Exhibition dates: 11th May – 5th September, 2022

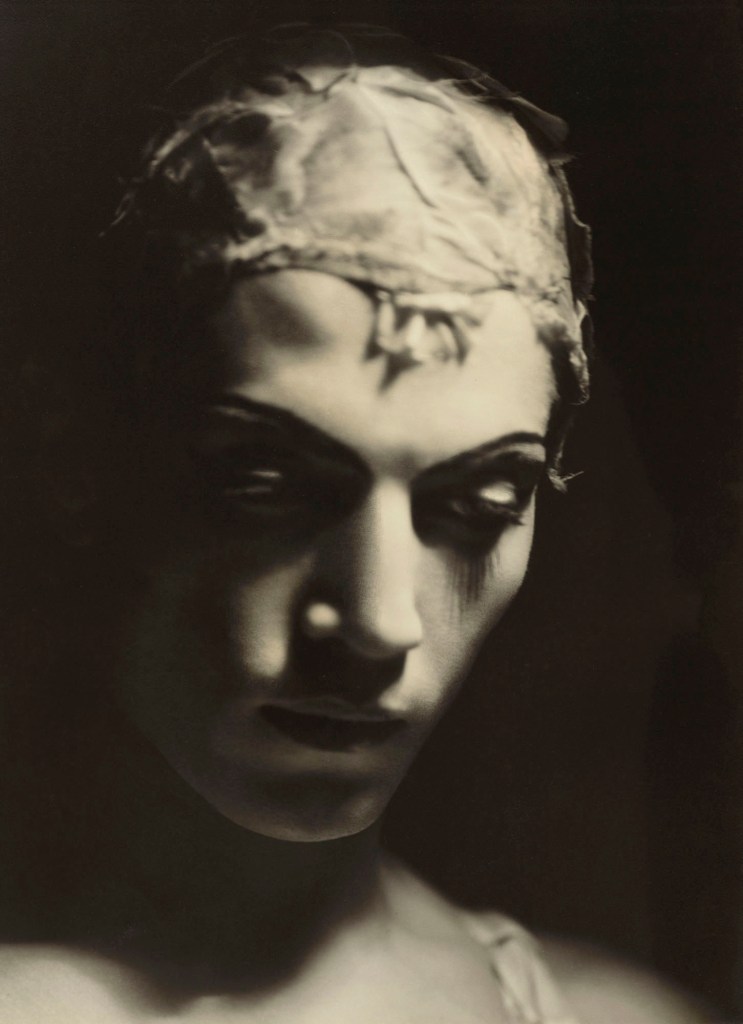

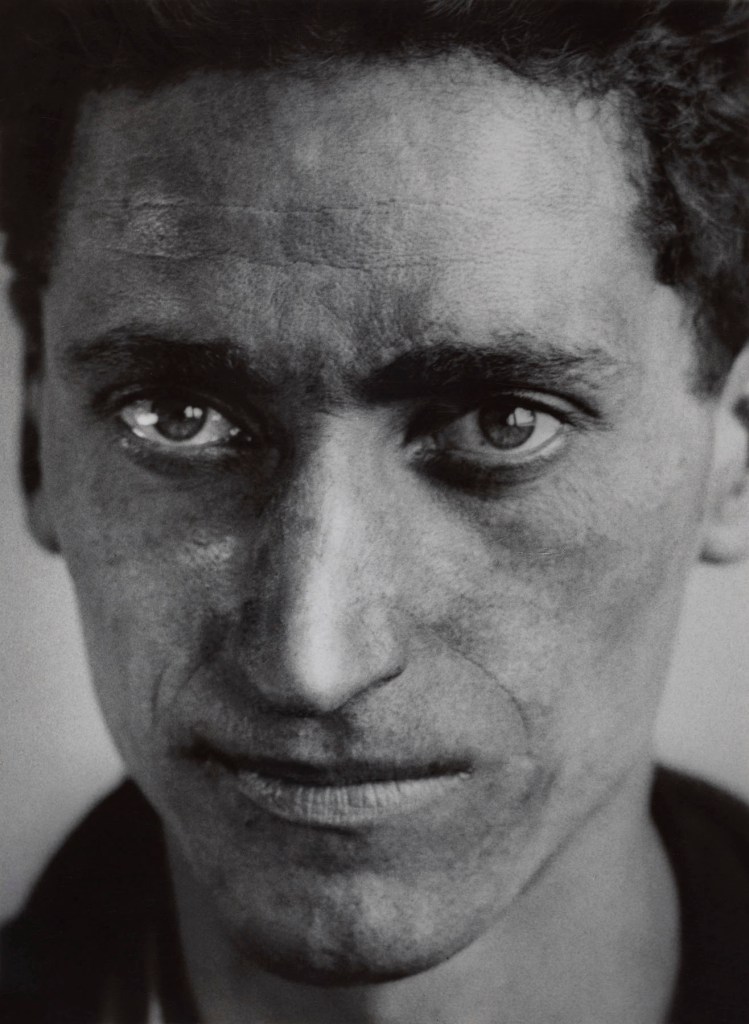

Ludwig Meidner (German, 1884-1966)

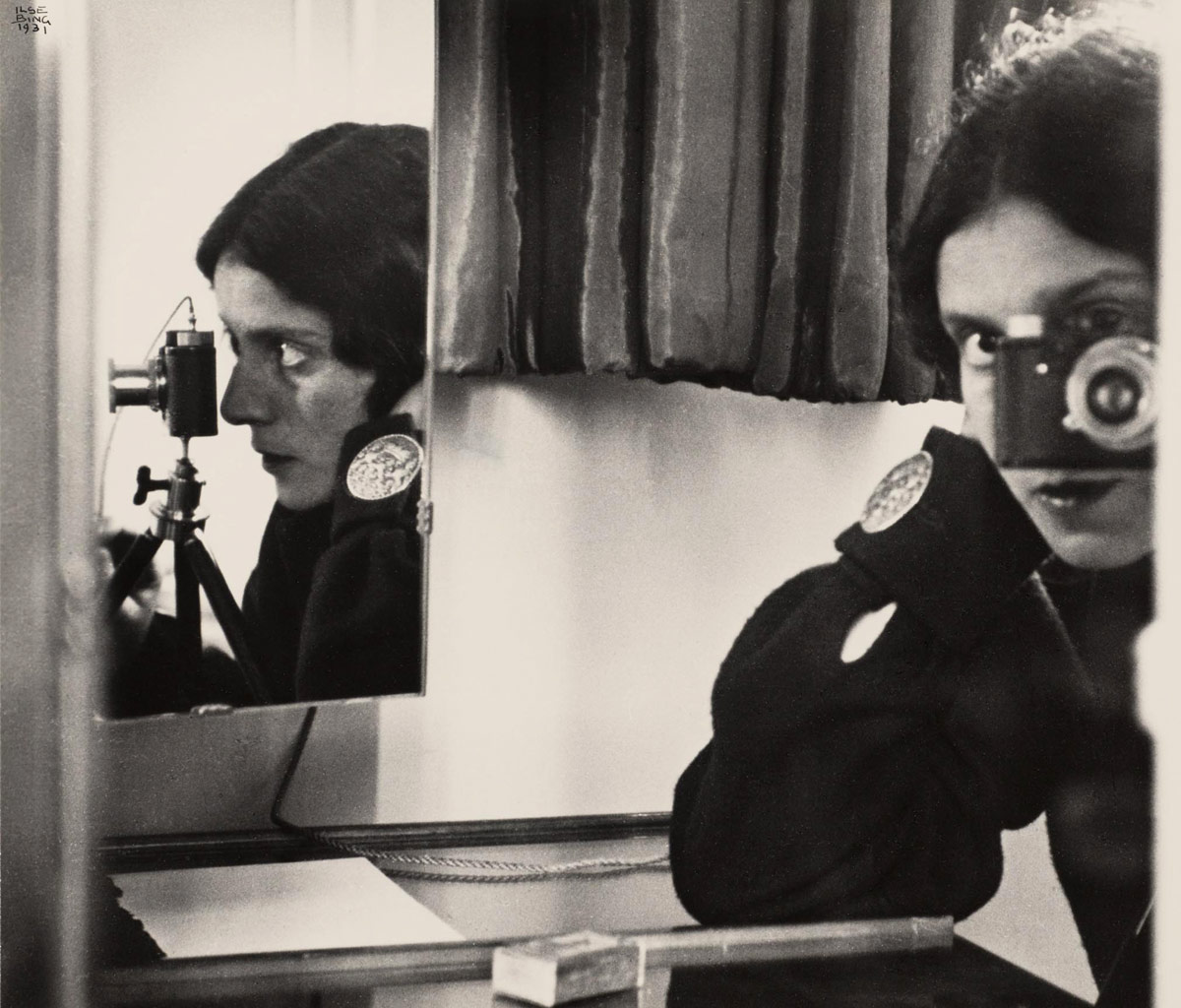

Selfportrait (installation view)

1913

Oil on canvas

Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt

Photo: Aubrey Perry

A portent of things to come…

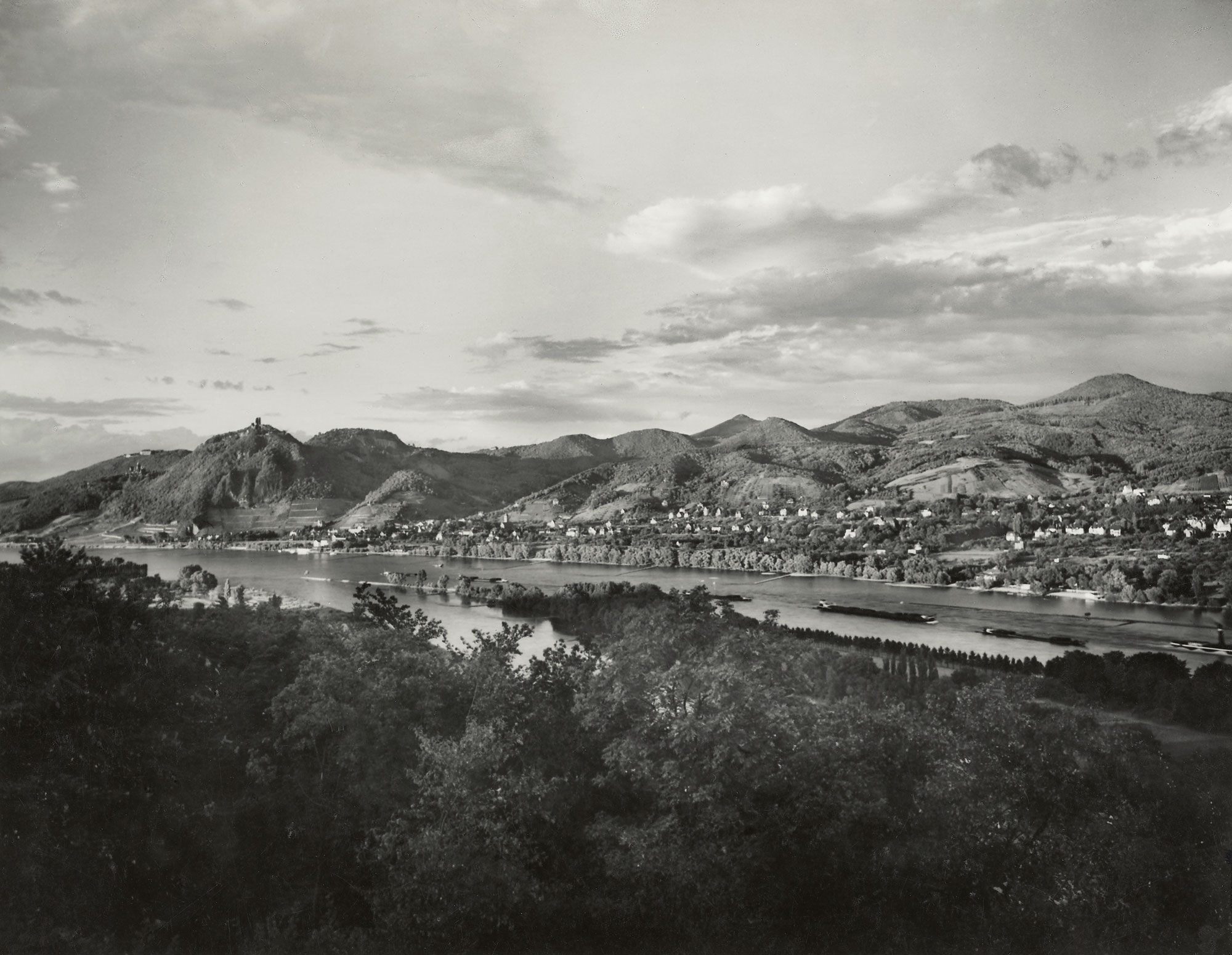

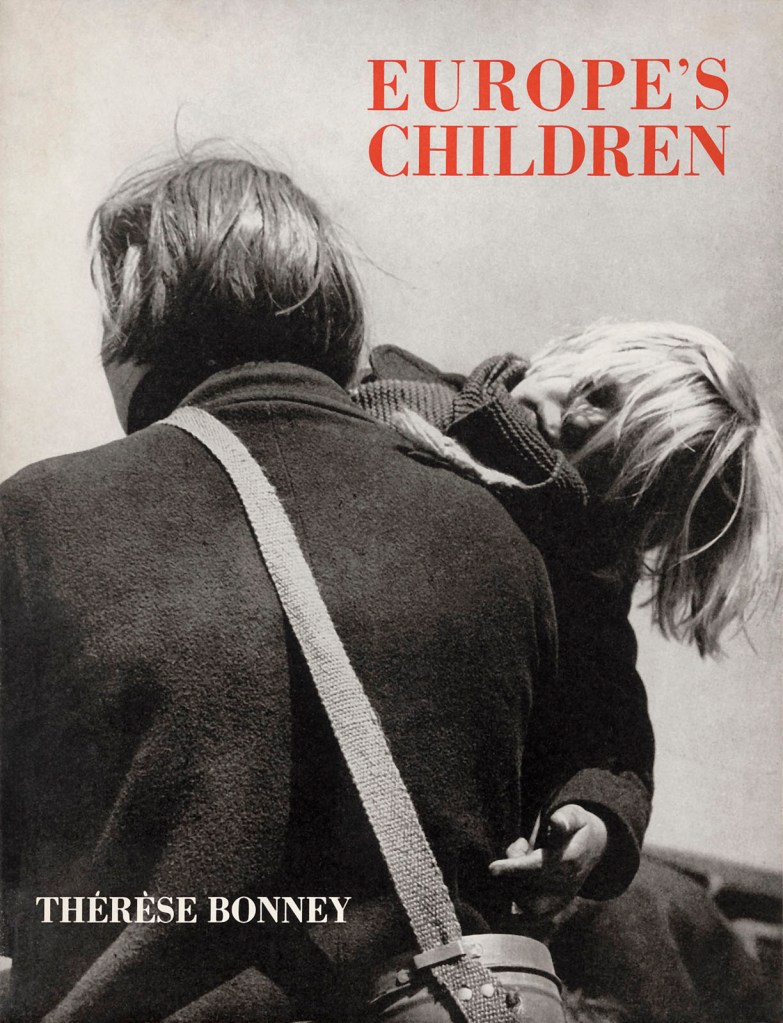

In Germany, the years 1919-1933 were an extraordinary period of turbulence, emancipation, depravation and creativity. After the humiliation of defeat at the end of the First World War, revolution swept Germany which led to the establishment of democracy through the Weimar Republic, which was born out of the struggle for a new social order and political system.

The flowering of German Expressionism (modern art labelled by Hitler Entartete Kunst or “Degenerate Art” in the 1920s) in painting and sculpture took place under the Weimar Republic of the 1920s and the country emerged as a leading centre of the avant-garde. This exhibition focuses on the art and culture of the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity), a style which was a challenge to Expressionism and which advocated a return to realism and social commentary in art. “As its name suggests, it offered a return to unsentimental reality and a focus on the objective world, as opposed to the more abstract, romantic, or idealistic tendencies of Expressionism.”1

This multidisciplinary exhibition is structured into eight thematic sections corresponding to the groups and sociocultural categories created by August Sander in his seminal work Menschen des 20. Jahrhunderts (People of the 20th century), “intended, as he stated, to be “a physiognomic image of an age,” and a catalogue of “all the characteristics of the universally human.””2 In other words, Sander focused more on “archetypes” than on individuals, using his photographs to classify groups of people, to create a taxonomic ordering of society. At the time physiognomy (the art of discovering temperament and character from outward appearance) – today classified as a pseudoscience but at the time regarded as a genuine science – used photography to classify individuals and groups, notably used by the Nazis to classify Untermensch, that is, “non-Aryan “inferior people” notably Jews, Roma, and Slavs (Poles, Serbs, Ukrainians, and Russians). The term was also applied to Mixed race and Black people. Jewish, Polish and Romani people, along with the physically and mentally disabled, as well as homosexuals and political dissidents were to be exterminated in the Holocaust.” (Wikipedia)

“[Johannes] Molzahn, [László] Moholy-Nagy and others anticipated photography’s eventual achievement of a universally accessible and highly efficient form of communication. Germany’s immediate future did not fulfil such emancipatory predictions. By the end of the Weimar Republic, it was clear that one of photography’s most significant achievements was repackaging physiognomy, the ancient practice of identifying and classifying people according to racial and ethnic type, as a modern visual language… Declarations of photography as a new universal language and its revival of physiognomic looking went hand in hand with the racialized and metaphysical pursuits of National Socialist photography. This continuity points to uncomfortable connections between Weimar modernism and the fascist ideology of totalitarian regimes. As Eric Kurlander points out … scholars acknowledge that National-Socialist-era culture developed from – rather than broke with – Weimar aesthetic traditions.”3

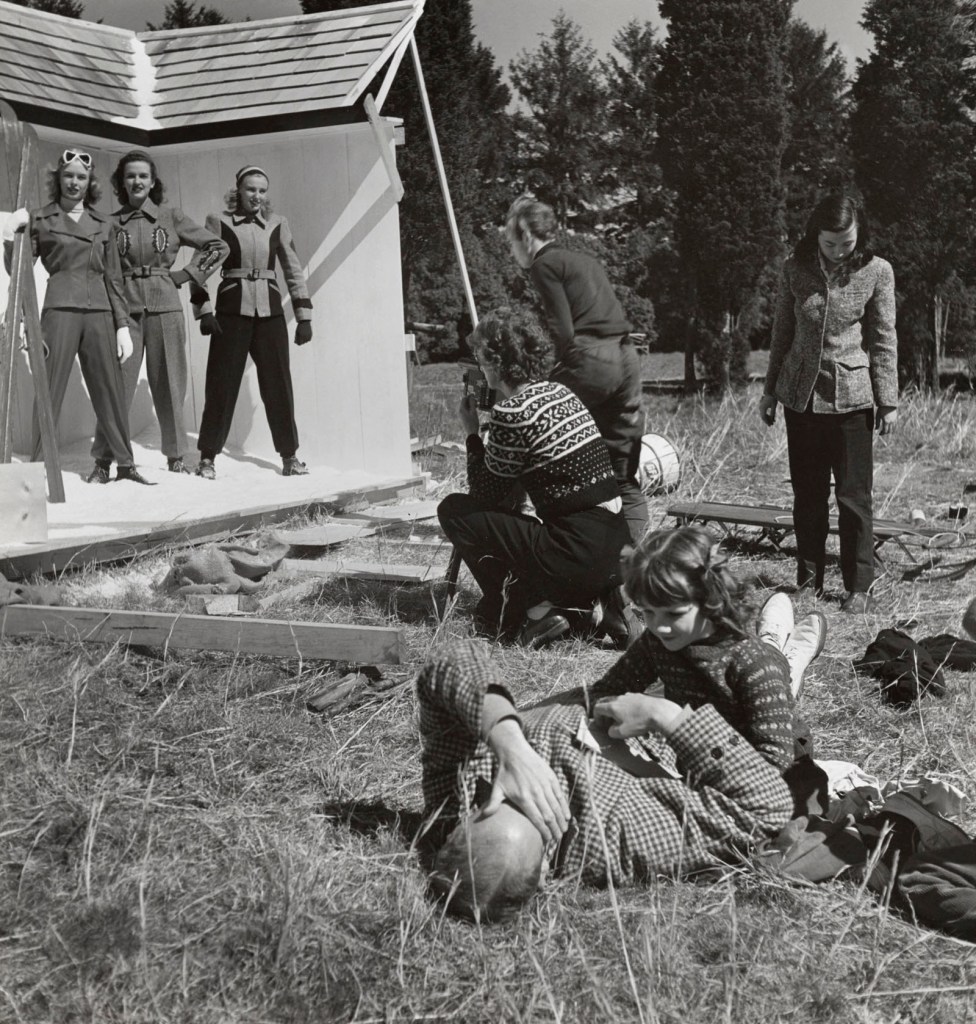

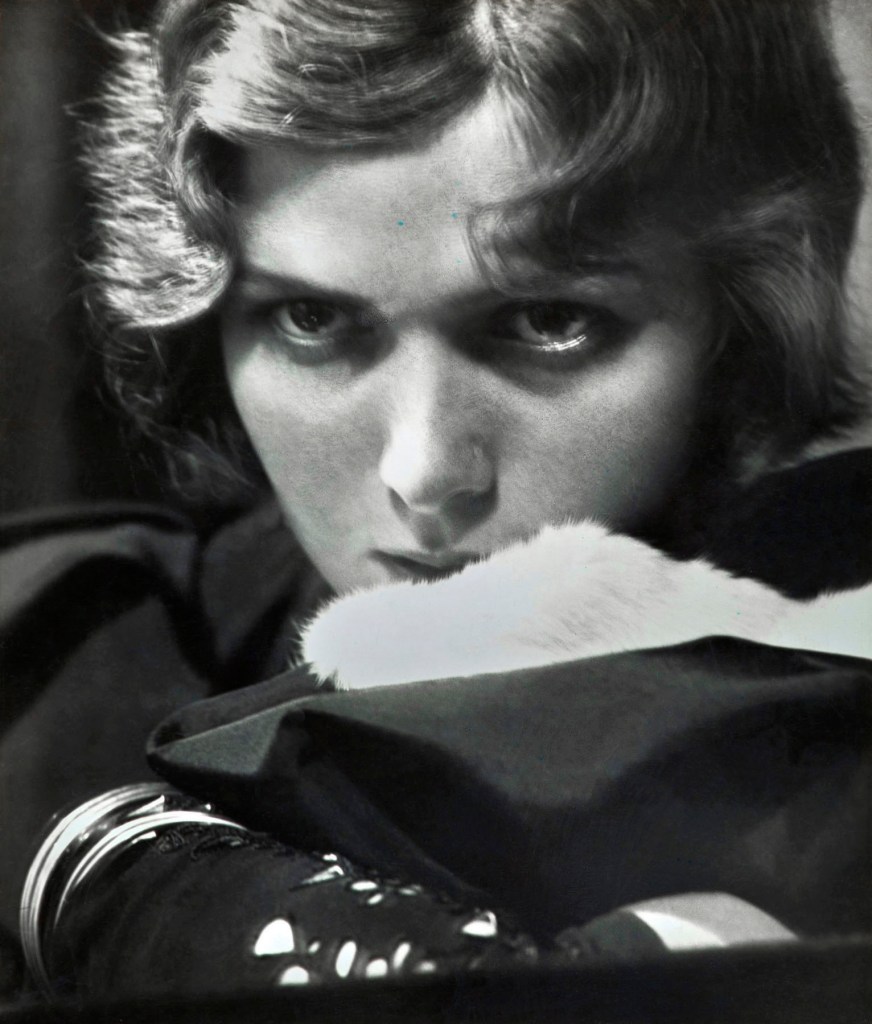

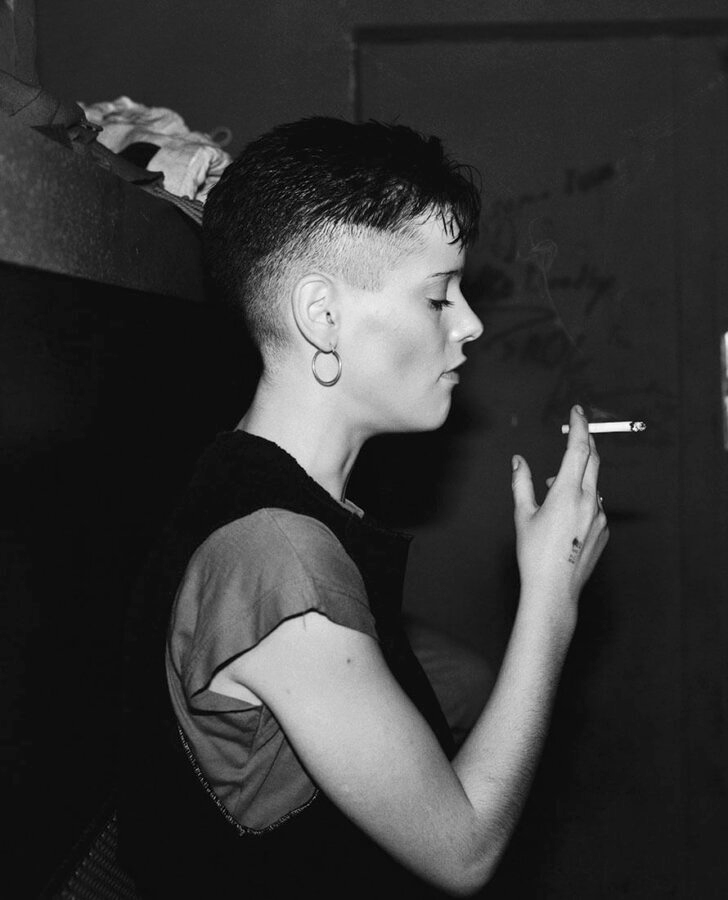

The Weimar Republic and its culture is full of contradictions. On the one hand you have changes in gender norms, such as the open appearance of homosexuality, the emergence of the emancipated female, the establishment of Magnus Hirschfeld’s Scientific-Humanitarian Committee and World League for Sexual Reform which carried out “the first advocacy for homosexual and transgender rights”, and the disclosed existence of people such as Lili Elbe, who was a Danish painter and transgender woman, and among the early recipients of sex reassignment surgery. At the time of Elbe’s last surgery, her case was already a sensation in newspapers of Denmark and Germany. “Artists are also interested in changes in gender norms, like August Sander, who photographs “La femme” in Menschen des 20. Jahrhunderts. With an almost sociological eye, they construct a typology of the emancipated Neue Frau (New Woman): Bubikopf (short variant of the bob cut), cigarette, wearing of a shirt or even a tie become recurring attributes in the female portraits of the time.” (Text from the exhibition)

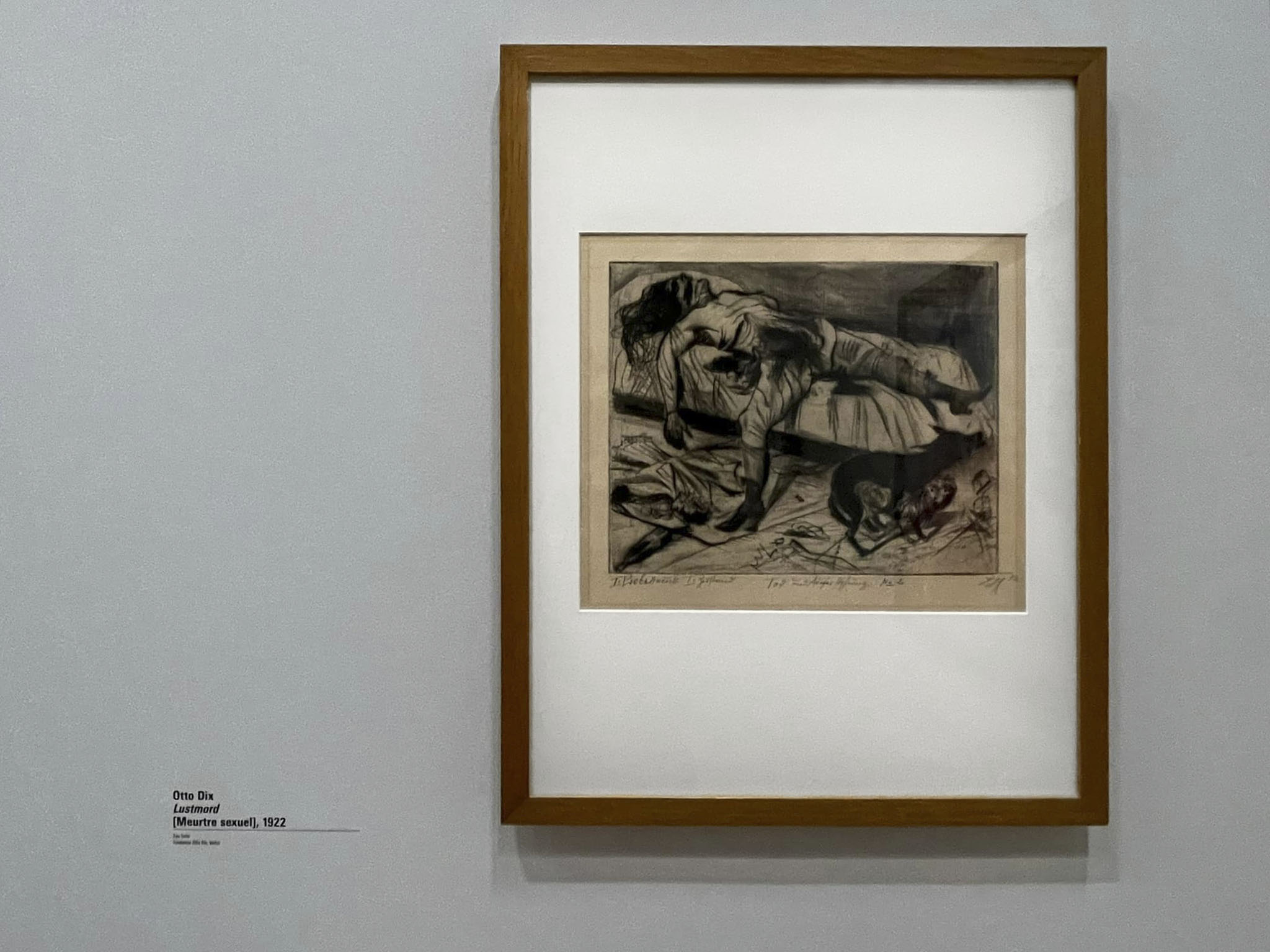

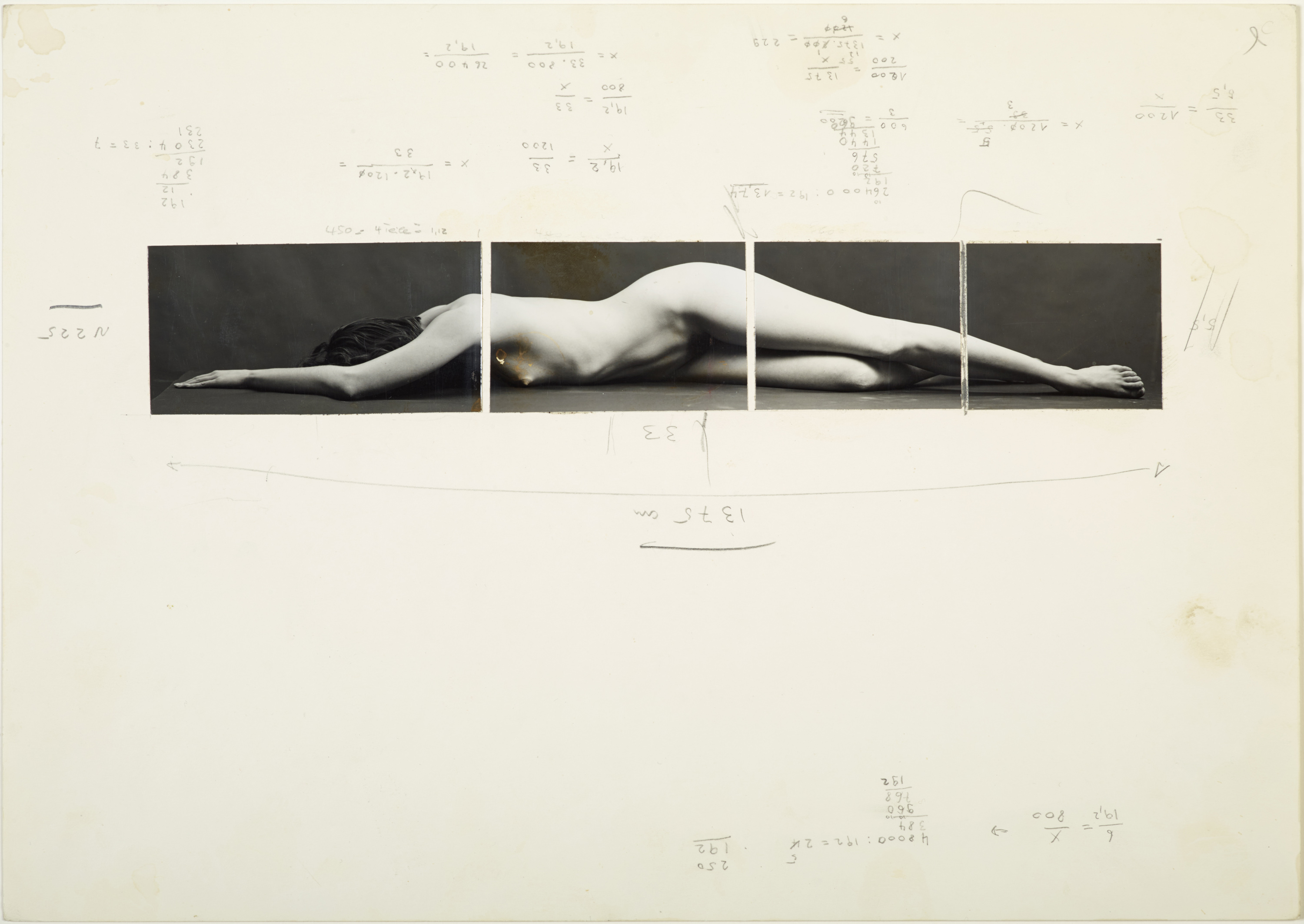

On the other hand you have male artists whose depiction of women – and not just the emancipated female – is highly misogynistic. Women are seen as a threat to men … and in many art works from this period, women’s bodies are mutilated, decapitated and hung. These art works attest to the misogyny of many male artists,4 to the desire of men to control women, to see them as fantasies (to be disfigured or killed), or to see them as unfit for purpose.

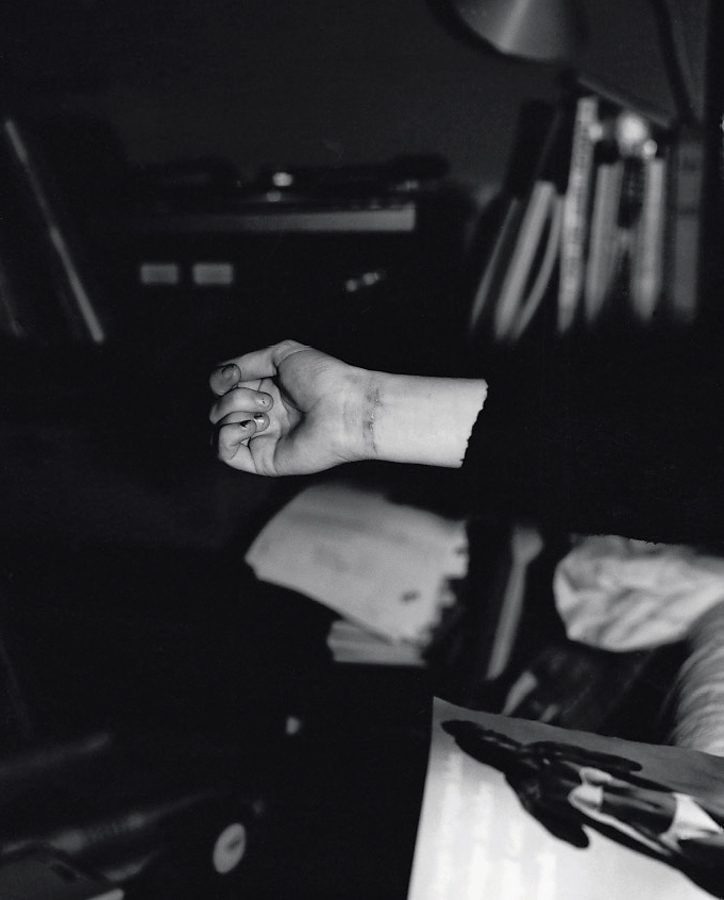

For example, Rudolf Schlichter’s smiling / grimacing Mutilated proletarian woman (1922-1923) who is missing a hand and half her forearm whilst still holding a child (which can just be seen in an installation image below), presages against her ability to be a “good” mother; Schlichter’s Der Künstler mit zwei erhängten Frauen (The Artist with Two Hanged Women) (1924) focuses on private fantasies of sexualised murder which was a recurrent theme within this period and the public interest in the rise of suicide; Otto Dix’s group of Lustmord (Sex Murder) paintings (one of which is pictured below) “attest to the anxieties of ’emasculated’, defeated men toward newly independent women. Such depraved fantasies of control, accomplished not by gunshots but gashes, were exploited and sensationalized in the rightwing press”5; and Heinrich Maria Davringhausen’s The Dreamer (1919, below) “is an especially surreal example: a grey-faced figure sits at a table, staring out; a bloody straight razor lays by his hand, while in the corner is a woman with her throat cut; above, the ceiling phases into a beach.”6

“The post-war period saw an emancipation of women, which influenced fashion towards masculinity: short hair, shirt, tie and flat chest. you see women active in all the technical fields previously reserved for male heroes. But… these are exceptions reserved for a certain urban high society because the traditional woman remains KKK (Kirchen, Küchen, Kinders: church, kitchen, children).

