Exhibition dates: 10th June – 8th October 2012

George Bellows (American, 1882-1925)

Stag at Sharkey’s

1909

Oil on canvas

92 x 122.6cm (36 1/4 x 48 1/4 in.)

The Cleveland Museum of Art, Hinman B. Hurlbut Collection

What a joy it is to be able to post this work!

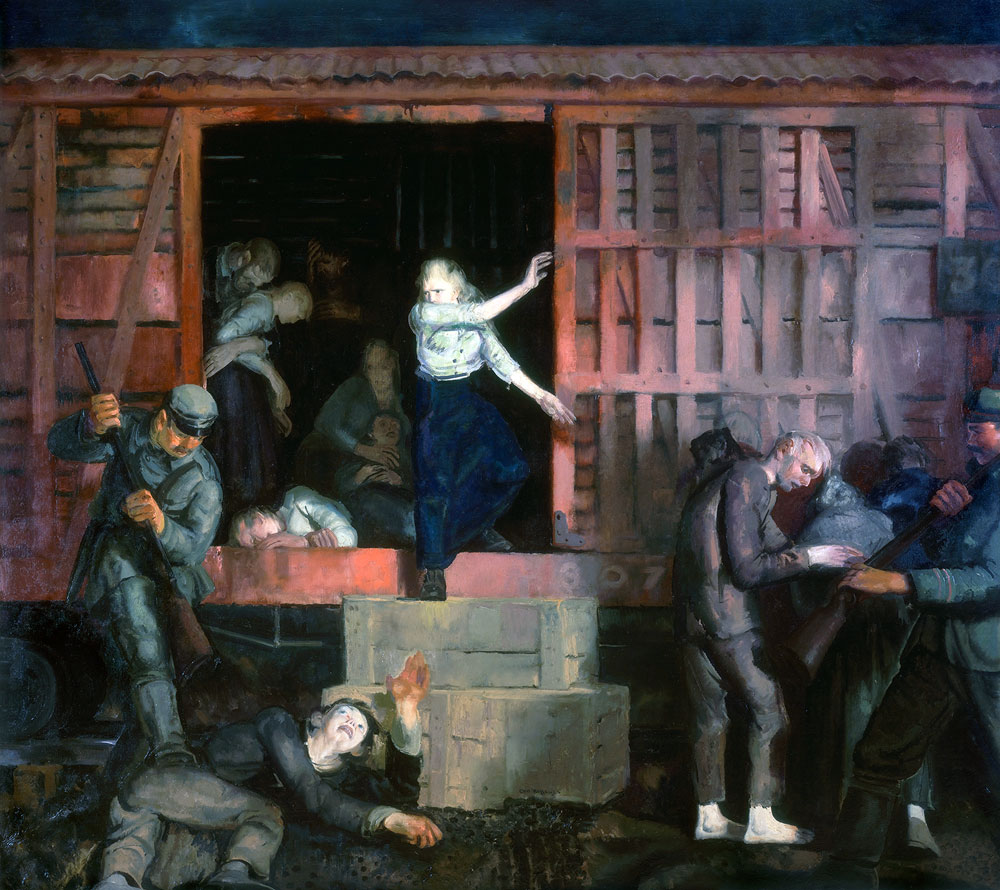

Bellows is one of my favourite artists. The energy and vigour of his work is outstanding, whether it be crashing waves on a rocky shore, the straining musculature of the male body in the boxing paintings and drawings or the more subtle renditions of colour and atmosphere in his portraits and cityscapes. There are hints of the darkness of Goya (especially in the painting The Barricade, 1918 / Francisco Goya, The Third of May 1808, 1814), the frontality of the portraits of Bronzino (with an added air of vulnerability) and, towards the end of his life, portends of what might have been had he lived – the simplification of line, form and colour in works such as Dempsey and Firpo (1924, below), reminiscent of, but distinct from, the work of his friend Edward Hopper.

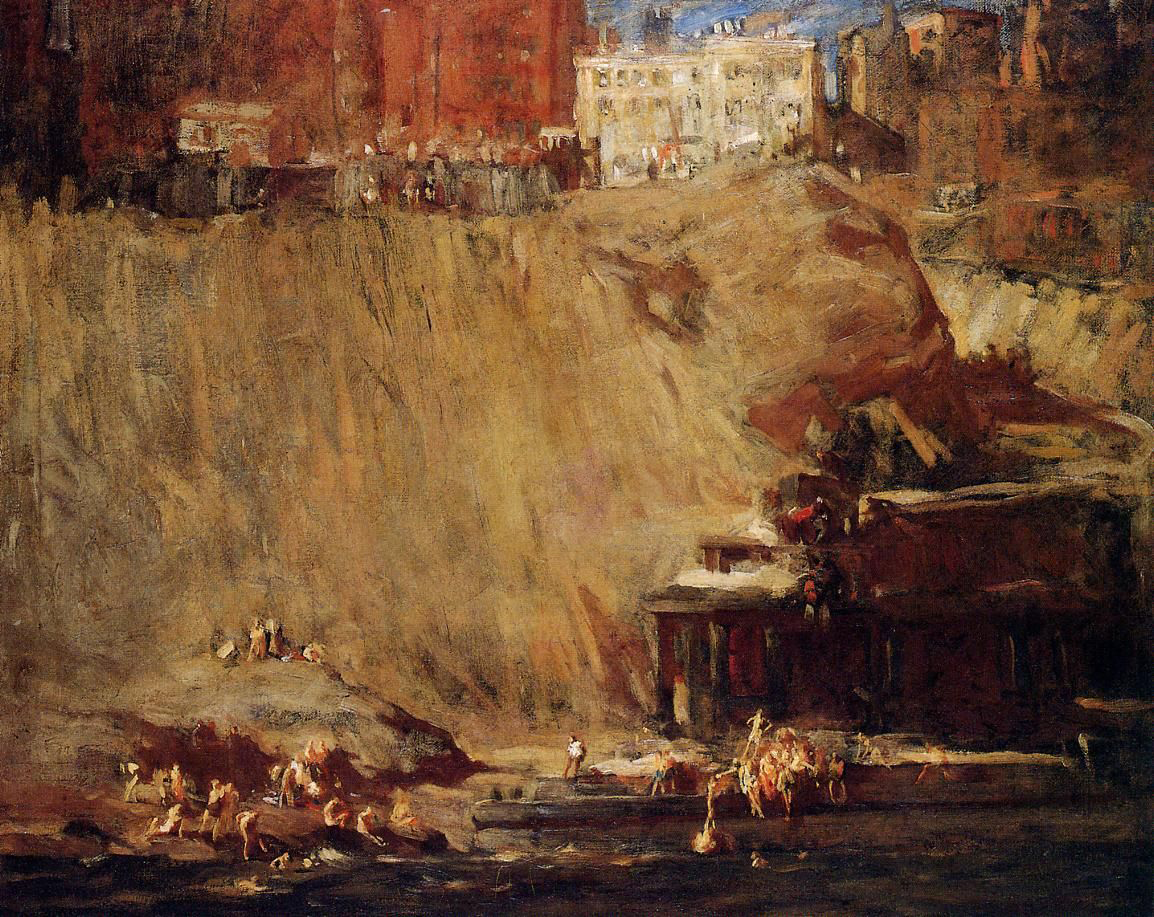

Bellows use of colour, light and form is extra ordinary. His use of chiaroscuro is infused with colour and movement, the volume of his modelling of the subjects depicted transcending their impressionistic base. The “shading” of his work is as much psychological as physical: the looming darkness of the buildings in Pennsylvania Station Excavation (1909, below), the churning foam of the desolate sea shore or the pensive look of Emma in the Purple Dress (1919, below). His understanding of the construction of the picture plane is exemplary. Note the use of diagonals and horizontals used in the construction of most of his paintings and drawings, especially the upraised hands, extended feet in his boxing portraits.

