November 2022

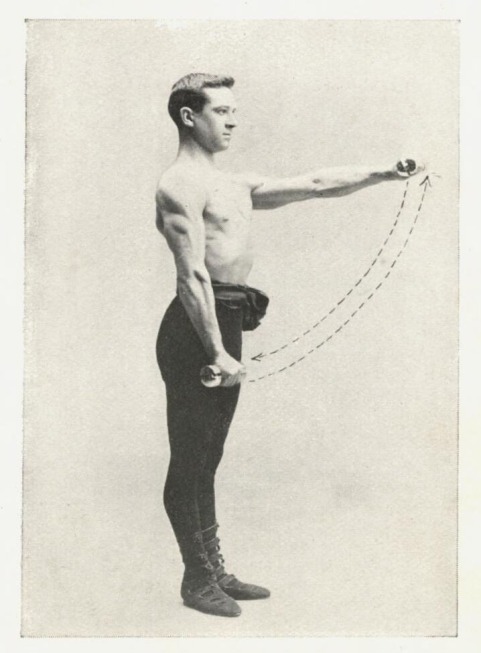

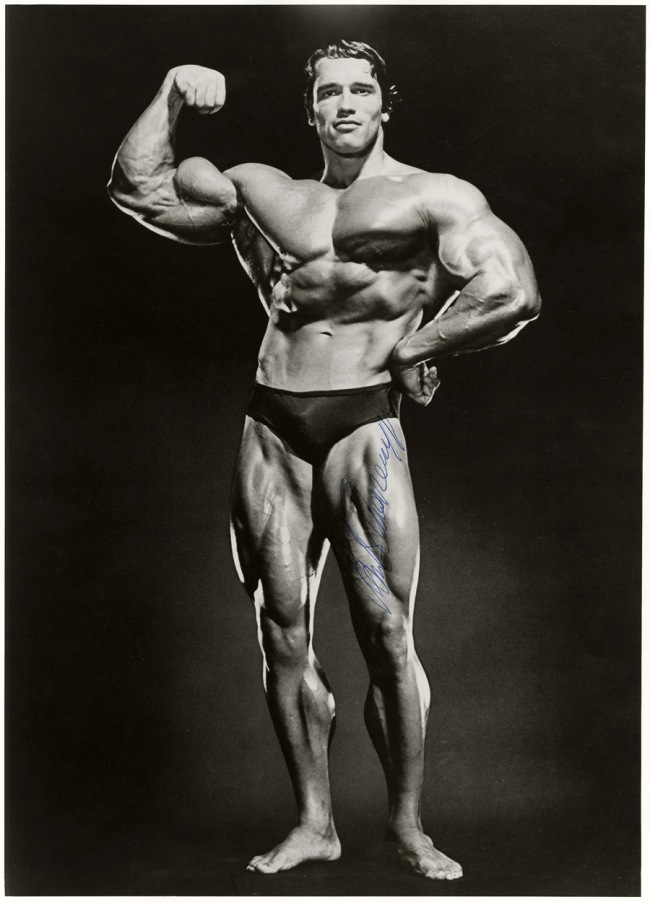

Eugen Sandow (German, 1867-1925)

Instructions for the use of Sandow’s spring grip dumb-bells (detail)

Between 1900 and 1909

(23 pages): illustrations; 18 cm

National Library of Australia, Canberra viewed 10 November 2022

Since the demise of my old website, my PhD research Pressing the Flesh: Sex, Body Image and the Gay Male (RMIT University, Melbourne, 2001) has no longer been available online.

I have now republished the second of twelve chapters, “Bench Press”, so that it is available to read. More chapters will be added as I get time. I hope the text is of some interest. Other chapters include Historical Pressings which examines the history of photographic images of the male body, including the male body as desired by gay men, and the portrayal in photography of the gay male body; In Press which investigates the photographic representation of the muscular male body in the (sometimes gay) media and gay male pornography; and Re-pressentation which alternative investigates ways of imag(in)ing the male body and the issues surrounding the re-pressentation of different body images for gay men.

Dr Marcus Bunyan November 2022

“Bench Press” chapter from Marcus Bunyan’s PhD research Pressing the Flesh: Sex, Body Image and the Gay Male RMIT University, Melbourne, 2001

Through plain language English (not academic speak) the text of this chapter investigates the development of gym culture, its ‘masculinity’1, ‘lifestyle’, and the images used to represent it. The text also examines the positive and negative effects of this culture on the individual and collective lives and bodies of gay men.

NB. This chapter should be read in conjunction with the Historical Pressings and Re-Pressentation chapters for a fuller overview of the development of the muscular male body. This chapter also contains descriptions of sexual activity.

Keywords

The Cult of Muscularity, male bodies, queer bodies, bodybuilding, gym culture, masculinity, images of masculinity, development of gym culture, gay men and gym culture, muscular mesomorph, gay lifestyle, self-esteem, body-esteem, Polite Porn, phallic armoured body, desire, HIV/AIDS, photography and the body, before/after photographs, gay desire

Sections

1/ The Cult of Muscularity

2/ The Body and the Social Environment

3/ Science, Photography and the Body

4/ Before / after photographs

5/ Power and the Muscular Body

6/ The Phallic Armoured Body

7/ Muscle Gods, Hot Jocks, and Gay Desire

8/ The Muscular Male Body: Positive and Negative Effects

Word count 7,036

Bench Press

The Cult of Muscularity

“… muscularity is a key term in appraising men’s bodies … this comes from men themselves. Muscularity is the sign of power – natural, achieved, phallic.”

Richard Dyer 2

Eugen Sandow (German, 1867-1925)

Instructions for the use of Sandow’s spring grip dumb-bells (detail)

Between 1900 and 1909

(23 pages): illustrations; 18 cm

National Library of Australia, Canberra viewed 10 November 2022

‘The Cult of Muscularity’ was formed in the last decade of the 19th century and the early decades of the 20th century in a reaction to the perceived effeminisation of heterosexual masculinity. Sporting and war heroes became national icons. Muscle proved the ‘masculinity’ of men, fit for power, fit to dominate women and less powerful men. The ‘ideal’ of the perfect masculine body can be linked to a concern for the position and power of men in an industrialised world.3

The position of the active, heroic hetero-male was under attack from the passivity of industrialisation, from the expansion of women’s rights and their ability to become breadwinners, and through the naming of deviant sexualities that were seen as a threat to the stability of society. By naming deviant sexualities they became visible to the general public for the fist time, creating apprehension in the minds of men gazing upon the bodies of other men lest they be thought of as ‘pansies’. (Remember that it was in this decade the trials of Oscar Wilde had taken place in England after he was accused of being a sodomite by The Marquis of Queensbury. It is perhaps no coincidence that the rules that governed boxing, a very masculine sport in which a man could become a popular hero, were named after his accuser. By all accounts he was a brute of a man who despised and beat his son Lord Alfred Douglas and sought revenge on his partner, Oscar Wilde, for their sexual adventures).

Muscles became the sign of heterosexual power, prowess, and virility. A man had control over his body and his physical world. His appearance affected how he interacted with this world, how he saw himself, and was seen by others, and how closely he matched the male physical ‘ideal’ impacted on his own levels of self-esteem. The gymnasium became a meeting point for exercise, for health, for male bonding, and to show off your undoubted ‘masculinity’.

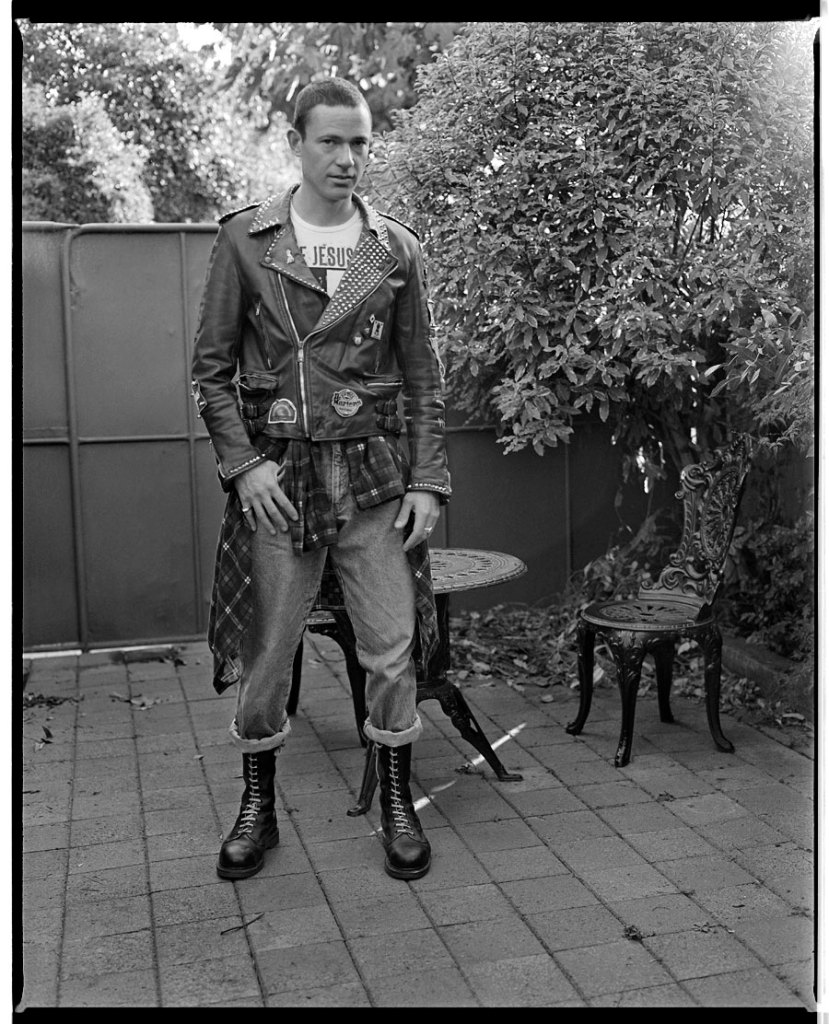

Anonymous photographer

Untitled [Gym group possibly German/Prussian]

c. 1890-1910

Silver gelatin photograph

Courtesy: Marcus Bunyan

Ultimately, going to the gym has more to do with fitting a certain ‘ideal’ image of ‘masculinity’, that of the muscular mesomorph, than it has to do with getting fit. Aerobic activity such as swimming or running are much more effective ways of getting fit. But what gym work does much better than aerobic activity is that it builds muscle mass. And for a man that wants to be recognised for his physical presence, having more muscle is the epitome of the ‘ideal’.

