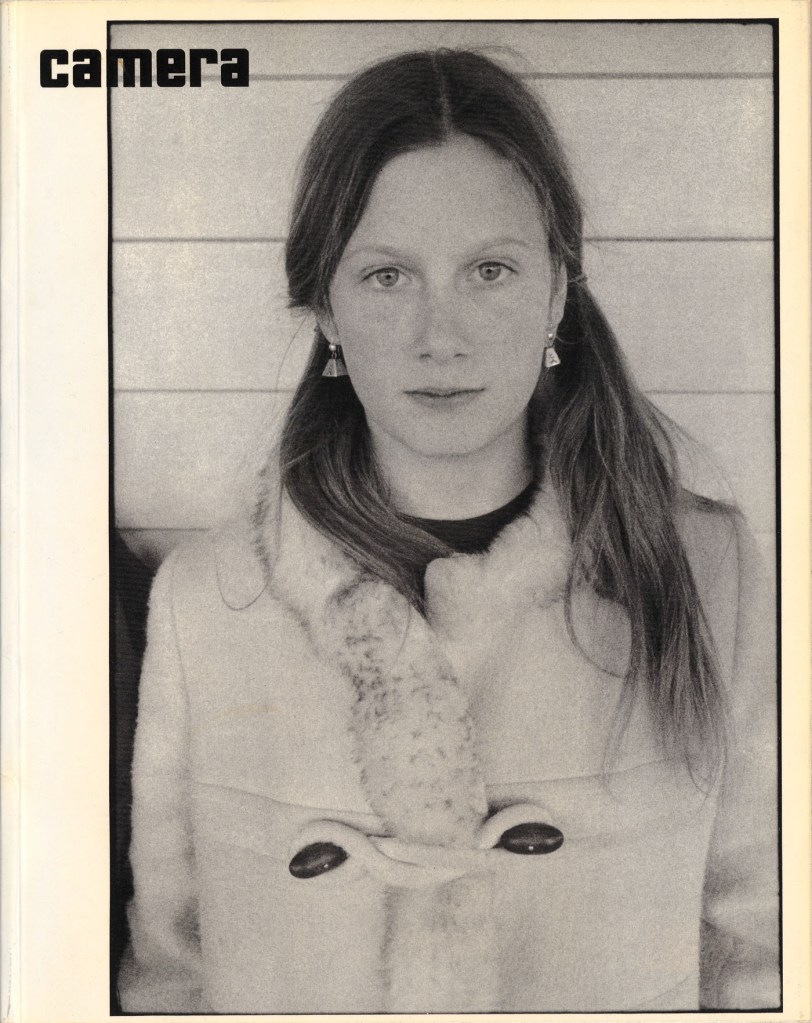

Exhibition dates: 6th October, 2024 – 6th April, 2025

Curator: Andrea Nelson, associate curator in the department of photographs, National Gallery of Art

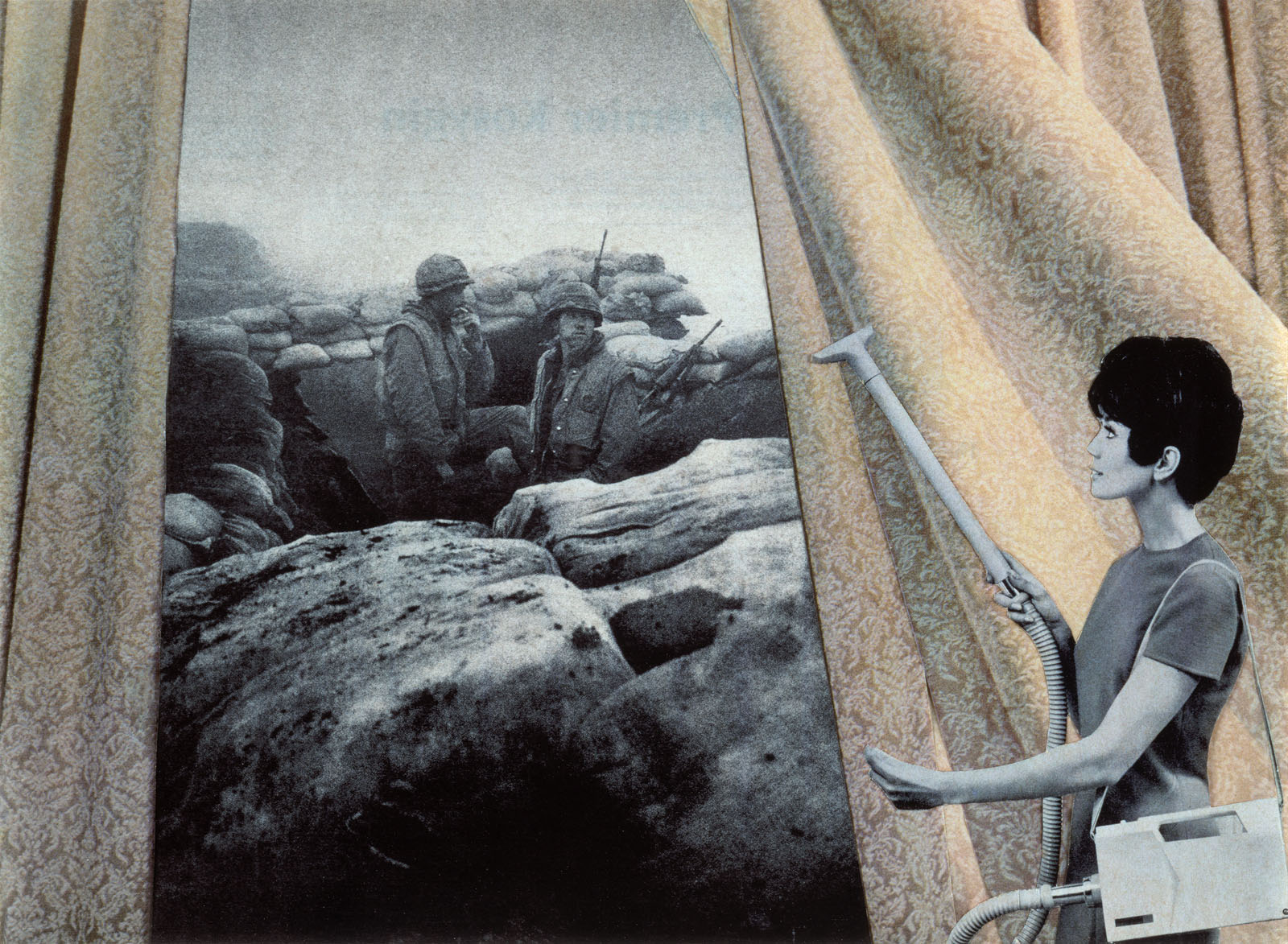

Martha Rosler (American, b. 1943)

Cleaning the Drapes

1967-1972, printed 2007

From the series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home

Inkjet print

Image: 44.2 x 60.4cm (17 3/8 x 23 3/4 in.)

National Gallery of Art

Gift of the Collectors Committee and Pepita Milmore Memorial Fund

Martha Rosler originally distributed photocopies from this series, House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, as flyers at anti – Vietnam War demonstrations. She made the original photomontages by combining gritty news photographs of fighting in Vietnam with homerelated advertisements culled from glossy women’s magazines. Here Rosler paired a woman cleaning patterned drapes with two tired soldiers smoking amid rocks and sandbags. The woman’s vacuum wand points to and echoes the soldiers’ rifles. The jolting collision of war imagery and affluent domestic space gives visual form to the description of the conflict as “the living room war” – so called because it appeared on television news nightly.

Wall text from the exhibition

“Ce n’est pas une pipe mais de la photographie, sous toutes ses formes variables et multivalentes”

René Magritte’s 1929 painting Ceci n’est pas une pipe is also known as La Trahison des images … The Treachery of Images.

Treachery – the betrayal of trust – is an apposite word in relation to photography of the 1970s. Finally, once and for all, documentary photography in America broke free of the West Coast fine art photography tradition of mainly white male artists and the “aura” of the fine art print (Walter Benjamin). Photography betrayed the trust placed in the authenticity of the image and its link to the “truth” of reality represented in the photograph to become a medium of variability, in concept, execution and outcome. Photography became whatever you wanted it to be.

Documentary photography and its link to the reality of the referent – its assumed representation of a truth that existed in reality – began to be subsumed into the whole of photography, just part of a conceptual, art, performative, staged, street, cameraless, documentary, fashion, photojournalist, activist, amoebic (from the Greek ἀμοιβή amoibe, meaning “change”), and viral (Paul Virilio) medium.

Photography had always been a medium of communication but now became multi-perspectival – whether that be imaginings of the mind relayed through photographs, conceptual ideas about the world and how we interact with it created and staged through photographs, or new colour photography that challenged the orthodoxy of fine art black and white West Coast American photography.

As Anne-Marie Willis observes on the On This Date In Photography website, “any curator who would challenge the orthodox Beaumont Newhall-style photo history limited to images that are distinctively photographic, aesthetic, and “Straight” … would open a Pandora’s box full of photographs pervasive across so many fields, of such limitless subject matters, and crossing so many disciplines that their histories in photography would be obscured.”1

This is the alleged treachery of multi-perspectival photography, the betraying of photographic histories that stretched back to the beginnings of the medium… but it had to be done for photography to fully open itself up to the imaginings of the human and the media flows of the world. “It was a time when photography challenged the art photography norm: photography should not, could not be restricted to what was considered ‘art’.”2

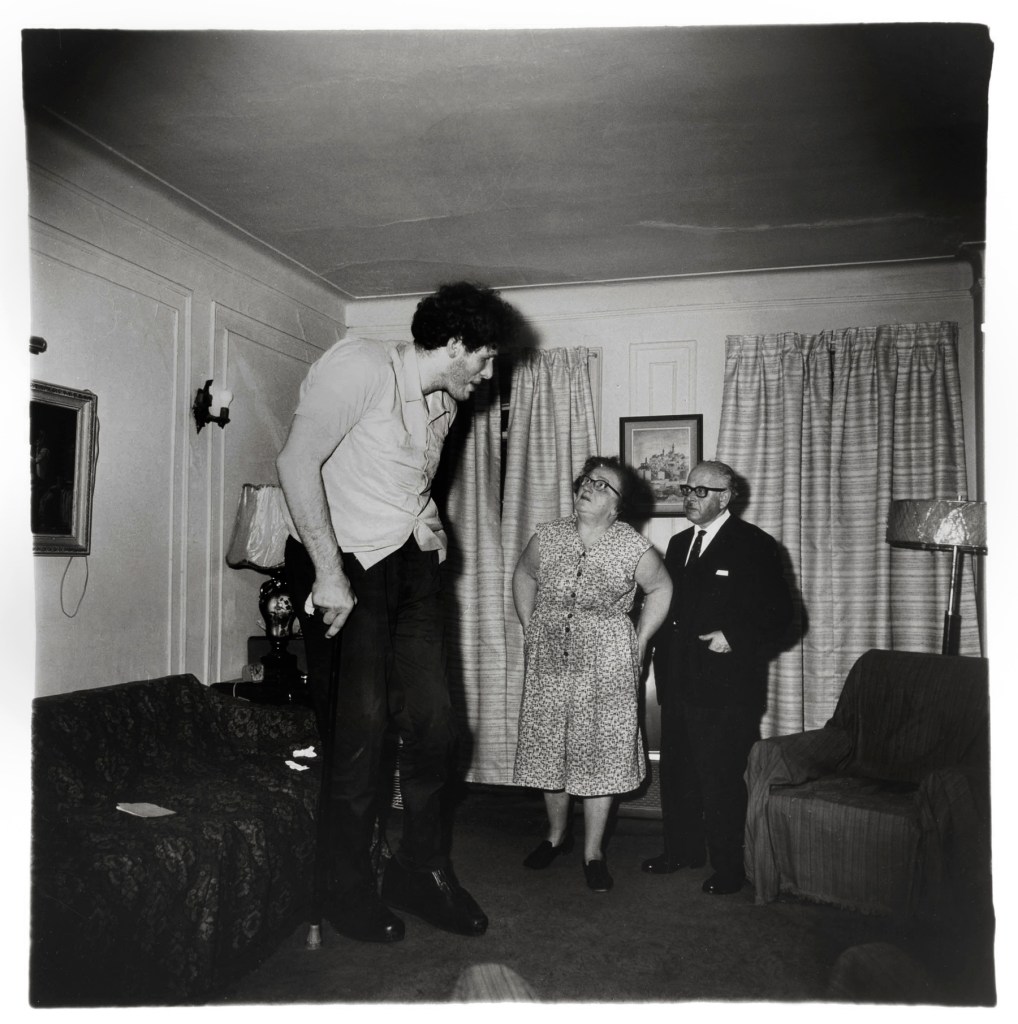

Thus, it is a great joy to see photographs from this stimulating exhibition, photographs that challenge the established “norm” of what photography should be. But what is surprising to me when looking at the complete list of photographs in this exhibition is the important artists who changed the face of photography in the 1970s who are not represented at all or only have one or two images on show:

Gordon Parks 0

Garry Winogrand 1

Lee Friedlander 2

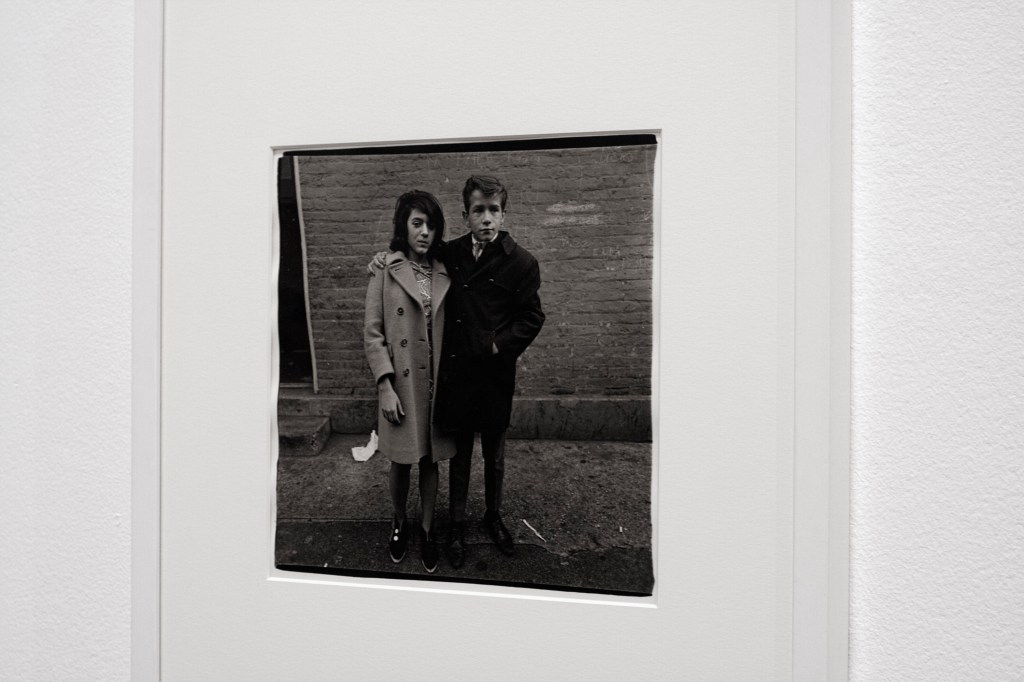

Diane Arbus 1

Robert Mapplethorpe 0

Robert Heinecken 0

Richard Avedon 0

Andy Warhol 1 Polaroid

Cindy Sherman 0

Barbara Kruger 0

Nan Goldin 1

Stephen Shore 1

Diane Arbus, who was instrumental in changing portrait photography at the time, only has one photograph in the exhibition; Barbara Kruger and Robert Heinecken, both “para-photographers” whose work stood “beside” or “beyond” traditional ideas associated with photography have none; Stephen Shore who, along with William Eggleston, was responsible for making colour photography acceptable in art photography has only one photograph.

But most surprisingly of all, Cindy Sherman whose Untitled Film Stills were made predominantly between 1977-1980 and who casts herself as clichés or feminine types, becoming both the artist and subject in the work … is not there at all. Her loss, her evisceration, and the absence of “arguably one of the most significant bodies of work made in the twentieth century and thoroughly canonized by art historians, curators, and critics,”3 is unfathomable.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ Anne-Marie Willis quoted in Dr James McArdle. “DECEMBER 14: CONTEXT,” on the On This Date In Photography website 15/12/2019 [Online] Cited 26/02/2025

2/ Ibid.,

3/ Exhibition Catalogue, New York, Museum of Modern Art, Cindy Sherman, 2012, p. 18 quoted in the “Untitled Film Stills” page on the Wikipedia website

Many thankx to the National Gallery of Art for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Martha Rosler (American, b. 1943)

Roadside Ambush

1967-1972, printed 2007

Inkjet print

Image/sheet: 50.8 x 61cm (20 x 24 in.)

National Gallery of Art

Gift of the Artist and Mitchell-Innes and Nash

Rosler originally distributed photocopies of House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home at anti–Vietnam War demonstrations. “I saw House Beautiful not as art,” she later reflected. “I wanted it to be agitational.” The artist created the original photomontages, from which these collages are derived, by combining news photographs of scorched battlefields in Vietnam with glossy advertisements for US homes, layering images of soldiers within cut-out silhouettes of men from polo-shirt advertisements; and splicing pictures of soldiers’ burials with those of military marches. By tying the destruction abroad to untroubled affluence at home, Rosler gave visual form to the description of the conflict as “the living-room war” – so called because it was the first war to be televised.

The exhibition The ’70s Lens: Reimagining Documentary Photography examines how new approaches to documentary photography that emerged during the 1970s reflected a radical shift in American life – and in the medium itself.

The 1970s was a decade of uncertainty in the US – soaring inflation, energy crises, the Watergate scandal, and protests about pressing social issues – and the profound upheaval that rocked the country formed the backdrop for a revolution in documentary photography. Now on view at @ngadc, The ’70s Lens: Reimagining Documentary Photography explores this compelling and contested moment of reinvention when the genre’s association with objectivity and truthfulness came into question. Featuring works from over eighty artists, the exhibition delves into how the camera was used to examine life in the US from a diverse range of perspectives, and in doing so, transformed the practice of documentary photography.

The ’70s Lens: A Conversation with Anthony Hernandez

Artist Anthony Hernandez discusses 50 years of work with curator Andrea Nelson on October 24, 2024. The conversation celebrates the exhibition The ’70s Lens: Reimagining Documentary Photography (October 2024 – April 2025).

Anthony Hernandez (b. 1947, Los Angeles, California) has crafted a richly varied oeuvre, ranging from a distinctive style of black-and-white street photography to colour photographs of abstracted details of his surroundings. Much of Hernandez’s work focuses on his native Los Angeles, revealing a unique insight into the people and landscape of the much-pictured city. Hernandez is a recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship (2018), the Rome Prize (1999) and has been named a United States Artists Fellow (2009).

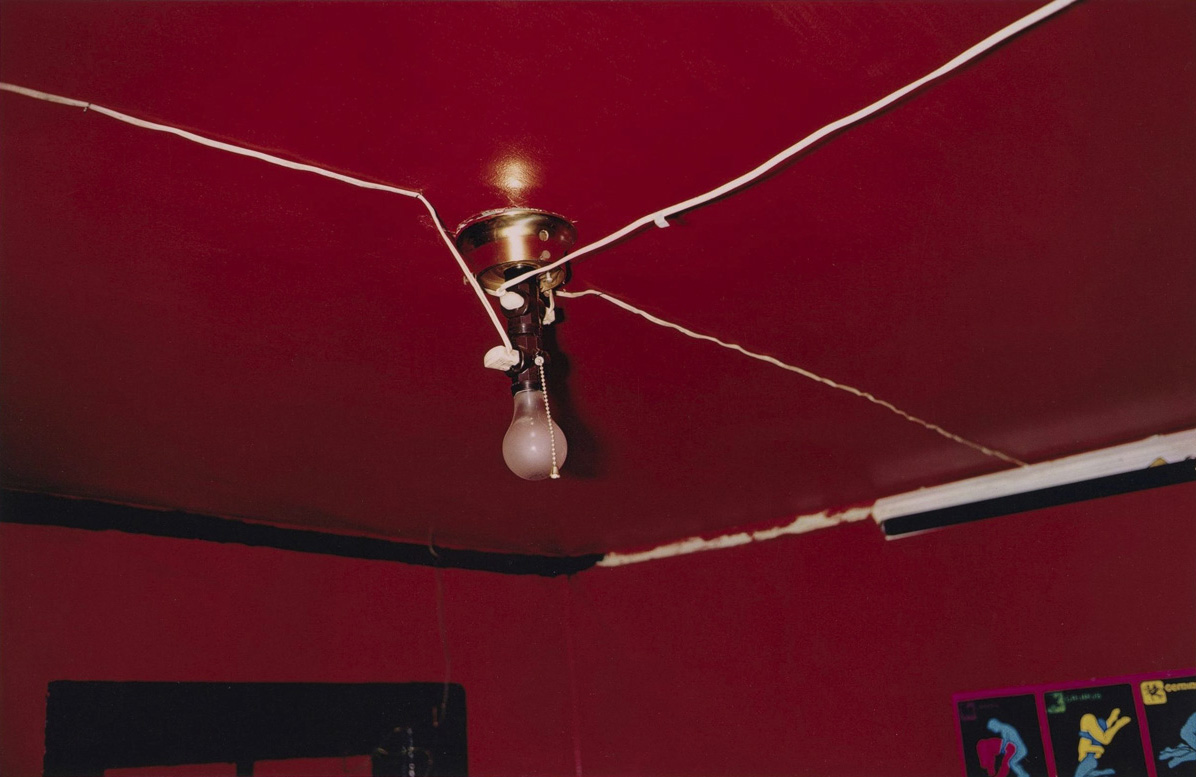

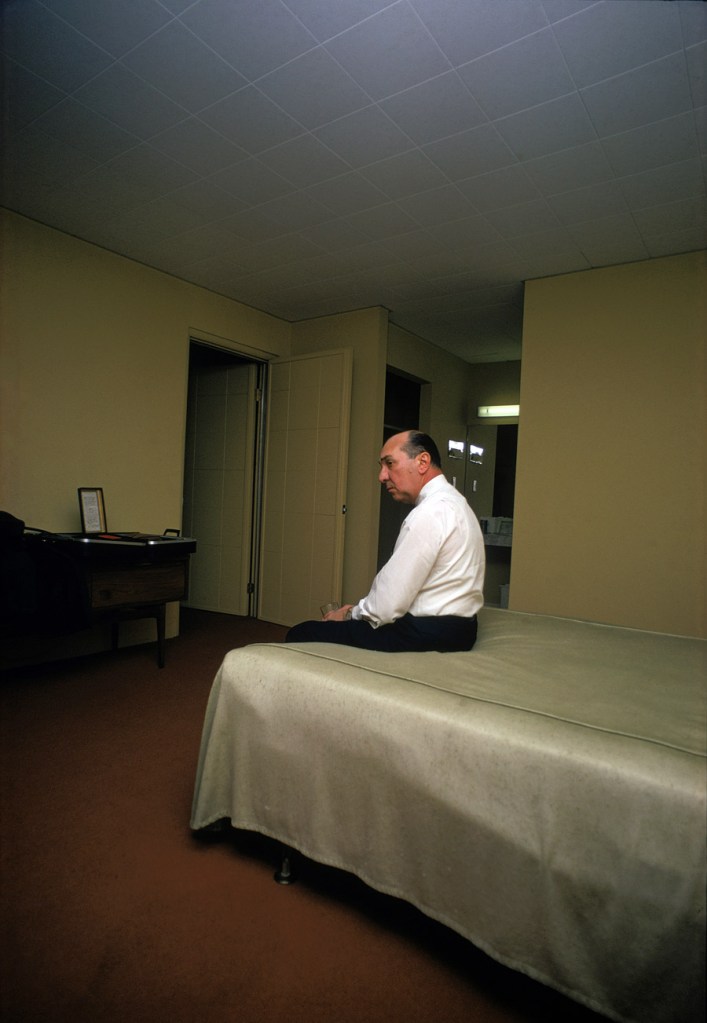

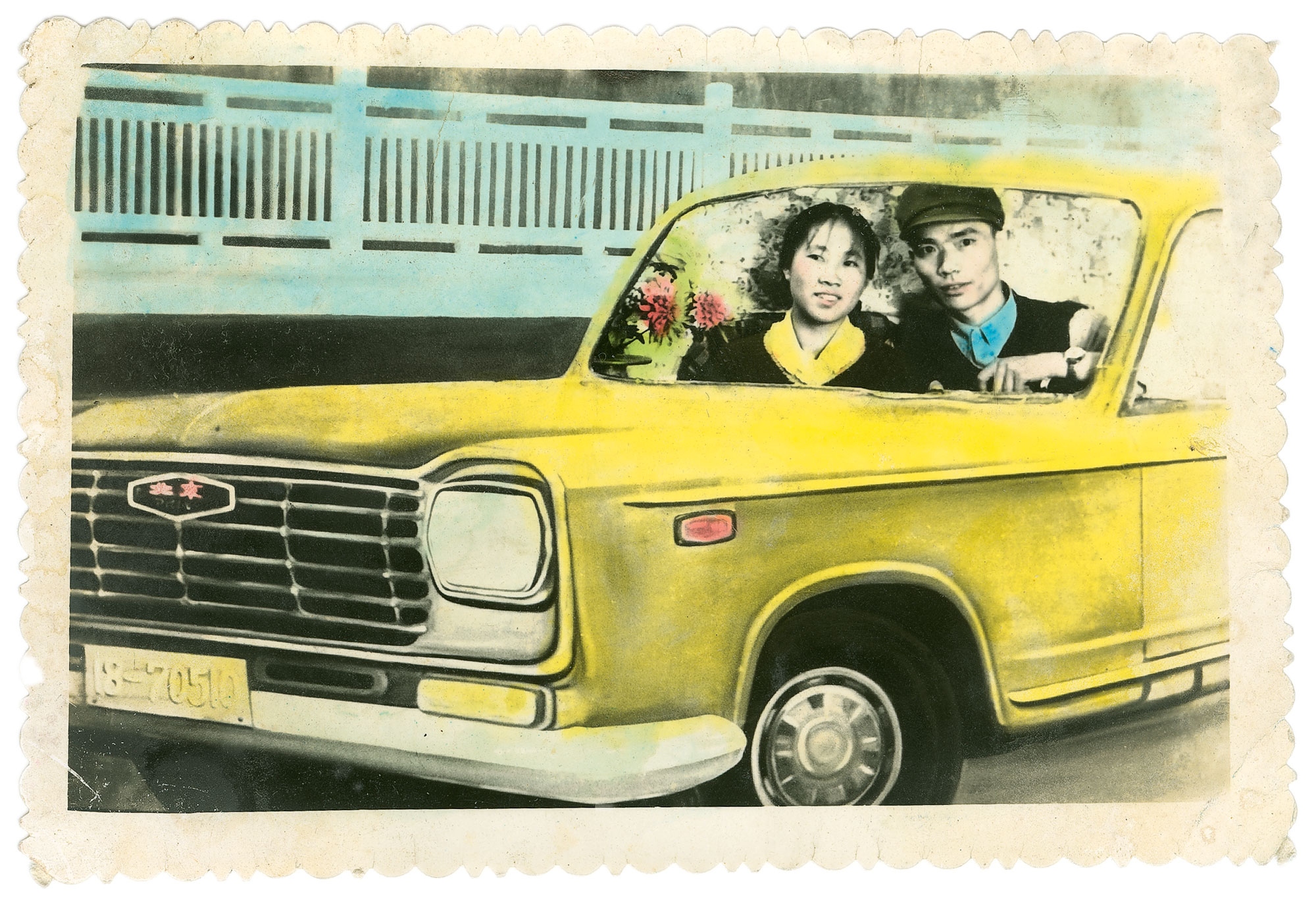

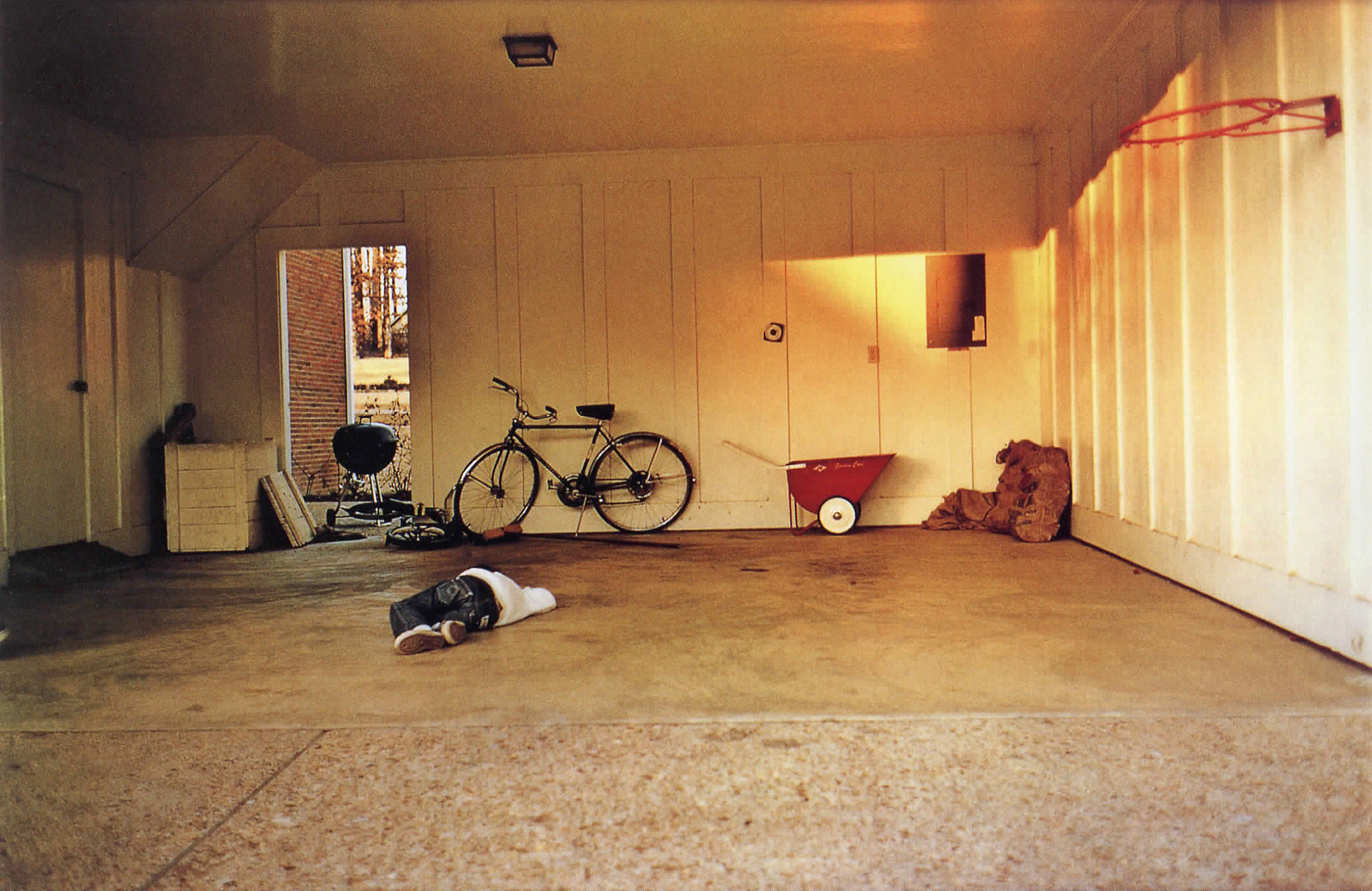

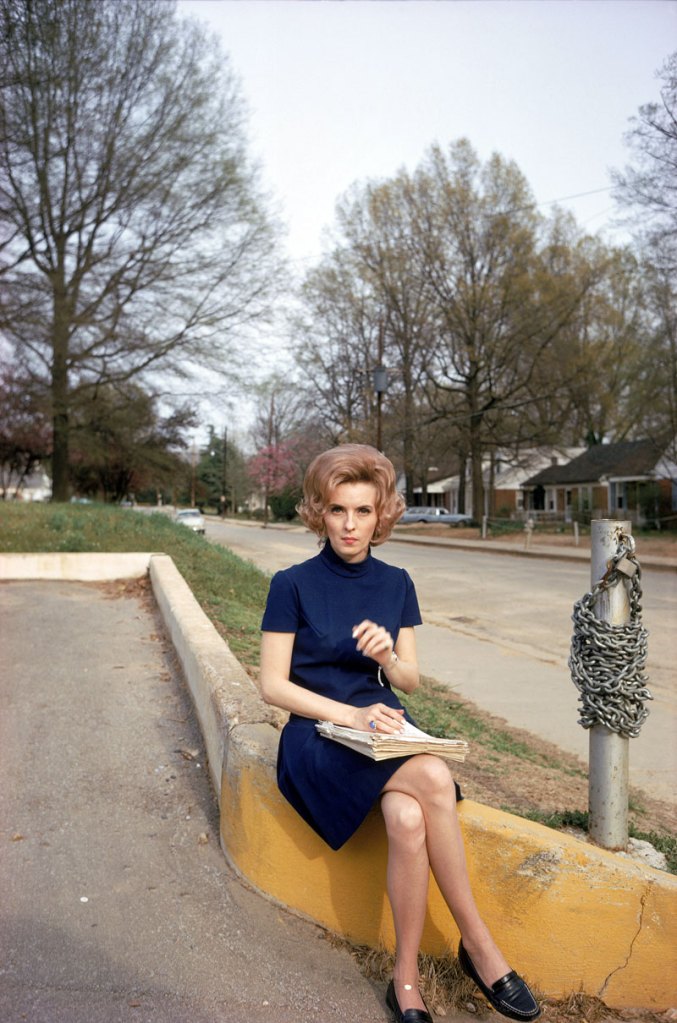

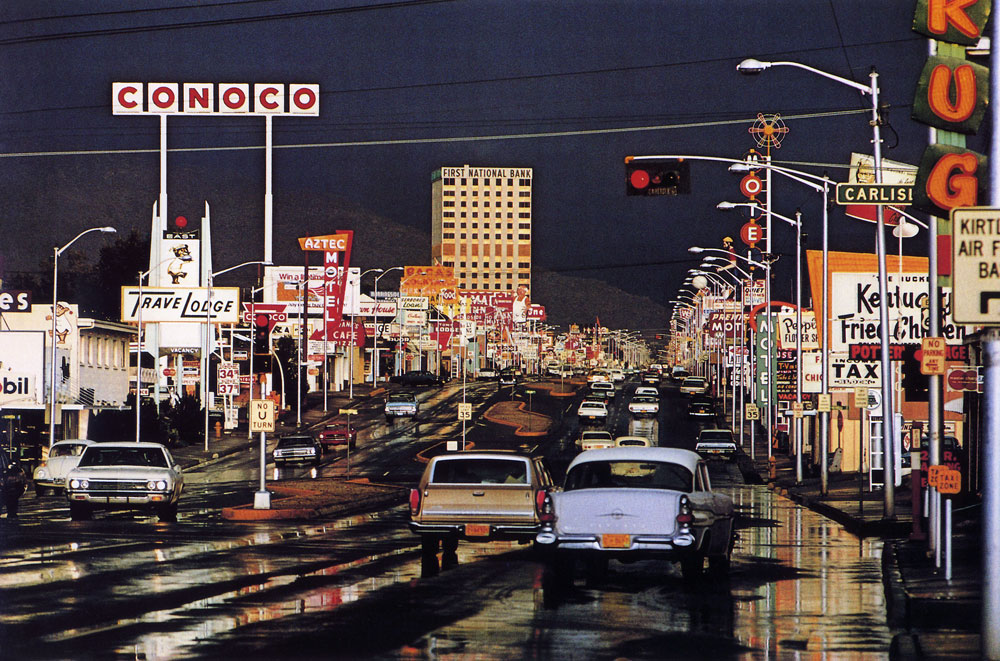

William Eggleston (American, b. 1939)

Memphis

1969-1970, printed 1980

Dye imbibition print

Image: 30.2 x 44.2cm (11 7/8 x 17 3/8 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Corcoran Collection

Gift of Mr. Morris R. Garfinkle

© Eggleston Artistic Trust

Eggleston is celebrated for his use of colour photography, which he began experimenting with in the late 1960s. Eggleston’s 1976 exhibition Colour Photographs, held at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, is considered a pivotal moment in the development of colour photography as a contemporary art form and widely credited with increasing recognition of the medium.

