Exhibition dates: 19th February – 30th May, 2016

Co-curators: Joel Smith, the Morgan’s Richard L. Menschel Curator and Department Head of Photography, and Lisa Hostetler, Curator in Charge of Photography at the Eastman Museum

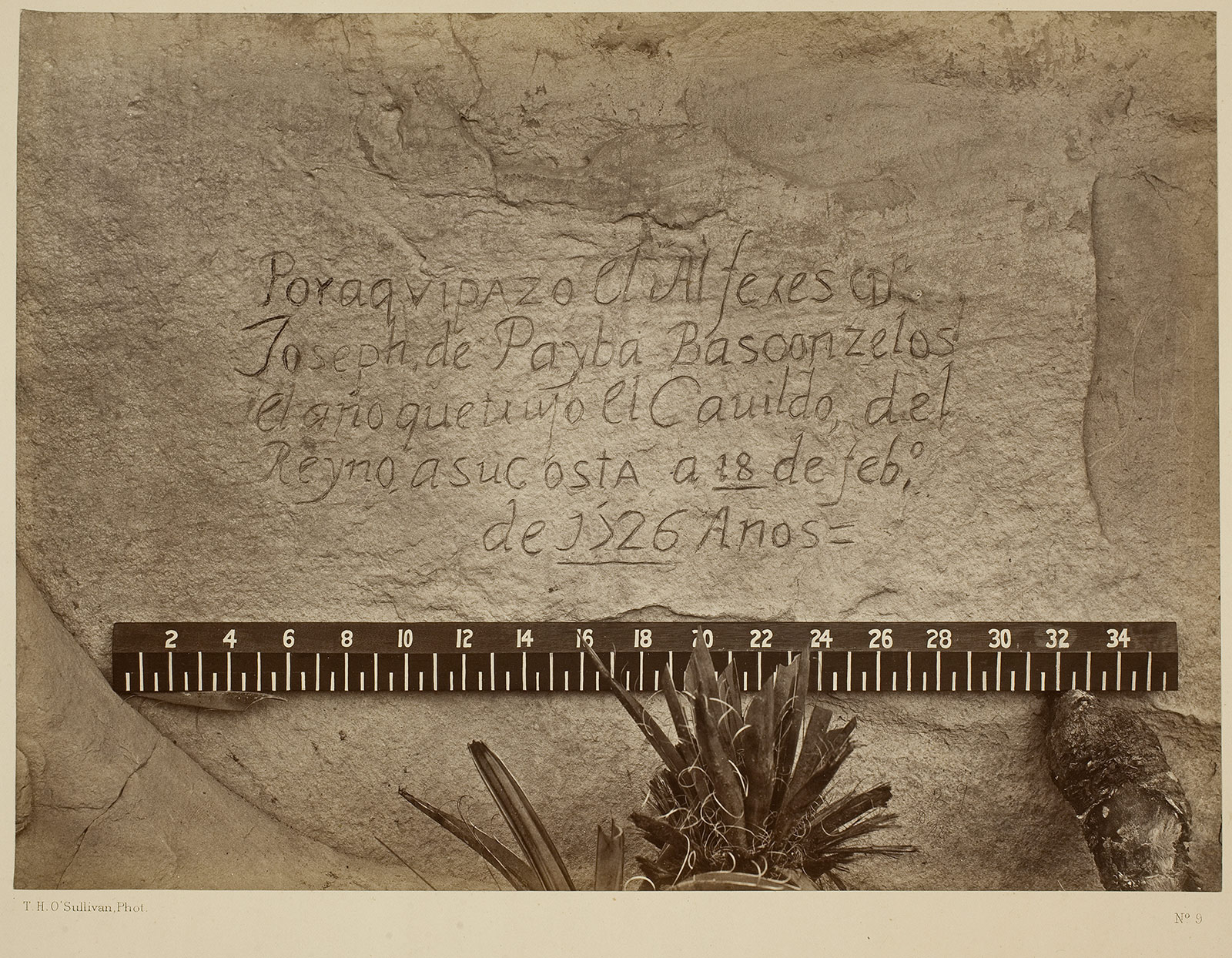

Timothy H. O’Sullivan (American born Ireland, 1840-1882)

Historic Spanish Record of the Conquest, South Side of Inscription Rock

1873

From the album Geographical Explorations and Surveys West of the 100th Meridian

Albumen silver print

George Eastman Museum, purchase

In 1873 O’Sullivan joined Lieutenant George Wheeler’s Geographic Survey in New Mexico and Arizona. At El Morro, a sandstone promontory covered with ancient petroglyphs and historic-era inscriptions, the photographer singled out this handsomely lettered sentence to record and measure. It states: By this place passed Ensign Don Joseph de Payba Basconzelos, in the year in which he held the Council of the Kingdom at his expense, on the 18th of February, in the year 1726. Nearby, the rock record now bears another inscription that reads T. H. O’Sullivan.

This looks to be a fascinating exhibition. I wish I could see it.

While Sight Reading cuts across conventional historical and geographic divisions, with the exhibition being organised into nine “conversations” among diverse sets of works, we must always remember that these “themes” are not exclusory to each other. Photographs do cross nominally defined boundaries and themes (as defined by history and curators) so that they can become truly subversive works of art.

Photographs can form spaces called heterotopia, “a form of concept in human geography elaborated by philosopher Michel Foucault, to describe places and spaces that function in non-hegemonic conditions. These are spaces of otherness, which are neither here nor there, that are simultaneously physical and mental, such as the space of a phone call or the moment when you see yourself in the mirror… Foucault uses the term “heterotopia” (French: hétérotopie) to describe spaces that have more layers of meaning or relationships to other places than immediately meet the eye.”1

In photographs, there is always more than meets the eye. There is the association of the photograph to multiple places and spaces (the histories of that place and space); the imagination of the viewer and the memories they bring to any encounter with a photograph, which may change from time to time, from look to look, from viewing to viewing; and the transcendence of the photograph as it brings past time to present time as an intimation of future time. Past, present and future spacetime are conflated in the act of just looking, just being. Positioning this “‘annihilation of time and space’ as a particular moment in a dynamic cycle of rupture and recuperation enables a deliberate focus on the process of transition.”2 And that transition, Doreen Massey argues, ignores often-invisible contingencies that define spaces those relations that have an effect upon a space but are not visible within it.3

Photographs, then, form what Deleuze and Guattari call assemblages4, where the assemblage is “the processes by which various configurations of linked components function in an intersection with each other, a process that can be both productive and disruptive. Any such process involves a territorialization; there is a double movement where something accumulates meanings (re-territorialization), but does so co-extensively with a de-territorialization where the same thing is disinvested of meanings. The organization of a territory is characterized by such a double movement … An assemblage is an extension of this process, and can be thought of as constituted by an intensification of these processes around a particular site through a multiplicity of intersections of such territorializations.”5 In other words, when looking at a photograph by William Henry Fox Talbot or Timothy H. O’Sullivan today, the meaning and interpretation of the photograph could be completely different to the reading of this photograph in the era it was taken. The photograph is a site of both de-territorialization and re-territorialization – it both gains and looses meaning at one and the same time, depending on who is looking at it, from what time and from what point of view.

Photographs propose that there are many heterotopias in the world, many transitions and intersections, many meanings lost and found, not only as spaces with several places of/for the affirmation of difference, but also as a means of escape from authoritarianism and repression. We must remember these ideas as we looking at the photographs in this exhibition.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Footnotes

1/ Heterotopia (space) on the Wikipedia website [Online] Cited 27/05/2016.

2/ McQuire, Scott. The Media City. London: Sage Publications, 2008, p. 14.

3/ Massey, Doreen. Space, Place and Gender. Cambridge: Polity Press, 1994, p. 5 in Wood, Aylish. “Fresh Kill: Information technologies as sites of resistance,” in Munt, Sally (ed.,). Technospaces: Inside the New Media. London: Continuum, 2001, pp. 163-164.

4/ Deleuze, Gilles and Guattari, Felix. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Minneapolisand London: University of Minneapolis Press, 1987.

5/ Wood, Aylish. “Fresh Kill: Information technologies as sites of resistance,” in Munt, Sally (ed.,). Technospaces: Inside the New Media. London: Continuum, 2001, p.166

Many thankx to the Morgan Library & Museum for allowing me to publish the text and photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Sight Reading: Photography and the Legible World exhibition sections

As its name declares, photography is a means of writing with light. Photographs both show and tell, and they speak an extraordinary range of dialects.

Beginning February 19 the Morgan Library & Museum explores the history of the medium as a lucid, literate – but not always literal – tool of persuasion in a new exhibition, Sight Reading: Photography and the Legible World. A collaboration with the George Eastman Museum of Film and Photography, the show features more than eighty works from the 1840s to the present and reveals the many ways the camera can transmit not only the outward appearance of its subject but also narratives, arguments, and ideas. The show is on view through May 30.

Over the past 175 years, photography has been adopted by, and adapted to, countless fields of endeavour, from art to zoology and from fashion to warfare. Sight Reading features a broad range of material – pioneering x-rays and aerial views, artefacts of early photojournalism, and recent examples of conceptual art – organised into groupings that accentuate the variety and suppleness of photography as a procedure. In 1936, artist László Moholy-Nagy (1895-1946) defined “the illiterate of the future” as someone “ignorant of the use of the camera as well as the pen.” The JPEG and the “Send” button were decades away, but Moholy-Nagy was not the first observer to argue that photography belonged to the arts of commentary and persuasion. As the modes and motives of camera imagery have multiplied, viewers have continually learned new ways to read the information, and assess the argument, embodied in a photograph.

“Traditional narratives can be found throughout the Morgan’s collections, especially in its literary holdings,” said Colin B. Bailey, director of the Morgan. “Sight Reading encourages us to use a critical eye to read and discover the stories that unfold through the camera lens and photography, a distinctly modern, visual language. We are thrilled to collaborate with the Eastman Museum, and together unravel a rich narrative, which exemplifies photography’s deep involvement in the stories of modern art, science, and the printed page.”

The exhibition

Sight Reading cuts across conventional historical and geographic divisions. Featuring work by William Henry Fox Talbot (1800-1877), Eadweard Muybridge (1830-1904), John Heartfield (1891-1968), Lewis Hine (1874-1940), Harold Edgerton (1903-1990), John Baldessari (1931-2020), Sophie Calle (b. 1953), and Bernd and Hilla Becher (1931-2007; 1934-2015), among many others, the exhibition is organised into nine “conversations” among diverse sets of works.

I. The Camera Takes Stock

Photography’s practical functions include recording inventory, capturing data imperceptible to the human eye, and documenting historical events. In the first photographically illustrated publication, The Pencil of Nature (1845), William Henry Fox Talbot used his image Articles of China to demonstrate that “the whole cabinet of a … collector … might be depicted on paper in little more time than it would take him to make a written inventory describing it in the usual way.” Should the photographed collection suffer damage or theft, Talbot speculated, “the mute testimony of the picture … would certainly be evidence of a novel kind” before the law.

A century later, Harold Edgerton, an electrical engineer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, used the pulsing light of a stroboscope to record states of matter too fleeting for the naked eye. Gun Toss, an undated image of a spinning pistol, is not a multiple exposure: the camera shutter opened and closed just once. But during that fraction of a second, seven bright flashes of light committed to film a seven-episode history of the gun’s trajectory through space.

William Henry Fox Talbot (British, 1800-1877)

Articles of China

c. 1843, printed c. 1845

Salted paper print from calotype negative

Collection of Richard and Ronay Menschel

In The Pencil of Nature (1845), the first photographically illustrated publication, Talbot used Articles of China to demonstrate that “the whole cabinet of a … collector … might be depicted on paper in little more time than it would take him to make a written inventory describing it in the usual way.” Should the collection suffer damage or theft, Talbot added, “the mute testimony of the picture … would certainly be evidence of a novel kind” before the law.

Harold Edgerton (American, 1903-1990)

Gun Toss

1936-1950

Gelatin silver print

Collection of Richard and Ronay Menschel

Edgerton, an electrical engineer, used the rapidly pulsing light of a stroboscope to record states of matter too fleeting to be perceived by the naked eye. This image of a spinning pistol is not a multiple exposure: the camera shutter opened and closed just once. But during that fraction of a second, seven bright flashes of light committed to film a seven-episode history of the gun’s trajectory through space.

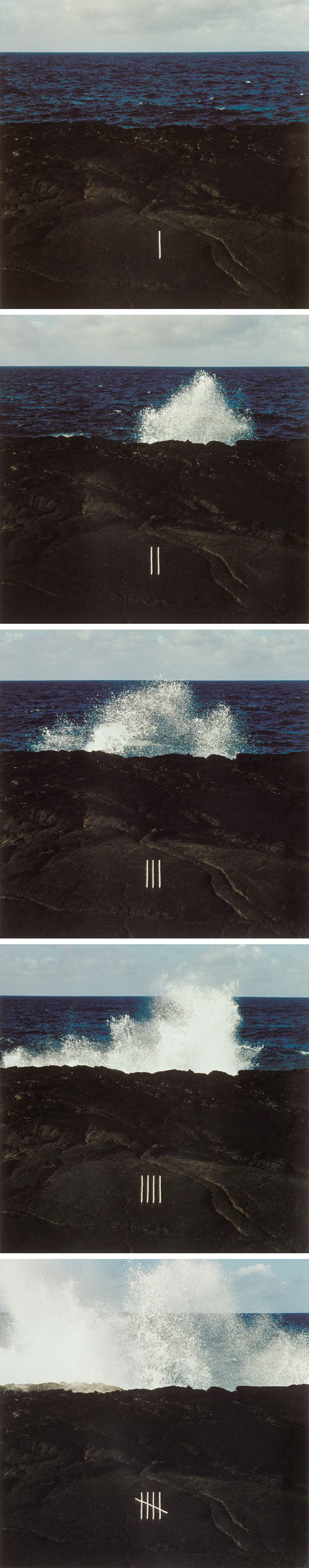

John Pfahl (American, 1939-2020)

Wave Theory I-V, Puna Coast, Hawaii, March 1978

1978

From the series Altered Landscapes

Chromogenic development (Ektacolor) process prints, 1993

George Eastman Museum, purchase

In this sequence, Pfahl twisted the conventions of photographic narrative into a perceptual puzzle. The numbered views appear to chronicle a single event: a wave breaking on the shore. Close inspection, however, reveals that the numeric caption in each scene is made of string laid on the rock in the foreground. The exposures, then, must have been made over a span of at least several minutes, not seconds – and in what order, one cannot say.

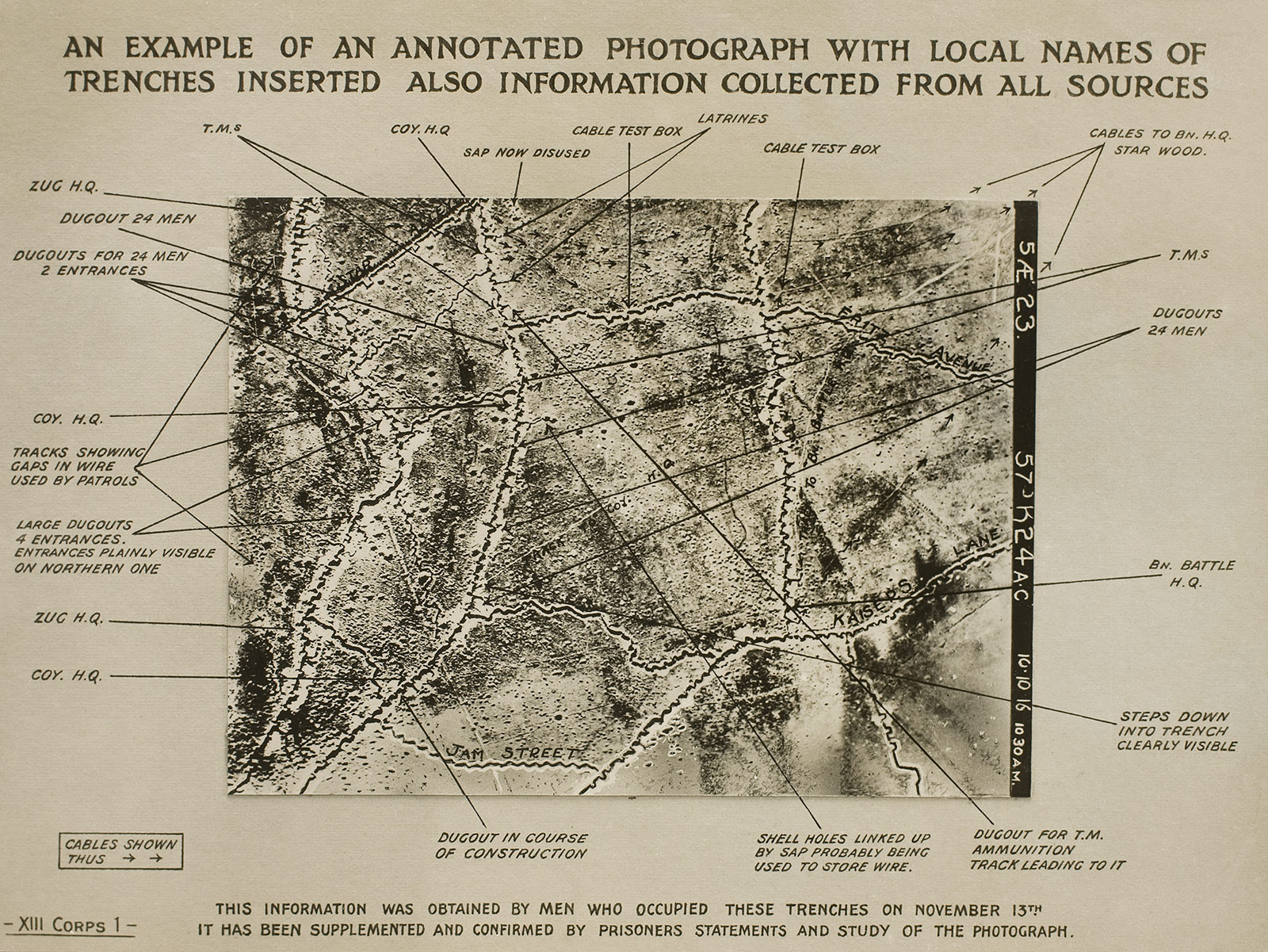

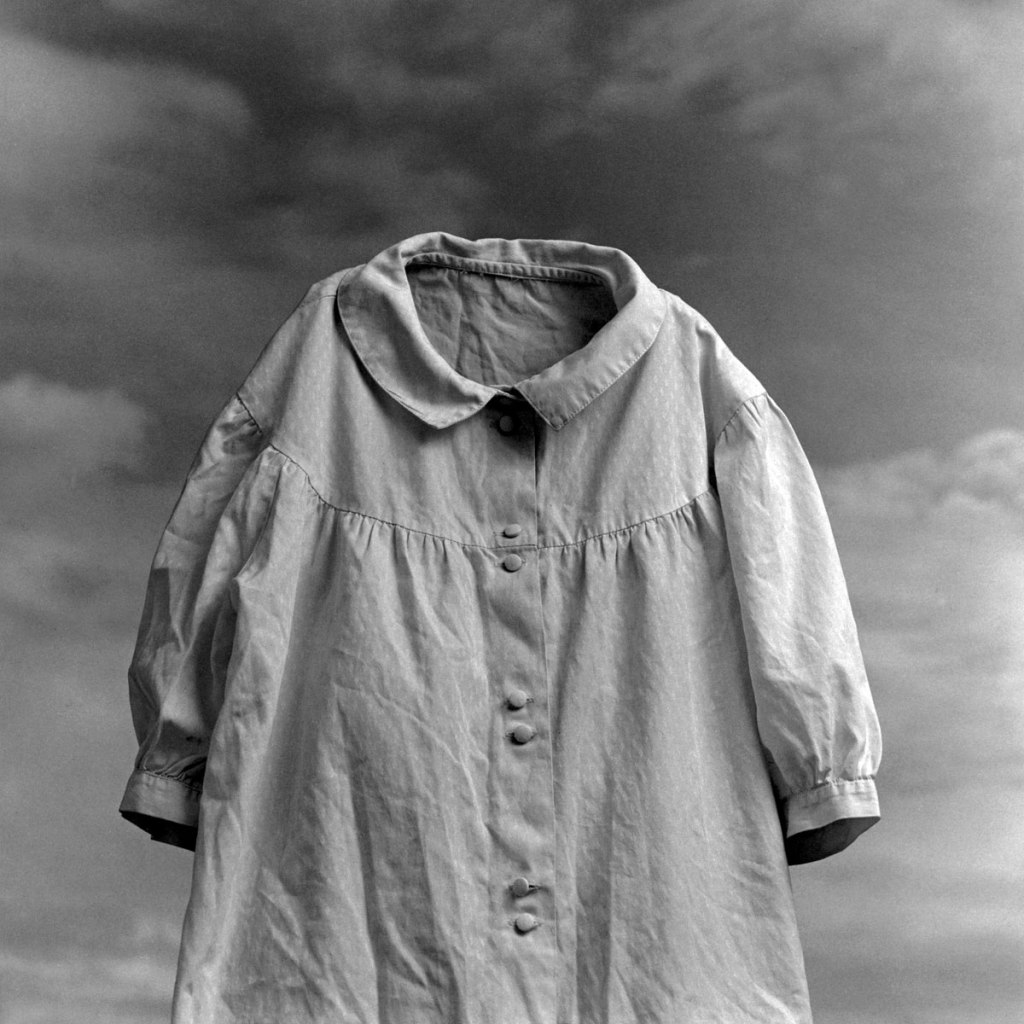

II. Crafting A Message

The camera is widely understood to be “truthful,” but what photographs “say” is a product of many procedures that follow the moment of exposure, including page layout, captioning, and cropping of the image. During World War I, military personnel learned to interpret the strange, abstract looking images of enemy territory made from airplanes. Their specialised training fundamentally altered the nature of wartime reconnaissance, even as the unusual perspective unique to aerial photography introduced a new dialect into the expanding corpus of modern visual language. An Example of an Annotated Photograph with Local Names of Trenches Inserted (1916), on view in the exhibition, shows that the tools of ground strategy soon included artificial bunkers and trenches, designed purely to fool eyes in the sky.

