Exhibition dates: 16th June – 28th October 2018

Georges Méliès (French, 1861-1938)

Le voyage dans la lune. Le clair de terre – (10e tableau)

A Trip to the Moon

1902

Courtesy Collection La Cinémathèque française

Another fantastic, esoteric exhibition that will resonant with a lot of human beings. The curators of L’envol (Flight) “have imagined an exhibition that examines mankind’s dream of flying – though without any reference to those who have actually made this dream come true.”

Man has long wanted to fly even though even though men are not birds. But we can, each in our own way, imagine what it is like to fly; we can dream about flying; we can meditate on flying; we can partake in shamanic rituals where our spirit becomes a bird (Carlos Castaneda); we can fly during orgasmic sex as we are taken out of our own body (la petite mort); we can loose ourselves ecstatically during a dance party when we commune with the cosmic beyond; or we can make films such as Alan Parker’s outstanding film Birdy where the protagonist “imagines himself flying like a bird around his room, throughout the house and outside in the neighbourhood.”

Many and varied are the ways human beings examine the melancholy and fantastical desire to fly.

In my own contemporary work, I investigate the moral and ethical reasons why a human being would want to fly the very latest piece of technology, a fighter plane, only to kill, bomb and maim. The reason to fly such war machines, to be as one with the latest technology, the speed, the thrill of flying – to fight for freedom, democracy, to bomb, to kill; and the moral and ethical choices that human beings make, to undertake one action over another.

Again, the melancholy and the fantastical, perhaps flight as a means of escape from the realities of the everyday, much as a child I often imagined being a bird and flying away, never to come back. So this exhibition has special resonance with me. What an incredible collection of ideas, feelings, dreams and fantastical creations these magnificent inventors have released into the universe, in order to defy a literal and promote a metaphysical gravity (love).

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to La maison rouge for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“Love is metaphysical gravity”

Buckminster Fuller

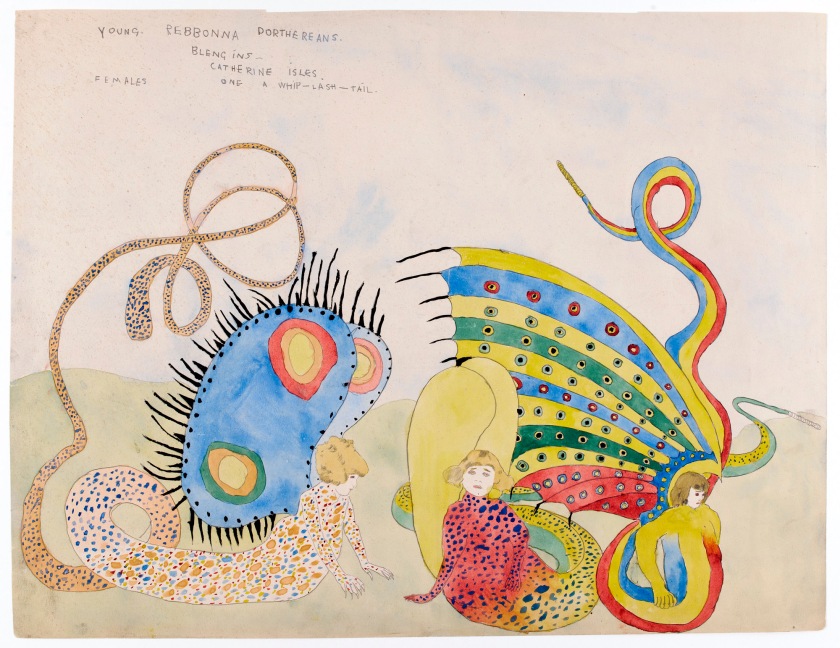

Henry Darger (American, 1892-1973)

Young Rebonna Dorthereans Blengins – Catherine Isles, Female, One Whip-Lash-Tail

1920-30

Pencil and watercolour on paper

© Kiyoko Lerner, Adagp, 2018

Courtesy Musée d’art moderne de la Ville de Paris

Henry Darger (American, 1892-1973)

Human headed Blengins of Calverine Island Catherine Isles

1920-30

Pencil and watercolour on paper

Henry Joseph Darger Jr. (c. April 12, 1892-April 13, 1973) was a reclusive American writer and artist who worked as a hospital custodian in Chicago, Illinois. He has become famous for his posthumously discovered 15,145-page, single-spaced fantasy manuscript called The Story of the Vivian Girls, in What Is Known as the Realms of the Unreal, of the Glandeco-Angelinian War Storm, Caused by the Child Slave Rebellion, along with several hundred drawings and watercolour paintings illustrating the story.

The visual subject matter of his work ranges from idyllic scenes in Edwardian interiors and tranquil flowered landscapes populated by children and fantastic creatures, to scenes of horrific terror and carnage depicting young children being tortured and massacred. Much of his artwork is mixed media with collage elements. Darger’s artwork has become one of the most celebrated examples of outsider art. …

In the Realms of the Unreal is a 15,145-page work bound in fifteen immense, densely typed volumes (with three of them consisting of several hundred illustrations, scroll-like watercolour paintings on paper derived from magazines and colouring books) created over six decades. Darger illustrated his stories using a technique of traced images cut from magazines and catalogues, arranged in large panoramic landscapes and painted in watercolours, some as large as 30 feet wide and painted on both sides. He wrote himself into the narrative as the children’s protector.

