Exhibition dates: 13th December, 2014 – 19th April, 2015

Exhibition coincides with the culmination of the Thomas Walther Collection Project, a four-year research collaboration between MoMA’s curatorial and conservation staff

Co-curators: Quentin Bajac, Chief Curator of Photography, MoMA, and Sarah Hermanson Meister, Curator in the Department of Photography, MoMA

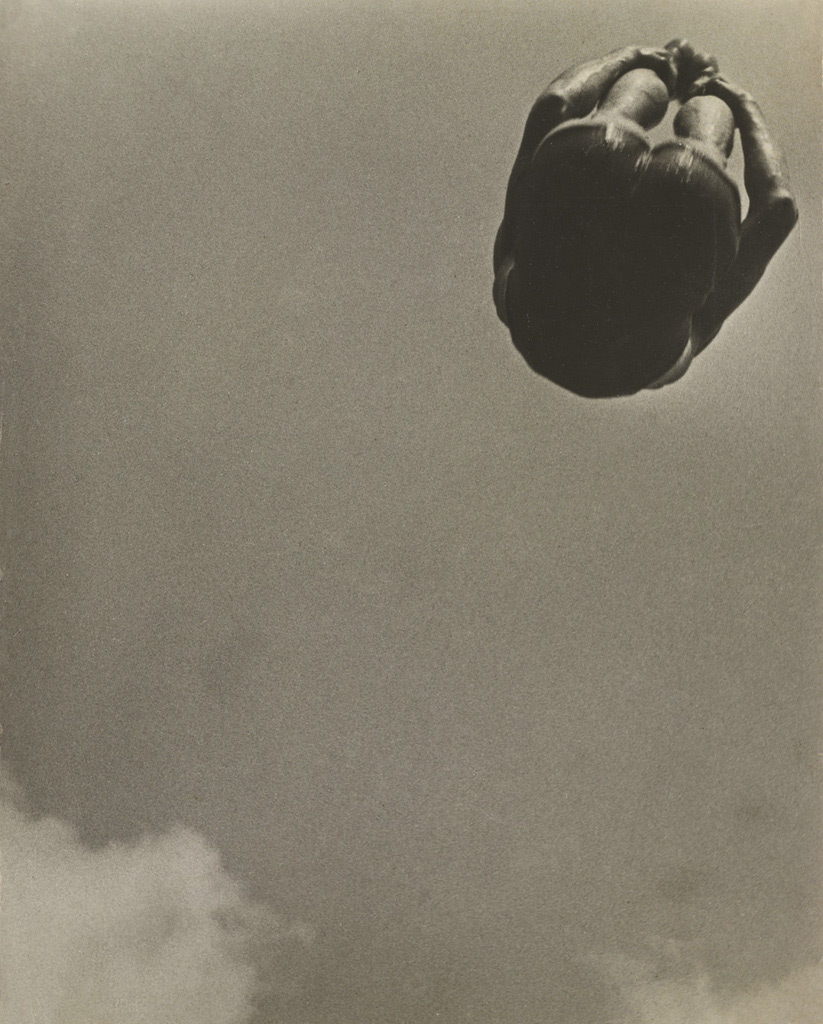

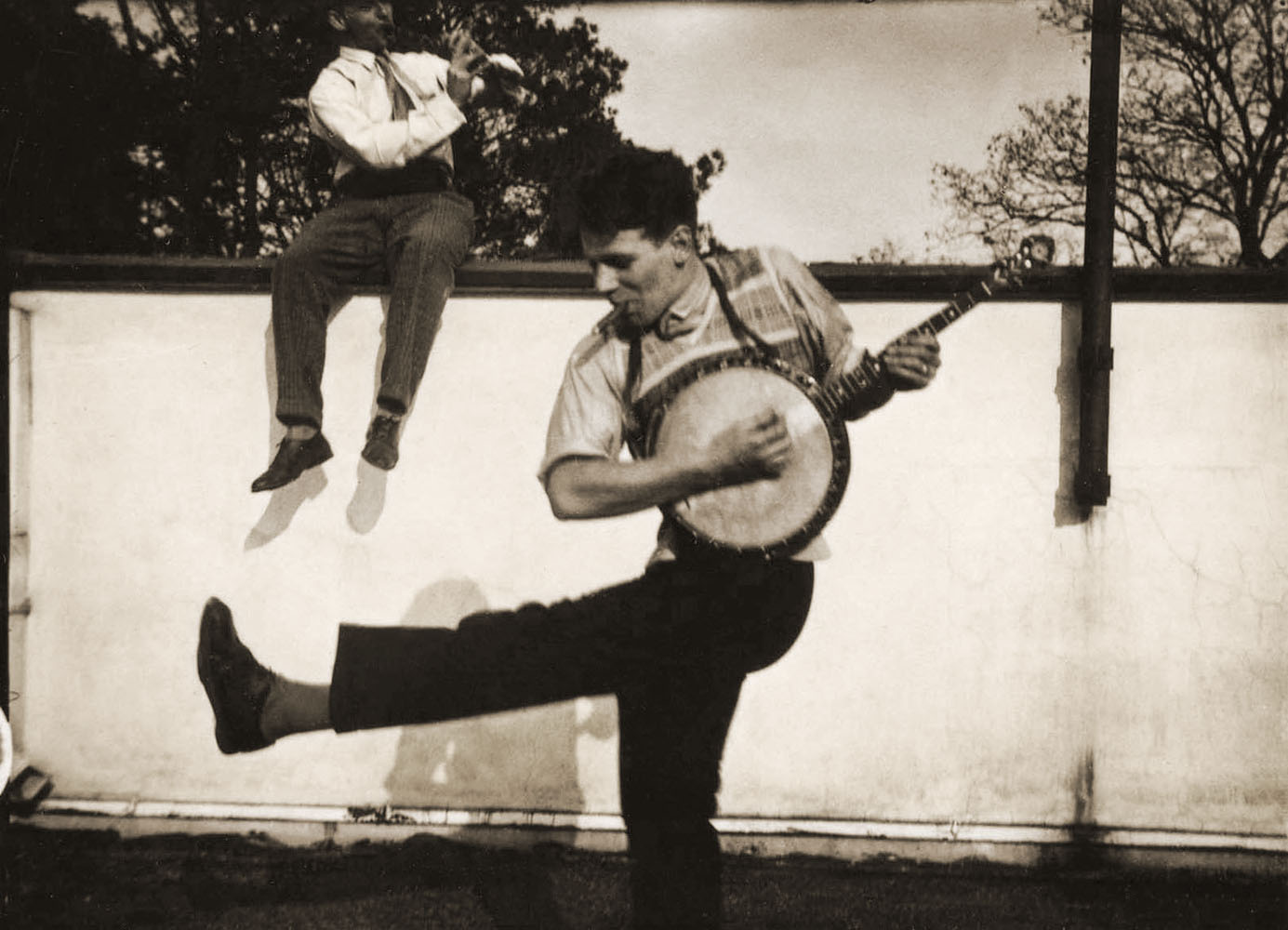

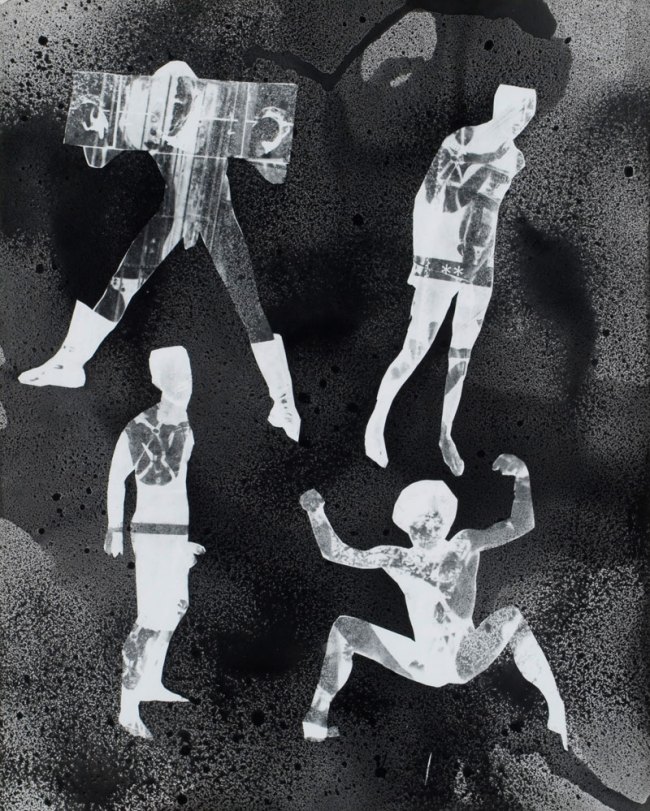

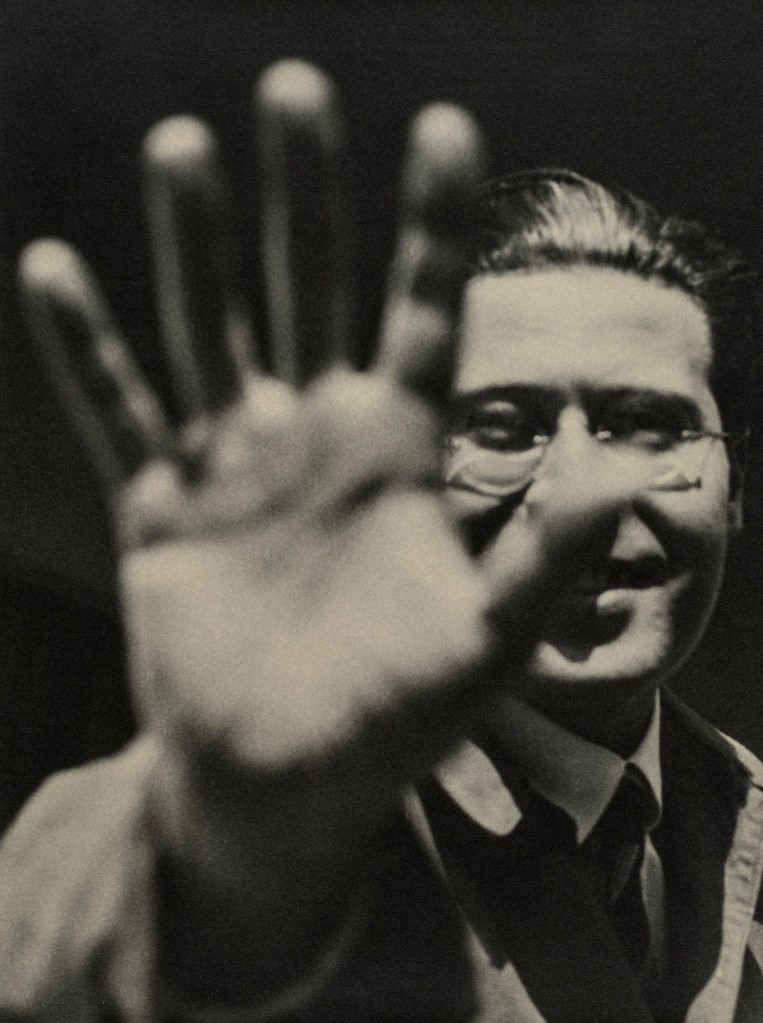

Unknown photographer

British ‘Chute Jumpers

1937

Gelatin silver print

5 15/16 x 6 15/16″ (15.1 x 17.6cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Thomas Walther

OMG, OMG, OMG if we had tele-transportation to travel around the world, I would be at this exhibition in an instant. Please MoMA, fly me to New York so that I can do a proper review of the exhibition!

Not only are there photographs from well known artists that I have never seen before – for example, the brooding mass of Boat, San Francisco (1925) by Edward Weston with the name of the boat… wait for it… ‘DAYLIGHT’ – there are also outstanding photographs from artists that I have never heard of before.

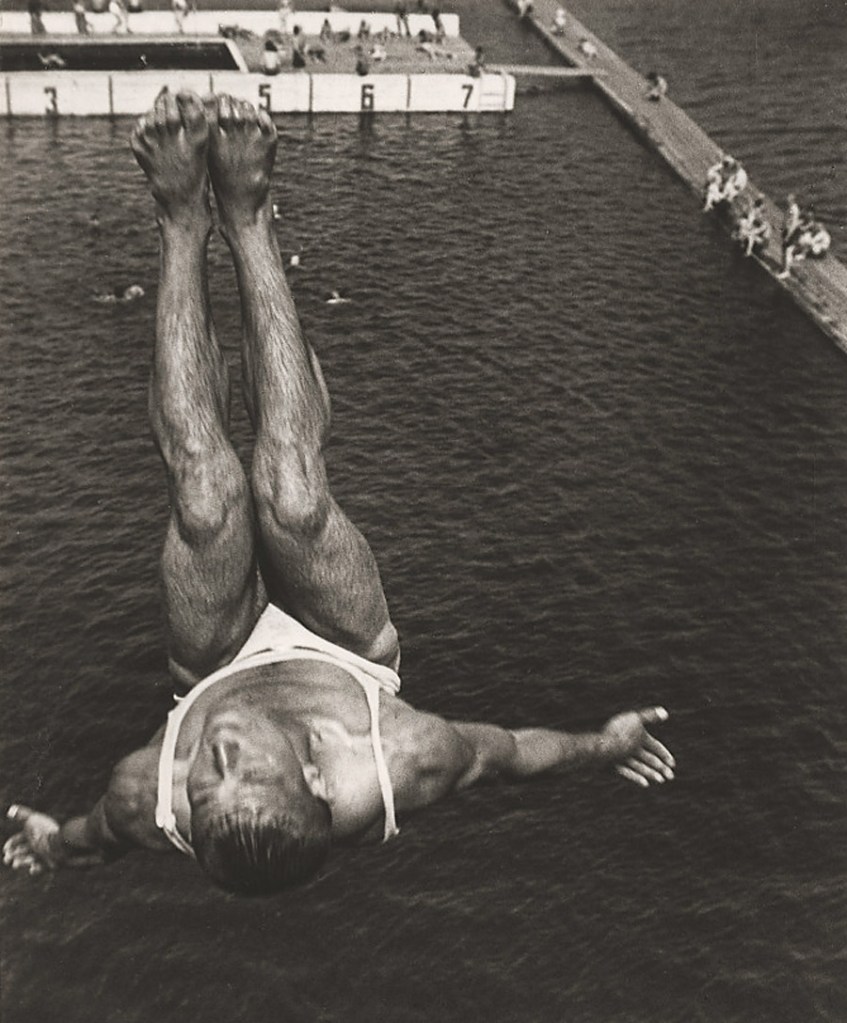

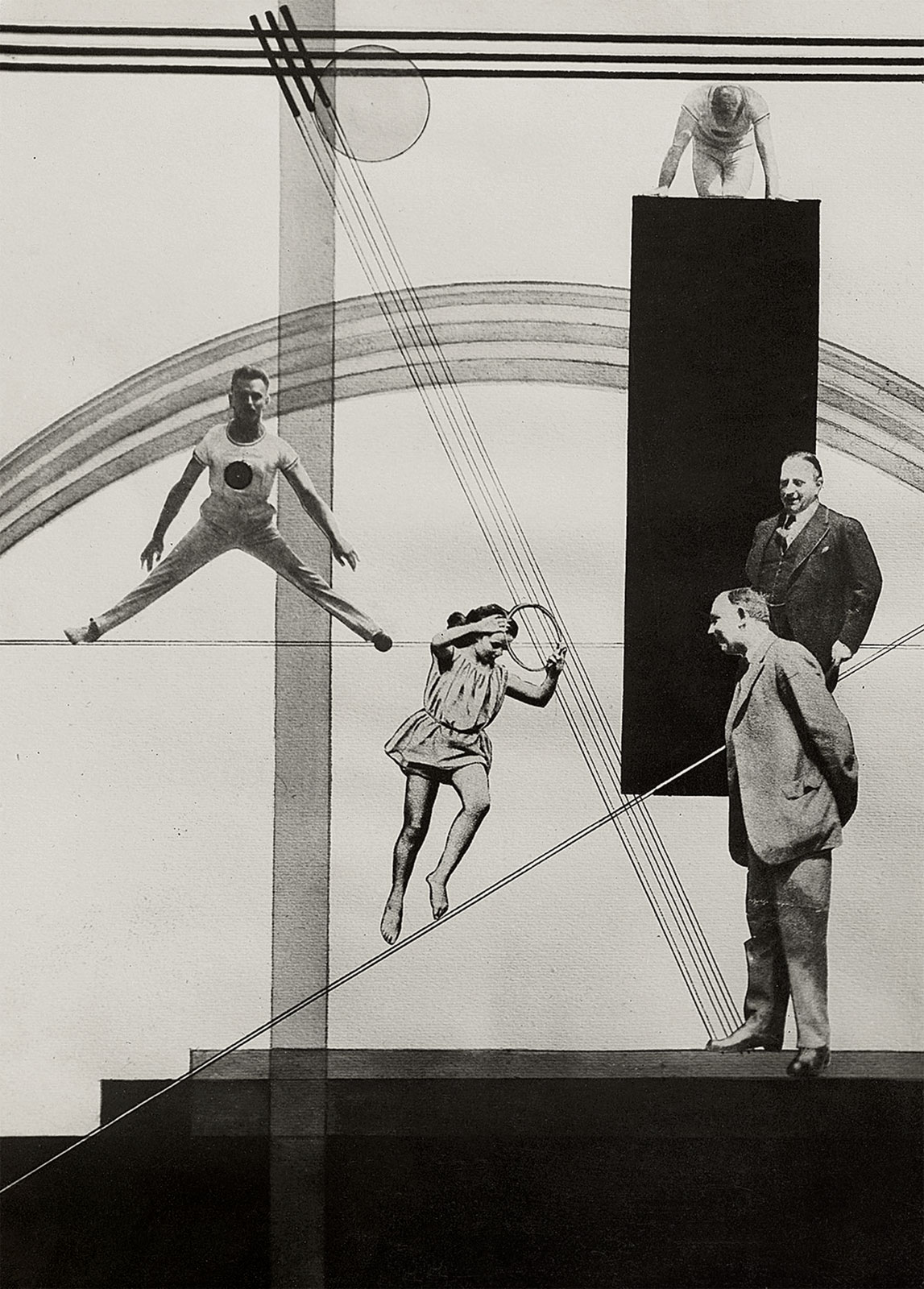

There is so much to like in this monster posting, from the glorious choreography of British ‘Chute Jumpers (1937) to the muscular symmetry and abstraction of Rodchenko’s Dive (1934); from the absolutely stunning light and movement of Riefenstahl’s Nocturnal Start of Decathlon 1,500m Race (August 1936) to the ecstatic, ghost-like swimming in mud apparitions of Kate Steinitz’s Backstroke (1930) – an artist who I knew nothing about (Kate Steinitz was a German-American artist and art historian affiliated with the European Bauhaus and Dadaist movements in the early 20th century. She is best known for her collaborative work with the artist Kurt Schwitters, and, in later life, her scholarship on Leonardo da Vinci). Another artist to flee Germany in the mid-1930s to evade the persecution of the Nazis.

In fact, when I looked through the checklist for this exhibition I observed the country of origin of the artist, and the date of their death. There are a lot of artists from Germany and France. Either they lived through the maelstrom of the Second World War and survived, escaped to America or England, or died during the war and their archive was lost (such as the artist Robert Petschow (German, 1888-1945). For some artists surviving the war was not enough either… trapped behind the Iron Curtain after repatriation, artists such as Edmund Kesting went unacknowledged in their lifetime. What a tough time it must have been. To have created this wonderful avant-garde art and then to have seen it dashed against the rocks of violence, prejudice and bigotry – firstly degenerate, then non-conforming to Communist ideals.

Out of the six sections of the exhibition (The Modern World, Purisms, Reinventing Photography, The Artist’s Life, Between Surrealism and Magic Realism, and Dynamics of the City) it would seem that the section ‘Reinventing Photography’ is the weakest – going from the checklist – with a lack of really memorable images for this section, hence only illustrated in this posting by one image. But this is a minor quibble. When you have images such as Anne W. Brigman’s A Study in Radiation (1924) or Edmund Kesting’s magnificent Glance to the Sun (Blick zur Sonne) (1928) who cares!

I just want to see them all and soak up their atmosphere.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

PS. There is an excellent website titled Object: Photo to accompany the exhibition. It contains sections that map and compare photographs, connect and map artists’ lives along with many more images from the collection, conservation analysis and essays about the works. Well worth a look.

Many thankx to the MoMA for allowing me to publish the photographs and text in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image. All images © The Museum of Modern Art

Note: Images below correspond to their sections in the exhibition.

