Exhibition dates: 29th April – 14 August 2016

Curator: Geoffrey Batchen

Installation view of the exhibition Emanations: The Art of the Cameraless Photograph at the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery with at left, Christian Marclay and at right, Hiroshi Sugimoto

Part 2 of a posting on the wonderful exhibition Emanations: The Art of the Cameraless Photograph at the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery / Len Lye Centre, New Plymouth, New Zealand.

While there is no doubt as to the quality and breadth of the work on display, nor how it has been curated or installed in these beautiful contemporary spaces, I question elements of the conceptual rationale that ground the exhibition. While curator Geoffrey Batchen correctly notes that “artists are coming back to the most basic and elemental chemistry of photography, hands on, making unique images where there is a direct relationship between the thing being imaged and then image itself” as a response to the dematerialisation of the image that occurs in a digital environment and the proliferation of reproductions of digital images his assertion in a Radio New Zealand interview that the cameraless photograph has a direct relationship to the world, unmediated – through the unique touch of the object on the photographic paper – is an observation that seems a little disingenuous.

Batchen observes in the quotation below, “it’s as if nature represents itself, completely unmediated and directly. In some ways … [this] is far more realist, far more true to the original object than any camera picture could be.” Note how he qualifies his assertion and position by the statement “in some ways”. The reality of the situation is that every photograph is mediated to one degree or another, whether through the use of the camera, the choice of developer, photographic paper, size, perspective and so forth. The physicality of the actual print and the context of capture and display are also mediated, in each instance and on every occasion. Every photograph is mediated through the choices of the photographer, even more so in the production of cameraless photographs (what to choose to photograph, where to position the object, what to draw with the light) because the artist has the ultimate control on what is being pictured (unlike the reality of the world). To say that cameraless photographs have a more direct and unmediated relationship to the world than analogue and digital photographs could not be further from the truth – it is just that the taxonomic system of ordering “reality” is of a different order.

Batchen further states in the Radio new Zealand interview that “in these photographs the object is still there, that’s the strange thing about cameraless photographs. There is a sense of presentness to this kind of photograph. … Cameraless photographs seem to exist in a kind of eternal present, and in that sense they complicate our understanding both of photography but also to the world that is being represented here.”

This is a contentious observation that argues for some special state of being that exists within the cameraless photograph which I believe does not exist. I argue that EVERY photograph possesses the POSSIBILITY of a sense of presentness of the object being photographed (whether it be landscape, portrait, street, abstract, etc…). It just depends whether the photographer is attuned to what is present before their eyes, whether they are attuned to the mediation of the camera and whether the print reveals what has been captured in the negative. Minor White’s “revelation of spirit”. A “hands on” process does not guarantee a more meaningful form of photographic authenticity, or cameraless photographs possess some inherent authentic reality (the appeal to the aura of the object, Benjamin), any more than analogue or digitally reproduced photographs do. They are all representations of a mediated reality in one form or another. Some photographs will simply not capture that “presence” no matter how hard you try, be they cameraless or not. Further, every photograph exists in an eternal present, bringing past time to present and, in the process of existence, transcending time. In this regard, to claim special status for cameraless photographs is a particularly incongruous and elliptical argument, an argument which posits an obfuscation of the theoretical history of photography.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

PS. I particularly love Len Lye’s work for its visual dexterity and robustness.

Many thankx to the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image. All images are photographed by Bryan James.

“You assume that the image caught by the camera is “the” image, but of course a camera is ultimately a device – about from the Renaissance on – in which perspective is organised within a box using a lens, based on a principle that light travels in straight lines. So what you get when you use a camera is a mediated image, an image constructed according to certain conventions developed during the Renaissance and beyond in which the world is developed … according to the rules of perspective, and we’ve learnt to accept those rules as, as reality itself. But … when you put an object directly onto a piece of paper without any mediation [of a machine], it’s as if nature represents itself, completely unmediated and directly. In some ways … [this] is far more realist, far more true to the original object than any camera picture could be.”

Geoffrey Batchen

Geoffrey Batchen: Cameraless Photography

From Standing Room Only, 2:25 pm on 17 April 2016 Radio New Zealand

Today, if you have a smartphone, you have a camera with you wherever you go. But how were the first ever photos taken? Professor of Art History at Victoria University and world-renowned historian Geoffrey Batchen is the curator of ‘Emanations: The Art of the Cameraless Photograph’ exhibition at the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery and Len Lye Centre in New Plymouth.

