Exhibition dates: 25th January – 3rd April 2013

Curator: Olga Sviblova

Varvara Stepanova (Russian, 1894-1958)

Red Army Men

1930

Photomontage for Abroad magazine

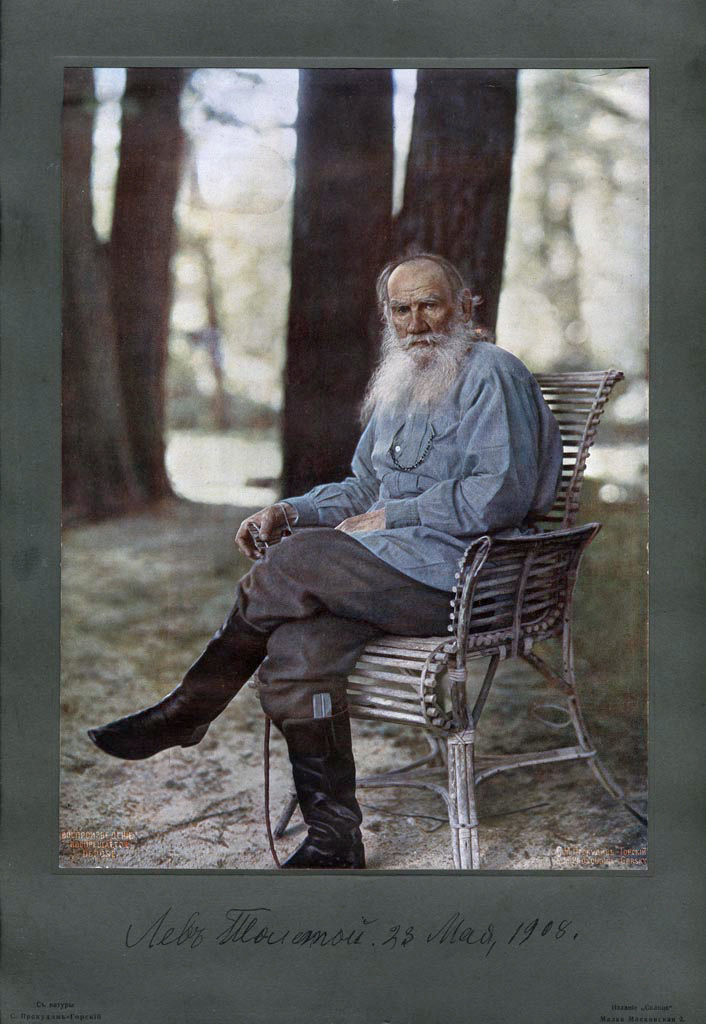

A bumper posting on a fascinating subject. The portrait of Tolstoy is incredible; more poignant are the photographs pre-World War I (the last days of the Tsarist dynasty), and pre-World War 2 (Portrait of Yury Rypalov, below). People stare into the camera with no idea of the maelstrom about to descend…

Marcus

.

Many thankx to Foam for allowing me to publish the text and photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

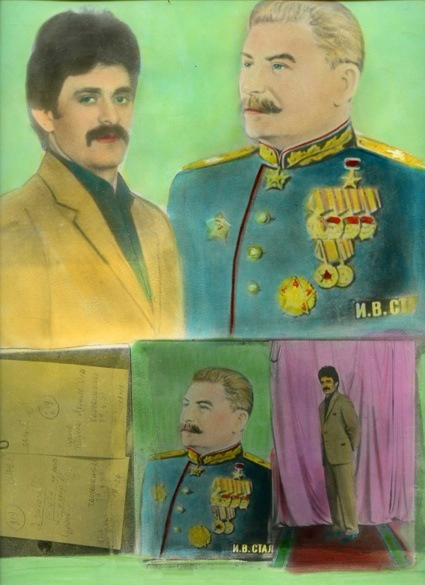

Boris Mikhailov (Ukranian, b. 1938)

Untitled

1971-1985

From the series Luriki

Vasily Ulitin (Russian, 1888-1976)

Flame of Paris

1932

Bromoil

Moscow House of Photography Museum

© Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow / Moscow House of Photography Museum

Dmitry Baltermants (Russian, 1912-1990)

