Exhibition dates: 2nd April – 2nd September 2013

PLEASE BE WARNED: LIKE “INCIDENTS OF WAR”, THIS POSTING IS DISTURBING AND NOT FOR THE FAINT HEARTED!

Andrew Joseph Russell (American, 1830-1902)

Slave Pen, Alexandria, Virginia (detail)

1863

Albumen silver print from glass negative

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gilman Collection, Purchase, The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 2005

© The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

There are some very poignant and disturbing photographs in this posting. The youth of some of the combatants (Private Wood sits against a blank wall in a photographer’s studio. He is sixteen years old and will not see seventeen. An orphan, he joined Company H in Social Circle, Georgia, on July 3, 1861, and before the end of the year died of pneumonia in a Richmond hospital). The sheer brutality and pointlessness of war. Bloated and twisted bodies, inflated like balloons. Starved and beaten human beings.

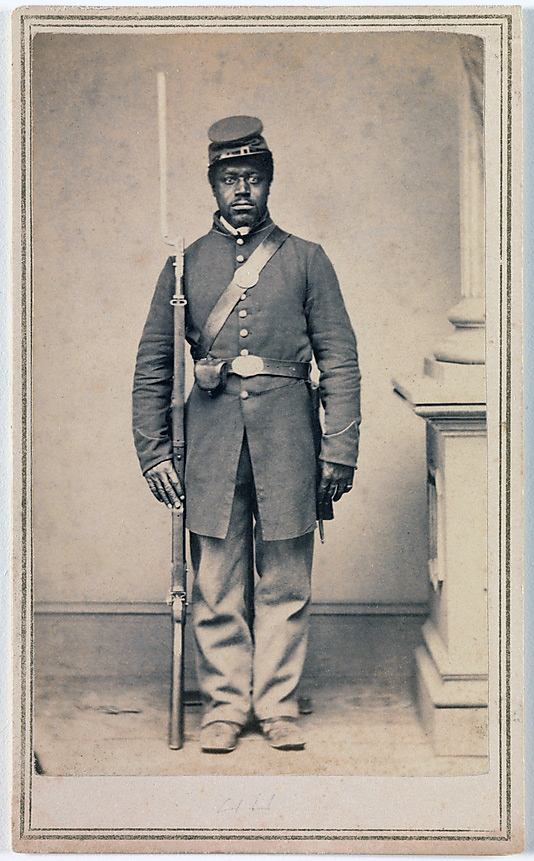

And yet, you look at the photograph “Slave Pen” – the office of those ‘Dealers in Slaves’ now guarded by Union soldiers (above) – or the photograph of Wilson, Branded Slave from New Orleans and the photograph of the anonymous African American soldier fighting for the Union cause directly below and you understand just one of the reasons that this was such a bloody conflict: it was about the right of all men to be free, to throw off the bonds of servitude.

To be replaced all these years later by another corrupted power – the power of government, the power of government to surveil its people at any and all times. The power of religion, money, the military and the gun.

Praise be the land of the free.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Metropolitan Museum of Art for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“It was, indeed, a ‘harvest of death.’ … Such a picture conveys a useful moral: It shows the blank horror and reality of war, in opposition to its pageantry. Here are the dreadful details! Let them aid in preventing such another calamity falling upon the nation.”

“Before the war, a child three years old, would sell in Alexandria, for about fifty dollars, and an able-bodied man at from one thousand to eighteen hundred dollars. A woman would bring from five hundred to fifteen hundred dollars, according to her age and personal attractions.”

Alexander Gardner

“In your hands, my dissatisfied fellow-countrymen, and not in mine, is the momentous issue of civil war. The Government will not assail you. You can have no conflict without being yourselves the aggressors. You have no oath registered in heaven to destroy the Government, while I shall have the most solemn one to ‘preserve, protect, and defend it’.”

“We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.”

“The dogmas of the quiet past, are inadequate to the stormy present. The occasion is piled high with difficulty, and we must rise – with the occasion. As our case is new, so we must think anew, and act anew.”

American President Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865)

Alexander Gardner (American born Scotland, 1821-1882)

Ruins of Gallego Flour Mills, Richmond

1865

Albumen silver prints from glass negatives

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1933

© The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

In 1861, at the outset of the Civil War, the Confederate government moved its capital from Montgomery, Alabama, to Richmond, Virginia, to be closer to the front and to protect Richmond’s ironworks and flour mills. On April 2, 1865, as the Union army advanced on Richmond, General Robert E. Lee gave the orders to evacuate the city. A massive fire broke out the following day, the result of a Confederate attempt to destroy anything that could be of use to the invading Union army. In addition to consuming twenty square blocks, including nearly every building in Richmond’s commercial district, it destroyed the massive Gallego Flour Mills, situated on the James River and seen here. Alexander Gardner, Mathew B. Brady’s former gallery manager, then his rival, made numerous photographs of the “Burnt District” as well as this dramatic panorama from two glass negatives. The charred remains have become over time an iconic image of the fall of the Confederacy and the utter devastation of war.

A display of three photographs of American Civil War soldiers in the exhibition, “Photography and the American Civil War” April 1, 2013 at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The three albumen silver prints are all by Gayford & Speidel, “Private Christopher Anderson, Company F, 108th Regiment, U.S. Colored Infantry, January-May 1865” (L), “Private Louis Troutman, Company F, 108th Regiment, U.S. Colored Infantry, January-May 1865”, (C) and “Private Gid White, Company F, 108th Regiment, U.S. Colored Infantry, January-May 1865”, (R).

AFP PHOTO/Stan HONDA

Unknown artist

Union Private, 11th New York Infantry (Also Known as the 1st Fire Zouaves)

May-June 1861

One-sixth plate ambrotype

Michael J. McAfee Collection

© The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

This melancholy young volunteer was a member of the Eleventh New York Infantry, an early war regiment organised in New York City in May 1861. Primarily composed of volunteers from the city’s many fire companies, the men were also known as the First Fire Zouaves. Along with other volunteer units, the Eleventh helped capture Alexandria, Virginia on May 24, 1861, just a day after the state formally seceded from the Union.

Unknown artist

Union Private, 11th New York Infantry (Also Known as the 1st Fire Zouaves) (detail)

May-June 1861

One-sixth plate ambrotype

Michael J. McAfee Collection

© The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Timothy H. O’Sullivan (American, born Ireland, 1840-1882)

A Harvest of Death, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania

July 1863

Printer: Alexander Gardner (American, Glasgow, Scotland 1821-1882 Washington, D.C.)

Publisher: Alexander Gardner (American, Glasgow, Scotland 1821-1882 Washington, D.C.)

