Exhibition dates: 11th November 2012 – 3rd February 2013

Curators: Anne Tucker, Natalie Zelt and Will Michels

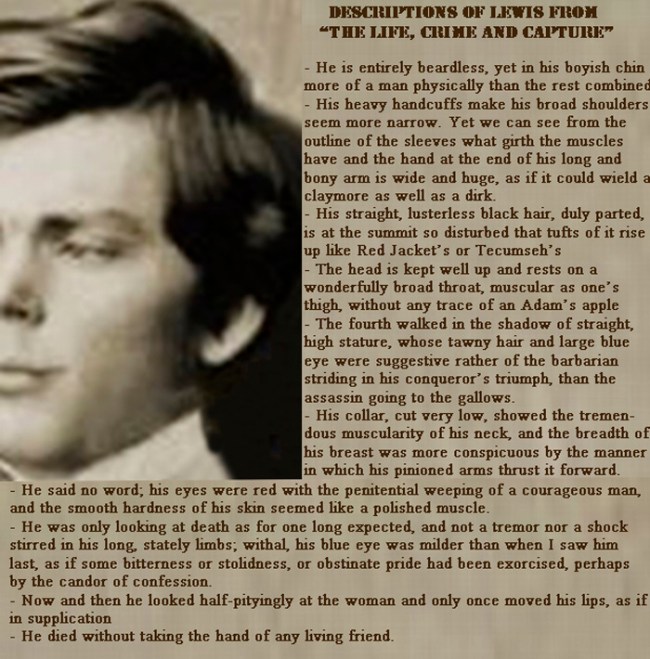

Roger Fenton (British, 1819-1869)

The Valley of the Shadow of Death

1855

This is the biggest posting on one exhibition that I have ever undertaken on Art Blart!

As befits the gravity of the subject matter this posting is so humongous that I have had to split it into 4 separate postings. This is how to research and stage a contemporary photography exhibition that fully explores its theme (NGV please note!). The curators reviewed more than one million photographs in 17 countries, locating pictures in archives, military libraries, museums, private collections, historical societies and news agencies; in the personal files of photographers and service personnel; and at two annual photojournalism festivals producing an exhibition that features 26 sections (an inspired and thoughtful selection) that includes nearly 500 objects that illuminate all aspects of WAR/PHOTOGRAPHY.

I have spent hours researching and finding photographs on the Internet to support the posting. It has been a great learning experience and my admiration for photographers of all types has increased. I have discovered the photographs and stories of new image makers that I did not know and some hidden treasures along the way. I hope you enjoy this monster posting on a subject matter that should be consigned to the history books of human evolution.

**Please be aware that there are graphic photographs in all of these postings.** Part 2, Part 3, Part 4

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston for allowing me to publish some of the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

On November 11, 2012, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, debuts an unprecedented exhibition exploring the experience of war through the eyes of photographers. WAR / PHOTOGRAPHY: Images of Armed Conflict and Its Aftermath features nearly 500 objects, including photographs, books, magazines, albums and photographic equipment. The photographs were made by more than 280 photographers, from 28 nations, who have covered conflict on six continents over 165 years, from the Mexican-American War of 1846 through present-day conflicts. The exhibition takes a critical look at the relationship between war and photography, exploring what types of photographs are, and are not, made, and by whom and for whom. Rather than a chronological survey of wartime photographs or a survey of “greatest hits,” the exhibition presents types of photographs repeatedly made during the many phases of war – regardless of the size or cause of the conflict, the photographers’ or subjects’ culture or the era in which the pictures were recorded. The images in the exhibition are organised according to the progression of war: from the acts that instigate armed conflict, to “the fight,” to victory and defeat, and images that memorialise a war, its combatants and its victims. Both iconic images and previously unknown images are on view, taken by military photographers, commercial photographers (portrait and photojournalist), amateurs and artists.

“‘WAR/PHOTOGRAPHY’ promises to be another pioneering exhibition, following other landmark MFAH photography exhibitions such as ‘Czech Modernism: 1900-1945’ (1989) and ‘The History of Japanese Photography’ (2003),” said Gary Tinterow, MFAH director. “Anne Tucker, along with her co-curators, Natalie Zelt and Will Michels, has spent a decade preparing this unprecedented exploration of the complex and profound relationship between war and photography.” “Photographs serve the public as a collective memory of the experience of war, yet most presentations that deal with the material are organised chronologically,” commented Tucker. “We believe ‘WAR / PHOTOGRAPHY’ is unique in its scope, exploring conflict and its consequences across the globe and over time, analysing this complex and unrelenting phenomenon.”

The earliest work in the exhibition is from 1847, taken from the first photographed conflict: the Mexican-American War. Other early examples include photographs from the Crimean War, such as Roger Fenton’s iconic The Valley of the Shadow of Death (1855) and Felice Beato’s photograph of the devastated interior of Fort Taku in China during the Second Opium War (1860). Among the most recent images is a 2008 photograph of the Battle Company of the 173rd Airborne Brigade in the remote Korengal Valley of Eastern Afghanistan by Tim Hetherington, who was killed in April 2011 while covering the civil war in Libya. Also represented with two photographs in the exhibition is Chris Hondros, who was killed with Hetherington. While the exhibition is organised according to the phases of war, portraits of servicemen, military and political leaders and civilians are a consistent presence throughout, including Yousuf Karsh’s classic 1941 image of Winston Churchill, and the Marlboro Marine (2004), taken by embedded Los Angeles Times photographer Luis Sinco of soldier James Blake Miller after an assault in Fallujah, Iraq. Sinco’s image was published worldwide on the cover of 150 publications and became a 2005 Pulitzer Prize finalist.

The exhibition was initiated in 2002, when the MFAH acquired what is purported to be the first print made from Joe Rosenthal’s negative of Old Glory Goes Up on Mount Suribachi, Iwo Jima (1945). From this initial acquisition, the curators decided to organise an exhibition that would focus on war photography as a genre. During the evolution of the project, the museum acquired more than a third of the prints in the exhibition. The curators reviewed more than one million photographs in 17 countries, locating pictures in archives, military libraries, museums, private collections, historical societies and news agencies; in the personal files of photographers and service personnel; and at two annual photojournalism festivals: World Press Photo (Amsterdam) and Visa pour l’Image (Perpignan, France). The curators based their appraisals on the clarity of the photographers’ observation and capacity to make memorable and striking pictures that have lasting relevance. The pictures were recorded by some of the most celebrated conflict photographers, as well as by many who remain anonymous. Almost every photographic process is included, ranging from daguerreotypes to inkjet prints, digital captures and cell-phone shots.

Press release from the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Yousuf Karsh (Armenian-Canadian, 1908-2002)

Winston Churchill

1941

Gelatin silver print

WAR/PHOTOGRAPHY: Images of Armed Conflict and Its Aftermath is organised into 26 sections, which unfold in the sequence that typifies the stages of war, from the advent of conflict through the fight, aftermath and remembrance. Each section showcases images appropriate to that category while cutting across cultures, time and place. Outside of this chronological approach are focused galleries for “Media Coverage and Dissemination” (with an emphasis on technology); “Iwo Jima” (a case study); and “Photographic Essays” (excerpts from two landmark photojournalism essays, by Larry Burrows and Todd Heisler).

