Exhibition dates: 21st March – 14th September 2014

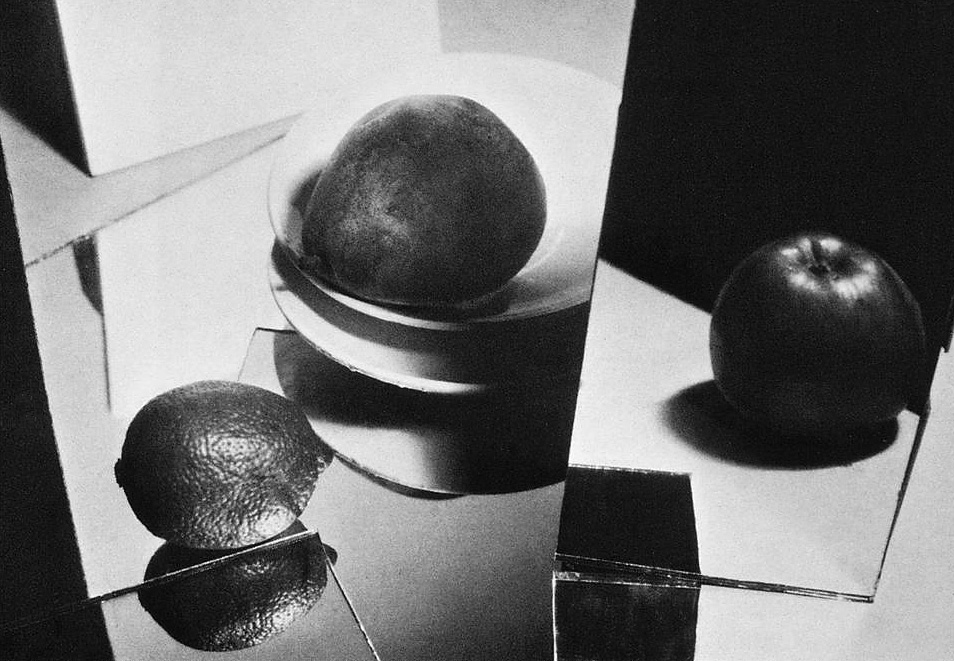

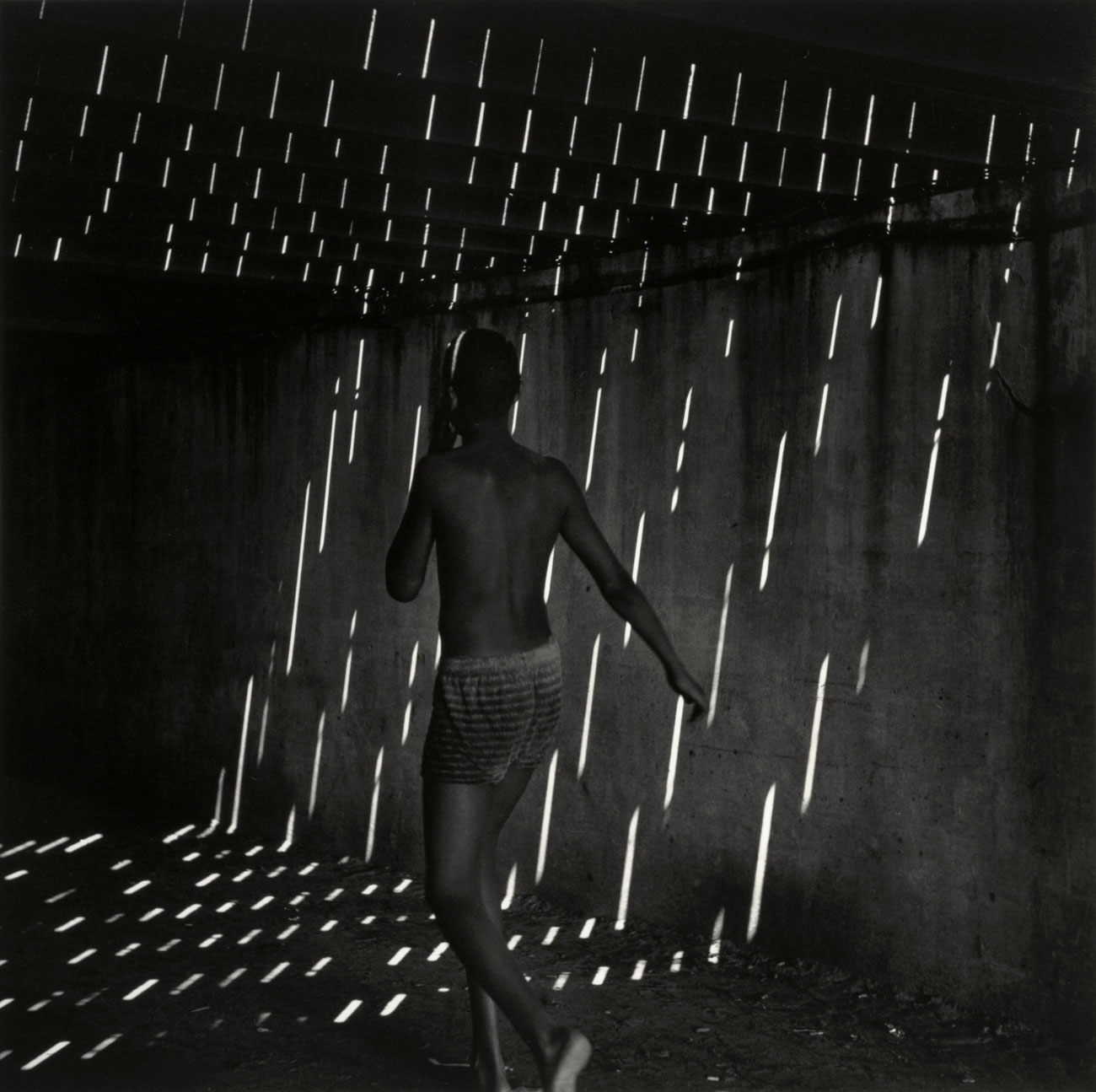

Florence Henri (French born America, 1893-1982)

Composition

Nd

When I started experimenting with a camera in the early 80s, my first experiments were with mirrors, shoes, tripod legs, cotton buds and reflections of myself in mirrors (with bright orange hair). I still have the commercially printed colour photos from the chemist lab!

Henri’s sophisticated, avante-garde, sculptural compositions have an almost ‘being there’ presence: a structured awareness of a way of looking at the world, a world in which the artist questions reality. She confronts the borders of an empirical reality (captured by a machine, the camera) through collage and mirrors, in order to take a leap of faith towards some form of transcendence of the real. Here she confronts the limitless freedom of creativity, of composition, to go beyond objectivity and science, to experience Existenz (Jaspers) – the realm of authentic being.*

These photographs are her experience of being in the world, of Henri observing the breath of being – the breath of herself, the breath of the objects and a meditation on those objects. There is a stillness here, an eloquence of construction and observation that goes beyond the mortal life of the thing itself. That is how these photographs seem to me to live in the world. I may be completely wrong, I probably am completely wrong – but that is how these images feel to me: a view, a perspective, the artist as prospector searching for a new way of authentically living in the world.

I really like them.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

*For his own existential philosophy, [Karl] Jaspers’ aim was to indirectly outline the metaphysical features of human Existenz – which means, what it’s like to experience being human in our full freedom – and to encourage every individual to realise his or her own authentic self-being by a subjective existential activity of thought which isn’t objectively describable.

