Exhibition dates: 27th June – 23rd September 2012

Installation view of the exhibition Painting in Photography. Strategies of Appropriation at the Städel Museum, Frankfurt showing Victor Burgin’s Office at Night (Red), 1985 (below)

“To understand the production of art at the end of tradition, which in our lifetime means art at the end of modernism, requires, as the postmodern debate has shown, a careful consideration of the idea of history and the notion of ending. Rather than just thinking ending as the arrival of the finality of a fixed chronological moment, it can also be thought as a slow and indecisive process of internal decomposition that leaves in place numerous deposits of us, in us and with us – all with a considerable and complex afterlife. In this context all figuration is prefigured. This is to say that the design element of the production of a work of art, the compositional, now exists prior to the management of form of, and on, the picture plane. Techniques of assemblage, like montage and collage – which not only juxtaposed different aesthetics but also different historical moments, were the precursors of what is now the general condition of production.”

“Art Byting the Dust” Tony Fry 1990 1

They said that photography would be the death of painting. It never happened. Recently they thought that digital photography would be the death of analogue photography. It hasn’t happened for there are people who care enough about analogue photography to keep it going, no matter what. As the quotation astutely observes, the digital age has changed the conditions of production updating the techniques of montage and collage for the 21st century. Now through assemblage the composition may be prefigured but that does not mean that there are not echoes, traces and deposits of other technologies, other processes that are not evidenced in contemporary photography.

As photography influenced painting when it first appeared and vice versa (photography went through a period known as Pictorialism where where it imitated Impressionist painting), this exhibition highlights the influence of painting on later photography. Whatever process it takes photography has always been about painting with light – through a pinhole, through a microscope, through a camera lens; using light directly onto photographic paper, using the light of the scanner or the computer screen. As Paul Virilio observes, no longer is there a horizon line but the horizon square of the computer screen, still a picture plane that evidences the history of art and life. Vestiges of time and technology are somehow always present not matter what medium an artist chooses. They always have a complex afterlife and afterimage.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

PS. I really don’t think it is a decomposition, more like a re/composition or reanimation.

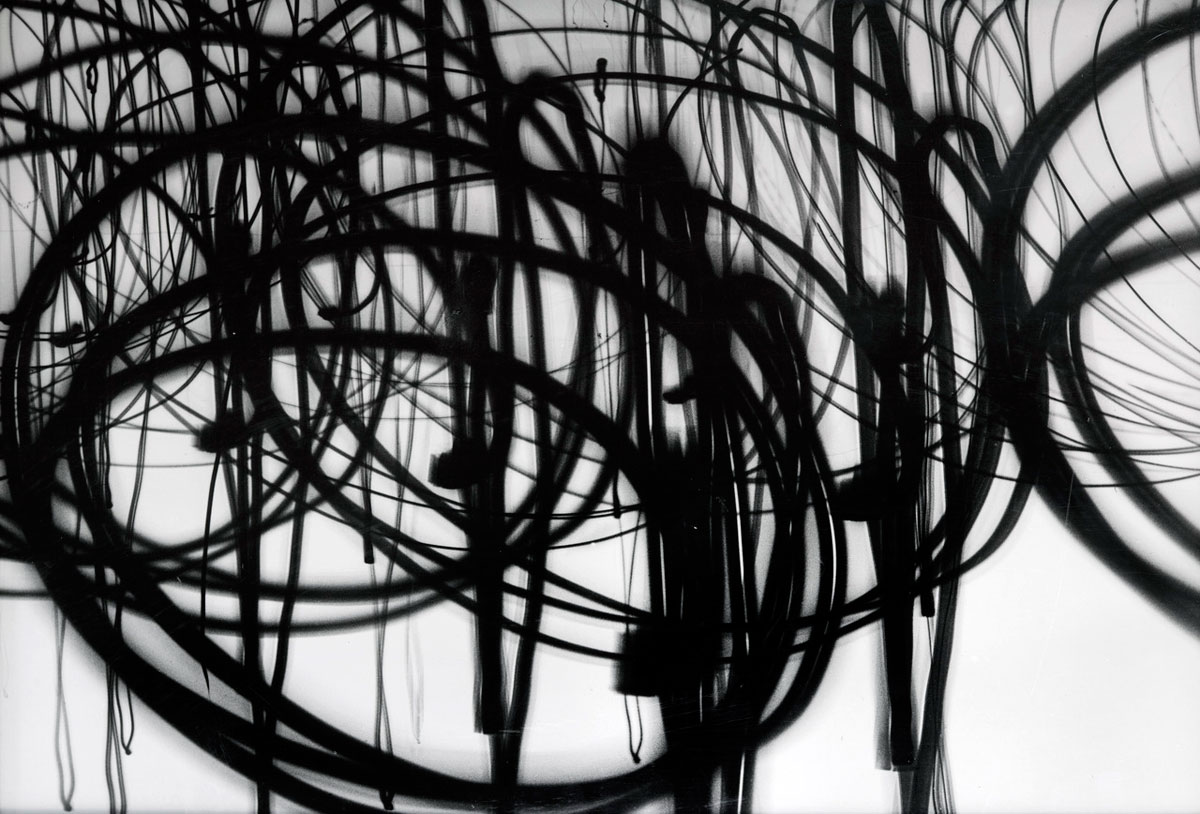

PPS. Notice how Otto Steinert’s Luminogramm (1952, below), is eerily similar to some of Pierre Soulages paintings.

1/ Fry, Tony. “Art Byting the Dust,” in Hayward, Phillip. Culture, Technology and Creativity in the Late Twentieth Century. London: John Libbey and Company, 1990, pp. 169-170

Many thankx to the Städel Musuem for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Victor Burgin (British, b. 1941)

Office at Night (Red)

1985

In a conceptual, analytical visual language, Burgin, who originally started out as a painter, refers to Edward Hopper’s painting “Office at Night” from 1940. It shows a New York office at night, in which the boss and secretary are still at work and alone. Burgin’s picture is part of a series about this depiction of a couple by Hopper (and the special role of the female motif in his work). Burgin’s picture consists of three panels, each of which uses a fictional register: letters (word), color (red is traditionally the color for lust and love) and photographic image (secretary).