Men’s talk

1950s

Colour print

Moscow House of Photography Museum

© Dmitry Baltermants Archive

© Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow / Moscow House of Photography Museum

Dmitry Baltermants (Russian, 1912-1990)

Rain

1960s

Colour print

Moscow House of Photography Museum

© Dmitry Baltermants Archive

© Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow / Moscow House of Photography Museum

Yakov Khalip (Russian, 1908-1980)

Sea cadets

End of 1940s

Artist’s colour print

On the reverse side text of congratulation to Alexander Rodchenko

Collection of Moscow House of Photography Museum

© Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow/ Moscow House of Photography Museum

The exhibition Primrose – Russian Colour Photography takes place as part of Netherlands-Russia 2013. The title refers to the primrose flower, used metaphorically here to represent the many colours in which it appears during early spring. Primrose – Russian Colour Photography presents a retrospective of the various attempts in Russia to produce coloured photographic images. This process began in the early 1850s, almost simultaneously with the discovery of the new medium itself. The colouring technique, based on the traditional methods of craftsmen who added colour into a certain contour design, has determined a whole independent trend in the history of photography in Russia, from ‘postcard’ landscapes and portraits to Soviet propaganda and reportage photography.

The use of colour in Russia stems from the early 1850s and practically coincides with the invention of the medium itself. The term colour photography is slightly disingenuous, since at first it referred to a toning technique in which black and white photographs were painted by hand. Traditionally this technique was used by specialised tradesmen who added colour to the photographs according to certain methods and within the contours of the image. This technique became so popular that it started a trend in and of itself and to a large extent determined the appearance and aesthetics of colour photography in Russia. Initially used especially for portraits, Pictorialist landscapes and nudes, it later also found favour with avant-garde artists. Interestingly enough these aesthetics also formed the starting point for Soviet propaganda and for portraits, political leaders and reportage.

Primrose – Russian Colour Photography can be viewed as a journey through various techniques and genres, meanings and messages, mass practices and individual experiments. The exhibition contains works by renowned photographers and artists such as Sergey Produkin-Gorsky, Ivan Shagin, Dmitry Baltermants and Robert Diament. But is also shows unique photos of Alexander Rodchenko and Varvara Stephanova, and recent works from the famous Luriki series by Boris Mikhailov, in which he mocked the visual culture of the Soviet propaganda.

Press release from the Foam website [Online] Cited 24/03/2020 no longer available online

Pyotr Pavlov (Russian, 1860-1924)

Moscow. Lubianka

1910s

Offprint

Collection of Moscow House of Photography Museum

© Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow / Moscow House of Photography Museum

Piotr Vedenisov (Russian, 1866-1937)

Tania, Natasha, Kolia and Liza Kozakov, Vera Nikolayevna Vedenisov and Elena Frantsevna Bazilev. Yalta

1910-1911

Copy; original – autochrome

Moscow House of Photography Museum

© Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow / Moscow House of Photography Museum

Piotr Vedenisov (Russian, 1866-1937)

Nikolskoye Simbirsk province

1910

Alexander Rodchenko (Russian, 1891-1956)

Race. “Dynamo” Stadium

1935

Artist’s gelatine silver print, gouache

Collection of Moscow House of Photography Museum

© A. Rodchenko – V. Stepanova Archive

© Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow / Moscow House of Photography Museum

Dmitry Baltermants (Russian, 1912-1990)

Meeting in the tundra

1972

From the Meetings with Chukotka series

Colour print Collection of Moscow House of Photography Museum

© Dmitry Baltermants Archive

© Moscow House of Photography Museum

Installation photographs of the exhibition Primrose – Russian Colour Photography at Foam, Amsterdam

Primrose

This exhibition with the metaphorical title Primrose demonstrates the appearance and development of colour in Russian photography from the 1860s to 1970s, and at the same time reveals the history of Russia in photography. With examples of works from classics of Russian photography such as P. Pavlov, K. Bergamasko, A. Eikhenvald, A. Rodchenko, V. Mikoshi, G. Petrusov, D. Baltermants and B. Mikhailov, as well as unknown photographers, we can see how life in Russia changed in the course of a century as it endured historical and socio-political catastrophes, also the diverse roles that photography played during this period.

