August 2018

Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949)

(Portrait of Indigenous Brazilian tradeswoman)

1861-1862

From Ethnographic portraits of indigenous women of Pernambuco and Bahia

Salt paper print, hand-painted

Art Blart has been mining a rich vein of (anti-)colonial art and photography over the past few months, and the next two posts continue this trend.

Tonight we have Ethnographic portraits of Indigenous women of Pernambuco and Bahia (Brazil, 1861-1862) by unknown local photographers, collected and compiled by the Swiss photographer Hermann Kummler in 1888-1891 into an album. These were vintage prints when he purchased them and already had significant historical interest.

Thus, we have unknown sitters photographed by unknown photographers, removed from their original context(s) – the family, business or photographers album perhaps – to be annotated in a foreign hand, the machinations of (colonial, male) power evidenced through the gaze of the camera. And text. Mulatto; Mestizo; Negress.

The underprivileged of society being punished in their men/iality: servile; submissive: menial attitudes; pertaining to or suitable for domestic servants. Mistress punishing a native child. Teacher with a schoolgirl in Bahia in one picture, becomes Native Brazilian lady-in-waiting and young child attend to a veiled aristocrat in another (note the same background curtain).

None of the sitters look happy. Most scowl at the camera, unsmiling at their lot, probably being forced to have their photograph taken. The hand-coloured photographs are even more absurd, the lurid colours creating caricatures of human beings, cut out figures with all semblance of humanity removed. Rather than reinforcing “the sense of individual style associated with these remarkable figures”, the photographs become pure representation of figurative form. The camera enacts the shaping of disputed, contested identities into a particular figure, a particular palatable form.

Why it is valuable to show these photographs is that we must be ever vigilant in understanding the networks of power, dispossession and enslavement that patriarchal societies use to marginalise the poor, the weak, the different for their gain. For it is men that are looking.

“The category of “masculinity” should be seen as always ambivalent, always complicated, always dependent on the exigencies (necessary conditions and requirements) of personal and institutional power … [masculinity is] an interplay of emotional and intellectual factors – an interplay that directly implicates women as well as men, and is mediated by other social factors, including race, sexuality, nationality, and class … Far from being just about men, the idea of masculinity engages, inflects, and shapes everyone.”1

Dr Marcus Bunyan

PS. “two of the Indigenous women (one of whom wears a cross), simply pose in the studio” – they are not in a studio, a curtain has been drawn over a back wall.

1/ Berger, Maurice; Wallis, Brian and Watson, Simon. Constructing Masculinity. Introduction. New York: Routledge, 1995, pp. 3-7.

These digitally cleaned photographs are published under “fair use” for the purposes of academic research and critical commentary. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Overview

Group of 19 ethnographic portraits of Indigenous women of Pernambuco and Bahia that were compiled by the Swiss photographer Hermann (Ermano) Kummler (1863-1949). With subjects of Indian and mixed-race descent, including vendors, wet nurses, maids, mothers and children, and merchants, including a mistress punishing a native child. Salted paper prints with trimmed corners, the images measuring 7 x 3 3/8 to 7 1/4 x 4 1/2 inches (17.8 x 8.4 to 18.4 x 11.4 cm).

7 are hand-coloured with gouache; the original mounts, 9 bright blue or green, 6 double mounted, measuring 9 1/4 x 7 to 8 1/4 x 11 1/4 inches (24.1 x 17.8 to 21 x 29.8 cm), most with Kummler’s caption notations, in ink, and each with his red hand stamp on prints (one) or mounts recto. 1861-1862

Kummler was a Swiss photographer who accompanied Als Kaufmann to Brazil, where they traveled extensively from 1888-91. Kummler apparently purchased vintage prints by local photographers (which he stamped and annotated), and eventually set up his own commercial studio in the town of Aarau. During the three year period he was in Brazil with Kaufmann, Kummler apparently made more than 130 photographs. Their journey was the subject of a monograph entitled Als Kaufmann in Pernambuco, Ein Reisebericht mit Bildern aus Brasiilien von Hermann Kummler (Als Kaufmann in Pernambuco 1888-1891. A travelogue with pictures from Brazil by Hermann Kummler), copiously illustrated with his images.