Since first picking up a camera in 1957, Eggleston has photographed his family, friends and the people that he encountered in his everyday life, particularly in his native Memphis. Eggleston is said to find the beauty in the everyday and his work has inspired many present day photographers, artists and filmmakers, including Martin Parr, Sofia Coppola, David Lynch and Juergen Teller.

Text from the National Gallery of Victoria website

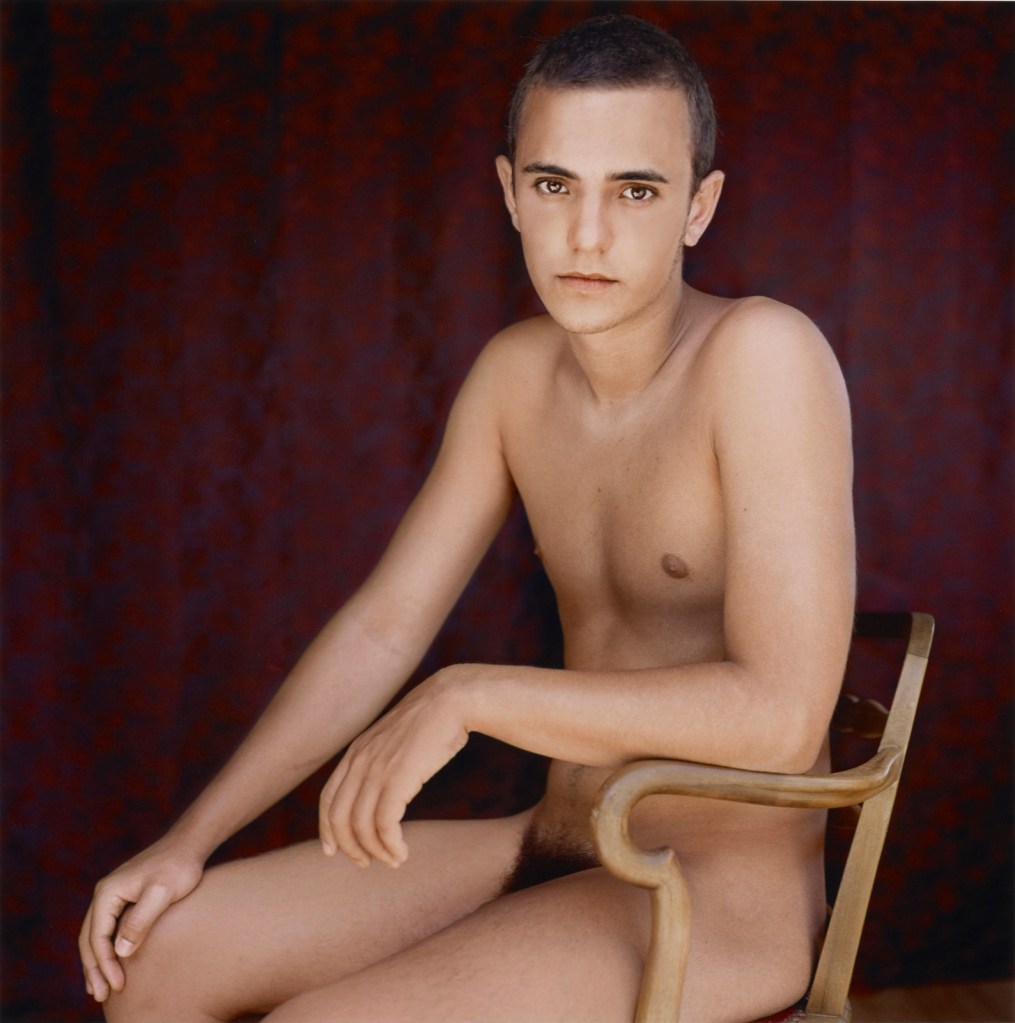

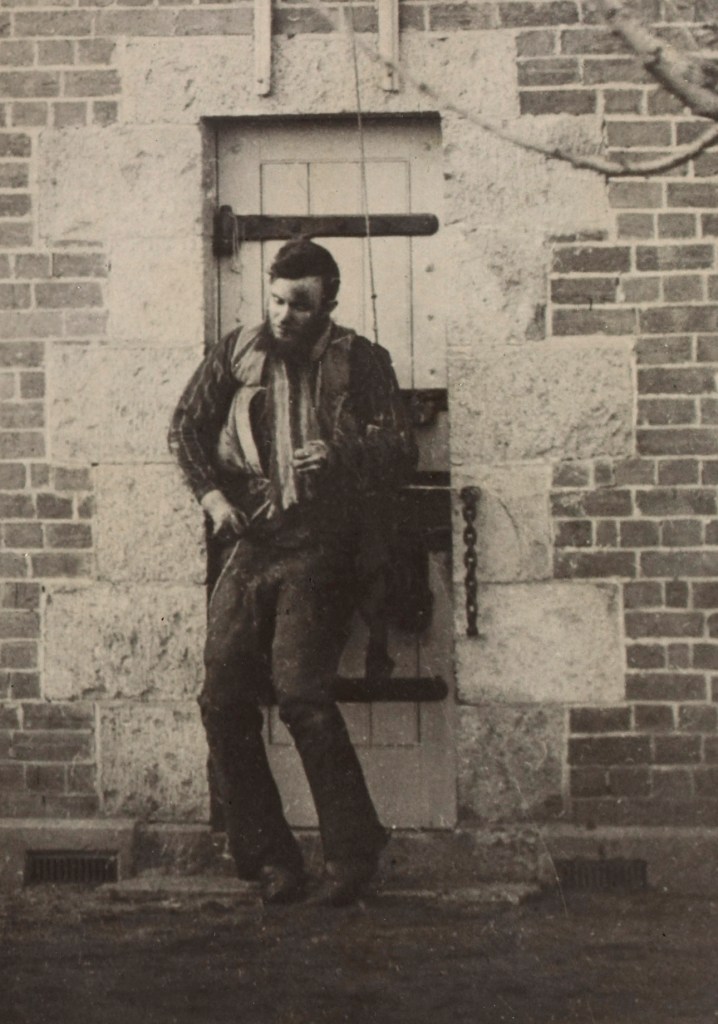

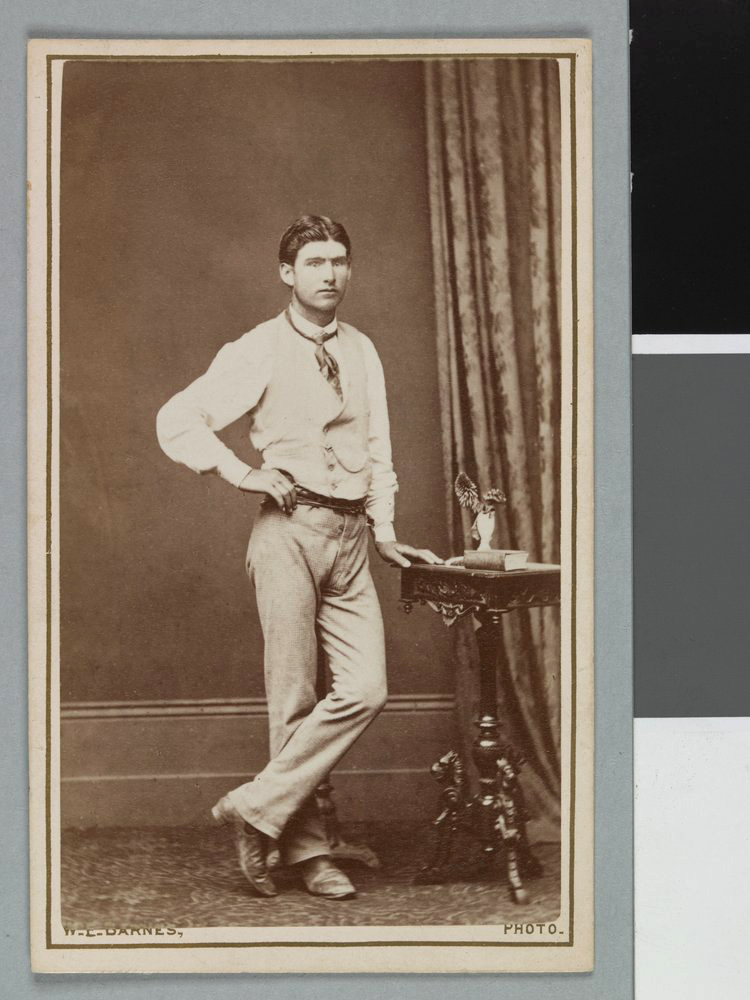

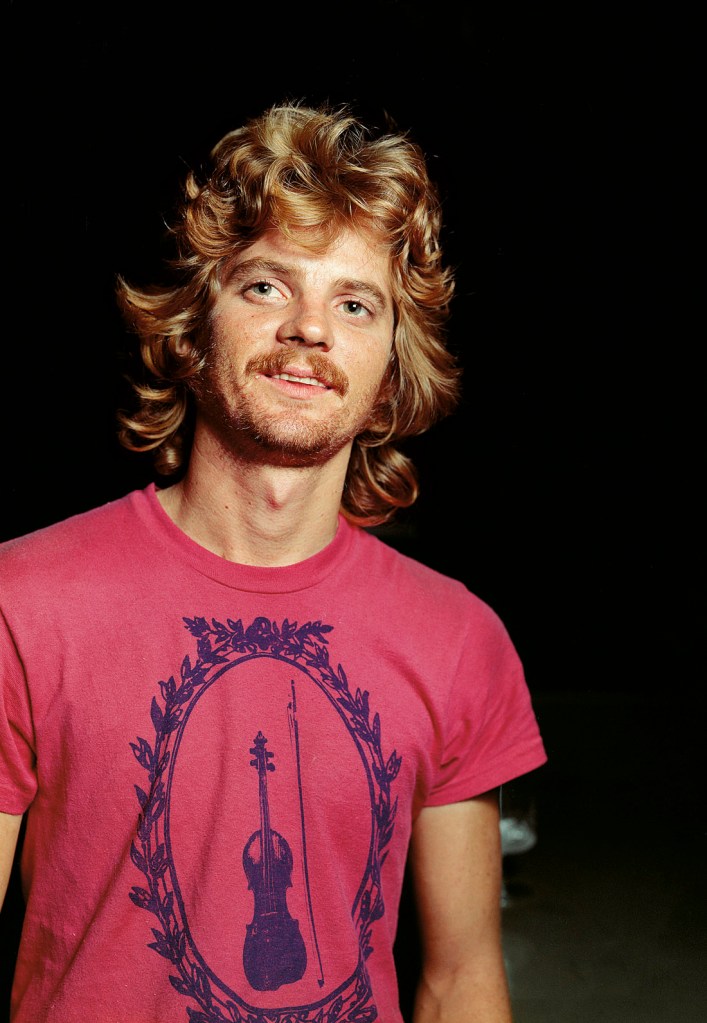

Anthony Friedkin (American, b. 1949)

Young Man, Troupers Hall, Hollywood

1969

From the series The Gay Essay

Gelatin silver print

National Portrait Gallery

Gift of Mary and Dan Solomon

In 1969, Anthony Friedkin was only 19 years old when he set out to document the queer communities of San Francisco and Los Angeles. The resulting project, The Gay Essay, is an expressive and nuanced portrait. Friedkin charts various facets of the culture, from street life and protests to parades and drag performances.

Friedkin’s photographs record the beginnings of the gay liberation movement in California. With a respectful intimacy he pictures individuals living true to themselves while defying prevailing social norms.

Wall text from the exhibition

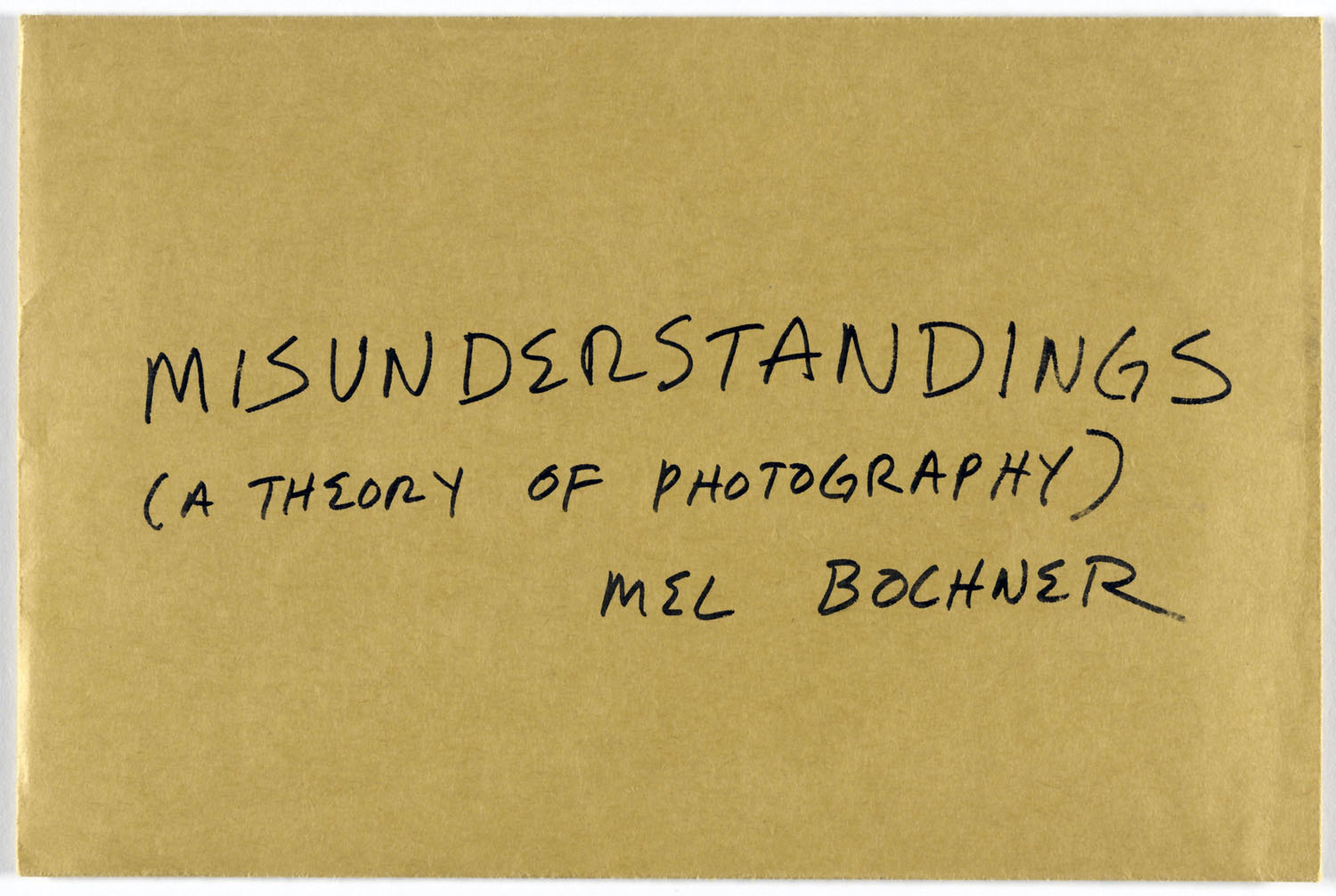

Mel Bochner (American, 1940-2025)

Misunderstandings (A Theory of Photography) (details)

1970

10 offset lithographs on notecards and envelope

Sheet (each): 12.7 x 20.32cm (5 x 8 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Gift of Mary and Dan Solomon

When Mel Bochner started documenting his works of sculpture with a camera, he realised that his practice had “become about photography without [my] wanting it to.” He studied the history of the medium and found conflicting ideas about what photography is or should be. By illustrating these “misunderstandings” with quotes from notable figures and sources, Bochner underscored the gap between a photograph itself and what it purports to represent. He even fabricated three of the quotations, further playing on photography’s tenuous relationship to truth. The photograph of the artist’s hand and forearm is also a misunderstanding: it is much smaller than the actual body part it depicts. It also appears to be a negative of a Polaroid photograph, but Polaroids exist only as positive prints.

Wall text from the exhibition

Mel Bochner was a key figure in the Conceptual Art movement of the 1960s and 70s. Bochner was part of a group of artists who challenged the traditional notion of art as a physical object to be admired for its aesthetic qualities and instead sought to explore the ideas and concepts behind the object, often using language and text as their medium.

Bochner’s early works were influenced by his interest in mathematics and logic, which he applied to create intricate geometric patterns. As his practice evolved, he incorporated language and words into his artwork, exploring the relationship between language, thought, and perception.

Text from the My Art Broker website

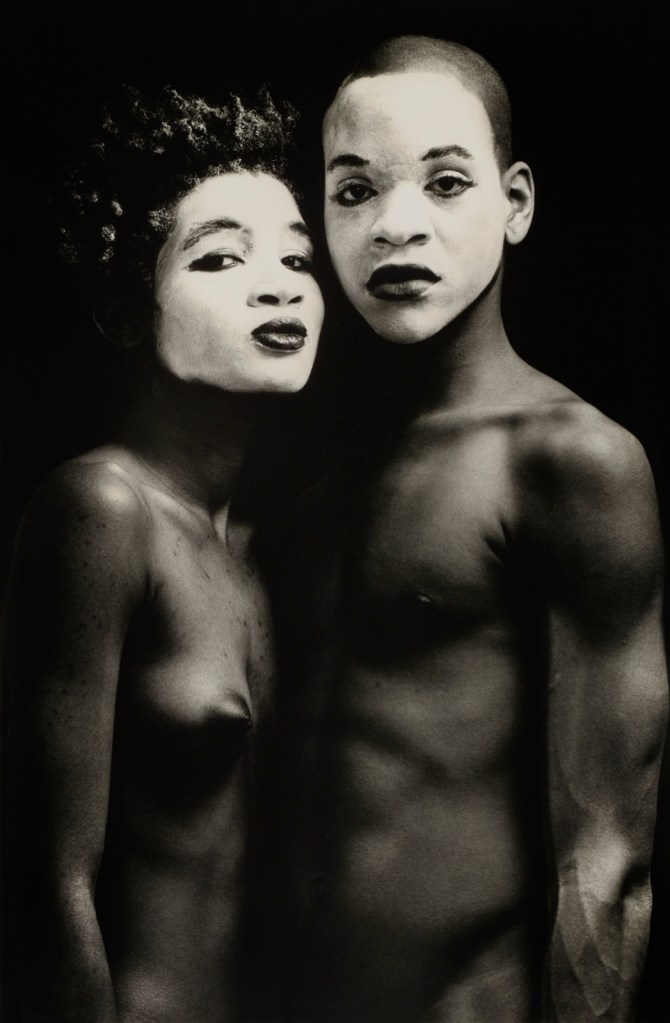

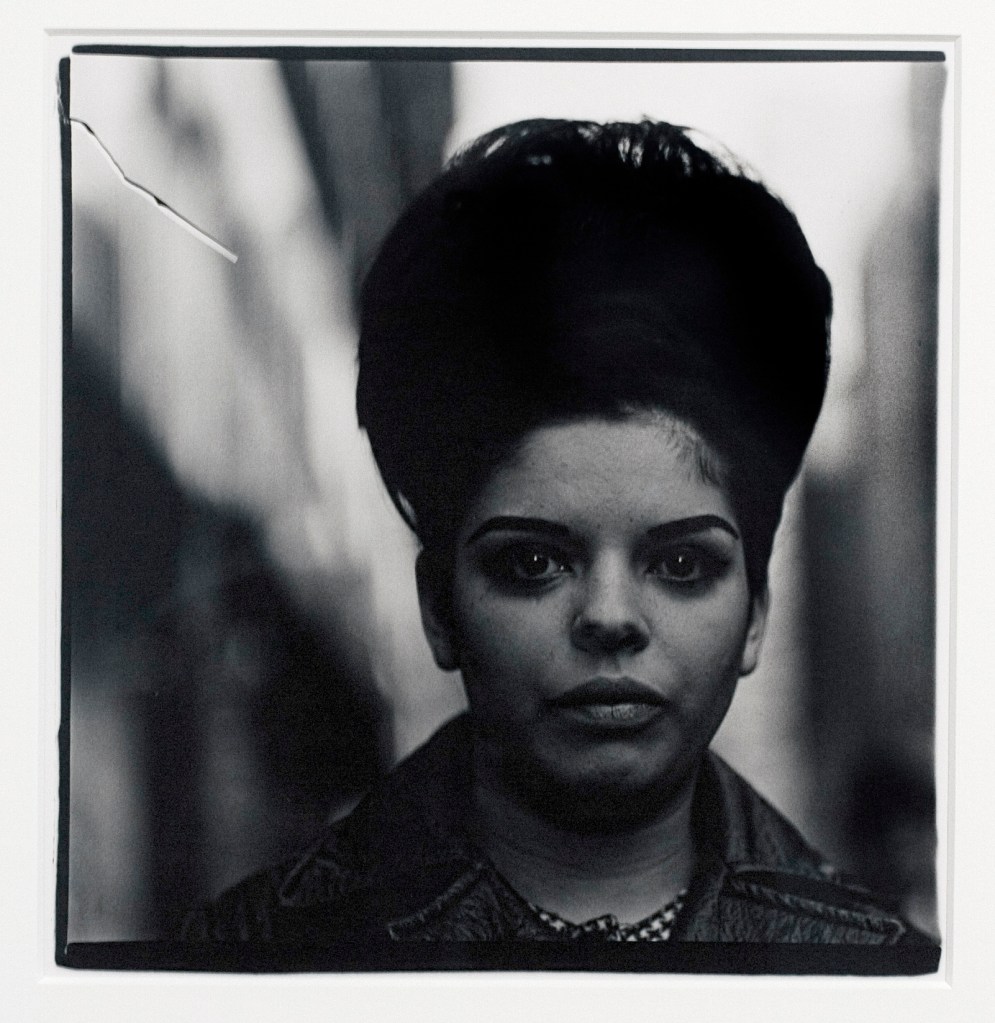

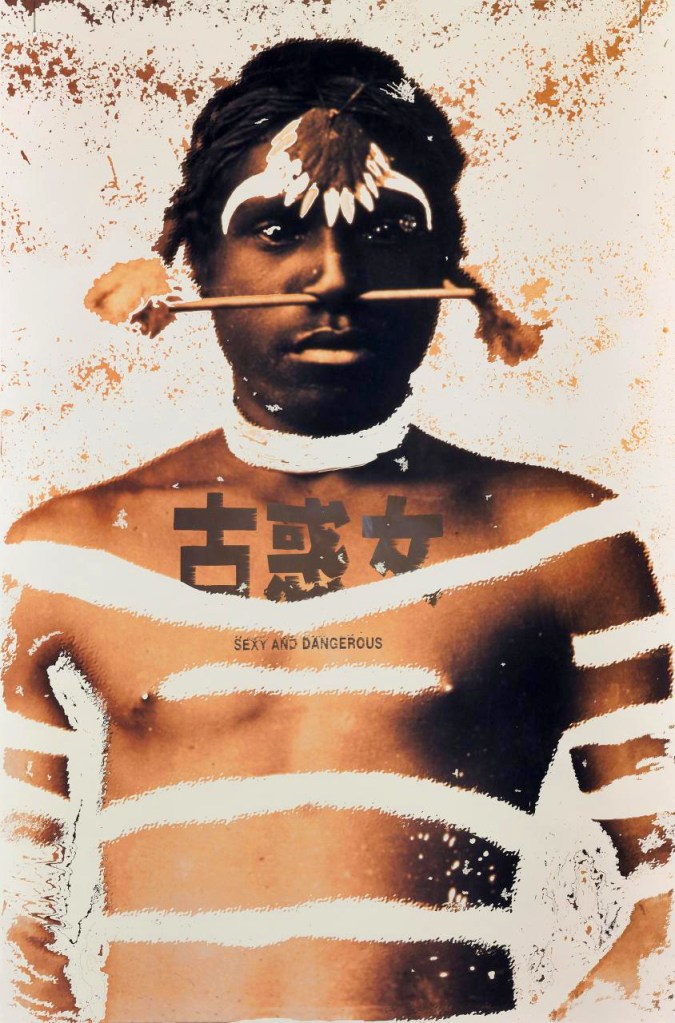

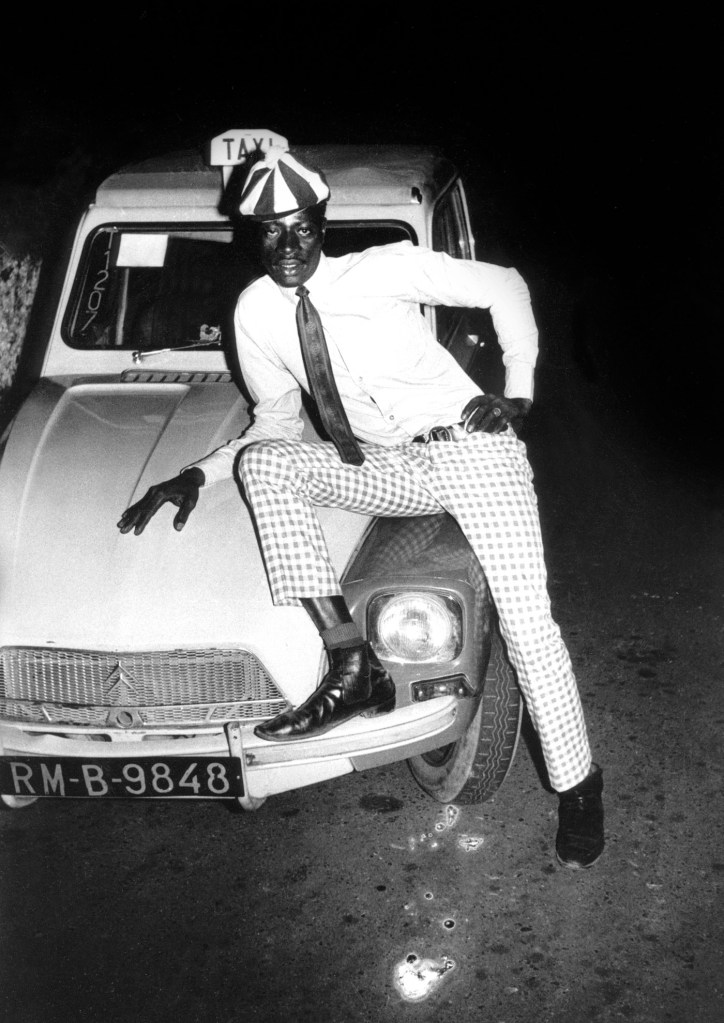

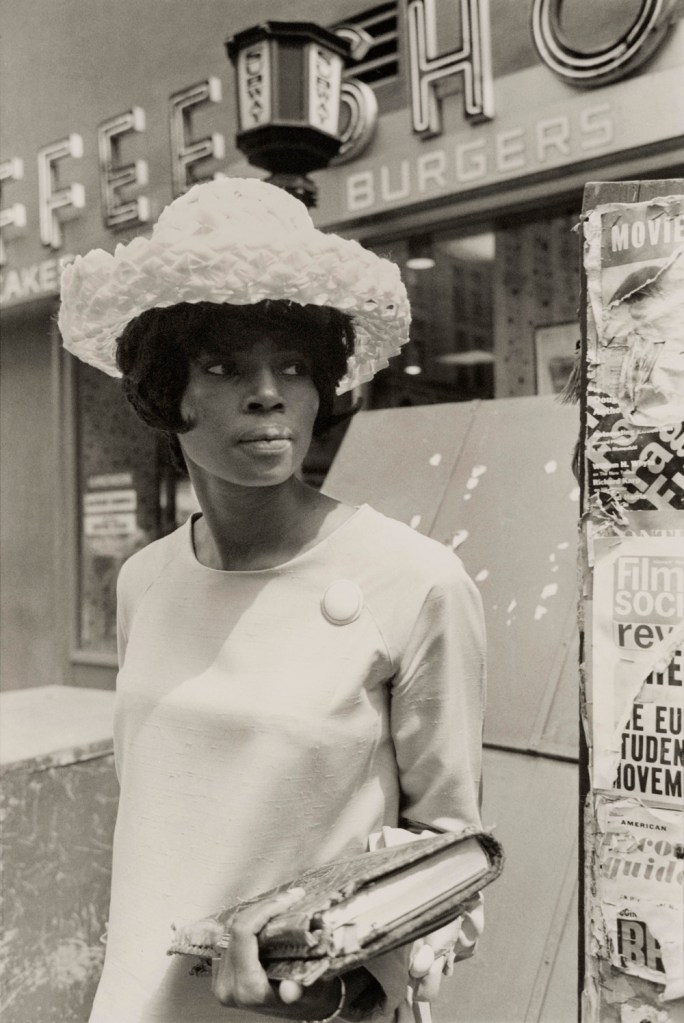

Anthony Barboza (American, b. 1944)

New York City

1970s

Gelatin silver print

Image/sheet: 23.7 × 16.1cm (9 5/16 × 6 1/4 in.)

