November 2011

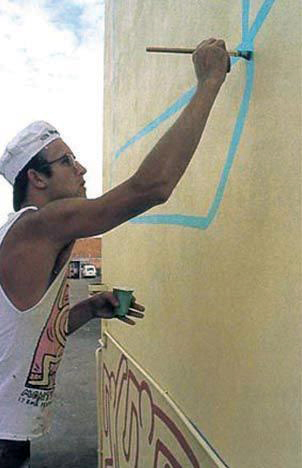

Keith Haring (American, 1958-1990)

Barking Dogs and Spaceships and Angels and Coyotes

both 1982

Subway drawings

Chalk on subway posters laid on canvas

In response to the polemic article “Brushed aside: artistic landmark must return to 1980s glory” by Hannah Mathews in The Age newspaper on November 17th, 2011 I feel compelled to offer a more balanced appraisal of the problems regarding the conservation and preservation of the Keith Haring Mural painted on a wall of the former Collingwood Technical School in Collingwood, Melbourne.

I was not going to publish this essay but now the time is right!

As I note in the essay Haring’s attitude to repainting seems to be at best ambiguous. As several people advocate, I support building a wall perpendicular to the original and painting a facsimile on the new wall. As the original is one of few remaining outdoor murals in the artists hand, I believe it is important to conserve what we have left of the original and painting a simulacra would satisfy those that want a “fresh” copy.

This essay is based on my own question, namely an investigation into the deterioration of a public work of art; the stabilisation of an ephemeral work; the role of the conservator in preserving the work; and the broader cultural perspectives involved when treating the work: reflections on the community from which it originates and notions of ownership and authorship. It was completed as part of my Master of Art Curatorship being undertaken at The University of Melbourne.

Please remember that this essay was written last year in September 2010, before the report from Arts Victoria and was then recently updated. Many thankx to Dr Ted Gott and to Andrew Thorn for their knowledge and help during the research for this essay.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

PS. Apologies that there are no image credits in the essay. If anyone knows the photographers please let me know and I will post but I hope they do not mind me using the photographs (in the interests of art, research and conservation).

Abstract

This essay will examine the history and conservation of The Keith Haring Mural painted on a wall of the former Collingwood Technical School in Collingwood, Melbourne. The essay will attempt to identify the issues involved with current attempts to conserve the mural, including issues of authorship, custodianship vs ownership, stabilisation of the mural and the debate between repainting and conserving. This essay is based on my own question, namely an investigation into the deterioration of a public work of art; the stabilisation of an ephemeral work; the role of the conservator in preserving the work; and the broader cultural perspectives involved when treating the work: reflections on the community from which it originates and notions of ownership and authorship.

Keywords

Keith Haring, Collingwood Technical School, Collingwood, Melbourne, painting, mural, public art, urban art, graffiti, Ted Gott, Andrew Thorn, THREAD, gay art group, homosexuality, HIV/AIDS, New York, National Gallery of Victoria, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Arts Victoria.

Word count: 5,056

Keith Haring Water Wall Mural at The National Gallery of Victoria, later destroyed

Introduction

In the early 1980s, New York artist and social activist Keith Haring (4th May, 1958 – 16th February, 1990) was on the brink of fame. He appeared at the Whitney Biennial and Sao Paulo Biennale in 1983 and made friendships with Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat.1 Haring was also gay; he died of HIV/AIDS at a young age. His folk art/graffiti style of bold figures and pagan inspired designs outlined in black and other colours investigated concepts of birth, life, death, power, money, technology and the relationship of human beings to the planet on which they live. Haring never feared confronting his viewer with difficult socio-political problems. Embedded in the street culture of the day, Haring was one of the first artists to be heavily influenced by disco dancing and rap music, his ghetto blaster blaring out as he painted his trademark murals. Today his work can be seen to represent the quintessential essence of the 1980s: through its use of colour; the vibrancy of the gyrating bodies; and the topicality of the issues the work addressed. His imagery “has become a widely recognised visual language of the 20th century”2 and his work represents a culture in which “notions of graffiti, advertising and design became increasingly blurred.”3

Early expressions of his creativity that are precursors to his mature style were the chalk drawings on black paper that Haring undertook in the subway stations of New York, using vacant advertising spaces. These drawings were made using quickness and stealth for fear of being caught and were ephemeral; either being destroyed when the next advert was pasted in place or, when his fame became greater, souvenired by acolytes.

