Exhibition dates: 21st April – 8th July 2018

Curator: Christiane Kuhlmann, Curator Photography and Media Art; with Andrea Lehner-Hagwood, Curatorial Assistant, Museum der Moderne Salzburg

Works by Nobuyoshi Araki, Masahisa Fukase, Takashi Hanabusa, Jun Jumoji, Daidõ Moriyama, Masaaki Nakagawa, Bishin Jumonji, Shunji Õkura, Issei Suda, Akihide Tamura, Shin Yanagisawa, Yoshihiro Tatsuki

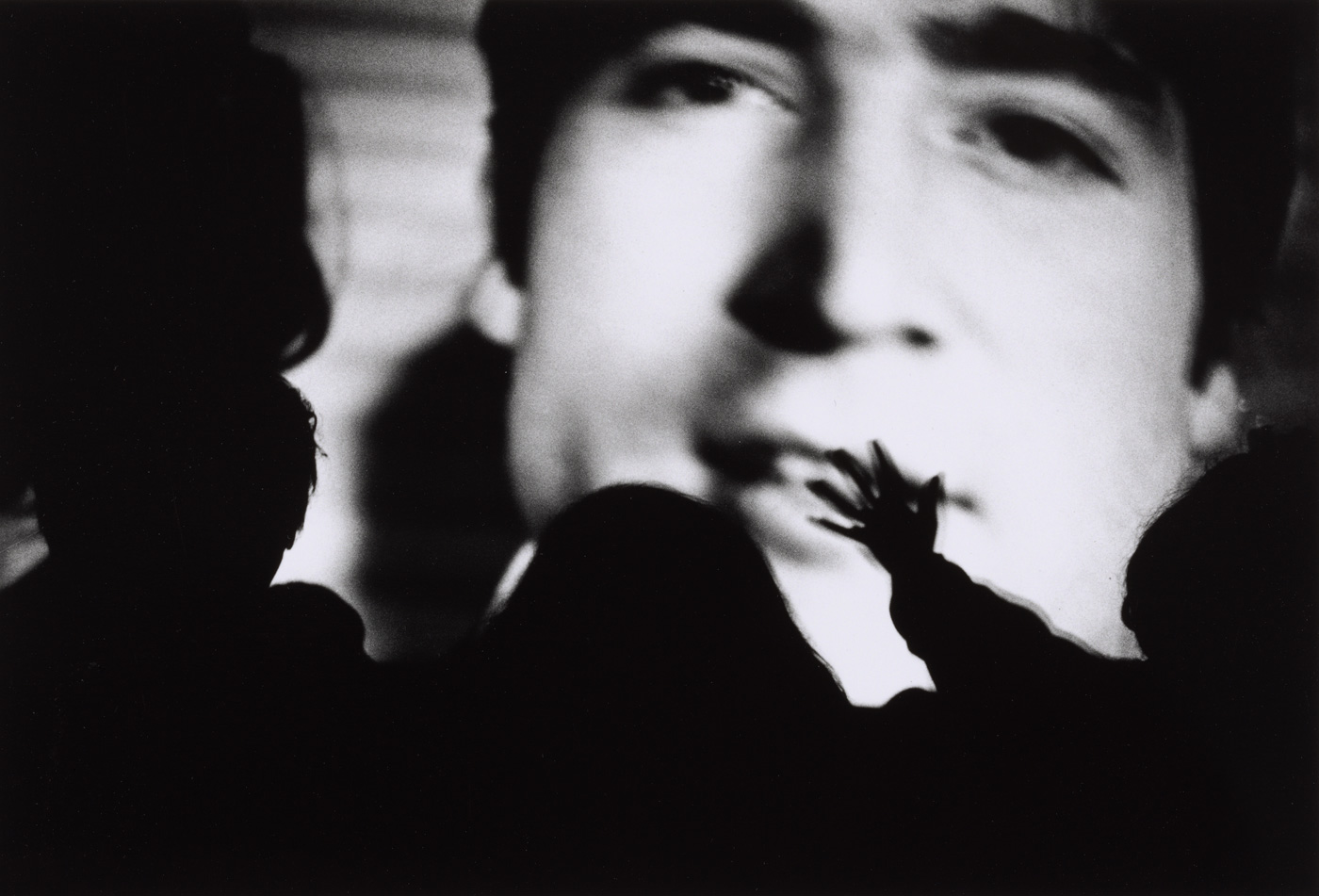

Daidō Moriyama (Japanese, b. 1938)

Lips from a Poster

1975

Gelatin silver print on Baryte paper

Museum der Moderne Salzburg

© Daidō Moriyama

Much as I love the grittiness and stark contrast of Japanese photography of the 1960-70s – its reaction against the pro-American optimism of The Family of Man exhibition that went to Tokyo in the 1950s, its rejection of journalistic illustration, its I-reality that is not a objective record but a personal story, “a poem composed in photography”, its spirit of ennui, a state of dissatisfaction with the status quo – there is also another, less edifying side to Japanese photography of this period.

Basically, it’s a male view of the world, any world, any reality, but always with the “I” at the front of it, the world of the male ego. A world where women are objectified, bound and gagged in pretty gruesome “erotic” sex scenes (not in this posting, but you can Google them online). No matter that the photographer had permission, these photographs are about male power and the male gaze. Nothing more, nothing less. A world where cameras pry on people having anonymous sex in the park in the dark. Let’s call it what it is, it’s misogynistic and voyeuristic.

The obverse of a concern for the sitter, or the landscape, or the object, can be observed (did you see what I did there… obverse / observe), in that there is a concern with the minutiae of life in extremis, rather than an empathy for it. Maybe that is the Japanese culture. Perhaps this microscopic analysis comes about because of the fast pace of their life, their mixture of state, religion, culture and capitalism, their violent history and the submissive place of women within that society (The traditional role of women in Japan has been defined as “three submissions”: young women submit to their fathers; married women submit to their husbands, and elderly women submit to their sons ~ Wikipedia)

There is something I cannot put my finger on about the power of the photograph to capture a dominance over women, the landscape, people, protests – a suppressed violence against the self?

I’m just thinking out loud here…

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Museum der Moderne Salzburg for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

The collections of the Museum der Moderne Salzburg include an outstanding and sizeable ensemble of Japanese photographs from the 1960s and 1970s. These works will be on view for the first time in many years in a series of exhibitions. The opening presentation is dedicated to the depiction of humans and perceptions of postwar Japanese society in transformation. A future second exhibition will focus on images of city and countryside.

