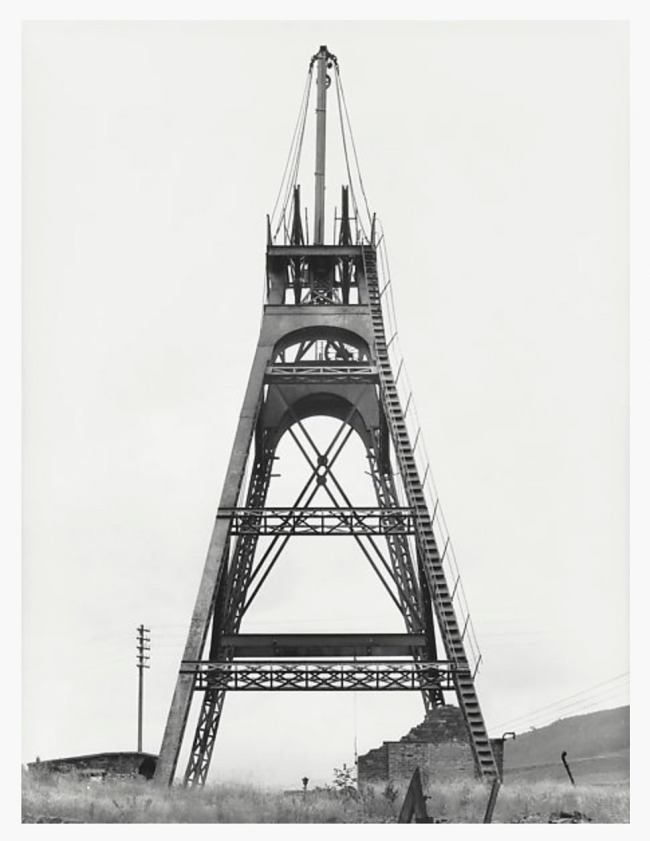

Here lies the wonder in the Bechers’ photographs. They are like rounding a hill and seeing a view spread out before you. In Cwmcynon Colliery, Mountain Ash, South Wales, 1966, a minehead stands above lines of terraced houses in the village. The giant pair of wheels on top of the single-tier steel headframe is an engineer’s structure. A device to do a job, not to win design awards. You could not dream up such structures, neither could you invent, say, your grandparents’ kitchen. These things arise from the conditions in which they are used.

They are the lines on the face of the world. The photographs are portraits of our history. And when the structures have been demolished and grassed over, as though they were never there, the pictures remain.

Michael Collins, “The long look,” Tate Research Publication, 2002 originally published in Tate Magazine issue 1 on the Tate website [Online] Cited 01/11/2022

Bernd and Hilla Becher (German, active 1959-2007)

Bernd Becher (German, 1931-2007)

Hilla Becher (German, 1934-2015)

Winding Towers (Belgium and France)

1967-1988

Gelatin silver prints

15 15/16 × 12 3/8 in. (40.5 × 31.5cm), each

The Doris and Donald Fisher Collection at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

Bernd and Hilla Becher (German, active 1959-2007)

Bernd Becher (German, 1931-2007)

Hilla Becher (German, 1934-2015)

Winding Tower, Cwm Cynon Colliery, Mountain Ash, South Wales, Great Britain

1966

Gelatin silver print

Image: 15 9/16 × 11 13/16 in. (39.6 × 30cm)

Purchase, Vital Projects Fund Inc. Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, Denise and Andrew Saul Fund, Louis V. Bell, Harris Brisbane Dick, Fletcher, and Rogers Funds and Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, and Jade Lau Gift, 2018

Bernd and Hilla Becher (German, active 1959-2007)

Bernd Becher (German, 1931-2007)

Hilla Becher (German, 1934-2015)

Winding Tower, Zeche Neu-Iserlohn, Bochum, Germany

1963

Gelatin silver print

Image: 15 9/16 × 11 1/4 in. (39.5 × 28.5cm)

Purchase, Vital Projects Fund Inc. Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, Denise and Andrew Saul Fund, Louis V. Bell, Harris Brisbane Dick, Fletcher, and Rogers Funds and Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, and Jade Lau Gift, 2018

