Exhibition dates: 17th May – 26th August 2013

Otto Wols (Alfred Otto Wolfgang Schulze) (German, 1913-1951)

Nicole Bouban, Autumn 1932 – October 1933 / january 1935-1937

1937, vintage print 1937

Gelatin silver print

300 x 240mm

Cabinet of Prints, Dresden State Art Collections

Another little known photographer (to me at least) that this archive likes promoting. Unfortunately the gallery did not supply many media images and there are few available online.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Otto Wols (Alfred Otto Wolfgang Schulze) (German, 1913-1951)

Untitled (Still life – wicker and birds)

1938 – August 1939, modern print 1970s

Gelatin silver paper (Agfa paper)

200 x 137 / 239 x 178mm

Cabinet of Prints, Dresden State Art Collections

Otto Wols (Alfred Otto Wolfgang Schulze) (German, 1913-1951)

Untitled (Still life – Grapefruit)

1938 – August 1939, early modern print without year

Gelatin silver paper (Agfa Brovira paper)

174 x 120 / 180 x 131mm

Cabinet of Prints, Dresden State Art Collections

Otto Wols (Alfred Otto Wolfgang Schulze) (German, 1913-1951)

Untitled (The Swiss Pavilion – Drahtfigurine)

1937, vintage print 1936-1937

Gelatin silver paper (Agfa Brovira paper)

242 x 180mm

Cabinet of Prints Dresden State Art Collections

Otto Wols (Alfred Otto Wolfgang Schulze) (German, 1913-1951)

Untitled (Paris – Eiffel Tower)

