Exhibition dates: 7th October, 2016 – 26th February, 2017

An exhibition showcasing Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer artistic life in New York City through the social networks of Leonard Bernstein, Mercedes de Acosta, Harmony Hammond, Bill T. Jones, Lincoln Kirstein, Greer Lankton, George Platt Lynes, Robert Mapplethorpe, Richard Bruce Nugent, and Andy Warhol.

Curators: Donald Albrecht, MCNY curator of architecture and design, and Stephen Vider, MCNY Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow.

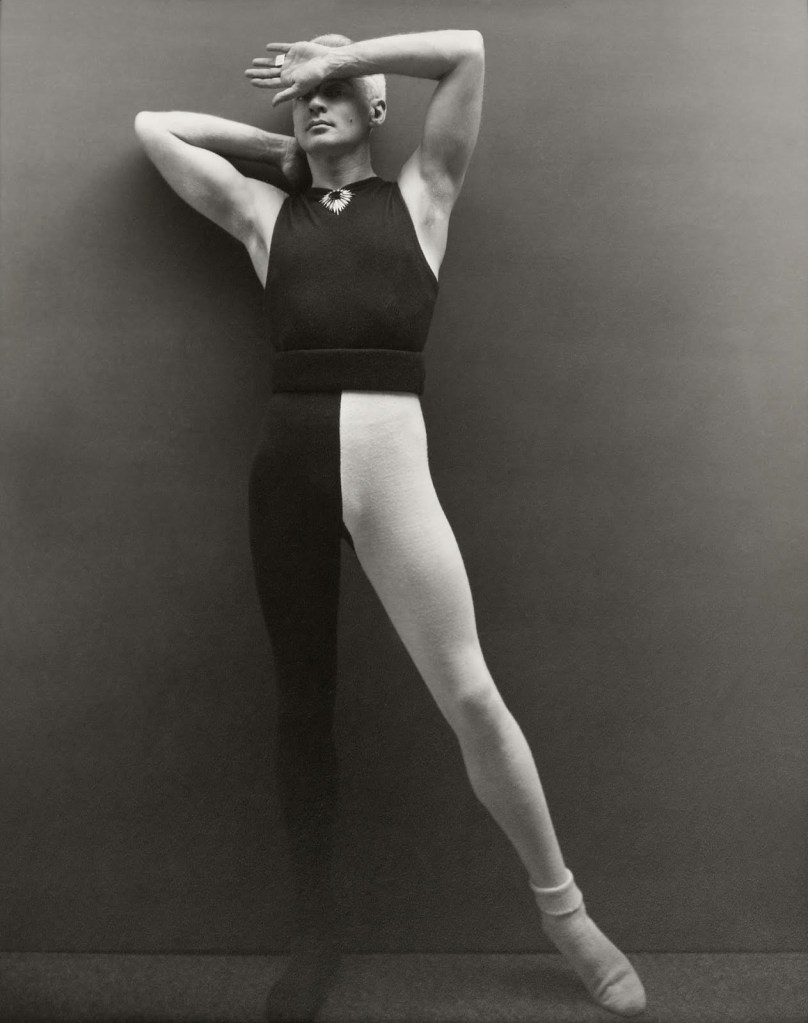

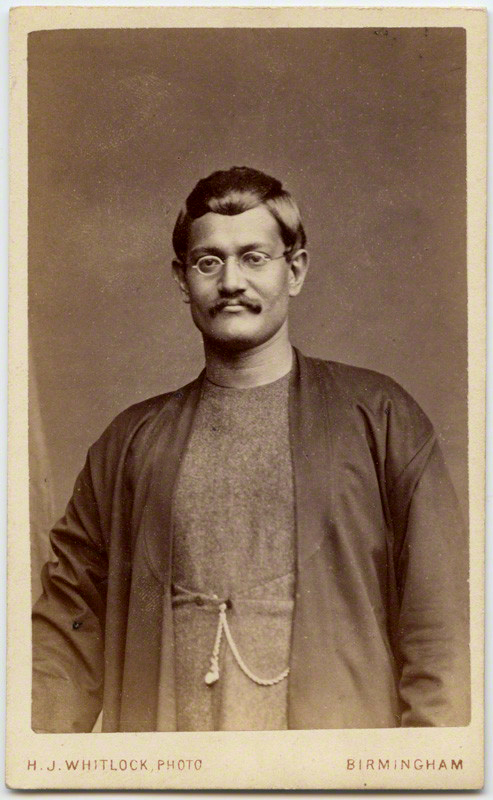

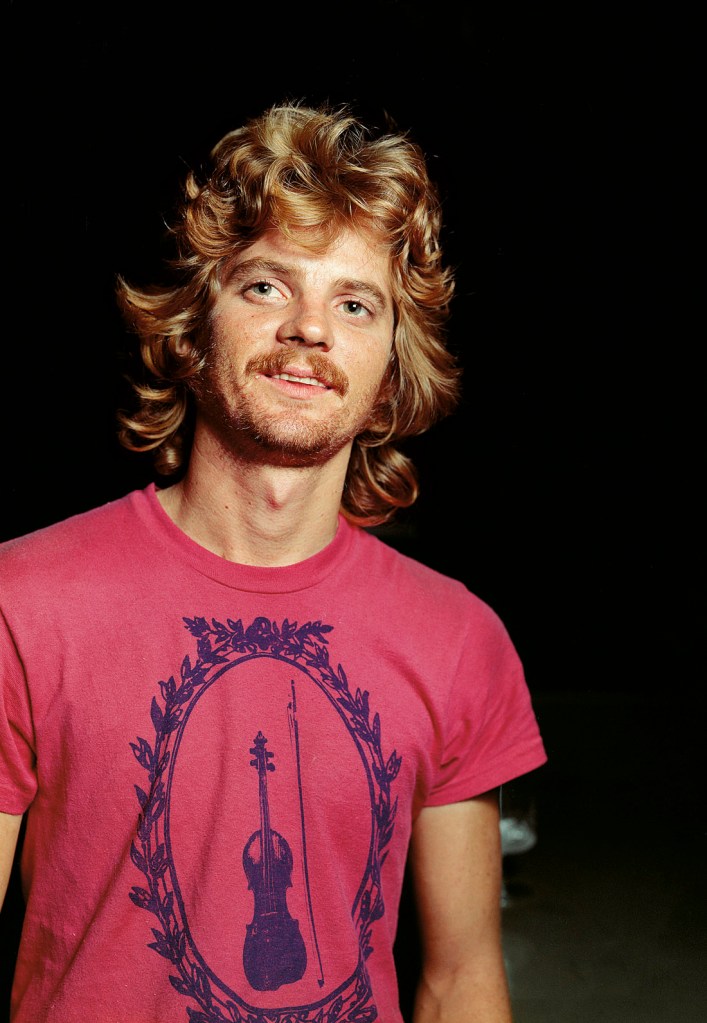

The Young Physique

October/November 1964

Collection of Kelly McKaig

Part two of this monster posting on the exhibition Gay Gotham: Art and Underground Culture in New York at the Museum of the City of New York.

Highlights include photographs by Carl Van Vechten; art work by and of Andy Warhol; a video of the “Panzy Craze” of the the 1920s and 1930s; a photograph of a very young and skinny Robert Mapplethorpe and some of his early art work; some wonderful subversiveness from Greer Lankton; two glorious photographs from one of my favourite artists, Peter Hujar; and a great selection of book covers and posters, including the ever so sensual, German Expressionist inspired Nocturnes for the King of Naples cover art by Mel Odom.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thank to the Museum of the City of New York for allowing me to publish the art work in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Themes ~

Printing

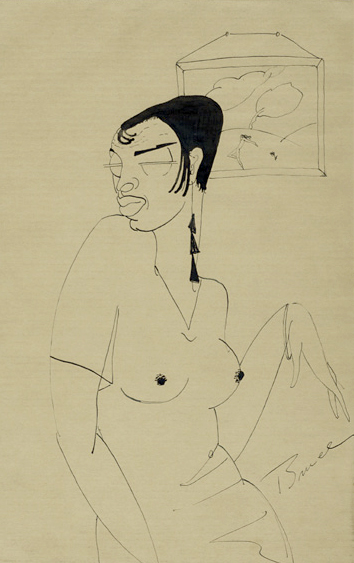

Foujita (Japanese-French, 1886-1968)

“Helen Morgan Jr. And Jean Malin at the Smart Club Abbey”

Vanity Fair

February 1931

Private collection

Léonard Tsuguharu Foujita (藤田 嗣治 Fujita Tsuguharu, November 27, 1886 – January 29, 1968) was a Japanese-French painter and printmaker born in Tokyo, Japan, who applied Japanese ink techniques to Western style paintings. He has been called “the most important Japanese artist working in the West during the 20th century”. His Book of Cats, published in New York by Covici Friede, 1930, with 20 etched plate drawings by Foujita, is one of the top 500 (in price) rare books ever sold, and is ranked by rare book dealers as “the most popular and desirable book on cats ever published”.

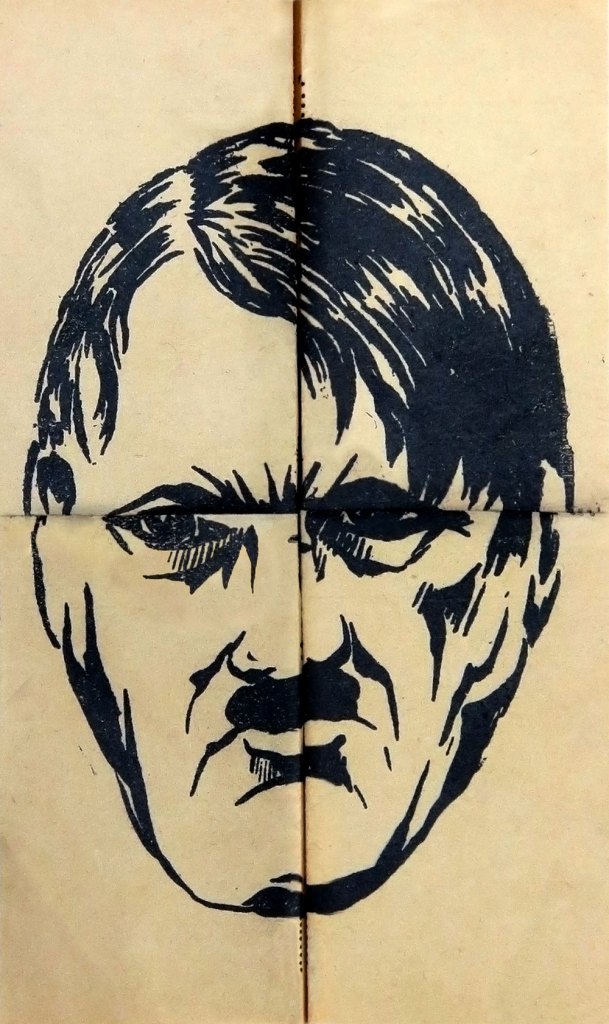

André Tellier (French, b. 1902)

Twilight Men (Greenberg, New York)

1931

Fales Library and Special Collections, New York University

First published in 1931, this is an extremely uncommon early novel set in New York City of homosexuality and a young man whose gay tendencies infuriates his father, who attempts to set him upon the “path of normality” by hiring a mistress to seduce him.

“Like many early gay novels, the book does not have a happy ending: the main character becomes addicted to drugs, murders his father, and kills himself. This theme (the gay monster or the gay degenerate) occurs very frequently before the 1960’s. Originally, this was the only way that a book with any kind of gay themes could even be published; that is, it was only palatable – or even legal – to feature a gay protagonist if that person “gets what’s coming to him” in the end.

The February 1934 issue of Chanticleer, a gay literary “magazine,” includes reviews by Henry Gerber of several novels, including Twilight Men. He wrote: “TWILIGHT MEN, by Andre Tellier, deals with a young Frenchman, who comes to America, is introduced into homosexual society in New York, becomes a drug addict for no obvious reason, finally kills his father and commits suicide. It is again excellent anti-homosexual propaganda, although the plot is too silly to convince anyone who has known homosexual people at all.”

Little has been written about the author, Andre Tellier, himself. He wrote other books, including A Woman of Paris, The Magnificent Sin, Vagabond April, and Witchfire; but nothing else is really known about him.”

Anonymous text. “First Pages: Twilight Men by Andre Tellier,” on the Somewhere Books website December 28, 2012 [Online] Cited 22/11/2012.

Blair Niles (American, 1880-1959)

Strange Brother (Horace Liveright, New York)

1931

Fales Library and Special Collections, New York University

Strange Brother is a gay novel written by Blair Niles published in 1931. The story is about a platonic relationship between a heterosexual woman and a gay man and takes place in New York City in the late 1920s and early 1930s. Strange Brother provides an early and objective documentation of homosexual issues during the Harlem Renaissance.

Mark Thornton, the story’s protagonist, moves to New York City in hopes of feeling like less of an outsider. At a nightclub in Harlem he meets and befriends June Westbrook. One night they witness a man named Nelly being arrested. June encourages Mark to investigate. This leads Mark to attend Nelly’s trial, where he is found guilty and sentenced to six months’ imprisonment on Welfare Island for his feminine affections and gestures. Next Mark researches the crimes against nature sections of the penal code. Shaken up by his findings and the events, Mark confesses his own homosexuality to June.

Mark and June’s friendship continues to grow, and June introduces Mark to a number of friends in her social circle. Various social interactions ensue including a dinner party for a departing professor, a trip to a nightspot featuring a singer called Glory who sings Creole Love Call and attending a drag ball. Despite reading Walt Whitman’s poetry collection Leaves of Grass, Edward Carpenter’s series of papers Love’s Coming of Age, and Countee Cullen’s poetry, Mark is afraid to come out. Subsequently, Mark is threatened with being outed at work. In response to this threat, Mark commits suicide by shooting himself.

Text from the Wikipedia website

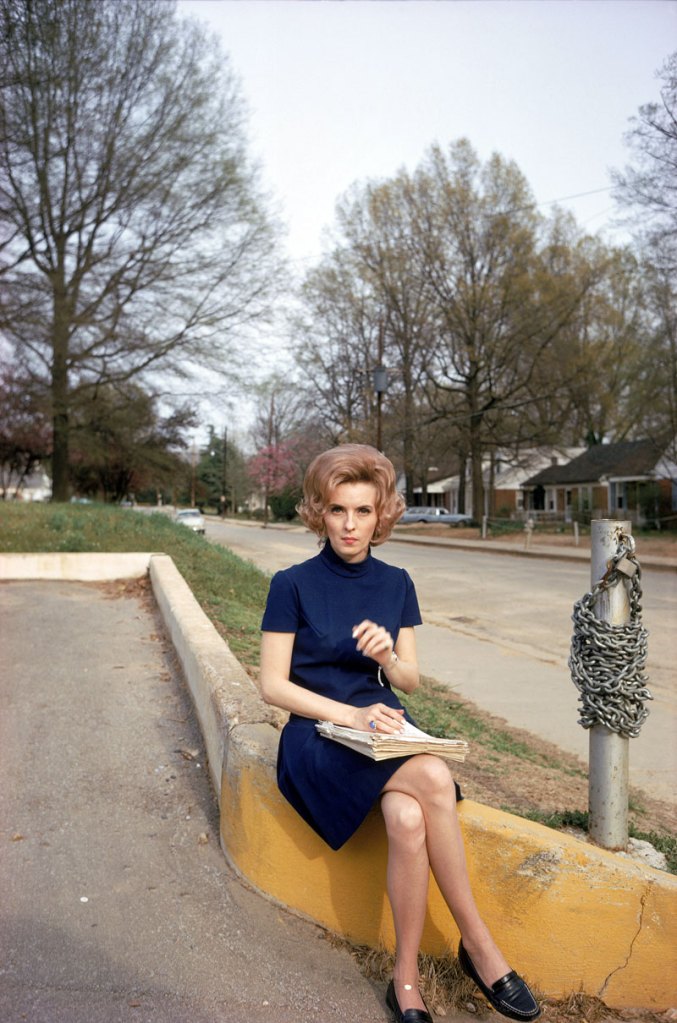

Ann Bannon (American, b. 1932)

I Am a Woman (Gold Medal Books, New York)

1959

Private collection

The classic 1950s novel from the Queen of Lesbian Pulp. “For contemporary readers the books offer a valuable record of gay and lesbian life in the 1950s. Most are set in Greenwich Village, and Ms. Bannon’s descriptions of bars, clubs and apartment parties vividly evoke a vanished community. Her characters also have historical value. Whereas most lesbians in pulp are stereotypes who get punished for their desires, Beebo and her friends are accessibly human. Their struggles with love and relationships are engrossing today, and half a century ago they were revolutionary.” ~ New York Times “Sex. Sleaze. Depravity. Oh, the twisted passions of the twilight world of lesbian pulp fiction.” ~ Chicago Free Press “Little did Bannon know that her stories would become legends, inspiring countless fledgling dykes to flock to the Village, dog-eared copies of her books in hand, to find their own Beebos and Lauras and others who shared the love they dared not name.” ~ San Francisco Bay Guardian “Ann Bannon is a pioneer of dyke drama.” ~ On Our Backs “When I was young, Bannon’s books let me imagine myself into her New York City neighbourhoods of short-haired, dark-eyed butch women and stubborn, tight-lipped secretaries with hearts ready to be broken. I would have dated Beebo, no question.” ~ Dorothy Allison “Bannon’s books grab you and don’t let go.” ~ Village Voice