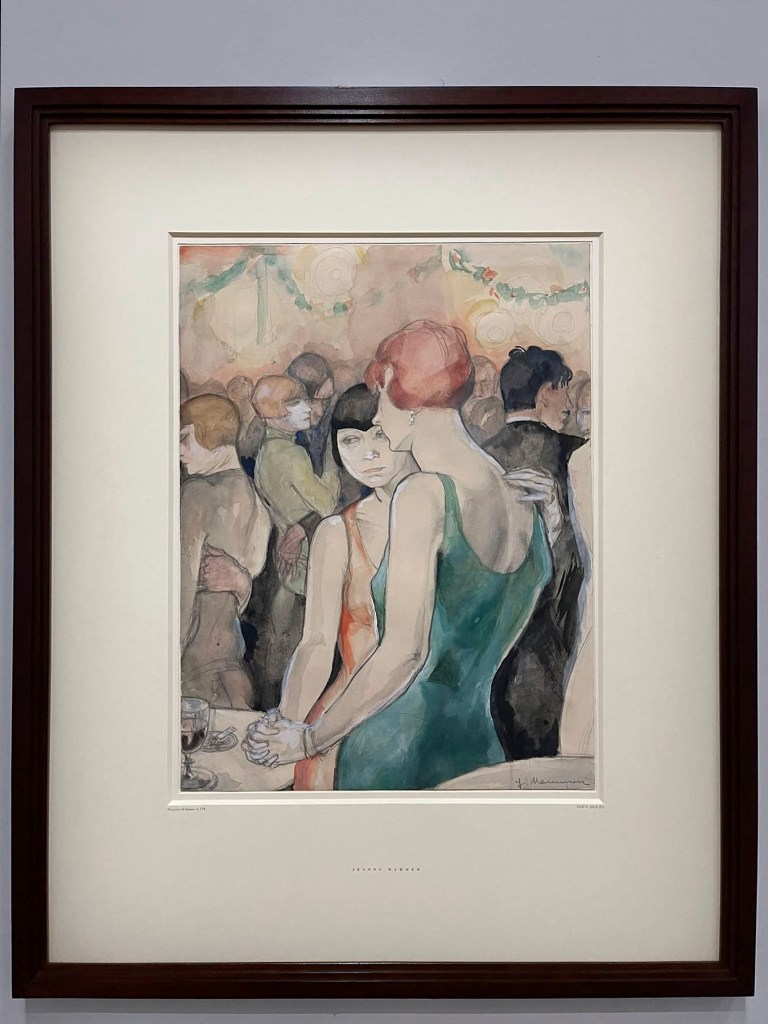

It is also the time of a liberation of morals, where Jeanne Mammen draws lesbian encounters… and Christian Schad of boys lovingly entwined… But, an opposite current is born towards a biological determinism of homosexuality, artists make violent reminders of the norm and Rudolf Schlichter, Karl Hubbuch or Otto Dix, for example, multiply the representations of sexual crimes by patients: the emancipated female is seen as a threat.”7

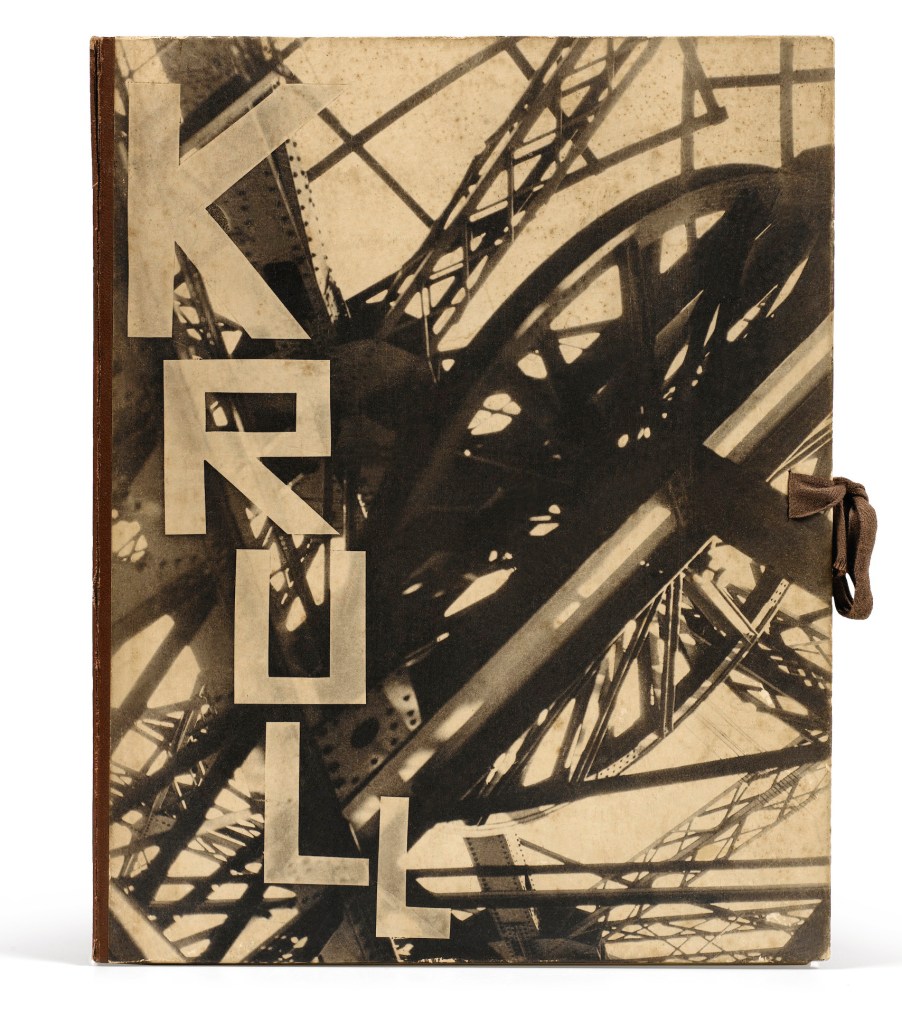

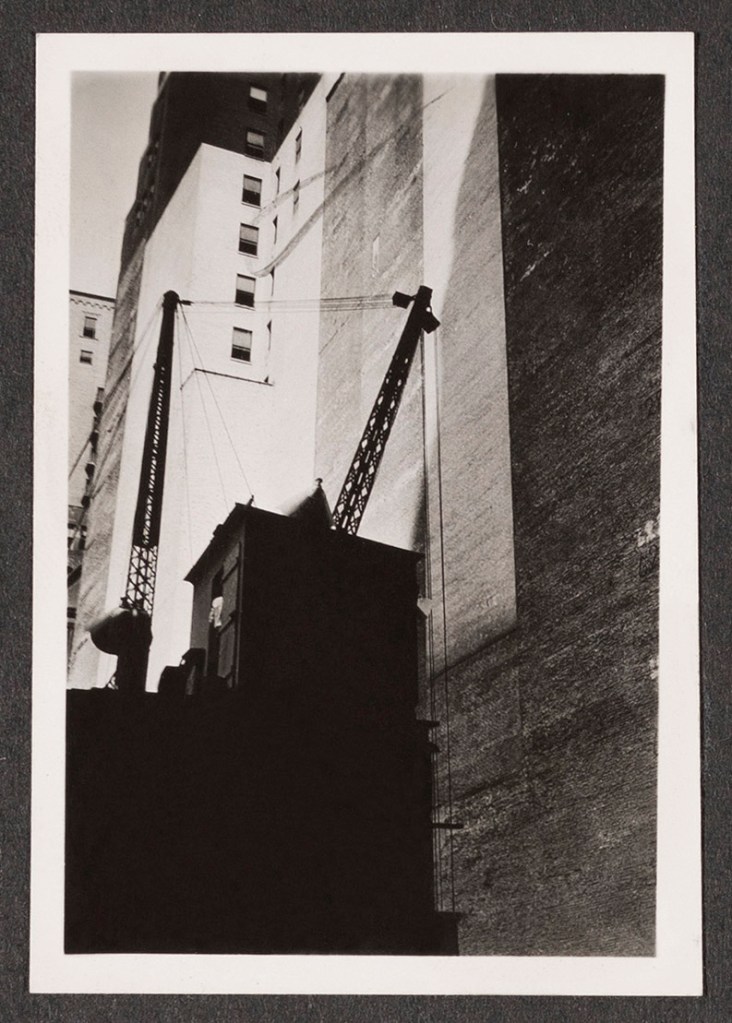

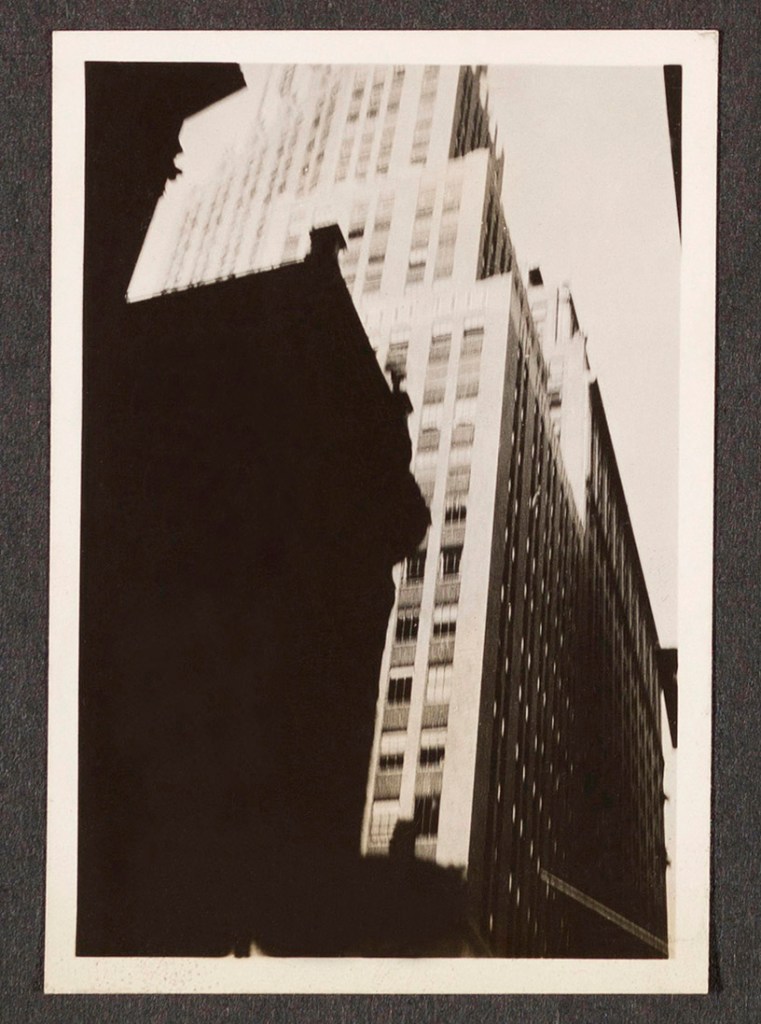

The interwar German interregnum was a period of incredible sensitivity and brutality at one and the same time. It was a period of disease (Spanish Flu), disfigurement (homecoming soldiers after the First World War), and economic depression and inflation (especially during the Great Depression of 1929). It was a period of the rise of the machine (machine gun, tank, aeroplane, total war). It saw the rise of aerodynamics, modernist architecture, graphic design, new typography, and photography (notably through the Bauhaus) as prolific forms of visual communication in which reading would be an obsolete skill. ‘”Stop reading! Look!” will be the motto in education,’ Molzahn wrote, ‘”Stop Reading! Look!” will be the guiding principle of daily newspapers’.”8 The period also saw the development of archetypes as socio-cultural norms, of the montage of “things” and their standardisation and rationalisation as utilities to be used (and abused).9

In Europe, the interwar period was one of the most wonderful eras of creativity the world has ever seen, the one to which I would most like to return if I had the possibility of going back in time. It was a period of transgression and experimentation, in which the new possibilities and new points of view opened up to the inquiring mind. The cabaret of life was in full flow in Europe in the interwar years: revolution and street battles, poverty and perversion, living for the moment… for tomorrow might never come, evidenced by the brutality a disillusioned society had witnessed during the First World War. The advances to social freedom and female emancipation which occurred during the period were only the scab that covered a gaping wound beneath, a wounding that would be brutally exposed anew during the repression, genocide and conflagration leading up to and during the Second World War. The depictions of life and death, of the i/rational, in the “objective” art of Neue Sachlichkeit were a portent of things to come…

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Word count: 1,235

Footnotes

1/ Anonymous text. “New Objectivity,” on the German Expressionism MoMA website Nd [Online] Cited 07/08/2022

2/ Anonymous text. “August Sander: People of the Twentieth Century. A Photographic Portrait of Germany,” press release on the Metropolitan Museum of Art website 2004 [Online] Cited 07/08/2022

3/ Pepper Stetler. “Photo Lessons: Teaching Physiognomy during the Weimar Republic,” in Christopher Webster (ed.,). Photography in the Third Reich, Open Book Publishers, 2021, p. 15-28 [Online] Cited 07/08/2022

4/ “During the years following World War I, and until the consolidation of the Nazi party in 1933, paintings and drawings of butchered, semi-nude women proliferated in the art galleries and publications of the Weimar Republic.2 This phenomenon coincided with the sensationalized serial killings of women and children by men who were known as – among other names – Lustmörders. Lustmord, a term derived from criminology and psychology, was the label assigned to this sensational genre.3 The Weimar Lustmördes clearly bother modern scholars, who are faced with the challenge that Weimar critics failed to comment on how these paintings represented the disfiguring of women. The misogyny of these works, uncommented upon in their own time, has become the central focus of much modern Lustmord scholarship, which ultimately defines this treatment of the female form as implicit attacks on the so-called New Woman, a name given to middle- and upper-class women pushing against the traditional roles and restrictions imposed upon them by society.”4

Stephanie Bender. “Lady Killers and Lust-Murderers: The Lustmord Paintings of Weimar Germany,” in Athanor XXIX (Vol. 29), 2011, pp. 77-83. Florida Online Journals [Online] Cited 07/08/2022

5/ Travis Diehl. “New Objectivity,” in Frieze magazine 10 March 2016 [Online] Cited 07/08/2022

6/ Ibid.,

7/ Anonymous text. “la Nouvelle Objectivité, Allemagne années 20,” on the Almanart website Nd [Online] Cited 04/08/2022 (translated from the French by Google translate)

8/ Johannes Molzahn. ‘Nicht mehr lessen! Sehen!’ Das Kunstblatt 12: 3 (1928), p. 80, quoted in Pepper Stetler, Op cit.,

9/ “Rationality is an important aspect of literary representations of Lustmord, and the suggestion of the metropolis as a rational sphere is linked to the role of the male protagonist.14 The male figure is depicted as intellectual and cultured, and even though he commits Lustmord, it is because his rational foundation has been somehow destroyed.15 The manifestation of this violence, this monstrosity that overtakes the rational male, is rooted in the feminine and consequently lashes out at women.”

Jay Michael Layne. “Uncanny Collapse: Sexual Violence and Unsettled Rhetoric in German-Language Lustmord Representations, 1900-1933” (PhD diss., University of Michigan, 2008, pp. 60-671) quoted in Stephanie Bender. “Lady Killers and Lust-Murderers: The Lustmord Paintings of Weimar Germany,” in Athanor XXIX (Vol. 29), 2011, pp. 77-83. Florida Online Journals [Online] Cited 07/08/2022

Many thankx to the Centre Pompidou for allowing me to publish some of the images in the posting. Thankx also to Aubrey Perry for the use of most of the installation photographs of the exhibition (except the five noted below)

0 – Introduction

1 – Prologue

2 – Standardisation

What is standardisation? The singularities are erased, in favour of recourse to models, standardised types, simple forms reproducible in series. Here we see paintings like those of George Grosz, with his faceless figures, schematic human beings with neutral expressions set in empty towns. This corresponds, in architecture, to the launch in Germany of major programs of housing estates, as in Frankfurt, for which the habitat is designed from standardized models. Here we see engravings made by Gernd Arntz, where people are schematized and geometricized. The silhouettes appear in a simple and subtle game of black and white: the stripes of a prisoner play with the grid, the attitudes of the workers are repeated to the rhythm of the wheels of the machine.

[Anglea Lampe, curator of the exhibition]: The attention of the artists is focused on the social belonging of the people. The sociological notion becomes important, especially with the group which was created in Cologne with the artists Gerd Arntz, Heinrich Hoerle, Franz W. Seiwert, who form the Cologne Progressives group with whom August Sander exhibits. Arntz produced the series of engravings Häuser der Zeit (12 Houses of the Time), where he represents social classes according to a set of codes. It’s a very political speech of the time. Arntz continues to develop this approach with the philosopher and economist Otto Neurath, who works in Vienna: he develops a universal visual language, called isotype. Isotype is the acronym for “international system of typographic picture education”, in other words it is the precursor of the pictogram or emoticons.

In the 1920s, there was the desire, this dream to create universal languages. These pictograms, which are associated with a colour code, make up, for example, a typology of professions, social categories or elements of daily life, for a democratization of knowledge. Economic and societal problems could be visualised and broadcast thanks to this new visual system… it really is a system of infographics before the letter.

3 – Visages de ce temps (Face of our time)

[Florian Ebner, curator of the “August Sander” section]: This two-part exhibition explores the dialogue between August Sander and the Progressive artists of Cologne. We see on the wall the portraits that Sander dedicated to artists and next to it, paintings by artists like Heinrich Hoerle, Franz Seiwert and Anton Räderscheidt. We see how much Sander is inspired by their art and it is a magical moment.

We see on a large table the exchanges between Sander and the Progressives of Cologne: the letters, but also the reproductions he made of their paintings. And at that moment, there is an opening in the picture rail which gives the perspective on the Sander corridor and we see the first group, Les Paysans (Farmers). We see these two forces that run through his work, both rooted in the land – he comes from Westerwald – and revolutionary energy. These are twelve sources of energy that make part of the productive tensions that marked his work.

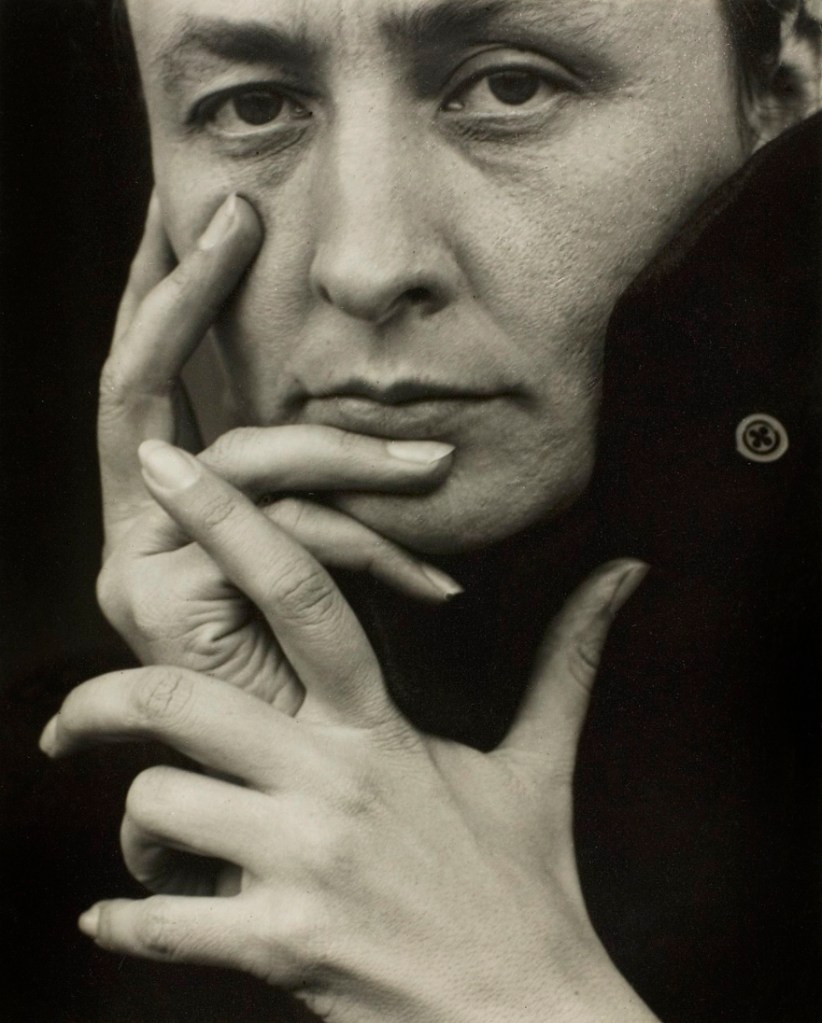

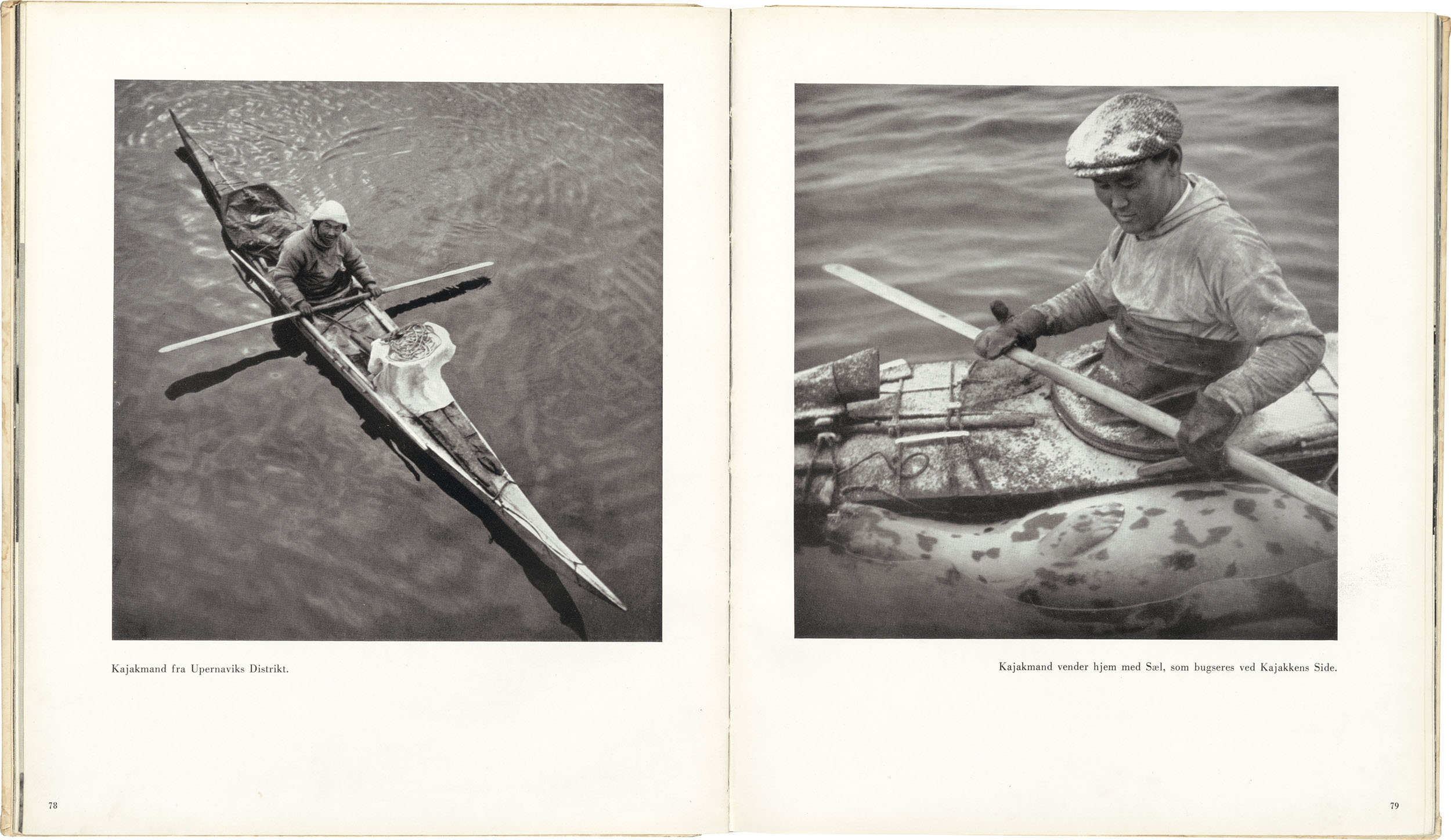

“By seeing, observing and thinking, with the aid of the photo apparatus and adding a date indication, we can fix universal history and, thanks to the expressive possibilities of photography as a universal language, influence all of humanity.” ~ August Sander

[Florian Ebner]: To return to photography as a universal language, the 1920s in Germany are marked by discussions on the different types of society. It is a society that has asked many questions about itself.

“The fundamental idea of my photographic work People of the Twentieth Century, which I began in 1910 and which contains about five to six hundred photos, a selection of which was published in 1929 under the Antlitz der Zeit (Face of Our Time), is nothing but a profession of faith in photography as a universal language and the attempt to paint a physiognomic portrait of the German man, based on the optical-chemical process of the photography, therefore on the pure shaping of light.” ~ August Sander

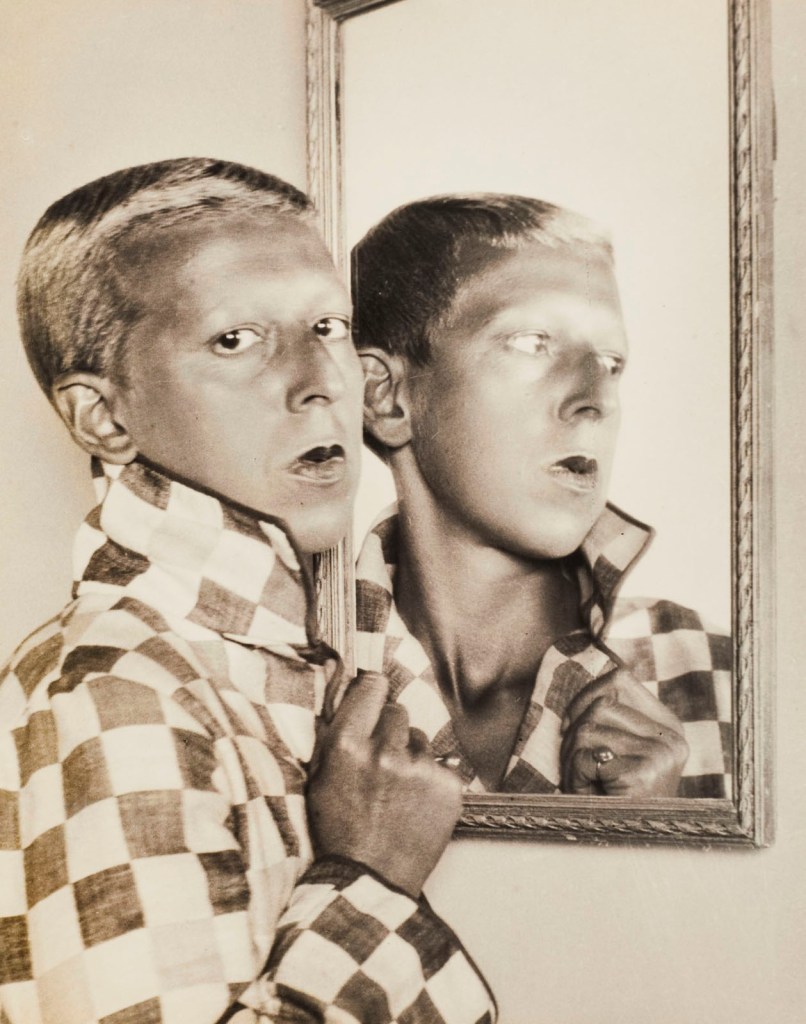

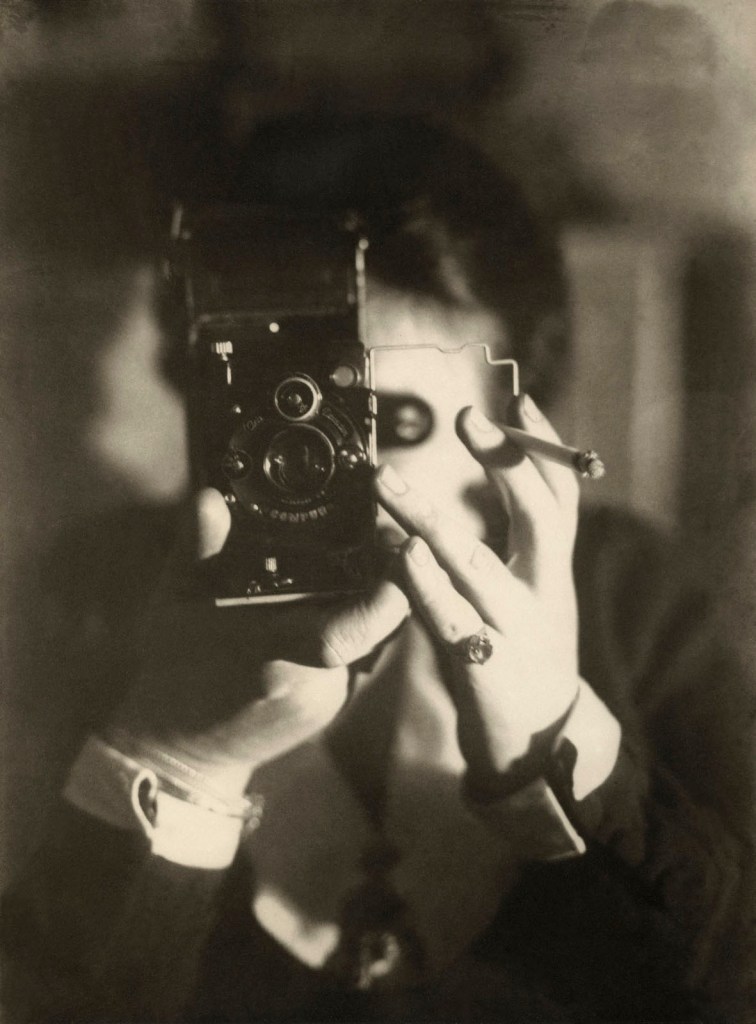

[Florian Ebner]: I think Sander’s portraiture embodies something specific in photography: he invites people to stage themselves in front of his camera, to take a posture for several seconds. It is therefore a “self-portrait assisted”, according to photography historian Olivier Lugon, and at the same time he assigns these people a place in his theory of society.

The idea of editing society is exactly that: then in his photographic archives, he assigns models and their images a place in these seven groups and 45 portfolios. Face of our time, his book, allows people to understand in a subtle and fine way the class differences of the Weimar Republic.

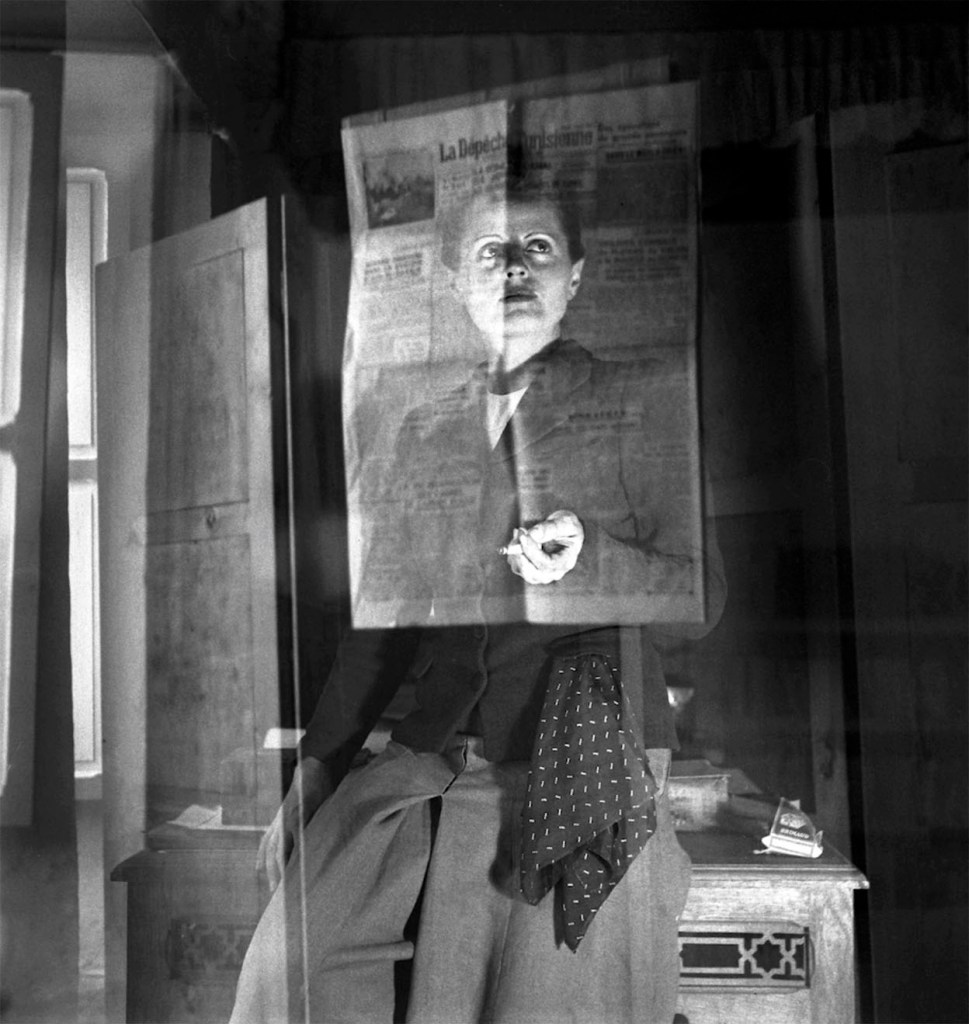

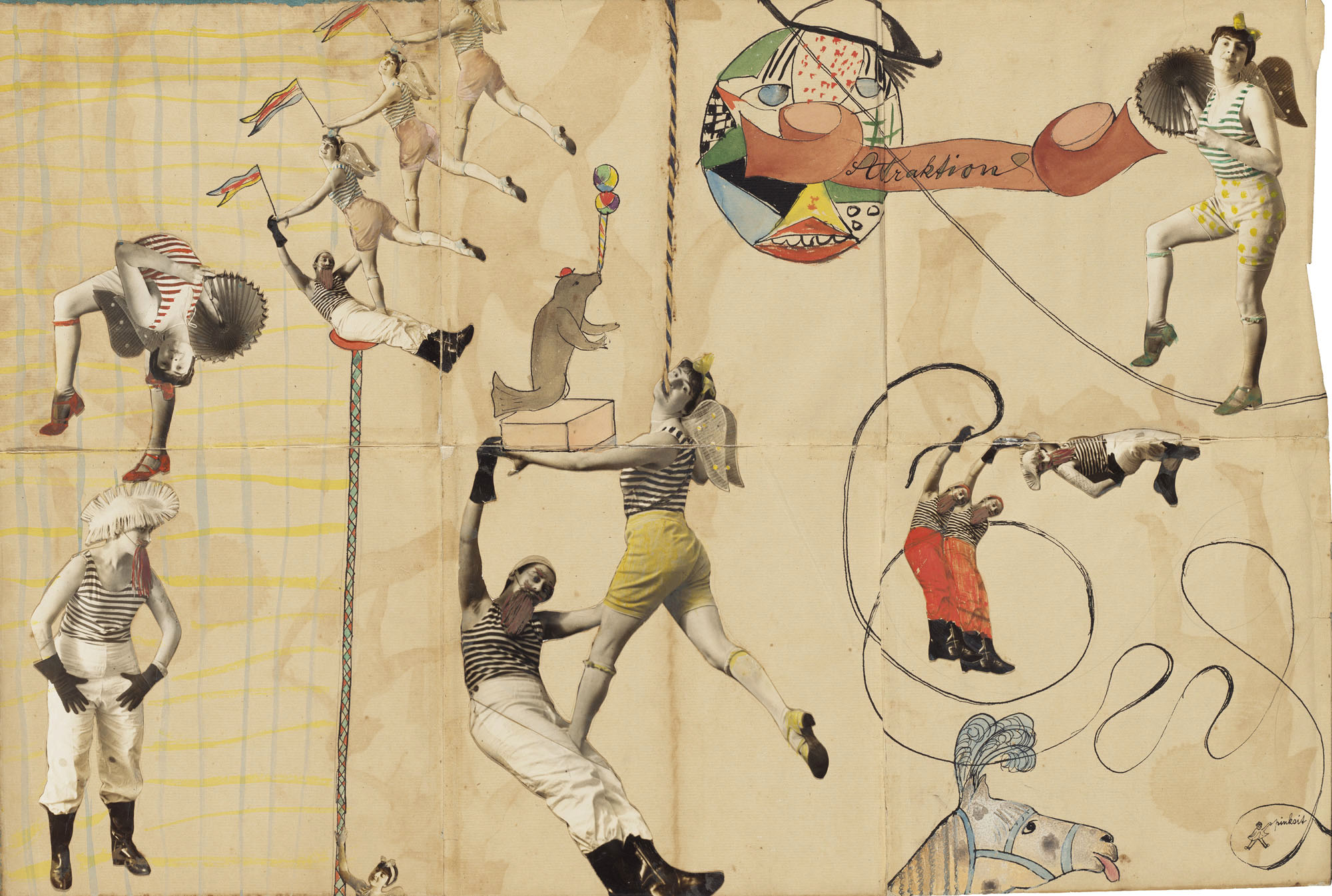

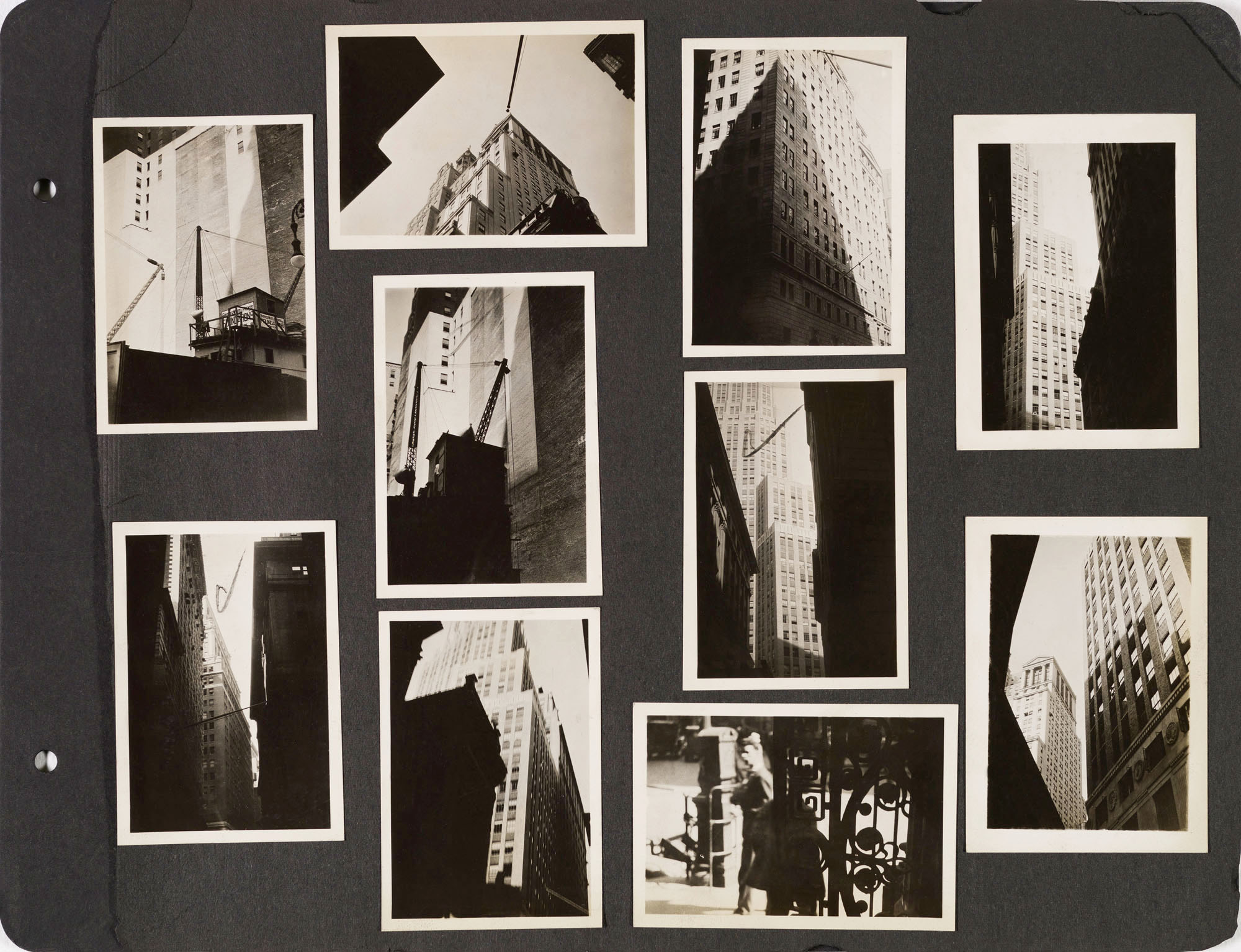

4 – Montage

Photomontage appeared during the war among Dada artists. A few years later, this technique is taken up in painting, photography, cinema, literature, to be put at the service of the analysis of society. The mix of patterns or information, dissociated in reality, allows artists to offer a form of visual synthesis of the time.