“Existence in one sense refers to the sum total of reality, and in another sense, the elusive characteristic of being which differentiates real things from fictional ones.7 For Jasper, Existence as it pertains to Being is called Encompassing. It is the form of our awareness of being which underlies all our scientific and common-sense knowledge and which is given expression in the myths and rituals of religion. This awareness is not that of an object, but reflection on the subjective situation of being. Thus existence is about reflection upon the horizon of life, accepting the limitless possibilities in reality and also accepting that even though we can enlarge the extent of our knowledge, we can never escape the fact that it is fragmentary and has a limit.

He says:

“By reflecting upon that course (the limitless horizon of reality) we ask about being itself, which always seems to recede from us, in the very manifestation of all the appearances we encounter. This being we call the encompassing. But the encompassing is not the horizon of our knowledge at any particular moment. Rather, it is the source from which all new horizons emerge, without itself ever being visible even as a horizon.9″”

Jaspers Karl, Philosophy of Existence. (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvanian Press, 1971), p. 18 quoted in Onyenuru Okechukwu. P. “The Theme of Existence in the Philosophy of Karl Jaspers,” No date, pp. 3-4 on the PhilPapers website [Online] Cited 16/06/2021.

Thankx to the Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich for allowing me to publish five of the photographs in the posting. The other images have all been sourced from the internet. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Florence Henri (French born America, 1893-1982)