One can only wonder what this incredible artist would have achieved had he lived into the 1960s like his friend Edward Hopper. For me he remains an absolute hero of mine. From the first time I ever saw his work (and I have only ever seen it in reproduction, imagine seeing it in the flesh!) I fell in love with his sensibility, his love of the world and the people in it. I cannot explain it more fundamentally than that. A love affair where his work touched my heart and that, really, is the greatest compliment that you can give an artist. That their art moves you.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the National Gallery of Art, Washington for allowing me to publish the reproductions of the paintings in this posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

George Bellows (American, 1882-1925)

Both Members of This Club

1909

Oil on canvas

133 x 177.8cm (52 3/8 x 70 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Chester Dale Collection

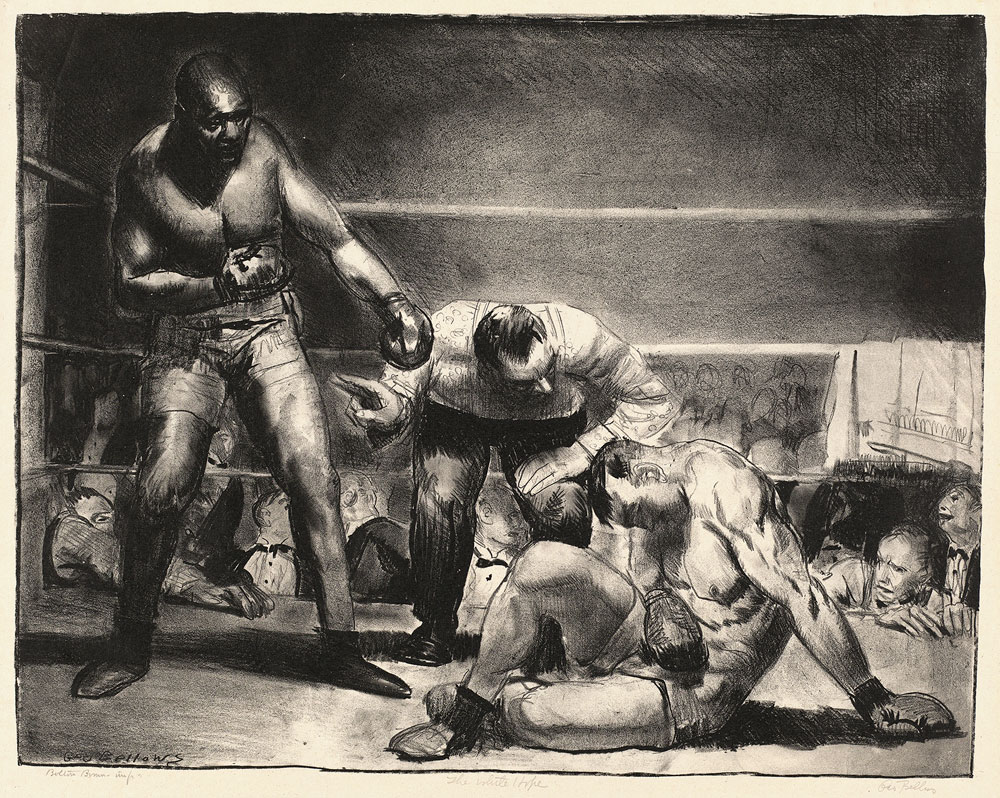

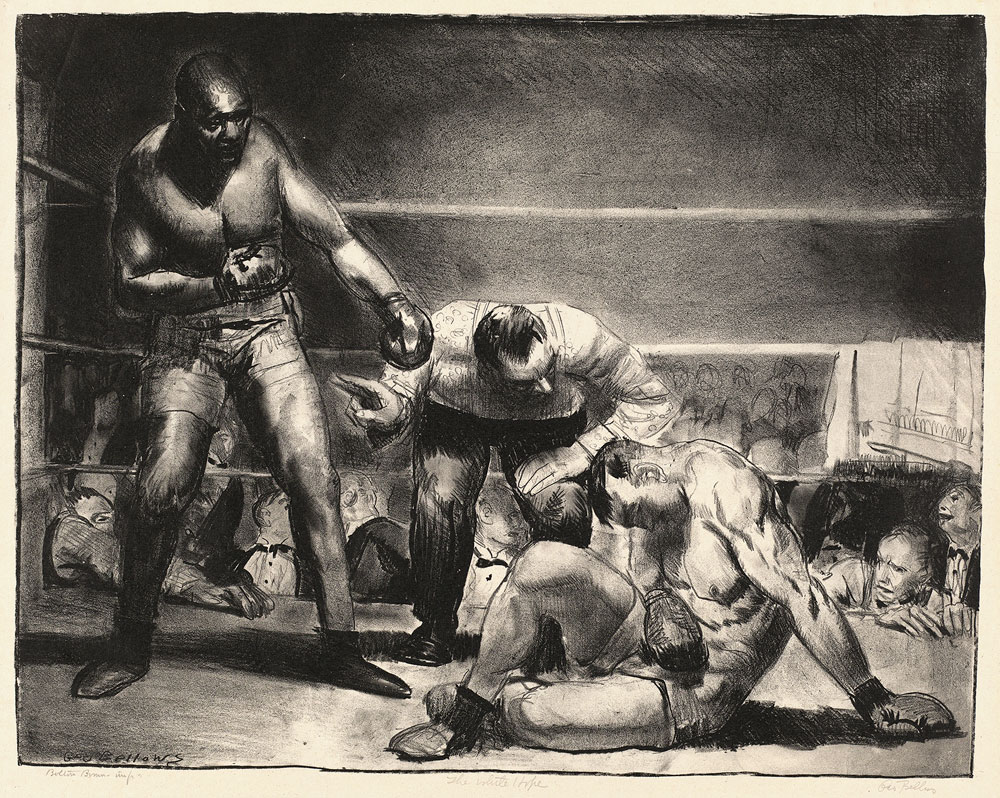

George Bellows (American, 1882-1925)

The White Hope

1921

Lithograph

37.4 x 47.6cm (14 3/4 x 18 3/4 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Andrew W. Mellon Fund

George Bellows (American, 1882-1925)

Counted Out, No.1

1921

Lithograph

31.8 x 28.5cm (12 1/2 x 11 1/4 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Andrew W. Mellon Fund

George Bellows (American, 1882-1925)

Dempsey through the Ropes

1923

Black crayon

54.61 x 49.85cm (21 1/2 x 19 5/8 in.)

Lent by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1925

George Bellows (American, 1882-1925)

Dempsey and Firpo

1924

Oil on canvas

129.5 x 160.7cm (51 x 63 1/4 in.)

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, Purchase, with funds from Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney

© Photograph by Sheldan C. Collins

When George Bellows died at the age of forty-two in 1925, he was hailed as one of the greatest artists America had yet produced. In 2012, the National Gallery of Art will present the first comprehensive exhibition of Bellows’ career in more than three decades. Including some 130 paintings, drawings, and lithographs, George Bellows will be on view in Washington from June 10 through October 8, 2012, then travel to The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, November 15, 2012, through February 18, 2013, and close at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, March 16 through June 9, 2013. The accompanying catalogue will document and define Bellows’ unique place in the history of American art and in the annals of modernism.

