Exhibition dates: 12th September, 2020 – 7th February, 2021

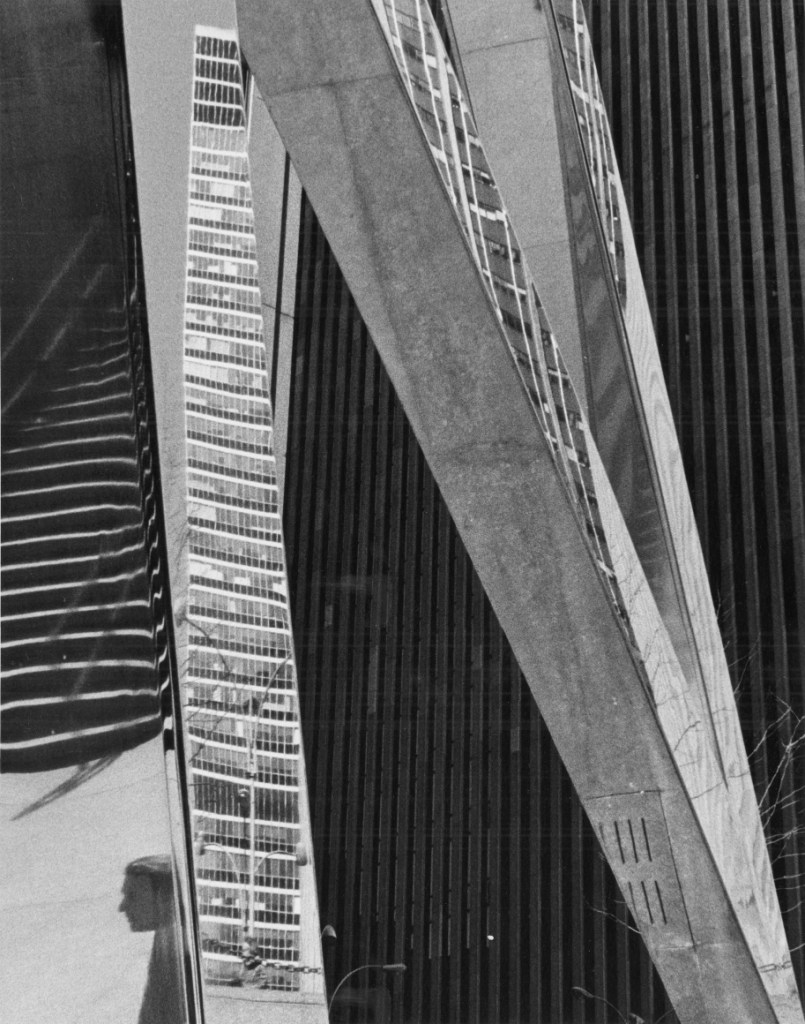

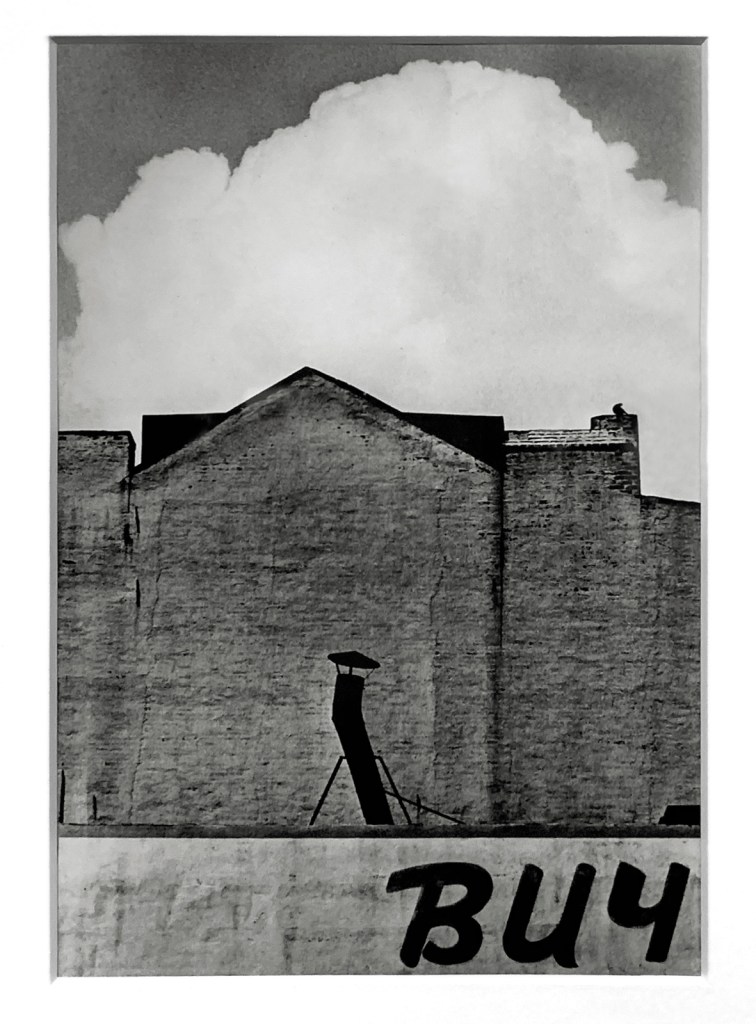

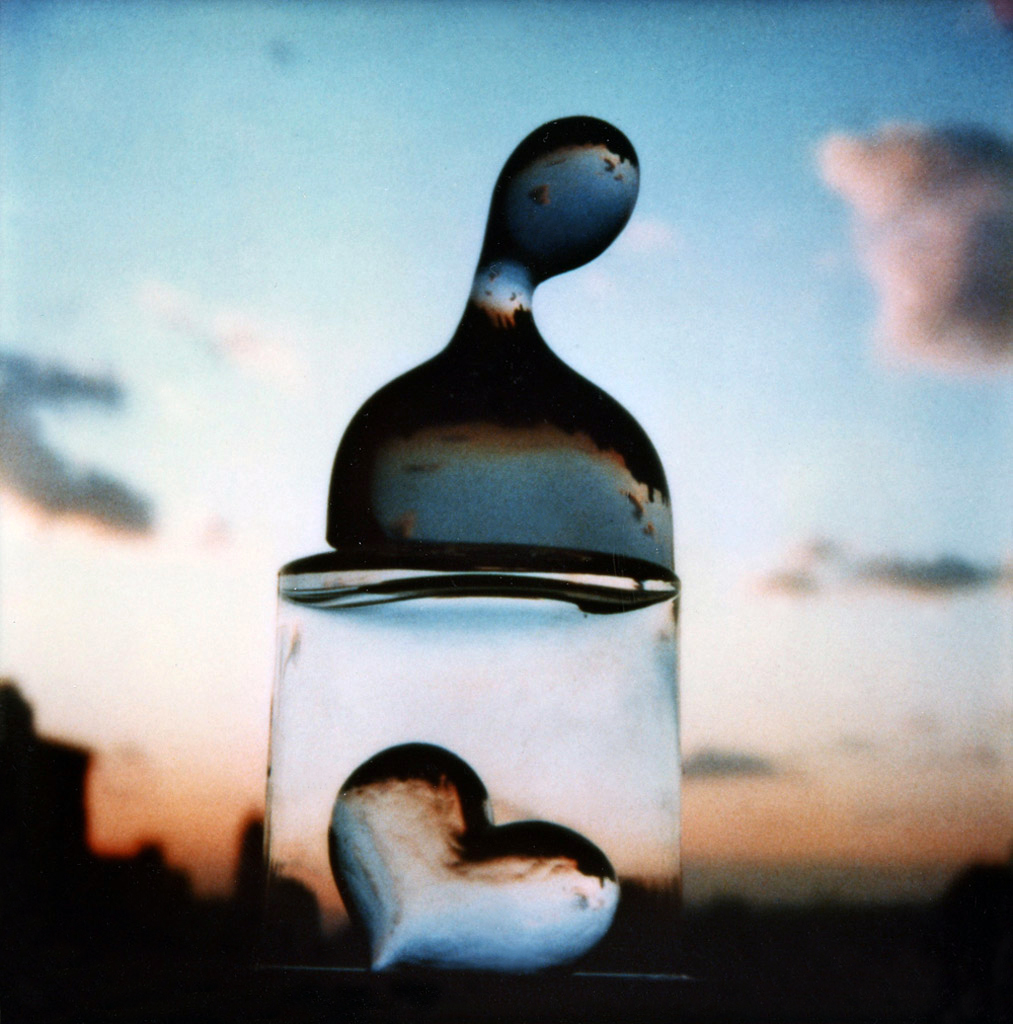

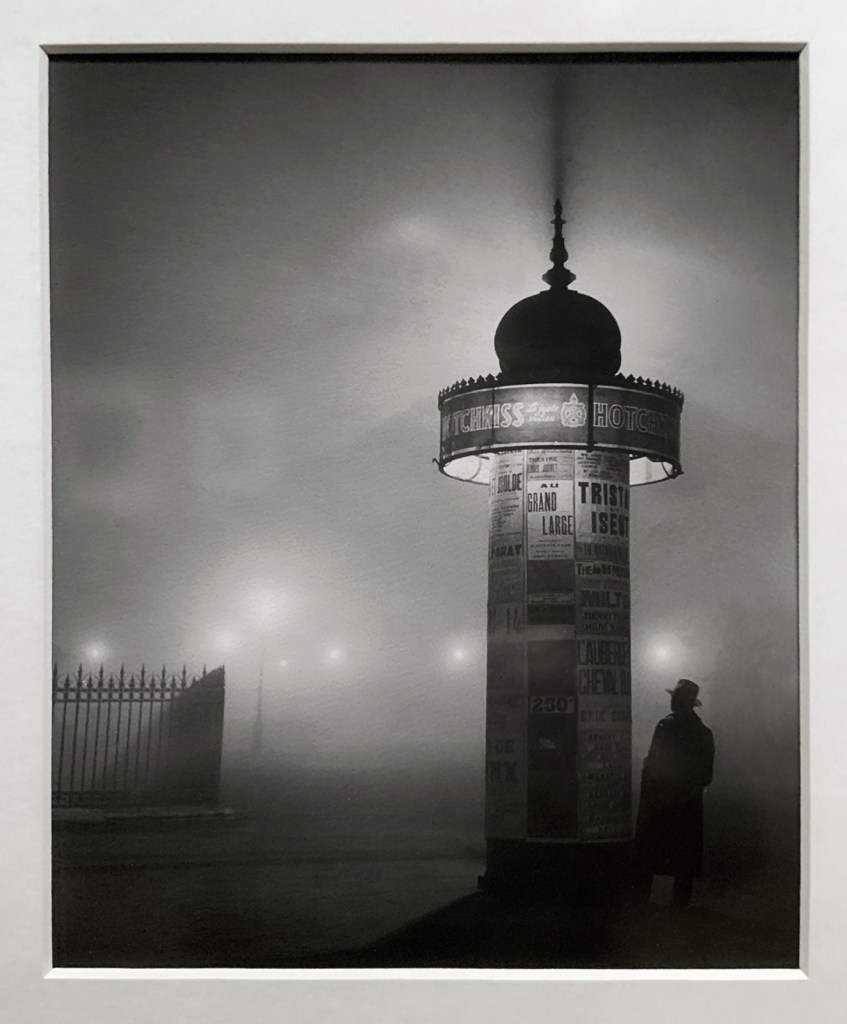

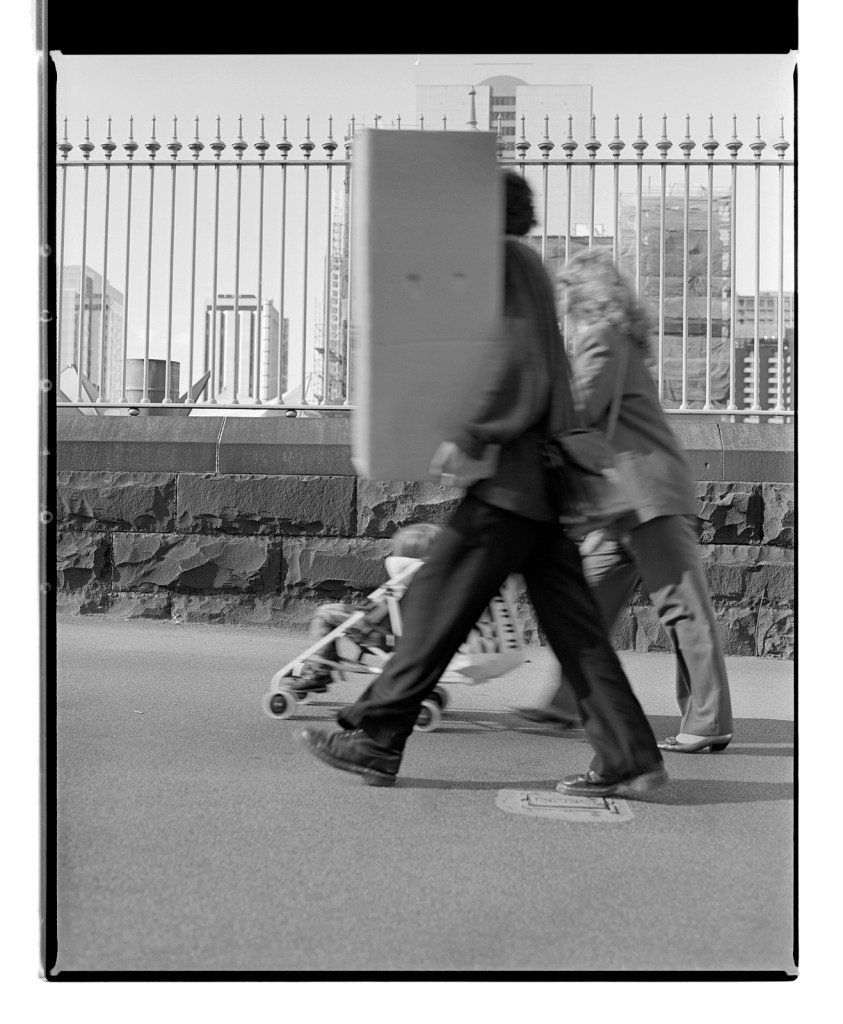

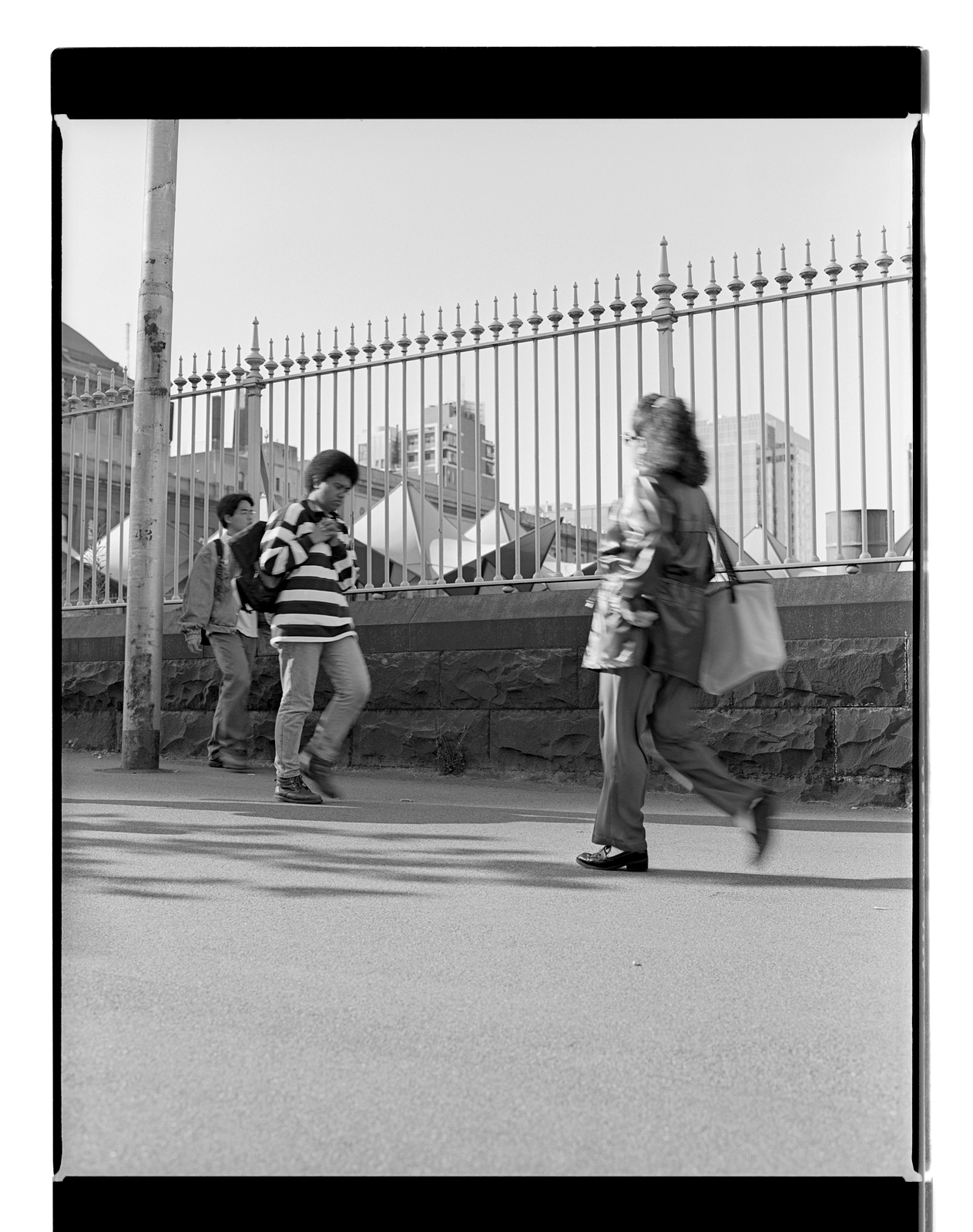

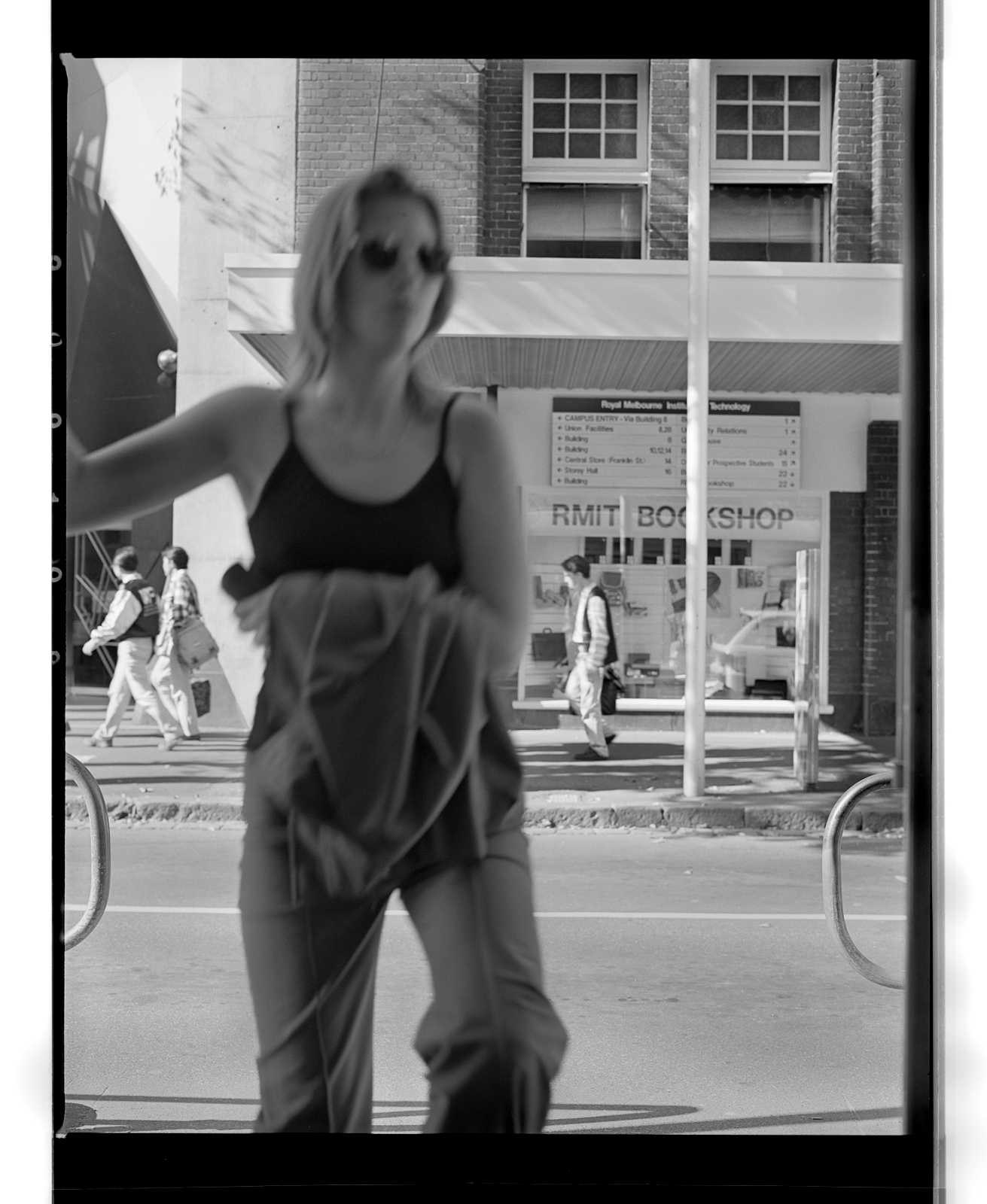

Thomas Ruff (German, b. 1958)

press++01.38

2015

C-Print

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020

Thomas Ruff is the true Renaissance man of contemporary photography. No greater compliment can be given.

His career in photography, as evidenced through the numerous bodies of work seen in this posting, has been an inquiry into the conceptualisation, status, presence, presentation, and representation of photographs in different contexts and media, through different technologies. A meditation on, and mediation into, the origins and purposes of photography and the interventions human beings enact to affect their outcomes.

His work “explores the most diverse genres and historical varieties of photography…”. For example, in the series press he combines front and back of an image, disrupting the reading of the image with contemporary hieroglyphs. In Zeitungsfotos he investigates the power of press photos and their deconstruction through the dot structure of the image. In Tableaux chinois he examines the use of photographs in political propaganda and looks at the artistic stylisation of the image. In one of my favourite series, jpeg, Ruff focuses on the pixellation and deconstruction of the image in compressed JPEG format photographs where, at a distance, the whole is more than the sum of the parts. This reminds me of the technique I witnessed when visiting Monet’s huge canvases of waterlilies at the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris – how when you got up close to the canvases, there were huge daubs and mounds of paint accreted on the surface of the paintings which made no sense at close range. It was only when you stepped back that it all made sense.

In essence this is what grounds the work of Thomas Ruff: that he digs and unearths the hidden strands, the interweaving, that lies beneath the surface of photographies. He intervenes in the negative, the print, the newspaper photograph, the light, the camera and the physicality of the print. He turns these literally hidden connections into lateral images – side views of the familiar that touch the human and the machine from different points of view.

To think of all these ideas, concepts, and then to develop them and bring them together in holistic bodies of work that the viewer remembers – and there is the rub, for so much contemporary photography is unremarkable, mortal – lifts Ruff’s photographs beyond the realm of time and space. In their distortions, their sublime beauty, their critical thinking, they become i/mortal. They become the complexity that is us.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“To understand how a pictorial genre actually works, I have to produce a series; I want to uncover the secret behind image generation.”

Thomas Ruff

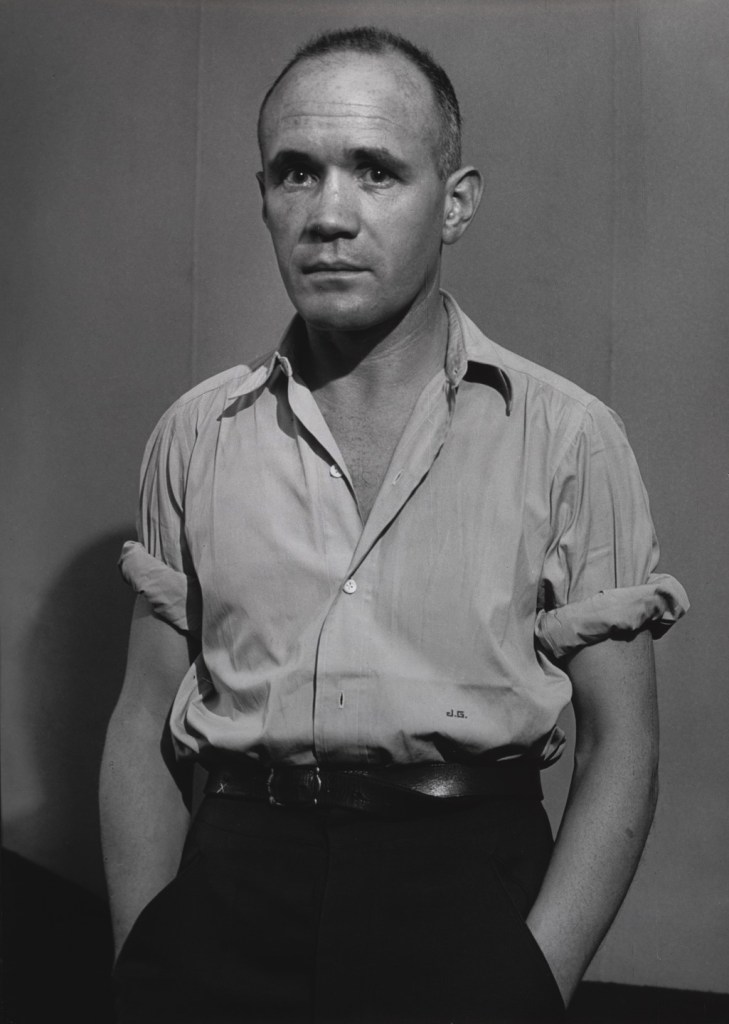

Thomas Ruff (b. 1958) is one of the internationally most important artists of his generation. Already as a student in the class of the photographers Bernd and Hilla Becher at the Düsseldorf Academy of Art in the early 1980s, he chose a conceptual approach to photography, which continues to determine his handling of the most diverse pictorial genres and historical possibilities of photography to this day.

Thomas Ruff’s contribution to contemporary photography thus consists in a special way in the development of a form of photography created without a camera: He uses images that have already been taken and that have already been distributed and optimised for specific purposes in other, largely non-artistic contexts. Ruff’s image sources for these series range from photographic experiments of the nineteenth century to photographs taken by space probes. He examined the archive processes of large image agencies and the pictorial politics of the People’s Republic of China. But also pornographic and catastrophic images from the Internet form starting points for his own series of works created over the past twenty years that have increasingly been developed on the computer.

They originate from newspapers, magazines, books, archives, and collections or were simply accessible to everyone on the Internet. In each series, Ruff explores the technical conditions of photography in the confrontation with these different pictorial worlds. At the same time, he focuses on the afterlife of images in publications, archives, databases, and on the Internet.

Short Biography Thomas Ruff

Thomas Ruff was born in Zell am Harmersbach in 1958 and studied with Bernd and Hilla Becher at the Düsseldorf Academy of Art from 1977 to 1985. From 2000 to 2005, he was himself Professor of Photography there. He first received international attention in 1987 with his series of larger-than-life portraits of friends and acquaintances who, as in passport photographs, gazed apathetically into the camera. In 1995, he represented Germany at the 46th Venice Biennale, together with Katharina Fritsch and Martin Honert. His works are collected internationally and are represented in numerous institutional collections.

Press release from the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen

Camera-less Photography

Thomas Ruff (b. 1958) is one of the internationally most important artists of his generation. Already as a student of the photographers Bernd and Hilla Becher at the Düsseldorf Academy of Art in the early 1980s, he chose a conceptual approach to photography. His work, which explores the most diverse genres and historical varieties of photography, represents one of the most versatile and surprising positions within contemporary art. The comprehensive exhibition at K20 focuses on series of pictures from two decades in which the artist hardly ever used a camera himself. Instead, he appropriated existing photographic material from a wide variety of sources for his often large-format pictures.

