Exhibition dates: 14th July – 15th October, 2017

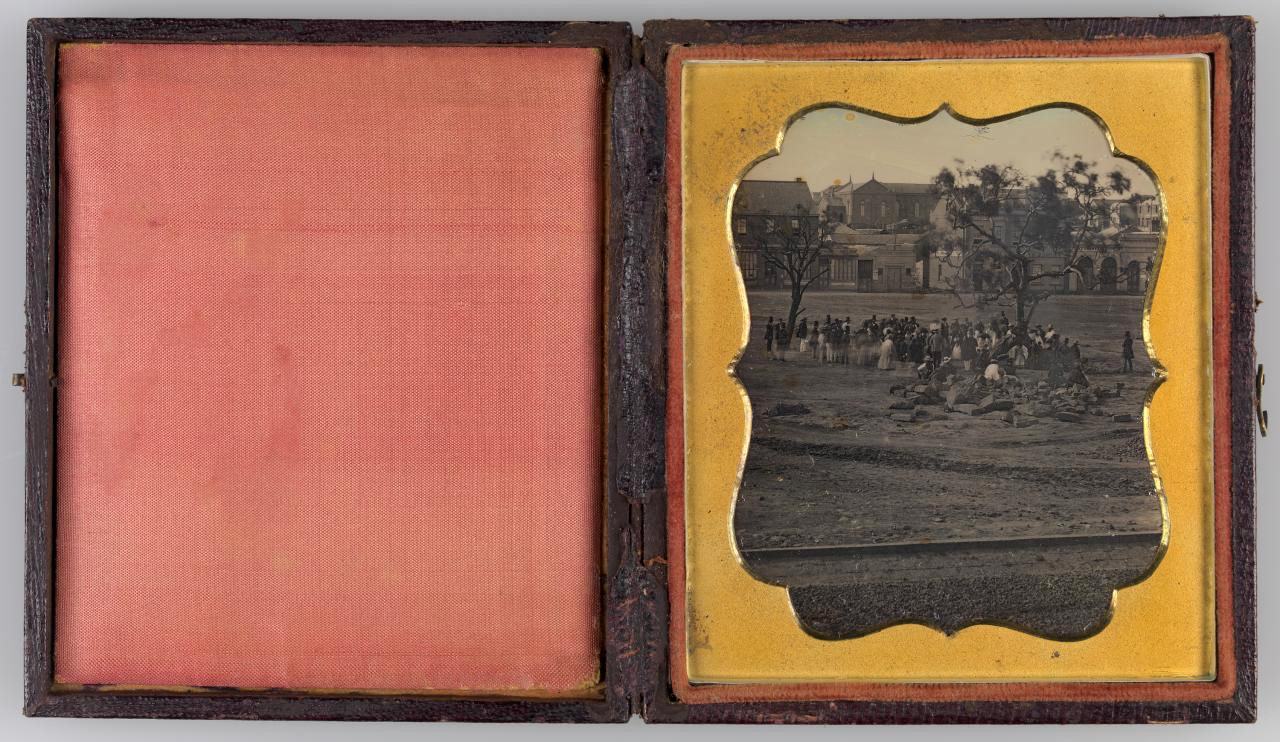

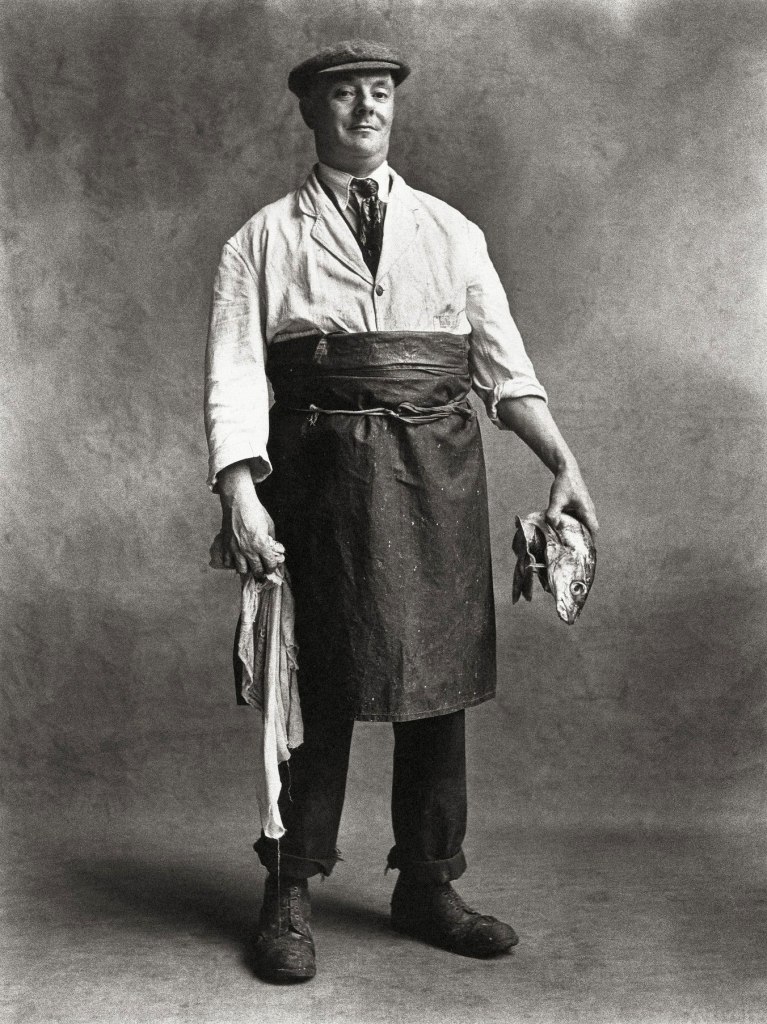

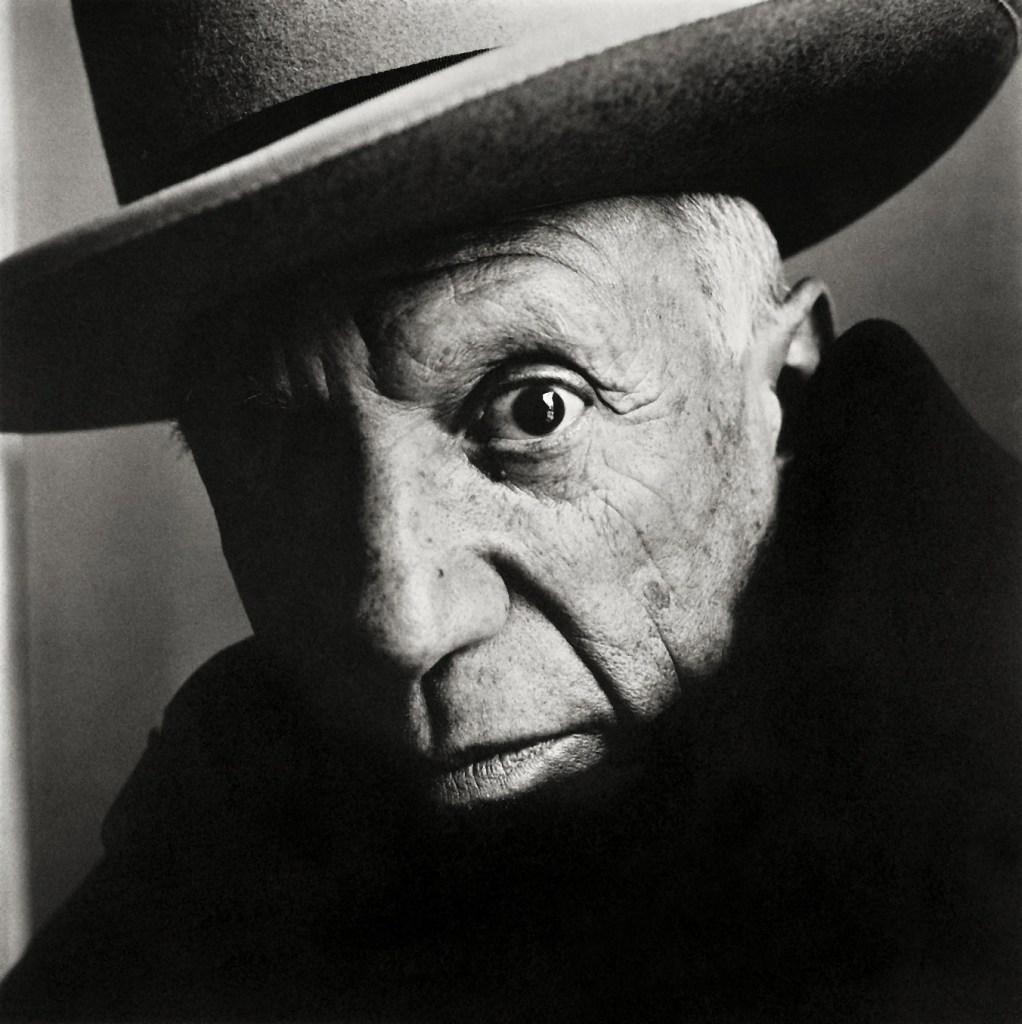

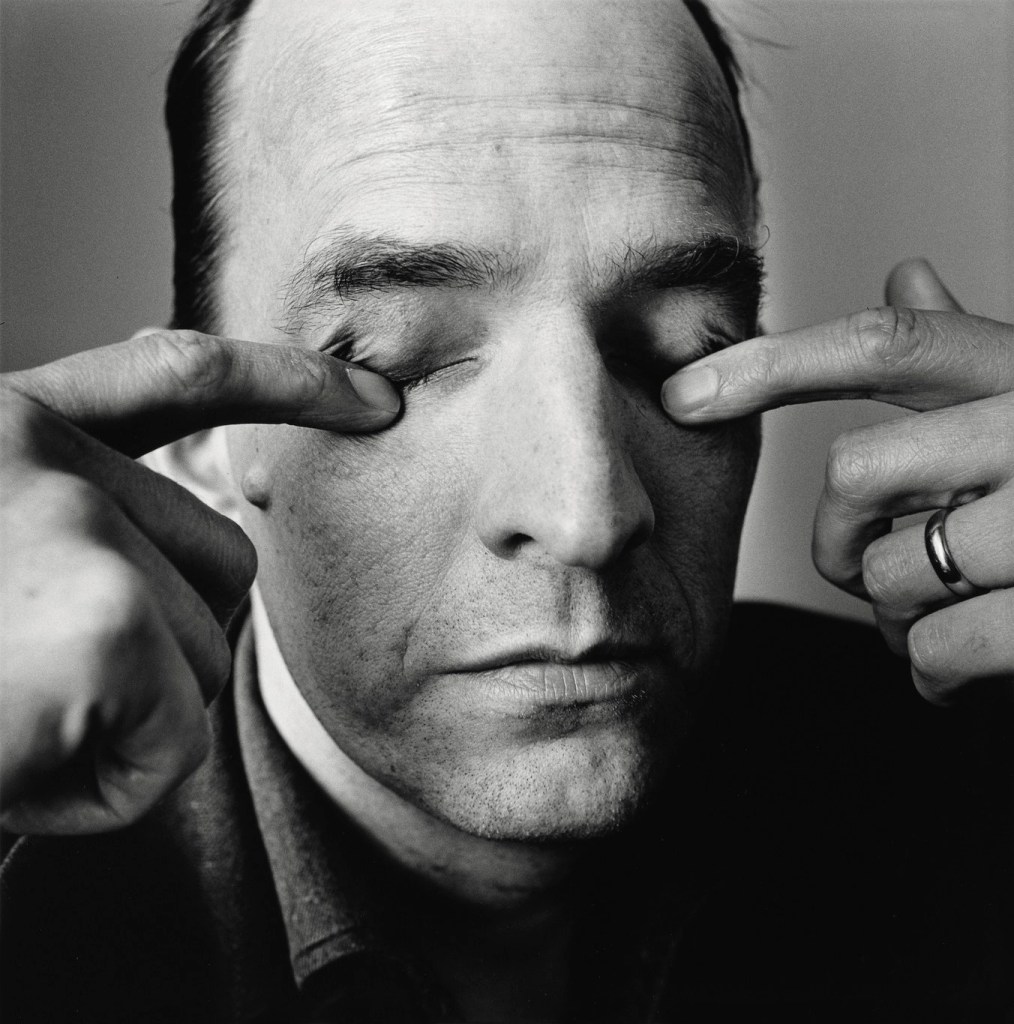

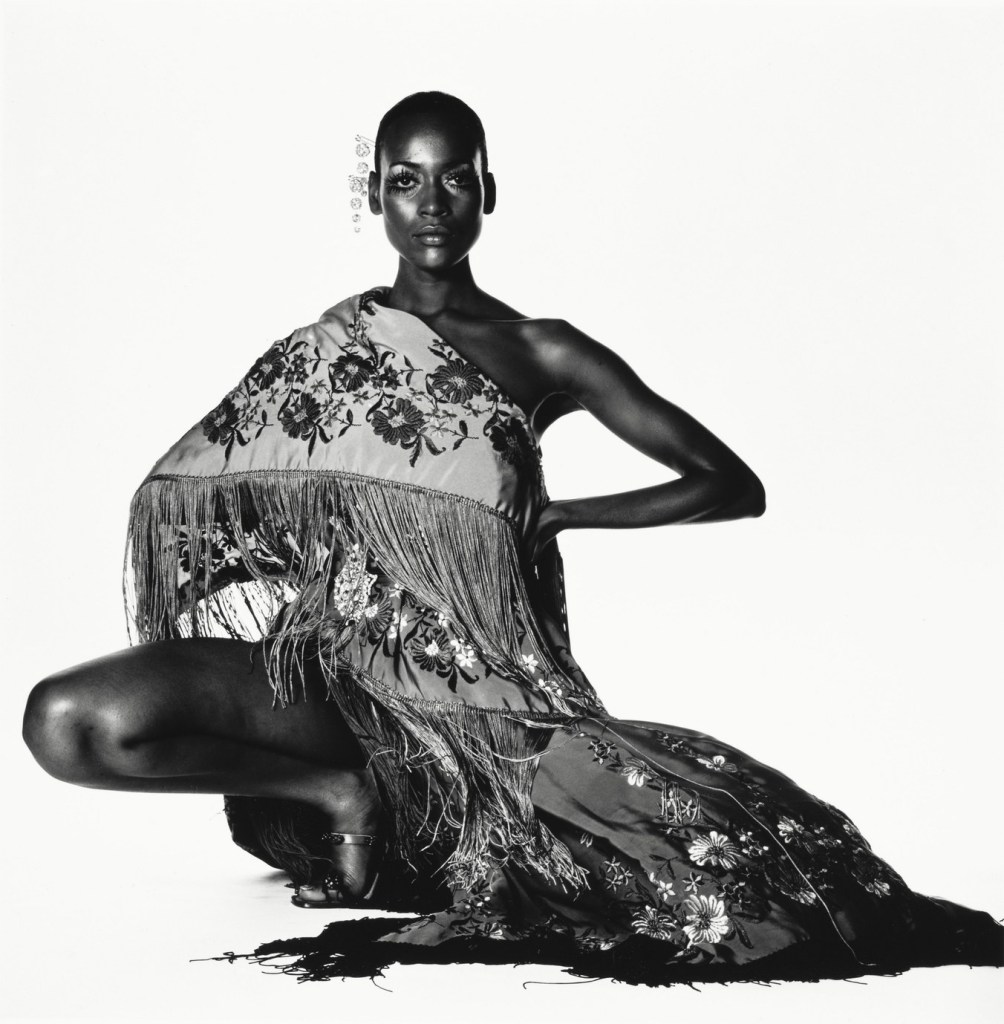

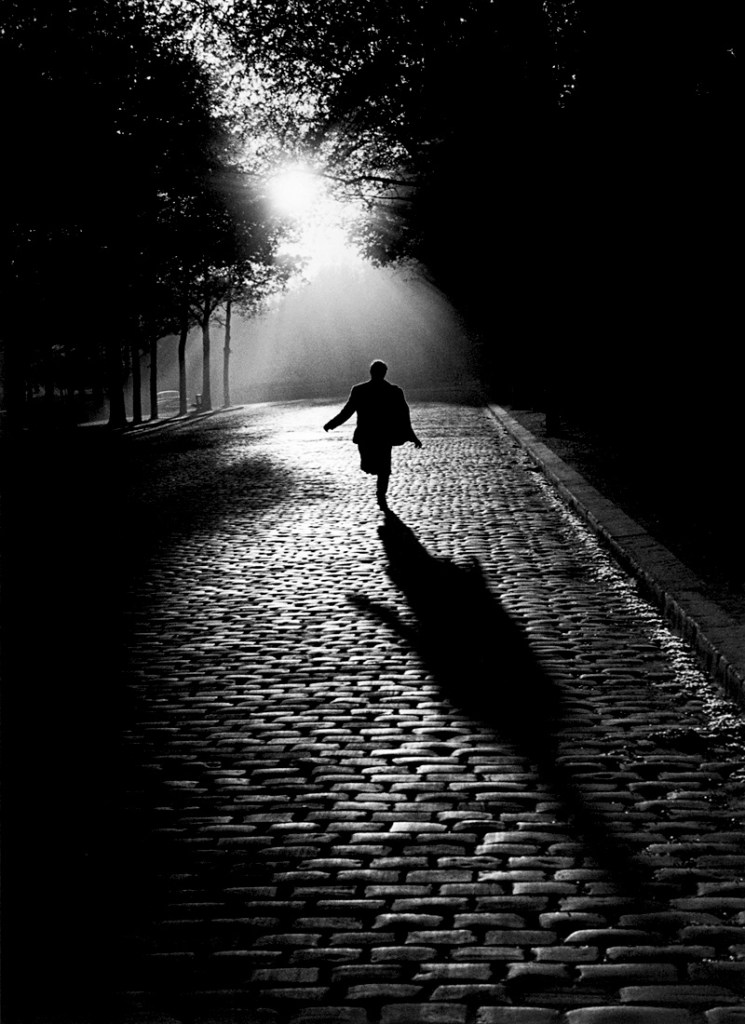

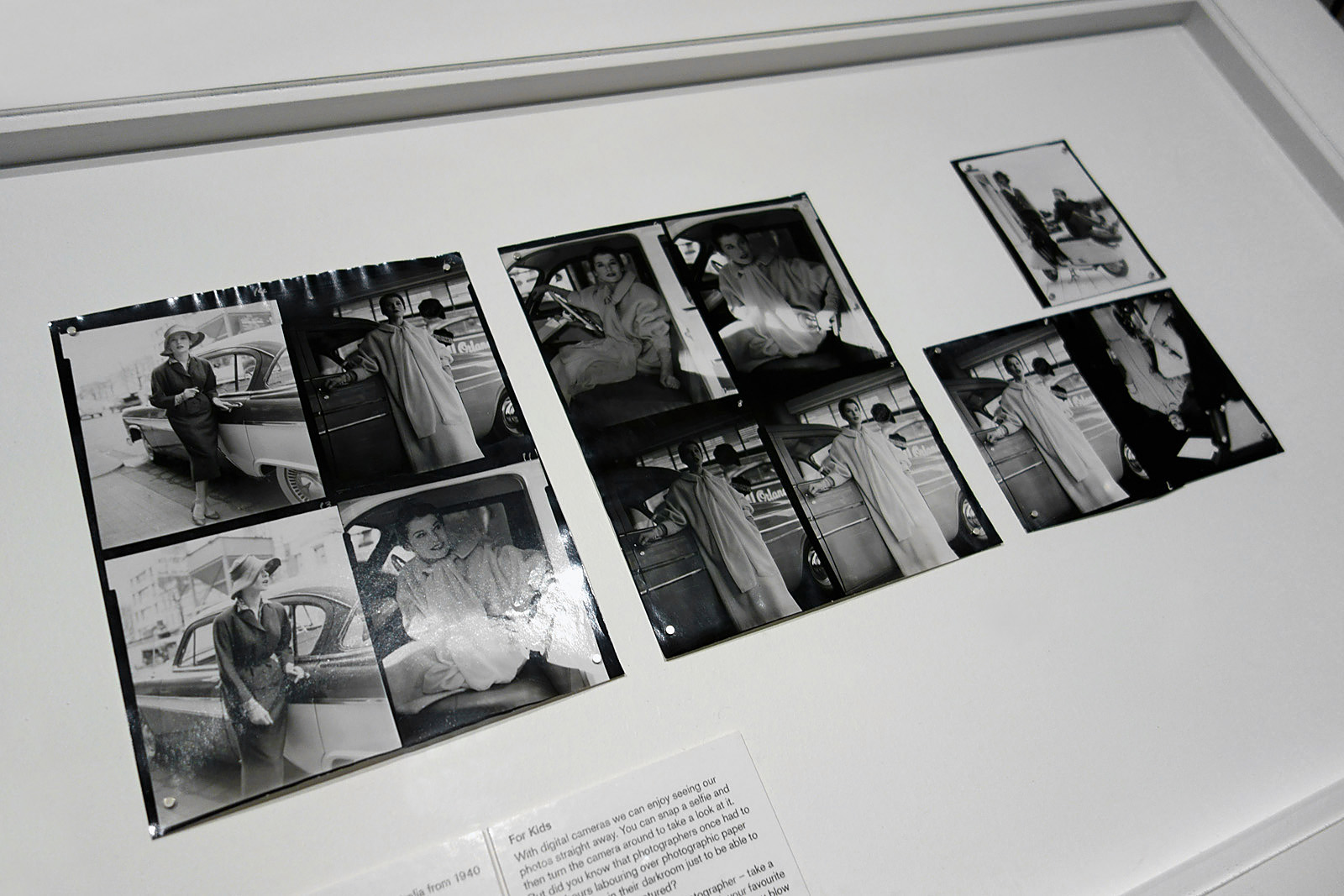

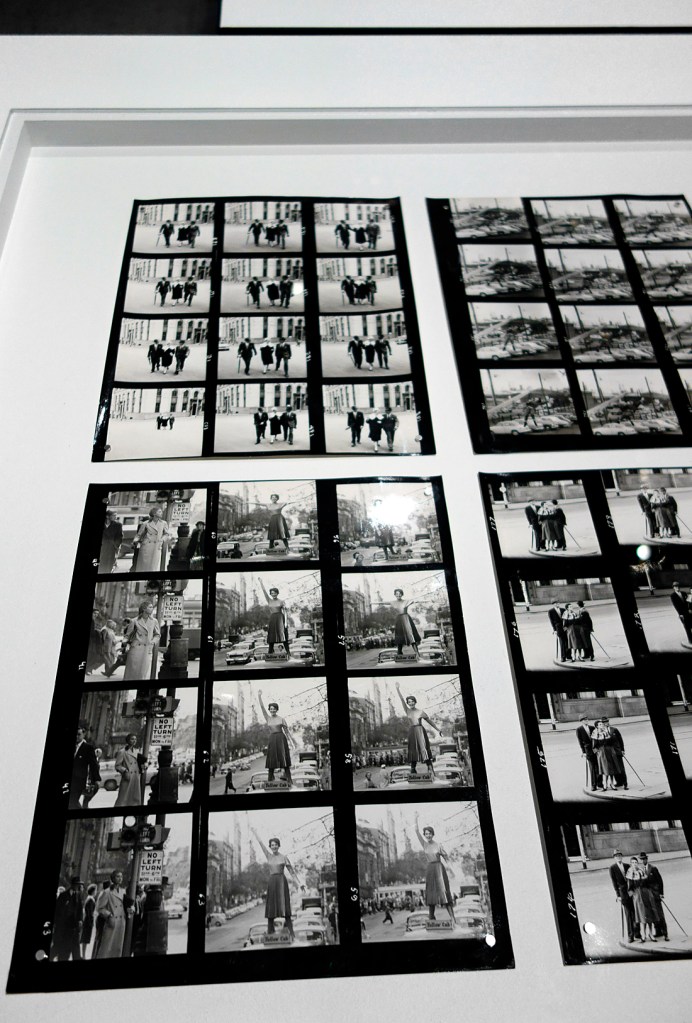

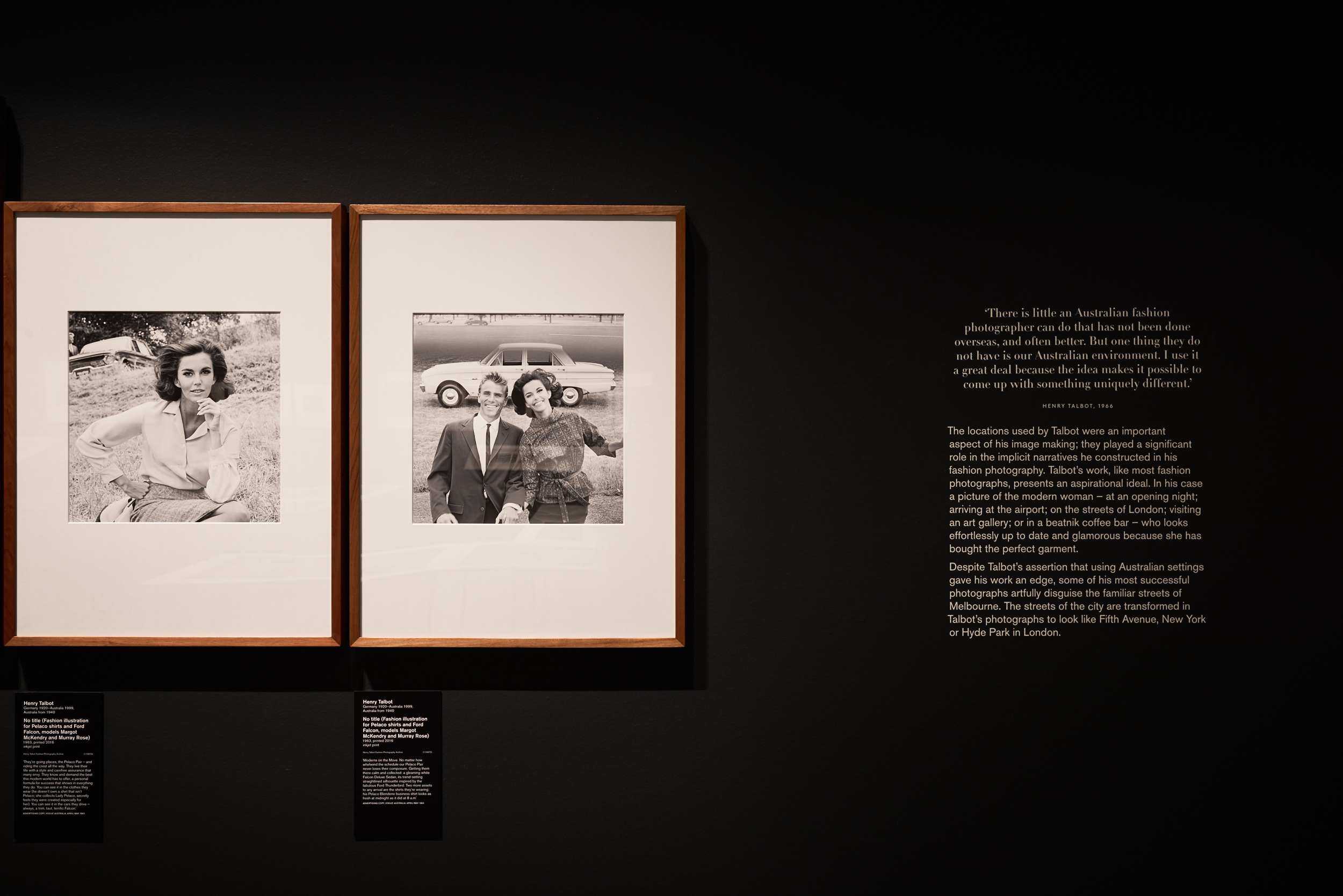

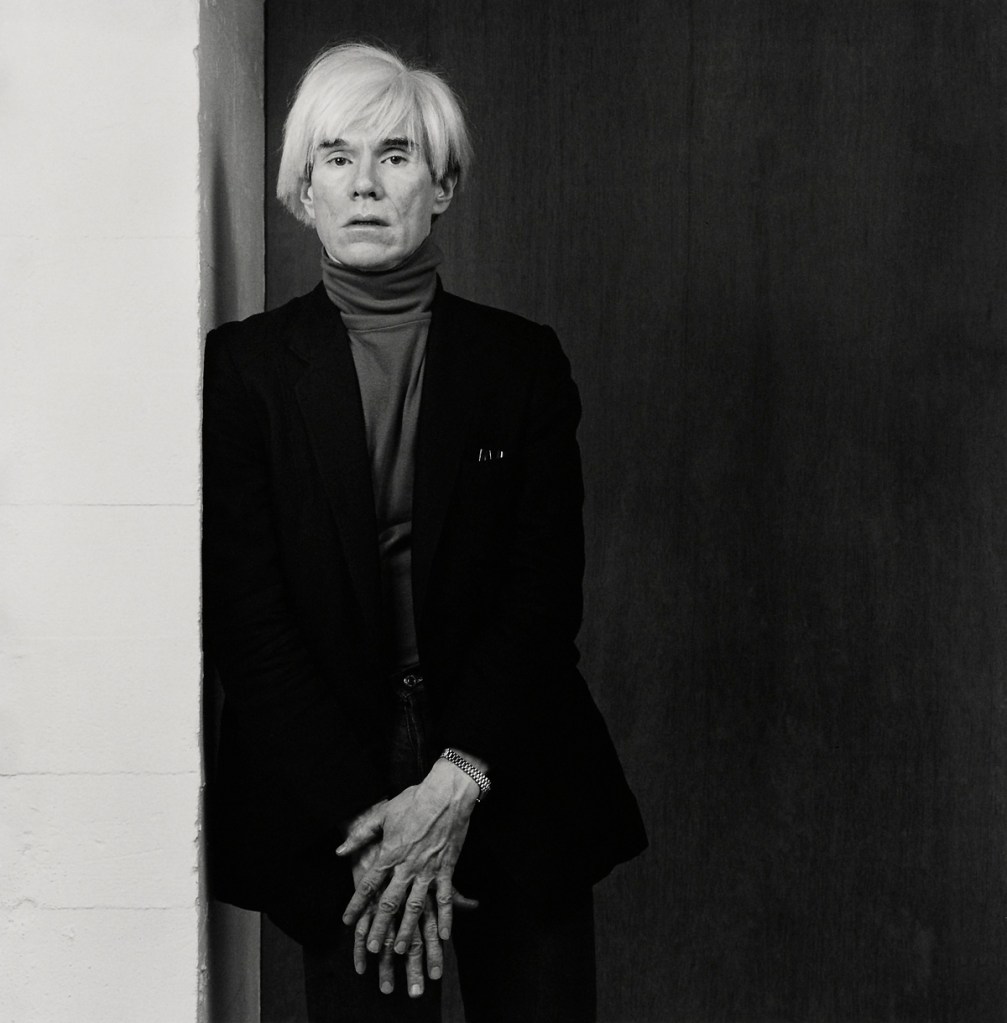

Installation view of the exhibition Brave New World: Australia 1930s at NGVA

Photo: Eugene Hyland

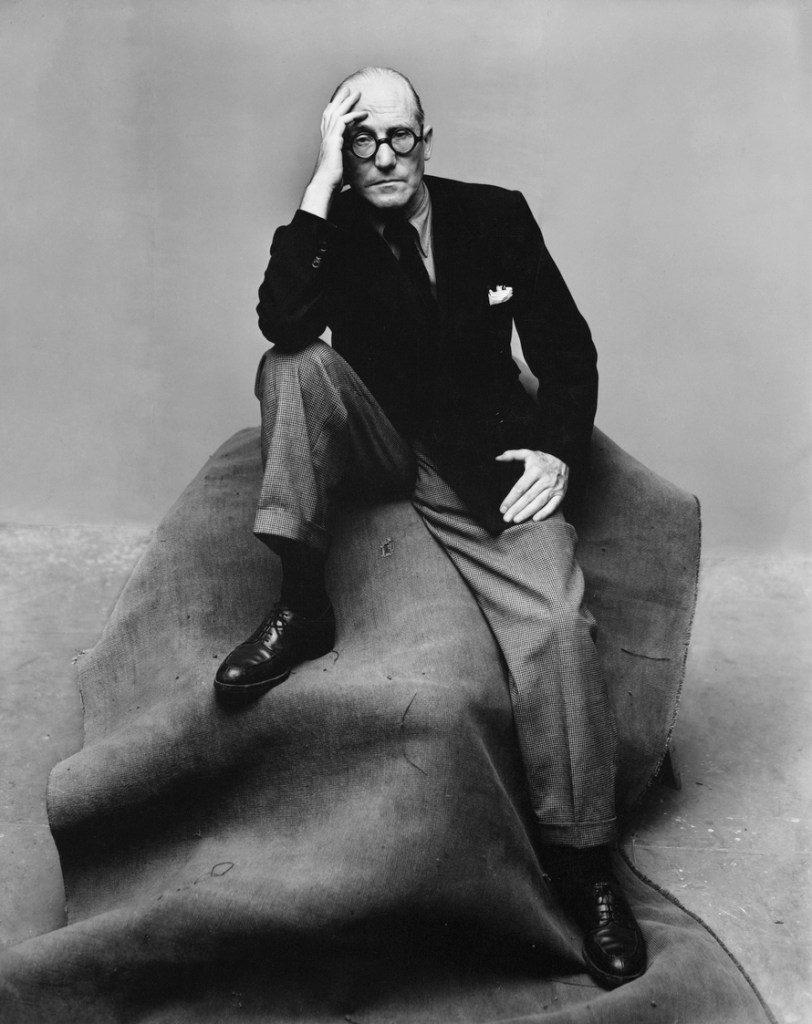

Brave New World: Australia 1930s at NGV Australia, Melbourne is a small but stylishly designed exhibition that presents well in the gallery spaces. The look and feel of the exhibition is superb, and it was a joy to see so many works in so many disparate medium brought together to represent a decade in the history of Australia: photography, sculpture, painting, drawing, ceramic art, magazine art, travel posters, Art Deco radios, film, couture, culture, Aboriginal art, and furniture making, to name but a few.

The strong exhibition addresses most of the concerns of the 1930s – The Great Depression, beach and body culture, style, fashion, identity, culture, prelude to WW2, dystopian and utopian cities etc., – but it all felt a little cramped and truncated. Such a challenging time period needed a more expansive investigation. What there is was excellent but one display case on slums or magazine art was not substantive enough. The same can be said for most of the exhibition.

There needed to a lot more about the impact of the Great Depression and people living in poverty, for you get the feeling from this exhibition that everyone was living the Modernist high-life, wearing fashionable frocks and smoking cigarettes sitting around beautifully designed furniture surrounded by geometric textiles. The reality is that this paradigm was the exception rather than the rule. Many people struggled to even feed themselves due to The Great Depression, and it was a time of extreme hardship for people in Australia. Life for many, many people in Australia during the 1930s was a life of disenfranchisement, assimilation, oppression, social struggle, poverty, hunger and a hand to mouth existence.

“After the crash unemployment in Australia more than doubled to twenty-one per cent in mid-1930, and reached its peak in mid-1932 when almost thirty-two per cent of Australians were out of work… The Great Depression’s impact on Australian society was devastating. Without work and a steady income many people lost their homes and were forced to live in makeshift dwellings with poor heating and sanitation.” (Text from “The Great Depression,” on the Australian Government website [Online] Cited 06/10/2017. No longer available online)

New artists and designers may have been emerging, new skyscrapers being built and the new ‘Modern Woman’ may have made her appearance but the changes only affected white, middle and upper social classes. Migrants, particularly those from Italy and southern Europe, were resented because they worked for less wages than others; and only brief mention is made of the White Australia policy in the exhibition but not by name (see text under Indigenous art and culture below). This section was more interested in how white artists appropriated Aboriginal design during this period for their own ends.

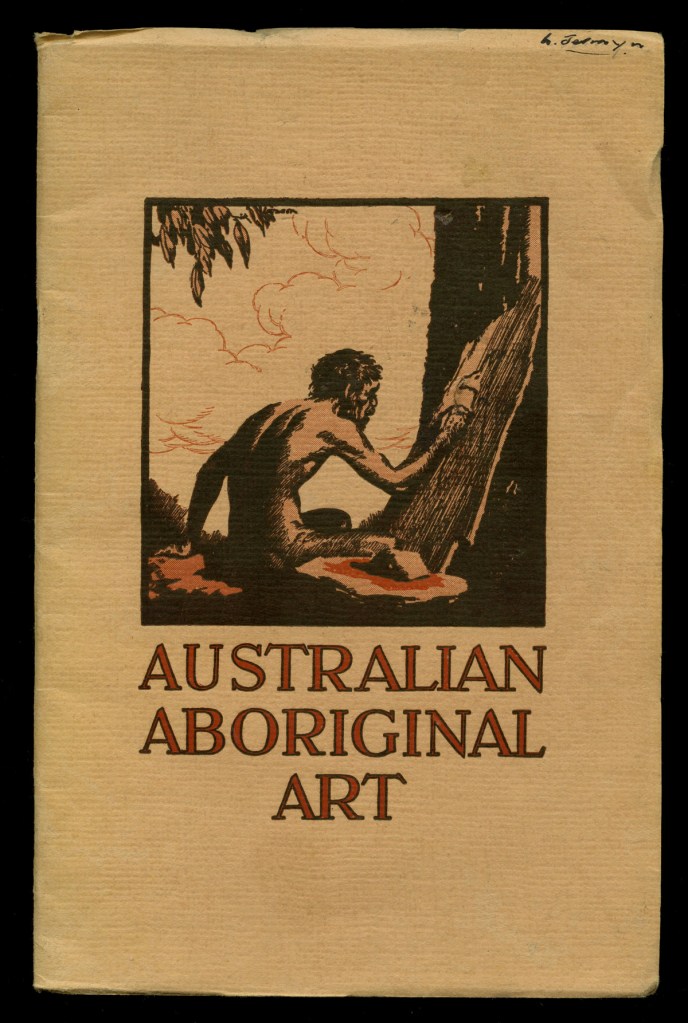

With this in mind, it is instructive to read sections of the illustrated handbook (see cover below, handbook not in the exhibition) produced by the National Museum of Victoria (in part, the forerunner of the NGV) to accompany a special exhibition of objects illustrating Australian Aboriginal Art in 1929:

“The subject of aboriginal Art – in this case the Art of the Australian Aboriginal – has to be approached with the utmost caution, for, though it comes directly within the domain of anthropology, it is in an indirect way a very important question in psychology and pedagogies. We possess some knowledge of our own mentality through the kind of offices of psychology; but though we have some – many in certain classes – material relics of our primitive and prehistoric ancestor, the only evidence of evolution of thought and the development of his powers of abstract conception must be derived from his art…

Still it appears possible that the study of primitive man, as represented by our Australian black, will throw some new light on the subject, and even if not more important than the old world pictographs themselves, his art work will enable the efforts of the Aurignacian and Magdalenian artists [cultures of the Upper Paleolithic in western Europe] to be better comprehended, and their import understood. But, for that study to achieve even a modicum of success, it is essential that the inquiring psychologist divest his mind of all civilized conceptions and mentality and assume those of the prehistoric man – or of the infant of the present day.”1

This is the attitude towards Aboriginal art that pervaded major art institutions right across Australia well into the 1950s. That the white has to “divest his mind of all civilised conceptions and mentality and assume those of the prehistoric man” – in other words, he has to become a savage – in order to understand Aboriginal art. It says a lot that the Trustees of the National Museum of Victoria then decided to reprint the illustrated handbook in 1952 without amendment, reprinting the publication originally used for the Exhibition in 1929. Nothing had changed in 22 years!