The largest part of the book, The Story of the Vivian Girls, in What is Known as the Realms of the Unreal, of the Glandeco-Angelinian War Storm Caused by the Child Slave Rebellion, follows the adventures of the daughters of Robert Vivian, seven princesses of the Christian nation of Abbieannia who assist a daring rebellion against the child slavery imposed by John Manley and the Glandelinians. Children take up arms in their own defense and are often slain in battle or viciously tortured by the Glandelinian overlords. The elaborate mythology includes the setting of a large planet, around which Earth orbits as a moon (where most people are Christian and mostly Catholic), and a species called the “Blengigomeneans” (or Blengins for short), gigantic winged beings with curved horns who occasionally take human or part-human form, even disguising themselves as children. They are usually benevolent, but some Blengins are extremely suspicious of all humans, due to Glandelinian atrocities.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Charles August Albert Dellschau (American, 1830-1923)

Untitled

1921

Book

Courtesy Collection abcd / Bruno Decharme

Charles August Albert Dellschau (4 June 1830 Brandenburg, Prussia-20 April 1923 Houston, Texas) was one of America’s earliest known visionary artists, who created drawings, collages and watercolours of airplanes and airships and bound them in 12 known large scrapbooks that were discovered decades after his death. …

After his death, Dellschau’s home remained in the hands of his descendants. His notebooks of paintings and drawings, as well as his diaries were left virtually untouched for half a century until the late 1960s. Following a fire, the house was cleared and at least 12 of the notebooks were placed on the sidewalk to be discarded. Fred Washington, a local antiques and used furniture dealer, spotted the books, and for $100 bought them from the trash collector. The books sat undisturbed in Washington’s store under a pile of discarded carpet for over a year. In 1968, Mary Jane Victor, an art student at the University of St. Thomas in Houston stumbled upon the notebooks, and persuaded Washington to lend some of them to the university for a display on the story of flight. She also brought them to the attention of art patron and collector Dominique de Menil. Mrs. de Menil purchased four of the notebooks for $1,500. Of the remaining books, seven were purchased Peter (Pete) G. Navarro, a Houston commercial artist and UFO researcher. After studying them, Navarro sold four of the notebooks to the Witte Museum in San Antonio, and the San Antonio Museum of Art. One notebook ultimately ended in the private abcd (art brut connaissance & diffusion) collection in Paris belonging to Bruno Decharme, a French filmmaker and art collector. The rest of the notebooks ended up in private hands. Some were dismantled and single pages were sold. In 2016, a double sided page dated 1919, sold for $22,500 at Christie’s.

Dellschau’s earliest known work is a diary dated 1899, and the last is an 80-page book dated 1921-1922, giving his career as an artist a 21-year span. His work was in large part a record of the activities of the “Sonora Aero Club,” of which he was a purported member. Dellschau’s writings describe the club as a secret group of flight enthusiasts who met in Sonora, California in the mid-19th century. According to Dellschau, one of the club members discovered a formula for an anti-gravity fuel called “NB Gas.” The club mission was to design and build the first navigable aircraft using the NB Gas for lift and propulsion. Dellschau called these flying machines Aeros. Dellschau never claimed to be a pilot or a designer of any of the airships; he identifies himself only as a draftsman for the Sonora Aero Club. His collages incorporate newspaper clippings (called “press blooms”) of then-current news articles about aeronautical advances and disasters.

Despite exhaustive research, including searches of census records, voting rosters, and death records, nothing has been found to substantiate the existence of this group except for a few gravestones in the Columbia Cemetery where several of the surnames are found. It is speculated that, like the voluminous “Realms of the Unreal” notebooks by outsider artist Henry Darger (1882-1973), the Sonora Aero Club is a fiction by Dellschau.

Text from the Wikipedia website

L’envol is the final exhibition at La maison rouge, which will close its doors for the last time on October 28, 2018. Antoine de Galbert has invited Barbara Safarova, Aline Vidal and Bruno Decharme as co-curators. Together, these specialists in art brut and contemporary art have imagined an exhibition that examines mankind’s dream of flying – though without any reference to those who have actually made this dream come true. As always at La maison rouge, the curators have considered the subject matter independently of “categories” to bring together works of art brut, modern, contemporary, ethnographic and folk art. A walk through the various themes reveals a succession of some 200 works, including installations, films, documents, paintings, drawings and sculptures.

In the beginning there was Dedalus, that inspired inventor who dreamed of escaping into the skies, taking his son Icarus with him. Harnessed to wings made from feathers and wax, they rose into the heavens, intoxicated with their flight, borne aloft into the atmosphere. We all know what happened next. Icarus ventured too near the sun, his wings melted and he hurtled into the sea to die. From legend to reality, the sky has always been a dangerous playground for mankind. This is no small undertaking by the 130 artists in Lenvol, as they endeavour to challenge the laws of gravity, break free of Earth’s magnetic field, launch themselves into the unknown or experience the gaseous envelope of the atmosphere between two periods of turbulence. Some are hedonists, others are activists, intent on saving mankind as the world heads for destruction, whether by building flying shelters or constructing utopias. The sky offers ample territory for experiment, shared between the extravagant artists who are convinced of their ability to overcome gravity and the gods that live there, and the conceptualists designing utopias – more poet than scientist.

Defying gravity

The dream of flying may be as old as mankind – and the sky may have lost some of its mystery thanks to progress in aviation – but men are not birds, all the same. Clothing oneself in feathers is not enough. We are earthly creatures, and the body alone will always struggle to leave the ground. We can never achieve this freedom nor expand the scope of our action without the will to surpass ourselves.

