September 2018

Robert B. Talfor (American born Britain)

Nitroglycerine works at station between Raft Nos. 26 and 27. Plate B of the photographic album Photographic Views of Red River Raft (detail)

1873

Hand-coloured albumen print, mounted recto only to pages with a stylised U.S. Corps of Engineers printed border

7 x 9 1/4 inches (17.8 x 23.5cm)

“In May Lieutenant Woodruff’s careful plans for using “tri-nitro-glycerine” to hasten the removal process, were put into operation and proved quite successful. It continued to be used on a half dozen of the rafts the last of May and through the month of June as the main channel of the river was widened.”

Hubert Humphreys. “Photographic Views of the Red River Raft, 1873,” p. 107

One of the great privileges of writing and researching for this website is the ability to pull disparate sources together from all over the world, so that the some of the most valuable information can be stored in one place – a kind of meta-posting, with informed comment, upon the context of place, time, identity and image. This is one such posting.

I had never known of these photographs before, nor of their photographer R.B. Talfor of whom I can find little information. I never knew the story of the Great Raft of the Red River, nor the heroism of Lieutenant Eugene A. Woodruff, in charge of the clearing operations, who sacrificed his life to look after others in the yellow fever epidemic in Shreveport in 1873. These stories deserve to be told, deserve a wider audience, for it is all we have left of this time and place.

The 113 photographic views, hand coloured albumen prints “are remarkable for both their historical narrative and aesthetic integrity.” They document not only the landscape but the lives of the crews working on the river. As Woodruff notes in his report of July 1, 1873, “With the view is a photographic map of the raft region, with location and axis of the camera for each view marked upon it and numbered to correspond with the number on the view. This album full of photographs, affording a complete and truthful panorama of the raft, will give a better idea of the nature of the work performed and of the character of the country than could be obtained form the most elaborate description.”

In other words, the photographs and accompanying map are a scientific and objective ordering of life and nature, “affording a complete and truthful panorama of the raft”, the nature of the work performed and the character of the country. Truth, panorama, nature, character. And yet, when you look at the whole series of photographs, they become something much more than just objective rendition.

Firstly, while Talfor maps out his “points of view” he resists, but for a few occasions, the 19th century axiom of placing a man in the landscape… to give the landscape scale by including a human figure. In their aesthetic integrity he lets the landscape speak for itself. But if you look at the sequencing of the plates in the album you observe that he alternates between photographs of open stretches of river taken in overcast / end of day light, and plates filled with a dark, mysterious, chthonic atmosphere, as though we the viewer are inhabiting a nightmarish underworld. Into this dark romanticism, this American Gothic, he throws great tree stumps being hauled out of the water, wind whipping through the trees (seen in the length of exposure of the images) and men with cable and plunger standing stock still in front of a tent full of NITROGLYCERIN! DANGER! KEEP AWAY!

Secondly, Talfor’s hand colouring of the photographs seems to add to this almost William Blake-esque, melancholy romanticism. While the light of the setting sun and its reflection over water add to the sublime nature of the scene, the clouds, in particular in plates such as XCVL and XXVI (note the tiny man among the logs), seem to roil in the sky, like mysterious wraiths of a shadowy atmosphere. It is as though Talfor was illustrating a poem of extreme complexity, not just an objective, social documentary enterprise of time and place, but a rendition of the light and darkness of nature as seen through the eyes of God. A transcendent liminality inhabits these images, one in which we cross the threshold into a transitional state between one world and the next, where the photographs proffer a ‘releasement toward things’ which, as Heidegger observes, grant us the possibility of dwelling in the world in a totally different way.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

These images are published under fair use on a non-commercial basis for educational and research purposes only. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image. The whole series can be see on the Swann Auction Galleries website.