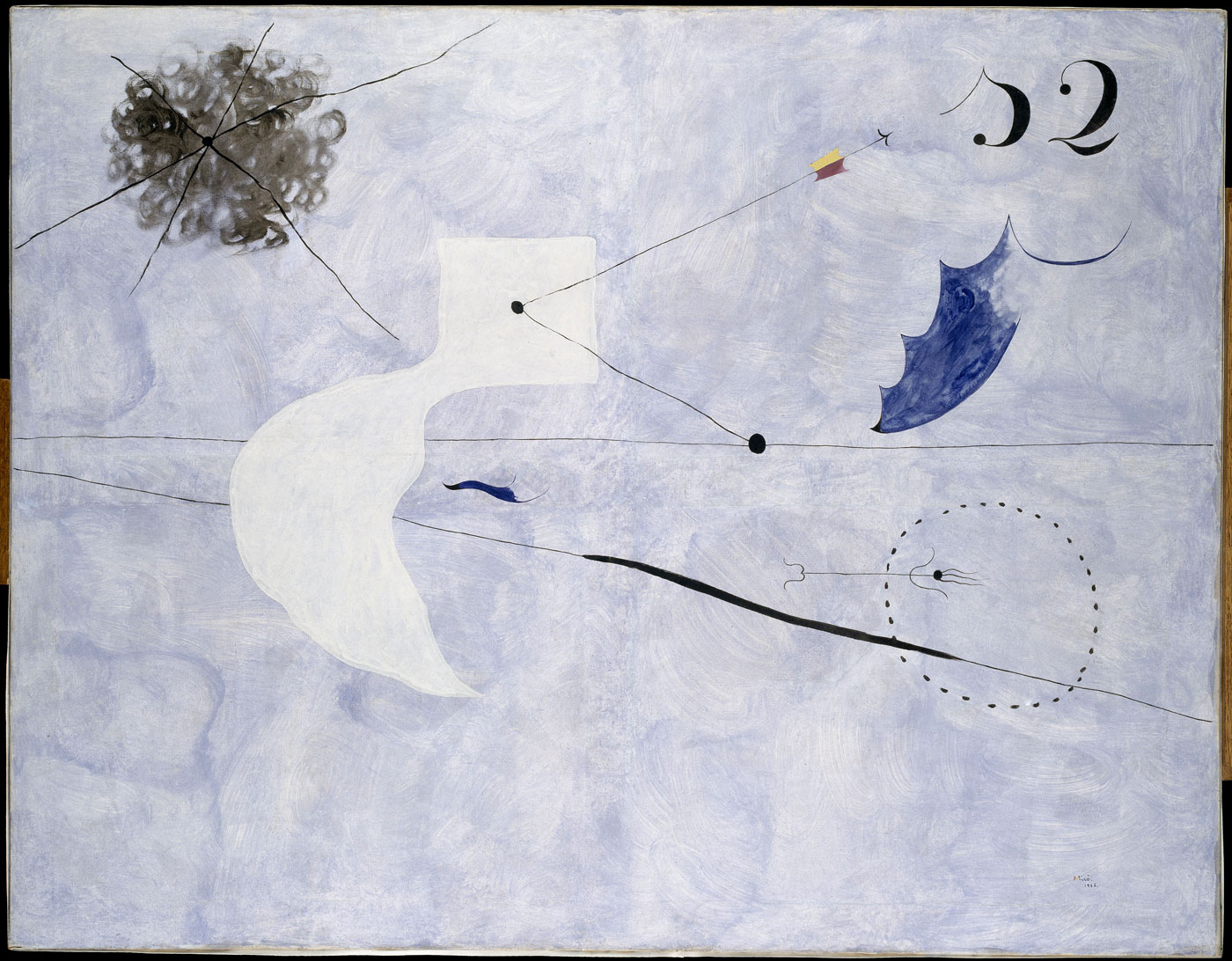

In László Moholy-Nagy’s photocollages of the late 1920s, figures cut out of the plates in mass market magazines appear in new configurations to convey messages of the artist’s devising. Images such as Massenpsychose (Mass Psychosis) (1927) propose a new kind of visual literacy for the machine age. To contemporary eyes, Moholy’s collages seem to foreshadow cut-and-paste strategies that would later characterise the visual culture of cyberspace.

László Moholy-Nagy (American born Hungary, 1895-1946)

Massenpsychose (Mass Psychosis)

1927

Collage, pencil, and ink

George Eastman Museum, Purchased with funds provided by Eastman Kodak Company

To make his photocollages of the late 1920s, Moholy-Nagy cut figures out of photographs and photomechanical reproductions and arranged them into new configurations that convey messages of his own devising. By extracting the images from their original context and placing them into relationships defined by drawn shapes and volumes, he suggested a new visual literacy for the modern world. In this world – one in which images course through mass culture at a psychotic pace – a two-dimensional anatomical drawing acquires sufficient volume to cast a man’s shadow and a circle of bathing beauties cues up for a pool sharp. To contemporary eyes, the language of Moholy-Nagy’s photo collages seems to foreshadow strategies common to the visual culture of cyberspace.

Unidentified maker

An Example of an Annotated Photograph with Local Names of Trenches Inserted

c. 1916

Gelatin silver print

George Eastman Museum

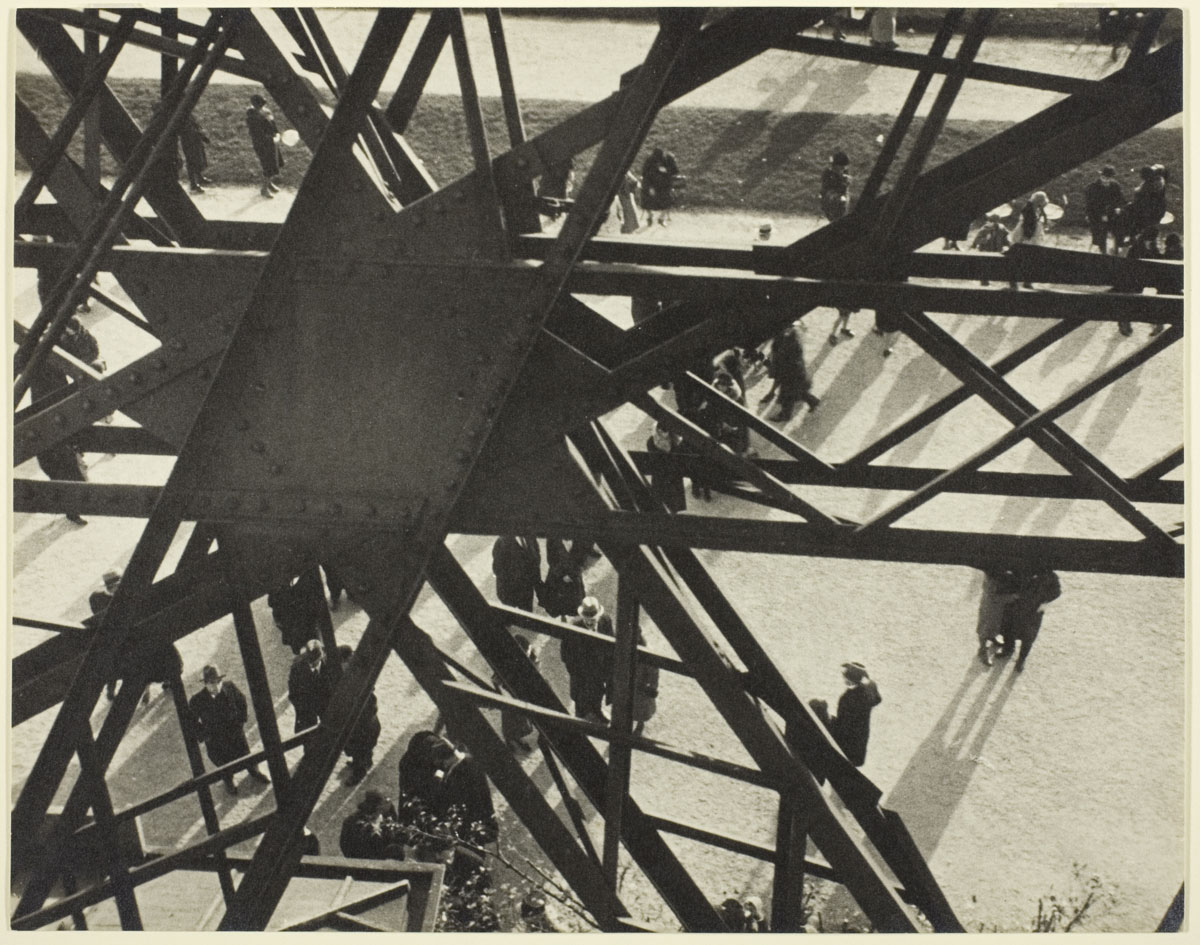

During World War I, aerial photography progressed from a promising technological experiment to a crucial strategic operation. As advances in optics and engineering improved the capabilities of cameras and aircraft, military personnel learned to identify topographic features and man-made structures in the images recorded from above. Such training fundamentally altered the significance and practice of wartime reconnaissance. At the same time, the unusual perspective unique to aerial photography introduced a new dialect into the expanding corpus of modern visual language.

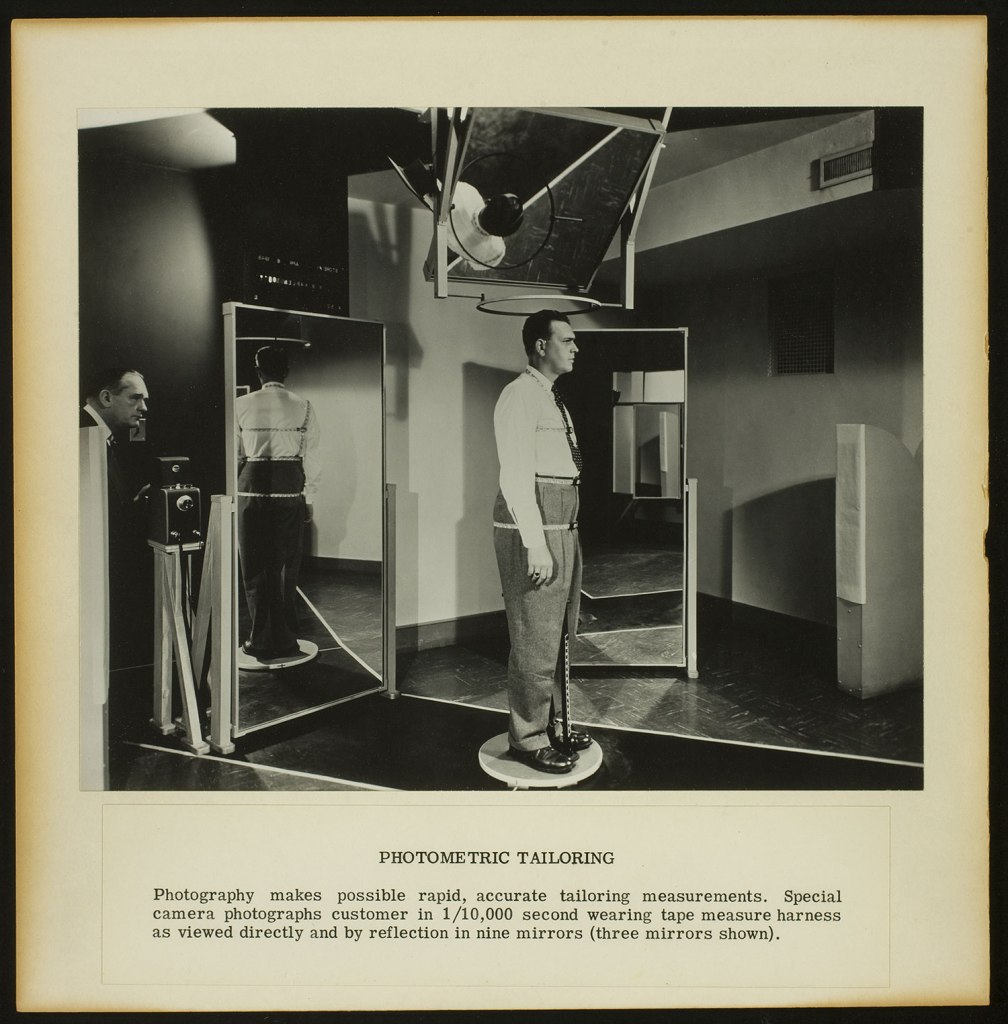

PhotoMetric Corporation, 1942-1974

PhotoMetric Tailoring

c. 1942-1948

Gelatin silver prints

George Eastman Museum

In an effort to streamline the field of custom tailoring, textile entrepreneur Henry Booth devised a method for obtaining measurements by photographing customers with a special camera and angled mirrors. The system was said to be foolproof, making it possible for any sales clerk to operate it. The resulting slides were sent to the manufacturer along with the customer’s order. A tailor translated the images into physical measurements using a geometric calculator, and the company mailed the finished garment to the customer.

III. Photographs in Sequence

Photography’s debut in the late 1830s happened to coincide with the birth of the modern comic strip. Ultimately the narrative photo sequence would lead to the innovations that gave rise to cinema, another form of storytelling altogether. Exact contemporaries of one another, Eadweard J. Muybridge in the United States and Étienne-Jules Marey (1830-1904) in France both employed cameras to dissect human movement. Muybridge used a bank of cameras positioned to record a subject as it moved, tripping wires attached to the shutters. The result was a sequence of “stop-action” photographs that isolated gestures not otherwise visible in real time. Beginning in 1882, Marey pursued motion studies with a markedly different approach. In the works for which he is best known, he exposed one photographic plate multiple times at fixed intervals, recording the arc of movement in a single image.

Étienne Jules Marey (French, 1830-1904)

Chronophotographic study of man pole vaulting

c. 1890

Albumen silver print

George Eastman Museum, Exchange with Narodni Technical Museum

Exact contemporaries, Muybridge and Marey (the former in the United States, the latter in France) both employed cameras to dissect human movement. Muybridge used a bank of cameras positioned and timed to record a subject as it moved, tripping wires attached to the shutters. The result was a sequence of “stop-action” photographs that isolated gestures not otherwise visible in real time. Beginning in 1882, Marey took a markedly different approach. In the works for which he is best known – such as the image of the man pole-vaulting – he exposed a single photographic plate multiple times at fixed intervals, recording the arc of movement in a single image. In Marey’s chronophotograph of a man on a horse, the action reads from bottom to top. The convention of arranging sequential photographic images from left to right and top to bottom, on the model of written elements on a page, was not yet firmly established.

William N. Jennings (American, b. England, 1860-1946)

Notebook pages with photographs of lightning

c. 1887

Gelatin silver prints mounted onto bound notepad paper

George Eastman Museum, Gift of 3M Foundation; Ex-collection of Louis Walton Sipley

With his first successful photograph of a lightning bolt on 2 September 1882, Jennings dispelled the then widely held belief – especially among those in the graphic arts – that lightning traveled toward the earth in a regular zigzag pattern. Instead, his images revealed that lightning not only assumed an astonishing variety of forms but that it never took the shape that had come to define it in art.

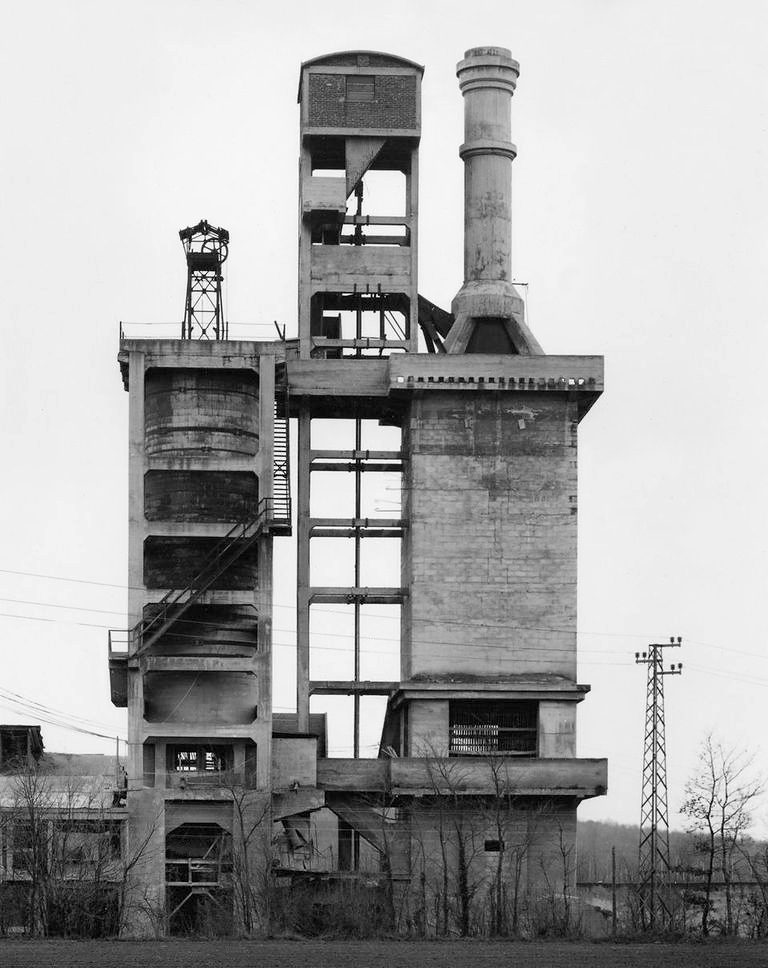

Bernd Becher (German, 1931-2007)

Hilla Becher (German, 1934-2015)

Industriebauten

1968

Gelatin silver prints in presentation box

George Eastman Museum, Purchase

The photographs in this portfolio were made only a few years into what would become the Bechers’ decades-long project of systematically documenting industrial architecture in Europe and the United States. The straightforward and rigidly consistent style of their work facilitates side-by-side comparison, revealing the singularity of structures that are typically understood to be generic.