Anonymous. “Victor Burgin” in the pdf “WONDERFULLY FEMININE! Interrogations of the feminine,” on the Kunst Stiftung DZ Bank website 2009 [Online] Cited 11/09/2024. Translated from the German by Google Translate

Installation view of the exhibition Painting in Photography. Strategies of Appropriation at the Städel Museum, Frankfurt showing at left, Thomas Ruff’s Substrat 10 (2002, below)

Thomas Ruff (German, b. 1958)

Substrat 10

2002

C-type print

186 x 238cm

DZ BANK Kunstsammlung

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2012

Installation view of the exhibition Painting in Photography. Strategies of Appropriation at the Städel Museum, Frankfurt showing at centre, Wolfgang Tillmans Paper drop (window) (2006, below)

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

paper drop (window)

2006

C-type print in artists frame

145 x 200cm

Property of Städelscher Museums-Verein e.V.

© Courtesy Galerie Buchholz, Köln / Berlin

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Acquired in 2008 with funds from the Städelkomitee 21. Jahrhundert

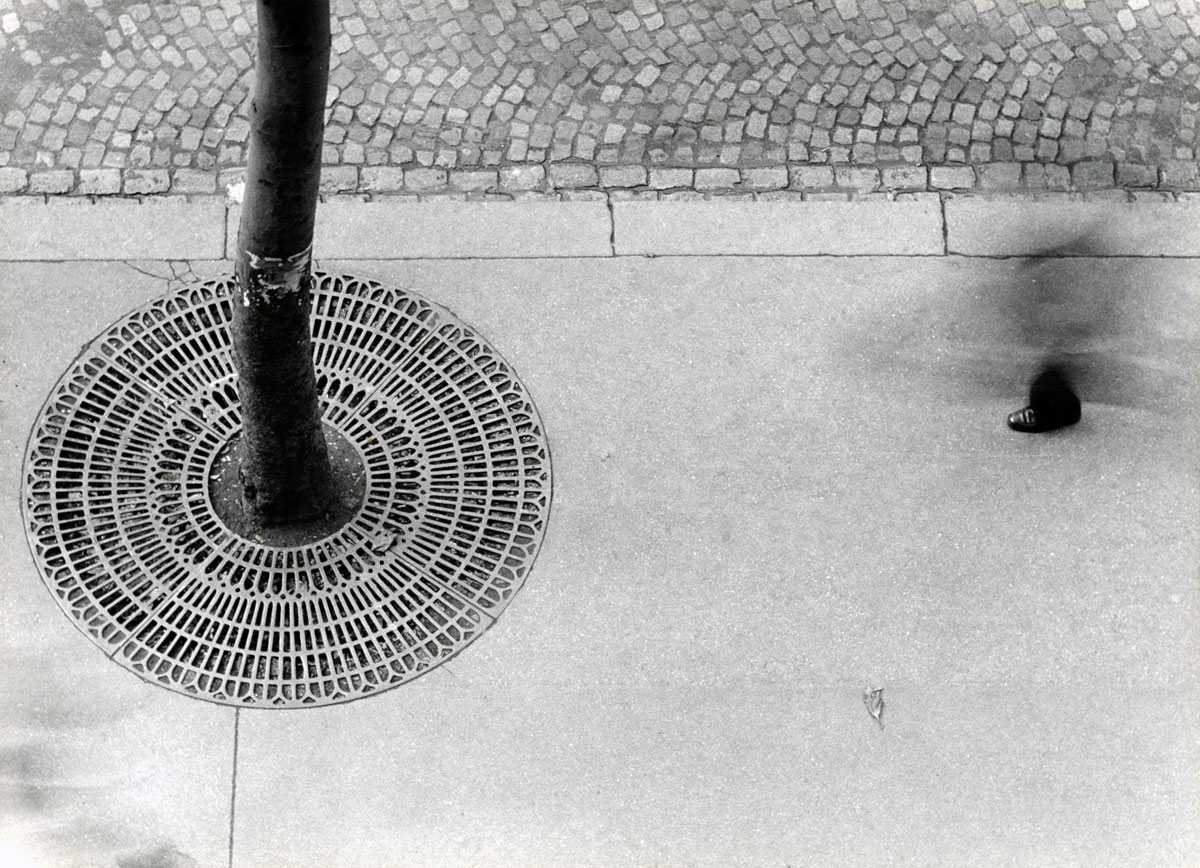

Otto Steinert (German, 1915-1978)

Ein-Fuß-Gänger

1950

Gelatin silver print

28.5 x 39cm

Courtesy Galerie Kicken Berlin

© Nachlass Otto Steinert, Museum Folkwang, Essen

Laszlo Moholy-Nagy (Hungarian, 1895-1946)

