Exhibition dates: 25th February – 7th June, 2015

Curators: Carol Jacobi, Curator, British Art 1850-1915, Tate Britain, Simon Baker, Curator, Photography and International Art, Tate, and Hannah Lyons, Assistant Curator, 1850-1915, Tate

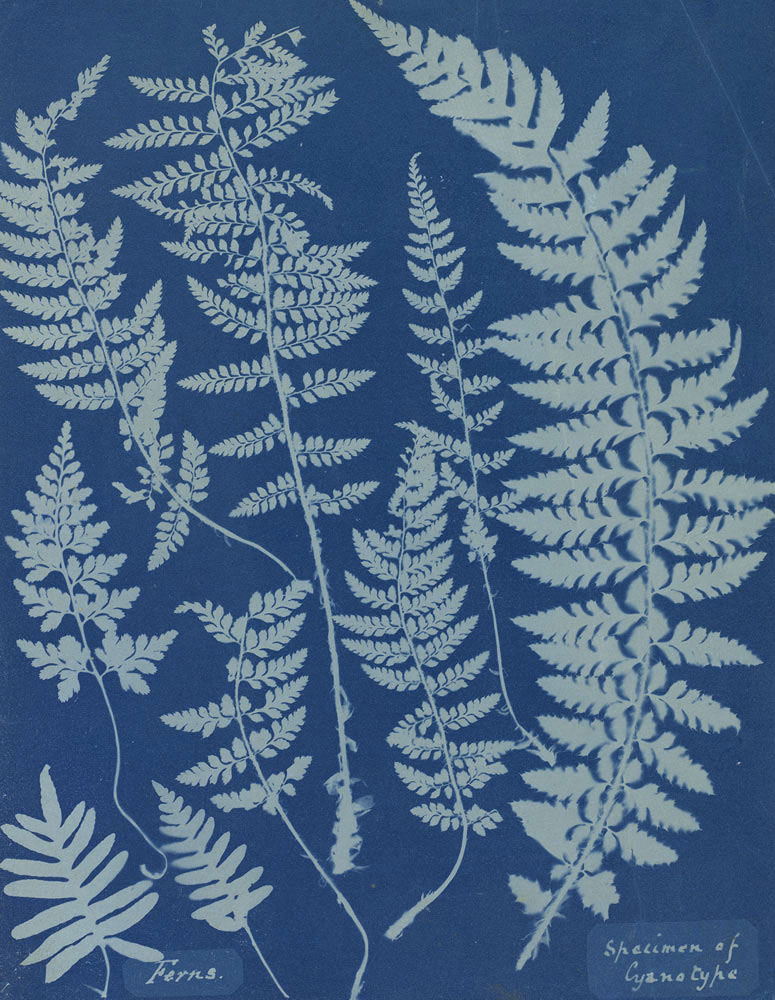

“Salt prints are the very first photographs on paper that still exist today. Made in the first twenty years of photography, they are the results of esoteric knowledge and skill. Individual, sometimes unpredictable, and ultimately magical, the chemical capacity to ‘fix a shadow’ on light sensitive paper, coated in silver salts, was believed to be a kind of alchemy, where nature drew its own picture.”

These salted paper prints, one of the earliest forms of photography, are astonishing. The delicacy and nuance of shade and feeling; possessing a soft, luxurious aesthetic that is astounding today… but just imagine looking at these images at the time they were taken. The shock, the recognition, the delight and the romance of seeing aspects of your life and the world around you, near and far, drawn in light – having a physical presence in the photographs before your eyes. The aura of the original, the photograph AS referent – unlike contemporary media saturated society where the image IS reality, endlessly repeated, divorced from the world in which we live.

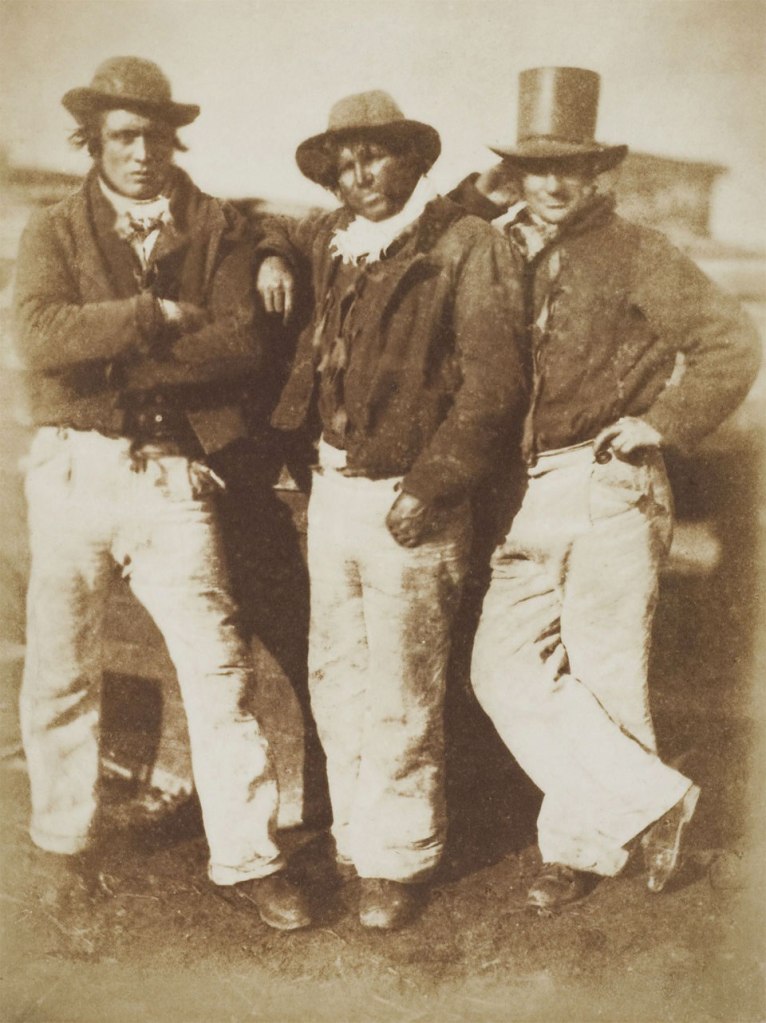

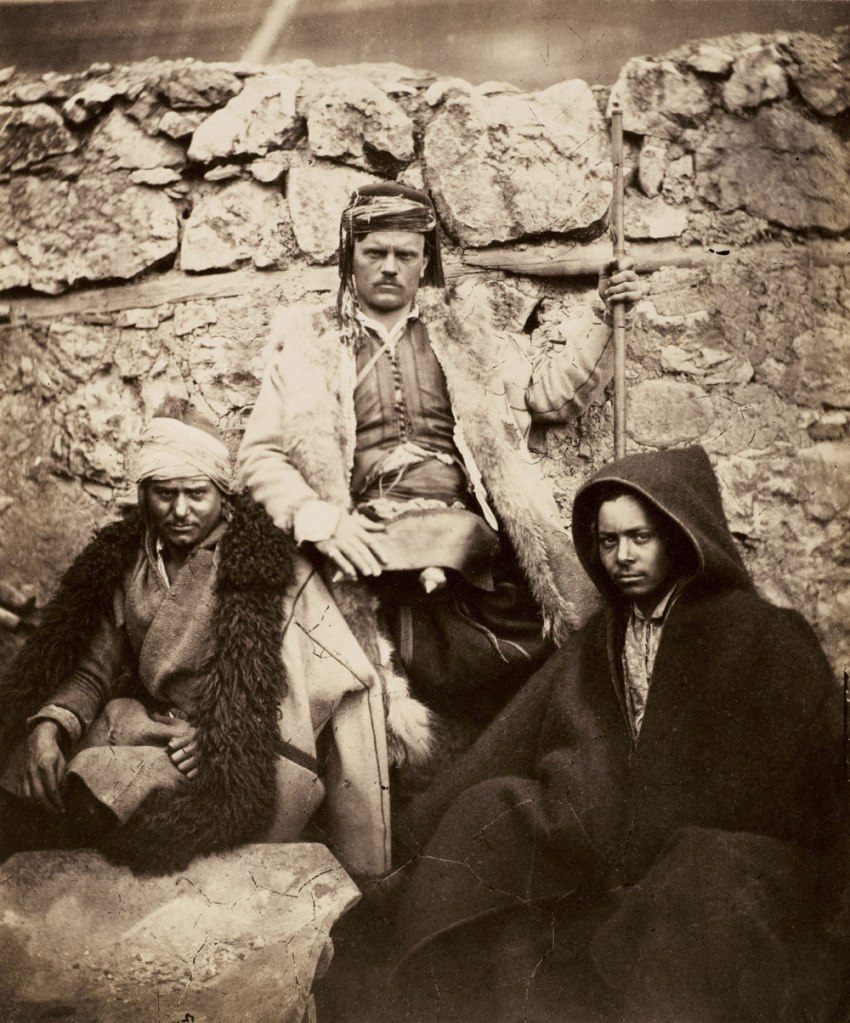

The posting has taken a long time to put together, from researching the birth and death dates of the artists (not supplied), to finding illustrative texts and biographies of each artist (some translated from the French). But the real joy in assembling this posting is when I sequence the images. How much pleasure does it give to be able to sequence Auguste Salzmann’s Terra Cotta Statuettes from Camiros, Rhodes followed by three Newhaven fishermen rogues (you wouldn’t want to meet them on a dark night!), and then the totally different feel of Fenton’s Group of Croat Chiefs. Follow this up with one of the most stunning photographs of the posting, Roger Fenton’s portrait Captain Mottram Andrews, 28th Regiment (1st Staffordshire) Regiment of Foot of 1855 and you have a magnificent, almost revelatory, quaternity/eternity.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to Tate Britain for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Calvert Jones (Welsh, December 4, 1804 – November 7, 1877)

The Fruit Sellers

c. 1843

Photograph, salted paper print from a paper negative

David Hill (Scottish, 1802-1870) and Robert Adamson (Scottish, 1821-1848)

Five Newhaven fisherwomen

c. 1844

Photograph, salted paper print from a paper negative

David Hill (Scottish, 1802-1870) and Robert Adamson (Scottish, 1821-1848)

The Gowan [Margaret and Mary Cavendish]

c. 1843-1844

Photograph, salted paper print from a paper negative

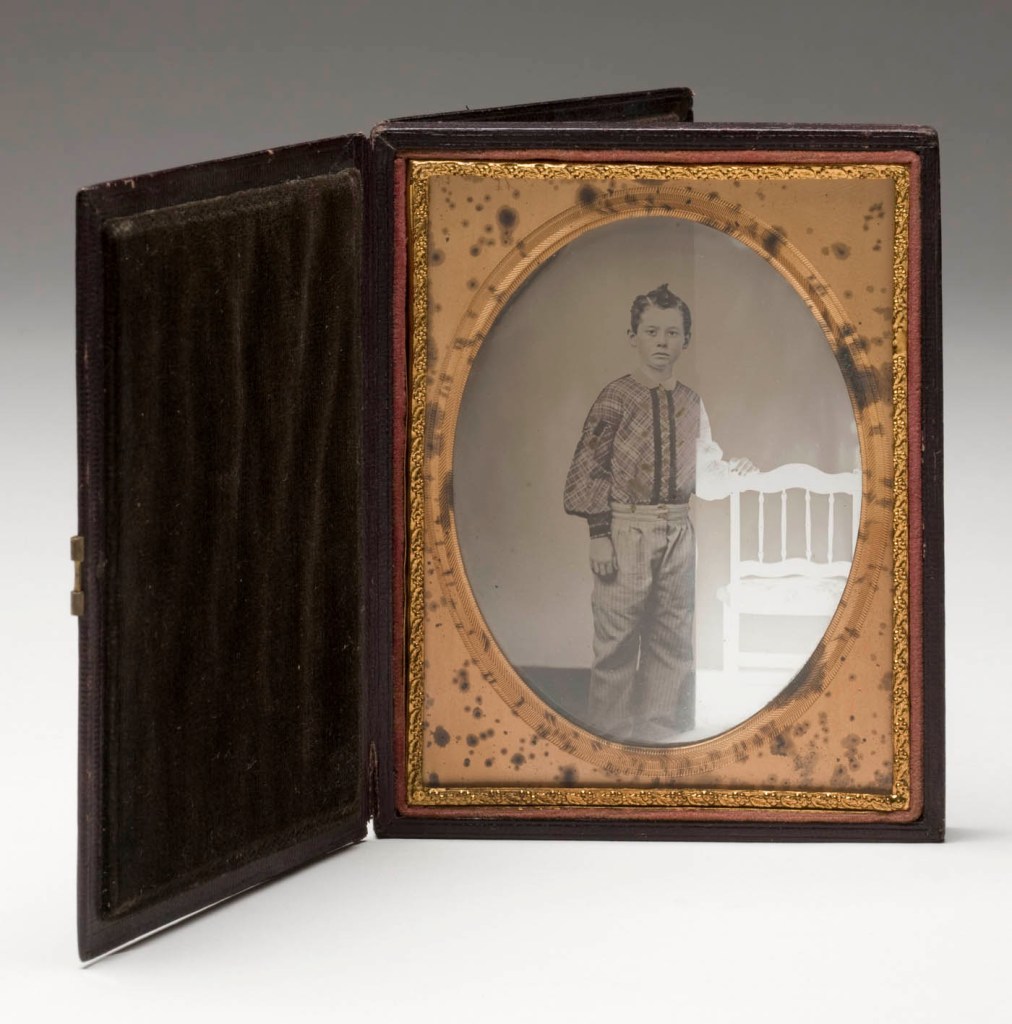

Salt and Silver: Early Photography 1840-1860 is the first major exhibition in Britain devoted to salt prints, the earliest form of paper photography. The exhibition features some of the rarest and best early photographs in the world, depicting daily activities and historic moments of the mid 19th century. The ninety photographs on display are among the few fragile salt prints that survive and are seldom shown in public. Salt and Silver: Early Photography 1840-1860 opens at Tate Britain on 25 February 2015.