Colour became widespread in Russian photography at approximately the same time as in Europe – in the 1860s. This was dependent on the manual tinting of photographic prints with watercolour and oil paints, either by the photographers themselves or by artists working with them. Above all this applies to solo or family portraits commissioned as a keepsake. The photographic studios of Nechayev, Ushakov & Eriks and Eikhenvald produced thousands of tinted portraits that became an important part of the domestic interior.

People were eager to see their own image in colour, and moreover in a picturesque form. The colouring of early photographic shots could also hide imperfections in the prints, including those introduced on albumenised paper. With time this paper turned yellow. To conceal this, the paper was tinted green, pink and other colours and coloured with watercolours, gouache, oils, or later aniline dyes. Sometimes the photograph was partially redrawn during the process of tinting, and foliate embellishments or different items of interior decoration appeared in the background.

By the end of the 19th century, by the 1880s and 1890s, colour photography was extended to architectural, landscape and industrial subject matter. For instance, the photographic studio of the Trinity and St. Sergius Monastery (photographic studios attached to Russian monasteries became a very common phenomenon) produced numerous coloured architectural images of Orthodox churches.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries Russia was on the one hand undergoing active europeanisation, as reflected in the style of architectural structures, interiors, costume and way of life, but meanwhile there was also a search for national identity, and new interest in the national particularities of inhabitants in the Russian Empire. Entire series of tinted photographs appeared, depicting people in national costumes – Russian, Tatar, Caucasian, Ukrainian, and so on.

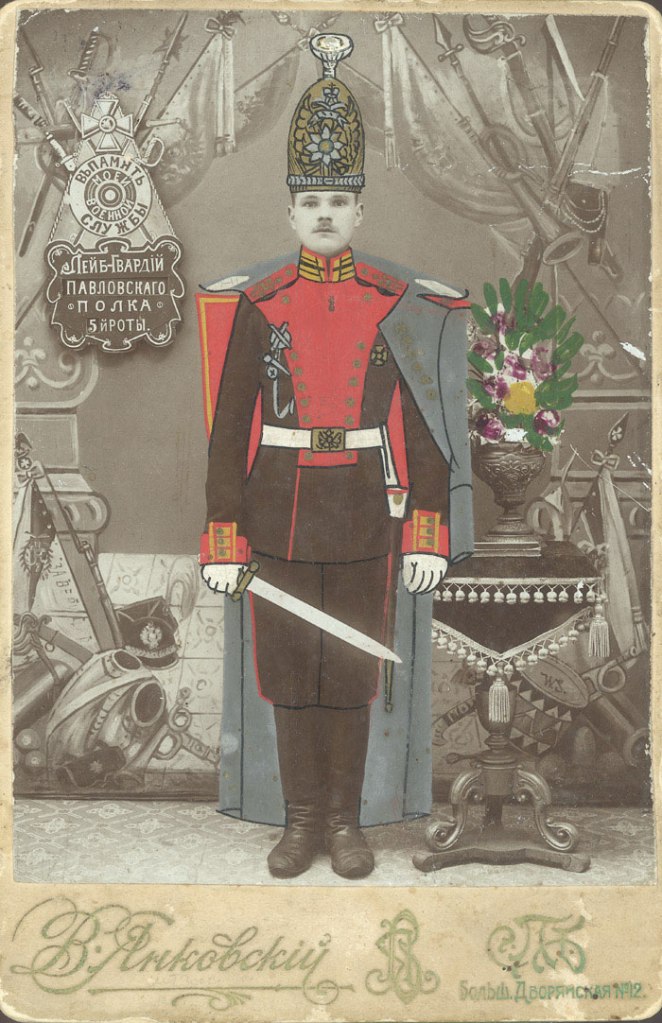

With the industrial boom of the late 19th and early 20th centuries people began to decorate their walls not only with tinted landscapes, but also photographs of industrial structures (eg Dmitri Yezuchevsky’s photograph Building the Bridge). In the early 20th century, in the 1910s, coloured photographs of Russian military officers, an important social class before the outbreak of the First World War, were particularly popular.