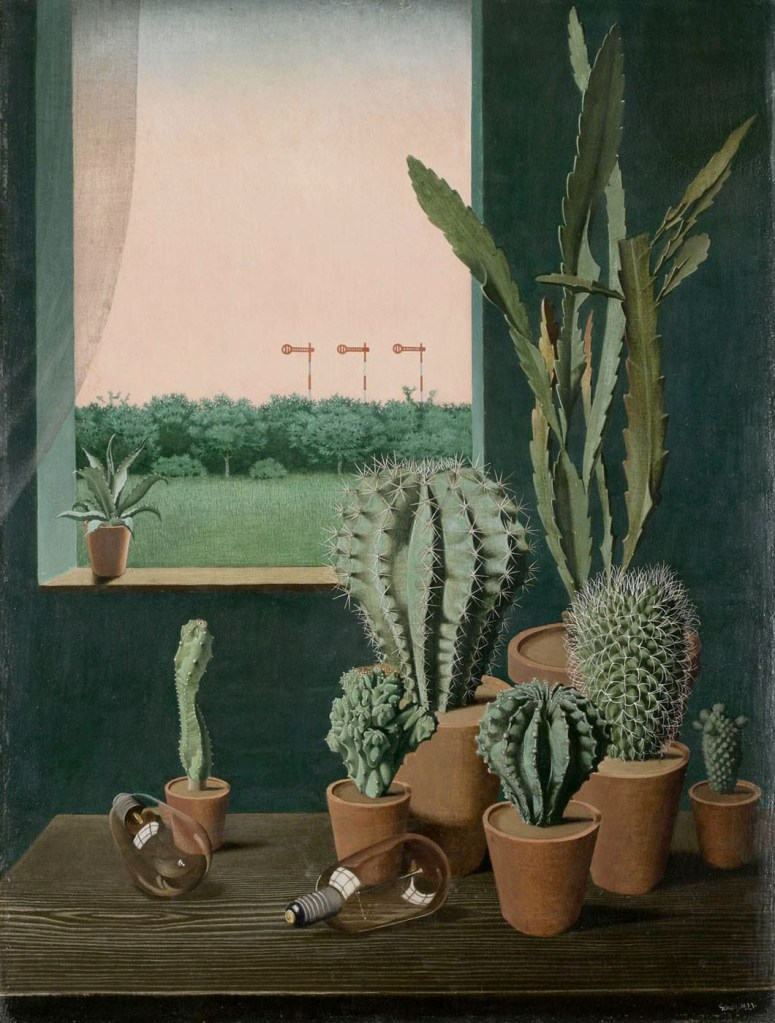

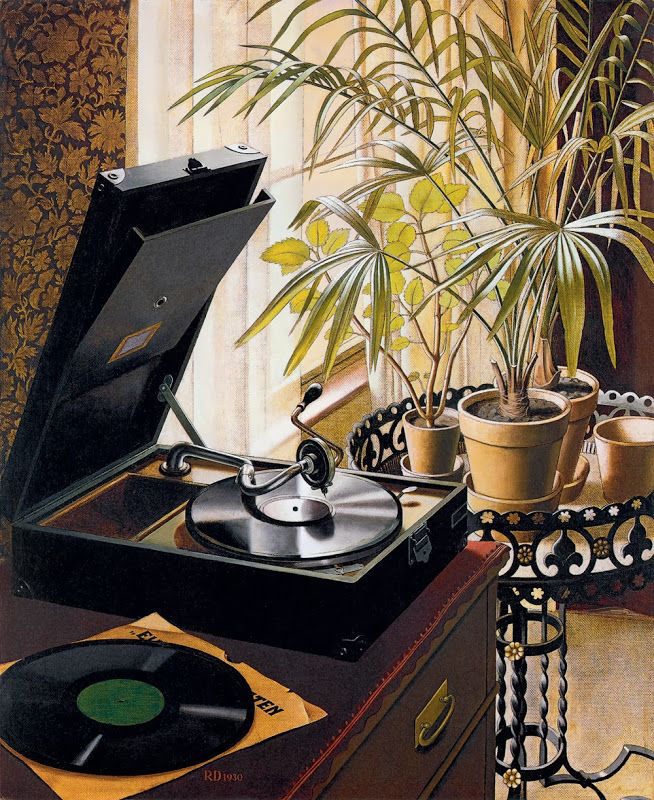

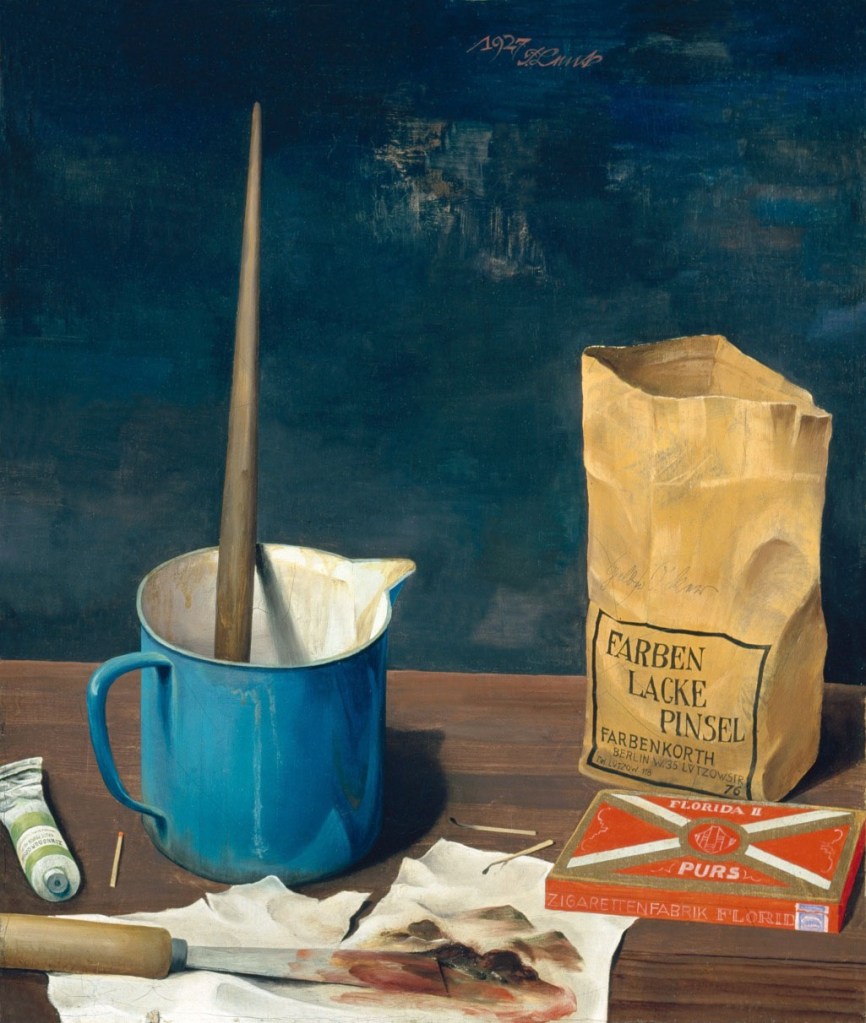

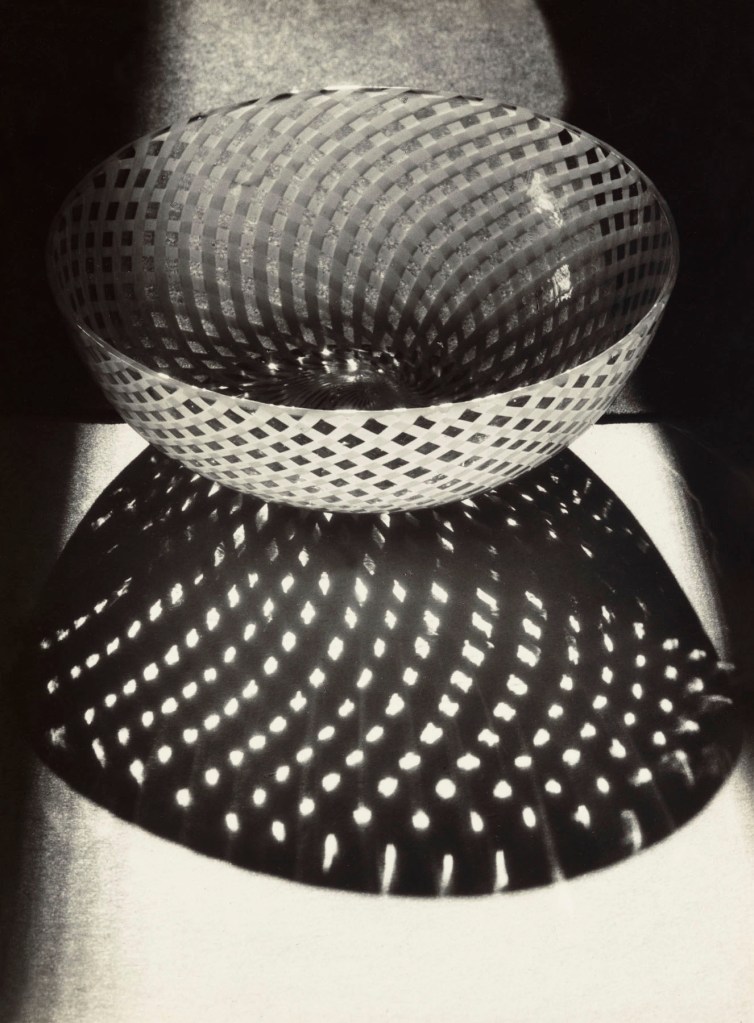

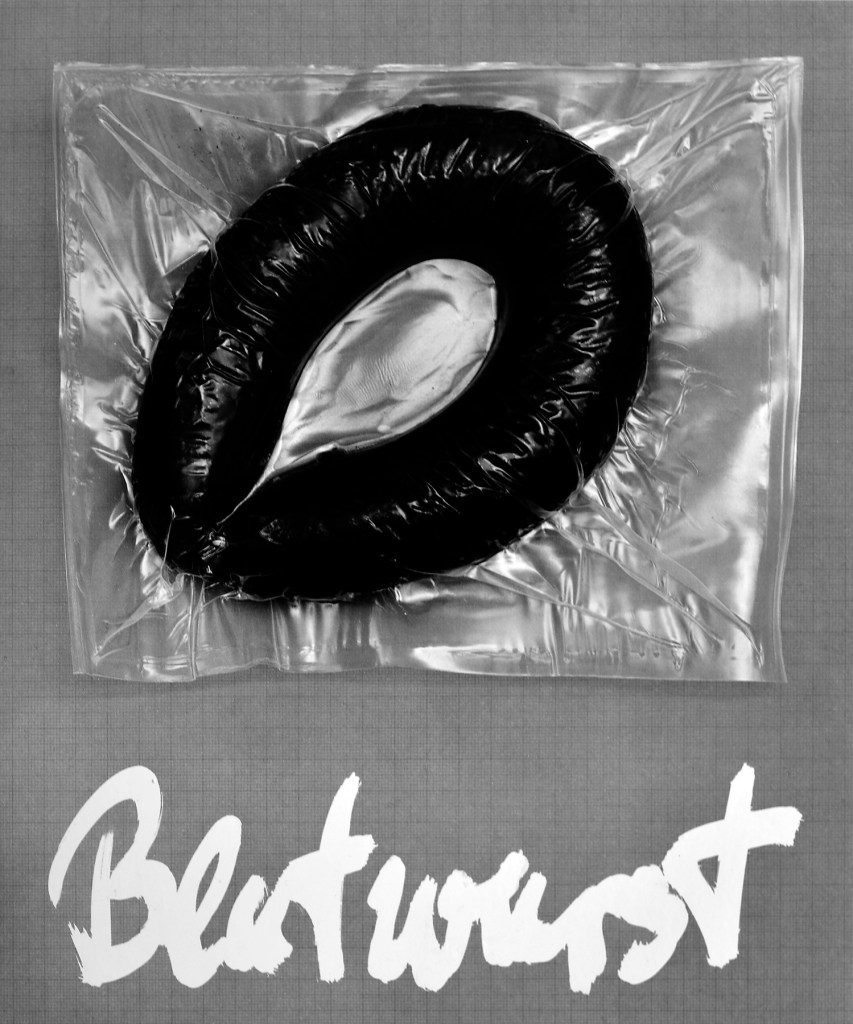

5 – Les Choses (Things)

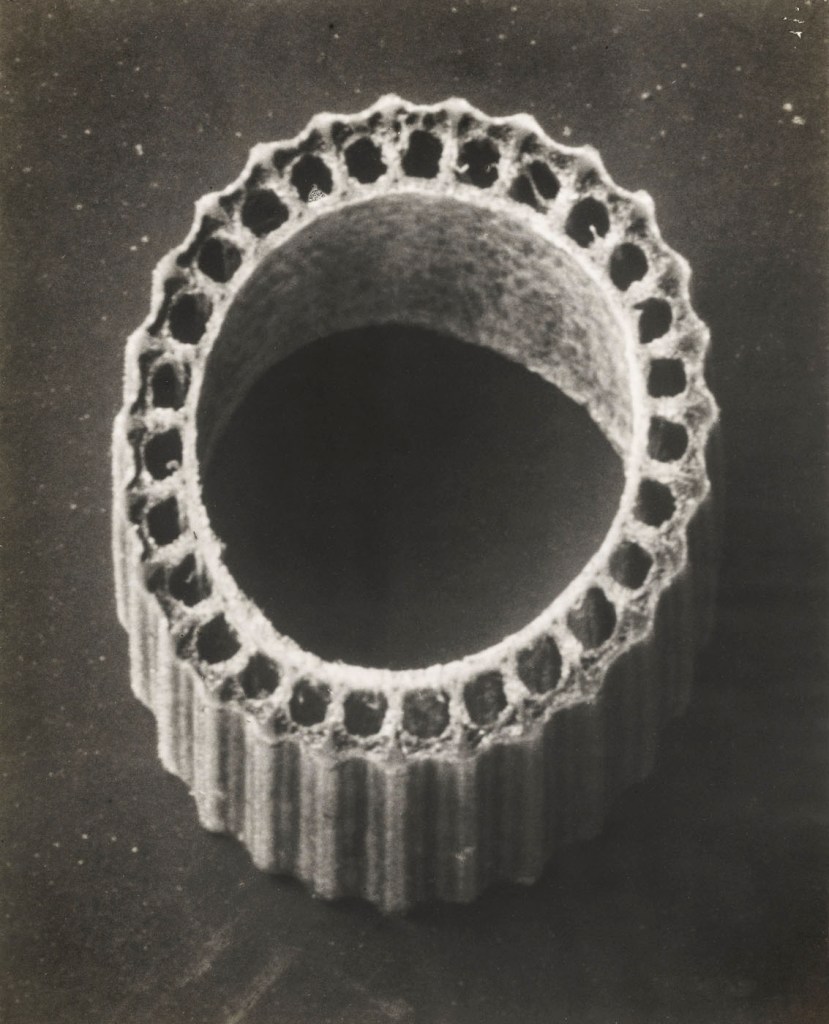

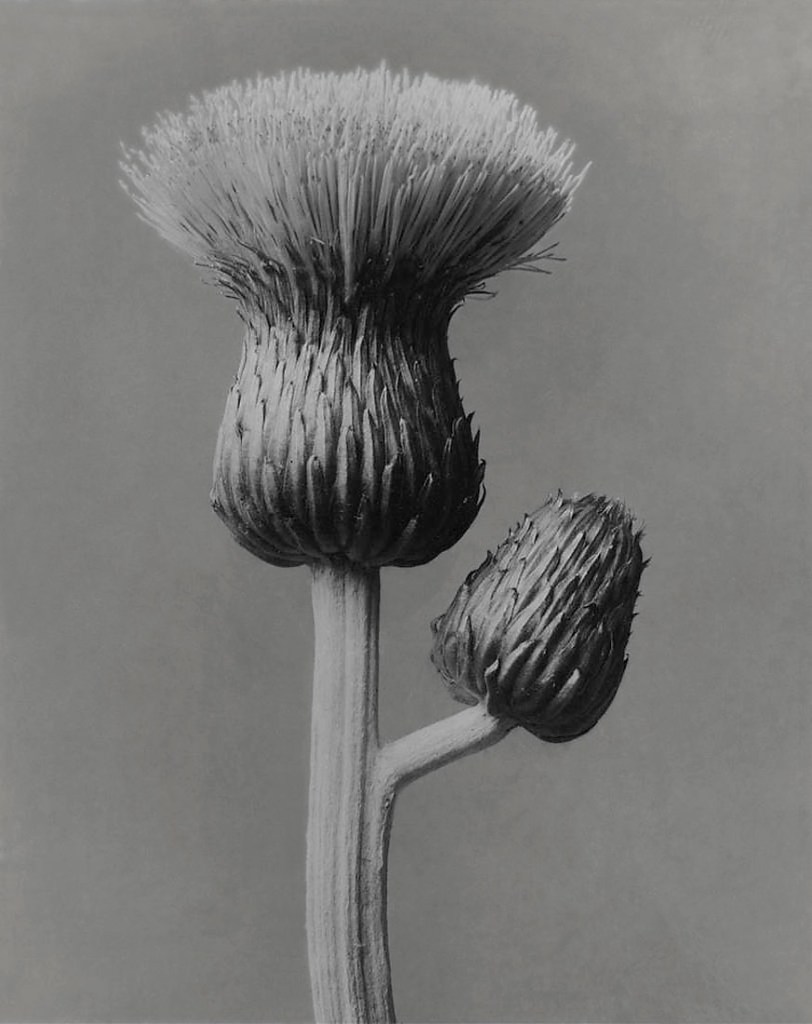

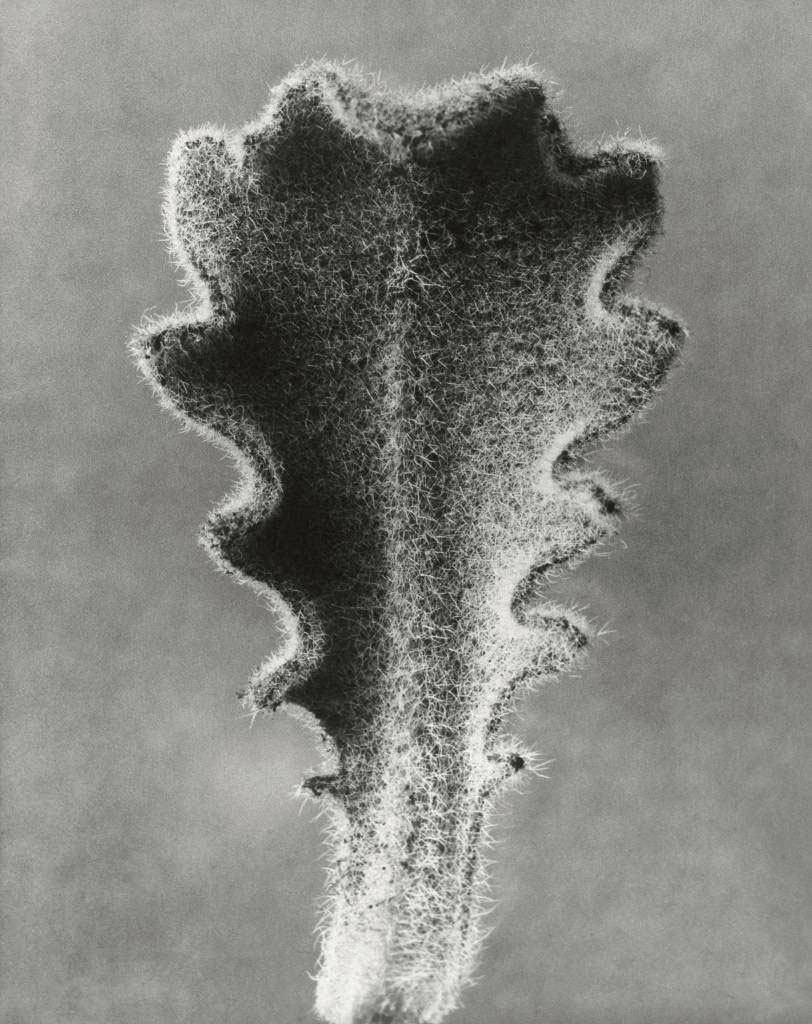

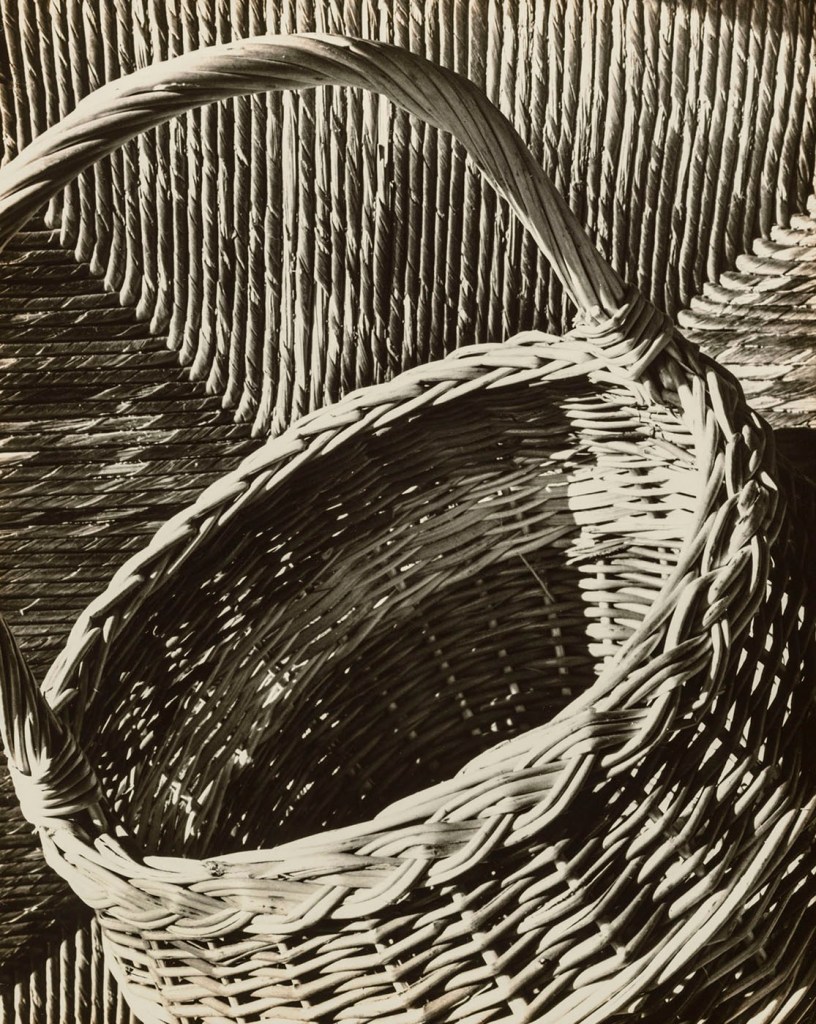

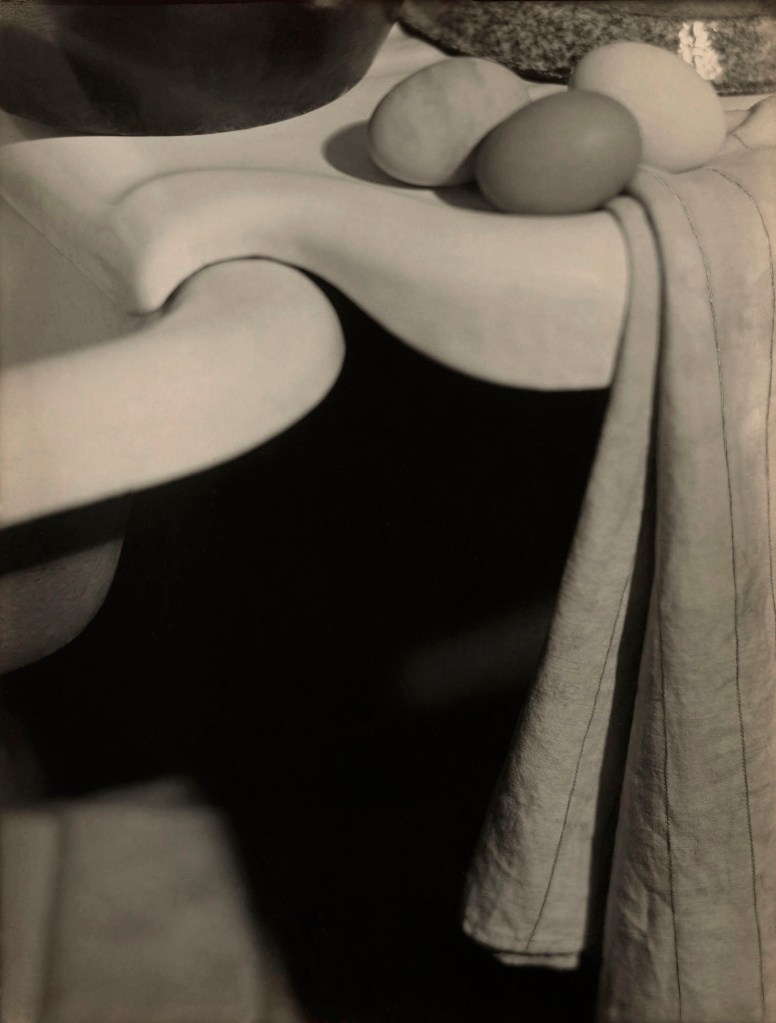

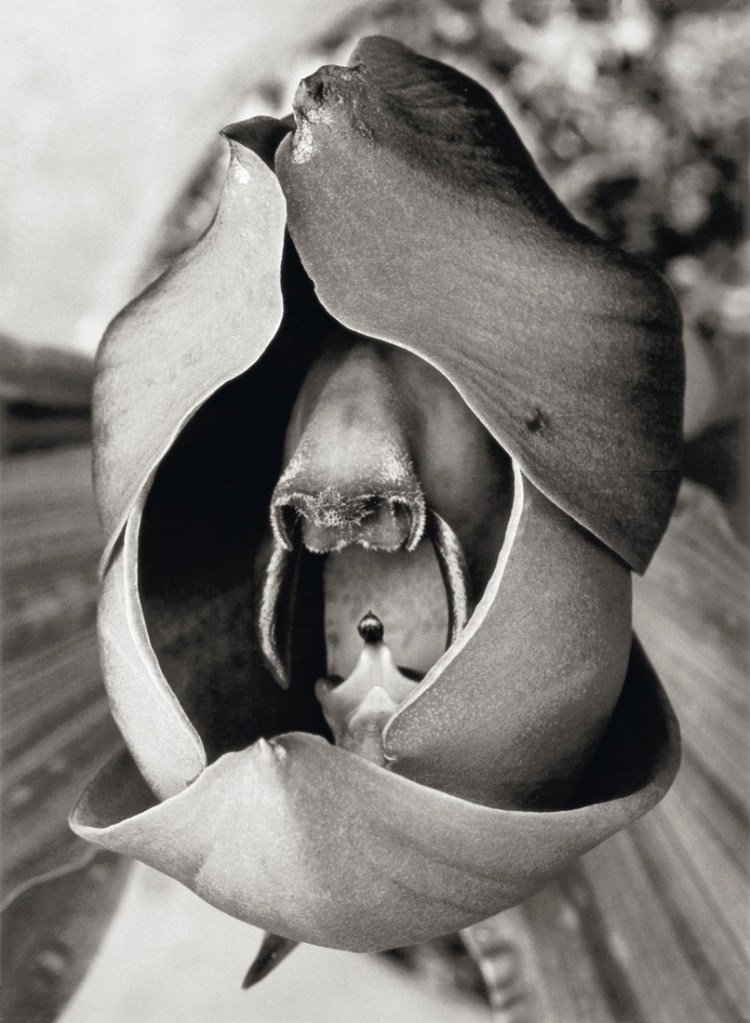

The scrutinising gaze of New Objectivity artists brings them take objects as models. Due to its supposedly objective technique, photography seems adapted to the precise rendering of things in their materiality. A dialogue is established between the two arts, painting and photography.

[Angela Lampe]: The paintings are animated by this tension between this inert plant and this bare and geometric environment which gives the false appearance of a bourgeois interior but which is completely artificial and fictitious. Architecture, geometric, abstract, these are the attributes that fascinate artists.

[Sophie Goetzmann]: No photo is objective from the moment there is a framing, a choice of motif, a choice of object photographed, we are in the order of choice. There is a whole practice of plant staging, sometimes point-based original views, close-ups, with attention to rendering detail and matter of these plants. These plants are photographed truly as objects. We are not interested in plants as living beings; they have no vividness, whether in paintings or photographs, they are very rigid, they are placed in neutral and empty environments. They are still life very dead!

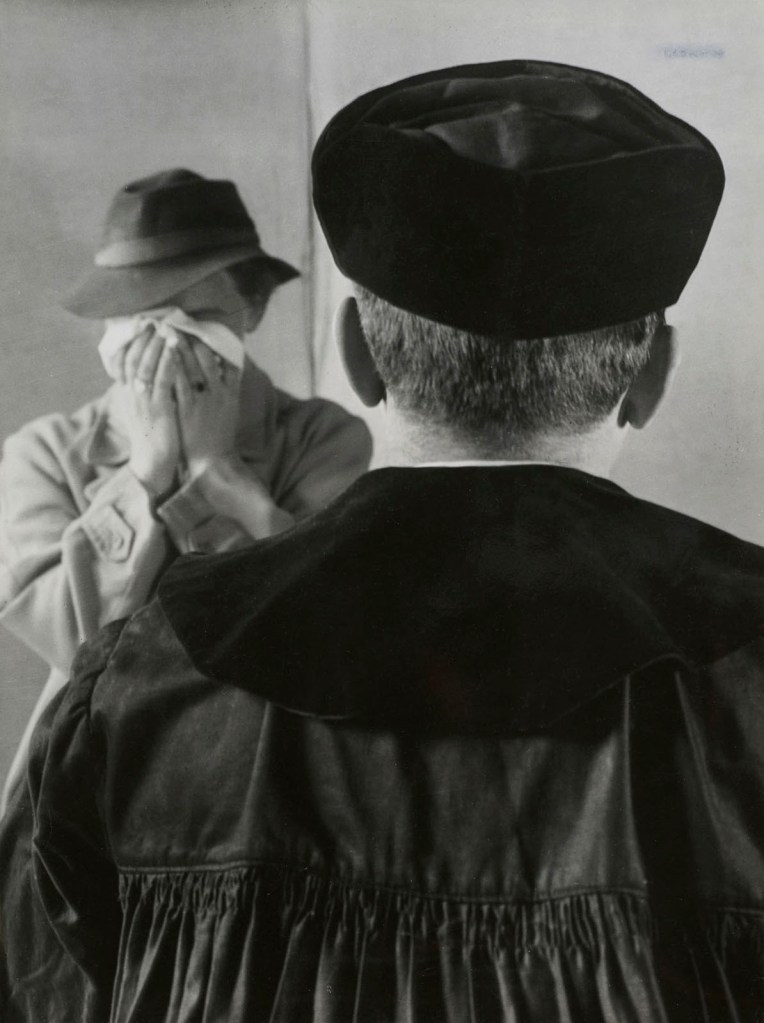

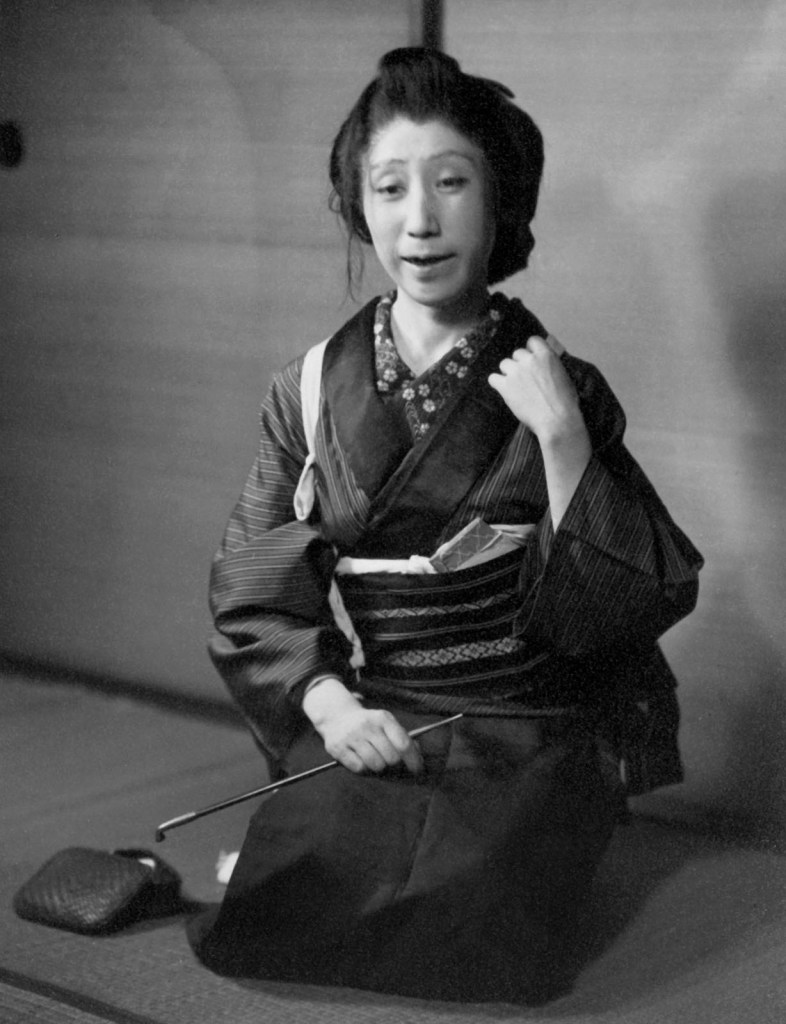

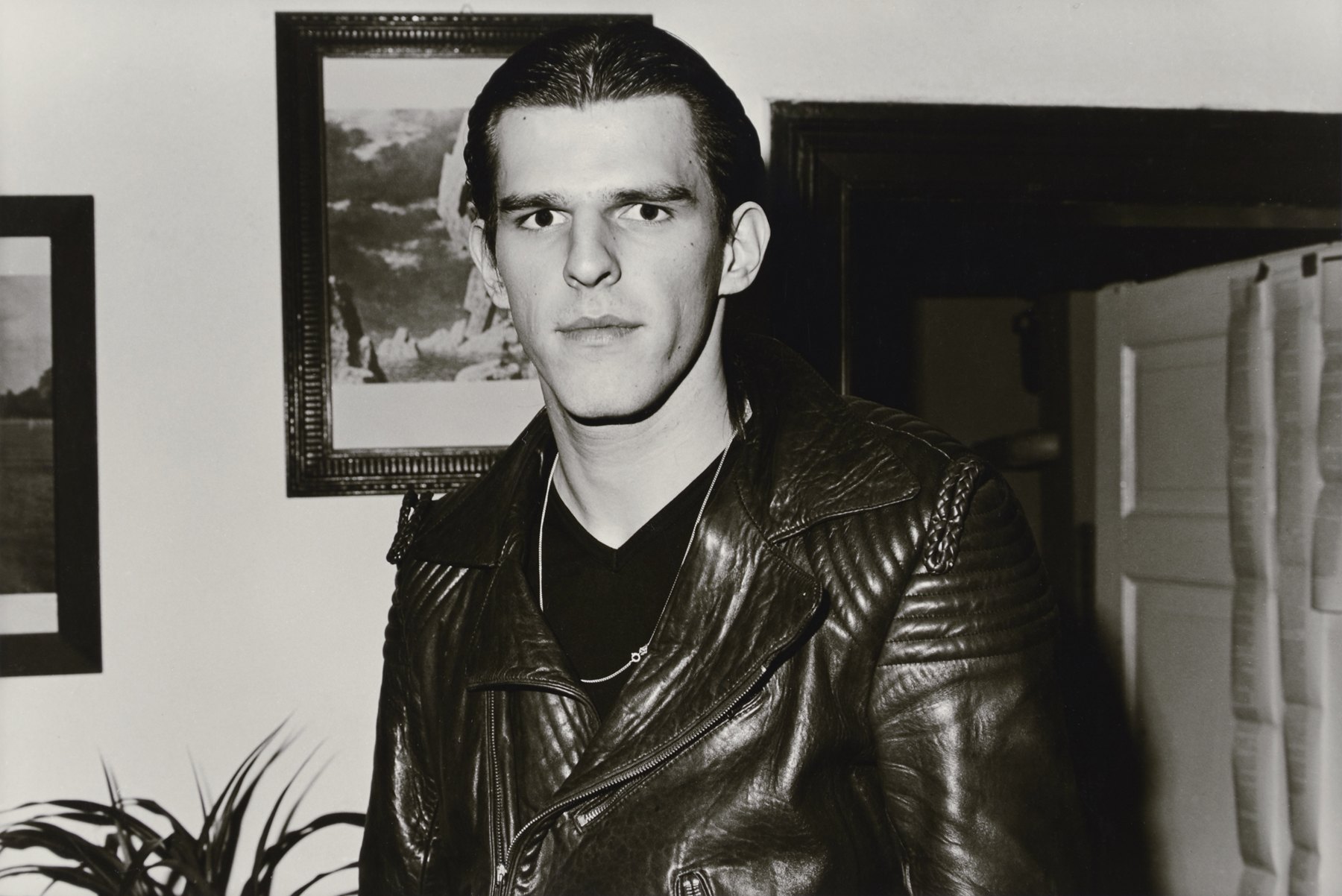

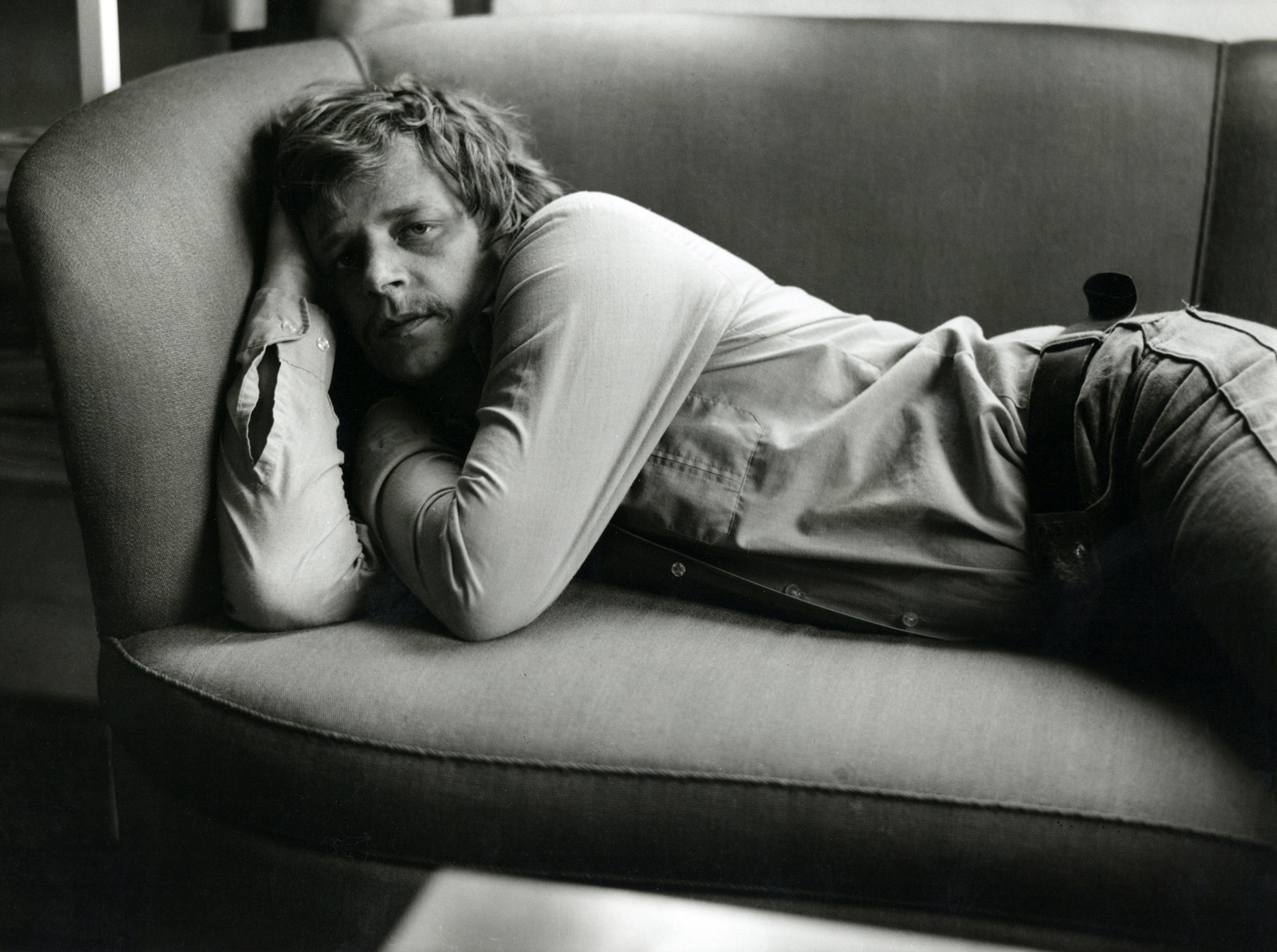

6 – Persona froide (Cold persona)