“Riding the subway from his uptown apartment to the clubs, Haring noticed black paper hanging next to advertisements in the cars, awaiting the next ad. He used this opportunity to draw in chalk on the black paper with all sorts of childlike imagery: barking dogs, babies, unisex figures, spaceships, TV sets, etc. The outline style of imagery could be appreciated individually as cartoon cels or together to form a narrative. The subway drawings magnify Haring’s cartoons into a new Pop Art that at once was urban narrative, science fiction and hieroglyphics. These subway drawings initiated his first one man shows.”4

As Ted Gott has commented, “… Haring was seen as revolutionary, around 1981, for the manner in which he mastered the freedom and fluidity of the graffiti artists’ calligraphic defacement of public property, and catapulted it over into a mainstream artistic form. By presenting the visual language of one social class in the medium [paint on canvas] and milieus [commercial art galleries] of another elite class, Haring broke the rules then prescribed by the art world…”5

Into this context of rising fame came John Buckley, inaugural Director of Melbourne’s new Centre for Contemporary Art (CCA, later called the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, or ACCA).6 Buckley met Haring in 1982 on a research visit to New York and invited him to Australia. After organising various grants to fund the trip, Haring arrived for a three-week visit. He was in Australia from 18th February to 8th March 1984 and completed three major projects (The Water Wall mural at The National Gallery of Victoria, the mural painted in the forecourt of The Art Gallery of New South Wales and the mural painted on the side of the former Collingwood Technical School).7 During this period he also completed other smaller works (such as a piece for the Hardware Club in Melbourne and the Glamorgan preparatory school, part of Geelong Grammar School), as well as thirteen large exhibition-quality ink drawings and four acrylic paintings.8 The latter were eventually used in the exhibition Keith Haring at ACCA’s new premises in Melbourne between 10th October – 17th November, 1985,9 and then returned to the artist by John Buckley. Some confusion exists in this matter as Haring states in his biography that his Australian experience wasn’t that hot and that he felt ripped off because the paintings he left in Australia were never returned to him, that there had never been any exhibition of his work and that the work had never been paid for.10

Since ACCA had not secured a physical home at the time of the arrival of Haring (later to be in the Botanical Gardens), Buckley arranged for Haring to paint a large mural on the inside of the water wall at The National Gallery of Victoria between 21st – 22nd February 1984. Haring then travelled to Sydney and painted the AGNSW mural between 28th February – 1st March 1984 before returning to Melbourne and painting the mural at The Collingwood Technical School in one day on Tuesday 6th March 1984.11 While the first two murals were intentionally impermanent (the Water Wall was supposed to last 3 months but was destroyed by vandalism just 2 weeks after its creation,12 Haring mistakenly believing that it was attacked as a protest against the mistaken belief that he had appropriated Aboriginal motifs in its composition13 and the AGNSW mural was painted over after one month to make way for the Biennale exhibition of 1984),14 the community based project in Collingwood would become Haring’s only large, permanent evidence of his visit to Australia:

“In his interview given at the Collingwood Technical School immediately upon completion of the project on 6 March 1984, Keith Haring said about the Collingwood mural: “I had fun. I mean, it’s the most fun I’ve had since I’ve been here. It’s more fun working here than it is inside a museum. [and] It’s the only permanent thing that I did while I was in Australia.””15

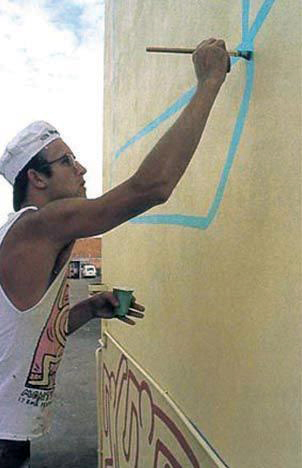

“The base tint of yellow was painted onto the wall with rollers by Collingwood Technical School staff on Monday 5 March 1984,”16 the day before Haring’s ‘performance’ when he painted the mural in just two main colours, red and green, in front of a large audience; the performance was photographed and videotaped giving us unique footage of the artist at work.17 The mural features a multi-layered frieze of dancing figures in the lower half of the mural and his fear of technology in the upper half, a “hybrid man/computer monster, his vision of a future de-humanising evolution, which was ridden by two human figures …”18

In all three murals the work was undertaken freehand with no use of preparatory drawings or grids using ladders and a cherry-picker to raise and lower the artist into position – all to the blare of his ghetto blaster. For Haring there was no turning back: “Whatever marks I make are immediately recorded and immediately on view. There are no “mistakes” because nothing can be erased.”19

Keith Haring painting The Keith Haring Mural, Johnston Street, Collingwood, Melbourne, 1984

The painting of The Keith Haring Mural, Johnston Street, Collingwood, Melbourne, 1984

Significance of the Mural

According to the Statement of Significance on the Heritage Council of Victoria database, “The Mural has historical and social significance as the work of a major artist. Keith Haring is considered one of the most significant artists of his generation. As a role model for gay artists and Aids activism his influence was international.

The Keith Haring Mural is of social significance as a landmark piece of public art in Melbourne. Its prominent inner city location is indicative of the changing physical and social landscape of a former working class suburb.

The Mural is also of social significance for its influence on young artists for its inner city setting and use of popular culture themes and imagery.”20

Emily Sharpe states that the mural may also be the last surviving extant [outdoor] mural in the world painted entirely by his hand,21 although this information is contradicted by The Haring Foundation in a quotation later in the essay (see the section ‘To restore or conserve?’ below, Footnote 49).