The photographic documentation of life in the Russian Empire in the early 20th century acquired the status of a State objective, largely because Tsar Nicholas II and his family were enthusiastic amateur photographers. In May 1909 Emperor Nicholas II gave an audience to the photographer Sergei Prokudin-Gorsky. In 1902 Prokudin-Gorsky had first announced a technique for creating colour photographs, and in 1903 he published a brochure entitled ‘Isochromatic Photography with Manual Cameras’. Prokudin-Gorsky used black-and-white plates sensitised according to his own formulae, and a camera of his own construction. Three rapid shots were taken successively through light filters coloured blue, green and red (the photographer managed to reduce the exposure time to an absolute minimum). From this triple negative a triple positive was prepared. A projector with three lenses in front of three frames on the photographic plate was used to view the shots. Each frame was projected through a colour filter of the same colour as that through which it had been photographed. A full-colour image appeared on the screen as the three images combined. Prokudin-Gorsky succeeded in making polygraphic reproductions of his shots, printed in the form of photo cards, and also as inserts for illustrated magazines.

Delighted with this invention, Emperor Nicholas II asked the photographer to take colour photographs of every aspect of life in the various regions that then constituted the Russian Empire. For this the photographer was issued with a specially equipped railway car. The government provided him with a small manned steamship able to traverse the shallows for his work on waterways, and a motorboat for the River Chusova. A Ford automobile was dispatched to Yekaterinburg for his shots of the Urals and the Ural mountain range. Prokudin-Gorsky was presented with official imperial documents that gave him access to all parts of the Empire, and government officials were ordered to assist Prokudin-Gorsky on his travels.

Meanwhile autochrome pictures by the Lumière brothers, with whom Prokudin-Gorsky worked after emigrating from Soviet Russia, became very popular in early 20th-century Russia. Autochromes, colour transparencies on a glass backing, were first produced on an industrial scale in 1907. Granules of potato starch tinted red, yellow and blue were applied to a glass plate. The granules worked as colour filters. Addition of a second layer of granules provided orange, violet and green hues. After that a light-sensitive emulsion was applied. The plate was exposed and developed. Autochromes could be viewed against the light, or projected with the aid of special apparatus, which at that time was manufactured by the Lumière brothers’ own company (diascopes, chromodiascopes, mirrored stereoscopes, etc.). The Lumière brothers’ autochromes were used, for example, by Pyotr Vedenisov, a prosperous nobleman and graduate of the Moscow Conservatoire, who settled in Yalta, in the Crimea, in the late 1880s. As was the case with the Lumière brothers’ autochromes, Vedenisov’s favoured subject matter was the photographer’s own family life. However, what was at first sight very private and personal photography later provided an excellent description of the typical lifestyle enjoyed by educated Russian noblemen in the early 20th century.

The onset of the First World War in 1914 and October Revolution in 1917 annihilated the Russia whose memory is preserved in the tinted photographs and autochromes of the second half of the 19th to early 20th centuries.

Vladimir Lenin and the new Soviet government actively supported photography in the early post-revolutionary years, seeing it as an important propaganda weapon for a country where 70% of the population were unable to read or write. At first there was emphasis on photo reportage, but very soon it became clear real change in a country where hunger and devastation ruled after the Revolution and Civil War was as insubstantial as the utopian dreams of ardent revolutionaries. From the mid-1920s photomontage was widespread in the Soviet Union, enthusiastically encouraged by the Bolsheviks. Photomontage allowed for a combination of documentary veracity and the new Soviet myths. In the 1920s it was practised by such highly talented modernists as A. Rodchenko, G. Klutsis, El Lissitzky, V. Stepanova and others. Photomontage embraced colour and became an ideological ‘visual weapon’.

From the mid-1920s A. Rodchenko regenerated the forgotten technique of hand colouring his own photographs. His use of tinting profited from his experience with photomontage (Mosselprom House Advertising Wall, Dynamo Running Stadium, etc.), and he also applied it to develop experiments with positive-negative printing (scenes from the film Albidum) and for very personal and even intimate portraits of his muse Regina Lemberg – Girl with Watering Can. In 1937, at the height of Stalin’s repression, A. Rodchenko began photographing classical ballet and opera, using the arsenal of his aesthetic opponents, the Russian Pictorialists, who by that time were subject to even harsher repression in the Soviet Union than modernist photographers. For Alexander Rodchenko soft focus, classical subject matter and toning typical of pictorial photography were a mediated way of expressing his internal escapism and tragic disillusionment with the Soviet utopia.

