Exhibition dates: 16th September, 2017 – 28th January, 2018

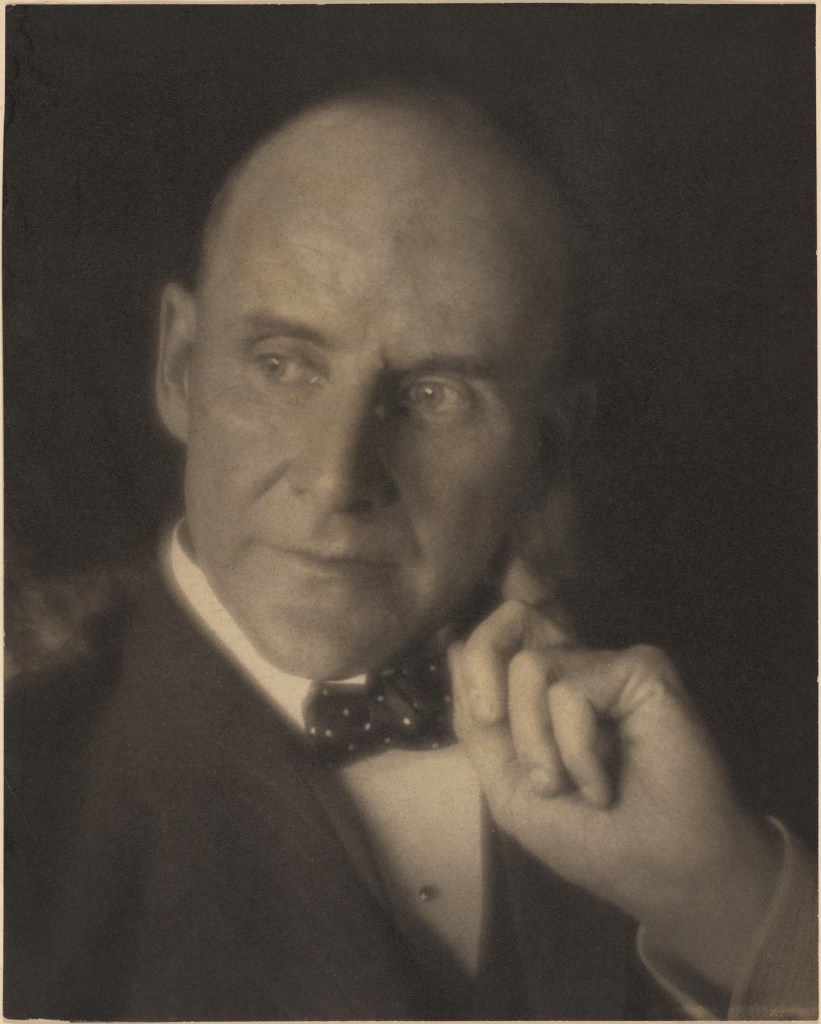

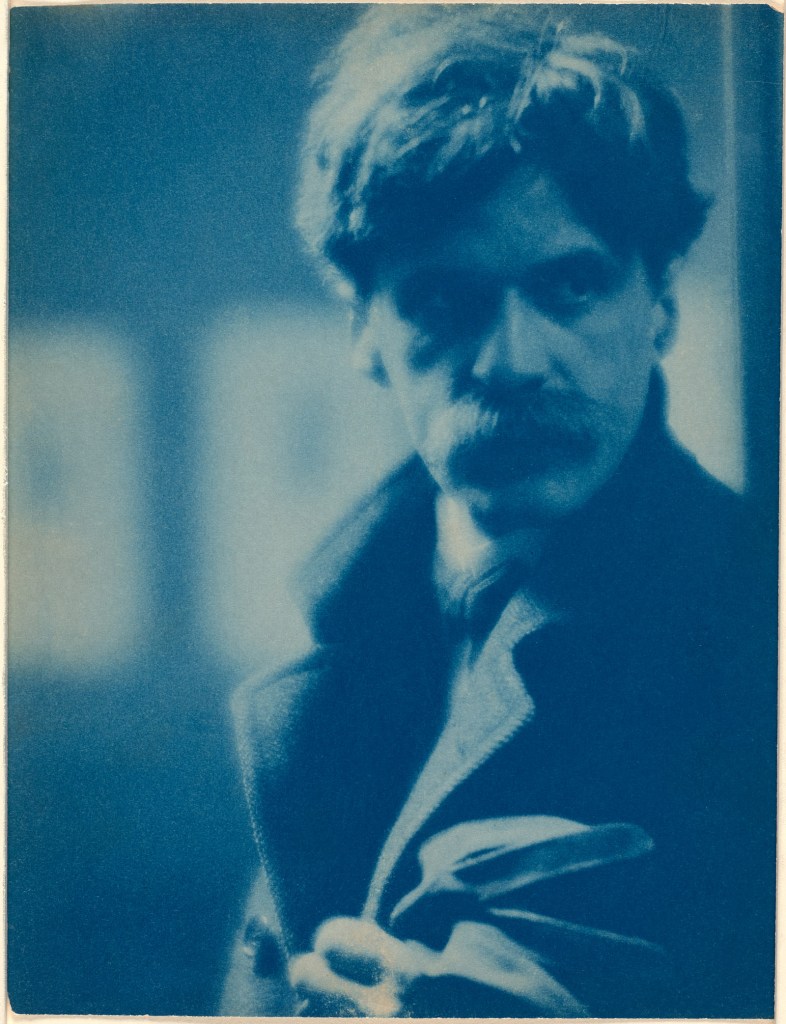

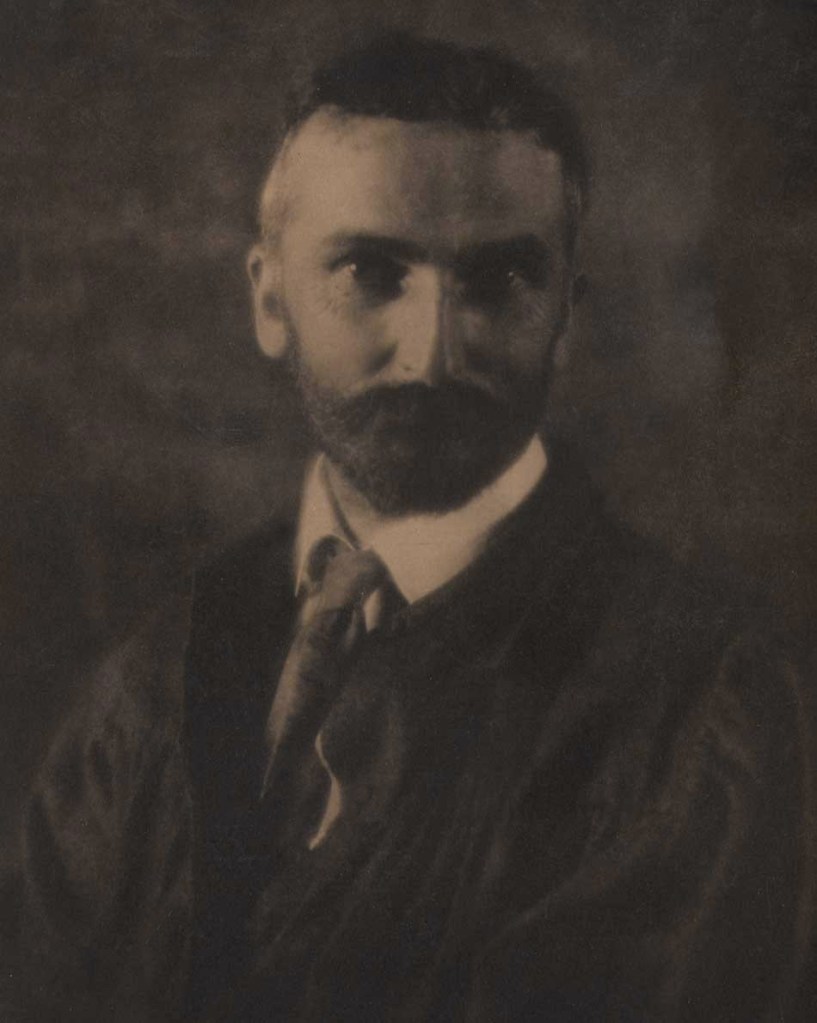

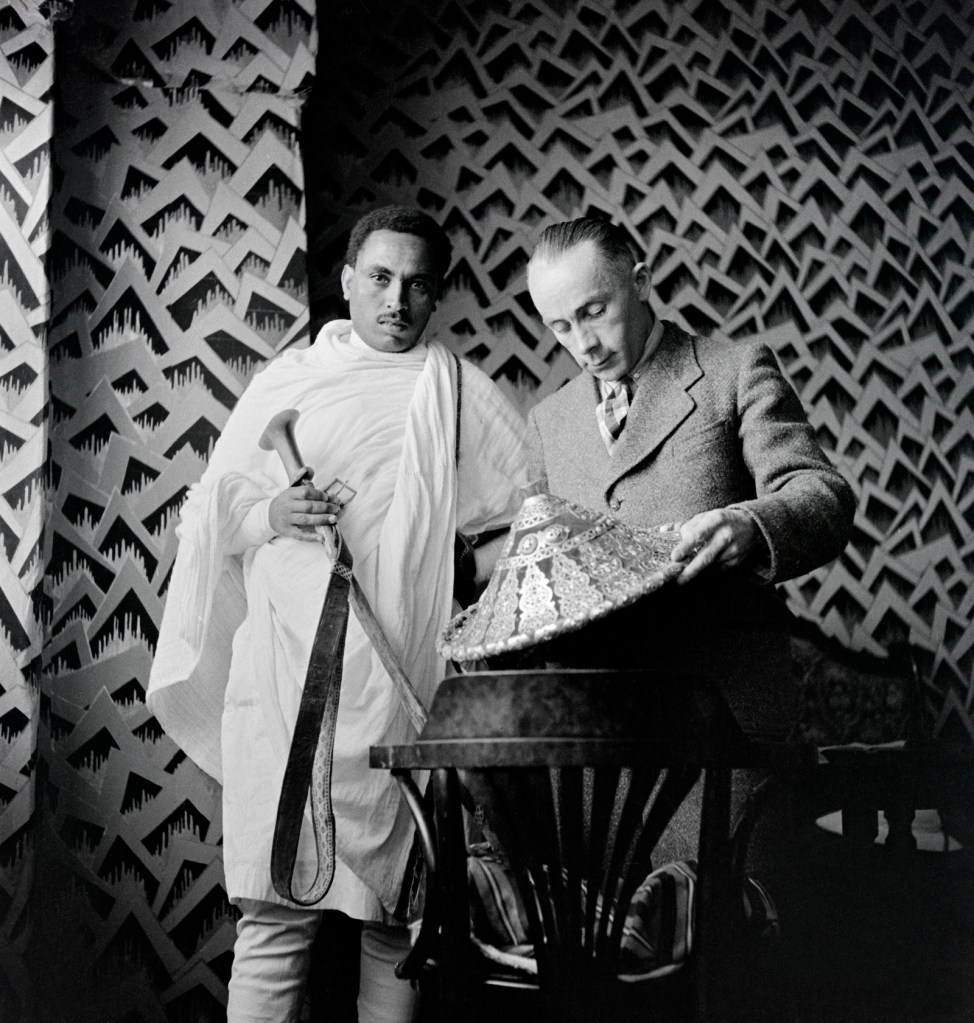

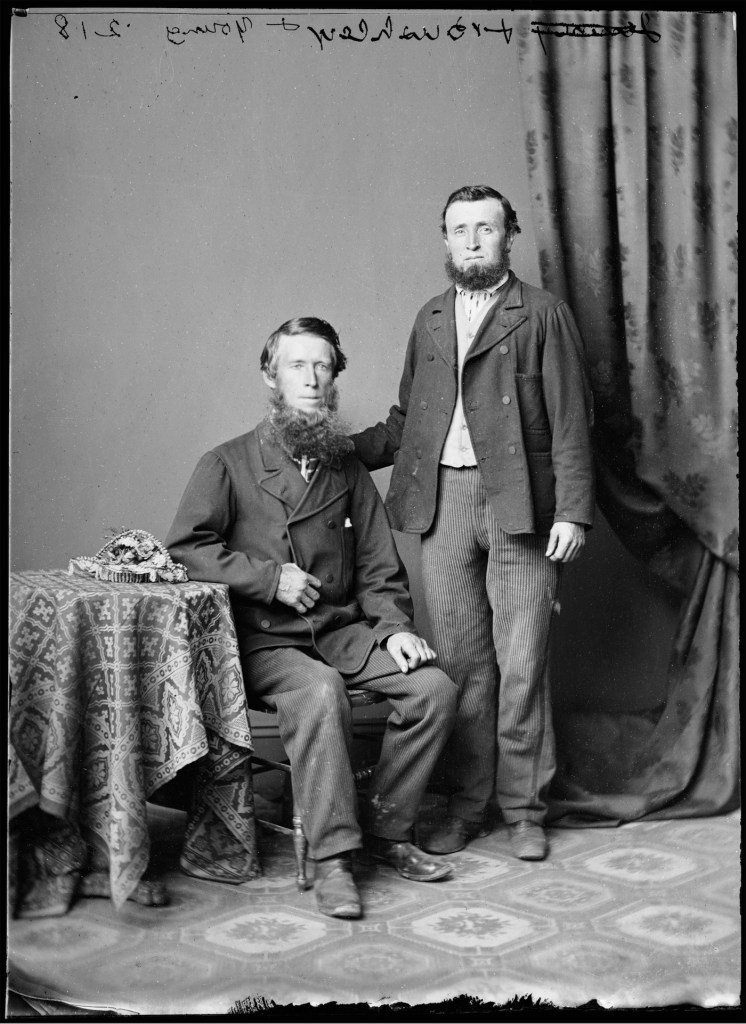

Charles DeForest Fredricks (American, 1823-1894)

Inmigrantes alemanes en Buenos Aires jugando cartas / German Immigrants in Buenos Aires Playing Cards

c. 1852

Daguerreotype

Courtesy of Carlos G. Vertanessian

Charles DeForest Fredricks (American, 1823-1894)

Charles DeForest Fredricks (December 11, 1823 – May 25, 1894) was an American photographer.

Charles D. Fredricks was born in New York City on December 11, 1823. He learned the art of the daguerreotype from Jeremiah Gurney in New York, while he worked as a casemaker for Edward Anthony. In 1843, at the suggestion of his brother, Fredricks sailed for Angostura, today Ciudad Bolívar, Venezuela. His business took him to Pará, Rio Grande do Sul, Montevideo, Buenos Aires. He enjoyed great success in South America, remaining there until some time in the early 1850s.

Following a brief period in Charleston, South Carolina, Fredricks moved to Paris in 1853. Here he became the first photographer to create life-sized portraits, which artists (like Jules-Émile Saintin) were hired to colour using pastel.

On his return to New York City, he rejoined Jeremiah Gurney, though it is not clear whether he was initially a partner or an employee. By 1854, he had developed an early process for enlarging photographs. His partnership with Gurney ended in 1855.

During the latter half of the decade he operated a studio in Havana. Here he received awards for his photographic oil colours and watercolours. During the 1860s he operated a studio on Broadway that was noted for its cartes de visites. In the early 1860s, Charles Fredricks personally photographed John Wilkes Booth (the assassin of President Lincoln) on several occasions at his studio.

He retired from photography in 1889 and died in Newark, New Jersey, five years later, on May 25, 1894.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Charles DeForest Fredricks (American, 1823-1894)

Inmigrantes alemanes en Buenos Aires jugando cartas / German Immigrants in Buenos Aires Playing Cards (detail)

c. 1852

Daguerreotype

Courtesy of Carlos G. Vertanessian

I knew very little about Argentinian photography before researching for this posting.

Such a rich historical photographic archive – Indigenous, political, activist, performative – engaged in the dissection of national identity construction. Lots of German émigrés, lots of strong women photographers e.g. Grete Stern, Annemarie Heinrich, Julio Pantoja and Graciela Sacco.

There is a deep probing in Argentinian photography. There is the irony of the not quite right and an investigation of the dark side, of danger, fear and violence, of loss, grief, rage and resignation. As one of the sections of the exhibition is titled, of Civilisation and Barbarism. A quotation in the posting observes, “One of the most effective means to exercise control of populations in contemporary capitalism is the production of fear.” Drop dead fear.

The bloodlines of the collective consciousness of the Argentinian people run very deep. The dead ones are still there…

Apologies for the lack of photographs in The Aesthetic Gesture section, there were just no good images available.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the J. Paul Getty Museum for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Gustavo Di Mario (Argentinian, b. 1969)

Malambistas I / Malambo Dancers I

Negative 2014, print 2016

Chromogenic print

60 x 50cm

Courtesy of Gustavo Di Mario

© Gustavo Di Mario

Gustavo Di Mario (Argentinian, b. 1969)

Carnaval

Negative 2005, printed 2015

Chromogenic print

50 x 63.1cm

The J. Paul Getty Museum, purchased with funds provided by the Photographs Council

© Gustavo Di Mario

From its independence in 1810 until the economic crisis of 2001, Argentina was perceived as a modern country with a powerful economic system, a strong middle class, a large European-immigrant population, and an almost nonexistent indigenous culture. This perception differs greatly from the way that other Latin American countries have been viewed, and underlines the difference between Argentina’s colonial and postcolonial process and those of its neighbours. Comprising three hundred works by sixty artists, this exhibition examines crucial periods and aesthetic movements in which photography had a critical role, producing – and, at times, dismantling – national constructions, utopian visions, and avant-garde artistic trends.

This exhibition is part of Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA, a far reaching and ambitious exploration of Latin American and Latino art in dialogue with Los Angeles, taking place from September 2017 through January 2018 at more than 70 cultural institutions across Southern California. Pacific Standard Time is an initiative of the Getty. The presenting sponsor is Bank of America.

Contradiction and Continuity examines the complexities of Argentina’s history over 160 years, stressing the creation of contradictory narratives and the role of photography in constructing them. The exhibition concentrates on photographs that are fabricated rather than found, such as narrative tableaux and performances staged for the camera. However, it also includes examples of what has been considered documentary photography but can be interpreted as imagery intended as political propaganda or expressions of personal ideology.

The exhibition comprises seven sections: Civilization and Barbarism; National Myths: The Indigenous People; National Myths: The Gaucho; National Myths: Evita and the Modern City; The Aesthetic Gesture; The Political Gesture; and Fissures. These themes were chosen to emphasise crucial historical moments and aesthetic movements in Argentina in which photography played a critical role.

Civilisation and Barbarism

In 1845 Domingo Sarmiento (1811-1888), a prominent Argentine intellectual, published the novel Facundo, subtitled Civilization and Barbarism. Sarmiento, who would later be elected president, presented his political ideas in terms of an opposition between civilisation, represented by the capital city of Buenos Aires and European culture, and barbarism, represented by colonial customs, the gauchos, and the indigenous peoples. This section of the exhibition employs these antagonistic themes to introduce some of the complexities of Argentina’s history and culture. Nineteenth-century albums show the growth and advancement of the country through views of Buenos Aires and images that refer to progressive strategies initiated during this period, including railroad construction and the development of the educational system. In contrast, the work of several contemporary artists embodies the lifestyle and popular culture of the vast interior provinces of Argentina.

Like Sarmiento, Juan Bautista Alberdi (1810-1884), another influential intellectual, viewed immigration as a definitive measure for modernising the country. In Bases, published in 1853, he addressed the necessity of implementing policies to encourage immigration. The studio photographs in this section depict the growing presence of immigrant communities. Immigration is a key component to understanding Argentine society that continues to inspire contemporary artists.

Esteban Gonnet (French, 1830-1868)

Recuerdos de Beunos Ayres / Memories of Beunos Aires

1864

Page opening: La pirámide / The Pyramid

Albumen print

Benito Panunzi (Italian, 1835-1896)

Monument to General San Martín

c. 1860-1869

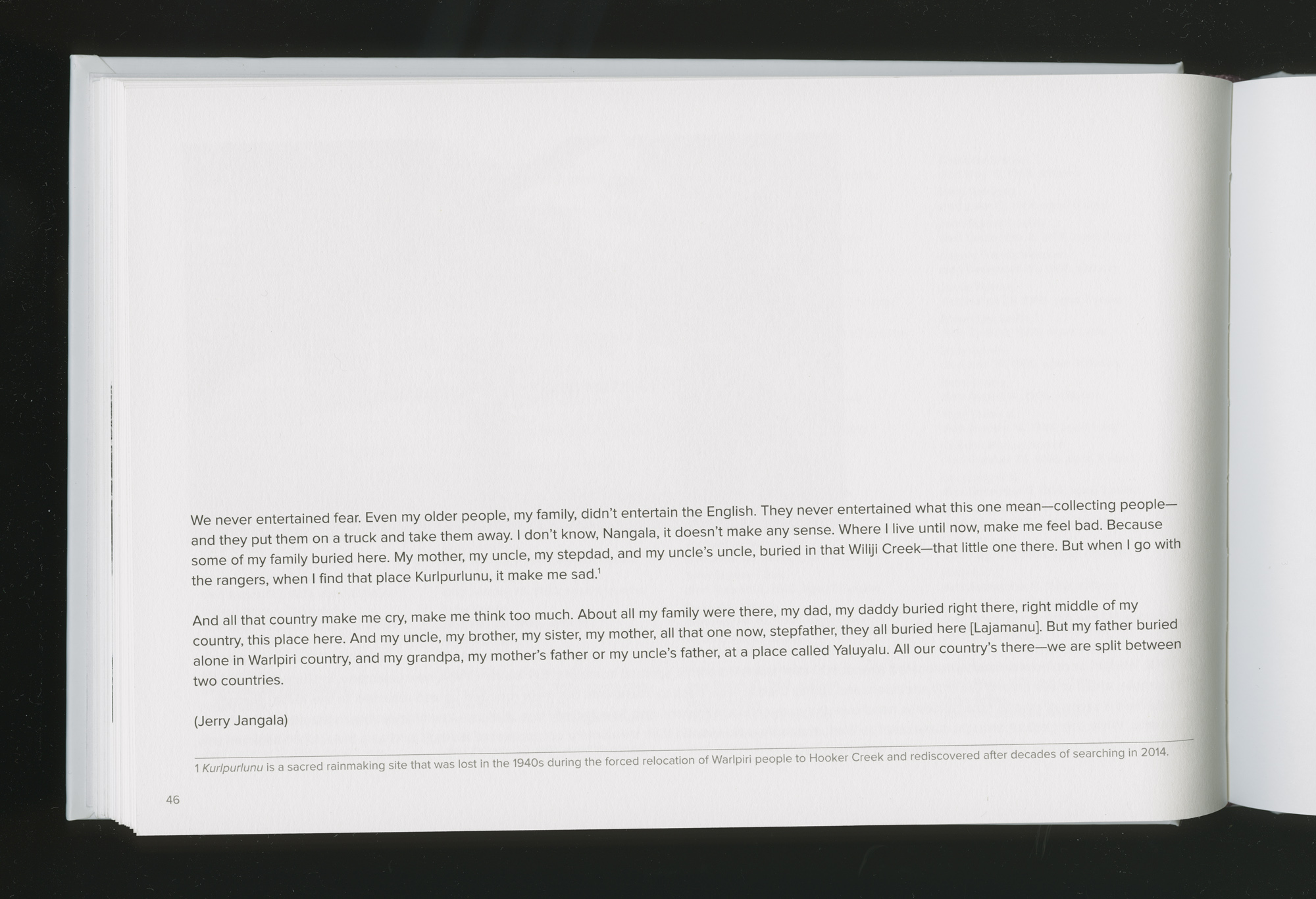

Albumen print

National Myths: The Gaucho

The National Myths section of the exhibition focuses on the construction of specific state symbols, including indigenous people, the gaucho, First Lady Eva Perón, and the city of Buenos Aires. Around 1880, coinciding with increasing waves of immigration and efforts at modernisation, an avid debate on national identity arose among Argentine intellectuals and politicians.

By 1910, when the Centennial of Independence was celebrated, the gaucho emerged as an emblematic figure in the national iconography. The gaucho was already a common theme in Costumbrista (customs and character types) paintings of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Criollismo (native culture), a movement of the late nineteenth century, stimulated a wider interest in gaucho-themed art, fiction, theatre, and photographs.