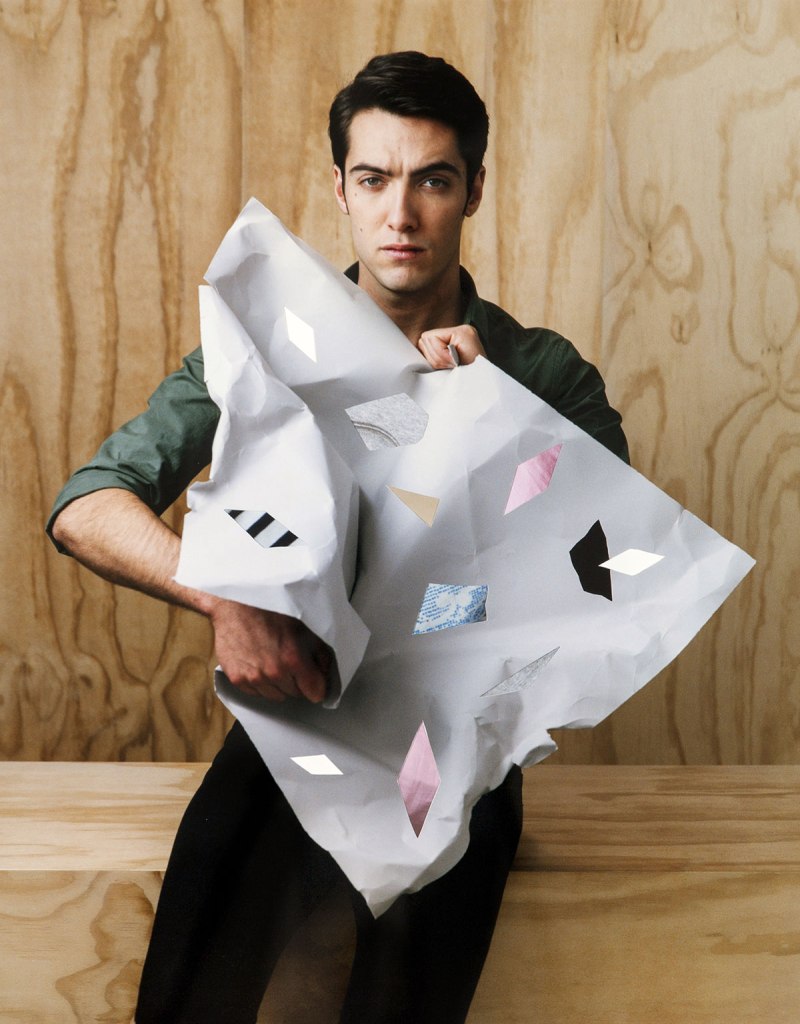

IV. The Legible Object

Some photographs speak for themselves; others function as the amplifier for objects that can literally be read through the image. In her series Sorted Books, American artist Nina Katchadourian (b. 1968) composes statements by combining the titles of books drawn from the shelves of libraries and collections. Indian History for Young Folks, 2012, shows three books from the turn of the twentieth century that she found in the Delaware Art Museum’s M.G. Sawyer Collection of Decorative Bindings. The viewer’s eye silently provides punctuation: “Indian history for young folks: Our village; your national parks.” Though at first glance it appears merely to arrange words into legible order, Katchadourian’s oblique statement – half verbal, half visual – would be incomplete if divorced from the physical apparatus of the books themselves.

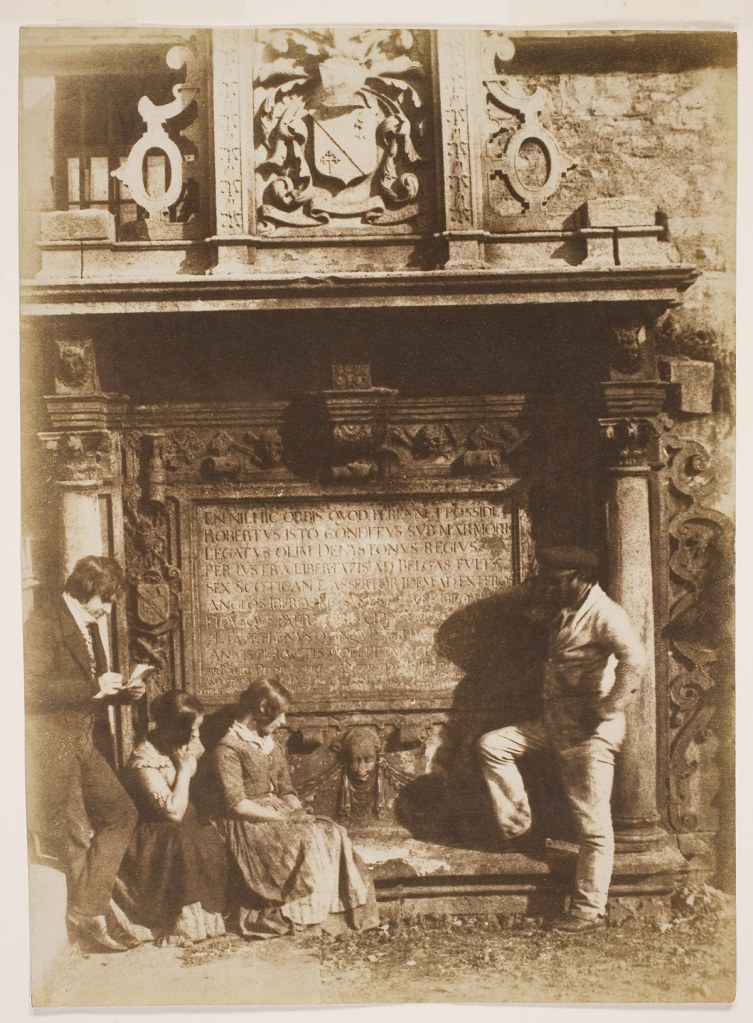

David Octavius Hill (Scottish, 1802-1870)

Robert Adamson (Scottish, 1821-1848)

The Artist and the Gravedigger (Denistoun Monument, Greyfriars Churchyard, Edinburgh)

c. 1845

Salted paper print from calotype negative

George Eastman Museum, Gift of Alvin Langdon Coburn

Hill, his two nieces, and an unidentified man pose for the camera at the tomb of Robert Denistoun, a seventeenth-century Scottish ambassador. Contemplative poses helped the sitters hold still during the long exposure, even while turning them into sculptural extensions of the monument. Hill puts pen to paper, perhaps playing the part of a graveyard poet pondering mortality. Above him, the monument’s Latin inscription begins: “Behold, the world possesses nothing permanent!”

Robert Cumming (American, 1943-2021)

Submarine cross-section; feature film, “Gray Lady Down” – Stage #12, March 14, 1977

1977

Inkjet print

George Eastman Museum, Gift of Nash Editions

In the Studio Still Lifes he photographed on the backlots of Universal Studios, Cumming sought to portray the mechanisms behind cinema vision “in their real as opposed to their screen contexts.” Admiring yet subversive, his documents use strategies native to the still camera – distance, point of view, and clear-eyed testimony – to translate Hollywood’s familiar illusions into worksites where “marble is plywood, stone is rubber, … rooms seldom have ceilings, and when the sun shines indoors, it casts a dozen shadows.”

Nina Katchadourian (American, b. 1968)

Indian History for Young Folks

2012

From Once Upon a Time in Delaware / In Quest of the Perfect Book

Chromogenic print

The Morgan Library & Museum, Purchase, Photography Collectors Committee

In her ongoing series Sorted Books, Katchadourian composes statements by combining the titles of books from a given library – in this case, the M. G. Sawyer Collection of Decorative Bindings at the Delaware Art Museum. Though her compositions are driven by the need to arrange words in a legible order, Katchadourian’s oblique jokes, poems, and koans would be incomplete if divorced from the cultural information conveyed by the physical books themselves.

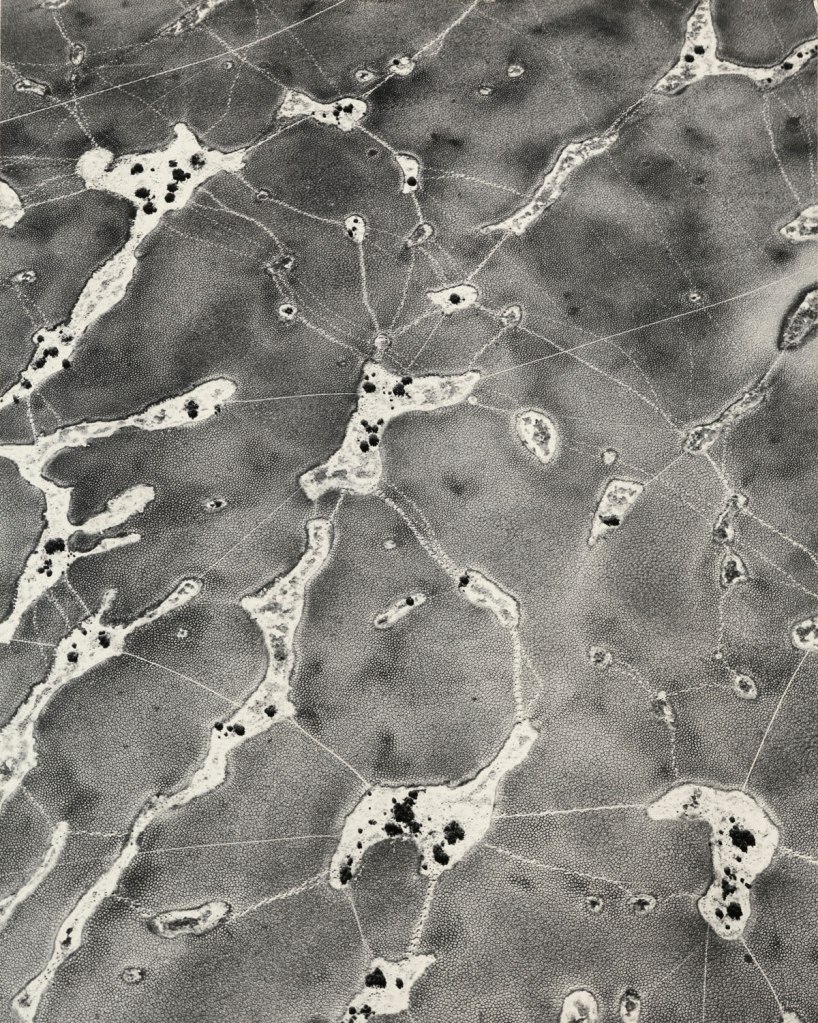

V. The Photograph Decodes Nature

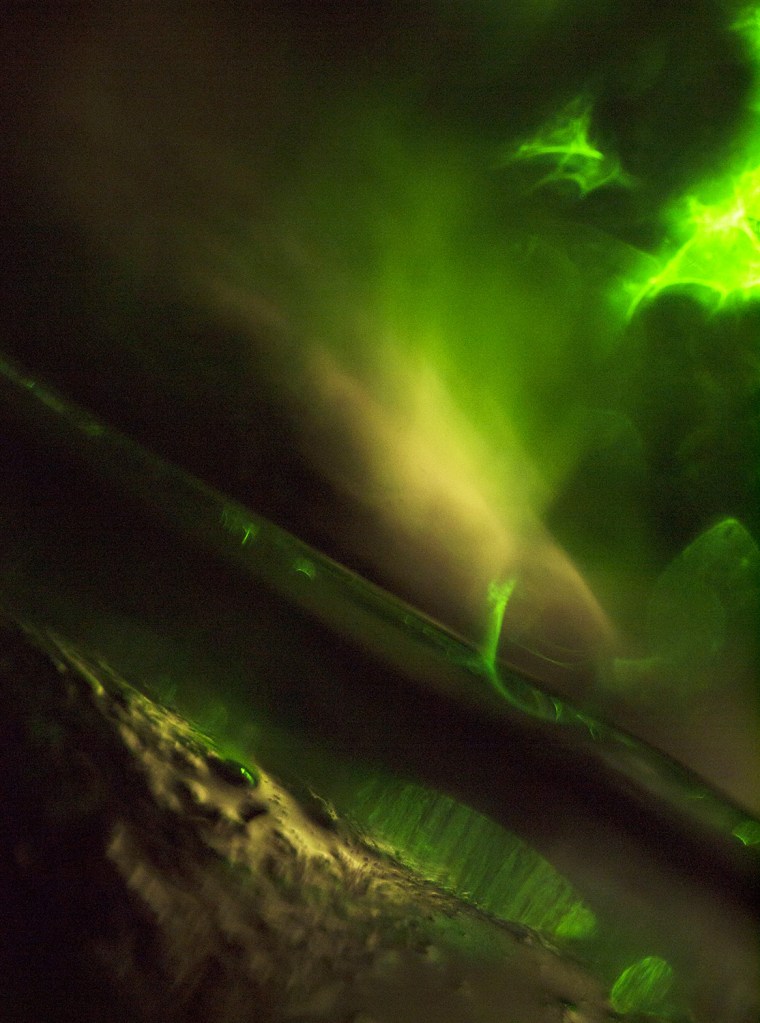

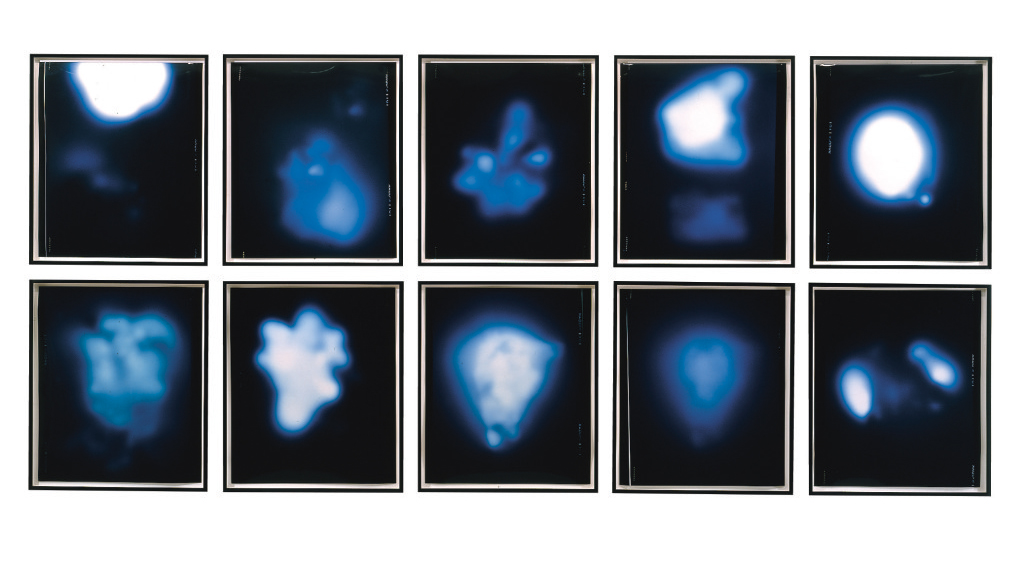

As early as 1840, one year after photography’s invention was announced, scientists sought to deploy it in their analysis of the physical world. Combining the camera with the microscope, microphotographs recorded biological minutiae, leading to discoveries that would have been difficult, if not impossible, to obtain by observing subjects in real time. Similarly, the development of X-ray technology in 1895 allowed scientists to see and understand living anatomy to an unprecedented degree. Such innovations not only expanded the boundaries of the visible world but also introduced graphic concepts that would have a profound impact on visual culture. In other ways, too, nature has been transformed in human understanding through the interpretive filter of the lens, as seen in Sight Reading in the telescopic moon views of astronomers Maurice Loewy (1833-1907) and Pierre Henri Puiseux (1855-1928) and in the spellbinding aerial abstractions of William Garnett (1916-2006).

William Garnett (American, 1916-2006)

Animal Tracks on Dry Lake

1955

Gelatin silver print

The Morgan Library & Museum, Purchased on the Charina Endowment Fund

After making films for the U.S. Signal Corps during World War II, Garnett used GI-Bill funding to earn a pilot’s license. By the early 1950s, he had the field of artistic aerial landscape virtually to himself. This print, showing the ephemeral traces of wildlife movement on a dry lake bed, appeared in Diogenes with a Camera IV (1956), one in a series of exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art that highlighted the great variety of ways in which artists used photography to invent new forms of visual truth.

William Henry Jackson (American, 1843-1942)

“Tea Pot” Rock

1870

Albumen silver print

George Eastman Museum, Purchase

Jackson made this photograph as a member of the survey team formed by Ferdinand V. Hayden to explore and document the territory now known as Yellowstone National Park. Hayden’s primary goal was to gather information about the area’s geological history, and Jackson’s photographs record with precision and clarity the accumulated layers of sediment that allow this natural landmark to be fit into a geological chronology. The human figure standing at the left of the composition provides information about the size of the rock, demonstrating that photographers have long recognised the difficulty of making accurate inferences about scale based on photographic images.