“We stand at once within the realm of that which hides itself from us, and hides itself just in approaching us. That which shows itself and at the same time withdraws is the essential trait of what we call the mystery… Releasement towards things and openness to the mystery belong together. They grant us the possibility of dwelling in the world in a totally different way…”

MartinHeidegger. ‘Discourse on Thinking’. New York: Harper & Row, 1966, pp. 55-56

Photographic Views of the Red River Raft

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers operation to remove obstacles from the Red River in Louisiana, 1873

113 hand coloured photographic views of the Red River made in April and May 1873, under the direction of C. W. Howell, U. S. Capt.; Corps of Engineers, and E. A. Woodruff, 1st Lieut. U. S. Corps of Engineers; to accompany the annual report on operations for the removal of the Raft; during the year ending June 30, 1873. The photographer was Robert B. Talfor. The portion of the Red River affected reached from Natchitoches Parish through north Caddo Parish, Louisiana. Hand-coloured albumen prints, the images measuring 7 x 9 1/4 inches (17.8 x 23.5cm), mounted recto only to pages with a stylised U.S. Corps of Engineers printed border, some with Talfor’s credit and plate number in the negative, and each with his credit again, the series title, and a plate number (I-CVII and A-F) on mount recto.

Only three extant copies are known to exist, with one in the Louisiana State University Libraries (which also, apparently, houses Talfor’s “photographic outfit” and correspondence associated with the Talfor family) and the other at the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

An extraordinary photographic record by the British-born Robert B. Talfor, who founded a photography studio in Greenport, New York in 1867. The pictures, which were shot in April and May 1873, are remarkable for both their historical narrative and aesthetic integrity. The photographs depict crews improving waterway navigation. But while these labourers were removing organic matter from the Red River to facilitate riverboat transport, the railroad industry was dominating the commercial landscape, dynamically shrinking geographic distances and improving transportation of goods.

Talfor’s career as a photographer apparently began during the Civil War, when he was a topographic engineer responsible for mapping battlefields. The transition to the Louisiana project is unclear but his prints capture the haunting beauty of the landscape and the pride of labourers.

Text from the Swann Auction Galleries website [Online] Cited 19 September 2018

Cover the photographic album Photographic Views of Red River Raft 1873

Robert B. Talfor

U.S. Steamer Aid at work, Raft No. 5, bow view. Plate A of the photographic album Photographic Views of Red River Raft

1873

Hand-coloured albumen print, mounted recto only to pages with a stylised U.S. Corps of Engineers printed border

7 x 9 1/4 inches (17.8 x 23.5cm)

Robert B. Talfor

The snagboat U.S. Aid. Plate C of the photographic album Photographic Views of Red River Raft

1873

Hand-coloured albumen print, mounted recto only to pages with a stylised U.S. Corps of Engineers printed border

7 x 9 1/4 inches (17.8 x 23.5cm)

Robert B. Talfor

Plate CI of the photographic album Photographic Views of Red River Raft

1873

Hand-coloured albumen print, mounted recto only to pages with a stylised U.S. Corps of Engineers printed border

7 x 9 1/4 inches (17.8 x 23.5cm)

Robert B. Talfor

Plate CII of the photographic album Photographic Views of Red River Raft

1873

Hand-coloured albumen print, mounted recto only to pages with a stylised U.S. Corps of Engineers printed border

7 x 9 1/4 inches (17.8 x 23.5cm)

Robert B. Talfor

Plate CVII of the photographic album Photographic Views of Red River Raft

1873

Hand-coloured albumen print, mounted recto only to pages with a stylised U.S. Corps of Engineers printed border

7 x 9 1/4 inches (17.8 x 23.5cm)

Plate CVII: Steamer Bryerly entering Red River through Sale & Murphy’s Canal (detail)

On May 16, 1873, R.B. Talfor photographed the R.T. Bryarly as she passed trough the channel opened by Lt. Eugene Woodruff’s crew. The R.T. Bryarly, on that day, became the first steamboat to enter the upper reaches of the Red River unhindered by the Great Raft at any point. For the next several months, until April 1874, the Corps of Engineers continued to work to ensure that the Raft would not re-form. The passage up the river by the the R.T. Bryarly, however, signalled that the work begun by Captain Shreve in 1833 had been successfully completed. The R.T. Bryarly sank at Pecan Point on the Red River on September 19, 1876.

