Exhibition dates: 19th July 2011 – 25th November 2012

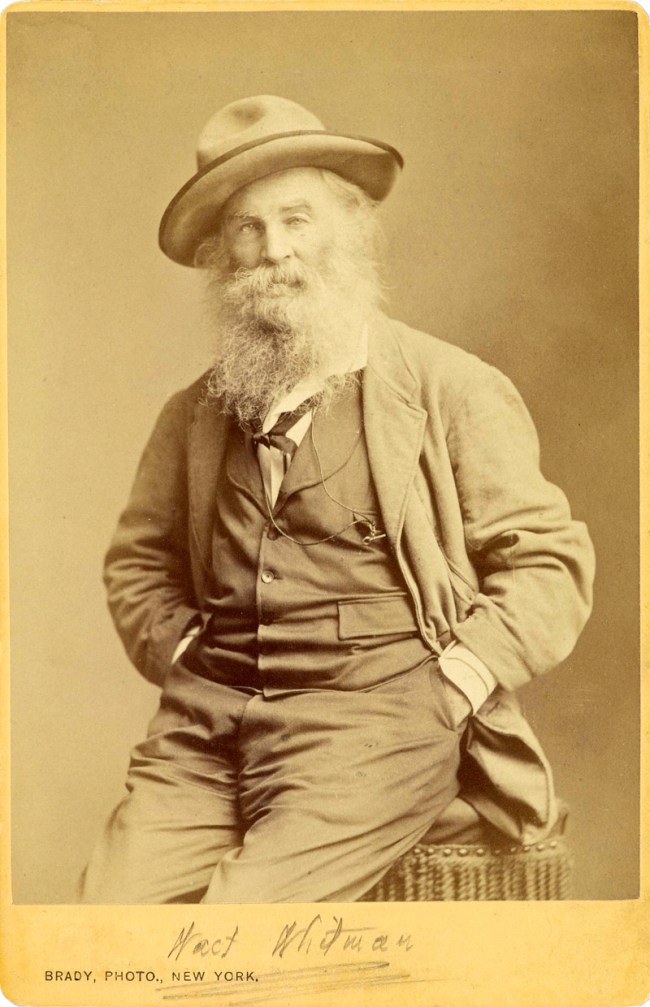

Anon

Bracelets

about 40-20 BC

Gold, emeralds, and pearls (modern)

Classical Department Exchange Fund

Photo: © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

“Today, in the West, we have come to regard diamond, pearl, emerald, sapphire, and ruby as the most precious of materials. That has not always been the case. Other substances have commanded equal attention, from feathers, claws, and mica appliqués to coral and rock crystal, serving a protective role, guarding their wearer from dangerous circumstances or malevolent forces. Other substances, especially those that are rare and available to a select few, are signifiers of wealth and power.”

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Continuing my love affair with exquisite jewellery. What splendour! I love them all…

Marcus

Many, many thankx to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston for allowing me to publish the reproduction of the jewellery in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the art works.

Anon

Armlet with feline-head terminals

Late 5th century BC

Gold

John Michael Rodocanachi Fund

Photo: © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Anon

Spool earring

Italic, Etruscan, Late Archaic or Classical Period

early 5th century BC

Gold

Francis Bartlett Donation of 1900

Photo: © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Anon

Cameo with portrait busts of an Imperial Julio-Claudian couple

mid-1st century AD

Sardonyx

Henry Lillie Pierce Fund

Photo: © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

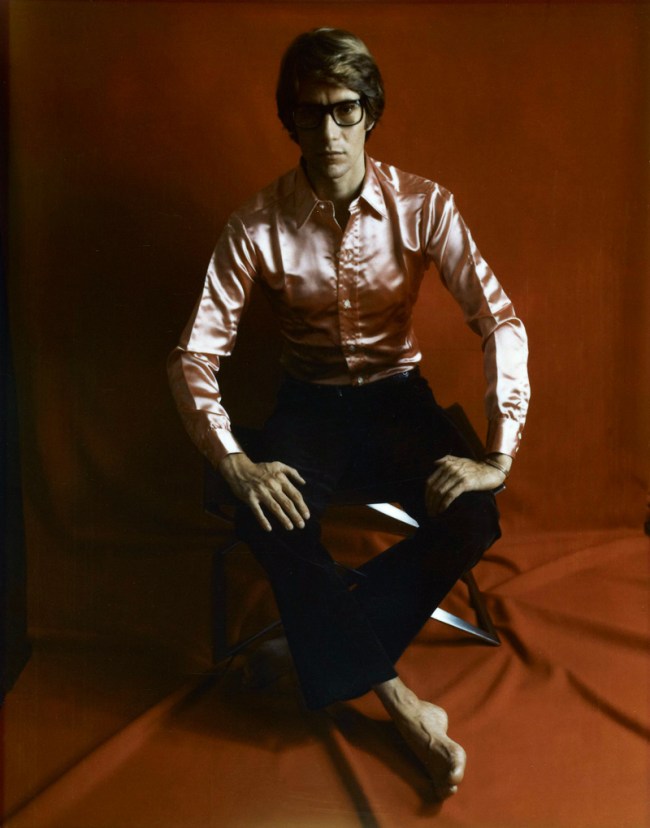

Paul Lienard (French, b. 1849)