Other small things in the exhibition rankle. The preponderance of the work of photographer Max Dupain is so overwhelming that from this exhibition, it would seem that he was the only photographer of note working in Australia throughout the decade. While Dupain was the first Modernist photographer in Australia, and a superb artist, Modernist photography was very much on the outer during most of the 1930s… the main art form of photography being that of Pictorialism. None of this under appreciated style of photography makes an appearance in this exhibition because it does not fit the theme of “Brave New World”. This dismisses the work of such people as Cecil Bostock, Harold Cazneaux, Henri Mallard, John Eaton et al as not producing “brave”, or valuable, portraits of a country during this time frame. This is a perspective that needs to be corrected.

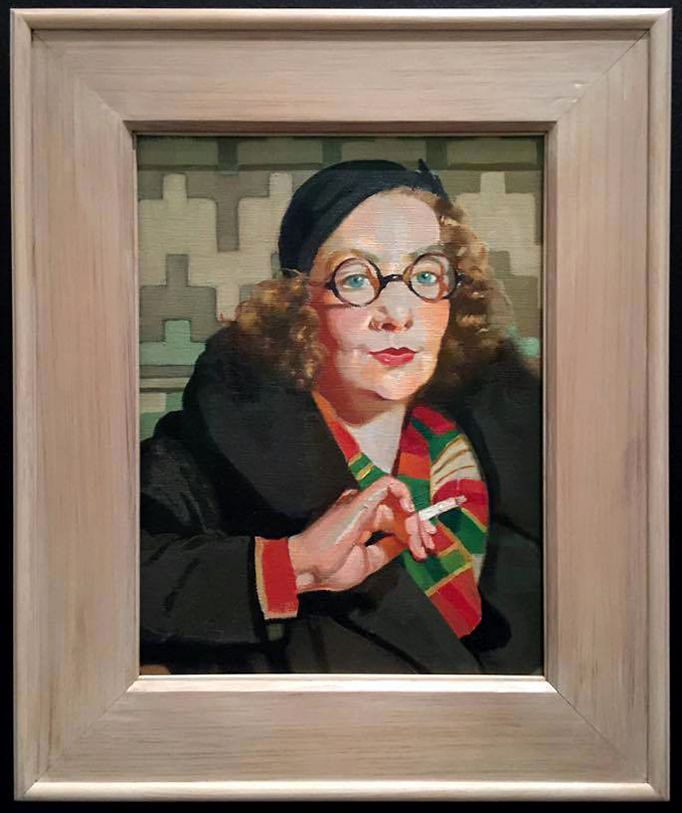

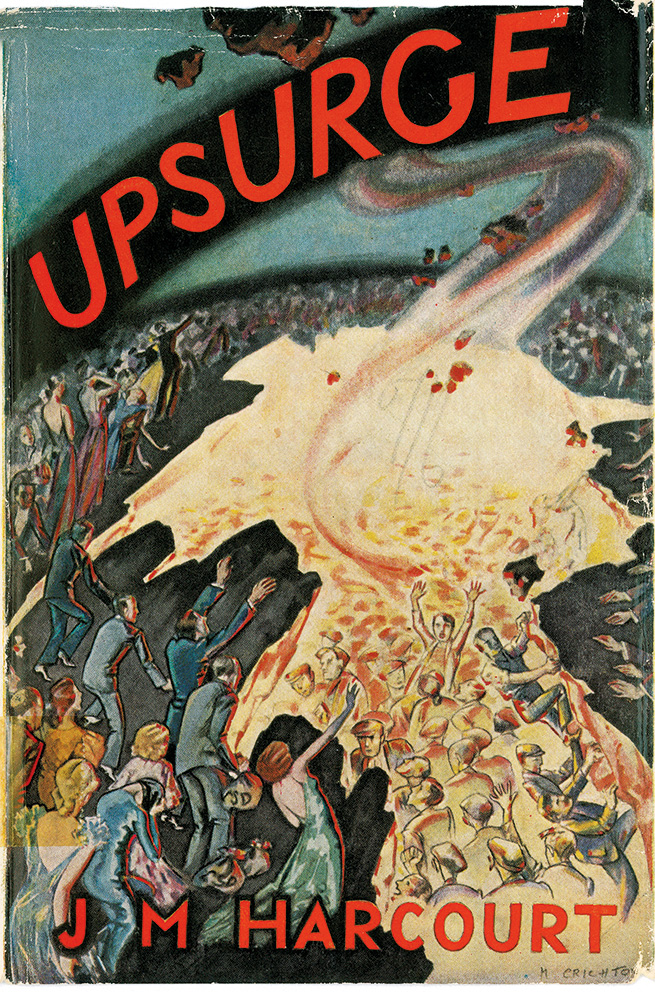

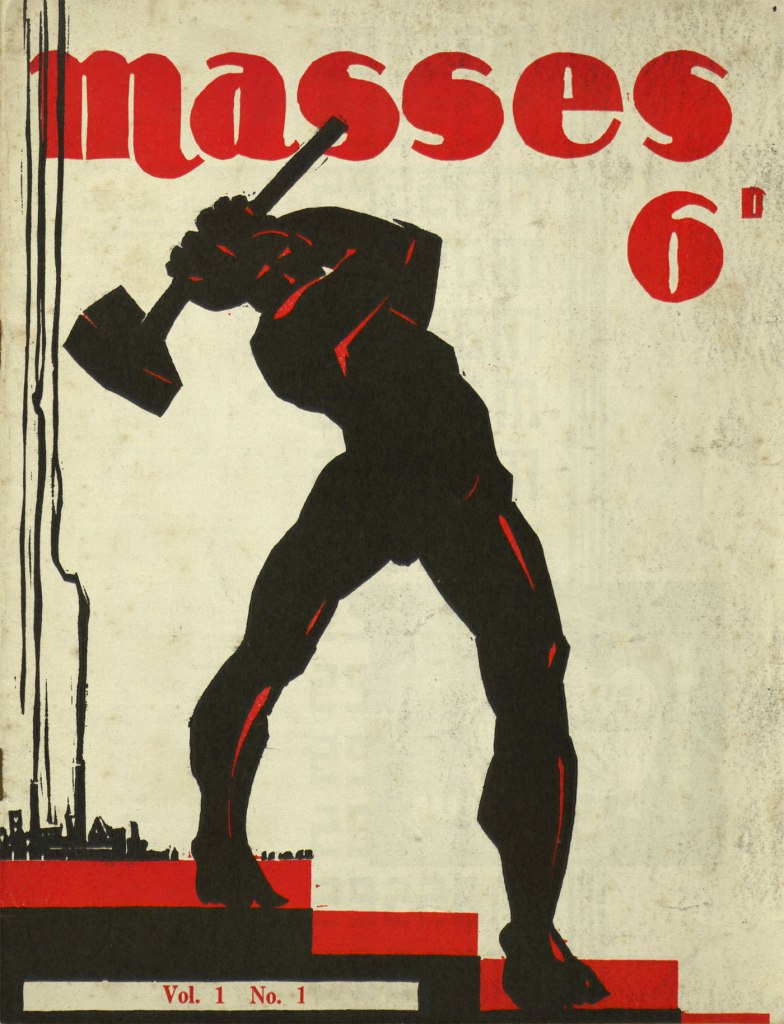

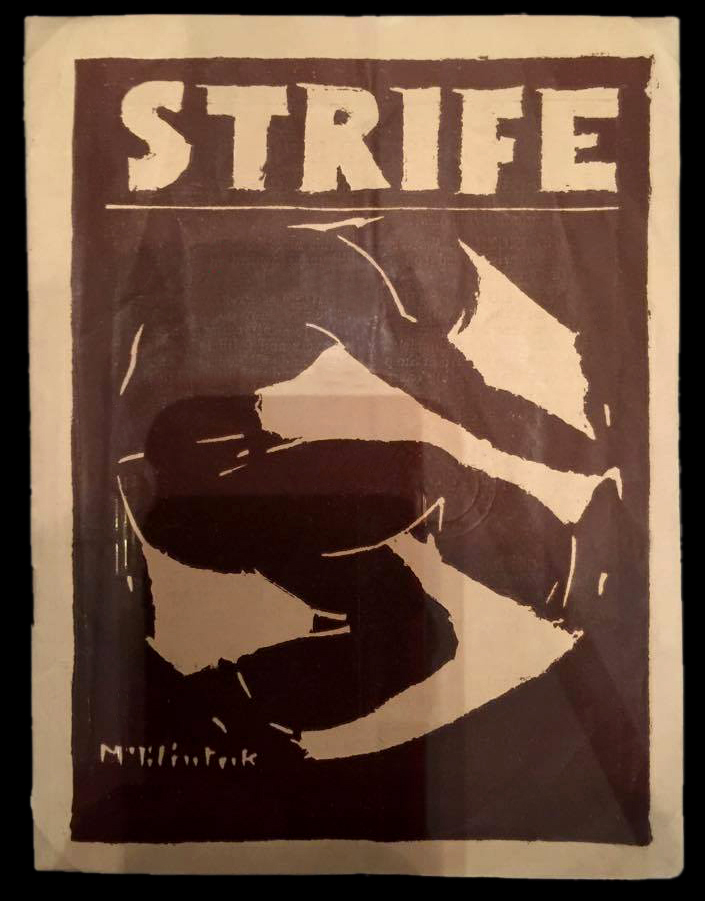

Highlights in this exhibition included an earthenware vase by Ethel Blundell; a painting by that most incredible of atmospheric painters, Clarice Beckett (how I long to own one of her paintings!); a wonderful portrait by the underrated Cybil Craig; two stunning Keast Burke photographs; two beautiful stained glass windows of a male and female lifesaver; the slum photographs of F. Oswald Barnett (more please!); and the graphic covers of mostly short-lived radical magazines.

These highlights are worth the price of admission alone. A must see before the exhibition closes.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Footnotes

1/ A. S. Kenyon. “The Art of the Australian Aboriginal.” in Australian Aboriginal Art. Melbourne: Trustees of the National Museum of Victoria, (1929) reprinted 1952, p. 15.

Many thankx to the National Gallery of Victoria for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Some installation photographs © Dr Marcus Bunyan. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

National Museum of Victoria

Australian Aboriginal Art (cover)

1952 (reprint of 1929 illustrated handbook)

Brown, Prior, Anderson Pty. Ltd., Melbourne (publishers)

Trustees of the National Museum of Victoria

39 pages

The 1930s was a turbulent time in Australia’s history. During this decade major world events, including the Depression and the rise of totalitarian regimes in Europe, shaped our nation’s evolving sense of identity. In the arts, progressive ideas jostled with reactionary positions, and artists brought substantial creative efforts to bear in articulating the pressing concerns of the period. Brave New World: Australia 1930s encompasses the multitude of artistic styles, both advanced and conservative, which were practised during the 1930s. Included are commercial art, architecture, fashion, industrial design, film and dance to present a complete picture of this dynamic time.

The exhibition charts the themes of celebrating technological progress and its antithesis in the nostalgia for pastoralism; the emergence of the ‘New Woman’ and consumerism; nationalism and the body culture movement; the increasing interest in Indigenous art against a backdrop of the government policy of assimilation and mounting calls for Indigenous rights; the devastating effects of the Depression and the rise of radical politics; and the arrival of European refugees and the increasing anxiety at the impending threat of the Second World War. Brave New World: Australia 1930s presents a fresh perspective on the extraordinary 1930s, revealing some of the social and political concerns that were pertinent then and remain so today.

Text from the NGV website

Harold Cazneaux (New Zealand 1878 – Australia 1953, Australia from 1886)

No title (Powerlines and chute)

c. 1935

Gelatin silver photograph

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased through The Art Foundation of Victoria with the assistance of the H. J. Heinz II Charitable and Family Trust, Governor, 1993

In 1934 BHP (Broken Hill Proprietary Company Limited) commissioned leading pictorialist photographer Harold Cazneaux to record their mining and steel operations for a special publication to mark their fiftieth anniversary in 1935. Cazneaux’s dramatic industrial images blended a soft, atmospheric focus with a modernist sense of space, form and geometry. In 1935-36 Australia exported close to 300,000 tonnes of iron ore to Japan; however, after Japan’s invasion of China in 1937 fear of its expansionist aims in the Pacific increased and soon afterwards the federal government announced a ban on the export of all iron ore to Japan.

Fred Ward (designer) (Australian, 1900-1990)

E. M. Vary, Fitzroy, Melbourne (attributed to) (manufacturer) active 1920s-1940s

Sideboard

c. 1932

Mountain ash (Eucalyptus sp.), painted wood, painted plywood, steel

(a-e) 84.0 x 119.7 x 48.7cm (overall)

Proposed acquisition

Side table

c. 1932

Mountain ash (Eucalyptus sp.), jarrah (Eucalyptus marginata), steel

55.7 x 66.0 x 49.2cm

Proposed acquisition

Tray table

c. 1932

Mountain ash (Eucalyptus sp.), blackwood (Acacia melanoxylon), steel

(a-b) 52.0 x 60.9 x 42.5cm (overall)

Proposed acquisition

A new generation of artists and designers

While modern art was a source of debate and controversy throughout the 1930s, modernism in architecture, interior design, industrial design and advertising became highly fashionable. In Melbourne a small group of designers pioneered modern design in Australia. Furniture designer Fred Ward first designed and made furniture for his home in Eaglemont, where he had established a studio workshop. It was admired by friends and he was encouraged to produce furniture for sale. In 1932 Ward opened a shop in Collins Street, Melbourne. There he offered his furniture, as well as linens and Scandinavian glass. The fabrics for curtains and upholstery were printed by Australian designer Michael O’Connell with bold designs that shocked some but were favoured by a new generation looking to create modern interiors.

More than in most periods, in the 1930s art, design and architecture were closely integrated with the changing realities of contemporary life. It was a time when the last vestiges of the conservative art establishment were swept away by a new generation of artists and designers who were to drive Australian art in the second half of the twentieth century.

Installation views of the exhibition Brave New World: Australia 1930s at NGVA with Max Dupain’s Illustration for Kelvinator advertisement at left and Ethel Blundell’s Vase centre on sideboard

Photos: Courtesy NGV Photographic Services

Fred Ward was one of the first and most important designers of modern furniture in Australia. He began making furniture around 1930, and in 1932 opened a shop in Collins Street selling his furniture, as well as textiles by Michael O’Connell and other modern design pieces. In 1934 Ward went into partnership with Myer Emporium and established the Myer Design Unit, for which he designed a line of modular ‘unit’ furniture for commercial production. Ward’s simple, functional aesthetic and use of local timbers with a natural waxed finish was in contrast to the luxurious materials and decorative motifs of the contemporary Art Deco style.

The armchair, sideboard and occasional tables were designed by Fred Ward and purchased by Maie Casey in the early 1930s. The wife of R. G. Casey, federal treasurer in the Lyons Government, Maie was a prominent supporter of modern art and design. Moving to Canberra in 1932, she furnished her house at Duntroon in a modern style with furniture by Ward and textiles by Michael O’Connell. The design of Ward’s armchair closely resembles a 1920s armchair by German Bauhaus furniture designer Erich Dieckmann, who was known for his standardised wooden furniture based on geometric designs.

Michael O’Connell designer (England 1898-1976, Australia 1920-1937)

Textile

c. 1933

Block printed linen

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne Purchased, 1988

Michael O’Connell pioneered modernist textiles in Melbourne and was an influential advocate of modern design. Working with his wife Ella from his studio in Beaumaris, O’Connell used woodblocks and linocuts to hand print onto raw linens and silks, which were used for fashion garments and home furnishing. O’Connell’s boldly patterned and highly stylised designs were considered startlingly modern. Some of his early fabrics featured ‘jazz age’ scenes of nightclubs and dancing, while later motifs were based on Australian flora and fauna, or derived from Oceanic and Aboriginal art.

Sam Atyeo (Australian, 1910-1990)

Album of designs: tables

c. 1933 – c. 1936

Album: watercolour, brush and coloured inks, coloured pencils, 14 designs tipped into an album of 16 grey pages, card covers, tape and stapled binding

30.0 x 19.2 cm (page) 30.0 x 20.8 x 0.8cm (closed)

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Gift of the artist, 1988

Sam Atyeo was a leading figure in Melbourne’s emerging modernist circles in the early 1930s, the partner of artist Moya Dyring and lover of Sunday Reed. He had studied at the National Gallery School, where he was a brilliant and rebellious student. Around 1932 Atyeo became friendly with Cynthia Reed, who managed Fred Ward’s furniture shop and interior design consultancy on Collins Street. After she opened Cynthia Reed Modern Furnishings in Little Collins Street, Atyeo designed furniture for Reed, that was strongly influenced by Ward’s designs.

Max Dupain (Australia 1911-1992)

Illustration for Kelvinator advertisement

1936

Gelatin silver photograph

32.8 x 25.3cm

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney

Purchased with funds provided by the Photography Collection Benefactors’ Program 2000

Ethel Blundell (Australian, 1918-2010, worked in Switzerland 1946-2010)

Vase

1936

Earthenware

17.6 x 16.8cm diameter

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Presented through The Art Foundation of Victoria by Mrs Margaret Howie, Governor, 1999

© Ethel Blundell

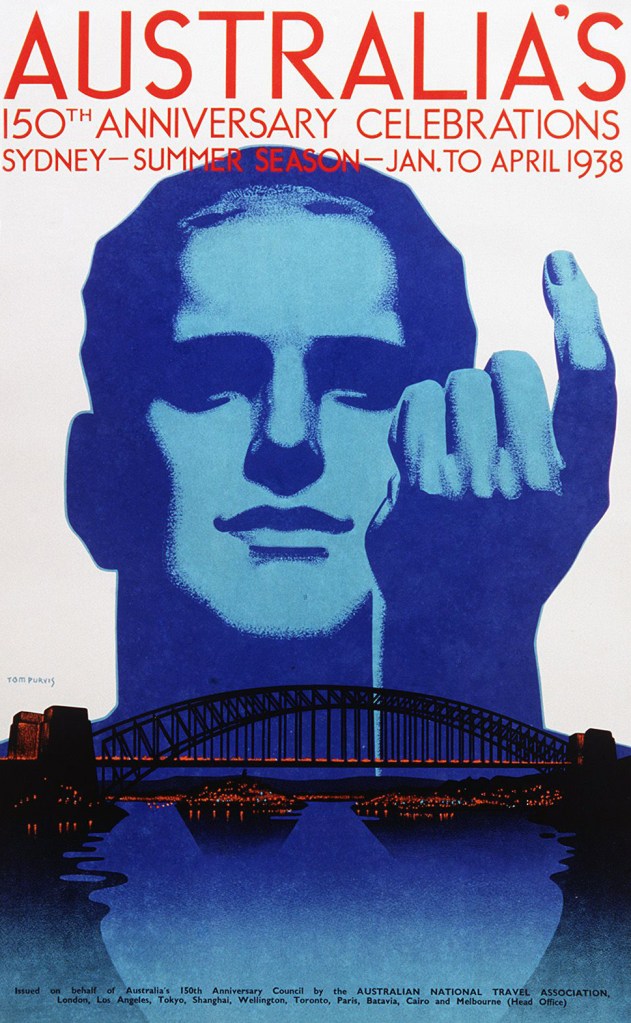

Utopian cities

Modernity reflected what was new and progressive in Australian urban life. The image of the city became an allegory for this in art, and efficiency and speed became watchwords for modernity. Many artists celebrated the city and technological advancements in works utilising a modern style of hard-edged forms, flat colours and dynamic compositions. The engineering marvel of the Sydney Harbour Bridge, which opened in 1932, was an ongoing source of fascination for artists, as were images of building the city, industry and modern modes of transport.

The skyscraper was also a powerful symbol of modern prosperity, especially when the Great Depression cast doubt on the inevitability of progress; hence the advent of tall buildings in Australian cities was hailed with relief and optimism. In 1932, at the peak of the Depression, the tallest building in Melbourne was opened: the Manchester Unity Building at the corner of Swanston and Collins streets. With its ornamental tower and spire taking its overall height to 64 metres, the building was welcomed by The Age newspaper as ‘a new symbol of enterprise and confidence, undaunted by the “temporary eclipse” of the country’s economic fortune’.

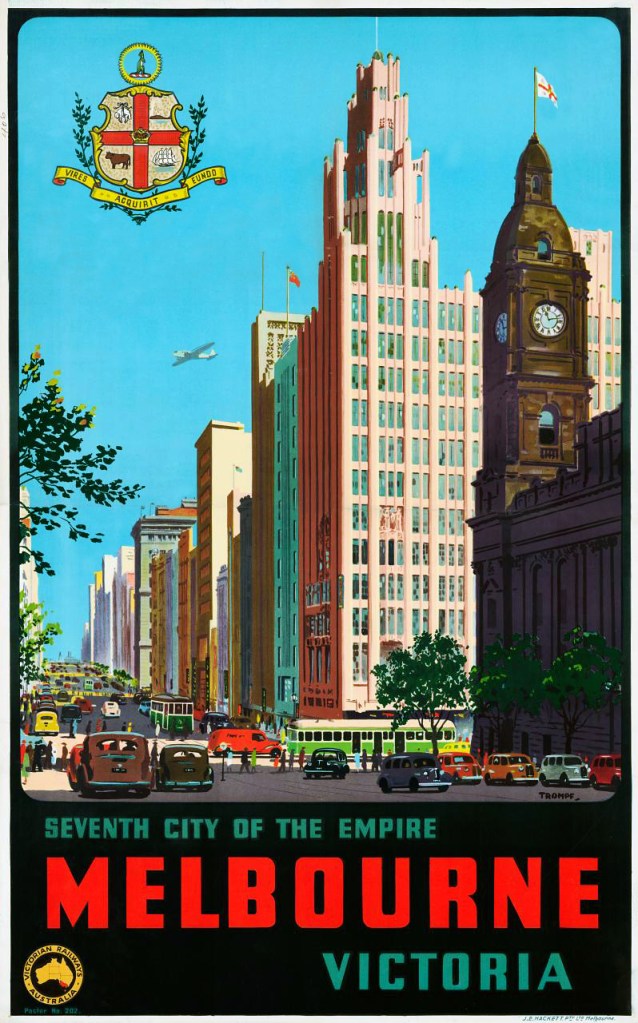

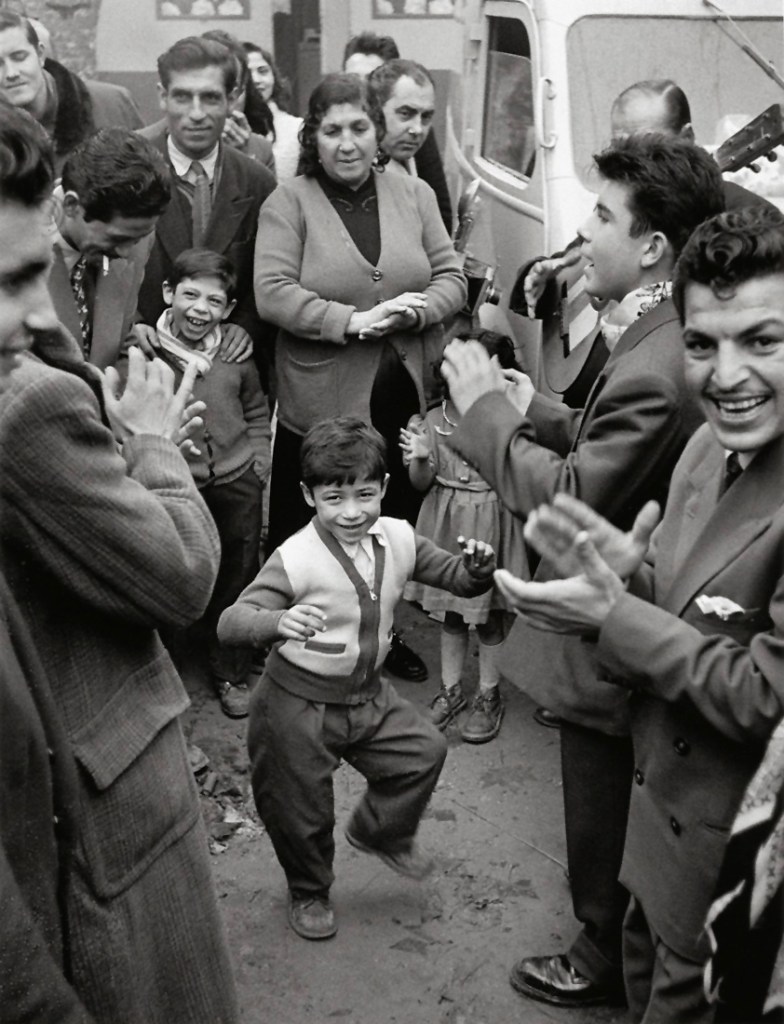

Installation view of the exhibition Brave New World: Australia 1930s at NGVA with Seventh city of the Empire – Melbourne, Victoria at left; and Evening dress at right

Photo: Eugene Hyland

Percy Trompf (Australian, 1902-1964)

Seventh city of the Empire – Melbourne, Victoria

1930s

Colour lithograph printed by J. E. Hackett, Melbourne

State Library Victoria, Melbourne

Gift of Mr Grant Lee, 2007

Percy Trompf’s poster celebrates Melbourne’s first skyscraper, the iconic Manchester Unity Building on the corner of Swanston and Collins streets. Designed by architect Marcus Barlow in the Art Deco ‘Gothic’ style, it was built at high speed between 1930 and 1932, and provided much needed employment during the Depression. At twelve storeys high and topped with a decorative tower it was Melbourne’s tallest building and contained the city’s first escalators. A powerful symbol of the city’s modernity, it was often featured in images of Melbourne.

Unknown, Australia

Evening dress

c. 1935

Silk

144cm (centre back), 36cm (waist, flat)

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Gift of Miss Irene Mitchell, 1975

Ethel Spowers (Australia 1890-1947, England and France 1921-1924)

The works, Yallourn

1933

Colour linocut, ed. 3/50

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

The Joseph Brown Collection

Presented through the NGV Foundation by Dr Joseph Brown AO OBE, Honorary Life Benefactor, 2004

Ethel Spowers and Eveline Syme were leading figures in modern art in Melbourne. In the 1920s they studied with modernist Claude Flight at the Grosvenor School in London, where they learnt to make colour linocuts that followed Flight’s principles of rhythmic design combined with flat colour. In April 1933 Spowers and Syme visited the Yallourn Power Station in Gippsland, which had been opened in 1928 and was the largest supplier of electricity to the state.

Vida Lahey (Australian, 1882-1968)

Sultry noon (Central Station Brisbane)

1931

Oil on canvas on plywood

44.7 x 49.2cm

Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane Purchased 1983

© QAGOMA

Clarice Beckett (Australian, 1887-1935)

Taxi rank

c. 1931

Oil on canvas on board

Kerry Stokes Collection, Perth

Installation view of Herbert Badham’s George Street, Sydney (1934) from the exhibition Brave New World: Australia 1930s at NGVA

Photo: Dr Marcus Bunyan

After serving in the Royal Australian Navy during the First World War, Herbert Badham studied at the Sydney Art School and began exhibiting in 1927. In his paintings he was a keen observer of everyday urban life: streets with shoppers, city workers on their lunch break and drinkers in the pub were painted in a contemporary, hard-edged realist style.

Max Dupain (Australian, 1911-1992)

Rush hour in King’s Cross

1938, printed c. 1986

Gelatin silver photograph

41.2 x 40.3cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased through The Art Foundation of Victoria with the assistance of Mr A.C. Goode, Fellow, 1987

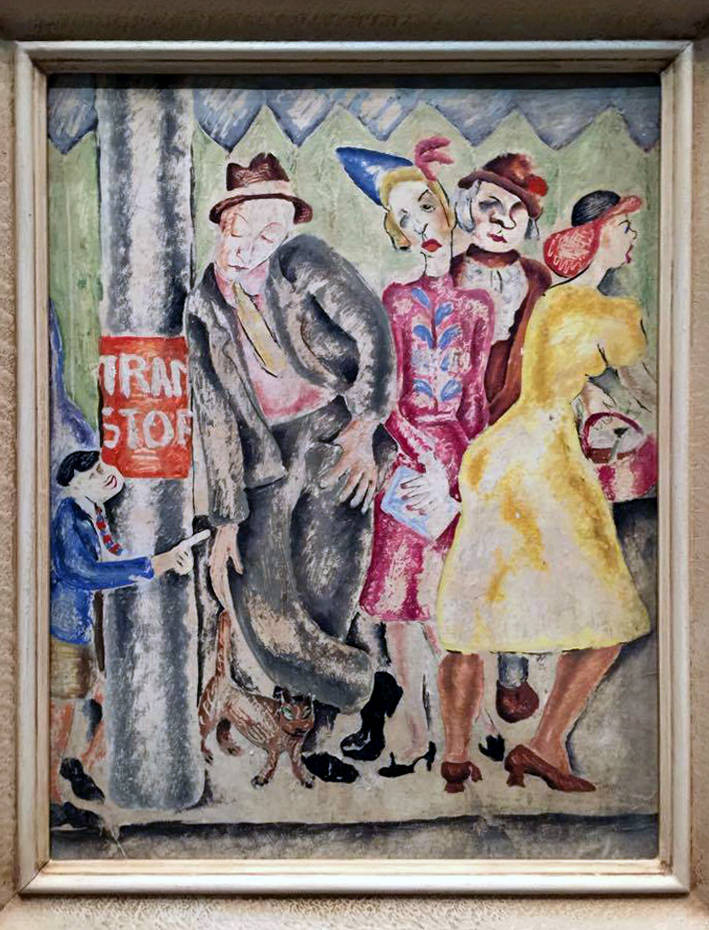

During the 1930s the city provided a rich source of imagery for artists working in modern styles, who celebrated the speed and efficiency of modern transport technology and expanding road and rail networks. Yet as car ownership increased during the 1930s, larger cities began to suffer congestion and the rush hour became part of urban life. Throughout the decade the pace and stress of modern life became a topic of public debate, with conservative commentators decrying this transformation of the Australian lifestyle.

Installation view of the exhibition Brave New World: Australia 1930s at NGVA with Max Dupain’s Rush hour in King’s Cross at right

Photo: Courtesy NGV Photographic Services

Installation view of the exhibition Brave New World: Australia 1930s at NGVA with Grace Cossington Smith’s The Bridge in-curve at right

Photo: Courtesy NGV Photographic Services

Grace Cossington Smith (Australia 1892-1984, England and Germany 1912-14, England and Italy 1949-1951)

The Bridge in-curve

1930

Tempera on cardboard

83.6 x 111.8cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Presented by the National Gallery Society of Victoria, 1967

© Estate of Grace Cossington Smith

The slow rise of the Sydney Harbour Bridge above the city was recorded by numerous painters, printmakers and photographers, including Sydney modernist Grace Cossington Smith. Her iconic The Bridge-in-curve depicts the bridge just before its two arches were joined in August 1930, and conveys the sense of wonder, achievement and hope that was inspired by this engineering marvel. By painting the emerging, rather than the complete bridge, Cossington Smith also focuses our attention on the energy and ambition required to create it.

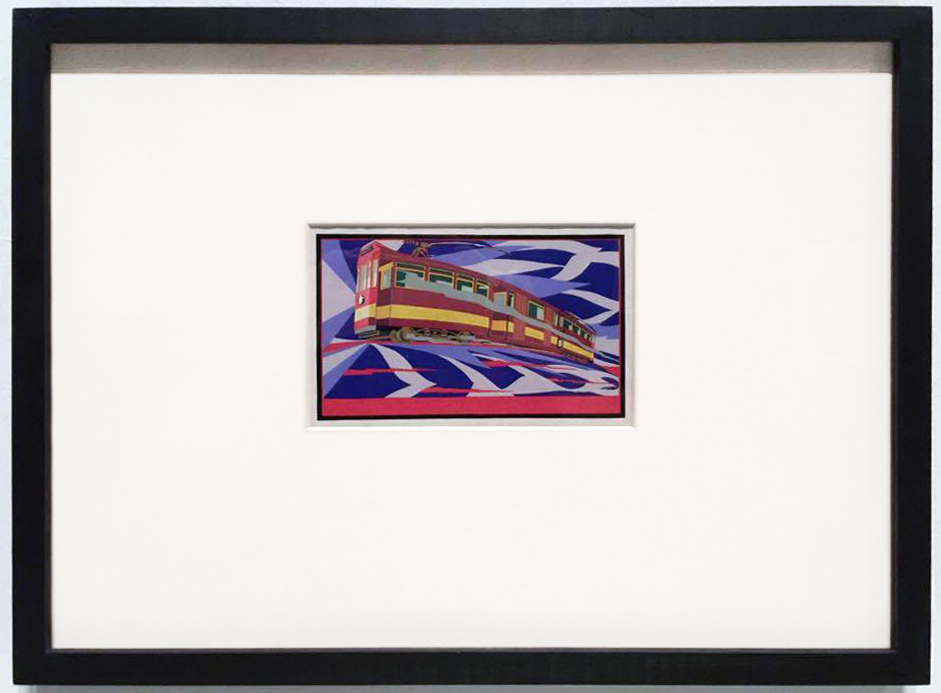

Installation view of Frank Hinder’s Trains passing (1940) from the exhibition Brave New World: Australia 1930s at NGVA

Photo: Dr Marcus Bunyan

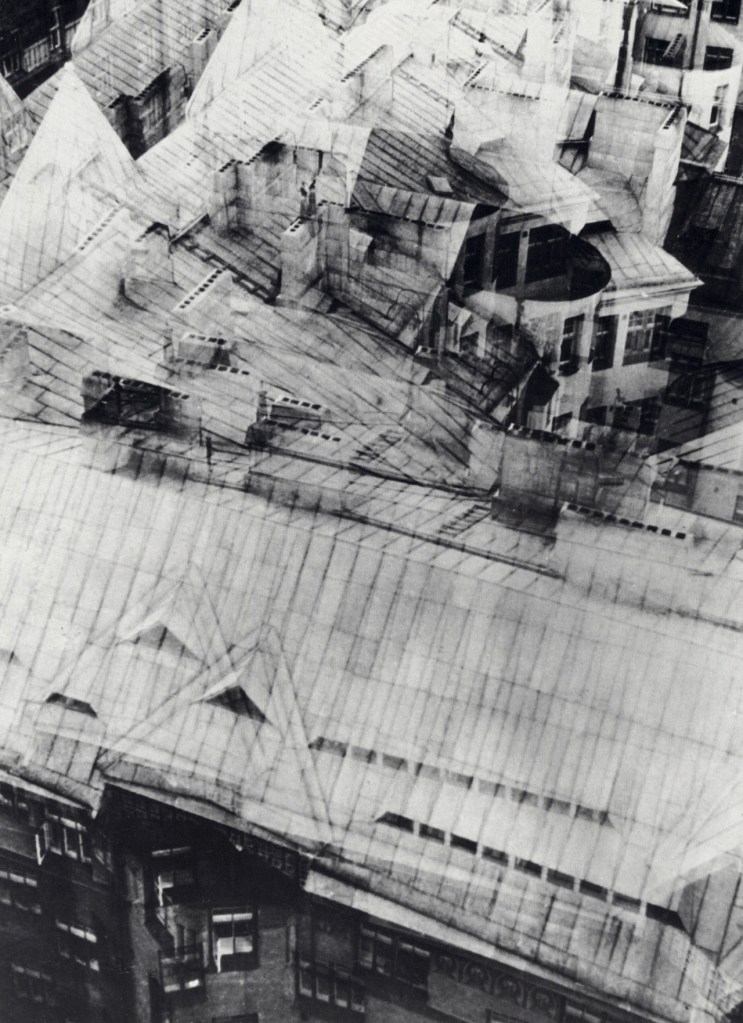

Frank Hinder (Australian, 1906-1992, United States 1927-1934)

Trains passing

1940

Oil on composition board

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Purchased 1974

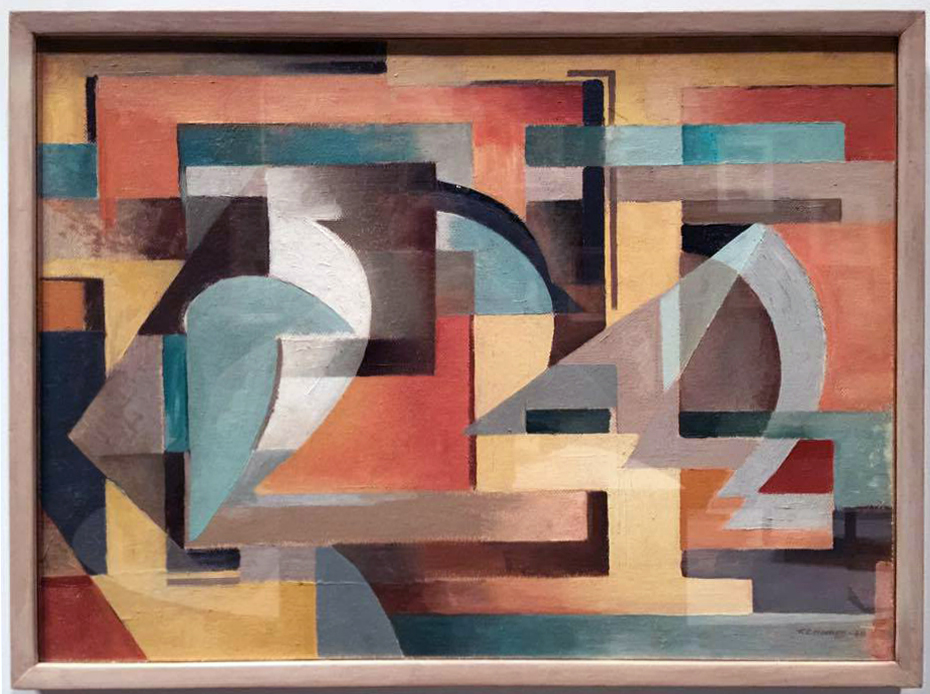

Frank Hinder was one of the first abstract artists in Australia. After living and studying in the United States, Hinder and his wife, the American sculptor Margel, returned to Sydney in 1934. There they became part of a small avant-garde group that included Grace Crowley, Rah Fizelle, Ralph Balson and the German sculptor and art historian Eleanore Lange, all of whom were interested in Cubist, Constructivist and Futurist art. Hinder later said that this work was inspired by seeing Lange, sitting next to him on a train, reflected in the windows of a passing train.

Frank Hinder (Australia 1906-1992, United States 1927-1934)

Commuters

1938

Tempera on paper on board

Private collection

Victorian Railways, Melbourne (publisher) (Australia, 1856-1976)

The Victorian Railways present The Spirit of Progress

1937

Booklet: colour photolithographs and letterpress,

12 pages, cardboard cover

printed by Queen City Printers, Melbourne

20.8 x 26.8cm (closed)

State Library Victoria, Melbourne

Launched in November 1937, The Spirit of Progress express passenger train was a source of immense pride to Victorians. Built in Newport, Victoria, the train featured many innovations, including all-steel carriages and full air-conditioning. Designed in the Art Deco, streamlined style by architectural firm Stephenson & Turner, the passenger carriages were fitted out to a level of comfort not previously seen in Australia, and included a full dining carriage. The train ran between Melbourne and the New South Wales state border at Albury, the longest non-stop train journey in Australia at that time, at an average speed of 84 kilometres per hour.

Installation view of Ivor Francis’ Speed! from the exhibition Brave New World: Australia 1930s at NGVA

Photo: Dr Marcus Bunyan

Ivor Francis (England 1906 – Australia 1993, Australia from 1924)

Speed!