Albumen silver print from glass negative

17.8 × 22.5cm (7 × 8 7/8 in.)

Gilman Collection, Museum Purchase, 2005

This photograph of the rotting dead awaiting burial after the Battle of Gettysburg is perhaps the best-known Civil War landscape. It was published in Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the War (1866), the nation’s first anthology of photographs. The Sketch Book features ten photographic plates of Gettysburg – eight by Timothy H. O’Sullivan, who served as a field operator for Alexander Gardner, and two by Gardner himself. The extended caption that accompanies this photograph is among Gardner’s most poetic: “It was, indeed, a ‘harvest of death.’ … Such a picture conveys a useful moral: It shows the blank horror and reality of war, in opposition to its pageantry. Here are the dreadful details! Let them aid in preventing such another calamity falling upon the nation.”

Timothy H. O’Sullivan (American, born Ireland, 1840-1882)

Alexander Gardner, printer

Field Where General Reynolds Fell, Gettysburg, July 1863

1863

Plate 37 in Volume 1 of Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the War

Albumen silver print from glass negative

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gilman Collection, Purchase, Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee Gift, 2005

© The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

This photograph of the aftermath of the Battle of Gettysburg appears in the two-volume opus Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the War (1865-1866). Gardner’s publication is egalitarian. Offended by Brady’s habit of obscuring the names of his field operators behind the deceptive credit “Brady,” Gardner specifically identified each of the eleven photographers in the publication; forty-four of the one hundred photographs are credited to Timothy O’Sullivan. Gardner titled the plate Field Where General Reynolds Fell, Battlefield of Gettysburg. But the photograph, its commemorative title notwithstanding, relates a far more common story: six Union soldiers lie dead, face up, stomachs bloated, their pockets picked and boots stolen. As Gardner described the previous plate, aptly titled The Harvest of Death, this photograph conveys “the blank horror and reality of war, in opposition to its pageantry.”

Unknown artist

Captain Charles A. and Sergeant John M. Hawkins, Company E, “Tom Cobb Infantry,” Thirty-eighth Regiment, Georgia Volunteer Infantry

1861-1862

Quarter-plate ambrotype with applied colour

David Wynn Vaughan Collection

Photo: Jack Melton

The vast majority of war portraits, either cased images or cartes de visite, are of individual soldiers. Group portraits in smaller formats are more rare and challenged the field photographer (as well as the studio gallerist) to conceive and execute an image that would honour the occasion and be desirable – saleable – to multiple sitters. For the patient photographer, this created interesting compositional problems and an excellent opportunity to make memorable group portraits of brothers, friends, and even members of different regiments.

In this quarter-plate ambrotype, Confederate Captain Charles Hawkins of the Thirty-eighth Regiment, Georgia Volunteer Infantry, on the left, sits for his portrait with his brother John, a sergeant in the same regiment. They address the camera and draw their fighting knives from scabbards. Charles would die on June 13, 1863, in the Shenandoah Valley during General Robert E. Lee’s second invasion of the North. John, wounded at the Battle of Gaines’s Mill in June 1862, would survive the war, fighting with his company until its surrender at Appomattox.