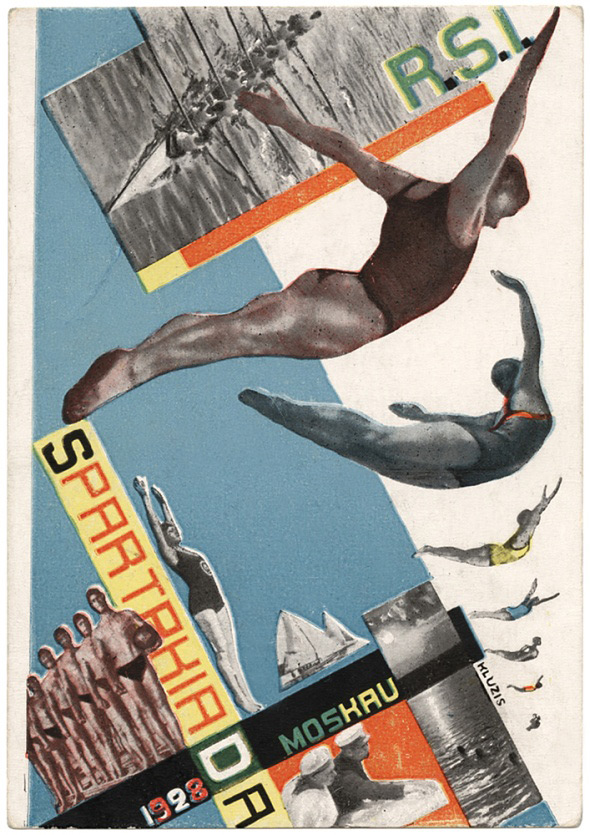

Gustav Klutsis (Latvian, 1895-1938)

Postcard for the All Union Spartakiada Sporting Event

1928

Offset lithograph

5 3/4 x 4 1/8″ (14.1 x 10.5cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

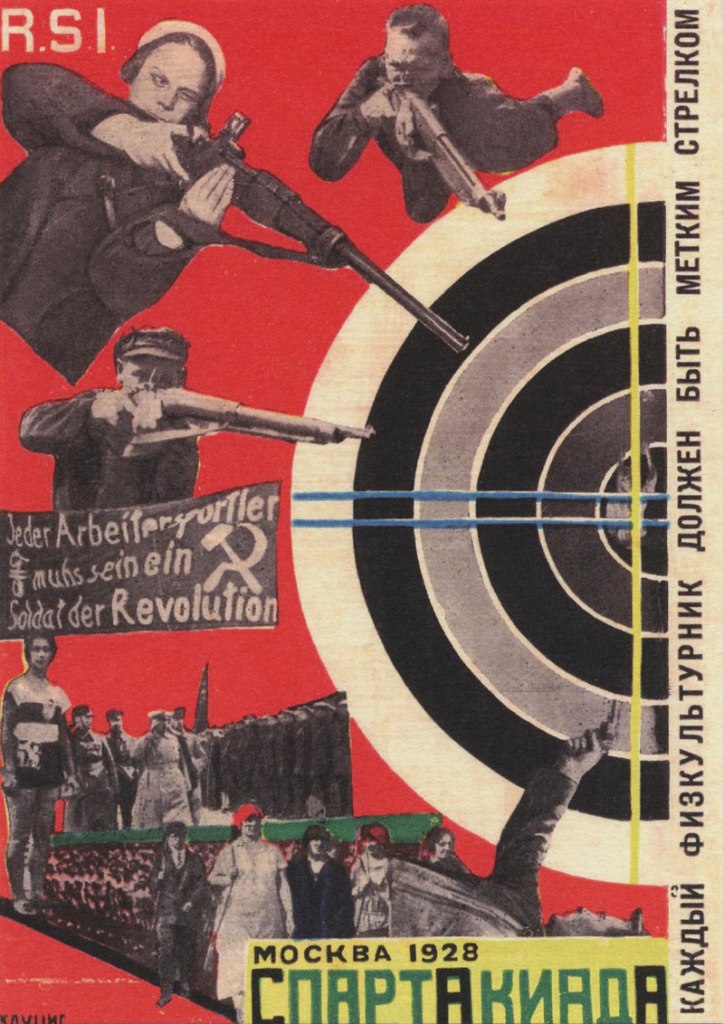

Gustav Klutsis (Latvian, 1895-1938)

Postcard for the All Union Spartakiada Sporting Event

1928

Offset lithograph

5 3/4 x 4 1/8″ (14.1 x 10.5cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

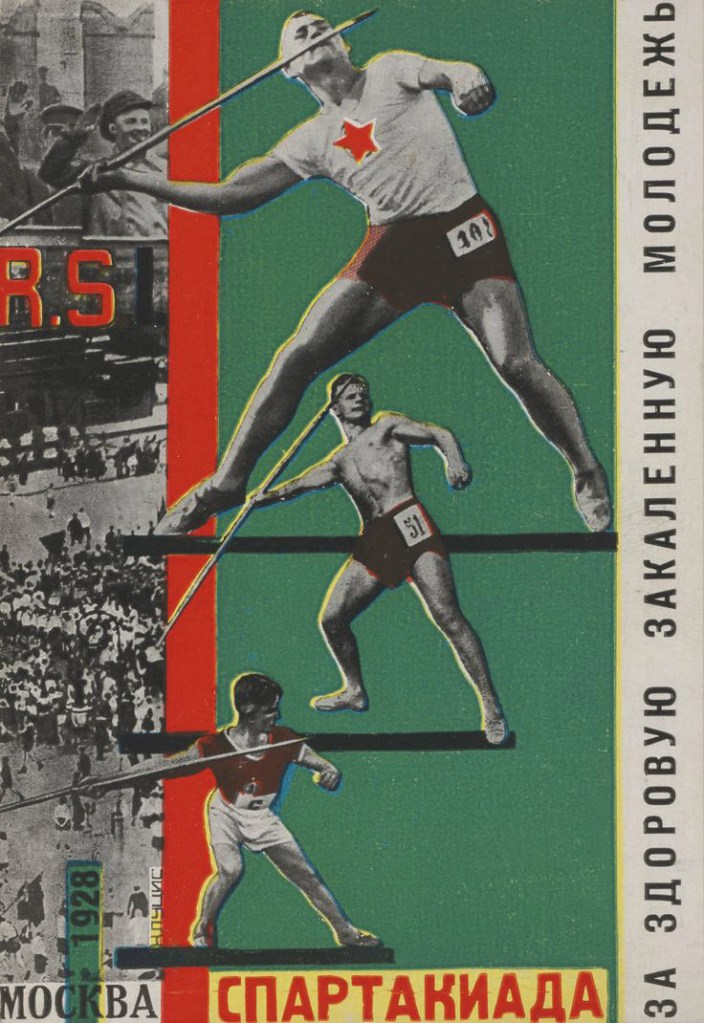

Gustav Klutsis (Latvian, 1895-1938)

Postcard for the All Union Spartakiada Sporting Event

1928

Offset lithograph

5 3/4 x 4 1/8″ (14.1 x 10.5cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

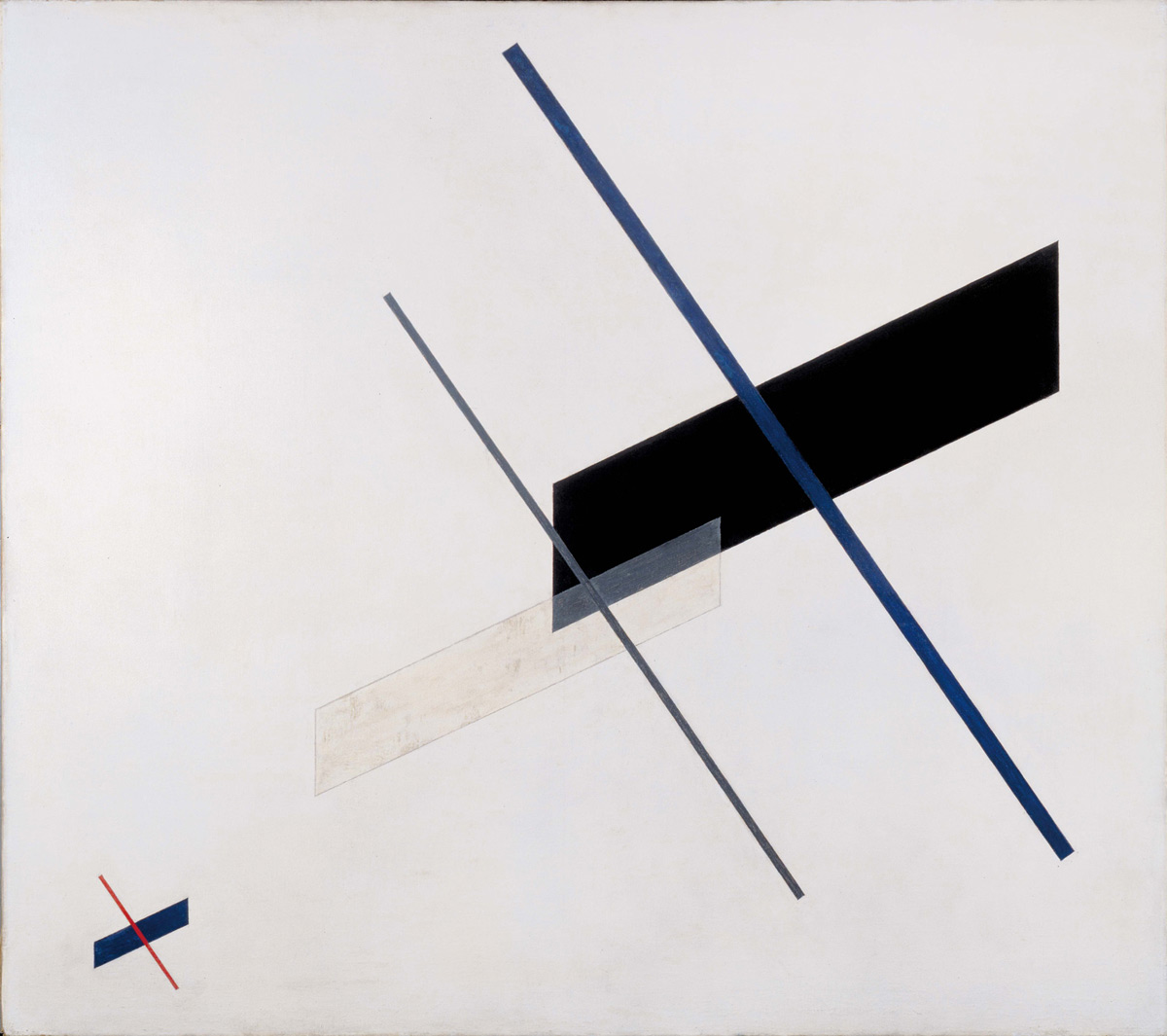

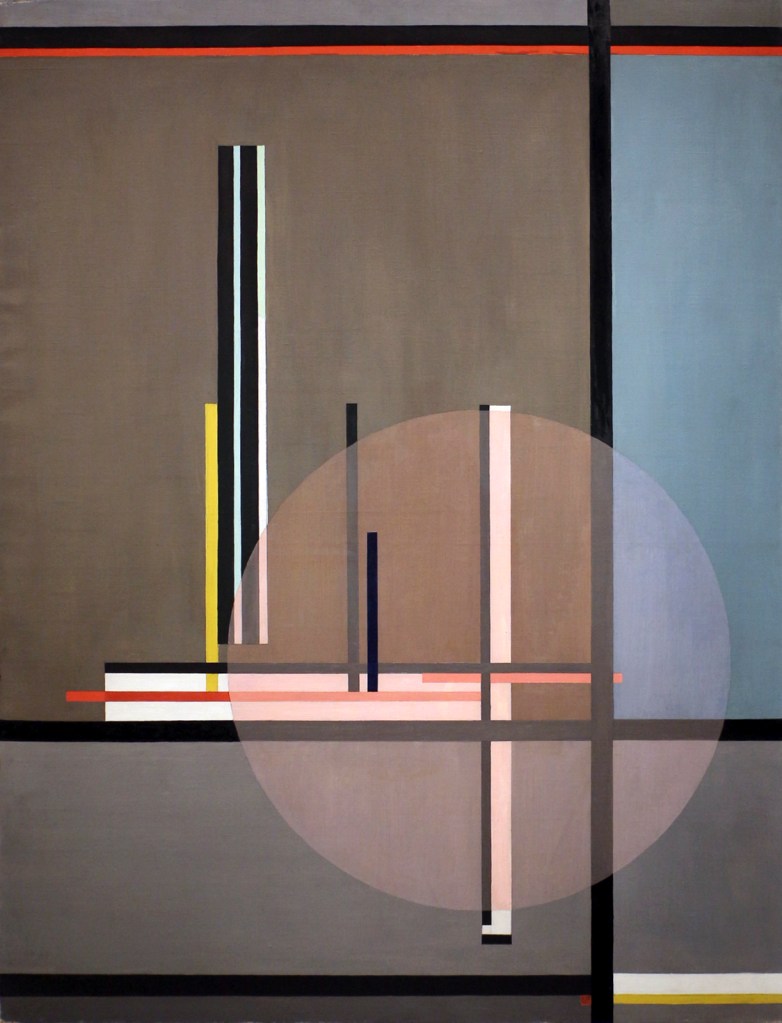

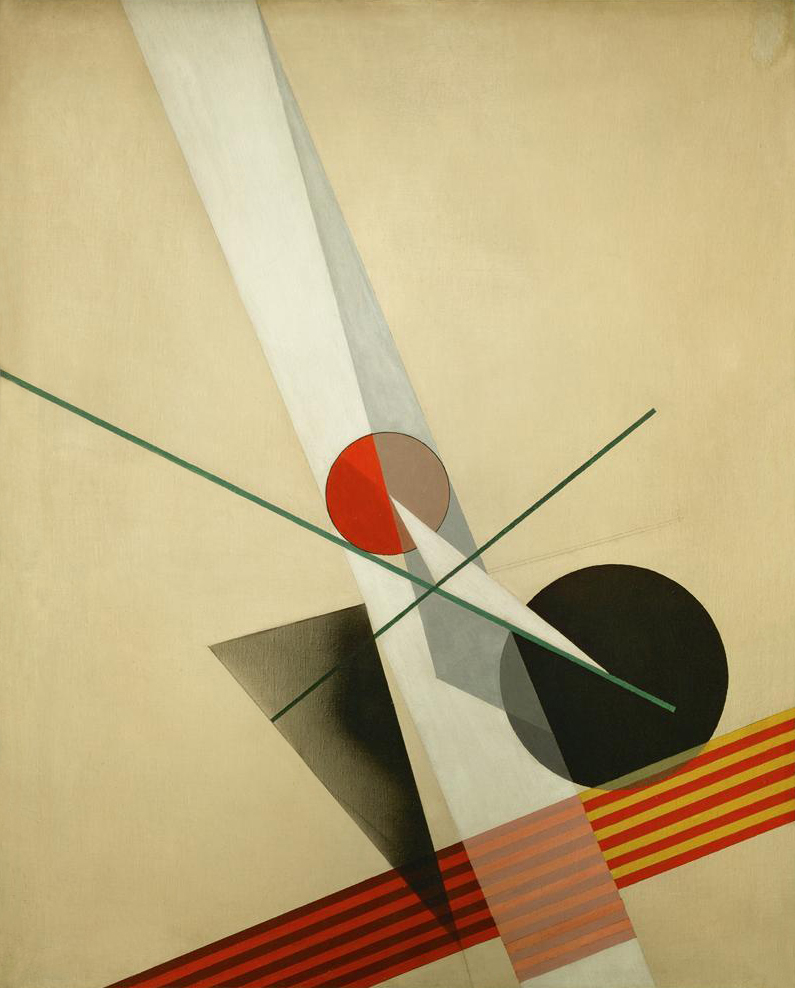

Gustav Klutsis (Latvian, 1895-1938)

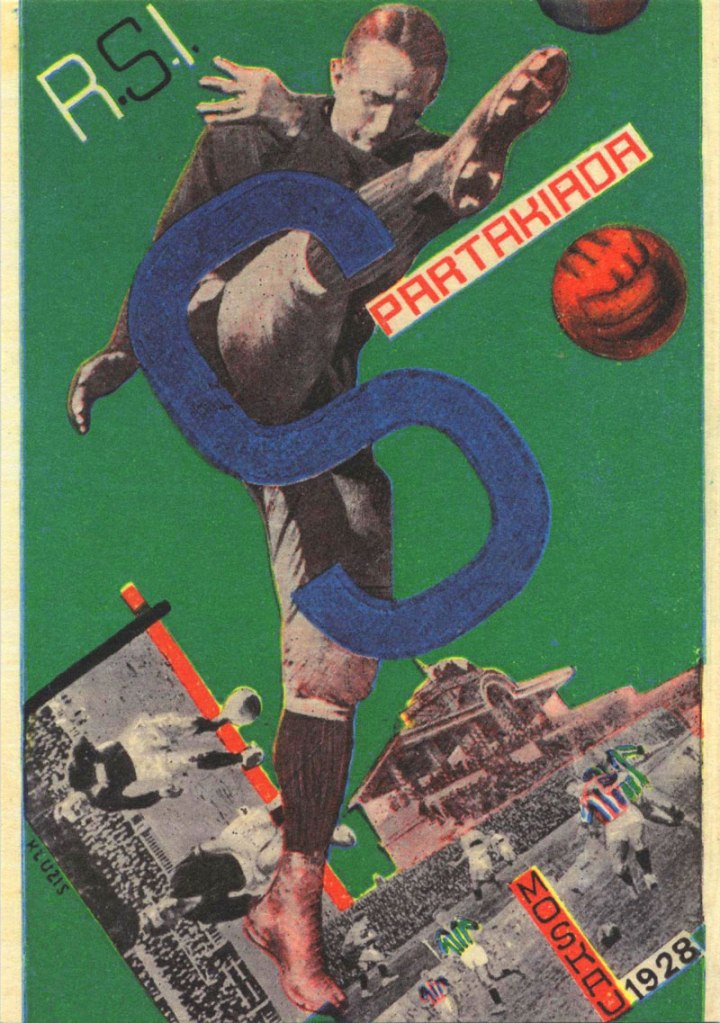

Latvian painter, sculptor, graphic artist, designer and teacher, active in Russia. He was an important exponent of Russian Constructivism. He studied in Riga and Petrograd (now St Petersburg), but in the 1917 October Revolution joined the Latvian Rifle Regiment to defend the Bolshevik government; his sketches of Lenin and his fellow soldiers show Cubist influence. In 1918 he designed posters and decorations for the May Day celebrations and he entered the Free Art Studios (Svomas) in Moscow, where he studied with Malevich and Antoine Pevsner. Dynamic City (1919; Athens, George Costakis priv. col., see Rudenstine, no. 339) illustrates his adoption of the Suprematist style. In 1920 Klucis exhibited with Pevsner and Naum Gabo on Tver’skoy Boulevard in Moscow; in the same year Klucis joined the Communist Party. In 1920-21 he started experimenting with materials, making constructions from wood and paper that combined the geometry of Suprematism with a more Constructivist concern with actual volumes in space. In 1922 Klucis applied these experiments to utilitarian ends when he designed a series of agitprop stands based on various combinations of loudspeakers, speakers’ platforms, display units, film projectors and screens. He taught a course on colour in the Woodwork and Metalwork Faculty of the Vkhutemas (Higher Artistic and Technical Workshops) from 1924 to 1930, and in 1925 helped to organise the Soviet section at the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris. During the 1920s he became increasingly interested in photomontage, using it in such agitprop posters as ‘We will repay the coal debt to the country’ (1928; e.g. New York, MoMA). During the 1930s he worked on graphic and typographical design for periodicals and official publications. He was arrested and died during the purges in World War II.

From Grove Art Online

© 2009 Oxford University Press

Gustav Klutsis (Latvian, 1895-1938)

Postcard for the All Union Spartakiada Sporting Event

1928

Offset lithograph

5 3/4 x 4 1/8″ (14.1 x 10.5cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

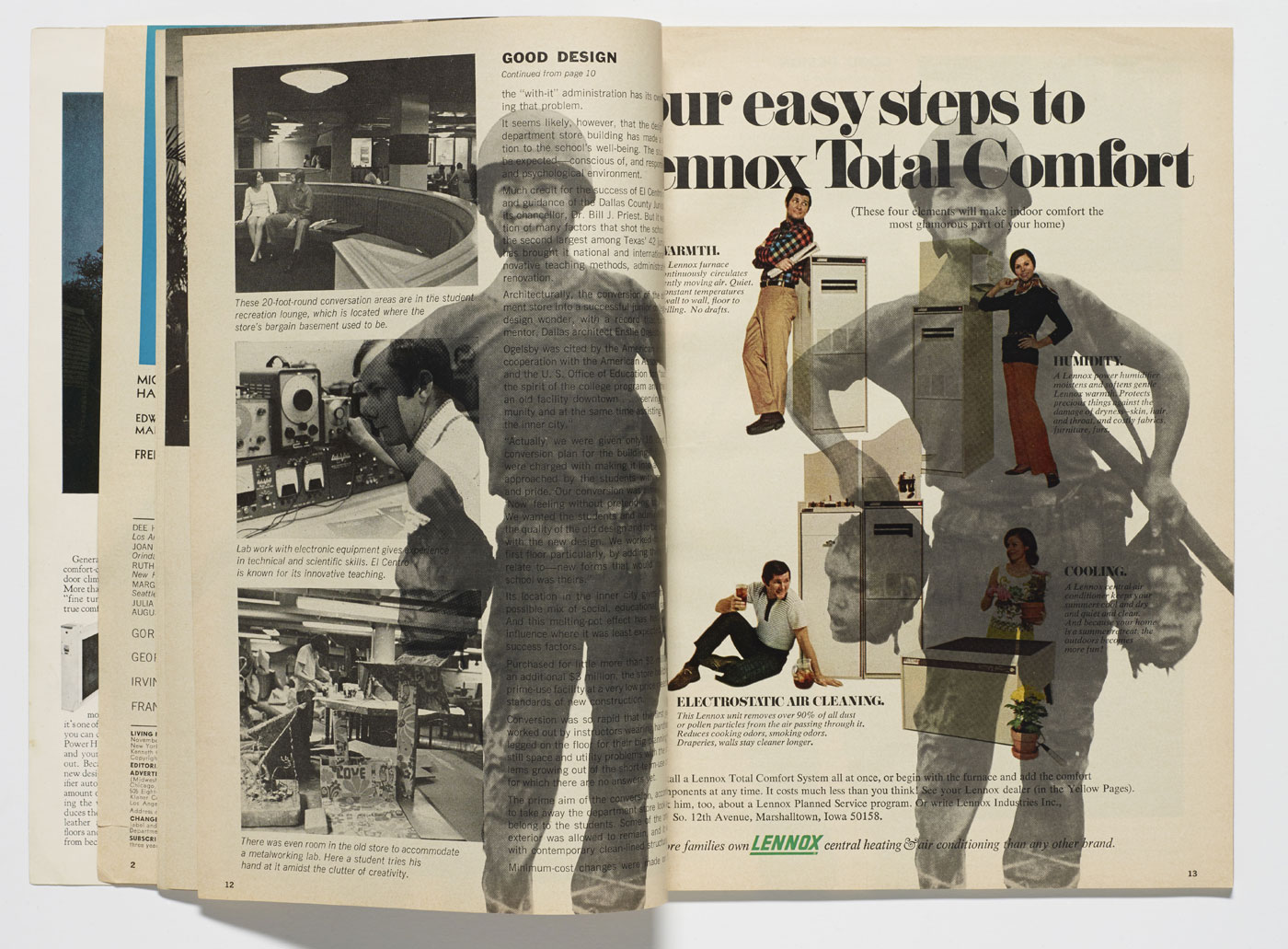

Modern Photographs from the Thomas Walther Collection, 1909-1949, on view from December 13, 2014, to April 19, 2015, explores photography between the First and Second World Wars, when creative possibilities were never richer or more varied, and when photographers approached figuration, abstraction, and architecture with unmatched imaginative fervour. This vital moment is dramatically captured in the photographs that constitute the Thomas Walther Collection, a remarkable group of works presented together for the first time through nearly 300 photographs. Made on the street and in the studio, intended for avant-garde exhibitions or the printed page, these objects provide unique insight into the radical intentions of their creators. Iconic works by such towering figures as Berenice Abbott, Karl Blossfeldt, Alvin Langdon Coburn, El Lissitzky, Lucia Moholy, László Moholy-Nagy, Aleksandr Rodchenko, and Paul Strand are featured alongside lesser-known treasures by more than 100 other practitioners. The exhibition is organised by Quentin Bajac, the Joel and Anne Ehrenkranz Chief Curator of Photography, and Sarah Hermanson Meister, Curator, Department of Photography, MoMA.

The exhibition coincides with Object: Photo. Modern Photographs: The Thomas Walther Collection 1909-1949, the result of a four-year collaborative project between the Museum’s departments of Photography and Conservation, with the participation of over two dozen leading international photography scholars and conservators, making it the most extensive effort to integrate conservation, curatorial, and scholarly research efforts on photography to date. That project is composed of multiple parts including a website that features a suite of digital-visualisation research tools that allow visitors to explore the collection, a hard-bound paper catalogue of the entire Thomas Walther collection, and an interdisciplinary symposium focusing on ways in which the digital age is changing our engagement with historic photographs.

Modern Photographs from the Thomas Walther Collection, 1909-1949, is organised thematically into six sections, suggesting networks between artists, regions, and objects, and highlighting the figures whose work Walther collected in depth, including André Kertész, Germaine Krull, Franz Roh, Willi Ruge, Maurice Tabard, Umbo, and Edward Weston. Enriched by key works in other mediums from MoMA’s collection, this exhibition presents the exhilarating story of a landmark chapter in photography’s history.”