1931

Colour process block print

Art Gallery of South Australia

Adelaide South Australian Government Grant 1986

Randille, Melbourne (maker) active 1930s

Night gown

c. 1938

Silk (a) 166cm (centre back) 38.9cm (waist, flat) (dress) (b) 121cm (centre back) 38cm (waist, flat) (slip)

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Presented by Mrs A. G. Pringle, 1982

Installation view of the exhibition Brave New World: Australia 1930s at NGVA with Max Dupain’s Rush hour in King’s Cross left and Frank Hinder’s Jackhammer third from right and Margel Hinder’s Man with jackhammer second right

Photo: Courtesy NGV Photographic Services

Margel Hinder (United States 1906 – Australia 1995, Australia from 1934)

Man with jackhammer

1939

Cedar

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased through the NGV Foundation with the assistance of J. B. Were & Son, Governor, 2001

American-born Margel Hinder was one of Australia’s leading modernist sculptors. She had studied art in Boston, where she met and married Sydney artist Frank Hinder. In 1934 they moved to Australia and became an important part of Sydney’s small modern art scene. In Man with jackhammer Hinder has simplified and contained the figure within a square frame, the strong diagonal form of the jackhammer creating a sense of compressed energy and force. Man and machine have fused in this celebration of industry and progress.

Frank Hinder (Australia 1906-1992, United States 1927-1934)

Jackhammer

1936

Airbrush on black paper

52 x 38cm

Private collection, Sydney

© Enid Hawkins

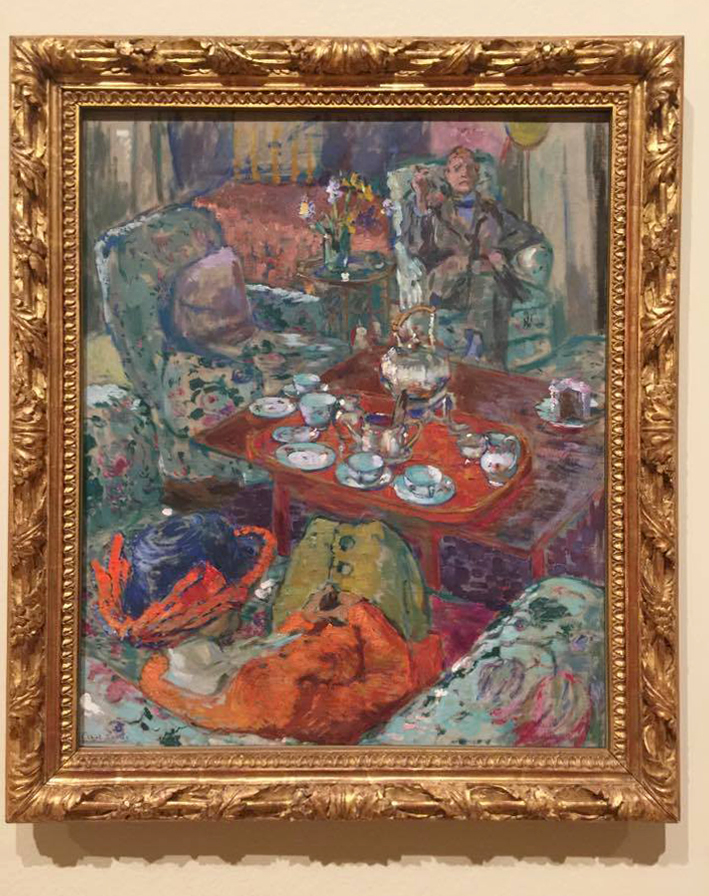

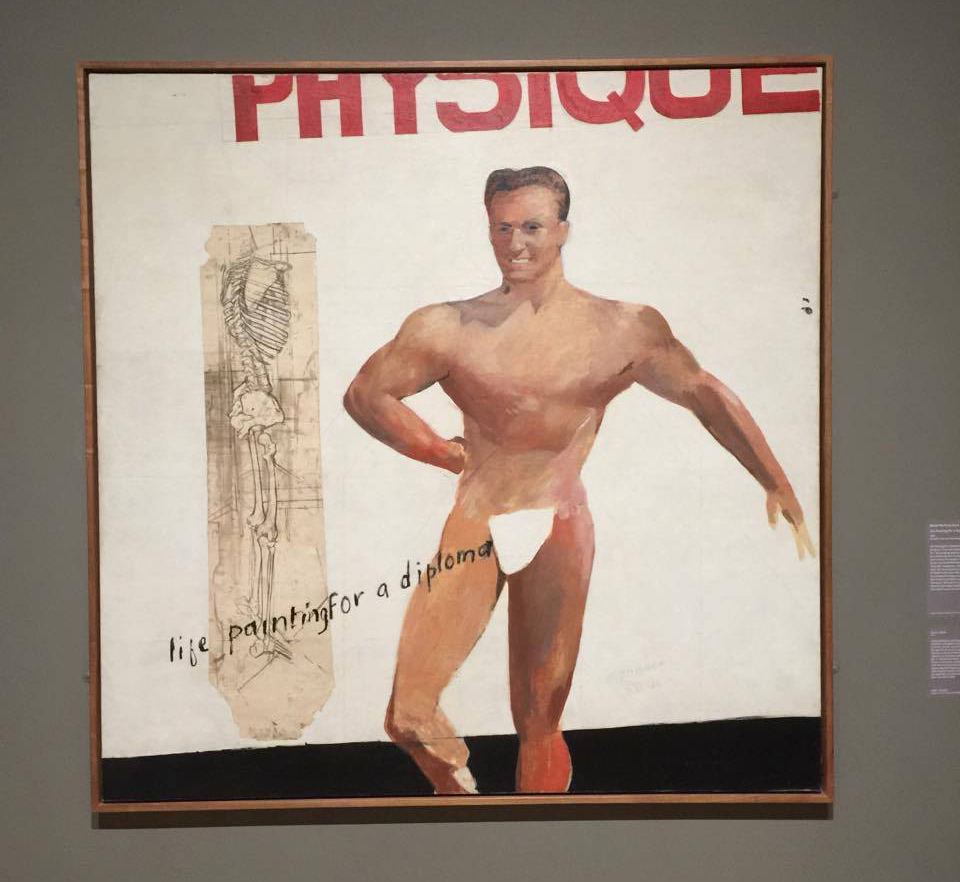

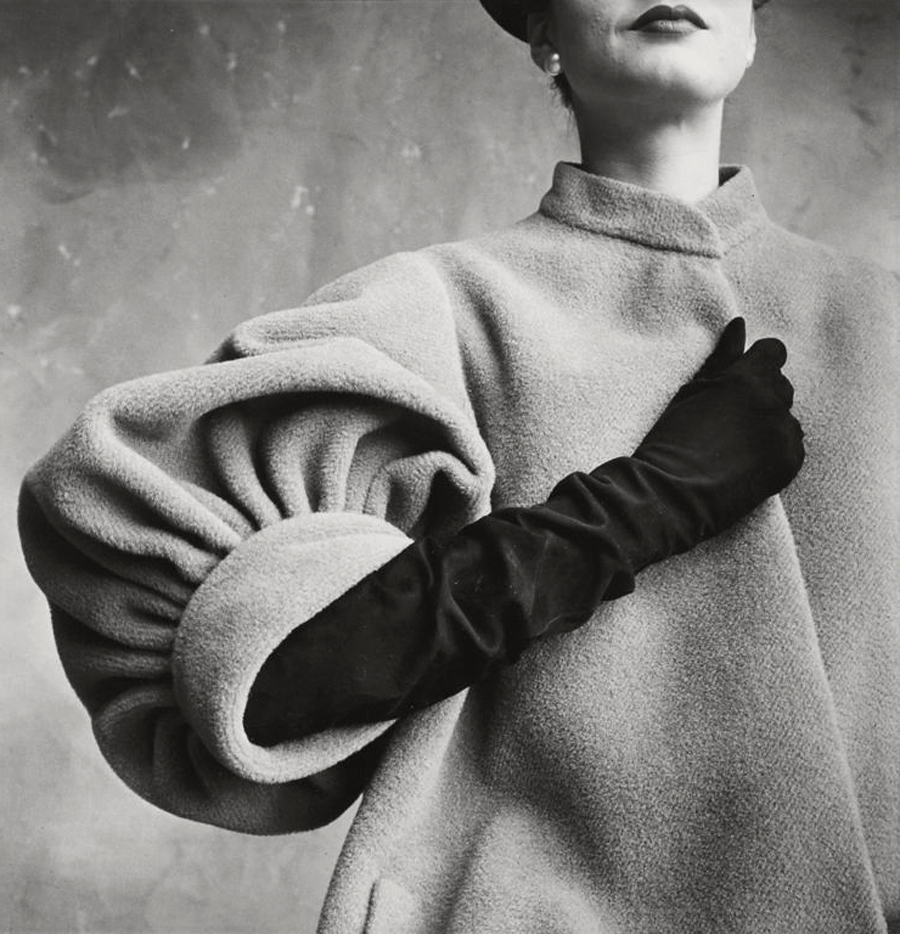

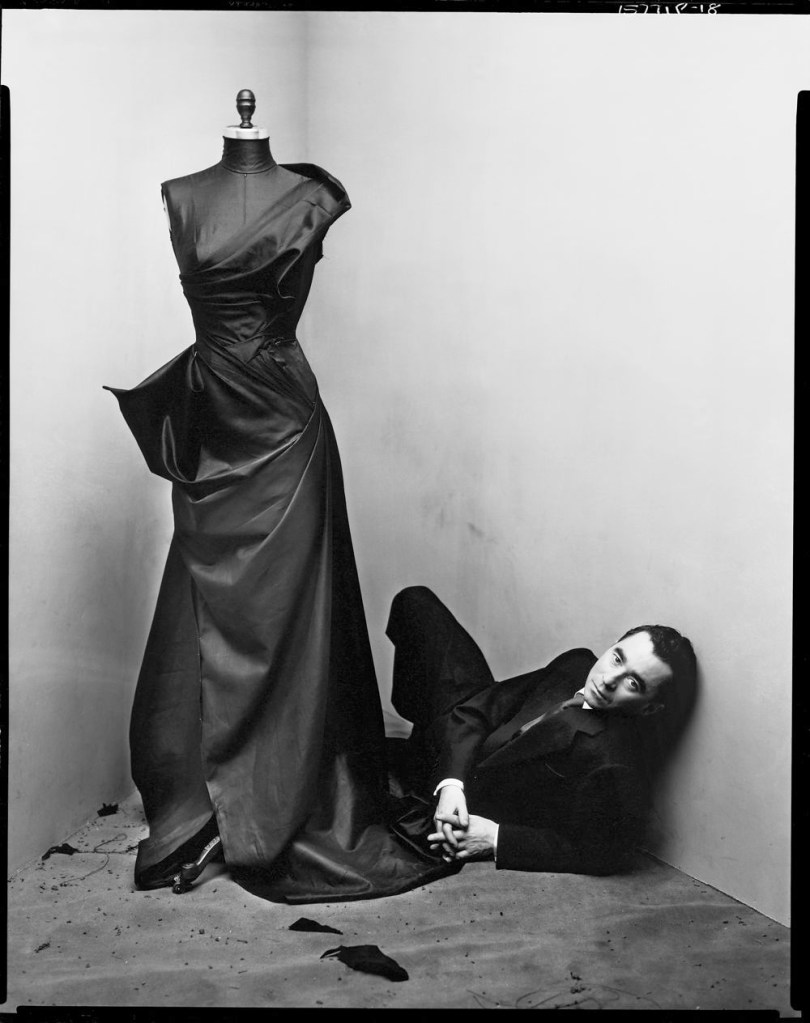

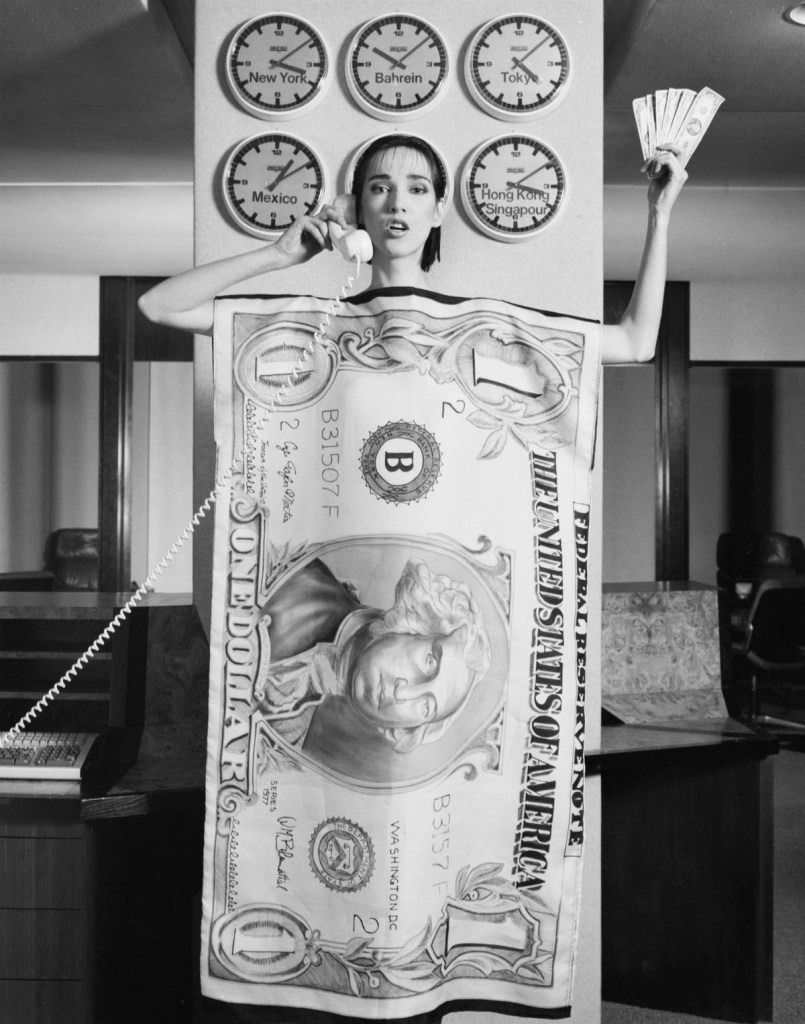

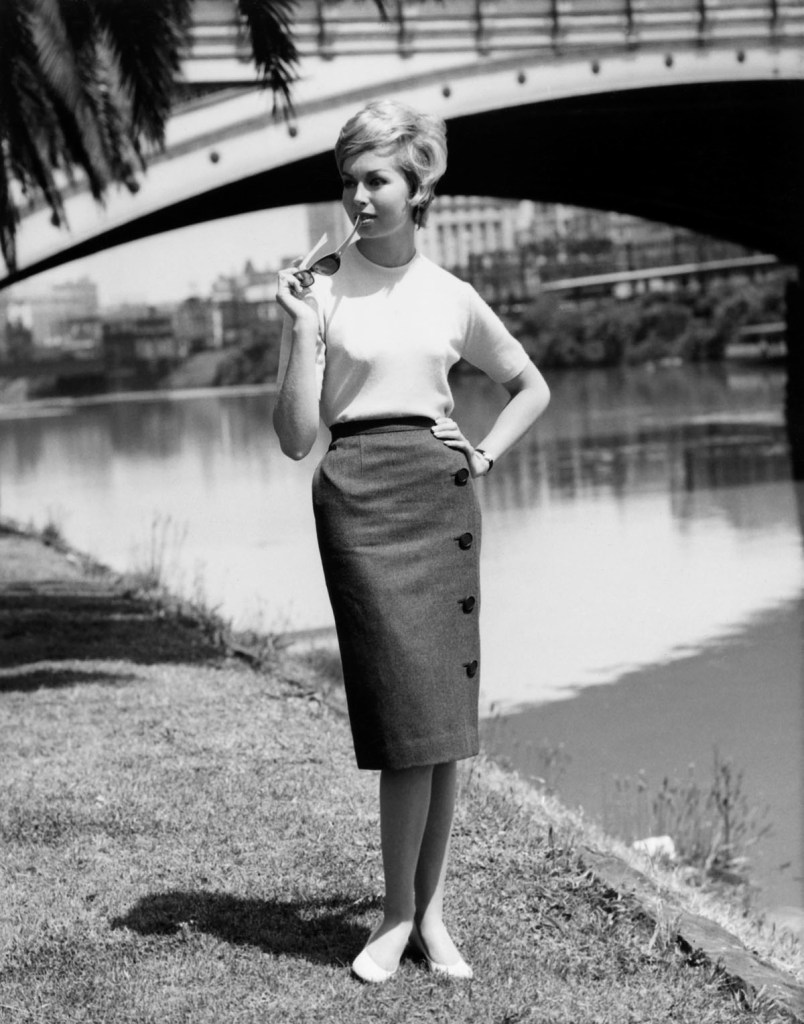

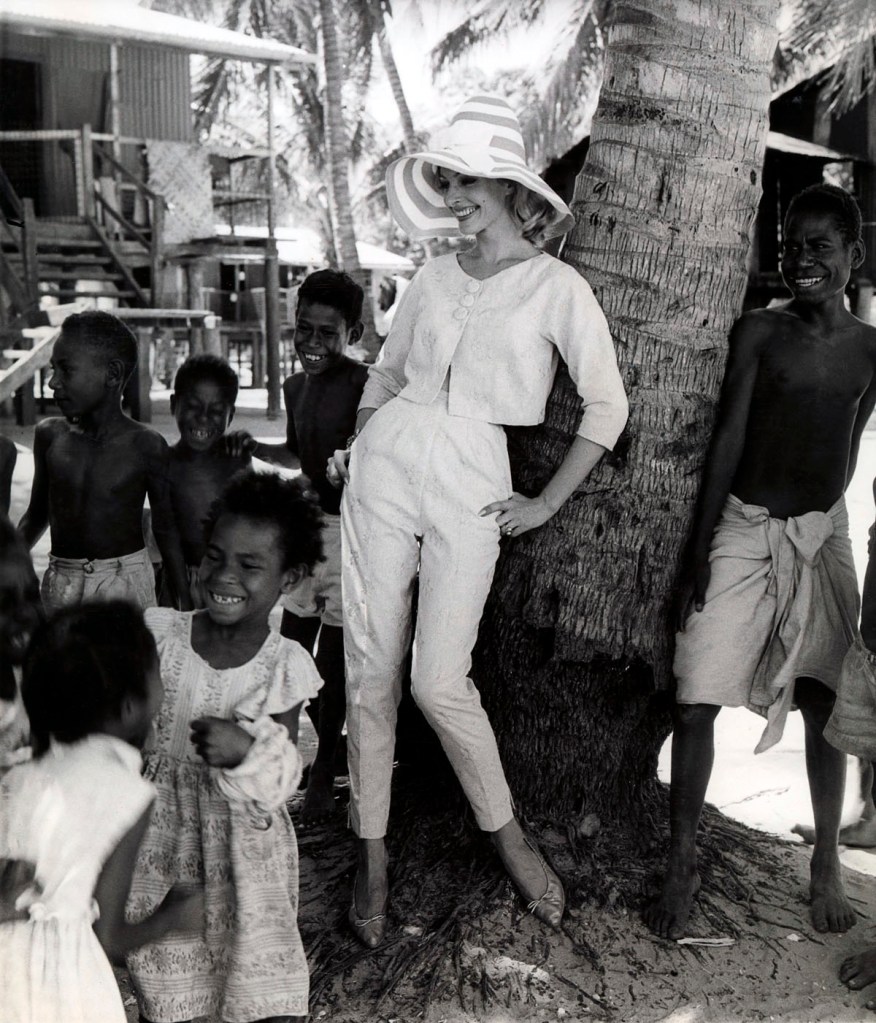

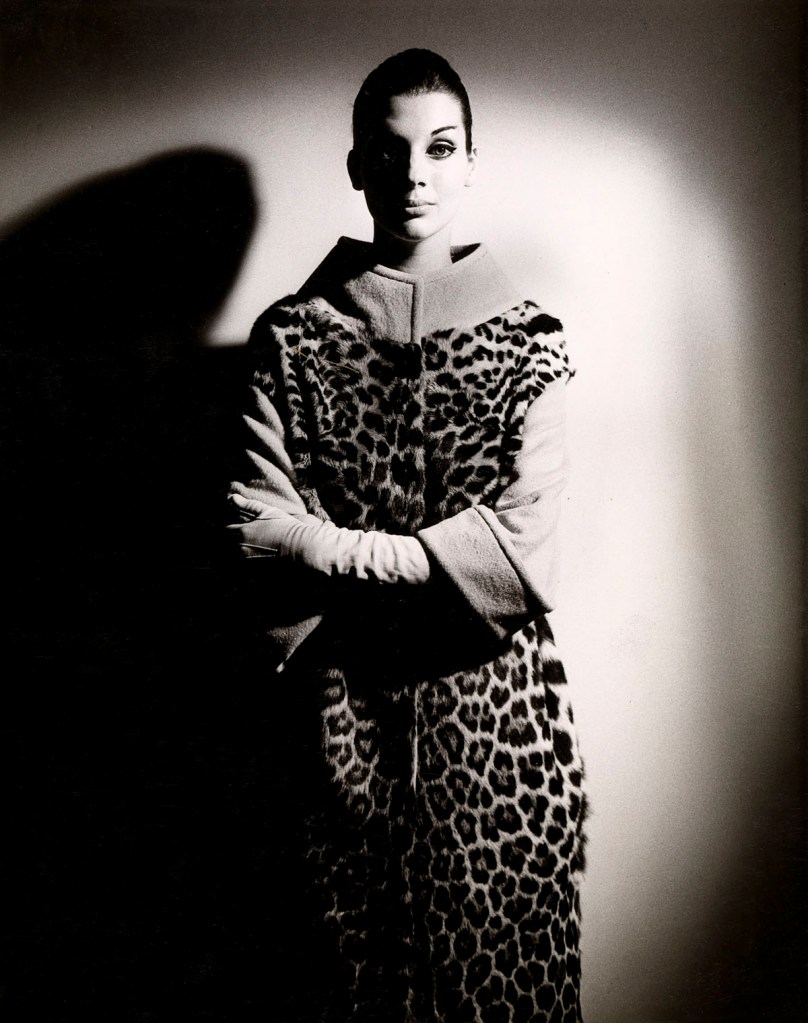

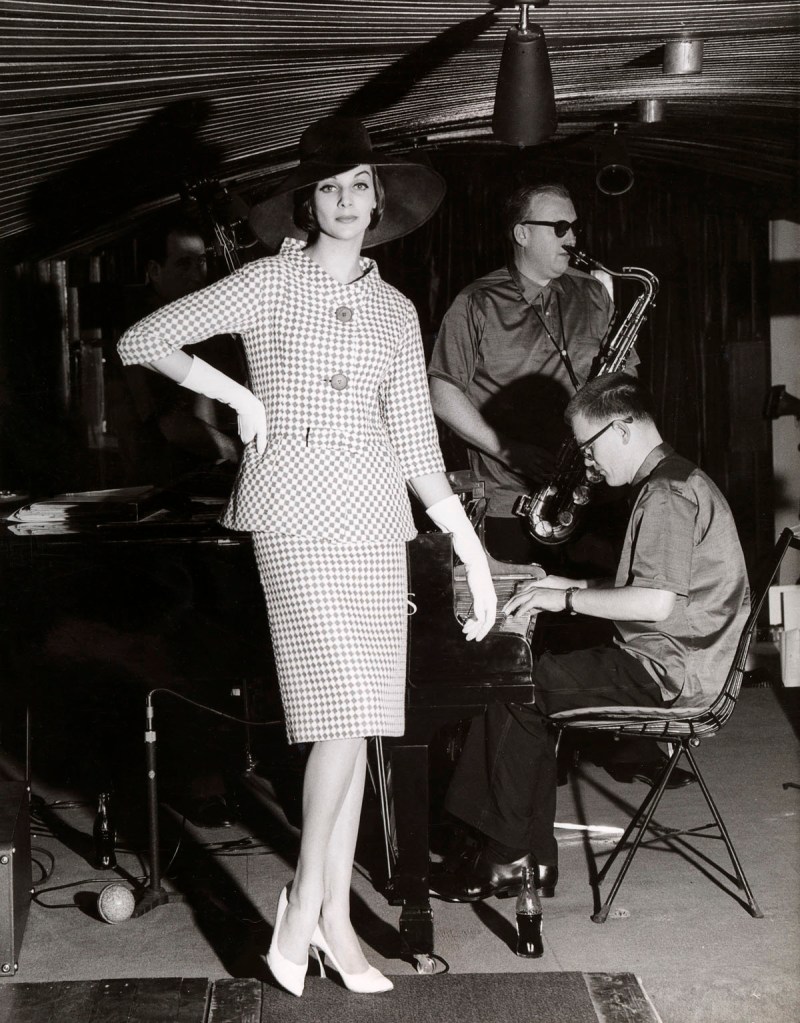

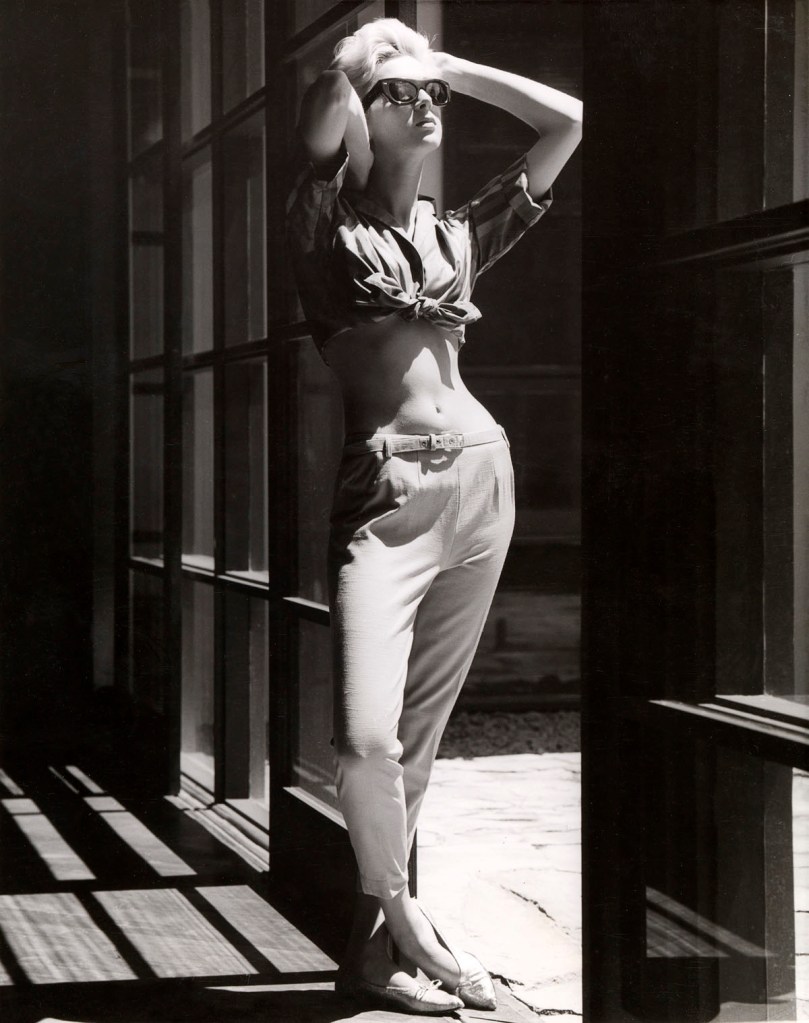

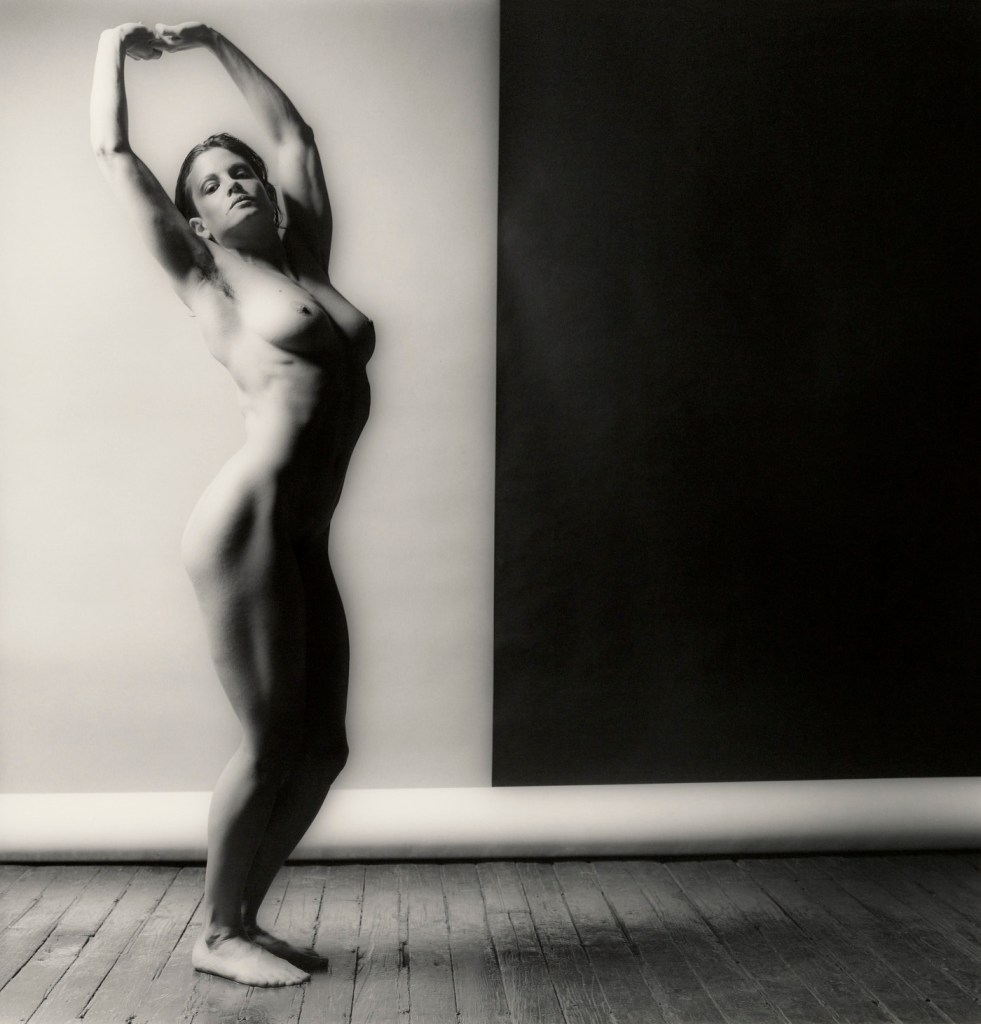

Modern Woman

In the 1930s the new ‘Modern Woman’ made her appearance as a more serious and emancipated version of the giddy 1920s ‘flapper’. A woman who worked, she often lived alone in one of the new city apartment buildings, visited nightclubs and showed less interest in traditional marriage and child rearing. A lean body type became fashionable and was enhanced by the lengthened hemlines and defined waists introduced by French couturier Jean Patou in 1929. This slender silhouette was supported by form-fitting foundation garments by manufacturers such as Berlei.

The Modern Woman became one of the most potent images of contemporary life, being celebrated in women’s magazines such as the ultra-stylish Home and the Australian Women’s Weekly, launched in 1933. While such magazines were congratulating her and promoting new consumer goods to the Modern Woman, at the same time she was criticised by conservative commentators. In 1937 photographer Max Dupain wrote: ‘There must be a great shattering of modern values if woman is to continue to perpetuate the race… In her shred of a dress and little helmet of a hat, her cropped hair, and stark bearing, the modern woman is a sort of a soldier… It is not her fault it is her doom’.

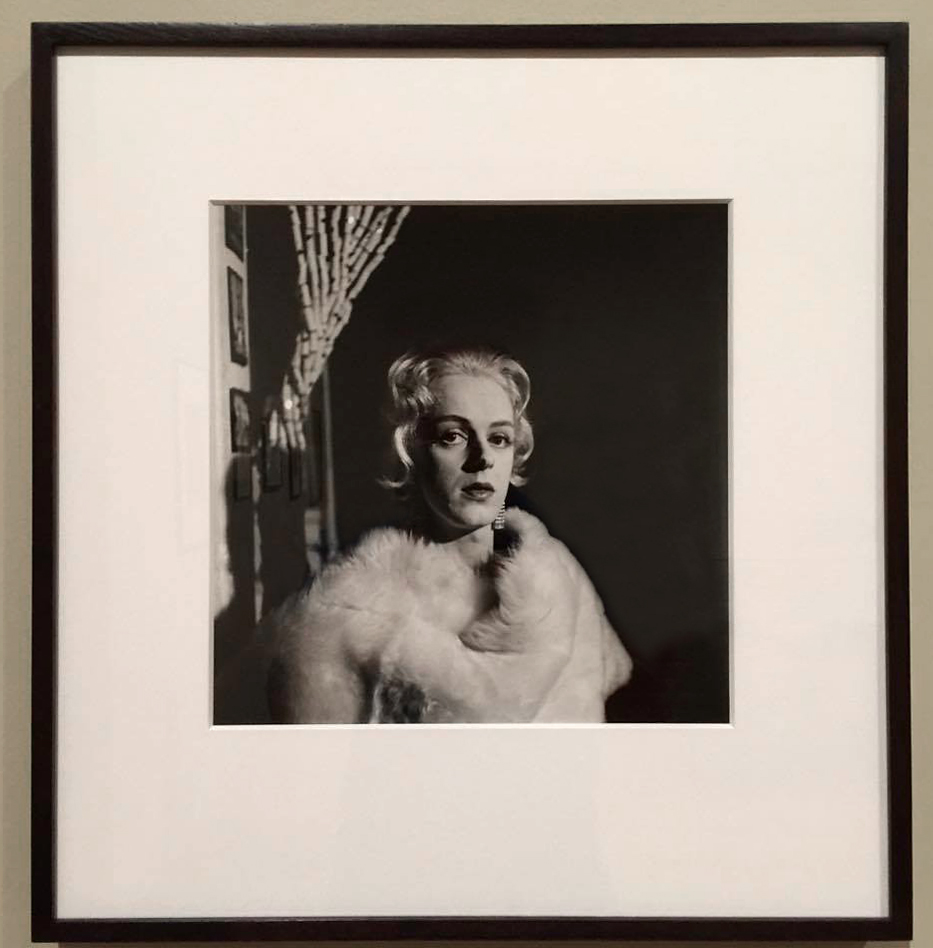

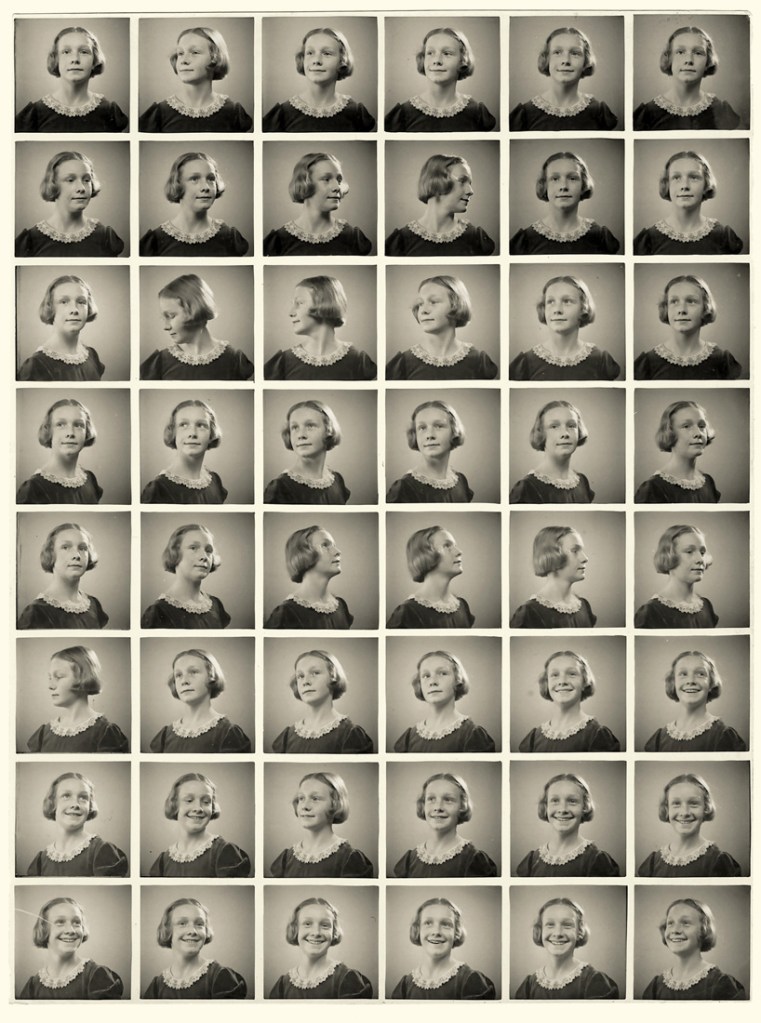

Installation view of the exhibition Brave New World: Australia 1930s at NGVA with Peter Purves Smith’s Maisie left, Cybil Craig’s Peggy second left and Peter Purves Smith’s Lucile at top right

Photo: Eugene Hyland

Installation view of the exhibition Brave New World: Australia 1930s at NGVA with Cybil Craig’s Peggy second left and Lina Bryans The babe is wise at right

Photo: Courtesy NGV Photographic Services

Peter Purves Smith (Australia 1912-1949, England 1935-1936, England and France 1938-1940)

Maisie

1938-1939

Gouache

National Portrait Gallery, Canberra

Bequest of Lady Maisie Drysdale 2001

In 1937 the striking, auburn-haired Maisie Newbold was a student at the George Bell School in Melbourne, where she met fellow student Peter Purves Smith and his best friend Russell Drysdale. Maisie and Purves Smith were married in 1946, only three years before latter’s premature death from tuberculosis. Purves Smith painted this portrait at the start of their relationship. It depicts Maisie as a stylish woman wearing the latest fashion, the angularity of her features contrasted by the soft fur of her collar and feathers of her hat. Many years later Maisie married Drysdale.

