Exhibition dates: 22nd June – 2nd September, 2018

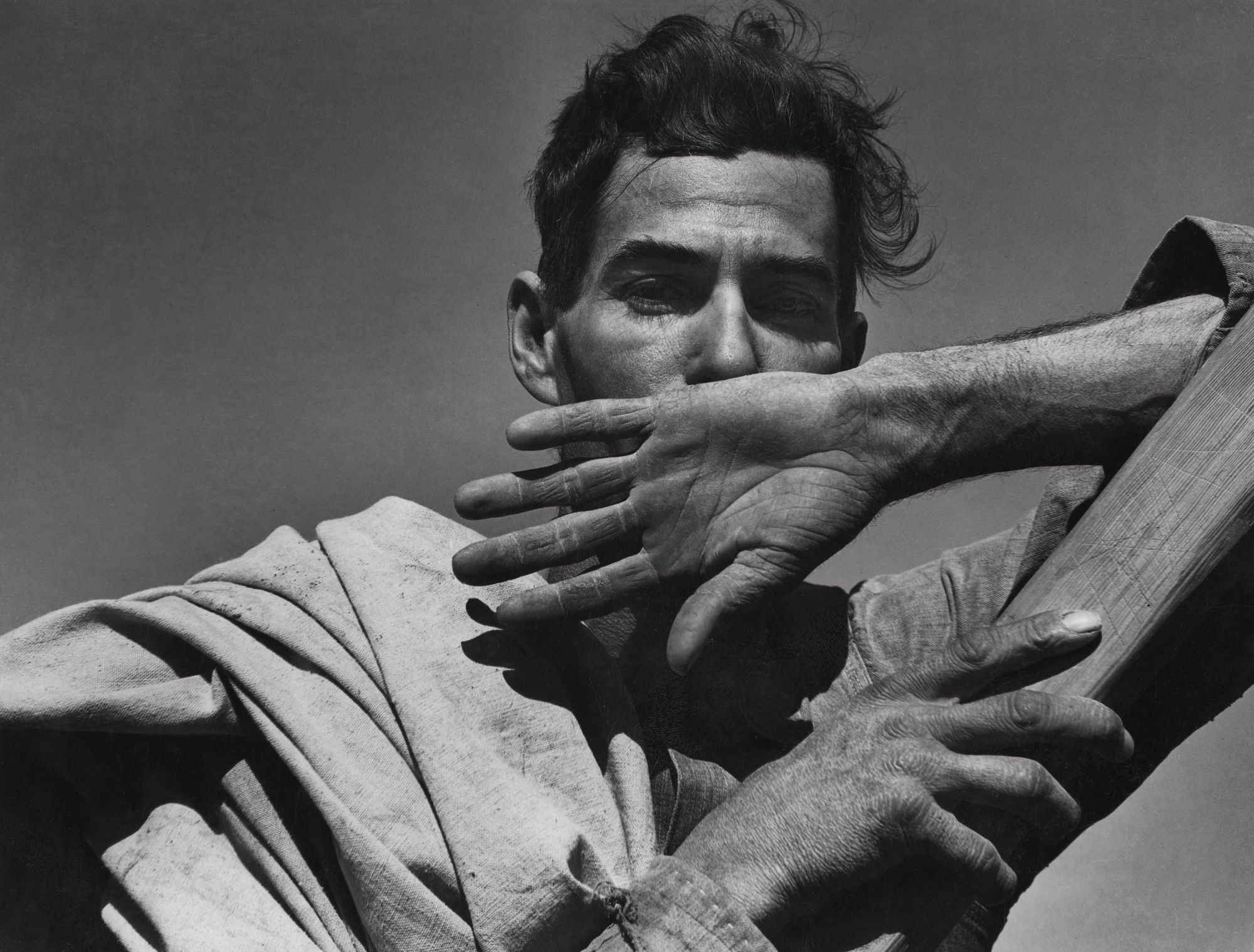

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Migratory Cotton Picker, Eloy, Arizona

1940

Silver gelatin print

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

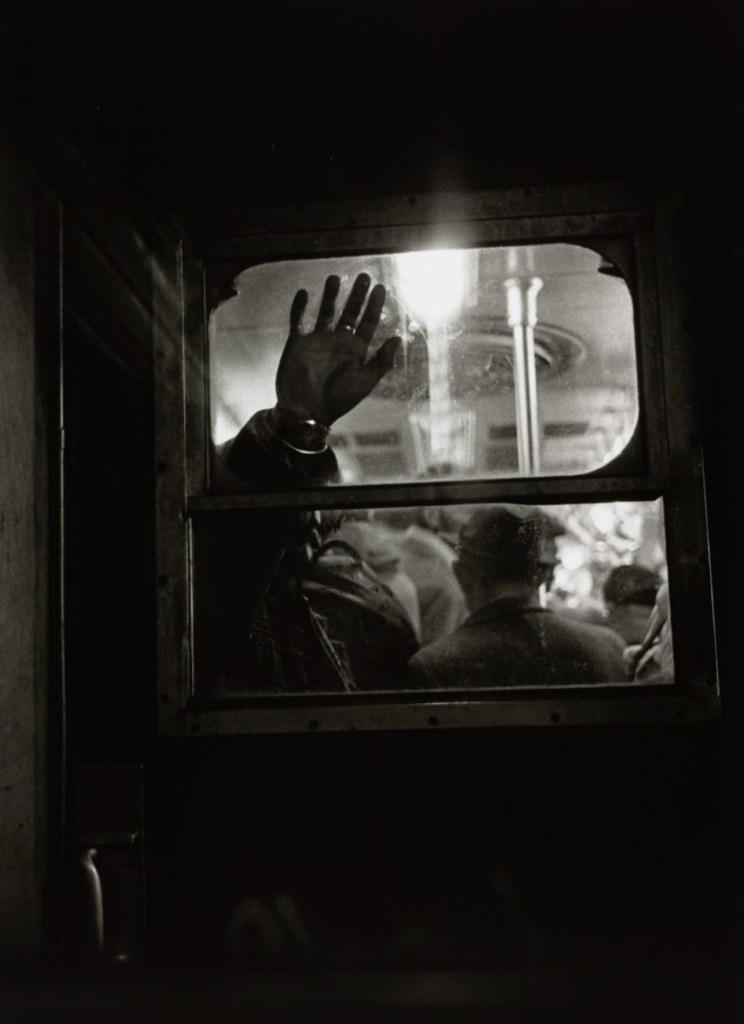

Damaged, desperate and displaced

I am writing this short text on a laptop in Thailand which keeps jumping lines and misspelling words. The experience is almost as disorienting as the photographs of Dorothea Lange, with their anguished angles and portraits of despair. Her humanist, modernist pictures capture the harsh era of The Great Depression and the 1930s in America, allowing a contemporary audience to imagine what it must have been like to walk along blistering roads with five children, not knowing where your next meal or drink of water is coming from.

Like Lewis Hine and Jacob Riis from an earlier era, Lange’s photographs are about the politics of seeing. They are about human beings in distress and how photography can raise awareness of social injustice and disenfranchisement in the name of cultural change.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

#dorothealange @barbicancentre

Many thankx to the Barbican Art Gallery for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California

1936

Silver gelatin print

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

Dorothea Lange took this photograph in 1936, while employed by the U.S. government’s Farm Security Administration (FSA) program, formed during the Great Depression to raise awareness of and provide aid to impoverished farmers. In Nipomo, California, Lange came across Florence Owens Thompson and her children in a camp filled with field workers whose livelihoods were devastated by the failure of the pea crops. Recalling her encounter with Thompson years later, she said, “I saw and approached the hungry and desperate mother, as if drawn by a magnet. I do not remember how I explained my presence or my camera to her, but I do remember she asked me no questions. I made five exposures, working closer and closer from the same direction.”1 One photograph from that shoot, now known as Migrant Mother, was widely circulated to magazines and newspapers and became a symbol of the plight of migrant farm workers during the Great Depression.