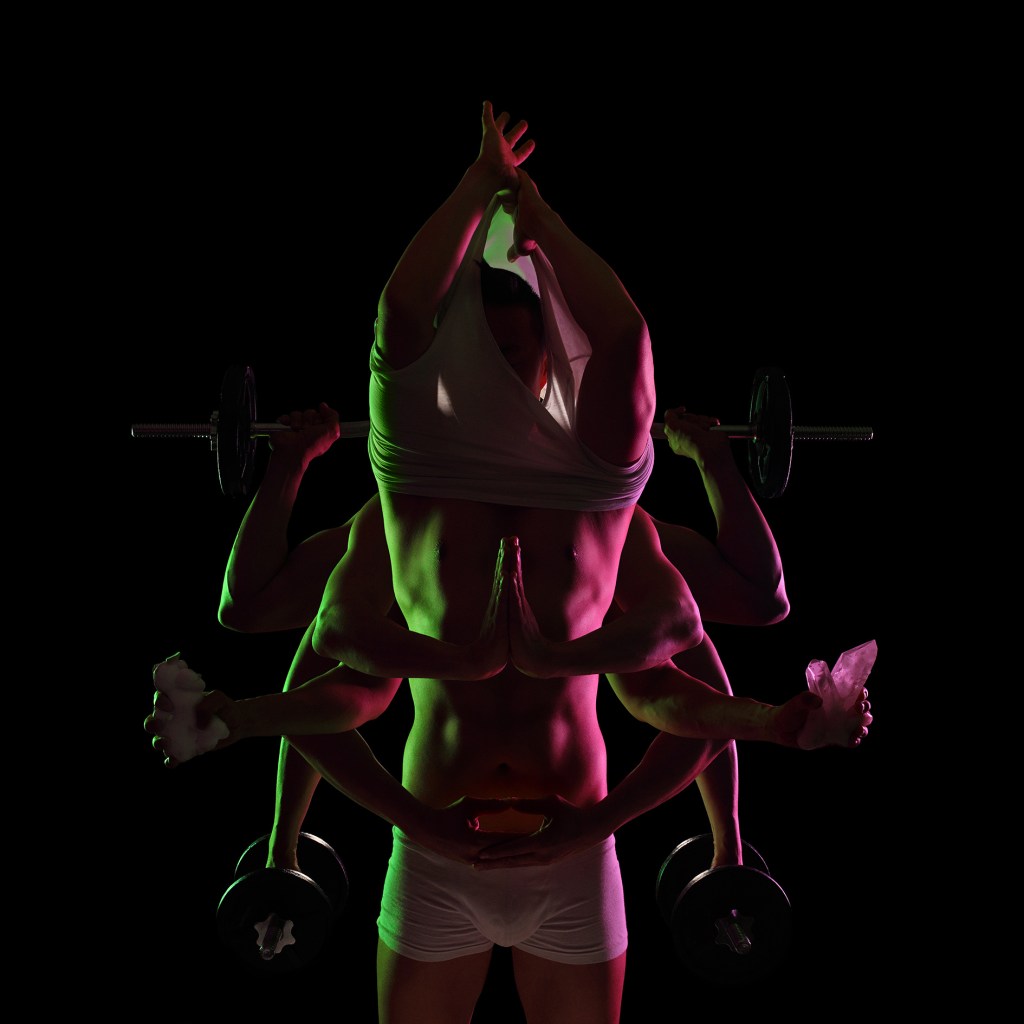

José Hernández’s epic narrative poem Martín Fierro (1872) and Eduardo Gutiérrez’s novel Juan Moreira (1879) were major influences. About 1890, amateur photographer Francisco Ayerza staged a series of romanticised photographs meant to illustrate a later edition of Fierro. Commercial studios accommodated women and children who wanted to be pictured as gauchos. More than a national symbol, the gaucho embodied the idealised masculinity of the virile Argentine man; the contemporary fashion photographs of Gustavo Di Mario present a queer interpretation of the gauchesque.

Francisco Ayerza (Argentinian, 1860-1901)

Estudio para la edición de “Martín Fierro,” gaucho con caballo / Study for an edition of Martín Fierro, Gaucho with Horse

c. 1890, print about 1900-1905

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of a private collection

Francisco Ayerza (1860 – Buenos Aires, Argentina – 1901), was a photographic artist founding member of the Argentine Photographic Society. He formed an artistic movement in Latin America .

At the end of the 19th century, Doctor Francisco Ayerza cultivated the still new photographic art as an amateur. He was one of the organizers of the Argentine Amateur Photographic Society, the first entity of the genre created in that country.

It was at Francisco Ayerza’s house (1266 Piedad Street) where a group of gentlemen met “with the aim of forming a society of photography amateurs”, which ultimately constituted the Argentine Amateur Photographic Society (1889). The following participated in the first session: Leonardo Pereyra, who was elected president; Germán Kühr, Francisco Ayerza (secretary), José María Gutiérrez, Roberto Wernicke, Ricardo N. Murray, Fritz Büsch, Juan Quevedo, Isidro Calderón de la Barca Piñeyro, Daniel MacKinglay, Leonardo Pereyra Iraola, Fernando Steinius and Fernando Denis. …

An aspect of the immediate reality that seduced Francisco Ayerza and his friends for its picturesque appearance was the Pampa, whose geography began to be altered by machinism and immigration, as documented by some prints. From this interest in the Argentine countryside and its customs was born the idea of photographically illustrating the Martín Fierro and, although they made many shots, it could not be finished, despite the efforts made by the authors in such an exhausting task, and although the selected field to photograph was the Estancia San Juan de Pereyra, very close to Buenos Aires.

Text translated from the Spanish Wikipedia website

Gustavo Di Mario (Argentinian, b. 1969)

Malambistas IV / Malambo Dancers IV

Negative 2014, print 2016

Chromogenic print

60 x 50cm

Courtesy of Gustavo Di Mario

© Gustavo Di Mario

Malambo was born in the Pampas around the 1600. Malambo is a peculiar native dance that is executed by men only. Its music has no lyrics and it is based entirely on rhythm. The malambo dancer is a master of tap dancing wearing gaucho’s boots. Among the most important malambo moves are: “la cepillada” (the foot sole brushes the ground), “el repique” (a strike to the floor using the back part of the boot) and the “floreos”. Malambo dancers’ feet barely touch the ground but all moves are energetic and complex. Together with tap dancing, malambo dancers use “boleadoras” and other aids such as “lazos”. Like “Payadas” for gauchos (improve singing), malambo was *the* competition among gaucho dancers.

Read more about the Malambo dance

Nicola Constantino (Argentinian, b. 1964)

Nicola alada, inspirado en Bacon inspirado en Rembrandt / Winged Nicola, Inspired by Bacon Inspired by Rembrandt

2010

Inkjet print

173 x 135cm

Courtesy of Nicola Constantino

© Nicola Constantino

Marcos López (Argentinian, b. 1958)

Reina del trigo. Gálvez, Provincia de Santa Fe (Queen of Wheat, Gálvez, Santa Fe Province)

1997, printed 2017

Hand-coloured inkjet print

50 × 70cm (19 11/16 × 27 9/16 in.)

Courtesy of the artist and Rolf Art, Buenos Aires

© Marcos López

Marcos López (Argentinian, b. 1958)

Gaucho Gil. Buenos Aires

2009, printed 2017

Hand-coloured inkjet print

144 × 100cm

Courtesy of Rolf Art and Marcos López

© Marcos López

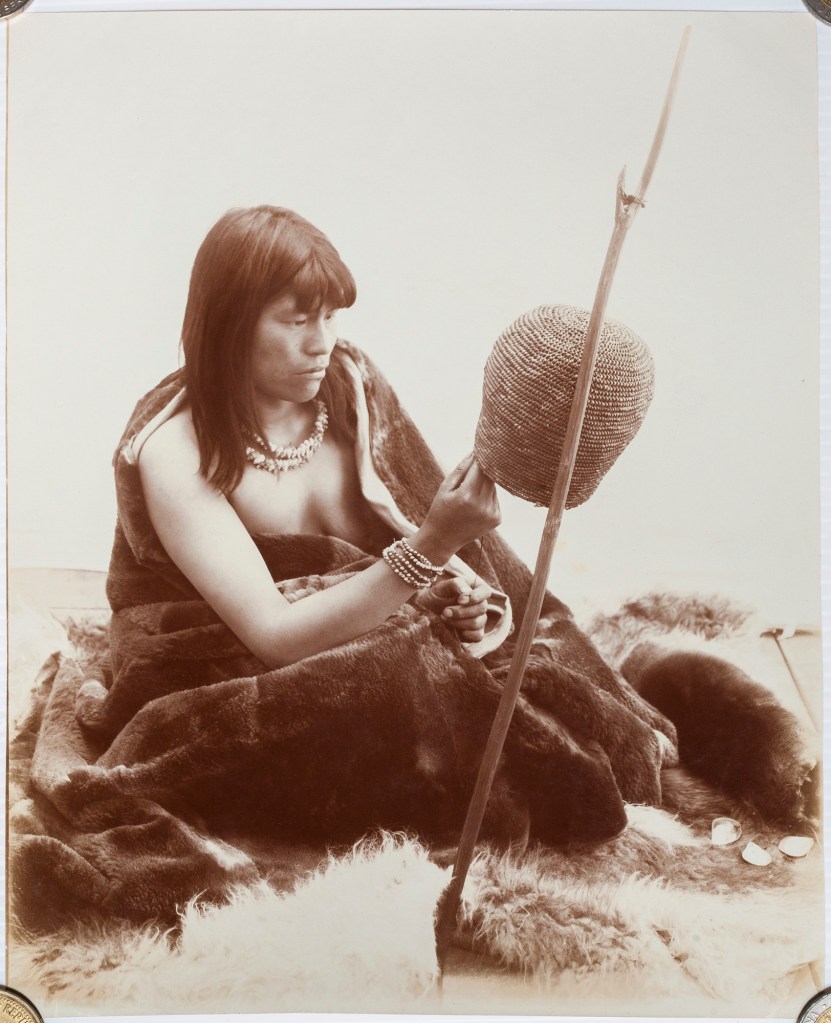

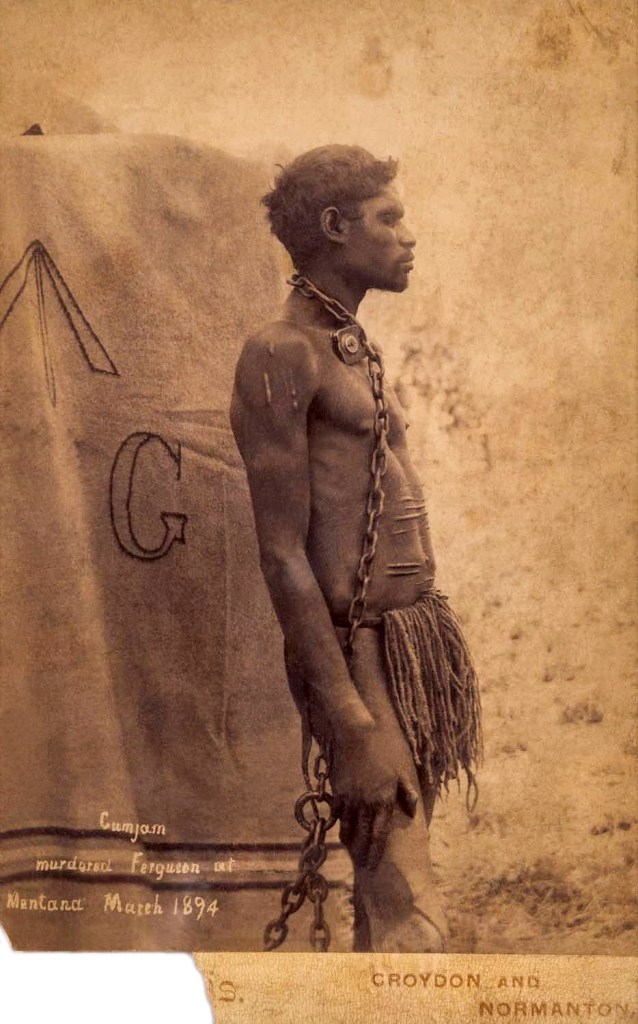

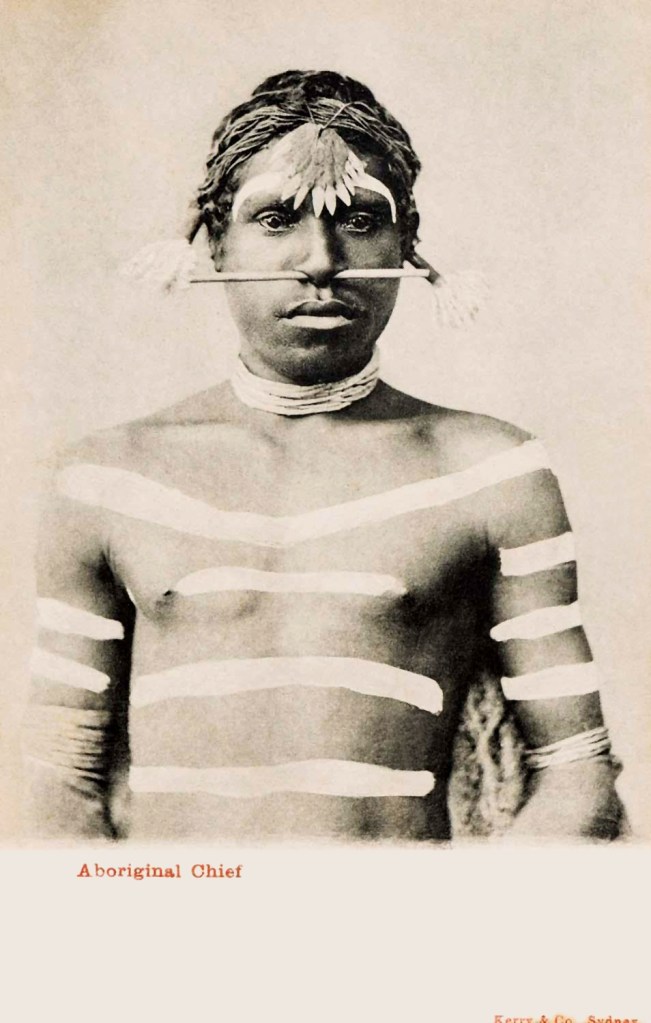

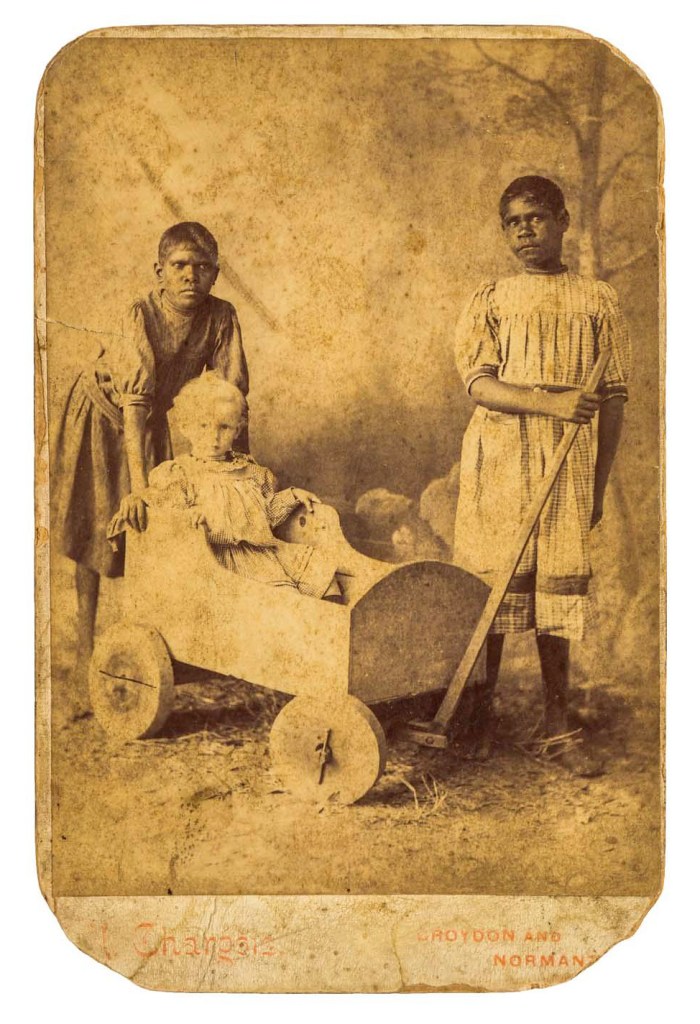

National Myths: The Indigenous People

While the gaucho became a national myth, “official” images rarely addressed the existence of indigenous peoples. The practice of recording their presence in photography, however, was well established by the late nineteenth century. It began in the portrait studios of Buenos Aires when native caciques (chiefs) visited the capital for peaceful negotiations, or when they were brought in as prisoners and made to pose in traditional garb. Later, photographers would travel by train or wagon to Native American settlements or plantations where indigenous people worked.

These staged compositions, as in the rest of Latin America, portrayed indigenous people as exotic and passive, objectifying them and emphasising their “otherness.” Sitters were always isolated from signs of the “civilised” or “Christian” world. The iconography found in these nineteenth- and early twentieth century photographs corresponds to a nostalgic image of a backward and subjugated group ignored by progress. Modernist and contemporary artists, such as Grete Stern and Guadalupe Miles, presented a different and more accurate view of these people. Both Stern and Miles immersed themselves in indigenous communities, portraying their subjects as individuals rather than stereotypes.

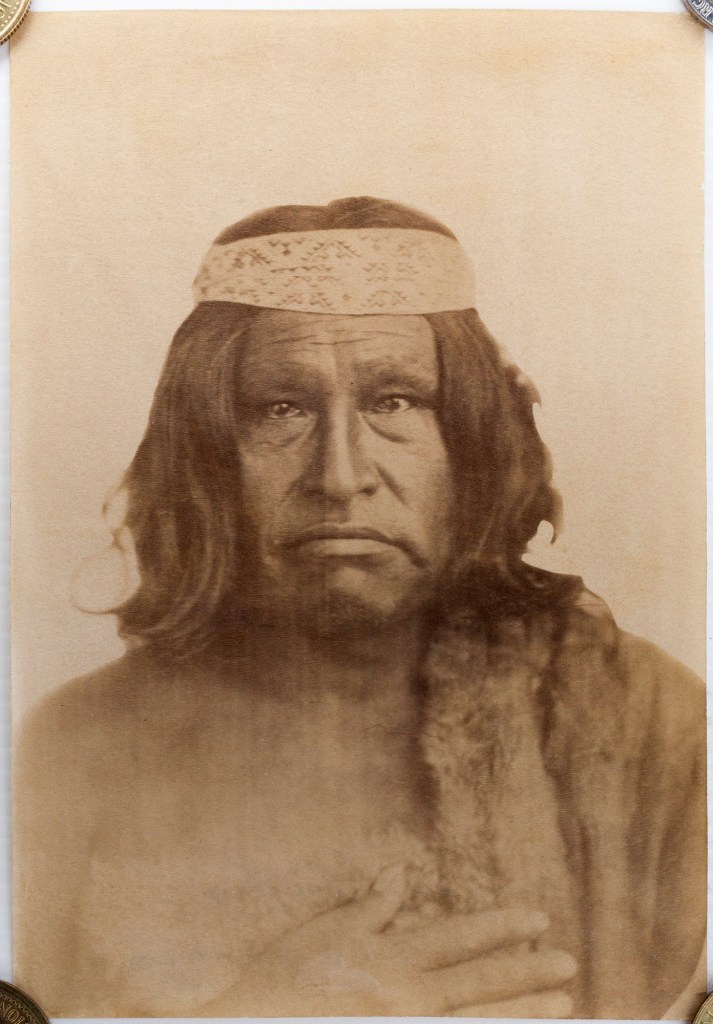

Esteban Gonnet (French, 1830-1868)

Cacique Tehuelche Casimiro Biguá / Tehuelche Chief, Casimiro Biguá

1864

Albumen print

14.1 x 9.7cm

Courtesy of the Daniel Sale Collection

Photo: Javier Augustín Rojas

Born in Grenoble, France, Esteban Gonnet moved to Argentina from Newcastle, England, in 1857. Gonnet became a photographer after arriving in Buenos Aires in 1857. He was a surveyor, working with his cousin Hippolyte Gaillard, also a surveyor.

Gonnet’s work reflected the rural lifetime and customs, showing the life and customs of Aboriginal people and paisanos of that era, although Gonnet also took photographies in urban places. In most of his photography he tried to show the typical image of the creole, stereotyping Argentine customs, and using objects as symbols that would create iconic images of the era. His photos were then sold abroad (mostly in Europe), when photography of travels or distant places where gaining in popularity. Gonnet’s innovative style of work consisted of the use of negative system rather than daguerreotype (that was the most common technique by then). Furthermore, Gonnet usually chose to take pictures outdoors instead of working at a studio, which was also his hallmark.

Text from Wikipedia website

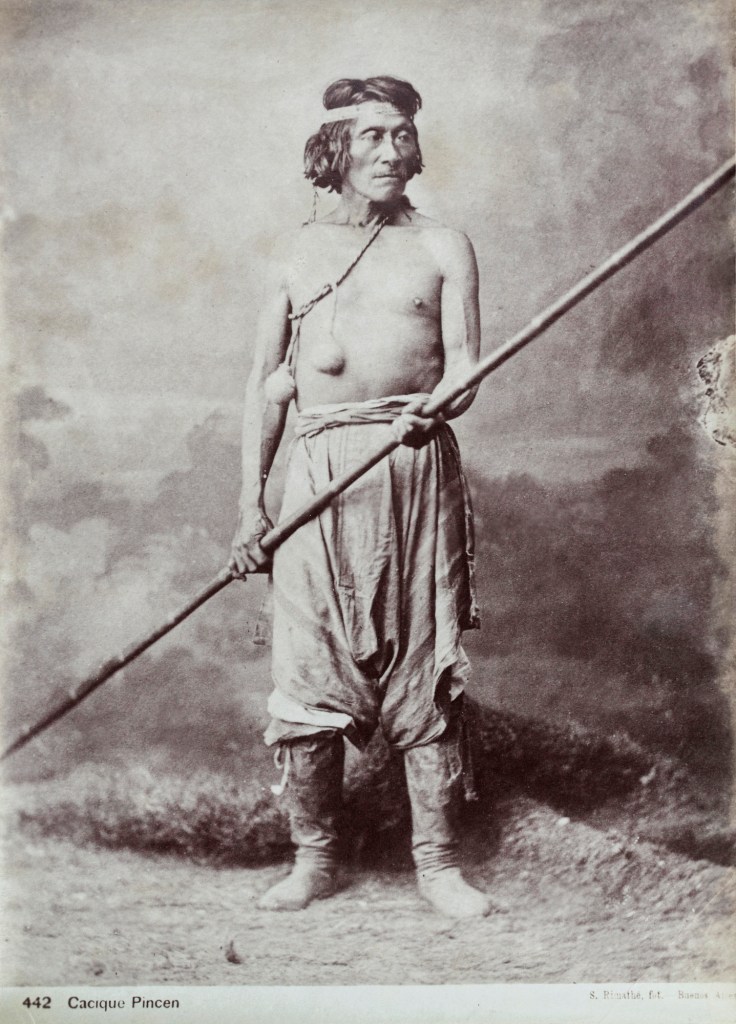

Antonio Pozzo (Argentinian born Italy, 1829-1910)

Cacique Pincén (Chief Pincén)

1878

Printed by Samuel Rimathé, Swiss, born Italy, 1863-unknown

Albumen print

20.2 x 14cm (7 15/16 x 5 1/2 in.)