Bernd and Hilla Becher (German, active 1959-2007)

Bernd Becher (German, 1931-2007)

Hilla Becher (German, 1934-2015)

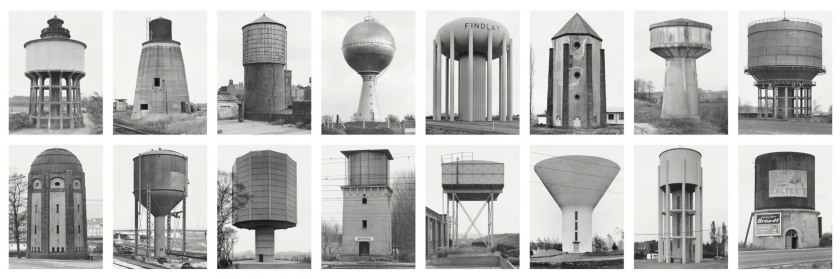

Water Towers (Germany, France, Belgium, United States, and Great Britain)

1963-1980

Gelatin silver prints

Estate Bernd & Hilla Becher, represented by Max Becher

Is there some quiet comedy in revealing all the ways industry has managed the single job of storing water?

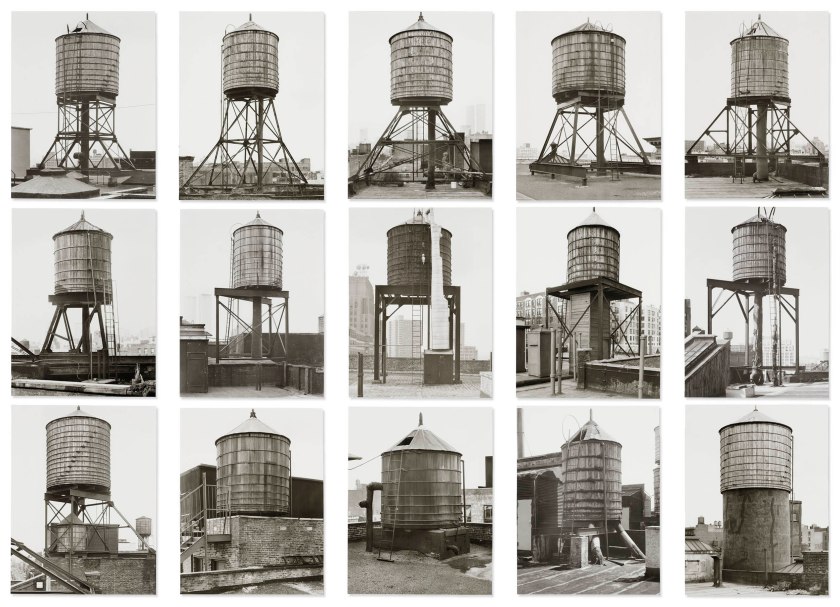

Bernd and Hilla Becher (German, active 1959-2007)

Bernd Becher (German, 1931-2007)

Hilla Becher (German, 1934-2015)

Water Towers (New York, United States)

1978-1979

Gelatin silver prints

15 15/16 × 12 3/8 in. (40.5 × 31.5cm), each

Estate Bernd & Hilla Becher, represented by Max Becher, courtesy Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur – Bernd & Hilla Becher Archive, Cologne

Bernd and Hilla Becher (German, active 1959-2007)

Bernd Becher (German, 1931-2007)

Hilla Becher (German, 1934-2015)

Water Towers (New York, United States)(detail)

1978-1979

Gelatin silver prints

15 15/16 × 12 3/8 in. (40.5 × 31.5cm), each

Estate Bernd & Hilla Becher, represented by Max Becher, courtesy Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur – Bernd & Hilla Becher Archive, Cologne

One wall is gridded up with photos of industrial cooling towers, portrayed in wildly detailed black-and-white.

Another gives us 30 different views of blast furnaces, at plants across Western Europe and the United States. You can just about make out each bolt in their twisting pipework.