In a patriarchal society, in other words in a society where men have power over women and other men, to have a masculine body was / is seen as the opposite of being feminine or gay – it emphasises the difference between the position of men and women / gays in society. They are seen as inferior whilst a mesomorphic body confirms ‘real’ men in positions of power over others. No wonder homosexuals found muscular working class men (‘rough trade’) so enticing a sexual fantasy in the early part of this century, and still do to this day.

Still, in being named by the majority limp-wristed ‘nancies’ and by accepting that label now historically ourselves, we forget that not all gay men were pansies with effeminate mannerisms, even in those times.

In contemporary society the division between straight and gay ‘masculine’ bodies has diminished. At dance parties it is now difficult to tell which is the gay body and which is the straight. In seeking acceptance and assimilation into the general society gay men have moulded their bodies on the ‘ideal’ of the muscular mesomorphic model. Both gay and straight men are likely to be striving after the same muscular mesomorphic ideal so much so that they may both become homogenised into a non-feminine, paradoxical asexual masculinity, where very little sexuality exudes from any-body at all!

Siegmund Klein – Strength & Health (March 1933) Vol. 1 No. 4

The Body and the Social Environment

The development of ‘The Cult of Muscularity’ may also have parallels in other social environments which were evolving at the turn of the century. For example, I think that the construction of the muscular mesomorphic body can be linked to the appearance of the first skyscrapers in cities in the United States of America. Skyscrapers were a way increasing visibility and surface area within the limited space of a crowded city. One of the benefits of owning a skyscraper like the Chrysler Building in New York, with its increased surface area, was that it got the company noticed. The same can be said of the muscular body. Living and interacting in the city, the body itself is inscribed by social interaction with its environment, its systems of regulation and its memories and historicities (his-tor-i-city, ‘tor’ being a large hill or formation of rocks).

Like a skyscraper, the muscular body has more surface area, is more visible, attracts more attention to its owner and is more admired. The owner of this body is desired because of his external appearance which may give him a feeling of superiority and power over others. However, this body image may also lead to low self-esteem and heightened body dissatisfaction in the owner (causing anxiety and insecurity in his identity) as he constantly strives to maintain and enhance his body to fulfil expectations he has of himself.

Of course, body image is never a static concept as the power of muscular images of the male body resides in their perceived value as a commodity. This value is re-enforced through social moral values, through fluid personal interactions, and through the desire of self and others for this type of body image; it is a hierarchical system of valuation. It relies on what type of body is seen as socially desirable and ‘beautiful’ in a collective sense, even though physical attractiveness is very much a personal choice.

In the four photographs from the 1930s (below) we can see a range of ethnic men portrayed, all seeking the attainment of what was, for them, the perfection of the muscular human form. Indian, Chinese, Black American and Phillipino are all represented. Compare this to today’s cast of body types from a gay muscle fitness video (soft core pornography video aimed squarely at the gay market) and you can see how the broad inclusion of different ethnic types has been tailored to the demographics of its particular buying public (‘masculine’ white gay male).

Today what is desirable in a masculine body seems to be even more limited in its stereotyping than was the case in the 1930s. Then, at least, there was a diversified range of ethnicity. Now, within the ‘lifestyle’ health and fitness magazines, the paradigm for the desirable male body is predominantly the tanned, toned, muscular white male. Thankfully, professional buff, body-builders do still come in all colours!

Anonymous photographer

Anselus T. Del Rosario

c. 1930

in Berry, Mark. Physical Improvement. Vol. II. Philadelphia: Milo Publishing Company, 1930, p. 78

Courtesy: Marcus Bunyan

“There is something unusual about the back of this young Phillipino, Anselus T. Del Rosario. The pose is rather original and offers suggestion to others.”

(left to right)

Anonymous photographer

Cheah Chin Poh

c. 1930

in Berry, Mark. Physical Improvement. Vol. II. Philadelphia: Milo Publishing Company, 1930, p. 261

Courtesy: Marcus Bunyan

Anonymous photographer

Prof. C. C. Shah

c. 1930

in Berry, Mark. Physical Improvement. Vol. II. Philadelphia: Milo Publishing Company, 1930, p. 261

Courtesy: Marcus Bunyan

Anonymous photographer

Wesley Williams

c. 1930

in Berry, Mark. Physical Improvement. Vol. II. Philadelphia: Milo Publishing Company, 1930, p. 154

Courtesy: Marcus Bunyan

Science, Photography and the Body

In the Victorian and Edwardian eras the knowledge of science, such as the science of physical fitness for example, allowed the body to become an object that was subject to technical expertise. Physical fitness was taken up by governments and their armies to enforce standards of fitness for recruits, the medical examination ensuring suitability for service and the fitness regime ensuring that all bodies were interchangeable and replaceable in the event of death on the battlefield. The body became a site of intervention; it became malleable and plastic, subject to the demands of the self and State. This trend continues at an unabated pace today especially within the personal sphere; in the ‘miracles’ of steroid enhancement, plastic surgery, implants and liposuction all there to help you attain the ‘perfect’ body. Now ALL bodies can start to look alike, interchangeable one with another.

Photography, also a relatively new science in that era (photography is both an art and a science), confirmed the ‘truth’ of the power of the muscular body through documentary evidence. The camera acted to legitimise the concerns of men over their body image through relationship of power to the practice of representation. Surveillance of the self became a major factor in the construction of your social identity. Through photographs you could judge for yourself whether you measured up to the ‘ideals’ put forward as valuable by society. Therefore images of muscular mesomorphs can and do affect the self-esteem of individuals through a powerful semiotic system that is embedded in the idealised body factually re-presented in a photograph.

This power is validated because people know the key to interpret the coded ‘sign’ language through which photographs, and indeed all images, speak. In neglecting to acknowledge alternative significations present within this semiotically coded power structure there is the opportunity for one dominant image to be chosen selectively over other types of less ‘valuable’ body images, eventually leading to the possible loss of the key to decode the desirability of ‘other’ body images.

The problem with dominant images that promote the masculinity and power of the muscular mesomorphic body is that they portray one supposed objective truth which is impossible, for there can be can many changing ‘truths’ (viewed from many subjective and objective positions).4 Personally, I believe we should see things not solely as they are from an objective point of view and not purely from an appeal to an “actively struggled for” subjectivity (as argued for by David Smail), but perhaps emerging from a knowledge of the fluid nature of truth, an ever changing combination of many variable truths. Being true to ourselves does not require a one-eyed point of view for we must try to see things from many different points of view to appreciate that there are many shifting, non-final subjective, objective and variable ‘truths’ in life.

Images can be a fabrication just as easily as they are supposed to speak the language of an objective ‘truth’. For example, in the 1870s Dr. Barnardo had photographs taken that showed rough, dirty, and dishevelled children arriving at his homes, and then paired them with photographs of the same children bright as a new pin, happy and working in the homes afterwards. These photographs were used to sell the story of children saved from poverty and oppression and happy in the homes; they appeared on cards which were sold to raise money to support the work of these homes. Dr. Barnardo was taken to court when one such pair of photographs was found to be a fabrication, an ‘artistic fiction’.5

Photographs can be used not only as a tool of observation but as a commodity, to advertise, support and sell the existence of a regime of power that controls the body, in the case of Dr. Barnardo the body of the child. In this way the body of the child becomes a commodity too.

Before / after photographs

Anonymous photographer

M. J. Poncela

c. 1930

in Berry, Mark. Physical Improvement. Vol. II. Philadelphia: Milo Publishing Company, 1930, p. 211

Courtesy: Marcus Bunyan

Anonymous photographer

George Renzi, Jr.

c. 1930

in Berry, Mark. Physical Improvement. Vol. II. Philadelphia: Milo Publishing Company, 1930, p. 210

Courtesy: Marcus Bunyan

Anonymous photographer

Untitled

c. 1952

‘Before photo/after photo, 35 day Johnson bodybuilding program advertisement’, in Rader, Peary (ed.,). Iron Man. Vol. 12. Dec-Feb. 1952, No. 4. Alliance, Nebraska: Iron Man Publishing Co., 1952, pp. 26-27.

Courtesy: Marcus Bunyan

Anonymous photographer

The New Theory of Evolution (Unretouched photographs taken over a period of less than 12 weeks)

1998

Experimental and Applied Sciences advertisement, 1998, in Low, Cheh N. (ed.,). Exercise for Men Only. New York: Chelo Publishing, December 1998, pp. 2-3.

The same process of commodification of the body can be seen in the ‘Before and After’ photographs from the 1930’s. The science of physical fitness has always sold product to go with its ideals and the use of before and after photos echoes those of Dr. Barnardo. Here I am looking at my own weak and puny body and then looking at these photographs and advertisements that are telling me: ‘You can have a bigger, better body in only (substitute x amount of time) days or weeks!’ You can attain the perfect male body. But it will cost you. In time, in money, in sacrifices, perhaps in failure. But you desire that body don’t you, you want that body, you want to belong!

The photographs from the 1930s show examples of bodily improvement over a period of one year, a reasonable amount of time given the improvement shown. As the century progressed however, the claims for products became more outlandish and photography was used to bolster these claims. In the 1952 photographs above for example, the photograph is used to authenticate the models physical improvement in just 35 days! Note, however, that in the second photograph the model is standing closer to the camera than in the first one, he has a tan which makes him look healthier, is oiled up, and his hair is bigger to give him more physical presence. He is also engaging the gaze of the viewer, returning his look, which in itself is a more challenging, defiant act.