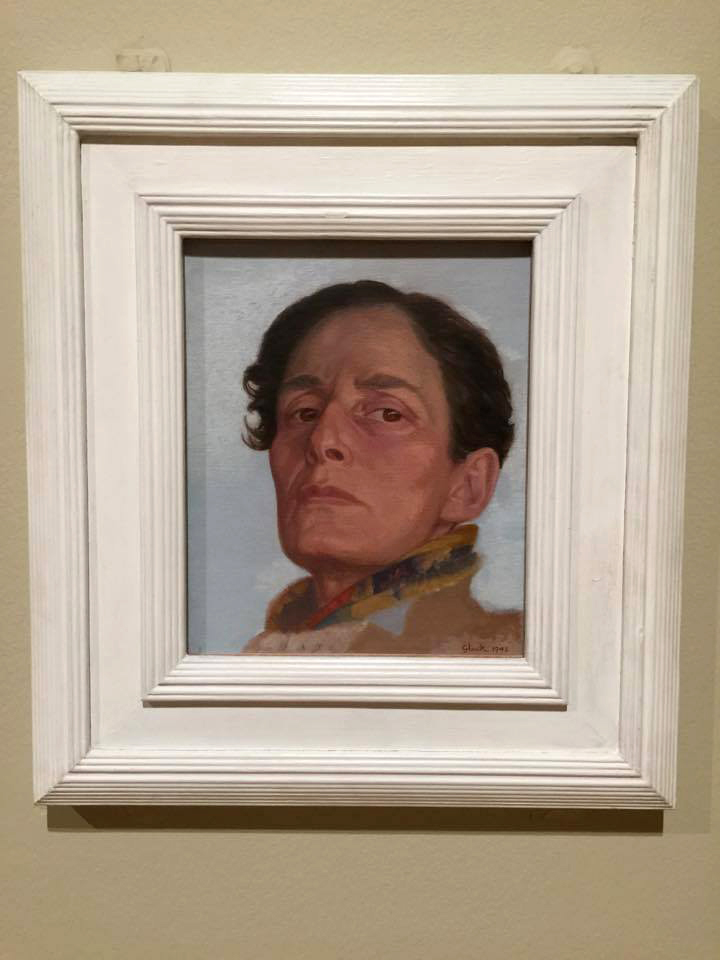

Installation view of Sybil Craig’s work Peggy c. 1932

Photo: Dr Marcus Bunyan

Sybil Craig (England 1901 – Australia 1909, Australia from 1902)

Peggy

c. 1932

Oil on canvas

40.4 x 30.4cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne Purchased, 1978

© The Estate of Sybil Craig

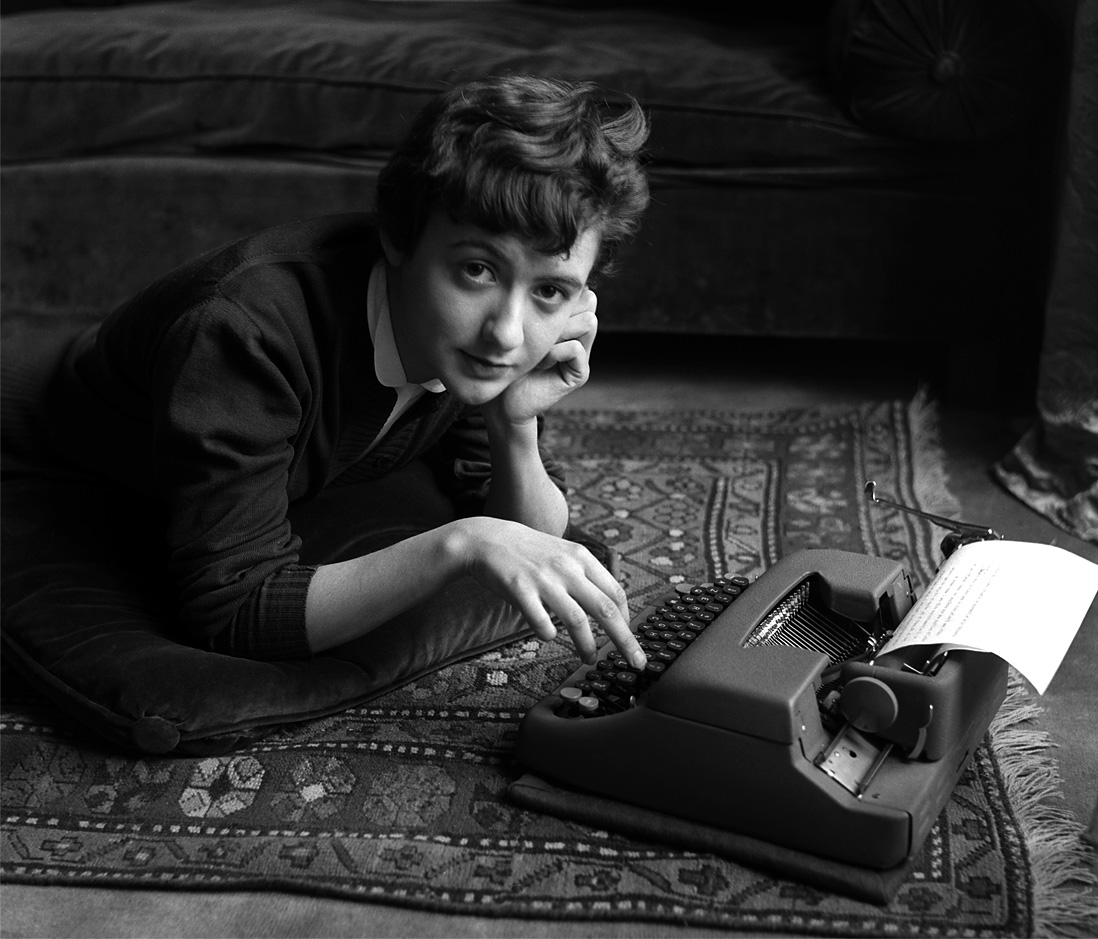

Lina Bryans (Germany (of Australian parents) 1909 – Australia 2000, Australia from 1910)

The babe is wise

1940

Oil on cardboard

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Gift of Miss Jean Campbell, 1962

Lina Bryans’s portrait of author Jean Campbell is titled after Campbell’s 1939 novel The Babe is Wise, a contemporary story set in Melbourne and in which the main protagonists are European migrants. A well-known figure in Melbourne’s literary circles, Campbell was noted for her ‘quick and slightly audacious wit’. Bryans had begun painting in 1937 with the support of William Frater. In the late 1930s she lived at Darebin Bridge House, which became an informal artists’ colony and meeting place for writers associated with the journal Meanjin.

Peter Purves Smith (Australian, 1912-1949, England 1935-1936, England and France 1938-1940)

Lucile

1937

Oil on board

Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane

Purchased 2011 with funds raised through the Queensland Art Gallery Foundation Appeal

Nora Heysen (Australian, 1911-2003, England and Italy 1934-1937)

Self-portrait

1932

Oil on canvas

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Acquired with the assistance of the Masterpieces for the Nation Fund 2011

During the first decade of her life as a professional artist, Nora Heysen completed numerous self-portraits. In many of these she depicts herself in the act of drawing or painting, holding a palette and brush or with other accoutrements of the artist, and thereby asserting her professional identity. Yet these are also highly charged works in which Heysen scrutinises herself (and the viewer) with an unflinching and unsmiling gaze.

Installation view of the exhibition Brave New World: Australia 1930s at NGVA with Arthur Challen’s Miss Moira Madden above chair

Photo: Eugene Hyland

Arthur Challen (Australian, 1911-1964)

Miss Moira Madden

1937

Oil on canvas

89.8 x 77.4cm (framed)