Press release from the MoMA website

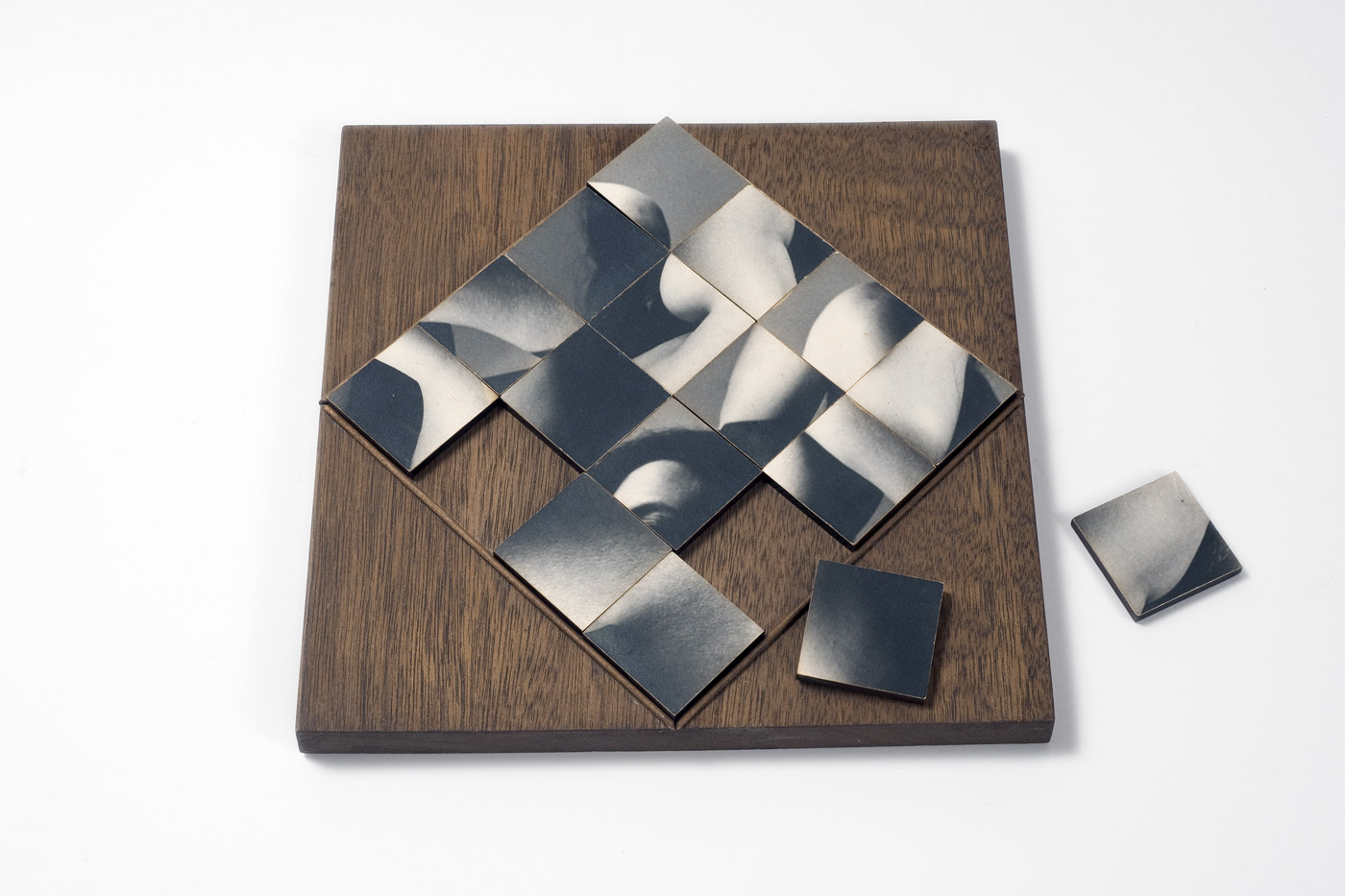

The Collection

In the 1920s and ’30s photography underwent a period of exploration, experimentation, technical innovation, and graphic discovery so dramatic that it generated repeated claims that the true age of discovery was not when photography was invented but when it came of age, in this era, as a dynamic, infinitely flexible, and easily transmissible medium. The Thomas Walther Collection concentrates on that second moment of growth. The Walther Collection’s 341 photographs by almost 150 artists, most of them European, together convey a period of collective innovation that is now celebrated as one of the major episodes of modern art.

The Project

Our research is based on the premise that photographs of this period were not born as disembodied images; they are physical things – discrete objects made by certain individuals at particular moments using specific techniques and materials. Shaped by its origin and creation, the photographic print harbours clues to its maker and making, to the causes it may have served, and to the treatment it has received, and these bits of information, gathered through close examination of the print, offer fresh perspectives on the history of the era. “Object: Photo” – the title of this study – reflects this approach.

In 2010, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation gave the Museum a grant to encourage deep scholarly study of the Walther Collection and to support publication of the results. Led by the Museum’s Departments of Photography and Conservation, the project elicited productive collaborations among scholars, curators, conservators, and scientists, who investigated all of the factors involved in the making, appearance, condition, and history of each of the 341 photographs in the collection. The broadening of narrow specialisations and the cross-fertilisation between fields heightened appreciation of the singularity of each object and of its position within the history of its moment. Creating new standards for the consideration of photographs as original objects and of photography as an art form of unusually rich historical dimensions, the project affords both experts and those less familiar with its history new avenues for the appreciation of the medium. The results of the project are presented in multiple parts: on the website, in a hard-bound paper catalogue of the entire Thomas Walther Collection (also titled Object: Photo), and through an interdisciplinary symposium focusing on the ways in which the digital age is changing our engagement with historic photographs.

Historical Context

The Walther Collection is particularly suited to such a study because its photographs are so various in technique, geography, genre, and materials as to make it a mine of diverse data. The revolutions in technology that made the photography of this period so flexible and responsive to the impulse of the operator threw open the field to all comers. The introduction of the handheld Leica in 1925 (a small camera using strips of 35mm motion-picture film), of enlargers to make positive prints from the Leica’s little negatives, and of easy-to-use photographic papers – each of these was respectively a watershed event. Immediately sensing the potential of these tools, artists began to explore the medium; without any specialised training, painters such as László Moholy-Nagy and Aleksandr Rodchenko could become photographers and teachers almost overnight. Excitedly and with an open sense of possibility, they freely experimented in the darkroom and in the studio, producing negative prints, collages and photomontages, photograms, solarisations, and combinations of these. Legions of serious amateurs also began to photograph, and manufacturers produced more types of cameras with different dimensions and capacities: besides the Leica, there was the Ermanox, which could function in low light, motion-picture cameras that could follow and stop action, and many varieties of medium- and larger-format cameras that could be adapted for easy transport. The industry responded to the expanding range of users and equipment with a bonanza of photographic papers in an assortment of textures, colours, and sizes. Multiple purposes also generated many kinds of prints: best for reproduction in books or newspapers were slick, ferrotyped glossies, unmounted and small enough to mail, while photographs for exhibition were generally larger and mounted to stiff boards. Made by practitioners ranging from amateurs to professional portraitists, journalists, illustrators, designers, critics, and artists of all stripes, the pictures in the Walther Collection are a true representation of the kaleidoscopic multiplicity of photography in this period of diversification.

Text from the MoMA website

Willi Ruge (German, 1882-1961)

Photo of Myself at the Moment of My Jump (Selbstfoto im Moment des Abspringens)

1931

Gelatin silver print

5 9/16 × 8 1/16″ (14.2 × 20.4cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Thomas Walther

Willi Ruge (German, 1882-1961)

With My Head Hanging Down before the Parachute Opened . . .

(Mit dem Kopf nach unten hängend, bei ungeöffnetem Fallschirm . . .)

1931

Gelatin silver print

5 1/2 × 8″ (14 × 20.3cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Thomas Walther

Willi Ruge (German, 1882-1961)

Seconds before Landing (Sekunden vor der Landung)

From the series I Photograph Myself during a Parachute Jump (Ich fotografiere mich beim Absturz mit dem Fallschirm)

1931

Gelatin silver print

8 1/16 × 5 9/16″ (20.4 × 14.1cm) (irreg.)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Thomas Walther

Willi Ruge (German, 1882-1961)

Seconds before Landing (Sekunden vor der Landung) (detail)

From the series I Photograph Myself during a Parachute Jump (Ich fotografiere mich beim Absturz mit dem Fallschirm)

1931

Gelatin silver print

8 1/16 × 5 9/16″ (20.4 × 14.1cm) (irreg.)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Thomas Walther

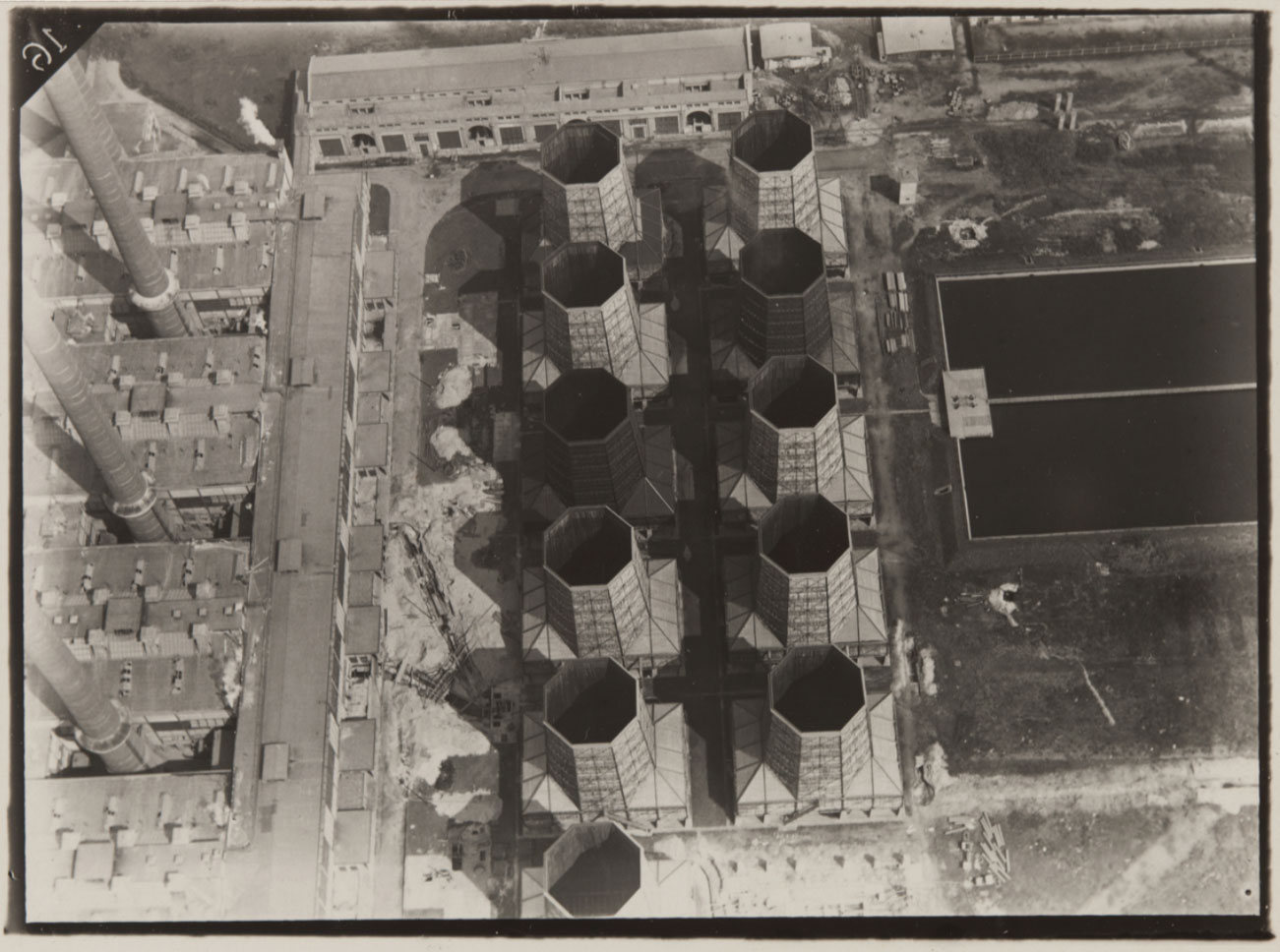

Robert Petschow (German, 1888-1945)

Lines of Modern Industry: Cooling Tower (Linien der modernen Industrie: Kühlturmanlage)

1920-29

Gelatin silver print

3 3/8 × 4 1/2″ (8.5 × 11.5cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Albert Renger-Patzsch, by exchange

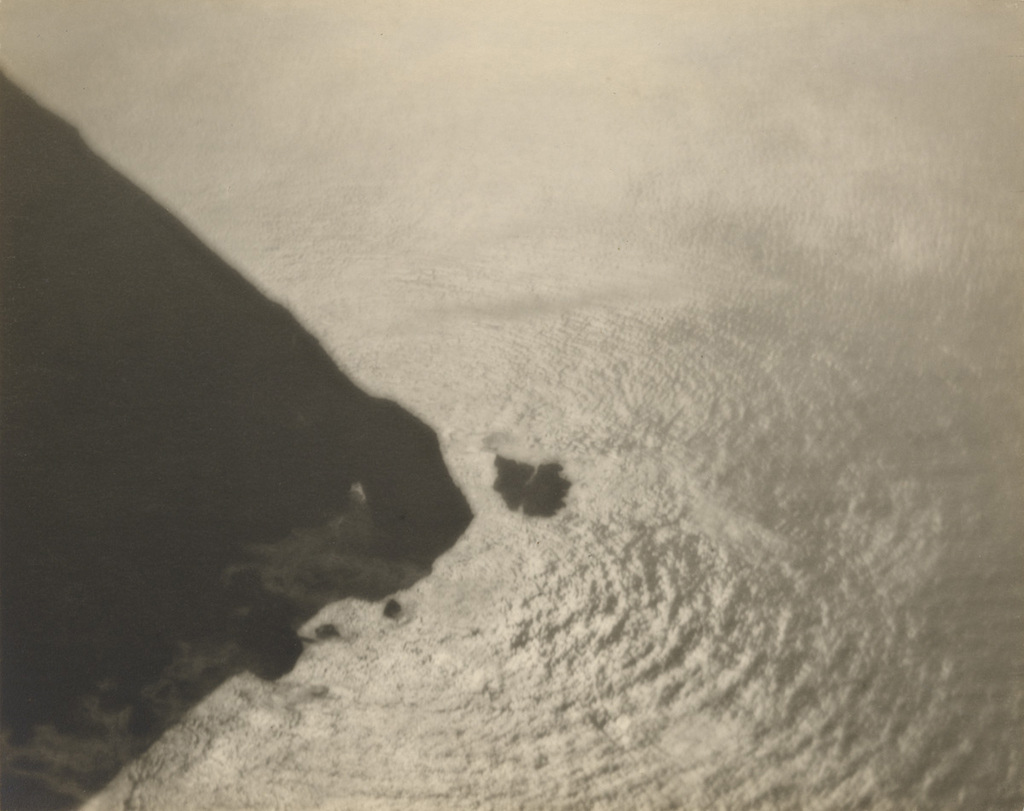

Robert Petschow (German, 1888-1945)

The Course of the Mulde with Sand Deposits in the Curves (Der Lauf der Mulde mit Versandungen in den Windungen)

1920-33

Gelatin silver print

3 3/8 × 4 1/2″ (8.5 × 11.5cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Albert Renger-Patzsch, by exchange

Robert Petschow (German, 1888-1945)

Robert Petschow was studying in Danzig as a free balloon pilot in the West Prussian air force. During the First World War Petschow was a balloon observer with the rank of lieutenant in Poland, France and Belgium. Maybe it was the work of a balloon observer which led him to photography, in which he was worked freelance from 1920. His images appeared in the prestigious photographic yearbook The German photograph in which he was presented with photographers such as Karl Blossfeldt, Albert Renger-Patzsch Chargesheimer and Erich Salomon. The book Land of the Germans, which was published in 1931 by Robert Diesel and includes many photographs of Petschow went on to be published in four editions. In 1931 he journeyed with the airship LZ 127, the “Graf Zeppelin” to Egypt. He participated as an unofficial member of the crew to document the trip photographically. In 1936, at the age of 48 years, Petschow joined the rank of captain in the Air Force and ended his work as a senior editor at the daily newspaper The West, a position he held from 1930. For the following years, there is no information to Petschow.

Robert Petschow died at the age of 57 years on 17 October 1945 in Haldensleben after he had to leave his apartment in Berlin-Steglitz due to the war. He left there a picture archive with about 30,000 aerial photographs, which fell victim of the war. His contemporaries describe Petschow as a humorous person and a great raconteur.

Translated from the German Wikipedia website by Google Translate

Aleksandr Rodchenko (Russian, 1891-1956)

Dive (Pryzhok v vodu)

1934

Gelatin silver print

11 11/16 x 9 3/8″ (29.7 x 23.8cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Shirley C. Burden, by exchange

Aleksandr Rodchenko (Russian, 1891-1956)

Dive (Pryzhok v vodu)

1934

Gelatin silver print

11 3/4 × 9 5/16″ (29.9 × 23.6cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Shirley C. Burden, by exchange

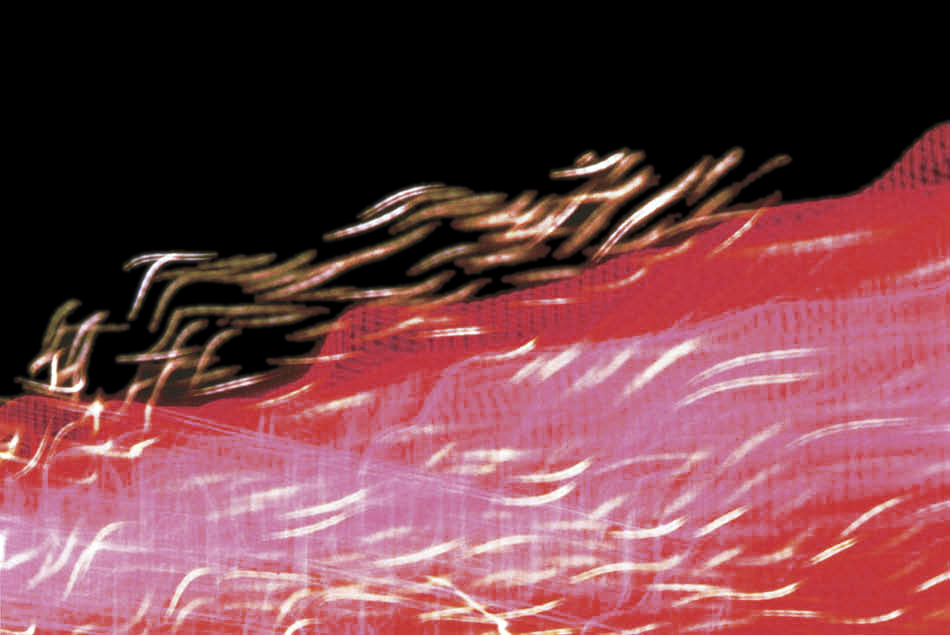

Leni Riefenstahl (German, 1902-2003)

Nocturnal Start of Decathlon 1,500m Race

(Nächtlicher Start zum 1500-m-Lauf des Zehnkampfes)

August 1936

Gelatin silver print 9 5/16 x 11 3/4″ (23.7 x 29.8cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Thomas Walther Collection. Abbott-Levy Collection funds, by exchange

Leni Riefenstahl (German, 1902-2003)

Untitled

1936

Gelatin silver print

9 3/16 x 11 5/8″ (23.4 x 29.5cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Thomas Walther Collection. Abbott-Levy Collection funds, by exchange

Kate Steinitz (American born Germany, 1889-1975)

Backstroke (Rückenschwimmerinnen)

1930

Gelatin silver print

10 1/2 × 13 7/16″ (26.6 × 34.1cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Thomas Walther

The Modern World

Even before the introduction of the handheld Leica camera in 1925, photographers were avidly exploring fresh perspectives, shaped by the unique experience of capturing the world through a lens and ideally suited to express the tenor of modern life in the wake of World War I. Looking up and down, these photographers found unfamiliar points of view that suggested a new, dynamic visual language freed from convention. Improvements in the light sensitivity of photographic films and papers meant that photographers could capture motion as never before. At the same time, technological advances in printing resulted in an explosion of opportunities for photographers to present their work to ever-widening audiences. From inexpensive weekly magazines to extravagantly produced journals, periodicals exploited the potential of photographs and imaginative layouts, not text, to tell stories. Among the photographers on view in this section are Martin Munkácsi (American, born Hungary, 1896-1963), Leni Riefenstahl (German, 1902-2003), Aleksandr Rodchenko (Russian, 1891-1956), and Willi Ruge (German, 1882-1961).

Anne W. Brigman (American born Hawaii, 1869-1950)

A Study in Radiation

1924

Gelatin silver print

7 11/16 × 9 3/4″ (19.6 × 24.8cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Mrs. B. S. Sexton and Mina Turner, by exchange

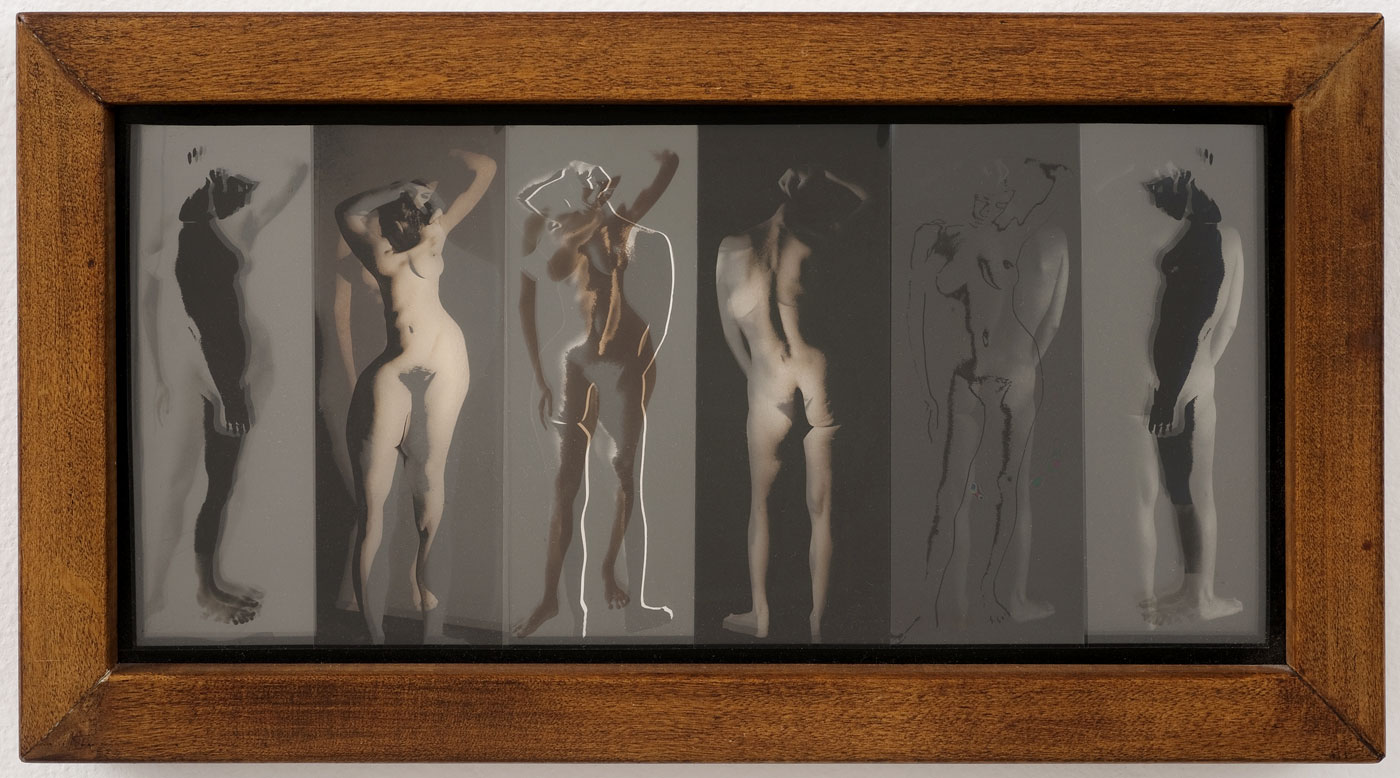

Bernard Shea Horne (American, 1867-1933)

Untitled

1916-17

Platinum print

8 1/16 × 6 1/8″ (20.5 × 15.5cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Thomas Walther

Bernard Shea Horne (American, 1867-1933)

Design

1916-1917

Platinum print

7 15/16 x 6 1/8″ (20.2 x 15.5cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Thomas Walther

Bernard Shea Horne (American, 1867-1933)

Bernard Shea Horne was the son of Joseph Horne, who built a legendary department store in Pittsburgh. The younger Horne retired from the family business when he was in his thirties and moved to northern Virginia to pursue his interests in golf and photography. In 1916 he enrolled at the Clarence H. White School of Photography, in New York, and became friends with one of its teachers, the avant-garde painter Max Weber. Horne produced numerous Weber-inspired design exercises, which he compiled into albums of twenty Platinum prints each. The four prints in the Thomas Walther Collection belonged to an album that he gave to Weber.