Photogram

c. 1923-1925

Unique photogram, toned printing-out paper

12.6 x 17.6cm

Courtesy Galerie Kicken Berlin

© Hattula Moholy-Nagy / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

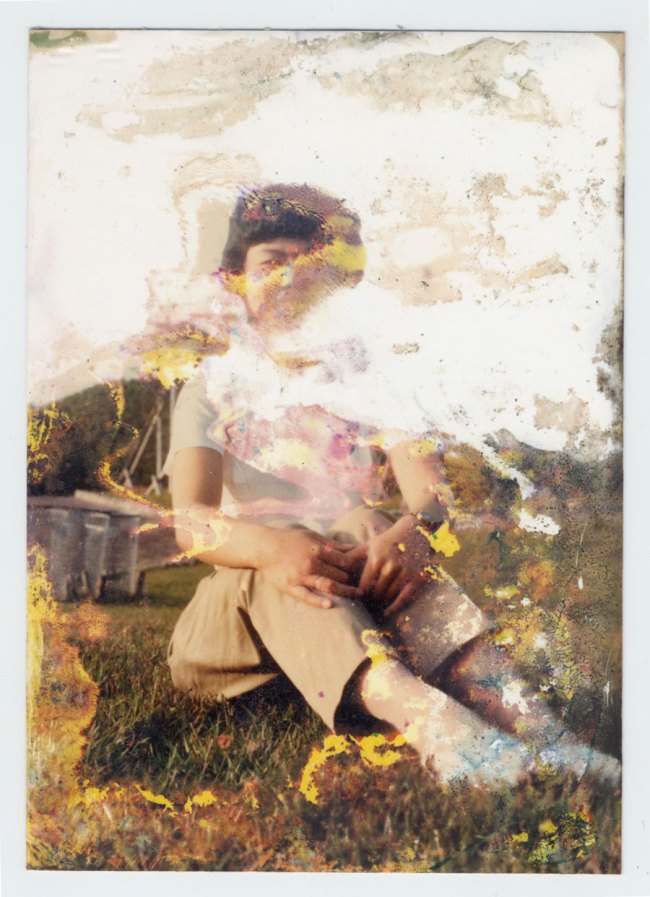

Robert Rauschenberg (American, 1925-2008)

10-80-C-17 (NYC)

1980

From the series: In + Out of City Limits: New York / Boston

Gelatin silver print on fibre-based paper

58 x 73cm

DZ BANK Kunstsammlung at the Städel Museum

© Estate of Robert Rauschenberg / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2012

Hiroshi Sugimoto (Japanese, b. 1948)

Sam Eric, Pennsylvania

1978

Gelatin silver print

42.5 x 54.5cm

Private collection, Frankfurt

© Hiroshi Sugimoto / Courtesy The Pace Gallery

Otto Steinert (German, 1915-1978)

Luminogramm

1952, printed c. 1952

Gelatin silver print

41.5 x 60cm

Courtesy Galerie Kicken Berlin

© Nachlass Otto Steinert, Museum Folkwang, Essen

From 27 June to 23 September 2012, the Städel Museum will show the exhibition “Painting in Photography. Strategies of Appropriation.” The comprehensive presentation will highlight the influence of painting on the imagery produced by contemporary photographic art. Based on the museum’s own collection and including important loans from the DZ Bank Kunstsammlung as well as international private collections and galleries, the exhibition at the Städel will centre on about 60 examples, among them major works by László Moholy-Nagy, Hiroshi Sugimoto, Wolfgang Tillmans, Thomas Ruff, Jeff Wall, and Amelie von Wulffen. Whereas the influence of the medium of photography on the “classic genres of art” has already been the subject of analysis in numerous exhibitions and publications, less attention has been paid to the impact of painting on contemporary photography to date. The show at the Städel explores the reflection of painting in the photographic image by pursuing various artistic strategies of appropriation which have one thing in common: they reject the general expectation held about photography that it will document reality in an authentic way.

The key significance of photography within contemporary art and its incorporation into the collection of the Städel Museum offer an occasion to fathom the relationship between painting and photography in an exhibition. While painting dealt with the use of photography in the mass media in the 1960s, today’s photographic art shows itself seriously concerned with the conditions of painting. Again and again, photography reflects, thematises, or represents the traditional pictorial medium, maintaining an ambivalent relationship between appropriation and detachment.