“George Bellows is arguably the most important figure in the generation of artists who negotiated the transition from the Victorian to the modern era in American culture,” said Earl A. Powell III, director, National Gallery of Art. “This exhibition will provide the most complete account of his achievements to date and will introduce Bellows to new generations.”

Works in the exhibition

Mentored by Robert Henri, leader of the Ashcan School in New York in the early part of the 20th century, George Bellows (1882-1925) painted the world around him. He was also an accomplished graphic artist whose illustrations and lithographs addressed a wide array of social, religious, and political subjects. The full range of his remarkable artistic achievement is presented thematically and chronologically throughout nine rooms in the West Building.

The exhibition begins with Bellows’ renowned paintings and drawings of tenement children and New York street scenes. These iconic images of the modern city were made during an extraordinary period of creativity for the artist that began shortly after he left his hometown of Columbus, Ohio, for New York in 1904. Encouraged by Henri, his teacher at the New York School of Art, Bellows sought out contemporary subjects that would challenge prevailing standards of taste, depicting the city’s impoverished immigrant population in River Rats (1906, private collection) and Forty-Two Kids (1907, Corcoran Gallery of Art).

In addition to street scenes, Bellows painted more formal studio portraits of New York’s working poor. These startling, frank subjects – such as Paddy Flannigan (1908, Erving and Joyce Wolf) – reflect the artist’s profound understanding of the realist tradition of portraiture practiced by such masters as Diego Velázquez, Frans Hals, Edouard Manet, and James McNeill Whistler.

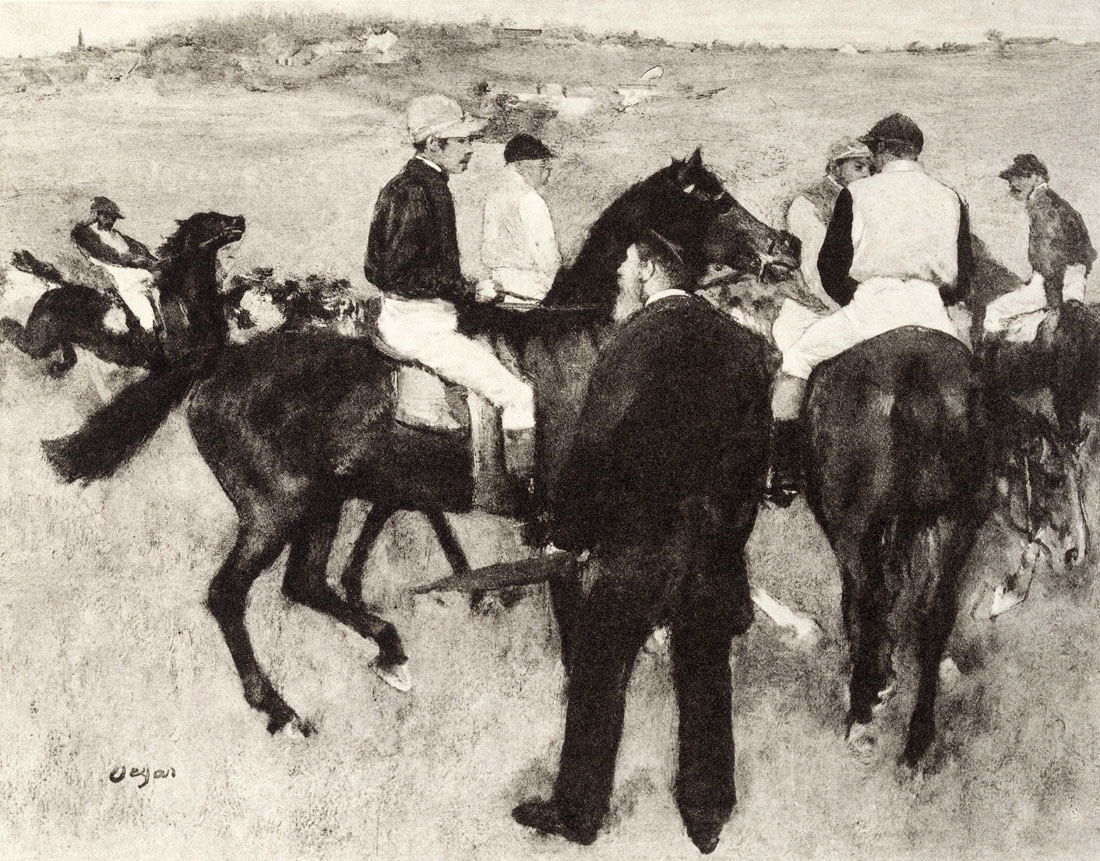

Bellows’ early boxing paintings chronicle brutal fights; to circumvent a state ban on public boxing, they were organised by private clubs in New York at that time. In his three acclaimed boxing masterpieces – Club Night (1907, National Gallery of Art), Stag at Sharkey’s (1909, Cleveland Museum of Art), and Both Members of This Club (1909, National Gallery of Art) – Bellows’ energetic, slashing brushwork matched the intensity and action of the fighters. These works will be on view together for the first time since 1982.