Installation view of Christian Marclay’s Large Cassette Grid No. 6, 2009 (left) and Allover (Rush, Barbra Streisand, Tina Turner, and Others), 2008 (right)

Christian Marclay (American, b. 1955)

Large Cassette Grid No. 6

2009

Cyanotype photograph

Christian Marclay (American, b. 1955)

Allover (Rush, Barbra Streisand, Tina Turner, and Others)

2008

Cyanotype photograph

Using hundreds of cassette tapes bought in thrift stores, Christian Marclay has scattered the entangled strands of the tapes across large sheets of specially prepared blueprint paper, deliberately adopting the “action painter” techniques of Jackson Pollock and similar artists. He then exposed them, sometimes multiple times, under a high-powered ultraviolet lamp. In other cases, the cassettes themselves were stacked in translucent grids to make a minimalist composition.

Installation view of the exhibition Emanations: The Art of the Cameraless Photograph at the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery with at left, Christian Marclay and at right, Hiroshi Sugimoto

Walead Beshty (American, b. 1976)

Two Sided Picture (RY), January 11, 2007, Valencia, California, Fujicolor Crystal Archive, 2007

Chromogenic photograph

In the series from which this work comes American photographic artist Walead Beshty cut and folded sheets of photographic paper into three-dimensional forms and then exposed each side to a specific colour of light, facilitating the production of multi-faceted prints with the potential to exhibit every possible colour combination. The trace of this process remains visible, with the original folds transformed into a network of contours on the surface of the print.

Hiroshi Sugimoto (Japanese, b. 1948)

Lightning Fields 168 (installation view)

2009

Hiroshi Sugimoto (Japanese, b. 1948)

Lightning Fields 168

2009

Gelatin silver photograph

Hiroshi Sugimoto’s photographs of static electricity were inspired by his unsuccessful efforts to banish such discharges from the surface of his negatives during the printing process. Sugimoto decided instead to try and harness such discharges for the purposes of image making. Utilising a Van der Graaf generator, he directed as many as 40,000 volts onto metal plates on which rested unexposed film. He soon changed tactics when he discovered that immersing the film in saline water during the discharge gave much better results.

Installation views of the exhibition Emanations: The Art of the Cameraless Photograph at the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery with at left, Andreas Müller-Pohle Digital Scores (after Nicéphore Niépce) 1995, and to the right in the second and third images, Susan Purdy

In 1995 the German artist Andreas Müller-Pohle took the digital code generated by a scan of the supposed “first photograph,” Nicéphore Niépce’s 1827 heliograph View from the window at Le Gras, and spread it across eight panels as a messy swarm of numbers and computer notations. Each of Müller-Pohle’s separations represents an eighth of a full byte of memory, a computer’s divided remembrance of the first photograph. The Scores are therefore less about Niépce’s photograph than about their own means of production (as the title suggests, they bear the same abstracted relation to an image as sheet music has to sound). We see here, not a photograph, but the new numerical rhetoric of digital imaging.

Installation view of Ian Burn (Australian, 1939-1993) Xerox book # 1, 1968 from the exhibition Emanations: The Art of the Cameraless Photograph at the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery

In the 1960s a number of artists sought to distil artwork from the new imaging technologies becoming commonly available. Ian Burn, an Australian artist then living in New York, made a series of Xerox Books in 1968 in which he churned out 100 copies of a blank sheet of white paper on a Xerox 660 photocopying machine, copying each copy in turn until the final sheet was filled with the speckled visual noise left by the machine’s own imperfect operations.

Installation view of the exhibition Emanations: The Art of the Cameraless Photograph at the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery

Installation views of the exhibition Emanations: The Art of the Cameraless Photograph at the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery with in foreground display case, Herbert Dobbie’s illustrated cyanotype books New Zealand Ferns (148 Varieties) 1880, 1882, 1892 and background, the cyanotypes of Anna Atkins

Herbert Dobbie, a railway station master and amateur botanist who emigrated to New Zealand from England in 1875, made cyanotype contact prints of specimens of all 148 known species of fern in his new country in 1880 and sold them in album form. Dobbie was responding to a fashion for collecting and displaying ferns among his local audience, a fashion driven in part by a nostalgia for a pre-modern style of life and in part by a developing nationalism. The end result is a group of images that hover somewhere between science and art, between popular aesthetic enjoyment and commercial profit.