Seaweed brooch

French, about 1908

Gold and mabe pearl

Height x width x depth: 5.4 x 11 x 1cm

Photo: © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

As the saying goes, “diamonds are a girl’s best friend” – at least in modern times – but as the exhibition Jewels, Gem, and Treasures: Ancient to Modern illustrates, ornaments made of ivory, shell, and rock crystal were prized in antiquity, while jewellery made of diamonds, emeralds, sapphires, rubies, and pearls became fashionable in later years. On view July 19, 2011, through November 25, 2012, this exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA), highlights some 75 objects representing the rich variety of jewels, gems, and treasures that have been valued over the course of four millennia.

Drawn from the MFA’s collection and select loans, these range from a 24th-century BC Nubian conch shell amulet, to Mary Todd Lincoln’s 19th-century diamond and gold suite, to a 20th-century platinum, diamond, ruby, and sapphire Flag brooch honouring the sacrifices of the Doughboys in World War I. Jewels, Gems, and Treasures is the inaugural exhibition in the MFA’s new Rita J. and Stanley H. Kaplan Family Foundation Gallery, which debuts on July 19. The gallery – one of only a few at US museums solely dedicated to jewellery – will feature works from the Museum’s outstanding collection of approximately 11,000 ornaments. It is named in recognition of the generosity of the Rita J. and Stanley H. Kaplan Family Foundation.

“The opening of the Museum’s first jewellery gallery provides an ongoing opportunity for the MFA’s collection to shine,” said Malcolm Rogers, Ann and Graham Gund Director of the MFA. “In this inaugural exhibition, visitors will see a wide range of gems that will both inform and dazzle in a beautiful new space that will allow the MFA to showcase its stellar assemblage of jewellery, which ranges from ancient to modern.”

Jewels, Gems, and Treasures sheds light on how various cultures throughout history have defined the concept of “treasure,” showcasing an exquisite array of necklaces, rings, bracelets, pendants, and brooches, as well as mineral specimens. In addition, the exhibition explains the significance of jewellery, which can be functional (pins, clasps, buckles, combs, and barrettes); protective (talismans endowed with healing or magical properties); and ornamental, making the wearer feel beautiful, loved, and remembered. Beyond functionality and adornment, jewellery can also establish one’s status and role in society. Rare gems and precious metals, made into fabulous designs by renowned craftsmen, have often served as symbols of wealth and power. This is especially evident in a section of the show where jewellery worn by celebrities is on view, including fashion designer Coco Chanel’s enamelled cuff bracelets accented with jewelled Maltese crosses (Verdura, New York, first half of 20th century) and socialite Betsey Cushing Whitney’s gold and diamond “American Indian” Tiara (Verdura, New York, about 1955), which she wore to her presentation to Queen Elizabeth II in 1956 as the wife of the US Ambassador to the Court of St. James.

The significance of precious materials in jewellery in the 20th century is explored in the exhibition, where several modern adornments from the MFA’s Daphne Farago Collection examine jewellery’s traditional roles in society. Among them are a 1985 brooch of iron, pyrite, and diamond rough by Falko Marx and a 1993 ring by Dutch jeweller Liesbeth Fit entitled Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend. (The Daphne Farago Collection comprises 650 pieces of contemporary craft jewellery made by leading American and European artists from about 1940 to the present.)

