Exhibition dates: 25th October 2019 – 2nd February 2020

Curator: Joel Smith

Duane Michals (American, b. 1932)

Self-Portrait Asleep in a Tomb of Mereruka Sakkara

1978

6 (5 x 7 inch) silver gelatin prints with hand-applied text

© Duane Michals, Courtesy DC Moore Gallery, New York

The Morgan Library & Museum

The things-for-which-there-are-no-words

Duane Michals is one of the greatest photographic storytellers of the twentieth century. His parables – seemingly simple stories used to illustrate a moral or spiritual lesson – resonate, vibrate, with energy, and insight into, the human condition. They are as profound as the air we breathe but cannot see – expressing the invisible, presencing the spiritual. I feel, I know these stories, intimately. Those things-for-which-there-are-no-words.

“Presencing. In 1885, Van Gogh, wrote a letter to his brother Theo: ‘Rembrandt goes so deep into the mysterious that he says things for which there are no words in any language. It is with justice that they call Rembrandt – [a] magician.’ (Letter from Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh [letter 534], on or about 10 October 1885, in Leo Jansen, Luijten and Nienke Bakker (eds.,). Vincent van Gogh: The Letters. Van Gogh Museum and the Huygens Institute, Amsterdam, 2009 [Online] Cited 11/10/2019)

The things-for-which-there-are-no-words remain hidden when approached with conceptual thought. They need to be experienced to be known. The currency of this experience, as we have seen, is deeply personal, but in allowing it we can touch on truth, perhaps even the truth.”1

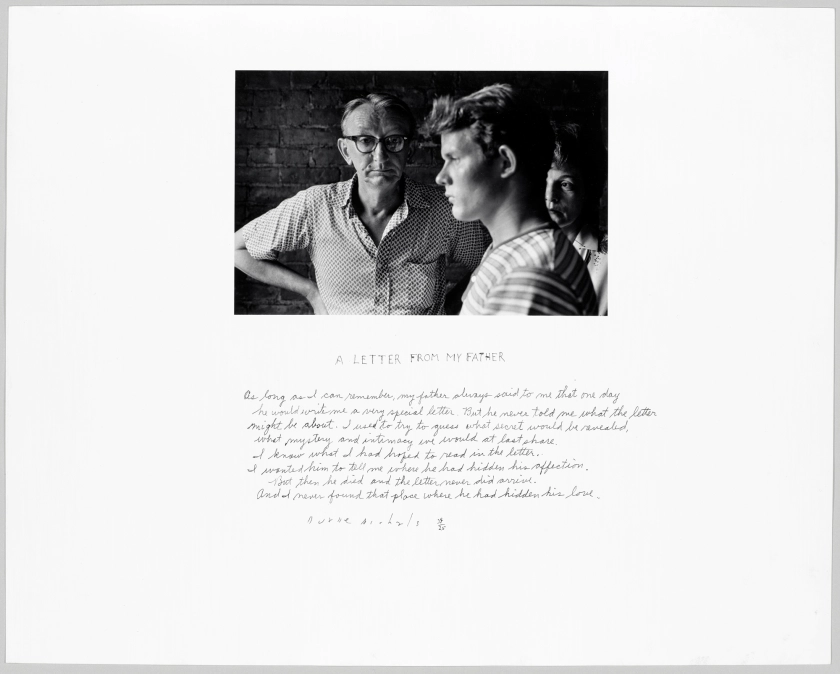

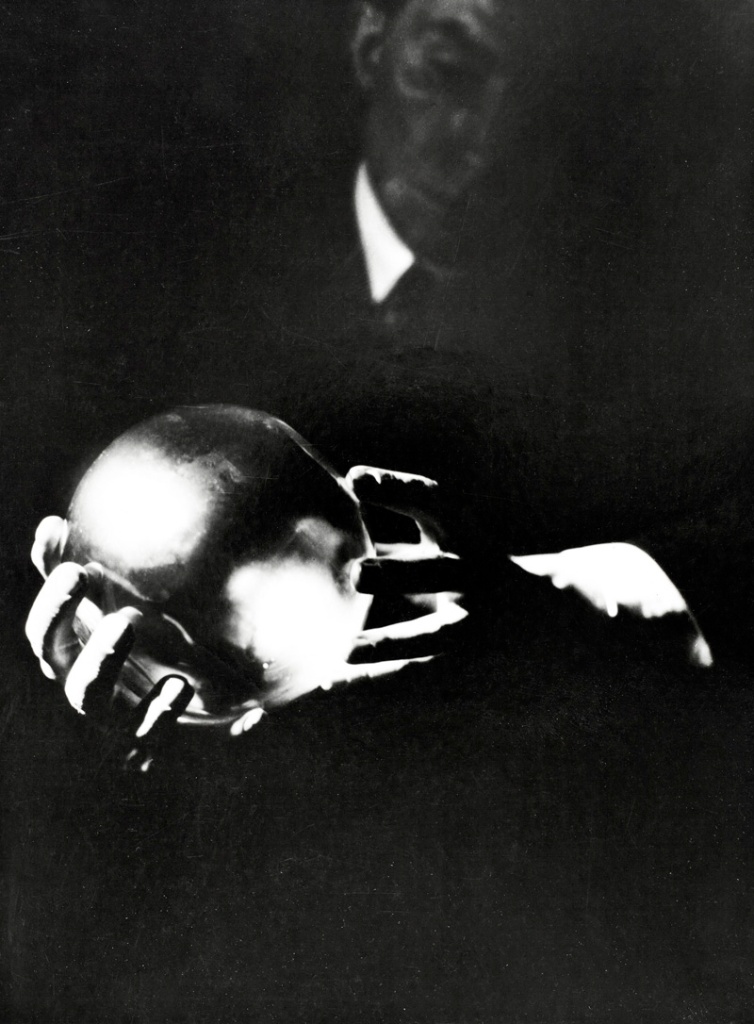

There are things here not seen in this photograph. The spirit leaves the body. William Blake and Duane Michals. Enchanted melancholy. The mysterious / music. In swift embrace. In love. In memory. In death. The fluidity of the line of the artist. Things are queer. The world implodes and ravages itself. Paradise is reborn. The letter, and love, from my father that I, also, never did receive. The nature of reality. Truth?

“I’m completely overwhelmed by the nature of our reality,” he is quoted as saying in the exhibition catalog about human evolution. “We’ve been working on this version of man for a thousand years. He lives longer, he’s healthier, but he’s still an unproven product. Still the same greedy little bastard.”

“For Michals, photography is not documentary in nature but theatrical and fictive: the camera is one of many tools humanity uses to construct a comprehensible version of reality. In his imaginative, visually rich photographs, the artist exploits the medium’s storytelling capacity,” says the press release. Isobel Crombie suggests the ‘medium’ of photography has ‘The ability to speak to us across time and to connect to the mind and the heart.’2

When I was young. What was time?

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ Kim Devereux. “Me and My Muse,” in the NGV Magazine Issue 19 Nov – Dec 2019, p. 55

2/ Isobel Crombie. “One Suggestive Moment,” in the NGV Magazine Issue 19 Nov – Dec 2019, p. 33

Many thankx to The Morgan Library & Museum for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

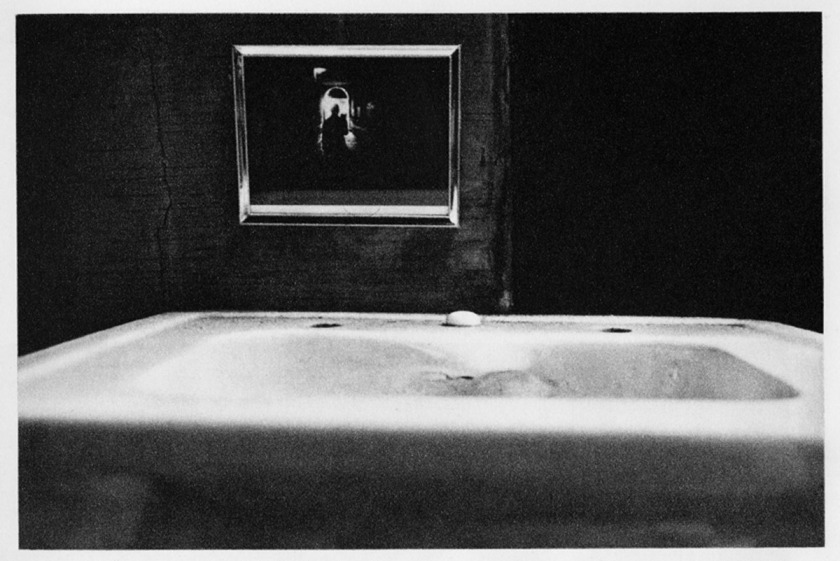

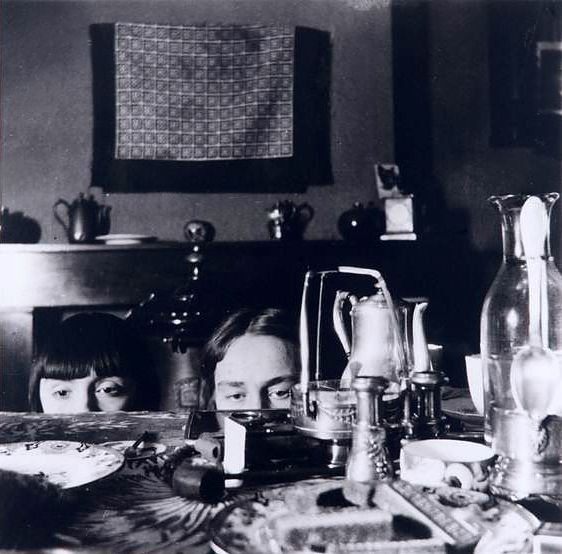

“I write with this photograph not to tell you what you can see, rather to express what is invisible.”

Duane Michals 1966 in Johnson, B. (ed.,) 2004, ‘Photography speaks: 150 photographers on their art’, Aperture, New York p. 150

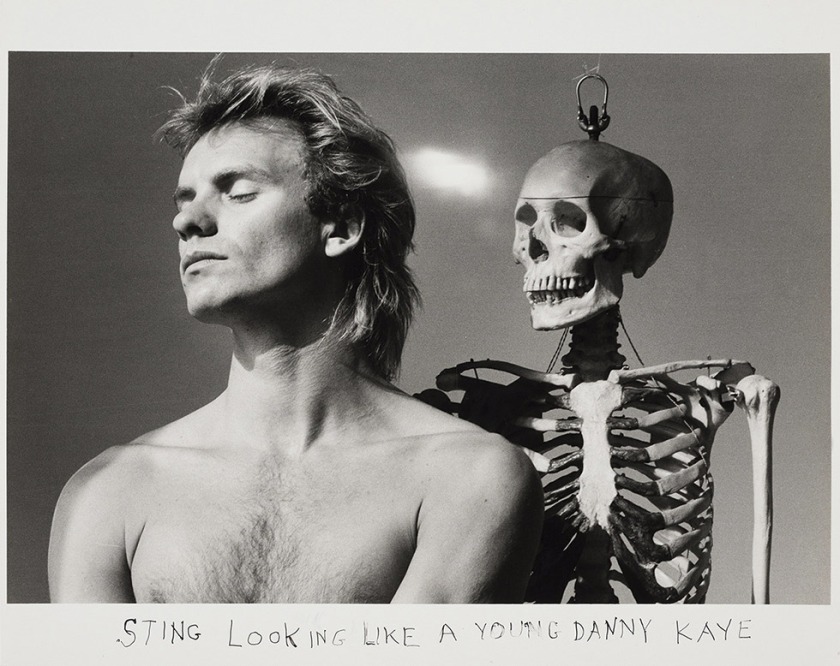

“I think photographs should be provocative and not tell you what you already know. It takes no great powers or magic to reproduce somebody’s face in a photograph. The magic is in seeing people in new ways.”