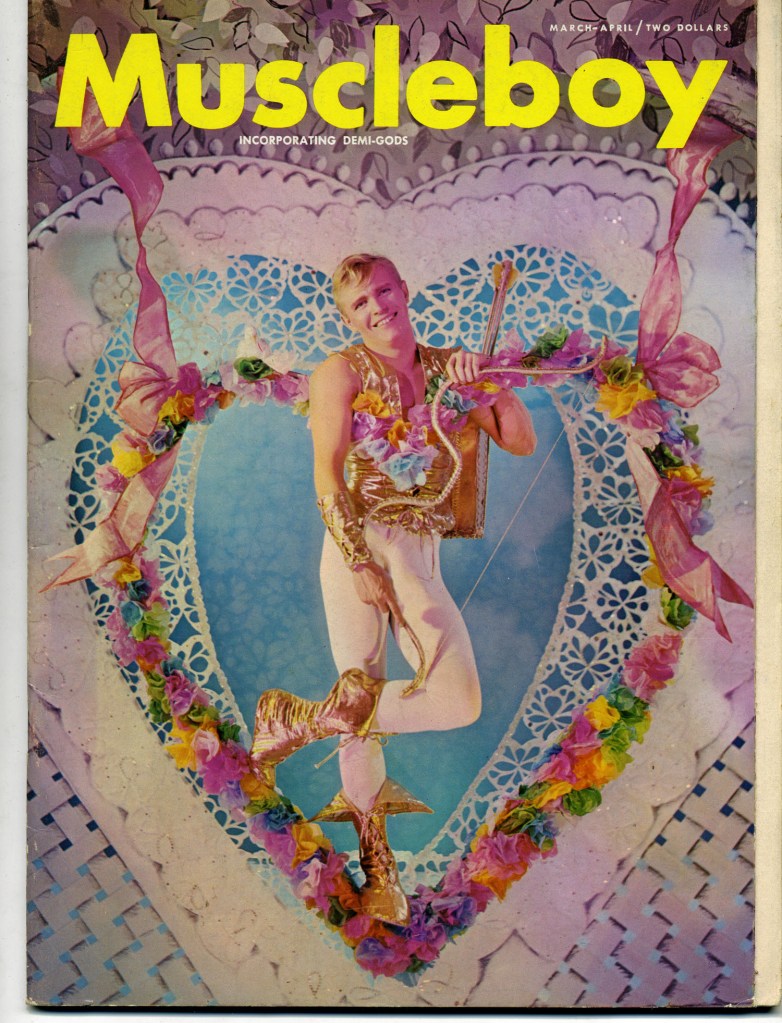

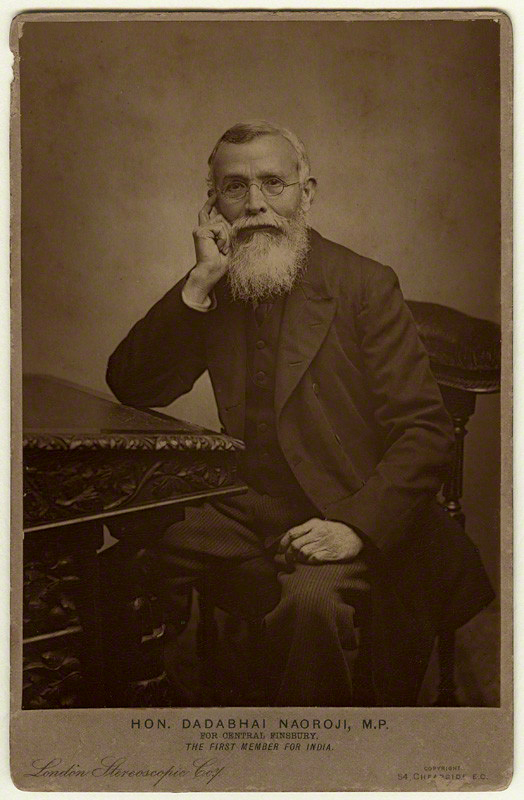

Muscleboy

March/April 1965

Collection of Kelly McKaig

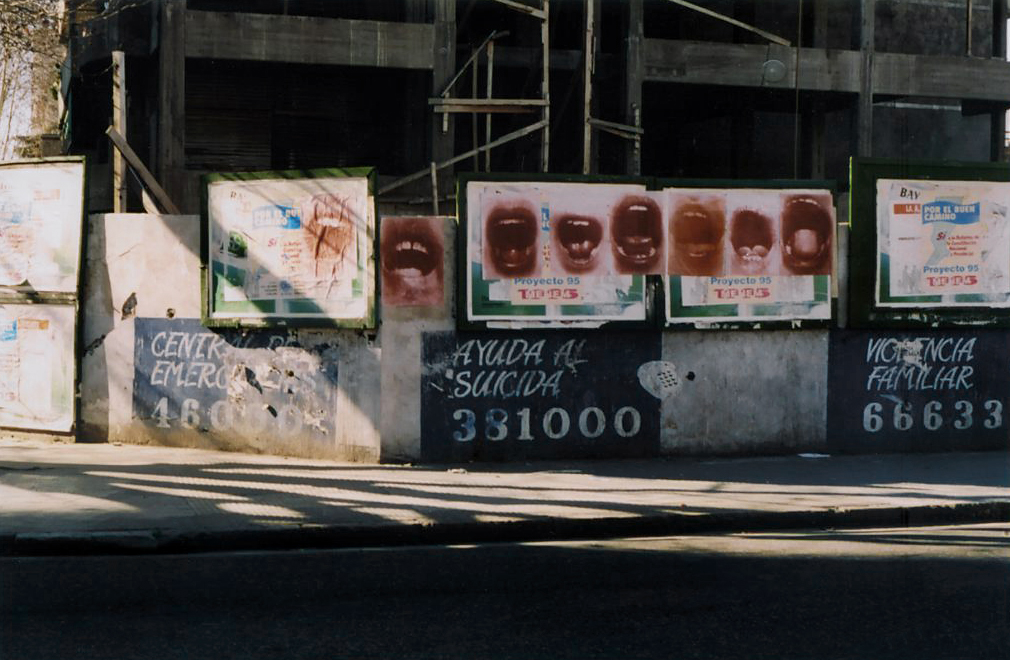

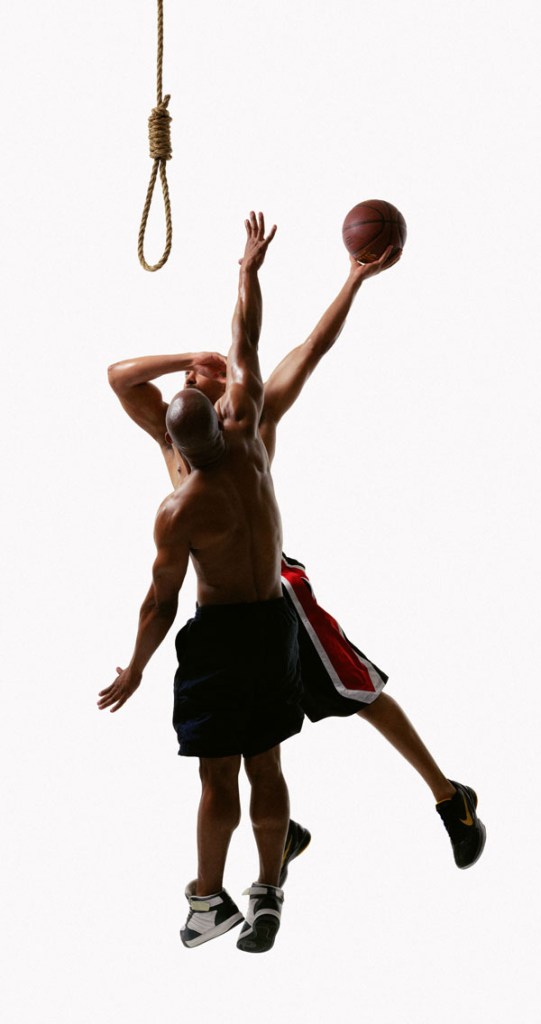

Design by Gran Fury for Art Against AIDS/On The Road and Creative Time, Inc.

Kissing Doesn’t Kill: Greed and Indifference Do

1989

Bus poster

Gran Fury, Courtesy The New York Public Library Manuscripts and Archives Division

Placemaking: Cruising

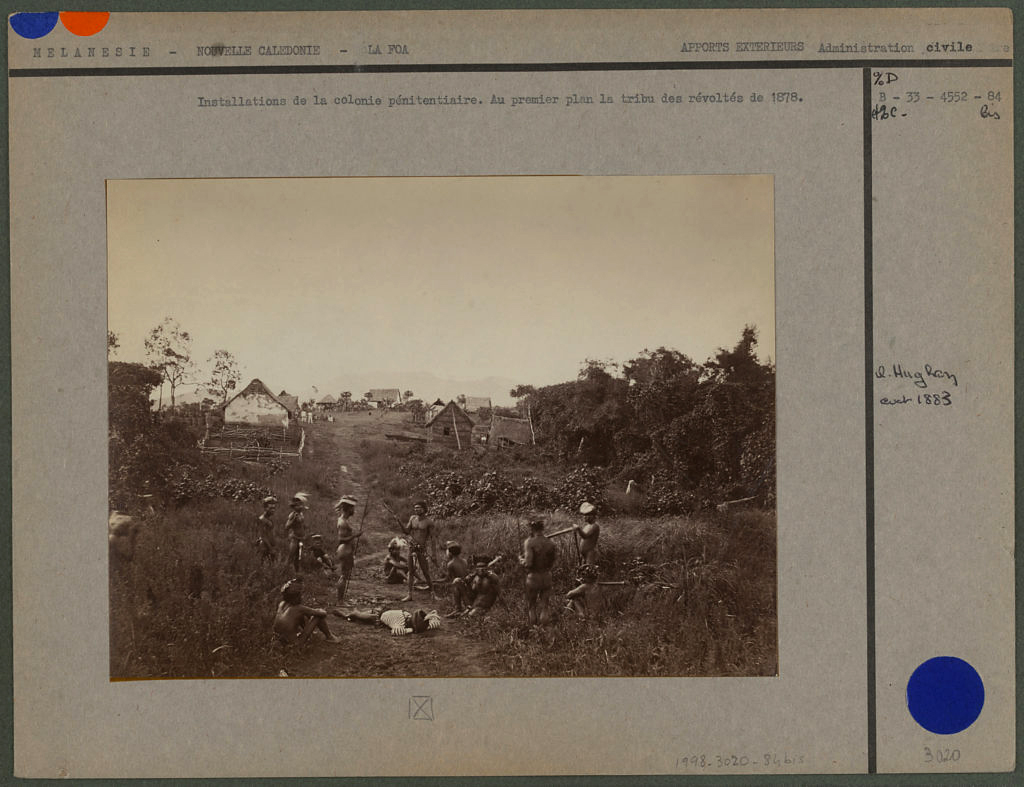

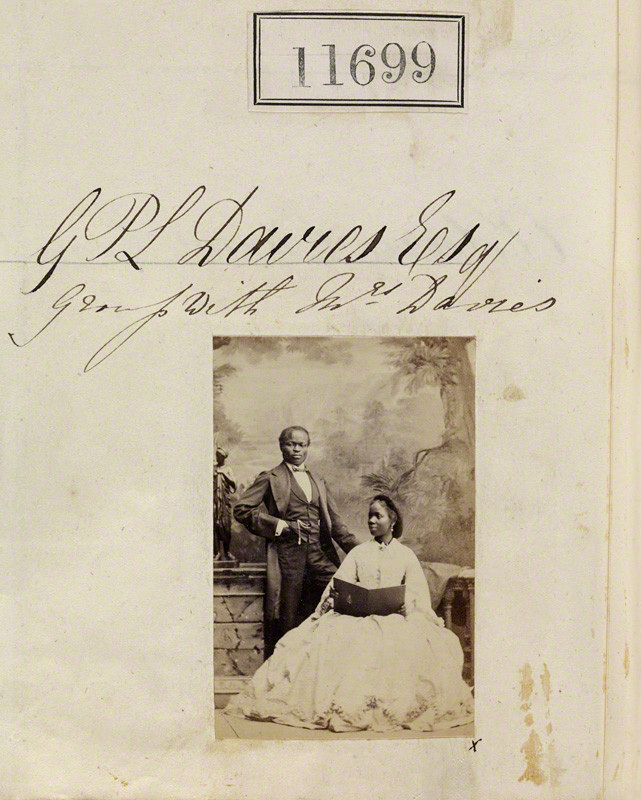

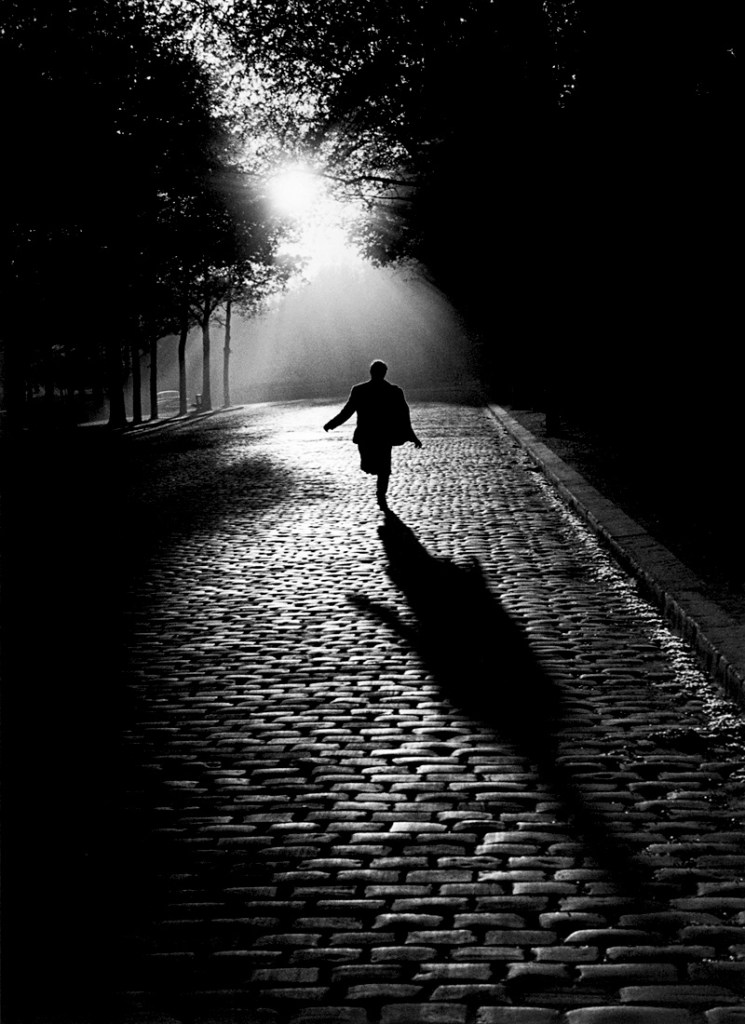

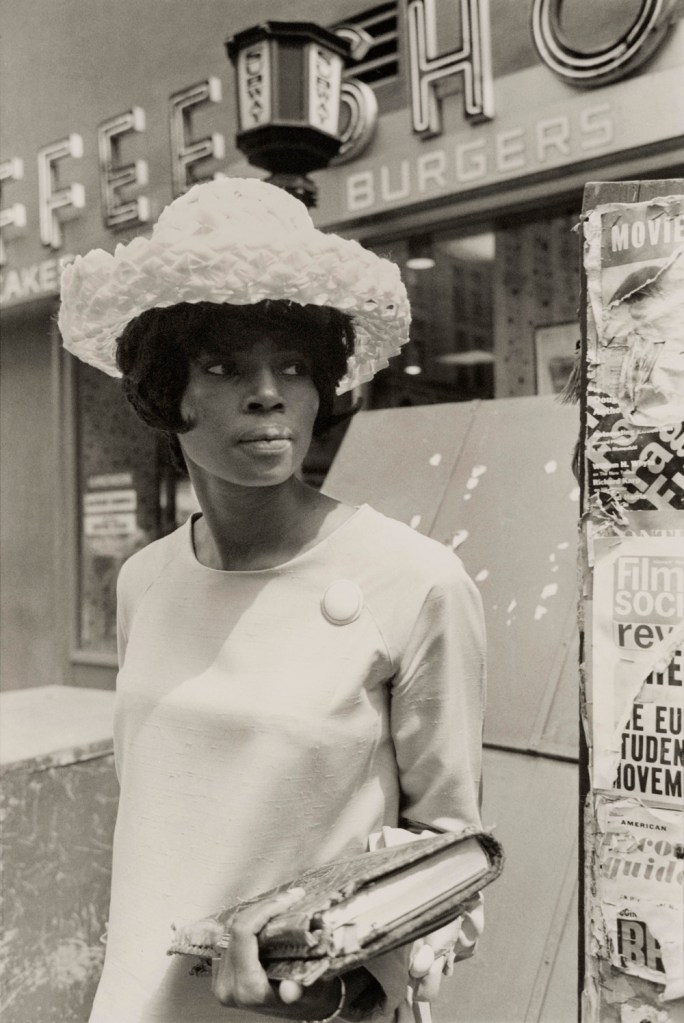

Anonymous photographer

New York City street photograph

1960s

Collection of Philip Aarons and Shelley Fox Aarons, New York

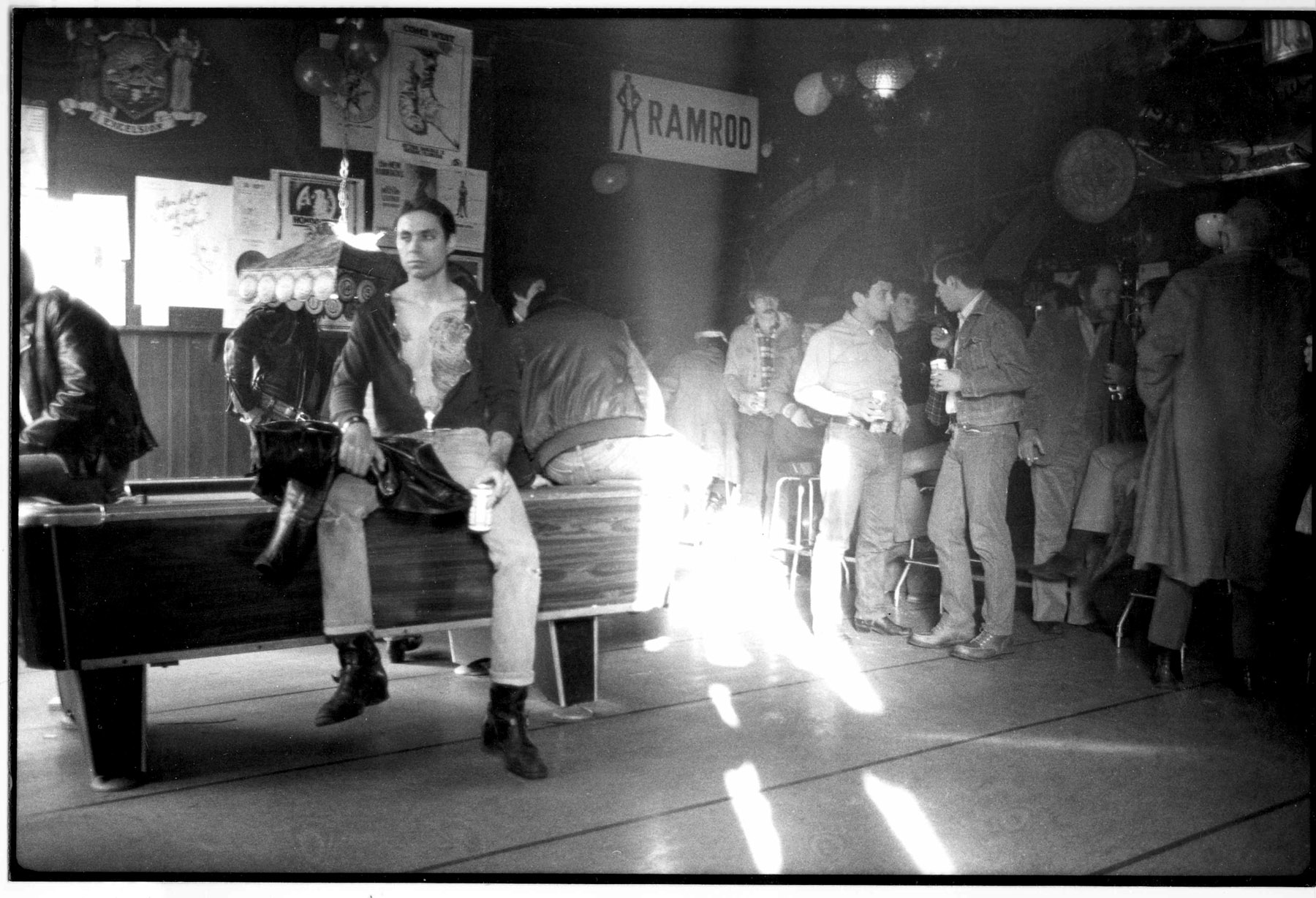

Leonard Fink (American, 1930-1993)

Charley Inside Ramrod

c. 1976

Courtesy LGBT Community Center National History Archive

THE RAMROD, 394 West Street, (between Charles and West 10th Streets). Constructed in the 1850’s this building (actually two, that were attached) housed S. J. Seely & Co., a lime dealer, and C. August, (on the corner) a porter house, and private residence. In the late 70’s it was one of the most popular leather bars in New York. Attracting a large motorcycle clientele, West Street always had a plethora of bikes parked out front. The doorman, Rico, had a long black bushy beard, and an ever present black cowboy hat, also he wore on his hand a glove with sharp stainless steel blades attached to it, (sort of a precursor to Freddie Kruger). The bar, and Rico could be very intimidating, if you were new, or “Brown” as the uninitiated were called… referring to the brown leather they wore.

Anonymous text. “Greenwich Village: A Gay History,” on the Huzzbears website [Online] Cited 15/02/2021. No longer available online

In June 1993, the Estate of Leonard Fink donated a photographic collection to The Center in New York City through its executor, Steven E. Bing. The materials in the Fink Estate was willed to four AIDS related organisations who gave all of the rights to the photos to the Center Archive. Some of these were signed “Len Elliot,” which might have ben a pseudonym of Fink’s. The collection consists of over 25,000 negatives and images capturing Greenwich Village and much of the spirit of the late 60s and 70s. Some of the most well known images in the collection are Fink’s work at “The Piers” along the Hudson River. Fink documented over 25 years of gay life in New York City but his photography was never exhibited or published in his lifetime. He was self taught and used an old 35mm camera while working out of a homemade darkroom in his West 92nd Street apartment.

Jeffrey James Keyes. “PHOTOS: An Exclusive Peek Inside The Estate of Leonard Fink,” on the Gay Cities website May 27, 2014 [Online] Cited 22/11/2021

Leonard Fink (American, 1930-1993)

Leonard Fink was an amateur photographer who documented over 25 years of gay life in New York including parades, bars, and especially the west side piers. He worked in complete obscurity and was apparently very reclusive. His photographs were seen by only a few close friends and were never exhibited or published in his lifetime. He seems to have taught himself photography using an old 35mm camera and a homemade darkroom in his small apartment on West 92nd street. He lived frugally, spending much of his income on photographic supplies which he bought in bulk and stored in his darkroom and his bedroom. He stored the prints and negatives in a file cabinet. By the time of his death, the photos in the file cabinet covered a period from 1954 to 1992. His photographs of gay life begin with groups of gay men photographed in Greenwich Village in 1967. His photographs of Gay Pride parades begin with the first parade in 1970. His earlier photographs are of friends, trips to Europe, and scenes in New York. Leonard Fink was a colourful and ubiquitous character in the Village and at Pride parades, usually appearing on roller skates in short cut-offs, and a tight t-shirt with cameras always around his neck. He sometimes arrived on a bicycle or a motorcycle. He was born in 1930. His father and older brother were both physicians. He worked for many years as an attorney for the New York Transit Authority. He died of AIDS in 1993.