Jewels, Gems, and Treasures begins with a look at jewellery made of organic materials – substances readily available and easy to work with, such as ivory, shell, wood, and coral. These range from a pair of ivory cuff bracelets from Early Kerma culture in modern Sudan (2400-2050 BC) to more sophisticated creations made possible through the advancement of tools. Examples include a gold, silver, carnelian and glass Egyptian Pectoral (1783-1550 BC) and a Nubian gold and rock crystal Hathor-headed crystal pendant (743-712 BC) recovered from the burial of a queen of King Piye, the great Kushite ruler who conquered Egypt in the eighth century BC. In addition to having magical properties that protected the wearer against malevolent forces, adornments such as these were often buried with their owners as their amuletic capabilities were needed during the arduous journey to the afterlife. On the other side of the globe, Mayans wore ear flares – conduits of spiritual energy – made of sacred green jadeite that represented key elements of human life. Various cultures throughout the ages at one point believed that amber could cure maladies, coral could safeguard children, an animal’s tooth or claw could invest the wearer with strength and ferocity, and gold and silver invoked the cosmic power of the sun and moon. In Medieval and Renaissance Europe, many hard stones were believed to have magical properties (some were even ground and consumed), and pendant reliquaries containing a holy person’s cremated ashes or bone fragments were often donned, along with rosaries (Rosary, South German, mid-17th century), as sacred adornments. Even today, zodiac ornaments and good luck charms are sometimes worn as tokens, recalling their earlier mystical importance.

Throughout much of history, jewellery’s role as a symbol of one’s elevated status has inspired the wealthy to seek out stones that sparkle, gold that gleams, and designs that reflect the greatest artistry money can buy. To illustrate this, Jewels, Gems, and Treasures features some of the most opulent works from the Museum’s jewellery collection, including an 1856 diamond wedding necklace and earrings suite given by arms merchant Samuel Colt to his wife (the 41.73-carat suite, purchased for $8,000, is now valued at $190,000) and Mary Todd Lincoln’s gold, enamel, and diamond brooch with matching earrings, which she acquired around 1864, shortly after the death of the Lincolns’ beloved son, Willy, and then sold in 1867 to pay mounting debts. Also on view is a Kashmir sapphire and diamond brooch (around 1900); a gold and diamond necklace made by August Holmström for Peter Carl Fabergé, the famous Russian jeweller to the czars; and cereal heiress Marjorie Merriweather Post’s lavish platinum brooch from the 1920s, featuring a spectacular 60-carat carved Mughal emerald surrounded by diamonds, which she purchased in anticipation of her presentation at the British court in 1929.