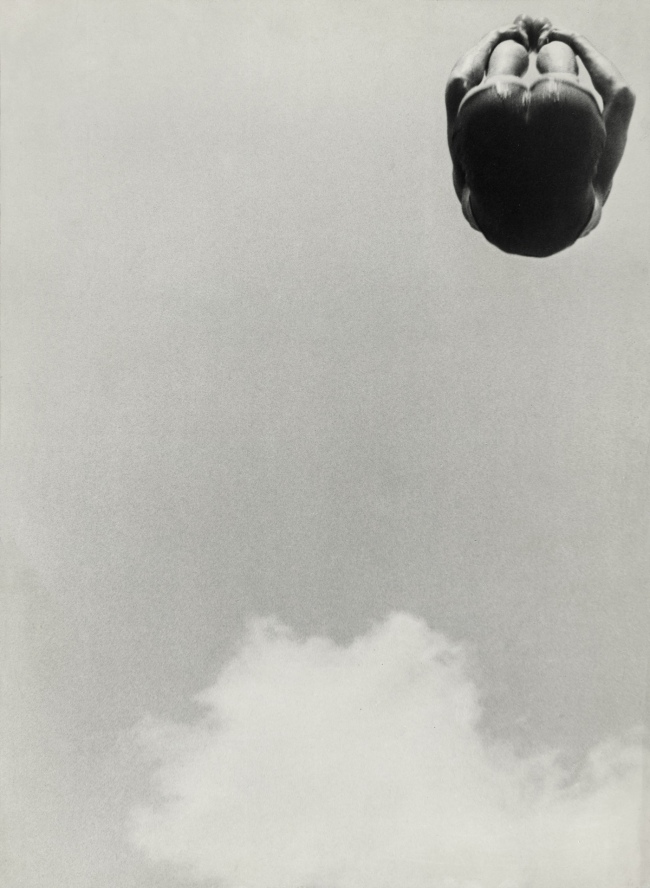

Devoid of wings, dancers soar upwards, defying the laws of gravity with no fear of falling or exhaustion (Loie Fuller, Nijinsky, Cuningham, etc.) Rodchenko, a photographer for the Russian propaganda machine, uses daring, low-angle shots to make his athletes appear to take off in flight, idealising the body to further the needs of the revolution whose heroes were held aloft.

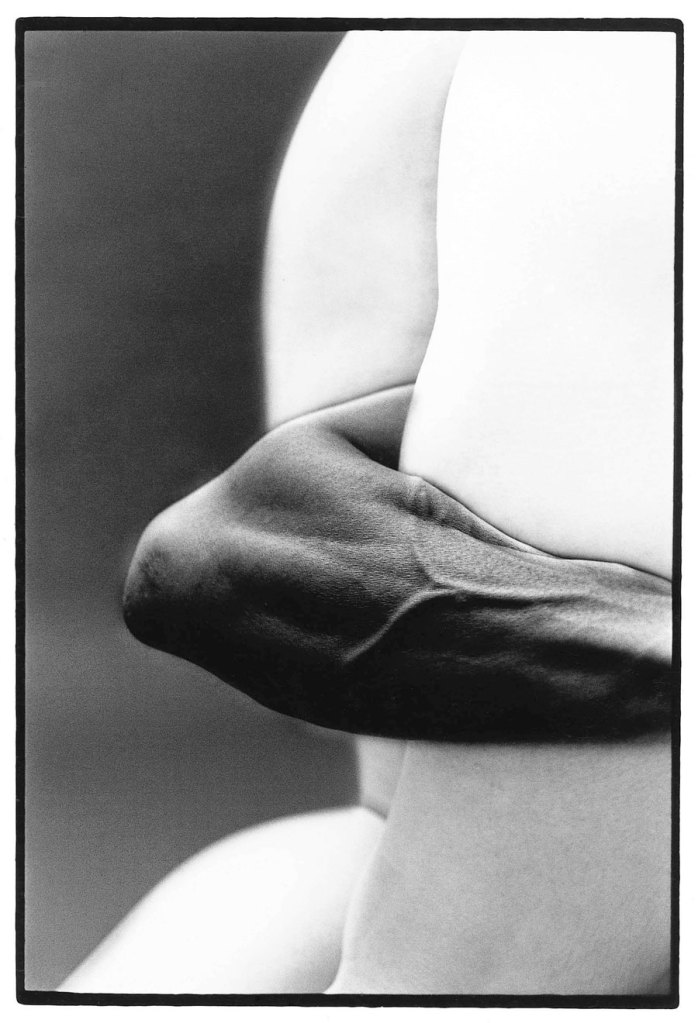

Lucien Pelen seeks anti-matter as he attempts to merge his body with the atmosphere. Arms outstretched, he launches himself into the air and, for a split second, achieves the ecstasy of flight before coming brutally back down to earth. Such is this fragile balance at the boundaries of possibility.

When Gustav Messmer attached springs to his shoes so he could bounce rather than walk, or fitted a bicycle with enormous bat-like wings, did he realise how precarious these inventions were? To hell with scepticism! Surely it takes some degree of madness to invent your own freedom?

Or engage in excesses like Rebecca Horn who, in search of new ways to experience the space around her, shrouds her ailing body in feather fans then seeks the limits of its extension, stretching these articulated wings as far as they will go before the mechanism gives way.

To infinity and beyond

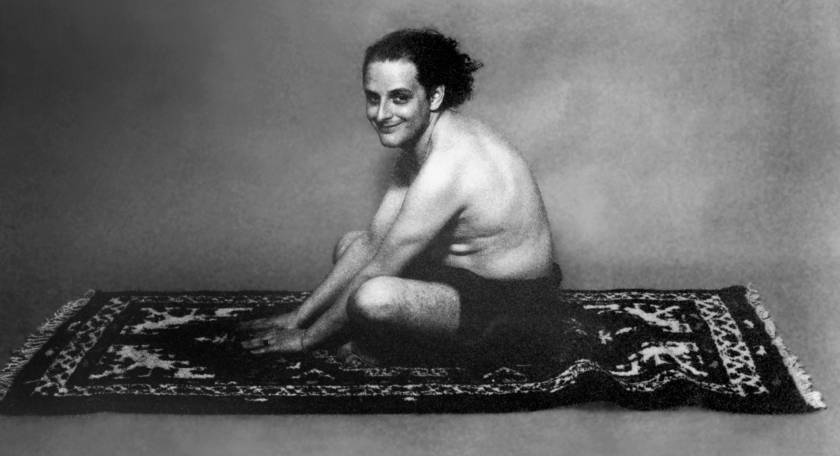

The weight of the world gives artists cause to wander in the shadow of earthly paradises. Fréderic Pardo, a psychedelic star, uses tempera, an ancient technique, to produce spaced-out paintings while high on LSD. He floats alongside magic carpets (Urs Lüthi), ridden by souls from an Arabian Nights dream. We discover a limitless space filled with superheroes, Batman and witches straddling broomsticks; a world teeming with chimera and fairies.

