Exhibition dates: On view from November 24, 2022. This permanent exhibition has no end date and can be visited permanently

Nikè, Goddess of Victory

100 BC-100 AD

Sardonyx in modern pendant

27.8 x 21 x 6.5mm (cameo)

38 x 30.25mm (frame)

© Photo and collection RMO, inv.no. GS 2022/4.88

The elegance and beauty of cameos

This posting is for my friend Terence who has been a collector of antiques for over 65 years, whereas I have been collecting only 45 years. I thank him for his friendship and advice…

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, RMO for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

The National Museum of Antiquities (Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, RMO) has acquired a unique collection of cameos. These are 444 miniature works of art of an exceptionally high level, ‘cut’ from colourful types of stone. The objects date from Classical Antiquity, the Middle Ages up to the seventeenth century. It concerns the private collection of Derek Content, an American of Dutch descent. With this acquisition, the collection of carved stones of the National Museum of Antiquities is one of the top collections in Europe. More than three hundred copies are now on display in the museum. The RMO bought almost the entire collection for over 5.4 million euros. Nearly the half of this sum was contributed by the Rembrandt Association, for the purchase of 42 masterpieces from the collection.

Dancing Maenad

c. 40-30 BC (cameo), 19th century (ring)

Sardonyx in gold ring

17 x 9.6 x 2.5mm

© Photo and collection RMO, inv.no. GS 2022/4.141

This white-grey sardonyx cameo is of exceptional quality. The stone shows the upper body of a dancing follower of Dionysos. She has thrown her head back in ecstasy, her curls flying in all directions. The cameo was probably made by a Greek artist.

Drunken Silenus on chariot with erotes and Psyche

c. 25-0 BC (cameo), 18th century (ring)

Sardonyx in gold ring

18.4 x 14.1mm (cameo)

22.1 x 18.1 x 4.2mm (frame)

© Photo and collection RMO, inv.no. inv.no. GS 2022/4.122

Silenus, an old satyr, lies heavily drunk on a cart pulled by two laughing erotes. Silenus is laughed at by Psyche, a naked woman with wings.

Satyr and drunken Silenus

c. 0-25 AD. (cameo), 19th century (pendant)

Sardonyx in gold pendant

33.4 x 24.5 x 5mm

© Photo and collection RMO, inv.no. GS 2022/4.124

The scene shows a drunken Silenus (a follower of Dionysos), who has fallen to the ground. On the left is a satyr trying to get him back on his feet. The original cameo was larger: on the right is a hand of a second satyr, also trying to help.

Elegance and beauty

The elegance and beauty of cameos are the focus of this permanent exhibition, which consists of more than a hundred specimens from the recently acquired Content Family Collection. The cameos (‘carved stones’) date from an elongated period: from Classical Antiquity and the Middle Ages to the seventeenth century. The Content Family Collection is the collection of Derek Content, an American of Dutch descent. The National Museum of Antiquities recently purchased almost its entire collection. Thanks to the acquisition, the museum’s collection of carved stones is one of the top collections in Europe.

Cameos: decorative stone objects

Cameos are small decorative stone objects in which a representation has been worked out in relief down to the smallest detail. Often they are no bigger than a fingertip. In ancient times cameos were popular as jewellery, showpiece and talisman. The depictions range from emperor portraits, gods and animals to symbols, spells and personal texts. You will see technically complex feats, unique specimens in their original setting and various text cameos. Some stones are thousands of years old, while others were made as recently as the seventeenth century.

Fund support

42 masterpieces of the new cameo collection have been purchased with considerable support from the Rembrandt Association , thanks in part to its Eleonora Jeuken-Tesser Fund, its 1931 Fund, its Antiquity and Archeology Fund, and the annual contribution of the Prince Bernhard Culture Fund. Other funding was obtained from the VriendenLoterij , private donations and private RMO funds: Elisabet Huss Fund, Van der Schans Fund, Asklepios Fund, Eega van Asklepios Fund and Gildemeester Fund.