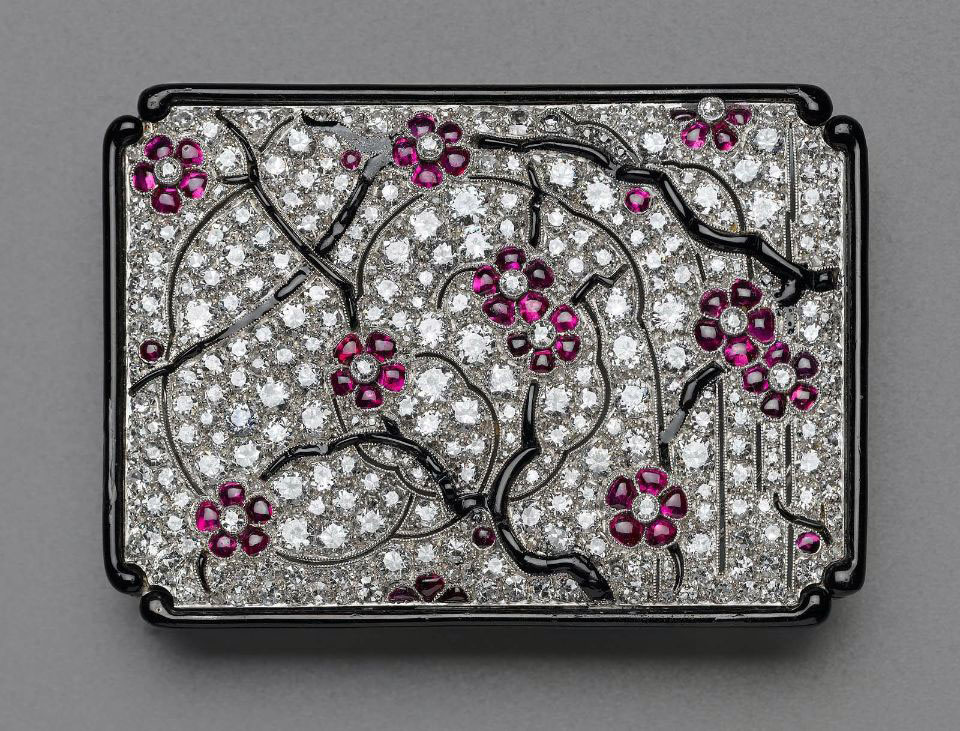

Also on view in the exhibition are superb adornments made by leading French Art Nouveau jewellers, which were fashioned for a wealthy and artistic clientele in the late 19th to early 20th centuries. The Art Nouveau movement, which originated in Europe, embraced an aesthetic that was avant-garde, sensuous, and symbolic – one that looked to the natural world, the Impressionists, and the arts of Japan for inspiration. In response to the “tyranny of the diamond” – the all white platinum and diamond jewellery previously in vogue – these elaborate, one-of-a kind pieces often featured coloured gems and unusual materials, such as horn, enamel, irregularly shaped pearls, steel, and glass. Examples in the show include René Lalique’s fanciful gold, silver, steel, and diamond Hair ornament with antennae (about 1900), and Paul Lienard’s gold and mabe pearl Seaweed brooch (about 1908). The Arts and Crafts movement, which emerged in Britain during the 1870s as a reaction to the mechanisation and poor working conditions of the Industrial Revolution, is represented by Marsh-bird brooch (1901-1902) by Charles Robert Ashbee, who sought to create a delicate stained-glass effect with this piece. The refined techniques of the Art Deco movement are evident in Japanesque brooch (about 1925), incorporating platinum, gold, enamel, diamonds, rubies, and onyx. The movement arose after World War I and continued through the 1930s. It was influenced by avant-garde ideology, as was the Art Nouveau and Arts and Crafts movements, but instead chose to express its aesthetic through geometric shapes, linear stylisation, and a return to platinum and diamonds.

Jewels, Gems, and Treasures also highlights a variety of interesting and unique pieces, such as a Suite of hummingbird jewelry (brooch and earrings, about 1870), made out of gold, ruby, and taxidermied hummingbirds; an ebony, ivory, silver lapis lazuli, and amber casket designed to showcase the amber cameos and intaglios collected by Arnold Buffum (about 1880-1885); an Indian silver and tiger claw necklace (19th century); and a gold, silver, agate, diamond, and ruby animal sculpture, The Balletta Bulldog (about 1910) made by the workshop of Peter Carl Fabergé Fabergé. In addition, the exhibition features jewellery as seen in William McGregor Paxton’s painting, The New Necklace (1910).

Press release from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston website

René Lalique (French, 1860-1945)

Hair ornament with antennae

c. 1900

Gold, silver, steel, and diamond

Height x width x depth: 8.8 x 12.5 x 7cm

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Gift of the Sataloff and Cluchey Family

© 2011 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

Photo: © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

This hair ornament with its whimsical character is a unique piece by Lalique. It features the unusual exclusive use of diamonds which were sparingly used by the Art Nouveau jewellers who preferred less precious stones and enamel to provide colour and opalescence. From the gold wire headband emerge two antenna composed of hollow silver cubes in which are set graduated brilliants each secured by four prongs. A steel wire runs through the cubes to form the curved shape of each antenna. Except for the scroll terminals of the antennae, each cube is individually mounted and stacked without being attached to each other so that they tremble when the wearer moves, accentuating the sparkle of the diamonds.

Probably by Lacloche Frères, Spanish, founded in 1875 (also working in Paris)

Japanesque brooch

French, about 1925

Platinum, gold, enamel, diamond, ruby, and onyx

Height x width x depth: 3.6 x 5.2 x 0.6cm

Photo: © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

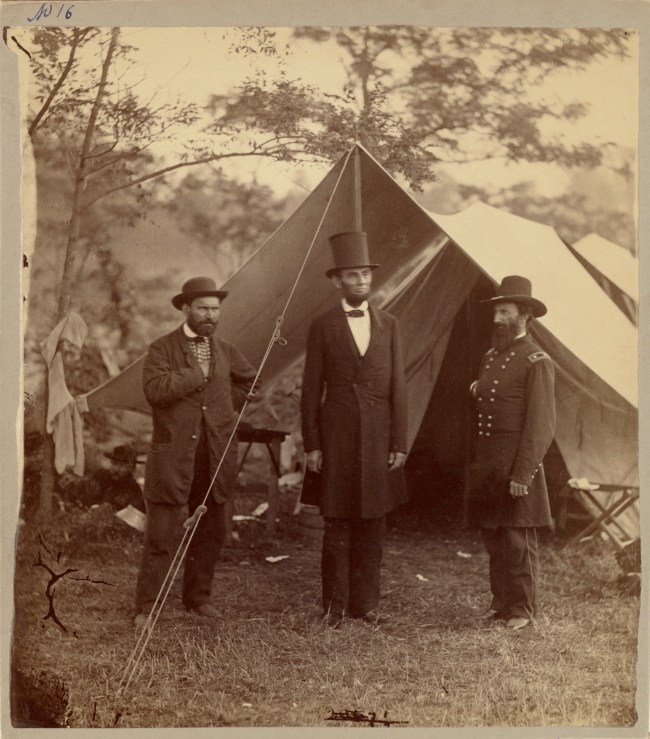

Anon

Brooch worn by Mary Todd Lincoln (American, 1818-1882)