In the history of Japanese photography, the idea of the “I-photo” is a kind of photographic adaptation of the literary convention of first-person narrative. The photographic image is conceived and employed as a medium articulating the photographer’s self as well as an instrument with which to scrutinise reality. A pioneer of postwar photography, Masahisa Fukase in the late 1960s created photographic series mixing documentary and fictional elements. His central motifs and models were his wife Yoko and their family. Nobuyoshi Araki, the best-known, most prolific, and probably also most provocative Japanese photography artist, launched his career as a fashion and advertising photographer in 1963. The collection contains highly personal photographic notes by him and his wife Yoko, who died early. Fukase, Araki, and the other Japanese “I-photographers” such as Issei Suda, Shin Yanagisawa, and Daidõ Moriyama regard the “I-photo” as a blend of truth and falsification that can elicit an emotional response and disconcert. The aesthetic of the pictures is characterised by hard black-and-white contrasts and lacerated abstract structures. It signals the artists’ rejection of the tradition of classical art photography while also probing the potentials of the medium itself. The Japanese photography scene is highly controversial; the spectrum of themes ranges from erotic depictions of bodies to political statements.

Daidō Moriyama (Japanese, b. 1938)

Untitled (l. a. r.)

c. 1970

Lips from a Poster

1975

3 gelatin silver prints on Baryte paper

Museum der Moderne Salzburg

Exhibition view of I-Photo. Japanese Photography 1960-1970 from the Collection

© Museum der Moderne Salzburg

Photo: Rainer Iglar

Daidō Moriyama (Japanese, b. 1938)

Stray Dog, Misawa

1971

From the series Hunter

Untitled

c. 1970

9 gelatin silver prints on Baryte paper

Museum der Moderne Salzburg

Exhibition view of I-Photo. Japanese Photography 1960-1970 from the Collection

© Museum der Moderne Salzburg

Photo: Rainer Iglar

Daidō Moriyama (Japanese, b. 1938)

Stray Dog, Misawa

1971

From the series Hunter

Gelatin silver print on Baryte paper

Museum der Moderne Salzburg

© Daidō Moriyama

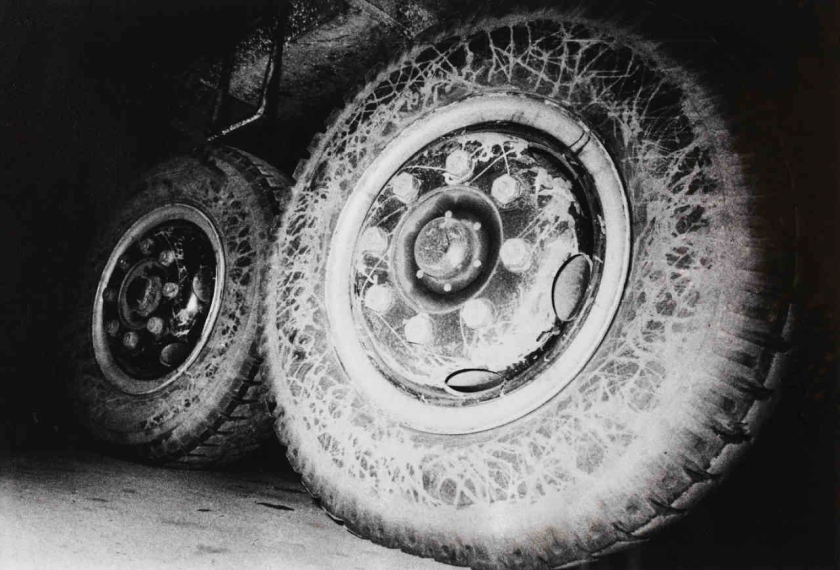

Daidō Moriyama (Japanese, b. 1938)

National Highway 1 AT Dawn 1, Asahi-cho, Kuwana City, Mie Prefecture

1968

Gelatin silver print on Baryte paper

6.50 x 9.72 in. (16.5 x 24.7cm)

Museum der Moderne Salzburg

© Daidō Moriyama

Daidō Moriyama (Japanese, b. 1938)

Daidō Moriyama is one of Japan’s leading contemporary photographers. He studied design and photography in Kōbe before moving to Tokyo in 1961 and deciding to focus entirely on photography. After a stint as Eikō Hosoe’s assistant, he went into business for himself as a photographer in 1964.

Like the art critic Kōji Taki and the photographers Yutaka Takanashi, Shōmei Tōmatsu, and Takuma Nakahira, Moriyama was a member of the group around the influential magazine Provoke (1968-1969). Although no more than three issues appeared in print, its importance in the history of the medium in Japan can hardly be overstated. The Provoke Manifesto declared that photography was capable of registering what could not be expressed in words. The visual style of the photographs Provoke would run was to be are-bure-boke, Japanese for “grainy, blurry, and out of focus” – a specification that still aptly describes Moriyama’s photographs; the same style is evident in his work for magazines such as Camera Mainichi, Asahi Journal, and Asahi Camera.

Moriyama’s inexhaustible signature theme is the city of Tokyo, but he has also worked elsewhere. In an interview, he once said: “For me cities are enormous bodies of people’s desire.” He still prowls the streets day after day, taking pictures of appealing or striking sights, never peering into his small compact camera’s viewfinder. Shots of traffic, of pedestrians and shop windows, of posters and details such as lips, eyes, or plants are recurrent motifs. Hard black-and-white contrasts lend his prints a strangely alien and otherworldly allure, but the depictions always remain anecdotal, as though from a dream. Moriyama’s photobooks may accordingly be read as photonovels of a sort. Japan A Photo Theater (1968) was the first book in this vein he published; his oeuvre has now grown to several hundred photobooks.

The Photographic Society of Japan, whose purpose is to promote photography in Japan, elected him its photographer of the year in 1983. In 2012, he received the Infinity Award for Lifetime Achievement of the International Center of Photography, New York, which honours outstanding accomplishments in photography and visual art.