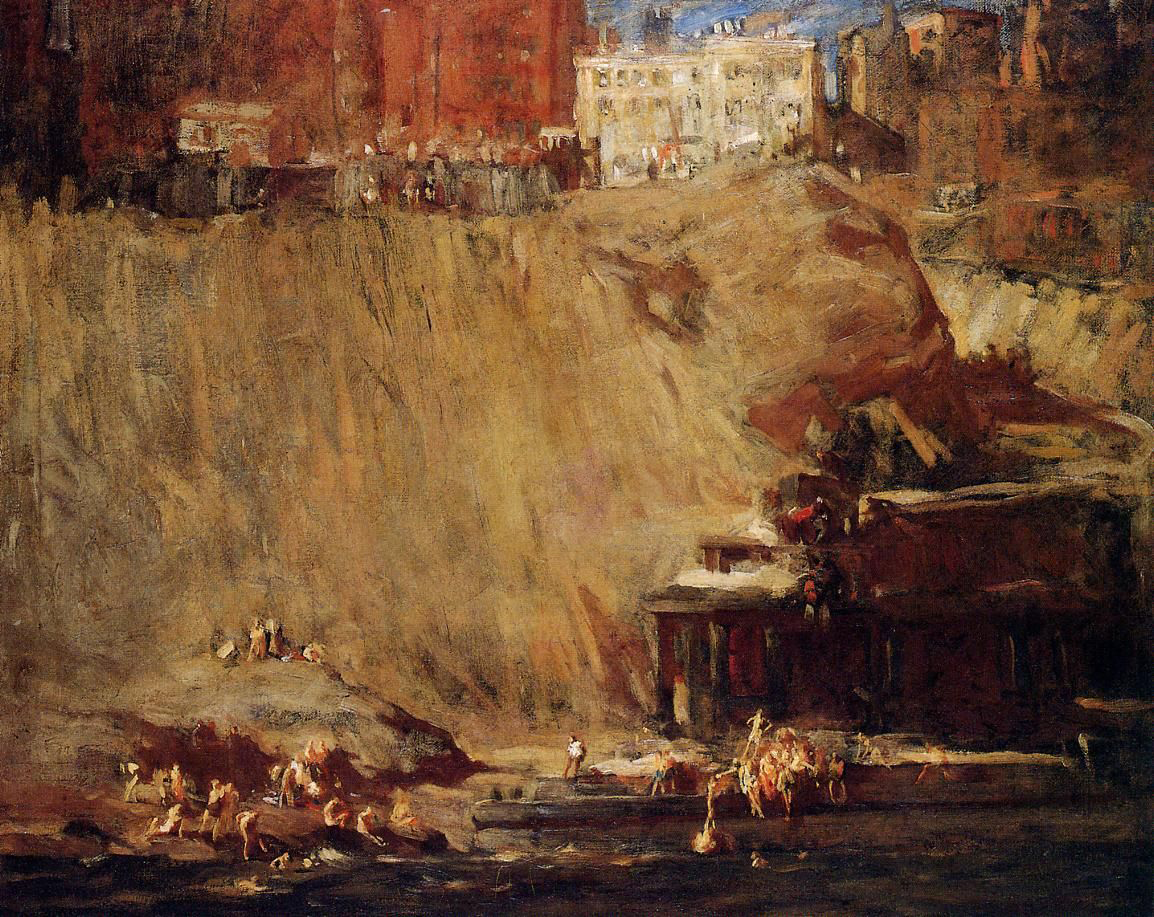

The series of four paintings Bellows devoted to the Manhattan excavation site for the Pennsylvania Railroad Station – a massive construction project that entailed razing two city blocks – focuses mainly on the subterranean pit in which workmen toiled. Never before exhibited together, these works range from a scene of the early construction site covered in snow in Pennsylvania Station Excavation (1909, Brooklyn Museum) to a view of the monumental station designed by McKim, Mead, and White coming to life in Blue Morning (1909, National Gallery of Art).

Bellows was fascinated with the full spectrum of life of the working and leisure classes in New York. From dock workers to Easter fashions paraded in the park, he chronicled a variety of subjects and used an array of palettes and painting techniques, from the cool grays and thin strokes of Docks in Winter (1911, private collection) to the jewel-like, encrusted surfaces of Snow-Capped River (1911, Telfair Museum of Art). While Bellows portrayed the bustling downtown commercial district of Manhattan in his encyclopaedic overview New York (1911, National Gallery of Art), he more often depicted the edges of the city near the shorelines of the Hudson and East Rivers in works such as The Lone Tenement (1909, National Gallery of Art) and Blue Snow, The Battery (1910, Columbus Museum of Art).

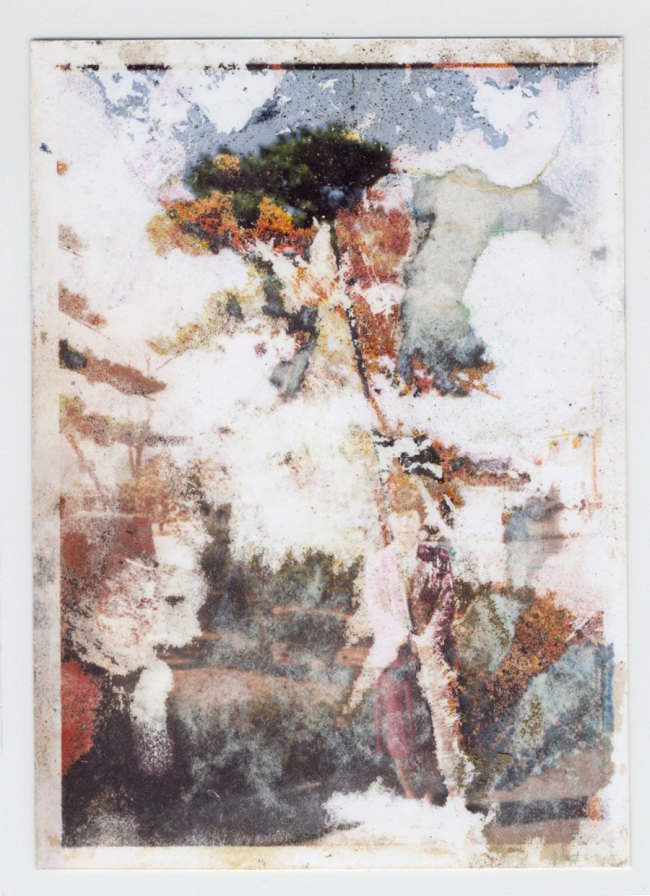

The artist visited Monhegan Island off the coast of Maine for the first time in 1911 and returned to Maine every summer from 1913 to 1916. In 1913 alone he created more than 100 outdoor studies. His seascapes account for half his entire output as a painter, with the majority done after the 1913 Armory Show. Shore House (1911, private collection) and The Big Dory (1913, New Britain Museum of American Art) are among Bellows’ most important seascapes and pay homage to his great American predecessor, Winslow Homer (1836-1910).