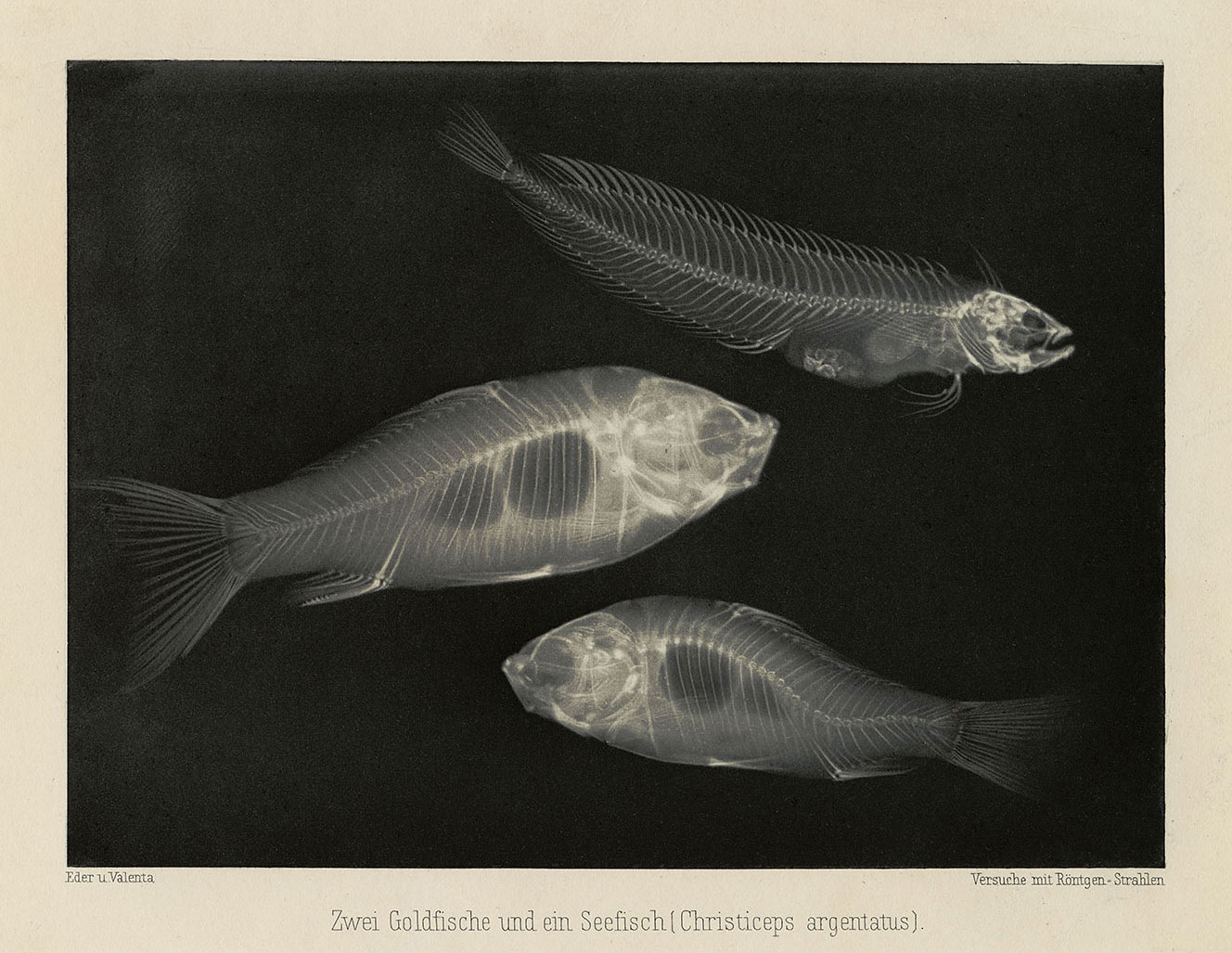

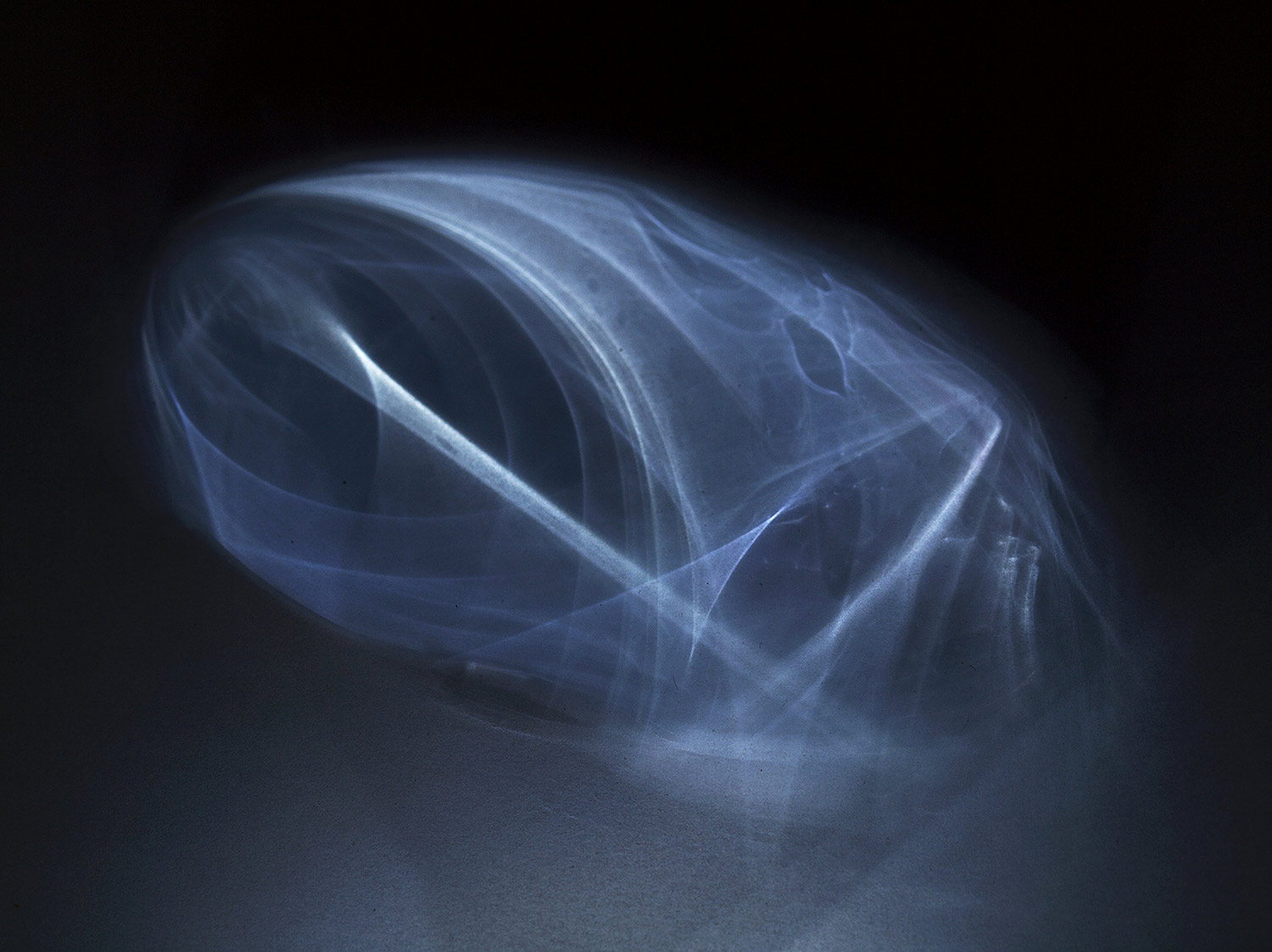

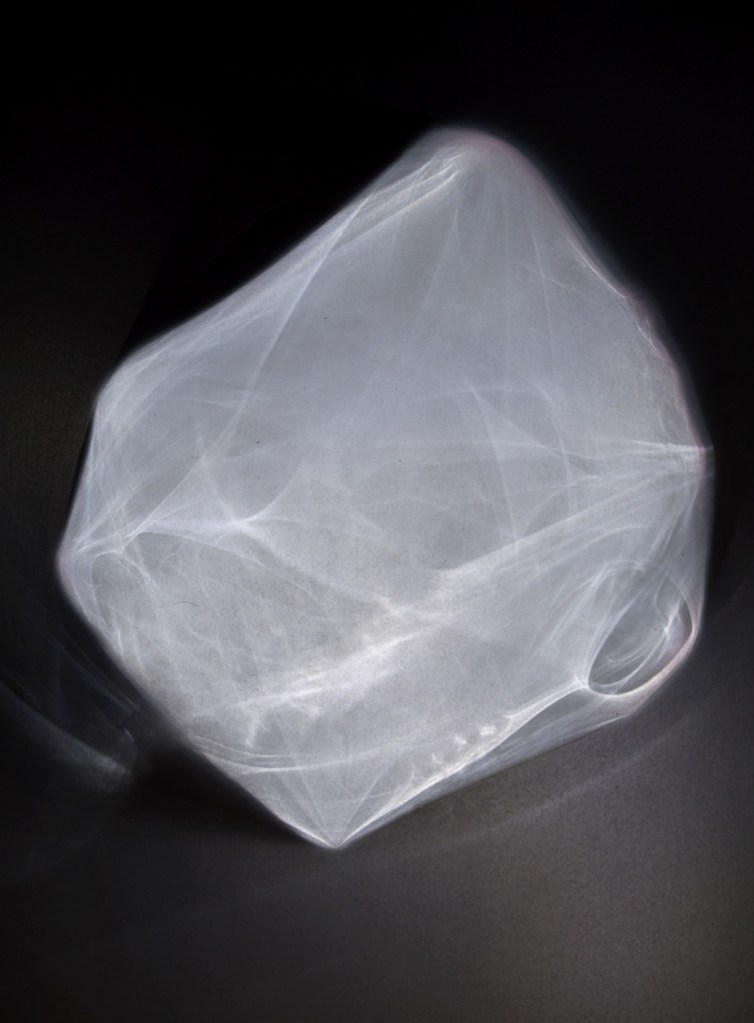

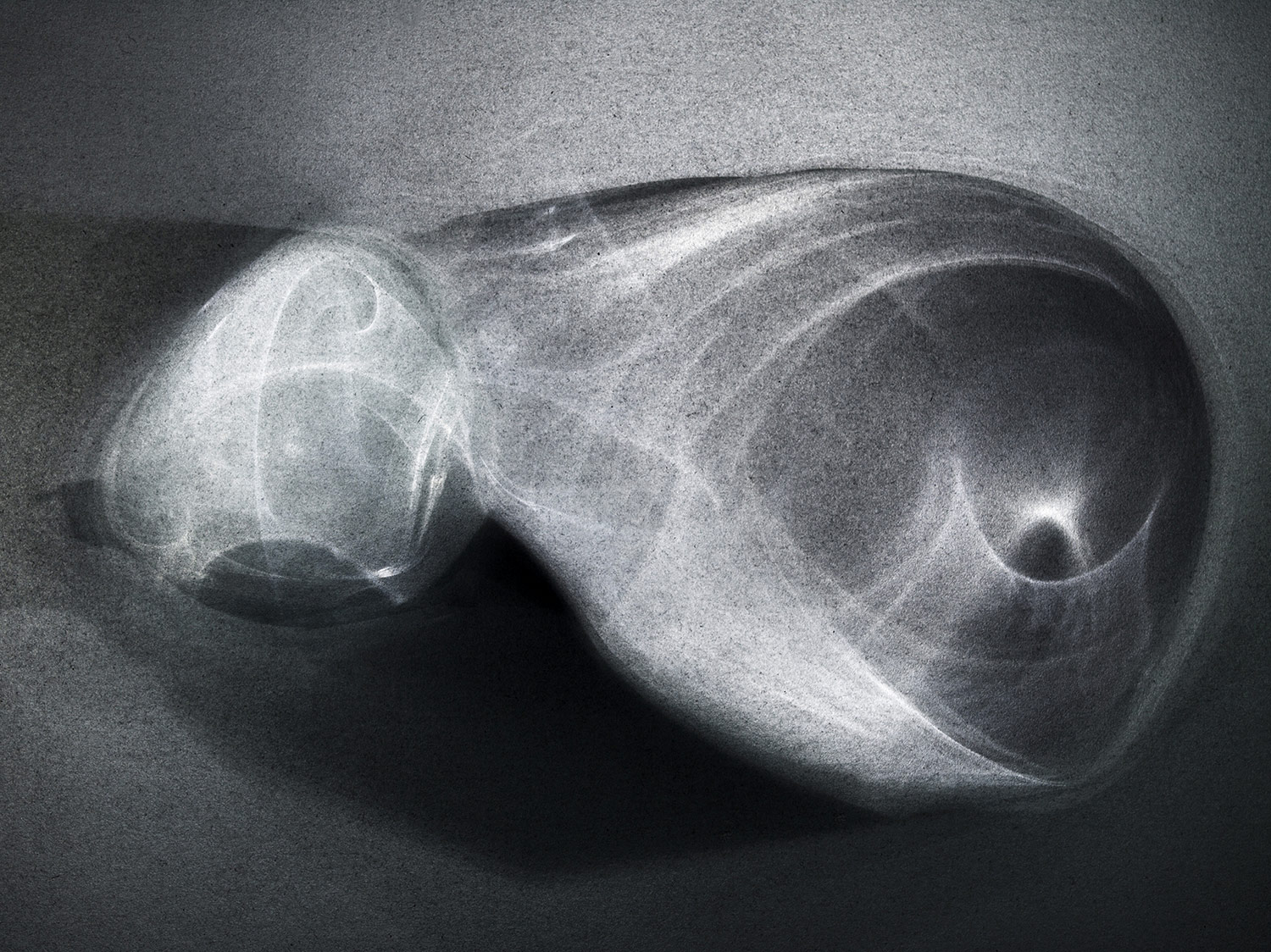

Dr Josef Maria Eder (Austrian, 1855-1944)

Eduard Valenta (Austrian, 1857-1937)

Zwei Goldfische und ein Seefisch (Christiceps argentatus)

Two goldfish and a sea fish (Christiceps argentatus)

1896

From the book Versuche über Photographie mittelst der Röntgen’schen Strahlen (Experiments on photography using X-rays)

Photogravure

George Eastman Museum, Gift of Eastman Kodak Company; Ex-collection of Josef Maria Eder

As early as 1840 – a year after photography’s invention was announced – scientists sought to deploy it in their analysis of the physical world. Combining the camera with the microscope, microphotographs recorded biological minutiae, leading to discoveries that would have been difficult, if not impossible, to obtain by observing subjects in real time. Similarly, the development of x-ray technology in 1895 allowed doctors to study living anatomy to an unprecedented degree. Such innovations not only expanded the boundaries of the visible world but also introduced graphic concepts that would have a profound impact on visual culture.

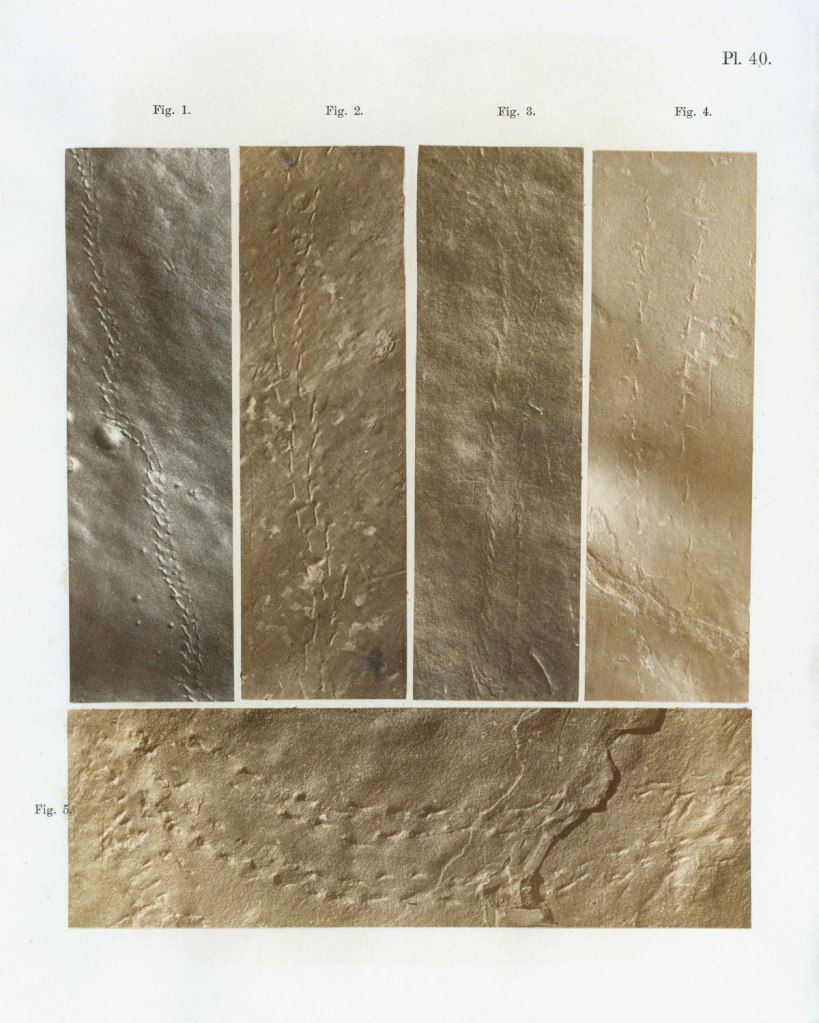

Dr James Deane (American, 1801-1858)

Ichnographs from the Sandstone of Connecticut River

1861

Book illustrated with 22 salted paper prints and 37 lithographs

George Eastman Museum, Gift of Alden Scott Boyer

These photographs, which depict traces of fossils discovered in a sandstone quarry, illustrate a book written by Massachusetts surgeon James Deane, who was the author of texts on medicine as well as natural history. Published posthumously using his notes and photographs as a guide, the volume is an early demonstration of photography’s potential as a tool of scientific investigation.

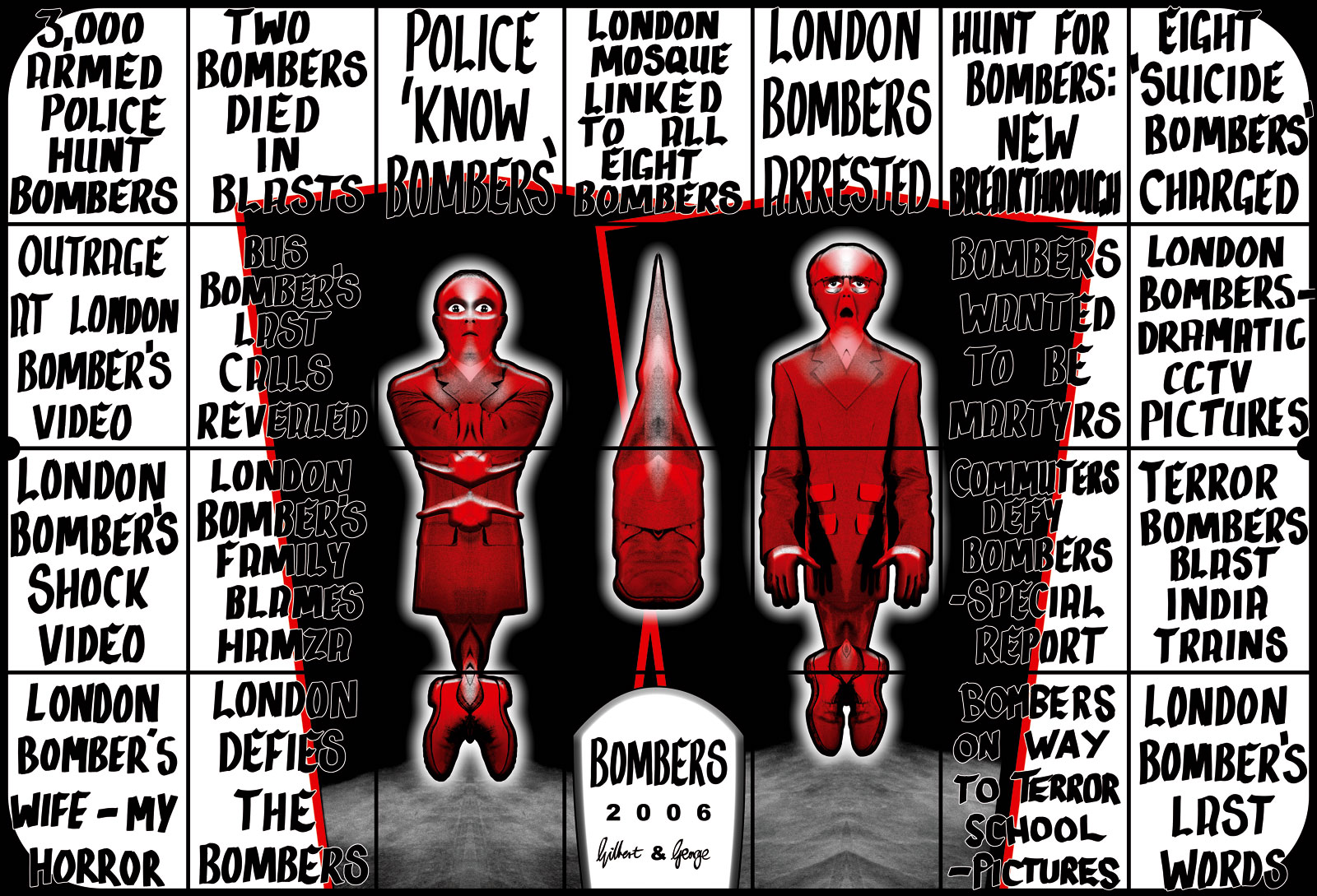

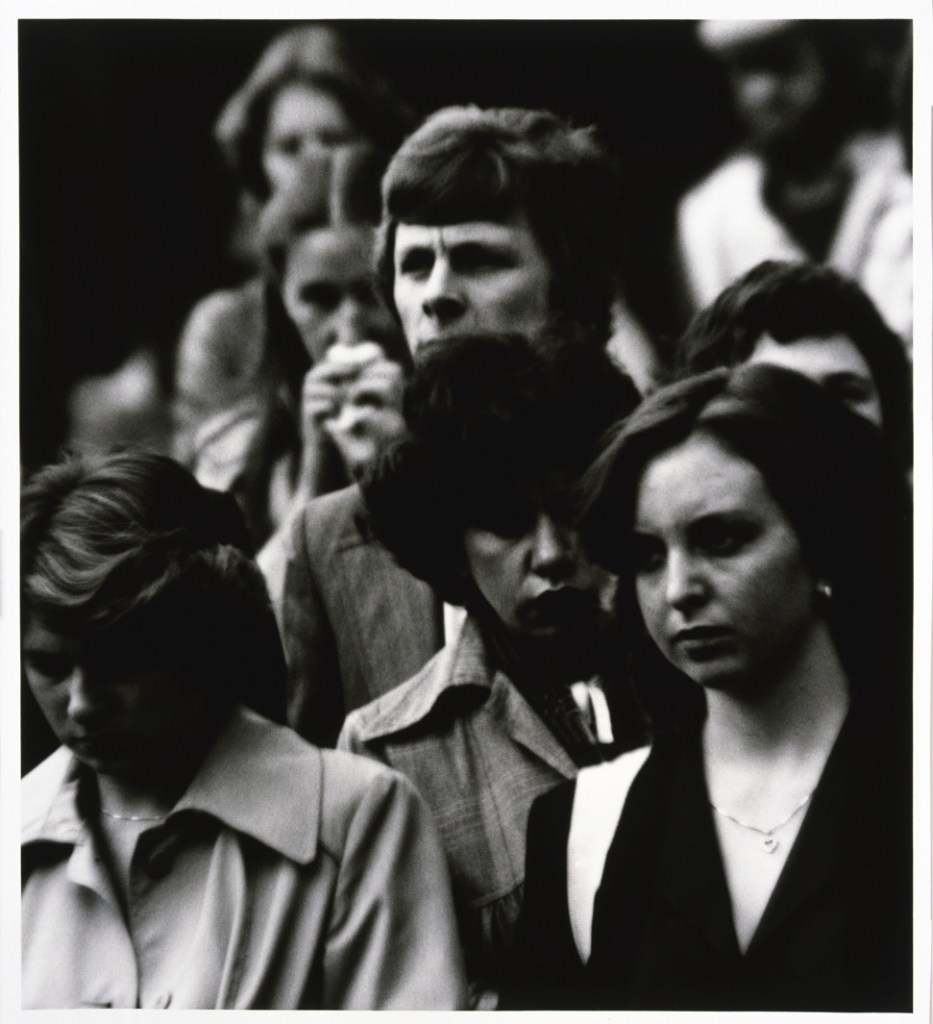

VI. The Photograph Decodes Culture

The photograph not only changed but to a great extent invented the modern notion of celebrity. Modern-age celebrities live apart from the general public, but their faces are more familiar than those of the neighbours next door. Since the mid-nineteenth century, viewers have come to “know” the famous through accumulated photographic sightings, which come in formats and contexts that vary as much as real-life encounters do. In four images that would have communicated instantly to their intended viewers in 1966, Jean-Pierre Ducatez (b. 1970) portrayed the Beatles through closeups of their mouths alone. The graphic shorthand employed by Jonathan Lewis in his series The Pixles is of a more recent variety, but he, too, relies on the visual familiarity conferred by tremendous celebrity. Each print in the series reproduces the iconic art of a Beatles album cover at life size (12 x 12 inches) but extremely low resolution (12 x 12 pixels). Like celebrities themselves, perhaps, the images look more familiar to the eye at a distance than close-up.