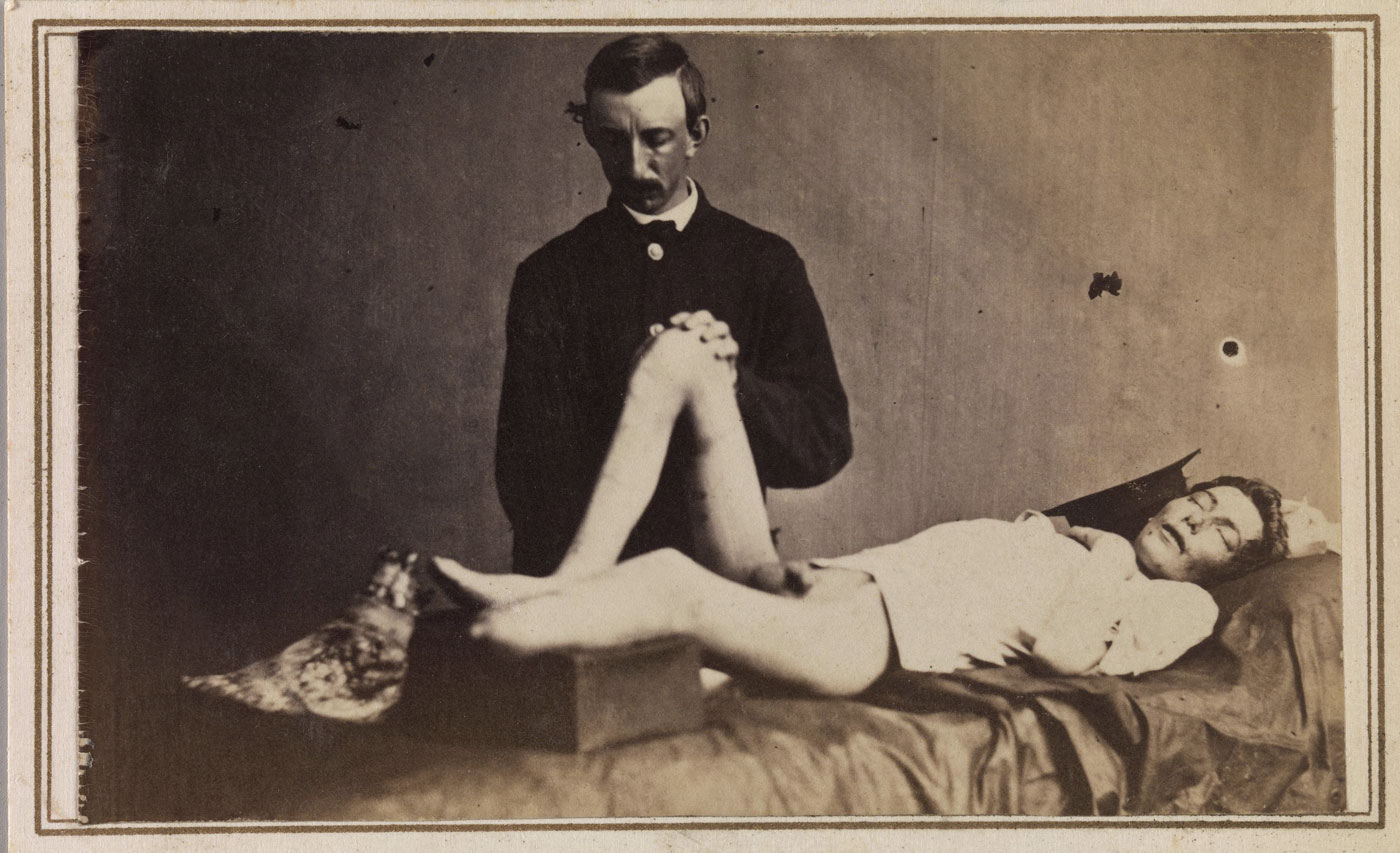

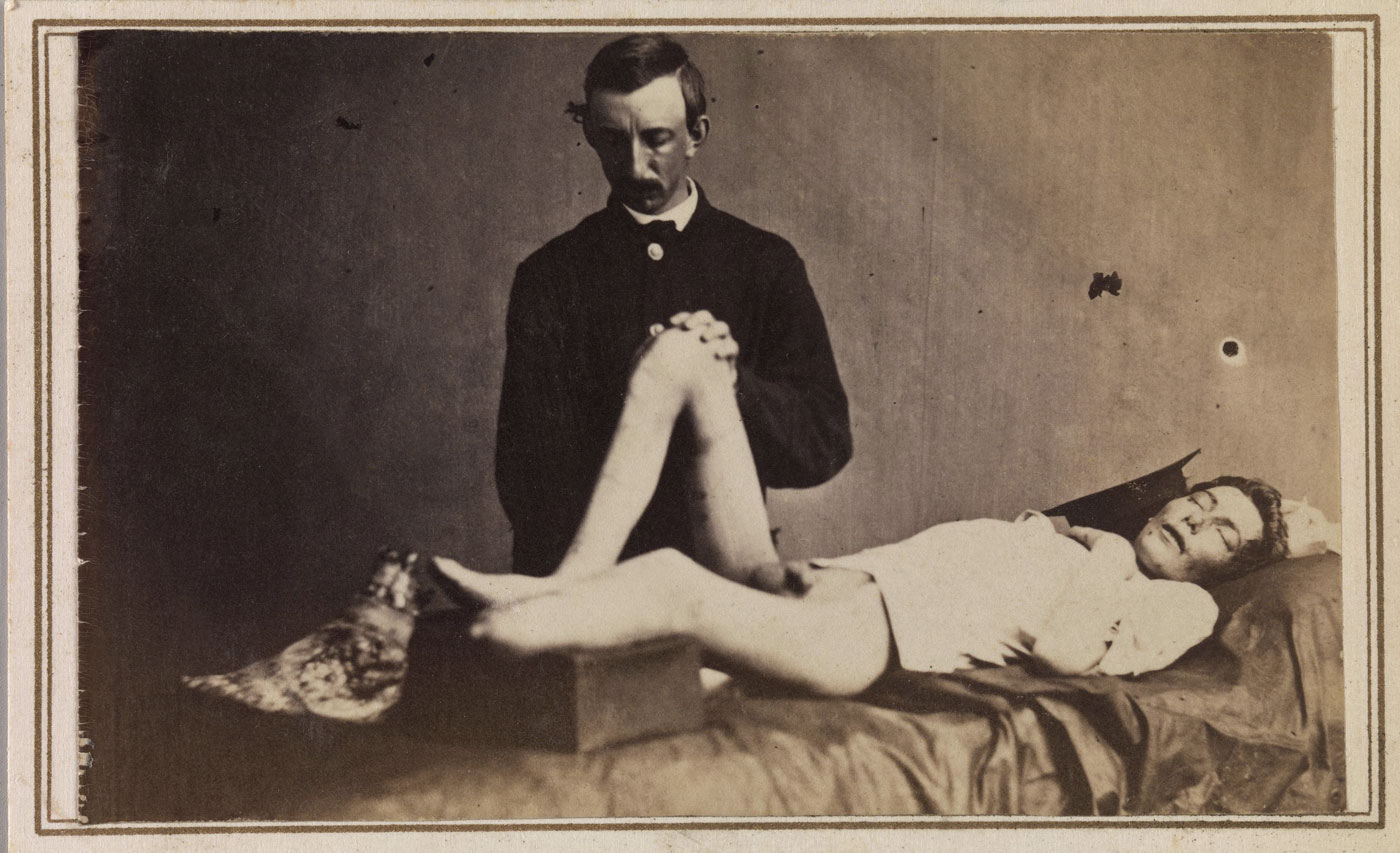

Reed Brockway Bontecou (American, 1824-1907)

Union Private John Parmenter, Company G, Sixty-seventh Pennsylvania Volunteers (Union Private John Parmenter Under Anesthesia on an Operating Table with His Amputated Foot)

June 21, 1865

Carte de visite format albumen silver print from glass negative

5.7 x 9.1 cm (2 1/4 x 3 9/16 in.)

Collection Stanley B. Burns, M.D.

In this remarkable carte de visite, Private Parmenter lies unconscious from anaesthesia on an operating table at Harewood Hospital in Washington, D.C. To save his patient’s life, Doctor Bontecou amputated the soldier’s wounded, ulcerous foot. Before the discovery of antibiotics, gangrene was a dreaded and deadly infection that greatly contributed to the high mortality rate of soldiers during the Civil War.

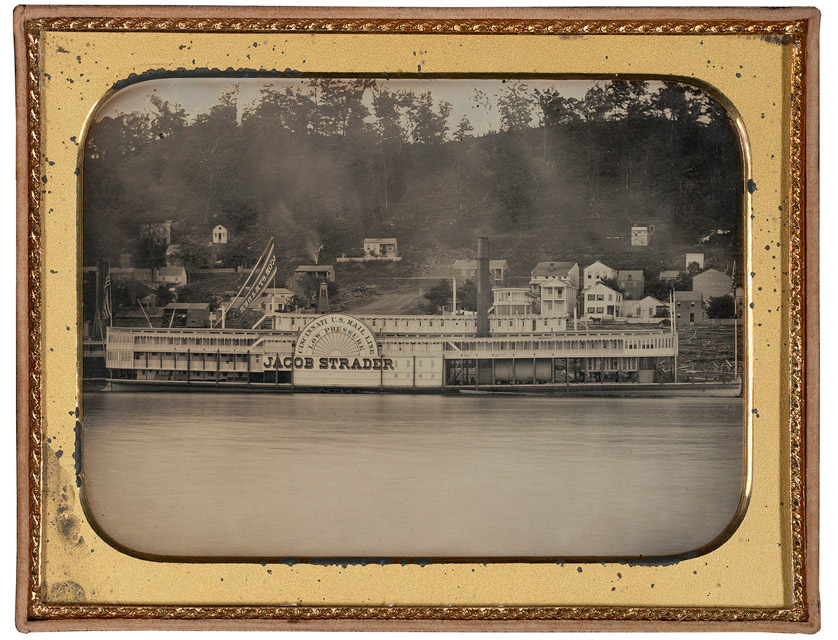

Andrew Joseph Russell (American, 1830-1902)

Slave Pen, Alexandria, Virginia

1863

Albumen silver print from glass negative

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gilman Collection, Purchase, The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 2005

© The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Better known for his later views commissioned by the Union Pacific Railroad, A. J. Russell, a captain in the 141st New York Infantry Volunteers, was one of the few Civil War photographers who was also a soldier. As a photographer-engineer for the U.S. Military Railroad Con struction Corps, Russell’s duty was to make a historical record of both the technical accomplishments of General Herman Haupt’s engineers and the battlefields and camp sites in Virginia. This view of a slave pen in Alexandria guarded, ironically, by Union officers shows Russell at his most insightful; the pen had been converted by the Union Army into a prison for captured Confederate soldiers.