Masahisa Fukase (Japanese, 1934-2012)

Untitled

1971

From the series Yoko

9 gelatin silver prints on Baryte paper (Vintage prints)

Museum der Moderne Salzburg

Exhibition view of I-Photo. Japanese Photography 1960-1970 from the Collection

© Museum der Moderne Salzburg

Photo: Rainer Iglar

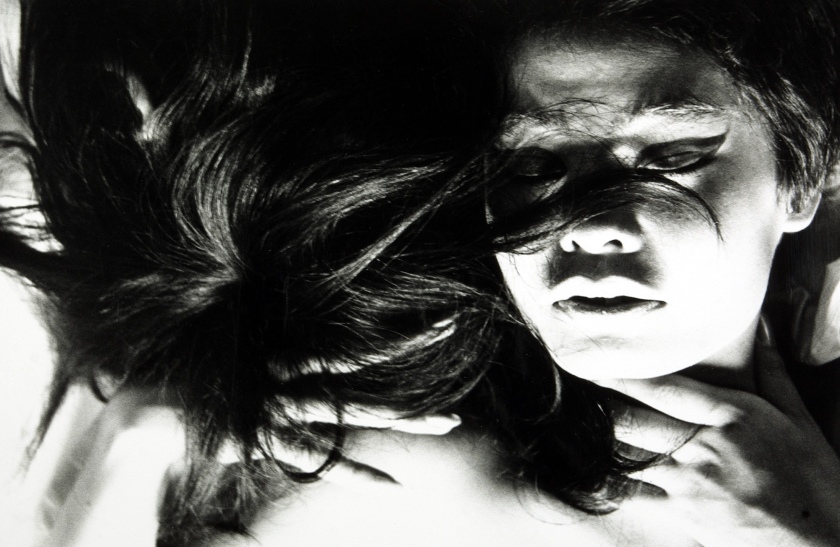

Masahisa Fukase (Japanese, 1934-2012)

Untitled

1961-1970

From the series Yoko

Gelatin silver print on Baryte paper

Museum der Moderne Salzburg

© Masahisa Fukase, Courtesy Michael Hoppen Gallery London

Masahisa Fukase (Japanese, 1934-2012)

Masahisa Fukase completed a PhD at the Institute of Photography at Nihon University, Tokyo, in 1956. He worked as a photographer for advertising agencies and various publishing houses until 1968 and then as a freelance photographer until his death in 2012. His work was included in the 1974 group exhibition New Japanese Photography at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, followed by numerous solo and group shows all over the world. In 1976, he received the annual Ina Nobuo Award, which has been given out by the Nikon Salon in Tokyo since 1976. At the 1992 Higashikawa International Photo Festival, his exhibition Karasu (Ravens) earned him a Higashikawa Photography Award in the Special Award category.

In the 1960s, his photography is largely focused on his own life and that of his wife Yoko. She stars in pictures that show her in all sorts of situations in life, private as well as public. Fukase captures Yoko as his bride, in the nude, during sex, or as a tourist in the street. He is also interested in the passage of time and ageing in general. After separating from Yoko, Fukase started photographing ravens as symbols of loneliness and loss. The photobook Karasu (Ravens) became one of the most coveted works of its kind in postwar Japan; it was first reprinted just last year.

Bishin Jumonji (Japanese, b. 1947)