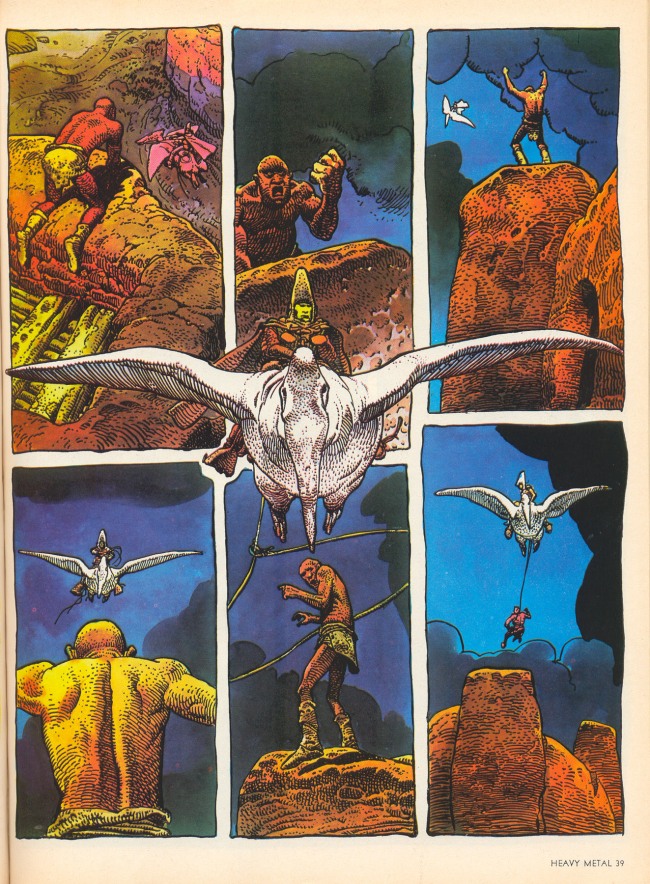

The sky seethes with mystery. Shamans, accustomed to travelling between worlds, converse with spirits and collect information while improbable creatures, part angel, part human, bump and bowl along (Henry Darger’s Blengins side by side with Moebius’s Arzach, Friedrich Schröder-Sonnenstern’s hybrids and Kiki Smith’s bird-women).

Engineering the impossible

Tatlin’s sculpture, more fine art than flying machine, seeks to rediscover an age-old, mythical experience. Letatlin is a melding of art, technique and utopia; an attempt at a personal dream. The year is 1929 and the Great Depression has spared no-one. Heads are hot with the desire to escape, minds filled with fantasies of infinity. “We must learn to fly through the air just as we learned to swim in the water or ride a bicycle,” Tatlin declared.

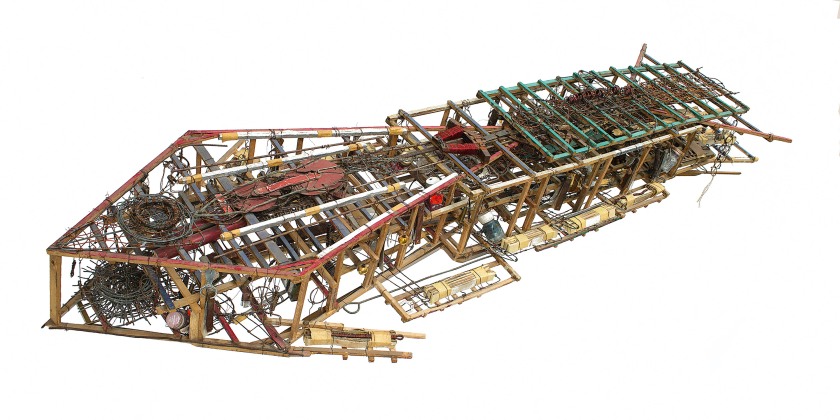

Some forty years later, Belgian artist Panamarenko appears to have taken him at his word. Obsessed with the freedom of flight, he makes sophisticated yet poetic constructions, bristling with bellows and motors. However crazy or technically unfeasible they may be, the artist never tires of convincing us they will lift him off the ground.