Keith Haring mural on the side of the former Collingwood Technical School in 2010 (painted 1984)

Issues in Conservation

During the period 1994-1995 a recently formed gay art group in Melbourne called THREAD (of which I was a part, the acronym of which is now lost to my memory) became concerned about the deterioration of the Keith Haring mural on the side of the Collingwood Technical School in Johnston Street, Collingwood. The group tried to engage the city of Yarra (the inner Melbourne municipality where the mural is located) and other organisations (The National Trust) about the possibility of repainting the mural due to the importance of the mural and its painting by an internationally renowned gay artist. Basically, as conservator Andrew Thorn succinctly puts it, “to repaint the mural on the basis of identity giving ownership.”22

While the intentions of the group were entirely honourable in such a proposal, on reflection and with the passing of the years, being older and wiser, I realise the error of our ways. While acknowledging that the group probably did want to take ownership of the mural on the basis of sexual identity at the time I think the group was just motivated by a desire to get something to happen and we did at least succeed in starting a dialogue between those that had an interest in conserving the mural. One of the problems was that none of us had conservation experience and, as Tom Dixon noted in a phone call to him about the mural,23 the representation of the group was never consistent as it was always a different person that you were talking to.

The profile of the mural was also raised through newspaper articles: “A series of newspaper articles drew attention to the vexed issues around its historic significance and increasing deterioration; these articles formed an important research component of the subsequent classification report” (The book in which this article is quoted incorrectly states that students helped Haring paint the mural – see p. 146).24 These concerns eventually led to the stabilisation of the mural by conservator Andrew Thorn in 1996 and its listing by the National Trust of Australia (Victoria) (NTAV) in 1997. During the treatment of the mural in 1996 Thorn undertook various conservation treatments, namely cleaning of the paint surface (including removal of stains), paint consolidation (fine cracking and detachments within the red paint and reattachment of the yellow paint), reattachments of lower render due to rising damp, consolidation and protection of the paint film with a protective coating system and reintegration of small areas of loss. A proposal for future maintenance was envisaged that included regular inspections, maintenance and care,25 but unfortunately it would seem that this maintenance has not been undertaken. In a recent report (2007) on the condition of the mural Thorn notes that, “incipient deterioration can be avoided, but if regular maintenance is not continued, the painting will be lost.”26 Thorn also notes that the resin gloss layer applied in 1996 to prevent AO (anti-oxidant) and UV (ultraviolet) deterioration “shows clear signs of degradation,” and should have been reapplied at 5 yearly intervals to maintain effectiveness.27 The report also notes that the yellow ground has become paler since 1996, the eroded reds need consolidation, the rising moisture is having a greater effect on the surface than previously and the green brushstrokes are beginning to show signs of loss.28

The missing door of the Keith Haring mural on the side of the former Collingwood Technical School in 2010 detail (painted 1984)

Keith Haring mural on the side of the former Collingwood Technical School in 2010 detail (painted 1984)

Ownership or custodianship

I support the concept of custodianship (or shared ownership) of a work of art rather than ownership per se. I believe that many people have a stake in the cultural value of a work of art and that custodianship, being a caretaker of the work, engages with the idea that the work belongs to everyone and that everyone should have access to enjoy it. Of course being gay offers a close affinity to the work of Keith Haring but, as Andrew Thorn notes, “that does not impart greater ownership of common property or of visual arts and imagery. It does give some ownership but not the right to snatch ownership from others.”29

In a separate email he continues, “At the same time it is necessary in giving ownership to wrest it from those that have claims and this process requires substantial diplomacy. It moves ownership from exclusive to shared. Ownership and identity are good and necessary things and if a work or an artist provides inspiration and support that is not to be denigrated and must be respected … Claiming of ownership is not an aggressive act but part of belonging and identity … It is necessary to engage in a community spirit to ensure a highly significant work and its maker are treated with the respect they deserve.”30

While the earlier attempts by the THREAD group could be seen as an attempt to obtain cultural ownership I acknowledge that this position is untenable. It must be a difficult task – the diplomacy of negotiating with all vested interests. But as Thorn rightly notes this comes down to the modern democratic process, the freedom to elect decision makers – not make the decisions themselves but delegate the responsibility to elected others. We must possess the ability to respect anybody’s relationship and enjoyment of the mural as much as we should respect Thorn’s professional judgment as an internationally renowned conservator to ensure this work is protected in the best possible way so that future generations can enjoy the work.

Keith Haring mural on the side of the former Collingwood Technical School in 2010 detail (painted 1984)

The conservator and the cultural landscape

The conservation of artefacts is an integral part of the cultural landscape. The nature of the cultural landscape is a fluid environment: a palimpsest where the authorship of the original work of art is a textual site, where “change (and decay), alteration, editing, revision and restoration represent the true life of objects.”31

“”The document is the textual site where the agents of textuality meet: author, copyist, editor, typesetter and reader.” In art and architecture there would be, besides artist and architect, builders, conservators, curators, preservationists, historians, viewers and users.”32 Embedded within the work are the memory and history of the object, within culture. Conservator Andrew Thorn observes, “It is a societal need to preserve the past and keep it for the future. Far more pragmatic issues dominate the profession [that of conservation] and unlike some contemporary art practice it does not need the props of modernist theory in any form to exist.”33

I beg to differ. Conservation exists only within culture. It is embedded within it and linked to the history and memory of the object. The nature of the cultural landscape and our heritage is a constitutive process: “an approach to heritage which understands it not as an object which is the static locus of some internal value, but as a process.”34 And that process invokes the social, cultural, economic and political contexts that include the act of interpretation and the concept of representation.