Nothing much has changed in advertising claims from the 1950s until today. In the unretouched sequence of photographs (above) from 1998 (for a leading supplier of sports nutritional supplements), we are asked to believe a new, super-fast “Theory of Evolution” exists, all achieved in less than 12 weeks.

I am not suggesting for one minute that these photographs actually lie. But they do restructure the ‘truth’. Firstly, the model does not have an ‘ordinary’ body to start with. You only have to look at the legs and arms in all four photographs to realise that this man is probably a bodybuilder who is out of condition and training. In the first photograph he is stooped, unkempt, unshaven, hairy, flat-footed & slovenly. Much the same as the photographs of children arriving at the Dr. Barnardo’s homes in the 1870s. Funny about that. As the sequence progresses he becomes happier, taller, more ‘pumped’ and ‘cut’ till he positively shines like burnished steel, his muscles glowing as he strides on the balls of his feet into the future. His fists become clenched to emphasise his bulging muscles and his manliness.

Hey, its a ‘lifestyle’ thing. Muscular men look after their bodies, have no moral disorders and are happier and more successful!

(left and right)

Anonymous photographer

Bill Good executing Stretching Exercise course

c. 1930

in Berry, Mark. Physical Improvement. Vol. I. Philadelphia: Milo Publishing Company, 1930, p. 143

Courtesy: Marcus Bunyan

Anonymous photographer

Bill Good executing Free Motion exercises

c. 1930

in Berry, Mark. Physical Improvement. Vol. I. Philadelphia: Milo Publishing Company, 1930, p. 127

Courtesy: Marcus Bunyan

Power and the Muscular Body

Increasingly, the body was not only able to exercise on its way to muscularity it was also able to exercise the ritual semiotic language of the hyper-masculine body as power over the social body in general. A sociology of the body was constructed based on the interaction with history, memory and context. Men sought to transform their body and the social body through the structures and rituals of power, naming deviants such as homosexuals as ‘other’ and therefore reducing them to an inferior status. It is not surprising that homosexual men are attracted to this power. For a long time they have been subject to persecution & derision, and saw themselves as inferior. Now, with the adoption of hyper-masculine bodies as the epitome of gay male image, gay men seek to be ‘real’ men perhaps even more than straight men. Unfortunately this may reinforce traditional patriarchal stereotypes within the gay community, a community that is supposed to pride itself on equality and diversity. The very things that homosexuals have long fought against, oppression and discrimination, may be confirmed in the exercising of power by the muscular ‘ideal’ within the gay community.

In the conformation of the power of the muscular body I suggest that gay men may have adopted a mask to cover their own insecurities in order to seek acceptance for themselves into the gay and general population. This mask has become more than just a facade for some gay men, it has become their reality. The owner of a body that measures up to the ideal may seek acceptance of him- self in the perfection of his own reflection. What he sees in this reflection is, perhaps, not his ‘true’ self but a mask that is put on, a pre-formed surface that reflects the values of the society from which it emanates, perhaps a surface that is only skin deep inscribed by his social enculturation and assimilation. Once put on this mask is very difficult to take off; how many times do we see the words “straight acting” in newspaper advertisements in the gay press describing what is sexually offered and wanted, as though being str8-acting enables our gay masculinity and makes us ‘real’ men? I believe it is no longer an ironic act for gay men to try and fulfil the straight hyper-masculine ideal, not a ‘camp’ ironic comment as it used to be, but a deadly serious endeavour. This has important repercussions for the psyche of all gay men and I discuss these repercussions later in this chapter and also in the (S)ex-press chapter.

As can be seen from the photographs within this text, there has been a development of the complete ‘look’ of the body over the last century. Beautiful muscles compliment a beautiful ‘lifestyle’6 and an equally beautiful tan. Appearance and the power of that appearance is now of the essence. The appearance of this ideal ‘lifestyle’ is available to everyone of us, regardless of social status or age, how rich or poor we are as gay men – yeah, right!

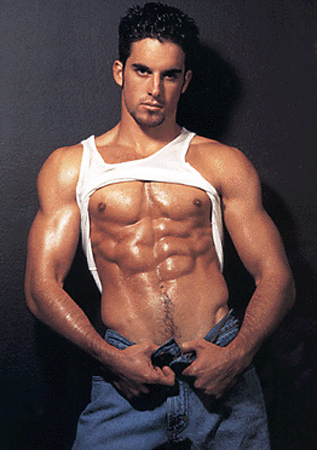

Raymond Vino

Steve Downs

1998

in Low, Cheh N. (ed.,). Exercise for Men Only. New York: Chelo Publishing, December 1998, p. 103.

(top to bottom)

Bob Jones (American)

Short Mens Class

Untitled

Untitled

1952

in Rader, Peary (ed.,). Iron Man. Vol. 12. Dec-Feb. 1952, No. 4. Alliance, Nebraska: Iron Man Publishing Co., 1952, p. 8

Courtesy: Marcus Bunyan

Now aren’t there some good looking men amongst this lot! I wonder how many of them were gay? Not an effeminate man to be seen here, you can bet your life. These are all ‘real’ he-men: strong, masculine and ruggedly virile examples of manhood. There is still a range of ethnicities present in these 1950s photographs, from Brazilians to Afro-Americans & men of Asian origin but there is not a hairy man amongst them. They probably shaved for the event, a very feminine thing for a man to do! These photographs also serve to illustrate another point: that although body shape might be slightly different when compared to each other, overall the bodies seem to form a homogenised whole, forms which seem to have been pressed from the same mould (‘template man’).

We observe the billboards with the fashionable ‘lifestyle’ Calvin Klein underwear ads, featuring some truly amazing bodies. We desire these bodies in all their airbrushed glory, ‘simulations’ of an ideal world where bodies are perfect, not all sorts of shapes and sizes as in the real world.

We lust after the perfect idealisation of the muscular body and the projected power that this ‘ideal’ body image and its lifestyle proposes. This perfection is never obtainable, of course, because we can always have bigger muscles, a better tan, more fashionable clothes, etc. … The ‘ideal’ is like a carrot on a stick, always just beyond our reach, like an ever receding dream.

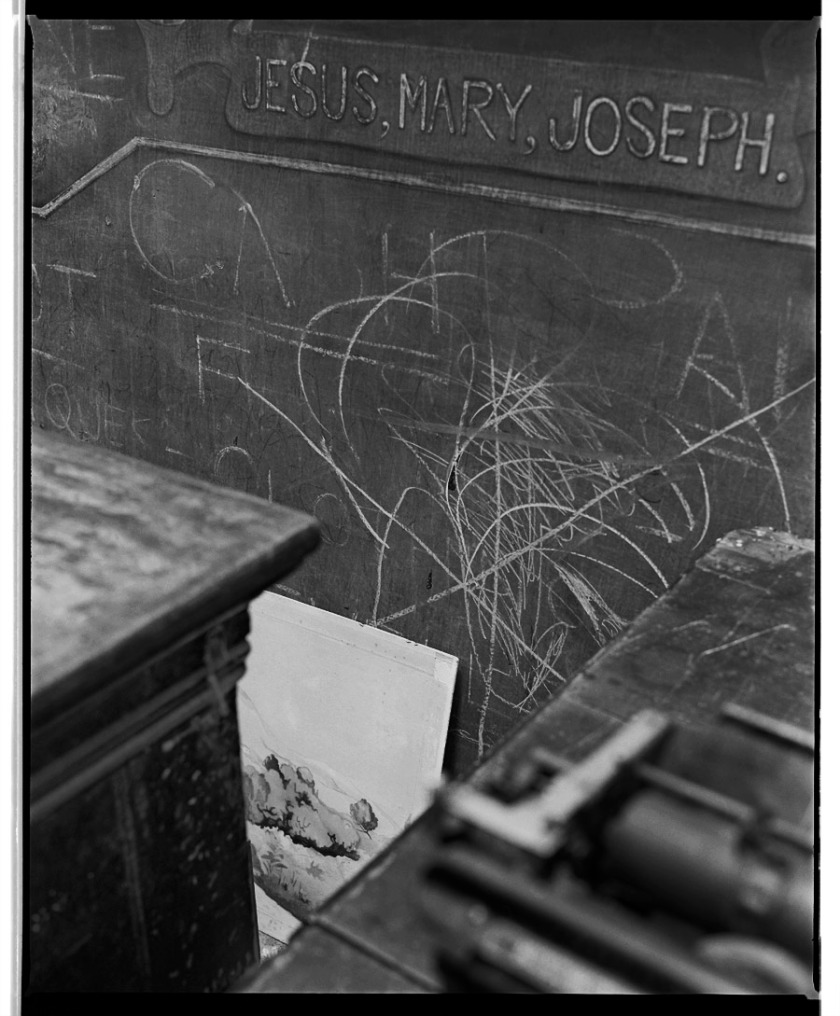

Anonymous

Untitled [Posing straps]

1952

Athletic Model Guild advertisement, in Rader, Peary (ed.,). Iron Man. Vol. 12. Dec-Feb. 1952, No. 4. Alliance, Nebraska: Iron Man Publishing Co., 1952, p. 50.