Anonymous text. “Leonard Fink Photographs,” on The Center website [Online] Cited 22/11/2021

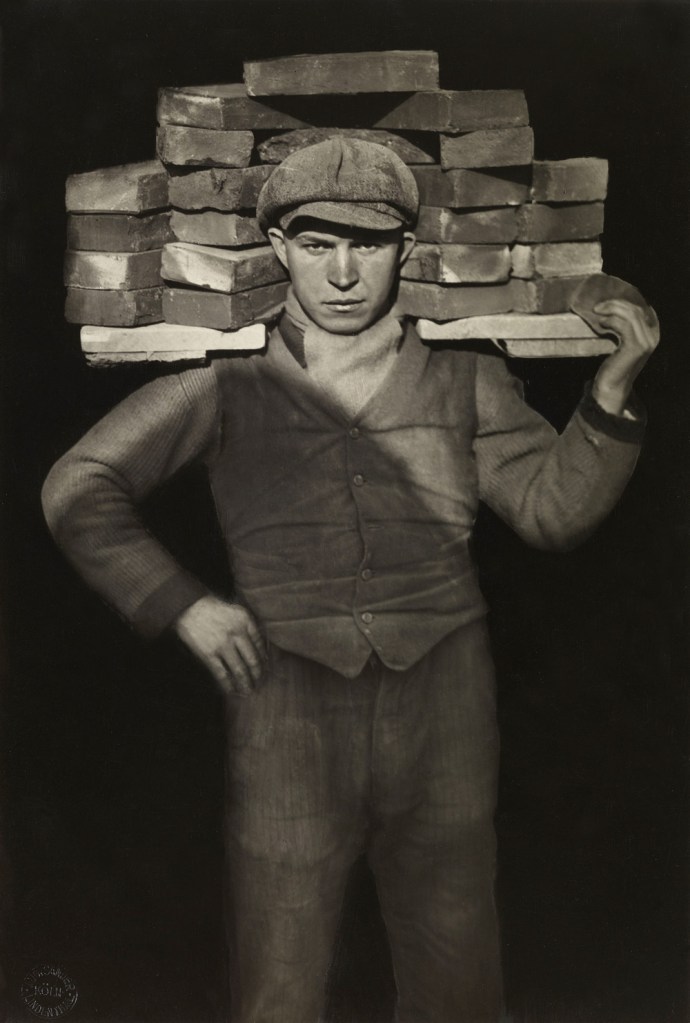

Posing

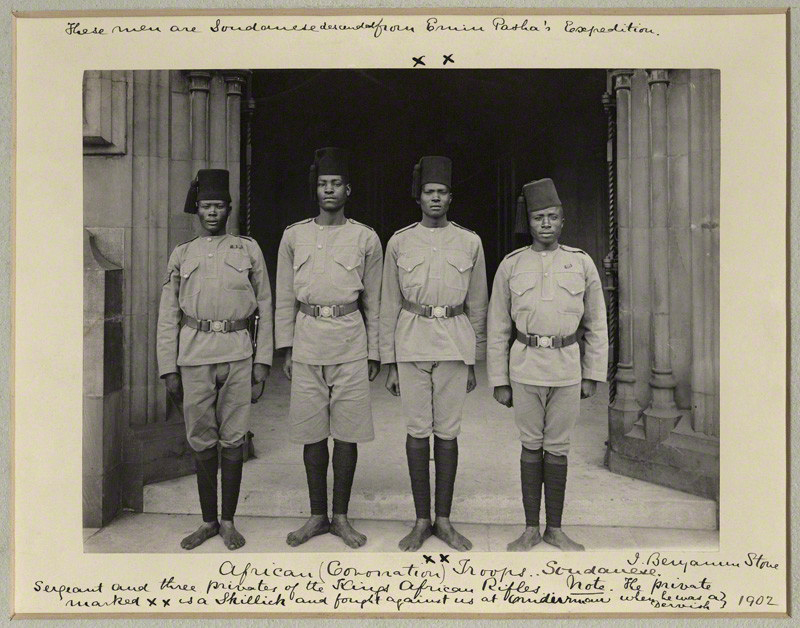

James VanDerZee (American, 1886-1983)

Beau of the Ball

1926

Gelatin silver print

Donna Mussenden VanDerZee

James VanDerZee (American, 1886-1983)

James Van Der Zee (June 29, 1886 – May 15, 1983) was an African-American photographer best known for his portraits of black New Yorkers. He was a leading figure in the Harlem Renaissance. Aside from the artistic merits of his work, Van Der Zee produced the most comprehensive documentation of the period. Among his most famous subjects during this time were Marcus Garvey, Bill “Bojangles” Robinson and Countee Cullen…

Van Der Zee worked predominantly in the studio and used a variety of props, including architectural elements, backdrops, and costumes, to achieve stylised tableaux vivant in keeping with late Victorian and Edwardian visual traditions. Sitters often copied celebrities of the 1920s and 1930s in their poses and expressions, and he retouched negatives and prints heavily to achieve an aura of glamour…

Works by Van Der Zee are artistic as well as technically proficient. His work was in high demand, in part due to his experimentation and skill in double exposures and in retouching negatives of children. One theme that recurs in his photographs was the emergent black middle class, which he captured using traditional techniques in often idealistic images. Negatives were retouched to show glamor and an aura of perfection. This affected the likeness of the person photographed, but he felt each photo should transcend the subject. His carefully posed family portraits reveal that the family unit was an important aspect of Van Der Zee’s life. “I tried to see that every picture was better-looking than the person.” “I had one woman come to me and say ‘Mr.Van Der Zee my friends tell thats a nice picture, But it doesn’t look like you.’ That was my style.” Said Van Der Zee.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Carl Van Vechten (American, 1880-1964)

Anna May Wong

1932

Gelatin silver print

Museum of the City of New York, Gift of Carl Van Vechten

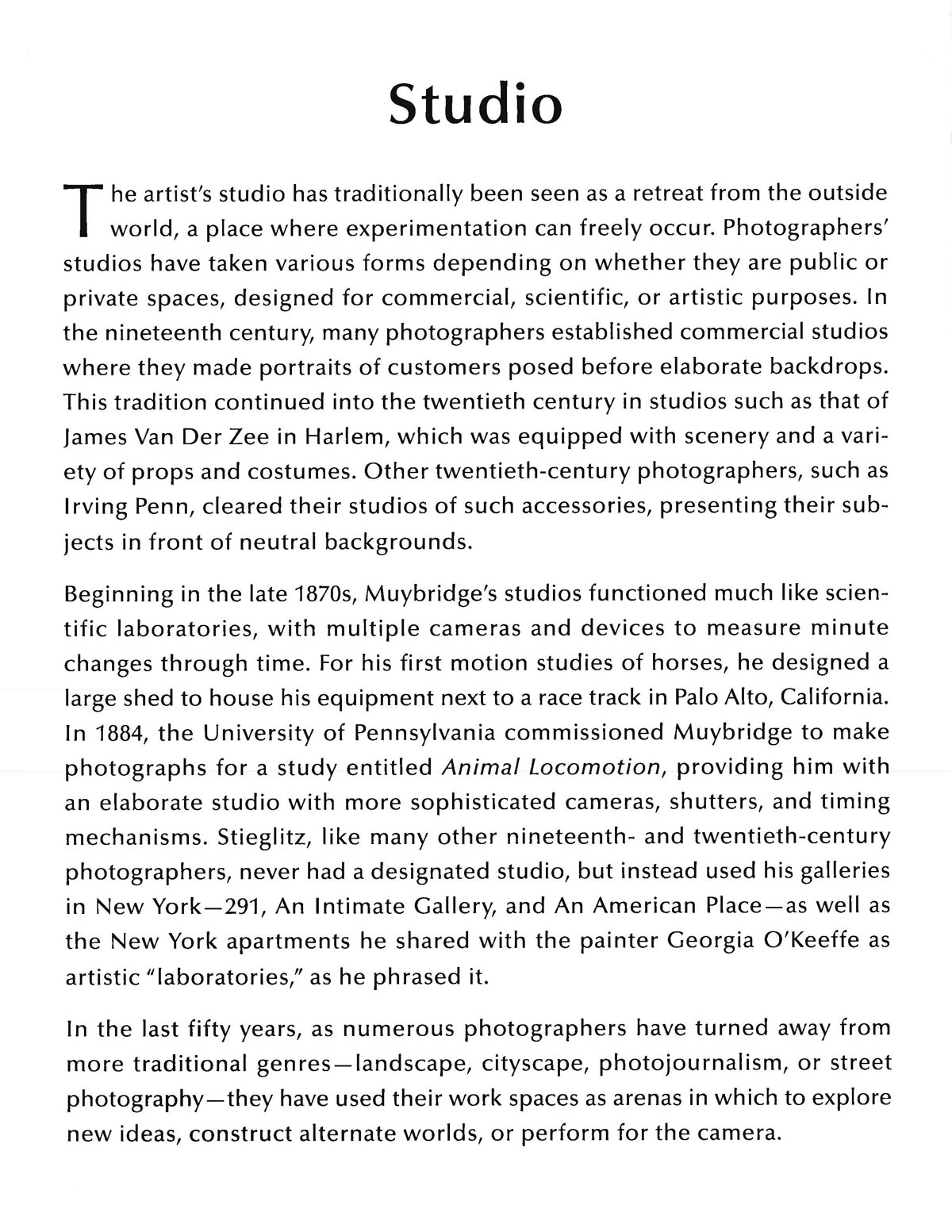

Carl Van Vechten (American, 1880-1964)

Little known today, Carl Van Vechten was a prolific novelist, critic, photographer, and promoter of all things modern, most actively engaged in the city’s cultural life during the 1920s and ’30s. The City Museum is rich in Van Vechten materials; its collections include about 2,200 photographs taken by him and 3,000 Christmas cards sent to him and his wife, film and theatre actress Fania Marinoff. Taken together, they chronicle Van Vechten’s influential circles of friends and colleagues – a hybrid mash-up that defines the modern America at the heart of White’s new book. Images and correspondence in the City Museum’s collection range from Harlem Renaissance poet Langston Hughes to writer Zelda Fitzgerald (wife of F. Scott), and playwright Eugene O’Neill.

Around 1920 Van Vechten gave up journalism for fiction and over the next decade wrote hotly debated novels about Jazz Age Manhattan. His 1923 book The Blind Bow-Boy, for example, is a classic of gay camp and a public expression of Van Vechten’s sexual orientation; while he and Marinoff were married from 1914 until Van Vechten’s death in 1964, he had numerous homosexual relationships… Van Vechten’s role in the Harlem Renaissance remains a controversial topic. To some he’s a valuable bridge between white and black New Yorkers, to others he’s an outsider who patronised and exploited his African-American subjects…

Carl Van Vechten abandoned writing altogether in the early 1930s and embraced photography, a field he would pursue until his death. All told, it is estimated that Van Vechten took some 15,000 photographs. Because his inherited wealth offered him financial independence, Van Vechten took pictures for his own pleasure, usually inviting local and visiting celebrities to a studio he set up in his own apartment. While Van Vechten was aware of the stylistic artifice of such contemporary commercial photographers as Edward Steichen and Cecil Beaton, he stood apart from them. He used a small-format camera, and his aesthetic, which included deep and dramatic shadows that sometimes obscured his subjects’ faces, resulted in picture-making that was far more immediate and spontaneous than that of his contemporaries. Using this technique, Van Vechten photographed musicians Billie Holiday and George Gershwin, Hollywood actors Laurence Olivier and Anna May Wong, and writers Sinclair Lewis and Clifford Odets, to name only a few. The sum of Van Vechten’s work, according to photography historian Keith F. Davis, “constitutes the single most integrated vision of American arts and letters produced in his era.”

Donald Albrecht. “Carl Van Vechten and Modern New York,” on the Museum of the City of New York website August 26, 2014 [Online] Cited 22/11/2021

Anna May Wong (American, 1905-1961)

Anna May Wong (January 3, 1905 – February 3, 1961) was an American actress. She is considered to be the first Chinese American movie star, and also the first Asian American actress to gain international recognition. Her long and varied career spanned silent film, sound film, television, stage and radio…

Wong’s image and career have left a legacy. Through her films, public appearances and prominent magazine features, she helped to humanise Asian Americans to white audiences during a period of overt racism and discrimination. Asian Americans, especially the Chinese, had been viewed as perpetually foreign in U.S. society but Wong’s films and public image established her as an Asian-American citizen at a time when laws discriminated against Asian immigration and citizenship. Wong’s hybrid image dispelled contemporary notions that the East and West were inherently different.

See an excellent short biography on the Wikipedia website

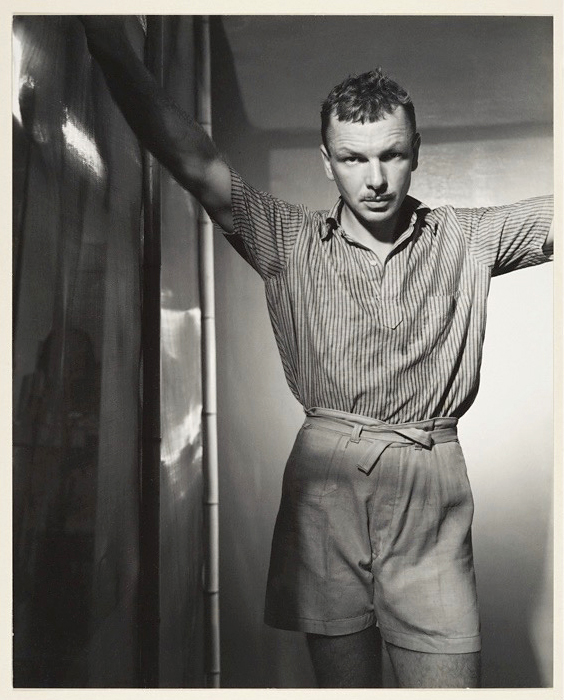

Carl Van Vechten (American, 1880-1964)

Hugh Laing

1941

Gelatin silver print

Museum of the City of New York, Gift of Carl Van Vechten

Hugh Laing (American, 1911-1988)

Hugh Laing (6 June 1911 – 10 May 1988) was one of the most significant dramatic ballet dancers of the 20th-century. He was the partner of choreographer Antony Tudor. Known for his good looks and the intensity of his stage presence, Laing was never considered a great technician, yet his powers of characterisation and his sense of theatrical timing were considered remarkable. His profile as a significant dancer of his era was almost certainly enhanced by Tudor’s choreographing to his undoubted strengths and Laing is generally regarded as one of the finest dramatic dancers of 20th-century ballet. He remained Tudor’s artistic collaborator and companion until the choreographer’s death in 1987.

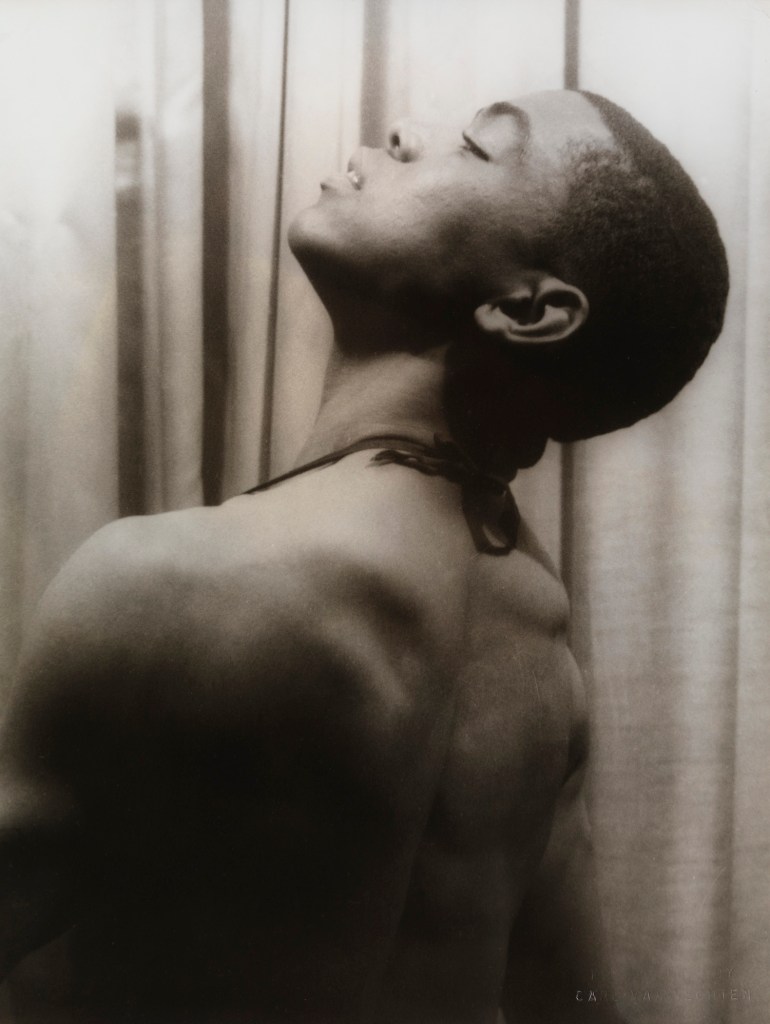

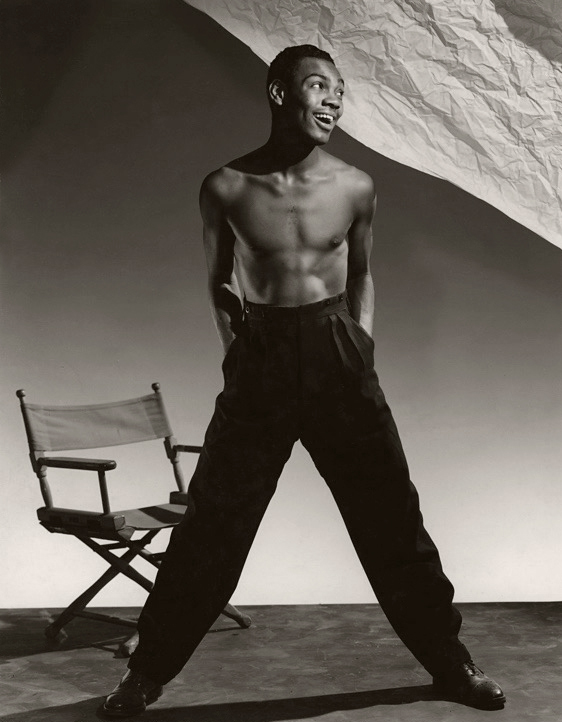

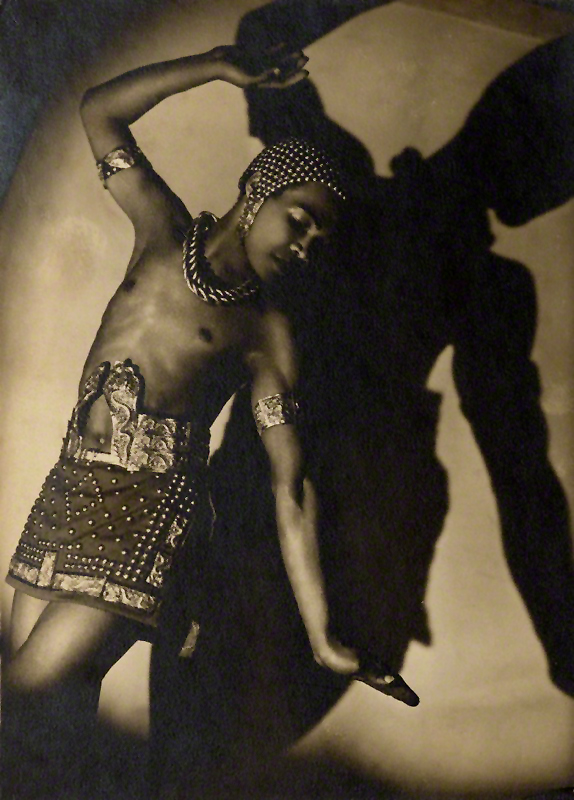

Carl Van Vechten (American, 1880-1964)

Alvin Ailey

1955

Gelatin silver print

Museum of the City of New York, Gift of Carl Van Vechten

Alvin Ailey (American, 1931-1989)

Alvin Ailey (January 5, 1931 – December 1, 1989) was an African-American choreographer and activist who founded the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater in New York City. He is credited with popularising modern dance and revolutionising African-American participation in 20th-century concert dance. His company gained the nickname “Cultural Ambassador to the World” because of its extensive international touring. Ailey’s choreographic masterpiece Revelations is believed to be the best known and most often seen modern dance performance…

Ailey made use of any combination of dance techniques that best suited the theatrical moment. Valuing eclecticism, he created more a dance style than a technique. He said that what he wanted from a dancer was a long, unbroken leg line and deftly articulated legs and feet (“a ballet bottom”) combined with a dramatically expressive upper torso (“a modern top”). “What I like is the line and technical range that classical ballet gives to the body. But I still want to project to the audience the expressiveness that only modern dance offers, especially for the inner kinds of things.”