An entire gallery surveys the vast Concordia coal plant in Oberhausen, Germany: Teeming photos present its gas-storage tanks, its “lean gas generator,” its “quenching tower,” its “coke pushers.”

These and something like another 450 images fill “Bernd & Hilla Becher,” a fascinating, frankly gorgeous show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Met’s curator of photography, Jeff Rosenheim, has organized a thorough retrospective for the Bechers, a German couple who made some of the most influential art photos of the past half-century. Bernd (1931-2007) and Hilla (1934-2015) mentored generations of students at Düsseldorf’s great Kunstakademie, whose alumni include major photographic artists such as Andreas Gursky and Candida Höfer.

But for all the heft of the heavy industry on view in the Met show – it’s easy to imagine the stink and smoke and racket that pressed in on the Bechers as they worked – you come away with an overall impression of lightness, of delightful order, even sometimes of gentle comedy.

Wall after wall of gridded grays soothe the eye and calm the soul, like the orderly, light-filled abstractions of Agnes Martin or Sol LeWitt. The very fact of gathering 16 different water towers, from both sides of the Atlantic, onto a single museum wall helps to domesticate them, removing their industrial angst and original functions and turning them into something like curios, or collectibles. A catalog essay refers to the Bechers’ “rigorous documentation of thousands of industrial structures,” which is right – but it’s the rigour of a trainspotter, not an engineer. Despite their concrete grandeur, the assorted water towers come off as faintly ridiculous: Whether you’re collecting cookie jars or vintage wines – or shots of water towers – it’s as much about our human instinct to amass and organise as it is about the actual things you collect.

Consider the 32 Campbell’s Soup Cans (1962) that launched Andy Warhol’s pop career, which are a vital precedent for the Bechers’ ordered seriality. You can read the Soup Cans as a critical portrayal of American consumerism, but a catalog of canned soups also reads as a quiet joke, at least when it’s presented for the sake of art, not shopping. Ditto, I think, for the Bechers’ famous “typologies” of industrial buildings, presented without anything like an industrial goal.

Indeed, the one thing you don’t come away with from the Becher show is real knowledge of mechanical engineering, or coal processing, or steel making. In long-ago student days, I cut out and framed a wallful of images from the Bechers’ glorious book of blast-furnace photos. (Their art has always existed as much in their books as in exhibitions.) After living with my furnaces for a decade or so, I can’t say I could have passed a quiz from Smelting 101.

Early coverage referred to the Bechers as “photographer-archaeologists” and the Met’s catalog talks about how they revealed the “functional characteristics of industrial structures.” There are certainly parallels between the preternatural clarity and unmediated “objectivity” of their images and earlier, purely technical and scientific photos meant to teach about the constructions and processes of industry. The Bechers admired such pictures. But however systematic their own project might seem, its goal was art, which means it was always bound to let function and meaning float free.

I think it’s best to imagine that they cast a doubting eye on earlier aspirations to scientific and technical order. After all, the Bechers hit their stride as artists in the 1960s and early ’70s, at just the moment when any aspiring intellectual was reading Thomas Kuhn’s “The Structure of Scientific Revolutions,” which pointed to how the sociology of science (who holds power in labs and who doesn’t) shapes what science tells us. French philosopher Roland Barthes had killed off the all-powerful author and let the rest of us be the true makers of meaning, even if that left it unstable. European societies were in turmoil as they faced the terrors of the Red Brigades and Baader-Meinhof gang, so brilliantly captured in the streaks and smears of Gerhard Richter, that other German giant of postwar art. The Bechers were working in that world of unsettled and unsettling ideas. By parroting the grammar of technical imagery, without actually achieving any technical goals, their photos seem to loosen technology’s moorings. By collecting water towers the way someone else might collect cookie jars, they cut industry down to size.

The Bechers weren’t the only artists working that seam. Their era’s conceptualists also played games with science and industry. When John Baldessari had himself photographed throwing three balls into the air so they’d form a straight line, he was simulating experimentation, not aiming for any real experimental result: The repeated throwing and its failure was the point, not the straight line that could never get formed, anyway. When the Bechers’ friend Robert Smithson poured oceans of glue down a hillside or bulldozed dirt onto a shed until its roof cracked, he was mimicking the moves of heroic construction, not aiming to build anything.