State Library of Victoria

Gift of Mrs S. M. Challen, 1966

© The Estate of Arthur Challen

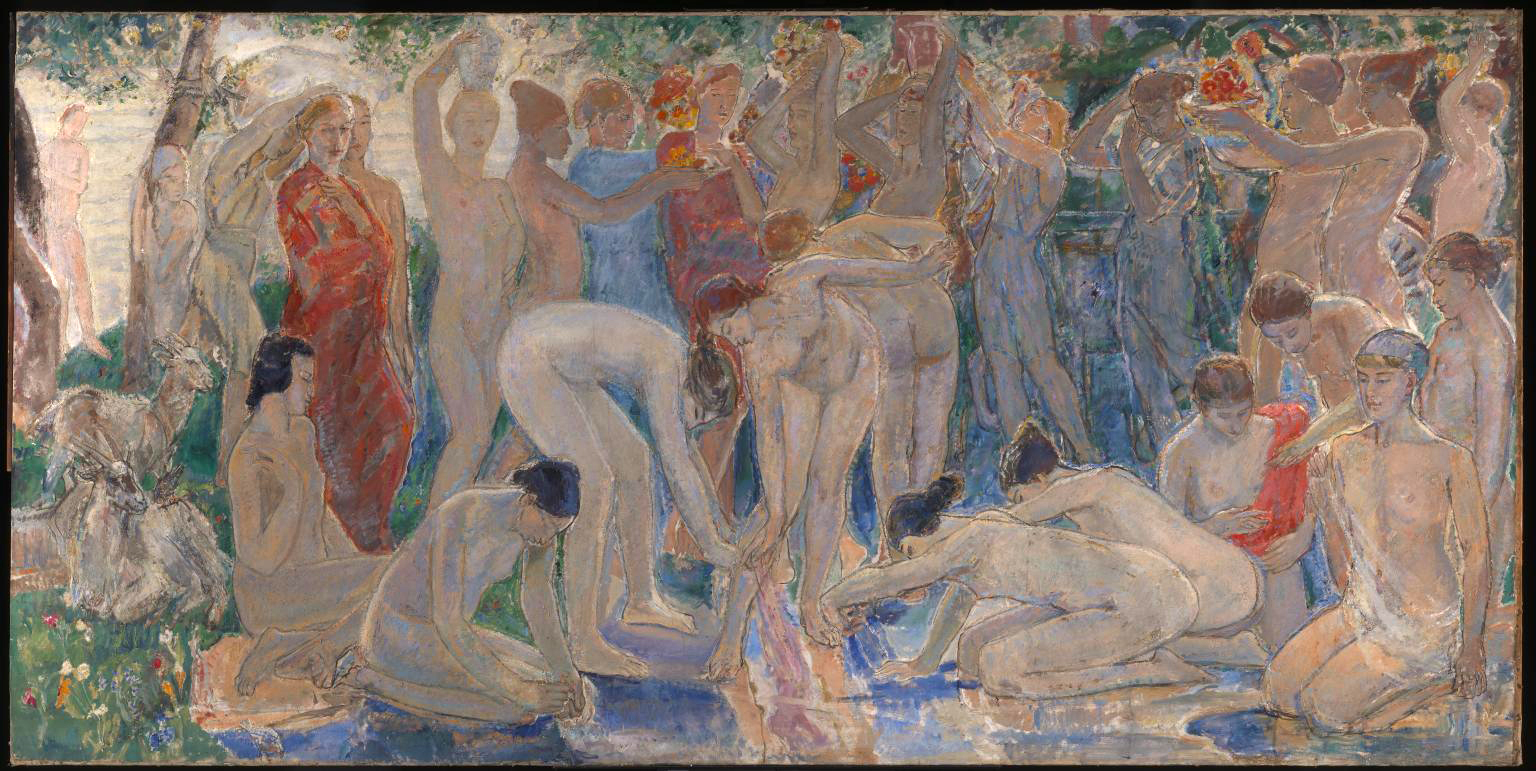

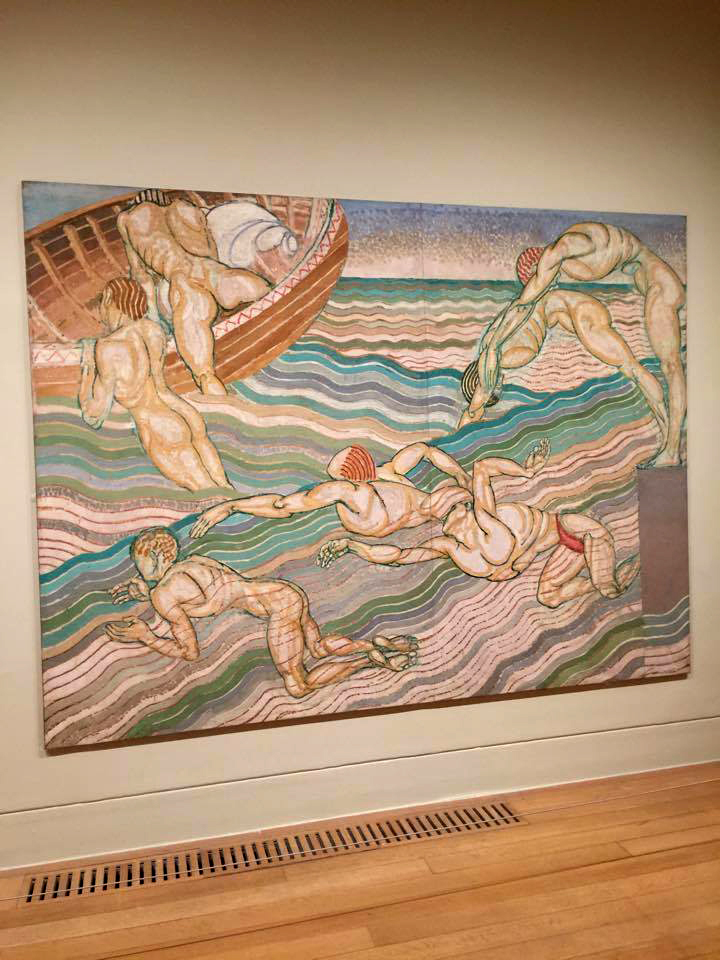

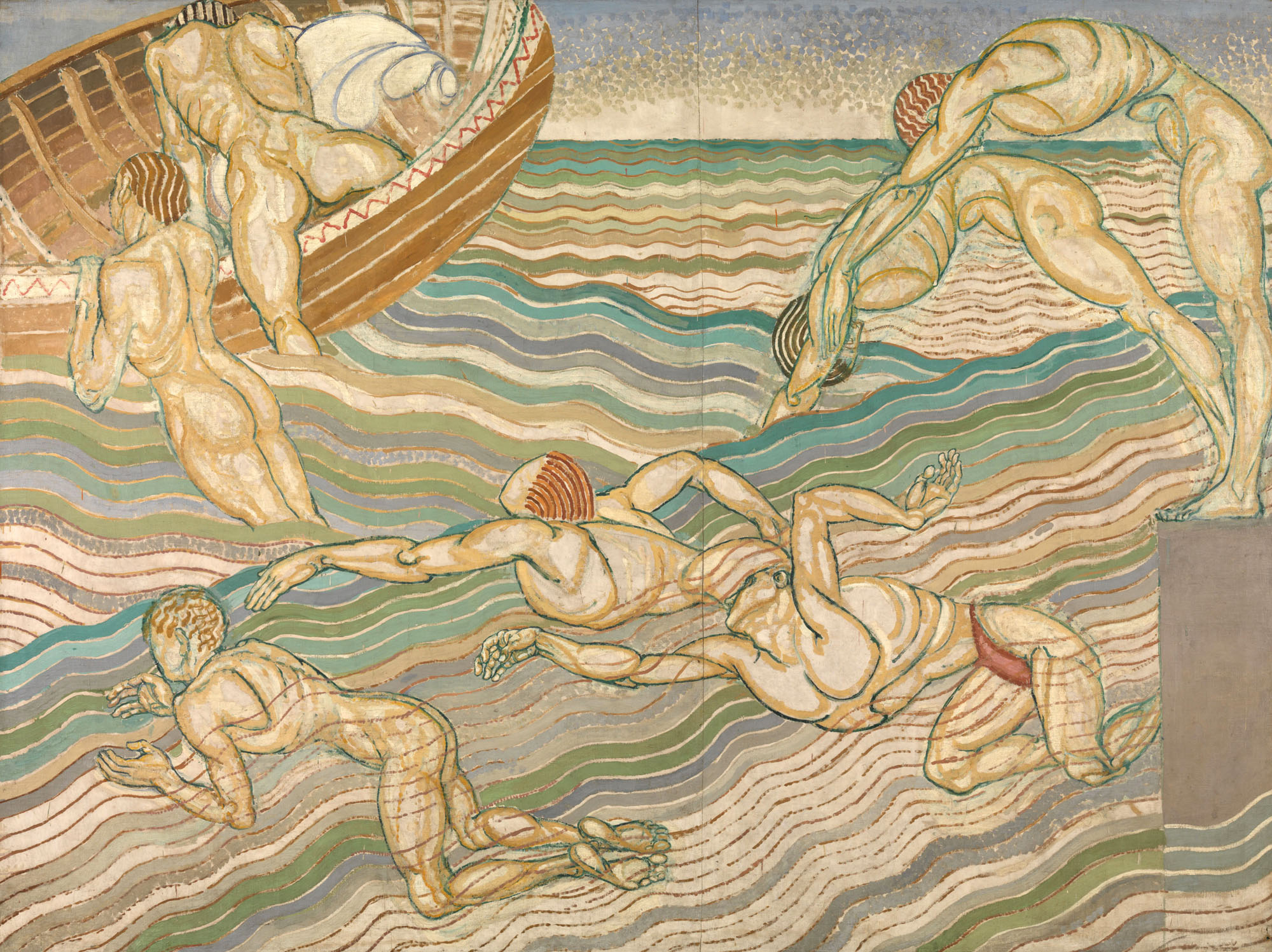

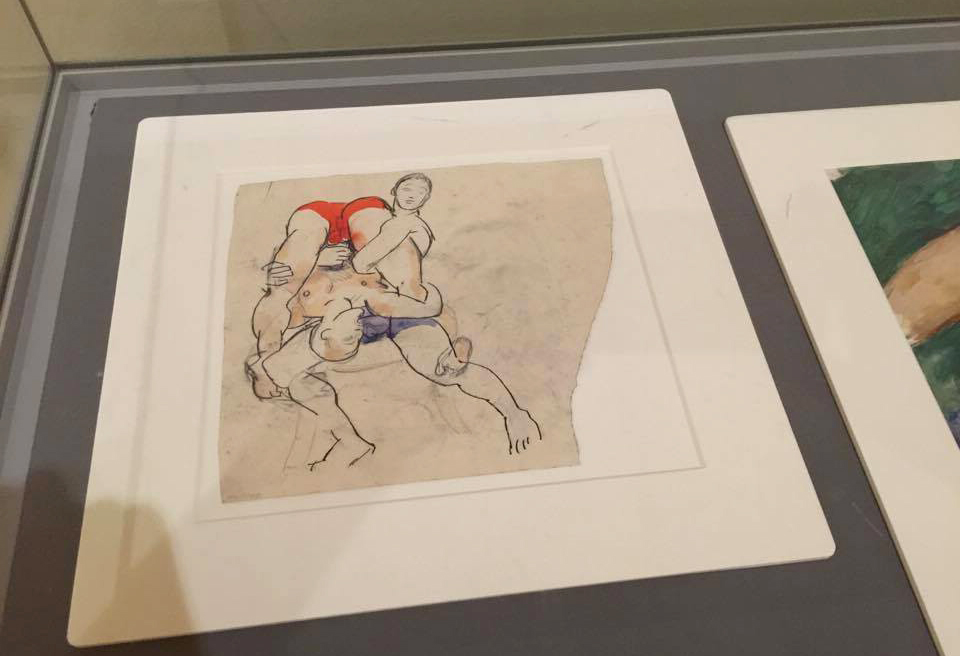

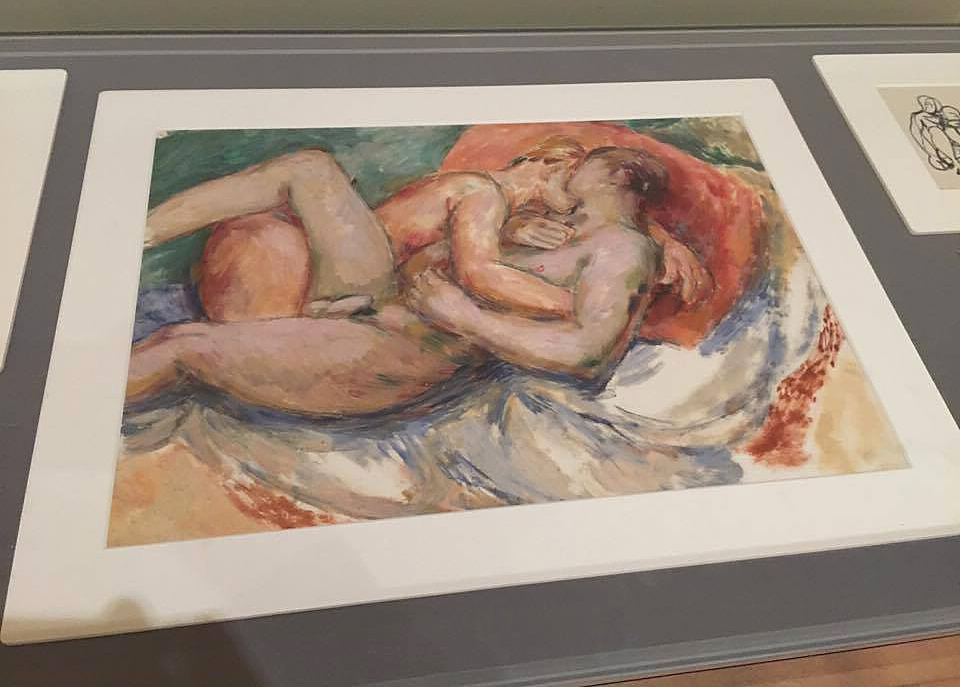

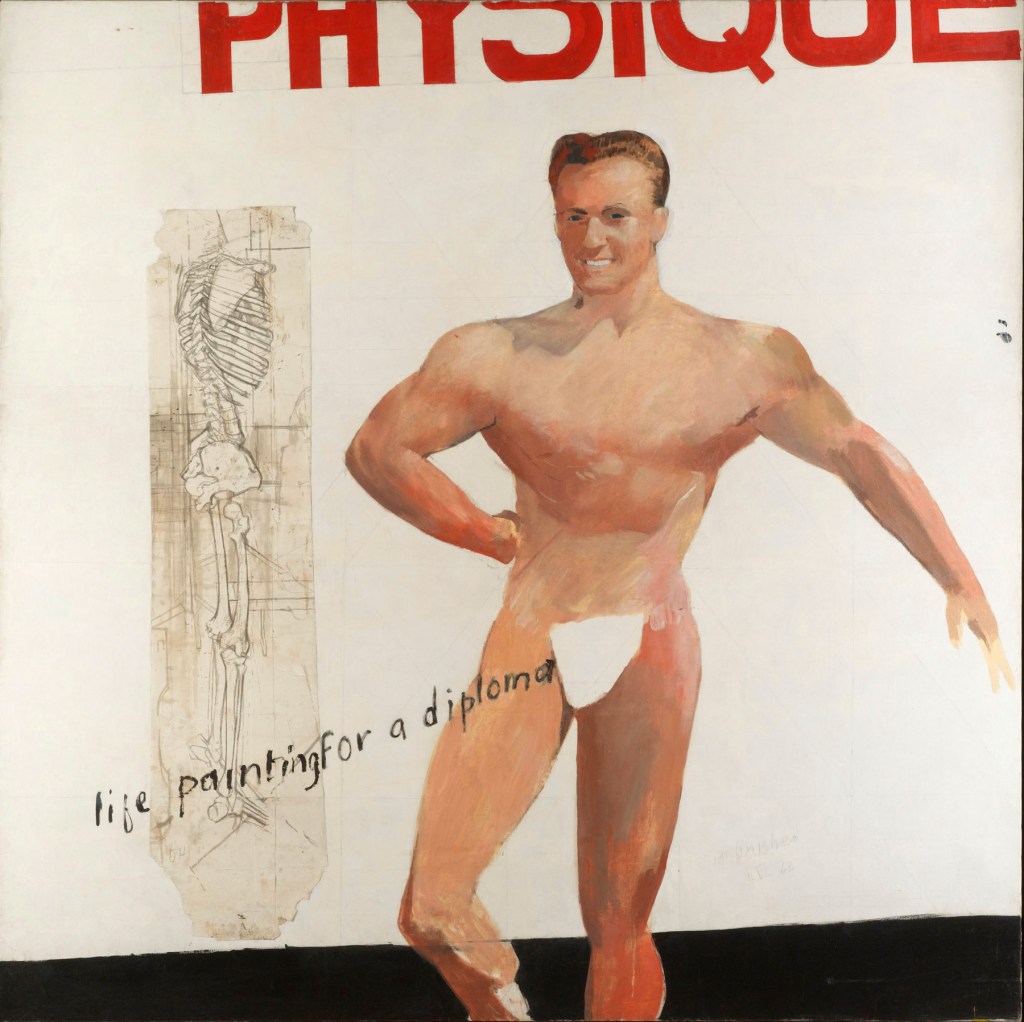

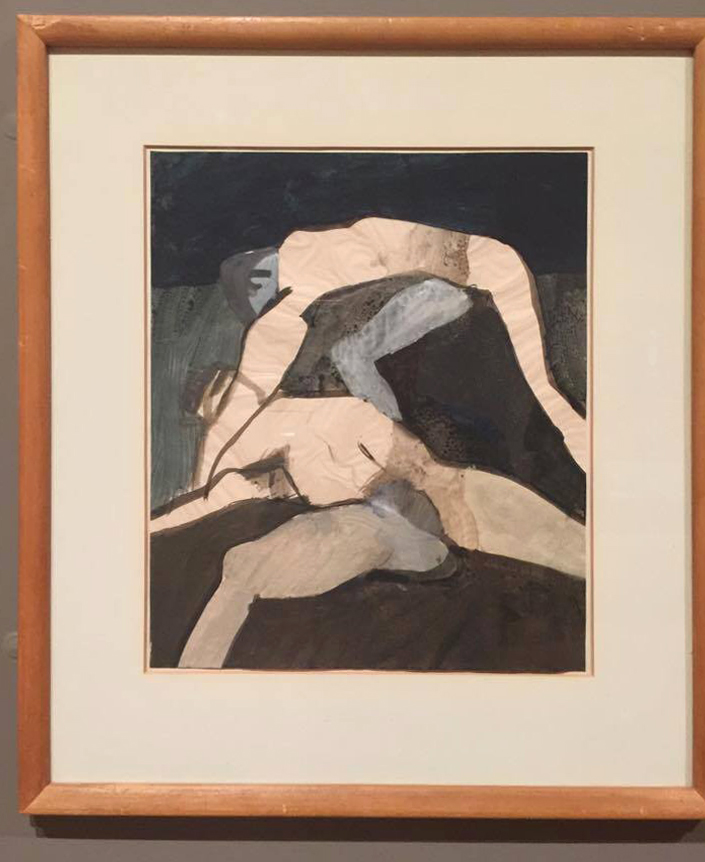

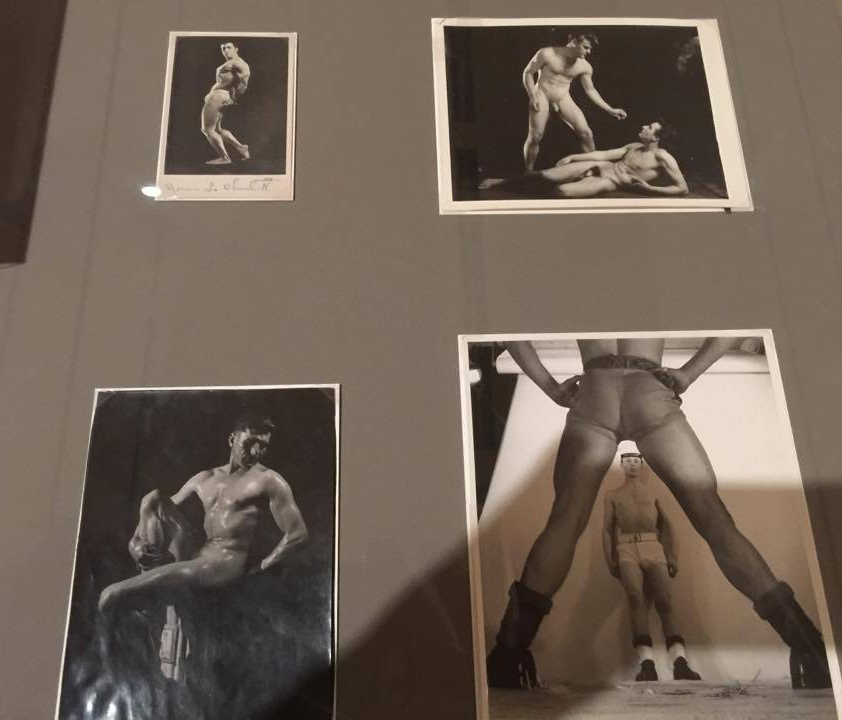

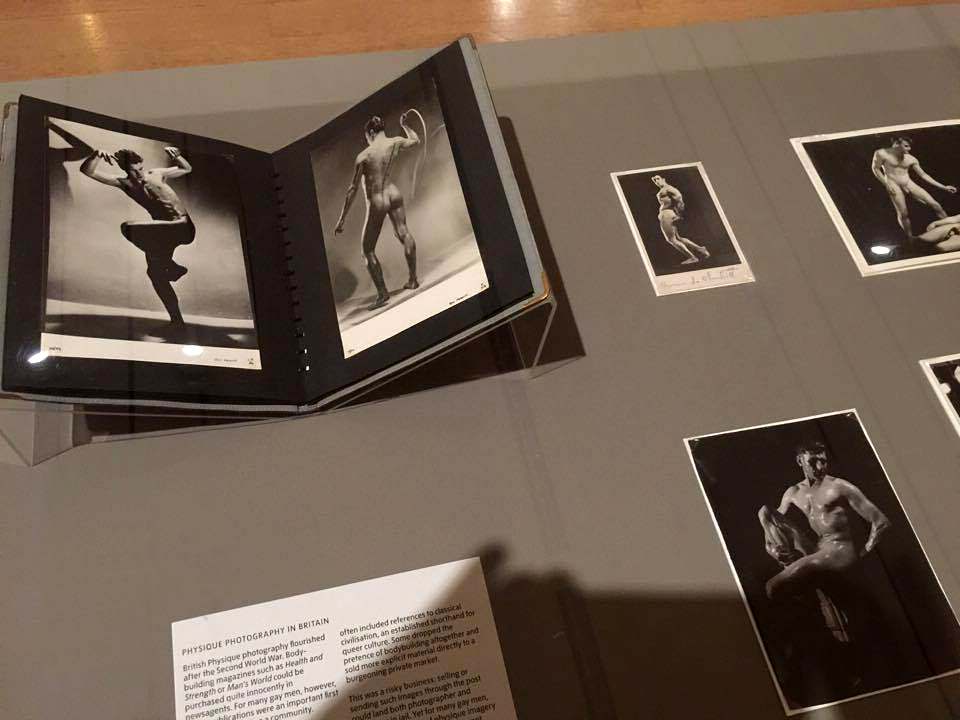

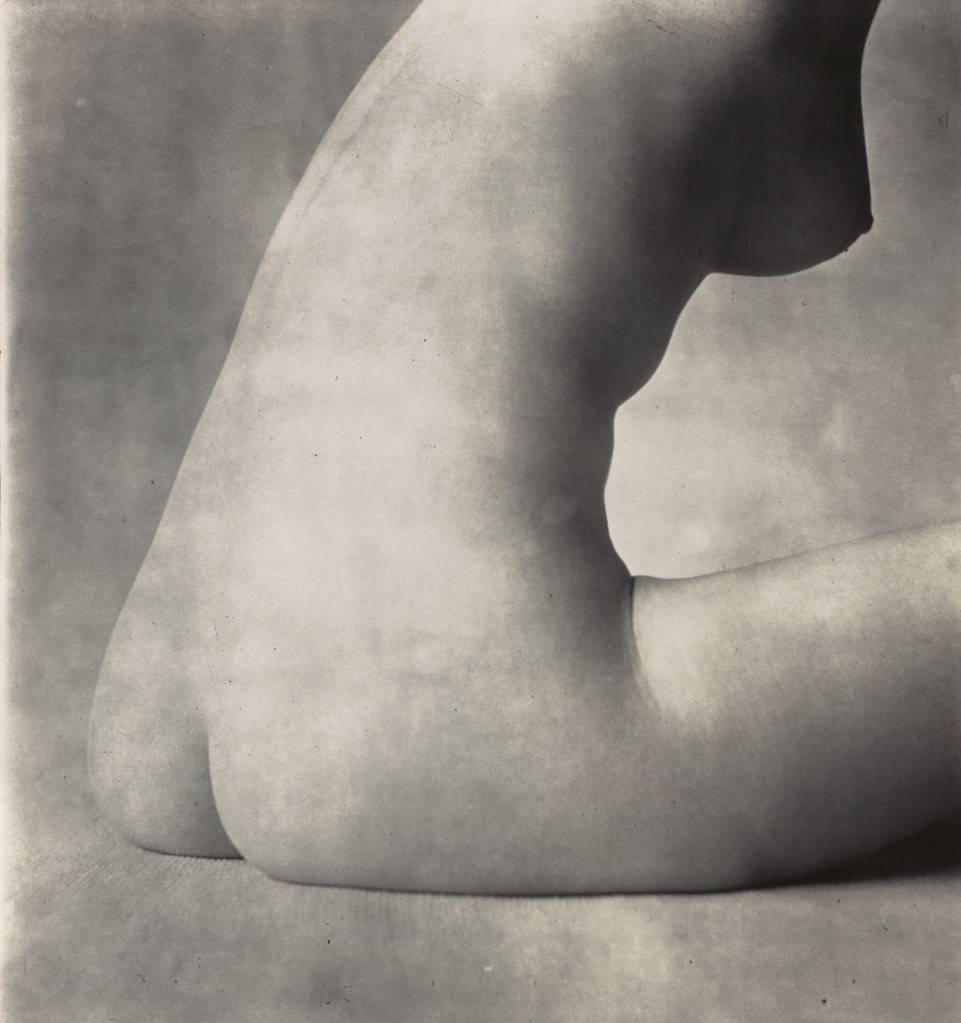

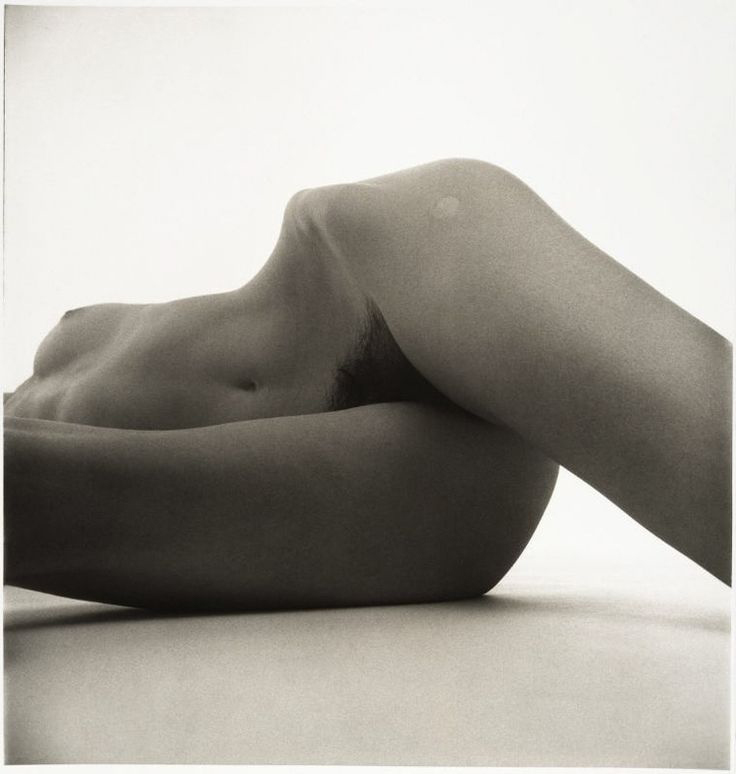

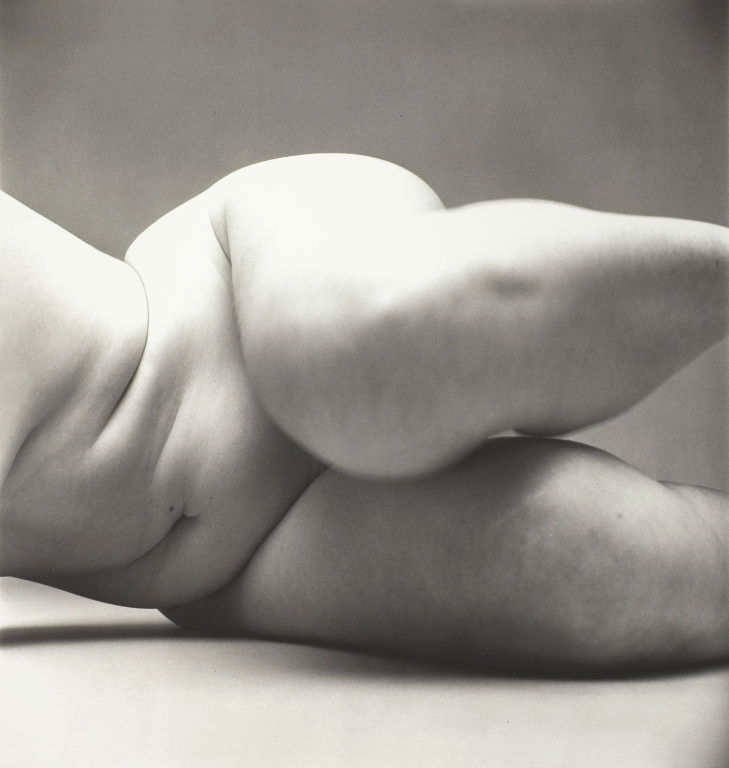

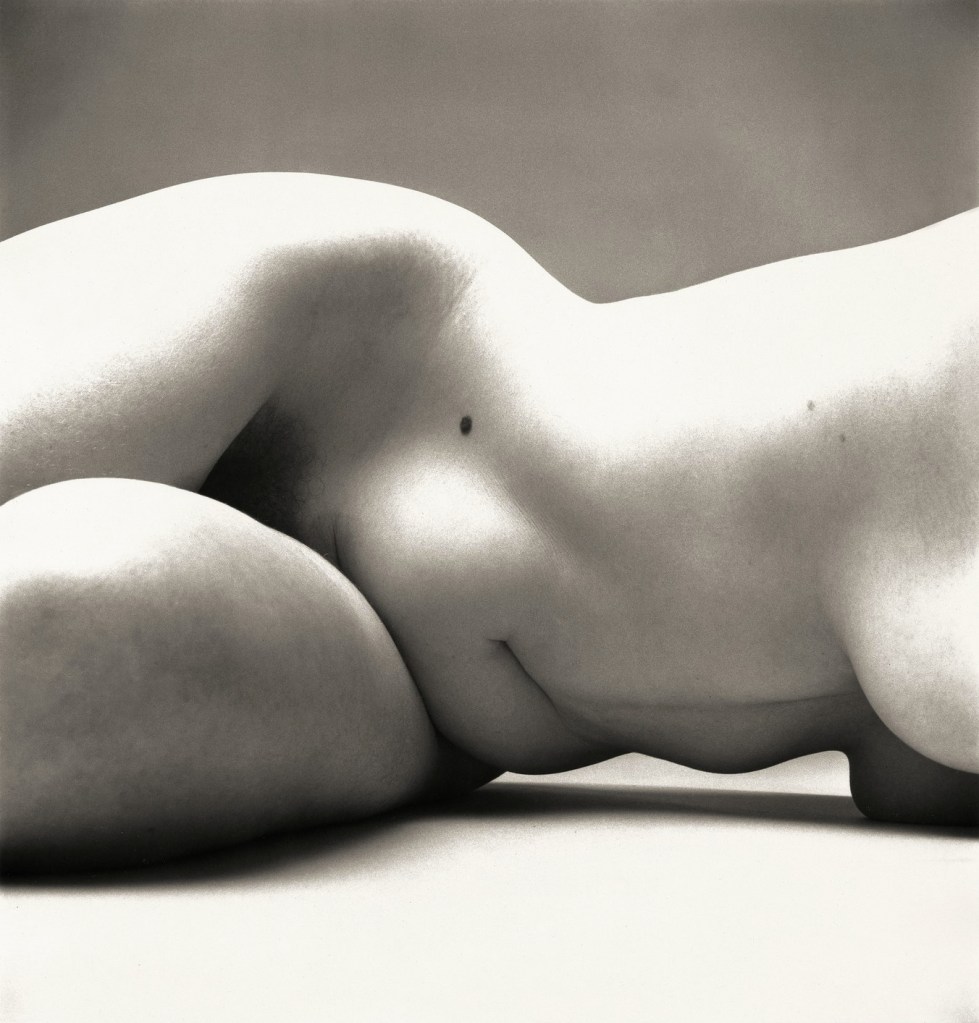

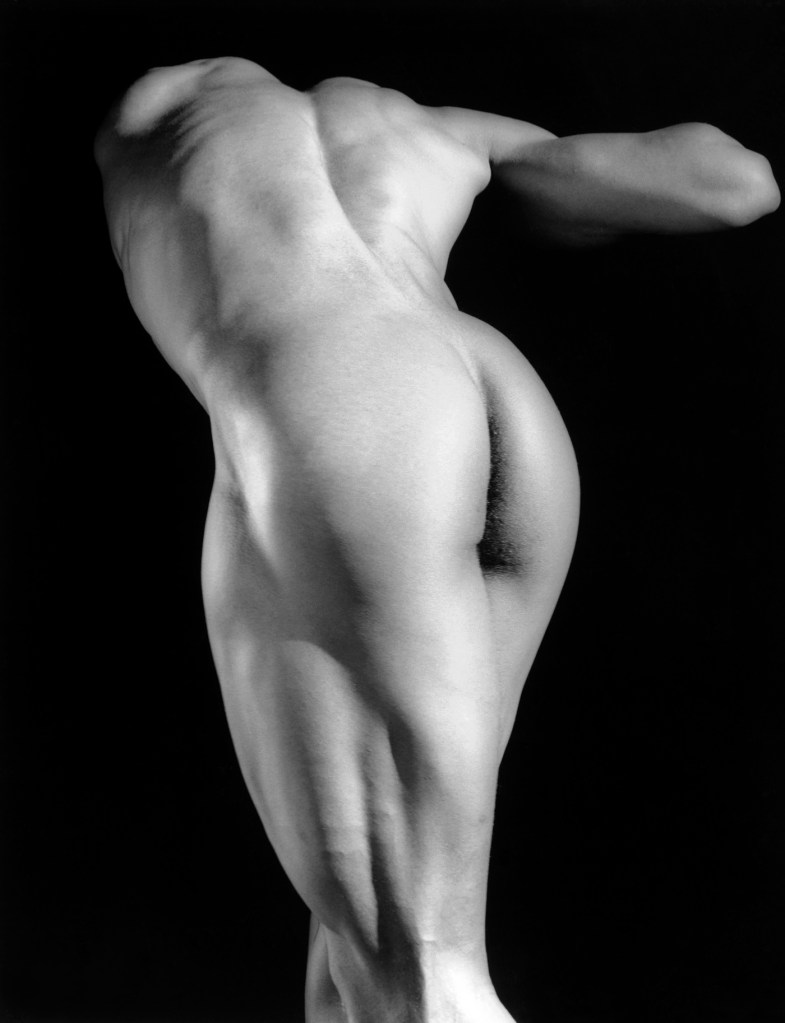

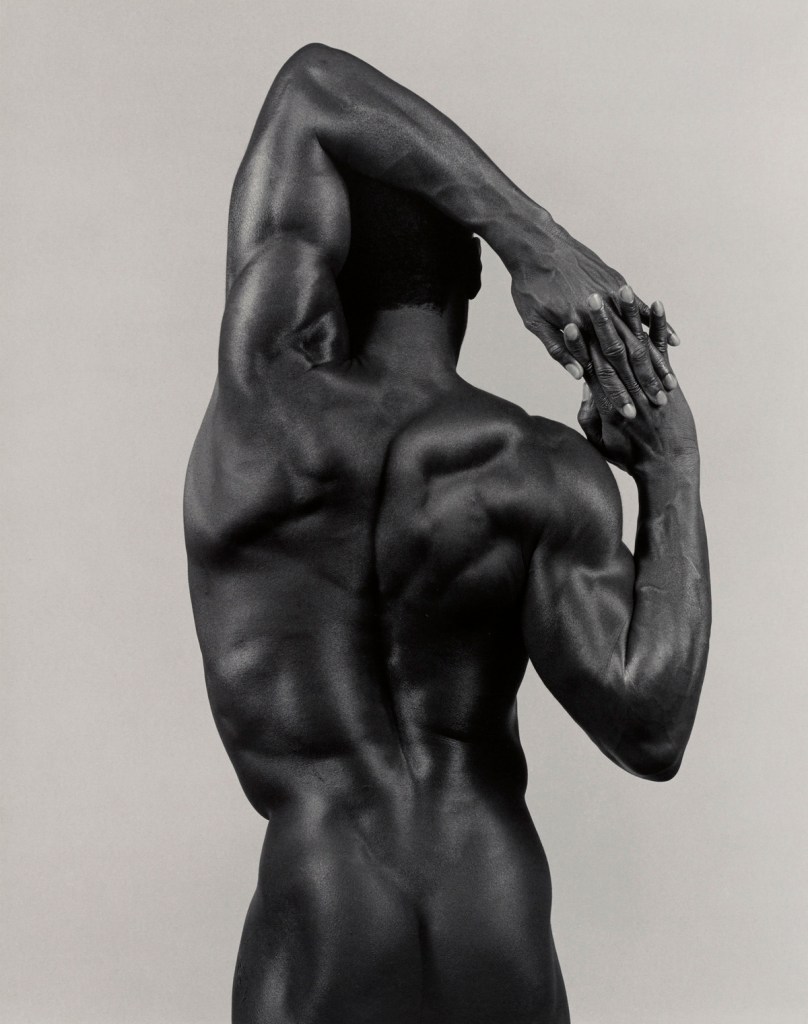

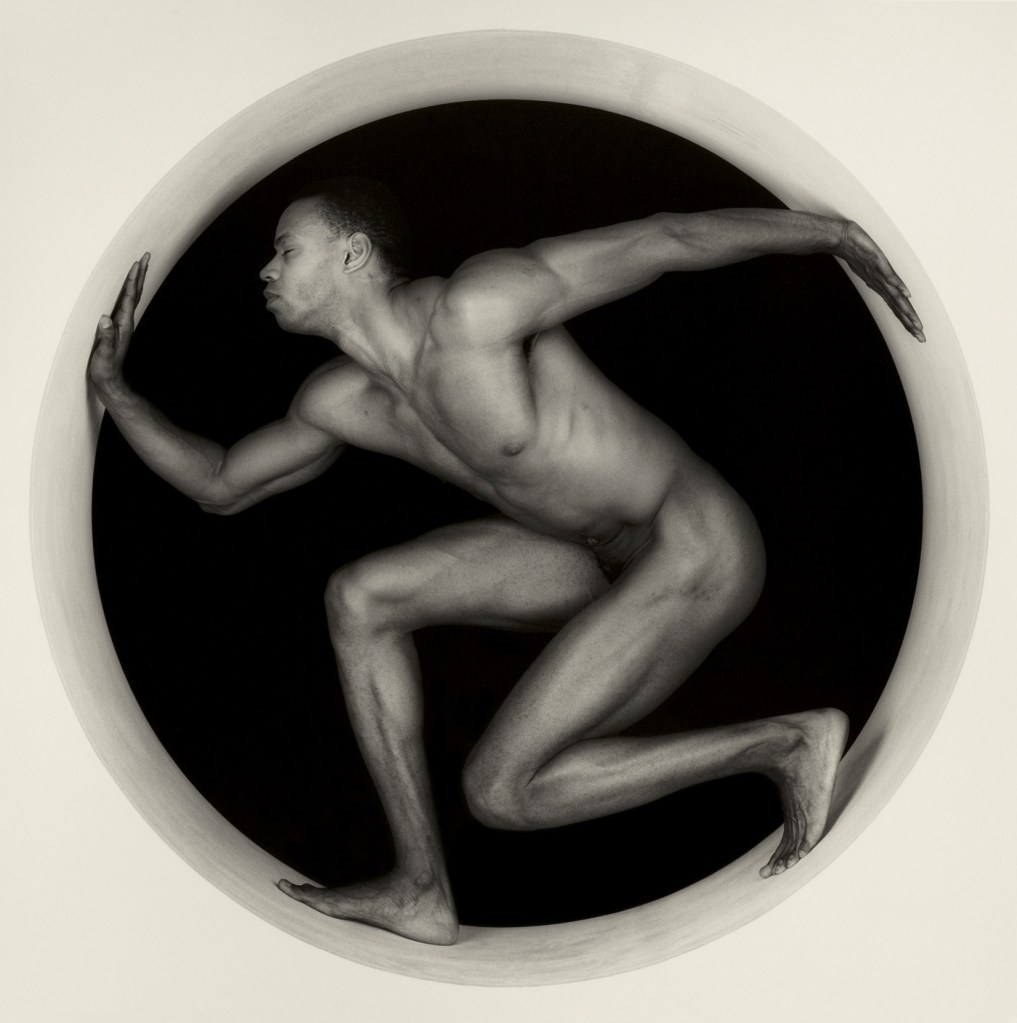

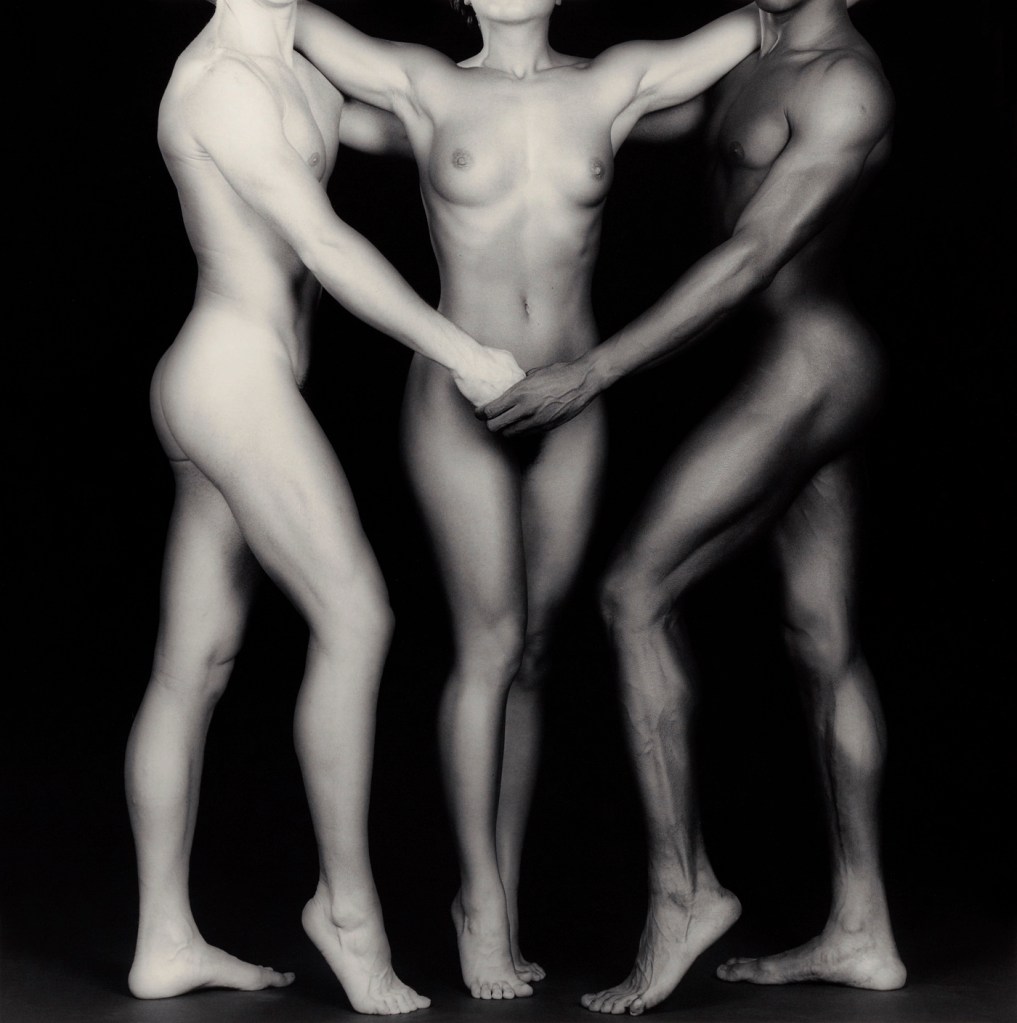

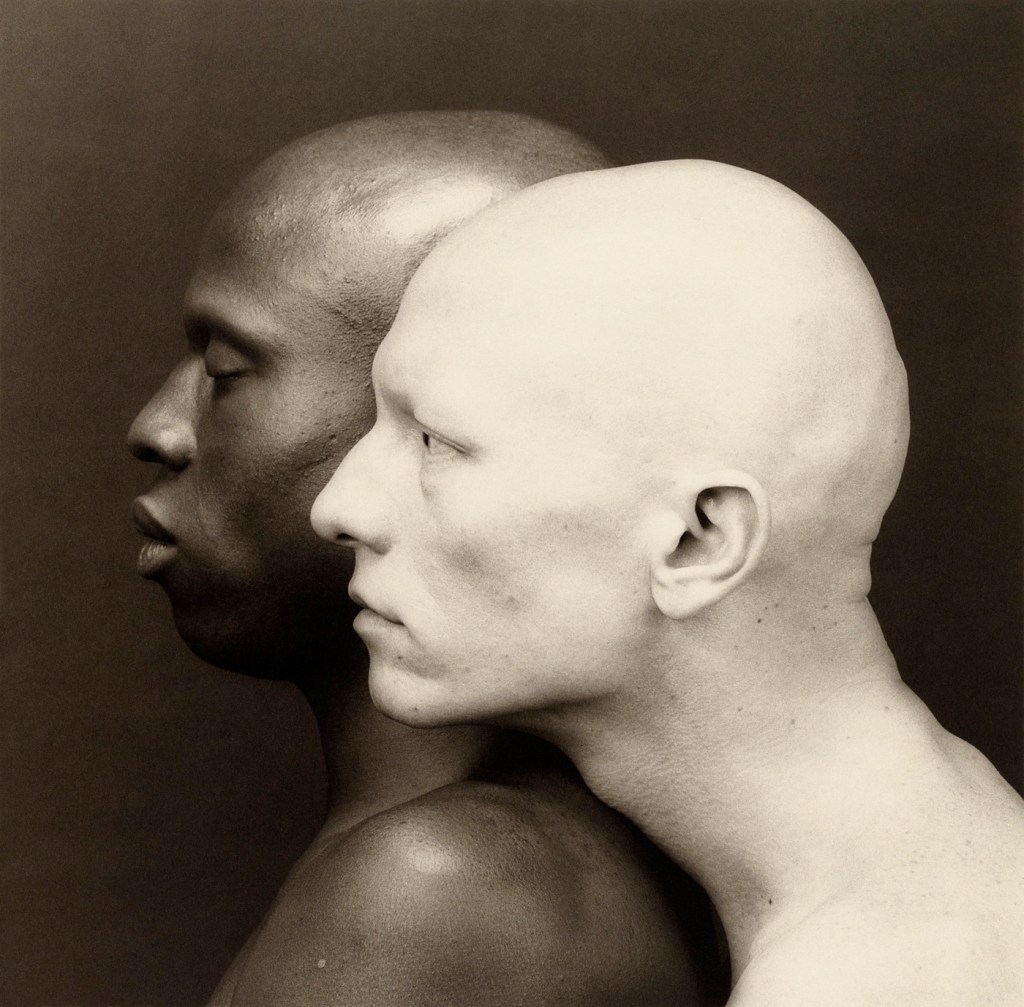

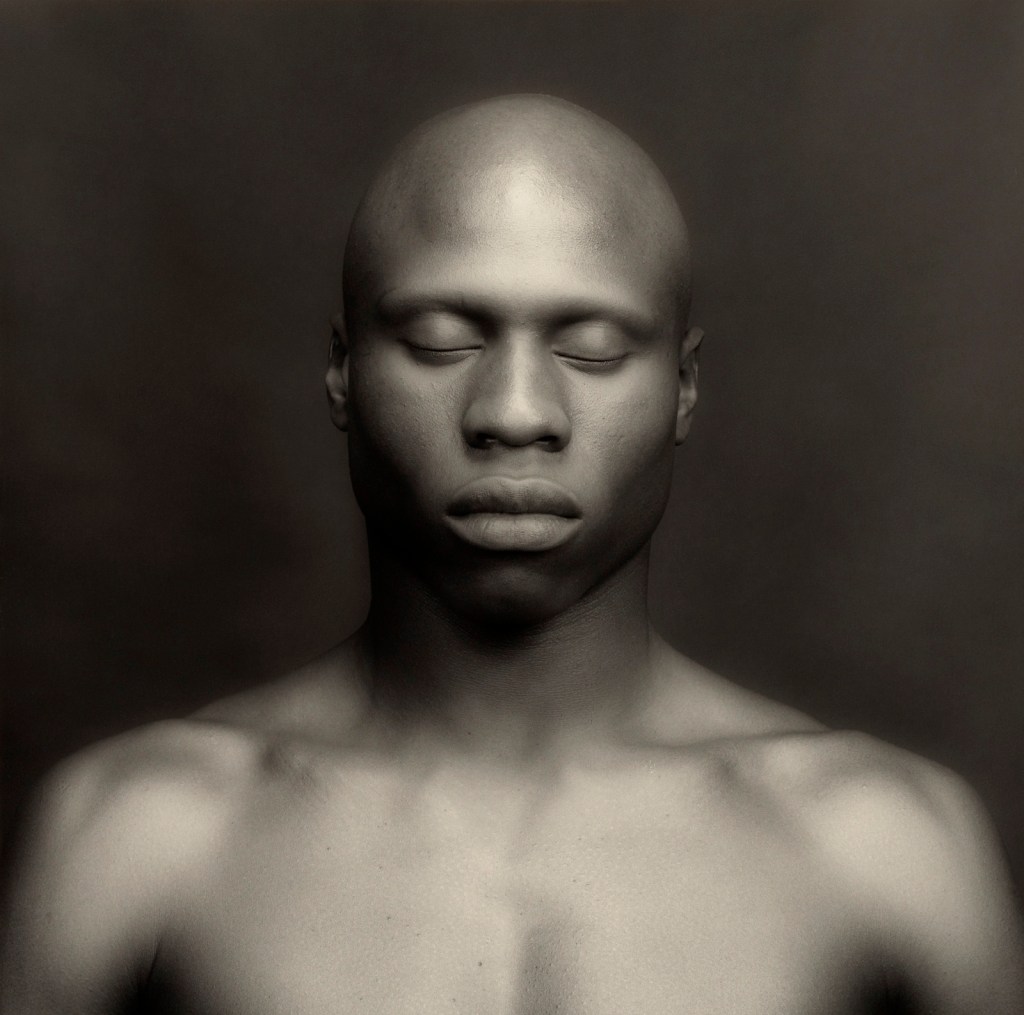

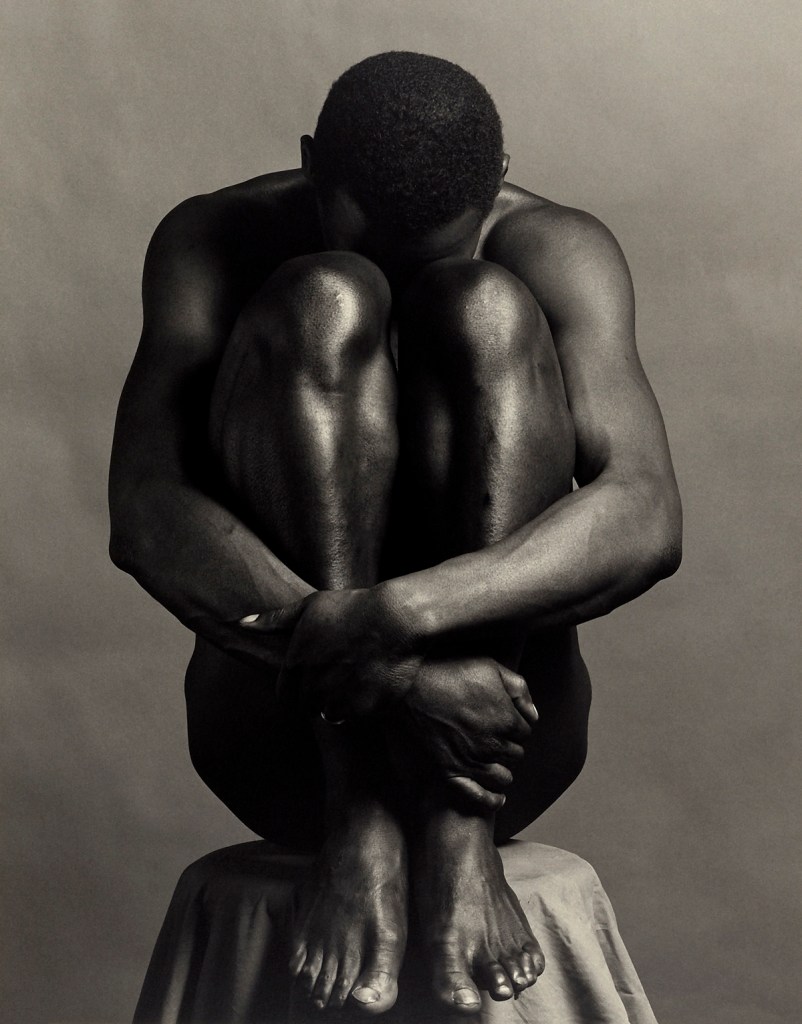

Body culture

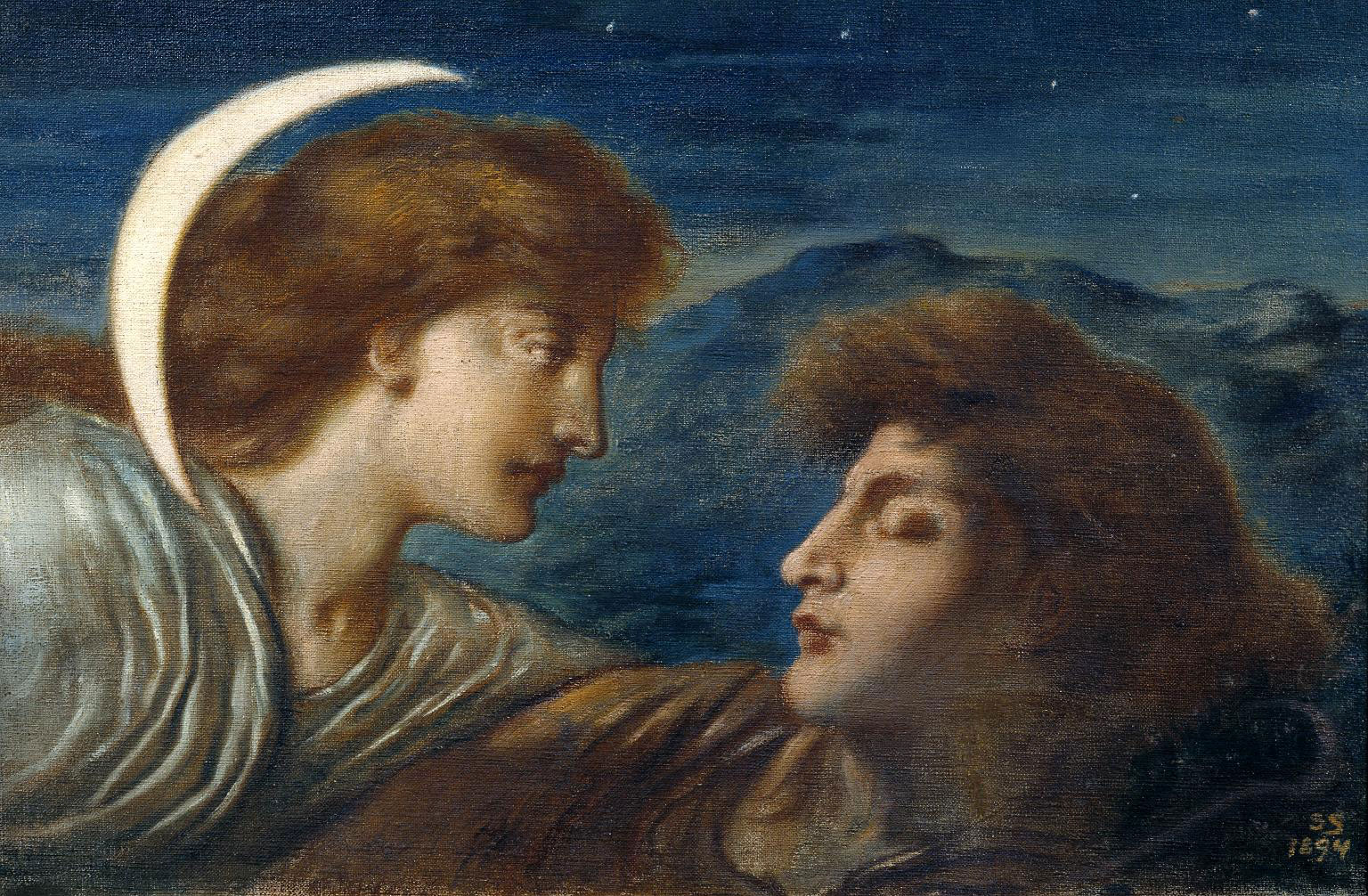

The terrible physical losses and psychological traumas of the First World War changed Australian society and prompted anxious concerns about the direction of the nation. For some this meant an inward-looking isolationism, a desire that Australian culture should develop independently and untouched by the ‘degenerate’ influences of Europe.

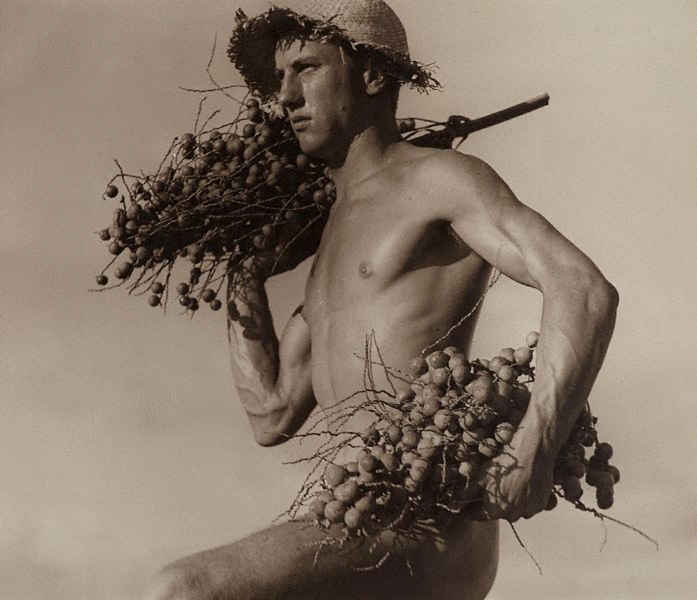

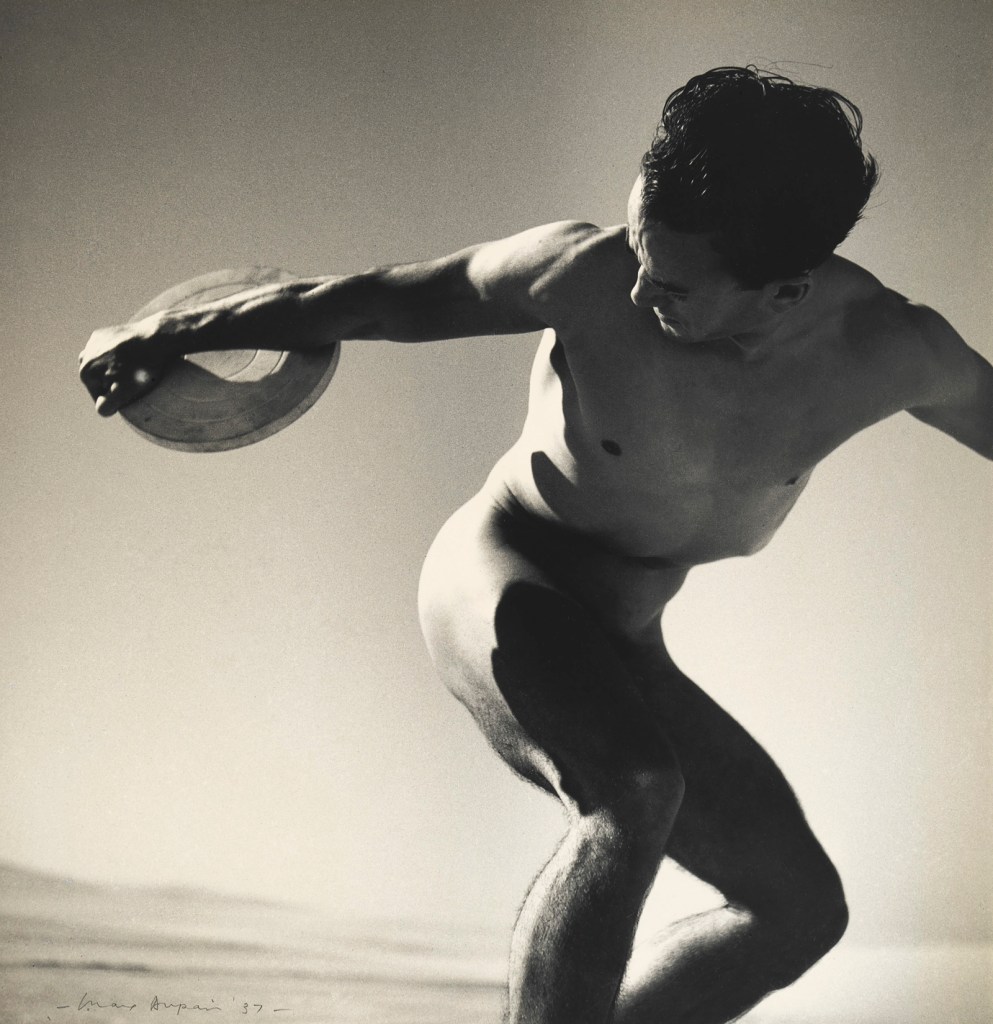

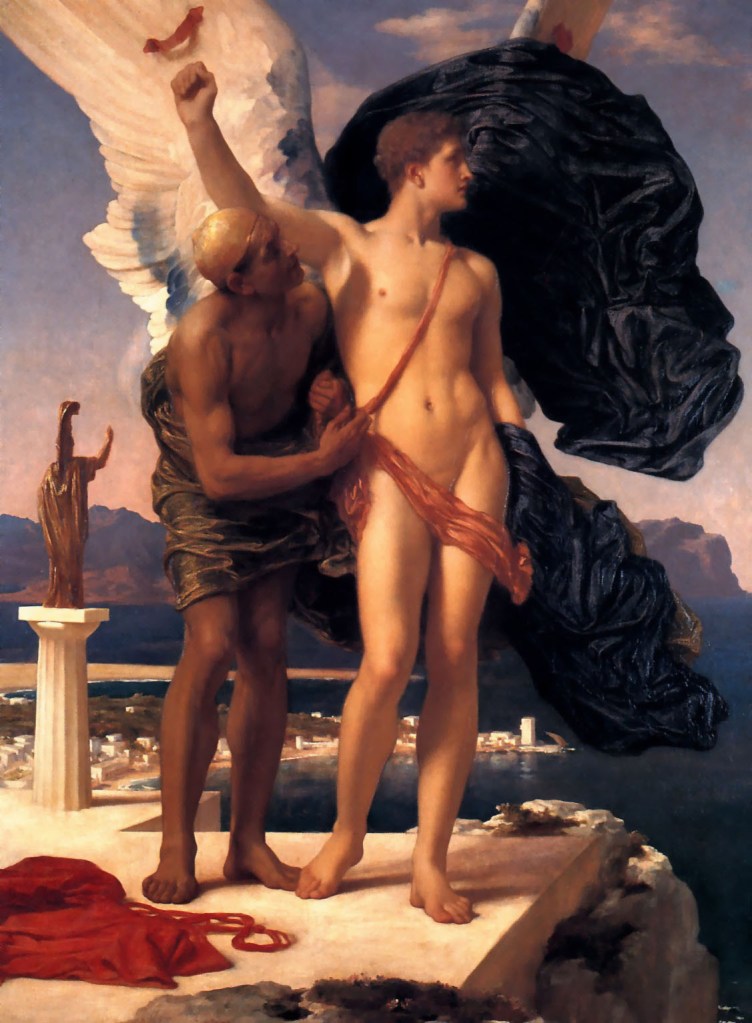

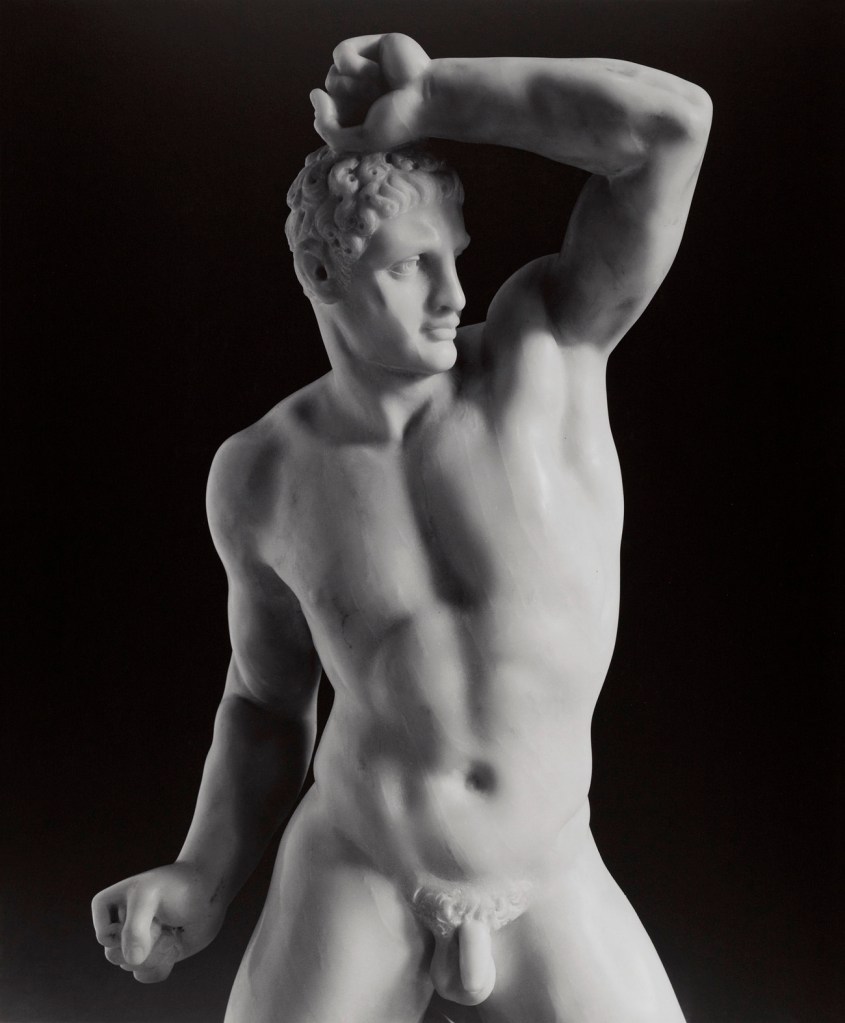

The search for rejuvenation frequently involved explorations of the capabilities and vulnerabilities of the human body. In the hands of artists, corporeal forms came to symbolise nationhood, most often expressed through references to the art of Classical Greece and mythological subjects. The evolution of a new Australian ‘type’ was also proposed in the 1930s – a white Australian drawn from British stock, but with an athletic and streamlined shape honed by time spent swimming and surfing on local beaches.

This art often has a distinctive quality to it, which in the light of history can sometimes make for disquieting viewing. With the terrible knowledge of how the Nazi Party in Germany subsequently used eugenics in its systematic slaughter of those with so-called ‘bad blood’, the Australian enthusiasm for ‘body culture’ can now seem problematic. Images of muscular nationalism soon lost their cache in Australia following the Second World War, tainted by undesirable fascistic overtones.

Keast Burke (New Zealand 1896 – Australia 1974, Australia from 1904)

Harvest

c. 1940

Gelatin silver photograph (25.6 x 30.5cm)

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Gerstl Bequest, 2000

Keast Burke (New Zealand 1896 – Australia 1974, Australia from 1904)

Husbandry 1

c. 1940

Gelatin silver photograph

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney

Gift of Iris Burke 1989

Max Dupain (Australian, 1911-1992)

Discus thrower

1937, printed (c. 1939)

Gelatin silver photograph

38.5 x 37.5cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased, 2003

Max Dupain (Australian, 1911-1992)

Souvenir of Cronulla

1937

Gelatin silver photograph

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased through The Art Foundation of Victoria with the assistance of National Australia Bank Limited, Honorary Life Benefactor, 1992

In the 1930s Max Dupain responded to Henri Bergson’s book Creative Evolution (1907) in which he considered creativity and intuition as central to the renewed development of society, and the artist as prime possessor of these powers. Vitalism, as this philosophy was termed, was believed to be expressed through polarised sexual energies. In this work Dupain focuses on the sexually differentiated ‘energies’ of men and women, associating women with the forces of nature.

Installation view of the exhibition Brave New World: Australia 1930s at NGVA with Daphne Mayo’s A young Australian in foreground

Photo: Eugene Hyland

Daphne Mayo (Australian, 1895-1982, England 1919-1923, France 1923-1925)

A young Australian

1930, cast 1931

Bronze, marble

(a-b) 51.0 x 35.2 x 18.1cm (overall)

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney Purchased 1930

© 1982 by The Surf Life Saving Foundation and the Uniting Church in Australia Property Trust (Q.)

Installation view of the exhibition Brave New World: Australia 1930s at NGVA with Dorothy Thornhill’s Neo-classical nudes and Resting Diana at left; Tom Purvis’ Australia’s 150th Anniversary Celebrations (wall print) at centre rear; and Jean Broome-Norton’s Abundance on plinth at right

Photo: Courtesy NGV Photographic Services

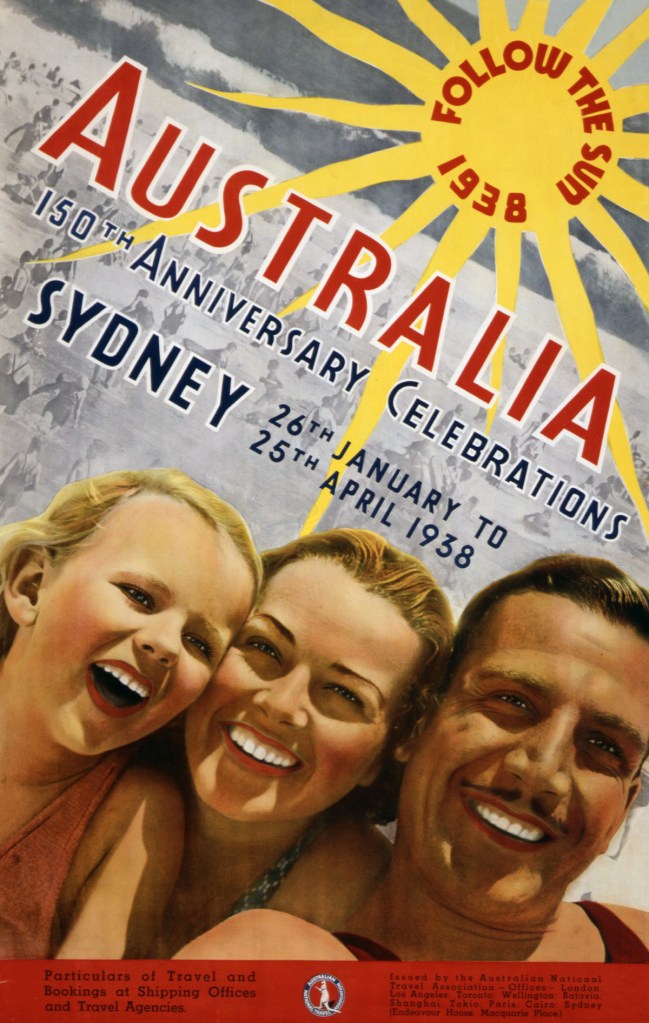

Tom Purvis (England, 1888-1959)

Australia’s 150th Anniversary Celebrations

c. 1938

Colour lithograph

Courtesy of Josef Lebovic Gallery, Sydney

Installation view of Dorothy Thornhill’s Neo-classical nudes from the exhibition Brave New World: Australia 1930s at NGVA

Photo: Dr Marcus Bunyan

Dorothy Thornhill (England 1910 – Australia 1987, New Zealand 1920-1929, Australia from 1929)

Resting Diana

1931

Oil on canvas

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Purchased 1977

The invocation of the Classical body as a modern prototype was a powerful idea in the 1930s. The Graeco- Roman goddess Diana, the virgin patron goddess of the hunt, was popularly invoked as an ideal of female perfection, and represented with a slender and athletic physique. Dorothy Thornhill’s Diana is a remarkable visualisation of such a ‘modern Diana’, her angular body and defined musculature reflecting the masculinisation of female bodies at this time. She is a formidable presence, the quiver of arrows slung nonchalantly across her shoulders a trophy of her victory over the male gender.