Duane Michals

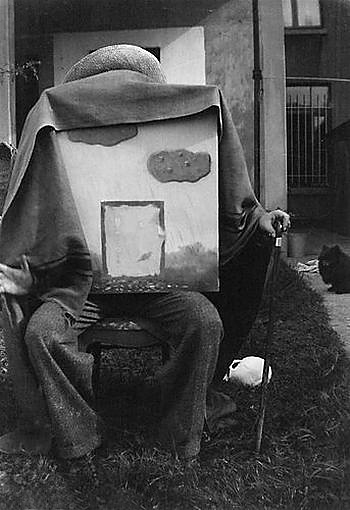

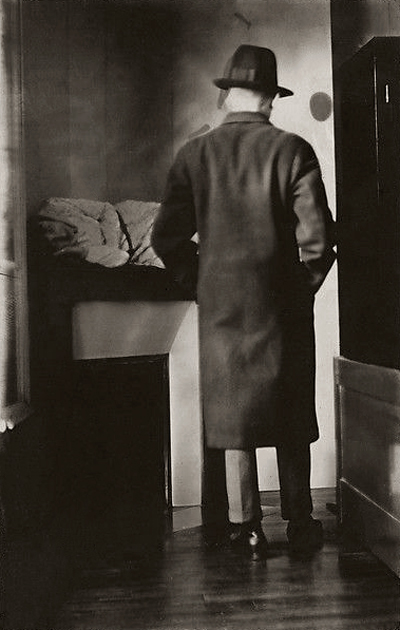

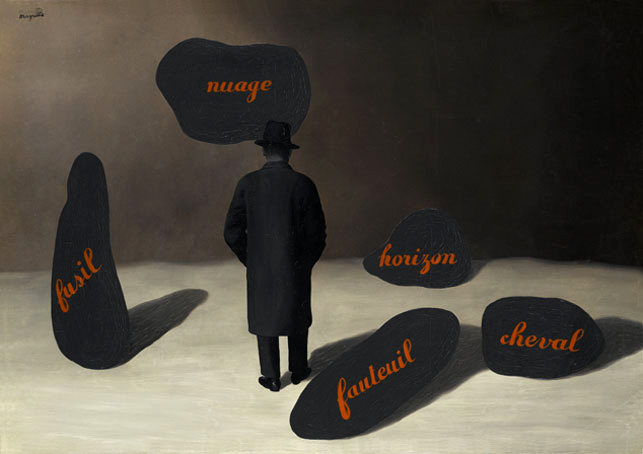

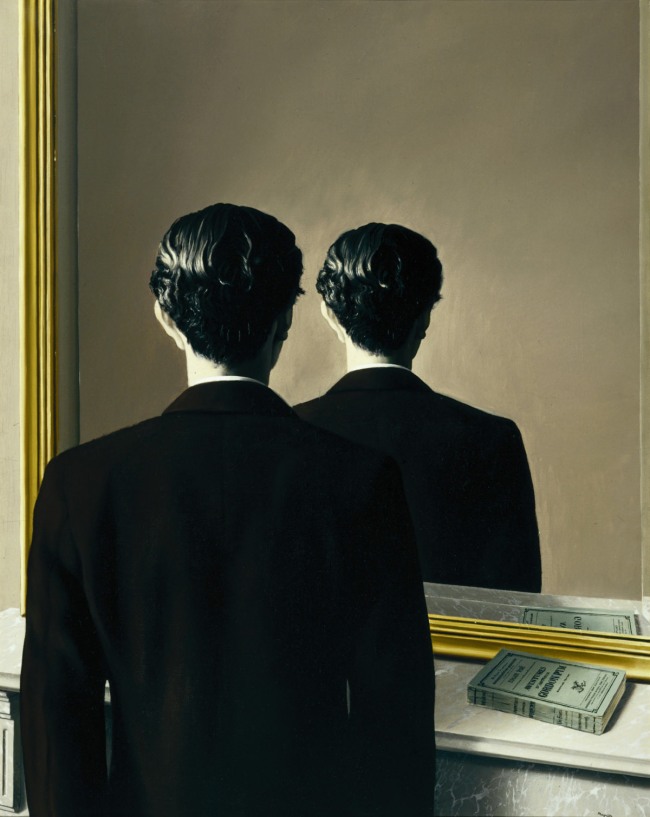

Duane Michals uses visual narrative, symbolism and metaphysical imagery to interpret the human condition. His photographic sequences have a film-like appearance and represent intangible elements of dreams, imagination, death, time, myth and spirit. A freelance commercial photographer, Michals began experimenting with sequence works in the 1960s, later adding text to illuminate emotion and philosophical ideas and following in the tradition of painters such as René Magritte and Giorgio de Chirico whom he greatly admired. His staged, fictive tableaux vivants are intimate scenes that explore the atmosphere of the invisible and metaphysical…

© Art Gallery of New South Wales Photography Collection Handbook, 2007

DEATH

Robert Wiles

Evelyn Francis McHale May 1, 1947

1947

Gelatin silver print

Overall: 9 1/2 × 8 in. (24.1 × 20.3cm)

Purchased on the Goldsmith Fund for Americana

The Morgan Library & Museum

“At the bottom of Empire State Building the body of Evelyn McHale reposes calmly in grotesque bier her falling body punched into the top of a car.”

LIFE Magazine caption

“On May Day, just after leaving her fiancé, 23-year-old Evelyn McHale wrote a note. “He is much better off without me. … I wouldn’t make a good wife for anybody,” she wrote. Then she crossed it out. She went to the observation platform of the Empire State Building. Through the mist she gazed at the street, 86 floors below. Then she jumped. In her desperate determination she leaped clear of the setbacks and hit a United Nations limousine parked at the curb. Across the street photography student Robert Wiles heard an explosive crash. Just four minutes after Evelyn McHale’s death Wiles got this picture of death’s violence and its composure.”

LIFE Magazine description

On 30 April she visited her fiancée in Easton presumably to celebrate his 24th birthday and boarded a train back to NYC at 7 a.m., 1 May 1947. Barry [Rhodes] stated to reporters that “When I kissed her goodbye she was happy and as normal as any girl about to be married.”

Of course we’ll never know what went through Evelyn’s mind on 66 mi train ride home. But after she arrived in New York she went to the Governor Clinton Hotel where she wrote a suicide note and shortly before 10:30 a.m. bought a ticket to the 86th floor observation deck of the Empire State Building.

Around 10:40 am Patrolman John Morrissey, directing traffic at Thirty-fourth Street and Fifth Avenue, noticed a white scarf floating down from the upper floors of the building. Moments later he heard a crash and saw a crowd converge on 34th street. Evelyn had jumped, cleared the setbacks, and landed on the roof of a United Nations Assembly Cadillac limousine parked on 34th street, some 200 ft west of Fifth Ave.

Across the street, Robert C. Wiles, a student photographer, also noticed the commotion and rushed to the scene where he took several photos, including this one, some four minutes after her death. Later, on the observation deck, Detective Frank Murray found her tan (or maybe gray, reports differ) cloth coat neatly folded over the observation deck wall, a brown make-up kit filled with family pictures and a black pocketbook with the note which read:

“I don’t want anyone in or out of my family to see any part of me. Could you destroy my body by cremation? I beg of you and my family – don’t have any service for me or remembrance for me. My fiance asked me to marry him in June. I don’t think I would make a good wife for anybody. He is much better off without me. Tell my father, I have too many of my mother’s tendencies.”

Lizz Buzz. “The Story Behind the “The Most Beautiful Suicide” Picture of Evelyn McHale (1947),” on the Atchuup! website April 23, 2019 [Online] Cited 17/11/2019

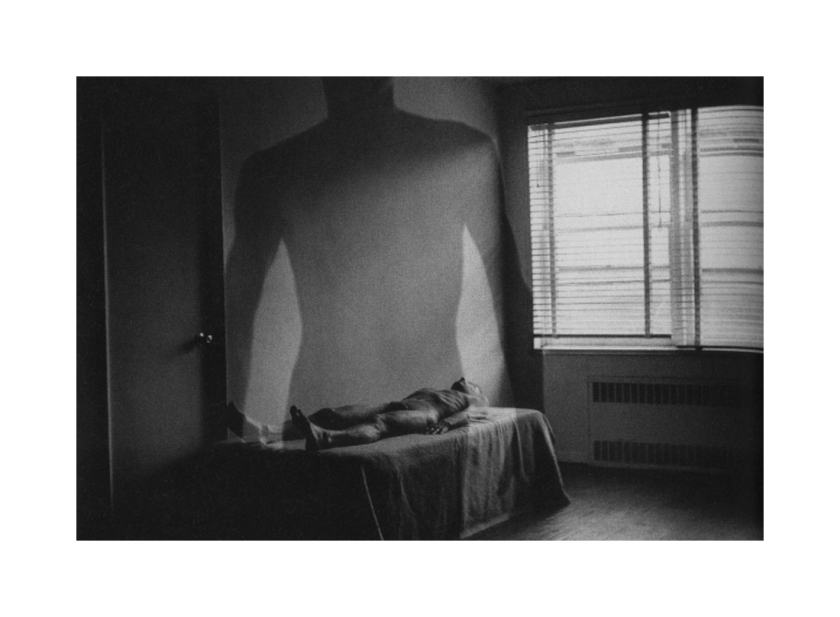

Duane Michals (American, b. 1932)

The Spirit Leaves the Body

1968

Gift of Richard and Ronay Menschel

The Morgan Library & Museum

Duane Michals (American, b. 1932)

I Build a Pyramid

1978

6 (5 x 7 inch) silver gelatin prints with hand-applied text

The Morgan Library & Museum

ILLUSION

Francesco Salviati (Italian, 1510-1563)

Emblematic Design with Two-Headed Horse and Moth

c. 1550-1563

Pen and brown ink, brown wash, on paper; framing lines at upper left and right edges in pen and brown ink

Overall: 7 1/2 × 7 3/8 in. (19.1 × 18.7cm)

Gift of János Scholz

The Morgan Library & Museum

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Satan Smiting Job with Boils

c. 1805-1810

Pen and black and grey ink, grey wash, and watercolour, over faint indications in pencil, on paper

Overall: 9 3/16 x 11 inches (233 x 280 mm)

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan (1837-1913) in 1909

The Morgan Library & Museum

Jehan Georges Vibert (French, 1840-1902)

A Cardinal in Profile

1880

Watercolour on paper

Overall: 4 7/8 × 3 3/8 in. (12.4 × 8.6cm)

Gift of John M. Thayer

The Morgan Library & Museum

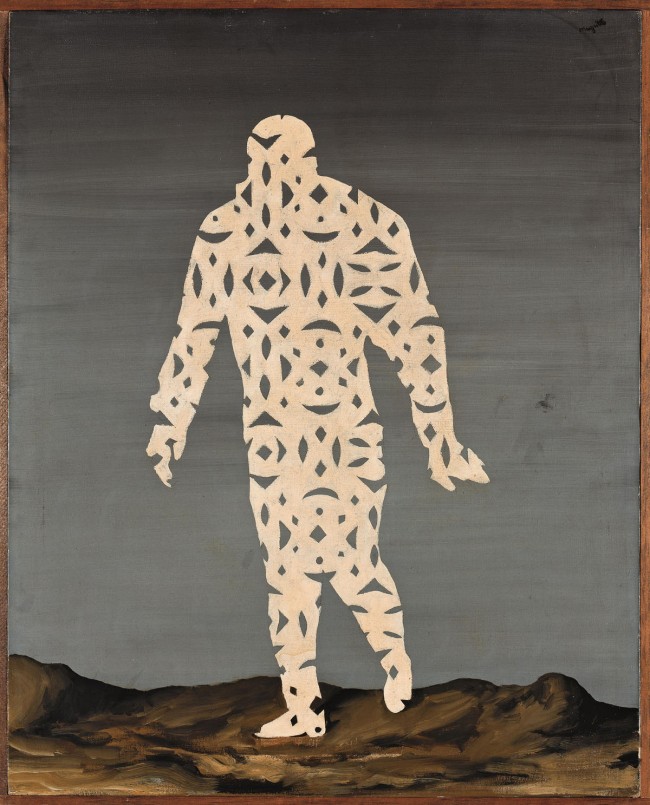

Henry Pearson (American, 1914-2006)