Courtesy: Marcus Bunyan

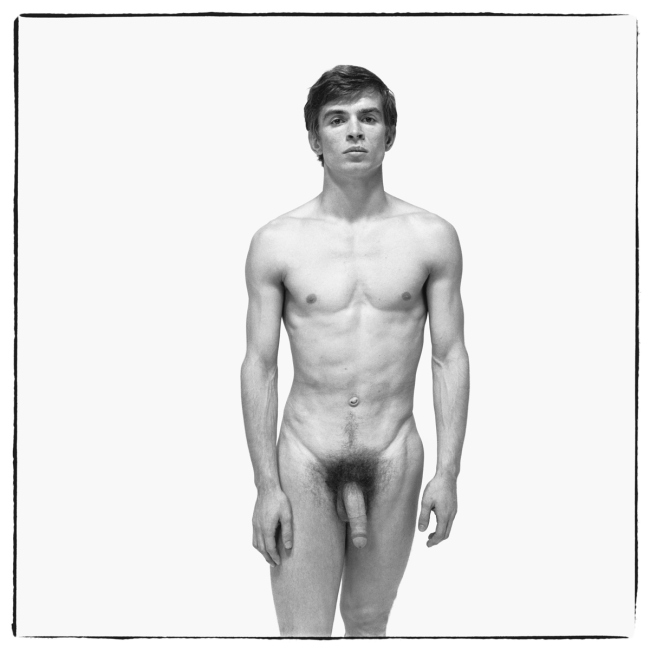

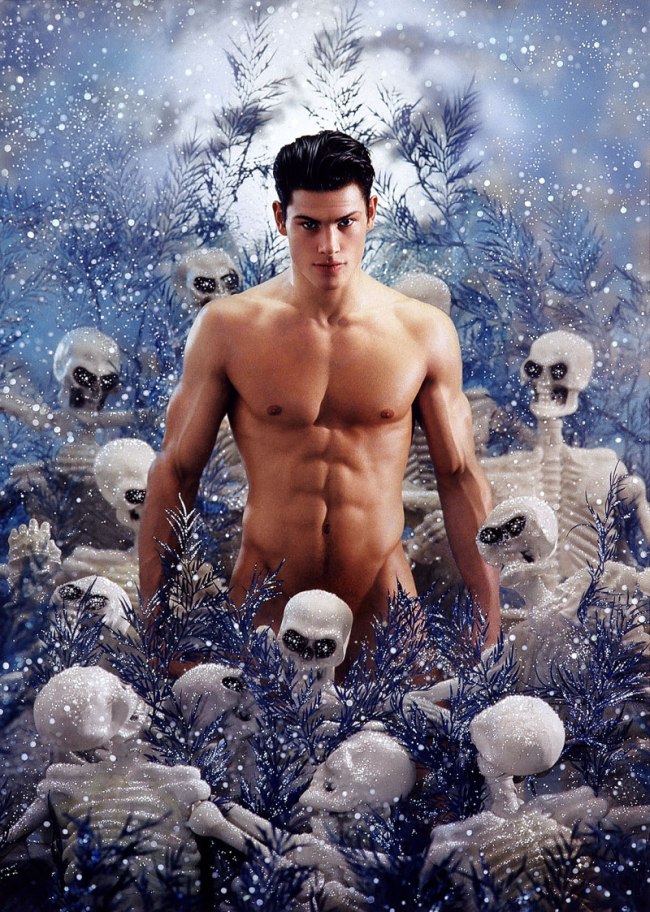

The Phallic Armoured Body

In much of the imagery of the muscular male the body becomes a substitute for the undisclosed and hidden power of the penis. The body becomes a huge phallus, hard and rigid, strong, erect, and powerful. The muscular body acts as a phallic symbol, surrounding itself with an implied sexual mystique, the physical embodiment of the male phallic power. But the penis can never live up to these expectations.7 After all the penis is just an appendage of limp flesh and looks faintly ridiculous most of the time!

Thus, the muscular body becomes a form of dominance display; hard, bulging muscles embodying the mystical potency and virility implied in its phallic construction. Gay men are attracted to the fantasy of a powerful phallus. They too want to be powerful. In some sections of the gay community (especially the ‘Muscle Marys’ as they are known) the muscular body is seen as the epitome of physical attractiveness. This body type has a powerful image, as much for the supposed power of its hidden penis as anything else. A big body can stand as a metaphor for the power of a big dick, something which some gay men seem obsessed with. Muscular gay men are often derided by other gay men by saying that ‘he must have a big body because he can’t have a big dick’, or if a gay man is obviously on steroids then his balls, ‘will have shrivelled up like walnuts and he will have no sex drive’.

I wonder whether this a truth or are some gay men just jealous?

The body as phallus has also become an armoured body, supposedly able to protect its occupant from the anxieties and stress of modern life. This body allows the occupant to control his environment through his body, not allowing any transgressive pleasures / messy secretions / intimacy / love to interject into his controlled armoured existence – no a(r)mour, no love. The body surface becomes an impervious barrier, all orifices closed to seepage across its boundaries. Hard, shiny and smooth nothing can penetrate this perfect projectile. This is especially significant with the onset of the HIV/AIDS virus. A big body was and is perhaps still seen as a healthy body, muscles becoming a sign and symbol of health within the gay community.

“Burn off more than you can chew” (below) is a contemporary advertisement that I believe illustrates the linkage between the phallic smooth, white muscular mesomorphic body and product. Advertising helps encourage the body to become a consumer of the product and postulates the body as a perfect product for consumption itself, at one and the same time. The model with the 6-pak looks longingly at the phallic, erect, penis shaped bar (a ‘bar’ in gay slang is a stiff cock), eats the bar to burn fat, to become ‘ripped’, so other men can gaze at and desire the perfection of his body as a product they wish to consume themselves by having sex with him. His body, his (chocolate) bar becomes a metaphor for the mythological power of his bulging (just) hidden penis.

Iron Man

(left to right)

Douglas (photographer)

“Vic Seipke of the N.E.YMCA of Detroit. Height 5’9″. 186 pounds, neck 18, chest 48, arm 17, waist 29, thigh 25, calf 16, ankle 9 and a half. Won Mr. Michigan, 3rd in Mr. Mid-America 7th in Mr. America.”

1952

in Rader, Peary (ed.,). Iron Man. Vol. 12. Dec-Feb. 1952, No. 4. Alliance, Nebraska: Iron Man Publishing Co., 1952, p. 23.

Courtesy: Marcus Bunyan

Anonymous photographer. “Bill Pearl, another pupil of the Stern gym is 21 and at a height of 5’9″ weighs 209, with a 17″ neck, 47″ chest, 32″ waist, 18″ arm, 8″ wrist, 25 and a half thigh and 16″ calf.”

1952,

in Rader, Peary (ed.,). Iron Man. Vol. 12. Dec-Feb. 1952, No. 4. Alliance, Nebraska: Iron Man Publishing Co., 1952, p. 22.

Courtesy: Marcus Bunyan

Bob Jones (photographer). “Jim Park, Mr. World”

1952, in Rader, Peary (ed.,). Iron Man. Vol. 12. Dec-Feb. 1952, No. 4. Alliance, Nebraska: Iron Man Publishing Co., 1952, p. 7.

Courtesy: Marcus Bunyan

Fritshe (photographer)

“Mike Barrilli, a pupil of Fritshe, won the Jr. Mr. Atlantic title in 1950. At 20 years of age he is 5’6″ tall and weighs 160 pounds of perfectly proportioned muscle.”

1952

in Rader, Peary (ed.,). Iron Man. Vol. 12. Dec-Feb. 1952, No. 4. Alliance, Nebraska: Iron Man Publishing Co., 1952, p. 21.

Courtesy: Marcus Bunyan

Anonymous photographer/designer

“Burn off more than you can chew”

c. 1999

Aussie Bodies advertisement in Clifton, Paul and Gennari, Isabelle (eds.,). Midsumma Festival 2000 guide. Melbourne: Midsumma Festival, 1999.

(left to right)