In 1917 Horne was elected president of the White School’s alumni association, a post he retained until 1925. In 1918 instructor Paul L. Anderson left the school, and Horne took his place as teacher of the technique class, a job he held until 1926. That a middle-aged man of independent means commuted to the school several days a week from Princeton, New Jersey, where he then lived with his two sons, suggests Horne’s devotion to White and his Pictorialist aims. During these years, Horne played a major role in the White School’s activities. In 1920 he was given a one-person show in the exhibition room of the school’s new building, a show that the alumni bulletin described as “interesting and varied in subject and technique, rich in bromoils, strong in design.” Supportive of the practical applications of artistic photography, in 1920 White joined his school to other institutions, including the American Institute of Graphic Arts and the Art Directors Club, to form The Art Center in New York. In 1926 Horne was given a one-person show at The Art Center, which marked the end of his active association with the school.

Abbaspour, Mitra, Lee Ann Daffner, and Maria Morris Hambourg

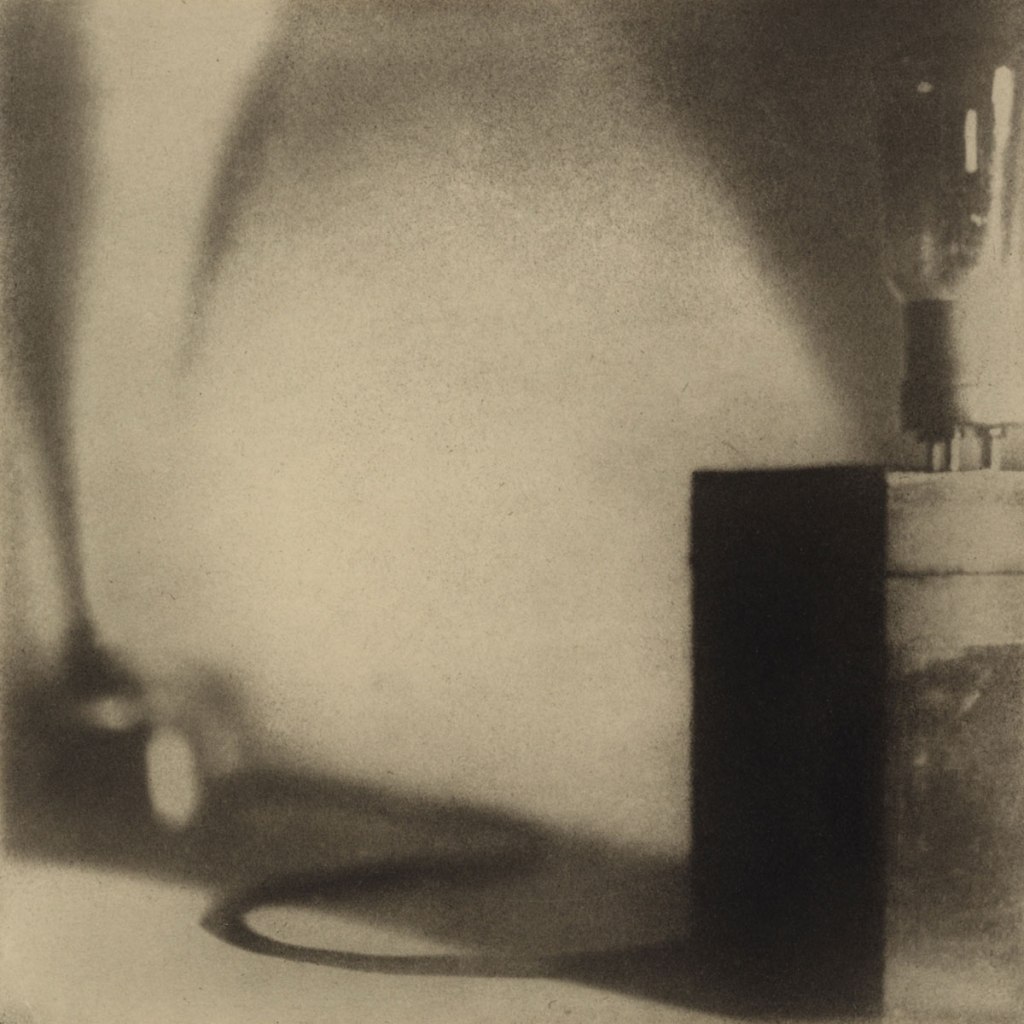

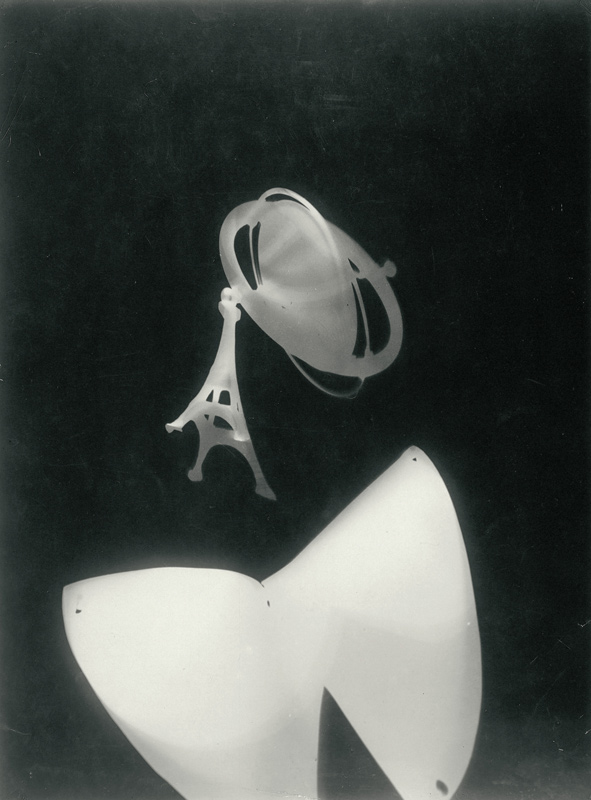

Jarislav Rössler (Czech, 1902-1990)

Untitled

1924

Pigment print

9 1/16 × 9 1/16″ (23 × 23 cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Thomas Walther Collection. Horace W. Goldsmith Fund through Robert B. Menschel

Jarislav Rössler (Czech, 1902-1990)

Jaroslav Rössler (1902-1990) was one of the Czech avant-garde photographers of the first half of the twentieth century whose work has only recently become known outside Eastern Europe. Czech photography in the twenties and thirties produced radical modernist works that incorporated principles of abstract art and constructivism; Jaroslav Rossler was one of the most important and distinctive artists of the period. He became known for his fusing of different styles, bringing together elements of Symbolism, Pictorialism, Expressionism, Cubism, Futurism, Constructivism, New Objectivity, and abstract art. His photographs often reduced images to elementary lines and shapes that seemed to form a new reality; he would photograph simple objects against a stark background of black and white, or use long exposures to picture hazy cones and spheres of light. From 1927 to 1935 he lived and worked in Paris, producing work influenced by constructivism and new objectivity. He used the photographic techniques and compositional approaches of the avant-garde, including photograms, large details, diagonal composition, photomontage, and double exposures, and experimented with colour advertising photographs and still lifes produced with the carbro print process. After his return to Prague, he was relatively inactive until the late 1950s, when he reconnected with Czech artistic and photographic trends of that period, including informalism. This book documents each stage of Rossler’s career with a generous selection of duotone images, some of which have never been published before. The photographs are accompanied by texts by Vladimir Birgus, Jan Mlcoch, Robert Silverio, Karel Srp, and Matthew Witkovsky.

Text from the Amazon website

Manuel Álvarez Bravo (Mexican, 1902-2002)

A Fish Called Sierra (Un pez que llaman sierra)

1944

Gelatin silver print

9 1/2 x 7 1/4″ (24.1 x 18.4cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Thomas Walther Collection

Edward Steichen Estate and gift of Mrs. Flora S. Straus, by exchange

Manuel Alvarez Bravo (Mexican, 1902-2002)

Somewhat Gay and Graceful (Un poco alegre y graciosa)

1942

Gelatin silver print

6 5/8 × 9 1/2″ (16.9 × 24.2cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Thomas Walther Collection. Grace M. Mayer Fund

Manuel Alvarez Bravo (Mexican, 1902-2002)

Day of Glory (Día de gloria)

1940s

Gelatin silver print

6 3/4 × 9 1/2″ (17.2 × 24.2cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Thomas Walther Collection. Grace M. Mayer Fund

Edward Weston (American, 1886-1958)

Steel: Armco, Middletown, Ohio

October 1922

Palladium print

9 1/16 × 6 7/8″ (23 × 17.4cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Thomas Walther

In Edward Weston’s journals, which he began on his trip to Ohio and New York in fall 1922, the artist wrote of the exhilaration he felt while photographing the “great plant and giant stacks of the American Rolling Mill Company” in Middletown, Ohio. He then went to see the great photographer and tastemaker Alfred Stieglitz. Were he still publishing the magazine Camera Work, Stieglitz told him, he would have reproduced some of Weston’s recent images in it, including, in particular, one of his smokestacks. The photograph’s clarity and the photographer’s frank awe at the beauty of the brute industrial subject seemed clear signs of advanced modernist tendencies.

In moving away from the soft focus and geometric stylisation of his recent images, such as Attic of 1921 (MoMA 1902.2001), Weston was discovering a more straightforward approach, one of considered confrontation with the facts of the larger world much like that of his close friend Johan Hagemeyer, who was photographing such modern subjects as smokestacks, telephone wires, and advertisements. Shortly before his trip east, Weston had met R. M. Schindler, the Austrian architect, and had been excited by his unapologetically spare, modern house and its implications for art and design. Weston was also reading avant-garde European art magazines full of images and essays extolling machines and construction. Stimulated by these currents, Weston saw that by the time he got to Ohio he was “ripe to change, was changing, yes changed.”

The visit to Armco was the critical pivot, the hinge between Weston’s Pictorialist past and his modernist future. It marked a clear leave-taking from his bohemian circle in Los Angeles and the first step toward the cosmopolitan connections he made in New York and in Mexico City, where he moved a few months later to live with the Italian actress and artist Tina Modotti. The Armco photographs went with him and became talismans of the sea change, emblematic works that decorated his studio in Mexico, along with a Japanese print and a print by Picasso. When he sent a representation of his best work to the Film und Foto exhibition in Stuttgart in 1929, one of the smokestacks was included.

In the midst of such transformation, Weston maintained tried-and-true darkroom procedures. He had used an enlarger in earlier years but had abandoned the technique because he felt that too much information was lost in the projection. Instead he increasingly favoured contact printing. To make the smokestack print, Weston enlarged his 3 ¼ by 4 ¼ inch (8.3 by 10.8 centimetre) original negative onto an 8 by 10 inch (20.3 by 25.4 centimetre) interpositive transparency, which he contact printed to a second sheet of film in the usual way, creating the final 8 by 10 inch negative. Weston was frugal; he was known to economise by purchasing platinum and palladium paper by the roll from Willis and Clements in England and trimming it to size. He exposed a sheet of palladium paper to the sun through the negative and, after processing the print, finished it by applying aqueous retouching media to any flaws. The fragile balance of the photograph’s chemistry, however, is evinced in a bubble-shaped area of cooler tonality hovering over the central stacks. The print was in Modotti’s possession at the time of her death in Mexico City, in 1942.

Lee Ann Daffner, Maria Morris Hambourg

Edward Weston (American, 1886-1958)

Boat, San Francisco

1925

Gelatin silver print

9 5/16 x 7 9/16″ (23.7 x 19.2cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Thomas Walther Collection. Grace M. Mayer Fund

Edward Weston (American, 1886-1958)

Tina

January 30, 1924

Gelatin silver print

9 1/16 x 6 7/8″ (23 x 17.5cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Thomas Walther Collection. Grace M. Mayer Fund and The Fellows of Photography Fund, by exchange

![Karl Blossfeldt (German, 1865-1932) 'Acanthus mollis' (Acanthus mollis [Akanthus, Bärenklau. Deckblätter, die Blüten sind entfernt, in 4facher Vergrößerung]) 1898-1928 Karl Blossfeldt (German, 1865-1932) 'Acanthus mollis' (Acanthus mollis [Akanthus, Bärenklau. Deckblätter, die Blüten sind entfernt, in 4facher Vergrößerung]) 1898-1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/karl-blossfeldt-german-1865e280931932-acanthus-mollis-web.jpg?w=825)

Karl Blossfeldt (German, 1865-1932)

Acanthus mollis (Acanthus mollis [Akanthus, Bärenklau. Deckblätter, die Blüten sind entfernt, in 4facher Vergrößerung])

1898-1928

Gelatin silver print

11 3/4 × 9 3/8″ (29.8 × 23.8cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Thomas Walther

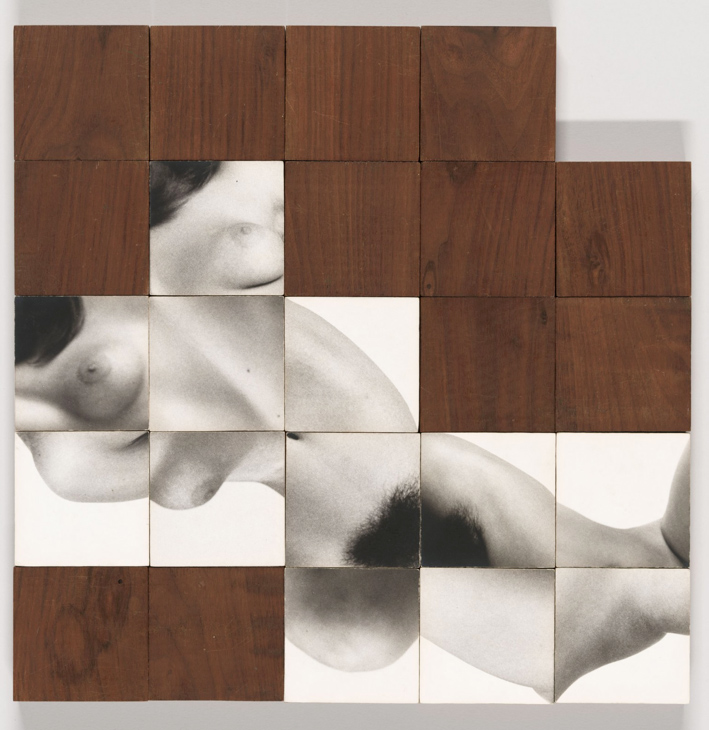

Purisms

The question of whether photography ought to be considered a fine art was hotly contested from its invention in 1839 into the 20th century. Beginning in the 1890s, in an attempt to distinguish their efforts from hoards of Kodak-wielding amateurs and masses of professionals, “artistic” photographers referred to themselves as Pictorialists. They embraced soft focus and painstakingly wrought prints so as to emulate contemporary prints and drawings, and chose subjects that underscored the ethereal effects of their methods. Before long, however, most avant-garde photographers had come to celebrate precise and distinctly photographic qualities as virtues. On both sides of the Atlantic, photographers were making this transition from Pictorialism to modernism, while occasionally blurring the distinction. Exhibition prints could be made with precious platinum or palladium, or matte surfaces that mimicked those materials. Perhaps nowhere is this variety more clearly evidenced than in the work of Edward Weston, whose suite of prints in this section suggests the range of appearances achievable with unadulterated contact prints from his large-format negatives. Other photographers on view include Karl Blossfeldt (German, 1865-1932), Manuel Álvarez Bravo (Mexican, 1902-2002), Jaromír Funke (Czech, 1896-1945), Bernard Shea Horne (American, 1867-1933), and Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946).

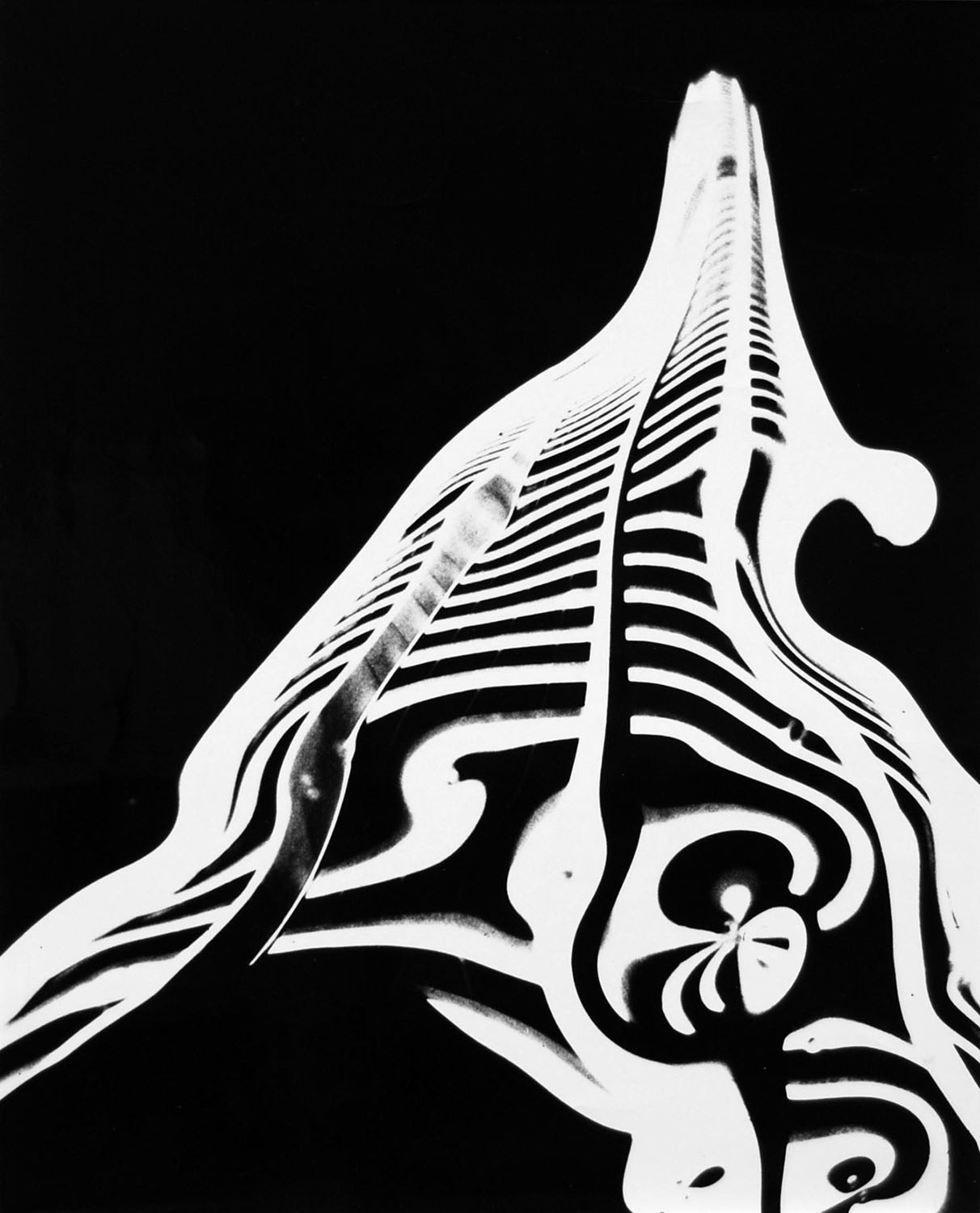

Alvin Langdon Coburn (American, 1882-1966)

Vortograph

1916-17

Gelatin silver print

11 1/8 x 8 3/8″ (28.2 x 21.2cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Thomas Walther Collection. Grace M. Mayer Fund

Vortograph

The intricate patterns of light and line in this photograph, and the cascading tiers of crystalline shapes, were generated through the use of a kaleidoscopic contraption invented by the American / British photographer Alvin Langdon Coburn, a member of London’s Vorticist group. To refute the idea that photography, in its helplessly accurate capture of scenes in the real world, was antithetical to abstraction, Coburn devised for his camera lens an attachment made up of three mirrors, clamped together in a triangle, through which he photographed a variety of surfaces to produce the results in these images. The poet and Vorticist Ezra Pound coined the term “vortographs” to describe Coburn’s experiments. Although Pound went on to criticise these images as lesser expressions than Vorticist paintings, Coburn’s work would remain influential.