Text from the book Red River Steamboats by Eric J. Brock, Gary Joiner. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 1999, p. 22 [Online] Cited 17/09/2018

Robert B. Talfor

Plate D of the photographic album Photographic Views of Red River Raft

1873

Hand-coloured albumen print, mounted recto only to pages with a stylised U.S. Corps of Engineers printed border

7 x 9 1/4 inches (17.8 x 23.5cm)

Robert B. Talfor

I.N. Kalbaugh on the Red River. Plate E of the photographic album Photographic Views of Red River Raft

1873

Hand-coloured albumen print, mounted recto only to pages with a stylised U.S. Corps of Engineers printed border

7 x 9 1/4 inches (17.8 x 23.5cm)

Plate E: I.N. Kalbaugh on the Red River. Steamer Kalbaugh between Raft Nos. 47 and 48 (detail)

Robert B. Talfor

Plate LIV of the photographic album Photographic Views of Red River Raft

1873

Hand-coloured albumen print, mounted recto only to pages with a stylised U.S. Corps of Engineers printed border

7 x 9 1/4 inches (17.8 x 23.5cm)

Robert B. Talfor

Plate LXXXVII of the photographic album Photographic Views of Red River Raft

1873

Hand-coloured albumen print, mounted recto only to pages with a stylised U.S. Corps of Engineers printed border

7 x 9 1/4 inches (17.8 x 23.5cm)

Driftwood log jams obstructing the river in Louisiana before their elimination with the aid of nitroglycerine.

Robert B. Talfor

Plate LXXXVIII of the photographic album Photographic Views of Red River Raft

1873

Hand-coloured albumen print, mounted recto only to pages with a stylised U.S. Corps of Engineers printed border

7 x 9 1/4 inches (17.8 x 23.5cm)

Robert B. Talfor

Plate VII of the photographic album Photographic Views of Red River Raft

1873

Hand-coloured albumen print, mounted recto only to pages with a stylised U.S. Corps of Engineers printed border

7 x 9 1/4 inches (17.8 x 23.5cm)

Foot of Raft No. 2. One of the several shore work parties that were under the direction of the U.S. Corps of Army Engineers.

Robert B. Talfor

Plate XCVL of the photographic album Photographic Views of Red River Raft

1873

Hand-coloured albumen print, mounted recto only to pages with a stylised U.S. Corps of Engineers printed border

7 x 9 1/4 inches (17.8 x 23.5cm)

Robert B. Talfor

Plate XLV of the photographic album Photographic Views of Red River Raft

1873

Hand-coloured albumen print, mounted recto only to pages with a stylised U.S. Corps of Engineers printed border

7 x 9 1/4 inches (17.8 x 23.5cm)

Plate XLV of the photographic album Photographic Views of Red River Raft

1873 (detail)

Robert B. Talfor

U.S. Aid, clearing logjam in the Red River, Louisiana. Plate XV of the photographic album Photographic Views of Red River Raft

1873

Hand-coloured albumen print, mounted recto only to pages with a stylised U.S. Corps of Engineers printed border

7 x 9 1/4 inches (17.8 x 23.5cm)

U.S. Steamer Aid at work. Raft No. 5, side view. Photograph showing the steam snag boat, US Aid, clearing logjam in the Red River, Louisiana

Robert B. Talfor

Plate XXIII of the photographic album Photographic Views of Red River Raft

1873

Hand-coloured albumen print, mounted recto only to pages with a stylised U.S. Corps of Engineers printed border

7 x 9 1/4 inches (17.8 x 23.5cm)