128th Psalm (Study for “Five Psalms”)

1968

Chinese ink on heavy paper

Overall: 23 1/2 × 18 in. (59.7 × 45.7cm)

Gift of Regina and Lawrence Dubin, M.D

The Morgan Library & Museum

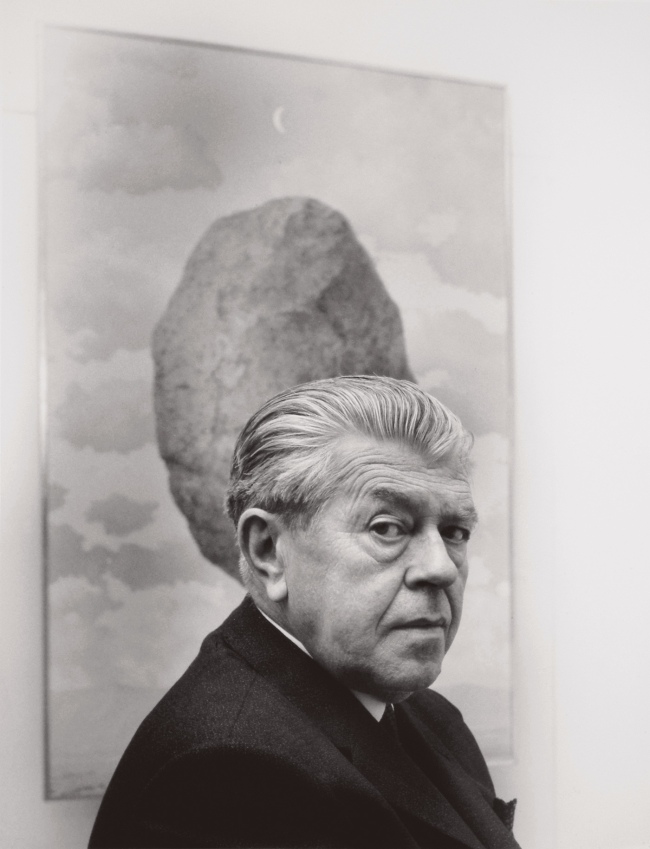

Duane Michals (American, b. 1932)

The Illuminated Man

1968

Gelatin silver print, unique print

Image: 15 5/8 x 22 7/8 inches

The Morgan Library & Museum

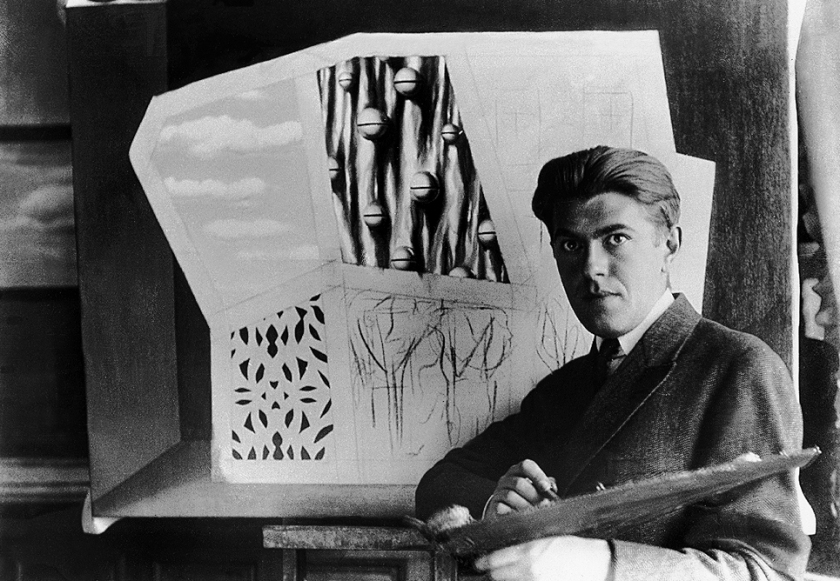

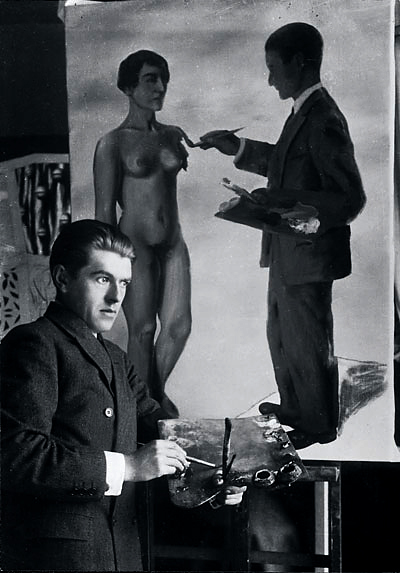

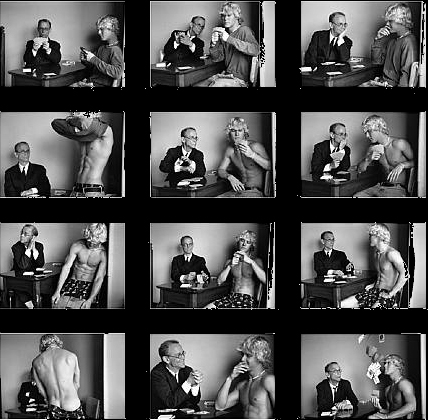

When Michals arrived in New York from Pittsburgh in the early 1950s, the city provided not only freedom from the strict conventions of his Catholic upbringing, but an opening to worlds of ideas and experiences that extended in all directions. By the early 1960s, he was living with his life partner, the architect Frederick Gorree (who passed away in 2017) and experimenting with the photographic image beyond the single frame, often including handwritten texts.

“Duane cut photography’s umbilical cord,” Smith said about the photographer’s contributions to the medium. “He saw there’s no reason to limit the camera to what you find in the world; it should be part of the history of expressing ideas.” Michals’s 1970 one-man show at the Museum of Modern Art confirmed his significance in establishing a new genre.

In the 1960s, he became interested in Buddhism and meditation, further expanding his artistic concerns. At the Morgan, Michals walked over to a large, eye-popping ink drawing by Henry Pearson, an abstract artist loosely associated with the Op Art movement. Pearson’s “128th Psalm (Study for ‘Five Psalms’)” from 1968, is a light-bulb-shaped form with lines emanating from the center like electrified nerve endings and pulsating out beyond the frame.

“This drawing is pure energy,” he said. That same year, Michals – who had not known Pearson’s work – made “The Illuminated Man,” a photograph of a male figure facing the camera, his head emanating light, suggesting enlightenment. “The Illuminated Man” and “128th Psalm” share the theme of spiritual radiance.