1937, modern printed 1970s

Gelatin silver print

205 x 139 / 240 x 178mm

Cabinet of Prints, Dresden State Art Collections

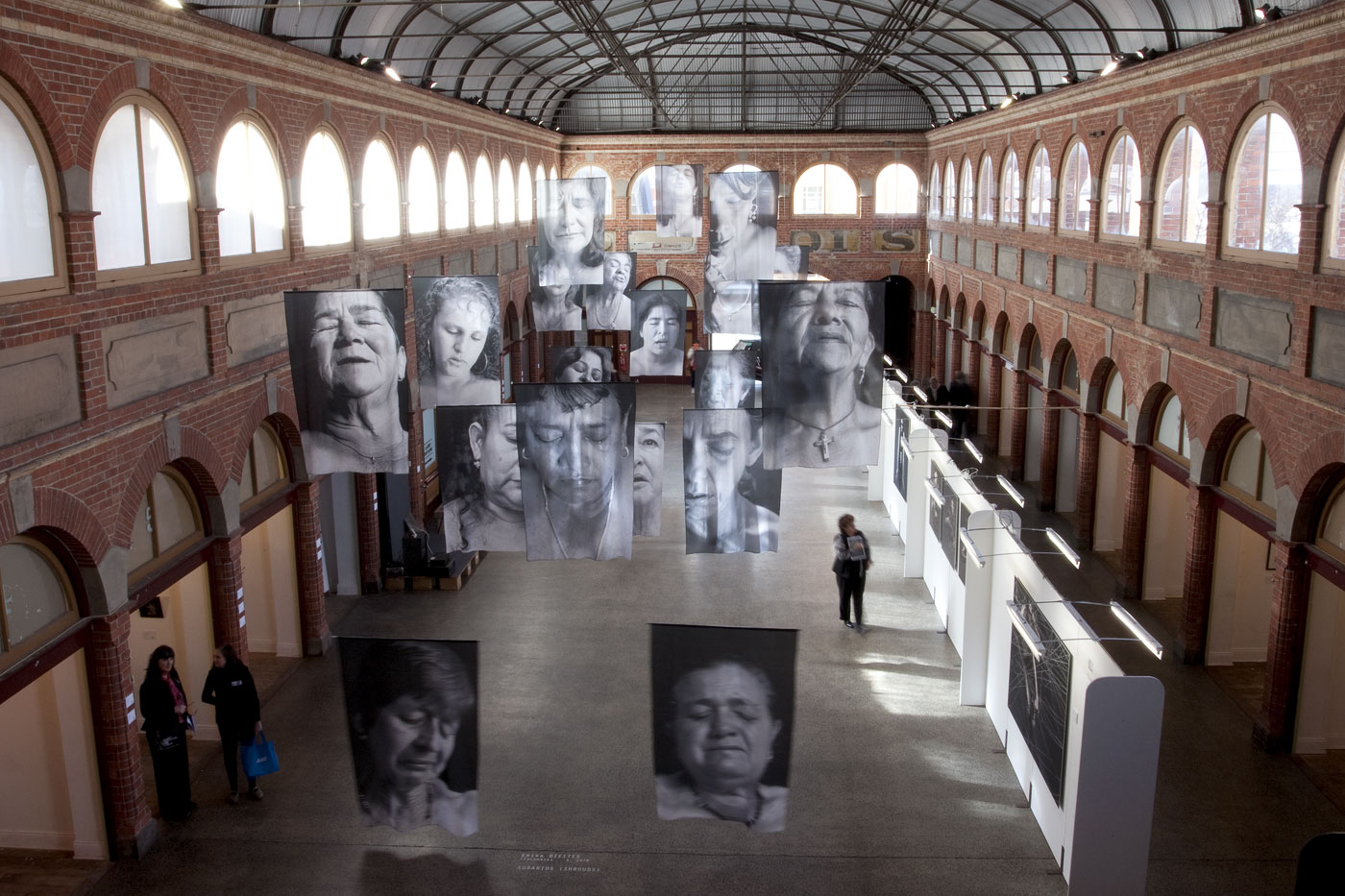

On the Occasion of the 100th Birthday of the Epochal Photographer, Painter and Graphic Artist. An exhibition by the Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden 17 May to 26 August 2013

Wols (1913-1951) is a key figure of post-war modernism. However, as this exhibition of his photography demonstrates, there are still aspects of his work which can come as a surprise and which amount to a remarkable discovery. Wols’ Photography: Images Regained, a retrospective marking the centenary of his birth, is the first exhibition to be devoted to a comprehensive exploration of his photographic work. It runs from 17 May to 26 August in the Dresden Kupferstich-Kabinett, and presents around 740 works, including modern prints from original negatives, contact prints and rare vintage prints made by Wols himself. The exhibition and its accompanying catalogue look beyond the myths surrounding Wols to focus on his artistic achievements, providing new insights based on recent art-historical reappraisal of works held in the Dresden collection.

In 1932 the artistically ambitious young nonconformist Wolfgang Schulze, alias Wols, left Dresden for Paris, where in 1951, at the age of 38, he was to die. Paris, at that time the undisputed metropolis of modernity and the avant-garde, held a magical attraction for young artists from all over the world intent on establishing themselves as photographers. In the brief period between 1932 and 1939 Wols created an impressive body of photographic work, a medium that he abandoned after 1945, when his attention turned to drawing and painting; after his death, this important aspect of his oeuvre was largely forgotten.

This presentation of Wols’ photography in the Dresden Kupferstich-Kabinett will later also be shown in Berlin, at the Martin-Gropius-Bau (15 March to 22 June 2014), a venue renowned for important photographic exhibitions, and a further showing in Paris is planned for autumn 2014. This means that this previously little-known, but central, body of work can be explored to an unprecedented extent in places which were of great significance at various stages in the artist’s life. Wols was born in Berlin, and briefly returned there as a young man, drawn to the creative force field of the Bauhaus, by then already in the process of dissolution; it was here that he received what was to be artistically crucial advice to move to Paris. In Dresden, in the intellectual circle of Ida Bienert, he had already become acquainted while still in his teens with facets of international modernism. Paris was where he ultimately achieved artistic fulfilment and recognition.

The exhibition draws on the important resources preserved in the estate of the artist’s sister, Elfriede Schulze-Battmann, now held in the Kupferstich-Kabinett. In addition to correspondence, this archive contains more than 1,000 works, most of which are modern prints made in the 1960s and 1970s, and is the world’s most extensive collection of Wols’ photographic work. The importance of Wols as a major figure of post-war modernism is underlined in two further exhibitions marking the 100th anniversary of his birth: Kunsthalle Bremen: Wols: Die Retrospektive (Wols. The Retrospective) (13 April – 11 August 2013); Museum Wiesbaden: Wols: Das große Mysterium (Wols. The Great Mystery) (17 October 2013 – 26 January 2014).

As a photographer (1913-1951) Wols continues to this day to be a discovery. The young, artistically ambitious, non-conformist left Dresden for Paris in 1932, where he began his artistic career as a portrait photographer. At that time, Paris, undisputedly the metropolis of the avant-garde and modern life, attracted free spirits from all over the world to seek their fortune. From 1932 to 1939 Wols created his impressive photographic oeuvre, which after 1945 he abandoned as a result of adverse circumstances and a shift in his interest to drawing and painting. In the years following his early death, the few preserved photos and negatives were nearly forgotten.

Today the Dresdener Kupferstich-Kabinett (Collection of Prints, Drawings and Photographs) holds the internationally most important collection of his photographic oeuvre, which was preserved in the estate of his sister, Elfriede Schulze-Battmann. It contains rare modern prints, produced from the original negatives in the 1960s and 1970s, and a small number of valuable vintage prints made by Wols himself.