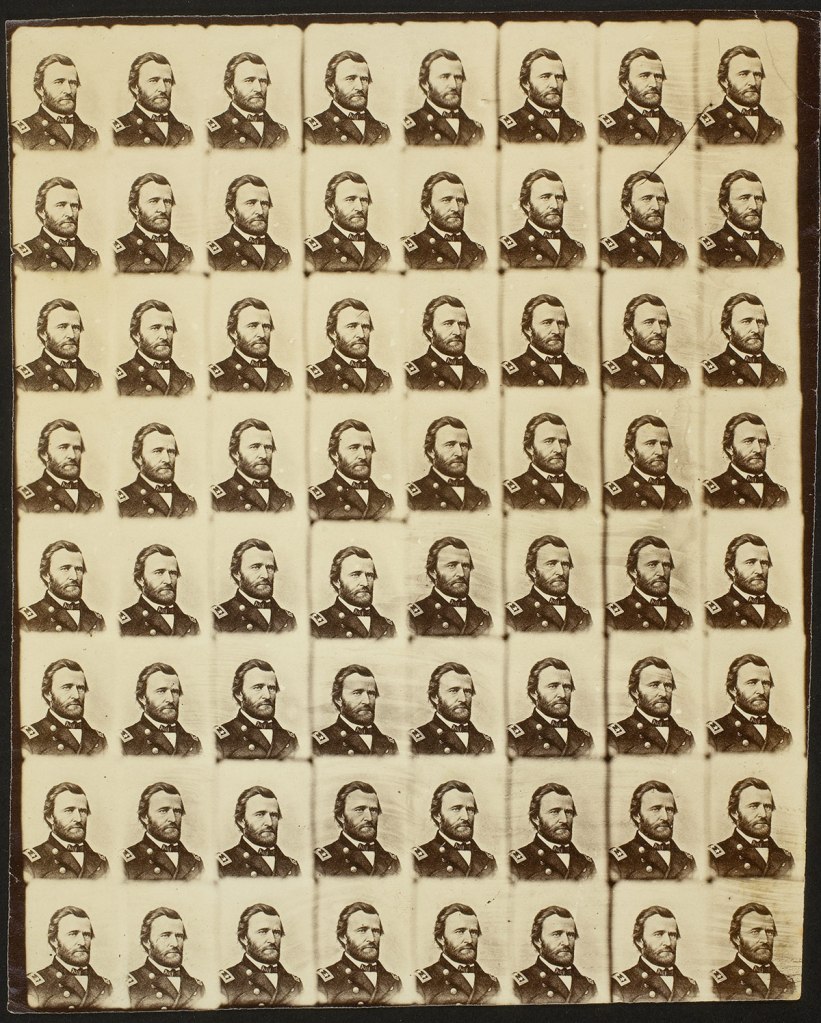

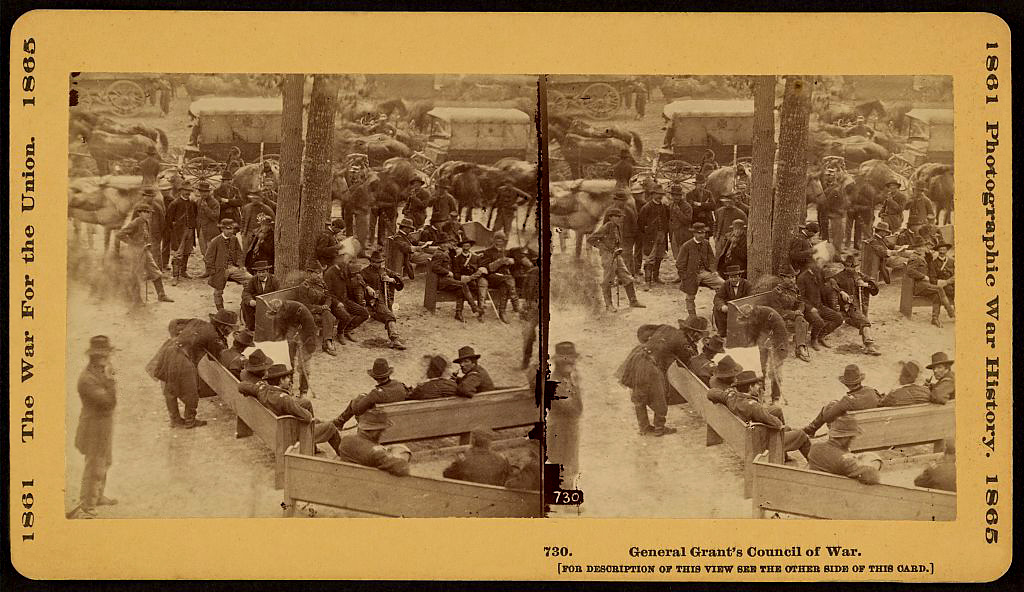

Unidentified maker

U. S. Grant

c. 1862

Albumen silver print

George Eastman Museum, Purchase

Timothy H. O’Sullivan (American born Ireland, 1840-1882)

A Council of War at Massaponax Church, Va. 21st May, 1864. Gens. Grant and Meade, Asst. Sec. of War Dana, and Their Staff Officers

1864

From the series Photographic Incidents of the War

Albumen silver print stereograph

George Eastman Museum, Gift of Albert Morton Turner

Modern celebrities live apart from the general public, yet their faces are more familiar than those of the neighbors next door. Since the mid-nineteenth century, viewers have come to “know” the famous through accumulated photographic sightings, which come in formats and contexts that vary as much as real-life encounters do. First as a Union hero in the American Civil War and later as president, Ulysses S. Grant (1822-1885) lived in the public imagination through news images, popular stereographs, campaign buttons, and ultimately the (photo-based) face on the $50 bill. Grant was even a subject for Francois Willème’s patented process for generating a sculpted likeness out of photographs made in the round – an early forerunner to the technology of 3-D printing.

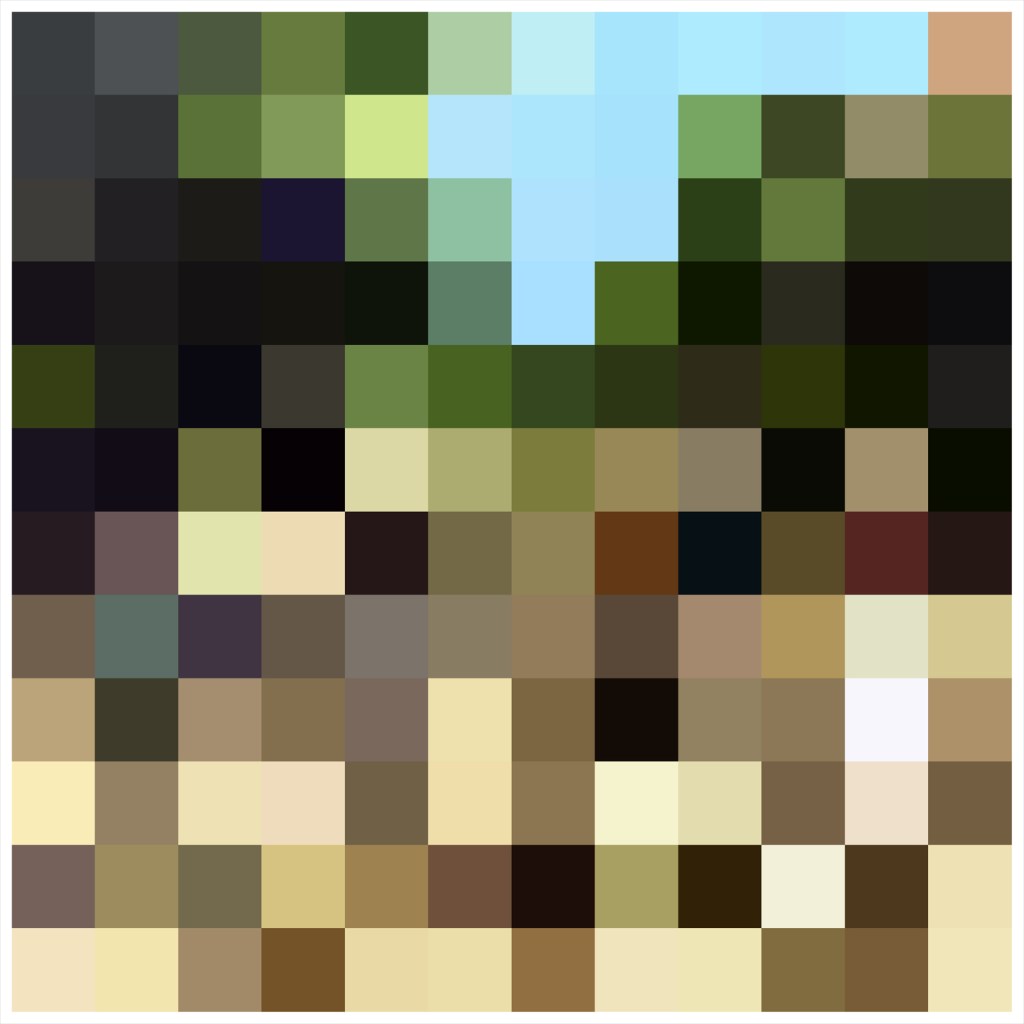

Jonathan Lewis (British, b. 1970)

Abbey Road

2003

From The Pixles

Inkjet print

George Eastman Museum, By exchange with the artist

Jonathan Lewis (British, b. 1970)

Please Please Me

2003

From The Pixles

Inkjet print

George Eastman Museum, By exchange with the artist

Jonathan Lewis (British, b. 1970)

Rubber Soul

2003

From The Pixles

Inkjet print

George Eastman Museum, By exchange with the artist

Synecdoche is a poetic device in which a part stands in for the whole. (In the phrase “three sails set forth,” sails mean ships.) In four images that would have communicated instantly to their intended viewers in 1966, Ducatez portrayed the Beatles solely through close-ups of their mouths. The graphic shorthand Lewis employs in his series The Pixles is of a more recent variety, though he, too, relies on the visual familiarity conferred by tremendous celebrity. Each print in the series reproduces a Beatles album cover at life size (12 x 12 inches) but extremely low resolution (12 x 12 pixels).