Tradeswomen are depicted with a teapot on a table, a comb, a basket laden with bottles or wares carefully balanced on their heads; maids hold embroidered cloth and a wet nurse is shown with an infant. A native lady-in-waiting (and a young child) attend to a gorgeously dressed aristocrat, who wears a long veil. The hand-coloured prints reinforce the sense of individual style associated with these remarkable figures; two of the Indigenous women (one of whom wears a cross), simply pose in the studio with trade womens objects.

Text from an auction house website

Pernambuco and Bahia

Pernambuco is a state of Brazil, located in the Northeast region of the country. Bahia is one of the 26 states of Brazil and is located in the Northeastern part of the country on the Atlantic coast.

Charles Darwin visited Bahia in 1832 on his famous voyage on the Beagle. In 1835, Bahia was the site of an urban slave revolt, particularly notable as the only predominately-Muslim slave rebellion in the history of the Americas. Under the Empire, Bahia returned 14 deputies to the general assembly and 7 senators; its own provincial assembly consisted of 36 members. In the 19th century, cotton, coffee, and tobacco plantations joined those for sugarcane and the discovery of diamonds in 1844 led to large influx of “washers” (garimpeiros = an independent prospector for minerals) until the still-larger deposits in South Africa came to light.

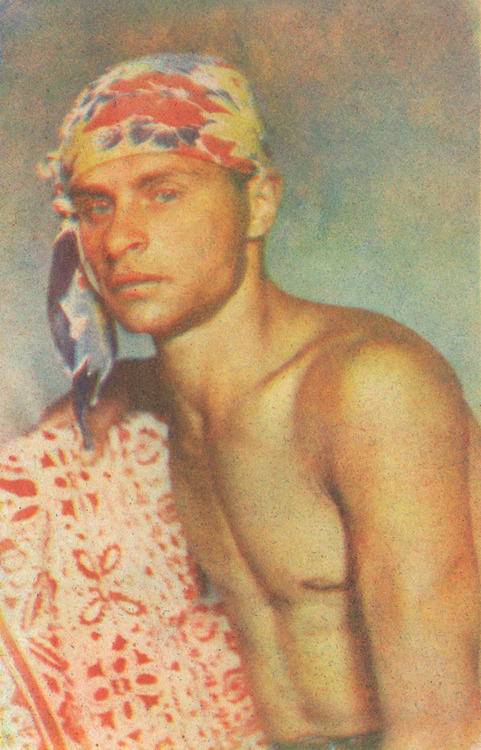

Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949)

Mullatin (Portrait of a Indigenous Brazilian woman wearing a cross)

1861-1862

From Ethnographic portraits of indigenous women of Pernambuco and Bahia

Salt paper print, hand-painted

Mulatto

Mulatto is a term used to refer to people born of one white parent and one black parent or to people born of a mulatto parent or parents. In English, the term is today generally confined to historical contexts. English speakers of mixed white and black ancestry seldom choose to identify themselves as “mulatto.” …

Mulattoes represent a significant part of the population of various Latin American and Caribbean countries: Brazil (49.1% mixed-race, Gypsy and Black, Mulattoes (20.5%), Mestiços, Mamelucos or Caboclos (21.3%), Blacks (7.1%) and Eurasian (0.2%).

In colonial Latin America, mulato could also refer to an individual of mixed African and Native American ancestry. In the 21st century, persons with indigenous and black African ancestry in Latin America are more frequently called zambos in Spanish or cafuzo in Portuguese.

According to the IBGE 2000 census, 38.5% of Brazilians identified as pardo, i.e. of mixed ancestry. This figure includes mulatto and other multiracial people, such as people who have European and Amerindian ancestry (called caboclos), as well as assimilated, westernised Amerindians, and mestizos with some Asian ancestry. A majority of mixed-race Brazilians have all three ancestries: Amerindian, European, and African. According to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics census 2006, some 42.6% of Brazilian identify as pardo, an increase over the 2000 census.