Laurajane Smith argues that, “heritage is heritage because it is subjected to the management and preservation/ conservation process, not because it simply ‘is’. The process does not just ‘find’ sites and places to manage and protect. It is itself a constitutive cultural process that identifies those things and places that can be given meaning and value as ‘heritage’, reflecting contemporary and cultural social values, debates and aspirations.”35 Gibson and Pendlebury unpack this statement further:

“In the first and most obvious sense, it follows from this position that there is nothing self-apparent or given about regimes of value and significance, rather these frameworks are specific to our particular social, cultural, economic and political contexts. Drawing on the anthropologist Marcel Mauss’s famous proscription on the cultural and historical specificity of contemporary personhood, objects, building and places are ‘formulated’ as heritage ‘only for us, amongst us’.”36

The value of an object cannot exist without reference to its historicity, its relationship to everything and everyone around us and conservation needs these frameworks of theory to have existence. As Foucault notes, “The space in which we live, which draws us out of ourselves, in which the erosion of our lives, our time and our history occurs, the space that claws and gnaws at us, is also, in itself, a heterogeneous space. In other words, we do not live in a kind of void, inside of which we could place individuals and things. We do not live inside a void that could be colored with diverse shades of light, we live inside a set of relations that delineates sites which are irreducible to one another and absolutely not superimposable on one another.”37

Complementary to Foucault’s notion of a set of relations that delineates sites and heterotopic spaces is how Janet Wolff positions these sites, these texts, within a sociology of cultural production:

“… the meaning which audiences ‘read’ in texts and other cultural products is partly constructed by those audiences. Cultural codes, including language itself, are complex and dense systems of meaning, permeated by innumerable sets of connotations and significations. This means that they can be read in different ways, with different emphases, and also in a more or less critical or detached frame of mind. In short, any reading of any cultural product is an act of interpretation … the way in which we ‘translate’ or interpret particular works is always determined by our own perspective and our own position in ideology. This means that the sociology of art cannot simply discuss ‘the meaning’ of a novel or painting, without reference to the question of who reads or sees it, and how. In this sense, a sociology of cultural production must be supplemented with, and integrated into, a sociology of cultural reception.”38

I understand that the conservator is not an editor (and here I am not abrogating the right of conservators to conserve, far from it). What I am proposing, however, is that an acknowledgment of the many voices that constitute the life and memory of an object, including the post-structuralist theory that analyses these histories and interpretations, be included in the negotiations with all parties and stakeholders. This perspective also acknowledges the changing contexts of interpretation of the Keith Haring Mural as it becomes ever more precious as one of the few outdoor murals left in the world painted in the author’s hand.

Keith Haring mural on the side of the former Collingwood Technical School in 2010 (painted 1984)

To restore or conserve?

“The painting can be preserved and not fade or deteriorate further if the recommendations of my 1996 and 2010 reports are adhered to. If you think this is not true you need to provide the evidence … it is assumed you respect my professional judgement in ensuring this work is protected in the best possible way so that all people can enjoy the masterpiece painted by Keith Haring as far into the future as possible. Over painting the mural ends the work of Keith Haring on that day.”39

The vexatious issue of restoring or conserving the Keith Haring mural has been an ongoing source of debate since the early attempts by the THREAD group to have the work “restored” (i.e. over painted) in the mid-1990s. Haring’s attitude to repainting seems to be at best ambiguous. The statement of significance of the mural when listed by The National Trust of Australia (Victoria) in 1997 notes that,

“Crucial to the fate of the mural and, given its exposure to the elements, is whether the artist himself would have accepted the deterioration of the mural or have condoned some form of restoration. Haring’s own feelings appear to have been ambivalent in the matter. In favour of restoring the mural i.e., repainting – is the fact that the simplistic three colour design devoid of subtle harmonies would not present serious problems in restoring it to its original condition. Opinion appears to be divided regarding the moral considerations in the matter and even the Estate of Keith Haring is unclear in this matter.”40

John Buckley “recalls a conversation with Haring who, with a characteristic lack of preciousness, said that the mural could, when needed, just be repainted by any good signwriter”41 but Andrew Thorn disputes this interpretation noting that “Keith talked about the continuity of his work. What Buckley stated contradicts the attitude presented by Haring throughout his biography. Another point to consider here is that Keith died within 6 years of completing the painting and I am certain beyond doubt that the condition of the painting even after 6 years would have been more or less pristine. There is no indication throughout the last two years of his life that Keith had any concern for his made works and that his declining health and the pain associated with that allowed him little time to consider anything other than his current work and failing health. If Buckley provides evidence of a friendship that Keith denies in his biography I for one would re-assess the intention of the artist.”42