Ailey’s dancers came to his company with training from a variety of other schools, from ballet to modern and jazz and later hip-hop. He was unique in that he did not train his dancers in a specific technique before they performed his choreography. He approached his dancers more in the manner of a jazz conductor, requiring them to infuse his choreography with a personal style that best suited their individual talents. This openness to input from dancers heralded a paradigm shift that brought concert dance into harmony with other forms of African-American expression, including big band jazz.

Text from the Wikipedia website

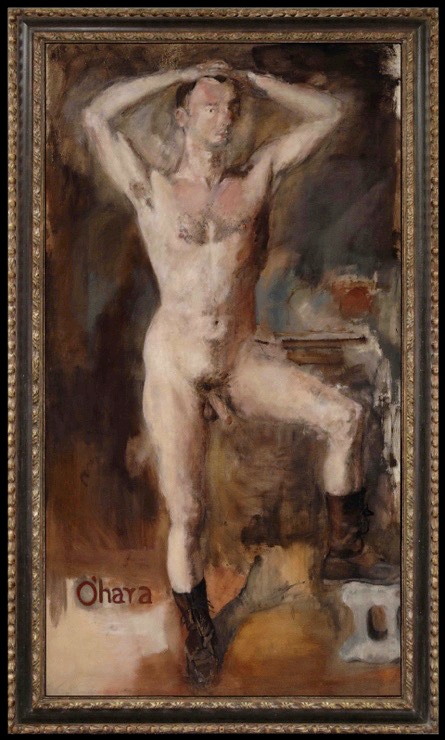

Larry Rivers (American, 1923-2002)

O’Hara Nude With Boots

1954

Oil on canvas

Collection of the Larry Rivers Foundation

“Among Rivers’ portraits of the mid-1950s, the most notable and controversial work for a discussion of the relationship among autobiography, sexuality, and art is O’Hara, which he painted during January 1954 as he re-entered an emotional relationship with the sitter. According to [poet Frank] O’Hara’s biographer, Brad Gooch, Rivers and O’Hara had a relatively short, turbulent romance that began in 1952m but during 1953 the two men became involved in other romantic relationships… Beginning in 1954, however, Rivers and O’Hara resumed their intimate relationship, which then lasted less than a year…

A nude of a contemporary figure on such a huge scale as O’Hara appeared unusual and even controversial in the 1950s New York art world. Rivers recalled that when the painting was first shown at the Whitney Annual in 1955, a guard often stood in front of it to ensure that the painting would not be defaced or damaged: “There was something about the male nude that seemed to be more of a problem than the female nude.” Some contemporary viewers where shocked by O’Hara, given its depiction of a naked male body with meticulous attention to the genitals.”

Dong-Yeon Koh. Larry Rivers and Frank O’Hara: Reframing Male Sexualities. Phd dissertation 2006, pp. 196-198.

Beauford Delaney (American, 1901-1979)

James Baldwin

c. 1957

Oil on canvas board

Halley K. Harrisburg and Michael Rosenfeld, New York

Beauford Delaney (American, 1901-1979)

Beauford Delaney (December 30, 1901 – March 26, 1979) was an American modernist painter. He is remembered for his work with the Harlem Renaissance in the 1930s and 1940s, as well as his later works in abstract expressionism following his move to Paris in the 1950s.

In his Introduction to the Exhibition of Beauford Delaney opening December 4, 1964 at the Gallery Lambert, James Baldwin wrote, “the darkness of Beauford’s beginnings, in Tennessee, many years ago, was a black-blue midnight indeed, opaque and full of sorrow. And I do not know, nor will any of us ever really know, what kind of strength it was that enabled him to make so dogged and splendid a journey.”

James Arthur Baldwin (American, 1924-1987)

James Arthur Baldwin (August 2, 1924 – December 1, 1987) was an American novelist, essayist, playwright, poet, and social critic. His essays, as collected in Notes of a Native Son (1955), explore palpable yet unspoken intricacies of racial, sexual, and class distinctions in Western societies, most notably in mid-20th-century America, and their inevitable if unnameable tensions. Some Baldwin essays are book-length, for instance The Fire Next Time (1963), No Name in the Street (1972), and The Devil Finds Work (1976).

Baldwin’s novels and plays fictionalise fundamental personal questions and dilemmas amid complex social and psychological pressures thwarting the equitable integration not only of black people, but also of gay and bisexual men, while depicting some internalised obstacles to such individuals’ quests for acceptance. Such dynamics are prominent in Baldwin’s second novel, Giovanni’s Room, written in 1956, well before the gay liberation movement.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Performing

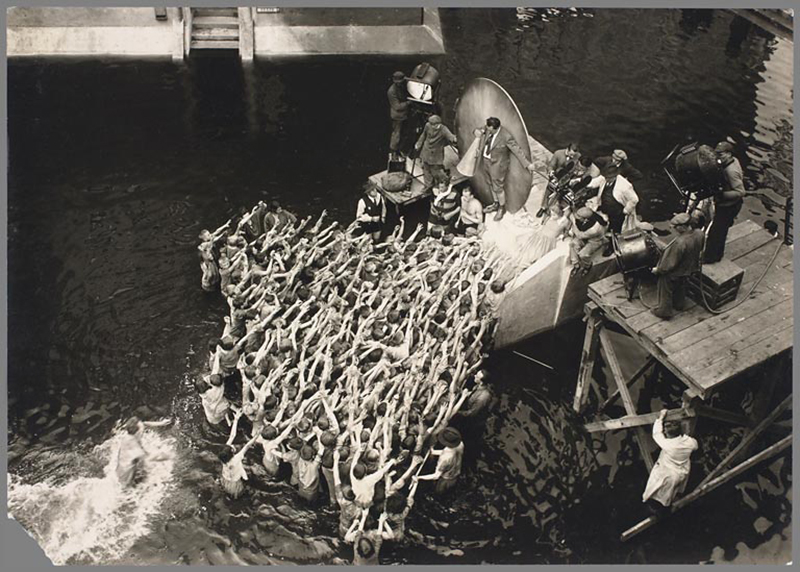

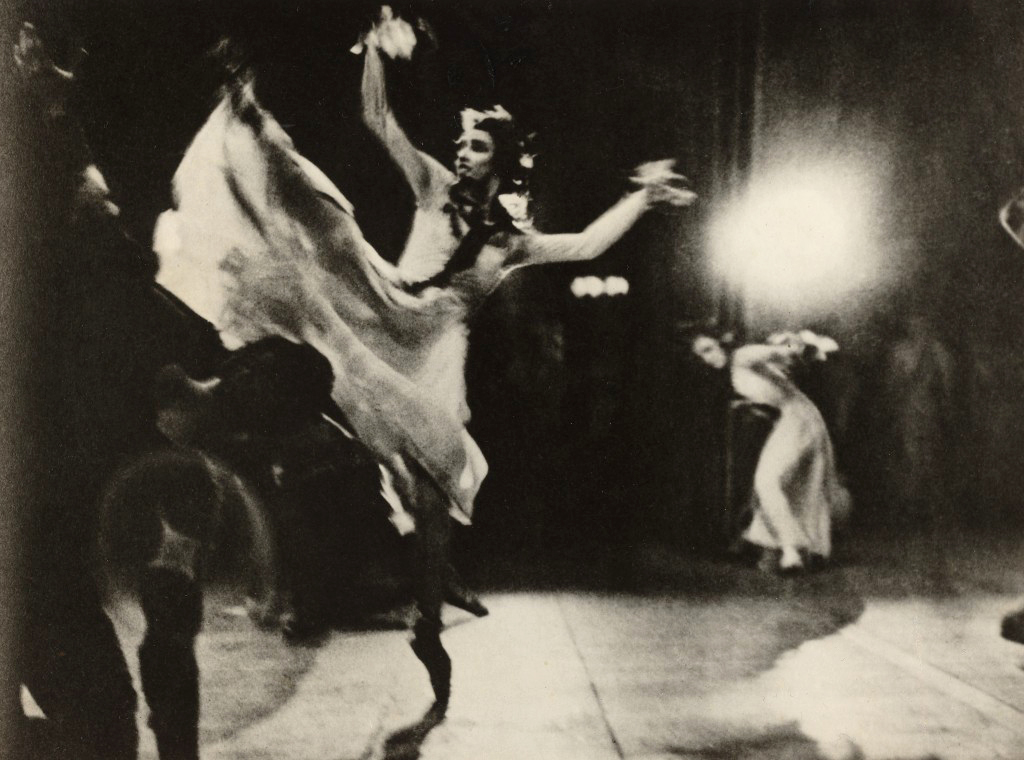

The Pansy Craze on Stage and Screen

New York’s queer cultures gained remarkable visibility on the city’s stages in the 1920 and 1930s. Broadway producers and nightclub owners put on plays and acts exploring gay and lesbian themes. They launched a popular “Panzy Craze,” where minorities where accepted. This period lasted until the mid-1930s when morals and ethics changed because of right-wing pressure. The film code was then in full force to protect society’s “morals” and there was, once more, open hostility towards minorities that latest into the 1970s.

With permission of the Museum of the City of New York for Art Blart

The Museum of the City of New York

Film compiliation

Produced by Cramersound

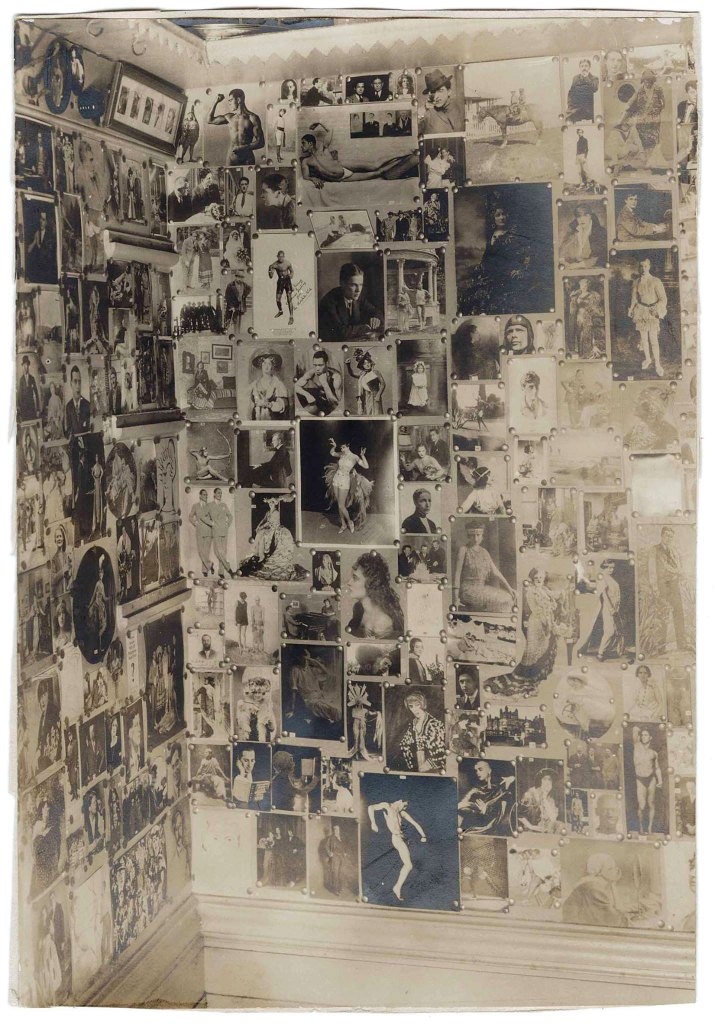

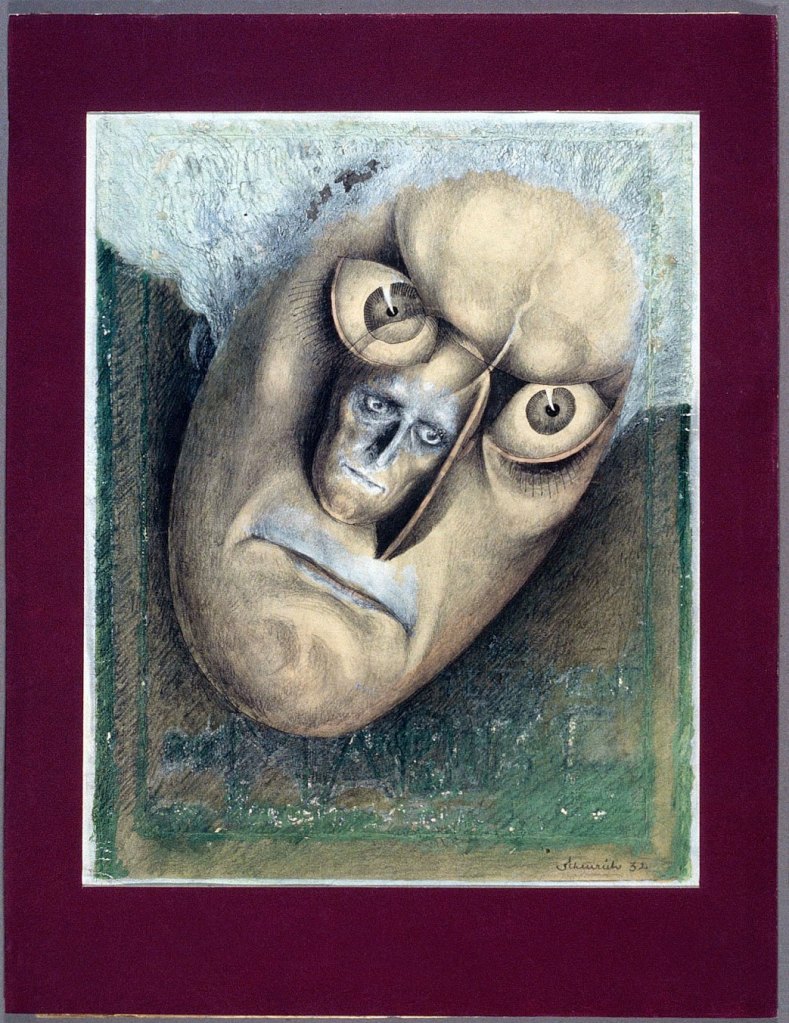

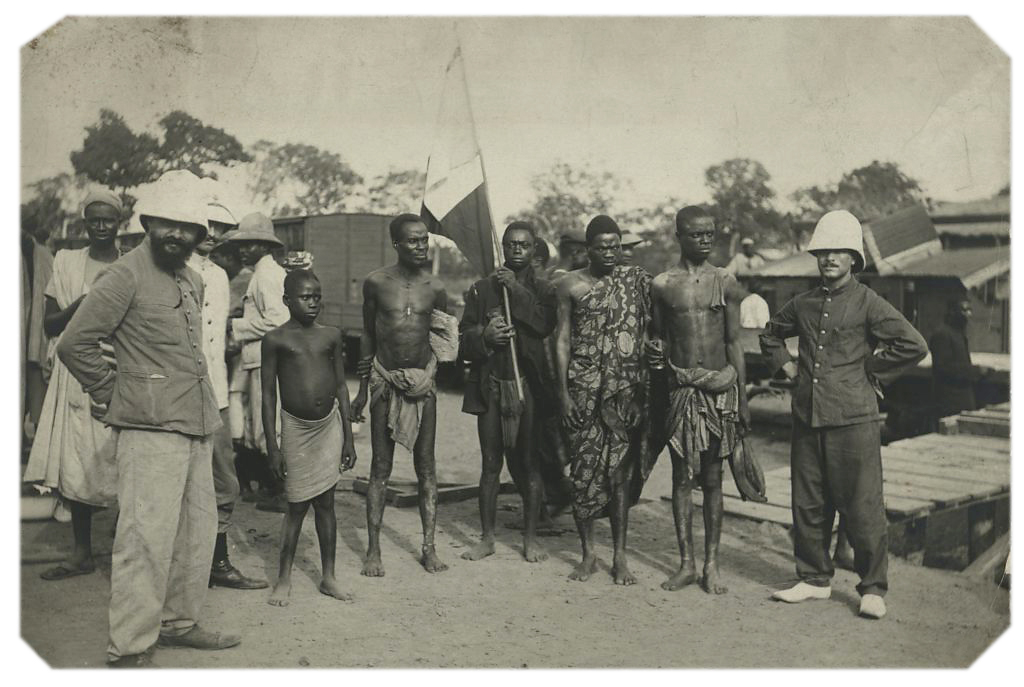

Max Ewing (American, 1903-1934)

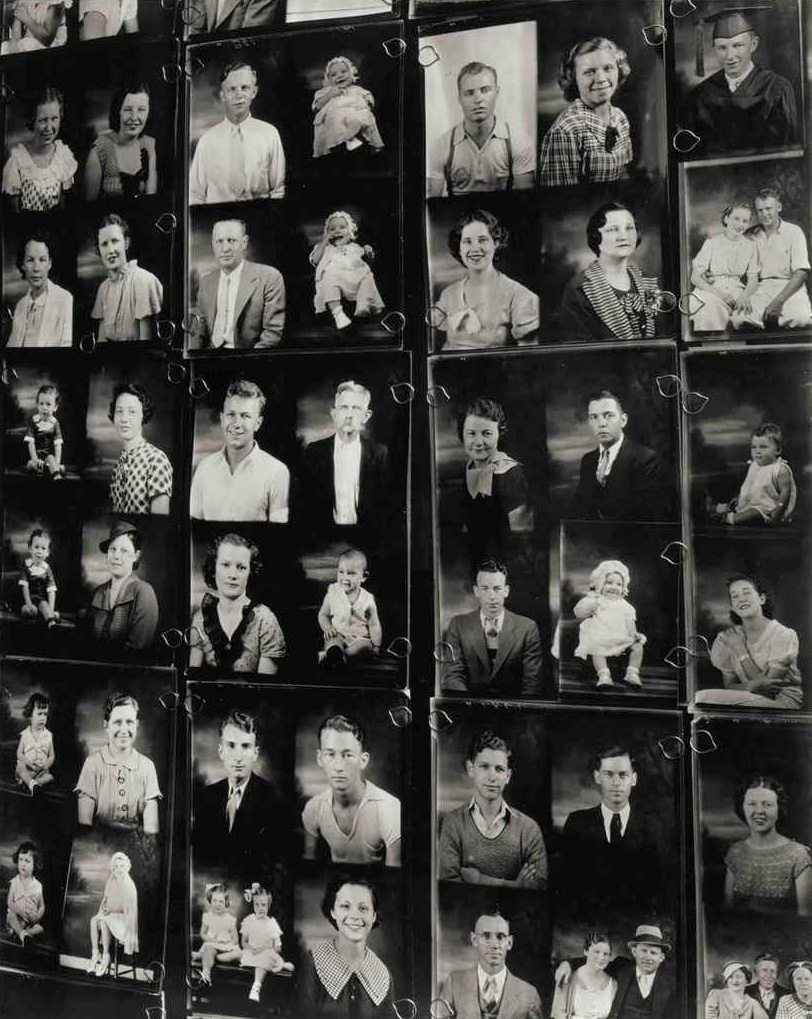

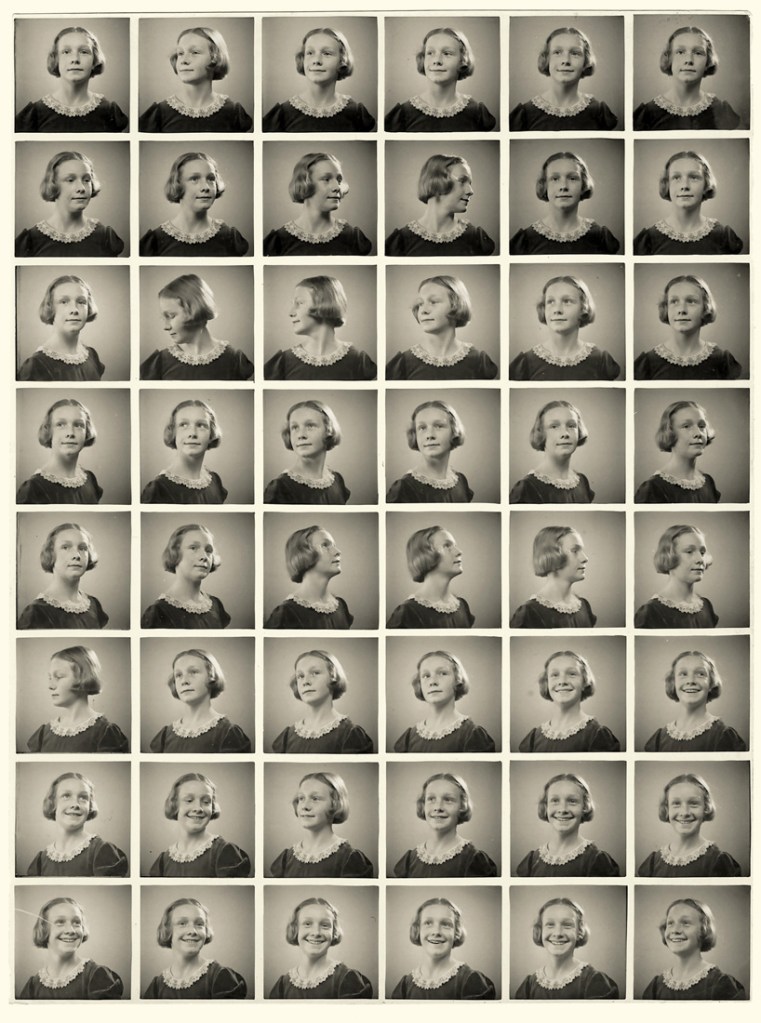

Gallery of Extraordinary Portraits

1928

Courtesy Yale University, Beinecke Rare Books and Manuscripts Library

Max Ewing’s Gallery of Extraordinary Portraits encapsulates the exhibition’s wider exploration of queer communities in 20th-century New York. Ewing was a novelist, composer, pianist, and sculptor who created this gallery in the walk-in closet of his Manhattan studio apartment on West 31st Street. His semi-public closet exhibition paid homage to interracial, gay, and artistic communities with images of friends and celebrities plastered floor to ceiling, corner to corner.