Carl Hensel

Untitled

Nd

in Dutton, Kenneth. The Perfectible Body. London: Cassell, 1995, p. 193

Anonymous photographer

Bob Paris

Nd

in Dutton, Kenneth. The Perfectible Body. London: Cassell, 1995, p. 248

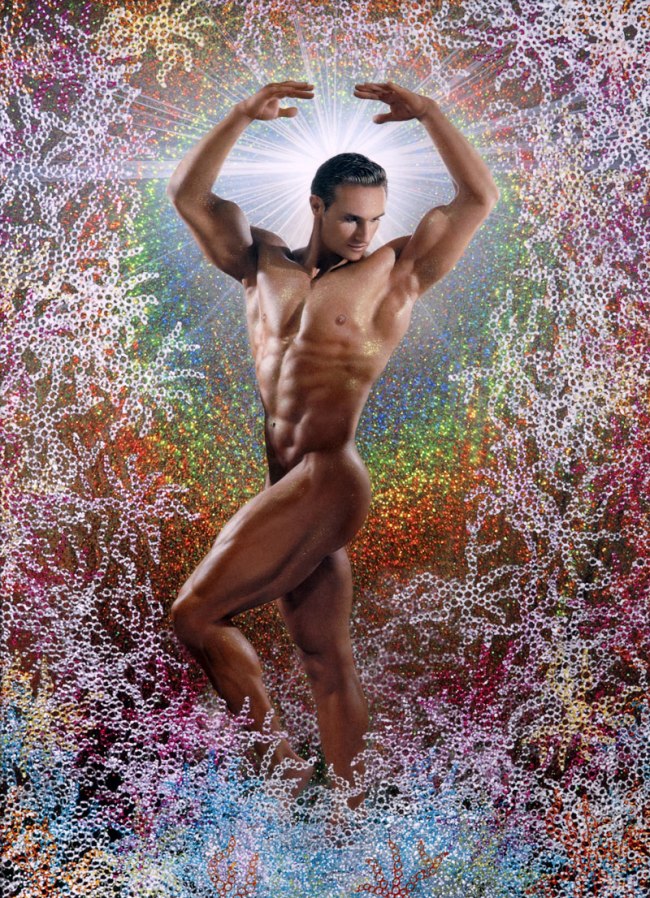

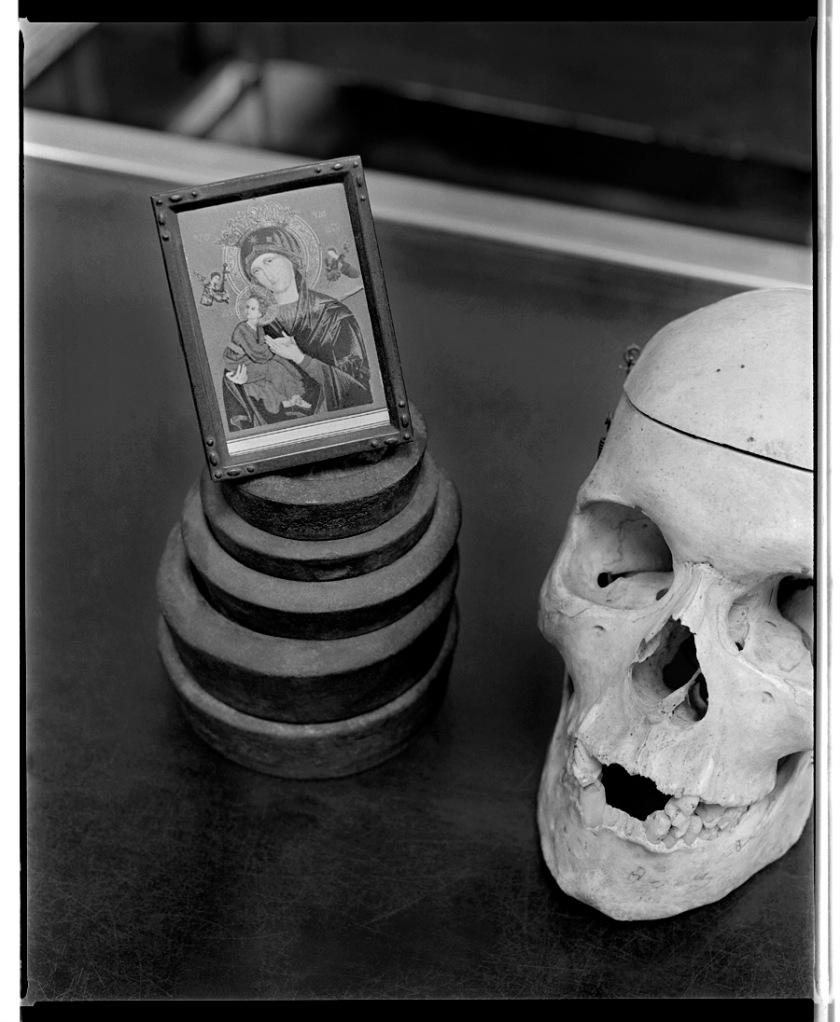

Muscle Gods, Hot Jocks, and Gay Desire

“It was my dream to get a body … I would see all of those guys with their muscles and I wanted to be one of them … It’s not even like I want to really even hang out with the muscle gods, I mean, after I do get into bed with one, it usually is a letdown. Beyond the sex, which is sometimes really dull, I’m usually saying to myself, why did you obsess over getting this guy? We never have anything in common. They’re usually so involved in their bodies – and it really is an all-consuming project to be a muscle god, and work out, like, all the time – that they don’t have any interests beyond talking about the gym and the scene. But that’s the thing about it. It’s the private club, the world of the muscle gods, and you don’t want to be excluded from it …”

Mark, 44 year-old New Yorker quoted in Signorile, Michelangelo. Life Outside. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1997, p. 168.

In the relationship between gay men and going to the gym to muscle up a sense of belonging to the group is an important factor. Often having been persecuted in early life gay men want to belong to a team, and if belonging to the team that is seen as the most desirable means getting a bigger body then so be it, they will do anything to get that body. Gay men can become muscle gods too!

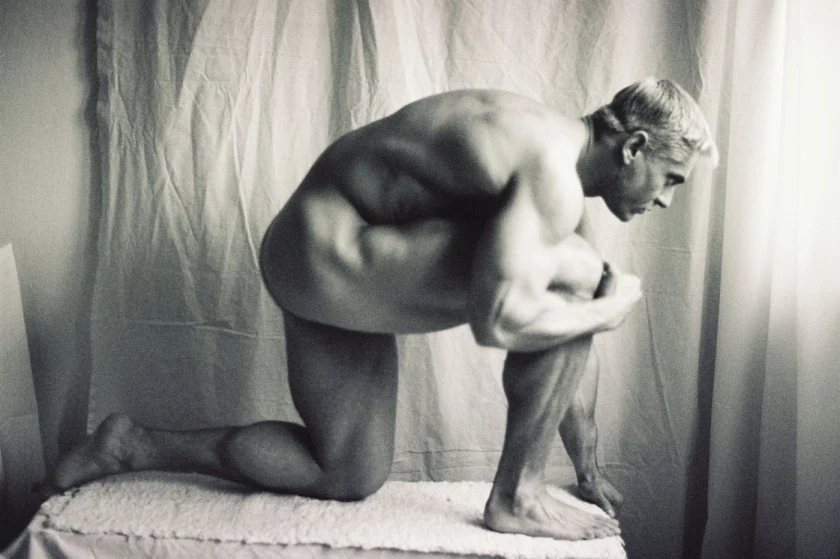

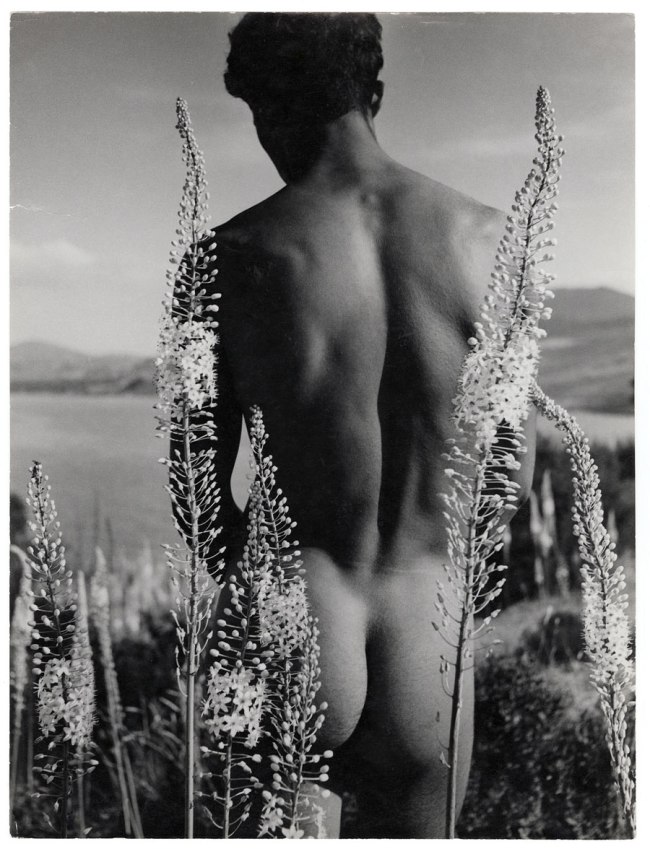

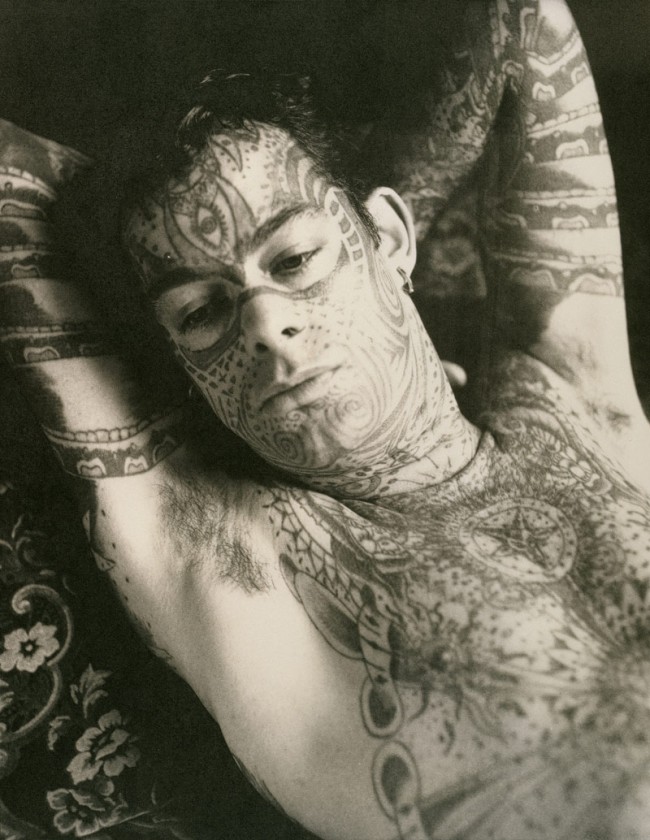

In the above photograph by Carl Hensel we can see one of these muscle gods, his body pumped up like a hooded cobra about to strike. The importance of his genital area is reduced thanks to the smallness of his posing pouch. In serious bodybuilding reducing the eroticism of the body is important in containing the possibility of homoerotic attraction when men view other men’s bodies. The supposed lack of homoeroticism in bodybuilding is upset when one of the fold, for example Bob Paris (above right), openly declares himself to be gay.

Men do lust after and desire other men’s bodies in any context.

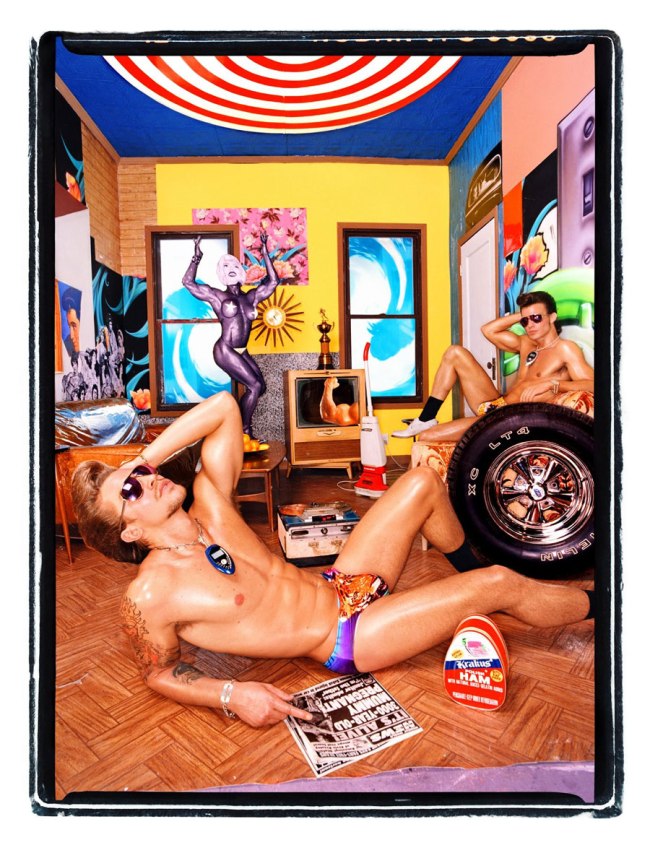

This desire has been commodified in contemporary muscular male imagery. The ‘hot jock’ stereotype has been legitimised as a site of lust and desire. The advertisement below comes from a magazine entitled Exercise for Men Only, a publication aimed primarily at ‘lifestyle’ straight and gay men. These images are not aimed at women. They reveal, as the ad says, “Every shape of their Stunning, Young, Muscular Bodies,” and appeal to men who admire, come along and “feel the heat” of these types of physique. This is soft porn of the entire body a la 1990s style, clothed in the justification of beautiful, artistic cinematography much as the photographers of the 1950s used the devise of association with classical ‘ideals’ to justify the publication of their images. Note how in this advertisement all the bodies conform to the stereotypical ‘ideal’ of the muscular, buff, tanned, white male.