What made the Bechers different from their peers is that they did their mimicking from the inside: They used the language of advanced photographic technology to inhabit the technophilic world they portrayed. Their photos are almost as constructed as any “lean gas generator” they might depict. The just-the-facts-ma’am objectivity of their images is only achieved through serious photographic artifice.

Take the Bechers’ four-square photos of four-square workers’ houses. Several houses are photographed from so close that, standing right in front of them, you’d never take in their entire facades at one glance, as the Bechers do in their images. It takes a wide-angle lens to allow that trick, and only if it’s installed on the kind of technical view camera whose bellows lets lens and film slide in opposite directions. That’s how the Bechers manage to line up our eyes with the top step on a stoop (we see it edge-on) while also catching the home’s gables, high above.

The preternatural level of detail on view and its glorious range of grays and blacks require negatives the size of a man’s hand, a tripod as big as a sapling, lens filters and an advanced darkroom technique. And the couple were relying on such labour-intensive technology at just the moment when most of their photographic peers, and millions of average people, had moved on to cameras and film that let them shoot on the fly, in lab-processed colour. With the Bechers, the “decisive moment” of 35 mm photography gets replaced by a gray-on-gray stasis that feels as though it could last forever – as though it’s as immovable as the steel girders it depicts.

But, in fact, those steel girders were more time-bound than the Bechers’ photos let on. “Just as Medieval thinking manifested itself in Gothic cathedrals, our era reveals itself in technological equipment and buildings,” the Bechers once declared, yet the era they revealed wasn’t really the one they were working in. In many cases, their factories and plants and mines were about to close when the Bechers shot them – a few had already been abandoned – as Western economies made the switch to services and design and computing. The outdatedness of the Bechers’ technique matches up with their subjects. Both represent a last-gasp moment in the “industrial” revolution, which is why there’s something almost poignant about this show.

One of its most revealing moments involves a film, not a photo, and it’s not even by the power couple. The Bechers’ young son, Max, who has since become a noted artist in his own right, once captured his parents in moving colour as they set out to document silos in the American Midwest. Max filmed Bernd and Hilla unloading their heavy-duty equipment, still much as it was in Victorian times, from a classic Volkswagen camper of the 1960s. It was an absurdly underpowered machine, but who could resist its colourful paint job or its mod lines and stylings?

To get the full meaning and impact of the Bechers’ Machine Age black-and-whites, they should really be viewed through the windows of their Information Age orange van.

Blake Gopnik. “Photography’s Delightful Obsessives,” on The New York Times website July 28, 2022 [Online] Cited 30/07/2022

Bernd and Hilla Becher (German, active 1959-2007)

Bernd Becher (German, 1931-2007)

Hilla Becher (German, 1934-2015)

Lime Kiln, Brielle, Netherlands

1968

Gelatin silver print

24 in. × 19 1/2 in. (61 × 49.5cm)

Estate Bernd & Hilla Becher, represented by Max Becher, courtesy Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur – Bernd & Hilla Becher Archive, Cologne

Lime, an important building material since ancient times, is used in the production of mortar and cement. Here, the Bechers focused their attention on six towering brick chimneys that look as much like sprouting asparagus as utilitarian structures. The artists chose a similar view of lime kilns for the cover image of Anonyme Skulpturen (1970), their ambitious first publication. The book presents comparative sequences of different industrial forms, from kilns and gasometers to cooling towers, blast furnaces, and winding towers.