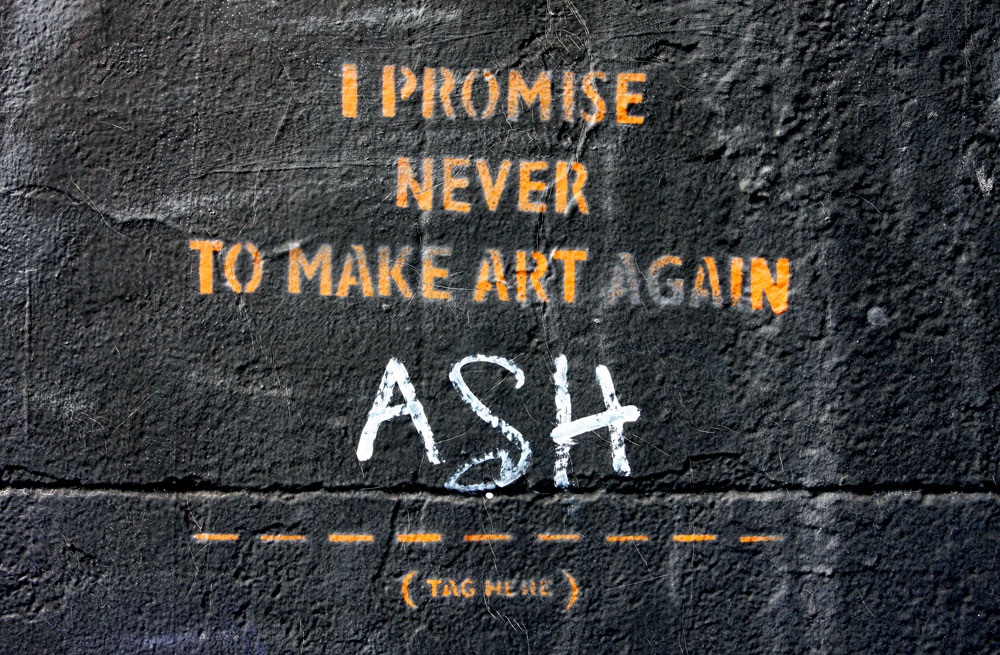

This brings up the thorny issue of the ephemerality of street art. “Art academic Chris McAuliffe expressed his view regarding the impermanence of this work, arguing that ‘… as graffiti, it should be left to fade … If you subject it to conservation procedures then you transpose graffiti into a realm that it was opposed to. You make it art’.“43 Personally I believe that all street art, whether officially sanctioned (like the Keith Haring mural) or not, is art. Distinction can only be made between street art / graffiti (not necessarily officially sanctioned: think the early chalk drawings of Haring or the street art of Banksy) and vandalism or tagging. Perhaps ephemerality is inherently built into street art, that documentation is enough to substantiate the life of the work, but that does not mean we have to sit by and let work be defaced or fade away without attempts at conservation.

According to Donna Wheeler there is an “unbreachable divide” between the two camps of Haring devotees. “Those on the conservatorial side see the mural as a cultural artefact, one that contains the artist’s rare and authentic touch evidenced in each singular brushstroke; they advocate a commitment to preservation, or stabilisation, with the caveat that even with their best efforts, the mural will continue to fade and eventually cease to exist. The Haring Foundation, and many others, including several curators and Haring’s original Australian contact, John Buckley, are hoping to restore, or more accurately, repaint the work, claiming that this would most closely follow Haring’s wishes. Yes, the original paint and brushstrokes would be forever lost, but Haring’s intent, creative vision and integral design will live on, in all its jellybean vibrancy.”44