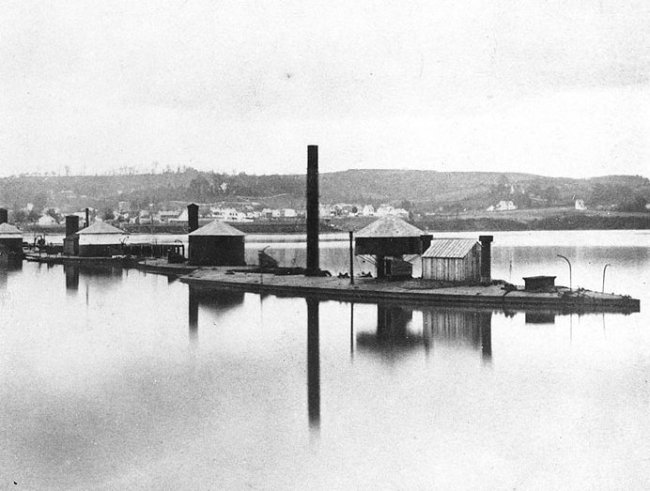

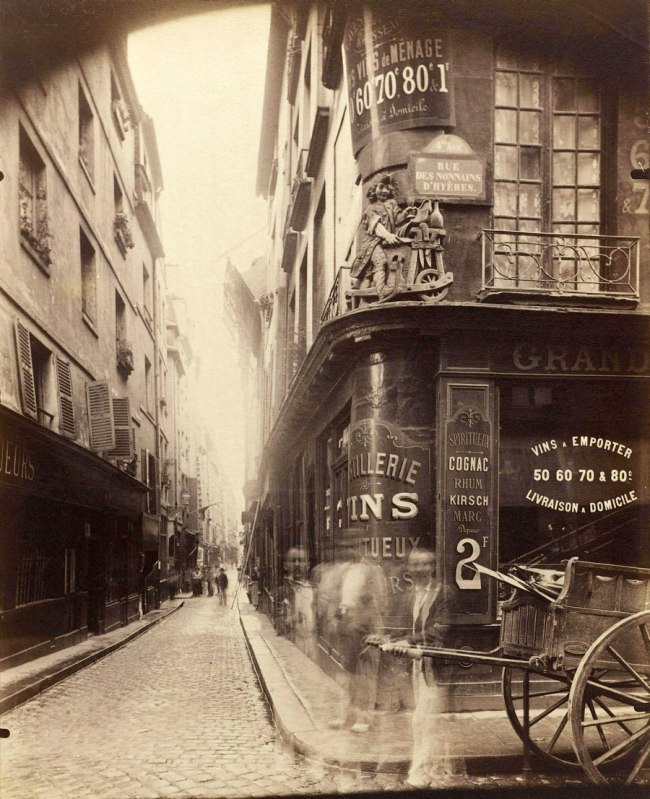

Media Coverage and Dissemination

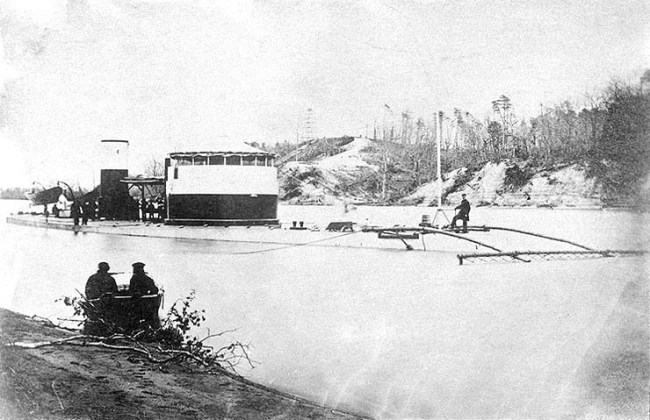

1. Media Coverage and Dissemination provides an overview of how technology has profoundly affected the ways that pictures from the front reach the public: from Roger Fenton and his horse-drawn photography van (commissioned by the British government to document the Crimean War), to Joe Rosenthal’s 1940s Anniversary Speed Graphic (4 x 5) camera, to pictures taken with the Hipstamatic app of an iPhone by photojournalist Michael Christopher Brown in Egypt during the protests and clashes of the Arab Spring. (22 images / objects)

Roger Fenton (British, 1819-1869)

The artist’s van [Marcus Sparling, full-length portrait, seated on Roger Fenton’s photographic van]

1855

Salted paper print

17.5 × 16.5cm

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division

Manufactured by Graflex, active 1912-1973

Anniversary Speed Graphic (4 x 5), “Scott S. Wigle camera” (First American-made D-Day picture)

c. 1940

Camera

Collection of George Eastman House (Gift of Graflex, Inc.)

An Advent of War

2. The photographs in An Advent of War depict the catalytic events of war. These moments of instigation are rarely captured, as photographers are not always present at the initial attack or provocation. Photographs that Robert Clark took on the morning of September 11, 2001, and the aerial view of torpedoes approaching Battleship Row during the Pearl Harbor attack, taken by an unknown Japanese airman on December 7, 1941, both convey with clarity the concept of war’s advent. (11 images).

Unknown photographer (Japanese)

War in Hawaiian Water. Japanese Torpedoes Attack Battleship Row, Pearl Harbor

December 7, 1941

Gelatin silver print

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, gift of Will Michels

Recruitment & Embarkation

3. Recruitment & Embarkation shows mobilisation: the movement toward the front. Mikhail Trakhman captures a Russian mother kissing her son goodbye in Kolkhoz farmer M. Nikolaïeva bids her son Ivan goodbye before he joins the partisans (1942), while a 1916 photograph by Josiah Barnes, known as the “Embarkation Photographer,” shows an archetypal moment: young Australian soldiers waving goodbye from a ship as they depart their home country to fight in World War I. (7 images)

Josiah Barnes (Australian, 1858-1921)

Embarkation of HMAT Ajana, Melbourne

July 8, 1916

Gelatin silver print (printed 2012)

On loan from the Australian War Memorial

Known as “the embarkation photographer”, the Kew, Melbourne photographer Josiah Barnes took an interest in photographing Australian troopships as they departed for war from Melbourne. He had two sons, “Norm and Victor, who left for war in 1916 (both returned to Australia after their service),” which may have fuelled his interest.

Mikhail Trakhman (Russian, 1918-1976)

Kolkhoz farmer M. Nikolaïeva bids her son Ivan goodbye before he joins the partisans

1942

Gelatin silver print

A kolkhoz was a form of collective farm in the Soviet Union which, alongside sovkhoz (state farm), formed the main components of the socialised farm sector which emerged after the October Revolution of 1917 as an antithesis to feudalism, aristocratic landlords, serfdom and individual farming.

Mikhail Trakhman

Mikhail Trakhman was born in Moscow in 1918. After graduating from school, he began working at the newsreel studio and at the same time studying for courses in the field of assistant operator. From 1938 he became the photo reporter of the Uchitelskaya Gazeta, and in 1939 he was drafted into the army and participated in the Soviet-Finnish war. During the Great Patriotic War, Mikhail Trakhman worked as a press photographer for the Soviet Information Bureau. His main instrument was the famous “Leica” camera, but often military weapons fell into his hands. He shot in besieged Leningrad, in Pskov and in Belarus, participated in the liberation of Poland and Hungary. The most famous are his photographs from the partisan series taken in the rear of the German troops. In his diaries, he wrote: “I take a lot of things, although I know that 80% of the shot will go to the basket, but I need to shoot it, since such things happen once in a lifetime.” Thanks to these photos, he entered the history of war reporting. Mikhail Trakhman was awarded the Order of the Red Star and the medal “For the Defense of Leningrad” and “Partisan Medal”, which he especially valued.