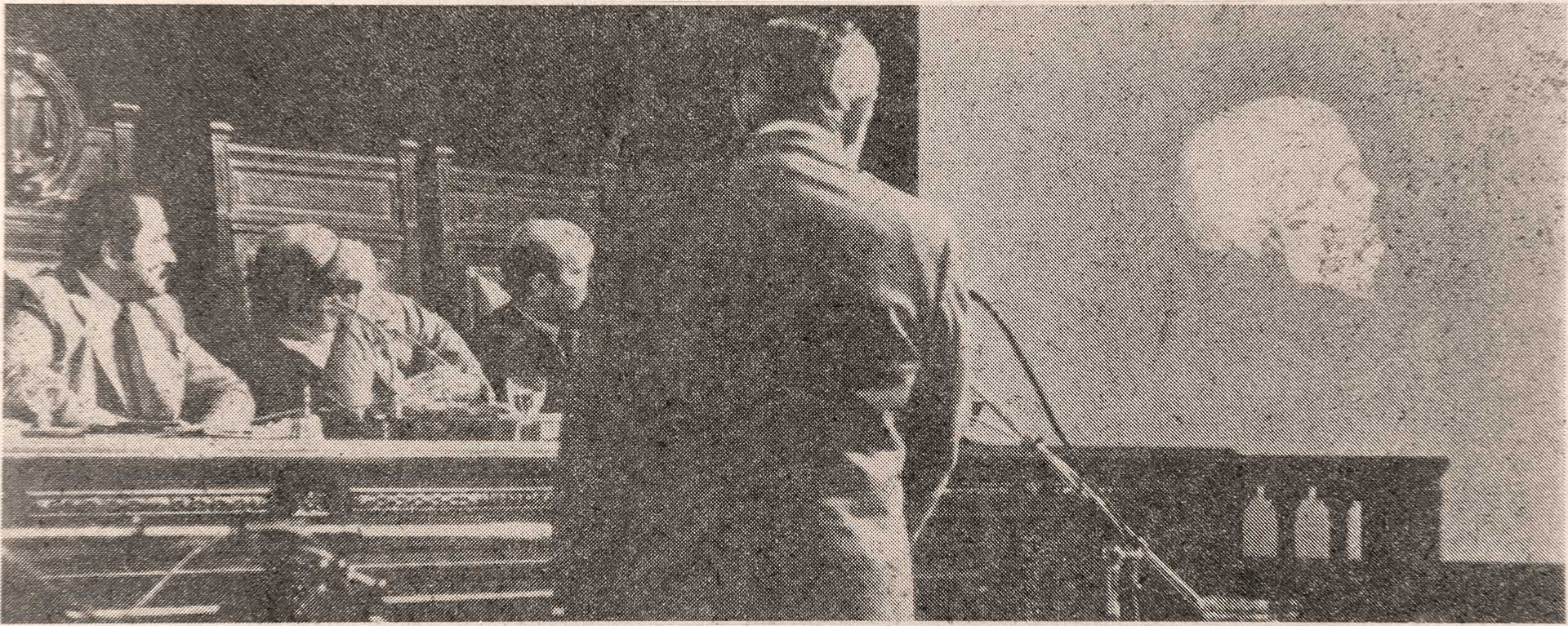

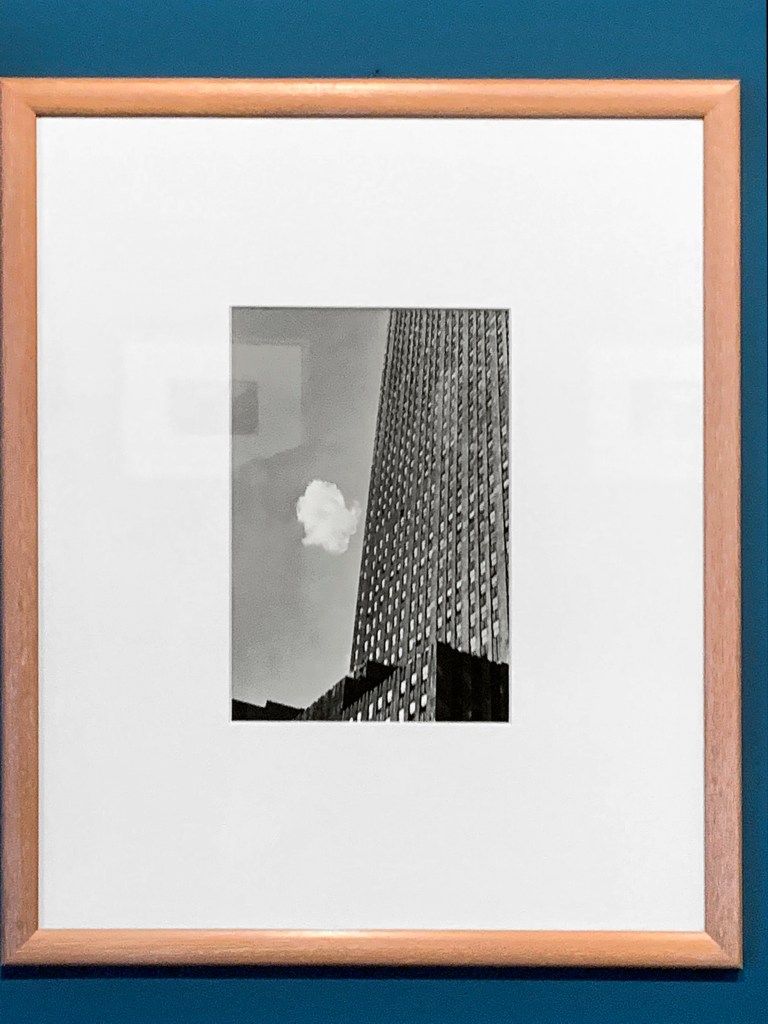

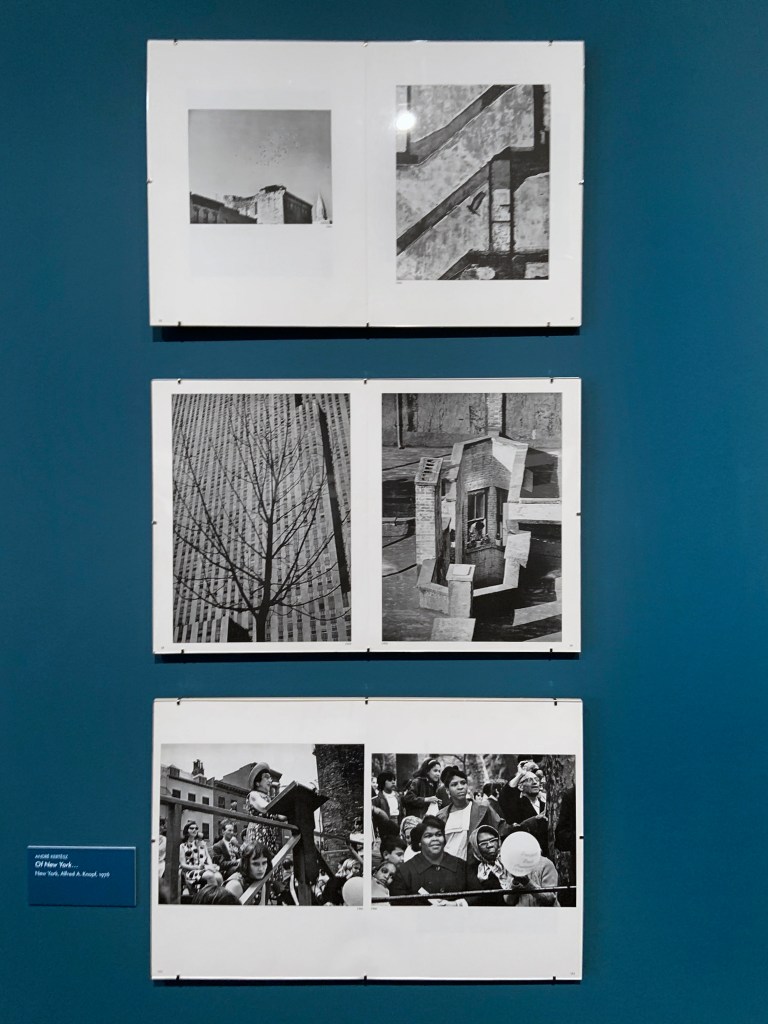

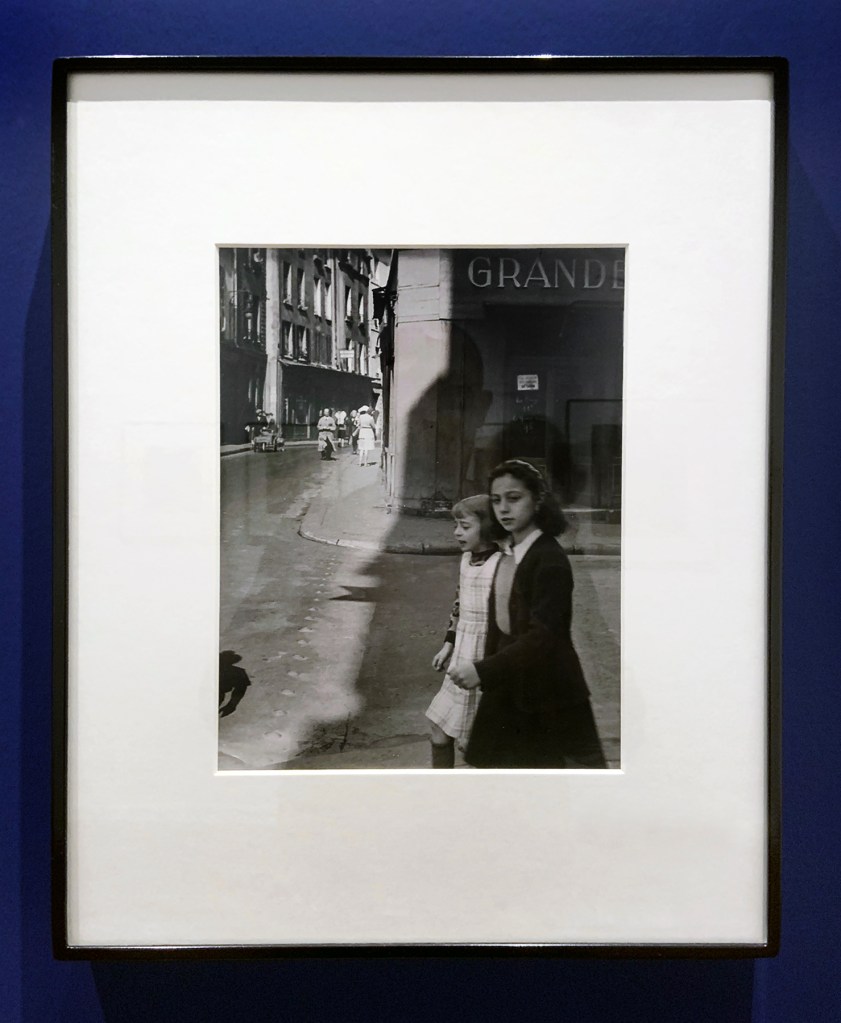

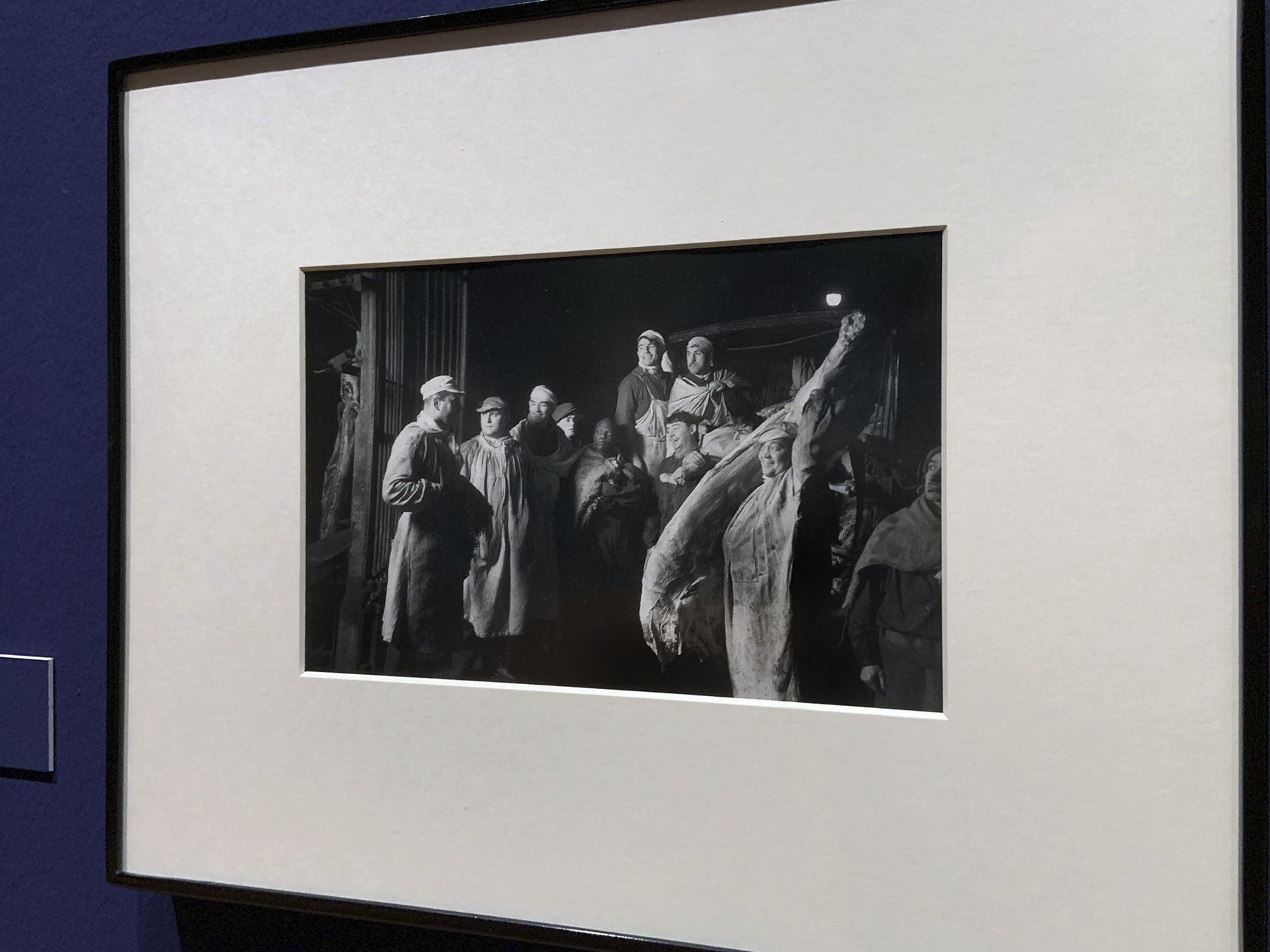

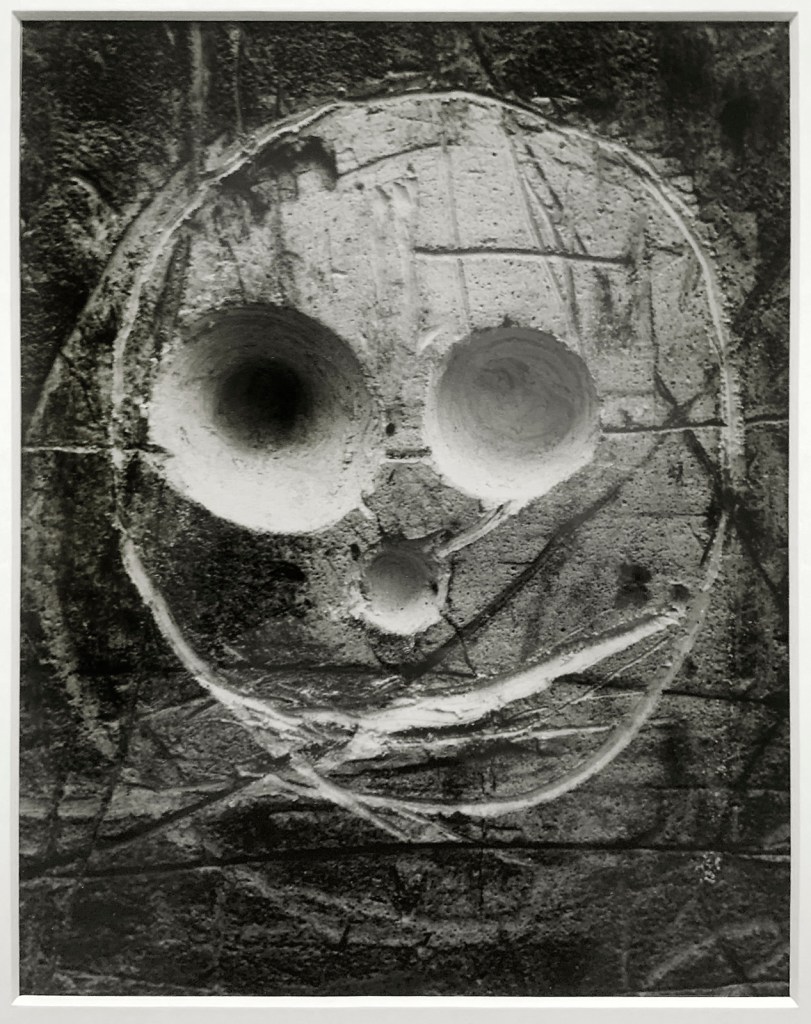

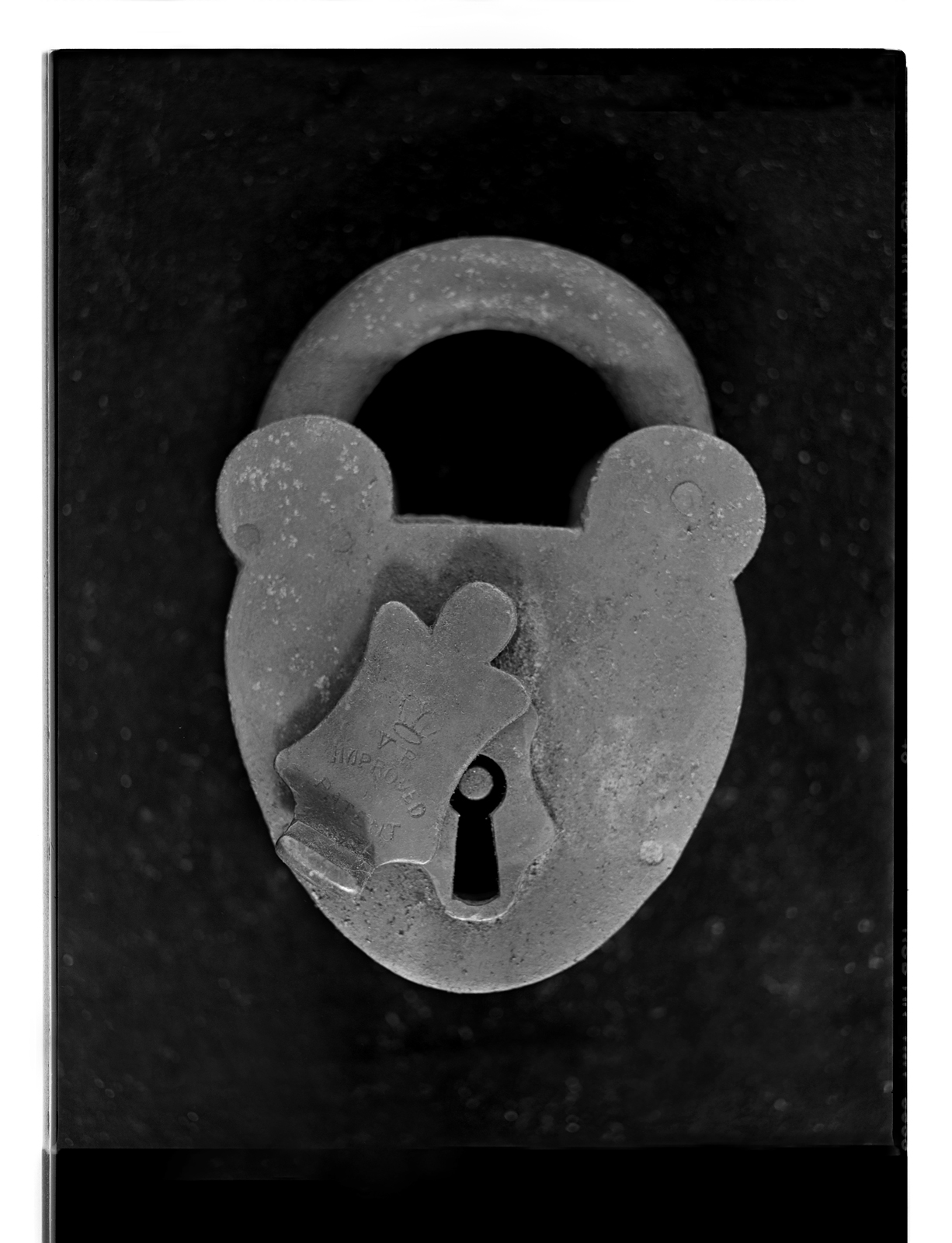

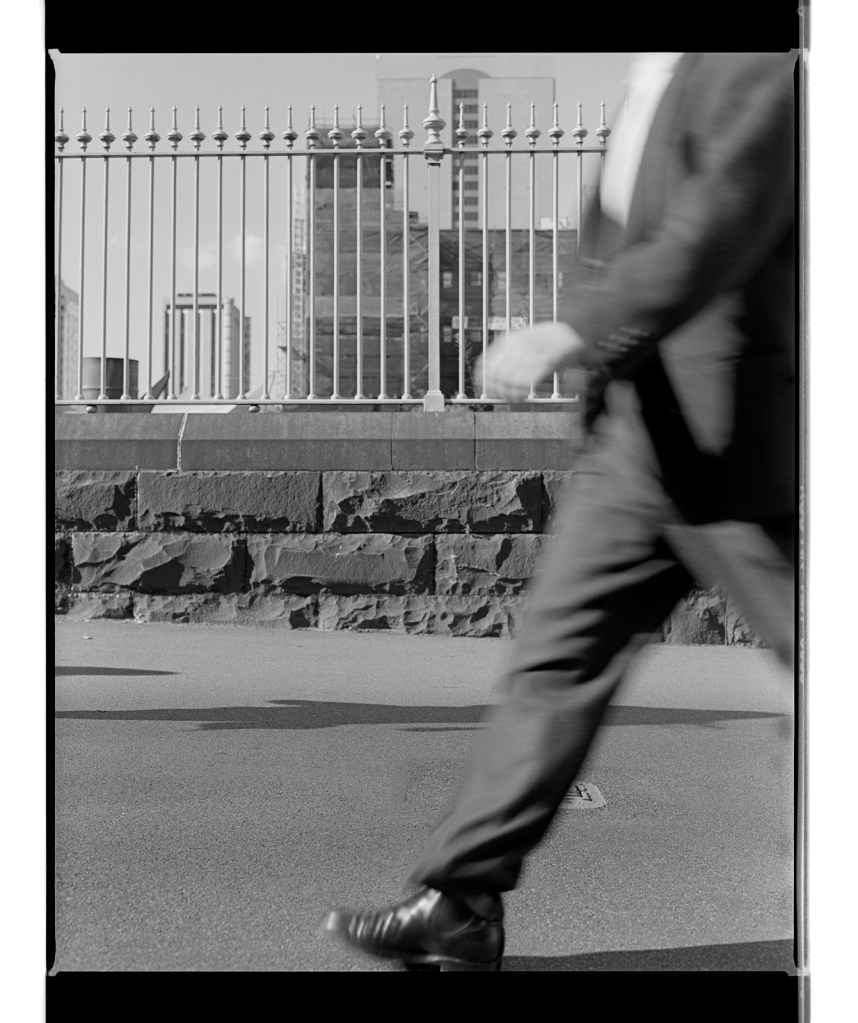

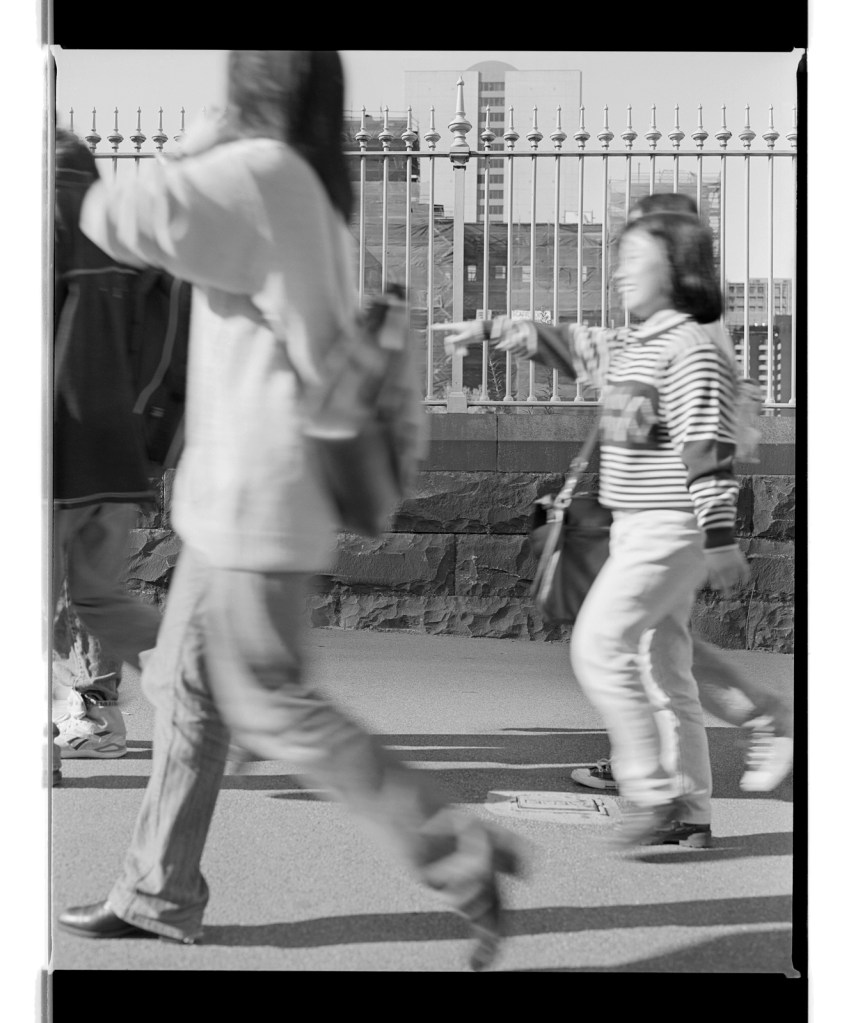

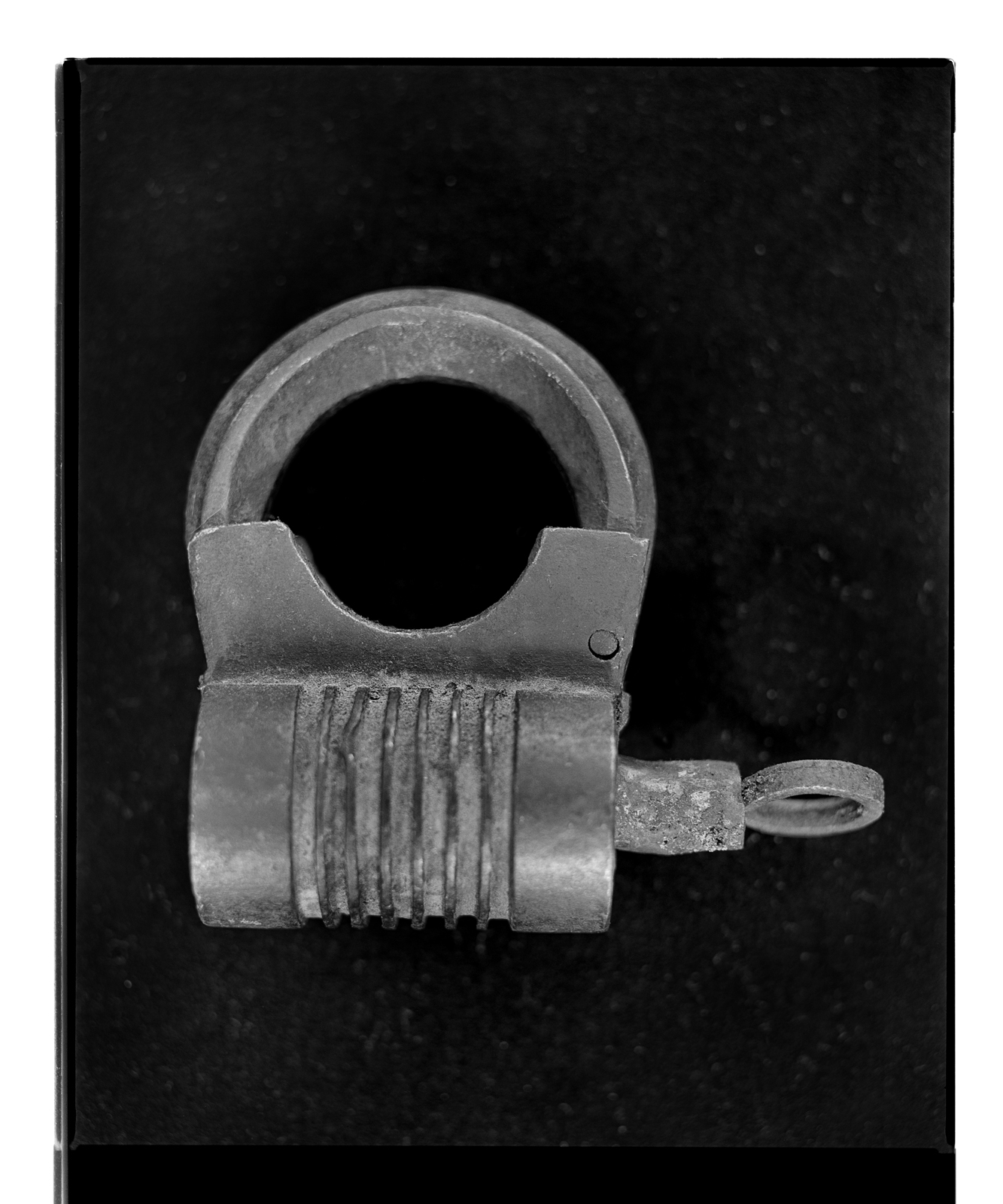

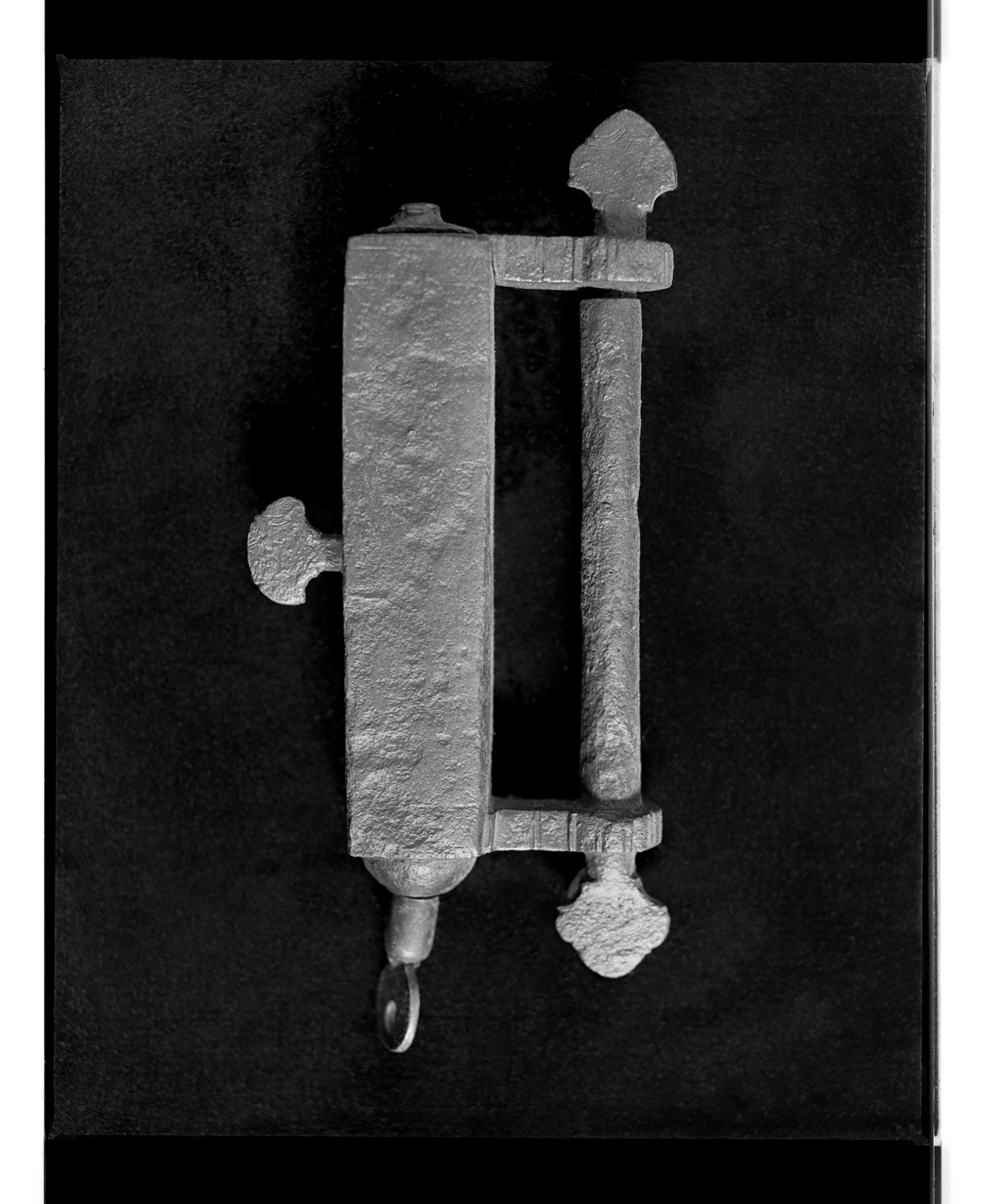

Thomas Ruff (German, b. 1958)

Zeitungsfoto 014

1990

C-Print

16.8 x 42.4cm

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020

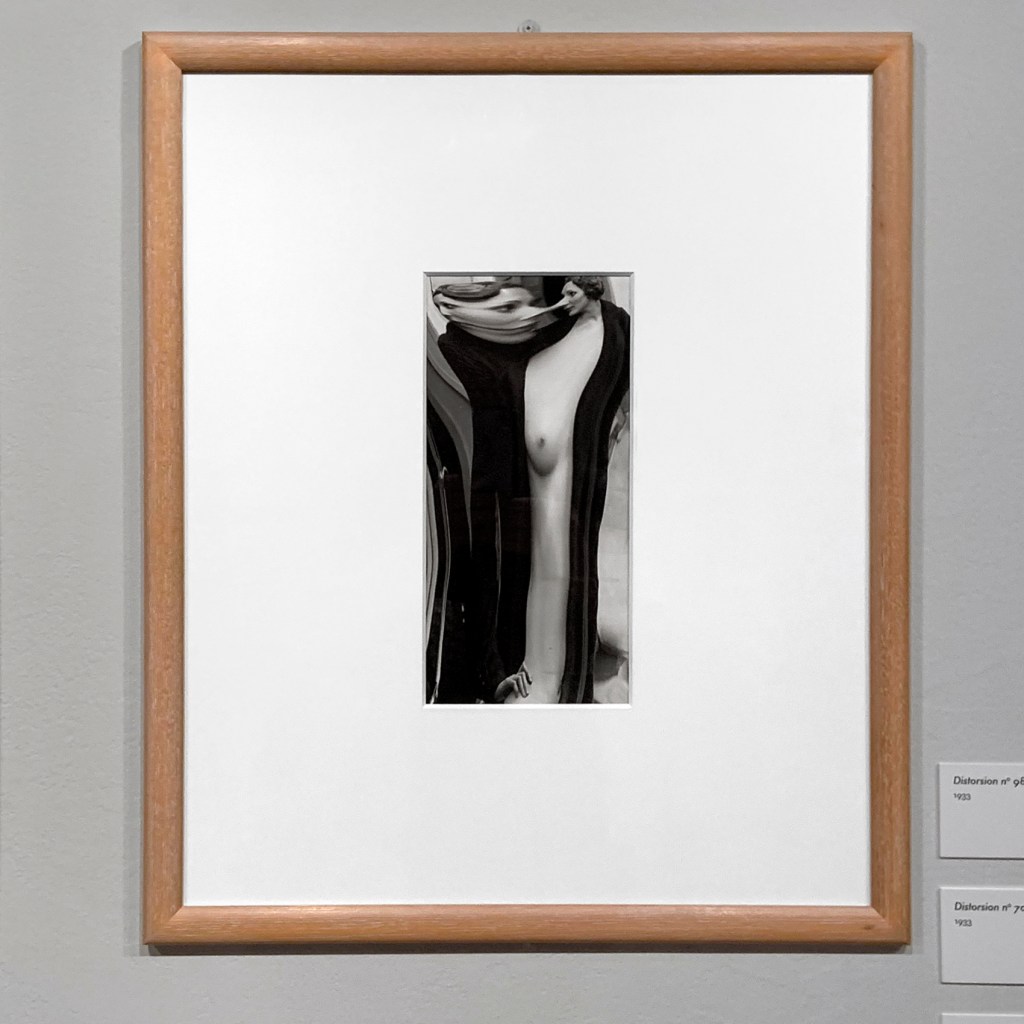

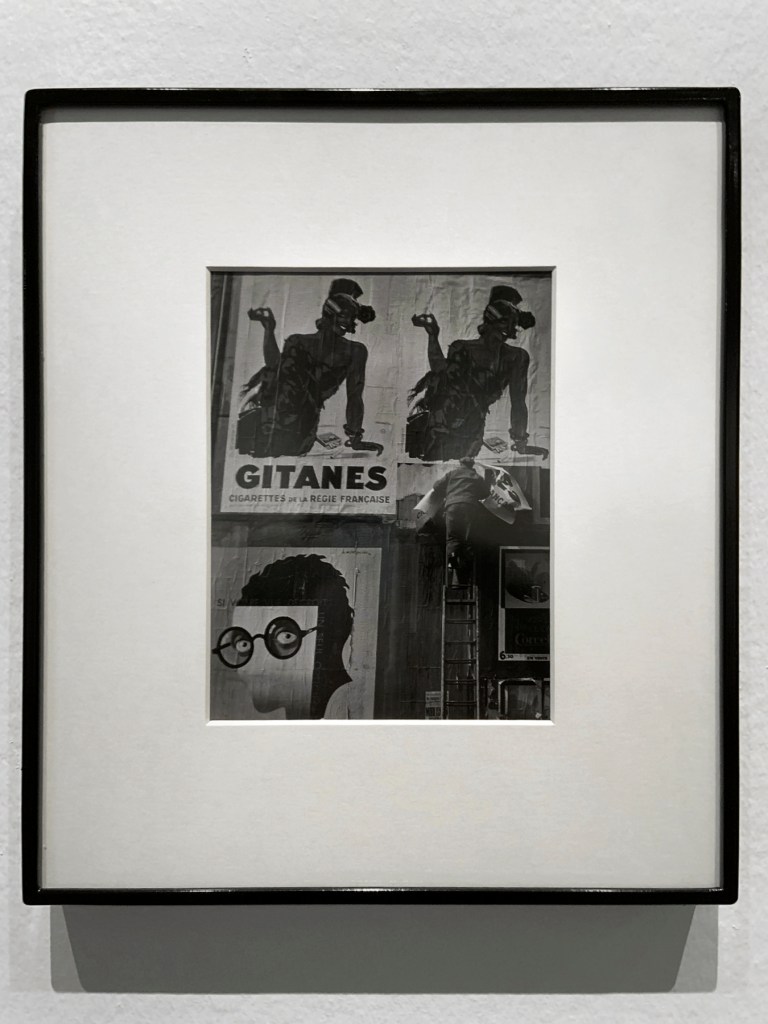

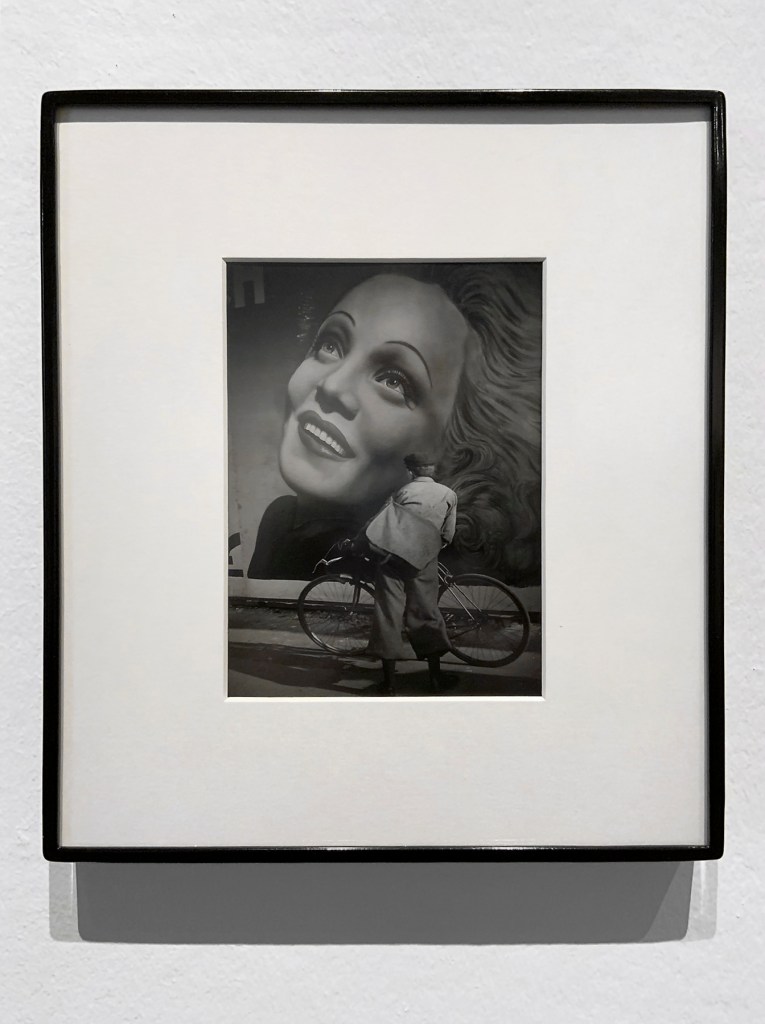

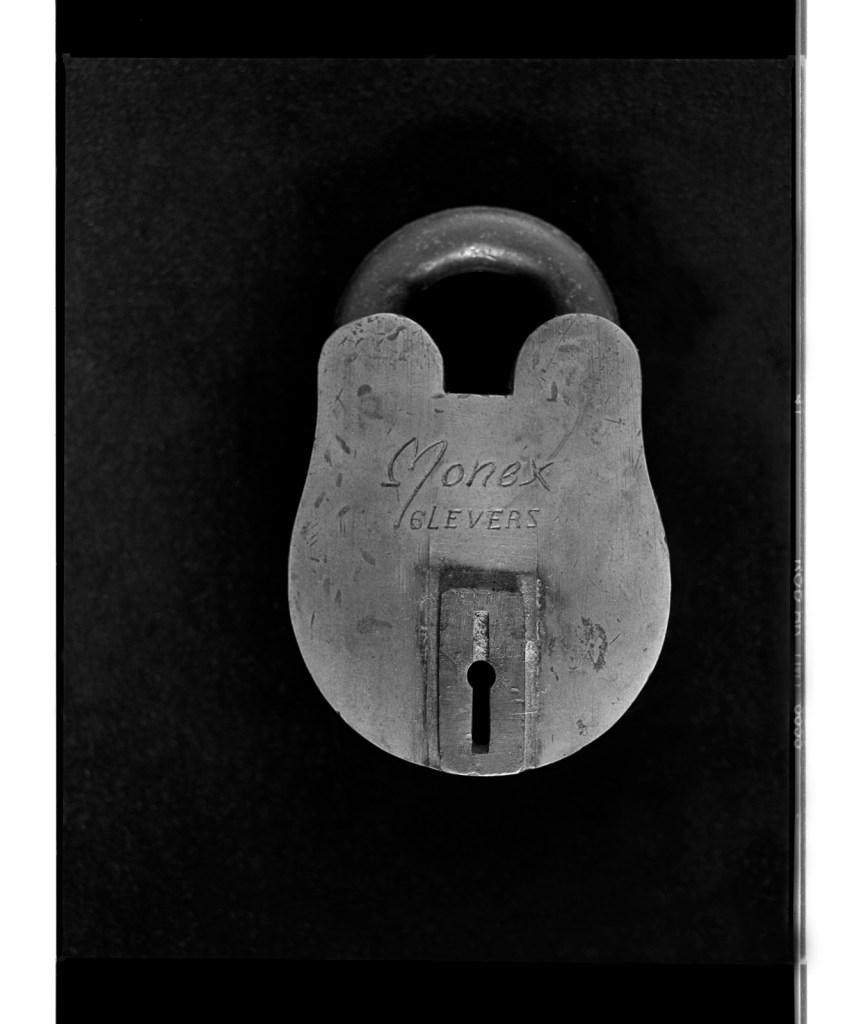

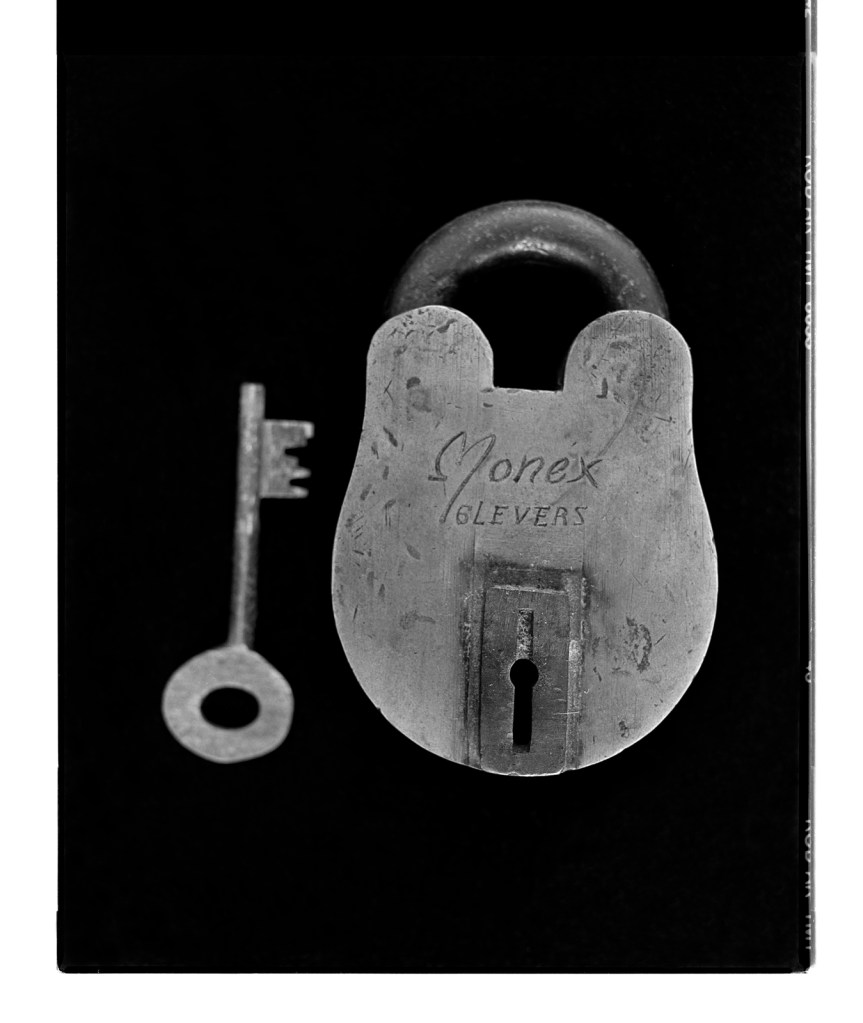

The Power of Press Photos

Where do we use photos? What happens when photos are printed? How do aesthetics and statements change?

The artist explores these questions in various series, in which he draws on image material from other photographers, processes this, and thematises contexts. For his series Zeitungsfotos, the artist collected and processed newspaper photos to test the familiarity with the motifs and their reliability as carriers of information. In the series press++, he reveals the work traces of newspaper staff in conflict with the photos that were taken especially for use in the newspaper. In his new series, Tableaux chinois, he examines the use of photographs in political propaganda and reveals the artistic stylisation of the photos with reference to the feasibility and time-related aesthetics of the printed products.