Bernd and Hilla Becher (German, active 1959-2007)

Bernd Becher (German, 1931-2007)

Hilla Becher (German, 1934-2015)

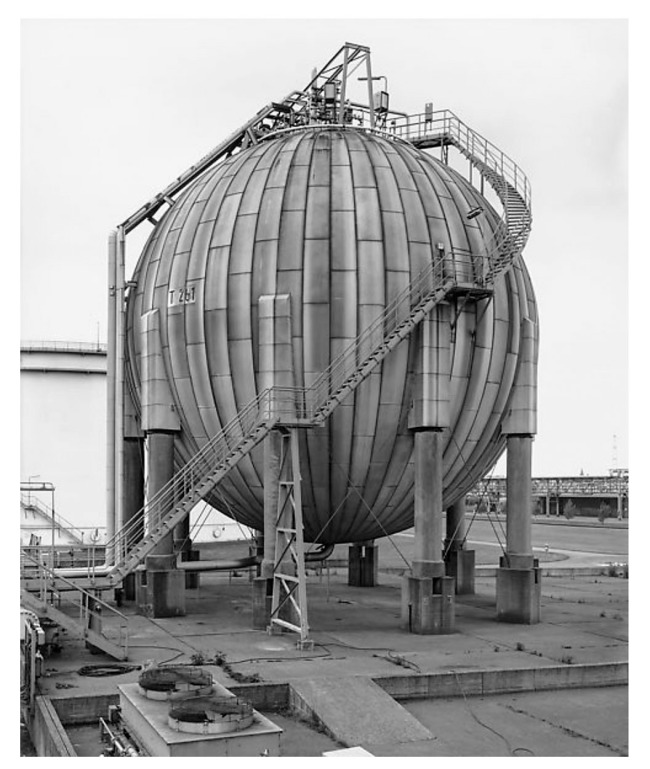

Gas Tank, Wesseling / Cologne, Germany

1983

24 in. × 19 13/16 in. (60.9 × 50.3cm)

Estate Bernd & Hilla Becher, represented by Max Becher, courtesy Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur – Bernd & Hilla Becher Archive, Cologne

Bernd and Hilla Becher (German, active 1959-2007)

Bernd Becher (German, 1931-2007)

Hilla Becher (German, 1934-2015)

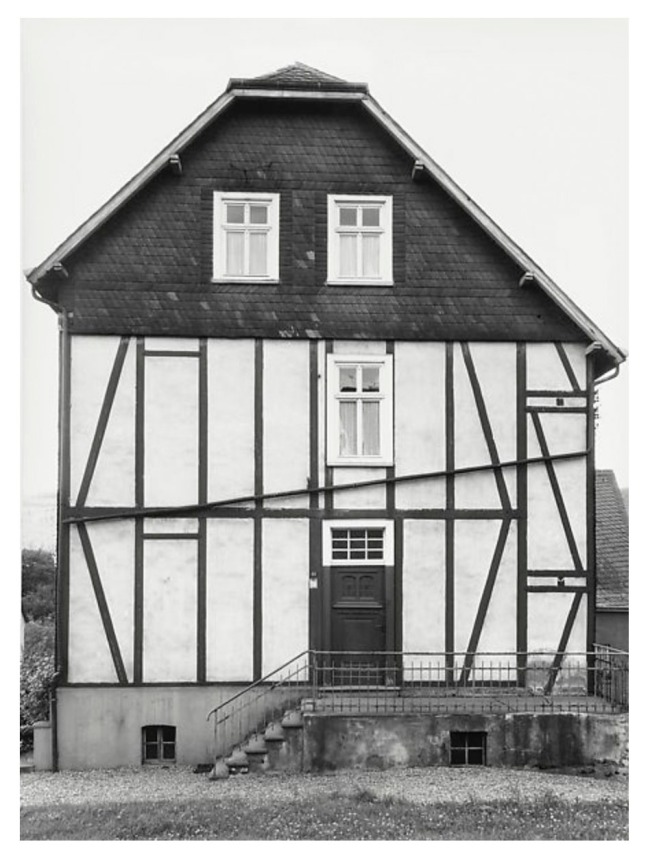

Framework House, Schloßblick 17, Kaan-Marienborn, Siegen, Germany

1962

Gelatin silver print

Image: 15 7/8 × 11 5/8 in. (40.3 × 29.6cm)

Purchase, Vital Projects Fund Inc. Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, Denise and Andrew Saul Fund, Louis V. Bell, Harris Brisbane Dick, Fletcher, and Rogers Funds and Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, and Jade Lau Gift, 2018

Both as artists and teachers, Bernd and Hilla Becher are the most important figures in European photography since 1950. Influenced by the formal rigour and typological method of prewar artists such as August Sander and Walker Evans, they were considered equals and fellow travellers by Minimalist sculptors such as Carl Andre and Sol LeWitt and paved the way for the medium’s integration into the broader arena of contemporary art. As professors at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, their influence was paramount on the celebrated generation of photographers known as the “Düsseldorf School” such as Thomas Struth, Andreas Gursky, Thomas Ruff, and Candida Höfer.