Sterling Paige

Gladys Bentley at the Ubangi Club in Harlem

early 1930s

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of the Visual Studies Workshop, Rochester, NY

1960-1995

Portraits

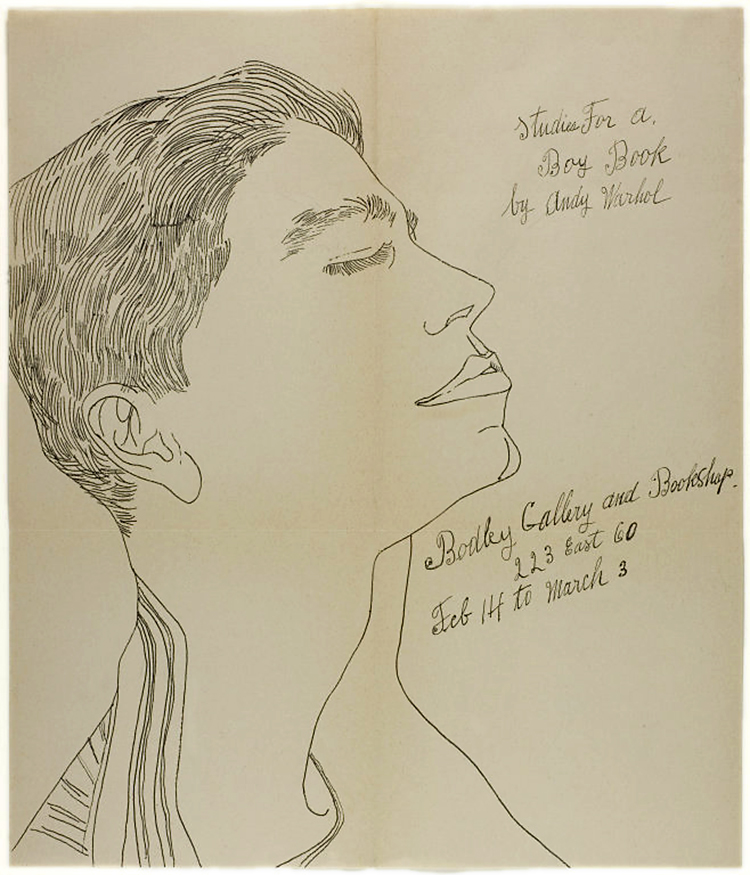

Andy Warhol

Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987)

Studies for a Boy Book exhibition announcement for Bodley Gallery

c. 1956

Offset lithograph Susan Sheehan Gallery, New York

Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987)

Gee, Merrie Shoes

1956

Hand coloured offset lithograph

Susan Sheehan Gallery, New York

Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987)

Cecil Beaton’s Feet

1961

Black ink on buff wove paper

Philadephia Museum of Art

The Henry P. Mcllhenny Collection in memory of Frances P. Mcllhenny, 1986

Cecil Beaton (British, 1904-1980)

Andy Warhol and Candy Darling, New York

1969

Gelatin silver print

© The Cecil Beaton Studio Archive at Sotheby’s

Candy Darling (November 24, 1944 – March 21, 1974) was an American transgender actress, best known as a Warhol Superstar. She starred in Andy Warhol’s films Flesh (1968) and Women in Revolt (1971), and was a muse of the protopunk band The Velvet Underground.

Edie Sedgwick Screen Test

Andy Warhol’s silent screen test for his future “super star.”

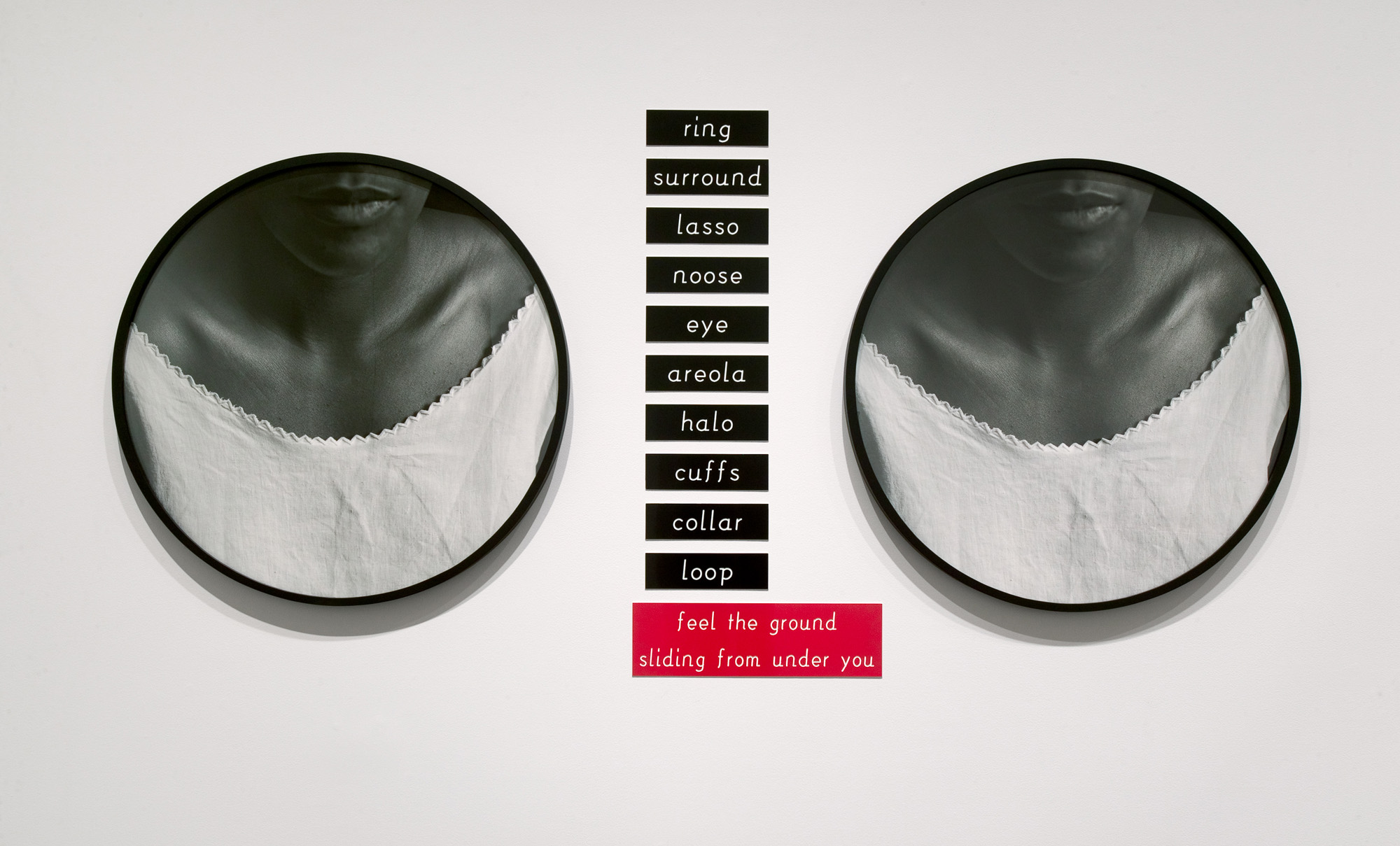

Harmony Hammond

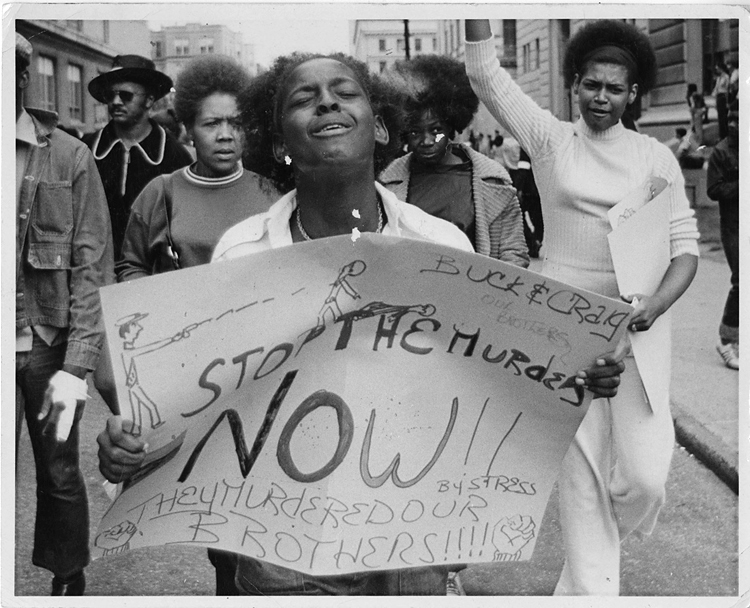

Liberation News Service #624, featuring Harmony Hammond, right, with daughter, Tanya, at the Christopher Street Liberation Day Gay Pride March, photograph by Cidne Hart for Liberation News Service, July 3, 1974

Private collection

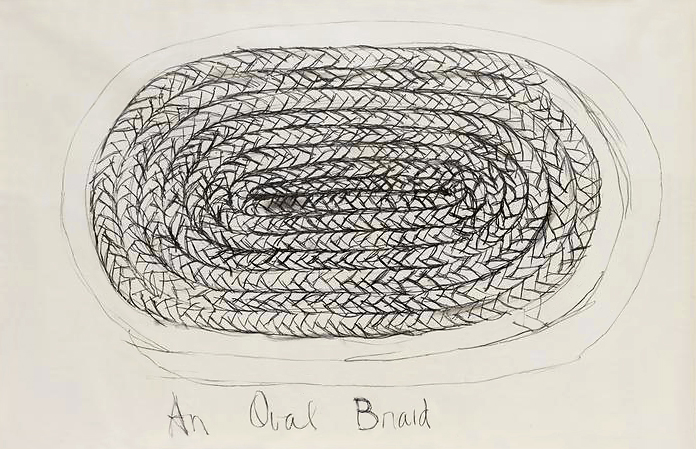

Harmony Hammond (American, b. 1944)

An Oval Braid

1972

Charcoal on paper

Courtesy the artist and Alexander Gray Associates, New York

Harmony Hammond (American, b. 1944)

Fan Lady meets Cactus Lady

1981

Lithograph

Courtesy the artist and Alexander Gray Associates, New York

Robert Mapplethorpe

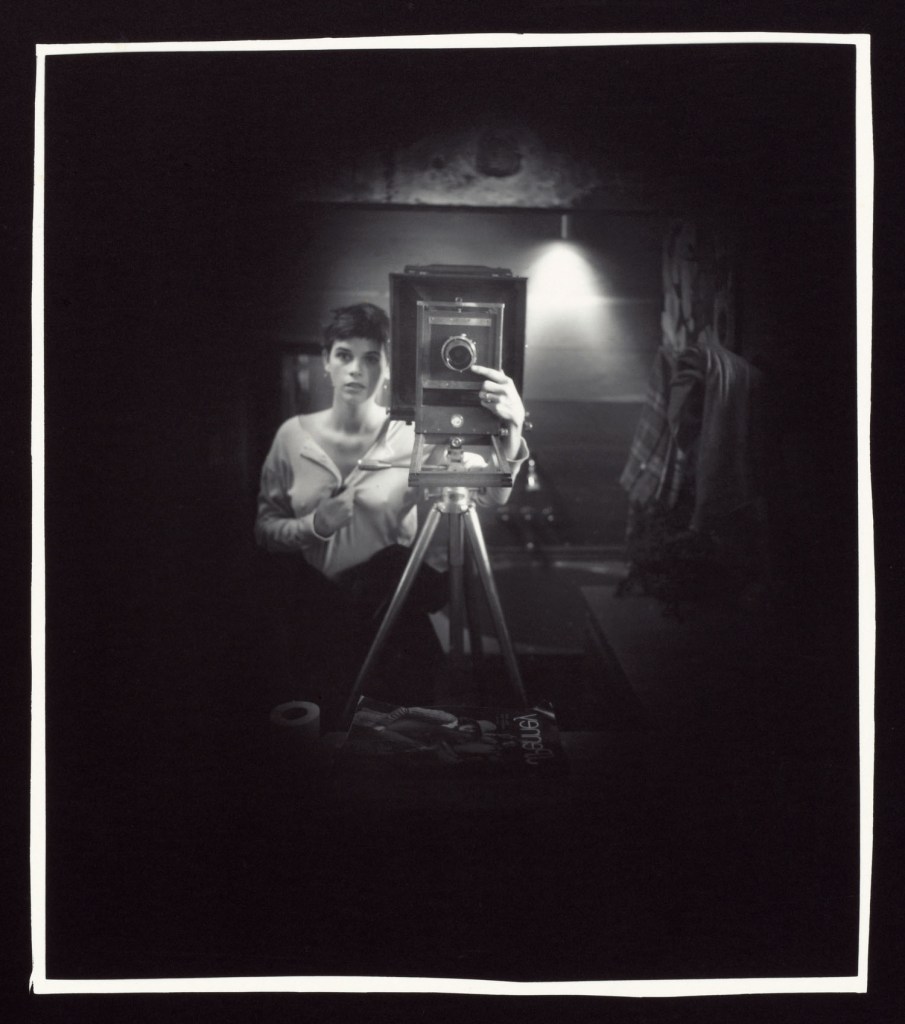

Judy Linn (American, b. 1947)

Robert Gets Dressed at the Chelsea, #3

1970

Modern digital print

Courtesy the Artist and Susanne Hilberry Gallery

Gay Power, Volume 1, No 16, April 15, 1970

Alternative Press Collection, Archives & Special Collections at the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries

Robert Mapplethorpe (American, 1946-1989)

Light Gallery invitation

1973

Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles California

Ultra Violet modeling Mapplethorpe-designed jewelry

c. 1975

Gift of the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation to The J. Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Isabelle Collin Dufresne (French-American, 1935-2014)

Isabelle Collin Dufresne (stage name Ultra Violet; 6 September 1935 – 14 June 2014) was a French-American artist, author, and both a colleague of Andy Warhol and one of the pop artist’s so-called superstars. Earlier in her career, she worked for and studied with surrealist artist Salvador Dalí. Dufresne lived and worked in New York City, and also had a studio in Nice, France…

In 1954, after a meeting with Salvador Dalí, she became his “muse”, pupil, studio assistant, and lover in both Port Lligat, Spain, and in New York City. Later, she would recall, “I realised that I was ‘surreal’, which I never knew until I met Dalí”. In the 1960s, Dufresne began to follow the progressive American Pop Art scene including Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg and James Rosenquist.

In 1963, Dalí introduced Dufresne to Andy Warhol, and soon she moved into the orbit of his unorthodox studio, “The Factory”. In 1964 she selected the stage name “Ultra Violet” at Warhol’s suggestion, because it was her preferred fashion – her hair colour at the time was often violet or lilac. She became one of many “superstars” in Warhol’s Factory, and played multiple roles in over a dozen films between 1965 and 1974…

In the 1980s, she gradually drifted away from the Factory scene, taking a lower profile and working independently on her own art. In her autobiography, published the year after Warhol’s unexpected demise in 1987, she chronicled the activities of many Warhol superstars, including several untimely deaths during and after the Factory years…

In 1990 she opened a studio in Nice and wrote another book detailing her own ideas about art, L’Ultratique. She lived and worked as an artist in New York City, and also maintained a studio in Nice for the rest of her life.

Text from the Wikipedia website

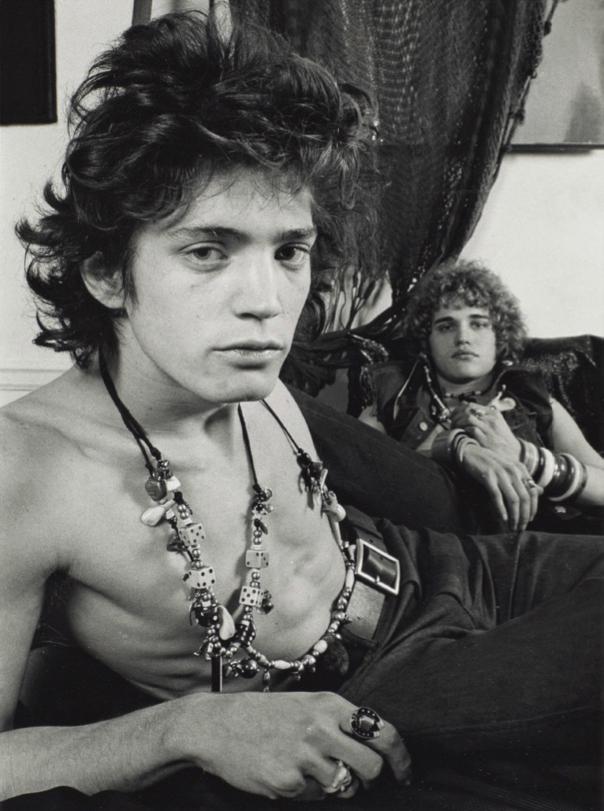

Valerie Santagto (American, b. 1947)

Robert Mapplethorpe, front, and Jay Johnson in Mapplethorpe designed jewellery

c. 1970-75

Gift of the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation to The J. Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art

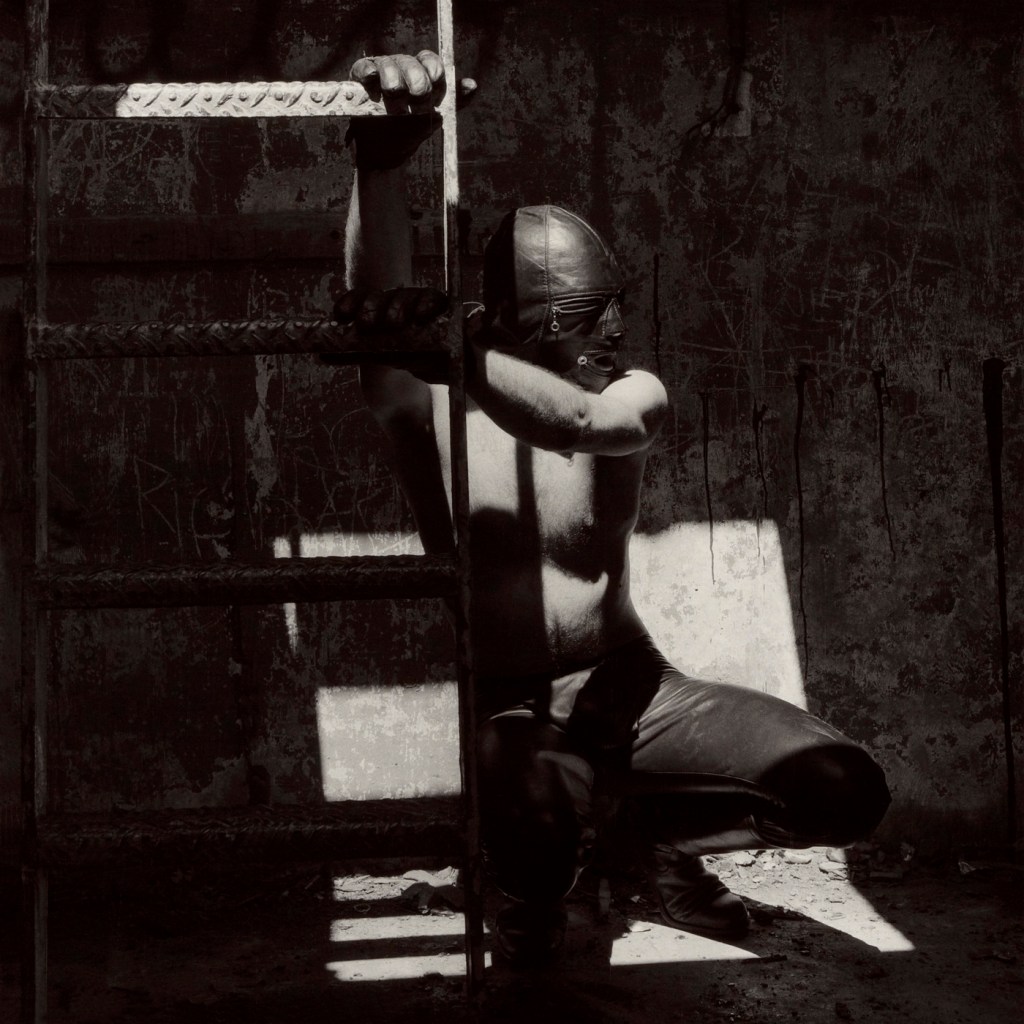

Robert Mapplethorpe (American, 1946-1989)