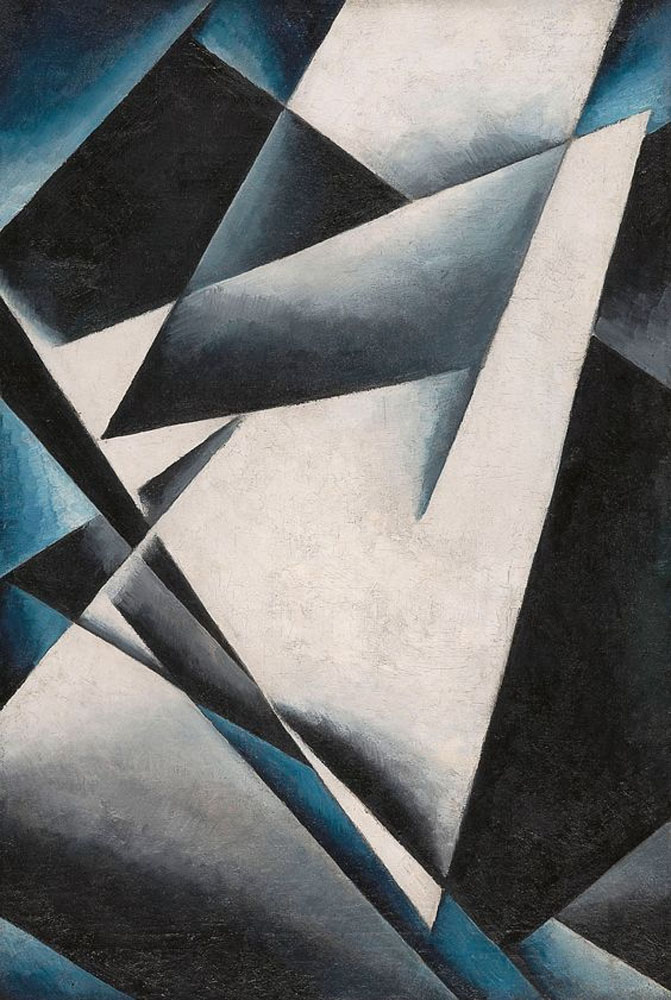

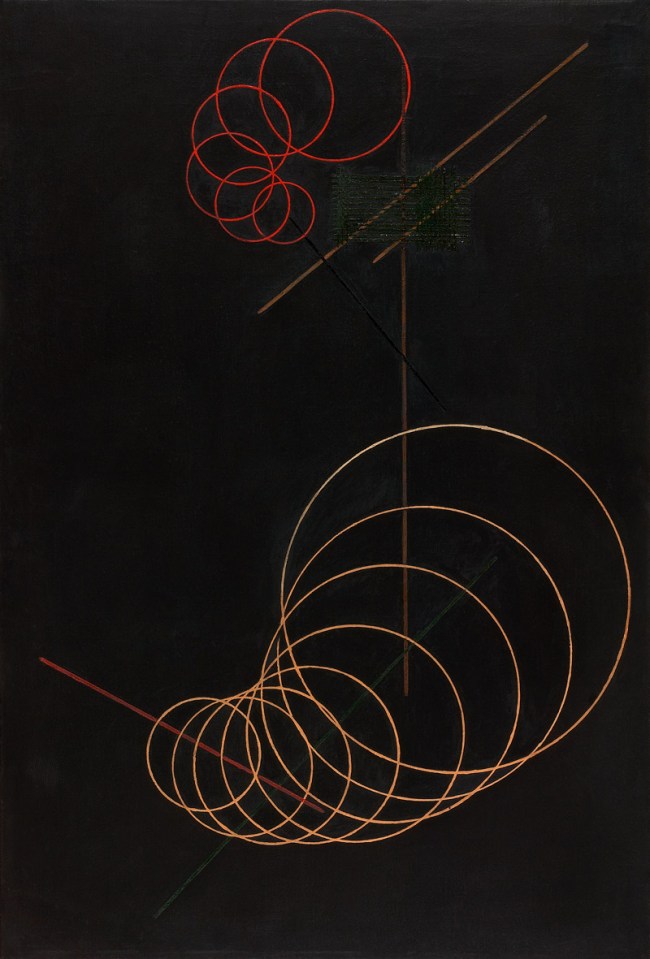

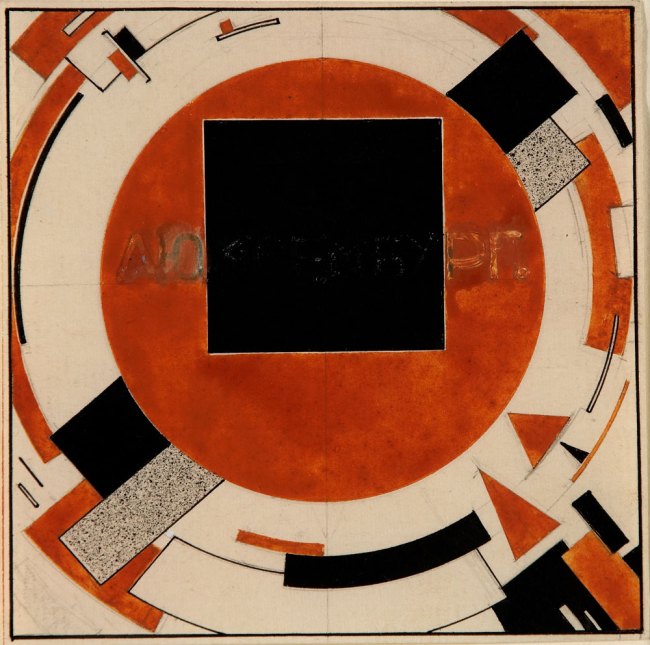

Numerous works presented in the Städel’s exhibition return to the painterly abstractions of the prewar and postwar avant-gardes, translate them into the medium of photography, and thus avoid a reproduction of reality. Early examples for the adaption of techniques of painting in photography are László Moholy-Nagy’s (1895-1946) photograms dating from the 1920s. For his photographs shot without a camera, the Hungarian artist and Bauhaus teacher arranged objects on a sensitised paper; these objects left concrete marks as supposedly abstract forms under the influence of direct sunlight. In Otto Steinert’s (1915-1978) non-representational light drawings or “luminigrams,” the photographer’s movement inscribed itself directly into the sensitised film. The pictures correlate with the gestural painting of Jackson Pollock’s Abstract Expressionism. A product of random operations during the exposure and development of the photographic paper, Wolfgang Tillmans’ (b. 1968) work “Freischwimmer 54” (2004) is equally far from representing the external world. It is the pictures’ fictitious depth, transparency, and dynamics that lend Thomas Ruff’s photographic series “Substrat” its extraordinary painterly quality recalling colour field paintings or Informel works. For his series “Seascapes” the Japanese artist Hiroshi Sugimoto (b. 1948) seems to have “emptied” the motif through a long exposure time: the sublime pictures of the surface of the sea and the sky – which either blur or are set off against each other – seem to transcend time and space.