National Gallery of Art

Pepita Milmore Memorial Fund

Anthony Barboza’s photography has been integral in shaping the image of Black America. A founding member of the Kamoinge Workshop, a group of Black photographers formed in New York in 1963, Barboza went on to establish a thriving commercial and personal practice focused largely on Black subjects. His affirmative representations of African Americans in daily life – like this photograph of two ultra-stylish men standing in front of a hotel coffee shop in midtown Manhattan – contributed to an empowering narrative for the Black community in the face of inequality and adversity. Describing his approach to making pictures on the street, Barboza commented, “”The photograph finds you, you don’t find the photograph.”

Wall text from the exhibition

Anthony Barboza (American, b. 1944)

New York City

1970s

Gelatin silver print

Image: 23.7 × 15.9cm (9 5/16 × 6 1/4 in.)

National Gallery of Art

Pepita Milmore Memorial Fund

Lee Friedlander (American, b. 1934)

Hillcrest, New York

1970

Gelatin silver print

Image: 20.3 x 30.5cm (8 x 12 in.)

National Gallery of Art

Patrons’ Permanent Fund

The fracturing of the image plane, where multiple, diverse realities are represented within one photograph, deconstructing the reality of fine art photography. ~ Marcus

Lee Friedlander’s layered compositions wittily observe connections between American life and commerce. In this dizzying photograph, Friedlander captures himself, at center, in a sideview mirror while at a filling station. In the reflection behind him we see a strip mall with the stores’ signs reversed. Near and far vie for attention and parts of the composition are blocked from our view.

The photograph with a World War I memorial similarly features vertical elements that break up the composition into separate frames. At left, the memorial’s soldier with rifle – who appears to be on guard – goes completely unnoticed as pedestrians make their way along a street full of storefronts.

Wall text from the exhibition

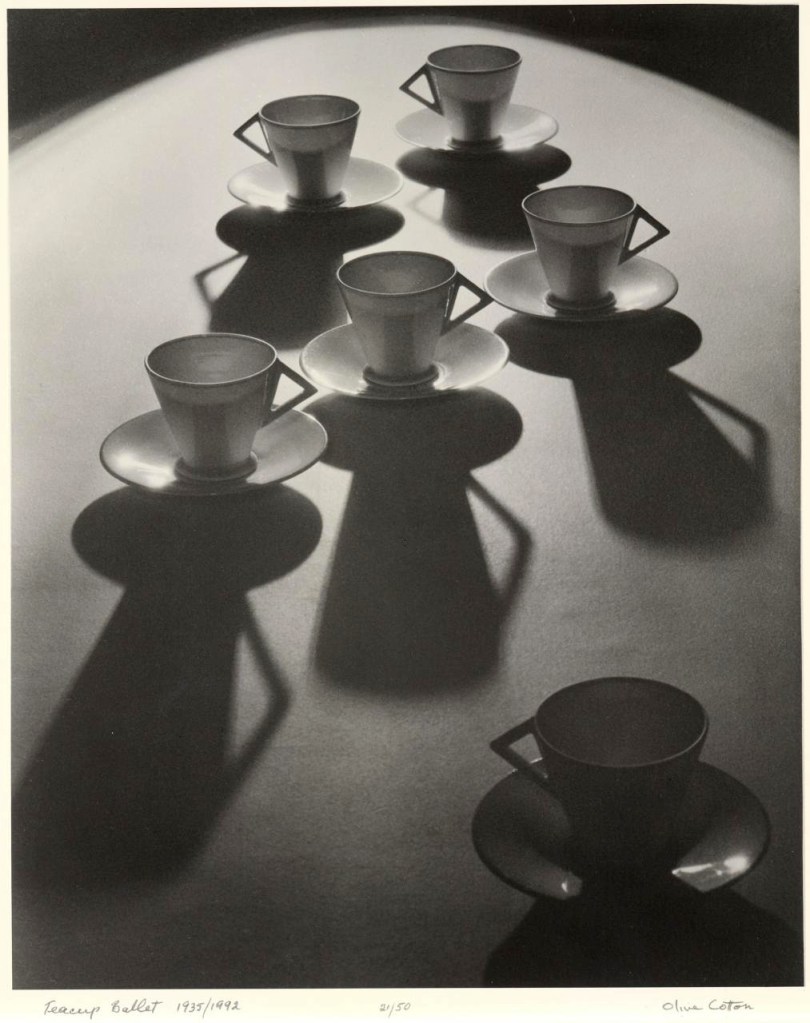

Kenneth Josephson (American, b. 1932)

Wyoming

1971

From the History of Photography series

Gelatin silver print

Image: 22.8 x 14.1cm (9 x 5 9/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art

Patrons’ Permanent Fund

Kenneth Josephson’s conceptual photography experiments with playful illusion to explore and question his medium. Josephson was a graduate among the first generation of photography candidates from the Illinois Institute of Design. A student of such masters as Aaron Siskind, Harry Callahan, and Minor White, Josephson went on to teach for 35 years at the Art Institute of Chicago, where he routinely taught the “Introduction to Photography” course as it inspired him to continue experimentation.

“This photograph of a photograph held in space causes the viewer to question assumptions about truthful representation according to size and scale; it also draws attention to the principle that photographic reality is constructed through an artist’s ideas and choices. The subject of the photograph is photography itself, and the ways that life is documented, manipulated, trivialised, and celebrated with photographs.”

Text from the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art website

Lewis Baltz (American, 1945-2014)

Tract House #4

1971

From the portfolio The Tract Houses

Gelatin silver print

Image/sheet: 14.5 × 22.5cm (5 11/16 × 8 7/8 in.)

National Gallery of Art

Corcoran Collection (Gift of the artist)

Lewis Baltz’s The Tract Houses captures the austere geometry of the shoddily built homes that sprang up in California’s suburban landscape beginning in the mid-1940s. Straight-edge architectural details, positioned strictly parallel to the picture plane, recall the reductive forms of minimalist art. Entire, recently constructed houses appear forlorn. None of the pictures include shadows, clouds, or people. Baltz’s series is a powerful critique of the transformation of the American landscape into an unending terrain of anonymous architecture. At the same time, the exquisitely rendered tones and textured surfaces emphasise the subtle beauty to be found in this bleak environment.

Wall text from the exhibition

With his iconic, minimalist photographs of suburban landscape, Lewis Baltz was at the forefront of a revolutionary shift in the medium of photography. Baltzs work exemplifies the ways in which photography started to loose the bonds of its isolation within its own segregated history and aesthetics and began to take its place among other media. In the late 1960s and early 1970s Baltz became fascinated by the stark, man-made landscape rolling over Californias then still-agrarian terrain. His earliest portfolio, The Tract Houses (1971), and his preliminary forays into a minimal aesthetic, The Prototype Works (1967-1976), illuminate his drive to capture the reality of a sprawling Western ecology gone wild.

Text from the Google Books website

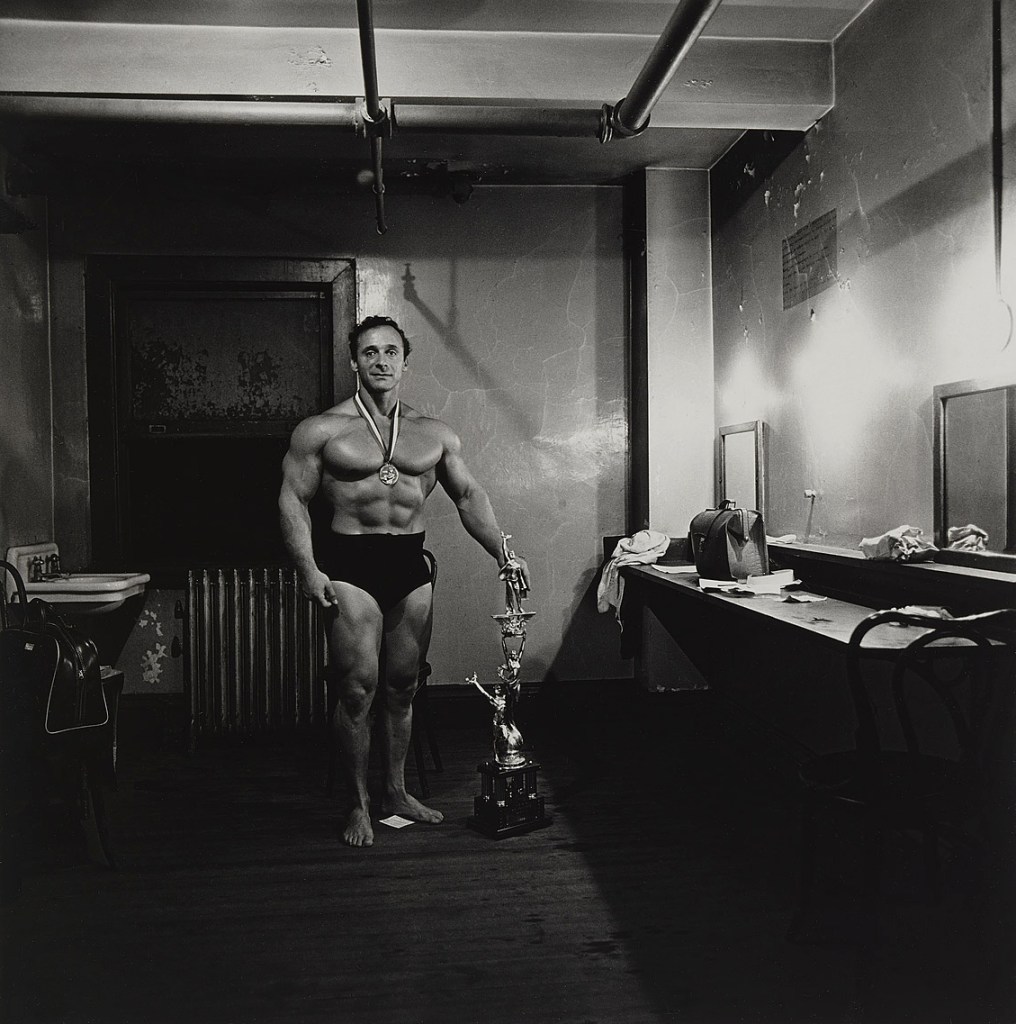

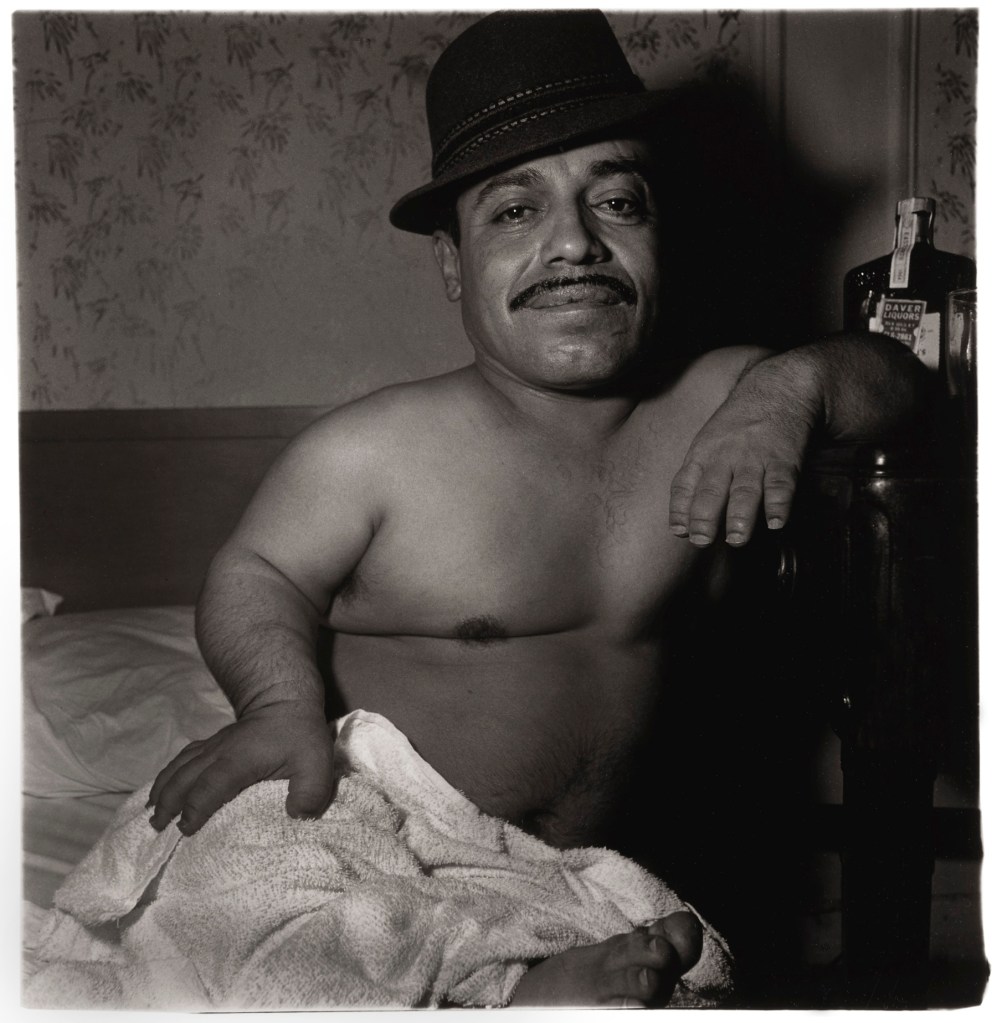

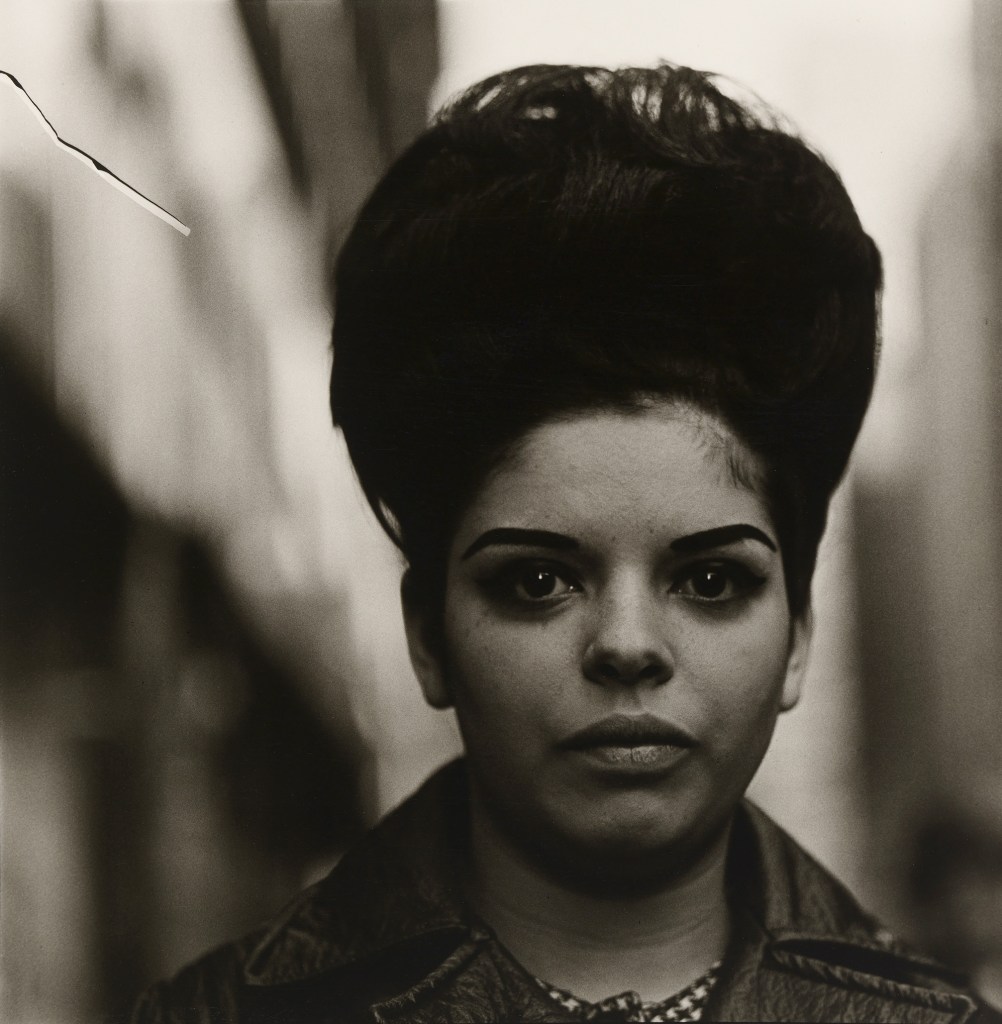

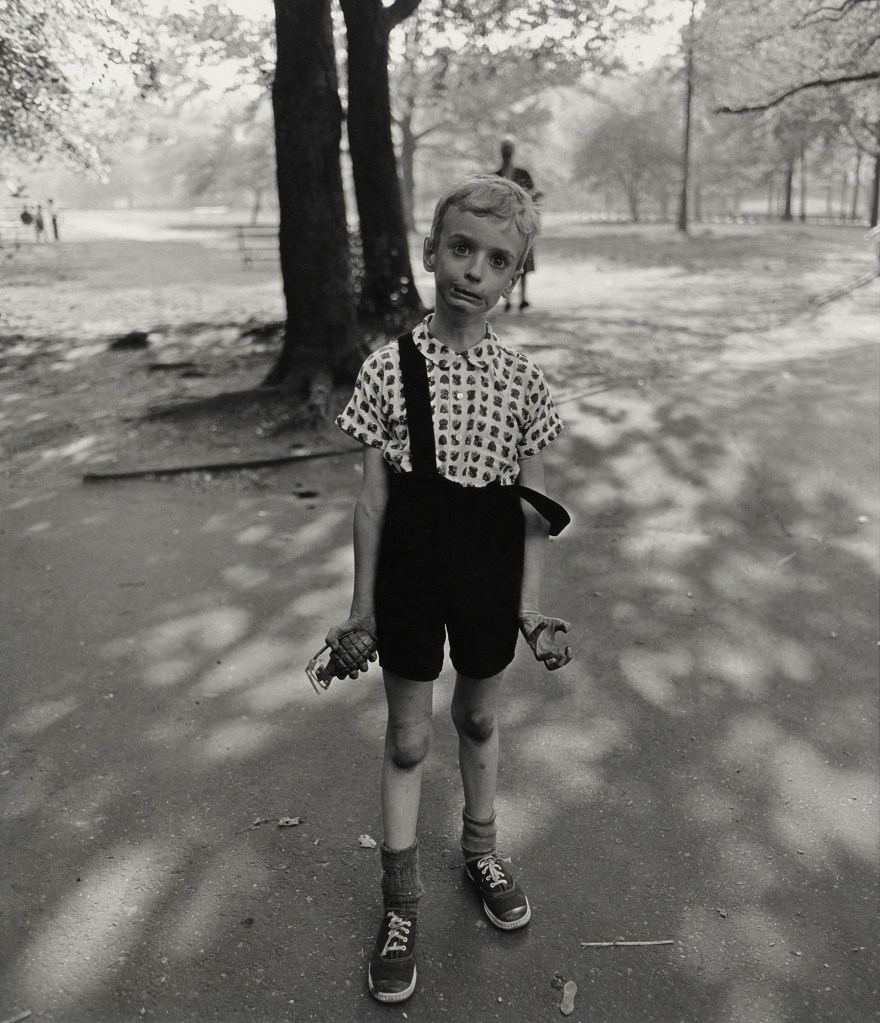

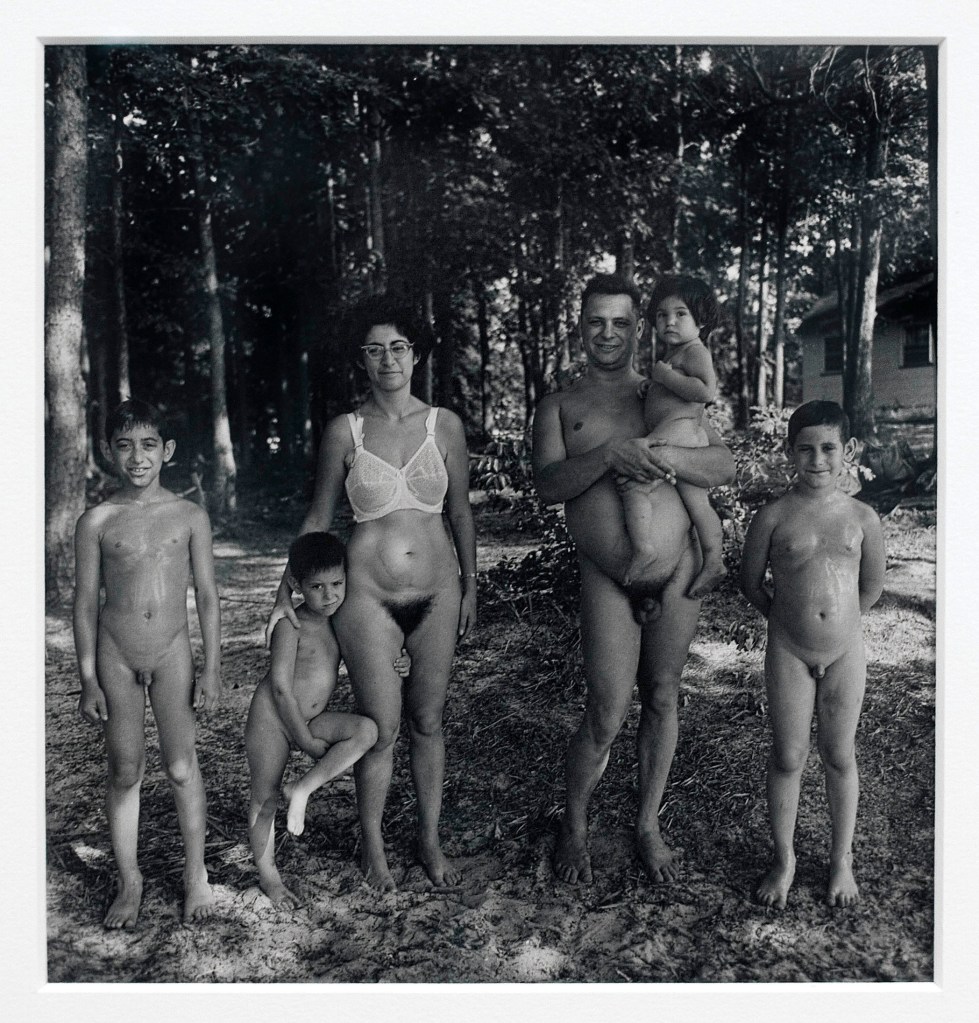

Diane Arbus (American, 1923-1971)

A young man and his girlfriend with hot dogs in the park

1971

Gelatin silver print

Image: 37.7 x 36.5cm (14 13/16 x 14 3/8 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Corcoran Collection

Gift of Stephen G. Stein

Diane Arbus prowled New York’s public spaces looking for humor and strangeness in the everyday. Here a young couple walks in Central Park, wearing similar clothes, hairstyles, and dejected expressions. Arbus’s carefully composed but disorienting photograph – the subjects are in crisp focus while the background is blurred – compels us to look anew at the familiar. Is this couple unhappy in love or expressing the uncertainty of the times? Arbus made this photograph the year she died. Her influence on documentary photography would continue through the decade.

Wall text from the exhibition

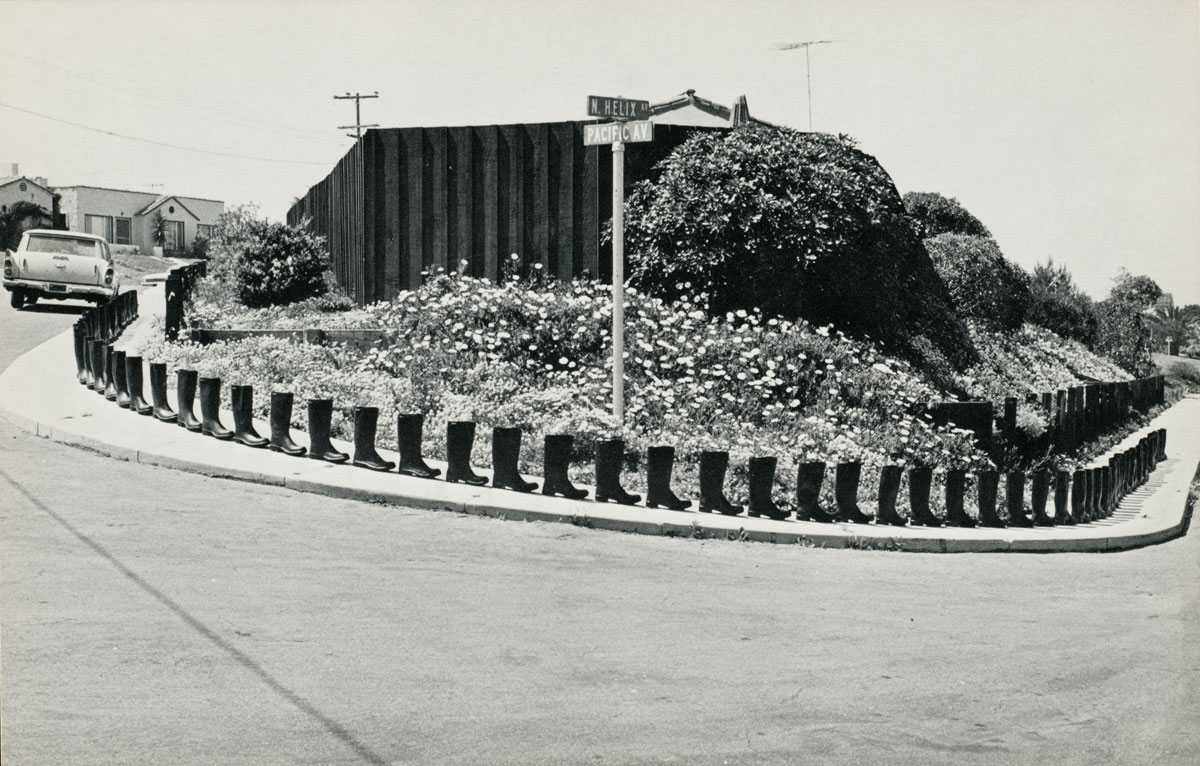

Eleanor Antin (American, b. 1935)

Philip Steinmetz (American, 1944-2013) (photographer)

100 Boots (details)

1971-1973

51 halftone prints (postcards)

image/sheet (each): 11.5 x 17.75cm (4 1/2 x 7 in.)

National Gallery of Art

Pepita Milmore Memorial Fund

In this epic visual narrative, black rubber boots stand in for a fictional hero traveling from California to New York City. Eleanor Antin created temporary installations with the boots, had them photographed (by Philip Steinmetz), and made 51 postcards, copies of which she mailed to approximately 1,000 people and institutions involved in the arts. The journey starts at a Bank of America and ends at Central Park – after a visit to the Museum of Modern Art, where the boots and a set of postcards and photographs were later exhibited. Using the postal service, Antin bypassed the traditional gallery system, which had long overlooked women artists. While many of these scenes are humorous, the empty army boots also recall the Vietnam War and the soldiers who did not come home.

Wall text from the exhibition

100 Boots, 1971-1973

For her 51-piece instalment 100 Boots Eleonor Antin positioned one hundred ordinary black rubber boots on various locations all over Southern California and consequently in New York City. She took photos, printed them on postcards and assembled a mailing list of about a thousand names – mainly artists, writers, critics, galleries, universities and museums – who received the various postcards over a period of two and a half years between 1971 and 1973. The first card, 100 Boots Facing the Sea, was mailed on the Ides of March, 1971, unannounced and without further comment. A few weeks later it was followed by 100 Boots on the Way to Church and three weeks thereafter by the next one.

In a total of 51 photographs, Eleanor Antin documented the travels of the 100 Boots, her so called “hero” – from a beach close to San Diego to a church, to a bank, to the supermarket, trespassing, under the bridge, to a saloon and on their travels eastward. Finally, on May 15th, 1973 100 Boots arrived at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. By this time, 100 Boots had long become an epic visual narrative and a picaresque work of conceptual art.

Text from the exhibition open spaces | secret places: composite works from the collection at Museum Der Moderne Salzburg, October 2012 – March 2013

Henry Wessel (American, 1942-2018)

Walapai, Arizona

1971

Gelatin silver print

Image: 26.51 x 39.85cm (10 7/16 x 15 11/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art

Gift of Mary and Dan Solomon and Patrons’ Permanent Fund

In 1975 New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape opens at the International Museum of Photography in Rochester, N.Y. It includes photographs by Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz, Bernd and Hilla Becher, Joe Deal, Frank Gohlke, Nicholas Nixon, John Schott, Stephen Shore, and Henry Wessel Jr.

“Henry Wessel began taking photographs while majoring in psychology at Pennsylvania State University in the mid-1960s. Travel throughout the United States in subsequent years led him to direct his gaze increasingly to details of human interaction with the natural and man-made environment. Wessel’s move to the West Coast in the early 1970s inspired him to incorporate light and climate into his work. His inclusion in the seminal exhibition New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape, organised in 1975 by the George Eastman House in Rochester, New York, solidified his reputation as a keen observer of the American topography.”

Text from Pacific Standard Time at the Getty

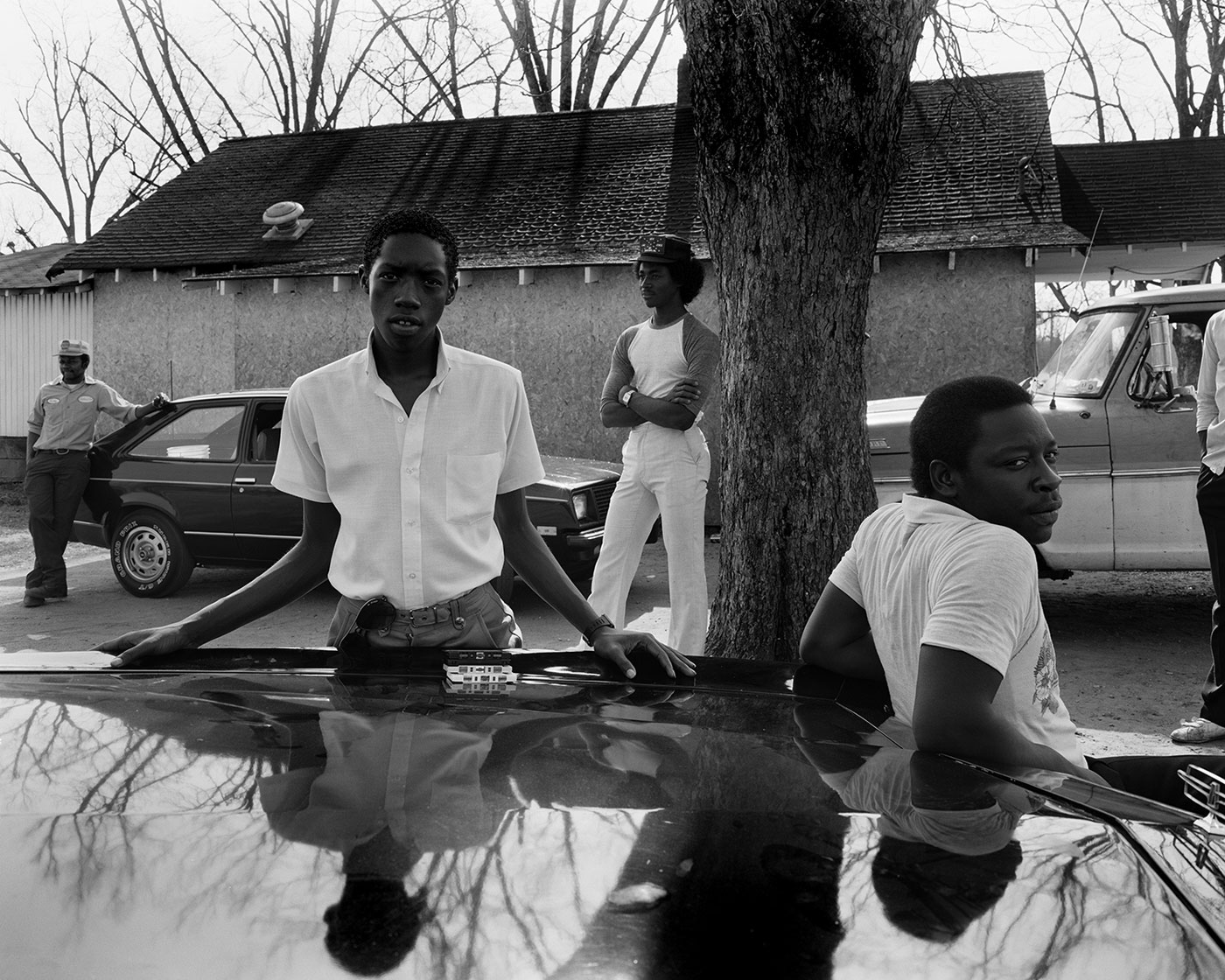

John Simmons (American, b. 1950)

Will on Chevy, Nashville, Tennessee

1971, printed 2024

Gelatin silver print

Image: 30.48 x 20.32cm (12 x 8 in.)