Composition

1931

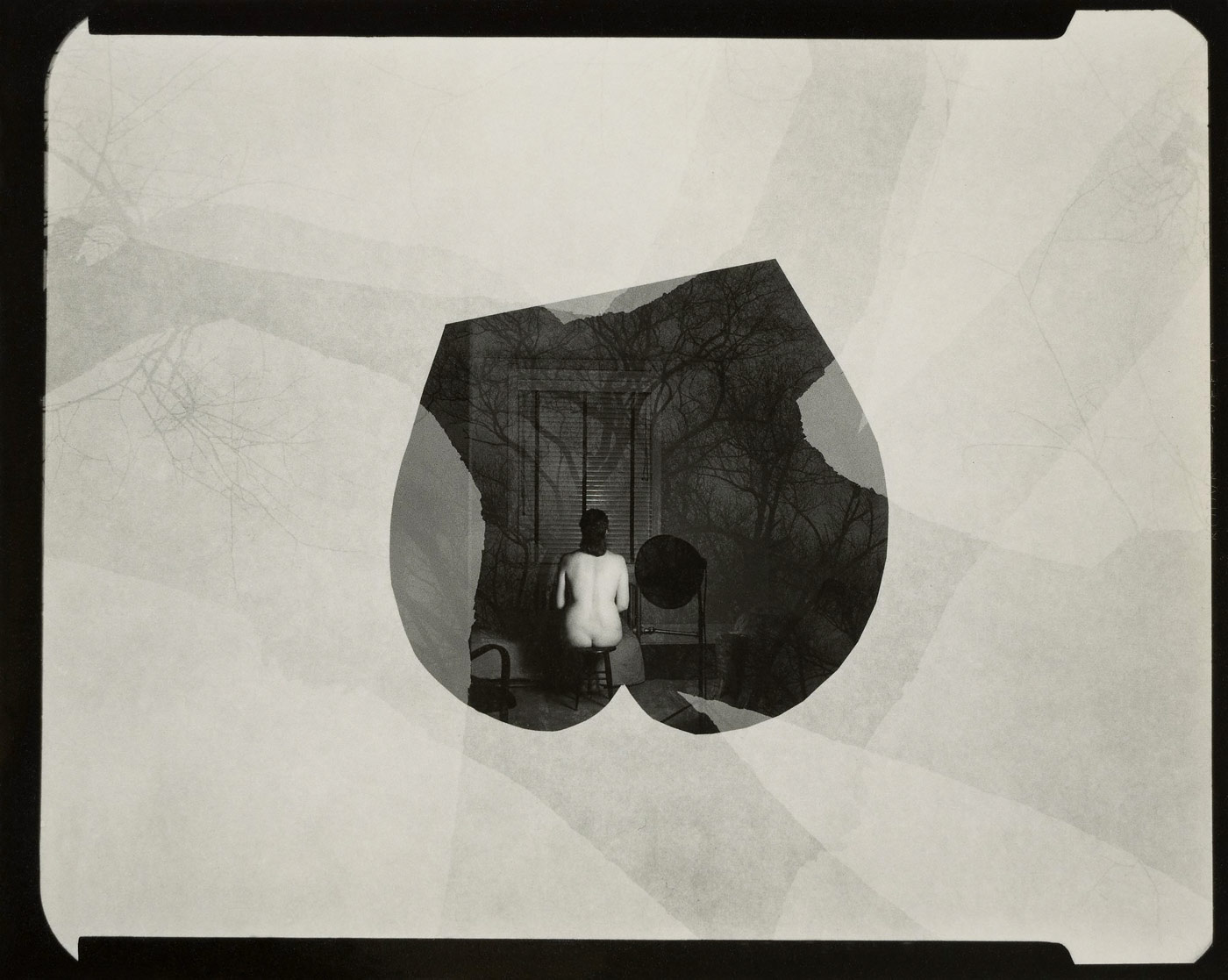

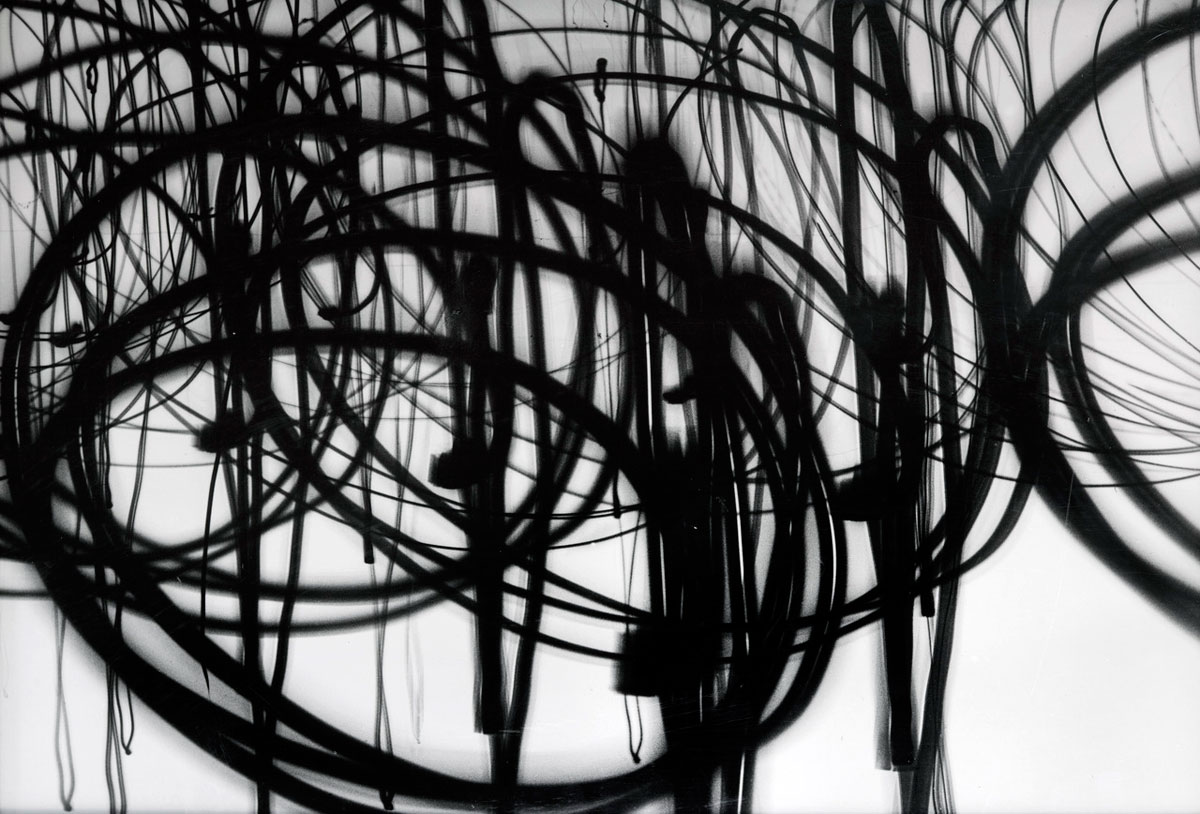

Florence Henri (French born America, 1893-1982)