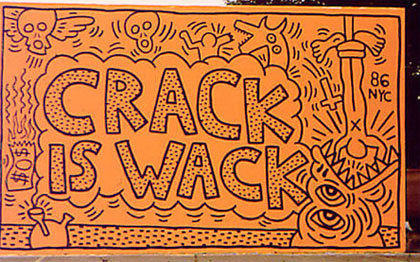

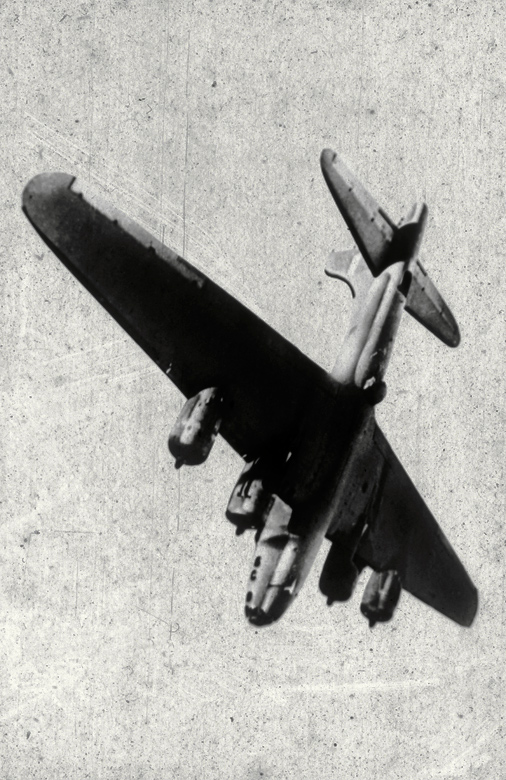

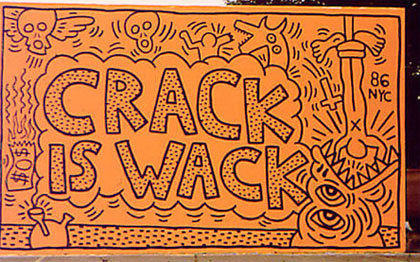

I disagree with the stance taken by those that wish to repaint the mural. The hand of the author would be lost and the mural would simply become a simulacra of the original, a sign value that is an illusion of reality, a repainting purporting to “look like” the original but actually nothing like it.45 Support for this stance are the photographs of the original Crack is Wack (1986) mural painted by Keith Haring and the over painted mural photographs shown by Andrew Thorn at the public forum into the future of the mural in April 2010.46 In this presentation Thorn, “illustrated the losses inherent with repainting and also showed that the most iconic Haring mural ‘Crack is Wack’, is not the painting that Haring is photographed in front of the day he completed it.”47

Thorn states, “I support making a new copy of the painting, I just believe it should not devalue the original. Repainting over the original destroys the original work by Keith Haring. What you have is a copy and an irretrievable original, that is to say you have destroyed the work of Keith Haring. This is against the law administered by Heritage Victoria and devalues the work monetarily. This may seem an odd point to raise but becomes more significant when one considers the copyright act in relation to artists and their rights. The law there clearly states that any action that devalues a work or diminishes the artist’s reputation is a violation of the copyright act. The Haring Foundation need to be aware of this international law and particularly in the context of the Crack is Wack no longer being the work of Keith Haring and thereby diminishing his reputation by deception.”

In reply the Haring Foundation note that, “the ONLY Haring mural that was completely repainted was the Crack is Wack mural in NYC, due to it’s absolutely dreadful condition. It, too, is a landmark and highly valued by its community, and while no longer the original, it most definitely remains a Keith Haring mural. There are several outdoor murals that are untouched: Tuttomondo in Pisa (cleaned only); Necker Hospital in Paris; murals in Amsterdam and Phoenix, AZ. Numerous outdoor murals were only cleaned and lightly repaired and there are over a dozen indoor murals in public institutions that are untouched …

The Haring Foundation does not always recommend a complete repainting, that would be silly. But the awful condition of the Collingwood mural is similar to that of Crack is Wack and therefore the Foundation does highly recommend that it be repainted. Further to Crack is Wack, when Keith originally painted it, he had no permission, and so was required by the city to paint it out, completely covering over his first version. Shortly thereafter, he was granted permission by the city, and the second version he painted was different from the first version. Keith’s first version is often reproduced in books and catalogs and this has led to the utterly incorrect assumption that the Haring Foundation actually destroyed his first version and replaced it with something completely different over it. Not true.”49

While it is correct that Haring returned on the following day and painted a second version, not a copy of the first, conservator Andrew Thorn states that, “Since his death in 1990, the west painting has been repainted with imagery not resembling either of the two original Haring works … and this has in turn been reapplied more or less faithfully in 2007. This last painting, the one currently visible, is the fourth in the series and bears no resemblance to either of the two original works … The current painting appears not to be the work of Keith Haring, but continues to be considered his signature outdoor work … Haring may have painted the third image, but there is no record of this … The third and seemingly anonymous rendition continues the overall message but with new iconography, and appears not to be the work of Keith Haring.”50

Thorn supports the painting of a facsimile, a replica of the original, as does artist and academic Dr Megan Evans: “I think the best option is to preserve it [the original] and then do a replica nearby which is done in honour of the Haring work. I think this would be more interesting conceptually also as to have a repainted work is like covering up the mark of the past and to make a facsimile is to recreate it in a contemporary context.”51 I agree with the concept of making a facsimile positioned close to the original. Perhaps this could be completed on a new wall that is perpendicular to the original wall that the mural is painted on. Of course the pertinent question would be the permissions needed to erect such a wall, the cost of its construction, the cost of painting the new mural and its upkeep.

Keith Haring (American, 1958-1990)

Crack is Wack

as completed by Haring in 1986 (1st version, now overpainted)

Current Crack is Wack

painted after 1990

Now you see it, now you don’t

This brings me to my final point: now you see it, now you don’t. While I must take at face value the assertion by Andrew Thorn that the mural can be preserved and not fade or deteriorate further if the recommendations of his 1996 and 2010 reports are adhered to, and while I respect his professional judgment in that statement, unfortunately past experience (i.e. the lack of maintenance of the mural between 1996, the year of the last stabilisation, and now) tells me that the mural will continue to deteriorate and fade unless a specific and regular maintenance plan is financially funded and put in place. Donna Wheeler observes that the mural “is but a shadow of its former self”52 and I agree with this assertion. I was shocked to see the mural when visiting it recently compared to how I remember it in 1996 (ah, memory!). Though still an original Haring, it is pale and wane, almost an imitation of itself (and that is an irony in itself), and it made me sad to see the mural in this condition, as I remember how vibrant it was back in the early 1990s.