As Lange described Thompson’s situation, “She and her children had been living on frozen vegetables from the field and wild birds the children caught. The pea crop had frozen; there was no work. Yet they could not move on, for she had just sold the tires from the car to buy food.”2 However, Thompson later contested Lange’s account. When a reporter interviewed her in the 1970s, she insisted that she and Lange did not speak to each other, nor did she sell the tires of her car. Thompson said that Lange had either confused her for another farmer or embellished what she had understood of her situation in order to make a better story.

Anonymous text. “Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California,” on the MoMA Learning website Nd [Online] Cited 16/02/2022

1/ Dorothea Lange, “The Assignment I’ll Never Forget,” Popular Photography 46 (February, 1960). Reprinted in Photography, Essays and Images, ed. Beaumont Newhall (New York: The Museum of Modern Art), p. 262-265

2/ Dorothea Lange, paraphrased in Karin Becker Ohm, Dorothea Lange and the Documentary Tradition (Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1980), p. 79

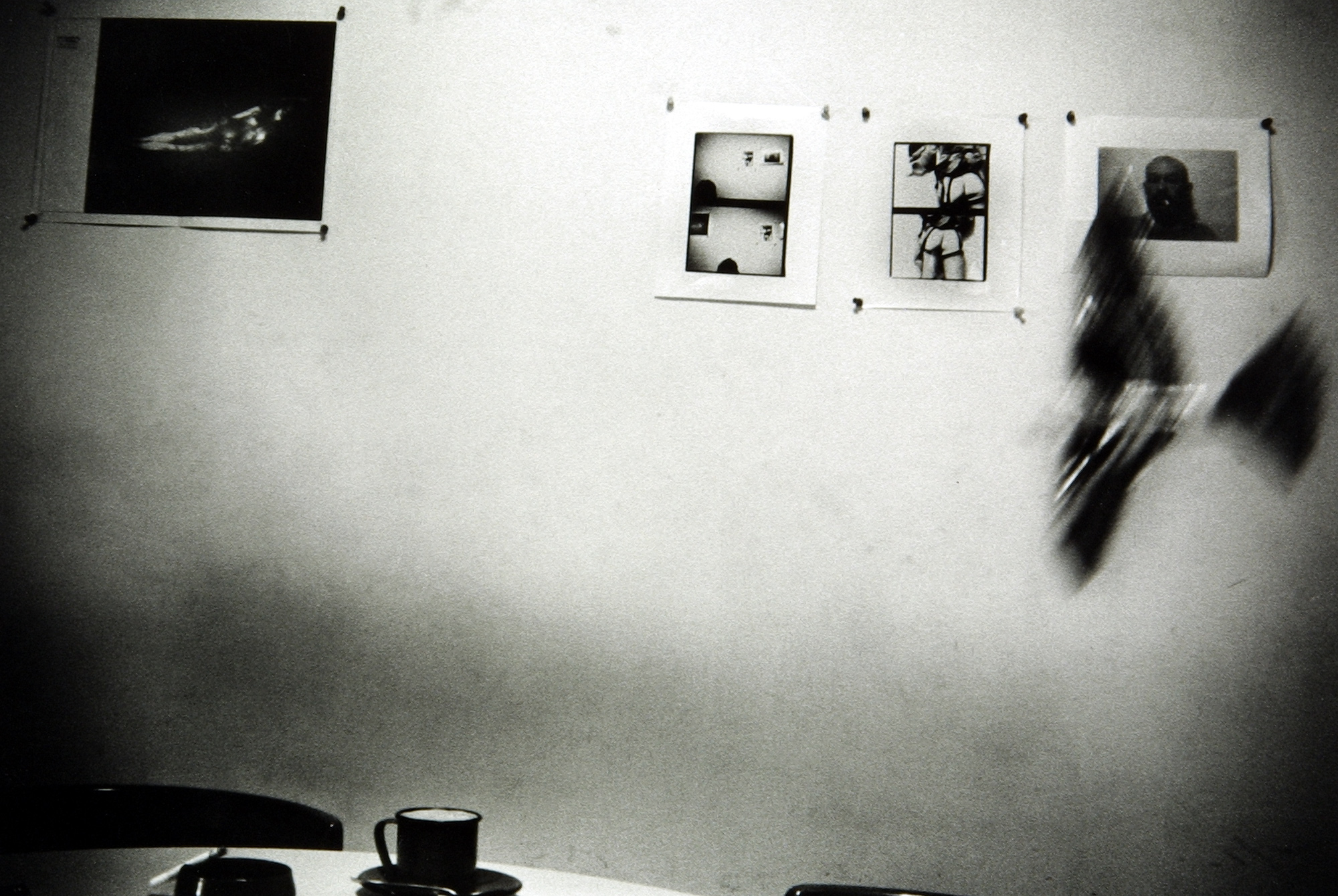

Installation views of the exhibition Dorothea Lange: Politics of Seeing at the Barbican Art Gallery, London showing Dorothea Lange’s photograph Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California 1936

Photos: Ian Gavan/Getty Images for Barbican Art Gallery

“I saw and approached the hungry and desperate mother, as if drawn by a magnet. I do not remember how I explained my presence or my camera to her, but I do remember she asked me no questions. I made five exposures, working closer and closer from the same direction. I did not ask her name or her history. She told me her age, that she was thirty-two. She said that they had been living on frozen vegetables from the surrounding fields, and birds that the children killed. She had just sold the tires from her car to buy food. There she sat in that lean- to tent with her children huddled around her, and seemed to know that my pictures might help her, and so she helped me. There was a sort of equality about it.” (From: Popular Photography, Feb. 1960).

The images were made using a Graflex camera. The original negatives are 4 x 5″ film. It is not possible to determine on the basis of the negative numbers (which were assigned later at the Resettlement Administration) the order in which the photographs were taken.

Hanna Soltys, Reference Librarian, Prints & Photographs Division. “Dorothea Lange’s “Migrant Mother” Photographs in the Farm Security Administration Collection” Photographs in the Farm Security Administration Collection,” on The Library of Congress website 1998 February 19, 2019 [Online] Cited 16/02/2022

Florence Owens Thompson: The Story of the “Migrant Mother” 2014

Thompson’s identity was discovered in the late 1970s; in 1978, acting on a tip, Modesto Bee reporter Emmett Corrigan located Thompson at her mobile home in Space 24 of the Modesto Mobile Village and recognised her from the 40-year-old photograph.[10] A letter Thompson wrote was published in The Modesto Bee and the Associated Press distributed a story headlined “Woman Fighting Mad Over Famous Depression Photo.” Florence was quoted as saying “I wish she [Lange] hadn’t taken my picture. I can’t get a penny out of it, she didn’t ask my name. She said she wouldn’t sell the pictures, she said she’d send me a copy. She never did.”

Lange was funded by the federal government when she took the picture, so the image was in the public domain and Lange never directly received any royalties. However, the picture did help make Lange a celebrity and earned her “respect from her colleagues.”

In a 2008 interview with CNN, Thompson’s daughter Katherine McIntosh recalled how her mother was a “very strong lady”, and “the backbone of our family”, she said: “We never had a lot, but she always made sure we had something. She didn’t eat sometimes, but she made sure us children ate. That’s one thing she did do.”

Anonymous text. “Florence Owens Thompson,” on the WikiVisually website Nd [Online] Cited 05/08/2018. No longer available online

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

White Angel Breadline, San Francisco

1933

Silver gelatin print

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

“There are moments such as these when time stands still and all you do is hold your breath and hope it will wait for you. And you just hope you will have enough time to get it organised in a fraction of a second on that tiny piece of sensitive film. Sometimes you have an inner sense that you have encompassed the thing generally. You know then that you are not taking anything away from anyone: their privacy, their dignity, their wholeness.” ~ Dorothea Lange 1963

Davis K F 1995, The photographs of Dorothea Lange, Hallmark Cards Inc, Missouri p. 20.

White angel breadline, San Francisco is Lange’s first major image that encapsulates both her sense of compassion and ability to structure a photograph according to modernist principles. The diagonals of the fence posts and the massing of hats do not reduce this work to the purely formal – the figure in the front middle of the image acts as a lightening rod for our emotional engagement.