Composition No 10

1928

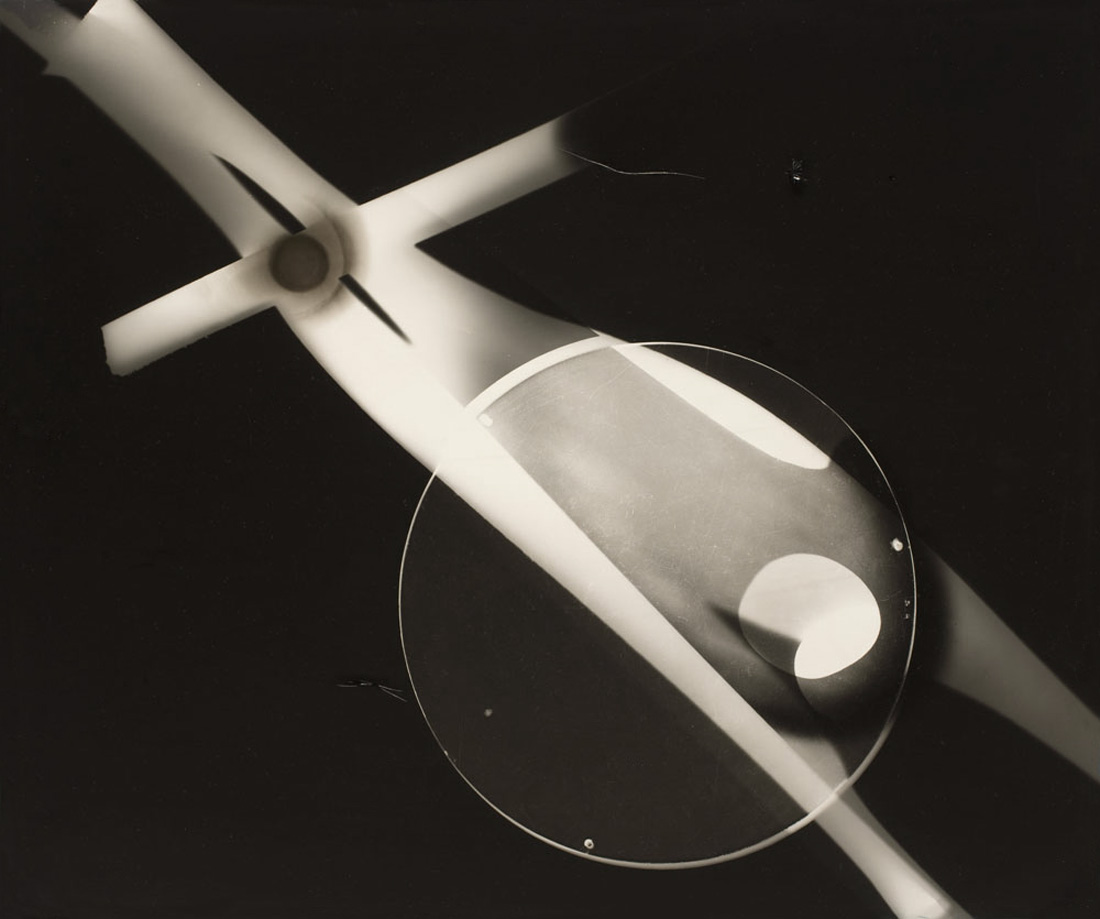

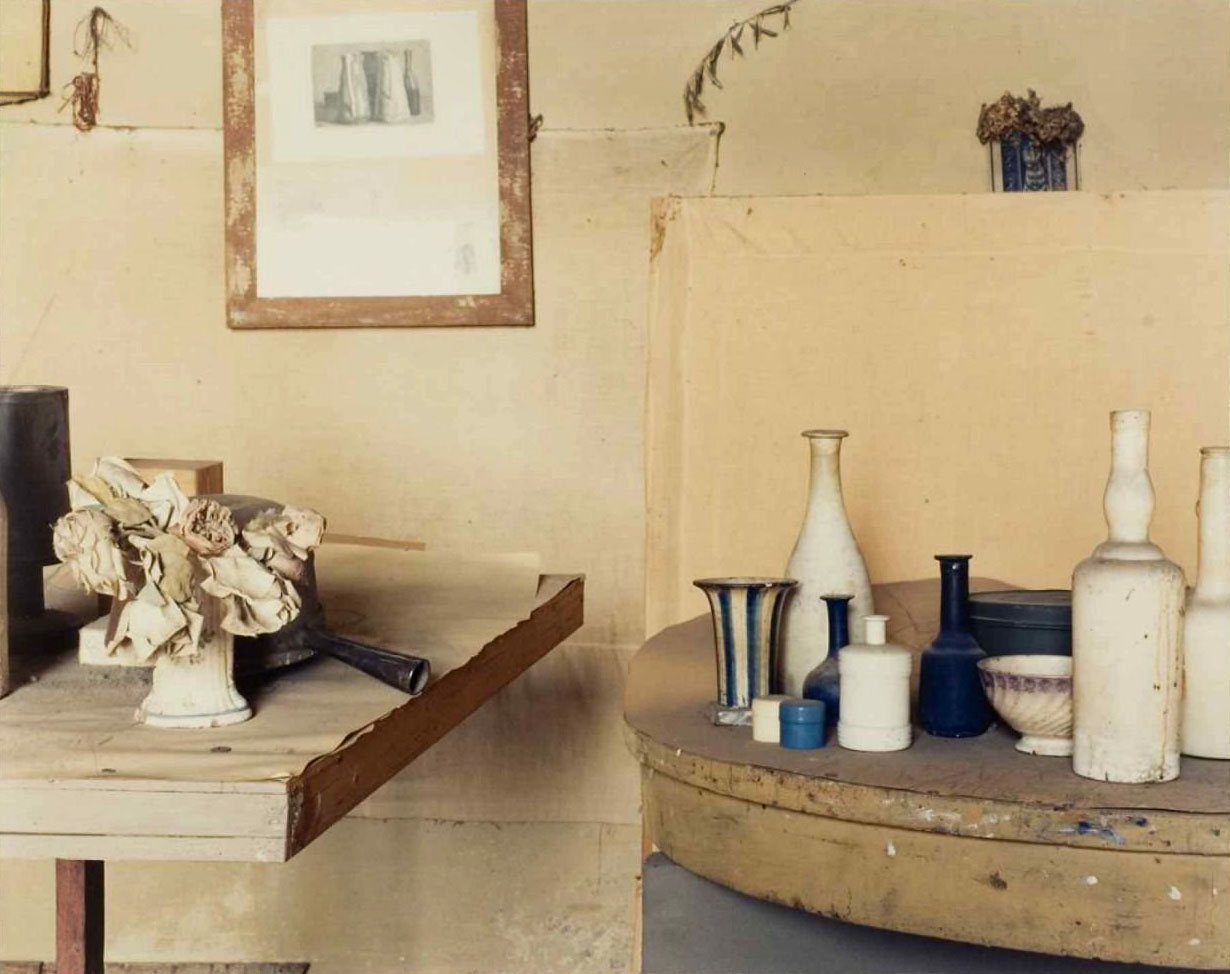

Florence Henri (French born America, 1893-1982)

Abstract Composition

1928

Stiftung Ann und Jürgen Wilde, Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich

The photographs and photo-montages of Florence Henri (1893-1982) attest to her broad artistic education and an unusual openness for new currents in the art of the time.

The artist, who had studied the piano under Ferruccio Busoni in Rome and painting in Paris under Fernand Léger, in Berlin under Johann Walter-Kurau and in Munich under Hans Hofmann, spent a brief semester as a guest at the Bauhaus in Dessau in 1927. Although photography was not part of the curriculum at the Bauhaus at this time, lecturers such as László Moholy-Nagy and Georg Muche, as well as pupils including Walter Funkat and Edmund Collein experimented intensively with this medium. It was here that Florence Henri gained the inspiration to become a photographer herself.

That same year she returned to Paris, stopped painting and devoted herself thoroughly to photography. She created extensive series of still lifes and portrait and self-portrait compositions, in which the artist divided up the pictorial space using mirrors and reflective spheres, expanding it structurally. The fragmented images created this way point to the inspiration Florence Henri gained from Cubist and Constructivist pictorial concepts.