Jean Broome-Norton (Australian, 1911-2002)

Abundance

1934

Plaster, bronze patination

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased through The Art Foundation of Victoria with the assistance of ICI Australia Limited, Fellow, 1994

“High-rise buildings, fast trains and engineering feats such as the Sydney Harbour Bridge jostled against the Great Depression, conservatism and a looming Second World War during the 1930s, one of the most turbulent decades in Australian history. The major exhibition at the NGV, Brave New World: Australia 1930s, will explore the way artists and designers engaged with these major issues providing a fresh look at a period characterised by both optimism and despair. The exhibition will present a broad-ranging collection of more than 200 works spanning photography, painting, printmaking, sculpture and decorative arts as well as design, architecture, fashion, graphics, film and dance.

Tony Ellwood, Director, NGV, commented, “Brave New World explores an important period of Australian art history during which Abstraction, Surrealism and Expressionism first emerged, and women artists arose as trailblazers of the modern art movement. It will offer an immersive look at the full spectrum of visual and creative culture of the period, from Max Dupain’s iconic depictions of the Australian body and beach culture to a vast display of nearly 40 Art Deco radios, which were an indispensable item for the Australian home during the 1930s.”

Presented thematically, Brave New World will show how artists and designers responded to major social and political concerns of the 1930s. The Great Depression, which saw Australia’s unemployment rate rise to 32% by 1932, is seen through the eyes of photographer F. Oswald Barnett in his powerful images of poverty-stricken inner Melbourne suburbs such as Fitzroy, Collingwood and Carlton, and in the works of Danila Vassilieff, Yosl Bergner, Arthur Boyd and Albert Tucker who were among the first artists to depict Australia’s working class and destitute.

In contrast, many other artists at the time chose to focus upon the vibrant city streets, cafes and buildings of contemporary Australian cities, such as renowned modernist Grace Cossington Smith with her energetic canvasses of flat colours and abstracted forms. Other artists featured in Brave New World including Hilda Rix Nicholas and Elioth Gruner concentrated on more traditional scenes of the Australian bush, which was seen as a place of respite from the frenetic pace of modern city life.

The exhibition will explore artists’ responses to the growing calls for Indigenous rights during the 1930s, which was accompanied by a rising interest in Aboriginal art and particularly the work of Albert Namatjira, the first Indigenous artist of renown in Australia; and the rise of the ‘modern woman’, a female who favoured urban living, freedom and equality over marriage and child rearing.

The 1930s also saw the idea of the ‘Australian body’, a tanned, muscular archetype shaped by sand and surf, come to the fore of the Australian identity. Artists who engaged with this idea, including Max Dupain, Charles Meere and Olive Cotton, will be presented in Brave New World. The exhibition will be accompanied by a fully-illustrated, 212-page hardback publication, featuring essays by leading writers on each of the exhibition themes. A series of public programs will also be offered including a major symposium, an Art Deco walking tour of Melbourne and a dance performance, recreating Demon machine (1924) by the Bodenweiser company that toured Australia in the late 1930s as well as an original solo by the choreographer, Carol Brown (NZ).

Press release from the NGV

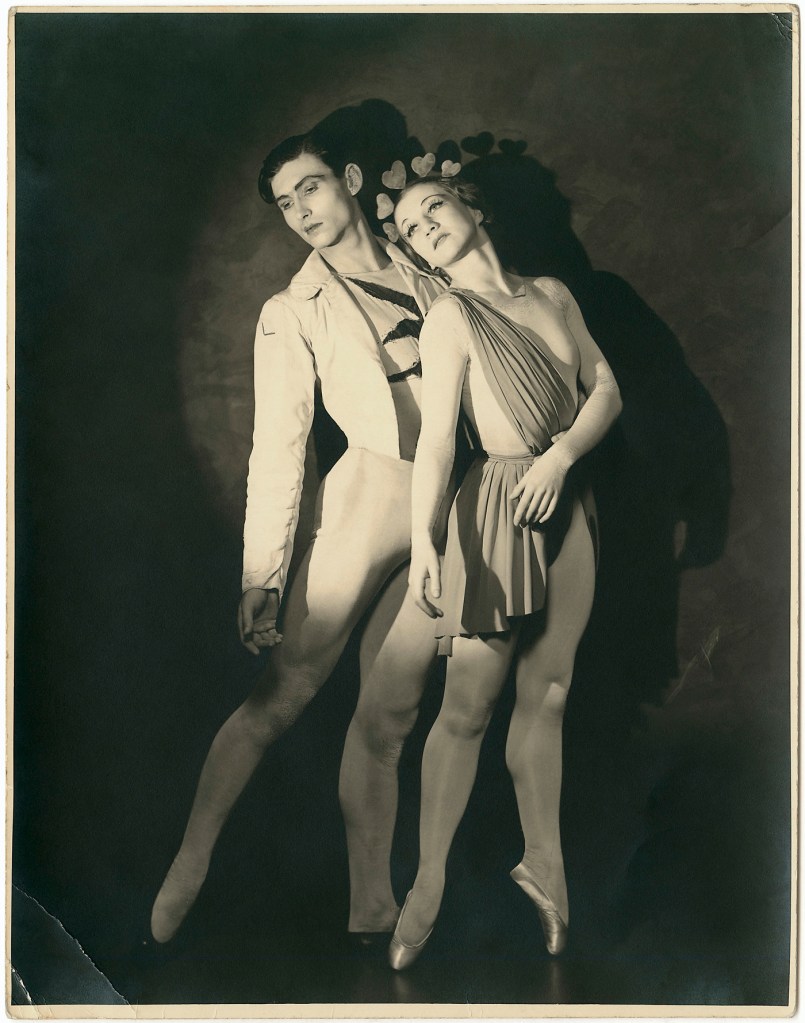

Nanette Kuehn (Germany 1911 – Australia 1980, Australia from 1937)

Borislav Runanine and Tamara Grigorieva in Jeux D’Enfants, original Ballets Russes, Australian tour

1939-1940

Gelatin silver photograph

Performing Arts Collection, Arts Centre, Melbourne

The Australian Ballet Collection. Gift of The Australian Ballet, 1998

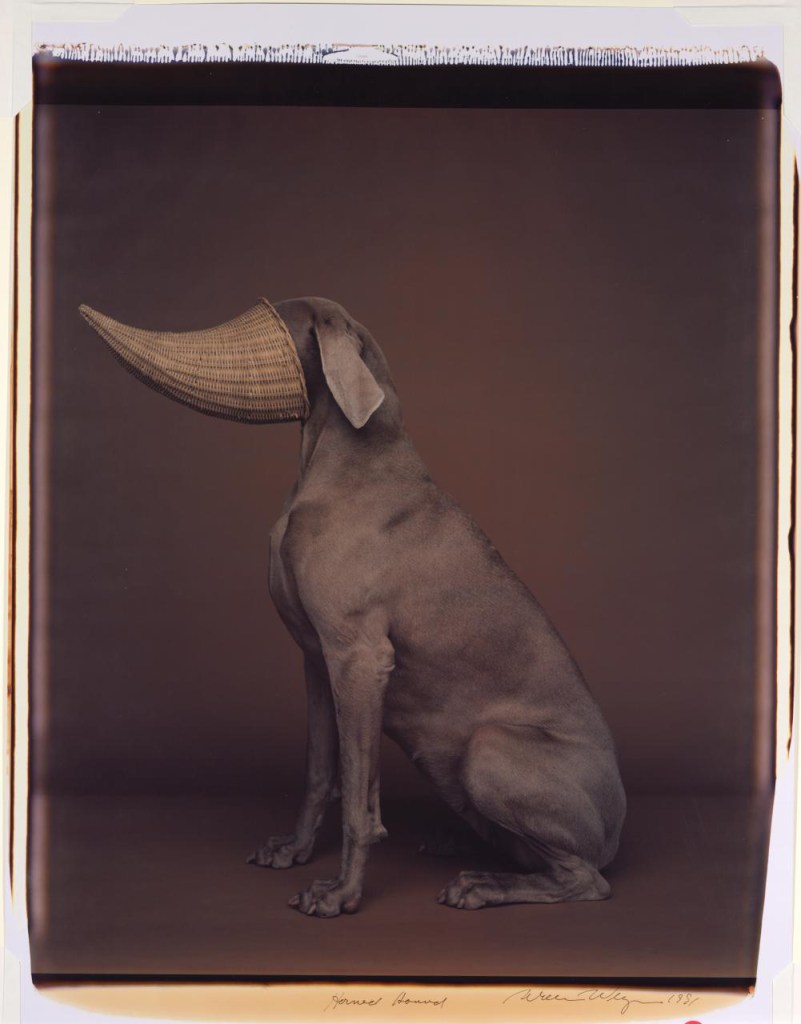

The expressive body: dance in Australia

If modern art encapsulated the ideals and conflicting forces of the early twentieth century, then modern dance embodied its restless vitality and the quest for a different kind of subjectivity and expression. To many, modern dance is the pivotal art form for a mid twentieth century concerned with plasticity, the expressive body and tensions between the individual and its collective formation.

The decade of the 1930s is framed by the 1928-1929 tour of Anna Pavlova’s dance company and the three tours of the remnant Ballets Russes companies (1936-1937, 1938-1939,1939-1940) that excited many aspiring modernist artists. These tours sowed the seeds for subsequent ballet narratives in Australia, because the eruption of war in 1939 meant that Ballets Russes dancers, including Helene Kirsova and Edouard Borovansky, stayed in the country and established ballet companies. While trained in Russian dance technique, these artists were also influenced by the aesthetics of change in European art and dance that included new bodily techniques, dynamic movement patterns and modern technologies. It was the individual dancers of modern dance, however, including Louise Lightfoot and Sonia Revid, who produced the expressive intensity of a more autonomous art of movement.

Installation views of the exhibition Brave New World: Australia 1930s at NGVA featuring a wall print of Sonia Revid dancing on Brighton beach c. 1935 by an unknown Australian photographer

Photos: Courtesy NGV Photographic Services

Australia, Unknown photographer

Sonia Revid dancing on Brighton beach

c. 1935

Courtesy of State Library Victoria, Melbourne

Sonia Revid was one of the leading proponents of modern interpretative dance in Melbourne. Born in Latvia, she studied with the great dancer Mary Wigman in Germany before coming to Australia in 1932. Revid is credited with introducing the ‘German Dance’ to Australian audiences, and in the mid 1930s established the Sonia Revid School of Art and Body Culture in Collins Street. She composed her own dances, one of the best known being Bushfire drama (1940), based on the 1939 Victoria Bushfires.

Max Dupain (Australian, 1911-1992)

Ballet (Emmy Towsey and Evelyn Ippen, Bodenwieser Dancers performing Waterlilies)

1937, printed (c. 1939)

Gelatin silver photograph

44.5 x 33.5cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased, 2003

Jack Cato (Australia 1889-1971, England 1909-1914, South Africa 1914-1920)

Helene Kirsova and Igor Youskevitch in Les Presages, Monte Carlo Russian Ballet

1936-1937

Gelatin silver photograph

24.8 x 19.4cm

Performing Arts Collection, Arts Centre, Melbourne

The Australian Ballet Collection

Gift of The Australian Ballet, 1998

Choreographed by Léonide Massine in 1933, Les Presages (Destiny) was a popular and avant-garde work during the Ballets Russes tours to Australia in 1936-1937. It was one of the first contemporary ballets to be choreographed to an existing musical score, Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony. Portrayed in this picture are two principal dancers from the Monte Carlo Ballets Russes: Hélène Kirsova, who remained in Australia and formed her own ballet company in Sydney in the early 1940s, and Igor Youskevitch, who became a leading American ballet dancer, appearing here in the role of the Hero.

Evelyn Ippen designer and maker active in Australia 1930s

Dress for Slavonic Dances

1939

Cotton, silk (velvet) (appliqué), elastic, metal (zip) for a production of the Bodenwieser Ballet, choreographed by Gertrud Bodenwieser

Performing Arts Collection, Arts Centre, Melbourne

Bodenwieser Collection. Gift of Barbara Cuckson, 2000

The Slavonic Dances were choreographed by Gertrud Bodenwieser to represent what she described as the ‘vigour and passionate feelings of the Slavonic people’, and toured with her first company in Australia in 1939. Loosely using folk-dance motifs, this ensemble work would have been a stylish crowd-pleaser in contrast to more serious dances. The appliqué and colourful flower motifs on this dress are similar to designs by Natalia Goncharova for the Ballets Russes, although the simplified appeal of its ‘red bodice, long, swirling skirt, and gathered white sleeves’ were probably designed by one of the company dancers, Evelyn Ippen.

Max Dupain (Australian, 1911-1992)

Tamara Tchinarova in Presages

Published in Art in Australia, February 15, 1937

National Gallery of Victoria

Melbourne Shaw Research Library

Australia Tunes Into The World

These radios comprise a selection of Australian designed and manufactured tabletop models from the 1930s at a time when this new method of communication became an integral part of every home. They reflect the rapid spread of the streamlined style to Australia from the United States, England and Europe, where industrial designers applied machine-age styling to everyday household appliances. The use of new synthetic plastics (Bakelite) and mass production helped to make radios affordable for ordinary people, even in the depths of the Depression, and radio transmission brought the world into every Australian home. As cheap alternatives to the expensive wooden console in the lounge room, these small, portable radios allowed individual family members to listen to serials, quizzes and popular music in other rooms such as the kitchen, bedroom and verandah, as well as in the workplace.

Radios of the 1930s are now appreciated as quintessential examples of Art Deco styling, and one of the first expressions of art meeting industry. These colourful and elegant radio sets were one of the first pieces of modern styling in the Australian home. They were also a symbol of modern technology and a new future.

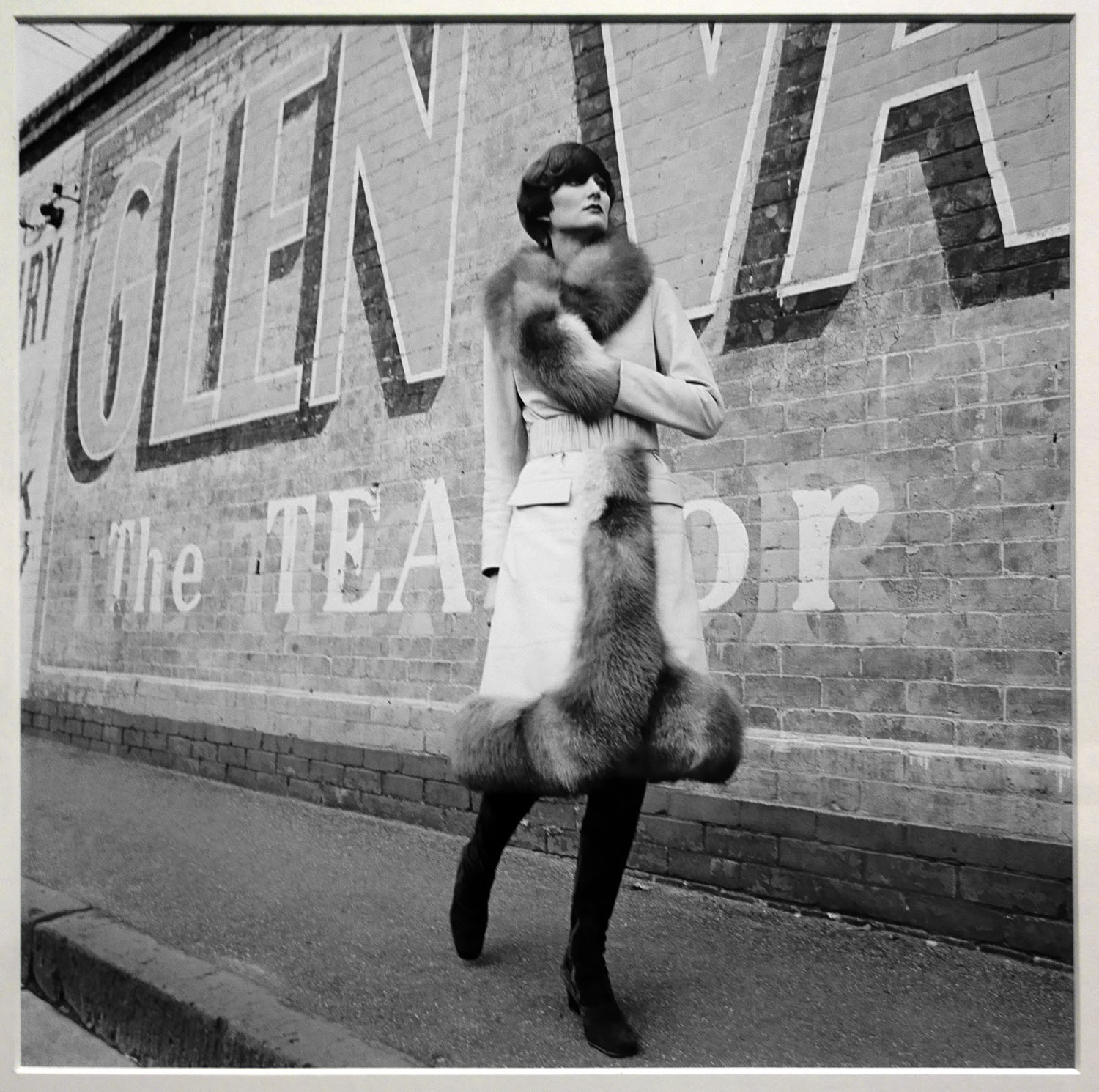

Installation view of Australian Art Deco radios from the exhibition Brave New World: Australia 1930s at NGVA

Photo: Eugene Hyland

Airzone (1931) Ltd, Sydney (manufacturer)

Mullard (white)

1938

Collection of Peter Sheridan and Jan Hatch

Airzone (1931) Ltd, Sydney (manufacturer)

Mullard (speckled green)

1938

Collection of Peter Sheridan and Jan Hatch

Airzone (1931) Ltd, Sydney (manufacturer)

Mullard (black)

1938

Collection of Peter Sheridan and Jan Hatch

Photo © Peter Sheridan

Amalgamated Wireless (Australasia) Ltd., Sydney (manufacturer) est. 1913

AWA ‘Egg crate’ (various colours)

1938

Bakelite

21.0 x 33.0 x 19.0cm (each)

Collection of Peter Sheridan and Jan Hatch

Photo © Peter Sheridan

Amalgamated Wireless (Australasia) Ltd., Sydney (manufacturer) est. 1913

AWA Radiolette ‘Empire State’ and cigarette box (green)

1934

Bakelite

(a) 28.0 x 27.0 x 15.0cm (radio) (b) 8.0 x 8.0 x 4.5cm (cigarette box)

Collection of Peter Sheridan and Jan Hatch

Photo © Peter Sheridan

Installation views of Australian Art Deco radios from the exhibition Brave New World: Australia 1930s at NGVA

Photos: Courtesy NGV Photographic Services

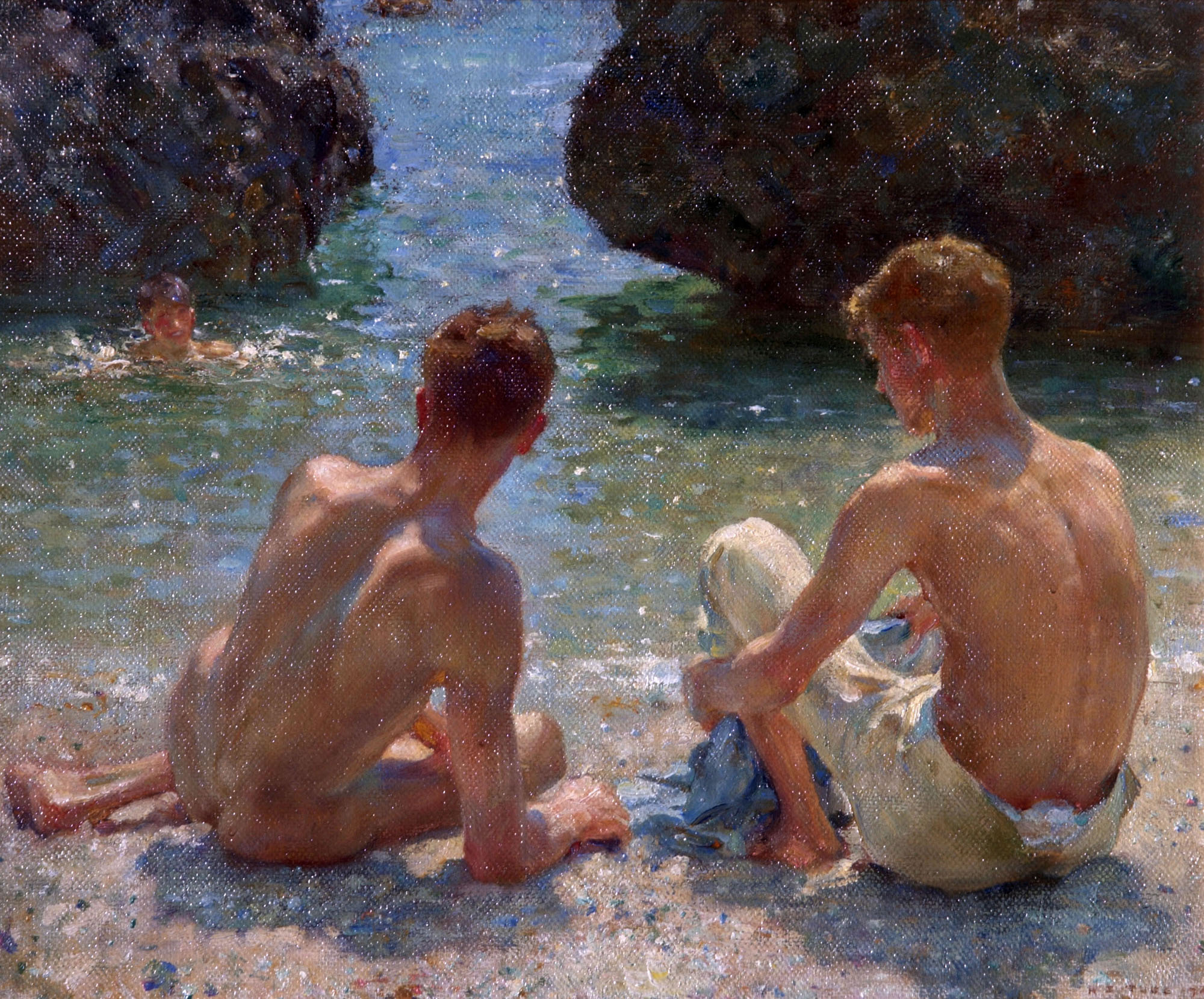

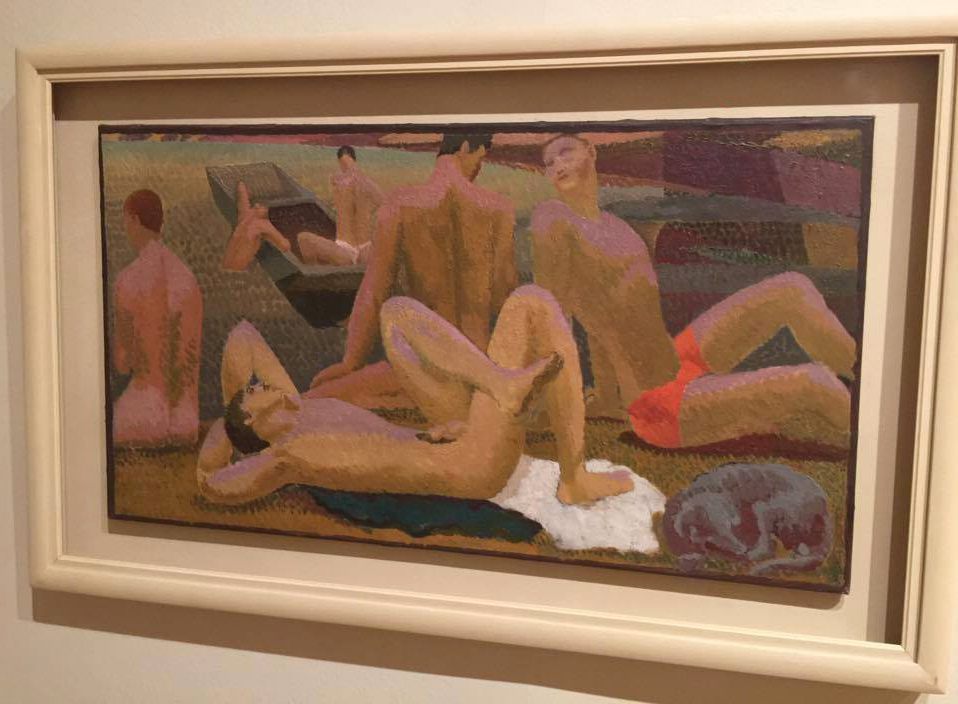

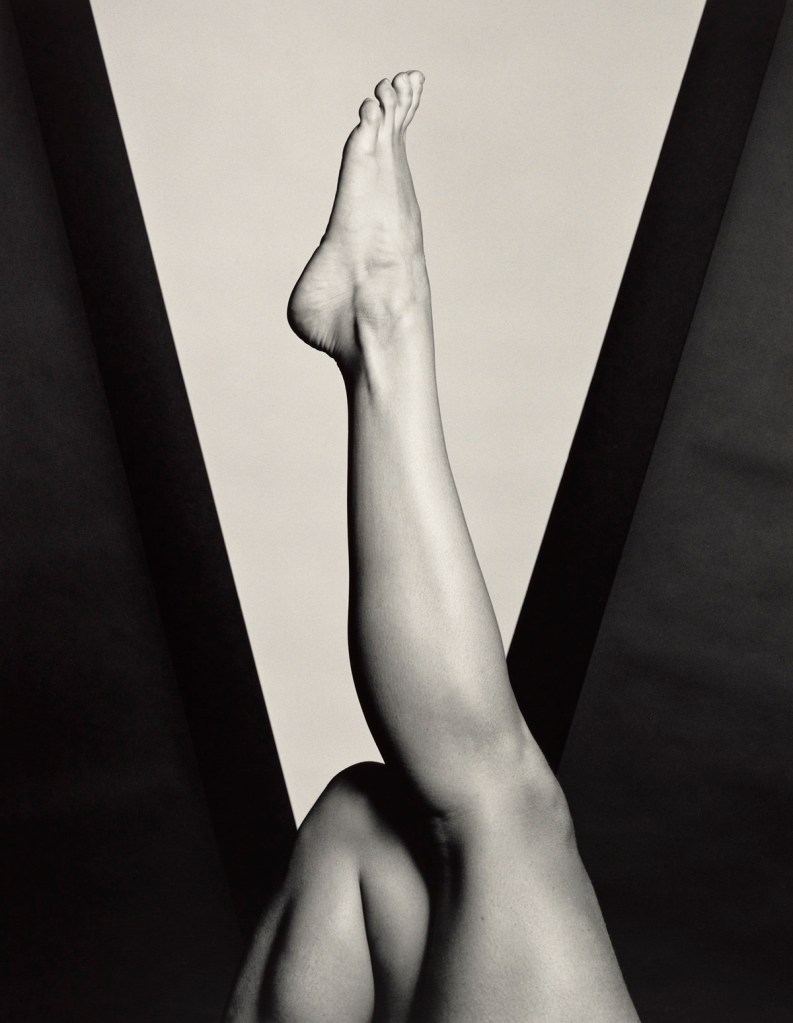

Sun and surf

The beach was a complex location in the Australian creative imagination. It was a democratic site in which the trappings of wealth and position were abandoned as people stripped down to their bathers. It was a place of hedonistic pleasures that offered sensuous engagement with sun and surf, and a primitive landscape where natural forces restored the bodies of those depleted by modern life. It was a playground for the tourist that was considered distinctively Australian. As war loomed again in the late 1930s, it was also a pseudo-militaristic zone in which the lifesaver was honed for ‘battle’ in the surf.

The lifesavers that helped protect the beach-going public were regularly praised as physical exemplars who could build the eugenic stock of the nation. As the Second World War approached, the connection of these trained lifesavers to military servicemen also became painfully apparent.

Male lifesavers were used by artists in promoting Australia to tourists: a poster commemorating the opening of the Sydney Harbour Bridge in 1932 positioned the lifesaver as the quintessential representative of Australian manhood. Douglas Annand and Arthur Whitmore’s virile lifesaver proudly gestures towards the new bridge, his muscles as strong and protective as the steel girders that span the harbour.

Max Dupain (Australian, 1911-1992)

On the beach. Man, woman, boy

1938

Gelatin silver photograph

39.2 x 47.2cm

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Purchased 1982

Showing a naked family on the beach, Max Dupain’s work is a perfect illustration of social concerns of the times. As Australia moved closer to engagement in another world war, fears about the poor physical fitness of the population were debated, with a ‘national fitness’ campaign instituted by the government in 1938. Dupain’s father, George, was one of the country’s first physical educationalists, opening the Dupain Institute of Physical Education and Medical Gymnastics in 1900 and writing extensively on the subject of health and fitness. Max Dupain attended the gym and was well versed in contemporary concerns about fitness.

Installation view of the exhibition Brave New World: Australia 1930s at NGVA

Photo: Eugene Hyland

Installation view of Male lifesaver, window and Female lifesaver, window (both c. 1935) from the exhibition Brave New World: Australia 1930s at NGVA

Photo: Dr Marcus Bunyan

Unknown, Melbourne

Male lifesaver, window

c. 1935

Stained glass, lead

47.5 x 40.8cm

Williamstown Swimming and Life Saving Club, Williamstown

Donated by C. J Dennis

‘On golden and milky sands, bodily excellence is displayed the year round, clearly defined by the sun in an atmosphere as viewless and benign as the air of Hellas as described by Euripides.’

J. S. Macdonald, 1931

Unknown, Melbourne

Female lifesaver, window

c. 1935

Stained glass, lead

47.0 x 40.9cm

Williamstown Swimming and Life Saving Club, Williamstown

Donated by Councillor R. T. Bell

Although much was made of the ‘gods of the golden sand’, as one poet glowingly described lifesavers, lifesaving clubs were not entirely male in membership. Women lifesavers also made their mark, albeit in more limited numbers and with much less recognition. At the Williamstown Lifesaving Club in Melbourne a woman lifesaver was included in this fine and very rare stained glass window that, along with its counterpart featuring a male lifesaver, graced the newly established clubhouse around 1935.

Installation view of the exhibition Brave New World: Australia 1930s at NGVA with the male and female lifesavers (centre); Max Dupain’s The carnival at Bondi (fourth from right); Sydney Bridge celebrations (second right); and Douglas Annand and Max Dupain’s Australia (right)

Photo: Courtesy NGV Photographic Services

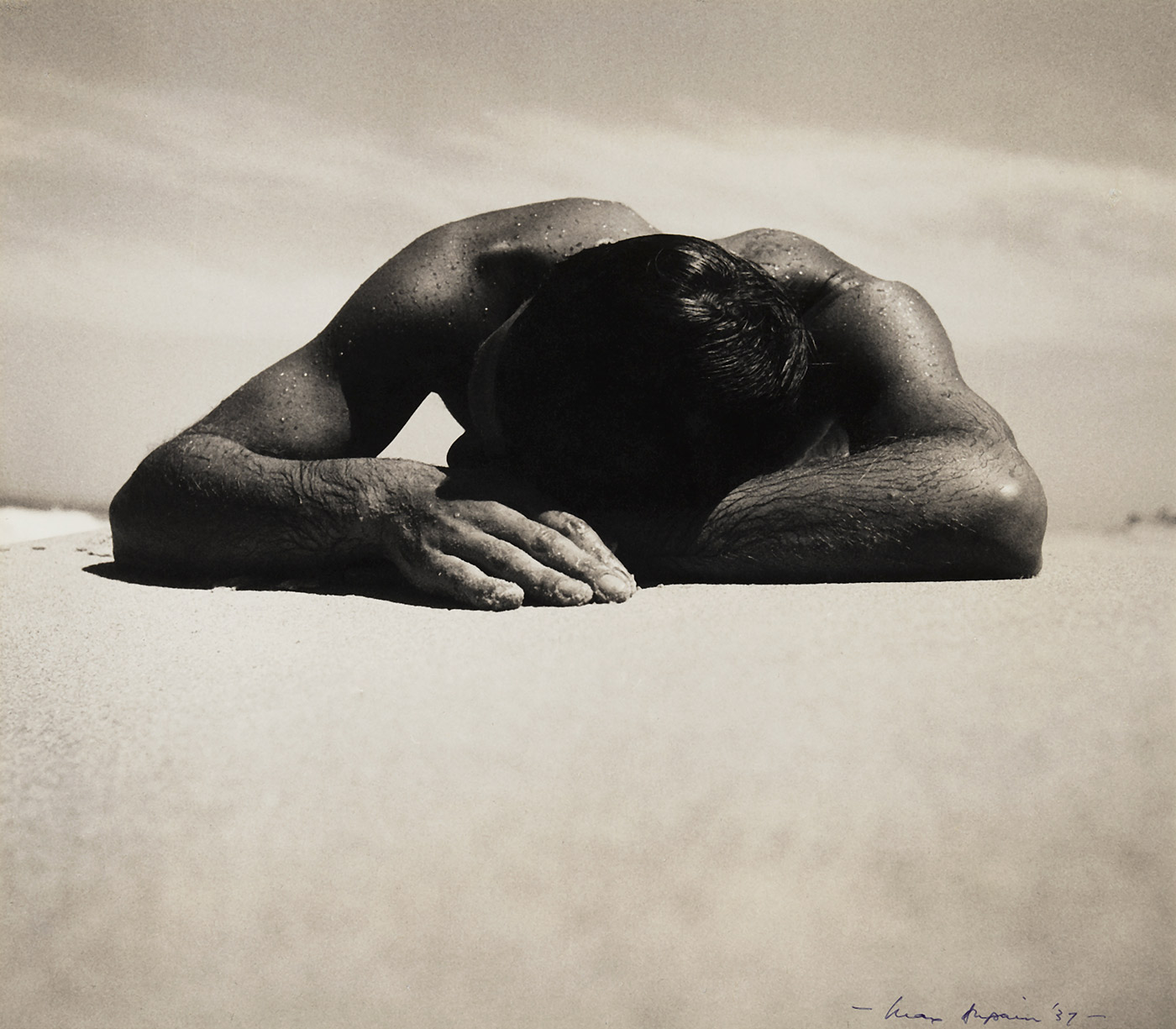

Max Dupain (Australian 1911-1992)

Sunbaker

(1938), dated 1937, printed c. 1975

Gelatin silver photograph

38.0 x 43.1cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased with the assistance of the Visual Arts Board, 1976

Taken on a camping trip near Culburra, on the Shoalhaven River in New South Wales, in January 1938, Max Dupain’s original version of the Sunbaker was a much darker image that existed at the time only in an album gifted to his friend Chris Van Dyke. Dupain lost the original negative and printed this variant version in 1975 for an exhibition. It is an image that is now considered an icon in Australian photography, and has come to represent key values of the interest in ‘body culture’, celebrating health and fitness in the context of the beach.

Max Dupain (Australian, 1911-1992)

The carnival at Bondi

1938

Gelatin silver photograph

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Purchased 1982

‘The lifesaving teams … are splendid examples of the physique, resourcefulness and vitality of our youth and manhood. They are typical of the outdoor life which Australians lead and they are living testimonies to the value of surfing and the vigour and stamina of our race.’

DAILY EXAMINER, July 1935

Max Dupain (Australian, 1911-1992)

Manly

1938, printed c. 1986

Gelatin silver photograph

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased from funds donated by Hallmark Cards Australia Pty Ltd, 1987

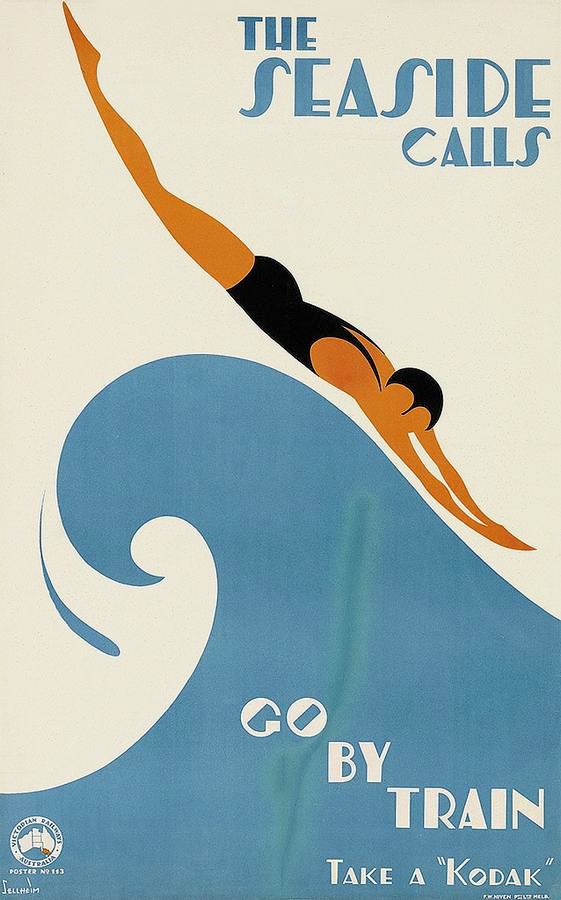

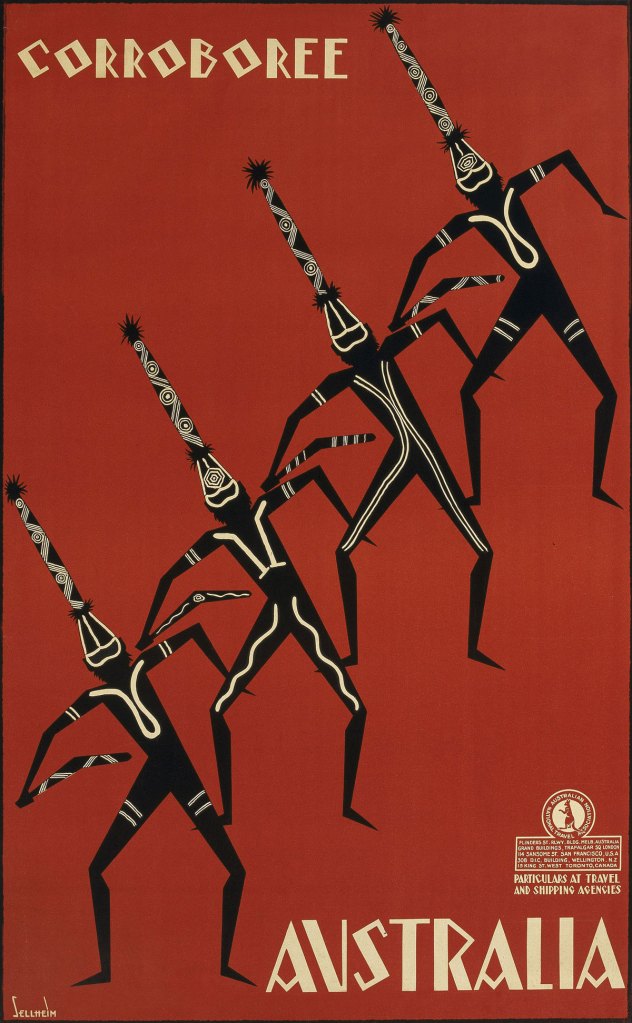

Gert Sellheim (Russia (of German parents) 1901 – Australia 1970, Australia from 1926)

The seaside calls – go by train – take a Kodak

1930s

Colour lithograph

Printed by F. W. Niven, Melbourne

State Library Victoria, Melbourne

Gift of Mr Grant Lee

Gert Sellheim was born to German parents in Estonia, at that time part of the Russian Empire. After studying architecture in Europe he travelled to Western Australia in 1926, before settling in Melbourne in 1931, where he began working as an industrial and commercial designer. Working for the Australian National Travel Association, Sellheim created a series of posters promoting beach holidays, which incorporated Art Deco motifs and typography. His most famous design is the flying kangaroo logo for Qantas, which he created in 1947.