Collection of Diran Sirinian

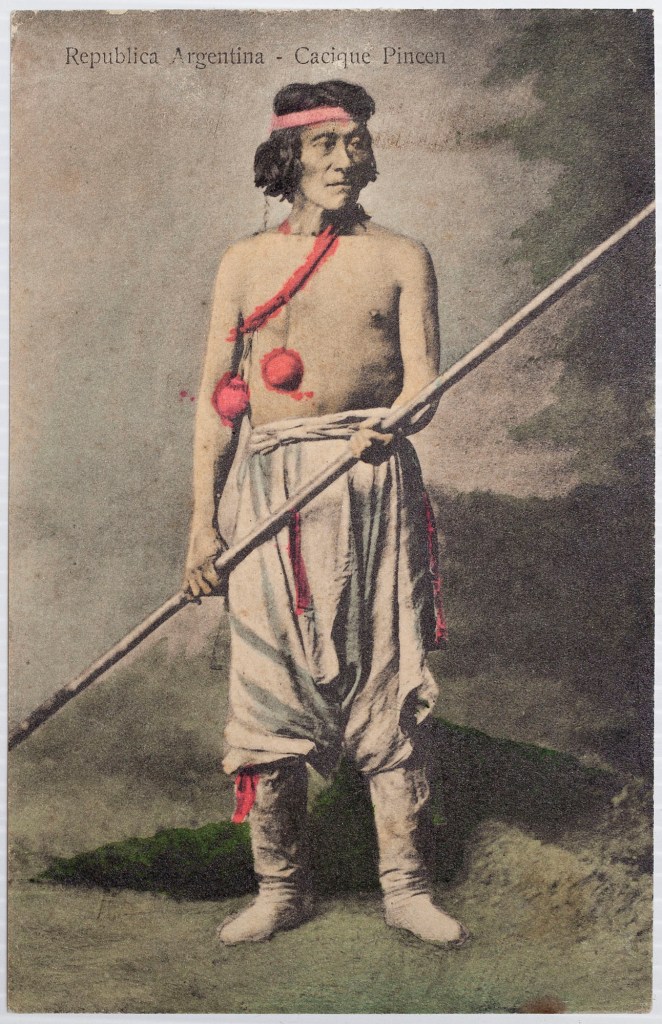

Antonio Pozzo (Argentinian born Italy, 1829-1910)

Cacique Pincén (Chief Pincén)

Negative 1878; print c. 1900

Unknown printer, active Argentina, c. 1900

Hand-coloured halftone postcard

13.7 x 8.7cm

Courtesy of the Daniel Sale Collection

Photo: Javier Augustín Rojas

Sociedad Fotográfica Argentina de Aficionados (Argentine, active 1889-1926)

India yagán u ona tejiendo una canasta / Yagán or Ona Woman Weaving a Basket

c. 1890s

Printing-out paper

21 x 17cm

Courtesy of the Daniel Sale Collection

Photo: Javier Augustín Rojas

Attributed to Carlos R. Gallardo (Argentinian, 1855-1938)

Esperando el ataque / Waiting for the Attack

1902

Gelatin silver print

15.5 x 22cm

Courtesy of the Diran Sirinian

Photo: Javier Augustín Rojas

Grete Stern (Argentinian born Germany, 1904-1999)

Mujer pilagá con sus hijos. Los Lomitas, Formosa / Pilagá Woman with her Kids. Las Lomitas, Formosa

1964

From the series Aborígenes del gran Chaco argentine / Indigenous People from the Argentine Gran Chaco

Gelatin silver print

30 x 38cm

Courtesy of a private collection

© Estate of Grete Stern courtesy Galería Jorge Mara – La Ruche, Buenos Aires, 2016

Grete Stern (9 May 1904 – 24 December 1999) was a German-Argentinian photographer. Like her husband Horacio Coppola, she helped modernise the visual arts in Argentina, and in fact presented the first exhibition of modern photographic art in Buenos Aires, in 1935. (Wikipedia)

In Berlin in 1927, Stern began taking private classes with Walter Peterhans, who was soon to become head of photography at the Bauhaus. A year later, in Peterhans’s studio, she met Ellen (Rosenberg) Auerbach, with whom she opened a pioneering studio specialising in portraiture and advertising. Named after their childhood nicknames, the studio ringl + pit embraced both commercial and avant-garde loyalties, creating proto-feminist works. In Buenos Aires during the same period, Coppola initiated his photographic experimentations, exploring his surroundings and contributing to the discourse on modernist practices across media in local cultural magazines. In 1929 he founded the Buenos Aires Film Club to introduce the most innovative foreign films to Argentine audiences. His early works show the burgeoning interest in new modes of photographic expression that led him to the Bauhaus in 1932, where he met Stern and they began their joint history.

Following the close of the Bauhaus and amid the rising threat of the Nazi powers in 1933, Stern and Coppola fled Germany. Stern arrived first in London, where her friends included activists affiliated with leftist circles and where she made her now iconic portraits of German exiles, including those of Bertolt Brecht and Karl Korsch. After traveling through Europe, camera in hand, Coppola joined Stern in London, where he pursued a modernist idiom in his photographs of the fabric of the city, tinged alternately with social concern and surrealist strangeness.

In the summer of 1935, Stern and Coppola embarked for Buenos Aires [the had married in the same year, divorcing in 1943], where they mounted an exhibition in the offices of the avant-garde magazine Sur, announcing the arrival of modern photography in Argentina. The unique character of Buenos Aires was captured in Coppola’s photographic encounters from the city’s centre to its outskirts, and in Stern’s numerous portraits of the city’s intelligentsia, from feminist playwright Amparo Alvajar to essayist Jorge Luis Borges to poet-politician Pablo Neruda.

Text from the MoMA website

Leonel Luna (Argentinian, b. 1965)

El rapto de Guinnard / The Kidnap of Guinnard

2002; print, 2017

Inkjet print on vinyl

112 x 72cm

Courtesy of a private collection

© Leonel Luna

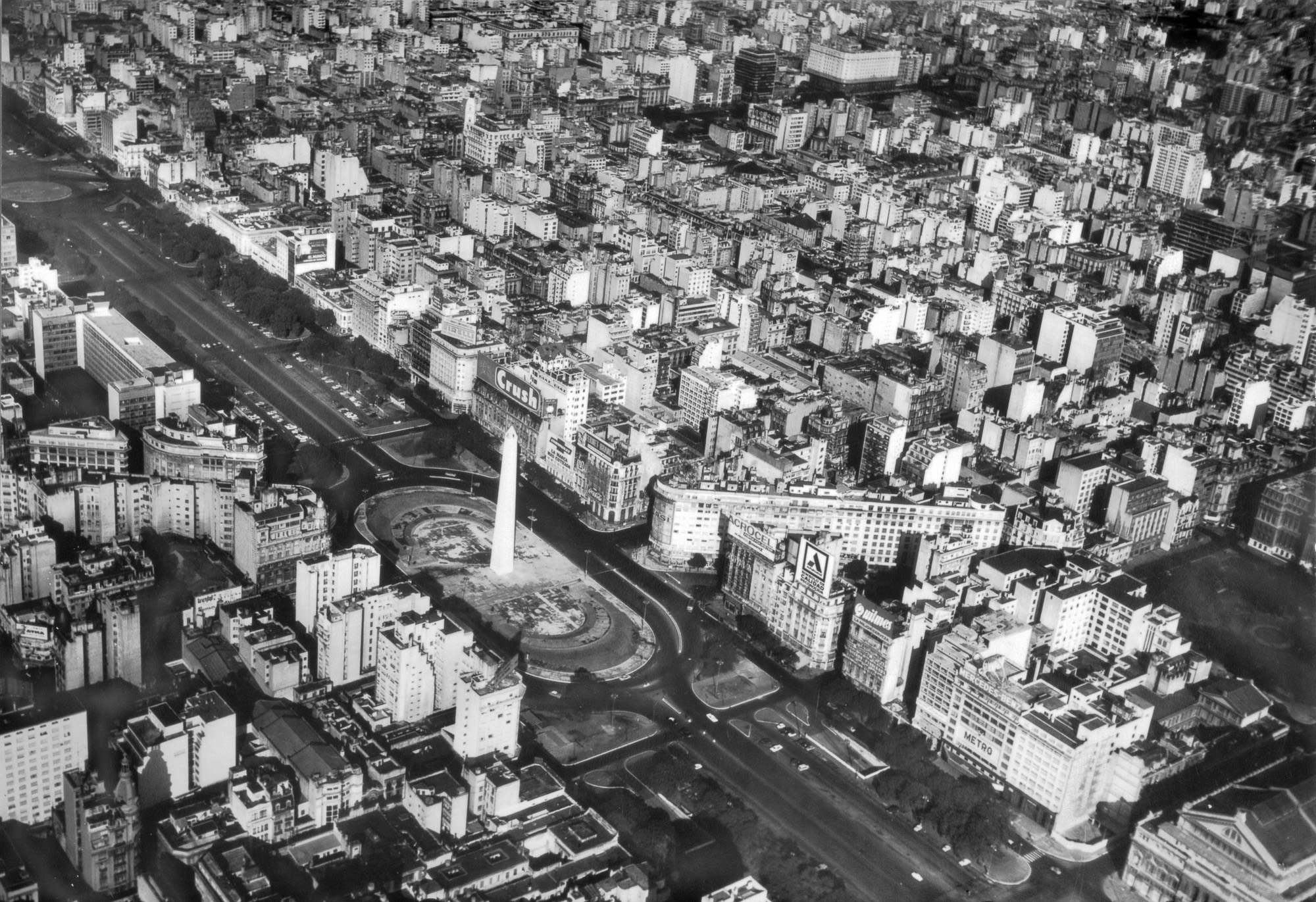

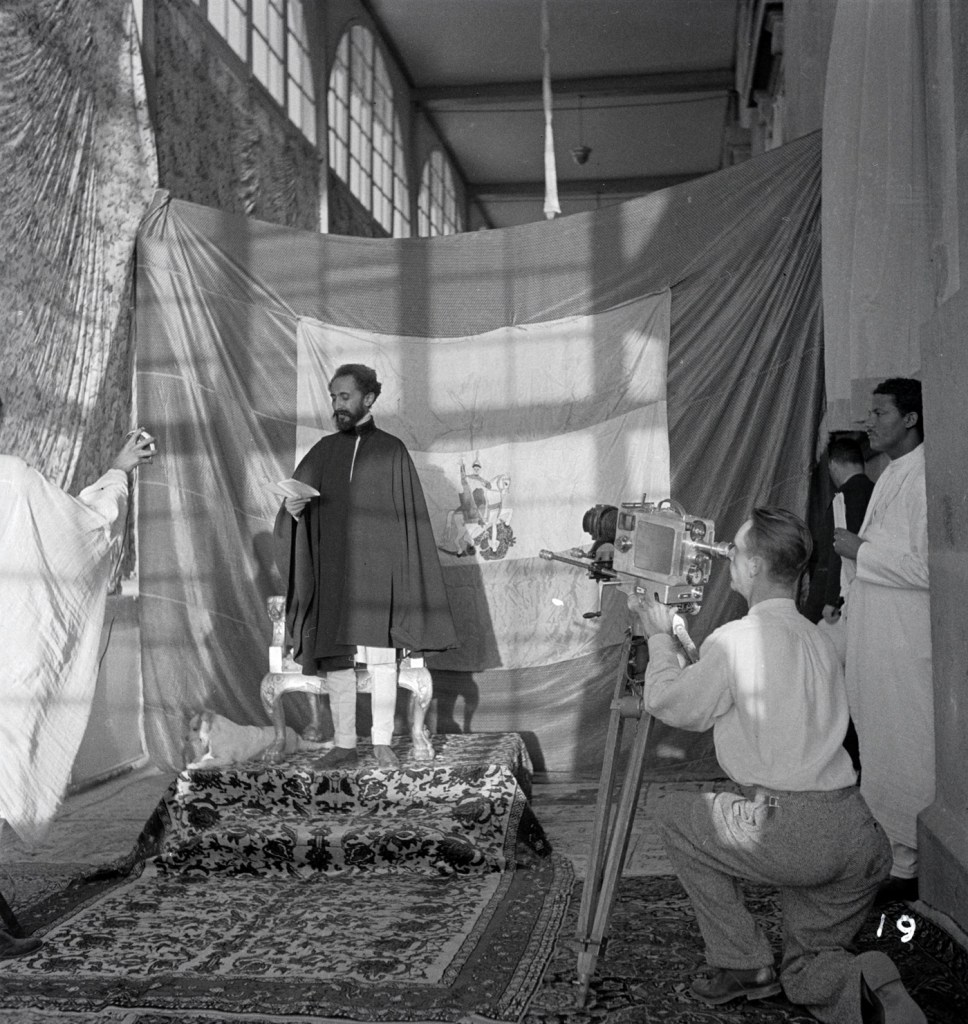

National Myths: Evita and the Modern City

Photography contributed substantially to the construction of the myths of Buenos Aires as the “Modern City” and Evita as the symbol of Peronism. From the 1930s into the 1950s, the capital, like other advanced cosmopolitan metropolises, continued to expand. Some of the emblematic streets and monuments of the city, such as the Obelisk (1936), Avenida 9 de Julio (begun 1935), and Avenida Corrientes (1936), were built or renovated during this period. Buenos Aires became a model of progress for photographers like Horacio Coppola and Sameer Makarius, who produced series reinforcing this view.

Photography was among the propagandistic strategies deployed by the populist Perón administration (1946-1955). Eva Duarte de Perón (1919-1952), known as Evita, had an important role during the first presidency of her husband, Juan Perón (1895-1974), and became the most enduring image of Peronist ideology. Numerous photographers contributed to building an image of Evita as both an elegant celebrity and a compassionate politician. While Juan Di Sandro, considered the father of photojournalism in Argentina, made her political life accessible through views of official events, Annemarie Heinrich helped create her “new” femininity in glamorous studio portraits. Jaime Davidovich’s installation Evita, Then and Now: A Video Scrapbook (1984) and Santiago Porter’s Evita (2008) offer contrasting – critical as well as multidimensional – views of this complex figure.

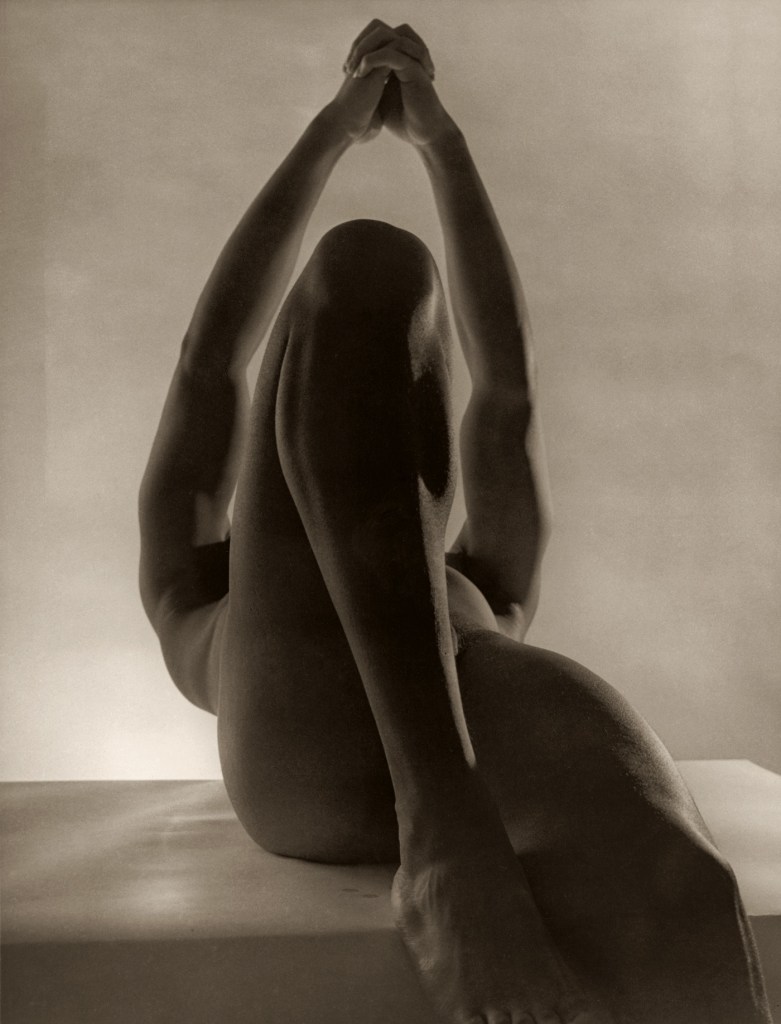

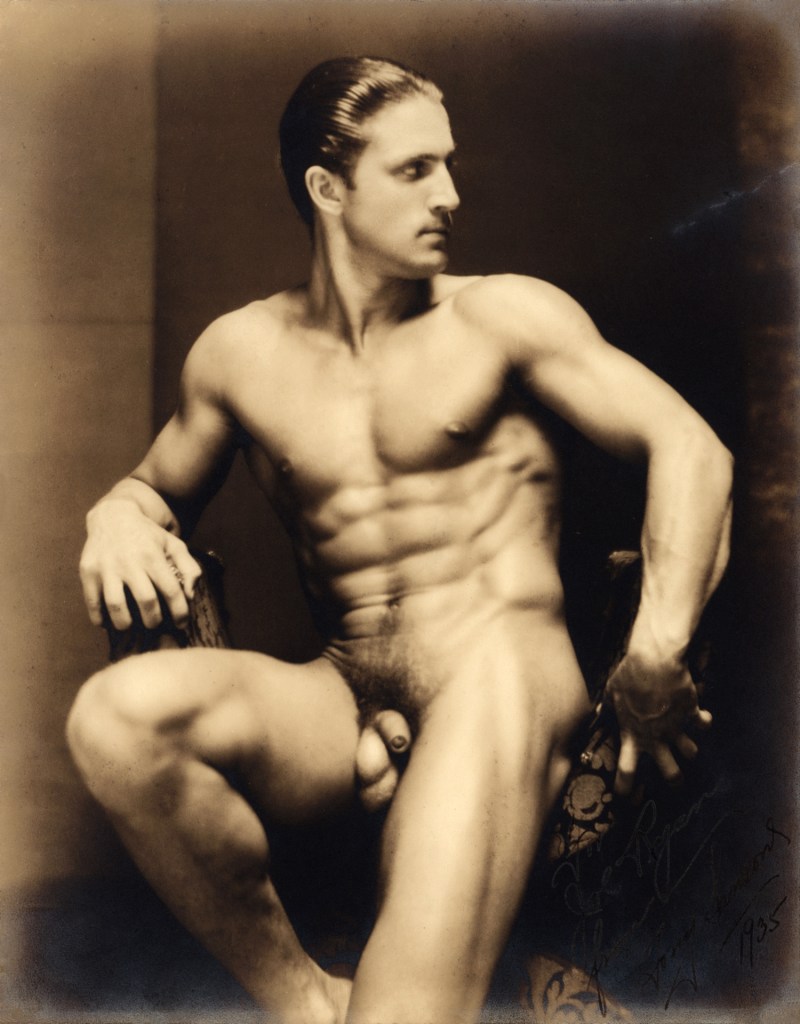

Annemarie Heinrich (Argentinian born Germany, 1912-2005)

Eva Perón

Negative 1944, print 1995

Gelatin silver print

32.5 x 27cm

Courtesy of Galería Vasari

© Archivo Heinrich Sanguinetti

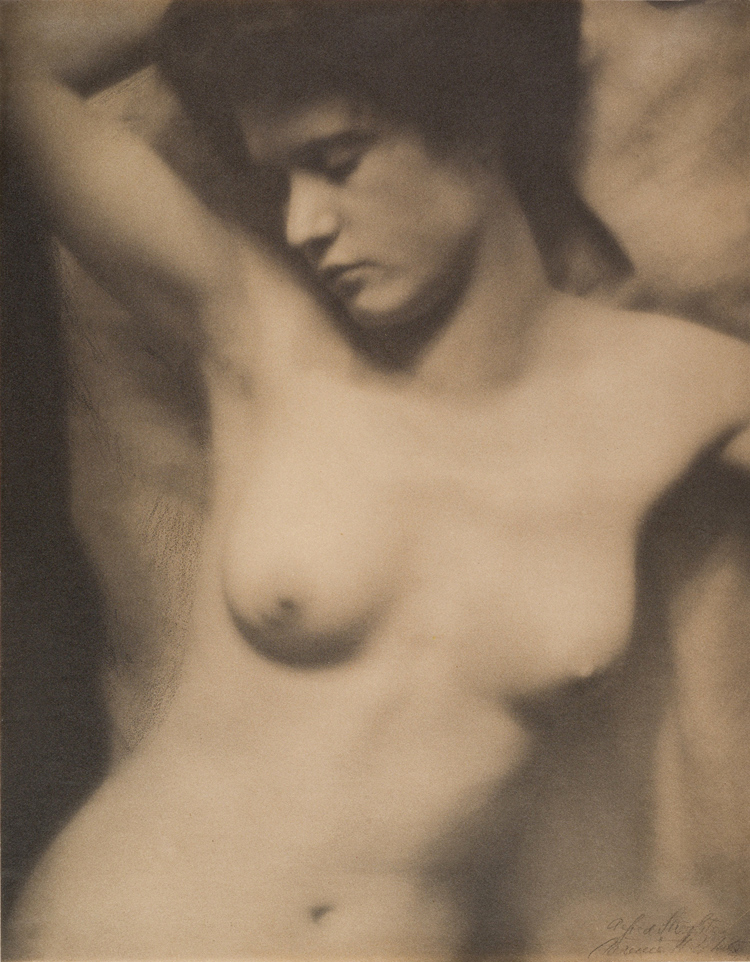

Annemarie Heinrich (9 January 1912 – 22 September 2005) was a German-born naturalised Argentine photographer, who specialised in portraits and nudity. She is known for having photographed various celebrities of Argentine cinema, such as Tita Merello, Carmen Miranda, Zully Moreno and Mirtha Legrand; as well as other cultural personalities like Jorge Luis Borges, Pablo Neruda and Eva Perón.

Heinrich was born in Darmstadt and moved to Larroque, Entre Ríos Province, with her family in 1926, her father having been injured during the First World War. In 1930 she opened her first studio in Buenos Aires. Two years later she moved to a larger studio, and began photographing actors from the Teatro Colón. Her photos were also the cover of magazines such as El Hogar, Sintonía, Alta Sociedad, Radiolandia and Antena for forty years.