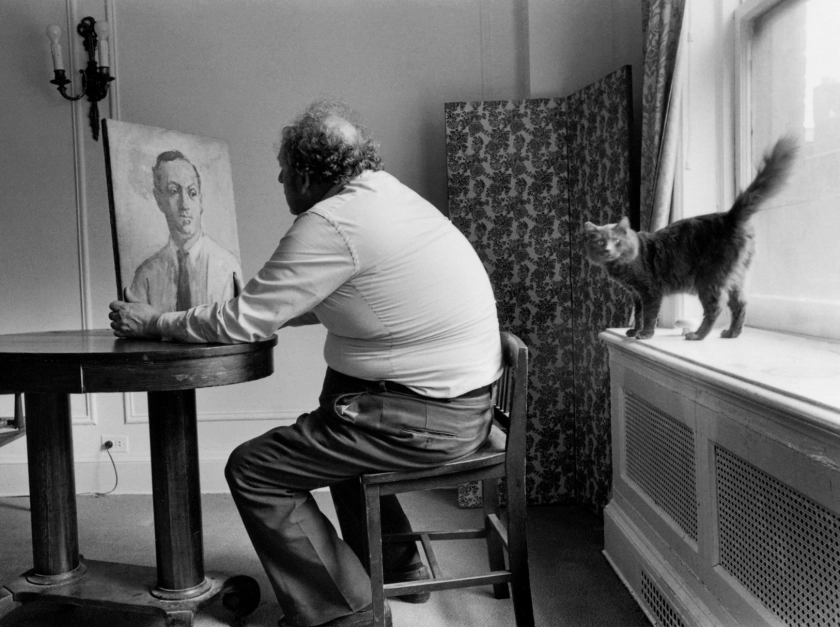

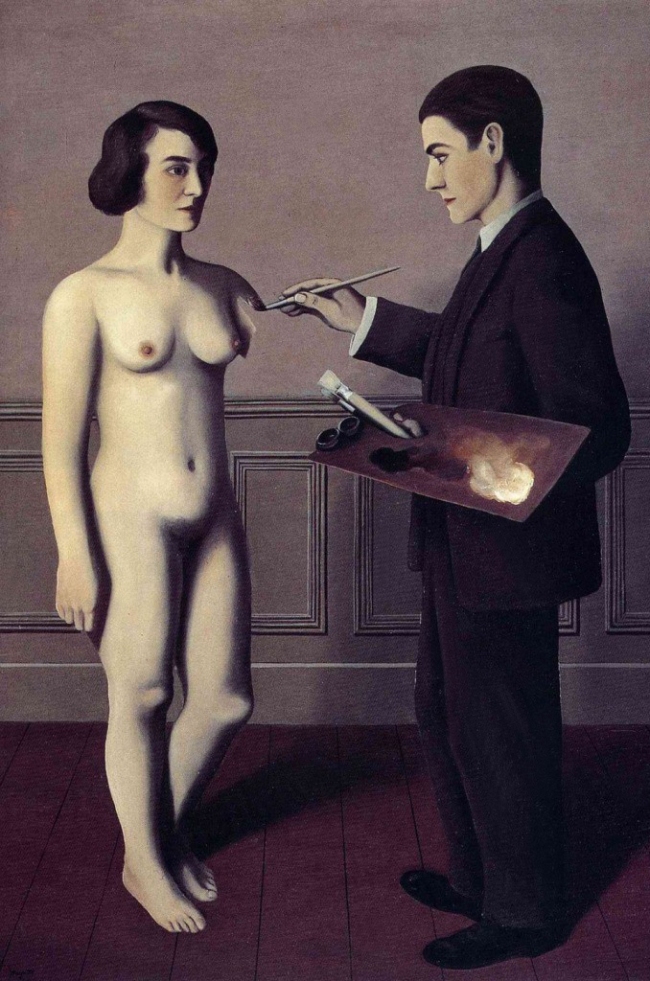

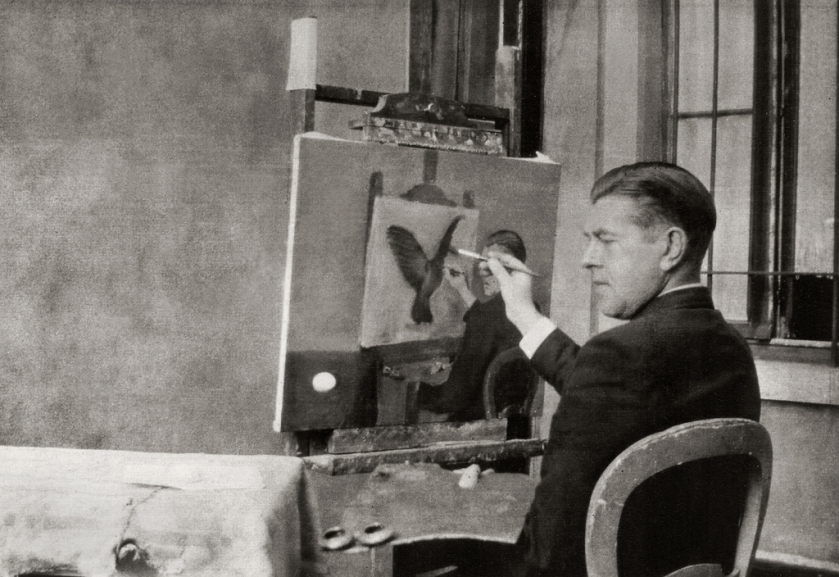

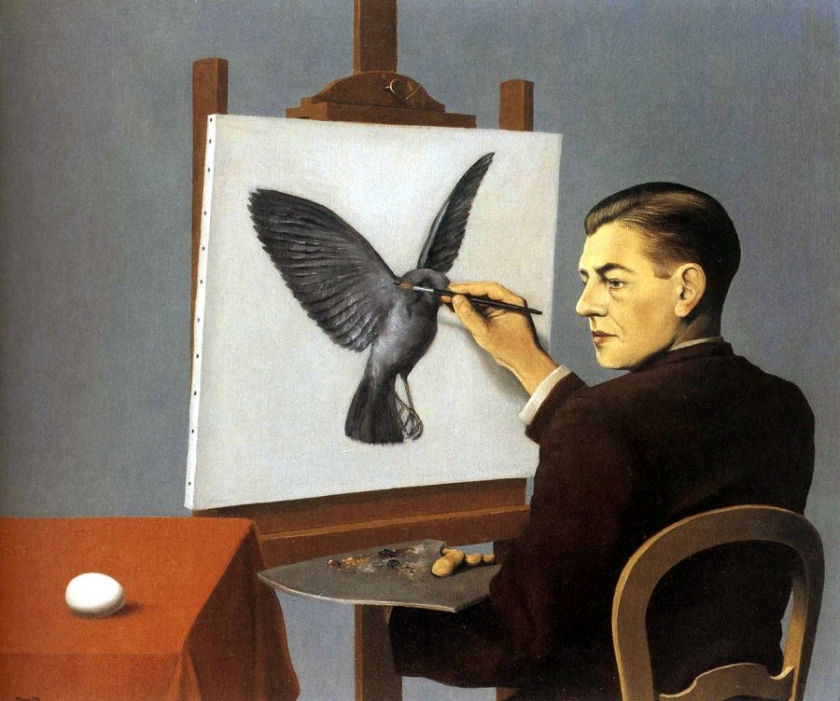

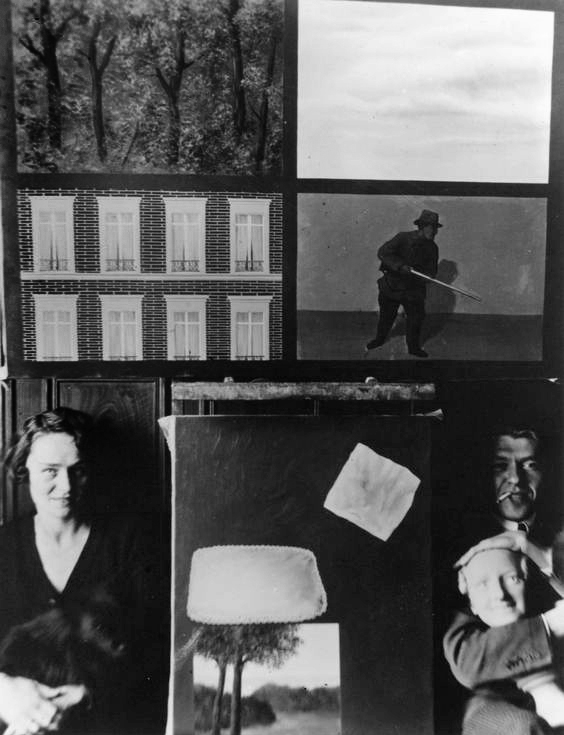

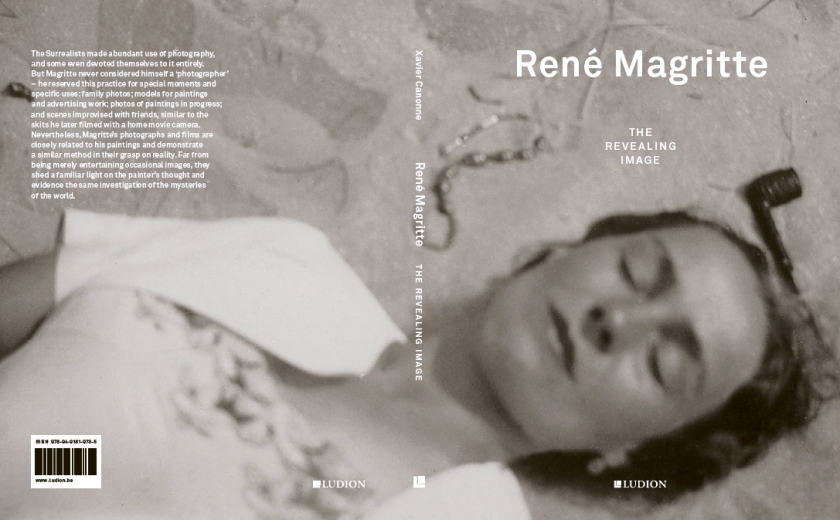

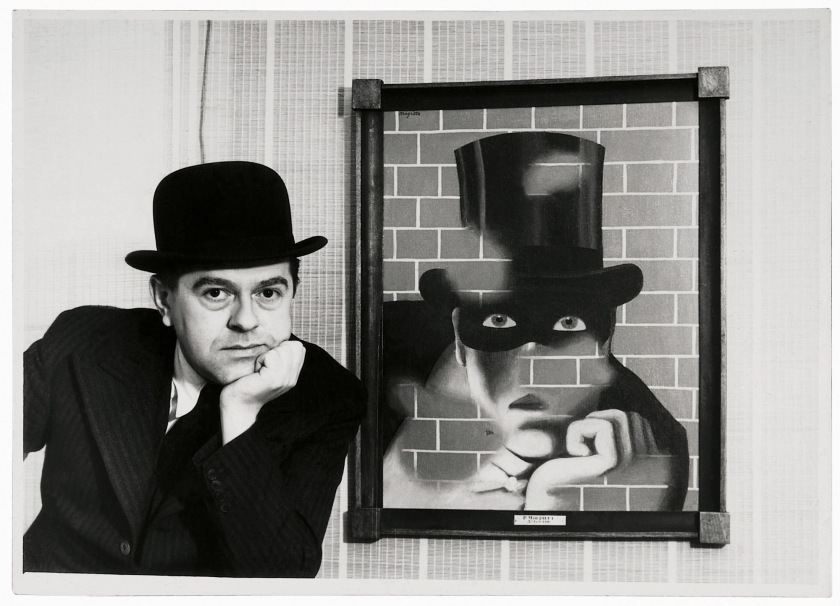

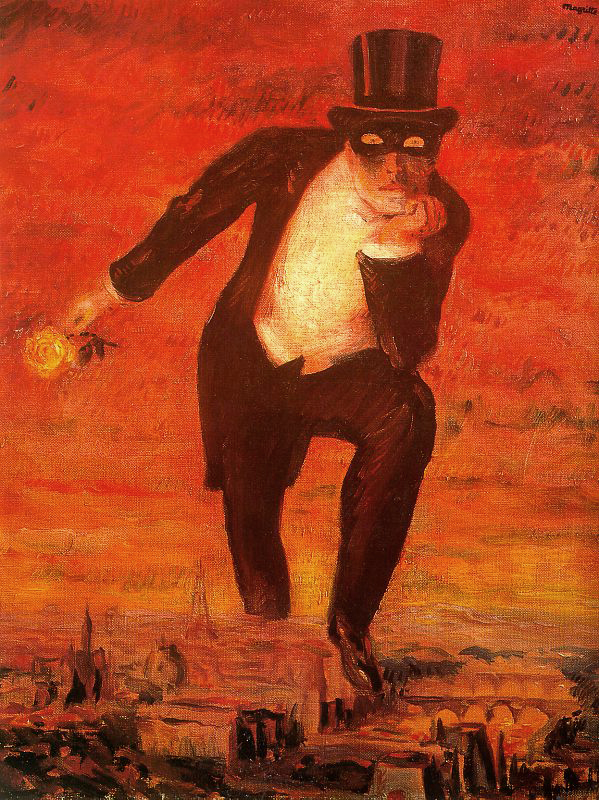

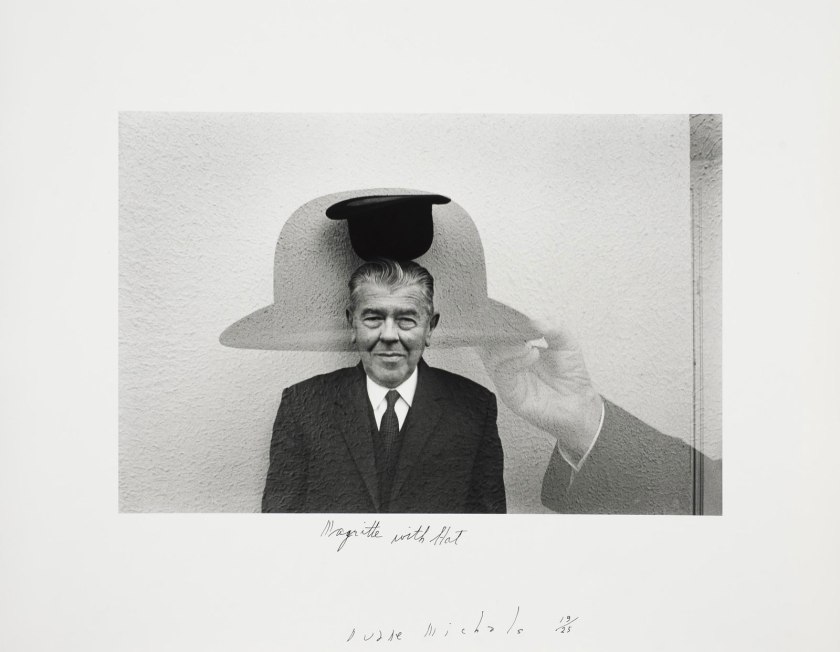

Michals cited a 1937 painting by René Magritte not in the Morgan Collection called “The Pleasure Principle.” It is a portrait of the poet Edward James, a patron of Surrealist art, his head a glowing light bulb. “I only discovered the painting later,” he said, after he had made his own photographic homage, in 1965, in which Magritte appears ghostlike in double exposure, against a canvas on an easel, behind an empty chair. “I was very proud to have had a similar idea to one of my deities,” he said.

Philip Gefter. “Duane Michals Searches the Morgan and Finds Himself,” on The New York Times website Oct 29, 2019 [Online] Cited 14/11/2019.

Duane Michals (American, b. 1932)

The Human Condition

1969

© Duane Michals via DC Moore Gallery

The Morgan Library & Museum

“The nature of consciousness is always the central question,” he asserted. In The Human Condition, his panel of six photographs from 1969 begins with a man standing on the 14th Street subway platform; the train arrives and he is bathed in a halo of light; the light becomes a swirl and in the last frame he is swept into a white disc the size of a galaxy passing through the night sky. From the immediate to the universal in six frames.