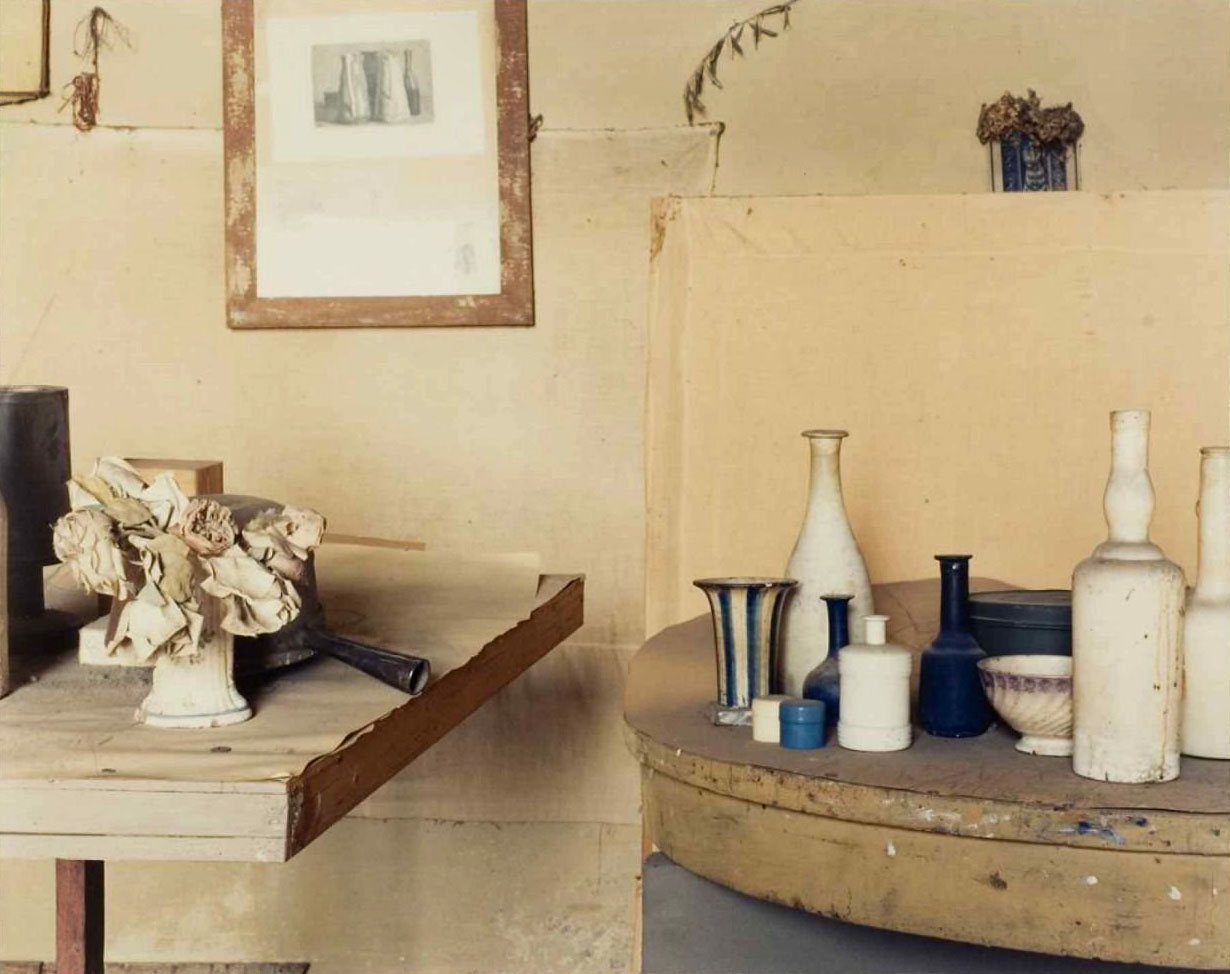

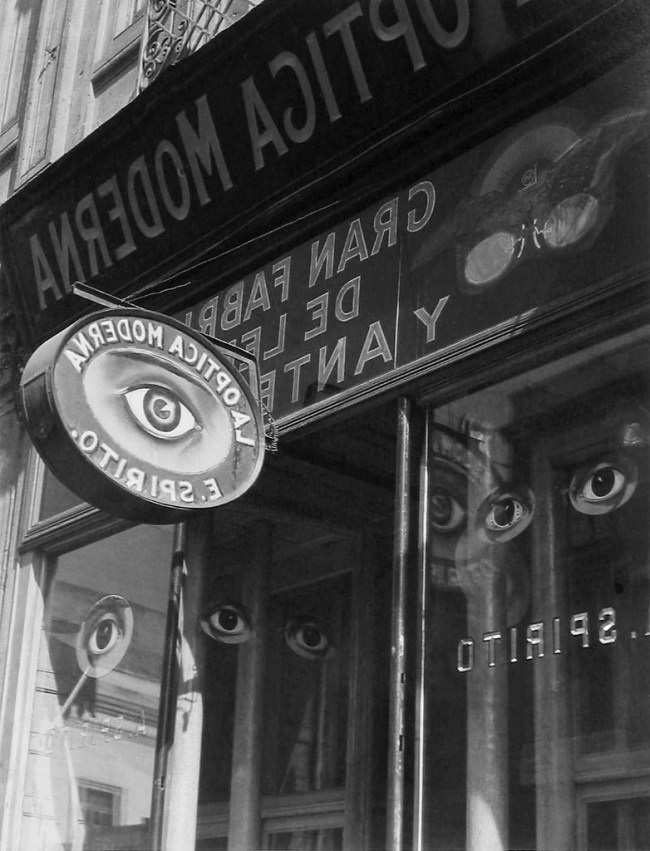

In addition to the photographs mentioned, the exhibition “Painting in Photography” includes works by artists who directly draw on the history of painting in their choice of motifs. The mise-en-scène piece “Picture for Women” (1979) by the Canadian photo artist Jeff Wall (b. 1946), which relates to Édouard Manet’s famous painting “Un Bar aux Folies-Bergère” from 1882, may be cited as an example for this approach. The camera positioned in the centre of the picture reveals the mirrored scene and turns into the eye of the beholder. The fictitious landscape pictures by Beate Gütschow (b. 1970), which consist of digitally assembled fragments, recall ideal Arcadian sceneries of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The photographs taken by Italian Luigi Ghirri (1943-1992) in the studio of Giorgio Morandi (1890-1964) “copy” Morandi’s still lifes by representing the real objects in the painter’s studio instead of his paintings.