Untitled

1971

3 gelatin silver prints on Baryte paper

Museum der Moderne Salzburg

Exhibition view of I-Photo. Japanese Photography 1960-1970 from the Collection

© Museum der Moderne Salzburg

Photo: Rainer Iglar

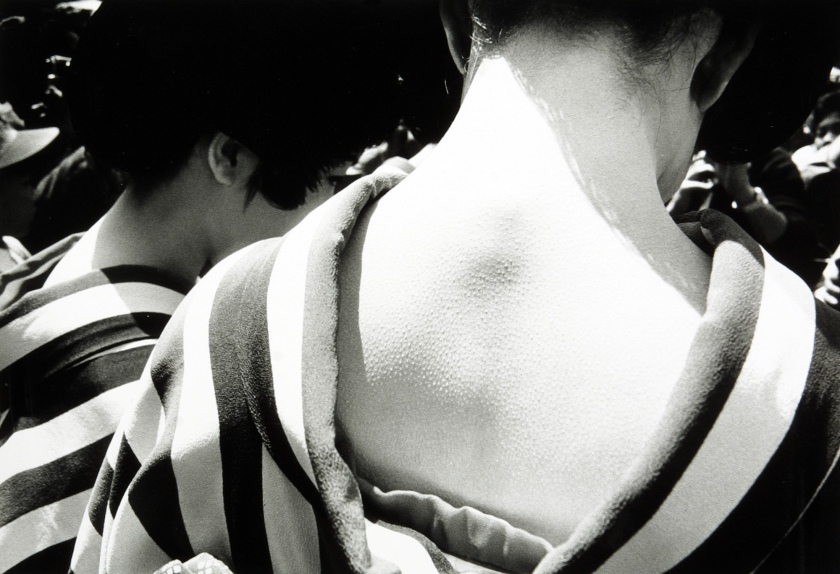

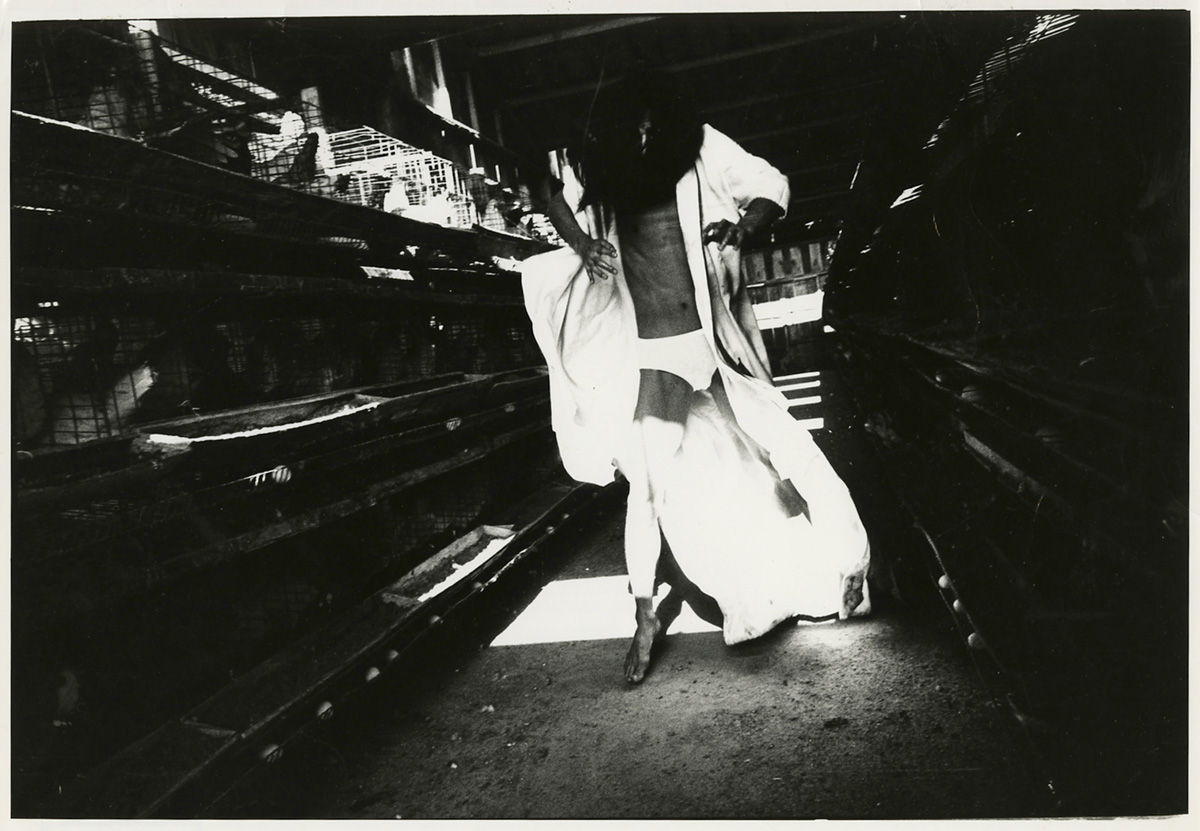

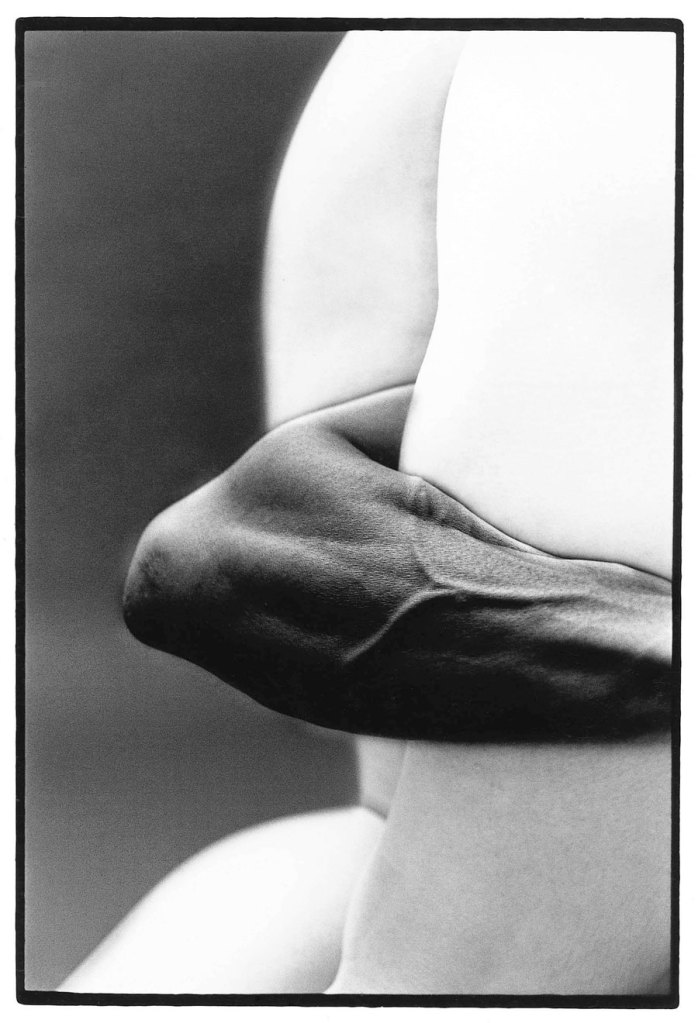

Bishin Jumonji (Japanese, b. 1947)

Untitled

1971

Gelatin silver print on Baryte paper

Museum der Moderne Salzburg

© Bishin Jumonji

Bishin Jumonji (Japanese, b. 1947)

Untitled

1971

Gelatin silver print on Baryte paper

Museum der Moderne Salzburg

© Bishin Jumonji

Bishin Jumonji (Japanese, b. 1947)

After studying at the Tokyo College of Photography, Bishin Jumonji became an assistant to the photographer Kishin Shinoyama, who had risen to renown with publications about Kabuki theater, erotic depictions in photography magazines, and work in unusual book formats such as flipbooks. Since 1971, Jumonji has worked both freelance and as an advertising photographer. This was also when he began to take pictures for the series on view, Untitled. Shot around Tokyo, the works portray families, day-trippers, a quartet of rock musicians, dancers, or bodybuilders – in short, representatives of modern Japan. The details are chosen so that the heads and faces do not appear in the prints. This underscores the subjective quality of photography as such while also conveying the anonymity of life in the megalopolis.

Otto Breicha had seen the series as early as 1974, when it was featured in New Japanese Photography, a group exhibition John Szarkowski organised at the MoMA in New York. Breicha decided to include it in Neue Fotografie aus Japan, the follow-up show he mounted in Graz in 1977.

In 1990, Jumonji receives the Domon Ken Award, one of the most important Japanese photography prizes. The work of the honourees is showcased at the Ginza Nikon Salon, Tokyo, and the Domon Ken Museum of Photography, Sakata, the first museum in Japan dedicated to photography. Some of Jumonji’s pictures are published in international magazines including the German newsweekly Stern.

Akihide Tamura (Japanese, b. 1947)

Yokohama, 1966 (l.)

Yokosuka, 1969 (r.)

7 gelatin silver prints on Baryte paper

From the series Base

Museum der Moderne Salzburg

Exhibition view of I-Photo. Japanese Photography 1960-1970 from the Collection

© Museum der Moderne Salzburg

Photo: Rainer Iglar

Akihide Tamura (Japanese, b. 1947)

Yokohama

1966

From the series Base

Gelatin silver print on Baryte paper

Museum der Moderne Salzburg

© Akihide Tamura

Akihide Tamura (Japanese, b. 1947)

Akihide Tamura studied at the Tokyo College of Photography and got his degree in 1967. Even before he graduated, the academy’s director, the photography critic Shigemori Koen, recognised his unusual approach. In 1974, the MoMA in New York featured Tamura’s House series in its group exhibition New Japanese Photography and acquired it for the museum’s collection. Taken over the course of a year – from July to July – the pictures show houses in abandoned landscapes. The alternation of day and night and the cycle of the seasons play a prominent part in the series.