National Gallery of Art

Alfred H. Moses and Fern M. Schad Fund

A fashionably dressed older man crosses the street with his umbrella. A young woman turns to look at the camera while holding hands with a man in uniform. These were people John Simmons encountered while studying art at Fisk University in Nashville. Raised on Chicago’s South Side, Simmons had first published photographs as a teenager in the African American newspaper Chicago Defender. Refuting white-centered media’s failure to show positive imagery of the Black experience, Simmons has focused on people enjoying everyday life.

“I always feel like my subject and I were meant to share that moment together,” he has said. “So many of the pictures I take, it was like our paths were meant to cross.”

Wall text from the exhibition

Simmons began his career at 15 as a photographer for the oldest African American-owned newspaper, The Chicago Daily Defender in 1965. Over his decades long career, he’s photographed icons of the Civil Rights Movement, turbulent protests and demonstrations, famed musicians and poignant intimate moments of everyday life. “I’m glad to see photographs I took back in my teens are still relevant today,” he says.

John Simmons quoted in Steve Simmons. “Photographer John Simmons, ‘Chronicler Of The Civil Rights Movement,’ Featured In Three Exhibits,” on the Linkedin website August 4, 2021 [Online] Cited 11/09/2021.

Helen Levitt (American, 1913-2009)

New York

1972

Dye imbibition print

Image: 23.5 x 36cm (9 1/4 x 14 3/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Patrons’ Permanent Fund

© Film Documents LLC, courtesy Zander Galerie, Cologne

Helen Levitt frequently made photographs of children on the streets of New York City, exploring their relationships to the urban setting as they played, imagined, and discovered together. After decades of working in black and white, Levitt became an early advocate of color documentary photography. Color allowed her to tell a fuller story of everyday life. Here, the green of the boy’s T-shirt is echoed in the poster and frame behind him. “I thought my photographs would be closer to reality if I got the color of the streets,” she said. “Black and white is an abstraction.”

Wall text from the exhibition

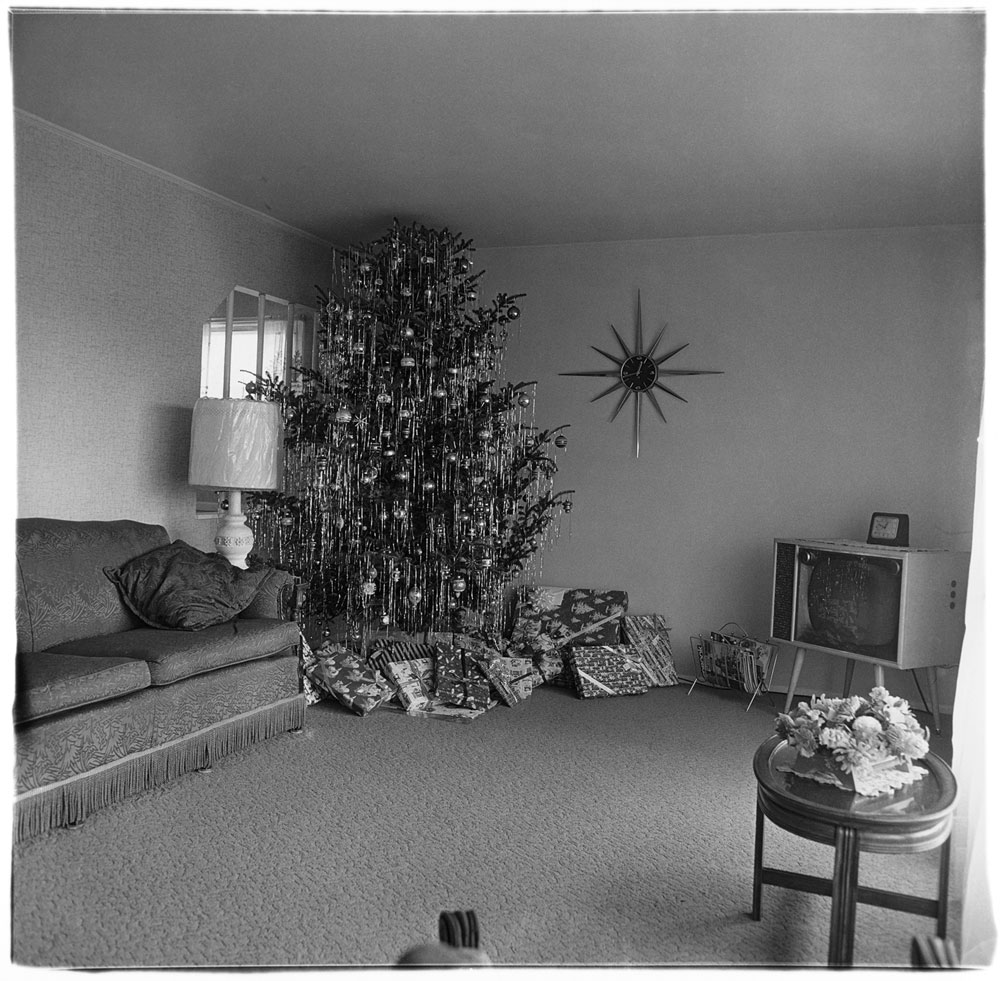

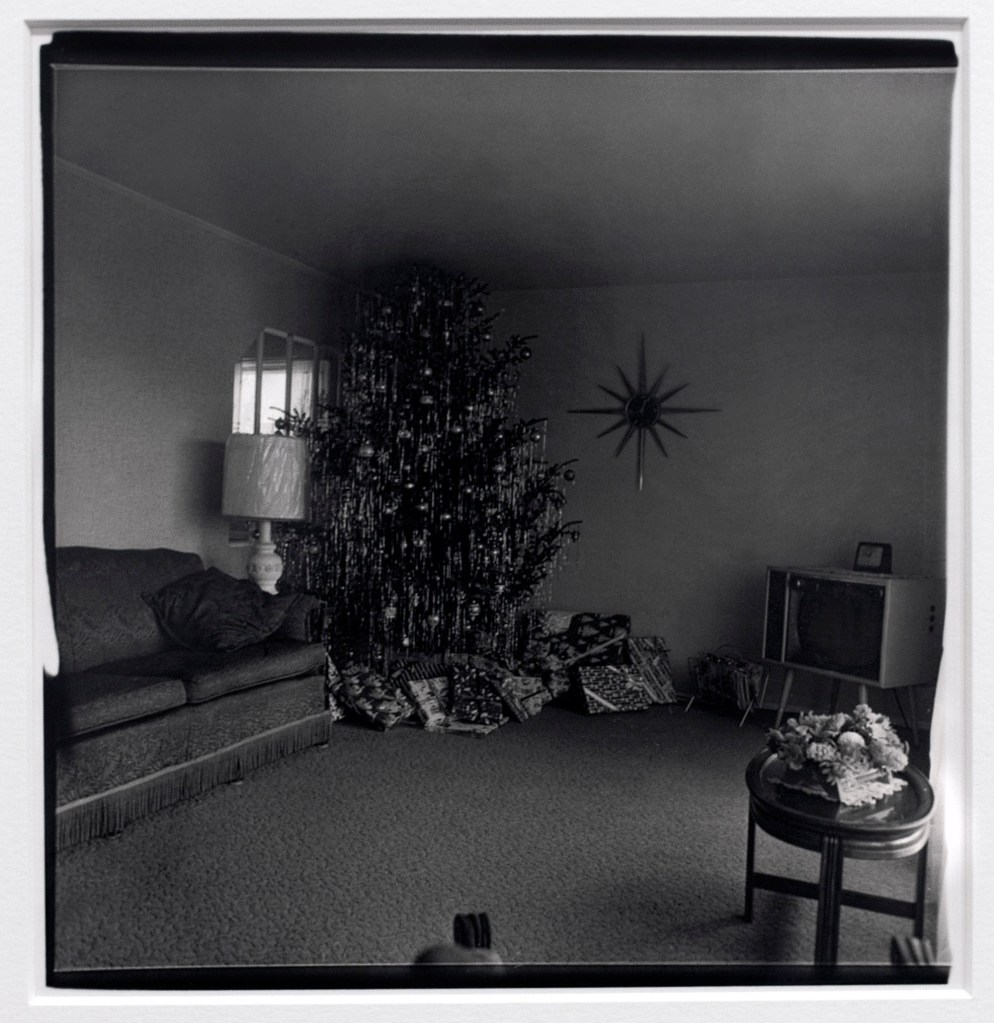

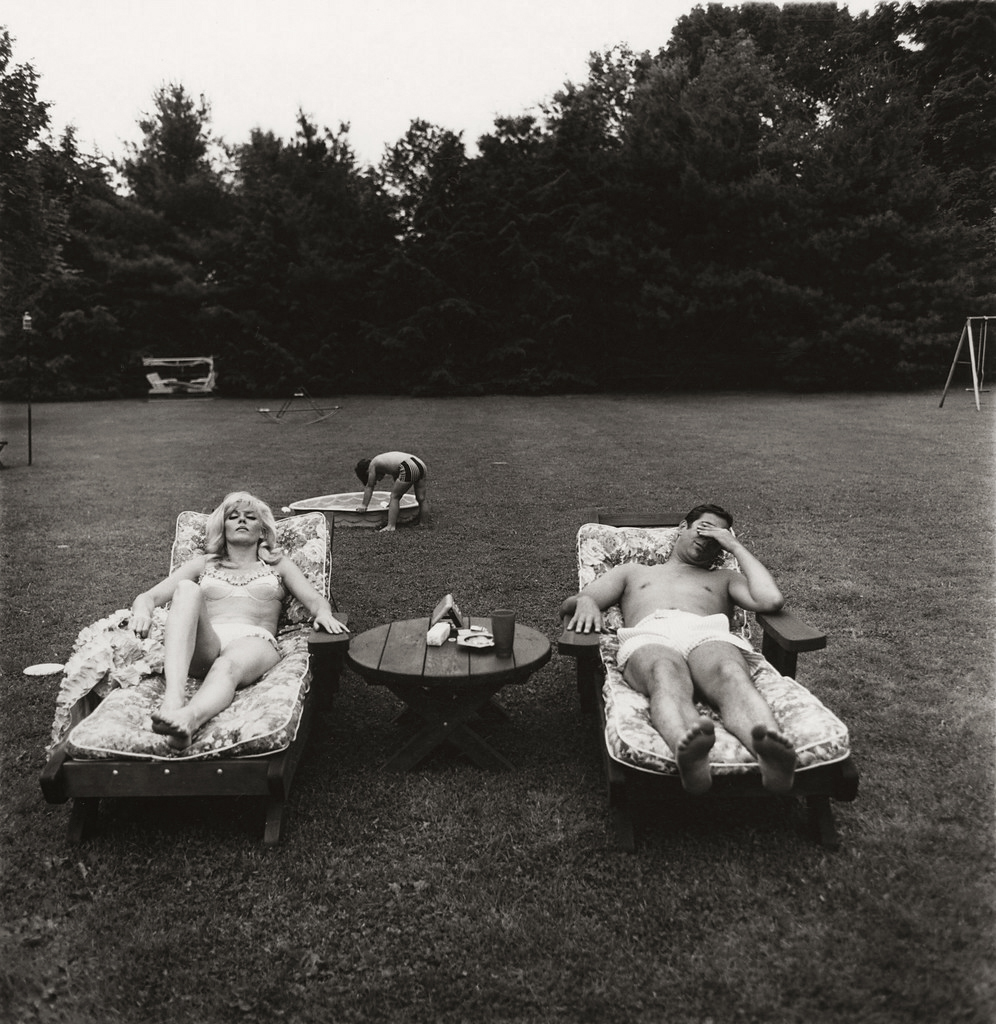

Bill Owens (American, b. 1938)

Ronald Reagan

1972

From the series Suburbia

Gelatin silver print

Image: 16.4 x 21.6cm (6 7/16 x 8 1/2 in.)

National Gallery of Art

Patrons’ Permanent Fund

Over the course of a year, Bill Owens made photographs of the housing developments that had recently sprung up outside of Oakland and San Francisco. With an eye to humor, he captured the apparent conformity and materialism of the new suburbs. Here, a home is decorated for Christmas. At center, Nativity figures sit atop a television console showing an old film featuring Ronald Reagan, who had been a movie actor before becoming a politician. Owens also respected the liberation that many suburbanites felt, as well as their determination to build better lives. In his book Suburbia (1972), he included quotations from his subjects describing the opportunities and challenges they faced in their new environments.

Wall text from the exhibition

Owens began his photographic career in the late 1960s as a staff photographer for a local newspaper in Livermore, California. During this period, he began his most noteworthy project, “Suburbia,” which would become a major body of work in American documentary photography.

“Suburbia” was published as a book in 1973, featuring Owens’ images and conversations with suburban dwellers. The project’s goal was to investigate the goals, aspirations, and inconsistencies of suburbia life, offering a critical yet sympathetic study of the American Dream.

Owens’ images depicted scenes of backyard barbecues, family gatherings, children at play, and the myriad rituals and social interactions that constituted suburban areas. He highlighted both the humor and the underlying intricacies of suburban life through his good observation and direct attitude.

What distinguished Owens’ work was his ability to see past the surface and capture the soul of his subjects. His images conveyed a sense of realism by portraying suburbanites in their natural settings and enabling their tales to flow through genuine moments captured in time.

Owens’ art struck a chord with a large audience because it highlighted a huge societal transition in America during the 1970s. Owens’ images challenged the idealized image of suburban life by exposing the hardships, wants, and inconsistencies inherent in the pursuit of the American Dream.

Anonymous. “Bill Owens,” on the Photo.com website Nd [Online] Cited 06/20/2025

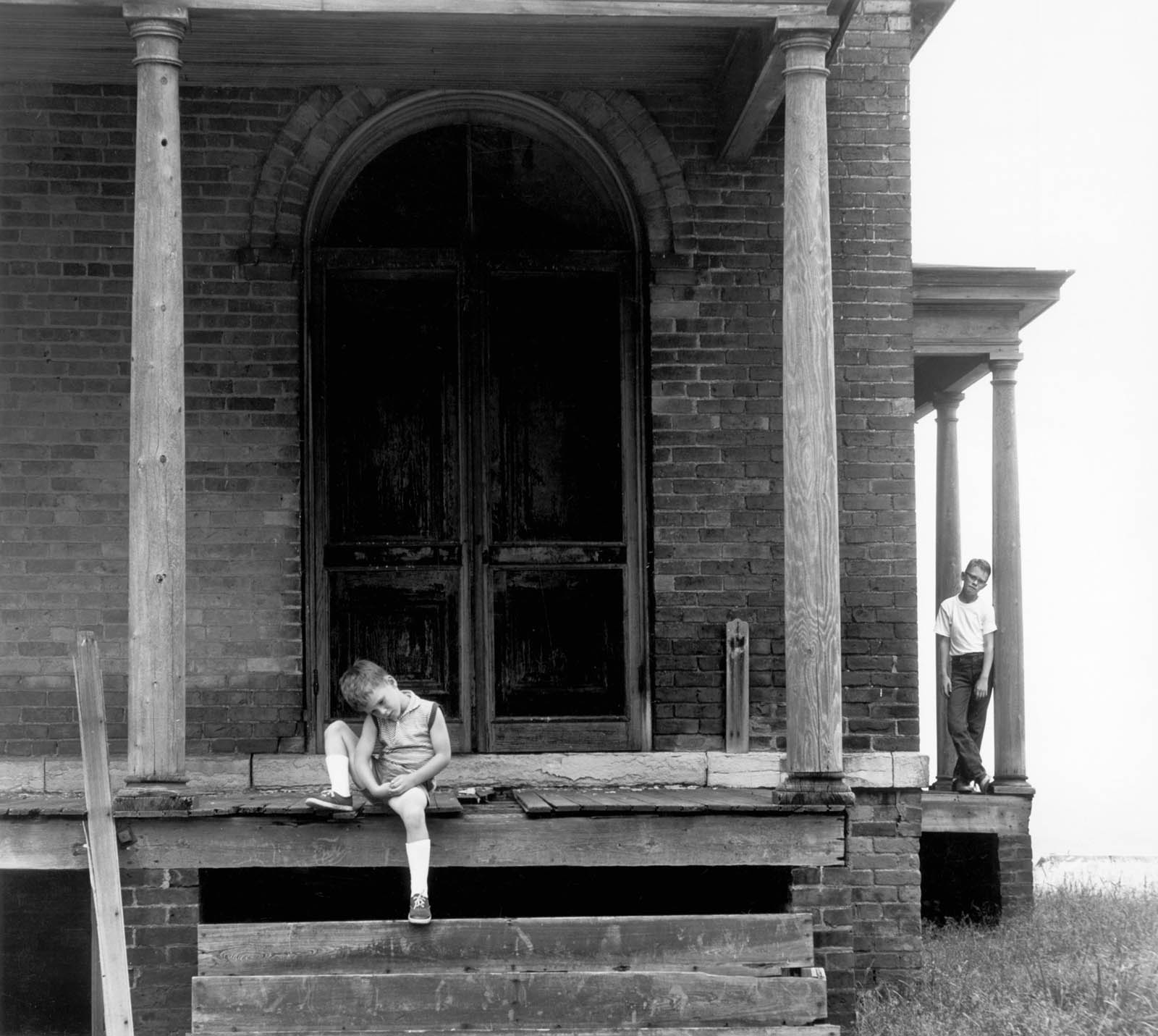

William Eggleston (American, b. 1939)

Sumner, Mississippi, Cassidy Bayou in the Background

c. 1972, printed 1986

Dye imbibition print

Image: 27.94 x 43.18cm (11 x 17 in.)

National Gallery of Art

Gift of Stephen G. Stein

© Eggleston Artistic Trust

See how documentary photography transformed during the 1970s.

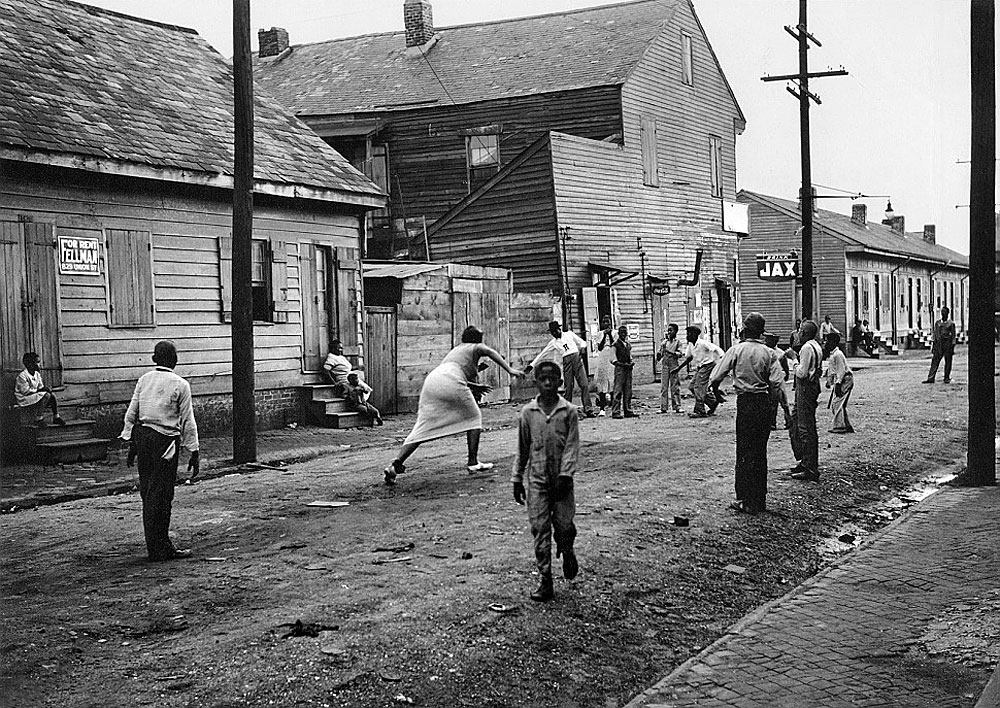

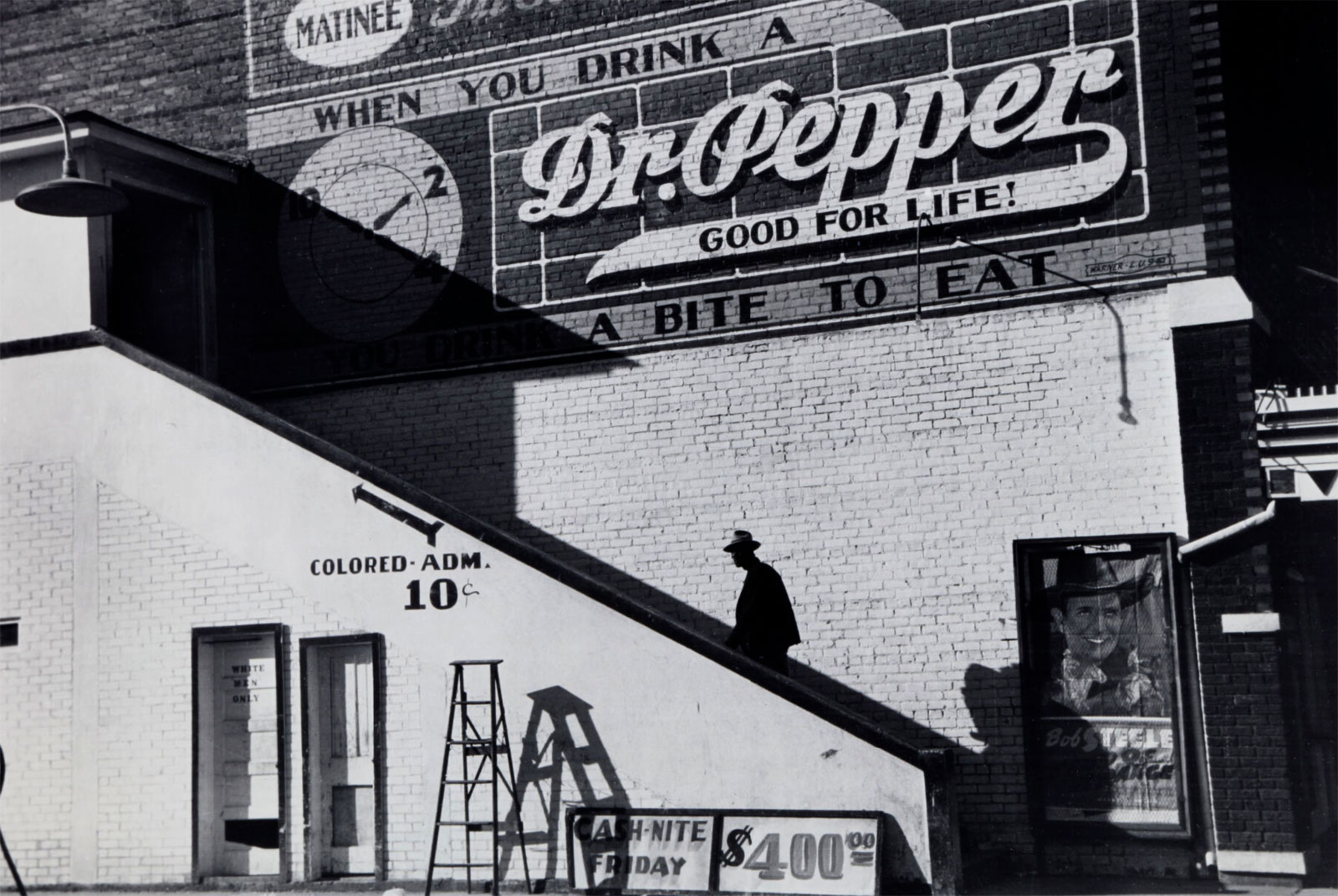

The 1970s was a decade of uncertainty in the United States. Americans witnessed soaring inflation, energy crises, and the Watergate scandal, as well as protests about pressing issues such as the Vietnam War, women’s rights, gay liberation, and the environment. The country’s profound upheaval formed the backdrop for a revolution in documentary photography. Activism and a growing awareness and acceptance of diversity opened the field to underrepresented voices. At the same time, artistic experimentation fueled the reimagining of what documentary photographs could look like.

Featuring some 100 works by more than 80 artists, The ’70s Lens examines how photographers reinvented documentary practice during this radical shift in American life. Mikki Ferrill and Frank Espada used the camera to create complex portraits of their communities. Tseng Kwong Chi and Susan Hiller demonstrated photography’s role in the development of performance and conceptual art. With pictures of suburban sprawl, artists like Lewis Baltz and Joe Deal challenged popular ideas of nature as pristine. And Michael Jang and Joanne Leonard made interior views that examine the social landscape of domestic spaces.

The questions these artists explored – about photography’s ethics, truth, and power – continue to be considered today.

Text from the National Gallery of Art

Lee Friedlander (American, b. 1934)

Doughboy. Stamford, Connecticut

1973

Gelatin silver print

Image: 17.8 x 27cm (7 x 10 5/8 in.)

National Gallery of Art

Robert B. Menschel Fund

William Eggleston (American, b. 1939)

Used Tires

1973

Dye imbibition print

Image: 33 x 48.5cm (13 x 19 1/8 in.)

National Gallery of Art

Patrons’ Permanent Fund

© Eggleston Artistic Trust

William Eggleston (American, b. 1939)

Greenwood, Mississippi

1973

Dye imbibition print

Image: 32.2 x 48.2cm (12 11/16 x 19 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Corcoran Collection

Gift of the Women’s Committee of the Corcoran Gallery of

Art

© Eggleston Artistic Trust

William Eggleston has said that he has “a democratic way of looking around,” where nothing is more important or less important. For him, everyday subjects are not boring but instead offer visual richness. Here, that richness has a pronounced edge. Eggleston directed his lens up to a red ceiling with a single bare lightbulb at center. We glimpse only the top of a doorframe and a fragment of an explicit poster. The saturated, bloodlike color that dominates the composition is shocking, even menacing. It also challenged Eggleston technically as he developed his skills with dye imbibition printing. Commonly known as dye transfer, the process was labor intensive but allowed for customisation and a wide range of colours and tones.

Wall text from the exhibition

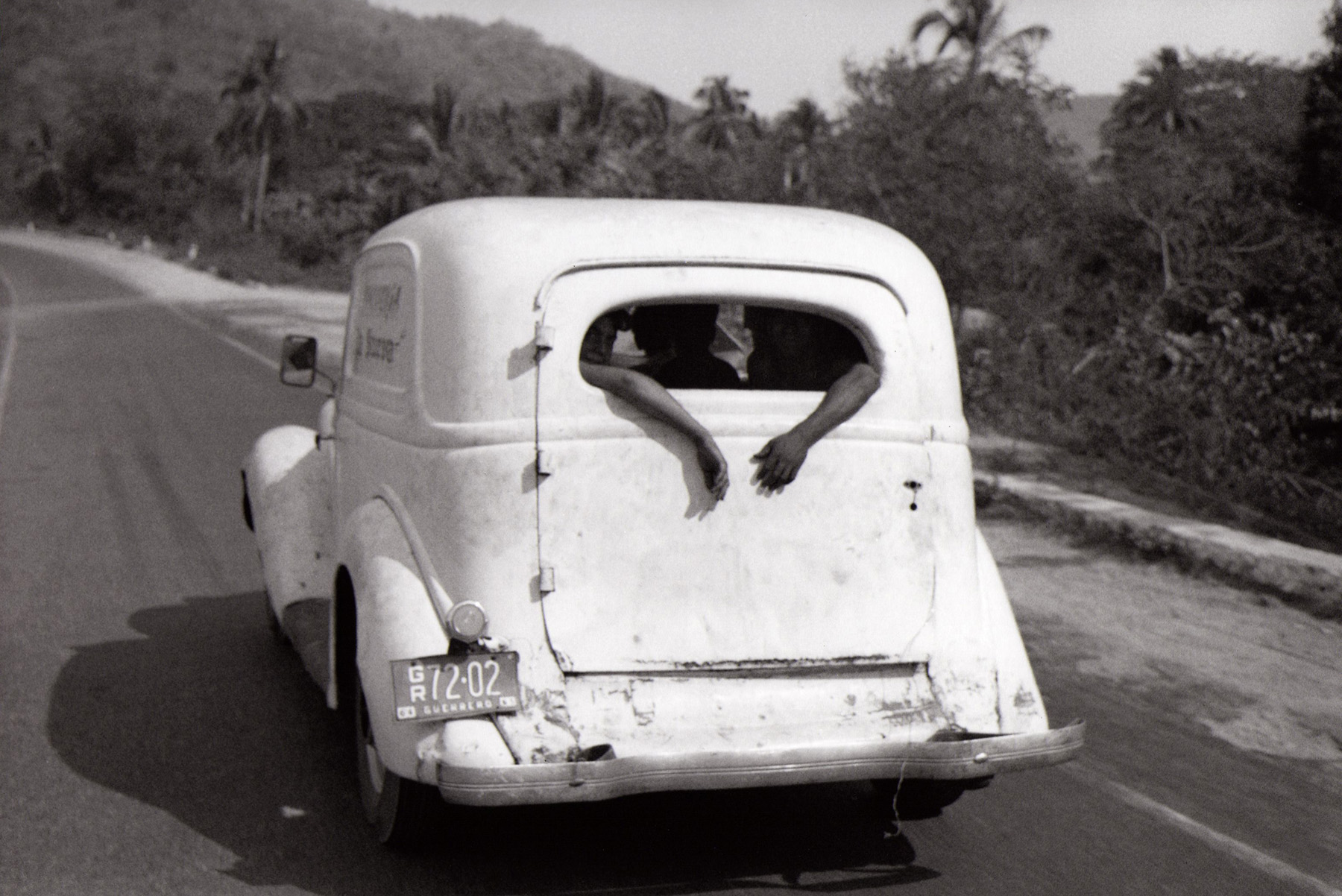

Mitchell Epstein (American, b. 1952)

Massachusetts Turnpike

1973, printed 2005

From the series Recreation

Chromogenic print

Image: 32.1 x 48.2cm (12 5/8 x 19 in.)

National Gallery of Art

Gift of Timothy and Suzanne Hyde in Honor of the 25th Anniversary of

Photography at the National Gallery of Art

© Black River Productions, Ltd.

Viewers of a certain age will recognize this setting as the parking lot of a Howard Johnson’s restaurant. HoJos, as they were nicknamed, were once ubiquitous along America’s highways. The cheery saturated colors belie the scene’s subject: a couple having a bad travel day. A man in suit and tie works under the hood of a beat-up Chevy Impala. His partner, wearing a pale pink skirt and top, arms crossed, appears frustrated. The cars zooming by seem to mock their immobility. Part of Mitch Epstein’s Recreation series, which documented Americans engaging in leisure activities, the photograph today evokes melancholy and nostalgia. Explaining his early turn to colour film, the artist said, “The world is in color, so why not photograph in color?”