© Art Gallery of New South Wales Photography Collection Handbook, 2007

“I had made some photographs of the state [of] people, in an area of San Francisco which revealed how deep the depression was. It was at that time beginning to cut very deep. This is a long process. It doesn’t happen overnight. Life, for people, begins to crumble on the edges; they don’t realise it…”

Dorothea Lange, interview, 1964

There was a real “White Angel” behind the breadline that served the needy men photographed by Dorothea Lange. She was a widow named Lois Jordan. Mrs. Jordan, who gave herself the name White Angel, established a soup kitchen during the Great Depression to feed those who were unemployed and destitute. Relying solely on donations, she managed to supply meals to more than one million men over a three-year period.

Jordan’s soup kitchen occupied a junk-filled lot in San Francisco located on the Embarcadero near Filbert Street. This area was known as the White Angel Jungle. The Jungle was not far from Lange’s studio. As she began to change direction from portrait to documentary photography, Lange focused her lens on the poignant scenes just beyond her window. White Angel Breadline is the result of her first day’s work to document Depression-era San Francisco. Decades later, Lange recalled: “[White Angel Breadline] is my most famed photograph. I made that on the first day I ever went out in an area where people said, ‘Oh, don’t go there.’ It was the first day that I ever made a photograph on the street.”

Anonymous text. “Dorothea Lange + White Angel Breadline: Meet the master artist through one of her most important works,” on The Kennedy Centre website Nd [Online] Cited 16/02/2022

Dorothea Lange’s Documentary Photographs

Hear Dorothea Lange discuss her photographs and the difficulty of leading a visual life.

Dorothea Lange’s stirring images of migrant farmers and the unemployed have become universally recognised symbols of the Great Depression. Later photographs documenting the internment of Japanese Americans and her travels throughout the world extended her body of work. Watch the video to hear Lange discuss how she began her documentary projects for the Farm Security Administration, and learn how she felt about some of her assignments and subjects.

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Drought Refugees

c. 1935

Silver gelatin print

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Family walking on highway – five children. Started from Idabel, Oklahoma, bound for Krebs, Oklahoma

June 1938

Silver gelatin print

Library of Congress

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Cars on the Road

August 1936

Silver gelatin print

Library of Congress

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Dust Bowl, Grain Elevator, Everett, Texas

June 1938

Silver gelatin print

Library of Congress

This summer, Barbican Art Gallery stages the first ever UK retrospective of one of the most influential female photographers of the 20th century, the American documentary photographer Dorothea Lange (1895-1965). A formidable woman of unparalleled vigour and resilience, the exhibition charts Lange’s outstanding photographic vision from her early studio portraits of San Francisco’s bourgeoisie to her celebrated Farm Security Administration work (1935-1939) that captured the devastating impact of the Great Depression on the American population. Rarely seen photographs of the internment of Japanese-Americans during the Second World War are also presented as well as the later collaborations with fellow photographers Ansel Adams and Pirkle Jones documenting the changing face of the social and physical landscape of 1950s America. Opening 22 June at Barbican Art Gallery, Dorothea Lange: Politics of Seeing is part of the Barbican’s 2018 season, The Art of Change, which explores how the arts respond to, reflect and potentially effect change in the social and political landscape.

Dorothea Lange: Politics of Seeing encompasses over 300 objects from vintage prints and original book publications to ephemera, field notes, letters, and documentary film. Largely chronological, the exhibition presents eight series in Lange’s oeuvre spanning from 1919 to 1957.

Jane Alison, Head of Visual Arts, Barbican, said: “This is an incredible opportunity for our visitors to see the first UK survey of the work of such a significant photographer. Dorothea Lange is undoubtedly one of the great photographers of the twentieth century and the issues raised through her work have powerful resonance with issues we’re facing in society today. Staged alongside contemporary photographer Vanessa Winship as part of The Art of Change, these two shows are unmissable.”

Opening the exhibition are Lange’s little known early portrait photographs taken during her time running a successful portrait studio in San Francisco between 1919 and 1935. Lange was at the heart of San Francisco’s creative community and her studio became a centre in which bohemian and artistic friends gathered after hours, including Edward Weston, Anne Brigman, Alma Lavenson, Imogen Cunningham, and Willard van Dyke. Works from this period include intimate portraits of wealthy West Coast families as well as of Lange’s inner circle, counting amongst others photographer Roi Partridge and painter Maynard Dixon, Lange’s first husband and father of her two sons.

The Great Depression in the early 1930s heralded a shift in her photographic language as she felt increasingly compelled to document the changes visible on the streets of San Francisco. Taking her camera out of the studio, she captured street demonstrations, unemployed workers, and breadline queues. These early explorations of her social documentary work are also on display.

The exhibition charts Lange’s work with the newly established historical division of the Farm Security Administration (FSA), the government agency tasked with the promotion of Roosevelt’s New Deal programme. Alongside Lange, the FSA employed a number of photographers, including Walker Evans, Ben Shahn and Arthur Rothstein, to document living conditions across America during the Great Depression: from urban poverty in San Francisco to tenant farmers driven off the land by dust storms and mechanisation in the states of Oklahoma, Arkansas and Texas; the plight of homeless families on the road in search of better livelihoods in the West; and the tragic conditions of migrant workers and camps across California. Lange used her camera as a political tool to critique themes of injustice, inequality, migration and displacement, and to effect government relief.

Highlights in this section are, among others, a series on sharecroppers in the Deep South that exposes relations of race and power, and the iconic Migrant Mother, a photograph which has become a symbol of the Great Depression, alongside images of vernacular architecture and landscapes, motifs often overlooked within Lange’s oeuvre. Vintage prints in the exhibition are complemented by the display of original publications from the 1930s to foreground the widespread use of Lange’s FSA photographs and her influence on authors including John Steinbeck, whose ground-breaking novel The Grapes of Wrath was informed by Lange’s photographs. Travelling for many months at a time and working in the field, she collaborated extensively with her second husband Paul Schuster Taylor, a prominent social economist and expert in farm labour with whom she published the seminal photo book An American Exodus: A Record of Human Erosion in 1939, also on display in the exhibition.