Philip Gefter. “Duane Michals Searches the Morgan and Finds Himself,” on The New York Times website Oct 29, 2019 [Online] Cited 14/11/2019

Duane Michals (American, b. 1932)

The Bewitched Bee

1986

Gelatin silver print

Gift of Duane Michals

The Morgan Library & Museum

IMAGE AND WORD

Duane Michals (American, b. 1932)

There Are Things Here Not Seen in This Photograph

1977

10 15/16 x 13 7/8 inches

The Morgan Library & Museum

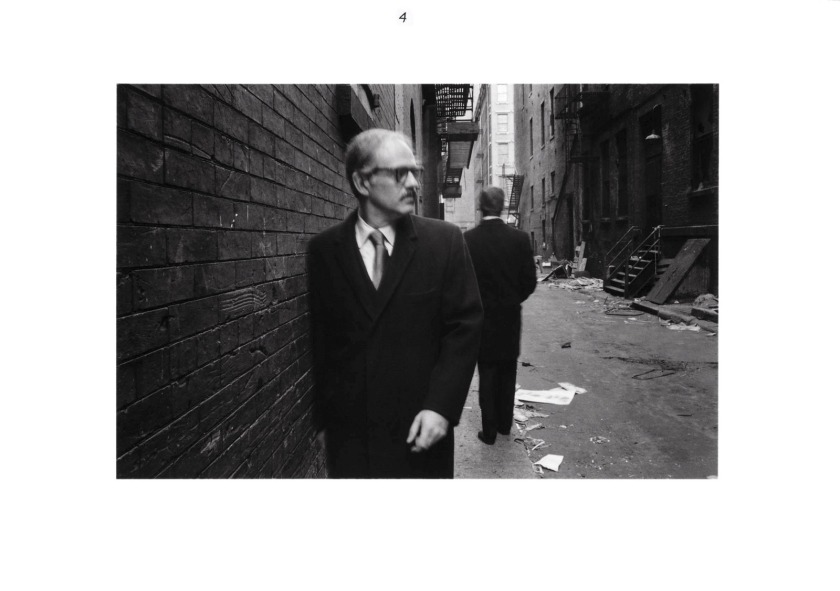

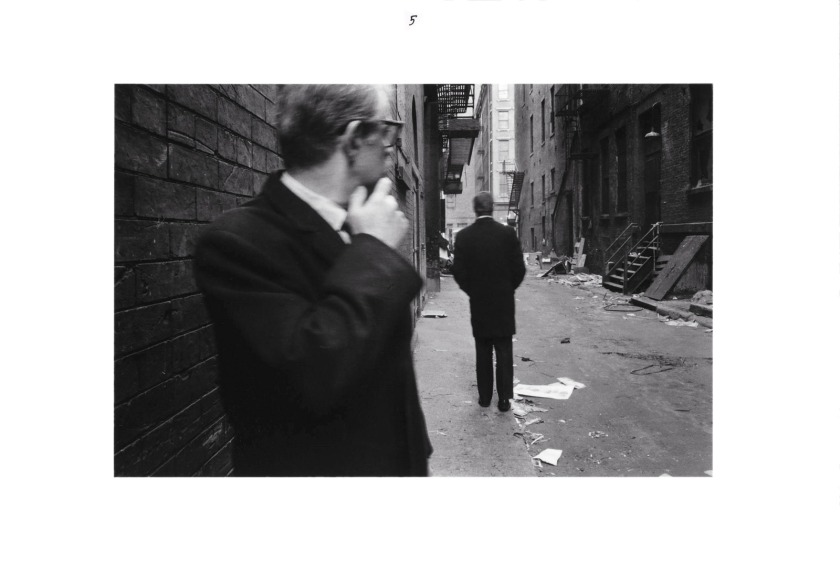

Duane Michals (American, b. 1932)

I Remember Pittsburgh 8

1982

Gelatin silver print

The Morgan Library & Museum

Ciro Ferri (Italian, 1634-1689)

Fame Painting a Portrait Held by Religion

17th century

Brush and brown and white gouache, pen and and brown ink, over black chalk, on brown toned paper

Overall: 11 x 7 9/16 inches (279 x 192 mm)

Purchased as the gift of the Fellows

The Morgan Library & Museum

Design for a frontispiece engraved by Gérard Audran for a volume of portraits of cardinals published by Giovanni Giacomo de’ Rossi

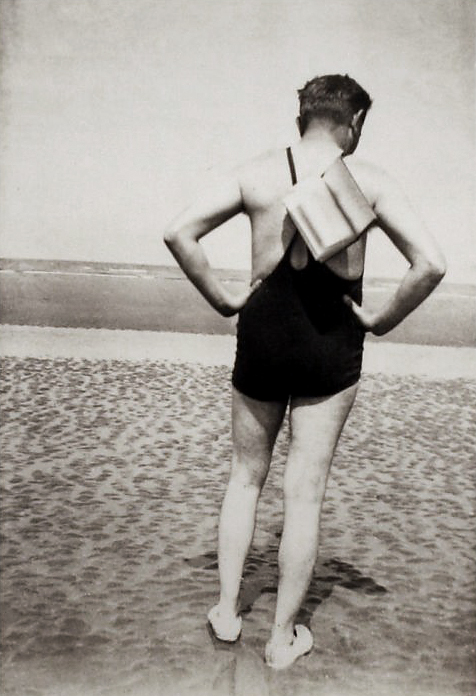

Irving Penn (American, 1917-2009)

Giorgio de Chirico, Rome

Rome, 1944 (negative), 1946-1947 (print)

Gelatin silver print on paper; mounted to cardstock

Image And Sheet: 7 1/16 × 7 3/8 in.

Gift of Irving Penn, 2006

The Morgan Library & Museum

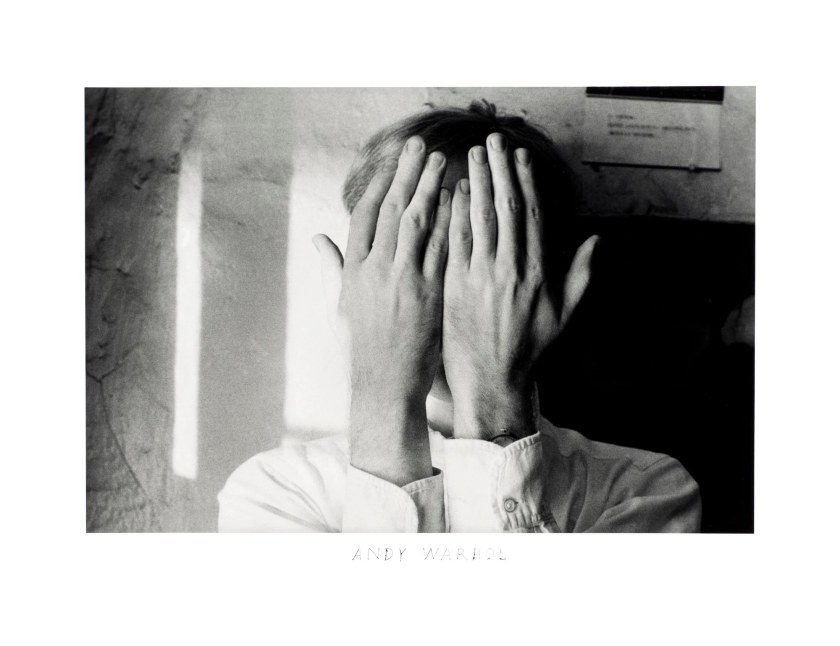

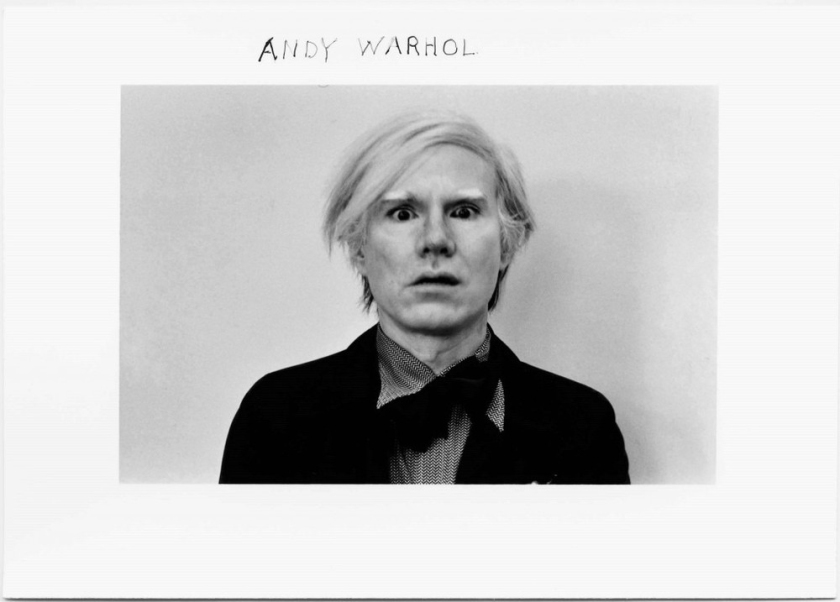

Duane Michals (American, b. 1932)

Andy Warhol

1958

Gelatin silver print

8 × 10 inches (20.3 × 25.4cm)

Collection of Richard and Ronay Menschel

The Morgan Library & Museum

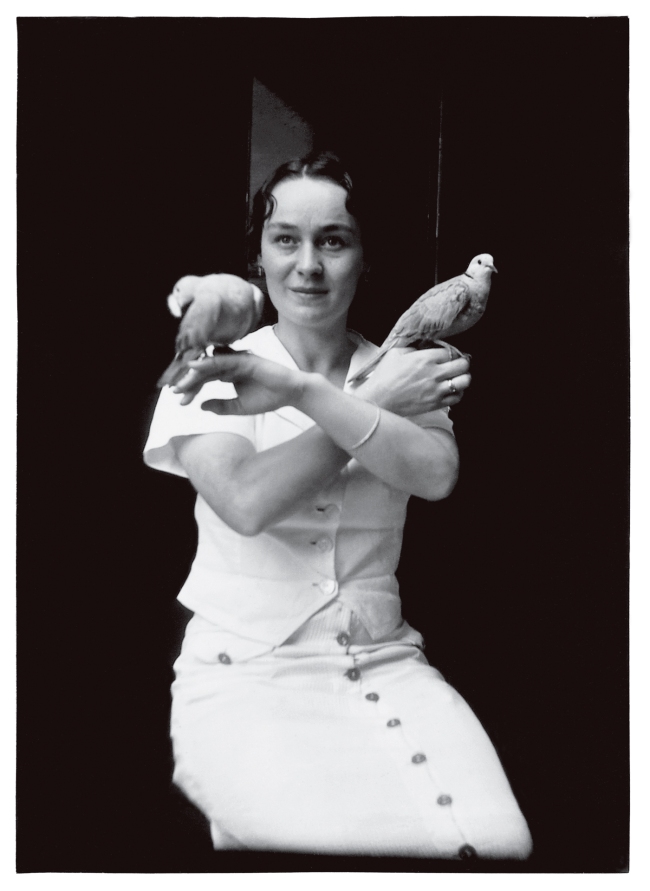

Duane Michals (American, b. 1932)

René Magritte at His Easel

1965

77/8 × 97/8 inches (20 × 25.1cm)

Collection of Richard and Ronay Menschel

The Morgan Library & Museum

Florian, Marquis de (1755-1794)

Red leather portfolio [realia] – Portefeuille de Monsieur de Voltaire and Donné à Monsieur de Florian

“Voltaire’s briefcase”

18th century

Leather, gold clasp

Stamped on front: “Portefeuille de Monsieur / de Voltaire”; on back: “Donné a Monsieur / de Florian”

Overall: 16 15/16 × 12 5/8 in. (43 × 32cm)

Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1911

Pierpont Morgan Library Dept. of Literary and Historical Manuscripts

The Morgan Library & Museum

Voltaire gave this briefcase to the marquis de Florian, the husband of his niece Elisabeth Mignot. Her sister, Marie-Louise Mignot, Mme Denis, was Voltaire’s companion for the last twenty-nine years of his life. With extensive decorative gold tooling. Exhibited numerous times at the Morgan Library as “Voltaire’s briefcase.”