Text from the Wikipedia website

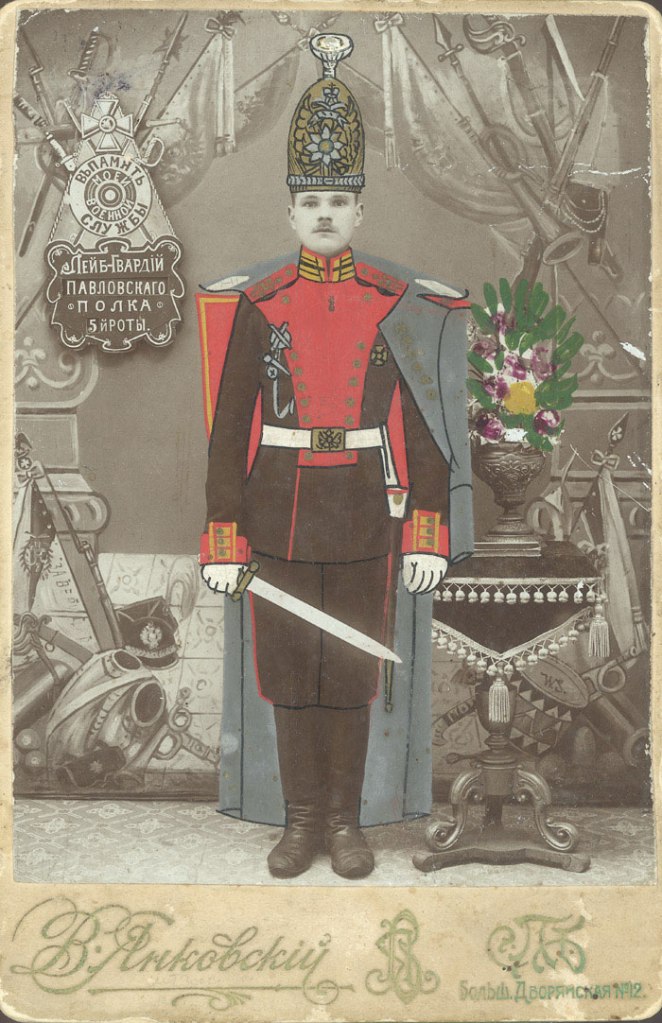

Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949)

Mestize (Portrait of a Brazilian woman)

1861-1862

From Ethnographic portraits of indigenous women of Pernambuco and Bahia

Salt paper print, hand-painted

Mestizo: (in Latin America) a person of mixed race, especially one having Spanish and American Indian parentage.

Mixed-race Brazilian

Brazilian censuses do not use a “multiracial” category. Instead, the censuses use skin colour categories. Most Brazilians of visibly mixed racial origins self-identify as pardos. However, many white Brazilians have distant non-white ancestry, while the group known as pardos likely contains non-mixed acculturated Amerindians. According to the 2010 census, “pardos” make up 82.277 million people, or 43.13% of Brazil’s population. …

History

Before the arrival of the Portuguese in 1500, Brazil was inhabited by nearly five million Amerindians. The Portuguese colonisation of Brazil started in the sixteenth century. In the first two centuries of colonisation, 100,000 Portuguese arrived in Brazil (around 500 colonists per year). In the eighteenth century, 600,000 Portuguese arrived (6,000 per year). Another race, Blacks, were brought from Africa as slaves, starting around 1550. Many came from Guinea, or from West African countries – by the end of the eighteenth century many had been taken from Congo, Angola and Mozambique (or, in Bahia, from Benin). By the time of the end of the slave trade in 1850, around 3.5 million slaves had been brought to Brazil – 37% of all slave traffic between Africa and the Americas.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a considerable influx of mainly European immigrants arrived in Brazil. According to the Memorial do Imigrante, Brazil attracted nearly 5 million immigrants between 1870 and 1953. Most of the immigrants were from Italy or Portugal, but also significant numbers of Germans, Spaniards, Japanese and Syrian-Lebanese.

The Portuguese settlers were the ones to start the intensive race-mixing process in Brazil. Miscegenation in Brazil… was not a pacific process as some used to believe: it was a form of domination from the Portuguese against the Native Brazilian and African populations. …

White/Amerindian

Most of the first colonists from Portugal who arrived in Brazil were singles or did not bring their wives. For that reason the first interracial marriages in Brazil occurred between Portuguese males and Amerindian females.

In Brazil, people of White/Indian ancestry are historically known as caboclos or mamelucos. They predominated in many regions of Brazil. One example are the Bandeirantes (Brazilian colonial scouts who took part in the Bandeiras, exploration expeditions) who operated out of São Paulo, home base for the most famous bandeirantes.

Indians, mostly free men and mamelucos, predominated in the society of São Paulo in the 16th and early 17th centuries and outnumbered Europeans. The influential families generally bore some Indian blood and provided most of the leaders of the bandeiras, with a few notable exceptions such as Antonio Raposo Tavares (1598-1658), who was European born.