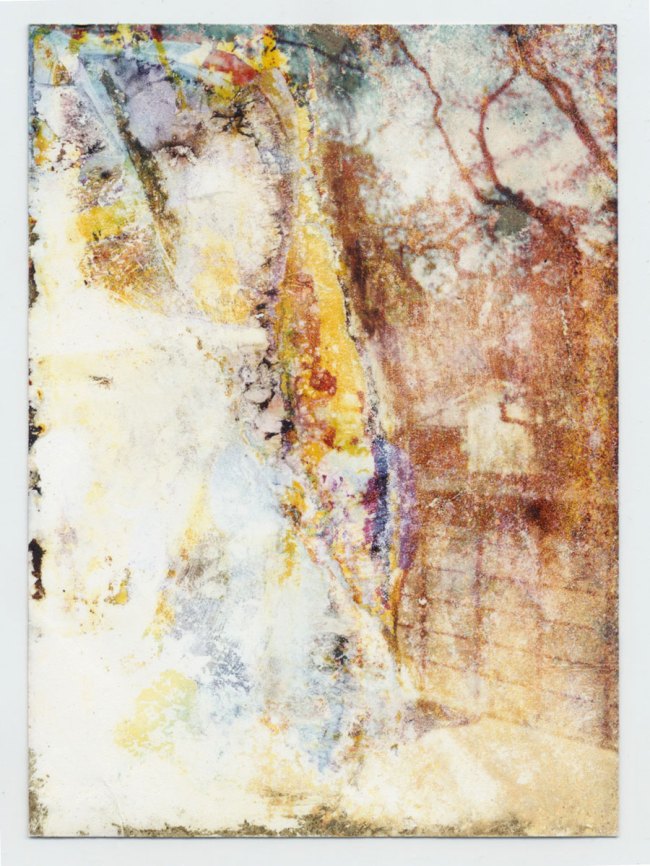

Another appropriative strategy sees the artist actually becoming active as a painter, transforming either the object he has photographed or its photographic representation. Oliver Boberg’s, Richard Hamilton’s, Georges Rousse’s and Amelie von Wulffen’s works rank in this category. For her series “Stadtcollagen” (1998-1999) Amelie von Wulffen (b. 1966) assembled drawing, photography, and painting to arrive at the montage of a new reality. The artist’s recollections merge with imaginary spaces offering the viewer’s fantasy an opportunity for his or her own associations.

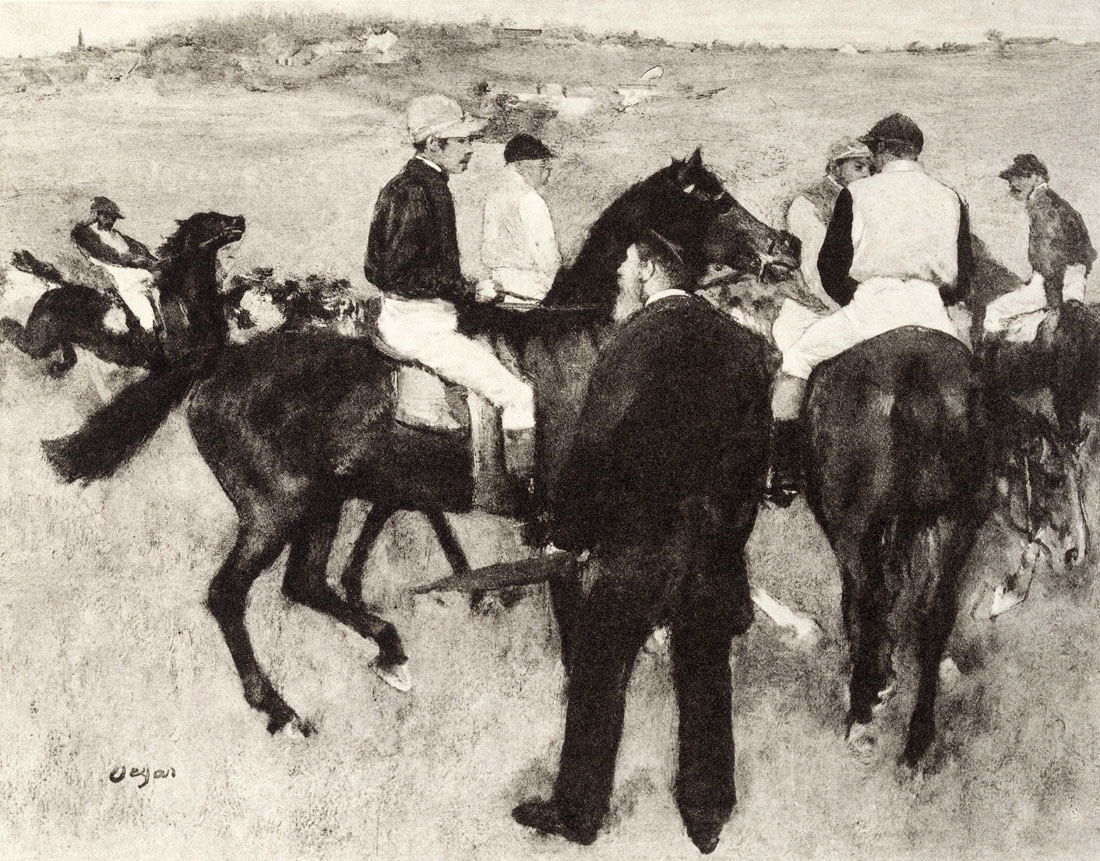

The exhibition also encompasses positions of photography for which painting is the object represented in the picture. The most prominent examples in this section come from Sherrie Levine (b. 1947) and Louise Lawler (b. 1947), both representatives of US Appropriation Art. From the late 1970s on, Levine and Lawler have photographically appropriated originals from art history. Levine uses reproductions of paintings from a catalogue published in the 1920s: she photographs them and makes lithographs of her pictures. Lawler photographs works of art in private rooms, museums, and galleries and thus rather elucidates the works’ art world context than the works as such.