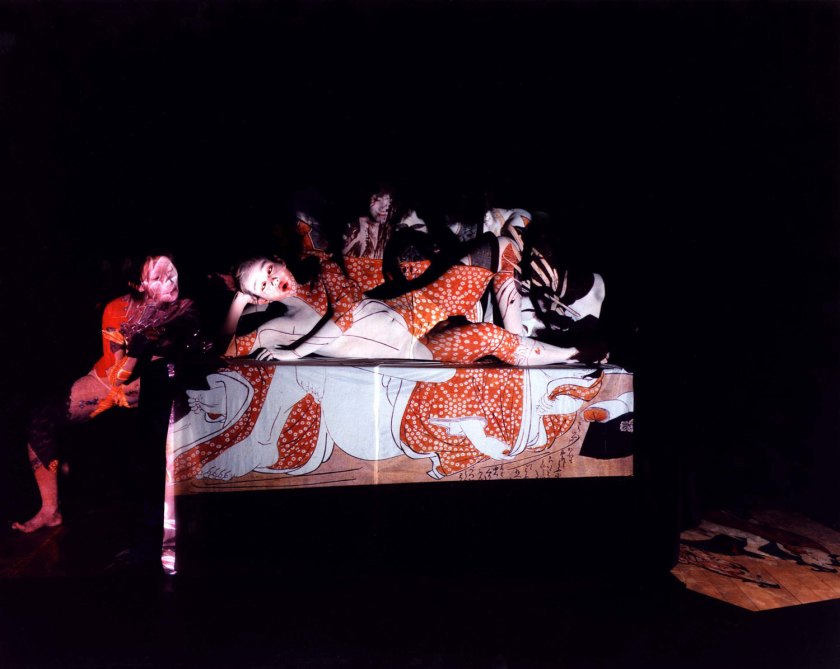

These are beautiful machines, created by the engineers of the impossible and of no purpose whatsoever – except for the dreams they inspire. Snuggling into Fabio Mauri’s Luna inspires a feeling of weightlessness with the senses immersed in a light, fluffy environment. Stationed on the deck of his Spacecraft, inspired as much by the Mercury project as Henry David Thoreau’s cabin in the woods, Stéphane Thidet combines musical arrangements with conversations between astronauts in an electroacoustic performance.

They shut themselves away in their own worlds, all the better to escape to another place, experience the extraordinary and relive childhood fantasies, but with adult toys. Roman Signer, for example, plays with explosives and sets off conflagrations that are both fascinating and illusory. After all, what is the point of smashing everyday objects to smithereens? Of starting up a helicopter in an inflatable pool when it will probably destroy everything around? What is the point of risking danger, other than to try and become one with the inventor of the world and reproduce the forces of nature.

Indoor aviators

Some of these dream merchants are inspired by an intercelestial mission. They are the off-the-wall artists, incomprehensible to the rational world, imbued with a different logic and convinced that flight can be achieved with contraptions made from bits and bobs. Theirs is a world free from explosions or falls, bolstered by belief and the quest for the absolute. Hans-Jörg Georgi, for one, is driven by the need to save humanity from inevitable destruction. His studio is crammed with the aeroplanes he painstakingly builds, day after day, from cardboard boxes stuck together with glue.

Karl Hans Janke is another master of the art of spaceship building, having produced an astonishing 4,500 drawings describing hundreds of technical innovations. Charles Dellschau is further testament to this obsessive dream of flying. He was a member of the Sonora Aero Club, a secret group of mid-nineteenth-century flight enthusiasts whose self-appointed mission was to build the world’s first navigable aircraft.

These are crazy escapades, guided only by the imagination and ultimately less dangerous, and just as exhilarating, as those undertaken by reality’s utopians. Adolf Wölfli chose to rise above it all, deliriously determined to embrace Creation, Space and Eternity. His associations of opposite perspectives produce apparently real and contradictory visions that are dizzying to behold.

Aviation’s spectacular progress has in no way diminished the dreams of these magnificent inventors. Two irreconcilable worlds continue to share the skies. And why shouldn’t artists seek inspiration from other suns? Despite his fall, Icarus is a hero for all eternity.

Excerpt from the exhibition catalogue, introduction by Aline Vidal.

Fabio Mauri (Italian, 1926-2009)

Luna

1968

Installation

Anonymous photographer

Untitled

c. 1940

Black and white photograph

Courtesy Collection abcd / Bruno Decharme

Alexandre Rodchenko (Russian, 1891-1956)

A leap

1934

Black and white photograph

Courtesy Collection Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow / Moscow House of Photography Museum

Photographs made from above or below or at odd angles are all around us today – in magazine and television ads, for example – but for Rodchenko and his contemporaries they were a fresh discovery. To Rodchenko they represented freedom and modernity because they invited people to see and think about familiar things in new ways.

Text from the MoMA website

Photography was important to Rodchenko in the 1920s in his attempt to find new media more appropriate to his goal of serving the revolution. He first viewed it as a source of preexisting imagery, using it in montages of pictures and text, but later he began to take pictures himself and evolved an aesthetic of unconventional angles, abruptly cropped compositions, and stark contrasts of light and shadow. His work in both photomontage and photography ultimately made an important contribution to European photography in the 1920s.