Between 1830 and 1836, at the height of the American cotton market, the District of Columbia, which at that time included Alexandria, Virginia, was considered the seat of the slave trade. The most infamous and successful firm in the capital was Franklin & Armfield, whose slave pen is shown here under a later owner’s name. Three to four hundred slaves were regularly kept on the premises in large, heavily locked cells for sale to Southern plantation owners. According to a note by Alexander Gardner, who published a similar view, “Before the war, a child three years old, would sell in Alexandria, for about fifty dollars, and an able-bodied man at from one thousand to eighteen hundred dollars. A woman would bring from five hundred to fifteen hundred dollars, according to her age and personal attractions.”

Late in the 1830s Franklin and Armfield, already millionaires from the profits they had made, sold out to George Kephart, one of their former agents. Although slavery was outlawed in the District in 1850, it flourished across the Potomac in Alexandria. In 1859, Kephart joined William Birch, J. C. Cook, and C. M. Price and conducted business under the name of Price, Birch & Co. The partnership was dissolved in 1859, but Kephart continued operating his slave pen until Union troops seized the city in the spring of 1861.

Unknown Artist, after an 1860 carte de visite by Mathew B. Brady

Presidential Campaign Medal with Portraits of Abraham Lincoln and Hannibal Hamlin

1860

Tintypes in stamped brass medallion

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, The Overbrook Foundation Gift, 2012

© The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

More than 200 of the finest and most poignant photographs of the American Civil War have been brought together for the landmark exhibition Photography and the American Civil War, opening April 2 at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Through examples drawn from the Metropolitan’s celebrated holdings of this material, complemented by exceptional loans from public and private collections, the exhibition will examine the evolving role of the camera during the nation’s bloodiest war. The “War between the States” was the great test of the young Republic’s commitment to its founding precepts; it was also a watershed in photographic history. The camera recorded from beginning to end the heartbreaking narrative of the epic four-year war (1861-1865) in which 750,000 lives were lost. This traveling exhibition will explore, through photography, the full pathos of the brutal conflict that, after 150 years, still looms large in the American public’s imagination.

At the start of the Civil War, the nation’s photography galleries and image purveyors were overflowing with a variety of photographs of all kinds and sizes, many examples of which will be featured in the exhibition: portraits made on thin sheets of copper (daguerreotypes), glass (ambrotypes), or iron (tintypes), each housed in a small decorative case; and larger, “painting-sized” likenesses on paper, often embellished with India ink, watercolour, and oils. On sale in bookshops and stationers were thousands of photographic portraits on paper of America’s leading statesmen, artists, and actors, as well as stereographs of notable scenery from New York’s Broadway to Niagara Falls to the canals of Venice. Viewed in a stereopticon, the paired images provided the public with seeming three-dimensionality and the charming pleasure of traveling the world in one’s armchair.

Photography and the Civil War will include: intimate studio portraits of armed Union and Confederate soldiers preparing to meet their destiny; battlefield landscapes strewn with human remains; rare multi-panel panoramas of the killing fields of Gettysburg and destruction of Richmond; diagnostic medical studies of wounded soldiers who survived the war’s last bloody battles; and portraits of Abraham Lincoln as well as his assassin John Wilkes Booth. The exhibition features groundbreaking works by Mathew B. Brady, George N. Barnard, Alexander Gardner, and Timothy O’Sullivan, among many others. It also examines in-depth the important, if generally misunderstood, role played by Brady, perhaps the most famous of all wartime photographers, in conceiving the first extended photographic coverage of any war. The exhibition addresses the widely held, but inaccurate, belief that Brady produced most of the surviving Civil War images, although he actually made very few field photographs during the conflict. Instead, he commissioned and published, over his own name and imprint, negatives made by an ever-expanding team of field operators, including Gardner, O’Sullivan, and Barnard.

The exhibition will feature Gardner’s haunting views of the dead at Antietam in September 1862, which are believed to be the first photographs of the Civil War seen in a public exhibition. A reporter for the New York Times wrote on October 20, 1862, about the images shown at Brady’s New York City gallery: “Mr. Brady has done something to bring home to us the terrible reality and earnestness of war. If he has not brought bodies and laid them in our dooryards and along the streets, he has done something very like it… Here lie men who have not hesitated to seal and stamp their convictions with their blood – men who have flung themselves into the great gulf of the unknown to teach the world that there are truths dearer than life, wrongs and shames more to be dreaded than death.”

Approximately 1,000 photographers worked separately and in teams to produce hundreds of thousands of photographs – portraits and views – that were actively collected during the period (and over the past century and a half) by Americans of all ages and social classes. In a direct expression of the nation’s changing vision of itself, the camera documented the war and also mediated it by memorialising the events of the battlefield as well as the consequent toll on the home front.

Among the many highlights of the exhibition will be a superb selection of early wartime portraits of soldiers and officers who sat for their likenesses before leaving their homes for the war front. In these one-of-a-kind images, a picture of American society emerges. The rarest are ambrotypes and tintypes of Confederates, drawn from the renowned collection of David Wynn Vaughan, who has assembled the country’s premier archive of Southern portraits. These seldom-seen photographs, and those by their Northern counterparts, will balance the well-known and often-reproduced views of bloody battlefields, defensive works, and the specialised equipment of 19th-century war.