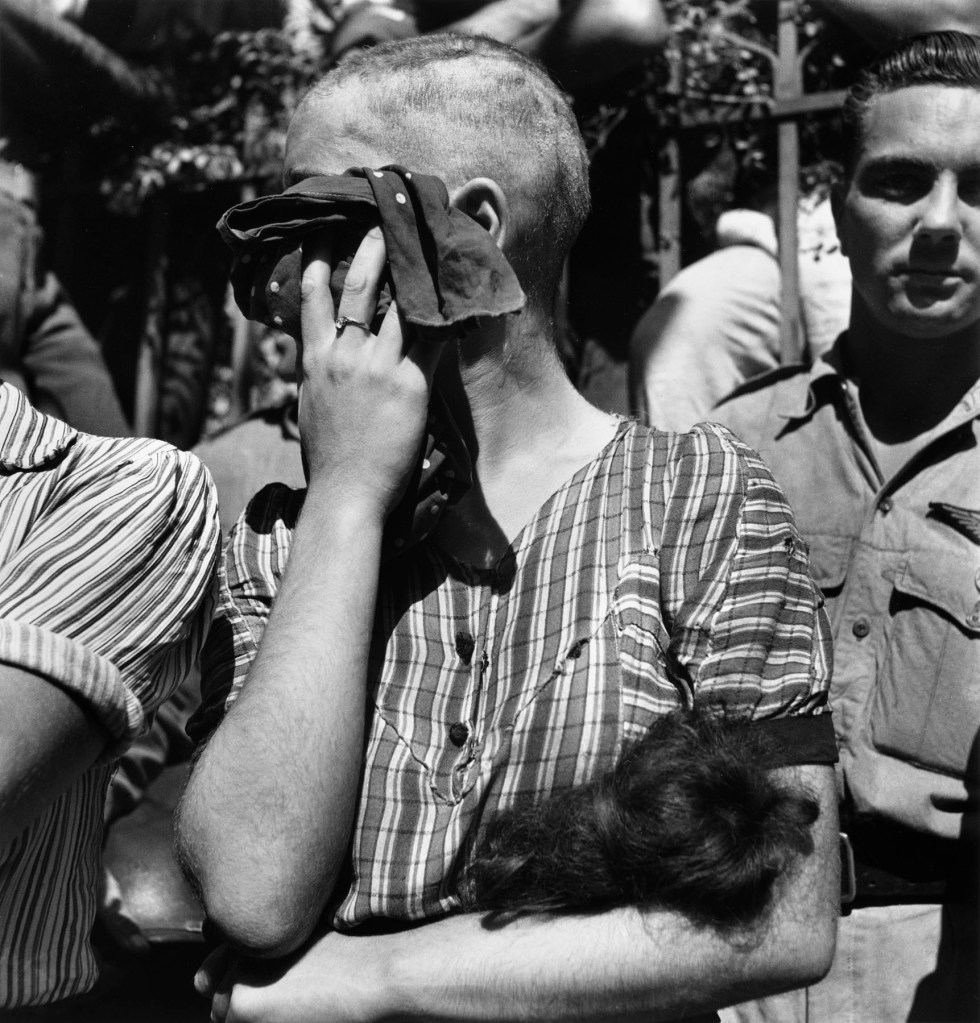

The four murderous years of the war that ended in defeat cause general disappointment. Humiliation breeds a culture of shame. In the 1920s appears what the university specialist in culture German Helmut Lethen calls the “cold persona”.

[Sophie Goetzmann]: Helmut Lethen explains that guilt and shame are two different things. Guilt is having made a mistake and racking your brain, torturing yourself with this mistake to try to fix it; so the guilt, according to him, has to do with interiority.

Shame is having made a mistake but, instead of going into introspection, it’s about thinking outward, to think, “What are people going to think of me? How do I save face with others, how do I erase this shame?”. This is what he calls the culture of shame, people are dominated by a shame of ideas that they never had before the First World War, in particular because everyone had gone merrily to war. The war was a real moment of patriotism in Germany as in France, and all these people found themselves face to face with the reality of war: mutilation, dead, traumatised, bereaved families. At the end of the First World War there is a kind of shame that takes hold people compared to their ideas of four years ago.

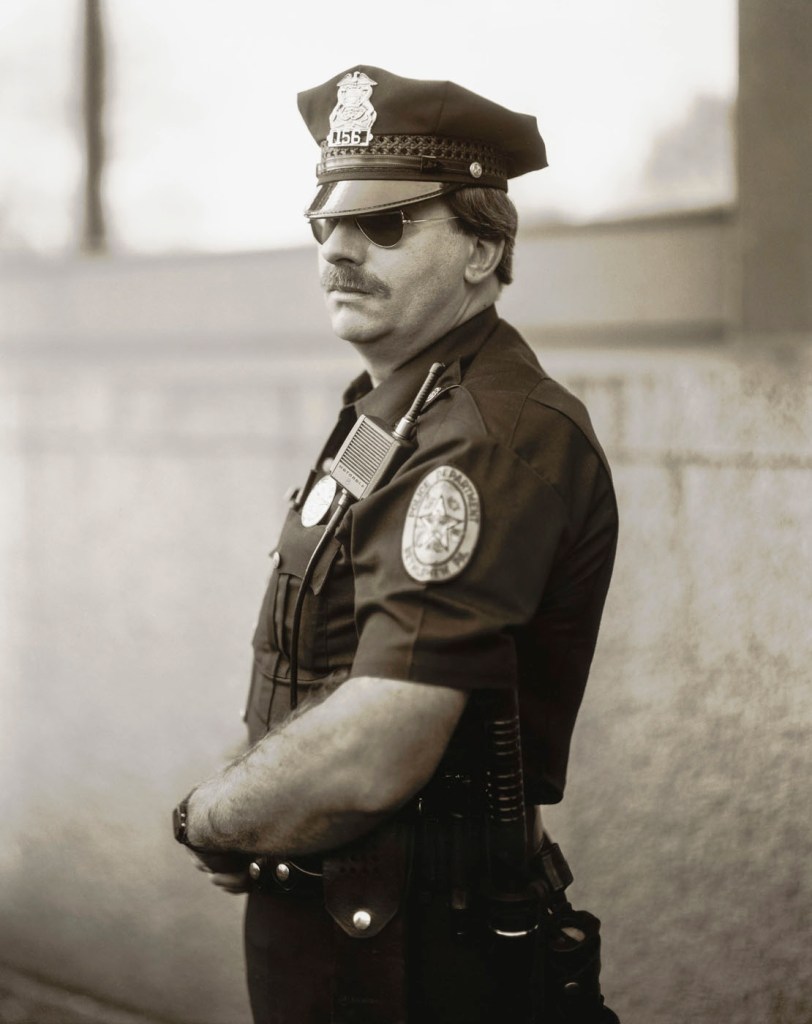

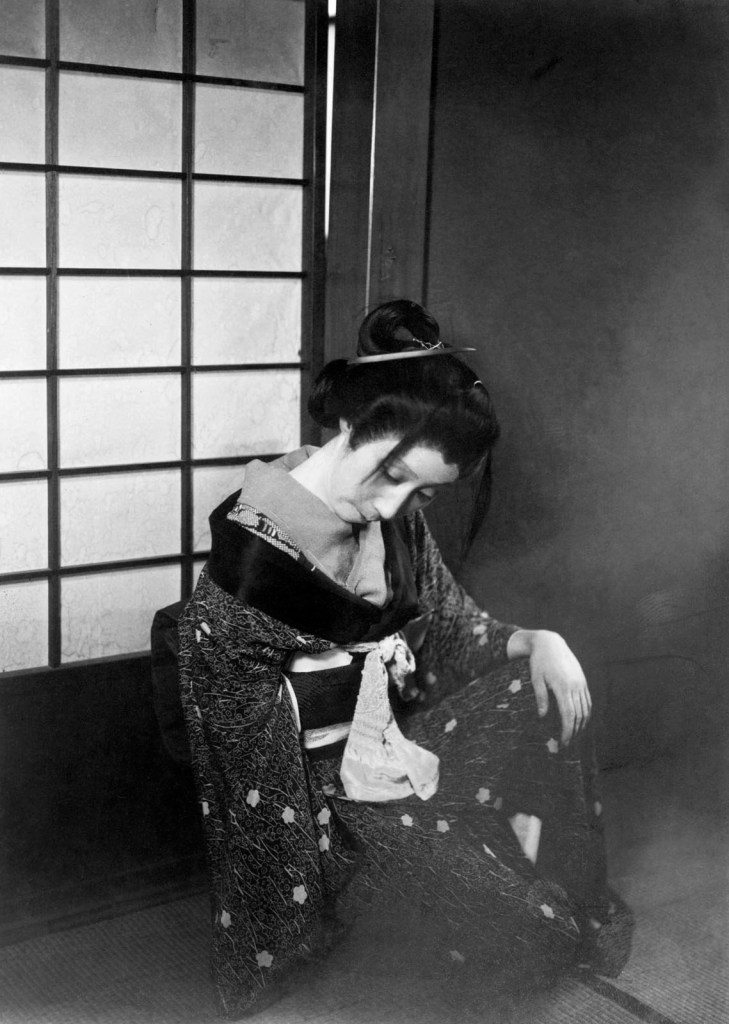

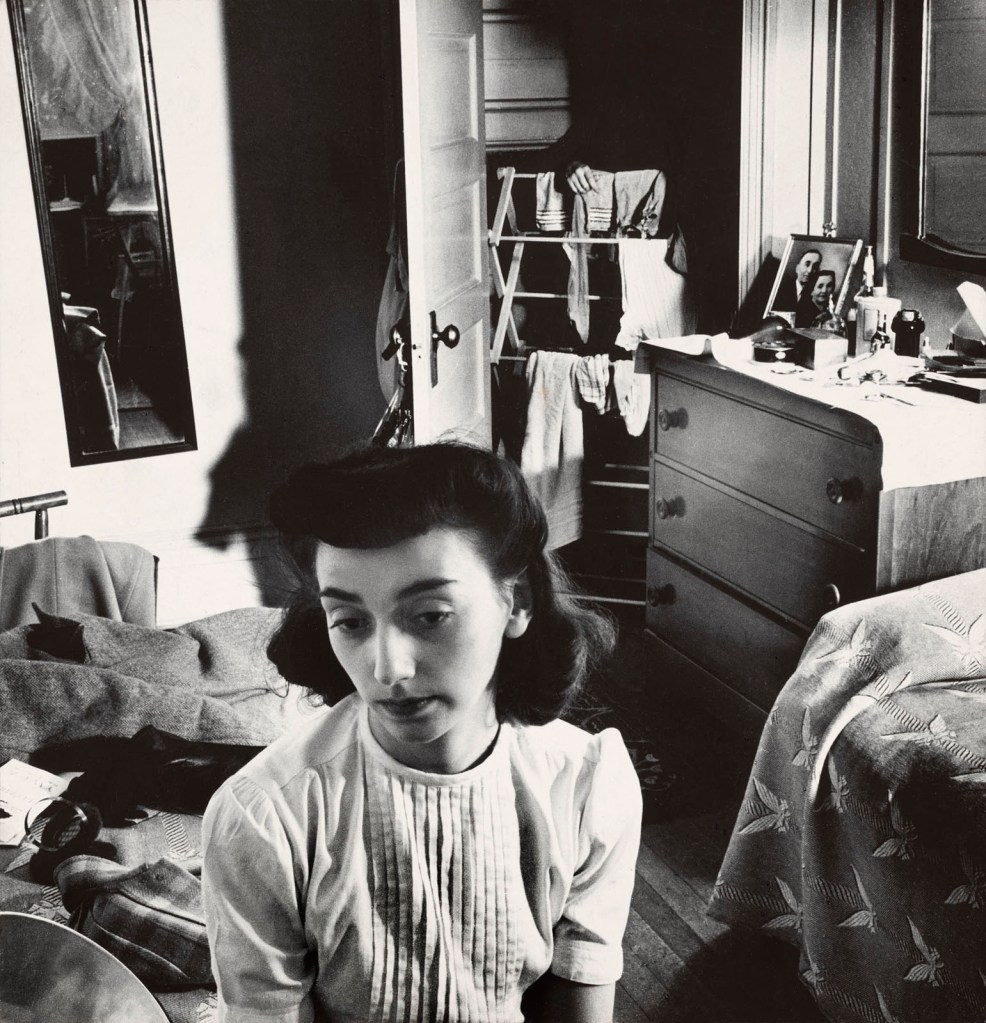

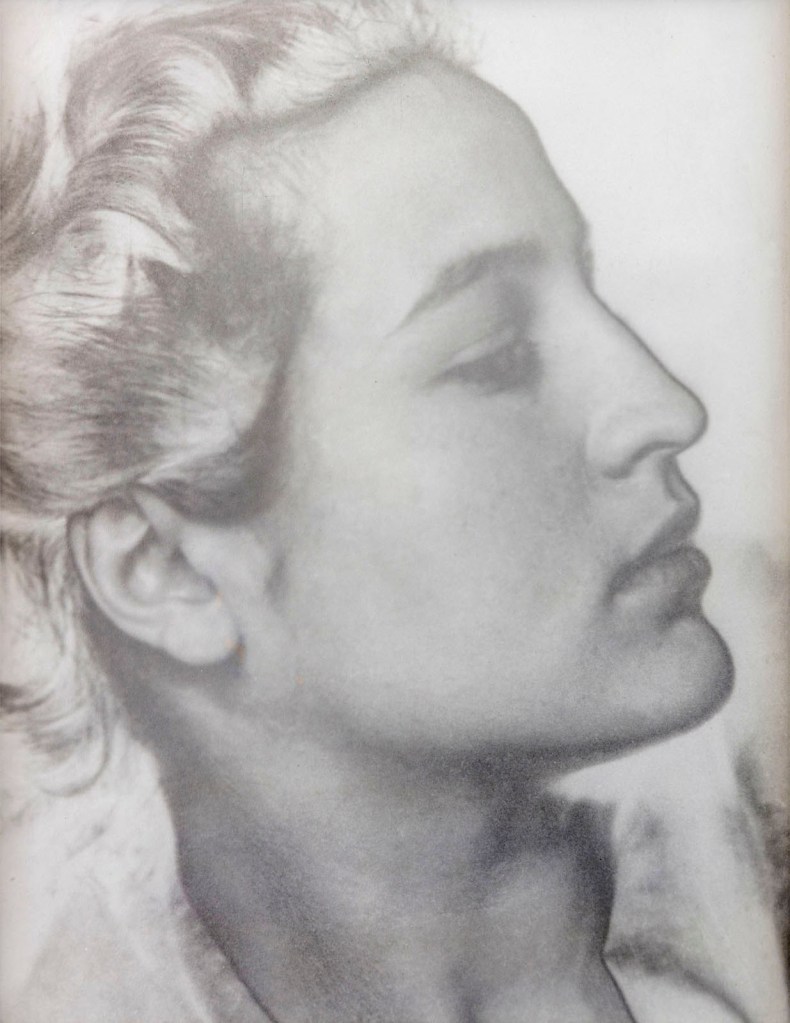

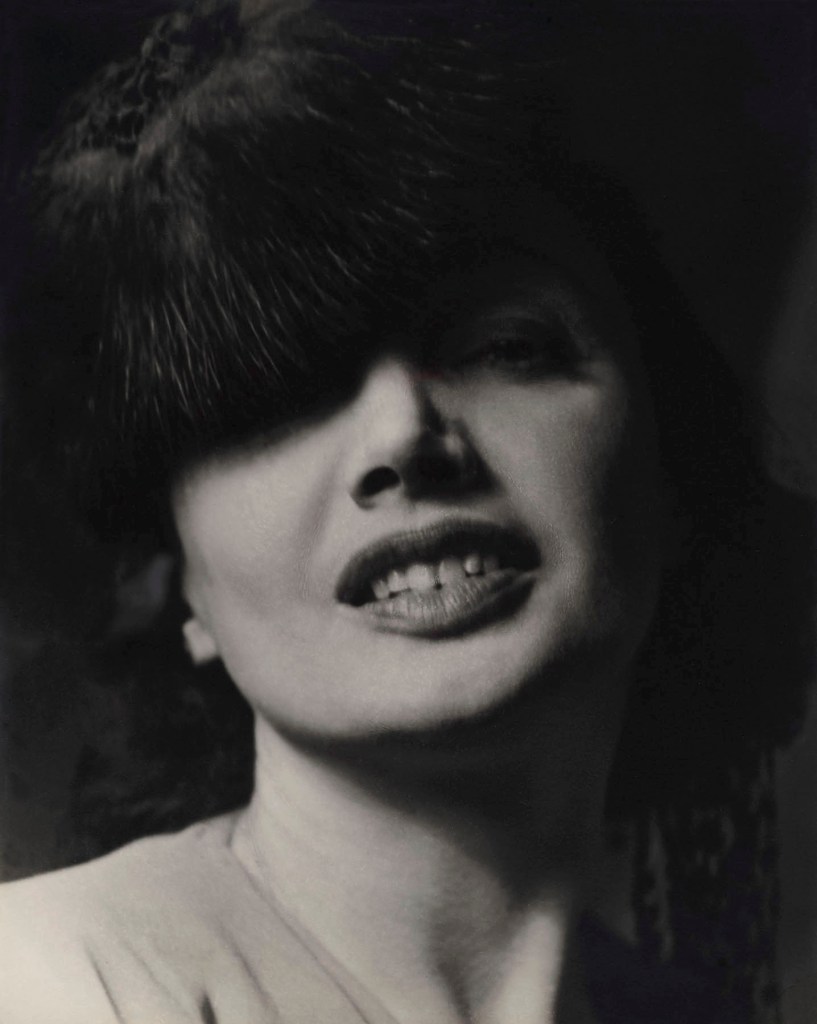

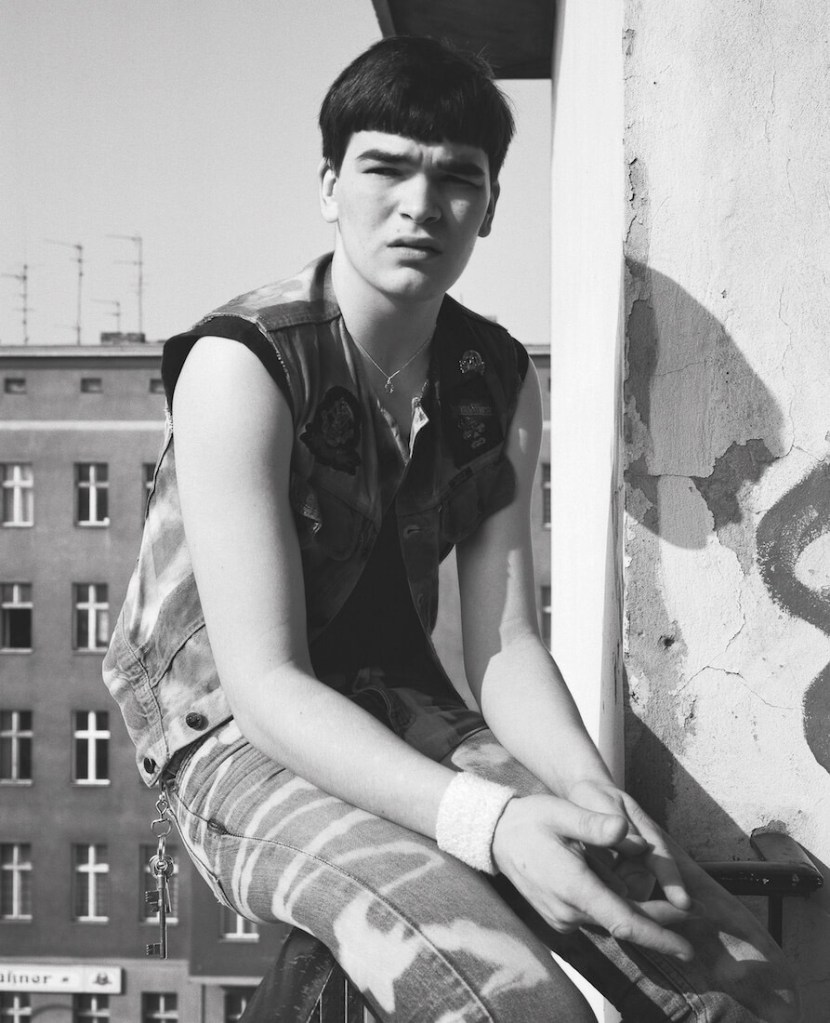

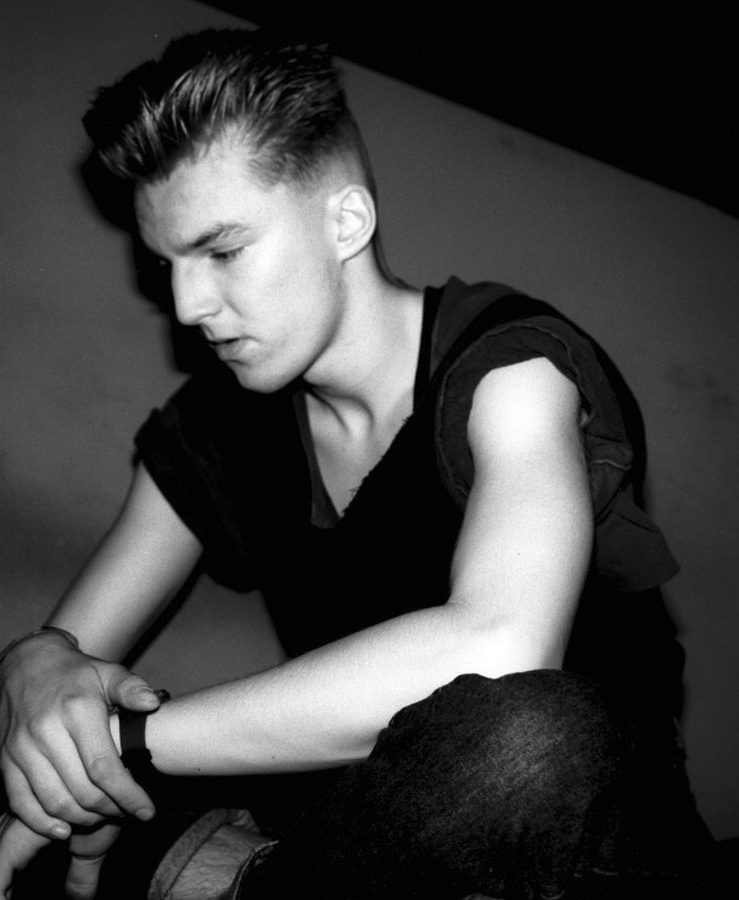

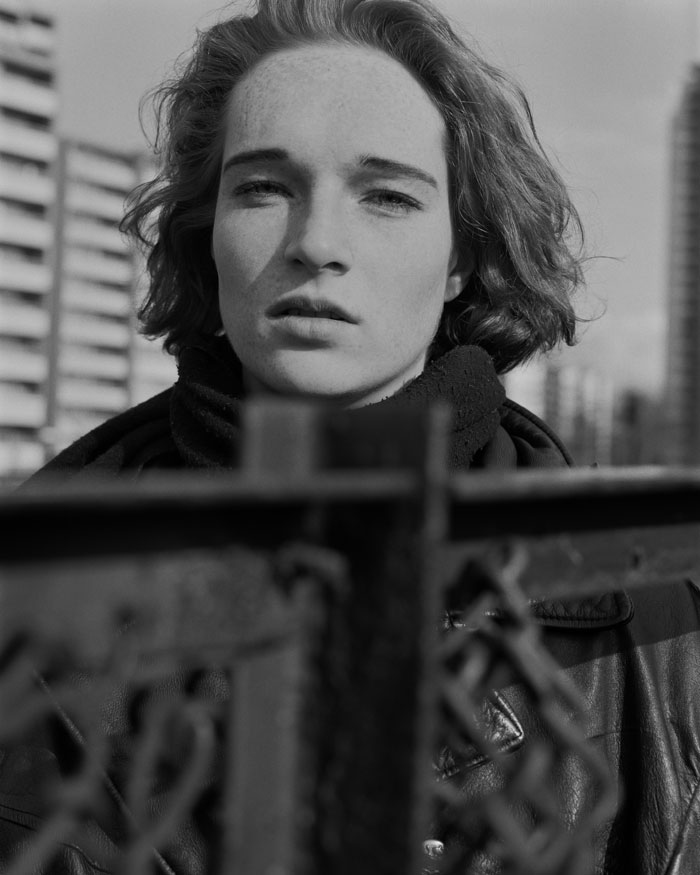

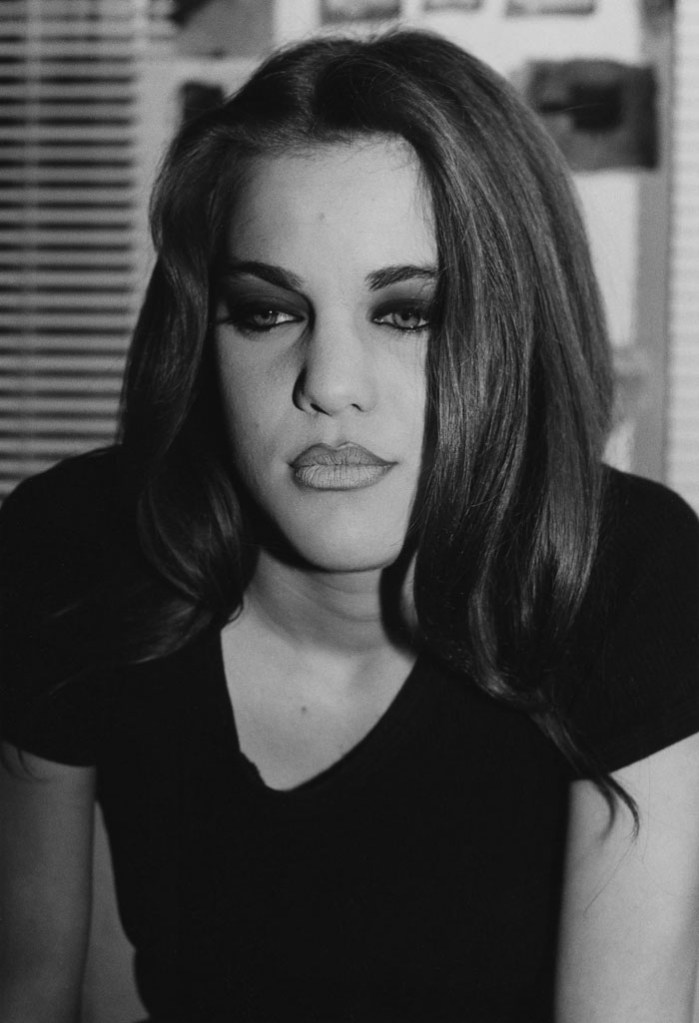

How is it transcribed in portraits and in attitudes in general? Through a new way of being, of playing the detached person, of protecting oneself using a mask of indifference. In portraits, people don’t smile, do not display any particular expression, are detached on a neutral background. At the same time, portraits say something about people. In place to express their interiority, they show their position in the social order or their occupation. New Objectivity artists put people in boxes and represent people according to their profession, their place of work.

The portraits say something in general, which is to hide one’s feelings. In this section, there is a portrait of a woman putting on makeup. The make-up is a symbol of this new social attitude which is to put a layer of make-up on oneself so as not to reveal one’s torment, one’s feelings to others, it becomes something embarrassing to do that. Another example is the painter Otto Dix who represents the journalist Sylvia von Harden without complacency, as a typical emancipated intellectual of the Weimar Republic. She has short hair, wears a monocle, smokes and drinks a glass of alcohol. His sentimental torments are reflected in the choice of attributes: her bottom is undone, her pose is constrained, she is uncomfortable in a feminized pink universe. Its interior is exposed.

[Florian Ebner] There is a second meeting point where the two paths intersect. This is Chapter 6: The Cold Persona for the New Objectivity Exposition and group 3 of Sander dedicated to the woman. For women, he thinks about five portfolios that attempt to describe the role of women in society. The first three describe the woman passively; it is always someone else who defines the woman: The Woman and the Child, The Woman and the Man, The Family. It’s still a quite conservative design about society and the role of women. The last two portfolios, The Elegant Woman, The Intellectual Woman underline the new role and type of woman, the Neue Frau, the new woman. We can see together, the very beautiful portrait painted by Otto Dix of the journalist Sylvia von Harden and that of a German radio secretary photographed by Sander: the game of gestures, the hand, the cigarette, the clothes, they could be sisters, twins.

It is a conception of the portrait that no longer speaks of the interiority of a person but how to describe a person by external attributes, by gesture, accessories, the habitus. At this point, the dialogue between the painted portraits and the photographs of August Sander is very rich.

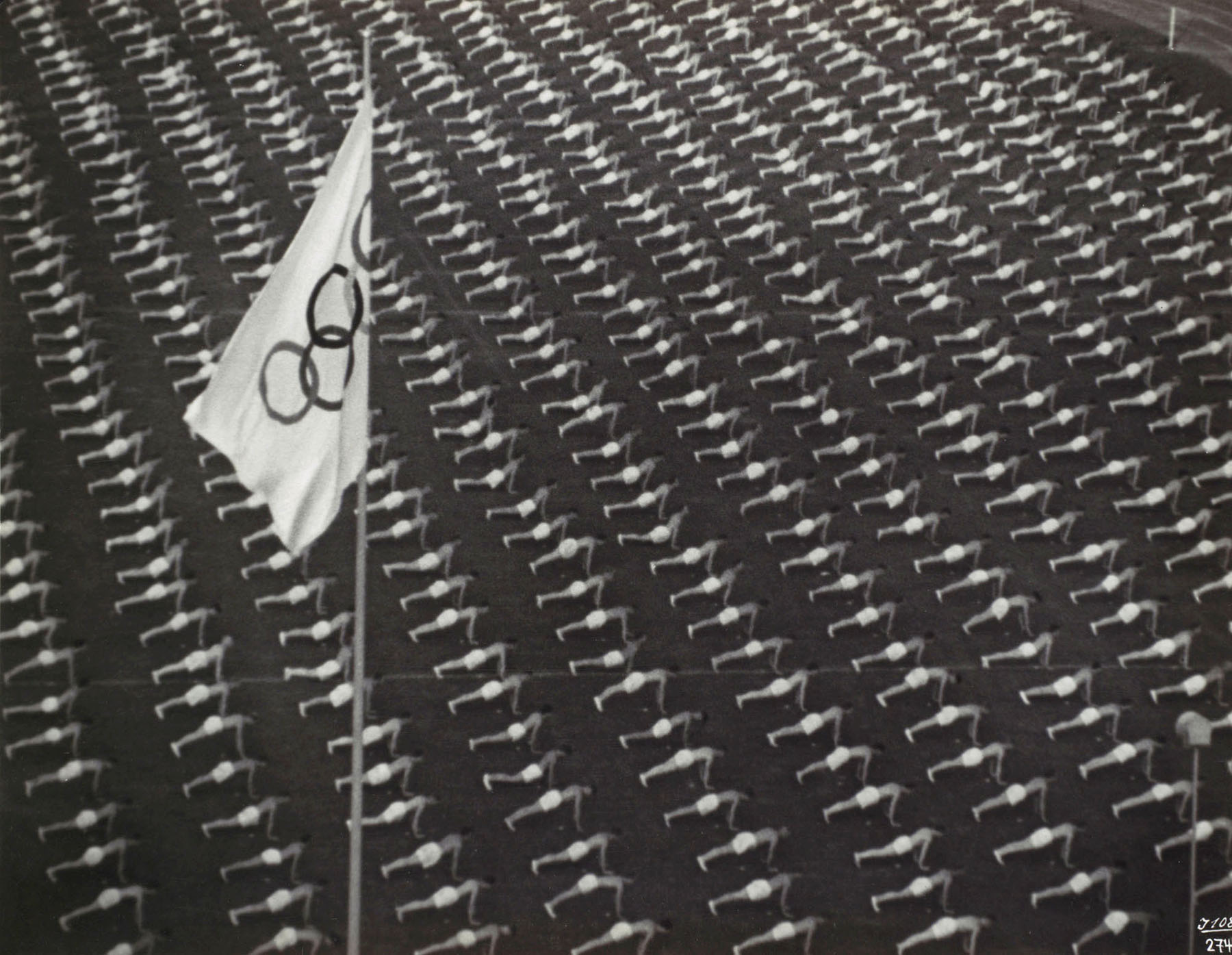

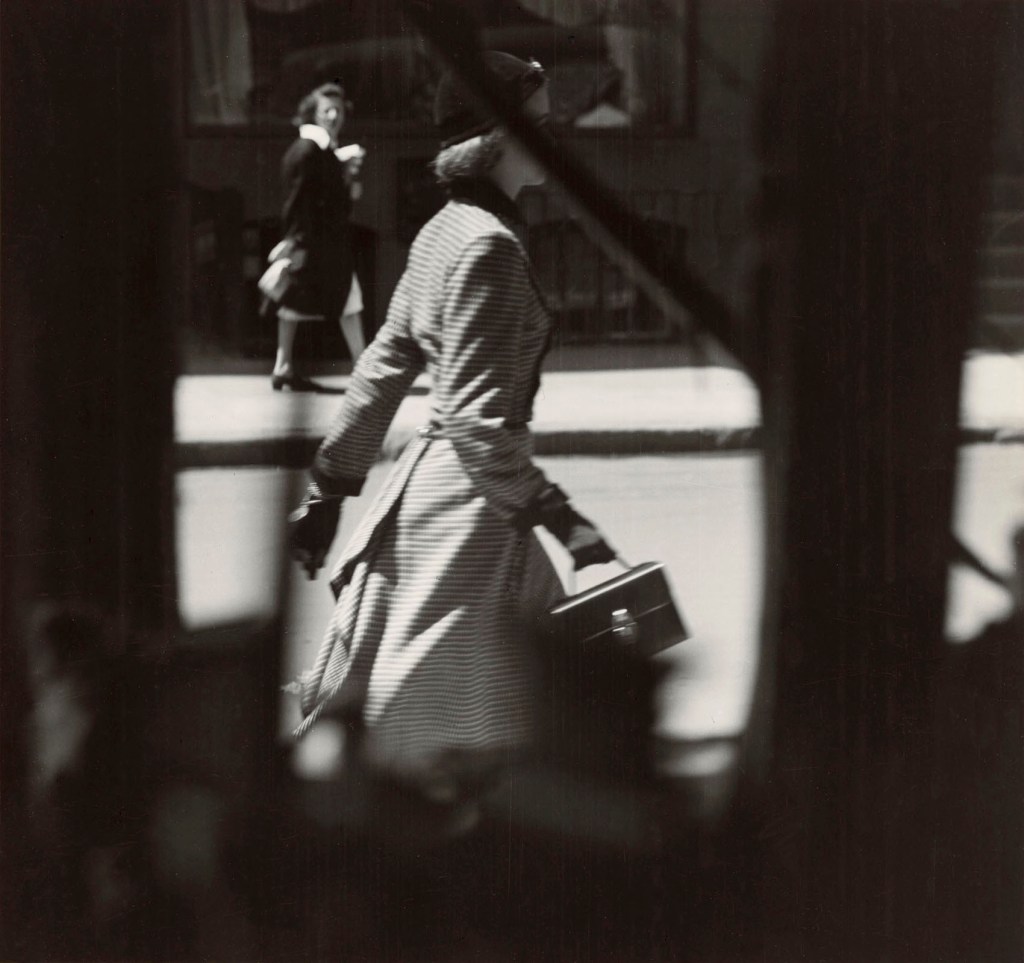

7 – Rationalité (Rationality)

After the war, it was the economic crisis in Germany, which experienced hyperinflation. In 1924, the Dawes Plan aimed to help Germany reconnect with the growth, thanks to the injection of American capital. It then develops in Germans a fascination for America which has invested generously. The model society of the United States is methodical, harmonious, innovative because it is governed by technology. It is in this context that rationalisation infuses culture in Germany, from how to organise interiors to popular entertainment, through graphic design.