White/Black

According to some historians, Portuguese settlers in Brazil used to prefer to marry Portuguese-born females. If not possible, the second option were Brazilian-born females of recent Portuguese background. The third option were Brazilian-born women of distant Portuguese ancestry. However, the number of White females in Brazil was very low during the Colonial period, causing a large number of interracial relationships in the country.

White/Black relationships in Brazil started as early as the first Africans were brought as slaves in 1550 where many Portuguese men starting marrying black women. The Mulattoes (people of White/Black ancestry) were also enslaved, though some children of rich aristocrats and owners of gold mines were educated and became important people in Colonial Brazil. Probably, the most famous case was Chica da Silva, a mixed-race Brazilian slave who married a rich gold mine owner and became one of the richest people in Brazil.

Other mulattoes largely contributed to Brazil’s culture: Aleijadinho (sculptor and architect), Machado de Assis (writer), Lima Barreto (writer), Chiquinha Gonzaga (composer), etc. In 1835, Blacks would have made up the majority of Brazil’s population, according to a more recent estimate quoted by Thomas Skidmore. In 1872, their number was shown to be much smaller according to the census of that time, outnumbered by pardos and Whites. …

Black/Amerindian

People of Black African and Native Brazilian ancestry are known as Cafuzos and are historically the less numerous group. Most of them have origin in black women who escaped slavery and were welcomed by indigenous communities, where started families with local amerindian men.

Text from the Wikipedia website

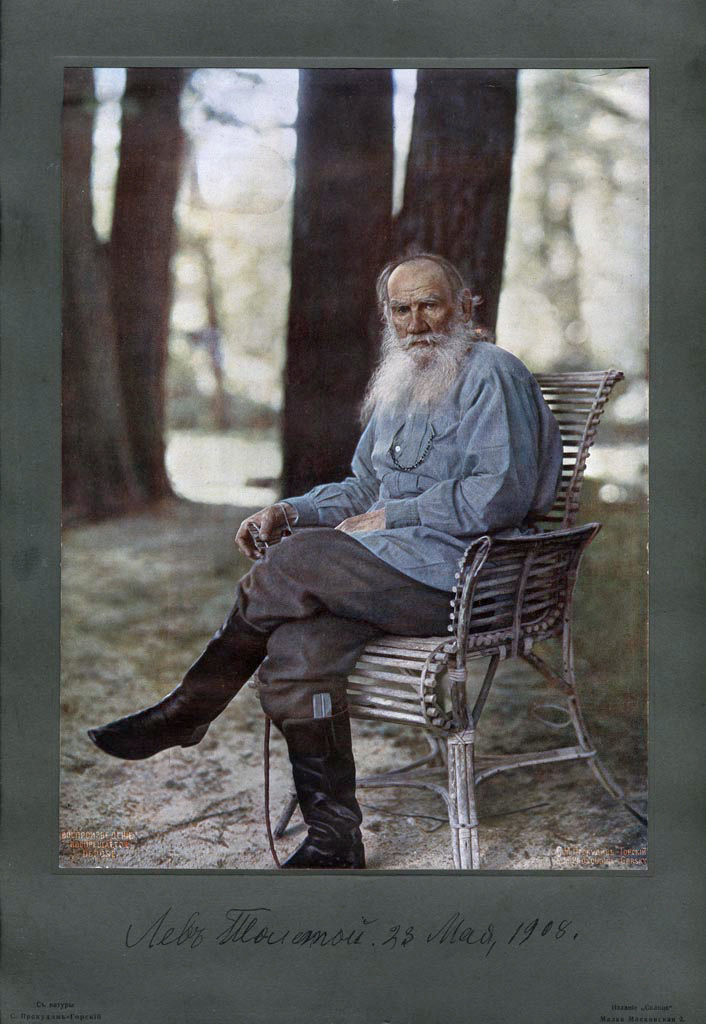

Modesto Brocos (Brazilian born Spain, 1853-1936)

A Redenção de Cam (Ham’s Redemption)

1895

Oil on canvas

199cm (78.3 in) x 166cm (65.3 in)

Public domain / Museu Nacional de Belas Artes

The painting shows a Brazilian family each generation becoming “whiter” (black grandmother, mulatto mother and white baby).

Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949)

(Portrait of Indigenous Brazilian tradeswoman)

1861-1862

From Ethnographic portraits of indigenous women of Pernambuco and Bahia

Salt paper print, hand-painted

Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949)

(Portrait of Indigenous Brazilian tradeswoman)

1861-1862

From Ethnographic portraits of indigenous women of Pernambuco and Bahia

Salt paper print, hand-painted

Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949)

(Portrait of a maid holding an embroidered cloth)

1861-1862

From Ethnographic portraits of indigenous women of Pernambuco and Bahia

Salt paper print, hand-painted

Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949)

(Portrait of wet nurse with infant)

1861-1862

From Ethnographic portraits of indigenous women of Pernambuco and Bahia

Salt paper print, hand-painted

Indigenous peoples in Brazil

Indigenous peoples in Brazil (Portuguese: povos indígenas no Brasil), or Indigenous Brazilians (Portuguese: indígenas brasileiros), comprise a large number of distinct ethnic groups who have inhabited what is now the country of Brazil since prior to the European contact around 1500. Unlike Christopher Columbus, who thought he had reached the East Indies, the Portuguese, most notably Vasco da Gama, had already reached India via the Indian Ocean route when they reached Brazil.

Nevertheless, the word índios (“Indians”) was by then established to designate the people of the New World and continues to be used today in the Portuguese language to designate these people, while a person from India is called indiano in order to distinguish the two.

At the time of European contact, some of the indigenous people were traditionally mostly semi-nomadic tribes who subsisted on hunting, fishing, gathering, and migrant agriculture. Many of the estimated 2,000 nations and tribes which existed in the 16th century suffered extinction as a consequence of the European settlement, and many were assimilated into the Brazilian population.

The indigenous population was largely killed by European diseases, declining from a pre-Columbian high of millions to some 300,000 (1997), grouped into 200 tribes. However, the number could be much higher if the urban indigenous populations are counted in all the Brazilian cities today. A somewhat dated linguistic survey found 188 living indigenous languages with 155,000 total speakers.

The rubber trade

The 1840s brought trade and wealth to the Amazon. The process for vulcanising rubber was developed, and worldwide demand for the product skyrocketed. The best rubber trees in the world grew in the Amazon, and thousands of rubber tappers began to work the plantations. When the Indians proved to be a difficult labor force, peasants from surrounding areas were brought into the region. In a dynamic that continues to this day, the indigenous population was at constant odds with the peasants, who the Indians felt had invaded their lands in search of treasure.

Urban Rights Movement

The urban rights movement is a recent development in the rights of indigenous peoples. Brazil has one of the highest income inequalities in the world, and much of that population includes indigenous tribes migrating toward urban areas both by choice and by displacement. Beyond the urban rights movement, studies have shown that the suicide risk among the indigenous population is 8.1 times higher than the non-indigenous population.

Many indigenous rights movements have been created through the meeting of many indigenous tribes in urban areas. For example, in Barcelos, an indigenous rights movement arose because of “local migratory circulation.” This is how many alliances form to create a stronger network for mobilisation. Indigenous populations also living in urban areas have struggles regarding work. They are pressured into doing cheap labor. Programs like Oxfam have been used to help indigenous people gain partnerships to begin grassroots movements. Some of their projects overlap with environmental activism as well.

Many Brazilian youths are mobilising through the increased social contact, since some indigenous tribes stay isolated while others adapt to the change. Access to education also affects these youths, and therefore, more groups are mobilising to fight for indigenous rights.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949)

(Portrait of Indigenous Brazilian tradeswoman)

1861-1862

From Ethnographic portraits of indigenous women of Pernambuco and Bahia

Salt paper print

Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949)

(Kellnerinnen im Grand Hotel / Waitresses in Grand Hotel)

1861-1862

From Ethnographic portraits of indigenous women of Pernambuco and Bahia

Salt paper print

Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949)

(Lehrerin mit Schülerin im Bahia / Teacher with a schoolgirl in Bahia)

1861-1862

From Ethnographic portraits of indigenous women of Pernambuco and Bahia

Salt paper print

Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949)

(Native Brazilian lady-in-waiting and young child attend to a veiled aristocrat)

1861-1862

From Ethnographic portraits of indigenous women of Pernambuco and Bahia

Salt paper print

Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949)

(Negerin mit dem Knaben in schlechter Stimmung / Negress with a boy in a bad mood)