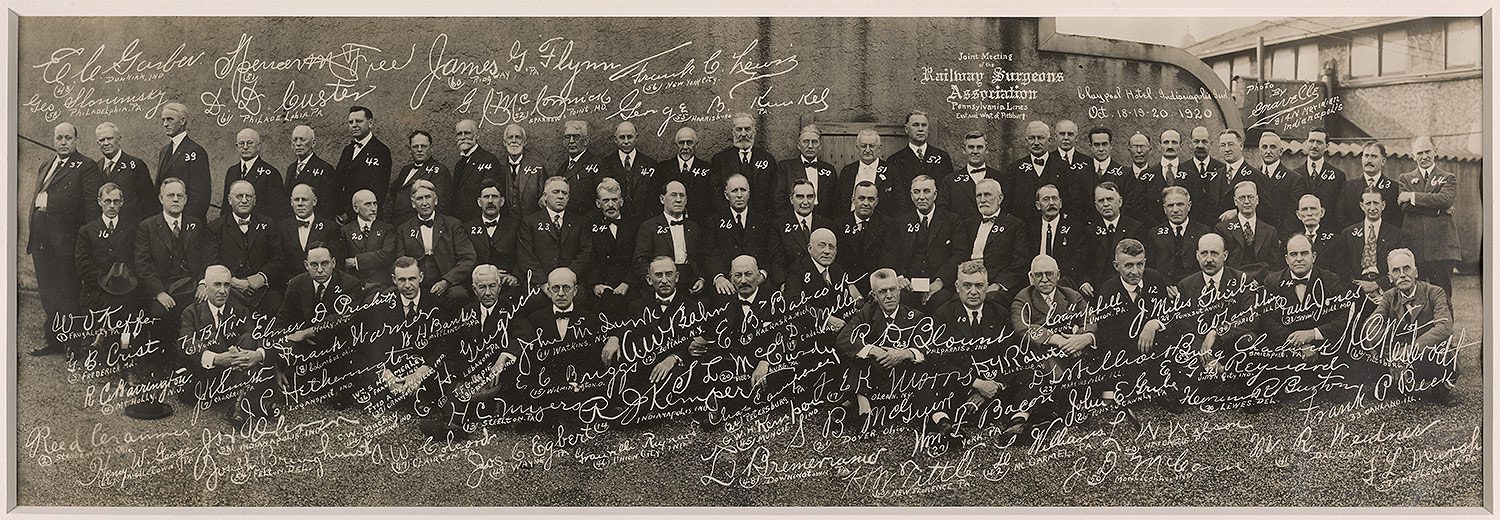

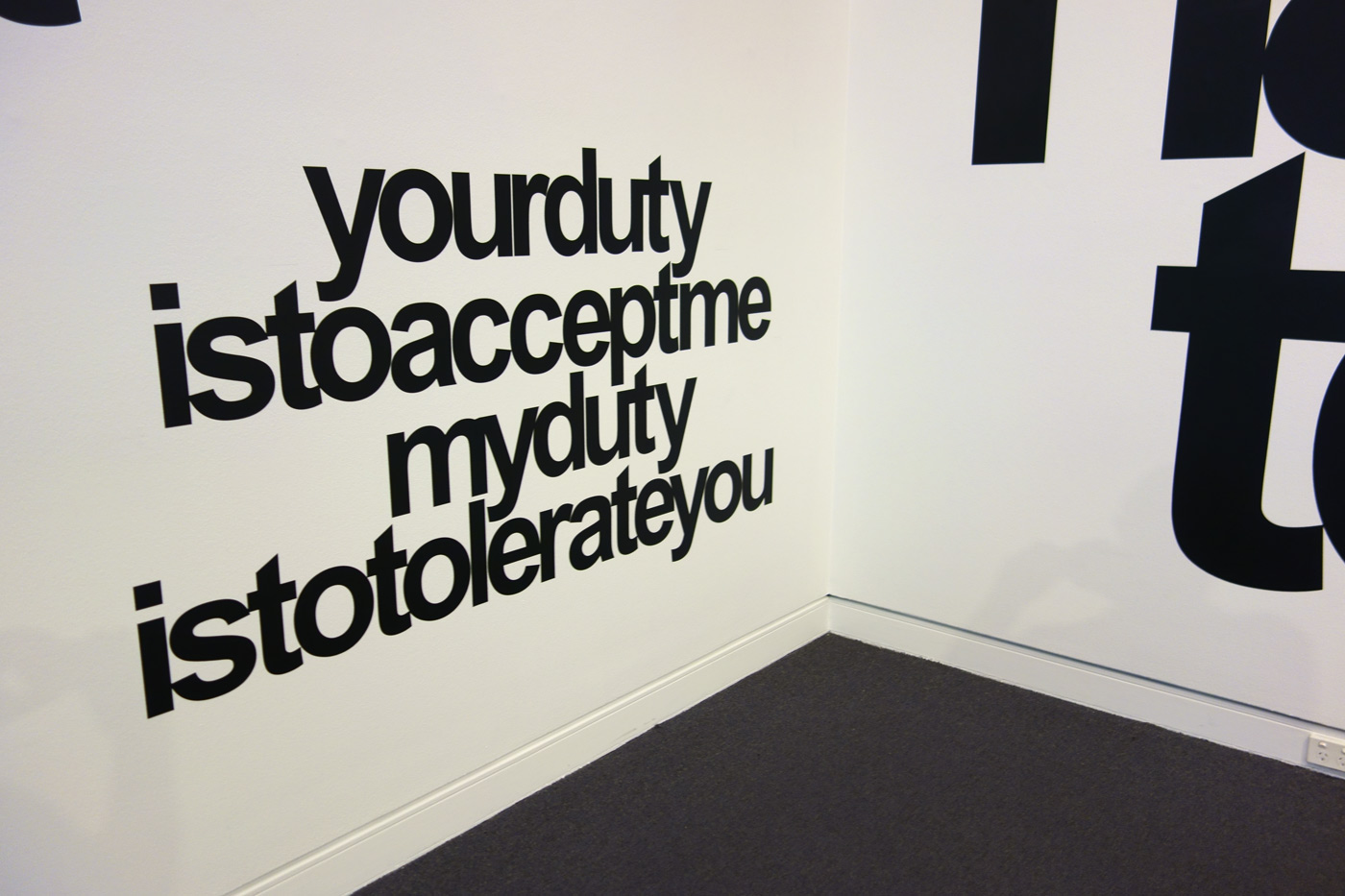

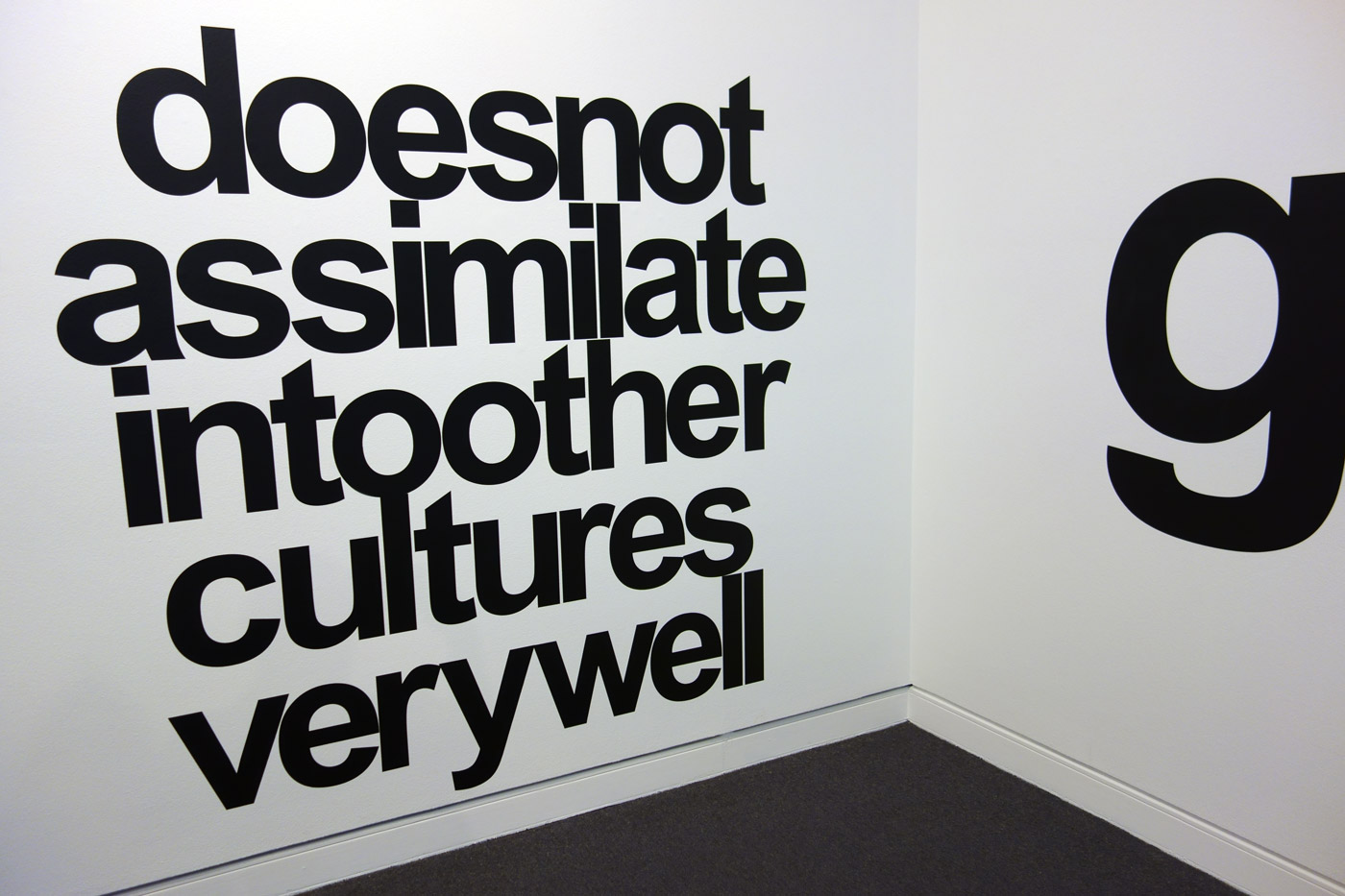

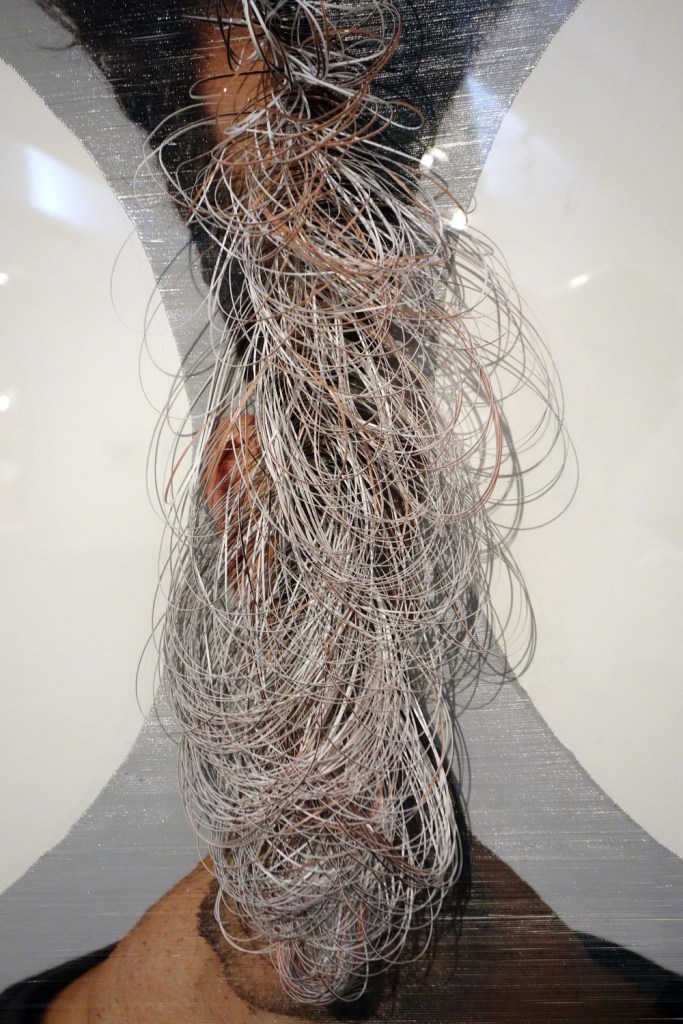

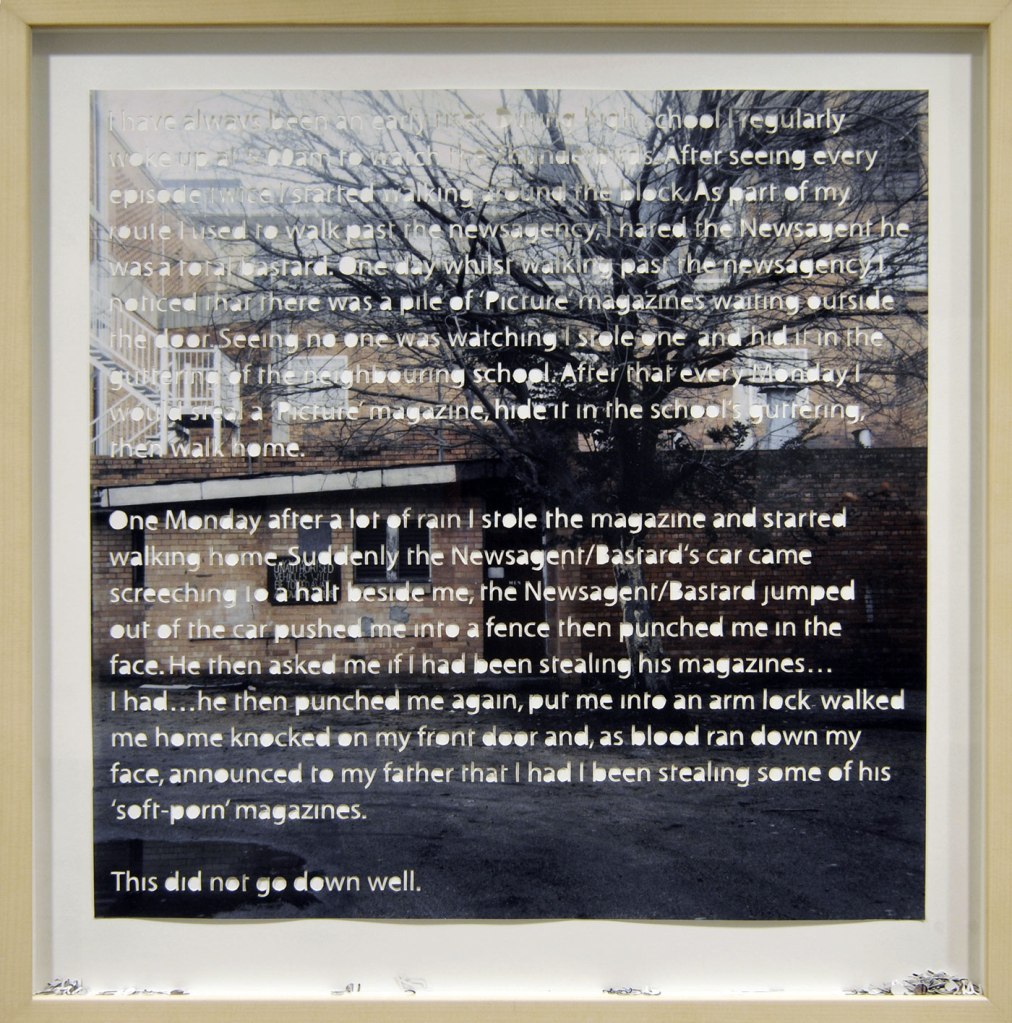

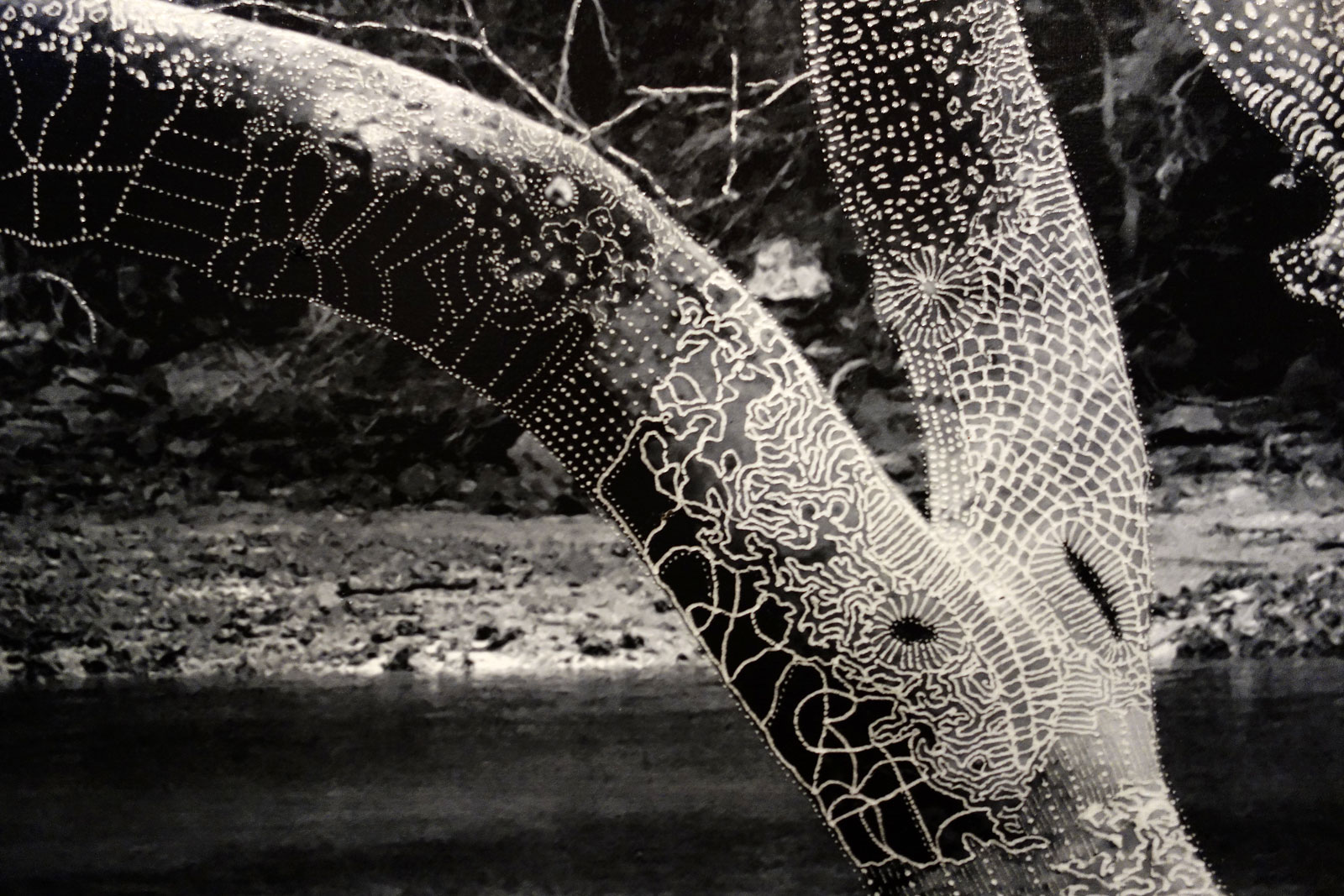

VII. Meaning is on the Surface

Photographs are not just windows onto the world but pieces of paper, which can themselves be inscribed or otherwise altered in ways that enrich or amend their meaning. The group portrait Joint Meeting of the Railway Surgeons Association, Claypool Hotel, Indianapolis (1920) is contact printed, meaning that the negative was the same size as the print. After the portrait sitting, the photographer appears to have presented the developed film to the sixty-four sitters for signing during the three days they were assembled for their convention. The result is a document that unites two conventional signifiers of character: facial features and the autograph.

Gravelle Studio, Indianapolis (American, active 1920)

Joint Meeting of the Railway Surgeons Association, Claypool Hotel, Indianapolis

1920

Gelatin silver print

The Morgan Library & Museum, Purchased as the gift of Peter J. Cohen

Panoramic group portraits such as this are made using a banquet camera, which admits light through a narrow vertical slit while rotating on its tripod. This image was contact printed, meaning the negative was the same size as the print. The photographer appears to have presented the developed film to the sixty-four sitters for signing during the three days they were assembled. The result is a document that unites two conventional signifiers of character: facial features and the autograph.

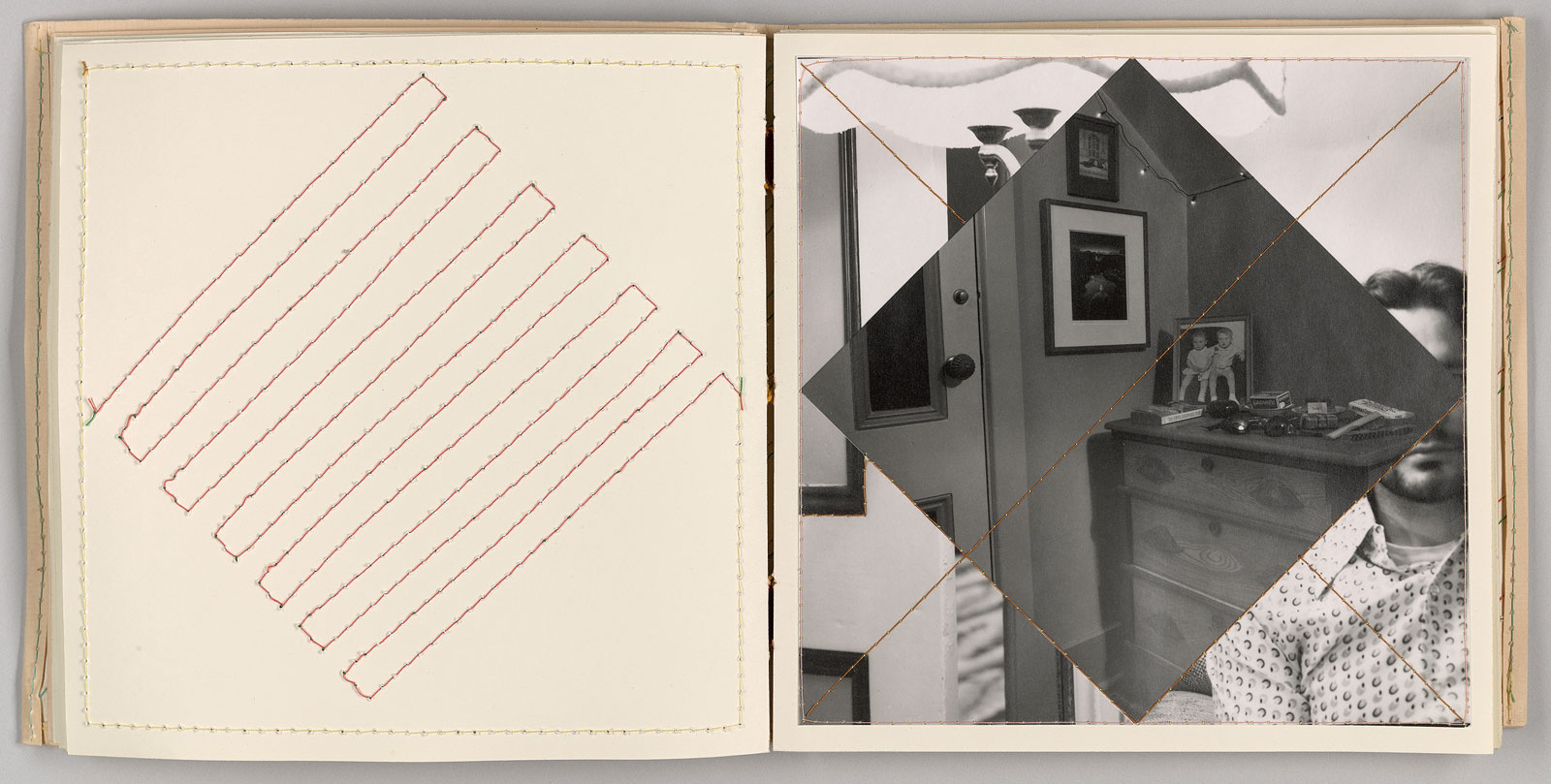

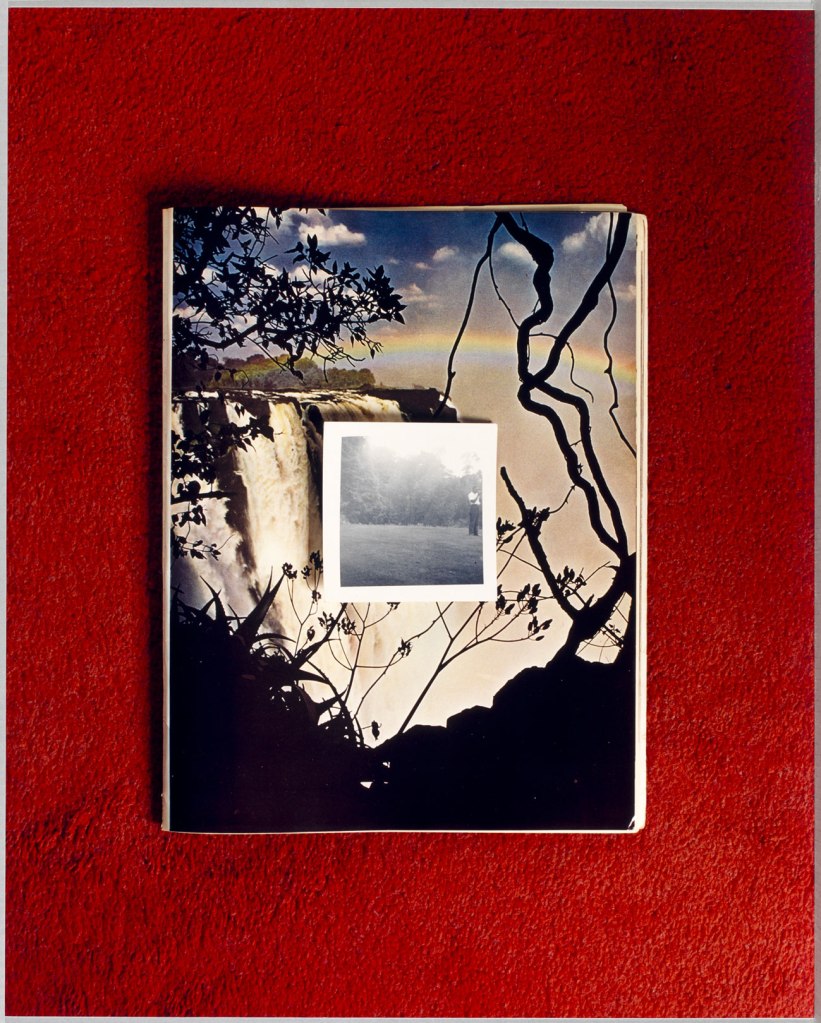

Keith Smith (American, b. 1938)

Book 151

1989

Bound book of gelatin silver prints, thread, and leather

Collection of Richard and Ronay Menschel

This unique object unites the arts of photography, quilting, and bookmaking. The composite image on each right-hand page appears to be made of prints cut apart and sewn together. In fact, Smith began by printing patchwork-inspired photomontages in the darkroom. He then stitched along many of the borders where abutting images meet, creating the illusion of a photographic crazy quilt.