Tamura’s life was defined by the wrenching changes Japan underwent after World War II. His work is an astute photographic record of these metamorphoses. For the series Base (1966-1970), he captured landscapes, people, and combat aircraft and other military planes at several American bases south of Tokyo. In retrospect, he wrote: “When I was a photography student, I knew that the military base existed in a territory that had been created due to the tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union and the possibility of a nuclear war. I was shaken by the incredibly beautiful and yet insane fighter jets before my eyes. The contradiction between my fear that the world would vanish in an instant if someone were to push the nuclear button and the exotic and eerie spell the military base cast over me left me perpetually torn.”

The works on view are part of the major cycle Erehwon – the title is the word “nowhere” read backwards – that Tamura worked on between 1967 and 1973. The series combines combat aircraft taking off and hurtling off into the sky, their engines a pair of glowing eyes, with ghostly portraits of children that gradually fade into the dark. The composition reflects the photographer’s mindset, a hard-to-pin-down blend of admiration and fear.

Diverse and controversial, sometimes mysterious and often at odds with stereotypical ideas about Japan: there is much to discover in Japanese photography from the 1960s and 1970s. The Museum der Moderne Salzburg now presents its extensive and singular collection in a two-part exhibition series.

For the first time in many years, the Museum der Moderne Salzburg puts its collection of c. 600 original prints of Japanese photography from the 1960s and 1970s, which was purchased in the museum’s early years, on display. The series of two shows begins with IPhoto. Japanese Photography 1960-1970 from the Collection, which presents works that focus on the depiction of the human being and the changes in postwar Japanese society.

“In this exhibition, my vigorous efforts to undertake a thorough review of our collections are bearing fruit, and so I am especially pleased that we are able to present our holdings of Japanese photography – a sizeable ensemble of outstanding works – which have not been seen by the public in a long time. The show also spotlights a chapter in the history of the museum, which started collecting and conserving photography early on. Otto Breicha, the museum’s first director, personally traveled to Japan to meet many of the artists and select works for the projected exhibition,” Sabine Breitwieser, Director of the Museum der Moderne Salzburg, observes. Curator of Photography and Media Art Christiane Kuhlmann emphasises that “this effort to champion Japanese culture and acquire Japanese art for the nascent collection constitutes a pioneering achievement.” “At the time, the primary media in which Japanese photographers presented their pictures were photobooks and magazines,” Kuhlmann notes, “so that vintage prints in the quality and form at our disposal are now hard or impossible to come by. Breicha’s initiative to build a centre for contemporary photography in Austria was in part motivated by his experiences in Japan.”

In the early 1960s, Japan enters a period of fast-paced economic growth, becoming a leading technology manufacturer. A quarter-century after the end of the war and the nuclear bombs over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan hosts Expo’70, the first world’s fair to be held in an Asian country. Tokyo grows into an enormous megalopolis; construction on an international airport that will connect it to the entire world begins in 1971. These developments mark the definite end of the island nation’s decades-long isolation from the West, bringing rapid changes that affect Japanese society as well. In the 1960s, millions of Japanese citizens rally to protest against educational and land reforms and the security treaty with the former enemy, the United States of America. The Japanese photography scene devises a new and dynamic visual language that reflects the country’s more expansive self-image. Distinctive features include the reflection on perception, the quest for novel ways to express the self, and a revised definition of the photographic medium. Hard black-and-white contrasts and lacerated abstract structures are characteristic of the aesthetic of these pictures.

The idea of the “I-photo” is an adaptation of the term “I-novel,” which designates a genre of first-person narrative fiction in Japanese literature. Conceiving of themselves as authors, the photographers understand the “Iphoto” as the instrument of an exploration of reality. Japan’s photography scene is often highly controversial, with themes ranging from erotic depictions of bodies to political statements. Western observers are bound to find some pictures enigmatic and unsettling; they run counter to how Japan is generally imagined abroad. Yet it was Western art institutions that, in the 1970s, first included Japanese contemporary photography in their programming. Neue Fotografie aus Japan (New Photography from Japan) was the title of the first exhibition in Europe that Otto Breicha mounted in Graz in 1977; with I-Photo. Japanese Photography 1960-1970 from the Collection, the Museum der Moderne Salzburg brings back the exhibits from that historic show, though with different emphases. The presentation includes works by the photographers associated with the magazine Provoke (1968-1969) in which reality seems to be dismantled into its constituent elements, as well as by artists such as Nobuyoshi Araki and Masahisa Fukase who pursued their own highly individual creative agendas. Also on display are pictures by the members of the Kompora group, who sought to render a lucid and accurate portrait of everyday life in a clinical visual idiom.

Press release from Museum der Moderne Salzburg

Exhibition view of I-Photo. Japanese Photography 1960-1970 from the Collection

© Museum der Moderne Salzburg

Photo: Rainer Iglar

Yoshihiro Tatsuki (Japanese, b. 1937)

Untitled

c. 1970

3 gelatin silver prints on Baryte paper

Museum der Moderne Salzburg

Exhibition view of I-Photo. Japanese Photography 1960-1970 from the Collection

© Museum der Moderne Salzburg

Photo: Rainer Iglar

Yoshihiro Tatsuki (Japanese, b. 1937)

Untitled

c. 1970

Gelatin silver print on Baryte paper

Museum der Moderne Salzburg

© Yoshihiro Tatsuki

Yoshihiro Tatsuki (Japanese, b. 1937)

Yoshihiro Tatsuki was born in 1937 in Tokushima, where his family had long run an established portrait studio. He studied at the Tokyo College of Photography (today’s Tokyo Polytechnic University) and graduated in 1958. Initially joining the advertising agency Adcenter in Tokyo as a photographer, Tatsuki went freelance in 1969, working for clients in the advertising, fashion, and publishing industries. In 1965, his series Just Friends and Fallen Angels, which had appeared in the photography magazine Camera Mainichi, earned him the emerging photographer’s award of the association of Japanese photography critics. The works garnered wide attention in Japan. Among his best-known creations are GIRL, EVES, Private Mariko Kaga, Aoi Toki, My America, and Portrait of Family.

Tatsuki has long focused on nude photography, combining traditional Japanese compositional templates with the characteristic poses of Western models. It is hard to tell whether he wants to debunk or cater to the – primarily Western – fantasy of the Geisha as concubine.