American, about 1860

Gold, enamel, and diamond

Depth x diameter: 1.3 x 3cm

Photo: © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The brooch is part of a suite with matching earrings. Each element is quatrefoil in shape and has a central diamond with a diamond surround. Eight smaller diamonds form a second tier of stones. The stones are all mine-cut and are probably original to the suite. The colour range is J-K with VS-VS1 clarity. there are some losses to the tracery enamel. The suite was featured in Frank Lesley’s Illustrated Newspaper (Oct. 26, 1867). It was part of a large group of Mrs. Lincoln’s clothes, jewellery, and furnishings that were offered for sale through Brady & Company of New York City. Apparently, Mrs. Lincoln fell into dire financial circumstances after the assassination of her husband, Abraham Lincoln. The sale price was listed as $350.00.

Charles Robert Ashbee (English, 1863-1942)

Marsh-bird brooch

1901-1902

Gold, silver, enamel, moonstone, topaz, and freshwater pearl

Height x width x depth: 9 x 10.5 x 1.5cm

Photo: © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The brooch was originally a hair ornament that was converted to a brooch (silver pin stem and “C” hook added). Conversion probably occurred shortly after the ornament was made. The hair comb was fabricated by A. Gebhardt and enamelist William Mark, both members of the Guild of Handicraft.

Anon

Hathor-headed crystal pendant

Napatan Period, reign of King Piye

743-712 BC

from el-Kurru, tomb Ku 55 (Sudan)

Gold, rock crystal

Height x diameter: 5.4 x 3.3cm

Photo: © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

John Paul Cooper (English, 1869-1933)

English Arts and Crafts brooch

1908

Gold (15 kt), ruby, moonstone, pearl, amethyst, and chrysoprase

Height x width x depth: 14 x 9.6 x 0.8cm

Photo: © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

John Paul Cooper, a leading figure in the British Arts and Crafts movement, was an architect, designer, and metalsmith. Born into an affluent Leicester family, Cooper prepared for a career as a writer but was discouraged from pursuing this endeavour by his industrialist father. Instead, he apprenticed to London architect John D. Sedding, a strong proponent of the ideas of John Ruskin and Henry Wilson, an architect with interests in craft, especially metalwork and jewellery. Afterwards, Cooper joined the “Birmingham Group” and served as head of the Metalwork Department of the Birmingham Municipal Art School (1901-1906). He exhibited regularly at the Arts and Crafts Society exhibitions and completed several important public commissions, including two crosses and a pair of altar vases for Birmingham Cathedral. Additionally, his work often appeared in article published in Studio and Art Journal.

Cooper’s interest in jewellery design and fabrication began shortly after his association with Wilson. Like Wilson, he eventually employed others to fabricate his jewellery designs although he sometimes did the chasing and repoussé work himself. The jewellery was crafted primarily in 15 kt gold, utilising semi-precious cabochons (domed, unfaceted stones) and mother-of-pearl. Unlike many Arts and Crafts jewellery designers, Cooper often worked his designs from a selection of stones, rather than creating a design and then finding suitable gems. He once commented that stones should “… play on one another as two notes of music…”

In addition to jewellery, Cooper’s workshop designed and fabricated ecclesiastical objects and various decorative arts, including hollowware and frames. Many of the objects incorporate unusual materials, such as coconut shell, ostrich-egg shell, and narwhal tusk. At the beginning of his career, he often used gesso and plaster modelling to decorate surfaces and, at the end of the 1890s, he began making wooden boxes which he covered with shagreen, a decorative veneer made from the skin of certain sharks and rays.

This brooch is a major work by Cooper. Created during a period when the artist relied less on chased representational imagery and more on stones, the ornament conveys a sense of refined opulence. Inspired by medieval and Celtic design, the brooch is both airy and graceful. The goldwork is decorated with finely chased leaves and tendrils and the bezel-set stones include ruby, pearl, moonstone, amethyst, and chrysoprase. It took 273 hours to produce the brooch and Lorenzo Colarosi, Cooper’s chief craftsman, was the primary fabricator. It’s possible that Cooper did the chasework. The drawing for the brooch, which is dated 3 December 1908, can be found in Stockbook I, p. 81 in the Cooper Family Archives. Cooper entitled the piece Big double gold brooch.