In the 1840s and 50s, the salt print technique introduced a revolutionary new way of creating photographs on paper. It was invented in Britain and spread across the globe through the work of British and international photographers – artists, scientists, adventurers and entrepreneurs of their day. They captured historic moments and places with an immediacy not previously seen, from William Henry Fox Talbot’s images of a modern Paris street and Nelson’s Column under construction, to Linnaeus Tripe’s dramatic views of Puthu Mundapum, India and Auguste Salzmann’s uncanny studies of statues in Greece.

In portraiture, the faces of beloved children, celebrities, rich and poor were recorded as photographers sought to catch the human presence. Highlights include Fox Talbot’s shy and haunting photograph of his daughter Ela in 1842 to Nadar’s images of sophisticated Parisians and Roger Fenton’s shell-shocked soldiers in the Crimean war.

William Henry Fox Talbot unveiled this ground-breaking new process in 1839. He made the world’s first photographic prints by soaking paper in silver iodide salts to register a negative image which, when photographed again, created permanent paper positives. These hand-made photographs ranged in colour from sepia to violet, mulberry, terracotta, silver-grey, and charcoal-black and often had details drawn on like the swishing tail of a horse. Still lifes, portraits, landscapes and scenes of modern life were transformed into luxurious, soft, chiaroscuro images. The bold contrasts between light and dark in the images turned sooty shadows into solid shapes. Bold contrasts between light and dark turned shadows into abstract shapes and movement was often captured as a misty blur. The camera drew attention to previously overlooked details, such as the personal outline of trees and expressive textures of fabric.

In the exciting Victorian age of modern invention and innovation, the phenomenon of salt prints was quickly replaced by new photographic processes. The exhibition shows how, for a short but significant time, the British invention of salt prints swept the world and created a new visual experience.

Salt and Silver: Early Photography 1840 – 1860 is organised in collaboration with the Wilson Centre for photography. It is curated by Carol Jacobi, Curator, British Art 1850-1915, Tate Britain, Simon Baker, Curator, Photography and International Art, Tate, and Hannah Lyons, Assistant Curator, 1850-1915, Tate. ‘Salt and Silver’ – Early Photography 1840-1860 is published by Mack to coincide with the exhibition and will be accompanied by a programme of talks and events in the gallery.

Press release from the Tate website

William Henry Fox Talbot (British, 11 February 1800 – 17 September 1877)

Scene in a Paris Street

1843

Photograph, salted paper print from a paper negative

By 1841, Talbot had dramatically reduced, from many minutes to just seconds, the exposure time needed to produce a negative, and on a trip to Paris to publicise his new calotype process he took a picture from his hotel room window, an instinctive piece of photojournalism. The buildings opposite are rendered in precise and exquisite detail, the black and white stripes of the shutters neat alternations of light and shade. In contrast to the solidity of the buildings are the carriages waiting on the street below; the wheels, immobile, are seen in perfect clarity, while the skittish horses are no more than ghostly blurs.

Florence Hallett. “Salt and Silver, Tate Britain: Early photographs that brim with the spirit of experimentation,” on The Arts Desk website, Wednesday, 25 February 2015 [Online] Cited 03/06/2015. Used under fair use conditions for the purposes of education and research

William Henry Fox Talbot (British, 11 February 1800 – 17 September 1877)

Nelson’s Column Under Construction, Trafalgar Square

1844

Salted paper print from a glass plate negative

William Henry Fox Talbot (British, 11 February 1800 – 17 September 1877)

Nelson’s Column Under Construction, Trafalgar Square

1844

Salted paper print from a glass plate negative

This is the first exhibition in Britain devoted to salted paper prints, one of the earliest forms of photography. A uniquely British invention, unveiled by William Henry Fox Talbot in 1839, salt prints spread across the globe, creating a new visual language of the modern moment. This revolutionary technique transformed subjects from still lifes, portraits, landscapes and scenes of daily life into images with their own specific aesthetic: a soft, luxurious effect particular to this photographic process. The few salt prints that survive are seldom seen due to their fragility, and so this exhibition, a collaboration with the Wilson Centre for Photography, is a singular opportunity to see the rarest and best early photographs of this type in the world.

“The technique went as follows: coat paper with a silver nitrate solution and expose it to light, thus producing a faint silver image. He later realised if you apply salt to the paper first and then spread on the silver nitrate solution the resulting image is much sharper. His resulting photos, ranging in colour from sepia to violet, mulberry, terracotta, silver-grey, and charcoal-black, were shadowy and soft, yet able to pick up on details that previously went overlooked – details like the texture of a horse’s fur, or the delicate silhouette of a tree.”

Priscilla Frank. “The First Paper Photographs Were Made With Salt, And They Look Like This,” on the Huffington Post website 03/06/2015 [Online] Cited 03/06/2015. Used under fair use conditions for the purposes of education and research

William Henry Fox Talbot (British, 11 February 1800 – 17 September 1877)

Cloisters, Lacock Abbey

1843

William Henry Fox Talbot (11 February 1800 – 17 September 1877)

William Henry Fox Talbot (11 February 1800 – 17 September 1877) was a British scientist, inventor and photography pioneer who invented the salted paper and calotype processes, precursors to photographic processes of the later 19th and 20th centuries. Talbot was also a noted photographer who made major contributions to the development of photography as an artistic medium. He published The Pencil of Nature (1844), which was illustrated with original prints from some of his calotype negatives. His work in the 1840s on photo-mechanical reproduction led to the creation of the photoglyphic engraving process, the precursor to photogravure. Talbot is also remembered as the holder of a patent which, some say, affected the early development of commercial photography in Britain. Additionally, he made some important early photographs of Oxford, Paris, Reading, and York.

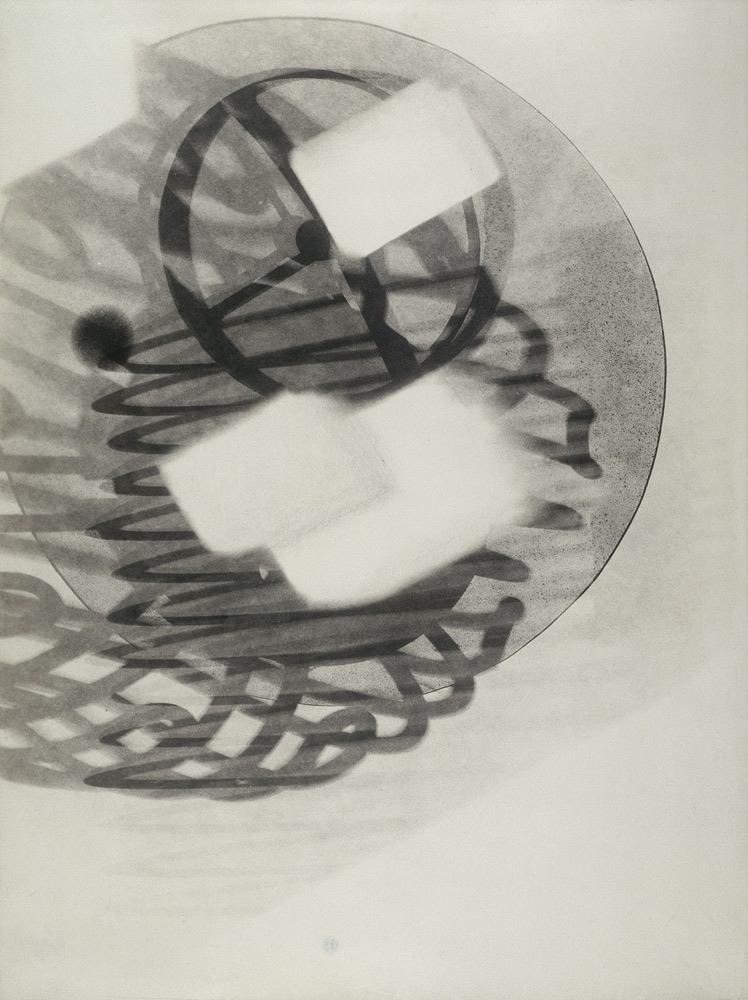

William Henry Fox Talbot (British, 11 February 1800 – 17 September 1877)

Study of China

1844

© Wilson Centre for Photography

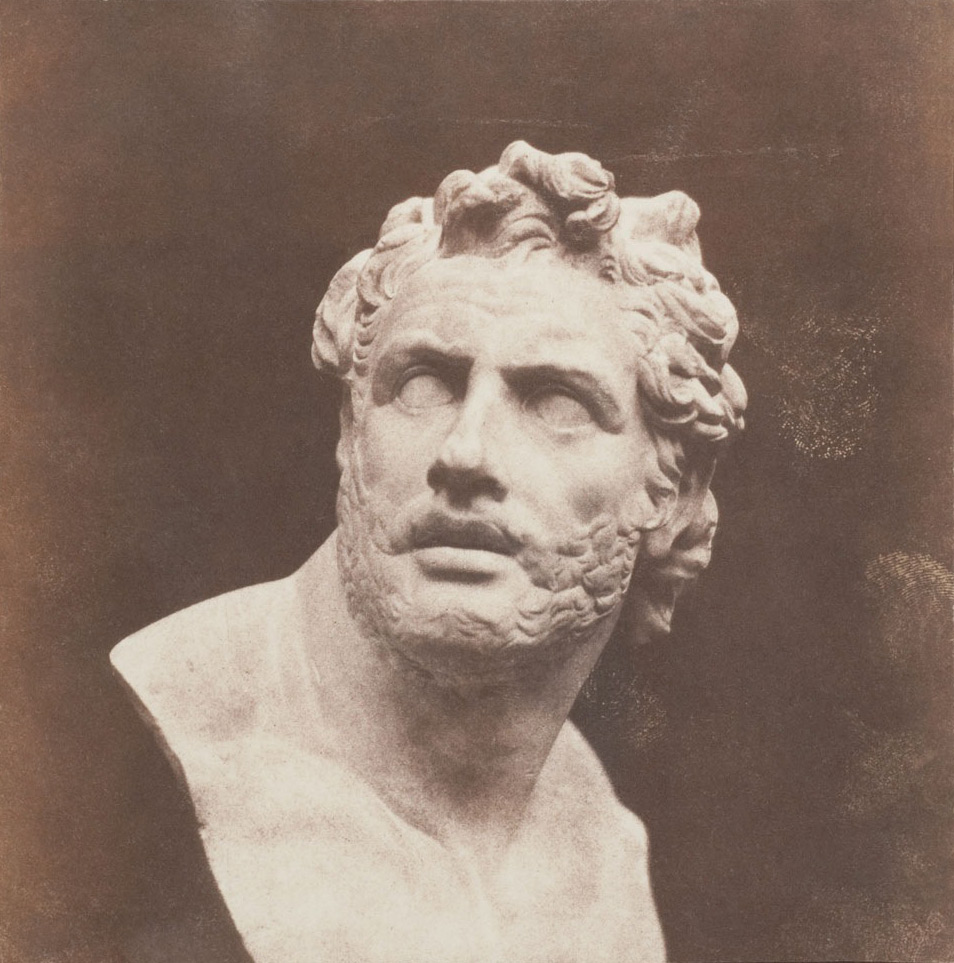

William Henry Fox Talbot (British, 11 February 1800 – 17 September 1877)

Plaster Bust of Patroclus

before February 1846

© Wilson Centre for Photography

John Beasly Greene (French-American, 1832-1856)

El Assasif, Porte de Granit Rose, No 2, Thébes

1854

Salted paper print from a waxed plate negative

John Beasly Greene (French-American, 1832-1856)

A French-born archeologist based in Paris and a student of photographer Gustave Le Gray, John Beasly Greene became a founding member of the Société Française de Photographie and belonged to two societies devoted to Eastern studies. Greene became the first practicing archaeologist to use photography, although he was careful to keep separate files for his documentary images and his more artistic landscapes.