The show will focus special attention on the remarkable images included in the two great wartime albums of original photographs: Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of War and George N. Barnard’s Photographic Views of Sherman’s Campaign, both released in 1866. The former publication includes 100 views commissioned, sequenced, and annotated by Alexander Gardner. This two-volume opus provides an epic documentation of the war seen through the photographs of 11 artists, including Gardner himself. It features 10 plates of Gettysburg, including Timothy O’Sullivan’s A Harvest of Death, Gettysburg, and Gardner’s Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter, Gettysburg, both of which are among the most well-known and important images from the early history of photography. The second publication includes 61 large-format views by a single artist, George N. Barnard, who followed the army campaign of one general, William Tecumseh Sherman, in the final months of the war – the “March to the Sea” from Tennessee to Georgia in 1864 and 1865. The exhibition explores how different Barnard’s photographs are from those in Gardner’s Sketch Book, and how distinctly Barnard used the camera to serve a nation trying to heal itself after four long years of war and brother-versus-brother bitterness.

Among the most extraordinary, if shocking, photographs in the exhibition are the portraits by Dr. Reed Brockway Bontecou of wounded and sick soldiers from the war’s last battles. Drawn from a private medical teaching album put together by this Civil War surgeon and head of Harewood Hospital in Washington, D.C., and on loan from the celebrated Burns Archive, the photographs are notable for their humanity and their aesthetics. They recall Walt Whitman’s words from 1865, that war “was not a quadrille in a ball-room. Its interior history will not only never be written, its practicality, minutia of deeds and passions, will never be suggested.” Bontecou’s medical portraits offer a glimpse of what the poet thought was not possible.

In addition to providing a thorough analysis of the camera’s incisive documentation of military activity and its innovative use as a teaching tool for medical doctors, the exhibition explores other roles that photography played during the war. It investigates the relationship between politics and photography during the tumultuous period and presents exceptional political ephemera from the private collection of Brian Caplan, including: a rare set of campaign buttons from 1860 featuring original tintype portraits of the competing candidates; a carved tagua nut necklace featuring photographic portraits of Confederate President Jefferson Davis and two members of his cabinet; and an extraordinary folding game board composed of photographic likenesses of President Lincoln and his generals. The show also includes an inspiring carte de visite portrait of the abolitionist and human rights activist Sojourner Truth. A former slave from New York State, she sold photographs of herself to raise money to educate emancipated slaves, and to support widows, orphans, and the wounded. And finally the exhibition includes the first photographically illustrated “wanted” poster, a printed broadside with affixed photographic portraits that led to the capture John Wilkes Booth and his fellow conspirators after the assassination of President Lincoln in April 1865.

Press release from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

![Unknown (American) '[Broadside for the Capture of John Wilkes Booth, John Surratt, and David Herold]' April 20, 1865 Unknown (American) '[Broadside for the Capture of John Wilkes Booth, John Surratt, and David Herold]' April 20, 1865](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/broadside-for-the-capture-of-john-wilkes-booth-web.jpg?w=534&h=1016)

Unknown (American)

[Broadside for the Capture of John Wilkes Booth, John Surratt, and David Herold]

Artist: Alexander Gardner (American, Glasgow, Scotland 1821-1882 Washington, D.C.)

Photography Studio: Silsbee, Case & Company (American, active Boston)

Photography Studio: Unknown

April 20, 1865

Ink on paper with three albumen silver prints from glass negatives

Sheet: 60.5 x 31.3cm (23 13/16 x 12 5/16 in.)

Each photograph: 8.6 x 5.4cm (3 3/8 x 2 1/8 in.)

Collages

Gilman Collection, Purchase, The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 2005

On the night of April 14, 1865, just five days after Lee’s surrender to Grant at Appomattox, John Wilkes Booth shot Lincoln at the Ford Theatre in Washington, D.C. Within twenty-four hours, Secret Service director Colonel Lafayette Baker had already acquired photographs of Booth and two of his accomplices. Booth’s photograph was secured by a standard police search of the actor’s room at the National Hotel; a photograph of John Surratt, a suspect in the plot to kill Secretary of State William Seward, was obtained from his mother, Mary (soon to be indicted as a fellow conspirator), and David Herold’s photograph was found in a search of his mother’s carte-de-visite album. The three photographs were taken to Alexander Gardner’s studio for immediate reproduction. This bill was issued on April 20, the first such broadside in America illustrated with photographs tipped onto the sheet.

The descriptions of the alleged conspirators combined with their photographic portraits proved invaluable to the militia. Six days after the poster was released Booth and Herold were recognised by a division of the 16th New York Cavalry. The commanding officer, Lieutenant Edward Doherty, demanded their unconditional surrender when he cornered the two men in a barn near Port Royal, Virginia. Herold complied; Booth refused. Two Secret Service detectives accompanying the cavalry, then set fire to the barn. Booth was shot as he attempted to escape; he died three hours later. After a military trial Herold was hanged on July 7 at the Old Arsenal Prison in Washington, D.C.

Surratt escaped to England via Canada, eventually settling in Rome. Two years later a former schoolmate from Maryland recognised Surratt, then a member of the Papal Guard, and he was returned to Washington to stand trial. In September 1868 the charges against him were nol-prossed after the trial ended in a hung jury. Surratt retired to Maryland, worked as a clerk, and lived until 1916.

Attributed to McPherson & Oliver (American, active New Orleans and Baton Rouge, Louisiana, 1860s)

The Scourged Back

April 1863

Albumen silver print from glass negative

8.7 x 5.5cm (3 7/16 x 2 3/16 in.)

International Center of Photography, Purchase, with funds provided by the ICP Acquisitions Committee, 2003

Gordon, a runaway slave seen with severe whipping scars in this haunting carte-de-visite portrait, is one of the many African Americans whose lives Sojourner Truth endeavoured to better. Perhaps the most famous of all known Civil War-era portraits of slaves, the photograph dates from March or April 1863 and was made in a camp of Union soldiers along the Mississippi River, where the subject took refuge after escaping his bondage on a nearby Mississippi plantation.

On Saturday, July 4, 1863, this portrait and two others of Gordon appeared as wood engravings in a special Independence Day feature in Harper’s Weekly. McPherson & Oliver’s portrait and Gordon’s narrative in the newspaper were extremely popular, and photography studios throughout the North (including Mathew B. Brady’s) duplicated and sold prints of The Scourged Back. Within months, the carte de visite had secured its place as an early example of the wide dissemination of ideologically abolitionist photographs.

J. W. Jones (American, active Orange, Massachusetts, 1860s)

Emaciated Union Soldier Liberated from Andersonville Prison

1865

Albumen silver print from glass negative

Image: 9 x 5.5cm (3 9/16 x 2 3/16 in.)

Brian D. Caplan Collection

Most soldiers who survived Andersonville Prison were marked for life. This portrait of an unidentified former prisoner is one of many that document the intense cruelty of prison life during the Civil War. It would be another eighty years, at the end of World War II, before anyone would see comparable pictures of man’s inhumanity to man.