Anon

Earring with Nike driving a two-horse chariot

About 350-325 BC

Gold

Henry Lillie Pierce Fund

Photo: © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

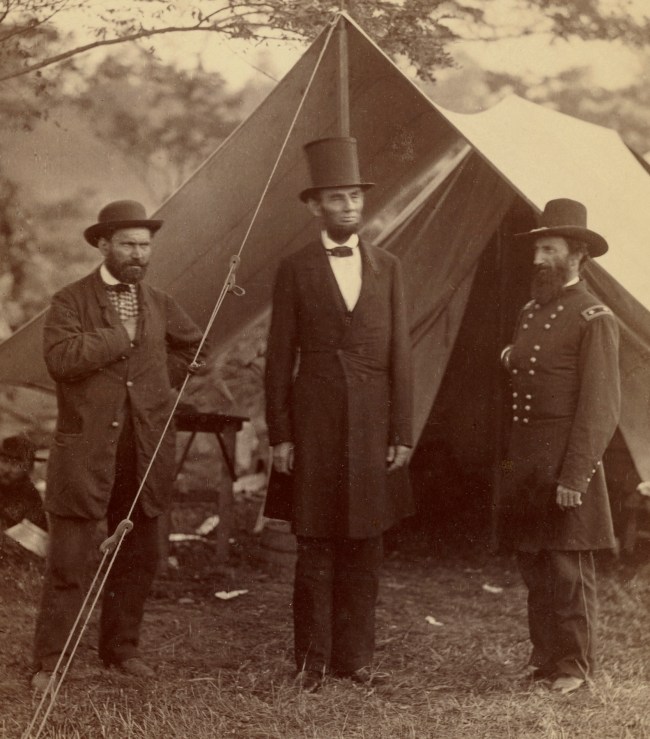

Possibly by Oscar Heyman & Bros. (American, founded in 1912 for Marcus & Co., American, 1892-1941)

Marjorie Merriweather Post’s platinum brooch

American, late 1920s

Platinum, diamond, and emerald featuring a spectacular 60-ct carved Mughal emerald surrounded by diamonds, which she purchased in anticipation of her presentation at the British court in 1929

Overall: 5.3 x 5.4 x 1.1cm

Photo: © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The brooch was purchased by Marjorie Merriweather Post (1887-1973) and is documented by two portraits; one by Frank O. Salisbury (Palm Beach Bath and Tennis Club) and the other by Douglas Chador (Hillwood Museum). Both date to 1952. The central stone in the brooch is a mid-17th century carved emerald that was purchased by Marcus and Co.’s agent in Bombay in the 1920s. Oscar Heyman & Bros. made many of the jewels marketed by Marcus & Co. during the 1920s.

Anon

Pin with sphinxes, lions, and bees

Late 5th century BC

Gold

Catharine Page Perkins Fund

Photo: © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Avenue of the Arts

465 Huntington Avenue

Boston, Massachusetts

Opening hours:

Saturday – Monday and Wednesday 10am – 5pm

Thursday – Friday 10am – 10pm

Closed Tuesdays

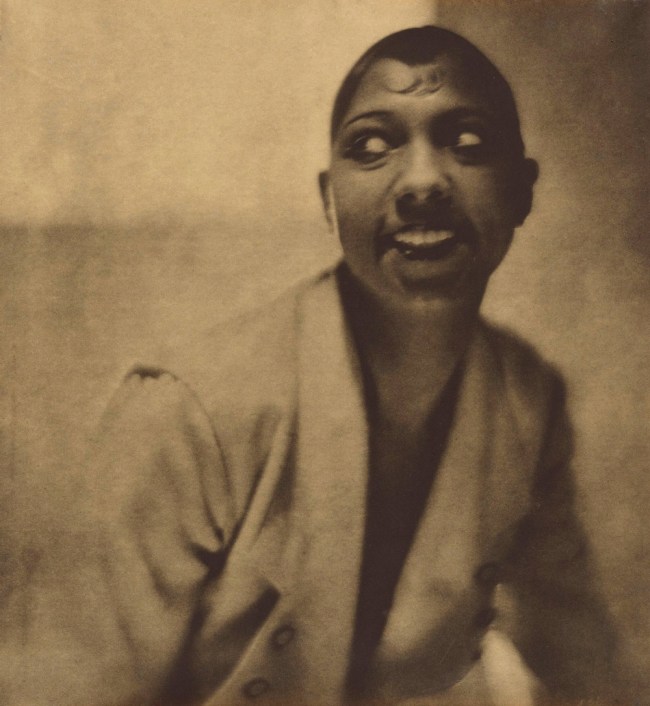

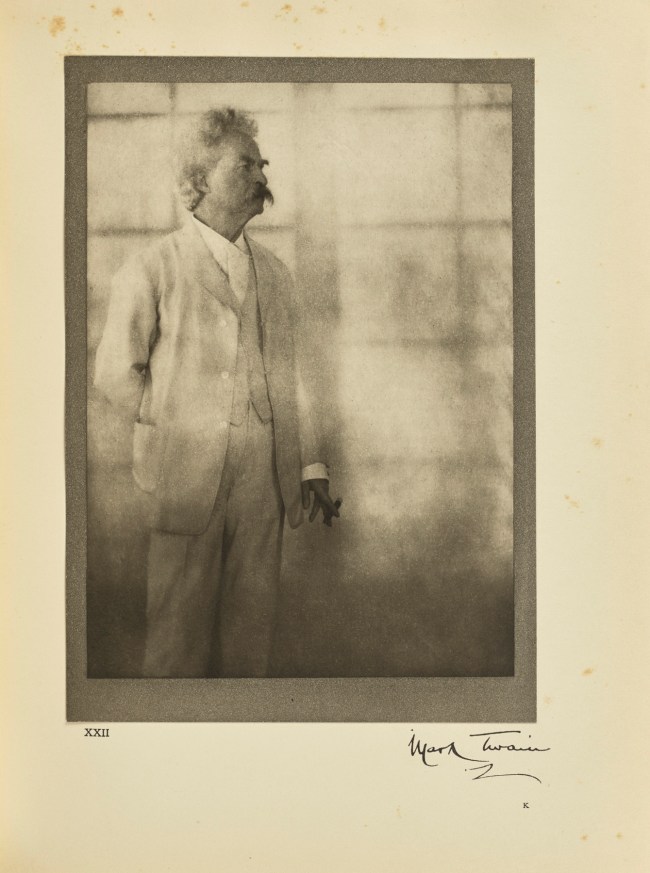

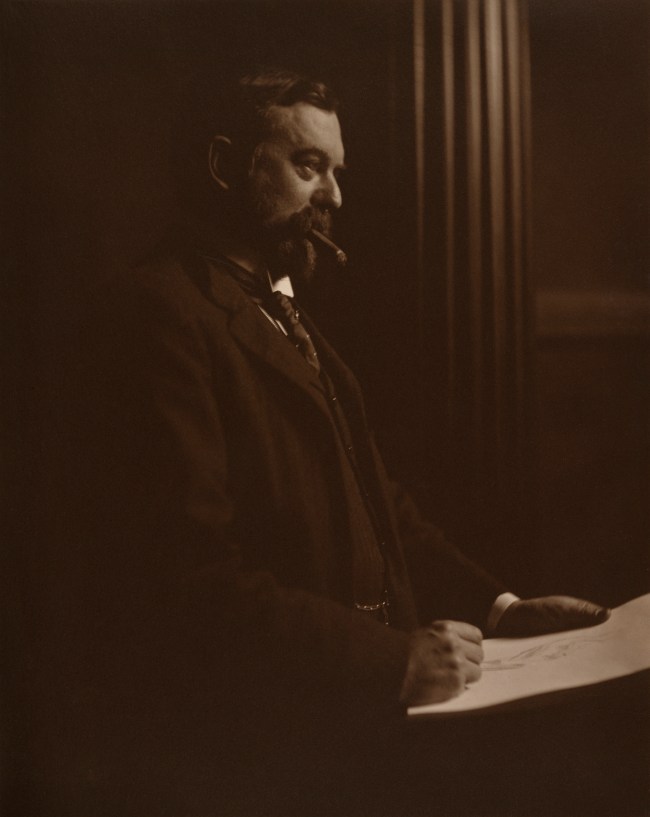

![Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946) '[Self-Portrait]' Negative 1907; print 1930 Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946) '[Self-Portrait]' Negative 1907; print 1930](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/stieglitz-self-portrait-1907.jpg?w=650&h=872)

![Sarah Choate Sears (American, 1858-1935) '[Julia Ward Howe]' about 1890 Sarah Choate Sears (American, 1858-1935) '[Julia Ward Howe]' about 1890](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/sears-julia-ward-howe.jpg?w=650&h=825)