Anonymous. “Mikhail Trakhman,” on the Lumiere Brothers Gallery website [Online] Cited 06/09/2020

Training

4. Training explores photographs of soldiers in boot camp or more-advanced phases of instruction and exercise. World War II Royal Navy officers gather around a desk to study different types of aircraft in a photograph by Sir Cecil Beaton. Also included is the iconic Vietnam-era photograph of a U.S. Marine drill sergeant reprimanding a recruit in South Carolina, from Thomas Hoepker’s series US Marine Corps boot camp, 1970. In one photograph, shot by a Japanese soldier and published in 1938 by Look magazine, Japanese soldiers use living Chinese prisoners in bayonet practice. (13 images)

Thomas Hoepker (German, 1936-2024)

A US Marine drill sergeant delivers a severe reprimand to a recruit, Parris Island, South Carolina

1970

From the series US Marine Corps boot camp, 1970

Inkjet print

Thomas Hoepker / Magnum Photos

© Thomas Hoepker / Magnum Photos

Daily Routine

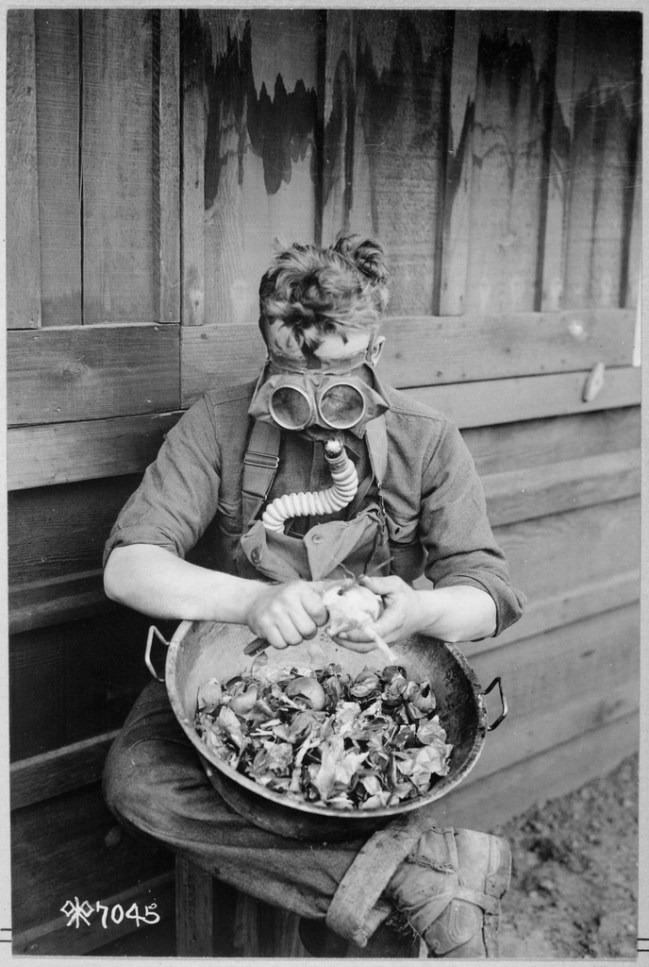

5. Daily Routine features moments of boredom, routine and playfulness. A member of the U.S. Army Signal Corps wears a gas mask as he peels onions. A 1942 photograph by Sir Cecil Beaton catches the off-guard expression of a Royal Navy man at a sewing machine, mending a signal flag. (13 images)

Anonymous photographer

Soldiers trying out their gas masks in every possible way. Putting the respirator to good use while peeling onions. 40th Division, Camp Kearny, San Diego, California

1918

National Archives and Records Administration

Cecil Beaton (English, 1904-1980)

A Royal Navy sailor on board HMS Alcantara uses a portable sewing machine to repair a signal flag during a voyage to Sierra Leone

March 1942

Gelatin silver print, printed 2012

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Gift of the Phillip and Edith Leonian Foundation

© The Imperial War Museums (neg. #CBM 1049)

HMS Alcantara

HMS Alcatara was an RML passenger liner of 22,209 tons and 19 knots launched in 1926, and taken up by the Royal Navy for conversion to an armed merchant cruiser to counter the threat posed by German surface raiders against shipping. When Jim Hingston joined her as an ordinary seaman at Freetown she was still largely in merchant dress, with wood panelling throughout. Much to the regret of her crew this was removed during their stay at Simonstown – the wisdom of that was apparent to them only too soon.

There were some 53 such ships in all, poorly armed, in Alcantara‘s case with eight 6 inch and two 3 inch guns, the former having a range of some 14,200 yards (13,000 metres). Such armament could not be much more than defensive, the intention being that the AMCs should radio the position of the German ship and not only give merchant shipping a chance to escape but delay the commerce raider long enough to allow regular RN warships to get to the scene.

Alcantara‘s opponent, the Thor, was laid down in 1938 as a freighter of 9,200 tons displacement and a speed of 18 knots, but commissioned as a commerce raider on 14 March 1940. Though she had only 6 150 mm guns they had a much greater range, at 20,000 yards, than Alcantara and other British AMCs. She also carried a scout floatplane. During the engagement with Alcantara on 28 July 1940 the Thor inflicted significant damage but the Alcantara successfully closed, and after being hit the Thor withdrew in order to avoid the risk of being crippled or being forced to abort her mission. In later encounters with AMCs the Thor severely damaged the Carnarvon Castle and sank Voltaire.

HMS Alcantara later had her 6 in armament upgraded and was equipped with a seaplane, but as the threat of surface raiders receded she was converted to her more natural role of troopship in 1943.

Reconnaissance, Resistance and Sabotage

6. Images of Reconnaissance, Resistance and Sabotage are scarce by nature, as they reveal spies in the act and could be used against those depicted or their families. A U.S. soldier on night watch sits atop a mountain in Afghanistan, wrapped in a blanket and peering into night-vision equipment, in a photograph by Adam Ferguson. A photograph by T. E. Lawrence (known as Lawrence of Arabia) documents the bombing of the Hejaz Railway during the Arab Revolt. Cas Oorthuys’ photograph Under German Occupation (Dutch Worker’s Front), Amsterdam (c. 1940-1945), taken with a camera hidden in his jacket, shows the back of a fellow countryman who is helping to conceal the photographer, with German troops in the distance. Also included is Arkady Shaikhet’s 1942 photograph Partisan Girl depicting Olga Mekheda, who was renowned for her ability to get through German roadblocks – even while pregnant. (10 images)

T.E. Lawrence (British, 1888-1935)

Untitled [A Tulip bomb explodes on the railway Hejaz Railway, near Deraa, Hejaz, Ottoman Empire]

1918

Collection of the MFA Houston

Cas Oorthuys (Dutch, 1908-1975)

Under German Occupation (Dutch Worker’s Front), Amsterdam

c. 1940-1945

Gelatin silver print

13 7/8 × 11 5/8 in. (35.2 × 29.5cm)

Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Museum purchase funded by Anne Wilkes Tucker in honor of the 50th wedding anniversary of Max and Isabell Smith Herzstein

Adam Ferguson (Australian, b. 1978)

September 4, Tangi valley, Wardak province, Afghanistan, a soldier of the U.S. Army 10th Mountain Division was attentively monitoring a highway

September 4, 2009

“To me, this picture epitomises the abstract idea of the ‘enemy’ that exists within the U.S. led war in Afghanistan: a young infantryman watches a road with a long-range acquisition sight surveying for insurgents planting Improvised Explosive Devices. U.S. Army Infantrymen rarely knowingly come face to face with their enemy, combat is fleeting and fought like cat and mouse, and the most decisive blows are determined by intelligence gathering, and then delivered through technology that maintains a safe distance, just like a video game.”