Wall text from the exhibition

I started to work in colour, which was a radical, and some thought foolish, move in 1973. Colour photography was not yet a medium for serious photography – it was used almost exclusively for slick advertising and illustration. Within a month of shooting in colour, though, I wanted to do nothing else…

As I developed, I learned that a photograph is other than the thing itself photographed, and this freed me to think about how I could use photography to fictional effect, even while my pictures were drawn from the real world…

Photography remains a tool with which I form and sharpen my response to the world around me. Anything and everything is photographable in an infinite number of ways. That excites me.

Mitch Epstein in Lewis Blackwell. PhotoWisdom: Master Photographers on Their Art quoted quoted in “Mitch Epstein – Meet The Master Photographer,” on the Milkbooks website Nd [Online] Cited 06/02/2025

Robert Adams (American, b. 1937)

Interstate 25, Denver, Colorado

1973

Gelatin silver print

Image: 15.2 x 19.3cm (6 x 7 5/8 in.)

National Gallery of Art

The Ahmanson Foundation and Gift of Robert and Kerstin Adams

© Robert Adams, Courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

Adams’ photographic vision is extra ordinary and I cannot fault his individual photographs. I become engrossed in them. I breathe their atmosphere. He has a resolution, both in terms of large format aesthetic, the aesthetic of beauty and of using materials, light and composition… that seems exactly right. He possesses that superlative skill of few great photographers, and by that I mean: sometimes he has true compassion** / parallel to a religious compassion, but not based on something higher / just perfect human. In some of his photographs (such as East from Flagstaff Mountain, Boulder County, Colorado 1975) he possesses real forgiveness, in others there is the perfection of cruel, the perfection of de/composition.

** achieved by Arbus, Atget and sometimes by Clift, Gowin.

And then, each image holds small clues vital to the overall conversation that is the accumulation of his work and it is in their collective accumulation of meaning that Adams’ photographs grow and build to shatter not just the American silence on environmental issues, but the deafening silence of the whole industrialised world. In their holistic nature, Adams’ body of work becomes punctum and because of this his work produces other “things”, things as great as anything the French literary theorist, essayist, philosopher, critic, and semiotician Roland Barthes wrote about. As in Barthes’ seminal work Camera Lucida, Adams’ work reminds us that the “photograph is evidence of ‘what has ceased to be’. Instead of making reality solid, it reminds us of the world’s ever changing nature.”1

Marcus Bunyan. “The quiet of the great beyond,” on the exhibition American Silence: The Photographs of Robert Adams at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, May – October 2022 on Art Blart: art and cultural memory archive website, September 25, 2022 [Online] Cited 06/02/2025

1/ Anonymous. “Roland Barthes,” on the Wikipedia website Nd [Online] Cited 23/09/2022

Michael Jang (American, b. 1951)

Study Hall

1973

Gelatin silver print

15.5 × 23.5cm (6 1/8 × 9 1/4 in.)

National Gallery of Art

Charina Endowment Fund

In Study Hall, Michael Jang’s extended family sits together on a couch reading comics and a television guide, a messy tray of Kraft Teez Dip and potato chips on the table in front of them. The covers of the decidedly not studious publications block their faces, becoming stand-ins for their portraits. In Aunts and Uncles (nearby), relatives are caught joking around while posing for an official family portrait in silly sunglasses.

Jang’s humorous photographs of his Chinese American family and the trappings of their suburban lives offer a refreshing take on the often staid genre of family portraiture. They also debunk the 1970s stereotype – think The Brady Bunch – that the “all-American” family could only be white.

Wall text from the exhibition

In his series The Jangs, Michael Jang photographed family at home. His humorous photographs of their suburban lives expanded the concept of the “all-American” family – the Chinese American Jangs didn’t look like The Brady Bunch.

In Study Hall, Jang’s cousins and aunt sit together on a couch reading comics and a television guide, a messy tray of potato chips and dip on the table in front of them. The covers of decidedly not studious publications block their faces, becoming stand-ins for their portraits.

Jang’s delightful series was almost entirely forgotten. The photographs, which he had first made while a student, sat in a box in the artist’s house for decades while he established a career as a commercial photographer.

In the 2000s, Jang reconsidered this series and shared it with museums, which began adding the photographs to their collections. His photographs took on a new light in the wake of a rise of anti-Asian hate during the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2021, Jang wheat pasted images from The Jangs on buildings in San Francisco’s Chinatown.

Text from the National Gallery of Art website

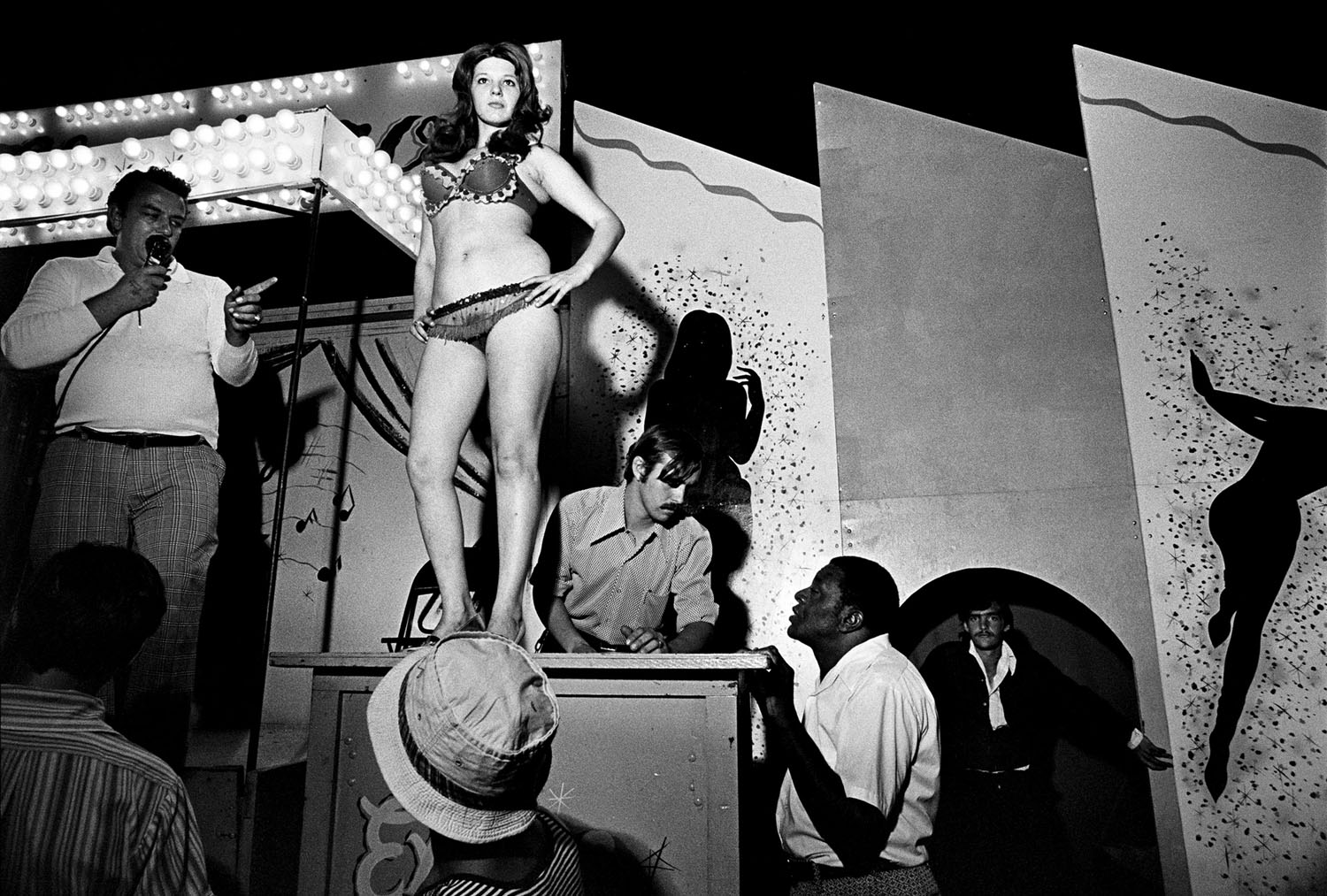

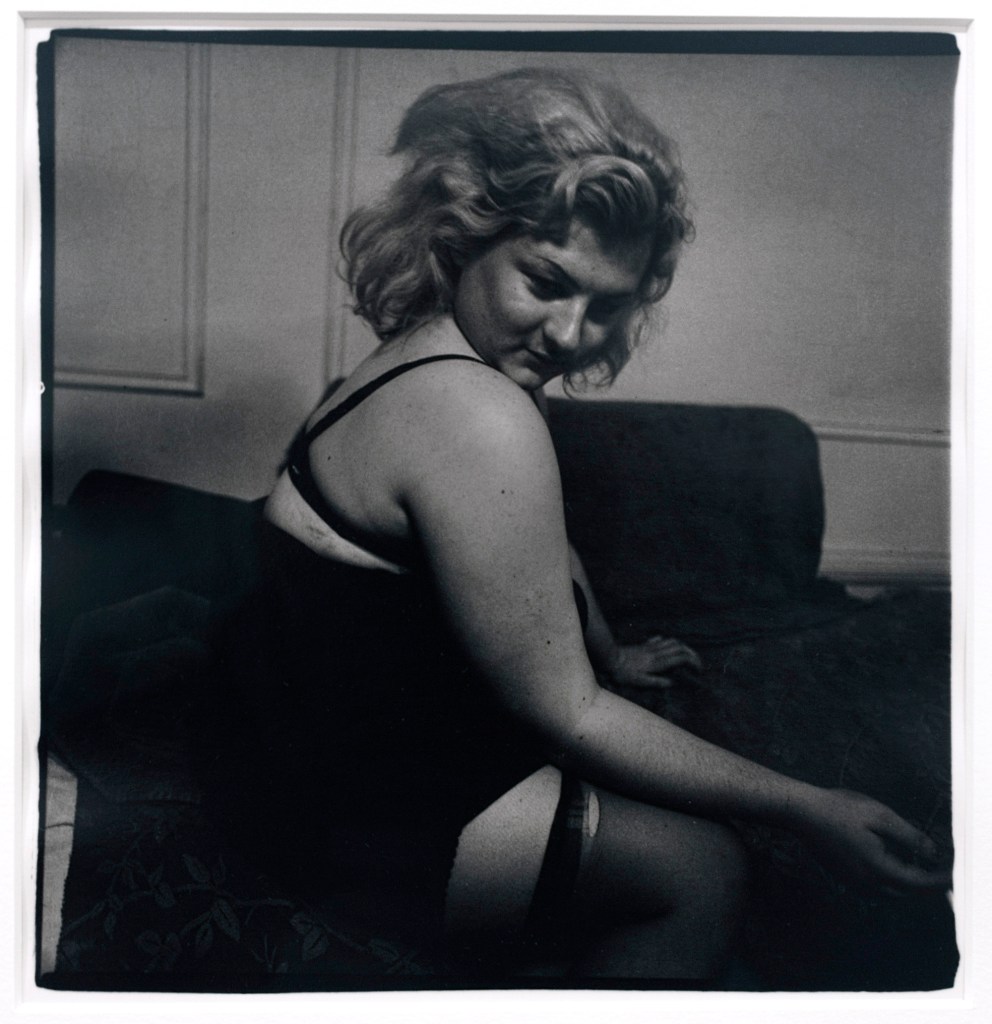

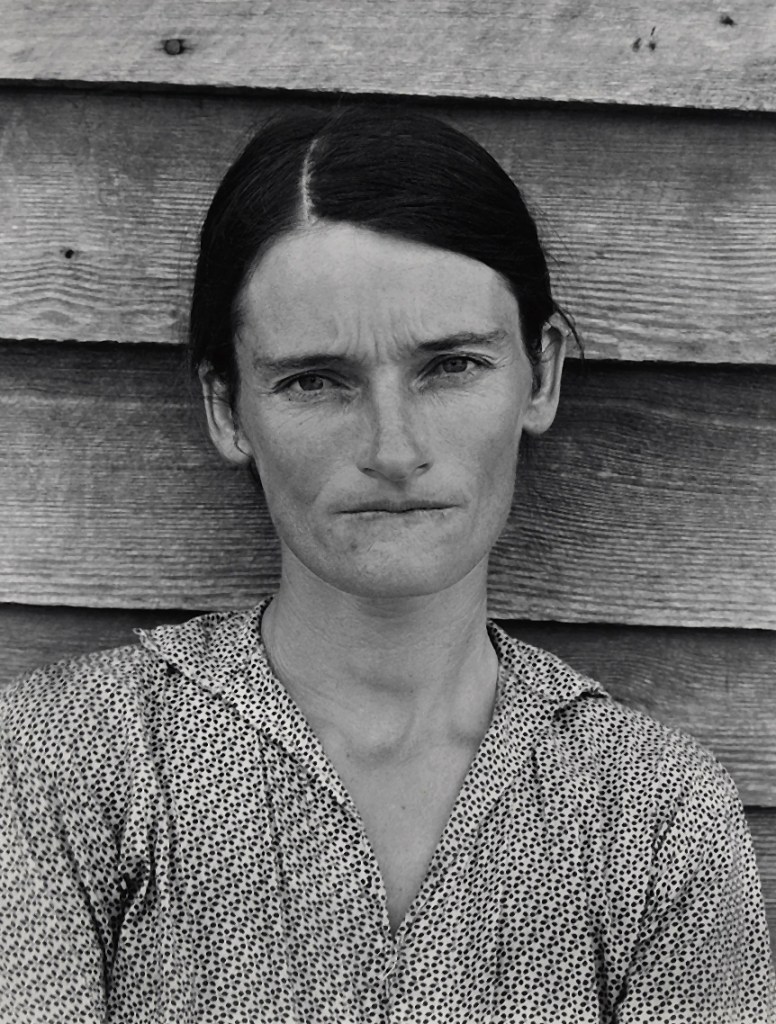

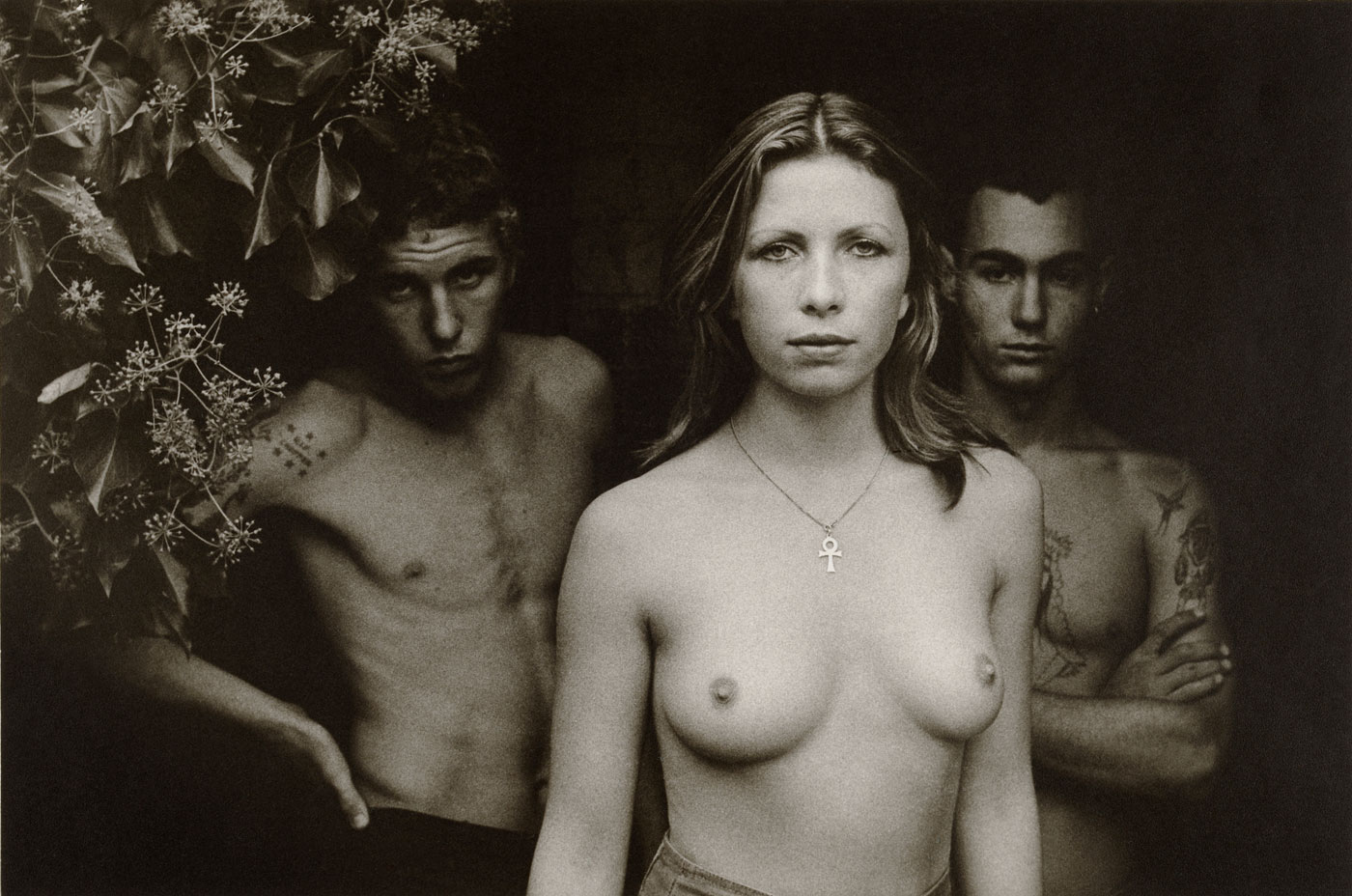

Susan Meiselas (American, b. 1948)

Lena on the Bally Box, Essex Junction, Vermont

1973

Gelatin silver print

Image: 22 x 32.5cm (8 11/16 x 12 13/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art

Anonymous Gift in honor of Sarah Greenough and Andrea Nelson

The final and most essential selection in this posting – Susan Meiselas’ 1972-1975 Carnival Strippers series – goes behind the “front” to document the lives of women who performed striptease for small-town carnivals in New England, Pennsylvania and South Carolina. “Meiselas’ frank description of these women brought a hidden world to public attention, and explored the complex role the carnival played in their lives: mobility, money and liberation, but also undeniable objectification and exploitation. Produced during the early years of the women’s movement, Carnival Strippers reflects the struggle for identity and self-esteem that characterised a complex era of change.” (Booktopia)

Intense, intimate and revealing, the series proves that we can think we know something (the phenomenal) and yet photography reveals how strange and different each world is – whether that be in trying to understand the mind of the artist and what they intended in a constructed photograph or, in this case, having an impression of someone else’s life, a life we can perceive (through the “presence” of the photograph) but never truly know (the noumenal).

Marcus Bunyan on the exhibition Known and Strange: Photographs from the Collection at the V&A Photography Centre on the Art Blart: art and cultural memory archive website, May 7, 2022 [Online] Cited 06/20/2025

Susan Meiselas (American, b. 1948)

Tentful of Marks, Tunbridge, Vermont

1974

Gelatin silver print

Image: 19.7 x 29.4cm (7 3/4 x 11 9/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Corcoran Collection

Museum Purchase, Photography Acquisition Fund

In Tentful of Marks, Susan Meiselas trains her camera from backstage on the legs and high heels of a carnival dancer. The all-male audience – the “marks” of the title – are in sharp focus, and they crowd around the small stage, lustfully gawking up at her. Meiselas spent three summers documenting women who performed striptease at small-town carnivals in New England, Pennsylvania, and South Carolina. In addition to making photographs, she recorded audiotapesof conversations with the dancers, giving them agency to describe their experience. Meiselas saw her project as a collaboration. Merging listening and looking, it expanded perspectives on a largely invisible and – from the dancers’ perspective – misunderstood world.

Wall text from the exhibition

Installation view of the exhibition The ’70s Lens: Reimagining Documentary Photography at the National Gallery of Art, Washington showing at left, Milton Rogovin’s photograph Jimmy Webster with His Father, Verne (1973, below); and at right, Jimmy Webster (1985)

With thankx to the official Milton Rogovin Facebook page for allowing me to publish this image.

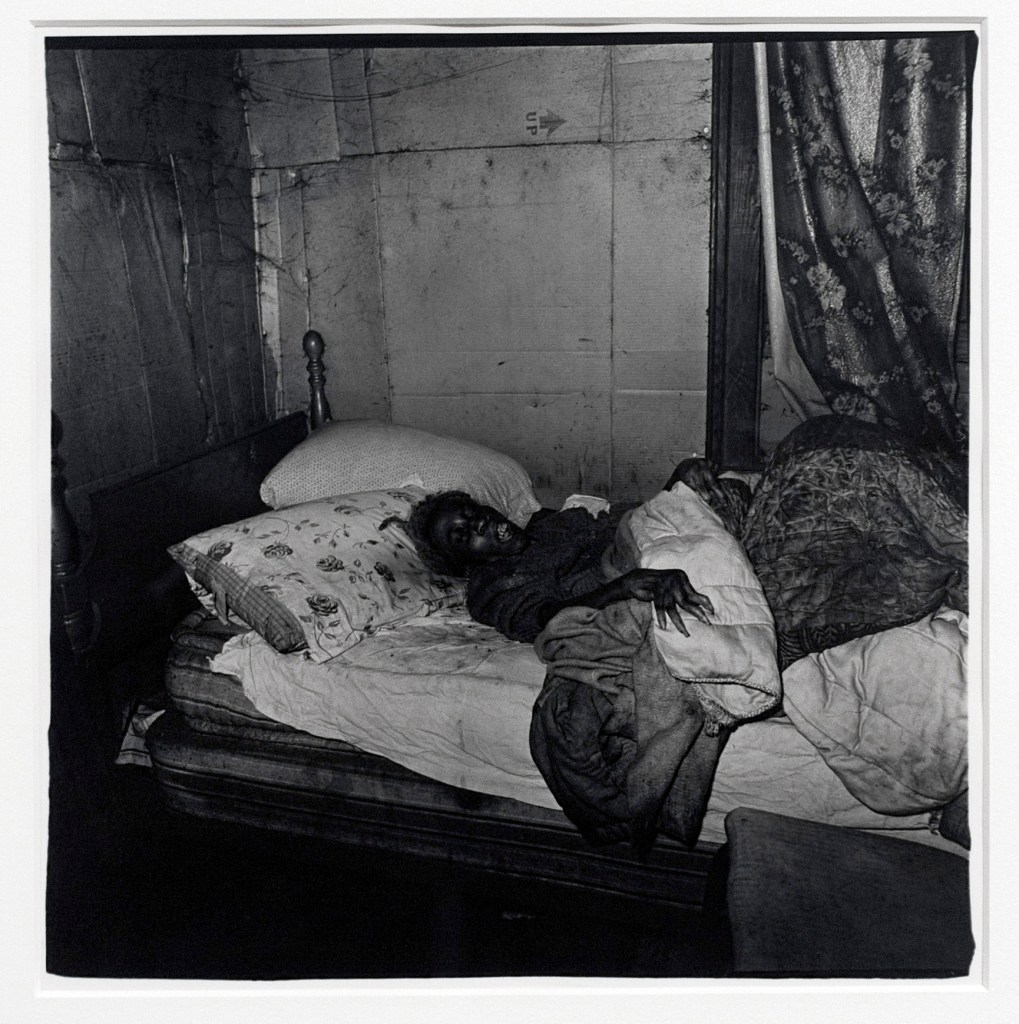

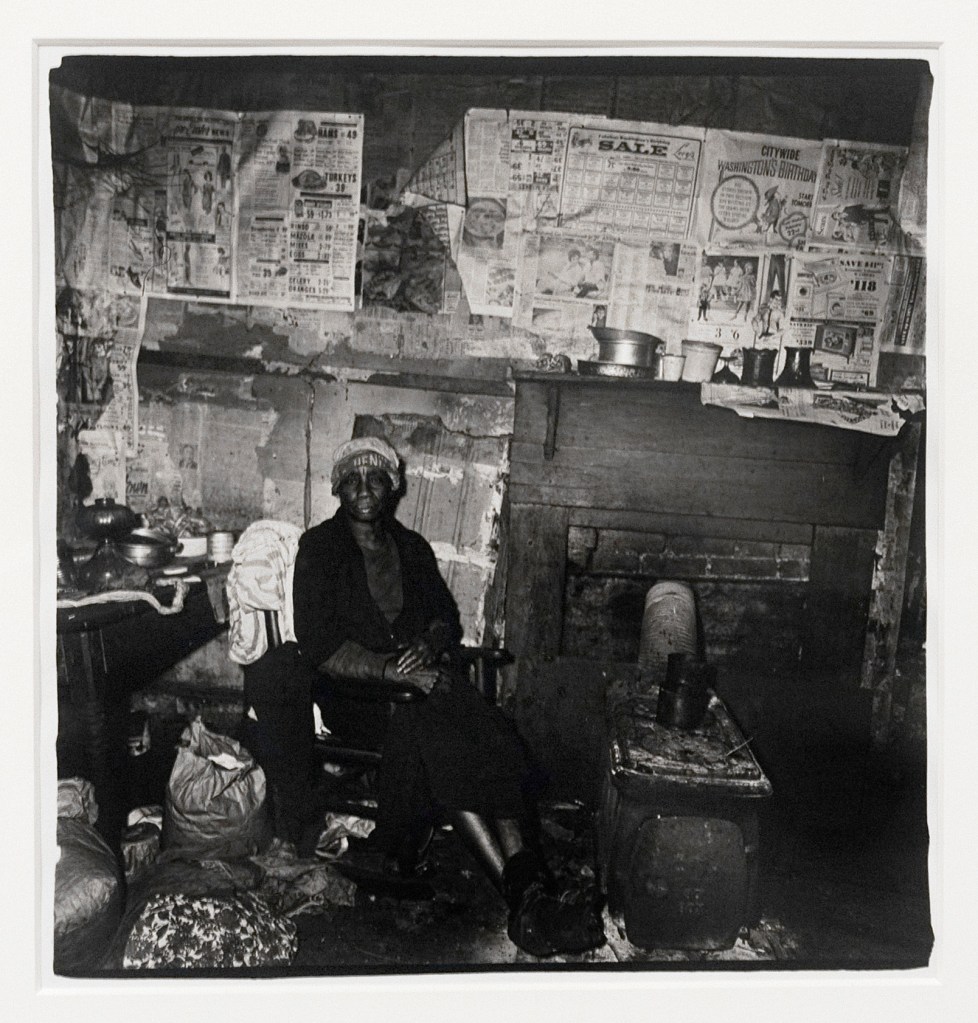

Milton Rogovin (American, 1909-2011)

Jimmy Webster with His Father, Verne

1973

Gelatin silver print

Image: 17.4 x 15.5cm (6 7/8 x 6 1/8 in.)

National Gallery of Art

Gift of Pierre Cremieux and Denise Jarvinen

With thankx to the official Milton Rogovin Facebook page for allowing me to publish this image.

Verne Webster, sitting on his front stoop, looks guardedly at the camera while sheltering his toddler son Jimmy in a protective embrace. This is an early work from Milton Rogovin’s 30-year series documenting Buffalo’s Lower West Side. The project focused on a six-block neighbourhood that was among Buffalo’s most diverse and most impoverished. Rogovin asked permission to photograph his subjects, let them choose their poses and settings, and gave them free prints. He returned every decade or so to photograph the same individuals. A nearby picture shows Jimmy 12 years later. Looking back at Rogovin’s photographs in 2003, Jimmy Webster said, “Whenever you look at his photographs, you just see people for who they are.”

Wall text from the exhibition

John Baldessari (American, 1931-2020)

Throwing three balls in the air to get a straight line: (best of thirty-six attempts)

1973

Colour offset photolithographs

National Gallery of Art Library

David K. E. Bruce Fund

West Coast conceptual art has a whimsical air. Artists such as John Baldessari and Ed Ruscha created scenarios that lampoon both the pretense of “high art” and the self-seriousness of conceptual art, particularly as the latter was developing in New York. Beneath the humor, however, their works spoke to more substantive issues like artistic failure and social mores. In 1973 Baldessari photographed his 36 attempts to throw three balls in the air to form a straight line. He never succeeded but included his 12 best attempts in a portfolio.

Wall text from the exhibition

Henry Wessel (American, 1942-2018)

Utah

1974

gelatin silver print

Image: 26.5 x 39.7cm (10 7/16 x 15 5/8 in.)

National Gallery of Art

Patrons’ Permanent Fund

Stephen Shore (American, b. 1947)

Holden Street

July 13, 1974

Chromogenic print

Image: 20.5 x 25.4cm (8 1/16 x 10 in.)

National Gallery of Art

Diana and Mallory Walker Fund

Stephen Shore’s photograph may appear casual, but it is carefully constructed. The vertical of the lamppost draws our attention to the shadowed foreground. Buildings and sidewalks on each side act as perspective lines that meet in the brighter background. Shore was exploring how three-dimensional space is rendered in two dimensions, particularly in a colour photograph. He was also examining where a once-powerful New England industrial town abruptly ended and the verdant countryside began. The lack of people, saturated colours, and clarity of detail – made possible by using a large-format 8 × 10 camera – give the picture an air of timelessness but also hyperreality.

Wall text from the exhibition

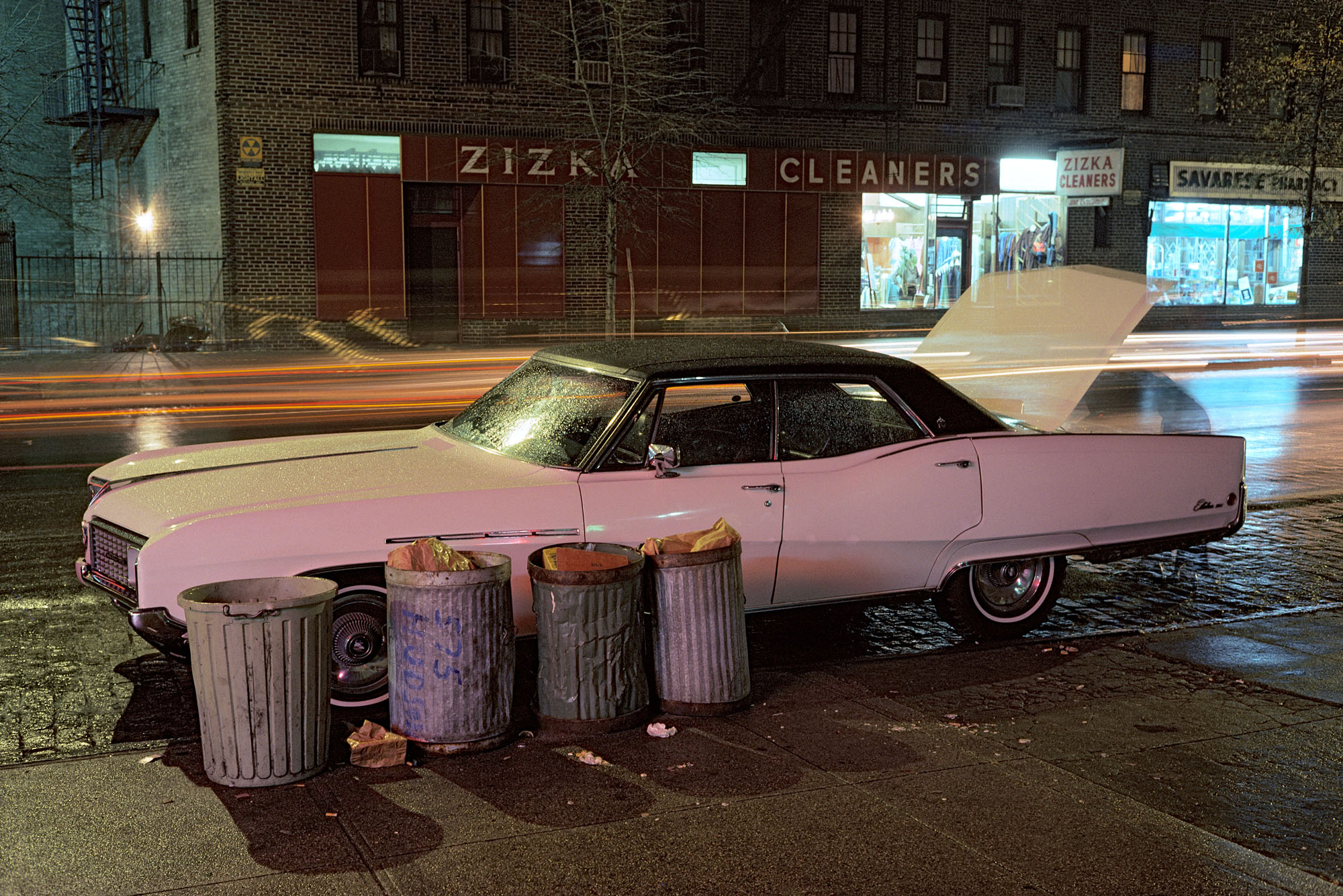

Thomas Barrow (American, 1938-2024)

Dart

1974, printed 1994

From the series Cancellations

Gelatin silver print

23.9 × 34.6cm (9 7/16 × 13 5/8 in.)