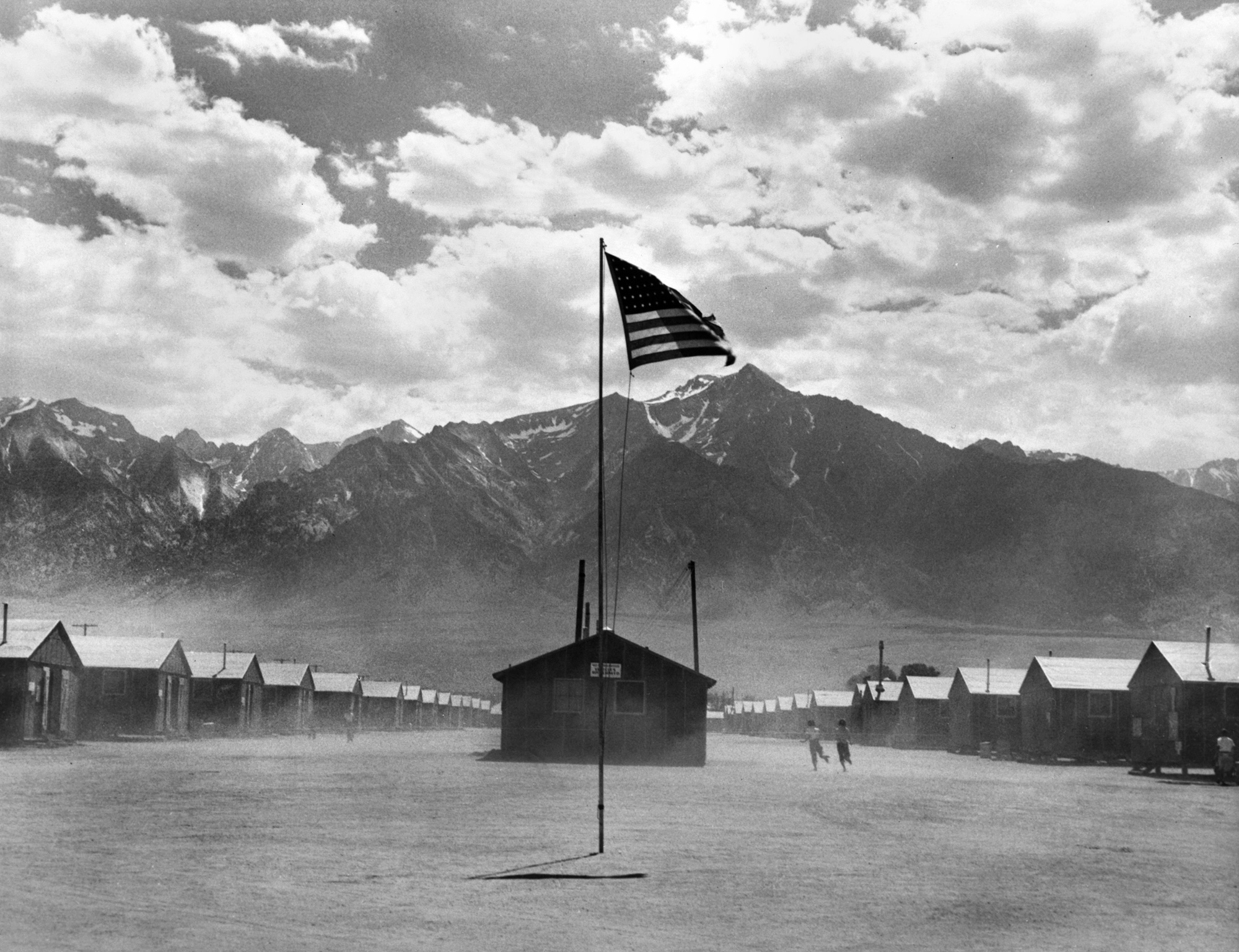

The exhibition continues with rarely seen photographs of the internment of more than 100,000 American citizens of Japanese descent that Lange produced on commission for the War Relocation Authority following the Japanese attack on the American naval base at Pearl Harbor in 1941. Lange’s critical perspective of this little discussed chapter in US history however meant that her photographs remained unpublished during the war and stored at the National Archives in Washington. It is the first time that this series will be shown comprehensively outside of the US and Canada.

Following her documentation of the Japanese American internment, Lange produced a photographic series of the wartime shipyards of Richmond, California with friend and fellow photographer Ansel Adams (1902-1984). Lange and Adams documented the war effort in the shipyards for Fortune magazine in 1944, recording the explosive increase in population numbers and the endlessly changing shifts of shipyard workers. Capturing the mass recruitment of workers, Lange turned her camera on both female and black workers, for the first time part of the workforce, and their defiance of sexist and racist attitudes.

The exhibition features several of Lange’s post-war series, when she photographed extensively in California. Her series Public Defender (1955-1957) explores the US legal defence system for the poor and disadvantaged through the work of a public defender at the Alameda County Courthouse in Oakland. Death of a Valley (1956-1957), made in collaboration with photographer Pirkle Jones, documents the disappearance of the small rural town of Monticello in California’s Berryessa Valley as a consequence of the damming of the Putah Creek. Capturing the destruction of a landscape and traditional way of life, the photographs testify to Lange’s environmentalist politics and have not been displayed or published since the 1960s.

The exhibition concludes with Lange’s series of Ireland (1954), the first made outside the US. Spending six weeks in County Clare in western Ireland, Lange captured the experience of life in and around the farming town of Ennis in stark and evocative photographs that symbolise Lange’s attraction to the traditional life of rural communities.

An activist, feminist and environmentalist, Lange used her camera as a political tool to critique themes of injustice, inequality, migration and displacement that bear great resonance with today’s world, a prime example of which is her most iconic image the Migrant Mother (1936). Working in urban and rural contexts across America and beyond, she focused her lens on human suffering and hardship to create compassionate and piercing portraits of people as well as place in the hope to forge social and political reform – from the plight of sharecroppers in the Deep South to Dust Bowl refugees trekking along the highways of California in search of better livelihoods.

Dorothea Lange: Politics of Seeing is organised by the Oakland Museum of California. The European presentation has been produced in collaboration with Barbican Art Gallery, London and Jeu de Paume, Paris.

Press release from the Barbican Art Gallery

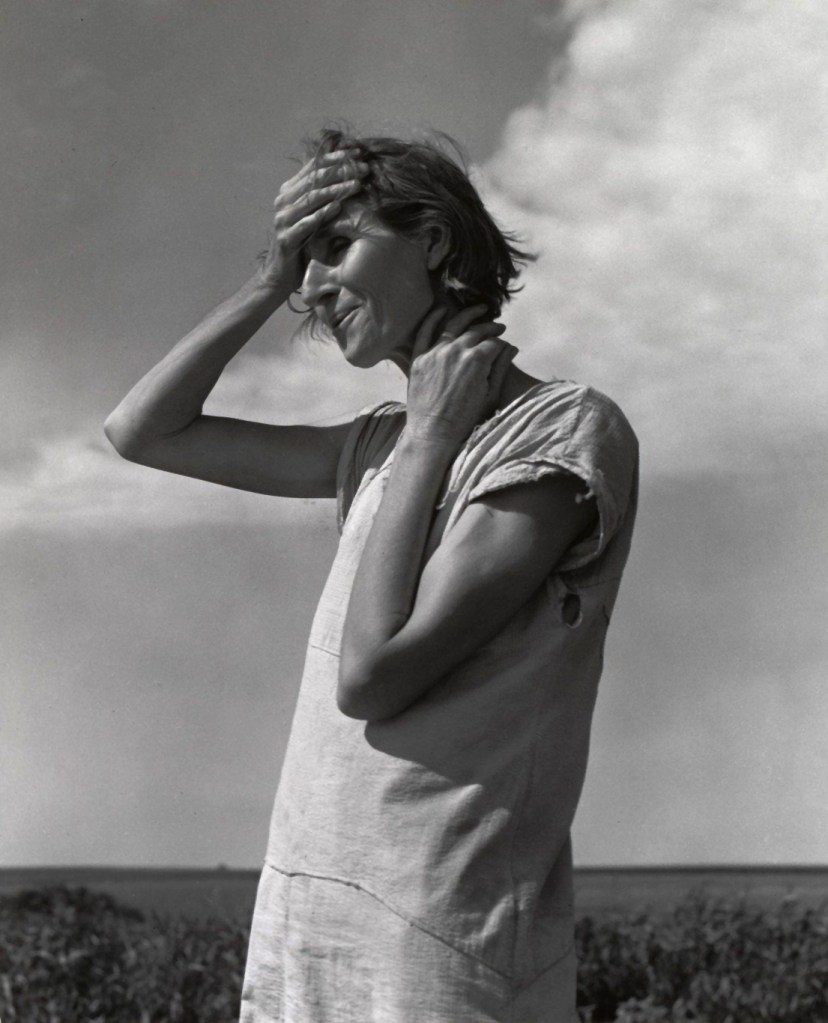

Installation views of the exhibition Dorothea Lange: Politics of Seeing at the Barbican Art Gallery, London showing in the bottom image at left, Lange’s Displaced Tennant Farmers, Goodlet, Hardeman Co., Texas 1937. ‘All displaced tenant farmers, the oldest 33. None able to vote because of Texas poll tax. They support an average of four persons each on $22.80 a month’; and at second left, Woman of the High Plains, Texas Panhandle June 1938 (below)

Photos: Ian Gavan/Getty Images for Barbican Art Gallery

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Woman of the High Plains, Texas Panhandle

June 1938

Silver gelatin print

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

Gift of Paul S. Taylor

Installation view of the exhibition Dorothea Lange: Politics of Seeing at the Barbican Art Gallery, London showing at second left top, Lange’s Mexican field labourer at station in Sacramento after 5 day trip from Mexico City. Imported by arrangements between Mexican and US governments to work in sugar beets. 6 October 1942; at second left bottom, Filipino Field Worker, Spring Plowing, Cauliflower Fields, Guadalupe, California. March 1937 (below); and at right, Damaged Child, Shacktown, Elm Grove, Oklahoma. 1936 (below)

Photos: Ian Gavan/Getty Images for Barbican Art Gallery

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Filipino Field Worker, Spring Plowing, Cauliflower Fields, Guadalupe, California