To a great extent this ‘ideal’ has been promulgated and propagated by the imagery used in American gay porn videos since the early 1980s. The imagery of Muscleforce (below) is a good example, linking as it does muscle and power within an eroticism of homosexual lust and desire.

(For more detailed information about the development of the imagery of gay pornography in the media please visit the gay male pornography section in the In-Press chapter).

The Muscular Male Body: Positive and Negative Effects

“Given their poor reception in the outside world, men who are physically weak understandably experience low self-confidence. What’s surprising is that their mirror opposites – the hunks and superjocks – often suffer from the same problem.”

Barry Glasner8

Looking at the positive side of developing a muscular body we find several benefits. Increased fitness is healthy and the gym provides a raised awareness of the bodies capabilities. The sense of belonging to a socially powerful group of people that comes with being part of a team may increase your self-esteem; your self-esteem may also be improved through the admiration of others for your body. More sexual intercourse may also occur because your body-type is seen as more desirable by men. James Hatzi from Colts Gym in Melbourne, Australia, sees no negative aspects to the pressure exerted on gay men to get a muscular body:

“They’ve got to eat right to look that way, they’ve got to exercise. So all the things they are doing are positive. If they build themselves up and look good, they’re always going to have a positive outlook. I can see only positive effects of people wanting to improve themselves.”9

Anonymous photographer

Muscle Heatwave

Vista Video advertisement, c. 1998

in Low, Cheh N. (ed.,). Exercise for Men Only. New York: Chelo Publishing, December 1998, p. 47.

Join Eight Muscular Young Fitness Stars in this Steamy Sequel to “Muscles in Paradise”

Exciting Sequences and Remarkable Photography reveal every shape of their Stunning, Young, Muscular Bodies

Come Along… Live the Adventure and Feel the Heat!

(Includes Beautiful Artistic Cinematography of the ENTIRE Male body)

Anonymous photographer

Muscleforce

c. 1996

Cover of Fox Studios pornography video

My research suggests that there are positive effects, such as higher levels of self-esteem (but not necessarily), more confidence in themselves, greater fitness and management of health, and the ability to have sex with more desirable partners. But there are also many negative effects which James Hatzi does not mention. Perhaps because he runs a gym?

Dr. Lina Ricciardelli, researcher on body image and eating disorders in The School of Psychology at Deakin University, Melbourne, conducted a study that found that gay men had the second highest level of body dissatisfaction after heterosexual women.10 Further, Arthur Blouin and Gary Goldfield have noted that,

“A relationship among self-esteem, proneness to depression, and body dissatisfaction has been reported among both males and females … Among males, body image concerns appear to be greatest for those who are below average weight for height with serious negative effects on self-esteem and social adjustment. As a result, it has been suggested that men who see themselves as underweight may pursue bodybuilding, male hormones, and steroids in order to attain an exaggerated “hypermesomorphic” look.”11

But becoming a bodybuilder does not alleviate these problems and indeed probably exacerbates them. Blouin and Goldfield go on to comment that,

“In addition to the body image dissatisfaction and abnormal eating practices exhibited in bodybuilders, bodybuilders reported perfectionism, feelings of ineffectiveness, low interoceptive awareness, and low self-esteem.”11

So much for James Hatzi not seeing any negative effects in bodybuilding!

One of the most important studies on the muscular mesomorphic body has been undertaken by Marc Mishkind, Linda Rodin, Lisa Silberstein and Ruth Striegel-Moore. They found that a majority of all men preferred the mesomorphic shape body over the ectomorphic (thin) or endomorphic (fat). Within the mesomorphic category most men preferred the hypermesomorphic or muscular mesomorphic body. They found that men have a greater degree of body satisfaction when their body shape fits this ‘ideal’. When there is a gap between their actual and ‘ideal’ body types, and the greater this gap, the lower their self-esteem. They observed that,

“The discrepancy between self and ideal is problematic only when men believe that those closest to the ideal reap certain benefits not available to those further away. Research strongly suggests that this is true, both because physical appearance is so important generally in our society and because of the specific benefits that accrue to mesomorphic men.”12

This is particularly true within the gay community, where attraction and sex are based primarily on physical appearance and the muscular mesomorphic shape is seen as the ‘ideal’. Indeed, Mishkind et al found that gay men, who place increased importance on aspects such as body build, grooming, dress and handsomeness,

“Expressed greater dissatisfaction with body build, waist, biceps, arms and stomach. Gay men also indicated a greater discrepancy between their actual and ideal body shapes than did “straight” men and showed higher scores on measures of eating disregulation and food and weight preoccupation.”12

(For a longer extract from the paper by Mishkind et al please see Appendix A after the footnotes)

In this research project I have taken this obsession with possessing the ideal muscular body in the gay community into largely unexplored territory. As can be seen from two of the interviews that I have conducted (See Story 4 and Story 5 in the Personal Press chapter) gay men are placing themselves at greater risk of contraction of the HIV/AIDS virus because of their need to possess the body of the ‘ideal’. This may mean taking risks such as having sex without a condom in order to achieve their desires.

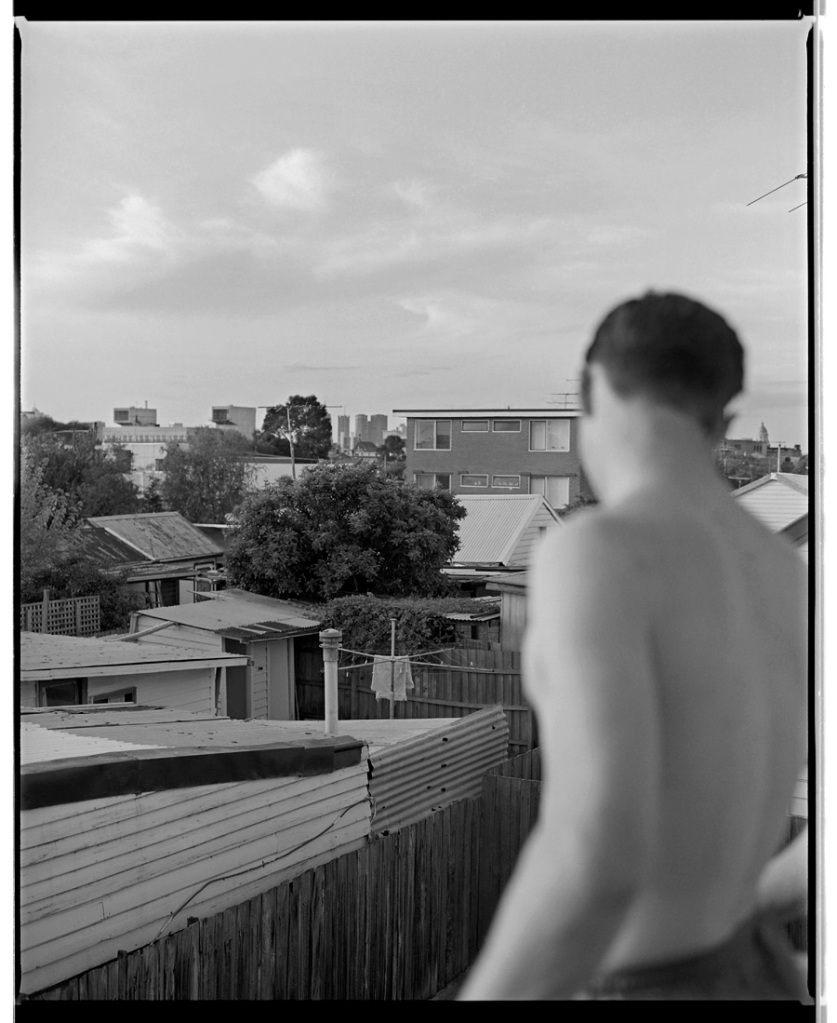

Personally I suffered from an acute lack of self-esteem in respect to my body image; I went to gym for years wanting a bigger body, desiring this kind of body for myself and in others. I could never achieve what I wanted and this made me really depressed; it undermined my self-esteem. But I learnt to live with the body I had and came to enjoy its familiarity. Now as I get older the youth and beauty thing is passing and I am no longer ‘forever young’. This is a difficult time for gay men and a lot (of gay men) enter counselling after the age of 35 to cope with this situation. Magazines with covers, articles and quotations like the one below, using the imagery of young men when advertising an issue on anti-ageing, don’t help either. You might not be this young but you can drool over (t)his aspect of youth that WE ALL strive to maintain.

Martin Ryter

Untitled

Nd

in Low, Cheh N. (ed.,). Exercise for Men Only. New York: Chelo Publishing, December 1998, Cover

“Talk about anti-ageing – our cover model looks as if he just graduated high school. The important thing to remember is that Martin Ryter’s cover shot reflects the aspects of youth that we all strive to maintain. You may not always look quite this young, but there is no reason why you can’t look your best at any age.”

100 anti-ageing tips.

Special Longevity/Anti-Ageing Issue.

Age-Defying Shoulder Regimen for men Over 35

(as though all our shoulders fall apart after 35!)

Human Growth Hormone: Nature’s Fountain of Youth.