[Angela Lampe]: The rationalisation of work developed by Taylor is imported into German companies, leading to rapid industrialisation and a mechanisation of tasks. The principle of rationalisation soon becomes a new norm that structures social and cultural life itself. For example, the graphic designer Paul Renner develops the Futura font, based on geometric shapes elementary. This new standard of rationality also applies to the development interior. Viennese architect Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky, who works in Frankfurt, designs a modern and functional kitchen.

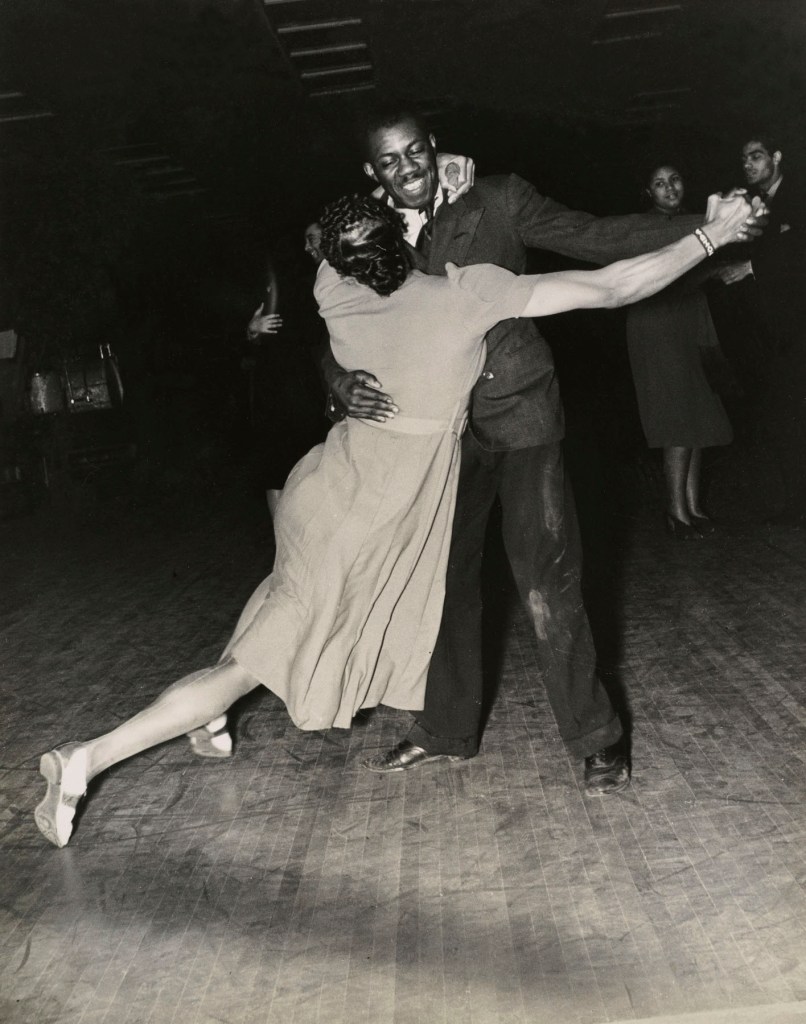

8 – Utilité

New musical styles imported from America appear in Germany in the 1920s and became very popular. especially jazz and dance music like foxtrot. Composers Ernst Krenek, Kurt Wild or Paul Hindemith drew inspiration from it to create a new musical genre, the Zeitoper, in French: topical opera. The plots take place in the contemporary world, the sets incorporate modern machines like trains, cars, telephones. The opera then addresses a wide audience and draws its references from popular culture.

[Angela Lampe]: There is a great democratisation of this, let’s say, elitist medium, which was the opera. An important figure in the theatre of the 1920s was Bertolt Brecht. At the antipodes of the lyrical outpourings of expressionism it was he, Bertolt Brecht, with the director Erwin Piscator, who developed new forms of theatre, what is called epic theatre, episches theater. In fiction, they introduce scenic devices into their plays that allow the viewer to analyse the plot in order to participate in its awakening Politics. They work from the effects of distancing. The introduction, for example, of the narrator or the break in the unity of the action are all elements generating a distance that encourages reflection. The goal is really to make the spectator.

There are other moments, which can be called moments of neo-objectivity, so Neue Sachlichkeit, in Brecht. It is the theme of sport, he is keen on sport. Moreover, he compares the theatre to sporting events, especially boxing, which really becomes a very important reference for his pieces. There is also his dry and very sober style, which distinguishes it as a representative of this New Objectivity, especially in his poetry.

It is prose that takes precedence over poetry. It’s really another form of literature, which is with an approach, let’s say, rather sociological than poetic. Brecht shares with the New Objectivity also the concern for a democratisation of art. He was interested in the possibilities offered by mass broadcasting devices. For example, he works with recorded poems and radio plays, so broadcast on the radio which spread very quickly in German homes during that time. It’s really a novelty of the mass media, as they say today, which makes it possible to disseminate and democratise culture.

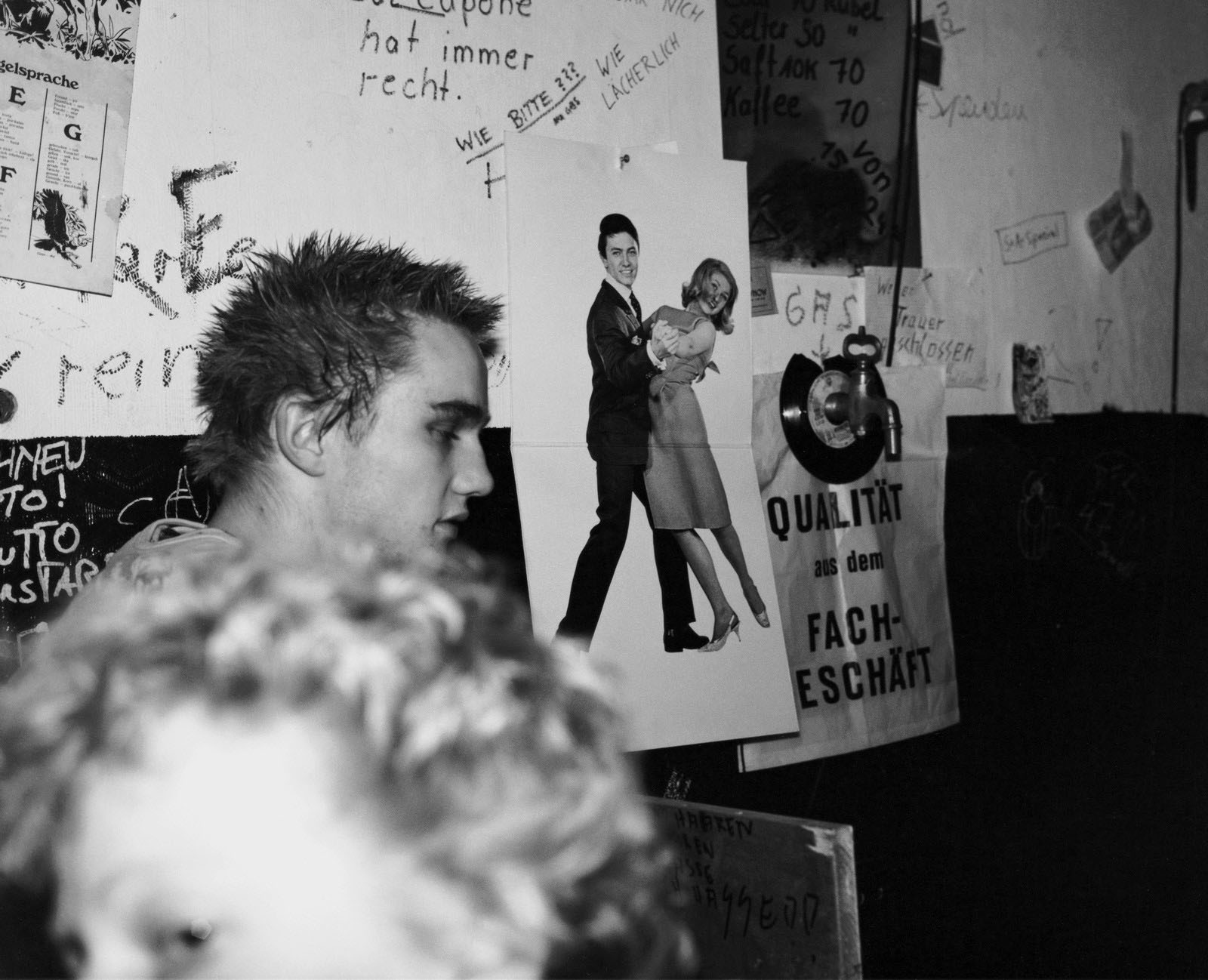

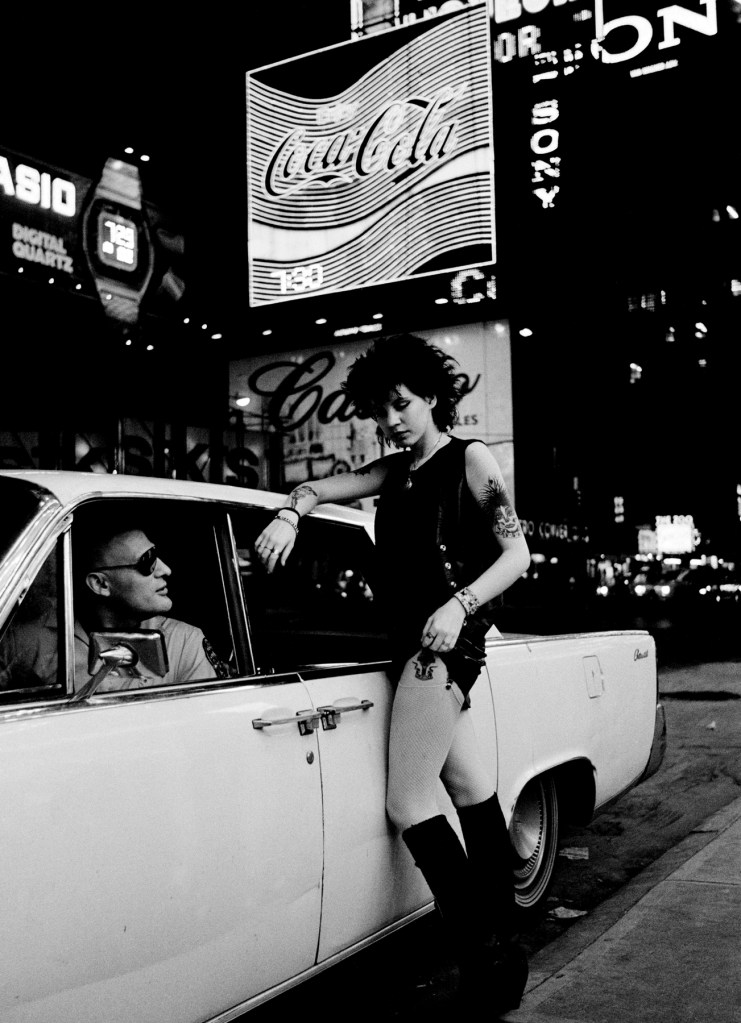

9 – Transgressions

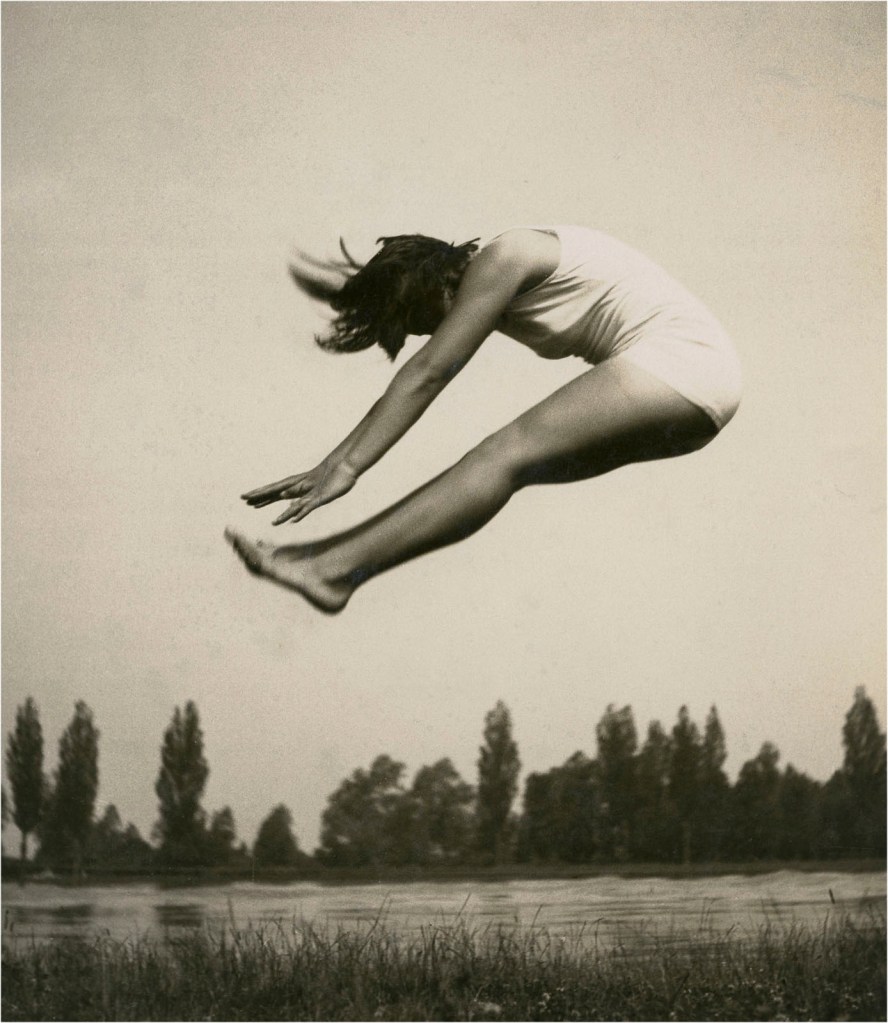

[Sophie Goetzmann]: We have two forms of transgression which are shown in these rooms. The transgression of gender norms, first: the idea of gender norms that will shift, especially in expression, in clothes, for example, that we are going to choose, and in particular the women of that time.

So, often, the women of the upper middle class, who live in the big cities, will resort to men’s fashion, dress boyishly, wear short hair, a flat torso, ties, to modify the feminine fashion of the time. So transgression of gender norms and transgression of heterosexuality because, in the Berlin of the 1920s, there was a whole

very important homosexual subculture, in particular through clubs, meeting places, restaurants, bars.

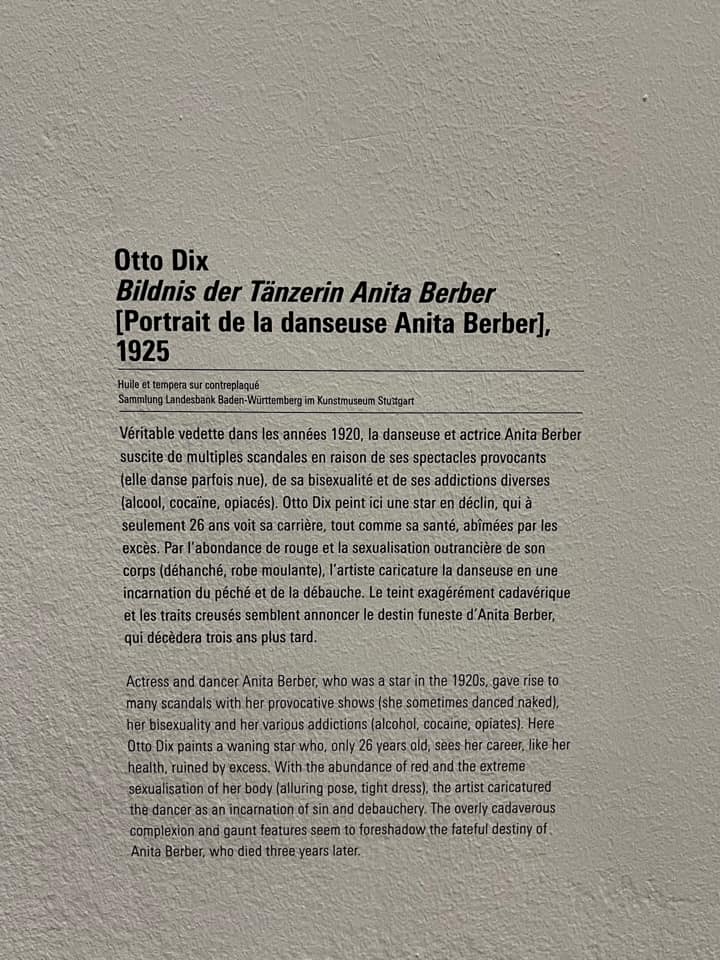

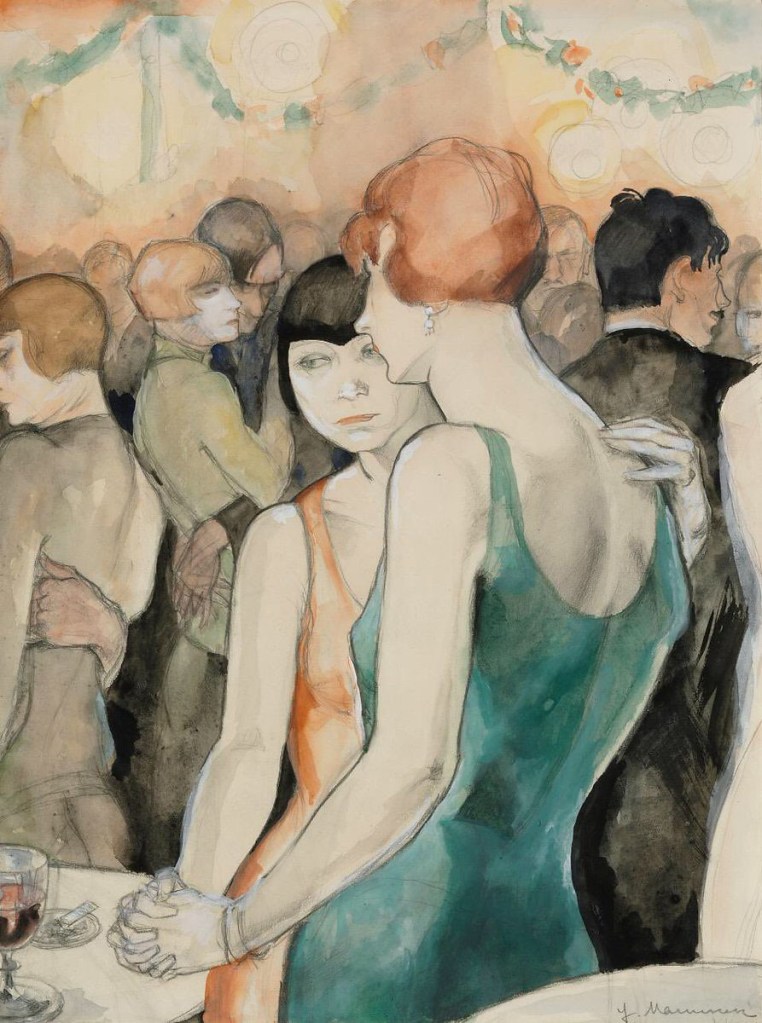

[Angela Lampe]: The painter and designer Jeanne Mammen creates watercolours featuring the daily life of lesbian meeting places, depicting the relationships between women with a certain tenderness, just like Christian Schad, who draws two young boys lovingly embraced. Otto Dix, in his portraits, depicts on the other hand its models according to a more heteronormative vision. The dancer Anita Berber, an openly bisexual star with multiple escapades, is caricatured as a personification of sin. All in red, she is presented as a figure really out of hell. She is truly the embodiment of Babylon, sinful.

[Sophie Goetzmann]: It is these two forms of transgression that are shown in the first two rooms. The last room in the section shows what is rather the opposite of a transgression, i.e. a reminder of the norm and the attitude of most male artists in the face of these transgressions, which is an attitude of anguish, which is an attitude of fear of seeing lesbian women who openly display their sexuality, to see gender norms that are blurred.

Doesn’t that open the door to a mix, too, of gender roles, a take on the power of women over men? So many of these men will multiply the images of women bruised, murdered, butchered, which also echoes the various facts of the time, where there is a whole phenomenon with serial killers that make the headlines, photographs of murders that are broadcast in the press. These are images that draw a lot of inspiration from this visual culture, almost, murder at that time. These are works that translate a certain anguish of these artists in the face of all these transgressions of the standards of gender and these transgressions of heterosexuality.

The shame felt by the men following the defeat of Germany after the First World War, is expressed through representations of violence against women because, too, women progressed on the social ladder during the First World War. Most of the time, positions that have been left vacant by men who went to the front were taken by women.

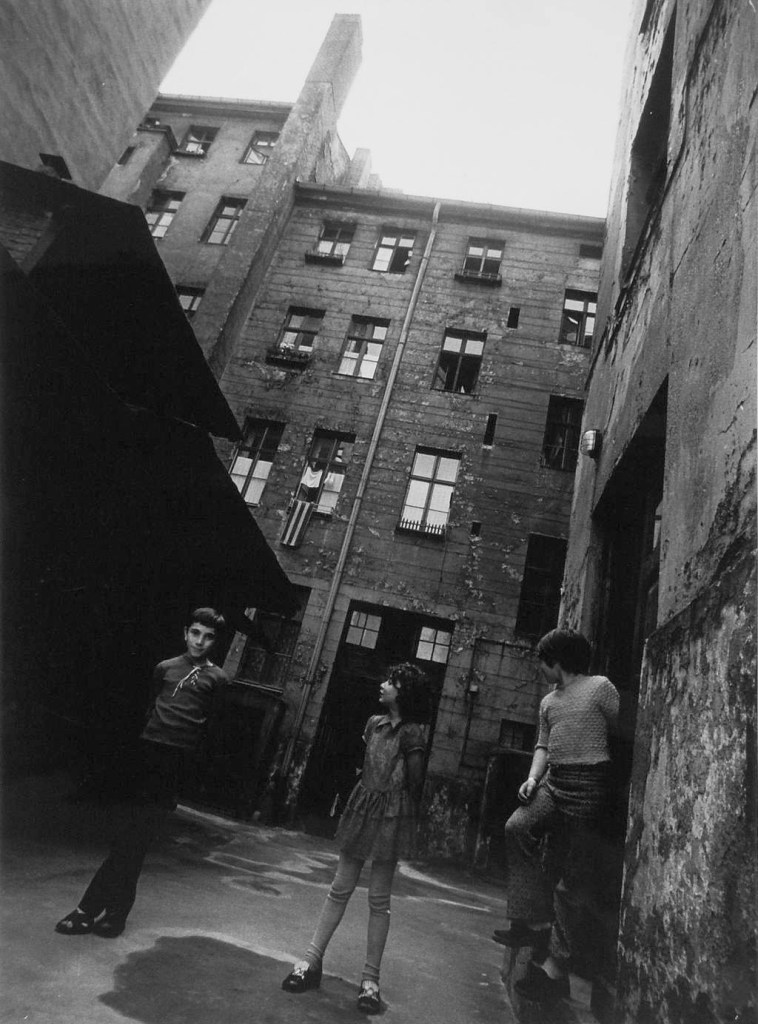

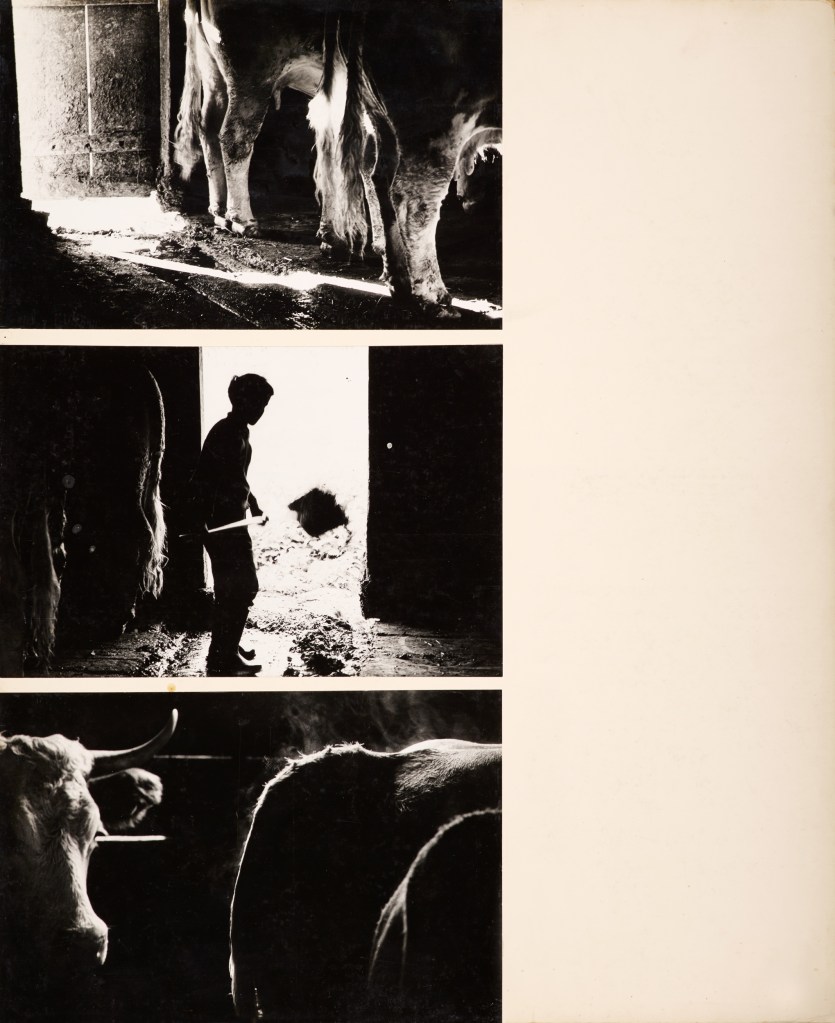

10 – Regard vers le bas (Look back)

In this last section, we are interested in artists who have been excluded, the losers from the appearance of Taylorism, who are obviously the workers who are

exploited and which become an interchangeable mass and simple cogs in enormous machinery that overtakes them. But also, all the people who live in a form of marginality, whether war-disabled, or the unemployed, or people who live on the fringes of cities and who do not go to shows, operas or Zeitoper, or Brecht’s shows which are visible in city centres, but who are completely excluded from all this entertainment and who are doomed to a form of marginality in their life, in their place of living, and who are completely crushed by the capitalist economic machinery.

[Angela Lampe]: Far from the bustling boulevards and their neon signs, the painters like Hans Baluschek and Hans Grundig paint those excluded from urban entertainment, like poor families moving through these terrains, waves relegated to the fringes of cities. During these years, there was really a gap between what we call the rich and poor, between underprivileged backgrounds and bourgeois backgrounds, even industrialised capitals. This gap was widening during these years.

[Florian Ebner]: So Sander is going to dedicate portfolio 11 to this group, La grande ville, where we also see the youth of the big city, the young high school girl, the young high school student, dressed in a very chic way, but we also see the uprooted from society, we also see the invalids of the First World War, we see the left-behinds of the system capitalist.

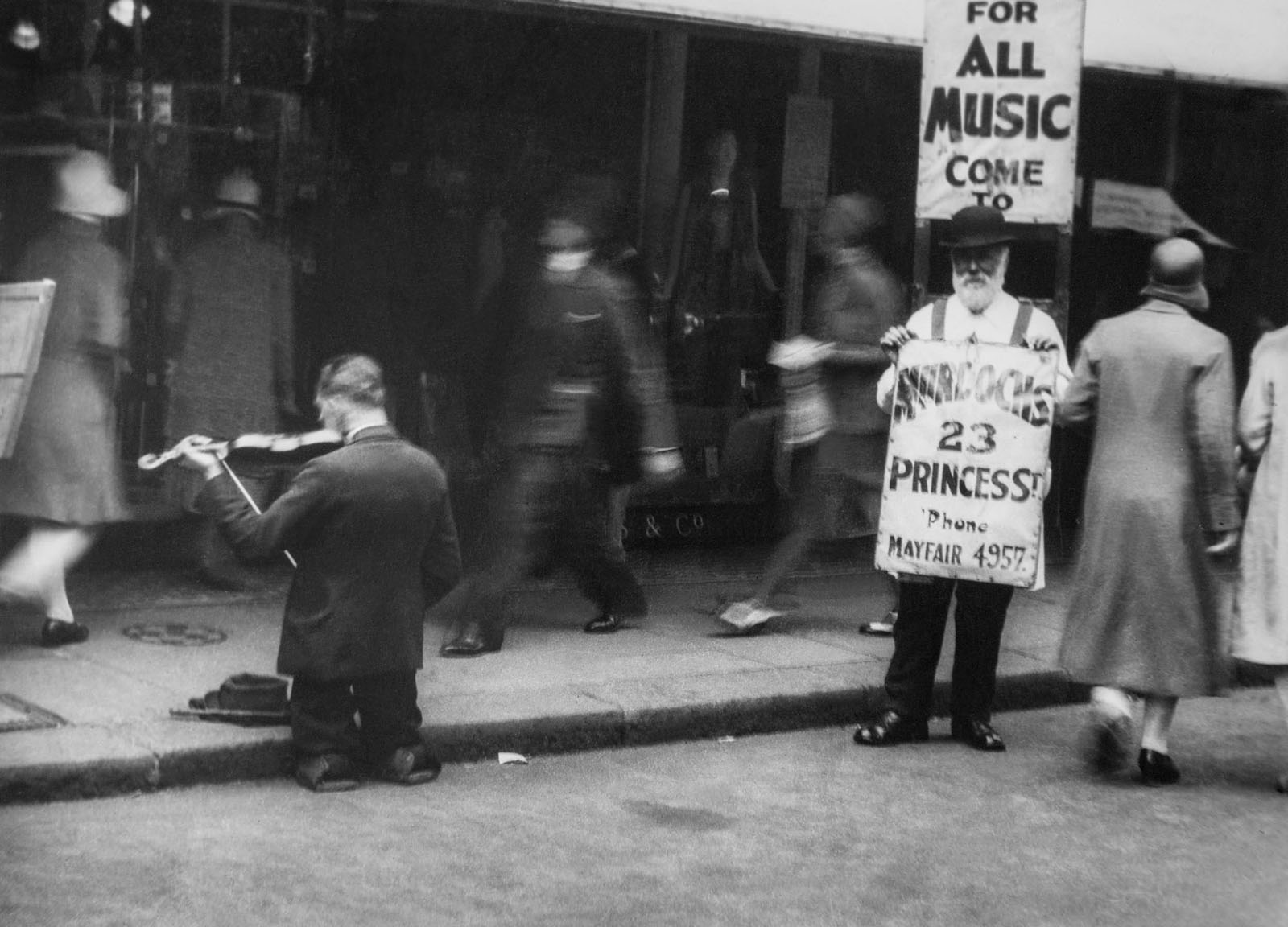

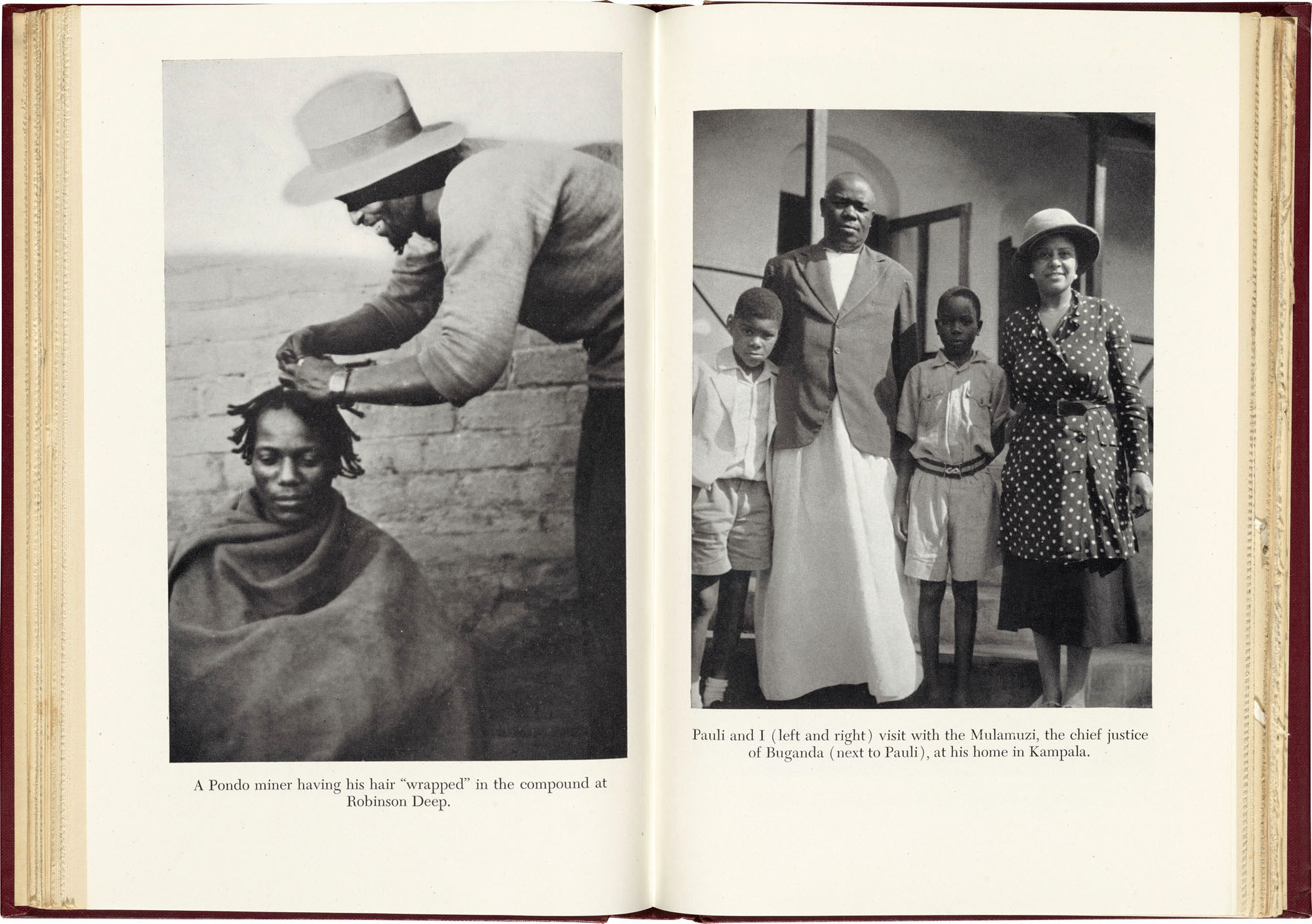

There is a portfolio called The People Who Came to My Door, which is as a sort of mise-en-abyme of his method. That is to say, he invites people who came to ask for money (beggars, hawkers, unemployed), to have their photograph taken in the frame of their door, in front of the entrance wall. It is a true typology of these people. And there is a very beautiful sentence, a very nice idea, where he asks himself: “Can you imagine taking in all the employment offices in Germany, at the same time, a photograph. What strong image would that give of poverty?”

“Here, the photo speaks a very cultured language that can be heard by everybody; it is another language, but just as expressive, as photography would speak if cameras were installed in the 365 existing unemployment offices today on the sole territory of the German Reich and if we made them work simultaneously. If we photographed the people in these offices, then we gathered the results thus obtained and we added the date, 1931, the tragedy of this photographic language would certainly be understandable, without further comment, by all men today and in times to come.” ~ August Sander

11 – Epilogue

Text from the exhibition podcast transcription on the Centre Pompidou website translated from the French by Google translate

This exhibition on the art and culture of the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) in Germany is the first overview presented in France of this artistic trend. Apart from painting and photography, the project brings together architecture, design, film, theatre, literature and music.

People of the 20th century, the masterwork by photographer August Sander, establishes the motif of a cross-section of a society, an “exhibition in the exhibition”, as a structural principle, the two interlinked perspectives opening up a large panorama of German art in the late 1920s.

This multidisciplinary exhibition is structured into eight thematic sections corresponding to the groups and sociocultural categories created by August Sander.

A review of German history in the context of contemporary Europe with populist movements and divergent societies in the throes of the digital revolution invites us to observe the political resonances and media analogies between yesterday’s situations and those of today.