In 1853 at the age of nineteen, Greene embarked on an expedition to Egypt and Nubia to photograph the land and document the monuments and their inscriptions. Upon his return, Louis Désiré Blanquart-Evrard published an album of ninety-four of these photographs. Greene returned to Egypt the following year to photograph and to excavate at Medinet-Habu in Upper Egypt, the site of the mortuary temple built by Ramses III. In 1855 he published his photographs of the excavation there. The following year, Greene died in Egypt, perhaps of tuberculosis, and his negatives were given to his friend, fellow Egyptologist and photographer Théodule Devéria.

Text from the Getty Museum website

James Robertson (British, 1813-1888) and Felice Beato (Italian-British, 1832 – 29 January 1909)

Pyramids at Giza

1857

Photograph, salted paper print from a glass plate negative

James Robertson (British, 1813-1888)

James Robertson (1813-1888) was an English photographer and gem and coin engraver who worked in the Mediterranean region, the Crimea and possibly India. He was one of the first war photographers.

Robertson was born in Middlesex in 1813. He trained as an engraver under Wyon (probably William Wyon) and in 1843 he began work as an “engraver and die-stamper” at the Imperial Ottoman Mint in Constantinople. It is believed that Robertson became interested in photography while in the Ottoman Empire in the 1840s.

In 1853 he began photographing with British photographer Felice Beato and the two formed a partnership called Robertson & Beato either in that year or in 1854 when Robertson opened a photographic studio in Pera, Constantinople. Robertson and Beato were joined by Beato’s brother, Antonio on photographic expeditions to Malta in 1854 or 1856 and to Greece and Jerusalem in 1857. A number of the firm’s photographs produced in the 1850s are signed Robertson, Beato and Co. and it is believed that “and Co.” refers to Antonio.

In late 1854 or early 1855 Robertson married the Beato brothers’ sister, Leonilda Maria Matilda Beato. They had three daughters, Catherine Grace (born in 1856), Edith Marcon Vergence (born in 1859) and Helen Beatruc (born in 1861). In 1855 Robertson and Felice Beato travelled to Balaklava, Crimea where they took over reportage of the Crimean War from Roger Fenton. They photographed the fall of Sevastopol in September 1855. Some sources have suggested that in 1857 both Robertson and Felice Beato went to India to photograph the aftermath of the Indian Rebellion, but it is more probable that Beato travelled there alone. Around this time Robertson did photograph in Palestine, Syria, Malta, and Cairo with either or both of the Beato brothers.

In 1860, after Felice Beato left for China to photograph the Second Opium War and Antonio Beato went to Egypt, Robertson briefly teamed up with Charles Shepherd back in Constantinople. The firm of Robertson & Beato was dissolved in 1867, having produced images – including remarkable multiple-print panoramas – of Malta, Greece, Turkey, Damascus, Jerusalem, Egypt, the Crimea and India. Robertson possibly gave up photography in the 1860s; he returned to work as an engraver at the Imperial Ottoman Mint until his retirement in 1881. In that year he left for Yokohama, Japan, arriving in January 1882. He died there in April 1888.

Text from the Wikipedia website

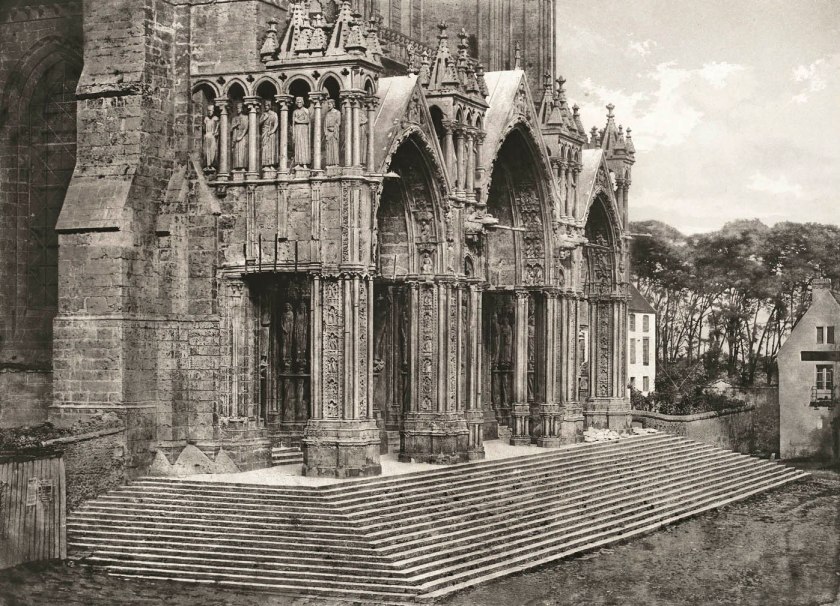

James Robertson (British, 1813-1888)

Base of the Obelisk of Theodosius, Constantinople

1855

Salted paper print from a glass plate negative

Exhibition of intriguing images that charts the birth of photography

Another week, another photography show about death. It’s not officially about death, mind you; it’s officially about the years 1840 to 1860, when photographers made their images on paper sensitised with silver salts. The process was quickly superseded, but the pictures created this way have a beautiful artistic softness and subtlety of tone, quite apart from the fact that every single new photograph that succeeded represented a huge leap forward in the development of the medium. You see these early practitioners start to grasp the scope of what might be possible. Their subjects change, from ivy-covered walls and carefully posed family groups to more exotic landscapes and subjects: Egypt, India, the poor, war.

By the time you get to Roger Fenton’s portrait Captain Lord Balgonie, Grenadier Guards of 1855 you have an inkling of how photography is changing how we understand life, for ever. Balgonie is 23. He looks 50. His face is harrowed by his service in the Crimean War, his eyes bagged with fatigue, fear and what the future may hold. He survived the conflict, but was broken by it, dying at home two years after this picture was taken. That is yet to come: for now, he is alive.

This sense of destiny bound within a picture created in a moment is what is new about photography, and you start to see it everywhere, not just in the images of war. It’s in William Henry Fox Talbot’s The Great Elm at Lacock: a huge tree against a mottled sky, battered by storms. It’s in John Beasly Greene’s near-abstract images of Egyptian statuary, chipped, cracked, alien. And it’s in the portraits of Newhaven fisherwomen by DO Hill and Robert Adamson (their cry was ‘It’s not fish, it’s men’s lives’). In a world where death is always imminent, photography arrives as the perfect way to preserve life, and the perfect way to leave your mark, however fleeting.

Chris Waywell. “Salt and Silver: Early Photography 1840-1860,” on the Time Out London website 22 July 2015 [Online] Cited 18/12/2022. Used under fair use conditions for the purposes of education and research

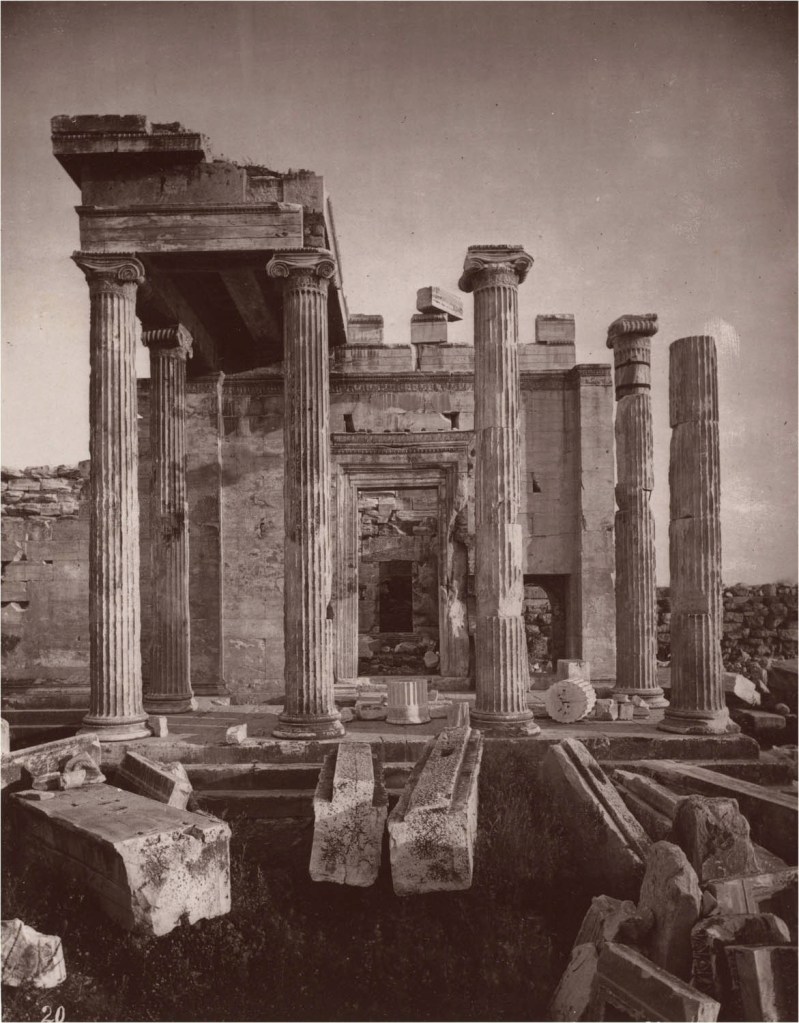

Eugene Piot (French, 1812-1890)

Le Parthénon de l’Acropole d’Athens

1852

Photograph, salted paper print from a paper negative

© Wilson Centre for Photography

Eugène Piot was a French journalist, art critic, art collector and photographer. His pen name was Nemo. Piot was born in Paris.

Paul Marés (French)

Ox cart in Brittany

c. 1857

Photograph, salted paper print from a paper negative

One of the most beautiful photographs in this exhibition is Paul Marès Ox Cart, Brittany, c. 1857. At first it seems a picturesque scene of bucolic tranquillity, the abandoned cart an exquisite study in light and tone. But on the cottage wall are painted two white crosses, a warning – apparently even as recently as the 19th century – to passers-by that the household was afflicted by some deadly disease. Photography’s ability to indiscriminately aestheticise is a dilemma that has continued to present itself ever since, especially in the fields of reportage and war photography.

Florence Hallett. “Salt and Silver, Tate Britain: Early photographs that brim with the spirit of experimentation,” on The Arts Desk website, Wednesday, 25 February 2015 [Online] Cited 03/06/2015. Used under fair use conditions for the purposes of education and research

Jean-Baptiste Frénet (French – Lyon, 31 January 1814 – Charly, 12 August 1889)

Horse and Groom

1855

Salted paper print from a glass plate negative

© Wilson Centre for Photography

Around 1850 Frénet meets in Lyon personalities involved in the nascent photography, and he has to discover this technique to reproduce the frescoes he painted in Ainay. Curious, he is passionate about this new medium that offers him a respite space in the setbacks he suffers with his painting.

Frénet applies the stereotyped views taken of the time involving heavy stagings and is one of the first to practice the instant, the familiar and intimate subject. Five years before Nadar he produces psychological portraits and engages in close-up. He sees photography as an art, the opinion which has emerged in the first issue of the magazine La Lumière (The Light), text of the young and ephemeral gravure company founded in 1851. Frénet open a professional practice photography in 1866 and 1867 in Lyon. Unknown to the general public, his photographic work was discovered in 2000 at the sale of his photographic collection, many parts were purchased by the Musée d’Orsay.