Text from the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, RMO website

Nereid with hippocampus and dolphin

25-0 BC

Sardonyx

16.6 x 12.5 x 9.5mm

© Photo and collection RMO, inv.no. GS 2022/4.112

This cameo is carved in very high relief from a sardonyx with a black and a white band. The nereid (sea nymph) seems to cling to a hippocampus. A dolphin swims among them. A hippocampus is a mythical sea creature with the head and forelegs of a horse, and the tail of a fish. The Nereids are the daughters of the sea god Nereus.

The Golden Fleece

c. 100 BC-100 AD (cameo), 19th century (pendant)

Sardonyx in enamelled gold pendant

33 x 23.9 x 5.2mm

© Photo and collection RMO, inv.no. GS 2022/4.242

The hero Phrixus kills the ram with the golden fleece (the “golden fleece”, symbol of royal authority), on whose back he and his sister Helle have escaped the vengeance of their stepmother Ino. Later, the Greek Jason obtains the golden fleece and thereby secures the claim to the throne of his homeland.

Shepherd with kid

1st century AD (cameo), 19th century (ring)

Sardonyx in gold ring

19.8 x 14 x approx. 2.5mm (cameo)

© Photo and collection RMO, inv.no. GS 2022/4.240

This is a typical cameo from the reign of Emperor Augustus, in which the lovely, idyllic nature and idealised pastoral world are central. In 1841 the cameo was set in a gold ring by Gustav Mollenborg, the court jeweller of the Swedish royal family. The ring has a hidden pocket in the shaft.

Portrait of a Lady / Livia Empress of Rome

0-25 AD

Carnelian

16.3 x 12.3 x 10mm

© Photo and collection RMO, inv.no. GS 2022/4.24

Carnelian (also called carnelian) is a brown-red stone, which was mined in ancient times in Arabia, India and Egypt. The name is derived from the Latin word caro, meaning “meat”. The relief is particularly deeply worked out. It shows a three-quarter perspective portrait of a young woman with a veil and headband. Her hairstyle is reminiscent of portraits of empresses from the Julio-Claudian imperial house, such as Livia and Antonia Minor.

Nero

mid 1st century AD

Sardonyx

30.3 x 28 x 5.2mm

© Photo and collection RMO, inv.no. GS 2022/4.74

This cameo shows the portrait of the young emperor Nero. He is shown in profile with idealised facial features. In his younger years he was popular, especially with the people. He participated in chariot races and acted as an actor and singer in the theatre. That was less in line with the norms and values of the Roman senators.

The National Museum of Antiquities of the Netherlands (Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, RMO) has purchased a unique collection of cameos. It consists of 444 miniature artworks of exceptional quality, ‘carved’ from colourful types of stone. The pieces date from Classical Antiquity through to the Middle Ages and the 17th century. They are from the private collection of Derek Content, an American of Dutch origin. With this acquisition, the RMO’s collection of ‘carved stones’ takes its place among the best collections in Europe. More than 300 of the cameos will henceforth be on display in the museum. The RMO bought almost the entire collection for over 5.4 million euros. Nearly the half of this sum was contributed by the Rembrandt Association, for the purchase of 42 masterpieces from the collection.

Cameos are small stone ornaments decorated with a scene in relief, often in the finest detail. In ancient times, cameos were popular as jewellery, showpieces and talismans. The depictions range from imperial portraits, gods and animals to symbols, proverbs and personal texts. The Content Family Collection contains many antique cameos, including technical feats of craftmanship, unique pieces in their original settings, and 93 text cameos – the largest collection in private hands. The purchase is an exceptional addition to the RMO’s collection. Both geographically and chronologically, the new cameo collection perfectly complements that of the RMO. Together they show the development of cameo art over two millennia, and offer insight into the private lives of people in ancient times.

42 Masterpieces in the new cameo collection were acquired with major support from the Rembrandt Association, thanks in part to its Eleonora Jeuken-Tesser Fund, its 1931 Fund, its Antiquities and Archaeology Theme Fund, and the annual contribution of the Prince Bernhard Culture Fund. The Rembrandt Association contributed 2.5 million euros, almost half of the total purchase amount. Additional funding was provided by the VriendenLoterij, private donations and private RMO funds: the Elisabet Huss Fund, the Van der Schans Fund, the Asklepios Fund, the Eega van Asklepios Fund and the Gildemeester Fund.