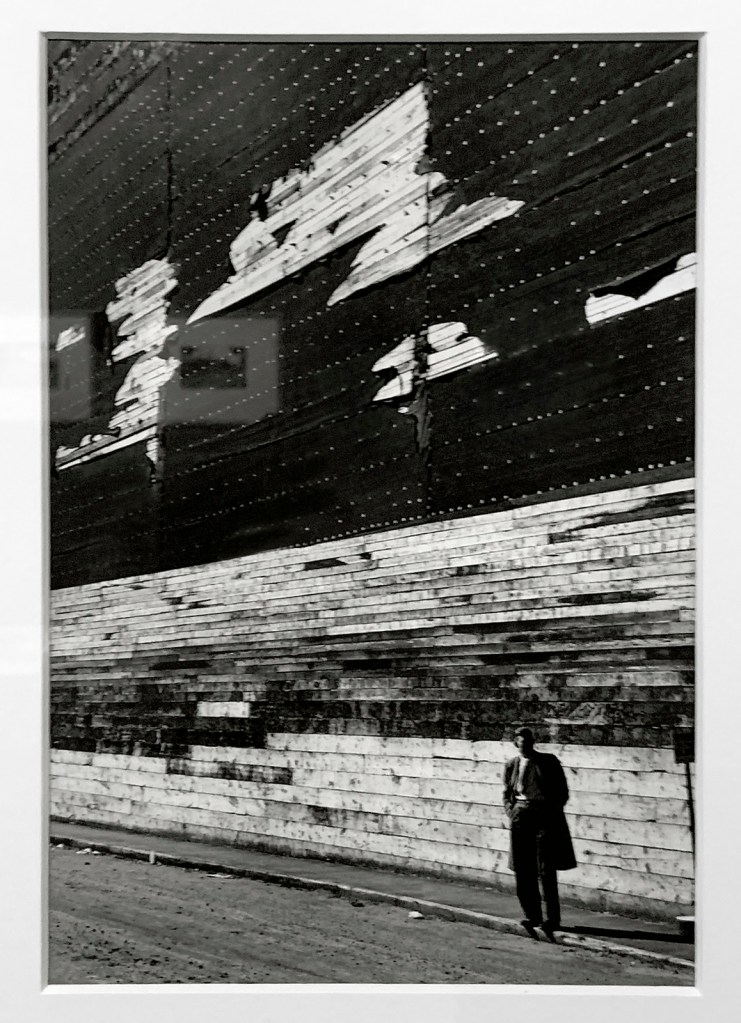

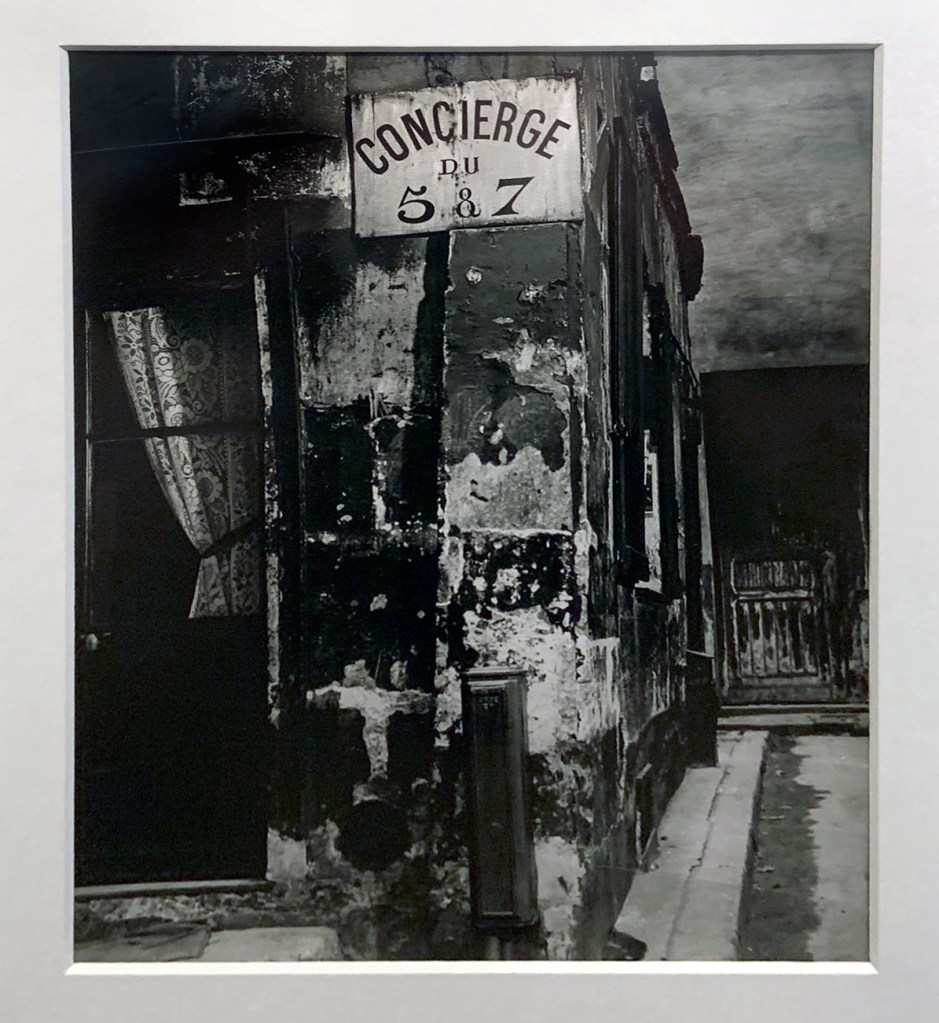

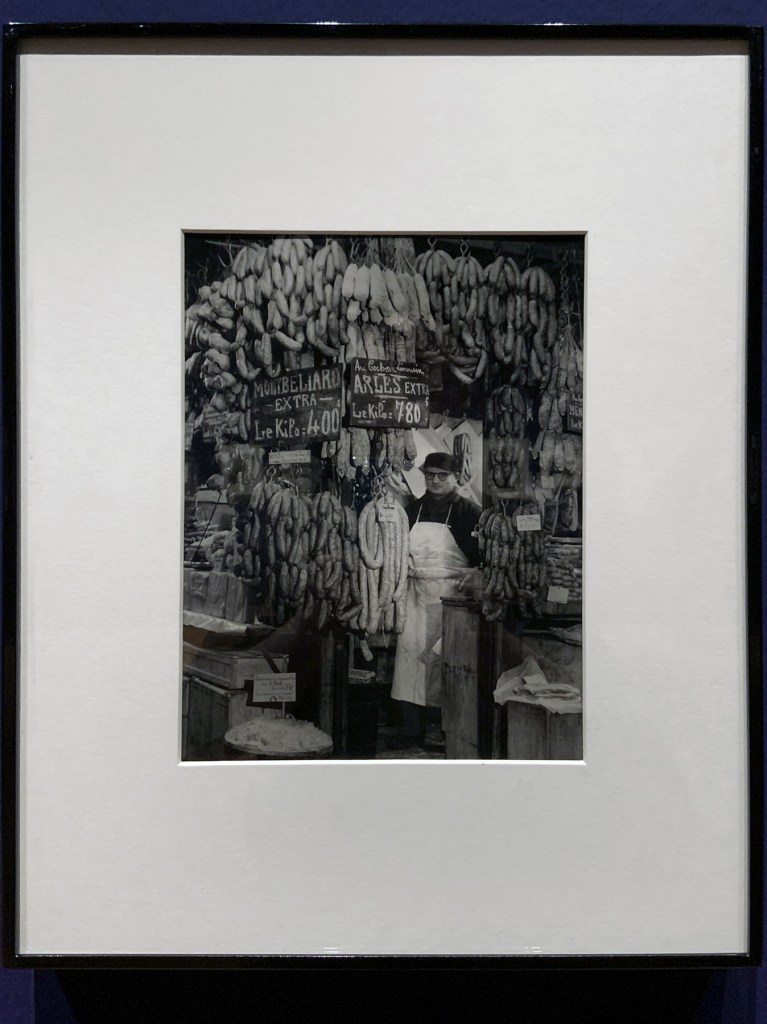

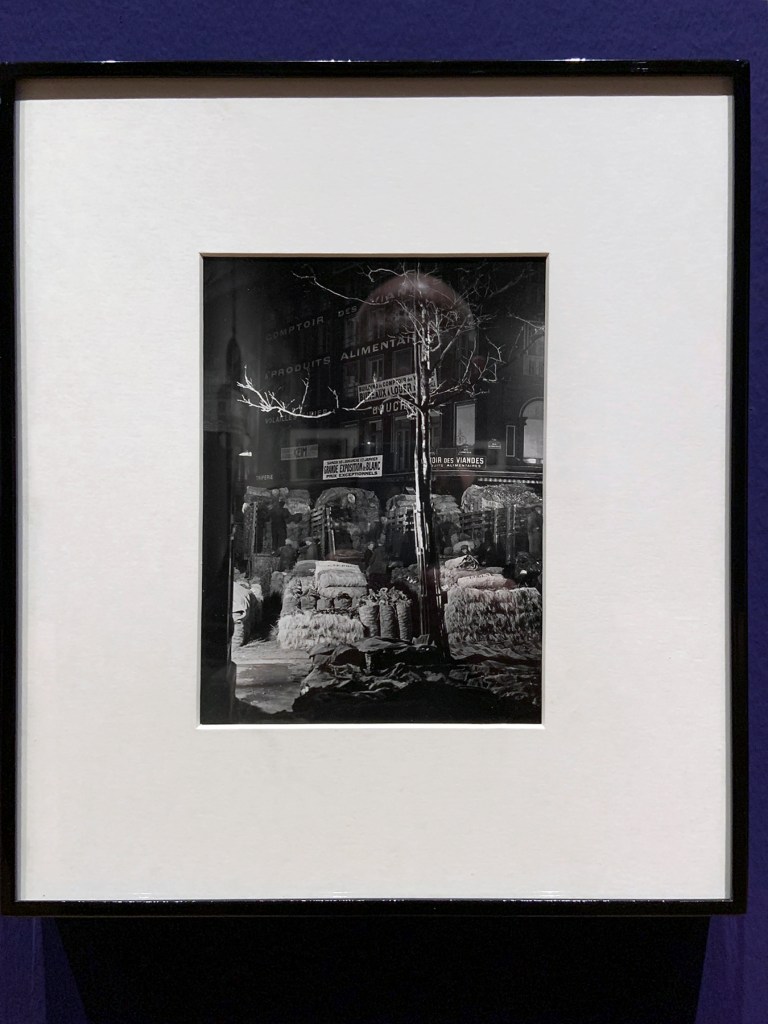

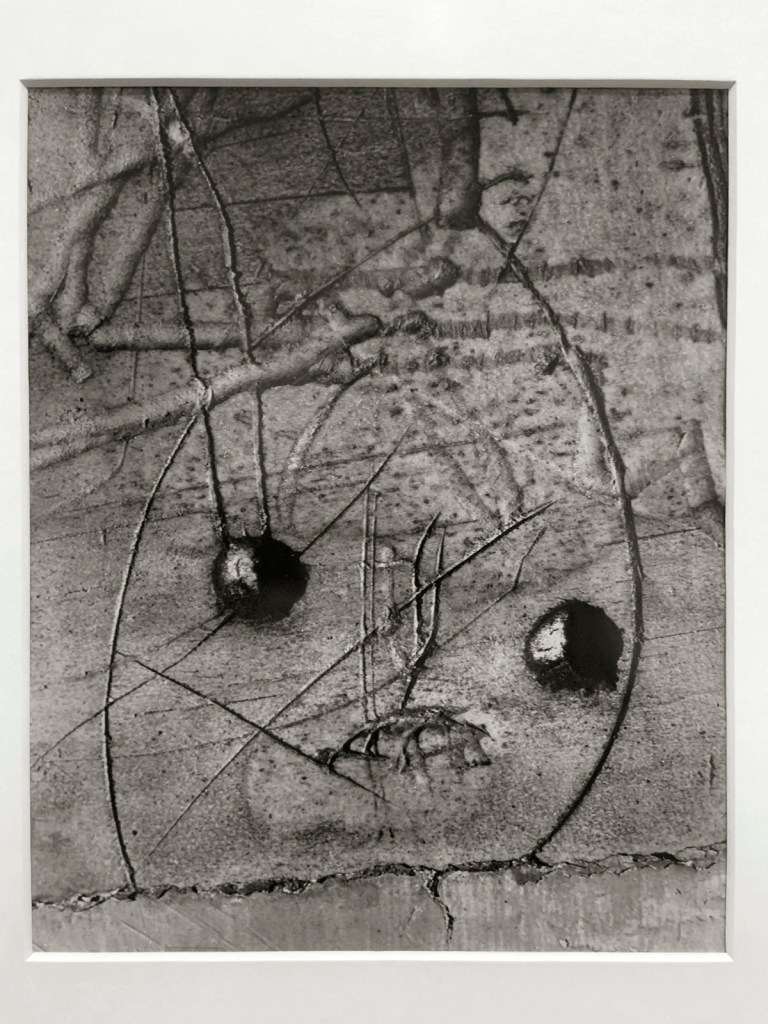

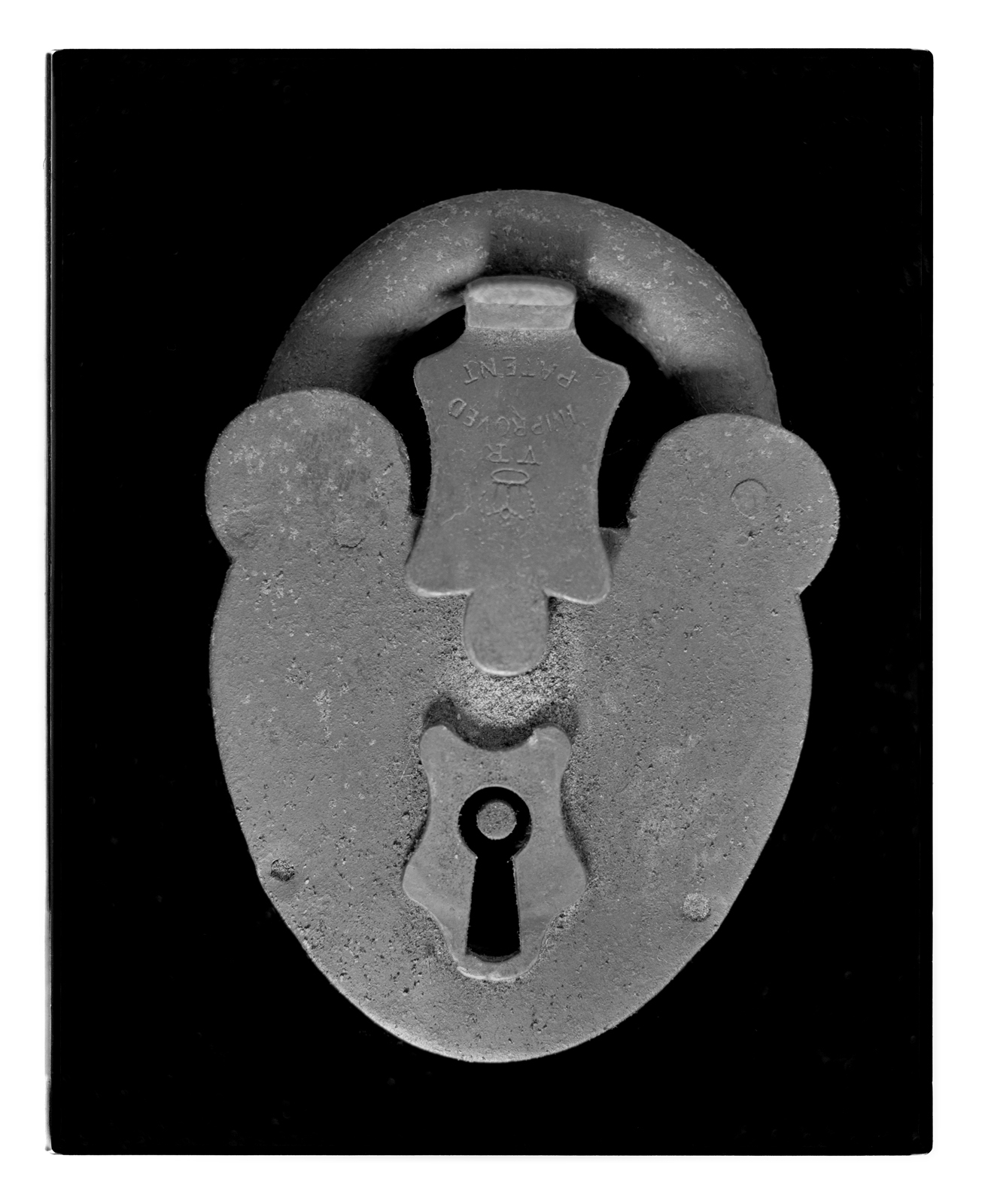

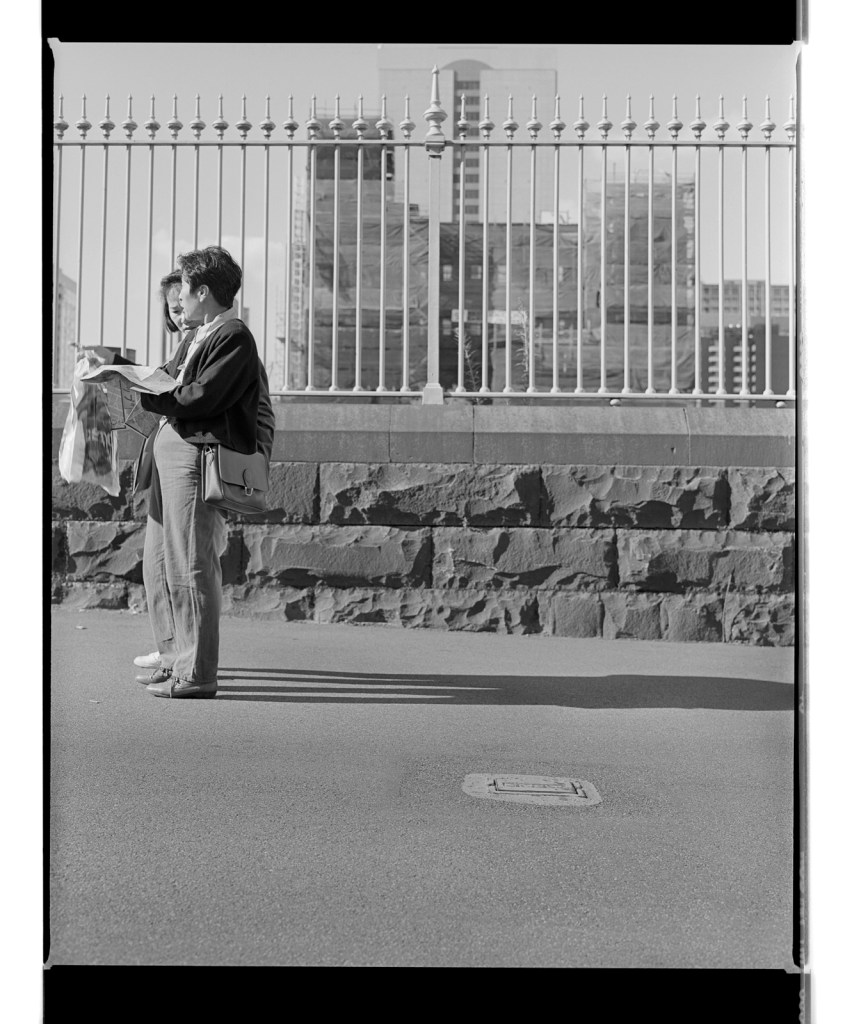

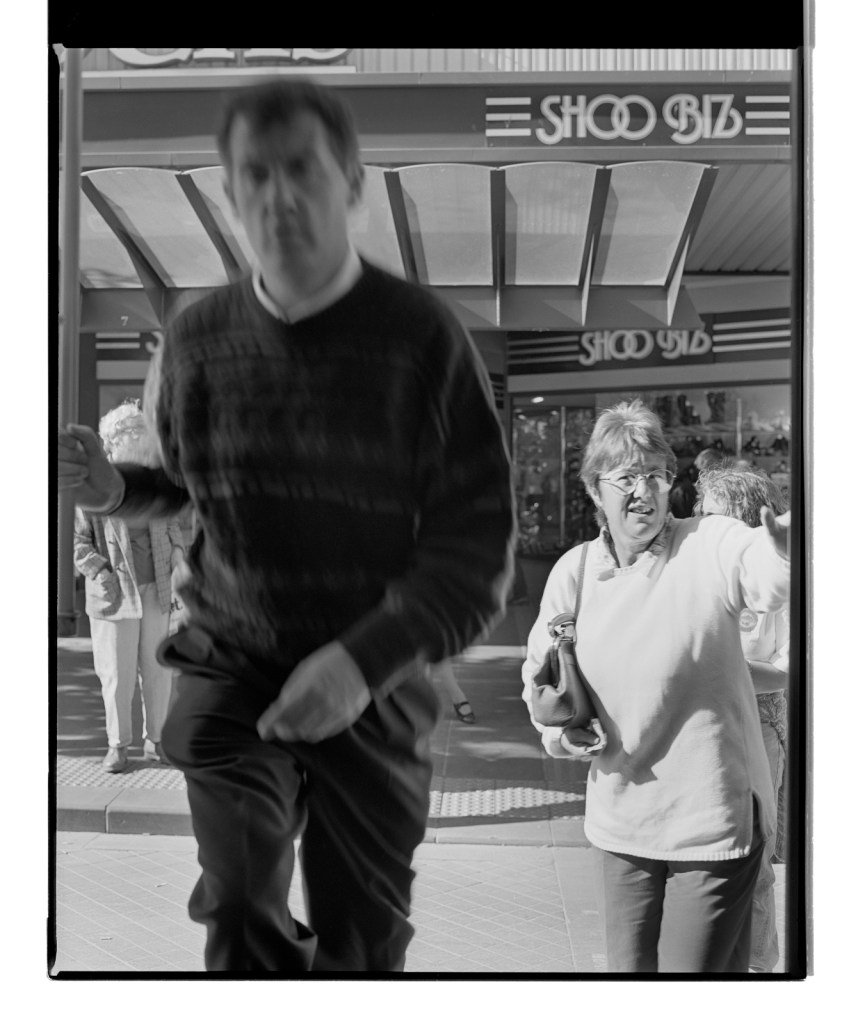

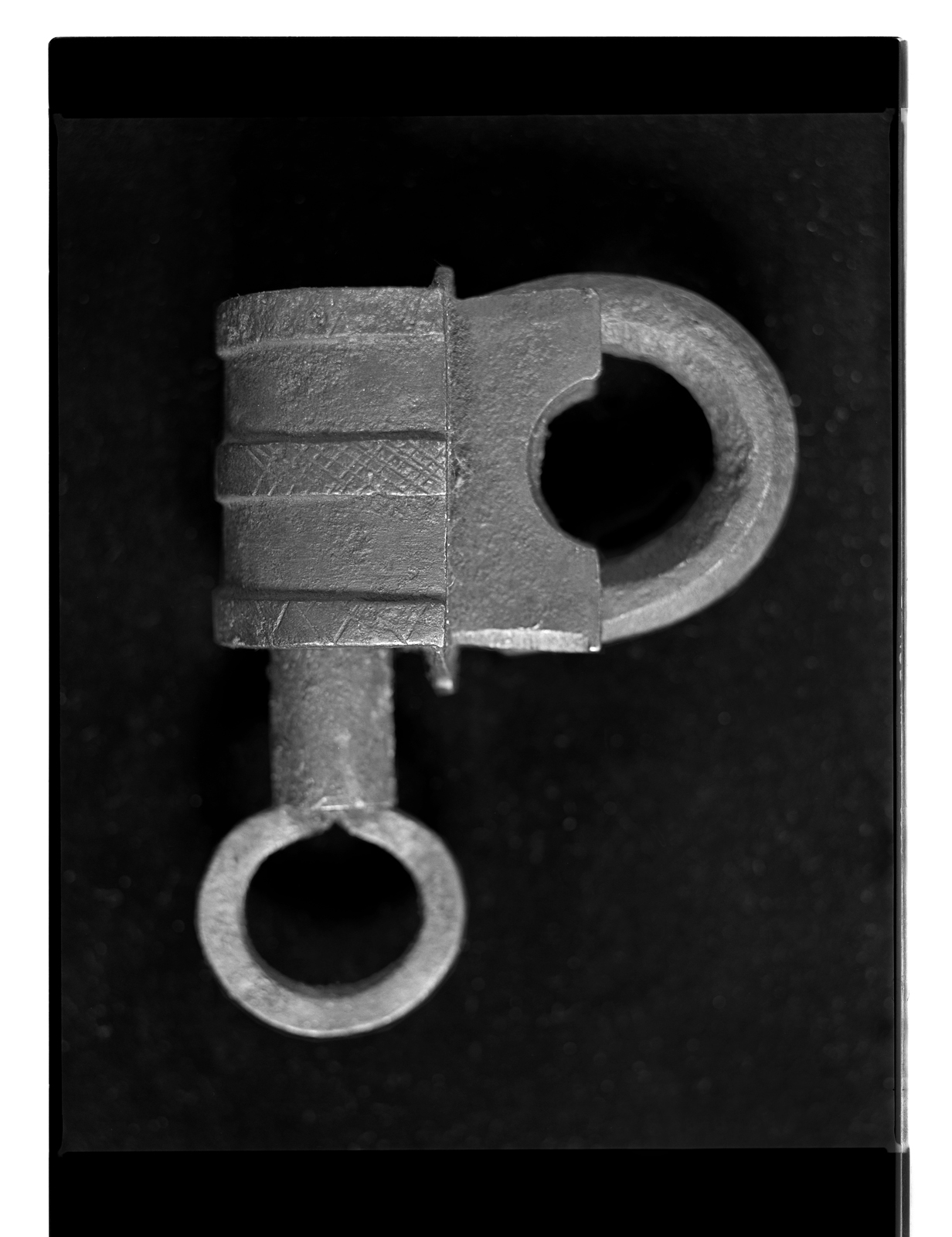

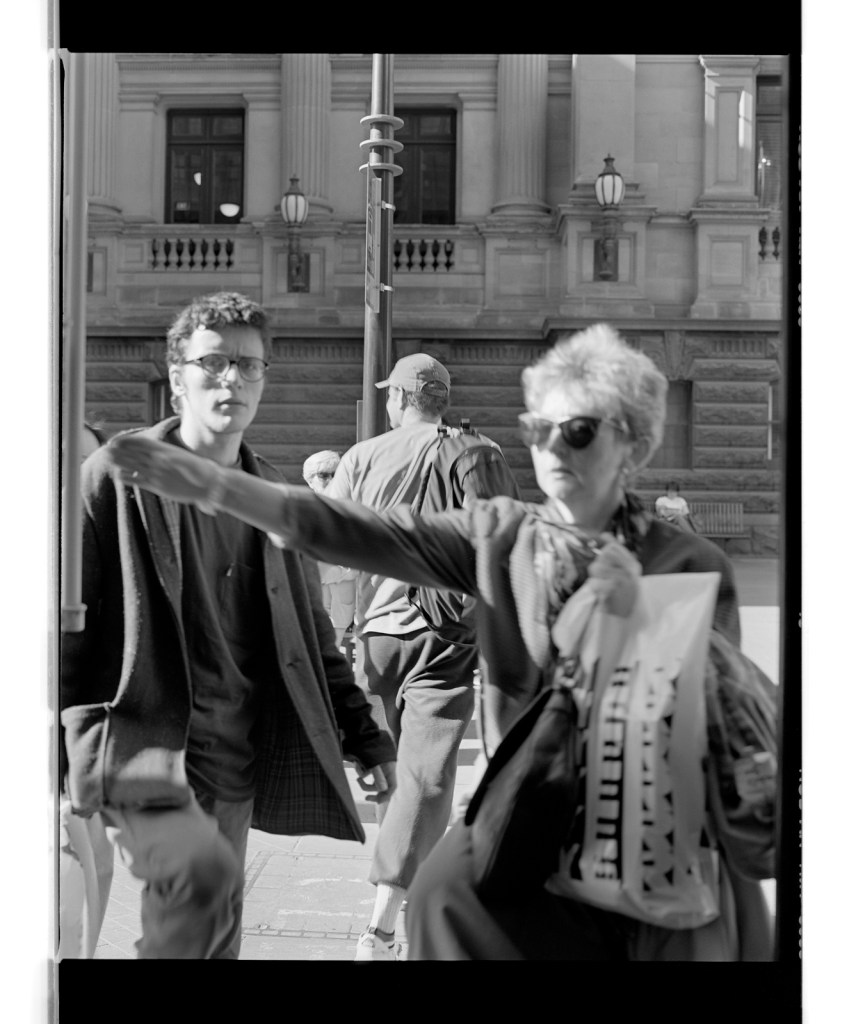

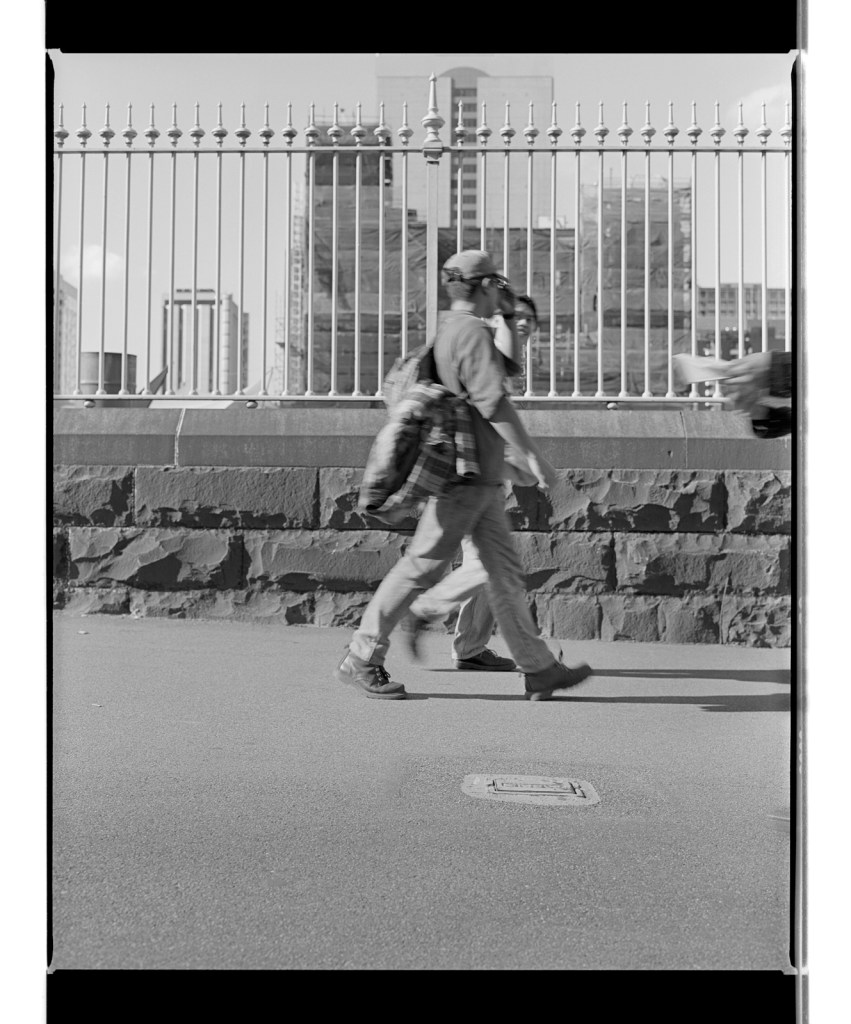

Thomas Ruff (German, b. 1958)

Zeitungsfoto 060

1990

C-Print

17.3 x 13.4cm

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020

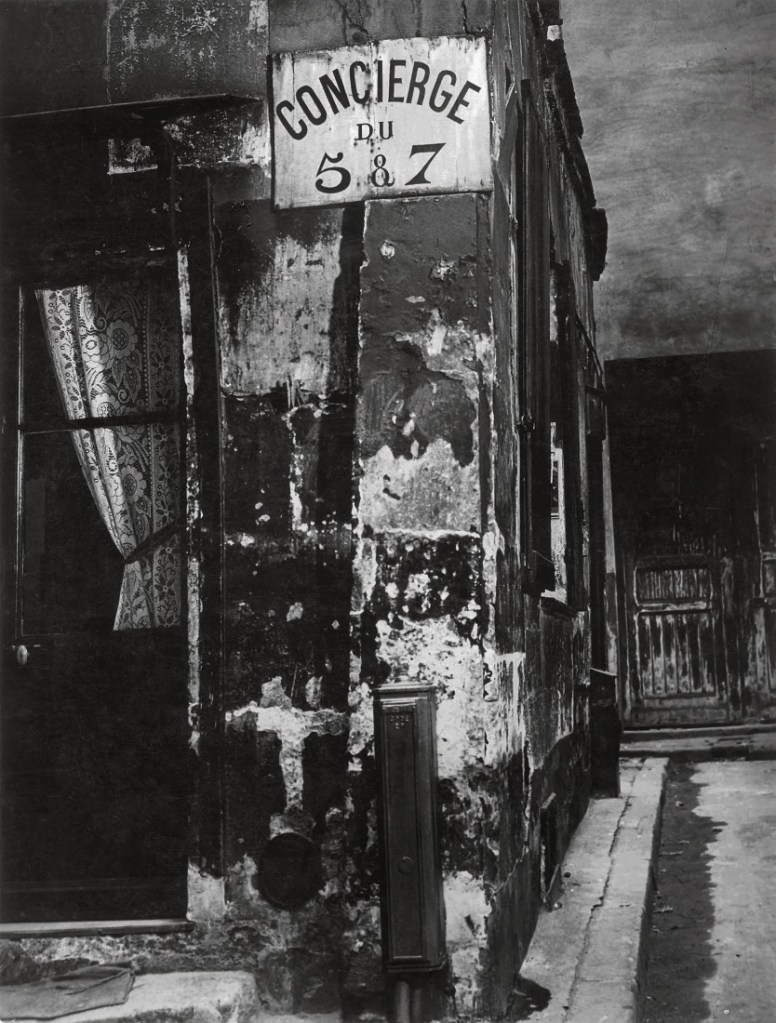

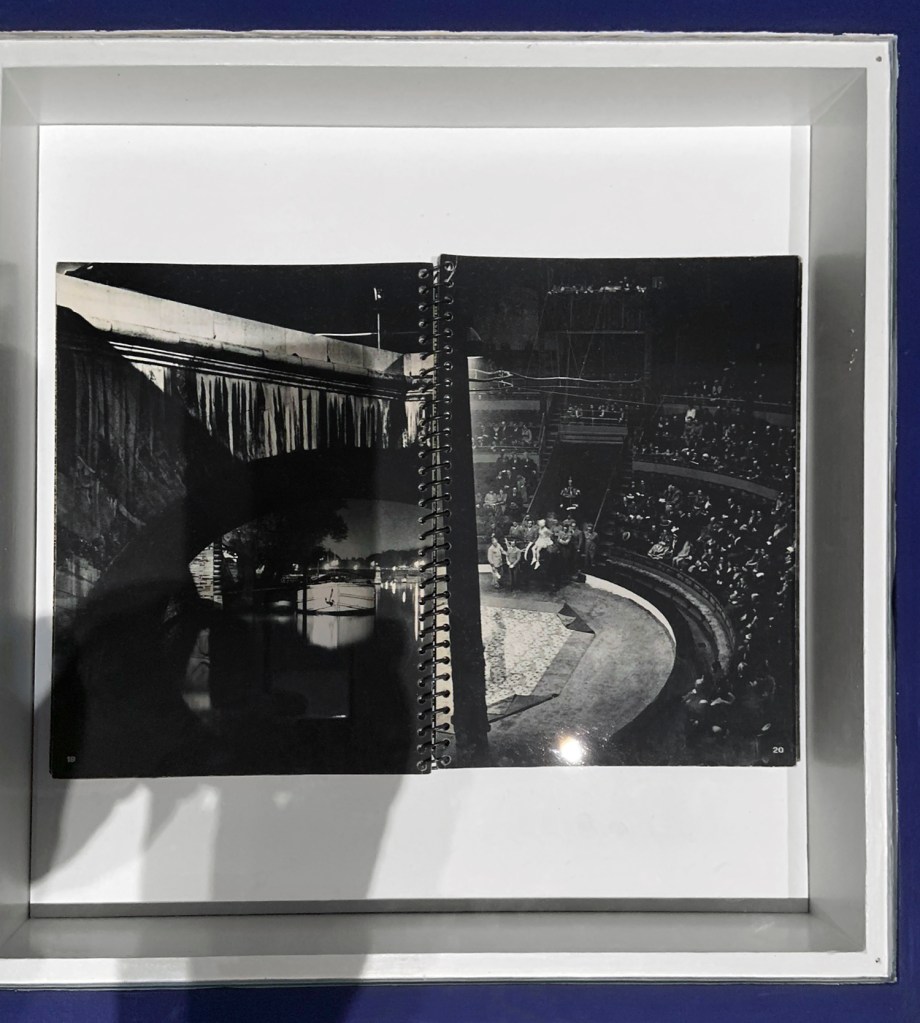

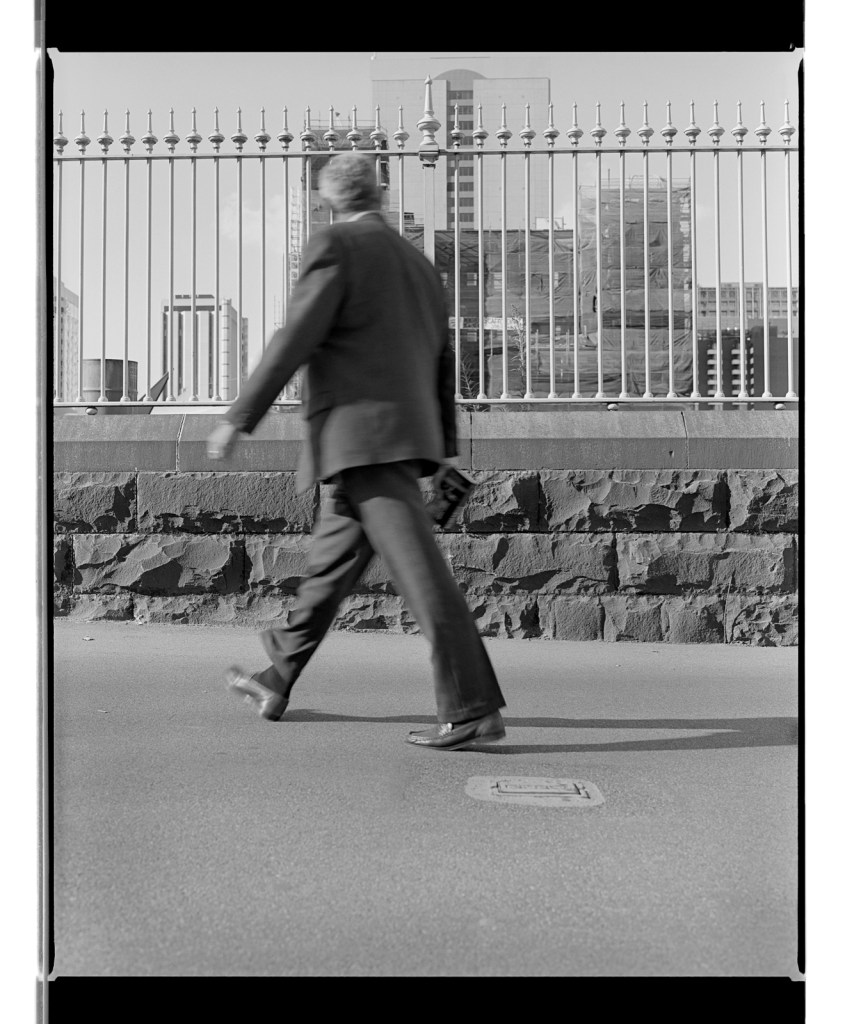

Zeitungsfotos

The works in the series Zeitungsfotos (Newspaper Photos) were created between 1990 and 1991 as colour prints framed with passe-partouts. They are based on a collection of images which the artist cut out of German-language daily and weekly newspapers between 1981 and 1991. The selected motifs from politics, business, sports, culture, science, technology, history, or contemporary events reflect in their entirety the collective pictorial world of a particular generation. The artist had the selected images reproduced without the explanatory captions and printed in double column width. In this way, he questions the informational value of the photographs and directs our attention to the rasterisation of newspaper print.