Translated from the French Wikipedia website

Edouard Denis Baldus (French, 1813-1889)

The Floods of 1856, Brotteaux Quarter of Lyon

1856

Photograph, salted paper print from a waxed paper negative

© Wilson Centre for Photography

In June 1856, in the midst of his work at the Louvre, Baldus set out on a brief assignment, equally without precedent in photography, that was in many ways its opposite: to photograph the destruction caused by torrential rains and overflowing rivers in Lyon, Avignon, and Tarascon. From a world of magnificent man-made construction, he set out for territory devastated by natural disaster; from the task of re-creating the whole of a building in a catalogue of its thousand parts, he turned to the challenge of evoking a thousand individual stories in a handful of transcendent images. Baldus created a moving record of the flood without explicitly depicting the human suffering left in its wake. The “poor people, tears in their eyes, scavenging to find the objects most indispensable to their daily needs,” described by the local Courier de Lyon, are all but absent from his photographs of the hard-hit Brotteaux quarter of Lyon, as if the destruction had been of biblical proportions, leaving behind only remnants of a destroyed civilization.

Malcolm Daniel. “Édouard Baldus (1813-1889),” in Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000 [Online] Cited 16/12/2022. Used under fair use conditions for the purposes of education and research

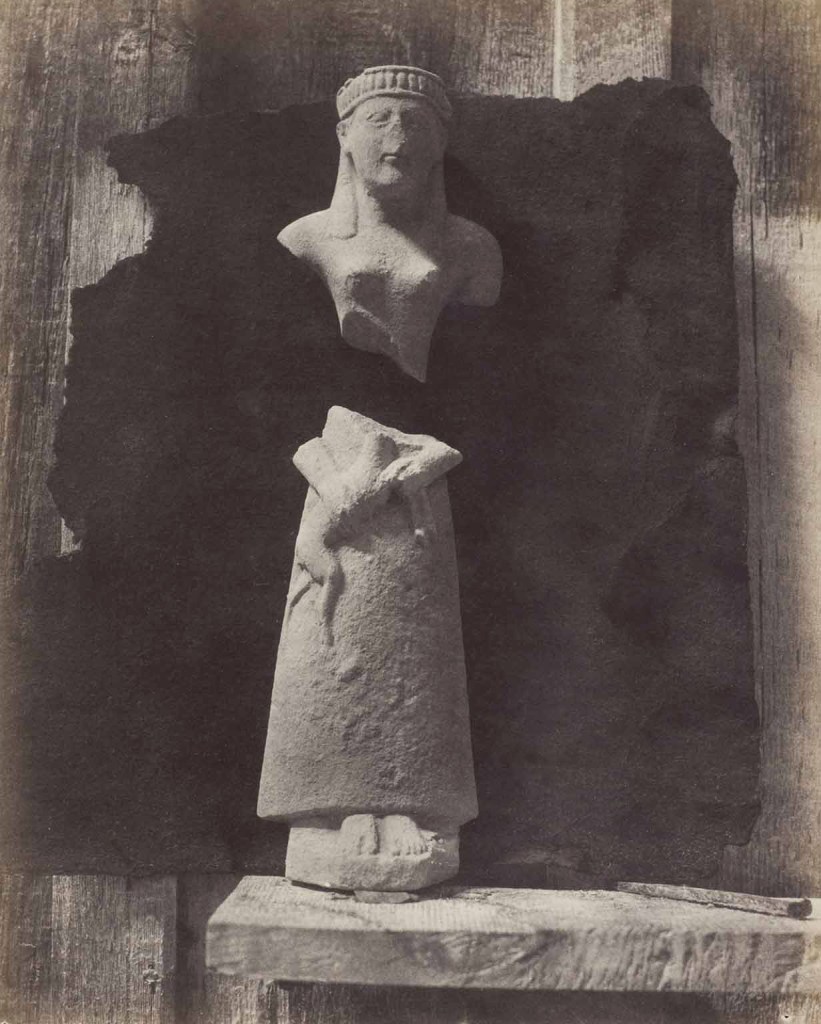

Auguste Salzmann (French, born April 14, 1824 in Ribeauvillé (Alsace) – died February 24, 1872 in Paris)

Terra Cotta Statuettes from Camiros, Rhodes

1863

© Wilson Centre for Photography

Auguste Salzmann (French, 1824-1872) painter, photographer and archaeologist who pioneered the use of photography in the recording of historic sites. He excavated archaeological material in Rhodes in collaboration with Alfred Biliotti.

David Hill (Scottish, 1802-1870) and Robert Adamson (Scottish, 1821-1848)

Newhaven fishermen

c. 1845

Photograph, salted paper print from a paper negative

© Wilson Centre for Photography

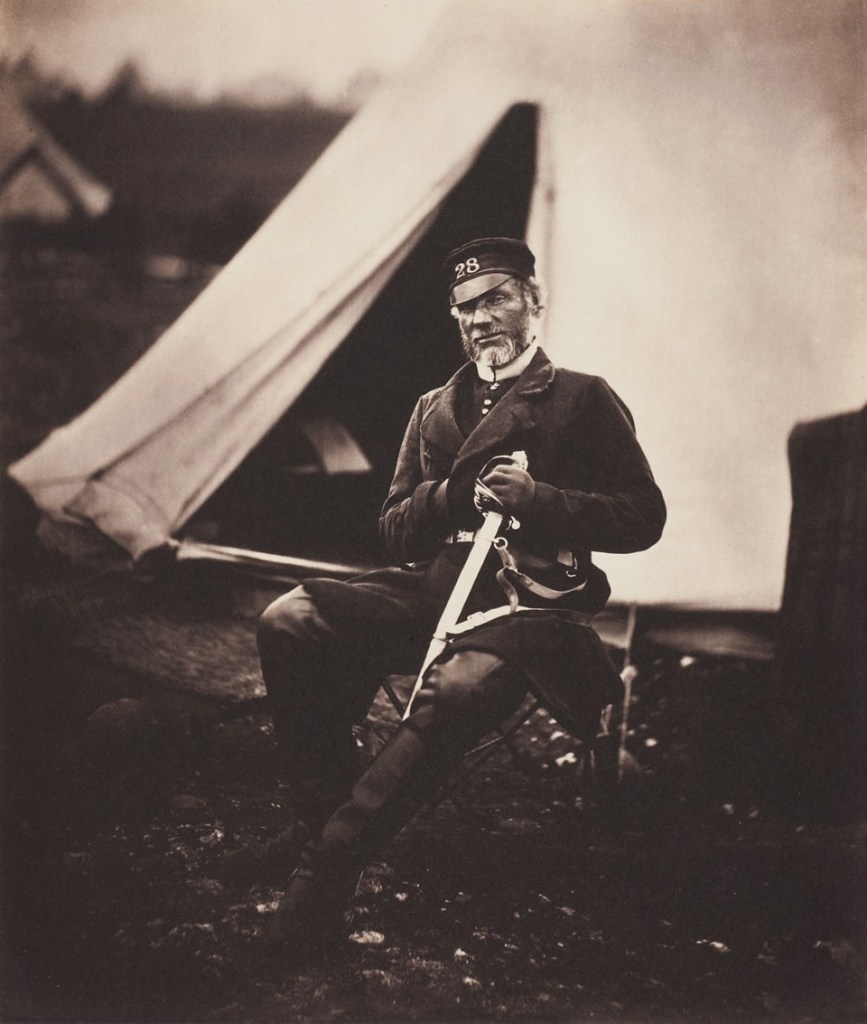

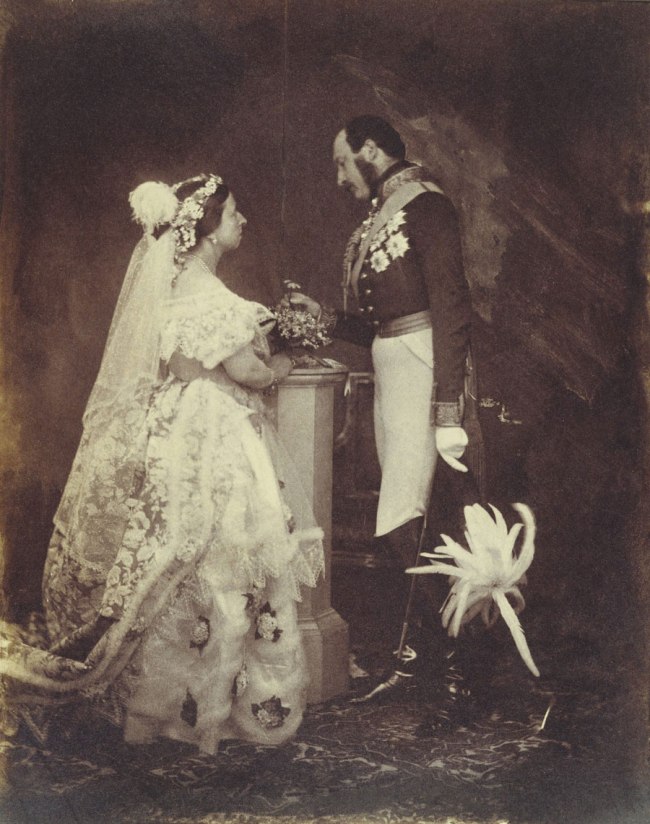

Roger Fenton (British, 28 March 1819 – 8 August 1869)

Cossack Bay, Balaclava

1855

It is likely that in autumn 1854, as the Crimean War grabbed the attention of the British public, that some powerful friends and patrons – among them Prince Albert and Duke of Newcastle, secretary of state for war – urged Fenton to go the Crimea to record the happenings. He set off aboard HMS Hecla in February, landed at Balaklava on 8 March and remained there until 22 June. The resulting photographs may have been intended to offset the general unpopularity of the war among the British people, and to counteract the occasionally critical reporting of correspondent William Howard Russell of The Times. The photographs were to be converted into woodblocks and published in the less critical Illustrated London News. Fenton took Marcus Sparling as his photographic assistant, a servant known as William and a large horse-drawn van of equipment…

Despite summer high temperatures, breaking several ribs in a fall, suffering from cholera and also becoming depressed at the carnage he witnessed at Sebastopol, in all Fenton managed to make over 350 usable large format negatives. An exhibition of 312 prints was soon on show in London and at various places across the nation in the months that followed. Fenton also showed them to Queen Victoria and Prince Albert and also to Emperor Napoleon III in Paris. Nevertheless, sales were not as good as expected.