National Gallery of Art

Randi and Bob Fisher Fund

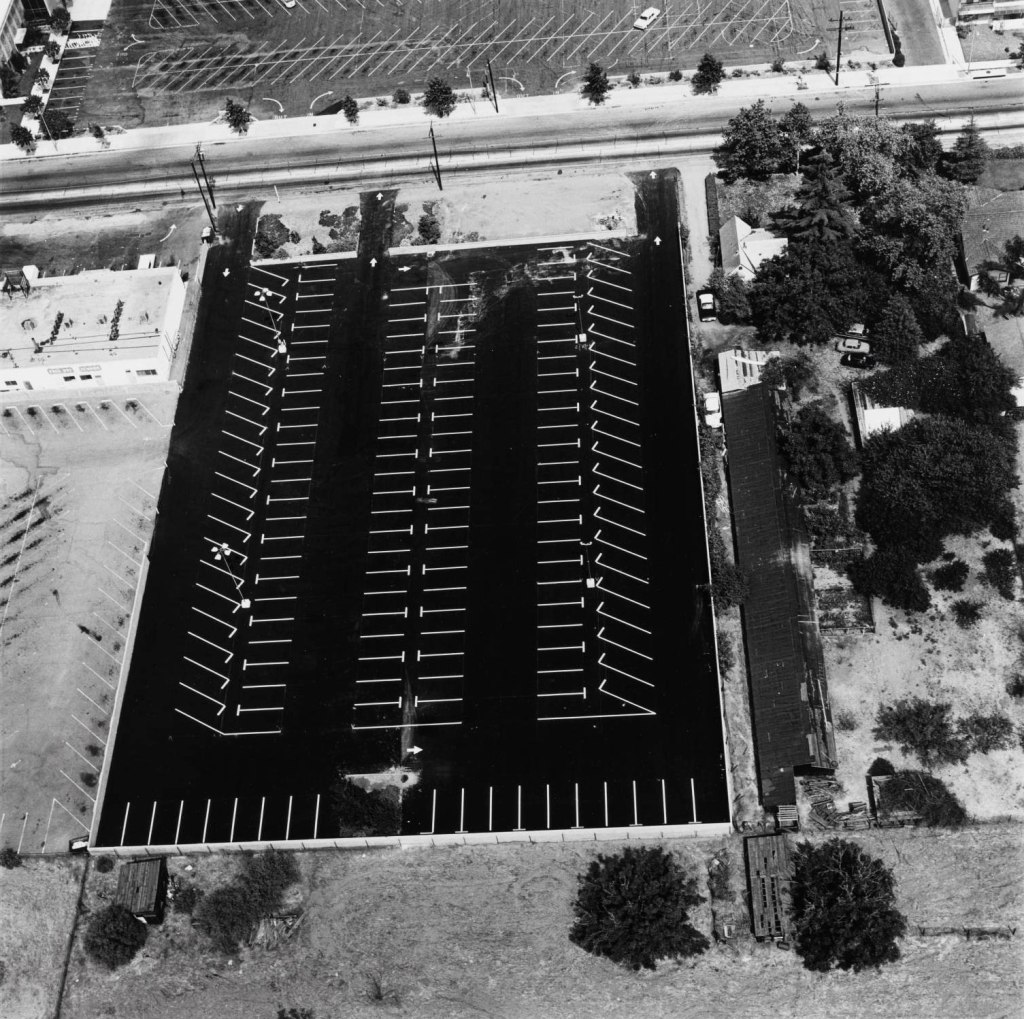

In Dart, Thomas Barrow photographed a huge arrow that appears to have plunged from the threatening clouds above into a parking lot shared by Snappy Photos, a Goodwill drop-off bin, and a K-Mart. The work is part of his series Cancellations, documenting the suburban sprawl overtaking much of the United States. Barrow “cancelled” his images before printing by slashing the negatives with an icepick. (“Cancelling” refers to the practice of defacing a printing plate or negative to ensure no more official prints can he made from it.) This action calls attention to the photograph’s surface and its materiality, which in turn emphasise the choices Barrow made in its production.

Wall text from the exhibition

Thomas F. Barrow is an artist working with photography more than he is a photographer… For Barrow, the ideas are what matter, not the material they are realized with.

Barrow’s Cancellations series is an early expression of this artistic philosophy. Created between 1973-1981, it began when Barrow moved from Rochester, New York to Albuquerque, New Mexico to teach at UNM. Like many photographers of this era (Lewis Baltz, Frank Gohlke, Robert Adams) Barrow was struck by the transformation underway with the (sub)urbanization of the Western landscape. However, he was inspired to do more than document with his camera; he wanted to challenge his viewers while subverting some fundamental truths of photography. Inspired by a cancelled Marcel Duchamp etching (a process where the etching plate is defaced to indicate that no more official prints may be made), he began defacing his negatives with an ice pick and hole punch, “cancelling” them before making the images.

Almost 40 years later, it’s still unclear whether Barrow is canceling the photograph or the scene in the picture. He is certainly calling attention to the matrix that produced the photograph, an unheard of practice at the time and still rare today. By defacing his negatives, he has created photographs that are as much about the physical image as they are about the subject in the photograph.

David Ondrik. “Cancellations by Thomas Barrow,” in Fraction Magazine Issue 49 on the Fraction Magazine website Nd [Online] Cited 07/02/2025

Blythe Bohnen (American, 1940-2022)

Self-Portrait: Triangular Motion, Small

1974

From the series Self-Portraits: Studies in Motion

Gelatin silver prints

National Gallery of Art

Gift of Herbert and Paula Molner

Most self-portraits offer some idea of the artist’s physical appearance and perhaps psychological state. The focus of Blythe Bohnen’s intentionally distorted self-portraits, however, is altogether different. Bohnen was interested in the physical element of artmaking – specifically, the role of her body’s movements or gestures in the creative process. Photographs usually capture an instant, but Bohnen instead used exposures of several seconds and the precise, predetermined gestures identified in her titles to distill the essence of motion. The portraits, blurry and disorienting, become more of a performance in time, condensed into a single image.

Wall text from the exhibition

John Pfahl (American, 1939-2020)

Six Oranges, Buffalo, New York

1975

Dye imbibition print

Image: 20.6 x 25.5cm (8 1/8 x 10 1/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art

Patrons’ Permanent Fund

© The John Pfahl Trust

For the works in his series Altered Landscape, John Pfahl playfully juxtaposed the organic and natural with the manipulated and constructed. In this picture, he placed six oranges on a path in the woods. Typically, if the fruits were all the same size they would appear to grow smaller the farther from the camera they were located. Here, however, the artist has reversed that expectation, with the smallest orange sitting nearest the camera and the largest in place at the top of the picture. Through his staging, Pfahl makes the viewer aware of how a camera, by recording three-dimensional space onto a two-dimensional surface, actually produces a distorted view.

Wall text from the exhibition

In 1981, Peter C. Bunnell observes in his Introduction to James Alinder’s book Altered Landscapes: The Photographs of John Pfahl, “Our momentary, fragmented and captured vision of disorder and emotion has been replaced by a cool rendering of purposefulness as if to accord another dimension of positivism to the moving force of contemporary human awareness. Pfahl’s work is an attack on the problems of space and, ultimately, existence from a rational point of view.”

Forty years later, these photographs seem not so much rational, or picturesque, as spiritual. The human construction touches the earth lightly, almost reverentially. As Pfahl notes, utmost care is taken not to alter the actual subject in a way he would consider harmful to his positivist respect for nature. In this delicate footprint, these photographs are very prescient of the dangers of our own Anthropocene – of climate change, of raging bushfires, drought, flood and bio-exinction. We are literally destroying this planet and its creatures. Bunnell states, “Pfahl’s imagery is a sure manifestation of the belief that society can produce an art suitable to its nature and, in this case, a specific kind of photographic presence that expresses current societal values.”

Unfortunately, it’s all too late. The lesson has not been learned.

Marcus Bunyan on the exhibition John Pfahl Altered Landscapes at Joseph Bellows Gallery, La Jolla, California, November – December 2019

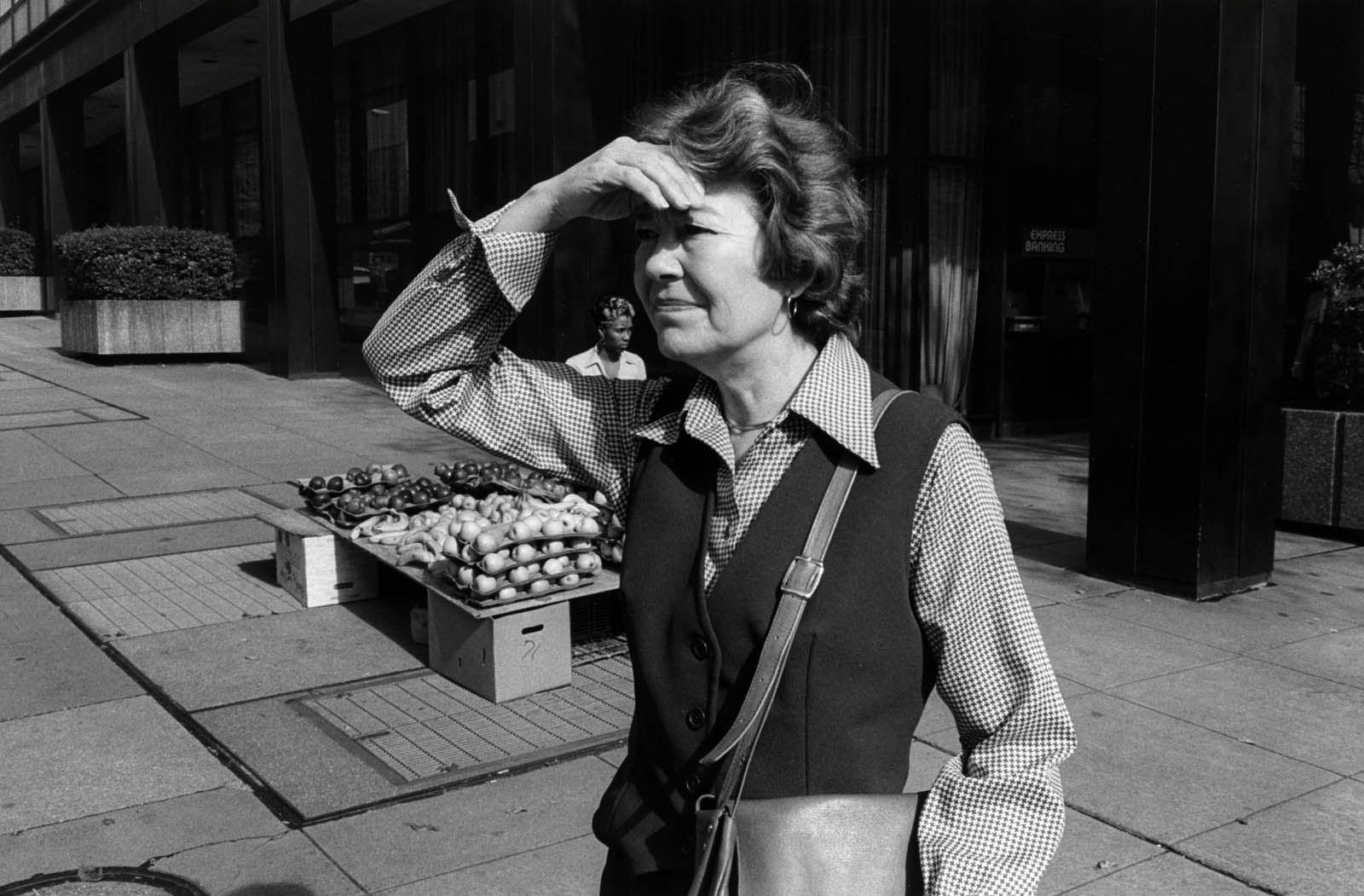

Anthony Hernandez (American, b. 1947)

Washington, DC #11

1975

Gelatin silver print

Image: 18.1 × 27.31cm (7 1/8 × 10 3/4 in.)

National Gallery of Art

Corcoran Collection (Museum Purchase)

Anthony Hernandez cleverly uses the crook of a woman’s raised arm to frame a fruit seller on the street behind her. A Los Angeles – based photographer, Hernandez was invited to Washington, DC, in 1975 to participate in The Nation’s Capital in Photographs, a bicentennial documentary project organized by the Corcoran Gallery of Art. Ignoring the city’s monuments, Hernandez captured life in commercial downtown areas where the architecture and people on the street defined the landscape. This sparsely populated composition evokes urban alienation. Neither figure seems aware of the other, and both look small against the austere modern building and grate-covered sidewalk that fill the background.

Wall text from the exhibition

Anthony Hernandez’s 1970s photographs of urban inhabitants are often focused on odd-looking people staring right at the camera. His subjects often appear surprised and slightly perturbed, as if caught unaware in private moments of thought or conversation.

Following two years of study at East Los Angeles College and two years of service in the United States Army as a medic in the Vietnam War, Hernandez took up photography in earnest around 1970. He walked the streets of his native Los Angeles, observing its inhabitants. In order to work quickly and intuitively, he would pre-focus the camera and then wait for subjects to come into the zone of focus – only briefly bringing the camera to his eye as he walked past them. He repeated this strategy in other cities, including London, Madrid, Saigon, and Washington, D.C.

Text from the J. Paul Getty Museum website

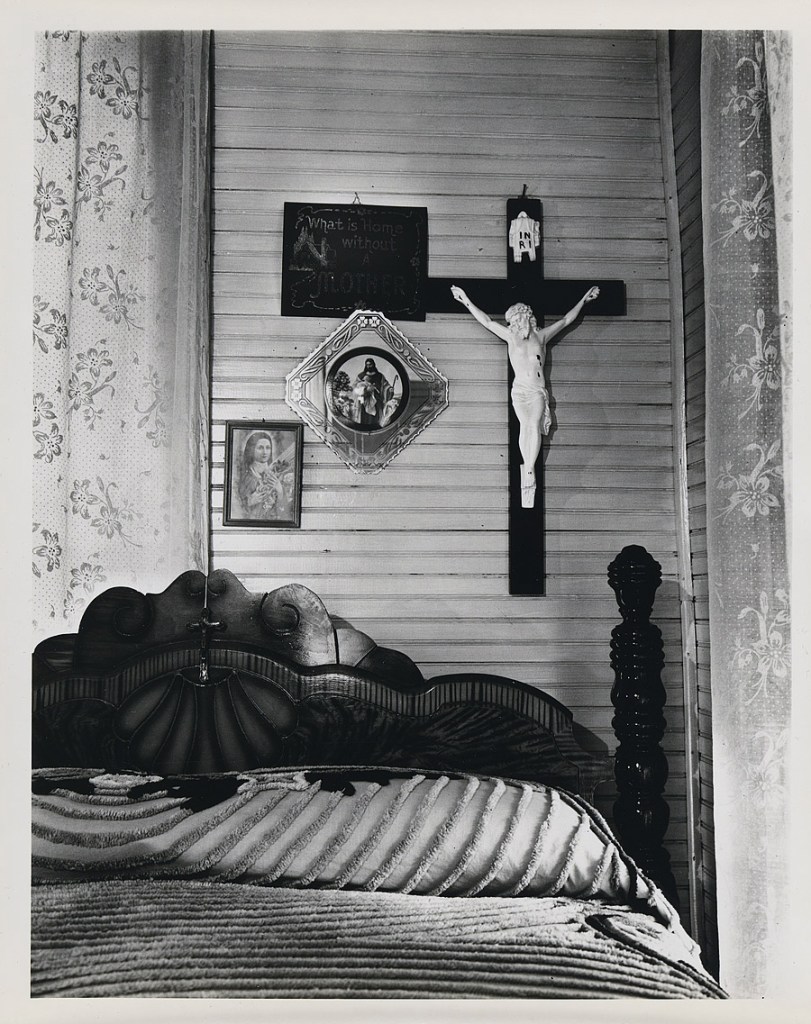

Joanne Leonard (American, b. 1940)

Memo Center with Wall Plaque

c. 1975

Gelatin silver print

Image: 33.3 × 43.1cm (13 1/8 × 16 15/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art

Gift of the Artist in honor of her daughter, Julia Marjorie Leonard

Dotted curtains, a flowered light switch plate, and a humorous wall plaque add a personal touch to this carefully framed picture of a so-called memo center – an area near a wall phone where notes could be jotted down that was popular in 1970s homes. A practitioner of what she called “intimate documentary,” feminist artist Joanne Leonard recorded familiar but often overlooked domestic spaces traditionally associated with women. She explained, “Through my work as an artist I’ve discovered that the realms of the personal and the public are rarely as separate as I once imagined.”

Wall text from the exhibition

In the 1970s Leonard began examining how domestic spaces are transformed through the presence of technology by photographing the interiors of her neighbours’ homes in West Oakland, California, later moving on to other locations. She captured personal objects in bedrooms and found repetition in the common appliances present in kitchen after kitchen. She also documented the proliferation of “memo centers” – areas where notes could be jotted down near the location of a telephone, which at this time was still tethered in place by a cord.

Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) Gallery label from 2022

Joanne Leonard (American, b. 1940)

Lupe’s Kitchen Window, San Leandro, California

c. 1975

Gelatin silver print

Image: 41.8 x 43.1cm (16 7/16 x 16 15/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art

Gift of the Artist in honor of her daughter, Julia Marjorie Leonard

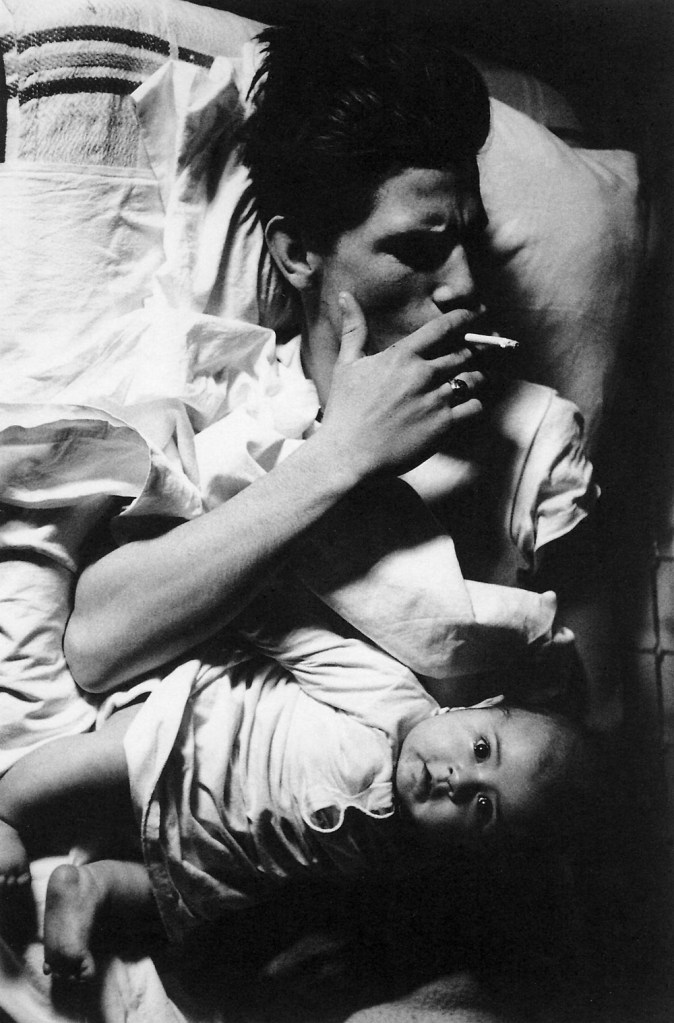

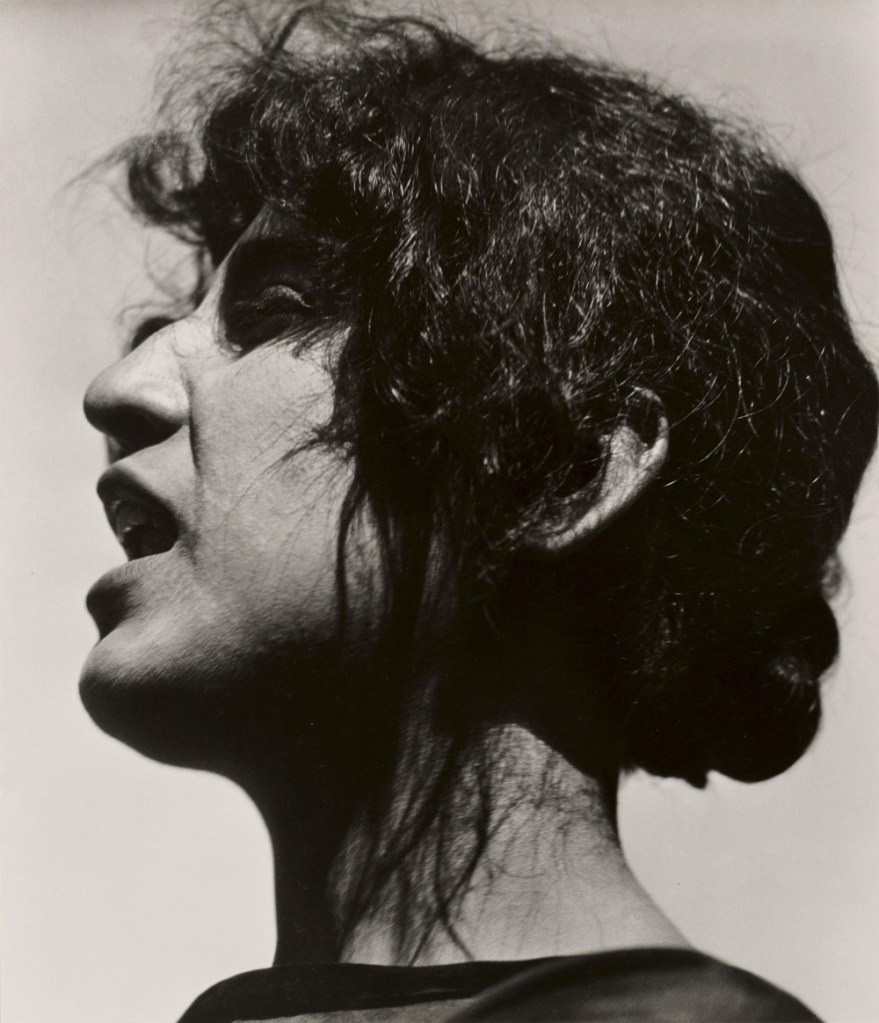

Peter Hujar (American, 1934-1987)

Susan Sontag

1975

Gelatin silver print

Image: 37.15 x 37.15cm (14 5/8 x 14 5/8 in.)

National Gallery of Art

Stephen G. Stein Employee Benefit Trust

Robert Cumming (American, 1943-2021)

67-Degree Body Arc Off Circle Center

1975, printed 2022

Inkjet print

Image: 148.59 x 185.42cm (58 1/2 x 73 in.)

National Gallery of Art

Gift of David Knaus

Sometimes Cumming used his own body as an eccentric subject, as in “67-degree body arc off circle center” from 1975. Shown in profile with his hips thrust forward, his torso arched back and his neck and head awkwardly aligned with the angle of his legs, he’s a mathematical or scientific demonstration whose geometry turns the graceful rationality of Leonardo da Vinci’s “Vitruvian Man” on its ear. The title’s geometric forms drawn around his body on the surface of the photograph might have been made with an oversized pen-nib, into which the hand on Cumming’s hip is discreetly hidden.

The artist’s photograph, like a drawing, is an artifice.

His work as a painter, sculptor and performance artist informed his distinctive, often witty approach to images made with a camera, which Cumming began to explore in 1969 and continued for more than a decade. Artists as diverse as Eve Sonneman, Jan Groover, Lew Thomas, Judy Fiskin and Lewis Baltz were blurring traditional boundaries in different but Conceptually cogent ways. Photography would never be the same.

Christopher Knight. “Robert Cumming, whose photographs transformed camera work, dies at 78,” on the Los Angeles Times website Dec. 21, 2021 [Online] Cited 07/02/2025

Francesca Woodman (American, 1958-1981)

House #3

c. 1975-1976, printed 1997-2004

Gelatin silver print

Image: 16.1 x 16.3cm (6 5/16 x 6 7/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art

Gift of the Heather and Tony Podesta Collection

At the far end of a decrepit room, the phantom-like figure of the photographer appears to be merging with, or emerging from, the wall. In contrast to the sharply rendered interior, she is an ethereal blur whose face can barely be made out. Both the creator and subject of most of her work, Francesca Woodman staged dreamlike performances that explore self-portraiture, the female body, and architectural space. Although sometimes carefully planned, they more often represented her spontaneous, imaginative responses to an environment. Woodman made this photograph in an abandoned house in Providence when she was in her late teens.

Wall text from the exhibition

The 1970s was a decade of uncertainty in the United States. Americans witnessed soaring inflation, energy crises, and the Watergate scandal, as well as protests about the Vietnam War, women’s rights, gay liberation, and the environment. The profound upheaval that rocked the country formed the backdrop for a revolution in documentary photography. Activism and growing support of multiculturalism opened the field to underrepresented voices, while artistic experimentation fuelled the reimagining of what documentary photographs could look like.

The ’70s Lens: Reimagining Documentary Photography examines this compelling and contested moment of reinvention when documentary photography’s automatic association with objectivity and truthfulness came into question. The photographs on view record subjects, communities, and landscapes previously overlooked and expand the boundaries of the genre. During this turbulent decade, documentary practice became more deeply entwined with fine art, while conceptual and performance artists used the medium to preserve their ideas and record their actions. An openness to individual expression and a turn from black and white to color film further transformed a field previously celebrated for accurately representing the world and its social ills.

Drawn primarily from the National Gallery’s collection and featuring some 100 photographs by more than 80 artists, The ’70s Lens is on view from October 6, 2024, through April 6, 2025, in the West Building.

“The profound upheaval in American life during the 1970s inspired artists to question the objective nature of documentary photography,” said Kaywin Feldman, director of the National Gallery. “The extraordinary photographs on view in this exhibition explore their diverse and compelling responses, revealing relevant connections to today’s thinking about community and who gets to represent it, as well as broader concepts including photographic truth, equity, and environmental responsibility.”

The Exhibition

Organised thematically, The ’70s Lens: Reimagining Documentary Photography examines how the many documentary approaches that emerged during the 1970s reflected a radical shift in American life – and in photography itself.