Text from The Art Story website

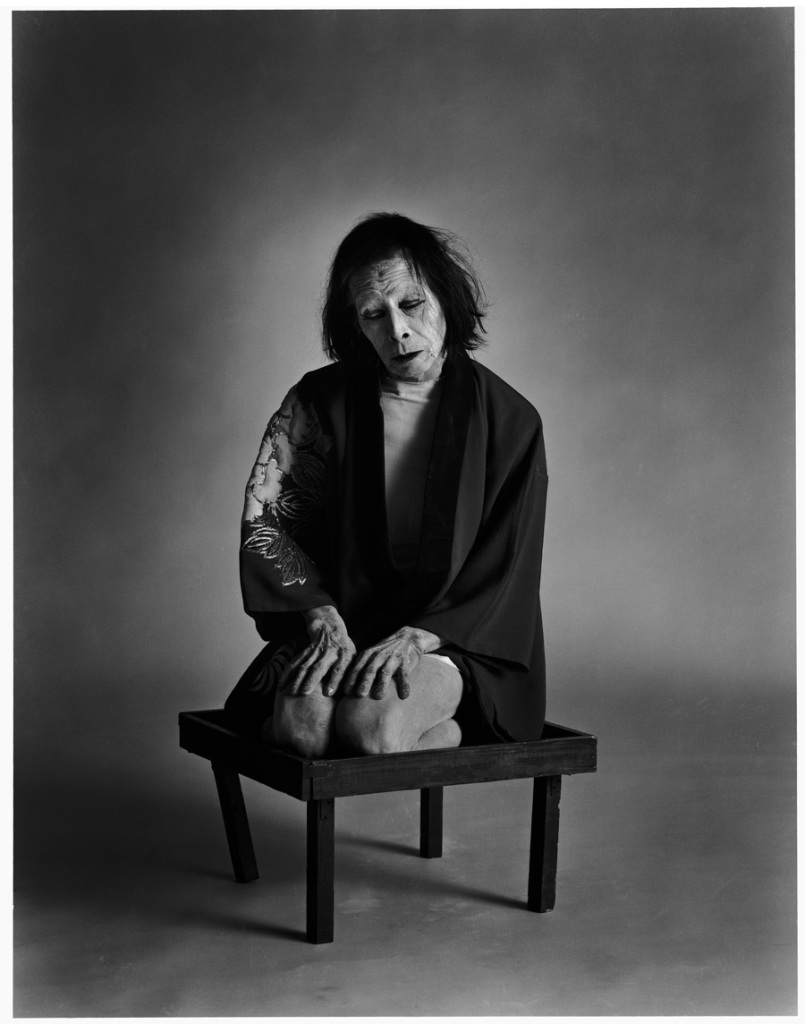

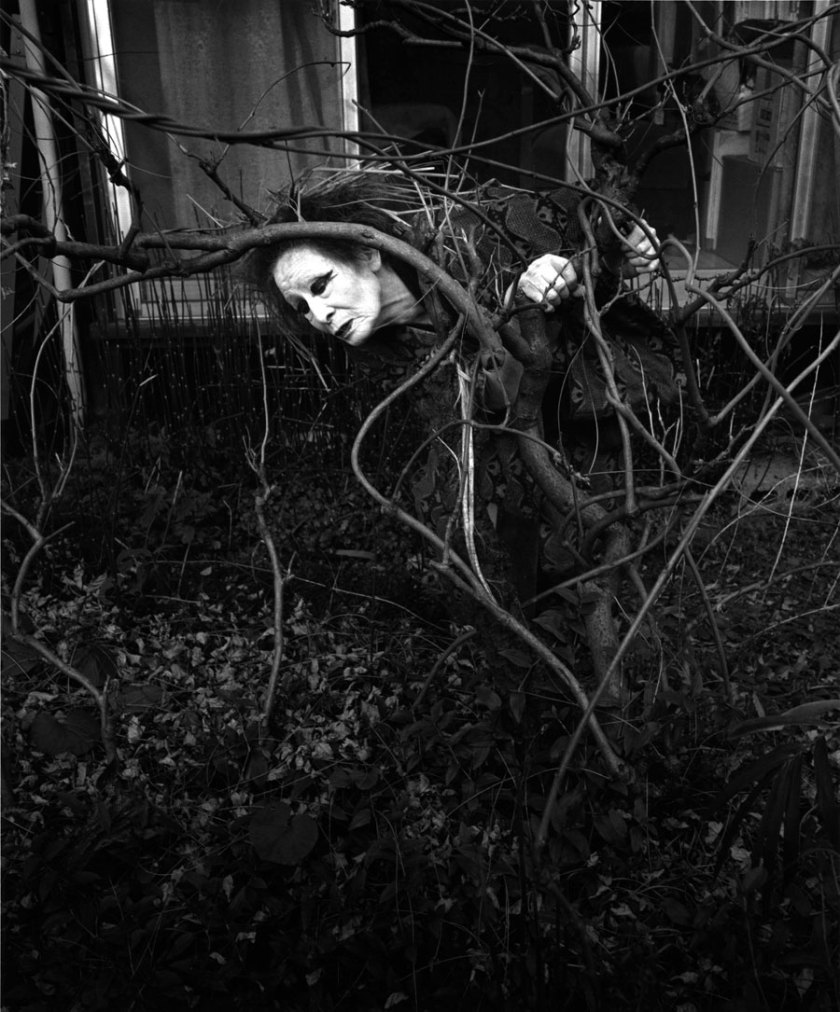

Eikoh Hosoe (Japan, b. 1933)

Kamaitachi 17

1965

Black and white photograph

© Eikoh Hosoe. Courtesy galerie Jean-Kenta Gauthier, Paris

Eikoh Hosoe’s groundbreaking Kamaitachi was originally released in 1969 as a limited-edition photobook of 1,000 copies. A collaboration with Tatsumi Hijikata, the founder of ankoku butoh dance, it documents their visit to a farming village in northern Japan and an improvisational performance made with local villagers, inspired by the legend of kamaitachi, a weasel-like demon who haunts rice fields and slashes people with a sickle. Hosoe photographed Hijikata’s spontaneous interactions with the landscape and the people they encountered. A seductive combination of performance and photography, the two artists enact an personal and symbolic investigation of Japanese society during a time of massive upheaval.

Text from the Aperture website

Emery Blagdon (American, 1907-1986)

Untitled

Nd

Courtesy Collection abcd / Bruno Decharme

From the late 1950s until his death in 1986, Emery Blagdon created a constantly changing installation of paintings and sculptures in a small building on his Nebraska farm. He believed in the power of “earth energies” and in his own ability to channel such forces in a space that, through constant adjusting and aesthetic power, could alleviate pain and illness.