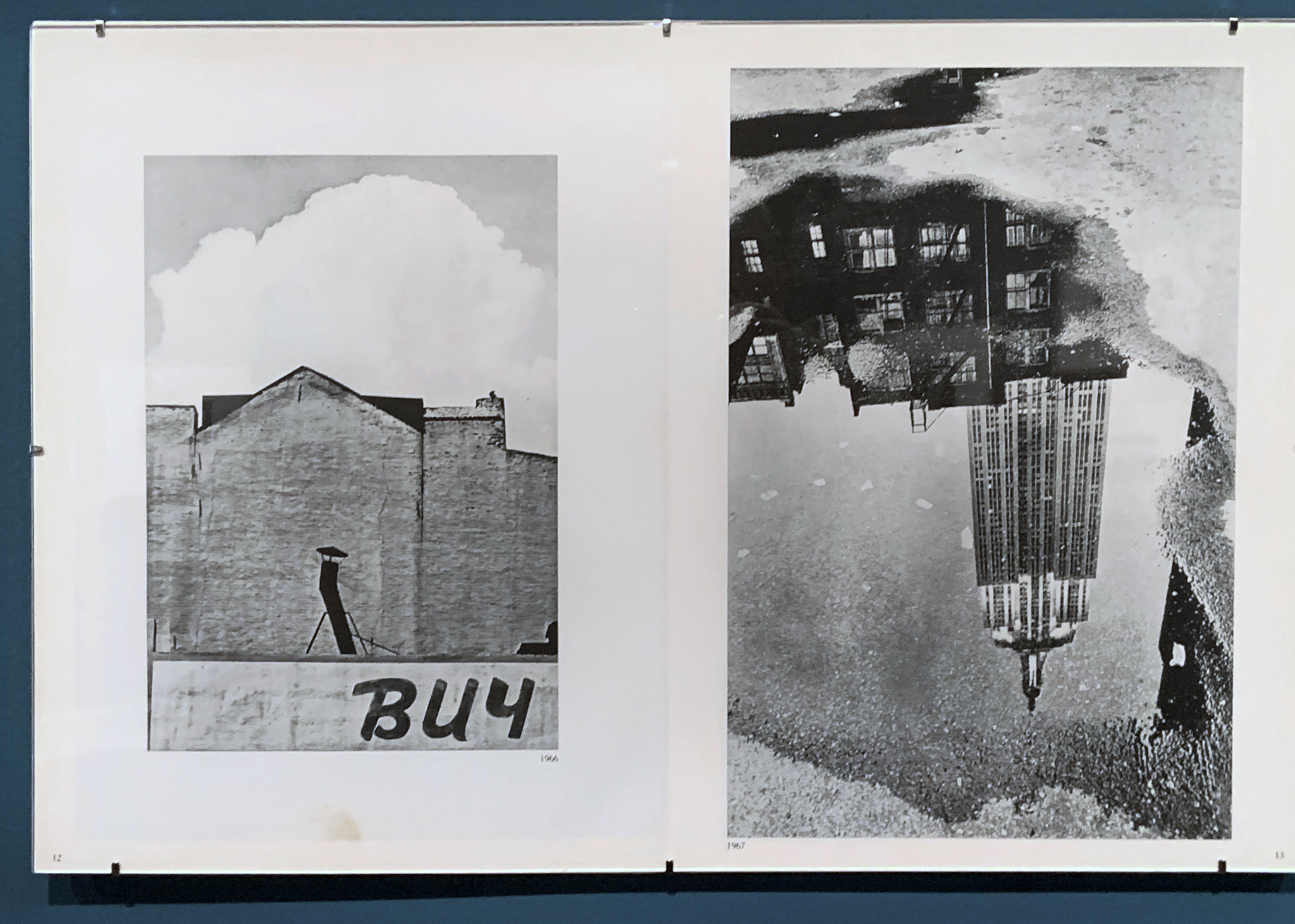

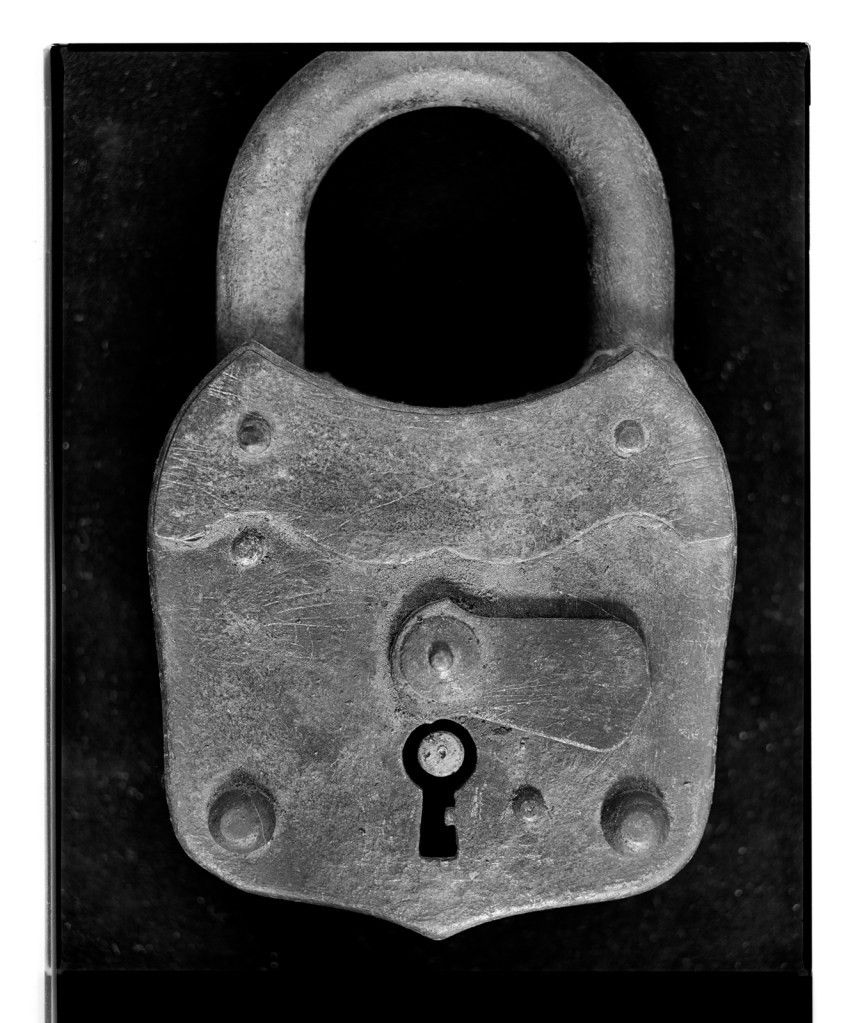

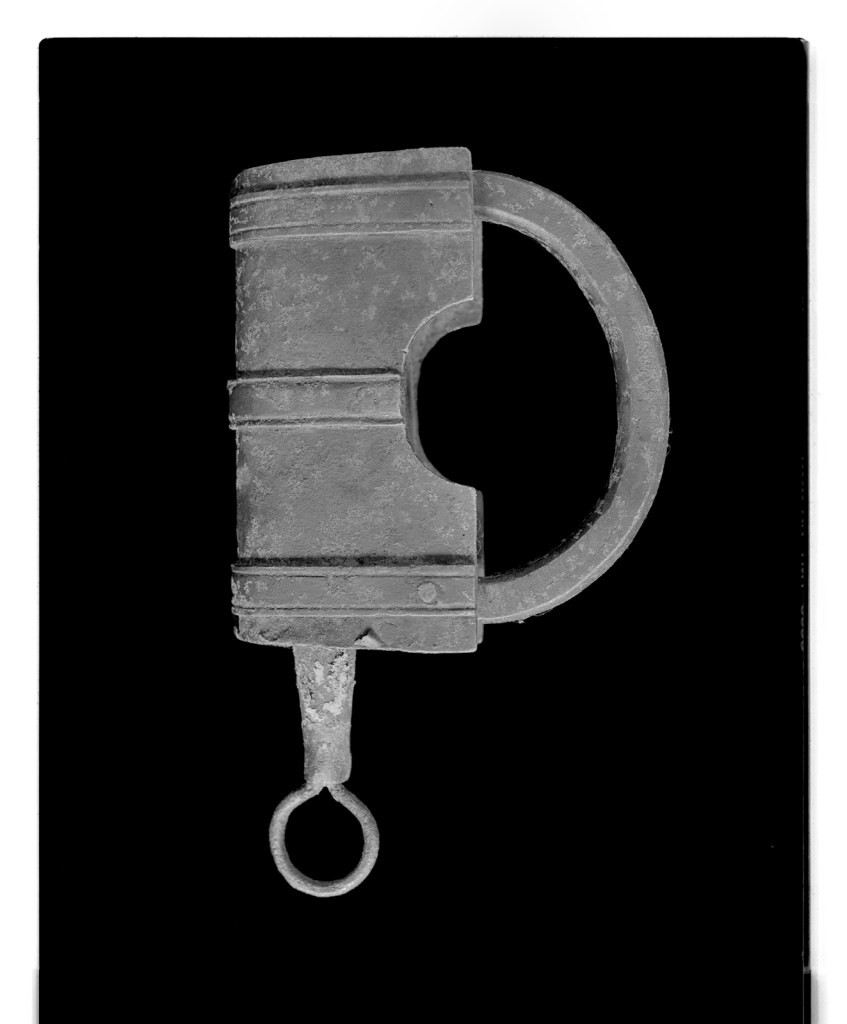

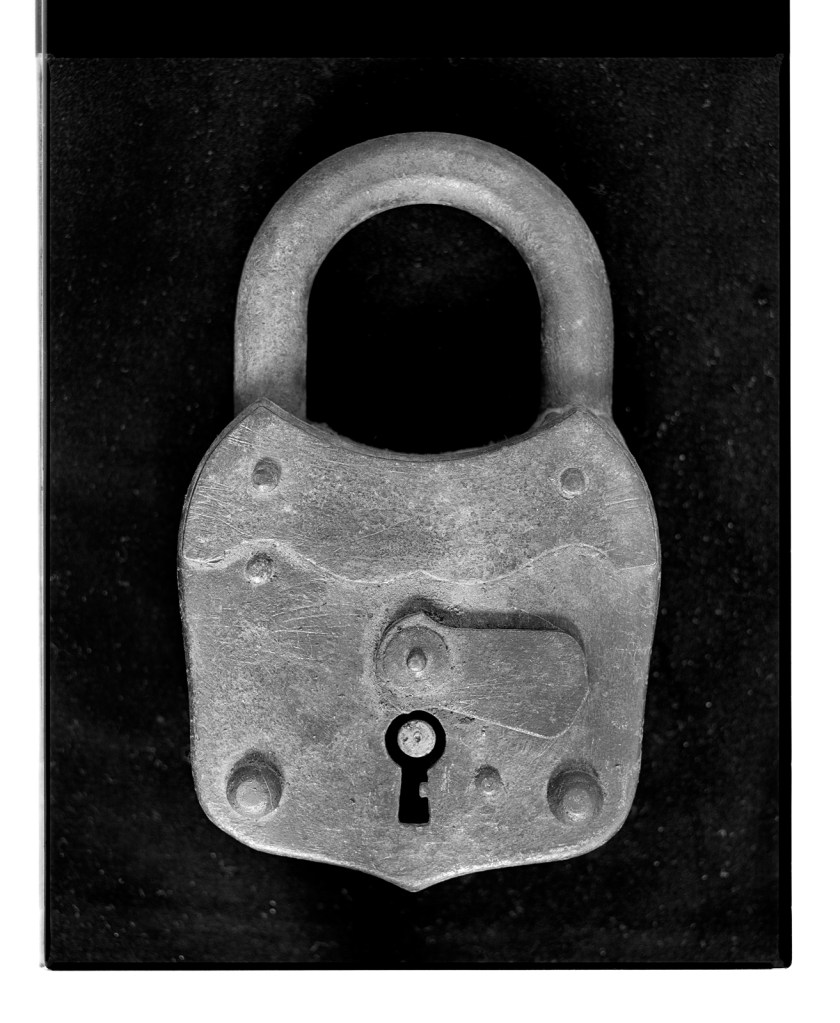

Thomas Ruff (German, b. 1958)