March 1937

Silver gelatin print

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

Gift of Paul S. Taylor

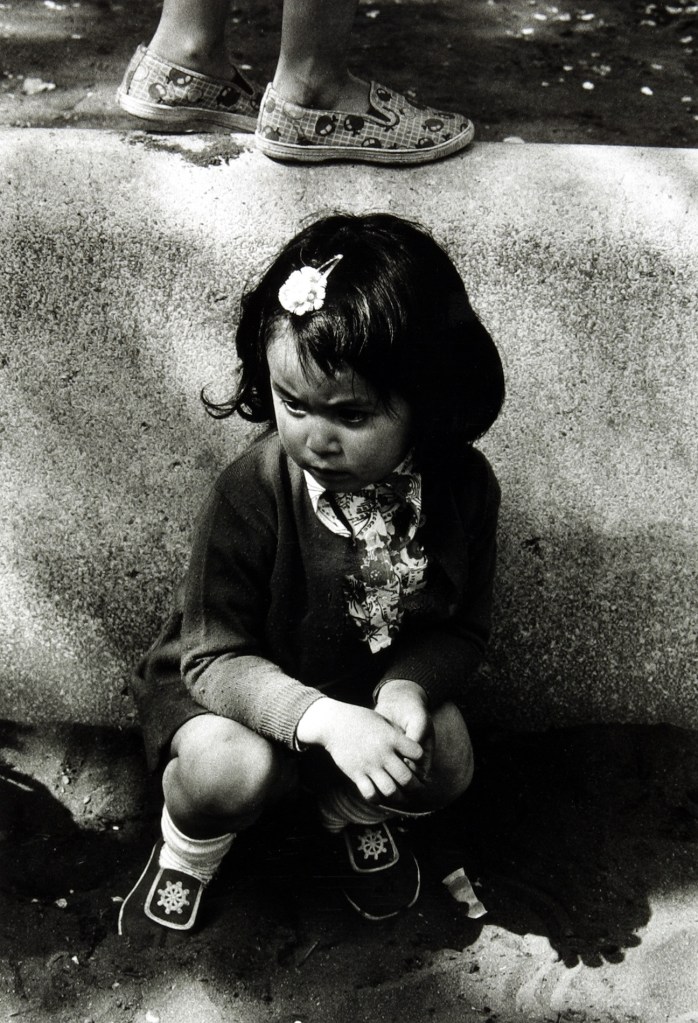

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Damaged Child, Shacktown, Elm Grove, Oklahoma

1936

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland

Gift of Paul S. Taylor

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

San Francisco, California. Flag of allegiance pledge at Raphael Weill Public School, Geary and Buchanan Streets. Children in families of Japanese ancestry were evacuated with their parents and will be housed for the duration in War Relocation Authority centers where facilities will be provided for them to continue their education

1942

Silver gelatin print

Courtesy National Archives, photo no. 210-G-C122

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Centerville, California. This evacuee stands by her baggage as she waits for evacuation bus. Evacuees of Japanese ancestry will be housed in War Relocation Authority centers for the duration

1942

Silver gelatin print

Courtesy National Archives, photo no. 210-G-C241

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Manzanar Relocation Center, Manzanar, California. An evacuee is shown in the lath house sorting seedlings for transplanting. These plants are year-old seedlings from the Salinas Experiment Station

1942

Silver gelatin print

Courtesy National Archives, photo no. 210-GC737

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Manzanar Relocation Center, Manzanar, California

July 3, 1942

Silver gelatin print

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

Paul S. Taylor (American, 1895-1984)

Dorothea Lange in Texas on the Plains

c. 1935

Silver gelatin print

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Sacramento, California. College students of Japanese ancestry who have been evacuated from Sacramento to the Assembly Center

1942

Silver gelatin print

Courtesy National Archives, photo no. 210-GC471

Installation views of the exhibition Dorothea Lange: Politics of Seeing at the Barbican Art Gallery, London showing in the bottom image, Lange’s photographs of Japanese Americans

Photos: Ian Gavan/Getty Images for Barbican Art Gallery

Installation view of the exhibition Dorothea Lange: Politics of Seeing at the Barbican Art Gallery, London showing Lange’s ‘Shipyards of Richmond’ photographs

Photos: Ian Gavan/Getty Images for Barbican Art Gallery

Boom Town: Shipyards of Richmond

In December 1941 the United States entered the Second World War ushering in a period of economic prosperity triggered by an exponential growth in defence spending. Almost overnight, the city of Richmond, located to the north of Oakland, became one of California’s major shipbuilding hubs producing large merchant vessels used to supply Allied troops.

Lured by the promised of work, the population of the San Francisco Bay Area exploded as men and women flocked to the west in vast numbers, prompting the San Francisco Chronicle to claim that the region was in the grips of a ‘second gold rush’. This huge expansion of population and industry also brought new social pressures as housing and other services were extremely limited. For African American community arriving from the rural South however such shortages were further exacerbated by racial discrimination and segregation.

In collaboration with Ansel Adams (1902-1984), Lange secured a commission from Fortune magazine to document 24-hours in the lives of the shipyard workers. Capturing the ever changing shifts of the round-the-clock shipyard population, Lange focused once again on the substandard living conditions of workers and their families, who were often forced to live in cramped temporary shelters, as well as on the lack of social cohesion.

Drawn to images that transgressed accepted attitudes towards gender and race, Lange settled her lens on African American female welders and stylishly dressed women flaunting their newfound independence and spending power. Creating heroic images of women at work, Lange’s photographs contributed to the archetypal image of ‘Rosie the Riveter’.

Wall text from the exhibition

Installation views of the exhibition Dorothea Lange: Politics of Seeing at the Barbican Art Gallery, London showing in the bottom image, Lange’s ‘Ireland’ photographs

Photos: Ian Gavan/Getty Images for Barbican Art Gallery

“There is no sense of hurry, and there is no sense of want, or wanting, or urge to buy more and more, and of bombardment of new goods and advertising. Just the name of the family over the store … A contented and relaxed people live on this island.

Dorothea Lange

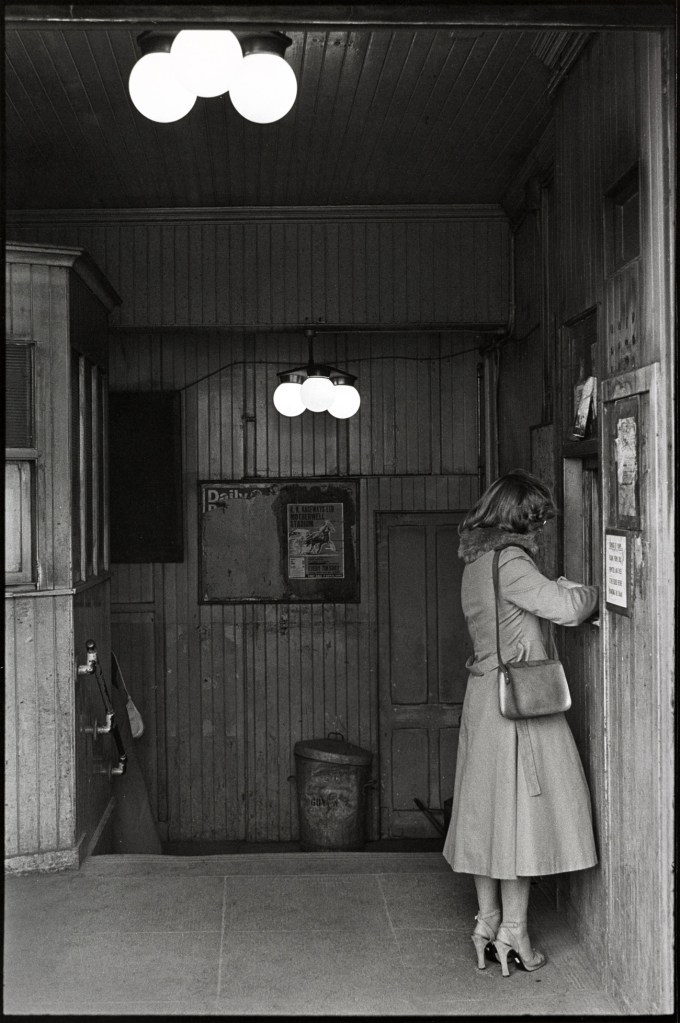

Ireland

Inspired by a book titled The Irish Countryman (1937) the the eminent anthropologist Conrad M. Arensberg, Lange persuaded the editors of LIFE to commission her and her son Daniel Dixon, a writer, to create an in-depth study of rural life in Ireland. The trip was her first overseas, and Lange spent six weeks in the autumn of 1954 photographing the experience of life around County Clare in western Ireland, a poor farming community whose younger inhabitants were flocking to the US in great numbers in the hope of realising the American Dream.