In 1932 general rules for socialist realism were published in the USSR, as the only creative method for all forms of art, including photographic. Soviet art had to reflect Soviet myths about the happiest people in the happiest country, not real life and real people. On this Procrustean bed it was hard not only for modernism with its constructivist aesthetics, but even Pictorialism, to fit into the aesthetics of Socialist realism.

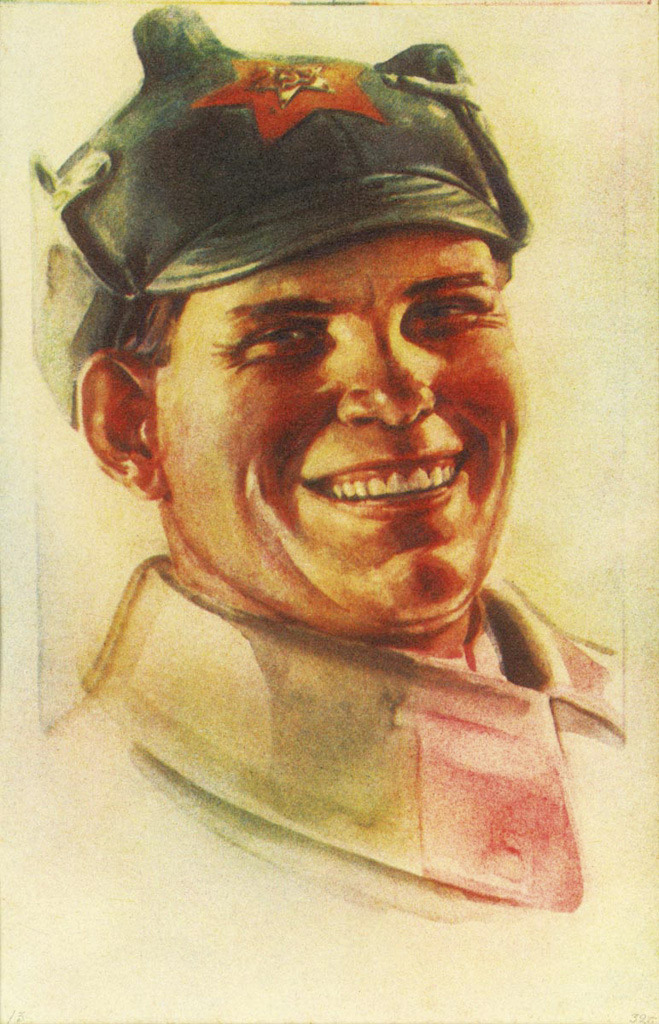

Pictorialism was one of the most important tendencies of early 20th-century Russian photography, and Russian Pictorialist photographers were awarded gold and silver medals at international exhibitions. Pictorial photography differed not only by the method of shooting and complex printing techniques intended to bring photography closer to painting, but also by the selection of traditional themes. Romantic landscapes and architectural ruins or nude studies were from the point of view of socialist realism dangerous remnants from the past. Some of the Pictorialist photographers ended up in Stalin’s prison camps, and were forbidden from practising their profession or settling in the capital or other large cities. Those who remained at liberty – for example, Vasily Ulitin, a participant in major international photo exhibitions and recipient of medals and diplomas in Paris, London, Berlin, Los Angeles, Toronto, Tokyo and Rome – tried with difficulty to adapt to the new reality and attempted to depict revolutionary subjects (Flames of Paris, Red Army Soldier), thereby gaining indulgence and the right to work from the Bolsheviks.

Almost simultaneously, in 1936 the German company Agfa and American company Kodak introduced colour film. Broad distribution and introduction to the amateur photography market were delayed by the outbreak of the Second World War. In the USSR colour photography only appeared at the end of the war. Production of Soviet-made colour film in the USSR was facilitated by German trophy equipment in 1946. From that year onwards Ivan Shagin and several other photographers began to relay their colour news chronicle to the country.