George Wertz (American, active Kansas City, Missouri, 1860s)

Private William Henry Lord, Company I, Eleventh Kansas Volunteer Cavalry

1863-1865

Albumen silver print from glass negative

8.4 x 5.6cm (3 5/16 x 2 3/16 in.)

W. Bruce and Delaney H. Lundberg Collection

Private William Henry Lord, a cavalryman, sits alert and ready for the next ride. A yet unmuddied enlistee from “Bleeding Kansas,” the last state to enter the Union before Fort Sumter, Lord was in the Eleventh Kansas Volunteer Cavalry; he was wounded in the shoulder in October 1864 but rejoined his company and was mustered out in September 1865.

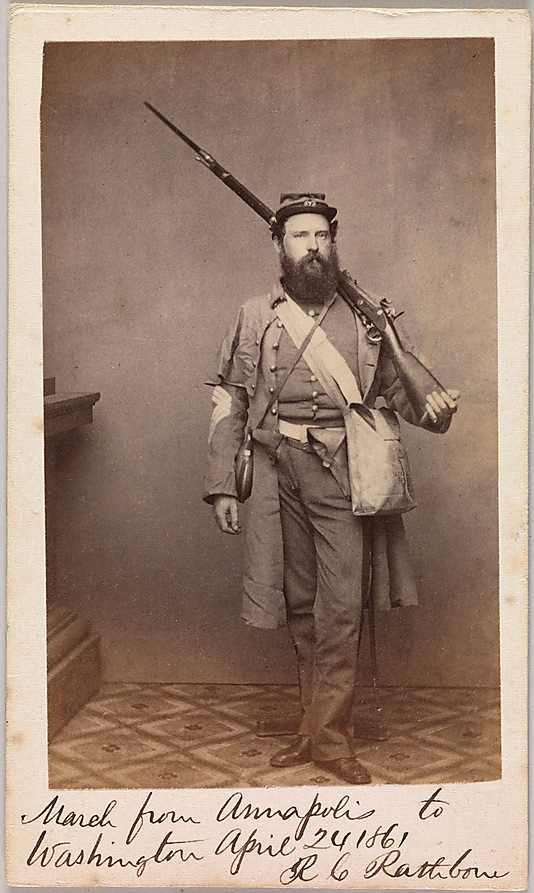

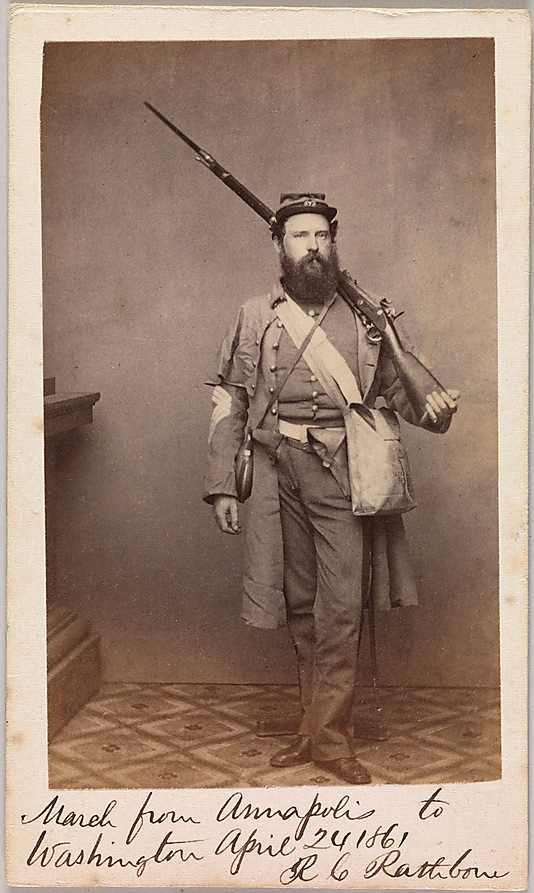

Unknown photographer

March from Annapolis to Washington, Robert C. Rathbone, Sergeant Major, Seventh Regiment, New York Militia

April 24, 1861

Albumen silver print from glass negative

8.9 x 5.4cm (3 1/2 x 2 1/8 in.)

Michael J. McAfee Collection

The Seventh Regiment, New York Militia was among the first military groups to leave for Washington, D.C., after Lincoln’s call to arms in April 1861. In or near Annapolis, en route to the nation’s capital, Sergeant Major Rathbone posed for his portrait. He annotated his likeness with enough information to suggest that this image might be the first (identifiable) photograph of a soldier made after the fall of Fort Sumter. Representative of thousands of similar portraits, this study of an officer seen against a blank wall with just a hint of a studio column is typical of the simplicity of the earliest war pictures.

Note the stand just visible behind Sergeant Major Rathbone’s feet to brace the sitter for the long exposures necessary.

Mathew B. Brady (American, near Lake George, New York 1823? – 1896 New York)

General Robert E. Lee

1865

Albumen silver print from glass negative

14 × 9.3cm (5 1/2 × 3 11/16 in.)

Gilman Collection, Museum Purchase, 2005

Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered his army to Union General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House, Virginia, on April 9, 1865. The Civil War was over. If not whole, the nation was at least reunited, and the slow recovery of Reconstruction could begin. As soon as he heard that Lee had left Appomattox and returned to Richmond, Mathew B. Brady headed there with his camera equipment. The Lees’ Franklin Street residence had survived the fires that had devastated many of the commercial sections of the city. Through the kindness of Mrs. Lee and a Confederate colonel, Brady received permission to photograph the general on April 16, 1865, just two days after President Lincoln’s assassination. Brady’s portrait of General Lee holding his hat, on his own back porch, is one of the most reflective and thoughtful wartime likenesses. The fifty-eight-year-old Confederate hero poses in the uniform he had worn at the surrender. It would be Brady’s last wartime photograph.

Charles Paxson (American, active New York, 1860s)

Wilson, Branded Slave from New Orleans

1863

Albumen silver print from glass negative

8.4 x 5.3cm (3 5/16 x 2 1/16 in.)

Private Collection, Courtesy of William L. Schaeffer

On January 30, 1864, to fan the anti-slavery cause and promote the sale of abolitionist photographs, Harper’s Weekly published this carte de visite and three others as wood engravings. The newspaper also included stirring bibliographies of the emancipated slaves. The editors noted that Wilson Chinn was about sixty years old. His former master, Volsey B. Marmillion, a sugar planter near New Orleans, “was accustomed to brand his negroes, and Wilson has on his forehead the letters ‘V.B.M.'”