Installation views of the exhibition Germany / 1920s / New Objectivity / August Sander at Centre Pompidou, Paris showing at right in the bottom image, works by Rudolf Schlichter: from left to right, Arbeiter mit Mütze (Worker with hat), 1926; Verstümmelte Proletarierfrau (Mutilated proletarian woman), 1922-1923; and Schwachsinnige II (Imbeciles II), 1923-1924

Photos: Centre Pompidou, Paris

Wall text from the exhibition Germany / 1920s / New Objectivity / August Sander at Centre Pompidou, Paris

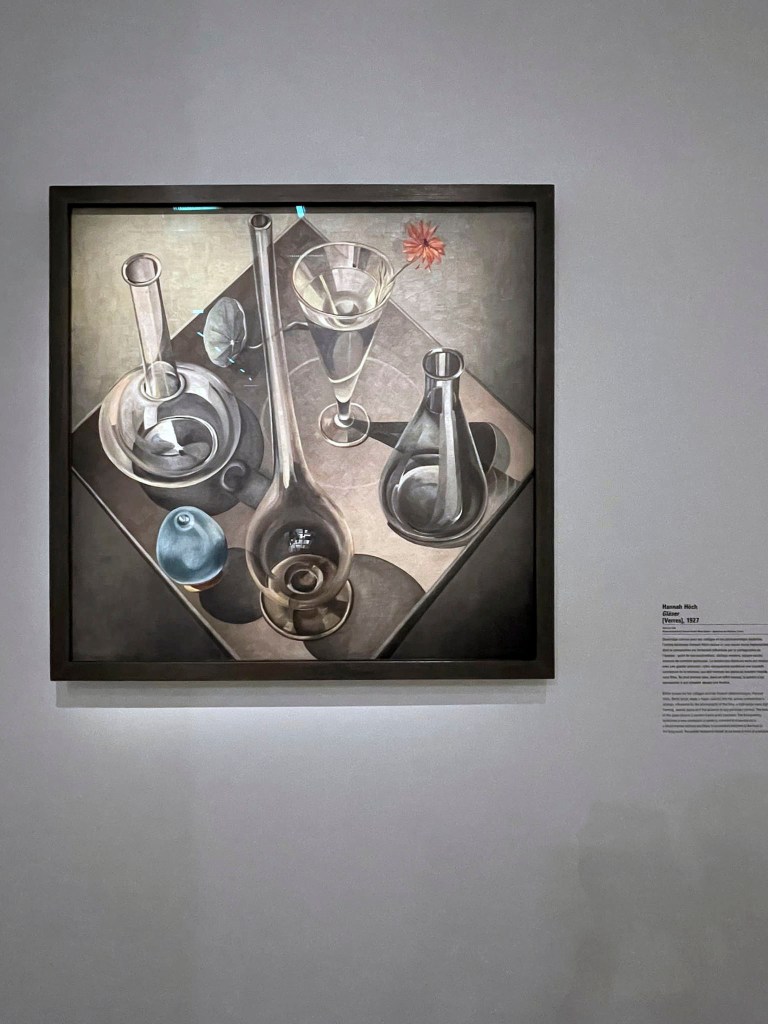

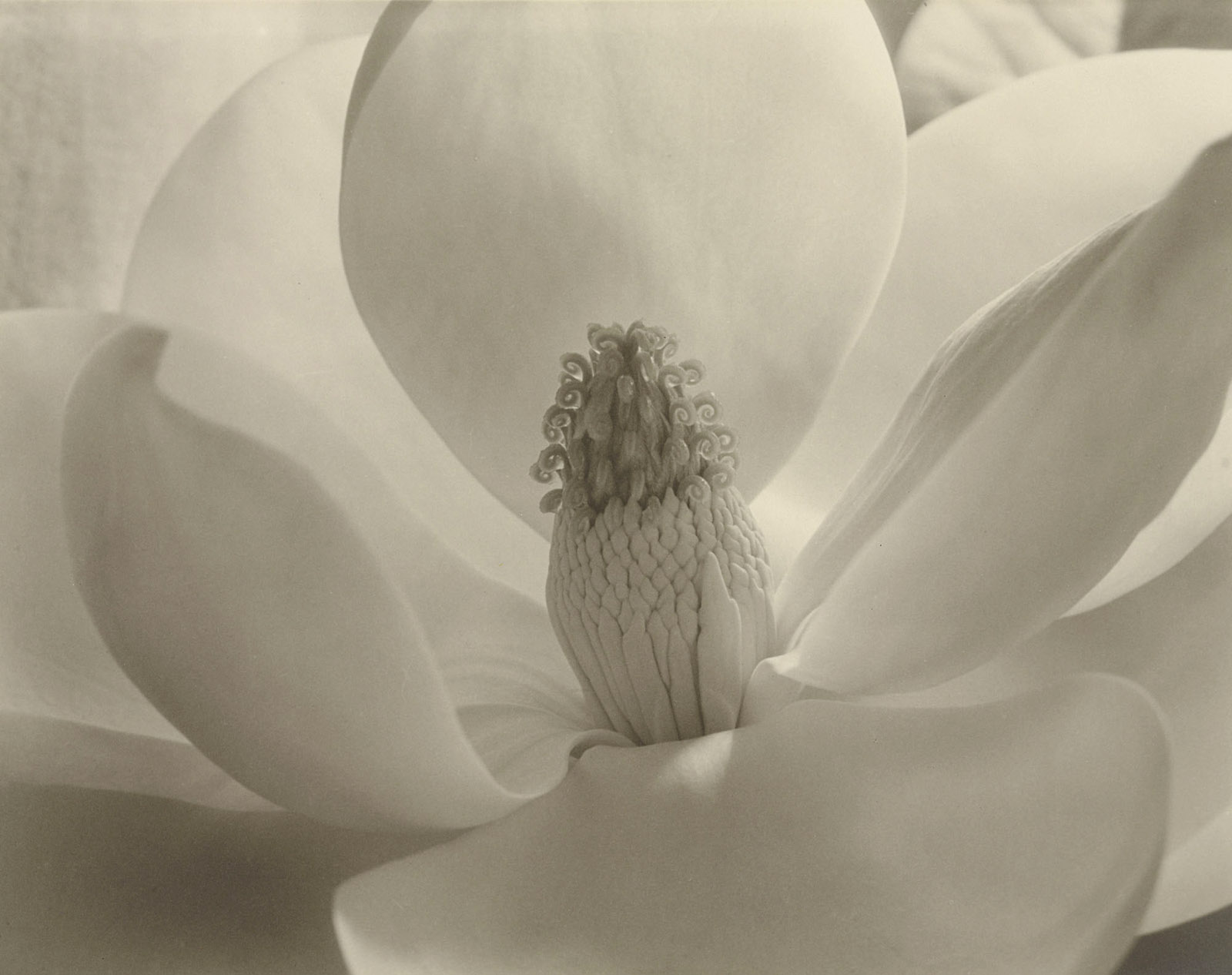

Les choses / Things

The artists of the New Objectivity were particularly interested in the genre of still life and represented objects with great clarity, their gaze being both scrutinising and cutting. Because of its supposed objectivity, photography seems particularly suited to the precise rendering of things in their materiality. Inspired by this hyperrealistic fidelity, the painters appropriated the visual language of photography. Rubber cacti and fig trees were very popular in 1920s Germany, where they were sought after for their exoticism. Artists are passionate about these plants then perceived as the plant equivalent of crystalline stone: architectural, geometric, abstract. Xaver Fuhr and Alexander Kanoldt paint figs with great meticulousness, in uncluttered compositions that bring out their clear structure. Georg Scholz values the stiffness of the cactus, in resonance with the rigid pictorial style of the New Objectivity.

This reified nature is part of a broader fascination with the world of objects. Photographers and painters are also interested in glass objects, light bulbs and tableware, often depicted in plunging or unusual perspectives.

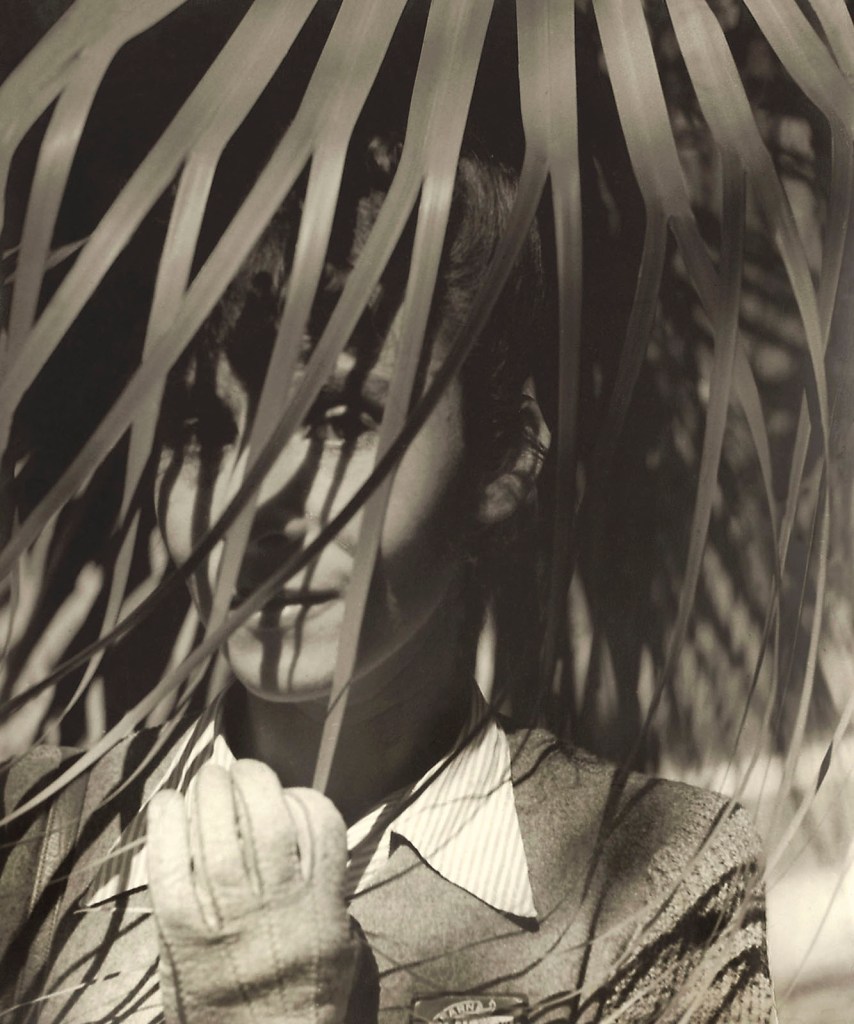

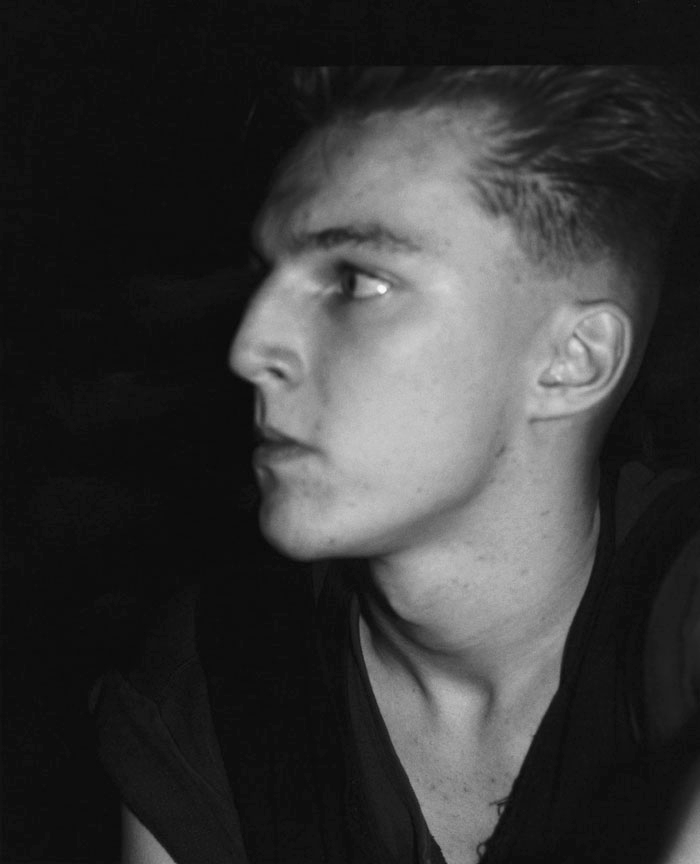

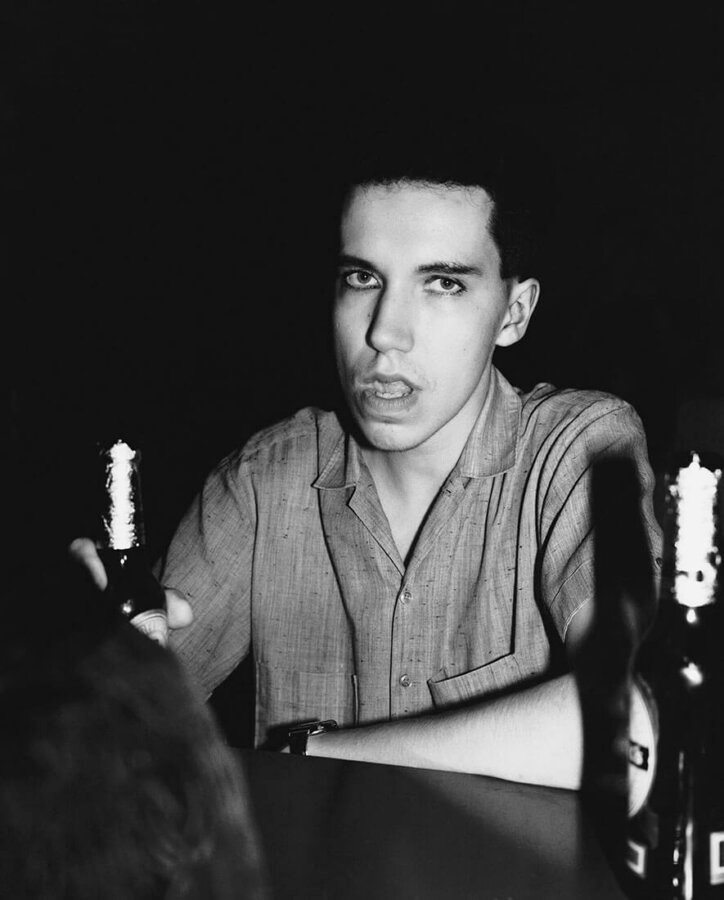

Persona froide / Cold persona

The four murderous years of the war ended in defeat engendered a form of general disillusion in Germany. According to literary historian Helmut Lethen, the humiliation inflicted by the victors gave rise to a culture of shame, characterised by widespread embarrassment about pre-war utopias. If guilt implies an introspective approach and supposes questioning oneself about one’s wrongs, shame is external and requires above all to preserve one’s image with others. In the 1920s, what Lethen called the “cold persona” appeared, a new social type that consisted of seeking to escape feelings of humiliation by displaying a mask of coldness and indifference.

This new behaviour profoundly modifies the practice of portraiture. Previously turned towards the interiority and the psychological expression of the model, it now focuses on the external signs of individuals. The artists of the New Objectivity thus represent less personalities than social types, defined by their profession. Often displayed in the very title of the work (businessman, textile merchant, doctor, etc.), it is also identifiable through attributes that allow it to be recognised.

In Menschen des 20. Jahrhunderts (People of the 20th century), August Sander devotes a group to “Socio-professional categories”, photographing less individual characters than occupations.

Like Julius Bissier, who represents himself forging his own image without emotion or affect (see below), the portraits appear cold, emptied of all feeling, in resonance with their often neutral and deserted backgrounds. The subjects appear alone and wear a detached expression, an absent, even empty gaze. Like the young girl represented by Lotte Laserstein, they seem to seek to disguise their feelings behind an impenetrable appearance.

Artists are also interested in changes in gender norms, like August Sander, who photographs “La femme” in Menschen des 20. Jahrhunderts. With an almost sociological eye, they construct a typology of the emancipated Neue Frau (New Woman): Bubikopf (short variant of the bob cut), cigarette, wearing of a shirt or even a tie become recurring attributes in the female portraits of the time.

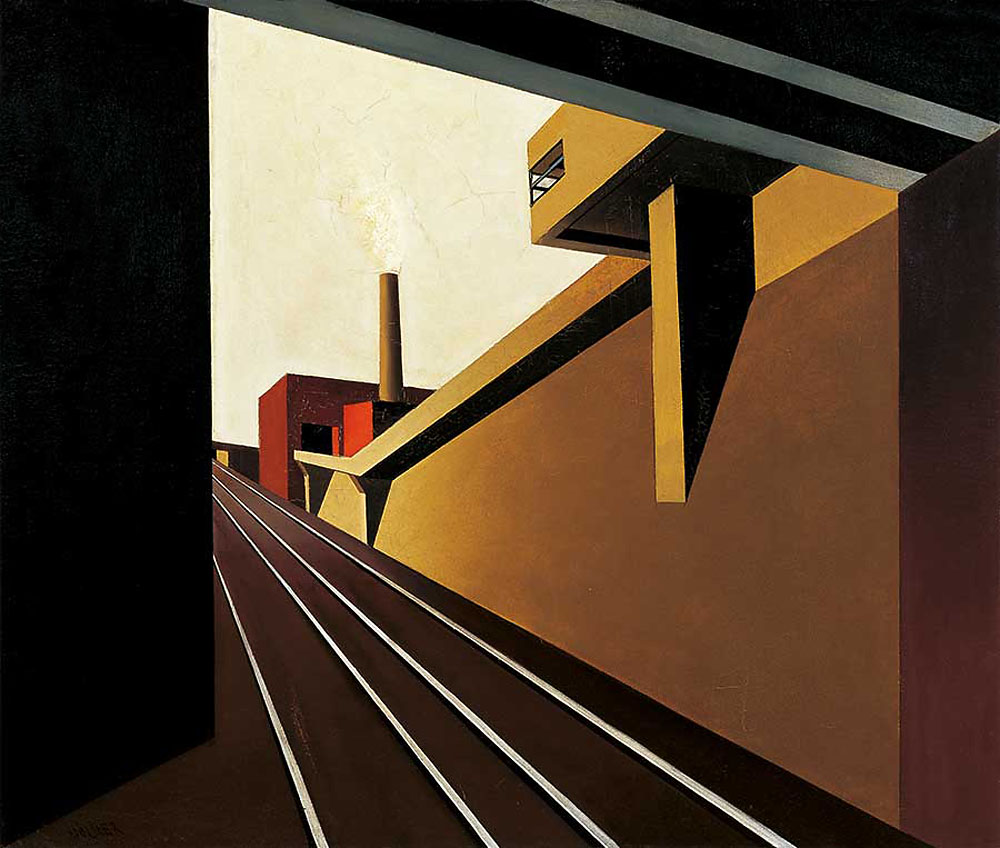

Rationalité / Rationality

The economic crisis and spectacular post-war inflation were followed by a period of stabilisation and relative growth, favoured in particular by the Dawes Plan and the injection of American capital in 1924. A fascination for America and its model of society seen as methodical and harmonious, governed by technique, was born in Germany.

The rationalisation of work developed by Taylor is imported into German companies, leading to rapid industrialisation and the mechanisation of tasks. The aestheticisation of machines is found in the artists of the New Objectivity, who praise their beauty. Carl Grossberg’s paintings show sparkling clean industrial sites in clean, meticulously detailed compositions. The cult of technology continued with the appearance of the radio, a new domestic machine perceived by the painter Max Radler or the playwright Bertolt Brecht as a potential tool for emancipation.

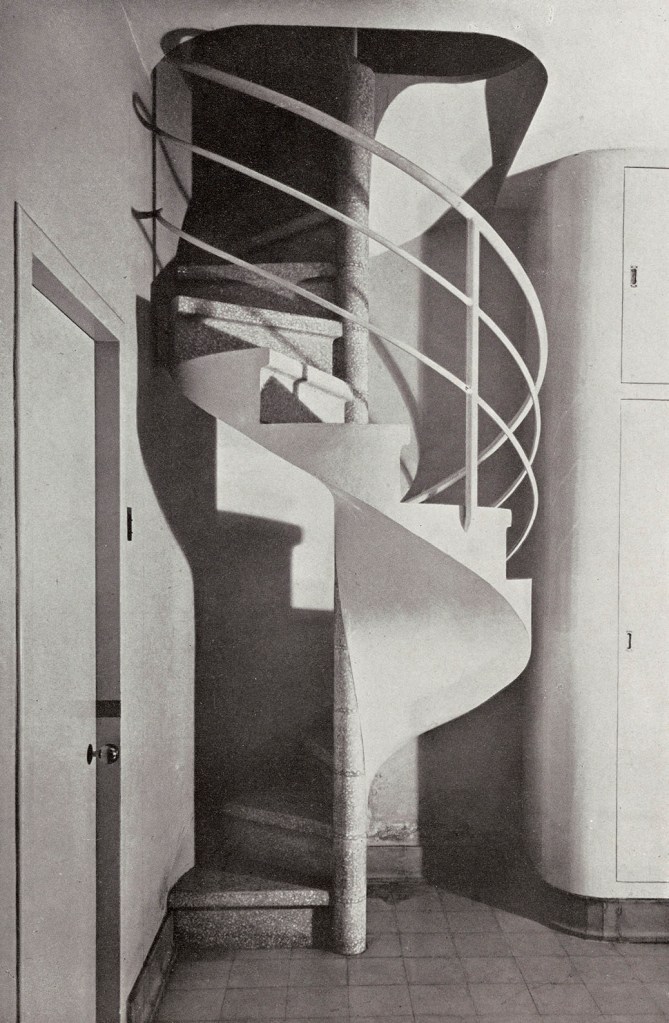

The principle of rationalisation soon becomes a new norm that structures social and cultural life. The interior layout of the small-sized accommodation is studied by the architects and designers to optimise the space. Along the same lines, Marcel Breuer and Franz Schuster developed sleek, space-saving furniture that freed up as much space as possible. The architect Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky has designed a modern and functional kitchen in Frankfurt, organised as a workspace to limit the movements of the housewife. This concern to improve the daily life of women is part of a general desire for emancipation: the 1920s are those of the appearance of a financially independent Neue Frau (New Woman), who leaves her traditional role to confront to modern technology or to sports previously reserved for men.

Transgressions

In Germany, traditional gender roles were redefined after the First World War. After occupying vacant positions during the conflict, women are now established in the labor market, and obtain the right to vote in 1918. This new position leads them to adopt an androgynous appearance by appropriating the codes of masculinity: short hair, shirt, tie and flat chest, as shown in Selbstbildnis als Malerin (Self-Portrait as a Painter) (1935, below) by Kate Diehn-Bitt (1900-1978), oil on plywood.

In Berlin, in the famous Eldorado cabaret, transvestite artists push this confusion of genres even further. An important homosexual subculture develops in these clubs tolerated by the police. The painter and designer Jeanne Mammen creates watercolours that capture the daily life of lesbian meeting places, depicting the relationships between women with a certain tenderness.

The portraits of Otto Dix, on the other hand, are more imbued with the homophobic stereotypes of the time. The dancer Anita Berber, openly bisexual star with multiple escapades, is caricatured as a personification of sin. Jeweller Karl Krall appears with disproportionately scooped and wide hips, echoing physiologist Eugen Steinach’s ideas about “feminized men”.

Transgressions of heterosexuality and decompartmentalisation of genres generate anxiety in some male artists which is reflected in their works by a violent reminder of the norm. Rudolf Schlichter, Karl Hubbuch or Otto Dix multiply the representations of Lustmörder, sexual crimes showing women violently murdered by knife or hanging.

Regard vers le bas / Look down

The fascination for industry and machines clashes with the harsh reality of the daily life of the most modest populations. Driven by a desire to represent the reverse side of triumphant capitalism, certain artists of the New Objectivity turn their gaze towards those invisible things that technical progress excludes or condemns. Although pretending to a representation objective of the social world, they refuse political neutrality, most of them being committed to the Communist Party.

Karl Völker and Oskar Nerlinger create portraits of anonymous crowds of workers in the oppressive environment of industrial architecture: de-individuated, they are no more than simple cogs in the capitalist economic machine. Using a detached style, the artists represent the precarious populations living on the edge of large modern urban centres, showcases of German capitalism. Far from the bustling boulevards and their neon signs, Hans Baluschek and Hans Grundig paint those excluded from urban entertainment, poor families living in vacant lots on the outskirts of cities.

Max Radler (Polish, 1904-1971)

Der Radiohörer (The Radio Listener)

1930

Oil on canvas

Wilhelm Heise (German, 1892–1965)

Verblühender Frühling. Selbstbildnis als Radiobastler (Faded Spring. Self-portrait as a radio amateur)

1926

Oil on canvas

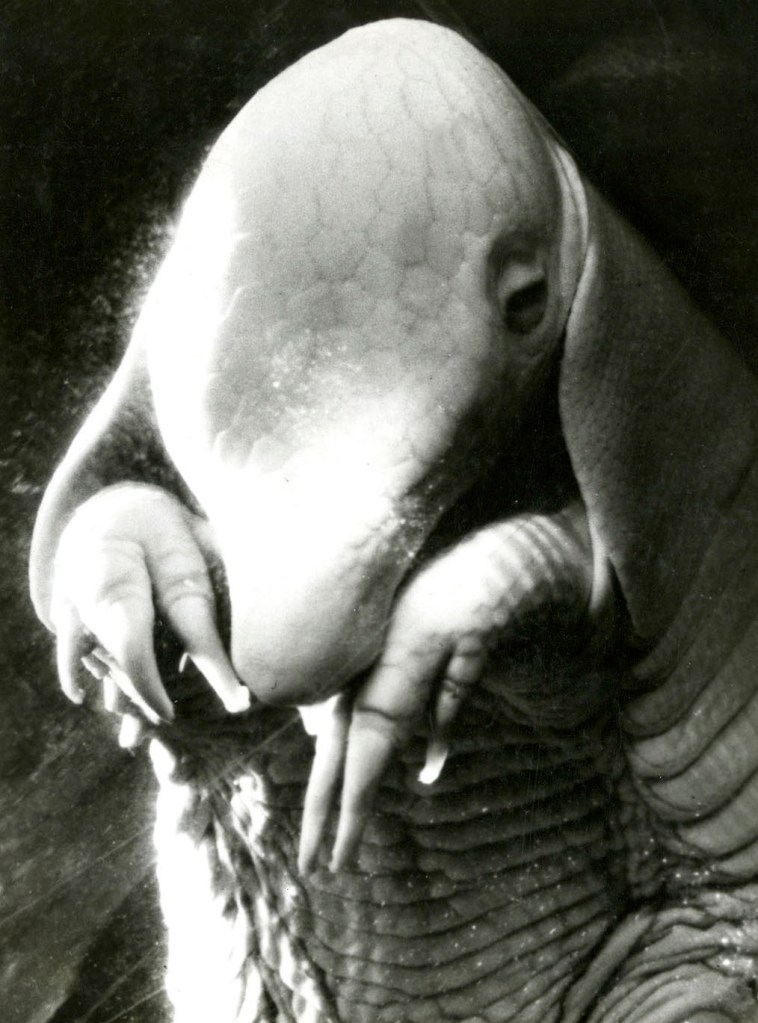

Raoul Hausmann (Austrian, 1886-1971)

Mechanischer Kopf (Der Geist Unserer Zeit) The Mechanical Head (The Spirit of Our Time)

1919

Assemblage

Wooden hairdresser’s puppet and various objects attached to it: telescopic beaker, a leather case, pipe stem, white cardboard bearing the number 22, a piece of a seamstress’ tape measure, a double decimeter, a watch cog, a roll of character d printing

32.5 x 21 x 20cm

Pompidou Centre collection

Purchase, 1974

“I wanted to unveil the spirit of our time, the spirit of everyone in its rudimentary state.”

Reducing the individual to a series of figures, this head criticises a harmful mechanisation revealed by the Great War. It also constitutes the announcement of a new, rational and impersonal man in tune with modern society. Anti-bourgeois and corrosive, does Raoul Hausmann reject the present or does he project himself into the future?

The most famous work by Hausmann, Mechanischer Kopf (Der Geist Unserer Zeit), “The Mechanical Head (The Spirit of Our Time)”, c. 1920, is the only surviving assemblage that Hausmann produced around 1919-1920. Constructed from a hairdresser’s wig-making dummy, the piece has various measuring devices attached including a ruler, a pocket watch mechanism, a typewriter, some camera segments and a crocodile wallet.

“Der Geist Unserer Zeit – Mechanischer Kopf specifically evokes the philosopher George Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770-1831). For Hegel… everything is mind. Among Hegel’s disciples and critics was Karl Marx. Hausmann’s sculpture might be seen as an aggressively Marxist reversal of Hegel: this is a head whose “thoughts” are materially determined by objects literally fixed to it. However, there are deeper targets in western culture that give this modern masterpiece its force. Hausmann turns inside out the notion of the head as seat of reason, an assumption that lies behind the European fascination with the portrait. He reveals a head that is penetrated and governed by brute external forces.”

Jonathan Jones. “The Spirit of Our Time – Mechanical Head, Raoul Hausmann (1919),” on The Guardian website Saturday 27th September 2003 quoted in “Raoul Hausmann,” on the Wikipedia website [Online] Cited 01/08/2022

Carl Grossberg (German, 1894-1940)

Jacquard-Weberei (Jacquard weaving workshop)

1934

Oil on wood

Hans Baluschek (German, 1870-1935)

Sommernacht (Summer Evening) (installation view)

1929

Oil on canvas

120 x 151cm

Photo: Aubrey Perry

Hans Baluschek (German, 1870-1935)

Sommernacht (Summer Evening)

1929

Oil on canvas

120 x 151cm

Hans Baluschek (German, 1870-1935)

Hans Baluschek (9 May 1870 – 28 September 1935) was a German painter, graphic artist and writer.

Baluschek was a prominent representative of German Critical Realism, and as such he sought to portray the life of the common people with vivid frankness. His paintings centred on the working class of Berlin. He belonged to the Berlin Secession movement, a group of artists interested in modern developments in art. Yet during his lifetime he was most widely known for his fanciful illustrations of the popular children’s book Little Peter’s Journey to the Moon (German title: Peterchens Mondfahrt).

Hans Baluschek, after 1920, was an active member of the Social Democratic Party of Germany, which at the time still professed a Marxist view of history.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Installation view of the exhibition Germany / 1920s / New Objectivity / August Sander at Centre Pompidou, Paris showing at left, Karl Hubbuch’s Twice Hilde II and Twice Hilde (c. 1929, below); and at right, Otto Dix’s An die Schönheit (Selbstbildnis) (To the beauty (Selfportrait)) (1922, below)

Photo: Centre Pompidou, Paris

Wall text from the exhibition Germany / 1920s / New Objectivity / August Sander at Centre Pompidou, Paris

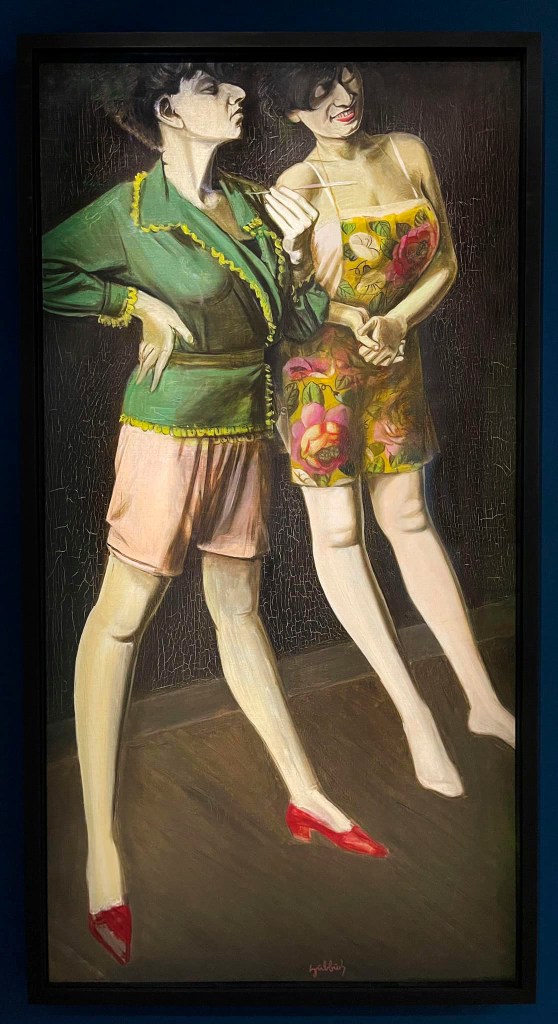

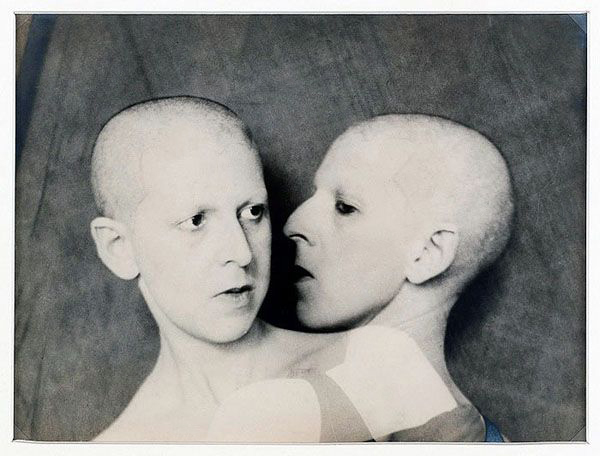

Karl Hubbuch (German, 1891-1979)

Zweimal Hilde II (Twice Hilde II) (installation view)

c. 1929

Oil on canvas mounted on masonite

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bomemsiza, Madrid

Photo: Aubrey Perry

Karl Hubbuch (German, 1891-1979)

Zweimal Hilde (Twice Hilde) (installation view)

c. 1929

Oil on canvas mounted on masonite

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bomemsiza, Madrid

Photo: Aubrey Perry

Karl Hubbuch, who was originally from Karlsruhe, often travelled to Berlin. It was there that he met George Grosz and Rudolf Schlichter, with whom he joined the radical Novembergruppe and Rote Gruppe, and later the Neue Sachlichkeit. Despite his radical ideological stance, the critical accent of his painting was tempered by the more moderate and classical style characteristic of the Karlsruhe artists.

Twice Hilde II is a double image of Hubbuch’s wife, whom he painted on numerous occasions. Hilde Isai (1905-1971), one of his drawing from life students at the Karlsruhe academy, whom he married in 1928, was an energetic and independent woman who eventually left her husband to devote herself to her passion for photography at the Dessau Bauhaus. The composition, in the manner of a Doppelgänger, was initially designed as a quadruple portrait which the artist later cut into two after the central part was damaged by a leak. The two pieces, which were exhibited together on a few occasions, and the preparatory drawings provide a progressive sequence of Hilde’s personality. Hubbuch, who was very fond of multiple portraits, instead of attempting to capture Hilde’s personality in a single figure, breaks it down into numerous facets, from the image on the left – which shows her seated with crossed legs on a modern tube chair designed by Marcel Breuer in a serious, prim pose wearing glasses that give her an intellectual air – to the provocative, coquettish woman in her underclothes on the far right of the Munich double portrait. Like most of the members of the German New Objectivity movement, Hubbuch was attracted by everyday scenes and by rendering various objects and textures in minute detail.

Although the painting has often been dated to 1923, in the catalogue of the retrospective exhibition of the painter’s work in 1981, the first serious critical study of his oeuvre, Wolfgang Hartmann ascribed it to 1929 on the grounds of particular stylistic features and the fact that Hubbuch did not meet Hilde until 1926.

Paloma Alarcó. “Karl Hubbuch,” on the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bomemsiza website Nd [Online] Cited 02/08/2022

Karl Hubbuch (German, 1891-1979)

Zweimal Hilde II (Twice Hilde II)

c. 1929

Oil on canvas mounted on masonite

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bomemsiza, Madrid

Otto Dix (German, 1891-1969)

An die Schönheit (Selbstbildnis) (To the beauty (Selfportrait))

1922

Oil on canvas

139.5 x 120.5cm

Von der Heydt-Museum Wuppertal, Wuppertal

© Adagp, Paris, 2022

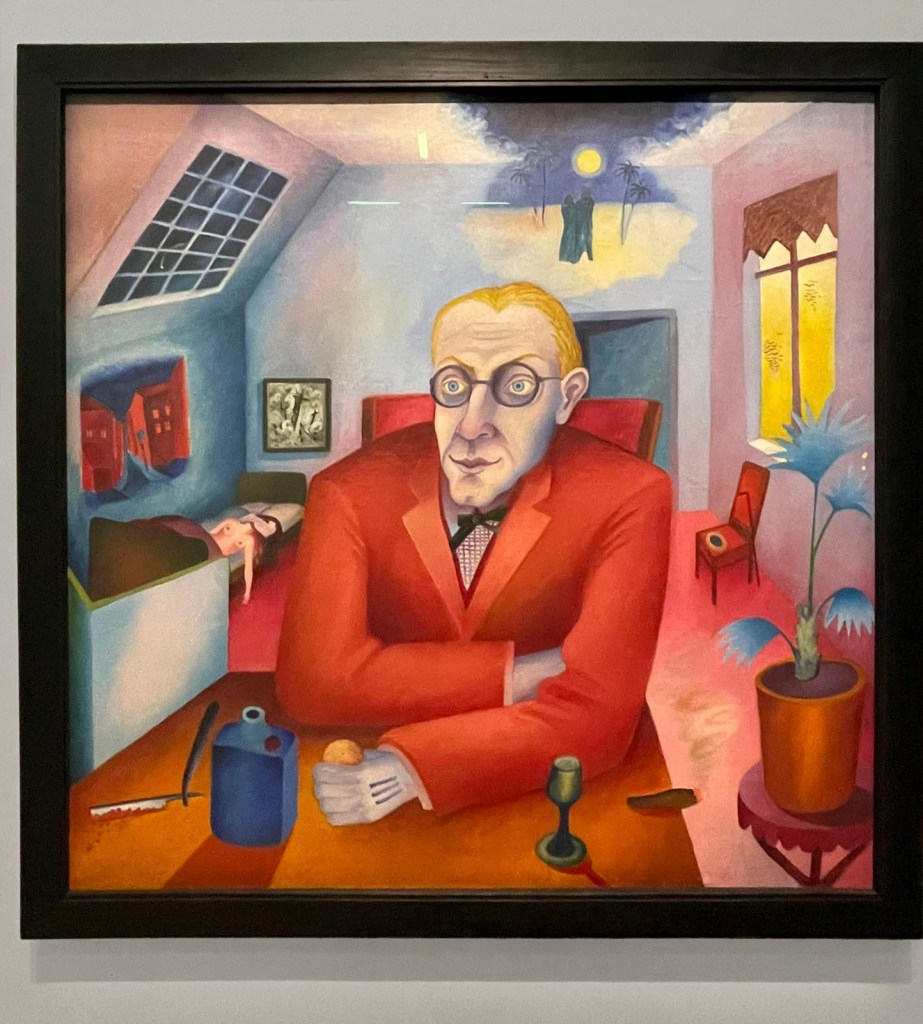

Heinrich Maria Davringhausen (German, 1894-1970)

The Dreamer II (installation view)

1919

Photo: Aubrey Perry

Heinrich Maria Davringhausen (German, 1894-1970)

Heinrich Maria Davringhausen (1894-1970) spent his youth in Aachen and studied sculpture at the Düsseldorf Art Academy in 1913-14, where he met Carlo Mense. Rhenish Expressionism, with its leanings towards Fauvism, Cubism and Futurism, exerted a formative influence on Davringhausen’s palette and composition.