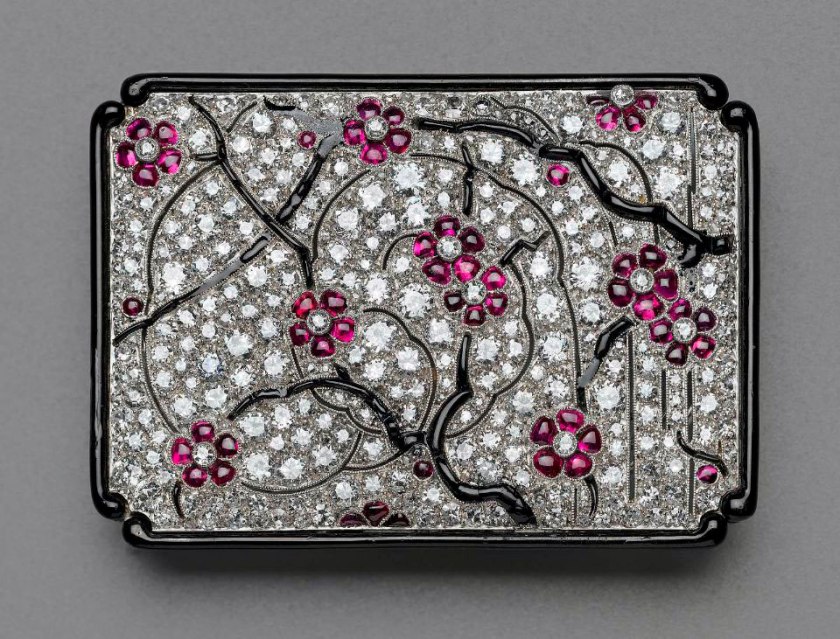

A place of honour in the museum’s galleries

The elegance and beauty of cameos form the focus of the new exhibition, Cameos. Miniature masterpieces. More than one hundred pieces are on display in the exhibition. A short film by artist duo Scheltens & Abbenes, known for photographing luxury fashion and design brands, features marble statues from the museum’s collection wearing the cameos like jewels – as they were once intended. The design of the exhibition and the idea for the film are by Anika Ohlerich (Archetypisch), and the graphic design is by Esther de Vries.

In future, the museum will use the new cameos in temporary exhibitions and educational programmes. Some two hundred of the new cameos have already been added to the museum’s permanent display on the Greeks and Romans. A publication (in Dutch) about the acquisition and the masterpieces is available for €10 in the museum shop and web shop.

Before and after the acquisition

Having started collecting cameos fifty years ago, Derek Content accumulated one of the largest private cameo collections in the world. Part of the Content Family Collection was on display at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford for more than a decade. The collection has been published several times and in full, most recently in 2018.

The original provenance of the stones is nevertheless difficult to determine in many cases. After all, cameos were found throughout the ancient world, and – like coins – their small size made them easy to trade: they were passed from hand to hand for centuries. For this reason, three years were spent documenting the cameos and their provenance history in preparation for the purchase. The acquisitions have since been added to the collection finder on the museum’s website (www.rmo.nl), along with descriptions, known provenance details and high-resolution photos. In this way, the entire collection has been made digitally accessible for interested parties and further research, both at and beyond the museum.

Press release from the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, RMO

Rider jumping from his horse

0-200 AD (cameo), 17th century (pendant)

Sardonyx in enamel gold pendant

22 x 17.7 x 6mm (cameo)

35.4 x 31mm (frame)

© Photo and collection RMO, inv.no. GS 2022/4.243

This cameo shows a snapshot: a rider holds his horse by the bridle and is depicted during the jump to the ground. On his left arm hangs a shield with an evil-fighting Medusa. The ascent and descent went without the use of stirrups. They were only introduced after the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the fifth century AD.

Handshake with text OMONOIA (‘Unity’)

200-300 AD

Sardonyx in original gold ring

15.3 x 14.2mm (cameo)

30 x 22.2mm (ring)

© Photo and collection RMO, inv.no. GS 2022/4.281

The bond between two spouses could be expressed with a double portrait or with an image of two clasped hands, of a lady with a bracelet and of a gentleman. In this case, the handshake is sealed with the text “OMONOIA” (“Unity”).