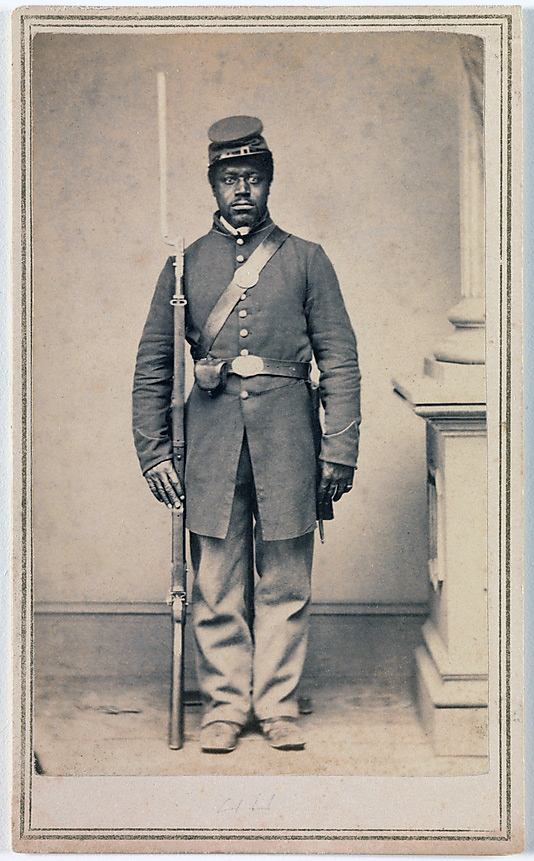

Gayford & Speidel (Active Rock Island, Illinois, 1860s)

Private Louis Troutman, Company F, 108th Regiment, U.S. Colored Infantry

January – May 1865

Albumen silver print from glass negative

8.8 x 5.4cm (3 7/16 x 2 1/8 in.)

Thomas Harris Collection

Samuel Masury (American, 1818-1874)

Frances Clalin Clayton

1864-1866

Albumen silver print from glass negative

9.4 x 5.6cm (3 11/16 x 2 3/16 in.)

Buck Zaidel Collection

Frances Clayton is an exception – a woman who served in the Union army by disguising herself as a man. In a popular carte de visite collected by soldiers at the end of the war, she poses here as Jack Williams and suggestively holds the handle of a cavalry sword between her crossed legs. The facts of her life story and military service are difficult to confirm, but it is believed that she served in the Missouri cavalry (or infantry) beside her husband, who died at the Battle of Stones River in late December 1862.

Reed Brockway Bontecou (American, 1824-1907)

Private Samuel Shoop, Company F, 200th Pennsylvania Infantry

April-May 1865

Albumen silver print from glass negative

18.9 × 13.1cm (7 7/16 × 5 3/16 in.)

Gift of Stanley B. Burns, M.D. and The Burns Archive, 1992

The last great battle of the Civil War was the siege of Petersburg, Virginia – a brutal campaign that led to Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s surrender on April 9, 1865. Samuel Shoop, a twenty-five-year-old private in Company F of the 200th Pennsylvania Volunteers, received a gunshot wound in the thigh at Fort Steadman on the first day of the campaign (March 25) and was evacuated to Harewood Hospital in Washington, D.C. His leg was amputated by Dr. Reed Brockway Bontecou, surgeon in charge, who also made this clinical photograph. It was intended, in part, to serve as a tool for teaching fellow army surgeons and is an extremely rare example of the early professional use of photography in America.

George N. Barnard (American, 1819-1902)

Bonaventure Cemetery, Four Miles from Savannah

1866

Albumen silver print from glass negative

34 x 26.4cm (13 3/8 x 10 3/8 in.)

Gilman Collection, Purchase, Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee Gift, 2005

Unknown photographer

Sojourner Truth, “I Sell the Shadow to Support the Substance”

1864

Albumen silver print from glass negative

Carte-de-visite

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Alfred Stieglitz Society Gifts, 2013

© The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Sojourner Truth (c. 1797 – November 26, 1883) was the self-given name, from 1843 onward, of Isabella Baumfree, an African-American abolitionist and women’s rights activist. Truth was born into slavery in Swartekill, Ulster County, New York, but escaped with her infant daughter to freedom in 1826. After going to court to recover her son, she became the first black woman to win such a case against a white man. Her best-known extemporaneous speech on gender inequalities, “Ain’t I a Woman?”, was delivered in 1851 at the Ohio Women’s Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio. During the Civil War, Truth helped recruit black troops for the Union Army; after the war, she tried unsuccessfully to secure land grants from the federal government for former slaves.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Mathew B. Brady (American born Ireland, 1823/1824-1896 New York)

Edward Anthony (American, 1818-1888)

Abraham Lincoln

February 27, 1860

Albumen silver print from glass negative

Carte-de-visite

The Meserve-Kunhardt Foundation

Three months before his nomination as the Republican Party candidate for president, Abraham Lincoln went East, stopping in New York City on February 27, 1860, to give a speech at the Cooper Institute (now the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art). Many considered Lincoln’s powerful antislavery lecture as his most important to date. The closing words spurred his audience and the country at large: “Let us have faith that right makes might, and in that faith, let us, to the end, dare to do our duty as we understand it.”

Earlier in the day he sat for this portrait at Mathew B. Brady’s gallery on Broadway and Tenth Street, just a few blocks from the lecture hall. Although his visit to the studio could not have lasted long, the result of this first of many portrait sessions with Brady was a simple but powerful image that would alter the visual landscape during the upcoming election. In a single exposure on a silver-coated sheet of glass, Brady captured the odd physiognomy of the man who would change the course of American history.

![Unknown photographer (American) '[Private James House with Fighting Knife, Sixteenth Georgia Cavalry Battalion, Army of Tennessee]' 1861-1862? Unknown photographer (American) '[Private James House with Fighting Knife, Sixteenth Georgia Cavalry Battalion, Army of Tennessee]' 1861-1862?](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/39-james-house-web.jpg?w=650&h=755)

Unknown photographer (American)

[Private James House with Fighting Knife, Sixteenth Georgia Cavalry Battalion, Army of Tennessee]

1861-1862?

Ambrotype

Sixth-plate; ruby glass

David Wynn Vaughan Collection

Image: Jack Melton

This portrait of a cavalryman is an excellent example of a well-armed Confederate soldier. Private House wears a slouch hat and a checked battle shirt seen through the gaps in a modified woollen shell jacket with tabbed button closures. He brandishes his fighting knife and for quick use has half removed a pocket revolver from its belted holster. Perhaps the most frightening weapons in House’s personal arsenal may be his focused stare and his set jaw.