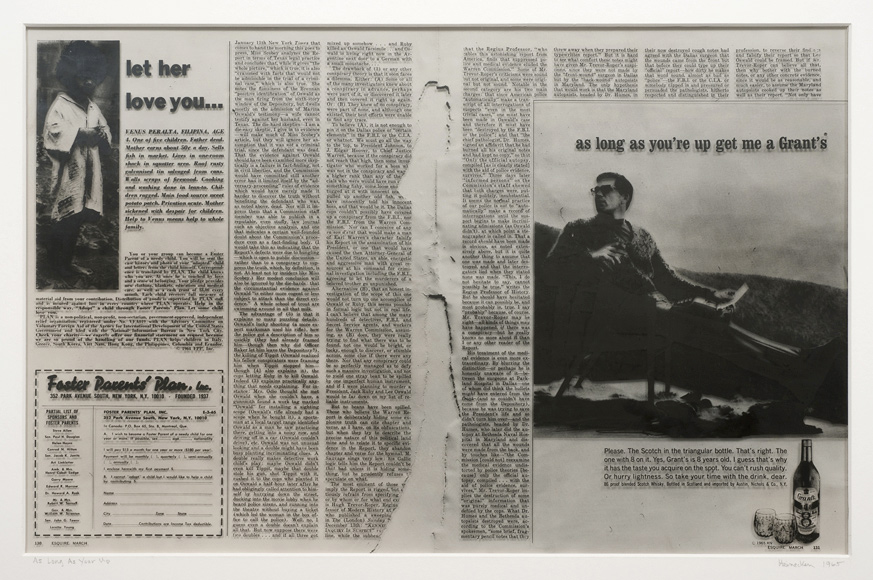

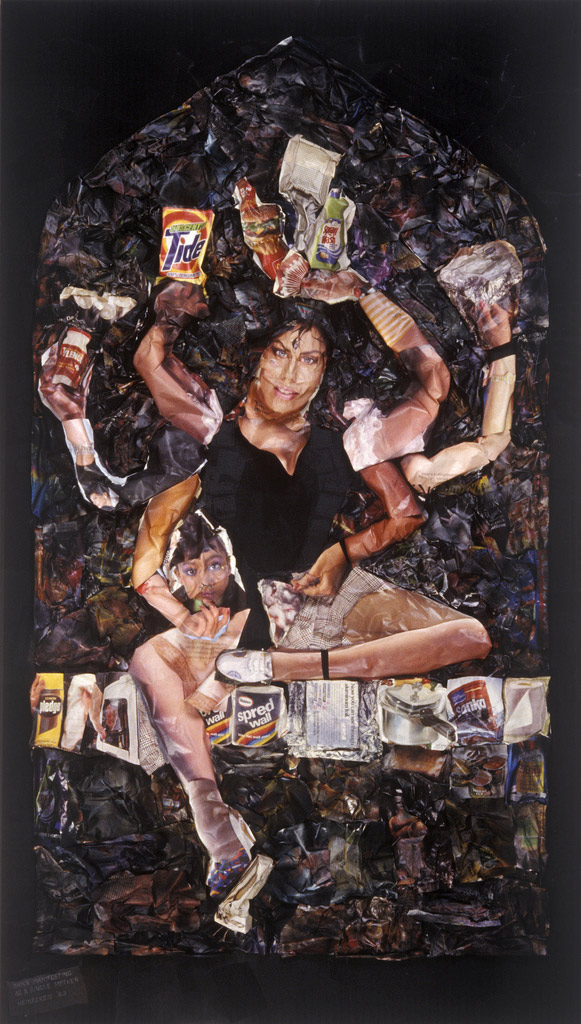

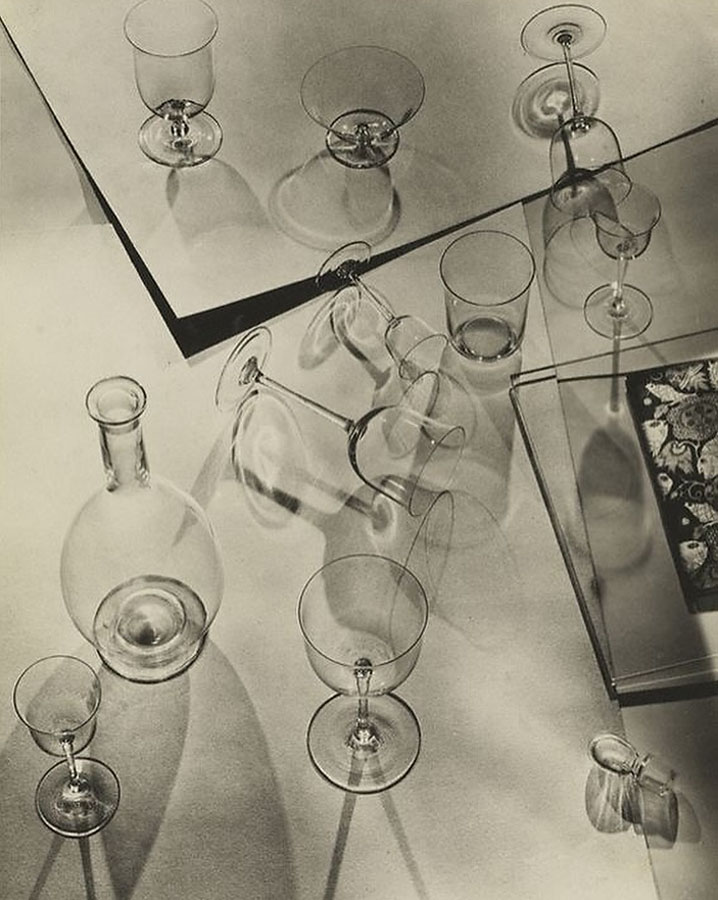

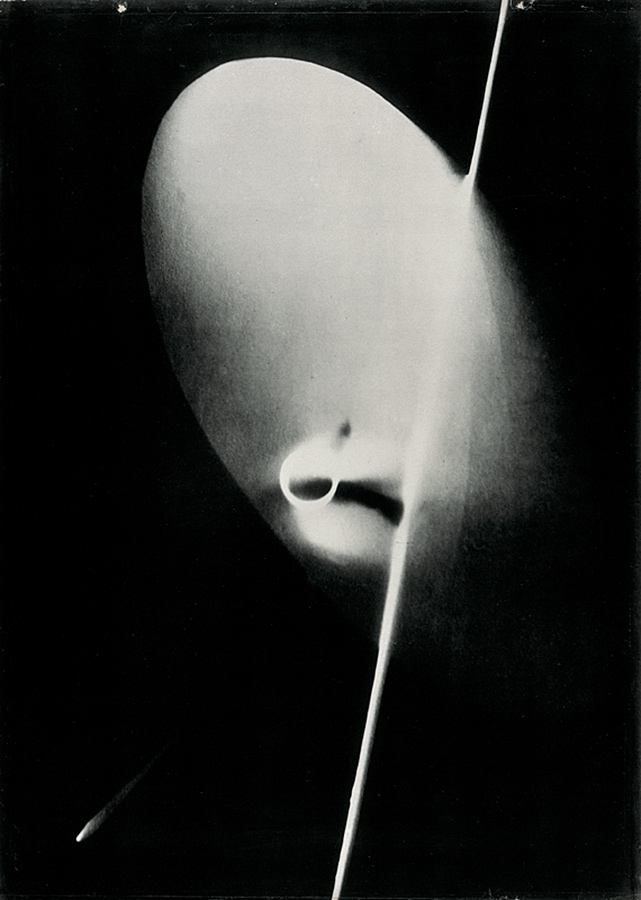

Reinventing Photography – Here Comes New Photographer

In 1925, László Moholy-Nagy articulated an idea that became central to the New Vision movement: although photography had been invented 100 years earlier, it was only now being discovered by the avant-garde circles for all its aesthetic possibilities. As products of technological culture, with short histories and no connection to the old fine-art disciplines – which many contemporary artists considered discredited – photography and cinema were seen as truly modern instruments that offered the greatest potential for transforming visual habits. From the photogram to solarisation, from negative prints to double exposures, the New Vision photographers explored the medium in countless ways, rediscovering known techniques and inventing new ones. Echoing the cinematic experiments of the same period, this emerging photographic vocabulary was rapidly adopted by the advertising industry, which appreciated the visual efficiency of its bold simplicity. Florence Henri (Swiss, born America, 1893-1982), Edward Quigley (American, 1898-1977), Franz Roh (German, 1890-1965), Franciszka Themerson and Stefan Themerson (British, born Poland, 1907-1988 and 1910-1988), and František Vobecký (Czech, 1902-1991) are among the numerous photographers represented here.

André Kertész (American born Hungary, 1894-1985)

Magda, Mme Beöthy, M. Beöthy, and Unknown Guest, Paris

1926-1929

Gelatin silver print

3 1/8 × 3 7/8″ (7.9 × 9.8cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Thomas Walther

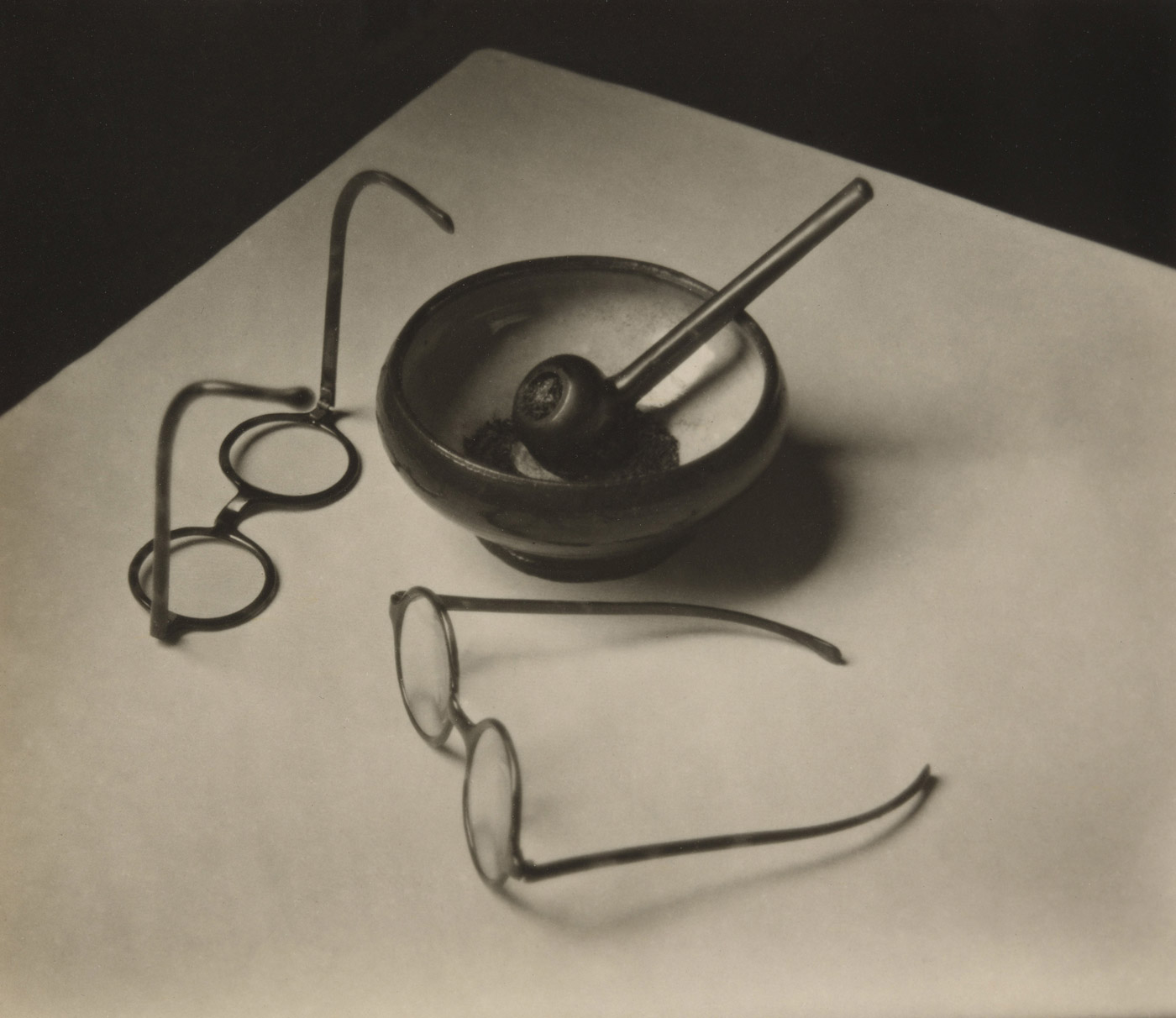

André Kertész (American born Hungary, 1894-1985)

Mondrian’s Glasses and Pipe

1926

Gelatin silver print

3 1/8 × 3 11/16″ (7.9 × 9.3cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Thomas Walther Collection. Grace M. Mayer Fund

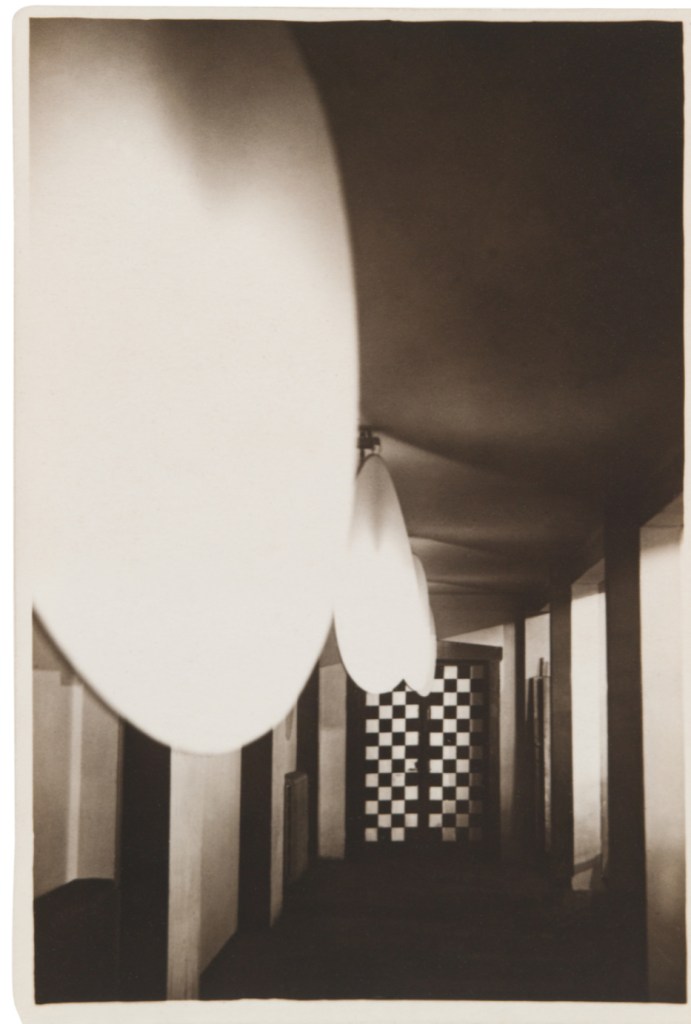

Unknown Photographer

White Party, Dessau (Weißes Fest, Dessau)

March 20, 1926

Gelatin silver print

3 x 1 15/16″ (7.6 x 5cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Thomas Walther Collection. Acquired through the generosity of Howard Stein

![Iwao Yamawaki (Japanese, 1898-1987) 'Lunch (12-2 p.m.)' (Mittagessen [12-2 Uhr]) 1931 Iwao Yamawaki (Japanese, 1898-1987) 'Lunch (12-2 p.m.)' (Mittagessen [12-2 Uhr]) 1931](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/iwao-yamawaki-japanese-1898e280931987-lunch-12e280932-p-m-web.jpg?w=725)

Iwao Yamawaki (Japanese, 1898-1987)

Lunch (12-2 p.m.) (Mittagessen [12-2 Uhr])

1931

Gelatin silver print

6 7/16 × 4 5/8″ (16.3 × 11.7cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Thomas Walther Collection. Abbott-Levy Collection funds, by exchange

Gertrud Arndt (German, 1903-2000)

At the Masters’ Houses (An den Meisterhäusern)

1929-1930

Gelatin silver print

8 7/8 x 6 1/4″ (22.6 x 15.8cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Thomas Walther

Gertrud Arndt (German, 1903-2000)

Gertrud Arndt (née Hantschk; 20 September 1903 – 10 July 2000) was a photographer associated with the Bauhaus movement. She is remembered for her pioneering series of self-portraits from around 1930.

Arndt’s photography, forgotten until the 1980s, has been compared to that of her contemporaries Marta Astfalck-Vietz and Claude Cahun. Over the five years when she took an active interest in photography, she captured herself and her friends in various styles, costumes and settings in the series known as Masked Portraits. Writing for Berlin Art Link, Angela Connor describes the images as “ranging from severe to absurd to playful.” Today Arndt is considered to be a pioneer of female self-portraiture, long predating Cindy Sherman and Sophie Calle.

Text from the Wikipedia website

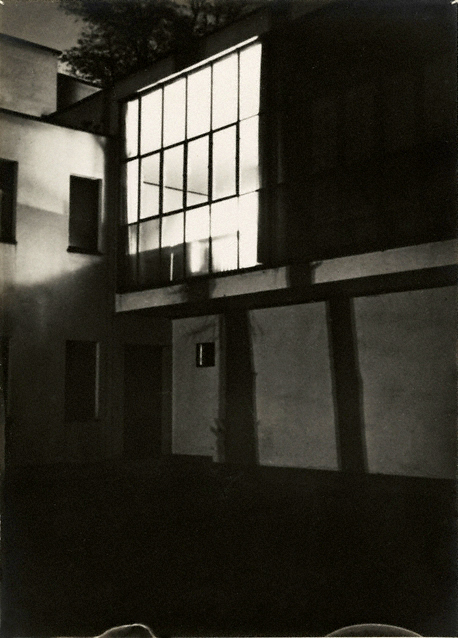

Iwao Yamawaki (Japanese, 1898-1987)

Untitled

1931

Gelatin silver print

8 11/16 x 6 1/2″ (22 x 16.5cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Thomas Walther Collection. Abbott-Levy Collection funds, by exchange

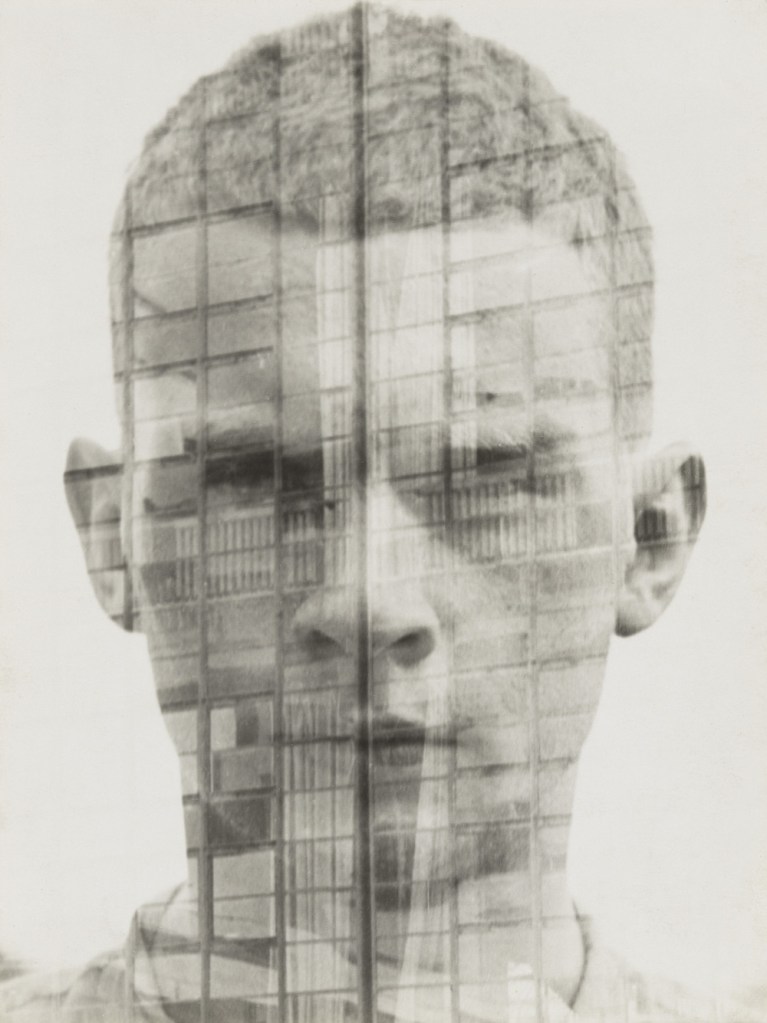

Hajo Rose (German, 1910-1989)

Untitled (Self-Portrait)

1931

Gelatin silver print

9 7/16 × 7 1/16″ (23.9 × 17.9cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Thomas Walther

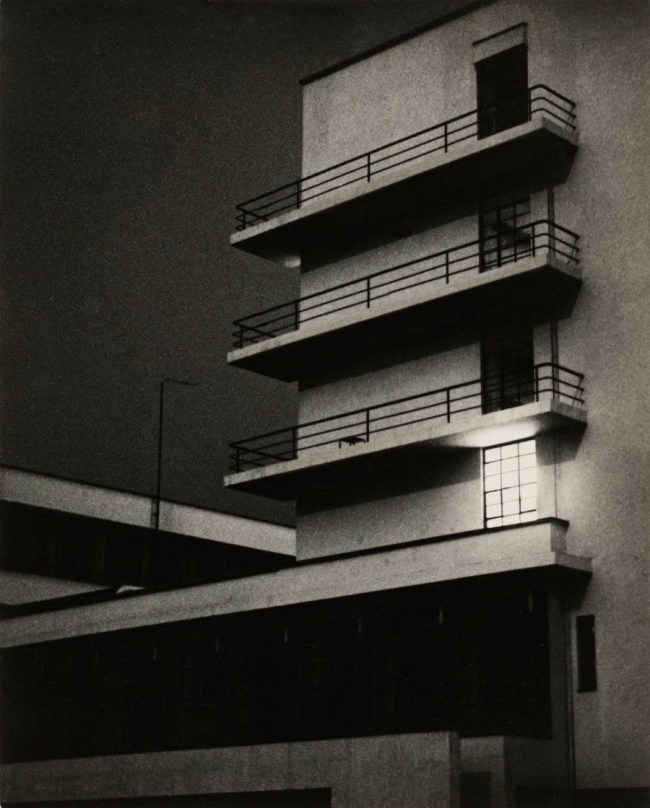

Hajo Rose (German, 1910-1989)

‘Finally – a house made of steel and glass!’ This was the enthusiastic reaction of Hajo Rose (1910-1989) to the Bauhaus building in Dessau when he began his studies there in 1930. Rose promoted the methods of the Bauhaus throughout his lifetime: as a lecturer at universities in Amsterdam, Dresden and Leipzig, and also as an artist and photographer.

Hajo Rose experimented with a wide variety of materials and techniques. The photomontage of his self-portrait combined with the Dessau Bauhaus building (c. 1930), the surrealism of his photograph Seemannsbraut (Sailor’s Bride, 1934), and the textile print designs that he created with a typewriter (1932) are examples of the extraordinary creativity of this artist. He also contributed to an advertising campaign for the Jena Glass Company: the first heat-resistant household glassware stood for modern product design and is still regarded as a kitchen classic today.

Shortly before the Bauhaus was closed, Hajo Rose was one of the last students to receive his diploma. Subsequent periods in various cities shaped his biography, which is a special example of the migratory experience shared by many Bauhaus members after 1933. After one year as an assistant in the Berlin office of László Moholy-Nagy, Hajo Rose immigrated to The Netherlands together with Paul Guermonprez, a Bauhaus colleague, in 1934. He worked there as a commercial artist and taught at the Nieuwe Kunstschool in Amsterdam. At the 1937 World Exposition in Paris, he won an award for his poster ‘Amsterdam’. After the Second World War, Rose worked as a graphic designer, photographer and teacher in Dresden and Leipzig. He continued to advocate Bauhaus ideas in the GDR, even though the Bauhaus was regarded in East Germany as bourgeois and formalistic well into the 1960s. Rose resigned from the Socialist Unity Party (SED) – in spite of the loss of his teaching position as a consequence. From that time, he worked as one of the few freelance graphic designers in the GDR. Hajo Rose died at the age of 79 – shortly before the fall of the Berlin Wall.