Heinrich’s work was shown in New York for the first time in 2016 at Nailya Alexander Gallery in the show “Annemarie Heinrich: Glamour and Modernity in Buenos Aires.” Heinrich is considered one of Argentina’s most important photographers.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Annemarie Heinrich (Argentinian born Germany, 1912-2005)

Veraneando en la ciudad / Spending the Summer in the City

1959

Gelatin silver print

18 x 18cm

Courtesy of the Guillermo Navone Collection

© Archivo Heinrich Sanguinetti

Juan Di Sandro (Argentinian born Italy, 1898-1988)

Avenida 9 de julio con obelisco. Vista panorámica / Avenida 9 de Julio with Obelisk. Panoramic View

1956

Gelatin silver print

29 x 42cm

Courtesy of Galería Vasari

© Familia Di Sandro

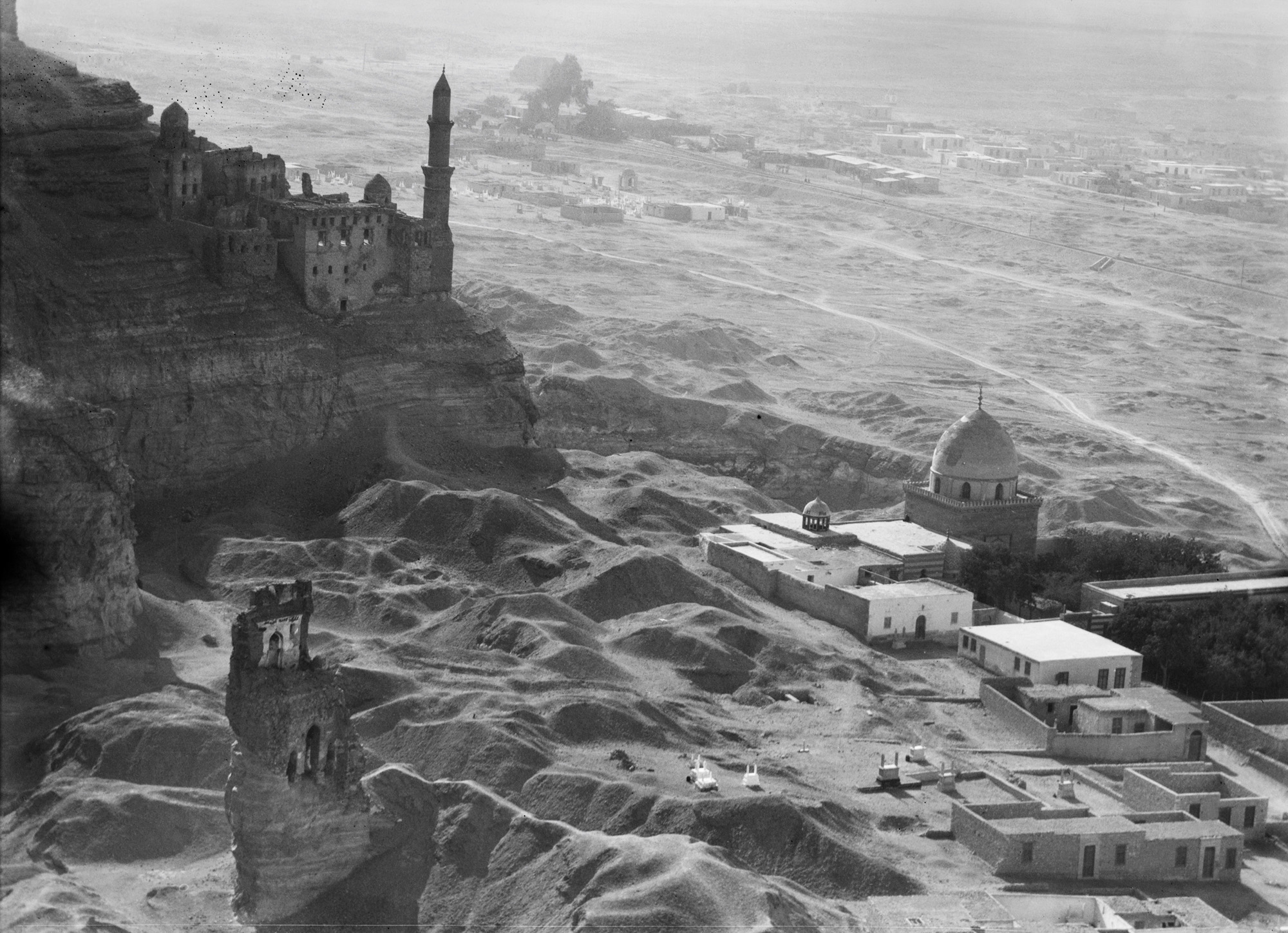

Sameer Makarius (Argentinian born Egypt, 1924-2009)

Obelisco / Obelisk

1957

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of Diran Sirinian

Photo: Javier Agustin Rojas

© Throckmorton Fine Arts

Sameer Makarius was without doubt one of the most prolific photographers in Buenos Aires during the 1950s and 60s. Almost every weekend, he ventured out taking along with him his two cameras, a Leica and an Olympus, to record his new home town. Makarius arrived in Buenos Aires in 1953 and the city must have made a real impact on him. Europe was scarred and slowly recuperating, but things were completely different here. A bustling, modern, elegant plus very confident capital was waiting to be explored. Taking photographs probably helped him to find his bearings and get to know the customs of the city’s inhabitants really well. But then, everybody’s past often determines both their present and their future. Makarius had studied art in Hungary and – being an artist – was inclined to a visual approach. He started out as a painter and abstraction, in all its various ramifications, was one of the main tendencies at the time, with Makarius following suit. Still, when he came to Argentina he was already principally interested in photography. At some stage, probably between the mid and late nineteen forties, a major shift had thus taken place and it is interesting to speculate why. Maybe, Makarius switched to photography because of practical reasons. Cameras were not only widely available at the time, but also coincided perfectly with his wandering life after the end of the war. Before moving to Argentina, he visited and lived in many countries, for example France and Switzerland. And, last but not least, because of his artistic background, he already knew how to deal with composition, light and shadow.

Marjan Groothuis. “Sameer Makarius,” on the Arte Aldia website Nd [Online] Cited 03/02/2022

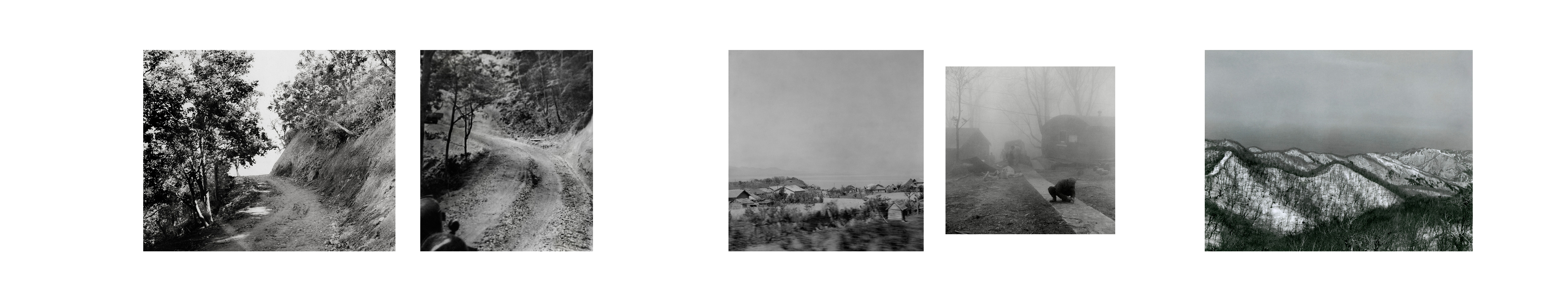

Santiago Porter (Argentinian, b. 1971)

Evita

2008

From the series Bruma II / Mist II

Inkjet print

154 x 123.5cm

Courtesy of the Collection Malba, Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires

© Santiago Porter

The Political Gesture

The gesture of “pointing out” had its origin in conceptual Argentine photography of the 1960s and 1970s. The artistic act evolved into radical actions as the sociopolitical situation in Argentina deteriorated. This section of the exhibition investigates photographs of political gestures provoked by the last dictatorship of 1976-83, in relation to the earlier conceptual practice presented in the adjacent gallery, “The Aesthetic Gesture.”

The action of showing a photograph of a person who was kidnapped or “disappeared” during the dictatorship was employed by the activist group Madres de Plaza de Mayo. In their weekly marches, the Mothers always wore white head scarves and carried photographs of their children on homemade signs demanding they “Return Alive.” With the arrival of democracy and Nunca Más (Never Again), the official 1984 report of crimes against humanity, trials of the military leaders began. However, over the next fifteen years, many of those who were culpable operated with impunity due to such regulations as the Full Stop Law (1986), the Law of Due Obedience (1987), and the Pardons Act (1990). During this time, activist artist groups, such as Grupo Etcétera… and Escombros, emerged to remind the public of crimes and atrocities, pointing out those assassins who had hoped to remain anonymous.

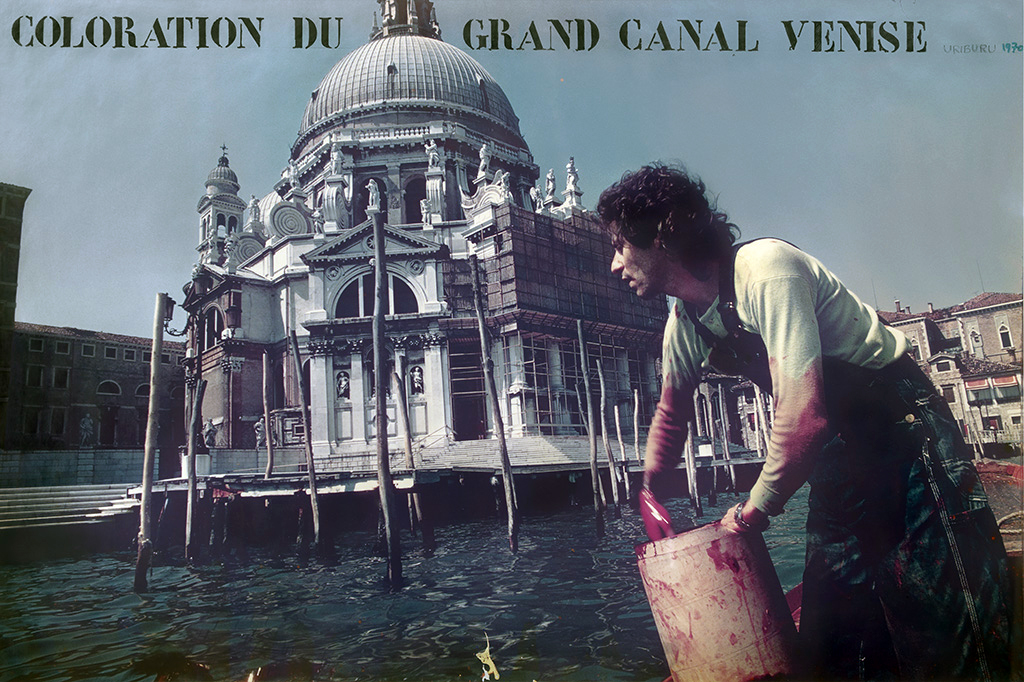

Nicolás García Uriburu (Argentinian, 1937-2016)

Le Geste – Coloration Du Grand Canale – Venise 1970 / The Gesture – Colouring the Grand Canal – Venice 1970

1968-70

Chromogenic print, stencil and ink

67 x 101cm

Courtesy of Rubén and Agustina Esposito

© Nicolás García Uriburu

Born in Buenos Aires in 1937, García Uriburu began painting at an early age and, in 1954, secured his first exhibition at the local Müller Gallery. He enrolled at the University of Buenos Aires, where he received a degree in architecture, and relocated to Paris with his wife, Blanca Isabel Álvarez de Toledo, in 1965. He would later father a child named “Azul” with Blanca. His Three Graces, a sculpture in the pop art style, earned him a Grand Prize at the National Sculpture Salon in 1968. Venturing into conceptual art, he mounted an acrylic display at the Iris Clert Gallery, creating an artificial garden that set a new direction for García Uriburu’s work towards environmental activism.

He was invited to the prestigious Venice Biennale in June 1968, where García Uriburu dyed Venice’s Grand Canal using fluorescein, a pigment which turns a bright green when synthesised by microorganisms in the water. Between 1968 and 1970, he repeated the feat in New York’s East River, the Seine, in Paris, and at the mouth of Buenos Aires’ polluted southside Riachuelo.

A pioneer in what became known as land art, he created a montage in pastel colours over photographs of the scenes in 1970, allowing the unlimited photographic reproduction of the work for the sake of raising awareness of worsening water pollution, worldwide. In addition to environmental conservation he also produced works of art that showcased humanistic naturalism and an antagonism between society and nature, such as: Unión de Latinoamérica por los ríos (Latin America Union for Rivers), and No a las fronteras políticas (No to Political Borders).

Text from the Wikipedia website

Eduardo Longoni (Argentinian, b. 1959)

Madres de Plaza de Mayo durante su habitual ronda / Mothers of Plaza de Mayo during Their Customary March

1981

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of and © Eduardo Longoni

Eduardo Gil (Argentinian, b. 1948)

Siluetas y canas. El Siluetazo. Buenos Aires 21-22 de setiembre, 1983 / Silhouettes and Cops. El Siluetazo. Buenos Aires, September 21-22, 1983

1983

Gelatin silver print

17.5 x 24.5cm

Courtesy of a private collection

© Eduardo Gil

Adriano Lestido (Argentinian, b. 1955)

Madre e hija de Plaza de Mayo / Mother and Daughter from Plaza de Mayo

1982, printed 1984

Gelatin silver image

16.5 x 21.2cm

Courtesy of Rolf Art and Adriana Lestido

© Adriana Lestido

Grupo Escombros (Argentine, active since 1988)

Mariposas (Butterflies)

1988

Pancartas (Signs) series

Chromogenic print (printed in monochrome) mounted on wood

40 × 60cm (15 3/4 × 23 5/8 in.)

Courtesy of the artists and WALDEN, Buenos Aires

© Grupo Escombros / WALDEN

Grupo Escombros was born in 1988, in full hyperinflation, as a group of street art or public art as it is usually defined. In that Argentina where the economic value of things changed hour by hour, everything seemed to collapse, including democracy reconquered at the cost of 30,000 missing and collective wounds that may never close.

When analysing this social, political and economic situation, the founding artists of the group asked themselves what would be left of the country. The answer was: “the rubble.” That day the group acquired its name. A name that today is more current than ever, because Argentina continues to collapse, relentlessly. Next to the name, and beyond the inevitable changes, there are characteristics that remained intact:

Most of the works were made outdoors, one street, a square, a cellar, an urban stream

They always express the sociopolitical reality that the country lives at that moment

It is expressed through all possible forms of communication: installations, manifestos, murals, objects, posters, poems, prints, talks, visual poems, graffiti, postcards, net art

Its members come from various disciplines: plastic, journalism, design, architecture. Their works are always collective, annulling the individualities that compose it. They do not belong to any political party or religious creed in particular. Despite constantly denouncing the conditions of absolute injustice in which the men, women and children of Argentina and Latin America live, it is a mistaken simplification to say that it is only a protest group.

Anonymous text from the Grupo Escombros website Nd [Online] 24/01/2018. No longer available online

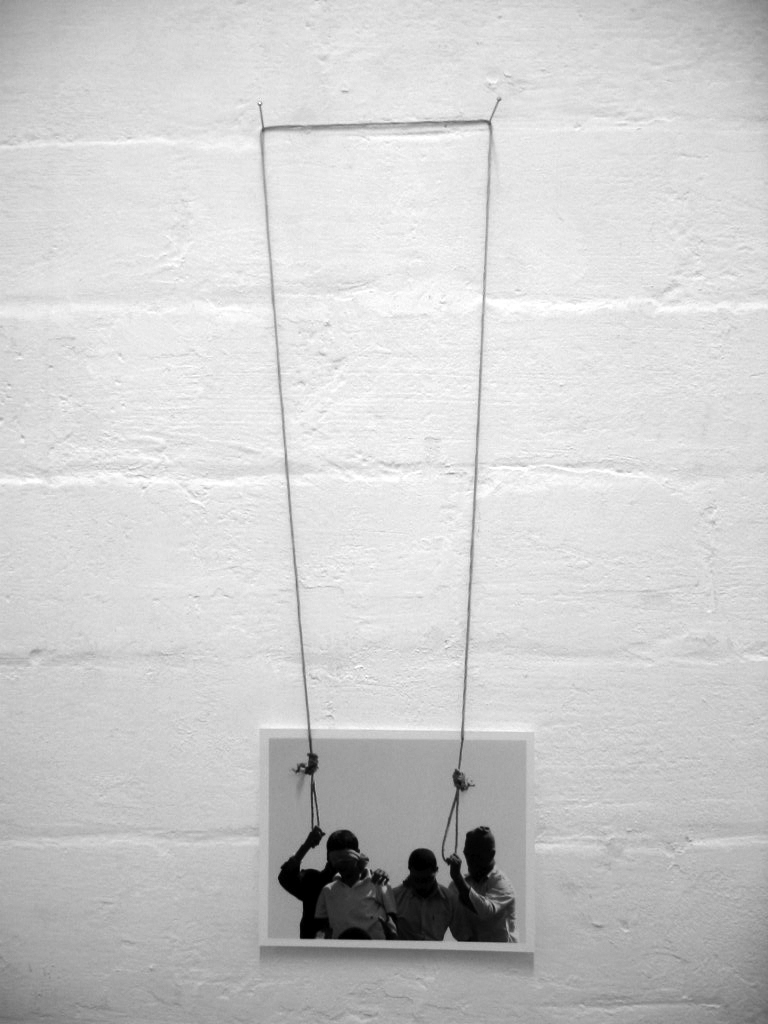

Grupo Etcétera (Argentine, active since 1997)

MÁSCARAS DESINHIBIDORAS – Escraches a los militares Riverso y Peyón / UNINHIBITING MASKS – Escraches to (Former) Military Officers Riverso and Peyón (2)

1998

Chromogenic print

15 x 21.5cm

Courtesy of Archivo Etcétera

© Etcétera Archive

Etcétera is a multi-disciplinary collective created in Buenos Aires in 1997. It is made up of artists with a background in poetry, theater, visual arts and music. Its original purpose was to bring artistic expression closer to places of social conflict and shift these problems to cultural production spaces. These experiences take place at contemporary art venues such as museums, galleries and cultural centres, but also in the streets, at festivals, during protests and demonstrations, using different strategies including contextual and ephemeral public interventions. They consider themselves part of the “committed art” movement. In 2005, they created the Fundación del Movimiento Internacional Errorista (International Errorist Movement Foundation) with other artists and activists. This international organisation seeks to consolidate error as a life philosophy. The co-founders of the collective, Loreto Garín Guzmán y Federico Zukerfeld, are responsible for coordinating all activities, archives and other initiatives since 2007.

Grupo Etcétera (Argentine, active since 1997)

ARGENTINA VS. ARGENTINA. Escrache to General Galtieri

1998

Chromogenic print

15 x 21.5cm

Courtesy of Archivo Etcétera

© Etcétera Archive

Escrache: Intimidatory action by citizens against persons in the political, administrative or military sphere, which consists in disseminating information about the abuses committed during their administration to their private homes or to any public place where they are identified.

Florencia Blanco (French, b. 1971)

María y Andrés Pedro. Lobería, Buenos Aires

2008

From the series Donde están los muertos? / Where Are the Dead Ones?

Chromogenic print

70 x 70cm

Courtesy of Florencia Blanco

© Florencia Blanco

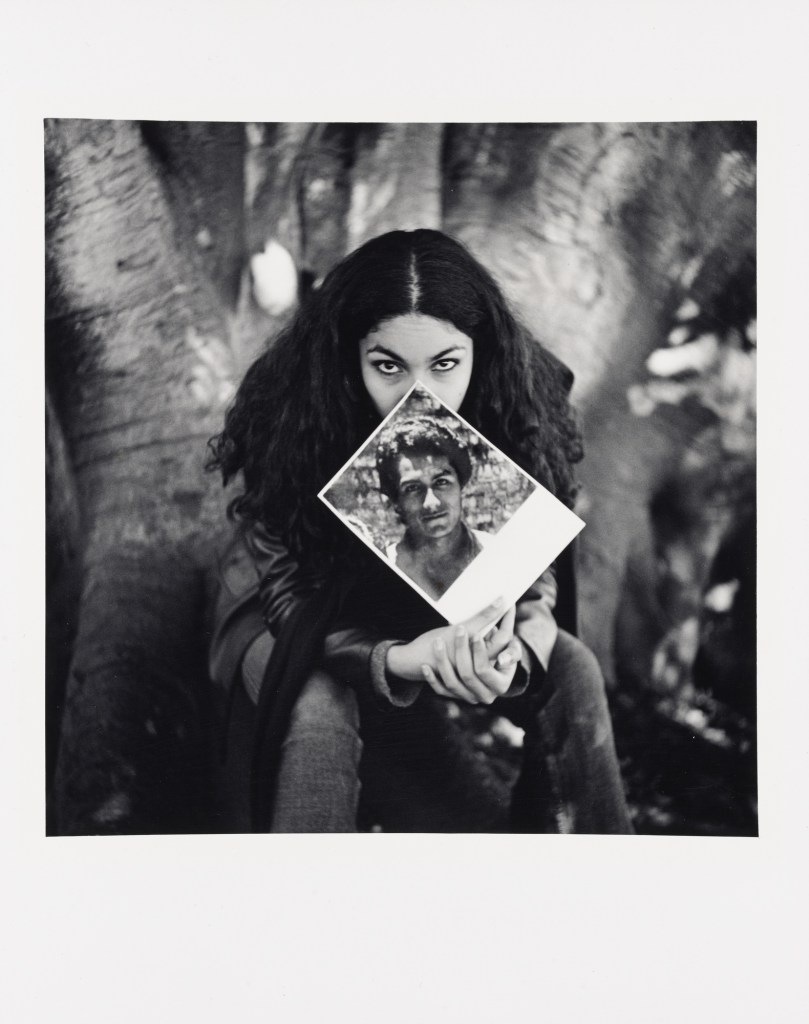

Julio Pantoja (Argentinian, b. 1961)

Laura Romero, 26 años, estudiante de artes de la serie Los hijos. Tucumán, veinte años despues /

Laura Romero, 26 Years Old, Art Student from the series The Sons and Daughters. Tucumán, Twenty Years Later

1996

Gelatin silver print

20.7 x 20.7cm

The J. Paul Getty Museum, purchased with funds provided by the Photographs Council

© Julio Pantoja

Julio Pantoja (Argentinian, b. 1961)

Natalia Ariñez, 23 años, esudiante de arquitectura / Natalia Ariñez, 23 Years Old, Architecture Student

1999

From the series The Sons and Daughters. Tucumán, Twenty Years Later

Gelatin silver print

20.7 x 20.7cm

The J. Paul Getty Museum, purchased with funds provided by the Photographs Council

© Julio Pantoja

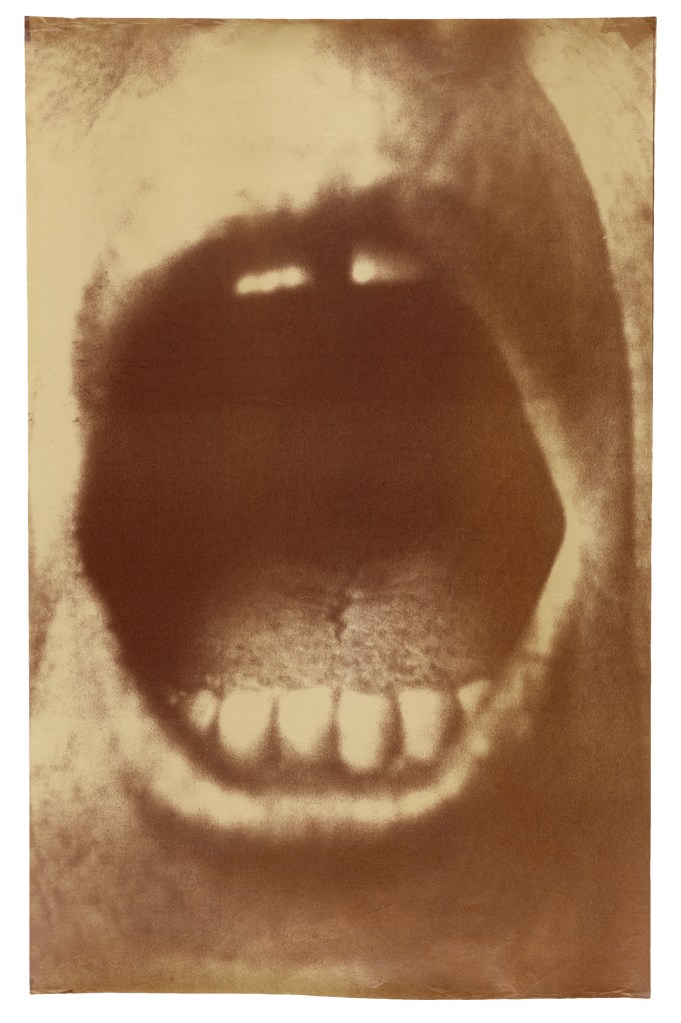

Graciela Sacco (Argentinian, b. 1956)

Untitled (#2)

1993

From the series Bocanada

Heliography on paper

72.1 x 50.1cm

The J. Paul Getty Museum purchase with funds provided by the Photographs Council

© Graciela Sacco

Graciela Sacco (Argentina, Rosario, 1956 – November 5, 2017) was a visual artist and teacher from Argentina. She worked mainly with photography, video and installation.She received great recognition for the wide participation of his work in individual and collective exhibitions in his country, fairs and international biennials as those in Mexico, Venice and Shanghai , the most important worldwide… She was an artist committed to the problems of her country. …

Through light, shadows, space, time and movement, she captures the themes he addresses, builds, dialogues and discusses in his works; her first technical interest was photography as a visual language to portray time in a certain space, a certain context lived in a fixed image, navigating analogue and digital media, working with techniques such as Heliography , through which she transfers images to the surface of objects chosen for their compositions, which have been previously emulsified with photosensitive substances which allows their printing and thus provide wooden blocks, acrylic sheets, PVC, paintings, windows, suitcases, dishes, spoons, knives of new meanings and meanings that speak beyond their own meaning; how to use an empty spoon with the “reflection” of the mouth that will eat from it to talk about a society that goes hungry and needs, because as she herself has said: “we are individuals different from each other in their personal growth, but with shared or unresolved needs that unite us and relate”. For this reason Bocanada (1993-2014) and “Body to Body” (1996-2014) become an active work as long as the situation is repeated or is not solved (societies with hunger and ignored basic needs), will remain valid, in force and it can be traced and displayed as many times as necessary.