Nobuyoshi Araki (Japanese, b. 1940)

Untitled

1971

From the series Sentimental Journey

7 gelatin silver prints on Baryte paper

Museum der Moderne Salzburg

Exhibition view of I-Photo. Japanese Photography 1960-1970 from the Collection

© Museum der Moderne Salzburg

Photo: Rainer Iglar

Nobuyoshi Araki (Japanese, b. 1940)

Untitled

1971

From the series Sentimental Journey

Gelatin silver print on Baryte paper

Museum der Moderne Salzburg

© Nobuyoshi Araki

Nobuyoshi Araki (Japanese, b. 1940)

Yoko, my Love

Nd

Gelatin silver print on Baryte paper (Vintage print)

Museum der Moderne Salzburg

© Nobuyoshi Araki

Nobuyoshi Araki (Japanese, b. 1940)

Nobuyoshi Araki studied photography and film studies at Chiba University from 1959 until 1963. After completing his degree, he joined an advertising agency; in the spare time left by his work as a commercial photographer, he started developing his own photographic ideas.

1970, the artist declared, would be “The First Year of Araki.” Increasingly dissatisfied with the status quo that prevailed in established photography, he launched a variety of creative experiments. The popular photography that dominated the market in Japan at the time, he thought, traded in illusions and dishonesty, and so he proposed to change the situation and create a new kind of photography that would reveal the true face of a society undergoing rapid change.

In 1971, he was married to Yoko. His documentation of their honeymoon was published as the small photobook Sentimental Journey. The travelogue – several pictures from it are in the Museum der Moderne Salzburg’s collection – opens with a portrait of Yoko on the train. The title and this picture are a reference to Doris Day’s 1945 worldwide hit. The series continues with shots of places, sights, and, again and again, pictures of Yoko, in the street, nude, or having sex. As Araki sees it, the book is a new form of reportage about life. Taking photographs and living, to his mind, are synonymous. In a statement accompanying Sentimental Journey, he writes: “The I-novel comes closer to photography.” The title of our exhibition, I-Photo, alludes to this Japanese literary genre, in which the author’s experiences, rendered in as much realistic detail as possible, form the material out of which a fictional story is wrought.

In 1992, Camera Austria, Graz, hosted Araki’s first solo exhibition in Europe. He is famous for his widely debated photographs of erotic bondage, but also for his photobooks, which now number almost six hundred.

Exhibition view of I-Photo. Japanese Photography 1960-1970 from the Collection featuring the work of Nobuyoshi Araki

© Museum der Moderne Salzburg

Photo: Rainer Iglar

Exhibition view of I-Photo. Japanese Photography 1960-1970 from the Collection

© Museum der Moderne Salzburg

Photo: Rainer Iglar

Takashi Hanabusa (Japanese, b. 1949)

Untitled

Nd

Gelatin silver print on Baryte paper

Museum der Moderne Salzburg

© Takashi Hanabusa

Takashi Hanabusa (Japanese, b. 1949)

Takashi (Lyu) Hanabusa was born in Osaka in 1949. After graduating from the Kuwasawa Design School, Tokyo, he joined the staff of the publishing house that produced the magazine Nippon Camera. In 1971, he became an assistant to the photographer Yutaka Takanashi, whose well-known series Tôshi-e (Towards the City) surveyed Tokyo as the Japanese began to embrace modern metropolitan life.

Hanabusa’s works build on this influence, documenting the city as a mysterious place defined by jarring contrasts between tradition and modernity, high tech and nature. His photographs are marked by deliberately ambiguous particulars, as when faces are obscured by shadows. The shots are framed so as to render bodies in fragments or bring out details in classic Japanese fabric patterns that European beholders cannot place.

Hanabusa has been a freelance photographer and member of the Japan Professional Photographers Society since 1973.

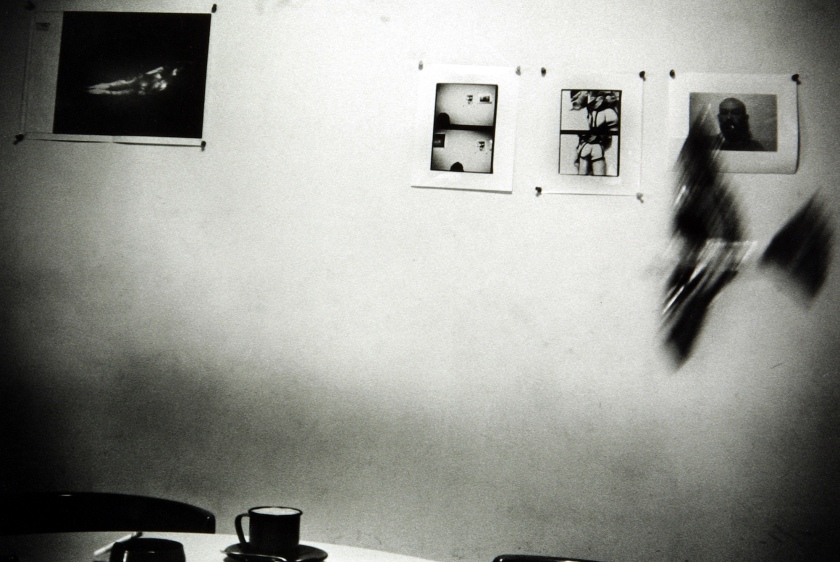

Masaaki Nakagawa (Japanese, 1943-2005)

Selfportrait, Against Wall of My Home

Nd

Gelatin silver print on Baryte paper

Museum der Moderne Salzburg

© Masaaki Nakagawa

Masaaki Nakagawa (Japanese, 1943-2005)

Masaaki Nakagawa completed his studies of Japanese literature at Kōnan University, Kōbe, in 1966. He then worked for various advertising agencies and created fashion shots and reportages for magazines. From 1969 until his death in 2005, he was a freelance photographer in Tokyo and taught at the Kuwasawa Design School.

Otto Breicha described Nakagawa as a storyteller and compared him to the American photographer Duane Michals, whose notion that “things are queer” seems to inform his Japanese colleague’s work as well. Created in series, Nakagawa’s sequences of pictures, rather than aiming for an obvious punch line, appear to move in circles. In the series Self-Portrait against Wall of My Home, the photographer’s shadow looms on the wall, as do things the title identifies as his possessions. Yet the pictures remain vague, almost ghostly, and it is not clear what the focus is on. In this respect, Nakagawa joins the ranks of those conceptual photographers who employ photography as a tool of pictorial analysis, scrutinising the medium’s intrinsic technical-visual potential.