~ Adam Ferguson

Arkady Shaikhet (Russian, 1898-1959)

Partisan Girl

1942

Gelatin silver print

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, gift of Marion Mundy

© Arkady Shaikhet Estate, Moscow, courtesy Nailya Alexander Gallery, NYC

Patrol & Troop Movement

7. Patrol & Troop Movement conveys the mass movements of peoples and personnel by land, sea and air, from the movement of troops and supplies to patrols by all five divisions of military service: Army, Navy, Marine Corps, Coast Guard and Air Force. Combat patrols are detachments of forces sent into hostile terrain for a range of missions, and they – as well as the photographers accompanying them – face considerable danger. João Silva’s three sequenced frames show, through his eyes, the tilted earth just after he was felled by an IED while on patrol in Afghanistan in 2010; he lost both legs in the incident. A tranquil, 1917 image by Australian James Frank Hurley depicts silhouetted soldiers walking in a line, their reflections captured in a body of water. A 1943 photograph by American Warrant Photographer Jess W. January USCGR shows members of the U.S. Coast Guard observing a depth-charge explosion hitting a German submarine that stalked their convoy. (14 images)

.

João Silva (South African born Portugal, b. 1966)

Soldiers of Charlie Company, 1st Battalion, 66th Armored Regiment, 4th Infantry Division react to photographer Joao Silva stepping on a mine in the Arghandab district of Kandahar Province, Afghanistan, on Oct. 23, 2010, in a three-photo combination. For American troops in heavily-mined Afghan villages, steering clear of improvised explosive devices is the most difficult task

October 23, 2010

© João Silva / The New York Times via Redux

Frank Hurley (Australian, 1885-1962)

Supporting troops of the 1st Australian Division walking on a duckboard track

1917

Warrant Photographer Jess W. January USCGR, American

USCG Cutter Spencer destroys Nazi sub

April 17, 1943

Gelatin silver print

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

The Wait

8. The Wait depicts a common situation of wartime. Susan Meiselas captures a tense moment during a 1978 street fight in Nicaragua, when muchachos with Molotov cocktails line up in an alleyway, ready to initiate an attack on the National Guard. Robert Capa shows two female French ambulance drivers in Italy during World War II, leaning against their vehicle, knitting, as they wait to be called. (8 images)

Robert Capa (American-Hungarian, 1913-1954)

Drivers from the French ambulance corps near the front, waiting to be called

Italy, 1944

Original album – Italy. Cassino Campaign. W.W.II.

© 2001 By Cornell Capa, Agentur Magnum

Susan Meiselas (American, b. 1948)

Muchachos Await Counter Attack by The National Guard, Matagalpa, Nicaragua

1978

Chromogenic print (printed 2006)

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, museum purchase with funds provided by Photo Forum 2006

© Susan Meiselas / Magnum Photos

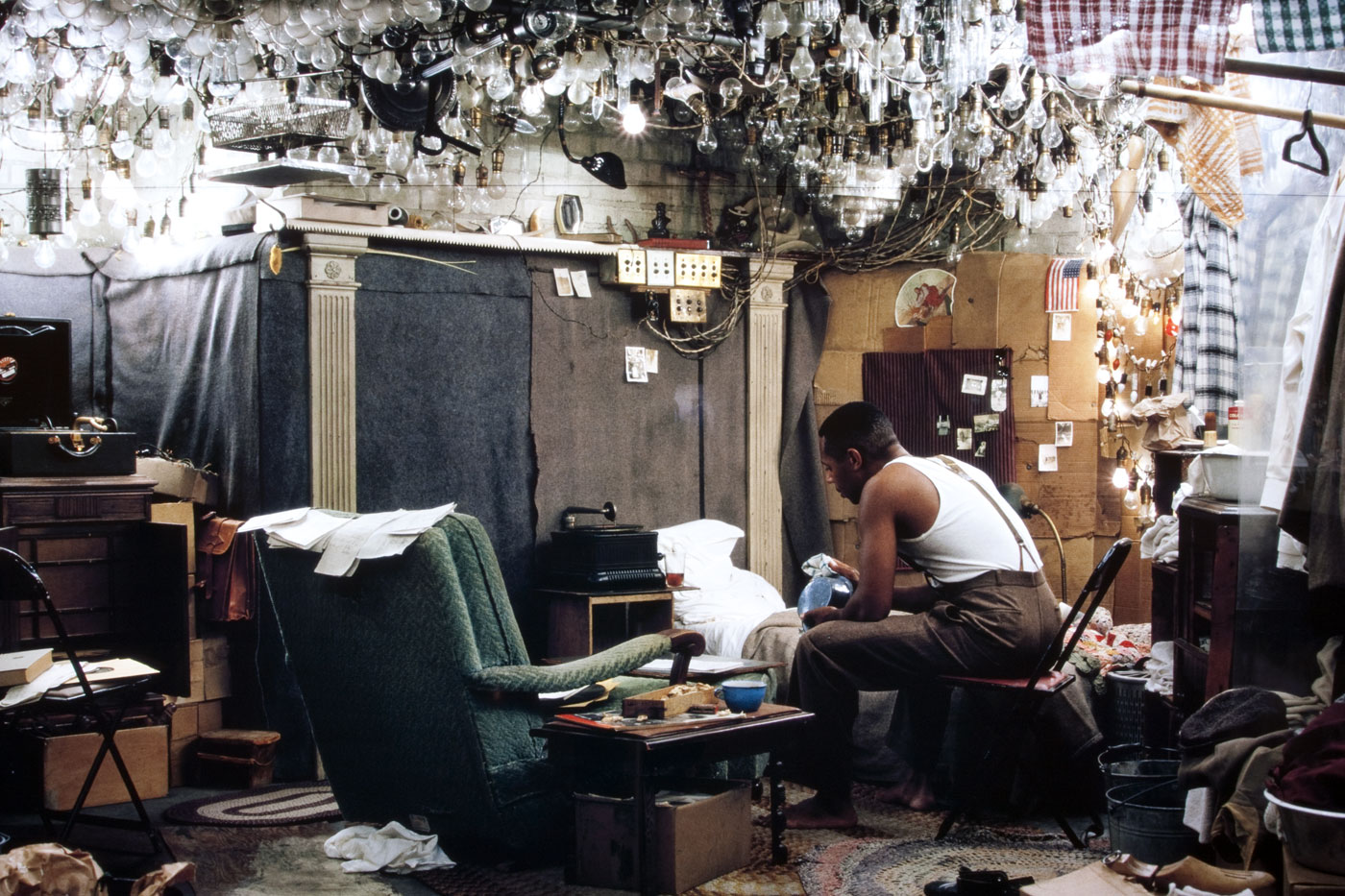

The Fight

9. The Fight is one of the most extensive sections in the exhibition. Dmitri Baltermants shot Attack – Eastern Front WWII (cover image of the exhibition catalogue) in 1941 from the trench, as men charged over him. Sky Over Sevastopol (1944), by Evgeny Khaldey, is an aerial photograph of planes on their way to a bombing raid of the strategically important naval point. Joe Rosenthal’s Over the Top – American Troops Move onto the Beach at Iwo Jima (1945) pictures infantrymen emerging from the protection of their landing craft into enemy fire. Staged photographs, presented as authentic documents, tend to proliferate during wartime, and several examples are included here. In 1942 the Public Relations Department of the War issued an assignment to photographers to create “representative” images of combat in North Africa for more dynamic images; official British photographer Len Chetwyn staged an Australian officer leading the charging line in the battle of El Alamein, using smoke in the background from the cookhouse to create a lively image. (21 images)

Len Chetwyn (English, 1909-1980)

Australians approached the strong point, ready to rush in from different sides

November 3, 1942

Silver gelatin photograph

Joe Rosenthal (American, 1911-2006)

Over the Top – American Troops Move onto the Beach at Iwo Jima

February 19, 1945 (printed February 23, 1945)

Gelatin silver print with applied ink

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, gift of Richard S. and Dodie Otey Jackson in honor of Ira J. Jackson, M.D., and his service in the Pacific Theater during World War II

© AP / Wide World Photos

Dmitri Baltermants (Russian, 1912-1990)