Before 1946 colour photographs of Soviet Russia were made only in isolated cases, on German or American film. Until the mid-1970s, in the USSR negative film for printing colour photographs was a luxury only available to a few official photographers who worked for major Soviet publications. It was used by such classics of Soviet photography as V. Mikosha, G. Petrusov, D. Baltermants, V. Tarasevich, and others. All of them were in one way or another obliged to follow the canons of socialist realism and practise staged reportage. In those days even still life studies of fruit bore an ideological message, being photographed for cookery books in which the Soviet people could see produce that remained absent in a hungry postwar country, where the ration-card system of food distribution was still functioning (Ivan Shagin, Lemons and Fruit, 1949).

From the late 1950s, in the Khrushchev Thaw after the debunking of Stalin’s cult of personality, the canons of socialist realism softened and permitted a certain freedom in aesthetics, allowing photography to move closer to reality (Dmitri Baltermants’ series Arbat Square). In the postwar period, during the 1950s to 1960s life gradually improved and coloured souvenir photo portraits again appeared on the mass market. They were usually produced by unknown and ‘unofficial’ photographers, since private photo studios that had carried out such commissions since the mid-19th century were now forbidden, and the State exercised a total monopoly on photography by the 1930s. Boris Mikhailov copied and enlarged such kitsch colour photographs as souvenirs to supplement his income at his photo laboratory in Kharkov in the early 1970s. He began collecting them. They form the basis for a new aesthetics he developed in the Lyrics series from the early 1980s. By tinting these naïve photographs he revealed and deconstructed the nature of Soviet myths.

Colour transparency film appeared on the Soviet mass market in the 1960s and 1970s. As opposed to colour negative film that requires a complicated and expensive development process for subsequent printing, colour slide film could be developed even in domestic surroundings. Above all it was widely used by amateurs, who created transparencies that could be viewed at home with a slide projector. An unofficial art form emerging in the USSR at this time developed the aesthetics and means for a new artistic conceptualisation of reality, quite different from the socialist realism that still prevailed, although somewhat modified. Photography took a significant role in this unofficial art. It was in the late 1960s and early 1970s that Boris Mikhailov began photographing his series Suzi Et Cetera on colour slide film.

More than half a century of Soviet power after the 1917 Revolution radically altered Russia. The surrounding reality has fallen into decline, and people brought up on Soviet slogans never thought to pay attention. But this was the only reality offered by our perception, and Boris Mikhailov tries to develop its colour, humanise it with his attention and give it the right of existence. Photography textbooks of that period were made up of one-third technical formulae and two-thirds description of what to photograph, and how. The photographer was certainly not required or even allowed to take nude studies. Corporeality and sexuality are inherent signs of an independent individual, of selfhood. The Soviet system specifically tried to level out any sense of selfhood, smothering it and challenging such ideas with the collective community and the impersonal ‘we’ of the Soviet nation. In photographing Suzi Et Cetera Boris Mikhailov disrupts the norms and reveals characters, his own and that of his subjects. It was impossible to show these shots in public, but slides could be projected at home, in the workshops of his artist friends or the small, often semi-underground clubs of the scientific and technical intelligentsia, who began to revive during Khrushchev’s Thaw after the Stalinist repression. Boris Mikhailov’s slide projections are now analogous to the apartment exhibitions of unofficial art. By means of colour he displayed the dismal standardisation and squalor of surrounding life, and his slide performances helped to unite people whose consciousness and life in those years began to escape from the dogmatic network of Soviet ideology, which permitted only one colour – red.

Curator Olga Sviblova

Director, Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow

Boris Mikhailov (Ukranian, b. 1938)