The first was a set of images reproduced and multiplied, a technique that took from the media and its means to advertise and promote ideas, events, news and products, but through art, taking advantage of the reproducibility of the same product, worth the redundancy, of modernity in the technification and technological evolution of the visual arts. It was born from the urban interventions that Sacco practiced in schools and public squares in Argentina, Brazil and European cities, in which she painted the streets with the image repeated hundreds of times of open mouths, which portray the hunger of the world, the poverty, the need, humility, problems that affect much of the world and that are of human and universal interest, anyone can understand or arouse.

Hence, the work can be reinterpreted anywhere in the world, alluding to the context in which it is presented. As in the second work mentioned in which is not hunger but protests and public demonstrations to claim rights and welfare of student and civil communities, then take advantage of public space as the space of free thought where they can be transformed, evidence and manifest the plurality of ideas and get the support or rejection of their listeners.

Google Translate from the Spanish Wikipedia entry

The Aesthetic Gesture

During the 1960s and 1970s, the art scene in Argentina fostered a radical break with traditional forms of art. The opening of new spaces dedicated to experimental art, most notably the Instituto Torcuato di Tella and CAyC (Centro de Arte y Comunicación), gave rise to conceptual art and the engagement of intellectual artists, who began to generate works in unconventional forms, including performances, actions, and installations.

Among these innovations was the “aesthetic gesture,” in which artists used actions and performances to “point out” or signal everyday life events, objects, and people, thus transforming them into works of art. Documented primarily with photographs, these pieces sought to invoke viewers as active participants in artistic actions, erasing the divisions between art and life. In his 1962 Vivo-Dito manifesto, for example, Alberto Greco advocated for “a living art”; and in his Signaling series of 1968, Edgardo Antonio Vigo “pointed out” common objects and events with the intention of producing aesthetic experiences. The difficult political climate of repression in the early 1970s, which culminated in the dictatorship period, provoked artists to undertake increasingly political productions.

Jaime Davidovich (Argentine-American, 1936-2016)

Tape Project: Sidewalk 1

1971

Gelatin silver print

The J. Paul Getty Museum

© Jaime Davidovich

Fissures

The democracy restored to Argentina in 1983 followed a neoliberal model, one that favoured free-market capitalism. The implementation of neoliberalism, during the presidency of Carlos Menem (1989-99), together with the catastrophic economic collapse of 2001, provoked the questioning of long-held national ideals. The works in this section utilise architecture to highlight aspects of national history in relation to current sociopolitical issues. Santiago Porter’s photographs reflect the prosperity of the past in contrast to the present fiscal situation. Similarly, Nuna Mangiante’s graphite-altered pictures revolve around the 2001 crisis and, specifically, the corralito (when citizens were not allowed to withdraw their money from banks).

The works in this section stress inequality and its consequences in contemporary Argentina. SUB, Photographic Cooperative’s series A puertas cerradas (Behind Closed Gates) documents the comfortable life of a wealthy family in a gated neighbourhood outside Buenos Aires, while Gian Paolo Minelli’s photographs focus on people living in Barrio Piedrabuena, an impoverished neighbourhood in the capital city. Ananké Asseff’s portraits of middle-class citizens with their guns attest to rising fear and paranoia in contemporary Argentine society.

Santiago Porter (Argentinian, b. 1971)

Casa de Moneda de la serie Bruma / The Mint

Negative, 2007; print, 2015

From the series Mist

inkjet print

The J. Paul Getty Museum, purchased with funds provided by the Photographs Council

© Santiago Porter

Martín Weber (Argentinian-Chilean, b. 1868)

El jugador / The Chess Player

1999

From the series Ecos del interior / Echoes from the Interior

Silver dye bleach print

84 x 99cm framed

Courtesy and © Martín Weber

In the mid-nineteenth century, Argentina opened up to several waves of immigration, mostly European, which arrived through the port of Buenos Aires. The country also experienced strong waves of emigration: the first was in the 40s and was followed by two of a more political nature. One during the political persecution at universities under the dictatorship of Juan Carlos Onganía and the second following the coup in 1976. None however compared with the emigration that took place as from December 2001, when unemployment reached 22%.

Martín Weber (Argentinian-Chilean, b. 1868)

Barras de colores / Color Bars

1996

From the series Ecos del interior / Echoes from the Interior

Silver dye bleach print

84 x 99cm framed

Courtesy and © Martín Weber

Black-and-white TV began to be broadcast during Peron’s regime. The inaugural transmission showed Evita’s speaking from Plaza de Mayo. Color TV arrived under the military dictatorship of 1978, in time to broadcast soccer’s World Cup.

Guadalupe Miles (Argentinian, b. 1971)

Sin título (Untitled)

2001, printed 2017

Chaco series

Inkjet print

100 × 100cm (39 3/8 × 39 3/8 in.)

Courtesy of the artist

© Guadalupe Miles

Guadalupe Miles (Argentinian, b. 1971)

Sin título (Untitled)

2001, printed 2017

Chaco series

Inkjet print

100 × 100cm (39 3/8 × 39 3/8 in.)

Courtesy of the artist

© Guadalupe Miles

Alessandra Sanguinetti (American, b. 1968)

Untitled

1996-2004

From the series En el sexto día / On the Sixth Day

Chromogenic (FujiFlex) print

73.7 x 73.7cm

Courtesy of Yossi milo Gallery, New York

© Alessandra Sanguinetti, Courtesy of Yossi milo Gallery, New York

Alessandra Sanguinetti (1968, New York, New York) is an American photographer. Born in New York, Sanguinetti moved to Argentina at the age of two and lived there until 2003. Sanguinetti has stated that she began taking photographs to create a sense of permanence in her life after realising that “everything is transitory.” Currently, she lives in San Francisco, California.

Her most involved project is a documentary photography project about two cousins – Guillermina and Belinda – as they grow up outside of Buenos Aires. The project began in 1999 when Sanguinetti visited her grandmother, Juana, in Argentina. She intended to take pictures of the animals which occupied her grandmother’s rural farm. However, she saw potential in her cousins, whom she had previously disregarded. Sanguinetti recounts this, “I was shooting them without even thinking it was work. My first idea was to just do a single story trying to figure out what they imagined life to be, just so I could get into their world.” Titled The Adventures of Guille and Belinda and the Enigmatic Meaning of their Dreams, the project follows them as they fantasise about becoming adults, early motherhood, and becoming young women while their relationship changes. In this particular collection of photographs, Alessandra makes commentaries about feminine conventions of beauty and behaviour, as well as gender roles and gender identity. She occasionally ridicules social expectations through her images, which are often satirical in nature. These commentaries are best typified in Petals (2000) and The Couple (1999). Her images focus on the lives of young women and children. Sanguinetti told Vice reporter, Bruno Bayley, “Children are fascinating… As a society, we project so much of our hopes, frustrations, denials, and aspirations on children, and they are so transparent in how they reflect everything that is thrust upon them. How could I not photograph them?”

Text from the Wikipedia website

Alessandra Sanguinetti (American, b. 1968)

Untitled

1996-2004

From the series En el sexto día / On the Sixth Day

Chromogenic (FujiFlex) print

73.7 x 73.7cm

Courtesy of Yossi milo Gallery, New York

© Alessandra Sanguinetti, Courtesy of Yossi milo Gallery, New York

Sebastián Friedman (Argentinian, b. 1973)

Segurismos #7

c. 2010-2011, printed 2016

From the series Segurismos

Chromogenic print

59.7 x 80cm

Courtesy of Sebastián Friedman

© Sebastián Friedman

SUB, Photographic Cooperative (Argentine, active since 2004)

Titi (She Has the Same Name as Her Mother, Silvina) and Lili, One of the Maids, Share Moments of Relaxation. Titi Was Born in San Jorge Village and Her Relationship with Liliana Has developed since Birth

2012, printed 2017

From the series A puertas cerradas (Behind Closed Gates)

Inkjet print

60 x 80cm

Courtesy of SUB, Photographic Cooperative

© Sub. Coop Todos los derechos reservados

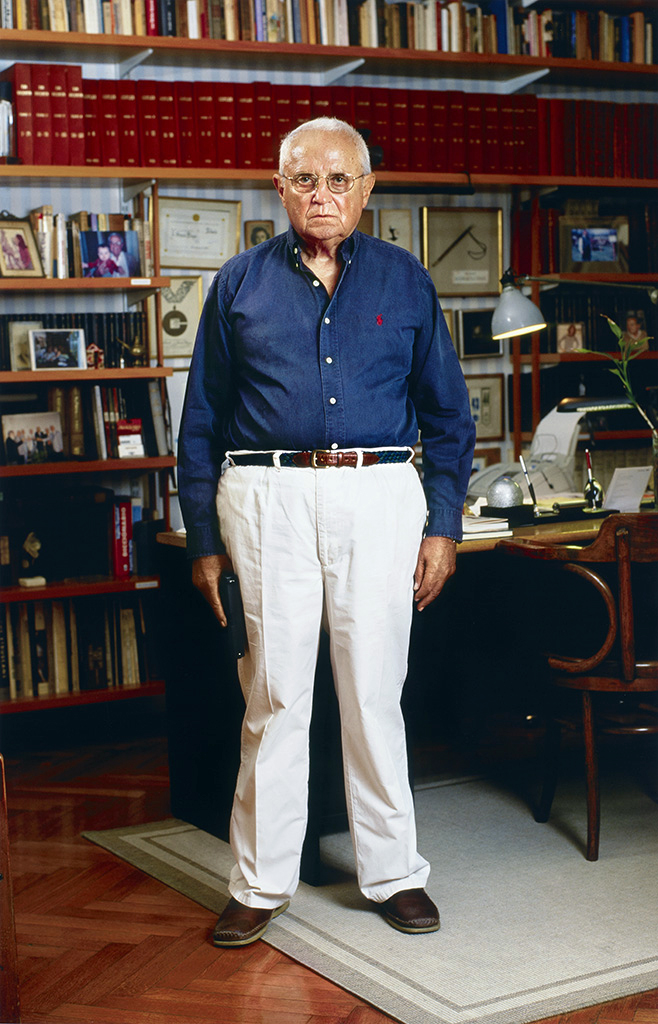

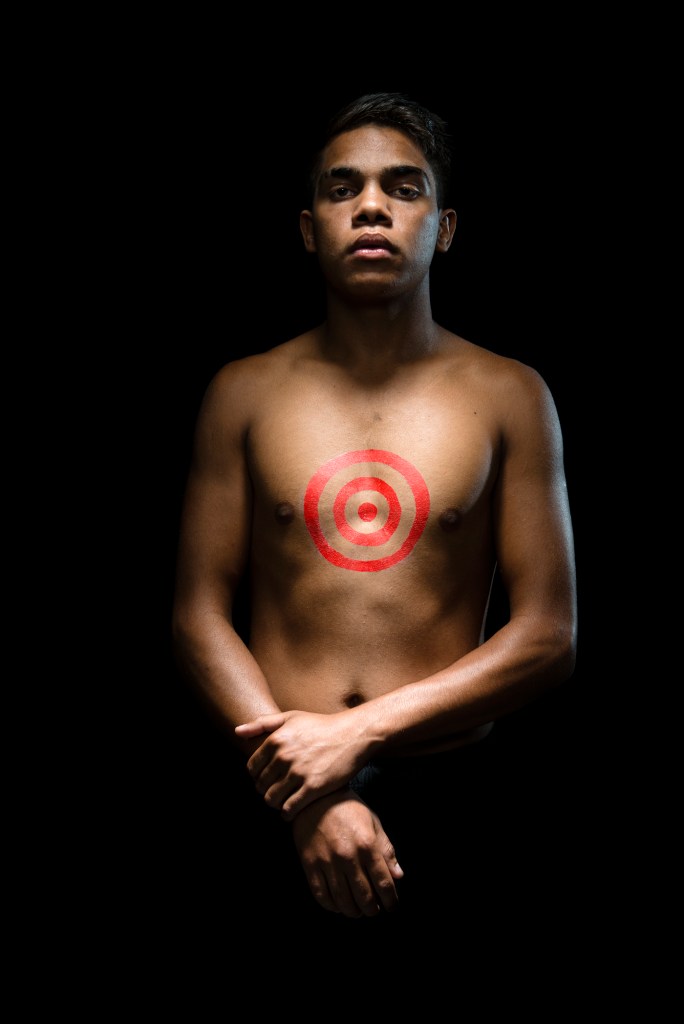

Ananké Asseff (Argentinian, b. 1971)

Luis

c. 2005-07, printed 2015

From the series Potential

198.6 x 129.2cm

Courtesy of Rolf Art and Ananké Asseff

© Ananké Asseff

One of the most effective means to exercise control of populations in contemporary capitalism is the production of fear.

To talk about one of my projects, in “Potential” I worked on the reaction of contemporary society when facing fear, and I got involved with Argentinian society more directly when I photographed the middle and upper classes with weapons in their houses. In this country, this is not something socially accepted, on the contrary. The embedded image of people carrying weapons is something associated with low-income earners and criminals. I put into question the prototype of the “suspect” that is generated by each society, but this issue, like all the other aspects that make up this project, goes beyond Argentinian society. It is something that involves us on a global level. At the time I made this work, people talked exhaustively about the lack of safety in Argentina and terrorism around the world. At the time I lived in Germany for a while (I got a scholarship from KHM) and the sense of insecurity was evident there as well, the weariness before someone unknown approaching or the presence of a stranger (a feeling that was much stronger if the other person looked like they were from the Middle East). Everything was exacerbated and worsened by the obsession of the mass media which propagated fear and terror in society. How awake we had to be (and still have to be) to avoid succumbing to these manipulations!

As Leonor Arfuch says, “certain registers of contemporary communication, certain topics and media obsessions allow the defining, and building, of tendentious trends and consensus, shared beliefs and feelings that invade our intimate and family structures, thus spreading easily into our personal history.”

Fear is a feeling that’s experienced individually but built within a society.

Anonymous text. “Argentina Notebook: Interview with Ananké Asseff,” on the Fototazo website 30/10/2015 [Online] Cited 03/02/2022

Ananké Asseff (Argentinian, b. 1971)

Alberto de la serie (POTENCIAL) / Alberto from the series (POTENTIAL)

c. 2005-2007; printed 2015

Inkjet print

The J. Paul Getty Museum, purchased with funds provided by the Photographs Council

© Ananké Asseff

Gian Paolo Minelli (Swiss, b. 1968)

Milton

2009, printed 2016

From the series Zona Sur Barrio Piedrabuena

54 x 66cm

Courtesy of Dot Fiftyone Gallery and the artist

© Gian Paolo Minelli

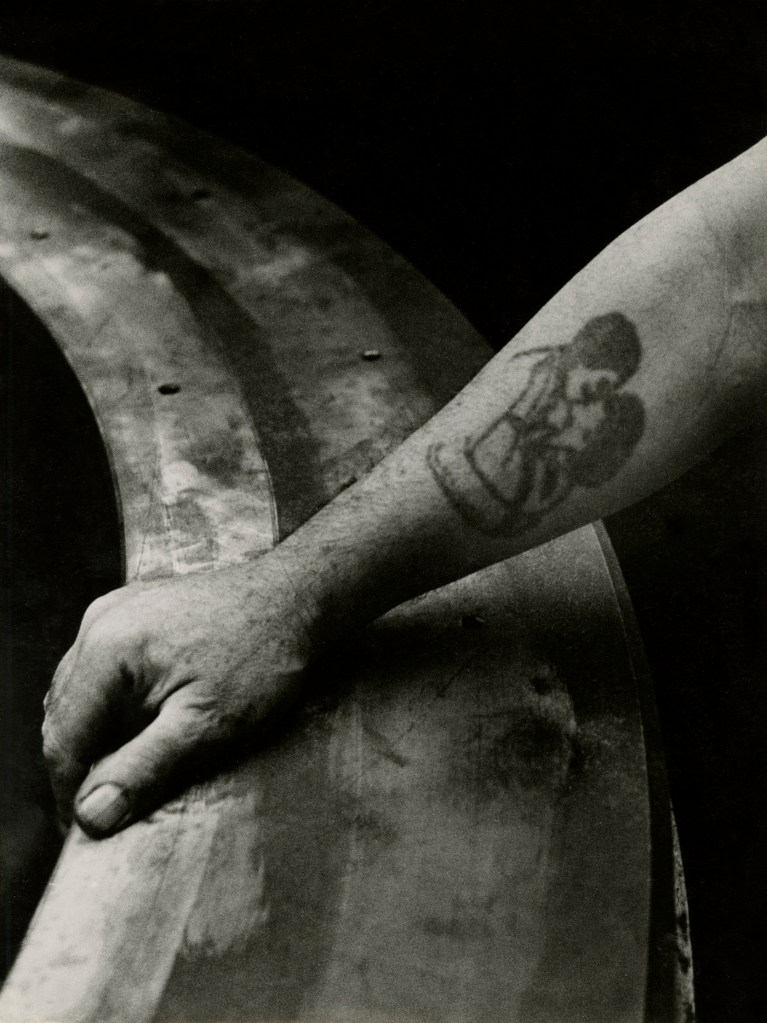

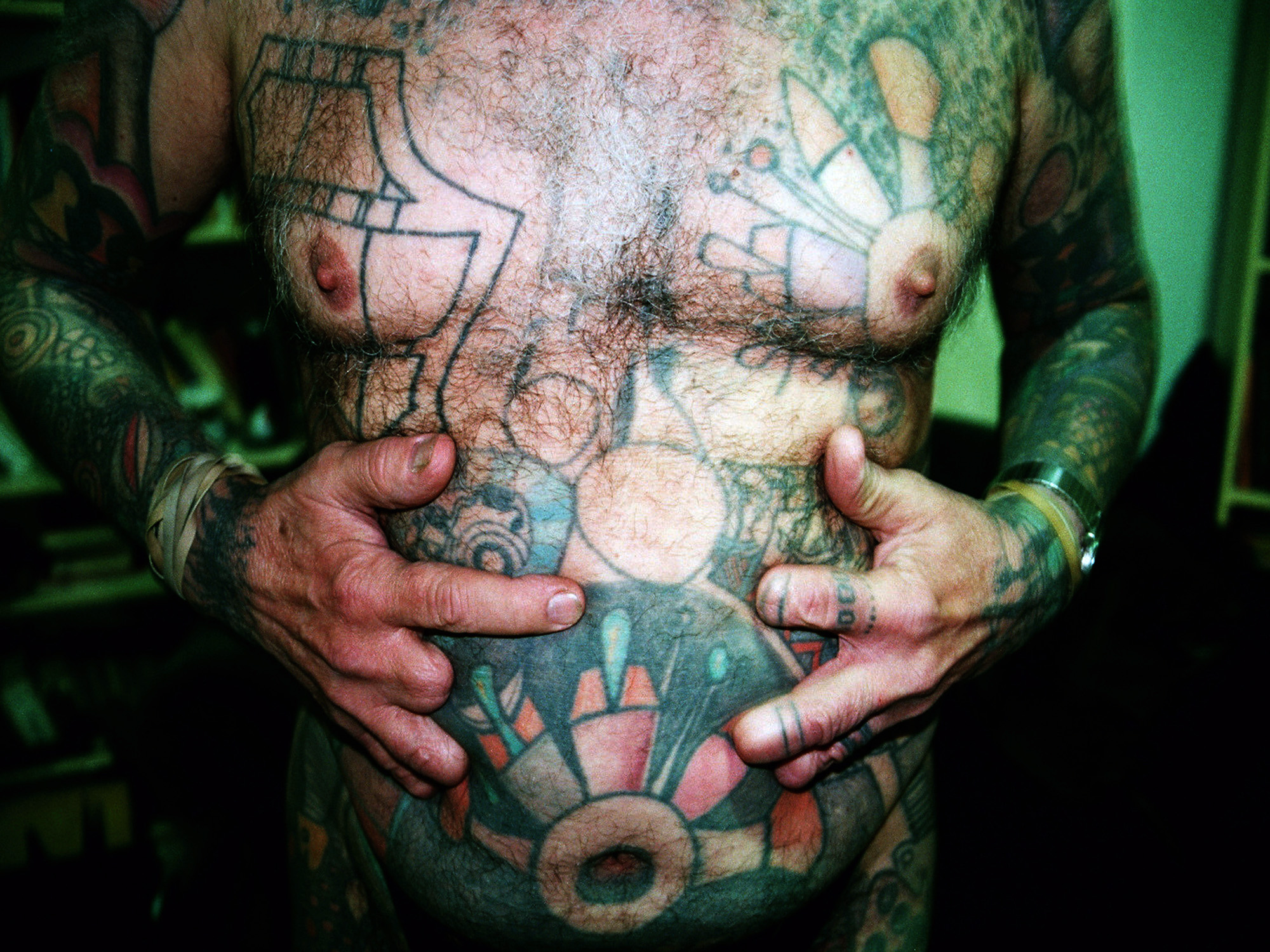

Gian Paolo Minelli (Swiss, b. 1968)

Luciano con tatuaje / Luciano with Tatoo

2009, printed 2016

From the series Zona Sur Barrio Piedrabuena

54 x 66cm

Courtesy of Dot Fiftyone Gallery and the artist

© Gian Paolo Minelli

The J. Paul Getty Museum

1200 Getty Center Drive

Los Angeles, California 90049

Opening hours:

Daily 10am – 5pm

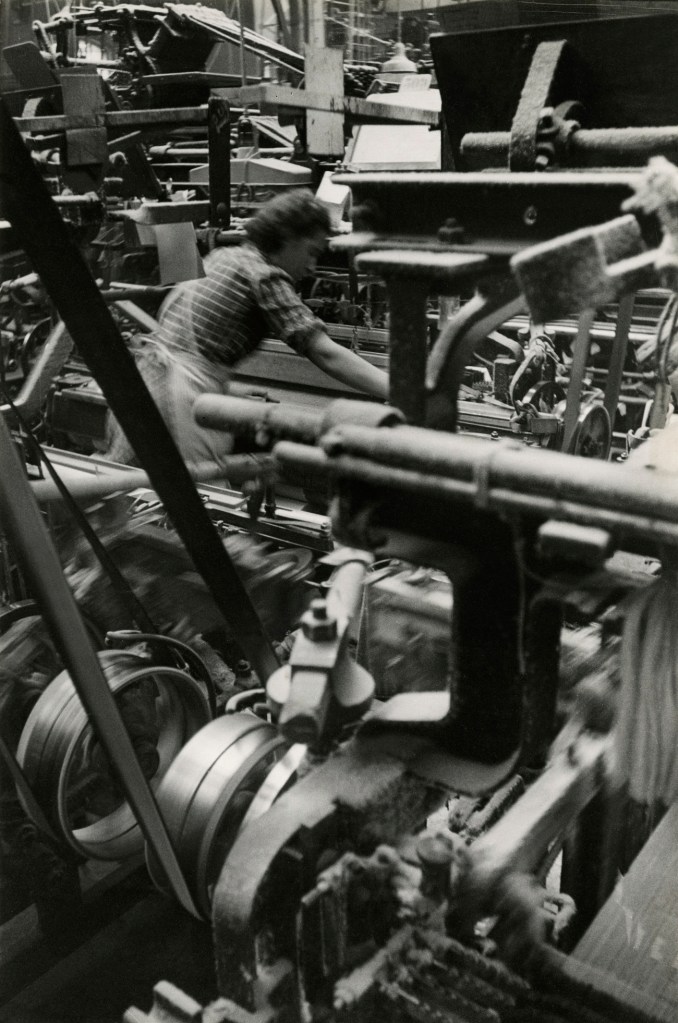

![Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Autoritratto, Zurigo [Self-portrait, Zurich]' 1927 from the exhibition Exhibition: 'Jakob Tuggener – Machine time' at Fotostiftung Schweiz, Winterthur, Zurich, Oct 2017 - Jan 2018 Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Autoritratto, Zurigo [Self-portrait, Zurich]' 1927 from the exhibition Exhibition: 'Jakob Tuggener – Machine time' at Fotostiftung Schweiz, Winterthur, Zurich, Oct 2017 - Jan 2018](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/jakob-tuggener-autoritratto-zurigo-1927-web.jpg?w=825)

![Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Nell'ufficio della fonderia, fabbrica di costruzioni meccaniche Oerlikon' [In the foundry office, Oerlikon mechanical engineering factory] 1937 Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Nell'ufficio della fonderia, fabbrica di costruzioni meccaniche Oerlikon' [In the foundry office, Oerlikon mechanical engineering factory] 1937](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/jakob-tuggener-nellufficio-della-fonderia-web.jpg?w=766)

![Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Navy Cut, Ateliers de construction mécanique Oerlikon (MFO)' [Navy Cut, Machine Shops Oerlikon (MFO)] 1940 Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Navy Cut, Ateliers de construction mécanique Oerlikon (MFO)' [Navy Cut, Machine Shops Oerlikon (MFO)] 1940](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/tuggener-navy-cut-web.jpg?w=763)

![Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Laboratorio di ricerca, fabbrica di costruzioni meccaniche Oerlikon' [Research laboratory, Oerlikon mechanical engineering factory] 1941 Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Laboratorio di ricerca, fabbrica di costruzioni meccaniche Oerlikon' [Research laboratory, Oerlikon mechanical engineering factory] 1941](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/jakob-tuggener-laboratorio-di-ricerca-web.jpg?w=709)

![Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Forgeron dans une fabrique de wagons de Schlieren' [Blacksmith in a Schlieren wagon factory] 1949 Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Forgeron dans une fabrique de wagons de Schlieren' [Blacksmith in a Schlieren wagon factory] 1949](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/tuggener-forgeron-dans-une-fabrique-de-wagons-web.jpg?w=741)

![Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Ballo ungherese, Grand Hotel Dolder, Zurigo, 1935' [Hungarian dance, Grand Hotel Dolder, Zurich, 1935] 1935 Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Ballo ungherese, Grand Hotel Dolder, Zurigo, 1935' [Hungarian dance, Grand Hotel Dolder, Zurich, 1935] 1935](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/tuggener-ballo-ungherese-web.jpg?w=757)

![Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Ballo ungherese, Grand Hotel Dolder, Zurigo, 1935' [Hungarian dance, Grand Hotel Dolder, Zurich, 1935] 1935 Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Ballo ungherese, Grand Hotel Dolder, Zurigo, 1935' [Hungarian dance, Grand Hotel Dolder, Zurich, 1935] 1935](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/jakob-tuggener-ballo-ungherese-web.jpg?w=698)

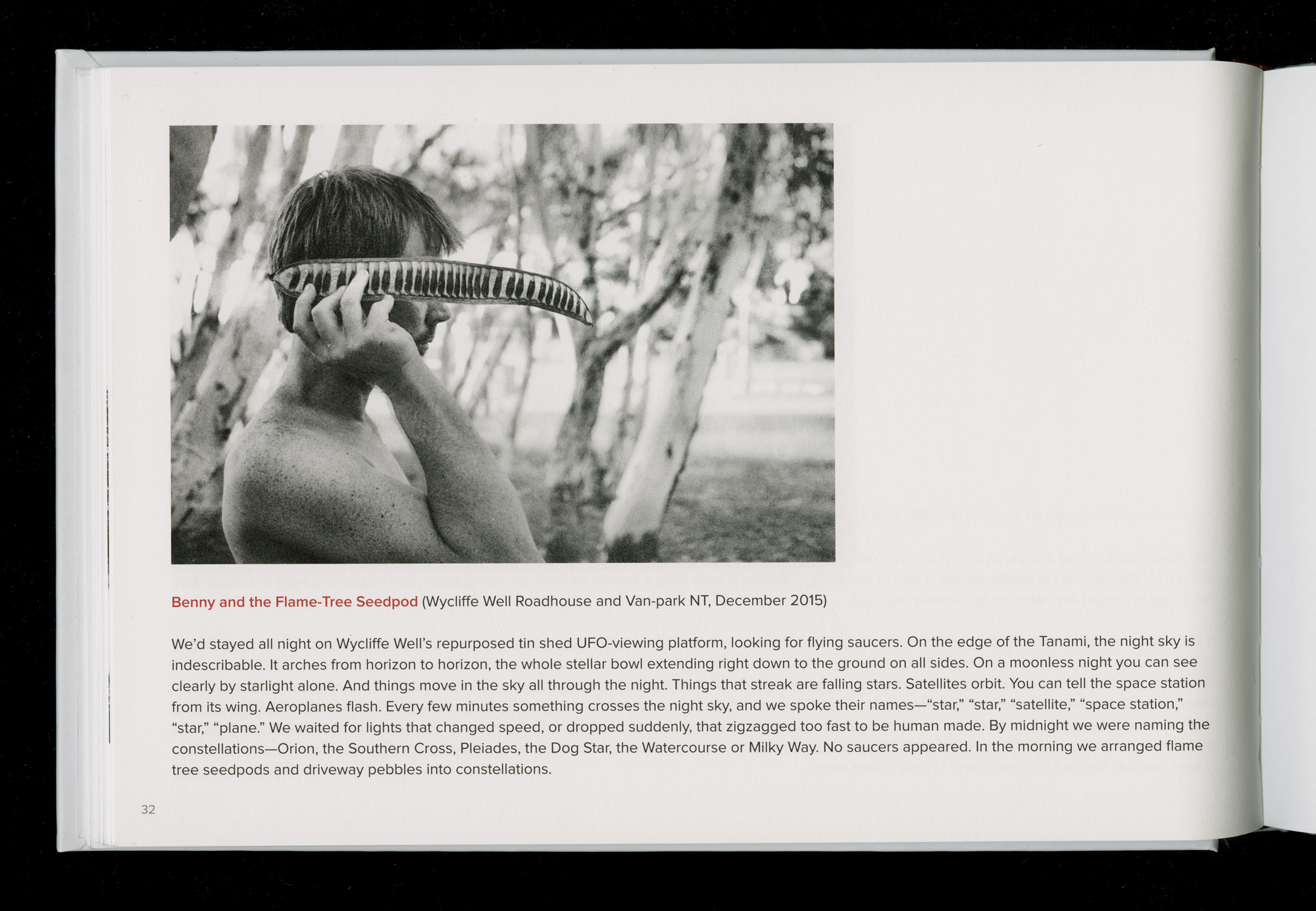

![Judith Crispin (Australian / Bpangerang, b. 1970) 'Four Kurdu-kurdu [Kids] with Trampoline' 2015 Judith Crispin (Australian / Bpangerang, b. 1970) 'Four Kurdu-kurdu [Kids] with Trampoline' 2015](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/four-kurdu-kurdu-kids-with-trampoline-web.jpg)

![Judith Crispin (Australian / Bpangerang, b. 1970) 'Wirntali-Jarra [Friends]' 2015 Judith Crispin (Australian / Bpangerang, b. 1970) 'Wirntali-Jarra [Friends]' 2015](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/wirntali-jarra-friends-web.jpg)

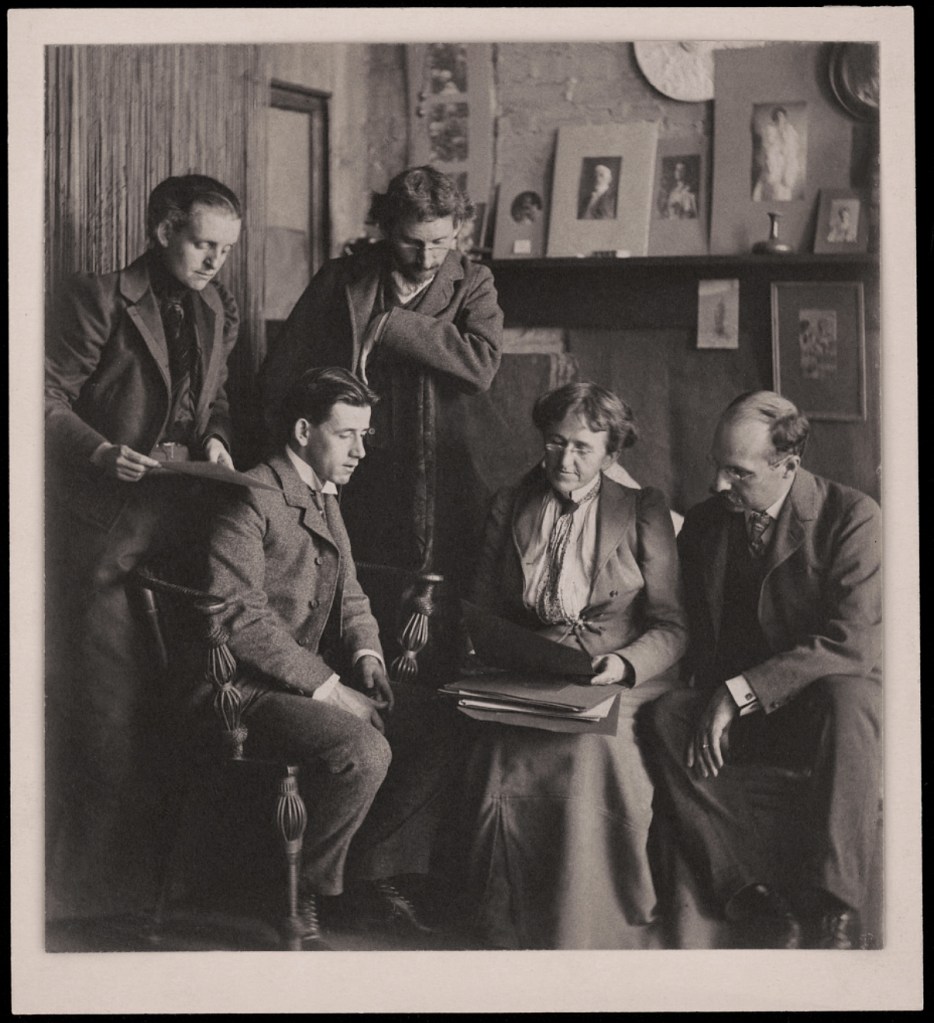

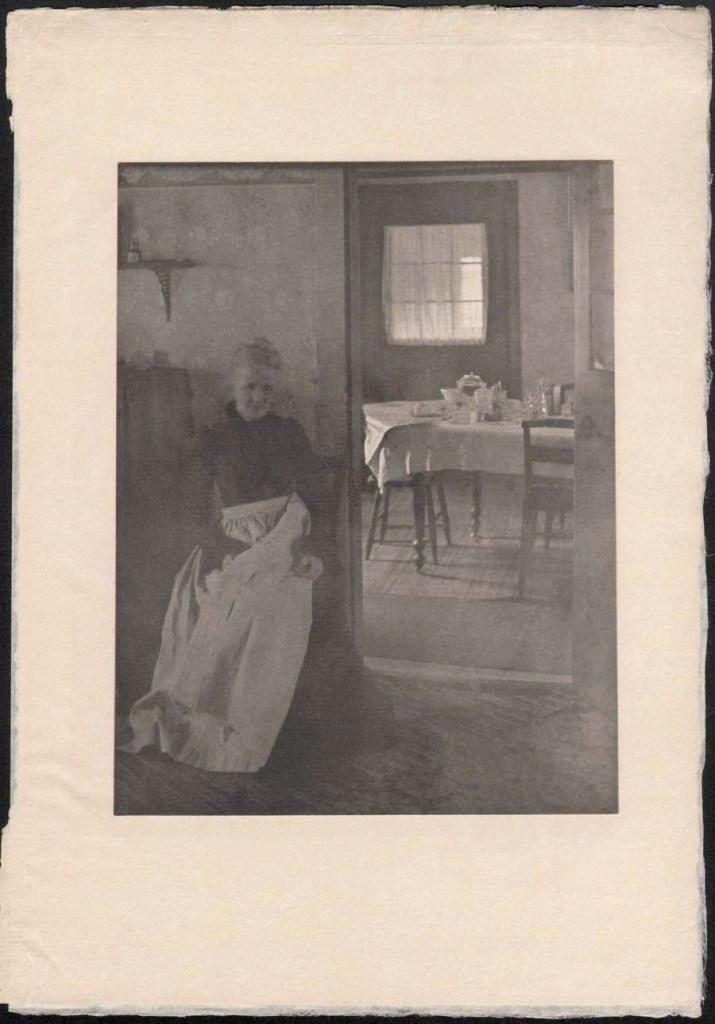

![William Herman Rau (1855-1920) 'Untitled [Clarence H. White works in Second Philadelphia Photographic Salon installation]' 1899 William Herman Rau (1855-1920) 'Untitled [Clarence H. White works in Second Philadelphia Photographic Salon installation]' 1899](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/clarence-h-white-works-in-second-philadelphia-photographic-salon-installation-1899-web.jpg?w=932)

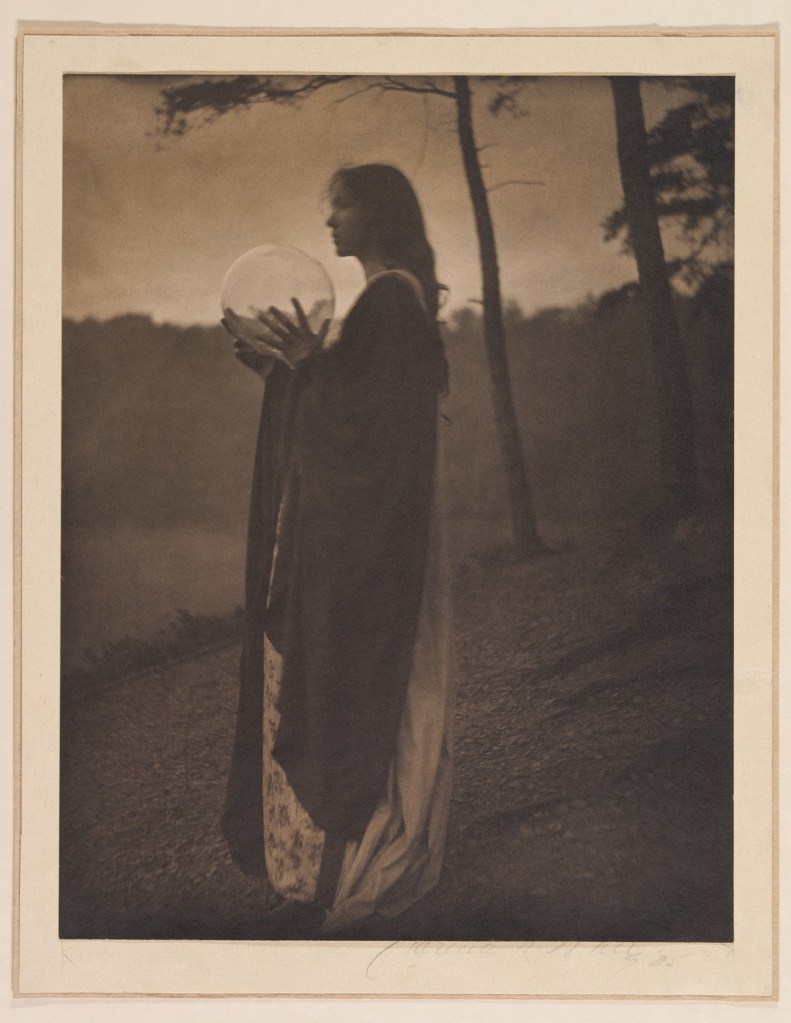

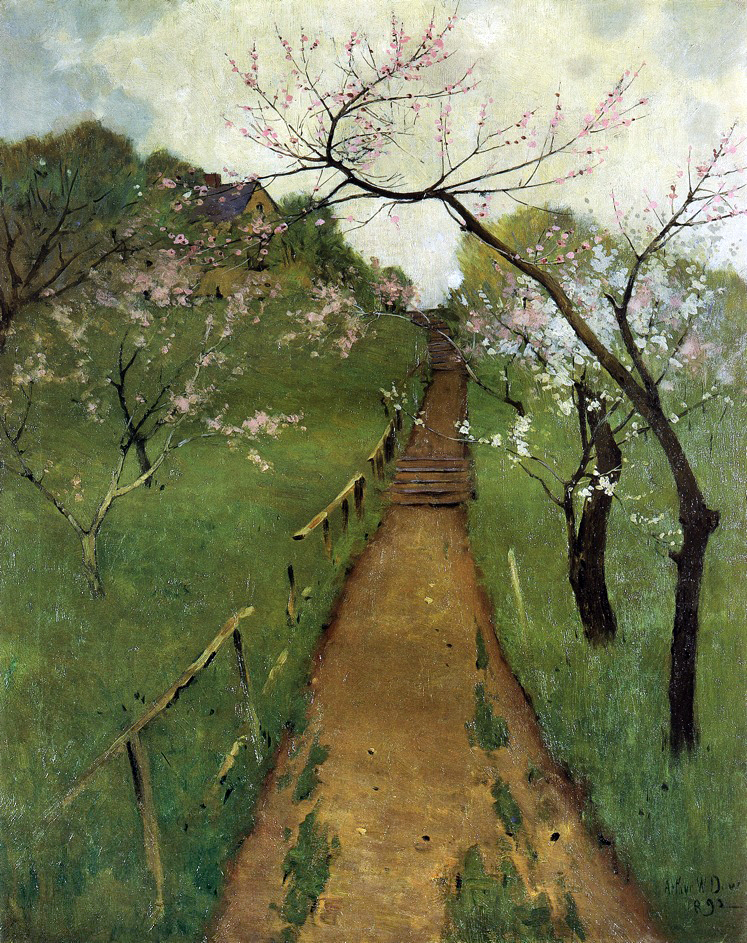

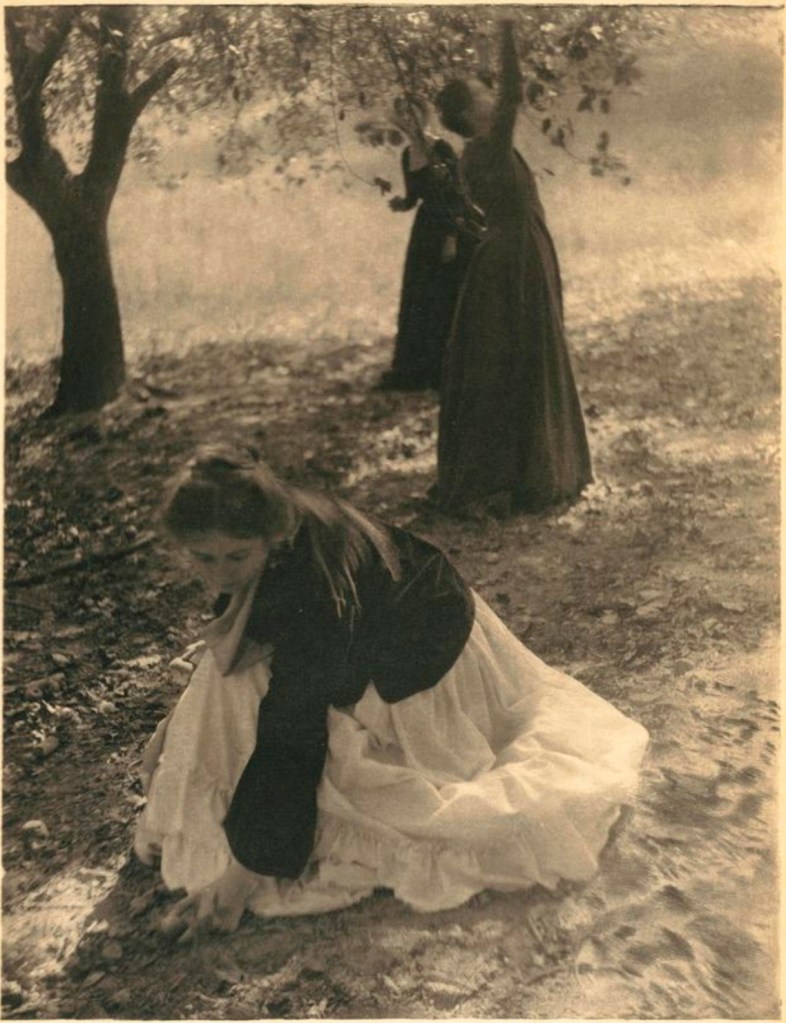

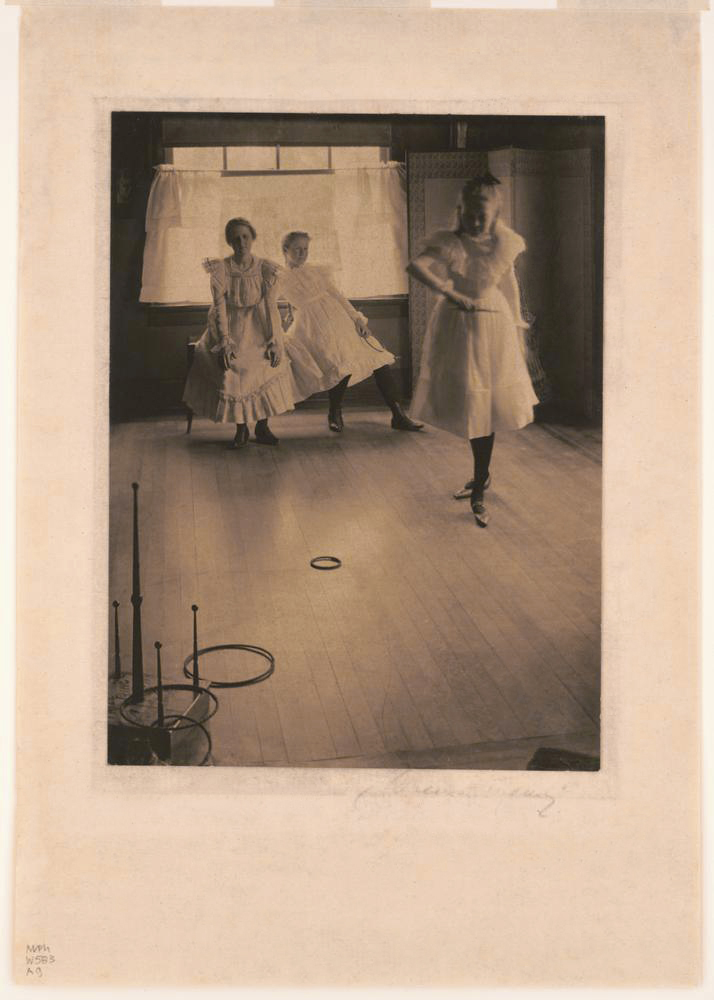

![Clarence H. White (American, 1871-1925) 'Spring - A Triptych [Letitia Felix]' 1898 Clarence H. White (American, 1871-1925) 'Spring - A Triptych [Letitia Felix]' 1898](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/clarence-h-white-spring-web.jpg)

![Clarence H. White (American, 1871-1925) 'Spring - A Triptych [Letitia Felix]' 1898 Clarence H. White (American, 1871-1925) 'Spring - A Triptych [Letitia Felix]' 1898](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/clarence-h-white-spring-a-triptych-1898-web.jpg?w=939)

![Clarence H. White (American, 1871-1925) 'Spring - A Triptych [Letitia Felix]' 1898 Clarence H. White (American, 1871-1925) 'Spring - A Triptych [Letitia Felix]' 1898](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/clarence-h-white-spring-a-triptych-1898-b-web.jpg?w=866)