Attack – Eastern Front WWII

1941

Silver gelatin photograph

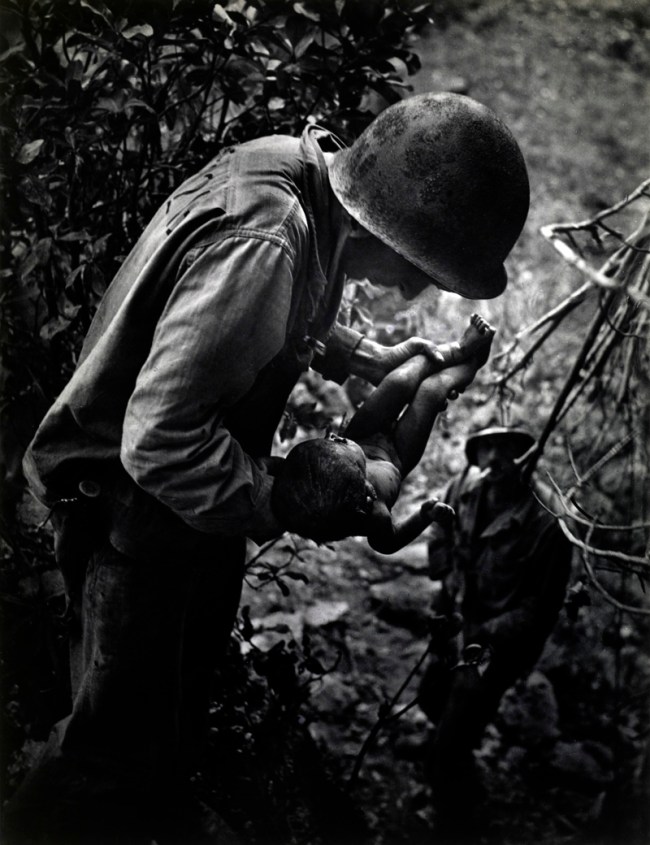

The Wait and Rescue

10. The Wait and Rescue bookend The Fight. Among the photographs in Rescue are Ambush of the 173rd AB, South Vietnam (1965), by Tim Page, showing soldiers immediately combing through a battleground to assist the wounded; American Lt. Wayne Miller’s image of a wounded gunner being lifted from the turret of a torpedo bomber; and Life magazine photographer W. Eugene Smith’s 1944 photograph of an American soldier rescuing a dying Japanese infant. Smith wrote about that moment, stating “hands trained for killing gently… extricated the infant” to be transported to medical care. (8 images)

Lt. Wayne Miller (American, 1918-2013)

Crewmen lifting Kenneth Bratton out of turret of TBF on the USS SARATOGA after raid on Rabaul

November 1943

Silver gelatin photograph

More information: Kenneth C. Bratton – Mississippi (WWII vet). He was born in Pontotoc, MS, December 17, 1918. He passed away April 15, 1982. Lt. Bratton won a purple heart for his bravery during the attack on Rabaul November 11, 1943.

Wayne Forest Miller (September 19, 1918 – May 22, 2013) was an American photographer known for his series of photographs The Way of Life of the Northern Negro. Active as a photographer from 1942 until 1975, he was a contributor to Magnum Photos beginning in 1958. …

War photographer

Miller then served as a lieutenant in the U.S. Navy where he was assigned to Edward Steichen’s World War II Naval Aviation Photographic Unit. He was among the first Western photographers to document the destruction at Hiroshima.

Text from the Wikipedia website

The Grumman TBF Avenger (designated TBM for aircraft manufactured by General Motors) is an American World War II-era torpedo bomber developed initially for the United States Navy and Marine Corps, and eventually used by several air and naval aviation services around the world.

The Avenger entered U.S. service in 1942, and first saw action during the Battle of Midway. Despite the loss of five of the six Avengers on its combat debut, it survived in service to become the most effective and widely-used torpedo bomber of World War II, sharing credit for sinking the super-battleships Yamato and Musashi (the only ships of that type sunk exclusively by American aircraft while under way) and being credited for sinking 30 submarines. Greatly modified after the war, it remained in use until the 1960s.

Text from the Wikipedia website

W. Eugene Smith (American, 1918-1978)

Dying Infant Found by American Soldiers in Saipan

June 1944

Gelatin silver print

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, gift of Will Michels in honor of Anne Wilkes Tucker

© Estate of W. Eugene Smith / Black Star

Aftermath

11. Aftermath, with four subsections, features photographs taken after the battle has ended. “Death” on the battlefield is one of the earliest types of war images: Felice Beato photographed the dead in the interior of Fort Taku in the Second Opium War (1860). George Strock’s Dead GIs on Buna Beach, New Guinea (1943), which ran in Life magazine with personal details about the casualties, was the first published photograph from any conflict of American dead in World War II. In 1966, Associated Press photographer Henri Huet documented an American paratrooper, who was killed in action, being raised to an evacuation helicopter. Incinerated Iraqi, Gulf War, Iraq, taken by Kenneth Jarecke, was published in Europe, but the American Associated Press editors withheld it in the United States. “Shell Shock and Exhaustion” shows impenetrable exhaustion after battle. In Don McCullin’s Shell-shocked soldier awaiting transportation away from the front line, Hué, Vietnam (1968), the man looks forward with the “thousand-yard stare.” Robert Attebury photographed Marines so exhausted after a 2005 battle in Iraq that lasted 17 hours that they fell asleep where they had been standing, amid the rubble of a destroyed building. “Grief and Battlefield Burial” were taken at the site of the conflict, including David Turnley’s 1991 picture of a weeping soldier who has just learned that the remains in a nearby body bag are those of a close friend. “Destruction of Property” shows collateral damage from war. Christophe Agou, for instance, photographed the smouldering steel remains of the twin towers of the World Trade Center in 2001. (39 images)

George Strock (American, 1911-1977)

Dead GIs on Buna Beach, New Guinea

January 1943

© George Strock / LIFE

Henri Huet (French, 1927-1971)

The body of an American paratrooper killed in action in the jungle near the Cambodian border is raised up to an evacuation helicopter, Vietnam

1966

Gelatin silver print (printed 2004)

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, museum purchase

© AP / Wide World Photos

Kenneth Jarecke (American, b. 1963)

Gulf War: Incinerated Iraqi soldier in personnel carrier

Nasiriyah, Iraq, March 1991

Felice Beato (Italian-British, 1832-1909)

Angle of North Taku Fort at which the French entered

August 21-22, 1860

Don McCullin (British, b. 1935)

Shell-shocked US soldier awaiting transportation away from the front line

Hue, Vietnam, 1968

© Don McCullin

David Turnley (American, b. 1955)

American Soldier Grieving for Comrade

Iraq, 1991

Ken Kozakiewicz (left) breaks down in an evacuation helicopter after hearing that his friend, the driver of his Bradley Fighting Vehicle, was killed in a “friendly fire” incident that he himself survived. Michael Tsangarakis (centre) suffers severe burns from ammunition rounds that blew up inside the vehicle during the incident. All of the soldiers were exposed to depleted uranium as a result of the explosion. They and the body of the dead man are on their way to a MASH (Mobile Army Surgical Hospital).