Lange was perhaps drawn to these tight-knit, rural communities because they symbolised a simpler, more self-sufficient way of life in contrast to the post-industrial thrust of the city that reflected her own Californian reality. Steeped in a romantic socialism, Lange’s evocative photographs depict County Clare’s inhabitants by and large as content and carefree in their rootedness to the land, oblivious to the seismic global changes taking place around them.

Travelling around the countryside from Tubber to Ennis, Lange captured country markets and fairs, pubs, local shops, and church-goers attending mass on the ‘island of the devout’, as LIFE later dubbed the country. The magazine published her story with 21 photographs in the 21 March 1955 issue, but largely omitted Dixon’s text.

Wall text from the exhibition

Barbican Art Gallery

Barbican Centre

Silk Street, London, EC2Y 8DS

Opening hours:

Sat – Wed 10am – 6pm (last entry 5pm)

Thu – Fri 10am – 8pm (last entry 7pm)

Bank Holidays 12 – 6pm (last entry 5pm)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of Indigenous Brazilian tradeswoman]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of Indigenous Brazilian tradeswoman]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women14-web.jpg?w=748)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) 'Mullatin [Portrait of a Indigenous Brazilian woman wearing a cross]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) 'Mullatin [Portrait of a Indigenous Brazilian woman wearing a cross]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women1-web.jpg?w=698)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) 'Mestize [Portrait of a Brazilian woman]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) 'Mestize [Portrait of a Brazilian woman]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women2-web.jpg?w=717)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of Indigenous Brazilian tradeswoman]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of Indigenous Brazilian tradeswoman]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women15-web.jpg?w=614)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of Indigenous Brazilian tradeswoman]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of Indigenous Brazilian tradeswoman]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women12-web.jpg?w=661)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of a maid holding an embroidered cloth]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of a maid holding an embroidered cloth]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women13-web.jpg?w=690)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of wet nurse with infant]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of wet nurse with infant]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women11-web.jpg?w=677)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of Indigenous Brazilian tradeswoman]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of Indigenous Brazilian tradeswoman]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women3-web.jpg?w=717)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) 'Hermann Kummler (compiler) (1863-1949) '[Kellnerinnen im Grand Hotel / Waitresses in Grand Hotel]' 1861-1862' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) 'Hermann Kummler (compiler) (1863-1949) '[Kellnerinnen im Grand Hotel / Waitresses in Grand Hotel]' 1861-1862' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women6-web.jpg?w=725)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Lehrerin mit Schülerin im Bahia / Teacher with a schoolgirl in Bahia]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Lehrerin mit Schülerin im Bahia / Teacher with a schoolgirl in Bahia]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women4-web.jpg?w=688)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Native Brazilian lady-in-waiting and young child attend to a veiled aristocrat]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Native Brazilian lady-in-waiting and young child attend to a veiled aristocrat]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women5-web.jpg?w=785)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Negerin mit dem Knaben in schlechter Stimmung / Negress with a boy in a bad mood]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Negerin mit dem Knaben in schlechter Stimmung / Negress with a boy in a bad mood]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women10-web.jpg?w=694)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of Brazilian woman servant and child]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of Brazilian woman servant and child]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women18-web.jpg?w=666)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of a young Brazilian woman]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of a young Brazilian woman]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women17-web.jpg?w=560)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of a Brazilian woman]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of a Brazilian woman]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women8-web.jpg?w=565)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of a Brazilian woman]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of a Brazilian woman]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women19-web.jpg?w=642)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of a Brazilian woman with two children]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of a Brazilian woman with two children]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women16-web.jpg?w=733)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of a Brazilian mother and child]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of a Brazilian mother and child]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women9-web.jpg?w=525)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Mistress punishing a native child]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Mistress punishing a native child]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women7-web.jpg?w=792)