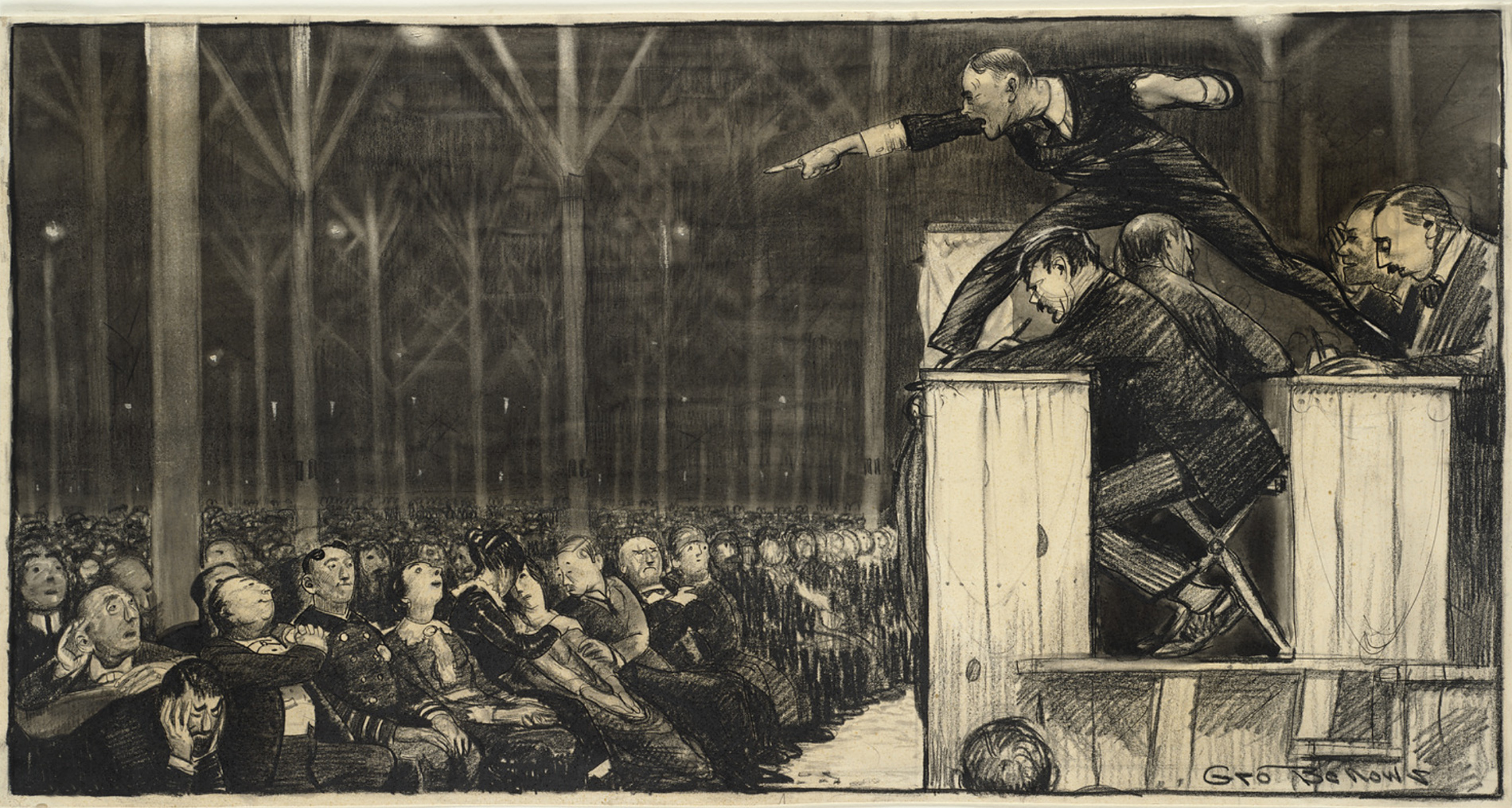

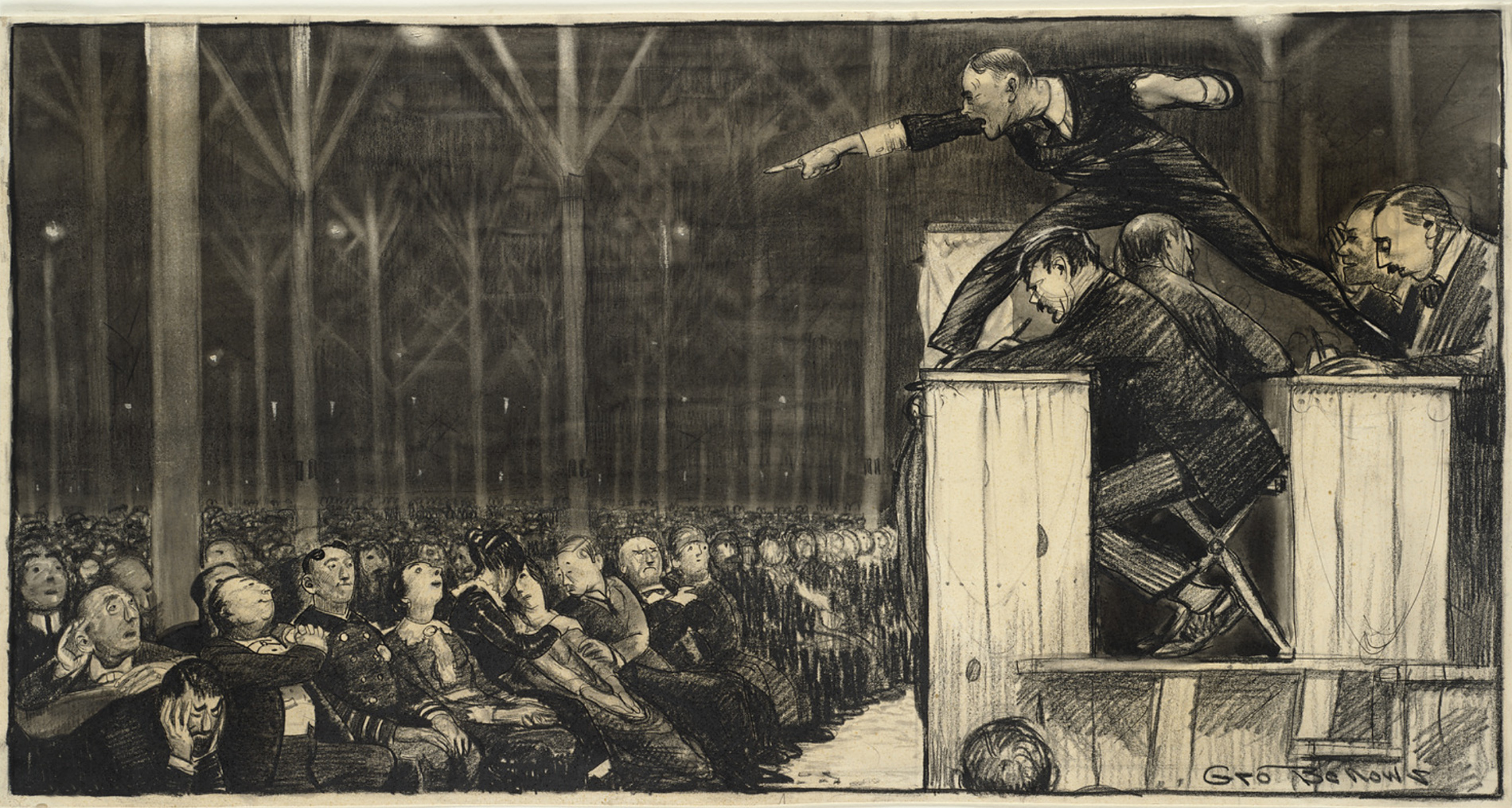

In 1912 Bellows started working more consistently as an illustrator for popular periodicals such as Collier’s and Harper’s Weekly, and in 1913 for the socialist magazine The Masses. These illustration assignments led him to record new aspects of American life ranging from sporting events to religious revival meetings, as seen in The Football Game (1912, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden) and Preaching (Billy Sunday) (1915, Boston Public Library). Along with Bellows’ more affordable and widely available lithographs (he installed a printing press in his studio in 1916), the published illustrations broadened the audience for his work.

Bellows supported the United States’ entry into World War I, resulting in an outpouring of paintings, lithographs, and drawings in 1918. For this extensive series, he relied on the published accounts of German atrocities in Belgium found in the 1915 Bryce Committee Report commissioned by the British government. The paintings evoke the tradition of grand public history paintings, as seen in Massacre at Dinant (1918, Greenville County Museum of Art), while the drawings and lithographs recall Francisco de Goya’s 18th-century print series The Disasters of War.

Bellows’ late works on paper survey modern American life, from the prisons of Georgia to the tennis courts of Newport, and highlight complex relationships between his various media. Taken from direct experience as well as fictional accounts, they range in tone from lightly satirical and humorous (Business-Men’s Bath, 1923, Boston Public Library) to profoundly disturbing and tragic (The Law Is Too Slow, 1922-1923, Boston Public Library).

In Emma at the Piano (1914, Chrysler Museum of Art), Bellows depicts his wife and lifelong artistic muse. His portraits of women constitute a larger body of work than his more famous boxing paintings. They cover all stages of life and include both the naive, youthful Madeline Davis (1914, Lowell and Sandra Mintz) and the more refined, matronly Mrs. T in Wine Silk (1919, Cedarhurst Center for the Arts).

The show will end with paintings in a variety of styles made in 1924, the year before the artist’s sudden death from appendicitis. Painted in Bellows’ studio in rural Woodstock, New York, these last works, including Dempsey and Firpo (1924, Whitney Museum of American Art), Mr. and Mrs. Philip Wase (1924, Smithsonian American Art Museum), and The White Horse (1922, Worcester Art Museum), will prompt visitors to contemplate the artist Bellows might have become had he lived into the 1960s, as did his friend and contemporary Edward Hopper (1882-1967).