1861-1862

From Ethnographic portraits of indigenous women of Pernambuco and Bahia

Salt paper print

Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949)

(Portrait of Brazilian woman servant and child)

1861-1862

From Ethnographic portraits of indigenous women of Pernambuco and Bahia

Salt paper print

Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949)

(Portrait of a young Brazilian woman)

1861-1862

From Ethnographic portraits of indigenous women of Pernambuco and Bahia

Salt paper print

Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949)

(Portrait of a Brazilian woman)

1861-1862

From Ethnographic portraits of indigenous women of Pernambuco and Bahia

Salt paper print

Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949)

(Portrait of a Brazilian woman)

1861-1862

From Ethnographic portraits of indigenous women of Pernambuco and Bahia

Salt paper print

Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949)

(Portrait of a Brazilian woman with two children)

1861-1862

From Ethnographic portraits of indigenous women of Pernambuco and Bahia

Salt paper print

Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949)

(Portrait of a Brazilian mother and child)

1861-1862

From Ethnographic portraits of indigenous women of Pernambuco and Bahia

Salt paper print

Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949)

(Mistress punishing a native child)

1861-1862

From Ethnographic portraits of indigenous women of Pernambuco and Bahia

Salt paper print

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of Indigenous Brazilian tradeswoman]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of Indigenous Brazilian tradeswoman]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women14-web.jpg?w=650&h=890)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) 'Mullatin [Portrait of a Indigenous Brazilian woman wearing a cross]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) 'Mullatin [Portrait of a Indigenous Brazilian woman wearing a cross]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women1-web.jpg?w=650&h=954)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) 'Mestize [Portrait of a Brazilian woman]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) 'Mestize [Portrait of a Brazilian woman]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women2-web.jpg?w=650&h=929)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of Indigenous Brazilian tradeswoman]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of Indigenous Brazilian tradeswoman]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women15-web.jpg?w=840)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of Indigenous Brazilian tradeswoman]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of Indigenous Brazilian tradeswoman]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women12-web.jpg?w=650&h=1007)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of a maid holding an embroidered cloth]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of a maid holding an embroidered cloth]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women13-web.jpg?w=650&h=965)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of wet nurse with infant]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of wet nurse with infant]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women11-web.jpg?w=650&h=983)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of Indigenous Brazilian tradeswoman]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of Indigenous Brazilian tradeswoman]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women3-web.jpg?w=650&h=929)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) 'Hermann Kummler (compiler) (1863-1949) '[Kellnerinnen im Grand Hotel / Waitresses in Grand Hotel]' 1861-1862' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) 'Hermann Kummler (compiler) (1863-1949) '[Kellnerinnen im Grand Hotel / Waitresses in Grand Hotel]' 1861-1862' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women6-web.jpg?w=650&h=918)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Lehrerin mit Schülerin im Bahia / Teacher with a schoolgirl in Bahia]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Lehrerin mit Schülerin im Bahia / Teacher with a schoolgirl in Bahia]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women4-web.jpg?w=650&h=968)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Native Brazilian lady-in-waiting and young child attend to a veiled aristocrat]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Native Brazilian lady-in-waiting and young child attend to a veiled aristocrat]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women5-web.jpg?w=650&h=848)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Negerin mit dem Knaben in schlechter Stimmung / Negress with a boy in a bad mood]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Negerin mit dem Knaben in schlechter Stimmung / Negress with a boy in a bad mood]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women10-web.jpg?w=650&h=959)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of Brazilian woman servant and child]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of Brazilian woman servant and child]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women18-web.jpg?w=650&h=999)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of a young Brazilian woman]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of a young Brazilian woman]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women17-web.jpg?w=840)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of a Brazilian woman]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of a Brazilian woman]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women8-web.jpg?w=840)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of a Brazilian woman]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of a Brazilian woman]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women19-web.jpg?w=840)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of a Brazilian woman with two children]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of a Brazilian woman with two children]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women16-web.jpg?w=650&h=908)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of a Brazilian mother and child]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Portrait of a Brazilian mother and child]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women9-web.jpg?w=840)

![Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Mistress punishing a native child]' 1861-1862 Hermann Kummler (compiler) (Swiss, 1863-1949) '[Mistress punishing a native child]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ethnographic-portraits-of-indigenous-women7-web.jpg?w=650&h=840)

You must be logged in to post a comment.