VIII. Photography and the Page

News of the world took on a newly visual character in the 1880s, when the technology of the halftone screen made it practical, at last, to render photographs in ink on the printed page.

Among the earliest examples of photojournalism is Paul Nadar’s (1820-1910) “photographic interview” with Georges Ernest Boulanger, a once-powerful French politician. The article’s introduction explains that the photographs were printed alongside the text in order to provide evidence of the encounter and to illustrate Boulanger’s dynamic body language during the conversation.

Stephen Henry Horgan (American, 1854-1941)

Shanty Town

April 1880

Photomechanical printing plate A Scene in Shantytown, New York, c. 1928

Lithograph

George Eastman Museum, Gift of 3M Foundation; Ex-collection of Louis Walton Sipley

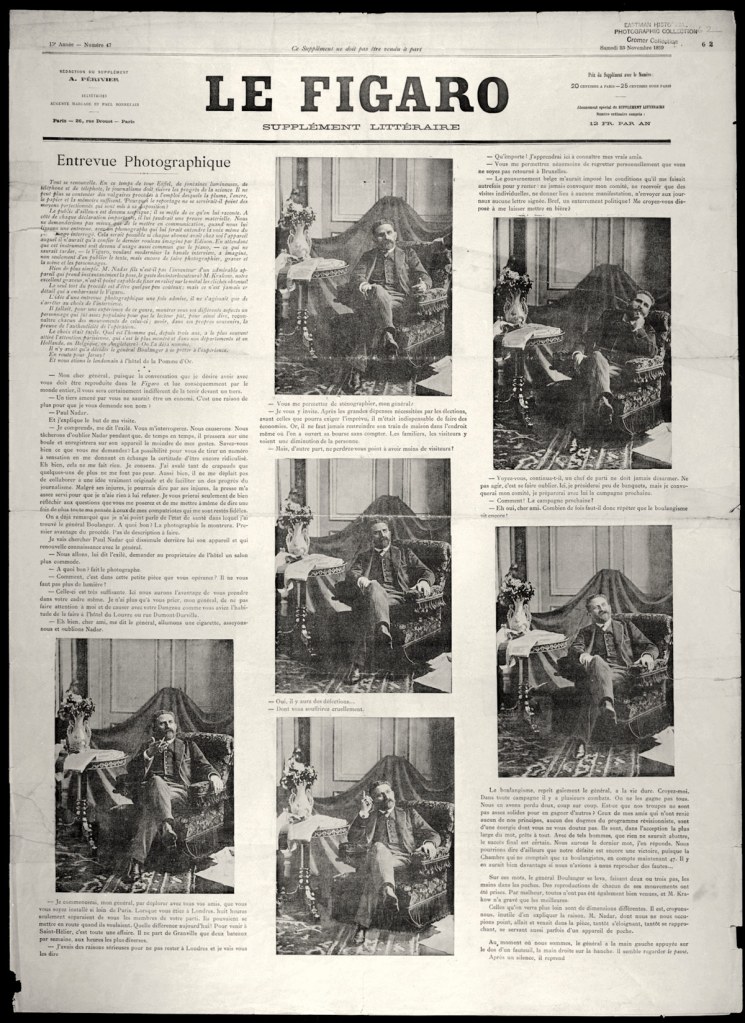

Paul Nadar (French, 1856-1939)

Interview with Georges Ernest Jean Marie Boulanger

1889

Le Figaro, 23 November 1889

Photomechanical reproduction

George Eastman Museum, gift of Eastman Kodak Company; ex-collection Gabriel Cromer

Among the earliest examples of photojournalism is Nadar’s “photographic interview” with Georges Ernest Boulanger, a once-powerful French politician who had fallen out of public favour by the time this was published. The article’s introduction explains that the photographs were printed alongside the text in order to provide evidence of the encounter and to illustrate Boulanger’s body language during the conversation.

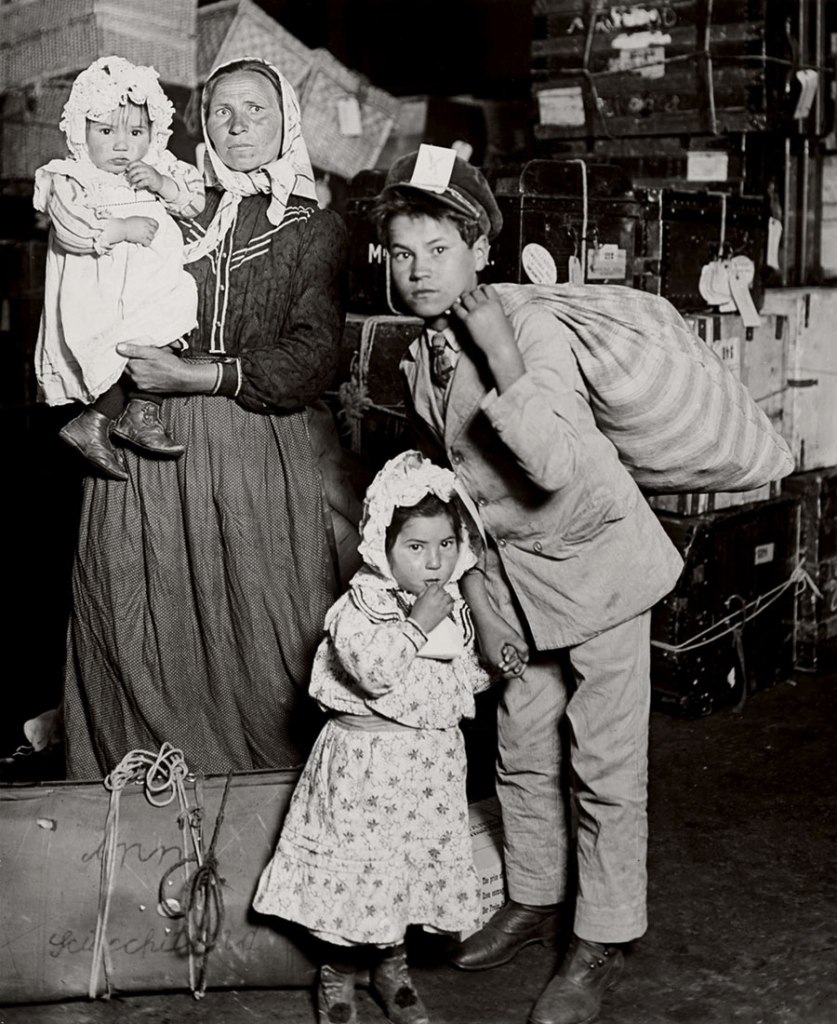

Lewis W. Hine (American, 1874-1940)

Italian Family Looking for Lost Baggage, Ellis Island

1905

Ellis Island Group, 1905

Gelatin silver print

George Eastman Museum, Gift of Photo League Lewis Hine Memorial Committee

In an effort to counter American xenophobia in the early years of the twentieth century, Hine photographed immigrants as they arrived at Ellis Island, composing his images to stir sympathy and understanding among viewers. He understood the importance of disseminating his photographs and actively sought to publish them in newspapers, magazines, and pamphlets. The white outline in the photograph on the right instructs the designer and printer where to crop the image for a photomontage featuring figures from multiple portraits.

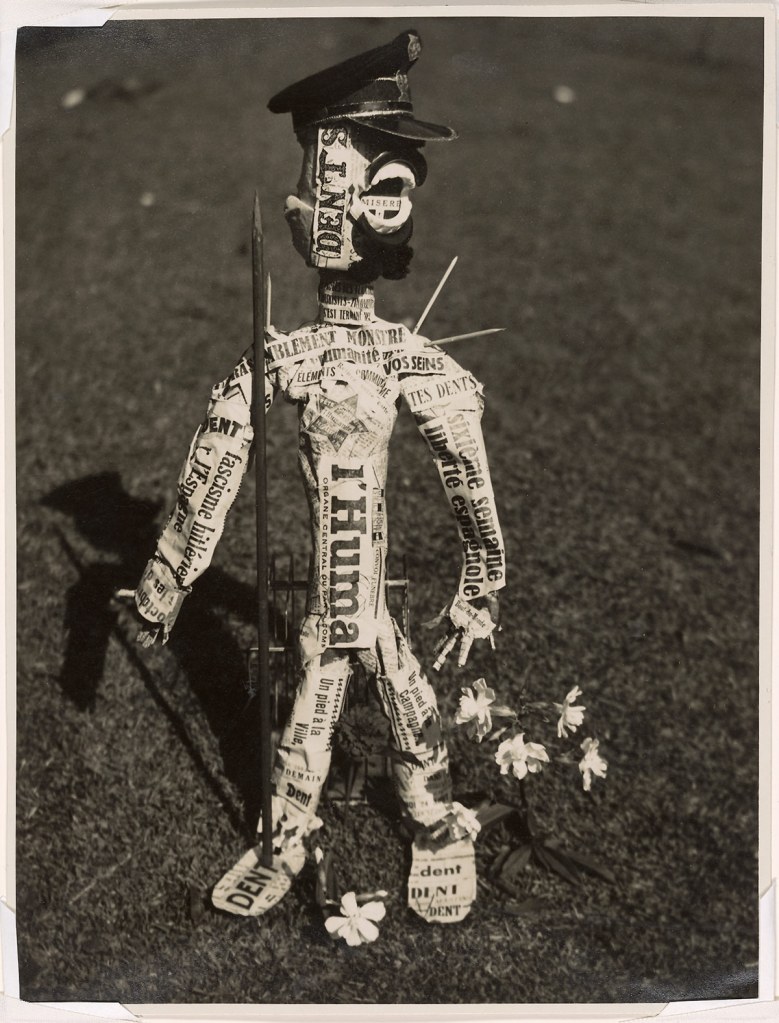

Claude Cahun (French, 1894-1954)

La Poupée (Puppet)

1936

Gelatin silver print

Collection of Richard and Ronay Menschel

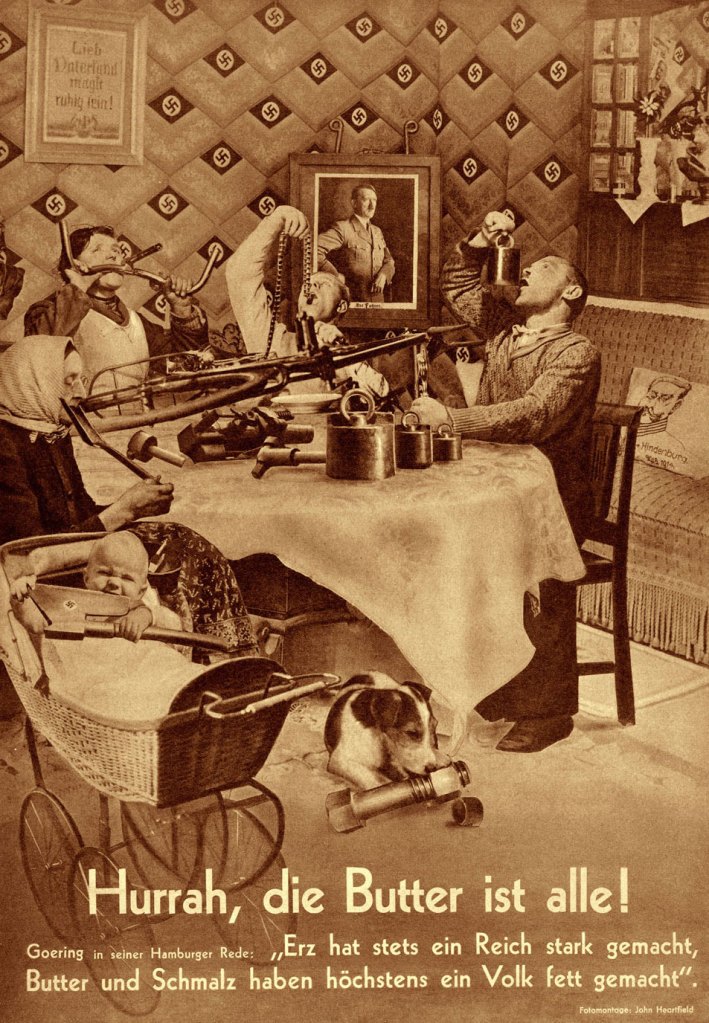

John Heartfield (German, 1891-1968)

Hurrah, die Butter ist alle! (Hooray, the Butter Is Finished!)

1935

Rotogravure

George Eastman Museum, purchase

This is one of 237 photomontages that Heartfield created between 1930 and 1938 for the antifascist magazine Arbeiter-Illustrierte-Zeitung (Worker’s Pictorial Newspaper). It is a parody of the “Guns Before Butter” speech in which Hermann G.ring exhorted German citizens to sacrifice necessities in order to aid the nation’s rearmament. The text reads: “Iron ore has always made an empire strong; butter and lard have at most made a people fat.” Heartfield combined details from several photographs to conjure the image of a German family feasting on tools, machine parts, and a bicycle in a swastika-laden dining room, complete with a portrait of Hitler, a framed phrase from a popular Franco-Prussian war-era song, and a throw pillow bearing the likeness of recently deceased president Paul von Hindenburg.

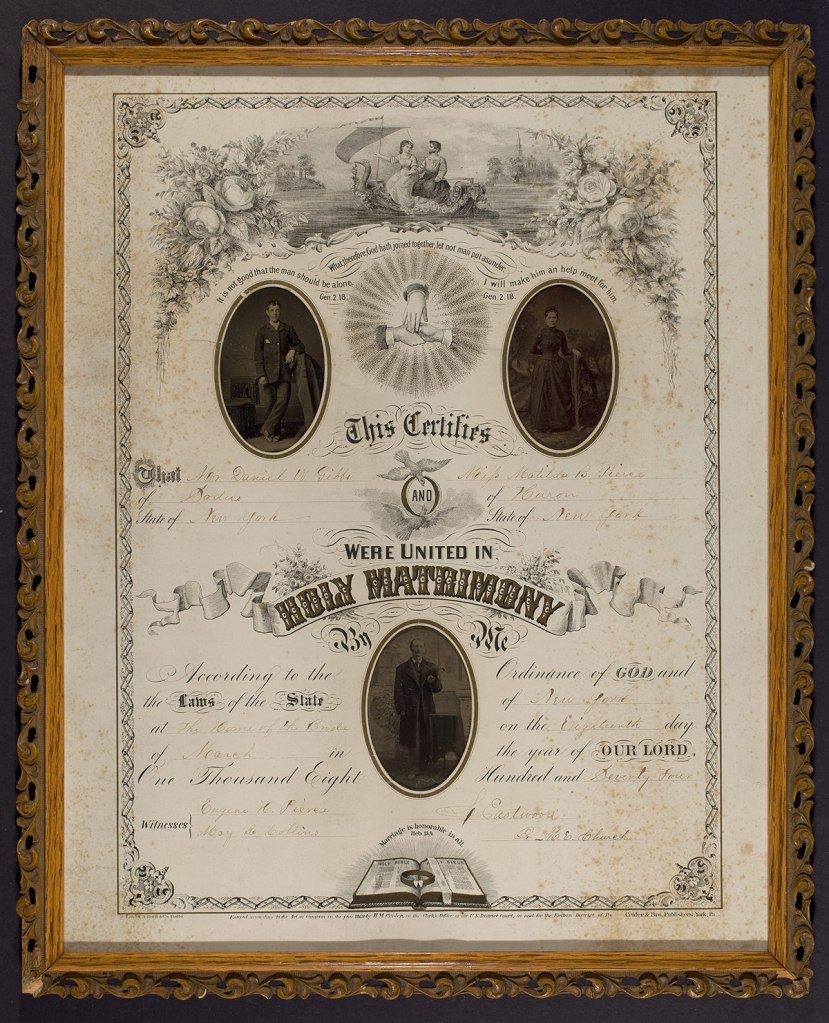

Unidentified maker

Certificate of Marriage between Daniel W. Gibbs and Matilda B. Pierce

c. 1874

Tintypes in prepared paper mount

George Eastman Museum, Purchase

Graphic cousins to one other, these wedding certificates are equipped with precut windows for photographs of the bride, groom, and officiant. The portraits, in partnership with the printed and inscribed text on the forms, contribute both to the documentary specificity of the certificates and to their value as sentimental souvenirs.