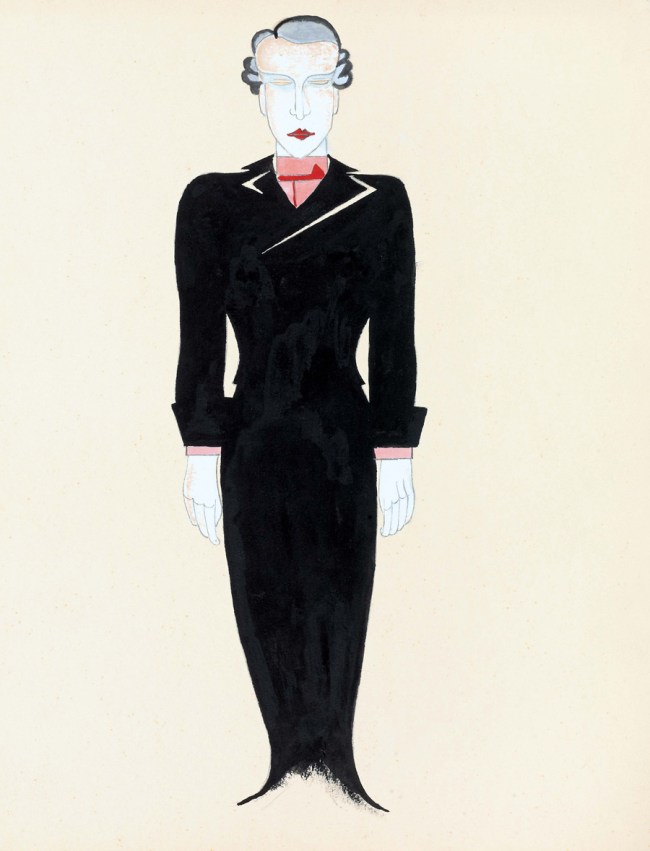

Edward Steichen (American born Luxembourg, 1879-1973)

Gertrude Lawrence

1928

Gelatin silver print

9 7/16 × 7 9/16″ (24 × 19.2cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Thomas Walther Collection. Edward Steichen Estate and gift of Mrs. Flora S. Straus, by exchange

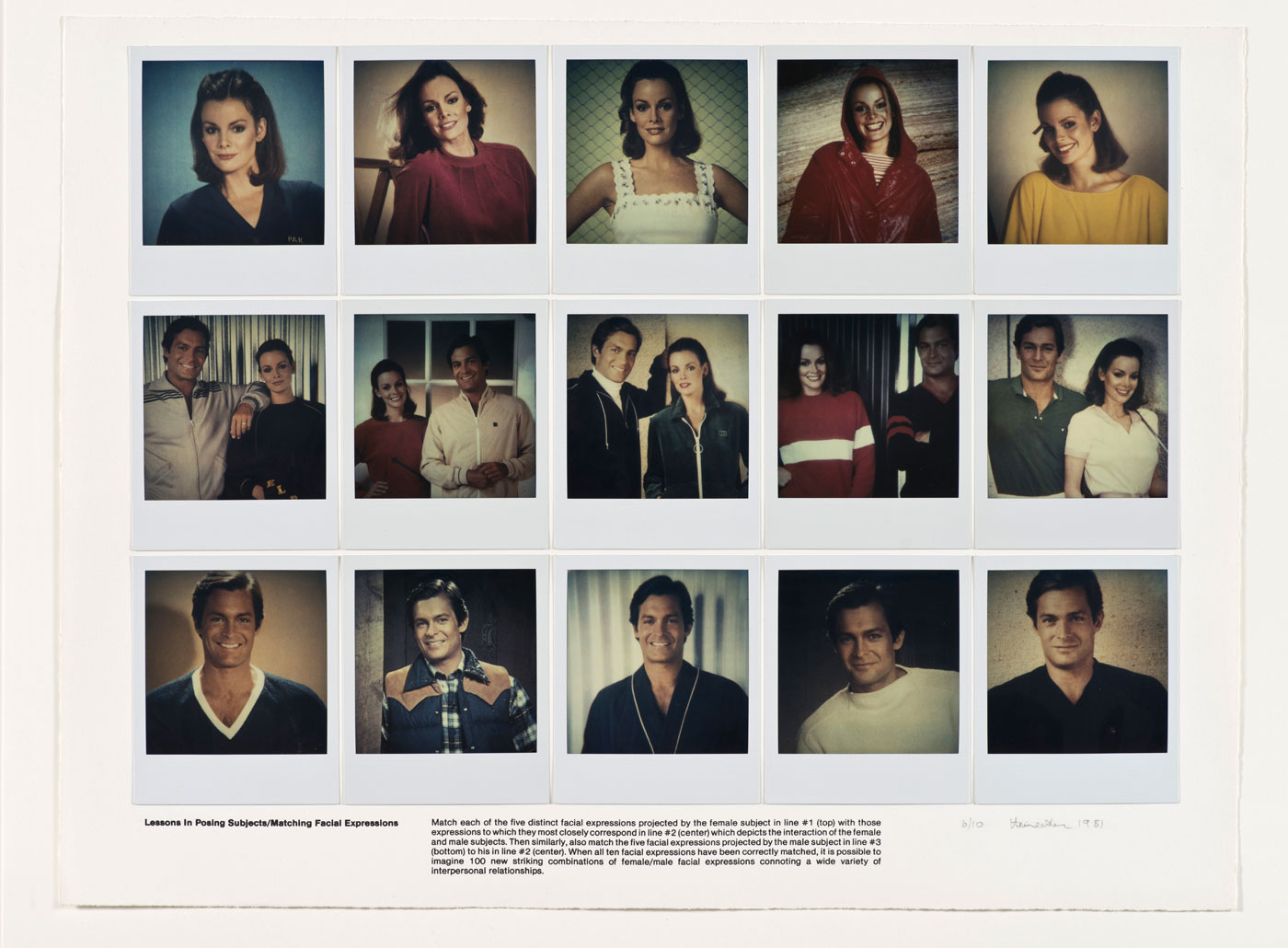

The Artist’s Life

Photography is particularly well suited to capturing the distinctive nuances of the human face, and photographers delighted in and pushed the boundaries of portraiture throughout the 20th century. The Thomas Walther Collection features a great number of portraits of artists and self-portraits as varied as the individuals portrayed. Additionally, the collection conveys a free-spirited sense of community and daily life, highlighted here with photographs made by André Kertész and by students and faculty at the Bauhaus. When the Hungarian-born Kertész moved to Paris in 1925, he couldn’t afford to purchase photographic paper, so he would print on less expensive postcard stock. These prints, whose small scale requires that the viewer engage with them intimately, function as miniature windows into the lives of Kertész’s bohemian circle of friends. The group of photographs made at the Bauhaus in the mid-1920s, before the medium was formally integrated into the school’s curriculum, similarly expresses friendships and everyday life captured and printed in an informal manner. Portraits by Claude Cahun (French, 1894-1954), Lotte Jacobi (American, born Germany, 1896-1990), Lucia Moholy (British, born Czechoslovakia, 1894-1989), Man Ray (American, 1890-1976), August Sander (German, 1876-1964) and Edward Steichen (American, born Luxembourg, 1879-1973) are among the highlights of this gallery.

Aenne Biermann (German, 1898-1933)

Summer Swimming (Sommerbad)

1925-1930

Gelatin silver print

7 x 7 7/8″ (17.8 x 20cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Thomas Walther Collection. Bequest of Ilse Bing, by exchange

Aenne Biermann (German, 1898-1933)

Aenne Biermann (March 8, 1898 – January 14, 1933), born Anna Sibilla Sternfeld, was a German photographer of Ashkenazi origin. She was one of the major proponents of New Objectivity, a significant art movement that developed in Germany in the 1920s.

Biermann was a self-taught photographer. Her first subjects were her two children, Helga and Gershon. The majority of Biermann’s photographs were shot between 1925 and 1933. Gradually she became one of the major proponents of New Objectivity, an important art movement in the Weimar Republic. Her work became internationally known in the late 1920s, when it was part of every major exhibition of German photography.

Major exhibitions of her work include the Munich Kunstkabinett, the Deutscher Werkbund and the exhibition of Folkwang Museum in 1929. Other important exhibitions include the exhibition entitled Das Lichtbild held in Munich in 1930 and the 1931 exhibition at the Palace of Fine Arts (French: Palais des Beaux Arts) in Brussels. Since 1992 the Museum of Gera has held an annual contest for the Aenne Biermann Prize for Contemporary German Photography, which is one of the most important events of its kind in Germany.

Text from the Wikipedia website

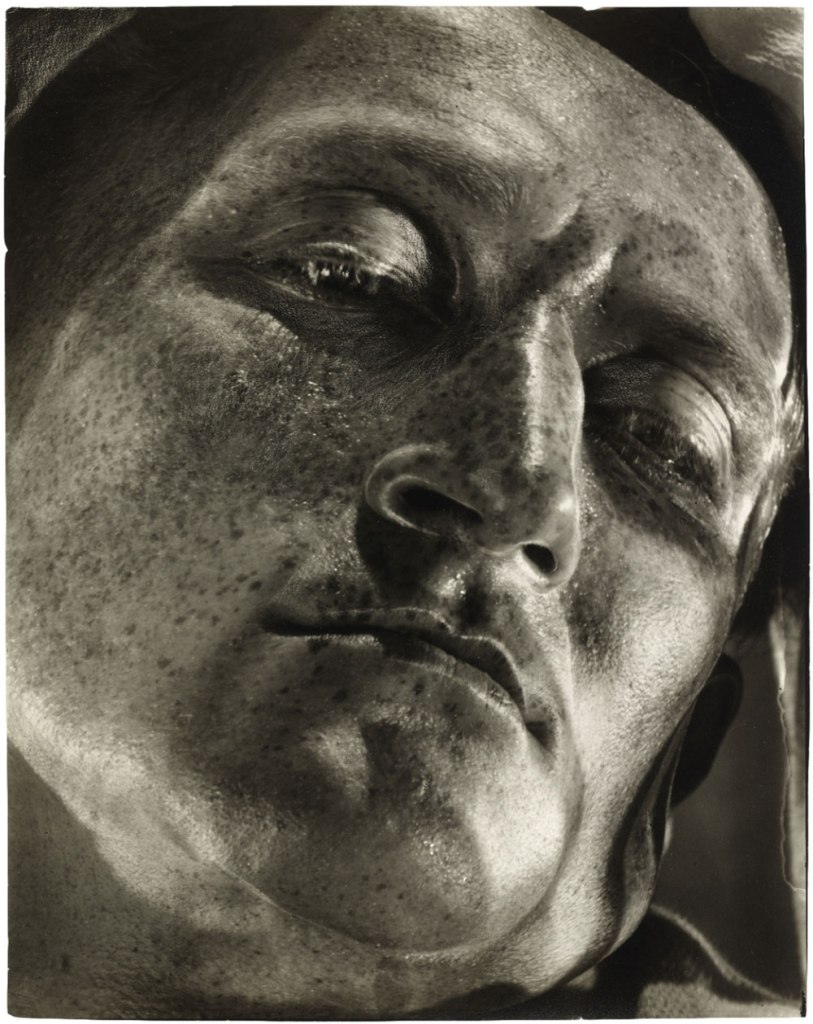

Helmar Lerski (Swiss born Germany, 1871-1956)

Metamorphosis 601 (Metamorphose 601)

1936

Gelatin silver print

11 7/16 × 9 1/16″ (29 × 23cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Thomas Walther Collection. The Family of Man Fund

Helmar Lerski (Swiss, born Germany 1871-1956)

There can hardly be another name in the international history of photography whose work has been so frequently misunderstood and so controversially evaluated as that of Helmar Lerski (1871-1956). “In every human being there is everything; the question is only what the light falls on”. Guided by this conviction, Lerski took portraits that did not primarily strive for likeness but which left scope for the viewer’s imagination, thus laying himself open to the criticism of betraying the veracity of the photographic image.

… Lerski’s pictures were only partly in line with the maxims of the New Photography, and they questioned the validity of pure objectivity. The distinguishing characteristics of his portraits included a theatrical-expressionistic, sometimes dramatic use of lighting inspired by the silent film. Although his close-up photographs captured the essential features of a face – eyes, nose and mouth –, his primary concern was not individual appearance or superficial likeness but the deeper inner potential: he emphasised the changeability, the different faces of an individual. Lerski, who sympathised with the political left wing, thereby infiltrated the photography of types that was practised (and not infrequently misused for racist purposes) by many of Lerski’s contemporaries.

… Helmar Lerski’s attitude was at its most radical in his work entitled Metamorphosis. This was completed within a few months at the beginning of 1936 in Palestine, to where Lerski and his second wife Anneliese had immigrated in 1932. In Verwandlungen durch Licht (this is the second title for this work), Lerski carried his theatrical talent to extremes. With the help of up to 16 mirrors and filters, he directed the natural light of the sun in constant new variations and refractions onto his model, the Bernese-born, at the time out-of-work structural draughtsman and light athlete Leo Uschatz. Thus he achieved, in a series of over 140 close-ups “hundreds of different faces, including that of a hero, a prophet, a peasant, a dying soldier, an old woman and a monk from one single original face” (Siegfried Kracauer). According to Lerski, these pictures were intended to provide proof “that the lens does not have to be objective, that the photographer can, with the help of light, work freely, characterise freely, according to his inner face.” Contrary to the conventional idea of the portrait as an expression of human identity, Lerski used the human face as a projection surface for the figures of his imagination. We are only just becoming aware of the modernity of this provocative series of photographs.

Peter Pfrunder

Fotostiftung Schweiz

Max Burchartz (German, 1887-1961)

Lotte (Eye) (Lotte [Auge])

1928

Gelatin silver print

11 7/8 x 15 3/4″ (30.2 x 40cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Thomas Walther Collection. Acquired through the generosity of Peter Norton

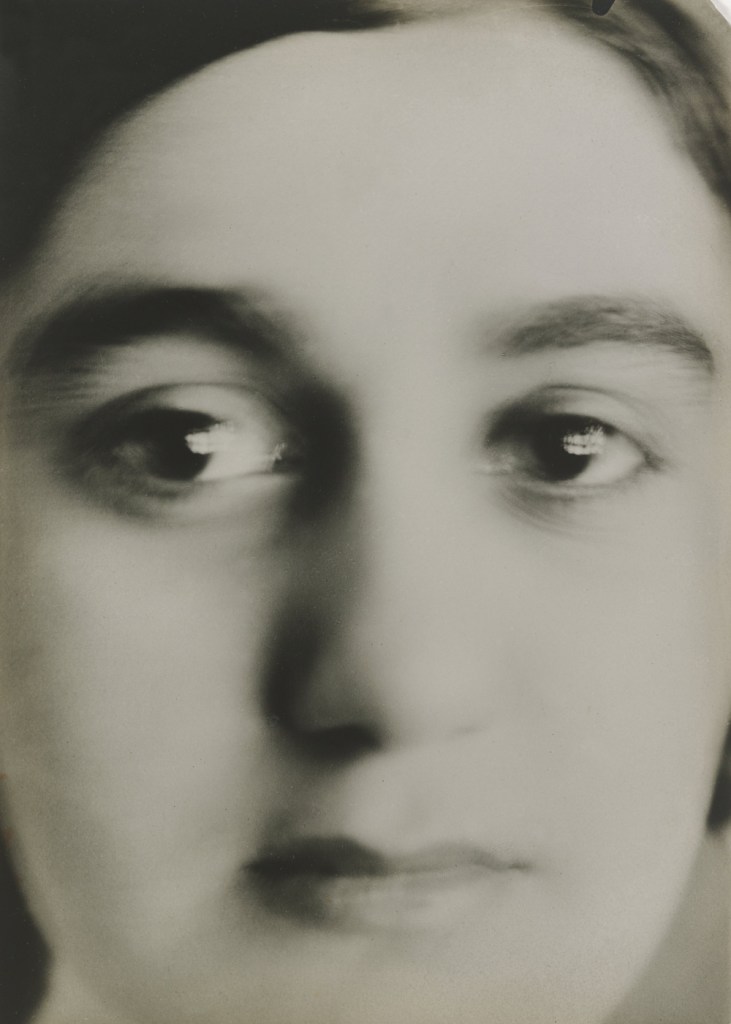

Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz (Polish, 1885-1939)

Anna Oderfeld, Zakopane

1911-1912

Gelatin silver print 6 11/16 × 4 3/4″ (17 × 12.1cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Mrs. Willard Helburn, by exchange

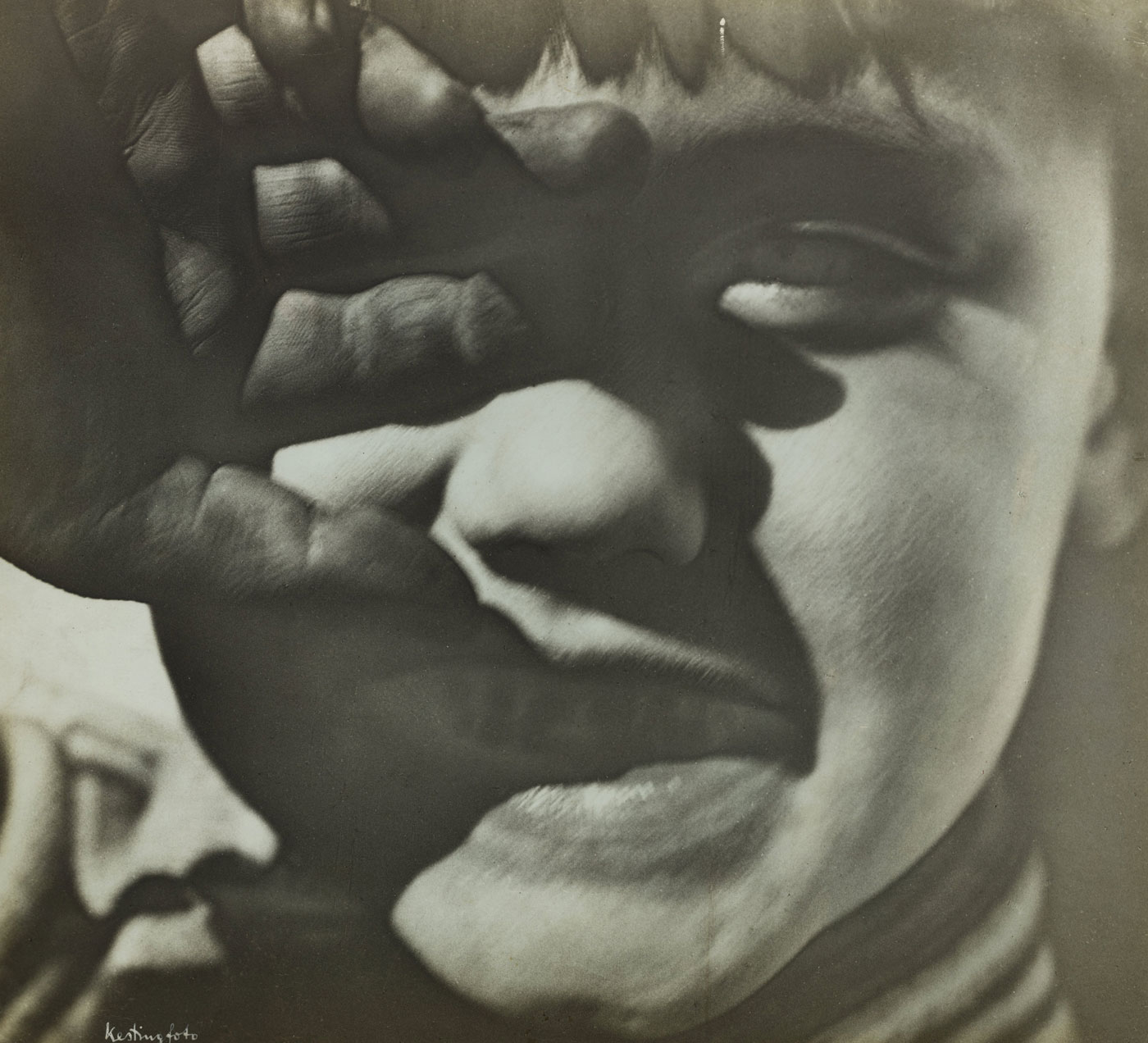

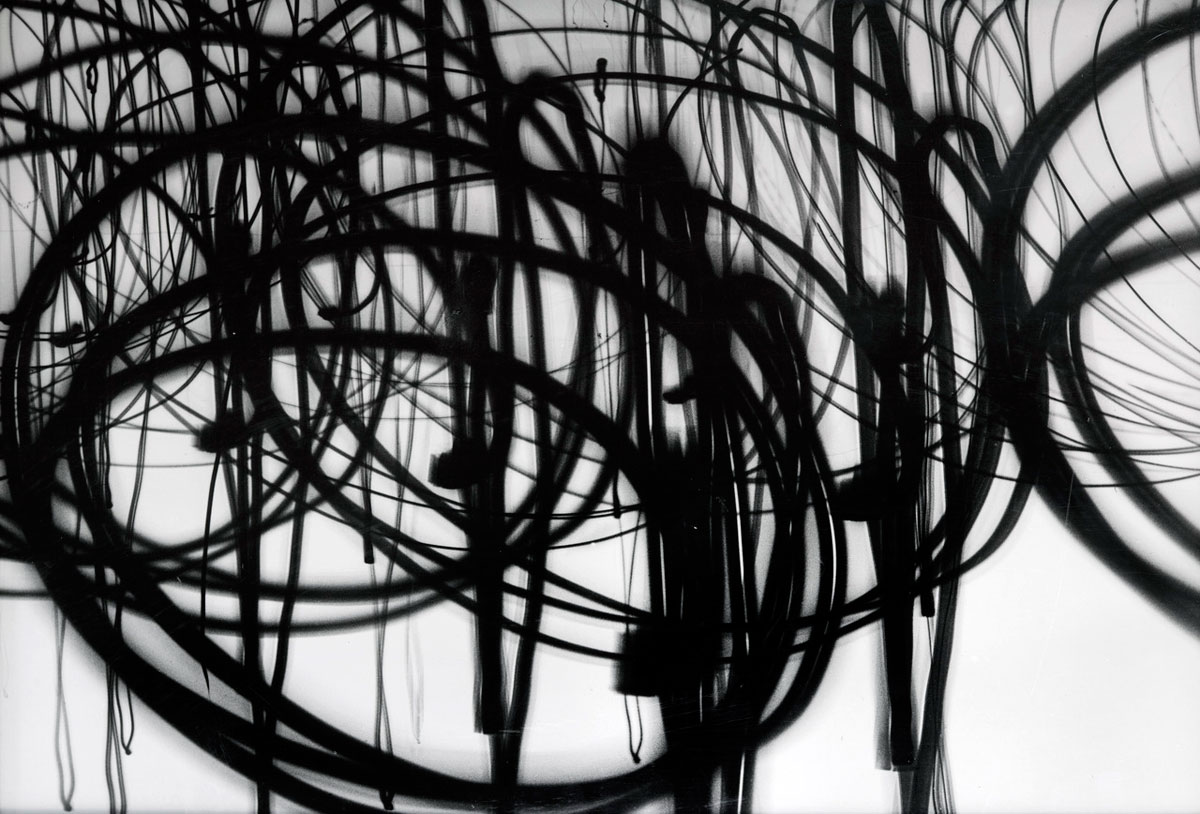

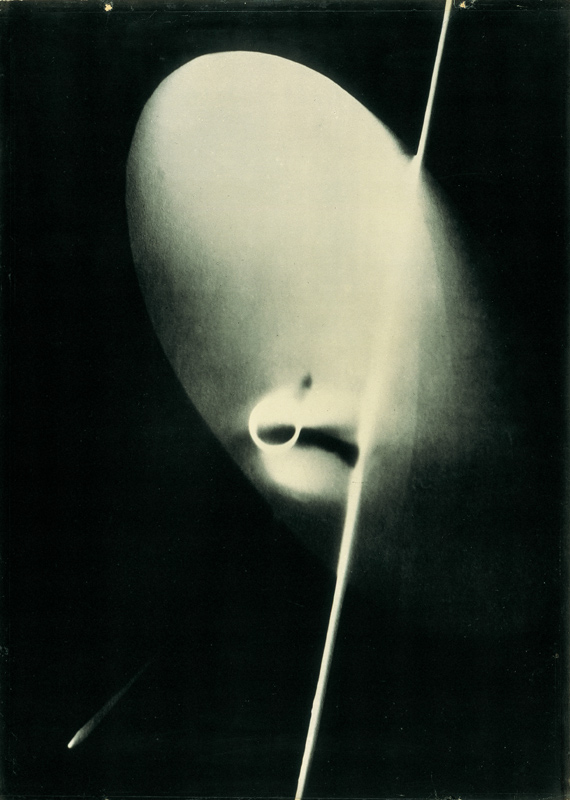

Edmund Kesting (German, 1892-1970)

Glance to the Sun (Blick zur Sonne)

1928

Gelatin silver print

13 1/16 x 14 1/2″ (33.2 x 36.8cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Thomas Walther

Edmund Kesting (German, 1892-1970)

Edmund Kesting (27 July 1892, Dresden – 21 October 1970, Birkenwerder) was a German photographer, painter and art professor. He studied until 1916 at the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts before participating as a soldier in the First World War, upon returning his painting teachers were Richard Müller and Otto Gussmann and in 1919 he began to teach as a professor at the private school Der Weg. In 1923 he had his first exposition in the gallery Der Sturm in which he showed photograms. When Der Weg opened a new academy in Berlin in 1927, he moved to the capital.