Blagdon used found materials like hay baling wire, magnets, and remnant paints from farm sales, but he also sought out special ingredients like salts and other “earth elements” through a nearby pharmacy. He called the individual pieces his “pretties,” but collectively they comprised The Healing Machine. Blagdon worked on his Healing Machine for more than three decades, tending, tinkering with, and reorganising its components every day and, in his own words, “according to the phases of the moon.” He believed it was a functional machine in which energies were drawn upward from the building’s earthen floor into the space, where they could bounce around and remain dynamic.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Lucien Pelen (French, b. 1978)

Chair n°2 (detail)

2005

Black and white photograph

Lucien Pelen / Courtesy Galerie Aline Vidal

Jacques-Henri Lartigue (French, 1894-1986)

L’envol de Bichonnade (The flight of Bichonnade or Bichonnade leaping)

Paris 1905

Gelatin silver print

Yves Klein (French, 1928-1962)

Leap into the Void

1960

Black and white argentic print

© Succession Yves Klein c/o Adagp, Paris

© Photo Collaboration Harry Shunk and Janos Kender

© J. Paul Getty Trust. The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles

As in his carefully choreographed paintings in which he used nude female models dipped in blue paint as paintbrushes, Klein’s photomontage paradoxically creates the impression of freedom and abandon through a highly contrived process. In October 1960, Klein hired the photographers Harry Shunk and Jean Kender to make a series of pictures re-creating a jump from a second-floor window that the artist claimed to have executed earlier in the year. This second leap was made from a rooftop in the Paris suburb of Fontenay-aux-Roses. On the street below, a group of the artist’s friends from held a tarpaulin to catch him as he fell. Two negatives – one showing Klein leaping, the other the surrounding scene (without the tarp) – were then printed together to create a seamless “documentary” photograph. To complete the illusion that he was capable of flight, Klein distributed a fake broadsheet at Parisian newsstands commemorating the event. It was in this mass-produced form that the artist’s seminal gesture was communicated to the public and also notably to the Vienna Actionists.

Text from The Metropolitan Museum of Art website

Philippe Thomassin

Flight Time 5h34′

1989-1991

Courtesy collection Antoine de Galbert

Photo: Célia Pernot

© Philippe Thomassin

Rebecca Horn (German, b. 1944)

The little Mermaid

1990

Courtesy collection Antoine de Galbert

Photo: Célia Pernot

© Rebecca Horn

Rebecca Horn (born 24 March 1944, Michelstadt, Hesse) is a German visual artist, who is best known for her installation art, film directing, and her body modifications such as Einhorn (Unicorn), a body-suit with a very large horn projecting vertically from the headpiece. She directed the films Der Eintänzer (1978), La ferdinanda: Sonate für eine Medici-Villa (1982) and Buster’s Bedroom (1990). Horn presently lives and works in Paris and Berlin.

Panamarenko (Belgian, 1940-2019)

Japanese Flying Pak 3

2001

Courtesy Galerie Jamar, Anvers

Photo: Wim Van Eesbeek

© Panamarenko

Panamarenko (pseudonym of Henri Van Herwegen, born in Antwerp, 5 February 1940) was a prominent assemblagist in Belgian sculpture. Famous for his work with aeroplanes as theme; none of which are able nor constructed to actually leave the ground.

Panamarenko studied at the academy of Antwerp. Before 1968, his art was inspired by pop-art, but early on he became interested in aeroplanes and human powered flight. This interest is also reflected in his name, which supposedly is an acronym for “Pan American Airlines and Company”.

Starting in 1970, he developed his first models of imaginary vehicles, aeroplanes, balloons or helicopters, in original and surprising appearances. Many of his sculptures are modern variants of the myth of Icarus. The question of whether his creations can actually fly is part of their mystery and appeal.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Ilya and Emilia Kabakov (American born Russia, b. 1933 and 1945)

How Can One Change Oneself

2010

Installation

Courtesy of the artist et Galleria Continua, San Gimignano/Beijing/Les Moulins/ Habana

© Ilya et Emilia Kabakov

The Kabakovs are amongst the most celebrated artists of their generation, widely known for their large-scale installations and use of fictional personas. Critiquing the conventions of art history and drawing upon the visual culture of the former Soviet Union – from dreary communal apartments to propaganda art and its highly optimistic depictions of Soviet life – their work addresses universal ideas of utopia and fantasy; hope and fear. …

The Kabakovs are best known for their ‘total’ installations, a type of immersive artwork that they pioneered. A ‘total installation’ completely immerses the viewer in a dramatic environment. They transform the gallery spaces they are displayed in, creating a new reality for the viewer to enter and experience. They often explore dark themes like power and control, oppression and destruction. Over their career, the Kabakovs have created almost two hundred total installations.

“Ilya’s world and work are based and built on fantasy and on the history of art. I, on the other hand, very early in life, somehow learned to combine both reality and fantasy and to live in both. My fantasy world is always close to and coexists with reality. Our life is very much based on this combination: I am trying to make reality seem like the realisation of fantasy, or, maybe, a continuation of fantasy, where there is no place for real, everyday situations and problems. Our life consists of our work, dreams and discussions.”

Emilia Kabakov, 2017

Text from the Tate website

Moebius (Jean Henri Gaston Giraud) (French, 1938-2012)

Arzach

1977

Heavy Metal Magazine, April 1977, Vol. I, No. 1

The first of Moebius’ Arzach comic series. Arzach made his debut in the first issue of Heavy Metal Magazine April – Vol. 1 No. 1. Arzach is seen flying atop his trusty pterodactyl in a strange world. Spotting a beautiful naked woman through a rounded window, Arzach is determined to win her heart, but what awaits him is utterly unexpected.

Jean Henri Gaston Giraud (French, 8 May 1938 – 10 March 2012) was a French artist, cartoonist, and writer who worked in the Franco-Belgian bandes dessinées (BD) tradition. Giraud garnered worldwide acclaim under the pseudonym Mœbius, as well as Gir outside the English-speaking world, used for the Blueberry series – his most successful creation in the non-English speaking parts of the world – and his Western-themed paintings. Esteemed by Federico Fellini, Stan Lee, and Hayao Miyazaki, among others, he has been described as the most influential bande dessinée artist after Hergé.