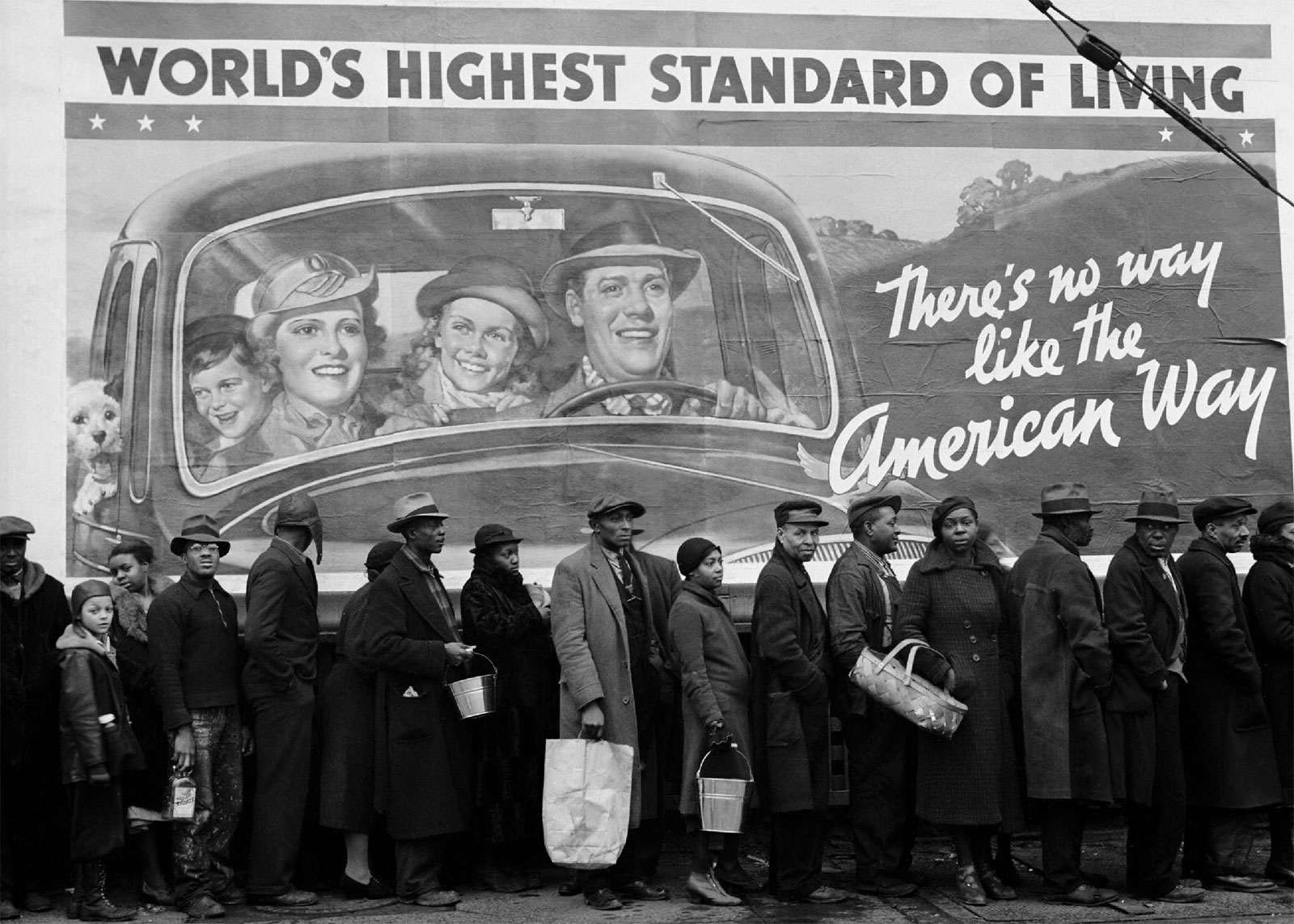

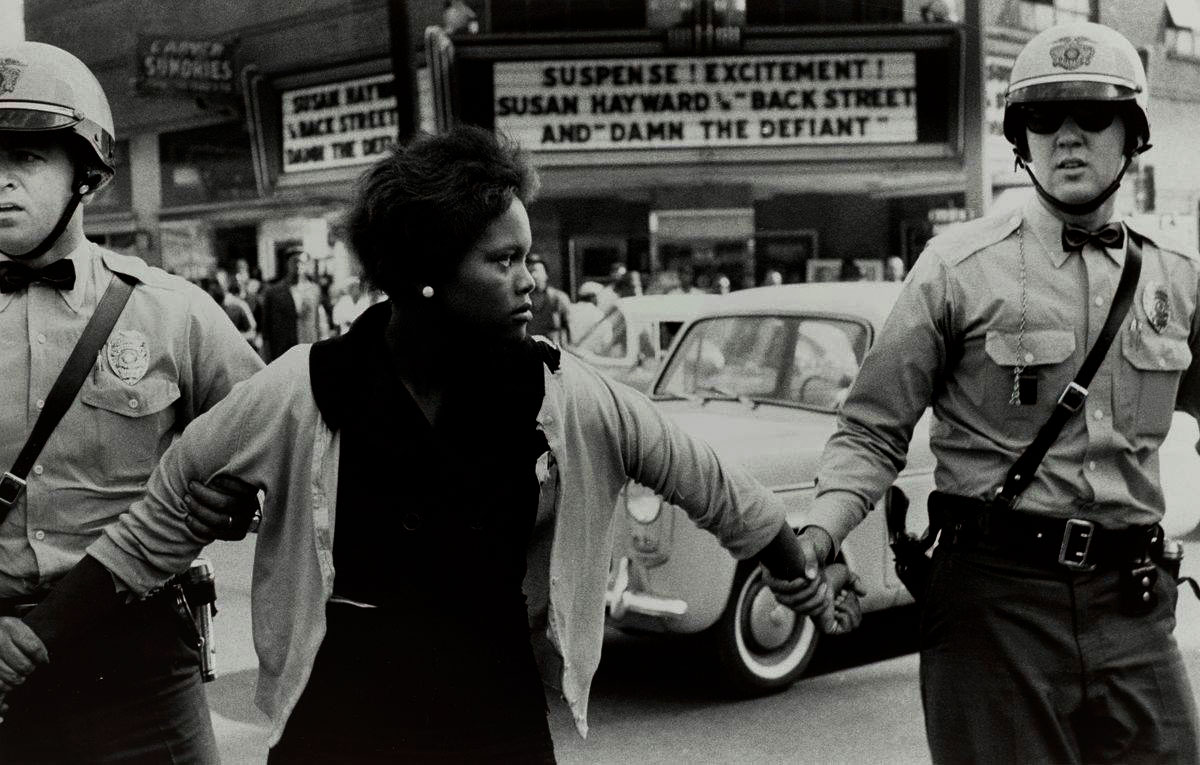

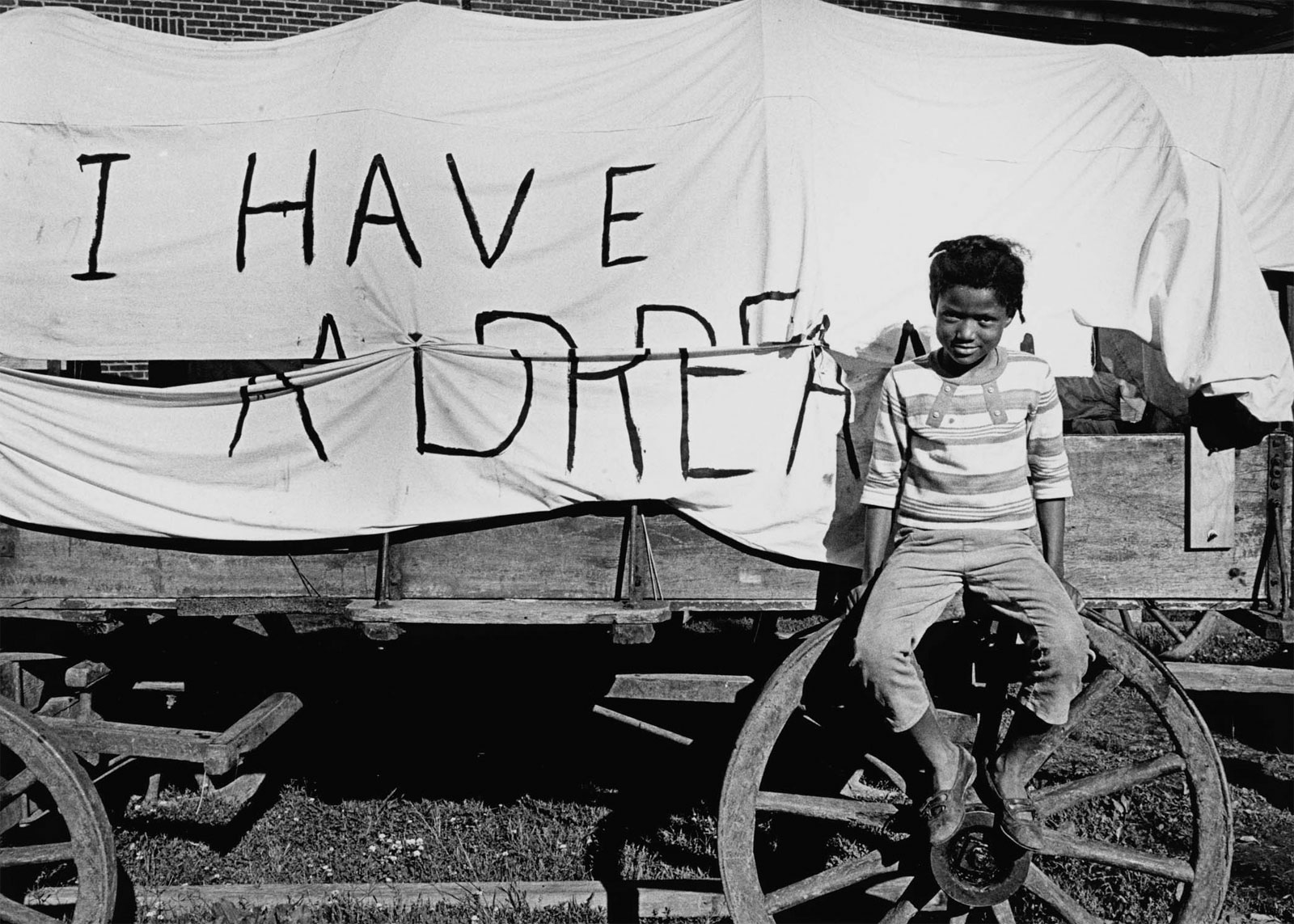

Seeing Community

Spurred by the civil rights movement and a growing recognition of the rich ethnic and cultural diversity within the United States, photographers – especially from the Black, Latinx, and LGBTQ+ communities – reclaimed documentary practice to represent the fullness of their lives. Responding to a history of misrepresentation by outsiders, Anthony Barboza, Frank Espada, Mikki Ferrill, Nan Goldin, Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe, John Simmons, among others, focused their cameras on close-knit neighborhoods, often their own, building trusting relationships with the people they photographed. These artists worked collaboratively with their subjects to challenge preconceived notions of their communities.

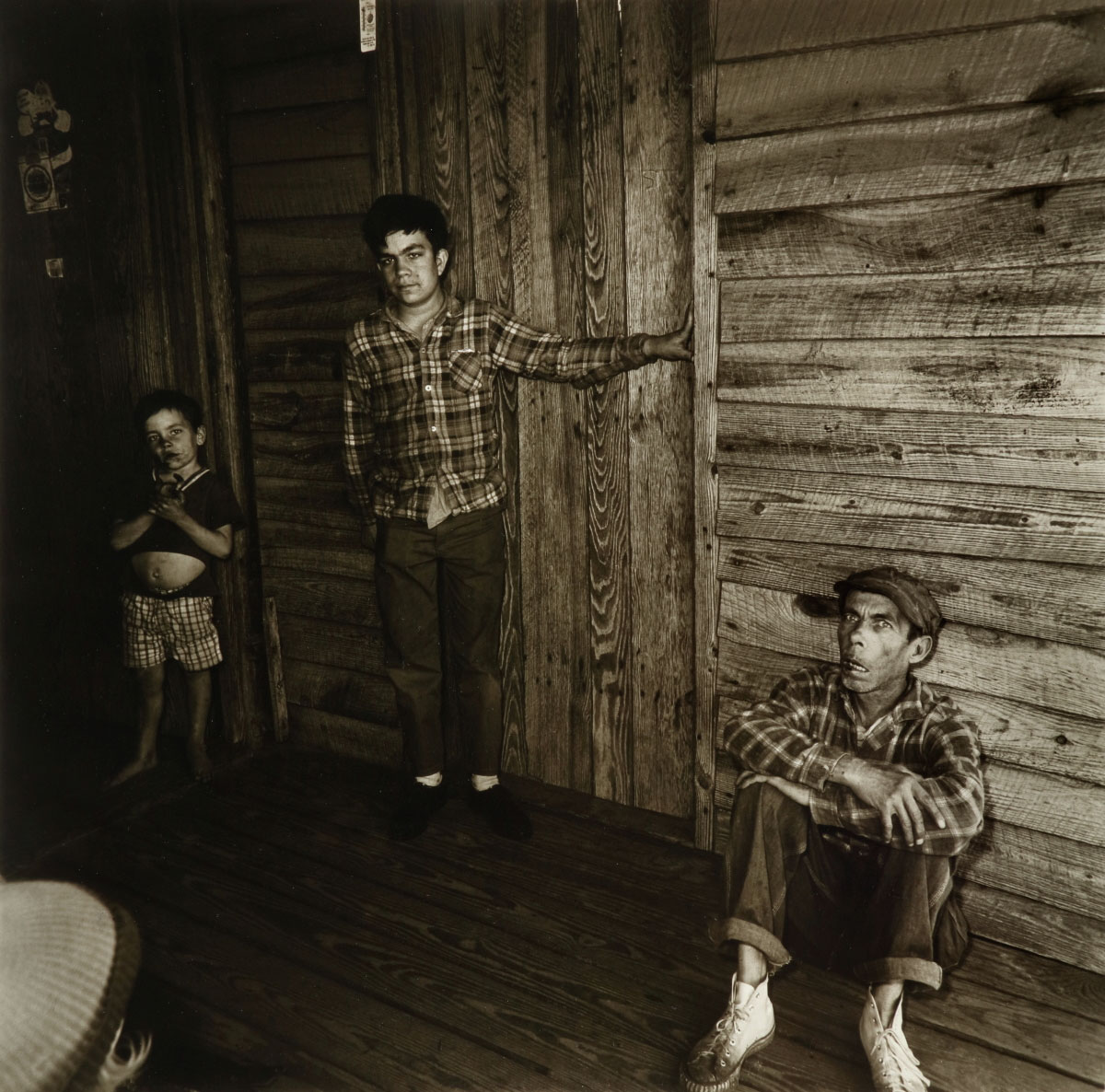

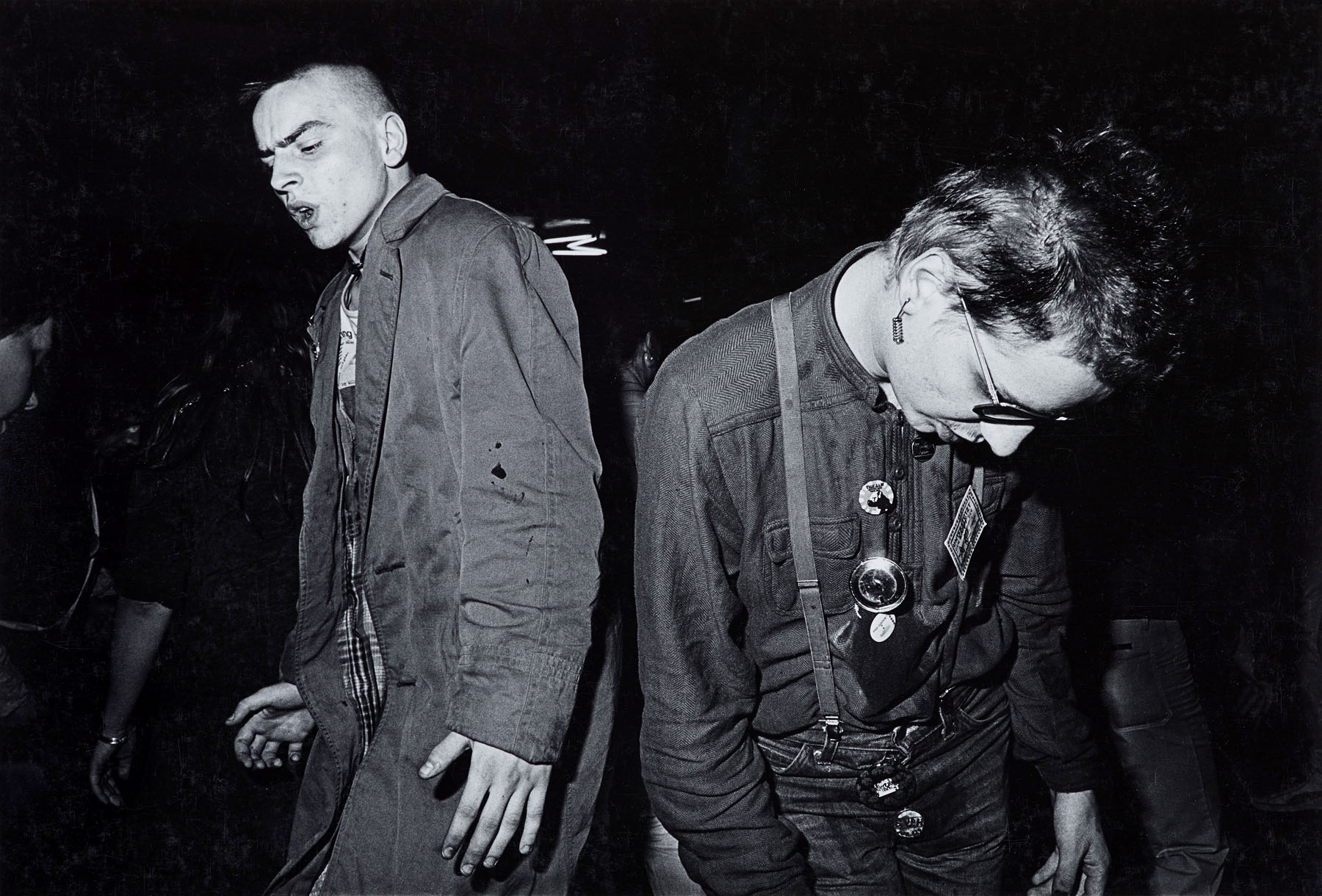

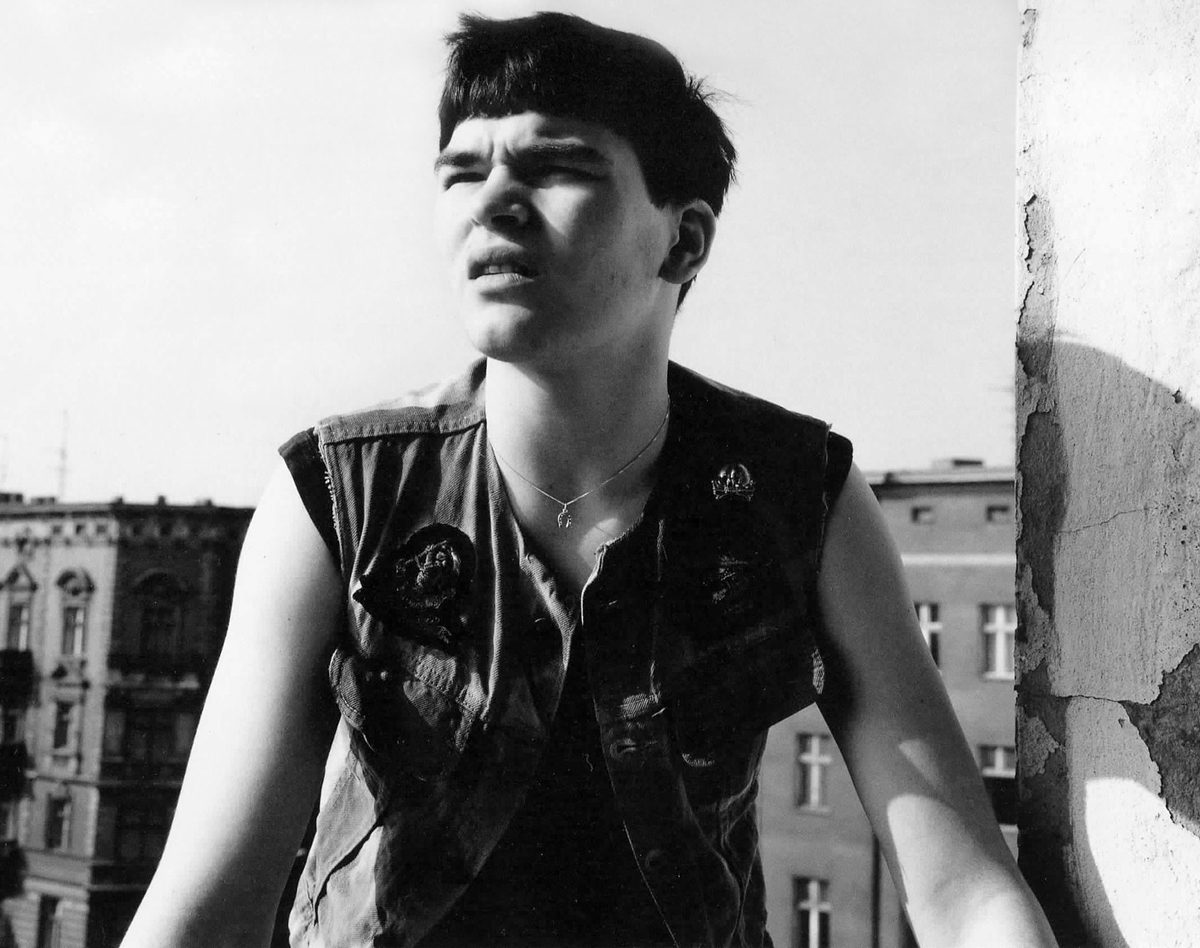

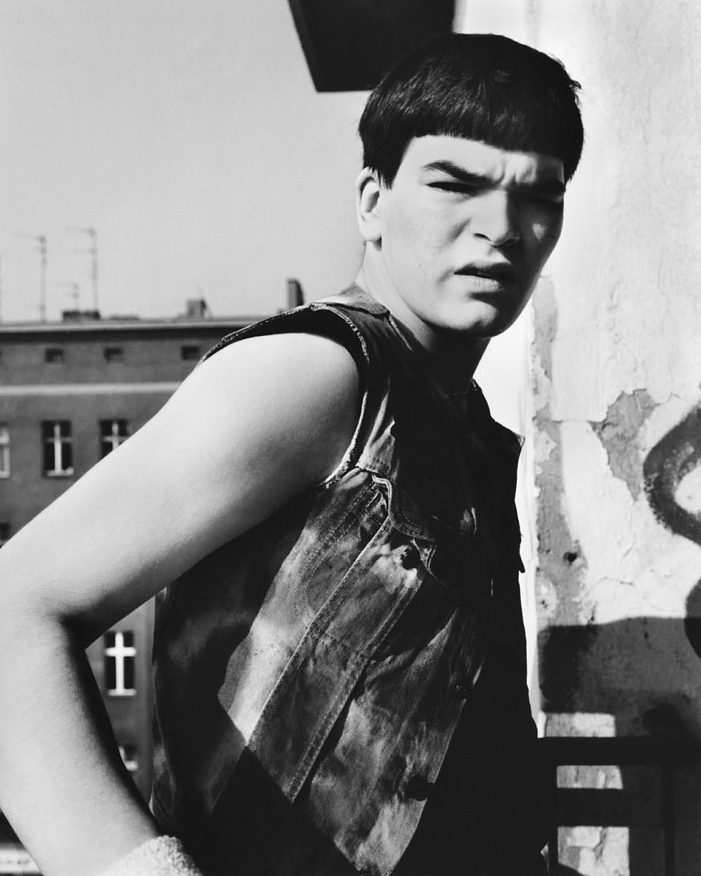

Experimental Forms

Influenced by the groundbreaking photographs made by Roy DeCarava and Robert Frank beginning in the 1950s, a new generation of documentary photographers used the camera to visualise the world and their place in it. By combining clear-eyed observation with individual expression, artists such as Jim Goldberg, Sophie Rivera, and Shawn Walker revealed the complexity of the human condition from a more personal perspective. Others, such as Diane Arbus, Lee Friedlander, Anthony Hernandez, and Garry Winogrand, focused their attention on the irony and ambivalence rooted in American culture of the time, depicting everyday life with a psychological frankness. Together their revitalization of portraiture and street photography merged documentary practice with fine-art photography.

Conceptual Documents

Documentary photography became central to the practice of many conceptual artists in the 1970s. For them, the idea behind a work was more important than the finished object. John Baldessari, Thomas Barrow, and Robert Cumming interrogated the conventions of photography’s widely assumed objectivity and truthfulness by highlighting the difference between photographic appearance and reality. Others, like Susan Hiller and Dennis Oppenheim, used the camera to record their creative process, often integrating photographs with texts to address larger social issues about gender and the environment.

Performance and the Camera

Documentary photography was also integral to performance-based art during the 1970s. Many artists used the medium to record their otherwise ephemeral actions – including those who made performances specifically for the camera. This photographic documentation became a new form of art inseparable from the overall conception of the performance. Senga Nengudi in collaboration with Maren Hassinger explored the elasticity of the body through choreographed actions. Ana Mendieta and Francesca Woodman examined their identities through interventions in the environment, while Tseng Kwong Chi, Marcia Resnick, and David Wojnarowicz staged journeys and constructed histories that pushed the boundaries between truth and fiction.

Life in Color

The art world’s embrace of color film in the 1970s transformed documentary photography. Commercial color processes had existed for more than 50 years, but serious documentary photography was strictly associated with black-and-white prints. Color photography’s status changed gradually over the decade, and especially in the wake of an exhibition of William Eggleston’s mundane but incisive photographs at the Museum of Modern Art in 1976. Pictures of everyday life made in color by William Christenberry, Mitch Epstein, Richard Misrach, and John Valadez held an immediacy that fascinated viewers and offered a new framework for reflecting on contemporary life.

Alternative Landscapes

The 1970s witnessed a radical shift in how landscapes were understood and photographed. Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz, and Joe Deal challenged popular ideas of nature as pristine and timeless with pictures of environmental destruction and suburban sprawl. From grain elevators to roadside motels, Frank Gohlke and John Schott focused on structures that form the built environment, revealing how humans have shaped their surroundings. The artists in this section documented with an austere eye, and at times subversive wit, a rampant consumer culture and the damage done in the name of progress.

Intimate Documentary

Many photographers in the 1970s turned their cameras on themselves and close family members to analyze the social landscape of domestic spaces. Often informed by second-wave feminism, they prioritized interiors and life at home as topics for artistic examination. Joanne Leonard has described her narrative-rich scenes of everyday life as “intimate documentary,” while Bill Owens observed the rise of suburbia as both a place and a mentality. Concerned that documentary photography was losing its activist force, Martha Rosler and Eleanor Antin engaged with politics – especially the home front during the Vietnam War – more directly.

Press release from the National Gallery of Art

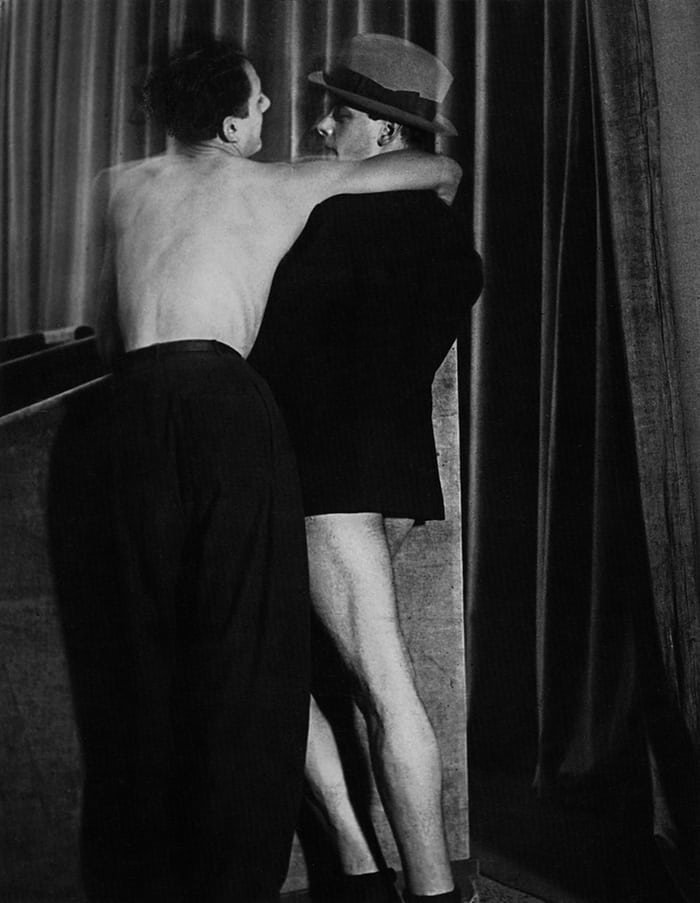

Sunil Gupta (Canadian born India, b. 1953)

Untitled #22

1976, printed 2023

From the series Christopher Street

Gelatin silver print

Image: 61 x 91.5cm (24 x 36 in.)

National Gallery of Art

Alfred H. Moses and Fern M. Schad Fund

© Sunil Gupta

Sunil Gupta documented the emergence of a gay public space in New York’s Greenwich Village during the 1970s. The India-born Gupta had arrived from his adopted home in Montreal in 1976 to study business, but quickly decided instead to fine-tune his photographic skills. Energized by the overtly gay environment – a result, in part, of LGBTQ+ demonstrations in 1969 known as the Stonewall uprising – he started photographing people on the streets. Not impartial, Gupta was enthralled by those he encountered, including two stylishly dressed men who seem to acknowledge Gupta’s camera. In the Christopher Street series, Gupta recorded the then extraordinary act of being openly gay – a practice both political and deeply personal.

Still moved by this project, the artist has recently started making large-scale prints from his original negatives.

Wall text from the exhibition

This series was shot in New York in 1976 when I spent a year studying photography with Lisette Model in the New School… I spent my weekends cruising with my camera, it was the heady days after Stonewall and before AIDS when we were young and busy creating a gay public space such as hadn’t really been seen before.

Text from the Sunil Gupta website

Ana Mendieta (Cuban-American, 1948-1985)

Untitled

1977-1978

From the Silueta Series

Gelatin silver print

Image: 33.8 x 49.5cm (13 5/16 x 19 1/2 in.)

National Gallery of Art

Gift of the Collectors Committee

In her Silueta Series, Cuban American artist Ana Mendieta used the outline of her body to carve and shape silhouettes into the land. Informed by her interest in Afro-Cuban ritual, her fusion of performance and earthworks explored spiritual connections between nature and the female body. Mendieta’s exile with her family from Communist Cuba to the United States in the 1960s left her with a deep sense of loss. She remarked, “I have no motherland; I feel a need to join with the earth.” Photography was crucial in documenting these ephemeral pieces, preserving them before they were lost to the elements. Hauntingly beautiful, the pictures enable Mendieta’s practice to be both transitory and enduring.

Wall text from the exhibition

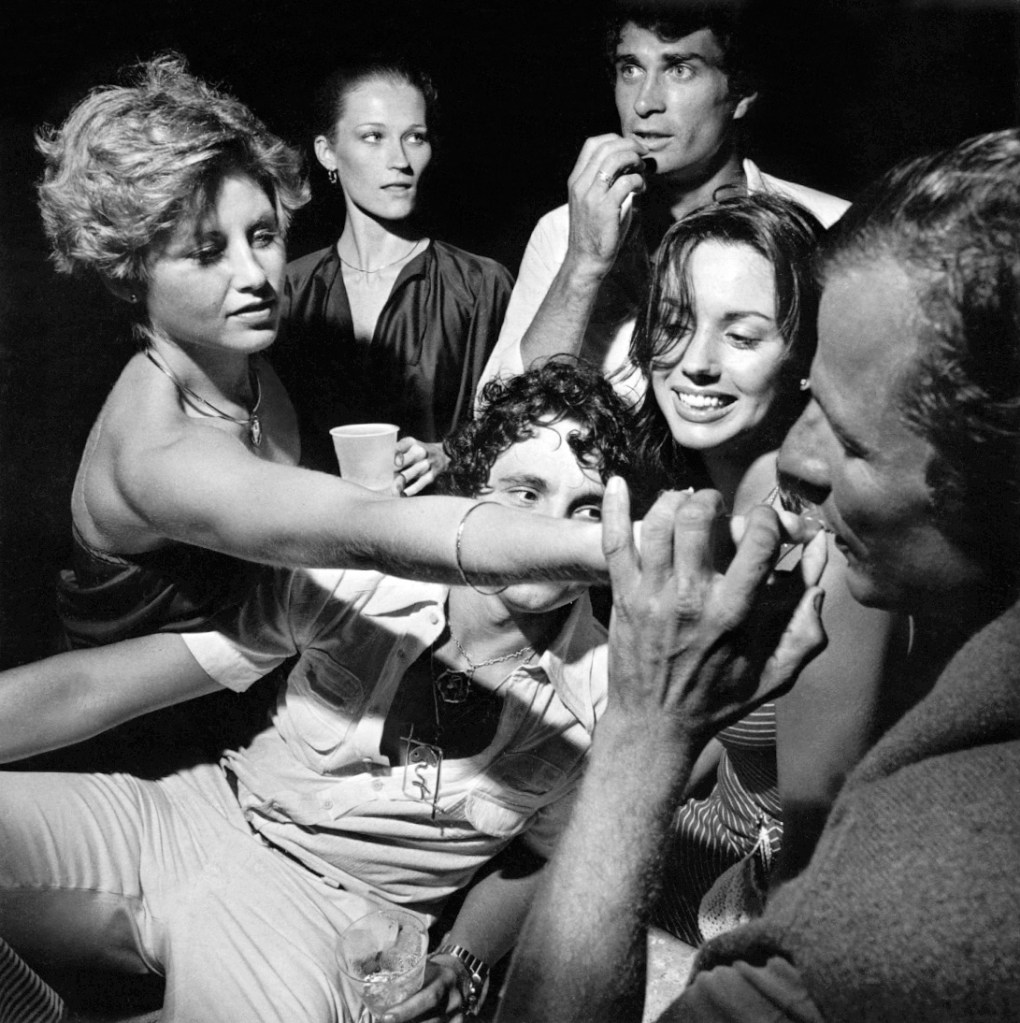

Larry Fink (American, 1941-2023)

Studio 54, New York City

May 1977

From the series Social Graces

Gelatin silver print

37.2 × 38cm (14 5/8 × 14 15/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art

Gift of Tony Podesta Collection, Washington, DC

Lynne Cohen (American-Canadian, 1944-2014)

Exhibition Hall

1977

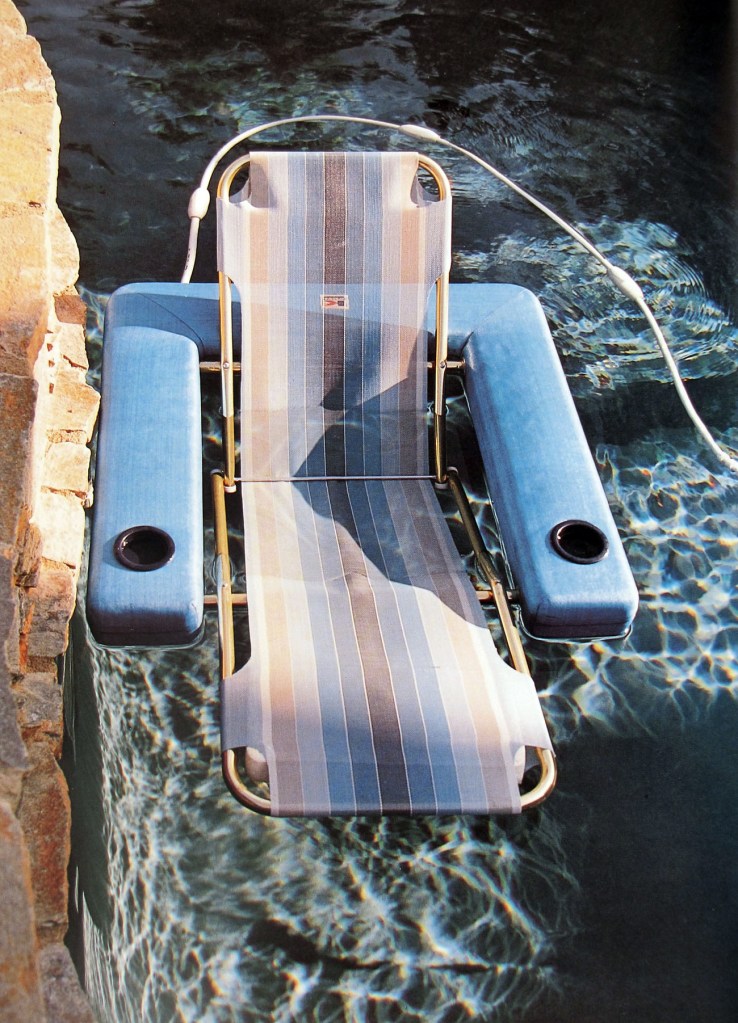

Gelatin silver print

Image (visible): 19 x 23.7cm (7 1/2 x 9 5/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art

Pepita Milmore Memorial Fund

© Estate of Lynne Cohen

In the photography of Lynne Cohen, you won’t see a single person. But you’ll find their traces everywhere. Her images feel haunted by people, as if the action has just ended or has yet to begin. Despite their absence, however, people are the true subject of the artist’s gaze. Former Gallery curator Ann Thomas explained in her essay for the 2001 National Gallery of Canada exhibition No Man’s Land: The Photography of Lynne Cohen: “While her photographs do not include human beings, they are on occasion more revealing about human behaviour than any group portrait.”