He formed relations with other vanguardists in Berlin and practiced various experimental techniques such as solarisation, multiple images and photograms, for which reason twelve of his works were considered degenerate art by the Nazi regime and were prohibited. Among the artists with whom he interacted are Kurt Schwitters, László Moholy-Nagy, El Lissitzky and Alexander Archipenko. At the end of World War II he formed part of a Dresden artistic group known as Künstlergruppe der ruf – befreite Kunst (Call to an art in freedom) along with Karl von Appen, Helmut Schmidt-Kirstein and Christoph Hans, among others. In this city he made an experimental report named Dresdner Totentanz (Dance of death in Dresden) as a condemnation of the bombing of the city. In 1946 he was named a member of the Academy of Art in the city.

He participated in the controversy between socialist realism and formalism that took place in the German Democratic Republic, therefore his work was not realist and could not be shown in the country between 1949 and 1959. In 1955 he began to experiment with chemical painting, making photographs without the use of a camera and only with the use of chemical products such as the developer and the fixer and photographic paper, for which he made exposures to light using masks and templates. Between 1956 and 1967 he was a professor at the Academy of Cinema and Television of Potsdam.

His artistic work was not recognised by the authorities of the German Democratic Republic until 1980, ten years after his death.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Maurice Tabard (French, 1897-1984)

Am I Beautiful? (Suis-je belle?)

1929

Gelatin silver print

9 5/16 × 6 15/16″ (23.6 × 17.7cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Shirley C. Burden, by exchange

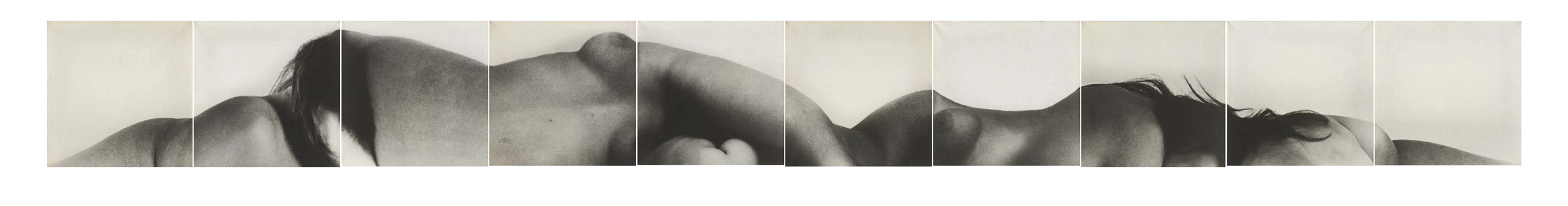

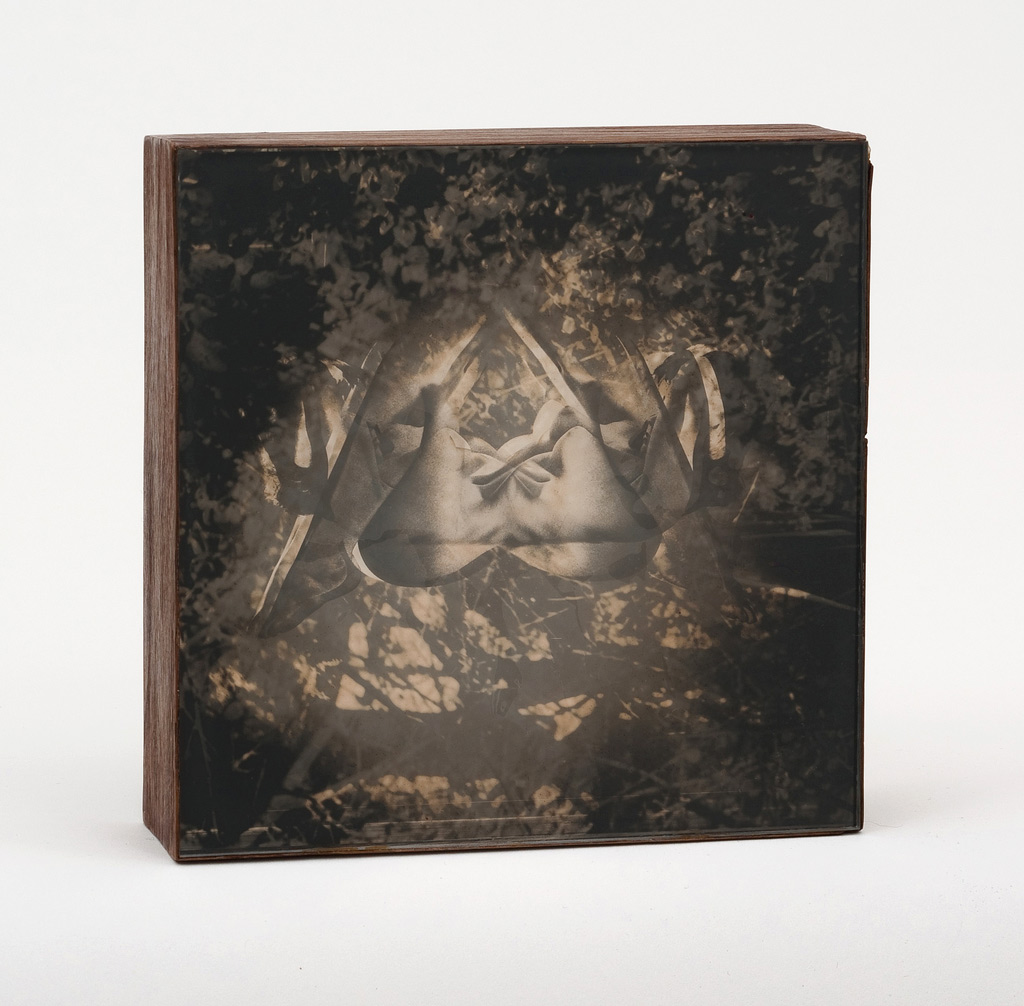

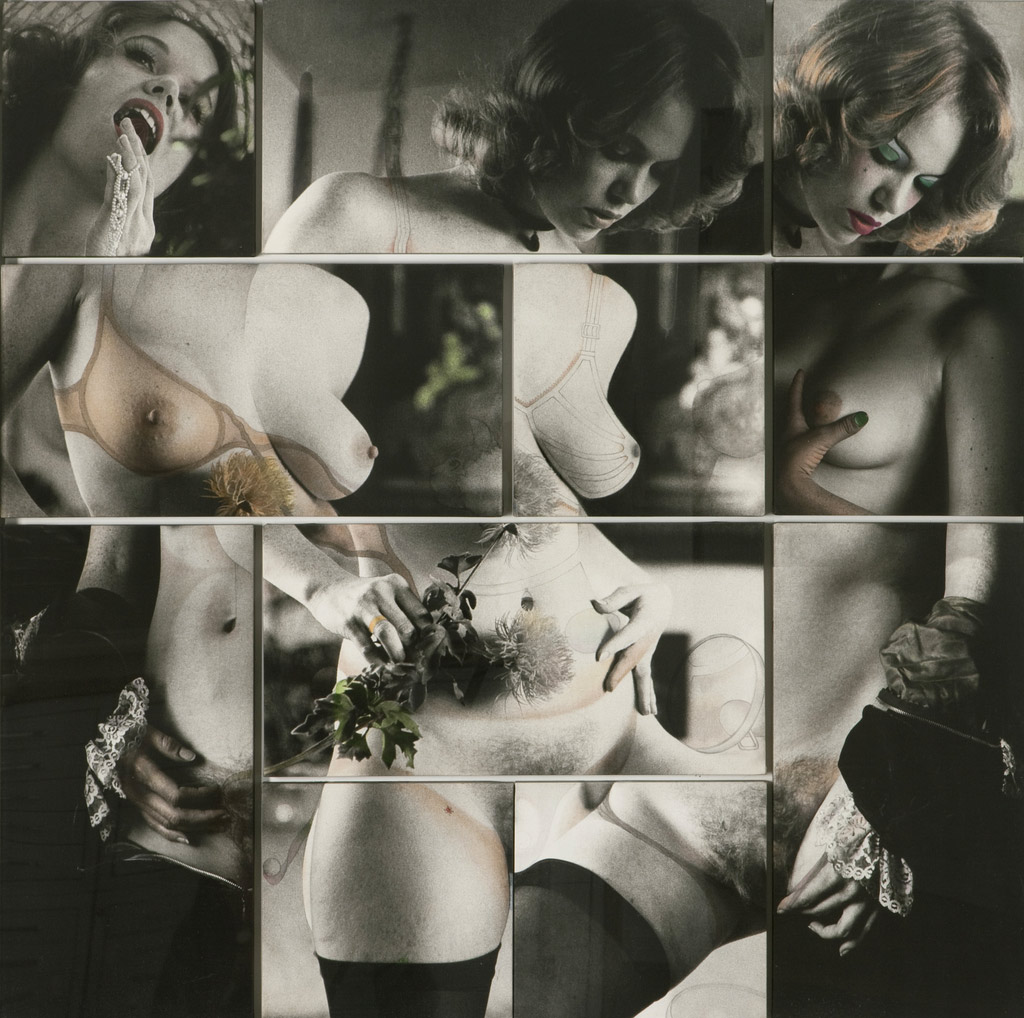

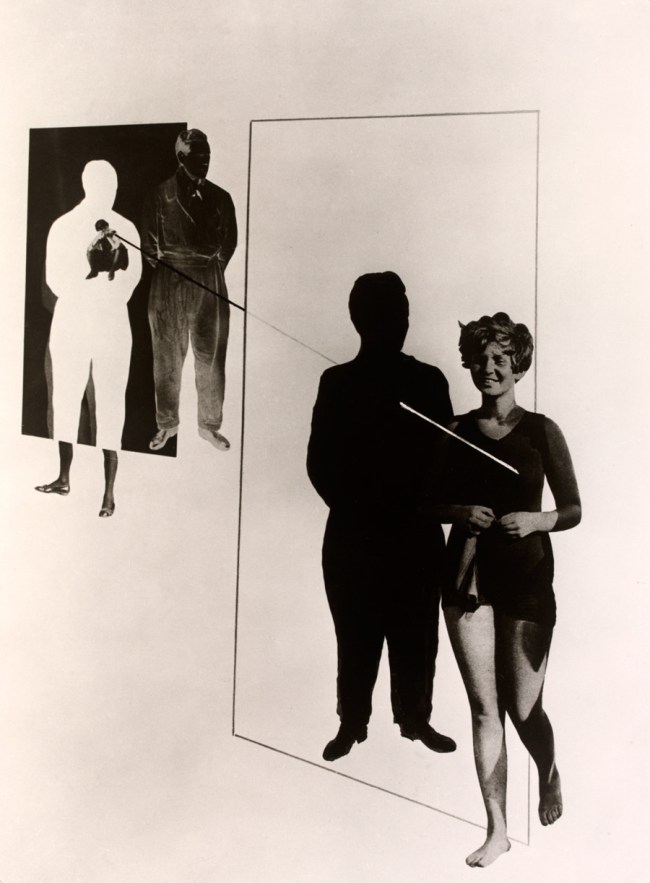

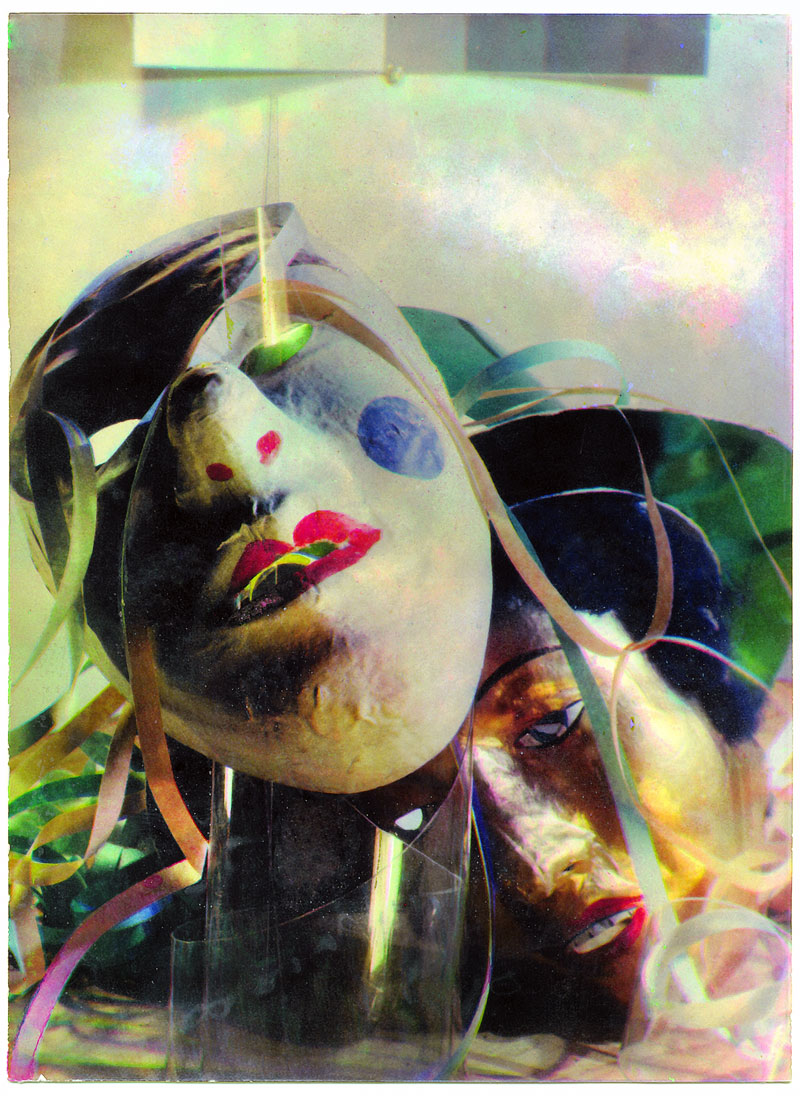

Between Surrealism and Magic Realism

In the mid-1920s, European artistic movements ranging from Surrealism to New Objectivity moved away from a realist approach by highlighting the strange in the familiar or trying to reconcile dreams and reality. Echoes of these concerns, centred on the human figure, can be found in this gallery. Some photographers used anti-naturalistic methods – capturing hyperreal, close-up details; playing with scale; and rendering the body as landscape – to challenge the viewer’s perception. Others, in line with Sigmund Freud’s definition of “the uncanny” as an effect that results from the blurring of distinctions between the real and the fantastic, offered visual plays on life and the lifeless, the animate and the inanimate, confronting the human body with surrogates in the form of dolls, mannequins, and masks. Photographers influenced by Surrealism, such as Maurice Tabard, subjected the human figure to distortions and transformations by experimenting with photographic techniques either while capturing the image or while developing it in the darkroom. Additional photographers on view include Aenne Biermann (German, 1898-1933), Jacques-André Boiffard (French, 1902-1961), Max Burchartz (German, 1887-1961), Helmar Lerski (Swiss, 1871-1956), and Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz (Polish, 1885-1939)

Berenice Abbott (American, 1898-1991)

Daily News Building, 220 East 42nd Street, Manhattan

November 21, 1935

Gelatin silver print

9 5/8 × 7 1/2″ (24.4 × 19.1cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Thomas Walther Collection. Abbott-Levy Collection funds, by exchange

Marjorie Content (American, 1895-1984)

Steamship Pipes, Paris

Winter 1931

Gelatin silver print

3 13/16 × 2 11/16″ (9.7 × 6.8cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Andreas Feininger, by exchange

Marjorie Content (American, 1895-1984)

Marjorie Content (1895-1984) was an American photographer active in modernist social and artistic circles. Her photographs were rarely published and never exhibited in her lifetime, but have become of interest to collectors and art historians. Her work has been collected by the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Chrysler Museum of Art; it has been the subject of several solo exhibitions. (Wikipedia)

Marjorie Content (1895-1984) was a modest and unpretentious photographer who kept her work largely to herself, never published or exhibited. Overshadowed by such close friends as Georgia O’Keefe and Alfred Stieglitz, she was more comfortable as a muse and source of encouragement for others, including her fourth husband, poet Jean Toomer. This text presents her beautiful, varied photographs and provides a glimpse into her life. Her pictures portray a variety of images including: New York’s frenetic cityscape distilled to essential patterns and rhythms; the Southwestern light and heat along with the strength and dignity of the Taos pueblo culture; and cigarettes and other everyday items arranged in jewel-like compositions. The discovery of the quality and extent of her work is proof that an artist’s determination can surmount a lack of recognition in her lifetime.

Text from the Amazon website

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Votive Candles, New York City

1929-1930

Gelatin silver print

8 1/2 x 6 15/16″ (21.6 x 17.7cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Willard Van Dyke and Mr. and Mrs. Alfred H. Barr, Jr., by exchange

Georgii Zimin (Russian, 1900-1985)

Untitled

1926

Gelatin silver print

3 11/16 x 3 1/4″ (9.4 x 8.3cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Thomas Walther

Georgii Zimin (Russian, 1900-1985)

Georgii Zimin was born in Moscow in 1900, where he lived and worked for his entire life. Before the Russian Revolution he enrolled as a student at the Artistic-Industrial Stroganov Institute, known after 1918 as SVOMAS (Free state art studios). Zimin continued his studies at VKhUTEMAS (Higher state artistic and technical studios), which replaced SVOMAS in 1920. It was during his time at the school that he published the portfolio Skrjabin in Lukins Tanz (Scriabin in Lukin’s dance), in an edition of one hundred. This set of Cubo-Futurist lithographs from 1922 features costumed dancers in erotic poses, complementing a ballet choreographed by Lev Lukin. This work garnered Zimin acknowledgment by the Academy of Arts and Sciences and marked his affiliation with the Russian Art of Movement group. Throughout the 1920s he showed regularly at Art of Movement exhibitions at GAKhN (State academy for artistic sciences), in Moscow. Zimin also experimented with photography in the late 1920s and early 1930s, producing photograms akin to those made by László Moholy-Nagy and others at the time. Later in life, he served as Art Director of Exhibitions at the Department of Trade and held a post at the All-Union Agricultural Exhibition.

~ Ksenia Nouril

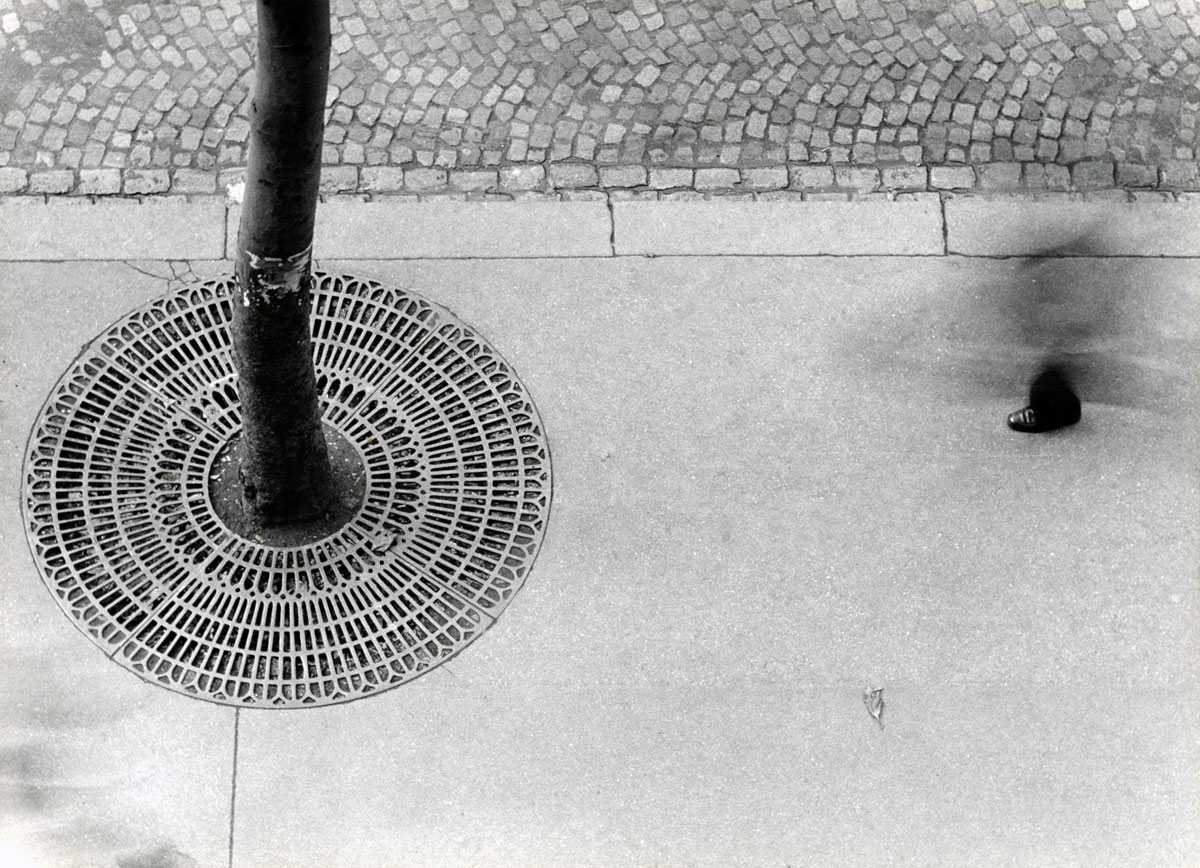

Umbo (Otto Umbehr) (German, 1902-1980)

Mystery of the Street (Mysterium der Strasse)

1928

Gelatin silver print

11 7/16 x 9 1/4″ (29 x 23.5cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Shirley C. Burden, by exchange

Umbo (Otto Umbehr) (German, 1902-1980)

Trained at the Bauhaus under Johannes Itten, a master of expressivity, Berlin-based photographer Umbo (born Otto Umbehr) believed that intuition was the source of creativity. To this belief, he added Constructivist structural strategies absorbed from Theo Van Doesburg, El Lissitzky, and others in Berlin in the early twenties. Their influence is evident in this picture’s diagonal, abstract construction and its spatial disorientation. It is also classic Umbo, encapsulating his intuitive vision of the world as a resource of poetic, often funny, ironic, or dark bulletins from the social unconscious.