Anna Atkins (English, 1799-1871)

Untitled (from the disassembled album Cyanotypes of British and Foreign Flowering Plants and Ferns)

c. 1854

Cyanotype photographs

The English photographer Anna Atkins issued albums of cyanotype prints of seaweed and algae from 1843, and these are often regarded as the earliest photographic books.

In the 1850s, Atkins collaborated with her friend Anne Dixon to produce at least three presentation albums of cyanotype contact prints, including Cyanotypes of British and Foreign Ferns (1853) and Cyanotypes of British and Foreign Flowering Plants and Ferns (1854). These albums included examples from places like Jamaica, New Zealand and Australia – a reminder that, for an English observer, all these places were but an extension of home, a part of the British Empire. These cyanotypes look as if they were made yesterday, offering a trace from the past that nevertheless always remains contemporary.

William Henry Fox Talbot (British, 1800-1877)

Floral patterned lace

c. 1845

Salted paper print

23.0 x 18.8 cm (irregular)

During the 1850s, William Henry Fox Talbot focused his energies on the invention of a way of producing photographic engravings on metal plates, so that permanent ink on paper imprints could be taken from them. In April 1858, having found a way to introduce an aquatint ground to the process, he filed a patent for a system which he called photoglyphic engraving.

Talbot described his invention in terms of an ability to make accurate photographic impressions without a camera: “The objects most easily and successfully engraved are those which can be placed in contact with the metallic plate, – such as the leaf of fern, the light feathery flowers of a grass, a piece of lace, etc. In such cases the engraving is precisely like the object; so that it would almost seem to any one, before the process was explained to him, as if the shadow of the object had itself corroded the metal, – so true is the engraving to the object.”

This photograph was made using the calotype process, patented in 1841 by its inventor, the English gentleman William Henry Fox Talbot. The increased exposure speeds allowed by the process made it easier to print positive photographs from a negative image, so that multiple versions of that image could be produced. In this case, a positive photograph has been made from a contact print of a piece of lace.

Installation views of the exhibition Emanations: The Art of the Cameraless Photograph at the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery featuring Len Lye’s cameraless photographic portraits

Len Lye (New Zealand, 1901-1980)

Georgia O’Keeffe

1947

Courtesy of the Len Lye Foundation Collection

Govett-Brewster Art Gallery/Len Lye Centre

Len Lye (New Zealand, 1901-1980)

Le Corbusier

1947

Courtesy of the Len Lye Foundation Collection and Archive

Govett-Brewster Art Gallery/Len Lye Centre

Lye’s subjects included notable artists such as Joan Miró, Hans Richter, and Georgia O’Keeffe (who brought some deer antlers to the shoot), the architect Le Corbusier, the jazz musician Baby Dodds, the scientist Nina Bull, and the writer W. H. Auden. But they also included a baby and a young woman who remain unnamed; Lye’s new partner, Ann Hindle; and Albert Bishop, a plumber who had come by to do some repairs. (Referencing the history of “silhouette” art)

Len Lye (New Zealand, 1901-1980)

Marks and Spencer in a Japanese Garden (Pond People)

1930

Courtesy of the Len Lye Foundation Collection and Archive

Govett-Brewster Art Gallery/Len Lye Centre

Len Lye’s earliest cameraless photographs were made around 1930 as he settled into the London art scene and before he emerged as a leading figure in experimental cinema. His practice was eclectic during this period. He exhibited paintings, batiks, photographs and sculpture as part of the Seven and Five Society, Britain’s leading avant-garde group. During a visit to Mallorca with his friends Robert Graves and Laura Riding, Lye made a number of photograms with plasticine and cellophane shapes arranged over the photographic paper. Two of these, Self-Planting at Night (Night Tree) and Watershed, were exhibited in the 1936 International Surrealist Exhibition in London.