Bernd and Hilla Becher (German, active 1959-2007)

Bernd Becher (German, 1931-2007)

Hilla Becher (German, 1934-2015)

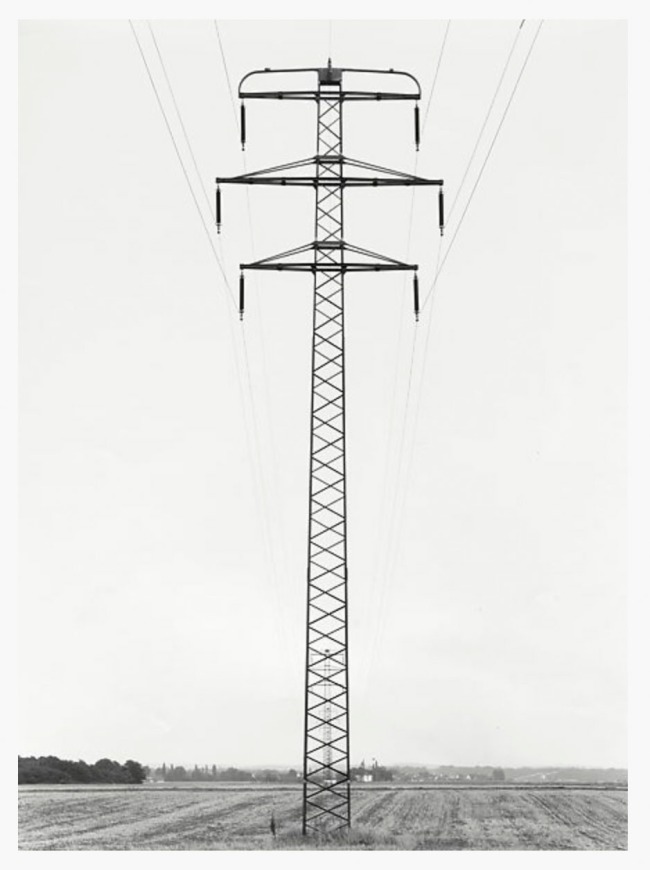

High Tension Pylon near Düsseldorf, Germany

1969

Gelatin silver print

Image: 15 13/16 × 11 11/16 in. (40.2 × 29.7cm)

Purchase, Vital Projects Fund Inc. Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, Denise and Andrew Saul Fund, Louis V. Bell, Harris Brisbane Dick, Fletcher, and Rogers Funds and Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, and Jade Lau Gift, 2018

Bernd and Hilla Becher (German, active 1959-2007)

Bernd Becher (German, 1931-2007)

Hilla Becher (German, 1934-2015)

High Tension Pylon near Düsseldorf, Germany

1969

Gelatin silver print

Image: 15 3/4 x 11 1/2 in. (40 x 29.2cm)

Purchase, Vital Projects Fund Inc. Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, Denise and Andrew Saul Fund, Louis V. Bell, Harris Brisbane Dick, Fletcher, and Rogers Funds and Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, and Jade Lau Gift, 2018

Bernd and Hilla Becher (German, active 1959-2007)

Bernd Becher (German, 1931-2007)

Hilla Becher (German, 1934-2015)