After he left the Bauhaus, Umbo worked as assistant to Walther Ruttmann on his film Berlin, Symphony of a Great City 1926. In 1928, photographing from his window either very early or very late in the day and either waiting for his “actors” to achieve a balanced composition or, perhaps, positioning them as a movie director would, Umbo exposed three negatives. He had an old 5 by 7 inch (12.7 by 17.8 centimetre) stand camera and a 9 by 12 centimetre (3 9/16 by 4 3/4 inch) Deckrullo Contessa-Nettle camera, but which he used for these overhead views is not known, as he lost all his prints and most negatives in the 1943 bombing of Berlin. The resulting images present a world in which the shadows take the active role. Umbo made the insubstantial rule the corporeal and the dark dominate the light through a simple but inspired inversion: he mounted the pictures upside down (note the signature in ink in the lower right) .

In 1928-29, Umbo was a founding photographer at Dephot (Deutscher Photodienst), a seminal photography agency in Berlin dedicated to creating socially relevant and visually fascinating photoessays, an idea originated by Erich Solomon. Simon Guttmann, who directed the business, hired creative nonconformists, foremost among them the bohemian Umbo, who slept in the darkroom; Umbo in turn drew the brothers Lore Feininger and Lyonel Feininger to the agency, which soon also boasted Robert Capa and Felix H. Man. Dephot hired Dott, the best printer in Berlin, and it was he who made the large exhibition prints, such as this one, ordered by New York gallerist Julien Levy when he visited the agency in 1931. Umbo showed thirty-nine works, perhaps also printed by Dott, in the 1929 exhibition Film und Foto, and he put Guttmann in touch with the Berlin organizer of the show; accordingly, Dephot was the source for some images in the accompanying book, Es kommt der neue Fotograf! (Here comes the new photographer!). Levy introduced Umbo’s photographs to New York in Surréalisme (January 1932) and showcased them again at the Julien Levy Gallery, together with images by Herbert Bayer, Jacques-André Boiffard, Roger Parry, and Maurice Tabard, in his 1932 exhibition Modern European Photography.

Maria Morris Hambourg, Hanako Murata

Umbo (Otto Umbehr) (German, 1902-1980)

Six at the Beach (Sechs am Strand)

1930

Gelatin silver print

9 3/8 × 7 1/8″ (23.8 × 18.1cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Shirley C. Burden, by exchange

Alvin Langdon Coburn (American, 1882-1966)

The Octopus

1909

Gelatin silver print

22 1/8 × 16 3/4″ (56.2 × 42.6cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Thomas Walther

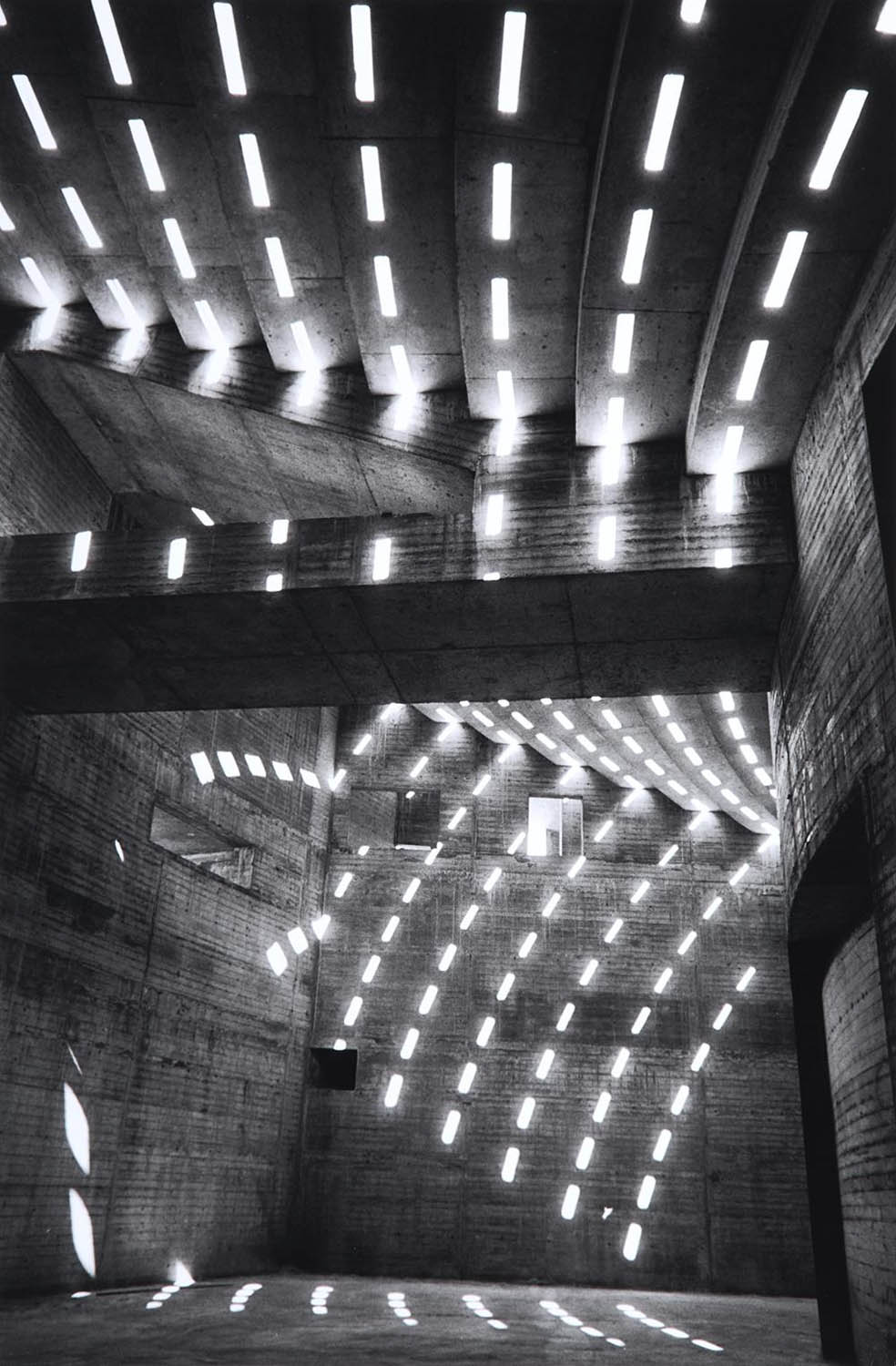

Dynamics of the City – Symphony of a Great City

In his 1928 manifesto “The Paths of Contemporary Photography,” Aleksandr Rodchenko advocated for a new photographic vocabulary that would be more in step with the pace of modern urban life and the changes in perception it implied. Rodchenko was not alone in this quest: most of the avant-garde photographers of the 1920s and 1930s were city dwellers, striving to translate the novel and shocking experience of everyday life into photographic images. Equipped with newly invented handheld cameras, they used unusual vantage points and took photos as they moved, struggling to re-create the constant flux of images that confronted the pedestrian. Reflections in windows and vitrines, blurry images of quick motions, double exposures, and fragmentary views portray the visual cacophony of the metropolis. The work of Berenice Abbott (American, 1898- 1991), Alvin Langdon Coburn (American, 1882-1966), Germanie Krull (Dutch, born Germany, 1897-1985), Alexander Hackenschmied (Czech, 1907-2004), Umbo (German, 1902-1980), and Imre Kinszki (Hungarian, 1901-1945) is featured in this final gallery.

The Museum of Modern Art

11 West 53 Street

New York, NY 10019

Phone: (212) 708-9400

Opening hours:

10.30 am – 5.30 pm

Open seven days a week

![Max Burchartz (German, 1887-1961) 'Lotte (Eye)' (Lotte [Auge]) 1928 Max Burchartz (German, 1887-1961) 'Lotte (Eye)' (Lotte [Auge]) 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/max-burchartz-lotte-eye-1928-web.jpg)

![Oliver Boberg (German, b. 1965) 'Unterführung' [Underpass] 1997 Oliver Boberg (German, b. 1965) 'Unterführung' [Underpass] 1997](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/r_p_oliver-boberg-unterfuehrungdruckbar-web.jpg)

![Lyonel Feininger (American, 1871-1956) 'Untitled [Street Scene, Double Exposure, Halle]' 1929-1930 Lyonel Feininger (American, 1871-1956) 'Untitled [Street Scene, Double Exposure, Halle]' 1929-1930](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/street-scene-double-exposure-halle-1929-1930.jpg)

![Lucia Moholy (British born Czechoslovakia, 1894-1989) 'Untitled [Southern View of Newly Completed Bauhaus, Dessau]' 1926 Lucia Moholy (British born Czechoslovakia, 1894-1989) 'Untitled [Southern View of Newly Completed Bauhaus, Dessau]' 1926](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/lucia-moholy-southern-view-of-newly-completed-bauhaus.jpg)

![Lyonel Feininger (American, 1871-1956) 'Untitled [Train Station, Dessau]' 1928-1929 Lyonel Feininger (American, 1871-1956) 'Untitled [Train Station, Dessau]' 1928-1929](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/gm_326238ex1.jpg)

![Lyonel Feininger (American, 1871-1956) 'Untitled [Night View of Trees and Street Lamp, Burgkühnauer Allee, Dessau]' 1928 Lyonel Feininger (American, 1871-1956) 'Untitled [Night View of Trees and Street Lamp, Burgkühnauer Allee, Dessau]' 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/night-view-of-trees-and-streetlamp-burgkc3bchnauer-allee-dessau-1928.jpg)

![Irene Bayer-Hecht (American, 1898-1991) 'Untitled [Students on the Shore of the Elbe River, near Dessau]' 1925 Irene Bayer-Hecht (American, 1898-1991) 'Untitled [Students on the Shore of the Elbe River, near Dessau]' 1925](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/irene-bayer-bauhacc88usler-am-strand-der-elbe-bei-dessau-web.jpg)

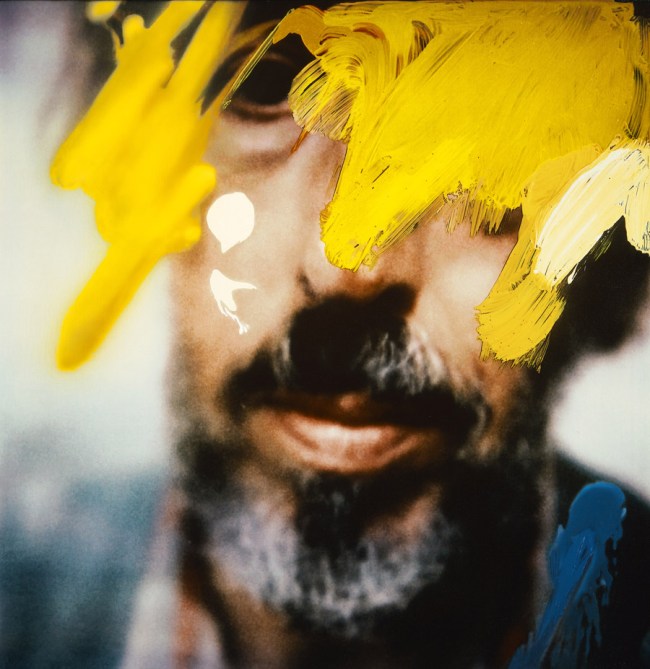

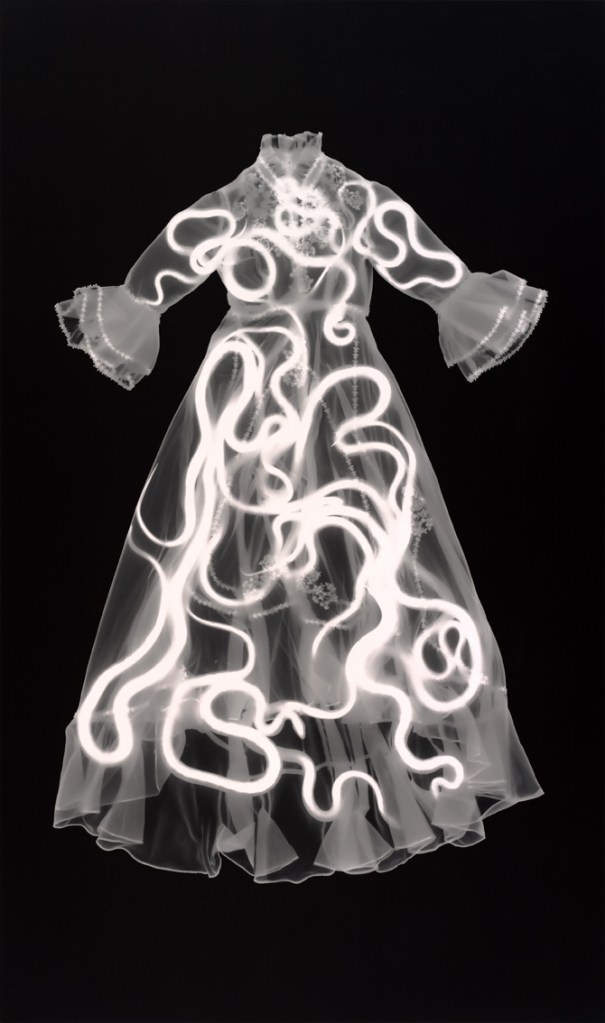

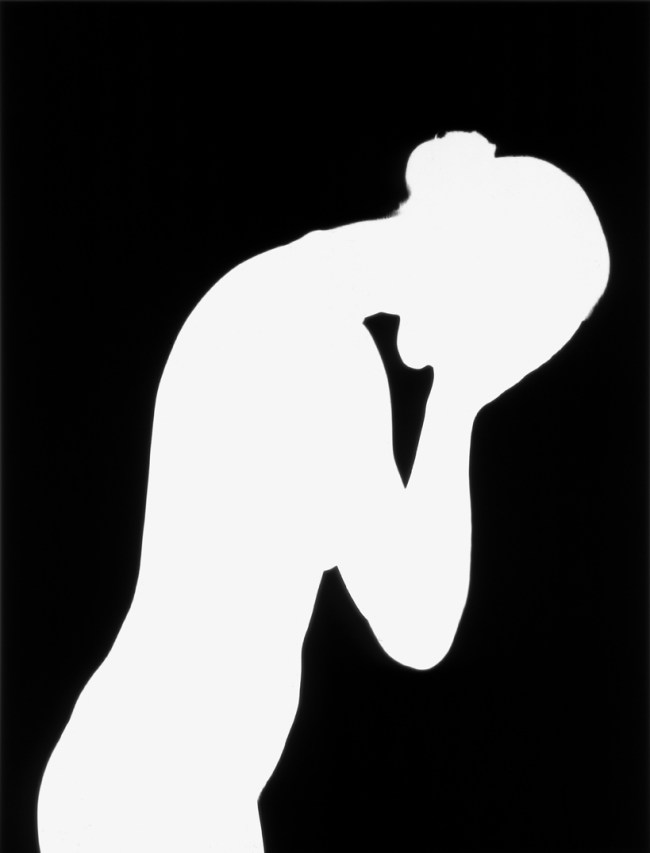

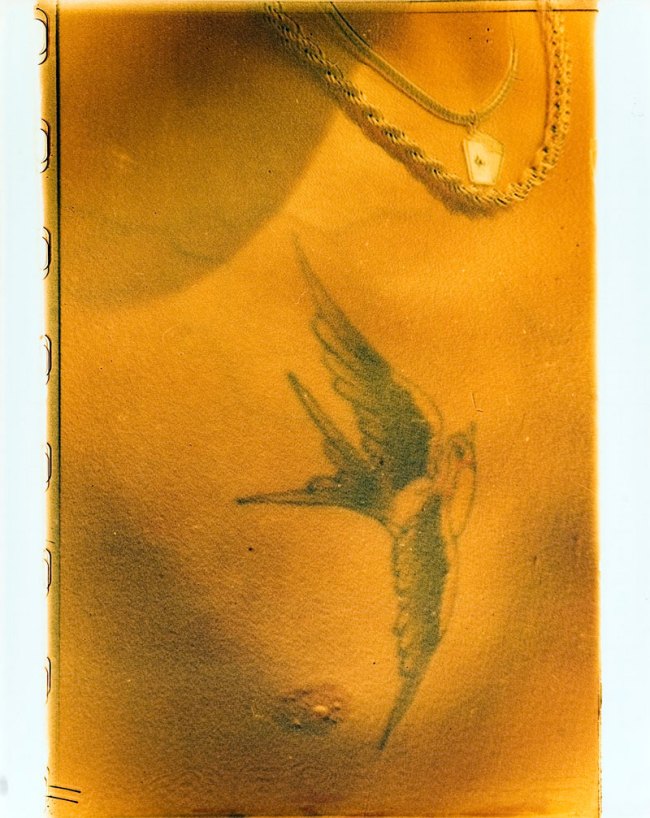

![Mark Morrisroe (American, 1959-1989) 'Untitled [Self-Portrait]' 1979 from the exhibition 'Mark Morrisroe' at Fotomuseum Winterthur Mark Morrisroe (American, 1959-1989) 'Untitled [Self-Portrait]' 1979 from the exhibition 'Mark Morrisroe' at Fotomuseum Winterthur](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/mark-morrisroe-untitled-self-portrait-19792.jpg)

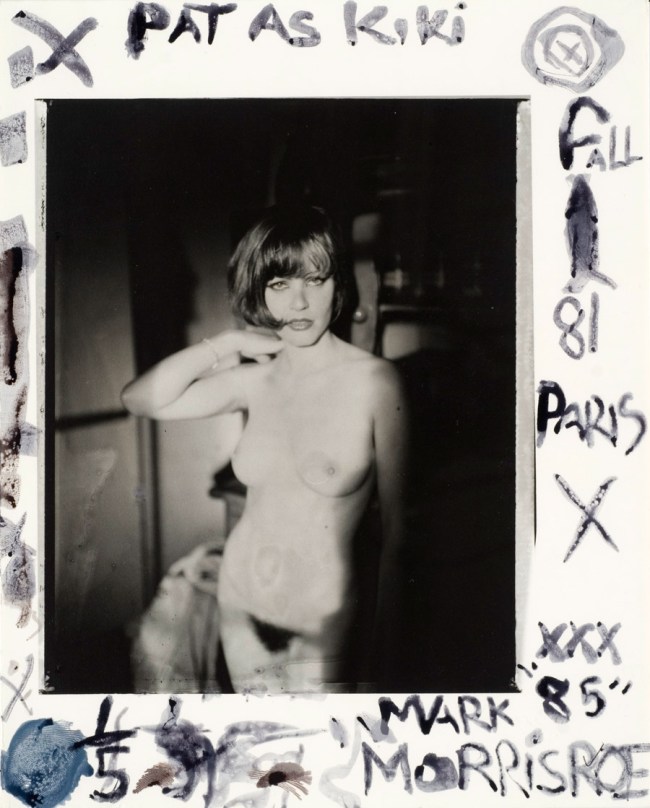

![Mark Morrisroe (American, 1959-1989) '

La Môme Piaf [Pat and Thierry]' 1982 from the exhibition 'Mark Morrisroe' at Fotomuseum Winterthur Mark Morrisroe (American, 1959-1989) '

La Môme Piaf [Pat and Thierry]' 1982 from the exhibition 'Mark Morrisroe' at Fotomuseum Winterthur](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/mark-morrisroe-la-mc3b4me-piaf-pat-and-thierry-1982.jpg?w=650)

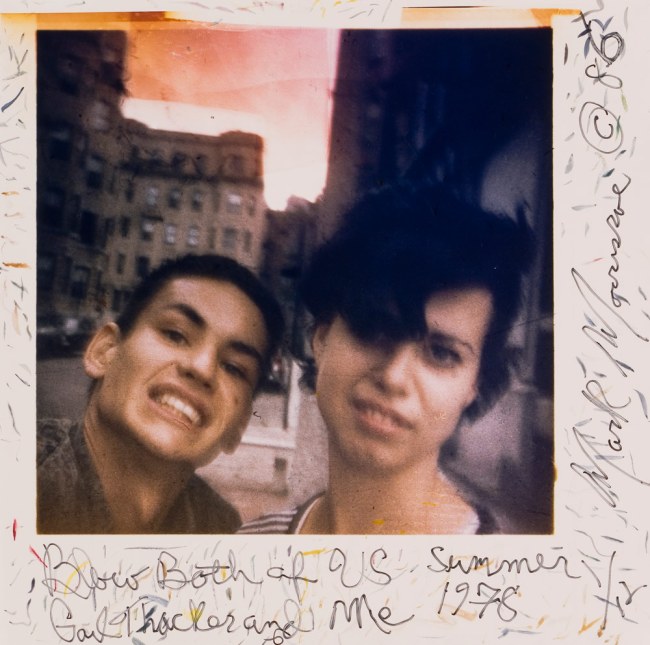

![Mark Morrisroe (American, 1959-1989) 'Untitled [Self-Portrait with Jonathan]' c. 1978 from the exhibition 'Mark Morrisroe' at Fotomuseum Winterthur Mark Morrisroe (American, 1959-1989) 'Untitled [Self-Portrait with Jonathan]' c. 1978 from the exhibition 'Mark Morrisroe' at Fotomuseum Winterthur](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/mark-morrisroe-untitled-self-portrait-with-jonathan-ca-1978.jpg?w=650)

![Mark Morrisroe (American, 1959-1989) 'Baby Steffenelli [John S.]' 1985 from the exhibition 'Mark Morrisroe' at Fotomuseum Winterthur Mark Morrisroe (American, 1959-1989) 'Baby Steffenelli [John S.]' 1985 from the exhibition 'Mark Morrisroe' at Fotomuseum Winterthur](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/02/morrisroe-baby-steffenelli.jpg?w=827)

![Mark Morrisroe (American, 1959-1989) 'Untitled [Self-Portrait]' 1986

from the exhibition 'Mark Morrisroe' at Fotomuseum Winterthur Mark Morrisroe (American, 1959-1989) 'Untitled [Self-Portrait]' 1986

from the exhibition 'Mark Morrisroe' at Fotomuseum Winterthur](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/mark-morrisroe-untitled-self-portrait-1986.jpg?w=650)

You must be logged in to post a comment.