Preparation for the work began in August, 1872. On November 25, “the small-pox infection being no longer feared,” the steamboat Aid, with two months provisions and two craneboats in tow, started up Red River. They had been outfitted and supplied in New Orleans. Shore parties had already been organized in Shreveport and work itself begun on December 1, a month before the arrival of the Aid. The details of this work, from the preparation in August to the opening of the upper river in May of the next year, are covered in the report dated July 1, 1873, from Lieutenant Woodruff to Captain Howell. The last page of this report included specific comments on the value of the previously discussed Photographic Views of Red River to Lieutenant Woodruff’s total report. The importance of these photographs in understand in the scope and nature of the raft removal is reflected in the following statement:

To accompany this I have prepared a series of photographic views showing every portion of the raft, parties at work, (etc). With the view is a photographic map of the raft region, with location and axis of the camera for each view marked upon it and numbered to correspond with the number on the view. This album full of photographs, affording a complete and truthful panorama of the raft, will give a better idea of the nature of the work performed and of the character of the country than could be obtained form the most elaborate description. [The map is in the Library of Congress]

Extract from Hubert Humphreys. “Photographic Views of the Red River Raft, 1873,” in Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association Vol. 12, No. 2 (Spring, 1971) pp. 101-108 (16 pages with photographs)

Robert B. Talfor

Steam saws on flat, foot Raft No. 23. Plate L of the photographic album Photographic Views of Red River Raft (detail)

1873

Hand-coloured albumen print, mounted recto only to pages with a stylised U.S. Corps of Engineers printed border

7 x 9 1/4 inches (17.8 x 23.5cm)

Robert B. Talfor

Plate VI of the photographic album Photographic Views of Red River Raft (detail)

1873

Hand-coloured albumen print, mounted recto only to pages with a stylised U.S. Corps of Engineers printed border

7 x 9 1/4 inches (17.8 x 23.5cm)

Robert B. Talfor

Raft No. 4 partially removed. Plate X of the photographic album Photographic Views of Red River Raft (detail)

1873

Hand-coloured albumen print, mounted recto only to pages with a stylised U.S. Corps of Engineers printed border

7 x 9 1/4 inches (17.8 x 23.5cm)

Raft No. 4 partially removed. Crane boat at work (removing dead tree)

Robert B. Talfor

Plate XVII of the photographic album Photographic Views of Red River Raft (detail)

1873

Hand-coloured albumen print, mounted recto only to pages with a stylised U.S. Corps of Engineers printed border

7 x 9 1/4 inches (17.8 x 23.5cm)

Crane boat at work

Robert B. Talfor

Plate XXV of the photographic album Photographic Views of Red River Raft (detail)

1873

Hand-coloured albumen print, mounted recto only to pages with a stylised U.S. Corps of Engineers printed border

7 x 9 1/4 inches (17.8 x 23.5cm)

Robert B. Talfor

Plate XXVI of the photographic album Photographic Views of Red River Raft (detail)

1873

Hand-coloured albumen print, mounted recto only to pages with a stylised U.S. Corps of Engineers printed border

7 x 9 1/4 inches (17.8 x 23.5cm)

Robert B. Talfor

Plate XXII of the photographic album Photographic Views of Red River Raft (detail)

1873

Hand-coloured albumen print, mounted recto only to pages with a stylised U.S. Corps of Engineers printed border

7 x 9 1/4 inches (17.8 x 23.5cm)

Robert B. Talfor

Plate XXVIII of the photographic album Photographic Views of Red River Raft (detail

1873

Hand-coloured albumen print, mounted recto only to pages with a stylised U.S. Corps of Engineers printed border

7 x 9 1/4 inches (17.8 x 23.5 cm)

Red River of the South

Schell and Hogan (illustration)

U.S. Snagboat ‘Helliopolis’

Nd

Engraving

The Heliopolis raised a one hundred and sixty foot tree in 1829, according to Captain Richard Delafield of the Corps of Engineers. By 1830 Shreve’s Snag Boats, or “Uncle Sam’s Tooth Pullers” as they were called, had improved navigation to the point that only one flatboat was lost on a snag during that year. During the 1830s Shreve set about cutting back trees on the banks of the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers to prevent the recurrence of snags.