Press release from the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden website

Otto Wols (Alfred Otto Wolfgang Schulze) (German, 1913-1951)

Plate with soup and conch

1936-1939

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2009

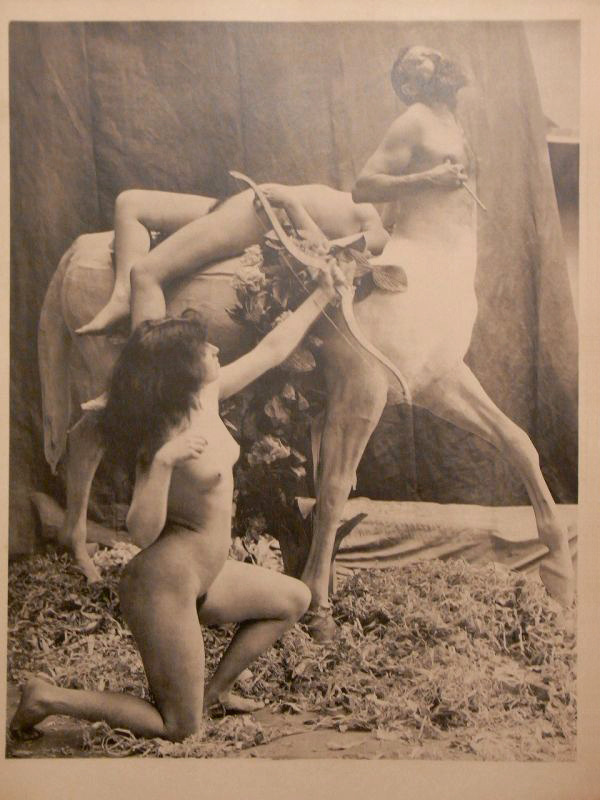

Otto Wols (Alfred Otto Wolfgang Schulze) (German, 1913-1951)

Doll with Robe

1937

From the series of studies Exposition Internationale de Paris. Pavillon de l’Elegance

Gelatin silver print on photo paper

26.3 x 17.8cm

Otto Wols (Alfred Otto Wolfgang Schulze) (German, 1913-1951)

Jean Sendy (Abelson) with monocle

c. 1930

Gelatin silver photograph

23.8 x 17.4cm (irreg.)

Jean Sendy (French, 1910-1978) is a French writer and translator, author of works on esoterica and UFO phenomena. He was also an early proponent of the ancient astronaut hypothesis.

He wrote the 1968 book The moon: The key to the Bible in which he claimed the God mentioned in Genesis of the Bible should be translated in plural as “Gods”, and that the “Gods” were actually space travellers (an alien race of humanoids). Sendy believed that Genesis was factual history of ancient astronauts colonising earth who became “angels in human memory”. The book contains similar ideas to that of the UFO religion Raëlism.

In his 1969 book Those Gods who made Heaven and Earth, Sendy claimed that space travellers 23,500 years ago arrived in the solar system in a large hollow sphere and seeded humanity.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Otto Wols (Alfred Otto Wolfgang Schulze) (German, 1913-1951)

Po Pol

1935

Gelatin silver print on photo paper

23 x 17.2cm

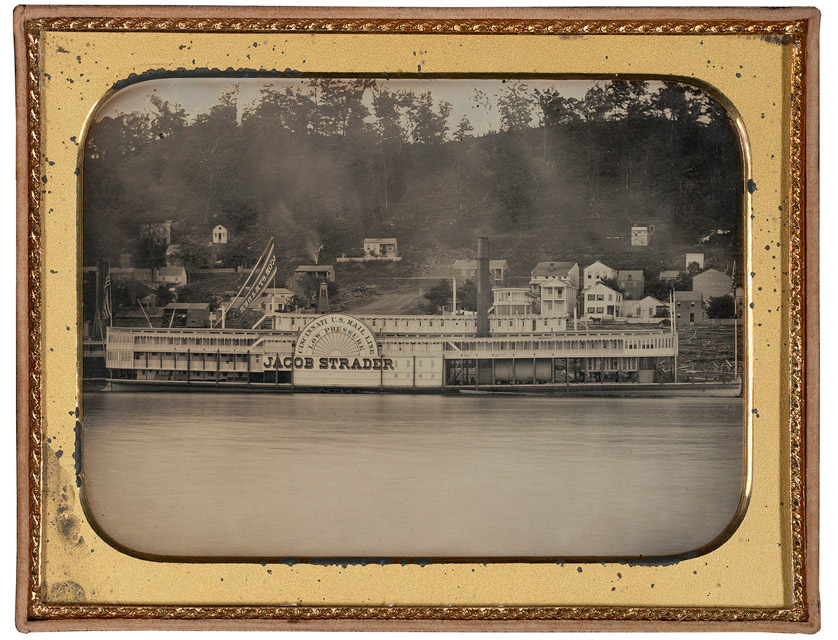

Otto Wols (Alfred Otto Wolfgang Schulze) (German, 1913-1951)

Untitled (Paris – Palisade) Fall 1932 – October 1933 / January 1935 – August 1939

1930, vintage print (Contact), 1930

Gelatin silver print

77 x 46mm

Cabinet of Prints, Dresden State Art Collections

Otto Wols (Alfred Otto Wolfgang Schulze) (German, 1913-1951)

Self Portrait

c. 1932-1933

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2013

Otto Wols (Alfred Otto Wolfgang Schulze) (German, 1913-1951)

Self-portrait

1938

Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Postfach 12 05 51

01006 Dresden

Phone: +49-351-49 14 2643

Opening hours:

Daily 10am – 6pm

Closed on Tuesdays

You must be logged in to post a comment.