“According to ACCA curator Hannah Mathews, when the mural was last stabilised in 1996, it was estimated that a tiny sum of A$200 ($178) was needed annually to maintain the work. A combination of factors including pollution and time has left the mural in its current degraded state. Some estimate that it could cost around A$25,000 ($22,000) to stabilise, with an additional A$1,000 ($900) a year for maintenance. Although the issue of whether to repaint the mural is up for debate, all parties agree that the work needs stabilisation as soon as possible to prevent further surface lifting and cracking of the paint … Yarra mayor Jane Garrett said … “Following the forum [Yarra Talking Art forum: “The Keith Haring Mural: yesterday, today, tomorrow” on 29th April 2010 held in Collingwood], [the] Council [is setting up] a working group, which will seek to include representatives from Skills Victoria, Heritage Victoria, the arts community and other stakeholders, to discuss the mural’s future and come to a consensus on the most appropriate way to preserve it.”53

All parties need to agree and as quickly as possible. While Haring was quite happy to send his work out into the world for the enjoyment of all it would be a disservice to his memory and his status as an internationally renowned artist to have the only Haring mural in Australia deteriorate further. Time is of the essence. As Mark Holsworth on his Melbourne Art & Culture Critic blog insightfully opines, “Street art is not the property of the street artists – it belongs to everyone. Even if the artist intends for the art to be ephemeral there is no reason for their wishes to be carried out; the person giving the gift does not get to determine how the gift is used.”54

In the final analysis everyone needs to come to consensus about the future of the Keith Haring Mural for without proper conservation and maintenance it will truly be a case of now you see it, no you don’t.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Word count: 5,056

Endnotes

1/ Keith Haring on Wikipedia [Online] Cited 25/09/2010

2/ Ibid.,

3/ Gott, Ted. “Fragile Memories: Keith Haring and the Water Window Mural at the National Gallery of Victoria,” in Art Bulletin of Victoria Vol. 43. Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, p. 8

4/ “Keith Haring New York,” on the Woodward Gallery website [Online] Cited 25/09/2010. No longer available online

5/ Gott, Ted. Op cit., pp. 7-8

6/ Gott, Ted. Op cit., p. 8

7/ Gott, Ted. Keith Haring’s Collingwood Mural. Draft of a paper given at a Keith Haring Public Forum, Collingwood, 29th April 2010 by Ted Gott, Senior Curator, International Art, National Gallery of Victoria

8/ Gott, Ted and Sullivan, Lisa. “Keith Haring in Australia.” in Art and Australia, Vol. 39, No.4, June-July-Aug 2002: (560)-567. ISSN: 0004-301X. Cited 09/10/2010

9/ Buckley, John. “Keith Haring” exhibition catalogue. Melbourne: Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (ACCA), 1985

10/ Gott, Ted and Sullivan, Lisa. Op. cit., p. 564. See also Footnote 15 and Gruen, John. Keith Haring: The Authorized Biography. New York: Prentice-Hall, 1991, p. 113

11/ Gott, Ted and Sullivan, Lisa. Op. cit.,

12/ Gott, Ted and Sullivan, Lisa. Op. cit., p. 562. See also Footnote 10 and Footnote 15. “Vandals,” Herald, Saturday 10th March 1984, p. 1; “Vandals smash gallery pane,” The Age, Monday 12th March , 1984, p. 19

13/ Gott, Ted and Sullivan, Lisa. Op. cit., Footnote 15 and Gruen, John. Keith Haring: The Authorized Biography. New York: Prentice-Hall, 1991, p. 113

14/ Gott, Ted and Sullivan, Lisa. Op. cit., p. 564

15/ Gott, Ted. Keith Haring’s Collingwood Mural. Op cit.,

16/ Gott, Ted. Keith Haring’s Collingwood Mural. Op cit.,

17/ Gott, Ted. Keith Haring’s Collingwood Mural. Op cit.,

18/ Gott, Ted and Sullivan, Lisa. Op. cit., p. 566. See also Gott, Ted. Keith Haring’s Collingwood Mural. Op cit.,

“Uniquely, we have a surviving record of Keith Haring’s own interpretation of the Collingwood mural, revealed during an interview conducted with the artist shortly after the painting’s completion on Tuesday 6 March 1984. There Keith Haring noted how: “What’s going on in the bottom is about – I mean, all these people are doing different things, right? Some of them are like dancing, like rap dancing, or acrobatics. Some of them are almost like they are fighting. But the way they are all together means that they can’t – I mean, if one of them comes out, the whole thing falls down. So they sort of depend on all of them to make it work. So it’s sort of like society or whatever, where the world only works when lots of individuals do their part, right?

The thing at the top is, I guess, the impending doom or impending possibility of technological … the confrontation between technology and the human element, which is still holding up the technology, and based on the technology. But it sort of takes a semi-circle in evolution, where people evolved up to a certain point, and now they’ve evolved so far that they’ve invented a computer or a machine to evolve further. And the computer is maybe evolving more than people were. So it’s about that sort of confrontation, I guess.””

19/ Gott, Ted and Sullivan, Lisa. Op. cit., p. 562. See also Footnote 8 and Haring, Keith. “Keith Haring,” in Flash Art, No. 116, March 1984, p. 22

20/ Anonymous. “Keith Haring Mural: Statement of Significance,” on Heritage Council of Victoria database [Online] Cited 04/10/2010

21/ Sharpe, Emily. “Saving Keith Haring Down Under: Melbourne work is last surviving wall painting by the late artist’s own hand,” on The Art Newspaper website. Published online 08/06/2010. Cited 06/08/2010. No longer available online

22/ Thorn, Andrew. Email to the author. 24/08/2010.