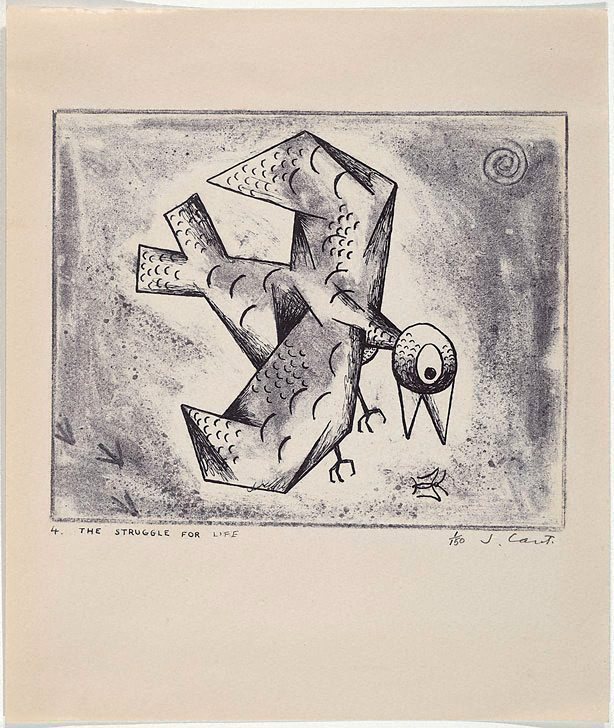

Installation view of the exhibition Emanations: The Art of the Cameraless Photograph at the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery featuring James Cant’s Six Signed Artist’s Prints 1948

James Cant (Australian, 1911-1982)

The struggle for life

1948

Cliché verre print (cyanotype blueprint from one hand-drawn glass plate)

35 x 29.6cm sheet

A number of Australian artists, some working in Melbourne and some in London, issued prints in the 1940s and early 50s using architectural blueprint (or cyanotype) paper, perhaps because, during the deprivations that attended the aftermath of World War Two, it was a cheap and available material for this purpose. James Cant, an artist interested in both Surrealism and Australian Aboriginal art, brought the two together in his designs for a portfolio of Six Signed Artist’s Prints that he issued in a print run of 150 in 1948. Each image was painted on a sheet of glass and then this glass was contact printed onto the blueprint paper to create a photograph.

In August 1834, while resident in Geneva, William Henry Fox Talbot had a friend make some drawings on sheets of varnished glass exposed to smoke, using an engraver’s needle to scratch through this darkened surface. The procedure came to be known as cliché verre.

Kilian Breier (German, 1931-2011)

Kilian Breier: Fotografik 1953-1990 (cover)

1991

The German artist Kilian Breier began making abstract photographs in the 1950s, some by folding his photographic paper and others by allowing rivulets of developer to flow across and stain it. A 1991 exhibition catalogue, Kilian Breier: Fotografik 1953-1990, gave the artist an opportunity to make a provocative gesture in line with his dedication to the self-generated image; he included in it a loose unfixed piece of signed photographic paper that continues to develop every time it is exposed to light. It therefore inhabits the book that protects it like a ghost, unable to be seen but nonetheless always present.

Max Dupain (Australian, 1911-1992)

Untitled rayograph [with water]

1936

Gelatin silver photograph

The Australian modernist photographer Max Dupain was a great admirer of the work of Man Ray. In 1935 Dupain reviewed a book of the American’s photographs for The Home magazine in Sydney, declaring that “He is alone. A pioneer of the 20th century who has crystallised a new experience in light and chemistry.” With this book as his inspiration, Dupain himself made a number of experimental cameraless photographs in the later 1930s.

Běla Kolářová (Czechoslovakia, 1923-2010)

Pecky broskve (z cyklu Stopy)

Peach Stones (From Traces series)

1961

Gelatin silver photograph from an artificial negative

Taking up photography in 1956 during the Cold War, the Czech artist Běla Kolářová wrote about the need to photograph things normally beneath the notice of photography, the negligible detritus of everyday life. Her initial experiments along these lines involved the making of prints from what she called “artificial negatives.” Collecting all sorts of discarded items (onion peels, peach pits), she either placed her scraps directly on celluloid or embedded them in a layer of paraffin, projecting the resulting image onto bromide paper using an enlarger. Kolářová also began to produce photographic images by placing her light-sensitive paper on a record turntable, rotating it at varying speeds, and allowing the light to produce a series of overlapping and wavy concentric circles.

Installation view of

György Kepes (Hungarian, 1906-2001)

Black, great and white light composition, 1949

Black and white calligraphy, 1951

Fluid patterns, 1938

(Calligraphic light), 1948

Optical transformation, 1938

Hieroglyphic body, 1942

(Magnetic pattern), 1938

Gelatin silver photographs (printed c. 1977)

The Hungarian-born artist György Kepes moved to the United States in the late 1930s, where he published a series of interdisciplinary books concerned with the “language of vision.” Informed by his study of psychological theory, Kepes particularly favoured the cameraless photograph as offering a kind of universal language, stressing the need for images that combined “transparency and interpenetration… the order of our time is to knead together the scientific and technical knowledge required, into an integrated whole on the biological and social plane.” Even when they appear to be abstractions, Kepes’s own photograms were intended as an expression of the interdependence of natural and manmade structures and as an advocacy for the interrelationship of art, science, and technology.