Portrait of a lady

200-300 AD

Sardonyx in original gold brooch with pearls

23.3 x 27.5mm (cameo)

59.5 x 24.2mm (frame)

© Photo and collection RMO, inv.no. GS 2022/4.49A

Athena

200-300 AD

Sardonyx in original gold setting

42.8 x 29mm (cameo)

52 x 40 x 10mm (frame)

© Photo and collection RMO, inv.no. GS 2022/4.91

Athena wears a cuirass and a helmet, from which her hair flows. The densely worked gold setting suggests that only the white layer of the cameo should be visible. At the back are two hooks to wear the piece of jewellery as a brooch or in a hairdo.

Hunter on horseback with panther

c. 300-500 AD

Sardonyx on slate

28.9 x 24 x 1.7mm

© Photo and collection RMO, inv.no. HS 2022 4.121

This cameo is carved from very thin grey-white sardonyx. For reinforcement, the stone has been attached to a slice of slate since ancient times. The scene is reminiscent of the mythical hero Bellerophon on the winged horse Pegasus. A rider on a prancing horse with wings can be seen. He stabs a panther in the mouth with a spear. The panther in turn pounces on a helpless hare.

Storks

300-500 AD

Sardonyx

17.5 x 20.6 x 3.7mm

© Photo and collection RMO, inv.no. GS 2022/4.225

Storks had a special significance in ancient times. It was thought that young storks took care of their needy parents and so the stork was worn in ring stones as a symbol of conscientiousness (pietas). The left animal drinks water and the right animal raises its head towards a fluttering butterfly.

The Virgin with text MP (left) and ΘΥ (right)

Byzantine 900-1100 century AD

Chalcedony in modern gold setting

23 x 22 x 8mm

© Photo and collection RMO, inv.no. GS 2022/4.401

This cameo shows a portrait of the Virgin Mary. Her face is surrounded by a circle of light (nimbus). She raises both hands in a gesture of blessing. The Greek letters on either side of Mary form an abbreviation for the words MHTHP ΘEOY, “Mother of God.”

Indian ashoka tree (saraca asoca)

Mughal dynasty, 1575-1625 AD

Sardonyx

50.3 x 32.3 x 8.5mm

© Photo and collection RMO | inv.no. GS2022/4.357

The cameo depicts an Indian Ashoka tree with three fan-shaped blossom bundles and leafy branches. The ashoka tree is a beloved theme in Indian classical poetry and art, with strong roots in Buddhism and Hinduism. The name means ‘that which brings no sorrow’. The tree has traditionally been attributed medicinal powers, especially with regard to gynaecological ailments.

Shah Jahan, Emperor of the Mughal Empire

Mughal dynasty, mid 17th century

Layered agate

31.9 x 26 x 6.4mm

© Photo and collection RMO, inv.no. GS 2022/4.354

With this portrait of Shah Jahan, the newly acquired Content collection can be linked to the RMO’s existing cameo collection. The famous Leiden Large Cameo (Gemma Constantiniana) from the Leiden collection was offered for sale in the 17th century in Hindoustan (India) by Dutch traders to the Great Mughal Shah Jahan. The sale fell through, after which the Grote Cameo was shipped back to the Netherlands.