Press release from the National Gallery of Art website

George Bellows (American, 1882-1925)

River Rats

1906

Oil on canvas

George Bellows (American, 1882-1925)

Forty-two Kids

1907

Oil on canvas

106.7 × 153cm (42 × 60 1/4 in.)

Corcoran Collection (Museum Purchase, William A. Clark Fund)

National Gallery of Arts, Washington

Open access

George Bellows (American, 1882-1925)

Beach at Coney Island

1908

Oil on canvas

106.7 x 152.4cm (42 x 60 in.)

Private collection

George Bellows (American, 1882-1925)

Blue Morning

1909

Oil on canvas

86.3cm (33.9 in) x 111.7cm (43.9 in)

National Gallery of Art

Chester Dale Collection

George Bellows (American, 1882-1925)

New York

1911

Oil on canvas

106.7 x 152.4cm (42 x 60 in.)

National Gallery of Art

Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon

George Bellows (American, 1882-1925)

The Big Dory

1913

Oil on panel

18 in (45.7cm) x 22 in (55.8cm)

New Britain Museum of American Art

Harriet Russell Stanley Fund

George Bellows (American, 1882-1925)

Riverfront, No. 1

1914

Oil on canvas

115.3 x 160.3cm (45 3/8 x 63 1/8 in.)

Columbus Museum of Art, Museum Purchase, Howald Fund

Public domain

George Bellows (American, 1882-1925)

Preaching (Billy Sunday)

c. 1915-1923

Crayon, ink, and wash on paper

Boston Public Library

Public domain

“I like to paint Billy Sunday, not because I like him, but because I want to show the world what I do think of him. Do you know, I believe Billy Sunday is the worst thing that ever happened to America? He is Prussianism personified. His whole purpose is to force authority against beauty. He is against freedom, he wants a religious autocracy, he is such a reactionary that he makes me an anarchist.” – GB, in “Touchstone,” p. 270. The artist’s intent to satirise Billy Sunday was evident to almost everyone but the evangelist himself. An earlier depiction of Billy Sunday in action is seen in “The Sawdust Trail” (M. 48) done in 1916 (below). (Mason)

Text from the Digital Commonwealth website

George Bellows (American, 1882-1925)

The Saw Dust Trail

1916

Oil on canvas

Milwaukee Art Museum, Layton Art Collection

The catalog quotes Bellows: “I paint Billy Sunday… to show the world what I do think of him. Do you know, I think Billy Sunday is the worst thing that ever happened to America? He is death to imagination, to spirituality, to art.”

George Bellows (American, 1882-1925)

Tennis at Newport

1920

Oil on canvas

109.2 x 137.2cm (43 x 54 in.)

James W. and Frances G. McGlothlin

George Bellows (American, 1882-1925)

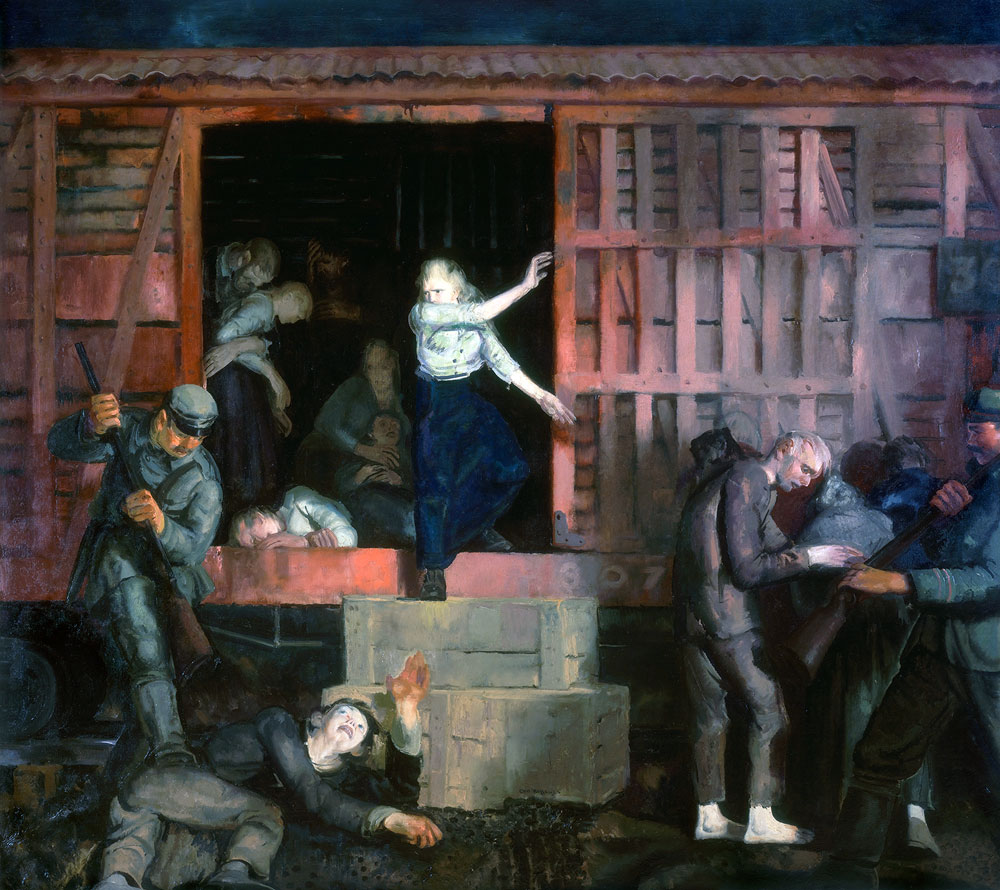

Return of the Useless

1918

Oil on canvas

149.9 x 167.6cm (59 x 66 in.)

Courtesy Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville

George Bellows (American, 1882-1925)

The Barricade

1918

oil on canvas

124.8 x 211.5cm (49 1/8 x 83 1/4 in.)

Birmingham Museum of Art, Museum purchase with funds provided by the Harold and Regina Simon Fund, the Friends of American Art, Margaret Gresham Livingston, and Crawford L. Taylor, Jr.

George Bellows

American, 1882-1925

Throughout his childhood in Columbus, Ohio, George Bellows divided much of his time between sports and art. While attending Ohio State University, he created illustrations for the school yearbook and played varsity baseball and basketball. After college Bellows rejected an offer for a professional athletic career with the Cincinnati Reds baseball team, instead pursuing a career as an artist.

In opposition to his father’s wishes, Bellows enrolled in the New York School of Art in 1904. There Bellows elected to study not with the popular and flamboyant William Merritt Chase, but rather with the unorthodox realist Robert Henri. Henri led a radical group of artists, including John Sloan and William Glackens, who exhibited under the name “The Eight.” Although Bellows was elected to the National Academy of Design, he rejected the superficial portrayal of everyday life promoted by the academies. Instead he and his colleagues emphasised the existing social conditions of the early twentieth century, especially in New York. Because their subjects were considered crude and at times even vulgar, critics dubbed them the Ashcan school. Bellows never became an official member of The Eight, but his choice of subjects – docks, street scenes, and prizefights – were typical of the group. Unlike the members of The Eight, Bellows’ enjoyed popular success during his lifetime, particularly with the boxing images that demonstrate his passionate interest in sports and a bold understanding of the human figure.