X Portfolio with Jim, Sausalito

1978

Black silk clamshell case with gelatin silver print photographs mounted on pure rag board

Designed by John Cheim

Courtesy Yoshi Gallery, New York and Cheim & Read, New York

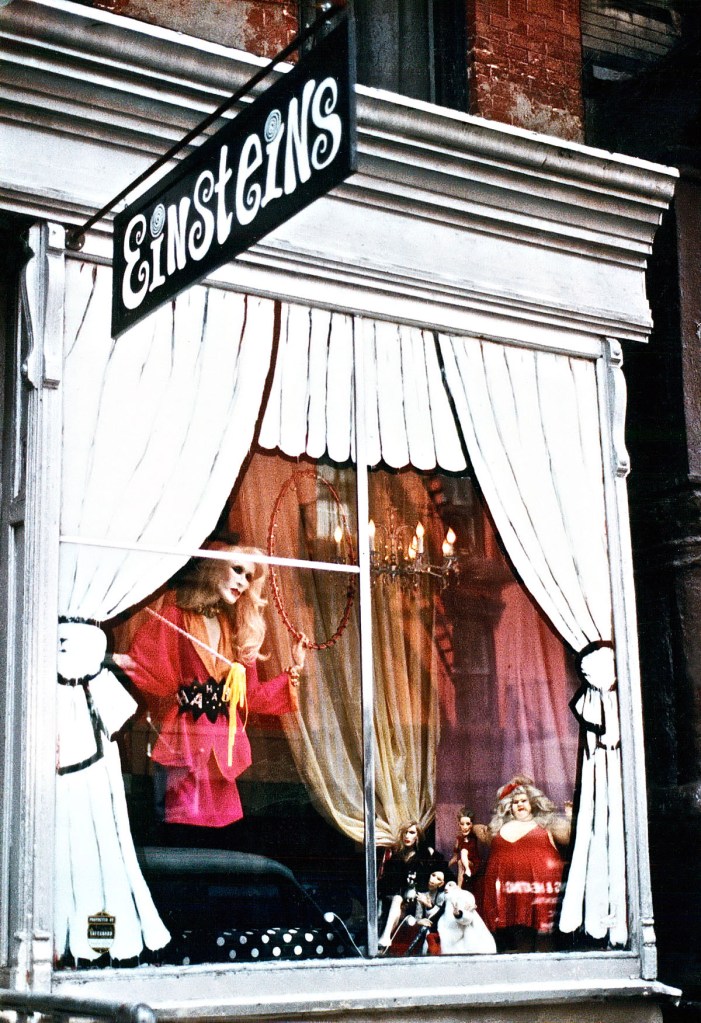

Greer Lankton

Einsteins installation designed by Paul Monroe for Gay Gotham, 2016

Courtesy of Greer Lankton Archives Museum

Greer Lankton (American, 1958-1996)

Mini-Einsteins

1987

Cardboard, glass, paint, styrofoam board

Andy Warhol

1990

Fabric, wire, glass, human hair

Teri Toye

1988

Fabric, wire, glass, human hair

Siamese Twins

1988

Paper, wire, fabric

Greer Lankton (American, 1958-1996) (dolls and photo)

Einsteins “Circus” window display by Greer Lankton and Paul Monroe

1986

Courtesy Paul Monroe for Greer Lankton Archives Museum

Greer Lankton (American, 1958-1996)

Greer Lankton (1958 – November 18, 1996) was an American artist known for creating lifelike, sewn dolls that were often modelled on friends and celebrities and posed in elaborate theatrical settings. She was a key figure in the East Village art scene of the 1980s in New York.

Gender and sexuality are recurring themes in Lankton’s art. Her dolls are created in the likeness of those society calls “freaks”, and have often been compared to the surrealist works of Hans Bellmer, who made surreal dolls with interchangeable limbs. She created figures that were simultaneously distressing and glamorous, as if they were both victim and perpetrator of their existence.

In 1981 Lankton was featured in the seminal “New York/New Wave” exhibition at P.S.1 in Long Island City, and began to show her work in the East Village at Civilian Warfare. She gained an almost cult following among East Village residents from her highly theatrical window displays she designed for Einstein’s, the boutique that was run by her husband, Paul Monroe, at 96 East Seventh Street. Besides her more emotionally charged dolls, Lankton also created commissioned portrait dolls. These include a 1989 doll of Diana Vreeland that was commissioned for a window display at Barney’s as well as shrines to her icons, such as Candy Darling.

Critic Roberta Smith described her works in the New York Times as: “Beautifully sewn, with extravagant clothes, make-up and hairstyles, they were at once glamorous and grotesque and exuded intense, Expressionistic personalities that reminded some observers of Egon Schiele. They presaged many of the concerns of 90’s art, including the emphasis on the body, sexuality, fashion and, in their resemblance to puppets, performance.”

Photographer Nan Goldin said of her work, “Greer was one of the pioneers who blurred the line between folk art and fine art.” She had spots in the prestigious Whitney Biennial and the Venice Biennale, both in 1995, where her busts of Candy Darling, circus fat ladies, and dismembered heads gained her notoriety…

Greer was friends with photographer Nan Goldin, and lived in her apartment in the early 80’s, often posing for her. She also played muse to photographers like David Wojnarowicz and Peter Hujar.

Text from the Wikipedia website

“Writing about the wax dolls of German artist Lotte Pritzel (to whom Lankton’s own work bears a strong family resemblance), Rainer Maria Rilke noted: “With the doll we had to assert ourselves, because if we surrendered to it there was nobody there. It made no response, so we got into the habit of doing things for it, splitting our own slowly expanding nature into opposing parts and to some extent using the doll to establish distance between ourselves and the amorphous world pouring into us” [“Dolls: On the Wax Dolls of Lotte Pritzel,” tr. Idris Parry]. This relationship imbues the doll with its “soul,” Rilke writes, arguing that it is the extremity of this attachment that leads us to both desire and reject the doll. Unalterable strangeness: Lankton’s own work is plotted along the rejection-desire axis, granting the work a peculiar levity that hovers between fearsome and friendly…

Lankton’s art is both realistic and unrealistic, a difficult balance that is not unlike Candy Darling’s work as an actor, which often operated at the juncture between self-conscious play and unanticipated reality to evoke, again, unalterable strangeness. Following Douglas Crimp’s description of the superstar as someone whose “self … recognises otherness already there in itself [and] performs its own self-alienation” [Our Kind of Movie: The Films of Andy Warhol, Cambridge: MIT Press, 2012], Lankton likewise performs the double work of representing bodies (hers and others) while asserting their alienation. Darling rehearsed and played herself in order to be someone else. It might be said that Lankton rehearsed and played others in order to be herself.”

Extract from “Unalterable Strangeness: Andrew Durbin and Paul Monroe on Greer Lankton,” on the Flash Art website, March – April 2015. No longer available online

Paul Monroe

Chanel No. 5 earrings

1985

Glass (actual miniature Chanel products filled with No. 5), 14k gold wire and glass pearls

Candelabra ring

1986

Metal, chain, glass jewels and wax

Paul Monroe and Greer Lankton (American, 1958-1996)

Teri Toye necklace

1985

Clay, acrylic paint, gold metal chain and rhinestones

Einsteins promotional cards 1986-1992

Einsteins business card, 1985

Nan Goldin (American, b. 1953)

Greer Lankton and Paul Monroe wedding

1987

Greer Lankton Archives Museum

Bill T. Jones

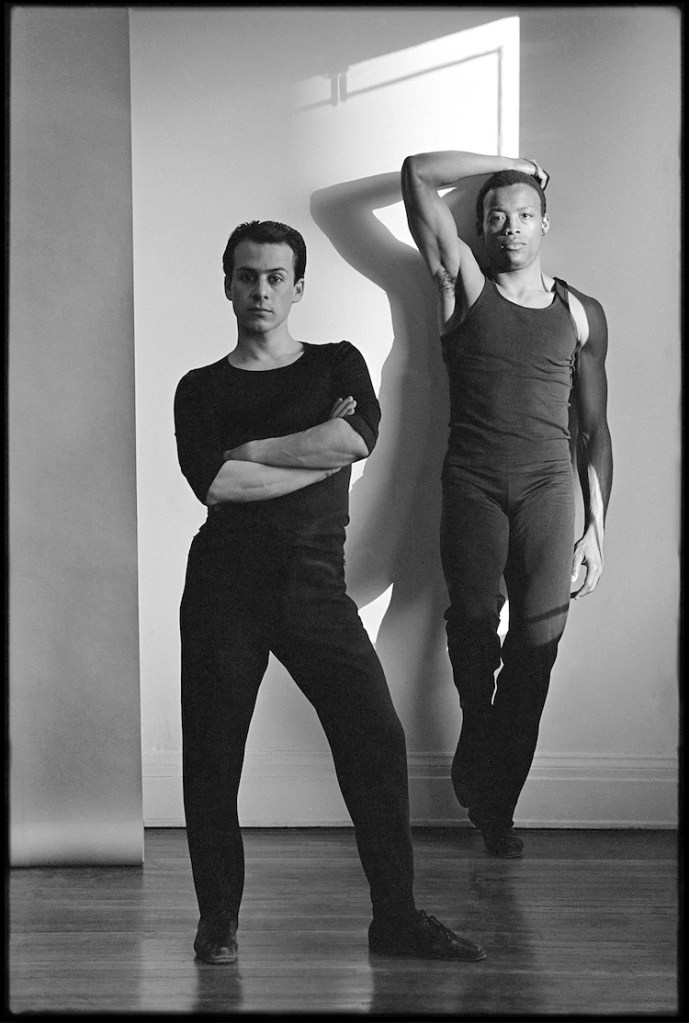

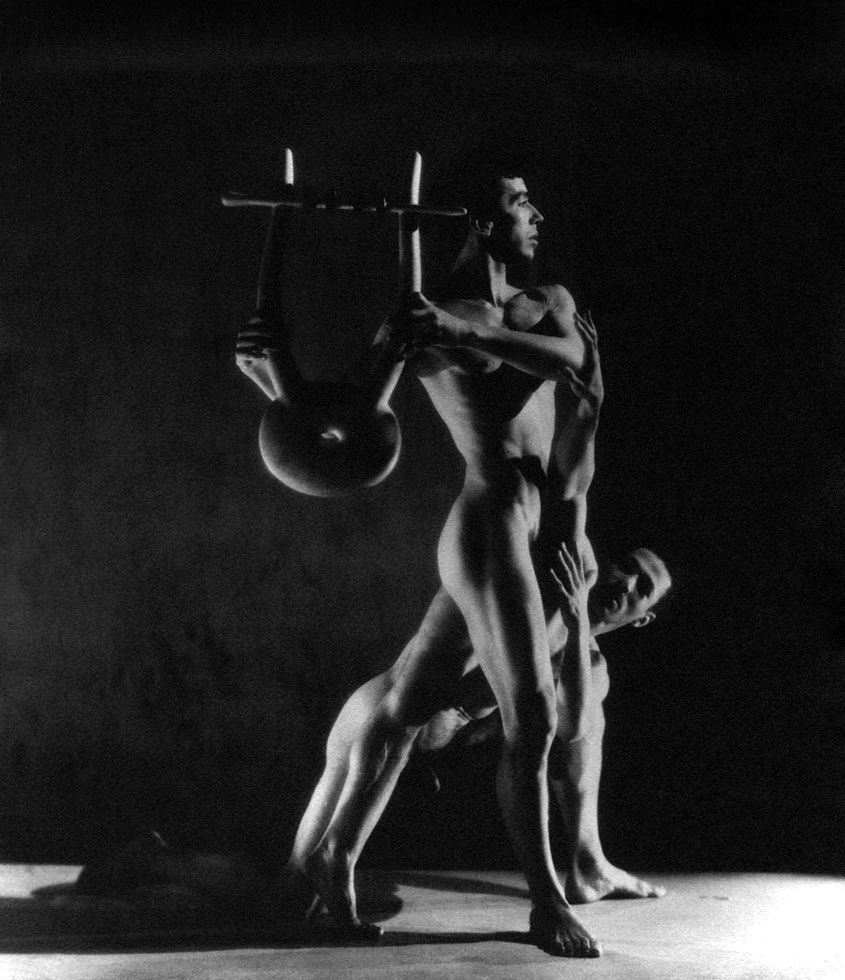

Lois Greenfield (American, b. 1949)

Bill T. Jones and Arnie Zane

1982

Modern print Courtesy Lois Greenfield Studio

Robert Mapplethorpe (American, 1946-1989)

Studio Portrait (Bill T. Jones and Arnie Zane)

1986

Private Collection of Bill T. Jones

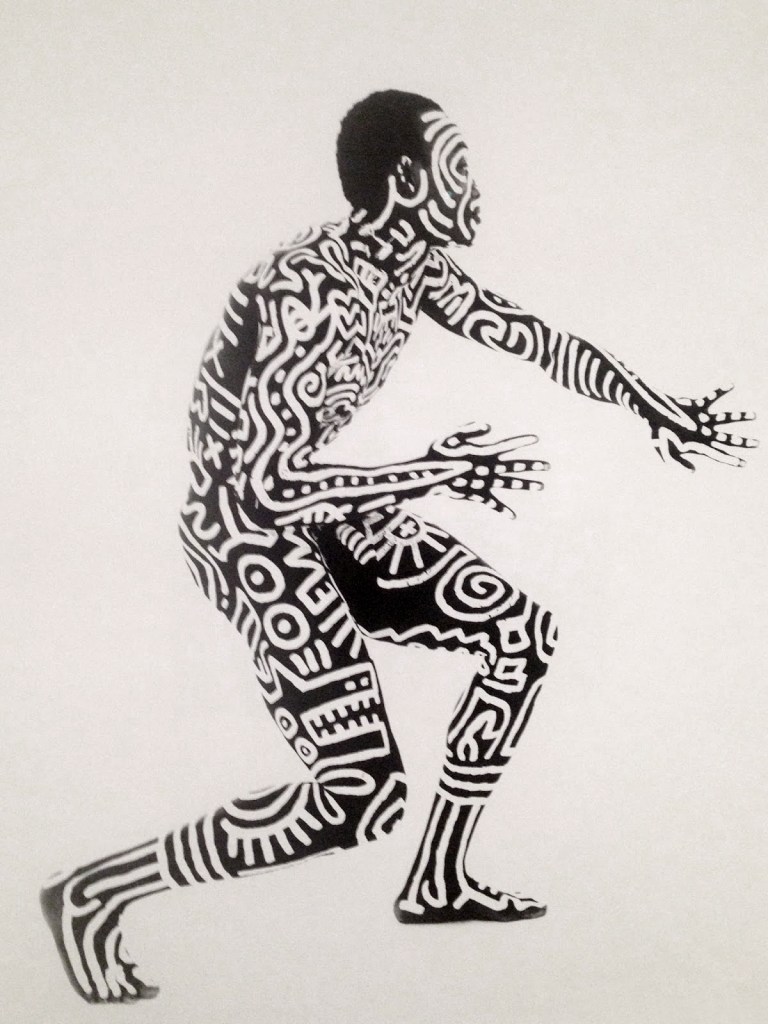

Tseng Kwong Chi (American born Hong Kong, 1950-1990)

Bill T. Jones Body Painting with Keith Haring

1983

Silver gelatin selenium-toned print

© Muna Tseng Dance Projects, Inc., New York. Body Drawing on Bill T. Jones by Keith Haring

© 1983 Keith Haring Foundation

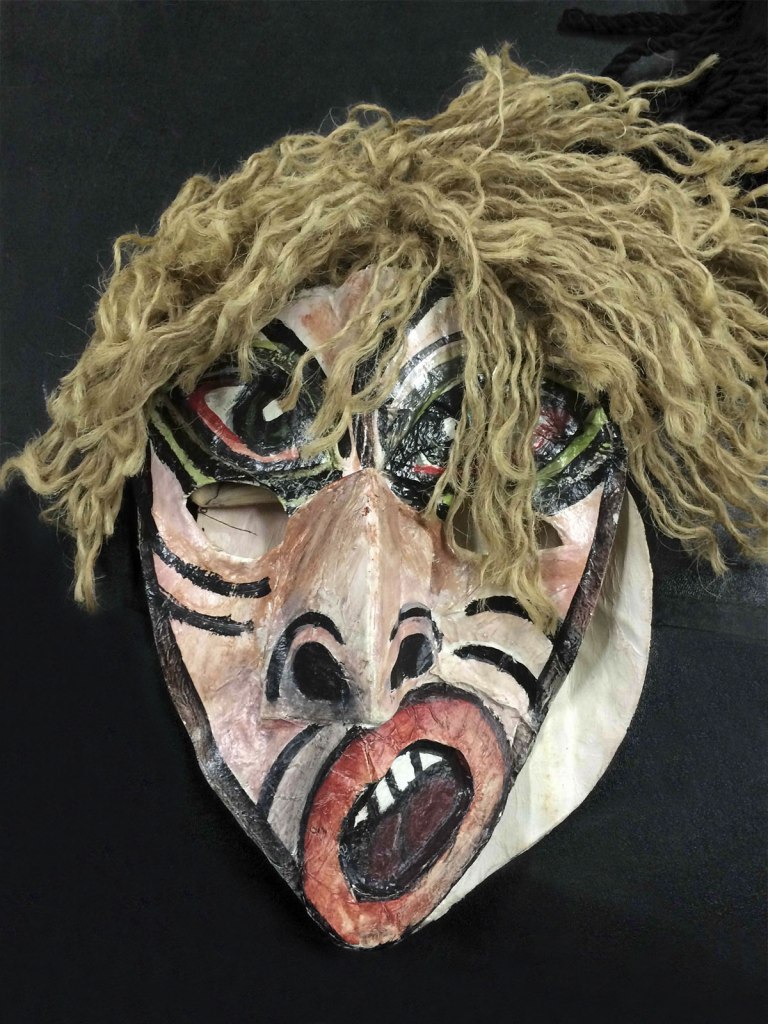

Huck Snyder (American, b. 1993)

Small mask from Last Supper at Uncle Tom’s Cabin

1990

Painted cardboard and fabric

New York Live Arts

Huck Snyder (American, b. 1993)

Huck Snyder was a visual artist and a designer of vivid stage settings for dancers and performance artists. He created sets and stage furniture that were surrealistic yet extremely simple and almost childlike at times. Imaginative and free in their execution and unmistakably his work, his sets often seemed inseparable from the vision of the performers with whom he worked. Huck had designed stage sets for the performance artist John Kelly beginning with sets for Diary of a Somnambulist in 1985…

Mr. Snyder also created sets for dances by Bill T. Jones and Bart Cook, and for theater pieces by Ishmael Houston-Jones. He conceived, directed and designed his own work “Circus,” a performance-art piece presented in 1987 at La Mama E.T.C. Mr. Snyder’s work has been displayed at the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, the Brooklyn Academy of Music and the Dance Theater Workshop in New York. His paintings and installations have been exhibited at galleries throughout the United States and in solo and group shows in Europe and Japan.