16th Cavalry Battalion was assembled in May, 1862, at Big Shanty, Georgia, and was composed of six companies. It served in East Tennessee and Southwest Virginia and took part in the engagements at Blue Springs, Bean’s Station, Cloyd’s Mountain, and Marion. In January, 1865, the battalion merged into the 13th Georgia Cavalry Regiment. Lieutenant Colonels F.M. Nix and Samuel J. Winn, and Major Edward Y. Clarke were its commanding officers.

![Unknown photographer (American) '[Private James House with Fighting Knife, Sixteenth Georgia Cavalry Battalion, Army of Tennessee]' 1861-1862? (detail) Unknown photographer (American) '[Private James House with Fighting Knife, Sixteenth Georgia Cavalry Battalion, Army of Tennessee]' 1861-1862? (detail)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/39-james-house-detail.jpg?w=650&h=754)

Unknown photographer (American)

[Private James House with Fighting Knife, Sixteenth Georgia Cavalry Battalion, Army of Tennessee] (detail)

1861-1862?

Ambrotype

Sixth-plate; ruby glass

David Wynn Vaughan Collection

Image: Jack Melton

Unknown photographer (American)

Union Sergent John Emery

1861-1865

Tintype

Plate: 8.9 x 6.4cm (3 1/2 x 2 1/2 in.)

Case: 10 × 8.9cm (3 15/16 × 3 1/2 in.)

The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Fund, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 2012

The only details presently known about this handsome, young Union sergeant wearing a striped bowtie and an imported English snake belt buckle derive from a small paper note found behind the portrait inside the thermoplastic case: “Uncle John Emery / brother of / Lucy King / buried at E. Concord / died in 1876 / buried at back in right corner.”

![Unknown photographer (American) '[Private Thomas Gaston Wood, Drummer, Company H, "Walton Infantry," Eleventh Regiment Georgia Volunteer Infantry]' 1861 Unknown photographer (American) '[Private Thomas Gaston Wood, Drummer, Company H, "Walton Infantry," Eleventh Regiment Georgia Volunteer Infantry]' 1861](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/private-thomas-gaston-wood-web.jpg?w=650&h=713)

Unknown photographer (American)

[Private Thomas Gaston Wood, Drummer, Company H, “Walton Infantry,” Eleventh Regiment Georgia Volunteer Infantry]

1861

Tintype

Plate: 6.4 x 5.1cm (2 1/2 x 2 in.)

David Wynn Vaughan Collection

Private Wood sits against a blank wall in a photographer’s studio. He is sixteen years old and will not see seventeen. An orphan, he joined Company H in Social Circle, Georgia, on July 3, 1861, and before the end of the year died of pneumonia in a Richmond hospital. Wood seems proud of his shell jacket and especially his kepi, which he marked under the brim with his initials. The photographer tipped up the cap to reveal the sitter’s handiwork, but the letters are laterally reversed in the tintype. As a musician, he poses without any prop other than his uniform, the buttons touched with gold.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

1000 Fifth Avenue at 82nd Street

New York, New York 10028-0198

Phone: 212-535-7710

Opening hours:

Sunday – Tuesday and Thursday: 10am – 5pm

Friday and Saturday: 10am – 9pm

Closed Wednesday

The Metropolitan Museum of Art website

LIKE ART BLART ON FACEBOOK

Back to top

![Ed Ruscha (American, b. 1937) '708 S. Barrington Ave. [The Dolphin]' 1965 Ed Ruscha (American, b. 1937) '708 S. Barrington Ave. [The Dolphin]' 1965](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/708-s-barrington-ave-the-dolphin-1965-web.jpg?w=650&h=644)

![Unknown (American) '[Broadside for the Capture of John Wilkes Booth, John Surratt, and David Herold]' April 20, 1865 Unknown (American) '[Broadside for the Capture of John Wilkes Booth, John Surratt, and David Herold]' April 20, 1865](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/broadside-for-the-capture-of-john-wilkes-booth-web.jpg?w=534&h=1016)

![Unknown photographer (American) '[Private James House with Fighting Knife, Sixteenth Georgia Cavalry Battalion, Army of Tennessee]' 1861-1862? Unknown photographer (American) '[Private James House with Fighting Knife, Sixteenth Georgia Cavalry Battalion, Army of Tennessee]' 1861-1862?](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/39-james-house-web.jpg?w=650&h=755)

![Unknown photographer (American) '[Private James House with Fighting Knife, Sixteenth Georgia Cavalry Battalion, Army of Tennessee]' 1861-1862? (detail) Unknown photographer (American) '[Private James House with Fighting Knife, Sixteenth Georgia Cavalry Battalion, Army of Tennessee]' 1861-1862? (detail)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/39-james-house-detail.jpg?w=650&h=754)

![Unknown photographer (American) '[Private Thomas Gaston Wood, Drummer, Company H, "Walton Infantry," Eleventh Regiment Georgia Volunteer Infantry]' 1861 Unknown photographer (American) '[Private Thomas Gaston Wood, Drummer, Company H, "Walton Infantry," Eleventh Regiment Georgia Volunteer Infantry]' 1861](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/private-thomas-gaston-wood-web.jpg?w=650&h=713)

![Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960) 'Five Day Forecast [Prévisions à cinq jours]' 1988 Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960) 'Five Day Forecast (Prévisions à cinq jours)' 1988](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/lsimpson_02-web.jpg)

![Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960) 'Stereo Styles [Styles stéréo]' 1988 Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960) 'Stereo Styles (Styles stéréo)' 1988](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/lsimpson_15-web.jpg)

![Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960) 'Waterbearer [Porteuse d'eau]' 1986 Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960) 'Waterbearer [Porteuse d'eau]' 1986](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/lornasimpson_004-web.jpg)

![Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960) 'Chess [Échecs]' 2013 Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960) 'Chess (Échecs)' 2013](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/lsimpson_08-web.jpg)

![Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960) 'Chess [Échecs]' 2013 Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960) 'Chess (Échecs)' 2013](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/lsimpson_07-web.jpg)

![Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960) 'Cloudscape [Paysage nuageux]' 2004 Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960) 'Cloudscape (Paysage nuageux)' 2004](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/lsimpson_10-web.jpg?w=650&h=645)

![Lewis Hine (American, 1874-1940) '[Man on girders, Empire State Building]' c. 1931 Lewis Hine (American, 1874-1940) '[Man on girders, Empire State Building]' c. 1931](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/man-on-girders-web.jpg?w=650&h=838)

![Lewis Hine (American, 1874-1940) '[Steelworker touching the tip of the Chrysler Building]' c. 1931 Lewis Hine (American, 1874-1940) '[Steelworker touching the tip of the Chrysler Building]' c. 1931](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/steelworker-touching-the-tip-web.jpg?w=650&h=930)

You must be logged in to post a comment.