“One of Uncle Sam’s Tooth Pullers”

The snag boats operated by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers were sometimes called “Uncle Sam’s Tooth Pullers,” referring to how the vessels extracted whole trees and logs that hindered navigation. U.S. Snag Boat No. 2 is shown pulling stumps from the river bottom.

From Harper’s Weekly, Nov. 2, 1889

Plan for Henry Shreve’s snag boat. Patent No. 913, September 12, 1838

Shreveport, the Great Raft and Eugene Augustus Woodruff

Shreveport is located on the Red River in northwestern Louisiana, positioned on the first sustainable high ground in the river valley north of the old French settlement of Natchitoches. When the town as incorporated in 1839, it was, for a short period, the westernmost municipality in the United States. Four years prior to this, the settlement began as Shreve Town. Hugging a one-square-mile diamond-shaped bluff and plateau, Shreveport seemed an ideal place for a town. The northern edge of the plateau rested against Cross Bayou. The combined water frontage of the bayou and the Red River afforded the town ample room for commercial growth. However, a major obstacle stood in its way.

Captain Henry Miller Shreve, the man for whom Shreveport is named, received a contract from the U.S. Army to remove a gain logjam known as the “Great Raft.” Shrove was widely acclaimed as the most knowledgeable expert in raft removal… The upstream portion of the raft at times extended in Oklahoma. Since the Red River had many meandering curves, a straight-line mile might have as many as 3 river miles within it. At its largest, the raft closed over 400 miles of river. By the time Shreve examined it, in about 1830, the raft extended about 110 miles.

Shrove bought in large vessels that he modified for the job. Some of these ripped the jam apart with grappling hooks. Others rammed the raft to loosen individual trees. Some of the vessels were built by taking two steamboats and joining them side by side into a catamaran. The captain built a small sawmill on the common deck. The most famous of these hybrid snag boats, as they were called, were the Archimedes and the Heliopolis. His crews consisted of slave labor and Irish immigrants. The work was very difficult and extremely dangerous. …

Shreve’s efforts did not end the problem with the raft. Periodic work was needed to clear the river as the raft formed again. The Civil War interrupted this work, but by 1870, Congress had realised that the rived must be opened. Appropriations were again made, and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers sent an engineering unit to deal with the issue. The team arrived in late 1871 under the command of First Lieutenant Eugene Augustus Woodruff. Woodruff, his brother, George, and their men set to work. They recorded their actions with maps and photographs. R.B. Talfor was the photographer assigned the duty of recording the work, and this may have been the first instance of an imbedded photographer assigned to a specific unit. Talfor and the Woodruff brothers took over one hundred images of the raft clearing. Today, their records remain the standard chronicle for a project of this type.

The unit’s primary snagboat was the U.S. Aid, a modern version of Henry Shreve’s Archimedes. This elegant stern-wheel vessel was the most advanced of its type in the late nineteenth century. Another technology used as a test bed for river clearing was the newly created explosive nitroglycerin. Because nitroglycerin was extremely dangerous to use and volatile to make, the nitroglycerin lab occasionally blew up – thankfully, with almost no casualties.