Text from The Morgan Library & Museum website

Duane Michals (American, b. 1932)

Candide, 2019

2019

Inspired by Voltaire

© Duane Michals via DC Moore Gallery

The Morgan Library & Museum

“The things we chose from the collection were so close to what my instincts are,” he said to Joel Smith, the curator of photography at the Morgan, who organised the show with Michals.

The photographer was referring to the kinship between things he chose and the irreverent nature of his own work. “I’m completely overwhelmed by the nature of our reality,” he is quoted as saying in the exhibition catalog about human evolution. “We’ve been working on this version of man for a thousand years. He lives longer, he’s healthier, but he’s still an unproven product. Still the same greedy little bastard.”

To illustrate the point, he reached for Voltaire’s briefcase among the holdings in the Morgan’s collection. It dates from the 1700s and is decorated with gold-leaf filigree on its red leather casing.

Smith recalled that Michals was so “wowed at the thought of Voltaire’s ideas living inside it and amused by the showbiz of its provenance” that he went home and painted a portrait of Candide on an old tintype, adding Voltaire’s bitterly ironic refrain in white block letters: “This Is the Best of All Possible Worlds.” The briefcase and Candide, 2019 are both in the show.

Yet, Michals doesn’t share Voltaire’s bleak view of existence. His own work is often characterised by an iconoclastic wit, imbued with serious metaphysical inquiry – a “curiosity about the nature of reality, in a much more profound sense than just a bunch of atoms.”

Philip Gefter. “Duane Michals Searches the Morgan and Finds Himself,” on The New York Times website Oct 29, 2019 [Online] Cited 14/11/2019

Auguste Rodin (French, 1840-1917)

Lucifer

c. 1900

Pencil and watercolour, on paper

Overall: 9 3/8 × 12 7/16 in. (23.8 × 31.6cm)

Gift of Alexandre P. Rosenberg

The Morgan Library & Museum

Egon Schiele (Austrian, 1890-1918)

Embrace

1914

Graphite on wove paper

Overall: 19 1/8 × 12 3/4 in. (48.6 × 32.4cm)

Bequest of Fred Ebb

The Morgan Library & Museum

[Looks at Egon Schiele’s drawing Embrace (p. 22)] There’s so much emotion in this; it’s so immediate. There’s a few things happening: physical entanglement, then you see the look on his face, registering some kind of emotional response. I love the idea: Schiele had no thought that in a hundred years we’d be standing here or how we’d be talking about it. Art is not really about the future.

Duane Michals in Illusions of the Photographer: Duane Michals at the Morgan exhibition catalogue 2019, p. 21

In this depiction of the artist in the arms of an unidentified companion, the jagged, seemingly erratic contours suggest a psychological agitation characteristic of Schiele’s self-portraits. A feeling of tension derives from the position of the artist’s head-turned away from the woman embracing him – as well as from the placement of the couple to the left of the sheet, with the figure of the woman cropped. The resulting asymmetry conveys the artist’s emotional unbalance and emphasises his egocentric character while demonstrating the amazing technical agility he brought to bear to express a wide range of emotions.

Text from The Morgan Library & Museum website

Duane Michals (American, b. 1932)

A Letter from My Father

1960 (image), 1975 (text)

15 3/4 × 19 7/8 inches (40 × 50.5cm)

Gift of Duane Michals

The Morgan Library & Museum

The Morgan Library & Museum proudly presents an exhibition combining a six-decade retrospective of Duane Michals with an artist’s-choice selection of works from all corners of the permanent collection. Michals is known for his picture sequences, inscribed photographs, and, more recently, films that pose emotional, conceptual, and cosmic questions beyond the scope of the lone camera image. Illusions of the Photographer: Duane Michals at the Morgan (October 25, 2019 to February 2, 2020) takes viewers on a tour of the artist’s mind, putting work from his expansive career in conversation with Old Master and modern drawings, books, manuscripts, and historical objects.

The first retrospective on Michals to be mounted by a New York City institution, the exhibition is organised around animating themes in the artist’s work: Theatre, Reflection, Love and Desire, Playtime, Image and Word, Nature, Immortality, Time, Death, and Illusion. It showcases his storytelling instincts, both in stand-alone staged photographs and in sequences. The exhibition also includes screenings of short films, Michals’s preferred medium in recent years.

For Michals, photography is not documentary in nature but theatrical and fictive: the camera is one of many tools humanity uses to construct a comprehensible version of reality. In his imaginative, visually rich photographs, the artist exploits the medium’s storytelling capacity. For example, the six images in I Build a Pyramid (1978) find the artist in Egypt, stacking stones in a modest pile that, from the camera’s perspective, appears to rival the scale of the ancient pharaohs’ monuments. Michals reveals that the scenario echoes his childhood habit of building cities from stones in his backyard in McKeesport, Pennsylvania. In the exhibition, Michals’s staged scenes are juxtaposed with those of his creative heroes, who include William Blake, Edward Lear, and Saul Steinberg. In his dual role as artist and curator he matches wits with writers, stage designers, toy makers, and his fellow portraitists of the past and the present.

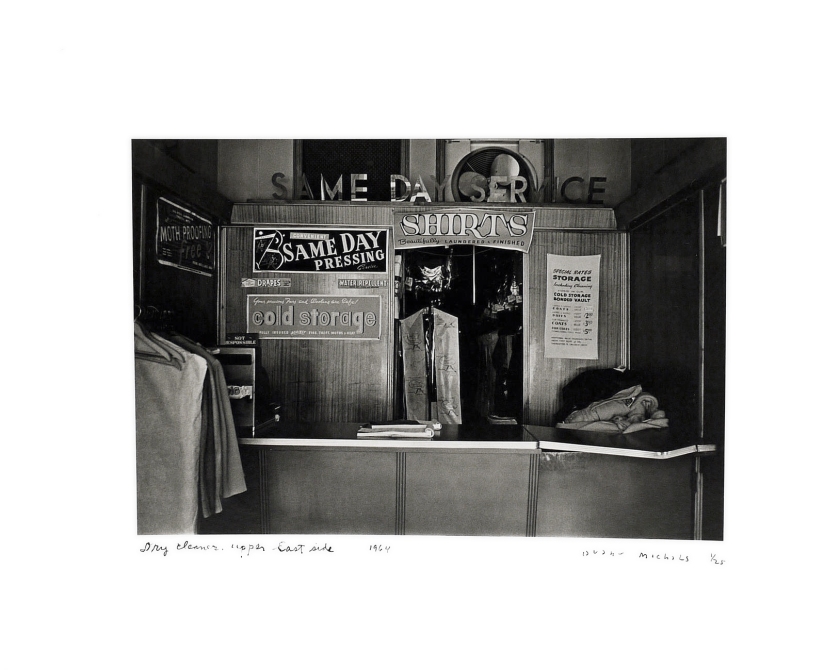

Since 2015 Michals has focused his creative efforts on filmmaking, a natural outgrowth of his directorial habits as a photographer. On a screen in the exhibition, three short films are featured amid a cycle of over 200 photographs from the series Empty New York (1964-1965), the project through which the artist first recognised his theatrical vision of reality. Michals will host two special programs of film screenings in the Morgan’s Gilder Lehrman Hall, introducing films that have never been screened publicly before.

Illusions of the Photographer revives the format of the 2015 exhibition Hidden Likeness: Emmet Gowin at the Morgan, which The New York Times said “all but redefined the genre” of the collection dive curated by a contemporary artist. The present project is a personal one for Michals, who explains, “The Morgan literally is my favourite museum in New York. I always learn something at the Morgan. I’m so thrilled about this show, because it’s probably going to be the very last time to see me there, with all my resources and touchstones. I’m … archaic, in a way. I’m eighty-seven! I’m of my generation. My references are not at all to what people are talking about today. I’m comfortable there, that’s where I belong – and that’s what I contribute.”

Joel Smith, the Morgan’s Richard L. Menschel Curator and Department Head, says “Duane Michals’s art is contemplative, confessional, and comedic. It transcends the conventional bounds, and audience, of photography. Through narration and sequencing he reorients the camera towards timeless human dilemmas; he derives poetic effects from technical errors such as double exposure and motion blur. His originality and intimacy as an artist come through in the discoveries he brings to light from the Morgan’s collection.”

Illusions of the Photographer: Duane Michals at the Morgan is accompanied by an 88-page softcover catalogue featuring a wide-ranging interview with the artist and illustrations of seventy works, including his selections from the Morgan’s collection and the previously unpublished 1969 title sequence.

About Duane Michals

Duane Michals (b. February 18, 1932, McKeesport, Pennsylvania) is an American photographer who often combines images with text in a format that recalls cinematic storytelling. Michals received his BA from the University of Denver in 1953. He began photographing for magazines in 1960 and became a prolific portraitist of artists such as Andy Warhol, René Magritte, and Marcel Duchamp. His first solo exhibition was held at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1970. Michals lives and works in New York City.

Press release from The Morgan Library & Museum [Online] Cited 14/11/2019

NATURE

James Jacques Joseph Tissot (French, 1836-1902)

God Creating the World

c. 1900-1902

Gouache on board

7 3/4 x 5 1/4 inches (201 x 135 mm)

Morgan Family Collection

James Jacques Joseph Tissot (French, 1836-1902)

God Creates Eve while Adam is Asleep

c. 1900-1902

Gouache on board

12 x 9 1/8 inches (305 x 233 mm)

Morgan Family Collection

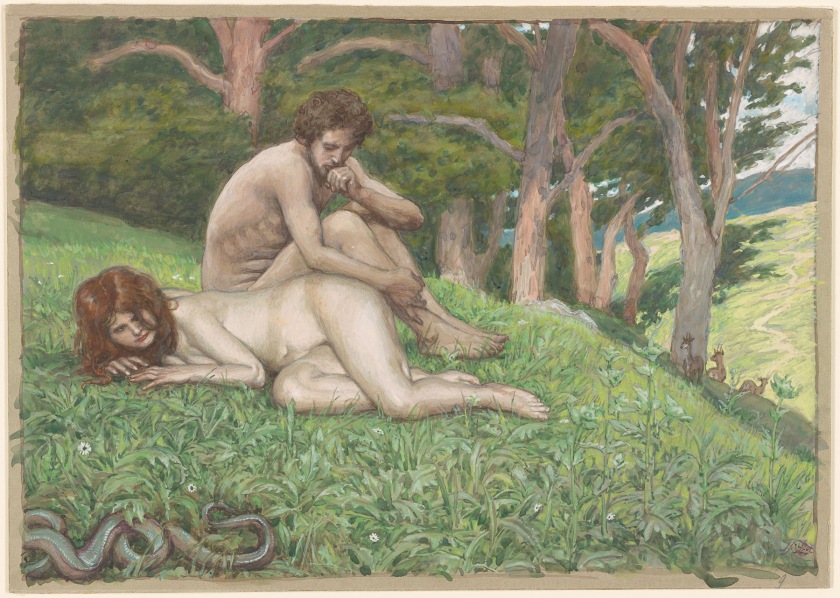

James Jacques Joseph Tissot (French, 1836-1902)

Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden

c. 1900-1902

Gouache on board

11 x 8 inches (279 x 203 mm)

Morgan Family Collection

James Jacques Joseph Tissot (French, 1836-1902)

Adam and Eve Perceive their Nakedness

c. 1900-1902

Gouache on board

12 1/8 x 8 3/4 inches (308 x 221 mm)

Morgan Family Collection

Duane Michals (American, b. 1932)

Paradise Regained

1968

6 silver gelatin prints with hand-applied text

… He picked up a panel of gouache drawings from around 1900 by French illustrator James Jacques Joseph Tissot titled “God Creating the World,” a biblical morality tale in a series of lighthearted scenes depicting the creation of Adam; then Eve; the two of them frolicking; Eve eating the apple; and their banishment from paradise. The Tissot sequence is among nearly 60 works in his final selection for the current exhibition Illusions of the Photographer: Duane Michals at the Morgan, through Feb. 2. His pick of drawings, paintings and artefacts resides in dialogue with 38 of Michals’s photographic works – his narrative sequences as well as stand-alone prints, projected images from a series titled “Empty New York,” and several of his recent short films.