Anonymous text. “Huck Snyder,” on the Visual AIDS website Nd [Online] Cited 22/11/2021

Themes ~

Downtown

Downtown invitations

Shazork! invitation, Danceteria

Late 1980s

Museum of the City of New York, Gift of Carrie Goteiner and Miriam Montaug Ashkenazy in memory of Haoui Montaug

Peter Hujar (American, 1934-1987)

Quentin Crisp

1982

Vintage gelatin silver print

© The Peter Hujar Archive; Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

Quentin Crisp (English, 1908-1999)

Quentin Crisp was born Denis Charles Pratt in Surrey, England, on December 25, 1908. A self-described flamboyant homosexual, Crisp changed his name in his early 20s as part of his process of reinvention. Teased mercilessly at school as a boy, Crisp left school in 1926. He studied journalism at King’s College London, but failed to graduate. He then moved on to take art classes at Regent Street Polytechnic. Crisp began visiting the cafés of Soho, London, and even worked as a prostitute for six months. Crisp was always true to himself and expressed himself by dying his long hair lavender, polishing his fingernails and toenails, and dressing in an often androgynous style. Despite the ridicule and violence often directed toward him, Crisp carried on. He tried to join the army with the outbreak of World War II, but was rejected by the medical board, who determined that he was suffering from sexual perversion. Instead, Crisp remained in London during the Blitz, entertaining American GIs, whose friendliness inculcated a love for Americans.

Crisp held a number of jobs, including engineer’s tracer, life model, and author. His most famous work, The Naked Civil Servant, detailed his life in a homophobic British society. When the book was adapted for television, Crisp began a new career as a performer and lecturer. He moved to Manhattan in 1981, when he was 72 years old; settling in a studio apartment in the Bowery. Upon meeting and spending time with Crisp, Sting was inspired to pen his hit song, “An Englishman in New York.”

Crisp continued to tour, write, and lecture; including instructions on how to live life with style and the importance of manners. Crisp landed a few roles on American television and the 1990s became his busiest decade as an actor. In 1992, Crisp took on the role of Elizabeth I in the film Orlando.

Quentin Crisp died in November 1999, just shy of his 91st birthday, while touring his one-man show.

Anonymous text. “Quentin Crisp,” on the Biography website Nd [Online] Cited 15/02/2017. No longer available online

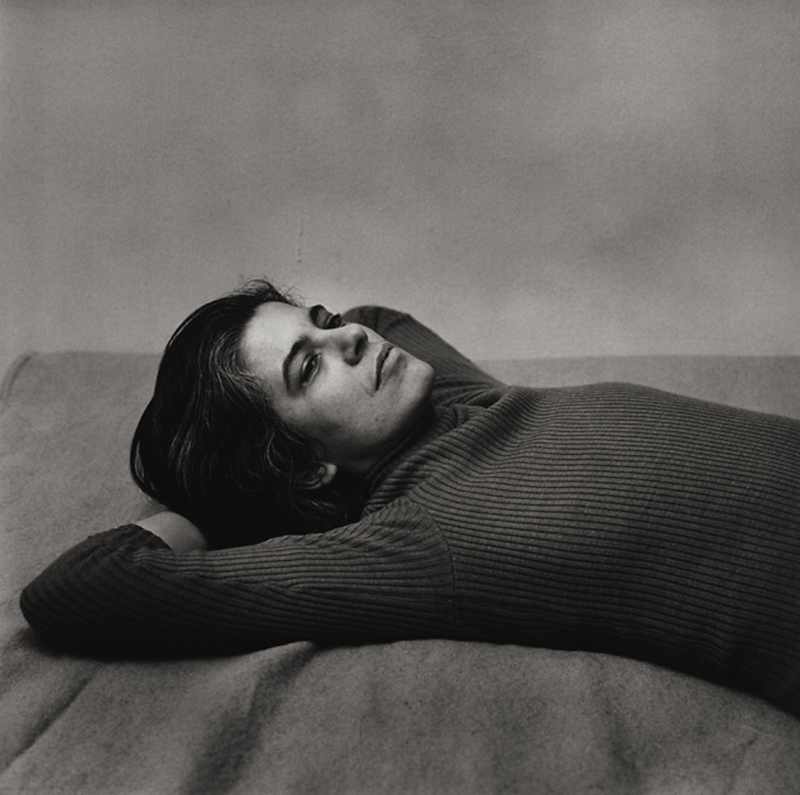

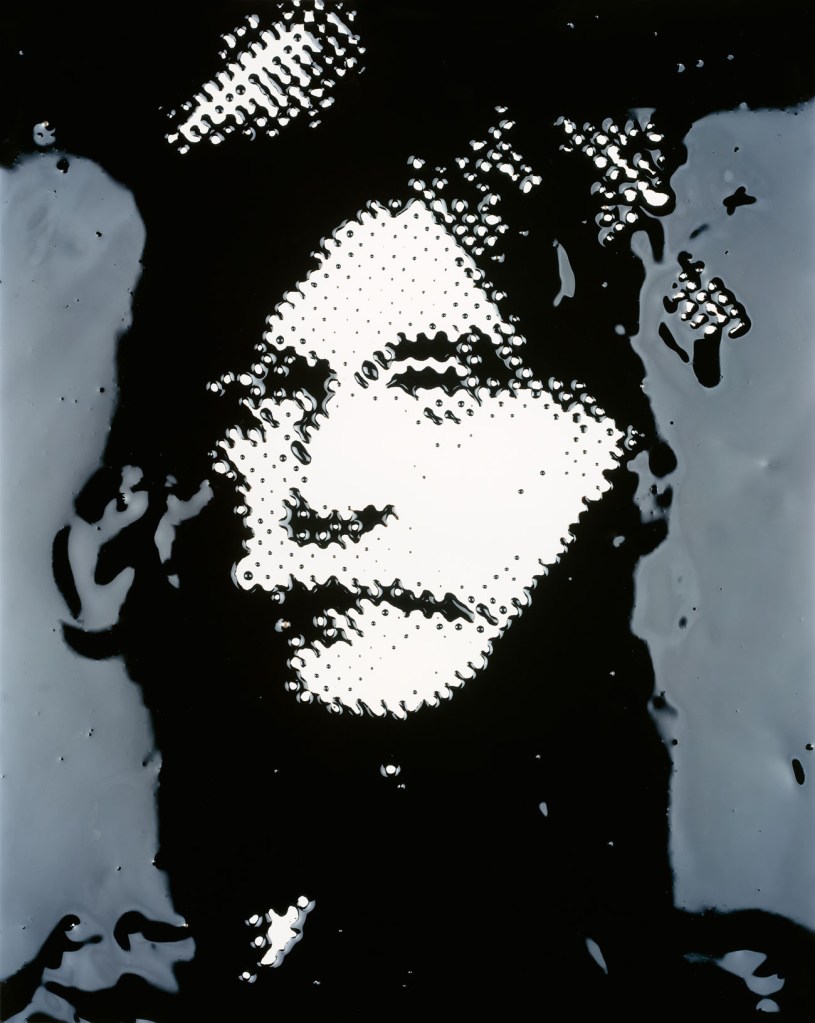

Peter Hujar (American, 1934-1987)

Susan Sontag

1975, printed 2014

Pigmented ink print

© The Peter Hujar Archive; Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

Peter Hujar (American, 1934-1987)

Peter Hujar (born 1934) died of AIDS in 1987, leaving behind a complex and profound body of photographs. Hujar was a leading figure in the group of artists, musicians, writers, and performers at the forefront of the cultural scene in downtown New York in the 1970s and early 80s, and he was enormously admired for his completely uncompromising attitude towards work and life. He was a consummate technician, and his portraits of people, animals, and landscapes, with their exquisite black-and-white tonalities, were extremely influential. Highly emotional yet stripped of excess, Hujar’s photographs are always beautiful, although rarely in a conventional way. His extraordinary first book, Portraits in Life and Death, with an introduction by Susan Sontag, was published in 1976, but his “difficult” personality and refusal to pander to the marketplace insured that it was his last publication during his lifetime.

Anonymous text. “About Peter Hujar” on the Peter Hujar Archive website [Online] Cited 22/11/2021

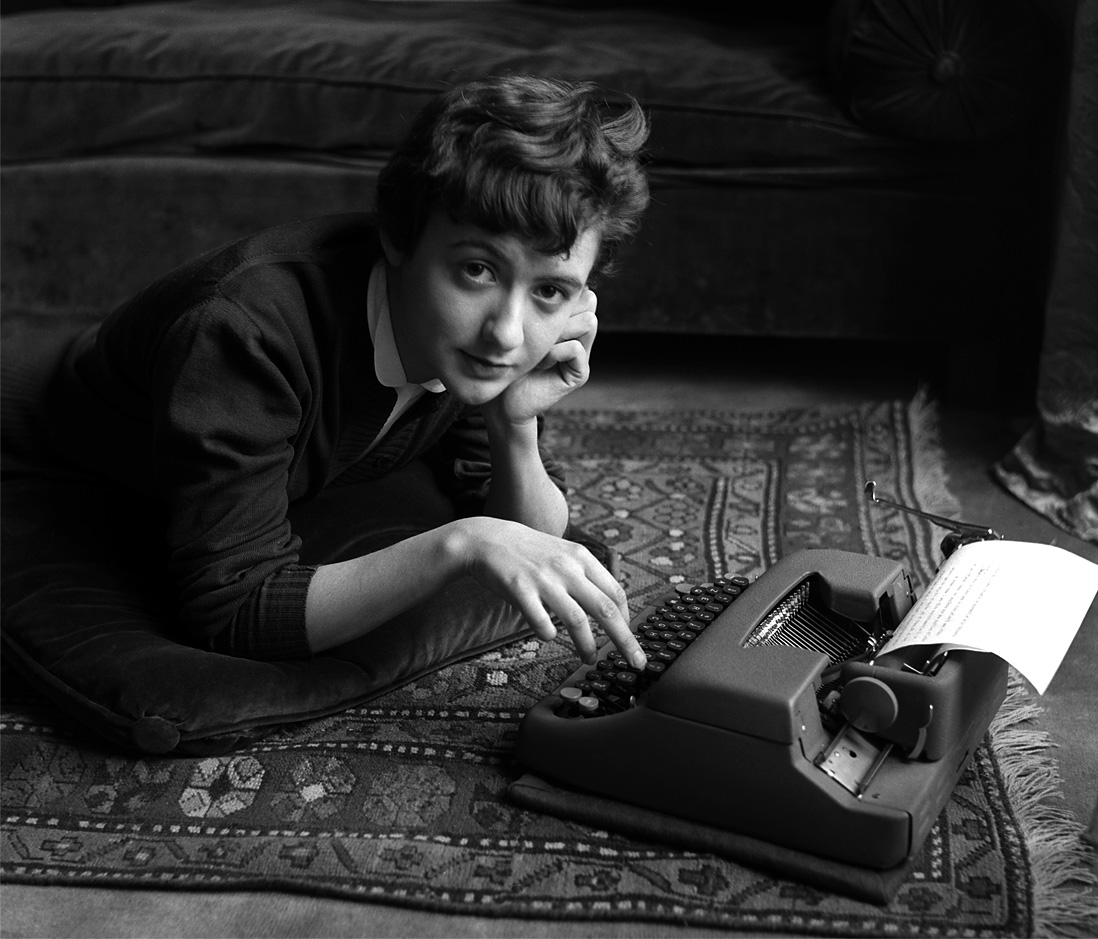

Susan Sontag (American, 1933-2004)

Susan Sontag (January 16, 1933 – December 28, 2004) was an American writer, filmmaker, teacher, and political activist. She published her first major work, the essay “Notes on ‘Camp'”, in 1964. Her best-known works include On Photography, Against Interpretation, Styles of Radical Will, The Way We Live Now, Illness as Metaphor, Regarding the Pain of Others, The Volcano Lover, and In America.

Sontag was active in writing and speaking about, or travelling to, areas of conflict, including during the Vietnam War and the Siege of Sarajevo. She wrote extensively about photography, culture and media, AIDS and illness, human rights, and communism and leftist ideology. Although her essays and speeches sometimes drew controversy, she has been described as “one of the most influential critics of her generation.” …

It was through her essays that Sontag gained early fame and notoriety. Sontag wrote frequently about the intersection of high and low art and expanded the dichotomy concept of form and art in every medium. She elevated camp to the status of recognition with her widely read 1964 essay “Notes on ‘Camp’,” which accepted art as including common, absurd and burlesque themes.

In 1977, Sontag published the series of essays On Photography. These essays are an exploration of photographs as a collection of the world, mainly by travellers or tourists, and the way we experience it… She became a role-model for many feminists and aspiring female writers during the 1960s and 1970s.

Text from the Wikipedia website

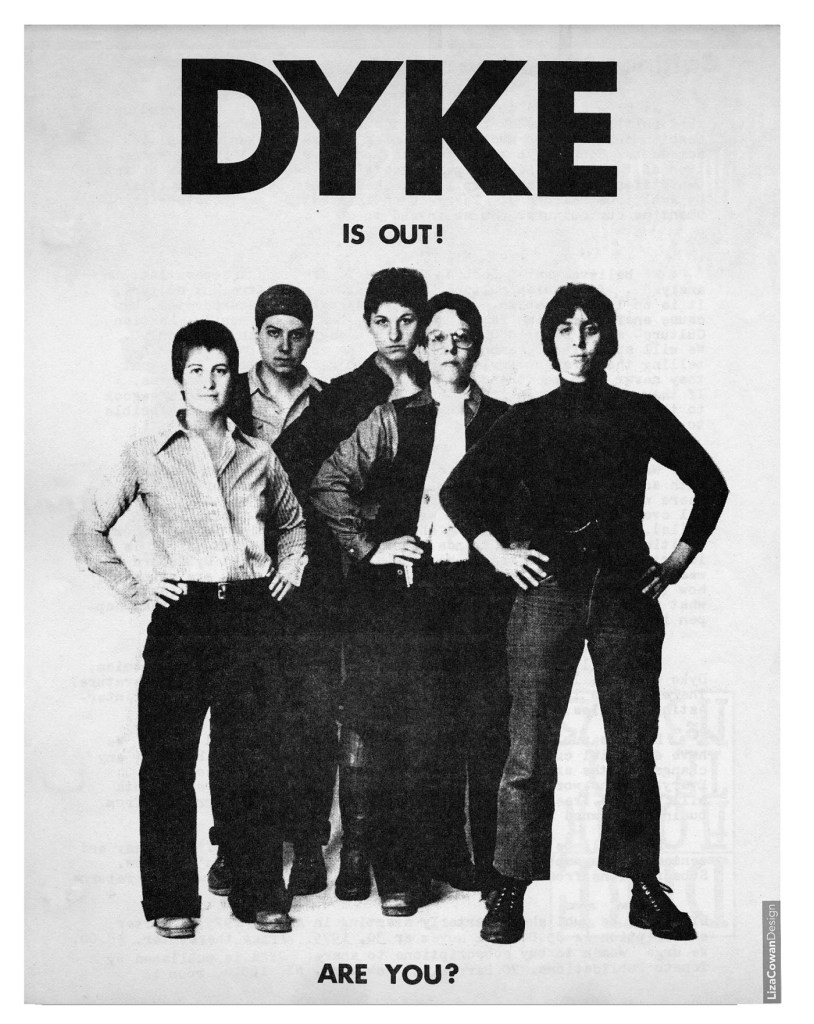

Printing

Liza Cowan (American) (designer)

DYKE, A Quarterly

c. 1974

Flyer

Courtesy Liza Cowan and Penny House

DYKE, A Quarterly Call for poster design flyer

1976

Illustration by Liza Cowan Penny House

Christopher Street

September 1977

Private collection

Christopher Street

June 1978

Private collection

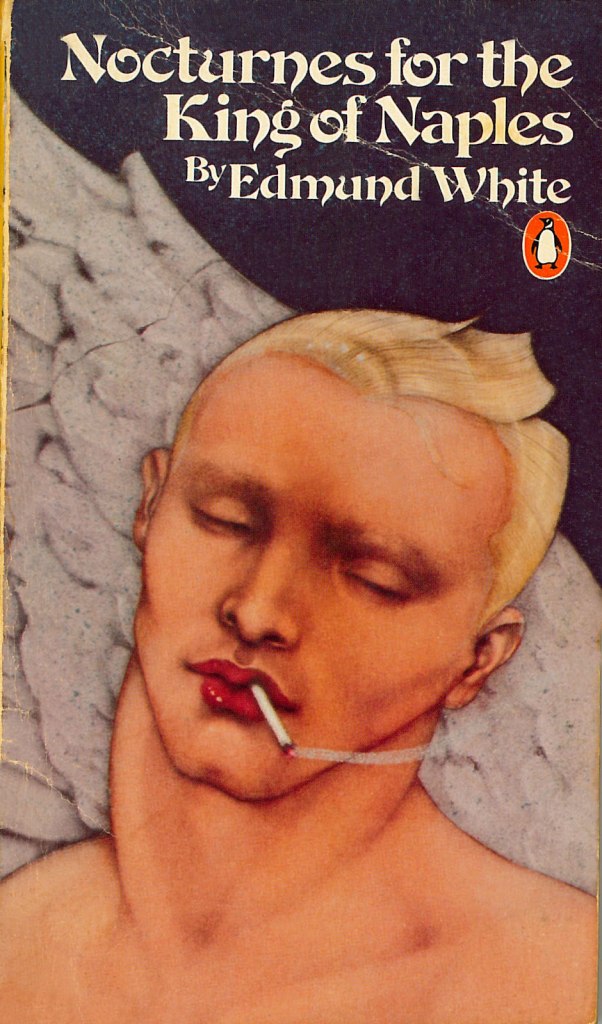

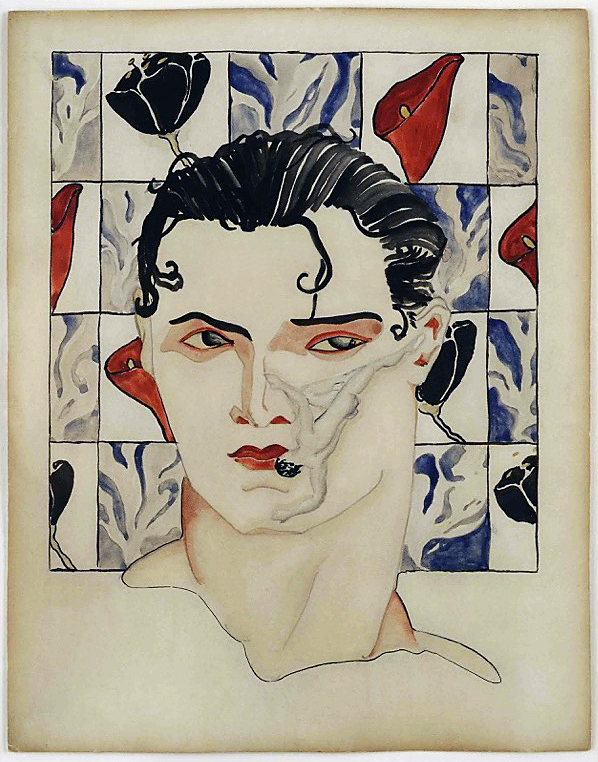

Edmund White (American, 1940-2025)

Nocturnes for the King of Naples

Paperback edition with cover art by Mel Odom, 1980 (originally published 1978)

Private collection

Edmund White (American, 1940-2025)

Edmund Valentine White III (1940-2025) is an American novelist, memoirist, playwright, biographer and an essayist on literary and social topics. Since 1999 he has been a professor at Princeton University. France made him Chevalier (and later Officier) de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres in 1993.

White’s books include The Joy of Gay Sex, written with Charles Silverstein (1977); his trilogy of semi-autobiographic novels, A Boy’s Own Story (1982), The Beautiful Room Is Empty (1988) and The Farewell Symphony (1997); and his biography of Jean Genet. Much of his writing is on the theme of same-sex love.

White has also written biographies of three French writers: Jean Genet, Marcel Proust and Arthur Rimbaud. He is the namesake of the Edmund White Award for Debut Fiction, awarded annually by Publishing Triangle.