press++21.11

2016

C-Print, Edition 02/04

260 x 185cm

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020

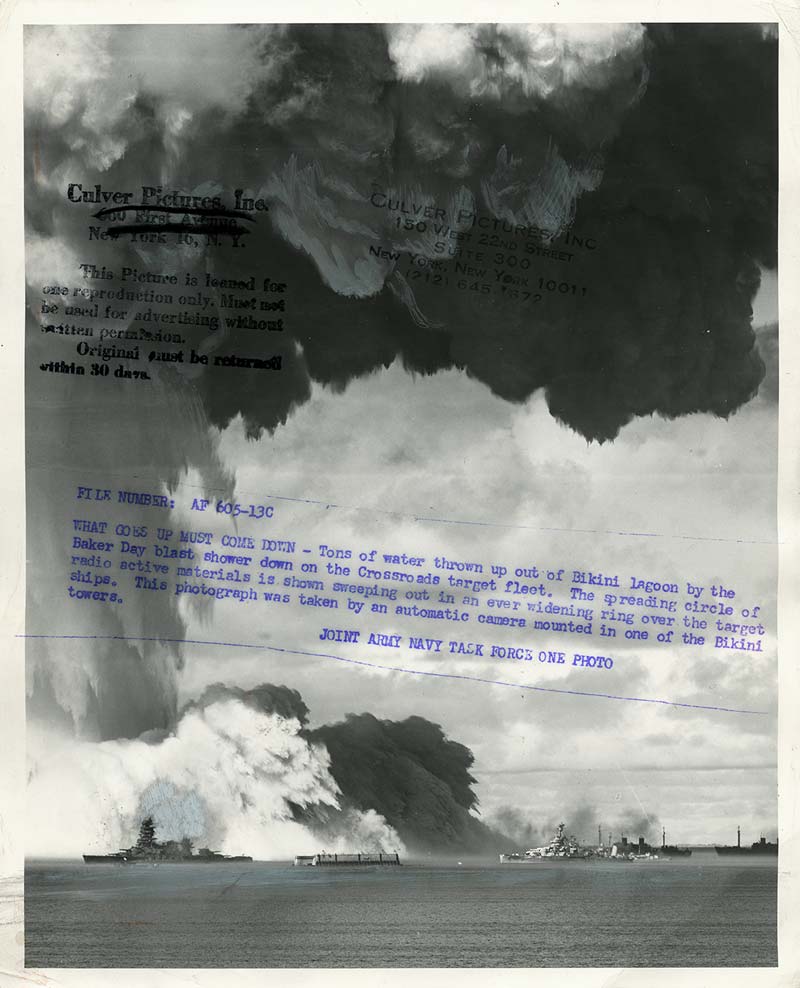

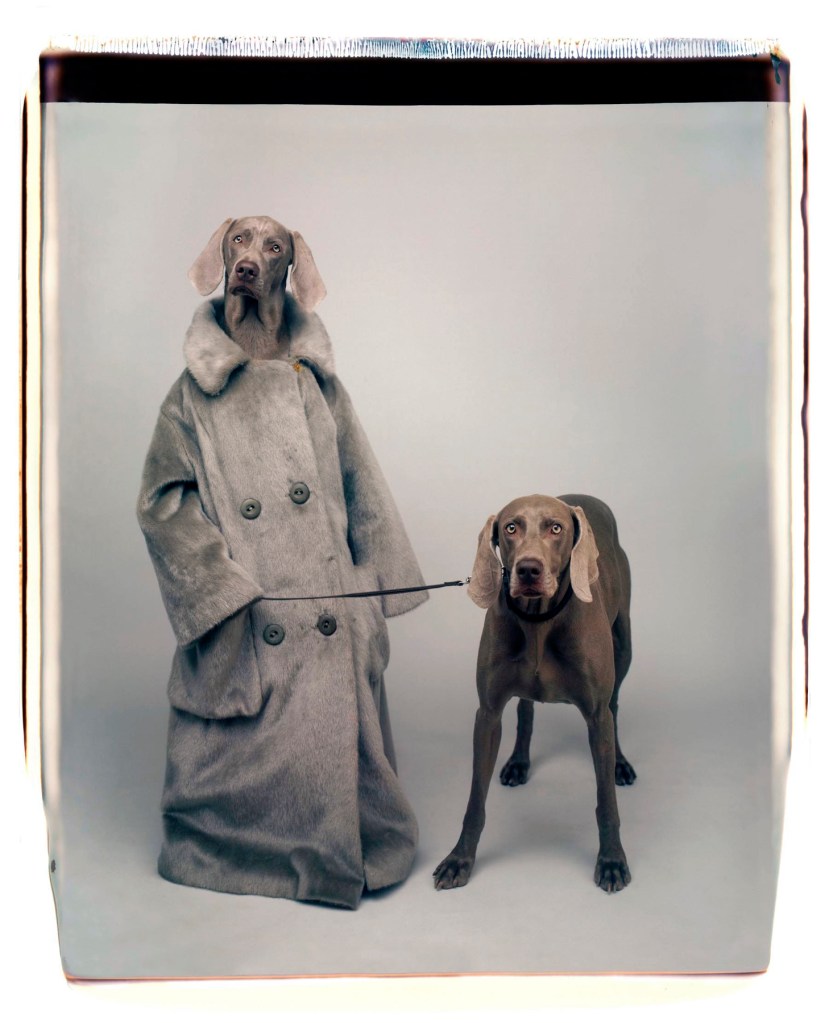

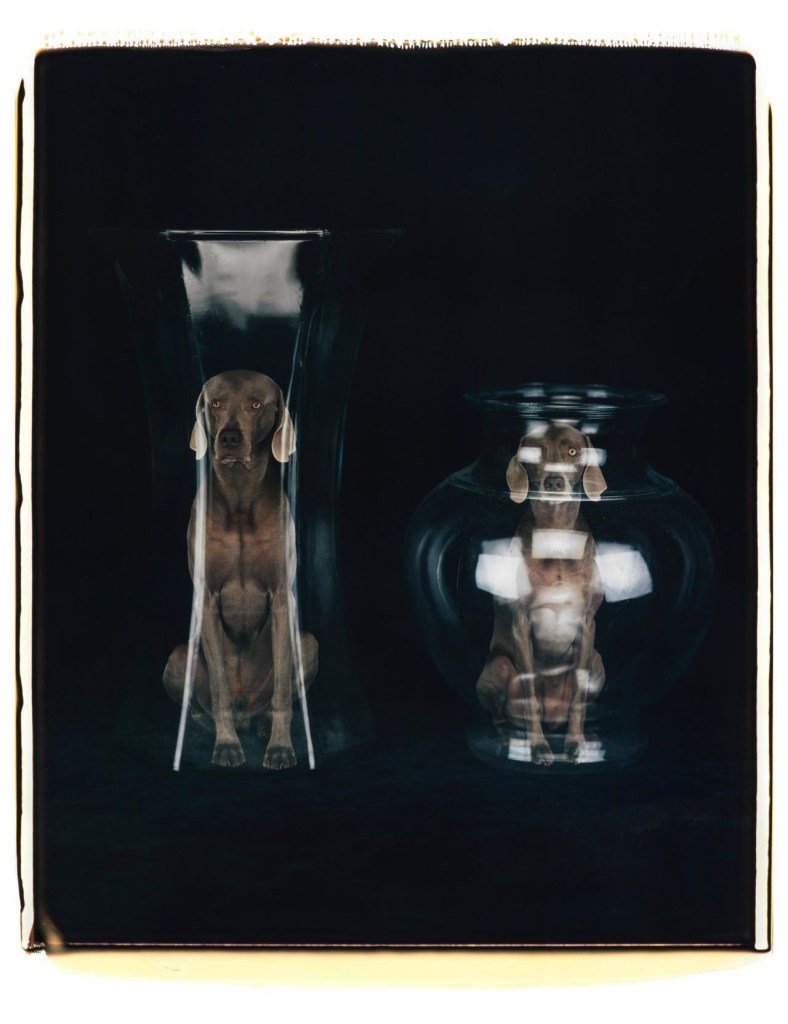

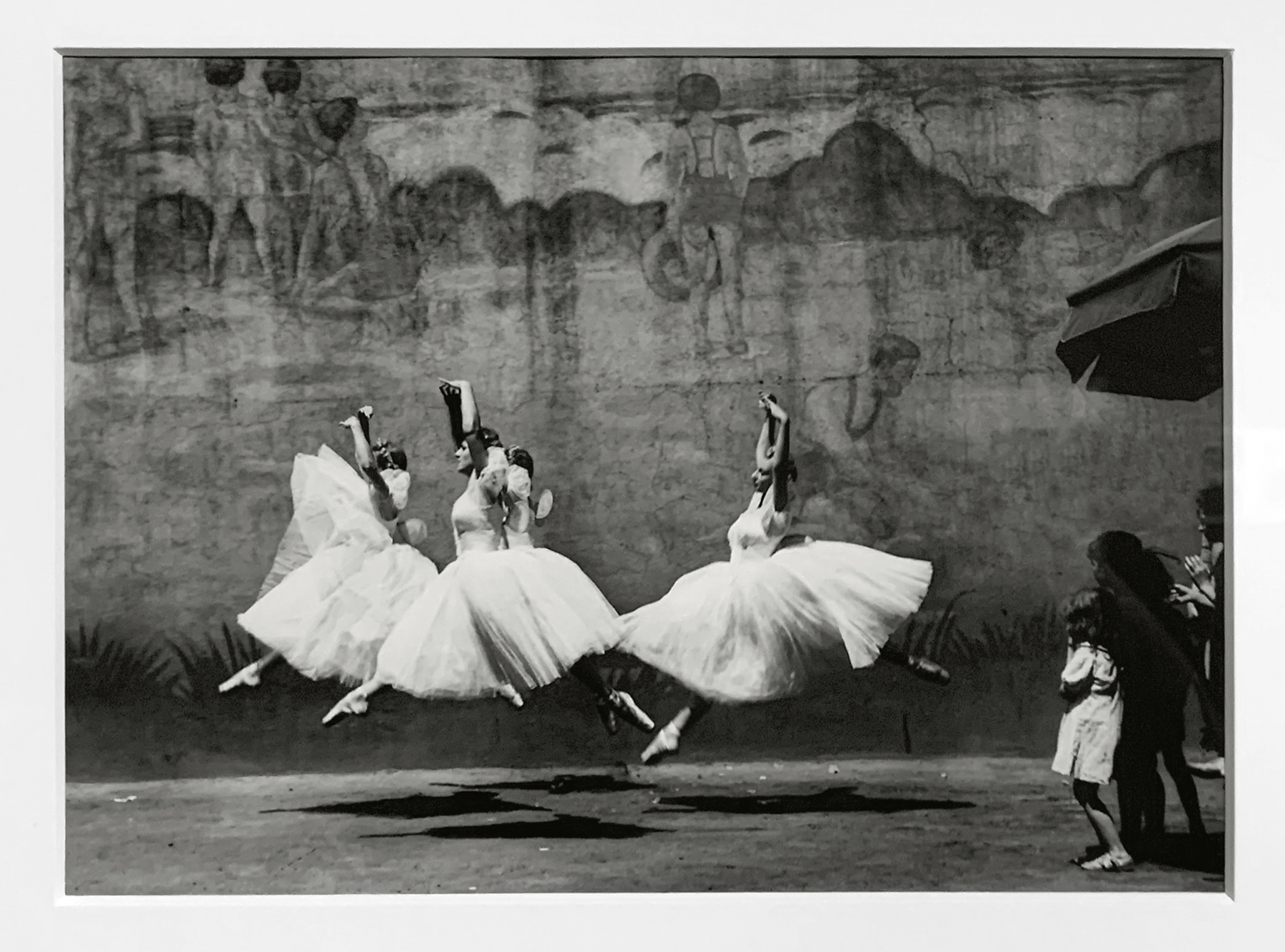

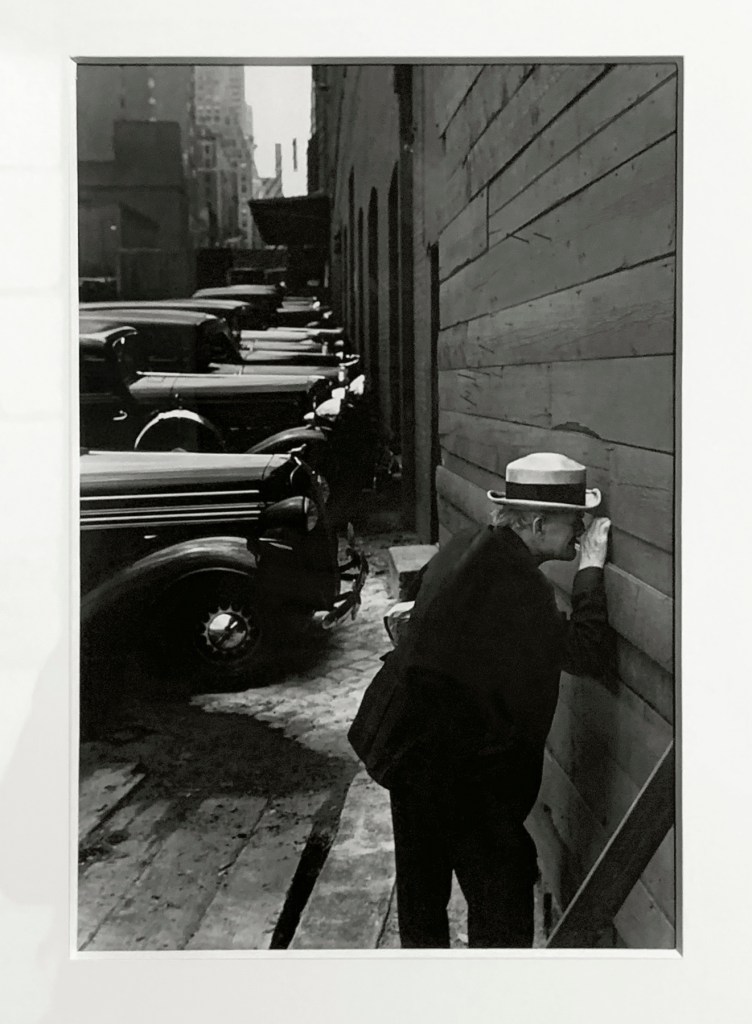

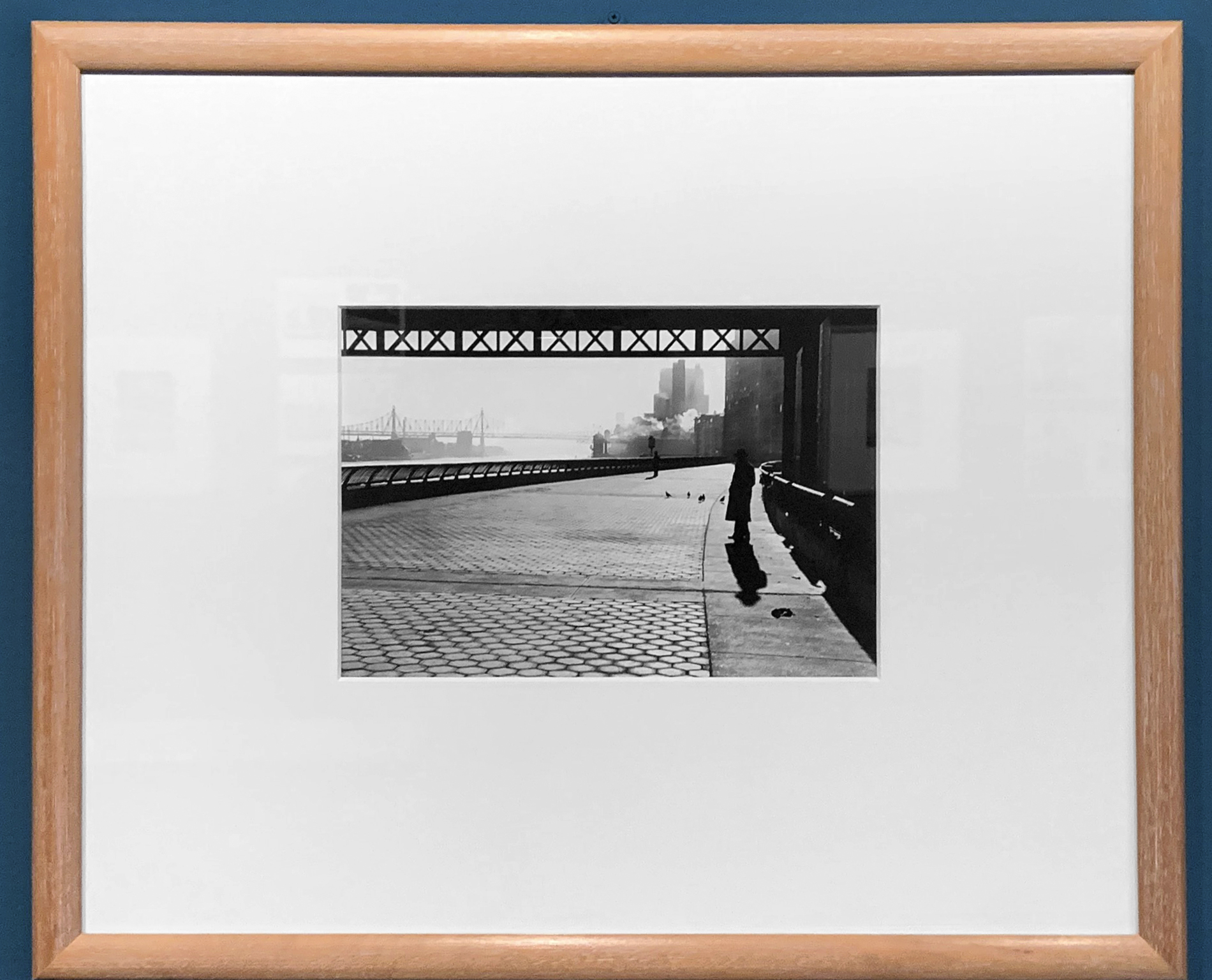

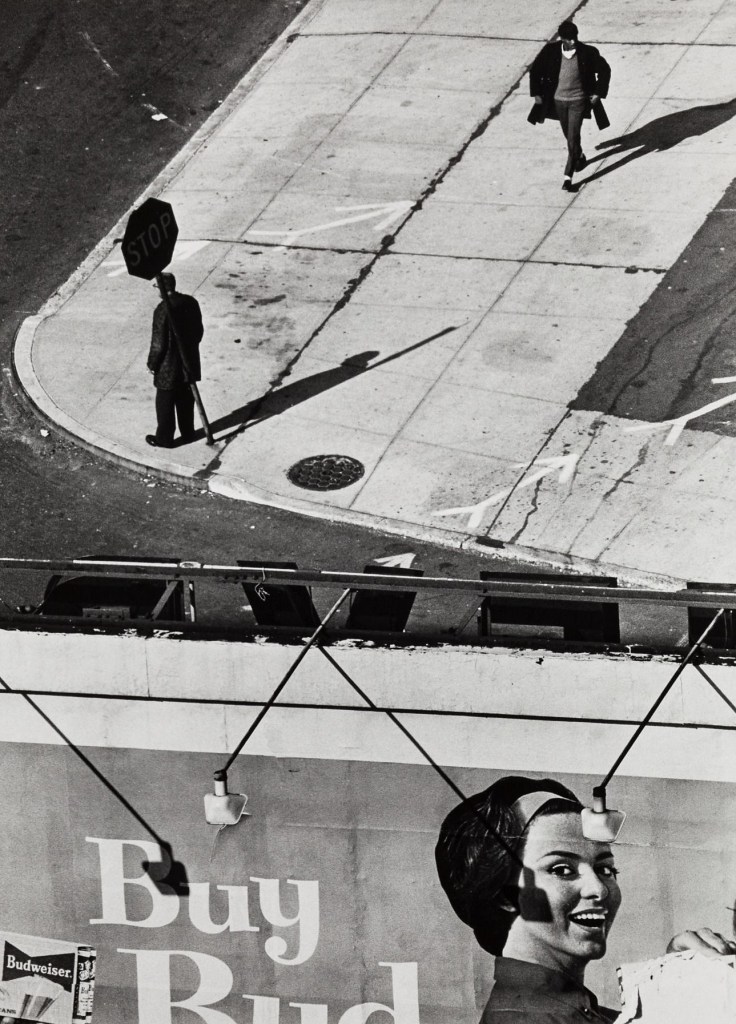

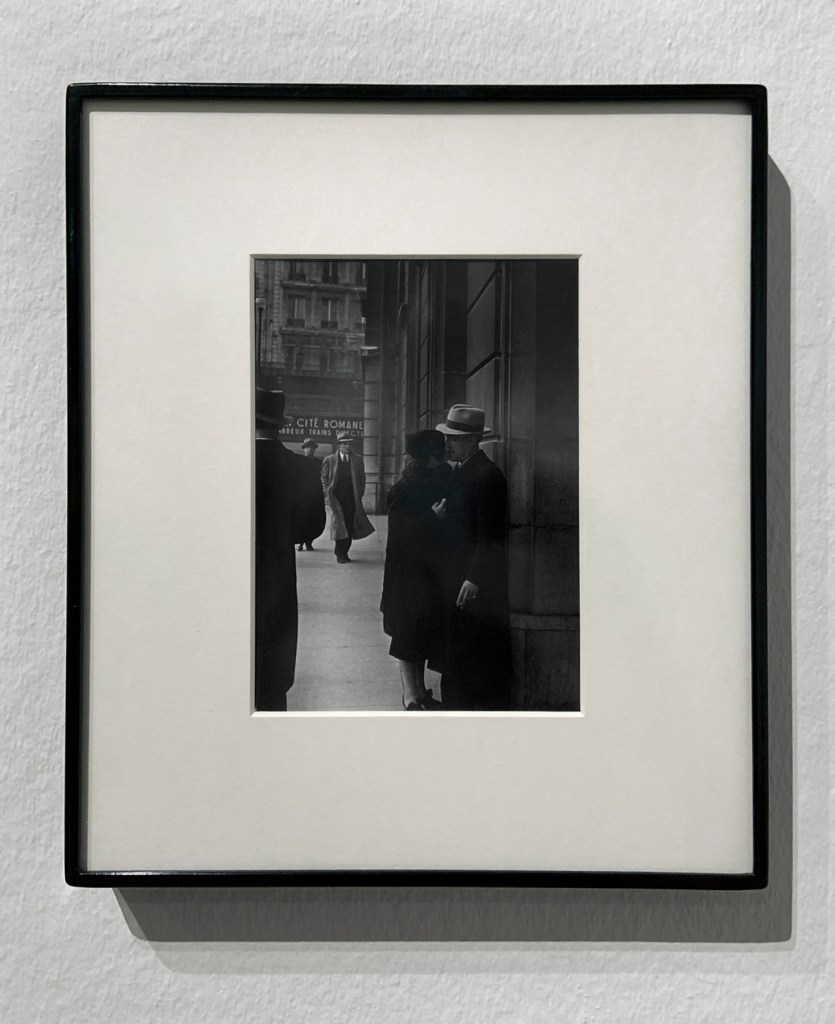

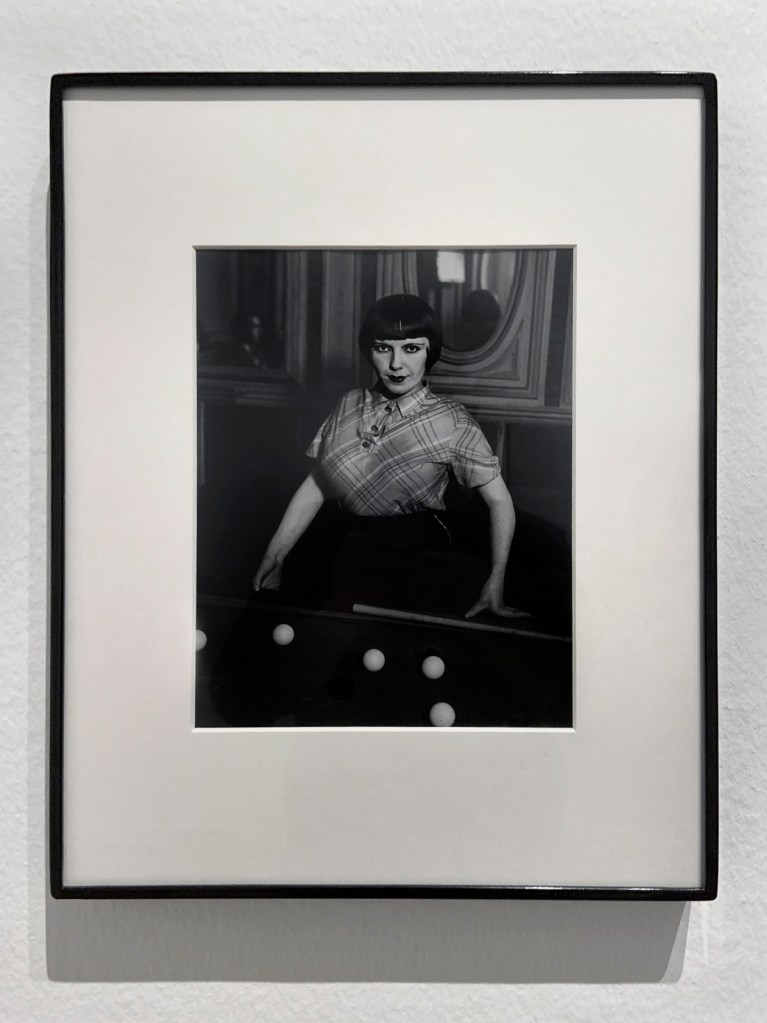

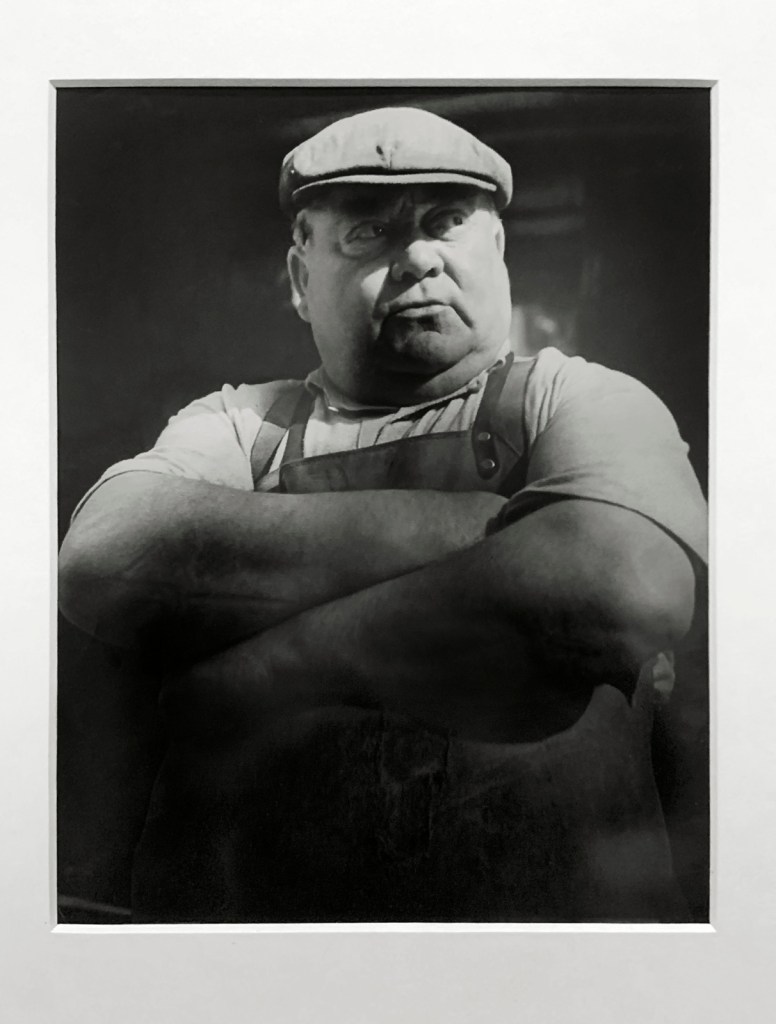

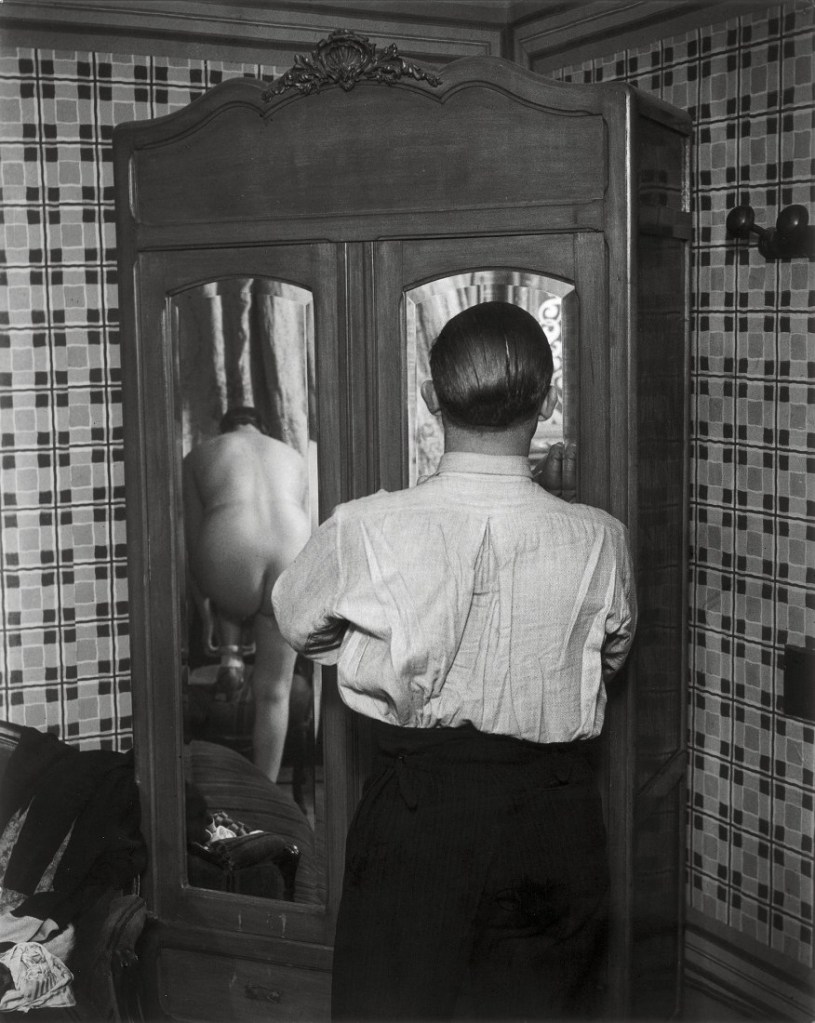

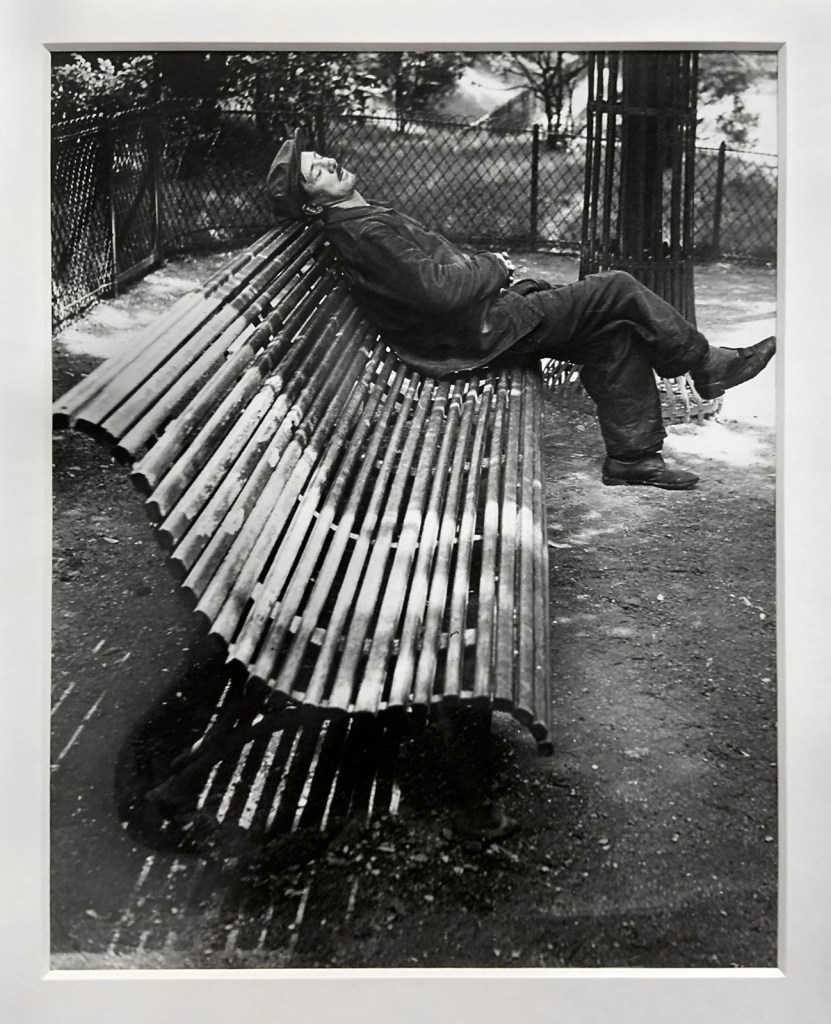

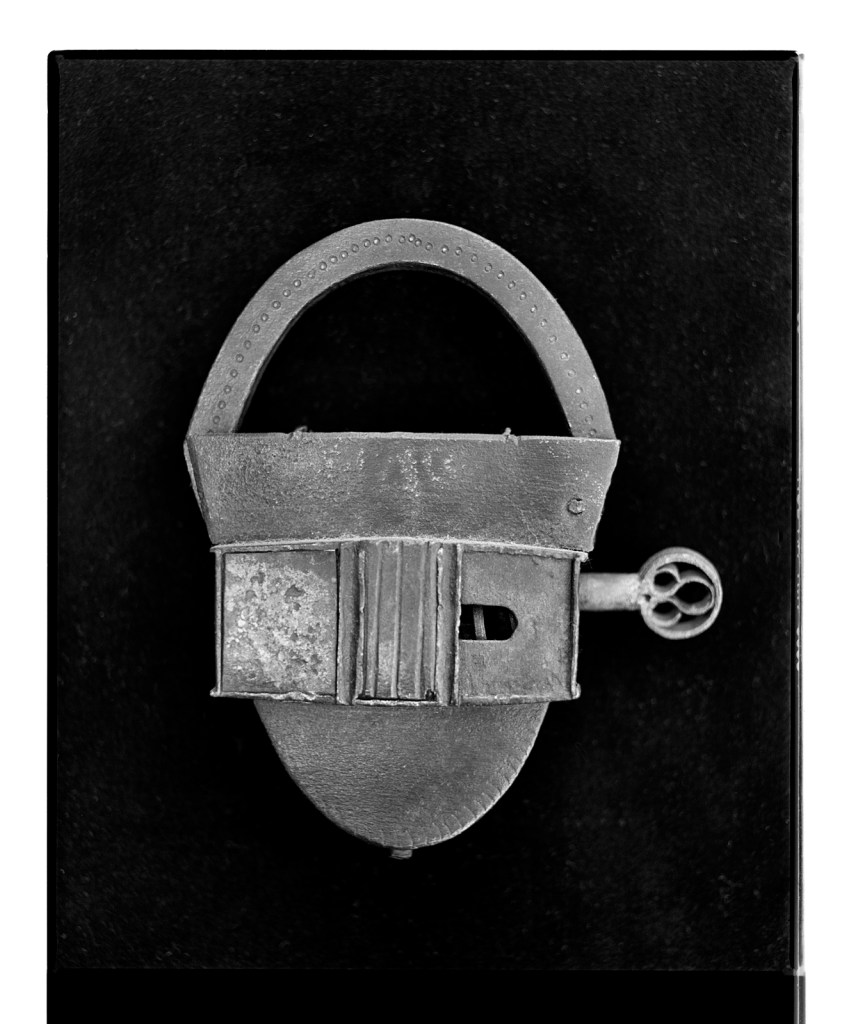

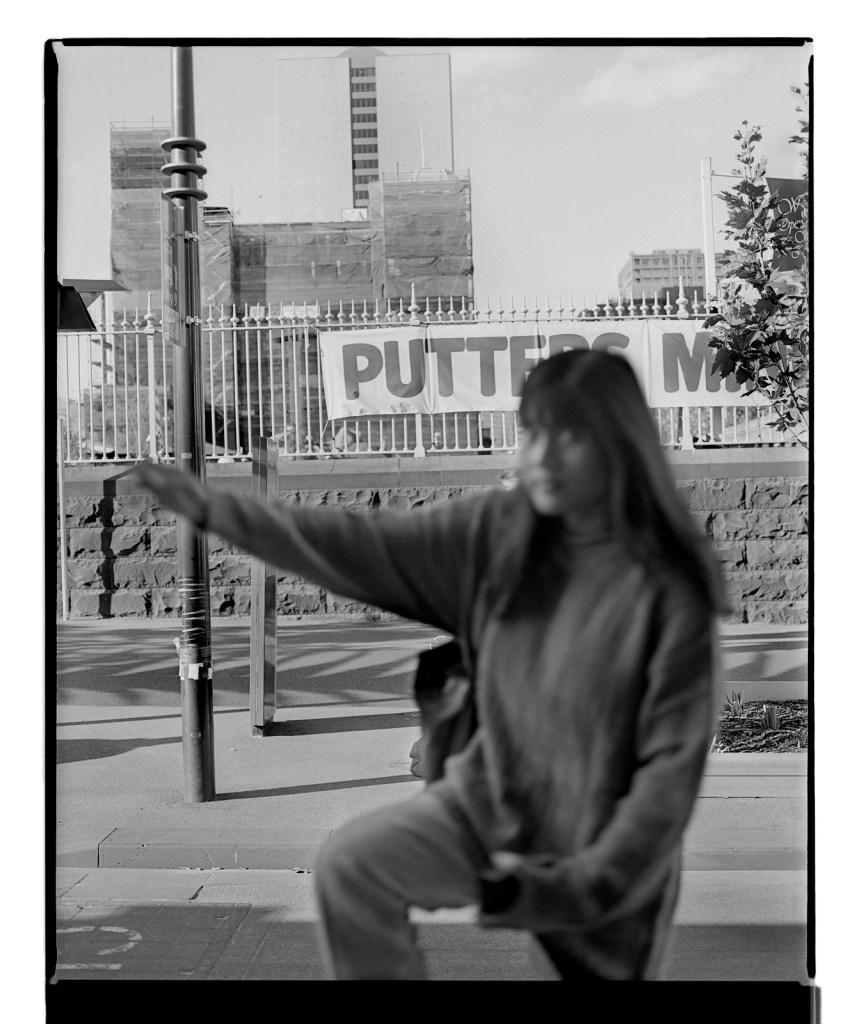

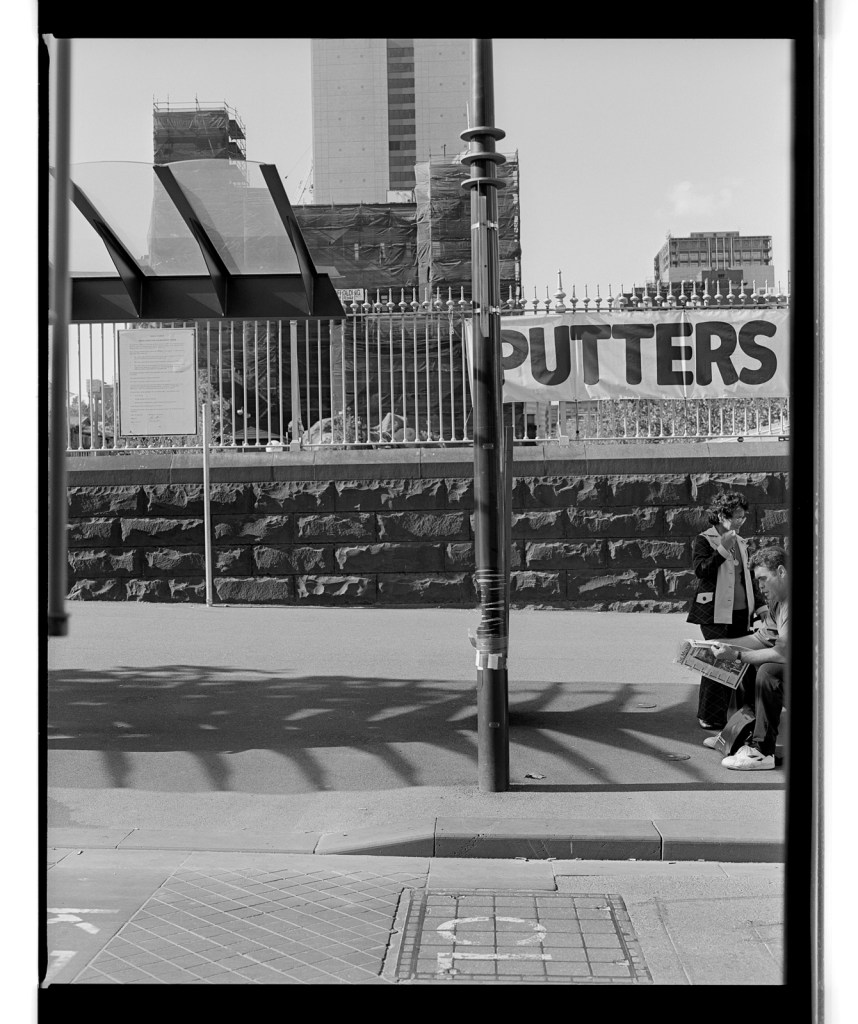

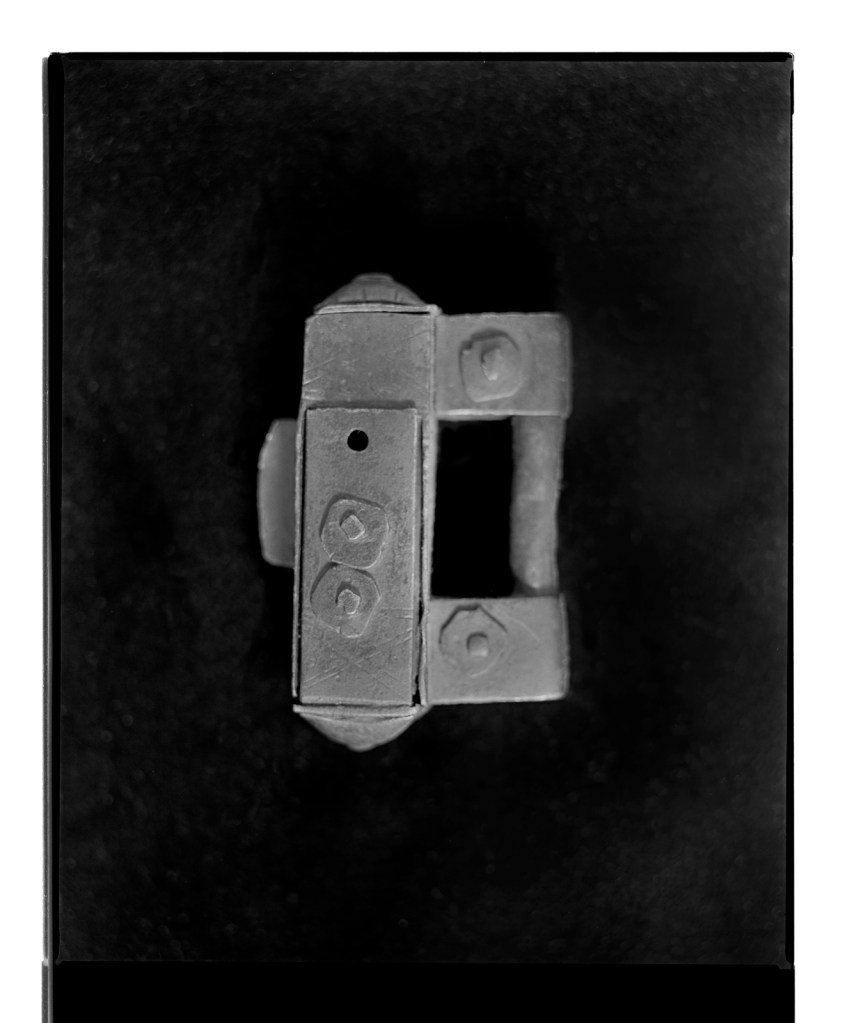

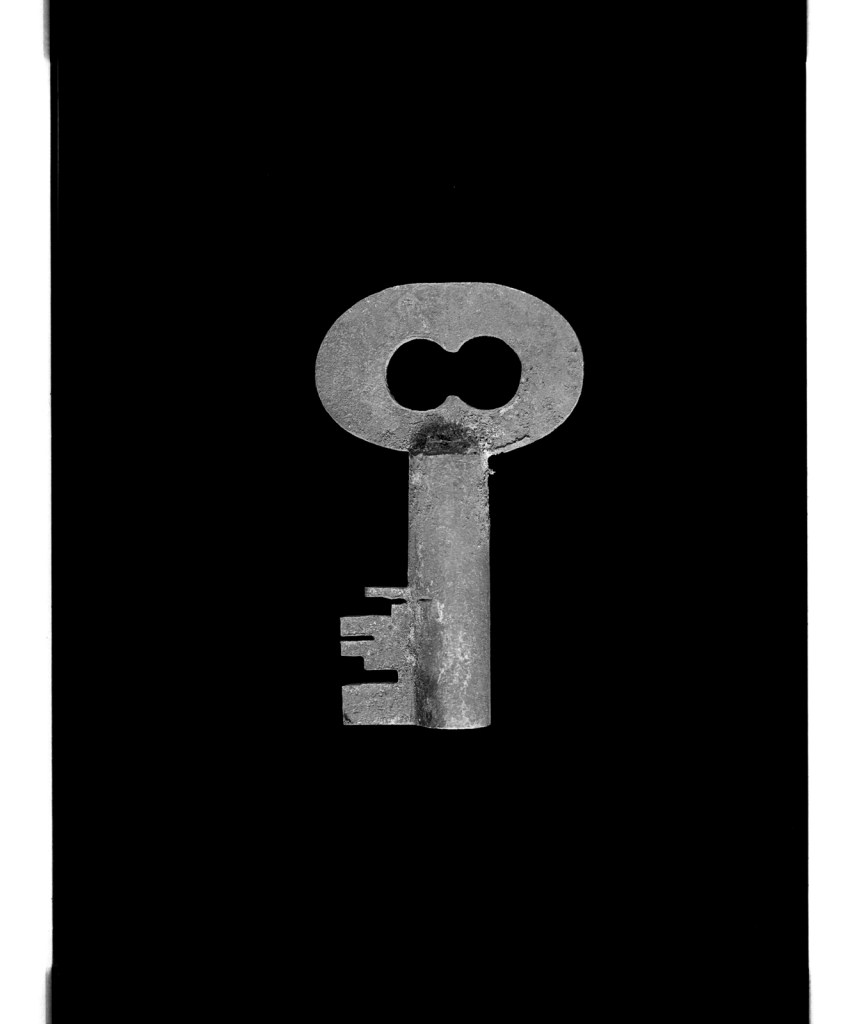

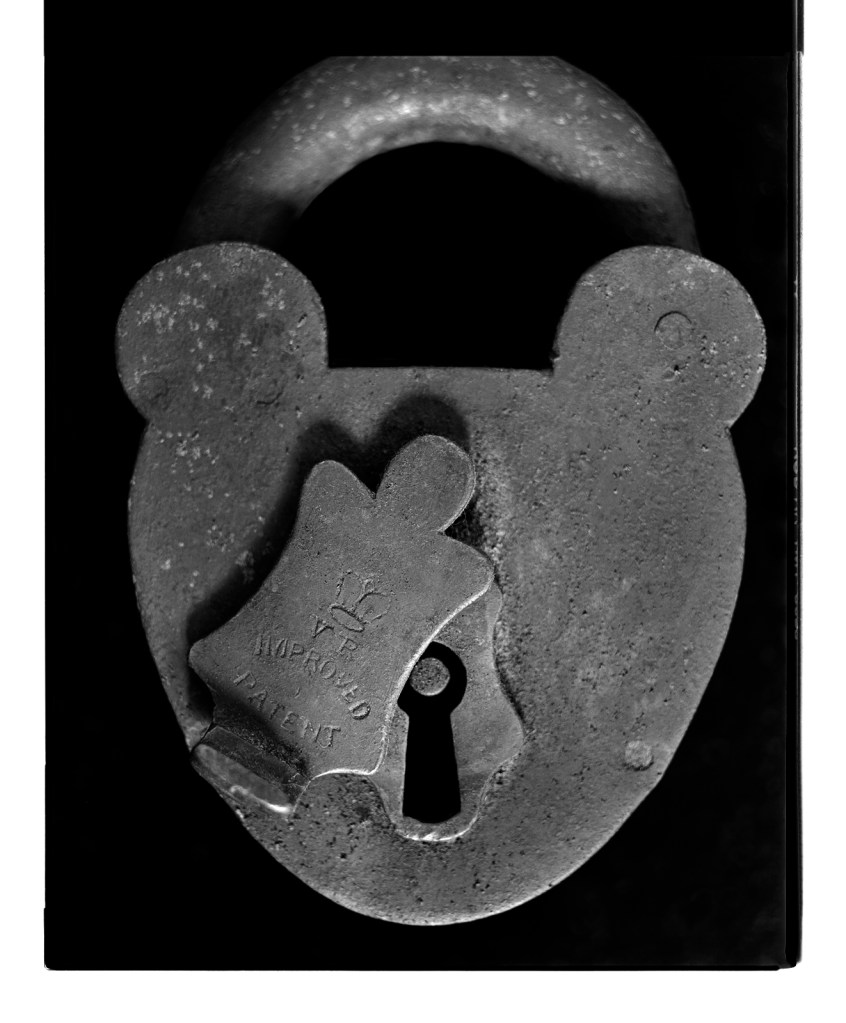

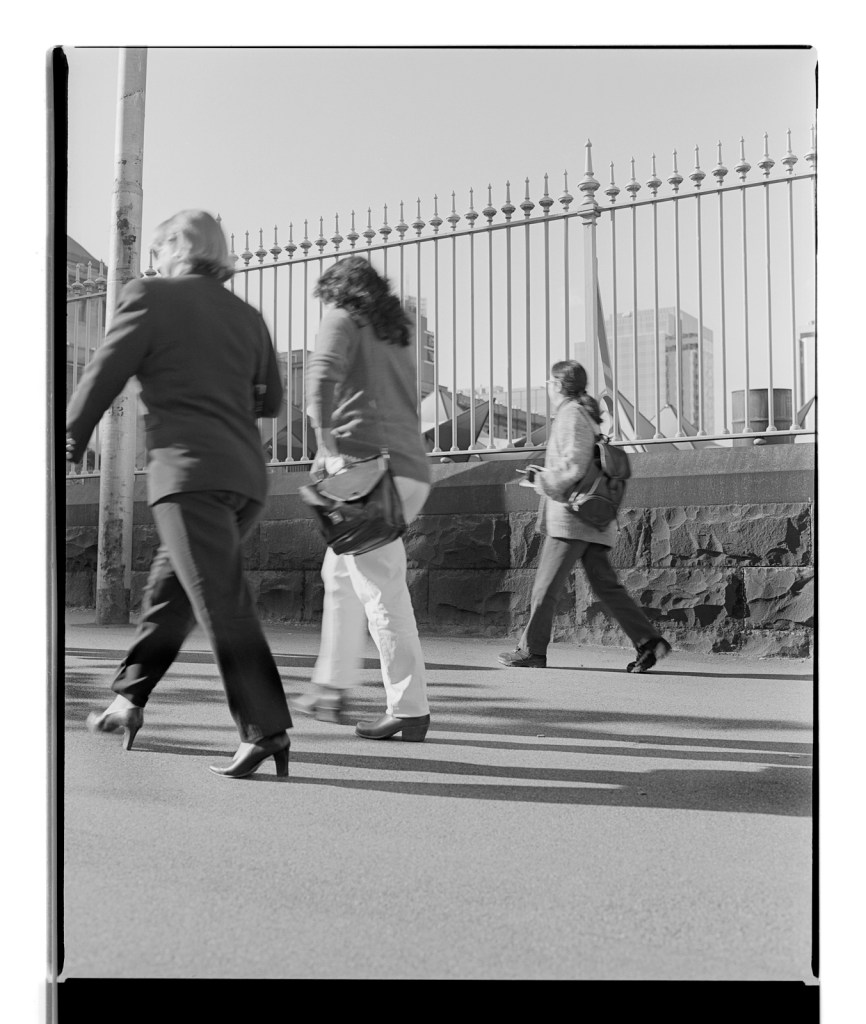

press++

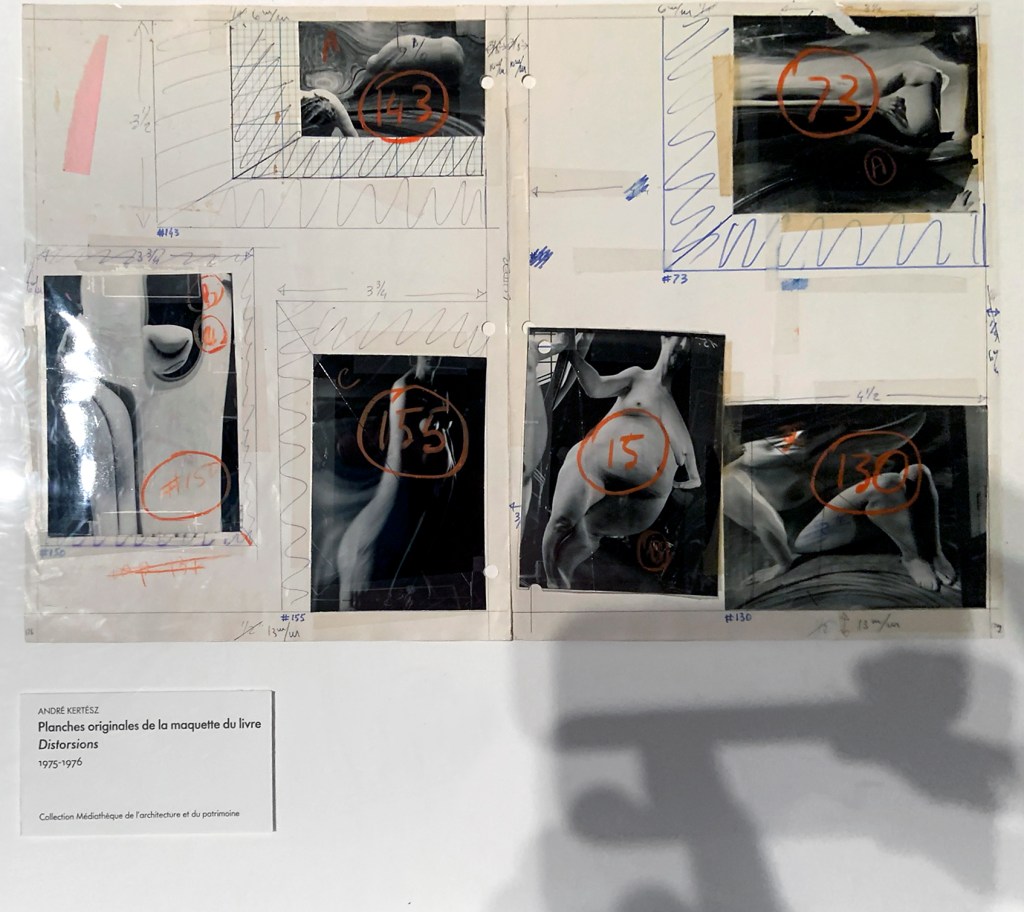

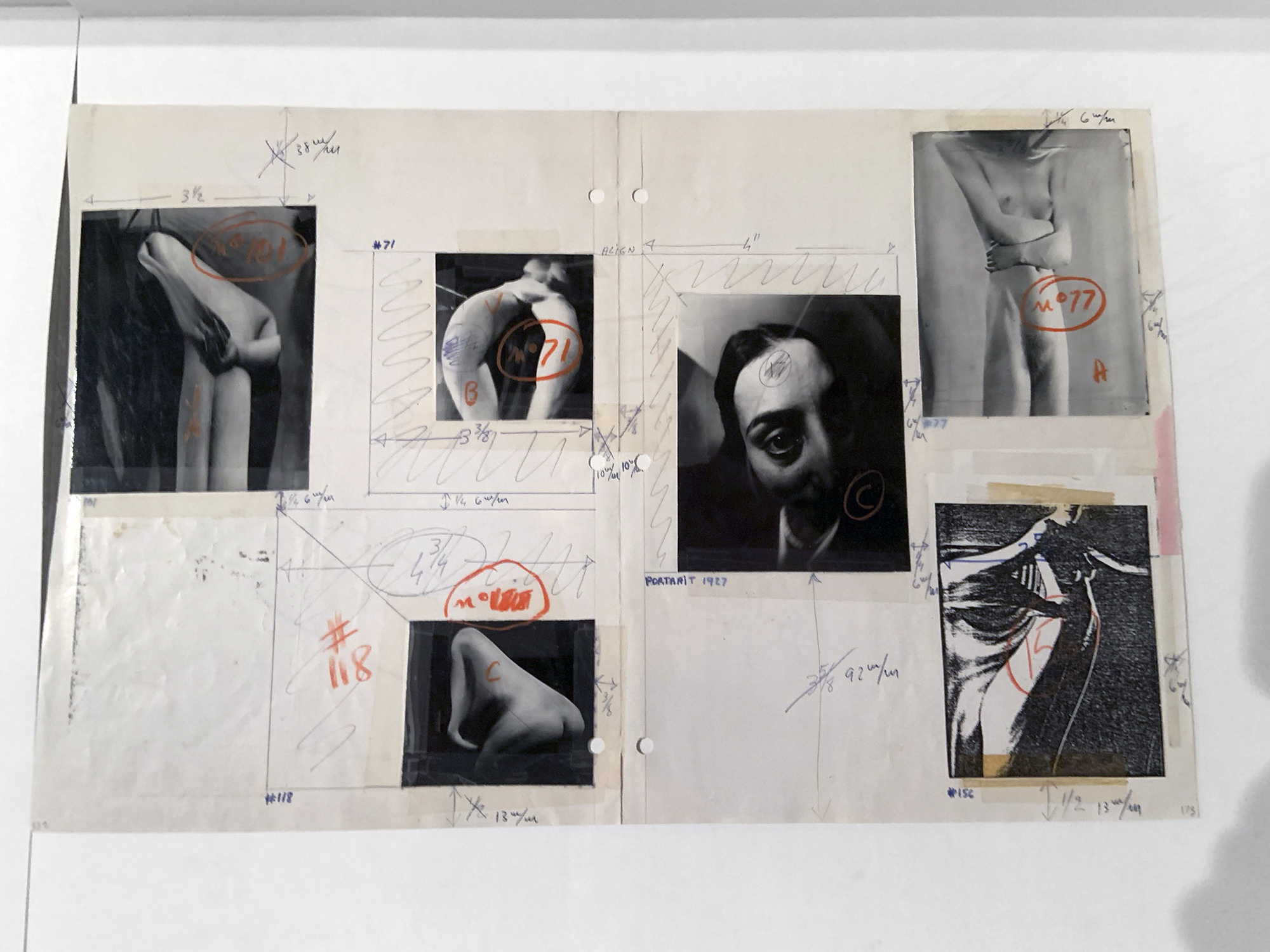

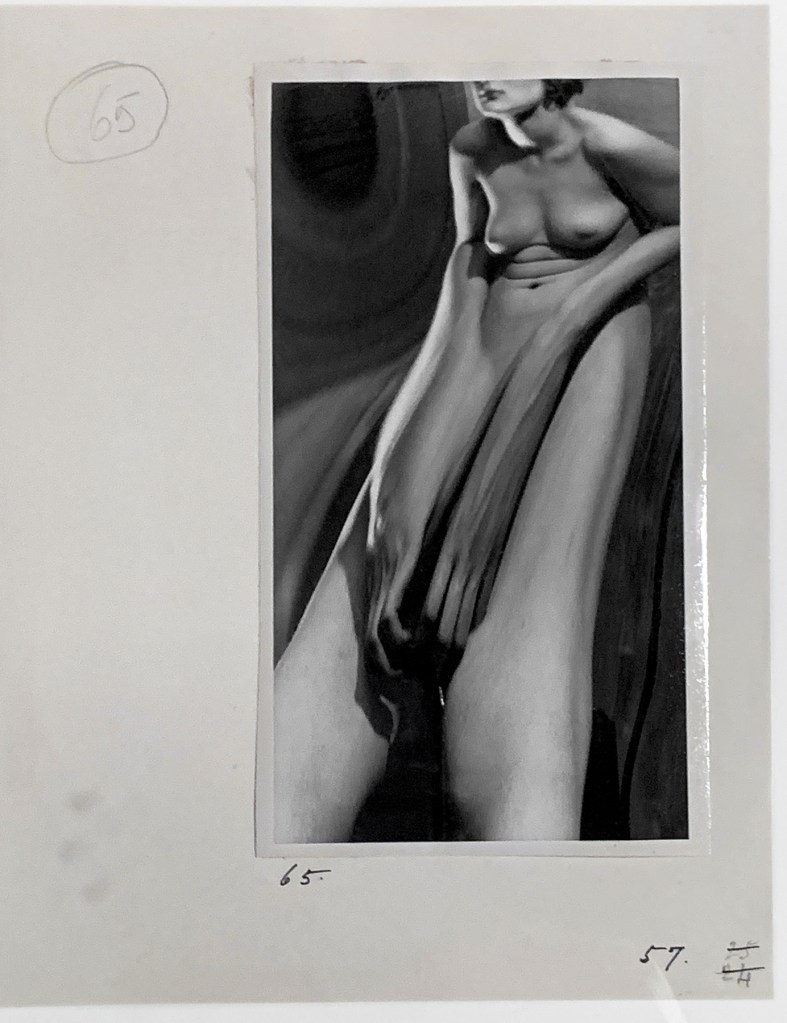

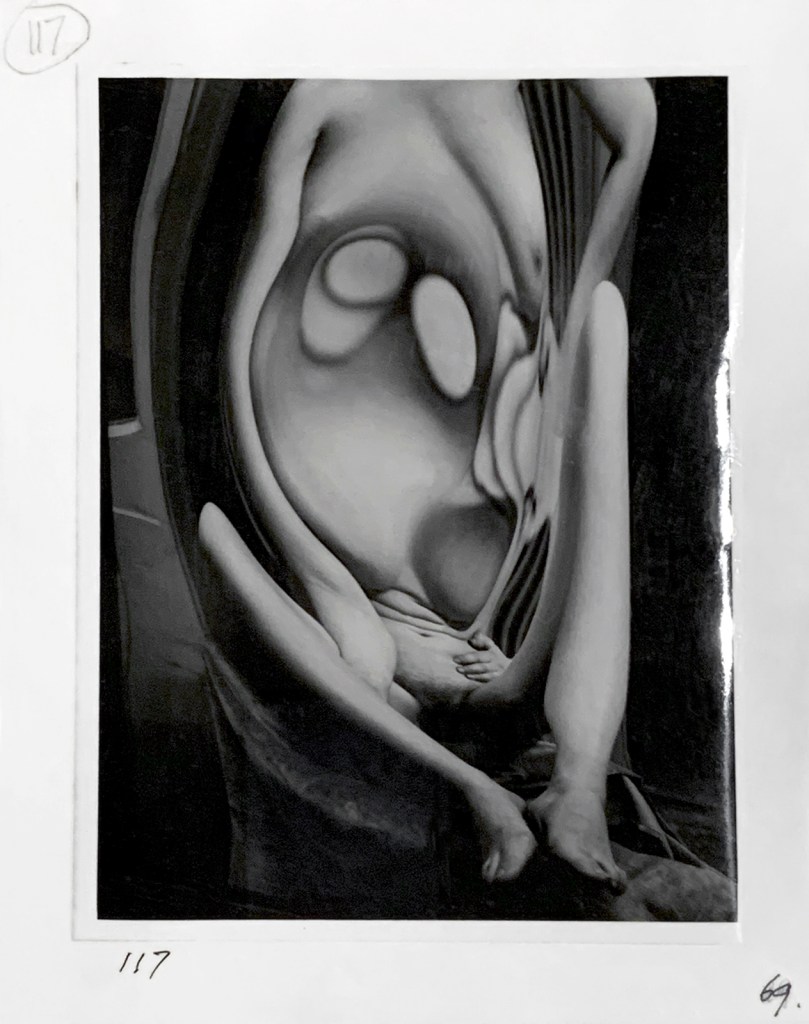

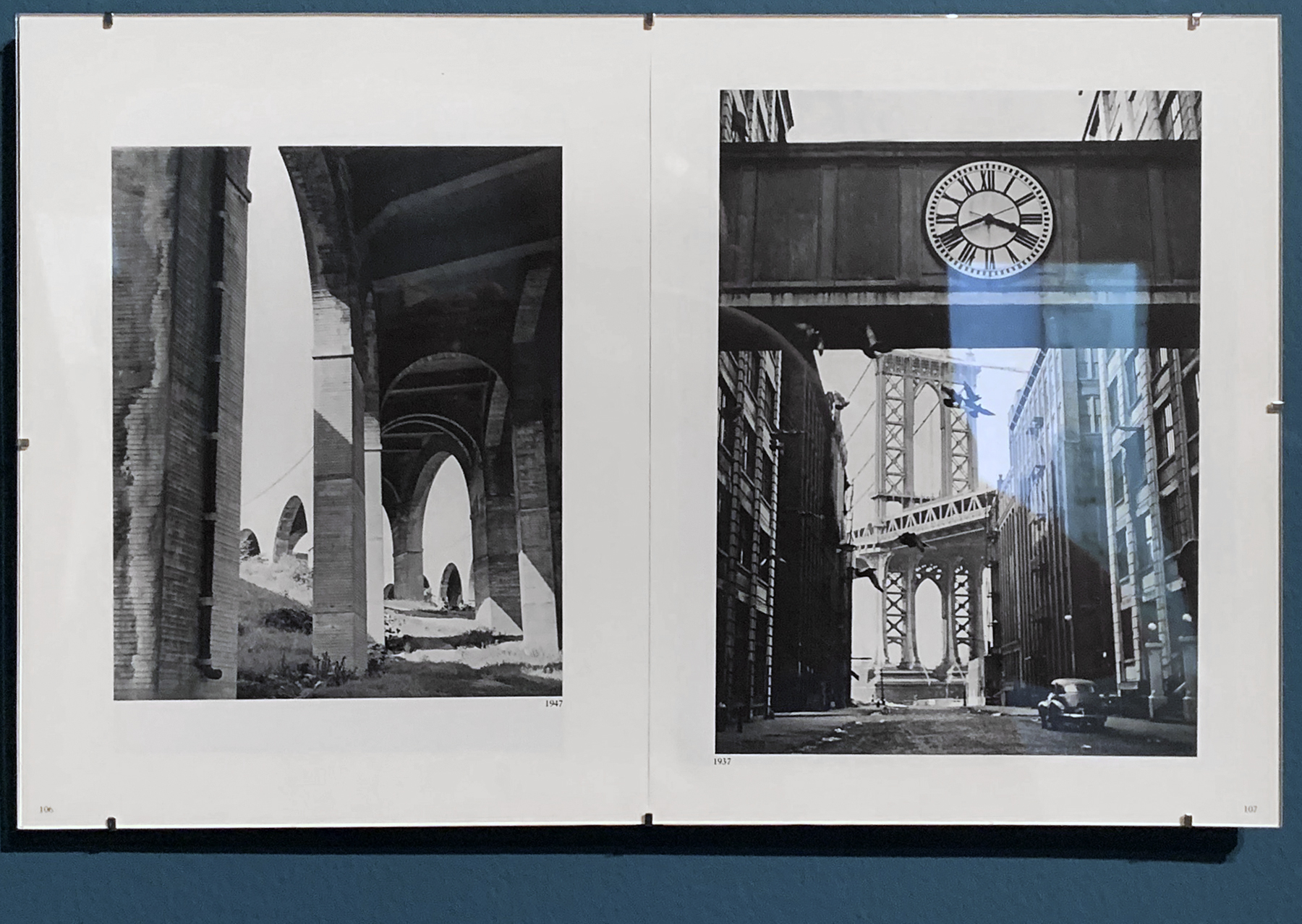

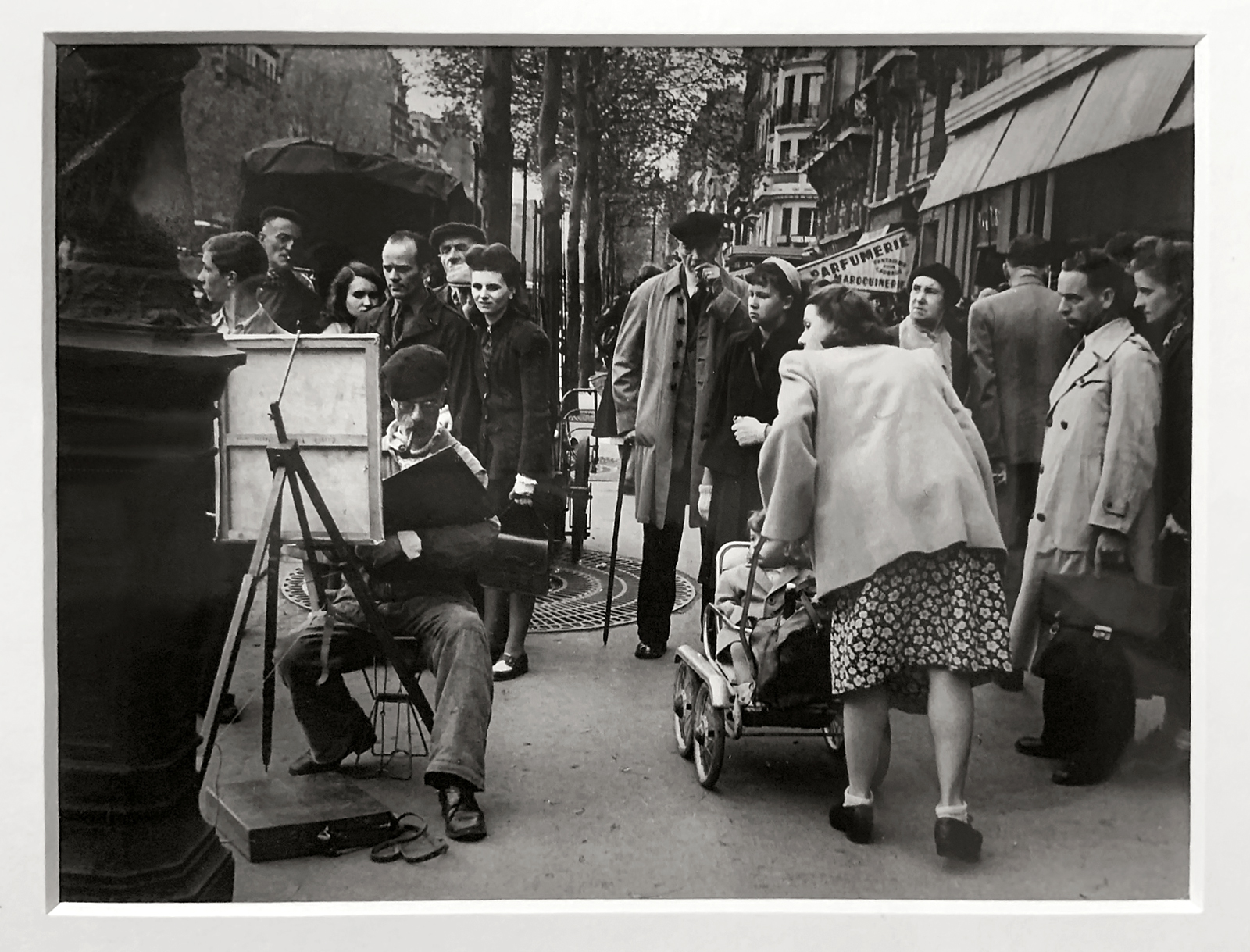

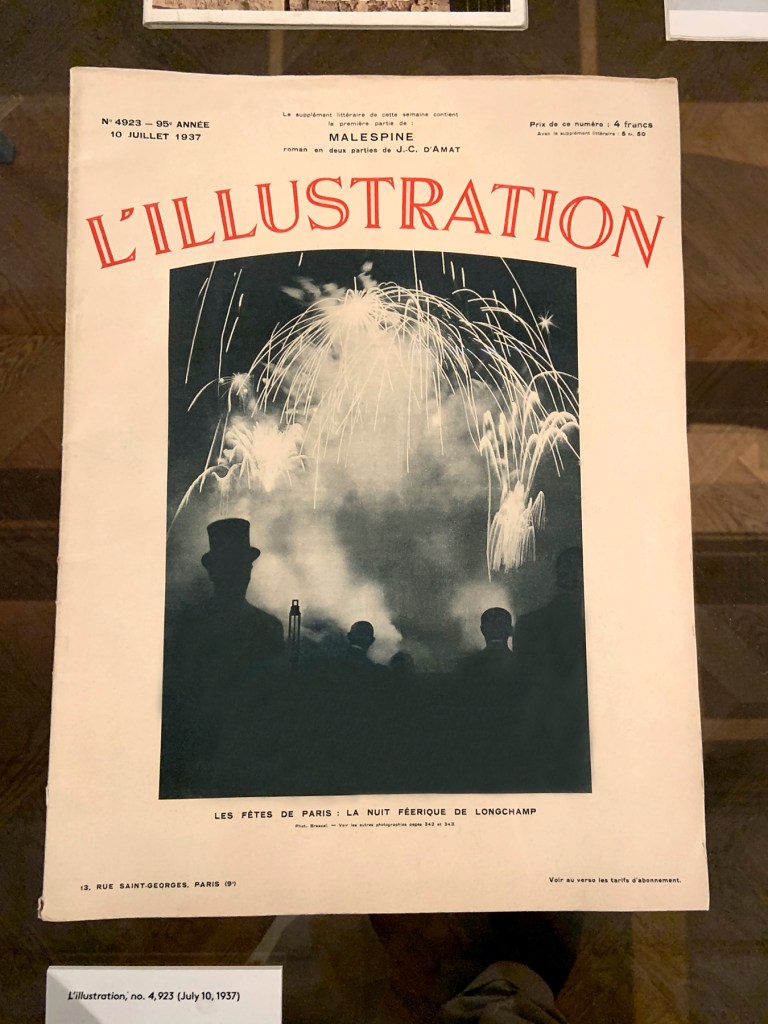

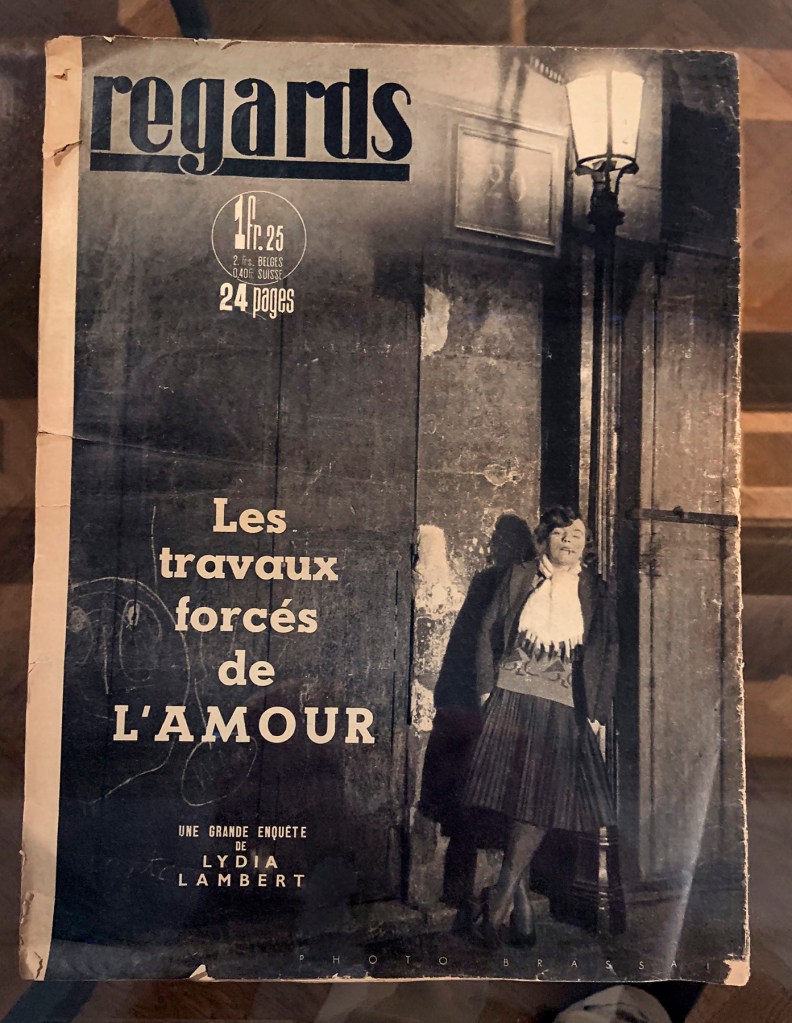

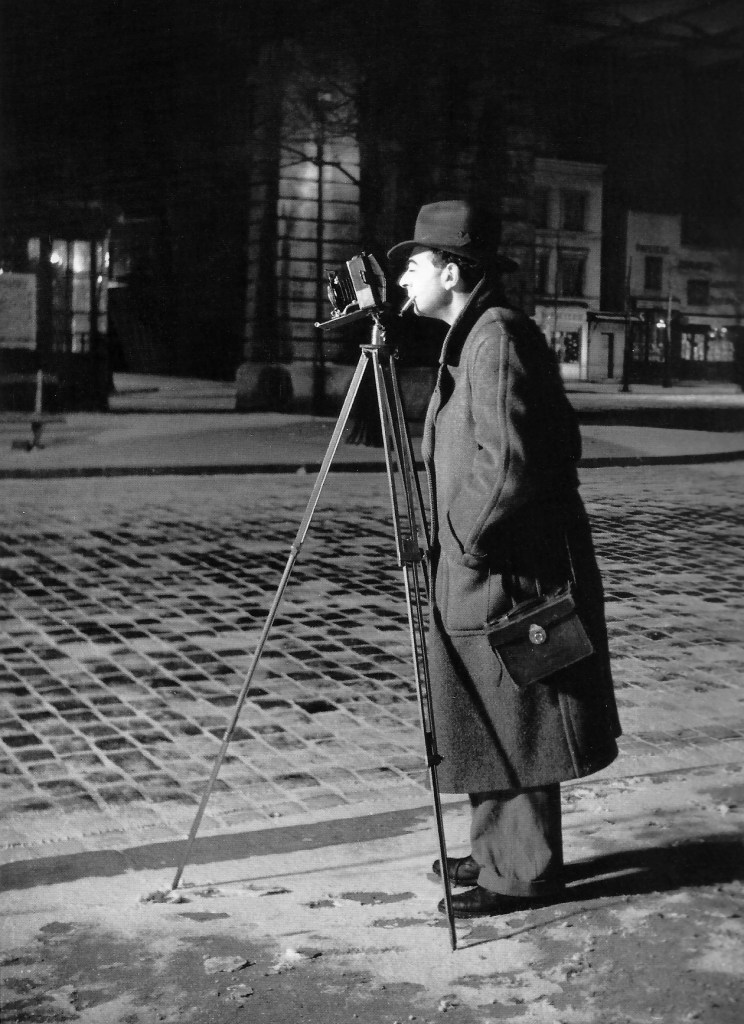

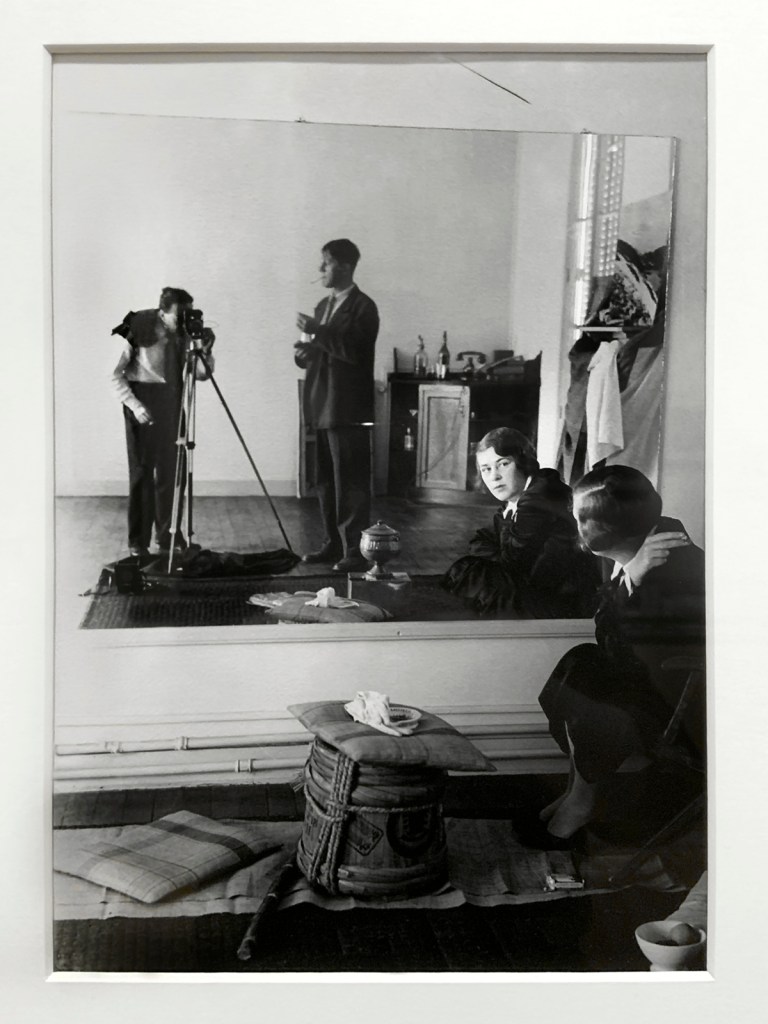

Black-and-white press photographs from the 1930s to the 1980s, which were taken primarily from American newspaper and magazine archives, are the source material for the press++ series. Thomas Ruff has been working on this series since 2015, scanning the front and back sides of the archive images and combining the two sides so that the partially edited photograph of the front side is fused with all the texts, remarks, and traces of use on the back side. When printed in large format, the often disrespectful handling of this type of photography becomes visible.

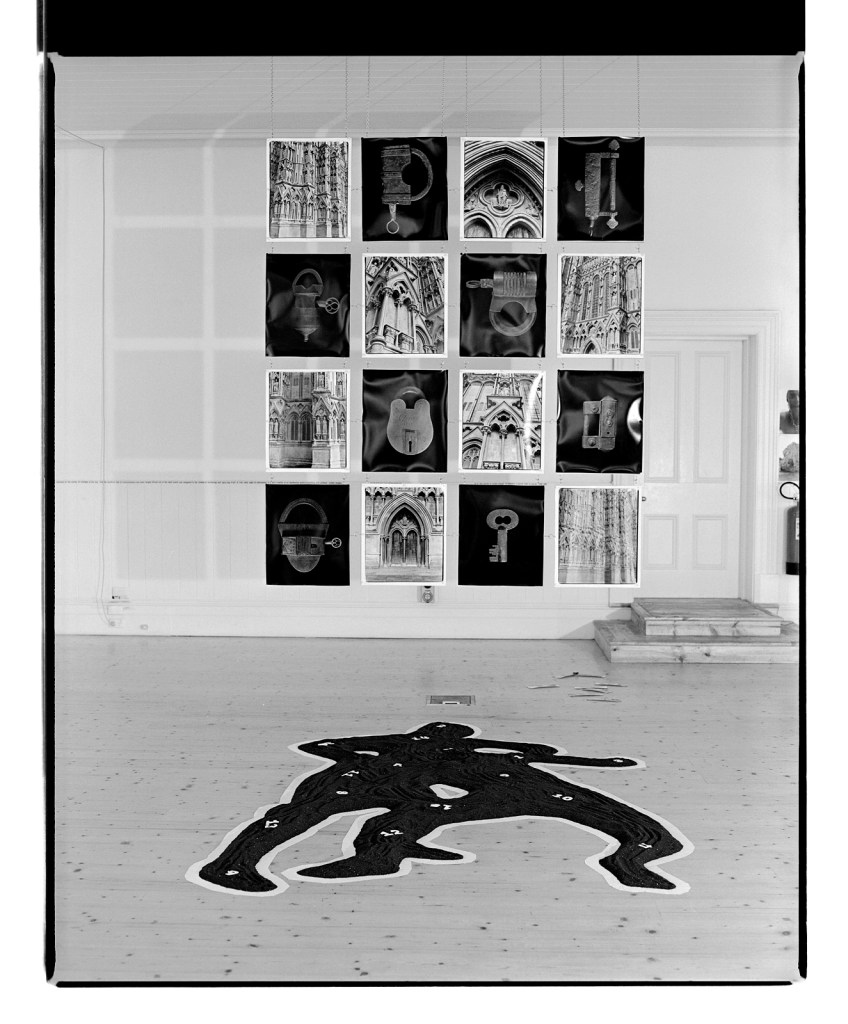

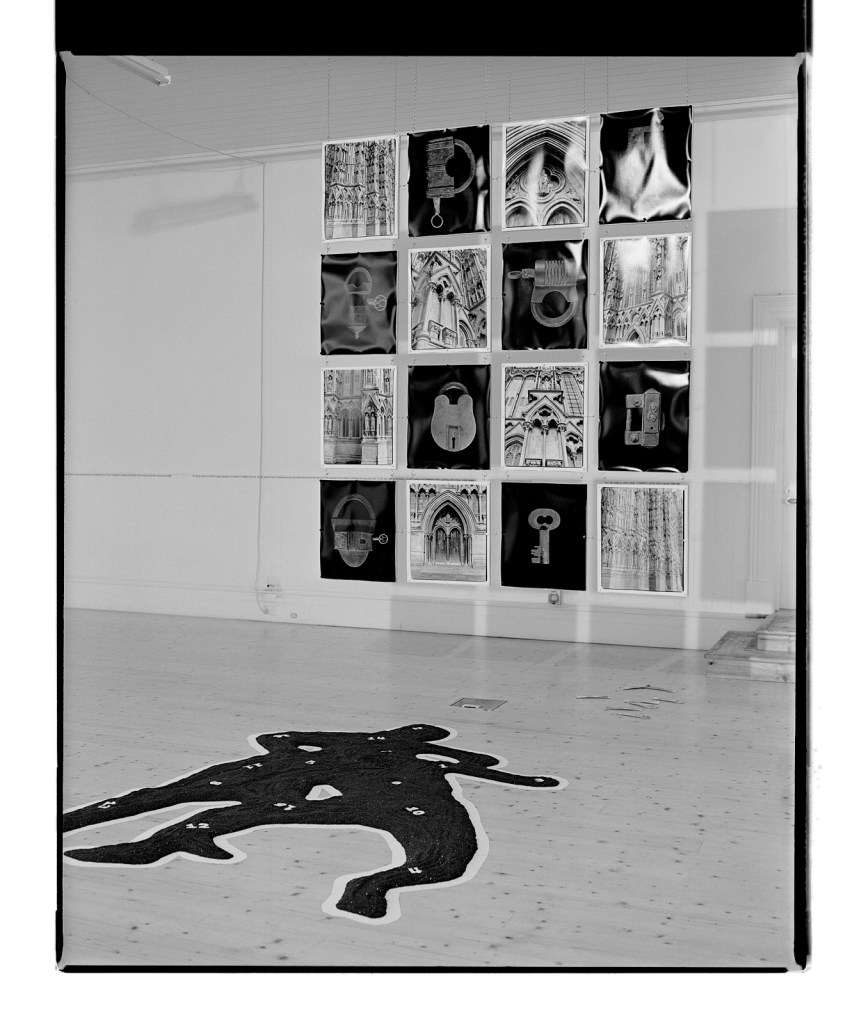

Thomas Ruff (German, b. 1958)

Kunstsammlung NRW, Düsseldorf 2020 showing photographs from Ruff’s series press++ (installation view)

WG Bildkunst 2020

Photo: WDR / Thomas Köster

Thomas Ruff (German, b. 1958)

press++ 60.10

2017

C-Print

225 x 185cm

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020

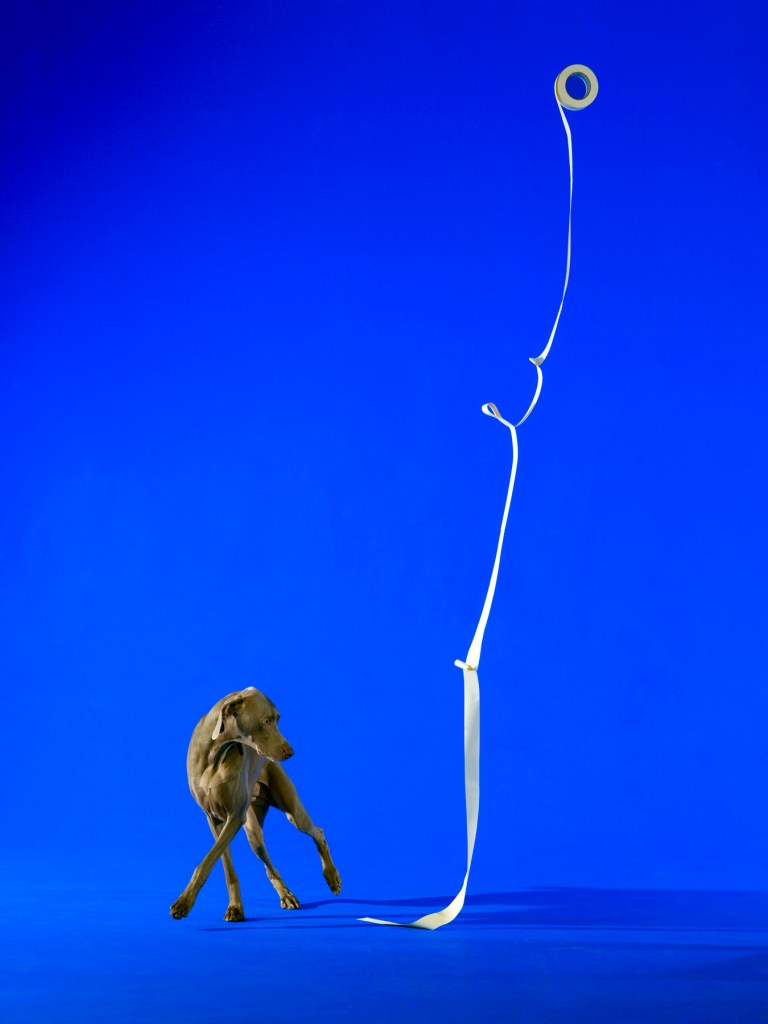

Going Digital

How are pictures made today? How do photos printed on paper differ from photos viewed on the Internet? Where are photos stored?