Masaaki Nakagawa was one of the photographers who assisted Otto Breicha during his research in Japan in preparation for the exhibition Neue Fotografie aus Japan.

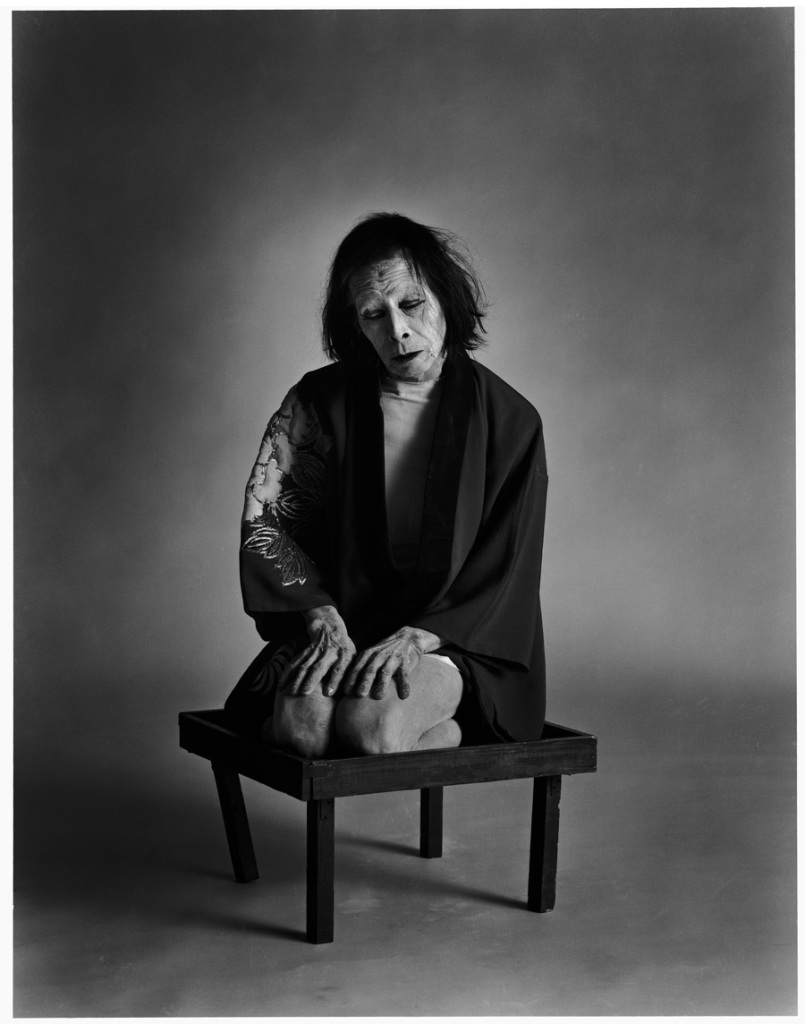

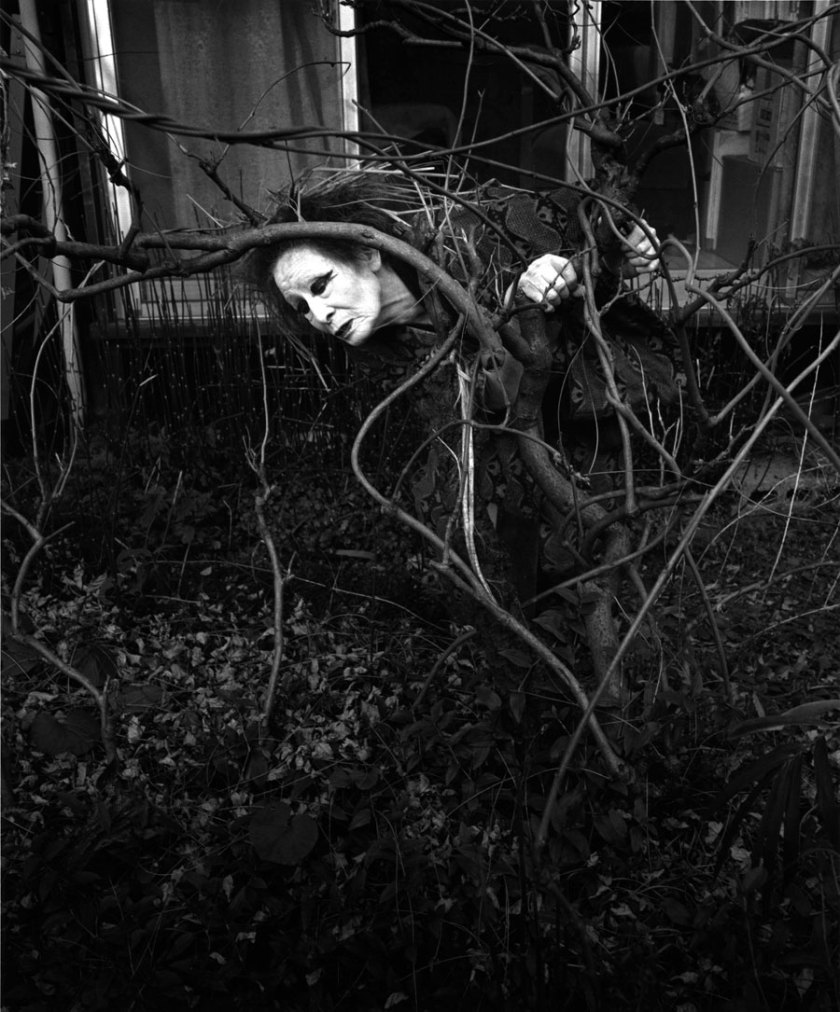

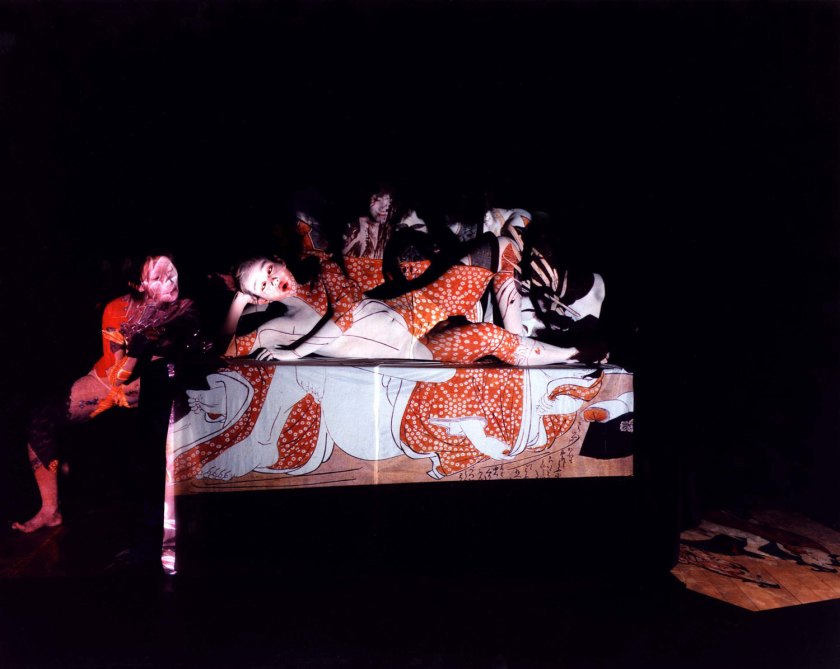

Issei Suda (Japanese, 1940-2019)

Untitled

1975-1976

From the series Fûshi Kaden

Gelatin silver print on Baryte paper

Museum der Moderne Salzburg

© Issei Suda

Issei Suda (Japanese, 1940-2019)

Issei Suda was trained at the Tokyo College of Photography, from which he graduated in 1962. From 1967 until 1970, he worked as a stage photographer for the avant-garde theater ensemble Tenjō Sajiki, which was led by the writer and filmmaker Shūji Terayama.

In the late 1960s, Suda and others opposed to the style championed by the magazine Provoke founded the group Kompora. The label is a typical Japanese compound, a contraction of the English terms “contemporary” and “photography.” The group’s key point of reference was Contemporary Photographers: Toward a Social Landscape, an exhibition held at the George Eastman House in Rochester, N.Y., in 1966. Their goal was to create lucid and accurate portrayals of everyday life in a clinical visual idiom. Despite the aspiration to cool objectivity, however, some of their pictures strike Western beholders as no less enigmatic and unsettling.

That is certainly the impression one gets from the works we present, a selection from the series Fûshi Kaden (1975-1976), which was published as a photobook – Suda’s first – by Asahi Sonorama in 1978. The series proposes a visual discourse on tradition and modernity. The enormous tension between Japan’s hyper-modern cities and the deep-rooted traditions lingering in rural areas is a theme that preoccupies Suda throughout his life. For Fûshi Kaden, he crisscrossed the country; many pictures were taken at the traditional festivals known as matsuri. The title is difficult to translate. It is a tribute to a theoretical disquisition on Nō theater penned in the early fifteenth century by one of its leading practitioners, the grand master Zeami Motokiyo. Sketching his vision of the beauty and style of drama, the author compares it to a flower that has not yet fully blossomed. But he also examines questions of inward perception and outward expression in theatrical performance. Issei Suda translates this vision into his mode of photography. The figures in his pictures sometimes seem to be involved in some kind of stage action and yet utterly unaware of it, as though only the photographer knew the director’s script.

Suda was a professor at the Osaka University of Arts and received the Domon Ken Award in 1997.

Shin Yanagisawa (Japanese, 1936-2008)

Untitled

1972

From the series In the Street, Toyama

Gelatin silver print on Baryte paper

Museum der Moderne Salzburg

© Estate of Shin Yanagisawa

Shin Yanagisawa (Japanese, 1936-2008)