Text from the Wikipedia website

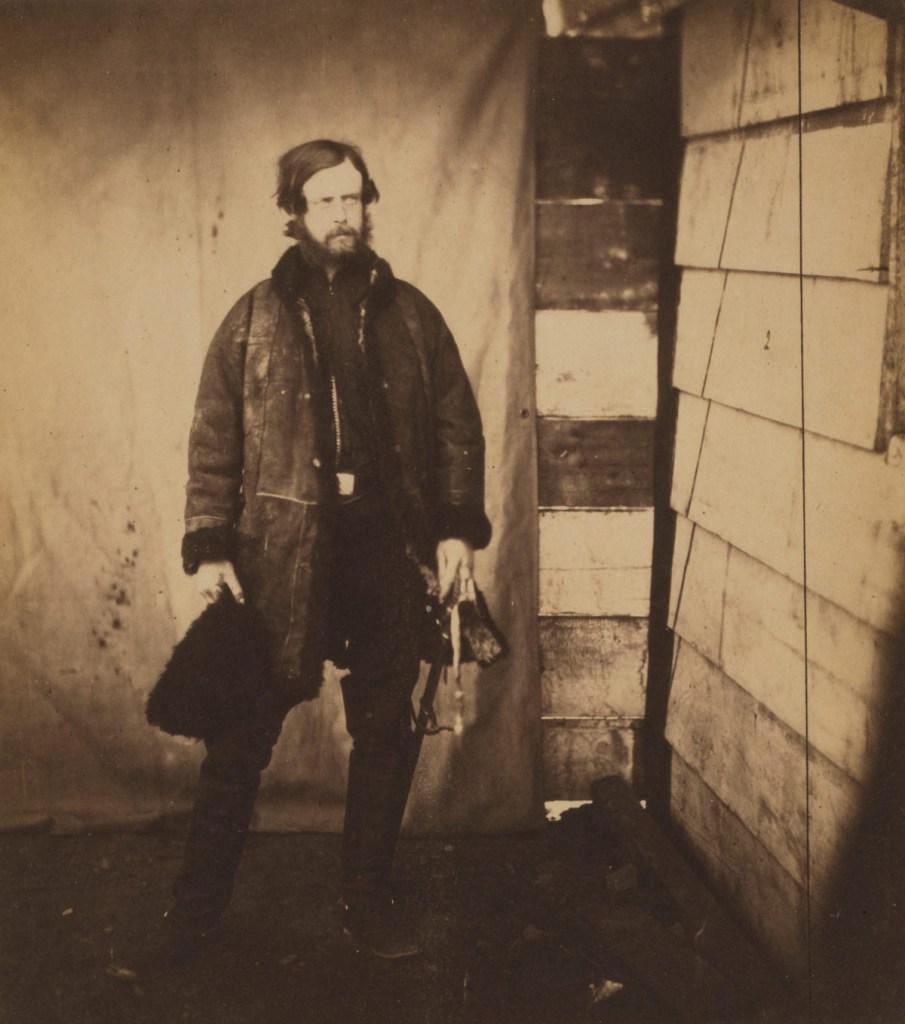

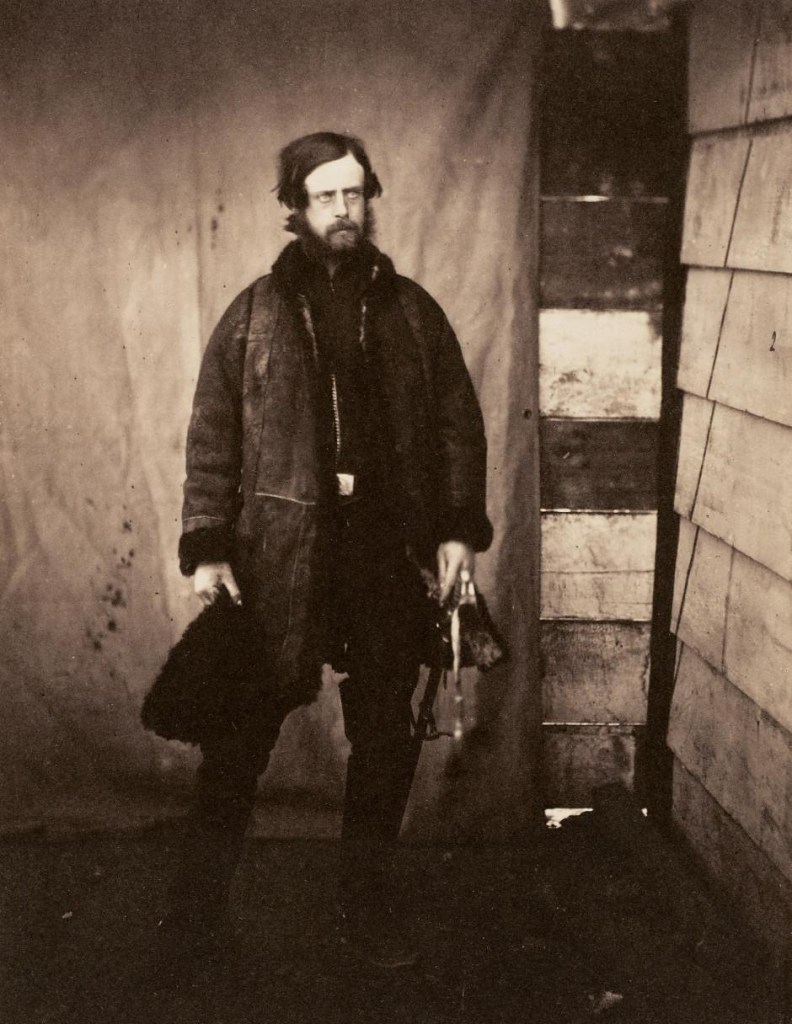

Roger Fenton (British, 28 March 1819 – 8 August 1869)

Group of Croat Chiefs

1855

Salted paper print from a glass plate negative

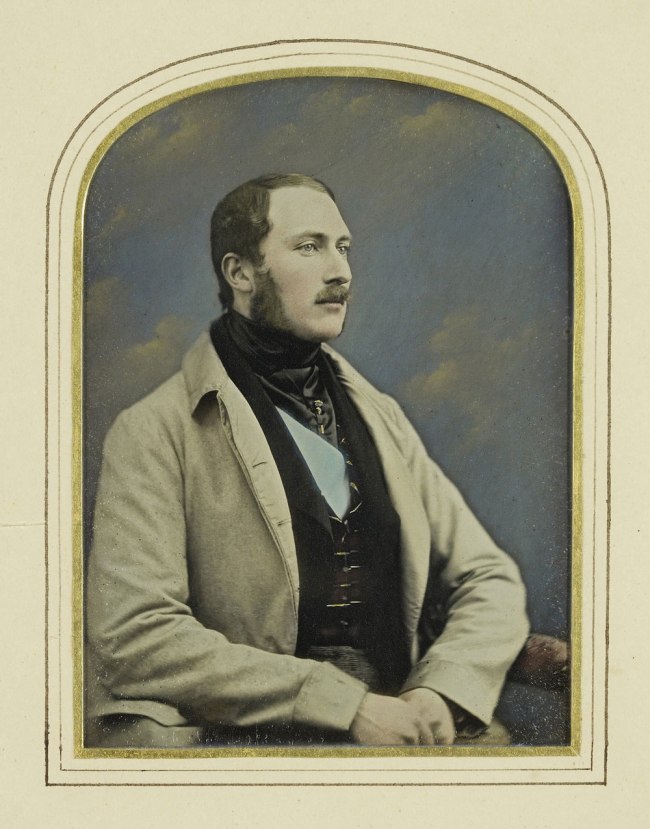

Roger Fenton (British, 28 March 1819 – 8 August 1869)

Captain Mottram Andrews, 28th Regiment (1st Staffordshire) Regiment of Foot

1855

Salted paper print from a glass plate negative

© Wilson Centre for Photography

Roger Fenton (British, 28 March 1819 – 8 August 1869)

Cantiniére

1855

Salted paper print from a glass plate negative

© Wilson Centre for Photography

A woman who carries a canteen for soldiers; a vivandière.

Roger Fenton (British, 28 March 1819 – 8 August 1869)

Captain Lord Balgonie, Grenadier Guards

1855

Photograph, salted paper print from a paper negative

Roger Fenton (British, 28 March 1819 – 8 August 1869)

Captain Lord Balgonie, Grenadier Guards

1855

Photograph, salted paper print from a paper negative

If I had to choose a figure it would be the Franco-American, archaeological photographer John Beasly Greene. His career was short and dangerous, he died at 24, but he challenged the trend towards clarity that dominated his field. Instead, he used the limits of the medium – burn-out, shadow, halation and the beautiful grainy texture of the print itself – to explore the poetic ambiguity of Egyptian sites.

This revolutionary photographic process transformed subjects, still lifes, portraits, landscapes and scenes of daily life into images. It brings it’s own luxurious aesthetic, soft textures, matt appearance and deep rich red tones, the variations seen throughout this exhibition is fascinating to observe. It’s also an incredible opportunity to view the original prints in an exhibition format, which has never been done before on a scale like this before.

The process starts with dipping writing paper in a solution of common salt, then partly drying it, coating it with silver nitrate, then drying it again, before applying further coats of silver nitrate, William Henry Fox Talbot pioneered what became known as the salt print and the world’s first photographic print! The specifically soft and luxurious aesthetic became an icon of modern visual language.

The few salt prints that survive are rarely seen due to their fragility. This exhibition is extremely important to recognise this historical process as well as a fantastic opportunity to see the rarest and best up close of early photographs of this type in the world.

Anon. “Salt and Silver: Early Photography 1840-1860,” on the Films not dead website [Online] Cited 03/06/2015. No longer available online. Used under fair use conditions for the purposes of education and research