The investigation into the various pictorial genres leads to the archives and image stores of the past and present. The Internet offers seemingly inexhaustible sources of images by providing fast access to digitised, originally analog image material from older times and digitally created photographic material. As a researching artist, Thomas Ruff also finds here material for his studies, image production, and reflection.

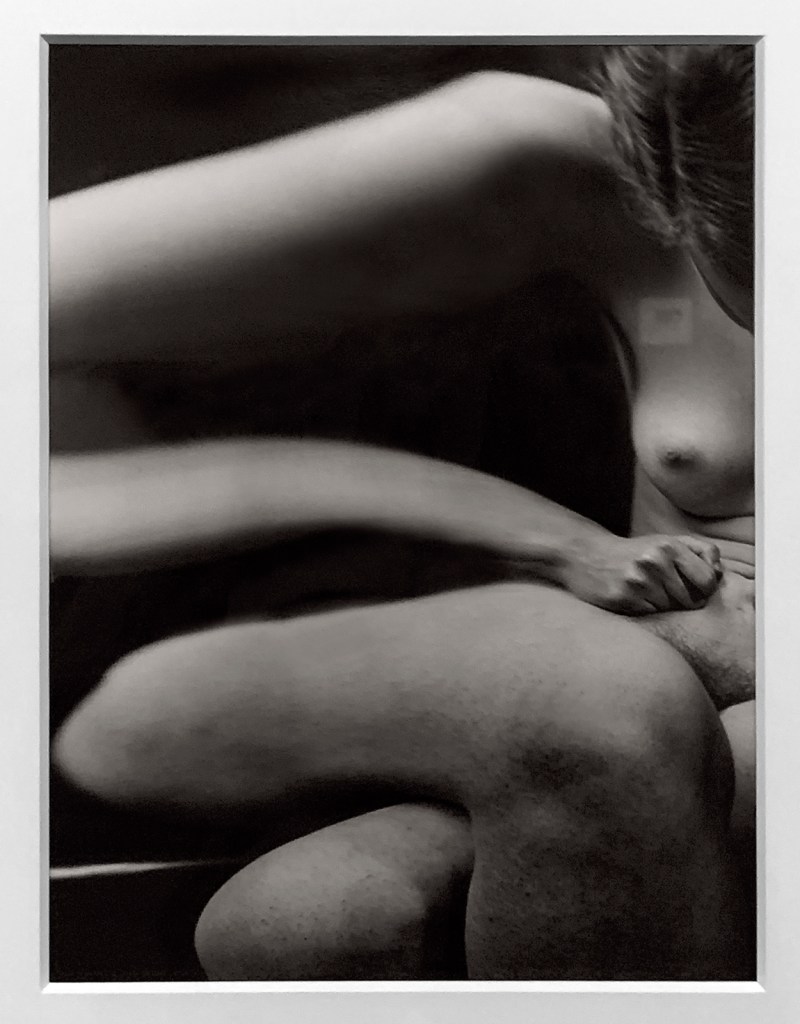

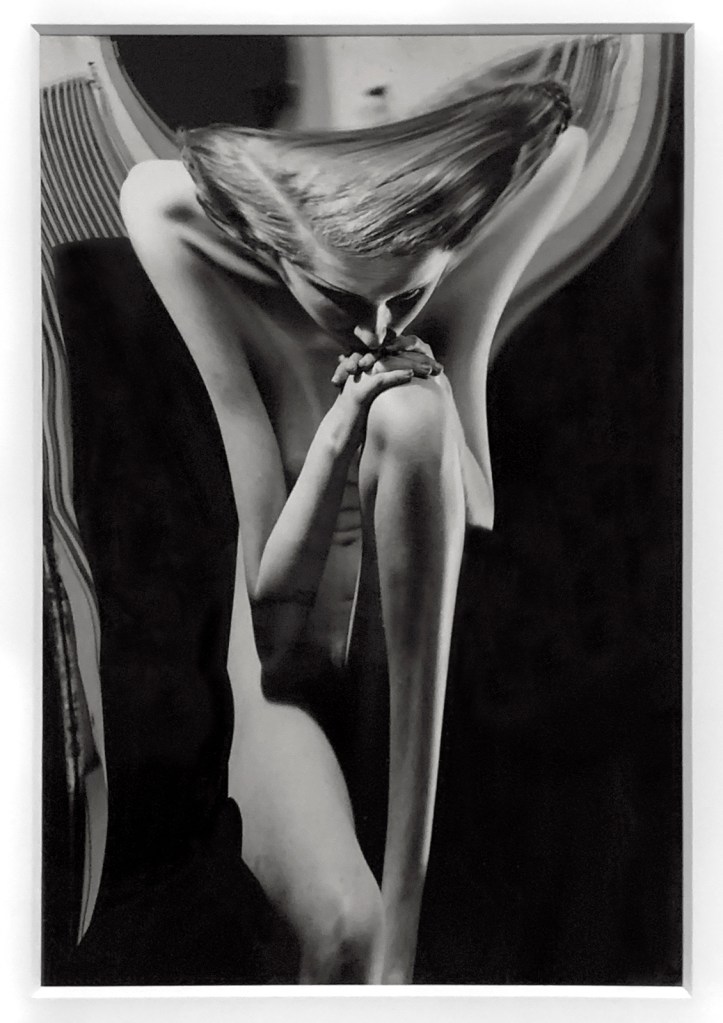

His large-format photos of the series nudes draw on motifs and forms of presentation of thumb nail galleries (compilations of small images as previews) with pornographic images as they can be found on the Internet. By making the coarse pixel structure of the Internet images of the turn of the millennium into a pictorial principle, he thematises the technical conditions of the photographic images in his works. With the series jpeg, he continued these investigations and connected his selection of media images with the question of a collective memory for images and contemporary history. In his latest series of Tableaux chinois, pixel structures create visual tension and irritation alongside the offset screens of the digitised printed products of Chinese propaganda of the Mao era – and suggest the question of the technical conditions of images at the time they were created.

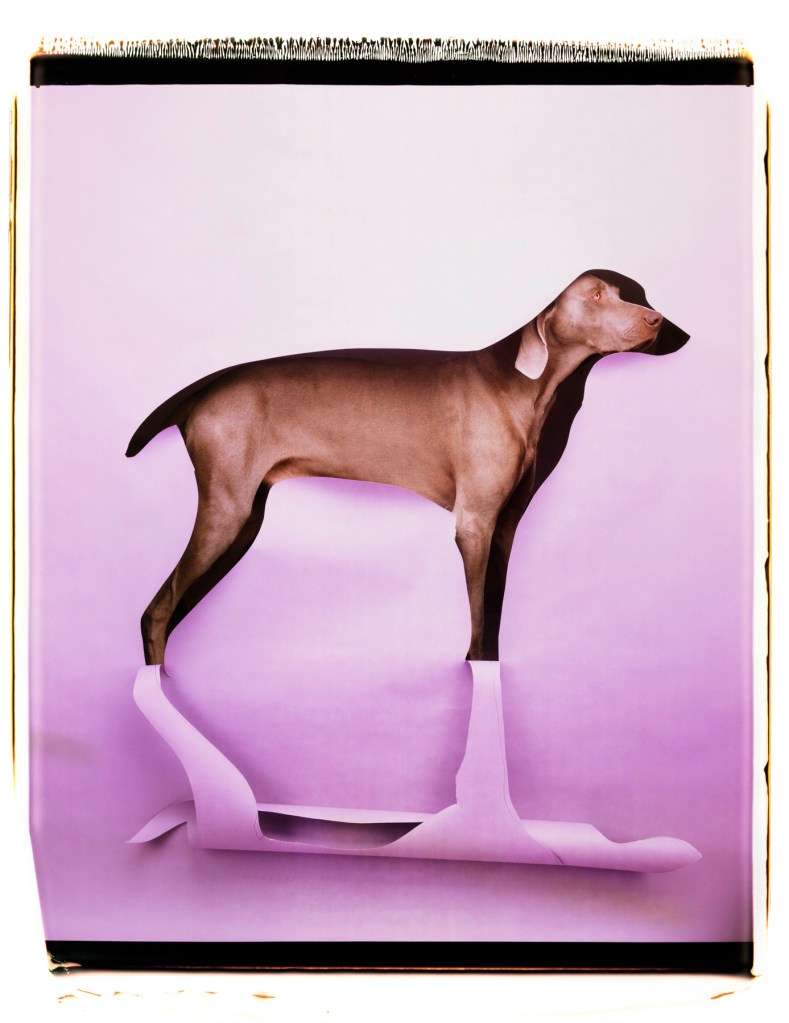

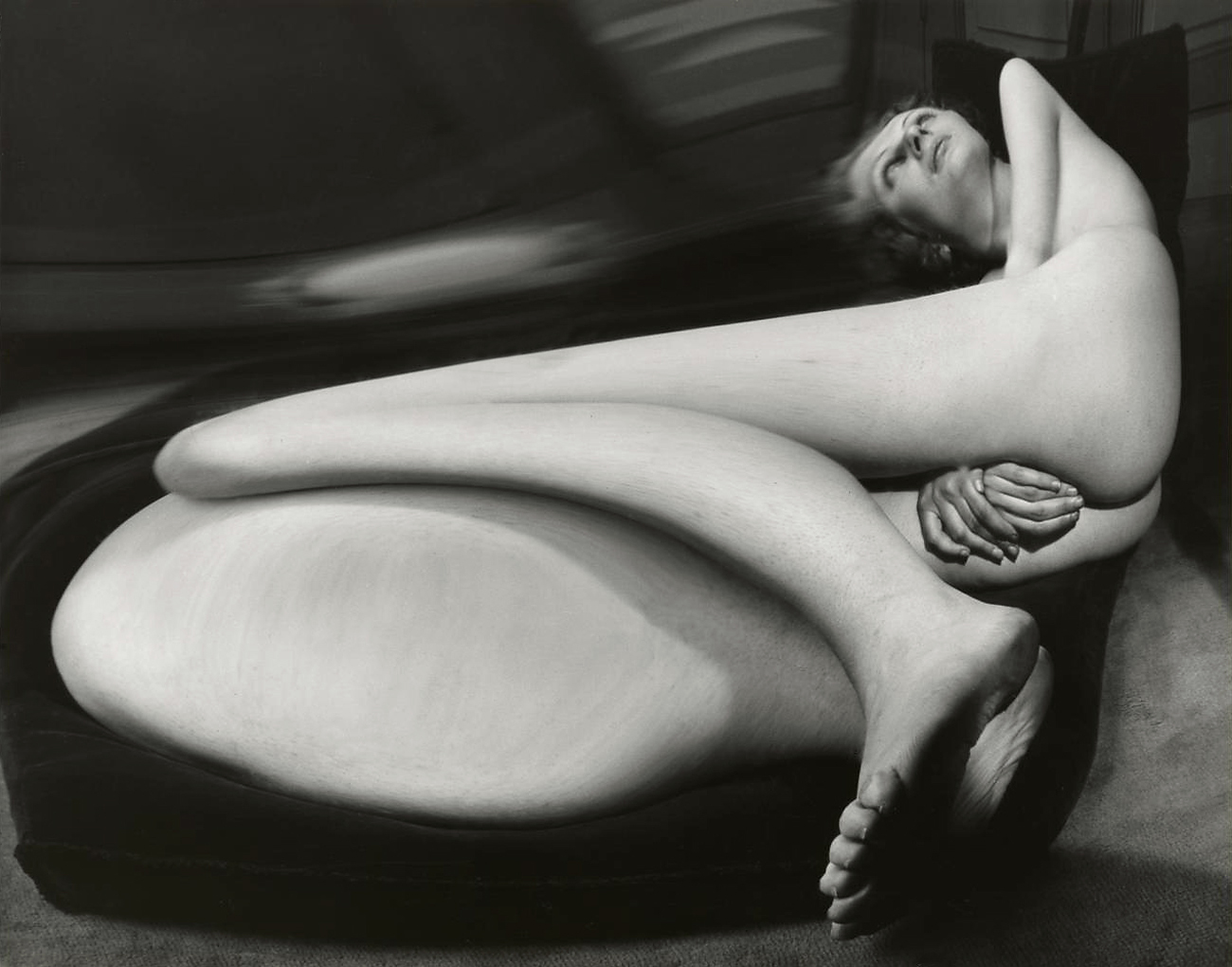

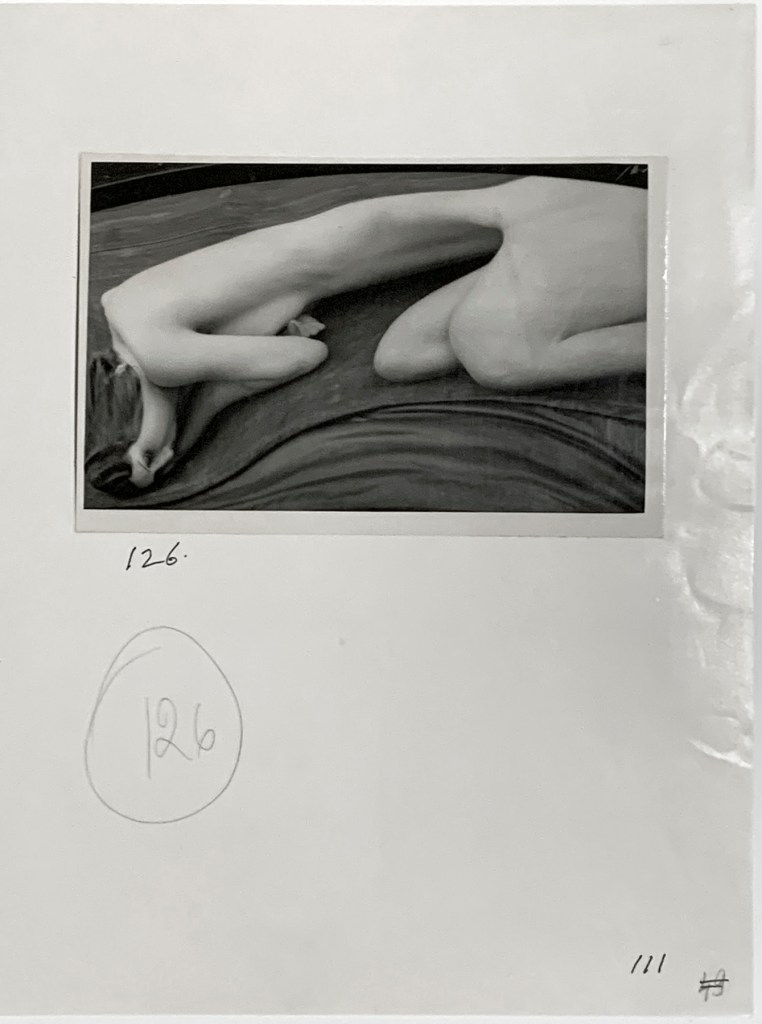

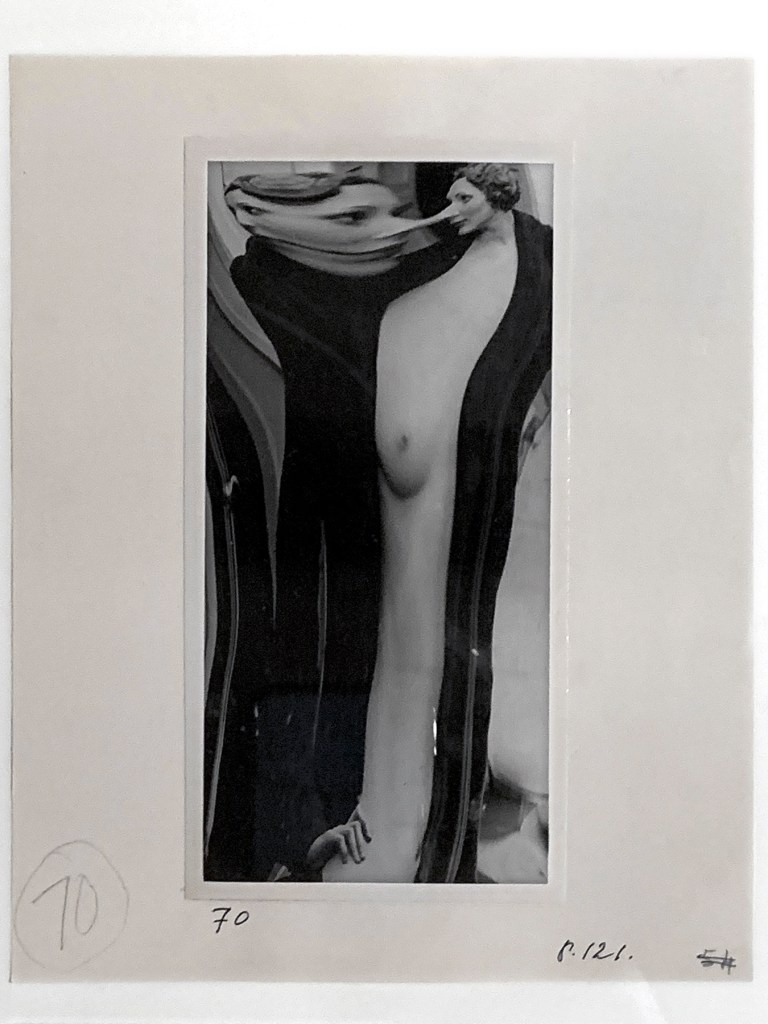

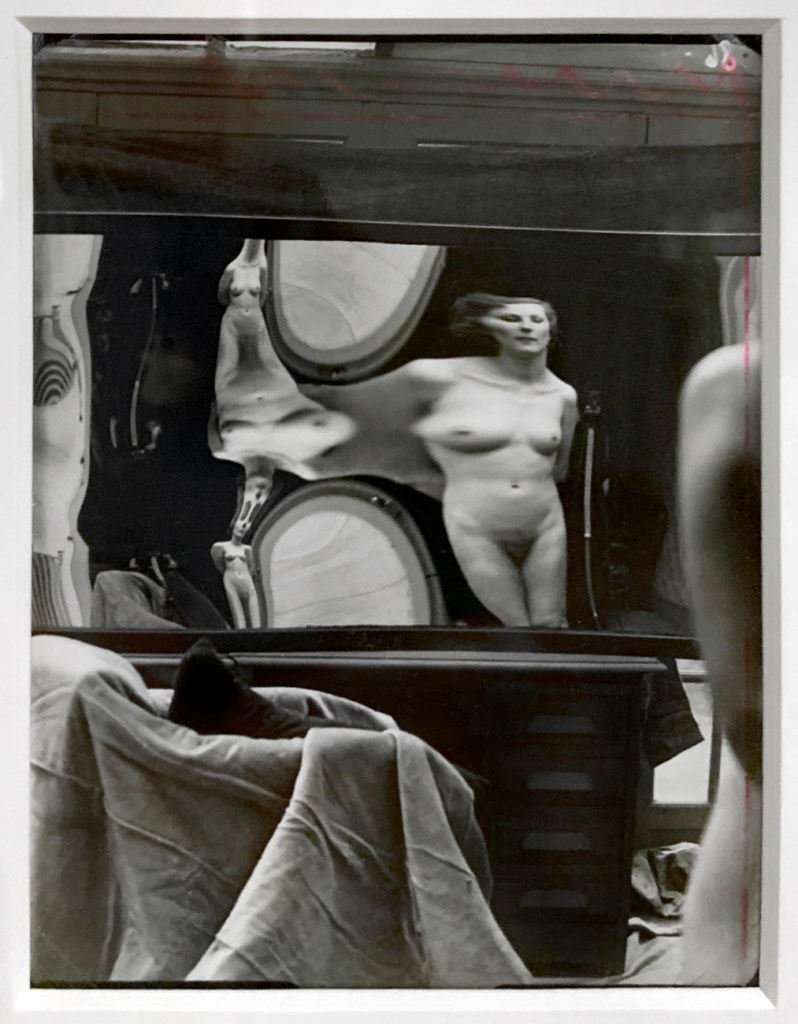

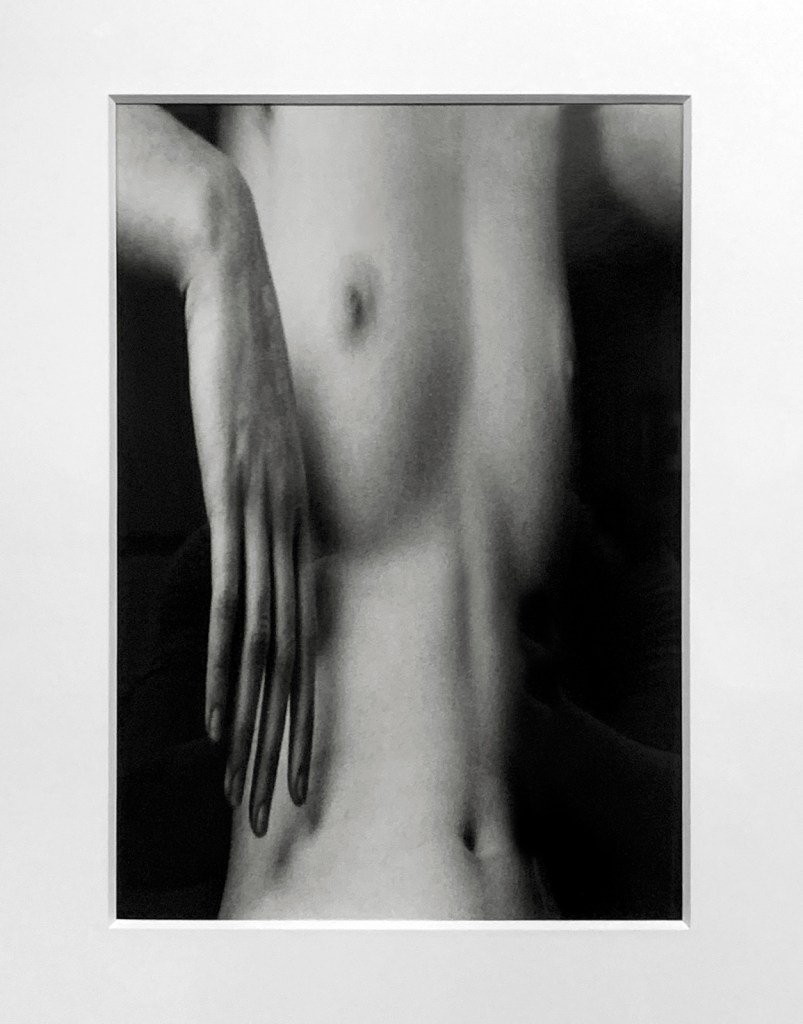

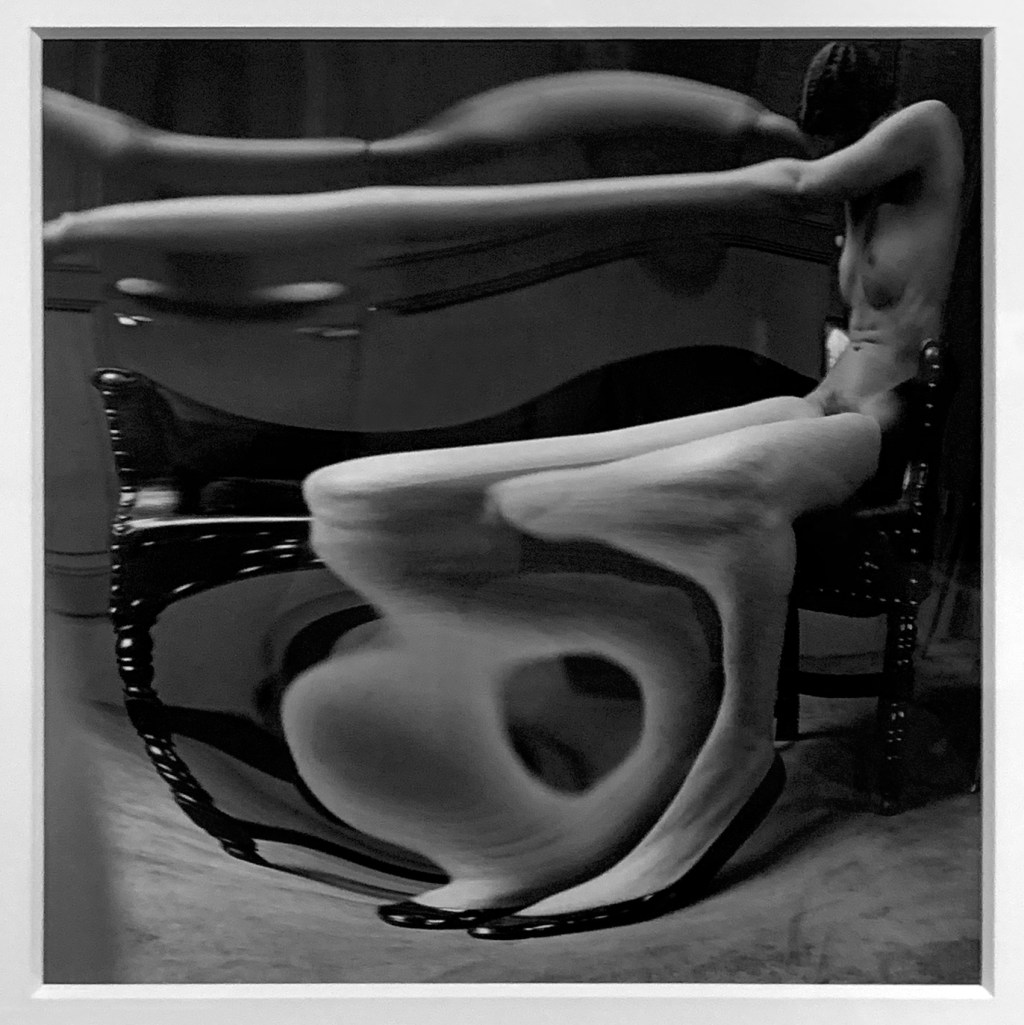

Thomas Ruff (German, b. 1958)

nudes pea10

1999

C-Print, Edition 1/2AP

102 x 129cm

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020

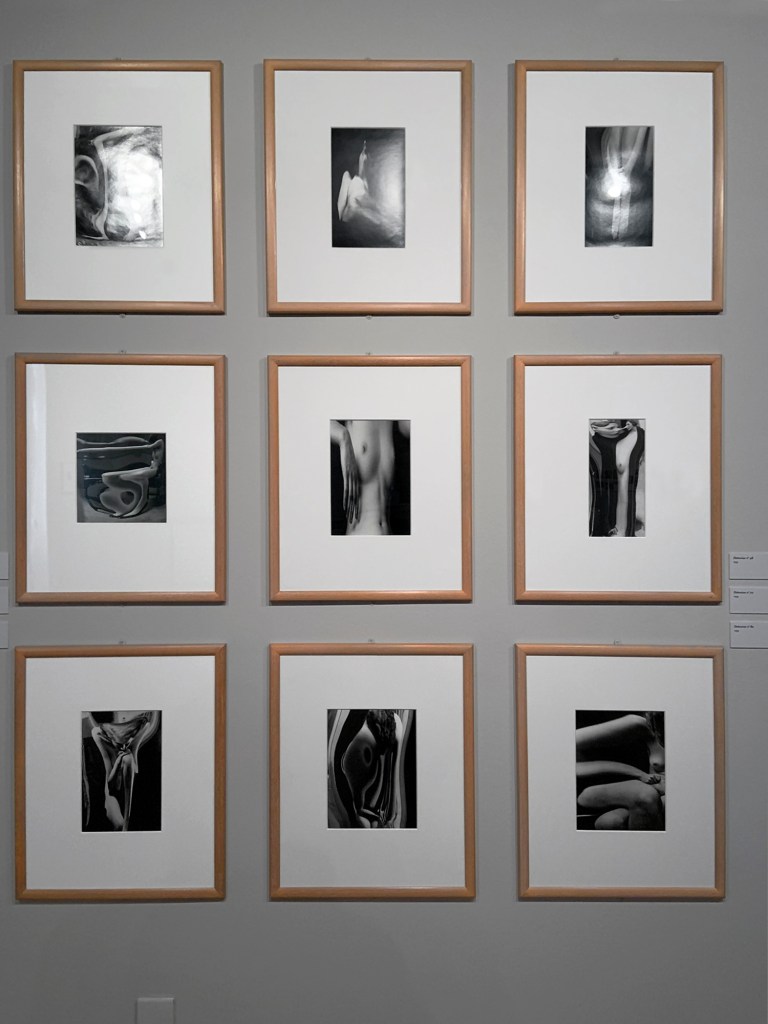

nudes

An Internet research into the genre of nudes drew Thomas Ruff’s attention to the field of pornography and the images that were freely available on the World Wide Web at the turn of the millennium. The motifs and the special formal features that characterised the state of the art at that time became the starting points for new works. The found pictures had a rough pixel structure, which had already aroused the artist’s interest before. Thomas Ruff processed the found pictures in such a way that their pixel structure was just barely visible in print. By using motion blur and soft focus, by varying the colours and removing details, he gave the “obscene” pictures a painterly appearance and directed the eye to the pictorial structure and composition. The artist selected his source images according to compositional aspects. The choice of motifs shows a broad spectrum of sexual fantasies and practices.