Total Body Training Builds Muscle after 40.

Power Chest Routine Halts the March of Time.

Nothing halts the march of time I’m afraid. What you have to get used to is accepting the fact, accepting that your body is getting older and changing, and you move on from there. Using a model that, as they say, looks as if he has just graduated high school is promoting the ‘ideal’ of the eternal youth. Gay men are obsessed by youth and beauty, and this magazine panders to their insecurities, telling them that they can beat the march of time, remaining ever youthful and desirable. This is a fallacy much as the strong muscular body is a deceptive phallacy, a hard armoured body that signifies the supposed sexual mystique of the phallus and the omnipotence of the hidden penis.

Another tool ‘Polite Porn’13 magazines such as ‘Exercise For Men Only’use are the poses of the models. ‘Shredded, ageless abs in just 6 weeks’ scream the headlines and there is the model with his hands wandering seductively down to his genital region via his unbuttoned trousers – the suggestiveness of the pose has nothing to do with abs at all and everything to do with sex.

Atomic Studio/Mark Howland

Untitled

Nd

in Low, Cheh N. (ed.,). Exercise for Men Only. New York: Chelo Publishing, December 1998, p. 36

J. Neu

Untitled

Nd

in Low, Cheh N. (ed.,). Exercise for Men Only. New York: Chelo Publishing, December 1998, p. 20.

Many of the poses in these magazines come straight out of pornography magazines and videos. Arms raised behind head to reveal the erotic under- arm area, genitals pressing against skimpy Lycra outfits so the outline of the cock can be seen, as in the example above. This has to be one of my favourite photographs from this issue, probably close to my ideal body-type (his height, smoothness, size of his arms, magnificent abs, lats, pecs, his button nose and his blue eyes). What would I do to have sex with him?

The body in all its glory becomes both an active and a passive site of desire. In the Prevail Sport advertisement (below) from the same issue of Exercise for Men Only, we can see the gaze of the model at top left actively challenging the desiring gaze of the viewer. At bottom left the hard body as phallus compliments the outlines of the erect penis in the underwear, hinting at its hidden power. At middle left and right the body becomes a passive masturbatory landscape for the viewer as the model is seemingly asleep, allowing the viewer to caress the body with his eyes without fear of rejection. The crotch and arse become the focus of this desire.

(For more information on the gaze please go to the Eye-Pressure chapter)

Anonymous photographer

Untitled

Nd

Prevail Sport underwear advertisement

in Low, Cheh N. (ed.,). Exercise for Men Only. New York: Chelo Publishing, December 1998, p. 15

It is very difficult not to take binary positions in regard to the positive and negative contributions of gym culture to the gay community throughout the Western world. Nothing in the world is ever solely black / white, straight / gay, masculine / feminine, but many shades of grey in-between. There are both positive and negative effects that emanate from gym culture and the desire of many gay men to attain a muscular mesomorphic body but on balance I believe that gym culture and its ‘lifestyle’ are quite exclusive and elitist. I would suggest that if you are going to try and attain the body that you desire then the best way to go about it is to fully understand the implications of your decision to try and attain that body before you start, and the reasons that lie behind your decision.

Brian Pronger has observed that,

“The ‘new gay man’ … is the man who has developed his body to reflect his desires and therefore his understanding of himself.”14

I disagree with this statement.

Contrary to what Brain Pronger proposes I suggest that the ‘new gay man’ who has developed his body has not necessarily developed a greater understanding of himself compared to any other gay man. I propose that what gay men are attracted to is a reflection, and it is only a reflection, a mirror image of how they would like to see themselves; this is not a greater understanding of themselves and having a developed body does not necessarily lead to a greater understanding of the Self. The (self)reflection of a person’s desires through the development of their body may indeed tell them (and you) something about their desires (for a similar body?), but I suggest that this desire has, in many cases, been directed by external forces; by society, reflected appraisal, social comparison and rituals of learned behaviour for example.

In some instances developing the body can be seen as a cure all by gay men to the problems that beset them – insecurities, fear of rejection, and the lack of love, intimacy and connection with other men to name just a few. Unfortunately the development of a muscular mesomorphic body may mask these problems behind a hard, armoured facade where no one can see what is going on, least of all the person that lives in the body. I believe that this is not encouraging or developing a greater understanding of the Self but is perhaps just the self gratification of personal desires enacted through the (self)reflexivity of a perfect image.

Is it not ironic that in a community that prides itself on diversity, the reliance of that community on one type of physical ideal of attractiveness mirrors the discrimination that so many gay men have suffered over the years at the hands of heterosexuals. The muscular mesomorphic stereotype, much as the stereotyping of gay men as effeminate in the past, does not serve the gay community well. It just provides a reinforcement of traditional ‘masculinity’ and its values in the form of the muscular mesomorphic body. I suggest that this type of body has become the outward sign of a patriarchal homosexuality, the dominance of some gay men over other gay men through a desirable visible symbology.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

2001

Footnotes

1/ Throughout my PhD and project notes (including the development of interview questions, the analysis of data, and the development of evolving theory), I have used the quotation below as the basis for my definition of the term ‘masculinity’.

“The category of “masculinity” should be seen as always ambivalent, always complicated, always dependent on the exigencies [meaning: necessary conditions and requirements] of personal and institutional power … [masculinity is] an interplay of emotional and intellectual factors – an interplay that directly implicates women as well as men, and is mediated by other social factors, including race, sexuality, nationality, and class … Far from being just about men, the idea of masculinity engages, inflects, and shapes everyone.”

Berger, Maurice, Wallis, Brian and Watson, Simon (eds.,). Constructing Masculinity. New York: Routledge, 1995, pp. 3-7. Introduction.

2/ Dyer, Richard. Only Entertainment. London: Routledge, 1992, p. 114, quoted in Stratton, Jon. The Desirable Body. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1996, p. 195.

3/ See Gorn, Elliott. The Manly Art. London: Robson Books, 1986.

4/ “Where objective knowing is passive, subjective knowing is active – rather than giving allegiance to a set of methodological rules which are designed to deliver up truth through some kind of automatic process [in this case the image], the subjective knower takes a personal risk in entering into the meaning of the phenomena to be known…

Those who have some time for the validity of subjective experience but intellectual qualms about any kind of ‘truth’ which is not ‘objective’, are apt to solve their problem by appealing to some kind of relativity. For example, it might be felt that we all have our own versions of the truth about which we must tolerantly agree to differ. While in some ways this kind of approach represents an advance on the brute domination of ‘objective truth’, it in fact undercuts and betrays the reality of the world given to our subjectivity. Subjective truth has to be actively struggled for: we need the courage to differ until we can agree.

Though the truth is not just a matter of personal perspective, neither is it fixed and certain, objectively ‘out there’ and independent of human knowing. ‘The truth’ changes according to, among other things, developments and alterations in our values and understandings … the ‘non-finality’ of truth is not to be confused with a simple relativity of ‘truths’.”

Smail, David. Illusion and Reality: The Meaning of Anxiety. London: J.M. Dent & Sons, 1984, pp. 152-153.

5/ See Tagg, John. The Burden of Representation: Essays on Photographies and Histories. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1988, p. 85.

6/ ‘Lifestyle’ was a term conceived by the Viennese psychiatrist Alfred Adler in the 1920s in order to describe the attitudes that inform a person’s experience of life. By the 1960s style, fashion and consumerism had overlaid its original meaning and now a ‘lifestyle’ is perhaps a style of life based on your ability to have, compete and move in valued social circles. It has become a combination of both materialism and psychiatry. Much as ‘homosexuality’ was medically named as a deviancy in the 1870s in order to control that deviancy through treatment and regulation, ‘lifestyle’ has links to the medical profession which names its [lifestyles that is] effects on the identity of the self.

“Lifestyle refers to a relatively integrated set of practices chosen by an individual in order to give material form to a particular narrative of self-identity. The more tradition loses its ability to provide people with a secure and stable sense of self, the more individuals have to negotiate lifestyle choices, and attach importance to these choices.”

Schilling, Chris. The Body and Social Theory. London: Sage Publications, 1993, pp. 181-183.

7/ “The penis can never live up to the mystique implied by the phallus. Hence the excessive, even hysterical quality of so much male imagery. The clenched fists, the bulging muscles, the hardened jaws, the proliferation of phallic symbols – they are all straining after what can hardly ever be achieved, the embodiment of the phallic physique.” (My italics).

Dyer, R. Only Entertainment. London: Routledge, 1992, p. 116, quoted in Stratton, Jon. The Desirable Body. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1996, p. 195.

8/ Glassner, Barry. Bodies – Why We Look the Way We Do (And How We Feel About It). New York: G.P. Puttnam, 1988, p. 122.

9/ Hatzi, James, quoted in Cho, Natasha. “The Mirror Has Two Faces,” in Melbourne Star Observer. Melbourne: Bluestone Media, 6th June, 1997, p. 9.

10/ Riccciardelli, Lina, commenting on her study in Cho, Natasha. “The Mirror Has Two Faces,” in Melbourne Star Observer. Melbourne: Bluestone Media, 6th June, 1997, p. 9.

11/ Blouin, Arthur and Goldfield, Gary. “Body Image and Steroid Use in Male Bodybuilders,” in International Journal of Eating Disorders Vol. 18. No. 2. John Wiley and Sons Inc., 1995, pp. 160-164.

12/ Mishkind, Marc, Rodin, Linda, Silberstein, Lisa and Striegel-Moore, Ruth. “The Embodiment of Masculinity: Cultural, Psychological and Behavioural Dimensions,” in Kimmel, M. (ed.,). Changing Men: New Directions in Research on Men and Masculinity. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, 1987, pp. 37-47.

13/ McKee, Alan. “Polite Porn,” in Brother Sister. Melbourne. 18th May, 1995, p. 13.

14/ Pronger, Brain. The Arena Of Masculinity: Sport, Homosexuality, and the Meaning of Sex. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1990.