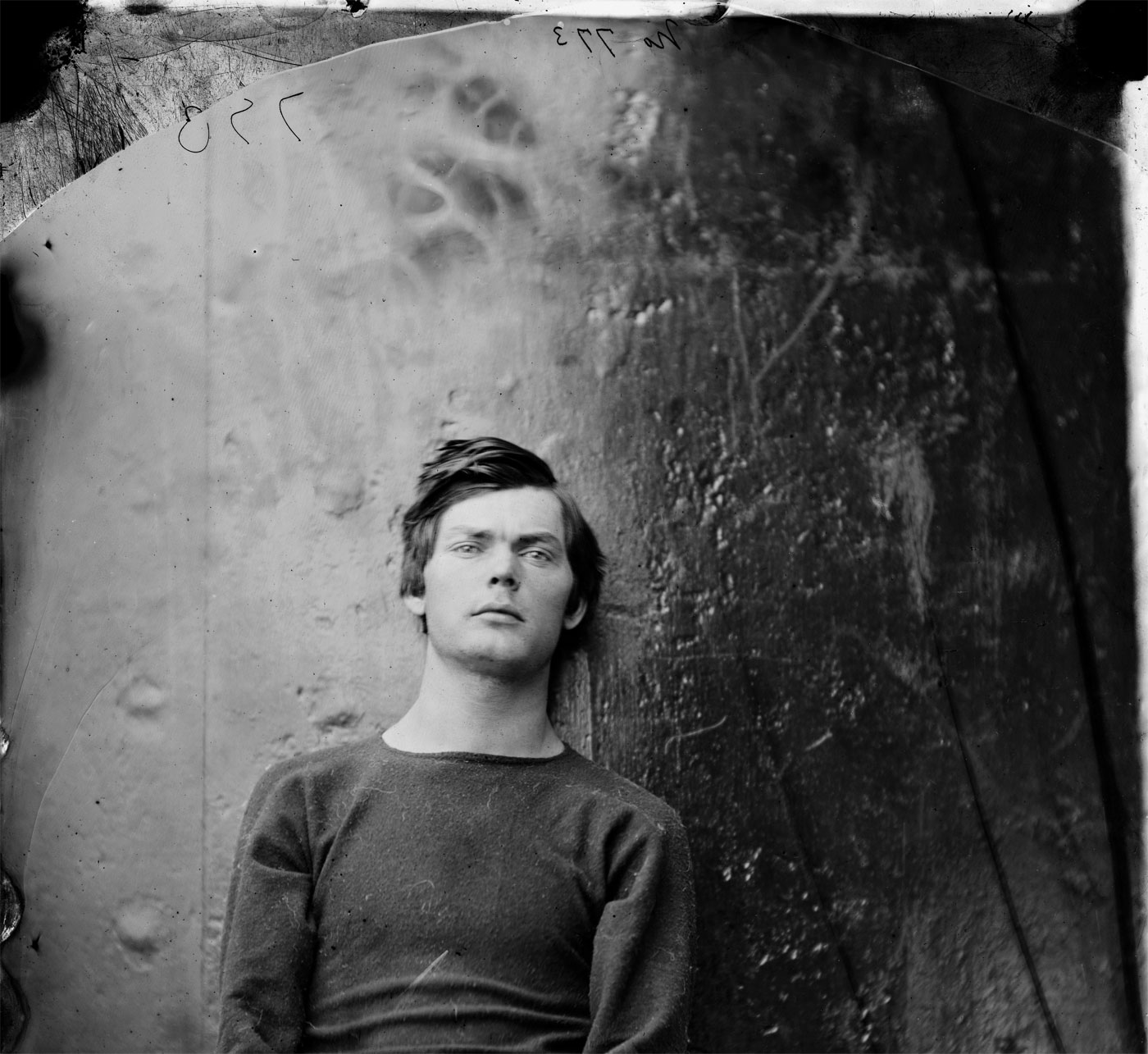

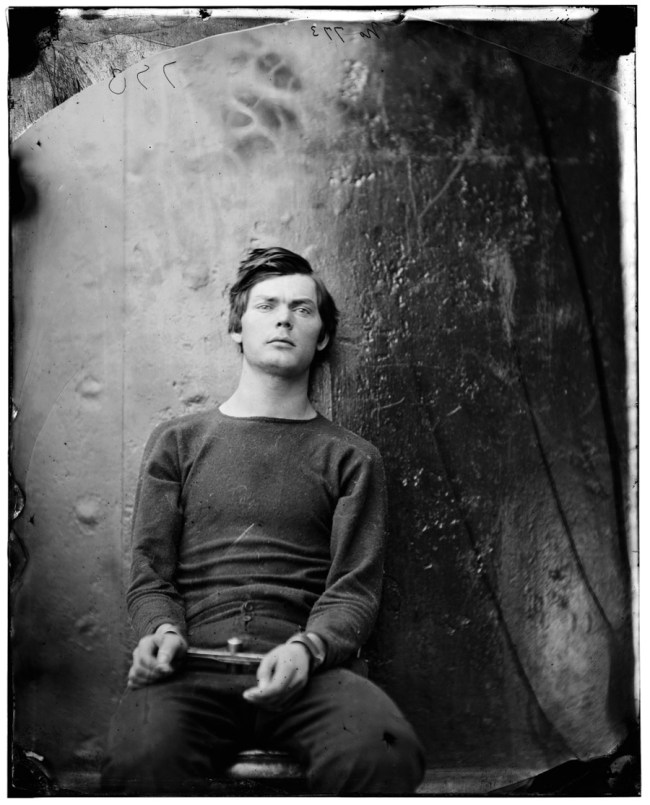

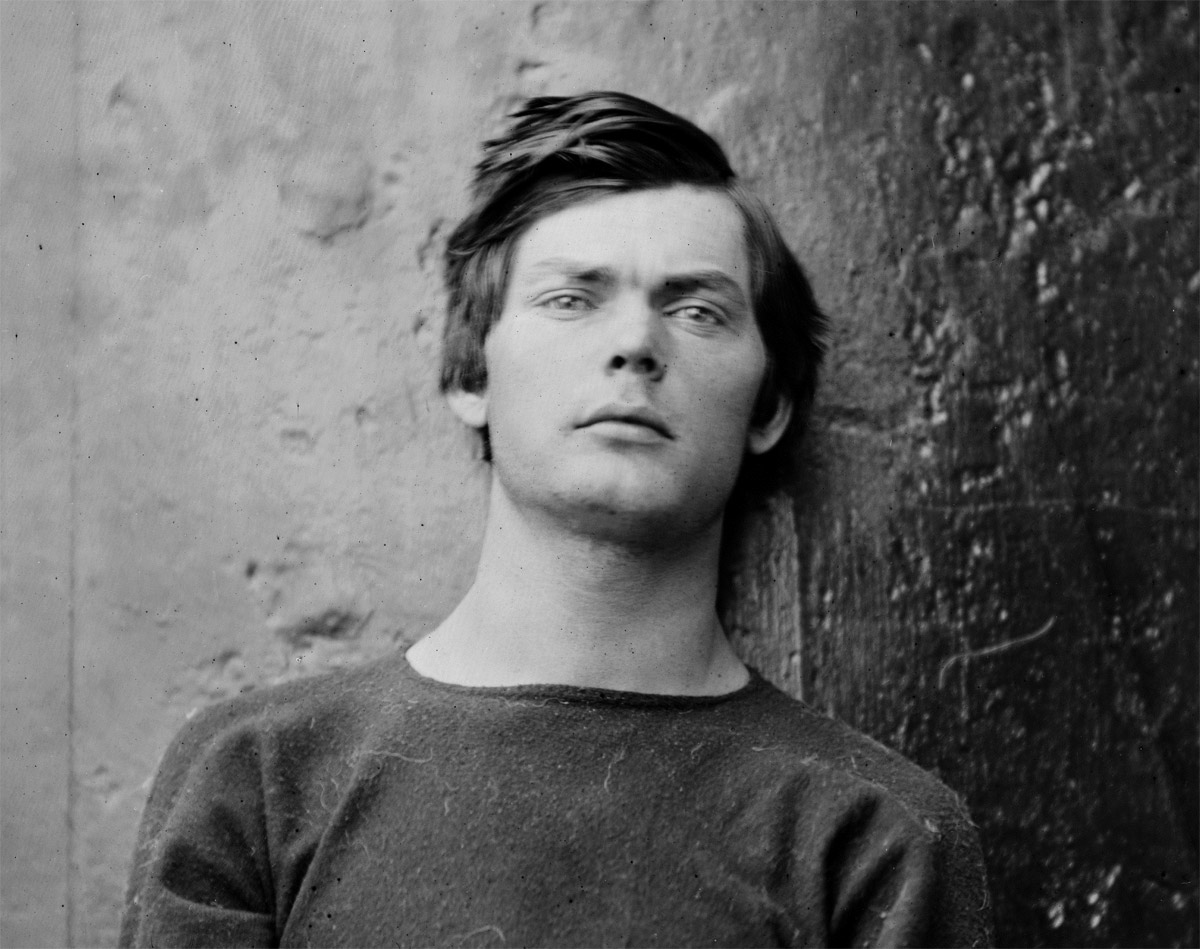

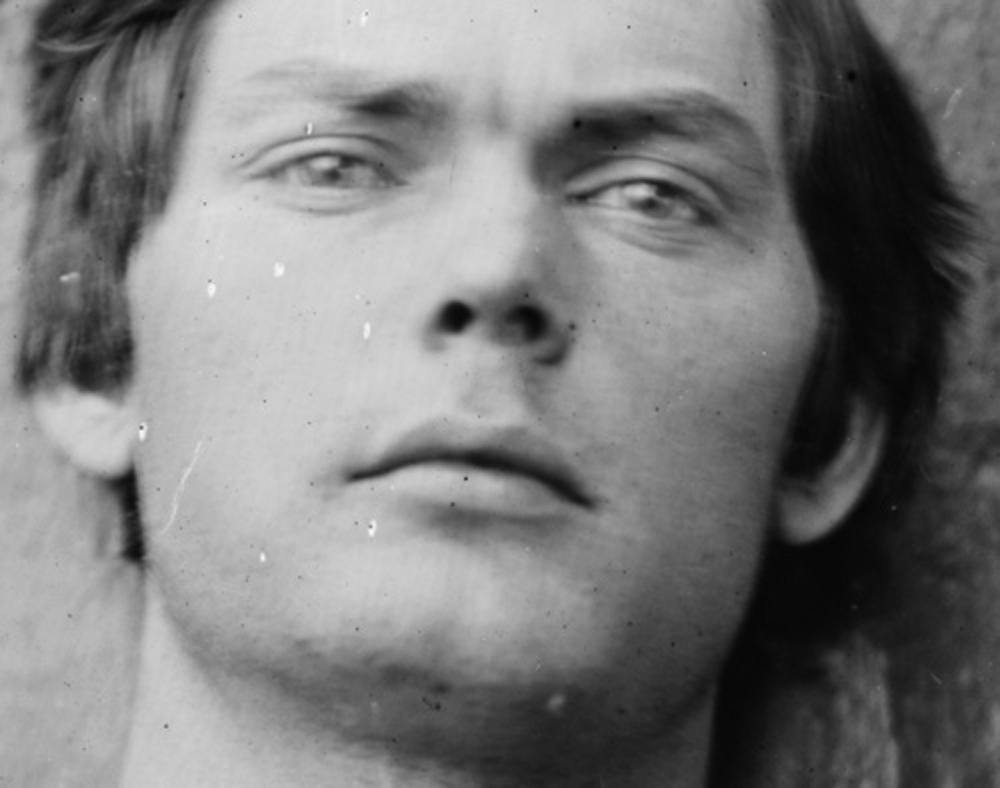

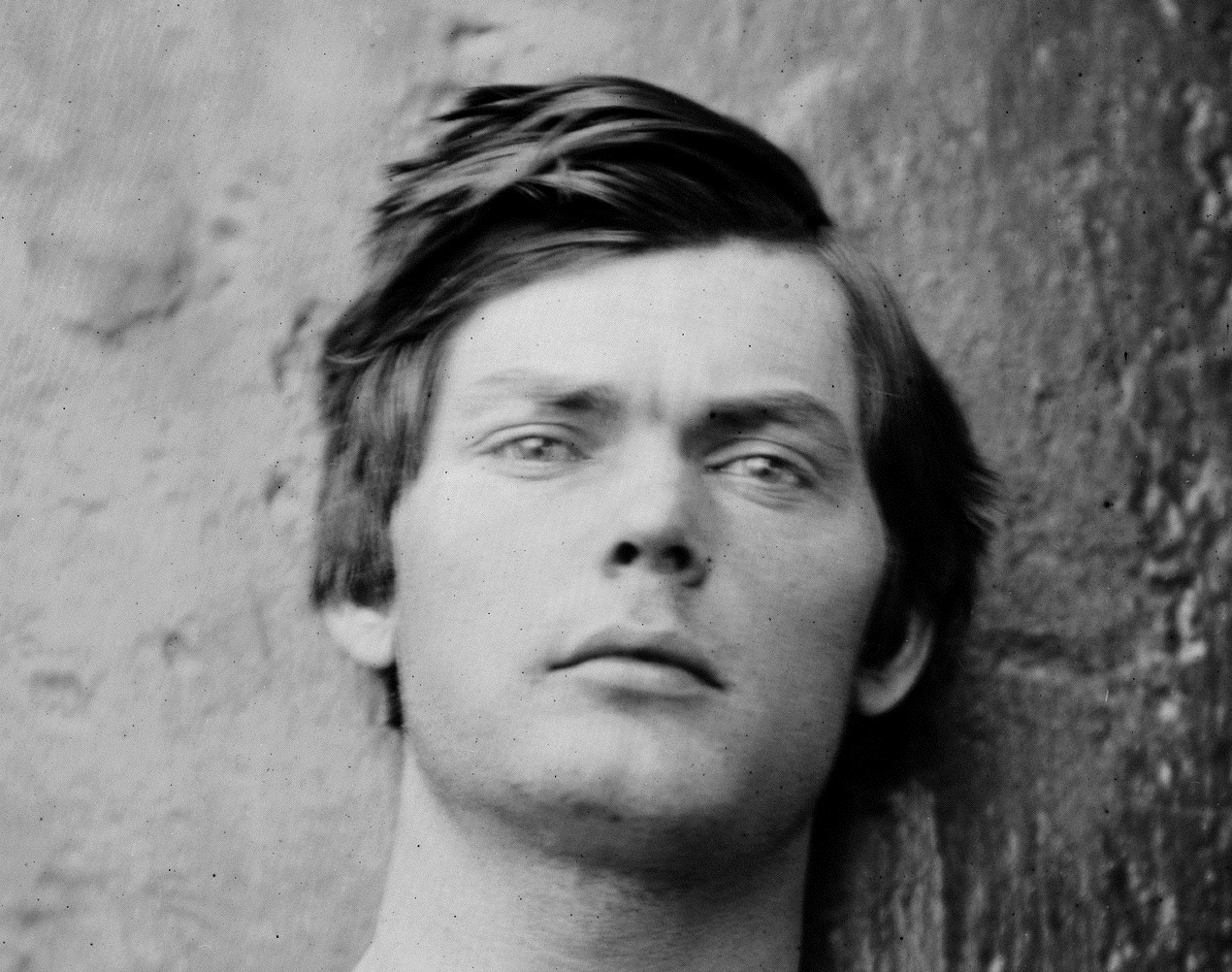

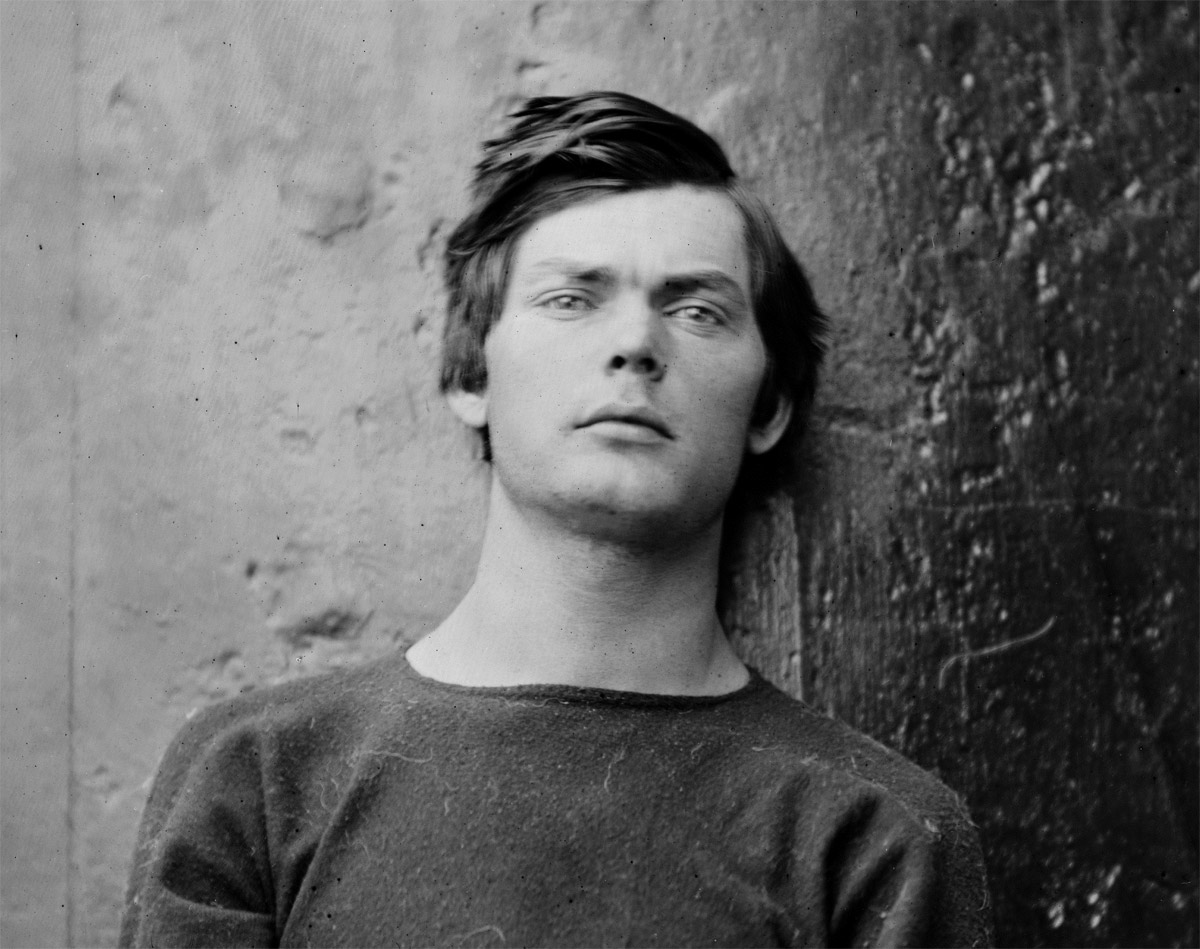

Prisoners of War (Civilian and Military)/Interrogation

12. Prisoners of War (Civilian and Military)/Interrogation is a frequently photographed subject because such pictures can be made outside an area of conflict. Moreover, the people in control often documented their prisoners as a show of power. The photographs in this section include the official recording of a prisoner of war before his execution by the Khmer Rouge, taken by Nhem Ein. (14 images)

Nhem Ein (Cambodian, b. 1959)

Untitled (prisoner #389 of the Khmer Rouge; man)

1975-1979

Gelatin silver print (printed 1994)

Courtesy of Museum of Modern Art

Arthur M. Bullowa Fund and Geraldine Murphy Fund

Digital image © The Museum of Modern Art / Licensed by SCALA Art Resource, NY. Used with permission of Photo Archive Group

Iwo Jima

13. Iwo Jima is a case study within the exhibition that presents the complete thematic narrative in photographs from a specific battle. Included in this section is the inspiration for the exhibition: Joe Rosenthal’s iconic, Pulitzer Prize-winning Old Glory Goes Up on Mount Suribachi, Iwo Jima, a photograph he took as an Associated Press photographer in World War II showing U.S. Marines and one Navy medic raising the American flag on the remote Pacific island. (25 images)