Untitled

1971-1985

From the series Luriki

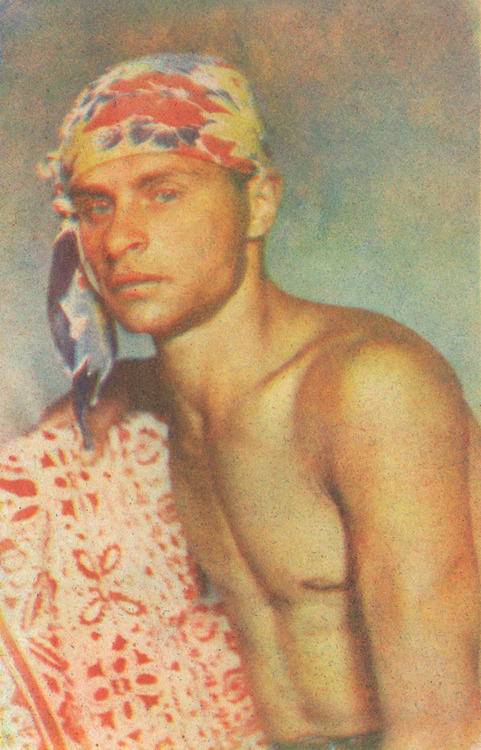

Vladislav Mikosha (Russian, 1909-2004)

Portrait of Yury Rypalov

1938-1939

V. Yankovsky

“In memory of my military service”. Saint Petersburg

Beginning of 1910s

Collodion, painting

Collection of Moscow House of Photography Museum

© Moscow House of Photography Museum

Elena Mrozovskaya (Russian, before 1892-1941)

Portrait of girl in Little Russia costume. Saint Petersburg

1900s

Gelatine silver print, painting

Collection of Moscow House of Photography Museum

© Moscow House of Photography Museum

A. Nechayev

Portrait of girl

1860s

Salted paper, covered by albumen, painting

Collection of Moscow House of Photography Museum

© Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow / Moscow House of Photography Museum

Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky (Russian, 1863-1944)

Portrait of Lev Tolstoy

23rd of May 1908

Offprint

Collection Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow

Piotr Vedenisov (Russian, 1866-1937)

Uknown woman, the Crimea, Yalta

1914

Piotr Vedenisov (Russian, 1866-1937)

Andrei Aleksandrovich Kozakov. Yalta

1911-1912

Copy; original – autochrome

Moscow House of Photography Museum

© Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow / Moscow House of Photography Museum

Piotr Vedenisov (Russian, 1866-1937)

Vera Kozakov in Folk Dress

1914

Collection of Moscow House of Photography Museum

© Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow / Moscow House of Photography Museum

The scenes in Vedenisov’s autochromes take place in Yalta or in the Simbirsk Government, where the Kozakov family, the photographer’s relations, resided. Piotr Vedenisov chooses his models among the members of this single large family. Vedenisov’s photos are mostly staged portraits. Other subjects include everyday life and travelling, feasts, pets, interiors and landscapes. Vedenisov’s autochromes are shot over a relatively short period of time, roughly from 1909 to 1914.

About the photographer

Piotr Ivanovich Vedenisov (1866-1937) was a Russian nobleman living in Yalta, who graduated at the Moscow Conservatorium in 1888. Beside his ultimate passion for music, he was enthusiastic about the history of Crimea and photography. In the early 20th century, Vedenisov masters a technical innovation: he could make colour autochromes on glass. It was a technique of creating works in colour, based on three stages of consecutive shooting through colour filters. It was further developed by the Lumière brothers who succeeded in placing all the filters on a single plate.

Text from the Foam website Nd [Online] Cited 19/09/2022

Piotr Vedenisov (Russian, 1866-1937)

Kolya Kozakov and the Dog Gipsy. Yalta

1910-1911

Collection of Moscow House of Photography Museum

© Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow / Moscow House of Photography Museum

Vasily Ulitin (Russian, 1888-1976)

Red Army man

1932

Dmitry Baltermants (Russian, 1912-1990)

Show window

Beginning of 1960s

Colour print

Collection of Moscow House of Photography Museum

© Dmitry Baltermants Archive

© Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow / Moscow House of Photography Museum

Ivan Shagin (Russian, 1904-1982)

Fruits

1949

Colour print

Collection of Moscow House of Photography Museum

© Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow / Moscow House of Photography Museum

Robert Diament (Russian, 1907-1987)

He has turned her head

Beginning of 1960s

Colour print

Collection Moscow House of Photography Museum

© Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow / Moscow House of Photography Museum

Foam

Keizersgracht 609

1017 DS Amsterdam

The Netherlands

Phone: + 31 20 5516500

Opening hours:

Mon – Wed 10am – 6pm

Thu – Fri 10am – 9pm

Sat – Sun 10am – 6pm

You must be logged in to post a comment.