Douglas Annand (Australian, 1903-1976)

Arthur Whitmore (Australian, 1910-1965)

Sydney Bridge celebrations

1932

Colour lithograph

47.6 x 63.6cm (image and sheet)

Australian National Maritime Museum Purchased, 1991

© Courtesy of the artist’s estate

Douglas Annand (Australian, 1903-1976)

Max Dupain (Australian, 1911-1992)

Australia

c. 1937

Colour and process lithograph

105.3 x 68.4cm (image and sheet)

Australian National Maritime Museum Purchased, 1991

© Courtesy of the artist’s estate

Douglas Annand (attributed to) (Australian, 1903-1976)

Follow the sun – Australia’s 150th Anniversary celebrations

1938

Colour lithograph and photolithograph

Courtesy of Josef Lebovic Gallery, Sydney

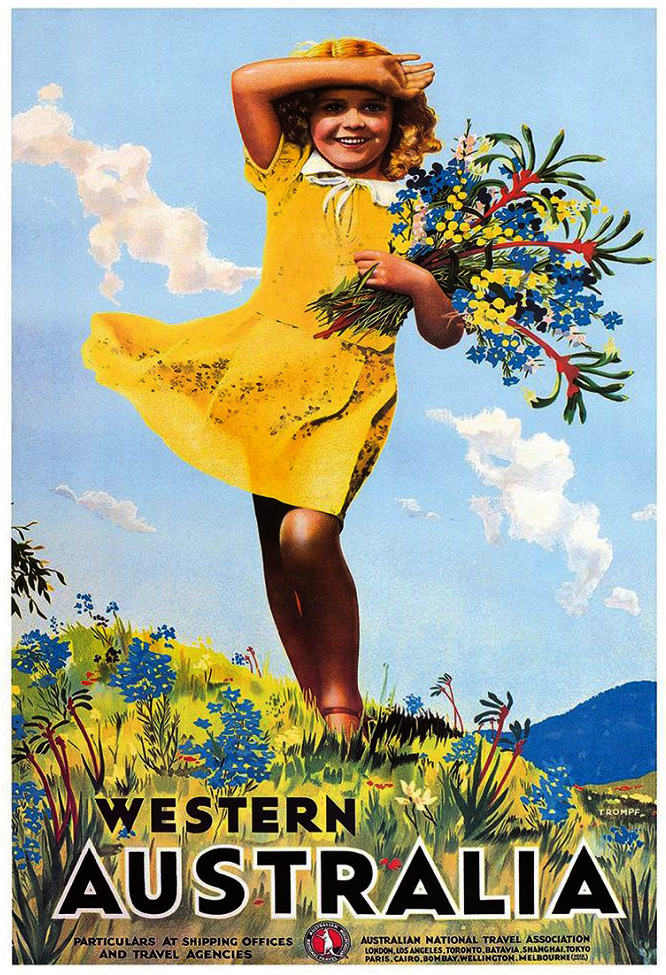

The 1930s were the heyday of the travel poster. Posters were commissioned by railway and tourism groups or shipping companies and airlines to promote Australian holiday destinations, both at home and overseas. The Australian National Travel Association was formed in 1929 to promote Australia to overseas markets. As part of its strategy it commissioned posters from leading graphic artists, such as Percy Trompf, James Northfield and Douglas Annand. From the late 1920s Australia began to actively promote itself to the world by using the beach, sun and surf as motifs.

Installation views of the exhibition Brave New World: Australia 1930s at NGVA with the work of John Rowell, Hilda Rix Nicholas, Gert Sellheim and Percy Trompf on the far wall, and Robert E. Coates Photographs of Australian Pavilion at New York World’s Fair (1939) on the projector screen at left

Photos: Courtesy NGV Photographic Services

The Australian Pavilion at the New York World’s Fair projected an image of Australia as a young and healthy nation, a place of industry, sport and tourism. Designed by John Oldham of Sydney architectural firm Stephenson & Turner, the modern design of the building was complemented by Douglas Annand’s interior displays featuring the latest graphic design, and audio-visual and photomontage techniques. These photographs of the Australian Pavilion at the New York World’s Fair were taken by commercial photographer Robert E. Coates.

Installation views of Robert E. Coates’ Photographs of Australian Pavilion at New York World’s Fair (1939) (digital images, looped)

Photos: Dr Marcus Bunyan

Pastoral landscapes

Along with the beach, another national myth evolved around the Australian bush. Although most Australians lived in cities, in the years following the First World War the nation became increasingly informed by a mythology centred on the bush and the landscape. For those who considered the modern city a profoundly depleting force, the bush was a touchstone of traditional ‘values’. It was nostalgically conceived of as an idyllic natural realm whose soil, literally and metaphorically, sustained its people. Both the classical Pastoral ideal of a land in which only sheep and cattle roam, and the Georgic tradition, which celebrated the achievements of agriculture, became dominant themes in landscape art.

Pastoral landscapes were admired above all as representing the antithesis of ‘decadent’ modern life. As art critic and gallery director J. S. Macdonald wrote, such art would ‘point the way in which life should be lived in Australia, with the maximum of flocks and the minimum of factories’. With their emphasis on farming and pastoral industries, such works affirmed white landownership, with Indigenous people largely absent.

John Rowell (Australian, 1894-1973)

Blue hills

c. 1936

Oil on canvas

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne Felton Bequest, 1936

Gert Sellheim (Russia (of German parents) 1901 – Australia 1970, Australia from 1926)

Spring in the Grampians

1930s

Colour photolithograph

State Library Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased 2000

Hilda Rix Nicholas (Australian, 1884-1961, Europe 1911-1918)

The fair musterer

c. 1935

Oil on canvas

Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane

Purchased 1971

As a young artist Hilda Rix Nicholas had a successful career in France before returning to Australia after the First World War. In 1934, several years after the birth of her son, Rix Nicholas returned to painting and depicted her new life living on the family property Knockalong, on the Monaro Plains in New South Wales. Depicting the governess of her young son holding the reins of her horse, dog at her feet, and sheep in the distance, in The fair musterer Rix Nicholas claims for women an active role in the masculine world of pastoral Australia.

Hilda Rix Nicholas (Australian, 1884-1961, Europe 1911-1918)

The shepherd of Knockalong

1933

Oil on canvas

Collection of Peter Rix, Sydney

Courtesy of Deutscher & Hackett

Depicting the artist’s husband and young son, The shepherd of Knockalong is a reminder of the traditional importance of the wool industry to the nation’s economy. With his legs firmly connected to the ground and pictured as a large figure dominating the landscape setting, the farmer is the benign owner and ‘shepherd’ of the land spreading out behind him, the presence of his young son ensuring dynastic succession. At a time when Aboriginal people were confined to reservations and denied citizenship, Hilda Rix Nicholas’s painting can also be considered as an assertion of the British colonisers’ right to ownership of Australia.

Percy Trompf (Australian, 1902-1964)

Western Australia

c. 1936

Colour lithograph

Courtesy of Josef Lebovic Gallery, Sydney

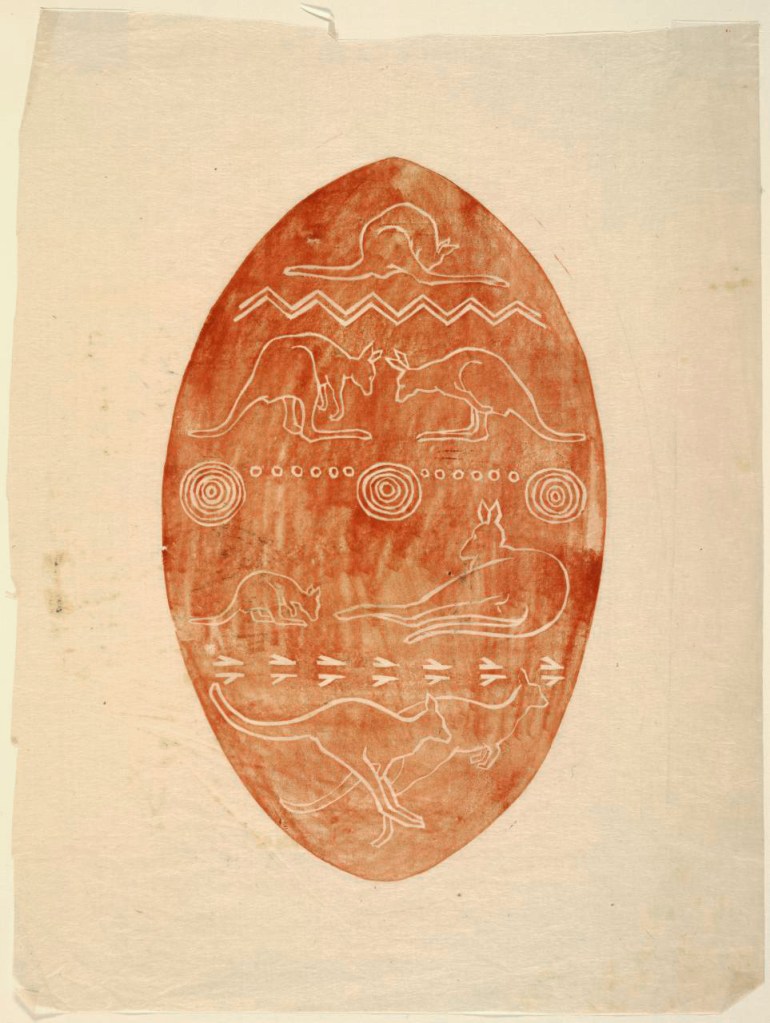

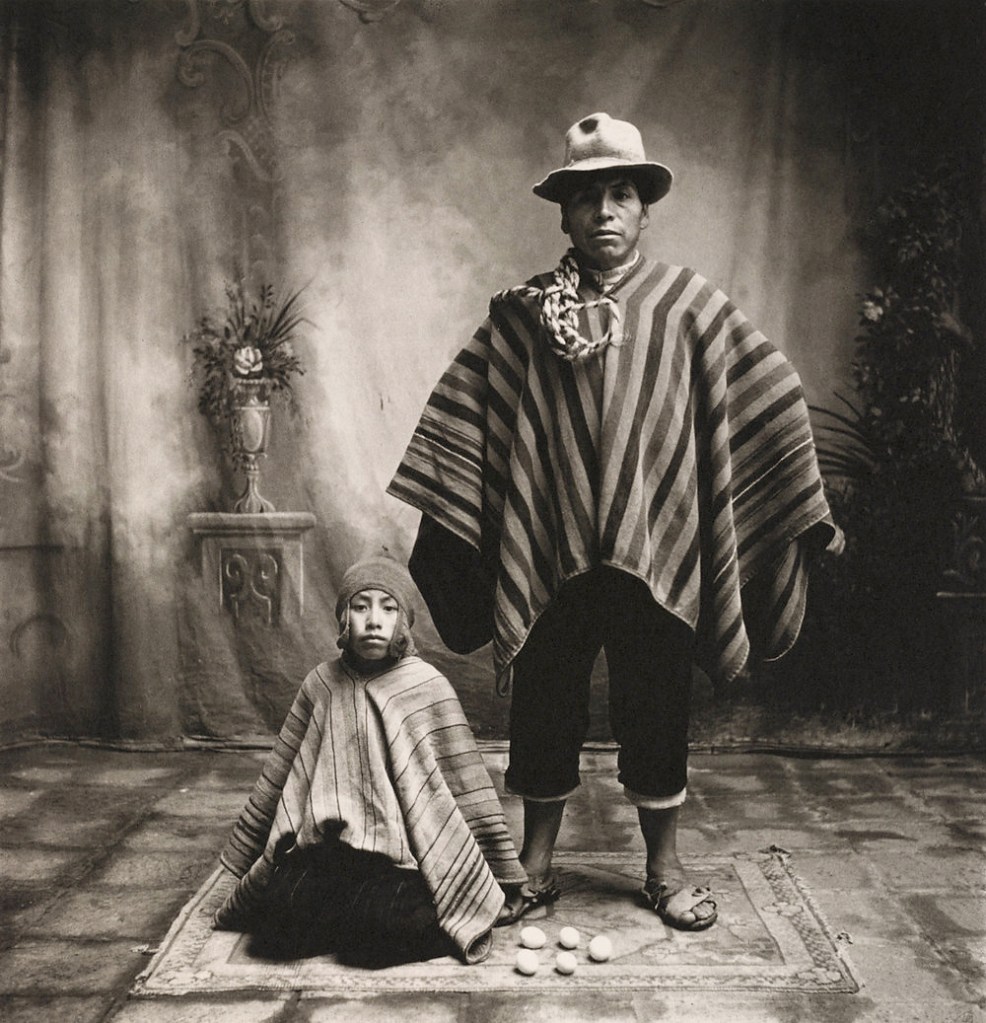

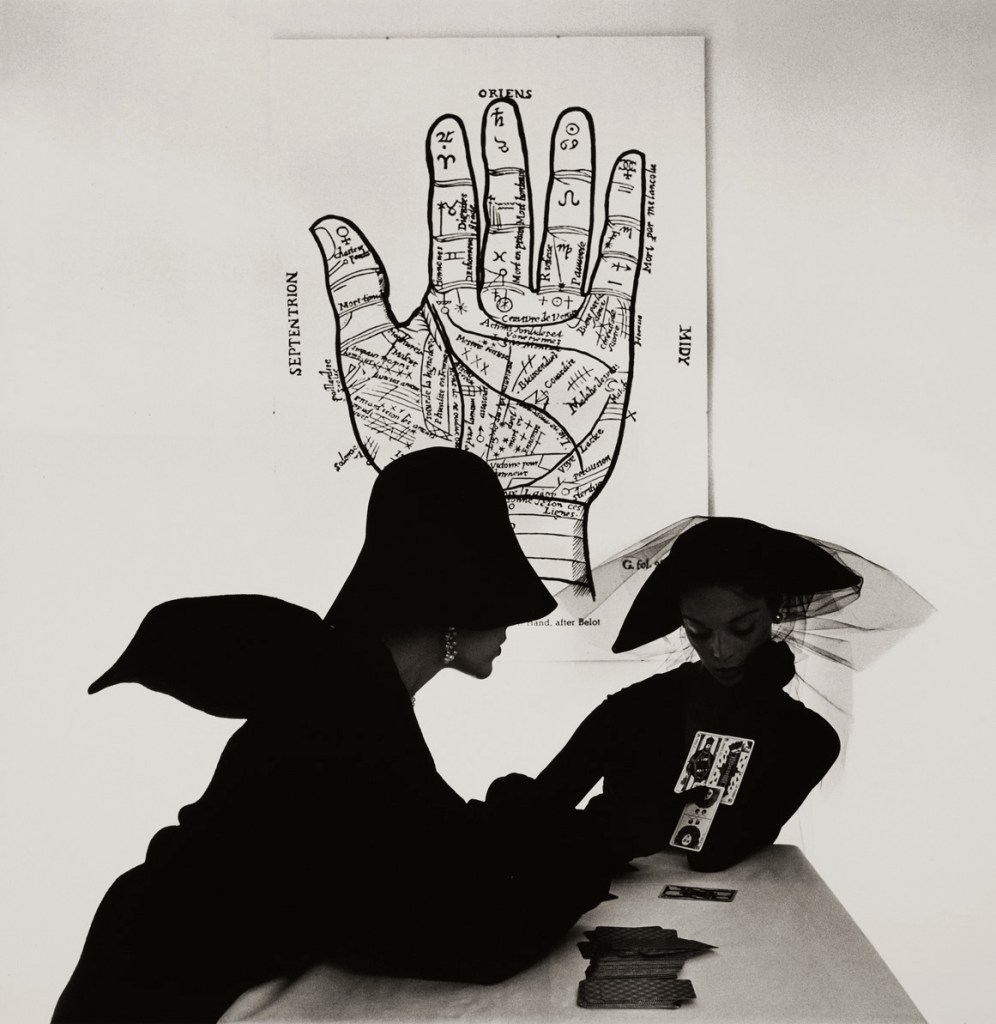

Indigenous art and culture

During the 1930s Aboriginal people were often pejoratively referred to as a ‘dying race’. The Australian Government continued to enforce a ‘divide and rule’ assimilationist policy. Determined by eugenics, this entailed removing Aboriginal people of mixed descent from their families and reserves, and absorbing them into the dominant society, with consequent loss of their own language and customary ritual practices. Increasingly during this period, Aboriginal people formed their own organisations and agitated for full citizenship rights.

This was also a decade that saw increasing awareness of, and interest in, Indigenous art. Albert Namatjira astonished Melbourne audiences at his first solo exhibition at the Athenaeum Gallery in 1938. Comprising forty-one watercolour paintings, all of his works sold within three days of the opening. The following year the Art Gallery of South Australia purchased one of Namatjira’s works. Indigenous art also inspired non-Indigenous artists, including Margaret Preston and Frances Derham who appropriated design elements in their works. The idea of ‘Aboriginalism’, in which settlers sought an Australian identity in the context of Britishness and the Empire, saw artists travelling to the outback to paint and sketch subjects they believed connected them to Indigenous history.

Frances Derham (Australian, 1894-1987, New Zealand and Ireland 1902-1908)

Kangaroo and Aboriginal motifs

1925-1940

Linocut printed in brown ink on buff paper

4.6 x 7.3cm (image) 12.6 x 10.3cm (sheet)

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Gift of Mr Richard Hodgson Derham, 1988

© Estate of Frances Derham

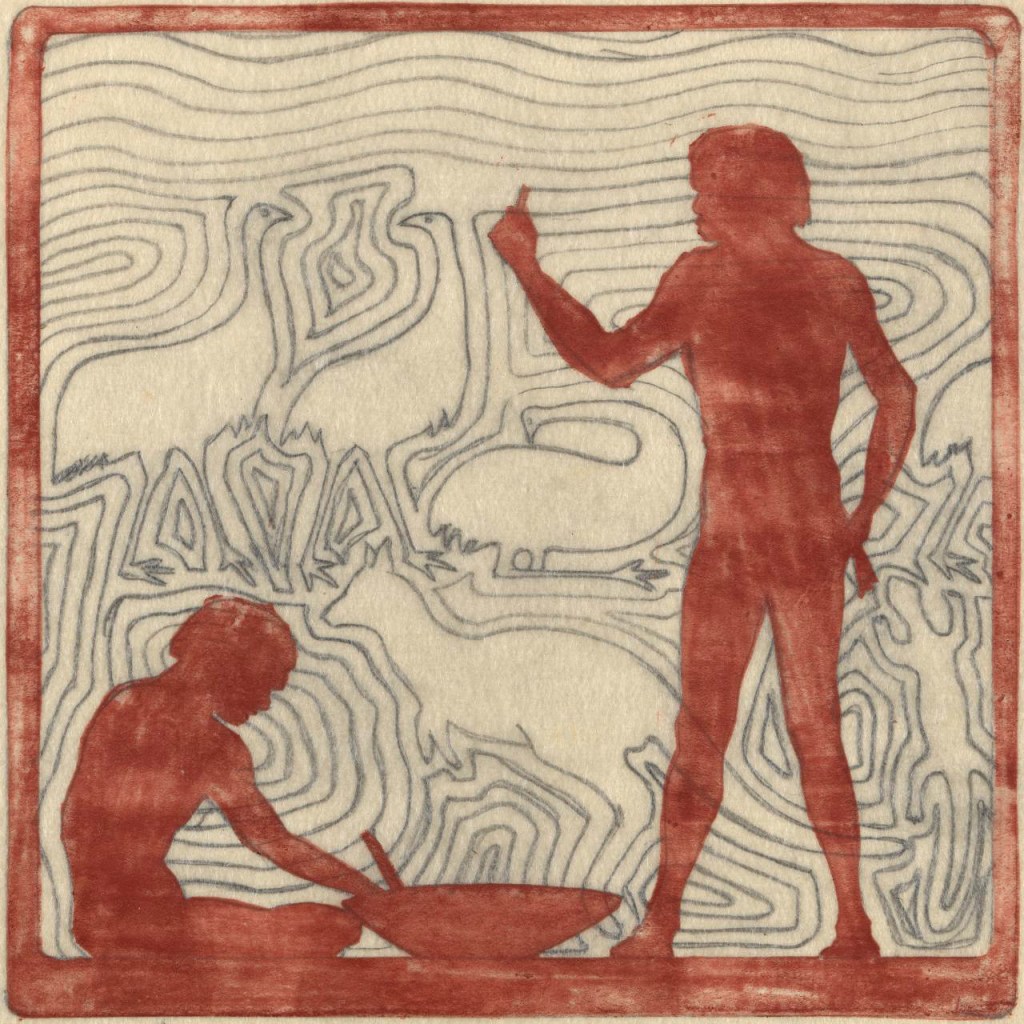

Best known as a progressive educator and advocate of children’s art, Frances Derham was also an active member of the Arts and Crafts Society of Victoria, and with potter Allan Lowe shared Margaret Preston’s interest in the appropriation of Indigenous art. From the mid 1920s Derham began to incorporate Aboriginal motifs into her linocuts and in 1929, synchronous with the exhibition Australian Aboriginal Art at the Museum of Victoria, Derham presented a lecture to the Arts and Crafts Society, entitled ‘The Interest of Aboriginal Art to the Modern Designer’.

Frances Derham (Australian, 1894-1987, New Zealand and Ireland 1902-1908)

Kangaroo (at the zoo)

c. 1931

Linocut printed in brown ink on Chinese paper

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Gift of Mr Richard Hodgson Derham, 1988

Frances Derham (Australia 1894-1987, New Zealand and Ireland 1902-1908)

The Aboriginal artist

1931

Colour linocut on Japanese paper

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Gift of Mr Richard Hodgson Derham, 1988

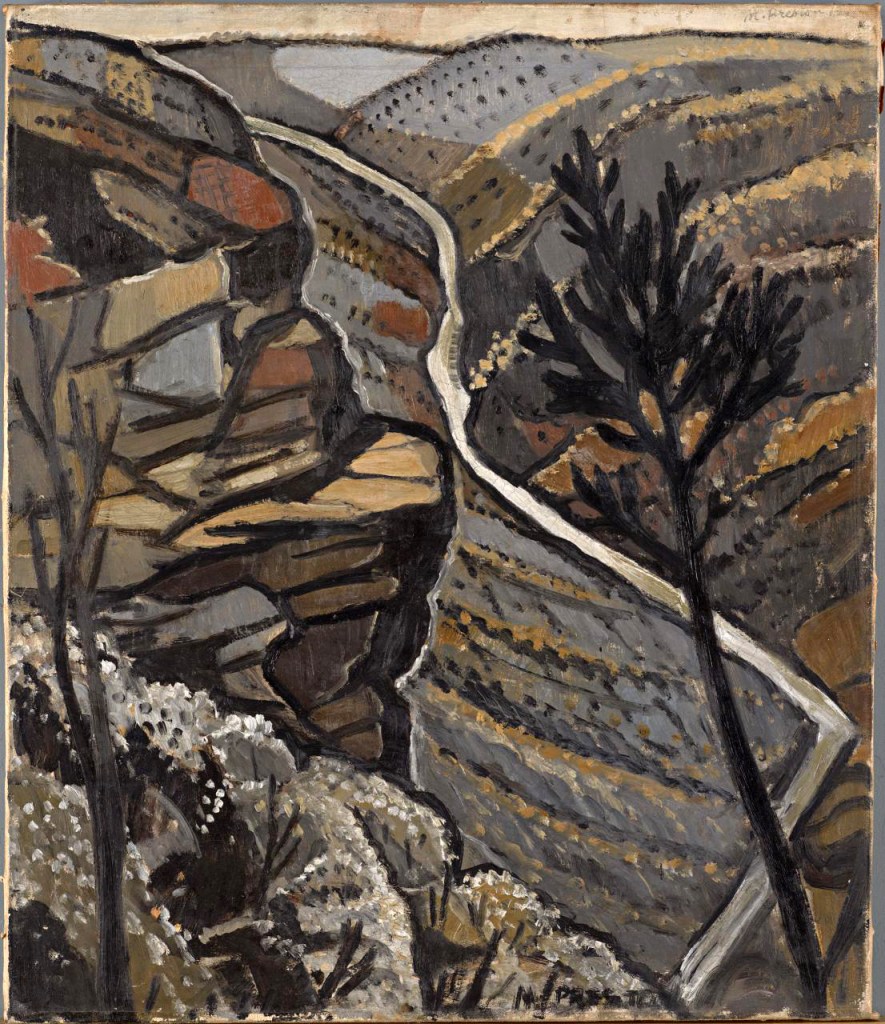

Margaret Preston (Australia 1875-1963, Germany and France 1904-1907, France, England and Ireland 1912-1919)

Shoalhaven Gorge, New South Wales

1940-1941

Oil and gouache on canvas

53.7 x 45.8cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased with funds donated from the Estate of Dr Donald Wright, 2008

© Margaret Preston/Licensed by VISCOPY, Australia

During the 1920s Margaret Preston considered Aboriginal art a source of good design in the decoration of household items. In the 1930s her study of Aboriginal culture intensified, as she developed a greater interest in its anthropological and cosmological elements. In 1940 Preston travelled to the Northern Territory to study Aboriginal art. On her return she developed a more explicit Aboriginal style in paintings featuring earthy tones, strong black outlines and patterns of dots and lines.

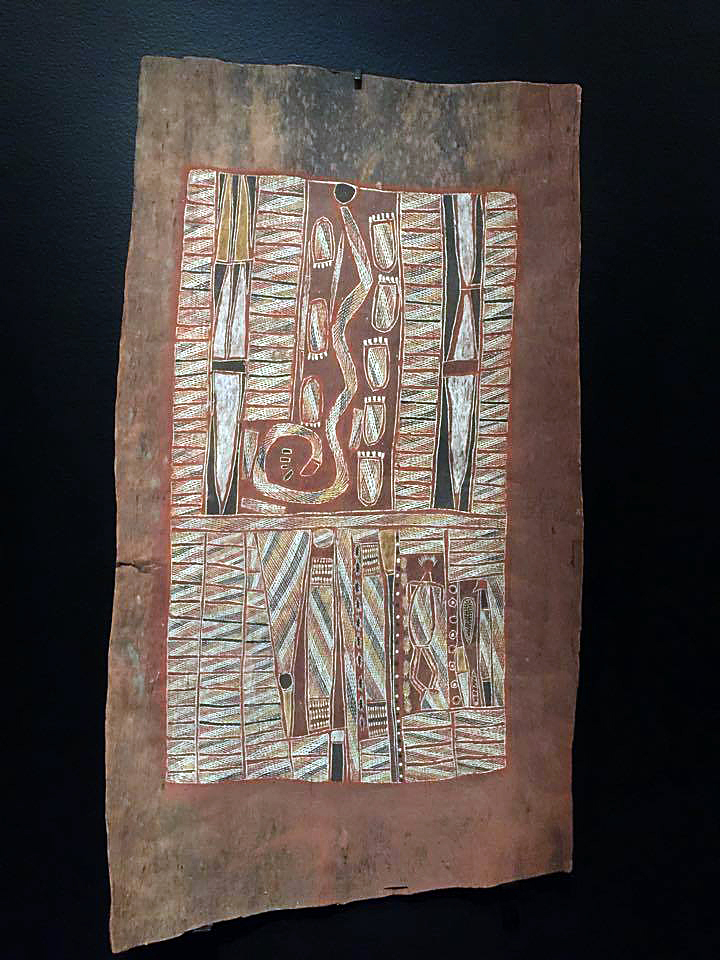

Unknown

Walamangu active (1930s)

Dhukurra dhaawu (Sacred clan story)

c. 1935

Earth pigments on Stringybark (Eucalyptus sp.), resin

128.3 x 63.9cm

The Donald Thomson Collection

Donated by Mrs Dorita Thomson to the University of Melbourne and on loan to Museums Victoria, Melbourne

During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, segregation was the main government policy regarding Aboriginal people. It was re-enforced by the 1909 Aborigines Protection Act, which gave the Aborigines Protection Board the power to control where Aboriginal people lived in New South Wales. In 1937 the Commonwealth Government adopted a policy of assimilation, whereby Aboriginal people of mixed descent were henceforth to be assimilated into white society, while others were confined to reserves. In 1931 Arnhem Land was declared an Aboriginal Reserve by the government and non-Indigenous entry into the region was restricted.

Tjam Yilkari Katani

Liyagalawumirr active 1930s

Wagilag dhaawu (Wagilag Sisters story) (installation view)

1937

Earth pigments on Stringybark (Eucalyptus sp.)

The Donald Thomson Collection Donated by Mrs Dorita Thomson to the University of Melbourne and on loan to Museums Victoria, Melbourne

Photo: Dr Marcus Bunyan

For Yolgnu people, painting on bark or objects is intimately connected with painting on the body, and the Yolgnu term barrawan means both ‘skin’ and ‘bark’. These paintings are transcriptions of the sacred designs that were painted onto men’s bodies and convey the power of the Yolgnu ancestors whose actions created their world. The Wagilag Sisters Dreaming story chronicles the creative acts of the sisters as they travelled across Arnhem Land. Such stories pass on important knowledge, cultural values and belief systems to later generations.

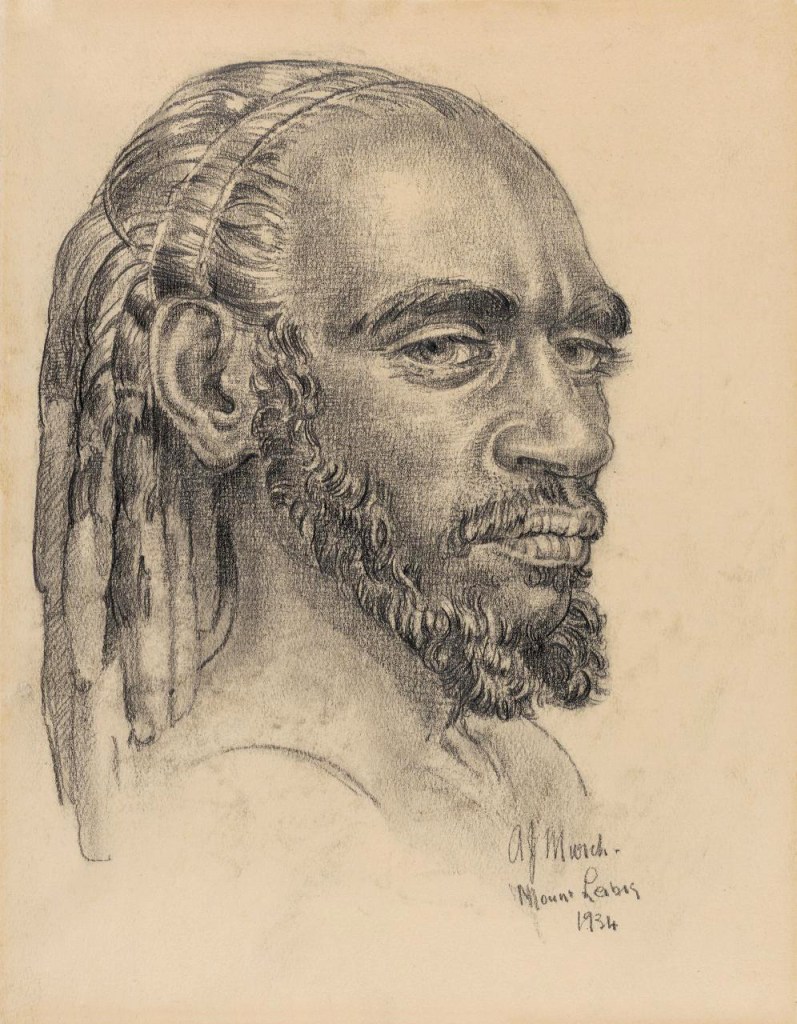

Arthur Murch (Australian, 1902-1989, Europe 1936-1940)

Walila, Pintupi tribe

1934

Pencil

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased, 1934

In 1933, on the invitation of Professor H. Whitridge Davies, Sydney artist Arthur Murch accompanied a research team from Sydney University to Hermannsburg Lutheran Mission, south-west of Alice Springs. Murch remained there for six weeks painting the landscapes and making portraits of Indigenous people. These were exhibited in Sydney soon after his return.

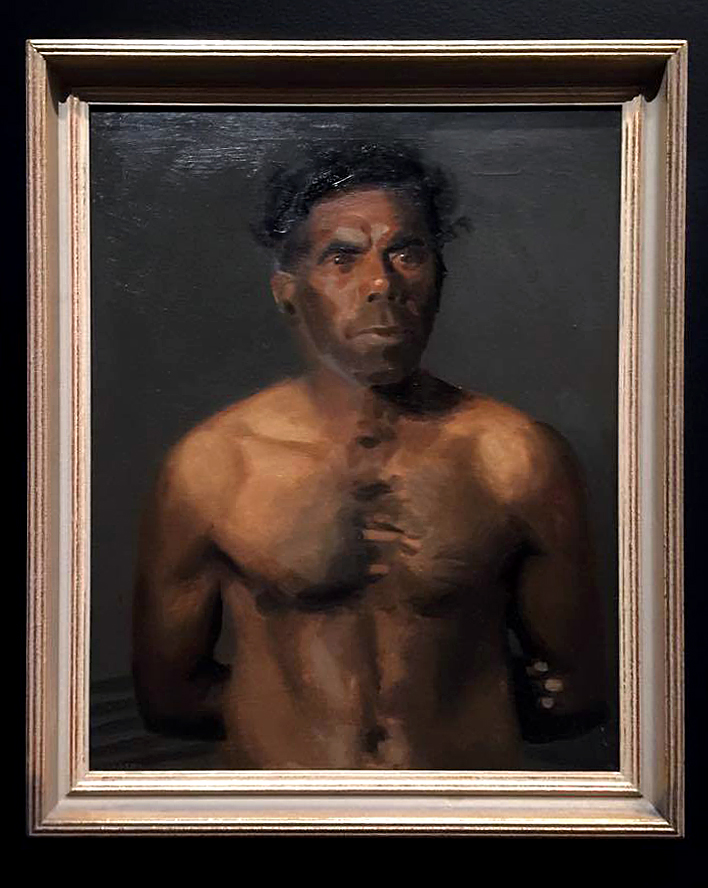

Percy Leason (Australia 1888 – United States 1959, United States from 1938)

Thomas Foster (installation view)

1934

Oil on canvas

State Library Victoria, Melbourne

Gift of Mrs Isabelle Leason, 1969

Photo: Dr Marcus Bunyan

Thomas Foster was born at Coranderrk Station in 1882, the son of Edward Foster and Betsy Benfield. Foster’s was one of the last portraits painted by Leason as part of the unfortunately titled exhibition The Last of the Victorian Aborigines. These portraits were debuted on 11 September at the Athenaeum Gallery in Collins Street, Melbourne, to great public acclaim. Foster, like most of Leason’s subjects, appears shirtless, his arms folded behind his back, pushing forward his chest and clearly showing his scarification marks.