Joe Rosenthal (American, 1911-2006)

Old Glory Goes Up on Mount Suribachi, Iwo Jima

February 23, 1945

Gelatin silver print

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, The Manfred Heiting Collection, gift of the Kevin and Lesley Lilly Family

© AP / Wide World Photos

Exhibition posting continued in Part 2…

Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

1001 Bissonnet Street

Houston, TX 77005

Opening hours:

Wednesday 11am – 5pm

Thursday 11am – 9pm

Friday, Saturday 11am – 6pm

Sunday 12.30 – 6pm

Closed Monday and Tuesday

![Roger Fenton (English, 1819-1869) 'The artist's van [Marcus Sparling, full-length portrait, seated on Roger Fenton's photographic van]' 1855 Roger Fenton (English, 1819-1869) 'The artist's van [Marcus Sparling, full-length portrait, seated on Roger Fenton's photographic van]' 1855](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/roger_fentons_waggon2.jpg?w=650&h=684)

![T.E. Lawrence. 'Untitled [A Tulip bomb explodes on the railway Hejaz Railway, near Deraa, Hejaz, Ottoman Empire]' 1918 T.E. Lawrence. 'Untitled [A Tulip bomb explodes on the railway Hejaz Railway, near Deraa, Hejaz, Ottoman Empire]' 1918](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/telawrence.jpg?w=840)

![Anonymous photographer. 'Untitled [Borough of Clunes Notice Strike ..rm Rate]' Nd Anonymous photographer. 'Untitled [Borough of Clunes Notice Strike ..rm Rate]' Nd](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/anon-borough-of-clunes-notice-strike-rm-rate-front-no-back3.jpg)