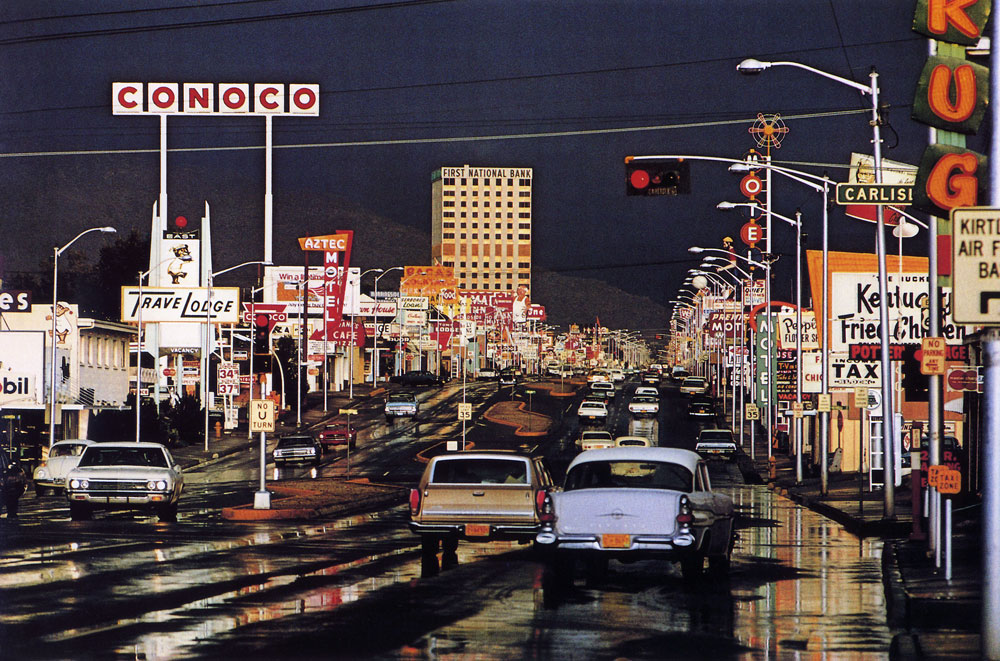

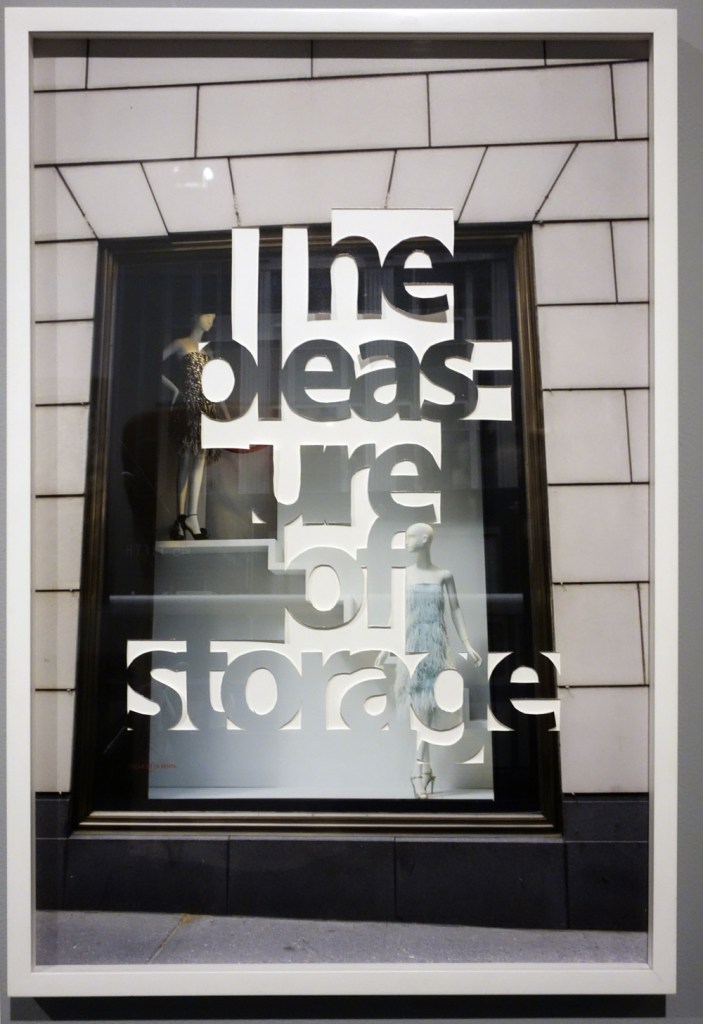

IX. Empire of Signs

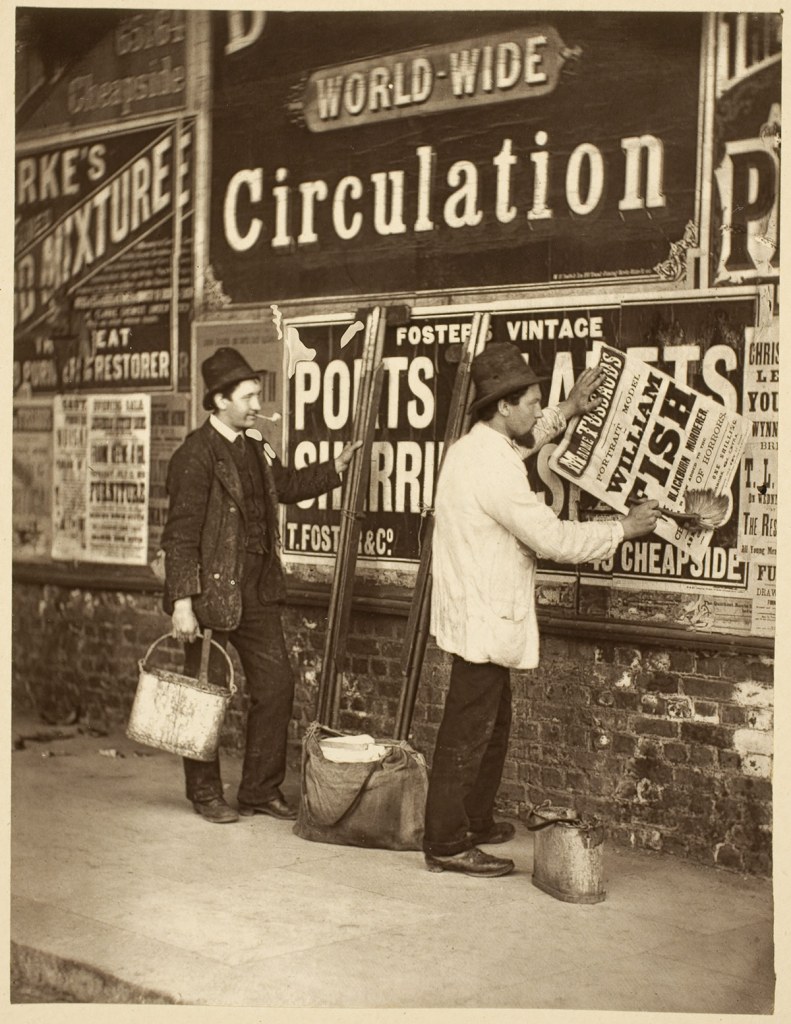

The plethora of signs, symbols, and visual noise endemic to cities has attracted photographers since the medium’s invention. Their records of advertisers’ strident demands for attention, shopkeepers’ alluring displays, and the often dizzying architectural density of metropolitan life chronicle sights that are subject to change without notice. The photographer’s perspective on contemporary social life – whether it is anecdotal, as in John Thompson’s (1837-1921) Street Advertising from Street Life in London (1877), or haunting, as in Eugène Atget’s (1857-1927) Impasse des Bourdonnais (c. 1908) – is embedded in each image.

John Thomson (Scottish, 1837-1921)

Street Advertising

1877

From Street Life in London, 1877

Woodburytype

George Eastman Museum, Gift of Alden Scott Boyer

Eugène Atget (French, 1857-1927)

Impasse des Bourdonnais

c. 1908

Albumen silver print

George Eastman Museum, Purchase

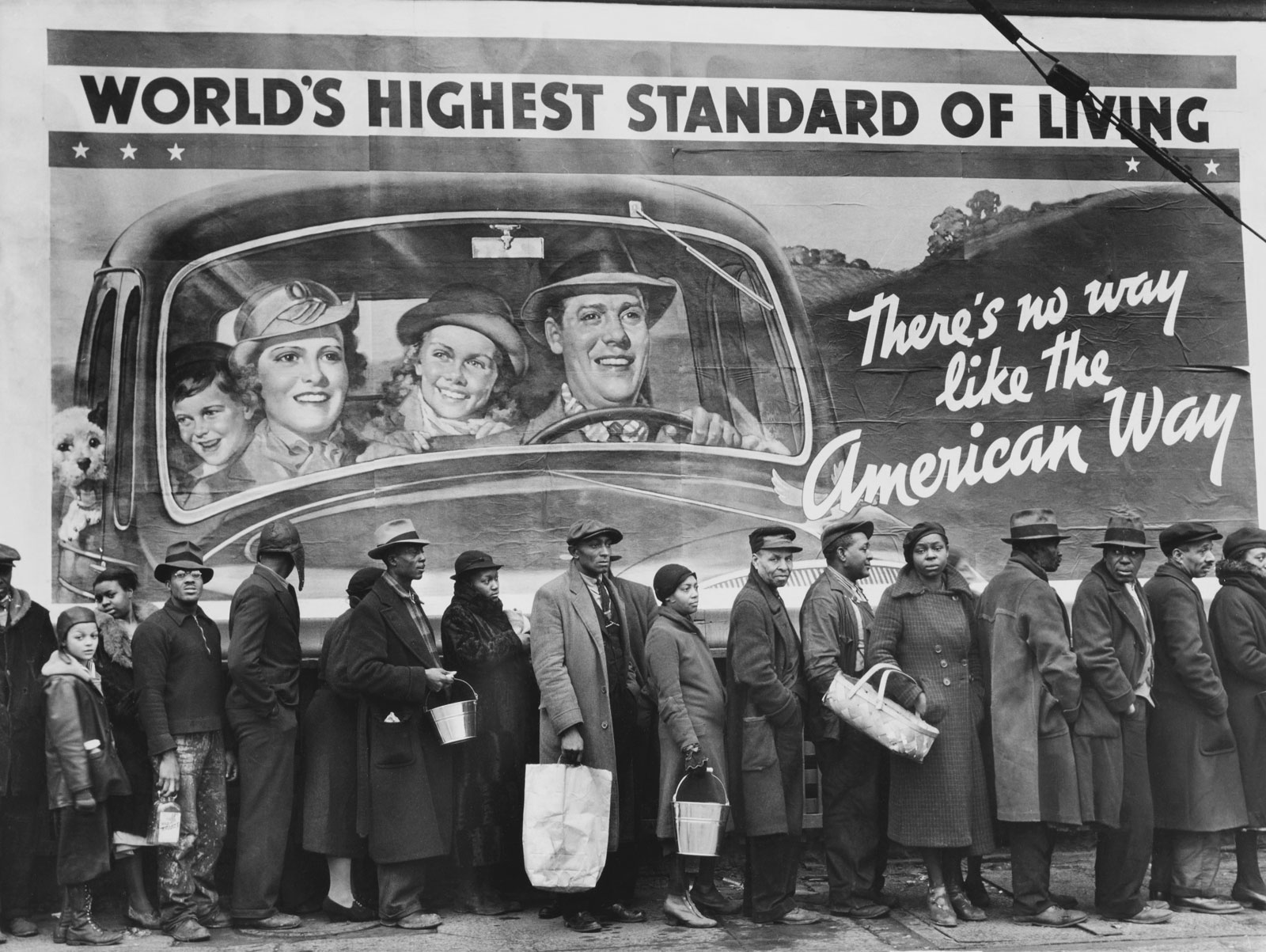

Margaret Bourke-White (American, 1904-1971)

At the Time of the Louisville Flood

1937

Gelatin silver print

George Eastman Museum

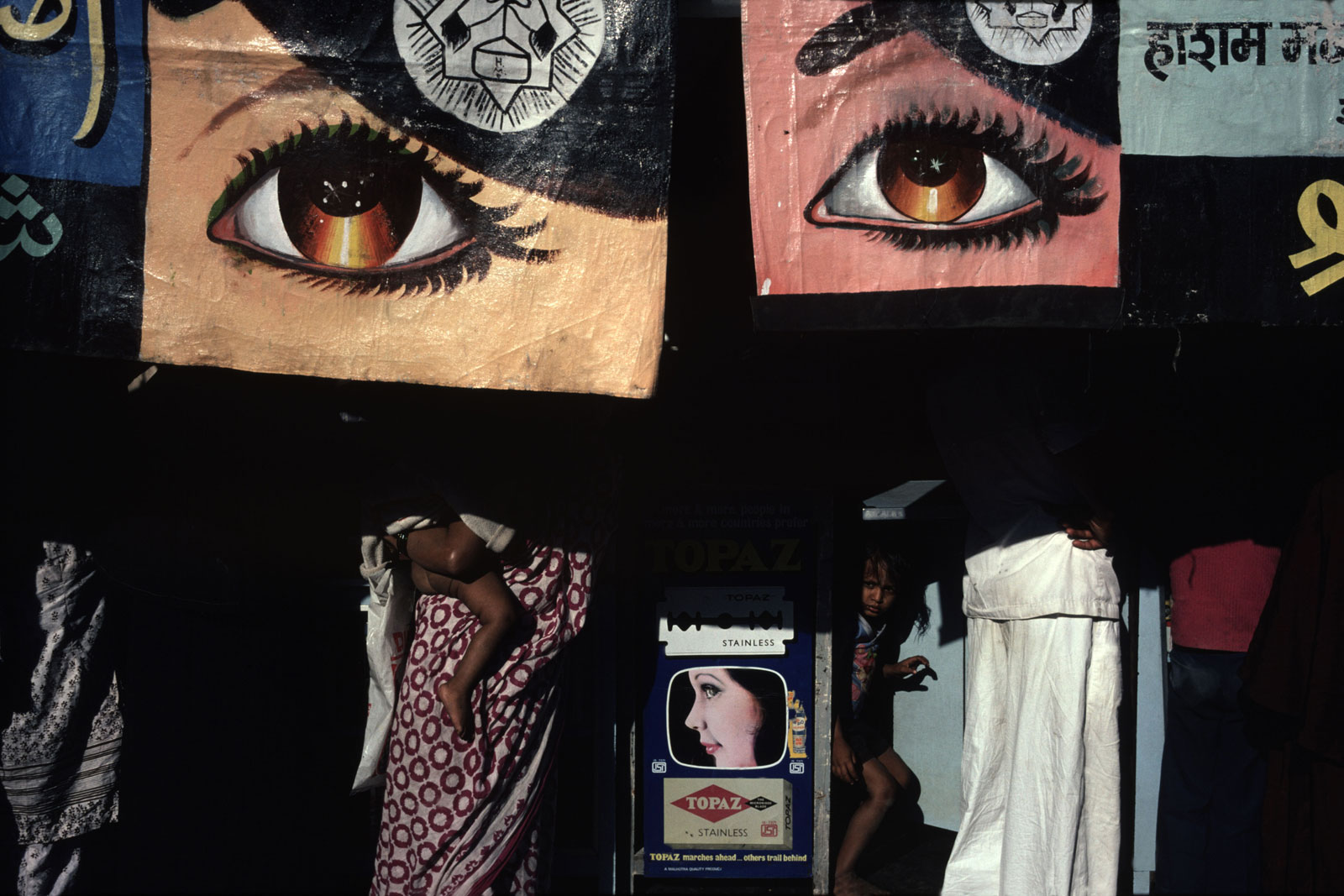

The plethora of signs, symbols, and visual noise endemic to cities has attracted photographers since the medium’s invention. Their records of advertisers’ strident demands for attention, shopkeepers’ alluring displays, and the often dizzying architectural density of metropolitan life chronicle sights that are subject to change without notice. The photographer’s perspective on contemporary social life – whether it is ironic, as in Margaret Bourke-White’s image of a line of flood victims before a billboard advertising middle-class prosperity, or bemused, as in Ferenc Berko’s photograph of columns of oversized artificial teeth on the street – is embedded in each image.

Ferenc Berko (American born Hungary, 1916-2000)

Rawalpindi, India

1946

Gelatin silver print

George Eastman House, Gift of Katharine Kuh

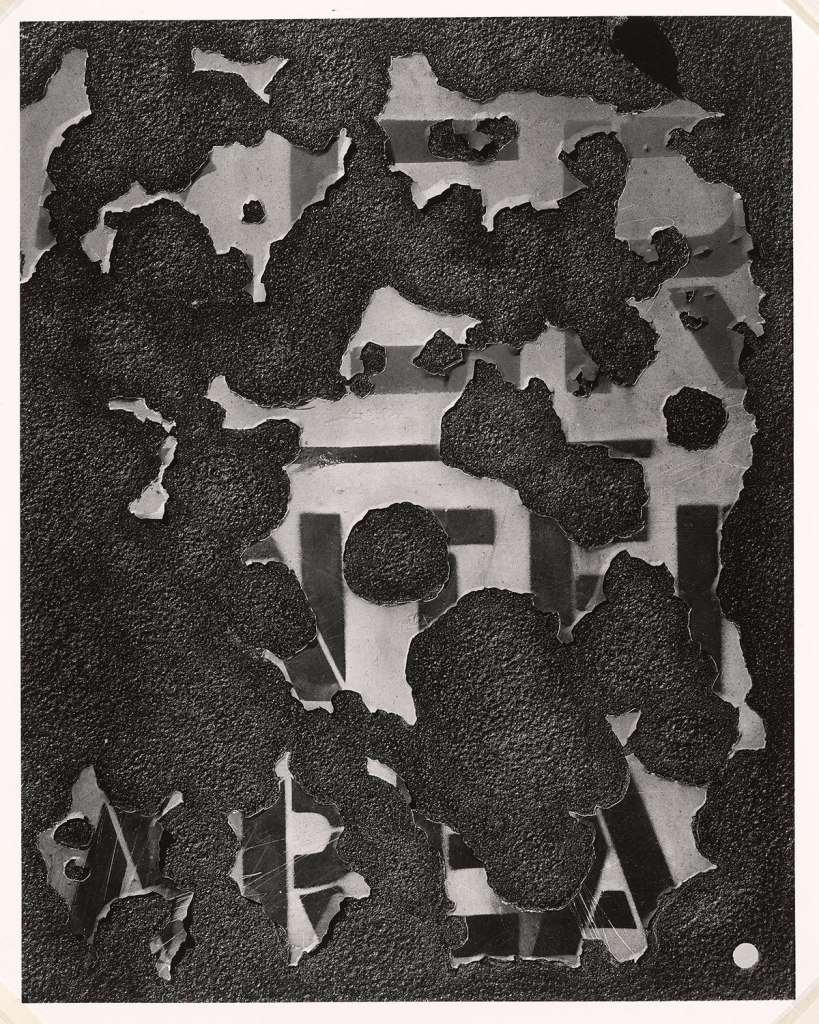

Aaron Siskind (American, 1903-1991)

New York 6

1951

Gelatin silver print

The Morgan Library & Museum, Gift of Richard and Ronay Menschel

Alex Webb (American, b. 1952)

India

1981

Chromogenic development print

George Eastman Museum, Purchased with funds from Charina Foundation

The Morgan Library & Museum

225 Madison Avenue, at 36th Street

New York, NY 10016-3405

Phone: (212) 685-0008

Opening hours:

Tuesday – Thursday, Saturday – Sunday: 10.30am – 5pm

Friday: 10.30am – 7pm

Closed Mondays

![Albert Renger-Patzsch (German, 1897-1966) 'Mantelpavian [Hamadryas Baboon]' c. 1925 from the exhibition 'The world is beautiful: photographs from the collection' at the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, Dec 2015 - April 2016 Albert Renger-Patzsch (German, 1897-1966) 'Mantelpavian [Hamadryas Baboon]' c. 1925 from the exhibition 'The world is beautiful: photographs from the collection' at the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, Dec 2015 - April 2016](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/albert-renger-patzsch-baboon-web.jpg)

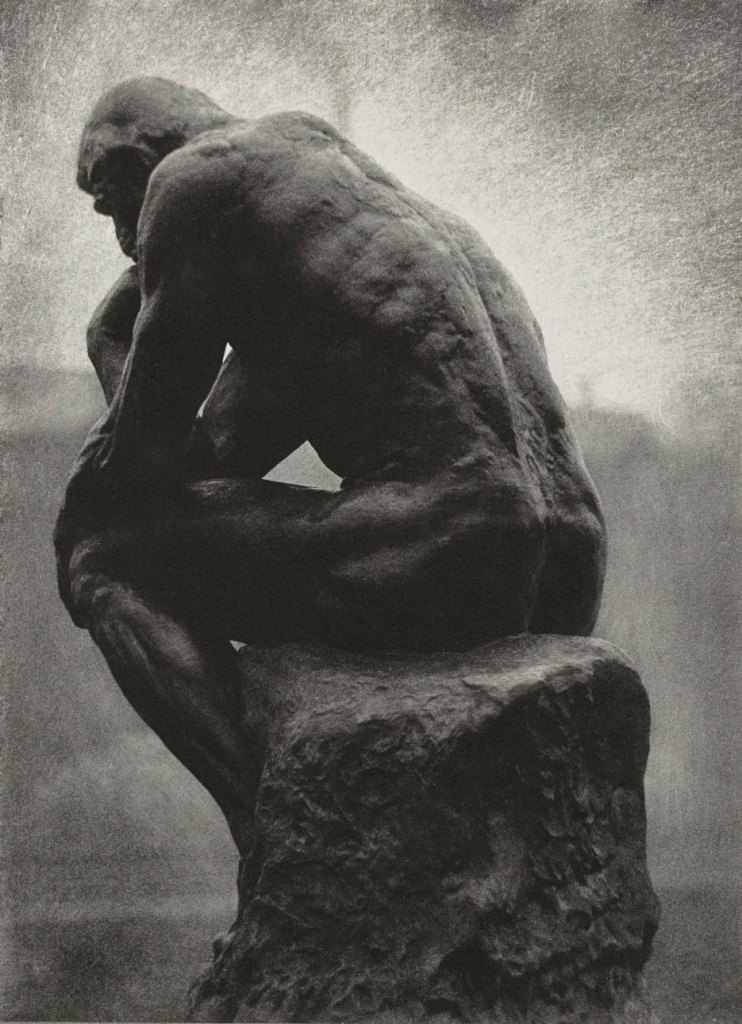

![Auguste Rodin (French, 1840-1917) 'Le Penseur [The Thinker]' 1903 Auguste Rodin (French, 1840-1917) 'Le Penseur [The Thinker]' 1903](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/rodin-le-penseur-web.jpg?w=768)

![Vassily Kandinsky (Russian, 1866-1944) 'Bild mit rotem Fleck [Tableau à la tache rouge / Image with red spot]' 25 February 1914 Vassily Kandinsky (Russian, 1866-1944) 'Bild mit rotem Fleck [Tableau à la tache rouge / Image with red spot]' 25 February 1914](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/kandinsky-bild-mit-rotem-fleck-web.jpg?w=1000)

You must be logged in to post a comment.