Through her experimental photography Florence Henri swiftly became a highly respected exponent of modern photography and participated in numerous international shows such as the trailblazing Werkbund exhibition ‘Film und Foto’ in 1929. After World War II, however, the artist no longer pursued her photographic interest with the same intensity as before, devoting herself instead almost exclusively to painting. This most certainly also contributed to her photographs largely falling into oblivion after 1945.

The emphasis in the exhibition Florence Henri. Compositions in the Pinakothek der Moderne has been placed on the artist’s compositions using mirrors and her photo-montages, It comprises some 65 photographs, including the portfolio published in 1974, as well as documents and historical publications from the holdings of the Ann and Jürgen Wilde Foundation. As such, Ann and Jürgen Wilde significantly contributed towards the rediscovery of this exceptional artist’s work. Her photographic oeuvre now has a permanent place within the art of the avant-garde.

Press release from the Pinakothek der Moderne website

Florence Henri (French born America, 1893-1982)

Still-Life Composition

1929

Florence Henri (French born America, 1893-1982)

Abstract Composition

1932

Florence Henri (French born America, 1893-1982)

Still-life with Lemon and Pear

c.1929

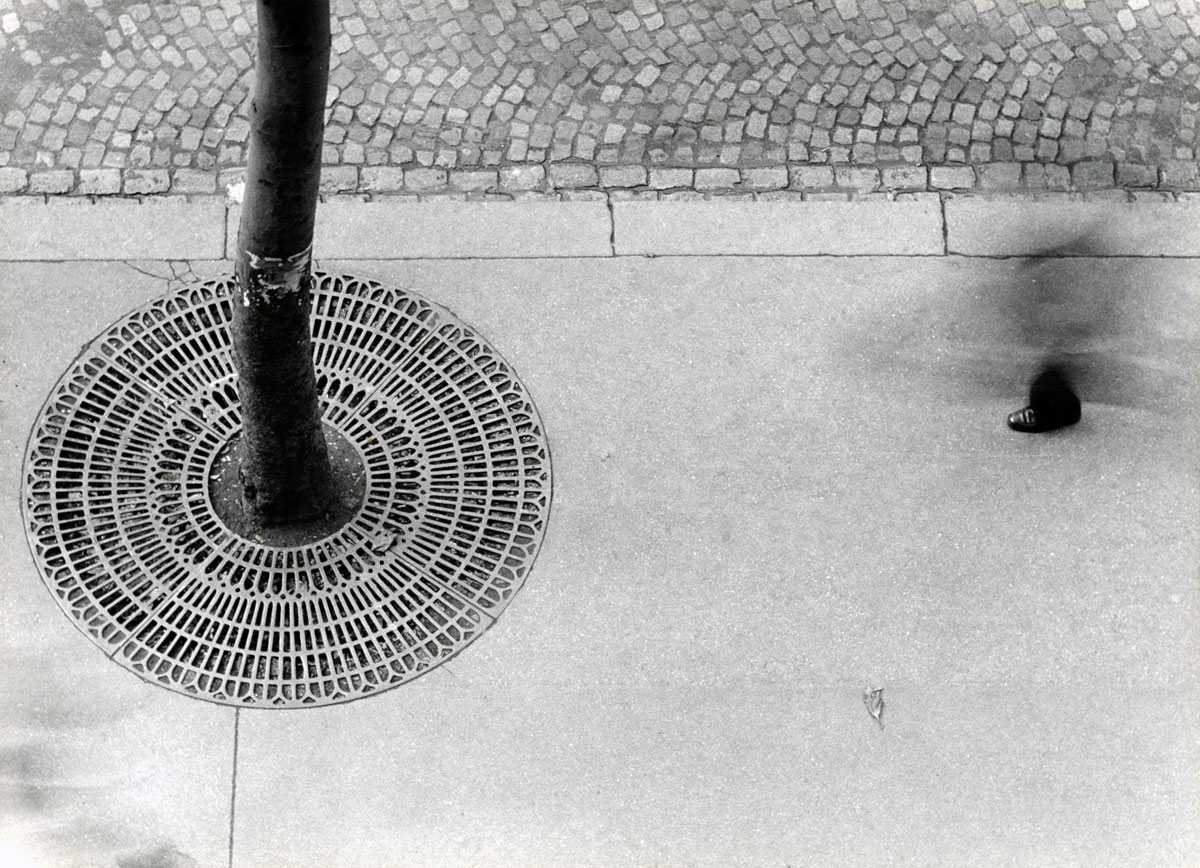

Florence Henri (French born America, 1893-1982)

Little Boot

1931

Florence Henri was born in New York on 28 June 1893; her father was French and her mother was German. Following her mother’s death in 1895, she and her father moved first to her mother’s family in Silesia; she later lived in Paris, Munich and Vienna and finally moved to the Isle of Wight in England in 1906. After her father’s death there three years later, Florence Henri lived in Rome with her aunt Anni and her husband, the Italian poet Gino Gori, who was in close touch with the Italian Futurists. She studied piano at the music conservatory in Rome.