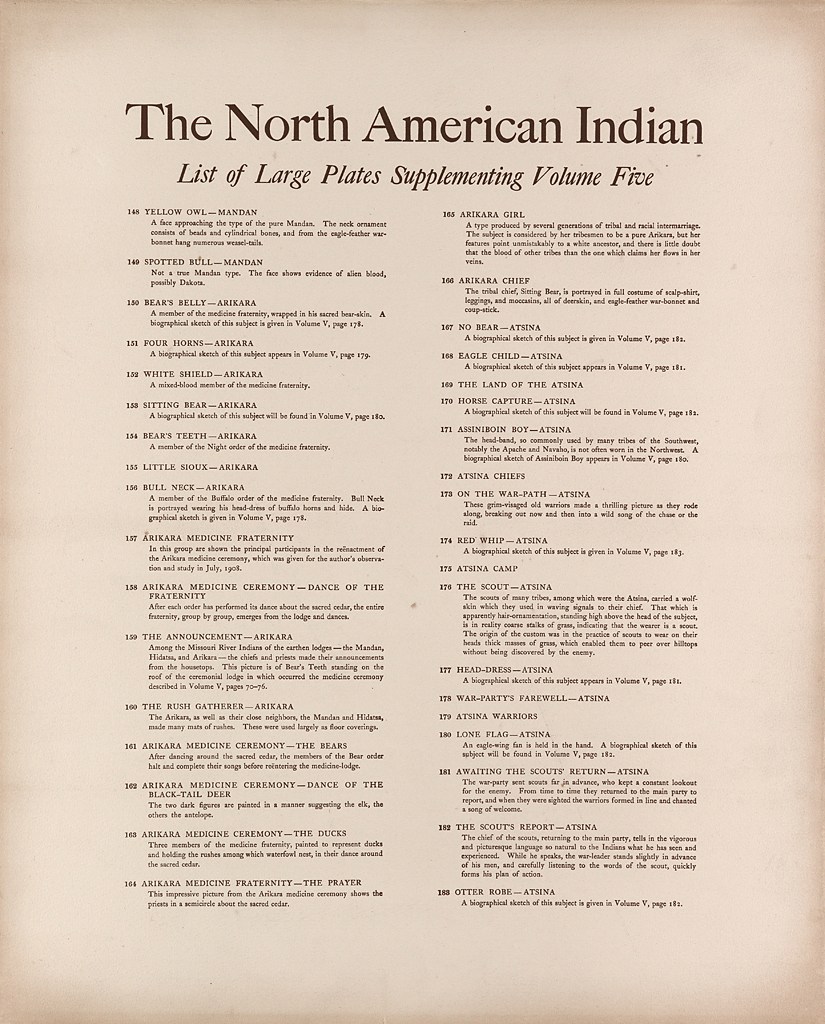

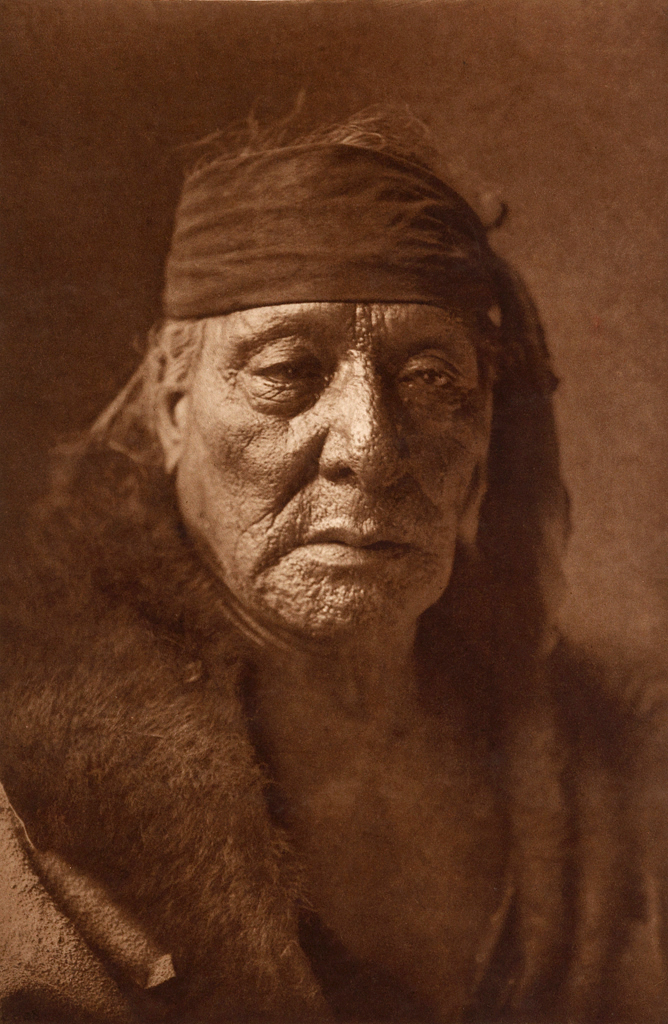

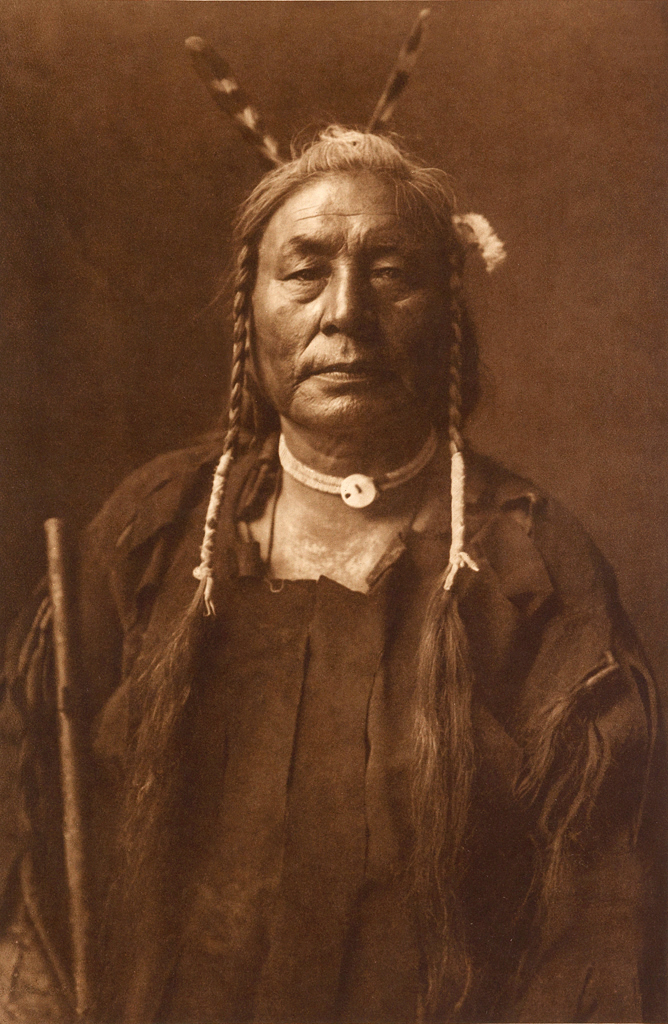

![Edward S. Curtis (American, 1868-1952) '[Bear's Belly, Arikara Indian half-length portrait, facing front, wearing bearskin]' c. 1908 from 'Edward S. Curtis (1868-1952) – The North American Indian' List of Large Plates Supplementing Volume V Edward S. Curtis (American, 1868-1952) '[Bear's Belly, Arikara Indian half-length portrait, facing front, wearing bearskin]' c. 1908 from 'Edward S. Curtis (1868-1952) – The North American Indian' List of Large Plates Supplementing Volume V](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/edward-s-curtis-1868-1952-the-north-american-indian-portfolio-v-1907-photogravure-on-vellum1-web.jpg?w=770)

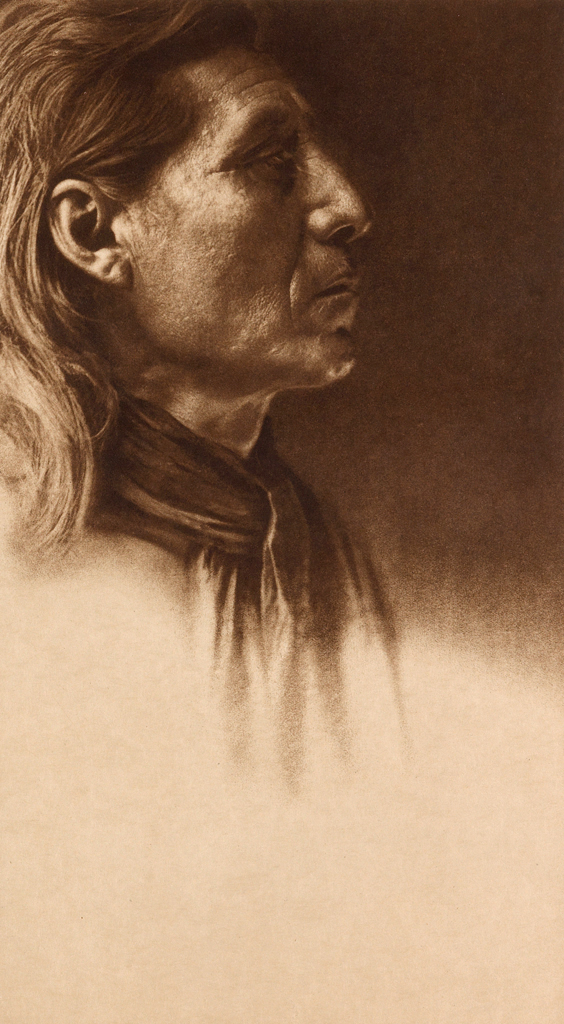

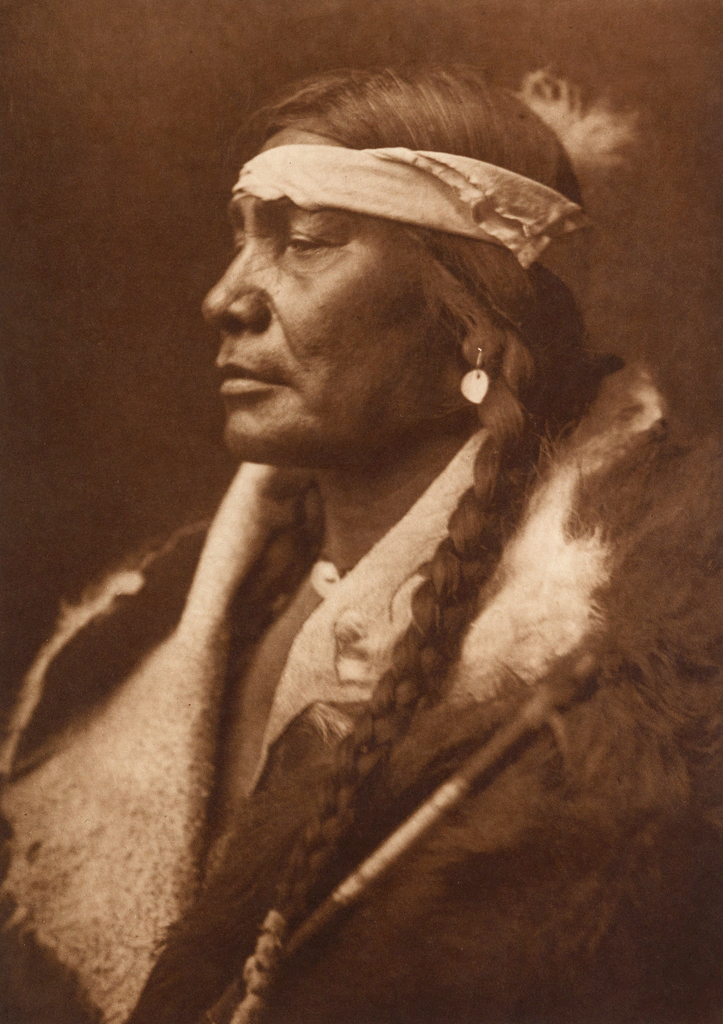

![Edward S. Curtis (American, 1868-1952) '[Arikara medicine ceremony - the Bears]' c. 1908 Edward S. Curtis (American, 1868-1952) '[Arikara medicine ceremony - the Bears]' c. 1908](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/edward-s-curtis-1868-1952-the-north-american-indian-portfolio-v-1907-photogravure-on-vellum6-web.jpg)