He pointed out a link between the Tissot drawings and his own “Paradise Regained,” from 1968: a suite of six images that begins with a well-dressed young couple sitting and facing the camera in an empty apartment. With each frame they get progressively undressed, and more and more plants fill up the space behind them. In the final image, they are naked amid a lush, domestic Eden.

“I had been looking at a lot of Rousseau paintings when I made the sequence,” Michals said, referring to the jungle scenes of the French Post-Impressionist. While he loves the Tissot panel, he admitted, “I’m a raging atheist,” distancing himself from its religious message. “I was a pretend Catholic and then I stopped pretending.” The spiritual dimension of “Paradise Regained” is balanced by the artist’s tongue-in-cheek view of urban life, where men and women only return to a natural state indoors, where everything is unnatural.

Philip Gefter. “Duane Michals Searches the Morgan and Finds Himself,” on The New York Times website Oct 29, 2019 [Online] Cited 14/11/2019

Jacob Hoefnagel (Flemish, 1573 – c. 1632)

Orpheus Charming the Animals

1613

Watercolour and gouache, heightened with white gouache, over traces of black chalk, on vellum mounted to panel; bordered in gold

Overall: 6 9/16 × 8 5/16 in. (16.7 × 21.1cm)

Purchased on the Sunny Crawford von Bülow Fund 1978

Morgan Family Collection

Duane Michals (American, b. 1932)

Warren Beatty

1967

Gelatin silver print

8 × 9 15/16 inches (20.3 × 25.2cm)

Purchased on the Photography Acquisition Fund

The Morgan Library & Museum

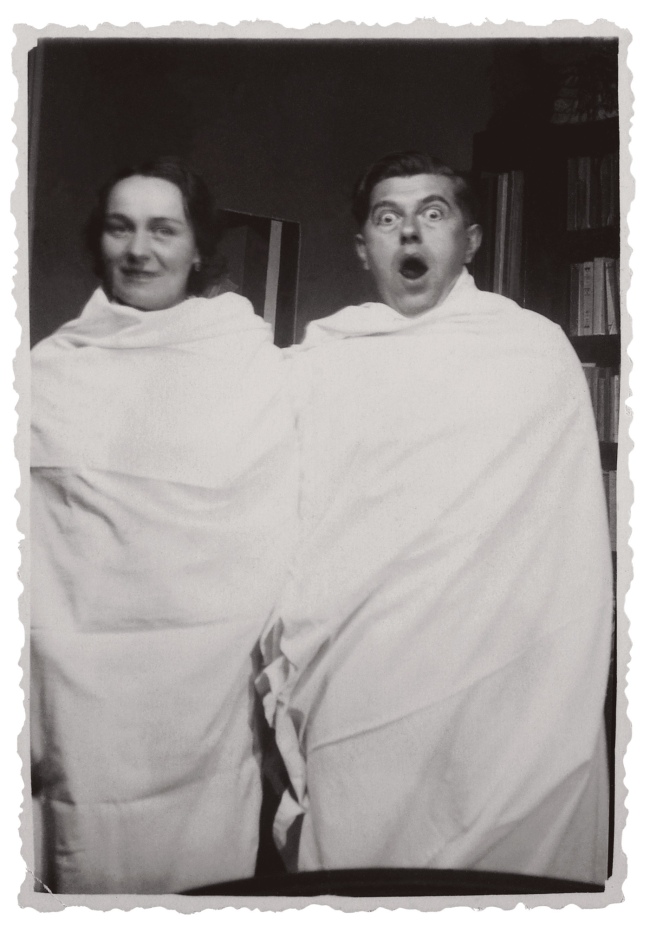

PLAYTIME

Duane Michals (American, b. 1932)

Things Are Queer

1973

Nine gelatin silver prints

Images: 5 × 7 inches (12.7 × 17.8cm) each

Gift of Duane Michals

The Morgan Library & Museum

REFLECTION

Wallace Studio, Manchester, New Hampshire

Untitled (Mirror)

c. 1880s

Cabinet card with rounded corners

Mount: 6 7/16 × 4 3/16 in. (16.4 × 10.6cm)

Print: 5 11/16 × 4 in. (14.4 × 10.2cm)

Gift of Adam Fuss

The Morgan Library & Museum

Carlo Galli Bibiena (1728 – c. 1778)

Interior of a Gallery

1750s

Pen and black ink and grey and brown wash

Sheet is framed by an overmount of paper that leaves around 8 5/8 x 11 7/8 inches visible

Overall: 9 1/4 × 12 13/16 in. (23.5 × 32.5cm)

Thaw Collection

The Morgan Library & Museum

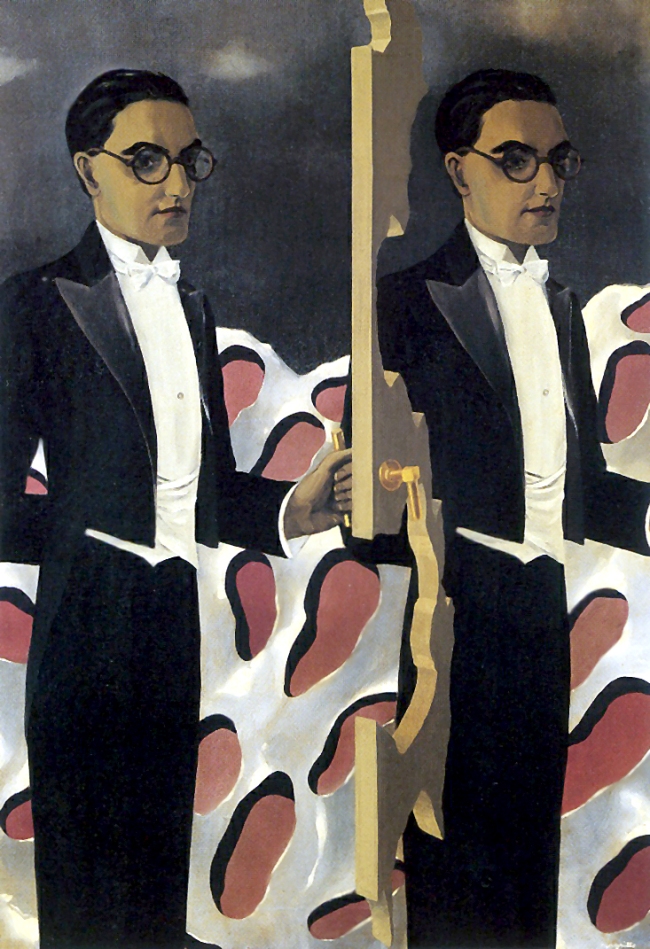

John F. Collins (American, 1888-1990)

Multiple Self-Portrait

1935

Gelatin silver print

Image: 13 3/4 × 10 9/16 in. (34.9 × 26.8cm)

Purchase on the Photography Collectors Committee Fund

The Morgan Library & Museum

Duane Michals (American, b. 1932)

A Story About a Story

1989

15 7/8 x 19 3/4 inches (40.3 × 50.2cm)

Purchased on the Photography Collectors Committee Fund

The Morgan Library & Museum

In Michals work, the immediate and the infinite spar. In the show is a single image by a little-known photographer named John F. Collins. The 1935 self-portrait shows Collins looking at us while holding a large photograph of himself; in that photograph he is looking down at the same photograph of himself. In each subsequent picture within a picture, he is looking out, and then into the photograph he is holding, into a spiralling infinity.

It is a striking parallel to Michals’ “A Story Within a Story” of 1989, in which a man leans against a mirror in the corner of the frame and faces a mirror in which his reflection echoes repeatedly as it recedes behind him. “This is a story about a man telling a story about a man. …” starts his text.

He might as well have been describing himself.

Philip Gefter. “Duane Michals Searches the Morgan and Finds Himself,” on The New York Times website Oct 29, 2019 [Online] Cited 14/11/2019

N. Institoris (d. 1845)

Interior of a Prison

c. 1825-1845

Pen and black ink, with grey wash, over pencil, on paper; verso contains slight sketch of a building, in graphite.

13 x 17 1/2 inches (330 x 445 mm)

Gift of Mrs. Donald M. Oenslager, 1982

The Morgan Library & Museum

Gabriel Pierre Martin Dumont (French, 1720-1791)

Perspective View of the Mechanical Works and Construction of a Theater. Verso: Sketch of an elevation of a colonnade

18th century

Pen and black ink, with grey wash, over graphite, on paper; verso: graphite

12 1/4 x 14 9/16 inches (310 x 369 mm)

Purchased as the gift of Mrs. Donald M. Oenslager in memory of her husband

The Morgan Library & Museum

Eugène Atget (French, 1857-1927)

Cour de Rouen

1898

Albumen print

Overall: 8 × 6 3/4 in. (20.3 × 17.1cm)

Purchased on the Photography Collectors Committee Fund

The Morgan Library & Museum

Louis Faurer (American, 1916-2001)

Penn Station Lovers

1946-1947, printed c. 1981

Gelatin silver print

14 x 11 in. (sheet)

Purchased as the gift of Elaine Goldman

The Morgan Library & Museum

Duane Michals (American, b. 1932)

Empty New York, Subway Interior

c. 1964

Gelatin silver print

8 × 10 inches (20.3 × 25.4cm)

Collection of Nancy and Burt Staniar

The Morgan Library & Museum

Duane Michals (American, b. 1932)

Empty New York, Dry cleaners upper East side

c. 1964

Gelatin silver print

8 × 10 inches (20.3 × 25.4cm)

Collection of Nancy and Burt Staniar

The Morgan Library & Museum

Duane Michals (American, b. 1932)

From the series Empty New York

c. 1964

Gelatin silver prints

8 × 10 inches (20.3 × 25.4cm)

Collection of Nancy and Burt Staniar

The Morgan Library & Museum

TIME

Herbert Matter (American born Switzerland, 1907-1984)

Alexander Calder hanging mobile in motion

1936

Gelatin silver print with additions by hand

5 9/16 × 6 3/16 in. (14.13 × 15.72cm)

Purchased as the gift of Richard and Ronnie Grosbard

The Morgan Library & Museum

Herbert Matter (April 25, 1907 – May 8, 1984) was a Swiss-born American photographer and graphic designer known for his pioneering use of photomontage in commercial art. The designer’s innovative and experimental work helped shape the vocabulary of 20th-century graphic design.

Biography

Born in Engelberg, Switzerland, Matter studied painting at the École des Beaux-Arts in Geneva [fr] and at the Académie Moderne in Paris under the tutalge of Fernand Léger and Amédée Ozenfant. He worked with Adolphe Mouron Cassandre, Le Corbusier and Deberny & Peignot. In 1932, he returned to Zurich, where he designed posters for the Swiss National Tourist Office and Swiss resorts. The travel posters won instant international acclaim for his pioneering use of photomontage combined with typeface.