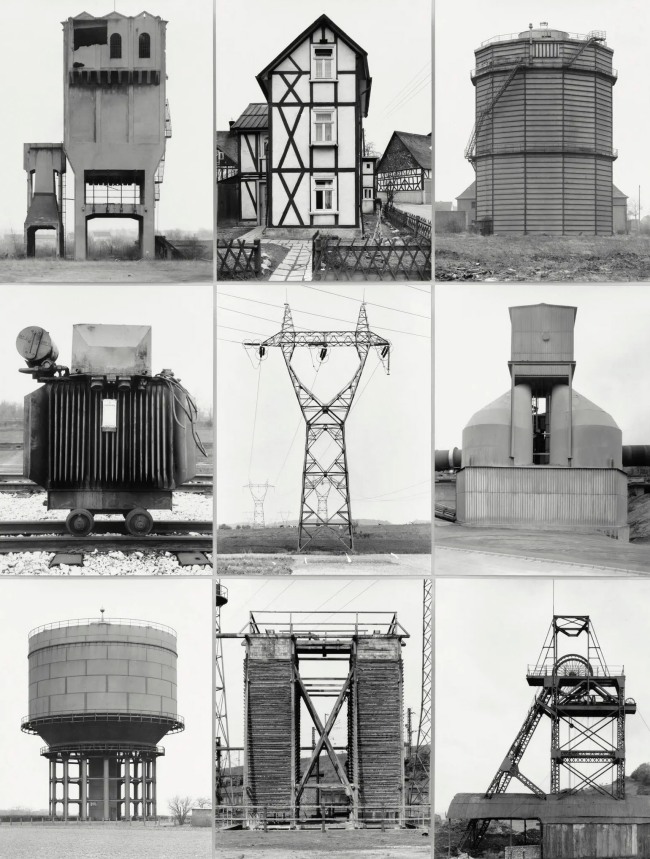

Comparative Juxtaposition, Nine Objects, Each with a Different Function

1961-1972

Gelatin silver prints

Estate Bernd & Hilla Becher, represented by Max Becher

These photographs show that the photographers Bernd and Hilla Becher were sometimes more interested in aesthetic form than in what industry actually does.

Bernd and Hilla Becher found artistic inspiration in the under appreciated beauty of the built environment, specifically, commonplace industrial and residential architecture. The Bechers’ use of typological ordering, as seen here in a grid of fifteen framework-house studies, can be traced to Hilla’s interest in the concepts of taxonomy and morphology, which are systems of biological classification based on shape and function. They called their assemblages “typologies” and used this effective graphic structure to compare similar and different forms, as would a researcher studying a collection of fossils or butterflies.

Bernd and Hilla Becher (German, active 1959-2007)

Bernd Becher (German, 1931-2007)

Hilla Becher (German, 1934-2015)

Terre Rouge, Esch-sur-Alzette, Luxembourg

1979

Gelatin silver print

17 5/8 × 23 1/2 in. (44.8 × 59.7cm)

Estate Bernd & Hilla Becher, represented by Max Becher, courtesy Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur – Bernd & Hilla Becher Archive, Cologne

Bernd and Hilla Becher (German, active 1959-2007)

Bernd Becher (German, 1931-2007)

Hilla Becher (German, 1934-2015)

Charleroi-Montignies, Belgium

1971

Gelatin silver print

19 in. × 23 1/4 in. (48.2 × 59cm)

Estate Bernd & Hilla Becher, represented by Max Becher, courtesy Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur – Bernd & Hilla Becher Archive, Cologne