During a visit to Berlin, Henri started to focus on painting, after meeting the art critic Carl Einstein and, through him, Herwarth Walden and other Berlin artists. In 1914, she enrolled at the Academy of Art in Berlin, and starting in 1922, trained in the studio of the painter Johannes Walter-Kurau. Before moving to Dessau, Henri studied painting with the Purists Fernand Léger and Amédée Ozenfant at the Académie Moderne in Paris. She arrived at the Bauhaus in Dessau in April 1927. She had already met the Bauhaus artists Georg Muche and László Moholy-Nagy and had developed a passion for Marcel Breuer’s tubular steel furniture. Up to July 1927, Henri attended the preliminary course directed by Moholy-Nagy, lived in the Hungarian artist’s house, and became a close friend of his first wife,Lucia Moholy, who encouraged her to take up photography. From the Moholy-Nagys, Henri learned the basic technical and visual principles of the medium, which she used in her initial photographic experiments after leaving Dessau. In early 1928, she abandoned painting altogether and from then on focused on photography, with which she established herself as a professional freelance photographer with her own studio in Paris – despite being self-taught.

Even during her first productive year as a photographer, László Moholy-Nagy published one of her unusual self-portraits, as well as a still life with balls, tyres, and a mirror, in i10. Internationale Revue. The first critical description of her photographic work, which Moholy-Nagy wrote to accompany the photos, recognises that her pictures represented an important expansion of the entire ‘problem of manual painting’, in which ‘reflections and spatial relationships, overlapping and penetrations are examined from a new perspectival angle’.

Mirrors become the most important feature in Henri’s first photographs. She used them both for most of her self-dramatisations and also for portraits of friends, as well as for commercial shots. She took part in the international exhibition entitled Das Lichtbild [The Photograph] in Munich in 1930, and the following year she presented her images of bobbins at a Foreign Advertising Photography exhibition in New York. The artistic quality of her photographs was compared with Man Ray, László Moholy-Nagy and Adolphe Baron de Mayer, as well as the with winner of the first prize at the exhibition, Herbert Bayer. Only three years after the new photographer had taken her first pictures, her self-portrait achieved the equal status with her male colleagues that she had been aiming for.

Up to the start of the Second World War, Henri established herself as a skilled photographer with her own photographic studio in Paris (starting in 1929). When the city was occupied by the Nazis, her photographic work declined noticeably. The photographic materials needed were difficult to obtain, and in any case Henri’s photographic style was forbidden under the Nazi occupation; she turned her attention again to painting. With only a few later exceptions, the peak of her unique photographic experiments and professional photographic work was in the period from 1927 to 1930.

Even in the 1950s, Henri’s photographs from the Thirties were being celebrated as icons of the avant-garde. Her photographic oeuvre was recognised during her lifetime in one-woman exhibitions and publications in various journals, including N-Z Wochenschau. She also produced photographs during this period, such as a series of pictures of the dancer Rosella Hightower. She died in Compiègne on 24 July 1982.

Text from the Florence Henri web page on the Bauhaus Online website [Online] Cited 06/07/2014. No longer available online

Florence Henri (French born America, 1893-1982)

Parisian Window

1929

Florence Henri (French born America, 1893-1982)

The Forum

1934

Florence Henri (French born USA, 1893-1982)

Rome

1933-1934

Florence Henri (French born America, 1893-1982)