George Bellows (American, 1882-1925)

Pennsylvania Station Excavation

1909

Oil on canvas

79.38 x 97.16cm (31 1/4 x 38 1/4 in.)

Brooklyn Museum, A. Augustus Healy Fund

George Bellows (American, 1882-1925)

The Lone Tenement

1909

Oil on canvas

123.2 x 153.4 x 12.7cm (48 1/2 x 60 3/8 x 5 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Chester Dale Collection

George Bellows (American, 1882-1925)

Rain on the River

1908

Oil on canvas

81.3 x 96.5cm (32 x 38 in.)

Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence, Jesse Metcalf Fund

© Photography by Erik Gould, courtesy of the Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence

George Bellows (American, 1882-1925)

Blue Snow, The Battery

1910

Oil on canvas

86.4 x 111.8cm (34 x 44 in.)

Columbus Museum of Art, Museum Purchase, Howald Fund

George Bellows (American, 1882-1925)

Shore House

1911

Oil on canvas

101.6 x 106.7cm (40 x 42 in.)

Private collection

George Bellows (American, 1882-1925)

Men of the Docks

1912

Oil on canvas

Randolph College, founded as Randolph-Macon Women’s College, 1891, Lynchburg

George Bellows (American, 1882-1925)

Summer Surf

1914

Oil on board

62.6 x 72.7 x 4.8cm (24 5/8 x 28 5/8 x 1 7/8 in.)

Delaware Art Museum, Wilmington

George Bellows (American, 1882-1925)

Forth and Back

1913

Oil on panel

38.1 x 49.5cm (15 x 19 1/2 in.)

Private collection

George Bellows (American, 1882-1925)

Churn and Break

1913

Oil on panel

45.7 x 55.9cm (18 x 22 in.)

Columbus Museum of Art, Gift of Mrs. Edward Powell

George Bellows (American, 1882-1925)

An Island in the Sea

1911

Oil on canvas

87 x 112.7cm (34 1/4 x 44 3/8 in.)

Columbus Museum of Art, Museum Purchase, Howald Fund

George Bellows (American, 1882-1925)

Emma in the Purple Dress

1919

Oil on panel

128.27 x 107.95 x 8.89cm (50 1/2 x 42 1/2 x 3 1/2 in.)

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Gift of Raymond J. and Margaret Horowitz

© Digital Image (C) 2009 Museum Associates / LACMA / Art Resource, NY

George Bellows (American, 1882-1925)

Emma in the Black Print

1919

Oil on canvas

101.9 x 81.9cm (40 1/8 x 32 1/4 in.)

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Bequest of John T. Spaulding

© Photograph 2012 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

George Bellows (American, 1882-1925)

Mrs. T in Wine Silk

1919

Oil on canvas

121.9 x 96.5cm (48 x 38 in.)

Cedarhurst Center for the Arts, Mt. Vernon, Gift of John R. and Eleanor R. Mitchell, 1973

George Bellows (American, 1882-1925)

Margarite

1919

Oil on panel

81.28 x 66.04cm (32 x 26 in.)

Private collection

George Bellows (American, 1882-1925)

Emma at the Piano

1914

Oil on panel

73cm (28.7 in) x 94cm (37 in)

Chrysler Museum of Art Blue

Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr.

George Bellows (American, 1882-1925)

Paddy Flannigan

1908

Oil on canvas

76.8 x 63.5cm (30 1/4 x 25 in.)

Erving and Joyce Wolf

George Bellows (American, 1882-1925)

Frankie, The Organ Boy

1907

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City

Purchase, acquired through the bequest of Ben and Clara Shlyen

George Bellows (American, 1882-1925)

Little Girl in White (Queenie Burnett)

1907

158 x 87cm (62 3/16 x 34 1/4 in.)

National Gallery of Arts, Washington

Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon

Open access

Advised by his friend and teacher Robert Henri to select subjects that reflected the realism of modern urban life, George Bellows portrayed the recreational activities of New York City’s lower-class children in such paintings as River Rats (1906, private collection), and Forty-two Kids (1907). In 1907 he painted two full-length portraits of individual children: Little Girl in White and Frankie the Organ Boy (both now at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO). Unlike his late 19th-century predecessors, who popularised the street urchin genre by representing well-scrubbed, idealised children playing with pets or engaged in entrepreneurial activities, Bellows portrayed his subjects in a bluntly realistic manner. The subject of this painting, Queenie Burnett, was the artist’s laundry delivery girl. Her underprivileged background is evident in her gaunt face, exaggeratedly large eyes, unkempt hair, and ungainly figure.

This was Bellows’s first figural work to be exhibited around the country – it was included in 15 public exhibitions during his lifetime – and he was awarded the first Hallgarten Prize when the painting was shown at the National Academy of Design in 1913.