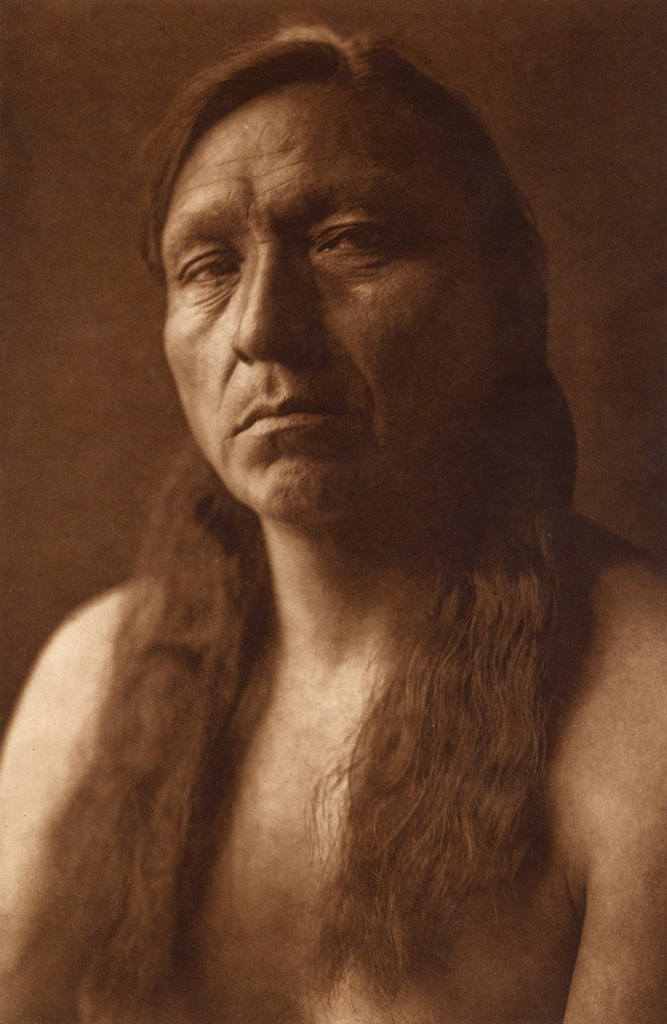

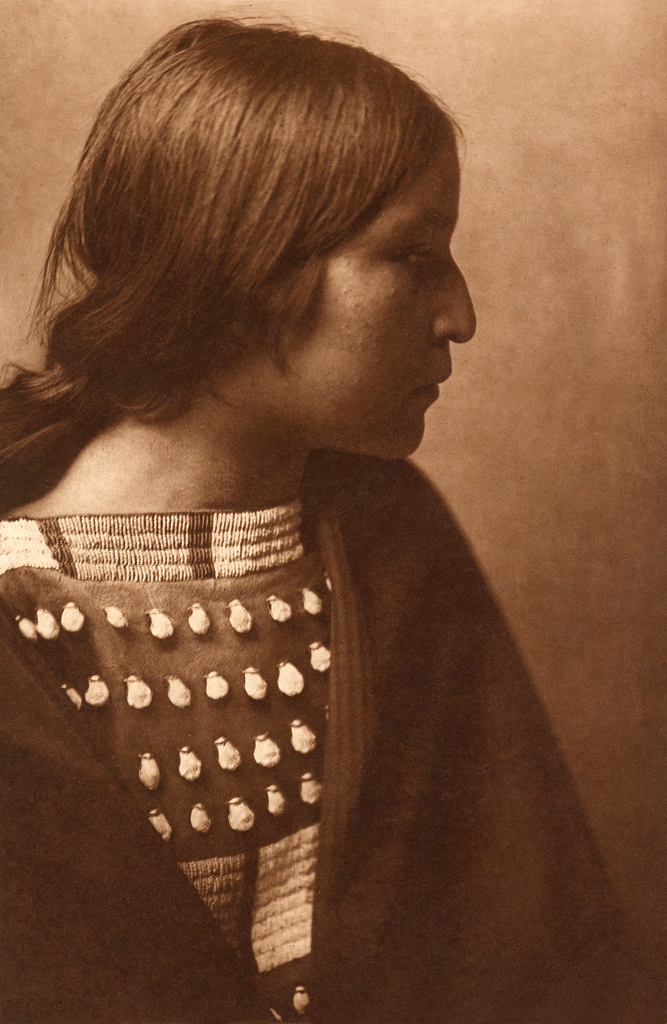

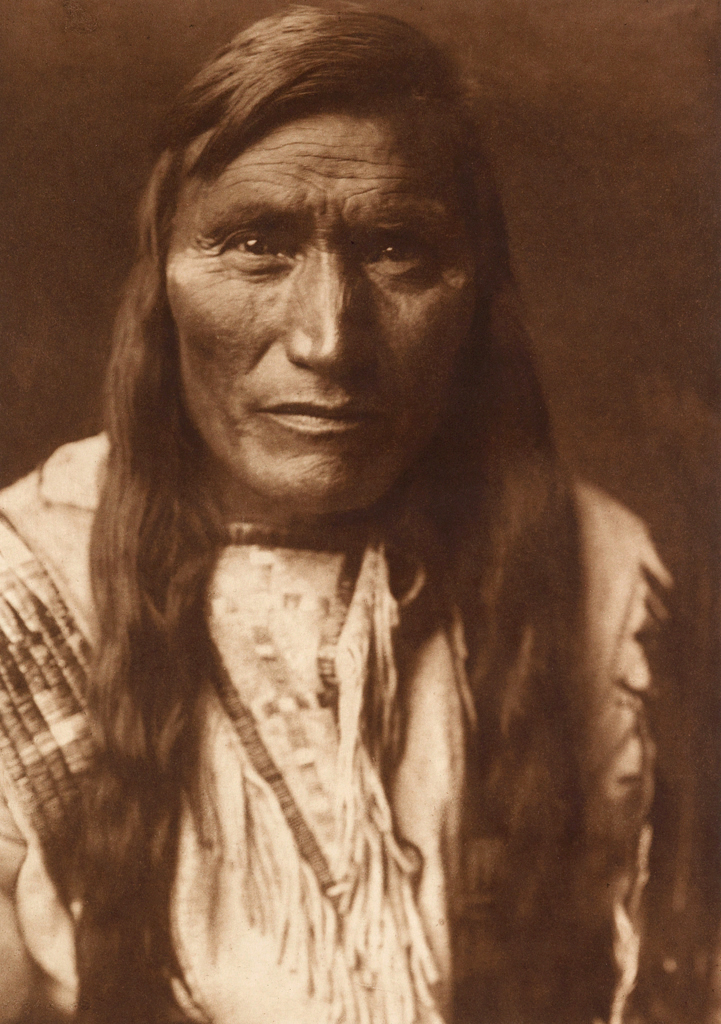

![Edward S. Curtis (American, 1868-1952) '[Atsina Indian, Red Whip, half-length portrait, seated, facing front, wearing feather, beaded buckskin shirt, holding pipe in left hand]' c. 1908 Edward S. Curtis (American, 1868-1952) '[Atsina Indian, Red Whip, half-length portrait, seated, facing front, wearing feather, beaded buckskin shirt, holding pipe in left hand]' c. 1908](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/edward-s-curtis-1868-1952-the-north-american-indian-portfolio-v-1907-photogravure-on-vellum19-web.jpg?w=671)

You must be logged in to post a comment.