Press release from the Städel Museum website

Sherrie Levine (American, b. 1947)

After Edgar Degas (detail)

1987

5 lithographs on hand-made paper

69 x 56cm

DZ BANK Kunstsammlung im Städel Museum, Frankfurt

© Sherrie Levine / Courtesy Jablonka Galerie, Köln

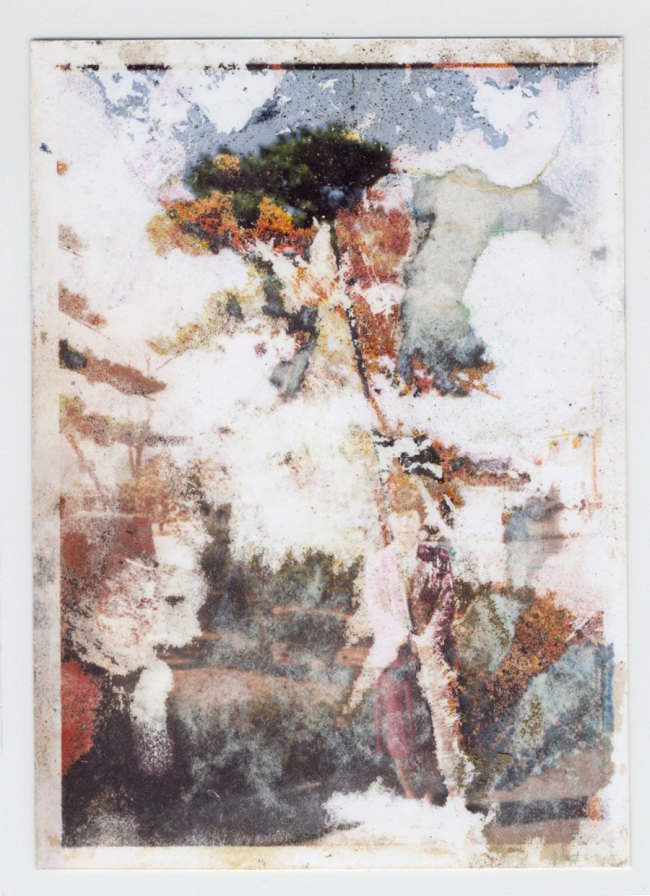

Beate Gütschow (German, b. 1970)

PN #1

2000

C-Print, mounted on aluminium dibond

Acquired in 2013, property of Städelscher Museums-Verein e.V.

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main, Eigentum des Städelschen Museums-Vereins e.V.

… these images do not evoke a sense of the sublime. On closer inspection, not only is the virginity of nature lost forever, but the innocence of perception is also denied. The natural realms presented here are simply too beautiful to be true. The beauty, wildness, and potentially threatening aspects of nature have been skillfully merged into a decorative whole, as they were in landscape painting from the 17th through to the 19th century. Beate Gütschow’s photographic works reproduce traditional patterns of depiction, incorporating landscape elements that recall compositions by Nicolas Poussin (1594-1665), Jacob van Ruisdael (1628-1682), Claude Lorrain (1600-1682), John Constable (1776-1837), and Philipp Otto Runge (1777-1810). The subjects portrayed by these landscape painters were based on an idealised worldview, the construction of which reflected the dominant philosophical ethos of their time. The artists themselves, however, presented this ideal in a manner bordering on the absolute. …

Beate Gütschow photographs landscapes with a medium-format analog camera, then converts the images into digital files. From this archived material she then constructs new landscapes in Photoshop, basing their spatial arrangements and compositional structures on the principles of landscape painting. As part of this subsequent editing process, she adjusts the light and colours in the images, applying lighting techniques from the realm of painting to her photographs. Because Gütschow uses only the retouching tool and other traditional darkroom techniques offered by Photoshop, not its painting tools, the photographic surface is preserved and the joins between the component parts are not immediately visible. These digital tools make it possible to employ a painterly method without the resulting picture being a painting. The viewer is given the impression that this is a completely normal photograph. When, however, an ideal landscape is presented in the form of a photograph, it appears more unnatural than the painted version of the same view. In this way, Gütschow’s work explores concepts of representation, colour, and light – the formal attributes of painting and photography – as well as the distinctions between documentation and staging.

Extract from Gebbers, Anna-Catharina. “Larger than Life,” in Beate Gütschow: ZISLS. Heidelberg, 2016, pp. 8-17. Translated by Jacqueline Todd [Online] Cited 23/08/2022