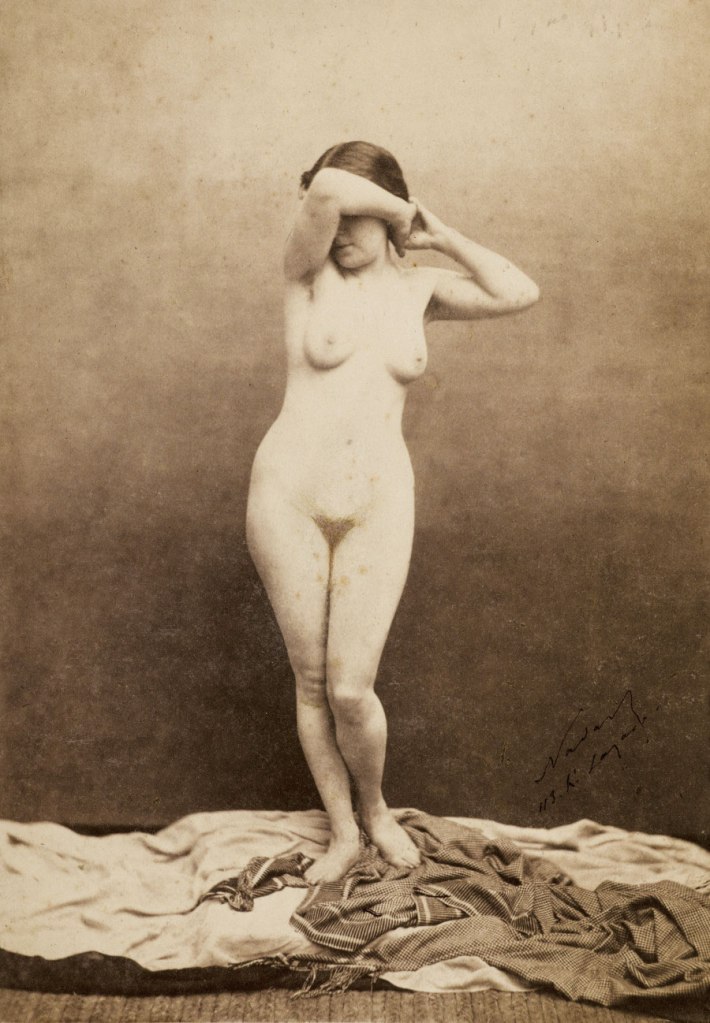

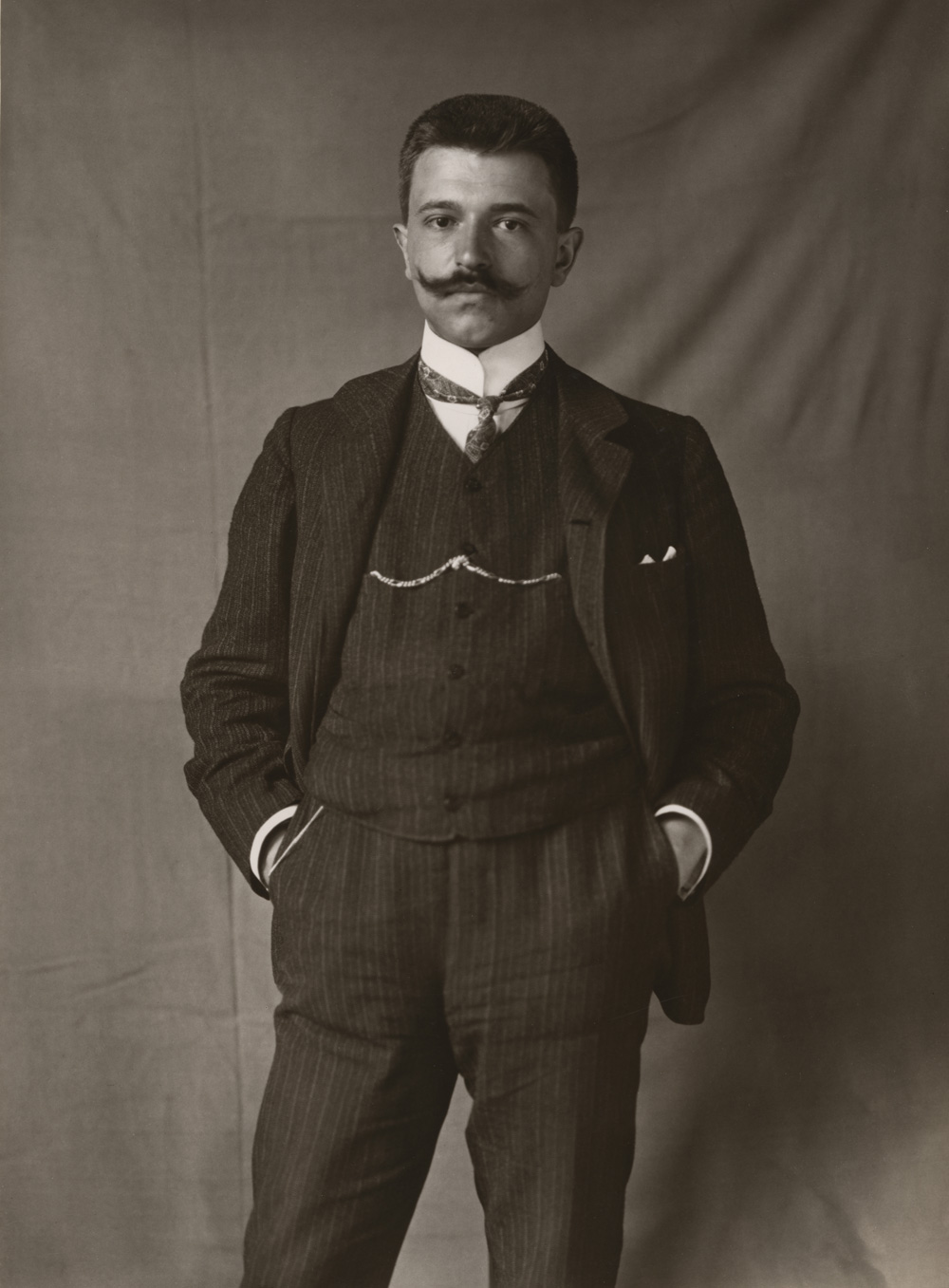

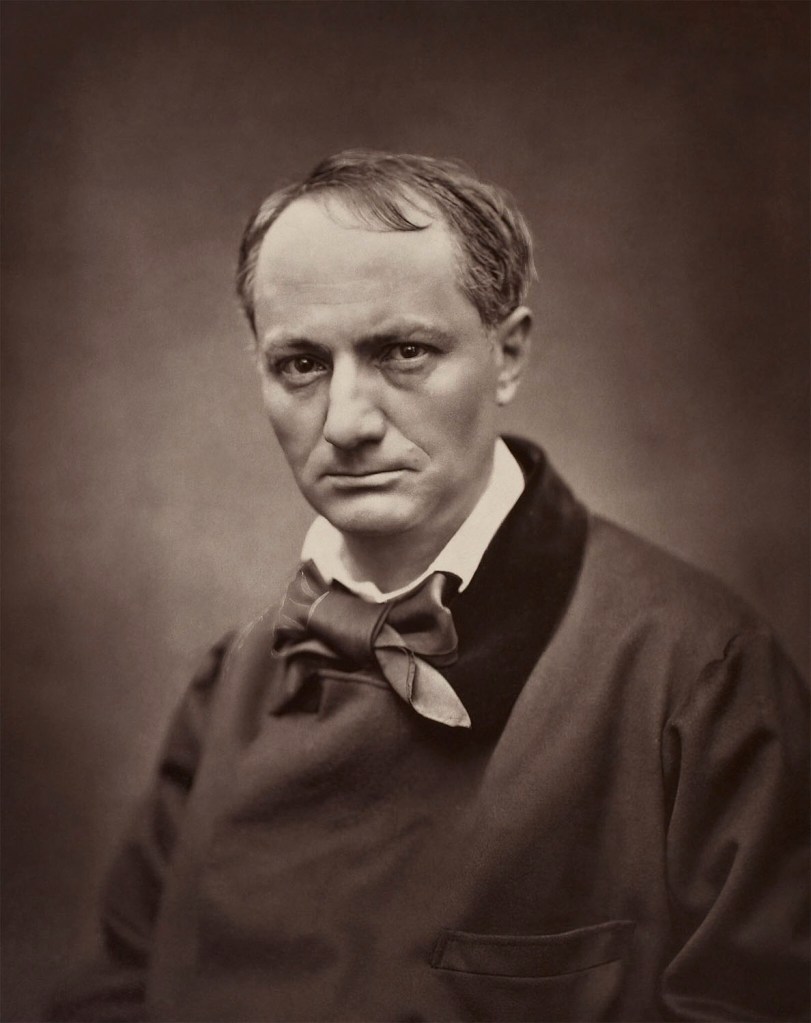

Félix Nadar (Gaspard Félix Tournachon) (French, 6 April 1820 – 23 March 1910)

Mariette

c. 1855

Photograph, salted paper print from a glass plate negative

© Wilson Centre for Photography

Tournachon’s nickname, Nadar, derived from youthful slang, but became his professional signature and the name by which he is best known today. Poor but talented, Nadar began by scratching out a living as a freelance writer and caricaturist. His writings and illustrations made him famous before he began to photograph. His keenly honed camera eye came from his successful career as a satirical cartoonist, in which the identifying characteristic of a subject was reduced to a single distinct facet; that skill proved effective in capturing the personality of his photographic subjects.

Nadar opened his first photography studio in 1854, but he only practiced for six years. He focused on the psychological elements of photography, aiming to reveal the moral personalities of his sitters rather than make attractive portraits. Bust- or half-length poses, solid backdrops, dramatic lighting, fine sculpturing, and concentration on the face were trademarks of his studio. His use of eight-by-ten-inch glass-plate negatives, which were significantly larger than the popular sizes of daguerreotypes, accentuated those effects.

At one point, a commentator said, “[a]ll the outstanding figures of [the] era – literary, artistic, dramatic, political, intellectual – have filed through his studio.” In most instances these subjects were Nadar’s friends and acquaintances. His curiosity led him beyond the studio into such uncharted locales as the catacombs, which he was one of the first persons to photograph using artificial light.

Text from the Getty Museum website. For more information on this artist please see the MoMA website.

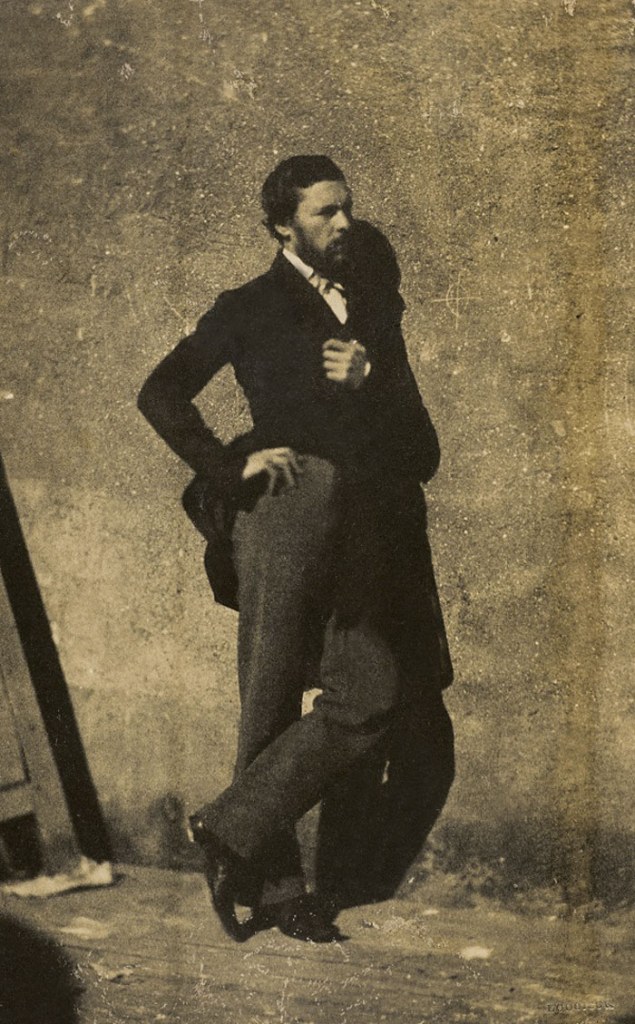

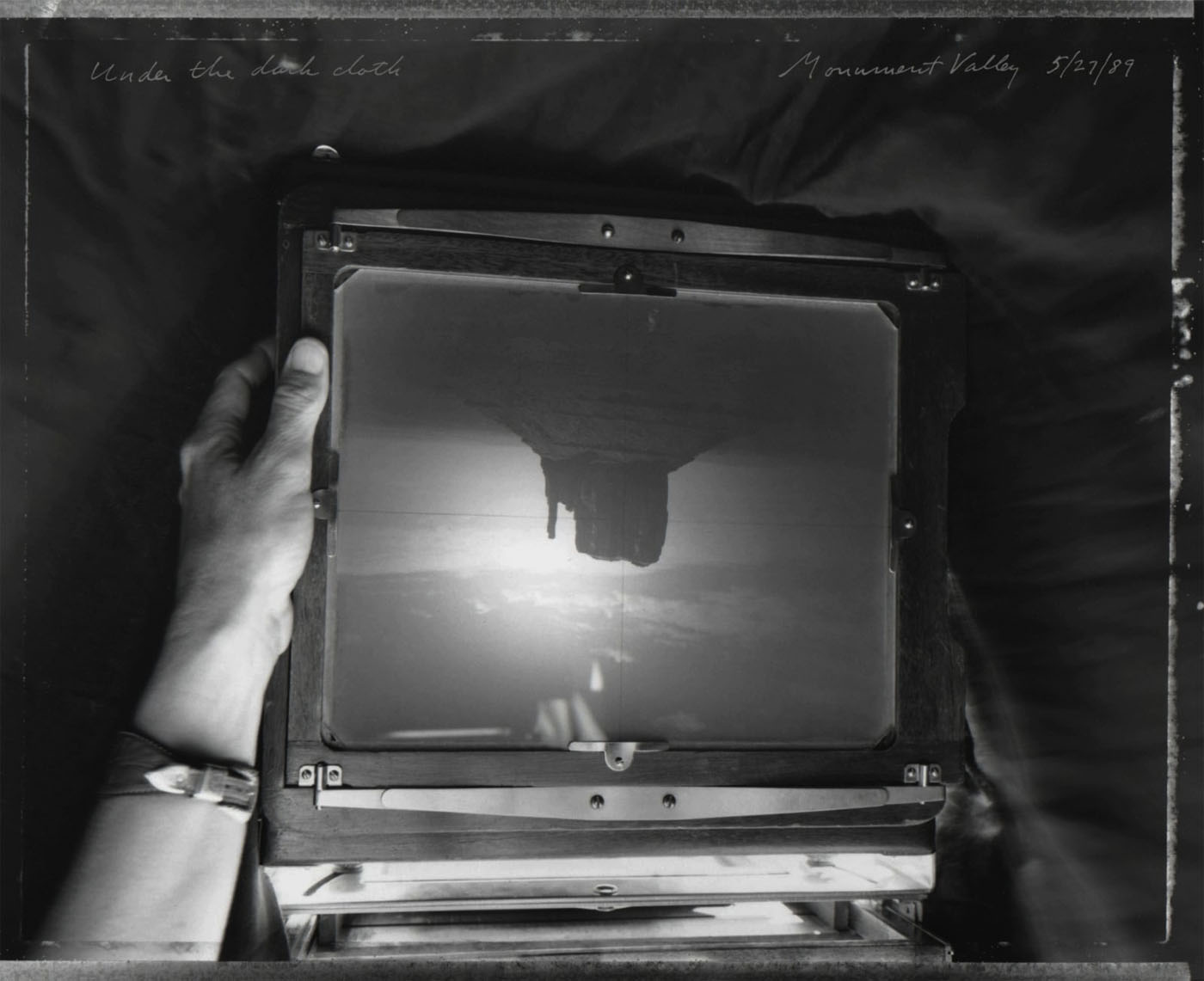

Lodoisch Crette Romet (1823-1872)

A Lesson of Gustave Le Gray in His Studio [Antoine-Emile Plassan]

1850-1853

24.2 x 17.7cm

Photograph, salted paper print from a paper negative

Jean-Baptiste Frénet (French – Lyon, 31 January 1814 – Charly, 12 August 1889)

Women and girls with a doll

c. 1855

© Wilson Centre for Photography

![John S. Johnston (American, c. 1839 - December 17, 1899) 'One of Dr Kane’s Men [possibly William Morton]' c. 1857 John S. Johnston (American, c. 1839 - December 17, 1899) 'One of Dr Kane’s Men [possibly William Morton]' c. 1857](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/john-s-johnston-one-of-dr-kanes-men-possibly-william-morton-c-1857-web.jpg?w=713)

John S. Johnston (American, c. 1839 – December 17, 1899)

One of Dr Kane’s Men [possibly William Morton]

c. 1857

John S. Johnston was a late 19th-century maritime and landscape photographer. He is known for his photographs of racing yachts and New York City landmarks and cityscapes. Very little is known about his life. He was evidently born in Britain in the late 1830s, and was active in the New York City area in the late 1880s and 1890s. He died in 1899.