Installation view of the work of Herbert Matter (left), Chargesheimer (centre), and Roger Catherineau (right)

Herbert Matter (American born Switzerland, 1907-1984)

Untitled

c. 1939-1943

Gelatin silver photograph

Born in Switzerland, Herbert Matter studied with Fernand Léger in Paris before working there and in Switzerland as a graphic designer, incorporating photographic images into his many posters. In 1935 he moved to the United States, involving himself in the design and art world he found there, with a special interest in the work of abstract painters. He produced a number of experimental photographs in this period, deliberately designed to break with what he called “the chains of documentation.” These included a calligraphic image made in 1944 by tracing brush strokes on a wet emulsion plate charged by an electrical current and a series of sinuous, painterly photographs, perhaps made by pouring chemicals on sheets of glass already marked with a resist and then printing from them.

Chargesheimer (German, 1924-1972)

Scenarium

1961

Gelatin silver chemigram

In 1961, the German artist Karl-Heinz Hargesheimer, who went by the single name of Chargesheimer, published a limited-edition book titled Lichtgrafik [Light Graphic]. He described the ten unique prints gathered in it as photochemische Malereien or “photo-chemical paintings,” inducing their strange combinations of gestural calligraphic marks and organic-looking surface using only developer and fixer on gelatin silver photographic paper.

Roger Catherineau (French, 1925-1962)

Photogramme

1957

Gelatin silver photograph

Starting in the 1950s, French artist Roger Catherineau drew on his interest in sculpture and dance to produce sinuous, layered photograms that look more like graphics than paintings. Their ambiguous depths were made even more elusive by the addition of coloured inks to their surfaces.

Installation view of the exhibition Emanations: The Art of the Cameraless Photograph at the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery with at left, Marco Breuer and at right, Lynn Cazabon

Installation view of

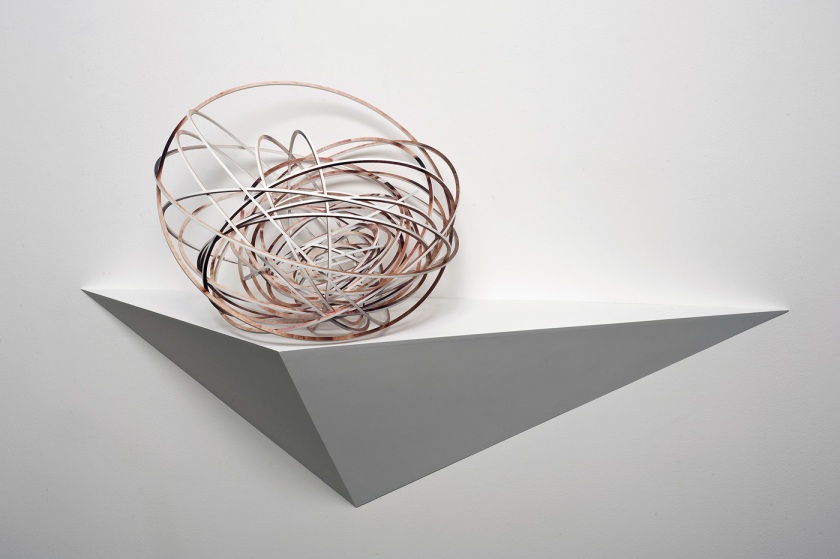

Danica Chappell (Australian, b. 1972)

Slippery Image #1, 2014-2015

Slippery Image #2, 2014-2015

Daguerreotype

Danica Chappell (Australian, b. 1972)

Traversing Edges & Corners (Orange #9), 2014

Traversing Edges & Corners (Orange #10), 2014

Tintype

The work of Australian artist Danica Chappell brings together the formal experiments of early modernist avant-garde groups, such as the Russian Constructivists and the German Bauhaus, with some of photography’s earliest techniques, resulting in geometrically patterned daguerreotypes and tintypes. These patterns of light and shadow animate the surface of Chappell’s metallic photographs, while also recording her work in the darkroom, her negotiation of radiation, object, body and time.