The Woodruffs found areas of clear water, appearing as a strong of lakes, and when the broke up the logs around them, the loosened trees and logs would sometimes form snags downstream. One of the unfortunate steamboats was the R.T. Bryarly, photographed by Talfor in 1873. Talker took his photograph from a recently cleared section of the rived. Piles of debris could clearly be seen on both banks as the steam picked its was up the river. The Bryarly plied the rived until September 19, 1876, when it hit a snag and was lost. The use of explosives and the improved snagboats finally conquered the river. …

… In mid-August 1873, an epidemic [of yellow fever] broke out it Shreveport. Everyone who could leave town did, and the population dwindled to about four thousand people before other towns sealed of the roads, railroads and streams to protect their residents. A quarter of the population who remained died within the first two weeks, and another 50 percent contracted yellow fever within the next six weeks. Most of the doctors and nurses died in the first month. …

In early September 1873, the army ordered its raft-clearing engineers out of the city, indicating that they should relocate farther south. Lieutenant Eugene Augustus Woodruff set his men, including his brother, George, to safety. He remained to help care for the residents of Shreveport. With most of the doctors dead or ill, Woodruff and six Roman Catholic priest ministered to the victims. By the end of September, all of these good men had died from yellow fever.

Gary D. Joiner and Ernie Roberson. Lost Shreveport: Vanishing Scenes from the Red River Valley. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2010 [Online] Cited 17/10/2018

Unknown photographer

Lt. Eugene Woodruff (age approx. 23)

c. 1866

USMA Archives

Lt. Eugene A. Woodruff (1843-1873), Red River Hero, died age 31

“He died because too brave to abandon his post even in the face of a fearful pestilence and too humane to let his fellow beings perish without giving all the aid in his power to save them,” wrote Capt. Charles W. Howell, responsible for Corps of Engineers works in Louisiana, in 1873. “His name should be cherished, not only by his many personal friends,” he continued, “but by the Army, as one who lived purely, labored faithfully, and died in the path of duty.”

Captain Howell penned that tribute to his deputy, Lt. Eugene A. Woodruff, a young officer whom Howell sent from New Orleans to the Red River of Louisiana as supervisor of the project to clear the great log raft, a formidable obstruction to navigation. Henry M. Shreve first cleared the Red River raft in the 1830s, but the raft formed again during years of inadequate channel maintenance resulting from meager congressional appropriations and neglect during the Civil War.

Lieutenant Woodruff left his workboats and crew on the Red River in September 1873 to visit Shreveport and recruit a survey party. When he arrived, he found Shreveport in the grip of a yellow-fever epidemic. Fearing he might carry the disease to his workmen if he returned to camp, he elected to stay in Shreveport and tend to the sick. He volunteered his services to the Howard Association, a Louisiana disaster-relief charity, and traveled from house to house in his carriage, delivering food, medicine, and good cheer to the sick and dying. He contracted the disease himself and died in late September, “a martyr,” reported the Shreveport newspaper, “to the blessed cause of charity.”

“His conduct of the great work on which he was engaged at the time of his death,” said the New Orleans District Engineer, “will be a model for all similar undertakings and the completion of the work a monument to his memory.” Captain Howell assigned responsibility for finishing the job on the Red River to Assistant Engineer George Woodruff, brother of the lieutenant.

Woodruff’s selfless actions not only eased the suffering of Shreveport residents, but his decision to remain in the town no doubt lessened the threat to his crew. Spared from the disease, the engineers successfully broke through the raft, clearing the river for navigation on 27 November 1873. An Ohio River snagboat built the following year received the name E. A. Woodruff in recognition of the lieutenant’s sacrifice. The vessel served until 1925. More than a century later the people of Shreveport continue to honor the memory of Lieutenant Woodruff.

Anonymous text and image from “Lt. Eugene A. Woodruff, Red River Hero,” on the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers website 2000 revised July 2021 [Online] Cited 22/02/2022

Unknown photographer

Untitled [Members of a Cavalry unit at Fort Grant, A.T. in 1876 showing the variety of both clothing and headgear in use by the Army in the mid-1870s]

1876

Yellow fever

Yellow fever is a viral disease that is transmitted by mosquitoes. Yellow fever can lead to serious illness and even death. It is called ‘yellow fever’ because in serious cases, the skin turns yellow in colour. This is known as ‘jaundice’. Symptoms of yellow fever may take 3 to 6 days to appear. Some infections can be mild but most lead to serious illness characterised by two stages. In the first stage fever, muscle pain, nausea, vomiting, headache and weakness occur. About 15 to 25 per cent of those with yellow fever progress to the second stage also known as the ‘toxic’ stage, of which half die within 10 to 14 days after onset of illness. Visible bleeding, jaundice, kidney and liver failure can occur during the second stage.