The Internet 20 years ago

Thomas Ruff began working on the series nudes in 1999. In the 1990s and early 2000s, the transmission rates of the World Wide Web were still relatively low. Although dial-up modems had been around since the 1970s, devices with a speed of 56 kBit/s did not come onto the market until 1998. Even dial-up via ISDN, which was available at much higher prices from 1989 onwards, only allowed 64 kBit/s. It was not until July 1999 that Deutsche Telekom switched on the first ADSL connections, enabling transmission rates of up to 768 kBit/s. Although two million households were already connected by the end of 2001, slow Internet remained the general rule, above all outside the metropolitan regions. Until well into the 2000s, website operators thus relied on the offering of highly compressed images.

As a result, photographic images found wide and rapid distribution, but always initially in a highly compressed, reduced form. Thomas Ruff was one of the first to deal artistically with the question of the status of photography in the age of the Internet, with the series nudes from 1999 onwards and the series jpeg from 2004 onwards.

Thomas Ruff (German, b. 1958)

Kunstsammlung NRW, Düsseldorf 2020 showing work from Ruff’s nudes (installation view)

WG Bildkunst 2020

Photo: WDR / Thomas Köster

Thomas Ruff (German, b. 1958)

jpeg ny01

2004

C-Print, Edition 1/1AP

256 x 188 cm

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020

Thomas Ruff (German, b. 1958)

jpeg msh01

2004

C-Print

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020

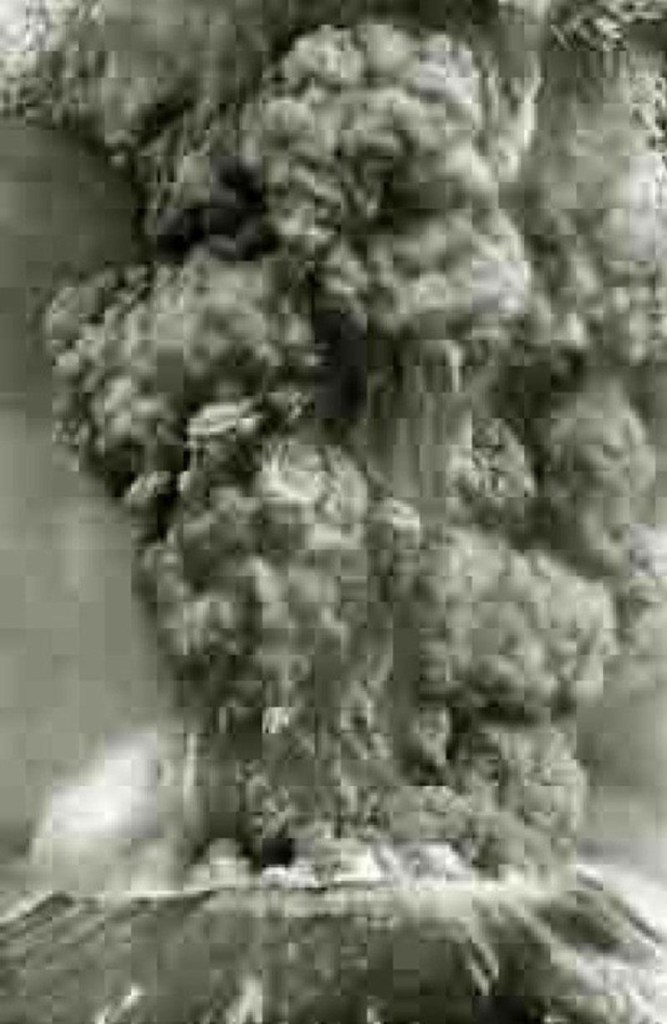

jpeg

Images distributed worldwide through the Internet, as well as scanned postcards and illustrations from photobooks, are the visual starting point of the jpeg series, on which Thomas Ruff has been working since 2004. In it, he focuses attention on a feature that determines all images compressed in JPEG format and becomes visible at high magnification. By intensifying the pixel structure and simultaneously enlarging the overall image, he creates a new image that resembles a geometric colour pattern when viewed closely but becomes a photographic image when viewed from a greater distance. Here, Ruff uses ideas from the painting of late Impressionism and combines these with the digital possibilities of the twenty-first century. By using the entire range of images published globally and simultaneously discussed in recent decades, he allows the series to become almost a visual lexicon of media imagery and a reflection of its characteristics determined by the medium.

Thomas Ruff (German, b. 1958)

Installation view K20, Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen showing work from Ruff’s jpeg series

Photo: Achim Kukulies

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020

Propaganda Images

What are photos used for? Which reality do photos depict? How do photos affect reality?

In addition to the motifs and the formal as well as technical possibilities of photography, Thomas Ruff examines the possible uses of photos. With his adaptations of images from Chinese propaganda material, he makes the ideological appropriation and manipulative character of the images his theme.

Thomas Ruff (German, b. 1958)

Installation view K20, Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen showing work from Ruff’s tableaux chinois series

Photo: Achim Kukulies

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020

Thomas Ruff (German, b. 1958)

tableau chinois_03

2019

C-Print, Edition 01/04

240 x 185cm

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020

Thomas Ruff (German, b. 1958)

tableau chinois_01

2019

C-Print

240 x 185cm

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020

Tableaux chinois

For many years, Thomas Ruff has been preoccupied with the subject of propaganda imagery. For Tableaux chinois, the artist scanned images from books on Mao published in China, as well as from the magazine‚ La Chine, published and distributed worldwide by the Chinese Communist Party. He stored them in such a way that the offset raster screen was preserved. He then duplicated the images and converted the offset raster of the duplicates into a large pixel structure. As a result of a long editing process on the computer, a composition is created which brings together the characteristics of the various time-related media and exposes the propaganda image as manipulated.

Thomas Ruff (German, b. 1958)

Installation view K20, Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen showing work from Ruff’s tableaux chinois series

Photo: Achim Kukulies

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020

Thomas Ruff (German, b. 1958)

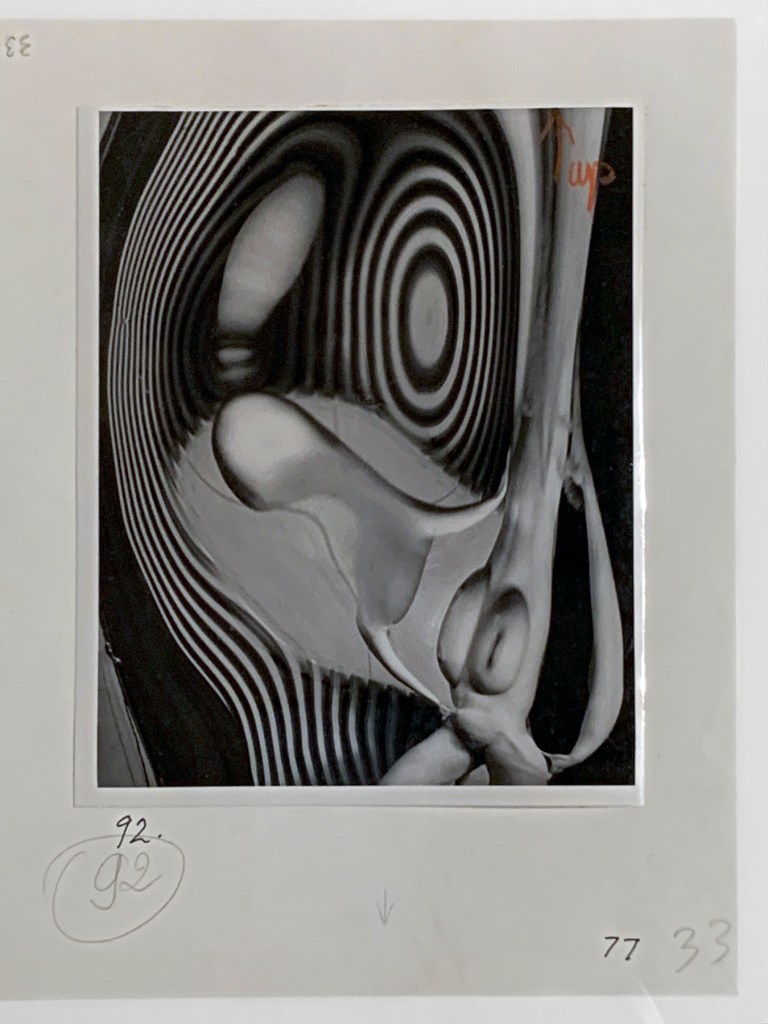

r.phg.07_II

2013

C-Print

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020

On Par with the Pioneers

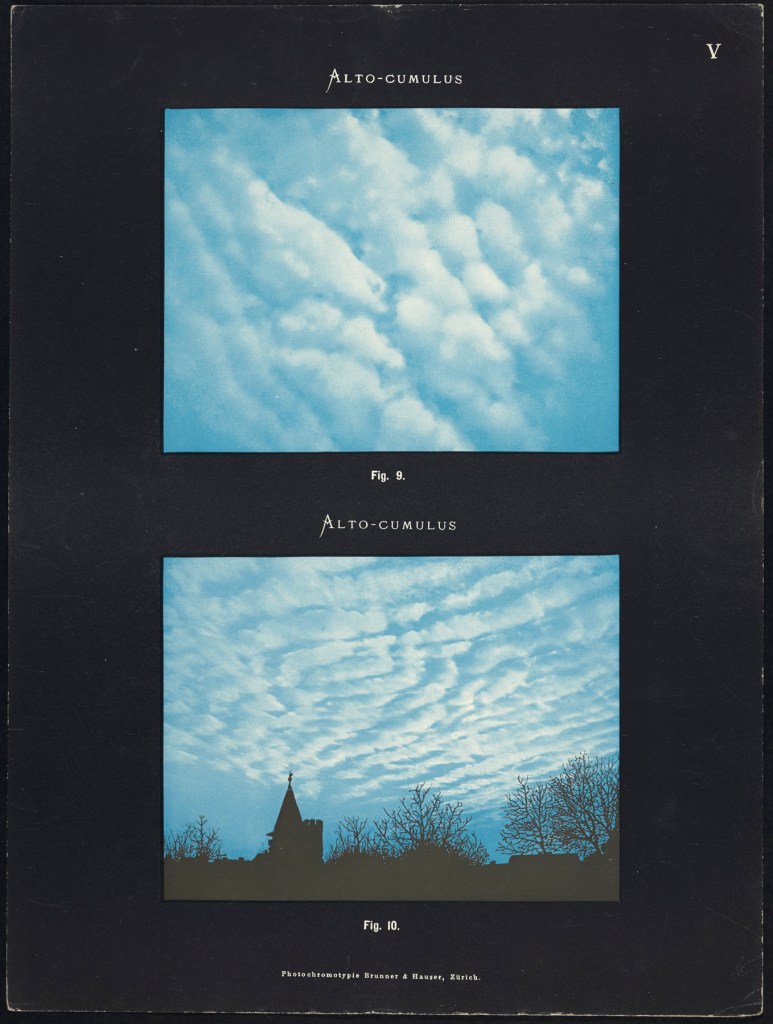

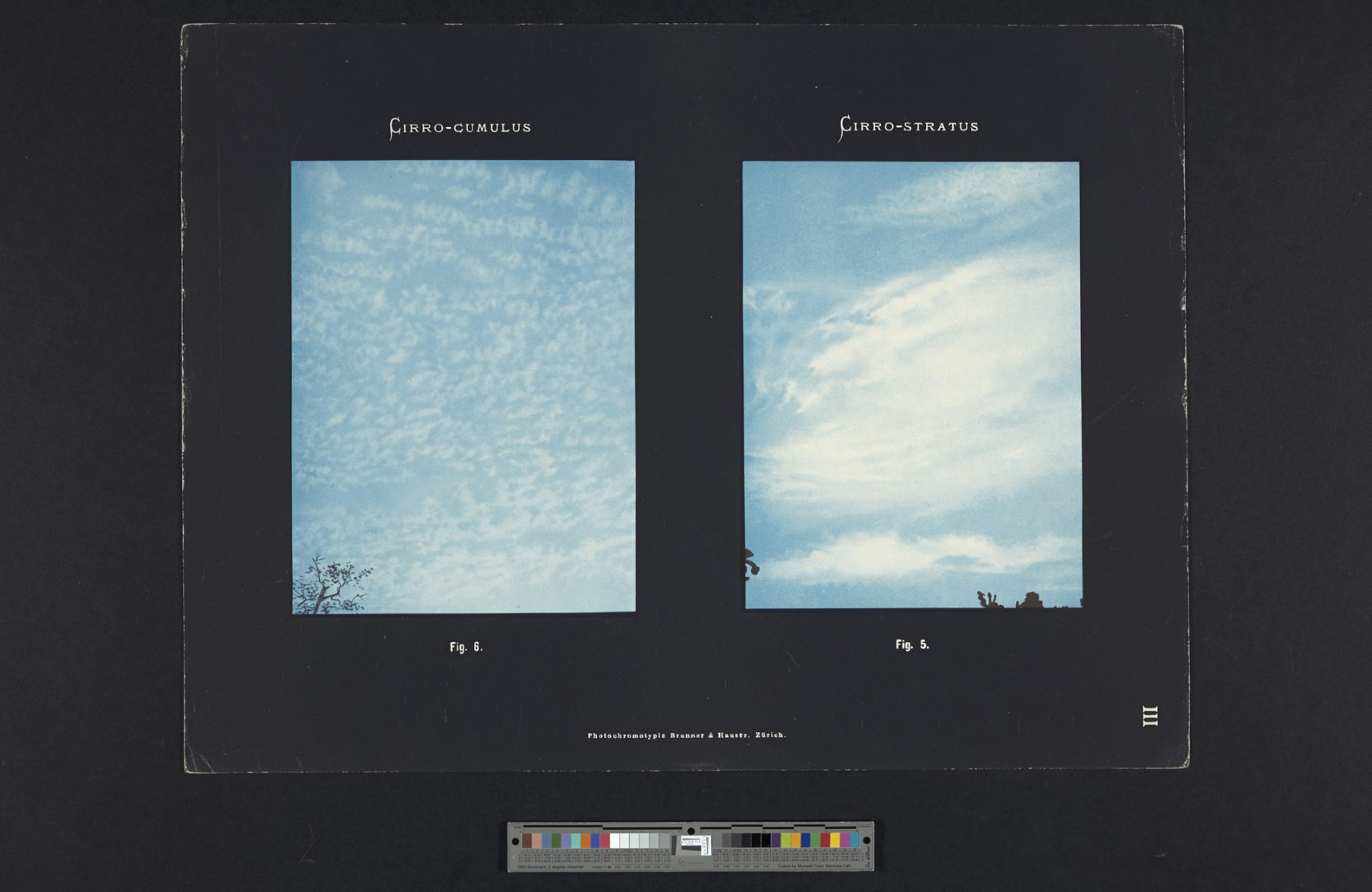

What is a negative? How have photographic techniques changed in the course of history? Does a digital image look different from an analog photo?

The transition from analog to digital photography took place in the 1990s, at a time when Thomas Ruff was already successful on an international level. In addition to the characteristics of digitally processed and circulated photos, he examined the special features of the production and processing of analog photography. The exhibited photo series reveal Ruff’s engagement with nearly 170 years of photographic history and technology.

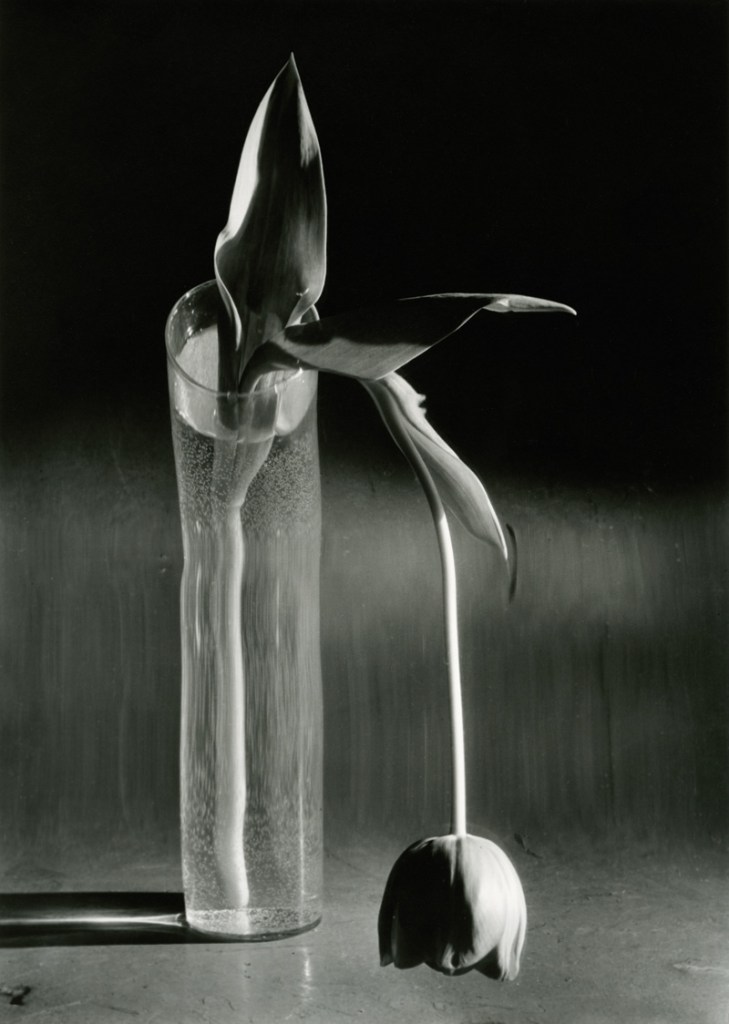

The series Negative pays tribute to the function and particular aesthetics of the negative, which recorded the image information in the light-sensitive coating of a transparent plate and had to be exposed again on prepared paper. The works in the series Tripe focus on the specific possibilities of working with the variant of paper negatives. Ruff reconstructs and explores the effect of pseudo-solarisation – as the great image magicians and experimenters of the 1920s and 1930s explored and used this – with analog and digital means in the series flower.s.

Thomas Ruff (German, b. 1958)

r.phg.08_II

2015

C-Print

185 x 281cm

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020

Thomas Ruff (German, b. 1958)

Installation view K20, Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen showing work from Ruff’s photograms series

Photo: Achim Kukulies

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020

Thomas Ruff (German, b. 1958)

Installation view K20, Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen showing at right a work from Ruff’s photograms series

WG Bildkunst 2020

Photo: WDR / Thomas Köster

Fotogramme

Fascinated by photograms of the 1920s, Thomas Ruff decided to explore the genre and develop a contemporary version of these camera-less photographs. Beyond the limitations of analog photograms, the artist has been developing his versions of photograms since 2012, using a virtual darkroom to simulate a direct exposure of objects on photosensitive paper.

With this, he was able to place objects (lenses, rods, spirals, paper strips, spheres, and other objects) generated with the help of a 3D program on or over a digital paper, correct their position, and in some cases expose them to coloured light. He could thus control the projection of the objects on the background in virtual space and print the image calculated by the computer in the size he wanted. In this way, he succeeded in capturing the concepts and aesthetics of the pioneers of “kameralosen Fotografie” in the 1910s and 1920s, generating images with light and transporting them into the twenty-first century using a technique appropriate to his own time.

Digital photograms with many different coloured light sources and transparent objects could not be produced with the equipment available to Thomas Ruff in 2014. The computing process required such high capacities that Ruff’s computers would have needed over a year for each image. In 2014, he was given the opportunity to have photograms calculated by a mainframe computer at the Supercomputing Centre of the Forschungszentrum Jülich. This required roughly eighteen terabytes of data for each image.

Thomas Ruff (German, b. 1958)

Installation view K20, Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen showing at left a work from Ruff’s photograms series

WG Bildkunst 2020

Photo: WDR / Thomas Köster

Thomas Ruff (German, b. 1958)

neg◊lapresmidi_01

2016

C-Print

23.4 x 31.4cm

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020

Negative

In 2014, Thomas Ruff began to work more intensively on the visual appearance of the source material of analog photography, the “negative”. In order to make its photographic reality and pictorial quality visible, he transformed historical photographs into “digital negatives” In the process, not only the light-dark distribution in the image changed; the brownish hue of the photographs printed on albumin paper also became a cool, artificial blue tone.

The aim of the processing was to highlight the photographic “negative”, which, in analog photography, was never the object of observation, but always a means to an end. In this series, it is treated as an “original” worth viewing, from which a photographic print is made, and which is in danger of disappearing completely due to digital photography.

The series covers the entire spectrum of historical black-and-white photography and is divided into different subgroups. On display are the series neg◊lapresmidi and neg◊marey.

L’Après-midi d’un faune

For more than ten years, Stephane Mallarmé worked on his poem‚ L’Après-midi d’un faune (The Afternoon of a Faun), which was published in 1876. This complex Symbolist poem tells of the encounter of a faun with a group of nymphs. In the end, the nymphs disappear. What remains is their shadow in the form of writing: the poem itself.

The work inspired the composer Claude Debussy to write his radical symphonic poem‚ Prélude à l’Après-midi d’un faune in 1894. Debussy did not want to illustrate the poem, but rather to evoke an enraptured mood that corresponds to the drowsiness of Mallarmé’s faun. At the same time, he referred structurally to the 110-line poem: Debussy’s‚ Prélude also has 110 bars.

1912 saw the premiere of‚ L’Après-midi d’un faune, the first scandalous choreography by the ballet dancer Vaslav Nijinsky. The dancers moved to Debussy’s music almost continuously in profile and along particular planes. The movements were consciously intended to be reminiscent of the linear concept of Greek vase painting.

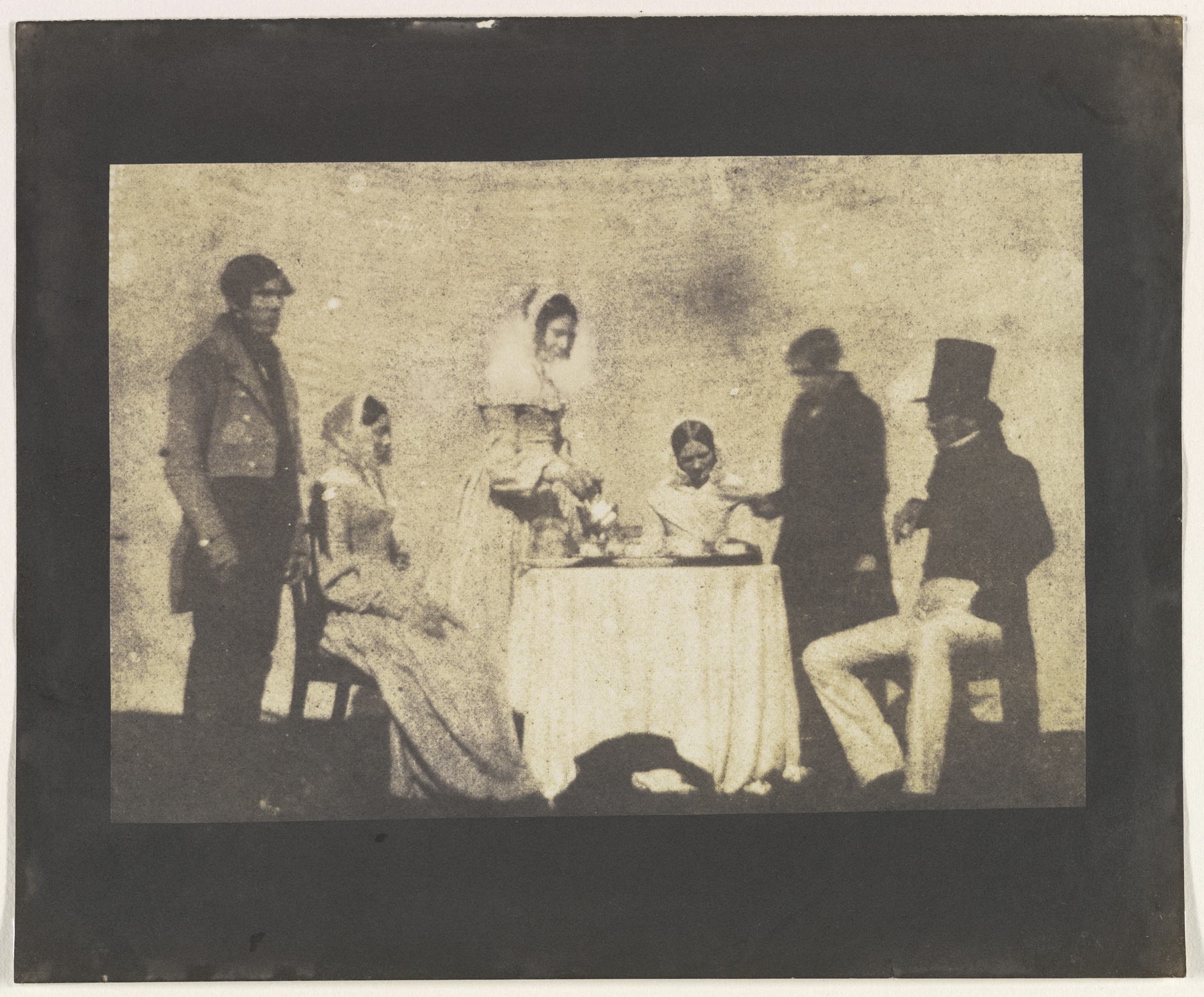

For the series neg◊lapresmidi, Thomas Ruff used photographs taken by Adolphe de Meyer during a performance of the ballet in 1912. In a sense, three turning points of the avant-garde culminate in Adolphe de Meyer’s photographs: the Symbolist poetry of Mallarmé, on which the ballet was based, the music of Debussy, and the choreography of Nijinski. Ruff’s inversions of Adolphe de Meyer’s photographs enrapture and alienate this moment and at the same time allow it to shine with particular intensity.

Capturing time

The series neg◊marey focuses on photographs taken by the physician Étienne-Jules Marey in the 1870s. At the time, he tried to take pictures of moving people and animals in order to better understand their movements. Almost simultaneously, the British-American photographer Eadweard Muybridge was working on similar experiments. While Muybridge devised elaborate constructions with which he captured individual moments of movement with several cameras connected in series, Marey developed a process in which movements from a single camera with interrupted exposure could be brought onto a single plate. By placing reflective dots on the test subject or animal, the movements could be captured precisely and in the same proportion as the interrupted exposure. This approach was reminiscent of the graphic method previously invented by Marey, which allowed the first continuous recordings of the pulse and the assignment of individual sections of the pulse curve to the respective heart activities.

Thomas Ruff (German, b. 1958)

neg◊marey_02

2016

C-Print

22.4 x 31.4cm

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020

Thomas Ruff (German, b. 1958)

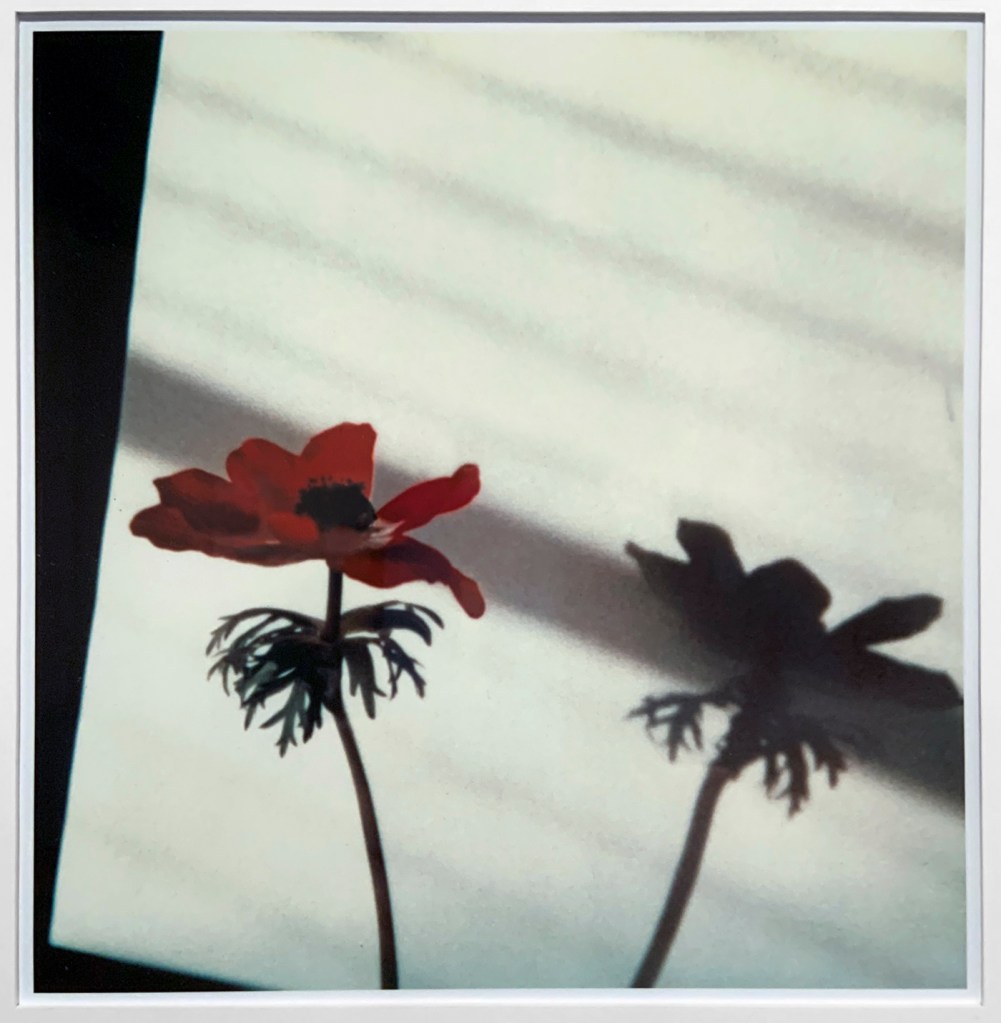

Installation view K20, Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen showing flower.s_10 from Ruff’s flower.s series

Photo: Achim Kukulies

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020

“Actually from time to time I try to take a photograph of a flower or several flowers but it just looks boring, it doesn’t work, so it seems that I cannot take photographs of flowers.”

Thomas Ruff

flower.s

Flower photograms by Lou Landauer (1897-1991), which Thomas Ruff had acquired, as well as the work on the photograms, gave him the idea of working with another photographic technique that has been used since the mid-nineteenth century: pseudo-solarisation (also called the Sabattier effect). This is a technique discovered by chance, in which the negative / positive is subjected to a diffuse second exposure during exposure in the darkroom, resulting in a partial reversal of light and shadow areas in the photographic image. For his series flower.s, which he has been working on since 2018, Ruff first photographs flowers or leaves with a digital camera, which he had arranged on a light table. During the subsequent processing on the computer, he applies the Sabattier effect.

Thomas Ruff (German, b. 1958)

flower.s_10

2019

C-Print

139 x 119cm

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020

Thomas Ruff (German, b. 1958)

tripe_12 Seeringham. Munduppum inside gateway

2018

C-Print, Edition 02/06

123.5 x 159.5cm

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020

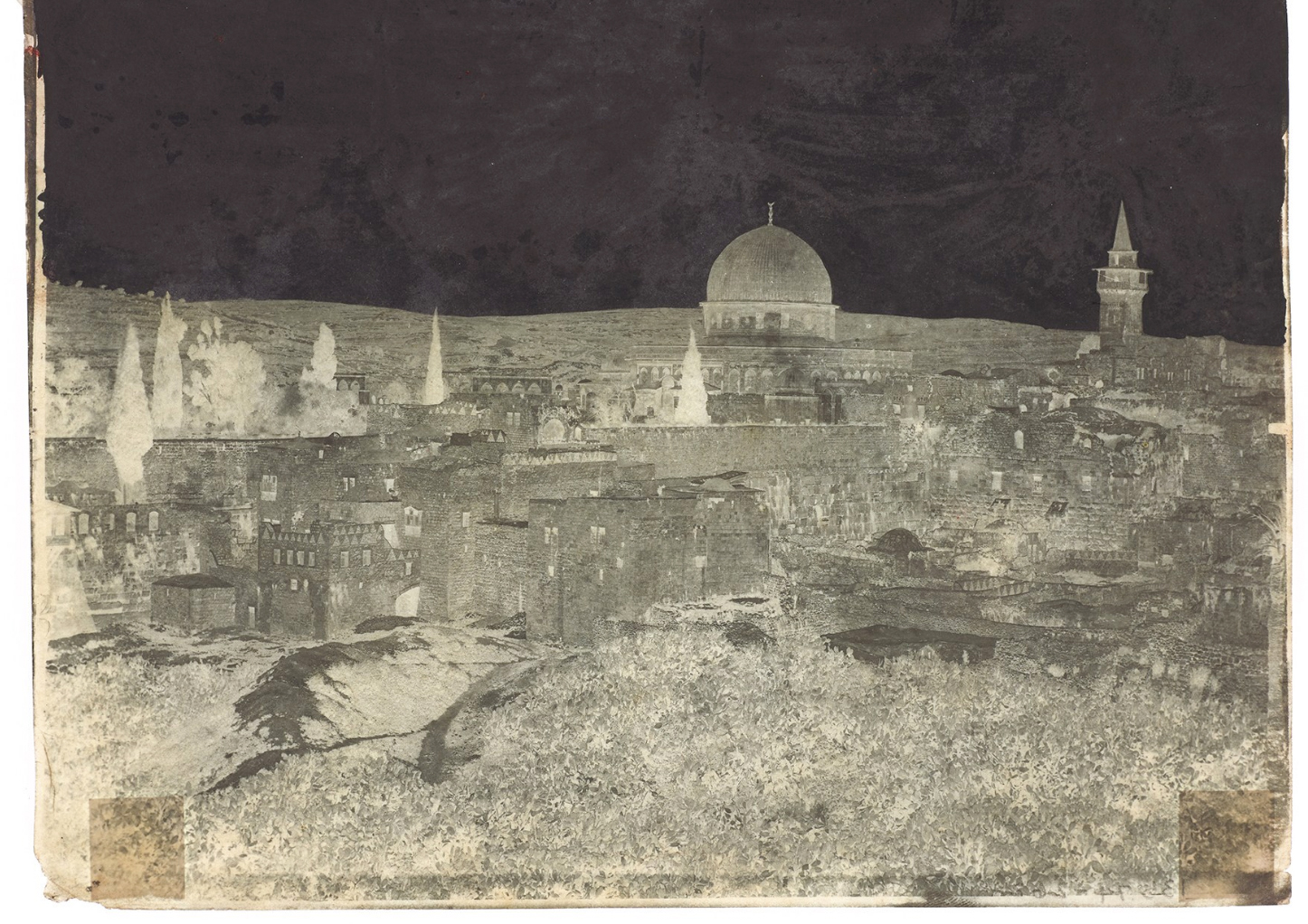

Tripe

Paper negatives, which Captain Linnaeus Tripe (1822-1902) had produced on behalf of the British government in Burma and Madras between 1856 and 1862 and that are now in the archives of the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, were the starting point for the series Tripe.

Thomas Ruff was able to view the existing negatives and selected several of these for his own work. All of them showed clear signs of ageing or damage. Ruff had the negatives digitally reproduced and then converted them into a positive, inverting the brownish hue of the negative into cyan blue.

He duplicated these positives and altered the coloration of the duplicate to the brown tone of the negative. He superimposed the two positive images as digital layers and removed parts of the layer of the brownish image, so that the coloration of the bluish image partially shines through. In a second step, he enlarged the images so that the texture of the paper, as well as all edits, damages, and changes become visible.