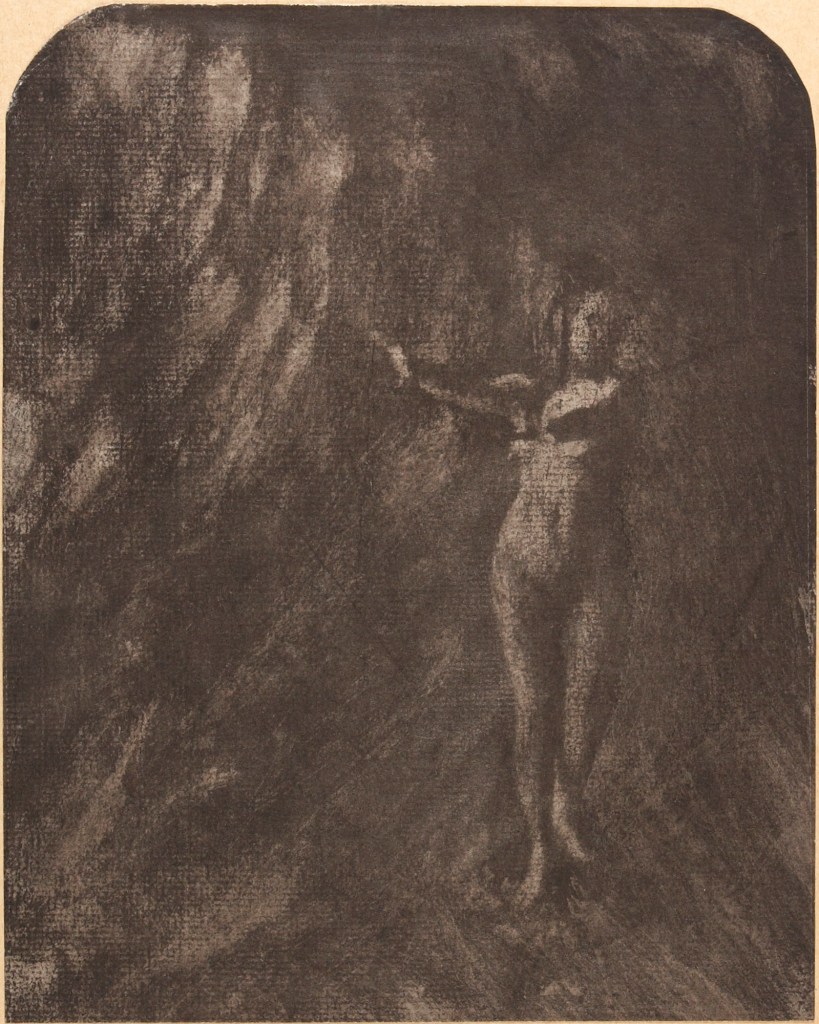

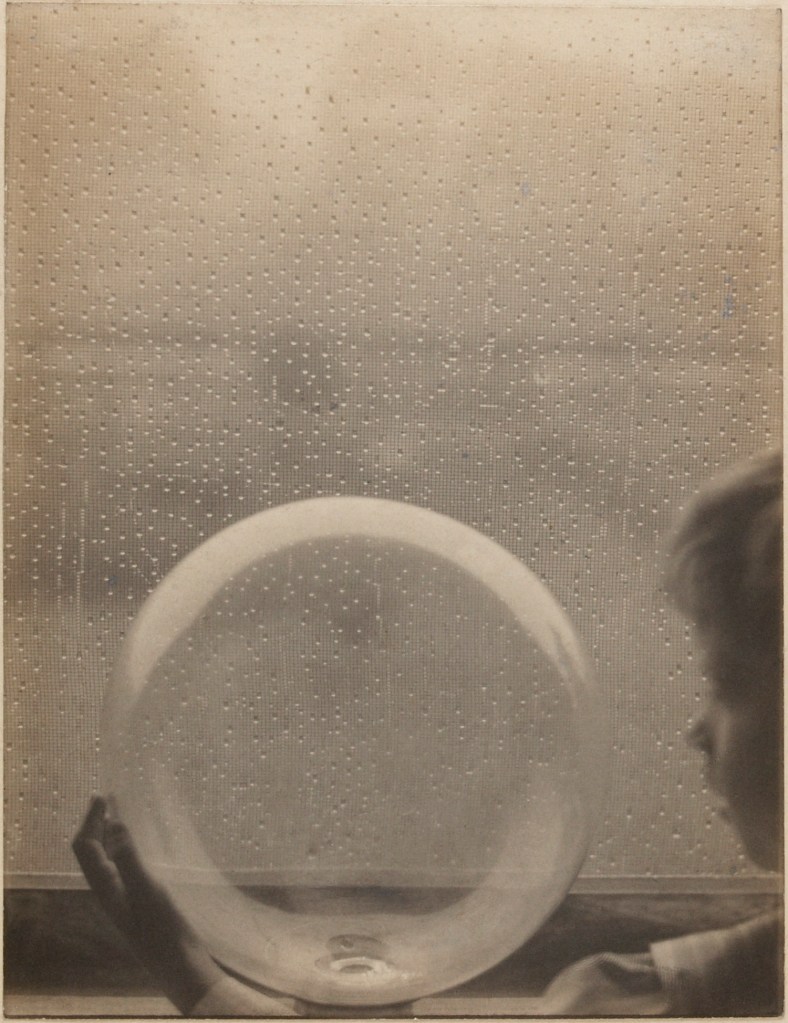

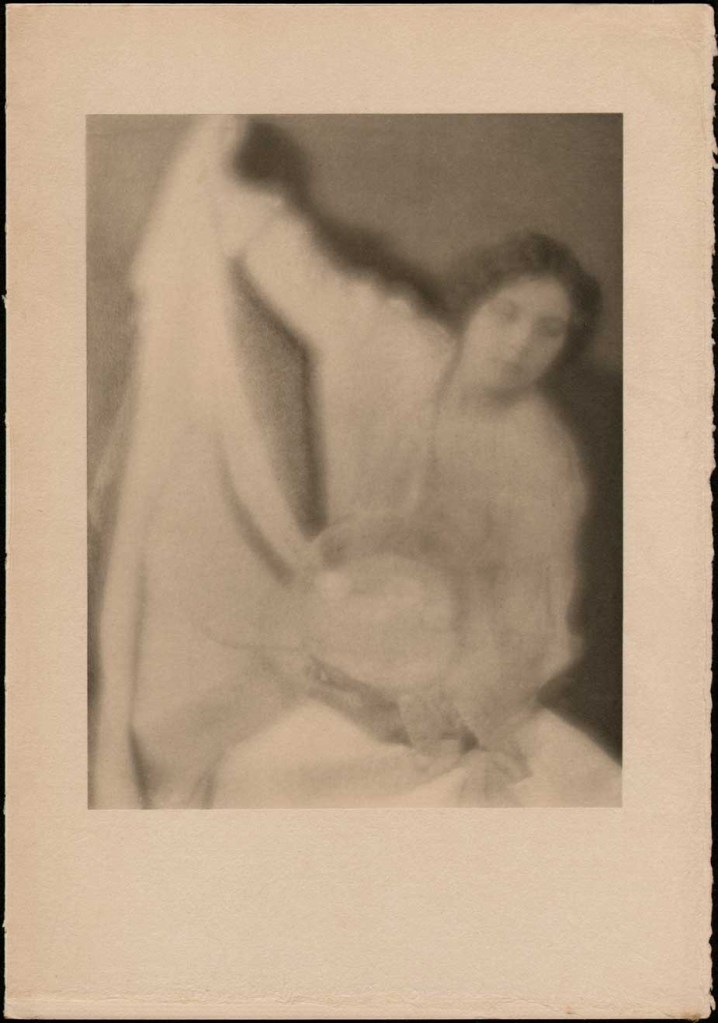

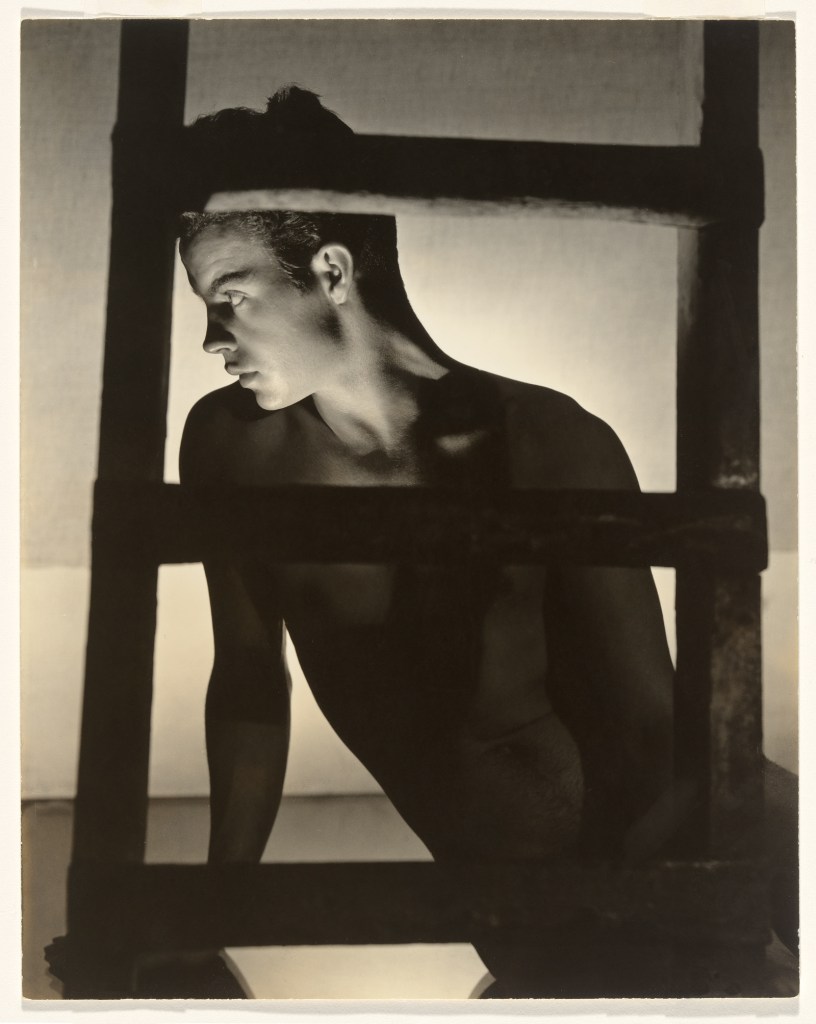

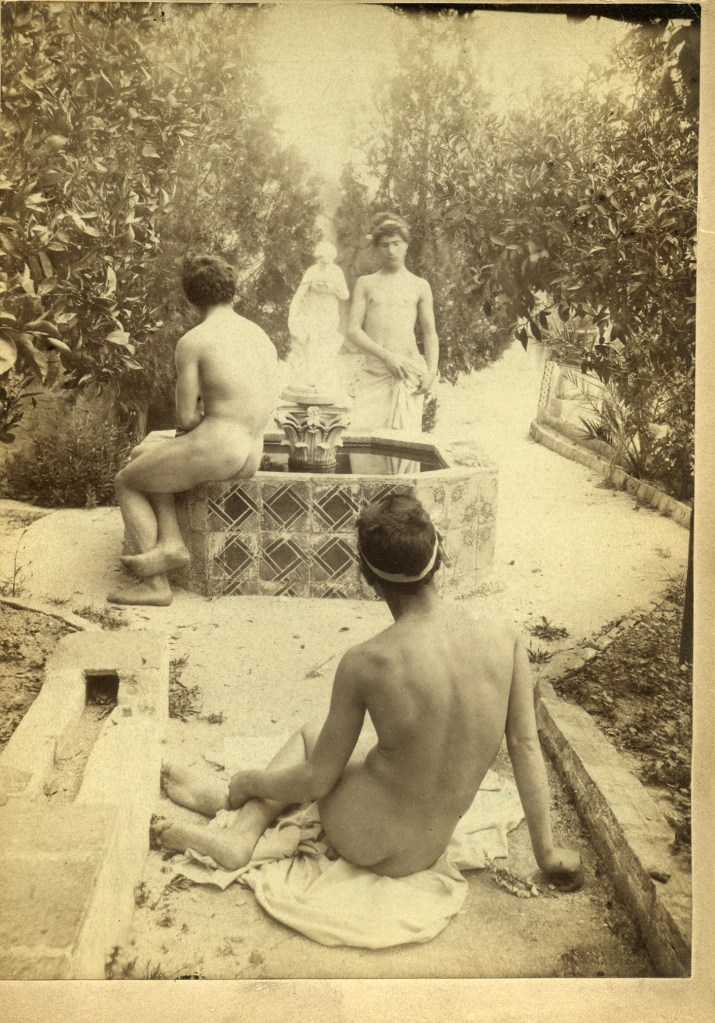

![Clarence H. White (American, 1871-1925) 'Untitled [Male academic nude]' c. 1900 Clarence H. White (American, 1871-1925) 'Untitled [Male academic nude]' c. 1900](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/clarence-h-white-untitled-male-academic-nude-c-1900-web.jpg?w=663)

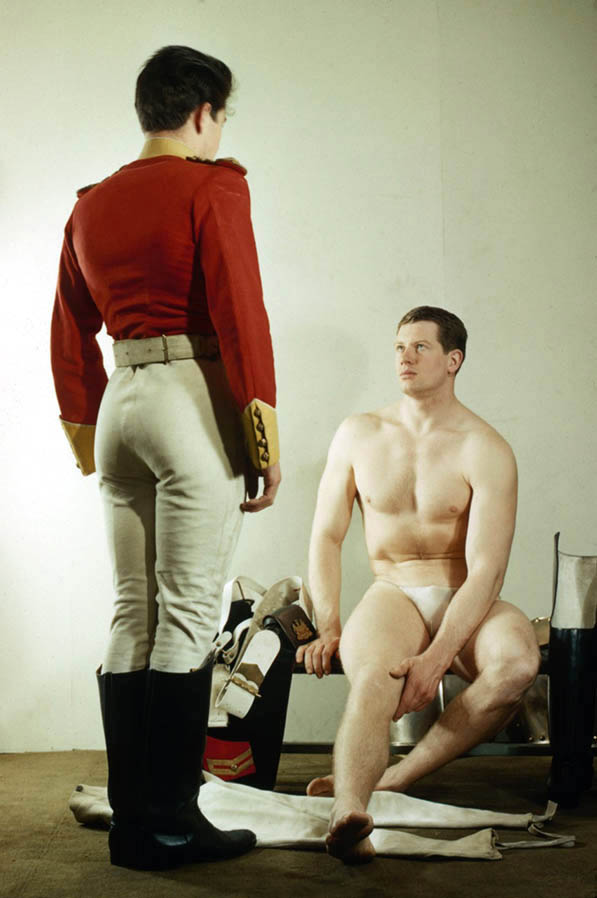

![Clarence H. White (American, 1871-1925) 'Untitled [Portrait of F. Holland Day with Male Nude]' 1902 Clarence H. White (American, 1871-1925) 'Untitled [Portrait of F. Holland Day with Male Nude]' 1902](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/clarence-h-white-portrait-of-f-holland-day-with-male-nude-1902-platinum-print-web.jpg?w=796)

![Clarence H. White (American, 1871-1925) 'Untitled [F. Holland Day lighting a cigarette]' 1902 Clarence H. White (American, 1871-1925) 'Untitled [F. Holland Day lighting a cigarette]' 1902](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/clarence-h-white-untitled-f-holland-day-lighting-a-cigarette-1902-web.jpg?w=809)

![Clarence H. White (American, 1871-1925) 'The Boy with His Wagon [1/3]' 1898 Clarence H. White (American, 1871-1925) 'The Boy with His Wagon [1/3]' 1898](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/clarence-h-white-boy-web.jpg?w=891)

![Clarence H. White (1871-1925) 'Untitled [Jean Reynolds in Newark, Ohio]' c. 1905 Clarence H. White (1871-1925) 'Untitled [Jean Reynolds in Newark, Ohio]' c. 1905](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/clarence-h-white-untitled-jean-reynolds-in-newark-ohio-c-1905-web.jpg?w=817)

![Clarence H. White (American, 1871-1925) 'Untitled [Interior of Weiant house, Newark, Ohio]' 1904 Clarence H. White (American, 1871-1925) 'Untitled [Interior of Weiant house, Newark, Ohio]' 1904](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/clarence-h-white-untitled-interior-of-weiant-house-newark-ohio-1904-web.jpg)

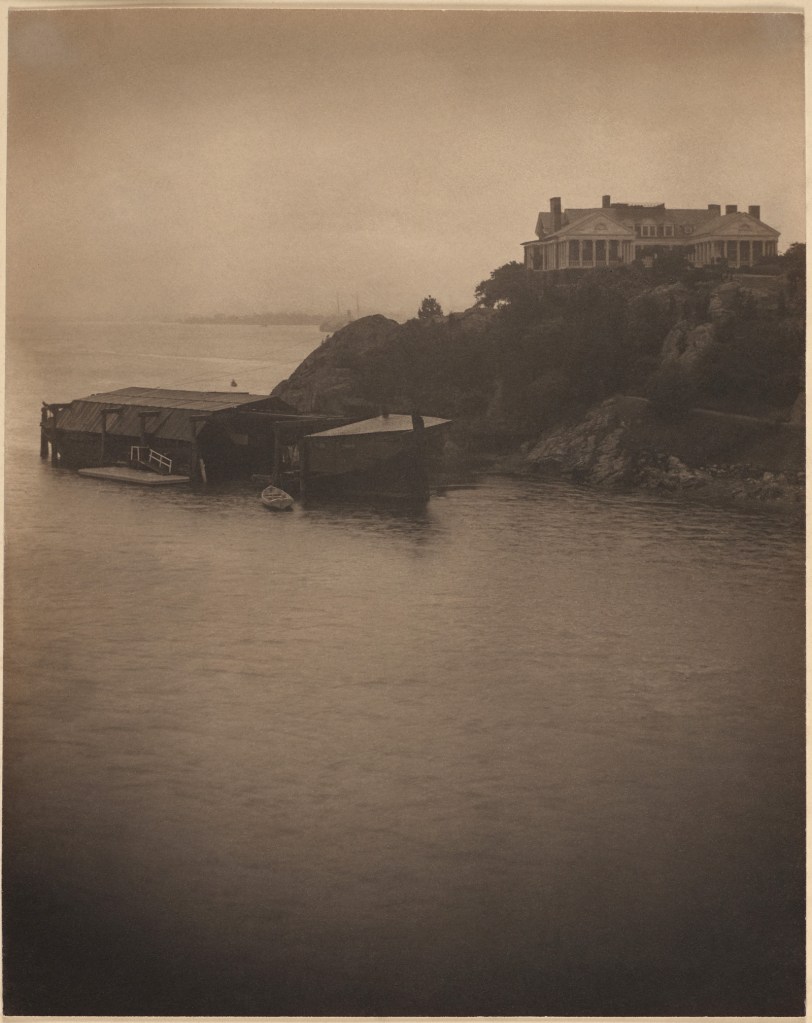

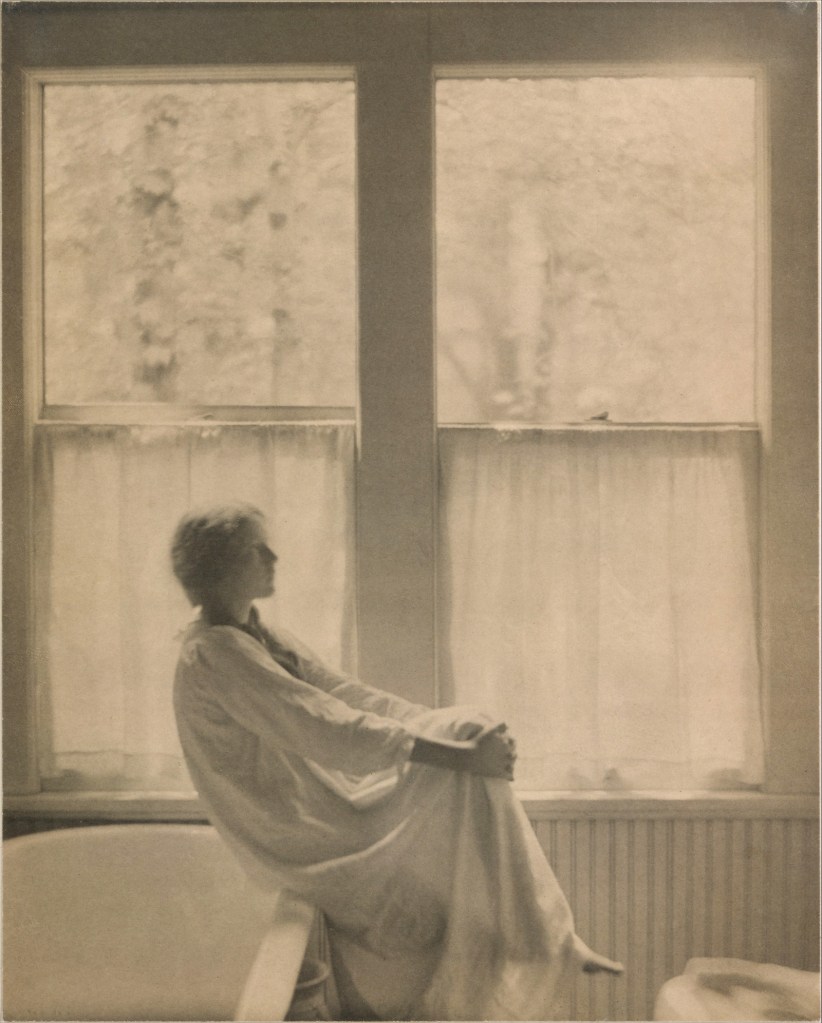

![Clarence H. White (American, 1871-1925) and Paul Burty Haviland (French, 1880-1950) 'Untitled [Florence Peterson]' 1909, printed after 1917 Clarence H. White (American, 1871-1925) and Paul Burty Haviland (French, 1880-1950) 'Untitled [Florence Peterson]' 1909, printed after 1917](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/white-haviland-untitled-florence-peterson-1909-printed-after-1917-web.jpg?w=820)

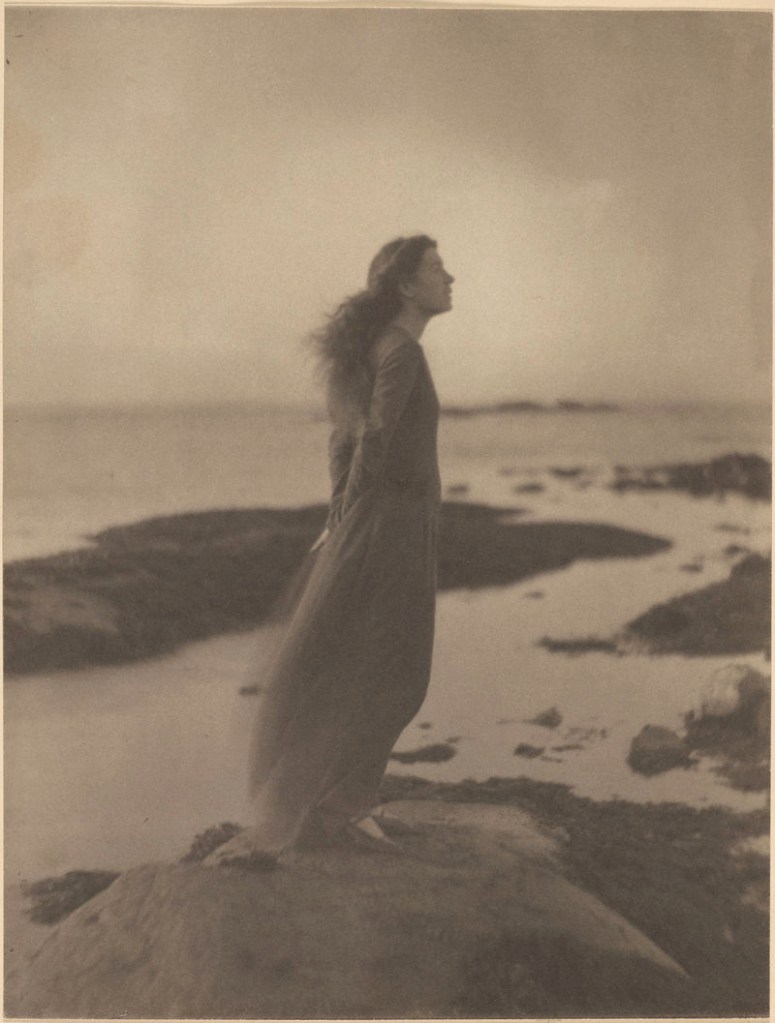

![Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946) and Clarence H. White (American, 1871-1925) 'Untitled [Miss Thompson]' 1907 Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946) and Clarence H. White (American, 1871-1925) 'Untitled [Miss Thompson]' 1907](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/stieglitz-and-white-untitled-miss-thompson-1907-web.jpg?w=794)