From her earliest photographs in 1971 to her final works before her death in 2014, Cohen made deadpan images of interior spaces, training her lens on the everyday peculiarities of living rooms, offices, banquet halls, social clubs, learning centres, salons, laboratories and shooting ranges. Her signature style used flat lighting, deep focus and symmetrical compositions to lend her works what she termed “a cool, dispassionate edge.” The works can be funny, sinister, maddening, familiar, bizarre and often surreal.

Although in later years Cohen would make prints large enough to envelope the viewer – introducing colour and shifting her choice of subject from domestic interiors and clubhouses to more restricted environments, such as military installations – her conceptual mission never wavered from the start. Her photography investigates how setting makes a simulation of experience, how reality is more engineered than we may care to recognize and how the spaces we design also design us in turn.

Chris Hampton. “Lynne Cohen: Art Surrounds Us,” on the National Gallery of Canada website November 22, 2024 [Online] Cite 07/02/2025

Joanne Leonard (American, b. 1940)

Dining Area and Patterned Wallpaper, Blake Street, Berkeley, California

c. 1977

Gelatin silver print

Image: 18 x 17.7cm (7 1/16 x 6 15/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art

Gift of the Artist in honor of her daughter, Julia Marjorie Leonard

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Arthur Rimbaud in New York (Diner)

1978-1979

Gelatin silver print

Image: 17.15 x 24.13cm (6 3/4 x 9 1/2 in.)

National Gallery of Art

Gift of Funds from Heather Muir Johnson

“Transition is always a relief. Destination means death to me. If I could figure out a way to remain forever in transition, in the disconnected and unfamiliar, I could remain in a state of perpetual freedom.”

~ David Wojnarowicz , Close to the Knives: A Memoir of Disintegration

David Wojnarowicz made a series of pictures featuring friends donning a homemade mask of the 19th-century French poet Arthur Rimbaud. Staged at sites around New York that were significant to the photographer, the surrogate self-portraits explore parallels between Wojnarowicz and Rimbaud – both gay artists who rebelled against the social mores of their times. The historical figure with its unchanging expression appears alone or apart from others, a man eerily out of time. The series also documents many of the then vibrant spaces of gay life shortly before the AIDS epidemic ravaged the city’s gay community. Wojnarowicz died from AIDS-related complications at the age of 37.

Wall text from the exhibition

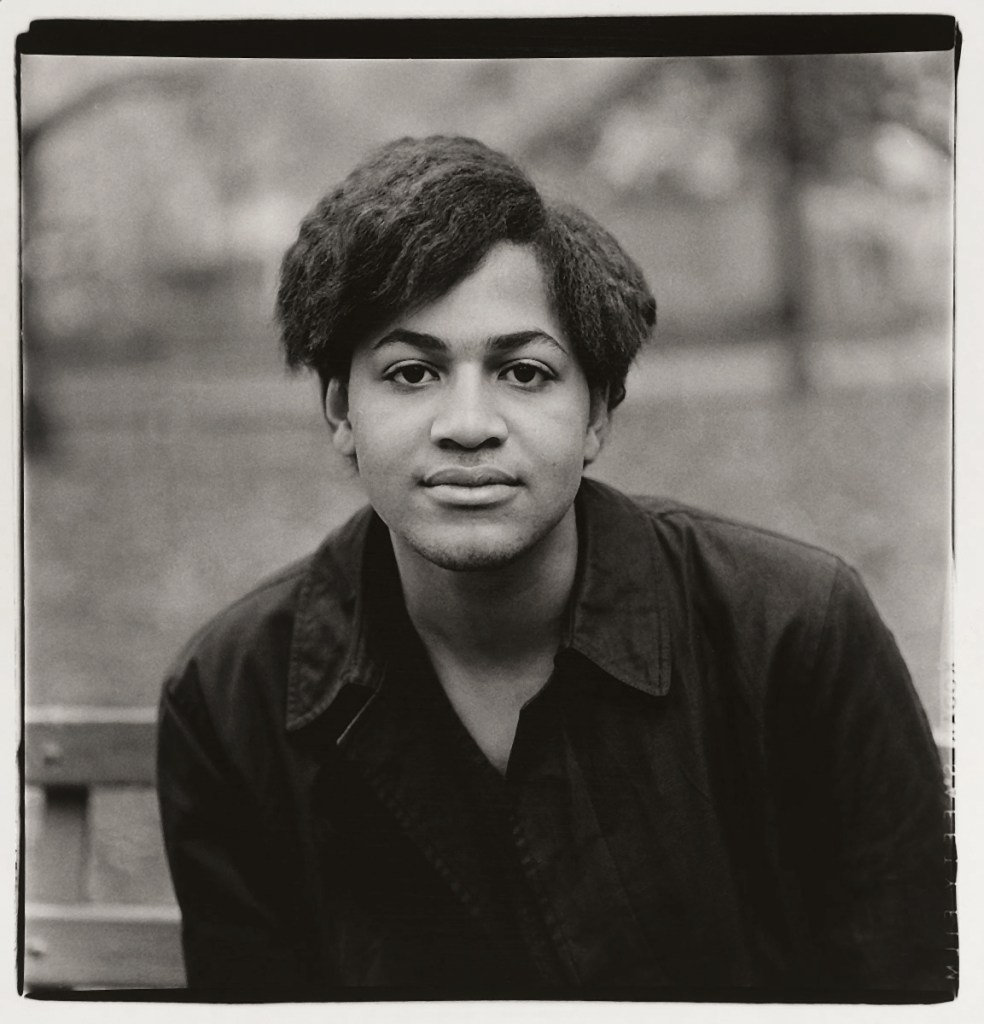

Sophie Rivera (American, 1938-2021)

Untitled

1978

Gelatin silver print

Image/sheet: 25.4 x 25.4cm (10 x 10 in.)

National Gallery of Art

Estate of Martin Hurwitz

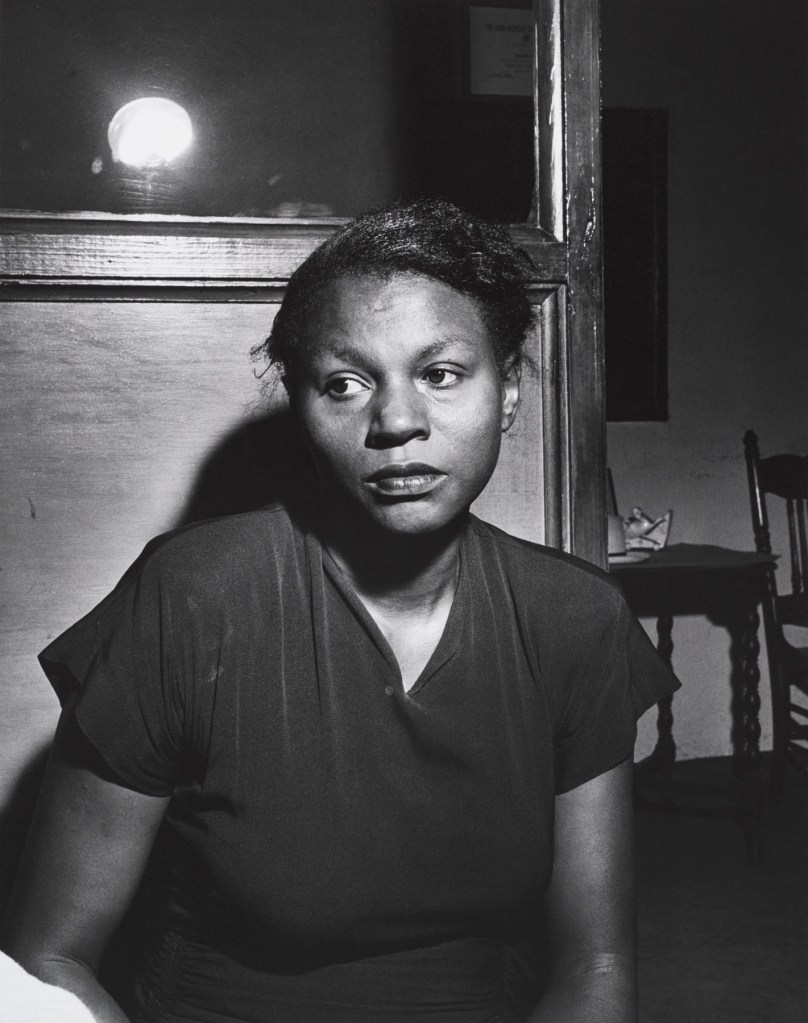

Bathed in light against a dark background, each sitter in Sophie Rivera’s portrait series of fellow New Yorkers of Puerto Rican descent, known as Nuyoricans, addresses the viewer directly. To find her subjects, Rivera asked passersby in her Harlem neighborhood if theywere Puerto Rican. If so, she invited them to her home to have their pictures taken. The mutual trust between artist and subject is reflected in the sitters’ grace and dignity.

Rivera, who defined herself as “an artist, Latino, and feminist,” sought to make Nuyoricans part of the distinguished history of American portrait photography. As she noted, “I have attempted to integrate my cultural heritage into an artistic continuum.”

Wall text from the exhibition

Rivera’s monumental portraits of Puerto Ricans in New York (or Nuyoricans) counteract the stereotypes that have circulated in the mass media. The artist found her subjects by asking passersby outside her building if they were Puerto Ricans. If they said yes, she invited them to her studio and photographed them against a dark background. Rivera’s subjects remain anonymous but never powerless. Her direct photographs allow the unassuming individuality of everyday people to speak for itself.

Our America: The Latino Presence in American Art, 2013

John M. Valadez (American, b. 1951)

Two Guys

c. 1978, printed 2016

From the East Los Angeles Urban Portrait Portfolio

Inkjet print

Sheet and image: 16 × 24 in. (40.6 × 61cm)

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Museum purchase through the Smithsonian Latino Initiatives Pool, administered by the Smithsonian Latino Center

© 1978, John M. Valadez

Multidisciplinary artist John Valadez has long been committed to depicting the lived experiences of Chicanx Angelenos like himself. Using the camera to record the world around him, Valadez first made photographs principally as source material for his drawings and paintings. In 1978 he exchanged black and white for colour film and made a series of powerful full-length portraits. His subjects included people he knew, such as the stylish young couple dressed for a birthday party, as well as people he encountered on the street, like the two men sporting identical clothes. Valadez’s aim, he said, was to capture people who weren’t being seen – by doing so, he has become a key chronicler of Chicanx identity.

Wall text from the exhibition

John M. Valadez (American, b. 1951)

Couple Balam

c. 1978, printed 2016

From the East Los Angeles Urban Portrait Portfolio

Inkjet print

Sheet and image: 16 × 24 in. (40.6 × 61cm)

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Museum purchase through the Smithsonian Latino Initiatives Pool, administered by the Smithsonian Latino Center

© 1978, John M. Valadez

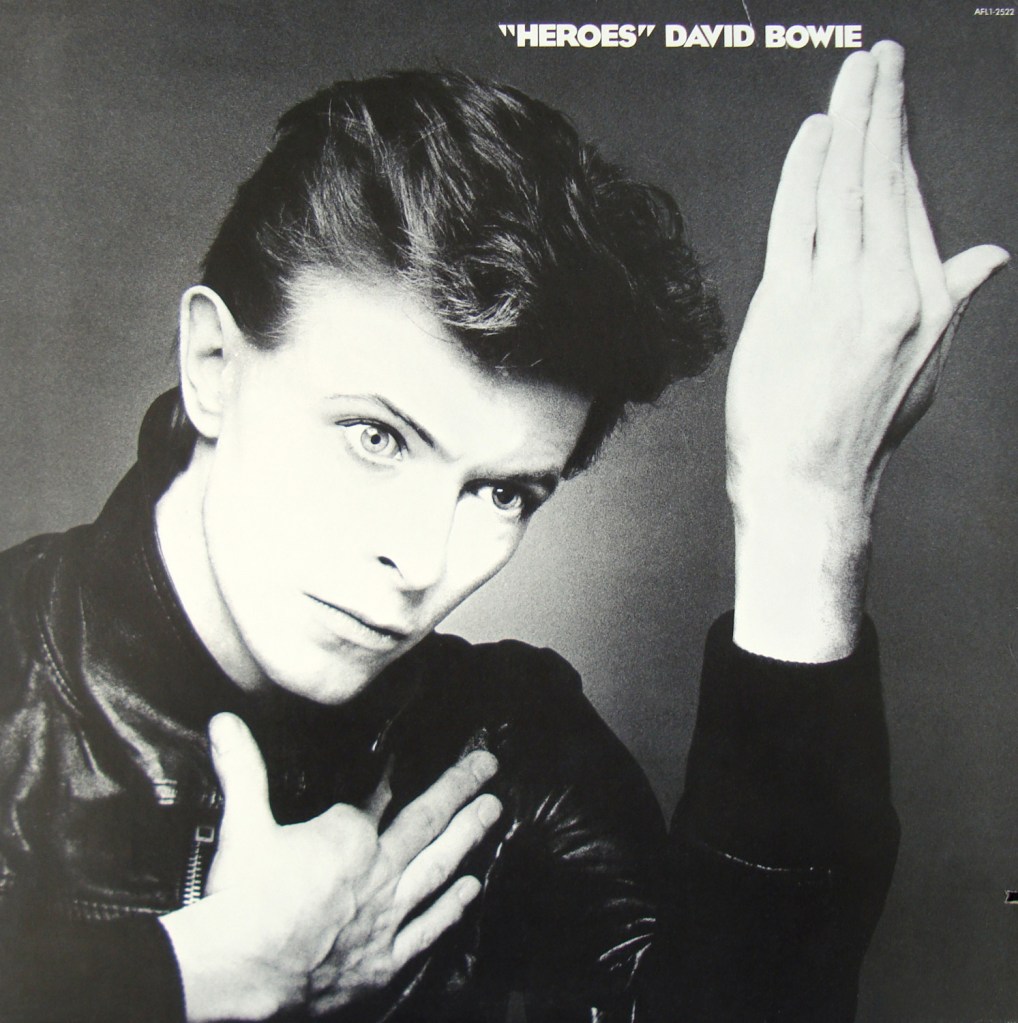

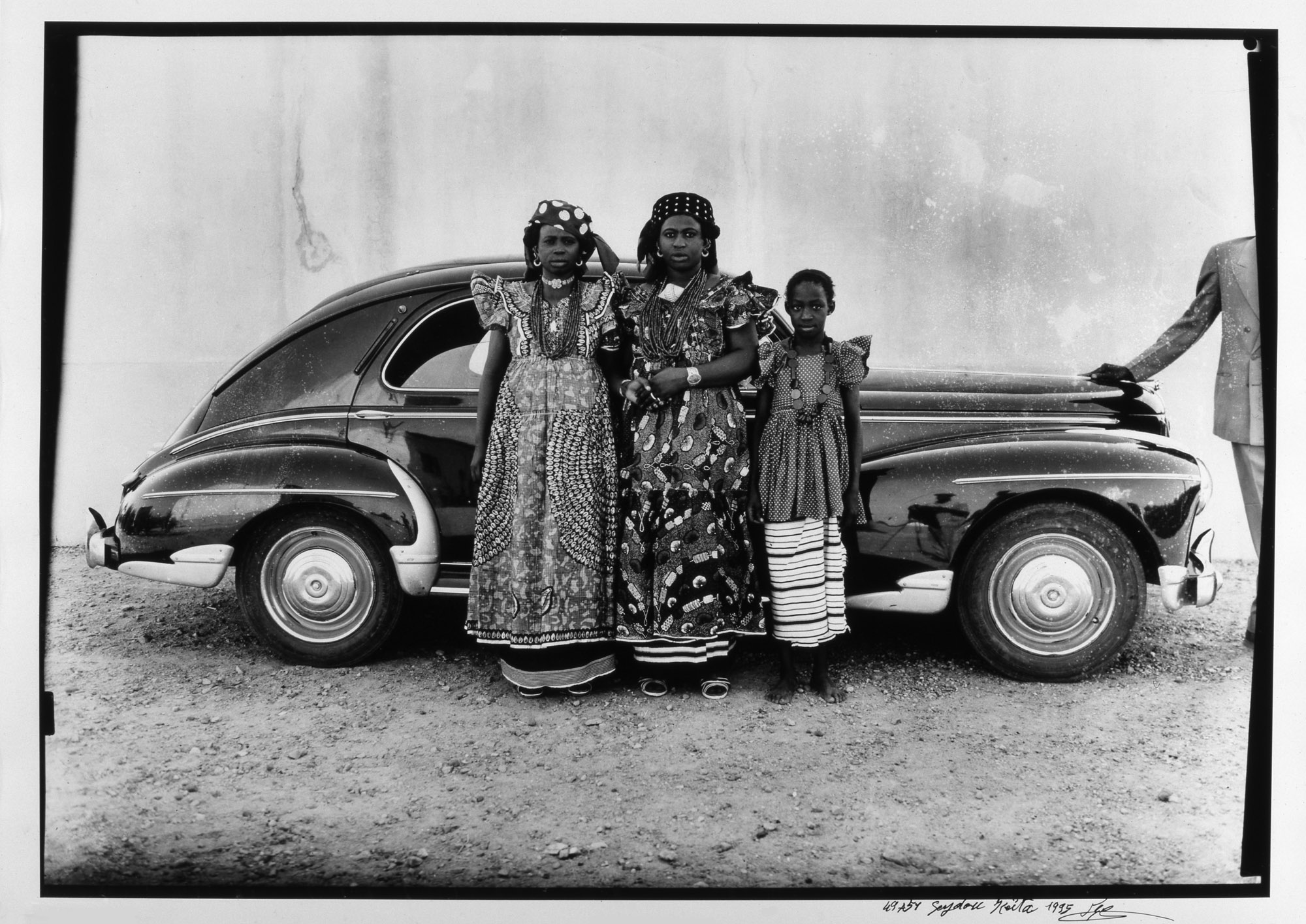

Tseng Kwong Chi (American born Hong Kong, 1950-1990)

New York, New York

1979, printed 2008

From the series East Meets West

Gelatin silver print

Image: 91.44 x 91.44cm (36 x 36 in.)

National Gallery of Art

Alfred H. Moses and Fern M. Schad Fund and Gift of Funds from Renee Harbers

Liddell

© Muna Tseng Dance Projects Inc.. Courtesy Yancey Richardson, New York

Tseng Kwong Chi leaps into the air in front of the Brooklyn Bridge, mimicking the joy of a first time visitor to New York. This work is from Tseng’s series East Meets West, which was inspired in part by the thaw in Chinese – United States relations following President Nixon’s visit to Beijing in 1972. A performance artist and photographer, Tseng made self-portraits as his adopted persona, Ambiguous Ambassador, at popular spots across the country. Assuming the guise of a Chinese official, Tseng – wearing what is now called a Mao suit – mischievously exposed cultural biases and notions of “the other” in American society. He made his selfies with a shutter release cable, which is visible in his right hand.

Wall text from the exhibition

Tseng Kwong Chi, known as Joseph Tseng prior to his professional career (Chinese: 曾廣智; c. 1950 – March 10, 1990), was a Hong Kong-born American photographer who was active in the East Village art scene in the 1980s.

Tseng was part of a circle of artists in the 1980s New York art scene including Keith Haring, Kenny Scharf, and Cindy Sherman. Tseng’s most famous body of work is his self-portrait series, East Meets West, also called the “Expeditionary Series”. In the series, Tseng dressed in what he called his “Mao suit” and sunglasses (dubbed a “wickedly surrealistic persona” by the New York Times), and photographed himself situated, often emotionlessly, in front of iconic tourist sites. These included the Statue of Liberty, Cape Canaveral, Disney Land, Notre Dame de Paris, and the World Trade Center. Tseng also took tens of thousands of photographs of New York graffiti artist Keith Haring throughout the 1980s working on murals, installations and the subway. In 1984, his photographs were shown with Haring’s work at the opening of the Semaphore Gallery’s East Village location in a show titled “Art in Transit”. Tseng photographed the first Concorde landing at Kennedy International Airport, from the tarmac. According to his sister, Tseng drew artistic influence from Brassai and Cartier-Bresson.

Text from the Wikipedia website

In these images Tseng inhabits a persona he referred to as the “Ambiguous Ambassador.” Wearing a Mao suit (the grey uniform associated with the Chinese Communist Party) and mirrored sunglasses, he poses next to landmarks and monuments, many of them emblems of American national identity. Like the Untitled Film Stills of Cindy Sherman – also produced in the late 1970s – East Meets West is a groundbreaking photographic work that illuminates the changeable and socially constructed nature of identity. It is also a rare piece of conceptual art to specifically reflect on the racialised experiences of Asian people in the United States. …

A gay man, Tseng was well-aware of the signifying power of dress, gesture, and posture. His donning of the Mao suit can be understood as racial camp – a playful, self-protective manoeuvre that did not prevent Tseng from being misinterpreted but did allow him to take control of the manner of the misreading. To those who perceived the levity with which Tseng wore the suit, something was revealed about his ironic sensibility. The dissonance of his appearance – the fact that the suit looked both “natural” and “unnatural” on him was not effaced but highlighted, at least to the knowing beholder. But when people were unable to see past type, the misconception did not come at the cost of Tseng’s psychic humiliation.

Tseng went on to create roughly 150 images comprising East Meets West. His performance of “Chineseness” in these photographs reveals his acute awareness of the stereotypes of Euro-American Orientalism. His blank, robotic demeanour in images such as Disneyland, California invite stock associations of the Chinese as “Yellow Peril,” and the repetition of this pose in numerous photographs would seem to tap into White America’s century-long dread of being overrun by Asian immigrants. In other images, Tseng’s stylishness and humor come through – some of the earliest photographs picture him coolly strolling the boardwalk and beaches of the popular gay vacation spot of Provincetown, Massachusetts, appearing more like a character from a French New Wave film than a visitor from the People’s Republic of China. The shutter release Tseng plainly grasps in many pictures reminds us that he is the author of these varied depicted realities; that, even as he presents himself to the Orientalist gaze, he is in command of the means of representation. Given that racial identities circulate and perpetuate via staged images – and that European American assumptions have traditionally driven those images – this is a significant gesture.

Extract from Melissa Ho. “Performing Ambiguity: The Art of Tseng Kwong Chi,” on the Smithsonian American Art Museum website June 23, 2022 [Online] Cited 06/02/2025

Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe (American, b. 1951)

An Afternoon with Aunt Tootie, Daufuskie Island, South Carolina

1979, printed 2007

Gelatin silver print

Image: 21.3 x 32.4cm (8 3/8 x 12 3/4 in.)

National Gallery of Art

Gift of Funds from Diana and Mallory Walker

© Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe

The Gullah Geechee – enslaved people who labored on the Sea Island plantations, and their descendants – built communities all along the eastern coast of the US, from North Carolina to Florida…

From 1977 to 1982, Moutoussamy-Ashe visited Daufuskie, building relationships with the Gullah Geechee people and snapshotting rare pictures of their quotidian life. Born in Chicago, Illinois, the photographer had just returned from a six-month independent study in west Africa before she traveled to the island. At the time of her initial visit, there were only 80 permanent residents left on Daufuskie, a drastic drop from the thousands of Gullah people who had once resided there. Today, just 3% of the island’s population is Black.

Moutoussamy-Ashe’s series of monochrome images include candids of weddings, stills of a church gathering and everyday portraits of the island, showing a way of life that is treasured and fast fading.

Like many historic Black alcoves, Daufuskie has been altered by decades of gentrification. After the American civil war, many Gullah people who were already on Daufuskie made the island their permanent home once the plantation owners had left. They cultivated the land and preserved their rich culture and language, an English-based creole. But development, unfair zoning practices and other challenges have caused a sharp decrease in the Black population on the island.

Moutoussamy-Ashe’s photos offer a more private understanding of Black folks in Daufuskie, one not defined by white developers who have turned Daufuskie into a destination for tourists. The area is a placid haven in Moutoussamy-Ashe’s images. Jake and his Boat Arriving on Daufuskie’s Shore, Daufuskie Island, SC, for instance, features a man paddling a boat across a rippling river. Swooping trees frame either side of the man, who peacefully rows the vessel. The landscape looks expansive, with the scenery appearing to go on for miles. Such scenes of stillness would become rare as residents were largely driven out by the encroachment of others.

Extract from Gloria Oladipo. “How an outsider captured the intimacy of Gullah Geechee life in 13 portraits,” on The Guardian website Sat 8 Feb 2025 [Online] Cited 06/02/2025

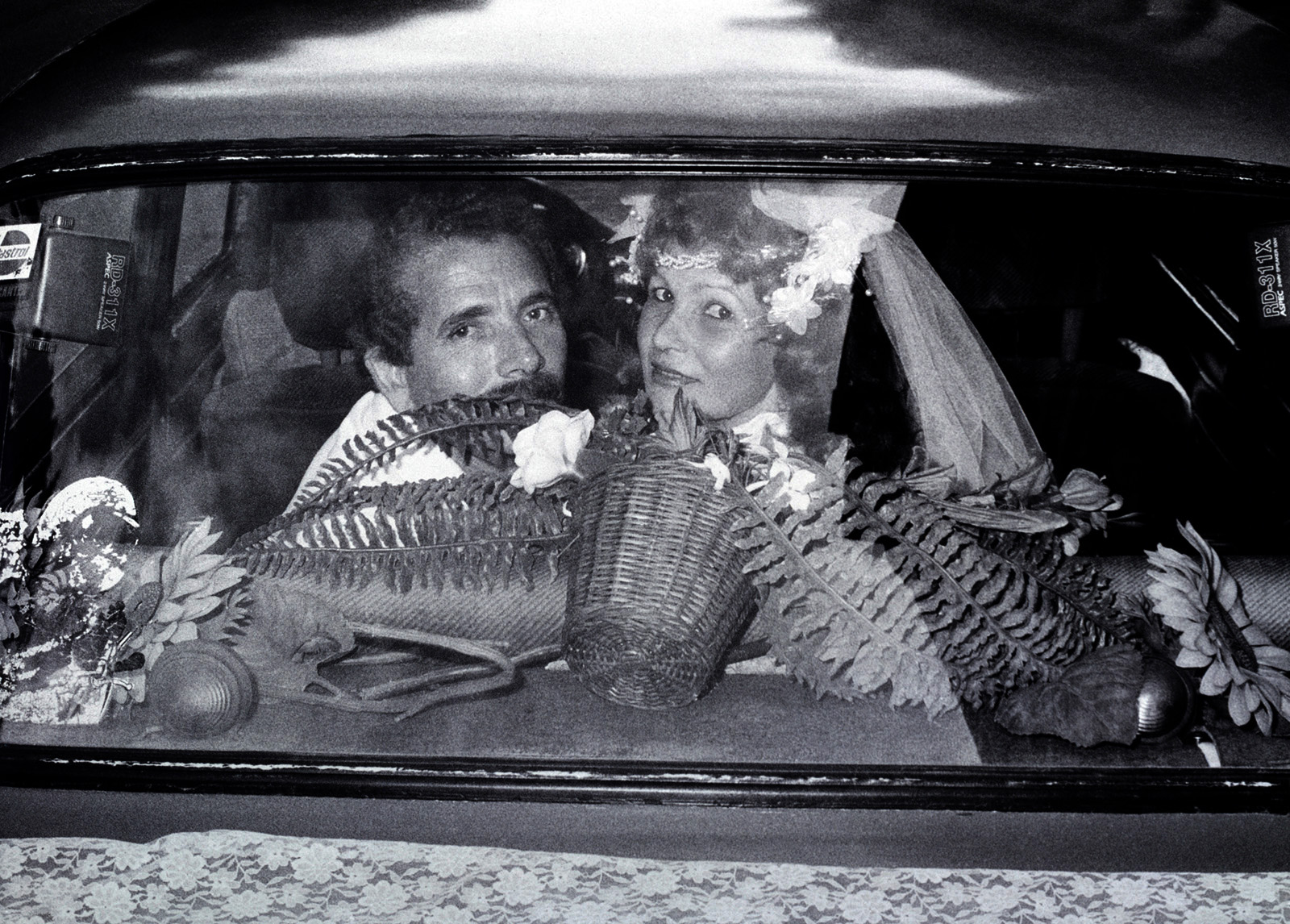

Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe (American, b. 1951)

Maid of Honor with Bride in Slippers, Daufuskie Island, South Carolina

1980, printed 2022

Gelatin silver print

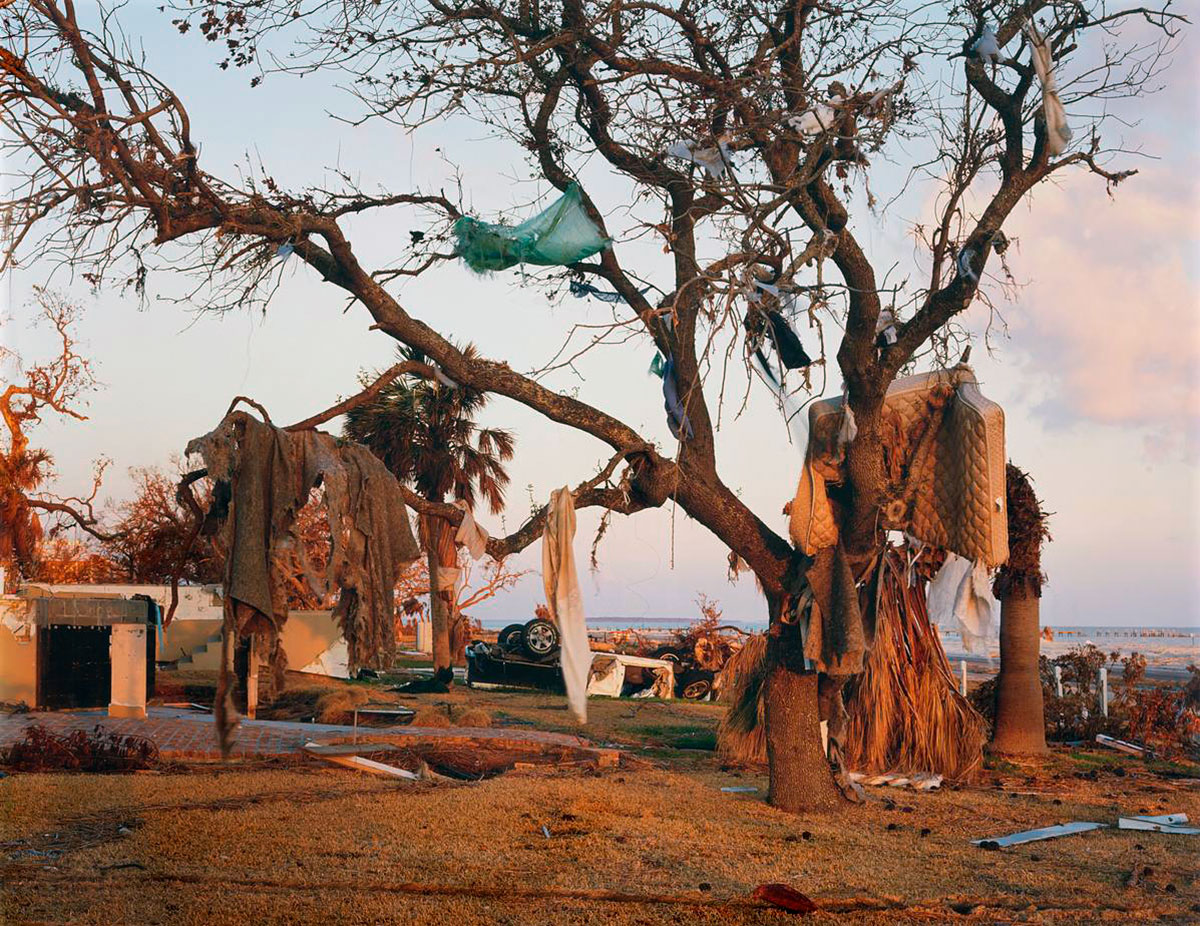

Image: 56.9 x 37.4cm (22 3/8 x 14 3/4 in.)