Abstract Composition

1929

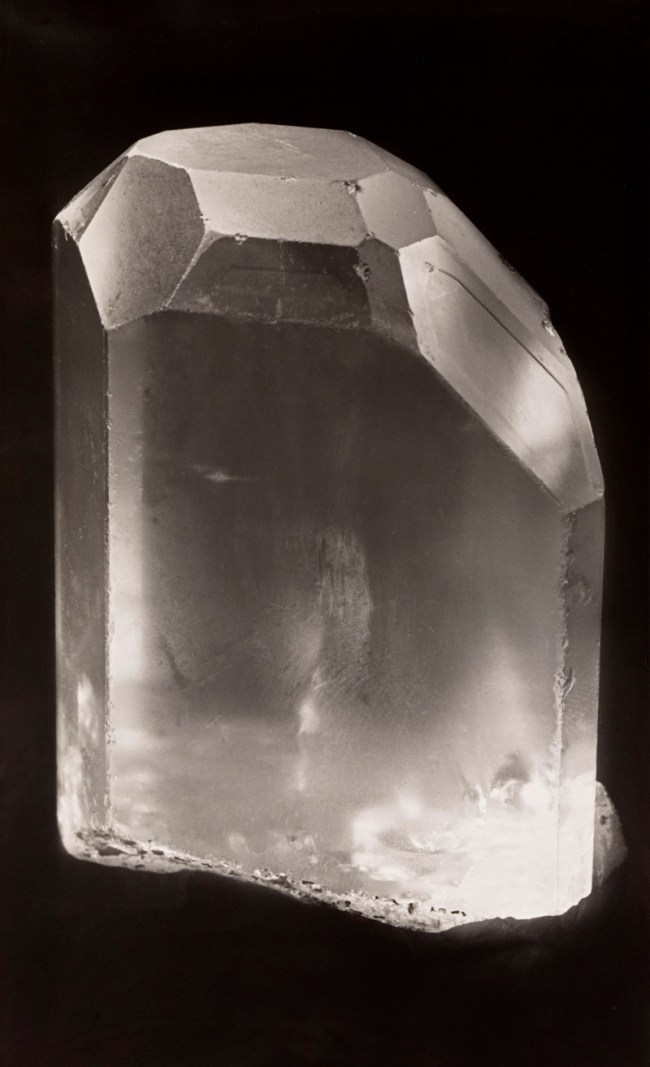

Florence Henri (French born America, 1893-1982)

Self-portrait in a mirror

1928

Florence Henri (French born America, 1893-1982)

A Bunch of Grapes

c. 1934

Florence Henri (French born America, 1893-1982)

Composition

1932

Stiftung Ann und Jürgen Wilde, Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich

Florence Henri (French born America, 1893-1982)

Untitled, USA

1940

Florence Henri (French born America, 1893-1982)

Paris Window

1929

Stiftung Ann und Jürgen Wilde, Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich

Florence Henri (French born America, 1893-1982)

Portrait

1928

Stiftung Ann und Jürgen Wilde, Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich

Florence Henri (French born America, 1893-1982)

Self Portrait

1928

Stiftung Ann und Jürgen Wilde, Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich

Pinakothek der Moderne

Barer Strasse 40

Munich

Opening hours:

Daily except Monday 10am – 6pm

Thursday 10am – 8pm

![Wols (German, 1913-1951) 'Untitled [Still life - dining table]' 1937 Wols (German, 1913-1951) 'Untitled [Still life - dining table]' 1937](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/wols_09_esstisch-web.jpg?w=650&h=673)

![Wols (German, 1913-1951) 'Untitled [Pavilion de l'Elegance - Creating a home with Alix (Germaine Krebs)]' 1937 Wols (German, 1913-1951) 'Untitled [Pavilion de l'Elegance - Creating a home with Alix (Germaine Krebs)]' 1937](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/wols_05_pavillon_de_l_elegance_2-web.jpg?w=650&h=950)

![Wols (German, 1913-1951) 'Untitled [Swiss Pavilion - Wire Figure]' 1937 Wols (German, 1913-1951) 'Untitled [Swiss Pavilion - Wire Figure]' 1937](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/wols_04_pavillon_drahtfigurine-web.jpg?w=650&h=871)

![Wols (German, 1913-1951) 'Untitled [Paris - Flea Market]' Autumn 1932 - October 1933 / January 1935 to 1936 Wols (German, 1913-1951) 'Untitled [Paris - Flea Market]' Autumn 1932 - October 1933 / January 1935 to 1936](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/wols_08_flohmarkt-web.jpg?w=650&h=870)

![Wols (German, 1913-1951) 'Untitled [Paris - Palisade]' Fall 1932 - October 1933 / January 1935 - August 1939 Wols (German, 1913-1951) 'Untitled [Paris - Palisade]' Fall 1932 - October 1933 / January 1935 - August 1939](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/wols_07_paris_palisade.jpg?w=650&h=1069)

![Wols (German, 1913-1951) 'Untitled [Paris - Eiffel Tower]' 1937 Wols (German, 1913-1951) 'Untitled [Paris - Eiffel Tower]' 1937](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/wols_03_eiffelturm-web.jpg?w=650&h=914)

![Wols (German, 1913-1951) 'Untitled [Still Life - Grapefruit]' 1938 - August 1939 Wols (German, 1913-1951) 'Untitled [Still Life - Grapefruit]' 1938 - August 1939](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/wols_06_pampelmuse-web.jpg?w=650&h=925)

![Fritz Winter (German, 1905-1976) 'Stufungen [Gradations]' 1934 Fritz Winter (German, 1905-1976) 'Stufungen [Gradations]' 1934](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/fritz-winter-stufungen-1934-web.jpg?w=650&h=921)

![Fritz Winter (German, 1905-1976) 'Weiß in Schwarz [White in Black]' 1934 Fritz Winter (German, 1905-1976) 'Weiß in Schwarz [White in Black]' 1934](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/fritz-winter-weic39f-in-schwarz-1934-web.jpg?w=650&h=880)

![Oliver Boberg (German, b. 1965) 'Unterführung' [Underpass] 1997 Oliver Boberg (German, b. 1965) 'Unterführung' [Underpass] 1997](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/r_p_oliver-boberg-unterfuehrungdruckbar-web.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.