Text from the National Gallery of Art website

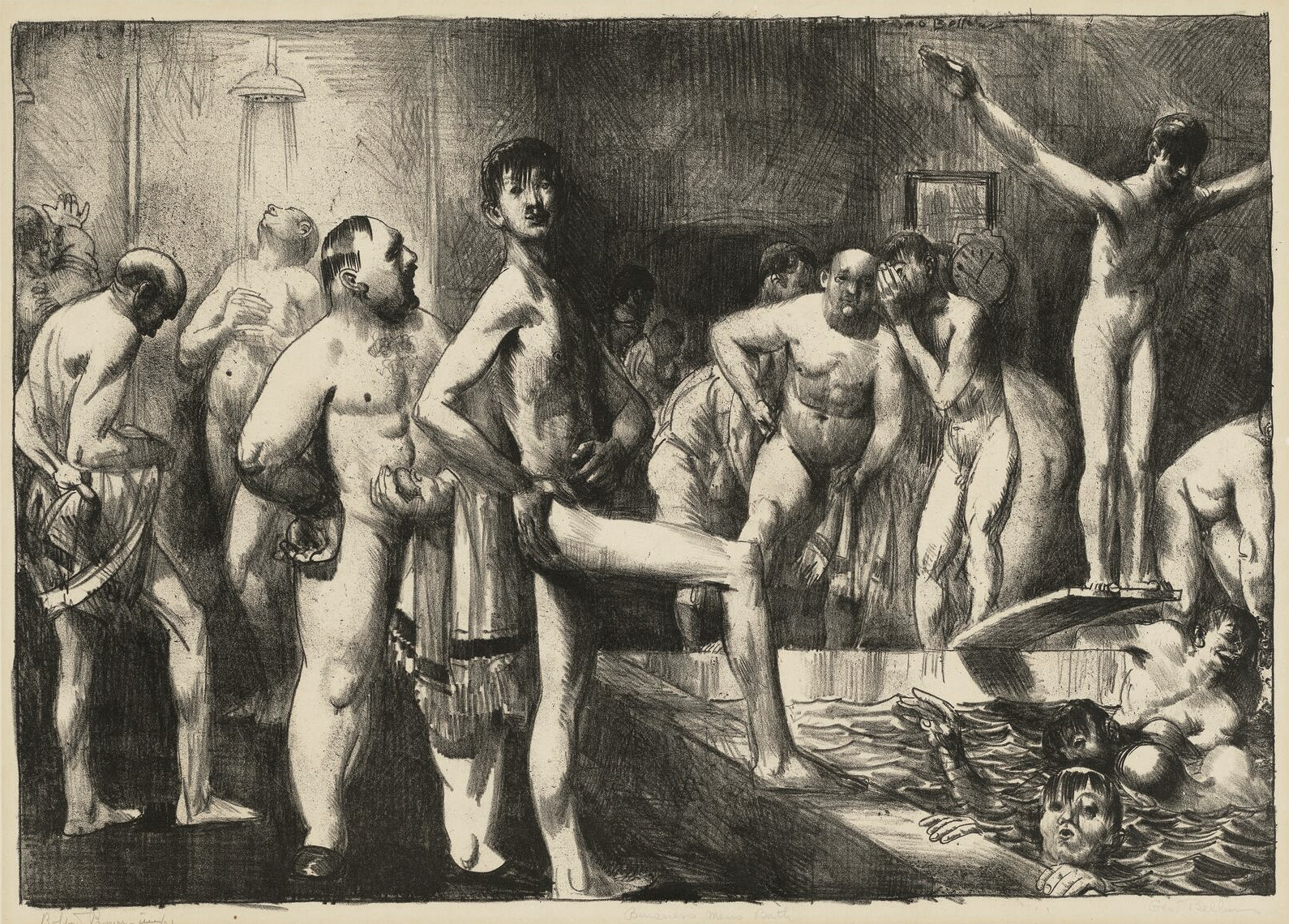

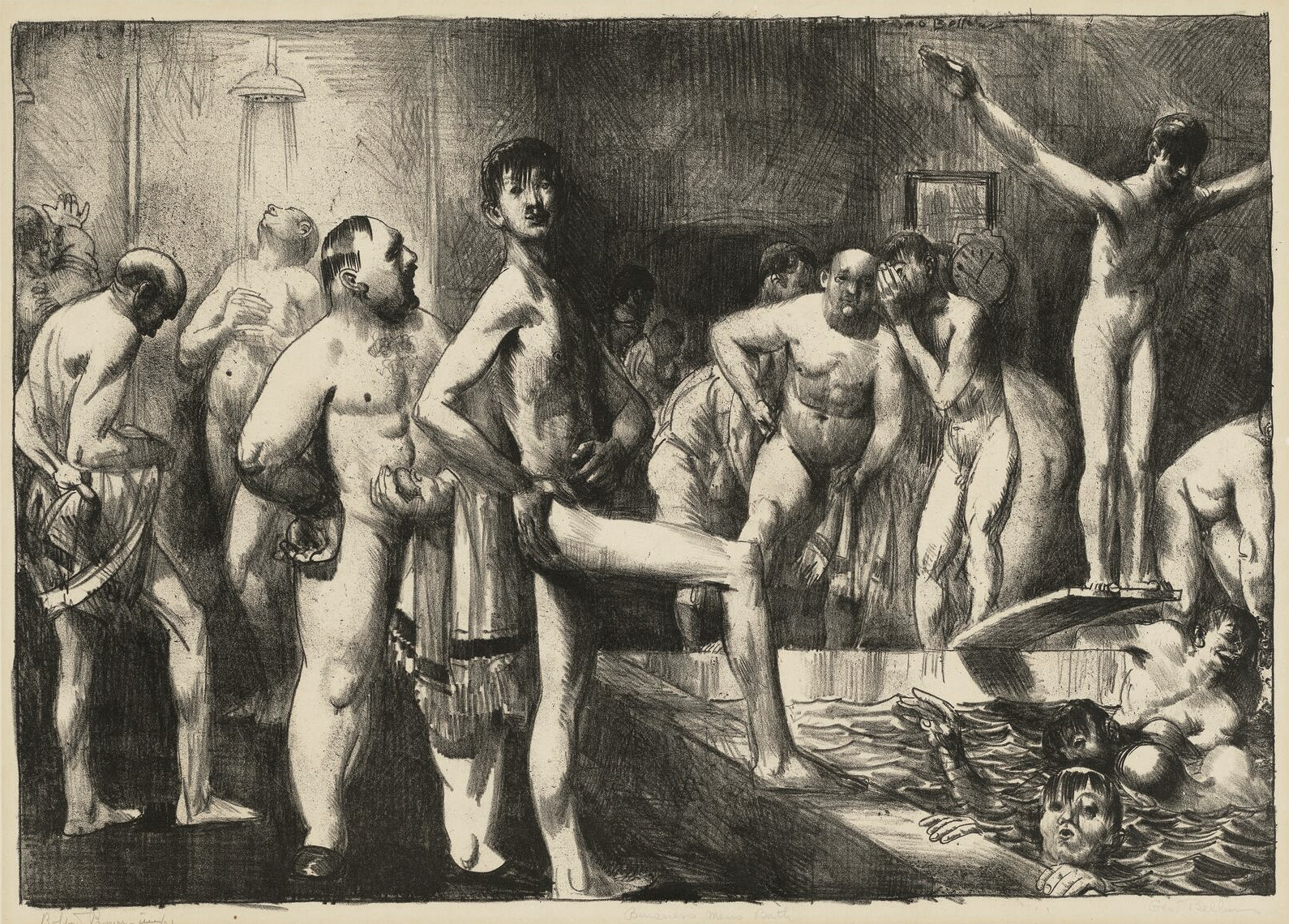

George Bellows (American, 1882-1925)

Business-Men’s Bath

1923

Lithograph

16 1/2 × 11 3/4in. (41.9 × 29.8cm)

Boston Public Library

George Bellows (American, 1882-1925)

The Law Is Too Slow

1922-1923

Boston Public Library

Print Department, Albert H. Wiggin Collection

Based upon a 1903 newspaper story, dateline Wilmington, Delaware, about a black man who burns at the stake while a mob of perpetrators stand and watch.

George Bellows (American, 1882-1925)

The White Horse

1922

Oil on canvas

86.6cm (34.1 in) x 111.7cm (44 in)

Worcester Art Museum

George Bellows (American, 1882-1925)

Mr. and Mrs. Phillip Wase

1924

Oil on canvas

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Gift of Paul Mellon

George Bellows spent summers in Woodstock, New York, where Mrs. Wase worked as a cleaning woman and her husband was a gardener. Bellows chose to show the couple stiffly posed and strangely detached from one another. Mrs. Wase’s face shows the worries of a lifetime, and Mr. Wase stares off into the distance, as if thinking of another time or place. Between them, a portrait, perhaps of Mrs. Wase as a bride, hangs on the wall. Their clothes match the shadowy gray of the parlour. Bellows painted suggestions of a brilliantly green summer day beyond the closed shutters, as if to emphasise the distance between youthful optimism and the resignation of old age. The artist experimented with new ways to paint portraits throughout his career, and from 1915 to 1920 he exhibited with the National Association of Portrait Painters, whose mission was to separate from ”the tiresomely conventional and perfunctory portrait.” (Myers, “‘The Most Searching Place in the World’: Bellows and Portraiture,” in Quick et al., The Paintings of George Bellows, 1992)

Text from the Smithsonian American Art Museum website

National Gallery of Art

National Mall between 3rd and 7th Streets

Constitution Avenue NW, Washington

Opening hours:

Daily 10.00am – 5.00pm

National Gallery of Art website

LIKE ART BLART ON FACEBOOK

Back to top

![Oliver Boberg (German, b. 1965) 'Unterführung' [Underpass] 1997 Oliver Boberg (German, b. 1965) 'Unterführung' [Underpass] 1997](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/r_p_oliver-boberg-unterfuehrungdruckbar-web.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.