William Morton

“Belief in the Open Polar Sea theory subsided until the mid-1800s, when Elisha Kent Kane set forth on a number of expeditions north with hopes of finding this theorised body of water. On an 1850s expedition organised by Kane, explorer William Morton, believing he discovered the Open Polar Sea, described a body of water containing…

“Not a speck of ice… As far as I could discern, the sea was open… The wind was due N(orth) – enough to make white caps, and the surf broke in on the rocks in regular breakers.”

Morton, however, did not find the Open Polar Sea – he found a small oasis of water. Morton’s quote is likely tinged with a desire to raise the spirits of his boss, Kane, who saw the Polar Sea as a possible utopia, an area brimming with life amidst a harsh arctic world.”

Keith Veronese. “The Open Polar Sea, a balmy aquatic Eden at the North Pole?” on the Gizmodo website 4/20/12 [Online] Cited 03/06/2015. Used under fair use conditions for the purposes of education and research

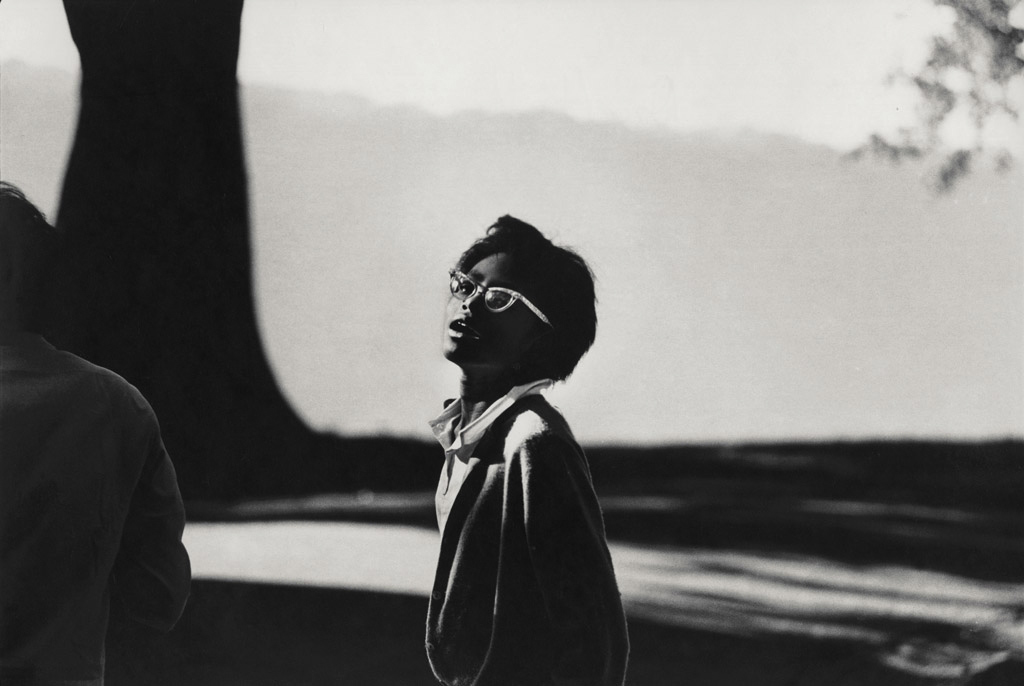

David Hill (Scottish, 1802-1870) and Robert Adamson (Scottish, 1821-1848)

Thought to be Elizabeth Rigby

c. 1844

Photograph, salted paper print from a paper negative

Jean-Baptiste Frénet (French – Lyon, 31 January 1814 – Charly, 12 August 1889)

Thought to be a Mother and Son

c. 1855

Photograph, salted paper print from a collodion negative transferred from glass to paper support

William Henry Fox Talbot (British, 11 February 1800 – 17 September 1877)

The Photographer’s Daughter, Ela Theresa Talbot

1843-1844

Roger Fenton (British, 28 March 1819 – 8 August 1869)

Portrait of a Woman

c. 1854

Photograph, salted paper print from a glass plate negative

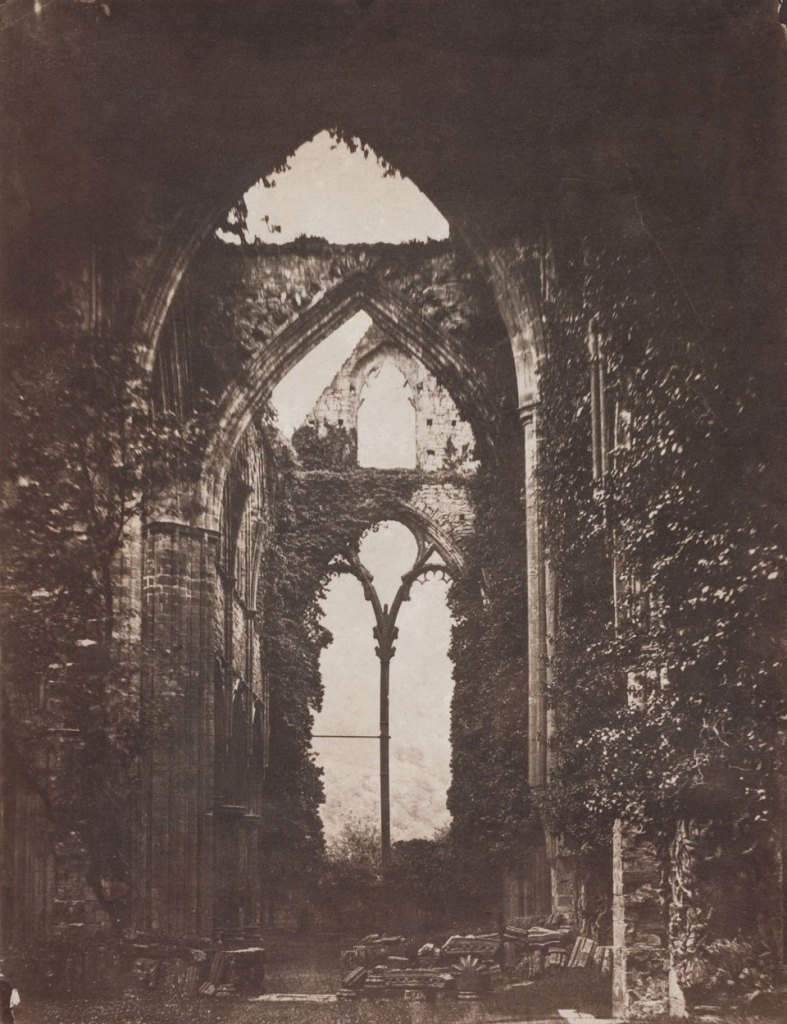

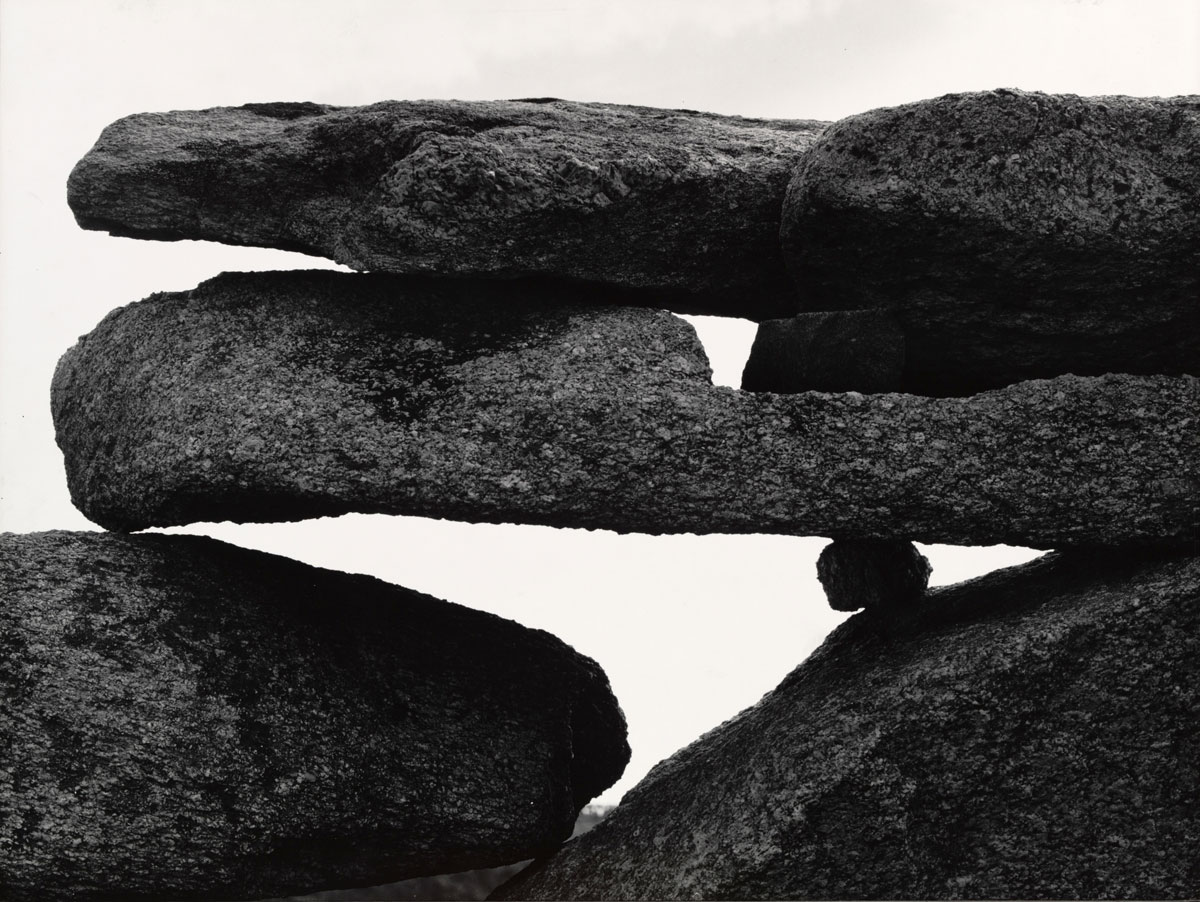

John Wheeley Gough (British, 1809-1862)

Gutch Abbey Ruins

c. 1858

© Wilson Centre for Photography

John Wheeley Gough (British, 1809-1862)

John Wheeley Gough Gutch (1809-1862) was a British surgeon and editor. He was also a keen amateur naturalist and geologist, and a pioneer photographer.

In 1851, Dr. Gutch gave up his medical practice to become a messenger for Queen Victoria, and he began photographing the many cities he visited on his diplomatic missions. During a trip to Constantinople, he became seriously ill, resulting in permanent partial paralysis that ended his public service career. While undergoing experimental treatments in Malvern, England, Dr. Gutch again turned to photography as a cure for his melancholy. His works were exhibited throughout London and Edinburgh from 1856-1861, and he became a frequent contributor to the Photographic Notes publication. Dr. Gutch’s camera of choice was Frederick Scott Archer’s wet-plate camera because he liked the convenience of developing glass negatives within the camera, which eliminated the need for a darkroom. However, the camera proved too cumbersome for him to handle, and had to be manipulated by one of his photographic assistants. His photographs were printed on salt-treated paper and were placed into albums he painstakingly decorated with photographic collages.

Dr. Gutch’s “picturesque” photographic style was influenced by artist William Gilpin. Unlike his mid-nineteenth century British contemporaries who recorded urban expansion, he preferred focusing on ancient buildings, rock formations, archaeological ruins, and tree-lined streams. In 1857, an assignment for Photographic Notes took him to Scotland, northern Wales, and the English Lake District, where he photographed the lush settings, but not always to his satisfaction. Two years’ later, he aspired to photograph and document the more than 500 churches in Gloucestershire, a daunting and quite expensive task. He fitted his camera with a Ross Petzval wide-angle lens and managed to photograph more than 200 churches before illness forced him to abandon the ambitious project. Fifty-three-year-old John Wheeley Gough Gutch died in London on April 30, 1862.