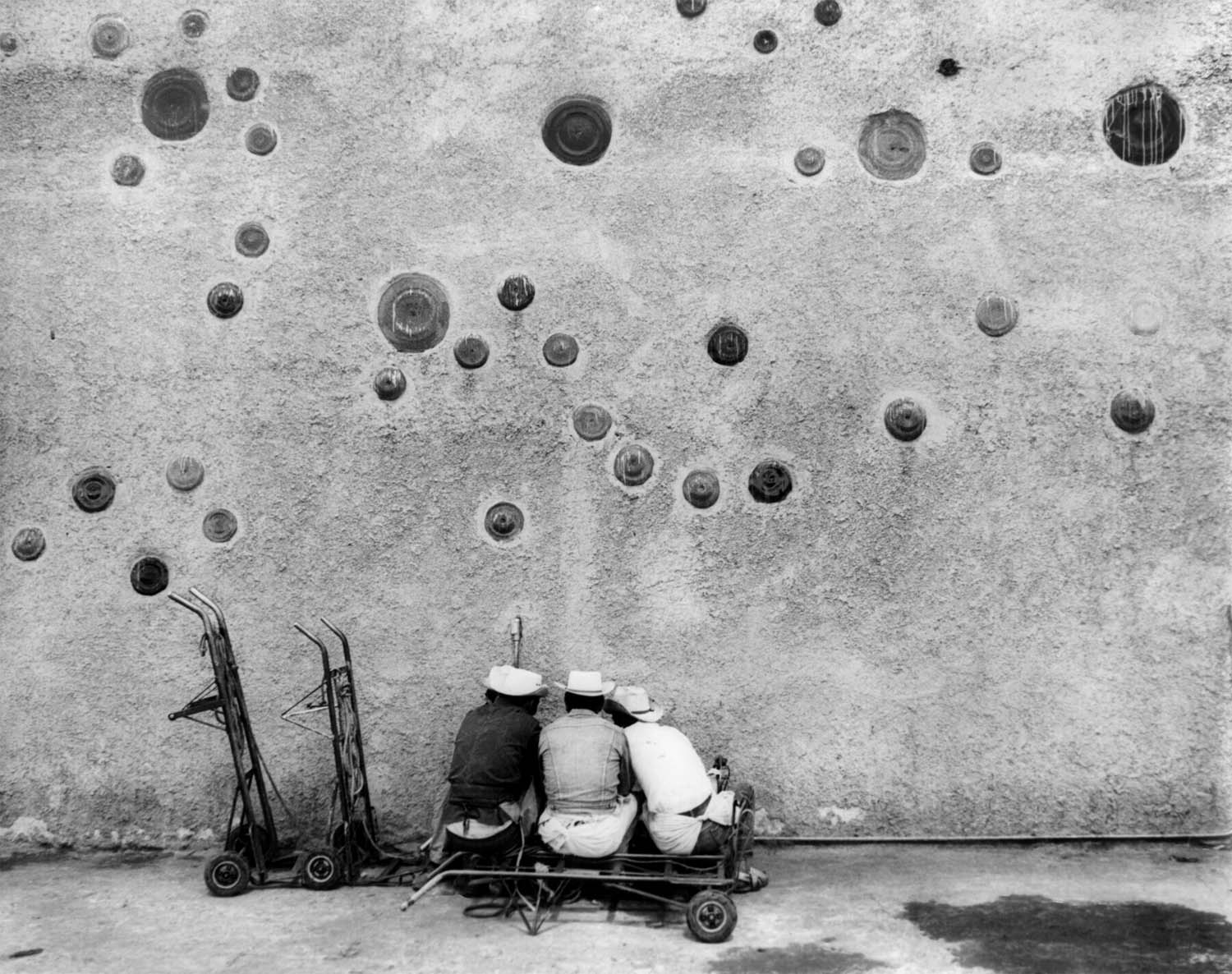

Luigi Ghirri (Italian, 1943-1992)

L’atelier de Giorgio Morandi, Bologne

1989

Luigi Ghirri (5 January 1943 – 14 February 1992) was an Italian artist and photographer who gained a far-reaching reputation as a pioneer and master of contemporary photography, with particular reference to its relationship between fiction and reality.

Amelie von Wulffen (German, b. 1966)

Untitled (City Collages, VIII)

1998

Oil paint, photographs on paper

42 x 59.7cm

Acquired in 2009 with funds from the Städelkomitee 21. Jahrhundert, property of Städelscher Museums-Verein e.V.

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main, Eigentum des Städelschen Museums-Vereins e.V.

The starting point for Amelie von Wulffen’s city collages is the urban architecture which she has photographed herself. These photographs are affixed to a surface and then processed pictorially: the artist alienates the perspective, adds abstract patterns and confronts the scene with quirky objects. The painted forms and unreal connections intervene in the relationship to reality of the supposedly objective photograph. The combination of photograph and painting is accompanied by a reflection on the characteristics of the medium concerned. The photographic reproduction of a situation which has been experienced may adequately record the place but not necessarily the memory. With this in mind, the artist sees painting as a suitable medium to equip photography with an authentic means of expression. During the chemical process of photography, real objects are registered on the light-sensitive material, just as the mood of the place and the memory of the artist are translated into the painting process. With regard to form, Wulffen reveals a wealth of references to Constructivism, Surrealism and Dadaism.

Text from the Städel Museum website

Art after 1945: Amelie von Wulffen

In our “Art after 1945” series, artists introduce their artworks in the Städel collection. In this episode Amelie von Wulffen explains her series “Stadtcollagen”.

Jeff Wall (Canadian, b. 1946)

Picture for Women

1979

Cibachrome transparency in lightbox

204.5 × 142.5cm (80.5 in × 56.1 in)

Picture for Women is a photographic work by Canadian artist Jeff Wall. Produced in 1979, Picture for Women is a key early work in Wall’s career and exemplifies a number of conceptual, material and visual concerns found in his art throughout the 1980s and 1990s. An influential photographic work, Picture for Women is a response to Édouard Manet’s Un bar aux Folies Bergère and is a key photograph in the shift from small-scale black and white photographs to large-scale colour that took place in the 1980s in art photography and museum exhibitions. …

Picture for Women is a 142.5 by 204.5 cm Cibachrome transparency mounted on a lightbox. Along with The Destroyed Room (1978), Wall considers Picture for Women to be his first success in challenging photographic tradition. According to Tate Modern, this success allows Wall to reference “both popular culture (the illuminated signs of cinema and advertising hoardings) and the sense of scale he admires in classical painting. As three-dimensional objects, the lightboxes take on a sculptural presence, impacting on the viewer’s physical sense of orientation in relationship to the work.”

Text from the Wikipedia website

Louise Lawler (American, b. 1947)

It Could Be Elvis

1994

Cibachrome, varnished with shellac

74.5 x 91cm

DZ BANK Kunstsammlung at the Städel Museum

© Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New York

Oliver Boberg (German, b. 1965)

Unterführung [Underpass]

1997

C-type print

75 x 84cm

DZ BANK Kunstsammlung

© Oliver Boberg / Courtesy L.A. Galerie – Lothar Albrecht, Frankfurt

Richard Hamilton (English, 1922-2011)

Eight-Self-Portraits (detail)

1994

Thermal dye sublimation prints

40 x 35cm

DZ BANK Kunstsammlung

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2012

Wolfgang Tillmans (German, b. 1968)

Freischwimmer 54

2004

C-type in artists frame

237 x 181 x 6cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

© Courtesy Galerie Buchholz, Köln / Berlin

Acquired in 2008 with funds from the Städelkomitee 21. Jahrhundert

Property of Städelscher Museums-Verein e.V.

Städel Museum

Schaumainkai 63

60596 Frankfurt

Opening hours:

Tuesday – Sunday 10am – 6pm

Closed Mondays

![Oliver Boberg (German, b. 1965) 'Unterführung' [Underpass] 1997 Oliver Boberg (German, b. 1965) 'Unterführung' [Underpass] 1997](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/r_p_oliver-boberg-unterfuehrungdruckbar-web.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.