Text from the Wikipedia website

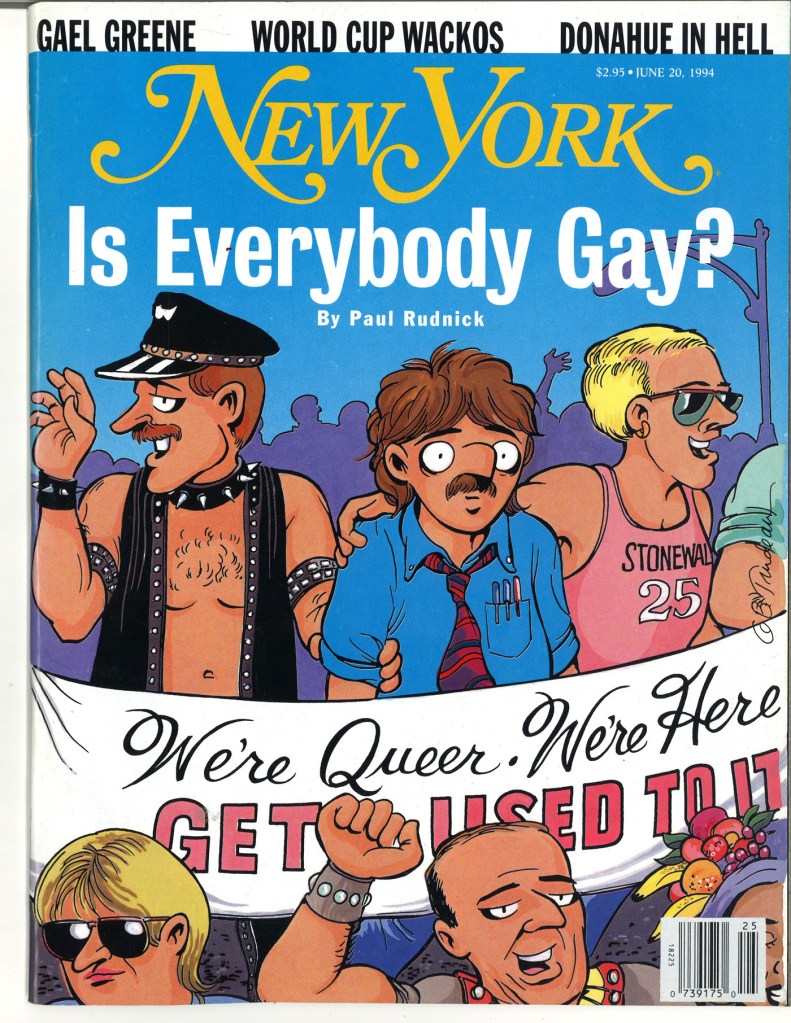

New York Magazine

June 20, 1994

1994

Courtesy New York Magazine

Posing

Eva Weiss (American born Hong Kong, b. 1950)

From left, Lois Weaver, Peggy Shaw, and Deb Margolin performing as Split Britches in ‘Upwardly Mobile Home’

1984

Contemporary archival print

Courtesy Eva Weiss Photography

Alice O’Malley (American, b. 1962)

Melanie Hope, Clit Club

c. 1992

Vintage gelatin silver print

Alice O’Malley Photography

Tseng Kwong Chi (American born Hong Kong, 1950-1990)

New York, NY (Statue of Liberty)

1979

Gelatin silver print

Muna Tseng Dance Projects Inc.

Tseng Kwong Chi (American born Hong Kong, 1950-1990)

Tseng Kwong Chi, known as Joseph Tseng prior to his professional career (Chinese: 曾廣智; c. 1950 – March 10, 1990), was a Hong Kong-born American photographer who was active in the East Village art scene in the 1980s.

Tseng was part of an circle of artists in the 1980s New York art scene including Keith Haring, Kenny Scharf, and Cindy Sherman. Tseng’s most famous body of work is his self-portrait series, East Meets West, also called the “Expeditionary Series”. In the series, Tseng dressed in what he called his “Mao suit” and sunglasses (dubbed a “wickedly surrealistic persona” by the New York Times), and photographed himself situated, often emotionlessly, in front of iconic tourist sites. These included the Statue of Liberty, Cape Canaveral, Disney Land, Notre Dame de Paris, and the World Trade Center. Tseng also took tens of thousands of photographs of New York graffiti artist Keith Haring throughout the 1980s working on murals, installations and the subway. In 1984, his photographs were shown with Haring’s work at the opening of the Semaphore Gallery’s East Village location in a show titled “Art in Transit”. Tseng photographed the first Concorde landing at Kennedy International Airport, from the tarmac. According to his sister, Tseng drew artistic influence from Brassai and Cartier-Bresson.

Text from the Wikipedia website

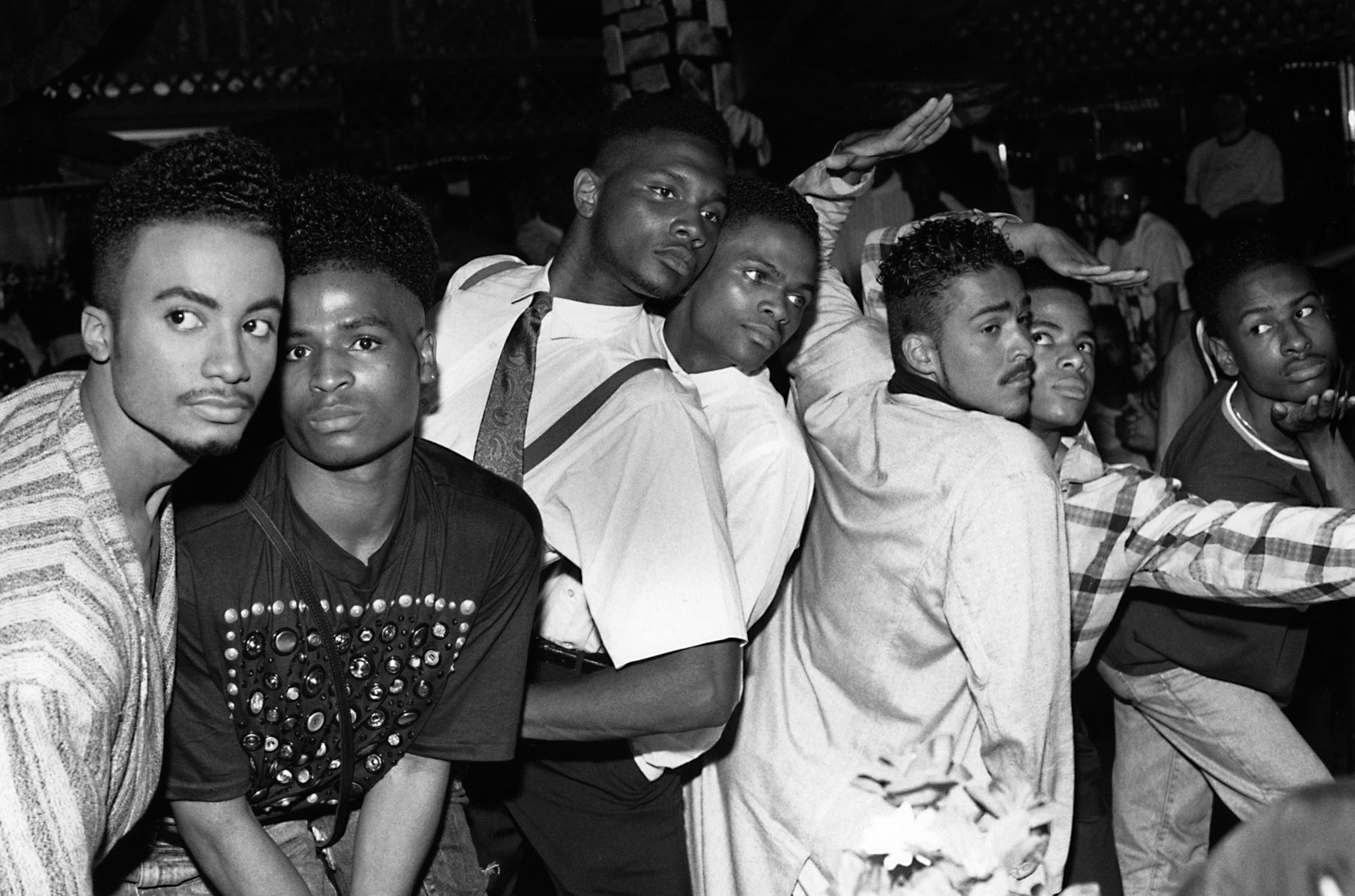

Chantal Regnault (French-Haitian)

From left, Whitney Elite, Ira Ebony, Stewart and Chris LaBeija, Ian and Jamal Adonis, Ronald Revlon, House of Jourdan Ball, New Jersey

1989

Gelatin silver print

© Chantal Regnault

Museum of the City of New York

1220 Fifth Ave at 103rd St.,

Opening hours:

Open Daily 10am – 6pm

![Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946) 'Untitled [O'Keeffe with sketchpad and watercolors]' 1918 from the exhibition 'Georgia O'Keeffe' at Tate Modern, London, July - Oct, 2016 Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946) 'Untitled [O'Keeffe with sketchpad and watercolors]' 1918 from the exhibition 'Georgia O'Keeffe' at Tate Modern, London, July - Oct, 2016](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/georgia_okeeffe_by_stieglitz_1918-web.jpg)

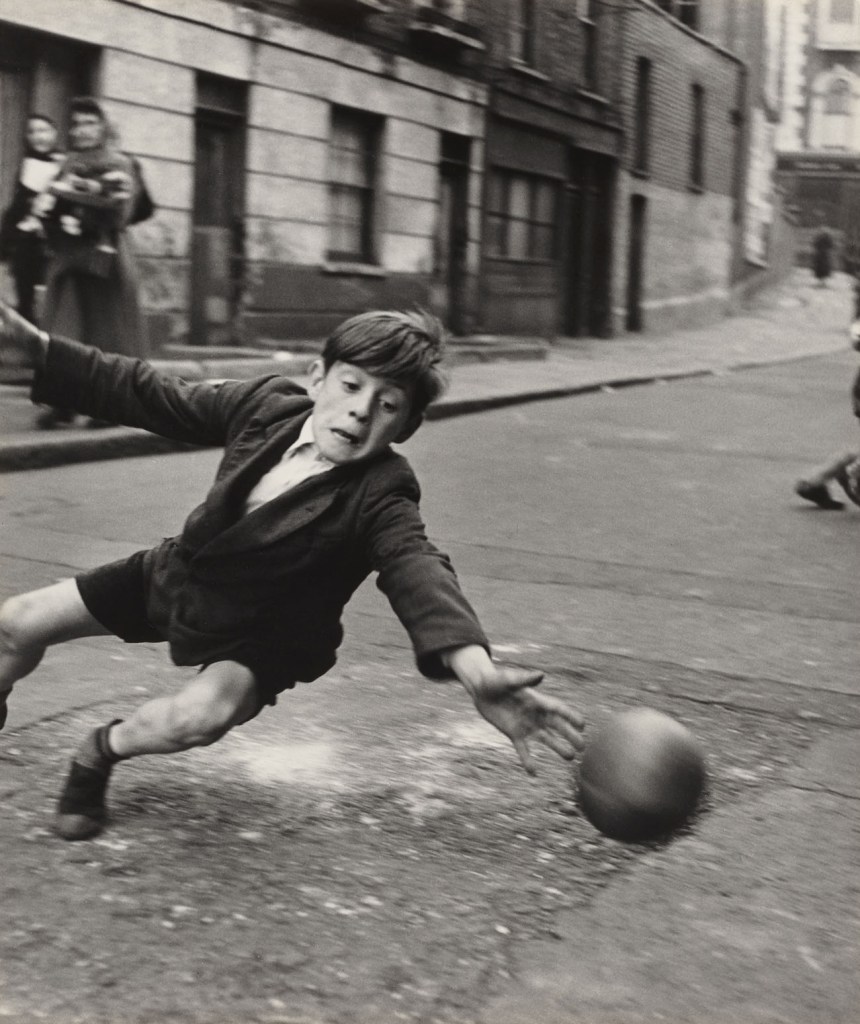

![Sabine Weiss (Swiss-French, 1924-2021) 'Enfants jouant, rue Edmond-Flamand' [Children playing, rue Edmond-Flamand] Paris, 1952 Sabine Weiss (Swiss-French, 1924-2021) 'Enfants jouant, rue Edmond-Flamand' [Children playing, rue Edmond-Flamand] Paris, 1952](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/weiss-children-playing-web.jpg?w=798)

![Sabine Weiss (Swiss-French, 1924-2021) 'Anna Karina pour la marque Korrigan' [Anna Karina for the brand Korrigan] 1958 Sabine Weiss (Swiss-French, 1924-2021) 'Anna Karina pour la marque Korrigan' [Anna Karina for the brand Korrigan] 1958](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/weiss-karina-web.jpg?w=812)

![Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'Dimanche après-midi à l'île Kolín' [Sunday afternoon at Kolín island] c. 1922–1926 Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'Dimanche après-midi à l'île Kolín' [Sunday afternoon at Kolín island] c. 1922–1926](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/sudek-dimanche-aprc3a8s-midi-c3a0-l_c3aele-kolc3adn-vers-1922e280931926-web1.jpg?w=898)

![Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'Portrait de mon ami Funke' [Portrait of my friend Funke] 1924 Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'Portrait de mon ami Funke' [Portrait of my friend Funke] 1924](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/sudek-portrait-de-mon-ami-funke-1924-web1.jpg?w=798)

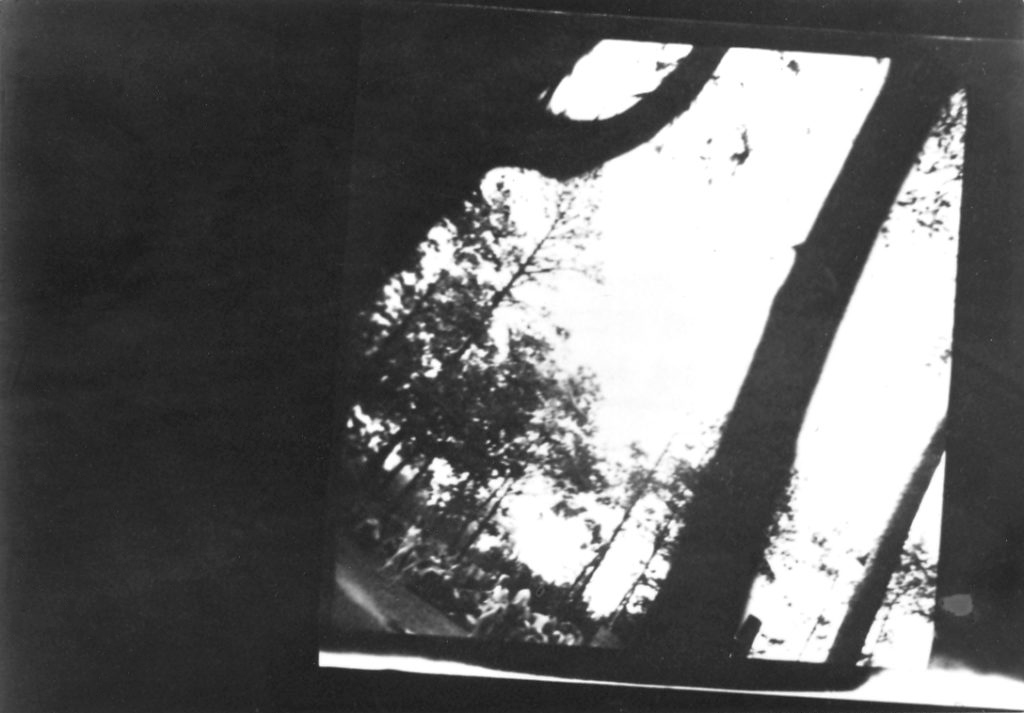

![Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'La Fenêtre de mon atelier' [The window of my studio] c. 1940-1948 Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'La Fenêtre de mon atelier' [The window of my studio] c. 1940-1948](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/sudek-la-fenc3aatre-de-mon-atelier-vers-1940e280931948-web1.jpg?w=708)

![Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'La Fenêtre de mon atelier' [The window of my studio] c. 1940–1954 Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'La Fenêtre de mon atelier' [The window of my studio] c. 1940–1954](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/josef-sudek-la-fenc3aatre-de-mon-atelier-vers-1940e280931954-web1.jpg?w=769)

![Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'La Fenêtre de mon atelier' [The window of my studio] c. 1940-1950 Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'La Fenêtre de mon atelier' [The window of my studio] c. 1940-1950](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/josef-sudek-la-fenc3aatre-de-mon-atelier-vers-1940e280931950-web1.jpg?w=838)

![Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'Quatre saisons: l'été' [Four seasons: summer] c. 1940-1954 Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'Quatre saisons: l'été' [Four seasons: summer] c. 1940-1954](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/josef-sudek-quatre-saisons-l_c3a9tc3a9-vers-1940e280931954-web1.jpg?w=738)

![Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'La Dernière Rose' [The Last Rose] 1956 Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'La Dernière Rose' [The Last Rose] 1956](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/sudek-la-dernic3a8re-rose-1956-web1.jpg?w=838)

![Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'Le Jardin Royal' [The Royal Garden] c. 1940-1946 Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'Le Jardin Royal' [The Royal Garden] c. 1940-1946](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/sudek-le-jardin-royal-vers-1940e280931946-web1.jpg?w=750)

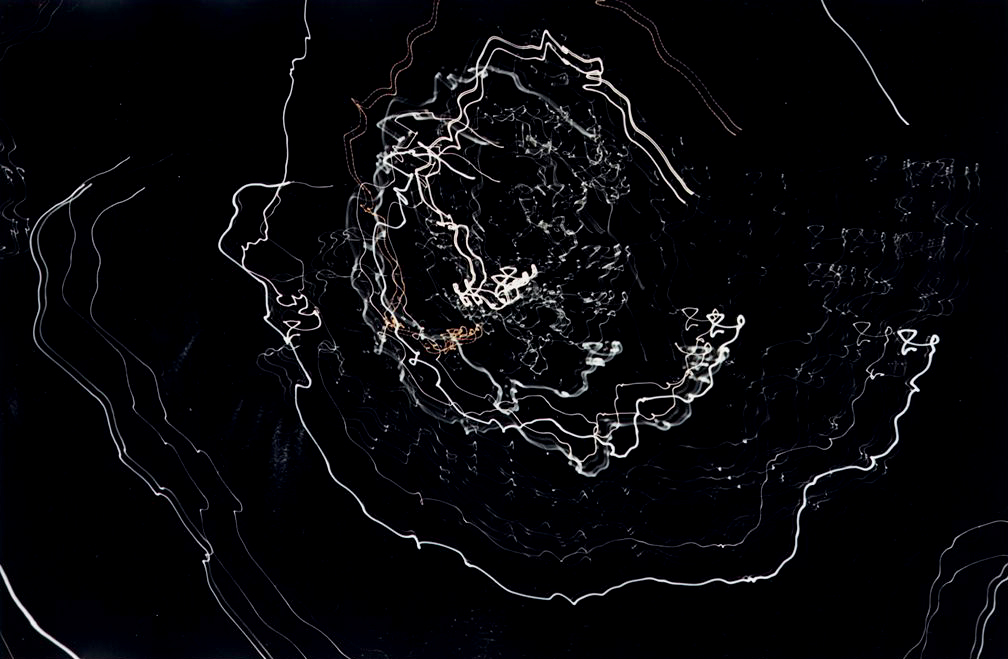

![Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'Prague pendant la nuit' [Prague at night] 1950 Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'Prague pendant la nuit' [Prague at night] 1950](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/sudek-prague-pendant-la-nuit-1950-web1.jpg)

![Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'Prague pendant la nuit' [Prague at night] c. 1950-1959 Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'Prague pendant la nuit' [Prague at night] c. 1950-1959](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/sudek-prague-pendant-la-nuit-vers-1950e280931959-web1.jpg)

![Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'Prague pendant la nuit' [Prague at night] c. 1950-1959 Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'Prague pendant la nuit' [Prague at night] c. 1950-1959](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/josef-sudek-prague-pendant-la-nuit-vers-1950e280931959-web1.jpg)

![Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'Le Jardin de Rothmayer' [The Rothmayer Garden] 1954-1959 Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'Le Jardin de Rothmayer' [The Rothmayer Garden] 1954-1959](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/sudek-le-jardin-de-rothmayer-1954e280931959-web1.jpg)

![Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'Dans le jardin' [In the garden] 1954-1959 Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'Dans le jardin' [In the garden] 1954-1959](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/sudek-dans-le-jardin-1954e280931959-web1.jpg)

![Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'Labyrinthe sur ma table' [Labyrinth on my table] 1967 Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'Labyrinthe sur ma table' [Labyrinth on my table] 1967](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/sudek-labyrinthe-sur-ma-table-1967-web1.jpg?w=826)

![Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'Labyrinthe de verre' [Glass Maze] around 1968-1972 Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'Labyrinthe de verre' [Glass Maze] around 1968-1972](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/sudek-labyrinthe-de-verre-vers-1968e280931972-web1.jpg?w=808)

![Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'Sans titre (Nature morte sur le rebord de la fenêtre)' [Untitled (Still life on the windowsill)] 1951 Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976) 'Sans titre (Nature morte sur le rebord de la fenêtre)' [Untitled (Still life on the windowsill)] 1951](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/josef-sudek-sans-titre-nature-morte-sur-le-rebord-de-la-fenc3aatre-1951-web1.jpg?w=836)

You must be logged in to post a comment.