Thomas Ruff (German, b. 1958)

Installation view K20, Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen showing the work tripe_15 Madura. The Blackburn Testimonial (2018) from the tripe series

Photo: Achim Kukulies

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020

Thomas Ruff (German, b. 1958)

tripe_15 Madura. The Blackburn Testimonial

2018

C-Print

123.5 x 159.5 cm

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020

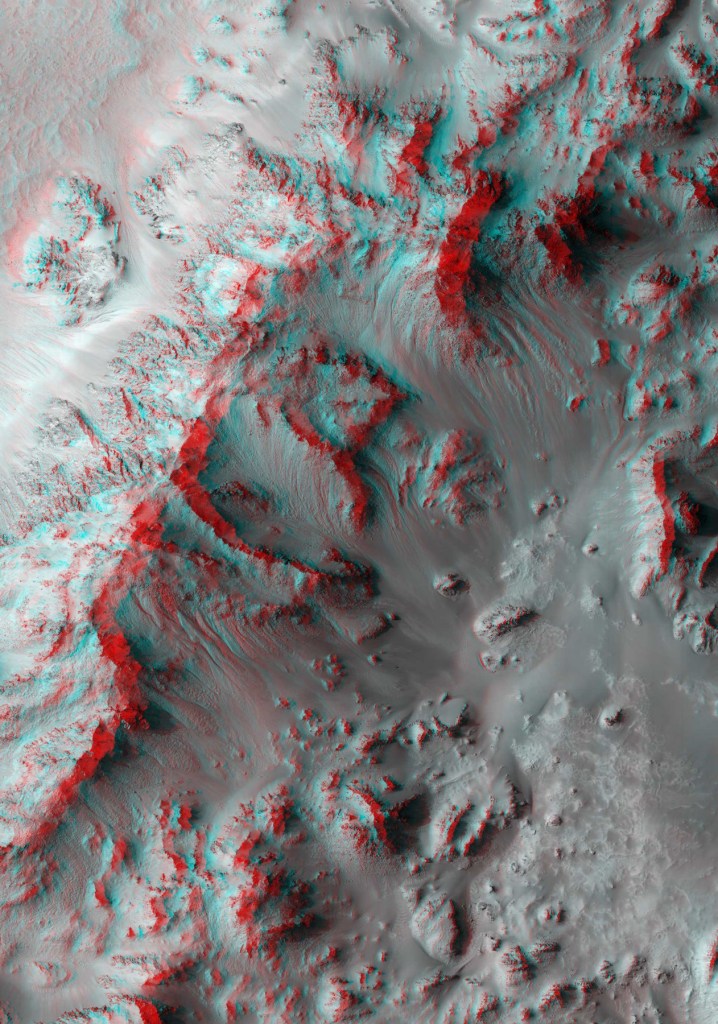

Thomas Ruff (German, b. 1958)

3D_m.a.r.s 16

2013

C-Print

255 x 185cm

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020

A Different Dimension

How do scientists use photographs? Does the tradition of travel photography still exist? Who invents new pictorial landscapes?

Photographs are used in many different areas. In space research, satellite photos are a basis for scientific knowledge about places that were previously inaccessible to humans. In the processing by the artist Thomas Ruff, these photographs become images of never-seen worlds and studies of the imagination, feasibility, and credibility of images.

Thomas Ruff (German, b. 1958)

Installation view K20, Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen showing work from Ruff’s ma.r.s series

Photo: Achim Kukulies

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020

ma.r.s.

During his research on photographs from outer space, Thomas Ruff came across photographs of Mars. These were taken by a camera within a probe sent into outer space by NASA in August 2005 and has been sending detailed images of the surface of the planet Mars to Earth since March 2006. The images are intended to enable scientists to obtain more precise knowledge of the surface, atmosphere, and water distribution of Mars.

For his series, created between 2010 and 2014, the artist processed these very naturalistic yet strange images in several steps; among other things, he transformed the black-and-white transmitted images, which were photographed vertically top-down, into an oblique view and then coloured them so that the surface of the distant planet appears accessible and almost familiar. The works of the subgroup “3D-ma.r.s.” illustrated here are photographs of the surface of Mars which were produced using the so-called anaglyph process. When viewed with red-green glasses, a spatial, three-dimensional image is created in the brain.

The raw material for Thomas Ruff’s series ma.r.s. is derived from HiRISE (High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment), a high-performance camera on board the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, a probe that has been transmitting images from the surface of Mars to Earth since 2006.

Thomas Ruff (German, b. 1958)

Installation view K20, Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen showing work from Ruff’s ma.r.s series

WG Bildkunst 2020

Photo: WDR / Thomas Köster

Thomas Ruff (German, b. 1958)

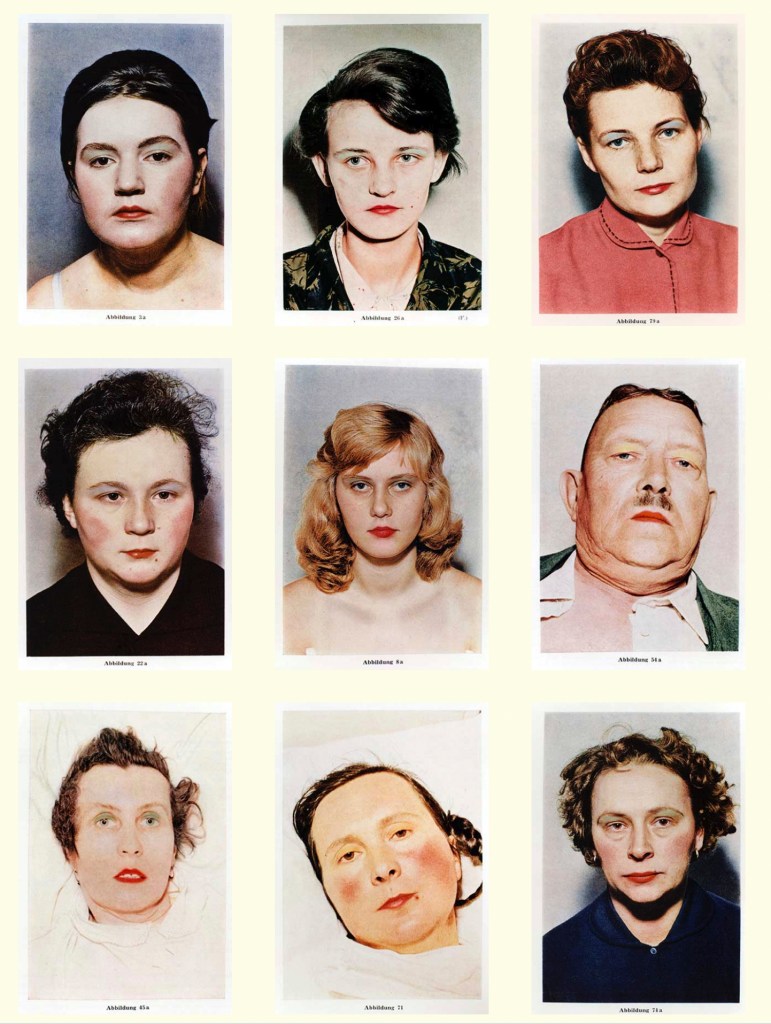

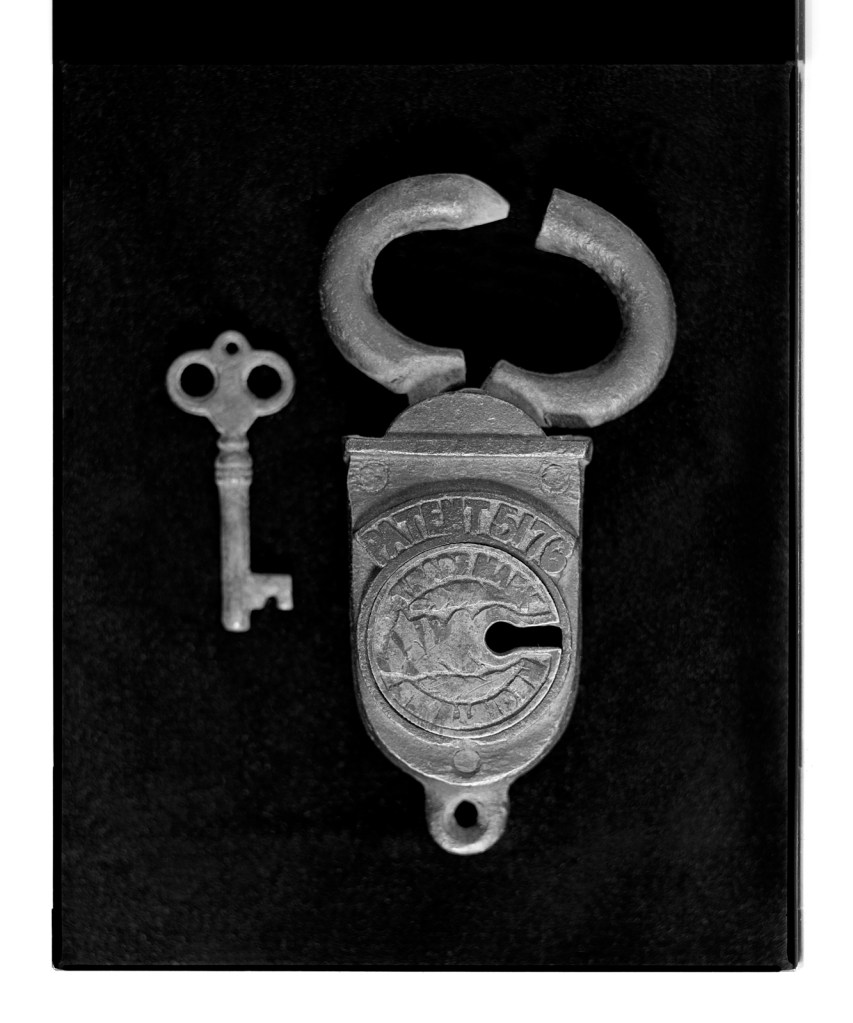

Retusche 01-09

1995

C-Print

14.7 x 10cm

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020

Retouching and Colour

How do photos become colourful? Why did photographers in the nineteenth century retouch their photos?

Since the early days of photography, monochrome and multicolour retouching has been used or images have been coloured. Thomas Ruff explores one possibility in his series Retusche (Retouching) as a form of embellishment and an approach to an ideal. His machines are heightened and isolated by colouring the motifs with typical colours of industrial production. For the work groups m.n.o.p. and w.g.l., the artist partially coloured photos of exhibition situations in order to highlight forms of presentation in museums and design intentions in exhibition practice.

Thomas Ruff (German, b. 1958)

Retusche 03

1995

C-Print, handkoloriert mit pigmentfreier Retuschierfarbe, Edition 01/01

14.7 x 10cm

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020

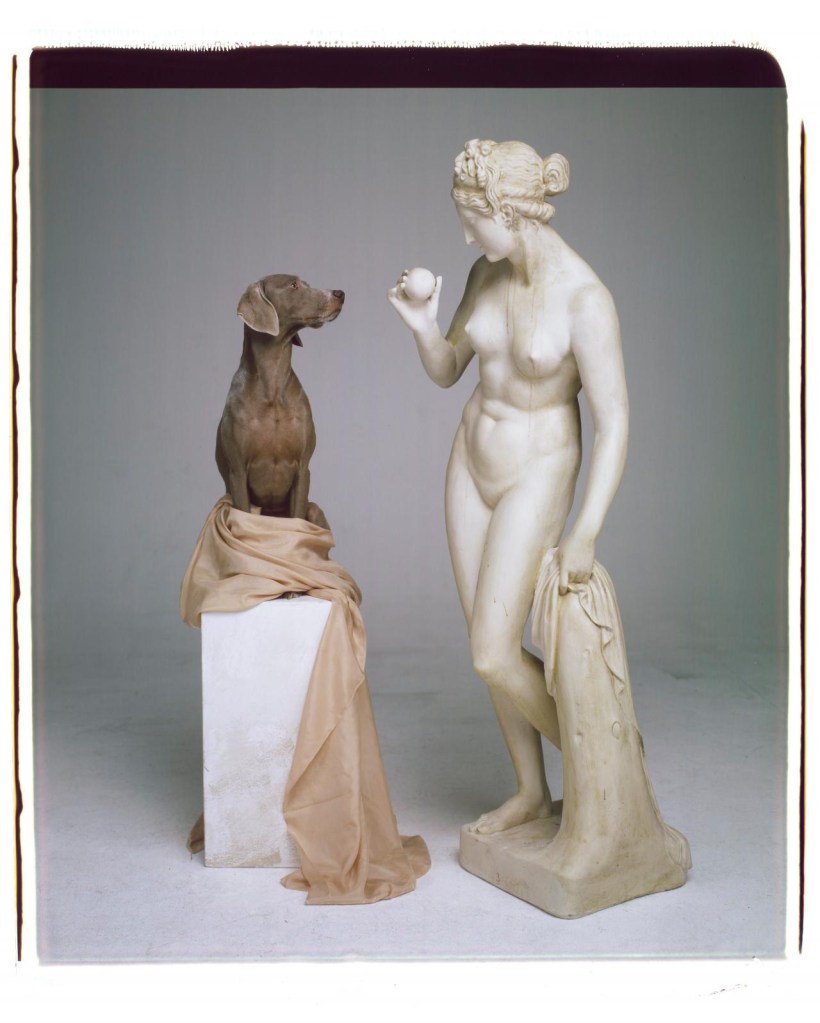

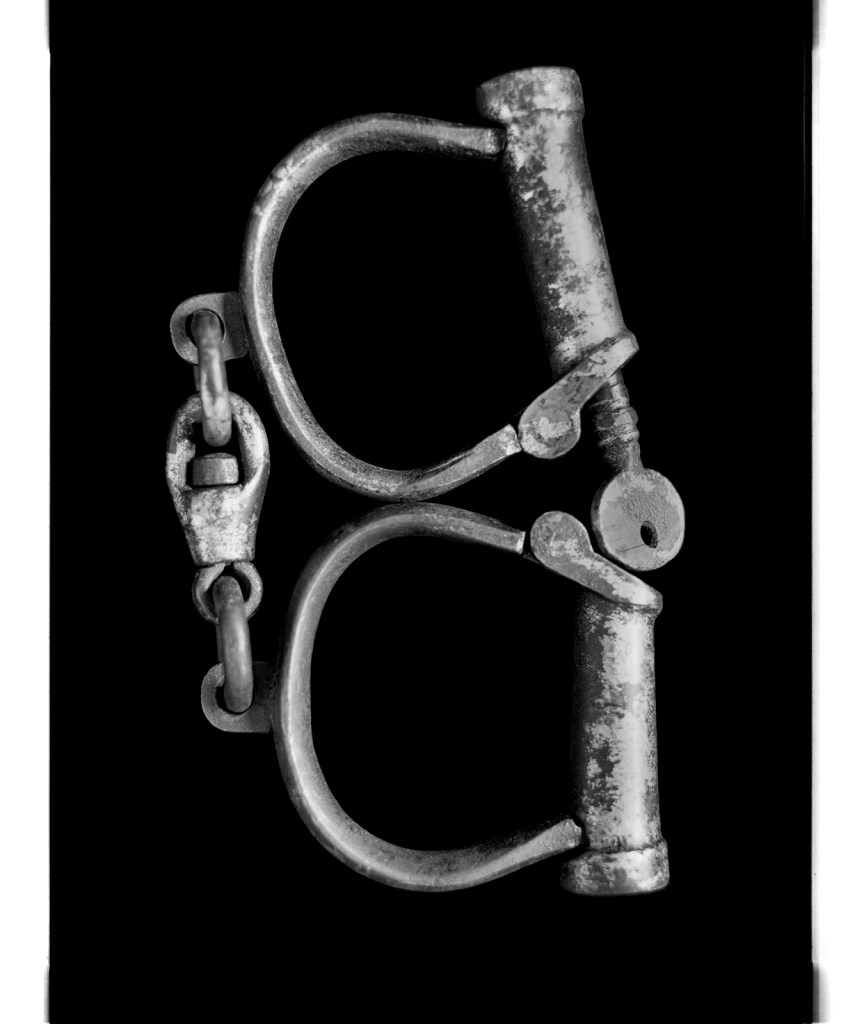

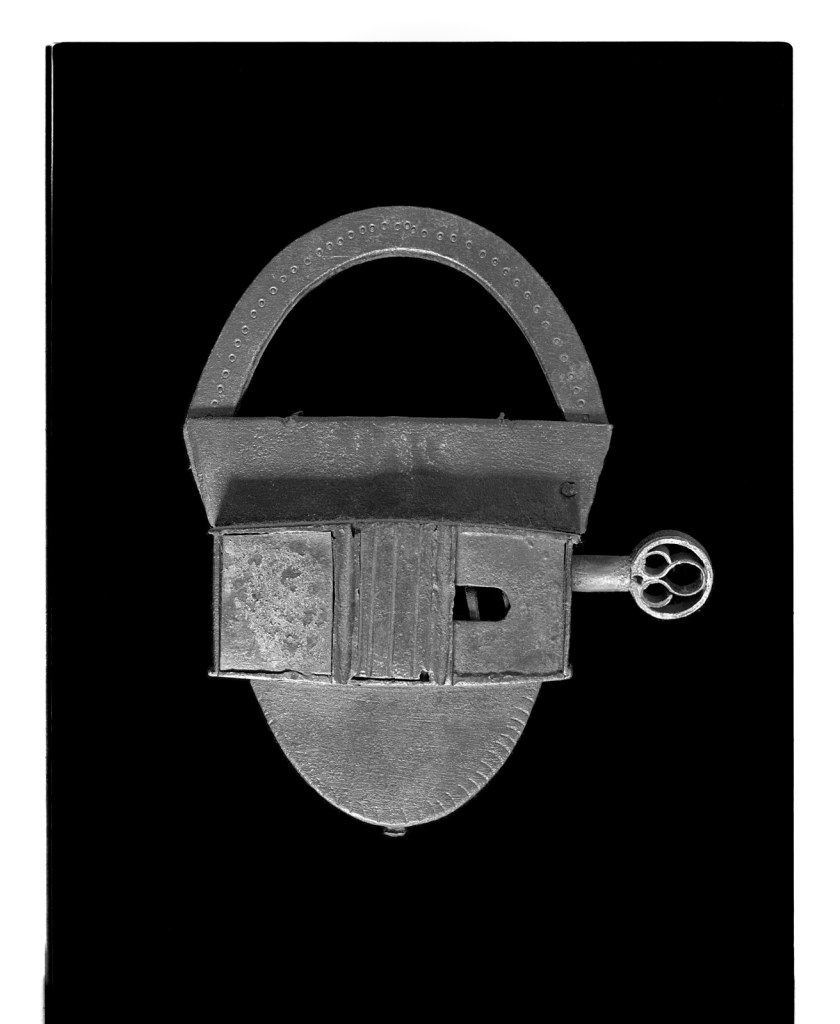

Retusche (Retouching)

A colour photograph of Sophia Loren, which Thomas Ruff had seen at an exhibition in Venice in 1995, drew his attention to a practice of representation as old as photography itself: the colouring of photographs. Whereas in the photograph of Sophia Loren, a star was “embellished”, by the additional colour, Ruff decided in 1995 to apply this practice to ten portraits he had seen in the medical textbook‚ Das Gesicht des Herzkranken (The Face of the Cardiac Patient) by Jörgen Schmidt-Voigt from the 1950s. He applied “make up” to the faces with a brush and protein glaze paint, applying eye shadow, rouge, and lipstick.

Thomas Ruff (German, b. 1958)

0946

2003

C-Print

150 x 195cm

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020

Maschinen (Machinery)

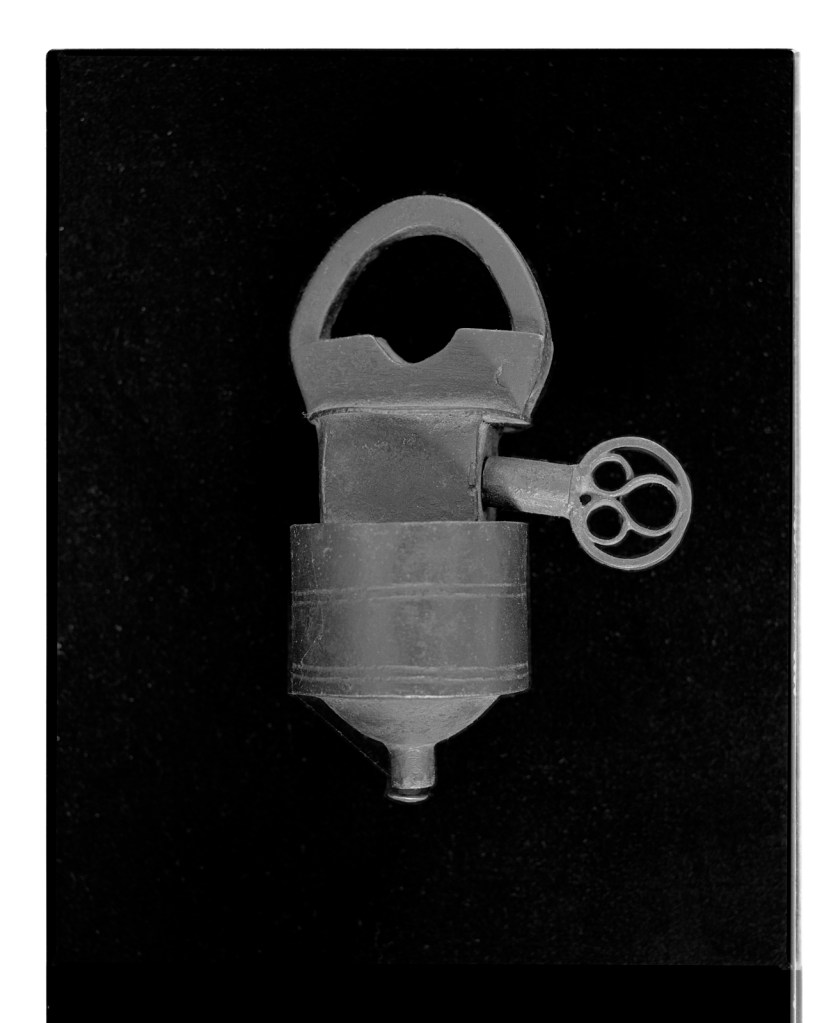

Around 2000, Thomas Ruff acquired roughly 2,000 photographs on glass negatives from the 1930s. These comprise the image archive of the former Rohde & Dörrenberg company from Düsseldorf-Oberkassel, which produced machines and machine parts. The photographs were originally taken for the production of the company catalog and reflect the company’s entire product range. To facilitate the manual cropping of the illustrated object at that time, the respective products were often photographed individually against a white background; the print was then retouched and further processed for final printing. Ruff emphasised this extremely elaborate preparation and image processing – the analog counterpart of digital processing by Photoshop – by colouring individual areas of the digitised images by means of deliberately set colours, similar to retouching, for the works in his series created between 2003 and 2005.

Catalog Illustrations

In the 1930s, the Rohde & Dörrenberg company from Düsseldorf Oberkassel published a catalog of its drills and milling machines. It also offered machines with which the customer could service the tools, such as sharpening apparatus, grinding machines, and the tip-tapering machine illustrated here. The images in the product catalog are hardly recognisable as photographs. The processing steps of cropping, retouching, and re-photographing resulted in an image that is more reminiscent of a technical drawing than a photograph of a machine in a workshop. Thomas Ruff’s series of pictures of machines thematise this elaborate path from photography to illustration in the product catalog and draws attention to the possibilities of staging and stylising objects in photography.

Thomas Ruff (German, b. 1958)

Installation view at Kunstsammlung NRW, Düsseldorf 2020 showing work from Ruff’s Maschinen (Machinery) series including at right, 0946 (2003)

WG Bildkunst 2020

Photo: WDR / Thomas Köster

Thomas Ruff (German, b. 1958)

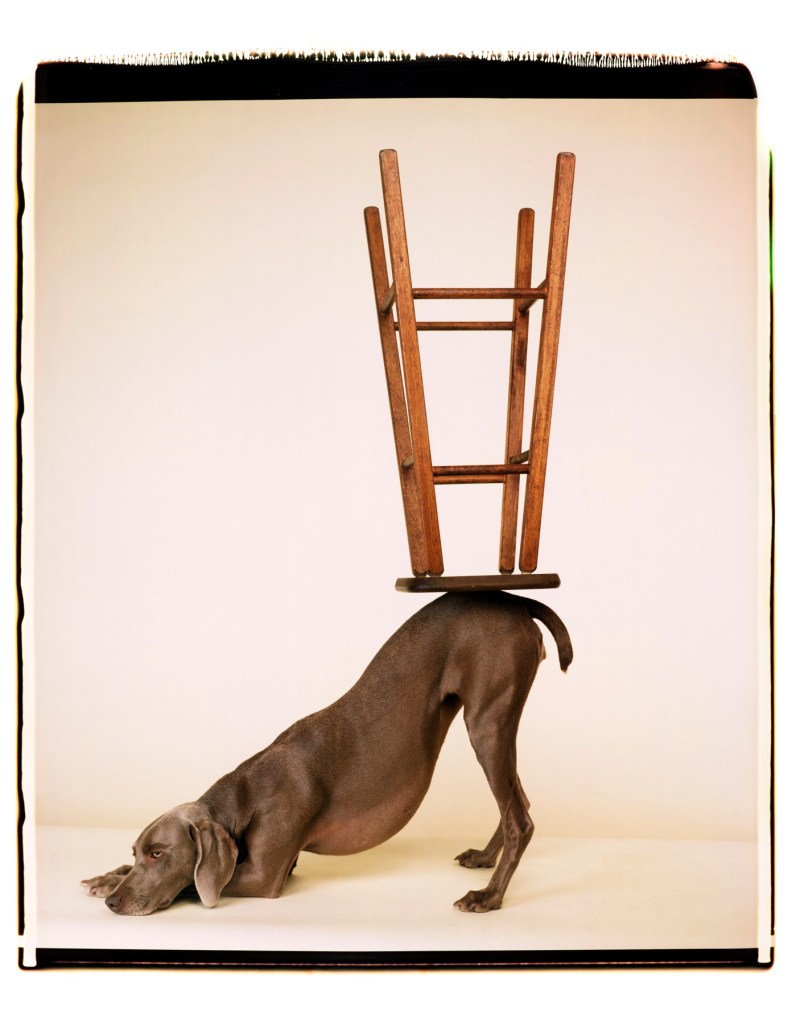

m.n.o.p.01

2013

C-Print, Edition 01/06

47.3 x 60cm

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020

m.n.o.p.

w.g.l.

Two series by Thomas Ruff are based on black-and-white photographs from famous museum presentations of the 1940s and 1950s in New York and London. Thomas Ruff partially coloured the installation photographs digitally with a colour scheme reminiscent of the 1950s and enlarged them. While the artworks were left untouched – out of respect for the artists and their works – he coloured the carpets, the walls covered with fabric, and the ceilings. Through this treatment, he underscored the exhibition aesthetic of the 1940s to the 1960s and, with the resulting abstract coloured surface compositions, emphasised the design work of the exhibition organisers.

All of this emphasises the contrast to today’s widespread notion of the exhibition space as a “white cube”. m.n.o.p. (2013) presents processed installation views of the presentation of the Museum of Non-Objective Painting in New York (now the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum) with works by Wassily Kandinsky, Rudolf Bauer, and other artists from the collection, which took place in the first museum building on 24 East 54th Street in 1948. The motifs from w.g.l. (2017) were taken from the exhibition‚ Jackson Pollock 1912-1956, one of the most important exhibitions in terms of the mediation of contemporary art, which was presented at the Whitechapel Gallery in London in 1958.

Thomas Ruff (German, b. 1958)

Kunstsammlung NRW, Düsseldorf 2020 (installation view)

WG Bildkunst 2020

Photo: WDR / Thomas Köster

With the exhibition Thomas Ruff, the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen presents a comprehensive overview of one of the most important representatives of the Düsseldorf School of Photography. The exhibition ranges from series from the 1990s, which document Ruff’s unique conceptual approach to photography, to a new series that is now being shown for the first time at K20: For Tableaux chinois, Ruff drew on Chinese propaganda photographs. Parallel to Thomas Ruff’s exhibition, the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen is also presenting highlights from the collection at K20 under the title Technology Transformation. Photography and Video in the Kunstsammlung, which also deals with artistic photography and technical imaging processes in art.

“With his manipulations of photographs from many different sources, Thomas Ruff comments in an incredibly clever way on how we see images in a digitalised world. Through his virtuoso handling of digital image processing, he confronts us with a critical examination of the image material he uses and its historical, political, and epistemological significance. Some of his most important series are represented in our collection, and we are very proud to dedicate a large-scale exhibition at K20 to this prominent representative of the Düsseldorf School of Photography,” states Susanne Gaensheimer, Director of the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen.

Thomas Ruff (b. 1958) is one of the internationally most important artists of his generation. Already as a student in the class of the photographers Bernd and Hilla Becher at the Düsseldorf Academy of Art in the early 1980s, he chose a conceptual approach to photography which is evident in all the workgroups within his multifaceted oeuvre and determines his approach to the most diverse pictorial genres and historical possibilities of photography. In order not to tie his investigations in the field of photography to the individual image found by chance, but rather to examine these in terms of image types and genres, Thomas Ruff works in series: “A photograph,” Ruff explains, “is not only a photograph, but an assertion. In order to verify the correctness of this assertion, one photo is not enough; I have to verify it on several photos.” The exhibition at K20 focuses on series of pictures from two decades in which the artist hardly ever used a camera himself. Instead, he appropriated existing photographic material from a wide variety of sources for his often large-format pictures.

Thomas Ruff’s contribution to contemporary photography thus consists in a special way in the development of a form of photography created without a camera. He uses images that have already been taken and that have already been disseminated in other, largely non-artistic contexts and optimised for specific purposes. The modus operandi and the origin of the material first became the subject of Ruff’s own work in the series of newspaper photographs, which were produced as early as 1990. The exhibition focuses precisely on this central aspect of his work. The pictorial sources that Ruff has tapped for these series range from photographic experiments of the nineteenth century to photo taken by space probes. He has questioned the archive processes of large picture agencies and the pictorial politics of the People’s Republic of China. Documentations of museum exhibitions, as well as pornographic and catastrophic images from the Internet, are starting points for his own series of works, as are the product photographs of a Düsseldorf-based machine factory from the 1930s. They originate from newspapers, magazines, books, archives, and collections or were simply available to everyone on the Internet. In each series, Ruff explores the technical conditions of photography in the confrontation with these different pictorial worlds: the negative, digital image compression, and even rasterisation in offset printing. At the same time, he also takes a look at the afterlife of images in publications, archives, databases, and on the Internet.

For Tableaux chinois, the latest series, which is being shown for the first time at K20, Ruff drew on Chinese propaganda photographs: products of the Mao era driven to perfection, which he digitally processed. In his artistic treatment of this historical material, the analog and digital spheres overlap; and in this visible overlap, Ruff combines the image of today’s highly digitalised China with the Chinese understanding of the state in the 1960s and its manipulative pictorial politics.

From the ma.r.s. series created between 2010 and 2014, there are eight works on view that have never been shown before, for which Ruff used images of a NASA Mars probe. Viewed through 3D glasses, the rugged surface of the red planet folds into the space in front of and behind the surface of the large-format images. Moving through the exhibition space and comprehending how the illusion is broken and tilted, one is introduced to Ruff’s concern to understand photography as a construction of reality that first and foremost represents a surface – a surface that is, however, set in a historical framework of technology, processing, optimisation, transmission, and distribution.

His hitherto oldest image sources are the paper negatives of Captain Linnaeus Tripe. When Tripe began taking photographs in South India and Burma, today’s Myanmar, for the British East India Company in 1854, he provided the first images of a world that was, for the British public, both far away and unknown. Since then, the world has become a world that has always been photographed. It is this already photographed world that interests the artist Thomas Ruff and for which he has also been called a ‘historian of the photographic’ (Herta Wolf). The exhibition therefore not only provides an overview of Ruff’s work over the past decades, but also highlights nearly 170 years of photographic history. In each series, Ruff formulates highly complex perspectives on the photographic medium and the world that has always been photographed.

Further series in the exhibition are the two groups of works referring to press photography, Zeitungsfotos (1990/91) and press++ (since 2015), the series nudes (since 1999) and jpeg (since 2004), which refer to the distribution of photographs on the Internet, as well as Fotogramme (since 2012), Negatives (since 2014), Flower.s (since 2019), Maschinen (2003/04), m.n.o.p. (2013), and w.g.l. (2017) – and, with Retouching (1995), a rarely shown series of unique pieces.

Text from the press kit from the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen

Thomas Ruff (German, b. 1958)

m.n.o.p.08

2013

C-Print

47.3 x 60cm

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020

Thomas Ruff (German, b. 1958)

w.g.l.01

2017

C-Print

42.6 x 60cm

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020

Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen

K20, Grabbeplatz 5

40213 Düsseldorf

Opening hours:

Tuesday – Friday 10am – 6pm

Saturday, Sunday, public holiday 11am – 6pm

The Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen is closed on December 24, 25 and 31

![Andrew Rumann (Australian, 1905-1974) 'Untitled [Departure from Circular Quay, Sydney for Fremantle and Singapore]' 1941 Andrew Rumann (Australian, 1905-1974) 'Untitled [Departure from Circular Quay, Sydney for Fremantle and Singapore]' 1941](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/embarkation-h.jpg?w=1024)

![Andrew Rumann (Australian, 1905-1974) 'Untitled [Departure from Circular Quay, Sydney for Fremantle and Singapore]' 1941 Andrew Rumann (Australian, 1905-1974) 'Untitled [Departure from Circular Quay, Sydney for Fremantle and Singapore]' 1941](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/embarkation-c.jpg?w=1024)

![Andrew Rumann (Australian, 1905-1974) 'Untitled [Departure from Circular Quay, Sydney for Fremantle and Singapore]' 1941 Andrew Rumann (Australian, 1905-1974) 'Untitled [Departure from Circular Quay, Sydney for Fremantle and Singapore]' 1941](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/embarkation-d.jpg?w=1024)

![Andrew Rumann (Australian, 1905-1974) 'Untitled [Departure from Circular Quay, Sydney for Fremantle and Singapore]' 1941 (detail) Andrew Rumann (Australian, 1905-1974) 'Untitled [Departure from Circular Quay, Sydney for Fremantle and Singapore]' 1941 (detail)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/embarkation-d-detail.jpg?w=1024)

![Anonymous photographer (Australian) 'Untitled [Encampment]' 1942-45 Anonymous photographer (Australian) 'Untitled [Encampment]' 1942-45](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/embarkation-j.jpg?w=1024)

![Anonymous photographer (Australian) 'Untitled [Women standing in front of an American Red Cross sign]' 1942-45 Anonymous photographer (Australian) 'Untitled [Women standing in front of an American Red Cross sign]' 1942-45](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/embarkation-i.jpg?w=1024)

![Anonymous photographer (Australian) 'Untitled [Post Exchange No. 2]' 1942-45 Anonymous photographer (Australian) 'Untitled [Post Exchange No. 2]' 1942-45](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/embarkation-k.jpg?w=1024)

![Anonymous photographer (Australian) 'Untitled [Post Exchange No. 2]' 1942-45 (detail) Anonymous photographer (Australian) 'Untitled [Post Exchange No. 2]' 1942-45 (detail)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/embarkation-k-detail.jpg?w=1022)

![Anonymous photographer (Australian) 'Untitled [Taking out the rubbish]' 1942-45 Anonymous photographer (Australian) 'Untitled [Taking out the rubbish]' 1942-45](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/embarkation-e.jpg?w=1024)

![Anonymous photographer (Australian) 'Untitled [BKC*23]' 1942-45 Anonymous photographer (Australian) 'Untitled [BKC*23]' 1942-45](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/embarkation-f.jpg?w=1024)

![Anonymous photographer (Australian) 'Untitled [BKC*23]' 1942-45 (detail) Anonymous photographer (Australian) 'Untitled [BKC*23]' 1942-45 (detail)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/embarkation-f-detail.jpg?w=1024)

![Anonymous photographer (Australian) 'Untitled [Transportation Corps US Army BKC*23]' 1942-45 Anonymous photographer (Australian) 'Untitled [Transportation Corps US Army BKC*23]' 1942-45](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/embarkation-g.jpg?w=1024)

![Anonymous photographer (Australian) 'Untitled [Transportation Corps US Army BKC*23]' 1942-45 (detail) Anonymous photographer (Australian) 'Untitled [Transportation Corps US Army BKC*23]' 1942-45 (detail)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/embarkation-g-detail.jpg?w=1024)

![Anonymous photographer (Australian) 'Untitled [Embarkation]' 1942-45 Anonymous photographer (Australian) 'Untitled [Embarkation]' 1942-45](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/embarkation-a.jpg?w=1024)

![Anonymous photographer (Australian) 'Untitled [Embarkation]' 1942-45 (detail) Anonymous photographer (Australian) 'Untitled [Embarkation]' 1942-45 (detail)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/embarkation-a-detail.jpg?w=1024)

![Lewis Carroll (British, Daresbury, Cheshire 1832 - 1898 Guildford) '[Alice Liddell]' June 25, 1870 from the exhibition '2020 Vision: Photographs, 1840s-1860s' at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Dec 2019 - Dec 2020 Lewis Carroll (British, Daresbury, Cheshire 1832 - 1898 Guildford) '[Alice Liddell]' June 25, 1870 from the exhibition '2020 Vision: Photographs, 1840s-1860s' at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Dec 2019 - Dec 2020](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/lewis-carroll-alice-liddell.jpg?w=898)

![Unknown photographer (American) '[Surveyor]' c. 1854 Unknown photographer (American) '[Surveyor]' c. 1854](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/anon-surveyor-a.jpg)

![Unknown photographer (American) '[Surveyor]' c. 1854 Unknown photographer (American) '[Surveyor]' c. 1854](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/anon-surveyor-b.jpg?w=878)

![Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) '[Classical Head]' probably 1839 Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) '[Classical Head]' probably 1839](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/bayard-classical-head.jpg?w=931)

![Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/anon-collaged-portraits-a.jpg?w=850)

![Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/anon-collaged-portraits-b.jpg?w=876)

![Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/anon-collaged-portraits-c.jpg)

![Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/anon-collaged-portraits-d.jpg)

![Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/anon-collaged-portraits-e.jpg)

![Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/anon-collaged-portraits-f.jpg?w=863)

![Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/anon-collaged-portraits-g.jpg)

![Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/anon-collaged-portraits-h.jpg?w=875)

![Unknown artist (American) '[Studio Photographer at Work]' c. 1855 Unknown artist (American) '[Studio Photographer at Work]' c. 1855](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/unknown-artist-american-studio-photographer-at-work-c-1855.jpg?w=825)

![Unknown artist (American) '[Boy Holding a Daguerreotype]' 1850s Unknown artist (American) '[Boy Holding a Daguerreotype]' 1850s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/unknown-american-active-1850s-boy-holding-a-daguerreotype-1850s.jpg?w=877)

![Carleton E. Watkins (American, 1829-1916) '[California Oak, Santa Clara Valley]' c. 1863 Carleton E. Watkins (American, 1829-1916) '[California Oak, Santa Clara Valley]' c. 1863](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/watkins-california-oak-santa-clara-valley.jpg?w=827)

![Pietro Dovizielli (Italian, 1804-1885) '[Spanish Steps, Rome]' c. 1855 Pietro Dovizielli (Italian, 1804-1885) '[Spanish Steps, Rome]' c. 1855](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/dovizielli-spanish-steps.jpg?w=787)

![Edouard Baldus (French (born Prussia), 1813-1889) '[Amphitheater, Nîmes]' c. 1853 Edouard Baldus (French (born Prussia), 1813-1889) '[Amphitheater, Nîmes]' c. 1853](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/baldus-amphitheater.jpg)

![Lewis Dowe (American, active 1860s-1880s) '[Dowe's Photograph Rooms, Sycamore, Illinois]' 1860s Lewis Dowe (American, active 1860s-1880s) '[Dowe's Photograph Rooms, Sycamore, Illinois]' 1860s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/lewis-dowe-dowes-photograph-rooms-sycamore-illinois-1860s.jpg)

![E. & H. T. Anthony (American) '[Specimens of New York Bill Posting]' 1863 E. & H. T. Anthony (American) '[Specimens of New York Bill Posting]' 1863](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/e-h-t-anthony-specimens-of-new-york-bill-posting-1863.jpg)

![Felice Beato (British (born Italy), Venice 1832-1909 Luxor) and James Robertson (British, 1813-1881) [Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem] 1856-1857 Felice Beato (British (born Italy), Venice 1832-1909 Luxor) and James Robertson (British, 1813-1881) [Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem] 1856-1857](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/beato-dome.jpg)

![R.C. Montgomery (American, active 1850s) '[Self-Portrait (?)]' 1850s R.C. Montgomery (American, active 1850s) '[Self-Portrait (?)]' 1850s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/r.c.-montgomery-self-portrait-1850s.jpg?w=623)

You must be logged in to post a comment.