Installation view of

Lynn Cazabon (American, b. 1964)

Diluvian

2010-2013

40 unique silver gelatin solar photographs

Diluvian, by American artist Lynn Cazabon, comprises a grid of unique contact prints, with their imagery and the means of its production both being directly generated by the work’s subject matter. Embedded in a simulated waste dump, covered with discarded cell phones and computer parts as well as organic material, expired sheets of gelatin silver paper were sprayed with baking soda, vinegar and water, sandwiched under a heavy sheet of glass, and left in direct sunlight for up to six hours, four prints at a time. The chemical reactions that ensued left visual traces – initially vividly coloured and then gradually fading when fixed – of our society’s flood of toxic consumer items, produced by the decomposing after-effects of those very items.

Installation view of

Marco Breuer (German, b. 1966)

Untitled (C-1378), 2013

Untitled (C-1598), 2014

Chromogenic paper, embossed/burned/scraped

Marco Breuer (German, b. 1966)

Untitled (C-1526), 2014

Chromogenic paper, burned/scraped

Marco Breuer (German, b. 1966)

Untitled (C-1338), 2013

Chromogenic paper, burned

By folding, scoring, burning, scouring, abrading, and/or striking his pieces of photographic paper, German-born, US-based artist Marco Breuer coaxes a wide range of colours, markings and textures from his chosen material. Both touched and tactile, Breuer’s photographs have become surrogate bodies, demonstrating the same fragility and relationship to violence as any other organism. And like any other body, they also bear the marks of time, not of a single instant from the past, like most photographs, but rather of a duration of actions that have left accumulated scars.

Installation views of the exhibition Emanations: The Art of the Cameraless Photograph at the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery with at centre, the work of Anne Noble

Anne Noble (New Zealand, b. 1954)

Bruissement: Bee Wing Photograms #10

2015

Pigment print on Canson baryta paper

320 x 110cm

Courtesy of the artist, Wellington

In recent times, the New Zealand artist Anne Noble has made a number of works that address the calamitous collapse of the global honeybee population. In these two cameraless photographs, cascading vertically down the wall like Chinese scroll paintings, we get to see the imprint of thousands of detached bee wings, their determined hum stilled by disease, human interference and a toxic ecology. The haunting beauty of these delicate traceries and strange shadows is also a warning. A beekeeper herself, Noble looks at bees as a living system under stress but also as a model for our own society; as she says, “what is happening to the bees we are likely doing to ourselves.”

Installation views of

Alison Rossiter (American, b. 1953)

Agfa Cykora, expired January 1942, processed 2013

Eastman Kodak Velox, expired March 1919a, processed 2014

Eastman Kodak Medalist E2, expired September 1956, processed 2010

Eastman Kodak Velox, expired March 1919b, processed 2014

Eastman Kodak PMC No.11, expired September 1937, processed 2013

Defender Argo, exact expiration date unknown, c. 1910, processed 2013

Velox T4, expiry date October 1, 1940, processed 2008

Unique gelatin silver photographs

Since 2007, American photographic artist Alison Rossiter has been buying old expired packets of unexposed film at auction or on the internet, some of them dating from as early as 1900. She then develops these sheets in her darkroom with no further exposure to light, never quite sure what the resulting object-image will look like. The one inscribed Velox T4, expiry date October 1, 1940, for example, was developed in 2008, and displays a Mark Rothko-like grid of pale impressions on a dark ground. These are the chemical traces left behind by the wrapping paper that once protected it from light. We’re looking, then, at an exposure – to chemicals as well as to leaked light – of approximately seventy years.

Installation view of

Matt Higgins (Australia)

Untitled 134-5, 2014

Untitled 254-5, 2014

Untitled 287-5, 2014

Untitled 292-5, 2014

Unique chemigram on gelatin silver photographic paper

Australian artist Matt Higgins makes what are called ‘chemigrams,’ created by the interplay of various manual and chemical processes on a single sheet of photographic paper or film. Higgins also uses resists to help create his patterned surfaces, from soft organic substances such as apple syrup to industrial compounds such as epoxy enamel. He thereby returns photography to its historical roots: the desire to coax images from a chemical reaction to light.

Installation views of the exhibition Emanations: The Art of the Cameraless Photograph at the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery

Govett-Brewster Art Gallery/Len Lye Centre

Queen St, New Plymouth, New Zealand

Phone: +64 6 759 6060

Email: info@govettbrewster.com

Opening hours:

Daily 10am – 5pm

![Max Dupain (Australian, 1911-1992) 'Untitled rayograph [with water]' 1936 Max Dupain (Australian, 1911-1992) 'Untitled rayograph [with water]' 1936](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/dupain-rayograph-water.jpg?w=650&h=830)

You must be logged in to post a comment.