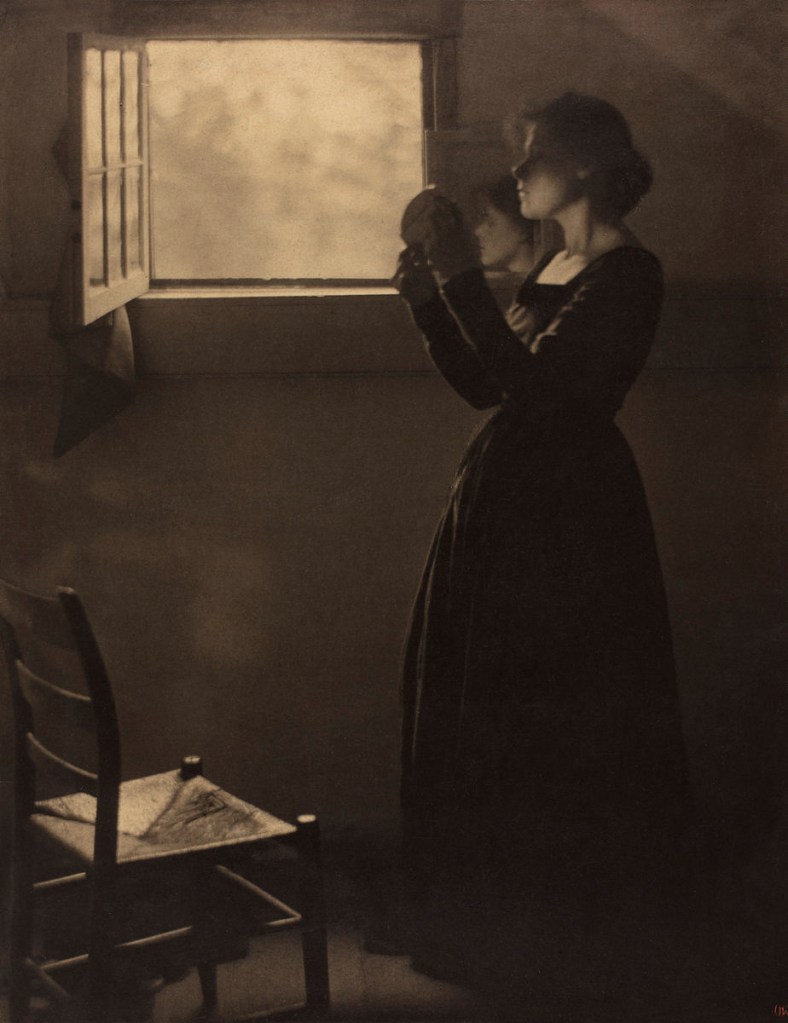

![Clarence H. White (American, 1871-1925) 'Untitled [Florence Peterson]' c. 1909 Clarence H. White (American, 1871-1925) 'Untitled [Florence Peterson]' c. 1909](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/clarence-h-white-untitled-florence-peterson-c-1909-web.jpg?w=754)

![Margaret Watkins (Canadian, 1884-1969) 'Untitled [Kitchen still life]' c. 1919-1920 Margaret Watkins (Canadian, 1884-1969) 'Untitled [Kitchen still life]' c. 1919-1920](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/margaret-watkins-untitled-kitchen-still-life-c-1919-20-web.jpg)

![Clarence H. White (American, 1871-1925) 'Untitled [Dome of the Church of Our Lady of Carmen, San Ángel, Mexico]' 1925 Clarence H. White (American, 1871-1925) 'Untitled [Dome of the Church of Our Lady of Carmen, San Ángel, Mexico]' 1925](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/clarence-h-white-dome-of-the-church-of-our-lady-of-carmen-1925-web.jpg?w=803)

![Unknown photographer. 'Untitled [Aboriginal ceremony]' c. 1892 Unknown photographer. 'Untitled [Aboriginal ceremony]' c. 1892](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/a-collection-of-five-photographs-nicholas-caire-and-unknown-photographers-king-billy-maloga-aboriginal-native-group-aboriginals-lake-tyers-aborignal-ceremony-d-web.jpg)

![J. W. Lindt. 'Untitled [Two men in rural Victoria]' c. 1880s J. W. Lindt. 'Untitled [Two men in rural Victoria]' c. 1880s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/a-collection-of-18-photographs-depicting-rural-scenes-in-victoria-circa-1880s-men-web.jpg?w=730)

![Unknown photographer. 'Untitled [Australian Aborigines in chains]' Nd Unknown photographer. 'Untitled [Australian Aborigines in chains]' Nd](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/australian-aborigines-c-web.jpg)

![Unknown photographer. 'Untitled [Aboriginal man smoking a pipe]' Nd Unknown photographer. 'Untitled [Aboriginal man smoking a pipe]' Nd](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/artist-unknown-aboriginal-man-smoking-a-pipe-web.jpg?w=627)

![Unknown photographer. 'Untitled [Aboriginal making fire]' Nd Unknown photographer. 'Untitled [Aboriginal making fire]' Nd](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/anonymous-photographer-aboriginal-making-fire-nd-web.jpg?w=637)

![Anonymous photographer. 'Untitled [Aboriginal with spear]' Nd Anonymous photographer. 'Untitled [Aboriginal with spear]' Nd](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/anonymous-photographer-aboriginal-with-spear-nd-web.jpg?w=699)

![Anonymous photographer. 'Untitled [Aboriginal with scars]' Nd Anonymous photographer. 'Untitled [Aboriginal with scars]' Nd](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/anonymous-photographer-aboriginal-with-scars-nd-web.jpg?w=752)

![Anonymous photographer. 'Untitled [Aboriginal group]' Nd Anonymous photographer. 'Untitled [Aboriginal group]' Nd](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/anonymous-photographer-aboriginal-group-nd-web.jpg)

![Anonymous photographer. 'Untitled [Aboriginal family group]' Nd Anonymous photographer. 'Untitled [Aboriginal family group]' Nd](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/anonymous-photographer-aboriginal-family-group-nd-web.jpg?w=781)

![Hermann and Marianne Aubel (authors) Karl Robert Langewiesche (publisher) 'Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time]' 1928 Hermann and Marianne Aubel (authors) Karl Robert Langewiesche (publisher) 'Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time]' 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/book-cover-web.jpg?w=757)

![Elvira (Munich) 'Isadora Duncan' from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 1 Published 1928 Elvira (Munich) 'Isadora Duncan' from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 1 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/isadora-duncan-p1-web11.jpg?w=680)

![Rudolf Jobst (Austrian, 1872-1952) 'Schwestern Wiesenthal [Wiesenthal sisters]' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 4 Published 1928 Rudolf Jobst (Austrian, 1872-1952) 'Schwestern Wiesenthal [Wiesenthal sisters]' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 4 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/schwestern-wiesenthal-p4-web2.jpg?w=1024)

![Hugo Erfurth (German, 1874-1948) 'Schwestern Wiesenthal [Wiesenthal sisters]' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 5 Published 1928 Hugo Erfurth (German, 1874-1948) 'Schwestern Wiesenthal [Wiesenthal sisters]' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 5 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/schwestern-wiesenthal-p5-web2.jpg?w=1024)

![Hugo Erfurth (German, 1874-1948) 'Grete Wiesenthal' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 6 Published 1928 Hugo Erfurth (German, 1874-1948) 'Grete Wiesenthal' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 6 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/grete-wiesenthal-p6-web2.jpg?w=712)

![Rudolf Jobst (Vienna) 'Else Wiesenthal' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 7 Published 1928 Rudolf Jobst (Vienna) 'Else Wiesenthal' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 7 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/else-wiesenthal-p7-web2.jpg?w=739)

![Hanns Holdt (German, 1887-1944) 'Sent M'Ahesa' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 10 Published 1928 Hanns Holdt (German, 1887-1944) 'Sent M'Ahesa' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 10 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/sent-m-ahesa-p10-web1.jpg?w=770)

![Franz Löwy (Austrian, 1883-1949) 'Sent M'Ahesa' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 11 Published 1928 Franz Löwy (Austrian, 1883-1949) 'Sent M'Ahesa' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 11 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/sent-m-ahesa-p11-web1.jpg?w=686)

![Hugo Erfurth (German, 1874-1948) 'Sent M'Ahesa' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 12 Published 1928 Hugo Erfurth (German, 1874-1948) 'Sent M'Ahesa' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 12 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/sent-m-ahesa-p12-web1.jpg?w=739)

![d'Ora (Arthur Benda) (Vienna) 'Sent M'Ahesa' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 13 Published 1928 d'Ora (Arthur Benda) (Vienna) 'Sent M'Ahesa' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 13 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/sent-m-ahesa-p13-web1.jpg?w=456)

![Hugo Erfurth (German, 1874-1948) 'Sent M'Ahesa' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 14 Published 1928 Hugo Erfurth (German, 1874-1948) 'Sent M'Ahesa' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 14 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/sent-m-ahesa-p14-web1.jpg?w=785)

![Hanns Holdt (Munich) 'Sent M'Ahesa' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 15 Published 1928 Hanns Holdt (Munich) 'Sent M'Ahesa' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 15 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/sent-m-ahesa-p15-web1.jpg)

![Hanns Holdt (German, 1887-1944) 'Sent M'Ahesa' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 16 Published 1928 Hanns Holdt (German, 1887-1944) 'Sent M'Ahesa' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 16 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/sent-m-ahesa-p16-web1.jpg?w=701)

![Franz Löwy (Austrian, 1883-1949) 'Sent M'Ahesa' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 17 Published 1928 Franz Löwy (Austrian, 1883-1949) 'Sent M'Ahesa' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 17 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/sent-m-ahesa-p17-web1.jpg?w=656)

![Hanns Holdt (German, 1887-1944) 'Sent M'Ahesa' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 18 Published 1928 Hanns Holdt (German, 1887-1944) 'Sent M'Ahesa' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 18 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/sent-m-ahesa-p18-web1.jpg?w=708)

![Minya Diez-Dührkoop (German, 1873-1929) 'Clotilde von Derp-Sacharoff' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 19 Published 1928 Minya Diez-Dührkoop (German, 1873-1929) 'Clotilde von Derp-Sacharoff' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 19 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/clotilde-von-derp-sacharoff-p19-web1.jpg?w=760)

![Hugo Erfurth (German, 1874-1948) 'Clotilde von Derp-Sacharoff' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 20 Published 1928 Hugo Erfurth (German, 1874-1948) 'Clotilde von Derp-Sacharoff' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 20 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/clotilde-von-derp-sacharoff-p20-web1.jpg?w=769)

![Hugo Erfurth (German, 1874-1948) Clotilde von Derp-Sacharoff c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 21 Published 1928 Hugo Erfurth (German, 1874-1948) Clotilde von Derp-Sacharoff c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 21 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/clotilde-von-derp-sacharoff-p21-web1.jpg?w=691)

![Hugo Erfurth (German, 1874-1948) 'Clotilde von Derp-Sacharoff' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 23 Published 1928 Hugo Erfurth (German, 1874-1948) 'Clotilde von Derp-Sacharoff' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 23 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/clotilde-von-derp-sacharoff-p23-web2.jpg?w=710)

![Hugo Erfurth (German, 1874-1948) 'Clotilde von Derp-Sacharoff' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 26 Published 1928 Hugo Erfurth (German, 1874-1948) 'Clotilde von Derp-Sacharoff' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 26 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/clotilde-von-derp-sacharoff-p26-web2.jpg?w=710)

![Atelier Veritas (Munich) (Stephanie Held-Ludwig) (German born Schaulen, Russia now Lithuania, 1871-1943) 'Clotilde von Derp-Sacharoff' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 27 Published 1928 Atelier Veritas (Munich) (Stephanie Held-Ludwig) (German born Schaulen, Russia now Lithuania, 1871-1943) 'Clotilde von Derp-Sacharoff' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 27 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/clotilde-von-derp-sacharoff-p27-web1.jpg?w=659)

!['Nijinski' From the works "The Russian Theater", Amalthea-Verlag, Vienna c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 28 Published 1928 'Nijinski' From the works "The Russian Theater", Amalthea-Verlag, Vienna c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 28 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/nijinski-p28-web1.jpg?w=709)

!['Nijinski' Portrait cards Verlag Leiser, Berlin - Wilmersdorf c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 29 Published 1928 'Nijinski' Portrait cards Verlag Leiser, Berlin - Wilmersdorf c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 29 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/nijinski-p29-web2.jpg?w=714)

![E. O. Hoppé (British, 1878-1972) 'Nijinski' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 30 Published 1928 E. O. Hoppé (British, 1878-1972) 'Nijinski' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 30 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/nijinski-p30-web2.jpg?w=590)

!['Nijinski' From the works "The Russian Theater", Amalthea-Verlag, Vienna c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 31 Published 1928 'Nijinski' From the works "The Russian Theater", Amalthea-Verlag, Vienna c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 31 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/nijinski-p31-web2.jpg?w=710)

!['Nijinski' Portrait cards Verlag Leiser, Berlin - Wilmersdorf c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 32 Published 1928 'Nijinski' Portrait cards Verlag Leiser, Berlin - Wilmersdorf c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 32 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/nijinski-p32-web1.jpg?w=686)

!['Nijinski' From the works "The Russian Theater", Amalthea-Verlag, Vienna c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 33 Published 1928 'Nijinski' From the works "The Russian Theater", Amalthea-Verlag, Vienna c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 33 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/nijinski-p33-web1.jpg?w=800)

!['Nijinski' From the works "The Russian Theater", Amalthea-Verlag, Vienna c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 35 Published 1928 'Nijinski' From the works "The Russian Theater", Amalthea-Verlag, Vienna c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 35 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/nijinski-p35-web2.jpg)

![d'Ora (Arthur Benda) (Vienna) 'Anna Pavlova' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 36 Published 1928 d'Ora (Arthur Benda) (Vienna) 'Anna Pavlova' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 36 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/anna-pavlova-p-36-web1.jpg?w=767)

![Hänse Herrmann (German, 1864-1932) 'Anna Pavlova' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 37 Published 1928 Hänse Herrmann (German, 1864-1932) 'Anna Pavlova' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 37 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/anna-pavlova-p-37-web1.jpg?w=737)

![Hänse Herrmann (German, 1864-1932) 'Anna Pavlova' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 38 Published 1928 Hänse Herrmann (German, 1864-1932) 'Anna Pavlova' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 38 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/anna-pavlova-p-38-web1.jpg?w=780)

![Hänse Herrmann (German, 1864-1932) 'Anna Pavlova' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 39 Published 1928 Hänse Herrmann (German, 1864-1932) 'Anna Pavlova' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 39 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/anna-pavlova-p-39-web1.jpg?w=750)

![Hänse Herrmann (German, 1864-1932) 'Anna Pavlova' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 40 Published 1928 Hänse Herrmann (German, 1864-1932) 'Anna Pavlova' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 40 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/anna-pavlova-p-40-web3.jpg?w=728)

![Hänse Herrmann (German, 1864-1932) 'Anna Pavlova' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 41 Published 1928 Hänse Herrmann (German, 1864-1932) 'Anna Pavlova' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 41 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/anna-pavlova-p-41-web3.jpg?w=801)

![Hänse Herrmann (German, 1864-1932) 'Anna Pavlova' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 42 Published 1928 Hänse Herrmann (German, 1864-1932) 'Anna Pavlova' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 42 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/anna-pavlova-p-42-web1.jpg?w=689)

![Hänse Herrmann (German, 1864-1932) 'Anna Pavlova' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 43 Published 1928 Hänse Herrmann (German, 1864-1932) 'Anna Pavlova' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 43 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/anna-pavlova-p-43-web2.jpg?w=793)

![Ernst Schneider (German, 1881-1959) 'Anna Pavlova' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 44 Published 1928 Ernst Schneider (German, 1881-1959) 'Anna Pavlova' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 44 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/anna-pavlova-p-44-web1.jpg?w=687)

![E. O. Hoppé (British, 1878-1972) 'Anna Pavlova' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 45 Published 1928 E. O. Hoppé (British, 1878-1972) 'Anna Pavlova' c. 1928 from Der Kunstlerische Tanz Unserer Zeit [The Artistic Dance of Our Time] p. 45 Published 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/anna-pavlova-p-45-web1.jpg?w=730)

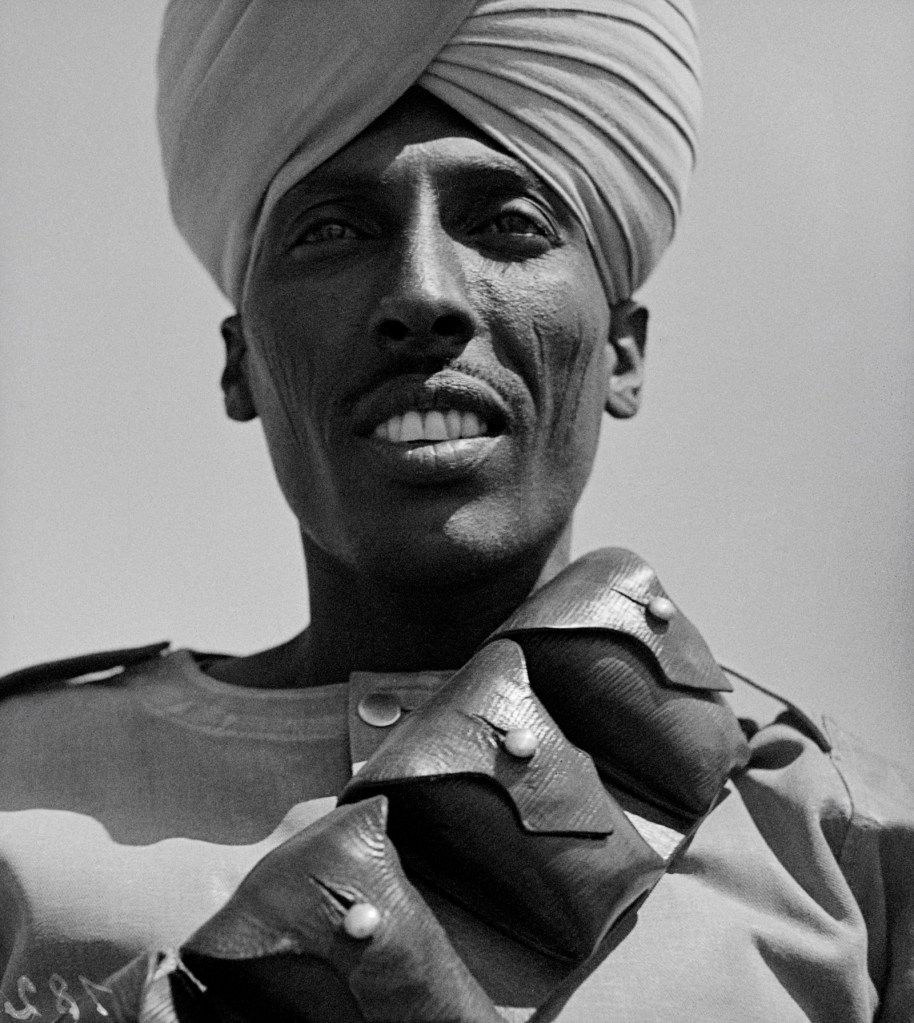

![Walter Mittelholzer (Swiss, 1894-1937) 'Wilde Schlussszene des Opfertanzes [Wild final scene of the sacrificial dance]' 1926-1927 Walter Mittelholzer (Swiss, 1894-1937) 'Wilde Schlussszene des Opfertanzes [Wild final scene of the sacrificial dance]' 1926-1927](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/lbs_mh02-03-0084-a-web.jpg)

![Walter Mittelholzer (Swiss, 1894-1937) 'Fremdenverkehr vor der Sphinx [Tourism in front of the Sphinx]' 1929 Walter Mittelholzer (Swiss, 1894-1937) 'Fremdenverkehr vor der Sphinx [Tourism in front of the Sphinx]' 1929](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/lbs_mh02-07-0161-web.jpg)

![Walter Mittelholzer (Swiss, 1894-1937) 'Itu-Mann vom Südosten Abessiniens [Itu man from southeastern Abyssinia]' c. 1934 Walter Mittelholzer (Swiss, 1894-1937) 'Itu-Mann vom Südosten Abessiniens [Itu man from southeastern Abyssinia]' c. 1934](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/lbs_mh02-22-0756-web.jpg?w=971)

![Walter Mittelholzer (Swiss, 1894-1937) 'Dankali-Mädchen [Dankali girl]' c. 1934 Walter Mittelholzer (Swiss, 1894-1937) 'Dankali-Mädchen [Dankali girl]' c. 1934](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/lbs_mh02-22-0775-web.jpg?w=969)

![Walter Mittelholzer (Swiss, 1894-1937) 'Flugplatz in Addis Abeba [Airfield in Addis Ababa]' c. 1934 Walter Mittelholzer (Swiss, 1894-1937) 'Flugplatz in Addis Abeba [Airfield in Addis Ababa]' c. 1934](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/lbs_mh02-22-0778-web.jpg?w=966)

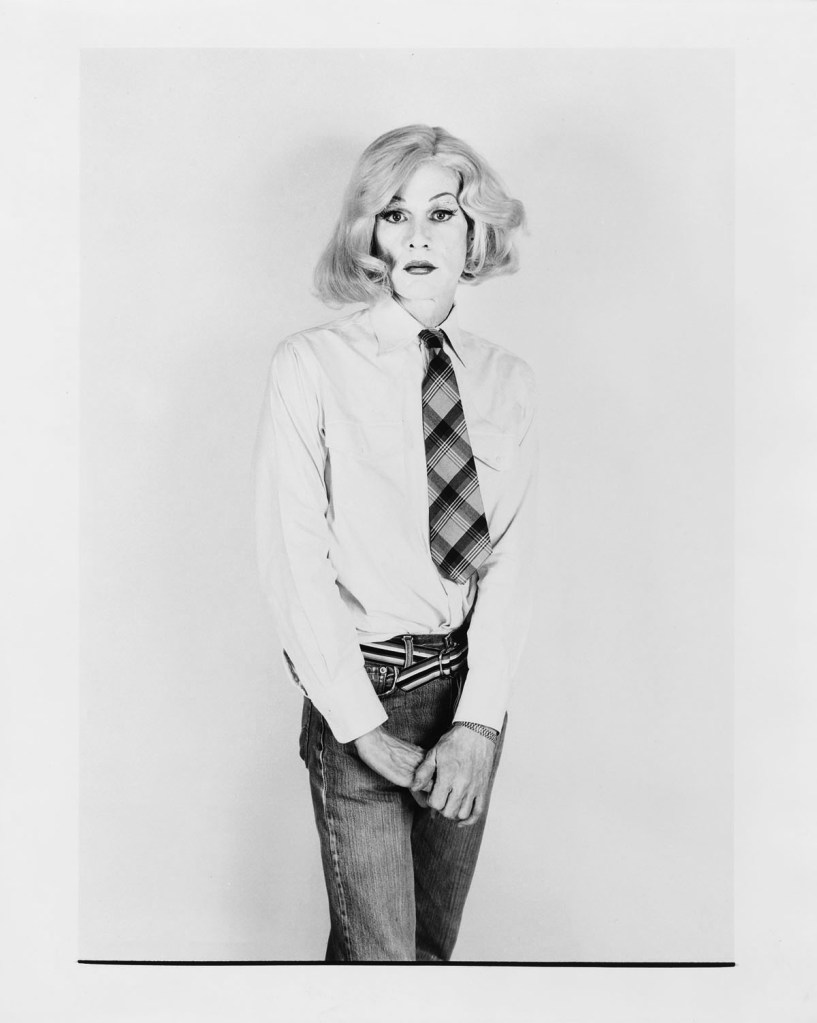

![Peter Elfes (Australia, b. 1961) 'Brenton [Heath-Kerr] as Tom of Finland' 1992 Peter Elfes (Australia, b. 1961) 'Brenton [Heath-Kerr] as Tom of Finland' 1992](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/elfes-brenton-heath-kerr-web.jpg?w=686)

![Unknown photographer. 'Untitled [Auschwitz victim]' N Unknown photographer. 'Untitled [Auschwitz victim]' Nd](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/unknown-photographer-untitled-auschwitz-victim-nd-web.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.