In the years that followed, Davringhausen travelled constantly and met Georg Schrimpf at the Monte Verità artists’ colony near Ascona. Several portraits were done of him in a realistically overpainted manner which show the artist against a coloured Futurist background. The loss of an eye in his childhood ensured that Davringhausen was spared military service when the first world war broke out. Heinrich Maria Davringhausen returned to Germany, moved to Munich in 1918 and joined the group of Düsseldorf artists known as Das junge Rheinland.

Under the influence of the Cologne “progressives”, Davringhausen now painted primarily abstract pictures with colour surfaces, some of them conceived in series. Between 1924 and 1925 the artist lived in Toledo, Spain, but chose to settle in Cologne in 1928, where he founded “Gruppe 32” with Anton Räderscheidt et al.

After he married Lore Auerbach, the daughter of a Jewish industrialist, Davringhausen emigrated with his wife to Cala Ratjada on Mallorca in 1933. The outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936 compelled Davringhausen to flee to Ascona via Marseilles and Paris. A year later his work was shown in the exhibition of Degenerate Art. In 1939 Davringhausen was expelled from Switzerland and moved with his family to Haut-de-Cagnes near Nice. After managing to escape from Les Milles, where he was interned in 1939-1940, Davringhausen hid with his wife in Auvergne, returning to Haut-de-Cagnes after the war.

Most of Davringhausen’s work was lost during the war due to his being outlawed by the National Socialists and being continually on the run. In the postwar years Davringhausen exhibited his work, which reveals a close affinity with “Neue Sachlichkeit”, at many galleries across the world.

By the close of the 1950s art history was beginning to take notice of the New Objectivist style. As a result, Heinrich Maria Davringhausen’s early work was shown at numerous exhibitions and was included in publications dealing with the “Neue Sachlichkeit” movement. The artist’s comprehensive body of late work is primarily geometric and abstract yet it did not win much recognition. Heinrich Maria Davringhausen died in Nice on 13 December 1970.

Kraftgenie. “Heinrich Maria Davringhausen,” on the Weimar website, Tuesday, June 8, 2010 [Online] Cited 02/08/2022

Heinrich Maria Davringhausen (German, 1894-1970)

The Dreamer

1919

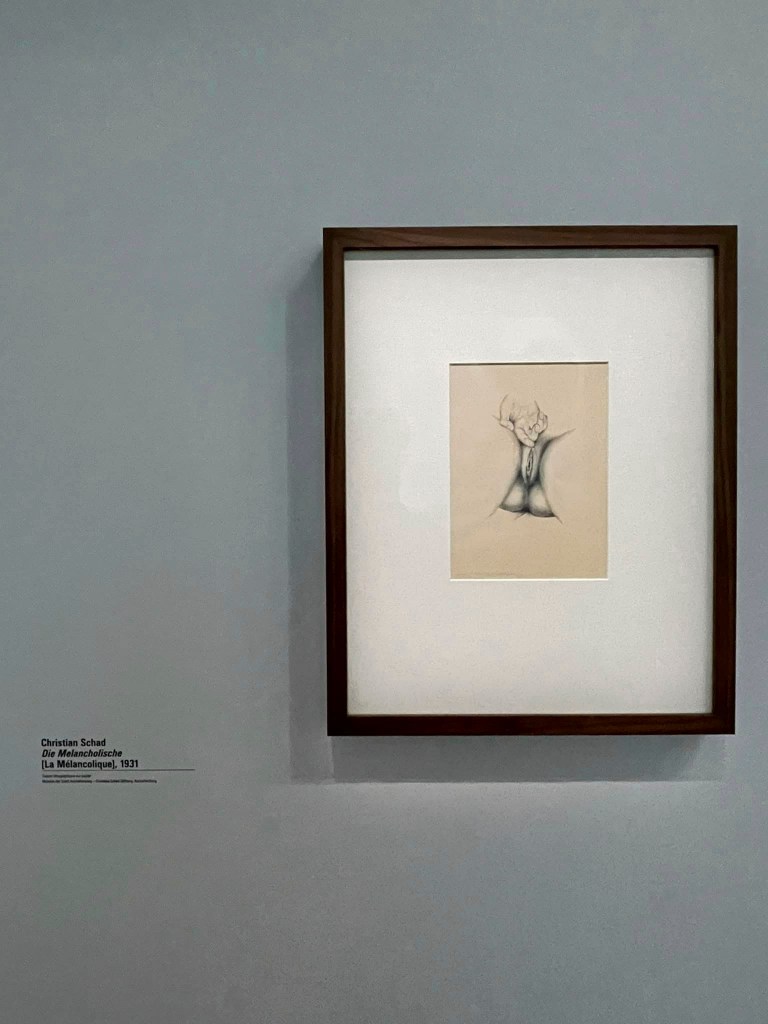

Christian Schad (German, 1894-1982)

Die Melancholische (The Melancholy) (installation view)

1931

Photo: Aubrey Perry

Christian Schad (21 August 1894 – 25 February 1982) was a German painter and photographer. He was associated with the Dada and the New Objectivity movements. Considered as a group, Schad’s portraits form an extraordinary record of life in Vienna and Berlin in the years following World War I.

The four devastating years of World War I, which ended in defeat for Germany, led to a general sense of disillusionment among the people. Abandoning the visionary, spiritual and psychological aesthetics of expressionism, the disabused artists turned to reality. In painting, this paradigm shift was reflected in the emergence of a more neutral and less expressive figurative style that tended towards greater objectivity.

The German empire was succeeded by a new political regime, the Weimar Republic, which promoted the development of a new democratic culture focused on the masses. The exaltation of the individual was replaced by an ideal of standardisation: singularities were erased in favour of models, standardised types and simple forms reproduced in series. In urban development, the unprecedented shortage of housing at the end of World War I led to the construction of large housing blocks with simple and identical forms, designed according to a principal of rationalisation. The notion of utility which was linked to the new objectivity movement, emerged in theatre, music and literature. This new concept promoted the creation of works intended for a wide audience, strongly anchored in their time and designed to be immediately understandable.

Art also expressed the social upheavals under the new German democracy. After World War I, women joined the labour market and obtained the right to vote in 1918; this very definition of traditional gender roles was a subject explored by painters and photographers. From 1924 onwards, the injection of American Capital ushered in a period of relative economic stabilisation, but many Germans remained excluded from the benefits of growth. Artists who are members of the communist party depicted labourers, the unemployed and beggars, driven by a desire to represent the underside of triumphant capitalism.

August Sander (German, 1876-1964)

Malerehepaar (Couple of painters) (Martha et Otto Dix)

1925-1926

Modern gelatin silver print

20.6 x 24.3 cm

Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur, Cologne

© Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur – August Sander Archiv, Cologne/ Adagp, Paris, 2022

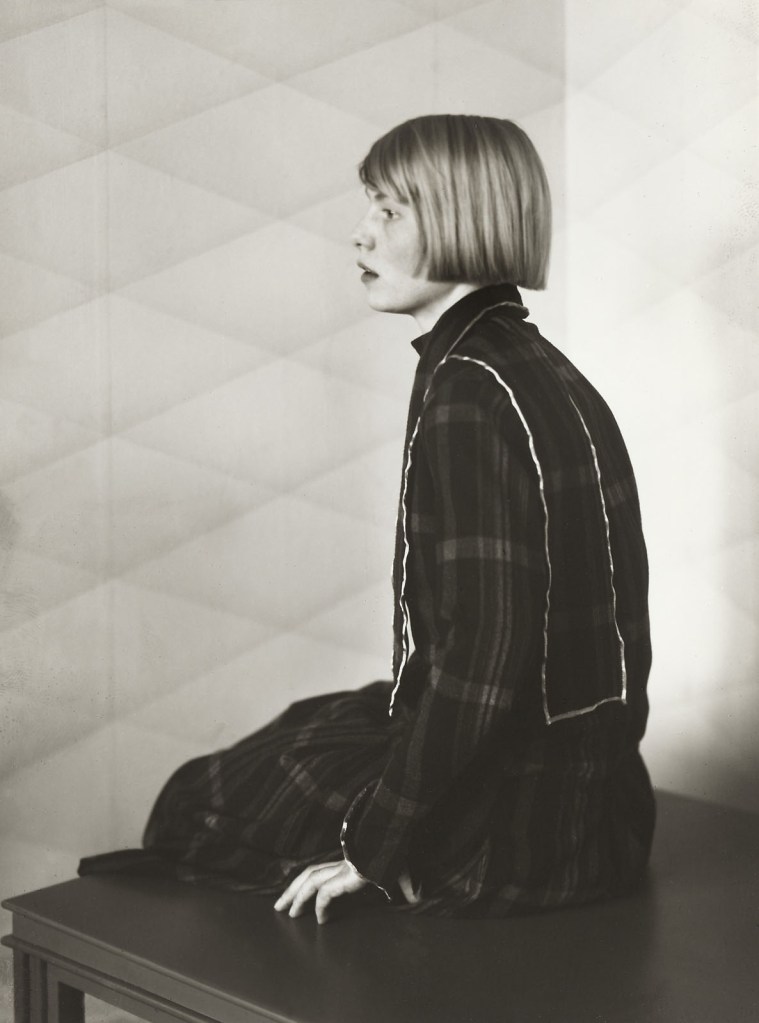

August Sander (German, 1876-1964)

Painter (Marta Hegemann)

c. 1925

Gelatin silver print

10 3/16 × 7 3/8″ (25.8 × 18.7cm)

© Die Photographische Sammlung / SK Stiftung Kultur – August Sander Archiv, Köln / Adagp, Paris

Carl Grossberg (German, 1894-1940)

Self portrait

1928

Oil on panel

70.1 x 60cm

August Sander (German, 1876-1964)

Hausierer (Peddler)

1930

Gelatin silver print

17.5 x 11.8cm (6.9 x 4.6 in)

August Sander (German, 1876-1964)

Bailiff

c. 1930

Gelatin silver print

10 3/16 × 7 3/8″ (25.8 × 18.7cm)

![August Sander (German, 1876-1964) '[Unemployed Man in Winter Coat, Hat in Hand]' 1920 August Sander (German, 1876-1964) '[Unemployed Man in Winter Coat, Hat in Hand]' 1920](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/unemployed-man-in-winter-coat-hat-in-hand-1920-august-sander1.jpg?w=677)

August Sander (German, 1876-1964)

[Unemployed Man in Winter Coat, Hat in Hand]

1920

Gelatin silver print

23.0 x 14.7cm (9 1/16 x 5 13/16 in)

August Sander (German, 1876-1964)

Frau eines Architekten (Dora Lüttgen) (Architect’s Wife (Dora Lüttgen))

1926

Gelatin silver print

25.8 × 18.7cm

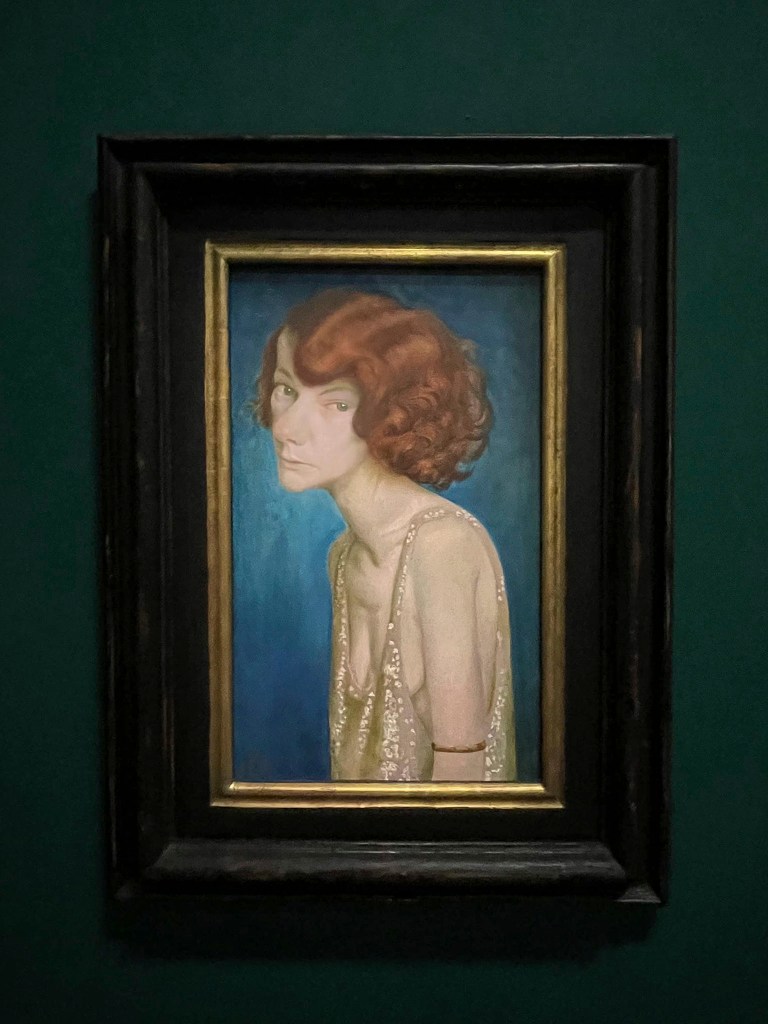

Otto Dix (German, 1891-1969)

Rothaarige Frau (Damenporträt) (Red-haired woman (female portrait))

1931

Photo: Aubrey Perry

Otto Dix (German, 1891-1969)

Rothaarige Frau (Damenporträt) Red-haired woman (female portrait)

1931

Installation view of the exhibition Germany / 1920s / New Objectivity / August Sander at Centre Pompidou, Paris showing at centre left, Rudolf Schlichter’s Margot (1924, below); and at second right, Otto Dix’s Bildnis der Journalistin Sylvia von Harden (Portrait of the journalist Sylvia von Harden) (1926, below)

Photo: Centre Pompidou, Paris

Rudolf Schlichter (German, 1890-1955)

Margot

1924

© Städel Museum

The prostitute Margot was portrayed several times by Rudolf Schlichter around 1924. Margot, portrayed in the pose of baroque portraits of rulers with a challenging look and self-confident right arm on her hips, bob haircut and cigarette, presents the type of the new woman. She buys her emancipation with the sale and – her swollen left eyelid indicates it – with the maltreatment of her body. The background shows a dreary tenement barracks, their “kingdom” is the street.

Text from the Städel Museum website

Rudolf Schlichter (German, 1890-1955)

Rudolf Schlichter (or Rudolph Schlichter) (December 6, 1890 – May 3, 1955) was a German painter and one of the most important representatives of the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) movement.

Schlichter was born in Calw, Württemberg. After an apprenticeship as an enamel painter at a Pforzheim factory he attended the School of Arts and Crafts in Stuttgart. He subsequently studied under Hans Thoma and Wilhelm Trübner at the Academy in Karlsruhe. Called for military service in World War I, he carried out a hunger strike to secure early release, and in 1919 he moved to Berlin where he joined the Communist Party of Germany and the “November” group. He took part in a Dada fair in 1920 and also worked as an illustrator for several periodicals.

A major work from this period is his Dada Roof Studio, a watercolour showing an assortment of figures on an urban rooftop. Around a table sit a woman and two men in top hats. One of the men has a prosthetic hand and the other, also missing a hand, appears on closer scrutiny to be mannequin. Two other figures in gas masks may also be mannequins. A child holds a pail and a woman wearing high button shoes (for which Schlichter displayed a marked fetish) stands on a pedestal, gesturing inexplicably.

In 1925 Schlichter participated in the “Neue Sachlichkeit” exhibit at the Mannheim Kunsthalle. His work from this period is realistic, a good example being the Portrait of Margot (1924, above) now in the Berlin Märkisches Museum. It depicts a prostitute who often modelled for Schlichter, standing on a deserted street and holding a cigarette.

When Adolf Hitler took power, bringing to an end the Weimar period, his activities were greatly curtailed. In 1935 he returned to Stuttgart, and four years later to Munich. In 1937 his works were seized as degenerate art, and in 1939 the Nazi authorities banned him from exhibiting. His studio was destroyed by Allied bombs in 1942.

At the war’s end, Schlichter resumed exhibiting works. His works from this period were surrealistic in character. He died in Munich in 1955.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Rudolf Schlichter (German, 1890-1955)

Damenkneipe (Ladies’ Bistro)

c. 1925

Watercolour, India ink and pencil on paper

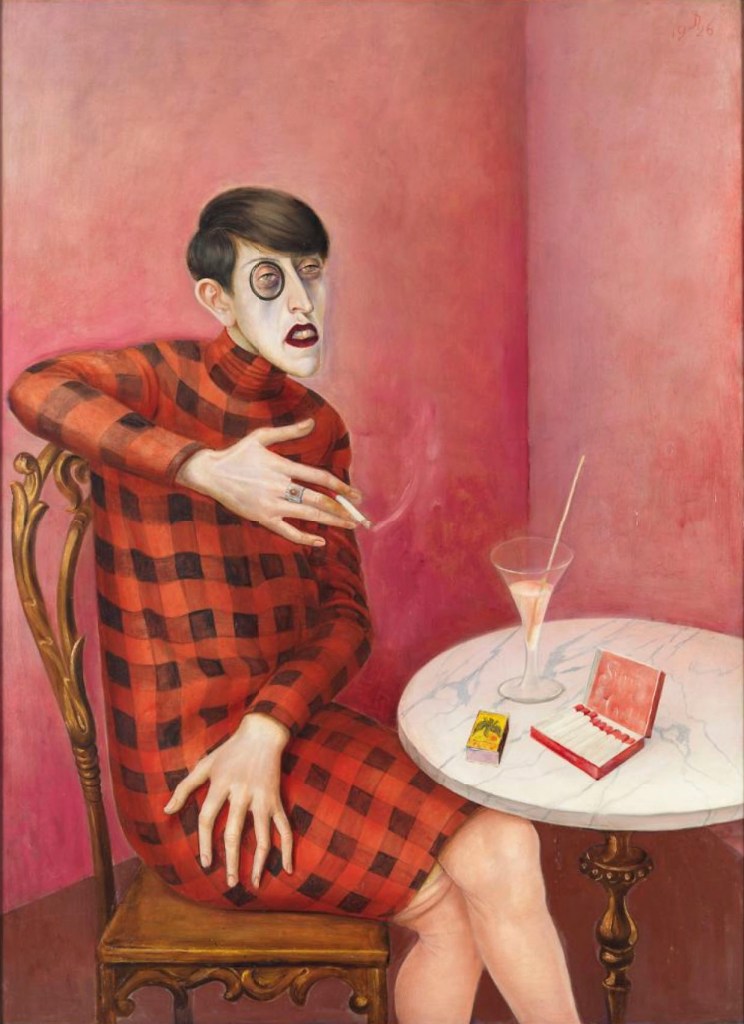

Otto Dix (German, 1891-1969)

Bildnis der Journalistin Sylvia von Harden (Portrait of the journalist Sylvia von Harden) (installation view)

1926

Oil and tempera on wood

121 x 89cm

Pompidou Centre collection

Purchase, 1961

Photo: Aubrey Perry

Otto Dix (German, 1891-1969)

Bildnis der Journalistin Sylvia von Harden (Portrait of the journalist Sylvia von Harden)

1926

Oil and tempera on wood

121 x 89cm

Pompidou Centre collection

Purchase, 1961

© Adagp, Paris

Photo credits: © Audrey Laurans – Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI /Dist. RMN-GP

Who is this woman who dares to appear in public alone, cigarette in hand, at a table of the Romanische Café, a haunt of the Berlin art worlds?

Sylvia von Harden was a journalist in Berlin in the 1920s. Her nonchalant stance is a statement of her emancipated intellectual role. Otto Dix undermines her arrogance with the detail of a loose stocking and her rather awkward pose. Her red-check dress contrast with the pink environment, typically Art Nouveau. The cold, satirical realism typifies the New Objectivity movement to which the painter belonged. Inspired by early 16th-century German masters (Cranach, Holbein), he embraced the tempera on wood panel technique as well as the choice to exhibit the ugliness.

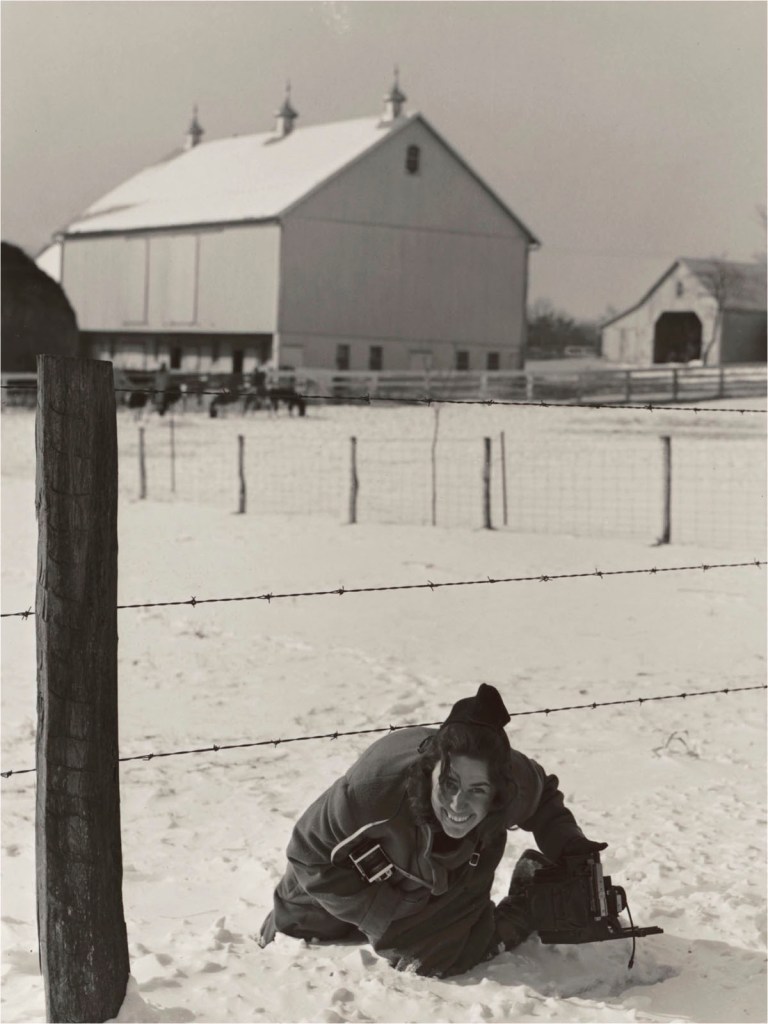

August Sander (German, 1876-1964)

Sekretärin beim Westdeutscher Rundfunk in Köln (Secretary at the Westdeutscher Rundfunk in Cologne)

1931

Gelatin silver print

28.6 x 20.5cm

Pompidou Centre collection

Purchase, 1979

© Die Photographische Sammlung / SK Stiftung Kultur – August Sander Archiv, Köln / Adagp, Paris

Photo credits: © Guy Carrard – Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI /Dist. RMN-GP

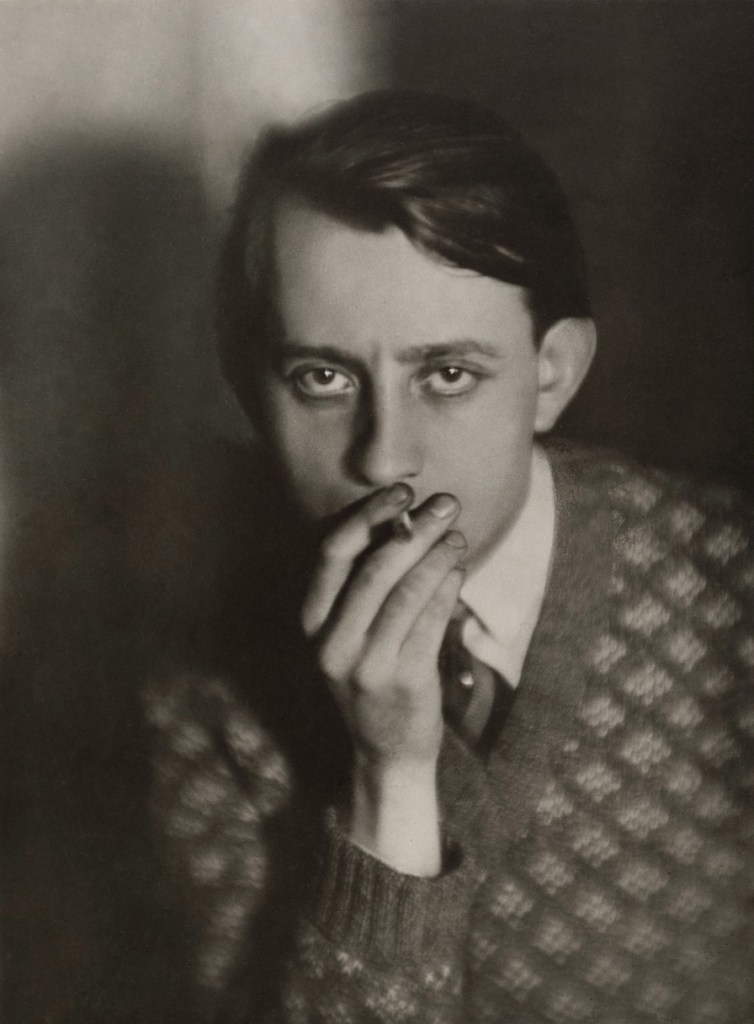

August Sander (German, 1876-1964)

Maler Anton Räderscheidt (Painter Anton Räderscheidt)

1926

Gelatin silver print

27.9 x 21.9cm

Pompidou Centre collection

Purchase, 1979

© Die Photographische Sammlung / SK Stiftung Kultur – August Sander Archiv, Köln / Adagp, Paris

Photo credits: © Adam Rzepka – Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI /Dist. RMN-GP

Anton Räderscheidt (German, 1892-1970)

Junger Mann mit gelben Handschuhen (Young man with yellow gloves)

1921

Oil on panel

27.4 x 18.6cm

Anton Räderscheidt (German, 1892-1970)

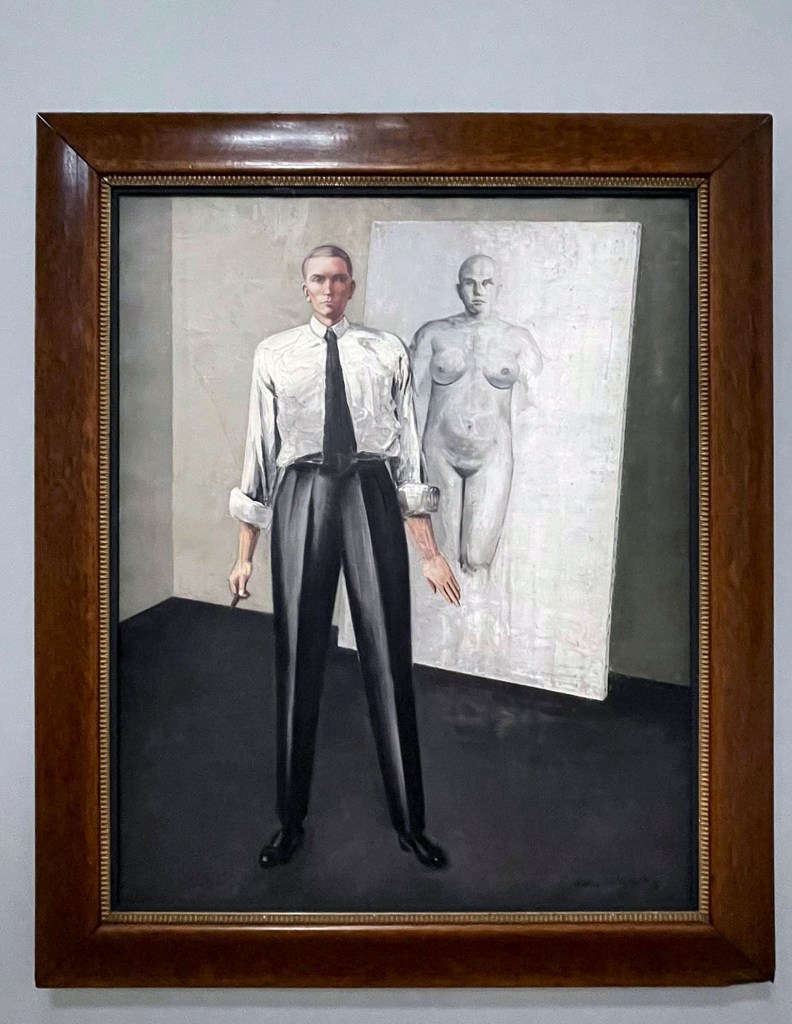

Anton Räderscheidt (October 11, 1892 – March 8, 1970) was a German painter who was a leading figure of the New Objectivity.

Räderscheidt was born in Cologne. His father was a schoolmaster who also wrote poetry. From 1910 to 1914, Räderscheidt studied at the Academy of Düsseldorf. He was severely wounded in the First World War, during which he fought at Verdun. After the war he returned to Cologne, where in 1919 he cofounded the artists’ group Stupid with other members of the local constructivist and Dada scene. The group was short-lived, as Räderscheidt was by 1920 abandoning constructivism for a magic realist style. In 1925 he participated in the Neue Sachlichkeit (“New Objectivity”) exhibition at the Mannheim Kunsthalle.

Many of the works Räderscheidt produced in the 1920s depict a stiffly posed, isolated couple that usually bear the features of Räderscheidt and his wife, the painter Marta Hegemann. The influence of metaphysical art is apparent in the way the mannequin-like figures stand detached from their environment and from each other. A pervasive theme is the incompatibility of the sexes, according to the art historian Dennis Crockett. Few of Räderscheidt’s works from this era survive, because most of them were either seized by the Nazis as degenerate art and destroyed, or were destroyed in Allied bombing raids. His work was also part of the painting event in the art competition at the 1932 Summer Olympics.

His marriage to Marta ended in 1933. In 1934-1935 he lived in Berlin. He fled to France in 1936, and settled in Paris, where his work became more colourful, curvilinear and rhythmic. He was interned by the occupation authorities in 1940, but he escaped to Switzerland. In 1949 he returned to Cologne and resumed his work, producing many paintings of horses shortly before adopting an abstract style in 1957.

Räderscheidt was to return to the themes of his earlier work in some of his paintings of the 1960s. After suffering a stroke in 1967, he had to relearn the act of painting. He produced a penetrating series of self-portraits in gouache in the final years of his life. Anton Räderscheidt died in Cologne in 1970.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Anton Räderscheidt (German, 1892-1970)

Junger Mann mit gelben Handschuhen (Young man with yellow gloves) (installation view)

1921

Oil on panel

27.4 x 18.6cm

Photo: Aubrey Perry

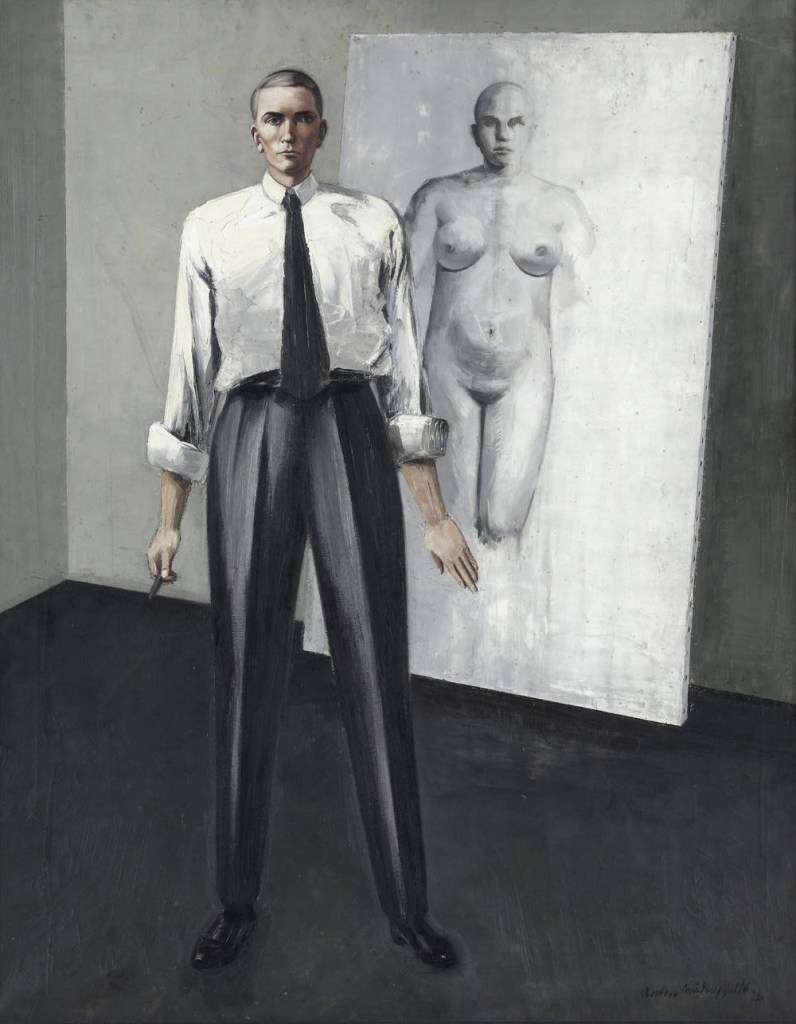

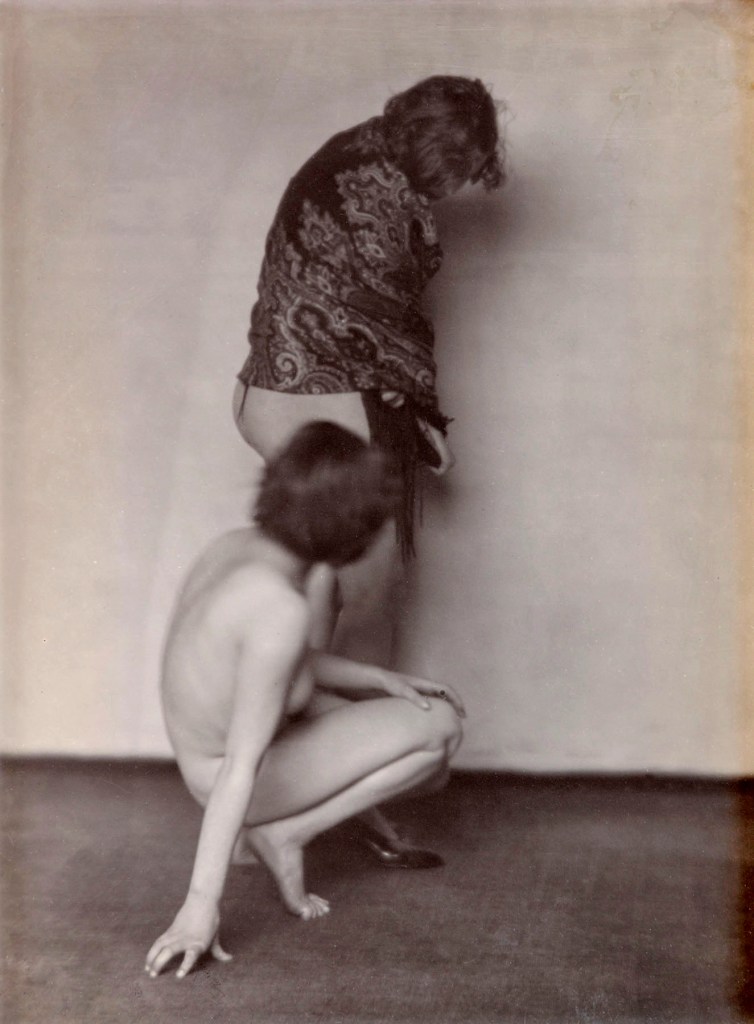

Anton Räderscheidt (German, 1892-1970)

Painter with Model (Self Portrait) (installation view)

1928

Photo: Aubrey Perry

Anton Räderscheidt (German, 1892-1970)

Painter with Model (Self Portrait)

1928

August Sander (German, 1876-1964)

Zirkusarbeiter (Circus Workers)

1926-1932

Gelatin silver print

28 x 21.10cm

From the Pompidou Centre collection

© Die Photographische Sammlung / SK Stiftung Kultur – August Sander Archiv, Köln / Adagp, Paris

Photo credits: © Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur – August Sander Archiv, Cologne/ Adagp, Paris, 2022

Installation views of the exhibition Germany / 1920s / New Objectivity / August Sander at Centre Pompidou, Paris showing Otto Dix’s Bildnis der Tänzerin Anita Berber (Portrait of the dancer Anita Berber) (1925, below)

Photos: Aubrey Perry

Wall text from the exhibition Germany / 1920s / New Objectivity / August Sander at Centre Pompidou, Paris

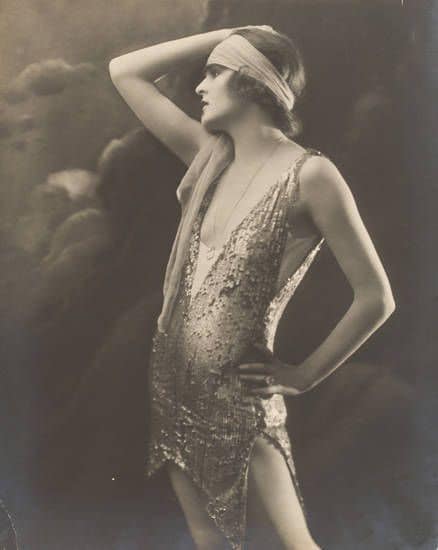

This is Anita Berber in real life. The painted portrait was her at 26. She died three years later. “Sex, drugs, and rock & roll”

Otto Dix (German, 1891-1969)

Bildnis der Tänzerin Anita Berber (Portrait of the dancer Anita Berber)

1925

© Sammlung Landesbank Baden-Württemberg im Kunstmuseum Stuttgart

Photo: Frank Kleinbac

Otto Dix (German, 1891-1969)

Lustmord (Sex Murder) (installation view)

1922

Photo: Aubrey Perry

Otto Dix (German, 1891-1969)

Lustmord (Sex Murder)

1922

Jeanne Mammen (German, 1890-1976)