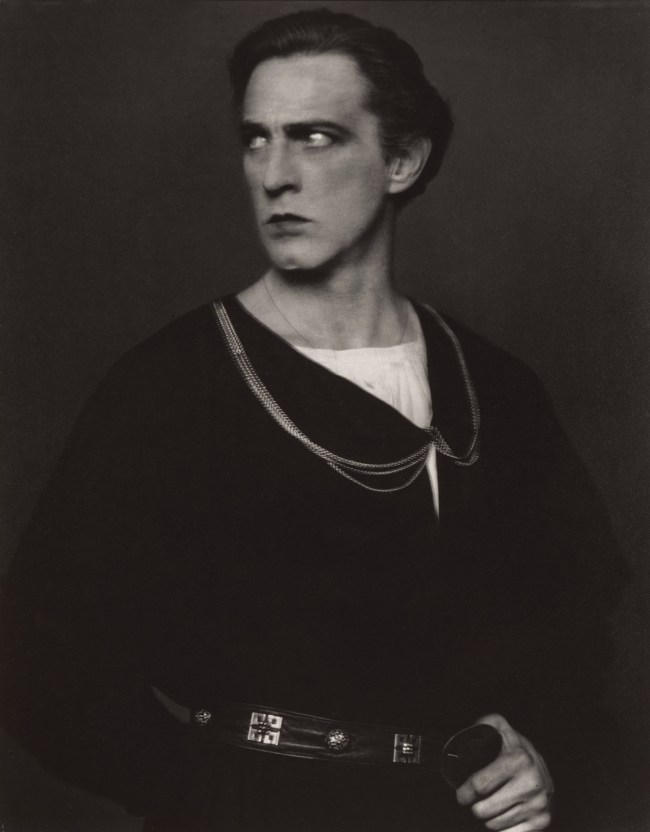

![Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) '[Sarah Bernhardt as the Empress Theodora in Sardou's "Theodora"]' Negative 1884; print and mount about 1889 Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) '[Sarah Bernhardt as the Empress Theodora in Sardou's "Theodora"]' Negative 1884; print and mount about 1889](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/nadar-sarah-bernhardt.jpg?w=650&h=994)

![Charles DeForest Fredricks (American, 1823-1894) '[Mlle Pepita]' 1863 Charles DeForest Fredricks (American, 1823-1894) '[Mlle Pepita]' 1863](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/fredricks-mlle-pepita.jpg?w=650&h=1046)

![André Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri (French, 1819-1889) '[Rosa Bonheur]' 1861-1864 André Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri (French, 1819-1889) '[Rosa Bonheur]' 1861-1864](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/disdecc81ri-rosa-bonheur.jpg?w=650&h=1062)

![John Robert Parsons (British, about 1826-1909) '[Portrait of Jane Morris (Mrs. William Morris)]' Negative July 1865; print after 1900 John Robert Parsons (British, about 1826-1909) '[Portrait of Jane Morris (Mrs. William Morris)]' Negative July 1865; print after 1900](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/parsons-portrait-of-jane-morris.jpg?w=650&h=779)

![Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'George Sand (Amandine-Aurore-Lucile Dupin), Writer' c. 1865 Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'George Sand (Amandine-Aurore-Lucile Dupin), Writer' c. 1865](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/realideal5-web.jpg?w=650&h=854)

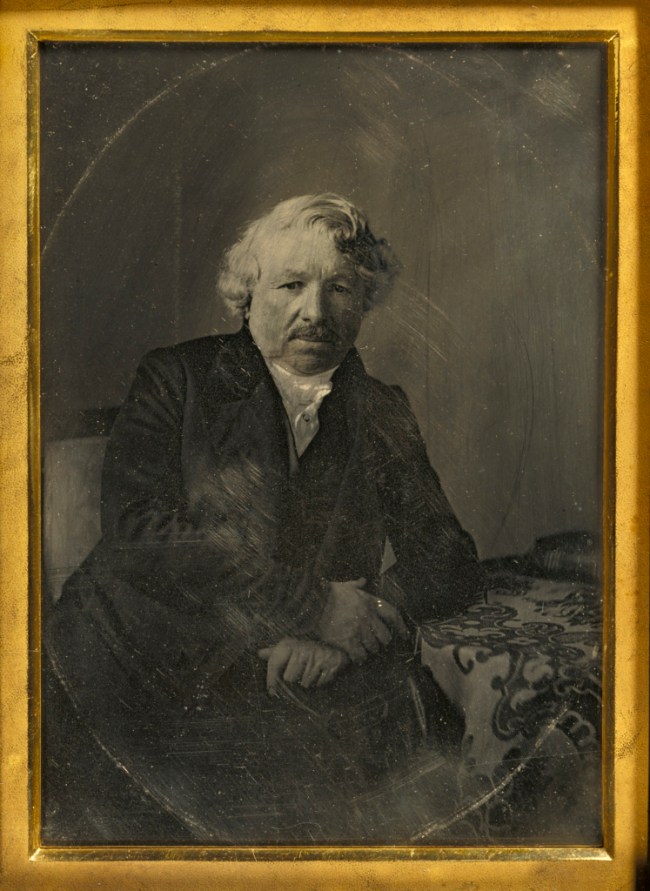

![Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'Alexander Dumas [père] (1802-1870) / Alexandre Dumas' 1855 Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'Alexander Dumas [père] (1802-1870) / Alexandre Dumas' 1855](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/nadar_alexander_dumas.jpg?w=650&h=803)

You must be logged in to post a comment.