Gert Sellheim (Russia (of German parents) 1901 – Australia 1970, Australia from 1926)

Corroboree Australia

1934

Colour lithograph printed by F. W. Niven, Melbourne

State Library Victoria, Melbourne

Gift of the Australian National Travel Association, 1934

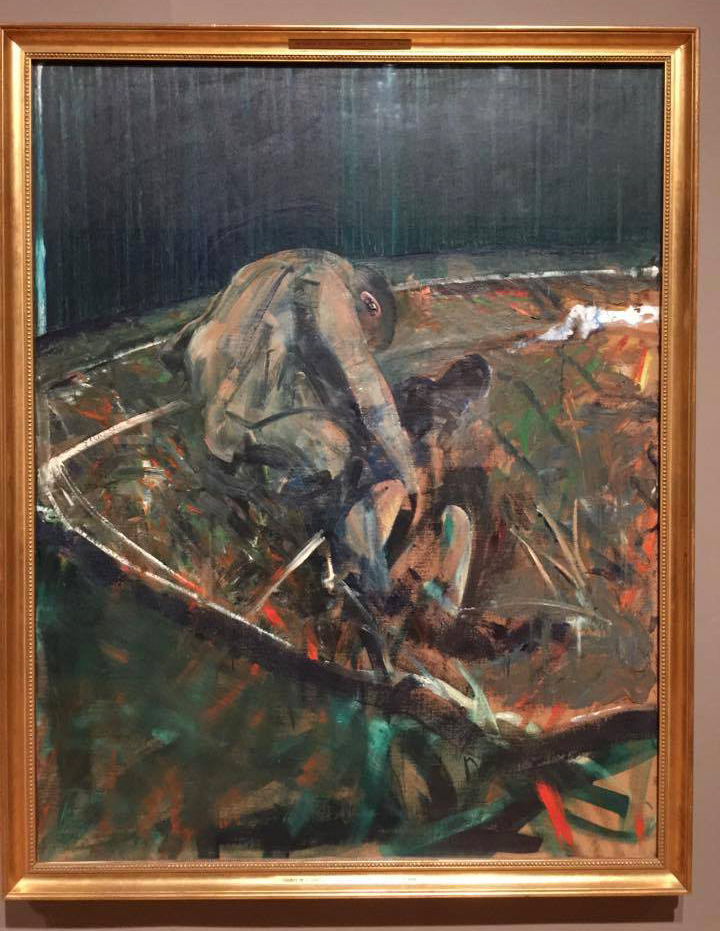

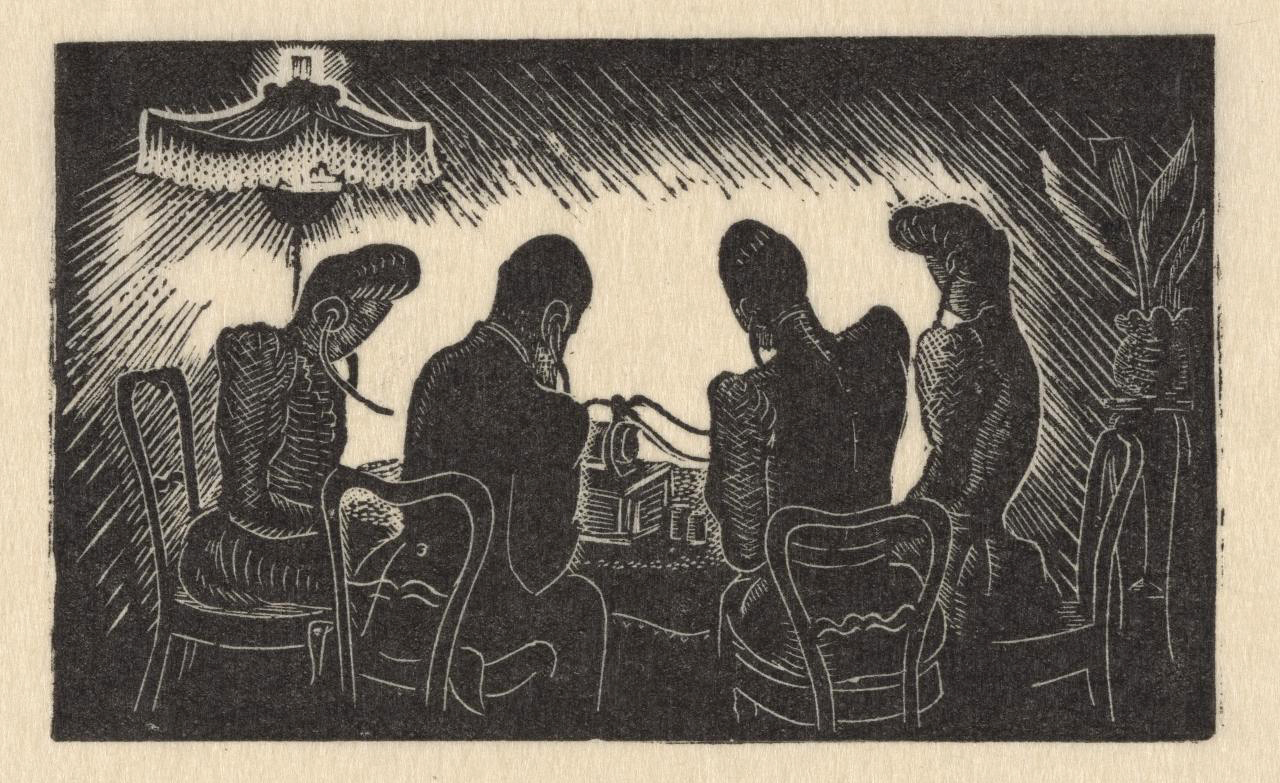

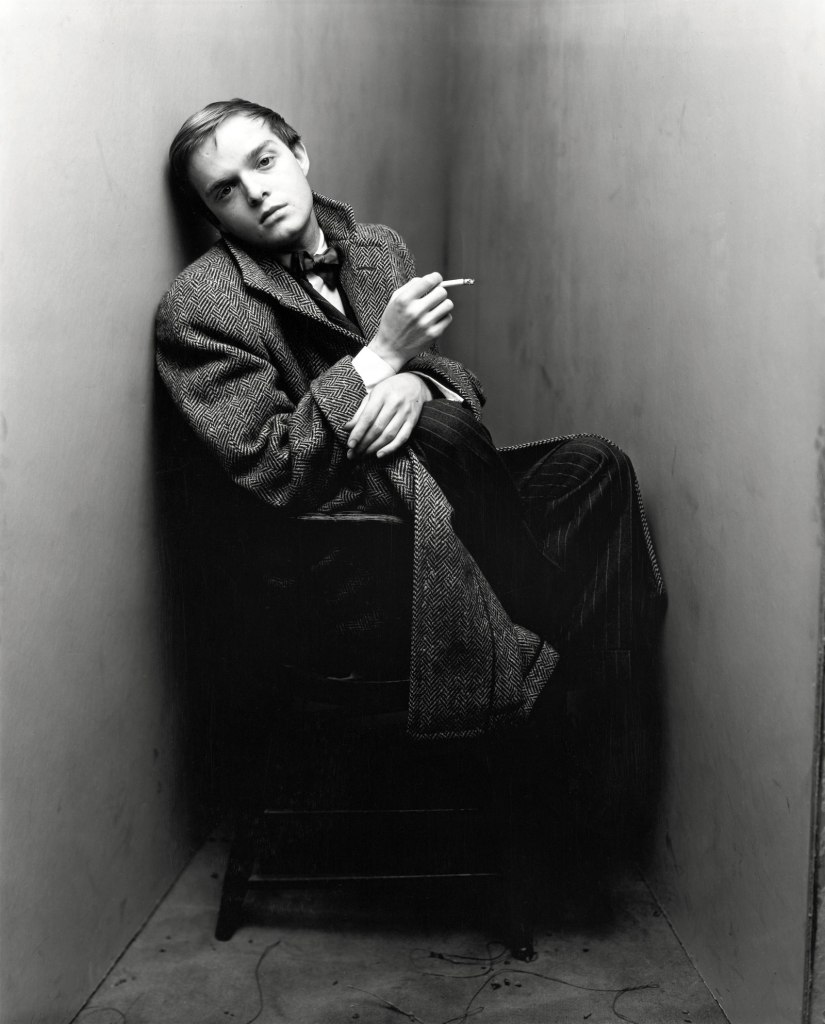

Dystopian cities

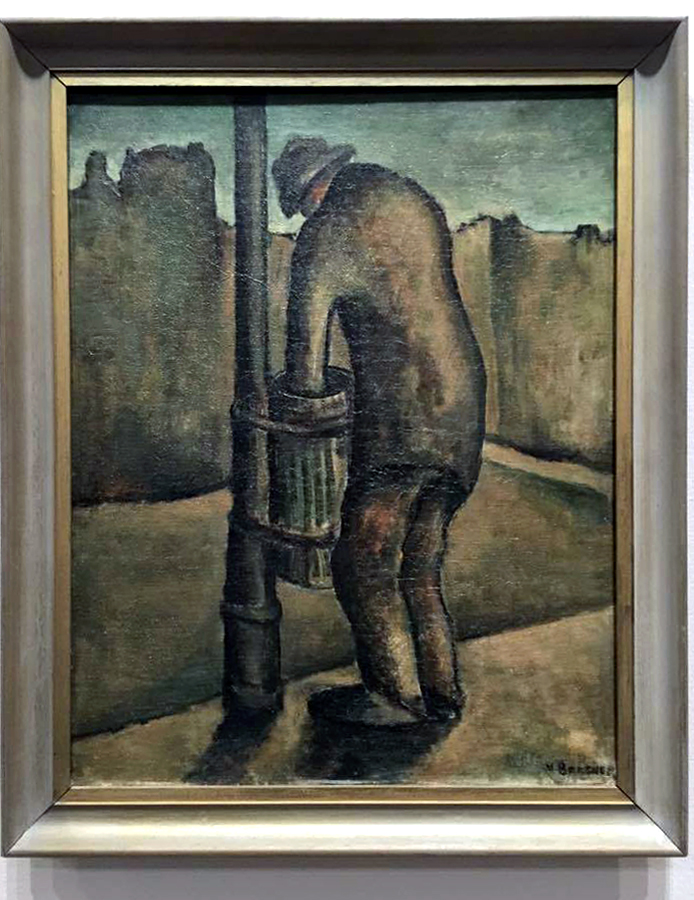

Australia was hit hard by the Great Depression. The worst year was 1932, when unemployment reached nearly thirty-two per cent, and by the following year almost a third of all unemployed men had been without work for three years. With wages cut and unemployment rising, many families were left struggling to survive and this poverty was most evident in run-down, inner-city areas. Two émigrés, Danila Vassilieff and Yosl Bergner, were the first Australian artists to turn their attention to the plight of the urban poor and the disposed. Their powerful, expressive style was influential upon young artists, including Arthur Boyd and Albert Tucker.

Economic hardship fostered bitterness and political unrest, and membership of radical groups on both the left and right increased. Boundaries between political agendas and art production became porous in this decade, and many artists believed, like Bergner, ‘that by painting we would change the world’. The complex enmeshment of the creative and political became a defining feature of the decade, and art in Australia became increasingly political, with the political realm involving itself with art.

By the end of the decade the worsening political situation overseas and a sense that another world war was inevitable contributed to a growing sense of unease. Many artists expressed this anxiety and foreboding in their works.

Laurence Le Guay (Australian, 1917-1990)

No title (War montage with globe)

c. 1939

Gelatin silver photograph

30.4 x 24.9cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased through the NGV Foundation with the assistance of Mrs Mem Kirby, Fellow, 2001

Max Dupain (Australian, 1911-1992)

Hot rhythm!

1936

Silver gelatin photograph

24.7 x 17.8cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

William Kimpton Bequest, 2016

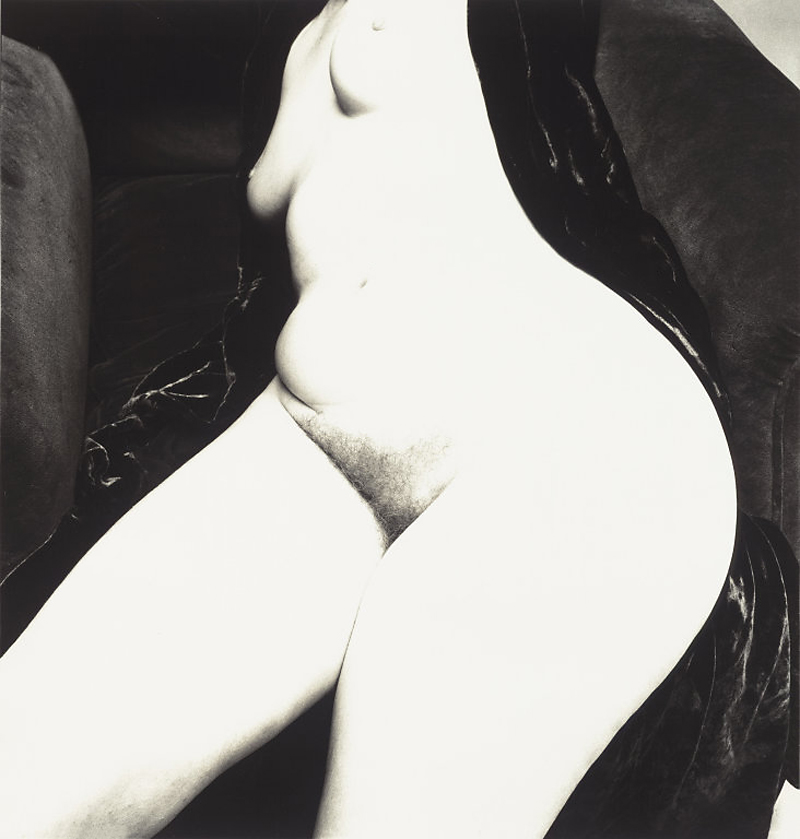

In this work, Max Dupain has the shadow of a slide trombone seemingly bisect the naked body of a woman in a photograph that, in the context of his known views, is less an erotic celebration of modern jazz culture and nightlife than a comment on the disruptive nature of modernity.

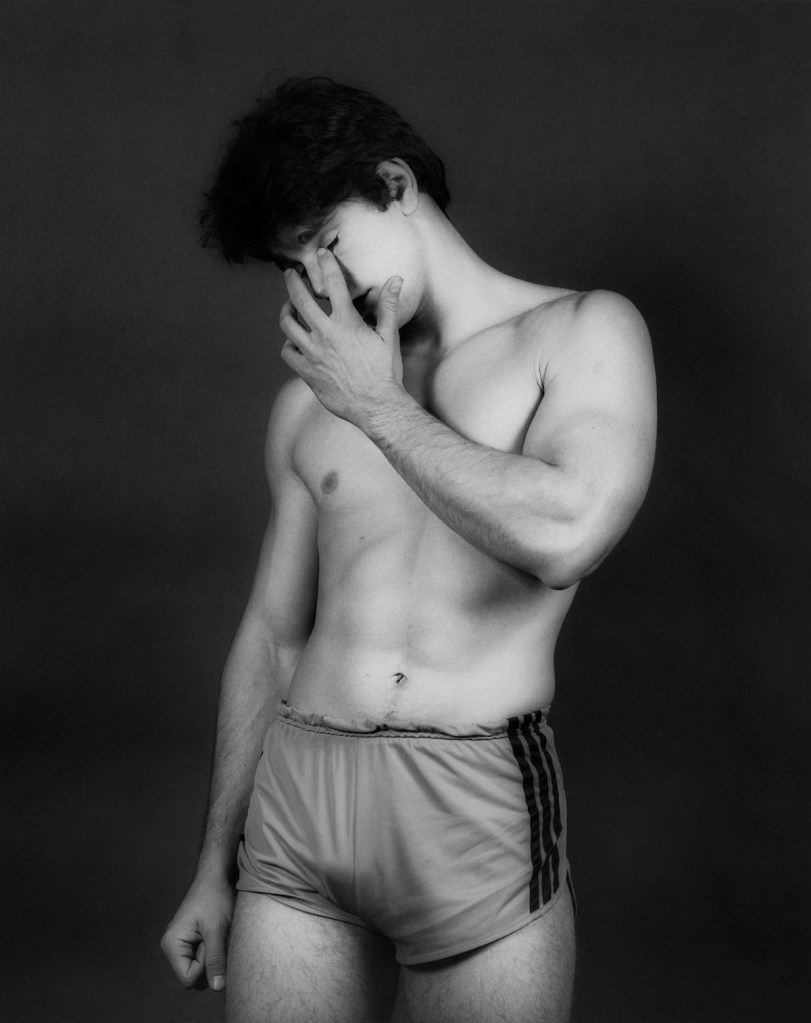

Max Dupain (Australian, 1911-1992)

Doom of youth

1937

Gelatin silver photograph

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Purchased 1982

In Doom of youth – a title taken from Wyndham Lewis’s 1932 polemical book of the same name – Max Dupain creates an allegorical photograph in which a naked male body represents his vision of modern Australia. Using symbols that suggest disempowerment, Dupain implies that the flywheel of mechanisation has doomed youth (the representatives of a nation’s future) to a bleak fate.

Max Dupain (Australian, 1911-1992)

Night with her train of stars and her gift of sleep

1936-1937

Gelatin silver photograph

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

William Kimpton Bequest, 2016

Referring to Edward Hughes’s 1912 Symbolist work of the same name, Max Dupain has replaced the painter’s dark-winged goddess of the night, who tries to calm the putti (or ‘stars’) that cling to her, with an updated modern version in which city lights replace starlight. The symbolism of the giant breast that towers over the electric lights of the urban landscape suggests an inversion of the natural for the man-made. The personification of night refers to the Greek goddess Nyx, a powerful force born of Chaos, and the mother of children including Sleep, Death and Pain. Given his often gloomy assessment of modernity, Dupain’s invocation of Nyx seems appropriate in the context.

Installation views of the exhibition Brave New World: Australia 1930s at NGVA with Herbert Badham’s Paint and morning tea second left and Albert Tucker’s Self-portrait third from right

Photos: Courtesy NGV Photographic Services

Herbert Badham (Australian, 1899-1961)

Paint and morning tea

1937

Oil on cardboard

75.6 x 71.5cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne Felton Bequest, 1937

© The Estate of Herbert Badham

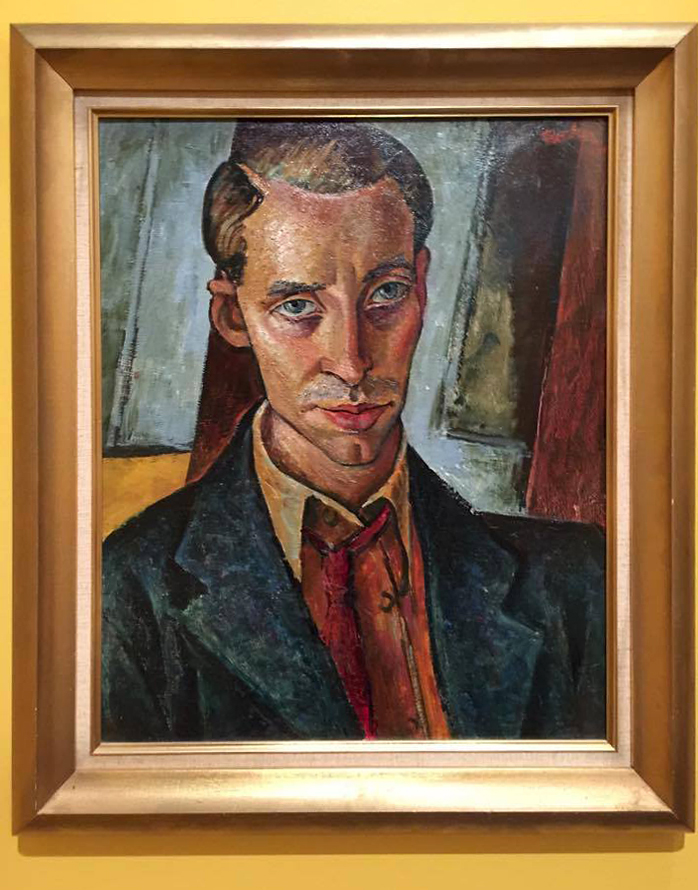

Installation view of the exhibition Brave New World: Australia 1930s at NGVA with Albert Tucker’s Self-portrait (1937) at left

Photo: Eugene Hyland

Installation view of Albert Tucker’s Self-portrait (1937) from the exhibition Brave New World: Australia 1930s at NGVA

Photo: Dr Marcus Bunyan

In the late 1930s Albert Tucker’s contact with émigré artists Yosl Bergner and Danila Vassilieff was to provide important encouragement for him to pursue his artistic vocation and to make art that was responsive to the issues of his time. In 1938 Tucker was a founding member of the Contemporary Art Society, and he became one of the most articulate voices in the often bitter debates between modernists and conservatives. In the 1940s, together with his partner Joy Hester, Tucker was a key member of the group of artists and writers that formed around John and Sunday Reed at Heide.

From 1936 until the early 1940s Albert Tucker chronicled himself with numerous painted and drawn self-portraits. In these works we witness a harrowing disintegration of his physical self, which mirrored the artist’s overwrought emotional state. He recalled: ‘It was a period when the whole world, and all the people I knew, seemed to be seething with ideas and energies and experiences; and my own mind was a seething mess … The highly emotional, overwrought expressionist paintings suited my state at the time’.

Installation view of the exhibition Brave New World: Australia 1930s at NGVA with work by Danila Vassilieff on the centre black wall including Street scene with graffiti (left), Truth, Woolloomooloo (second left) and Young girl (Shirley) the large painting at right; and F. Oswald Barnett’s photographs of Melbourne slums in the display cabinet

Photos: Courtesy NGV Photographic Services

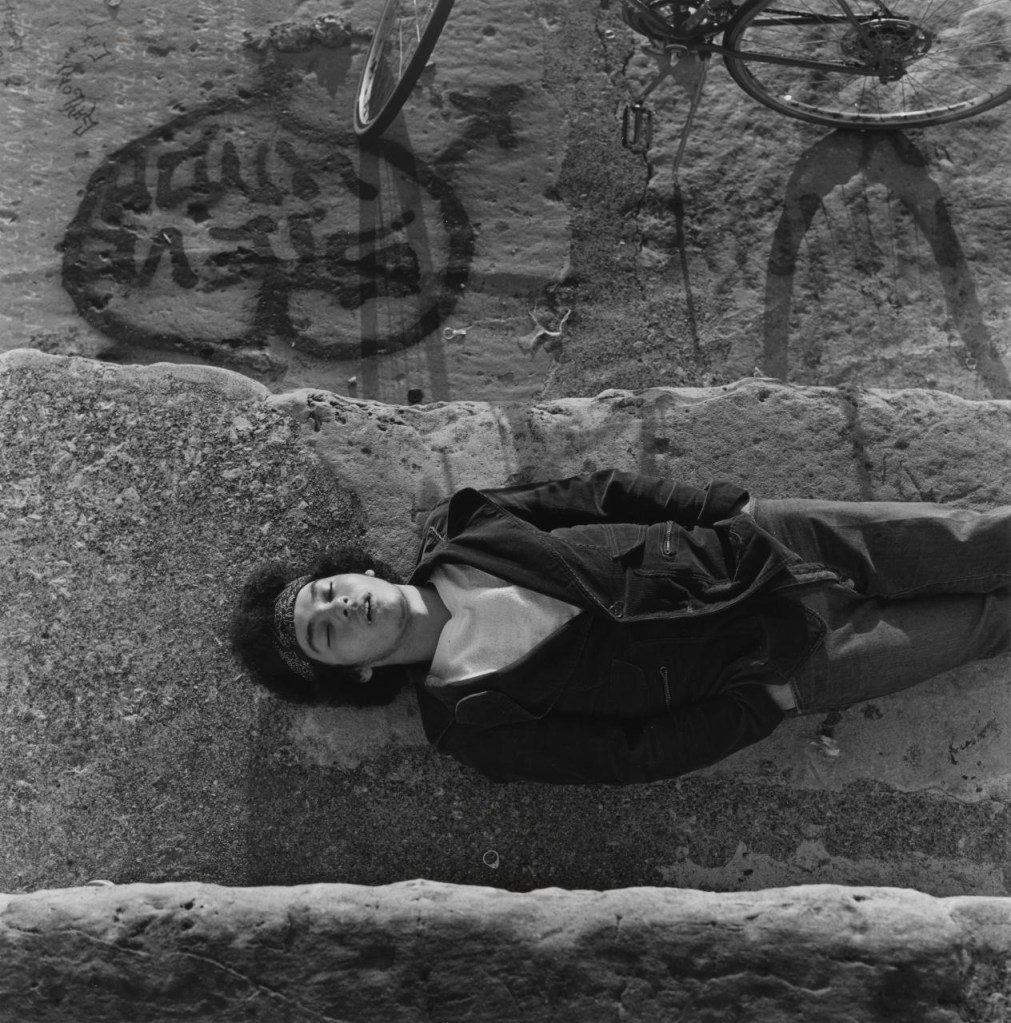

Installation view of Danila Vassilieff ‘s Street scene with graffiti (1938) from the exhibition Brave New World: Australia 1930s at NGVA

Photo: Dr Marcus Bunyan

Danila Vassilieff (Russia 1897 – Australia 1958, Australia from 1923, Central and South America, Europe, England 1929-1934)

Truth, Woolloomooloo

1936

Oil on canvas

Private collection

It is notable that the first artists to depict the poverty of inner-city slums were two recently arrived émigrés, Danila Vassilieff and Yosl Bergner. Russian-born Vassilieff, who had fought with the white Russian army, first arrived in Australia in 1923 before leaving again in 1929. On his return in 1935 he painted a series of dark streetscapes, depicting the inner suburban areas of Woolloomooloo and Surry Hills in Sydney. Moving to Melbourne, Vassilieff’s expressionist style influenced many young artists, including Lina Bryans, Albert Tucker, Arthur Boyd and Sidney Nolan.

Danila Vassilieff (Russia 1897 – Australia 1958, Australia from 1923, Central and South America, Europe, England 1929-1934)

Young girl (Shirley)

1937

Oil on canvas on composition board

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

National Gallery Society of Victoria Century Fund, 1984

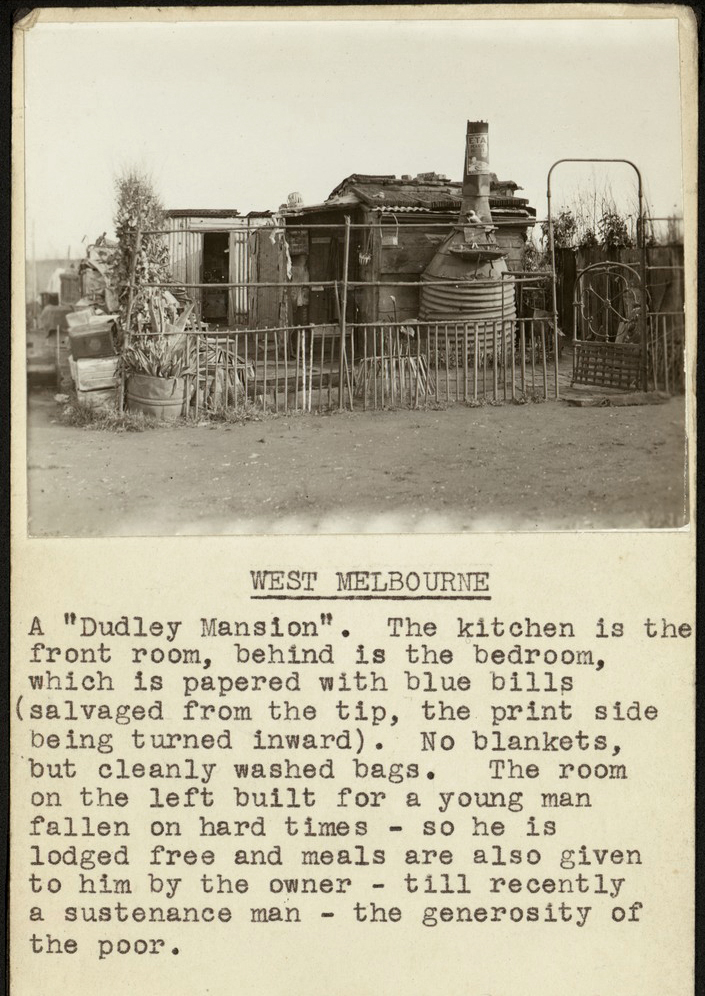

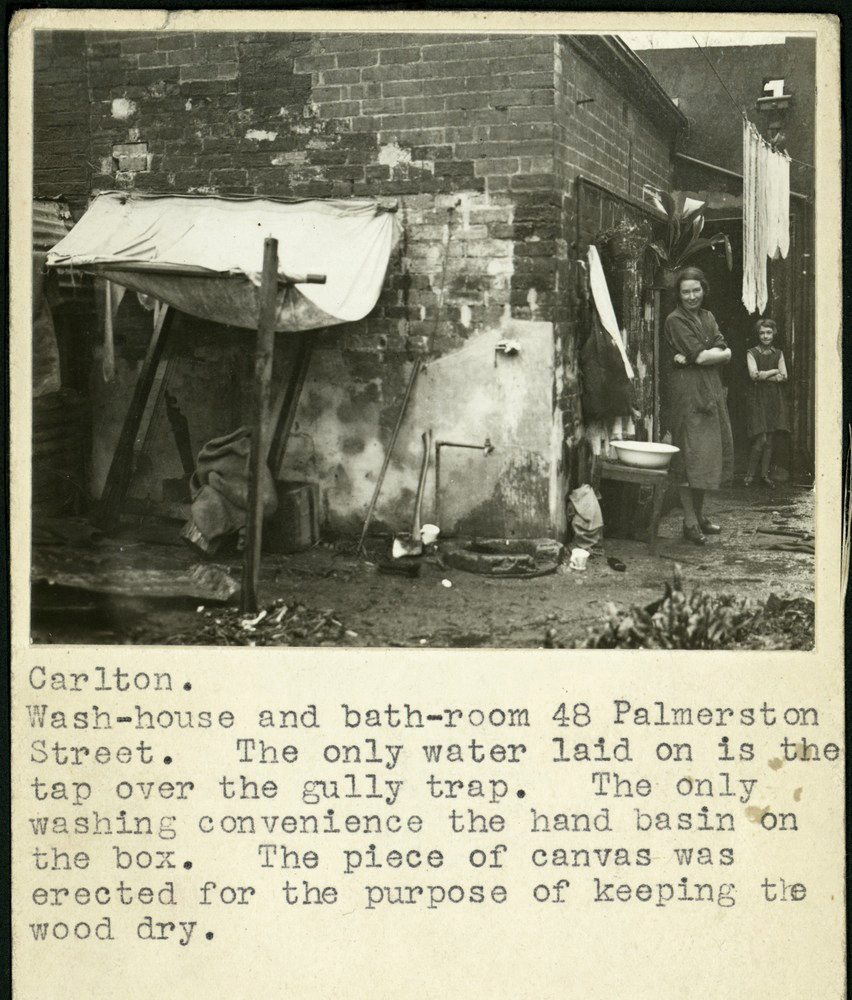

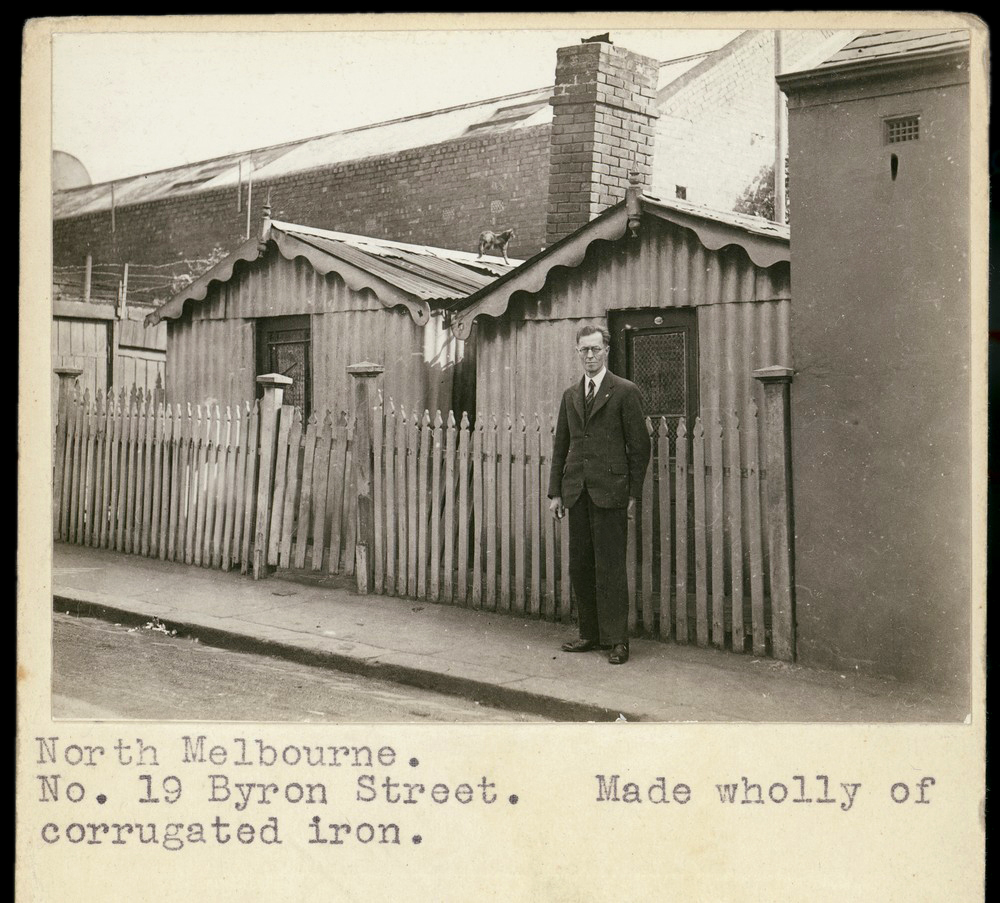

F. Oswald Barnett (Australian, 1883-1972)

Fitzroy. View from the Brotherhood of St Lawrence

Fitzroy. Rear view of house

North Melbourne. Group of children in Erskine Place

West Melbourne. A Dudley Mansion

Carlton. Wash-house and bath-room, 48 Palmerston Street

North Melbourne. No. 19 Byron Street

West Melbourne rubbish tip

c. 1930 – c. 1935

Gelatin silver photograph and typewriting on card

State Library Victoria, Melbourne

F. Oswald Barnett Collection

Gift of Department of Human Services, Victoria 2001

One of the most visible and lasting effects of the Great Depression was the housing crisis in the poor working class areas of Melbourne and Sydney. Many of the nineteenth-century houses had fallen into disrepair, overcrowding was endemic and a great number of families lived in squalid and unhealthy conditions. Throughout the decade ‘slum’ abolition movements in Melbourne and Sydney ran public campaigns to place public housing on the political agenda, leading to the creation of the first state Housing Commissions.

In Melbourne, Methodist layman F. Oswald Barnett led a campaign calling for slum demolition and the rehousing of residents in government-financed housing. He took hundreds of photographs that were used in public lectures and to illustrate the 1937 report of the Housing Investigation and Slum Abolition Board. This led to the creation of the Housing Commission of Victoria in 1938, with its first major project being the Garden City estate at Fishermans Bend. In Sydney a similar campaign led to the Housing Improvement Act of 1936 and the construction of the first fifty-six home units at Erskineville. (NGV)

The photographs in the F. Oswald Barnett Collection were taken by Barnett and other unidentified photographers in the 1930s. Many of them were used to illustrate a government report on slum housing and/or made into lantern slides for lectures in a public campaign. F. Oswald Barnett was born in Brunswick, Victoria. A committed Methodist and housing reformer, he led a crusade against Melbourne’s inner city slums. In 1936 he was appointed to the Slum Abolition Board and from 1938-1948 he was the vice-chair of the Housing Commission. In this position he attempted to shape compassionate public housing policy. He later protested vigorously against proposed high-rise housing (Monash Biographical Dictionary of 20th century Australia).

See my text, “Communities dismantled,” on the photographs of Frederick Oswald Barnett.

Scenes from Melbourne during the depression (extract)

c. 1935

Black and white film transferred to media player

1 min. 51 sec. silent (looped)

Courtesy of National Film and Sound Archive of Australia, Canberra

Video: Dr Marcus Bunyan

While there is an abundance of newspaper and documentary photographs which document the 1930s shanty towns, slums, relief and charity works, there is very little moving image recordings available. Instead, the moving image medium at the time was primarily focused on providing entertainment that would allow the audience temporary relief from the Depression. This rare footage depicts slum areas of inner Melbourne, and provides great insight into the horrible living conditions that many Australian families experienced.

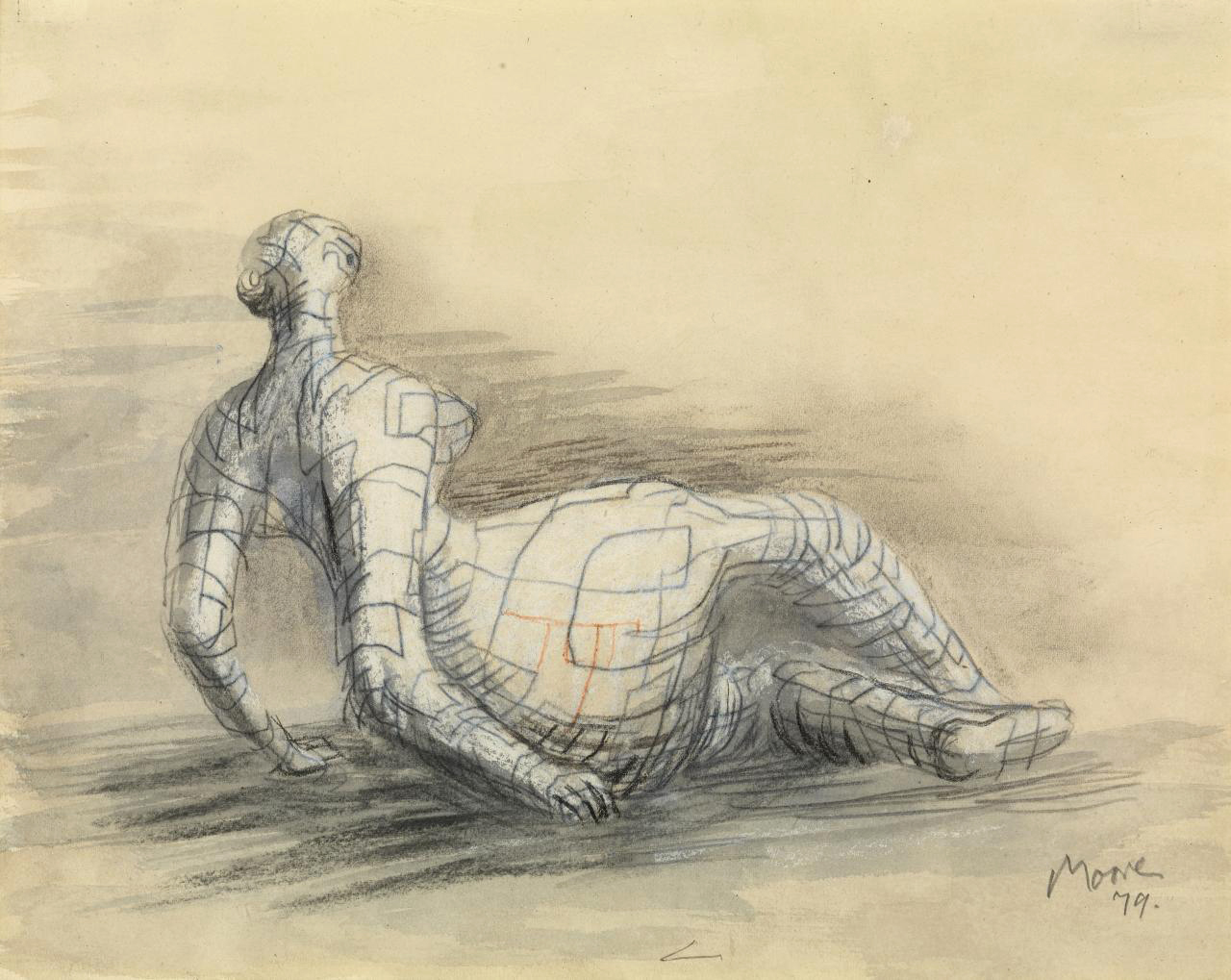

Ola Cohn (Australian, 1892-1964, England 1926-1930)

The sundowner

1932

Painted plaster

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Gift of Jack and Zena Cohn, 2016

Ola Cohn studied sculpture with Henry Moore at the Royal College of Art in London in the 1920s. She returned to Melbourne in 1930, where the following year her solo exhibition established her as a leading proponent of modern sculpture. During the Depression the sight of ‘swagmen’ or ‘sundowners’ became commonplace as unemployed men travelled across the country in order to find work. In 1932 Cohn submitted this maquette of a sundowner to a competition for a full-scale sculpture to be erected in Fitzroy Gardens in Melbourne: unsurprisingly it was not chosen as the winning entry.

Installation view of the exhibition Brave New World: Australia 1930s at NGVA with Bernard Smith’s The advance of Lot and his Brethren at centre and Albert Tucker’s The futile city at right

Photo: Eugene Hyland

Installation view of Bernard Smith’s The advance of Lot and his Brethren from the exhibition Brave New World: Australia 1930s at NGVA

Photo: Dr Marcus Bunyan

Bernard Smith (Australian, 1916-2011, England and Europe 1948-1951)

The advance of Lot and his Brethren

1940

Oil on canvas

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Gift of the artist, 2008

In the early 1930s, artists depicted the city as a modern utopia, a place of triumphant progress and aspiration later in the decades, a new radical iconography of the city as a place of moral decay and corruption appeared. Painted at the start of the Second World War, Lot and his brethren expresses Bernard Smith’s despair at the conflagration that the world had been plunged into. Based on the biblical story of Lot, who fled from God’s destruction of Sodom, Smith depicts Karl Marx as the saviour who leads his people from the burning city.

Albert Tucker (Australian, 1914-1999, Europe and United States 1947-1960)

The futile city

1940

Oil on cardboard

Heide Museum of Modern Art, Bulleen, Melbourne

Purchased from John and Sunday Reed, 1980

At the start of the Second World War Surrealism was an important influence upon Albert Tucker, as were the writings of T. S. Eliot. The futile city was inspired by Eliot’s epic poem The Waste Land (1922): ‘I came on T. S. Eliot, and instantly I recognised a twin soul because here was horror, outrage, despair, futility, and all the images that went with them. He confirmed my own feelings and also became a source … because of the images that would involuntarily form while I was reading the poetry’.

Installation view of the exhibition Brave New World: Australia 1930s at NGVA with Yosl Bergner’s Citizen (c. 1940) at left

Photo: Eugene Hyland

Installation view of Yosl Bergner’s Citizen (c. 1940) from the exhibition Brave New World: Australia 1930s at NGVA

Photo: Dr Marcus Bunyan