![National Photo Company. 'Untitled [Group of bricklayers holding their tools and a baby]' Nd National Photo Company. 'Untitled [Group of bricklayers holding their tools and a baby]' Nd](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/national-photo-company-nd-front1.jpg)

![E. B. Pike. 'Untitled [Older man with moustache and parted beard]' Nd E. B. Pike. 'Untitled [Older man with moustache and parted beard]' Nd](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/e-b-pike-back2.jpg)

![Otto von Hartitzsch (Australian born Germany. 1838-1910) 'Untitled [Man with quaffed hair and very thin tie]' 1867-1883 Otto von Hartitzsch (Australian born Germany. 1838-1910) 'Untitled [Man with quaffed hair and very thin tie]' 1867-1883](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/otto-von-hartitzsch-adelaide-1867-back2.jpg?w=655)

![Profesor Hawkins (Australian, active 1861-1875) 'Untitled [Chinese women with handkerchief]' c. 1858-1875 Profesor Hawkins (Australian, active 1861-1875) 'Untitled [Chinese women with handkerchief]' c. 1858-1875](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/professor-hawkins-melbourne-front3.jpg)

![J. R. Tanner (Australian, active 1866-1899) 'Untitled [Two woman wearing elaborate hats]' 1875 J. R. Tanner (Australian, active 1866-1899) 'Untitled [Two woman wearing elaborate hats]' 1875](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/j-r-tanner-1875-front1.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.