Shin Yanagisawa, who was born in Tokyo in 1936, was a member of the eminent generation of Japanese photographers who, in the 1960s and 1970s, saw contemporary life in their country with fresh eyes, discovering themes for photography that still inform how we imagine Japan between tradition and modernity. Yanagisawa studied at the Tokyo College of Photography in Shibuya and then worked as a freelance photographer.

He was interested in the changing face of the landscape and the raw reality of nature as well as the many facets of life in the big city. The series Traces of the City (1965-1970) reflects the worldview of an entire generation; as early as 1979, it was the subject of a solo presentation in Tokyo. Yanagisawa also contributed work to numerous group shows, including the famous 15 Photographers Exhibition at the Tokyo National Museum of Modern Art (1974), which featured work by Daidō Moriyama und Yutaka Takanashi as well.

The shots we present are a selection from the series In the Street (1972) and show a group of dancers and performers in costumes that would seem to fit in seamlessly with our vision of traditional Japanese culture. Upon closer inspection, however, dissonant notes creep in, especially when individuals turn to face the camera directly or a flashlight illuminates the situation. They reveal Yanagisawa’s presence as the photographer or, more properly, author of the picture. He has abandoned the position of the uninvolved observer, and although he is not visible in the picture as such, he becomes an active participant in the action before the camera. This approach may be regarded as characteristic of the principle of I-photography.

After concluding his active career as a photographer, Shin Yanagisawa wrote about various aspects of photography.

Shunji Ōkura (Japanese, b. 1936)

Untitled

Nd

Gelatin silver print on Baryte paper

Museum der Moderne Salzburg

© Shunji Ōkura

Shunji Ōkura (Japanese, b. 1936)

A grandson of the Japanese painter Kawai Gyokudō, Shunji Ōkura graduated from Dokkyo High School, Tokyo, in 1956. In 1958, he became an assistant to the photographer Akira Satō while also starting out as a freelance photographer, creating fashion shots for the magazines Fukuso, Wakai Josei, and So-en. Numerous photographs appeared in periodicals such as Camera Mainici, Hanashin No Tokushu, and Sunday Mainichi.

In the photographs in the Museum der Moderne Salzburg’s collection, Ōkura devotes himself to a classic subject of photography: the children’s portrait. These are situation-bound snapshots taken a playground; no posing was involved. It is interesting to note how the photographer embraces the way children see the world. Some parts of the scene are invisible in the low-angle shots or obscured by other objects, while Ōkura’s portraits suggest profound empathy; we feel we get a sense of these children’s fears and anxieties.

Museum der Moderne Salzburg

Mönchsberg 32

5020 Salzburg

Phone: +43 662 842220

Opening hours:

Tuesday – Sunday: 10am – 6pm

Wednesday: 10am – 8pm

Monday: closed

You must be logged in to post a comment.