He went to the United States in 1936 and was hired by legendary art director Alexey Brodovitch. Work for Harper’s Bazaar, Vogue and other magazines followed. In the 1940s, photographers, including Irving Penn, at Vogue’s studios at 480 Lexington Avenue often used them for shooting the advertising work commissioned by outside clients. The practice was at first tolerated, but by 1950 it was banned on the grounds that it “has interfered with our own interests and has been a severe handicap to our editorial operations”. In response Matter and three other Condé Nast photographers Serge Balkin, Constantin Joffé and Geoffrey Baker left to establish Studio Enterprises Inc. in the former House & Garden studio on 37th Street (Penn stayed on but also left in 1952).

From 1946 to 1966 Matter was design consultant with Knoll Associates. He worked closely with Charles and Ray Eames. From 1952 to 1976 he was professor of photography at Yale University and from 1958 to 1968 he served as design consultant to the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York and the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston. He was elected to the New York Art Director’s Club Hall of Fame in 1977, received a Guggenheim Fellowship in photography in 1980 and the AIGA medal in 1983.

As a photographer, Matter won acclaim for his purely visual approach. A master technician, he used every method available to achieve his vision of light, form and texture. Manipulation of the negative, retouching, cropping, enlarging and light drawing are some of the techniques he used to achieve the fresh form he sought in his still lifes, landscapes, nudes and portraits. As a filmmaker, he directed two films on his friend Alexander Calder: “Sculptures and Constructions” in 1944 and “Works of Calder” (with music by John Cage) for the Museum of Modern Art in 1950.

Close friends of Matter and his wife Mercedes were the painters Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, fellow Swiss photographer Robert Frank and Alberto Giacometti. Matter’s wife Mercedes was the daughter of the American modernist painter Arthur Beecher Carles, and was herself the chief founder of the New York Studio School.

“The absence of pomposity was characteristic of this guy”, said another designer, Paul Rand, about Matter. His creative life was devoted to narrowing the gap between so-called fine and applied arts. Matter died on May 8, 1984, in Southampton, New York.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Saul Steinberg (American born Romania, 1914-1999)

Untitled (Cat and wheel of time)

1965

Ink (black, blue, red, green, brown) and pencil on laid Strathmore

19 × 25 in. (48.26 × 63.5cm)

Gift of the Saul Steinberg Foundation

The Morgan Library & Museum

Saul Steinberg defined drawing as “a way of reasoning on paper,” and he remained committed to the act of drawing. Throughout his long career, he used drawing to think about the semantics of art, reconfiguring stylistic signs into a new language suited to the fabricated temper of modern life. Sometimes with affection, sometimes with irony, but always with virtuoso mastery, Saul Steinberg peeled back the carefully wrought masks of 20th-century civilisation.

Text from The Morgan Library & Museum website

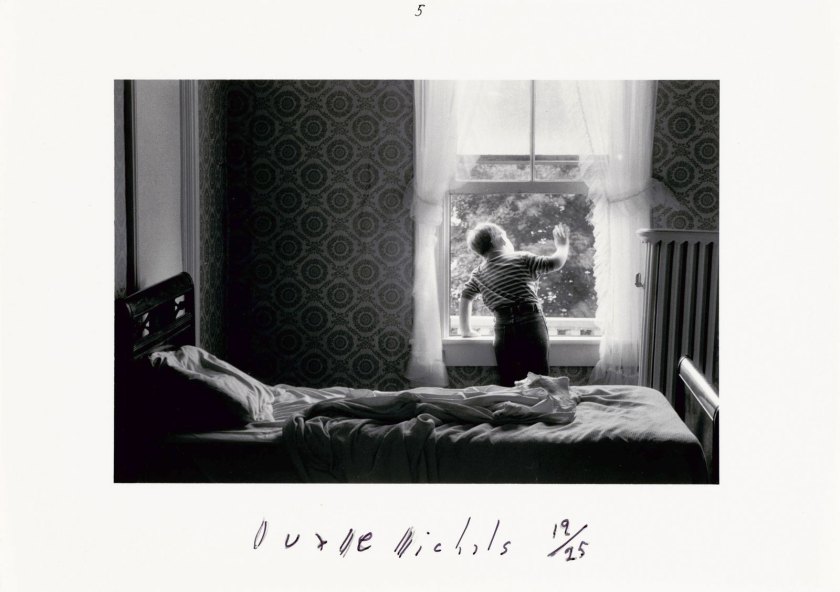

Duane Michals (American, b. 1932)

When He Was Young

1979

8 x 9 15/16 inches (20.3 × 25.2cm)

Purchased on the Photography Collectors Committee Fund

The Morgan Library & Museum

Duane Michals (American, b. 1932)

What is Time?

1994

Gelatin silver print

16 × 19 7/8 inches (40.6 × 50.5cm)

Gift of Duane Michals

The Morgan Library & Museum

Included in his selection from the Morgan is an amusing drawing by Saul Steinberg, “Cat and the Wheel of Time,” 1965, in which the months of the year, the days of the week, and the hours of the day are written in circles inside a large wheel following a small cat down a hill. “Time has always been central to so much of my thinking,” Michals said. Smith handed him his text and image piece, What Is Time? from 1994, in which an eternally handsome young man holds an old-fashioned round clock to his ear. The text beneath it begins, “Time is the duration of everything, and life is an event, a fluttering of wings … the moment is the interval between now and then and, then, again.”

Philip Gefter. “Duane Michals Searches the Morgan and Finds Himself,” on The New York Times website Oct 29, 2019 [Online] Cited 14/11/2019

The Morgan Library & Museum

225 Madison Avenue at 36th Street, New York, NY

Phone: (212) 685-0008

Opening hours:

Tuesday – Thursday, Saturday – Sunday: 10.30 am – 5 pm

Friday: 10.30am – 7pm

Closed Mondays

![Florian, Marquis de (1755-1794) 'Red leather portfolio [realia]' 18th century Florian, Marquis de (1755-1794) 'Red leather portfolio [realia]' 18th century](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2019/11/voltaire-briefcase.jpg?w=840)

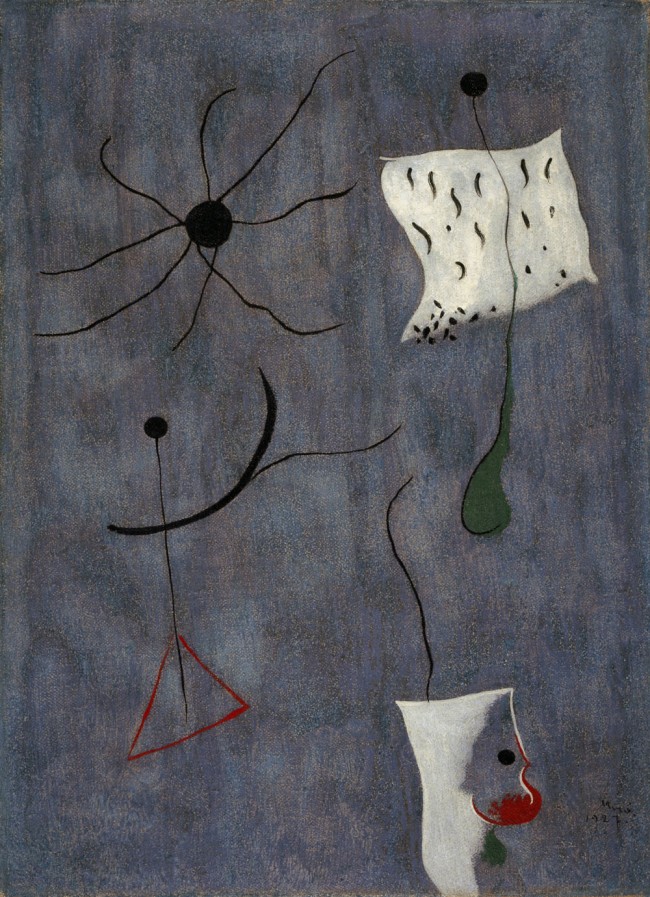

![René Magritte (Belgium 1898-1967) 'Les Amants [The lovers]' 1928 René Magritte (Belgium 1898-1967) 'Les Amants [The lovers]' 1928](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2017/10/magritte-the-lovers-web.jpg?w=840)

![Joan Miró (Spanish, 1893-1983) 'Tête de Paysan Catalan' [Head of a Catalan Peasant] 1925 Joan Miró (Spanish, 1893-1983) 'Tête de Paysan Catalan' [Head of a Catalan Peasant] 1925](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2016/08/joan-mirc3b3-tc3aate-de-paysan-catalan-web.jpg?w=650&h=837)

![Francis Picabia (French, 1879-1953) 'Fille née sans mère' [Girl Born without a Mother] c. 1916-1917 Francis Picabia (French, 1879-1953) 'Fille née sans mère' [Girl Born without a Mother] c. 1916-1917](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/francis-picabia-fille-nc3a9e-sans-mc3a8re-web.jpg)

![Max Ernst (German, 1891-1976) 'La Joie de vivre' [The Joy of Life] 1936 Max Ernst (German, 1891-1976) 'La Joie de vivre' [The Joy of Life] 1936](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/max-ernst-la-joie-de-vivre-1936-web.jpg)

![Dorothea Tanning (American, 1910-2012) 'Eine Kleine Nachtmusik' [A Little Night Music] 1943 Dorothea Tanning (American, 1910-2012) 'Eine Kleine Nachtmusik' [A Little Night Music] 1943](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/dorothea-tanning-eine-kleine-nachtmusik-1943-web.jpg)

![Salvador Dalí (Spanish, 1904-1989) 'Couple aux têtes pleines de nuages' [Couple with their Heads Full of Clouds] 1936 Salvador Dalí (Spanish, 1904-1989) 'Couple aux têtes pleines de nuages' [Couple with their Heads Full of Clouds] 1936](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/salvador-dalc3ad-couple-aux-tc3aates-pleines-de-nuages-web.jpg)

![Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881-1973) 'Tête' [Head] 1913 Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881-1973) 'Tête' [Head] 1913](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2016/08/tc3aate-head-1913-by-pablo-picasso-web.jpg?w=650&h=872)

![Max Ernst (German, 1891-1976) 'Jeune homme intrigué par le vol d’une mouche non-euclidienne' [Young Man Intrigued by the Flight of a Non-Euclidean Fly] 1942–1947 Max Ernst (German, 1891-1976) 'Jeune homme intrigué par le vol d’une mouche non-euclidienne' [Young Man Intrigued by the Flight of a Non-Euclidean Fly] 1942–1947](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2016/08/32_ernst-max_jeune-homme-intriguc3a9-1942-47-web.jpg?w=650&h=815)

![Max Ernst (German, 1891-1976) 'Une semaine de bonté' [A Week of Kindness] 1934 Max Ernst (German, 1891-1976) 'Une semaine de bonté' [A Week of Kindness] 1934](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2016/08/ernst-une-semaine-de-bontc3a9-web.jpg?w=650&h=874)

![Max Ernst (German, 1891-1976) 'Une semaine de bonté' [A Week of Kindness] 1934 Max Ernst (German, 1891-1976) 'Une semaine de bonté' [A Week of Kindness] 1934](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2016/08/ernst-une-semaine-de-bontc3a9-web2.jpg?w=650&h=881)

![Alberto Giacometti (Italian, 1901-1966) 'Objet désagréable, à jeter' [Disagreeable Object, to be Thrown away] 1931 Alberto Giacometti (Italian, 1901-1966) 'Objet désagréable, à jeter' [Disagreeable Object, to be Thrown away] 1931](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/alberto-giacometti-objet-dc3a9sagrc3a9able-web.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.