His most famous works include the series Blueberry, created with writer Jean-Michel Charlier, featuring one of the first antiheroes in Western comics. As Mœbius, he created a wide range of science-fiction and fantasy comics in a highly imaginative, surreal, almost abstract style. These works include Arzach and the Airtight Garage of Jerry Cornelius. He also collaborated with avant garde filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky for an unproduced adaptation of Dune and the comic book series The Incal.

Mœbius also contributed storyboards and concept designs to numerous science-fiction and fantasy films, such as Alien, Tron, The Fifth Element, and The Abyss. Blueberry was adapted for the screen in 2004 by French director Jan Kounen.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Sethembile Msezane (South African, b. 1991)

Chapungu – The Day Rhodes Fell [University of Cape Town, South Africa]

2015

Coloured photograph

Courtesy private collection

© Sethembile Msezane

Sethembile Msezane was born in 1991 in KwaZulu Natal, South Africa. She lives and works in Cape Town, South Africa. Using interdisciplinary practice encompassing performance, photography, film, sculpture and drawing, Msezane creates commanding works heavy with spiritual and political symbolism. The artist explores issues around spirituality, commemoration and African knowledge systems. She processes her dreams as a medium through a lens of the plurality of existence across space and time, asking questions about the remembrance of ancestry. Part of her work has examined the processes of myth-making which are used to construct history, calling attention to the absence of the black female body in both the narratives and physical spaces of historical commemoration.

Text from the Tyburn Gallery website

“The Rhodes Must Fall protests had been going on for a month, kickstarted by an activist smearing his statue with excrement. During a lecture, students were asked whether they were for or against. Most said “for”, that it was a painful reminder of our colonial past, but one student – with a piece of paper that said “#procolonialism” on her chest – called protesters neanderthals, and said, “If you’re against the statue you’re against enlightenment and education, and you shouldn’t be at university.”

I knew it was only a matter of time before the statue fell, but at 11am on 9 April my supervisor said: “It’s coming down today.” I’d prepared my costume for the occasion and rushed to get ready. A friend helped me transport my plinth and wings. I arrived just before 2pm and was up on the plinth by quarter past. It was a little nerve-racking to be so high up because I was wearing high heels.

I looked at people’s phones and sunglasses, trying to see the reflection of the statue coming down. I saw the shadow move and thought, “This is the moment.” That’s when I lifted my wings.

I was up there for four hours. I would hold up my wings for about two minutes, take a 10-minute break and then put them up again. My legs hurt, but I didn’t realise how sore my arms were until I came down – they were shaking. My feet were blue, I was sunburnt; I had heat stroke and blurry vision from looking directly into the sun. I went home, had a shower and went straight to sleep. I felt like we were beginning to question this idealistic “rainbow nation”.”

I first saw the picture the next day on Facebook. When someone told me it was all over the global news, I was surprised.”

Sethembile Msezane. “Sethembile Msezane performs at the fall of the Cecil Rhodes statue, 9 April 2015,” on The Guardian website, Sat 16 May 2015

Agnès Geoffray (French, b. 1973)

Suspendue

2016

Black and white photograph

Courtesy of the artist

© Agnès Geoffray

Largely inspired by The Defaming Portrait and by the hung man’s figure, the series Les Suspendus uses assemblage and montage to rephrase a new reality, which combines two images in a series of several diptychs. Agnès Geoffray interrogates the fictional power of imagery through her own staging and through assembled images. She accomplishes this by presenting multiple associations to the idea of suspension as a frozen moment between falling and ascension, collapsing and rising. Geoffray creates a gap and confusion between preexisting images and her own, which makes the resulting image appear as if it is part of an archive. Geoffray multiplies the references, axes of meaning of the text and genres of her work through still life, archive and stage settings to create a space, which plays with the unlimited possibilities of interpretation. The images convey the relic of the gestures and the violence connected to them, like a memory or a future memory of disorders and disasters.

Urs Lüthi (Swiss, b. 1947)

Selfportrait (flying carpet)

1976

Black and white photograph

Courtesy private collection

© Urs Lüthi, Pro Litteris

Urs Lüthi (born 1947, Kriens) is a Swiss conceptual artist who attended the School of Applied Arts in Zurich. Noted for using his body and alter ego as the subject of his artworks, he has worked in photography, sculpture, performance, silk-screen, video and painting.

Fabio Mauri (Italian, 1926-2009)

Macchina per fissare acquerelli [Machine for fixing watercolours]

2007

Courtesy succession de Fabio Mauri et Hauser & Wirth, Zürich

© Fabio Mauri, Adagp, 2018

Photo: Sandro Mele

Several important themes can be found in Mauri’s work, all shaped into his works of art: the Screen, the Prototypes, the Projections, the Photography as Painting, the substantial Identity of Expressive Structures, the lasting relationship between Thought and World and between Thought as World. Mauri’s work, as complex as an history essay, becomes his autobiography, compact and uniform in its development and multifaceted in the attention to the contemporary world: an analysis where the fate of the individual and history co-exist.

François Burland (Swiss, b. 1958)

Fusée Soviet Union

2013

Photo: Romain Mader et Nadja Kilchhofer

© François Borland, Atomik Magic Circus

La maison rouge

Fondation antoine de galbert

10 bd de la bastille – 75012

Paris France

Phone: +33 (0) 1 40 01 08 81

Opening hours:

Wednesday to Sunday from 11am to 7pm

Late nights Thursday until 9pm

![Fabio Mauri (Italian, 1926-2009) 'Macchina per fissare acquerelli [Machine for fixing watercolours]' 2007 Fabio Mauri (Italian, 1926-2009) 'Macchina per fissare acquerelli [Machine for fixing watercolours]' 2007](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/10/fabiomauri-web.jpg?w=650&h=977)

You must be logged in to post a comment.