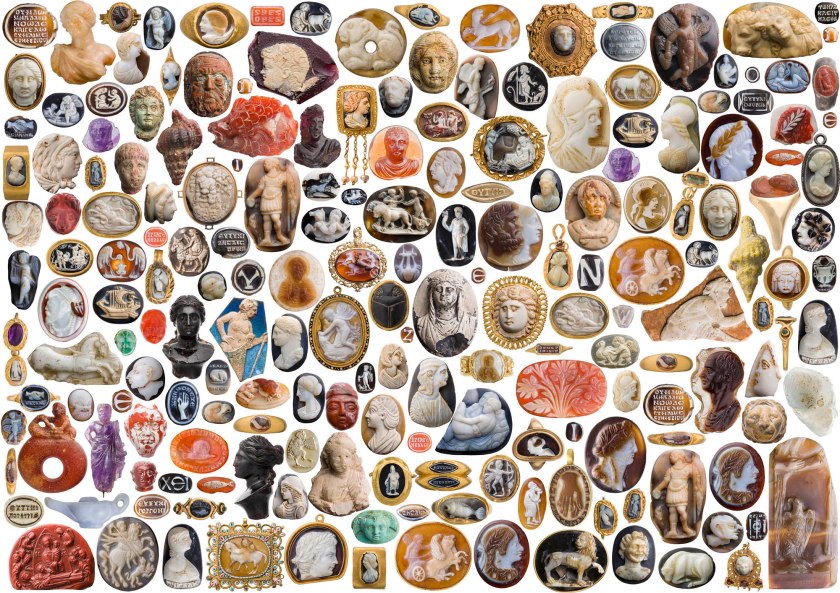

Cameos Compilation

© Photo and collection RMO

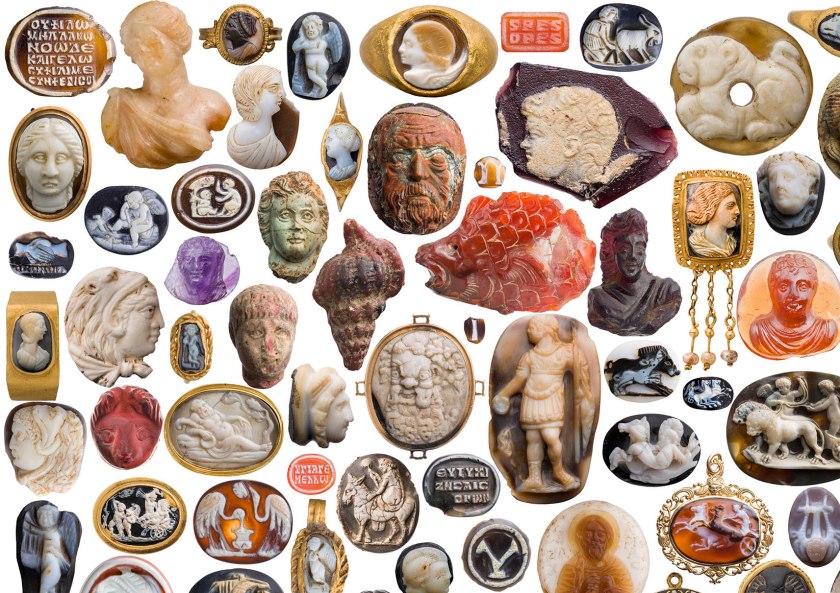

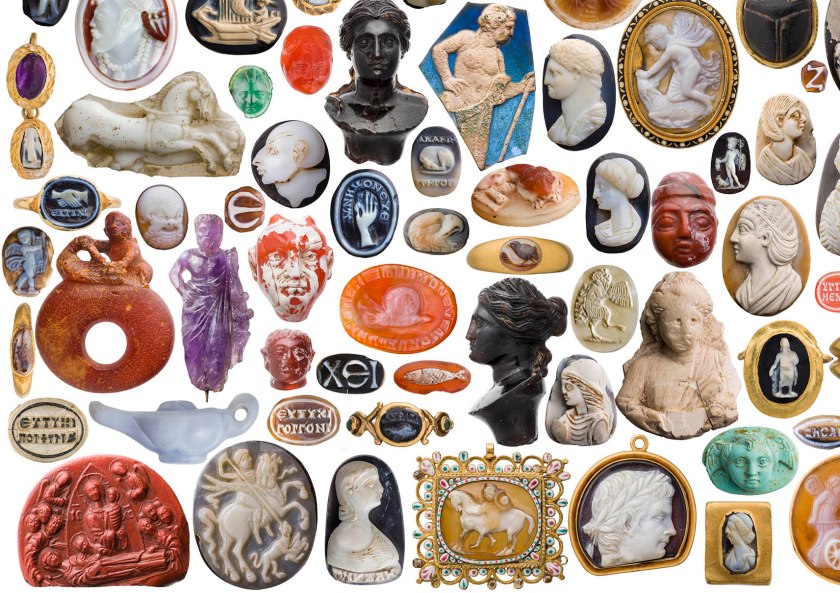

Cameos Compilation (details)

© Photo and collection RMO

Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, RMO

Rapenburg 28, 2311 EW Leiden

Phone: 071 – 5163 163

Opening hours:

Daily 10am – 5pm

Closed on January 1, April 27, October 3 and December 25

You must be logged in to post a comment.