Appendix A

Extract from Mishkind, Marc, Rodin, Linda, Silberstein, Lisa and Striegel-Moore, Ruth. “The Embodiment of Masculinity: Cultural, Psychological and Behavioural Dimensions,” in Kimmel, M. (ed.,). Changing Men: New Directions in Research on Men and Masculinity. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, 1987, pp. 37-47.

How Men Feel About Their Bodies

One index of men’s bodily concern is their degree of satisfaction with their physical appearance … Studies suggest that men carry with them images of both their own body and also their ideal body, and that these two images are non identical … Dissatisfaction [amongst men] is not general and diffuse but highly specific and differentiated. Men consistently express their greatest dissatisfaction toward chest, weight and waist … Given that men experience significant body dissatisfaction because they see themselves as deviating from the ideal, it becomes crucial to determine the ideal male body type. When asked about physique preferences, the overwhelming majority of males report that they would prefer to be mesomorphic (ie., of well-proportioned, average build) as opposed to ectomorphic (thin) or endomorphic (fat).

This preference is expressed by boys as young as 5 and 6 (R. Lerner and E. Gellert. “Body Build Identifications, Preference, and Aversion in Children,” in Developmental Psychology 1. 1969, pp. 456-462; and R. Lerner and C. Schroeder. “Physique Identification, Preference and Aversion in Kindergarten Children,” in Developmental Psychology 5. 1971, p. 538) and also by college-age men (L. A. Tucker. “Relationship between perceived somatotype and body cathexis of college males,” in Psychological Reports 50. 1982, pp. 983-989). Within the mesomorphic category, a majority select what we shall refer to as the hypermesomorphic or muscular mesomorphic body as preferred (Tucker, 1982). This physique is the “muscle-man”-type body characterized by well-developed chest and arm muscles and wide shoulders tapering down to a narrow waist. Men indicate greater body satisfaction to the extent that their self- reported (Tucker, 1982) or actual (S. Jourard and P. Secord. “Body Size and Body Cathexis,” in Journal of Consulting Psychology 18. 1954, p. 184; and A. Sugerman and F. Haronian. “Body Type and Sophistication of Body Concept,” in Journal of Personality 32. 1964, pp. 380-394) body shape resembles this ideal.

That many men feel bodily dissatisfaction because they do not resemble the mesomorphic or hypermesomorphic ideal might not in itself be particularly distressing. The discrepancy between self an ideal is problematic only when men believe that those closest to the ideal reap certain benefits not available to those further away. Research strongly suggests that this is true, both because physical appearance is so important generally in our society and because of the specific benefits that accrue to mesomorphic men.

Mesomorphy and Masculinity

We believe that the muscular mesomorph is the ideal because it is intimately tied to cultural views of masculinity and the male sex role, which prescribes that men be powerful, strong, efficacious – even domineering and destructive. The embodiment of masculinity, the muscular mesomorph is seen as more efficacious, experiencing greater mastery and control over the environment, and feeling more invulnerable … and men consider physical attractiveness virtually equivalent to physical potency (R. M. Lerner, J. B. Orlos and J. R. Knapp. “Physical attractiveness, physical effectiveness, and self-concept in late adolescents,” in Adolescence 11. 1976, pp. 313-326). Hence they experience an intimate relationship between body image and potency – that is, masculinity – with the muscular mesomorph representing the masculine ideal. A man who fails to resemble the body ideal is, by implication, failing to live up to sex-role norms, and may thus experience the consequences of violating such norms.

MARCUS: This is very interesting in regards to the relationship between gay men and the ‘ideal’ body image of the muscular mesomorph. I believe that gay men have a very strong relationship between body image and potency. The hard, armoured, muscular body can be seen as a huge phallus, a metaphor for the power of the hidden penis. From my own experience I know that most gay men have a thing about penis size (“he was hung like a cashew,” meaning he had a very small cock, or “he was hung like a donkey,” meaning he had a very large cock are common phrases) and some are real ‘size queens’. When the penis is hidden the external form of the body becomes a conduit for its power. Perhaps this is one of the reasons why gay men desire the muscular mesomorphic body so much, because of the perceived relationship between potency, the hidden size of the cock and the hard body. I do not agree with Mishkind et al that potency equates solely to masculinity. I think that potency is about a sexual virility and desire that is independent from, but connected to, masculinity. Masculinity is not just about men, it is about history, identity, women, society, culture, behaviour and many more perspectives. To equate potency with masculinity without qualifying that masculinity operates from multiple perspectives and in many diverse areas is I think a mistake.

A Man’s Body And His Sense Of Self

Studies have revealed consistently a significant correlation between men’s body satisfaction and self-esteem, the average correlation of these studies being around 0.5. Although some studies have found a stronger relationship between body-esteem and self-esteem for women than for men (R. M. Lerner, S. A. Karabenick and J. L. Stuart. “Relations among physical attractiveness, body attitudes, and self concept in male and female college students,” in Journal of Psychology 85. 1973, pp. 119-129; and P. F. Secord and S. M. Jourard. “The appraisal of body cathexis: Body cathexis and the self,” in Journal of Consulting Psychology 17. 1953, pp. 343-347), others have found comparable or even greater relationships between body satisfaction and measures of self-esteem, anxiety, and depression for men than for women (S. Franzoi and S. Shields. “The Body Esteem Scale: Multidimensional Structure and Sex Differences in a College Population,” in Journal of Personality Assessment 48. 1984, pp. 173-178; and B. Goldberg and C. Folkins. “Relationship of Body-Image to Negative Emotional Attitudes,” in Perceptual and Motor Skills 39. 1974, pp. 1053-1054). How a man feels about himself is thus tied closely to how he feels about his body. It remains for researchers to examine the relative importance of body image to a man’s sense of self when compared to other variables such as career achievement, but the data already available suggest that feeling about body play a significant role in self-esteem.

Efforts To Decrease The Gap Between Actual And Ideal Body Shape

We have seen that a great number of men acknowledge a gap between their actual and ideal body types, and that the greater this gap, the lower their self-esteem. As a result, men feel motivated to close this gap. This often depends upon which parts of the body are the foci of dissatisfaction. In a large-scale factor-analytic study, Franzoi and Shields (1984) found three primary dimensions along which men’s bodily satisfaction and dissatisfaction occur …

MARCUS: According to Mishkind et al basically:

1/ physical attractiveness (face);

2/ upper body strength (muscles); and

3/ physical conditioning (fitness)

Given that the physical effects of endurance workouts may be less readily visible than the effects of bodybuilding, we surmise that men who want to be recognized for their physical masculinity are more likely to opt for muscle building as their form of physical exercise … A man who strives to bridge the self-denial gap will experience a heightened attentiveness to and focus on his body. This may render his standards more perfectionist (and hence more out of reach) and enhance his perceptions of his shortcomings. Both his limitations and the gap itself can become increasingly salient. To the extent that he feels he falls short, he will experience the shame of failure. He may also feel ashamed at being so focused on his body, presumably because this has been associated traditionally with the female sex-role type …

Thus far we have focused only on the negative consequences of trying to attain the masculine body ideal. There a powerfully positive consequences. The more a man experiences himself as closing the self-ideal gap – for example, through exercising – the more positive he will feel toward body and self … (My italics). The more a man works toward attaining his body ideal and the closer he perceives himself to approximating it, the greater his sense of self-efficacy.

Subcultures Of High Bodily Concern

The increased cultural attention given to the male body and the increasing demands placed on men to achieve the mesomorphic build push men further along the continuum of bodily concern. Men are likely experiencing more body dissatisfaction, preoccupation with weight, and concern with their physical attractiveness and body shape now than they did even two decades ago … we might expect that subgroups of men that place relatively greater emphasis on physical appearance would be at greater risk or excessive weight control behaviours and even eating disorders.

An illustrative group is the gay male subculture, which places an elevated importance on all aspects of a man’s physical self – body build, grooming, dress, handsomeness (S. Kleinberg. Alienated Affections: Being Gay in America. New York: St. Martin’s, 1980; and R. Lakoff and R. Scherr. Face Value: The Politics of Beauty. Boston: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1984). We predicted that gay men would be at a heightened risk of body dissatisfaction and for eating disorders. In a sample of heterosexual and homosexual college men, gay men expressed greater dissatisfaction with body build, waist, biceps, arms, and stomach. Gay men also indicated a greater discrepancy between their actual and ideal body shapes than did “straight” men and showed higher scores on measures of eating disregulation and food and weight preoccupation. If the increased focus on appearance continues for men in general, such concerns and eating disorders may begin to increase among all men. (My italics).

Conclusions

The body plays a central role in men’s self-esteem, and men are striving in growing numbers to achieve the male body image. This may have a profound impact on their psychological and physical health. We suspect that the causes and consequences of bodily concern reviewed here represent a growing cultural trend, attributable to increased emphasis on self-determination of health and the ambiguity of current male and female sex roles. (My italics).

Mishkind, Marc, Rodin, Linda, Silberstein, Lisa and Striegel-Moore, Ruth. “The Embodiment of Masculinity: Cultural, Psychological and Behavioural Dimensions,” in Kimmel, M. (ed.,). Changing Men: New Directions in Research on Men and Masculinity. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, 1987, pp. 37-47.

![Anonymous photographer. 'Untitled [Gym group possibly German/Prussian]' c. 1890-1910 Anonymous photographer. 'Untitled [Gym group possibly German/Prussian]' c. 1890-1910](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2022/11/gym-group-1.jpg?w=840)

![Anonymous. 'Untitled [Posing straps]' 1952 Anonymous. 'Untitled [Posing straps]' 1952](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2022/11/posing-strap.jpg?w=840)

![Peter Elfes (Australia, 1961-) 'Brenton [Heath-Kerr] as Tom of Finland' 1992 Peter Elfes (Australia, 1961-) 'Brenton [Heath-Kerr] as Tom of Finland' 1992](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2017/11/elfes-brenton-heath-kerr-web.jpg?w=650&h=970)

![Unknown photographer. 'Untitled [Auschwitz victim]' N Unknown photographer. 'Untitled [Auschwitz victim]' Nd](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2017/11/unknown-photographer-untitled-auschwitz-victim-nd-web.jpg?w=840)

You must be logged in to post a comment.