Although yellow fever is most prevalent in tropical-like climates, the northern United States were not exempted from the fever. The first outbreak in English-speaking North America occurred in New York City in 1668, and a serious one afflicted Philadelphia in 1793. English colonists in Philadelphia and the French in the Mississippi River Valley recorded major outbreaks in 1669, as well as those occurring later in the 18th and 19th centuries. The southern city of New Orleans was plagued with major epidemics during the 19th century, most notably in 1833 and 1853. Its residents called the disease “yellow jack”…

The yellow fever epidemic of 1793 in Philadelphia, which was then the capital of the United States, resulted in the deaths of several thousand people, more than 9% of the population. The national government fled the city, including President George Washington. Additional yellow fever epidemics struck Philadelphia, Baltimore, and New York City in the 18th and 19th centuries, and traveled along steamboat routes from New Orleans. They caused some 100,000-150,000 deaths in total.

In 1853, Cloutierville, Louisiana, had a late-summer outbreak of yellow fever that quickly killed 68 of the 91 inhabitants. A local doctor concluded that some unspecified infectious agent had arrived in a package from New Orleans. 650 residents of Savannah, Georgia died from yellow fever in 1854. In 1858, St. Matthew’s German Evangelical Lutheran Church in Charleston, South Carolina, suffered 308 yellow fever deaths, reducing the congregation by half. A ship carrying persons infected with the virus arrived in Hampton Roads in southeastern Virginia in June 1855. The disease spread quickly through the community, eventually killing over 3,000 people, mostly residents of Norfolk and Portsmouth. In 1873, Shreveport, Louisiana, lost almost a quarter of its population to yellow fever. In 1878, about 20,000 people died in a widespread epidemic in the Mississippi River Valley. That year, Memphis had an unusually large amount of rain, which led to an increase in the mosquito population. The result was a huge epidemic of yellow fever. The steamship John D. Porter took people fleeing Memphis northward in hopes of escaping the disease, but passengers were not allowed to disembark due to concerns of spreading yellow fever. The ship roamed the Mississippi River for the next two months before unloading her passengers. The last major U.S. outbreak was in 1905 in New Orleans.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Snag

In forest ecology, a snag refers to a standing, dead or dying tree, often missing a top or most of the smaller branches. In freshwater ecology it refers to trees, branches, and other pieces of naturally occurring wood found sunken in rivers and streams; it is also known as coarse woody debris. …

Maritime hazard

Also known as deadheads, partially submerged snags posed hazards to early riverboat navigation and commerce. If hit, snags punctured the wooden hulls used in the 19th century and early 20th century. Snags were, in fact, the most commonly encountered hazard, especially in the early years of steamboat travel. In the United States, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers operated “snagboats” such as the W. T. Preston in the Puget Sound of Washington State and the Montgomery in the rivers of Alabama to pull out and clear snags. Starting in 1824, there were successful efforts to remove snags from the Mississippi and its tributaries. By 1835, a lieutenant reported to the Chief of Engineers that steamboat travel had become much safer, but by the mid-1840s the appropriations for snag removal dried up and snags re-accumulated until after the Civil War.