23/ Dixon, Tom. Member of the Public Art Committee of the National Trust of Australia (Victoria) (NTAV). Telephone conversation with the author 26/08/2010. The Public Art Committee considers murals, mosaics, and sculptures; and such works can be found in parks and reserves, public streets, squares and buildings; and publicly accessible parts of privately owned buildings.

24/ Masterson, Andrew. “Off the wall art,” in The Age. Melbourne: Summer Age supplement. December 27th, 1994, p. 4-5 quoted in Gibson, Lisanne and Pendlebury, John R. “Values not Shared: The Street Art of Melbourne’s City Laneways,” chapter in Valuing historic environments. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2009, p. 146

25/ Thorn, Andrew. “Conservation Treatment Report.” The Keith Haring Mural Johnston Street, Collingwood. Final Report prepared for Northern Institute, 1997.

26/ Thorn, Andrew. “Review of Condition and Treatment.” The Keith Haring Mural Johnston Street, Collingwood. Prepared for City of Yarra, 2007, p. 1

27/ Ibid., p. 2

28/ Ibid., p. 3-5

29/ Thorn, Andrew. Email to the author. 23/08/2010.

30/ Thorn, Andrew. Email to the author. 24/08/2010.

31/ McCaughy, Patrick. Review of “Securing the Past: Conservation in Art, Architecture and Literature” by Paul Eggert in The Australian, December 02, 2009. [Online] Cited 12/06/2010. No longer available online

32/ Ibid.,

33/ Thorn, Andrew. Email to the author. 23/08/2010.

34/ Gibson, Lisanne and Pendlebury, John R. Valuing historic environments. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2009, p. 72

35/ Smith, Laurajane. Uses of Heritage. Oxford: Routledge, 2006, p. 3 (italics in original) quoted in Gibson, Lisanne and Pendlebury, John R. Valuing historic environments. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2009, p. 72

36/ Mauss, Marcel. “A category of the human mind: The notion of person; the notion of self,” in Carrithers, M., Collins, S. and Lukes, S. (eds.,). The Category of the Person: Anthropology, Philosophy, History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985, p. 22, cited in Gibson, Lisanne and Pendlebury, John R. Valuing historic environments. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2009, p. 72

37/ Foucault, Michel. Of Other Spaces (1967), “Heterotopias.” Diacritics 16 (Spring 1986), pp. 22-27

38/ Wolff, Janet. The Social Production of Art. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1993, p. 97

39/ Thorn, Andrew. Email to the author. 23/08/2010.

40/ National Trust of Australia (Victoria). Classification Report for ‘Keith Haring Mural’, Johnston Street, Collingwood, File number 6675. Extract from Statement of Significance, 4th August 1997 quoted in Gibson, Lisanne and Pendlebury, John R. “Values not Shared: The Street Art of Melbourne’s City Laneways,” in Valuing historic environments. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2009, p. 146

41/ Wheeler, Donna. “When Keith Came To Town,” on Holiday Goddess, Female-Friendly Travel website. [Online] Cited 06/08/2010. No longer available online

42/ Thorn, Andrew. Email to the author. 23/08/2010.

43/ McAuliffe, Chris quoted in Masterson, Andrew “Off the wall art,” in The Age. Melbourne: Summer Age supplement. December 27th, 1994, p. 4-5 quoted in Gibson, Lisanne and Pendlebury, John R. Valuing historic environments. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2009, p. 72

44/ Op. cit.,

45/ See Tseëlon, E. The Masque of Femininity: The Representation of Women in Everyday Life. London: Sage, 1995, p. 128

46/ Yarra Talking Arts forum. “The Keith Haring mural: yesterday, today, tomorrow.” Thursday 29th April, 2010

47/ Thorn, Andrew. Email to the author. 23/08/2010.

48/ Ibid.,

49/ Gruen, Julia. “Save the Keith Haring Mural” web page on Facebook [Online] Cited 21/11/2011. No longer available online

50/ Thorn, Andrew. “Another Red Haring,” keynote paper presented at the International Council of Museums Conservation Committee (ICOMCC) triennial Conference, Lisbon, October 2011

51/ Evans, Megan. Email to the author. 08/09/2010.

52/ Wheeler, Donna Op cit.,

53/ Sharpe, Emily Op cit.,

54/ Holsworth, Mark. “Another Banksy Gone,” on Melbourne Art & Culture Critic blog. [Online] Cited 06/10/2010.

LIKE ART BLART ON FACEBOOK

Back to top

![Karl Grill (German active Donaueschingen, Germany 1920s) 'Untitled [Spiral Costume, from the Triadic Ballet]' c. 1926-1927 Karl Grill (German active Donaueschingen, Germany 1920s) 'Untitled [Spiral Costume, from the Triadic Ballet]' c. 1926-1927](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/grill-spiral-costume-from-the-triadic-ballet.jpg?w=650&h=906)

You must be logged in to post a comment.