Transvestitenlokal (Local transvestite)

c. 1931

Watercolour and pencil

29.50 x 58cm

From the Pompidou Centre collection

© BPK, Berlin, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Dietmar Katz

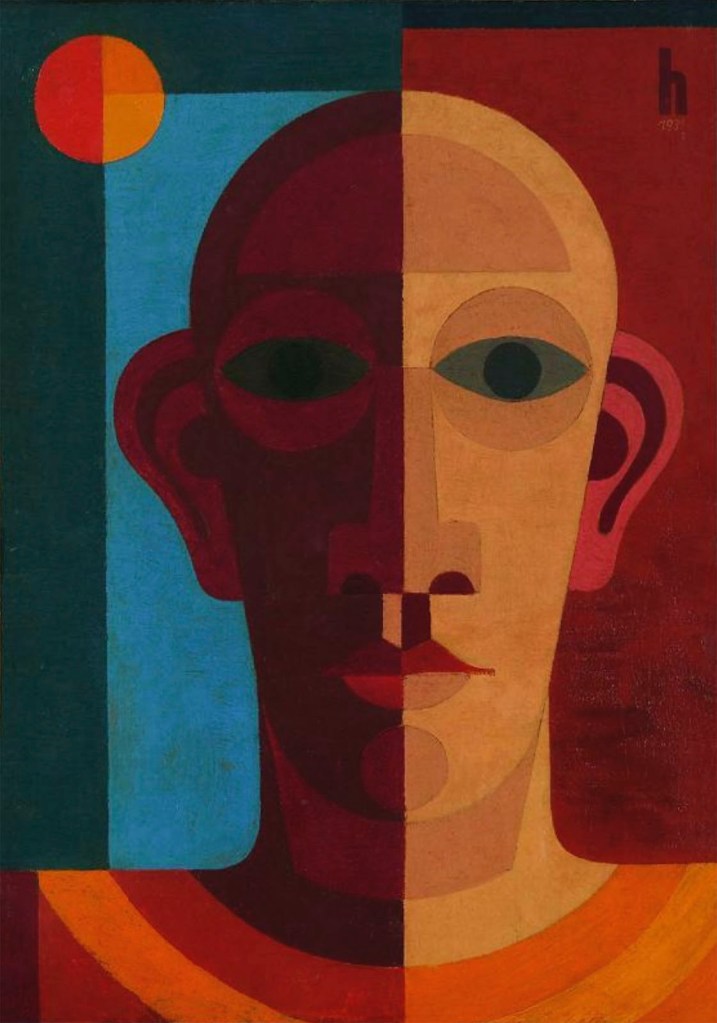

Heinrich Hoerle (German, 1895-1936)

Selfportrait

c. 1931

Oil on canvas

41 x 29cm

![August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Painter [Heinrich Hoerle]' 1928-1932 August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Painter [Heinrich Hoerle]' 1928-1932](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/sander-maler-web.jpg?w=819)

August Sander (German, 1876-1964)

Painter (Heinrich Hoerle)

1928-1932

Gelatin silver print

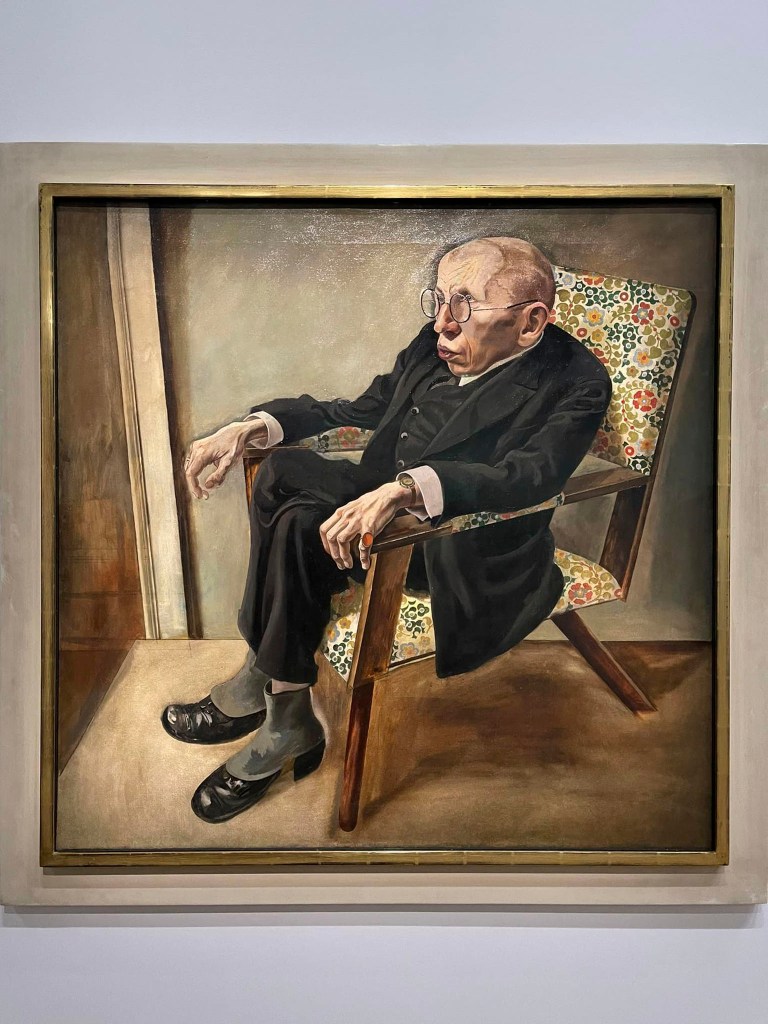

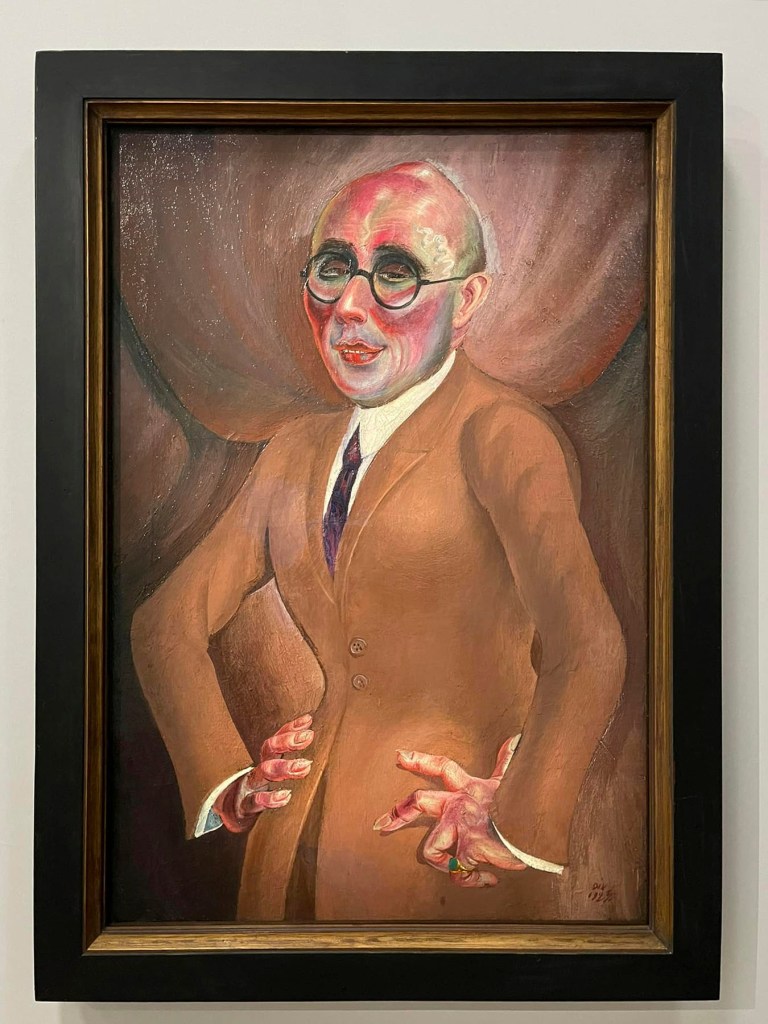

George Grosz (Georg Ehrenfried Gross) (German, 1893-1959)

Porträt des Schriftstellers Max Herrmann-Neiße (Portrait of the writer Max Herrmann-Neisse) (installation view)

1925

Oil on canvas

100 x 101.50cm

From the Pompidou Centre collection

Photo: Aubrey Perry

Wall text from the exhibition Germany / 1920s / New Objectivity / August Sander at Centre Pompidou, Paris

George Grosz (Georg Ehrenfried Gross) (German, 1893-1959)

Porträt des Schriftstellers Max Herrmann-Neiße (Portrait of the writer Max Herrmann-Neisse)

1925

Oil on canvas

100 x 101.50cm

From the Pompidou Centre collection

© The estate of George Grosz, Princeton, N.J. / Adagp, Paris

Photo credits: © BPK, Berlin, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Cem Yücetas

![August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Proletarian Intellectuals' [Else Schuler, Tristan Rémy, Franz Wilhelm Seiwert, Gerd Arntz] c. 1925 August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Proletarian Intellectuals' [Else Schuler, Tristan Rémy, Franz Wilhelm Seiwert, Gerd Arntz] c. 1925](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/august-sander-proletarian-intellectuals.jpg?w=809)

August Sander (German, 1876-1964)

Proletarian Intellectuals [Else Schuler, Tristan Rémy, Franz Wilhelm Seiwert, Gerd Arntz]

c. 1925

Gelatin silver print

From the Pompidou Centre collection

Heinrich Jost (German, 1889-1948)

Werbefaltblatt “Für Fotomontage Futura” (Promotional leaflet “For photomontage Futura”)

Nd

Press advertisement in four inserted pages

From the Pompidou Centre collection

Photo credits: © Archiv der Massenpresse P. Rössler

Erich Wegner (German, 1899-1980)

Wirtshaustheke (Pub bar)

c. 1927

Canvas on plywood

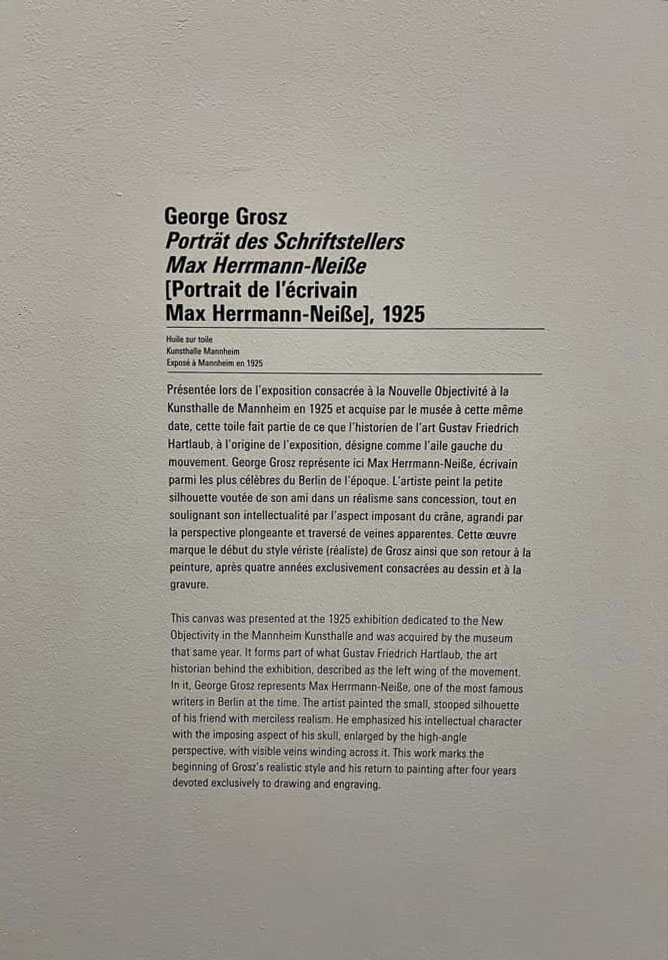

Walter Schulz-Matan (German, 1899-1965)

Der Fayencesammler (The faience collector)

1927

Oil on canvas

© Münchner Stadtmuseum

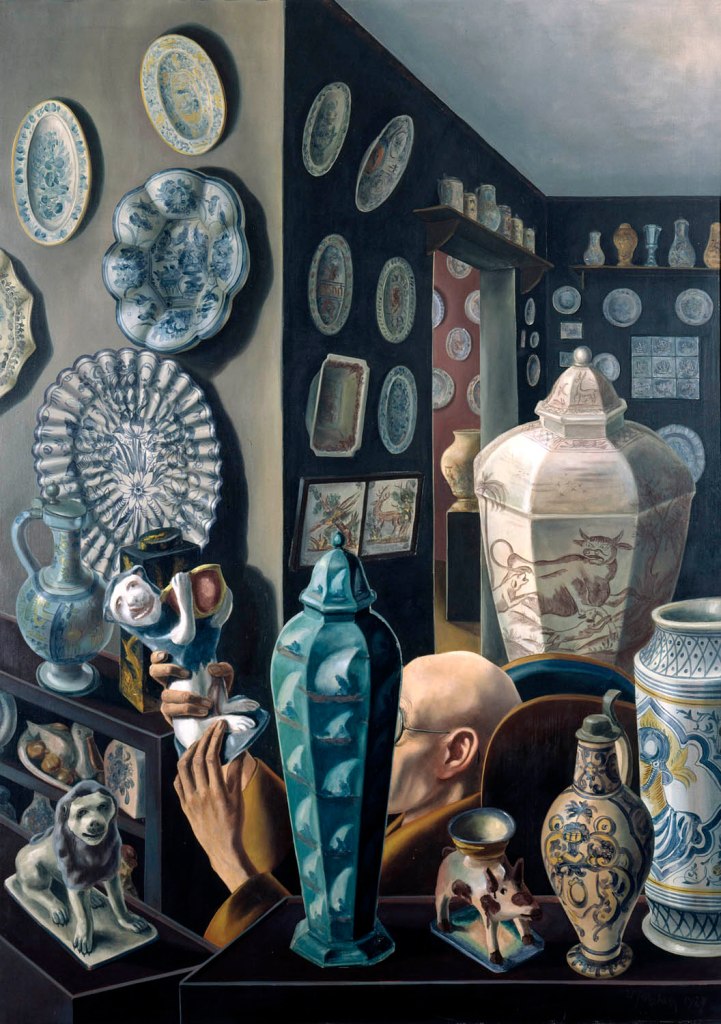

Hannah Höch (German, 1889-1978)

Gläser (Glasses) (installation view)

1927

Oil on canvas

77.50 x 77.50cm

From the Pompidou Centre collection

Photo: Aubrey Perry

Better known for her Dadaist collages and photomontages, the Berlin artist Hannah Höch creates here a hyperrealistic still life whose composition is strongly influenced by photography of the time: overhanging point of view, tight framing, neutral space, absence of context particular. The texture of the glass objects is rendered with great precision: this transparency symbolises a new conception of painting, which must show the objects in a limpid manner, without filter. In the very foreground, in an inverted reflection, the painter has represented herself at her easel in front of a window.

Hannah Höch (German, 1889-1978)

Gläser (Glasses)

1927

Oil on canvas

77.50 x 77.50cm

From the Pompidou Centre collection

© Adagp, Paris

Photo credits: © BPK, Berlin, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / image MHK

Albert Renger-Patzsch (German, 1897-1966)

Gläser (Glasses)

1926-1927

Gelatin silver print

From the Pompidou Centre collection

© Albert Renger-Patzch-Archiv / Ann & Jürgen Wilde / Adagp, Paris

Photo credits: © Albert Renger-Patzsch Archiv / Ann und Jürgen Wilde, Zülpich / Adagp, Paris, 2022

Aenne Biermann (German, 1898-1933)

Bärwurz

Between 1926-1928

Gelatin silver print

48 x 35.50cm

From the Pompidou Centre collection

Photo credits: © Stiftung Ann und Jürgen Wilde, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Munich

Sasha Stone (1895, Russia – 1940, France)

Wenn Berlin Konstantinopel wäre (If Berlin were Constantinople)

Before 1929

Photo montage

From the Pompidou Centre collection

Public domain

Photo credits: © Museum Folkwang Essen – ARTOTHEK

Installation view of the exhibition Germany / 1920s / New Objectivity / August Sander at Centre Pompidou, Paris showing at second left, Franz Wilhelm Seiwert’s Wandbild für einen Fotografen (Mural for a Photographer) (1925, below); and at right, George Grosz’s Konstruktion (Ohne Titel) (1920, below)

Photo: Aubrey Perry

Franz Wilhelm Seiwert (German, 1894-1933)

Wandbild für einen Fotografen (Mural for a Photographer) (installation view)

1925

Oil on canvas

109.5 × 154.5cm

Photo: Aubrey Perry

Franz Wilhelm Seiwert (German, 1894-1933)

Wandbild für einen Fotografen (Mural for a Photographer)

1925

Oil on canvas

109.5 × 154.5cm

![George Grosz (Georg Ehrenfried Gross) (German, 1893-1959) 'Construction (Untitled)' (Konstruktion [Ohne Titel]) 1920 (installation view) George Grosz (Georg Ehrenfried Gross) (German, 1893-1959) 'Construction (Untitled)' (Konstruktion [Ohne Titel]) 1920 (installation view)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/germany-installation-g.jpg?w=744)

George Grosz (Georg Ehrenfried Gross) (German, 1893-1959)

Konstruktion (Ohne Titel) (Construction (Untitled)) (installation view)

1920

Photo: Aubrey Perry

![George Grosz. 'Construction (Untitled) (Konstruktion [Ohne Titel])' 1920 George Grosz. 'Construction (Untitled) (Konstruktion [Ohne Titel])' 1920](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/grosz-construction.jpg?w=768)

George Grosz (Georg Ehrenfried Gross) (German, 1893-1959)

Konstruktion (Ohne Titel) (Construction (Untitled))

1920

Franz Wilhelm Seiwert (German, 1894-1933)

Freudlose Gasse (Joyless Street) (installation view)

1927

Oil on canvas

65.5 x 80cm

Photo: Aubrey Perry

Franz Wilhelm Seiwert (German, 1894-1933)

Franz Wilhelm Seiwert (March 9, 1894 – July 3, 1933) was a German painter and sculptor in a constructivist style. He was also politically active as a communist making significant contributions, both graphic and theoretical to Die Aktion.

Seiwert was born in Cologne. He was seriously burned in 1901, at the age of seven, in an experimental radiological treatment. As a result, he subsequently lived with the fear that his life would be short.

He studied from 1910 to 1914 at the Cologne School of Arts and Crafts. In 1919 he met Max Ernst and took part in Dada activities. He was invited to exhibit in the large Dada exhibit in Cologne but withdrew at the last moment. In that same year he formed the Stupid group which included Heinrich Hoerle and Anton Räderscheidt. According to Ernst, “Stupid was a secession from Cologne Dada. As far as Hoerle and especially Seiwert were concerned, Dada’s activities were aesthetically too radical and socially not concrete enough”.

His first large solo exhibition was in Cologne at the Kunstverein in 1923, and by the mid-1920s he was a leader of the “Group of Progressive Artists”, who sought to reconcile constructivism with realism while expressing radical political views. In 1929 he founded the magazine “a-z”, a journal of progressive art. This became a vehicle for the exposition of Figurative Constructivism.

Seiwert was actively involved in the international discussions concerning proletarian culture during the revolutionary upsurge following the First World War. “Throw out the old false idols! In the name of the coming proletarian culture.”

Seiwert was the leading theorist of Figurative Constructivism describing its origins as “From the expressionist-cubist art-form abstract constructivism was developed, which in turn led into Figurative Constructivism”.

When Hitler came to power in 1933, Seiwert briefly fled to the mountain range Siebengebirge, but his health was badly deteriorating, and friends brought him back to Cologne, where he died on July 3, 1933.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Franz Wilhelm Seiwert (German, 1894-1933)

Freudlose Gasse (Joyless Street) (installation view)

1927

Oil on canvas

65.5 x 80cm

Installation view of the exhibition Germany / 1920s / New Objectivity / August Sander at Centre Pompidou, Paris showing at left, Kate Diehn-Bitt’s Self Portrait as an Artist (1935, below); at middle, Gert Wollheim’s Untitled (Couple) (1926, below); and at right, Otto Dix’s Portrait of the Jeweller Karl Krall (1923, below)

Photo: Aubrey Perry

Kate Diehn-Bitt (German, 1900-1978)

Self Portrait as an Artist (installation view)

1935

Photo: Aubrey Perry

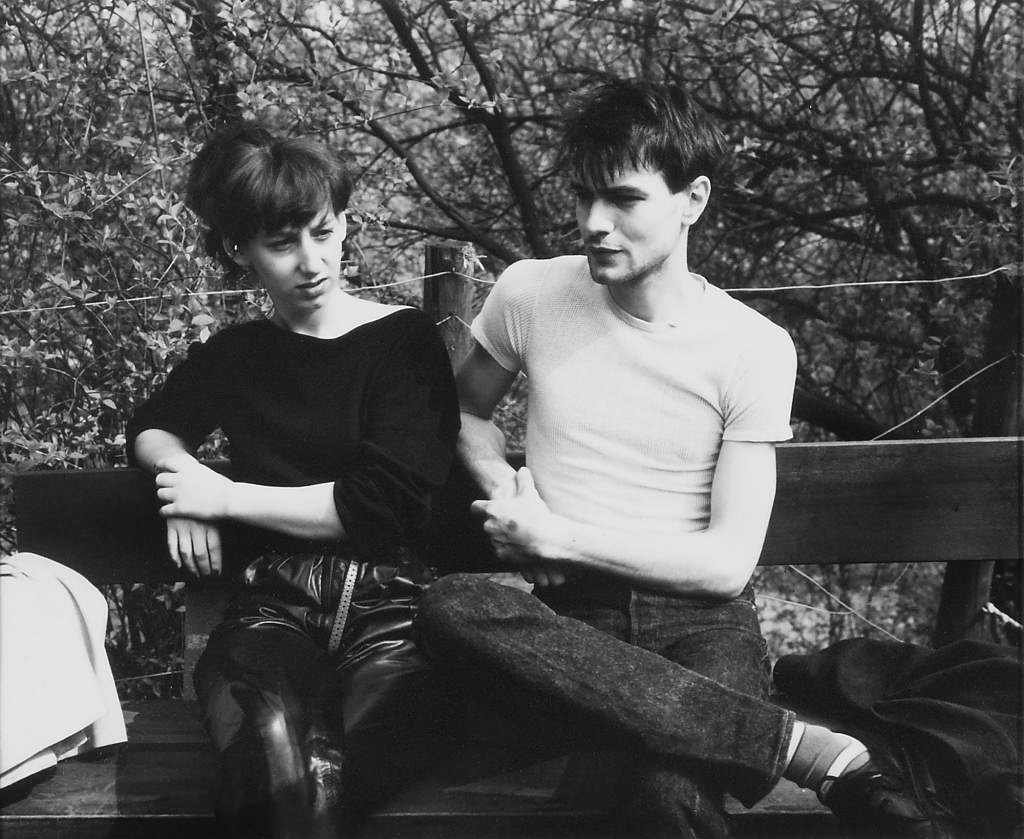

Gert Wollheim (German, 1894-1974)

Untitled (Couple) (installation view)

1926

Oil on canvas

Photo: Aubrey Perry

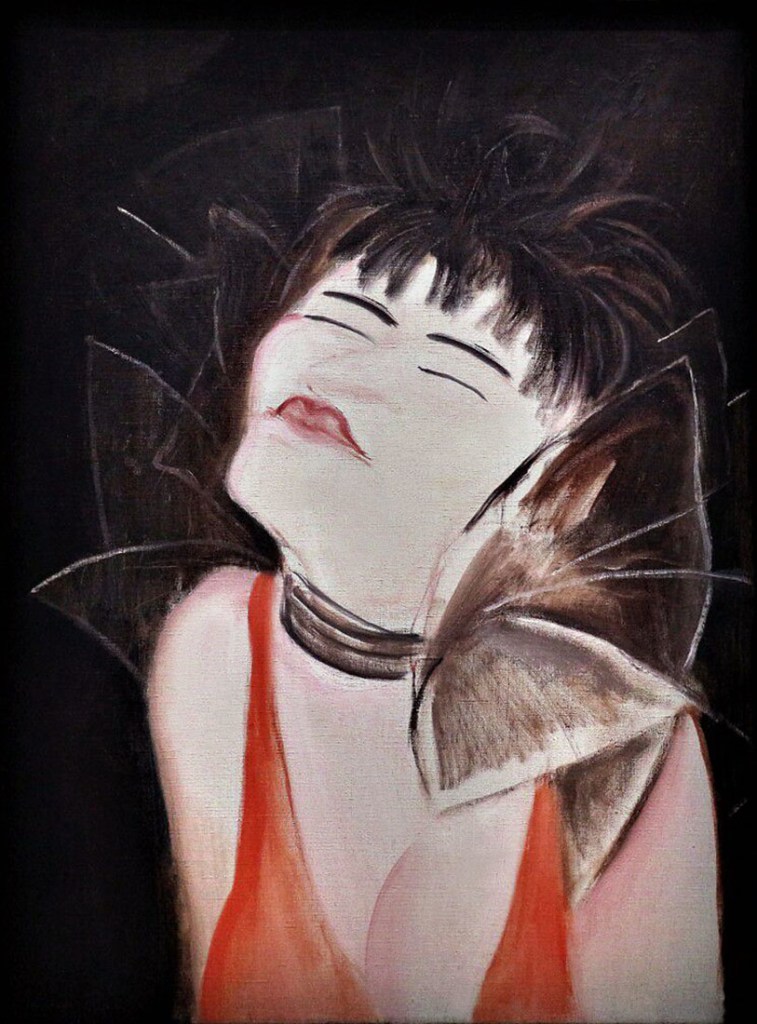

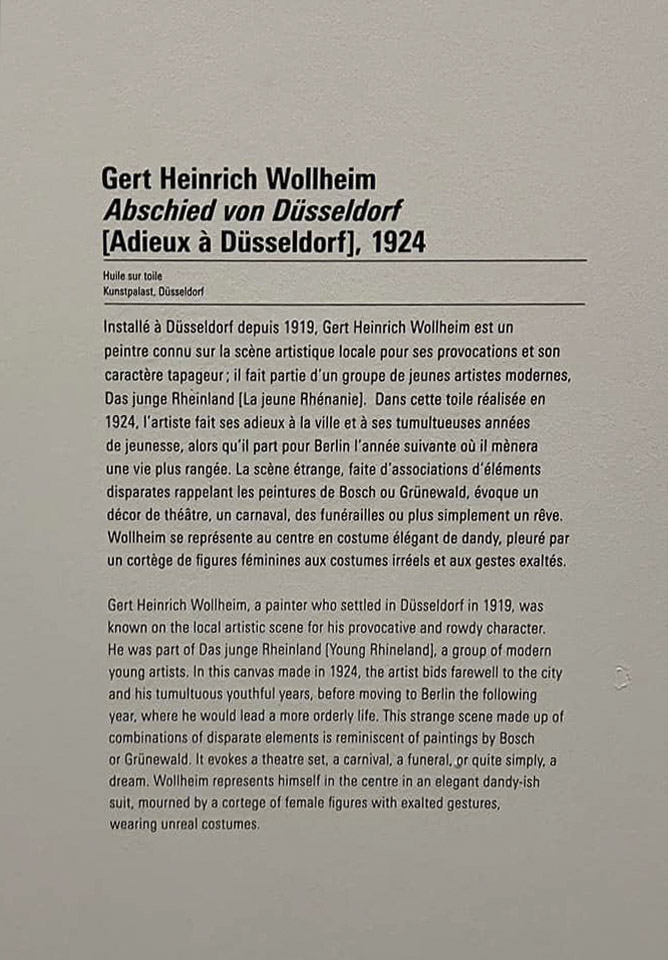

Gert Heinrich Wollheim (German, 1894-1974)

Gert Heinrich Wollheim (11 September 1894 – 22 April 1974) was a German expressionist painter later associated with the New Objectivity, who fled nazi Germany and worked in the United States after 1947.

Gert Heinrich Wollheim was born in Dresden-Loschwitz. From 1911 to 1913, he studied at the College of Fine Arts in Weimar , where his instructors included Albin Egger-Lienz and Gottlieb Forster. From 1914-1917 he was in military service in World War I, where he sustained an abdominal wound. After the war he lived in Berlin until 1919, when Wollheim, Otto Pankok (whom he had met at the academy in Weimar), Ulfert Lüken, Hermann Hundt and others created an artists’ colony in Remels, East Frisia.

At the end of 1919, Wollheim and Pankok went to Düsseldorf and became founding members of the “Young Rhineland” group, which also included Max Ernst, Otto Dix, and Ulrich Leman. Wollheim was one of the artists associated with the art dealer Johanna Ey, and in 1922 he was taken to court over a painting displayed at her gallery. In 1925, he moved to Berlin, and his work, which always emphasised the theatrical and the grotesque, began a new phase of coolly objective representation. His work was part of the art competitions at the 1928 Summer Olympics and the 1932 Summer Olympics.

After Hitler seized power in 1933 Wollheim’s works were declared degenerate art and many were destroyed. He fled to France and became active in the Resistance. He was one of the co-founders of the Union des Artistes Allemandes Libres, an organisation of exiled German artists founded in Paris in autumn 1937. In that same year, he became the companion of the dancer Tatjana Barbakoff. Meanwhile, in Munich, three of his pictures were displayed in the defamatory Nazi exhibition Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) in 1937.

From Paris, Wollheim fled to Saarbrücken and later to Switzerland. He was arrested in 1939 and held in a series of labour camps in France (Vierzon, Ruchard, Gurs and Septfonds) until his escape in 1942, after which he and his wife hid in the Pyrénées with the help of a peasant woman. At war’s end in 1945 he returned to France.

In 1947 he moved to New York and became an American citizen. He died in New York in 1974.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Gert Wollheim (German, 1894-1974)

Untitled (Couple)

1926

Oil on canvas

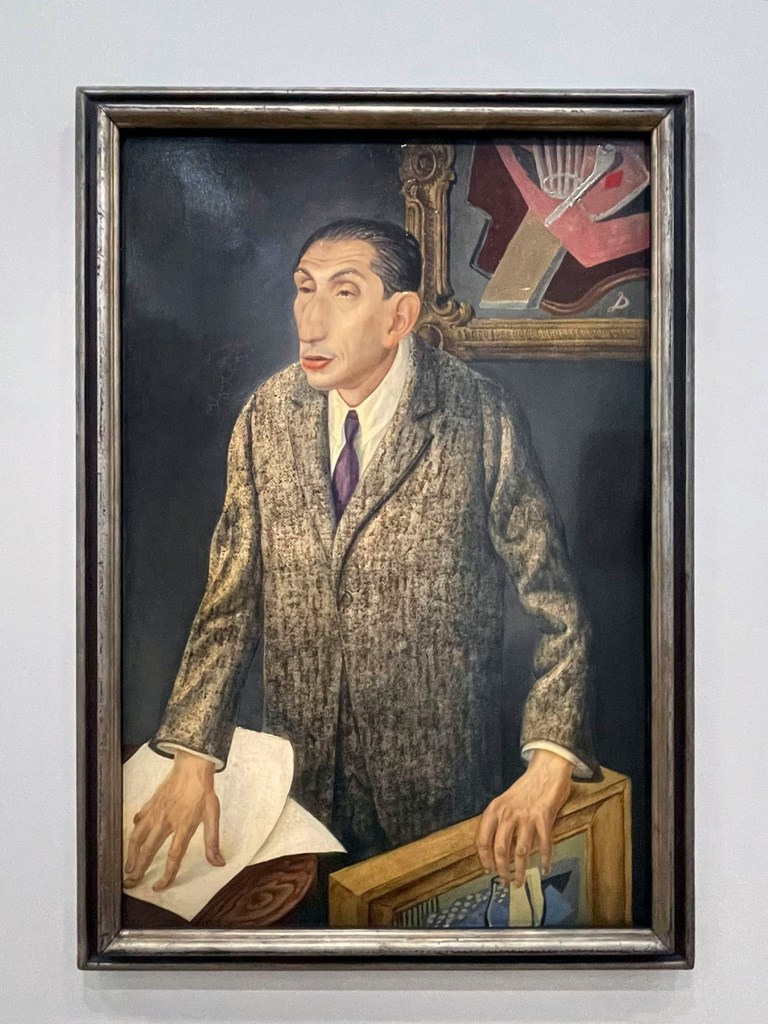

Otto Dix (German, 1891-1969)

Portrait of the Jeweller Karl Krall (installation view)

1923

Kunst- und Museumsverein im Von der Heydt-Museum Wuppertal

Photo: Aubrey Perry

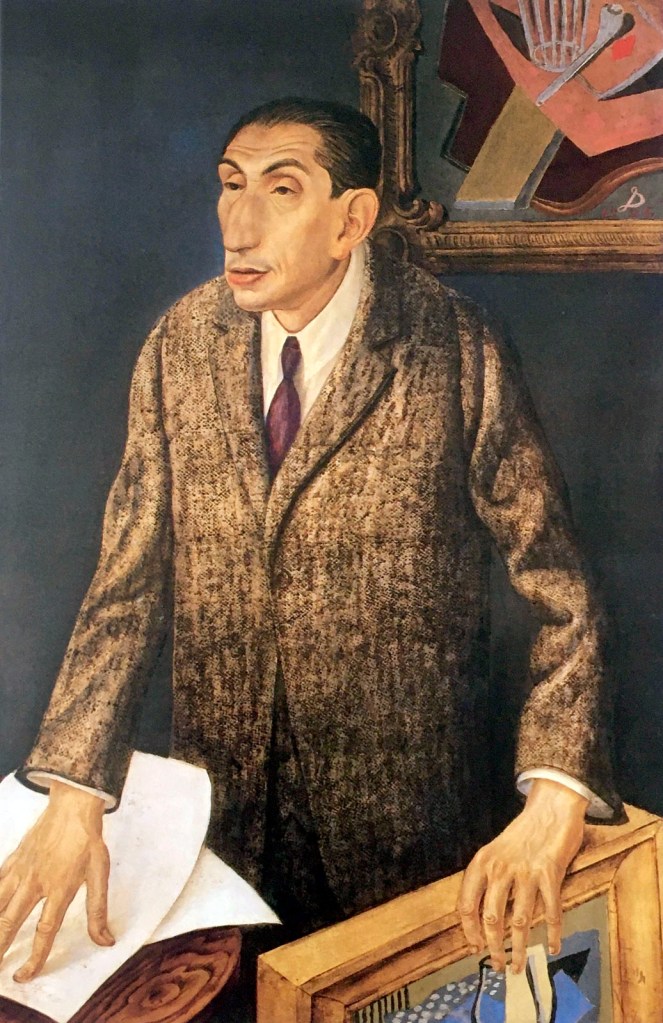

When the Nazis came to power in 1933, Dix was dismissed from his professorship teaching art at the Dresden Academy, where he had worked since 1927. The reason given was that, through his painting, he had committed a ‘violation of the moral sensibilities and subversion of the militant spirit of the German people’.

In the years following, some 260 of his works were confiscated by the Nazi Propaganda Ministry. Several of these works, including The Jeweller Karl Krall 1923, appeared in the Entartete Kunst (degenerate art) exhibition of 1937-1938. The exhibition was staged by the Nazis to destroy the careers of those artists they considered mentally ill, inappropriate or unpatriotic.

Otto Dix (German, 1891-1969)

Portrait of the Jeweller Karl Krall (Der Juwelier Karl Krall)

1923

Kunst- und Museumsverein im Von der Heydt-Museum Wuppertal

Photo: Antje Zeis-Loi, Medienzentrum Wuppertal

© DACS 2017

Otto Dix (German, 1891-1969)

Portrait of the Art Dealer Alfred Flechtheim (installation view)

1926

Photo: Aubrey Perry

Alfred Flechtheim entered the art world as a collector of Far Eastern art. In 1910, he married the daughter of a wealthy Dortmund merchant. This union helped provide him with the means to open a gallery in 1913. On the eve of the First World War, Flechtheim’s gallery was filled with works by the French avant-garde. He had a reputation as Francophile with a particular affection for Cubism. In Düsseldorf, local artists unfairly suggested that he had turned his back on German art. In this unflattering, uncommissioned work by Dix, he is surrounded by Cubist works. He clutches one in one hand and bills in another. To Dix, he’s little more than a salesman in a cheap suit, hawking foreign merchandise for the local Bourgeoisie.

Otto Dix (German, 1891-1969)

Portrait of the Art Dealer Alfred Flechtheim

1926

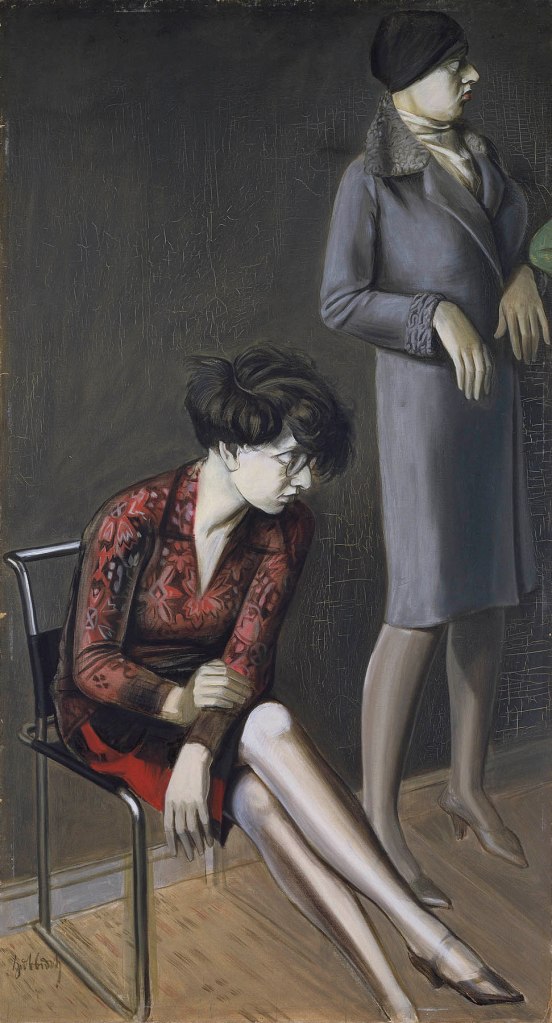

Julius Bissier (German, 1893-1965)

Bildhauer mit Selbstbildnis (Sculptor with Self-portrait)

1928

Oil on canvas

77 x 61cm

Museum für Neue Kunst, Städtische Museen Freiburg, Germany

Jeanne Mammen (German, 1890-1976)

Two Women, Dancing (installation view)

c. 1928

Watercolour and pencil on paper

48 x 36cm

Private Collection, Berlin

Photo: Aubrey Perry