Text from the Wikipedia webiste

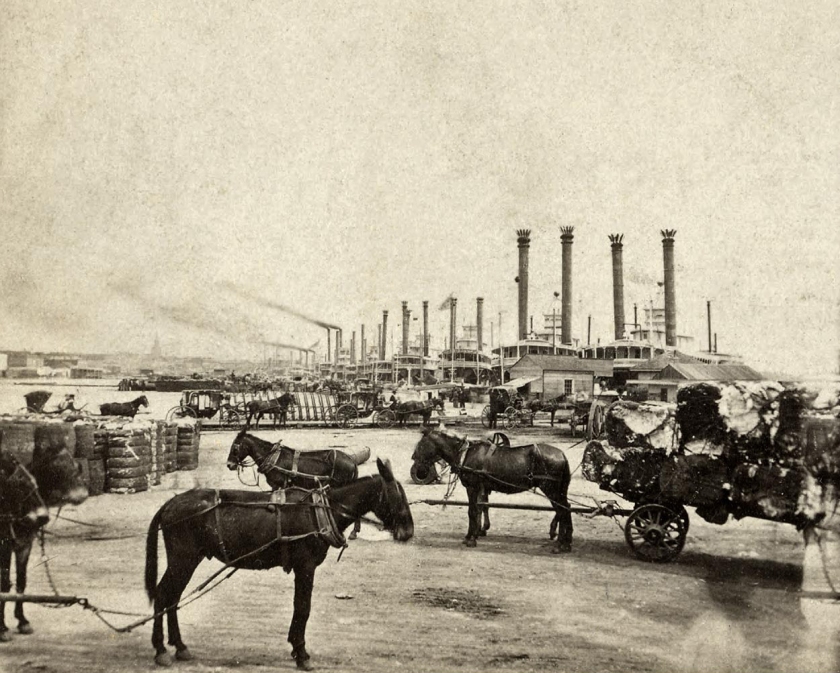

S.T. (Samuel Tobias) Blessing (American, b. 1830-1897)

New Orleans Levee

c. 1866-1870

From a stereographic view, on wet or dry plate glass negative

Samuel Tobias Blessing (1830-1897) was a successful daguerreotypist, ambrotypist, photographer, daguerrean, and photographic stock dealer. He was active in La Grange, Texas in 1856, and Galveston, Texas 1856 c.-1861, and in New Orleans 1861-1890s. From 1856, Blessing partnered with Samuel Anderson, operating bi-state studios and stock depots in Trenton Street, Galverston, and at 120 Canal Street, New Orleans, moving to 137 Canal Street in 1856. Their partnership was dissolved in 1863. After the Civil War, Blessing turned his attention to making stereographs, publishing New Orleans in Stereoscope in 1866. Other stereographic series included Views of New Orleans & Vicinity, and Public Buildings in New Orleans.

Text and image from the Steamboat Times website

Unknown photographer

New Orleans Levee

c. 1867-1868

Wet plate negative on glass, or Tintype positive

Four boats in this New Orleans scene have been positively identified. They are from right to left, B.L. HODGE (No.2), MONSOON, ST. NICHOLAS, and CUBA. The remaining boats, also right to left, are not confirmed but may be the BART ABLE, GEORGE D. PALMER, and the FLICKER.

The B.L. HODGE No.2 was built in 1867, and the MONSOON was lost to a snag on the Red River on Dec. 21, 1868, heavily loaded with cotton. Therefore the photograph was taken sometime during 1867-1868. The PALMER was lost after hitting the Quincy bridge on Oct. 2, 1868, which would further narrow the timeframe for this scene.

Text and image from the Steamboat Times website

![Unknown photographer. 'Untitled [Members of a Cavalry unit at Fort Grant, A.T. in 1876 showing the variety of both clothing and headgear in use by the Army in the mid-1870s]' 1876 Unknown photographer. 'Untitled [Members of a Cavalry unit at Fort Grant, A.T. in 1876 showing the variety of both clothing and headgear in use by the Army in the mid-1870s]' 1876](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/us-army-uniforms-1870s-web.jpg?w=840)

You must be logged in to post a comment.