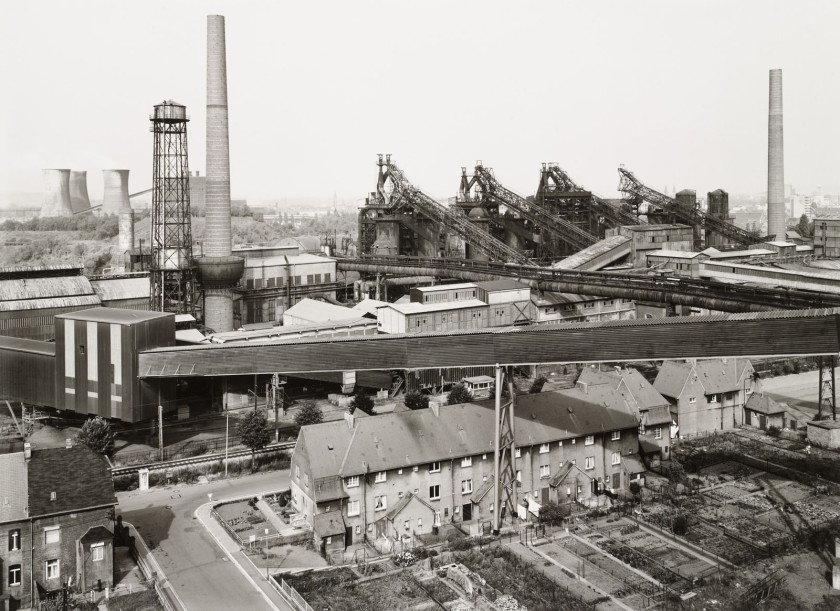

Bernd and Hilla Becher (German, active 1959-2007)

Bernd Becher (German, 1931-2007)

Hilla Becher (German, 1934-2015)

Duisburg-Bruckhausen, Ruhr Region, Germany

1999

19 3/8 × 23 7/8 in. (49.2 × 60.6cm)

Estate Bernd & Hilla Becher, represented by Max Becher, courtesy Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur – Bernd & Hilla Becher Archive, Cologne

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

1000 Fifth Avenue at 82nd Street

New York, New York 10028-0198

Phone: 212-535-7710

Opening hours:

Thursday – Tuesday 10am – 5pm

Closed Wednesday

![Bernd Becher (German, 1931-2007) '[Assemblage of Pipes]' 1964 or later Bernd Becher (German, 1931-2007) '[Assemblage of Pipes]' 1964 or later](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2022/10/bernd-becher-assemblage-of-pipes.jpg?w=650&h=679)

![Hilla Becher (German, 1934-2015) '[Mountain Elm Leaf]' 1965 Hilla Becher (German, 1934-2015) '[Mountain Elm Leaf]' 1965](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2022/10/hilla-becher-hilla-becher-mountain-elm-leaf.jpg?w=650&h=869)

![Hilla Becher (German, 1934-2015) '[Spruce Branch]' 1965 Hilla Becher (German, 1934-2015) '[Spruce Branch]' 1965](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2022/10/hilla-becher-spruce-branch.jpg?w=650&h=874)

![Hilla Becher (German, 1934-2015) '[Shell, for the German Industrial Exhibition, Khartoum, Sudan]' 1961 Hilla Becher (German, 1934-2015) '[Shell, for the German Industrial Exhibition, Khartoum, Sudan]' 1961](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2022/10/hilla-becher-shell-for-the-german-industrial-exhibition.jpg?w=650&h=837)

![J. E. Bray (Australian, 1832-1891) 'Untitled ["McDonnell's Tavern opposite Railway Station, remains of Dan Kelly and Hart in coffins"]' 1880 J. E. Bray (Australian, 1832-1891) 'Untitled ["McDonnell's Tavern opposite Railway Station, remains of Dan Kelly and Hart in coffins"]' 1880](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2017/10/bray-je-mcdonnells-railway-tavern-web.jpg?w=840)

![Installation view of the exhibition 'An Unorthodox Flow of Images' at the Centre for Contemporary Photography (CCP), Melbourne, September - November 2017 showing (7) J. E. Bray's 'Untitled ["McDonnell's Tavern opposite Railway Station, remains of Dan Kelly and Hart in coffins"]' 1880 cabinet card (right) and (8) a photograph by an unknown photographer Hunters of Ned Kelly 1880 (left) Installation view of the exhibition 'An Unorthodox Flow of Images' at the Centre for Contemporary Photography (CCP), Melbourne, September - November 2017 showing (7) J. E. Bray's 'Untitled ["McDonnell's Tavern opposite Railway Station, remains of Dan Kelly and Hart in coffins"]' 1880 cabinet card (right) and (8) a photograph by an unknown photographer Hunters of Ned Kelly 1880 (left)](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2017/10/installation-d-web.jpg?w=840)

You must be logged in to post a comment.