Anonymous text. “John Wheeley Gough Gutch,” on the Historic Camera website Nd [Online] Cited 03/06/2015. Used under fair use conditions for the purposes of education and research

William Henry Fox Talbot (British, 11 February 1800 – 17 September 1877)

The Great Elm at Lacock

1843-1845

Photograph, salted paper print from a paper negative

© Wilson Centre for Photography

Tate Britain

Millbank, London SW1P 4RG

United Kingdom

Phone: +44 20 7887 8888

Opening hours:

10.00am – 18.00pm daily

![David Hill (Scottish, 1802-1870) and Robert Adamson (Scottish, 1821-1848) 'The Gowan [Margaret and Mary Cavendish]' c. 1843-1848 David Hill (Scottish, 1802-1870) and Robert Adamson (Scottish, 1821-1848) 'The Gowan [Margaret and Mary Cavendish]' c. 1843-1848](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/david-hill-and-robert-adamson-the-gowan-margaret-and-mary-cavendish-c-1843-1848-web.jpg)

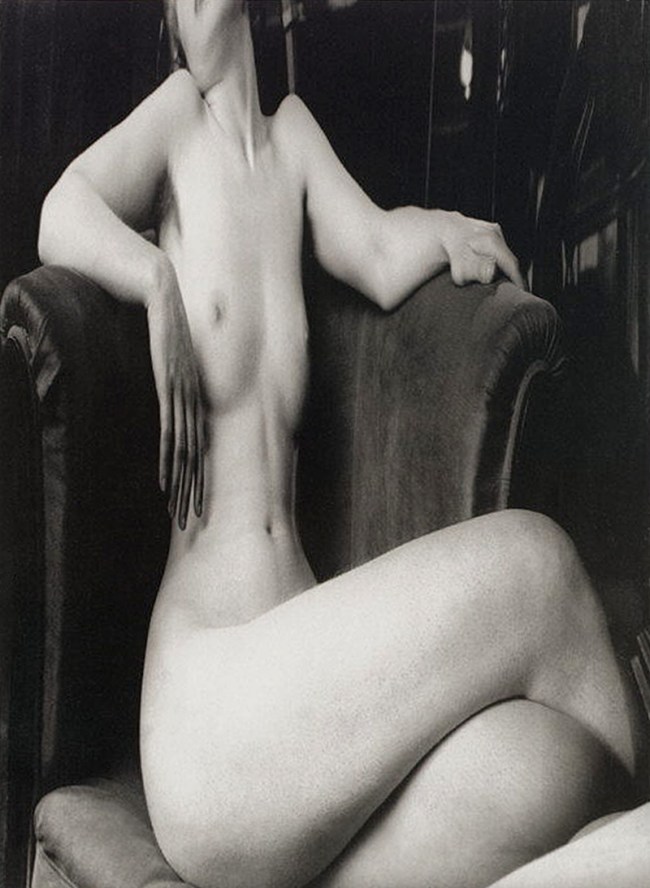

![Franck-François-Genès Chauvassaignes (French, 1831 - after 1900) 'Untitled [Female Nude in Studio]' 1856-1859 Franck-François-Genès Chauvassaignes (French, 1831 - after 1900) 'Untitled [Female Nude in Studio]' 1856-1859](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/chauvassaignes_seated-nude-web.jpg?w=650)

![Félix-Jacques-Antoine Moulin (French, 1800 - after 1875) 'Untitled [Two Standing Female Nudes]' c. 1850 Félix-Jacques-Antoine Moulin (French, 1800 - after 1875) 'Untitled [Two Standing Female Nudes]' c. 1850](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/moulin_two-nudes-standing-web.jpg?w=650)

![Unknown photographer (French) '[Seated Female Nude]' c. 1850 Unknown photographer (French) '[Seated Female Nude]' c. 1850](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/seated-female-nude.jpg)

![Julien Vallou de Villeneuve (French, 1795-1866) '[Standing Female Nude]' c. 1853 Julien Vallou de Villeneuve (French, 1795-1866) '[Standing Female Nude]' c. 1853](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/julien-vallou-de-villeneuve-standing-female-nude.jpg)

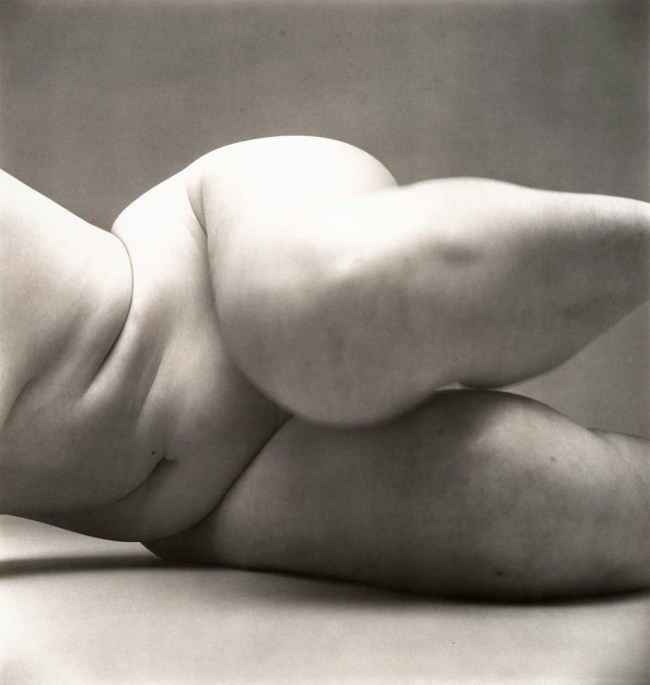

![Eugène Durieu (French, 1800-1874) 'Untitled [Seated Female Nude]' 1853-1854 Eugène Durieu (French, 1800-1874) 'Untitled [Seated Female Nude]' 1853-1854](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/durieu_nude_ph8976-web.jpg?w=650)

![Charles Alphonse Marlé (French, 1821 - after 1867) 'Untitled [Standing Male Nude]' c. 1855 Charles Alphonse Marlé (French, 1821 - after 1867) 'Untitled [Standing Male Nude]' c. 1855](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/marle_standing-male-nude-web.jpg?w=650)

![Nadar (French, Paris 1820 - 1910 Paris) '[Standing Female Nude]' 1860-1861 Nadar (French, Paris 1820 - 1910 Paris) '[Standing Female Nude]' 1860-1861](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/nadar-standing-female-nude.jpg)

![Unknown photographer (French) '[Nude with Mirror]' c. 1850 Unknown photographer (French) '[Nude with Mirror]' c. 1850](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/nude-with-mirror.jpg)

![Julien Vallou de Villeneuve (French, 1795-1866) '[Reclining Female Nude]' c. 1853 Julien Vallou de Villeneuve (French, 1795-1866) '[Reclining Female Nude]' c. 1853](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/julien-vallou-de-villeneuve-reclining-female-nude.jpg)

![Unknown photographer (French) '[Standing Female Nude]' c. 1856 Unknown photographer (French) '[Standing Female Nude]' c. 1856](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/standing-female-nude.jpg)

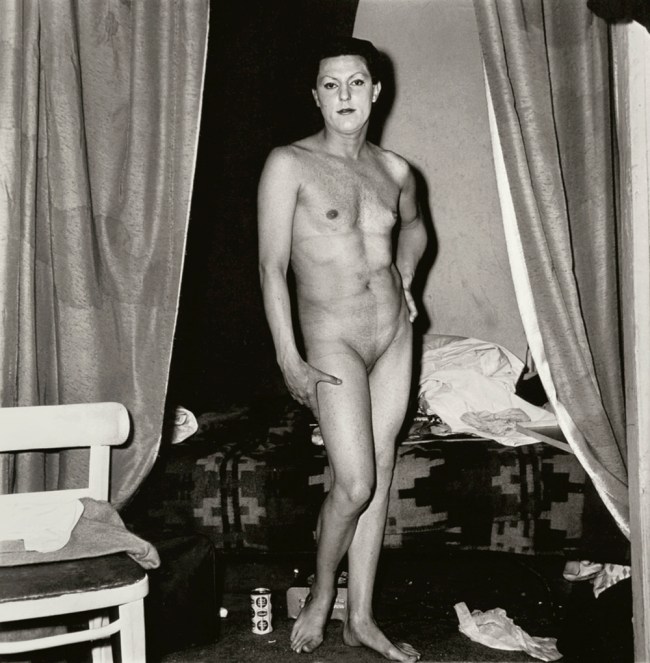

![Unknown photographer (French) '[Standing Male Nude]' c. 1856 Unknown photographer (French) '[Standing Male Nude]' c. 1856](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/standing-male-nude.jpg)

![Unknown photographer (French) '[Female Nude with Mask]' c. 1870 Unknown photographer (French) '[Female Nude with Mask]' c. 1870](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/female-nude-with-mask.jpg)

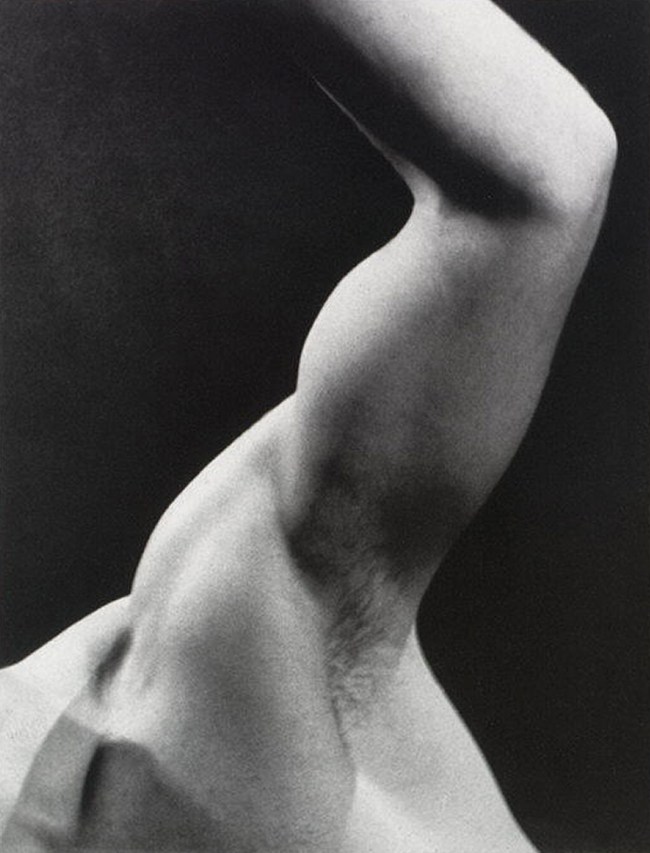

![Albert Londe (French, 1858-1917) Paul Marie Louis Pierre Richer (French, 1849-1933) '[Male Musculature Study]' c. 1890 Albert Londe (French, 1858-1917) Paul Marie Louis Pierre Richer (French, 1849-1933) '[Male Musculature Study]' c. 1890](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/male-study.jpg)

![Guglielmo Plüshow (Italian born Germany, 1852–1930) '[Young Male Nude Seated on Leopard Skin]' 1890s-1900s Guglielmo Plüshow (Italian born Germany, 1852–1930) '[Young Male Nude Seated on Leopard Skin]' 1890s-1900s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/plushow-young-male-nude-seated-on-leopard-skin.jpg)

![Lady Ottoline Violet Anne Cavendish-Bentinck Morrell (British, 1873-1938) '[Cavorting by the Pool at Garsington]' c. 1916 Lady Ottoline Violet Anne Cavendish-Bentinck Morrell (British, 1873-1938) '[Cavorting by the Pool at Garsington]' c. 1916](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/cavendish-bentinck-morrell-cavorting-by-the-pool-at-garsington.jpg)

![Lady Ottoline Violet Anne Cavendish-Bentinck Morrell (British, 1873-1938) '[Cavorting by the Pool at Garsington]' c. 1916 Lady Ottoline Violet Anne Cavendish-Bentinck Morrell (British, 1873-1938) '[Cavorting by the Pool at Garsington]' c. 1916](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/cavendish-bentinck-morrell-cavorting-by-the-pool-at-garsington-a.jpg)

![Edward Weston (American, Highland Park, Illinois 1886 - 1958 Carmel, California) '[Nude]' 1925 Edward Weston (American, Highland Park, Illinois 1886 - 1958 Carmel, California) '[Nude]' 1925](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/weston-nude.jpg)

![George Platt Lynes (American, East Orange, New Jersey 1907–1955 New York) '[Male Nude]' 1930s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/lynes-male-nude-1.jpg)

![Mark Morrisroe (American, 1959-1989) 'Untitled [Two Men in Silhouette]' c. 1987 Mark Morrisroe (American, 1959-1989) 'Untitled [Two Men in Silhouette]' c. 1987](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/16_morrisroe_untitled-web.jpg?w=650)

![Carleton Watkins (American, 1829-1916) '[Solar Eclipse]' January 1, 1889 Carleton Watkins (American, 1829-1916) '[Solar Eclipse]' January 1, 1889](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/carleton-watkins-solar-eclipse.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.